表現性の失語症

Expressive aphasia; 表現能力の失語症

☆ 表現性失語症は、ブロカ失語としても知られ、言語(話し言葉、手話、または書き言葉)を生成する能力の部分的な喪失を特徴とする失語症の一種である が、理解力は一般に維持されている。発話には一般に重要な内容の単語が含まれるが、前置詞や冠詞など、物理的な意味よりも文法的な意味が強い機能語は除か れる。その人が意図したメッセージは理解されるかもしれないが、文法的に正しい文章にはならない。表現性失語の非常に重篤な病型では、1語しか発語 できないこともある[4][5]。一般に、表現性失語では複雑な文法を理解することが困難なため、理解力は軽度から中等度に障害される。失語症は、ブローカ野などの脳の前方領域の後天的な損傷によって引き起こされる。表出性失語は、意味的意義を欠く文法的な文章で話すことができ、一 般に理解にも問題がある受容性失語とは対照的である。また、表出性失語は、発話のための運動計画を作成し、順序立てることができないことを特徴とする運動 障害である失語症とも異なる。

| Expressive

aphasia, also known as Broca's aphasia, is a type of aphasia

characterized by partial loss of the ability to produce language

(spoken, manual,[1] or written), although comprehension generally

remains intact.[2] A person with expressive aphasia will exhibit

effortful speech. Speech generally includes important content words but

leaves out function words that have more grammatical significance than

physical meaning, such as prepositions and articles.[3] This is known

as "telegraphic speech". The person's intended message may still be

understood, but their sentence will not be grammatically correct. In

very severe forms of expressive aphasia, a person may only speak using

single word utterances.[4][5] Typically, comprehension is mildly to

moderately impaired in expressive aphasia due to difficulty

understanding complex grammar.[4][5] It is caused by acquired damage to the anterior regions of the brain, such as Broca's area.[6] It is one subset of a larger family of disorders known collectively as aphasia. Expressive aphasia contrasts with receptive aphasia, in which patients are able to speak in grammatical sentences that lack semantic significance and generally also have trouble with comprehension.[3][7] Expressive aphasia differs from dysarthria, which is typified by a patient's inability to properly move the muscles of the tongue and mouth to produce speech. Expressive aphasia also differs from apraxia of speech, which is a motor disorder characterized by an inability to create and sequence motor plans for speech.[8] |

表現性失語症

は、ブロカ失語としても知られ、言語(話し言葉、手話、[1]または書き言葉)を生成する能力の部分的な喪失を特徴とする失語症の一種であるが、理解力は

一般に維持されている。発話には一般に重要な内容の単語が含まれるが、前置詞や冠詞など、物理的な意味よりも文法的な意味が強い機能語は除かれる[3]。

その人が意図したメッセージは理解されるかもしれないが、文法的に正しい文章にはならない。表現性失語の非常に重篤な病型では、1語しか発語できないこと

もある[4][5]。一般に、表現性失語では複雑な文法を理解することが困難なため、理解力は軽度から中等度に障害される[4][5]。 失語症は、ブローカ野などの脳の前方領域の後天的な損傷によって引き起こされる[6]。表出性失語は、意味的意義を欠く文法的な文章で話すことができ、一 般に理解にも問題がある受容性失語とは対照的である。また、表出性失語は、発話のための運動計画を作成し、順序立てることができないことを特徴とする運動 障害である失語症とも異なる[8]。 |

| Signs and symptoms Broca's (expressive) aphasia is a type of non-fluent aphasia in which an individual's speech is halting and effortful. Misarticulations or distortions of consonants and vowels, namely phonetic dissolution, are common. Individuals with expressive aphasia may only produce single words, or words in groups of two or three.[8] Long pauses between words are common and multi-syllabic words may be produced one syllable at a time with pauses between each syllable.[8] The prosody of a person with Broca's aphasia is compromised by shortened length of utterances and the presence of self-repairs and disfluencies.[9] Intonation and stress patterns are also deficient.[10] For example, in the following passage, a patient with Broca's aphasia is trying to explain how he came to the hospital for dental surgery: Yes... ah... Monday... er... Dad and Peter H... (his own name), and Dad.... er... hospital... and ah... Wednesday... Wednesday, nine o'clock... and oh... Thursday... ten o'clock, ah doctors... two... an' doctors... and er... teeth... yah.[10] The speech of a person with expressive aphasia contains mostly content words such as nouns, verbs, and some adjectives. However, function words like conjunctions, articles, and prepositions are rarely used except for "and" which is prevalent in the speech of most patients with aphasia. The omission of function words makes the person's speech agrammatic.[8] A communication partner of a person with aphasia may say that the person's speech sounds telegraphic due to poor sentence construction and disjointed words.[8][10] For example, a person with expressive aphasia might say "Smart... university... smart... good... good..."[9] Self-monitoring is typically well preserved in patients with Broca's aphasia.[8] They are usually aware of their communication deficits, and are more prone to depression and outbursts from frustration than are patients with other forms of aphasia.[11] In general, word comprehension is preserved, allowing patients to have functional receptive language skills.[12] Individuals with Broca's aphasia understand most of the everyday conversation around them, but higher-level deficits in receptive language can occur.[13] Because comprehension is substantially impaired for more complex sentences, it is better to use simple language when speaking with an individual with expressive aphasia. This is exemplified by the difficulty to understand phrases or sentences with unusual structure. A typical patient with Broca's aphasia will misinterpret "the man is bitten by the dog" by switching the subject and object to "the dog is bitten by the man."[14] Typically, people with expressive aphasia can understand speech and read better than they can produce speech and write.[8] The person's writing will resemble their speech and will be effortful, lacking cohesion, and containing mostly content words.[15] Letters will likely be formed clumsily and distorted and some may even be omitted. Although listening and reading are generally intact, subtle deficits in both reading and listening comprehension are almost always present during assessment of aphasia.[8] Because Broca's area is anterior to the primary motor cortex, which is responsible for movement of the face, hands, and arms, a lesion affecting Broca's areas may also result in hemiparesis (weakness of both limbs on the same side of the body) or hemiplegia (paralysis of both limbs on the same side of the body).[8] The brain is wired contralaterally, which means the limbs on right side of the body are controlled by the left hemisphere and vice versa.[16] Therefore, when Broca's area or surrounding areas in the left hemisphere are damaged, hemiplegia or hemiparesis often occurs on the right side of the body in individuals with Broca's aphasia. Severity of expressive aphasia varies among patients. Some people may only have mild deficits and detecting problems with their language may be difficult. In the most extreme cases, patients may be able to produce only a single word. Even in such cases, over-learned and rote-learned speech patterns may be retained–[17] for instance, some patients can count from one to ten, but cannot produce the same numbers in novel conversation. Manual language and aphasia In deaf patients who use manual language (such as American Sign Language), damage to the left hemisphere of the brain leads to disruptions in their signing ability.[1] Paraphasic errors similar to spoken language have been observed; whereas in spoken language a phonemic substitution would occur (e.g. "tagle" instead of "table"), in ASL case studies errors in movement, hand position, and morphology have been noted. Agrammatism, or the lack of grammatical morphemes in sentence production, has also been observed in lifelong users of ASL who have left hemisphere damage. The lack of syntactic accuracy shows that the errors in signing are not due to damage to the motor cortex, but rather area manifestation of the damage to the language-producing area of the brain. Similar symptoms have been seen in a patient with left hemisphere damage whose first language was British Sign Language,[18] further showing that damage to the left hemisphere primarily hinders linguistic ability, not motor ability. In contrast, patients who have damage to non-linguistic areas on the left hemisphere have been shown to be fluent in signing, but are unable to comprehend written language.[1] Overlap with receptive aphasia In addition to difficulty expressing oneself, individuals with expressive aphasia are also noted to commonly have trouble with comprehension in certain linguistic areas. This agrammatism overlaps with receptive aphasia, but can be seen in patients who have expressive aphasia without being diagnosed as having receptive aphasia. The most well-noted of these are object-relative clauses, object Wh- questions, and topicalized structures (placing the topic at the beginning of the sentence).[19] These three concepts all share phrasal movement, which can cause words to lose their thematic roles when they change order in the sentence.[19] This is often not an issue for people without agrammatic aphasias, but many people with aphasia rely heavily on word order to understand roles that words play within the sentence.[20] |

徴候と症状 ブローカ失語(表出性失語)は非流暢性失語の一種で、発話が訥弁で努力性である。子音と母音の誤発声や歪曲、すなわち音韻分解がよくみられる。表出性失語 の患者は、単一の単語、または2つか3つのグループの単語しか発語しないことがある[8]。単語間の長い休止は一般的であり、多音節の単語は各音節間に休 止を挟んで一度に1音節ずつ発語されることがある[8]。 たとえば、次の文章では、ブローカ失語症の患者が、歯科手術のために来院した経緯を説明しようとしている: はい...あ... 月曜日...えーと...。お父さんとピーター・H...(自分の名前)と、お父さんが...病院に行って...ああ...。水曜日... 水曜日の9時...そして... 木曜日...10時、ああ...医者...2人...医者...そして...歯...や」[10]。 表現性失語症の人の発話には、名詞、動詞、いくつかの形容詞などの内容語がほとんど含まれる。しかし、接続詞、冠詞、前置詞などの機能語は、失語症患者の 発話に多く見られる「および」を除いて、ほとんど使われない。機能語が省略されることで、失語症者の発話は非文法的になる[8]。失語症者のコミュニケー ション・パートナーは、文の組み立てが悪く、単語がばらばらになるため、失語症者の発話が電信的に聞こえると言うことがある[8][10]。例えば、表現 性失語症者は「頭がいい...大学...頭がいい...いい...いい...」と言うことがある[9]。 ブローカ失語症の患者では、セルフモニタリングは一般的によく保たれている[8]。通常、コミュニケーション障害を自覚しており、他の失語症の患者よりも抑うつや欲求不満からの暴発を起こしやすい[11]。 一般に、言葉の理解力は保たれるため、患者は機能的な受容言語能力を持つことができる[12]。ブローカ失語の患者は身の回りの日常会話のほとんどを理解 できるが、より高度な受容言語の障害が起こることがある[13]。より複雑な文では理解力がかなり損なわれるため、表出性失語の患者と話すときは簡単な言 葉を使う方がよい。このことは、特異な構造をもつ句や文の理解が困難であることに例証される。ブローカ失語症の典型的な患者は、主語と目的語を入れ替えて 「犬が犬に噛まれた」を「犬が男に噛まれた」と誤訳する[14]。 一般に、表出性失語の患者は、発話を理解し、読むことができるが、発話を作り出し、書くことはできない[8]。聴解と読解は一般に無傷であるが、読解と聴解の両方における微妙な障害は、失語症の評価ではほとんど常に認められる。 ブローカ野は、顔、手、腕の運動をつかさどる一次運動野の前方にあるため、ブローカ野に影響を及ぼす病変は、片麻痺(身体の同じ側の両手足の脱力)または 片麻痺(身体の同じ側の両手足の麻痺)をもたらすこともある。 [したがって、左半球のブローカ野またはその周辺領域が損傷を受けると、ブローカ失語症の患者ではしばしば体の右側に片麻痺または片麻痺が生じる。 表現性失語の重症度は患者によって異なります。軽度の失語しかない人もおり、言葉の問題を発見することは困難である。最も極端な症例では、1語しか発語で きないこともある。そのような場合でも、過剰に学習された暗記された発話パターンが保持されていることがある-例えば、1から10まで数えることはできて も、新規の会話で同じ数字を発することができない患者がいる- [17] 。 手話と失語症 手話(アメリカ手話など)を使用する聴覚障害者では、脳の左半球の損傷により、手話能力に障害が生じる[1]。音声言語と同様のパラファシスエラーが観察 されており、音声言語では音素置換が起こる(例えば、「table」の代わりに「tagle」)のに対し、ASLの症例研究では、動作、手の位置、形態に おけるエラーが指摘されている。左半球に障害を持つ生涯ASL使用者においても、アグラマティズム(文生成における文法形態素の欠如)が観察されている。 構文の正確さの欠如は、手話の誤りが運動皮質の損傷によるものではなく、脳の言語生成領域の損傷の領域症状であることを示している。同様の症状は、左半球 に障害があり、第一言語がイギリス手話であった患者にも認められており[18]、左半球の障害は、運動能力ではなく、主として言語能力を阻害していること がさらに示されている。対照的に、左半球の非言語野に損傷を受けた患者は、手話は流暢であるが、書き言葉を理解できないことが示されている[1]。 受容性失語症との重複 表現性失語症の患者は、自己表現が困難であることに加えて、特定の言語領域における理解にも問題があることが一般的に指摘されている。このアグラマティズ ムは受容性失語症と重複するが、受容性失語症と診断されずに表現性失語症の患者にみられることもある。これらのうち最もよく知られているのは、目的語関係 節、目的語Wh-疑問文、およびトピック構造(トピックを文頭に置く)である[19]。これら3つの概念はすべて句運動を共有しており、文中の順序が変わ ると、単語が主題的役割を失うことがある[19]。これは、文法失語症でない人にとっては問題にならないことが多いが、失語症患者の多くは、文中で単語が 果たす役割を理解するために語順に大きく依存している[20]。 |

| Causes More common Stroke or brain anoxia. Brain tumor Brain trauma Less common Autoimmune disease Paraneoplastic syndrome Micrometastasis neurodegenerative disorders Certain infections (e.g., Bartonella henselae[21]) Metabolic disease (e.g., hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state[22]) Common causes The most common cause of expressive aphasia is stroke. A stroke is caused by hypoperfusion (lack of oxygen) to an area of the brain, which is commonly caused by thrombosis or embolism. Some form of aphasia occurs in 34 to 38% of stroke patients.[23] Expressive aphasia occurs in approximately 12% of new cases of aphasia caused by stroke.[24] In most cases, expressive aphasia is caused by a stroke in Broca's area or the surrounding vicinity. Broca's area is in the lower part of the premotor cortex in the language dominant hemisphere and is responsible for planning motor speech movements. However, cases of expressive aphasia have been seen in patients with strokes in other areas of the brain.[8] Patients with classic symptoms of expressive aphasia in general have more acute brain lesions, whereas patients with larger, widespread lesions exhibit a variety of symptoms that may be classified as global aphasia or left unclassified.[23] Expressive aphasia can also be caused by trauma to the brain, tumor, cerebral hemorrhage[25] and by extradural abscess.[26] Understanding lateralization of brain function is important for understanding which areas of the brain cause expressive aphasia when damaged. In the past, it has been believed that the area for language production differs between left and right-handed individuals. If this were true, damage to the homologous region of Broca's area in the right hemisphere should cause aphasia in a left-handed individual. More recent studies have shown that even left-handed individuals typically have language functions only in the left hemisphere. However, left-handed individuals are more likely to have a dominance of language in the right hemisphere.[6] Uncommon causes Less common causes of expressive aphasia include primary autoimmune phenomenon and autoimmune phenomenon that are secondary to cancer (as a paraneoplastic syndrome) have been listed as the primary hypothesis for several cases of aphasia, especially when presenting with other psychiatric disturbances and focal neurological deficits. Many case reports exist describing paraneoplastic aphasia, and the reports that are specific tend to describe expressive aphasia.[27][28][29][30][31] Although most cases attempt to exclude micro-metastasis, it is likely that some cases of paraneoplastic aphasia are actually extremely small metastasis to the vocal motor regions.[30] Neurodegenerative disorders may present with aphasia. Alzheimer's disease may present with either fluent aphasia or expressive aphasia. There are case reports of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease presenting with expressive aphasia.[32][33] |

原因 一般的なもの 脳卒中または脳の無酸素状態。 脳腫瘍 脳外傷 少ない 自己免疫疾患 腫瘍随伴症候群 微小転移 神経変性疾患 特定の感染症(例:Bartonella henselae[21]) 代謝性疾患(例えば、高スモラー高血糖状態[22])。 一般的な原因 表出性失語の最も一般的な原因は脳卒中である。脳卒中は、一般に血栓症または塞栓症によって起こる脳の領域への低灌流(酸素不足)によって引き起こされ る。脳卒中患者の34~38%に何らかの失語症がみられる[23]。表現性失語は、脳卒中による失語症の新規症例の約12%にみられる[24]。 ほとんどの場合、表現性失語はブローカ野またはその周辺の脳卒中によって引き起こされる。ブローカ野は、言語優位半球の運動前野の下部にあり、言語運動計 画を担当している。しかし、表現性失語症の症例は、脳の他の領域に脳卒中を起こした患者にもみられる。一般に表現性失語症の古典的な症状を示す患者は、よ り急性の脳病変を有するが、より大きく広範な病変を有する患者は、グローバル失語症に分類されるか、分類されないまま放置される可能性のあるさまざまな症 状を示す[23]。 表現性失語は、脳の外傷、腫瘍、脳出血[25]、硬膜外膿瘍[26]によっても起こりうる。 脳機能の側方化を理解することは、脳のどの部位が損傷されると表現性失語症を引き起こすかを理解する上で重要である。過去には、言語を産生する部位は左利 きの人と右利きの人で異なると信じられてきた。もしそうであれば、右半球にあるブローカ野の相同領域を損傷すると、左利きの人に失語症が起こるはずであ る。最近の研究では、左利きの人でも、言語機能は左半球にしかないことが一般的であることが示されている。しかし、左利きの人は右半球に言語の優位性を持 つ可能性が高い[6]。 まれな原因 表現性失語症のあまり一般的でない原因には、原発性自己免疫現象や、がん(腫瘍随伴症候群として)に続発する自己免疫現象があり、特に他の精神医学的障害 や局所神経学的欠損を呈する失語症のいくつかの症例の主要な仮説として挙げられている。腫瘍随伴性失語を記述した症例報告は数多く存在し、特異的な報告は 表現性失語を記述する傾向がある。 [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] ほとんどの症例は微小転移を除外しようとしているが、腫瘍随伴性失語の一部の症例は、実際には声帯運動領域への極めて小さな転移である可能性が高い。 神経変性疾患は失語症を呈することがある。アルツハイマー病では、流暢性失語または表出性失語を呈することがある。表現性失語を呈するクロイツフェルト・ヤコブ病の症例報告がある。 |

| Diagnosis Expressive aphasia is classified as non-fluent aphasia, as opposed to fluent aphasia.[34] Diagnosis is done on a case-by-case basis, as lesions often affect the surrounding cortex and deficits are highly variable among patients with aphasia.[35] A physician is typically the first person to recognize aphasia in a patient who is being treated for damage to the brain. Routine processes for determining the presence and location of lesion in the brain include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans. The physician will complete a brief assessment of the patient's ability to understand and produce language. For further diagnostic testing, the physician will refer the patient to a speech-language pathologist, who will complete a comprehensive evaluation.[36] In order to diagnose a patient with Broca's aphasia, there are certain commonly used tests and procedures. The Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) classifies individuals based on their scores on the subtests; spontaneous speech, auditory comprehension, repetition, and naming.[8] The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE) can inform users what specific type of aphasia they may have, infer the location of lesion, and assess current language abilities. The Porch Index of Communication Ability (PICA) can predict potential recovery outcomes of the patients with aphasia. Quality of life measurement is also an important assessment tool.[37] Tests such as the Assessment for Living with Aphasia (ALA) and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) allow for therapists to target skills that are important and meaningful for the individual.[8] In addition to formal assessments, patient and family interviews are valid and important sources of information. The patient's previous hobbies, interests, personality, and occupation are all factors that will not only impact therapy but may motivate them throughout the recovery process.[36] Patient interviews and observations allow professionals to learn the priorities of the patient and family and determine what the patient hopes to regain in therapy. Observations of the patient may also be beneficial to determine where to begin treatment. The current behaviors and interactions of the patient will provide the therapist with more insight about the client and their individual needs.[8] Other information about the patient can be retrieved from medical records, patient referrals from physicians, and the nursing staff.[36] In non-speaking patients who use manual languages, diagnosis is often based on interviews from the patient's acquaintances, noting the differences in sign production pre- and post-damage to the brain.[18] Many of these patients will also begin to rely on non-linguistic gestures to communicate, rather than signing since their language production is hindered.[38] |

診断 表現性失語症は、流暢な失語症とは対照的に、非流暢性失語症に分類される。病変が周囲の皮質に影響を及ぼすことが多く、失語症の患者によって障害が大きく異なるため、診断はケースバイケースで行われる [35] 。 脳の損傷に対して治療を受けている患者の失語症を最初に認識するのは、一般的に医師である。脳内の病変の存在と位置を決定するためのルーチンのプロセスに は、磁気共鳴画像法(MRI)およびコンピュータ断層撮影法(CT)スキャンが含まれる。医師は、患者の言語を理解し生成する能力の簡単な評価を行う。さ らなる診断検査のために、医師は患者を言語聴覚士に紹介し、言語聴覚士が包括的な評価を行う。 ブローカ失語症の患者を診断するために、一般的に使用される検査と手順がある。ボストン診断失語症検査(BDAE)は、どのようなタイプの失語症の可能性 があるか、病変の位置を推測し、現在の言語能力を評価することができる。PICA(Porch Index of Communication Ability)は、失語症患者の回復の可能性を予測することができる。生活の質の測定も重要な評価手段である。ALA(Assessment for Living with Aphasia)やSWLS(Satisfaction with Life Scale)などの検査により、療法士は個人にとって重要で意味のある技能に的を絞ることができる [8] 。 正式な評価に加え、患者と家族の面接は有効かつ重要な情報源である。患者の以前の趣味、興味、性格、職業はすべて、治療に影響を与えるだけでなく、回復過 程を通して患者の動機づけとなる可能性のある要素である。 [36] 患者の面接と観察により、専門家は患者と家族の優先事項を知り、患者が治療で何を取り戻したいと考えているかを判断することができる。患者を観察すること は、治療の開始点を決定する上でも有益である。患者の現在の行動や相互作用から、セラピストはクライエントや個々のニーズについてより深い洞察を得ること ができる。 [8] 患者に関するその他の情報は、医療記録、医師からの患者紹介、看護スタッフから得ることができる。 手話を使用する非言語話者患者の場合、診断はしばしば患者の知人からの聞き取り調査に基づいて行われ、脳の損傷前後の手話生成の違いに注目する[18]。 このような患者の多くは、言語生成が妨げられているため、手話ではなく非言語的ジェスチャーに頼ってコミュニケーションをとるようになる[38]。 |

| Treatment Currently, there is no standard treatment for expressive aphasia. Most aphasia treatment is individualized based on a patient's condition and needs as assessed by a speech language pathologist. Patients go through a period of spontaneous recovery following brain injury in which they regain a great deal of language function.[39] In the months following injury or stroke, most patients receive traditional treatment for a few hours per day. Among other exercises, patients practice the repetition of words and phrases. Mechanisms are also taught in traditional treatment to compensate for lost language function such as drawing and using phrases that are easier to pronounce.[40] Emphasis is placed on establishing a basis for communication with family and caregivers in everyday life. Treatment is individualized based on the patient's own priorities, along with the family's input.[8][41] A patient may have the option of individual or group treatment. Although less common, group treatment has been shown to have advantageous outcomes. Some types of group treatments include family counseling, maintenance groups, support groups and treatment groups.[42] Melodic intonation therapy Melodic intonation therapy was inspired by the observation that individuals with non-fluent aphasia sometimes can sing words or phrases that they normally cannot speak. "Melodic Intonation Therapy was begun as an attempt to use the intact melodic/prosodic processing skills of the right hemisphere in those with aphasia to help cue retrieval words and expressive language."[43] It is believed that this is because singing capabilities are stored in the right hemisphere of the brain, which is likely to remain unaffected after a stroke in the left hemisphere.[44] However, recent evidence demonstrates that the capability of individuals with aphasia to sing entire pieces of text may actually result from rhythmic features and the familiarity with the lyrics.[45] The goal of Melodic Intonation Therapy is to utilize singing to access the language-capable regions in the right hemisphere and use these regions to compensate for lost function in the left hemisphere. The natural musical component of speech was used to engage the patients' ability to produce phrases. A clinical study revealed that singing and rhythmic speech may be similarly effective in the treatment of non-fluent aphasia and apraxia of speech.[46] Moreover, evidence from randomized controlled trials is still needed to confirm that Melodic Intonation Therapy is suitable to improve propositional utterances and speech intelligibility in individuals with (chronic) non-fluent aphasia and apraxia of speech.[47][48] Melodic Intonation Therapy appears to work particularly well in patients who have had a unilateral, left hemisphere stroke, show poor articulation, are non-fluent or have severely restricted speech output, have moderately preserved auditory comprehension, and show good motivation. MIT therapy on average lasts for 1.5 hours per day for five days per week. At the lowest level of therapy, simple words and phrases (such as "water" and "I love you") are broken down into a series of high- and low-pitch syllables. With increased treatment, longer phrases are taught and less support is provided by the therapist. Patients are taught to say phrases using the natural melodic component of speaking and continuous voicing is emphasized. The patient is also instructed to use the left hand to tap the syllables of the phrase while the phrases are spoken. Tapping is assumed to trigger the rhythmic component of speaking to utilize the right hemisphere.[44] FMRI studies have shown that Melodic Intonation Therapy (MIT) uses both sides of the brain to recover lost function, as opposed to traditional therapies that utilize only the left hemisphere. In MIT, individuals with small lesions in the left hemisphere seem to recover by activation of the left hemisphere perilesional cortex. Meanwhile, individuals with larger left-hemisphere lesions show a recruitment of the use of language-capable regions in the right hemisphere.[44] The interpretation of these results is still a matter of debate. For example, it remains unclear whether changes in neural activity in the right hemisphere result from singing or from the intensive use of common phrases, such as "thank you", "how are you?" or "I am fine." This type of phrases falls into the category of formulaic language and is known to be supported by neural networks of the intact right hemisphere.[49] A pilot study reported positive results when comparing the efficacy of a modified form of MIT to no treatment in people with nonfluent aphasia with damage to their left-brain. A randomized controlled trial was conducted and the study reported benefits of utilizing modified MIT treatment early in the recovery phase for people with nonfluent aphasia.[50] Melodic Intonation Therapy is used by music therapists, board-certified professionals that use music as a therapeutic tool to effect certain non-musical outcomes in their patients. Speech language pathologists can also use this therapy for individuals who have had a left hemisphere stroke and non-fluent aphasias such as Broca's or even apraxia of speech. Further information: Music therapy for non-fluent aphasia Constraint-induced therapy Constraint-induced aphasia therapy (CIAT) is based on similar principles as constraint-induced movement therapy developed by Dr. Edward Taub at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.[40][51] Constraint-induced movement therapy is based on the idea that a person with an impairment (physical or communicative) develops a "learned nonuse" by compensating for the lost function with other means such as using an unaffected limb by a paralyzed individual or drawing by a patient with aphasia.[52] In constraint-induced movement therapy, the alternative limb is constrained with a glove or sling and the patient is forced to use the affected limb. In constraint-induced aphasia therapy the interaction is guided by communicative need in a language game context, picture cards, barriers making it impossible to see other players' cards, and other materials, so that patients are encouraged ("constrained") to use the remaining verbal abilities to succeed in the communication game.[51] Two important principles of constraint-induced aphasia therapy are that treatment is very intense, with sessions lasting for up to 6 hours over the course of 10 days and that language is used in a communication context in which it is closely linked to (nonverbal) actions.[40][51] These principles are motivated by neuroscience insights about learning at the level of nerve cells (synaptic plasticity) and the coupling between cortical systems for language and action in the human brain.[52] Constraint-induced therapy contrasts sharply with traditional therapy by the strong belief that mechanisms to compensate for lost language function, such as gesturing or writing, should not be used unless absolutely necessary, even in everyday life.[40] It is believed that CIAT works by the mechanism of increased neuroplasticity. By constraining an individual to use only speech, it is believed that the brain is more likely to reestablish old neural pathways and recruit new neural pathways to compensate for lost function.[53] The strongest results of CIAT have been seen in patients with chronic aphasia (lasting over 6 months). Studies of CIAT have confirmed that further improvement is possible even after a patient has reached a "plateau" period of recovery.[40][51] It has also been proven that the benefits of CIAT are retained long term. However, improvements only seem to be made while a patient is undergoing intense therapy.[40] Recent work has investigated combining constraint-induced aphasia therapy with drug treatment, which led to an amplification of therapy benefits.[54] Medication In addition to active speech therapy, pharmaceuticals have also been considered as a useful treatment for expressive aphasia. This area of study is relatively new and much research continues to be conducted. The following drugs have been suggested for use in treating aphasia and their efficacy has been studied in control studies. Bromocriptine – acts on Catecholamine Systems[55] Piracetam – mechanism not fully understood, but most likely interacts with cholinergic and glutamatergic receptors, among others[55] Cholinergic drugs (Donepezil, Aniracetam, Bifemelane) – acts on acetylcholine systems[55] Dopaminergic psychostimulants: (Dexamphetamine, Methylphenidate)[55] The most effect has been shown by piracetam and amphetamine, which may increase cerebral plasticity and result in an increased capability to improve language function. It has been seen that piracetam is most effective when treatment is begun immediately following stroke. When used in chronic cases it has been much less efficient.[56] Bromocriptine has been shown by some studies to increase verbal fluency and word retrieval with therapy than with just therapy alone.[55] Furthermore, its use seems to be restricted to non-fluent aphasia.[54] Donepezil has shown a potential for helping chronic aphasia.[54] No study has established irrefutable evidence that any drug is an effective treatment for aphasia therapy.[55] Furthermore, no study has shown any drug to be specific for language recovery.[54] Comparison between the recovery of language function and other motor function using any drug has shown that improvement is due to a global increase plasticity of neural networks.[55] Transcranial magnetic stimulation In transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), magnetic fields are used to create electrical currents in specified cortical regions. The procedure is a painless and noninvasive method of stimulating the cortex. TMS works by suppressing the inhibition process in certain areas of the brain.[57] By suppressing the inhibition of neurons by external factors, the targeted area of the brain may be reactivated and thereby recruited to compensate for lost function. Research has shown that patients can demonstrate increased object naming ability with regular transcranial magnetic stimulation than patients not receiving TMS.[57] Furthermore, research suggests this improvement is sustained upon the completion of TMS therapy.[57] However, some patients fail to show any significant improvement from TMS which indicates the need for further research of this treatment.[58] Treatment of underlying forms Described as the linguistic approach to the treatment of expressive aphasia, treatment begins by emphasizing and educating patients on the thematic roles of words within sentences.[59] Sentences that are usually problematic will be reworded into active-voiced, declarative phrasings of their non-canonical counterparts.[59] The simpler sentence phrasings are then transformed into variations that are more difficult to interpret. For example, many individuals who have expressive aphasia struggle with Wh- sentences. "What" and "who" questions are problematic sentences that this treatment method attempts to improve, and they are also two interrogative particles that are strongly related to each other because they reorder arguments from the declarative counterparts.[59] For instance, therapists have used sentences like, "Who is the boy helping?" and "What is the boy fixing?" because both verbs are transitive- they require two arguments in the form of a subject and a direct object, but not necessarily an indirect object.[59] In addition, certain question particles are linked together based on how the reworded sentence is formed. Training "who" sentences increased the generalizations of non-trained "who" sentences as well as untrained "what" sentences, and vice versa.[59] Likewise, "where" and "when" question types are very closely linked. "What" and "who" questions alter placement of arguments, and "where" and "when" sentences move adjunct phrases.[59] Training is in the style of: "The man parked the car in the driveway. What did the man park in the driveway?"[59] Sentence training goes on in this manner for more domains, such as clefts and sentence voice.[59] Results: Patients' use of sentence types used in the TUF treatment will improve, subjects will generalize sentences of similar category to those used for treatment in TUF, and results are applied to real-world conversations with others.[59] Generalization of sentence types used can be improved when the treatment progresses in the order of more complex sentences to more elementary sentences. Treatment has been shown to affect on-line (real-time) processing of trained sentences and these results can be tracked using fMRI mappings.[59] Training of Wh- sentences has led improvements in three main areas of discourse for aphasics: increased average length of utterances, higher proportions of grammatical sentences, and larger ratios of numbers of verbs to nouns produced.[59] Patients also showed improvements in verb argument structure productions and assigned thematic roles to words in utterances with more accuracy.[59] In terms of on-line sentence processing, patients having undergone this treatment discriminate between anomalous and non-anomalous sentences with more accuracy than control groups and are closer to levels of normalcy than patients not having participated in this treatment.[59] Mechanisms of recovery Mechanisms for recovery differ from patient to patient. Some mechanisms for recovery occur spontaneously after damage to the brain, whereas others are caused by the effects of language therapy.[54] FMRI studies have shown that recovery can be partially attributed to the activation of tissue around the damaged area and the recruitment of new neurons in these areas to compensate for the lost function. Recovery may also be caused in very acute lesions by a return of blood flow and function to damaged tissue that has not died around an injured area.[54] It has been stated by some researchers that the recruitment and recovery of neurons in the left hemisphere opposed to the recruitment of similar neurons in the right hemisphere is superior for long-term recovery and continued rehabilitation.[60] It is thought that, because the right hemisphere is not intended for full language function, using the right hemisphere as a mechanism of recovery is effectively a "dead-end" and can lead only to partial recovery.[61] There is evidence to support that, among all types of therapies, one of the most important factors and best predictors for a successful outcome is the intensity of the therapy. By comparing the length and intensity of various methods of therapies, it was proven that intensity is a better predictor of recovery than the method of therapy used.[62] Prognosis In most individuals with expressive aphasia, the majority of recovery is seen within the first year following a stroke or injury. The majority of this improvement is seen in the first four weeks in therapy following a stroke and slows thereafter.[23] However, this timeline will vary depending upon the type of stroke experienced by the patient. Patients who experienced an ischemic stroke may recover in the days and weeks following the stroke, and then experience a plateau and gradual slowing of recovery. On the contrary, patients who experienced a hemorrhagic stroke experience a slower recovery in the first 4–8 weeks, followed by a faster recovery which eventually stabilizes.[63] Numerous factors impact the recovery process and outcomes. Site and extent of lesion greatly impacts recovery. Other factors that may affect prognosis are age, education, gender, and motivation.[64] Occupation, handedness, personality, and emotional state may also be associated with recovery outcomes.[8] Studies have also found that prognosis of expressive aphasia correlates strongly with the initial severity of impairment.[24] However, it has been seen that continued recovery is possible years after a stroke with effective treatment.[40] Timing and intensity of treatment is another factor that impacts outcomes. Research suggests that even in later stages of recovery, intervention is effective at improving function, as well as, preventing loss of function.[39] Unlike receptive aphasia, patients with expressive aphasia are aware of their errors in language production. This may further motivate a person with expressive aphasia to progress in treatment, which would affect treatment outcomes.[23] On the other hand, awareness of impairment may lead to higher levels of frustration, depression, anxiety, or social withdrawal, which have been proven to negatively affect a person's chance of recovery.[65] |

治療 現在のところ、表出性失語症に対する標準的な治療法はない。失語症の治療のほとんどは、言語聴覚士が評価した患者の状態とニーズに基づいて個別に行われる。脳損傷後、患者は自然回復の時期を経て、多くの言語機能を回復する [39] 。 受傷または脳卒中後数ヵ月間は、ほとんどの患者が従来の治療を1日数時間受ける。他の練習の中で、患者は単語やフレーズの反復練習を行う。伝統的治療で は、絵を描いたり、発音しやすいフレーズを使ったりするなど、失われた言語機能を補うためのメカニズムも指導される[40]。 日常生活における家族や介護者とのコミュニケーションの基礎を確立することが重視される。治療は、家族の意見とともに、患者自身の優先順位に基づいて個別に行われる[8][41]。 患者には、個別治療または集団治療の選択肢がある。あまり一般的ではないが、集団治療は有利な結果をもたらすことが示されている。集団治療の種類には、家族カウンセリング、維持グループ、支援グループ、治療グループなどがある [42] 。 旋律的イントネーション療法 旋律的イントネーション療法は、非流暢性失語症の人が通常話すことのできない単語やフレーズを歌うことができるという観察から着想を得た。「旋律的イント ネーション療法は、失語症者の右半球の無傷の旋律的/プロソディックな処理能力を用いて、単語や表現言語の検索を助ける試みとして始められた。 [44]しかし、失語症の人が文章全体を歌うことができるのは、実際にはリズムの特徴や歌詞に親しんでいることに起因している可能性があることが、最近の 証拠によって証明されている[45]。 メロディック・イントネーション療法の目的は、歌うことによって右半球の言語可能領域にアクセスし、これらの領域を使って左半球で失われた機能を補うこと である。音声の自然な音楽的要素を利用して、患者のフレーズ生成能力を引き出すのである。さらに、メロディックイントネーション療法が、(慢性)非流暢性 失語症および失語症の患者において、命題発語および発話明瞭度の改善に適していることを確認するためには、ランダム化比較試験による証拠がまだ必要である [47][48]。 メロディック・イントネーション療法は、片側の左半球に脳卒中があり、構音に乏しく、非流暢性または発話が著しく制限され、聴覚的理解力が中程度に保た れ、意欲が良好な患者に特に有効である。MIT療法は、平均して1日1.5時間、週5日間行われる。最も低いレベルの治療では、簡単な単語やフレーズ (「水」や「愛してる」など)を高音と低音の音節に分解していく。治療レベルが上がるにつれて、より長いフレーズが教えられ、セラピストによるサポートは 少なくなる。患者は自然なメロディーを使ってフレーズを言うように指導され、連続的な発声が強調される。また、患者はフレーズを話している間、左手でフ レーズの音節をたたくように指導される。タッピングは、右半球を活用するために、話し方のリズミカルな要素を誘発すると想定されている[44]。 FMRIの研究から、メロディック・イントネーション・セラピー(MIT)は、左半球のみを利用する従来のセラピーとは対照的に、失われた機能を回復させ るために脳の両側を利用することが示されている。MITでは、左半球の病変が小さい人は、左半球の腓骨皮質の活性化によって回復するようである。一方、左 半球に大きな病変を持つ人は、右半球の言語使用可能な領域の使用のリクルートメントを示す。例えば、右半球の神経活動の変化が、歌唱によるものなのか、そ れとも "ありがとう"、"お元気ですか"、"私は元気です "といった一般的なフレーズの集中的な使用によるものなのかは、依然として不明である。この種のフレーズは定型言語のカテゴリーに属し、無傷の右半球の神 経ネットワークによってサポートされていることが知られている[49]。 パイロット研究では、左脳に損傷を受けた非流暢性失語症患者において、修正型MITの有効性を無治療と比較したところ、肯定的な結果が得られたことが報告 された。ランダム化比較試験が実施され、非流暢性失語症の患者に対して、回復期の早い段階で修正MIT治療を利用することの有益性が報告された[50]。 メロディック・イントネーション・セラピーは、音楽療法士によって使用されており、音楽療法士は、患者に特定の非音楽的転帰をもたらす治療ツールとして音 楽を使用する認定専門家である。言語聴覚士は、左半球の脳卒中や、ブローカ失語、あるいは失行性失語などの非流暢性失語症の患者にもこの療法を用いること ができる。 さらに詳しい情報 非流暢性失語症に対する音楽療法 拘束誘発療法 拘束誘発失語症療法(CIAT)は、アラバマ大学バーミンガム校のEdward Taub博士によって開発された拘束誘発運動療法と同様の原理に基づいている。 [40] [51] 拘束誘発運動療法は、(身体的またはコミュニケーション上の)障害を持つ人が、麻痺のある人が障害のない手足を使ったり、失語症の患者が絵を描いたりする など、他の手段で失われた機能を補うことによって「学習された不使用」を身につけるという考えに基づいている。 [52] 拘束誘発運動療法では、代わりの手足を手袋やスリングで拘束し、患者に障害のある手足を使わせる。拘束誘発性失語症療法では、言語ゲーム、絵カード、他の プレイヤーのカードが見えないようにする障壁、その他の材料などの状況において、コミュニケーション上の必要性によって相互作用が誘導されるため、患者は コミュニケーション・ゲームで成功するために残された言語能力を使うように促される(「拘束される」)[51]。 拘束誘発性失語症療法の2つの重要な原則は、治療が非常に集中的であり、セッションが10日間にわたって最大6時間続くことと、言語が(非言語的な)行動 と密接に結びついたコミュニケーションの文脈で使用されることである。 [40][51]これらの原則は、神経細胞レベルでの学習(シナプス可塑性)およびヒトの脳における言語と行動の皮質システム間の結合に関する神経科学的 洞察によって動機づけられている[52]。拘束誘発療法は、ジェスチャーや筆記など、失われた言語機能を補うためのメカニズムは、日常生活においても、絶 対に必要な場合を除き、使用すべきではないという強い信念によって、従来の療法と大きく対照をなしている[40]。 CIATは、神経可塑性の増大というメカニズムによって機能すると考えられている。音声のみを使用するように個人を拘束することで、脳が古い神経経路を再確立し、失われた機能を補うために新しい神経経路を採用する可能性が高くなると考えられている[53]。 CIATの最も強力な効果は、慢性失語症(6ヵ月以上持続)の患者に認められている。CIATの研究では、患者が回復の「プラトー」期間に達した後でも、 さらなる改善が可能であることが確認されている。しかし、改善がみられるのは、患者が強力な治療を受けている間だけであるようである[40]。最近の研究 では、拘束誘発性失語症治療と薬物治療を組み合わせることが検討されており、その結果、治療効果が増幅された[54]。 薬物療法 積極的な言語療法に加えて、医薬品も表出性失語症の有用な治療法として考えられてきた。この分野の研究は比較的新しく、多くの研究が続けられている。 失語症の治療には以下の薬剤の使用が示唆されており、対照試験でその有効性が検討されている。 ブロモクリプチン-カテコールアミン系に作用する[55]。 ピラセタム-機序は完全には解明されていないが、特にコリン作動性受容体およびグルタミン酸作動性受容体と相互作用する可能性が高い[55]。 コリン作動性薬物(ドネペジル、アニラセタム、ビフェメラン)-アセチルコリン系に作用する[55]。 ドパミン作動性精神刺激薬:(デキサンフェタミン、メチルフェニデート)[55]。 ピラセタムとアンフェタミンが最も高い効果を示し、大脳の可塑性を高め、言語機能を向上させる能力を高める可能性がある。ピラセタムは、脳卒中直後に治療を開始した場合に最も効果的であることがわかっている。慢性の症例に使用した場合、ピラセタムの効率はかなり低下した。 ブロモクリプチンは、治療単独よりも治療によって言語流暢性と単語検索が増加することがいくつかの研究で示されている[55]が、その使用は非流暢性失語症に限定されているようである[54]。 ドネペジルは慢性失語症に効果がある可能性を示している[54]。 どの薬物も失語症治療に有効であるという反論の余地のない証拠を確立した研究はない[55]。 さらに、どの薬物も言語回復に特異的であることを示した研究はない[54]。どの薬物を使用しても、言語機能と他の運動機能の回復を比較すると、改善は神 経ネットワークのグローバルな可塑性の増加によることが示されている[55]。 経頭蓋磁気刺激 経頭蓋磁気刺激(TMS)では、磁場を用いて特定の皮質領域に電流を流す。この方法は、痛みを伴わず、非侵襲的に大脳皮質を刺激する方法である。TMS は、脳の特定の領域における抑制過程を抑制することによって作用する[57]。外的要因によるニューロンの抑制を抑制することによって、脳の標的領域が再 活性化され、それによって失われた機能を補うために採用される可能性がある。研究によると、定期的な経頭蓋磁気刺激により、TMSを受けていない患者より も物体の命名能力が向上することが示されている[57] 。 基礎的形態の治療 表出性失語症の治療に対する言語学的アプローチと表現されるこの治療法は、文中の単語の主題的役割を強調し、患者を教育することから始まる[59]。通常 問題となる文は、非正規の対応する能動態の宣言的な言い回しに言い換えられる。例えば、表現性失語症の人の多くは、Wh-文に苦労している。「What (何)」と「Who(誰)」の質問は、この治療法が改善を試みる問題のある文であり、宣言的な対応から引数を並べ替えるため、互いに強く関連する2つの疑 問助詞でもある。 「59]。さらに、特定の疑問助詞は、言い直された文がどのように形成されるかに基 づいて、互いに連結される。同様に、"where "と "when "の質問タイプは非常に密接に関連しています。「What "と "who "の質問は引数の配置を変え、"where "と "when "の文は付加句を動かす[59]: 「その男は車を車道に停めた。男は車道に車を停めたが、何を停めたのだろう?"[59]。文の訓練は、裂け目や文の音声など、より多くの領域についてこの 方法で行われる[59]。 結果 TUFの治療で使用された文型の患者の使用は改善され、被験者はTUFの治療で使用された文型と類似したカテゴリーの文を般化し、結果は他の人との実世界 の会話に適用される[59]。使用された文型の般化は、治療がより複雑な文からより初歩的な文の順に進むと改善される。Wh-文の訓練は、失語症患者の談 話における3つの主要な領域、すなわち、発話の平均長さの増加、文法的な文の割合の増加、および生成される名詞に対する動詞の数の割合の増加を改善させ た。 [59] また、患者は動詞の引数構造の産出においても改善を示し、発話中の単語に主題的役割をより正確に割り当てた[59]。オンライン文処理に関しては、この治 療を受けた患者は対照群よりも正確に異常文と非異常文を弁別し、この治療を受けなかった患者よりも正常レベルに近づいている[59]。 回復のメカニズム 回復のメカニズムは患者によって異なる。回復のメカニズムには、脳の損傷後に自然に起こるものもあれば、言語療法の効果によって起こるものもある [54]。FMRIの研究によると、回復の一部は、損傷部位の周囲の組織の活性化と、失われた機能を補うためにこれらの部位に新しいニューロンが動員され ることに起因している。また、非常に急性の病変では、損傷部位の周囲で死滅していない損傷組織に血流と機能が戻ることによって回復が起こることもある [54]。一部の研究者は、右半球の同様のニューロンのリクルートに対して、左半球のニューロンのリクルートと回復は、長期的な回復と継続的なリハビリ テーションに優れていると述べている。 [右半球は完全な言語機能を目的としていないため、回復のメカニズムとして右半球を使用することは事実上「行き詰まり」であり、部分的な回復にしかつなが らないと考えられている。 あらゆる種類の治療法の中で、最も重要な要因の1つであり、 成果の最良の予測因子は、治療の強度であることを裏付ける 証拠がある。様々な治療法の治療期間と治療強度を比較することで、使用する治療法よりも治療強度の方が回復の予測因子として優れていることが証明された。 予後 表出性失語症のほとんどの患者では、脳卒中または受傷後1年以内に回復がみられる。この改善の大部分は、脳卒中後の最初の4週間の治療でみられ、その後は 緩やかになる[23]が、この時期は患者が経験した脳卒中の種類によって異なる。虚血性脳卒中の患者は、脳卒中後数日から数週間で回復し、その後、プラ トーを経験し、徐々に回復が遅くなる。反対に、出血性脳卒中の患者は、最初の4~8週間は回復が遅く、その後回復が早まり、最終的には安定する[63]。 回復過程と転帰には多くの要因が影響する。病変部位と範囲は回復に大きく影響する。予後に影響を及ぼす可能性のある他の因子は、年齢、教育、性別、意欲である。 [64] 職業、手の大きさ、性格、感情状態も回復の結果に関連する可能性がある。 表出性失語症の予後は、最初の障害の重症度と強い相関があることも研究で明らかにされている[24]。しかし、効果的な治療により、脳卒中から数年後でも 継続的な回復が可能であることが確認されている[40]。回復の後期であっても、介入は機能改善だけでなく、機能喪失の予防にも有効であることが研究に よって示唆されている[39]。 受容性失語症とは異なり、表出性失語症の患者は言語産出における自分の誤りを自覚している。このことは、表出性失語症患者の治療に対する意欲を高め、治療 成績に影響を与える可能性がある[23]。他方、障害を自覚することで、フラストレーション、抑うつ、不安、社会的引きこもりのレベルが高くなり、回復の 可能性に悪影響を及ぼすことが証明されている[65]。 |

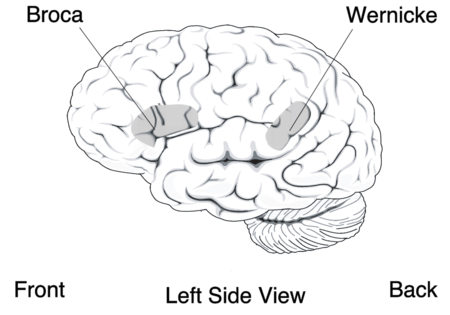

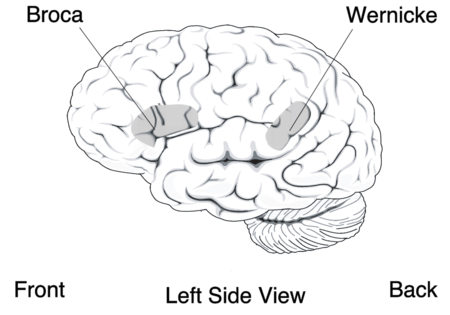

| History Expressive aphasia was first identified by the French neurologist Paul Broca. By examining the brains of deceased individuals having acquired expressive aphasia in life, he concluded that language ability is localized in the ventroposterior region of the frontal lobe. One of the most important aspects of Paul Broca's discovery was the observation that the loss of proper speech in expressive aphasia is due to the brain's loss of ability to produce language, as opposed to the mouth's loss of ability to produce words.[6] The discoveries of Paul Broca were made during the same period of time as the German Neurologist Carl Wernicke, who was also studying brains of aphasiacs post-mortem and identified the region now known as Wernicke's area. Discoveries of both men contributed to the concept of localization, which states that specific brain functions are all localized to a specific area of the brain. While both men made significant contributions to the field of aphasia, it was Carl Wernicke who realized the difference between patients with aphasia that could not produce language and those that could not comprehend language (the essential difference between expressive and receptive aphasia).[6] |

歴史 表現性失語症は、フランスの神経学者ポール・ブローカによって初めて同定された。生前に表現性失語症を発症した死亡者の脳を調べることによって、彼は言語 能力が前頭葉の腹側後方に局在していると結論づけた。ポール・ブローカの発見の最も重要な側面のひとつは、表出性失語症における適切な発話の喪失は、口か ら言葉を生み出す能力の喪失とは対照的に、脳が言葉を生み出す能力を喪失したことに起因するという観察であった[6]。 ポール・ブローカの発見は、ドイツの神経学者カール・ウェルニッケと同時期になされた。ウェルニッケもまた、死後の失語症者の脳を研究し、現在ウェルニッ ケ野として知られている部位を特定した。両氏の発見は、特定の脳機能はすべて脳の特定の領域に局在しているという「局在」の概念に貢献した。2人とも失語 症の分野に大きな貢献をしたが、言語を産出できない失語症患者と言語を理解できない失語症患者の違い(表出性失語症と受容性失語症の本質的な違い)に気づ いたのはカール・ウェルニッケであった[6]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆