イヴ・コゾフスキー・セジウィック

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, 1950-2009

☆イヴ・コソフスキー・セジウィック(Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick,1950年5月2日 - 2009年4月12日)は、ジェンダー研究、クィア理論の分野におけるアメリカの学者である。セジウィックはクィア理論の分野で画期的とされる本を数冊出 版し、彼女の批評的著作はクィア・スタディーズの分野の創設に貢献し、彼女はその分野で最も影響力のある人物の一人であった。セ ジウィックのエッセイはポスト構造主義、多文化主義、ゲイ・スタディーズを批評する際の枠組みとなった。

| Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick

(/ˈsɛdʒwɪk/; May 2, 1950 – April 12, 2009) was an American academic

scholar in the fields of gender studies, queer theory, and critical

theory. Sedgwick published several books considered groundbreaking in

the field of queer theory,[1] and her critical writings helped create

the field of queer studies, in which she was one of the most

influential figures.[2][3][4] Sedgwick's essays became the framework

for critics of poststructuralism, multiculturalism, and gay studies.[5] In her 1985 book Between Men, she analyzed male homosocial desire and English literature. In 1991, she published "Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl", an article that received attention as part of an American culture war and criticism for associating the works of Jane Austen with sex. She coined the terms homosocial and antihomophobic.[6][7][8] Sedgwick argued that an understanding of virtually any aspect of modern Western culture would be incomplete if it failed to incorporate a critical analysis of modern homo/heterosexual definition.[3][4] Drawing on feminist scholarship and the work of Michel Foucault, Sedgwick analyzed homoerotic subplots in the work of writers like Charles Dickens and Henry James. Her works reflected an interest in a range of issues, including queer performativity, experimental critical writing, the works of Marcel Proust, non-Lacanian psychoanalysis, artists' books, Buddhism and pedagogy, the affective theories of Silvan Tomkins and Melanie Klein, and material culture, especially textiles and texture. |

イヴ・コソフス

キー・セジウィック(Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, /↪Lm_l_292↩ɪk/、1950年5月2日 -

2009年4月12日)は、ジェンダー研究、クィア理論の分野におけるアメリカの学者である。セジウィックはクィア理論の分野で画期的とされる本を数冊出

版し[1]、彼女の批評的著作はクィア・スタディーズの分野の創設に貢献し、彼女はその分野で最も影響力のある人物の一人であった[2][3][4]。セ

ジウィックのエッセイはポスト構造主義、多文化主義、ゲイ・スタディーズを批評する際の枠組みとなった[5]。 1985年の著書『Between Men』では、男性のホモソーシャルな欲望と英文学を分析。1991年、「Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl(ジェーン・オースティンと自慰する少女)」を発表。この論文は、ジェーン・オースティンの作品とセックスを関連づけることで、アメリカの文化戦 争の一部として注目され、批判を浴びた。彼女はホモソーシャルとアンチホモフォビックという言葉を作った[6][7][8]。 セジウィックは、近代西洋文化の事実上あらゆる側面についての理解は、近代のホモ/異性愛の定義についての批判的分析を組み込まなければ不完全なものにな ると主張した[3][4]。フェミニズムの学問とミシェル・フーコーの研究に基づき、セジウィックはチャールズ・ディケンズやヘンリー・ジェイムズのよう な作家の作品におけるホモエロティックな小筋を分析した。彼女の作品は、クィア・パフォーマティヴィティ、実験的批評文、マルセル・プルーストの作品、非 ラカ派の精神分析、アーティストの本、仏教と教育学、シルヴァン・トムキンスとメラニー・クラインの感情理論、物質文化、特にテキスタイルと質感など、さ まざまな問題への関心を反映している。 |

| Biography Eve Kosofsky was raised in a Jewish family in Dayton, Ohio, and in Bethesda, Maryland.[9] She had two siblings: a sister, Nina Kopesky and a brother, David Kosofsky.[5] She received her undergraduate degree from Cornell University and her masters and Ph.D. from Yale University in the field of English,[5] where studied under Allan Bloom, among others.[10] At Cornell, she was among the first women to be elected to live at the Telluride House,[11] where she met her husband[12] She taught writing and literature at Hamilton College, Boston University, and Amherst College while developing a critical approach focusing on hidden social codes and submerged plots in familiar writers.[5] She held a visiting lectureship at University of California, Berkeley, and taught at the School of Criticism and Theory when it was located at Dartmouth College. She was also the Newman Ivey White Professor of English at Duke University, and then a Distinguished Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.[13] During her time at Duke, Sedgwick and her colleagues were in the academic avant-garde of the culture wars,[14] using literary criticism to question dominant discourses of sexuality, race, gender, and the boundaries of literary criticism. Sedgwick first presented her particular collection of critical tools and interests in the influential volumes Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (1985) and Epistemology of the Closet (1990).[15] She married Hal Sedgwick in 1969.[14] Sedgwick and her husband were happily married for nearly forty years, although from the beginning of their relationship until her death they lived independently from one another, usually in different states. Sedgwick described her relationship with her husband as "vanilla" — but it gained both psychological and autobiographical depth as she turned her critical gaze toward friends' experiences of the AIDS epidemic.[16] Her sexuality was confusing to some people as a queer theorist, that used queer as general term, but Sedgwick never publicly identified as anything aside from straight.[17] She received the 2002 Brudner Prize at Yale, a lifetime achievement award, for her extensive work in LGBT studies. In 2006, she was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[18] She taught graduate courses in English as Distinguished Professor at The City University of New York Graduate Center (CUNY Graduate Center) until her death in New York City[19] Death In 1990, she found a lump on her breast while she was getting her post-doctoral fellowship. She underwent a radical mastectomy where all of her right breast and all of the lymph nodes from her right armpit were removed. She underwent chemotherapy.[20] In the fall of 1996, cancer was found in Sedgwick's spine as well.[21] She received treatment at Memorial Sloan Kettering for six months, where she had a series of radiation treatments to the portion of her spine affected by cancer.[20] By 2005, Sedgwick's basic cancer treatment had been stable.[21] In the beginning of 2006, it was found that Sedgwick's cancer had resurfaced and spread again in her bone and liver.[21] She died on April 12, 2009, at age 58 in New York City, after moving closer to her husband, though they continued to live separately.[22] |

経歴 イヴ・コソフスキーはオハイオ州デイトンとメリーランド州ベセスダのユダヤ人家庭で育った[9]。 姉はニーナ・コペスキー、弟はデイヴィッド・コソフスキー[5]。コーネル大学で学士号、イェール大学で修士号と博士号を取得し、英語の分野でアラン・ブ ルームらに師事した[5]。 [コーネル大学では、テルライド・ハウスに住む最初の女性の一人に選ばれ[11]、そこで夫と知り合った[12]。ハミルトン大学、ボストン大学、アマー スト大学で文章と文学を教えるかたわら、身近な作家の隠れた社会的コードや沈潜したプロットに焦点を当てた批評的アプローチを発展させた[5]。カリフォ ルニア大学バークレー校で客員講師を務め、批評理論学部がダートマス大学にあったころは同学部で教鞭をとった。また、デューク大学のニューマン・アイ ヴィー・ホワイト英語教授、ニューヨーク市立大学大学院センターの特別教授を務めた[13]。 デューク大学在学中、セジウィックと彼女の同僚たちは、文化戦争のアカデミック・アヴァンギャルドに属し、セクシュアリティ、人種、ジェンダー、そして文 芸批評の境界に関する支配的な言説に疑問を投げかけるために文芸批評を利用していた[14]。セジウィックは、『Between Men』という影響力のある本の中で、彼女特有の批評手段や関心を初めて提示した: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire』(1985年)、『Epistemology of the Closet』(1990年)[15]。 彼女は1969年にハル・セジウィックと結婚した[14]。セジウィックと彼女の夫は40年近く幸せな結婚生活を送ったが、関係が始まってから彼女が亡く なるまで、ふたりは互いに独立し、通常は別々の州で暮らしていた。セジウィックは夫との関係を「バニラ」と表現していたが、エイズ流行の友人たちの体験に 批評的なまなざしを向けるにつれて、心理学的、自伝的な深みを増していった[16]。彼女のセクシュアリティは、クィアという一般的な言葉を使うクィア理 論家として一部の人々を混乱させたが、セジウィックはストレート以外の何者でもないと公言することはなかった[17]。 LGBT研究での広範な功績が認められ、2002年にイェール大学で生涯功労賞であるブラドナー賞を受賞。2006年にはアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出さ れた[18]。ニューヨークで亡くなるまで、ニューヨーク市立大学大学院センター(CUNY Graduate Center)の特別教授として英語の大学院課程で教鞭をとっていた[19]。 死 1990年、ポスドク取得中に乳房にしこりを発見。彼女は根治的乳房切除術を受け、右乳房のすべてと右脇の下のリンパ節をすべて切除した。1996年秋、 セジウィックの背骨にもがんが見つかり[21]、メモリアル・スローン・ケタリングで6ヶ月間治療を受け、がんに侵された背骨の部分に一連の放射線治療を 受けた[20]。 2005年までに、セジウィックの基本的ながん治療は安定していた[21]。2006年の初めに、セジウィックのがんが再浮上し、骨と肝臓に再び広がっていることが判明した[21]。2009年4月12日、ニューヨークで58歳で死去した。 |

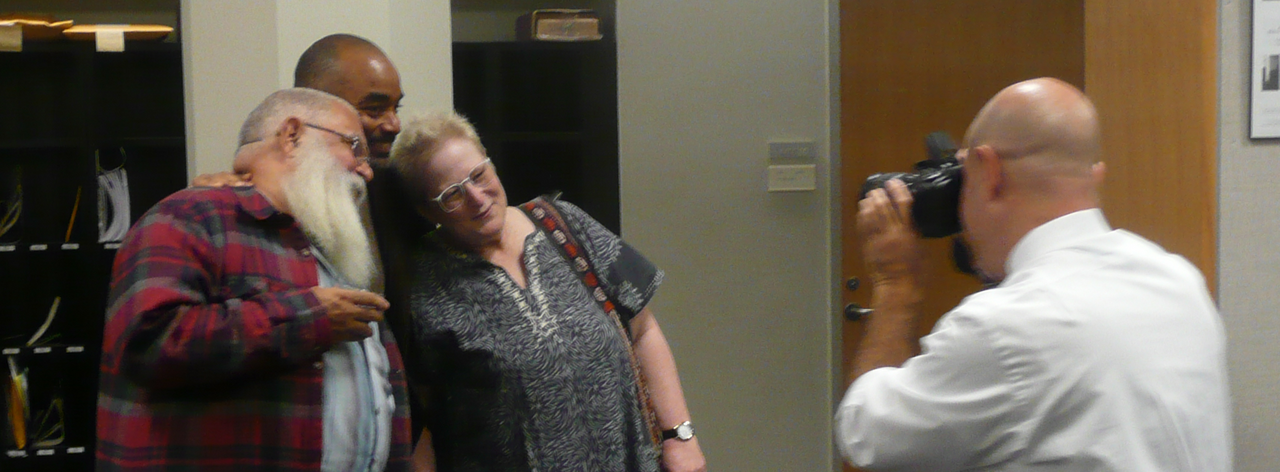

Ideas and literary criticism (L-R) Samuel R. Delany, Robert Reid-Pharr, and Eve Sedgwick pose for a picture Sedgwick's work ranges across a wide variety of media and genres; poetry and artworks are not easily separated from the rest of her texts. Disciplinary interests included literary studies, history, art history, film studies, philosophy, cultural studies, anthropology, women's studies and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) studies. Her theoretical interests have been synoptic, assimilative, and eclectic.[23] The queer lens Sedgwick aimed to make readers more alert to the "potential queer nuances" of literature, encouraging the reader to displace their heterosexual identifications in favor of searching out "queer idioms."[24] Thus, besides obvious double entendres, the reader is to realize other potentially queer ways in which words might resonate. For example, in Henry James, Sedgwick was said to have observed that words and concepts like 'fond', 'foundation', 'issue', 'assist', 'fragrant', 'flagrant', 'glove', 'gage', 'centre', 'circumference', 'aspect', 'medal' and words containing the sound 'rect', including any words that contain their anagrams, may all have "anal-erotic associations."[24] Sedgwick drew on the work of literary critic Christopher Craft to argue that both puns and rhymes might be re-imagined as "homoerotic because homophonic"; citing literary critic Jonathan Dollimore, Sedgwick suggests that grammatical inversion might have an equally intimate relation to sexual inversion; she suggested that readers may want to "sensitise" themselves to "potentially queer" rhythms of certain grammatical, syntactical, rhetorical, and generic sentence structures; scenes of childhood spanking were eroticised, and associated with two-beat lines and lyric as a genre; enjambment (continuing a thought from one line, couplet, or stanza to the next without a syntactical break) had potentially queer erotic implications; finally, while thirteen-line poems allude to the sonnet form, by rejecting the final rhyming couplet it was possible to "resist the heterosexual couple as a paradigm", suggesting instead the potential masturbatory pleasures of solitude.[25] [25]Edwards, Jason (2009). Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (1st ed.). New York, NY: Routledge., p. 59-60 Sedgwick encouraged readers to consider "potential queer erotic resonances" in the writing of Henry James.[26] Drawing on and herself performing a "thematics of anal fingering and 'fisting-as-écriture'" (or writing) in James's work, Sedgwick put forward the idea that sentences whose "relatively conventional subject-verb-object armature is disrupted, if never quite ruptured, as the sac of the sentence gets distended by the insinuation of one more, qualifying phrase or clause" can best be apprehended as either giving readers the vicarious experience of having their rectums penetrated with a finger or fist, or of their own "probing digit" inserted into a rectum. Sedgwick makes this claim based on certain grammatical features of the text.[26] Reparative reading Sedgwick argues that much academic criticism springs from a hermeneutics of suspicion as coined by Paul Ricœur. She suggests that critics should instead approach texts and look at "their empowering, productive as well as renewing potential to promote semantic innovation, personal healing and social change."[27] This is Sedgwick's idea of reparative reading which to her is the opposite of "paranoid reading" which focuses on the problematic elements in a given text. Reparative readings "contrasts with familiar academic protocols like maintaining critical distance, outsmarting (and other forms of one-upmanship), refusing to be surprised (or if you are, then not letting on), believing the hierarchy, becoming boss."[28] Rita Felski argues that reparative reading can be defined as "a stance that looks to a work of art for solace and replenishment rather than viewing it as something to be interrogated and indicted."[29] Felski's claims around postcritique and postcritical reading draw heavily on Sedgwick's reparative approach.[30] |

思想と文芸批評 (左から右)ポーズをとるサミュエル・R・ディラニー、ロバート・リード=ファー、イヴ・セジウィック セジウィックの作品は幅広いメディアとジャンルに及んでおり、詩や芸術作品は他のテキストと簡単に切り離すことはできない。文学研究、歴史学、美術史、映 画研究、哲学、カルチュラル・スタディーズ、人類学、女性学、レズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュアル、トランスジェンダー、インターセックス(LGBTI) 研究などの分野に関心を持つ。彼女の理論的関心は、共観的、同化的、折衷的である[23]。 クィア・レンズ セジウィックは、読者に文学の「潜在的なクィア的ニュアンス」にもっと注意を向けさせることを目的とし、「クィア的イディオム」[24]を探し出すことを 優先し、異性愛者としてのアイデンティティを捨てるよう促している。例えば、ヘンリー・ジェイムズにおいてセジウィックは、「fond」、 「foundation」、「issue」、「assist」、「fragrant」、「flagrant」、「glove」、「gage」、 「center」、「circumference」、「aspect」、「medal」といった単語や概念、そして「rect」という音を含む単語(それ らのアナグラムを含むあらゆる単語を含む)は、すべて「肛門-エロティックな連想」を持つ可能性があると観察したと言われている[24]。 セジウィックは文芸批評家クリストファー・クラフトの仕事を引き合いに出し、ダジャレも韻文も「同音であるがゆえにホモエロティック」であると捉え直すこ とができるかもしれないと主張している。文芸批評家ジョナサン・ドリモアを引き合いに出し、セジウィックは文法的反転が性的反転と同様に親密な関係を持つ かもしれないと示唆している。彼女は、読者は特定の文法的、構文的、修辞的、一般的な文構造の「潜在的にクィアな」リズムに「感化」されたいと思うかもし れないと示唆している; 最後に、13行詩はソネット形式を連想させるが、最後の韻を踏んだ連句を拒絶することで、「パラダイムとしての異性愛のカップルに抵抗する」ことが可能で あり、代わりに孤独の潜在的な自慰的快楽を示唆する。 [25]Edwards, Jason (2009). Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (1st ed.). New York, NY: Routledge., p. 59-60. セジウィックは読者に対して、ヘンリー・ジェイムズの文章における「潜在的なクィア的エロティックな共鳴」を考慮するよう勧めている。 [セジウィックは、ジェイムズの作品における「肛門の指使いと "fisting-as-écriture"(あるいは書くこと)の主題学」を引用し、また自らもそれを実践することで、「文の嚢が完全に破壊されること はないにせよ、比較的従来の主語-動詞-目的語のアーマチュアが破壊される、 セドウィックは、「比較的従来の主語-動詞-目的語のアーマチュアが、もう一つの修飾語句や節を挿入することによって、文の嚢が膨張する」文章は、読者に 指や拳で直腸を貫かれるような、あるいは読者自身の「探る指」が直腸に挿入されるような、身をもって体験させるものであると理解するのが最も適切である、 と主張する。セジウィックはテクストのある文法的特徴に基づいてこの主張をしている[26]。 修復的読解 セジウィックは、学問的批評の多くが、ポール・リクールの造語である「疑いの解釈学」から生まれていると主張する。セジウィックは、批評家はテキストに接 近し、「意味論的な革新、個人的な癒し、社会的な変化を促進するために、テキストに力を与え、生産的であると同時に更新的な可能性を見出す」べきだと提案 している。修復的読解は、「批評的距離の維持、出し抜くこと(および他の形の一枚上手)、驚くことを拒否すること(あるいは驚いたとしてもそれを漏らさな いこと)、ヒエラルキーを信じること、ボスになることといった、おなじみの学問的プロトコルと対照的である。 「28]リタ・フェルスキーは、修復的読書とは「芸術作品を尋問され非難されるべきものとして見るのではなく、慰めと補給を求めて作品に目を向ける姿勢」 と定義できると論じている[29]。ポスト批評とポスト批評的読書をめぐるフェルスキーの主張は、セジウィックの修復的アプローチに大きく依拠している [30]。 |

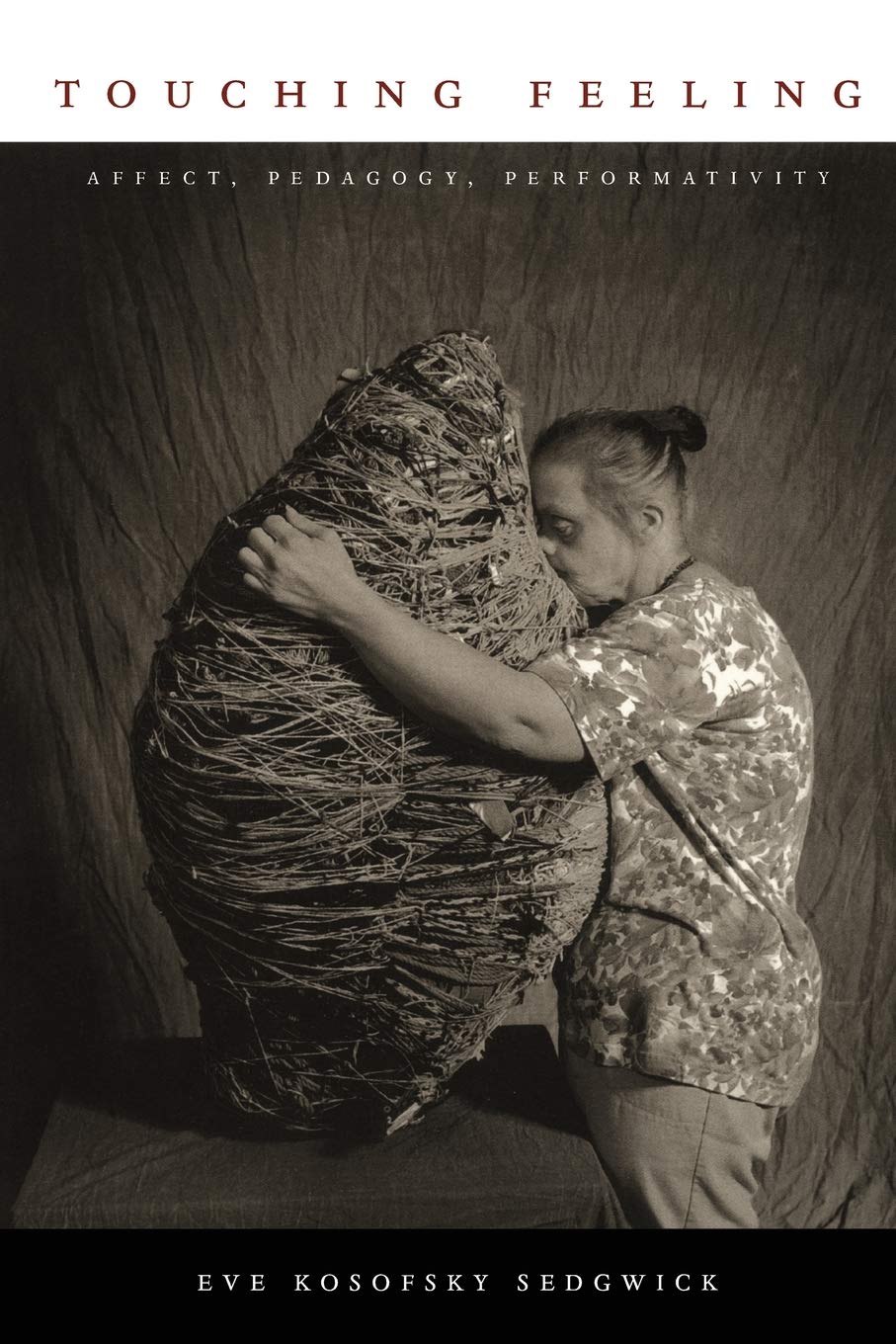

| Body of work Sedgwick published several foundational books in the field of queer theory, including Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (1985), Epistemology of the Closet (1990), and Tendencies (1993). Sedgwick also coedited several volumes and published a book of poetry Fat Art, Thin Art (1994) as well as A Dialogue on Love (1999). Her first book, The Coherence of Gothic Conventions (1986), was a revision of her doctoral thesis. Her last book Touching Feeling (2003) maps her interest in affect, pedagogy, and performativity. Jonathan Goldberg edited her late essays and lectures, many of which are segments from an unfinished study of Proust. According to Goldberg, these late writings also examine such subjects as Buddhism, object relations and affect theory, psychoanalytic writers such as Melanie Klein, Silvan Tomkins, D.W. Winnicott, and Michael Balint, the poetry of C. P. Cavafy, philosophical Neoplatonism, and identity politics.[31] Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (1985) According to Sedgwick, Between Men demonstrates "the immanence of men's same-sex bonds, and their prohibitive structuration, to male-female bonds in nineteenth-century English literature." The book explores the oppressive effects on women and men of a cultural system where male-male desire could become intelligible only by being routed through nonexistent desire involving a woman. Sedgwick's "male homosocial desire" referred to all male bonds. Sedgwick used the sociological neologism "homosocial" to distinguish from "homosexual" and to connote a form of male bonding often accompanied by a fear or hatred of homosexuality,[32] rejecting the then-available lexical and conceptual alternatives to challenge the idea that hetero-, bi- and homosexual men and experiences could be easily differentiated.[33] She argued that one could not readily distinguish these three categories from one another, since what might be conceptualized as "erotic" depended on an "unpredictable, ever-changing array of local factors."[33] Epistemology of the Closet (1990) Sedgwick's inspiration for Epistemology came from reading D. A. Miller's essay, 'Secret Subjects, Open Subjects', subsequently included in The Novel and the Police (1988). In Epistemology of the Closet, Sedgwick argues that "virtually any aspect of modern Western culture, must be, not merely incomplete, but damaged in its central substance to the degree that it does not incorporate a critical analysis of modern homo/heterosexual definition." According to Sedgwick, the homo/heterosexual definition has become so tediously argued over because of a lasting incoherence "between seeing homo/heterosexual definition on the one hand as an issue of active importance primarily for a small, distinct, relatively fixed homosexual minority ... [and] seeing it on the other hand as an issue of continuing, determinative importance in the lives of people across the spectrum of sexualities." "Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl" Sedgwick is perhaps best known not for her books, but rather for an article she published in 1991, "Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl."[34] The very title of her article attracted much attention from the media, most of it very negative.[34] The conservative American cultural critic Roger Kimball used the title of her article as evidence of left-wing "corruption" in higher education in his 1990 book Tenured Radicals, when Sedgwick delivered a talk on her upcoming article at a conference of the Modern Language Association in late 1989.[35] When Tenured Radicals was published in April 1990, Sedgwick's little known speech at the Modern Language Association suddenly became famous. Sedgwick felt Kimball's criticism of her in Tenured Radicals was highly unfair, given she had not actually written the article, which was published only in the summer of 1991, and therefore he dismissed her article only on the basis of the title.[35] The British critic Robert Irvine wrote that much of the negative reaction that "Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl" generated, which became the subject of heated debate in the American "culture war" between liberals and conservatives, was due to the fact that many people could not accept the thesis that Jane Austen had anything to do with sex.[34] In her article, Sedgwick juxtaposed three treatments of female suffering, namely Marianne Dashwood's emotional frenzy when Willoughby abandons her in Sense and Sensibility, a 19th-century French medical account of the "cure" inflicted on a girl who liked to masturbate, and the critic Tony Tanner's "vengeful" treatment of Emma Woodhouse as a woman who had to be taught her place.[34] Sedgwick argued that by the middle of the 18th century, the "sexual identity" of the onanist was well established in British disclosures and that Austen writing at the beginning of the 19th century would have been familiar with it.[36] Sedgwick used Austen's description of Marianne Dashwood, whose "eyes were in constant inquiry", whose "mind was equally abstracted from everything actually before them" as she was "restless and dissatisfied" and unable to sit still.[37] She then compared Sense and Sensibility with the 1881 document "Onanism and Nervous Disorders in Two Little Girls" where the patient X has a "roving eye", "cannot keep still" and is "incapable of anything".[38] In Sedgwick's viewpoint, the description of Patient X, who could not stop masturbating and was in a constant state of hysteria as the doctor tried to keep her from masturbating by such methods as having her hands tied together, closely matched Austen's description of Marianne Dashwood.[37] Sedgwick argued that both patient X and Dashwood were seen as suffering from an excess of sexuality that needed to be brought under control, arguing that though Elinor Dashwood did things considerably more gently than the doctor who repeatedly burned Patient X's clitoris both were agents of discipline and control.[39] Sedgwick argued that the pleasure that Austen's readers take from Marianne's suffering is typical of Austen scholarship, which was centered around what Sedgwick called the central theme of a "A Girl Being Taught a Lesson".[40] As a prime example of what she called the "Victorian sadomasochistic pornography" of Austen scholarship, she used Tanner's treatment of Emma Woodhouse as a woman who has to be taught her place.[40] Furthermore, Sedgwick accused Austen scholars of presenting Austen herself as a "punishable girl" full of a "self-pleasing sexuality" who was ever ready to be "violated".[41] Sedgwick ended her essay by writing that most Austen scholars wanted to de-eroticize her books, as she argued there was an implicit lesbian sexual tension between the Dashwood sisters, and scholars needed to stop repressing the "homo-erotic longing" contained in Austen's novels.[42] Tendencies (1993) In 1993, Duke University Press published a collection of Sedgwick's essays from the 1980s and early 1990s. The book was the first entry in Duke's influential "Series Q", which was initially edited by Michele Aina Barale, Jonathan Goldberg, Michael Moon, and Sedgwick herself. The essays span a wide range of genres, including elegies for activists and scholars who died of AIDS, performance pieces, and academic essays on topics such as sado-masochism, poetics and masturbation. In Tendencies, Sedgwick first publicly embraces the word 'queer', defining it as: "the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone's gender, of anyone's sexuality aren't made (or can't be made) to signify monolithically."[43] According to trans theorist Jay Prosser, Tendencies is also relevant, for it is here that Sedgwick "has revealed her personal transgendered investment lying at and as the great heart of her queer project."[44] He goes on to quote Sedgwick: Nobody knows more fully, more fatalistically than a fat woman how unbridgeable the gap is between the self we see and the self as whom we are seen... and no one can appreciate more fervently the act of magical faith by which it may be possible, at last, to assert and believe, against every social possibility, that the self we see can be made visible as if through our own eyes to the people who see us... Dare I, after this half-decade, call it with all a fat woman's defiance, my identity? – as a gay man.[45] A Dialogue on Love (1999) In 1991, Sedgwick was diagnosed with breast cancer and subsequently wrote the book A Dialogue on Love.[46] Sedgwick recounts the therapy she undergoes, her feelings toward death, depression, and her gender uncertainty before her mastectomy and chemotherapy.[46] The book incorporates both poetry and prose, as well as Sedgwick's own words and her therapist's notes. Though the title connotes the Platonic dialogues, the form of the book was inspired by James Merrill's "Prose of Departure" which followed a seventeenth-century Japanese form of persiflage known as haibun.[47] Sedgwick uses the form of an extended, double-voiced haibun to explore possibilities within the psychoanalytic setting, particularly those that offer alternatives to Lacanian-inflected psychoanalysis, and new ways for thinking about sexuality, familial relations, pedagogy, and love. The book also reveals Sedgwick's growing interest in Buddhist thought, textiles, and texture.[47] Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (2003) Touching Feeling is written as a reminder of the early days of queer theory, which Sedgwick discusses briefly in the introduction in order to reference the affective conditions—chiefly the emotions provoked by the AIDS epidemic—that prevailed at the time and to bring into focus her principal theme: the relationship between feeling, learning, and action. Touching Feeling explores critical methods that may engage politically and help shift the foundations for individual and collective experience. In the opening paragraph, Sedgwick describes her project as the exploration of "promising tools and techniques for non dualistic thought and pedagogy." Sedgwick integrates works by Henry James, JL Austin, Judith Butler, Silvan Tompkins, and others, incorporating different levels of emotions and how they come together in our collective lives. Touching Feeling focuses on not only Sedgwick's illness, but illness in general and how we deal with it. |

著作 セジウィックは、『Between Men』(1985年)、『Epistemology of Closet』(1990年)、『Tendencies』(1993年)など、クィア理論の基礎となる書籍を出版: Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire』(1985年)、『Epistemology of the Closet』(1990年)、『Tendencies』(1993年)など。また、詩集『Fat Art, Thin Art』(1994年)や『A Dialogue on Love』(1999年)を出版。最初の著書『The Coherence of Gothic Conventions』(1986年)は博士論文を改稿したもの。前著『Touching Feeling』(2003年)は、情動、教育学、パフォーマティヴィティに対する彼女の関心を図式化したものである。ジョナサン・ゴールドバーグは、彼 女の後期のエッセイや講義を編集した。ゴールドバーグによれば、これらの後期の著作は、仏教、対象関係論と感情理論、メラニー・クライン、シルヴァン・ト ムキンス、D.W.ウィニコット、マイケル・バリントといった精神分析作家、C.P.カヴァフィの詩、哲学的新プラトン主義、アイデンティティ政治といっ た主題についても考察している[31]。 『Between Men: 英文学と男性のホモソーシャルな欲望』(1985年) セジウィックによれば、『Between Men』は「19世紀イギリス文学における男性の同性間の絆とその禁止的な構造化が、男性と女性の絆に内在している」ことを実証している。 本書は、男性同士の欲望が、女性を含む存在しない欲望を経由することでしか理解できない文化システムが、女性と男性に与える抑圧的な影響を探求している。 セジウィックの言う「男性のホモソーシャルな欲望」とは、すべての男性の絆を指していた。セジウィックは「ホモソーシャル」という社会学的な新語を用いて 「ホモセクシャル」と区別し、しばしば同性愛に対する恐怖や憎悪を伴う男性の結合の形態を意味した[32]。 [33]彼女は、何が「エロティック」として概念化されるかは「予測不可能で常に変化し続ける局所的な要因の配列」[33]に依存するため、これら3つの カテゴリーを互いに容易に区別することはできないと主張した。 『クローゼットの認識論』(1990年) セジウィックが『認識論』の着想を得たのは、その後『小説と警察』(1988年)に収録されたD・A・ミラーのエッセイ「秘密の主題、開かれた主題」を読んだことによる。 セジウィックは『クローゼットの認識論』の中で、「事実上、現代西洋文化のあらゆる側面は、現代のホモ/異性愛の定義に関する批判的分析を組み込んでいな い限り、単に不完全であるだけでなく、その中心的な本質が損なわれているに違いない」と論じている。 [そして他方では、セクシュアリティのスペクトルを超えた人々の人生において、継続的で決定的な重要性を持つ問題であるとみなす。" 「ジェーン・オースティンと自慰する少女」 セジウィックが最もよく知られているのは、おそらく著書ではなく、1991年に発表した論文、"Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl "であろう[34]。 [34]保守的なアメリカの文化批評家ロジャー・キンボールは1990年に出版した著書『Tenured Radicals』の中で、セジウィックが1989年末に現代言語学会の会議で彼女の論文に関する講演を行った際に、彼女の論文のタイトルを高等教育にお ける左翼的な「腐敗」の証拠として用いた[35]。1990年4月に『Tenured Radicals』が出版されると、セジウィックの現代言語学会でのあまり知られていない講演は突然有名になった。セジウィックは、『Tenured Radicals』におけるキンボールの自分に対する批判は、1991年の夏に出版されたばかりのその論文を実際に書いていないことを考えると、非常に不 当であると感じ、そのため彼は彼女の論文をタイトルだけで否定した。 [35] イギリスの批評家ロバート・アーヴァインは、『ジェーン・オースティンと自慰する少女』が巻き起こした否定的な反応の多くは、アメリカのリベラル派と保守 派の「文化戦争」において激しい議論の対象となったが、それは多くの人々がジェーン・オースティンがセックスと何か関係があるという論文を受け入れること ができなかったことに起因していると書いている[34]。 [34]Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005 page 111. すなわち、『分別と多感』の中でウィロビーに捨てられたマリアンヌ・ダッシュウッドの感情的狂乱、自慰行為が好きな少女に施された「治療」に関する19世 紀のフランスの医学的記述、そして批評家トニー・タナーがエマ・ウッドハウスを「復讐に燃えた」扱いをし、自分の立場を教えなければならない女性として 扱ったことである。 34]セジウィックは、18世紀半ばまでには、オナニストという「性的アイデンティティ」はイギリスの情報開示の中で十分に確立されており、19世紀初頭 に書かれたオースティンはそれを熟知していただろうと主張した[36]。セジウィックはオースティンのマリアンヌ・ダッシュウッドについての記述を用い、 その「目は絶えず探究しており」、「心は同じように目の前の現実のすべてから抽象化されており」、「落ち着きがなく、不満で」じっとしていることができな かったとした[37]。 [セジウィックの視点によれば、自慰行為をやめられず、医師が両手を縛るなどの方法で自慰行為をさせまいとするため、常にヒステリー状態にあった患者Xの 描写は、オースティンのマリアンヌ・ダッシュウッドの描写と密接に一致していた。 [セジウィックは、患者Xもダッシュウッドも、コントロール下に置く必要のある過剰な性欲に苦しんでいると見なされていたと主張し、エリナー・ダッシュ ウッドは患者Xのクリトリスを繰り返し焼いた医師よりもかなり優しく物事を行ったが、どちらも規律とコントロールの代理人であったと論じている[39]。 セジウィックは、オースティンの読者がマリアンヌの苦しみから快楽を得ることは、セジウィックが「レッスンを受ける少女」と呼ぶものを中心テーマとする オースティン研究の典型であると主張した[40]。彼女がオースティン研究の「ヴィクトリア朝のサドマゾ的ポルノグラフィ」と呼ぶものの代表例として、彼 女はタナーがエマ・ウッドハウスを自分の居場所を教えられなければならない女性として扱っていることを取り上げた。 [さらにセジウィックは、オースティン研究者がオースティン自身を「自己悦楽的なセクシュアリティ」に満ちた「懲罰的な少女」であり、常に「侵害」される 用意ができているような存在として提示していると非難した[41]。セジウィックは、ダッシュウッド姉妹の間には暗黙のレズビアンの性的緊張があり、オー スティンの小説に含まれる「ホモ・エロティックな憧れ」を抑圧することをやめる必要があると主張し、オースティン研究者の多くはオースティンの著書の脱エ ロ化を望んでいると書いてエッセイを締めくくった[42]。 テンデンシーズ(1993年) 1993年、デューク大学出版局は1980年代から1990年代初頭にかけてのセジウィックのエッセイ集を出版した。本書はデューク大学の影響力のある 「シリーズQ」の最初の作品であり、当初はミケーレ・アイナ・バラレ、ジョナサン・ゴールドバーグ、マイケル・ムーン、そしてセジウィック自身が編集を担 当した。エイズで亡くなった活動家や学者への追悼文、パフォーマンス作品、サド・マゾヒズム、詩学、マスターベーションなどのトピックに関する学術的エッ セイなど、幅広いジャンルのエッセイが収録されている。セジウィックは『テンデン シーズ』の中で、初めて「クィア」という言葉を公に受け入れ、次のように定義している: 「誰のジェンダーも、誰のセクシュアリティも、その構成要素が一義的に意味づけされない(あるいはさせられない)ときの、可能性、ギャップ、オーバーラッ プ、不協和音と共鳴、意味の欠落や過剰の開かれたメッシュ」[43]。Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. "Tendencies." Durham and London: Duke University Press (Series Q), 1993. pg. 8. トランス理論家のジェイ・プロッサーによれば、『Tendencies』もまた、セジウィックが「彼女の個人的なトランスジェンダーとしての投資が、彼女のクィア・プロジェクトの大きな核心に横たわっていることを明らかにした」[44]この作品と関係がある: 私たちが見ている自己と、私たちが見られている自己との間にある埋めようのない隔たりがどれほど大きいかを、太った女性ほど十分に、宿命的に知っている者 はいない......そして、私たちが見ている自己を、私たちを見る人々に対して、あたかも私たち自身の目を通して見えるようにすることができると、あら ゆる社会的可能性に反して主張し、信じることが、ついに可能になるかもしれない魔法のような信仰行為を、これほど熱烈に評価できる者はいな い......」。この半世紀を経て、太った女性のような反抗的な態度で、自分のアイデンティティと呼ぶ勇気があるだろうか?- ゲイとして[45]。 『愛についての対話』(1999年) 1991年、セジウィックは乳がんと診断され、その後『A Dialogue on Love(愛についての対話)』という本を書いた[46]。セジウィックは、乳房切除と化学療法を受ける前に受けた治療、死に対する感情、うつ病、性別の 不確かさについて語っている[46]。この本には、詩と散文の両方、そしてセジウィック自身の言葉とセラピストのメモが盛り込まれている。タイトルはプラ トニック・ダイアローグを暗示しているが、この本の形式は、俳文として知られる17世紀の日本の韻文形式を踏襲したジェームズ・メリルの「出発の散文」に 触発されたものである[47]。セジウィックは、拡張された二重声の俳文の形式を用いて、精神分析の設定における可能性、特にラカンの影響を受けた精神分 析に代わるものや、セクシュアリティ、家族関係、教育学、愛についての新しい考え方を探求している。本書はまた、セジウィックが仏教思想、織物、質感への 関心を高めていることも明らかにしている[47]。 フィーリングに触れる: 感情、教育学、パフォーマティヴィティ (2003) セドウィックは序章で、当時蔓延していた感情的状況、とりわけエイズの流行によって引き起こされた感情に言及し、彼女の主要なテーマである感情、学習、行 動の関係に焦点を当てるために、クィア理論の黎明期を思い起こさせるように書かれている。『Touching Feeling』は、政治的に関与し、個人的・集団的経験の基盤を転換させるのに役立つ批評的方法を探求している。冒頭でセジウィックは、自身のプロジェ クトを「非二元論的な思考と教育法のための有望なツールとテクニック」の探求と説明している。セジウィックは、ヘンリー・ジェイムズ、JL・オースティ ン、ジュディス・バトラー、シルヴァン・トンプキンスなどの作品を統合し、さまざまなレベルの感情と、それらが私たちの集団生活の中でどのように組み合わ されていくのかを組み込んでいる。Touching Feeling』では、セジウィックの病気だけでなく、病気全般と私たちがそれにどう対処するかに焦点を当てている。 |

| Awards and recognitions 1987 Guggenheim fellowship for Literary Criticism 1998 David R Kessler Award for LGBTQ studies, CLAGS: The Center for LGBTQ Studies[48] 2002 Brudner Prize for her academic contributions to the field of LGBT Studies, Yale University.[49] List of publications This is a partial list of publications by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick: The Coherence of Gothic Conventions (ISBN 0-405-12650-6), 1980 Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (ISBN 9780231176293), 1985 Epistemology of the Closet (ISBN 0-520-07874-8), 1990 Tendencies (ISBN 0-8223-1421-5), 1993 Fat Art, Thin Art (ISBN 0-8223-1501-7), 1994 Performativity and Performance (ISBN 978-0-415-91055-2), 1995, coedited with Andrew Parker Shame & Its Sisters: A Silvan Tomkins Reader (ISBN 978-0-8223-1694-7), 1995, coedited with Adam Frank Gary in Your Pocket: Stories and Notebooks of Gary Fisher (ISBN 978-0-8223-1799-9), 1996, coedited with Gary Fisher Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction (ISBN 978-0-8223-2040-1), 1997, coedited with Jacob Press A Dialogue on Love (ISBN 0-8070-2923-8), 2000 Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (ISBN 0-8223-3015-6), 2003 The Weather in Proust (ISBN 0822351587), 2011 [Censorship & Homophobia] (Guillotine press), 2013 Writing the History of Homophobia (ISBN 978-0-8223-7663-7), 2014. Bathroom Songs: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick as a Poet (ISBN 978-1-947447-30-1), 2017, edited by Jason Edwards Queerer than Fiction: Studies in the Novel, vol. 28, no. 3, 1996 [1] |

受賞歴と栄誉 1987年 グッゲンハイム文学批評フェローシップ 1998年 デイヴィッド・R・ケスラー賞(LGBTQ研究分野)、CLAGS:LGBTQ研究センター[48] 2002年 ブルドナー賞(LGBT研究分野への学術的貢献)、イェール大学 [49] 出版物一覧 イヴ・コソフスキー・セジウィックの出版物の一部を以下に示す: 『ゴシック慣習の一貫性』(ISBN 0-405-12650-6)、1980年 『男たちの間:英国文学と男性の同性愛的欲望』(ISBN 9780231176293)、1985年 クローゼットの認識論(ISBN 0-520-07874-8)、1990年 傾向(ISBN 0-8223-1421-5)、1993年 太った芸術、痩せた芸術(ISBN 0-8223-1501-7)、1994年 『パフォーマンス性とパフォーマンス』(ISBN 978-0-415-91055-2)、1995年、アンドルー・パーカーと共同編集 『恥とその姉妹たち:シルヴァン・トンプキンス・リーダー』(ISBN 978-0-8223-1694-7)、1995年、アダム・フランクと共同編集 『ゲイリー・イン・ユア・ポケット:ゲイリー・フィッシャーの物語とノート』(ISBN 978-0-8223-1799-9)、1996年、ゲイリー・フィッシャーと共同編集 『小説を見つめる:フィクションにおけるクィアな読み方』(ISBN 978-0-8223-2040-1)、1997年、ジェイコブ・プレスと共同編集 『愛についての対話』(ISBN 0-8070-2923-8)、2000年 『触れる感情:情動、教育学、パフォーマンス性』(ISBN 0-8223-3015-6)、2003年 プルーストの天気(ISBN 0822351587)、2011年 [検閲とホモフォビア](ギロチン・プレス)、2013年 ホモフォビアの歴史を書く(ISBN 978-0-8223-7663-7)、2014年 『バスルーム・ソングス:詩人としてのイヴ・コソフスキー・セジウィック』(ISBN 978-1-947447-30-1)、2017年、ジェイソン・エドワーズ編 『フィクションよりクィア:小説研究』第28巻第3号、1996年[1] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eve_Kosofsky_Sedgwick |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆