フィリピノ語

Filipino language

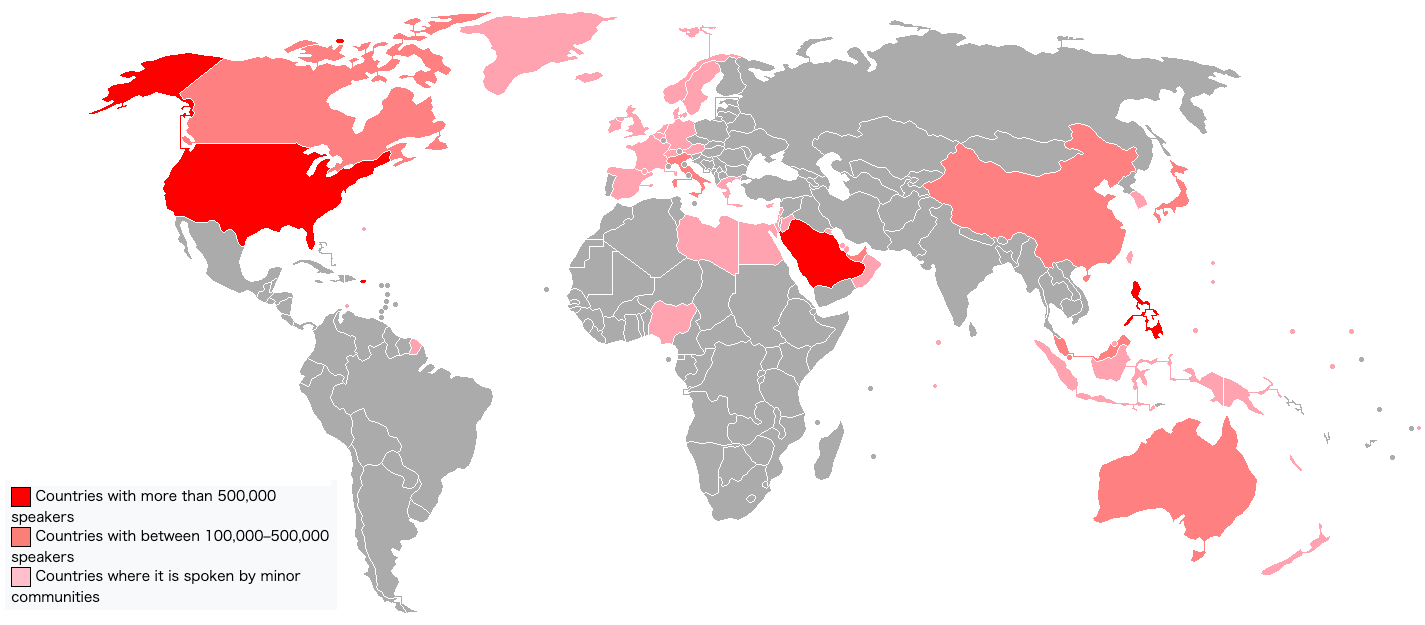

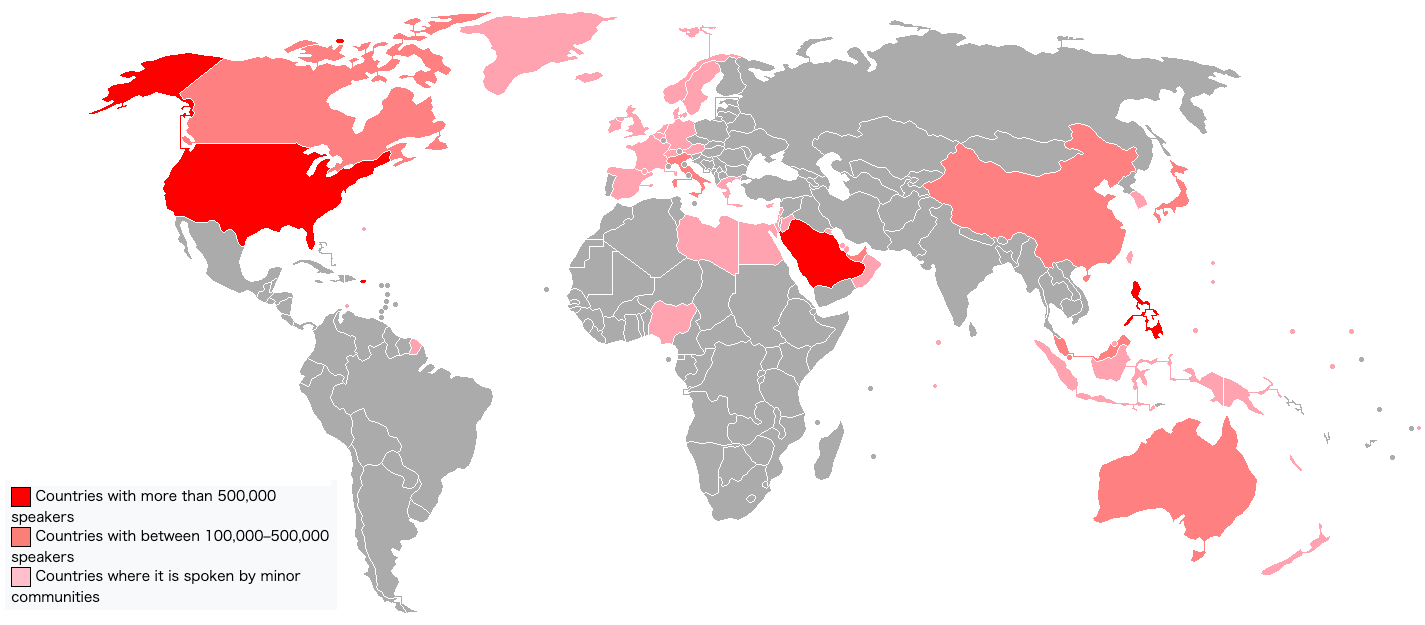

☆ フィリピノ語(英語: /ˌfɪləˈpiːnoʊ/ ⓘ FIL-ə-PEE-noh;[1] ウィカン・フィリピノ語、[ˈwikɐŋ filiˈpino̞])は、 フィリピンの国語(Wikang pambansa / Pambansang wika)であり、主要な共通語(Karaniwang wika)であり、英語とともにフィリピンの2つの公用語(Wikang opisyal/Opisyal na wika)の1つである。 [2] これはあくまで事実上の標準形であり、マニラ首都圏やその他の都市部で話され、書き表されるタガログ語の標準形ではない。[3][4] 1987年の憲法では、フィリピノ語はフィリピンの他の言語によってさらに豊かにされ、発展することが義務付けられている。[5] フィリピン語は、他のオーストロネシア語族の言語と同様に、動詞-主語-目的語の語順を一般的に使用するが、主語-動詞-目的語の語順も使用できる。フィ リピン語は、フィリピン諸語に共通する形態統語的整列のトリガーシステムに従う。語順は主辞先行である。膠着語であるが、屈折も示す。声調言語ではなく、 ピッチアクセント言語および音節時間言語であると考えられる。9つの基本的な品詞がある。

| Filipino (English:

/ˌfɪləˈpiːnoʊ/ ⓘ FIL-ə-PEE-noh;[1] Wikang Filipino, [ˈwikɐŋ

filiˈpino̞]) is the national language (Wikang pambansa / Pambansang

wika) of the Philippines, the main lingua franca (Karaniwang wika), and

one of the two official languages (Wikang opisyal/Opisyal na wika) of

the country, along with English.[2] It is only a de facto and not a de

jure standardized form of the Tagalog language,[3] as spoken and

written in Metro Manila, the National Capital Region, and in other

urban centers of the archipelago.[4] The 1987 Constitution mandates

that Filipino be further enriched and developed by the other languages

of the Philippines.[5] Filipino, like other Austronesian languages, commonly uses verb-subject-object order, but can also use subject-verb-object order. Filipino follows the trigger system of morphosyntactic alignment that is common among Philippine languages. It has head-initial directionality. It is an agglutinative language but can also display inflection. It is not a tonal language and can be considered a pitch-accent language and a syllable-timed language. It has nine basic parts of speech. |

フィリピノ語(英語: /ˌfɪləˈpiːnoʊ/ ⓘ

FIL-ə-PEE-noh;[1] ウィカン・フィリピノ語、[ˈwikɐŋ filiˈpino̞])は、 フィリピンの国語(Wikang

pambansa / Pambansang wika)であり、主要な共通語(Karaniwang

wika)であり、英語とともにフィリピンの2つの公用語(Wikang opisyal/Opisyal na wika)の1つである。 [2]

これはあくまで事実上の標準形であり、マニラ首都圏やその他の都市部で話され、書き表されるタガログ語の標準形ではない。[3][4]

1987年の憲法では、フィリピノ語はフィリピンの他の言語によってさらに豊かにされ、発展することが義務付けられている。[5] フィリピン語は、他のオーストロネシア語族の言語と同様に、動詞-主語-目的語の語順を一般的に使用するが、主語-動詞-目的語の語順も使用できる。フィ リピン語は、フィリピン諸語に共通する形態統語的整列のトリガーシステムに従う。語順は主辞先行である。膠着語であるが、屈折も示す。声調言語ではなく、 ピッチアクセント言語および音節時間言語であると考えられる。9つの基本的な品詞がある。 |

| Background The Philippines is a multilingual state with 175 living languages originating and spoken by various ethno-linguistic groups. Many of these languages descend from a common Malayo-Polynesian language due to the Austronesian migration from Taiwan. The common Malayo-Polynesian language split into different languages, and usually through the Malay language, the lingua franca of maritime Southeast Asia, these were able to adopt terms that ultimately originate from other languages such as Japanese, Hokkien, Sanskrit, Tamil, and Arabic. The Malay language was generally used by the ruling classes and the merchants from the states and various cultures in the Philippine archipelago for international communication as part of maritime Southeast Asia. In fact, Filipinos first interacted with the Spaniards using the Malay language. In addition to this, 16th-century chroniclers of the time noted that the kings and lords in the islands usually spoke around five languages.[citation needed]  Spanish intrusion into the Philippine islands started in 1565 with the fall of Cebu. The eventual capital established by Spain for its settlement in the Philippines was Manila, situated in a Tagalog-speaking region, after the capture of Manila from the Muslim Kingdom of Luzon ruled by Raja Matanda with the heir apparent Raja Sulayman and the Hindu-Buddhist Kingdom of Tondo ruled by Lakan Dula. After its fall to the Spaniards, Manila was made the capital of the Spanish settlement in Asia due to the city's commercial wealth and influence, its strategic location, and Spanish fears of raids from the Portuguese and the Dutch.[6] The first dictionary of Tagalog, published as the Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, was written by the Franciscan Pedro de San Buenaventura,[7] and published in 1613 by the "Father of Filipino Printing" Tomás Pinpin in Pila, Laguna. A latter book of the same name was written by Czech Jesuit missionary Paul Klein (known locally as Pablo Clain) at the beginning of the 18th century. Klein spoke Tagalog and used it actively in several of his books. He wrote a dictionary, which he later passed to Francisco Jansens and José Hernández.[8] Further compilation of his substantial work was prepared by Juan de Noceda and Pedro de Sanlúcar and published as Vocabulario de la lengua tagala in Manila in 1754 and then repeatedly[9] re-edited, with the latest edition being published in 2013 in Manila.[10] Spanish served in an official capacity as language of the government during the Spanish period. Spanish played a significant role in unifying the Philippines, a country made up of over 7,000 islands with a multitude of ethnicities, languages, and cultures. Before Spanish rule, the archipelago was not a unified nation, but rather a collection of independent kingdoms, sultanates, and tribes, each with its own language and customs. During the American colonial period, English became an additional official language of the Philippines alongside Spanish; however, the number of speakers of Spanish steadily decreased.[11] The United States initiated policies that led to the gradual removal of Spanish from official use in the Philippines. This was not done through an outright ban, but rather through a strategic shift in language policy that promoted English as the primary language for education, governance, and law. Spanish was designated an optional and voluntary language under the 1987 Constitution, along with Arabic. |

背景 フィリピンは多言語国家であり、さまざまな民族言語グループによって175の言語が生み出され、話されている。これらの言語の多くは、台湾からのオースト ロネシア語族の移住により、共通のマライ・ポリネシア語から派生したものである。共通のマライ・ポリネシア語は異なる言語に分岐し、通常は東南アジアの海 洋地域の共通語であるマレー語を通じて、日本語、福建語、サンスクリット語、タミル語、アラビア語など、最終的には他の言語に由来する用語を採用すること が可能となった。マレー語は、東南アジアの海洋地域の一部として、フィリピン諸島内の各州やさまざまな文化圏の支配階級や商人たちによって、国際的なコ ミュニケーションに一般的に使用されていた。実際、フィリピン人が最初にスペイン人と交流したのはマレー語を使用してのことだった。さらに、16世紀の当 時の年代記編者たちは、島々の王や領主たちは通常5つの言語を話していたと記している。  スペインによるフィリピン諸島への侵入は、1565年のセブ陥落から始まった。スペインがフィリピンに定住するために最終的に首都として選んだのは、ラ ジャ・マタンダが統治するイスラム教のルソン王国と、ラカン・ドゥラが統治するヒンドゥー教・仏教のトンド王国の跡継ぎであるラジャ・スレイマンが支配す るタガログ語圏に位置するマニラであった。スペイン人による陥落後、マニラは、その商業的な富と影響力、戦略的な立地、ポルトガルやオランダからの襲撃に 対するスペインの懸念から、アジアにおけるスペインの植民地支配の首都とされた。 タガログ語の最初の辞書は『Vocabulario de la lengua tagala』として出版され、フランシスコ会のペドロ・デ・サン・ブエナヴェンチュラによって書かれた。同じタイトルの後続の書籍は、18世紀初頭に チェコ出身のイエズス会宣教師ポール・クライン(現地ではパブロ・クレインとして知られる)によって書かれた。クラインはタガログ語を話し、いくつかの著 書で積極的に使用した。彼は辞書を執筆し、後にフランシスコ・ヤンセンズとホセ・エルナンデスに引き継がれた。[8] 彼の膨大な著作のさらなる編集はフアン・デ・ノセダとペドロ・デ・サンルーカルによって準備され、1754年にマニラで『Vocabulario de la lengua tagala』として出版された。その後、繰り返し[9]再編集され、最新版は2013年にマニラで出版された。[10] スペイン語はスペイン統治時代には公用語として政府で使用されていた。 7,000以上の島々からなり、多様な民族、言語、文化から構成されるフィリピンを統一するにあたり、スペイン語は重要な役割を果たした。 スペインによる支配以前、この諸島は統一された国民国家ではなく、それぞれ独自の言語や習慣を持つ独立した王国、スルタン国、部族の集合体であった。アメ リカによる植民地時代には、スペイン語に加えて英語がフィリピンの公用語となったが、スペイン語話者の数は着実に減少した。[11] アメリカは、フィリピンにおけるスペイン語の公式使用を徐々に排除する政策を開始した。これは、スペイン語を全面的に禁止するという形ではなく、むしろ教 育、統治、法律の主要言語として英語を推進するという言語政策の戦略的転換によって行われた。スペイン語は、1987年の憲法により、アラビア語とともに 任意選択の言語として指定された。 |

| Designation as the national language While Spanish and English were considered "official languages" during the American colonial period, there existed no "national language" initially. Article XIII, section 3 of the 1935 constitution establishing the Commonwealth of the Philippines provided that: The National Assembly shall take steps toward the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages. Until otherwise provided by law, English and Spanish shall continue as official languages. On November 13, 1936, the first National Assembly of the Philippine Commonwealth approved Commonwealth Act No. 184; creating the Institute of National Language (later the Surián ng Wikang Pambansâ or SWP) and tasking it with making a study and survey of each existing native language, hoping to choose which was to be the base for a standardized national language.[12] Later, President Manuel L. Quezon later appointed representatives for each major regional language to form the NLI. Led by Jaime C. De Veyra, who sat as the chair of the Institute and as the representative of Samar-Leyte-Visayans, the Institute's members were composed of Santiago A. Fonacier (representing the Ilokano-speaking regions), Filemon Sotto (the Cebu-Visayans), Casimiro Perfecto (the Bikolanos), Felix S. Sales Rodriguez (the Panay-Visayans), Hadji Butu (the languages of Muslim Filipinos), and Cecilio Lopez (the Tagalogs).[13] The Institute of National Language adopted a resolution on November 9, 1937 recommending Tagalog to be basis of the national language. On December 30, President Quezon issued Executive Order No. 134, s. 1937, approving the adoption of Tagalog as the language of the Philippines, and proclaimed the national language of the Philippines so based on the Tagalog language. Quezon himself was born and raised in Baler, Aurora, which is a native Tagalog-speaking area. The order stated that it would take effect two years from its promulgation.[14] On December 31 of the same year, Quezon proclaimed Tagalog as the basis of the Wikang Pambansâ (National Language) giving the following factors:[13] Tagalog is widely spoken and is the most understood language in all the Philippine Regions. It is not divided into smaller daughter languages, as Visayan or Bikol are. Its literary tradition is the richest of all Philippine languages, the most developed and extensive (mirroring that of the Tuscan language vis-à-vis Italian). From at least before 1935, more books were written in Tagalog than in any other Philippine language. Tagalog has always been the language of Manila, the political centre of the Philippines in much of its history as a multiethnic country and a considerable economic centre of the Philippine islands since time immemorial. The Katipunan generally used the Tagalog language for its operations, and the Philippine Revolution and the First Philippine Republic operationally used Spanish afterwards, but many of the leaders of the revolution spoke Tagalog, more so among ethnic groups from central to southern Luzon including some adjacent islands. Tagalog also became a choice for some non-Tagalog Filipino revolutionary leaders and nationalists in some of their publications, especially if they were to publish in Manila. The Katipunan extended the meaning of the term Tagalog to all people native to the Philippine islands, including Cebuanos, Ilocanos, Kapampangans, etc, and extended the term Katagalugan to the whole Philippine islands not just native Tagalog-speaking areas, building a Tagalog Republic, the reason being a unified opposition against Spanish hegemony. On June 7, 1940, the Philippine National Assembly passed Commonwealth Act No. 570 declaring that the Filipino national language would be considered an official language effective July 4, 1946[15] (coinciding with the country's expected date of independence from the United States). That same year, the Balarílà ng Wikang Pambansâ (English: Grammar of the National Language) of grammarian Lope K. Santos introduced the 20-letter Abakada alphabet which became the standard of the national language.[16] The alphabet was officially adopted by the Institute for the Tagalog-Based National Language. |

国語としての指定 スペイン語と英語は、アメリカ植民地時代には「公用語」とされていたが、当初は「国語」は存在していなかった。1935年のフィリピン連邦を定めた憲法第13条3項では、次のように規定されている。 国民議会は、現存する土着言語のひとつを基盤とした共通の国語の開発と採用に向けた措置を講じるものとする。法律で別途規定されるまでは、英語とスペイン語は公用語として存続するものとする。 1936年11月13日、フィリピン連邦の第1回国民議会は連邦法第184号を承認し、国立言語研究所(後のSurián ng Wikang PambansâまたはSWP)を設立し、標準化された国語のベースとなる言語を選択するために、現存する各々の土着言語の研究と調査を行うよう命じた。 [12]その後、マニュエル・ケソン大統領は 各主要地域言語の代表者たちを任命し、NLIを結成した。 ハイメ・C・デ・ベイラが代表を務め、同研究所の議長とサマール・レイテ・ビサヤ諸島出身者の代表を兼任した。研究所のメンバーは、サンティアゴ・A・ (イロカノ語話者地域代表)、フィレモン・ソット(セブ・ビサヤ人)、カシミロ・パーフェクト(ビコラノ人)、フェリックス・S・セールス・ロドリゲス (パナイ・ビサヤ人)、ハジ・ブトゥ(イスラム系フィリピン人の言語)、セシリオ・ロペス(タガログ人)で構成されていた。[13] 1937年11月9日、国家語研究所はタガログ語を国語の基礎とすることを推奨する決議を採択した。12月30日、ケソン大統領は行政命令第134号 (1937年)を発令し、フィリピンの言語としてタガログ語を採用することを承認し、フィリピンの国語をタガログ語を基礎とするものとした。ケソン自身 は、タガログ語が母語として話される地域であるアウロラ州バレルで生まれ育った。この命令は、公布から2年後に発効すると定めていた。[14] 同年12月31日、ケソンはタガログ語を「ウィカン・パンバンサ(国語)」の基礎と定め、以下の理由を挙げた。 タガログ語は広く話されており、フィリピン全地域で最も理解されている言語である。 ビサヤ語やビコール語のように、より小さな言語に分かれていない。 文学の伝統はフィリピン諸語の中で最も豊かで、最も発達し、広範である(イタリア語に対するトスカーナ語のそれと類似している)。少なくとも1935年以前から、タガログ語で書かれた書籍はフィリピン諸語の他のどの言語よりも多かった。 タガログ語は、多民族国家として長い歴史を持つフィリピンにおいて、政治の中心地であるマニラの言語であり、フィリピン諸島の経済の中心地でもあった。 カティプナンは通常、タガログ語を活動に使用し、フィリピン革命およびその後のフィリピン第一共和国はスペイン語を使用したが、革命の指導者の多くはタガ ログ語を話し、特にルソン島中部から南部、および周辺の島々の出身者にはその傾向が強かった。タガログ語は、一部のタガログ語話者ではないフィリピン人革 命指導者やナショナリストの出版物でも使用され、特にマニラで出版される場合はその傾向が強かった。カティプナンはタガログという言葉をセブ人、イロコス 人、パンパンガ人などフィリピン諸島に先住するすべての人々を指すように拡大解釈し、また、カタルグアンという言葉をタガログ語話者の先住地域だけでなく フィリピン諸島全体を指すように拡大解釈し、スペインの覇権に対する統一された反対勢力としてタガログ共和国を樹立した。 1940年6月7日、フィリピン国民議会は連邦法第570号を可決し、フィリピンの国語を1946年7月4日(米国からの独立が予想される同国の記念日) より公用語とすることを宣言した[15]。同じ年、文法学者ロペ・K・サントス(Lope K. Santos)が著した『フィリピン語文法(Balarílà ng Wikang Pambansâ)』(英語名:Grammar of the National Language)で、20文字の「アバカダ・アルファベット(Abakada alphabet)」が紹介され、これがフィリピンの国語の標準となった。[16] このアルファベットは、タガログ語を基盤とするフィリピン国語協会(Institute for the Tagalog-Based National Language)によって正式に採用された。 |

| Further history In 1959, the language became known as Pilipino in an effort to disassociate it from the Tagalog ethnic group.[17] The changing of the name did not, however, result in universal acceptance among non-Tagalogs, especially Cebuanos who had previously not accepted the 1937 selection.[18] The 1960s saw the rise of the purist movement where new words were being coined to replace loanwords. This era of "purism" by the SWP sparked criticisms by a number of persons. Two counter-movements emerged during this period of "purism": one campaigning against Tagalog and the other campaigning for more inclusiveness in the national language. In 1963, Negros Occidental congressman Innocencio V. Ferrer took a case reaching the Supreme Court questioning the constitutionality of the choice of Tagalog as the basis of the national language (a case ruled in favor of the national language in 1970). Accusing the national language as simply being Tagalog and lacking any substantial input from other Philippine languages, Congressman Geruncio Lacuesta eventually led a "Modernizing the Language Approach Movement" (MOLAM). Lacuesta hosted a number of "anti-purist" conferences and promoted a "Manila Lingua Franca" which would be more inclusive of loanwords of both foreign and local languages. Lacuesta managed to get nine congressmen to propose a bill aiming to abolish the SWP with an Akademia ng Wikang Filipino, to replace the balarila with a Gramatica ng Wikang Filipino, to replace the 20-letter Abakada with a 32-letter alphabet, and to prohibit the creation of neologisms and the respelling of loanwords. This movement quietened down following the death of Lacuesta.[19][18][20] The national language issue was revived once more during the 1971 Constitutional Convention. While there was a sizable number of delegates in favor of retaining the Tagalog-based national language, majority of the delegates who were non-Tagalogs were even in favor of scrapping the idea of a "national language" altogether.[21] A compromise was reached and the wording on the 1973 constitution made no mention of dropping the national language Pilipino or made any mention of Tagalog. Instead, the 1973 Constitution, in both its original form and as amended in 1976, designated English and Pilipino as official languages and provided for development and formal adoption of a common national language, termed Filipino, to replace Pilipino. Neither the original nor the amended version specified either Tagalog or Pilipino as the basis for Filipino; Instead, tasking the National Assembly to:[22][23] take steps toward the development and formal adoption of a common national language to be known as Filipino. In 1987, a new constitution designated Filipino as the national language and, along with English, as an official language.[24] That constitution included several provisions related to the Filipino language.[2] Article XIV, Section 6, omits any mention of Tagalog as the basis for Filipino, and states that:[2] as Filipino evolves, it shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages. And also states in the article: Subject to provisions of law and as the Congress may deem appropriate, the Government shall take steps to initiate and sustain the use of Filipino as a medium of official communication and as language of instruction in the educational system. and: The regional languages are the auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein. Section 17(d) of Executive Order 117 of January 30, 1987 renamed the Institute of National Language as Institute of Philippine Languages.[25] Republic Act No. 7104, approved on August 14, 1991, created the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (Commission on the Filipino Language, or KWF), superseding the Institute of Philippine Languages. The KWF reports directly to the President and was tasked to undertake, coordinate and promote researches for the development, propagation and preservation of Filipino and other Philippine languages.[26] On May 13, 1992, the commission issued Resolution 92-1, specifying that Filipino is the indigenous written and spoken language of Metro Manila and other urban centers in the Philippines used as the language of communication of ethnic groups.[27] However, as with the 1973 and 1987 Constitutions, 92-1 went neither so far as to categorically identify, nor so far as to dis-identify this language as Tagalog. Definite, absolute, and unambiguous interpretation of 92–1 is the prerogative of the Supreme Court in the absence of directives from the KWF, otherwise the sole legal arbiter of the Filipino language.[original research?] Filipino was presented and registered with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), by Ateneo de Manila University student Martin Gomez, and was added to the ISO registry of languages on September 21, 2004, with it receiving the ISO 639-2 code fil.[28] On August 22, 2007, it was reported that three Malolos City regional trial courts in Bulacan decided to use Filipino, instead of English, in order to promote the national language. Twelve stenographers from Branches 6, 80 and 81, as model courts, had undergone training at Marcelo H. del Pilar College of Law of Bulacan State University following a directive from the Supreme Court of the Philippines. De la Rama said it was the dream of Chief Justice Reynato Puno to implement the program in other areas such as Laguna, Cavite, Quezon, Aurora, Nueva Ecija, Batangas, Rizal, and Metro Manila, all of which mentioned are natively Tagalog-speaking.[29] |

さらに歴史を遡ると 1959年には、タガログ族の民族グループとの関連を断つため、この言語は「ピリピノ語」と呼ばれるようになった。[17] しかし、名称の変更は、タガログ族以外のグループ、特に1937年の選択を以前から受け入れていなかったセブアノ人たちの間で、必ずしも広く受け入れられ る結果にはならなかった。[18] 1960年代には、外来語に代わる新しい単語を造る純粋主義運動が台頭した。SWPによる「純粋主義」の時代は、多くの人格による批判を招いた。この「純 粋主義」の時代には、2つの反対運動が起こった。1つはタガログ語に反対する運動、もう1つは国民語にさらに多くの言語を取り入れることを求める運動であ る。1963年には、ニグロス・オクシデンタル州選出の下院議員イノセンシオ・V・フェレールが、国民語の基盤としてタガログ語が選ばれたことの合憲性を 問う訴訟を最高裁に持ち込んだ(1970年に国民語支持の判決が下った)。国民語が単にタガログ語であり、フィリピンの他の言語からの実質的な貢献が欠け ていると非難した下院議員ジェルンシオ・ラクエスタは、最終的に「言語近代化アプローチ運動」(MOLAM)を主導した。ラクエスタは「反純粋主義」の会 議を数多く主催し、外国語と現地語の両方の借用語をより多く取り入れる「マニラ・リングアフランカ」を推進した。ラクエスタは、アカデミア・ング・ウィカ ン・フィリピノ(Akademia ng Wikang Filipino)によるSWPの廃止、バラリラ(balarila)をグラマティカ・ング・ウィカン・フィリピノ(Gramatica ng Wikang Filipino)に置き換え、20文字のアバカダ(Abakada)を32文字のアルファベットに置き換え、新語の創出と借用語の綴りの変更を禁止する ことを目的とした法案を提出するよう、9人の議員を説得した。ラクエスタの死後、この運動は沈静化した。[19][18][20] 1971年の憲法制定会議で、国語問題は再び浮上した。タガログ語をベースとする国語の維持を支持する代議員の数はかなりの数に上ったが、タガログ語話者 ではない代議員の大多数は、「国語」という概念そのものを完全に廃止することに賛成していた。[21] 妥協案がまとまり、1973年憲法の文言には国語ピリピノの廃止について一切言及されておらず、タガログ語についても言及されていない。代わりに、 1973年憲法は、当初の形でも1976年の改正後も、英語とピリピノ語を公用語と定め、ピリピノ語に代わる共通の国語としてフィリピノ語を開発し、正式 に採用することを規定した。当初の形でも改正後も、フィリピノ語の基盤としてタガログ語またはピリピノ語のどちらかを指定したわけではなく、代わりに国民 議会に次のような任務を課した。 フィリピノとして知られる共通の国民語の開発と正式な採用に向けた措置を講じる。 1987年、新憲法はフィリピノを国語とし、英語とともに公用語として指定した。[24] その憲法にはフィリピノ語に関連するいくつかの規定が含まれていた。[2] 第14条6項では、フィリピノの基盤としてのタガログ語に関する言及を一切省略し、次のように規定している。 フィリピノ語の発展に伴い、フィリピン語およびその他の既存の言語を基礎として、さらに発展させ、充実させるものとする。 また、同条には次のように記されている。 法律の規定に従い、議会が適切とみなす場合、政府は、公式なコミュニケーションの手段および教育制度における指導言語としてフィリピノ語の使用を開始し、維持するための措置を講じるものとする。 そして、 地方言語は、地方における補助公用語であり、補助教育言語としての役割を果たす。 1987年1月30日付の大統領令第117号第17項(d)により、フィリピン国民語研究所はフィリピン諸語研究所と改称された。[25] 1991年8月14日に承認された共和国法第7104号により、フィリピン諸語研究所に代わるフィリピン語委員会(Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino、KWF)が設立された。KWFは大統領に直接報告を行い、フィリピノ語およびその他のフィリピン諸語の発展、普及、保存のための研究の 実施、調整、推進を任務としている。[26] 1992年5月13日、委員会は決議92-1を発行し、フィリピノ語は マニラ首都圏およびフィリピンのその他の都市部における先住民族の話し言葉および書き言葉であり、民族間のコミュニケーションの言語として使用されていると規定した。[27] しかし、1973年と1987年の憲法と同様に、92-1では、この言語をタガログ語として明確に特定することも、特定しないこともしていない。KWFか らの指示がない場合、92-1の明確かつ絶対的で曖昧さのない解釈は、フィリピン語の唯一の法的裁定者である最高裁判所の専権事項である。 フィリピノ語は、アテネオ・デ・マニラ大学の学生であるマーティン・ゴメスによって国際標準化機構(ISO)に提出され、登録された。2004年9月21日にはISOの言語登録簿に追加され、ISO 639-2コード「fil」が割り当てられた。 2007年8月22日、ブラカン州のマロロス市の3つの地方裁判所が、国語の普及を目的として英語ではなくフィリピノ語を使用することを決定したと報道さ れた。モデル裁判所として、第6支部、第80支部、第81支部から12人の速記者が、フィリピン最高裁判所の指示に従ってブラカン州立大学マルセロ・H・ デルピラ・カレッジ・オブ・ローで研修を受けた。デ・ラ・ラマは、ラグナ、カヴィテ、ケソン、アウロラ、ヌエバ・エシハ、バタンガス、リサール、メトロ・ マニラなど、タガログ語が母国語として話されている他の地域でも同様のプログラムを実施することがレイナト・プノ最高裁長の夢であったと述べた。[29] |

| Commemoration Since 1997, a month-long celebration of the national language occurs during August, known in Filipino as Buwan ng Wika (Language Month). Previously, this lasted only a week and was known as Linggo ng Wika (Language Week). The celebration coincides with the month of birth of President Manuel L. Quezon, regarded as the "Ama ng Wikang Pambansa" (Father of the national language). In 1946, Proclamation No. 35 of March 26 provided for a week-long celebration of the national language.[15] this celebration would last from March 27 until April 2 each year, the last day coinciding with birthday of the Filipino writer Francisco Baltazar, author of the Tagalog epic Florante at Laura. In 1954, Proclamation No. 12 of March 26 provided that the week of celebration would be from March 29 to April 4 every year.[30] This proclamation was amended the following year by President Ramon Magsaysay by Proclamation No. 186 of September 23, moving the dates of celebration to August 13–19, every year.[31] Now coinciding with the birthday of President Manuel L. Quezon. The reason for the move being given that the original celebration was a period "outside of the school year, thereby precluding the participation of schools in its celebration".[31] In 1988, President Corazon Aquino signed Proclamation No. 19, reaffirming the celebration every August 13 to 19. In 1997, the celebration was extended from a week to a month by Proclamation 1041 of July 15 signed by President Fidel V. Ramos.[32] |

記念 1997年より、8月にはフィリピノ語で「言語月間(Buwan ng Wika)」として知られる1ヶ月間の国語記念日が設けられている。以前は1週間のみで、「言語週間(Linggo ng Wika)」と呼ばれていた。この記念日は、「国語の父(Ama ng Wikang Pambansa)」として知られるマヌエル・ケソン大統領の誕生月に合わせて行われる。 1946年、3月26日付布告第35号により、国民の祝日として1週間の祝典が定められた。[15] この祝典は毎年3月27日から4月2日まで続き、最終日はフィリピンの作家フランシスコ・バルタザール(タガログ語の叙事詩『フロランテとラウラ』の作 者)の誕生日と重なる。 1954年、3月26日付の布告第12号により、祝賀の週は毎年3月29日から4月4日までと定められた。[30] この布告は翌年、ラモン・マグサイサイ大統領により9月23日付の布告第186号で改正され、祝賀の日程は毎年8月13日から19日へと変更された。 [31] 現在は、マニュエル・ケソン大統領の誕生日に合わせて行われている。当初の祝祭日が「学校の学期外に行われていたため、学校が祝祭に参加できなかった」こ とが、移動の理由として挙げられている。[31] 1988年、コラソン・アキノ大統領は宣言第19号に署名し、8月13日から19日までの祝祭を再確認した。1997年、フィデル・V・ラモス大統領が署名した7月15日付の宣言第1041号により、祝祭は1週間から1か月に延長された。[32] |

| Comparison of Filipino and Tagalog It is argued that current state of the Filipino language is contrary to the intention of Republic Act (RA) No. 7104 that requires that the national language be developed and enriched by the lexicon of the country's other languages.[33][citation needed] It is further argued that, while the official view (shared by the government, the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, and a number of educators) is that Filipino and Tagalog are considered separate languages, in practical terms, Filipino may be considered the official name of Tagalog, or even a synonym of it.[34] Today's Filipino language is best described as "Tagalog-based".[35] The language is usually called Tagalog within the Philippines and among Filipinos to differentiate it from other Philippine languages, but it has also come to be known as Filipino to differentiate it from the languages of other countries; the former implies a regional origin, the latter national. This is similar to the comparison between Castilian and Spanish, or Mandarin and Chinese. Political designations aside, Tagalog and Filipino are linguistically the same, sharing, among other things, the same grammatical structure. On May 23, 2007, Ricardo Maria Nolasco, KWF chair and a linguistics expert, acknowledged in a keynote speech during the NAKEM Conference at the Mariano Marcos State University in Batac, Ilocos Norte, that Filipino was simply Tagalog in syntax and grammar, with as yet no grammatical element or lexicon coming from Ilokano, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, or any of the other Philippine languages. He said further that this is contrary to the intention of Republic Act No. 7104, which requires that the national language be developed and enriched by the lexicon of the country's other languages, something toward which the commission was working.[36][37] On August 24, 2007, Nolasco elaborated further on the relationship between Tagalog and Filipino in a separate article, as follows: Are "Tagalog," "Pilipino" and "Filipino" different languages? No, they are mutually intelligible varieties, and therefore belong to one language. According to the KWF, Filipino is that speech variety spoken in Metro Manila and other urban centers where different ethnic groups meet. It is the most prestigious variety of Tagalog and the language used by the national mass media. The other yardstick for distinguishing a language from a dialect is: different grammar, different language. "Filipino", "Pilipino" and "Tagalog" share identical grammar. They have the same determiners (ang, ng and sa); the same personal pronouns (siya, ako, niya, kanila, etc.); the same demonstrative pronouns (ito, iyan, doon, etc.); the same linkers (na, at and ay); the same particles (na and pa); and the same verbal affixes -in, -an, i- and -um-. In short, same grammar, same language.[3] In connection with the use of Filipino, or specifically the promotion of the national language, the related term Tagalista is frequently used. While the word Tagalista literally means "one who specializes in Tagalog language or culture" or a "Tagalog specialist", in the context of the debates on the national language and "Imperial Manila", the word Tagalista is used as a reference to "people who promote or would promote the primacy of Tagalog at the expense of [the] other [Philippine] indigenous tongues".[38] |

フィリピノ語とタガログ語の比較 フィリピノ語の現状は、国民の言語をその国の他の言語の語彙によって発展させ、豊かにするという共和国法(RA)第7104号の意図に反しているという意見がある。[33][要出典] さらに、フィリピン語とタガログ語は別個の言語であるという公式見解(政府、フィリピン語委員会、多数の教育者によって共有されている)がある一方で、実 際にはフィリピン語はタガログ語の公式名称、あるいは同義語であるとみなされる可能性もあるという意見もある。[34] 今日のフィリピン語は「タガログ語を基盤とする」と表現するのが最も適切である。 [35] フィリピン国内およびフィリピン人同士の間では、他のフィリピン諸語と区別するために通常「タガログ語」と呼ばれているが、他国の言語と区別するために 「フィリピノ語」と呼ばれることも多くなっている。前者は地域的な起源を、後者は国民的な起源を意味する。これは、カスティーリャ語とスペイン語、あるい は標準中国語と中国語の比較に似ている。 政治的な名称はさておき、タガログ語とフィリピノ語は言語学的に同じであり、とりわけ文法構造が同じである。2007年5月23日、イロコス・ノルテ州バ タックのマリアノ・マルコス州立大学で開催されたNAKEM会議の基調講演で、KWF議長であり言語学の専門家であるリカルド・マリア・ノラスコ氏は、 フィリピノ語は単にタガログ語の構文と文法であり、イロカノ語、セブアノ語、ヒリガイノン語、またはその他のフィリピン諸語から派生した文法要素や語彙は まだ存在しないと認めた。さらに、これは共和国法第7104号の意図に反するものであると彼は述べた。同法は、国民の他の言語の語彙によって国語を発展さ せ、豊かにすることを求めている。これは、委員会が取り組んでいることでもある。[36][37] 2007年8月24日、ノラスコは別の記事でタガログ語とフィリピノ語の関係についてさらに詳しく説明し、次のように述べた。 「タガログ語」、「ピリピノ語」、「フィリピノ語」は異なる言語なのか? いいえ、これらは相互に理解可能なバリエーションであり、したがって1つの言語に属する。KWFによると、フィリピノは、異なる民族が共存するメトロ・マ ニラやその他の都市部で話されている言語である。フィリピノはタガログの中でも最も格式の高い言語であり、国民のマスメディアで使用されている言語であ る。言語と方言を区別するもう一つの基準は、異なる文法、異なる言語である。「フィリピノ」、「ピリピノ」、「タガログ」は同一の文法を共有している。そ れらは同じ限定詞(ang、ng、sa)、同じ人称代名詞(siya、ako、niya、kanilaなど)、同じ指示代名詞(ito、iyan、 doonなど)、同じ連結詞(na、at、ay)、同じ助詞(na、pa)、同じ動詞接尾辞(-in、-an、i-、-um)を共有している。つまり、同 じ文法、同じ言語である。[3] フィリピノ語の使用、特に国語の推進に関連して、関連用語であるタガリストという言葉が頻繁に使用される。タガリスタという言葉は文字通りには「タガログ 語や文化に精通した人」または「タガログ語の専門家」を意味するが、国民語や「帝国マニラ」に関する議論の文脈では、タガリスタという言葉は「他のフィリ ピン固有の言語を犠牲にしてタガログ語の優位性を推進する、または推進しようとする人々」を指す言葉として使われている。[38] |

| Example A Filipino speaker, recorded in the Philippines This is a translation of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[39] Usually, the diacritics are not written, and the syntax and grammar are based on that of Tagalog. |

例 フィリピンで録音されたフィリピン語話者 これは世界人権宣言第1条の翻訳である。[39]通常、発音区別符号は記載されず、構文と文法はタガログ語に基づいている。 |

| English Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

Filipino Pangkalahatáng Pagpapahayág ng Karapatáng Pantáo |

| Now, therefore, the General Assembly proclaims this UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction. |

Ngayón, samakatuwíd, ang Pangkalahatáng Kapulungán ay nagpapahayág ng PANGKALAHATÁNG PAGPAPAHAYÁG NA ITÓ NG MGÁ KARAPATÁN NG TÁO bílang pangkalahatáng pamantáyang maisasagawâ pára sa lahát ng táo at bansâ, sa layúning ang báwat táo at báwat galamáy ng lipúnan, na láging nása ísip ang Pahayág na itó, ay magsíkap sa pamamagítan ng pagtutúrò at edukasyón na maitagúyod ang paggálang sa mgá karapatán at kalayáang itó at sa pamamagítan ng mgá hakbáng na pagsúlong na pambansâ at pandaigdíg, ay makamtán ang pangkalahatán at mabísang pagkilála at pagtalíma sa mgá itó, magíng ng mgá mamamayán ng mgá Kasáping Estádo at ng mgá mamamayán ng mgá teritóryo na nása ilálim ng kaniláng nasasakúpan. |

| Article 1 |

Únang Artíkulo |

| All

human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are

endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another

in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Báwat

táo'y isinílang na may láyà at magkakapantáy ang tagláy na dangál at

karapatán. Silá'y pinagkaloóban ng pangangatwíran at budhî na

kailángang gamítin nilá sa pagtuturíngan nilá sa díwà ng pagkakapatíran. |

| Philippine literature Philippine Braille Filipino Sign Language Filipino orthography Filipino alphabet Abakada alphabet Suyat Tagalog grammar Tagalog language Tagalog phonology Tagalog Wikipedia Taglish List of loanwords in Tagalog Commission on the Filipino Language UP Diksiyonaryong Filipino |

フィリピン文学 フィリピン点字 フィリピン手話 フィリピン正書法 フィリピン・アルファベット アバカダ・アルファベット スヤット タガログ語文法 タガログ語 タガログ語音韻論 タガログ語版ウィキペディア タグリッシュ タガログ語の借用語一覧 フィリピノ語委員会 UP辞書 |

| Sources Commission on the Filipino Language Act, August 14, 1991 "1973 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines", Official Gazette, Government of the Philippines, archived from the original on June 25, 2017, retrieved May 22, 2020 "The Amended 1973 Constitution", Official Gazette, Government of the Philippines, archived from the original on March 8, 2021, retrieved May 22, 2020 Constitution of the Philippines, February 2, 1987 The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, Chanrobles Law Library, February 2, 1987, retrieved February 12, 2017 Tabbada, Emil V. (2005), Gripaldo, Rolando M.; McLean, George F. (eds.), "Filipino Cultural Traits: Claro R. Ceniza Lectures", Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change, IIID, Southeast Asia, vol. 4, Washington, D.C.: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, ISBN 1-56518-225-1 Kaplan, Robert B.; Baldauf, Richard B. Jr. (2003), Language and Language-in-Education Planning in the Pacific Basin, Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 1-4020-1062-1 Manipon, Rene Sanchez (January–February 2013), "The Filipíno Language" (PDF), Balanghay: The Philippine Factsheet, archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2013 Patke, Rajeev S.; Holden, Philip (2010), The Routledge Concise History of Southeast Asian Writing in English, Abingdon, Oxon, United Kingdom: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-87403-5 Paz, Leo; Juliano, Linda (2008), Hudson, Thom; Clark, Martyn (eds.), "Filipino (Tagalog) Language Placement Testing in Selected Programs in the United States", Case Studies in Foreign Language Placement: Practices and Possibilities, Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii, National Language Resource Center, pp. 7–16, ISBN 978-0-9800459-0-1 Rubrico, Jessie Grace U. (2012), Indigenization of Filipino: The Case of the Davao City Variety, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: University of Malaya |

出典 フィリピノ語法委員会、1991年8月14日 「フィリピン共和国憲法(1973年)」、フィリピン政府官報、2017年6月25日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2020年5月22日取得 「改正1973年憲法」、フィリピン政府官報、2021年3月8日アーカイブ、2020年5月22日取得 1987年2月2日フィリピン憲法 フィリピン共和国憲法、チャンロブルズ・ロー・ライブラリー、1987年2月2日、2017年2月12日取得 Tabbada, Emil V. (2005), Gripaldo, Rolando M.; McLean, George F. (eds.), 「Filipino Cultural Traits: Claro R. Ceniza Lectures」, Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change, IIID, Southeast Asia, vol. 4, Washington, D.C.: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, ISBN 1-56518-225-1 カプラン、ロバート・B.、リチャード・B.・ジュニア・バルダウフ(2003年)、『環太平洋地域における言語と言語教育計画』、オランダ、ドルドレヒト:クラウアー・アカデミック・パブリッシャーズ、ISBN 1-4020-1062-1 Manipon, Rene Sanchez (2013年1月–2月), 「The Filipíno Language」 (PDF), Balanghay: The Philippine Factsheet, archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2013 Patke, Rajeev S.; Holden, Philip (2010), The Routledge Concise History of Southeast Asian Writing in English, Abingdon, Oxon, United Kingdom: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-87403-5 Paz, Leo; Juliano, Linda (2008), Hudson, Thom; Clark, Martyn (eds.), 「フィリピン語(タガログ語)の米国における選択プログラムにおけるレベル分けテスト」, Practices and Possibilities, Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii, National Language Resource Center, pp. 7–16, ISBN 978-0-9800459-0-1 Rubrico, Jessie Grace U. (2012), Indigenization of Filipino: The Case of the Davao City Variety, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: University of Malaya |

| Additional sources New Vicassan's English–Pilipino Dictionary by Vito C. Santos, ISBN 971-27-0349-5 Learn Filipino: Book One by Victor Eclar Romero ISBN 1-932956-41-7 Lonely Planet Filipino/Tagalog (Travel Talk) ISBN 1-59125-364-0 Lonely Planet Pilipino Phrasebook ISBN 0-86442-432-9 UP Diksyonaryong Filipino by Virgilio S. Almario (ed.) ISBN 971-8781-98-6, and ISBN 971-8781-99-4 English–Pilipino Dictionary, Consuelo T. Panganiban, ISBN 971-08-5569-7 Diksyunaryong Filipino–English, Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, ISBN 971-8705-20-1 New English–Filipino Filipino–English Dictionary, by Maria Odulio de Guzman ISBN 971-08-1776-0 "When I was a child I spoke as a child": Reflecting on the Limits of a Nationalist Language Policy by Danilo Manarpaac. In: The politics of English as a world language: new horizons in postcolonial cultural studies by Christian Mair. Rodopi; 2003 ISBN 978-90-420-0876-2. p. 479–492. |

追加情報源 ヴィト・C・サントス著『ニュー・ビカサン英ピリピノ辞典』ISBN 971-27-0349-5 ビクター・エクラル・ロメロ著『フィリピノ語を学ぼう:第1巻』ISBN 1-932956-41-7 ロンリープラネット『フィリピノ語/タガログ語(トラベルトーク)』ISBN 1-59125-364-0 ロンリープラネット フィリピノ語会話集 ISBN 0-86442-432-9 Virgilio S. Almario (編) 著『UP ディクショナリー・オブ・フィリピノ』ISBN 971-8781-98-6、およびISBN 971-8781-99-4 英語-ピリピノ語辞書、コンスエロ・T・パンガバン著、ISBN 971-08-5569-7 フィリピノ語-英語辞書、フィリピノ語委員会著、ISBN 971-8705-20-1 新英語-フィリピノ語・フィリピノ語-英語辞書、マリア・オドゥリオ・デ・グズマン著、ISBN 971-08-1776-0 「子供の頃は子供らしく話していた」:ナショナリストの言語政策の限界について、ダニロ・マナルパアクによる考察。『世界言語としての英語の政治学:ポス トコロニアル文化研究の新地平』クリスチャン・メール著。ロドピ出版、2003年。ISBN 978-90-420-0876-2。479~492ページ。 |

| Commission on the Filipino Language Archived April 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Language planning in multilingual countries: The case of the Philippines, discussion by linguist and educator Andrew Gonzalez Weedon, Alan (August 10, 2019). "The Philippines is fronting up to its Spanish heritage, and for some it's paying off". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. "...a third of the Filipino language is derived from Spanish words, constituting some 4,000 'loan words'". Tupas, Ruanni (2015). "The Politics of "P" and "F": A Linguistic History of Nation-Building in the Philippines". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 36 (6): 587–597. doi:10.1080/01434632.2014.979831. S2CID 143332545. Rubrico, Jessie Grace U. (2012). "Indigenization of Filipino: The Case of the Davao City Variety". Language Links Foundation, Incorporated – via academia.edu. Atienza, Ela L. (1994). "Drafting the 1987 Constitution : The Politics of Language". Philippine Political Science Journal. 18 (37–38): 79–101. doi:10.1080/01154451.1994.9754188. Published online: April 18, 2012 |

Commission on the Filipino Language Archived April 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine 多言語国家における言語計画:フィリピンの事例、言語学者・教育者アンドリュー・ゴンザレスによる議論 ウィードン、アラン(2019年8月10日)。「フィリピンはスペインの遺産に正面から向き合っており、一部ではそれが功を奏している」。ABCニュー ス。オーストラリア放送協会。「フィリピン語の3分の1はスペイン語の単語に由来しており、約4,000の『借用語』を構成している」。 Tupas, Ruanni (2015). 「「P」と「F」の政治学:フィリピンにおける国民形成の言語学的歴史」. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 36 (6): 587–597. doi:10.1080/01434632.2014.979831. S2CID 143332545. Rubrico, Jessie Grace U. (2012). 「Indigenization of Filipino: The Case of the Davao City Variety」. Language Links Foundation, Incorporated – via academia.edu. Atienza, Ela L. (1994). 「1987年憲法の起草:言語の政治学」. Philippine Political Science Journal. 18 (37–38): 79–101. doi:10.1080/01154451.1994.9754188. 2012年4月18日オンライン公開 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filipino_language |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆