ラテンアメリカにおけるフェミニズム

Feminism in Latin America

Protest on International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women 2019 in Mexico City

☆ ラ テンアメリカのフェミニズムは、ラテンアメリカの女性のための平等な政治的、経済的、文化的、個人的、社会的権利を定義し、確立し、達成することを目的と した運動の集まりである。これには、教育や雇用における女性の平等な機会の確立を目指すことも含まれる。女性の権利と平等を提唱または支持することによっ てフェミニズムを実践する人々がフェミニストである。 ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムは、何世紀にもわたる植民地主義、アフリカからの奴隷の輸送と服従、先住民の虐待などの文脈の中で存在している。現代のラテ ンアメリカのフェミニズムの起源は、女性解放運動を包含する1960年代と1970年代の社会運動にさかのぼることができるが、それ以前のフェミニズムの 思想は、文書による記録が残る前から広がっていた。ラテンアメリカとカリブ海地域のさまざまな地域によって、フェミニズムの定義は、文化的、政治的、社会 的な関与があったさまざまなグループによって異なる。 ラテンアメリカのフェミニズム運動の勃興には、5つの重要な要因がある。ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムの革命の始まりは、1800年代にエクアドルのマヌ エラ・サエンスとアルゼンチンのフアナ・マヌエラ・ゴリティという2人の女性から始まったと言われている。これらの運動以前は、植民地支配の後、女性には ほとんど何の権利もなかった。しかし、裕福なヨーロッパの家庭に属する女性たちは、教育の機会を多く得ていた。その後、1920年代にフェミニズムが再燃 し、女性の権利のための政治的・教育的変革に向かった。1930年代から50年代にかけて、プエルトリカンの女性グループが、現在ラテンアメリカ女性の運 動と考えられているものを創設した。これらの運動の中には、工場で裁縫師として働くなど、針産業の創設も含まれていた。そして1960年代には、女性の身 体的・経済的権利を擁護する運動へと変化した。1970年代には、自由市場資本主義と結びついた自由放任主義のために、運動は下火になった。新自由主義の 崩壊後、1980年代には政治的権利に向けたフェミニズム運動が復活した。1980年代はまた、ドメスティック・バイオレンスというトピックにも光が当た り始めた。1990年代には、女性の法的平等に向けて前進した。今日の社会では、ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムは、民族やテーマ意識によって複数のサブカ テゴリーに分類されている。

★家父長制は[その体制を補完/保全する]社会科学や人類学の術語というよりも現今の性抑圧体制という敵を表現するインデックスであり反家父長制は闘争の言語あるいはスローガンと考えれば学生たちにはすっきりすると思います

| Latin

American feminism is a collection of movements aimed at defining,

establishing, and achieving equal political, economic, cultural,

personal, and social rights for Latin American women.[1][2] This

includes seeking to establish equal opportunities for women in

education and employment. People who practice feminism by advocating or

supporting the rights and equality of women are feminists.[3] Latin American feminism exists in the context of centuries of colonialism, the transportation and subjugation of slaves from Africa, and the mistreatment of native people.[4][5] The origins of modern Latin American feminism can be traced back to the 1960s and 1970s social movements, where it encompasses the women's liberation movement, but prior feminist ideas have expanded before there were written records. With various regions in Latin America and the Caribbean, the definition of feminism varies across different groups where there has been cultural, political, and social involvement. The emergence of the Latin American feminism movement is contributed to five key factors. It has been said that the beginning of the revolution for Latin American feminism started in the 1800s with two women, Manuela Sáenz in Ecuador and Juana Manuela Gorriti in Argentina. Prior to these movements, women had close to no rights after colonialism. However, women who belonged to wealthier, European families had more opportunities in education. Then in the 1920s, feminism was reignited and moved towards political and educational changes for women's rights. In the 1930-50s a Puerto Rican group of women founded what is now considered the current movement for Latin American women. Some of these movements included founding the needle industry such as working as sewists in factories. Then in the 1960s, the movement changed to advocate for bodily and economic rights of women. The 1970s had a downfall in the movement due to a laissez-faire liberalism combined with free market capitalism. After the fall of neoliberalism, the 1980s brought a resurgence of the feminist movement towards political rights. The 1980s also began to shed light on the topic of domestic violence. The 1990s made strides towards the legal equality of women. In today's society, Latin American feminism has been broken down into multiple subcategories by either ethnicity or topic awareness. |

ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムは、ラテンアメリカの女性のための平等な

政治的、経済的、文化的、個人的、社会的権利を定義し、確立し、達成することを目的とした運動の集まりである[1][2]。これには、教育や雇用における

女性の平等な機会の確立を目指すことも含まれる。女性の権利と平等を提唱または支持することによってフェミニズムを実践する人々がフェミニストである

[3]。 ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムは、何世紀にもわたる植民地主義、アフリカからの奴隷の輸送と服従、先住民の虐待などの文脈の中で存在している[4] [5]。現代のラテンアメリカのフェミニズムの起源は、女性解放運動を包含する1960年代と1970年代の社会運動にさかのぼることができるが、それ以 前のフェミニズムの思想は、文書による記録が残る前から広がっていた。ラテンアメリカとカリブ海地域のさまざまな地域によって、フェミニズムの定義は、文 化的、政治的、社会的な関与があったさまざまなグループによって異なる。 ラテンアメリカのフェミニズム運動の勃興には、5つの重要な要因がある。ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムの革命の始まりは、1800年代にエクアドルのマヌ エラ・サエンスとアルゼンチンのフアナ・マヌエラ・ゴリティという2人の女性から始まったと言われている。これらの運動以前は、植民地支配の後、女性には ほとんど何の権利もなかった。しかし、裕福なヨーロッパの家庭に属する女性たちは、教育の機会を多く得ていた。その後、1920年代にフェミニズムが再燃 し、女性の権利のための政治的・教育的変革に向かった。1930年代から50年代にかけて、プエルトリカンの女性グループが、現在ラテンアメリカ女性の運 動と考えられているものを創設した。これらの運動の中には、工場で裁縫師として働くなど、針産業の創設も含まれていた。そして1960年代には、女性の身 体的・経済的権利を擁護する運動へと変化した。1970年代には、自由市場資本主義と結びついた自由放任主義のために、運動は下火になった。新自由主義の 崩壊後、1980年代には政治的権利に向けたフェミニズム運動が復活した。1980年代はまた、ドメスティック・バイオレンスというトピックにも光が当た り始めた。1990年代には、女性の法的平等に向けて前進した。今日の社会では、ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムは、民族やテーマ意識によって複数のサブカ テゴリーに分類されている。 |

| Latin American and Latino feminist theory Since feminist theory often relies on Western literary works rather than personal experiences, Latin American feminist theory is a construct that has appeared only recently in order to give Latina women legitimacy in Eurocentric contexts. Latin American feminist theorists are known to not only get their sources from Western countries, but also from Latin American history, personal accounts, and research in the social sciences. There is a controversy known as “epistemic privilege” (epistemic privilege is known as the privilege a person knows or has first-hand experience on a particular subject. For example, a woman would know what issues impact them more than a man would), regarding how most Latina feminist philosophers enjoy a cultural and economic privilege that distances them from the living conditions of the majority of Latin American women. Feminist philosopher Ofelia Schutte has argued that “feminist philosophy requires a home in a broader Latin American Feminist theory and not in the discipline of philosophy in Latin America.” [6] Because Latin America is a vast area, the diversity of this feminist theory can make it difficult to characterize. However, several notable Latin feminist theorists include Ros Tobar, Ofelia Schutte, and Gloria Anzaldúa. Latina feminist philosopher Maria Lugones addressed ethnocentric racism, bilingualism, multiculturalism, and “interlinking registers of address.” Many Latina feminists borrow concepts that Lugones introduced, such as “the role of language, bodies, objects, and places.”[7] Graciela Hierro, born in 1928 in Mexico addressed “feminist ethics and the roles of feminism in public and academic spaces.[6] |

ラテンアメリカとラテンアメリカのフェミニズム理論 フェミニズム理論は、個人的な経験よりもむしろ西洋の文学作品に依拠することが多いため、ラテンアメリカのフェミニズム理論は、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な文 脈の中でラテンアメリカの女性に正当性を与えるために、つい最近登場した概念である。ラテンアメリカのフェミニスト理論家は、欧米諸国からだけでなく、ラ テンアメリカの歴史、個人の体験談、社会科学の研究からも情報源を得ることで知られている。認識論的特権」(epistemic privilege)という論争がある(認識論的特権とは、ある人が特定のテーマについて知っている、あるいは直接経験した特権として知られている)。例 えば、女性は男性よりも自分たちにどのような問題が影響を与えるかを知っている)。ラテンアメリカのフェミニスト哲学者の多くが、ラテンアメリカの女性の 大多数の生活環境から距離を置く文化的・経済的特権を享受していることに関してである。フェミニスト哲学者のオフェリア・シュッテは、「フェミニスト哲学 は、ラテンアメリカの哲学分野ではなく、より広範なラテンアメリカのフェミニスト理論に本拠地を置く必要がある」と主張している。[6] ラテンアメリカは広大な地域であるため、このフェミニズム理論の多様性が特徴づけを困難にしている。しかし、注目すべきラテン・フェミニストの理論家に は、ロス・トバル、オフェリア・シュッテ、グロリア・アンサルドゥアなどがいる。ラテン系フェミニストの哲学者マリア・ルゴネスは、エスノセントリックな 人種差別主義、バイリンガリズム、多文化主義、"interlinking registers of address "を取り上げた。多くのラティーナ・フェミニストは、「言語、身体、物、場所の役割」といったルゴネスが導入した概念を借用している[7]。1928年メ キシコ生まれのグラシエラ・ヒエロは、「フェミニズムの倫理と公的・学問的空間におけるフェミニズムの役割」に取り組んでいる[6]。 |

| Causes There is a fairly solid consensus among academics and activists that women's participation in leftist movements has been one of the central reasons for the development of Latin American feminism.[8] However, some Latin American countries were able to attain legal rights for women in rightist, conservative contexts.[9] Julie Shayne argues that there are five factors which contributed to the emergence of revolutionary feminism: experience in revolutionary movements showed challenge to the status-quo perception of gender behaviour logistical trainings a political opening unmet basic needs by revolutionary movements a collective feminist consciousness |

原因 左翼運動への女性の参加が、ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムの発展の中心的な理由のひとつであるということは、学者や活動家の間でかなり確固としたコンセン サスが得られている[8]。しかし、ラテンアメリカの中には、右翼的で保守的な文脈の中で女性の法的権利を獲得できた国もある[9]。ジュリー・シェーン は、革命的フェミニズムの出現に貢献した5つの要因があると論じている: 革命運動における経験は、ジェンダー行動に対する現状認識への挑戦を示した。 ロジスティック・トレーニング 政治的開放 革命運動が満たさない基本的ニーズ 集団的なフェミニスト意識 |

| History and the Evolution of Feminism in Latin America |

ラテンアメリカにおけるフェミニズム進化の歴史(下記に別掲) |

| Indigenous feminism in Latin America Indigenous Latin American feminists face a myriad of struggles, including little to no political representation across all of Latin America. It was not until the 2000s that indigenous feminist leaders were able to gain any political power. In 2006, Bolivia elected Evo Morales for president, who spearheaded a new Bolivian movement called the Movement for Socialism. This movement allowed Indigenous working-class women to become members of parliament as well as serve in other branches of the government. Though this important transition of power was more peaceful and much more inclusive than in any other country in Latin America, in other countries, obstacles still remain for indigenous women to have any representation or political identity. The Mayan women that live in Guatemala and parts of southern Mexico, for example, have struggled to gain any political mobility over the last few years due to immigration crises, and economic and educational disadvantages.[34] |

ラテンアメリカにおける先住民フェミニズム ラテンアメリカの先住民フェミニストたちは、ラテンアメリカ全土で政治的代表権がほとんどないなど、無数の闘争に直面している。先住民フェミニストの指導 者たちが政治的権力を獲得できるようになったのは、2000年代に入ってからである。2006年、ボリビアはエボ・モラレスを大統領に選出し、彼は社会主 義運動と呼ばれるボリビアの新しい運動の先頭に立った。この運動により、先住民の労働者階級の女性たちが国会議員になり、政府の他の部門でも活躍できるよ うになった。この重要な政権移行は、ラテンアメリカの他のどの国よりも平和的で包括的なものであったが、他の国々では、先住民の女性が何らかの代表や政治 的アイデンティティを持つための障害はまだ残っている。たとえば、グアテマラやメキシコ南部の一部に住むマヤの女性たちは、移民問題や経済的・教育的不利 のために、ここ数年、政治的な流動性を得るのに苦労してきた[34]。 |

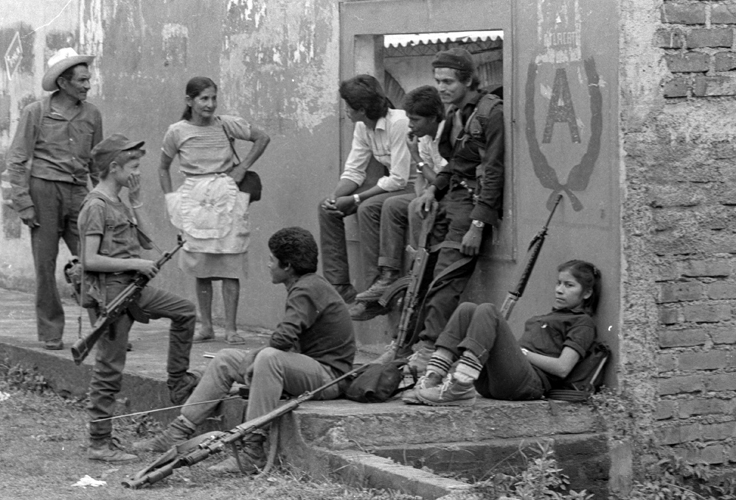

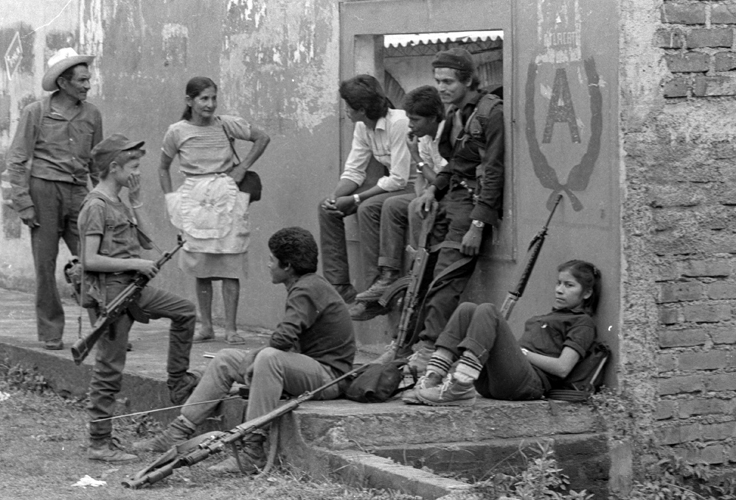

Revolutionary/feminist mobilization Men and Women both participated in revolutions that presented Revolutionary Feminism. These soldiers are fighting in the civil war in El Salvador. Some experts, such as Julie Shayne, believe that in Latin America the phenomenon of female, feminism movements should be called revolutionary feminism. Julie Shayne argues that a revolutionary feminism is one born of revolutionary mobilization.[35] As Shayne was researching this phenomenon in El Salvador during the 1980s, she came across Lety Mendez, a former member and head of the women's secretariat of the Frente Farabundo Marti para la Liberacion Nacional, one of the major political parties of El Salvador. Mendez was at the forefront of the Salvadoran Civil War, and she knew from direct experience how necessary women are to any revolution, though she also believed their role is often forgotten. Mendez explained that women were one of the sole reasons the left had support and were able to move through El Salvador.[36][37] In the late 1990s, Shayne traveled to Cuba and interviewed Maria Antonia Figuero: she and her mother had worked alongside Castro during the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. Figueroa also described an experience of women essentially carrying a revolution on their backs, but being undermined in the role they played in the revolution or not being to progress past the machismo and sexism, both of which were still rampant after their respective revolutions.[36][38] Both of these women's feminist ideologies were born out of the need for equality they saw was either not being met or being disregarded after their countries’ successful or attempted revolutions. This feminism born out of the fight against oppressive regimes has given way to a new look of feminism that can be found throughout Latin America.[36][38] Feminist mobilization or gathering can be seen in Shaye's research of Chilean women and their nation's government-organized mothers’ center. She witnessed that the gathering of these women and the sharing of their stories of oppression and domestic violence led the way to “Strategic (feminist) mobilization”. These gatherings were not only unique to Chile, but were found throughout Latin America - Bogota, Colombia (1981), Lima, Perú (1983), Bertioga, Brazil (1985), Taxco, Mexico (1987), and San Bernardo, Argentina (1990) - through the 1980s known as Encuentros. These biannual meetings brought together grassroot and professional feminists and allowed these women to discuss their experiences and the progression of their countries.[36][38] |

革命/フェミニズムの動員 男性も女性も、革命的フェミニズムを提示する革命に参加した。この兵士たちはエルサルバドルの内戦で戦っている。 ジュリー・シェインのような何人かの専門家は、ラテンアメリカでは女性、フェミニズム運動という現象は革命的フェミニズムと呼ぶべきだと考えている。ジュリー・シェーンは、革命的フェミニズムとは革命的動員から生まれたものだと主張している[35]。 1980年代にエルサルバドルでこの現象を研究していたシェインは、エルサルバドルの主要政党の一つであるFrente Farabundo Marti para la Liberacion Nacionalの元メンバーで女性事務局長のLety Mendezに出会った。メンデスはサルバドル内戦の最前線におり、革命に女性がいかに必要かを直接の経験から知っていた。メンデスは、左翼がエルサルバ ドルで支持を得、活動できた唯一の理由のひとつは女性であったと説明した[36][37]。 1990年代後半、シェインはキューバを訪れ、マリア・アントニア・フィゲロ(Maria Antonia Figuero)にインタビューした。フィゲロアはまた、女性が本質的に革命を背負っていたにもかかわらず、革命で果たした役割を貶められたり、マチズモ や性差別を乗り越えられなかったりした経験を語っている。 これらの女性たちのフェミニズムのイデオロギーはどちらも、彼女たちが見た平等の必要性が、それぞれの国の革命の成功や試みの後に満たされなかったり、軽 視されたりしたことから生まれたものであった。抑圧的な体制との戦いから生まれたこのフェミニズムは、ラテンアメリカ全土で見られるフェミニズムの新たな 姿を生み出した[36][38]。 フェミニズムの動員や集会は、シェイによるチリの女性たちと政府が組織した母親センターの研究に見ることができる。彼女は、これらの女性たちが集まり、抑 圧や家庭内暴力についての彼女たちの物語を共有することが、「戦略的(フェミニスト的)動員」への道を開くことを目撃した。こうした集会はチリだけのもの ではなく、1980年代を通じて、コロンビアのボゴタ(1981年)、ペルーのリマ(1983年)、ブラジルのベルティオガ(1985年)、メキシコのタ クスコ(1987年)、アルゼンチンのサンベルナルド(1990年)など、ラテンアメリカ各地でエンキュエントロスとして知られている。これらの年2回の 会議では、草の根のフェミニストとプロのフェミニストが一堂に会し、彼女たちが自分たちの経験と自国の進歩について話し合うことができた[36] [38]。 |

| Issues on agenda Post-suffrage feminism in Latin America covers mainly three big streams: the feminist stream, the stream in political parties and the stream of women from political parties.[39] Some issues of great concern include: voluntary maternity/responsible paternity, divorce law reform, equal pay, personal autonomy, challenging the consistently negative and sexist portrayal of women in the media, access to formal political representation. Women of the popular classes tend to focus their agendas on issues of economic survival and racial and ethnic justice. In recent years, Latin American feminists have also challenged Eurocentric feminist frameworks, promoted literature and art by women of color, and establish their own social groups. They have also sought to challenge traditional nationalists who oppress women and use their political influence to subjugate non-heterosexuals, women, and people of color.[40] |

課題 ラテンアメリカにおける参政権獲得後のフェミニズムは、主に3つの大きな流れ、すなわちフェミニストの流れ、政党の流れ、政党からの女性の流れをカバーし ている[39]。大きな関心事として、自発的な出産/責任ある父性、離婚法改革、同一賃金、個人の自律、メディアにおける一貫して否定的で性差別的な女性 描写への挑戦、正式な政治的代表へのアクセスなどが挙げられる。庶民階級の女性たちは、経済的生存と人種的・民族的正義の問題に議題を絞る傾向がある。 近年、ラテンアメリカのフェミニストたちは、ヨーロッパ中心主義的なフェミニズムの枠組みに異議を唱え、有色人種の女性による文学や芸術を推進し、独自の 社会的グループを設立している。彼らはまた、女性を抑圧し、その政治的影響力を利用して非異性愛者や女性、有色人種を服従させる伝統的なナショナリストに 挑戦しようとしている[40]。 |

| Latina suffragists Latina suffragists refer to suffrage activists of Latin American origin who advocated for women's right to vote. [icon] This section needs expansion with: examples and additional citations of latina suffragists specific to Latin American countries. You can help by adding to it. (March 2019) One of the most notable Latina suffragists is Adelina Otero-Warren from the state of New Mexico. Ortero-Warren was a prominent local organizer for the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage organized by Alice Paul. She was chosen by Paul to organize suffragists on behalf of the Congressional Union in 1917.[41] Other prominent Latina Suffragists include: Josefina Fierro de Bright was an activist in the Latin American Community. In 1972 she was a vital part of the Citizens Committee for the defense of Mexican American Youth which later was known as Sleepy Lagoon Defense committee.[42] The committee was formed after the murder at Sleepy Lagoon with the intention that the Mexican American defendants on trial would receive justice under the Constitutions and without Josefina Fierro de Bright it would not have been possible.[42] She owned and invested in several businesses that lead into a vast network of powerful prominent people including bankers and financial institutions.[42] When funding was needed to defend the Mexican American defendants during the Sleepy Lagoon trial Josefina Fierro de Bright would use her various connections to obtain the funds. Josefina Fierro de Bright was also an activist for labor rights and for was a secretary for National Congress of Spanish Speaking Peoples. The committee examined minority labor groups that endured unfair conditions and were prohibited from joining labor unions during the Great depression.[42] She was the executive secretary for El Congreso for a short period of time and was known for the protests that she held for discrimination.[43] These protests help develop awareness of the multiple types of discrimination that Latina women were experiencing within the labor force. Luisa Moreno was a social activist that fought for equality for women. She was from Guatemala and was previously known as Blanca Rosa Rodriguez Lopez,[44] however, to disguise her wealthy upbringing she changed her name when she immigrated to the United States. Luisa Moreno first began her activism in America as a trade union organizer.[44] She was able to obtain contract coverings for 13,000 cigar workers.[44] This ability aided Luisa Moreno's journey to being the first female vice presidents of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA).[43] Luisa Moreno was able to advocate for feminism in the workplace which led to maternity leave, child care and equal pay.[43] Luisa Moreno was the first person to initiate the first U.S. pan-Latino civil rights conference [45] and was pivotal in El Congreso as an accomplished union organizer where her leadership helped network a national assembly. Luisa Moreno was additionally recognized for her advocacy of education across class. She felt education was the way to emancipate women form ignorance and feminism would aid women in being mindful of their surroundings.[45] Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez, President of the College Equal Suffrage League.[46] Maria G.E. de Lopez was president of this league when women won the right to vote in California in 1911.[47] Maria G.E. de Lopez, a high school teacher, was the first person in the state of California to give speeches in support of women's suffrage in Spanish.[48][49] |

ラテン系参政権活動家 ラティーナ参政権論者(Latina suffragists)とは、女性の選挙権を主張したラテンアメリカ出身の参政権活動家を指す。 [アイコン] このセクションでは、ラテンアメリカ諸国に特有のラティーナ参政権運動家の例と追加引用の拡張が必要である。あなたはそれを追加することによって助けることができる。(2019年3月) 最も注目すべきラティーナ参政権運動家の一人は、ニューメキシコ州のアデリーナ・オテロ=ウォレンである。オテロ=ウォレンは、アリス・ポールが組織した 「女性参政権のための議会連合」の著名な地方組織者だった。彼女は1917年に議会連合を代表して参政権運動家を組織するためにポールによって選ばれた [41]。 他の著名なラティーナ女性参政権論者は以下の通りである: ホセフィナ・フィエロ・デ・ブライトはラテンアメリカ共同体の活動家であった。1972年、彼女は後にスリーピー・ラグーン弁護委員会として知られるよう になるメキシコ系アメリカ人青少年擁護市民委員会の重要な一員であった[42]。この委員会はスリーピー・ラグーンでの殺人事件の後、裁判中のメキシコ系 アメリカ人被告が憲法の下で正義を受けることを意図して結成されたが、ホセフィナ・フィエロ・デ・ブライトがいなければそれは不可能であっただろう。 [42]彼女は、銀行家や金融機関を含む有力な著名人との広大なネットワークにつながるいくつかのビジネスを所有し、投資していた[42]。スリーピー・ ラグーン裁判中にメキシコ系アメリカ人被告を弁護するために資金が必要になったとき、ホセフィナ・フィエロ・デ・ブライトは資金を得るために彼女のさまざ まなコネクションを利用した。ホセフィナ・フィエロ・デ・ブライトは労働権の活動家でもあり、スペイン語圏民族全国会議の書記を務めた。彼女は短期間エ ル・コングレソの事務局長を務め、差別に対する抗議活動を行ったことで知られる[43]。 これらの抗議活動は、ラティーナ女性が労働力の中で経験しているさまざまな差別に対する認識を深めるのに役立った。 ルイサ・モレノは、女性の平等のために闘った社会活動家である。彼女はグアテマラ出身で、以前はブランカ・ロサ・ロドリゲス・ロペスとして知られていたが [44]、裕福な生い立ちを偽るために、アメリカに移住したときに名前を変えた。ルイサ・モレノがアメリカで最初に活動を始めたのは、労働組合のオーガナ イザーとしてであった[44]。 彼女は13,000人の葉巻労働者の契約カバーを獲得することができた[44]。この能力は、ルイサ・モレノが全米缶詰農業包装関連労働者組合 (UCAPAWA)の初の女性副会長になるのを助けた。 [ルイサ・モレノは、職場におけるフェミニズムを提唱し、出産休暇、育児、同一賃金を実現した[43]。ルイサ・モレノは、米国初の汎ラティーノ公民権会 議[45]を主導した最初の人物であり、熟練した組合組織員としてエル・コングレソで極めて重要な役割を果たし、彼女のリーダーシップによって全国集会が ネットワーク化された。ルイサ・モレノはさらに、階級を超えた教育の提唱でも評価された。彼女は、教育こそが女性を無知から解放する方法であり、フェミニ ズムは女性が周囲に配慮することを助けるものだと考えていた[45]。 マリア・アンパロ・ルイス・デ・バートン マリア・グアダルーペ・エヴァンゲリーナ・デ・ロペス、大学平等選挙連盟会長[46]。 マリア・G.E.・デ・ロペスは、1911年にカリフォルニア州で女性が選挙権を獲得したとき、このリーグの会長だった[47]。高校教師であったマリ ア・G.E.・デ・ロペスは、カリフォルニア州で初めてスペイン語で女性参政権を支持する演説を行った人物であった[48][49]。 |

| Feminism in Argentina Feminism in Brazil Feminism in Chile Feminism in Haiti Feminism in Honduras Feminism in Mexico Feminism in Paraguay Feminism in Trinidad and Tobago |

アルゼンチンのフェミニズム ブラジルのフェミニズム チリのフェミニズム ハイチのフェミニズム ホンジュラスのフェミニズム メキシコのフェミニズム パラグアイのフェミニズム トリニダード・トバゴのフェミニズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminism_in_Latin_America |

|

| References 01. Hawkesworth, Mary E. (March 15, 2006). Globalization and Feminist Activism (1st ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-0-7425-3783-5. Beasley, Chris (1999). What is Feminism? An Introduction to Feminist Theory. New York: Sage Publications Ltd. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-0-7619-6335-6. OCLC 41018494. OL 8030446M. Hooks, Bell (2000). Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-1733-5. "Conquest and Colonization". The Women of Colonial Latin America. Cambridge University Press. 2000-05-18. pp. 32–51. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511840074.004. ISBN 978-0-521-47052-0. Rivera Berruz, Stephanie (2023), "Latin American Feminism", in Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2023 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2025-03-04 Gracia, Jorge; Vargas, Manuel (2013). Zalta, Edward (ed.). "Latin American Philosophy". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2016-10-11. Roelofs, Monique (2016). "Navigating Frames of Address: María Lugones on Language, Bodies, Things, and Places". Hypatia. 31 (2): 370–387. doi:10.1111/hypa.12233. ISSN 0887-5367. JSTOR 44076476. Roelofs, Monique (2016). "Navigating Frames of Address: María Lugones on Language, Bodies, Things, and Places". Hypatia. 31 (2): 370–387. doi:10.1111/hypa.12233. ISSN 0887-5367. S2CID 147187056. Shayne, Julie (2007). Feminist Activism in Latin America, in The Encyclopedia of Sociology. Blackwell Publishing. pp. Vol no. 4: 1685–1689. 10. Barrig, Maruja; Beckman, Ericka (2001). "Latin American Feminism". NACLA Report on the Americas. 34 (5): 21. doi:10.1080/10714839.2001.11724593. S2CID 157954944. Ixkic Bastian Duarte, Ángela (September 2012). "From the Margins of Latin American Feminism: Indigenous and Lesbian Feminisms". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 38 (1): 153–178. doi:10.1086/665946. ISSN 0097-9740. Newman, Louise Michele (1999). White Women's Rights: The Racial Origins of Feminism in the United States. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512466-8. Murray, Pamela S. (May 2001). "'Loca' or 'Libertadora'?: Manuela Sáenz in the Eyes of History and Historians, 1900–c.1990". Journal of Latin American Studies. 33 (2): 291–310. doi:10.1017/S0022216X01006083. ISSN 1469-767X. Langer, Erick D. (2015-06-26). "The Tupac Amaru Rebellion". Journal of Social History shv008. doi:10.1093/jsh/shv008. ISSN 0022-4529. Schmidt, Ella (July 2016). "History as Narration: Resistance and Subaltern Subjectivity in Micaela Bastidas' 'Confession'". Feminist Review. 113 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1057/fr.2016.5. ISSN 0141-7789. O'Conner, Erin (2014). Mother's Making Latin America: Genders, Households, and Politics since 1825. US: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-27144-5. Collins, Marie M.; Weil-Sayre, Sylvie (1973). "Flora Tristan: Forgotten Feminist and Socialist". Nineteenth-Century French Studies. 1 (4): 229–234. ISSN 0146-7891. JSTOR 23535978. Collins, Marie M.; Weil-Sayre, Sylvie (1973). "Flora Tristan: Forgotten Feminist and Socialist". Nineteenth-Century French Studies. 1 (4): 229–234. ISSN 0146-7891. JSTOR 23535978. Hohman, Maura (2023-05-09). "When Women Took Up Arms to Fight in Mexico's Revolution". HISTORY. Retrieved 2025-03-05. 20. Mitchell, Stephanie (July 2015). "Revolutionary Feminism, Revolutionary Politics: Suffrage under Cardenismo". The Americas. 72 (3): 439–468. doi:10.1017/tam.2015.33. ISSN 0003-1615. Charleswell, Cherise (2014). "Latina Feminism: National and Transnational Perspectives". The Hampton Institute. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2016-10-11. Cochrane, Kira (2013-05-07). "Women 1963: 50 years on". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2019-04-09. Retrieved 2016-12-11. Tobar, Ros (2003). "Feminism is Socialism, Liberty, and Much More". Journal of Women's History. 15 (3): 129–134. doi:10.1353/jowh.2003.0085. ISSN 1042-7961. S2CID 144225258. Anzaldúa, Gloria (1999). Borderlands/La frontera: La nueva mestiza. Vol. 1 (Fourth ed.). San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. Miranda, Nicolás. "Los cordones industriales, la revolución chilena y el frentepopulismo". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-05-26. Swarthout, Kelley (2009). "Masculine/Feminine: Practices of Difference(s)". RILCE. Revista de Filología Hispánica. 25 (2): 442–444. doi:10.15581/008.25.26469. S2CID 252986375. Duarte, ngela Ixkic Bastian (2012). "From the Margins of Latin American Feminism: Indigenous and Lesbian Feminisms". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 38: 153–178. doi:10.1086/665946. S2CID 225088482. Schutte, Ofelia (2011). "Engaging Latin American Feminisms Today: Methods, Theory, Practice". Hypatia. 26 (4): 783–803. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2011.01200.x. S2CID 43597159. Castillo, Debra; Dudley, Mary Jo; Mendoza, Breny (eds.). "Rethinking Feminisms in the Americas" (PDF). Latin American Studies Program Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-15. 30. "Movimiento feminista en América latina". 6 September 2005. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015. Espinosa Damián, Gisela. "Feminismo popular y feminismo indígena. Abriendo brechas desde la subalternidad". Archived from the original on 2015-05-26. Retrieved 2015-05-26. Friedman, Elisabeth. "Feminism Under Construction". NACLA Report on the Americas. 47 (4). Hernández Castillo, R. Aída (2010). "The Emergence of Indigenous Feminism in Latin America". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 35 (3): 539–545. doi:10.1086/648538. S2CID 225089179. Montenegro, Marisela; Capdevila, Rose; Sarriera, Heidi Figueroa (2012). "Editorial introduction: Towards a transnational feminism: Dialogues on feminisms and psychologies in a Latin American context". Feminism & Psychology. 22 (2): 220–227. doi:10.1177/0959353511415830. S2CID 143454107. Telling To Live: Latina Feminist Testimonios. Durham: Duke University Press. 2001. pp. 3. ISBN 978-0-8223-2765-3. Miñoso, Yuderkys Espinosa; Flores, Joan (2010). "The Feminism-Lesbianism Relationship in Latin America". The Politics of Sexuality in Latin America. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 401–405. ISBN 978-0-8229-6062-1. JSTOR j.ctt5vkfk6.37. Corrales, Javier. "LGBT Rights and Representation in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Influence of Structure, Movements, Institutions, and Culture" (PDF). The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. pp. 4–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-14. Retrieved 2017-04-20. Aguiar, José Carlos G. (2012). "Reviewed work: The Politics of Sexuality in Latin America. A Reader on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights, Javier Corrales, Mario Pecheny". Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe / European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies (93): 144–145. JSTOR 23294485. "Taking Stock: A Hundred Years After Women's Suffrage in Latin America". NACLA. Retrieved 2024-11-13. 40. "Explained: Abortion Rights in Mexico and Latin America". WCAU NBC10 Philadelphia. 2019-09-29. Retrieved 2024-11-13. "Women Strike in Latin America and Beyond". NACLA. Archived from the original on 2021-12-26. Retrieved 2023-03-06. center, Gate (2022-11-29). "The political participation of indigenous women in Latin America and the Caribbean | Press release". Gate Center. Retrieved 2025-12-04. Bastian Duarte, Ángela Ixkic (2012). "From the Margins of Latin American Feminism: Indigenous and Lesbian Feminisms". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 38: 153–178. doi:10.1086/665946. S2CID 225088482. Siede, Rachel. "Indigenous Women's Access to Justice in Latin America" (PDF). Shayne J. (2004). The Revolution Question: Feminisms in El Salvador, Chile, and Cuba. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick. Shayne, Julie D. The Revolution Question: Feminisms in El Salvador, Chile, and Cuba. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2004. Alvarez, Sonia (Winter 1992). "Feminisms in Latin America: From Bogota to San Bernardo". Signs. 12 (2): 393–434. JSTOR 3174469. Sternbach, Nancy Saporta; Navarro-Aranguren, Marysa; Chuchryk, Patricia; Alvarez, Sonia E. (1992). "Feminisms in Latin America: From Bogotá to San Bernardo". Signs. 17 (2): 393–434. doi:10.1086/494735. JSTOR 3174469. S2CID 143308679. Soldaderas in the Mexican Military: Myth and History. University of Texas Press. 1990. doi:10.7560/776302. ISBN 978-0-292-75708-0. 50. Chant, Sylvia (February 1992). "Shirlene Soto, Emergence of the Modern Mexican Woman: Her Participation in Revolution and Struggle for Equality 1910–1940 (Denver, Colorado: Arden Press, 1990), pp. xvi+199, $16.95 pb". Journal of Latin American Studies. 24 (1): 210–211. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00023130. ISSN 0022-216X. Hutchison, Elizabeth Quay (2020-01-01). "Women, Gender, and Sexuality in the Cuban Revolution". Radical History Review. 2020 (136): 185–197. doi:10.1215/01636545-7857356. ISSN 0163-6545. Murray, Nicola (1979). "Socialism and Feminism: Women and the Cuban Revolution, Part I". Feminist Review (2): 57–73. doi:10.2307/1395000. ISSN 0141-7789. JSTOR 1395000. Vargas, V (1992). The Feminist Movement in Latin America: Between Hope and Disenchantment. Development and Change. pp. 195–204. Telling to Live: Latina Feminist Testimonios. Durham: Duke University Press. 2001. pp. 4. ISBN 978-0-8223-2765-3. "Taking Stock: A Hundred Years After Women's Suffrage in Latin America". NACLA. Retrieved 2024-11-12. "Womens Suffrage Movement-1915". New Mexico Office of the State Historian. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018. Larralde, Carlos. 2010. "Josefina Fierro and the Sleepy Lagoon Crusade, 1942-1945." Southern California Quarterly 92 (2): 117–60. doi:10.2307/41172517. "Latina Feminism." The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2023, latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/2301798. Vicki L. Ruiz, "Of Poetics and Politics: The Border Journeys of Luisa Moreno," in Sharon Harley, ed., Women's Labor in the Global Economy: Speaking in Multiple Voices (New Brunswick, NJ, 2007), 28–45, here 29–34. 60. RUIZ, VICKI L. 2016. "AHA Presidential Address Class Acts: Latina Feminist Traditions, 1900-1930." American Historical Review 121 (1): 1. Ingen, L.V. (February 2004). "The Limits of State Suffrage for California Women Candidates in the Progressive Era". Pacific Historical Review. 73 (1): 21–48. doi:10.1525/phr.2004.73.1.21. JSTOR 10.1525/phr.2004.73.1.21. Leonard, John William (1914). "Who's Who of America". 64. "Woman's who's who of America, 1914-15". Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018. "LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Women's Rights in Los Angeles" (PDF). Survey LA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018. |

参考文献 01. Hawkesworth, Mary E. (2006年3月15日). 『グローバリゼーションとフェミニスト活動』(初版). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-0-7425-3783-5. ビーズリー、クリス(1999)。『フェミニズムとは何か? フェミニスト理論入門』。ニューヨーク:セージ出版。pp. 3–11。ISBN 978-0-7619-6335-6。OCLC 41018494。OL 8030446M. フックス、ベル (2000). 『フェミニズムは万人のためのもの:情熱的政治学』. プルート・プレス. ISBN 978-0-7453-1733-5. 「征服と植民地化」. 『植民地時代のラテンアメリカ女性』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. 2000年5月18日. pp. 32–51. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511840074.004. ISBN 978-0-521-47052-0. リベラ・ベルルス、ステファニー(2023)、「ラテンアメリカ・フェミニズム」、ザルタ、エドワード・N.;ノデルマン、ウリ(編)、『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』(2023年夏版)、形而上学研究所、スタンフォード大学、2025年3月4日取得 グラシア、ホルヘ;バルガス、マヌエル(2013)。ザルタ、エドワード(編)。「ラテンアメリカ哲学」。『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』。2020年1月26日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2016年10月11日に閲覧。 ローロフス、モニーク(2016)。「言及の枠組みを航行する:言語、身体、事物、場所に関するマリア・ルゴネス」『ヒュパティア』31巻2号: 370–387頁。doi:10.1111/hypa.12233。ISSN 0887-5367。JSTOR 44076476。 ロエロフス、モニーク (2016). 「言及の枠組みを航行する:言語、身体、事物、場所に関するマリア・ルゴネス」. 『ヒュパティア』. 31 (2): 370–387. doi:10.1111/hypa.12233. ISSN 0887-5367. S2CID 147187056. シェイン、ジュリー(2007)。『ラテンアメリカにおけるフェミニスト活動』、『社会学百科事典』所収。ブラックウェル出版。第4巻: 1685–1689頁。 10. バリグ、マルハ; ベックマン、エリカ(2001)。「ラテンアメリカ・フェミニズム」。『NACLA Report on the Americas』34 (5): 21. doi:10.1080/10714839.2001.11724593. S2CID 157954944. イクシック・バスティアン・ドゥアルテ、アンヘラ(2012年9月)。「ラテンアメリカ・フェミニズムの周辺から:先住民族とレズビアンのフェミニズ ム」。『サインズ:文化と社会における女性ジャーナル』38巻(1): 153–178頁。doi:10.1086/665946。ISSN 0097-9740。 ニューマン、ルイーズ・ミシェル(1999)。『白人女性の権利:アメリカ合衆国におけるフェミニズムの人種的起源』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-512466-8。 マレー、パメラ・S.(2001年5月)。「『狂女』か『解放者』か?:歴史と歴史家たちの眼差しに映るマヌエラ・サエンス、1900年~1990年 頃」。ラテンアメリカ研究ジャーナル. 33 (2): 291–310. doi:10.1017/S0022216X01006083. ISSN 1469-767X. ランガー、エリック D. (2015-06-26). 「トゥパク・アマルの反乱」. 社会史ジャーナル shv008. doi:10.1093/jsh/shv008. ISSN 0022-4529. シュミット、エラ(2016年7月)。「物語としての歴史:ミカエラ・バスティダスの『告白』における抵抗と下層主体の主観性」。フェミニスト・レビュー。113 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1057/fr.2016.5. ISSN 0141-7789。 オコナー、エリン(2014)。『母親が作り上げたラテンアメリカ:1825 年以降のジェンダー、家庭、政治』。米国:ワイリー・ブラックウェル。ISBN 978-1-118-27144-5。 コリンズ、マリー M.、ウェイル・セイヤー、シルヴィ(1973)。「フローラ・トリスタン:忘れられたフェミニスト、社会主義者」。『19 世紀フランス研究』 1 (4): 229–234. ISSN 0146-7891. JSTOR 23535978. コリンズ、マリー M.、ウェイル・セイヤー、シルヴィ (1973)。「フローラ・トリスタン:忘れられたフェミニスト、社会主義者」。19 世紀フランス研究。1 (4): 229–234. ISSN 0146-7891. JSTOR 23535978. ホーマン、モーラ (2023-05-09) 「メキシコ革命で女性が武器を取り戦ったとき」 『HISTORY』 2025年3月5日取得。 20. ミッチェル、ステファニー(2015年7月)。「革命的なフェミニズム、革命的な政治:カルデニズム下の参政権」 『The Americas』 72 (3): 439–468. doi:10.1017/tam.2015.33. ISSN 0003-1615. チャールズウェル、シェリーズ(2014)。「ラティーナ・フェミニズム:国家的および超国家的視点」。ハンプトン研究所。2020年1月26日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2016年10月11日に取得。 コクラン、キラ(2013年5月7日)。「女性たち1963:50年後の今」。ガーディアン。2019年4月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2016年12月11日に取得。 トバー、ロス(2003)。「フェミニズムは社会主義であり、自由であり、それ以上のものだ」。女性史ジャーナル. 15 (3): 129–134. doi:10.1353/jowh.2003.0085. ISSN 1042-7961. S2CID 144225258. アンサルドゥア、グロリア (1999). ボーダーランズ/ラ・フロンテラ:ラ・ヌエバ・メスティサ. 第1巻(第4版)。サンフランシスコ:オント・ルート・ブックス。 ミランダ、ニコラス。「産業地帯、チリ革命、そして人民戦線」。2015年9月24日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2015年5月26日に取得。 スワースアウト、ケリー(2009)。「男性的/女性的:差異の実践」。RILCE. Revista de Filología Hispánica. 25 (2): 442–444. doi:10.15581/008.25.26469. S2CID 252986375. ドゥアルテ、アンヘラ・イクシック・バスティアン (2012). 「ラテンアメリカ・フェミニズムの周辺から:先住民族とレズビアンのフェミニズム」. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 38: 153–178. doi:10.1086/665946. S2CID 225088482. シュッテ、オフェリア (2011). 「今日のラテンアメリカ・フェミニズムとの関わり:方法、理論、実践」『ヒュパティア』26巻4号:783–803頁。doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2011.01200.x。S2CID 43597159。 カスティージョ、デブラ;ダドリー、メアリー・ジョー;メンドーサ、ブレニー(編)。「アメリカ大陸におけるフェミニズムの再考」 (PDF)。コーネル大学ラテンアメリカ研究プログラム、ニューヨーク州イサカ。2012年6月15日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。 30. 「ラテンアメリカにおけるフェミニスト運動」。2005年9月6日。2015年5月26日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2015年5月26日に取得。 エスピノサ・ダミアン、ギセラ。「大衆フェミニズムと先住民族フェミニズム。従属性からの突破口を開く」。2015年5月26日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2015年5月26日に取得。 フリードマン、エリザベス。「構築中のフェミニズム」。『NACLA Report on the Americas』47巻4号。 エルナンデス・カスティーヨ、R. アイーダ(2010)。「ラテンアメリカにおける先住民族フェミニズムの台頭」。『Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society』35巻3号:539–545頁。doi:10.1086/648538。S2CID 225089179. モンテネグロ、マリセラ;カプデビラ、ローズ;サリエラ、ハイディ・フィゲロア(2012)。「編集者序文:越境的フェミニズムへ向けて:ラテンアメリカ 文脈におけるフェミニズムと心理学の対話」。フェミニズム&心理学。22巻2号:220–227頁。doi: 10.1177/0959353511415830. S2CID 143454107. 語ることで生きる:ラティーナ・フェミニストの証言。ダーラム:デューク大学出版局。2001年。3頁。ISBN 978-0-8223-2765-3。 ミニョソ、ユデルキス・エスピノサ; フローレス、ジョアン (2010). 「ラテンアメリカにおけるフェミニズムとレズビアニズムの関係」. 『ラテンアメリカにおけるセクシュアリティの政治学』. ピッツバーグ大学出版局. pp. 401–405. ISBN 978-0-8229-6062-1. JSTOR j.ctt5vkfk6.37. コラレス、ハビエル。「ラテンアメリカとカリブ海地域におけるLGBTの権利と表現:構造、運動、制度、文化の影響」 (PDF)。ノースカロライナ大学チャペルヒル校。pp. 4–12。2017年1月14日にオリジナルからアーカイブ (PDF)。2017年4月20日に取得。 アギアール、ホセ・カルロス・G. (2012). 「書評対象:ラテンアメリカにおけるセクシュアリティの政治学。レズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュアル、トランスジェンダーの権利に関する読本、ハビエル・ コラレス、マリオ・ペチェニー著」。『ヨーロッパ・ラテンアメリカ・カリブ研究レビュー』 (93): 144–145. JSTOR 23294485. 「現状分析:ラテンアメリカにおける女性参政権獲得から100年」。NACLA。2024年11月13日閲覧。 40. 「解説:メキシコとラテンアメリカにおける中絶の権利」。WCAU NBC10 フィラデルフィア。2019年9月29日。2024年11月13日閲覧。 「ラテンアメリカおよびその他の地域における女性のストライキ」. NACLA. 2021年12月26日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2023年3月6日取得. center, Gate (2022年11月29日). 「ラテンアメリカおよびカリブ海地域における先住民族女性の政治参加 | プレスリリース」. Gate Center. 2025年12月4日取得. バスティアン・ドゥアルテ、アンヘラ・イクシック(2012)。「ラテンアメリカフェミニズムの周辺から:先住民族とレズビアンのフェミニズム」。『サイ ンズ:文化と社会における女性ジャーナル』。38: 153–178。doi:10.1086/665946。S2CID 225088482。 シーデ、レイチェル。「ラテンアメリカにおける先住民族女性の司法へのアクセス」 (PDF)。 シェイン J. (2004). 『革命の問い:エルサルバドル、チリ、キューバにおけるフェミニズム』. ラトガース大学出版局、ニューブランズウィック。 シェイン、ジュリー D. 『革命の問い:エルサルバドル、チリ、キューバにおけるフェミニズム』. ニュージャージー州ニューブランズウィック、ロンドン:ラトガース大学出版、2004年。 アルバレス、ソニア(1992年冬)。「ラテンアメリカのフェミニズム:ボゴタからサン・ベルナルドまで」。サインズ。12 (2): 393–434. JSTOR 3174469. スターンバック、ナンシー・サポルタ、ナヴァロ・アランギュレン、マリサ、チュクリク、パトリシア、アルバレス、ソニア E. (1992). 「ラテンアメリカのフェミニズム:ボゴタからサン・ベルナルドまで」. Signs. 17 (2): 393–434. doi:10.1086/494735. JSTOR 3174469。S2CID 143308679。 メキシコ軍における女性兵士:神話と歴史。テキサス大学出版。1990年。doi:10.7560/776302。ISBN 978-0-292-75708-0。 50. Chant, Sylvia (1992年2月). 「Shirlene Soto, 『現代メキシコ女性の出現:革命への参加と平等のための闘争 1910–1940』(コロラド州デンバー:Arden Press, 1990年)、xvi+199ページ、16.95ドル(ペーパーバック)」. Journal of Latin American Studies. 24 (1): 210–211. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00023130. ISSN 0022-216X. ハッチソン、エリザベス・キー(2020-01-01)。「キューバ革命における女性、ジェンダー、セクシュアリティ」。『ラディカル・ヒストリー・レ ビュー』。2020 (136): 185–197. doi:10.1215/01636545-7857356. ISSN 0163-6545. マレー、ニコラ (1979). 「社会主義とフェミニズム:女性とキューバ革命、第一部」. フェミニスト・レビュー (2): 57–73頁。doi:10.2307/1395000。ISSN 0141-7789。JSTOR 1395000。 バルガス、V(1992)。『ラテンアメリカにおけるフェミニスト運動:希望と幻滅の間』。開発と変化。195–204頁。 生きるために語る:ラティーナ・フェミニストの証言。ダーラム:デューク大学出版局。2001年。pp. 4。ISBN 978-0-8223-2765-3。 「現状分析:ラテンアメリカにおける女性参政権獲得から100年」。NACLA。2024年11月12日閲覧。 「女性参政権運動-1915年」. ニューメキシコ州歴史家事務所. 2018年12月9日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2018年12月8日閲覧. ララルデ, カルロス. 2010. 「ホセフィーナ・フィエロとスリーピー・ラグーン運動, 1942-1945年」. 南カリフォルニア季刊 92 (2): 117–60. doi:10.2307/41172517. 「ラティーナ・フェミニズム」『アメリカのモザイク:ラティーノ・アメリカン体験』ABC-CLIO, 2023, latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/2301798. ヴィッキー・L・ルイス、「詩学と政治について:ルイーザ・モレノの国境を越えた旅路」、シャロン・ハーレー編『グローバル経済における女性の労働:複数の声で語る』(ニュージャージー州ニューブランズウィック、2007年)、28–45頁、ここでは29–34頁。 60. ルイス、ヴィッキー・L. 2016. 「AHA会長講演:1900-1930年のラティーナ・フェミニスト伝統」『アメリカ歴史評論』121巻1号:1頁。 インゲン、L.V.(2004年2月)。「進歩主義時代におけるカリフォルニア女性候補者の州選挙権の限界」『太平洋歴史評論』73巻1号:21-48 頁。doi:10.1525/phr.2004.73.1.21. JSTOR 10.1525/phr.2004.73.1.21. レナード、ジョン・ウィリアム (1914). 「Who's Who of America」. 64. 「アメリカ女性人物事典、1914-15年版」。2018年12月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2018年12月8日に取得。 「ロサンゼルス市全域歴史的文脈声明 文脈:ロサンゼルスにおける女性の権利」 (PDF). Survey LA. 2018年12月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた (PDF). 2018年12月8日に取得。 |

☆ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムの歴史(History and the Evolution of Feminism in Latin America)

| 1800s Although the term feminist would not be used to describe women's rights advocates until the 1890s, many women of the nineteenth century, mostly elite or middle class, tried to challenge dominant gender norms.[12] Manuela Sáenz was a woman born in 1797 in Quito, New Granada (Modern-Day Ecuador), who lived to be a heroine figure to many due to her involvement with Simón Bolívar as not only a supporting voice to his idea of independence but also the woman who saved him from an assassination attempt, guiding him to safety through a bedroom window.[13] Her significance did not come immediately, rather it took feminist voices in the modern day to bring her to the spotlight to claim that she was a feminist symbol of her time.[13] In addition to Sáenz, there were several other women who actively participated on the frontline of war efforts in support of Latin American independence and women's empowerment. Micaela Bastidas, the wife of Tupac Amaru, a Peruvian indigenous revolutionary who fought against the Spanish Empire. Micaela Bastidas directly assisted in the logistics of the attempted revolution but later was captured and tortured to death by the Spanish Empire. She remained strong-willed until the time of her death and did not release sensitive and crucial information about the attempted revolution during her imprisonment.[14][15] Juana Manuela Gorriti, an Argentinian journalist and writer born in 1818, advocated greater rights for women and wrote literary works with women protagonists that were both "romantic and political".[citation needed] Similar to Sáenz, Gorriti held tertulias for literary men and women, one of whom was Clorinda Matto de Turner, a novelist sympathetic towards Indians and critical of the priesthood in Peru. Gorriti also worked with Teresa González, an avid writer who ran a girls' school and advocated education for women.[16] Flora Tristan, born in 1803 to a Frenchwoman and Peruvian aristocrat, significantly impacted early feminism and socialism from Latin America into Europe. Tristan was an early feminist and socialist who wanted to bring awareness to the fact that working women and men were a class like any other, deserving of working rights and recognition. In Workers' Union, a book published in 1843, she attempts to bring this notion to the French workers and advocates for the creation of a workers' union, believing that the working class needed to recognize itself as a unified social class. She also strongly argued for women's right to work and earn a fair wage, seeing economic independence as the key to women's ability to choose relationships based on love rather than being sold into marriage by their families. Although she did not live to see its success, her friend Elisa Lemonnier later carried forward this vision, establishing the first professional school for women in 1862.[17] While on a mission to reclaim her inheritance in 1833, Tristan also found time to write two books published in 1835 (Peregrinations of a Pariah and Of the Necessity of Welcoming Foreign Women), which documented her experiences as a woman traveling the world and highlighted the social situation of women in large cities. These books became successful, especially Peregrinations of a Pariah, which helped expose the exploitation of working women, including nuns and prostitutes, while also shedding light on the broader struggles of Black and Indigenous women in Peru. Towards the later years of her life, she dedicated herself fully to traveling to factories and holding meetings aimed at uniting workers—both men and women—to organize and emerge as a class. She eventually fell ill, likely due to continuous travel, and died in late 1844.[18] |

1800年代 フェミニストという用語が女性の権利擁護者を指すようになるのは1890年代まで待たねばならなかったが、19世紀の多くの女性、主に上流階級や中産階級の女性たちは、支配的な性役割規範に挑戦しようとした。[12] マヌエラ・サエンスは1797年、ヌエバ・グラナダ(現在のエクアドル)のキトで生まれた女性である。彼女はシモン・ボリバルの独立思想を支える声として だけでなく、暗殺未遂から彼を救い、寝室の窓から安全な場所へ導いた女性として、多くの人々にとって英雄的存在となった。[13] 彼女の重要性は即座に認められたわけではなく、現代のフェミニストたちの声によって初めて脚光を浴び、当時のフェミニストの象徴として位置づけられたので ある。[13] サエンス以外にも、ラテンアメリカの独立と女性のエンパワーメントを支援するため、戦争の最前線で積極的に活動した女性たちが数人いた。ミカエラ・バス ティダスは、スペイン帝国に抵抗したペルー先住民革命家トゥパク・アマルの妻である。彼女は革命計画の兵站支援に直接関与したが、後にスペイン帝国に捕ら えられ拷問の末に死亡した。死の瞬間まで意志を貫き、投獄中も革命計画に関する機密情報を一切漏らさなかった。[14] [15] フアナ・マヌエラ・ゴリティは、1818年に生まれたアルゼンチンのジャーナリストであり作家である。彼女は女性の権利拡大を提唱し、「ロマンチックかつ 政治的」な女性主人公を登場させる文学作品を執筆した。[要出典] サエンスと同様に、ゴリティも文学者たちのためのテルトゥリアを開催した。その参加者の中には、ペルーの先住民に同情し、聖職者を批判した小説家、クロリ ンダ・マット・デ・ターナーもいた。ゴリティはまた、女子学校を経営し、女性の教育を提唱した熱心な作家、テレサ・ゴンサレスとも協力した。 フローラ・トリスタンは、1803年にフランス人女性とペルーの貴族の間に生まれ、ラテンアメリカからヨーロッパにかけての初期のフェミニズムと社会主義 に大きな影響を与えた。トリスタンは、働く女性も男性も他の階級と同様、労働権と認識に値する存在であるという事実を人々に認識させたいと願った、初期の フェミニストであり社会主義者であった。1843年に出版された著書『労働者組合』の中で、彼女はフランス人労働者にこの考え方を伝え、労働者階級は自ら を統一された社会階級として認識すべきだと信じ、労働者組合の創設を提唱している。彼女はまた、女性が働き公正な賃金を得る権利を強く主張した。経済的自 立こそが、家族に売られるように結婚させられるのではなく、愛に基づく関係を女性が選択できる鍵だと考えたのだ。彼女はその成功を見届けることはなかった が、友人エリザ・ルモニエが後にこの構想を継承し、1862年に初の女性向け職業学校を設立した。[17] 1833年に相続財産を取り戻す旅の途中、トリスタンは1835年に出版された二冊の著作(『放浪のパラヤ』と『外国女性を受け入れる必要性について』) を執筆する時間も見つけた。これらは世界を旅する女性としての彼女の経験を記録し、大都市における女性の社会的状況を浮き彫りにした。これらの著作は成功 を収め、特に『追放者の放浪記』は修道女や売春婦を含む労働女性の搾取を暴くと同時に、ペルーにおける黒人女性や先住民族女性の広範な苦闘を浮き彫りにし た。晩年になると、彼女は工場を巡り、男女の労働者を結束させて階級として組織化・台頭させるための集会開催に全力を注いだ。おそらく絶え間ない移動が原 因で病に倒れ、1844年後半に死去した。 |

| 1900s–1920s In the late half of the 19th century, there were three main areas of feminists' discussions: suffrage, protective labour laws, and access to education. In 1910, Argentina held the first meeting of the International Feminist Congresses (topic of equality). The second meeting was in 1916 in Mexico. The 1910s saw many women, such as Aleida March, gain prominence during the revolutions of Mexico, Cuba, and Nicaragua. Additionally, Amelio Robles, born in 1889, was a notable man in a peasant army and the Confederation of Veterans of the Revolution who, by modern United States standards, would be considered a trans man.[19] A prominent international figure born during this time was Gabriela Mistral, who in 1945 won the Nobel Prize in literature and became a voice for women in Latin America. She upheld conservative gender norms, even at one point saying, "perfect patriotism in women is perfect motherhood", and that as a teacher she was "married" to the state. However, feminist theorists contend that her personal experiences contradict her language, because she never married, she had a "mannish" appearance, and her close personal relationships with women suggest that she might have been a closet lesbian.[16] |

1900年代~1920年代 19世紀後半、フェミニストたちの議論は主に三つの分野に分かれていた。選挙権、労働保護法、そして教育へのアクセスである。1910年、アルゼンチンで国際女性会議(平等を主題とする)の初会合が開催された。第二回会合は1916年にメキシコで行われた。 1910年代には、メキシコ、キューバ、ニカラグアの革命の中で、アレイダ・マルチのような多くの女性が注目を集めた。さらに、1889年生まれのアメリ オ・ロブレスは、農民軍と革命退役軍人連盟において著名な人物であり、現代のアメリカ基準ではトランス男性と見なされるだろう。[19] この時期に生まれた国際的な著名人としてガブリエラ・ミストラルが挙げられる。彼女は1945年にノーベル文学賞を受賞し、ラテンアメリカ女性の代弁者と なった。保守的な性別規範を支持し、「女性の完璧な愛国心とは完璧な母性である」と述べたこともある。また教師として国家と「結婚している」とも語った。 しかしフェミニスト理論家たちは、彼女の個人的経験が言説と矛盾すると主張する。未婚であったこと、男っぽい外見、女性との親密な関係から、彼女は隠れた レズビアンだった可能性を示唆しているのだ。[16] |

| 1930s–1950s The Partido Nacional Revolucionario (PNR), the dominant political party in Mexico, declared on February 25, 1937, that it would permit "organized" women, who belonged to government-supporting organizations, labor unions, or agrarian leagues, to cast ballots in internal party elections. Under President Lázaro Cárdenas, this action represented a compromise. Although Cárdenas and other PNR leaders were in favor of women's suffrage in theory, they were concerned that granting women full voting rights would lead to conservative voting trends that could cause the party to lose. The suffragists were not happy with the little progress, but this partial action allowed the PNR to seem in favor of suffrage without risking electoral consequences.[20] The 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s were full of Latina feminists who pioneered the current Latin American Feminist movement. It was the beginning of the suffragist movement for many Latin American women. The first elected woman mayor of any major capital city in the Americas, Felisa Rincon de Gautier, was "an active participant in Puerto Rico's women's suffrage movement" that was won in 1932, and her child care programs "inspired the United States' Head Start program."[21] In revolutionary Mexico, politics involved complex power struggles at multiple levels. Marìa del Refugio "Cuca" Garcìa had to negotiate state and local power institutions that operated somewhat independently of Mexico City as part of her challenge to national political authority. Historian Alan Knight pointed out that despite the revolutionary government's promotion of "effective suffrage," elections frequently lacked democratic integrity, showing the absence of an identifiable feeling of civic duty in politics during the 1930s. Although the results of elections were rarely determined only by the popular vote, Ben Fallaw and other academics show that elections might still be important.[20] Most women advocating for equal rights had to cling to femininity to gain respect, but feminist theorist Julia de Burgos used her writings to "openly contest the prevailing notion that womanhood and motherhood are synonymous." Additionally, Dr. Leila Gonzalez was involved in the "Brazilian Black movement" and helped develop "the practice of Black Feminism in Brazil."[21] |

1930年代~1950年代 メキシコで支配的な政党であった国民革命党(PNR)は、1937年2月25日、政府支持団体、労働組合、または農民同盟に所属する「組織化された」女性 に党内選挙での投票を許可すると宣言した。ラサロ・カルデナス大統領の下、この措置は妥協案であった。カルデナスや他のPNR指導者は理論上は女性参政権 を支持していたが、女性に完全な投票権を与えると保守的な投票傾向が生まれ、党が敗北する恐れがあると懸念していた。参政権運動家たちはこのわずかな進展 に満足しなかったが、この部分的な措置によりPNRは選挙上のリスクを負わずに参政権支持を装うことができた。[20] 1930年代、1940年代、1950年代は、現在のラテンアメリカ女性運動の礎を築いたラティーナ女性活動家たちが活躍した時代であった。多くのラテン アメリカ女性にとって、これが参政権運動の始まりとなった。アメリカ大陸の主要首都で初の女性市長に選出されたフェリサ・リンコン・デ・ゴティエは、 1932年に勝利した「プエルトリコ女性参政権運動の積極的な参加者」であり、彼女の保育プログラムは「米国のヘッドスタート計画に影響を与えた」 [21]。革命期のメキシコでは、政治は複数のレベルで複雑な権力闘争を伴っていた。マリア・デル・レフヒオ・「クカ」・ガルシアは、国家の政治権威への 挑戦の一環として、メキシコシティからある程度独立して機能する州や地方の権力機構と交渉せざるを得なかった。歴史家アラン・ナイトは、革命政府が「実効 的な選挙権」を推進したにもかかわらず、選挙には民主的な正当性が欠如することが多く、1930年代の政治において明確な市民的義務感が存在しなかったこ とを指摘している。選挙結果は国民投票のみで決まることは稀だったが、ベン・ファロウら研究者は、それでも選挙が重要であった可能性を示している。 [20] 平等な権利を求める女性の多くは、尊敬を得るために女性らしさに固執せざるを得なかった。しかしフェミニスト理論家のジュリア・デ・ブルゴスは著作を通じ て「女性性と母性が同義であるという通念に公然と異議を唱えた」。さらにレイラ・ゴンサレス博士は「ブラジルの黒人運動」に関わり、「ブラジルにおける黒 人フェミニズムの実践」の発展に貢献した。[21] |

| 1960s–1970s At the end of the 1960s, many Latin American women started forming groups of reflection and activism for defending women's rights. Initially, those women were from the middle class and a significant part came from the various left groups.[22] Unlike their predecessors, however, Latin American feminists of the 1960s focused on social justice rather than suffrage. They emphasized "reproductive rights, equal pay in the job market, and equality of legal rights."[23] This type of Latin American feminism was a result of the activism of Latina women against their position of subordinance, not a reaction to women gaining more legal rights in the United States and Europe. As Gloria Anzaldúa said, we must put history "through a sieve, winnow out the lies, look at the forces that we as a race, as women, have been part of."[24] Such female groups arose amid the sharp radicalization of class struggles on the continent, which resulted in labor and mass rising. The most evident manifestations of these were the Chilean industrial belts Cordón Industrial,[25] the Cordobazo in Argentina (a 1969 civil uprising), student mobilizations in Mexico and others. These facts could be regarded as the sharpest experience and numerous movements of urban and rural guerrilla came to the scene. For those reasons, Latin American feminist theorist Ros Tobar says that Chilean feminism is closely tied to socialism. Authoritarian regimes reinforced "the traditional family, and the dependent role of women, which is reduced to that of mother." Because dictatorships institutionalized social inequality, many Latin American feminists tie authoritarian governments with fewer rights for women. Slogans, such as "Women give life, the dictatorships exterminate it," "In the Day of the National Protest: Let's make love not the beds," and "Feminism is Liberty, Socialism, and Much More," portrayed the demands of many Latin American feminists.[23] Latin American feminist theorist Nelly Richard of Chile explored how feminism and gay culture broke down rigid structures of life in Chile and were essential to the liberation of women in her novel Masculine/Feminine: Practices of Difference.[26] Feminist meetings continued to occur, initially every two years; later, every three years. Topics discussed included recent accomplishments, strategies, possible future conflicts, ways to enhance their strategies and how to establish, through such ways varied, rich and immense coordination between the national and transnational levels. However, the mid-70s saw the decline of such movements due to the policy of neoliberalism in the region. When dictatorial regimes settled over the majority of the continent, these prevented the development of feminist movements. This was due not only to the establishment of a reactionary ideology based on the defense of tradition and family, but also to the political persecution and state terrorism with its consequences such as torture, forced exile, imprisonment, disappearances and murders of political, social and trade union activists. While the right wing of politicians considered feminists to be subversive and rebellious, the left, in contrast, named them the "small bourgeois". It was also during this time that leftist feminist organizations gained attention for their efforts. This is most prominently seen in the "Women of Young Lords" of Puerto Rico. The Young Lords were, at first, Boricuan, Afro-Taino men who fought for basic human rights and "openly challenged machismo, sexism, and patriarchy." Bianca Canales, Luisa Capetillo, Connie Cruz, and Denise Oliver became leaders in the Young Lords, and facilitated a "Ten-Point Health Program."[21] Most feminisms in Latin America arose out of the context of military dictatorships and masculine domination. However, a lot of marginalized women began questioning hegemonic feminism in the 1970s. These women, whether they were Afro-descendant, lesbians, Indigenous, transgender, sex workers, domestic workers, etc., began to look at different, interlocking types of oppression.[27] Gloria Anzaldúa, of Indigenous descent, described her experience with intersectionality as a "racial, ideological, cultural, and biological crosspollination", and called it a "new mestiza consciousness."[24] Various critiques of "internal colonialism of Latin American states toward their own indigenous populations" and "Eurocentrism in the social sciences" emerged, giving rise to Latin American Feminist Theory.[28] |

1960年代から1970年代にかけて 1960年代の終わり頃、多くのラテンアメリカの女性たちが、女性の権利を守るための考察と活動を行うグループを作り始めた。当初、彼女たちは中産階級出 身で、かなりの部分が様々な左翼グループに属していた[22]。しかし、1960年代のラテンアメリカフェミニストたちは、先人たちとは異なり、参政権よ りも社会正義に焦点を当てた。彼女たちは「生殖に関する権利、労働市場における同一賃金、法的権利の平等」を強調した。[23] この種のラテンアメリカフェミニズムは、米国や欧州で女性が法的権利を獲得したことへの反応ではなく、従属的立場に対するラティーナ女性たちの活動の結果 であった。グロリア・アンサルドゥアが述べたように、我々は歴史を「ふるいにかけ、嘘をふるい落とし、人種として、女性として、我々が属してきた力を見な ければならない」のだ。[24] こうした女性団体は、大陸における階級闘争の急激な激化の中で生まれた。それは労働運動と大衆蜂起をもたらした。最も顕著な例はチリの工業地帯「コルド ン・インダストリアル」[25]、アルゼンチンの「コルドバゾ」(1969年の市民蜂起)、メキシコでの学生動員などである。これらの事実は最も鋭い経験 と見なされ、数多くの都市・農村ゲリラ運動が舞台に登場した。 こうした理由から、ラテンアメリカ女性主義理論家ロス・トバルはチリ女性主義が社会主義と密接に結びついていると述べる。権威主義体制は「伝統的家族と、 母という役割に還元される女性の従属的立場」を強化した。独裁政権が社会的不平等を制度化したため、多くのラテンアメリカ女性主義者は権威主義政府と女性 の権利後退を結びつける。「女は命を与える、独裁は命を絶つ」 「全国抗議の日:ベッドではなく愛を作ろう」「フェミニズムは自由であり、社会主義であり、それ以上のものだ」といったスローガンは、多くのラテンアメリ カ女性主義者の要求を表していた[23]。チリの女性主義理論家ネリー・リチャードは、小説『男性的/女性的:差異の実践』において、フェミニズムとゲイ 文化がチリの硬直した生活構造をいかに打破し、女性の解放に不可欠であったかを探求した。[26] フェミニスト会議は当初2年ごと、後に3年ごとに開催され続けた。議論された主題には、最近の成果、戦略、将来起こりうる対立、戦略強化の方法、そして多様な手法を通じて国内レベルと国際レベルの間で豊かで広範な連携を確立する方法が含まれた。 しかし、1970年代半ばには、この地域における新自由主義政策の影響で、こうした運動は衰退した。大陸の大半を支配した独裁政権は、フェミニスト運動の 発展を阻んだ。これは伝統と家族防衛に基づく反動的イデオロギーの確立だけでなく、政治的迫害や国家テロリズム——拷問、強制亡命、投獄、失踪、政治・社 会・労働組合活動家の殺害といった結果を伴う——によるものでもあった。 右派政治家はフェミニストを破壊的で反抗的と見なした一方、左派は逆に彼らを「小ブルジョワ」と呼んだ。 この時期、左派フェミニスト組織の活動が注目を集めた。最も顕著な例がプエルトリコの「ヤング・ローズの女性たち」である。ヤング・ローズは当初、ボリク アン(プエルトリコ系)とアフロ・タイノ系の男性たちで構成され、基本的人権を求めて闘い、「男尊女卑、性差別、家父長制に公然と挑戦した」。ビアンカ・ カナレス、ルイーサ・カペティージョ、コニー・クルーズ、デニース・オリバーがヤング・ローズの指導者となり、「十項目の健康プログラム」を推進した [21]。 ラテンアメリカのフェミニズムの多くは、軍事独裁政権と男性優位の文脈から生まれた。しかし1970年代、多くの周縁化された女性たちがヘゲモニック・ フェミニズムに疑問を持ち始めた。アフリカ系、レズビアン、先住民、トランスジェンダー、性労働者、家事労働者など、これらの女性たちは相互に絡み合う様 々な抑圧の形態を認識し始めたのである。[27] 先住民系のグロリア・アンサルドゥアは、自身の交差性体験を「人種的・思想的・文化的・生物学的交配」と表現し、「新たなメスティーサ意識」と呼んだ。 [24] 「ラテンアメリカ諸国による自国内の先住民に対する内部植民地主義」や「社会科学におけるヨーロッパ中心主義」に対する様々な批判が生まれ、ラテンアメリカ・フェミニスト理論が台頭した。[28] |

| 1980s The feminist movement returned to be an important protagonist in the early 1980s after the fall of dictatorships and the establishment of new democratic regimes throughout the region, with the dictatorship managing to interrupt the continuity with the previous stage. Feminists of the 1980s, e.g., Nancy Fraser, referring to violence against women, questioned the established limits of discussion and politicized problems which before had not ever been politicized, expanded their audiences, created new spaces and institutions in which the opposing interpretations could be developed and from where they could reach wider audiences.[29] During the repressive period and particularly during the early years of democracy, human rights groups played a major role on the continent. These movements, organized to denounce the torture, disappearances, and crimes of the dictatorship, were headed mainly by women (mothers, grandmothers and widows). In order to understand the change in the language of feminist movements, it is necessary to bear in mind two things: the first is that it was women who headed revelations and subsequent struggle for the punishment of those who were responsible for the state terrorism, and the second is the policy, especially of the United States, to prioritize human rights in the international agenda.[30] Feminists were able to achieve goals because of political parties, international organizations and local labour groups. Latin American feminist movements had two forms: as centers of feminist work, and as part of the broad, informal, mobilized, volunteer, street feminist movement. At the IV meeting in Mexico in 1987[31], a document was signed on the myths of the feminist movement impeding its development. This document has a great impact; it states that feminism has a long way to go because it is a radical transformation of society, politics and culture. The myths listed are: Feminists are not interested in power Feminists do politics in a different way All feminists are the same There is a natural unity for the mere fact of being women Feminism exists only as a policy of women towards women The movement is a small group The women's spaces ensure for themselves a positive space Personal is automatically political The consensus is democracy. This is important because each country in Latin America was able to push feminism in different ways – for example, through democracy, socialism, and even under authoritarian regimes (although this was less common).[10] These myths were commonly disputed at Latin American and Caribbean meetings in the 1980s called Encuentros, a space created to "strengthen feminist networks," exchange analysis, and confront "conditions of oppression."[citation needed] Though the Encuentros constructed a common space, the people there made sure it was a place of political dialogue, not of a sisterhood.[32] One of the few points of unity found during these Encuentros was the effect colonialism and globalization had on their respective countries.[10] |

1980年代 独裁政権が崩壊し、地域全体で新たな民主的体制が確立された後、1980年代初頭にはフェミニズム運動が再び重要な主役として台頭した。独裁政権は前段階との連続性を断ち切ることに成功していた。 1980年代のフェミニストたち、例えばナンシー・フレイザーは、女性に対する暴力に言及し、確立された議論の限界に疑問を投げかけ、これまで政治化され ていなかった問題を政治化し、対象者を拡大し、対立する解釈を展開できる新たな空間や機関を創出し、そこからより広い聴衆に到達できるようにした。 [29] 抑圧期、特に民主化初期において、人権団体は大陸で主要な役割を果たした。独裁政権による拷問、失踪、犯罪を告発するために組織されたこれらの運動は、主 に女性(母親、祖母、未亡人)が主導した。フェミニスト運動の言語変化を理解するには、二点を念頭に置く必要がある。第一に、国家テロの責任者を処罰する ための暴露と闘争を主導したのは女性たちであったこと。第二に、特に米国が国際アジェンダにおいて人権を優先する政策を取ったことである。[30] フェミニストたちは、政党、国際機関、地域の労働団体によって目標を達成できた。ラテンアメリカのフェミニスト運動は二つの形態を取った。一つはフェミニ スト活動の拠点としての形態、もう一つは広範で非公式、動員型、ボランティア、街頭フェミニスト運動の一部としての形態である。 1987年のメキシコにおける第4回会合[31]では、フェミニスト運動の発展を阻害する神話に関する文書が署名された。この文書は大きな影響力を持つ。そこでは、フェミニズムは社会・政治・文化の根本的変革であるため、まだ長い道のりがあると述べられている。 列挙された神話は以下の通りである: フェミニストは権力に関心を持たない フェミニストは異なる方法で政治を行う 全てのフェミニストは同じである 女性であるという事実だけで自然な結束が生まれる フェミニズムは女性による女性のための政策としてのみ存在する 運動は小規模な集団である 女性の空間は自らに肯定的な空間を保証する 個人的なことは自動的に政治的である 合意形成こそが民主主義である。これは重要な点だ。なぜならラテンアメリカの各国は、民主主義や社会主義、さらには権威主義体制下(これは比較的稀だったが)といった異なる方法でフェミニズムを推進できたからだ。[10] これらの神話は、1980年代にラテンアメリカ・カリブ海地域で開催された「エンクエントロス」と呼ばれる会合で頻繁に議論された。この場は「フェミニス トネットワークの強化」、分析の交換、「抑圧の条件」への対峙を目的として創設された。エンクエントロスは共通の空間を構築したが、参加者はそこが姉妹愛 の場ではなく政治的対話の場であることを明確にした[32]。これらのエンクエントロスで数少ない合意点の一つは、植民地主義とグローバル化が各国の社会 に与えた影響であった[10]。 |

| 1990s The neoliberal policies that began in the late 1980s and reached their peak on the continent during the decade of the 1990s made the feminist movement fragmented and privatized. Many women began to work in multilateral organizations, finance agencies, etc., and became bridges between financing bodies and female movements. It was around this time that many feminists, feeling discomfort with the current hegemonic feminism, began to create their own, autonomous organizations.[16] In 1994, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) became "a catalyst for indigenous women's organization in Mexico" and created "The Women's Revolutionary Law." Their example of indigenous feminism led the way for other indigenous tribes, such as the Mayans, Quechuas, and Quiches.[21] Zapatista women were made public in 1994. They are used as inspiration and symbolic tools to feminists throughout the world, and are often referred to in scholarly essays and articles.[33] In 1993, many feminists tried to bring together these autonomous organizations in Latin America and the Caribbean, which led to the Beijing Global Conference on Women of 1995.[10] Scholars argue that there is a strong correlation between the improvement of legal rights for Latin American women and the country's struggle for democracy. For example, because of women's active protests against President Abdala Bucaram's government, Ecuador's Constitution of 1998 saw many new legal rights for women. MUDE, or Women for Democracy, has stated that "what is not good for democracy is not good for women."[citation needed] However, this is not always the case. Peru had an authoritarian regime, but it had a quota for at least thirty percent of candidates in a race to be women. It is important to note, though, that the advance of Latin American women's legal equality does not get rid of the social and economic inequality present.[10] |

1990年代 1980年代後半に始まり、1990年代に大陸で頂点に達した新自由主義政策は、フェミニスト運動を分断し、私的領域へと押し込んだ。多くの女性が国際機 関や金融機関などで働き始め、資金提供団体と女性運動の架け橋となった。この時期、当時の支配的なフェミニズムに違和感を抱いた多くのフェミニストが、独 自の自律的な組織を作り始めた。[16] 1994年、サパティスタ民族解放軍(EZLN)は「メキシコにおける先住民族女性組織化の触媒」となり、「女性の革命法」を制定した。彼らの先住民族 フェミニズムの事例は、マヤ族、ケチュア族、キチェ族など他の先住民族部族の先駆けとなった。[21] サパティスタの女性たちは1994年に公の場に現れた。彼女たちは世界中のフェミニストにとってインスピレーションと象徴的なツールとして用いられ、学術 論文や記事で頻繁に言及されている。[33] 1993年には、多くのフェミニストがラテンアメリカとカリブ海地域のこれらの自律組織を結集させようと試み、それが1995年の北京世界女性会議につな がった。[10] 学者らは、ラテンアメリカ女性における法的権利の向上と、その国の民主主義への闘争との間に強い相関関係があると主張する。例えば、アブダラ・ブカラム大 統領政権に対する女性の積極的な抗議活動により、エクアドルの1998年憲法では女性のための多くの新たな法的権利が認められた。民主主義のための女性た ち(MUDE)は「民主主義にとって良くないことは、女性にとっても良くない」と表明している[出典必要]。しかし、必ずしもそうとは限らない。ペルーは 権威主義体制だったが、選挙候補者の少なくとも30%を女性に割り当てるクオータ制を設けていた。ただし、ラテンアメリカ女性の法的平等が進んでも、存在 する社会経済的不平等が解消されるわけではない点に留意する必要がある[10]。 |

21st Century Protest on International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women 2019 in Mexico City. The emergence of economic neoliberal models at the beginning of the 21st century led to a revival of the movement in the world, which was accompanied by an attempt at feminist dialogue with other social movements. A new feature is the feminist participation in global mobilization at different government meetings and in multinational organizations where there is a discussion of humanity's future. With the rise of globalization and international policies, many feminist political and academic organizations have been institutionalized. The more professional tactics of NGOs and political lobbying have given Latina feminists more influence on public policy, but at the cost of giving up "bolder, more innovative proposals from community initiatives."[34] In addition, the Colectivo Feminista Sexualidade Saude (CFSS) of Brazil currently "provides health education for women and professionals," where they encourage self-help and focus on "women's mental health, violence against women, and child mortality."[21] Today, there are also feminist groups that have spread to the United States. For example, the Latina Feminist Group formed in the 1990s is composed of women from all places in Latin America. Although groups like these are local, they are all-inclusive groups that accept members from all parts of Latin America. Members of the organizations are predominantly from European – Native American backgrounds, with some members being completely descendants of Native American people.[35] Today, there is a weak relationship between lesbianism and feminism in Latin America. Since the 1960s, lesbians have become a viable group in Latin America. They have established groups to fight misogynist oppression against lesbians, fight AIDS in the LGBT community, and support one another. However, because of many military coups and dictatorships in Latin America, feminist lesbian groups have had to break up, reinvent, and reconstruct their work. Dictatorships in the 1970s and 1980s in Chile and Argentina were examples of the resistance to these feminist lesbian groups in Latin America.[36] In the 2000s, Latin American feminist groups set goals for their communities. Such goals call for the consolidation of a more organized LGBT community across Latin America. Other goals overall look to change smaller domestic policies that in any way discriminate against members of the LGBT community. They also aim to have more people in office, to network better with the broader Latin people.[37] They have set goals to advocate for LGBT rights in the political world, from organizations and political groups, to acknowledge their rights, and encourage other countries to protect feminists and other members of the LGBT community in Latin America. Leaders such as Rafael de la Dehesa have contributed to describing early LGBT relations in parts of Latin America through their writings and advocacy. De la Dehesa, a Harvard alumnus, has published books such as Queering the Public Sphere in Mexico and Brazil: Sexual Rights Movements in Emerging Democracies that advocate for a shift in popular culture that accepts queer Latinos. His work, Global Communities and Hybrid Cultures: Early Gay and Lesbian Electoral Activism in Brazil and Mexico, explains the gay communities and puts them in context to coincide with the history of those countries. Rafael has also introduced the idea of normalizing LGBT issues in patriarchal conservative societies such as Mexico and Brazil to suggest that being gay should no longer be considered taboo in the early 2000s.[38] The first female mayor of Mexico City, one of the largest cities in the Western Hemisphere, was Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo, who took office in December 2018. Nearly a century after women in Latin America were granted the right to vote, this is significant in a continent that continues to struggle with gender inequality. In large part due to gender quotas, nations including Bolivia, Argentina, Costa Rica, and Mexico have achieved or are on the verge of achieving gender parity in national legislatures, showing an increase in women's political engagement throughout the region over the past 20 years. Along with Sheinbaum Pardo's election, Epsy Campbell Barr became the first female Afro-descendant vice president of Costa Rica in May 2018.[39] Legalizing abortion and preventing violence against women are two issues that are at the heart of the current Latin American feminist movement. As a powerful response to gender-based violence, the Ni Una Menos campaign has grown to represent a larger fight for women's rights across the area.[40] This is a social movement that emerged as a response to violence against women in Latin America. It has evolved to encompass and incorporate the fight for other rights as well.[41] |

21世紀 2019年、メキシコシティにおける「女性に対する暴力撤廃国際デー」抗議活動。 21世紀初頭に経済的新自由主義モデルが登場したことで、世界的にこの運動が再興した。これに伴い、フェミニズムが他の社会運動との対話を試みる動きも見 られた。新たな特徴は、人類の未来が議論される様々な政府会議や多国籍機関におけるグローバルな動員へのフェミニスト参加だ。 グローバリゼーションと国際政策の台頭に伴い、多くのフェミニスト政治・学術組織が制度化された。NGOや政治ロビー活動におけるより専門的な戦術は、ラ ティーナ・フェミニストに公共政策への影響力をもたらしたが、その代償として「コミュニティ主導のより大胆で革新的な提案」を放棄することになった。 [34] さらに、ブラジルのコレクティーボ・フェミニスタ・セクシダージ・サウデ(CFSS)は現在「女性と専門職向けの健康教育を提供」しており、自助を奨励しつつ「女性のメンタルヘルス、女性に対する暴力、乳幼児死亡率」に焦点を当てている[21]。 今日では、アメリカ合衆国に広がったフェミニスト団体も存在する。例えば1990年代に結成されたラティーナ・フェミニスト・グループは、ラテンアメリカ 全域の女性で構成されている。こうした団体は地域に根ざしているが、ラテンアメリカ全域からのメンバーを受け入れる包括的なグループだ。組織のメンバーは 主にヨーロッパ系と先住民系の背景を持ち、完全な先住民系の子孫であるメンバーもいる。[35] 現在、ラテンアメリカにおけるレズビアン運動とフェミニズムの結びつきは弱い。1960年代以降、レズビアンはラテンアメリカで確固たる集団となった。レ ズビアンに対する女性蔑視的抑圧への抵抗、LGBTコミュニティにおけるエイズ対策、相互支援を目的とした団体を設立してきた。しかしラテンアメリカで頻 発した軍事クーデターや独裁政権のため、フェミニスト系レズビアン団体は解散を余儀なくされ、活動を再構築せざるを得なかった。1970年代から1980 年代にかけてのチリやアルゼンチンの独裁政権は、ラテンアメリカにおけるこうしたフェミニスト・レズビアン団体への抵抗の例であった。[36] 2000年代に入り、ラテンアメリカのフェミニスト団体は自らのコミュニティに向けた目標を設定した。そうした目標は、ラテンアメリカ全域でより組織化さ れたLGBTコミュニティの統合を求めるものである。その他の目標は、LGBTコミュニティのメンバーを差別するあらゆる国内政策の変更を目指すものだ。 また、より多くの人材を公職に就かせ、広範なラテン系住民との連携強化も目的としている[37]。組織や政治団体に対し、LGBTの権利を認め、ラテンア メリカにおけるフェミニストやその他のLGBTメンバーを保護するよう他国に促すため、政治の世界でLGBTの権利を擁護する目標も掲げている。ラファエ ル・デ・ラ・デエサのような指導者は、著作や提唱活動を通じてラテンアメリカ地域における初期のLGBT関係を描き出すことに貢献してきた。ハーバード大 学出身のデ・ラ・デエサは、『メキシコとブラジルにおける公共圏のクィア化:新興民主主義国における性的権利運動』といった書籍を出版し、クィアなラテン 系を受け入れる大衆文化への転換を提唱している。彼の著作『グローバル・コミュニティとハイブリッド文化:ブラジルとメキシコにおける初期のゲイ・レズビ アン選挙運動』は、ゲイコミュニティを説明し、それらの国々の歴史と連動する文脈に位置づけている。ラファエルはまた、2000年代初頭において、メキシ コやブラジルのような家父長制保守社会においてLGBT問題を正常化するという考え方を導入し、ゲイであることがもはやタブー視されるべきではないと示唆 した。 西半球最大級の都市であるメキシコシティ初の女性市長に、2018年12月にクラウディア・シェインバウム・パルドが就任した。ラテンアメリカで女性に選 挙権が与えられてからほぼ1世紀を経ての出来事であり、依然としてジェンダー不平等に苦しむ大陸において重要な意味を持つ。ジェンダー・クオータ制が大き な要因となり、ボリビア、アルゼンチン、コスタリカ、メキシコなどの国々は、国会の男女比が均等化、あるいはその実現間近であり、この 20 年間でこの地域全体において女性の政治参加が増加していることを示している。シェインバウム・パルドの当選と並行して、2018 年 5 月には、エプシー・キャンベル・バーがコスタリカ初のアフリカ系女性副大統領に就任した。 中絶の合法化と女性に対する暴力の防止は、現在のラテンアメリカのフェミニズム運動の中心的な課題である。ジェンダーに基づく暴力に対する強力な対応とし て、「Ni Una Menos(一人も失わない)」キャンペーンは、この地域全体の女性の権利のためのより大きな闘争を代表するまでに成長した[40]。これは、ラテンアメ リカにおける女性に対する暴力への対応として生まれた社会運動である。この運動は、他の権利のための闘争も包含し、取り込むように発展してきた[41]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminism_in_Latin_America |

★Rita Laura Segato (b.1951)

| Rita Laura Segato

(born 14 August 1951) is an Argentine-Brazilian academic, who has been

called "one of Latin America's most celebrated feminist

anthropologists"[1] and "one of the most lucid feminist thinkers of

this era".[2] She is specially known for her research oriented towards

gender in indigenous villages and Latin American communities, violence

against women and the relationships between gender, racism and

colonialism. One of her specialist areas is the study of gender

violence.[2] Segato was born in Buenos Aires and educated at the Instituto Interamericano de Etnomusicología y Folklore de Caracas.[3] She has an MA and a PhD in anthropology (1984) from Queens University, Belfast. She teaches Anthropology at the University of Brasília, where she holds the UNESCO Chair of Anthropology and Bioethics;[4] since 2011 she has taught on the Postgraduate Programme of Bioethics and Human Rights.[1] She additionally carries out research on behalf of Brazil's National Council for Scientific and Technological Development. In 2016, along with Prudencio García Martínez, Segato was an expert witness in the Sepur Zarco case,[5] in which senior officers at a military base in Guatemala were convicted of crimes against humanity as a result of the holding of fourteen women in sexual and domestic slavery. The defence tried to challenge the expertise of the witnesses, but their appeal was unsuccessful.[6] Her works were an inspiration to the Chilean collective LASTESIS from Valparaíso for the song and performance A Rapist in Your Path, which was performed by women throughout America[7][8] Europe and Australia.[8] |

リタ・ラウラ・セガト[Rita Laura Segato]

(1951年8月14日生まれ)はアルゼンチンとブラジルの二重国籍を持つ学者である。彼女は「ラテンアメリカで最も著名なフェミニスト人類学者の一人」

[1]であり、「この時代で最も明晰なフェミニスト思想家の一人」と呼ばれている。[2]

特に先住民集落やラテンアメリカ共同体におけるジェンダー問題、女性に対する暴力、ジェンダーと人種差別・植民地主義の関連性を研究対象として知られる。

専門分野の一つはジェンダーに基づく暴力の研究である。[2] セガートはブエノスアイレス生まれで、カラカスにある米州民族音楽学・民俗学研究所で学んだ。[3] クイーンズ大学ベルファスト校にて人類学の修士号(1984年)と博士号を取得。ブラジリア大学で人類学を教授し、ユネスコ人類学・生命倫理学講座を保持 している[4]。2011年からは生命倫理学・人権学大学院プログラムで教鞭を執る[1]。加えてブラジル国立科学技術開発評議会の委託研究も実施してい る。 2016年、プルデンシオ・ガルシア・マルティネスと共に、セガトはセプル・サルコ事件[5]の専門家証人として参加した。この事件では、グアテマラの軍 事基地の上級将校らが、14人の女性を性的・家事奴隷として拘束した結果、人道に対する罪で有罪判決を受けた。弁護側は証人の専門性を争おうとしたが、上 訴は認められなかった[6]。彼女の著作は、チリのバルパライソ出身の集団LASTESISが制作した楽曲・パフォーマンス『A Rapist in Your Path』のインスピレーション源となった。この作品はアメリカ大陸[7][8]、ヨーロッパ、オーストラリアの女性たちによって上演された[8]。 |

| Awards and Recognitions Premio Latinoamericano y Caribeño de Ciencias Sociales CLACSO 50 Años (2017)[9] Honorary degree granted by the Universidad Autónoma de Entre Ríos (2018)[10] Honorary degree granted by the Universidad Nacional de Salta (2018)[11] Honorary degree granted by the University of El Salvador (2021)[12] |

受賞歴と栄誉 ラテンアメリカ・カリブ社会科学賞 CLACSO 50周年(2017年)[9] エントレ・リオス自治大学より名誉学位授与(2018年)[10] サルタ国立大学より名誉学位を授与された(2018年)[11] エルサルバドル大学より名誉学位を授与された(2021年)[12] |

| Publications Santos e Daimones. O politeísmo afrobrasileiro e a tradição arquetipal. Editora da Universidade de Brasília. 1995. Las Estructuras Elementales de la Violencia. Ensayos sobre género entre la antropología, el psicoanálisis y los Derechos Humanos. Prometeo - Universidad Nacional de Quilmes. 2003. ISBN 987-558-018-X. Series: Derechos Humanos. Viejos problemas, nuevas miradas Dirigida por Baltasar Garzón.[13] La nación y sus otros: raza, etnicidad y diversidad religiosa en tiempos de políticas de la identidad. Prometeo Libros. 2007. ISBN 978-987-574-155-3. Los presos hablan sobre los derechos humanos en la cárcel. La Grieta, por Donde Asoma la Palabra. 2009. ISBN 978-987-25040-0-7. Co-authored with Rodolfo Brardinelli and Claudia Cesaroni La escritura en el cuerpo de las mujeres asesinadas en Ciudad Juárez. Tinta Limón. 2013. ISBN 978-987-27390-4-1. L’Oedipe Noir (París: Petite Bibliothèque Payot, editorial Payot et Rivages, 2014) Las nuevas formas de la guerra y el cuerpo de las mujeres (México, DF: Pez en el Árbol, 2014) Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo XXI. Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento. 2014. ISBN 978-987-630-192-3. (Obra colectiva) Aníbal Quijano: textos de fundación. Del Signo. 2014. ISBN 978-987-3784-04-0. (Co-authored) Des/decolonizar la universidad. Del Signo. 2015. ISBN 978-987-3784-16-3. (Co-authored) Genealogías críticas de la colonialidad en América Latina, África, Oriente. CLACSO. 2016. ISBN 978-987-722-157-2. (Co-authored) Construir estrategias para erradicar la violencia de género. Al Margen. 2016. ISBN 978-987-618-224-9. (Co-authored) La crítica de la colonialidad en ocho ensayos. Prometeo Libros. 2016. ISBN 978-987-574-825-5. La guerra contra las mujeres. Tinta Limón - Traficantes de sueños. 2017. ISBN 978-987-3687-26-6. Mujeres intelectuales : feminismos y liberación en América Latina y el Caribe. Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales - CLACSO. 2017. ISBN 978-987-722-247-0. (Co-authored) Más allá del decenio de los pueblos afrodescendientes. Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales - CLACSO. 2017. ISBN 978-987-722-267-8. (Co-authored) Contrapedagogías de la crueldad. Prometeo Libros. 2018. ISBN 978-987-574-911-5. |

出版物 『聖人と悪魔たち。アフリカ系ブラジル人の多神教と原型的な伝統』ブラジリア大学出版局、1995年。 『暴力の根源的構造。人類学、精神分析学、人権におけるジェンダーに関するエッセイ』プロメテオ - キルメス国立大学、2003年。ISBN 987-558-018-X。シリーズ:人権。古い問題、新しい視点。バルタサール・ガルソン監修。[13] 国家とその他者たち:アイデンティティ政策の時代における人種、民族、宗教的多様性。プロメテオ・リブロス。2007年。ISBN 978-987-574-155-3。 囚人たちが刑務所における人権について語る。ラ・グリエタ、言葉が現れる場所。2009年。ISBN 978-987-25040-0-7。ロドルフォ・ブラルディネッリ、クラウディア・チェザローニとの共著。 シウダード・フアレスで殺害された女性たちの体に書かれた文字。ティンタ・リモン。2013年。ISBN 978-987-27390-4-1。 L’Oedipe Noir(パリ:Petite Bibliothèque Payot、出版社 Payot et Rivages、2014年) 戦争の新しい形と女性の身体(メキシコシティ:Pez en el Árbol、2014年) 21世紀における左翼の再構築。Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento. 2014. ISBN 978-987-630-192-3. (共著) Aníbal Quijano: textos de fundación. Del Signo. 2014. ISBN 978-987-3784-04-0. (共著) 大学を脱植民地化する。デル・シグノ。2015年。ISBN 978-987-3784-16-3。(共著) ラテンアメリカ、アフリカ、オリエントにおける植民地性の批判的系譜。CLACSO。2016年。ISBN 978-987-722-157-2。(共著) ジェンダーに基づく暴力を根絶するための戦略を構築する。Al Margen。2016年。ISBN 978-987-618-224-9。(共著) 8つのエッセイによる植民地性の批判。Prometeo Libros。2016年。ISBN 978-987-574-825-5。 女性に対する戦争。Tinta Limón - Traficantes de sueños。2017年。ISBN 978-987-3687-26-6。 女性知識人:ラテンアメリカとカリブ海地域におけるフェミニズムと解放。ラテンアメリカ社会科学評議会 - CLACSO。2017年。ISBN 978-987-722-247-0。(共著) アフリカ系住民のための10年を超えて。ラテンアメリカ社会科学評議会 - CLACSO。2017年。ISBN 978-987-722-267-8。(共著) 残酷さの反教育学。プロメテオ・リブロス。2018年。ISBN 978-987-574-911-5。 |

| References 01. "History and patriarchal violence". The UCL Centre for Gender and Global Health. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018. "Rita Segato: "Una falla del pensamiento feminista es creer que la violencia de género es un problema de hombres y mujeres"". La Tinta (in Spanish). 22 September 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2018. "Rita Segato" (in Spanish). CGA. December 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018. "Rita Segato". LATEINAMERIKA-INSTITUT (LAI). 28 May 2018. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2018. 05. Jo-Marie Burt (25 February 2016). "Former Military Commissioner Accuses Reyes Girón of Ordering Gang Rape". International Justice Monitor. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018. Jo-Marie Burt; Paulo Estrada (21 July 2017). "Court Ratifies Historic Sepur Zarco Sexual Violence Judgment". International Justice Monitor. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018. McGowan, Charis (2019-12-06). "Chilean anti-rape anthem becomes international feminist phenomenon". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2020-03-03. Timmers, Laurie (2019-12-07). "'A rapist in your path': The feminist anthem spreading round the world". euronews. Archived from the original on 2023-03-24. Retrieved 2020-03-03. "Centro de Estudos Avançados Multidisciplinares - Clacso homenageia a prof. Rita Segato". www.ceam.unb.br. Archived from the original on 2018-12-26. Retrieved 2020-09-13. 10. "La Uader distinguió como Doctora Honoris Causa a Rita Segato". ahora.com.ar (in European Spanish). 25 July 2018. Archived from the original on 2020-10-29. Retrieved 2020-09-13. "La FCG inicia un vínculo con Montpellier Business School". fcg.uader.edu.ar (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-10-29. Retrieved 2020-09-13. "UES otorgará Doctorado Honoris Causa a la reconocida antropóloga Rita Segato". ues.edu.sv (in European Spanish). 21 October 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-10-22. Retrieved 2021-10-22. 13. "Las Estructuras Elementales de la Violencia" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2018-09-09. |

参考文献 01. 「歴史と家父長制的暴力」. UCLジェンダー・グローバルヘルスセンター. 2018年9月9日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2018年9月9日閲覧. 「リタ・セガート:『フェミニスト思想の欠陥は、ジェンダーに基づく暴力が男性と女性の問題だと信じる点にある』」. ラ・ティンタ(スペイン語)。2017年9月22日。2022年9月22日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2018年9月9日に取得。 「リタ・セガート」(スペイン語)。CGA。2014年12月。2018年12月23日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2018年9月9日に取得。 「リタ・セガト」。LATEINAMERIKA-INSTITUT (LAI)。2018年5月28日。2023年11月30日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2018年9月9日に閲覧。 05. ジョー・マリー・バート (2016年2月25日)。「元軍事委員、レイエス・ヒロンが集団強姦を命令したと告発」。国際司法モニター。2018年9月9日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2018年9月9日閲覧。 ジョ=マリー・バート; パウロ・エストラーダ (2017年7月21日). 「裁判所、セプル・サルコ性暴力事件の画期的判決を承認」. 国際司法モニター. 2018年9月9日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2018年9月9日閲覧。 マッゴーワン、カリス(2019年12月6日)。「チリの反レイプ賛歌が国際的なフェミニスト現象に」。ガーディアン。ISSN 0261-3077。2022年9月22日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年3月3日に取得。 ティマーズ、ローリー (2019-12-07). 「『道にレイプ犯がいる』:世界に広がるフェミニストのアンセム」. ユーロニュース. 2023-03-24にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2020-03-03に取得. 「多分野高等研究センター - Clacsoがリタ・セガト教授を称える」。www.ceam.unb.br。2018年12月26日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年9月13日に閲覧。 10. 「ラ・ウアデル大学がリタ・セガトに名誉博士号を授与」。ahora.com.ar(ヨーロッパスペイン語)。2018年7月25日。2020年10月29日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年9月13日に閲覧。 「FCGがモンペリエ・ビジネススクールとの提携を開始」。fcg.uader.edu.ar(スペイン語)。2020年10月29日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年9月13日閲覧。 「UESが著名な人類学者リタ・セガトに名誉博士号を授与」。ues.edu.sv(スペイン語)。2021年10月21日。2021年10月22日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年10月22日に取得。 13. 「暴力の基礎構造」 (PDF)。2018年5月4日にオリジナルからアーカイブ (PDF)。2018年9月9日に取得。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rita_Laura_Segato |

★Julieta Paredes Carvajal (b.1967)

| Julieta Paredes Carvajal

(born c. 1967) is an Aymara Bolivian poet, singer-songwriter, writer,

graffiti artist, anarchist and decolonial feminist activist. In 2003

she began Mujeres creando comunidad (women creating community) out of

the activism of community feminism.[1] |

フリアエタ・パレデス・カルバハル(1967年頃生まれ)は、アイマラ

族のボリビア人詩人、シンガーソングライター、作家、グラフィティアーティスト、アナキスト、脱植民地主義フェミニスト活動家である。2003年、彼女は

コミュニティフェミニズムの活動から「ムヘレス・クレアンド・コムニダッド(女性たちがコミュニティを創る)」を始めた。 |