★フランシス・ベーコン★

Francis Bacon (28 October 1909 – 28 April 1992)

☆ フランシス・ベーコン(1909年10月28日 - 1992年4月28日)はアイルランド生まれのイギリス人で、生々しく不穏なイメージで知られる具象画家である。人間の形に焦点を当て、磔刑像、教 皇の肖像、自画像、親しい友人の肖像などを題材とし、時には幾何学的な構造の中に抽象化された人物が孤立することもあった。様々な作品分類を拒否 し、ベーコンは「事実の残酷さ」を表現しようと努めたと述べている。彼の死後、ベーコンの名声は着実に高まり、彼の作品は美術市場で最も高く評価され、求 められるようになった。1990年代後半には、1950年代初期の法 王の絵や1960年代の肖像画など、以前は破壊されたと思われていた数多くの大作が再び現れ、オークションで記録的な価格をつけた。

| ★Francis

Bacon (28

October 1909 – 28 April 1992) was an Irish-born British[1] figurative

painter known for his raw, unsettling imagery. Focusing on the human

form, his subjects included crucifixions, portraits of popes,

self-portraits, and portraits of close friends, with abstracted figures

sometimes isolated in geometrical structures.[2] Rejecting various

classifications of his work, Bacon said he strove to render "the

brutality of fact."[2] He built up a reputation as one of the giants of

contemporary art with his unique style.[3] Bacon said that he saw images "in series", and his work, which numbers in the region of 590 extant paintings along with many others he destroyed,[4] typically focused on a single subject for sustained periods, often in triptych or diptych formats. His output can be broadly described as sequences or variations on single motifs; including the 1930s Picasso-influenced bio-morphs and Furies, the 1940s male heads isolated in rooms or geometric structures, the 1950s "screaming popes," the mid-to-late 1950s animals and lone figures, the early 1960s crucifixions, the mid-to-late 1960s portraits of friends, the 1970s self-portraits, and the cooler, more technical 1980s paintings. Bacon did not begin to paint until his late twenties, having drifted in the late 1920s and early 1930s as an interior decorator, bon vivant and gambler.[5] He said that his artistic career was delayed because he spent too long looking for subject matter that could sustain his interest. His breakthrough came with the 1944 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, which sealed his reputation as a uniquely bleak chronicler of the human condition. From the mid-1960s he mainly produced portraits of friends and drinking companions, either as single, diptych or triptych panels. Following the suicide of his lover George Dyer in 1971 (memorialised in his Black Triptychs, and a number of posthumous portraits) his art became more sombre, inward-looking and preoccupied with the passage of time and death. The climax of his later period is marked by the masterpieces Study for Self-Portrait (1982) and Study for a Self-Portrait—Triptych, 1985–86. Despite his existentialist and bleak outlook, Bacon was charismatic, articulate and well-read. A bon vivant, he spent his middle age eating, drinking and gambling in London's Soho with like-minded friends including Lucian Freud (although they fell out in the mid-1970s, for reasons neither ever explained), John Deakin, Muriel Belcher, Henrietta Moraes, Daniel Farson, Tom Baker and Jeffrey Bernard. After Dyer's suicide he largely distanced himself from this circle, and while still socially active and his passion for gambling and drinking continued, he settled into a platonic and somewhat fatherly relationship with his eventual heir, John Edwards. Since his death, Bacon's reputation has grown steadily, and his work is among the most acclaimed, expensive and sought-after on the art market. In the late 1990s a number of major works, previously assumed destroyed,[6] including early 1950s pope paintings and 1960s portraits, re-emerged to set record prices at auction. |

フ

ランシス・ベーコン(1909年10月28日 -

1992年4月28日)はアイルランド生まれのイギリス人[1]で、生々しく不穏なイメージで知られる具象画家である。人間の形に焦点を当て、磔刑像、教

皇の肖像、自画像、親しい友人の肖像などを題材とし、時には幾何学的な構造の中に抽象化された人物が孤立することもあった[2]。様々な作品分類を拒否

し、ベーコンは「事実の残酷さ」を表現しようと努めたと述べている[2]。 ベーコンはイメージを「シリーズで」見ていたと言い、現存する590点にも及ぶ彼の作品は、彼が破壊した他の多くの作品とともに[4]、通常、一つの主題 に持続的に焦点を当て、しばしば三連画や二連画の形式で描かれる。彼の作品は、1930年代のピカソの影響を受けた生物形態やフューリー、1940年代の 部屋や幾何学的な構造の中に孤立した男性の頭部、1950年代の「叫ぶ教皇」、1950年代中期から後期の動物や孤独な人物、1960年代初期の磔刑像、 1960年代中期から後期の友人の肖像、1970年代の自画像、1980年代の冷静でより技巧的な絵画など、単一のモチーフの連続またはバリエーションと して大まかに表現することができる。 ベーコンが絵を描き始めたのは20代後半になってからで、1920年代後半から1930年代前半にかけては室内装飾家、ボンヴィヴァン、ギャンブラーとし て漂流していた[5]。1944年の三連作『磔刑像の台座に立つ人物のための3つの習作』でブレイク。1960年代半ばからは、主に友人や飲み仲間の肖像 画を、一枚絵、二枚絵、三枚絵のパネルとして制作した。1971年に恋人のジョージ・ダイアーが自殺した後(『ブラック・トリプティック』や遺作となった 数多くの肖像画で追悼されている)、彼の芸術はより陰鬱で内向的なものとなり、時間の経過と死へのこだわりが強くなった。晩年のクライマックスは、傑作 『自画像のための習作』(1982年)と『自画像のための習作-トリプティクスのための習作』(1985-86年)である。 実存主義的で荒涼とした見通しとは裏腹に、ベーコンはカリスマ性があり、明晰で読書家だった。快活な彼は、中年期をルシアン・フロイト(1970年代半ば に不仲になったが、その理由は両者とも説明していない)、ジョン・ディーキン、ミュリエル・ベルチャー、ヘンリエッタ・モラエス、ダニエル・ファーソン、 トム・ベイカー、ジェフリー・バーナードら気の合う友人たちとロンドンのソーホーで食べ、飲み、ギャンブルに明け暮れた。ダイアーが自殺した後、彼はこの サークルから大きく距離を置き、まだ社交的でギャンブルと飲酒への情熱は続いていたが、最終的な後継者であるジョン・エドワーズとはプラトニックで、どこ か父親のような関係に落ち着いた。 彼の死後、ベーコンの名声は着実に高まり、彼の作品は美術市場で最も高く評価され、求められるようになった。1990年代後半には、1950年代初期の法 王の絵や1960年代の肖像画など、以前は破壊されたと思われていた数多くの大作[6]が再び現れ、オークションで記録的な価格をつけた。 |

| Early life Francis Bacon was born on 28 October 1909 in 63 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, Ireland.[7] At that time, all of Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom. His father, army Captain Anthony Edward Mortimer Bacon, known as Eddy, was born in Adelaide, South Australia, to an English father and an Australian mother.[8] Eddy was a veteran of the Boer War, a racehorse trainer, and grandson of Major-General Anthony Bacon, who claimed descent from Sir Nicholas Bacon, elder half-brother of The 1st Viscount St Albans (better known to history as Sir Francis Bacon), the Elizabethan statesman, philosopher and essayist.[9] Bacon's mother, Christina Winifred Firth, known as Winnie, was heiress to a Sheffield steel business and coal mine. Bacon had an older brother, Harley,[10] two younger sisters, Ianthe and Winifred, and a younger brother, Edward. Bacon was raised by the family nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, from Cornwall, known as "Nanny Lightfoot", a maternal figure who remained close to him until her death. During the early 1940s, he rented the ground floor of 7 Cromwell Place, South Kensington, John Everett Millais's old studio, and Nanny Lightfoot helped him install an illicit roulette wheel there, organised by Bacon and his friends.[11] The family moved house often, moving between Ireland and England several times, leading to a sense of displacement which remained with Bacon throughout his life. The family lived in Cannycourt House in County Kildare from 1911,[10] later moving to Westbourne Terrace in London, close to where Bacon's father worked at the Territorial Force Records Office. They returned to Ireland after the First World War. Bacon lived with his maternal grandmother and step-grandfather, Winifred and Kerry Supple, at Farmleigh, Abbeyleix, County Laois, although the rest of the family again moved to Straffan Lodge near Naas, County Kildare.[citation needed] Bacon was shy as a child, and enjoyed dressing up. This, and his effeminate manner, angered his father. A story emerged in 1992[12] of his father having had Bacon horsewhipped by their grooms. In 1924, shortly after the establishment of the Irish Free State, his parents moved to Gloucestershire, first to Prescott House in Gotherington, then Linton Hall near the border with Herefordshire. At a fancy-dress party at the Firth family home, Cavendish Hall in Suffolk, Bacon dressed as a flapper with an Eton crop, beaded dress, lipstick, high heels, and a long cigarette holder. In 1926, the family moved back to Straffan Lodge. His sister, Ianthe, twelve years his junior, recalled that Bacon made drawings of ladies with cloche hats and long cigarette holders.[13] Later that year, Bacon was thrown out of Straffan Lodge following an incident in which his father found him admiring himself in front of a large mirror wearing his mother's underwear.[14] |

生い立ち フランシス・ベーコンは1909年10月28日、アイルランドのダブリン、ロウアー・バゴット・ストリート63番地に生まれた[7]。当時、アイルランド 全土はまだイギリスの一部だった。父アンソニー・エドワード・モーティマー・ベーコン陸軍大尉(通称エディ)は、南オーストラリア州アデレードでイギリス 人の父とオーストラリア人の母の間に生まれた。 [エディはボーア戦争の退役軍人で、競走馬の調教師であり、アンソニー・ベーコン少将の孫であった。アンソニー・ベーコンは、エリザベス朝時代の政治家、 哲学者、エッセイストであった第1代セント・オルバンズ子爵(歴史上、フランシス・ベーコン卿として知られる)の異母兄ニコラス・ベーコン卿の子孫である と主張していた[9]。ベーコンには兄ハーレー、2人の妹イアンテとウィニフレッド、弟エドワードがいた[10]。ベーコンは、「ナニー・ライトフット」 として知られるコーンウォール出身のジェシー・ライトフットという乳母に育てられた。1940年代初頭、彼はジョン・エヴェレット・ミレイの古いアトリエ であったサウス・ケンジントンのクロムウェル・プレイス7番地の1階を借り、ナニー・ライトフットはベーコンと彼の友人たちが企画した不正なルーレットを そこに設置するのを手伝った[11]。 一家は頻繁に家を引っ越し、アイルランドとイギリスを何度も行き来した。一家は1911年からキルデア州のカニーコート・ハウスに住み[10]、後にロン ドンのウェストボーン・テラスに引っ越した。第一次世界大戦後、二人はアイルランドに戻る。ベーコンは、母方の祖母と継祖父であるウィニフレッドとケ リー・サップルとともに、ラオス州アベレイスのファームリーで暮らしたが、残りの家族は再びキルデア州ナース近くのストラファン・ロッジに移った[要出 典]。 ベーコンは子供の頃から内気で、着飾るのが好きだった。これと女々しい態度が父親を怒らせた。1992年[12]、父親がベーコンを花婿たちに馬で鞭打た せたという話が浮上した。 1924年、アイルランド自由国が成立した直後、両親はグロスターシャーに移り住み、最初はゴザリントンのプレスコット・ハウスに、その後ヘレフォード シャーとの州境に近いリントン・ホールに移った。サフォーク州にあるファース家の家、キャベンディッシュ・ホールでの仮装パーティーで、ベーコンはイート ン・クロップ、ビーズのドレス、口紅、ハイヒール、長いタバコホルダーというフラッパーに扮した。1926年、一家はストラファン・ロッジに戻った。12 歳年下の妹イアンテは、ベーコンがクローシュハットと長いタバコホルダーをつけた女性の絵を描いていたことを思い出した[13]。 その年の暮れ、母親の下着を身につけ、大きな鏡の前で自画自賛しているところを父親に見つかったベーコンは、ストラファン・ロッジを追い出された [14]。 |

| London, Berlin and Paris Bacon spent the latter half of 1926 in London, on an allowance of £3 a week from his mother's trust fund, reading Nietzsche. Although poor (£5 was then the average weekly wage),[15] Bacon found that by avoiding rent and engaging in petty theft, he could survive. To supplement his income, he briefly tried his hand at domestic service, but although he enjoyed cooking, he became bored and resigned. He was sacked from a telephone-answering position at a shop selling women's clothes in Poland Street in Soho, after writing a poison pen letter to the owner. Bacon found himself drifting through London's homosexual underworld, aware that he was able to attract a certain type of rich man, something he was quick to take advantage of, having developed a taste for good food and wine. One was a relative of Winnie Harcourt-Smith, another breeder of racehorses, who was renowned for his manliness. Bacon claimed his father had asked this "uncle" to take him 'in-hand' and 'make a man of him'. Bacon had a difficult relationship with his father, once admitting to being sexually attracted to him.[16] In 1927 Bacon moved to Berlin, where he first saw Fritz Lang's Metropolis and Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin, both later to be influences on his work. He spent two months in Berlin, though Harcourt-Smith left after one – "He soon got tired of me, of course, and went off with a woman ... I didn't really know what to do, so I hung on for a while." Bacon then spent the next year-and-a-half in Paris. He met Yvonne Bocquentin, pianist and connoisseur, at the opening of an exhibition. Aware of his own need to learn French, Bacon lived for three months with Madame Bocquentin and her family at their house near Chantilly. He travelled into Paris to visit the city's art galleries.[17] At the Château de Chantilly (Musée Condé) he saw Nicolas Poussin's Massacre of the Innocents, a painting which he often referred to in his later work.[18] Return to London Bacon moved to London in the winter of 1928/29, to work as an interior designer. He took a studio at 17 Queensberry Mews West, South Kensington, sharing the upper floor with Eric Allden – his first collector – and his childhood nanny, Jessie Lightfoot. In 1929, he met Eric Hall, his patron and lover in an often torturous and abusive relationship. Bacon left the Queensberry Mews West studio in 1931 and had no settled space for some years. He probably shared a studio with Roy De Maistre, circa 1931/32 in Chelsea.[19] Furniture and rugs The 1933 Crucifixion was his first painting to attract public attention, and was in part based on Pablo Picasso's The Three Dancers of 1925. It was not well received; disillusioned, he abandoned painting for nearly a decade, and suppressed his earlier works.[20] He visited Paris in 1935 where he bought a secondhand book on anatomical diseases of the mouth containing high quality hand-coloured plates of both open mouths and oral interiors,[21] which haunted and obsessed him for the remainder of his life. These and the scene with the nurse screaming on the Odessa steps from the Battleship Potemkin later became recurrent parts of Bacon's iconography, with the angularity of Eisenstein's images often combined with the thick red palette of his recently purchased medical tome. In the winter of 1935–36, Roland Penrose and Herbert Read, making a first selection for the International Surrealist Exhibition, visited his studio at 71 Royal Hospital Road, Chelsea saw "three or four large canvases including one with a grandfather clock", but found his work "insufficiently surreal to be included in the show". Bacon claimed Penrose told him "Mr. Bacon, don't you realise a lot has happened in painting since the Impressionists?" In 1936 or 1937 Bacon moved from 71 Royal Hospital Road to the top floor of 1 Glebe Place, Chelsea, which Eric Hall had rented. The following year, Patrick White moved to the top two floors of the building where De Maistre had his studio, on Eccleston Street and commissioned from Bacon, by now a friend, a writing desk (with wide drawers and a red linoleum top). Expressing one of his basic concerns from the late 1930s, Bacon said that his artistic career was delayed because he spent too long looking for subject matter that could sustain his interest.[5] In January 1937, at Thomas Agnew and Sons, 43 Old Bond Street, London, Bacon exhibited in a group show, Young British Painters, which included Graham Sutherland and Roy De Maistre. Eric Hall organised the show. He showed four works: Figures in a Garden (1936); Abstraction, Abstraction from the Human Form (known from magazine photographs) and Seated Figure (also lost). These paintings prefigure Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944) in alternatively representing a tripod structure (Abstraction), bared teeth (Abstraction from the Human Form), and both being biomorphic in form. On 1 June 1940, Bacon's father died. Bacon was named sole Trustee/Executor of his father's will, which requested the funeral be as "private and simple as possible". Unfit for active wartime service, Bacon volunteered for civil defence and worked full-time in the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) rescue service; the fine dust of bombed London worsened his asthma and he was discharged. At the height of the Blitz, Eric Hall rented a cottage for Bacon and himself at Bedales Lodge in Steep, near Petersfield, Hampshire. Figure Getting Out of a Car (ca. 1939/1940) was painted here but is known only from an early 1946 photograph taken by Peter Rose Pulham. The photograph was taken shortly before the canvas was painted over by Bacon and retitled Landscape with Car. An ancestor to the biomorphic form of the central panel of Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), the composition was suggested by a photograph of Hitler getting out of a car at one of the Nuremberg rallies. Bacon claims to have "copied the car and not much else".[22] Bacon and Hall in 1943 took the ground floor of 7 Cromwell Place, South Kensington, formerly the house and studio of John Everett Millais. High-vaulted and north-lit, its roof was recently bombed – Bacon was able to adapt a large old billiard room at the back as his studio. Lightfoot, lacking an alternative location, slept on the kitchen table. They held illicit roulette parties, organised by Bacon with the assistance of Hall. |

ロンドン、ベルリン、パリ ベーコンは1926年の後半をロンドンで過ごし、母親の信託基金から週3ポンドの小遣いをもらい、ニーチェを読んでいた。貧しかったが(当時の週給は5ポ ンドが平均)[15]、家賃を免れ、ささいな窃盗に手を染めることで、生き延びることができた。収入を補うため、一時は家事サービスにも手を出したが、料 理は好きだったものの、退屈して辞職。ソーホーのポーランド・ストリートにある婦人服を売る店で電話応対の仕事をしていたが、店主に毒ペンで手紙を書いて クビになった。ベーコンはロンドンのホモセクシャルの裏社会を漂い、自分がある種の金持ちを惹きつけることができることに気づいた。そのうちの一人はウィ ニー・ハーコート=スミスの親戚で、彼もまた競走馬のブリーダーであり、男前で有名だった。ベーコンは、父親がこの "叔父 "に、彼を "手にかけ"、"男にする "ように頼んだと主張した。ベーコンは父との関係が難しく、父に性的魅力を感じていたことを認めたこともあった[16]。 1927年、ベーコンはベルリンに移り住み、そこで初めてフリッツ・ラングの『メトロポリス』とセルゲイ・エイゼンシュテインの『戦艦ポチョムキン』を見 た。彼はベルリンで2ヶ月を過ごしたが、ハーコート=スミスは1ヶ月で出て行った。私はどうしたらいいのかわからなかったので、しばらくの間しがみついて いました」。ベーコンはそれから1年半をパリで過ごした。ある展覧会のオープニングで、ピアニストで鑑定家のイヴォンヌ・ボッカンタンに出会った。フラン ス語を学ぶ必要性を感じていたベーコンは、シャンティイ近郊のボッカンタン夫人とその家族の家に3ヶ月間滞在した。シャンティイ城(コンデ美術館)でニコ ラ・プッサンの『無辜の民の虐殺』を鑑賞。 ロンドンへの帰還 1928年から29年にかけての冬、ベーコンはインテリア・デザイナーとして働くためにロンドンに移り住む。サウス・ケンジントンのクイーンズベリー・ ミューズ・ウエスト17番地にアトリエを構え、上階を最初のコレクターであるエリック・アルデン、幼少期の乳母ジェシー・ライトフットとシェアした。 1929年、ベーコンはエリック・ホールと出会う。エリックはベーコンのパトロンであり、恋人であった。ベーコンは1931年にクイーンズベリー・ミュー ズ・ウエストのスタジオを去り、数年間は落ち着ける場所がなかった。1931年から32年頃にかけて、チェルシーでロイ・デ・マイスターとスタジオを共有 していたと思われる[19]。 家具と絨毯 1933年の《磔刑》は、パブロ・ピカソが1925年に描いた《三人の踊り子》を下敷きにして描いたもので、初めて世間の注目を集めた。1935年にパリ を訪れ、そこで購入した口の解剖学的疾患に関する古本には、口を開けた状態や口腔内の質の高い手彩色のプレートが掲載されており[21]、このプレートは 彼の残りの人生を悩ませ、執着させた。これらと『戦艦ポチョムキン』のオデッサの階段で悲鳴を上げる看護婦のシーンは、後にベーコンのイコノグラフィーの 反復的な部分となり、エイゼンシュテインのイメージの角ばった感じは、最近購入した医学書の厚い赤のパレットとしばしば組み合わされた。 1935年から36年の冬、国際シュルレアリスム展の一次選考を行ったローランド・ペンローズとハーバート・リードが、チェルシーのロイヤル・ホスピタ ル・ロード71番地にある彼のアトリエを訪れ、「祖父の時計が描かれたものを含む3、4点の大きなキャンバス」を見たが、彼の作品は「展覧会に出品するに はシュールさが足りない」と判断した。ベーコンはペンローズにこう言われたと主張した。"ベーコンさん、印象派以来、絵画の世界でいろいろなことが起こっ ていることに気づいていないのですか?"。1936年か1937年、ベーコンはロイヤル・ホスピタル・ロード71番地から、エリック・ホールが借りていた チェルシーのグリーブ・プレイス1番地の最上階に引っ越した。翌年、パトリック・ホワイトは、デ・マイスターがアトリエを構えていたエクレストン・スト リートの建物の最上階の2階に引っ越し、友人でもあったベーコンにライティングデスク(幅広の引き出しと赤いリノリウムの天板)を注文した。ベーコンは、 1930年代後半からの基本的な懸念のひとつを表明し、自分の芸術家としてのキャリアが遅れたのは、興味を持続できる題材を探すのに時間をかけすぎたから だと語った[5]。 1937年1月、ロンドンのオールド・ボンド・ストリート43番地にあるThomas Agnew and Sonsで、ベーコンは、グラハム・サザーランドやロイ・デ・メイストールを含むグループ展「Young British Painters」に出展。この展覧会はエリック・ホールが企画した。彼は4点の作品を展示した: Figures in a Garden」(1936年)、「Abstraction」、「Abstraction from the Human Form」(雑誌の写真で知られる)、「Seated Figure」(これも失われている)。これらの絵画は、三脚の構造(抽象)、むき出しの歯(人体形態からの抽象)を交互に表し、どちらも生物形態的であ るという点で、《磔刑台座の人物像のための3つの習作》(1944)を予感させる。 1940年6月1日、ベーコンの父が死去。ベーコンは父の遺言の唯一の管財人/遺言執行人に指名され、葬儀は「できる限り私的で簡素なもの」にするよう求 められた。戦時中の積極的な任務に適さなかったベーコンは、民間防衛に志願し、空襲予防(ARP)の救助活動にフルタイムで従事した。空襲の最中、エリッ ク・ホールはベーコンと自分のために、ハンプシャー州ピーターズフィールド近郊のスティープにあるベダレス・ロッジにコテージを借りた。Figure Getting Out of a Car」(1939/1940年頃)はここで描かれたが、ピーター・ローズ・プラムが撮影した1946年初期の写真によってのみ知られている。この写真 は、キャンバスがベーコンによって塗り替えられ、『車のある風景』と改題される直前に撮影されたものだ。十字架像の台座に立つ人物のための3つの習作』 (1944年)の中央パネルに見られる生物形態的なフォルムの祖先であるこの構図は、ニュルンベルクの集会のひとつで車から降りたヒトラーの写真によって 示唆された。ベーコンは「車を模写しただけで、他はあまり模写していない」と主張している[22]。 1943年、ベーコンとホールはサウス・ケンジントンのクロムウェル・プレイス7番地の1階を借りる。高い吹き抜けと北側からの採光があり、屋根は最近爆 撃を受けたばかりだった。ライトフットは代わりの場所がなく、キッチンのテーブルの上で寝た。二人は、ベーコンがホールの助けを借りて企画した違法なルー レット・パーティーを開いていた。 |

| Early success Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944. Oil and pastel on Sundeala board. Tate Britain, London By 1944 Bacon had gained confidence and moved toward developing his unique signature style.[23] His Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion had summarised themes explored in his earlier paintings, including his examination of Picasso's biomorphs, his interpretations of the Crucifixion, and the Greek Furies. It is generally considered his first mature piece;[24] he regarded his works before the triptych as irrelevant. The painting caused a sensation when exhibited in 1945 and established him as a foremost post-war painter. Remarking on the cultural significance of Three Studies, John Russell observed in 1971 that "there was painting in England before the Three Studies, and painting after them, and no one ... can confuse the two."[25] Painting (1946) was shown in several group shows including in the British section of Exposition internationale d'art moderne (18 November – 28 December 1946) at the Musée National d'Art Moderne, for which Bacon travelled to Paris. Within a fortnight of the sale of Painting (1946) to the Hanover Gallery Bacon used the proceeds to decamp from London to Monte Carlo. After staying at a succession of hotels and flats, including the Hôtel de Ré, Bacon settled in a large villa, La Frontalière, in the hills above the town. Hall and Lightfoot would come to stay. Bacon spent much of the next few years in Monte Carlo apart from short visits to London. From Monte Carlo, Bacon wrote to Sutherland and Erica Brausen. His letters to Brausen show he painted there, but no paintings are known to survive. Bacon said he became "obsessed" with the Casino de Monte Carlo, where he would "spend whole days". Falling in debt from gambling here, he was unable to afford a new canvas. This compelled him to paint on the raw, unprimed side of his previous work, a practice he kept throughout his life.[26] In 1948, Painting (1946) sold to Alfred Barr for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York for £240. Bacon wrote to Sutherland asking that he apply fixative to the patches of pastel on Painting (1946) before it was shipped to New York. (The work is now too fragile to be moved from MoMA for exhibition elsewhere.) At least one visit to Paris in 1946 brought Bacon into more immediate contact with French postwar painting and with Left Bank ideas such as Existentialism.[27] He had, by this time, embarked on his lifelong friendship with Isabel Rawsthorne, a painter closely involved with Giacometti and the Left Bank set.[28] They shared many interests, including ethnography and classical literature.[29] Late 1940s In 1947, Sutherland introduced Bacon to Brausen, who represented Bacon for twelve years. Despite this, Bacon did not mount a one-man show in Brausen's Hanover Gallery until 1949.[30] Bacon returned to London and Cromwell Place late in 1948. The following year Bacon exhibited his "Heads" series, most notable for Head VI, Bacon's first surviving engagement with Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X (three 'popes' were painted in Monte Carlo in 1946 but were destroyed). He kept an extensive inventory of images for source material, but preferred not to confront the major works in person; he viewed Portrait of Innocent X only once, much later in his life.[31] |

初期の成功 磔刑台の人物のための3つの習作、1944年。油彩、パステル、スンデラボード テート・ブリテン、ロンドン 1944年までに、ベーコンは自信をつけ、彼独自の特徴的なスタイルを発展させる方向に進んでいた[23]。《磔刑像の台座の人物のための3つの習作》 は、ピカソの生物形態、磔刑像の解釈、ギリシアのフューリーを考察するなど、彼の初期の絵画で探求されたテーマをまとめたものであった。一般的には、この 作品は彼の最初の成熟した作品と考えられている[24]。1945年に展示されるとセンセーションを巻き起こし、戦後を代表する画家としての地位を確立し た。ジョン・ラッセルは1971年、《3つの習作》の文化的意義を指摘し、「イギリスには《3つの習作》以前にも絵画があり、それ以後にも絵画があった。 絵画』(1946年)は、国立近代美術館で開催された国際現代美術展(1946年11月18日~12月28日)のイギリス部門を含むいくつかのグループ展 に出品され、ベーコンはそのためにパリに渡った。ハノーヴァー・ギャラリーに《絵画》(1946年)を売却してから2週間のうちに、ベーコンはその収益金 でロンドンからモンテカルロに放浪した。オテル・ド・レをはじめとするホテルやアパートを転々とした後、ベーコンはモンテカルロの丘の上にあるラ・フロン タリエールという大きな別荘に落ち着いた。ホールとライトフットも滞在した。ベーコンはその後数年の大半をモンテカルロで過ごし、短期間のロンドン訪問は 別だった。モンテカルロから、ベーコンはサザーランドとエリカ・ブラウゼンに手紙を書いた。ブラウゼンへの手紙から、彼がモンテカルロで絵を描いたことが わかるが、絵は現存していない。ベーコンはカジノ・ド・モンテカルロに「取り憑かれた」ようになり、そこで「丸一日を過ごした」と語っている。ここでの ギャンブルで借金を背負った彼は、新しいキャンバスを買う余裕がなかった。そのため、彼は以前の作品の下塗りされていない生の面に絵を描くことを余儀なく され、その習慣を生涯続けた[26]。 1948年、《Painting》(1946年)は、ニューヨーク近代美術館(MoMA)のためにアルフレッド・バーに240ポンドで売却された。ベーコ ンはサザーランドに手紙を書き、《絵画》(1946)がニューヨークへ輸送される前に、パステルの斑点に定着剤を塗るよう依頼した。(1946年に少なく とも1度パリを訪れたことで、ベーコンは戦後のフランス絵画や実存主義などの左岸の思想と、より身近に接することになる[27]。この頃、ベーコンはジャ コメッティや左岸一派と密接な関係にあった画家イザベル・ローストホーンとの生涯にわたる友情に着手していた[28]。 1940年代後半 1947年、サザーランドはベーコンをブラウゼンに紹介し、ブラウゼンは12年間ベーコンの代理人を務めた。1948年、ベーコンはロンドンとクロムウェ ル・プレイスに戻る。 その翌年、ベーコンは「頭部」シリーズを発表し、中でも、ベラスケスの《教皇イノセント10世の肖像》(1946年にモンテカルロで3点の「教皇」が描か れたが破壊された)とベーコンが初めて関わった《頭部VI》が注目された。彼は資料となるイメージの膨大な在庫を保管していたが、主要な作品と直接対面す ることは好まず、『イノセント10世の肖像』を鑑賞したのは、かなり後年のことである[31]。 |

| 1950s Bacon's main haunt was The Colony Room, a private drinking club at 41 Dean Street in Soho, known as "Muriel's" after Muriel Belcher, its proprietor.[32][33] Belcher had run the Music-box club in Leicester Square during the war, and secured a 3 – 11pm drinking licence for the Colony Room bar as a private-members club. Bacon was an early member, joining the day after its opening in 1948.[34] He was 'adopted' by Belcher as a 'daughter', and allowed free drinks and £10 a week to bring in friends and rich patrons. In 1948 he met John Minton, a regular at Muriel's, as were the painters Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Patrick Swift and the Vogue photographer John Deakin.[35] In 1950, Bacon met the art critic David Sylvester, then best known for his writing on Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti. Sylvester had admired and written about Bacon since 1948. Bacon's artistic inclinations in the 1950s moved towards his abstracted figures which were typically isolated in geometrical cage-like spaces, and set against flat, nondescript backgrounds. Bacon said that he saw images "in series", and his work typically focused more on a single subject for sustained periods, often in triptych or diptych formats. Although his decisions might have been driven by the fact that in the 1950s he tended to produce group works for specific showings, usually leaving things until the last minute, there is significant development in his aesthetic choices during this period which influenced his preference for the represented content in his paintings. Bacon was impressed by Goya, African landscapes and wildlife, and took photographs in Kruger National Park. On his return journey he spent a few days in Cairo, and wrote to Erica Brausen of his intent to visit Karnak and Luxor, and then travel via Alexandria to Marseilles. The visit confirmed his belief in the supremacy of Egyptian art, embodied by the Sphinx. He returned in early 1951. On 30 April 1951, Jessie Lightfoot, his childhood nanny, died at Cromwell Place; Bacon was gambling in Nice when he learned of her death. She had been his closest companion, joining him in London on his return from Paris, and lived with him and Eric Alden at Queensberry Mews West, and later with Eric Hall near Petersfield, in Monte Carlo and at Cromwell Place. Stricken, Bacon sold the 7 Cromwell Place apartment. In 1958 he aligned with the Marlborough Fine Art gallery, who remained as his sole dealer until 1992. In return for a 10-year contract, Marlborough advanced him money against current and future paintings, with the price of each determined by its size. A painting measuring 20 inches by 24 inches was valued at £165 ($462), while one of 65 inches by 78 inches was valued at £420 ($1,176); these were sizes Bacon favoured. According to the contract, the painter would try to supply the gallery with £3,500 ($9,800) worth of pictures each year.[36] |

1950年代 ベーコンの主な行きつけは、ソーホーのディーン・ストリート41番地にあったプライベート・クラブ、コロニー・ルームで、経営者のミュリエル・ベルチャー にちなんで「ミュリエルズ」と呼ばれていた[32][33]。ベルチャーは戦時中、レスター・スクエアでミュージック・ボックス・クラブを経営しており、 コロニー・ルーム・バーにはプライベート・メンバー・クラブとして午後3時から11時までの飲酒ライセンスを確保していた。ベーコンは初期のメンバーで、 1948年の開店翌日に入会した[34]。彼はベルチャーに「娘」として「養子」にされ、友人や金持ちの常連客を呼び込むために無料の酒と週10ポンドの 支払いを許された。1948年、彼は画家のルシアン・フロイト、フランク・アウアーバック、パトリック・スウィフト、ヴォーグの写真家ジョン・ディーキン らと同様、ミュリエルの常連だったジョン・ミントンと出会う[35]。 1950年、ベーコンは、ヘンリー・ムーアやアルベルト・ジャコメッティに関する著作で当時最もよく知られていた美術評論家デイヴィッド・シルヴェスター に出会う。シルヴェスターは1948年以来、ベーコンを賞賛し、ベーコンについて書いていた。1950年代のベーコンの芸術的傾向は、幾何学的な檻のよう な空間に孤立し、何の変哲もない平坦な背景を背景にした抽象的な人物像へと向かっていった。ベーコンは、イメージを「シリーズで」見ていたと語っており、 彼の作品は通常、ひとつの主題に焦点を当て、持続的に、しばしば三連画や二連画の形式で制作された。1950年代には、特定の展覧会のためにグループ作品 を制作する傾向があり、通常はギリギリまで物事を放置していたという事実が、彼の決断を促したのかもしれないが、この時期の彼の美的選択には大きな発展が あり、それが絵画における表現内容の嗜好に影響を及ぼしている。 ベーコンはゴヤやアフリカの風景、野生動物に感銘を受け、クルーガー国立公園で写真を撮った。帰路、彼はカイロで数日を過ごし、カルナックとルクソールを 訪れ、アレクサンドリア経由でマルセイユに向かう意向をエリカ・ブラウゼンに手紙で伝えた。この訪問によって、スフィンクスに象徴されるエジプト美術の至 高性を確信した。彼は1951年初めに帰国した。 1951年4月30日、幼少期の乳母であったジェシー・ライトフットがクロムウェル・プレイスで亡くなった。彼女の死を知ったとき、ベーコンはニースで ギャンブルをしていた。彼女はベーコンにとって最も親しい伴侶であり、パリから帰国するとロンドンで合流し、クィーンズベリー・ミューズ・ウエストで彼と エリック・オールデン、後にピーターズフィールド近くのエリック・ホール、モンテカルロ、クロムウェル・プレイスで共に暮らした。苦境に立たされたベーコ ンは、クロムウェル・プレイス7番地のアパートを売却。 1958年、マールボロ・ファイン・アート・ギャラリーと提携。同社は1992年までベーコンの唯一のディーラーであった。マールボロは、10年間の契約 と引き換えに、現在および将来の絵画に対して資金を提供し、それぞれの価格はそのサイズによって決定された。20インチ×24インチの絵は165ポンド (462ドル)、65インチ×78インチの絵は420ポンド(1,176ドル)で、これらはベーコンが好んだサイズだった。契約によれば、画家は毎年 3,500ポンド(9,800ドル)相当の絵をギャラリーに提供するよう努めることになっていた[36]。 |

| 1960s and 1970s Bacon met George Dyer in 1963 at a pub,[37] although a much-repeated myth claims they met when Dyer burgled Bacon's flat.[38] Dyer was about 30 years old, from London's East End. He came from a family steeped in crime, and had till then spent his life drifting between theft and prison. Bacon's earlier relationships had been with older and tumultuous men. His first lover, Peter Lacy, tore up Bacon's paintings, beat him in drunken rages, at times leaving him on streets half-conscious.[39] Bacon was now the dominating personality, attracted to Dyer's vulnerability and trusting nature. Dyer was impressed by Bacon's self-confidence and success, and Bacon acted as a protector and father figure to the insecure younger man.[40] Dyer was, like Bacon, a borderline alcoholic and similarly took obsessive care with his appearance. Pale-faced and a chain-smoker, Dyer typically confronted his daily hangovers by drinking again. His compact and athletic build belied a docile and inwardly tortured personality, although the art critic Michael Peppiatt describes him as having the air of a man who could "land a decisive punch". Their behaviours eventually overwhelmed their affair, and by 1970 Bacon was merely providing Dyer with enough money to stay more or less permanently drunk.[40] As Bacon's work moved from the extreme subject matter of his early paintings to portraits of friends in the mid-1960s, Dyer became a dominating presence.[41] Bacon's paintings emphasise Dyer's physicality, yet are uncharacteristically tender. More than any other of Bacon's close friends, Dyer came to feel inseparable from his portraits. The paintings gave him stature, a raison d'etre, and offered meaning to what Bacon described as Dyer's "brief interlude between life and death".[42] Many critics have described Dyer's portraits as favourites, including Michel Leiris and Lawrence Gowing. Yet as Dyer's novelty diminished within Bacon's circle of sophisticated intellectuals, Dyer became increasingly bitter and ill at ease. Although Dyer welcomed the attention the paintings brought him, he did not pretend to understand or even like them. "All that money an' I fink they're reely 'orrible," he observed with choked pride.[43] Dyer abandoned crime but descended into alcoholism. Bacon's money attracted hangers-on for benders around London's Soho. Withdrawn and reserved when sober, Dyer was highly animated and aggressive when drunk, and often attempted to "pull a Bacon" by buying large rounds and paying for expensive dinners for his wide circle. Dyer's erratic behaviour inevitably wore thin with his cronies, with Bacon, and with Bacon's friends. Most of Bacon's art world associates regarded Dyer as a nuisance – an intrusion into the world of high culture to which their Bacon belonged.[44] Dyer reacted by becoming increasingly needy and dependent. By 1971, he was drinking alone and only in occasional contact with his former lover. In October 1971, Dyer joined Bacon in Paris for the opening of Bacon's retrospective at the Grand Palais. The show was the high point of Bacon's career to date, and he was now described as Britain's "greatest living painter". Dyer was a desperate man, and although he was "allowed" to attend, he was well aware that he was slipping out of the picture. To draw Bacon's attention, he planted cannabis in his flat and phoned the police,[45] and attempted suicide on a number of occasions.[46] On the eve of the Paris exhibition, Bacon and Dyer shared a hotel room, but Bacon was forced to escape in disgust to the room of gallery employee Terry Danziger-Miles, as Dyer was entertaining an Arab rent boy with "smelly feet". When Bacon returned to his room the next morning, 24 October, together with Danziger-Miles and Valerie Beston, they discovered Dyer in the bathroom dead, seated on the toilet. With the agreement of the hotel manager, the party agreed not to announce the death for two days.[47] Bacon spent the following day surrounded by people eager to meet him. In mid-evening of the following day he was "informed" that Dyer had taken an overdose of barbiturates and was dead. Bacon continued with the retrospective and displayed powers of self-control "to which few of us could aspire", according to Russell.[48] Bacon was deeply affected by the loss of Dyer, and had recently lost four other friends and his nanny. From this point, death haunted his life and work.[49] Though outwardly stoic at the time, he was inwardly broken. He did not express his feelings to critics, but later admitted to friends that "daemons, disaster and loss" now stalked him as if his own version of the Eumenides (Greek for The Furies).[50] Bacon spent the remainder of his stay in Paris attending to promotional activities and funeral arrangements. He returned to London later that week to comfort Dyer's family. During the funeral many of Dyer's friends, including hardened East-End criminals, broke down in tears. As the coffin was lowered into the grave one friend was overcome and screamed "you bloody fool!" Bacon remained stoic during the proceedings, but in the following months suffered an emotional and physical breakdown. Deeply affected, over the following two years he painted a number of single canvas portraits of Dyer, and the three highly regarded "Black Triptychs", each of which details moments immediately before and after Dyer's suicide.[51] |

ベー

コンは1963年にジョージ・ダイアーとパブで知り合ったが[37]、ダイアーがベーコンのアパートに押し入ったときに知り合ったという俗説がまことしや

かに語られている[38]。彼は犯罪に染まった家庭の出身で、それまでは窃盗と刑務所の間を漂うような生活を送っていた。ベーコンの以前の交際相手は、年

上の波乱万丈な男たちだった。最初の恋人であったピーター・レイシーは、ベーコンの絵を破り捨て、酔って暴れたベーコンを殴り、半ば意識不明のまま路上に

置き去りにしたこともあった[39]。ダイヤーはベーコンの自信と成功に感銘を受け、ベーコンは自信のない若い男にとって庇護者であり父親のような役割を

果たした[40]。 ダイアーもベーコンと同様、アルコール依存症に罹患していた。青白い顔でチェーンスモーカーだったダイヤーは、毎日二日酔いになると、また酒を飲むのが常 だった。美術批評家のマイケル・ペピアットは、彼を「決定的なパンチを放つ」ことができる男のような雰囲気を持っていたと評している。二人の振る舞いはや がて不倫関係を圧倒するようになり、1970年までにはベーコンはダイアーに、多かれ少なかれ永久に酔っ払っていられるだけの金を提供するに過ぎなくなっ ていた[40]。 ベーコンの作品が初期の過激な題材から、1960年代半ばに友人の肖像画へと移行するにつれ、ダイアーが圧倒的な存在感を放つようになる[41]。ベーコ ンの親しい友人の誰よりも、ダイアーは彼の肖像画と切っても切れない関係にあると感じるようになった。絵画は彼に身長と存在意義を与え、ベーコンがダイ アーの「生と死の間の短い間奏曲」と表現したものに意味を与えた[42]。ミシェル・レイリスやローレンス・ゴーイングをはじめ、多くの批評家がダイアー の肖像画をお気に入りと評している。しかし、洗練された知識人たちからなるベーコンのサークル内でダイアーの新しさが薄れていくにつれ、ダイアーは次第に 辛辣になり、心を病んでいった。ダイヤーは、絵画が彼にもたらした注目は歓迎したものの、それを理解したふりはしなかったし、好きでもなかった。「あれだ けの金をもらっておきながら、本当にひどい絵だと思う」と、彼は胸を詰まらせながら言った[43]。 ダイヤーは犯罪を捨てたが、アルコール依存症に陥った。ベーコンの金はロンドンのソーホー界隈で酒盛りをする常連客たちを惹きつけた。シラフの時は引っ込 み思案で控えめだったダイアーだが、酔うと非常に活発で攻撃的になり、しばしば大酒を奢ったり、彼の広いサークルのために高価な夕食を払ったりして、 「ベーコンを引き出そう」とした。ダイアーの常軌を逸した行動は、必然的に彼の取り巻きやベーコン、そしてベーコンの友人たちとの関係を悪くした。ベーコ ンの画壇関係者の多くは、ダイアーのことを厄介者、つまりベーコンが属するハイカルチャーの世界に侵入してくる存在とみなしていた[44]。1971年ま で、彼は一人で酒を飲み、かつての恋人と時折連絡を取るだけだった。 1971年10月、ダイヤーはグラン・パレで開催されたベーコンの回顧展のオープニングのため、パリでベーコンと合流した。この回顧展はベーコンのこれま でのキャリアの頂点に立つものであり、彼は今や英国で「最も偉大な存命中の画家」と評されていた。ダイヤーは自暴自棄になっており、出席は「許可」された ものの、自分が絵から抜け落ちていることは十分承知していた。パリの展覧会の前夜、ベーコンとダイヤーはホテルの一室をシェアしたが、ダイヤーが「足の臭 い」アラブ人のレントボーイを接待していたため、ベーコンは嫌気がさしてギャラリーの従業員テリー・ダンジガー・マイルズの部屋に逃げざるを得なかった。 翌朝10月24日、ベーコンがダンジガー・マイルズとヴァレリー・ベストンと共に部屋に戻ると、バスルームでダイアーがトイレに座ったまま死んでいるのを 発見した。ホテルの支配人の同意を得て、一行は2日間この死を公表しないことに同意した[47]。 ベーコンは翌日、彼に会いたがる人々に囲まれて過ごした。翌日の夜半、彼はダイアーがバルビツール酸の過剰摂取で死亡したことを「知らされた」。ベーコン は回顧展を続け、ラッセルによれば「私たちのほとんどが憧れることのできない」自制心を見せた[48]。ベーコンはダイヤーを失ったことに深く心を痛め、 最近も他の4人の友人と乳母を亡くしていた。このときから、死は彼の人生と作品につきまとうようになった[49]。彼は批評家たちに自分の感情を表現する ことはなかったが、後に友人たちに、「悪魔、災難、喪失」が、まるで自分版のエウメニデス(ギリシャ語で「怒れる者たち」の意)のようにつきまとっている ことを認めた[50]。その週の終わりにはロンドンに戻り、ダイヤーの家族を慰めた。 葬儀の最中、イーストエンドの常習犯を含むダイヤーの友人の多くが泣き崩れた。棺が墓に下ろされたとき、ある友人は感極まって、"この血まみれの愚か者 が!"と叫んだ。ベーコンは葬儀の間、ストイックな態度を崩さなかったが、その後数カ月は感情的にも肉体的にも衰弱していった。深い影響を受けたベーコン は、その後2年間、ダイヤーの肖像画をキャンバス1枚で何枚も描き、高く評価されている3枚の「黒い三連画」は、ダイヤーが自殺する直前と直後の瞬間を描 いたものである[51]。 |

| Death While on holiday, Bacon was admitted to the private Clinica Ruber, Madrid in 1992, where he was cared for by the Handmaids of Maria.[52] His chronic asthma, which had plagued him all his life, had developed into a more severe respiratory condition and he could not talk or breathe very well. He died of a heart attack on 28 April 1992. He bequeathed his estate (then valued at £11 million) to his heir and sole legatee John Edwards; in 1998, at Edwards' request, Brian Clarke, a friend of Bacon and Edwards, was installed as sole executor of the estate by the High Court, following the Court's severing of all ties between Bacon's former gallery, Marlborough Fine Art, and his estate.[53] In 1998 the director of the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin secured Edwards' and Clarke's donation of the contents of Bacon's studio at 7 Reece Mews, South Kensington.[54] The contents of his studio were surveyed, moved, and reconstructed in the gallery.[55] |

死 休暇中の1992年、ベーコンはマドリードの私立クリニカ・ルベールに入院し、マリアの侍女たちによってケアされた[52]。生涯彼を悩ませてきた慢性喘 息は、より深刻な呼吸器疾患へと発展し、話すことも呼吸もうまくできなくなっていた。 1992年4月28日、心臓発作により死去。1998年、エドワーズの要請により、ベーコンとエドワーズの友人であったブライアン・クラークが、高等法院 により、ベーコンの元ギャラリーであるマールボロ・ファイン・アートと遺産との関係を断ち切られ、遺産の単独執行人に任命された[53]。 [1998年、ダブリンのヒュー・レーン・ギャラリーのディレクターは、サウス・ケンジントンのリース・ミューズ7番地にあるベーコンのスタジオの内容の エドワーズとクラークの寄付を確保した[54]。 |

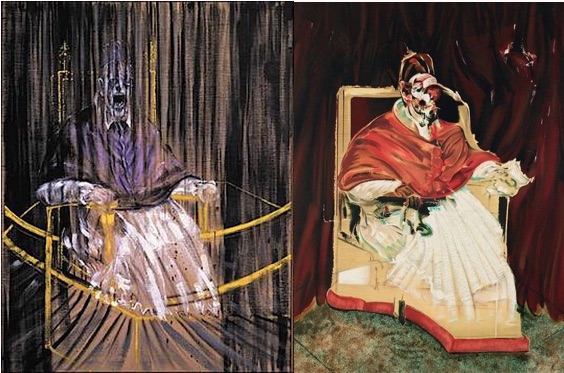

| Themes The Crucifixion The imagery of the crucifixion weighs heavily in the work of Francis Bacon.[56] Critic John Russell wrote that the crucifixion in Bacon's work is a "generic name for an environment in which bodily harm is done to one or more persons and one or more other persons gather to watch".[57] Bacon admitted that he saw the scene as "a magnificent armature on which you can hang all types of feeling and sensation".[58] He believed the imagery of the crucifixion allowed him to examine "certain areas of human behaviour" in a unique way, as the armature of the theme had been accumulated by so many old masters.[58] Though he came to painting relatively late in life – he did not begin to paint seriously until his late 30s – crucifixion scenes can be found in his earliest works.[59] In 1933, his patron Eric Hall commissioned a series of three paintings based on the subject.[60] The early paintings were influenced by such old masters as Matthias Grünewald, Diego Velázquez and Rembrandt,[59] but also by Picasso's late 1920s/early 1930s biomorphs and the early work of the Surrealists.[61]  Popes Bacon's series of Popes, largely quoting Velázquez's famous portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650, Galeria Doria Pamphili, Rome) are striking images which further develop motifs already found in his earlier works, like the Study for Three Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, such as the screaming open mouth. The figures of the popes, pictorially isolated by partly curved parallel lines indicating psychological forces and symbolising inner energy like strength of feeling, are alienated from their original representation and, stripped of their representation of power to allegories of suffering humanity.[62] Reclining figures Many of Bacon's paintings are "inhabited" by reclining figures. Single, or, as in triptychs, repeated with variations, they can be commented by symbolic indexes (like circular arrows as signs for rotation), turning painted images to blueprints for moving images of the type of contemporary GIFs. The composition of especially the nude figures is influenced by the sculptural work of Michelangelo. The multi-phasing of his rendition of the figures, which often is also applied to the sitters in the portraits, is also a reference to Eadweard Muybridge's chronophotography.[62] The screaming mouth  Still from Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 silent film Battleship Potemkin The inspiration for the recurring motif of screaming mouths in many Bacons of the late 1940s and early 1950s was drawn from a number of sources, including medical text books. Kathleen Clark's 1939 book of X-Ray photographs was a major source.[63] He also used the works of Matthias Grünewald[64] and photographic stills of the nurse in the Odessa Steps scene in Eisenstein's 1925 silent film Battleship Potemkin. Bacon saw the film in 1935, and viewed it frequently thereafter. He kept in his studio a photographic still of the scene, showing a close-up of the nurse's head screaming in panic and terror and with broken pince-nez spectacles hanging from her blood-stained face. He referred to the image throughout his career, using it as a source of inspiration.[65] Bacon described the screaming mouth as a catalyst for his work, and incorporated its shape when painting the chimera. His use of the motif can be seen in one of his first surviving works,[66] Abstraction from the Human Form. By the early 1950s it became an obsessive concern, to the point, according to art critic and Bacon biographer Michael Peppiatt, "it would be no exaggeration to say that, if one could really explain the origins and implications of this scream, one would be far closer to understanding the whole art of Francis Bacon."[67] |

テーマ 磔刑 磔刑のイメージはフランシス・ベーコンの作品に重くのしかかっている[56]。 批評家ジョン・ラッセルは、ベーコンの作品における磔刑は「身体的危害が一人または複数の人物に加えられ、それを見物するために一人または複数の他の人物 が集まる環境の総称」であると書いている[57]。 [57]ベーコンは、このシーンを「あらゆる種類の感情や感覚をぶら下げることができる壮大なアーマチュア」[58]として見ていたことを認めている。彼 は、このテーマのアーマチュアは非常に多くの古い巨匠たちによって蓄積されていたため、磔刑のイメージによって「人間の行動のある領域」をユニークな方法 で調べることができると考えていた[58]。 1933年、彼のパトロンであったエリック・ホールは、この主題に基づいた3点の絵画シリーズを依頼した[60]。 初期の絵画は、マティアス・グリューネヴァルト、ディエゴ・ベラスケス、レンブラントといったオールドマスターの影響を受けており[59]、またピカソの 1920年代後半から1930年代前半のビオモーフやシュルレアリスムの初期の作品からも影響を受けている[61]。  教皇 ベラスケスの有名な教皇イノセント10世の肖像画(1650年、ガレリア・ドリア・パンフィーリ、ローマ)を主に引用したベーコンの教皇シリーズは、「磔 刑台座の3人の人物のための習作」のような彼の初期の作品にすでに見られるモチーフをさらに発展させた印象的なイメージである。教皇たちの姿は、心理的な 力を示し、感情の強さのような内なるエネルギーを象徴する、部分的に湾曲した平行線によって絵画的に孤立しており、本来の表現から疎外され、力の表現を剥 ぎ取られ、苦しむ人間の寓意となっている[62]。 横たわる人物 ベーコンの絵画の多くには、横たわる人物が「居住」している。一人で、あるいは三連作のように変化しながら繰り返され、それらは象徴的な指標(回転を示す 円形の矢印のようなもの)によって解説され、描かれたイメージを現代のGIFのような動画像の設計図に変える。特にヌード人物の構図は、ミケランジェロの 彫刻作品に影響を受けている。彼の人物描写の多面的なフェイズは、しばしば肖像画の被写体にも適用され、エドワード・マイブリッジのクロノフォトグラ フィーの引用でもある[62]。 叫ぶ口  セルゲイ・エイゼンシュテインの1925年のサイレント映画『戦艦ポチョムキン』より。 1940年代後半から1950年代前半にかけて、多くのベーコンに繰り返し登場する叫び声のような口というモチーフのインスピレーションは、医学の教科書 を含む多くの情報源から引き出された。また、マティアス・グリューネヴァルトの作品[64]や、エイゼンシュテインの1925年のサイレント映画『戦艦ポ チョムキン』のオデッサ階段のシーンに登場する看護婦のスチール写真も使用した。ベーコンは1935年にこの映画を鑑賞し、その後も頻繁に鑑賞した。パ ニックと恐怖で悲鳴を上げ、血に染まった顔から割れたピンスネズの眼鏡をぶら下げた看護婦の頭のアップが写っている。彼はキャリアを通じてこのイメージを 参照し、インスピレーションの源とした[65]。 ベーコンは、叫び声を上げる口を自分の作品の触媒として説明し、キメラを描く際にその形を取り入れた。彼のこのモチーフの使用は、現存する最初の作品のひ とつである[66]『人間の形からの抽象』で見ることができる。1950年代初頭までに、このモチーフは強迫観念的な関心事となり、美術評論家でありベー コンの伝記作家であるマイケル・ペピアットによれば、「この叫び声の起源と意味合いを本当に説明することができれば、フランシス・ベーコンの芸術全体を理 解することにはるかに近づくだろう」と言っても過言ではないだろう[67]。 |

| Legacy, omission |

レガシー(省略) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon_(artist) |

● 「具象を乗り越えるためには2つの方法がある。ひとつは抽象的形態に向かうこと、もうひとつは、〈図像:フィギュール〉に向かうことである」(ドュルーズ 2022:52)

ジル・ドゥールズ『フランシス・ベーコン:感覚の論理学』宇野邦一訳、河出書房新社, 2022.

| Le

corps-sans-organes (abrégé en CsO par les auteurs) est un concept

développé par les philosophes français Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari

dans leurs œuvres communes : L'Anti-Œdipe et Mille Plateaux. Gilles

Deleuze en avait déjà dit quelques mots dans Proust et les signes

(1964)1 et Logique du sens (1969). Cependant, l'expression de « corps

sans organes » a tout d'abord été formulée par le poète français

Antonin Artaud, notamment dans Pour en finir avec le jugement de dieu. Le poète, qui se dit « insurgé du corps », oppose ce qu'il appelle parfois le corps « atomique » au corps anatomique, le corps-tombeau qui enferme les hommes ; il s'agit donc pour lui de « faire danser l'anatomie humaine », le corps sans organes étant un corps-acte qui participe ainsi d'une recréation de l'homme, ce qu'il nomme « l'Homme incréé ». |

無器官身体(著者らはCsOと略す)とは、フランスの哲学者ジル・ドゥ

ルーズとフェリックス・ガタリが共同著作『L'Anti-Œdipe』と『Mille

Plateaux』の中で展開した概念である。ジル・ドゥルーズはすでに、『プルーストと記号』(1964年)1や『感覚の論理』(1969年)の中で、

この概念について少し述べていた。しかし、「器官なき身体」という表現は、フランスの詩人アントナン・アルトーが、特に『Pour en finir

avec le jugement de dieu』の中で初めて定式化したものである。 自らを「肉体の反乱者」と呼ぶこの詩人は、時に「原子」身体と呼ばれるものを、人間を幽閉する身体爆弾である解剖学的身体と対立させた。彼にとって、それ は「人体解剖学を踊らせる」問題であり、臓器のない身体は、人間の再創造に参加する身体行為であり、彼が「創造されざる人間」と呼んだものであった。 |

| Clarification du concept CsO Pour comprendre le CsO il est important de saisir la définition deleuzienne du désir. Dans L'Anti-Œdipe (1972), Deleuze et Guattari remettent en cause explicitement la conception psychanalytique du désir. Ce qui constitue le thème central de l'Anti-Œdipe, c'est que, pour Deleuze et Guattari, le désir n'est pas une scène de théâtre (où se joue Hamlet par exemple), mais une usine qui produit sans cesse, qui crée des agencements, qui est cause de déterritorialisation et de reterritorialisation, des agencements machiniques de choses, des machines désirantes. Le désir compris comme usine nous permet dès lors de concevoir les machines désirantes. Car dans la nature et dans tout corps il n'y a que des agencements machiniques, une multiplicité de machines, machine désirante, mais aussi machine-organe, machine-énergie, et des couples, accouplements de machines. Deleuze unit l'homme et la nature au travers d'un processus couplant les machines : « L'homme et la nature produisent l'un dans l'autre »— paradigme de la coextensivité du corps et de la nature, corps intensif, corps immanent traversé de seuils, de niveaux, de vecteurs, de gradients d'intensité. Le CsO est une production du désir, il s'oppose à l'organisme que nous font les machines désirantes. Le corps souffre de ne pas avoir d'autre organisation, ou pas d'organisation du tout... Le CsO est un corps sans image (« avant » la représentation organique), une anti-production, mais il est inévitable parce qu'il nous pénètre sans cesse, et sans cesse nous le pénétrons. Le CsO est un programme, une expérimentation et non un fantasme. Produit comme un tout à côté de parties auxquelles il s'ajoute, le CsO s'oppose à l'organisme. Car c'est par le corps, et par les organes, que le désir passe et non par l'organisme. Dans Francis Bacon : logique de la sensation (1981), Deleuze explique que « le corps sans organes se définit donc par un organe indéterminé, tandis que l’organisme se définit par des organes déterminés. » « Au lieu d’une bouche et d’un anus qui risquent tous deux de se détraquer, pourquoi n’aurait-on pas un seul orifice polyvalent pour l’alimentation et la défécation ? On pourrait murer la bouche et le nez combler l’estomac et creuser un trou d’aération directement dans les poumons — ce qui aurait dû être fait dès l’origine.2 » Il y a de multiples possibilités du CsO selon les désirs, les êtres... Citons comme exemple le corps hypocondriaque, dont les organes se détruisent, ou le corps schizophrène, qui mène la lutte contre ses propres organes. Si Deleuze aime à prendre l'exemple du schizophrène, en citant notamment l'œuvre d'Antonin Artaud, il signale que le CsO peut aussi être « gaieté, extase, danse... » mais l'expérimentation n'est pas anodine, elle peut entraîner la mort. Il faut, par conséquent, être prudent même si l'expérimentation du CsO est une question de vie ou de mort. Car pour Deleuze il ne faut pas, comme le prétend la psychanalyse, retrouver notre « moi » mais aller au-delà. Deleuze dit, dans son Abécédaire, qu'« on ne délire pas sur papa-maman, on délire le monde ». Aussi précise-t-il dans Mille plateaux : « Remplacer l'anamnèse par l'oubli, l'interprétation par l'expérimentation. » Deleuze s'oppose à l'idée du désir perçu comme manque ou fantasme. Pour Deleuze, le grand livre sur le CsO est l'Éthique de Baruch Spinoza : les attributs, les substances, les intensités ignorent l'opposition de l'un et du multiple puisqu'il y a multiplicité de fusions, d'abouchemenents, de glissements : « Le corps n'est plus qu'un ensemble de clapets, sas, écluses, bols ou vases communicants3 » Le CsO est comme un œuf sur lequel, et dans lequel, des intensités circulent, intensités qu'il produit et distribue dans un espace intensif, inétendu. |

CsO概念の明確化 CsOを理解するためには、ドゥルーズの欲望の定義を理解することが重要である。L'Anti-Œdipe』(1972年)において、ドゥルーズとガタリ は欲望に関する精神分析的概念に明確に挑戦している。L'Anti-Œdipe』の中心的なテーマは、ドゥルーズとガタリにとって欲望とは舞台(たとえば ハムレットが演じられる場所)ではなく、絶えず生産し、配置を生み出し、非領域化と再領域化を引き起こす工場であり、物事の機械的配置、欲望の機械である ということである。欲望を工場として理解することで、欲望する機械を考えることができる。自然の中にも、あらゆる身体の中にも、機械的な配置、機械の多重 性、欲望機械、機械器官、機械エネルギー、機械のカップル、結合しか存在しないからである。ドゥルーズは、機械をカップリングさせるプロセスを通じて、人 間と自然を一体化させる。「人間と自然は、他方の中に一方を生み出す」-身体と自然の共時性、集中的身体、閾値、レベル、ベクトル、強度の勾配によって横 断される内在的身体というパラダイムである。 CsOは欲望の産物であり、欲望する機械が私たちのために作る有機体とは対照的である。身体は、他の組織を持たないこと、あるいはまったく組織を持たない ことに苦しんでいる......。CsOはイメージのない身体(有機的表象の「前」)であり、反生産的なものであるが、CsOは常に私たちを貫き、私たち も常にCsOを貫くので、それは必然的なものである。CsOはプログラムであり、実験であり、空想ではない。CsOは、それが加えられる部分とともに全体 として制作され、有機体と対立する。欲望が通過するのは身体を通してであり、器官を通してであって、有機体を通してではないからである。 フランシス・ベーコン:感覚の論理』(1981年)の中で、ドゥルーズ は「器官のない身体はこのように不確定な器官によって定義されるのに対して、有機体は確定的な器官によって定義される」と説明している。"口と肛門が両方 ともおかしくなる危険性がある代わりに、摂食と排便のための多目的オリフィスをひとつにすべきではないだろうか。口と鼻を壁で塞いで胃を満たし、肺に直接 通気孔を掘ることもできる。 CsOには、人によってさまざまな可能性がある。例えば、臓器が自らを破壊する心気症の身体や、自らの臓器と闘う精神分裂病の身体。ドゥルーズは、特にア ントナン・アルトーの作品を引き合いに出して、精神分裂病患者の例を好んで使うが、CsOは「陽気、恍惚、ダンス...」でもあり得るが、実験は無害では なく、死に至ることもあると指摘する。だから私たちは、たとえCsOの実験が生死に関わることであっても、注意しなければならない。ドゥルーズにとって、 私たちは精神分析が主張するように「自己」を再発見するのではなく、「自己」を超えていかなければならない。ドゥルーズは『Abécédaire』の中 で、「私たちはママやパパを絶賛するのではなく、世界を絶賛するのだ」と述べている。Mille Plateaux』では、「アナムネシスを忘却に、解釈を実験に置き換える」と述べている。ドゥルーズは、欠乏や空想としての欲望という考え方に反対して いる。 ドゥルーズにとって、CsOに関する偉大な書物はバルーク・スピノザの『倫理学』である。属性、物質、強度は、融合、曖昧さ、滑りの多重性が存在するため、一と多の対立を無視する。 CsOは、強度が循環する卵のようなものであり、その強度はCsOによって生み出され、集中的で拡張されていない空間に分配される。 |

| Bibliographie Gilles Deleuze, Proust et les signes, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, coll. « Quadrige », 1998 (1re éd. 1964), 224 p. (ISBN 2130478581) Gilles Deleuze, Logique du sens, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Critique », 1969, 392 p. (ISBN 2707301523) Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari, L'Anti-Œdipe : Capitalisme et schizophrénie, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Critique », 1972, 494 p. (ISBN 2-7073-0067-5) Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari, Mille Plateaux : Capitalisme et schizophrénie 2, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Critique », 1980, 645 p. (ISBN 2-7073-0307-0) Gilles Deleuze, « Le corps sans organes et la figure de Bacon », dans Francis Bacon. Logique de la sensation, Paris, Seuil, coll. « L'ordre philosophique », 2002 (1re éd. 1981) (EAN 9782020500142), p. 47-52. Arnaud Villani, « Corps sans organes », dans Robert Sasso (dir.) et Arnaud Villani (dir.), Le Vocabulaire de Gilles Deleuze, Nice, Centre de Recherches en Histoire des Idées, coll. « Les Cahiers de Noesis » (no 3), 2003, p. 62-66. Gilles Deleuze et Claire Parnet, Dialogues, Paris, Flammarion, coll. « Champs », 2004 (1re éd. 1995), 187 p. (ISBN 2-08-081343-9) Évelyne Grossman, Le corps de l'informe, textes réunis et présentés par Évelyne Grossman, Textuel, no 42, Paris 7 - Denis Diderot - revue de l'UFR, 2002, 224 p. Florence Andoka, « Machine désirante et subjectivité dans 'L'Anti-Œdipe de Deleuze et Guattari », Philosophique, Annales littéraires de l'Université de Franche-Comté, vol. 15, 12, p. 85-94 (lire en ligne [archive], consulté le 7 avril 2023). Serge Agnessan, Corps sans organes, Éditions Poètes de brousse, Montréal, 2022, 82 p. |

|

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corps-sans-organes |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099