ファクンド

Facundo

☆

ファクンド:文明と野蛮(原題:Facundo: Civilización i

Barbarie)は、1845年にドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエントによって書かれた本である。彼は作家でありジャーナリストであり、後にアル

ゼンチンの第七代大統領となった人物だ。この作品はラテンアメリカ文学の礎石であり、創造的ノンフィクションとして、この地域の発展、近代化、権力、文化

について考えるための枠組みを定義するのに貢献した。副題に「文明と野蛮」を冠した本作は、19世紀初頭のアルゼンチンに現れた文明と野蛮の対比を描く。

文学評論家ロベルト・ゴンサレス・エチェバリアは、この作品を「あらゆる分野・ジャンルにおいてラテンアメリカ人が書いた最も重要な書物」と評している。

[1]

ファクンドは、1820年代から1830年代にかけてアルゼンチン地方を恐怖に陥れたカウディージョ(地方支配者)フアン・ファクンド・キロガの生涯を描

く。同書の英訳者の一人であるキャスリーン・ロスは、著者が『ファクンド』を出版した目的の一つは「アルゼンチンの独裁者フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスの

専制政治を糾弾するため」であったと指摘している。[2]

フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスは1829年から1832年、そして1835年から1852年までアルゼンチンを支配した。サルミエントがチリに亡命し、そ

こで本書を執筆したのはロサスによる弾圧のためである。サルミエントはロサスをファクンドの後継者と見なしている。両者ともカウディージョであり、アルゼ

ンチン地方の自然から派生した野蛮性の代表者だからだ。[3]

ロスが説明するように、サルミエントの著書は「アルゼンチンの国民」を描写し、「地理的条件が人格に及ぼす影響」「田舎の『野蛮』な性質と都市の『文明

化』的影響」「ヨーロッパ移民に門戸を大きく開いた時にアルゼンチンを待つ偉大な未来」を説明しているのである。[2]

本文全体を通して、サルミエントは文明と野蛮の二項対立を探求している。キンバリー・ボールが指摘するように、「文明は北ヨーロッパ、北アメリカ、都市、

ユニテリアン派、パス、リバダビアと結びつけられる」[4]一方、「野蛮はラテンアメリカ、スペイン、アジア、中東、田舎、連邦派、ファクンド、ロサスと

結びつけられる」[4]。ファクンドがこの対立を表現した手法こそが、サルミエントの著作に深い影響を与えた所以である。ゴンサレス・エチェバリアの言葉

を借りれば、「文明と野蛮の弁証法をラテンアメリカ文化の中心的対立として提示したファクンドは、植民地時代に始まり今日まで続く論争の骨格を形作った」

のである[5]。

『ファクンド』初版は1845年に連載形式で刊行された。サルミエントは第二版(1851年)で最後の二章を削除したが、1874年版ではそれらを復元し

た。その章が本の発展にとって重要だと判断したからである。

最初の英語訳はメアリー・タイラー・ピーボディ・マンによるもので、1868年に出版された。カトリーヌ・ロスによる現代的で完全な翻訳は、2003年に

カリフォルニア大学出版局から刊行された。

Facundo:

Civilization and Barbarism (original Spanish title: Facundo:

Civilización i Barbarie) is a book written in 1845 by Domingo Faustino

Sarmiento, a writer and journalist who became the seventh president of

Argentina. It is a cornerstone of Latin American literature: a work of

creative non-fiction that helped to define the parameters for thinking

about the region's development, modernization, power, and culture.

Subtitled Civilization and Barbarism, Facundo contrasts civilization

and barbarism as seen in early 19th-century Argentina. Literary critic

Roberto González Echevarría calls the work "the most important book

written by a Latin American in any discipline or genre".[1] Juan Facundo Quiroga Facundo describes the life of Juan Facundo Quiroga, a caudillo who had terrorized provincial Argentina in the 1820s and 1830s. Kathleen Ross, one of Facundo's English translators, points out that the author also published Facundo to "denounce the tyranny of the Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas".[2] Juan Manuel de Rosas ruled Argentina from 1829 to 1832 and again from 1835 to 1852; it was because of Rosas that Sarmiento was in exile in Chile, where he wrote the book. Sarmiento sees Rosas as heir to Facundo: both are caudillos and representatives of a barbarism that derives from the nature of the Argentine countryside.[3] As Ross explains, Sarmiento's book is therefore engaged in describing the "Argentine national character, explaining the effects of Argentina's geographical conditions on personality, the 'barbaric' nature of the countryside versus the 'civilizing' influence of the city, and the great future awaiting Argentina when it opened its doors wide to European immigration".[2] Throughout the text, Sarmiento explores the dichotomy between civilization and barbarism. As Kimberly Ball observes, "civilization is identified with northern Europe, North America, cities, Unitarians, Paz, and Rivadavia",[4] while "barbarism is identified with Latin America, Spain, Asia, the Middle East, the countryside, Federalists, Facundo, and Rosas".[4] It is in the way that Facundo articulates this opposition that Sarmiento's book has had such a profound influence. In the words of González Echevarría: "in proposing the dialectic between civilization and barbarism as the central conflict in Latin American culture Facundo gave shape to a polemic that began in the colonial period and continues to the present day".[5] The first edition of Facundo was published in installments in 1845. Sarmiento removed the last two chapters of the second edition (1851), but restored them in the 1874 edition, deciding that they were important to the book's development. The first translation into English, by Mary Tyler Peabody Mann, was published in 1868. A modern and complete translation by Kathleen Ross appeared in 2003 from the University of California Press. |

ファクンド:文明と野蛮(原題:Facundo:

Civilización i

Barbarie)は、1845年にドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエントによって書かれた本である。彼は作家でありジャーナリストであり、後にアル

ゼンチンの第七代大統領となった人物だ。この作品はラテンアメリカ文学の礎石であり、創造的ノンフィクションとして、この地域の発展、近代化、権力、文化

について考えるための枠組みを定義するのに貢献した。副題に「文明と野蛮」を冠した本作は、19世紀初頭のアルゼンチンに現れた文明と野蛮の対比を描く。

文学評論家ロベルト・ゴンサレス・エチェバリアは、この作品を「あらゆる分野・ジャンルにおいてラテンアメリカ人が書いた最も重要な書物」と評している。

[1] Juan Facundo Quiroga ファクンドは、1820年代から1830年代にかけてアルゼンチン地方を恐怖に陥れたカウディージョ(地方支配者)フアン・ファクンド・キロガの生涯を描 く。同書の英訳者の一人であるキャスリーン・ロスは、著者が『ファクンド』を出版した目的の一つは「アルゼンチンの独裁者フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスの 専制政治を糾弾するため」であったと指摘している。[2] フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスは1829年から1832年、そして1835年から1852年までアルゼンチンを支配した。サルミエントがチリに亡命し、そ こで本書を執筆したのはロサスによる弾圧のためである。サルミエントはロサスをファクンドの後継者と見なしている。両者ともカウディージョであり、アルゼ ンチン地方の自然から派生した野蛮性の代表者だからだ。[3] ロスが説明するように、サルミエントの著書は「アルゼンチンの国民」を描写し、「地理的条件が人格に及ぼす影響」「田舎の『野蛮』な性質と都市の『文明 化』的影響」「ヨーロッパ移民に門戸を大きく開いた時にアルゼンチンを待つ偉大な未来」を説明しているのである。[2] 本文全体を通して、サルミエントは文明と野蛮の二項対立を探求している。キンバリー・ボールが指摘するように、「文明は北ヨーロッパ、北アメリカ、都市、 ユニテリアン派、パス、リバダビアと結びつけられる」[4]一方、「野蛮はラテンアメリカ、スペイン、アジア、中東、田舎、連邦派、ファクンド、ロサスと 結びつけられる」[4]。ファクンドがこの対立を表現した手法こそが、サルミエントの著作に深い影響を与えた所以である。ゴンサレス・エチェバリアの言葉 を借りれば、「文明と野蛮の弁証法をラテンアメリカ文化の中心的対立として提示したファクンドは、植民地時代に始まり今日まで続く論争の骨格を形作った」 のである[5]。 『ファクンド』初版は1845年に連載形式で刊行された。サルミエントは第二版(1851年)で最後の二章を削除したが、1874年版ではそれらを復元し た。その章が本の発展にとって重要だと判断したからである。 最初の英語訳はメアリー・タイラー・ピーボディ・マンによるもので、1868年に出版された。カトリーヌ・ロスによる現代的で完全な翻訳は、2003年に カリフォルニア大学出版局から刊行された。 |

| Background While exiled in Chile, Sarmiento wrote Facundo in 1845 as an attack on Juan Manuel de Rosas, the Argentine dictator at the time. The book was a critical analysis of Argentine culture as he saw it, represented in men such as Rosas and the regional leader Juan Facundo Quiroga, a warlord from La Rioja. For Sarmiento, Rosas and Quiroga were caudillos—strongmen who did not submit to the law.[6] However, if Facundo's portrait is linked to the wild nature of the countryside, Rosas is depicted as an opportunist who exploits the situation to perpetuate himself in power.[7] Sarmiento's book is a critique and also a symptom of Argentina's cultural conflicts. In 1810, the country had gained independence from the Spanish Empire, but Sarmiento complains that Argentina had yet to cohere as a unified entity. The country's chief political division saw the Unitarists (or Unitarians, with whom Sarmiento sided), who favored centralization, counterposed against the Federalists, who believed that the regions should maintain a good measure of autonomy. This division was in part a split between the city and the countryside. Then as now, Buenos Aires was the country's largest and wealthiest city as a result of its access to river trade routes and the South Atlantic. Buenos Aires was exposed not only to trade but to fresh ideas and European culture. These economic and cultural differences caused tension between Buenos Aires and the land-locked regions of the country.[8] Despite his Unitarian sympathies, Sarmiento himself came from the provinces, a native of the Western town of San Juan.[9] |

背景 チリに亡命中、サルミエントは1845年に『ファクンド』を執筆した。これは当時のアルゼンチン独裁者フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスへの攻撃を目的とした ものである。本書は、ロサスやラ・リオハ出身の軍閥指導者フアン・ファクンド・キロガといった人物に象徴される、サルミエントが見たアルゼンチン文化に対 する批判的分析であった。サルミエントにとって、ロサスとキロガはカウディージョ、すなわち法に従わない強権者であった[6]。しかしファクンドの描写が 田舎の荒々しい性質と結びついているのに対し、ロサスは権力を永続させるために状況を利用する日和見主義者として描かれている。[7] サルミエントの著書は、アルゼンチンの文化的対立に対する批判であると同時に、その対立の表れでもある。1810年、この国はスペイン帝国から独立を果た したが、サルミエントはアルゼンチンが未だ統一された国家としてまとまっていないと嘆いている。当時の主要な政治的対立軸は、中央集権を支持する統一主義 者(サルミエントが支持した立場)と、地域が相当の自治権を保持すべきと主張する連邦主義者との対立であった。この対立は、都市と地方の分裂を部分的に反 映していた。当時も今も変わらず、ブエノスアイレスは河川交易路と南大西洋へのアクセスにより、国内最大かつ最も豊かな都市であった。ブエノスアイレスは 交易だけでなく、新たな思想やヨーロッパ文化にも晒されていた。こうした経済的・文化的異なる点が、ブエノスアイレスと内陸部との間に緊張を生んだ [8]。統一主義者としての同情を抱きつつも、サルミエント自身は地方出身であり、西部の町サンフアンの出身であった[9]。 |

| Argentine civil war Main article: Argentine Civil War Argentina's divisions led to a civil war that began in 1814. A frail agreement was reached in the early 1820s, which led to the unification of the Republic just in time to wage the Cisplatine War against the Empire of Brazil, but the relations between the Provinces reached again the point of breaking-off in 1826, when Unitarist Bernardino Rivadavia was elected president and tried to enforce a newly enacted centralist Constitution. Supporters of decentralized government challenged the Unitarist Party, leading to the outbreak of violence. Federalists Juan Facundo Quiroga and Manuel Dorrego wanted more autonomy for the provinces and were inclined to reject European culture.[10] The Unitarists defended Rivadavia's presidency, as it created educational opportunities for rural inhabitants through a European-staffed university program. However, under Rivadavia's rule, the salaries of common laborers were subjected to government wage ceilings,[11] and the gauchos ("cattle-wrangling horsemen of the pampas")[12] were either imprisoned or forced to work without pay.[11] A series of governors were installed and replaced beginning in 1828 with the appointment of Federalist Manuel Dorrego as the governor of Buenos Aires.[13] However, Dorrego's government was very soon overthrown and replaced by that of Unitarist Juan Lavalle.[14] Lavalle's rule ended when he was defeated by a militia of gauchos led by Rosas. By the end of 1829, the legislature had appointed Rosas as governor of Buenos Aires.[15] Under Rosas's rule, many intellectuals fled either to Chile, as did Sarmiento, or to Uruguay, as Sarmiento himself notes.[16] |

アルゼンチン内戦 詳細記事: アルゼンチン内戦 アルゼンチンの分裂は1814年に始まった内戦へとつながった。1820年代初頭に脆弱な合意が成立し、ブラジル帝国とのシスパタナ戦争に間に合う形で共 和国の統一が実現した。しかし1826年、統一主義者のベルナルディーノ・リバダビアが大統領に選出され、新たに制定された中央集権的な憲法の施行を試み たことで、諸州間の関係は再び決裂の危機に陥った。地方分権を支持する勢力は統一主義党に反発し、暴力事件が発生した。連邦主義者のフアン・ファクンド・ キロガとマヌエル・ドレゴは州の自治権拡大を求め、ヨーロッパ文化の受け入れに消極的だった[10]。一方、統一主義者はリバダビア政権を支持した。同政 権はヨーロッパ人教員による大学プログラムを通じて、農村住民に教育機会を提供していたからだ。しかしリバダビア政権下では、一般労働者の賃金が政府によ る賃金上限に縛られ[11]、ガウチョ(パンパスの牧畜騎手)[12]は投獄されるか無給労働を強いられた。[11] 1828年、連邦主義者のマヌエル・ドレゴがブエノスアイレス州知事に任命されたことを皮切りに、一連の知事が任命され、交代していった。[13] しかし、ドレゴの政権は間もなく打倒され、統一主義者のフアン・ラバジェの政権に取って代わられた。[14] ラバジェの統治は、ロサス率いるガウチョの民兵に敗北したことで終焉を迎えた。1829年末までに、議会はロサスをブエノスアイレス総督に任命した。 [15] ロサスの支配下では、サルミエントのようにチリへ、あるいはサルミエント自身が記すようにウルグアイへ、多くの知識人が逃亡した。[16] |

| Juan Manuel de Rosas Main articles: Juan Manuel de Rosas and Historiography of Juan Manuel de Rosas  Portrait of Rosas by Raymond Monvoisin According to Latin American historian John Lynch, Juan Manuel de Rosas was "a landowner, a rural caudillo, and the dictator of Buenos Aires from 1829 to 1852".[17] He was born into a wealthy family of high social status, but Rosas's strict upbringing had a deep psychological influence on him.[18] Sarmiento asserts that because of Rosas's mother, "the spectacle of authority and servitude must have left lasting impressions on him".[19] Shortly after reaching puberty, Rosas was sent to an estancia and stayed there for about thirty years. In time, he learned how to manage the ranch and he established an authoritarian government in the area. While in power, Rosas incarcerated residents for unspecified reasons, acts which Sarmiento argues were similar to Rosas's treatment of cattle. Sarmiento argues that this was one method of making his citizens like the "tamest, most orderly cattle known".[20] Juan Manuel de Rosas's first term as governor lasted only three years. His rule, assisted by Juan Facundo Quiroga and Estanislao López, was respected and he was praised for his ability to maintain harmony between Buenos Aires and the rural areas.[21] The country fell into disorder after Rosas's resignation in 1832, and in 1835 he was once again called to lead the country. He ruled the country not as he did during his first term as governor, but as a dictator, forcing all citizens to support his Federalist regime.[22] According to Nicolas Shumway, Rosas "forced the citizens to wear the red Federalist insignia, and his picture appeared in all public places... Rosas's enemies, real and imagined, were increasingly imprisoned, tortured, murdered, or driven into exile by the mazorca, a band of spies and thugs supervised personally by Rosas. Publications were censored, and porteño newspapers became tedious apologizers for the regime".[23] |

フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサス 主な記事: フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサス と フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスの歴史学  ロサスの肖像画 レイモンド・モンヴォワザン作 ラテンアメリカ史家ジョン・リンチによれば、フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスは「大地主であり、地方の軍閥指導者であり、1829年から1852年までブエ ノスアイレスの独裁者であった」という。[17] 彼は社会的地位の高い裕福な家庭に生まれたが、厳格な教育が彼に深い心理的影響を与えた。[18] サルミエントは、ロサスの母親の影響で「権威と隷属の光景が彼に永続的な印象を残したに違いない」と主張する。[19] 思春期を迎えた直後、ロサスは牧場(エスタンシア)に送られ、約30年間をそこで過ごした。やがて牧場の経営術を学び、その地域に権威主義的な統治体制を 確立した。権力掌握中、ロサスは不明確な理由で住民を投獄したが、サルミエントはこれをロサスが家畜を扱う手法に類似していると論じている。サルミエント によれば、これは市民を「最も従順で秩序正しい家畜」のように仕立てる手法の一つであったという。[20] フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスの最初の知事任期はわずか3年だった。フアン・ファクンド・キロガとエスタニスラオ・ロペスの支援を受けた彼の統治は尊重さ れ、ブエノスアイレスと地方の調和を維持する能力が称賛された。[21] 1832年にロサスが辞任すると国は混乱に陥り、1835年に彼は再び国の指導者として招かれた。彼は最初の知事時代とは異なり、独裁者として国を統治 し、全ての市民に自らの連邦主義体制への支持を強制した。[22] ニコラス・シュムウェイによれば、ロサスは「市民に赤い連邦主義の徽章の着用を強制し、彼の肖像は全ての公共の場所に掲げられた... 実在する敵も想像上の敵も、ロサスが個人的な統制下に置くスパイと凶悪犯の集団「マソルカ」によって次々と投獄され、拷問され、殺害され、あるいは亡命に 追いやられた。出版物は検閲され、ブエノスアイレスの新聞は政権の退屈な擁護者となった」と記している。[23] |

| Domingo Faustino Sarmiento Main article: Domingo Faustino Sarmiento  Portrait of Sarmiento at the time of his exile in Chile; by Franklin Rawson In Facundo, Sarmiento is both the narrator and a main character. The book contains autobiographical elements from Sarmiento's life, and he comments on the entire Argentine circumstance. He also expresses and analyzes his own opinion and chronicles some historic events. Within the book's dichotomy between civilization and barbarism, Sarmiento's character represents civilization, steeped as he is in European and North American ideas; he stands for education and development, as opposed to Rosas and Facundo, who symbolize barbarism. Sarmiento was an educator, a civilized man who was a militant adherent to the Unitarist movement. During the Argentine civil war he fought against Facundo several times, and while in Spain he became a member of the Literary Society of Professors.[24] Exiled to Chile by Rosas when he started to write Facundo, Sarmiento would later return as a politician. He was a member of the Senate after Rosas's fall and president of Argentina for six years (1868–1874). During his presidency, Sarmiento concentrated on migration, sciences, and culture. His ideas were based on European civilization; for him, the development of a country was rooted in education. To this end, he founded Argentina's military and naval colleges.[25] |

ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント 主な記事:ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント  チリ亡命時のサルミエントの肖像、フランクリン・ローソン作 『ファクンド』では、サルミエントは語り手であり、主人公でもある。この本には、サルミエントの生涯の自伝的要素が含まれており、彼はアルゼンチンの状況 全体についてコメントしている。また、彼は自分の意見を表明、分析し、いくつかの歴史的出来事を記録している。この本の中で、文明と野蛮という二分法の中 で、サルミエントのキャラクターは、ヨーロッパや北米の思想に染まった文明を代表している。彼は、野蛮を象徴するロサスやファクンドとは対照的に、教育と 発展を象徴している。 サルミエントは教育者であり、文明人としてユニタリスト運動に熱心に従事した。アルゼンチン内戦ではファクンドと幾度も戦った。スペイン滞在中には教授文 学協会の一員となった[24]。『ファクンド』の執筆を始めた際、ロサスによってチリへ追放されたが、後に政治家として帰国した。ロサスの失脚後は上院議 員を務め、1868年から1874年までの6年間アルゼンチン大統領に就任した。大統領在任中、サルミエントは移民政策、科学、文化に注力した。彼の思想 はヨーロッパ文明に基づくもので、国家の発展は教育に根ざすと考えていた。この目的のために、アルゼンチンの陸軍士官学校と海軍兵学校を設立した [25]。 |

Synopsis Horses graze on flat scrub land. The Argentine plains, or pampas. For Sarmiento, this bleak, featureless geography was a key factor in Argentina's "failure" to achieve civilization by the mid-19th century. After a lengthy introduction, Facundo's fifteen chapters divide broadly into three sections: chapters one to four outline Argentine geography, anthropology, and history; chapters five to fourteen recount the life of Juan Facundo Quiroga; and the concluding chapter expounds Sarmiento's vision of a future for Argentina under a Unitarist government.[3] In Sarmiento's words, the reason why he chose to provide Argentine context and use Facundo Quiroga to condemn Rosas's dictatorship is that "in Facundo Quiroga I do not only see simply a caudillo, but rather a manifestation of Argentine life as it has been made by colonization and the peculiarities of the land".[26] Argentine context  Map of South American, with the pampas encompassing a south-eastern area bordering the Atlantic Ocean. South America, showing the extent of the pampas in Argentina, Uruguay and southern Brazil Facundo begins with a geographical description of Argentina, from the Andes in the west to the eastern Atlantic coast, where two main river systems converge at the boundary between Argentina and Uruguay. This river estuary, called the Río de la Plata, is the location of Buenos Aires, the capital. Through his discussion of Argentina's geography, Sarmiento demonstrates Buenos Aires' advantages; the river systems were communications arteries which, by enabling trade, helped the city to achieve civilization. Buenos Aires failed to spread civilization to the rural areas and as a result, much of the rest of Argentina was doomed to barbarism. Sarmiento also argues that the pampas, Argentina's wide and empty plains, provided "no place for people to escape and hide for defense and this prohibits civilization in most parts of Argentina".[27] Despite the barriers to civilization caused by Argentina's geography, Sarmiento argues that many of the country's problems were caused by gauchos like Juan Manuel de Rosas, who were barbaric, uneducated, ignorant, and arrogant; their character prevented Argentine society's progress toward civilization.[28] Sarmiento then describes the four main types of gaucho, and these characterizations aid in understanding Argentine leaders such as Juan Manuel de Rosas.[29] Sarmiento argues that, without an understanding of these Argentine character types, "it is impossible to understand our political personages, or the primordial, American character of the bloody struggle that tears apart the Argentine Republic".[30] Sarmiento then moves on to the Argentine peasants, who are "independent of all need, free of all subjection, with no idea of government".[31] The peasants gather at taverns, where they spend their time drinking and gambling. They display their eagerness to prove their physical strength with horsemanship and knife fights. Rarely these displays led to deaths, and Sarmiento notes that Rosas's residence was sometimes used as a refuge on such occasions, before he became politically powerful.[29] According to Sarmiento, these elements are crucial to an understanding of the Argentine Revolution, in which Argentina gained independence from Spain. Although Argentina's war of independence was prompted by the influence of European ideas, Buenos Aires was the only city that could achieve civilization. Rural people participated in the war to demonstrate their physical strengths rather than because they wanted to civilize the country. In the end, the revolution was a failure because the barbaric instincts of the rural population led to the loss and dishonor of the civilized city—Buenos Aires.[32] |

あらすじ 馬が平坦な低木地帯で草を食む。 アルゼンチンの平原、パンパスである。サルミエントにとって、この荒涼とした特徴のない地形こそが、19世紀半ばまでにアルゼンチンが文明を達成できな かった「失敗」の主要因だった。 長い序論の後、『ファクンド』の15章は大きく三つの部分に分けられる。第1章から第4章ではアルゼンチンの地理、人類学、歴史を概説し、第5章から第 14章ではフアン・ファクンド・キロガの生涯を綴り、最終章では統一政府下におけるアルゼンチンの未来像をサルミエントが論じる。[3] サルミエント自身の言葉によれば、アルゼンチンの文脈を提供しファクンド・キロガを用いてロサスの独裁を非難する理由とは、「ファクンド・キロガに単なる カウディージョ(指導者)を見るだけでなく、植民地化と土地の特殊性によって形成されたアルゼンチン生活の現れを見る」からである。[26] アルゼンチンの文脈  南米地図。パンパスは南東部の大西洋沿岸地域を覆っている。 南米地図。アルゼンチン、ウルグアイ、ブラジル南部に広がるパンパスの範囲を示す ファクンドはアルゼンチンの地理的描写から始まる。西のアンデス山脈から東の大西洋岸まで、二大河川系がアルゼンチンとウルグアイの国境で合流する地点ま でを扱う。この河口地帯はリオ・デ・ラ・プラタと呼ばれ、首都ブエノスアイレスが位置する。アルゼンチンの地理論を通じて、サルミエントはブエノスアイレ スの優位性を示す。河川網は交通の動脈であり、貿易を可能にすることで都市の文明化を促進したのだ。しかしブエノスアイレスは文明を地方へ広めることに失 敗した。その結果、アルゼンチンその他の地域の大半は野蛮な状態に陥った。サルミエントはさらに、アルゼンチンの広大で何もない平原であるパンパスは「人 々が逃げ隠れして身を守る場所を提供せず、これがアルゼンチン大部分における文明の発展を妨げている」と主張する。[27] 地理的要因による文明化の障壁にもかかわらず、サルミエントはアルゼンチンの多くの問題はフアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスのようなガウチョたちによって引き 起こされたと主張する。彼らは野蛮で、無学で、無知で、傲慢だった。彼らの性格がアルゼンチン社会の文明化への進歩を阻んだのだ。[28] サルミエントは次に、ガウチョの四つの主要類型を記述する。これらの特徴付けは、フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスのようなアルゼンチン指導者を理解する助け となる。[29] サルミエントは、これらのアルゼンチン人的類型を理解しなければ、「我々の政治的人物や、アルゼンチン共和国を引き裂く血みどろの闘争の根源的なアメリカ 的性格を理解することは不可能だ」と主張する。[30] サルミエントは次にアルゼンチンの農民について論じる。彼らは「あらゆる必要から独立し、あらゆる服従から自由で、政府という概念を持たない」存在だ。 [31] 農民たちは酒場に集まり、酒を飲み賭博に興じる。彼らは乗馬やナイフ闘争で肉体的な強さを証明しようとする熱意を見せる。こうした見せびらかしが死に至る ことは稀で、サルミエントはロサスが政治的に力を持つ前、こうした事態の際には彼の邸宅が避難所として使われることもあったと記している。[29] サルミエントによれば、これらの要素はアルゼンチン革命を理解する上で極めて重要だ。この革命でアルゼンチンはスペインから独立を果たした。アルゼンチン の独立戦争はヨーロッパ思想の影響で引き起こされたものの、文明化を達成できたのはブエノスアイレスという都市だけだった。農村の人々が戦争に参加したの は、国を文明化したいからではなく、自らの肉体的な強さを誇示するためであった。結局、革命は失敗に終わった。なぜなら農村人口の野蛮な本能が、文明化さ れた都市——ブエノスアイレス——の敗北と不名誉をもたらしたからである。[32] |

Life of Juan Facundo Quiroga Juan Facundo Quiroga (portrait by Fernando García del Molino) As the central character of Sarmiento's Facundo, he represents barbarism, the antithesis of civilization. The second section of Facundo explores the life of its titular character, Juan Facundo Quiroga—the "Tiger of the Plains".[33] Despite being born into a wealthy family, Facundo received only a basic education in reading and writing.[34] He loved gambling, being called el jugador (the player)[35]—in fact, Sarmiento describes his gambling as "an ardent passion burning in his belly".[36] As a youth Facundo was antisocial and rebellious, refusing to mix with other children,[33] and these traits became more pronounced as he matured. Sarmiento describes an incident in which Facundo killed a man, writing that this type of behaviour "marked his passage through the world".[36] Sarmiento gives a physical description of the man he considers to personify the caudillo: "[he had a] short and well built stature; his broad shoulders supported, on a short neck, a well-formed head covered with very thick, black and curly hair", with "eyes ... full of fire".[33] Facundo's relations with his family eventually broke down, and, taking on the life of a gaucho, he joined the caudillos in the province of Entre Ríos.[37] His killing of two royalist prisoners after a jailbreak saw him acclaimed as a hero among the gauchos, and on relocating to La Rioja, Facundo was appointed to a leadership position in the Llanos Militia. He built his reputation and won his comrades' respect through his fierce battlefield performances, but hated and tried to destroy those who differed from him by being civilized and well-educated.[38] In 1825, when Unitarist Bernardino Rivadavia became the governor of the Buenos Aires province, he held a meeting with representatives from all provinces in Argentina. Facundo was present as the governor of La Rioja.[39] Rivadavia was soon overthrown, and Manuel Dorrego became the new governor. Sarmiento contends that Dorrego, a Federalist, was interested neither in social progress nor in ending barbaric behaviour in Argentina by improving the level of civilization and education of its rural inhabitants. In the turmoil that characterized Argentine politics at the time, Dorrego was assassinated by Unitarists and Facundo was defeated by Unitarist General José María Paz.[40] Facundo escaped to Buenos Aires and joined the Federalist government of Juan Manuel de Rosas. During the ensuing civil war between the two ideologies, Facundo conquered the provinces of San Luis, Córdoba and Mendoza.[41] On return to his San Juan home, which Sarmiento says Facundo governed "solely with his terrifying name",[42] he realized that his government lacked support from Rosas. He went to Buenos Aires to confront Rosas, who sent him on another political mission. On his way back, Facundo was shot and killed at Barranca Yaco, Córdoba.[43] According to Sarmiento, the murder was plotted by Rosas: "An impartial history still awaits facts and revelations, in order to point its finger at the instigator of the assassins".[44] |

フアン・ファクンド・キロガの生涯 フアン・ファクンド・キロガ(フェルナンド・ガルシア・デル・モリーノ作肖像画) サルミエントの『ファクンド』における中心人物として、彼は文明の対極にある野蛮性を体現している。『ファクンド』の第2部では、その表題人物であるフア ン・ファクンド・キロガ——「平原の虎」——の生涯が描かれる[33]。裕福な家庭に生まれたにもかかわらず、ファクンドが受けた教育は読み書きの基礎に 過ぎなかった[34]。彼は賭博を愛し、「エル・ハジュラド(賭博師)」と呼ばれた[35]——実際、サルミエントは彼の賭博への情熱を「腹の底で燃え盛 る熱烈な情熱」と表現している。[36] ファクンドは若き日に反社会的で反抗的であり、他の子供たちと混血することを拒んだ[33]。こうした性質は成長するにつれてより顕著になった。サルミエ ントはファクンドが人を殺害した事件を記述し、この種の行動が「彼の世界における軌跡を刻んだ」と記している。[36] サルミエントは、カウディージョの象徴と見なす男の身体的特徴をこう描写している:「背は低くがっしりした体格。短い首の上に広い肩が乗り、その上には非 常に濃く黒く縮れた髪に覆われた整った頭部が載っていた」。そして「目は…炎のように燃えていた」。[33] ファクンドは家族との関係を断ち切り、ガウチョの生活を送る中でエントレ・リオス州の軍閥に加わった。[37]脱獄事件で王党派の囚人二人を殺害したこと でガウチョたちの英雄となり、ラ・リオハ州に移住後はリャノス民兵隊の指導的立場に就いた。彼は戦場での猛烈な活躍で名声を築き、仲間からの尊敬を得た が、文明的で教養のある者とは異なる立場に立ち、彼らを憎み、排除しようとした。[38] 1825年、統一主義者のベルナルディーノ・リバダビアがブエノスアイレス州知事に就任すると、アルゼンチン全州の代表者との会合を開いた。ファクンドは ラ・リオハ州知事として出席した。[39] しかしリバダビアはすぐに失脚し、マヌエル・ドレゴが新総督となった。サルミエントによれば、連邦主義者であるドレゴは、社会進歩にも、農村住民の文明化 と教育水準向上によるアルゼンチンの野蛮な行為の終焉にも関心を持たなかった。当時のアルゼンチン政治を特徴づけた混乱の中で、ドレゴは統一主義者に暗殺 され、ファクンドは統一主義者のホセ・マリア・パス将軍に敗北した。[40] ファクンドはブエノスアイレスへ逃れ、フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスの連邦派政権に加わった。両イデオロギー間の内戦が続く中、ファクンドはサン・ルイス 州、コルドバ州、メンドーサ州を征服した。[41] 故郷サン・フアンに戻ると、サルミエントによればファクンドは「その恐るべき名声だけで」統治していたが[42]、ロサスからの支援が得られていないこと に気づいた。彼はロサスと対峙するためブエノスアイレスへ向かったが、ロサスから別の政治的任務を命じられた。帰途、ファクンドはコルドバ州バランカ・ヤ コで銃撃され死亡した[43]。サルミエントによれば、この暗殺はロサスが画策したものだ。「公平な歴史は、暗殺者の首謀者を指弾するために、未だ事実と 真相の解明を待っている」[44]。 |

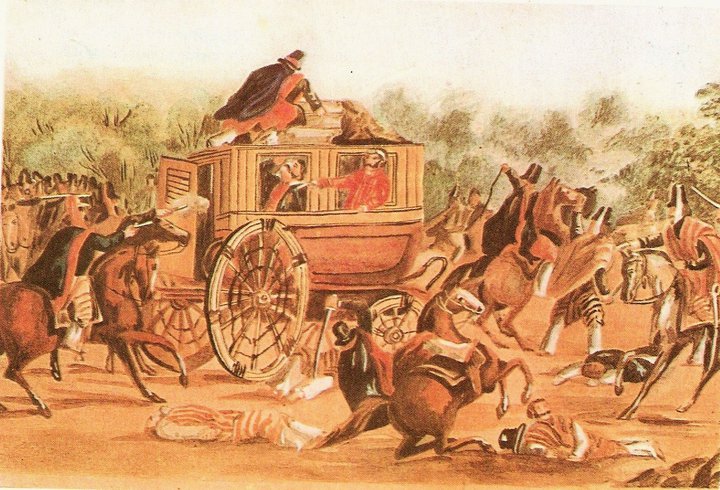

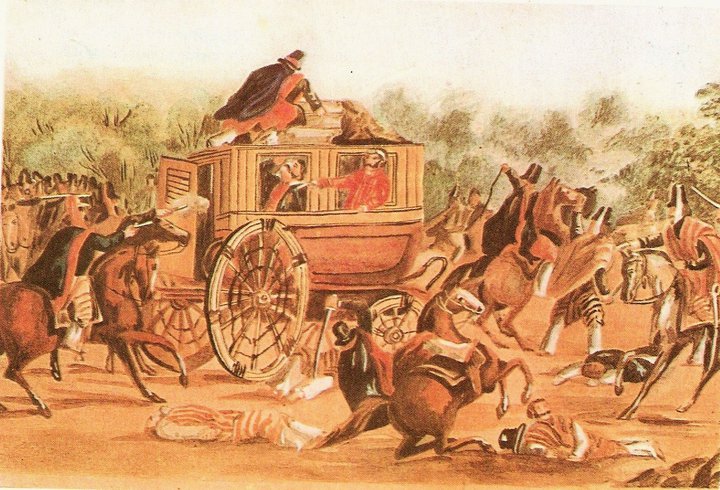

Consequences of Facundo's death Assassination of Facundo Quiroga at Barranca Yaco In the book's final chapters, Sarmiento explores the consequences of Facundo's death for the history and politics of the Argentine Republic.[45] He further analyzes Rosas's government and personality, commenting on dictatorship, tyranny, the role of popular support, and the use of force to maintain order. Sarmiento criticizes Rosas by using the words of the dictator, making sarcastic remarks about Rosas's actions, and describing the "terror" established during the dictatorship, the contradictions of the government, and the situation in the provinces that were ruled by Facundo. Sarmiento writes, "The red ribbon is a materialization of the terror that accompanies you everywhere, in the streets, in the bosom of the family; it must be thought about when dressing, when undressing, and ideas are always engraved upon us by association".[46] Finally, Sarmiento examines the legacy of Rosas's government by attacking the dictator and widening the civilization–barbarism dichotomy. By setting France against Argentina—representing civilization and barbarism respectively—Sarmiento contrasts culture and savagery: France's blockade had lasted for two years, and the 'American' government, inspired by 'American' spirit, was facing off with France, European principles, European pretensions. The social results of the French blockade, however, had been fruitful for the Argentine Republic, and served to demonstrate in all their nakedness the current state of mind and the new elements of struggle, which were to ignite a fierce war that can end only with the fall of that monstrous government.[47] |

ファクンドの死がもたらした結果 バランカ・ヤコにおけるファクンド・キロガ暗殺 本書の最終章で、サルミエントはファクンドの死がアルゼンチン共和国の歴史と政治に与えた影響を考察している。[45] さらに彼はロサスの政権と人物像を分析し、独裁、専制政治、民衆支持の役割、秩序維持のための武力行使について論じている。サルミエントは独裁者の言葉を 用いてロサスを批判し、ロサスの行動を皮肉り、独裁政権下で確立された「恐怖」、政府の矛盾、ファクンドが支配していた州の状況を描写する。サルミエント はこう記す。「赤いリボンは、君がどこへ行っても付きまとう恐怖の具現だ。街中であれ、家族の懐中であれ。服を着る時も脱ぐ時も考えねばならず、連想に よって常に我々の心に刻み込まれるのだ」[46] 最後にサルミエントは、独裁者を攻撃し文明と野蛮の二項対立を広げることで、ロサス政権の遺産を検証する。フランスとアルゼンチンを対置し(それぞれ文明と野蛮を象徴)、文化と未開を対比させるのだ: フランスの封鎖は二年続き、「アメリカ的」精神に鼓舞された「アメリカ的」政府は、フランス、すなわちヨーロッパの原理とヨーロッパの野望と対峙してい た。しかしフランス封鎖の社会的結果はアルゼンチン共和国にとって実り多いものであり、当時の精神状態と新たな闘争要素をありのままに露呈させた。それら は激しい戦争を引き起こす要素であり、その戦争はあの怪物のような政権の崩壊をもってしか終結し得ないのだ。[47] |

| Genre and style Spanish critic and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno comments of the book, "I never took Facundo by Sarmiento as a historical work, nor do I think it can be very valued in that regard. I always thought of it as a literary work, as a historical novel".[48] However, Facundo cannot be classified as a novel or a specific genre of literature. According to González Echevarría, the book is at once an "essay, biography, autobiography, novel, epic, memoir, confession, political pamphlet, diatribe, scientific treatise, [and] travelogue".[5] Sarmiento's style and his exploration of the life of Facundo unify the three distinct parts of his work. Even the first section, describing Argentina's geography, follows this pattern, since Sarmiento contends that Facundo is a natural product of this environment.[49] The book is partly fictional, as well: Sarmiento draws on his imagination in addition to historical fact in describing Rosas. In Facundo, Sarmiento outlines his argument that Rosas's dictatorship is the main cause of Argentina's problems. The themes of barbarism and savagery that run through the book are, to Sarmiento, consequences of Rosas's dictatorial government.[50] To make his case, Sarmiento often has recourse to strategies drawn from literature. |

ジャンルとスタイル スペインの批評家であり哲学者でもあるミゲル・デ・ウナムノは、この本について次のように述べている。「私はサルミエントの『ファクンド』を歴史作品とは 決して考えてこなかったし、その点で高く評価できるとも思わない。私は常にこれを文学作品、歴史小説として捉えてきた」[48]と述べている。しかし 『ファクンド』は小説や特定の文学ジャンルに分類することはできない。ゴンサレス・エチェバリアによれば、この書物は同時に「随筆、伝記、自伝、小説、叙 事詩、回顧録、告白、政治パンフレット、痛烈な批判、学術論文、旅行記」である。[5] サルミエントの文体とファクンドの生涯への探求が、この作品の三つの異なる部分を統一している。アルゼンチンの地理を記述する最初の部分でさえ、このパ ターンに従っている。なぜならサルミエントは、ファクンドがこの環境の自然な産物だと主張しているからだ。[49] この本は部分的に虚構でもある。サルミエントはロサスを描くにあたり、歴史的事実に加えて想像力を働かせている。『ファクンド』において、サルミエントは アルゼンチンの諸問題の主因がロサスの独裁にあるとの主張を展開する。本書に貫かれる野蛮と残虐のテーマは、サルミエントにとってロサス独裁政権の結果で ある。[50] 論証のため、サルミエントはしばしば文学的手法に依拠する。 |

| Themes Civilization and barbarism  4th edition in Spanish. Paris, 1874. Facundo is not only a critique of Rosas's dictatorship, but a broader investigation into Argentine history and culture, which Sarmiento charts through the rise, controversial rule, and downfall of Juan Facundo Quiroga, an archetypical Argentine caudillo. Sarmiento summarizes the book's message in the phrase "That is the point: to be or not to be savages".[51] The dichotomy between civilization and barbarism is the book's central idea; Facundo Quiroga is portrayed as wild, untamed, and standing opposed to true progress through his rejection of European cultural ideals—found at that time in the metropolitan society of Buenos Aires.[52] The conflict between civilization and barbarism mirrors Latin America's difficulties in the post-Independence era. Literary critic Sorensen Goodrich argues that although Sarmiento was not the first to articulate this dichotomy, he forged it into a powerful and prominent theme that would impact Latin American literature.[53] He explores the issue of civilization versus the cruder aspects of a caudillo culture of brutality and absolute power. Facundo set forth an oppositional message that promoted a more beneficial alternative for society at large. Although Sarmiento advocated various changes, such as honest officials who understood enlightenment ideas of European and Classical origin, for him education was the key. Caudillos like Facundo Quiroga are seen, at the beginning of the book, as the antithesis of education, high culture, and civil stability; barbarism was like a never ending litany of social ills.[54] They are the agents of instability and chaos, destroying societies through their blatant disregard for humanity and social progress.[55] If Sarmiento viewed himself as civilized, Rosas was barbaric. Historian David Rock argues that "contemporary opponents reviled Rosas as a bloody tyrant and a symbol of barbarism".[56] Sarmiento attacked Rosas through his book by promoting education and "civilized" status, whereas Rosas used political power and brute force to dispose of any kind of hindrance. In linking Europe with civilization, and civilization with education, Sarmiento conveyed an admiration of European culture and civilization which at the same time gave him a sense of dissatisfaction with his own culture, motivating him to drive it towards civilization.[57] Using the wilderness of the pampas to reinforce his social analysis, he characterizes those who were isolated and opposed to political dialogue as ignorant and anarchic—symbolized by Argentina's desolate physical geography.[58] Conversely, Latin America was connected to barbarism, which Sarmiento used mainly to illustrate the way in which Argentina was disconnected from the numerous resources surrounding it, limiting the growth of the country.[55] American critic Doris Sommer sees a connection between Facundo's ideology and Sarmiento's readings of Fenimore Cooper. She links Sarmiento's remarks on modernization and culture to the American discourse of expansion and progress of the 19th century.[59] |

テーマ 文明と野蛮  スペイン語第4版。パリ、1874年。 ファクンドはロサス独裁政権への批判であるだけでなく、アルゼンチンの歴史と文化に対する広範な考察でもある。サルミエントは、典型的なアルゼンチンのカ ウディージョであるフアン・ファクンド・キロガの台頭、論争を呼んだ統治、そして没落を通じて、この考察を展開している。サルミエントは本書のメッセージ を「要はそこだ:野蛮人であるか否か」という一節で要約している[51]。文明と野蛮の二項対立が本書の核心思想であり、ファクンド・キロガは野性的で制 御不能な存在として描かれ、当時のブエノスアイレス都心部社会に見られたヨーロッパ的文化的理想を拒絶することで、真の進歩に抗う者として位置づけられて いる。[52] 文明と野蛮の対立は、独立後のラテンアメリカが直面した困難を映し出している。文学評論家ソレンセン・グッドリッチは、サルミエントがこの二項対立を初め て明確にしたわけではないが、ラテンアメリカ文学に影響を与える強力かつ顕著なテーマとして確立したと論じている。[53] 彼は、文明と、残虐性と絶対的権力を特徴とするカウディージョ文化の粗野な側面との対立という問題を考察している。ファクンドは社会全体にとって有益な代 替案を提唱する対抗メッセージを打ち出した。サルミエントは欧州や古典由来の啓蒙思想を理解する正直な官吏など様々な変革を主張したが、彼にとって教育が 鍵であった。ファクンド・キロガのようなカウディージョは、本書の冒頭で教育・高尚な文化・社会の安定に対する対極的存在として描かれる。野蛮は終わりの ない社会悪の連鎖のようであった。[54] 彼らは不安定と混沌の媒介者であり、人間性や社会的進歩への露骨な無視によって社会を破壊する。[55] サルミエントが自らを文明的と見做したならば、ロサスは野蛮であった。歴史家デイヴィッド・ロックは「当時の反対派はロサスを血にまみれた暴君、野蛮の象 徴として罵倒した」と論じる。[56] サルミエントは著書で教育と「文明的」地位を推進することでロサスを攻撃した。一方ロサスは政治的権力と暴力であらゆる妨害を排除した。ヨーロッパを文明 と結びつけ、文明を教育と結びつけることで、サルミエントはヨーロッパ文化への憧憬を表明すると同時に、自国文化への不満を募らせ、それを文明へと導こう としたのである。[57] パンパスの荒野を社会分析の補強として用いて、彼は、政治対話から孤立し、それに反対する者たちを、アルゼンチンの荒涼とした地理的特徴に象徴される、無 知で無秩序な者たちとして特徴づけている。[58] 逆に、ラテンアメリカは野蛮と結びつけられ、サルミエントは主に、アルゼンチンが周囲の多くの資源から切り離され、国の成長が制限されていることを説明す るためにこの概念を用いた。[55] アメリカの批評家ドリス・ソマーは、ファクンドのイデオロギーとサルミエントのフェニモア・クーパーの解釈との関連性を見出している。彼女は、サルミエントの近代化と文化に関する見解を、19 世紀のアメリカの拡大と進歩に関する言説と結びつけている。[59] |

| Writing and power In the history of post-independence Latin America, dictatorships have been relatively common—examples range from Paraguay's José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia in the 19th century to Chile's Augusto Pinochet in the 20th. In this context, Latin American literature has been distinguished by the protest novel, or dictator novel; the main story is based around the dictator figure, his behaviour, characteristics and the situation of the people under his regime. Writers such as Sarmiento used the power of the written word in order to criticize government, using literature as a tool, an instance of resistance and as a weapon against repression.[60] Making use of the connection between writing and power was one of Sarmiento's strategies. For him, writing was intended to be a catalyst for action.[61] While the gauchos fought with physical weapons, Sarmiento used his voice and language.[62] Sorensen states that Sarmiento used "text as [a] weapon".[60] Sarmiento was writing not only for Argentina but for a wider audience too, especially the United States and Europe; in his view, these regions were close to civilization; his purpose was to seduce his readers toward his own political viewpoint.[63] In the numerous translations of Facundo, Sarmiento's association of writing with power and conquest is apparent.[64] Since his books often serve as vehicles for his political manifesto, Sarmiento's writings commonly mock governments, with Facundo being the most prominent example.[65] He elevates his own status at the expense of the ruling elite, almost portraying himself as invincible due to the power of writing. Toward the end of 1840, Sarmiento was exiled for his political views. Covered with bruises received the day before from unruly soldiers, he wrote in French, "On ne tue point les idées" (misquoted from "on ne tire pas des coups de fusil aux idées", which means "ideas cannot be killed by guns"). The government decided to decipher the message, and on learning the translation, said, "So! What does this mean?".[66] With the failure of his oppressors to understand his meaning, Sarmiento is able to illustrate their ineptitude. His words are presented as a "code" that needs to be "deciphered",[66] and unlike Sarmiento those in power are barbaric and uneducated. Their bafflement not only demonstrates their general ignorance, but also, according to Sorensen, illustrates "the fundamental displacement which any cultural transplantation brings about", since Argentine rural inhabitants and Rosas's associates were unable to accept the civilized culture which Sarmiento believed would lead to progress in Argentina.[67] |

書き物と権力 独立後のラテンアメリカの歴史において、独裁政権は比較的頻繁に存在した。例を挙げれば、19世紀のパラグアイのホセ・ガスパール・ロドリゲス・デ・フラ ンシアから、20世紀のチリのアウグスト・ピノチェトに至るまでである。こうした文脈において、ラテンアメリカ文学は抗議小説、すなわち独裁者小説によっ て特徴づけられてきた。物語の主軸は独裁者の人物像、その行動や特性、そしてその体制下で生きる民衆の状況に据えられる。サルミエントのような作家たち は、政府を批判するために文字の力を利用した。文学を抵抗の手段、抑圧に対する武器として用いたのである。[60] 文字と権力の結びつきを利用することは、サルミエントの戦略の一つであった。彼にとって、文字は行動の触媒となることを意図していた。[61] ガウチョたちが物理的な武器で戦う一方で、サルミエントは自らの声と言葉を用いた。[62] ソレンセンは、サルミエントが「テキストを武器として用いた」と述べている[60]。サルミエントの執筆対象はアルゼンチン国内だけでなく、特に米国や欧 州といったより広い読者層にも向けられていた。彼の見解では、これらの地域は文明に近い存在であり、読者を自らの政治的見解へと引き込むことが目的だった [63]。『ファクンド』の数々の翻訳版において、サルミエントが文章と権力・征服を結びつける姿勢は明らかである。[64] 彼の著作はしばしば政治的宣言の媒体となるため、サルミエントの文章は政府を嘲笑するのが通例であり、『ファクンド』がその最も顕著な例である。[65] 彼は支配層を犠牲にして自らの地位を高め、文章の力によってほぼ無敵であるかのように自らを描写している。1840年末、サルミエントは政治的見解により 追放された。前日に無法な兵士たちから受けた打撲傷に覆われながら、彼はフランス語で「思想は銃弾で殺せない」(「on ne tire pas des coups de fusil aux idées」の誤記)と記した。政府はこのメッセージを解読しようと決め、翻訳を知ると「はあ? これはどういう意味だ?」と言った[66]。抑圧者たち が彼の真意を理解できなかったことで、サルミエントは彼らの無能さを浮き彫りにした。彼の言葉は「解読」が必要な「暗号」として提示され[66]、権力者 たちはサルミエントとは異なり野蛮で無教養であることが示された。彼らの困惑は、単なる無知を示すだけでなく、ソレンセンによれば「あらゆる文化的移植が もたらす根本的な乖離」を浮き彫りにしている。アルゼンチンの農村住民やロサスの側近たちは、サルミエントがアルゼンチンの進歩をもたらすと信じた文明文 化を受け入れることができなかったからだ。[67] |

| Legacy For translator Kathleen Ross, Facundo is "one of the foundational works of Spanish American literary history".[2] It has been enormously influential in setting out a "blueprint for modernization",[68] with its practical message enhanced by a "tremendous beauty and passion".[2] However, according to literary critic González Echevarría it is not only a powerful founding text but "the first Latin American classic, and the most important book written about Latin America by a Latin American in any discipline or genre".[1][2] The book's political influence can be seen in Sarmiento's eventual rise to power. He became president of Argentina in 1868 and was able to apply his theories to ensure that his nation achieved civilization.[69] Although Sarmiento wrote several books, he viewed Facundo as authorizing his political views.[70] According to Sorensen, "early readers of Facundo were deeply influenced by the struggles that preceded and followed Rosas's dictatorship, and their views sprang from their relationship to the strife for interpretive and political hegemony".[71] González Echevarría notes that Facundo provided the impetus for other writers to examine dictatorship in Latin America, and contends that it is still read today because Sarmiento created "a voice for modern Latin American authors".[5] The reason for this, according to González Echevarría, is that "Latin American authors struggle with its legacy, rewriting Facundo in their works even as they try to untangle themselves from its discourse".[5] Subsequent dictator novels, such as El Señor Presidente by Miguel Ángel Asturias or The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa, drew upon its ideas,[5] and a knowledge of Facundo enhances the reader's understanding of these later books.[72] One irony of the impact of Sarmiento's essay genre and fictional literature is that, according to González Echevarría, the gaucho has become "an object of nostalgia, a lost origin around which to build a national mythology".[72] While Sarmiento was trying to eliminate the gaucho, he also transformed him into a "national symbol".[72] González Echevarría further argues that Juan Facundo Quiroga also continues to exist, since he represents "our unresolved struggle between good and evil, and our lives' inexorable drive toward death".[72] According to translator Kathleen Ross, "Facundo continues to inspire controversy and debate because it contributes to national myths of modernization, anti-populism, and racist ideology".[73] |

レガシー 翻訳者キャスリーン・ロスによれば、『ファクンド』は「スペイン語圏アメリカ文学史における基礎的作品の一つ」である[2]。この作品は「近代化の青写 真」を提示する上で極めて大きな影響力を持ち[68]、その実践的なメッセージは「圧倒的な美しさと情熱」によってさらに強化されている[2]。しかし、 文学評論家ゴンサレス・エチェバリアによれば、これは単なる強力な創始的テキストではなく、「最初のラテンアメリカ古典であり、あらゆる分野・ジャンルに おいてラテンアメリカ人によって書かれたラテンアメリカに関する最も重要な書物」である[1][2]。本書の政治的影響は、サルミエントが最終的に権力の 座に就いたことに見られる。彼は1868年にアルゼンチン大統領となり、自らの理論を適用して国民が文明を達成することを保証した。[69] サルミエントは複数の著作を残したが、『ファクンド』こそが自らの政治的見解を正当化するものと見なしていた。[70] ソレンセンによれば、「『ファクンド』の初期読者は、ロサス独裁政権の前後における闘争に深く影響を受けており、彼らの見解は解釈と政治的ヘゲモニーをめ ぐる争いとの関係から生まれた」という。[71] ゴンサレス・エチェバリアは、『ファクンド』が他の作家たちにラテンアメリカの独裁政権を考察する契機を与えたと指摘し、サルミエントが「現代ラテンアメ リカ作家のための声」を創出したため、今日でも読まれ続けていると主張する。[5] ゴンサレス・エチェバリアによれば、その理由は「ラテンアメリカ作家たちがその遺産と格闘し、自らの作品の中で『ファクンド』を書き換えつつ、その言説か ら自らを解きほぐそうとする」からである。[5] ミゲル・アンヘル・アストリアスの『大統領閣下』やマリオ・バルガス・リョサの『山羊の饗宴』といった後の独裁者小説は、この作品の思想を借用している [5]。ファクンドの知識は、これらの後世の著作を理解する上で読者の助けとなる。[72] サルミエントの論説体裁と虚構文学が与えた影響の皮肉な点は、ゴンサレス・エチェバリアによれば、ガウチョが「ノスタルジーの対象、国民神話を構築するた めの失われた起源」となったことだ[72]。サルミエントはガウチョを消去法による排除しようとしたが、同時に彼を「国家的象徴」へと変容させたのであ る。[72] ゴンサレス・エチェバリアはさらに、フアン・ファクンド・キロガもまた存在し続けていると論じる。なぜなら彼は「我々の善と悪の未解決の葛藤、そして死へ と向かう人生の不可避的な推進力」を体現しているからだ。[72] 翻訳者キャスリーン・ロスによれば、「ファクンドは近代化、反ポピュリズム、人種差別的イデオロギーという国民的神話に貢献するため、今も論争と議論を喚 起し続けている」という。[73] |

| Publication and translation history The first edition of Facundo was published in instalments in 1845, in the literary supplement of the Chilean newspaper El Progreso. The second edition, also published in Chile (in 1851), contained significant alterations—Sarmiento removed the last two chapters on the advice of Valentín Alsina, an exiled Argentinian lawyer and politician.[3] However, the missing sections reappeared in 1874 in a later edition, because Sarmiento saw them as crucial to the book's development.[74] Facundo was first translated in 1868, by Mary Mann, a friend of Sarmiento, with the title Life in the Argentine Republic in the Days of the Tyrants; or, Civilization and Barbarism. More recently, Kathleen Ross has undertaken a modern and complete translation, published in 2003 by the University of California Press. In Ross's "Translator's Introduction," she notes that Mann's 19th-century version of the text was influenced by Mann's friendship with Sarmiento and by the fact that he was at the time a candidate in the Argentine presidential election: "Mann wished to further her friend's cause abroad by presenting Sarmiento as an admirer and emulator of United States political and cultural institutions". Hence Mann's translation cut much of what made Sarmiento's work distinctively part of the Hispanic tradition. Ross continues: "Mann's elimination of metaphor, the stylistic device perhaps most characteristic of Sarmiento's prose, is especially striking".[75] |

出版と翻訳の歴史 『ファクンド』初版は1845年、チリ紙『エル・プログレソ』の文芸別冊に連載された。第二版(1851年、同じくチリで出版)には大幅な改変が加えられ ており、サルミエントは亡命中のアルゼンチン人弁護士・政治家バレンティン・アルシーナの助言に従い、最終二章を削除した。[3] しかし、欠落した部分は1874年の後続版で再収録された。サルミエントはそれらを作品の発展に不可欠と見なしたからである。[74] 『ファクンド』の最初の英訳は1868年、サルミエントの友人メアリー・マンによるもので、『暴君の時代におけるアルゼンチン共和国の生活、あるいは文明 と野蛮』という題名で出版された。近年ではキャスリーン・ロスが現代的な完全訳を手掛け、2003年にカリフォルニア大学出版局より刊行された。ロスの 「訳者序文」によれば、マンの19世紀版翻訳は、当時のサルミエントがアルゼンチン大統領選挙の候補者であったこと、及びマン自身のサルミエントとの親交 に影響されていたという: 「マンは、サルミエントを米国政治・文化制度の崇拝者かつ模倣者として提示することで、友人の大義を国外で推進しようとした」。ゆえにマンの翻訳は、サル ミエントの著作をヒスパニック伝統の特異な一部たらしめていた要素の多くを削ぎ落とした。ロス氏は続ける:「サルミエントの散文においておそらく最も特徴 的な修辞技法である隠喩表現を、マンが排除した点は特に顕著である」。[75] |

| Footnotes |

|

| References Ball, Kimberly (1999), "Facundo by Domingo F. Sarmiento", in Moss, Joyce; Valestuk, Lorraine (eds.), Latin American Literature and Its Times, vol. 1, World Literature and Its Times: Profiles of Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events That Influenced Them, Detroit: Gale Group, pp. 171–180, ISBN 0-7876-3726-2 Bravo, Héctor Félix (1990), "Profiles of educators: Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (1811–88)", Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 20, number 2 (74), Paris: UNESCO: International Bureau of Education: 247–256, doi:10.1007/BF02196326, S2CID 189873123 Carilla, Emilio (1955), Lengua y estilo en el Facundo (in Spanish), Buenos Aires: Universidad nacional de Tucumán, OCLC 2010266 Chang-Rodríguez, Raquel (1988), Voces de Hispanoamérica: antología literaria (in Spanish), New York: Heinle & Heinle, ISBN 0-8384-1603-9 González Echevarría, Roberto (1985), The Voice of the Masters: Writing and Authority in Modern Latin American Literature, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-78716-2 González Echevarría, Roberto (2003), "Facundo: An Introduction", in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (ed.), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 1–16 Ludmer, Josefina (2002), The Gaucho Genre: A Treatise on the Motherland, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, ISBN 0-8223-2844-5. Trans. Molly Weigel. Lynch, John (1981), Argentine Dictator: Juan Manuel de Rosas 1829–1852, New York, US: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-821129-5 Mann, Horace (1868), "Biographical Sketch of the Author", in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (ed.), Life in the Argentine Republic in the Days of the Tyrants, or, Civilization and Barbarism, New York: Hafner, pp. 276–396. Book is by Domingo Sarmiento. Martínez Estrada, Ezequiel (1969), Sarmiento (in Spanish), Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, ISBN 950-845-107-6 Newton, Jorge (1965), Facundo Quiroga: Aventura y leyenda (in Spanish), Buenos Aires: Plus Ultra Rockland, Michael Aaron (2015), Sarmiento's Travels in the U.S. in 1847, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 9781400870899 Ross, Kathleen (2003), "Translator's Introduction", in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (ed.), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, trans. Kathleen Ross, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 17–26 Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (2003), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (published 1845), ISBN 0-520-23980-6 The first complete English translation. Trans. Kathleen Ross. Shumway, Nicolas (1993), The Invention of Argentina, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-08284-2 Sorensen Goodrich, Diana (1996), Facundo and the Construction of Argentine Culture, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-72790-9 Weiner, Mark S. (2011), Domingo Sarmiento and the Cultural History of Law in the Americas (PDF), Newark, New Jersey: Rutgers Law Review |

参考文献 ボール、キンバリー(1999)、「ファクンド(ドミンゴ・F・サルミエント著)」、『ラテンアメリカ文学とその時代』第1巻、ジョイス・モス、ロレイ ン・ヴァレステュク編、『世界文学とその時代:著名な文学作品とそれに影響を与えた歴史的出来事の概説』、デトロイト:ゲイル・グループ、171–180 頁、 ISBN 0-7876-3726-2 ブラボ、ヘクター・フェリックス(1990)、「教育者たちの肖像:ドミンゴ・ファウスティノ・サルミエント(1811–88)」、『プロスペクツ:比較 教育学季刊』第20巻第2号(74)、パリ:ユネスコ国際教育局、247–256頁、 doi:10.1007/BF02196326, S2CID 189873123 カリジャ、エミリオ(1955年)『ファクンドにおける言語と文体』(スペイン語)、ブエノスアイレス:トゥクマン国立大学、OCLC 2010266 チャン=ロドリゲス、ラケル(1988)『ヒスパノアメリカの声:文学アンソロジー』(スペイン語)、ニューヨーク:ハインレ&ハインレ、ISBN 0-8384-1603-9 ゴンサレス・エチェバリア、ロベルト(1985)『巨匠たちの声:近代ラテンアメリカ文学における執筆と権威』、テキサス州オースティン:テキサス大学出版局、 ISBN 0-292-78716-2 ゴンサレス・エチェバリア、ロベルト(2003)、「ファクンド:序説」、ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント(編)、『ファクンド:文明と野蛮』、カリフォルニア州バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局、pp. 1–16 ルドメル、ホセフィーナ(2002)『ガウチョ・ジャンル:母国に関する論考』ノースカロライナ州ダーラム:デューク大学出版局、ISBN 0-8223-2844-5。訳:モリー・ウェイゲル。 リンチ、ジョン(1981)『アルゼンチンの独裁者:フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサス 1829–1852』米国ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局、ISBN 0-19-821129-5 マン、ホラティウス(1868年)、「著者の略歴」、ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント(編)、『暴君の時代におけるアルゼンチン共和国の生活、 あるいは文明と野蛮』、ニューヨーク:ハフナー、pp. 276–396。本書はドミンゴ・サルミエントによるものである。 マルティネス・エストラーダ、エセキエル(1969年)、『サルミエント』(スペイン語)、ブエノスアイレス:エディトリアル・スダメリカーナ、ISBN 950-845-107-6 ニュートン、ホルヘ(1965)『ファクンド・キロガ:冒険と伝説』(スペイン語)、ブエノスアイレス:プラス・ウルトラ ロックランド、マイケル・アーロン(2015)『1847年サルミエントの米国旅行』、プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局、ISBN 9781400870899 ロス、キャスリーン(2003)、「訳者序文」、ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント(編)、『ファクンド:文明と野蛮』、訳キャスリーン・ロス、カリフォルニア州バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局、17-26頁 サルミエント、ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ(2003)、『ファクンド:文明と野蛮』、カリフォルニア州バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局(1845年刊行)、ISBN 0-520-23980-6。初の完全英訳。訳:キャスリーン・ロス。 シュムウェイ、ニコラス(1993)『アルゼンチンの発明』カリフォルニア大学出版局、ISBN 0-520-08284-2 ソレンセン・グッドリッチ、ダイアナ(1996)、『ファクンドとアルゼンチン文化の構築』、オースティン:テキサス大学出版局、ISBN 0-292-72790-9 ワイナー、マーク・S.(2011)、『ドミンゴ・サルミエントとアメリカ大陸における法の文化史』(PDF)、ニューアーク、ニュージャージー州:ラトガース・ロー・レビュー |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Facundo |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099