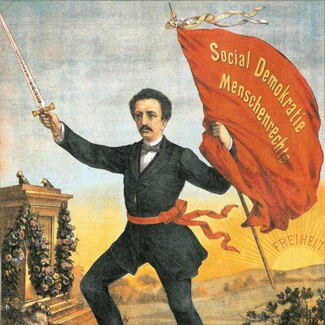

Ferdinand Lassalle. 1825-1864

フェルディナンド・ラッサール

Ferdinand Lassalle. 1825-1864

| Ferdinand

Lassalle

(11 April 1825 – 31 August 1864) was a Prussian-German jurist,

philosopher, socialist and politician who is best remembered as the

initiator of the social-democratic movement in Germany. "Lassalle was

the first man in Germany, the first in Europe, who succeeded in

organising a party of socialist action", according to Élie Halévy. Or,

as Rosa Luxemburg put it: "Lassalle managed to wrestle from history in

two years of flaming agitation that needed decades to come about". As an agitator, he coined the terms night-watchman state and iron law of wages. |

フェルディナント・ラサール(1825年4月11日-1864年8月

31日)は、プロイセン系ドイツ人の法学者、哲学者、社会主義者、政治家であり、ドイツにおける社会民主主義運動の創始者として最もよく知られている。エ

リー・ハレヴィによれば、「ラッサールはドイツで初めて、ヨーロッパで初めて、社会主義政党を組織することに成功した人物」である。あるいは、ローザ・ル

クセンブルクはこう言った: 「ラッサールは、数十年の歳月を必要とした燃えるような扇動を、2年間で歴史から奪い取ることに成功した」。 アジテーターとして、夜警国家や賃金の鉄則という言葉を生み出した。 |

| Biography Early life Lassalle was born Ferdinand Johann Gottlieb Lassal on 11 April 1825 in Breslau, Silesia (now Wrocław, Poland). His father Heyman Lassal was a Jewish silk merchant and intended his son for a business career, sending him to the commercial school at Leipzig. However, Lassalle soon transferred to university, studying first in the University of Breslau and later at the University of Berlin. There, Lassalle studied philology and philosophy and became a devotee of the philosophical system of Georg Hegel. Lassalle changed his name at a young age to disassociate himself from Judaism.[1] Lassalle passed his university examinations with distinction in 1845 and thereafter traveled to Paris to write a book on Heraclitus.[2] There, Lassalle met the poet Heinrich Heine, who wrote of his intense young friend in 1846: "I have found in no one so much passion and clearness of intellect united in action. You have good right to be audacious – we others only usurp this divine right, this heavenly privilege".[3] Back in Berlin to work on his book, Lassalle met Countess Sophie von Hatzfeldt, a woman in her early 40s who had been separated from her husband of many years and who had an ongoing dispute with him regarding the disposition of the couple's property. Lassalle volunteered himself to her cause and the offer was readily accepted.[4] Lassalle first challenged her husband to a duel, but his challenge was rejected.[4] An eight-year legal battle followed in which Lassalle defended Countess von Hatzfeldt's interests in 36 different courtrooms.[5] Ultimately, a settlement was made in her favor, bringing her a substantial fortune. In her gratitude, she agreed to pay Lassalle an annual income of 5,000 thalers (about £750) for the rest of his life.[6] 1848 Revolution and its aftermath Lassalle was a committed socialist from an early age. During the German Revolutions of 1848, he spoke at public meetings in favor of the revolutionary-democratic cause and urged the citizens of Düsseldorf to prepare themselves for armed resistance in advance of the violence that was expected after the decision of the Prussian government to dissolve the National Assembly.[7] Lassalle was subsequently arrested for his involvement in this activity and he was charged with inciting armed opposition to the state.[8] Although Lassalle was acquitted of this serious charge, he was kept in prison until he could be tried on a lesser charge of inciting resistance against public officials.[9] He was convicted of this lesser charge and the 23-year-old Lassalle served a sentence of six months in prison.[9] Banned from residence in Berlin in the aftermath of his conviction, Lassalle moved to the Rhineland, where he continued to pursue the lawsuit of the Countess von Hatzfeldt (settled in 1854) and finished his work on the philosophy of Heraclitus, (completed in 1857 and published in two volumes the following year).[10] Reaction to the book was mixed as some declared the work seminal while others, including Karl Marx, considered it a mere recitation of Hegelian axioms.[11] However, even the book's detractors had to admire the scope of the work and the publication gave Lassalle lasting status among German intellectuals.[11] During this period, Lassalle was not politically active, although he remained interested in labor affairs. He left his legal practice and philosophy in favor of drama, authoring a play called Franz von Sickingen, a Historical Tragedy.[12] Sent anonymously to the Royal Theatre, the play was rejected by a manager, causing Lassalle to publish it under his own name in 1859.[12] The work was characterized by Edward Bernstein, an early and sympathetic biographer, as awkward and prone to excessive oratory, unsuited for the stage despite several effective scenes.[12] Lassalle wanted to live in Berlin and despite the ban in 1859 made his return disguised as a wagon driver.[13] Lassalle appealed to his friend, the aging scholar Alexander von Humboldt, to intercede on his behalf before the king to rescind the ban and allow his return.[13] The appeal was successful and Lassalle was again officially allowed to live in the Prussian capital.[13] Lassalle avoided revolutionary activity for several years thereafter.[13] He became a political commentator and wrote a short book on the war in Italy in which he warned Prussia against rushing to the aid of the Austrian Empire in its war with France. Lassalle followed this with a larger work on legal theory, published in two volumes in 1861 as Das System der erworbenen Rechte (The System of Acquired Rights).[14] According to Bernstein, Lassalle wanted the book "to establish a legal and scientific principle which shall once for all determine under what circumstances, and how far laws may be retroactive without violating the idea of right itself"; that is, determining the circumstances under which laws may be made retroactive when they come into conflict with previously established laws.[15] |

略歴 生い立ち ラッサールは1825年4月11日、シレジアのブレスラウ(現ポーランドのヴロツワフ)でフェルディナンド・ヨハン・ゴットリーブ・ラッサルとして生まれ た。父親のヘイマン・ラッサールはユダヤ人の絹商人で、息子をライプツィヒの商業学校に通わせ、実業家としてのキャリアを積ませようとした。しかし、ラッ サールはすぐに大学に進み、最初はブレスラウ大学、後にベルリン大学で学んだ。そこで言語学と哲学を学び、ゲオルク・ヘーゲルの哲学体系に傾倒した。ラッ サールはユダヤ教との関係を断ち切るため、若くして名前を変えた[1]。 1845年、ラッサールは優秀な成績で大学の試験に合格し、その後、ヘラクレイトスに関する本を書くためにパリに渡った[2]。そこでラッサールは詩人の ハインリッヒ・ハイネと出会い、1846年、ハイネは彼の若き情熱的な友人についてこう書いている: 「私はこれほど情熱的で明晰な知性が一体となって行動している人を見たことがない。あなたには大胆になる権利がある。私たち他人は、この神聖な権利、この 天の特権を簒奪するだけだ」[3]。 本の執筆のためにベルリンに戻ったラッサールは、長年連れ添った夫と死別し、夫婦の財産の処分について夫と論争を続けていた40代前半の女性、ゾフィー・ フォン・ハッツフェルト伯爵夫人に出会った。ラッサールは彼女のために自ら志願し、その申し出は快諾された[4]。ラッサールはまず彼女の夫に決闘を申し 込んだが、彼の挑戦は拒否された[4]。 その後8年にわたる法廷闘争が続き、ラッサールは36の異なる法廷でフォン・ハッツフェルト伯爵夫人の利益を弁護した[5]。最終的に、彼女に有利な和解 が成立し、多額の財産がもたらされた。彼女は感謝の意を表し、ラサールに対して生涯5,000ターラー(約750ポンド)の年収を支払うことに同意した [6]。 1848年革命とその余波 ラッサールは幼い頃から熱心な社会主義者であった。1848年のドイツ革命の最中、彼は市民集会で革命的・民主的大義を支持する演説を行い、プロイセン政 府が国民議会解散を決定した後に予想される暴力に備え、デュッセルドルフ市民に武装抵抗の準備をするよう促した[7]。 ラッサールはこの重い罪では無罪となったが、公務員に対する抵抗を扇動したという軽い罪で裁かれるまで刑務所に入れられた[9]。 彼はこの軽い罪で有罪判決を受け、23歳のラッサールは6ヶ月の服役をした[9]。 有罪判決の余波でベルリンでの居住を禁止されたラッサールは、ラインラントに移り住み、フォン・ハッツフェルト伯爵夫人の訴訟(1854年に和解)を続 け、ヘラクレイトスの哲学に関する著作(1857年に完成、翌年に2巻で出版)を完成させた。 [10]この本に対する反応は賛否両論で、ある者はこの著作を決定的なものであるとし、またカール・マルクスを含むある者はヘーゲルの公理を暗唱している に過ぎないとした[11]。しかし、この本を非難する者でさえ、その著作の広さを賞賛せざるを得ず、この出版によってラッサールはドイツの知識人の間で永 続的な地位を得た[11]。 この時期、ラッサールは労働問題に関心を持ち続けたものの、政治的な活動はしていなかった。王立劇場に匿名で送られた戯曲は支配人に却下され、ラッサール は1859年に自分の名前で出版することになった[12]。この作品は、初期の同情的な伝記作家であるエドワード・バーンスタインによって、いくつかの効 果的なシーンがあるにもかかわらず、不器用で過剰な弁舌が多く、舞台には不向きであると評された[12]。 ラッサールはベルリンでの生活を望み、1859年に禁止令が出されたにもかかわらず、荷馬車の運転手に変装してベルリンに戻った[13]。ラッサールは友 人であり、老齢の学者であったアレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトに、禁止令を取り消し、彼の帰還を許可するよう国王に代わって取り次いでくれるよう訴え た[13]。この訴えは成功し、ラッサールは再び正式にプロイセンの首都に住むことを許された[13]。 ラッサールはその後数年間は革命活動を避け、政治評論家となり、イタリア戦争に関する短い本を書き、フランスとの戦争でオーストリア帝国を援助しようとす るプロイセンに警告を発した[13]。ベルンシュタインによれば、ラッサールはこの本を「権利の観念そのものを侵害することなく、どのような状況下で、ど こまで法律を遡及させることができるかを決定する法的かつ科学的な原理を確立すること」、すなわち、法律が以前に制定された法律と抵触する場合に遡及させ ることができる状況を決定することを目的としていた[15]。 |

| Political activism Only briefly engaged in the revolutionary struggle during 1848, Lassalle reentered public politics in 1862, motivated by a constitutional struggle in Prussia.[14] King Wilhelm I, who became king on 2 January 1861, had repeatedly clashed with the liberal Chamber of Deputies, resulting in multiple dissolutions of the Diet.[14] As a recognized legal scholar, Lassalle was asked to make public addresses dealing with the nature of the constitution and its relationship to the social forces within society.[16] Lassalle replied by giving a speech wherein he set out that constitutional matters are merely questions of power. The liberal press was enraged by his speech. Lassalle reacted by holding the same lecture twice again.[17] In another speech, delivered in Berlin on 12 April 1862, later known as the Workers' Program, Lassalle assigned moral primacy in society to the working class over the bourgeosie, an assertion regarded as dangerous by the Prussian censorship.[18] The entire print run of 3,000 copies of the pamphlet of Lassalle's speech was seized by the authorities, who issued a legal charge against Lassalle for allegedly endangering the public peace.[18] Lassalle was brought to trial to answer this accusation in Berlin on 16 January 1863.[18] Lawsuits would continue to interfere with his political activity for the rest of his life. After a widely publicized trial at which he presented his own defense, Lassalle was convicted of the charges levied against him, sentenced to four months' imprisonment and assessed the costs of the trial.[19] This term was later replaced by a fine upon appeal.[19] Foundation of the socialist party On 22 October 1862, a few worker delegates that had visited London that had come back with left-wing ideas, published an open letter about the political and economic situation of the working class. Lassalle was delighted to find workers whose ideas went even further than the socialist statements which he made in public, and replied with his own open letter in which he called for a workers party, independent of the liberal German Progress Party.[20] By arguing that the working class had nothing to gain from the liberal party, he was in a state of war with the liberal party and newspapers for the next months until his death.[21] Lassalle soon began a new career as a political agitator, traveling around Germany, giving speeches and writing pamphlets in an attempt to organise and rouse the working class. As he tried to make the working class break with the liberals, this would eventually lead to an alliance with the reactionary Prince Bismarck. In 1864, Lassalle made several secret appeals to Bismarck, later the main proponent of the Anti-Socialist Laws, in favor of the immediate implementation of progressive policies such as universal suffrage. He also asked for the protection of his own publications from police seizure.[22] Lassalle attempted to make common cause with the conservative Bismarck in his book Herr Basitat-Schulze, declaring that he "must inform Your Excellency that this work will bring about the utter destruction of Liberals and the whole Progressive bourgeoisie".[23] Lassalle asked Bismarck to exert his influence at the Ministry of Justice to prevent the seizure of the book.[23] The book subsequently appeared without police interference, but Bismarck, occupied with other matters, refused a request by Lassalle for another meeting and no further direct contacts between the pair were made.[24] Élie Halévy would later write on this situation: Lassalle was the first man in Germany, the first in Europe, who succeeded in organising a party of socialist action. Yet he viewed the emerging bourgeois parties as more inimical to the working class than the aristocracy and hence he supported universal manhood suffrage at a time when the liberals preferred a limited, property-based suffrage which excluded the working class and enhanced the middle classes. This created a strange alliance between Lassalle and Bismarck. When in 1866 Bismarck founded the Confederation of Northern Germany on a basis of universal suffrage, he was acting on advice which came directly from Lassalle. And I am convinced that after 1878, when he began to practise "State Socialism" and "Christian Socialism" and "Monarchial Socialism," he had not forgotten what he had learnt from the socialist leader.[25] The only stated purpose of the party was the winning of equal, universal and direct suffrage by peaceful and legal means.[26] Personality Lassalle was remembered by biographers as a contradictory personality, earnestly committed to the benefit of the masses, but driven by personal ambition and possessing extreme vanity. Indeed, one early biographer declared: [His vanity] was one of the most striking, though at the same time most harmless traits of his character. His vanity was of the kind that neither hurts nor offends. Vanity seemed natural to him as it is to the peacock, and if he had been less vain he would have been less interesting. Even in his manhood, when at the head of a popular agitation, he was excessively fond of dressing well. He appeared both on the platform and in the Court of Law attired like a fop. He was in the habit, too, of comparing himself with great men. Now it was Socrates, now Luther, or Robespierre, or Cobden, or Sir Robert Peel, and once he found his parallel by going to Faust. Heine told him that he had good reason to be proud of his attainments, and Lassalle took Heine at his word.[27] Bertrand Russell said about Lassalle: "No one has ever understood the power of agitation and organisation better than Lassalle … The secret of his influence lay in his overpowering and imperious will, in his impatience of the passive endurance of evil, and in his absolute confidence in his own power. His whole character is that of an epicurean god, unwittingly become man, awakening suddenly to the existence of evil, and finding with amazement that his will is not omnipotent to set it right."[28] Death and legacy  Lassalle's tomb in Breslau, now the Old Jewish Cemetery, Wrocław In Rigi Kaltbad, Lassalle met a young woman named Helene von Dönniges and during the summer of 1864 they decided to marry. She was the daughter of a Protestant family[29] then living in Geneva, who wanted nothing to do with Lassalle. The father, a historian, prevented Helene from seeing him and Lassalle protested vehemently. Apparently under duress, she soon renounced Lassalle in favour of another suitor, a Wallachian prince named Iancu Racoviță, to whom she had previously been betrothed.[30] Lassalle sent dueling challenges both to Helene's father von Dönniges and to Racoviță, who accepted. Lassalle had no experience in the use of pistols and only one day to exercise. At the Carouge, a suburb of Geneva, a duel was held on the morning of 28 August. Lassalle was shot in the abdomen by Racoviță and died three days later on 31 August 1864.[30] Following the duel Racoviţă fell ill and died not long after Helene von Dönniges married him. At the time of his death, Lassalle's political party had 4,610 members and no detailed political program.[26] The ADAV continued after his death, going on to help establish the Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1875. Ferdinand Lassalle is buried in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), in the Old Jewish Cemetery. |

政治活動 1848年の革命闘争に短期間携わっただけだったラサールは、1862年、プロイセンにおける憲法闘争に突き動かされ、再び公の政治に参画した[14]。 1861年1月2日に国王となったヴィルヘルム1世は、自由主義派の代議院と衝突を繰り返し、その結果、何度も国会が解散させられた[14]。 ラサールは、憲法の問題は単に権力の問題に過ぎないとする演説を行い、それに答えた。リベラル派のマスコミは彼の演説に激怒した。ラッサールは同じ講演を 2度行うことで反発した[17]。 1862年4月12日にベルリンで行われた別の演説(後に『労働者綱領』として知られる)では、ラサールは社会における道徳的な優位性をブルジョアジーよ りも労働者階級に譲るとし、この主張はプロイセンの検閲によって危険視された[18]。 ラサールの演説のパンフレットの印刷部数3,000部はすべて当局によって押収され、当局はラサールに対して公共の平和を脅かしたとして法的告発を行った [18]。 1863年1月16日、ラサールはベルリンでこの告発に答えるために裁判にかけられた[18]。ラッサールは、自身の弁護を行った裁判の結果、有罪判決を 受け、4ヶ月の禁固刑と裁判費用の支払いを命じられた[19]。この禁固刑は、後に上訴により罰金刑に置き換えられた[19]。 社会主義党の設立 1862年10月22日、左翼的な思想を持ってロンドンを訪れた数人の労働者代表が、労働者階級の政治的・経済的状況についての公開書簡を発表した。ラッ サールは、自分が公の場で発表した社会主義的な声明よりもさらに進んだ思想を持つ労働者を見つけたことを喜び、自由主義的なドイツ進歩党から独立した労働 者党の結成を呼びかける自身の公開書簡で返信した[20]。 労働者階級が自由主義政党から得るものは何もないと主張することで、彼はその後亡くなるまでの数ヶ月間、自由主義政党や新聞社と抗争状態にあった [21]。ラッサールはすぐに政治的扇動家としての新たなキャリアをスタートさせ、労働者階級を組織化し奮起させようと、ドイツ各地を回り、演説を行い、 パンフレットを書いた。労働者階級を自由主義派と決別させようとしたラッサールは、やがて反動的なビスマルク公と同盟を結ぶことになる。 1864年、ラッサールは、後に反社会主義法の主唱者となるビスマルクに、普通選挙などの進歩的な政策を直ちに実施するよう何度も密かに訴えた。また、自 身の出版物を警察の差し押さえから保護するよう求めた[22]。ラッサールは、著書『Herr Basitat-Schulze』において、保守派のビスマルクと共闘を試み、「閣下には、この著作が自由主義者と進歩的ブルジョアジー全体の完全な破滅 をもたらすことをお伝えしなければなりません」と宣言した[23]。 [23]ラッサールはビスマルクに、この本の押収を阻止するために司法省に影響力を行使するよう要請した。 その後、この本は警察の干渉を受けずに出版されたが、ビスマルクは他の問題で手一杯であったため、ラッサールからの再度の面会の要請を拒否し、それ以降、 二人が直接接触することはなかった[24]。 エリー・ハレヴィは後にこの状況について書いている: ラッサールはドイツで初めて、ヨーロッパで初めて、社会主義政党を組織することに成功した人物であった。しかし、彼は新興のブルジョア政党を貴族階級より も労働者階級に不利なものとみなし、それゆえ、自由主義者たちが労働者階級を排除し、中産階級を強化する制限された財産に基づく参政権を好んだ時代に、彼 は普通選挙を支持した。このため、ラッサールとビスマルクの間には奇妙な同盟関係が生まれた。1866年にビスマルクが普通選挙を基礎とする北ドイツ盟約 者団を創設したとき、彼はラサールからの直接の助言に基づいて行動していた。そして、1878年以降、彼が「国家社会主義」、「キリスト教社会主義」、 「君主制社会主義」を実践し始めたとき、彼は社会主義指導者から学んだことを忘れていなかったと私は確信している[25]。 党の唯一の目的は、平和的かつ合法的な手段によって平等で普遍的な直接選挙権を獲得することであった[26]。 人格 ラッサールは伝記作家たちから、大衆のために真摯に取り組む一方で、個人的な野心に駆られ、極端な虚栄心を持つ、矛盾した性格の持ち主であったと記憶され ている。実際、ある初期の伝記作家はこう断言している: [彼の虚栄心は)彼の性格の最も顕著な特徴の一つであったが、同時に最も無害な特徴でもあった。彼の虚栄心は、傷つけることも不快にさせることもない種類 のものだった。彼の虚栄心は、孔雀がそうであるように、彼にとって自然なものであった。もし見栄っ張りでなかったら、もっと面白みのない人物になっていた だろう。壇上でも法廷でも、見栄を張った格好で現れた。また、自分を偉人と比較する習慣もあった。ソクラテス、ルター、ロベスピエール、コブデン、ロバー ト・ピール卿などである。ハイネは彼に、彼には自分の業績を誇るだけの理由があると言い、ラッサールはハイネの言葉を信じた[27]。 バートランド・ラッセルはラサールについて、「ラサールほど扇動と組織の力を理解した者はいない......彼の影響力の秘密は、その圧倒的で不遜な意 志、悪を受動的に我慢することへの焦り、自分の力への絶対的な自信にあった。彼の全人格は、知らず知らずのうちに人間となった叙事詩的な神のものであり、 悪の存在に突然目覚め、自分の意志がそれを正すための全能ではないことに驚きながら気づくのである」[28]。 死と遺産  ブレスラウにあるラッサールの墓(現在はヴロツワフの旧ユダヤ人墓地)。 リギ・カルトバードで、ラッサールはヘレーネ・フォン・デンニゲスという若い女性と出会い、1864年の夏に結婚を決めた。彼女は当時ジュネーヴに住んで いたプロテスタントの家庭[29]の娘で、ラサールとは関わりたくないと思っていた。父親は歴史学者で、ヘレーネが彼と会うのを阻止し、ラッサールは激し く抗議した。どうやら強要されていたようで、彼女はすぐにラサールを捨て、別の求婚者、イアンク・ラコヴィツァというワラキアの王子を選んだ。 ラッサールは、ヘレネの父フォン・ドニゲスとラコヴィツァの双方に決闘の申し入れを行い、ラサールはこれを受け入れた。ラッサールはピストルの使用経験が なく、練習も1日しかしていなかった。8月28日の朝、ジュネーブ郊外のカルージュで決闘が行われた。ラサールはラコヴィツァに腹部を撃たれ、3日後の 1864年8月31日に死亡した[30]。決闘の後、ラコヴィツァは病に倒れ、ヘレーネ・フォン・ドニゲスと結婚して間もなく亡くなった。 彼の死後もADAVは存続し、1875年にはドイツ社会民主党の設立に貢献した。 フェルディナント・ラッサールはブレスラウ(現在のポーランド、ヴロツワフ)の旧ユダヤ人墓地に埋葬されている。 |

| Political relations Relations with Marx Lassalle and Marx became friends during the Revolutions of 1848. When the protests were crushed, Lassalle was imprisoned and Marx fled Germany. They continued correspondence through letters, and would not meet again until 1861. In the meantime Marx grew to distrust Lassalle under influence of Engels, who had never much sympathy for him. Marx often responded to Lassalle's warm letters by mirroring this tone, but in his letters to Engels he expressed antipathy towards Lassalle, including calling him "the Jewish nigger Lassalle".[31] Lassalle continued to believe that their friendship was genuine until at least 1862.[32] Franz Mehring called Marx's "attitude to Lassalle [...] the most difficult psychological problem his life offers".[33] The difference in character between the two men presented itself in a clear manner when they had to defend themselves for their support of 1848 revolutions, in front of a jury:[34] Marx refrains from all oratorical flourish; he goes straight to the point, in simple and terse language; sentence by sentence he develops incisively, and with ruthless logic, his own standpoint, and, without any peroration, ends with a summary of the political situation. Anyone would think that Marx’ own personality was in no wise concerned, and that his only business was to deliver a political lecture to the jury. Lassalle’s peroration, on the other hand, lasts almost from beginning to end; he exhausts himself in images – often very beautiful – and superlatives. It is all sentiment, and whether he refers to the cause he represented or to himself, he never speaks to the jury, but to the gallery, to an imaginary mass meeting, and after declaring a vengeance that should be "as tremendous" as "the insult offered the people," he ended with a recitation from Schiller’s Tell. — Eduard Bernstein Also on theoretical and political matters, their opinions diverged. Indeed, Marx's essay Critique of the Gotha Program is written in part as a reaction to Lassalle's ideas within the socialist party of Germany. Lassalle was a German patriot, and supported Prussia in its quest for German unification. In February 1864, Lassalle wrote to Engels that despite being a republican since infancy, "I have come to the conviction that nothing could have a greater future or a more beneficent role than the monarchy, if it could only make up its mind to become a social monarchy. In that case I would passionately bear its banner, and the constitutional theories would be quickly enough thrown into the lumber room".[35] Marx was international, Lassalle was national. Marx regards social equivalence as only feasible in his Social Democratic Republic, from which religion was banned, and his idea is a federation of European Republics. Lassalle saw that the European nationalities were still firmly established, that national ideas were a factor of supreme importance, and that religion would long retain an influence which no one could afford to neglect, and he thought it possible, even under existing political circumstances, to give the initial impulse to a movement for transforming social conditions.[36] — Georg Morris Brandes Relations with Bismarck  Minister President of Prussia Otto von Bismarck, with whom Lassalle started political relations On 11 May 1863, Otto von Bismarck, Minister President of Prussia, wrote a letter to Lassalle. This letter was delivered and the two met face to face within 48 hours.[37] This was the first of several such meetings, during which Bismarck and Lassalle freely exchanged views on matters of common concern. This Bismarck-Lassalle correspondence was not made public until 1927 and was therefore not mentioned by earlier biographers.[37] In September 1878, Bismarck was pressed by Social Democratic representative August Bebel in the Reichstag to provide details about his past relationship with Lassalle, prompting the Chancellor to make the following statement: I saw him, and since my first conversation I have never regretted doing so. [...] I saw him perhaps three or four times altogether. There was never the possibility of our talks taking the form of political negotiations. What could Lassalle have offered me? He had nothing behind him. [...] But he attracted me as an individual. He was one of the most intelligent and likable men I had ever come across. He was very ambitious and by no means a republican. He was very much a nationalist and a monarchist. His ideal was the German Empire, and here was our point of contact. As I have said he was ambitious, on a large scale, and there is perhaps room for doubt as to whether, in his eyes, the German Empire ultimately entailed the Hohenzollern or the Lassalle dynasty. [...] Our talks lasted for hours and I was always sorry when they came to an end.[38] Eduard Bernstein noted that it is highly unlikely that Bismarck was telling the truth about their relation.[39] Political ideas Owing to his premature death by a duel at age 39, just two years after his serious entry into German radical politics, Lassalle's actual contributions to socialist theory are modest. He was remembered by Richard T. Ely, one of the earliest serious scholars of international socialism, as a popularizer of the ideas of others rather than an innovator: Lassalle's writings did not advance materially the theory of social democracy. He drew from Rodbertus and Marx in his economic writings, but he clothed their thoughts in such manner as to enable ordinary laborers to understand them, and this they never could have done without his help. [...] Lassalle's speeches and pamphlets were eloquent sermons on texts taken from Marx. Lassalle gave to Ricardo's law of wages the designation the iron law of wages, and expounded to the laborers its full significance. [...] Laborers were told that this law could be overthrown only by the abolition of the wages system. How Lassalle really thought this was to be accomplished is not so evident.[40] State In contrast with Marx and his adherents, Lassalle rejected the idea that the state was a class-based power structure with the function of preserving existing class relations and destined to wither away in a future classless society. Instead, Lassalle considered the state as an independent entity, an instrument of justice essential for the achievement of the socialist program.[41] Iron law of wages Lassalle accepted the idea first posited by the classical economist David Ricardo that wage rates in the long term tended towards the minimum level necessary to sustain the life of the worker and to provide for his reproduction. In accord with the law of rent, Lassalle coined his own iron law of wages. Lassalle argued that individual measures of self-help by wage workers were destined to failure and that only producers' cooperatives established with the financial aid of the state would make economic improvement of the workers' lives possible.[42] From this, it followed that the political action of the workers to capture the power of the state was paramount and the organization of trade unions to struggle for ephemeral wage improvements is more or less a diversion from the primary struggle. Philosophy Lassalle considered Johann Gottlieb Fichte as "one of the mightiest thinkers of all peoples and ages", praising Fichte's Addresses to the German Nation in a May 1862 speech as "one of the mightiest monuments of fame which our people possesses, and which, in depth and power, far surpass everything of this sort which has been handed down to us from the literature of all time and peoples".[43] |

政治的関係 マルクスとの関係 ラッサールとマルクスは1848年の革命時に友人となった。革命が鎮圧されると、ラッサールは投獄され、マルクスはドイツを脱出した。二人は手紙を通じて 文通を続け、1861年まで再会することはなかった。その間、マルクスはエンゲルスの影響を受けてラサールへの不信感を募らせ、エンゲルスはラサールにあ まり同情しなかった。マルクスはラサールからの温かい手紙にしばしばその口調を反映して返事をしたが、エンゲルスへの手紙ではラサールを「ユダヤ人の黒人 のラサール」と呼ぶなど、反感を表明していた[31]。 二人の性格の違いは、1848年の革命を支持したことを陪審員の前で弁明しなければならなかったとき、明確な形で現れた[34]。 マルクスは、演説家としての華美さをいっさい排し、単純で簡潔な言葉で要点を端的に述べ、一文一文、冷酷な論理で自らの立場を鋭く展開し、何の弁明もな く、政治状況の要約で締めくくる。誰が読んでも、マルクス自身の人格には何の関心もなく、彼の唯一の仕事は陪審員に政治的な講義をすることだと思うだろ う。一方、ラッサールの述懐はほとんど最初から最後まで続き、彼はイメージ(多くの場合、非常に美しい)と最上級の表現に終始する。そして、「民衆を侮辱 した」のと同じくらい「途方もない」復讐を宣言した後、シラーの『テル』の朗読で締めくくった。 - エドゥアルド・ベルンシュタイン 理論的、政治的な問題についても、二人の意見は分かれた。実際、マルクスのエッセイ『ゴータ綱領批判』は、ドイツの社会主義党内におけるラッサールの思想 への反発として書かれた部分もある。ラッサールはドイツの愛国者であり、ドイツ統一を目指すプロイセンを支持していた。1864年2月、ラッサールはエン ゲルスに宛てて、幼い頃から共和主義者であったにもかかわらず、「君主制ほど大きな未来や有益な役割を持つものはないと確信するに至った。その場合、私は 情熱的にその旗を掲げ、立憲主義理論はすぐに材木庫に投げ込まれるだろう」[35]。 マルクスは国際的であったが、ラッサールは国内的であった。マルクスは、社会的等価性は宗教が禁止された社会民主共和国においてのみ実現可能であり、彼の 構想はヨーロッパ共和国の連合体であると考えた。ラッサールは、ヨーロッパの民族性はまだ強固に確立されており、民族的思想は至極重要な要素であり、宗教 は長い間、誰も無視することのできない影響力を保持していることを見抜いており、既存の政治状況の下でも、社会状況を変革する運動に初期衝動を与えること は可能だと考えていた[36]。 - ゲオルク・モリス・ブランデス ビスマルクとの関係  プロイセン公使オットー・フォン・ビスマルクと政治的関係を結ぶ。 1863年5月11日、プロイセン公使オットー・フォン・ビスマルクはラサール宛に手紙を書いた。この手紙は48時間以内に配達され、二人は対面した [37]。このような会談は何度か行われ、その中でビスマルクとラッサールは共通の関心事について自由に意見を交換した。このビスマルクとラッサールの往 復書簡は1927年まで公開されなかったため、それ以前の伝記作家は言及していない[37]。 1878年9月、ビスマルクは帝国議会で社会民主党のアウグスト・ベーベル議員から、ラサールとの過去の関係について詳しく説明するよう迫られ、首相は次 のように述べた: 私は彼に会いましたが、最初の会話以来、そのことを後悔したことはありません。[......)彼と会ったのは全部で3、4回だろう。政治的な交渉という 形で話をする可能性はなかった。ラサールが私に何を提案できたというのだろうか。彼には何もなかった。[しかし、彼は個人として私を惹きつけた。彼は私が 出会った中で最も知的で好感の持てる男性の一人だった。彼は非常に野心的で、決して共和主義者ではなかった。彼は非常にナショナリストであり、君主主義者 だった。彼の理想はドイツ帝国であり、ここが私たちの接点だった。彼の目には、ドイツ帝国が最終的にホーエンツォレルン朝を意味するのか、それともラサー ル朝を意味するのかについては、おそらく疑問の余地があるだろう。[......)私たちの話は何時間も続いたが、話が終わるときはいつも残念だった」 [38]。 エドゥアルド・ベルンシュタインは、ビスマルクが二人の関係について真実を語っていた可能性は極めて低いと指摘している[39]。 政治思想 ドイツの急進政治に本格的に参入してわずか2年後、39歳で決闘によって早世したため、ラッサールの社会主義理論への実際の貢献は控えめである。国際社会 主義の最も初期の本格的な研究者の一人であるリチャード・T・イーリー(Richard T. Ely)は、彼は革新者ではなく、他者の思想の普及者として記憶している: ラサールの著作は、社会民主主義の理論を実質的に前進させるものではなかった。ラサールの著作は、社会民主主義の理論を実質的に前進させるものではなかっ た。彼は経済学の著作でロドベルトゥスとマルクスから学んだが、普通の労働者が理解できるように彼らの思想を衣服にしたのであり、これは彼の助けなしには 決してできなかったことである。[中略)ラサールの演説やパンフレットは、マルクスから引用した文章をもとにした雄弁な説教であった。ラサールはリカルド の賃金法則に賃金の鉄則という呼称を与え、労働者にその完全な意義を説いた。[中略)労働者は、この法則は賃金制度の廃止によってのみ打倒できると告げら れた。ラサールが本当にこれをどのように達成しようと考えていたかは、それほど明らかではない。 国家 マルクスやその支持者たちとは対照的に、ラッサールは、国家が階級に基づく権力構造であり、既存の階級関係を維持する機能を持ち、将来の無階級社会では衰 退する運命にあるという考えを否定した。その代わりに、ラッサールは国家を独立した存在であり、社会主義プログラムの達成に不可欠な正義の道具であると考 えた[41]。 賃金の鉄則 ラサールは、古典派経済学者デイヴィッド・リカルドが最初に提唱した、長期的には賃金は労働者の生活を維持し、その再生産を賄うために必要な最低水準に向 かう傾向にあるという考え方を受け入れた。ラサールは賃料の法則と一致させ、独自の賃金の鉄則を作り出した。ラッサールは、賃金労働者による個々の自助努 力は失敗する運命にあり、国家の財政的援助を受けて設立された生産者協同組合のみが労働者の生活の経済的改善を可能にすると主張した[42]。このことか ら、国家権力を掌握するための労働者の政治的行動が最も重要であり、刹那的な賃金改善のために闘う労働組合の組織は、多かれ少なかれ主要な闘いからの転用 であることが導かれた。 哲学 ラッサールはヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテを「あらゆる民族と時代の最も偉大な思想家の一人」とみなし、1862年5月の演説でフィヒテの『ドイツ国民 への演説』を「わが民族が有する最も偉大な名声の記念碑の一つであり、その深さと力において、あらゆる時代と民族の文学からわれわれに伝えられてきたこの 種のあらゆるものをはるかに凌駕している」と賞賛した[43]。 |

| Works German editions Die Philosophie Herakleitos des Dunklen von Ephesos (The Philosophy of Heraclitus the Obscure of Ephesus) Berlin: Franz Duncker, 1858. Der italienische Krieg und die Aufgabe Preussens: eine Stimme aus der Demokratie (The Italian War and the Tasks of Prussia: A Voice of Democracy). Berlin: Franz Duncker, 1859. Das System der erworbenen Rechte (The System of Acquired Rights). Two volumes. Leipzig: 1861. Über Verfassungswesen: zwei Vorträge und ein offenes Sendschreiben (On The Essence of a Constitution: Two Lectures and an Open Letter). Berlin: 1862. Offenes Antwortschreiben an das Zentralkomitee zur Berufung eines Allgemeinen Deutschen Arbeiter-Kongresses zu Leipzig (Open Letter Answering the Central Committee on the Convening of a General German Workers' Congress in Leipzig). Zürich: Meyer and Zeller, 1863. Zur Arbeiterfrage: Lassalle's Rede bei der am 16. April in Leipzig abgehaltenen Arbeiterversammlung nebst Briefen der Herren Professoren Wuttke und Dr. Lothar Bucher. (On the Labor Problem: Lassalle's Speech on the 16th of April [1863] at a Leipzig Workers' Meeting, Together with the Letters of Professor Wuttke and Dr. Lothar Bucher). Leipzig: 1863. Herr Bastiat-Schulze von Delitzsch, der ökonomische Julian, oder Kapital und Arbeit (Mr. Bastiat-Schulze von Delitzsch, the Economic Julian, or, Capital and Labour). Berlin: Reinhold Schlingmann, 1864. Reden und Schriften (Speeches and Writings). In three volumes. New York: Wolff and Höhne, n.d. [1883]. Gesammelte Reden und Schriften (Collected Speeches and Writings). In 12 volumes. Berlin: P. Cassirer, 1919–1920. vol. 1 | vol. 2 | vol. 3 | vol. 4 | vol. 5 | vol. 6 | vol. 7 | vol. 8 | vol. 9 | vol. 10 | vol. 11 | vol. 12 English translations The Working Man's Programme: An Address. Edward Peters, trans. London: The Modern Press, 1884. What is Capital? F. Keddell, trans. New York: New York Labor News Co., 1900. Lassalle's Open Letter to the National Labor Association of Germany. John Ehmann and Fred Bader, trans. New York: International Library Publishing, 1901. Originally published in US in 1879. Franz von Sickingen: A Tragedy in Five Acts. Daniel DeLeon, trans. New York: New York Labor News, 1904. Voices of Revolt, Volume 3: Speeches of Ferdinand Lassalle with a Biographical Sketch. Introduction by Jakob Altmaier. New York: International Publishers, 1927. |

作品 ドイツ語版 『エフェソスのヘラクレイトスの哲学』(The Philosophy of Heraclitus the Obscure of Ephesus) ベルリン:フランツ・ダンカー、1858年。 『イタリア戦争とプロイセンの課題:民主主義からの声』(The Italian War and the Tasks of Prussia: A Voice of Democracy) ベルリン:フランツ・ダンカー、1859年。 獲得した権利の体系(The System of Acquired Rights)。2巻。ライプツィヒ:1861年。 憲法について:2つの講演と公開書簡(On The Essence of a Constitution: Two Lectures and an Open Letter)。ベルリン:1862年。 ライプツィヒでのドイツ労働者総会議の招集に関する中央委員会への公開回答書(Open Letter Answering the Central Committee on the Convening of a General German Workers' Congress in Leipzig)。チューリヒ:マイヤー・アンド・ツェラー、1863年。 労働問題について:4月16日にライプツィヒで開催された労働者集会でラッサールが行った演説、およびヴットケ教授とロタール・ブッハー博士の手紙(On the Labor Problem: Lassalle『s Speech on the 16th of April [1863] at a Leipzig Workers』 Meeting, Together with the Letters of Professor Wuttke and Dr. Lothar Bucher)。ライプツィヒ:1863年。 バスティア・シュルツェ・フォン・デリッツシュ、経済学者ジュリアン、あるいは資本と労働(Mr. Bastiat-Schulze von Delitzsch, the Economic Julian, or, Capital and Labour)。ベルリン:ラインホルト・シュリングマン、1864年。 演説と著作(Speeches and Writings)。3巻。ニューヨーク:Wolff and Höhne、発行年不明 [1883年]。 演説と著作集(Collected Speeches and Writings)。12巻。ベルリン:P. Cassirer、1919年~1920年。 第 1 巻 | 第 2 巻 | 第 3 巻 | 第 4 巻 | 第 5 巻 | 第 6 巻 | 第 7 巻 | 第 8 巻 | 第 9 巻 | 第 10 巻 | 第 11 巻 | 第 12 巻 英語訳 『労働者のプログラム:演説』 エドワード・ピーターズ訳。ロンドン:モダン・プレス、1884 年。 資本とは何か?F. ケデル訳。ニューヨーク:ニューヨーク・レイバー・ニュース社、1900年。 ラッサールのドイツ全国労働協会への公開書簡。ジョン・エマンとフレッド・ベイダー訳。ニューヨーク:インターナショナル・ライブラリー・パブリッシング、1901年。1879年に米国で初版発行。 フランツ・フォン・ジッキンゲン:5幕の悲劇。ダニエル・デレオン訳。ニューヨーク:ニューヨーク・レイバー・ニュース、1904年。 反乱の声、第3巻:フェルディナンド・ラッサールの演説と略伝。ヤコブ・アルトマイヤーによる序文。ニューヨーク:インターナショナル・パブリッシャーズ、1927年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Lassalle |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099