マルクーゼと『エロスと文明』

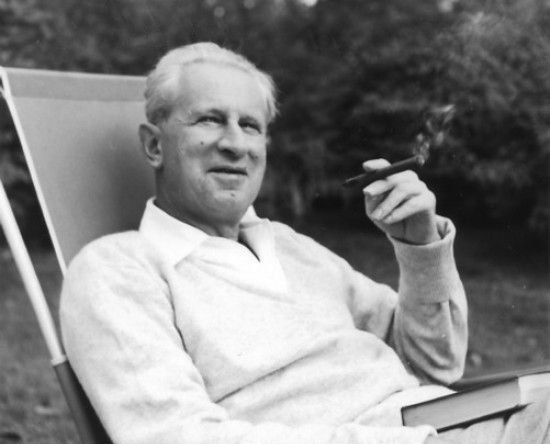

Herbert Marcuse and his book, Eros and Civilization, 1955.

◎マルクーゼさんのこと:ハーバート・マルクーゼ(1898年7月19日 - 1979年7月29日)は、ドイツ系アメリカ人の哲学者、社会学者、政治理論家で、批判理論のフランクフルト学派のひとり。 1943年から1950年にかけて、マルクーゼはアメリカ政府の戦略サービス局OSS(中央情報局CIAの前身)に勤務し、『ソビエト・マルクス主義』と いう本でソビエト連邦共産党のイデオロギーを批判している。A Critical Analysis』(1958)でソ連共産党のイデオロギーを批判した。1960年代から1970年代にかけて、西ドイツ、フランス、アメリカの新左翼や 学生運動の卓越した理論家として知られるようになり、彼を「新左翼の父」と見なす人もいる。 代表作に『エロスと文明』(1955年)『一次元的人間』(1964年)などがある。彼のマルクス主義の研究は、1960年代から1970年代にかけて、 米国内外の多くの急進的な知識人や政治活動家に影響を与えた。

| Herbert

Marcuse (/mɑːrˈkuːzə/; German: [maʁˈkuːzə]; July 19, 1898 – July 29,

1979) was a German-American philosopher, sociologist, and political

theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Born

in Berlin, Marcuse studied at the Humboldt University of Berlin and

then at Freiburg, where he received his PhD.[4] He was a prominent

figure in the Frankfurt-based Institute for Social Research – what

later became known as the Frankfurt School. He was married to Sophie

Wertheim (1924–1951), Inge Neumann (1955–1973), and Erica Sherover

(1976–1979).[5][6][7] In his written works, he criticized capitalism,

modern technology, Soviet Communism and popular culture, arguing that

they represent new forms of social control.[8] Between 1943 and 1950, Marcuse worked in US government service for the Office of Strategic Services (predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency) where he criticized the ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the book Soviet Marxism: A Critical Analysis (1958). In the 1960s and the 1970s he became known as the preeminent theorist of the New Left and the student movements of West Germany, France, and the United States; some consider him "the Father of the New Left".[9] His best-known works are Eros and Civilization (1955) and One-Dimensional Man (1964). His Marxist scholarship inspired many radical intellectuals and political activists in the 1960s and 1970s, both in the United States and internationally. |

ハーバート・マルクーゼ(/mɑˈ, German:

[maːzə]; 1898年7月19日 -

1979年7月29日)は、ドイツ系アメリカ人の哲学者、社会学者、政治理論家で、批判理論のフランクフルト学派の関係者である。ベルリンに生まれたマル

クーゼは、ベルリンのフンボルト大学、フライブルク大学で学び、博士号を取得した[4]。フランクフルトを拠点とする社会調査研究所(後にフランクフルト

学派と呼ばれる)の有力者であった。彼はソフィー・ヴェルトハイム(1924-1951)、インゲ・ノイマン(1955-1973)、エリカ・シェロー

バー(1976-1979)と結婚した[5][6][7]

著作では、資本主義、近代技術、ソ連共産主義と大衆文化が社会統制の新しい形式を示していると主張して批判している[8]。 1943年から1950年にかけて、マルクーゼはアメリカ政府の戦略サービス局OSS(中央情報局CIAの前身)に勤務し、『ソビエト・マルクス主義』と いう本でソビエト連邦共産党のイデオロギーを批判している。A Critical Analysis』(1958)でソ連共産党のイデオロギーを批判した。1960年代から1970年代にかけて、西ドイツ、フランス、アメリカの新左翼や 学生運動の卓越した理論家として知られるようになり、彼を「新左翼の父」と見なす人もいる[9]。 代表作に『エロスと文明』(1955年)『一次元的人間』(1964年)などがある。彼のマルクス主義の研究は、1960年代から1970年代にかけて、 米国内外の多くの急進的な知識人や政治活動家に影響を与えた。 |

| Early years Herbert Marcuse was born July 19, 1898, in Berlin, to Carl Marcuse and Gertrud Kreslawsky. Marcuse's family was a German upper-middle-class Jewish family that was well integrated into German society.[10] Marcuse's formal education began at Mommsen Gymnasium and continued at the Kaiserin-Augusta Gymnasium in Charlottenburg from 1911 to 1916.[10] In 1916, he was drafted into the German Army, but only worked in horse stables in Berlin during World War I. He then became a member of a Soldiers' Council that participated in the aborted socialist Spartacist uprising. In 1919 he attended Humboldt University in Berlin, taking classes for four semesters. In 1920 he transferred to the University of Freiburg to concentrate on German literature, philosophy, politics, and economics.[10] He completed his Ph.D. thesis at the University of Freiburg in 1922 on the German Künstlerroman, after which he moved back to Berlin, where he worked in publishing. Two years later he married Sophie Wertheim, a mathematician. He returned to Freiburg in 1928 to study with Edmund Husserl and write a habilitation with Martin Heidegger, which was published in 1932 as Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity (Hegels Ontologie und die Theorie der Geschichtlichkeit). This study was written in the context of the Hegel renaissance that was taking place in Europe with an emphasis on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's ontology of life and history, idealist theory of spirit and dialectic.[11] |

生い立ち ハーバート・マルクーゼは1898年7月19日、ベルリンでカール・マルクーゼとゲルトルート・クレスラフスキーの間に生まれた。1916年にドイツ軍に 徴兵されるが、第一次世界大戦中はベルリンの馬小屋で働くのみで、その後、社会主義スパルタクス団の蜂起に参加する兵士評議会のメンバーとなる。 1919年、ベルリンのフンボルト大学に入学し、4学期間授業を受ける。1922年、フライブルク大学でドイツ語のキュンストラーマン(芸術小説)に関す る博士論文を完成させ、その後、ベルリンに戻り、出版社で働く。2年後、数学者のソフィー・ヴェルトハイムと結婚した。 1928年にフライブルクに戻り、エドムンド・フッサールに学び、マルティン・ハイデガーとハビリテーション論文を書き、1932年に『ヘーゲルの存在論 と歴史性の理論(Hegels Ontologie und die Theorie der Geschichtlichkeit)』として出版されることになった。この研究は、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルの生命と歴史の存在 論、観念論的精神論、弁証法に重点を置いてヨーロッパで起こっていたヘーゲル・ルネサンスの文脈で書かれた[11]。 |

| Emigration to the United States In 1932 Marcuse stopped working with Heidegger, who later joined the Nazi Party in 1933. Marcuse understood that he would not qualify as a professor under the Nazi regime as the Nazis seized power and anti-Semitism increased.[10] Marcuse was then hired to work in the Institute of Social Research in the Frankfurt School. The Institute deposited their endowment in Holland in anticipation of the Nazi takeover, so Marcuse never got to actually work in the Frankfurt School.[10] Marcuse began his work with the Institute in Geneva, where a branch office was formed.[10] While a member of the Frankfurt School (also known as the Institute of Social Research), Marcuse developed a model for critical social theory, created a theory of the new stage of state and monopoly capitalism, described the relationships between philosophy, social theory, and cultural criticism, and provided an analysis and critique of German National Socialism. Marcuse worked closely with critical theorists while at the institute.[11] After leaving Germany for Switzerland in May 1933, Marcuse emigrated to the United States in June 1934. Marcuse served at the Institute's Columbia University branch from 1934 through 1942. He traveled to Washington, D.C., in 1942, to work for the Office of War Information, afterwards the Office of Strategic Services. Marcuse then went on to teach at Brandeis University and the University of California, San Diego later in his career.[10] In 1940, he became a US citizen and resided in the country until his death in 1979.[10] Although he never returned to Germany to live, he remained one of the major theorists associated with the Frankfurt School, along with Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno (among others). In 1940 he published Reason and Revolution, a dialectical work studying G. W. F. Hegel and Karl Marx. |

アメリカへの移住 1932年、マルクーゼはハイデガーとの共同作業を停止した。ハイデガーは1933年にナチス党に入党している。マルクーゼは、ナチスが政権を握り、反ユ ダヤ主義が強まったため、ナチス政権下では教授としての資格がないことを理解していた[10]。その後、マルクーゼはフランクフルト学派の社会研究所で働 くことになった。フランクフルト学派(社会調査研究所)のメンバーとして、マルクーゼは批判的社会理論のモデルを構築し、国家独占資本主義の新段階の理論 を作り、哲学、社会理論、文化批評の関係を説明し、ドイツの国家社会主義の分析と批判を提供した[10]。1933年5月にドイツからスイスへ渡り、 1934年6月にアメリカへ移住。マルクーゼは1934年から1942年まで研究所のコロンビア大学支部に在籍していた。1942年にはワシントン D.C.に渡り、戦争情報局(後の戦略サービス局)で働くことになった。1940年にアメリカ国籍を取得し、1979年に亡くなるまでアメリカに住んでい た[10]。ドイツに戻って生活することはなかったが、マックス・ホルクハイマーやテオドール・W・アドルノらとともに、フランクフルト学派に関わる主要 な理論家の一人であった。1940年には、ヘーゲルとカール・マルクスを研究した弁証法的著作『理性と革命』を出版している。 |

| World War II During World War II, Marcuse first worked for the US Office of War Information (OWI) on anti-Nazi propaganda projects. In 1943, he transferred to the Research and Analysis Branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency. Directed by the Harvard historian William L. Langer, the Research and Analysis (R & A) Branch was the largest American research institution in the first half of the twentieth century. At its zenith between 1943 and 1945, it employed over twelve hundred, four hundred of whom were stationed abroad. In many respects, it was the site where post-World War II American social science was born, with protégés of some of the most esteemed American university professors, as well as numerous European intellectual émigrés, in its ranks. These men comprised the "theoretical brain trust" of the American war machine, which, according to its founder, William J. Donovan, would function as a "final clearinghouse" for the secret services. Although this group did not determine war strategy or tactics, it would be able to assemble, organize, analyze, and filter the immense flow of military information directed toward Washington, thanks to the unique capacity of the gathered specialists to interpret the relevant sources.[12] In March 1943, Marcuse joined fellow Frankfurt School scholar Franz Neumann in R & A's Central European Section as senior analyst; there he rapidly established himself as "the leading analyst on Germany".[13] After the dissolution of the OSS in 1945, Marcuse was employed by the US Department of State as head of the Central European section, becoming an intelligence analyst of Nazism. A compilation of Marcuse's reports was published in Secret Reports on Nazi Germany: The Frankfurt School Contribution to the War Effort (2013). He retired after the death of his first wife in 1951. |

第二次世界大戦 第二次世界大戦中、マルクーゼはまずアメリカの戦争情報局(OWI)で反ナチスのプロパガンダ・プロジェクトに携わった。1943年、彼は中央情報局 (CIA)の前身である戦略サービス局(OSS)の調査分析部門に移った。 ハーバード大学の歴史学者ウィリアム・L・ランガーが指揮を執る研究分析部門は、20世紀前半のアメリカ最大の研究機関であった。1943年から1945 年にかけての全盛期には、1,200人以上の従業員を抱え、そのうち400人は海外に駐在していた。第二次世界大戦後のアメリカの社会科学が生まれた場所 であり、アメリカの著名な大学教授の子弟や、ヨーロッパの知識人移民が多数在籍していた。 これらの人々は、アメリカの戦争マシンの「理論的頭脳集団」を構成し、創設者のウィリアム・J・ドノバンによれば、秘密部局の「最終情報収集機関」として 機能することになった。このグループは戦争戦略や戦術を決定することはなかったが、集められた専門家の関連情報源を解釈するユニークな能力のおかげで、ワ シントンに向けられた膨大な軍事情報の流れを集め、整理し、分析し、フィルターすることができるようになった[12]。 1943年3月、マルクゼは同じフランクフルト学派の学者であるフランツ・ノイマンのもとでR&Aの中欧セクションの上級分析官として加わり、そこで彼は 急速に「ドイツに関する主要な分析官」としての地位を確立した[13]。 1945年のOSS解散後、マルクゼはアメリカ国務省に中欧課長として採用され、ナチズムの情報分析官となった。マルクーゼの報告書をまとめたものが『ナ チス・ドイツに関する秘密報告書』として出版されている。The Frankfurt School Contribution to the War Effort』(2013年)。1951年、最初の妻の死後、引退。 |

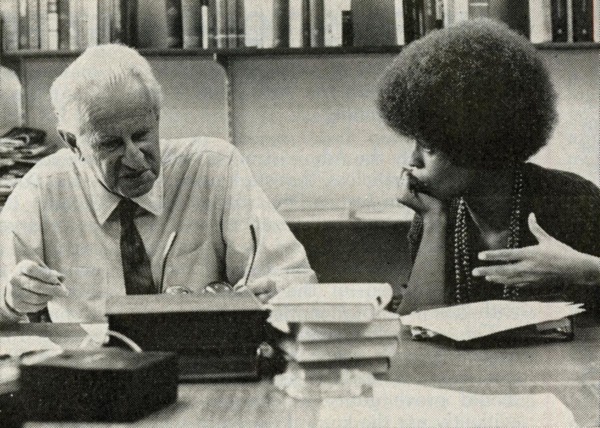

| Post-war Marcuse first began his teaching career as a political theorist at Columbia University, then at Harvard University in 1952. Marcuse worked at Brandeis University from 1954 to 1965, then at the University of California San Diego from 1965 to 1970.[14] It was during his time at Brandeis that he wrote his most famous work, One-Dimensional Man (1964).[15] Marcuse was a friend and collaborator of the political sociologist Barrington Moore Jr. and of the political philosopher Robert Paul Wolff, and also a friend of the Columbia University sociology professor C. Wright Mills, one of the founders of the New Left movement. In his "Introduction" to One-Dimensional Man, Marcuse wrote, "I should like to emphasize the vital importance of the work of C. Wright Mills."[16] In the post-war period, Marcuse rejected the theory of class struggle and the Marxist concern with labor, instead claiming, according to Leszek Kołakowski, that since "all questions of material existence have been solved, moral commands and prohibitions are no longer relevant." He regarded the realization of man's erotic nature as the true liberation of humanity, which inspired the utopias of Jerry Rubin and others.[17] Marcuse's critiques of capitalist society (especially his 1955 synthesis of Marx and Sigmund Freud, Eros and Civilization, and his 1964 book One-Dimensional Man) resonated with the concerns of the student movement in the 1960s. Because of his willingness to speak at student protests and his essay "Repressive Tolerance" (1965),[11] Marcuse soon became known in the media as "Father of the New Left."[11][18] Contending that the students of the sixties were not waiting for the publication of his work to act,[18] Marcuse brushed the media's branding of him as "Father of the New Left" aside lightly,[18] saying "It would have been better to call me not the father, but the grandfather, of the New Left."[18] His work strongly influenced intellectual discourse on popular culture and scholarly popular culture studies. He had many speaking engagements in the US and Western Bloc in the late 1960s and 1970s. He became a close friend and inspirer of the French philosopher André Gorz. Marcuse defended the arrested East German dissident Rudolf Bahro (author of Die Alternative: Zur Kritik des real existierenden Sozialismus [trans., The Alternative in Eastern Europe]), discussing in a 1979 essay Bahro's theories of "change from within."[19] |

戦後 マルクーゼは、まずコロンビア大学で政治理論家として教鞭をとり、1952年にハーバード大学で教鞭をとるようになる。1954年から1965年までブラ ンダイス大学、1965年から1970年までカリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校に勤務した[14]。ブランダイス大学時代に彼の最も有名な著作『一次元的 人間』(1964年)を執筆している[15]。 マルクーゼは政治社会学者のバーリントン・ムーア・ジュニアや政治哲学者のロバート・ポール・ウルフの友人であり、共同研究者であり、また新左翼運動の創 始者の一人であるコロンビア大学の社会学教授C・ライト・ミルズの友人であった。マルクーゼは『一次元的人間』の「はじめに」で、「C・ライト・ミルズの 仕事の重要性を強調したい」と書いている[16]。 戦後、マルクゼは階級闘争の理論とマルクス主義の労働に対する関心を否定し、その代わりにLeszek Kołakowskiによれば、「物質的存在に関するすべての問題は解決されたので、道徳的命令と禁止はもはや関係がない」と主張している。彼は人間のエ ロティックな性質の実現を人類の真の解放とみなしており、それはジェリー・ルービンらのユートピアを触発するものであった[17]。 マルクーゼの資本主義社会に対する批判(特に1955年のマルクスとジークムント・フロイトの統合である『エロスと文明』と1964年の『一次元的人 間』)は1960年代の学生運動の関心事と共鳴するものであった。マルクーゼは、学生の抗議行動で積極的に発言し、また彼のエッセイ「抑圧的寛容」 (1965年)により、すぐにメディアで「新左翼の父」として知られるようになった[11][18]。 "11"[18]60年代の学生たちは彼の著作の出版を待って行動したわけではないと主張し、マルクーゼは「私を新左翼の父ではなく、祖父と呼んだ方がよ かった」と述べ、メディアが彼を「新左翼の父」と呼ぶことを軽く受け流した[18]。彼の作品は大衆文化や大衆文化研究に対する知的言説に強い影響を与え ている。彼は1960年代後半から1970年代にかけて、アメリカや西側諸国において多くの講演活動を行った。彼はフランスの哲学者アンドレ・ゴルツと親 しい友人となり、インスピレーションを与えた。 マルクーゼは、逮捕された東ドイツの反体制派ルドルフ・バーロ(『Die Alternative』の著者)を擁護した。1979年のエッセイでバーロの「内部からの変化」の理論について論じている[19]。 |

| Marriages Marcuse married three times. His first wife was mathematician Sophie Wertheim (1901–1951), whom he married in 1924 and had his first son Peter with in 1928. Before emigrating to New York in 1934, they resided in Freiburg, Berlin, Geneva, and Paris. They lived in Los Angeles/Santa Monica and Washington, D.C. in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1951 Sophie Wertheim passed away due to cancer.[5] He would later marry Inge Neumann (1914–1973), the widow of his close friend Franz Neumann (1900–1954). After his second wife Inge died in 1973, Marcuse married Erica Sherover (1938–1988), a former graduate student at the University of California, in 1976.[7] |

結婚について マルクーゼは3度結婚した。最初の妻は数学者のソフィー・ヴェルトハイム(1901-1951)で、1924年に結婚し、1928年に長男ペーターをもう けた。1934年にニューヨークに移住するまでは、フライブルク、ベルリン、ジュネーブ、パリに住んだ。1930年代から1940年代にかけては、ロサン ゼルス、サンタモニカ、ワシントンD.C.に住んだ。1951年、ソフィー・ヴェルトハイムは癌のため死去した[5]。その後、親友フランツ・ノイマン (1900-1954)の未亡人インゲ・ノイマン(1914-1973)と結婚することになる。1973年に2番目の妻インゲが亡くなった後、マルクーゼ は1976年にカリフォルニア大学の元大学院生エリカ・シェローヴァー(1938-1988)と結婚した[7]。 |

| Children In his first marriage with Sophie Wertheim, they had one son Peter Marcuse born (1928). Peter Marcuse was a professor emeritus of urban planning at Columbia University located in New York. Although Marcuse didn't have any children with Inge Neumann Marcuse, he helped raise her two sons, Thomas Neumann and Michael Neumann.[20] Thomas (now Osha) is a Berkeley-based writer, activist, lawyer, and muralist. Michael works as a philosophy professor at Trent University in Toronto.[6] Marcuse's granddaughter is the novelist Irene Marcuse and his grandson, Harold Marcuse, is a professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. |

子供たち ソフィー・ヴェルトハイムとの最初の結婚で、一人の息子ピーター・マルクーゼが生まれた(1928年)。ピーター・マルクーゼは、ニューヨークのコロンビ ア大学名誉教授(都市計画学)であった。インゲ・ノイマン・マルクーゼとの間に子供はいなかったが、彼女の2人の息子、トーマス・ノイマンとマイケル・ノ イマンの子育てに協力した[20] トーマス(現オーシャ)はバークレーを拠点に作家、活動家、弁護士、壁画家として活動している。マイケルはトロントのトレント大学で哲学の教授として働い ている[6]。 マルクーゼの孫娘は小説家のアイリーン・マルクーゼ、孫のハロルド・マルクーゼはカリフォルニア大学サンタバーバラ校の歴史学の教授である。 |

| Death On July 29, 1979, ten days after his eighty-first birthday, Marcuse died after suffering a stroke during his trip to Germany. He had just finished speaking at the Frankfurt Römerberggespräche, and was on his way to the Max Planck Institute for the Study of the Scientific-Technical World in Starnberg, on invitation from second-generation Frankfurt School theorist Jürgen Habermas. |

死去 1979年7月29日、80歳の誕生日を迎えて10日後、マルクーゼはドイツ旅行中に脳卒中で倒れ、亡くなった。フランクフルトのレーマーベルク・シュプ レヒコールでの講演を終え、フランクフルト学派の第二世代の理論家ユルゲン・ハーバーマスの招待でシュタルンベルクのマックス・プランク科学技術世界研究 所へ向かう途中であった。 |

| Philosophy and views Marcuse's concept repressive desublimation, which has become well-known, refers to his argument that postwar mass culture, with its profusion of sexual provocations, serves to reinforce political repression. If people are preoccupied with inauthentic sexual stimulation, their political energy will be "desublimated"; instead of acting constructively to change the world, they remain repressed and uncritical. Marcuse advanced the prewar thinking of critical theory toward a critical account of the "one-dimensional" nature of bourgeois life in Europe and America. His thinking could, therefore, also be considered an advance of the concerns of earlier liberal critics such as David Riesman.[21][22] Two aspects of Marcuse's work are of particular importance, first, his use of language more familiar from the critique of Soviet or Nazi regimes to characterize developments in the advanced industrial world; and second, his grounding of critical theory in a particular use of psychoanalytic thought.[23] |

思想・見解 マルクーゼの「抑圧的脱昇華」という概念はよく知られているが、これは、戦後のマスカルチャーが性的挑発を氾濫させ、政治的抑圧を強化するのに役立ってい るという主張である。人々が不真面目な性的刺激に夢中になれば、政治的エネルギーは「脱昇華」され、世界を変えるために建設的に行動する代わりに、抑圧さ れ、無批判のままである。マルクーゼは、戦前の批評理論の考え方を、ヨーロッパとアメリカのブルジョア生活の「一面的」な性質に対する批判的な説明に向け て発展させた。それゆえ、彼の思考はデヴィッド・リースマンのような初期のリベラルな批評家の懸念を前進させたと考えることもできる[21][22]。 マルクーゼの仕事の2つの側面は特に重要であり、第1に先進工業世界における発展を特徴づけるためにソ連やナチス政権の批判からより馴染み深い言葉を使っ たこと、第2に精神分析思想の特定の使用における批判理論の根拠となったことである[23]。 |

| Marcuse's early "Heideggerian

Marxism" During his years in Freiburg, Marcuse wrote a series of essays that explored the possibility of synthesizing Marxism and Heidegger's fundamental ontology, as begun in the latter's work Being and Time (1927). This early interest in Heidegger followed Marcuse's demand for "concrete philosophy," which, he declared in 1928, "concerns itself with the truth of contemporaneous human existence."[24] These words were directed against the neo-Kantianism of the mainstream, and against both the revisionist and orthodox Marxist alternatives, in which the subjectivity of the individual played little role.[25] Though Marcuse quickly distanced himself from Heidegger following Heidegger's endorsement of Nazism, thinkers such as Jürgen Habermas have suggested that an understanding of Marcuse's later thinking demands an appreciation of his early Heideggerian influence.[26] |

マルクーゼの初期の "ハイデガー的マルクス主義" フライブルク時代、マルクーゼは、マルクス主義とハイデガーの『存在と時間』(1927年)で始まった基本的存在論の統合の可能性を探る一連のエッセイを 執筆していた。このハイデガーへの初期の関心は、マルクーゼが1928年に宣言した「同時代の人間存在の真実に関わる具体的な哲学」を要求したことに続い ていた[24]。これらの言葉は主流の新カント主義に対して、また個人の主観性がほとんど役割を演じない修正主義や正統派のマルクス主義の代案に対して向 けられたものであった。 [25] ハイデガーがナチズムを支持した後、マルクーゼはすぐにハイデガーから距離を置いたが、ユルゲン・ハーバーマスのような思想家はマルクーゼの後の思考を理 解するためには彼の初期のハイデガー的影響を評価する必要があることを示唆している[26]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Marcuse |

◎エロスと文明——ハーバート・マルクーゼが挑戦す る人類学以外の文明論批判

| Eros and

Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud

(1955; second edition, 1966) is a book by the German philosopher and

social critic Herbert Marcuse, in which the author proposes a

non-repressive society, attempts a synthesis of the theories of Karl

Marx and Sigmund Freud, and explores the potential of collective memory

to be a source of disobedience and revolt and point the way to an

alternative future. Its title alludes to Freud's Civilization and Its

Discontents (1930). The 1966 edition has an added "political preface". |

エロスと文明。この本は、ドイツの哲学者・社会評論家であるハーバー

ト・マルクーゼが、非抑圧的社会を提案し、カール・マルクスとジークムント・フロイトの理論の統合を試み、集団記憶が反抗と反逆の源となり、別の未来への道を示す可能性について探求したもので

ある。タイトルはフロイトの『文明とその不満』(1930年)を暗示している。1966年版には「政治的序文」が追加されている。 |

| One of Marcuse's best known

works, the book brought him international fame. Both Marcuse and many

commentators have considered it his most important book, and it was

seen by some as an improvement over the previous attempt to synthesize

Marxist and psychoanalytic theory by the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich.

Eros and Civilization helped shape the subcultures of the 1960s and

influenced the gay liberation movement, and with other books on Freud,

such as the classicist Norman O. Brown's Life Against Death (1959) and

the philosopher Paul Ricœur's Freud and Philosophy (1965), placed Freud

at the center of moral and philosophical inquiry. Some have evaluated

Eros and Civilization as superior to Life Against Death, while others

have found the latter work superior. It has been suggested that Eros

and Civilization reveals the influence of the philosopher Martin

Heidegger. Marcuse has been credited with offering a convincing

critique of neo-Freudianism, but critics have accused him of being

utopian in his objectives and of misinterpreting Freud's theories.

Critics have also suggested that his objective of synthesizing Marxist

and psychoanalytic theory is impossible. |

マルクーゼの代表作のひとつで、この本は彼に国際的な名声をもたらし

た。マルクーゼも多くの論者も、彼の最も重要な著作とみなしており、精神分析家ヴィルヘルム・ライヒによるマルクス主義と精神分析理論の統合というそれま

での試みを改善したものと見る向きもあった。また、古典学者ノーマン・O・ブラウンの『死に対する生命』(1959年)や哲学者ポール・リクールの『フロ

イトと哲学』(1965年)といったフロイトに関する他の書籍とともに、フロイトは道徳や哲学的な探求の中心に位置づけられるようになった。『エロスと文

明』は『死に対して生きる』より優れているという評価もあれば、後者の方が優れているという評価もある。エロスと文明』には、哲学者マルティン・ハイデ

ガーの影響が見られると指摘されている。マルクスは新フロイト主義に対して説得力のある批判を行ったと評価されているが、批評家は彼の目的がユートピア的

であり、フロイトの理論を誤って解釈していると非難している。また、マルクス主義と精神分析学の理論を統合するという彼の目的は不可能であるとも指摘され

ている。 |

| In the "Political Preface" that

opens the work, Marcuse writes that the title Eros and Civilization

expresses the optimistic view that the achievements of modern

industrial society would make it possible to use society's resources to

shape "man's world in accordance with the Life Instincts, in the

concerted struggle against the purveyors of Death." He concludes the

preface with the words, "Today the fight for life, the fight for Eros,

is the political fight."[1] Marcuse questions the view of Sigmund

Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, that "civilization is based on

the permanent subjugation of the human instincts". He discusses the

social meaning of biology — history seen not as a class struggle, but a

fight against repression of our instincts. He argues that "advanced

industrial society" (modern capitalism) is preventing us from reaching

a non-repressive society "based on a fundamentally different experience

of being, a fundamentally different relation between man and nature,

and fundamentally different existential relations".[2] Marcuse also discusses the views of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller,[3] and criticizes the psychiatrist Carl Jung, whose psychology he describes as an "obscurantist neo-mythology". He also criticizes the neo-Freudians Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, Harry Stack Sullivan, and Clara Thompson.[4] |

この作品の冒頭を飾る「政治的序文」の中で、マルクスは、「エロスと文

明」というタイトルには、近代工業社会の成果によって、社会の資源を使って「死の供給者に対する協調的な闘いの中で、生命本能に従って人間の世界を形作る

ことが可能になるだろう」という楽観的な見方が示されていると書いている[1]。彼は序文を「今日、生命のための戦い、エロスのための戦いは政治的な戦い

である」という言葉で結んでいる[1]。

マルクーゼは精神分析の創始者ジークムント・フロイトの「文明は人間の本能を永久に服従させることに基づく」という見解に疑問を呈している。彼は生物学の

社会的意味を論じ、歴史は階級闘争としてではなく、本能の抑圧に対する闘いとしてとらえる。彼は「先進工業社会」(現代の資本主義)が「根本的に異なる存

在の経験、根本的に異なる人間と自然の関係、根本的に異なる実存的関係に基づく」非抑圧的な社会への到達を阻んでいると主張する[2]。 またマルクスは哲学者であるイマヌエル・カントやフリードリヒ・シラーの見解についても議論し[3]、精神科医のカール・ユングを批判し、その心理学を 「曖昧主義的新神話」であると評している。また、新フロイト派のエーリッヒ・フロム、カレン・ホーニー、ハリー・スタック・サリバン、クララ・トンプソン も批判している[4]。 |

| Mainstream media Eros and Civilization received positive reviews from the philosopher Abraham Edel in The Nation and the historian of science Robert M. Young in the New Statesman.[6][7] The book was also reviewed by the anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn in The New York Times Book Review and discussed by Susan Sontag in The Supplement to the Columbia Spectator.[8][9] Later discussions include those in Choice by H. N. Tuttle,[10] R. J. Howell,[11] and M. A. Bertman.[12] The art critic Roger Kimball discussed the book in The New Criterion.[13] Edel credited Marcuse with distinguishing between what portion of the burden repressive civilization places on the fundamental drives is made necessary by survival needs and what serves the interests of domination and is now unnecessary because of the advanced science of the modern world, and with suggesting what changes in cultural attitudes would result from relaxation of the repressive outlook.[6] Young called the book important and honest, as well as "serious, highly sophisticated and elegant". He wrote that Marcuse's conclusions about "surplus repression" converted Freud into an "eroticised Marx", and credited Marcuse with convincingly criticizing the neo-Freudians Fromm, Horney, and Sullivan. Though maintaining that both they and Marcuse confused "ideology with reality" and minimized "the biological sphere", he welcomed Marcuse's view that "the distinction between psychological and political categories has been made obsolete by the condition of man in the present era."[7] Sontag wrote that together with Brown's Life Against Death (1959), Eros and Civilization represented a "new seriousness about Freudian ideas" and exposed most previous writing on Freud in the United States as irrelevant or superficial.[9] Tuttle suggested that Eros and Civilization could not be properly understood without reading Marcuse's earlier work Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity (1932).[10] Howell wrote that the book had been improved upon by C. Fred Alford's Melanie Klein and Critical Social Theory (1989).[11] Bertman wrote that Eros and Civilization was exciting and helped make Marcuse influential.[12] Kimball identified Eros and Civilization and One-Dimensional Man (1964) as Marcuse's most influential books, and wrote that Marcuse's views parallel those of Norman O. Brown, despite the difference of tone between the two thinkers. He dismissed the ideas of both Marcuse and Brown as false and harmful.[13] |

メインストリーム・メディア 『エロスと文明』はThe Nation誌で哲学者のAbraham Edel、New Statesman誌で科学史家のRobert M. Youngから好評を博した[6][7]。またNew York Times Book Review誌で人類学者のClyde Kluckhohnから、The Supplement to the Columbia Spectatorでスーザンソンタグから論評を受けた[8][9]。 [8][9] 後にH・N・タトル、[10] R・J・ハウエル、M・A・ベルトマンによる『選択』での議論がある。 12] 美術評論家のロジャー・キンブルは『ニュー・クリティリオン』でこの本について議論した[13]。 エーデルは、抑圧的な文明が基本的な衝動に与える負担のうち、生存の必要性によって必要とされる部分と、支配の利益に役立ち、現代世界の科学の進歩によっ て不要となった部分を区別し、抑圧的な見通しを緩和することによって文化意識にどんな変化が生じるかを示唆したことでマークーゼを評価している[6]。 ヤングはこの本を重要かつ正直であり、「真面目で高度な、上品」だと評価している。彼は、「余剰抑圧」に関するマルクーゼの結論がフロイトを「エロティッ クなマルクス」に変換したと書き、マルクーゼが新フロイト派のフロム、ホーニー、サリヴァンを説得的に批判していると評価した。ソンタグは、ブラウンの 『死に対する生命』(1959年)と共に『エロスと文明』は「フロイトの思想に対する新しい真剣さ」を表しており、アメリカにおけるフロイトに関するそれ までの著作のほとんどが無関係であるか表面的であることを暴露したと書いている[9]。 タトルはマルクーゼの初期の著作である『ヘーゲルの存在論と歴史性の理論』(1932年)を読まなければ『エロスと文明』を適切に理解することができない と示唆した[10]。 ハウエルはこの本がC・フレッド・アルフォード『メラニー・クラインと社会批判理論』(1989年)によって改善されていると書いている[11]。 [11] バートマンは『エロスと文明』が刺激的であり、マルクーゼの影響力を高めるのに役立ったと書いている[12] キンブルは『エロスと文明』と『一次元の人間』(1964年)をマルクーゼの最も影響力のある本としており、2人の思想家の間のトーンの違いにもかかわら ずマルクーゼの見解はノーマン・O・ブラウンのものと平行していると書いている。彼はマルクーゼとブラウンの両方の思想を誤りであり有害であると断じた [13]。 |

| Mattick credited Marcuse with

renewing "the endeavor to read Marx into Freud", following the

unsuccessful attempts of Wilhelm Reich, and agreed with Marcuse that

Freudian revisionism is "reformist or non-revolutionary". However, he

wrote that Freud would have been surprised at the way Marcuse read

revolutionary implications into his theories. He noted that Marcuse's

way of overcoming the dilemma that "a full satisfaction of man’s

instinctual needs is incompatible with the existence of civilized

society" was Marxist, despite the fact that Marcuse nowhere mentioned

Marx and referred to capitalism only indirectly, as "industrial

civilization". He argued that Marcuse tried to develop ideas that were

already present in "the far less ambiguous language of Marxian theory",

but still welcomed the fact that Marcuse made psychoanalysis and

dialectical materialism reach the same desired result. However, he

concluded that Marcuse's "call to opposition to present-day conditions

remains a mere philosophical exercise without applicability to social

actions."[14] Whitfield noted that Marcuse considered Eros and Civilization his most important book, and wrote that it "merits consideration as his best, neither obviously dated nor vexingly inaccessible" and that it "was honorable of Marcuse to try to imagine how the fullest expression of personality, or plenitude, might extinguish the misery that was long deemed an essential feature of the human condition." He considered the book "thrilling to read" because of Marcuse's conjectures about "how the formation of a life without material restraints might somehow be made meaningful." He argued that Marcuse's view that technology could be used to create a utopia was not consistent with his rejection of "technocratic bureaucracy" in his subsequent work One-Dimensional Man. He also suggested that it was the work that led Pope Paul VI to publicly condemn Marcuse in 1969.[15] |

マティックは、ヴィルヘルム・ライヒの試みが失敗したのに続いて、「フ

ロイトにマルクスを読み込もうとする試み」をマルクーゼが新たに行ったと評価し、フロイトの修正主義が「改革主義あるいは非革命的」であるとするマルクー

ゼに同意している。しかし、彼は、マルクーゼが彼の理論に革命的な含意を読み込んだことにフロイトは驚いただろうと書いている。彼は、「人間の本能的欲求

の完全な充足は文明社会の存在と両立しない」というジレンマを克服するためのマルキューの方法が、マルクスにはどこにも言及せず、資本主義についても「産

業文明」として間接的にしか言及していないにもかかわらず、マルクス主義的であると指摘している。彼は、マルクーゼが「マルクス理論のはるかに曖昧でない

言語」の中にすでに存在していた思想を発展させようとしたと主張したが、それでもマルクーゼが精神分析と弁証法的唯物論を同じ望ましい結果に到達させたこ

とは歓迎された。しかし彼はマルキューの「現在の状況への反対を呼びかけることは、社会的行動への適用性を持たない単なる哲学的な運動にとどまっている」

と結論づけた[14]。 ホイットフィールドは、マルクーゼが『エロスと文明』を最も重要な本と考えていたことを指摘し、「明らかに時代遅れでもなく、むずかしくもなく、彼の最高 傑作として考慮するに値する」、「人格の完全な表現、すなわちプレニチュードは、人間の条件の本質的特徴と長く考えられていた不幸をどのように消滅させ得 るかを想像しようとしたマルクーゼは高潔だった」、と書いている[14]。物質的な束縛のない人生の形成が、どのようにして意味を持つようになるのか」と いうマルクーゼの推測から、この本を「読んでいてスリリング」だと考えたのである。彼は、テクノロジーがユートピアをつくるために利用できるというマル キューの見解は、その後の作品『一次元人間』における「テクノクラート的官僚主義」の否定と一致しないと主張した。また、1969年にローマ法王パウロ6 世がマルクーゼを公に非難するきっかけとなった作品であるとも指摘した[15]。 |

| Reviews in academic journals Eros and Civilization received positive reviews from the psychoanalyst Martin Grotjahn in The Psychoanalytic Quarterly,[16] Paul Nyberg in the Harvard Educational Review,[17] and Richard M. Jones in American Imago,[18] and a negative review from the philosopher Herbert Fingarette in The Review of Metaphysics.[19] In the American Journal of Sociology, the book received a positive review from the sociologist Kurt Heinrich Wolff and later a mixed review from an author using the pen-name "Barbara Celarent".[20][21][22] The book was also discussed by Margaret Cerullo in New German Critique.[23] Grotjahn described the book as a "sincere and serious" philosophical critique of psychoanalysis, adding that it was both well-written and fascinating. He credited Marcuse with developing "logically and psychologically the instinctual dynamic trends leading to the utopia of a nonrepressive civilization" and demonstrating that "true freedom is not possible in reality today", being reserved for "fantasies, dreams, and the experiences of art." However, he suggested that Marcuse might be "mistaken in the narrowness of his concept of basic, or primary, repression".[16] Nyberg described the book as "brilliant", "moving", and "extraordinary", concluding that it was, "perhaps the most important work on psychoanalytic theory to have appeared in a very long time."[17] Jones praised Marcuse's interpretation of psychoanalysis; he also maintained that Marcuse, despite not being a psychoanalyst, had understood psychoanalytic theory and shown how it could be improved upon. However, he believed Marcuse left some questions unresolved.[18] |

学術誌での評価 『エロスと文明』は、The Psychoanalytic Quarterlyで精神分析家のMartin Grotjahn、Harvard Educational ReviewでPaul Nyberg、American ImagoでRichard M. Jonesからポジティブなレビューを受け[16]、The Review of Metaphysicsで哲学者Herbert Fingaretteからネガティブなレビューがありました[18]。 [19] 『アメリカン・ジャーナル・オブ・ソシオロジー』では、社会学者のクルト・ハインリッヒ・ウォルフから肯定的な評価を受け、後に「バーバラ・セラレント」 というペンネームを使った著者から複雑な評価を受けた[20][21][22] また『新ドイツ批評』でマーガレット・セルロがこの本を取り上げていた[23]。 グロートヤーンはこの本を精神分析に対する「誠実で真剣な」哲学的批判であるとし、よく書けていて魅力的であると付け加えている。彼はマルクーゼが「非抑 圧的な文明のユートピアに至る本能的な動的傾向」を論理的、心理的に展開し、「真の自由は今日の現実では不可能」であり、「空想、夢、芸術の経験」に留ま ることを証明したと評価する。しかし、彼はマルクーゼが「基本的な、あるいは一次的な抑圧の概念の狭さにおいて間違っている」かもしれないと示唆した [16]。ナイバーグはこの本を「輝かしい」、「感動的」、「驚異的」だと述べ、「おそらく非常に長い間現れた精神分析理論に関する最も重要な仕事」だと 結論付けた。 「ジョーンズはマルクーゼの精神分析に対する解釈を称賛し、マルクーゼが精神分析家ではないにもかかわらず、精神分析理論を理解し、それをどのように改善 することができるかを示していると主張していました。しかし、彼はマルクーゼがいくつかの疑問を未解決のままにしていると考えていた[18]。 |

| Fingarette considered Marcuse

the first to develop the idea of a utopian society free from sexual

repression into a systematic philosophy. However, he noted that he used

the term "repression" in a fashion that drastically changed its meaning

compared to "strict psychoanalytic usage", employing it to refer to

"suppression, sublimation, repression proper, and restraint". He also

questioned the accuracy of Marcuse's understanding of Freud, arguing

that he was actually presenting "analyses and conclusions already

worked out and accepted by Freud". He also questioned whether his

concept of "sensuous rationality" was original, and criticized him for

failing to provide sufficient discussion of the Oedipus complex. He

concluded that he put forward an inadequate "one-dimensional,

instinctual view of man" and that his proposed non-repressive society

was a "fantasy-Utopia".[19] Wolff considered the book a great work. He praised the "magnificent" scope of Eros and Civilization and Marcuse's "inspiring" sense of dedication. He noted that the book could be criticized for Marcuse's failure to answer certain questions and for some "omissions and obscurities", but considered these points to be "of minor importance."[20] Celarent considered Eros and Civilization a "deeper book" than One-Dimensional Man (1964) because it "addressed the core issue: How should we live?" However, Celarent wrote that Marcuse's decision to analyze the issue of what should be done with society's resources with reference to Freud's writings "perhaps curtailed the lifetime of his book, for Freud dropped quickly from the American intellectual scene after the 1970s, just as Marcuse reached his reputational peak." Celarent identified Marx's Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867–1883) as a source of Marcuse's views on production and labor markets, and described his "combination of Marx and Freud" as "very clever". Celarent credited Marcuse with using psychoanalysis to transform Marx's concept of alienation into "a more subtle psychological construct", the "performance principle". In Celarent's view, it anticipated arguments later made by the philosopher Michel Foucault, but with "a far more plausible historical mechanism" than Foucault's "nebulous" concept of discourse. However, Celarent considered Marcuse's chapter giving "proper Freudian reasons for the historicity of the reality principle" to be of historical interest only, and wrote that Marcuse proposed a "shadowy utopia". Celarent suggested that Eros and Civilization had commonly been misinterpreted, and that Marcuse was not concerned with advocating "free love and esoteric sexual positions."[21] |

フィンガレットは、マルクスを、性的抑圧のないユートピア社会という思

想を初めて体系的な哲学として展開した人物とみなしている。しかし、彼は「抑圧」という言葉を、「抑圧、昇華、適切な抑圧、抑制」というように、「厳密な

精神分析的用法」とは大幅に意味を変えて使っていることを指摘した。また、マルキューのフロイトに対する理解の正確さにも疑問を呈し、実際には「フロイト

によってすでになされ、受け入れられている分析と結論」を提示しているのだと主張した。さらに、彼の「感覚的合理性」という概念が独創的であるかどうかも

疑問視し、エディプス・コンプレックスについても十分な議論がなされていないと批判している。そして、彼が提示したのは不十分な「一次元的で本能的な人間

観」であり、彼が提案した抑圧的でない社会は「幻想のユートピア」であると結論づけた[19]。 ヴォルフはこの本を偉大な作品だと考えていた。彼は『エロスと文明』の「壮大な」範囲とマルクーゼの「感動的な」献身的な感覚を賞賛している。彼はこの本 がマルクーゼがある質問に答えなかったことやいくつかの「省略と不明瞭さ」について批判される可能性があると指摘したが、これらの点を「小さな重要性」で あると考えた[20]。 セラレントは『エロスと文明』が『一次元人間』(1964年)よりも「深い本」だと考えたのは「核心の問題を扱っているからである。私たちはどのように生 きるべきなのか "という核心的な問題を扱っていたからである。しかし、セラレントは、フロイトの著作を参照して社会の資源をどうすべきかという問題を分析しようとしたマ ルキューの決断が、"おそらく彼の本の寿命を縮めた。""マルクーゼが評判のピークに達した1970年代以降、フロイトはアメリカの知的シーンから急速に 姿を消した。"と書いている。セラレントはマルクスの『資本論』を同定した。また、マルクスとフロイトの「組み合わせ」は「非常に巧妙」であると述べてい る。セラレントは、マルクスが精神分析を用いて、疎外という概念を「より微妙な心理的構成」である「パフォーマンス原理」に変換したことをマルクスに認め ている。セラレントの考えでは、それは後に哲学者ミシェル・フーコーによってなされる議論を先取りしていたが、フーコーの「漠然とした」言説の概念よりも 「はるかにもっともらしい歴史的メカニズム」であった。しかし、セラレントは、「現実原理の歴史性についてのフロイト的な適切な理由」を与えるマルクーゼ の章は、歴史的な興味しか持たないと考え、マルクーゼは「影のユートピア」を提案したと書いている。セラレントは、『エロスと文明』は一般的に誤解されて おり、マルクーゼは「自由恋愛や難解な性的ポジション」を提唱することには関心がないことを示唆していた[21]。 |

| Discussions in Theory &

Society Jay described the book as one of Marcuse's major works, and his "most utopian" book. He maintained that it completed Marcuse's "theory of remembrance", according to which "memory subverts one-dimensional consciousness and opens up the possibility of an alternative future", and helped Marcuse advance a form of critical theory no longer able to rely on revolutionary proletariat. However, he criticized Marcuse's theory for its "undefined identification of individual and collective memory", writing that Marcuse failed to explain how the individual was in "archaic identity with the species". He suggested that there might be an affinity between Marcuse's views and Jung's, despite Marcuse's contempt for Jung. He criticized Marcuse for his failure to undertake experiments in personal recollection such as those performed by the philosopher Walter Benjamin, or to rigorously investigate the differences between personal memory of an actual event in a person's life and collective historical memory of events antedating all living persons. Jay suggested that the views of the philosopher Ernst Bloch might be superior to Marcuse's, since they did more to account for "the new in history" and more carefully avoided equating recollection with repetition.[24] |

理論と社会における議論 ジェイは、本書をマルクーゼの代表作の一つであり、彼の「最もユートピア的」な本であるとした。そして、「記憶が一次元の意識を破壊し、別の未来の可能性 を開く」というマルクーゼの「想起の理論」を完成させ、もはや革命的プロレタリアートに頼ることのできない批判理論の形態をマルキューが前進させるのに役 立ったと主張した。しかし、彼はマルクーゼの理論が「個人的記憶と集団的記憶の不定型な同一化」であると批判し、マルクーゼは個人が「種との古風な同一 性」の中にいることを説明できなかったと書いている。彼は、マルクーゼがユングを軽蔑しているにもかかわらず、マルクーゼの見解とユングの見解の間に親和 性があるかもしれないと示唆した。彼は、哲学者ヴァルター・ベンヤミンが行ったような個人的回想の実験を行わず、また、ある人物の人生における実際の出来 事に関する個人的記憶と、生きているすべての人物に先立つ出来事に関する集合的歴史記憶との間の差異を厳密に調査しなかったことを理由に、マルクーゼを批 判しているのである。ジェイは哲学者エルンスト・ブロッホの見解がマルキューよりも優れているかもしれないと示唆しており、それは彼らが「歴史における新 しいもの」をより説明し、より注意深く記憶と反復を同一視することを避けているからである[24]。 |

| Chodorow considered the work of

Marcuse and Brown important and maintained that it helped suggest a

better psychoanalytic social theory. However, she questioned their

interpretations of Freud, argued that they see social relations as an

unnecessary form of constraint and fail to explain how social bonds and

political activity are possible, criticized their view of "women,

gender relations, and generation", and maintained that their use of

primary narcissism as a model for union with others involves too much

concern with individual gratification. She argued that Eros and

Civilization shows some of the same features that Marcuse criticized in

Brown's Love's Body (1966), that the form of psychoanalytic theory

Marcuse endorsed undermines his social analysis, and that in his

distinction between surplus and basic repression, Marcuse did not

evaluate what the full effects of the latter might be in a society

without domination. She praised parts of the work, such as his chapter

on "The Transformation of Sexuality into Eros", but maintained that in

some ways it conflicted with Marcuse's Marxism. She criticized

Marcuse's account of repression, noting that he used the term in a

"metaphoric" fashion that eliminated the distinction between the

conscious and the unconscious, and argued that his "conception of

instinctual malleability" conflicted with his proposal for a "new

reality principle" based on the drives and made his critique of Fromm

and neo-Freudianism disingenuous, and that Marcuse "simply asserted a

correspondence between society and personality organization".[25] |

チョードロウは、マルクーゼとブラウンの仕事を重要視し、それがよりよ

い精神分析的社会理論を示唆するのに役立ったとしている。しかし、フロイトの解釈には疑問を呈し、社会関係を不必要な制約とみなし、社会的結合や政治活動

がいかに可能であるかを説明できないとし、「女性、ジェンダー関係、世代」についての彼らの見方を批判し、他者との結合のモデルとして第一次ナルシズムを

用いるのは、個人の満足への関心が強すぎるとしている。また、『エロスと文明』には、マルクーゼがブラウンの『愛の肉体』(1966年)で批判したような

特徴が見られること、マルクーゼが支持した精神分析理論の形式は彼の社会分析を弱めること、余剰抑圧と基本抑圧を区別する際に、支配のない社会で後者がも

たらす全影響を評価していないことを指摘し、『エロスと文明』を評価した。また、「セクシュアリティのエロスへの変容」の章など、この著作の一部を評価し

つつも、ある意味でマルクス主義と相反するものであるとしている。彼女はマルクーゼの抑圧についての説明を批判し、彼が意識と無意識の区別を排除する「比

喩的」な方法でこの言葉を使ったことを指摘し、彼の「本能的な可鍛性の概念」は衝動に基づく「新しい現実原理」の提案と矛盾し、フロムや新フロイト主義に

対する彼の批判を不誠実なものにしたと主張し、マルクーゼが「社会と人格組織の間の対応を単に主張した」[25]としている。 |

| Alford, writing in 1987, noted

that Marcuse, like many of his critics, regarded Eros and Civilization

as his most important work, but observed that Marcuse's views have been

criticized for being both too similar and too different to those of

Freud. He wrote that recent scholarship broadly agreed with Marcuse

that social changes since Freud's era have changed the character of

psychopathology, for example by increasing the number of narcissistic

personality disorders. He credited Marcuse with showing that narcissism

is a "potentially emancipatory force", but argued that while Marcuse

anticipated some subsequent developments in the theory of narcissism,

they nevertheless made it necessary to reevaluate Marcuse's views. He

maintained that Marcuse misinterpreted Freud's views on sublimation and

noted that aspects of Marcuse's "erotic utopia" seem regressive or

infantile, as they involved instinctual gratification for its own sake.

Though agreeing with Chodorow that this aspect of Marcuse's work is

related to his "embrace of narcissism", he denied that narcissism

serves only regressive needs, and argued that "its regressive potential

may be transformed into the ground of mature autonomy, which recognizes

the rights and needs of others." He agreed with Marcuse that "in spite

of the reified power of the reality principle, humanity aims at a

utopia in which its most fundamental needs would be fulfilled."[26] |

1987年に書かれたアルフォードは、マルクーゼが彼の多くの批評家と

同様に、『エロスと文明』を彼の最も重要な著作とみなしていることを指摘しつつ、マルキューの見解がフロイトの見解と似すぎたり違いすぎたりしていると批

判されていることを観察している。彼は、フロイトの時代以降の社会の変化が、例えば自己愛性パーソナリティ障害の数を増加させることによって、精神病理学

の性格を変化させたという点については、最近の学問は広くマルクーゼと一致していると書いている。彼は、マルクーゼがナルシシズムが「潜在的に解放的な

力」であることを示したと評価しつつ、マルクーゼはその後のナルシシズム理論の発展を予期していたが、それにもかかわらずマルクーゼの見解を再評価する必

要が出てきたと論じた。彼は、マルクーゼがフロイトの昇華に関する見解を誤って解釈していると主張し、マルクーゼの「エロティック・ユートピア」の側面

が、それ自体のための本能的な満足を伴うため、退行的あるいは幼児的であるように見えると指摘している。チョードロウは、マルクーゼのこうした側面が彼の

「ナルシシズムの受容」と関連していることに同意しつつも、ナルシシズムが退行的な欲求にのみ奉仕することを否定し、「その退行の可能性は、他者の権利と

欲求を認める成熟した自律性の基盤へと転換されうる」と論じた。彼はマルクーゼに同意して、「現実原理の再定義された力にもかかわらず、人類はその最も基

本的な欲求が満たされるようなユートピアを目指している」[26]。 |

| Discussions in other journals Other discussions of the work include those by the philosopher Jeremy Shearmur in Philosophy of the Social Sciences,[27] the philosopher Timothy F. Murphy in the Journal of Homosexuality,[28] C. Fred Alford in Theory, Culture & Society,[29] Michael Beard in Edebiyat: Journal of Middle Eastern Literatures,[30] Peter M. R. Stirk in the History of the Human Sciences,[31] Silke-Maria Weineck in The German Quarterly,[32] Joshua Rayman in Telos,[33] Daniel Cho in Policy Futures in Education,[34] Duston Moore in the Journal of Classical Sociology,[35] Sean Noah Walsh in Crime, Media, Culture,[36] the philosopher Espen Hammer in Philosophy & Social Criticism,[37] the historian Sara M. Evans in The American Historical Review,[38] Molly Hite in Contemporary Literature,[39] Nancy J. Holland in Hypatia,[40] Franco Fernandes and Sérgio Augusto in DoisPontos,[41] and Pieter Duvenage in Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe.[42] In Zeitschrift für Kritische Theorie, the book was discussed by Shierry Weber Nicholsen and Kerstin Stakemeier.[43][44] In 2013, it was discussed in Radical Philosophy Review.[45] It received a joint discussion from Arnold L. Farr, the philosopher Douglas Kellner, Andrew T. Lamas, and Charles Reitz,[46] and additional discussions from Stefan Bird-Pollan and Lucio Angelo Privitello.[47][48] The Radical Philosophy Review also reproduced a document from Marcuse, responding to criticism from the Marxist scholar Sidney Lipshires.[49] In 2017, Eros and Civilization was discussed again in the Radical Philosophy Review by Jeffrey L. Nicholas.[50] |

他のジャーナルにおける議論 この作品に関する他の論考としては、哲学者ジェレミー・シアマーによる『Philosophy of the Social Sciences』、[27] 哲学者ティモシー・F・マーフィーによる『Journal of Homosexuality』、[28] C・フレッド・アルフォードによる『Theory, Culture & Society』、[29] マイケル・ビアードによる『Edebiyat: Journal of Middle Eastern Literatures, [30] Peter M. R. Stirk in the History of the Human Sciences, [31] Silke-Maria Weineck in The German Quarterly, [32] Joshua Rayman in Telos, [33] Daniel Cho in Policy Futures in Education, [34] Duston Moore in the Journal of Classical Sociology, [35] Sean Noah Walsh in Crime, Media, Culture, [36] the philosopher Espen Hammer in the Philosophy & Social Criticism, [37] the historian Sara M. Evans in The American Historical Review, [37] the historian Sara M. Evans in the American Historical Review, [38] the historian Sara M. Evans in The American Historical Review、[38] Molly Hite in Contemporary Literature、[39] Nancy J. Holland in Hypatia、[40] Franco Fernandes and Sérgio Augusto in DoisPontos、[41] Pieter Duvenage in Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappeである。 [42]『Zeitschrift für Kritische Theorie』誌では、シエリー・ウェーバー・ニコルセンとケルスティン・シュテークマイヤーによって論じられた[43][44]。 2013年には『Radical Philosophy Review』誌で論じられた[45]。アーノルド・L・ファー、哲学者のダグラス・ケルナー、アンドリュー・T. ラマス、チャールズ・ライツ[46]、そしてステファン・バード=ポランとルチオ・アンジェロ・プリヴィテッロによる追加的な議論も行われた[47] [48]。2017年、『エロスと文明』はジェフリー・L・ニコラスによって『ラディカル・フィロソフィー・レビュー』で再び議論された[50]。 |

| Shearmur identified the

historian Russell Jacoby's criticism of psychoanalytic "revisionism" in

his work Social Amnesia (1975) as a reworking of Marcuse's criticism of

neo-Freudianism.[27] Murphy criticized Marcuse for failing to examine

Freud's idea of bisexuality.[28] Alford criticized the Frankfurt School

for ignoring the work of the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein despite the

fact that Klein published a seminal paper two years before the

publication of Eros and Civilization.[29] Beard described the book as

an "apocalyptic companion" to Life Against Death, and wrote that

between them the books provided "one of the most influential blueprints

for radical thinking in the decade which followed."[30] Stirk argued

that Marcuse's views were a utopian theory with widespread appeal, but

that examination of Marcuse's interpretations of Kant, Schiller, and

Freud showed that they were based on a flawed methodology. He also

maintained that Marcuse's misinterpretation of Freud's concept of

reason undermined Marcuse's argument, which privileged a confused

concept of instinct over an ambiguous sense of reason.[31] Weineck

credited Marcuse with anticipating later reactions to Freud in the

1960s, which maintained in opposition to Freud that the "sacrifice of

libido" is not necessary for civilized progress, though she considered

Marcuse's views more nuanced than such later ideas. She endorsed

Marcuse's criticisms of Fromm and Horney, but maintained that Marcuse

underestimated the force of Freud's pessimism and neglected Freud's

Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920).[32] |

シャーマースは歴史家のラッセル・ジャコビーが彼の著作Social Amnesia(1975年)の中で精神分析的「修正主義」を批判したことをネオフロイト主義に対するマルクーゼの批判の焼き直しとして特定した[27] 。マーフィーはフロイトの両性愛に対する考えを検証しなかったとしてマルクーゼを批判した[28] 。アルフォードはクラインがEros and Civilizationの出版の2年前に決定的論文を出版したにもかかわらず精神分析家のメラニー・クラインの仕事を無視したとフランクフルト学派を批 判している。 [29] ビアードはこの本を『死に対する生命』の「黙示録的な仲間」として説明し、この2冊の本が「その後の10年間におけるラディカルな思考に対して最も影響力 のある青写真の1つ」を提供したと書いている[30] スタークは、マルクーゼの見解が広くアピールする理想郷的理論だったが、カント、シラー、フロイトに対するマルクーゼの解釈の検討によってそれが欠陥ある 方法論に基づいていることを示したと論じている。また、フロイトの理性の概念に対するマルクスの誤った解釈が、曖昧な理性の感覚よりも混乱した本能の概念 を特権化するマルクスの議論を弱体化させたと主張していた[31] ワイネックは、「リビドーの犠牲」は文明の進歩に必要ではないとフロイトと対立して主張した1960年代のフロイトに対する後の反応を先取りしたとマルコ スを評価したが、彼女はマルクスの見解をそうした後の思想よりもニュアンスがあるとみなしている。彼女はマルクーゼのフロムとホーニーに対する批判を支持 したが、マルクーゼがフロイトの悲観主義の力を過小評価しており、フロイトの『快楽原則を超えて』(1920年)を軽視していると主張している[32]。 |

| Cho compared Marcuse's views to

those of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, writing that the similarities

between them were less well known than the differences.[34] Moore wrote

that while the influence of the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead on

Marcuse has received insufficient attention, essential aspects of

Marcuse's theory can be "better understood and appreciated when their

Whiteheadian origins are examined."[35] Holland discussed Marcuse's

ideas in relation to those of the cultural anthropologist Gayle Rubin,

in order to explore the social and psychological mechanisms behind the

"sex/gender system" and to open "new avenues of analysis and liberatory

praxis based on these authors' applications of Marxist insights to

cultural interpretations" of Freud's writings.[40] Hammer argued that

Marcuse was "incapable of offering an account of the empirical dynamics

that may lead to the social change he envisions, and that his appeal to

the benefits of automatism is blind to its negative effects" and that

his "vision of the good life as centered on libidinal self-realization"

threatens the freedom of individuals and would "potentially undermine

their sense of self-integrity." Hammer maintained that, unlike the

philosopher Theodor W. Adorno, Marcuse failed to "take temporality and

transience properly into account" and had "no genuine appreciation of

the need for mourning." He also argued that "political action requires

a stronger ego-formation" than allowed for by Marcuse's views.[37]

Evans identified Eros and Civilization as an influence on 1960s

activists and young people.[38] |

Choは、マルキューの見解を精神分析家ジャック・ラカンの見解と比較

し、両者の類似点は相違点よりもあまり知られていないと書いている[34]。Mooreは、哲学者アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドのマルクーゼへの

影響は十分に注目されていないが、マルキューの理論の本質的側面は「ホワイトヘッド的起源を検討することでよりよく理解され評価される」ことができると書

いている[35]。

「ホランドは、「性/ジェンダー・システム」の背後にある社会的・心理的メカニズムを探求し、フロイトの著作の「文化的解釈に対するマルクス主義の洞察の

応用に基づく分析と解放の実践の新しい道」を開くために、文化人類学者ゲイル・ルービンの考えと関連してマルクーゼの考えを論じている[35]。

[40]

ハマーは、マルクスは「彼が思い描く社会的変化をもたらすかもしれない経験的力学の説明を提供することができず、自動性の利点への彼の訴えはその否定的効

果に盲目である」し、彼の「リビドー的自己実現を中心とする善き人生のビジョン」は個人の自由を脅かし、「自己統合の感覚を損ねる可能性があるだろう」、

と論じている。ハマーは、哲学者テオドール・W・アドルノとは異なり、マルクーゼは「時間性とはかなさを適切に考慮する」ことができず、「喪の必要性に対

する真の理解を持っていない」と主張している。また彼はマルクーゼの見解によって許されるよりも「政治的行動はより強い自我の形成を必要とする」と主張し

ていた[37]。エヴァンスは『エロスと文明』を1960年代の活動家や若者たちに影響を与えたものとして特定していた[38]。 |

| Hite identified the book as an

influence on Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow (1973), finding

this apparent in Pynchon's characterization of Orpheus as a figure

connected with music, memory, play, and desire. She added that while

Marcuse did not "appeal to mind-altering drugs as adjuncts to

phantasy", many of his readers were "happy to infer a recommendation."

She argued that while Marcuse does not mention pedophilia, it fits his

argument that perverse sex can be "revelatory or demystifying, because

it returns experience to the physical body".[39] Duvenage described the

book as "fascinating", but wrote that Marcuse's suggestions for a

repression-free society have been criticized by the philosopher Marinus

Schoeman.[42] Farr, Kellner, Lamas, and Reitz wrote that partly because

of the impact of Eros and Civilization, Marcuse's work influenced

several academic disciplines in the United States and in other

countries.[46] Privitello argued that the chapter on "The Aesthetic

Dimension" had pedagogical value. However, he criticized Marcuse for

relying on an outdated 19th-century translation of Schiller.[48]

Nicholas endorsed Marcuse's "analysis of technological rationality,

aesthetic reason, phantasy, and imagination."[50] |

Hiteは、この本がThomas

Pynchonの小説『重力の虹』(1973年)に影響を与えたとし、Pynchonがオルフェウスを音楽、記憶、遊び、欲求と結びついた人物であるとし

たことに、このことが明らかであると述べている。また、マルクスは「幻想を実現するための補助的なものとして、精神に作用する薬物を訴えてはいない」もの

の、彼の読者の多くは「喜んで推奨していると推察される」とも述べている。彼女は、マルクーゼが小児性愛について言及していない一方で、倒錯したセックス

が「経験を肉体に戻すので、啓示的あるいは脱神秘的」であることができるという彼の議論に合致していると主張した[39]。

デュベナージはこの本を「魅力的」だと述べているが、抑制のない社会に対するマルクーゼの提案が哲学者マリヌス・シューマンによって批判されていると書い

ている[42]。

[ファー、ケルナー、ラマ、ライツは、『エロスと文明』の影響もあって、マルクーゼの仕事はアメリカや他の国のいくつかの学問分野に影響を与えたと書いて

いる[46]。

プリヴィテロは「美的次元」の章は教育的価値があると論じている。しかし彼はマルクーゼが時代遅れの19世紀のシラーの翻訳に依存していると批判していた

[48]。ニコラスはマルクーゼの「技術的合理性、美的理性、幻影、そして想像力の分析」を支持していた[50]。 |

| Other evaluations, 1955–1986 Brown commended Eros and Civilization as the first book, following the work of Reich, to "reopen the possibility of the abolition of repression".[51] The philosopher Paul Ricœur compared his philosophical approach to Freud in Freud and Philosophy (1965) to that of Marcuse in Eros and Civilization.[52] Paul Robinson credited Marcuse and Brown with systematically analyzing psychoanalytic theory in order to reveal its critical implications. He believed they went beyond Reich and the anthropologist Géza Róheim in probing the dialectical subtleties of Freud's thought, thereby reaching conclusions more extreme and utopian than theirs. He found Lionel Trilling's work on Freud, Freud and the Crisis of Our Culture (1955), of lesser value. He saw Brown's exploration of the radical implications of psychoanalysis as in some ways more rigorous and systematic than that of Marcuse. He noted that Eros and Civilization has often been compared to Life Against Death, but suggested that it was less elegantly written. He concluded that while Marcuse's work is psychologically less radical than that of Brown, it is politically bolder, and unlike Brown's, succeeded in transforming psychoanalytic theory into historical and political categories. He deemed Marcuse a finer theorist than Brown, believing that he provided a more substantial treatment of Freud.[53] |

その他の評価、1955年~1986年 ブラウンは『エロスと文明』をライヒの仕事に続いて「抑圧の廃止の可能性を再開した」最初の本であると評価していた[51]。哲学者のポール・リクールは 『フロイトと哲学』(1965)におけるフロイトに対する彼の哲学的アプローチと『エロスと文明』のマルキュースのそれを比較していた[52]。 ポール・ロビンソンはマルキュースとブラウンを精神分析理論をその批判的意味を明らかにするために系統的に分析しているとして信頼していた。彼は彼らがラ イヒや人類学者のゲザ・ロハイムを超えてフロイトの思想の弁証法的な機微を探り、それによって彼らのものよりも極端でユートピア的な結論に到達したと考え ていた。彼は、ライオネル・トリリングのフロイトに関する著作『フロイトとわれわれの文化の危機』(1955年)の価値は低いと考えていた。精神分析のラ ディカルな意味合いについてのブラウンの探求は、ある意味で、マルクーゼのそれよりも厳密で体系的であると彼は考えている。彼は、『エロスと文明』がしば しば『死に対する生命』と比較されることを指摘しながらも、『死に対する生命』の方がよりエレガントに書かれていることを示唆した。そして、マルクーゼの 仕事は、ブラウンよりも心理的には過激ではないが、政治的には大胆であり、ブラウンのものとは異なり、精神分析理論を歴史的・政治的カテゴリーに変換する ことに成功していると結論づけた。彼はマルクーゼをブラウンよりも優れた理論家とみなし、フロイトをより実質的に扱っていると考えていた[53]。 |

| The philosopher Alasdair

MacIntyre criticized Marcuse for focusing on Freud's metapsychology

rather than on psychoanalysis as a method of therapy. He believed that

Marcuse followed speculations that were difficult to either support or

refute, that his discussion of sex was pompous, that he failed to

explain how people whose sexuality was unrepressed would behave, and

uncritically accepted Freudian views of sexuality and failed to conduct

his own research into the topic. He criticized him for his dismissive

treatment of rival theories, such as those of Reich. He also suggested

that Marcuse's goal of reconciling Freudian with Marxist theories might

be impossible, and, comparing his views to those of the philosopher

Ludwig Feuerbach, argued that by returning to the themes of the Young

Hegelian movement Marcuse had retreated to a "pre-Marxist"

perspective.[54] Phil Brown criticized Marcuse's attempt to "synthesize Marx and Freud", arguing that such a synthesis is impossible. He maintained that Marcuse neglected politics, disregarded the class struggle, advocated "sublimation of human spontaneity and creativity", and failed to criticize the underlying assumptions of Freudian thinking.[55] The gay rights activist Dennis Altman followed Robinson in criticizing Marcuse for failing to clarify "whether sexual repression causes economic subordination or vice versa" or to "connect his use of Freud's image of the primal crime with his ideas about the repression of nongenital and homosexual drives". Though influenced by Marcuse, he commented that Eros and Civilization was referred to surprisingly rarely in gay liberation literature. In an afterword to the 1993 edition of the book, he added that Marcuse's "radical Freudianism" was "now largely forgotten" and had never been "particularly popular in the gay movement."[56] |

哲学者のアラスデア・マッキンタイアは、マルクーゼが治療の方法として

の精神分析ではなく、フロイトの形而上学に焦点を当てたことを批判した。彼は、マルクスは支持も反論も困難な思索を続け、彼のセックスについての議論は尊

大であり、セクシュアリティが抑制されていない人々がどのように行動するかを説明できず、フロイトのセクシュアリティについての見解を無批判に受け入れ、

このテーマについて独自の調査を行わなかったと考えていた。また、ライヒのような対抗理論を否定的に扱っていると批判した。彼はまたフロイトの理論とマル

クス主義の理論を調和させるというマルクーゼの目標が不可能かもしれないことを示唆し、彼の見解を哲学者のルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハの見解と比較し

て、若きヘーゲル運動のテーマに戻ることによってマルクーゼが「前マルクス主義」の視点に後退したと主張している[54]。 フィル・ブラウンはマルクスの「マルクスとフロイトを合成する」試みを批判し、そのような合成は不可能であると論じていた。彼はマルクーゼが政治を軽視 し、階級闘争を無視し、「人間の自発性と創造性の昇華」を提唱し、フロイト的思考の根本的な前提を批判することができなかったと主張していた[55]。 ゲイ権利活動家のデニス・アルトマンは、ロビンソンに続いて、「性的抑圧が経済的従属を引き起こすのかその逆なのか」あるいは「原罪というフロイトのイ メージと非生殖性や同性愛の欲望の抑制に関する彼のアイデアとを結びつける」ことができなかったとマルクーゼを批判している。マルクーゼの影響を受けなが らも、「エロスと文明」がゲイ解放の文献で言及されることは驚くほど少なかったとコメントしている。1993年版のあとがきで、彼はマルクーゼの「ラディ カルなフロイト主義」は「今やほとんど忘れられて」おり、「ゲイ運動で特に人気があった」ことはないと付け加えている[56]。 |

| The social psychologist Liam

Hudson suggested that Life Against Death was neglected by radicals

because its publication coincided with that of Eros and Civilization.

Comparing the two works, he found Eros and Civilization more

reductively political and less stimulating.[57] The critic Frederick

Crews argued that Marcuse's proposed liberation of instinct was not a

real challenge to the status quo, since, by taking the position that

such a liberation could only be attempted "after culture has done its

work and created the mankind and the world that could be free", Marcuse

was accommodating society's institutions. He accused Marcuse of

sentimentalism.[58] The psychoanalyst Joel Kovel described Eros and

Civilization as more successful than Life Against Death.[59] The

psychotherapist Joel D. Hencken described Eros and Civilization as an

important example of the intellectual influence of psychoanalysis and

an "interesting precursor" to a study of psychology of the

"internalization of oppression". However, he believed that aspects of

the work have limited its audience.[60] Myriam Malinovich considered Marcuse's earlier Young Hegelian writings more representative of his actual thinking than Eros and Civilization. She concluded that all the esoteric Fruedian theory and endorsements of libertine sexual behavior were ultimately meant only to colorfully illustrate what Marcuse had previously written about concerning the alienating force of the Power Principle.[61] |

社会心理学者のリーアム・ハドソンは、『死に対する生命』の出版が『エ

ロスと文明』の出版と重なったために急進派に軽視されたことを示唆した[57]。批評家のフレデリック・クルーズは、マルクーゼが提案した本能の解放は現

状に対する真の挑戦ではなく、そのような解放は「文化がその仕事を果たし、自由になりうる人間と世界を創造した後に」しか試みられないという立場を取るこ

とによって、マルクーゼは社会の制度を受け入れていると主張した[57]。彼はマルクーゼを感傷主義で非難していた[58]。

精神分析家のジョエル・コヴェルは『エロスと文明』を『死に対する生命』よりも成功したと評していた[59]。心理療法家のジョエル・D・ヘンケンは『エ

ロスと文明』を精神分析の知的影響の重要な例、「圧迫の内部化」の心理学の研究に対する「興味深い前兆」であると評していた。しかしながら、彼はこの作品

の側面がその読者を限定していると考えていた[60]。 Myriam Malinovichは『エロスと文明』よりもマルクスの初期のヤング・ヘーゲル的な著作の方が彼の実際の思考を代表するものであると考えていた。彼女は 難解なフルイドの理論と自由主義的な性行為の推奨は結局のところ、マルキューが以前に書いた権力原理の疎外する力に関することを色鮮やかに説明するためだ けのものであると結論付けている[61]。 |

| The social psychologist Liam

Hudson suggested that Life Against Death was neglected by radicals

because its publication coincided with that of Eros and Civilization.

Comparing the two works, he found Eros and Civilization more

reductively political and less stimulating.[57] The critic Frederick

Crews argued that Marcuse's proposed liberation of instinct was not a

real challenge to the status quo, since, by taking the position that

such a liberation could only be attempted "after culture has done its

work and created the mankind and the world that could be free", Marcuse

was accommodating society's institutions. He accused Marcuse of

sentimentalism.[58] The psychoanalyst Joel Kovel described Eros and

Civilization as more successful than Life Against Death.[59] The

psychotherapist Joel D. Hencken described Eros and Civilization as an

important example of the intellectual influence of psychoanalysis and

an "interesting precursor" to a study of psychology of the

"internalization of oppression". However, he believed that aspects of

the work have limited its audience.[60] Myriam Malinovich considered Marcuse's earlier Young Hegelian writings more representative of his actual thinking than Eros and Civilization. She concluded that all the esoteric Fruedian theory and endorsements of libertine sexual behavior were ultimately meant only to colorfully illustrate what Marcuse had previously written about concerning the alienating force of the Power Principle.[61] |

社会心理学者のリーアム・ハドソンは、『死に対する生命』の出版が『エ

ロスと文明』の出版と重なったために急進派に軽視されたことを示唆した[57]。批評家のフレデリック・クルーズは、マルクーゼが提案した本能の解放は現

状に対する真の挑戦ではなく、そのような解放は「文化がその仕事を果たし、自由になりうる人間と世界を創造した後に」しか試みられないという立場を取るこ

とによって、マルクーゼは社会の制度を受け入れていると主張した[57]。彼はマルクーゼを感傷主義で非難していた[58]。

精神分析家のジョエル・コヴェルは『エロスと文明』を『死に対する生命』よりも成功したと評していた[59]。心理療法家のジョエル・D・ヘンケンは『エ

ロスと文明』を精神分析の知的影響の重要な例、「圧迫の内部化」の心理学の研究に対する「興味深い前兆」であると評していた。しかしながら、彼はこの作品

の側面がその読者を限定していると考えていた[60]。 Myriam Malinovichは『エロスと文明』よりもマルクスの初期のヤング・ヘーゲル的な著作の方が彼の実際の思考を代表するものであると考えていた。彼女は 難解なフロイトの理論と自由主義的な性行為の推奨は結局のところ、マルクーゼが以前に書いた権力原理の疎外する力に関することを色鮮やかに説明するためだ けのものであると結論付けている[61]。 |

| Kellner compared Eros and

Civilization to Ricœur's Freud and Philosophy and the philosopher

Jürgen Habermas's Knowledge and Human Interests (1968). However, he

suggested that Ricœur and Habermas made better use of several Freudian

ideas.[62] The sociologist Jeffrey Weeks criticized Marcuse as

"essentialist" in Sexuality and Its Discontents (1985). Though granting

that Marcuse proposed a "powerful image of a transformed sexuality"

that had a major influence on post-1960s sexual politics, he considered

Marcuse's vision "utopian".[63] The philosopher Jeffrey Abramson credited Marcuse with revealing the "bleakness of social life" to him and forcing him to wonder why progress does "so little to end human misery and destructiveness". He compared Eros and Civilization to Brown's Life Against Death, the cultural critic Philip Rieff's Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (1959), Ricœur's Freud and Philosophy, and Habermas's Knowledge and Human Interests, writing that these works jointly placed Freud at the center of moral and philosophical inquiry. However, he argued that while Marcuse recognized the difficulties of explaining how sublimation could be compatible with a new and non-repressive social order, he presented a confused account of a "sublimation without desexualization" that could make this possible. He described some of Marcuse's speculations as bizarre, and suggested that Marcuse's "vision of Eros" is "imbalanced in the direction of the sublime" and that the "essential conservatism" of his stance on sexuality had gone unnoticed.[64] The philosopher Roger Scruton criticized Marcuse and Brown, describing their proposals for sexual liberation as "another expression of the alienation" they condemned.[65] The anthropologist Pat Caplan identified Eros and Civilization as an influence on student protest movements of the 1960s, apparent in their use of the slogan, "Make love not war".[66] Victor J. Seidler credited Marcuse with showing that the repressive organizations of the instincts described by Freud are not inherent in their nature but emerge from specific historical conditions. He contrasted Marcuse's views with Foucault's.[67] |

ケルナーは『エロスと文明』をリクールの『フロイトと哲学』や哲学者ユ

ルゲン・ハーバーマスの『知識と人間の利益』(1968年)と比較している。しかし彼はリクールとハーバマスがフロイトのいくつかの考えをよりよく利用し

ていることを示唆した[62]。社会学者のジェフリー・ウィークスは『セクシュアリティとその不満』(1985)でマルクーゼを「本質主義者」として批判

している。マルクーゼが1960年代以降の性の政治に大きな影響を与えた「変容したセクシュアリティの力強いイメージ」を提案したことを認めながらも、彼

はマルクーゼのビジョンを「ユートピア的」であるとみなしていた[63]。 哲学者のジェフリー・アブラムソンはマルクーゼが彼に「社会生活の殺風景さ」を明らかにし、進歩がなぜ「人間の不幸と破壊を終わらせるためにほとんど」し ないのかを考えさせたと評価している[63]。彼は『エロスと文明』をブラウンの『死に対する生命』、文化評論家のフィリップ・リエフの『フロイト』と比 較している。そして、『エロスと文明』を、ブラウン『死に対する生命』、文化評論家フィリップ・リーフ『フロイト:道徳主義者の心』(1959)、リクー ル『フロイトと哲学』、ハーバーマス『知と人間の利益』と比較し、これらの著作が共同でフロイトを道徳と哲学的探求の中心に据えていると書いた。しかし、 マルクーゼは、昇華が新しい抑圧的でない社会秩序といかに両立しうるかを説明することの難しさを認識しながらも、それを可能にする「脱色なき昇華」の説明 を混同して提示したと論じた。彼はマルクーゼのいくつかの思索を奇妙なものと評し、マルクーゼの「エロスのビジョン」が「崇高な方向にアンバランス」であ り、彼のセクシュアリティに対する姿勢の「本質的な保守性」が気づかれなかったと示唆した[64]。 哲学者のロジャー・スクルトンはマルクスとブラウンの性的解放のための提案を彼らが非難した「疎外のもう一つの表現」と評して批判した[65]。人類学者 のパット・キャプランはエロスと文明が1960年代の学生の抗議運動に対する影響であるとし、彼らが「戦争ではなく愛を作れ」というスローガンを使うこと に明白であるとした[66]。ヴィクター J. シードラーは、フロイトによって述べられた本能の抑制組織が本質的には固有ではなく特定の歴史的条件から出現していると示したマルクスに信頼をおいてい る。彼はマルクーゼの見解をフーコーの見解と対比させていた[67]。 |

| Other evaluations, 1987–present The philosopher Seyla Benhabib argued that Eros and Civilization continues the interest in historicity present in Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity and that Marcuse views the sources of disobedience and revolt as being rooted in collective memory.[68] Stephen Frosh found Eros and Civilization and Life Against Death to be among the most important advances towards a psychoanalytic theory of art and culture. However, he considered the way these works turn the internal psychological process of repression into a model for social existence as a whole to be disputable.[69] The philosopher Richard J. Bernstein described Eros and Civilization as "perverse, wild, phantasmal and surrealistic" and "strangely Hegelian and anti-Hegelian, Marxist and anti-Marxist, Nietzschean and anti-Nietzschean", and praised Marcuse's discussion of the theme of "negativity".[70] Edward Hyman suggested that Marcuse's failure to state clearly that his hypothesis is the "primacy of Eros" undermined his arguments and that Marcuse gave an insufficiently through consideration of metapsychology.[71] |

その他の評価(1987年~現在) 哲学者のセイラ・ベンハビブは、『エロスと文明』がヘーゲルの『存在論』と『歴史性の理論』に存在する歴史性への関心を継続し、マルクーゼが不服従と反乱 の源を集合的記憶に根ざしたものとして見ていると論じた[68]。 スティーブン・フロッシュは『エロスと文明』と『死に対する生命』が芸術と文化の精神分析理論に対する最も重要な進歩であると認めた[69]。しかしなが ら、彼はこれらの作品が抑圧の内的な心理的プロセスを社会的存在全体のモデルに転化する方法は議論の余地があると考えた[69]。哲学者のリチャード・ J・バーンスタインは『エロスと文明』を「倒錯、野生、幻影、超現実的」、「奇妙なほどヘーゲル的で反ヘーゲル的、マルクス主義者で反マルクシスト、ニー チェ的で反ニーチェ」だとし、「否定」のテーマに対するマルキューの論評を賞賛した[70]。 [70] エドワード・ハイマンは、マルクーゼが自分の仮説が「エロスの優位性」であることを明確に述べなかったことが彼の議論を弱体化させ、マルクーゼが形而上心 理学の考察を十分に通していなかったと示唆した[71]。 |

| Kenneth Lewes endorsed Marcuse's

criticism of the "pseudohumane moralizing" of neo-Freudians such as

Fromm, Horney, Sullivan, and Thompson.[72] Joel Schwartz identified

Eros and Civilization as "one of the most influential Freudian works

written since Freud's death". However, he argued that Marcuse failed to

reinterpret Freud in a way that adds political to psychoanalytic

insights or remedy Freud's "failure to differentiate among various

kinds of civil society", instead simply grouping all existing regimes

as "repressive societies" and contrasting them with a hypothetical

future non-repressive society.[73] Kovel noted that Marcuse studied

with Heidegger but later broke with him for political reasons and

suggested that the Heideggerian aspects of Marcuse's thinking, which

had been in eclipse during Marcuse's most active period with the

Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, reemerged, displaced onto

Freud, in Eros and Civilization.[74] The economist Richard Posner maintained that Eros and Civilization contains "political and economic absurdities" but also interesting observations about sex and art. He credited Marcuse with providing a critique of conventional sexual morality superior to the philosopher Bertrand Russell's Marriage and Morals (1929), but accused Marcuse of wrongly believing that polymorphous perversity would help to create a utopia and that sex has the potential to be a politically subversive force. He considered Marcuse's argument that capitalism has the ability to neutralize the subversive potential of "forces such as sex and art" interesting, though clearly true only in the case of art. He argued that while Marcuse believed that American popular culture had trivialized sexual love, sex had not had a subversive effect in societies not dominated by American popular culture.[75] The historian Arthur Marwick identified Eros and Civilization as the book with which Marcuse achieved international fame, a key work in the intellectual legacy of the 1950s, and an influence on the subcultures of the 1960s.[76] The historian Roy Porter argued that Marcuse's view that "industrialization demanded erotic austerity" was not original, and was discredited by Foucault in The History of Sexuality (1976).[77] |

ケネス・ルイスはフロム、ホーニー、サリバン、トンプソンなどの新フロ

イト主義者の「似非人道的道徳化」に対するマルクーゼの批判を支持した[72]。ジョエル・シュワルツは『エロスと文明』を「フロイトの死後に書かれた最

も影響力のあるフロイトの著作の一つ」として特定した。しかし、彼はマルクゼが精神分析的洞察に政治的なものを加えるような方法でフロイトを再解釈するこ

とも、フロイトの「様々な種類の市民社会を区別することの失敗」を改善することもできず、その代わりに単に既存のすべてのレジームを「抑圧社会」としてグ

ループ化し、それらを仮想の未来の非抑圧社会と対比していると論じている[73]。

[コヴェルはマルクーゼがハイデガーに学んだが、後に政治的な理由から彼と決別したことを指摘し、マルクーゼがフランクフルト社会研究所で最も活動してい

た時期に食われていたマルクーゼの思考のハイデガー的側面が、『エロスと文明』でフロイトに置き換わって再登場していると示唆していた[74]。 経済学者のリチャード・ポズナーは『エロスと文明』には「政治的・経済的不条理」が含まれているが、セックスと芸術についての興味深い観察も含まれている と主張している。彼はマルクーゼが哲学者バートランド・ラッセルの『結婚と道徳』(1929)よりも優れた従来の性道徳の批判を提供したと評価している が、多形的な倒錯がユートピアの創造に役立つと間違って信じ、セックスが政治的に破壊的な力となる可能性を秘めているとマルクーゼを非難している。彼は、 資本主義が「セックスや芸術のような力」の破壊的な潜在力を中和する能力を持っているというマルクーゼの議論を、芸術の場合にのみ明らかに正しいが、興味 深いものだと考えた。歴史家のアーサー・マーウィックは、『エロスと文明』をマルクーゼが国際的名声を獲得した本であり、1950年代の知的遺産における 重要な作品であり、1960年代のサブカルチャーに影響を与えた本であるとした[75]。 [歴史家のロイ・ポーターは、「産業化がエロティックな緊縮を要求した」というマルクーゼの見解はオリジナルではなく、フーコーによって『性の歴史』 (1976年)で否定されたと論じている[77]。 |

| The philosopher Todd Dufresne

compared Eros and Civilization to Brown's Life Against Death and the

anarchist author Paul Goodman's Growing Up Absurd (1960). He questioned

to what extent Marcuse's readers understood his work, suggesting that

many student activists might have shared the view of Morris Dickstein,

to whom it work meant, "not some ontological breakthrough for human

nature, but probably just plain fucking, lots of it".[78] Anthony

Elliott identified Eros and Civilization as a "seminal" work.[79] The

essayist Jay Cantor described Life Against Death and Eros and

Civilization as "equally profound".[80] The philosopher James Bohman wrote that Eros and Civilization "comes closer to presenting a positive conception of reason and Enlightenment than any other work of the Frankfurt School."[81] The historian Dagmar Herzog wrote that Eros and Civilization was, along with Life Against Death, one of the most notable examples of an effort to "use psychoanalytic ideas for culturally subversive and emancipatory purposes". However, she believed that Marcuse's influence on historians contributed to the acceptance of the mistaken idea that Horney was responsible for the "desexualization of psychoanalysis."[82] The critic Camille Paglia wrote that while Eros and Civilization was "one of the centerpieces of the Frankfurt School", she found the book inferior to Life Against Death. She described Eros and Civilization as "overschematic yet blobby and imprecise".[83] |

哲学者のトッド・デュフレーヌは、『エロスと文明』をブラウンの『死に

対する生命』やアナーキスト作家ポール・グッドマンの『不条理の成長』(1960年)と比較している。彼はマルクーゼの読者が彼の作品をどの程度理解して

いたのかを疑問視し、多くの学生活動家がこの作品が「人間性のための存在論的な突破口ではなく、おそらく単なるクソ、たくさん」を意味していたモリス・

ディクスタインの見解を共有していたかもしれないと示唆している[78]。

アンソニー・エリオットは『エロスと文明』を「精髄」作品として特定している[79]。エッセイストのジェイ・カンターは『生と死』と『エロスと文明』を

「同様に深い」ものとして記述している[80]。 哲学者のジェームズ・ボーマンは『エロスと文明』を「フランクフルト学派の他のどの作品よりも理性と啓蒙の肯定的な概念を提示するのに近い」と書いている [81]。歴史家のダグマー・ヘルツォークは『エロスと文明』を『死に対する生命』と並んで「文化的破壊と解放のために精神分析の考えを使用」しようとす る最も顕著な例の一つだと書いている。しかし、彼女は、歴史家に対するマルクーゼの影響が、ホーニーが「精神分析の脱俗化」に責任があったという誤った考 えを受け入れることに貢献したと考えていた[82]。批評家カミーユ・パリアは、『エロスと文明』が「フランクフルト学派の中心的な作品の一つ」でありな がら、この本は『死に対して生きる』に劣ると書いている。彼女は『エロスと文明』を「過度なまでに図式的でありながら、ぶよぶよして不正確」であると評し ている[83]。 |

| Other views The gay rights activist Jearld Moldenhauer discussed Marcuse's views in The Body Politic. He suggested that Marcuse found the gay liberation movement insignificant, and criticized Marcuse for ignoring it in Counterrevolution and Revolt (1972), even though many gay activists had been influenced by Eros and Civilization. He pointed to Altman as an activist who had been inspired by the book, which inspired him to argue that the challenge to "conventional norms" represented by gay people made them revolutionary.[84] Rainer Funk wrote in Erich Fromm: His Life and Ideas (2000) that Fromm, in a letter to the philosopher Raya Dunayevskaya, dismissed Eros and Civilization as an incompetent distortion of Freud and "the expression of an alienation and despair masquerading as radicalism" and referred to Marcuse's "ideas for the future man" as irrational and sickening.[85] |

その他の見解 ゲイの権利活動家であるJearld Moldenhauerは、『The Body Politic』の中でマルクーゼの見解を論じている。彼は、マルクーゼがゲイ解放運動を重要視していないことを示唆し、多くのゲイ活動家が『エロスと文 明』に影響を受けていたにもかかわらず、『反革命と反乱』(1972年)でマルクーゼがこれを無視したと批判している。彼はこの本に触発された活動家とし てアルトマンを挙げ、ゲイの人々が代表する「従来の規範」に対する挑戦が彼らを革命的にしていると主張するきっかけとなった[84] ライナー・ファンクは『エーリッヒ・フロム: His Life and Ideas』(2000年)で、フロムは哲学者のラヤ・デュナエフスカヤに宛てた手紙の中で『エロスと文明』をフロイトの無能な歪曲であり「急進主義を 装った疎外と絶望の表現」だと断じ、マルクーゼの「未来の人間に対する考え」を非合理で気持ちが悪いと言及したことを述べている[85]。 |

| The gay rights activist Jeffrey

Escoffier discussed Eros and Civilization in GLBTQ Social Sciences,

writing that it "played an influential role in the writing of early

proponents of gay liberation", such as Altman and Martin Duberman, and

"influenced radical gay groups such as the Gay Liberation Front's Red

Butterfly Collective", which adopted as its motto the final line from

the "Political Preface" of the 1966 edition of the book: "Today the

fight for life, the fight for Eros, is the political fight." Escoffier

noted, however, that Marcuse later had misgivings about sexual

liberation as it developed in the United States, and that Marcuse's

influence on the gay movement declined as it embraced identity

politics.[86] According to P. D. Casteel, Eros and Civilization is, with One-Dimensional Man, the work Marcuse is best known for.[87] |

ゲイの権利活動家ジェフリー・エスコフィエは、『GLBTQ社会科学』

で『エロスと文明』を取り上げ、アルトマンやマーティン・デュバーマンといった「初期のゲイ解放論者の著作に影響力を及ぼし」、「ゲイ解放戦線の赤い蝶集

団のような過激なゲイ集団に影響を与え」、同書が1966年度版の「政治序文」の最後の一行を標語に採用したと書いている。「今日、生命のための戦い、エ

ロスのための戦いは、政治的な戦いなのだ」。しかし、エスコフィエは、マルクーゼが後にアメリカで発展した性的解放に疑念を抱いており、ゲイ運動がアイデ

ンティティ・ポリティクスを受け入れるにつれてマルクーゼの影響力は低下していったと指摘している[86]。 P・D・カスティールによれば、『エロスと文明』は『一次元的人間』と並んでマルクーゼが最もよく知られた著作である[87]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Marcuse |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆