ヨーロッパ中心主義

Eurocentrism

☆ヨーロッパ中心主義(Eurocentrism、Eurocentricity、

Western-centrism)[1]とは、西洋を世界史の中心と見なす、または他の文化よりも優れていると考える思想を指す。ヨーロッパ中心主義の

正確な範囲は、西洋世界全体からヨーロッパ大陸、さらに狭くは西ヨーロッパ(特に冷戦時代)までさまざまです。歴史的にこの用語が用いられる場合、ヨー

ロッパの視点から見た歴史を客観的または絶対的なものとして提示すること、またはヨーロッパの植民地主義やその他の帝国主義形態に対する弁解的な立場を指

すことがあります。[2][3][4]

「ヨーロッパ中心主義」という用語は 1970 年代後半に誕生したが、1990

年代になって、工業化国が開発途上国に対して行った脱植民地化、開発、人道支援の文脈で頻繁に使用されるようになり、広く普及した。以来、この用語は、西

欧の進歩叙述、非西欧の貢献を軽視または無視した西欧の学者たちを批判し、西欧の認識論と先住民の認識論を対比するために用いられてきた。[5][6]

[7]

| Eurocentrism (also

Eurocentricity or Western-centrism)[1] refers to viewing the West as

the center of world events or superior to other cultures. The exact

scope of Eurocentrism varies from the entire Western world to just the

continent of Europe or even more narrowly, to Western Europe

(especially during the Cold War). When the term is applied

historically, it may be used in reference to the presentation of the

European perspective on history as objective or absolute, or to an

apologetic stance toward European colonialism and other forms of

imperialism.[2][3][4] The term "Eurocentrism" dates back to the late 1970s but it did not become prevalent until the 1990s, when it was frequently applied in the context of decolonization and development and humanitarian aid that industrialised countries offered to developing countries. The term has since been used to critique Western narratives of progress, Western scholars who have downplayed and ignored non-Western contributions, and to contrast Western epistemologies with indigenous epistemologies.[5][6][7] |

ヨーロッパ中心主義(Eurocentrism、

Eurocentricity、Western-centrism)[1]とは、西洋を世界史の中心と見なす、または他の文化よりも優れていると考える思

想を指す。ヨーロッパ中心主義の正確な範囲は、西洋世界全体からヨーロッパ大陸、さらに狭くは西ヨーロッパ(特に冷戦時代)までさまざまです。歴史的にこ

の用語が用いられる場合、ヨーロッパの視点から見た歴史を客観的または絶対的なものとして提示すること、またはヨーロッパの植民地主義やその他の帝国主義

形態に対する弁解的な立場を指すことがあります。[2][3][4] 「ヨーロッパ中心主義」という用語は 1970 年代後半に誕生したが、1990 年代になって、工業化国が開発途上国に対して行った脱植民地化、開発、人道支援の文脈で頻繁に使用されるようになり、広く普及した。以来、この用語は、西 欧の進歩叙述、非西欧の貢献を軽視または無視した西欧の学者たちを批判し、西欧の認識論と先住民の認識論を対比するために用いられてきた。[5][6] [7] |

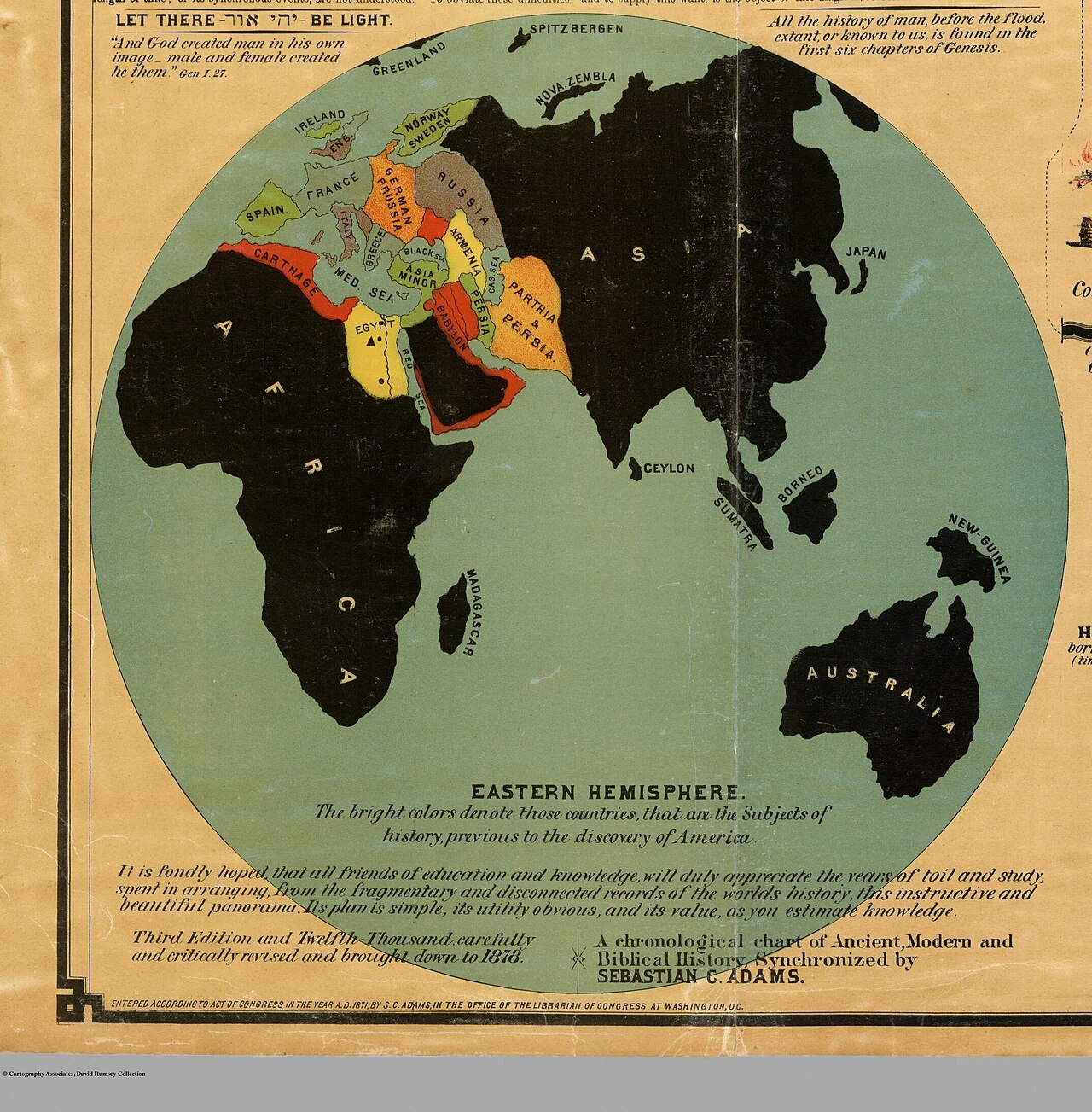

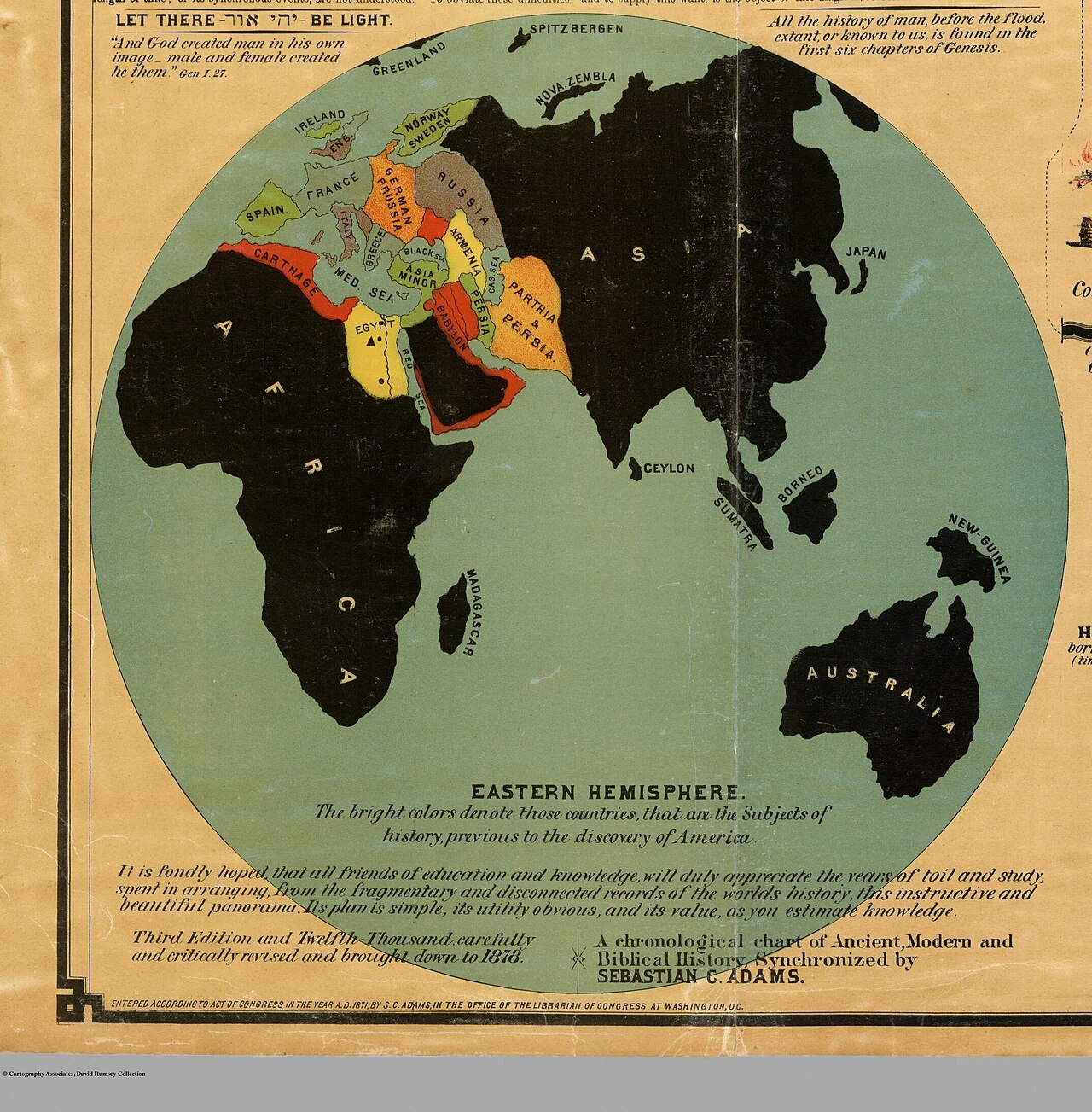

A map of the Eastern Hemisphere from Adams Synchronological Chart or Map of History. "The bright colors denote those countries that are the Subjects of history, previous to the discovery of America". |

アダムズの「歴史の同期図」または「歴史の地図」による東半球の地図。「明るい色は、アメリカ大陸の発見以前の、歴史の主題となった国々を表している」。 |

| Terminology Eurocentrism as the term for an ideology was coined by Samir Amin in the 1970s. The adjective Eurocentric, or Europe-centric, has been in use in various contexts since at least the 1920s.[8] The term was popularised (in French as européocentrique) in the context of decolonization and internationalism in the mid-20th century.[9] English usage of Eurocentric as an ideological term in identity politics was current by the mid-1980s.[10] The abstract noun Eurocentrism (French eurocentrisme, earlier europocentrisme) as the term for an ideology was coined in the 1970s by the Egyptian Marxian economist Samir Amin, then director of the African Institute for Economic Development and Planning of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.[11] Amin used the term in the context of a global, core–periphery or dependency model of capitalist development. English usage of Eurocentrism is recorded by 1979.[12][13] According to Amin, Eurocentrism dates back to the Renaissance, and did not flourish until the 19th century.[14] The coinage of Western-centrism is younger, attested in the late 1990s, and specific to English.[15] |

用語 「ヨーロッパ中心主義」という用語は、1970年代にサミール・アミンによって造語された。 形容詞「ヨーロッパ中心主義的」または「ヨーロッパ中心」は、少なくとも1920年代からさまざまな文脈で使用されてきた。[8] この用語は、20世紀半ばの脱植民地化と国際主義の文脈で(フランス語の「européocentrique」として)普及した。[9] 英語で「ヨーロッパ中心主義」をアイデンティティ政治におけるイデオロギー用語として使用することが一般的になったのは、1980年代半ば頃だ。[10] イデオロギーを表す抽象名詞「ヨーロッパ中心主義」(フランス語:eurocentrisme、以前は europocentrisme)は、1970年代に、エジプト出身のマルクス主義経済学者であり、当時国連アフリカ経済委員会アフリカ経済開発計画研究 所所長だったサミール・アミンによって造られた。アミンは、この用語を、資本主義発展のグローバルな中心-周辺モデル、あるいは依存モデルという文脈で使 用した。英語での「ヨーロッパ中心主義」の使用は1979年に記録されている。[12][13] アミンによると、ヨーロッパ中心主義はルネサンス時代にまでさかのぼり、19世紀まで盛んにはならなかった。[14] 「西洋中心主義」という用語はより新しく、1990年代後半に確認され、英語に特有のものだ。[15] |

| History According to historian Enrique Dussel, Eurocentrism has its roots in Hellenocentrism.[16] Art historian and critic Christopher Allen points out that since antiquity, the outward-looking spirit of Western civilization has been more curious about other peoples and more open about learning about them than any other: Herodotus and Strabo travelled through Ancient Egypt and wrote about it in detail; Western explorers mapped the whole surface of the globe; Western scholars carried out fundamental research into all the languages of the world and established the sciences of archaeology and anthropology.[17][relevant?] |

歴史 歴史家エンリケ・ドゥセルによると、ヨーロッパ中心主義はヘレノセントリズムにそのルーツがある[16]。美術史家であり評論家のクリストファー・アレン は、古代以来、西洋文明は他の文明よりも他者に対して好奇心が強く、他者について学ぶことにオープンであったと指摘している。ヘロドトスやストラボンは古 代エジプトを旅し、その様子を詳細に記した。西洋の探検家は地球の表面全体を地図に描き、西洋の学者たちは世界のあらゆる言語について基礎的な研究を行 い、考古学や人類学という科学を確立した。[17][関連性あり? |

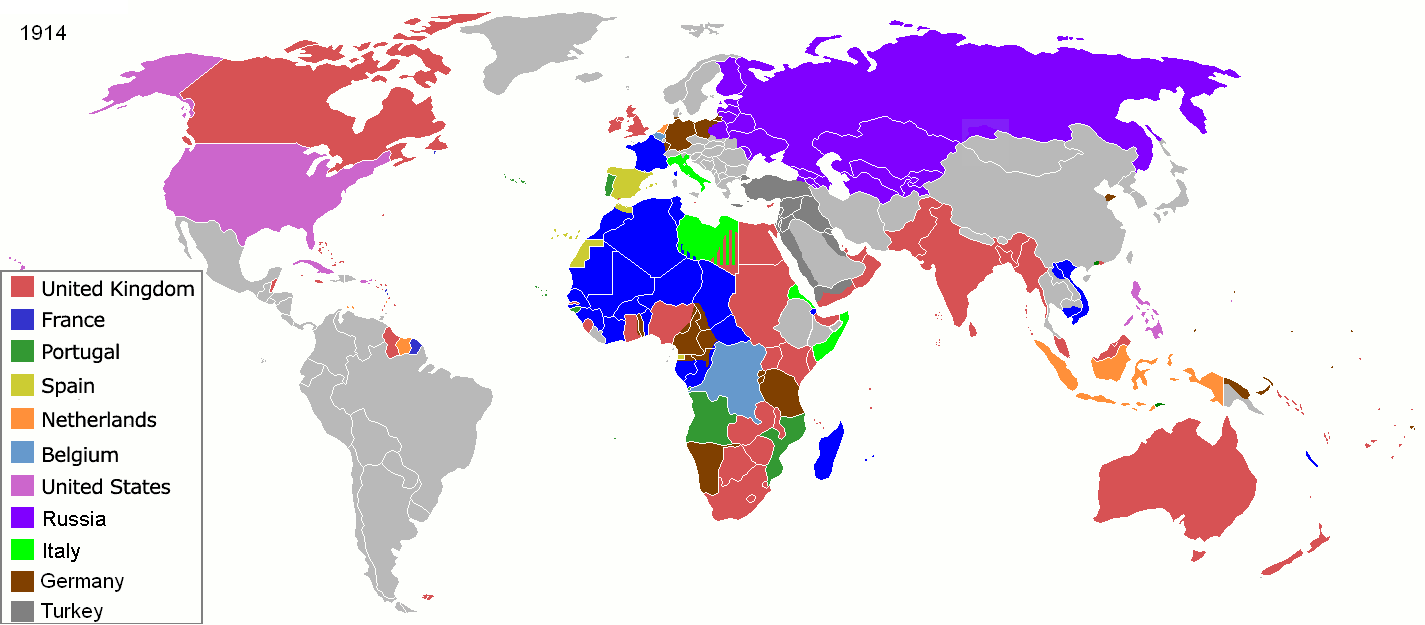

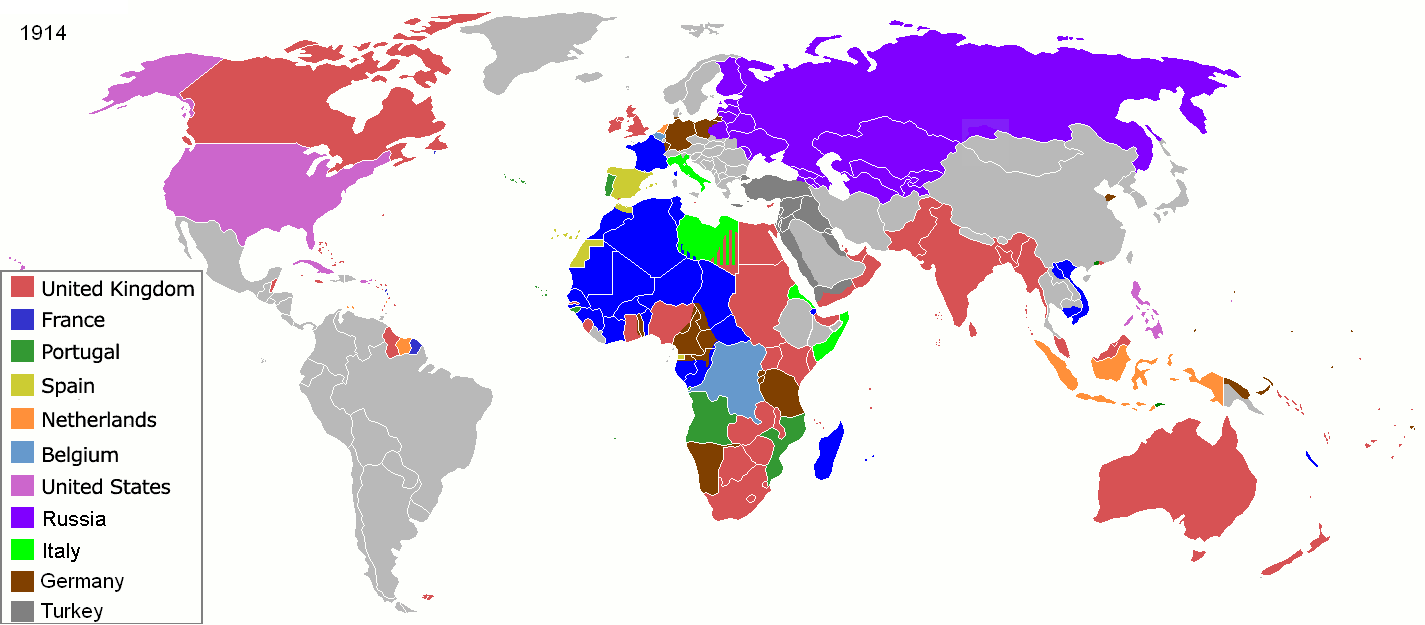

| European exceptionalism Further information: Great Divergence, The European Miracle, Middle Ages, Age of Discovery, Colonialism, Progressivism, and Western world  European colonial powers in 1914, before the start of World War I During the European colonial era, encyclopedias often sought to give a rationale for the predominance of European rule during the colonial period by referring to a special position taken by Europe compared to the other continents. Thus Johann Heinrich Zedler, in 1741, wrote that "even though Europe is the smallest of the world's four continents, it has for various reasons a position that places it before all others.... Its inhabitants have excellent customs, they are courteous and erudite in both sciences and crafts".[18] The Brockhaus Enzyklopädie (Conversations-Lexicon) of 1847 still expressed an ostensibly Eurocentric approach and claimed about Europe that "its geographical situation and its cultural and political significance is clearly the most important of the five continents, over which it has gained a most influential government both in material and even more so in cultural aspects".[19] European exceptionalism thus grew out of the Great Divergence of the Early Modern period, due to the combined effects of the Scientific Revolution, the Commercial Revolution, and the rise of colonial empires, the Industrial Revolution and a Second European colonization wave. The assumption of European exceptionalism is widely reflected in popular genres of literature, especially in literature for young adults (for example, Rudyard Kipling's 1901 novel Kim[20]) and in adventure-literature in general. Portrayal of European colonialism in such literature has been analysed in terms of Eurocentrism in retrospect, such as presenting idealised and often exaggeratedly masculine Western heroes, who conquered "savage" peoples in the remaining "dark spaces" of the globe.[21] The European miracle, a term coined by Eric Jones in 1981,[22] refers to the surprising rise of Europe during the Early Modern period. During the 15th to 18th centuries, a great divergence took place, comprising the European Renaissance, the European Age of Discovery, the formation of European colonial empires, the Age of Reason, and the associated leap forward in technology and the development of capitalism and early industrialization. As a result, by the 19th century European powers dominated world trade and world politics. In Lectures on the Philosophy of History, published in 1837, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel describes world history as starting in Asia but shifting to Greece and Italy, and then north of the Alps to France, Germany and England.[23][24] Hegel interpreted India and China as stationary countries, lacking inner momentum. Hegel's China replaced the real historical development with a fixed, stable scenario, which made it the outsider of world history. Both India and China were waiting and anticipating a combination of certain factors from outside until they could acquire real progress in human civilization.[25] Hegel's ideas had a profound impact on western historiography and attitudes. Some scholars disagree with his ideas that the Oriental countries were outside of world history.[26]  Courtyard of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, circa 1670 |

ヨーロッパの例外主義 詳細情報:大分岐、ヨーロッパの奇跡、中世、大航海時代、植民地主義、進歩主義、西洋世界  第一次世界大戦開始前の1914年のヨーロッパの植民地支配国 ヨーロッパの植民地時代、百科事典は、植民地時代におけるヨーロッパの支配の優位性を説明するために、ヨーロッパが他の大陸に比べて特別な立場にあることをしばしば指摘していました。 例えば、ヨハン・ハインリヒ・ツェドラーは1741年に「ヨーロッパは世界の4大陸のうち最も小さいが、さまざまな理由から他のすべてに先立つ地位を占めている。その住民は優れた習慣を持ち、礼儀正しく、科学と技術の両面で博学である」と記した。[18] 1847年の『ブロックハウス百科事典(会話事典)』は、依然として明らかにヨーロッパ中心主義的なアプローチを表明し、ヨーロッパについて「その地理的 位置、文化的、政治的重要性は、5大陸の中で明らかに最も重要であり、物質的側面だけでなく、文化的な側面においても、最も影響力のある政府を獲得してい る」と主張している。[19] このように、ヨーロッパの例外主義は、科学革命、商業革命、植民地帝国の台頭、産業革命、そして第二次ヨーロッパ植民地化の流れが相まって、近世初期の「大分岐」から生まれたものだよ。 ヨーロッパの例外主義の仮定は、文学のポピュラーなジャンル、特に若者向け文学(例えば、ラドヤード・キップリングの1901年の小説『キム』[20]) や冒険文学全般に広く反映されている。このような文学におけるヨーロッパの植民地主義の描写は、世界に残った「暗黒の空間」で「野蛮な」人民を征服した、 理想化され、しばしば誇張された男らしい西洋の英雄たちを描いているなど、後になってヨーロッパ中心主義の観点から分析されている[21]。 1981年にエリック・ジョーンズが造語した「ヨーロッパの奇跡」[22]とは、近世におけるヨーロッパの驚異的な台頭を指す。15世紀から18世紀にか けて、ヨーロッパのルネサンス、ヨーロッパの発見の時代、ヨーロッパの植民地帝国の形成、合理主義の時代、および関連する技術革新と資本主義の初期工業化 を含む大きな分岐が起こった。その結果、19世紀までにヨーロッパ諸国は世界貿易と世界政治を支配するようになった。 1837年に発表された『歴史哲学講義』で、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルは、世界史はアジアで始まり、ギリシャとイタリアへ移り、そ の後アルプス以北のフランス、ドイツ、イギリスへ移ったと記述している。[23][24] ヘーゲルはインドと中国を内的な推進力に欠ける停滞した国と解釈した。ヘーゲルの中国は、現実の歴史的発展を固定された安定したシナリオで置き換え、世界 史の外部に追いやった。インドと中国は、人間文明の真の進歩を獲得するまで、外部からの特定の要因の組み合わせを待ち望んでいた。[25] ヘーゲルの思想は、西洋の歴史学と態度に深い影響を与えた。一部の学者は、東洋諸国が世界史の外にあるという彼の考えに反対している。[26]  1670年頃のアムステルダム証券取引所の庭 |

| Max

Weber (1864-1920) suggested that capitalism is the speciality of

Europe, because Oriental countries such as India and China do not

contain the factors which would enable them to develop capitalism in a

sufficient manner.[27][need quotation to verify] Weber wrote and

published many treatises in which he emphasized the distinctiveness of

Europe. In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905), he

wrote that the "rational" capitalism, manifested by its enterprises and

mechanisms, only appeared in the Protestant western countries, and a

series of generalised and universal cultural phenomena only appear in

the west.[28] Even the state, with a written constitution and a government organised by trained administrators and constrained by rational law, only appears in the West, even though other regimes can also comprise states.[29] ("Rationality" is a multi-layered term whose connotations are developed and escalated as with the social progress. Weber regarded rationality as a proprietary article for western capitalist society.) |

マッ

クス・ヴェーバー(1864-1920)は、インドや中国などの東洋諸国には資本主義を十分に発展させる要因がないため、資本主義はヨーロッパの特殊性で

あると主張した[27][要出典]。ヴェーバーは、ヨーロッパの特殊性を強調した多くの論文を執筆、発表している。『プロテスタントの倫理と資本主義の精

神』(1905年)では、企業とその仕組みによって表れる「合理的な」資本主義は、プロテスタントの西洋諸国でのみ出現し、一連の一般化・普遍化した文化

現象も西洋でのみ出現すると述べている。[28] 憲法が制定され、訓練を受けた行政官によって組織され、合理的な法律によって制約されている国家でさえ、他の体制も国家を構成することはできるにもかかわ らず、西洋にのみ出現している。[29](「合理性」は多層的な用語であり、その意味は社会の進歩とともに発展し、拡大している。ヴェーバーは、合理性を 西洋の資本主義社会の専有物と見なしていた。 |

| Anticolonialism Even in the 19th century, anticolonial movements had developed claims about national traditions and values that were set against those of Europe in Africa and India. In some cases, as China, where local ideology was even more exclusionist than the Eurocentric one, Westernization did not overwhelm longstanding Chinese attitudes to its own cultural centrality.[30] Orientalism developed in the late 18th century as a disproportionate Western interest in and idealization of Eastern (i.e. Asian) cultures. By the early 20th century, some historians, such as Arnold J. Toynbee, were attempting to construct multifocal models of world civilizations. Toynbee also drew attention in Europe to non-European historians, such as the medieval Tunisian scholar Ibn Khaldun. He also established links with Asian thinkers, such as through his dialogues with Daisaku Ikeda of Soka Gakkai International.[31] |

反植民地主義 19 世紀においても、反植民地運動は、アフリカやインドにおいて、ヨーロッパの伝統や価値観に対抗する、自国の伝統や価値観を主張する動きを展開していまし た。中国のように、ヨーロッパ中心主義よりもさらに排他的なイデオロギーが根付いていた場合、西洋化によって、自国の文化の中心性に対する長年の考え方が 覆されることはなかったのです。[30] オリエンタリズムは、18世紀後半、西洋が東洋(すなわちアジア)の文化に過度の関心と理想化を抱くことで発展した。 20世紀初頭には、アーノルド・J・トインビーのような歴史家たちが、多焦点的な世界文明モデルを構築しようとしていた。トインビーはまた、ヨーロッパに おいて非ヨーロッパの歴史家、例えば中世のチュニジアの学者イブン・ハルドゥーンに注目させた。彼はまた、創価学会国際の池田大作との対話を通じて、アジ アの思想家とのつながりを築いた。[31] |

| Transformations of eurocentrism Authors show that since its first conceptualization, the concept of eurocentrism has evolved. Alina Sajed and John Hobson[32] point to the emergence of a critical eurocentrism, stressing that 'while [critical IR theory] is certainly critical of the West, nevertheless its tendency towards "Eurofetishism" –by which Western agency is reified at the expense of non-Western agency– leads it into a "critical Eurocentrism". Expanding on their work, Audrey Alejandro has put forward the idea of a postcolonial eurocentrism, understood as an emerging form of Eurocentrism that follows the criteria of Eurocentrism commonly mentioned in the literature – denial of 'non-Western' agency, teleological narrative centred on the 'West' and idealization of the 'West' as normative referent—but whose system of value is the complete opposite of the one embodied by traditional Eurocentrism: With postcolonial Eurocentrism, Europe is also considered to be the primary "proactive" subject of world politics—but, in this case, by being described as the leading edge of global oppression, not progress. Indeed, according to postcolonial Eurocentrism, European capacity to homogenise the world according to its own standards of unification is considered to be a malevolent process (i.e. the destruction of diversity) rather than a benevolent one (i.e. a show of positive leadership). In both forms of Eurocentrism, the discourse performs "the West" as the main actor capable of organising the world in its image. European exceptionalism remains the same—although, from the postcolonial Eurocentric view, Europe is not considered to be the best actor ever, but the worst.'[33] |

ヨーロッパ中心主義の変容 著者らは、ヨーロッパ中心主義という概念が最初に提唱されて以来、その概念は進化してきたことを示している。Alina Sajed と John Hobson[32] は、批判的ヨーロッパ中心主義の出現を指摘し、「(批判的国際関係論は)確かに西洋を批判しているが、それにもかかわらず、非西洋の主体を犠牲にして西洋 の主体を物象化する「ヨーロッパ崇拝」への傾向により、批判的ヨーロッパ中心主義に陥っている」と強調している。彼らの研究を拡大し、オードリー・アレハ ンドロは「ポストコロニアル・ユーロセントリズム」という概念を提唱した。これは、ユーロセントリズムの新たな形態として理解され、 文献で一般的に言及されるヨーロッパ中心主義の基準(非西洋の主体性の否定、「西洋」を中心とした目的論的物語、「西洋」を規範的参照対象として理想化) を満たしているが、その価値観は伝統的なヨーロッパ中心主義の価値観とはまったく逆のものだ。ポストコロニアル・ヨーロッパ中心主義では、ヨーロッパも世 界政治の主要な「積極的な」主体とみなされていますが、この場合は、進歩の先駆者ではなく、世界的な抑圧の先駆者として描かれているのです。実際、ポスト コロニアル・ヨーロッパ中心主義によれば、ヨーロッパが自らの統一基準に従って世界を均質化する能力は、慈悲深いプロセス(つまり、多様性の破壊)ではな く、悪意に満ちたプロセス(つまり、積極的なリーダーシップの表れ)とみなされている。どちらのヨーロッパ中心主義においても、この言説は、「西洋」を、 自らのイメージに従って世界を組織化できる主要な主体として表現している。ヨーロッパの例外主義は変わらない——ただし、ポストコロニアル・ヨーロッパ中 心主義の視点からは、ヨーロッパは史上最高の主体ではなく、最悪の主体と見なされている。[33] |

| Recent usage Arab journalists detected Eurocentrism in western media coverage of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, when the depth and scope of coverage and concern contrasted with that devoted to longer-running contemporary wars outside Europe such as those in Syria and in Yemen.[34] In football, the term Eurocentrism is used to critique the economic dominance UEFA has over club football teams from the rest of the world and how it negatively impacts the sport.[35][36][37] |

最近の使用例 アラブのジャーナリストたちは、2022年2月のロシアのウクライナ侵攻に関する欧米メディアの報道において、報道の深さと範囲、および懸念が、シリアや イエメンなど、ヨーロッパ以外で長期化している現代戦争に対する報道とは対照的であることから、ヨーロッパ中心主義を指摘した。[34] サッカーでは、欧州サッカー連盟(UEFA)が世界の他の地域のクラブチームに対して持つ経済的な優位性と、それがスポーツに与える悪影響を批判するために、「ヨーロッパ中心主義」という用語が使われている。[35][36][37] |

| Debate and academic discourse Eurocentrism has been a particularly important concept in development studies.[38] Brohman (1995) argued that Eurocentrism "perpetuated intellectual dependence on a restricted group of prestigious Western academic institutions that determine the subject matter and methods of research".[38] In treatises on historical or contemporary Eurocentrism that appeared since the 1990s, Eurocentrism is mostly cast in terms of dualisms such as civilised/barbaric or advanced/backward, developed/undeveloped, core/periphery, implying "evolutionary schemas through which societies inevitably progress", with a remnant of an "underlying presumption of a superior white Western self as referent of analysis."[39] Eurocentrism and the dualistic properties that it labels on non-European countries, cultures and persons have often been criticised in the political discourse of the 1990s and 2000s, particularly in the greater context of political correctness, race in the United States and affirmative action.[40][41] In the 1990s, there was a trend of criticising various geographic terms current in the English language as Eurocentric, such as the traditional division of Eurasia into Europe and Asia[42] or the term Middle East.[43] Eric Sheppard, in 2005, argued that contemporary Marxism itself has Eurocentric traits (in spite of "Eurocentrism" originating in the vocabulary of Marxian economics), because it supposes that the third world must go through a stage of capitalism before "progressive social formations can be envisioned".[5] Andre Gunder Frank harshly criticised Eurocentrism. He believed that most scholars were the disciples of the social sciences and history guided by Eurocentrism.[6] He criticised some Western scholars for their ideas that non-Western areas lack outstanding contributions in history, economy, ideology, politics and culture compared with the West.[44] These scholars believed that the same contribution made by the West gives Westerners an advantage of endo-genetic momentum which is pushed towards the rest of the world, but Frank believed that the Oriental countries also contributed to the human civilization in their own perspectives. Arnold Toynbee in his A Study of History, gave a critical remark on Eurocentrism. He believed that although western capitalism shrouded the world and achieved a political unity based on its economy, the Western countries cannot "westernize" other countries.[45] Toynbee concluded that Eurocentrism is characteristic of three misconceptions manifested by self-centerment, the fixed development of Oriental countries and linear progress.[46] |

議論と学術的言説 ヨーロッパ中心主義は、開発学において特に重要な概念となっている[38]。ブローム(1995)は、ヨーロッパ中心主義は「研究の対象や方法を決定する、限られた一流の西洋学術機関への知的依存を永続させた」と主張している[38]。 1990年代以降に出版された、歴史的または現代的なヨーロッパ中心主義に関する論文では、 ヨーロッパ中心主義は、文明/野蛮、先進/後進、発展/未発達、中心/周辺といった二項対立の枠組みで捉えられ、これらは「社会が不可避的に進歩する進化 論的枠組み」を暗示し、分析の基準となる「優越的な白人西洋自己」という潜在的な前提が残っている。[39] ヨーロッパ中心主義と、それが非ヨーロッパ諸国、文化、人格に付与する二元的な特性は、1990年代から2000年代の政治言説、特にポリティカル・コレ クトネス、アメリカの人種問題、アファーマティブ・アクションなどの大きな文脈の中で、しばしば批判されてきた。[41] 1990年代には、ヨーロッパとアジアへの伝統的な区分[42] や「中東」という用語など、英語で使用されているさまざまな地理的用語をヨーロッパ中心主義的であると批判する傾向があった。[43] エリック・シェパードは2005年に、現代のマルクス主義は(マルクス経済学用語に「ヨーロッパ中心主義」という用語があるにもかかわらず)第三世界は 「進歩的な社会構造を構想する」前に資本主義の段階を経なければならないと想定しているため、ヨーロッパ中心主義的特徴を持っていると主張した。[5] アンドレ・グンダー・フランクは、ヨーロッパ中心主義を厳しく批判した。彼は、ほとんどの学者はヨーロッパ中心主義に導かれた社会科学や歴史の弟子である と信じていた[6]。彼は、西洋以外の地域は、西洋に比べて歴史、経済、イデオロギー、政治、文化において顕著な貢献をしていないという一部の西洋学者の 考えを批判した。[44] これらの学者たちは、西欧がもたらした同じ貢献が、西欧人に内発的な勢いの優位性を与え、それが世界に残る地域に押し付けられると主張したが、フランク は、東方諸国も独自の視点から人類文明に貢献したと主張した。 アーノルド・トインビーは『歴史の研究』において、ヨーロッパ中心主義に批判的なコメントを述べた。彼は、西洋の資本主義が世界を覆い、その経済に基づい て政治的統一を達成したものの、西洋諸国は他の国を「西洋化」することはできないと主張した。[45] トインビーは、ヨーロッパ中心主義は、自己中心性、東方諸国の発展の固定化、線形的進歩という3つの誤解によって特徴付けられると結論付けた。[46] |

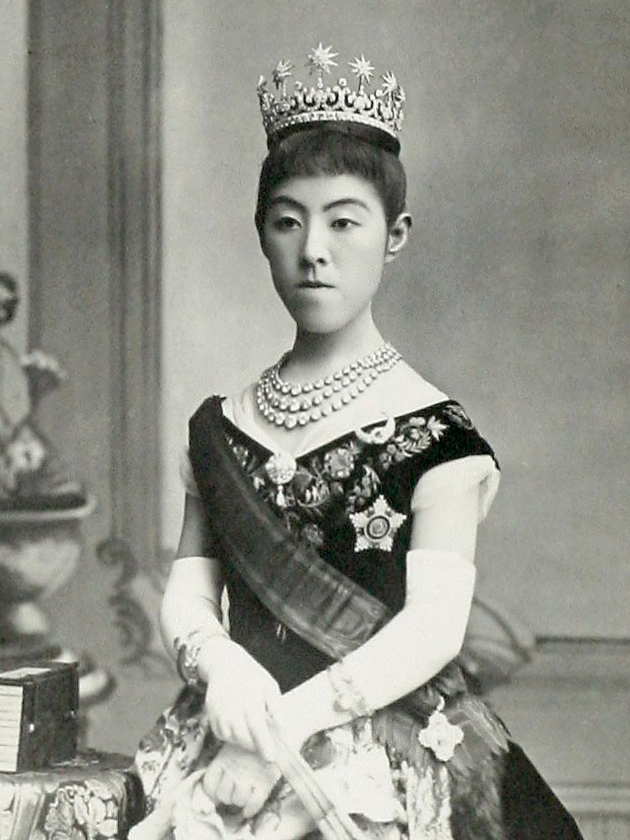

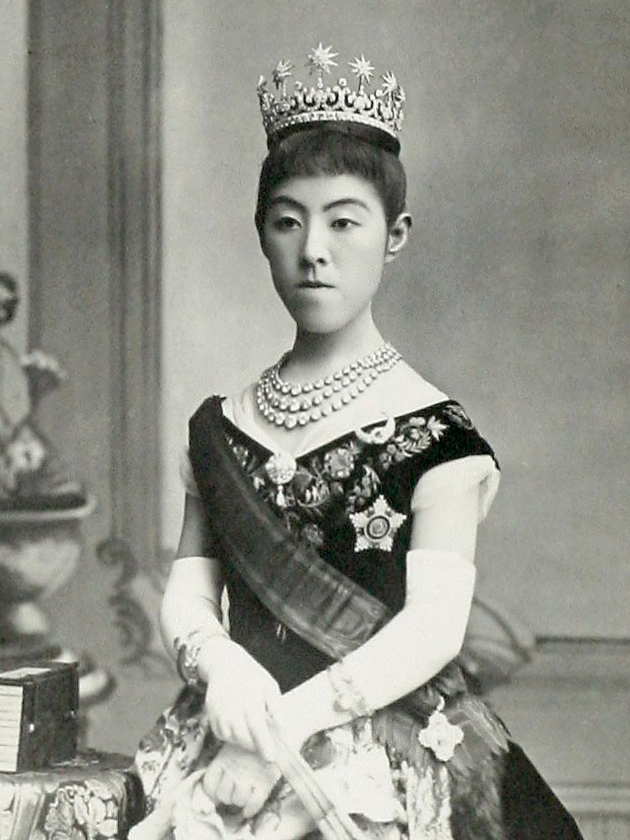

Japanese Empress Shōken in Western garb, a sign of the reform taken under the Meiji era (1868- 1912) There has been some debate on whether historical Eurocentrism qualifies as "just another ethnocentrism", as it is found in most of the world's cultures, especially in cultures with imperial aspirations, as in the Sinocentrism in China; in the Empire of Japan (c. 1868–1945), or during the American Century. James M. Blaut (2000) argued that Eurocentrism indeed went beyond other ethnocentrisms, as the scale of European colonial expansion was historically unprecedented and resulted in the formation of a "colonizer's model of the world".[47] Indigenous philosophies have been noted to greatly contrast with Eurocentric thought. Indigenous scholar James (Sákéj) Youngblood Henderson states that Eurocentricism contrasts greatly with Indigenous worldviews: "the discord between Aboriginal and Eurocentric worldviews is dramatic. It is a conflict between natural and artificial contexts."[7] Indigenous scholars Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Linco state that "in some ways, the epistemological critique initiated by Indigenous knowledge is more radical than other sociopolitical critiques of the West, for the Indigenous critique questions the very foundations of Western ways of knowing and being."[48] The terms Afrocentrism vs. Eurocentrism have come to play a role in the 2000s to 2010s in the context of the academic discourse on race in the United States and critical whiteness studies, aiming to expose white supremacism and white privilege.[49] Molefi Kete Asante, the foremost theorist of Afrocentricity, have argued that there is a prevalence of Eurocentric thought in the processing of much of academia on African affairs.[50][51][52] He questions "Why Africans would want to see their own culture through the prism of Europe" and asserts that "African languages and cultures must be mined for valuable, positive, and creative ways of knowing, ritualizing, and developing human capacity."[53] Similarly, Yoshitaka Miike, the founding theorist of Asiacentricity, has critiqued theoretical, methodological, and comparative Eurocentrism in knowledge production about Asian societies and cultures.[54][55][56] He claims that "looking at Asia only with a Eurocentric critical eye and looking at the West only with a Eurocentric uncritical eye poses a serious problem in understanding and appreciating the fullest potentials of humanity and communication."[57] In an article, 'Eurocentrism and Academic Imperialism,' Professor Seyed Mohammad Marandi at the University of Tehran states that Eurocentric thought exists in almost all aspects of academia in many parts of the world, especially in the humanities.[58] Edgar Alfred Bowring states that in the West, self-regard, self-congratulation and denigration of the 'Other' run more deeply and those tendencies have infected more aspects of their thinking, laws and policy than anywhere else.[59][60] Luke Clossey and Nicholas Guyatt have measured the degree of Eurocentrism in the research programs of top history departments.[61] Some authors have focused on how scholars who denounce Eurocentrism often inadvertently reproduce Eurocentrism through culturally biased norms.[62][63] The methodologist Audrey Alejandro refers to this process as a "recursive paradox": "It is a methodo-epistemological recursive paradox that [International Relations] critical scholars experience, producing a discourse that is implicitly counter-productive to the anti-Eurocentric values they advocate."[64] |

西洋風の服装をした日本の皇后昭憲、明治時代(1868年~1912年)に実施された改革の象徴 歴史的なヨーロッパ中心主義が「単なる別の民族中心主義」に該当するかどうかについては議論がある。これは、世界の多くの文化、特に帝国主義的な野心を持 つ文化(中国の漢民族中心主義、日本帝国(1868年頃~1945年)、またはアメリカ世紀など)に見られるからだ。ジェームズ・M・ブラウト(2000 年)は、ヨーロッパの植民地拡大の規模が歴史上例を見ないほど大きく、その結果「植民地支配者の世界モデル」が形成されたことから、ヨーロッパ中心主義は 他の民族中心主義を超えたと主張している。[47] 先住民の哲学は、ヨーロッパ中心主義の思想とは大きく対照的であると指摘されている。先住民学者ジェームズ・ヤングブラッド・ヘンダーソンは、ヨーロッパ 中心主義は先住民の世界観と大きく対照的であると述べている。「先住民の世界観とヨーロッパ中心主義の世界観との不調和は劇的だ。それは、自然と人工の文 脈の対立だ」。[7] 先住民学者ノーマン・K・デンジンとイヴォンナ・S・リンコは、「ある意味で、先住民の知識によって開始された認識論的批判は、西洋に対する他の社会政治 的批判よりも過激だ。なぜなら、先住民の批判は、西洋の認識や存在の基盤そのものを疑問視しているからだ」と述べています。[48] アフロセントリズム対ヨーロッパセントリズムという用語は、2000年代から2010年代にかけて、米国における人種に関する学術的言説や、白人至上主義 や白人の特権を暴露することを目的とした批判的な白人研究(クリティカル・ホワイトネス研究)の文脈で重要な役割を果たすようになった。[49] アフロセントリズムの主要な理論家であるモレフィ・ケテ・アサンテは、アフリカに関する学問の多くにおいて、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な思考が支配的であると 主張している。[50][51][52] 彼は、「なぜアフリカ人は、ヨーロッパのプリズムを通して自分たちの文化を見たいと思うのか」と疑問を投げかけ、「アフリカの言語や文化は、人間の能力を 知り、儀礼化し、発展させるための、価値のある、前向きで創造的な方法として活用されなければならない」と主張している。[53] 同様に、アジアセントリズムの創始的理論家である三池義隆は、アジアの社会と文化に関する知識生産における理論的、方法論的、比較的なヨーロッパ中心主義 を批判している。[54][55][56] 彼は、「アジアをヨーロッパ中心主義的な批判的な目だけで見、西欧をヨーロッパ中心主義的な無批判的な目だけで見ることは、人類とコミュニケーションの最 大の可能性を理解し評価する上で深刻な問題となる」と主張している。[57] テヘラン大学のセイエド・モハマド・マランド教授は、『ヨーロッパ中心主義と学術的帝国主義』という論文で、ヨーロッパ中心主義的思考は、世界の多くの地 域、特に人文学のほぼすべての分野に存在すると述べている。[58] エドガー・アルフレッド・ボウリングは、西洋では自己評価、自己賛美、「他者」の誹謗中傷がより深く根付いており、その傾向は他のどの地域よりも、思考、 法律、政策の多くの側面に感染していると述べている。[59][60] ルーク・クロシーとニコラス・ガイアットは、一流の歴史学部の研究プログラムにおけるヨーロッパ中心主義の程度を測定した。[61] 一部の著者は、ヨーロッパ中心主義を非難する学者たちが、文化的に偏った規範を通じて、しばしば不注意にヨーロッパ中心主義を再現していることに焦点を当 てている[62][63]。方法論者のオードリー・アレハンドロは、このプロセスを「再帰的パラドックス」と呼んでいる。「これは、国際関係学の批判的学 者たちが経験する方法論的・認識論的な再帰的パラドックスであり、彼らが提唱する反ヨーロッパ中心主義の価値観に暗黙のうちに逆効果な言説を生み出してい る」と。[64] |

| Africa Colonial historiography Main article: African historiography § Colonial historiography [Africa] is no historical part of the World, it has no movement or development to exhibit. Historical movements in it- that is in the northern part- belong to the Atlantic or European World. Carthage displayed there an important transitionary phase of civilization; but, as a Phoenician colony, it belongs to Asia. Egypt will be considered in reference to the passage of the human mind from its Eastern to its Western phase, but it does not belong to the African Spirit. What we properly understand by Africa, is the Unhistorical, Underdeveloped spirit, still involved in the conditions of mere nature, and which have to be presented here only as on the threshold of the World’s History. — Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Lectures in the Philosophy of World History (1837)[65] Since most African societies used oral tradition to record their history, there was little written history of the continent prior to the colonial period. Colonial histories focussed on the exploits of soldiers, colonial administrators, and "colonial figures", using limited sources and written from an entirely European perspective, ignoring the viewpoint of the colonised under the pretence of white supremacism. Colonial historians considered Africans racially inferior, uncivilised, exotic, and historically static, viewing their colonial conquest as proof of Europe's claims to superiority.[66]: 36 The most widespread genre of colonial narrative involved the Hamitic hypothesis, which claimed the inherent superiority of light-skinned people over dark-skinned people. Colonisers considered only "Hamitic Africans" to be "civilisation", and by extension all major advances and innovations in Africa were thought to derive from them. Oral sources were deprecated and dismissed by most historians, who claimed that Africa had no history other than that of Europeans in Africa.[67]: 627 Some colonisers took interest in the other viewpoint and attempted to produce a more detailed history of Africa using oral sources and archaeology, however they received little recognition at the time.[68] African historiography became organised at the academic level in the mid 20th century. Despite a movement towards utilising oral sources in a multidisciplinary approach and their growing legitimacy in historiography, contemporary historians are still tasked with decolonising African historiography, building the institutional frameworks incorporating African epistemologies, and representing an African perspective.[69][70][71] |

アフリカ 植民地史学 主な記事:アフリカ史学 § 植民地史学 [アフリカ] は、世界の一部として歴史的に存在しておらず、動きや発展も見られない。アフリカ、すなわちその北部における歴史的動きは、大西洋世界またはヨーロッパ世 界に属している。カルタゴは、その地で文明の重要な過渡期を迎えたが、フェニキアの植民地として、アジアに属している。エジプトは、人間の精神が東から西 へ移行する過程において考慮されるが、アフリカの精神に属するものではない。私たちがアフリカとして正しく理解するものは、歴史的でない、未発達な精神で あり、まだ自然の条件に縛られており、ここでは世界の歴史の門戸に立つものとしてのみ提示されるべきものだ。 —ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル、『世界史の哲学講義』(1837年)[65] アフリカの大部分の社会は口承伝統によって歴史を記録していたため、植民地時代以前は、大陸に関する書かれた歴史はほとんど存在しなかった。植民地史は、 限られた資料を基に、完全にヨーロッパの視点から書かれ、白人至上主義を口実にして被植民地住民の視点を無視し、兵士や植民地行政官、および「植民地人 物」の功績に焦点を当てていた。植民地史家は、アフリカ人を人種的に劣った、文明化されていない、異国的な存在と見なし、彼らの植民地征服をヨーロッパの 優越性の証拠とみなした。[66]: 36 植民地時代の物語で最も普及したジャンルは、浅黒い肌の人々は浅黒い肌の人々よりも本質的に優れていると主張する「ハミット仮説」だった。植民者たちは、 「文明」とは「ハミット系アフリカ人」のみであると見なし、さらに、アフリカのすべての主要な進歩や革新は彼らに由来すると考えていた。口頭伝承はほとん どの歴史家によって軽視され、アフリカにはヨーロッパ人のアフリカ史以外の歴史はないと主張された。[67]: 627 一部の植民地支配者は、この反対の立場に興味を持ち、口頭伝承と考古学を用いてより詳細なアフリカ史を執筆しようとしたが、当時ほとんど認められなかっ た。[68] アフリカの歴史学は、20 世紀半ばに学術的なレベルで組織化されました。多分野的なアプローチで口頭伝承を利用しようとする動きがあり、歴史学におけるその正当性も高まっているに もかかわらず、現代の歴史家は、アフリカの歴史学を脱植民地化し、アフリカの認識論を取り入れた制度的枠組みを構築し、アフリカの視点を表現するという課 題に依然として直面しています。[69][70][71] |

| Latin America Eurocentrism affected Latin America through colonial domination and expansion.[72] This occurred through the application of new criteria meant to "impose a new social classification of the world population on a global scale".[72] Based on this occurrence, a new social-historic identities were newly produced, although already produced in America. Some of these names include; 'Whites', 'Negroes', 'Blacks', 'Yellows', 'Olives', 'Indians', and 'Mestizos'.[72] With the advantage of being located in the Atlantic basin, 'Whites' were in a privileged to control gold and silver production.[72] The work which created the product was by 'Indians' and 'Negroes'.[72] With the control of commercial capital from 'White' workers. And therefore, Europe or Western Europe emerged as the central place of new patterns and capitalist power.[72] |

ラテンアメリカ ヨーロッパ中心主義は、植民地支配と拡大を通じてラテンアメリカに影響を与えた。[72] これは、「世界人口に新たな社会分類を世界規模で押し付ける」ことを目的とした新しい基準の適用によって起こった。[72] この出来事に基づいて、アメリカ大陸ではすでに存在していたものの、新たな社会歴史的アイデンティティが新たに生み出された。これらの名称には、「白 人」、「ニグロ」、「黒人」、「黄色人種」、「オリーブ人」、「インディアン」、「メスティゾ」などがある[72]。大西洋盆地に位置するという利点によ り、「白人」は金や銀の生産を支配する特権的な立場にあった。[72] 製品を生み出したのは「インディアン」と「ニグロ」たちだった。[72] 「白人」労働者による商業資本の支配。その結果、ヨーロッパ、あるいは西ヨーロッパが、新しいパターンと資本主義の権力の中心地として台頭した。[72] |

Islamic world Ottoman Turkish statesman and diplomat Mustafa Reşid Pasha, the principal architect of the Edict of Gülhane. The goal of the decree was to help modernize the Ottoman Empire militarily and socially so that it could compete with the Great Powers of Europe. Eurocentrism's effect on the Islamic world has predominantly come from a fundamental statement of preventing the account of lower-level explanation and account of Islamic cultures and their social evolution, mainly through eurocentrism's idealist construct.[73] This construct has gained power from the historians revolving their conclusions around the idea of a central point that favours the notion that the evolution of societies and their progress are dictated by general tendencies, leading to the Islamic world's evolution becoming more of a philosophical topic of history instead of historical fact.[73] Along with this, eurocentrism extends to trivialise and marginalise the philosophies, scientific contributions, cultures, and other additional facets of the Islamic world.[74] Stemming from Eurocentrism's innate bias towards Western civilization came the creation of the concept of the "European Society," which favoured the components (mainly Christianity) of European civilization and allowed eurocentrists to brand diverging societies and cultures as "uncivilized".[75] Prevalent during the nineteenth century, the labelling of uncivilised in the eyes of eurocentrists enabled Western countries to classify non-European and non-white countries as inferior, and limit their inclusion and contribution in actions like international law. This exclusion was seen as acceptable by individuals like John Westlake, a professor of international law at the University of Cambridge at the time, who commented that countries with European civilizations should be those which comprise the international society, and that countries like Turkey and Persia should only be allowed a part of international law.[75] |

イスラム世界 オスマン帝国の政治家・外交官で、ギュルハネ勅令の主要立案者であるムスタファ・レシド・パシャ。この勅令の目的は、オスマン帝国を軍事的・社会的に近代化し、ヨーロッパの列強と競争できるようにすることだった。 イスラム世界に対するヨーロッパ中心主義の影響は、主にヨーロッパ中心主義の理想主義的構築物を通じて、イスラム文化とその社会的進化に関する下位レベル の説明や記述を排除する根本的な主張から生じてきた。[73] この構築物は、歴史家たちが結論を、社会の進化と進歩は一般的な傾向によって決定されるという考えを支持する中心点に回すことで力を得てきた。これによ り、イスラム世界の進化は歴史的事実ではなく、歴史の哲学的なテーマとして扱われるようになった。[73] これと共に、ヨーロッパ中心主義は、イスラム世界の哲学、科学的貢献、文化、その他の側面を軽視し、周辺化させる傾向がある。[74] ヨーロッパ中心主義の西洋文明に対する固有の偏見から、「ヨーロッパ社会」という概念が生まれ、ヨーロッパ文明の構成要素(主にキリスト教)が優先され、 ヨーロッパ中心主義者は、異なる社会や文化を「未開」とレッテルを貼ることができるようになった。[75] 19世紀に広く見られた、ヨーロッパ中心主義者による「文明化されていない」というラベル付けは、西洋諸国が非ヨーロッパ諸国や非白人諸国を劣ったものと 分類し、国際法などの行動におけるそれらの参加と貢献を制限することを可能にした。この排除は、当時ケンブリッジ大学国際法教授だったジョン・ウェストレ イクのような人物によって正当化され、彼は「国際社会を構成すべきはヨーロッパ文明を有する国々であり、トルコやペルシャのような国々は国際法のほんの一 部しか認められるべきではない」とコメントした。[75] |

| Orientalism Eurocentrism's reach has not only affected the perception of the cultures and civilizations of the Islamic world, but also the aspects and ideas of Orientalism, a cultural idea that distinguished the "Orient" of the East from the "Occidental" Western societies of Europe and North America, and which was originally created so that the social and cultural milestones of the Islamic and Oriental world would be recognised. This effect began to take place during the nineteenth century when the Orientalist ideals were distilled and shifted from topics of sensuality and deviating mentalities to what is described by Edward Said as "unchallenged coherence".[76] Along with this shift came the creation of two types of orientalism: latent, which covered the Orient's constant durability through history, and manifest, a more dynamic orientalism that changes with the new discovery of information.[76] The eurocentric influence is shown in the latter, as the nature of manifest Orientalism is to be altered with new findings, which leaves it vulnerable to the warping of its refiner's ideals and principles. In this state, eurocentrism has used orientalism to portray the Orient as "backwards" and bolster the superiority of the Western world and continue the undermining of their cultures to further the agenda of racial inequality.[76] With those wanting to represent the eurocentric ideals better by way of orientalism, there came a barrier of languages, being Arabic, Persian, and other similar languages. With more researchers wanting to study more of Orientalism, there was an assumption made about the languages of the Islamic world: that having the ability to transcribe the texts of the past Islamic world would give great knowledge and insight on oriental studies. In order to do this, many researchers underwent training in philology, believing that an understanding of the languages would be the only necessary training. This reasoning came as the belief at the time was that other studies like anthropology and sociology were deemed irrelevant as they did not believe it misleading to this portion of mankind.[77] |

オリエンタリズム ヨーロッパ中心主義の影響は、イスラム世界の文化や文明の認識だけでなく、東洋の「オリエント」とヨーロッパや北米の「西洋」社会とを区別する文化的な概 念であるオリエンタリズムの側面や考えにも及んだ。オリエンタリズムは、イスラム世界と東洋世界の社会的・文化的マイルストーンを認識するために、もとも と創り出されたものだった。この影響は19世紀に始まり、オリエンタリズムの理想が精錬され、官能性や異常な精神構造といったテーマから、エドワード・サ イードが「挑戦されない一貫性」と表現する概念へと移行した。[76] この移行に伴い、2種類のオリエンタリズムが生まれた。一つは、歴史を通じてオリエントの持続性を覆い隠す「潜在的オリエンタリズム」、もう一つは、新た な情報の発見と共に変化する「顕在的オリエンタリズム」だ。[76] 顕在的オリエンタリズムの性質は新たな発見によって変化するため、後者においてヨーロッパ中心主義の影響が顕著に現れる。この状態では、ヨーロッパ中心主 義はオリエンタリズムを利用して東方世界を「後進的」と描き、西洋世界の優越性を強化し、その文化を貶めることで人種的不平等を助長するアジェンダを推進 してきた。[76] オリエンタリズムによってヨーロッパ中心主義の理想をよりよく表現したいと考える人々にとって、アラビア語、ペルシア語、その他の類似の言語という言語の 障壁があった。オリエンタリズムをより深く研究したいと考える研究者が増えるにつれ、イスラム世界の言語について、過去のイスラム世界のテキストを転写で きる能力があれば、オリエント研究に関する深い知識と洞察が得られるという仮定が生まれた。この目的のため、多くの研究者は言語学の訓練を受け、言語の理 解が唯一の必要な訓練だと信じていた。この考え方は、当時、人類学や社会学のような他の研究は、この人類の一部に誤導を与えると信じられていたため、無関 係だと考えられていたからだ。[77] |

| Beauty standards and the cosmetic industry Due to colonialism, Eurocentric beauty ideals have had varying degrees of impact on the cultures of non-Western countries. The influence on beauty ideals across the globe varies by region, with Eurocentric ideals having a relatively strong impact in South Asia but little to no impact in East Asia.[78] However, Eurocentric beauty ideals have also been on the decline in the United States, especially with the success of Asian female models, which may be signaling a breakdown in the hegemony of White American beauty ideals.[79] In Vietnam, Eurocentric beauty ideals have been openly rejected, as local women consider Western women's ideal of beauty as being overweight, masculine and unattractive.[80] Another study questioning the impact of Eurocentric beauty ideals in South Asia noted that Indian women won a relatively high number of international beauty pageants, and that Indian media tends to use mostly Indian female models. The authors cite the dominance of the Bollywood film industry in India, which tends to minimize the impact of Western ideals.[81] |

美容基準と化粧品業界 植民地主義により、ヨーロッパ中心の美容観は、非西洋諸国の文化にさまざまな影響を与えてきた。美容観への影響は地域によって異なり、南アジアではヨー ロッパ中心の美容観が比較的強い影響力を持っているが、東アジアではほとんど影響が見られない。[78] しかし、欧米中心の美の理想は、米国でも、特にアジアの女性モデルの成功により、衰退傾向にあり、これは白人アメリカ人の美の理想のヘゲモニーの崩壊を意 味しているかもしれない。[79] ベトナムでは、現地の女性は西洋女性の美の理想を太りすぎで男性的で魅力がないと考えているため、欧米中心の美の理想は公然と拒絶されている。[80] 南アジアにおけるヨーロッパ中心の美の理想の影響を疑問視する別の研究では、インドの女性が国際的な美人コンテストで比較的多くの優勝者を輩出しており、 インドのメディアは主にインド人女性モデルを採用する傾向があることが指摘されている。著者らは、西洋の理想の影響を最小限に抑える傾向のある、インドの ボリウッド映画産業の優位性をその理由として挙げている。[81] |

| Clark doll experiment Main article: Kenneth and Mamie Clark § Doll experiments In the 1940s, psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark conducted experiments called "the doll tests" to examine the psychological effects of segregation on African-American children. They tested children by presenting them with four dolls, identical in all but skin tone. The children were instructed to choose which doll they preferred and were asked the race of the doll. Most of the children chose the white doll. The Clarks stated in their results that the perceptions of the African-American children had been altered by the discrimination they faced.[82] The tested children also labelled the white dolls with positive descriptions. |

クラーク人形実験 主な記事:ケネスとマミー・クラーク § 人形実験 1940年代、心理学者ケネスとマミー・クラークは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の子供たちに人種差別が与える心理的影響を調べるために、「人形実験」と呼ばれ る実験を行った。彼らは、肌の色以外はすべて同じ4体の人形を子供たちに見せ、実験を行った。子供たちは、好きな人形を選び、その人形の「人種」を尋ねら れた。ほとんどの子供たちは、白人の人形を選んだ。クラーク夫妻は、この実験結果から、アフリカ系アメリカ人の子供たちの認識は、彼らが直面している差別 によって変化していると結論付けた[82]。また、実験に参加した子供たちは、白人の人形に肯定的な形容詞を付けた。 |

| Mexican doll experiment In 2012, Mexicans recreated the doll test. Mexico's National Council to Prevent Discrimination presented a video where children had to pick the "good doll", and the doll that looks like them. By doing this experiment, the researchers sought to analyse the degree to which Mexican children are influenced by modern-day media accessible to them.[83] Most of the children chose the white doll; they also stated that it looked like them. The people who carried out the study noted that Eurocentrism is deeply rooted in different cultures, including Latin cultures.[84] |

メキシコの人形実験 2012年、メキシコ人はこの人形実験を再現した。メキシコ差別防止全国協議会は、子供たちに「良い人形」と、自分に似ている人形を選ぶよう求めたビデオ を公開した。この実験により、研究者たちは、メキシコの子供たちが、彼らがアクセスできる現代のメディアの影響をどの程度受けているかを分析しようとし た。[83] ほとんどの子供たちは、白人の人形を選び、その人形が自分たちに似ているとも述べました。この調査を行った人々は、ヨーロッパ中心主義はラテン文化を含む さまざまな文化に深く根付いていると指摘しています。[84] |

| Skin lightening Skin lightening has become a common practice in some countries. A 2011 study found that, in Tanzania, motivation for the use of skin lightening products is to look more 'European'.[85] However, in East Asia, the practice began long before exposure to Europeans – tan skin was associated with lower-class field work, and thus constant exposure to sun, while having pale skin signified belonging to the upper-class.[86][87] Skin bleaching can have negative health effects.[88] One study observed that, among the female population of Senegal in West Africa, 26% of women were using skin lightening creams at the time. The most common products used were hydroquinone and corticosteroids. 75% of women who used these creams showed adverse cutaneous effects, mainly acne.[89] |

肌の美白 肌の美白は、一部の国では一般的な慣習となっています。2011年の研究によると、タンザニアでは、美白製品を使用する動機は「よりヨーロッパ人らしく見 える」ためです。[85] しかし、東アジアでは、ヨーロッパ人と接触する前からこの慣習は始まっていました。日焼けした肌は、下層階級の農作業と関連付けられ、常に太陽にさらされ ていることを意味し、一方、色白の肌は上流階級に属していることを意味していました。[86][87] 肌の美白は、健康に悪影響を及ぼす可能性があります。[88] ある研究では、西アフリカのセネガル女性人口のうち、26% の女性が当時、美白クリームを使用していたことが明らかになりました。最もよく使用されていた製品は、ハイドロキノンとコルチコステロイドでした。これら のクリームを使用した女性の 75% に、主にニキビなどの皮膚への悪影響が見られました。[89] |

| East Asia In East Asia, the impact of Eurocentrism in beauty advertisements has been minimal. Anti-European undercurrents in local advertisements for female-oriented products are quite common. European models are hired for around half of advertisements made by European brands such as Estée Lauder and L'Oréal, while local Japanese cosmetics brands tend to use exclusively East Asian female models.[90] In Singapore, a country with a large population of Chinese people. European women are ranked below Chinese women in the female beauty hierarchy. According to the author, the blonde hair of Swedish women reduced their femininity, because it was racialized as a Western trait. The authors also noted that these women's Swedish husbands were highly attracted to local East Asian women, which further reduced the self-esteem of the blonde Swedish women living in Singapore.[91] The use of European female models has actually declined within Japan, and some Japanese skincare companies have discontinued the use of Western female models entirely, while others have even portrayed white women as explicitly inferior to Asian women, on the basis of their lighter hair color.[92] There is a widespread belief in Japan that Japanese women's skin color is "better" than white women's,[93] and the placement of European female models in local advertisements does not reflect any special status of white women within Japan.[94] |

東アジア 東アジアでは、美容広告におけるヨーロッパ中心主義の影響はごくわずかだ。女性向け製品の現地広告には、反ヨーロッパの傾向が広く見られる。エスティロー ダーやロレアルなどのヨーロッパのブランドが制作する広告の約半数はヨーロッパのモデルを採用しているが、日本の化粧品ブランドは東アジアの女性モデルの みを採用する傾向がある。[90] 中国系住民の多いシンガポールでは、女性の美のヒエラルキーにおいて、ヨーロッパの女性は中国人の女性よりも下位にランク付けされている。著者によると、 スウェーデン人女性のブロンドの髪は、西洋人の特徴として人種差別的に認識されていたため、女性らしさを損ねていたという。また、これらの女性のスウェー デン人夫は、現地の東アジア系の女性に非常に惹かれており、シンガポールに住むブロンドのスウェーデン人女性の自尊心をさらに低下させていたと著者は指摘 している。[91] 日本では、ヨーロッパの女性モデルの使用は実際に減少しており、一部の日本のスキンケア企業は西洋の女性モデルの使用を完全に中止し、他の企業は、髪の色 が薄いことを理由に、白人女性をアジア人女性よりも明らかに劣った存在として描写している。[92] 日本では、日本人女性の肌の色が白人女性よりも「優れている」という広範な信念が存在し、[93] 現地の広告にヨーロッパ人女性モデルを起用することは、日本における白人女性の特別な地位を反映したものではない。[94] |

| Brazil The beauty ideal for women in Brazil is the morena; a mixed-race brown woman who is supposed to represent the best characteristics of every racial group in Brazil.[95] According to Alexander Edmond's book Pretty Modern: Beauty, Sex, and Plastic Surgery in Brazil, whiteness plays a role in Latin American, specifically Brazilian, beauty standards, but it is not necessarily distinguished based on skin colour.[96] Edmonds said the main ways to define whiteness in people in Brazil is by looking at their hair, nose, then mouth before considering skin colour.[96] Edmonds focuses on the popularity of plastic surgery in Brazilian culture. Plastic surgeons usually applaud and flatter mixtures when emulating aesthetics for performing surgery, and the more popular mixture is African and European.[97] This shapes beauty standards by racialising biological and popular beauty ideals to suggest that mixture with whiteness is better.[96] Donna Goldstein's book Laughter Out of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shantytown also addresses how whiteness influences beauty in Brazil. Goldstein notes that in Brazil, there is a hierarchy for beauty that places being mixed race at the top and pure, un-admixed black characteristics at the bottom, calling them ugly.[98][99] In Erica Lorraine William's Sex Tourism in Bahia: Ambiguous Entanglements, Williams notes that there is no Eurocentric beauty ideal for women in Brazil.[100] White Brazilian women are aware that foreign male sex tourists are not interested in them, and that they prefer brown and black women over white Brazilian women.[100] One white woman in Brazil complained that she is not noticed by "gringos" and that they prefer black and Mestiza women for sexual liaisons.[100] |

ブラジル ブラジルの女性の美の理想は、モレナと呼ばれる混血の褐色の女性で、ブラジルのあらゆる人種の最良の特性を体現していると考えられている。[95] アレクサンダー・エドモンドの著書『Pretty Modern: Beauty, Sex, and Plastic Surgery in Brazil』によると、白さはラテンアメリカ、特にブラジルの美の基準において重要な役割を果たしているが、必ずしも肌の色によって区別されるわけでは ない。[96] エドモンズは、ブラジル人の白さを定義する主な方法は、肌の色よりも、まず髪、鼻、そして口を見て判断すると述べている。[96] エドモンズは、ブラジル文化における整形手術の人気に焦点を当てている。整形外科医は通常、手術を行う際に美しさを模倣する際に、混血を称賛し、お世辞を 言う傾向があり、最も人気のある混血はアフリカ人とヨーロッパ人だ。[97] これにより、生物学的および一般的な美の理想を人種化することで、白人との混血の方が良いという美の基準が形成されている。[96] ドナ・ゴールドスタインの著書『Laughter Out of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shantytown』も、ブラジルにおける白人性が美に与える影響について述べている。ゴールドスタインは、ブラジルには美のヒエラルキーがあり、混血 が最上位、純粋で混血のない黒人の特徴が最下位であり、それらを醜いと呼んでいると指摘している。[98][99] エリカ・ロレイン・ウィリアムズの『Sex Tourism in Bahia: Ambiguous Entanglements』の中で、ウィリアムズは、ブラジルにはヨーロッパ中心の女性の美の理想は存在しない、と指摘している。[100] 白人ブラジル人女性は、外国人男性性観光客が自分たちに興味を示さず、白人ブラジル人女性よりも褐色や黒人女性を好むことを認識している。[100] ブラジル在住の白人女性は、白人男性から注目されず、性的な関係では黒人やメスティサ女性を好むと不満を漏らしている。[100] |

| Pro-Eurocentrism Colonial mentality Discovery doctrine Orientalism Anti-Eurocentrism The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation Other centrisms Afrocentrism Asiacentrism Americentrism Ethnocentrism Hellenocentrism Indocentrism Sinocentrism Related topics Atlanticism History of Western civilization Pan-Arabism Pan-European identity Universalism in geography Western culture Western values |

親ヨーロッパ中心主義 植民地主義的思考 発見主義 オリエンタリズム 反ヨーロッパ中心主義 孔雀の羽の紋章:数学の非ヨーロッパ的起源 西洋文明の東洋起源 その他の中心主義 アフリカ中心主義 アジア中心主義 アメリカ中心主義 民族中心主義 ヘレニズム中心主義 インド中心主義 中国中心主義 関連トピック アトランティシズム 西洋文明史 汎アラブ主義 汎ヨーロッパアイデンティティ 地理学における普遍主義 西洋文化 西洋の価値観 |

| Akmal, M.; Zulkifle, M.; Ansari,

A. H. (2010). "IBN Nafis – A Forgotten Genius in the Discovery of

Pulmonary Blood Circulation". Heart Views. 11 (1): 26–30. PMC 2964710.

PMID 21042463. Samir Amin, Accumulation on a World Scale, Monthly Review Press, 1974. Samir Amin: L'eurocentrisme, critique d'une idéologie. Paris 1988, engl. Eurocentrism, Monthly Review Press 1989, ISBN 0-85345-786-7 Ansari, A. S. Bazmee (1976). "Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Yahya al-Razi: Universal Scholar and Scientist". Islamic Studies. 15 (3): 155–166. JSTOR 20847003. Bademci, Gulsah; Batay, Funda; Sabuncuoglu, Hakan (26 April 2005). "First detailed description of axial traction techniques by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu in the 15th century". European Spine Journal. 14 (8): 810–812. doi:10.1007/s00586-005-0889-3. PMC 3489253. PMID 15856337. Bernal, M. Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Rutgers University Press (1987) ISBN 0-8135-1277-8) Bessis, Sophie (2003). Western Supremacy: The Triumph of an Idea. Zed Books. ISBN 9781842772195 Blaut, J. M. (1993) The Colonizer's Model of the World: Geographical Diffusionism and Eurocentric History. Guilford Press. ISBN 0-89862-348-0 Blaut, J. M. (2000) Eight Eurocentric Historians. Guilford Press. ISBN 1-57230-591-6 Bairoch, Paul (1993). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-03462-1. Baudet, E. H. P. (1959). Paradise on Earth: Some Thoughts on European Images of Non-European Man. Translated by Elizabeth Wentholt. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ASIN B0007DKQMW. Elders, Leo J. (2018). "Avicenna". Thomas Aquinas and His Predecessors: The Philosophers and the Church Fathers in His Works. Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 283–305. doi:10.2307/j.ctv8j74r.19. ISBN 978-0-8132-3028-3. Fancy, Nahyan (2013). "Medical Commentaries: A Preliminary Examination of Ibn al-Nafīsʾs Shurūḥ, the Mūjaz and Subsequent Commentaries on the Mūjaz". Oriens. 41 (3/4): 525–545. doi:10.1163/18778372-13413412. JSTOR 42637276. Frank, Andre Gunder (1998) ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. University of California Press. Haushofer, Karl (1924) Geopolitik des pazifischen Ozeans, Berlin, Kurt Vowinckel Verlag. Van der Pijl, Kees, The Discipline of Western Supremacy: Modes of Foreign Relations and Political Economy, Volume III, Pluto Press, 2014, ISBN 9780745323183 Kren, Claudia (December 1971). "The Rolling Device of Naṣir al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī in the De spera of Nicole Oresme?". Isis. 62 (4): 490–498. doi:10.1086/350791. S2CID 144526697. Lambropoulos, Vassilis (1993) The Rise of Eurocentrism: Anatomy of interpretation, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Lefkowitz, Mary (1996). Not Out of Africa: How Afrocentrism Became an Excuse to Teach Myth as History. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-09837-8. Lin, Daren (2008). "A Foundation of Western Ophthalmology in Medieval Islamic Medicine". University of Western Ontario Medical Journal. 78 (1): 41–45. Lindqvist, Sven (1996). Exterminate all the brutes. New Press, New York. ISBN 9781565843592 Malhotra, Rajiv (2013). Being Different: An Indian Challenge to Western Universalism. Noida: Harpercollins India. Masoud, Mohammad T.; Masoud, Faiza; Urquhart, John; Cattermole, Giles N. (2006). "How Islam Changed Medicine". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 332 (7533): 120–121. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7533.120-a. JSTOR 25455873. PMC 1326979. PMID 16410601. MA'ṢŪMĪ, M. ṢAGHĪR ḤASAN (1967). "Imām Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī and his Critics". Islamic Studies. 6 (4): 355–374. JSTOR 20832894. Mozaffari, S. Mohammad; Zotti, Georg (2012). "Ghāzān Khān's Astronomical Innovations at Marāgha Observatory". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 132 (3): 395. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.132.3.0395. Nowsheravi, A. R. (1983). "Muslim Hospitals in the Medieval Period". Islamic Studies. 22 (2): 51–62. JSTOR 23076050. Preiswerk, Roy; Perrot, Dominique (1978). Ethnocentrism and History: Africa, Asia, and Indian America in Western Textbooks. New York and London: NOK. ISBN 978-0-88357-071-5. Rabasa, Jose (1994) Inventing America: Spanish Historiography and the Formation of Eurocentrism (Oklahoma Project for Discourse and Theory, vol. 2), University of Oklahoma Press Rüsen, Jörn (December 2004). "How to Overcome Ethnocentrism: Approaches to a Culture of Recognition by History in the Twenty-First Century1". History and Theory. 43 (4): 118–129. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2004.00301.x. Said, Edward (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books. ISBN 9780394428147 Schmidl, P. G. (2007) "ҁUrḍī: Mu'ayyad (al‐Milla wa‐) al‐Dīn (Mu'ayyad ibn Barīk [Burayk]) al‐ҁUrḍī (al‐ҁĀmirī al‐Dimashqī)". In: Hockey T. et al. (eds) The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer, New York Shohat, Ella and Stam, Robert (1994) Unthinking Eurocentrism: multiculturalism and the media. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06325-6 Smith, John D. (March 1992). "The Remarkable Ibn al-Haytham". The Mathematical Gazette. 76 (475): 189–198. doi:10.2307/3620392. JSTOR 3620392. S2CID 118597450. Tbakhi, Abdelghani; Amr, Samir S. (March 2008). "Ibn Rushd (Averroës): Prince of Science". Annals of Saudi Medicine. 28 (2): 145–147. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.145. PMC 6074522. PMID 18398288. Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1965). The Rise of Christian Europe. London: Thames & Hudson. ASIN B000O894GO. Vlassopoulos, K. (2011). Unthinking the Greek polis: Ancient Greek history beyond Eurocentrism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Xypolia, Ilia (2016) "Eurocentrism and Orientalism" in The Encyclopedia of Postcolonial Studies |

アクマル、M.;ズルキフレ、M.;アンサリ、A. H. (2010). 「イブン・ナフィス – 肺の血液循環の発見における忘れられた天才」. Heart Views. 11 (1): 26–30. PMC 2964710. PMID 21042463. サミル・アミン, 世界規模の蓄積, Monthly Review Press, 1974. サミル・アミン: ヨーロッパ中心主義, 思想批判. パリ 1988, 英訳 Eurocentrism, Monthly Review Press 1989, ISBN 0-85345-786-7 Ansari, A. S. Bazmee (1976). 「アブ・バクル・ムハンマド・イブン・ヤヒヤ・アル・ラズィ:普遍的な学者および科学者」. Islamic Studies. 15 (3): 155–166. JSTOR 20847003. バデムチ, グルサ; バタイ, ファンダ; サブンチョグル, ハカン (2005年4月26日). 「15世紀にセレフェディン・サブンチョグルによって初めて詳細に記述された軸牽引技術」. ヨーロッパ脊椎ジャーナル. 14 (8): 810–812. doi:10.1007/s00586-005-0889-3. PMC 3489253. PMID 15856337. ベルナル, M. 『ブラック・アテナ:古典文明のアフロアジア的ルーツ』 Rutgers University Press (1987) ISBN 0-8135-1277-8) ベシス, ソフィー (2003). 西洋の優越性: 思想の勝利. ゼッド・ブックス. ISBN 9781842772195 ブラウト, J. M. (1993) 植民者の世界モデル: 地理的拡散主義とヨーロッパ中心史観. ギルフォード・プレス. ISBN 0-89862-348-0 ブラウト、J. M. (2000) 『8人のヨーロッパ中心主義の歴史家』. ギルフォード・プレス. ISBN 1-57230-591-6 バイロッチ、ポール (1993). 『経済学と世界史:神話とパラドックス』. シカゴ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-226-03462-1. ボーデ, E. H. P. (1959). 地上楽園: ヨーロッパ人の非ヨーロッパ人像に関する考察. 翻訳: エリザベス・ウェントホルト. コネチカット州ニューヘイブン: イエール大学出版局. ASIN B0007DKQMW. エルダーズ, レオ J. (2018). 「アヴィセンナ」. トマス・アクィナスとその先駆者たち:彼の著作における哲学者と教会父たち. ワシントンD.C.: カトリック大学出版局. pp. 283–305. doi:10.2307/j.ctv8j74r.19. ISBN 978-0-8132-3028-3. ファンシー、ナヒヤン (2013). 「医学解説:イブン・アル・ナフィスのシュルフ、ムジャズ、およびムジャズに関するその後の解説の予備的考察」. Oriens. 41 (3/4): 525–545. doi:10.1163/18778372-13413412. JSTOR 42637276. フランク、アンドレ・グンダー (1998) 『ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age』 カリフォルニア大学出版局。 ハウソファー、カール (1924) 『太平洋の地理政治学』、ベルリン、クルト・ヴォヴィンケル出版社。 ファン・デル・ピル、キース、『西洋の覇権主義の規律:外交関係と政治経済の方法』、第 III 巻、Pluto Press、2014 年、ISBN 9780745323183 クレン、クラウディア (1971 年 12 月)。「ニコール・オレスメの『デ・スペラ』におけるナシル・アル=トゥーシーの回転装置?」、『アイシス』、62 (4): 490–498。doi:10.1086/350791。S2CID 144526697。 ランブロポロス、ヴァシリオス(1993)『ヨーロッパ中心主義の台頭:解釈の解剖学』、ニュージャージー州プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。 レフコウィッツ、メアリー(1996)。『アフリカからではない:アフリカ中心主義が神話を歴史として教える口実となった経緯』。ニューヨーク:ベーシック・ブックス。ISBN 978-0-465-09837-8。 Lin, Daren (2008). 「中世イスラム医学における西洋眼科の基礎」. University of Western Ontario Medical Journal. 78 (1): 41–45. Lindqvist, Sven (1996). Exterminate all the brutes. New Press, New York. ISBN 9781565843592 マルホトラ、ラジブ(2013)。異なること:西洋の普遍主義に対するインディアンの挑戦。ノイダ:Harpercollins India。 Masoud, Mohammad T.; Masoud, Faiza; Urquhart, John; Cattermole, Giles N. (2006). 「イスラム教が医学を変えた方法」。BMJ: British Medical Journal. 332 (7533): 120–121. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7533.120-a. JSTOR 25455873. PMC 1326979. PMID 16410601. マースーミー, M. サギール・ハサン (1967). 「イマーム・ファクル・アル=ディーン・アル=ラーズィーとその批判者たち」. イスラム研究. 6 (4): 355–374. JSTOR 20832894. モザファリ, S. モハマド; ゾッティ, ゲオルグ (2012). 「ガザン・カーンのマラガ天文台における天文学的革新」. アメリカ東方学会誌. 132 (3): 395. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.132.3.0395. Nowsheravi, A. R. (1983). 「中世のイスラム病院」. Islamic Studies. 22 (2): 51–62. JSTOR 23076050. Preiswerk, Roy; Perrot, Dominique (1978). 民族中心主義と歴史:西洋の教科書におけるアフリカ、アジア、およびインディアンアメリカ。ニューヨークおよびロンドン:NOK。ISBN 978-0-88357-071-5。 ラバサ、ホセ (1994) 『アメリカを発明する:スペインの歴史学とヨーロッパ中心主義の形成』 (オクラホマ言説と理論プロジェクト、第 2 巻)、オクラホマ大学出版局 リュゼン、ヨルン (2004年12月)。「民族中心主義を克服する方法:21 世紀の歴史による認識の文化へのアプローチ1」。『歴史と理論』43(4): 118–129. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2004.00301.x. サイード、エドワード(1978)。『オリエンタリズム』。パンテオン・ブックス。ISBN 9780394428147 シュミトル、P. G. (2007) 「ҁUrḍī: Mu『ayyad (al‐Milla wa‐) al‐Dīn (Mu』ayyad ibn Barīk [Burayk]) al‐ҁUrḍī (al‐ҁĀmirī al‐Dimashqī)」。Hockey T. et al. (eds) The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer, New York Shohat, Ella and Stam, Robert (1994) Unthinking Eurocentrism: multiculturalism and the media. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06325-6 スミス、ジョン・D. (1992年3月)。「The Remarkable Ibn al-Haytham」 『The Mathematical Gazette』 76 (475): 189–198. doi:10.2307/3620392. JSTOR 3620392. S2CID 118597450. Tbakhi, Abdelghani; Amr, Samir S. (2008年3月). 「イブン・ルシュド(アヴェロエス):科学の王子」. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 28 (2): 145–147. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.145. PMC 6074522. PMID 18398288. Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1965). The Rise of Christian Europe. London: Thames & Hudson. ASIN B000O894GO. ヴラソプロス, K. (2011). ギリシャのポリスを再考する: ヨーロッパ中心主義を超えた古代ギリシャ史. ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. キシポリア, イリア (2016) 「ヨーロッパ中心主義とオリエンタリズム」『ポストコロニアル研究事典』 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eurocentrism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099