エリック・ホッファー

Eric Hoffer, 1902-1983

★エリック・ホッファー(Eric Hoffer、1902年7月25日 - 1983年5月21日)[1]は、アメリカの道徳・社会哲学者。10冊の著作があり、1983年2月に大統領自由勲章を受章。彼の最初の著書である 『The True Believer』(1951年)は古典として広く認知され、学者と一般人の両方から批評家の称賛を受けたが、ホッファーは『The Ordeal of Change』(1963年)が彼の最高傑作であると考えていた、らしい。

☆ ■知識人は常に本を出版している。そのほとんどは、それが人生である以上、気づかれることのない痕跡を残し、どこかの大学図書館の地下墓地に埋もれてしま う。その文章や段落は、職人の技術によって何千回も磨かれた小川の楕円形の石を思わせる。 ■1951年に出版されたエリック・ホッファー(Eric Hoffer)の小さな古典『真の信奉者(トゥルー・ビリーバー)』は、その支持者の多様さと地位の高さゆえに、おそらくこのようなケースなのだろ う。宗教的なものであれ、民族主義的なものであれ、革命的なものであれ、大衆運動の本質についての一連の考察である。 ■ホッファーの最初の後押しをしたのは、ドワイト・アイゼンハワー大統領だった。歴史上最も邪悪な大衆運動の軍隊を打ち破ったこの元将軍は、『トゥルー・ ビリーバー』に惚れ込み、誰にでも薦め続けた。数十年後、ビルとヒラリー・クリントンは選挙戦でこの本を一緒に読み直した。ホッファーは、最終的にホワイ トハウスを勝ち取った米国内のナショナリストの覚醒への手がかりを提供した。 ■ホッファー自身が冒頭で述べているように、この本は網羅的な著作ではなく、個人的な考察の大要である。彼の結論は、調査や統計データに基づいているので はなく、彼の個人的な経験の多様性と、彼が多くのノートに小さな格言として書き留めた読書に基づいている。その結果は複雑だ。一方では、もちろん、この文 章は注意深く読まれるべきものである。私たちは現代の大学の研究のような厳密なものを扱っているわけではない。 ■「何かを考え出す才能がない限り、自由は煩わしい重荷である。「輝かしい未来の鮮明な視覚化によって解放される希望は、大胆さと自己忘却の最も強力な源 である。 ■ホッファーが世論に与えた影響は、謎に包まれ彷徨い続けた彼の不思議な伝記によって高まった。ホッファーがジャーナリストや大学教授としてではなく、旧 約聖書の預言者のように書いているとすれば、それは彼の人生が呪いと叙事詩の両方の特徴を持っていたからである。 ■大柄で不機嫌、傷だらけの手を持つホッファーは、1902年にブロンクスのドイツ系移民の家庭に生まれたという。彼の独立独歩の性格は、子供時代の試練 によって形成された。ホッファーは、英語とドイツ語が読めるようになった5歳の時、母親の腕の中で階段から落ちたという。母は間もなく亡くなり、彼は視力 を失ったが、10代のある日、理由もなく視力を取り戻した。 ■「学校には行かなかった。15歳までほとんど目が見えなかった」と、哲学者は吟遊詩人ホメロスに見えない橋をかけるかのように回想する。「視力が戻った とき、私は文字に飢えるようになった。英語でもドイツ語でも、手に入るものは何でも無差別に読んだ」。 ■世界大恐慌の時代、ホッファーは西海岸に渡り、さまざまな旅回りの仕事をした。浮浪者、ブラセロ、金鉱探鉱者、そして最後にはサンフランシスコのウォー ターフロントで港湾労働者となった。読書熱が冷めることはなく、1951年、50代後半で最初の本を出版した。この本は後にアイゼンハワーの手に渡ること になる。 ■名声を得てからも、ホッファーは僧侶としての生活を変えようとしなかった。カリフォルニア大学バークレー校で教職に就き、メディアに登場することもあっ た。しかし、サンフランシスコのチャイナタウンの下宿に住み続け、電話もテレビもなく、しばしば用事も受け付けなかった。 ■ホッファーの人生は、名声を得た瞬間からしか検証できない。それ以前のすべて、特に幼年期と青年期は、中年期に彼がインタビュアーに語った矛盾した奇妙 な話と、彼の言葉だけに依存している。 ■伝記『Eric Hoffer: The Longshoreman Philosopher(エリック・ホッファー:港湾労働者の哲学者)』の著者で、この哲学者の論文が所蔵されている保守系シンクタンク、フーバー研究所 のメンバーであるトム・ベテルによれば、ホッファーがアメリカで生まれたかどうかさえ定かではない。例えば、彼が生涯を通じて強いドイツ語訛りで話してい たのは不思議である。少なからぬ仮説は、ホッファーは実際にはドイツで生まれ、若いころのある時点でアメリカに移住し、法的な地位を得ることはなかったと いうものだ。本人が主張した年齢より4歳年上だった可能性さえある。1934年、彼のアメリカの "足跡 "がぼんやりと浮かび始める。 ■真の信奉者には多くの青春時代があった。冷戦時代には共産主義正統主義の魅力に警鐘を鳴らし、2001年からはジハード主義者の心理を理解する目的で復 活し、2016年以降はトランプ主義の文脈で何千回も引用されている。 ■本書は2017年、ハーパーの「抵抗の図書館」コレクションの一部として再出版された。「レジスタンス」とは、ドナルド・トランプに反対するプロのジャー ナリスト、コメディアン、知識人たちの非公式な集団の名前である。 ■念のために言っておくと、表紙と裏表紙には、大物の手口を完璧に定義するホッファーの言葉が引用されている。表表紙には、本のタイトルそのものよりも大 きく、「民族主義運動は、過去の偉大さの記憶を蘇らせるか、捏造する」(すなわち、アメリカを再び偉大にする)。裏表紙には「カオスは彼らの本領だ。古い 秩序に亀裂が入り始めると、狂信者は憎むべき現在を高みへと飛躍させるため、全力で無謀な行動に出る。彼は世界が突然終わりを迎えるビジョンを喜ぶ。 ■右派の『トゥルー・ビリーバー』は今、「反人種主義」という新しい「目覚め」の教義を解剖するために使われている。この教義は、大学から米国の制度的基 盤へと広がりつつあり、昨年の夏にその噴火の瞬間を迎えた。ニューヨークのような都市での大規模な抗議行動、人種再教育ワークショップ、絶え間ないアイデ ンティティの魔女狩りは、ホッファーが著書の中で言及している兆候の多くを明らかにするだろう。 ■まるでライバルの容赦ない視線を首の後ろで感じているかのように、半ダースもの引用でそれぞれの考えを補強しがちな学者たちとは異なり、ホッファーはシ ンプルにそれを言う。これが、『真の信奉者(トゥルー・ビリーバー)』が、マルクス・アウレリウスの『瞑想録』やニッコロ・マキャベリの『君主論』に似ている理由であ る。 ■いつかこの古典はその輝きを失い、地下図書館のひとつに置かれる日が来るかもしれない。しかし、今のところ、この本が何十年にもわたり、米国の政治イデ オロギーのほぼすべてで読まれ、推薦されているという事実は、放浪の哲学者に対する尊敬の証としか言いようがない。

Argemino

Barro , Eric

Hoffer: el filósofo errante que entendió los fanatismos, より翻訳

| Eric Hoffer

(July 25, 1902 – May 21, 1983)[1] was an American moral and social

philosopher. He was the author of ten books and was awarded the

Presidential Medal of Freedom in February 1983. His first book, The

True Believer (1951), was widely recognized as a classic, receiving

critical acclaim from both scholars and laymen,[2] although Hoffer

believed that The Ordeal of Change (1963) was his finest work.[3] The

Eric Hoffer Book Award is an international literary prize established

in his honor.[4] The University of California, Berkeley awards an

annual literary prize named jointly for Hoffer.[5] |

エ

リック・ホッファー(Eric Hoffer、1902年7月25日 -

1983年5月21日)[1]は、アメリカの道徳・社会哲学者。10冊の著作があり、1983年2月に大統領自由勲章を受章。彼の最初の著書である

『The True

Believer』(1951年)は古典として広く認知され、学者と一般人の両方から批評家の称賛を受けたが[2]、ホッファーは『The

Ordeal of Change』(1963年)が彼の最高傑作であると考えていた[3]。

エリック・ホッファー・ブック・アワードは、彼に敬意を表して設立された国際的な文学賞である[4]。

カリフォルニア大学バークレー校は、ホッファーの連名で毎年文学賞を授与している[5]。 |

| Early life Many elements of Hoffer's early life are unverified,[6] but in autobiographical statements, Hoffer claimed to have been born in 1902[7][6] in The Bronx, New York City, New York, to Knut and Elsa (Goebel) Hoffer.[8] His parents were immigrants from Alsace, then part of Imperial Germany. By age five, Hoffer could already read in both English and his parents' native German.[9][10] When he was five, his mother fell down the stairs with him in her arms. He later recalled, "I lost my sight at the age of seven. Two years before, my mother and I fell down a flight of stairs. She did not recover and died in that second year after the fall. I lost my sight and, for a time, my memory."[11] Hoffer spoke with a pronounced German accent all his life, and spoke the language fluently. He was raised by a live-in relative or servant, a German immigrant named Martha. His eyesight inexplicably returned when he was 15. Fearing he might lose it again, he seized on the opportunity to read as much as he could. His recovery proved permanent, but Hoffer never abandoned his reading habit. Hoffer was a young man when he also lost his father. The cabinetmaker's union paid for Knut Hoffer's funeral and gave Hoffer about $300 insurance money. He took a bus to Los Angeles and spent the next 10 years wandering, as he remembered, “up and down the land, dodging hunger and grieving over the world.”[12] Hoffer eventually landed on Skid Row, reading, occasionally writing, and working at odd jobs.[9] In 1931, he considered suicide by drinking a solution of oxalic acid, but he could not bring himself to do it.[13] He left Skid Row and became a migrant worker, following the harvests in California. He acquired a library card where he worked, dividing his time "between the books and the brothels." He also prospected for gold in the mountains. Snowed in for the winter, he read the Essays by Michel de Montaigne. Montaigne impressed Hoffer deeply, and Hoffer often made reference to him. He also developed a respect for America's underclass, which he said was "lumpy with talent." |

生い立ち ホッファーの生い立ちに関する多くの要素は未確認であるが[6]、自伝的記述の中で、ホッファーは1902年にニューヨークのブロンクスでクヌート・ホッ ファーとエルザ(ゲーベル)・ホッファーの間に生まれたと主張している[7][6]。 両親は当時帝国ドイツの一部であったアルザスからの移民であった。5歳のとき、母親がホッファーを抱いたまま階段から転落。7歳のときに視力を失った。そ の2年前、母と私は階段から落ちた。母は回復せず、転落事故から2年目に亡くなった。私は視力を失い、一時は記憶も失いました」[11] ホッファーは生涯、顕著なドイツ訛りで話し、流暢にドイツ語を話した。彼は住み込みの親戚か使用人であるドイツ移民のマーサに育てられた。15歳の時、不 可解なことに視力が戻った。再び失明することを恐れた彼は、できる限り本を読む機会を得た。視力は永久に回復しなかったが、ホッファーは読書の習慣を捨て なかった。 ホッファーは若くして父親を亡くした。家具職人の組合がクヌート・ホッファーの葬儀代を支払い、ホッファーに300ドルほどの保険金を渡した。ホッファー はバスでロサンゼルスに向かい、それから10年間、「飢えをしのぎながら、世界を悲嘆に暮れながら、土地をあちこちさまよった」と本人は回想している [12]。 1931年、彼はシュウ酸の溶液を飲んで自殺することを考えたが、実行には移せなかった。そこで図書館のカードを手に入れ、"本と売春宿のあいだ "に時間を割いた。彼はまた、山で金を探した。雪に閉ざされた冬、彼はミシェル・ド・モンテーニュの『随想録』を読んだ。モンテーニュはホッファーに深い 感銘を与え、ホッファーはしばしばモンテーニュに言及した。彼はまた、"才能の塊 "であるアメリカの下層階級に尊敬の念を抱いた。 |

| Career He wrote a novel, Four Years in Young Hank's Life, and a novella, Chance and Mr. Kunze, both partly autobiographical. He also penned a long article based on his experiences in a federal work camp, "Tramps and Pioneers." It was never published, but a truncated version appeared in Harper's Magazine after he became well known.[14] Hoffer tried to enlist in the U.S. Army at age 40 during World War II, but he was rejected due to a hernia.[15] Instead, he began work as a longshoreman on the docks of San Francisco in 1943.[16] At the same time, he began to write seriously. Hoffer left the docks in 1964, and shortly after became an adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley.[17] He later retired from public life in 1970.[18] “I'm going to crawl back into my hole where I started,” he said. “I don't want to be a public person or anybody's spokesman... Any man can ride a train. Only a wise man knows when to get off.”[12] In 1970, he endowed the Lili Fabilli and Eric Hoffer Laconic Essay Prize for students, faculty, and staff at the University of California, Berkeley. Hoffer called himself an atheist but had sympathetic views of religion and described it as a positive force.[19] He died at his home in San Francisco in 1983 at the age of 80.[20] |

経歴 小説『Four Years in Young Hank's Life』と小説『Chance and Mr. また、連邦政府のワークキャンプでの体験を基にした長編記事 "Tramps and Pioneers "も執筆。これは出版されることはなかったが、彼がよく知られるようになった後、切り詰めたものがハーパーズ誌に掲載された[14]。 ホッファーは第二次世界大戦中、40歳でアメリカ陸軍に入隊しようとしたが、ヘルニアのために拒否された[15]。代わりに、1943年にサンフランシスコの波止場で港湾労働者として働き始めた[16]。 ホッファーは1964年に波止場を去り、まもなくカリフォルニア大学バークレー校の非常勤教授となった[17]。 その後、1970年に公の場から引退した[18]。「公人にはなりたくないし、誰かのスポークスマンにもなりたくない。どんな人間でも列車に乗ることはで きる。賢明な人間だけが、いつ降りるかを知っている」[12] 1970年、彼はカリフォルニア大学バークレー校の学生、教職員を対象に、リリ・ファビリ&エリック・ホッファー饒舌エッセイ賞を寄付した。 ホッファーは自らを無神論者と称したが、宗教に同情的であり、宗教を肯定的な力として表現した[19]。 1983年、サンフランシスコの自宅で80歳の生涯を閉じた[20]。 |

| Working-class roots Hoffer was influenced by his modest roots and working-class surroundings, seeing in it vast human potential. In a letter to Margaret Anderson in 1941, he wrote: "My writing is done in railroad yards while waiting for a freight, in the fields while waiting for a truck, and at noon after lunch. Towns are too distracting." He once remarked, "my writing grows out of my life just as a branch from a tree." When he was called an intellectual, he insisted that he simply was a longshoreman. Hoffer has been dubbed by some authors a "longshoreman philosopher."[10][21] |

労働者階級のルーツ ホッファーは、自身のささやかなルーツと労働者階級に囲まれた環境に影響を受け、そこに人間の大きな可能性を見出していた。1941年、マーガレット・ア ンダーソンに宛てた手紙の中で、彼はこう書いている。「私の執筆は、貨物を待っている間の鉄道操車場、トラックを待っている間の野原、そして昼食後の正午 に行われる。街は気が散りすぎる。私の書くものは、ちょうど木から枝が伸びるように、私の人生から生えてくるのだ "と。知識人と呼ばれたとき、彼は単に港湾労働者だと主張した。ホッファーは何人かの作家から「港湾労働者の哲学者」と呼ばれている[10][21]。 |

| Personal life Hoffer, who was an only child, never married. He fathered a child with Lili Fabilli Osborne, named Eric Osborne, who was born in 1955 and raised by Lili Osborne and her husband, Selden Osborne.[22] Lili Fabilli Osborne had become acquainted with Hoffer through her husband, a fellow longshoreman and acquaintance of Hoffer's. Despite this, Selden Osborne and Hoffer remained on good terms.[16] Hoffer referred to Eric Osborne as his son or godson. Lili Fabilli Osborne died in 2010 at the age of 93. Prior to her death, Osborne was the executor of Hoffer's estate, and vigorously controlled the rights to his intellectual property. In his 2012 book Eric Hoffer: The Longshoreman Philosopher, journalist Tom Bethell revealed doubts about Hoffer's account of his early life. Although Hoffer claimed his parents were from Alsace-Lorraine, Hoffer himself spoke with a pronounced Bavarian accent.[23] He claimed to have been born and raised in the Bronx but had no Bronx accent. His lover and executor Lili Fabilli stated that she always thought Hoffer was an immigrant. Her son, Eric Fabilli, said that Hoffer's life might have been comparable to that of B. Traven and considered hiring a genealogist to investigate Hoffer's early life, to which Hoffer reportedly replied, "Are you sure you want to know?" Pescadero land-owner Joe Gladstone, a family friend of the Fabilli's who also knew Hoffer, said of Hoffer's account of his early life: "I don't believe a word of it." To this day, no one ever has claimed to have known Hoffer in his youth, and no records apparently exist of his parents, nor indeed of Hoffer himself until he was about forty, when his name appeared in a census. |

私生活 一人っ子だったホッファーは結婚しなかった。彼はリリ・ファビリ・オズボーンとの間にエリック・オズボーンという子供をもうけたが、その子は1955年に 生まれ、リリ・オズボーンと彼女の夫セルデン・オズボーンによって育てられた[22]。リリ・ファビリ・オズボーンは、ホッファーの知人で港湾労働者仲間 の夫を通じてホッファーと知り合った。にもかかわらず、セルデン・オズボーンとホッファーは良好な関係を保っていた[16]。 ホッファーはエリック・オズボーンを息子あるいは名付け子と呼んでいた。リリ・ファビリ・オズボーンは2010年に93歳で死去。生前、オズボーンはホッファーの遺産執行人であり、彼の知的財産に関する権利を精力的に管理していた。 2012年の著書『Eric Hoffer: The Longshoreman Philosopher)』の中で、ジャーナリストのトム・ベテルはホッファーの生い立ちに関する記述に疑問があることを明らかにした。ホッファーは両親 がアルザス・ロレーヌ出身だと主張していたが、ホッファー自身は顕著なバイエルン訛りで話していた[23]。恋人であり遺言執行人であったリリ・ファビリ は、ホッファーは移民だとずっと思っていたと述べている。彼女の息子であるエリック・ファビリは、ホッファーの人生はB.トラヴェンに匹敵するかもしれな いと語り、ホッファーの初期の人生を調査するために系図学者を雇うことを検討したが、ホッファーは "本当に知りたいの?"と答えたと伝えられている。ペスカデロの土地所有者であるジョー・グラッドストーンは、ファビリ家の家族ぐるみの友人であり、ホッ ファーとも面識があった。今日に至るまで、ホッファーの若い頃を知る人物は誰もおらず、彼の両親の記録も、ホッファー自身の記録も、国勢調査に名前が載る 40歳頃まで残っていないようだ。 |

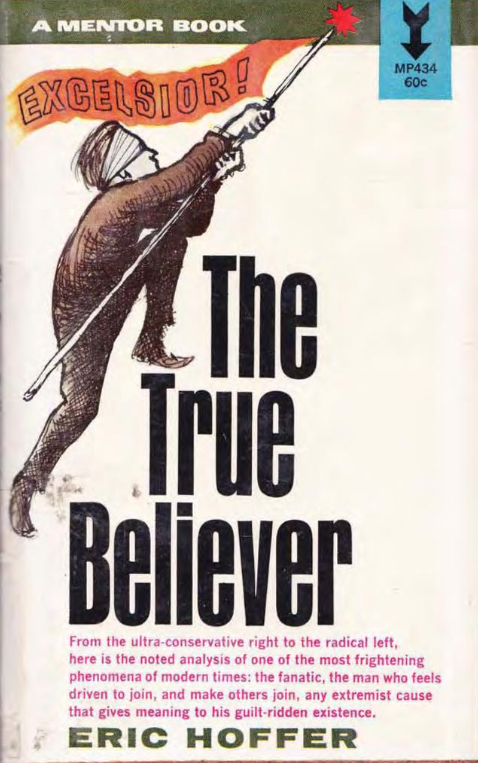

| Books and opinions The True Believer Main article: The True Believer Hoffer came to public attention with the 1951 publication of his first book, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, which consists of a preface and 125 sections, which are divided into 18 chapters. Hoffer analyzes the phenomenon of "mass movements," a general term that he applies to revolutionary parties, nationalistic movements, and religious movements. He summarizes his thesis in §113: "A movement is pioneered by men of words, materialized by fanatics and consolidated by men of actions."[24] Hoffer argues that fanatical and extremist cultural movements, whether religious, social, or national, arise when large numbers of frustrated people, believing their own individual lives to be worthless or spoiled, join a movement demanding radical change. But the real attraction for this population is an escape from the self, not a realization of individual hopes: "A mass movement attracts and holds a following not because it can satisfy the desire for self-advancement, but because it can satisfy the passion for self-renunciation."[25] Hoffer consequently argues that the appeal of mass movements is interchangeable: in the Germany of the 1920s and the 1930s, for example, the Communists and National Socialists were ostensibly enemies, but sometimes enlisted each other's members, since they competed for the same kind of marginalized, angry, frustrated people. For the "true believer," Hoffer argues that particular beliefs are less important than escaping from the burden of the autonomous self. Harvard historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. said of The True Believer: "This brilliant and original inquiry into the nature of mass movements is a genuine contribution to our social thought."[26] Later works Subsequent to the publication of The True Believer (1951), Eric Hoffer touched upon Asia and American interventionism in several of his essays. In "The Awakening of Asia" (1954), published in The Reporter and later his book The Ordeal of Change (1963), Hoffer discusses the reasons for unrest on the continent. In particular, he argues that the root cause of social discontent in Asia was not government corruption, "communist agitation," or the legacy of European colonial "oppression and exploitation," but rather that a "craving for pride" was the central problem in Asia, suggesting a problem that could not be relieved through typical American intervention.[27] During the Vietnam War, despite his objections to the antiwar movement and acceptance of the notion that the war was somehow necessary to prevent a third world war, Hoffer remained skeptical concerning American interventionism, specifically the intelligence with which the war was being conducted in Southeast Asia. After the United States became more involved in the war, Hoffer wished to avoid defeat in Vietnam because of his fear that such a defeat would transform American society for ill, opening the door to those who would preach a stab-in-the-back myth and allow for the rise of an American version of Hitler.[28] In The Temper of Our Time (1967), Hoffer implies that the United States as a rule should avoid interventions in the first place: "the better part of statesmanship might be to know clearly and precisely what not to do, and leave action to the improvisation of chance." In fact, Hoffer indicates that "it might be wise to wait for enemies to defeat themselves," as they might fall upon each other with the United States out of the picture. The view was somewhat borne out with the Cambodian-Vietnamese War and Chinese-Vietnamese War of the late 1970s. |

書籍と意見 真のビリーバー 主な記事 真の信仰者 ホッファーは1951年に最初の著書『The True Believer』を出版し、世間の注目を集めるようになった: この本は序文と125のセクションから成り、18の章に分かれている。ホッファーは、革命政党、民族主義運動、宗教運動などを総称した「大衆運動」という 現象を分析している。運動は、言葉の人びとによって開拓され、狂信者たちによって具体化され、行動の人びとによって統合される」[24]。 ホッファーは、狂信的で過激な文化運動は、宗教的であれ、社会的であれ、国家的であれ、自分たち個人の生活が無価値であるか、甘やかされていると考え、不 満を抱く大勢の人々が、急進的な変化を求める運動に参加するときに生じると論じている。しかし、このような人々にとっての真の魅力は、自己からの逃避で あって、個人の希望の実現ではない: 「大衆運動が支持者を惹きつけ、維持するのは、それが自己向上への欲求を満たすことができるからではなく、自己放棄への情熱を満たすことができるからであ る」[25]。 例えば、1920年代と1930年代のドイツでは、共産主義者と国家社会主義者は表向きは敵同士であったが、疎外され、怒りや不満を抱えた同じような人々 を求めて競争していたため、時には互いのメンバーを参加させることもあった。真の信者」にとって、特定の信念は、自律的な自己の重荷から逃れることよりも 重要ではないとホッファーは主張する。 ハーバード大学の歴史家アーサー・M・シュレシンジャー・ジュニアは、『トゥルー・ビリーバー』について、「大衆運動の本質に関するこの素晴らしく独創的な探究は、われわれの社会思想への真の貢献である」と述べている[26]。 その後の作品 The True Believer』(1951年)の出版後、エリック・ホッファーはいくつかのエッセイでアジアとアメリカの介入主義に触れている。The Reporter』に掲載された「The Awakening of Asia」(1954年)や、後に出版された『The Ordeal of Change』(1963年)では、ホッファーはアジア大陸の不安の理由について論じている。特に彼は、アジアにおける社会的不満の根本原因は、政府の腐 敗や「共産主義者の扇動」でもなく、ヨーロッパ植民地時代の「抑圧と搾取」の遺産でもなく、むしろ「誇りへの渇望」がアジアの中心的な問題であり、典型的 なアメリカの介入では解消できない問題であることを示唆していると主張している[27]。 ベトナム戦争中、彼は反戦運動に反対し、戦争が第三次世界大戦を防ぐために何らかの形で必要であったという考え方を受け入れていたにもかかわらず、ホッ ファーはアメリカの介入主義、特に東南アジアで戦争が実施されていたインテリジェンスに関して懐疑的な態度をとり続けていた。アメリカが戦争により深く関 与するようになった後、ホッファーはベトナムでの敗北を避けることを望んだ。そのような敗北はアメリカ社会を悪い方向に変容させ、背後からの刺殺神話を説 く人々への扉を開き、アメリカ版ヒトラーの台頭を許すことになるのではないかという恐れからであった[28]。 The Temper of Our Time』(1967年)の中でホッファーは、そもそもアメリカは原則として介入を避けるべきだと示唆している: 「ステーツマンシップのより良い部分は、何をすべきでないかを明確かつ正確に知り、行動を偶然の即興に委ねることかもしれない」。実際、ホッファーは「敵 が自らを打ち負かすのを待つのが賢明かもしれない」と述べている。この見解は、1970年代後半のカンボジア・ベトナム戦争と中国・ベトナム戦争である程 度実証された。 |

| Papers Hoffer's papers, including 131 of the notebooks he carried in his pockets, were acquired in 2000 by the Hoover Institution Archives. The papers fill 75 feet (23 m) of shelf space. Because Hoffer cultivated an aphoristic style, the unpublished notebooks (dated from 1949 to 1977) contain very significant work. Although available for scholarly study since at least 2003, little of their contents has been published. A selection of fifty aphorisms, focusing on the development of unrealized human talents through the creative process, appeared in the July 2005 issue of Harper's Magazine.[29] |

論文 ホッファーがポケットに忍ばせていた131冊のノートを含む彼の資料は、2000年にフーバー研究所アーカイブズが取得した。ホッファーがポケットに忍ば せていた131冊のノートを含む書類は、2000年にフーバー研究所公文書館に寄贈された。ホッファーはアフォリスティックな文体を好んだため、未発表の ノート(1949年から1977年までのもの)には非常に重要な作品が含まれている。少なくとも2003年以降は学術的な研究に利用されているが、その内 容はほとんど出版されていない。50の格言のセレクションは、創造的なプロセスを通じて実現されていない人間の才能の開発に焦点を当て、『ハーパーズ・マ ガジン』誌2005年7月号に掲載された[29]。 |

| Published works 1951 The True Believer: Thoughts On The Nature of Mass Movements. ISBN 0-06-050591-5 1955 The Passionate State of Mind, and Other Aphorisms. ISBN 1-933435-09-7 1963 The Ordeal of Change. ISBN 1-933435-10-0 1967 The Temper of Our Time. ISBN 978-1-933435-22-0 1968 Nature and The City 1969 Working and Thinking on the Waterfront: A Journal, June 1958 to May 1959 1971 First Things, Last Things 1973 Reflections on the Human Condition. ISBN 1-933435-14-3 1976 In Our Time 1979 Before the Sabbath 1982 Between the Devil and the Dragon: The Best Essays and Aphorisms of Eric Hoffer. ISBN 0-06-014984-1 1983 Truth Imagined. ISBN 1-933435-01-1 |

出版作品 1951 真のビリーバー 大衆運動の本質についての考察 ISBN 0-06-050591-5 1955年 『情熱的な心の状態、そしてその他の格言』(日本評論社 ISBN 1-933435-09-7 1963 変革の試練 ISBN 1-933435-10-0 1967 現代の気質 ISBN 978-1-933435-22-0 1968年 自然と都市 1969 ウォーターフロントで働き、考える: 1958年6月から1959年5月までの日記 1971年 最初のもの、最後のもの 1973年 人間の条件に関する考察 ISBN 1-933435-14-3 1976年 『イン・アワ・タイム 1979年 安息日の前に 1982 悪魔と竜の間で エリック・ホッファーのエッセイと格言集。ISBN 0-06-014984-1 1983年 想像された真実 ISBN 1-933435-01-1 |

| Interviews Conversations with Eric Hoffer, twelve-part television interview by James Day of KQED, San Francisco, 1963.[30] "Eric Hoffer: The Passionate State of Mind" with Eric Sevareid, CBS, September 19, 1967[31] (re-broadcast on November 14, due to popular demand). "The Savage Heart: A Conversation with Eric Hoffer," with Eric Sevareid, CBS, January 28, 1969.[31] Awards and recognition 1971, May – Honorary Doctorate; Stonehill College 1971, June – Honorary Doctorate; Michigan Technological University 1978 – Bust of Eric Hoffer by sculptor Jonathan Hirschfeld; commissioned by Charles Kittrell and placed in Bartlesville, Oklahoma 1983, February 13 – Presidential Medal of Freedom awarded by Ronald Reagan 1985, September 17 – Skygate unveiling in San Francisco; dedication speech by Eric Sevareid |

インタビュー エリック・ホッファーとの対話』(1963年、サンフランシスコ、KQEDのジェームズ・デイによる12回にわたるテレビインタビュー)[30]。 「エリック・ホッファー エリック・セヴァレイドとの "The Passionate State of Mind"、CBS、1967年9月19日[31](好評につき11月14日に再放送)。 「野蛮な心 エリック・ホッファーとの対話」、エリック・セヴァレイドと、CBS、1969年1月28日[31]。 受賞歴 1971年5月 ストーンヒル・カレッジより名誉博士号授与 1971年 6月 ミシガン工科大学より名誉博士号授与 1978年 - 彫刻家ジョナサン・ハーシュフェルドによるエリック・ホッファーの胸像、チャールズ・キトレルの依頼でオクラホマ州バートルズヴィルに設置。 1983年 2月13日 - ロナルド・レーガンより大統領自由勲章を授与される。 1985年9月17日 - サンフランシスコでスカイゲートの除幕式。 |

| American philosophy List of American philosophers Ivan Ilyin Eric Voegelin[32][page needed] |

アメリカ哲学 アメリカの哲学者一覧 イワン・イリイン エリック・ヴォーゲリン[32][要ページ] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Hoffer |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆