フレデリック・ダグラス

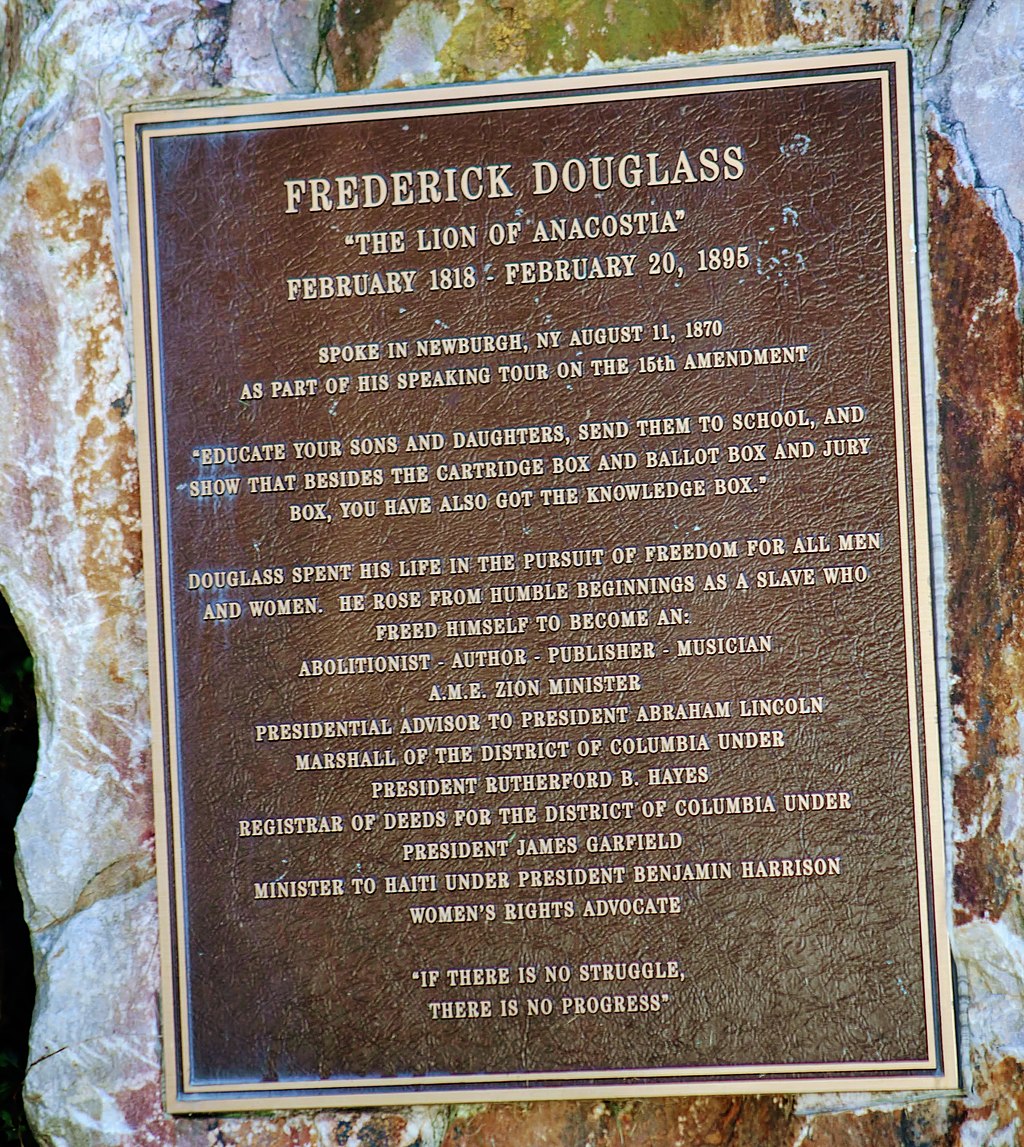

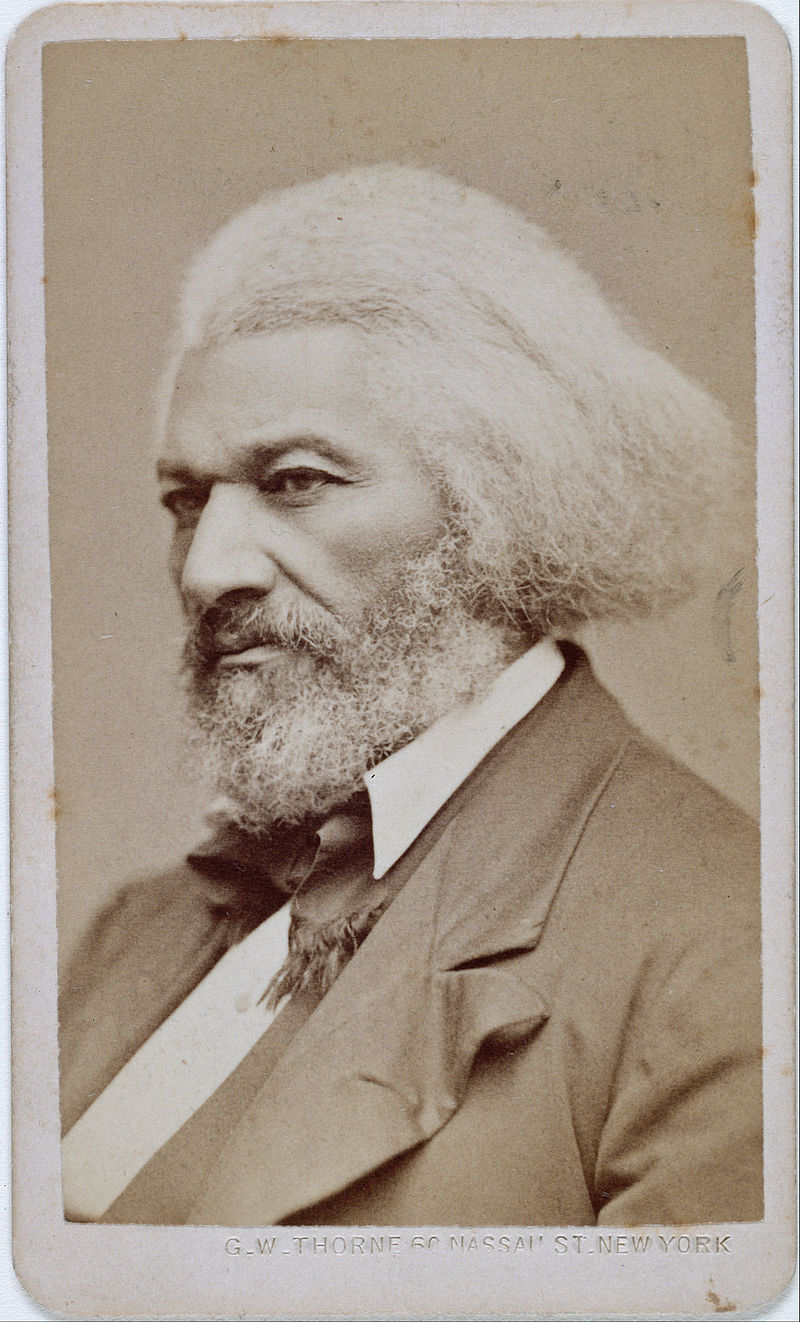

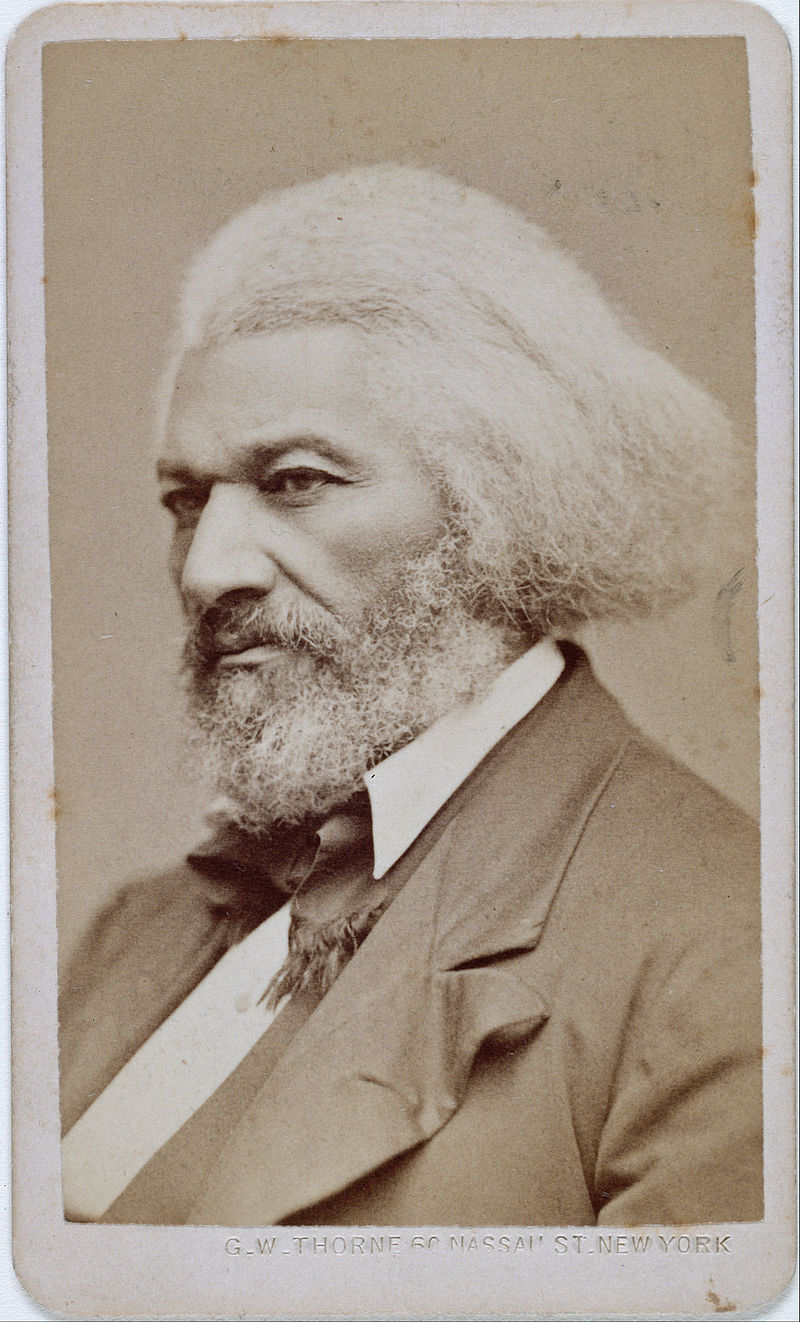

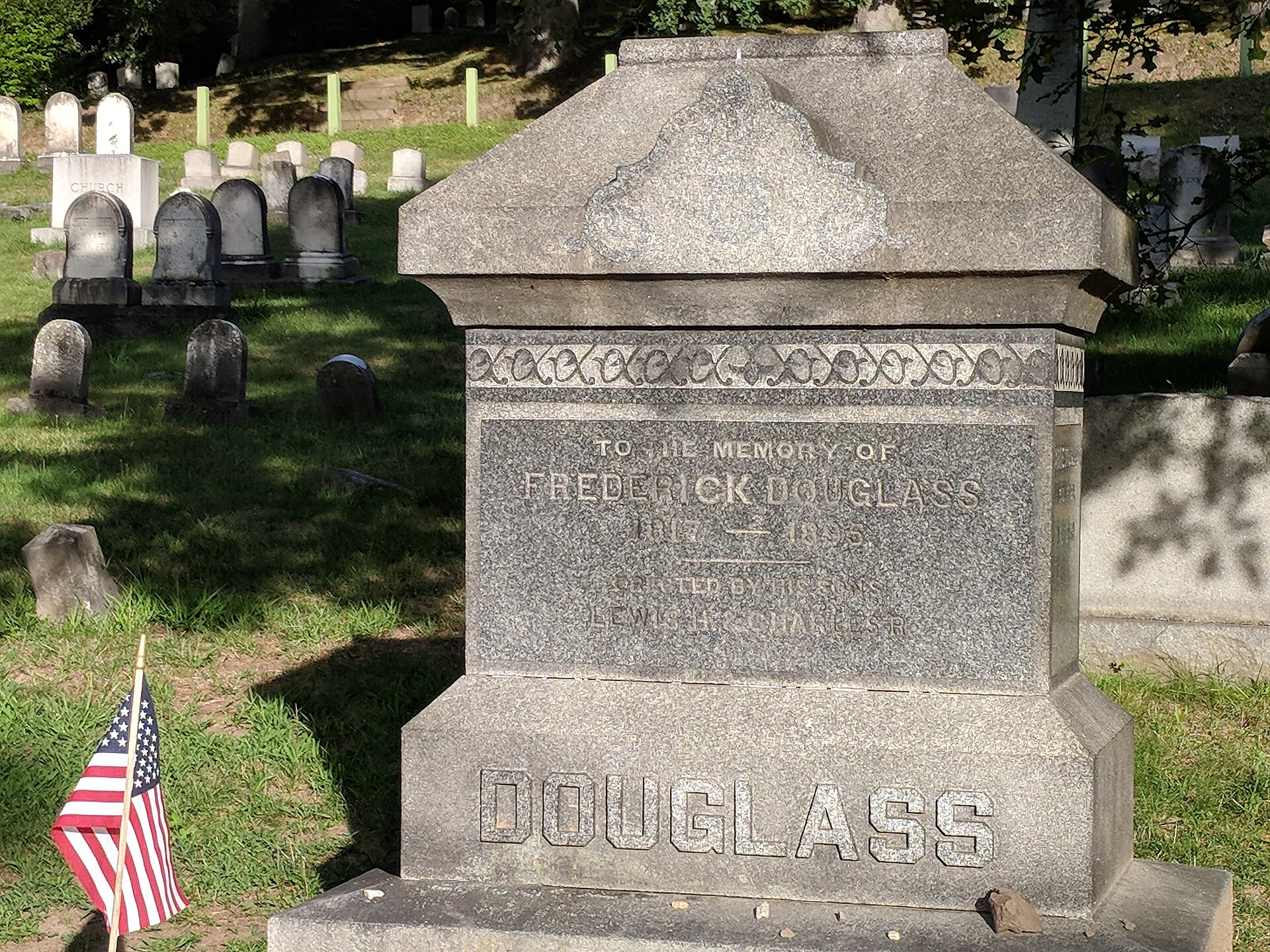

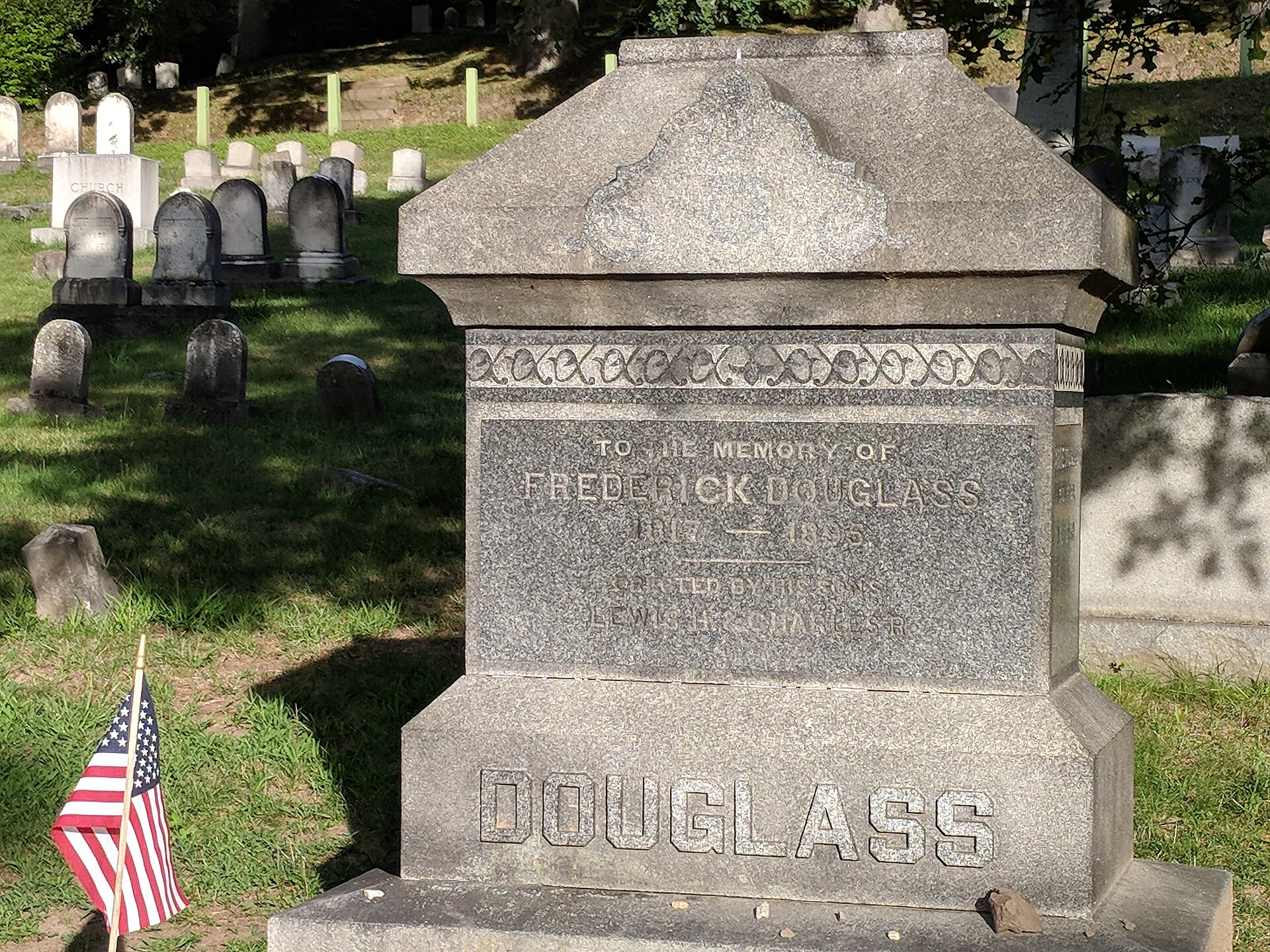

Frederick Douglass, 1817(or 1818)-1895

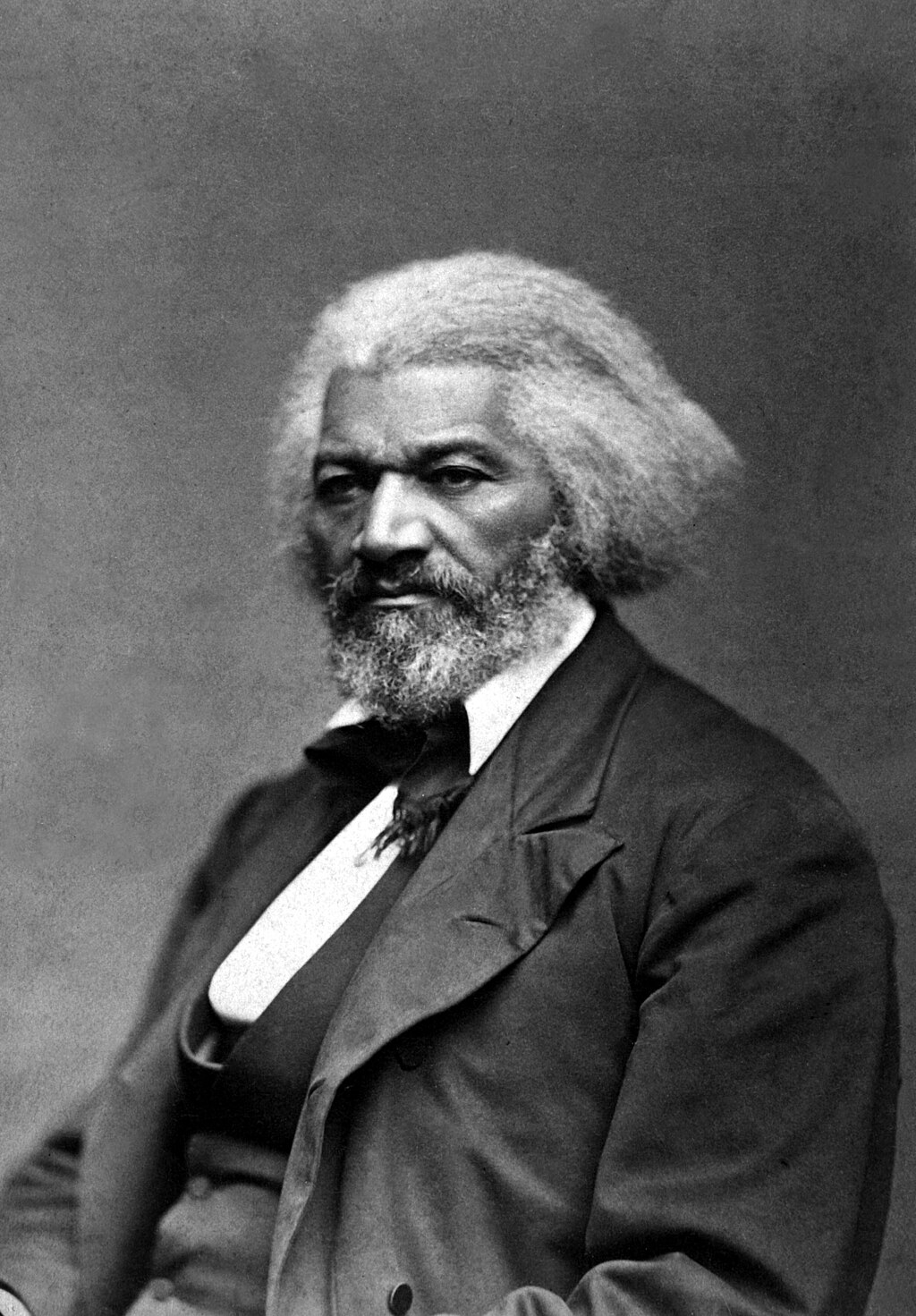

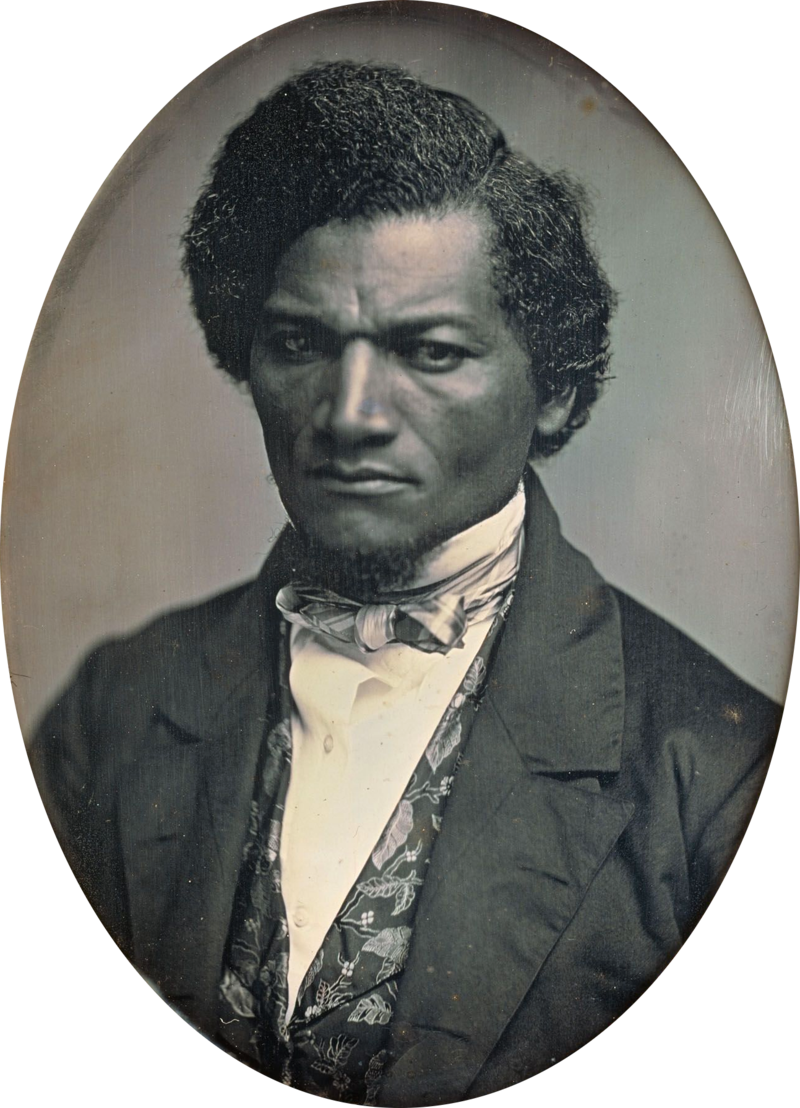

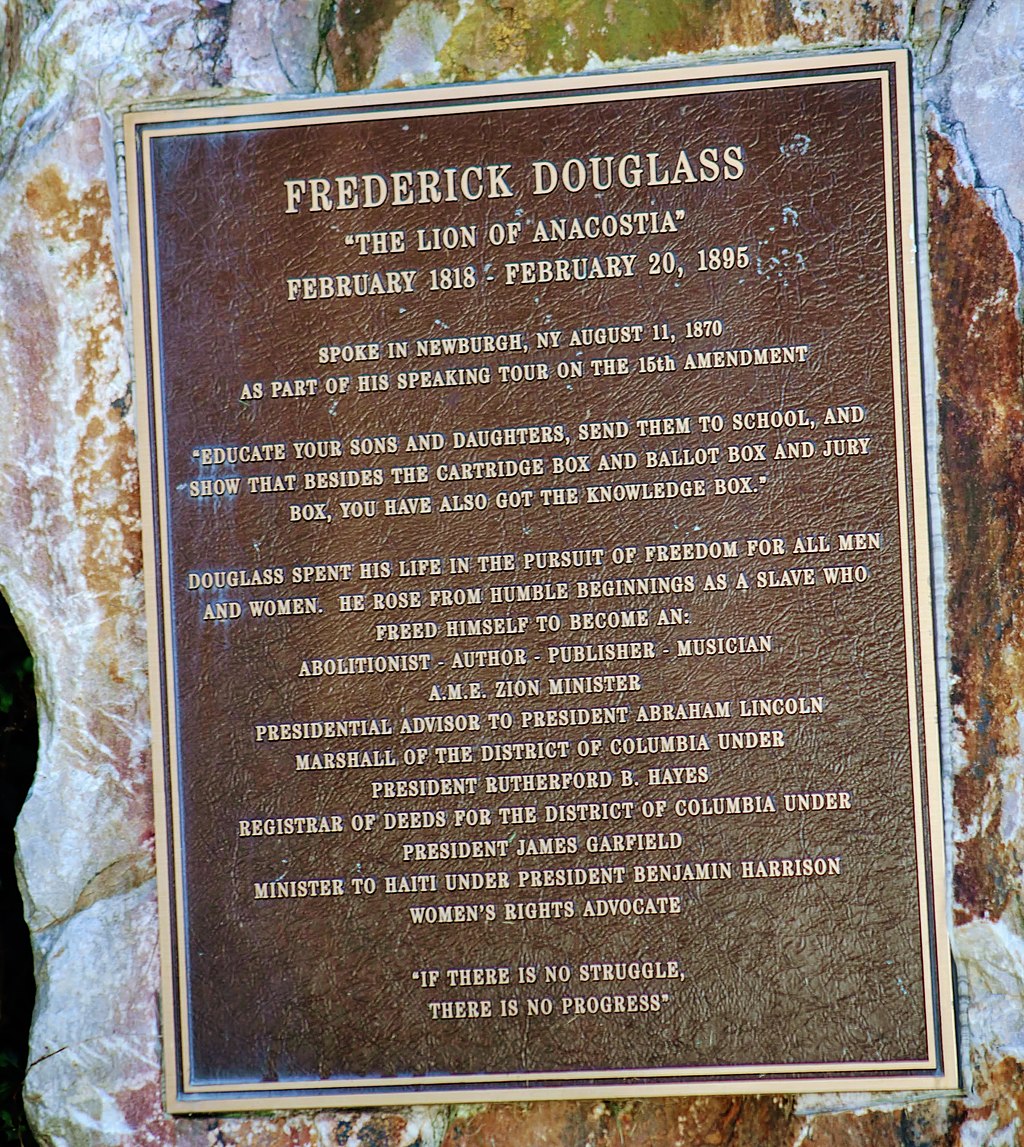

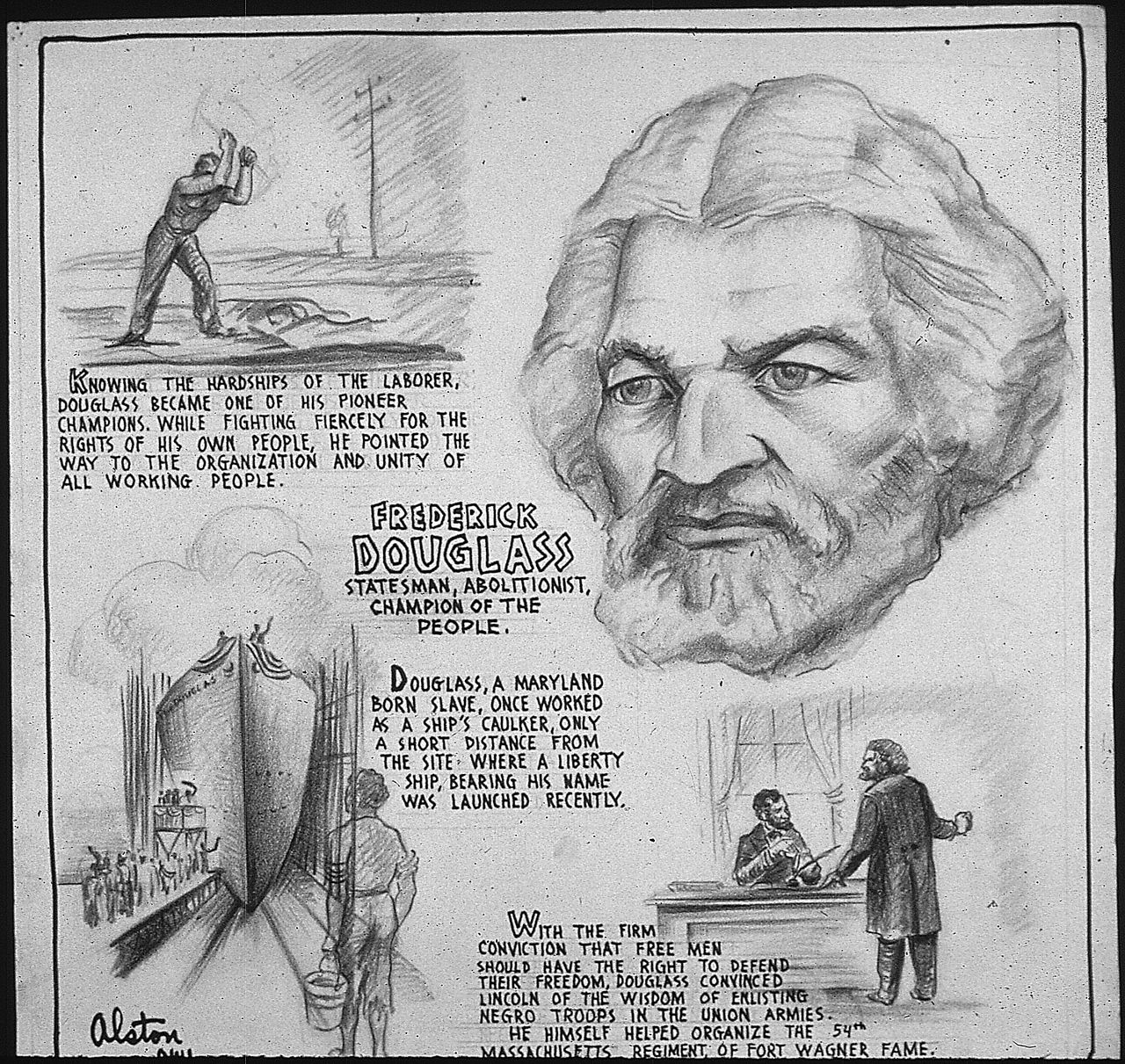

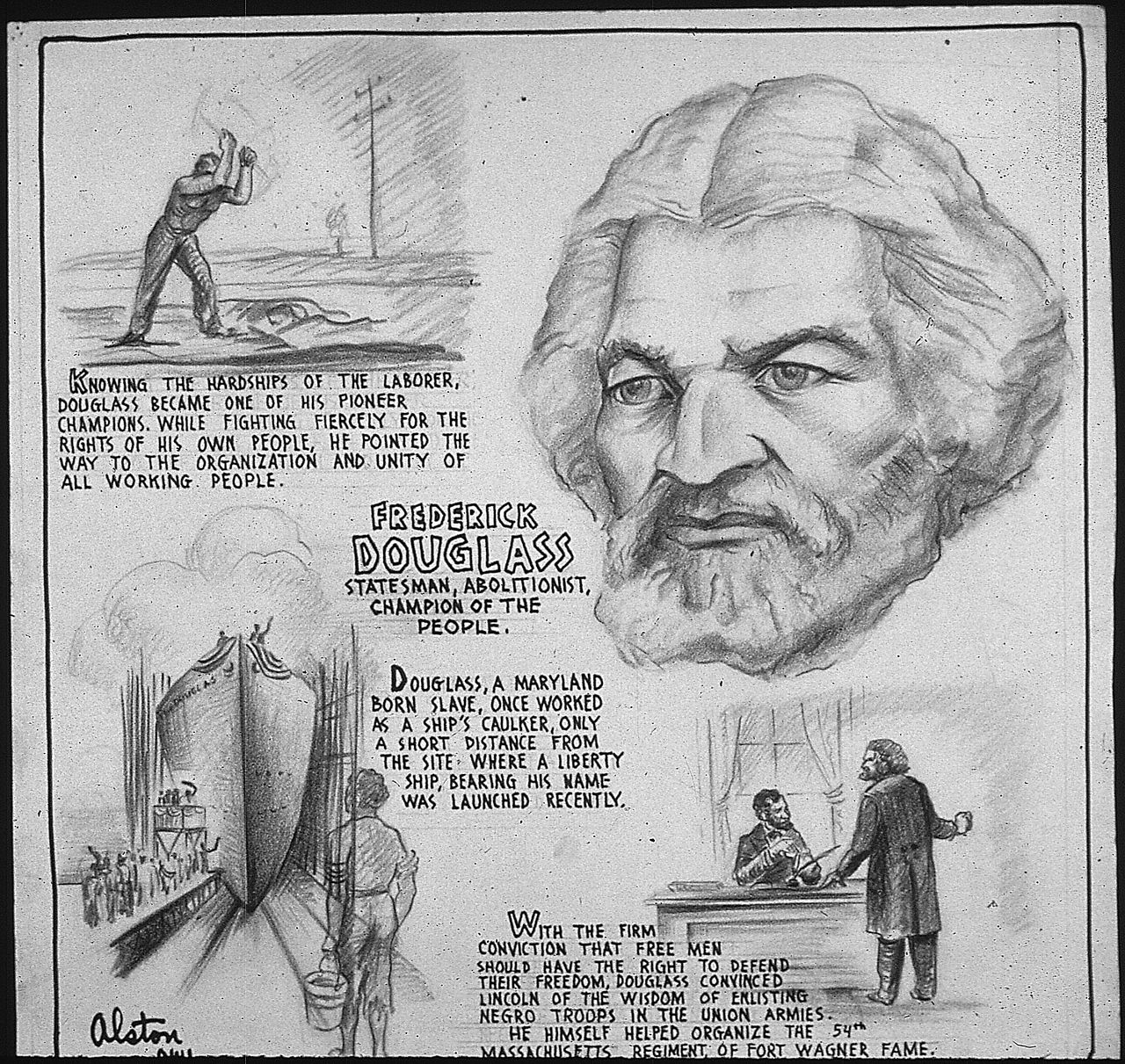

☆ フレデリック・ダグラス(Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey、1817年2月頃または1818年2月[a] - 1895年2月20日)は、アメリカの社会改革者、奴隷廃止論者、演説家、作家、政治家である。彼は19世紀におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の公民権運動の 最も重要な指導者となった。

| Frederick Douglass

(born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, c. February 1817 or

February 1818[a] – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer,

abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He became the most

important leader of the movement for African-American civil rights in

the 19th century. After escaping from slavery in Maryland in 1838, Douglass became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, during which he gained fame for his oratory[4] and incisive antislavery writings. Accordingly, he was described by abolitionists in his time as a living counterexample to claims by supporters of slavery that enslaved people lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.[5] Northerners at the time found it hard to believe that such a great orator had once been enslaved. It was in response to this disbelief that Douglass wrote his first autobiography.[6] Douglass wrote three autobiographies, describing his experiences as an enslaved person in his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), which became a bestseller and was influential in promoting the cause of abolition, as was his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). Following the Civil War, Douglass was an active campaigner for the rights of freed slaves and wrote his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. First published in 1881 and revised in 1892, three years before his death, the book covers his life up to those dates. Douglass also actively supported women's suffrage, and he held several public offices. Without his knowledge or consent, Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States, as the running mate of Victoria Woodhull on the Equal Rights Party ticket.[7] Douglass believed in dialogue and in making alliances across racial and ideological divides, as well as, after breaking with William Lloyd Garrison, in the anti-slavery interpretation of the U.S. Constitution.[8] When radical abolitionists, under the motto "No Union with Slaveholders", criticized Douglass's willingness to engage in dialogue with slave owners, he replied: "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."[9] |

フ

レデリック・ダグラス(Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey、1817年2月頃または1818年2月[a] -

1895年2月20日)は、アメリカの社会改革者、奴隷廃止論者、演説家、作家、政治家である。彼は19世紀におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の公民権運動の

最も重要な指導者となった。 1838年にメリーランド州で奴隷から逃れた後、ダグラス氏はマサチューセッツ州とニューヨーク州で奴隷廃止運動の全国的な指導者となり、その間に雄弁 [4]と鋭い奴隷制度反対の著作で名声を博した。そのため、奴隷制支持者たちが奴隷はアメリカ市民として自立して活動するだけの知的能力を持たないという 主張に対して、奴隷制廃止論者たちは彼を奴隷制の生き証人と見なした[5]。当時の北部の人々は、このような偉大な演説家がかつて奴隷であったとは信じ難 かった。この不信感に応える形で、ダグラスはその最初の自伝を書いたのである[6]。 ダグラスは3冊の自伝を執筆し、奴隷としての経験を『フレデリック・ダグラスの生涯の物語』(1845年)で綴った。この本はベストセラーとなり、奴隷廃 止運動の推進に大きな影響を与えた。2冊目の著書『私の束縛と私の自由』(1855年)も同様であった。南北戦争後、ダグラス氏は解放奴隷の権利獲得運動 に積極的に取り組み、最後の自叙伝『フレデリック・ダグラスの生涯』を執筆した。1881年に初版が発行され、1892年に改訂された。この本は、ダグラ ス氏の死の3年前に出版され、それまでの生涯を網羅している。ダグラス氏はまた、女性の参政権獲得にも積極的に取り組み、いくつかの公職も務めた。彼の知 らぬところ、また同意を得ることなく、ダグラス氏は、平等権利党のビクトリア・ウッドハル候補の副大統領候補として、アフリカ系アメリカ人として初めてア メリカ合衆国副大統領候補となった[7]。 ダグラス氏は、対話と人種やイデオロギーの違いを超えた同盟関係を信条とし、 また、ウィリアム・ロイド・ギャリソンと決別した後、アメリカ合衆国憲法の奴隷制度廃止解釈を支持した。[8] 奴隷制度廃止論者たちが「奴隷所有者と手を結ぶな」を合言葉に、奴隷所有者と対話をしようとするダグラスを批判したとき、彼はこう答えた。「私は正しいこ とを行うために誰とでも、間違ったことを行うために誰とも結束しないだろう」[9]。 |

| Early life and slavery Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay in Talbot County, Maryland. The plantation was between Hillsboro and Cordova;[10] his birthplace was likely his grandmother's cabin[b] east of Tappers Corner and west of Tuckahoe Creek.[11][12][13] In his first autobiography, Douglass stated: "I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it."[14] In successive autobiographies, he gave more precise estimates of when he was born, his final estimate being 1817.[10] However, based on the extant records of Douglass's former owner, Aaron Anthony, historian Dickson J. Preston determined that Douglass was born in February 1818.[2] Though the exact date of his birth is unknown, he chose to celebrate February 14 as his birthday, remembering that his mother called him her "Little Valentine."[1][15] Birth family Douglass's mother, enslaved, was of African descent and his father, who may have been her master, apparently of European descent;[16] in his Narrative (1845), Douglass wrote: "My father was a white man."[10] According to David W. Blight's 2018 biography of Douglass, "For the rest of his life he searched in vain for the name of his true father."[17] Douglass's genetic heritage likely also included Native American.[18] Douglass said his mother Harriet Bailey gave him his name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey and, after he escaped to the North in September 1838, he took the surname Douglass, having already dropped his two middle names.[19] He later wrote of his earliest times with his mother:[20] The opinion was also whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion, I know nothing. ... My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant. ... It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age. ... I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone. After separation from his mother during infancy, young Frederick lived with his maternal grandmother Betsy Bailey, who was also enslaved, and his maternal grandfather Isaac, who was free.[21] Betsy would live until 1849.[22] Frederick's mother remained on the plantation about 12 miles (19 km) away, visiting Frederick only a few times before her death when he was 7 years old. Returning much later, about 1883, to purchase land in Talbot County that was meaningful to him, he was invited to address "a colored school": I once knew a little colored boy whose mother and father died when he was six years old. He was a slave and had no one to care for him. He slept on a dirt floor in a hovel, and in cold weather would crawl into a meal bag head foremost and leave his feet in the ashes to keep them warm. Often he would roast an ear of corn and eat it to satisfy his hunger, and many times has he crawled under the barn or stable and secured eggs, which he would roast in the fire and eat. That boy did not wear pants like you do, but a tow linen shirt. Schools were unknown to him, and he learned to spell from an old Webster's spelling-book and to read and write from posters on cellar and barn doors, while boys and men would help him. He would then preach and speak, and soon became well known. He became Presidential Elector, United States Marshal, United States Recorder, United States diplomat, and accumulated some wealth. He wore broadcloth and didn't have to divide crumbs with the dogs under the table. That boy was Frederick Douglass.[23] Early learning and experience The Auld family At the age of 6, Douglass was separated from his grandparents and moved to the Wye House plantation, where Aaron Anthony worked as overseer.[13] After Anthony died in 1826, Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld, who sent him to serve Thomas' brother Hugh Auld and his wife Sophia Auld in Baltimore. From the day he arrived, Sophia saw to it that Douglass was properly fed and clothed, and that he slept in a bed with sheets and a blanket.[24] Douglass described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman, who treated him "as she supposed one human being ought to treat another."[25] Douglass felt that he was lucky to be in the city, where he said enslaved people were almost freemen, compared to those on plantations. When Douglass was about 12, Sophia Auld began teaching him the alphabet. Hugh Auld disapproved of the tutoring, feeling that literacy would encourage enslaved people to desire freedom. Douglass later referred to this as the "first decidedly antislavery lecture" he had ever heard. "'Very well, thought I,'" wrote Douglass. "'Knowledge unfits a child to be a slave.' I instinctively assented to the proposition, and from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom."[26] Under her husband's influence, Sophia came to believe that education and slavery were incompatible and one day snatched a newspaper away from Douglass.[27] She stopped teaching him altogether and hid all potential reading materials, including her Bible, from him.[24] In his autobiography, Douglass related how he learned to read from white children in the neighborhood and by observing the writings of the men with whom he worked.[28] Douglass continued, secretly, to teach himself to read and write. He later often said, "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom."[29] As Douglass began to read newspapers, pamphlets, political materials, and books of every description, this new realm of thought led him to question and condemn the institution of slavery. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator, an anthology that he discovered at about age 12, with clarifying and defining his views on freedom and human rights. First published in 1797, the book is a classroom reader, containing essays, speeches, and dialogues, to assist students in learning reading and grammar. He later learned that his mother had also been literate, about which he would later declare: I am quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess, and for which I have got—despite of prejudices—only too much credit, not to my admitted Anglo-Saxon paternity, but to the native genius of my sable, unprotected, and uncultivated mother—a woman, who belonged to a race whose mental endowments it is, at present, fashionable to hold in disparagement and contempt.[30] William Freeland When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he "gathered eventually more than thirty male slaves on Sundays, and sometimes even on weeknights, in a Sabbath literacy school."[31] Edward Covey In 1833, Thomas Auld took Douglass back from Hugh ("[a]s a means of punishing Hugh," Douglass later wrote). Thomas sent Douglass to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker". He whipped Douglass so frequently that his wounds had little time to heal. Douglass later said the frequent whippings broke his body, soul, and spirit.[32] The 16-year-old Douglass finally rebelled against the beatings, however, and fought back. After Douglass won a physical confrontation, Covey never tried to beat him again.[33][34] Recounting his beatings at Covey's farm in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass described himself as "a man transformed into a brute!"[35] Still, Douglass came to see his physical fight with Covey as life-transforming, and introduced the story in his autobiography as such: "You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man."[36] |

幼少期と奴隷生活 フレデリック・オーガスタス・ワシントン・ベイリーは、メリーランド州タルボット郡チェサピーク湾東岸で奴隷として生まれた。 プランテーションはヒルズボロとコルドバの間にあった[10]。彼の出生地は、タッパーズコーナーの東、タッカホークリークの西にある祖母の小屋[b]で あった可能性が高い[11][12][13]。最初の自伝で、ダグラスは以下の様に述べている。「自分の正確な年齢は知らない。年齢が記載された真正の記 録を一度も見たことがないからだ」[14] 彼は、後続の自伝で、生まれた時期についてより正確な推定値を提示し、最終的な推定値は1817年となった[10]。しかし、ダグラスの以前の所有者アー ロン・アンソニーの現存する記録に基づき、歴史家のディクソン・J・プレストンは、ダグラスは1818年2月に生まれたと断定した 1818年である[2]。正確な生年月日は不明だが、彼は2月14日を自分の誕生日として祝うことにした。母親が彼を「リトル・バレンタイン(小さなバレ ンタイン)」と呼んでいたことを思い出したからだ[1][15]。 生みの親 奴隷であったダグラスの母親はアフリカ系アメリカ人であり、母親の主だったと思われる父親はヨーロッパ系アメリカ人であった[16]。『自叙伝』 (1845年)の中で、ダグラス氏は「私の父は白人だった」と書いている[10]。デビッド・W・ブライトによる2018年のダグラス氏伝記によると、 「彼は生涯を通じて、実の父親の名前を探し求め続けたが、無駄に終わった」[17]。ダグラス氏の遺伝的背景には、おそらくネイティブアメリカンも含まれ ていた[18]。ダグラス氏は、 母親のハリエット・ベイリーが彼にフレデリック・オーガスタス・ワシントン・ベイリーという名前をつけた。1838年9月に北部へ逃亡した後、彼はすでに 2つのミドルネームを捨てていたため、姓をダグラスとした。 彼は後に、母親と一緒に過ごした幼い頃の様子を次のように書いている。 私の主人が私の父親であるという噂もささやかれていたが、この噂が正しいかどうかは私にはわからない。私と母は私がまだ赤ん坊のときに引き離され た。...私が逃げ出したメリーランド州の一部では、幼い子どもを母親から引き離すのが一般的な習慣である。...私は、昼間に母親を見た記憶がない。母 は夜、私のそばにいた。一緒に横になり、私を寝かしつけてくれたが、私が目を覚ますずっと前にいなくなっていた。 幼少期に母親と引き離されたフレデリックは、奴隷であった母方の祖母ベッツィー・ベイリーと、自由民であった母方の祖父アイザックとともに暮らした [21]。ベッツィーは1849年まで生きた[22]。フレデリックの母親は、約19km離れたプランテーションに残り、フレデリックが7歳の時に亡くな るまで、数回しかフレデリックを訪ねてこなかった。 1883年頃、自分にとって意味のあるタルボット郡の土地を購入するために、はるかに遅れて戻ってきた彼は、「有色人種の学校」で演説するよう招待された。 私は、6歳のときに両親を亡くした小さな有色人種の少年を知っていた。彼は奴隷で、世話をしてくれる人もいなかった。彼は掘っ立て小屋で土の床に寝てお り、寒い日には食事袋に頭から入り、足を灰の中に置いて暖かくしていた。彼はよくトウモロコシを焼いて空腹を満たし、納屋や馬小屋に忍び込んで卵を盗み、 それを火で焼いて食べたこともあった。 その少年はあなたのようにズボンをはかず、麻のシャツを着ていた。学校は彼にとって未知の世界であり、古いウェブスターのスペリングブックでスペルの書き 方を学び、納屋や馬小屋のドアに貼られたポスターで読み書きを学んだ。彼は説教や講演を行い、すぐに有名になった。大統領選挙人、連邦保安官、連邦記録 官、外交官となり、ある程度の財産も蓄えた。ブロードクロスを着て、テーブルの下で犬にパンくずを分ける必要もなくなった。その少年こそ、フレデリック・ ダグラスだった[23]。 初期の学習と経験 オールド家 6歳のとき、ダグラスは祖父母と引き離され、アーロン・アンソニーが監督として働いていたワイ・ハウス農園に移された[13]。1826年にアンソニーが 死去した後、ダグラスはトーマス・オールドの妻ルクレティア・オールドに引き取られ、ボルチモアに住むトーマスの弟ヒュー・オールドと妻ソフィア・オール ドのもとに送られた。到着したその日から、ソフィアはダグラスにきちんと食事と衣服を与え、シーツと毛布が敷かれたベッドで眠れるようにした[24]。ダ グラスは彼女を「思いやりがあり、心優しい女性」と表現し、「彼女は、人間としてあるべき接し方を、私にしていた」と語っている[25]。ダグラスは、プ ランテーションで働く人々に比べ、奴隷の人々がほとんど自由人であるようなこの街にいることが幸運だと感じていた。 ダグラスが12歳になった頃、ソフィア・オールドは彼にアルファベットを教え始めた。ヒュー・オールドは、識字能力は奴隷の人々に自由を求める気持ちを抱 かせるとして、この教育に反対していた。ダグラスは後に、これが自分が聞いた「最初の決定的な反奴隷制の講義」だったと語っている。 「なるほど、そうだと思った」とダグラスは書いている。「『知識は子供を奴隷にするのにふさわしくない』。私は直感的にその主張に同意し、その瞬間から奴 隷から自由への直接的な道筋を理解した」[26]。 夫の影響を受け、ソフィアは教育と奴隷制は両立しないと考え、ある日、新聞をダグラスから奪い取った[27]。彼女は彼に教えることを完全にやめ、 聖書を含むすべての読み物を彼から隠した[24]。自伝の中で、ダグラスは近所の白人の子供たちから読み方を学び、一緒に働いていた男たちの文字を観察す ることで読み方を習得した経緯を語っている[28]。 ダグラスはひそかに読み書きを独学で続けた。彼は後にしばしば、「知識は奴隷から自由への道である」と語った[29]。ダグラスが新聞、パンフレット、政 治資料、あらゆる種類の書籍を読むようになったとき、この新しい思考領域が彼を奴隷制度に疑問を抱かせ、非難へと導いた。後年、ダグラスは、12歳頃に発 見した『コロンビアン・オラター』というアンソロジーが、自由と人権に関する自分の考えを明確にし、定義づけるのに役立ったと語っている。1797年に初 めて出版されたこの本は、エッセイ、スピーチ、対談などを収録した教室用の読み物で、生徒が読み書きや文法を学ぶのに役立つ。 後に彼は、母親も読み書きができたことを知り、後にこう宣言した。 私は、自分が持つ文学への愛着、そして偏見にもかかわらず、あまりにも多くの称賛を得ている文学への愛着を、自分が認めるアングロサクソン人の血筋による ものというよりも、保護も教養もない、黒人の母、つまり、現在、その精神的な資質について、軽蔑と侮蔑の対象となっている人種に属する女性によるものだと 考えることに、まったく抵抗がないし、むしろ喜んでいる。 ウィリアム・フリーランド ウィリアム・フリーランドに雇われたダグラスは、「日曜日に、時には平日の夜にも、安息日の識字学校に30人以上の男性奴隷を集めた」[31]。 エドワード・コーヴィー 1833年、トーマス・オールドはヒューからダグラスを取り戻した(「ヒューを罰する手段として」と、ダグラスは後に書いている)。トーマスは、奴隷解放 者として評判の貧しい農夫エドワード・コヴィーのもとで働かせることにした。コヴィーは頻繁にダグラスを鞭打ち、その傷が癒える間もないほどだった。ダグ ラスは後に、度重なる鞭打ちによって、肉体も精神も魂も壊されたと語っている[32]。しかし、16歳になったダグラスはついに暴行に反抗し、反撃した。 ダグラスが肉体的対決に勝った後、コヴィーは二度と彼を殴ろうとしなかった[33][34]。 『フレデリック・ダグラスの生涯の物語』の中で、コヴィーの農場で受けた虐待について振り返り、ダグラスは自分自身を「野獣と化した男!」と表現した [35]。それでもダグラスは、コヴィーとの肉体的戦いを人生を変える出来事として捉え、自伝の中で次のように紹介している。「ある男が奴隷にされたのを 見ただろう。今度は奴隷が人間になるのを見ることになるだろう。」[36] |

| Escape from slavery Douglass first tried to escape from Freeland, who had hired him from his owner, but was unsuccessful. In 1837, Douglass met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman in Baltimore about five years his senior. Her free status strengthened his belief in the possibility of gaining his own freedom. Murray encouraged him and supported his efforts by aid and money.[37]  Anna Murray Douglass, Douglass's wife for 44 years, portrait c. 1860 On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped by boarding a northbound train of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad in Baltimore.[38] The area where he boarded was formerly thought to be a short distance east of the train depot, in a recently developed neighborhood between the modern neighborhoods of Harbor East and Little Italy. This depot was at President and Fleet Streets, east of "The Basin" of the Baltimore harbor, on the northwest branch of the Patapsco River. Research cited in 2021, however, suggests that Douglass in fact boarded the train at the Canton Depot of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad on Boston Street, in the Canton neighborhood of Baltimore, further east.[39][40][41] Douglass reached Havre de Grace, Maryland, in Harford County, in the northeast corner of the state, along the southwest shore of the Susquehanna River, which flowed into the Chesapeake Bay. Although this placed him only some 20 miles (32 km) from the Maryland–Pennsylvania state line, it was easier to continue by rail through Delaware, another slave state. Dressed in a sailor's uniform provided to him by Murray, who also gave him part of her savings to cover his travel costs, he carried identification papers and protection papers that he had obtained from a free black seaman.[37][42][43] Douglass crossed the wide Susquehanna River by the railroad's steam-ferry at Havre de Grace to Perryville on the opposite shore, in Cecil County, then continued by train across the state line to Wilmington, Delaware, a large port at the head of the Delaware Bay. From there, because the rail line was not yet completed, he went by steamboat along the Delaware River farther northeast to the "Quaker City" of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, an anti-slavery stronghold. He continued to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York City. His entire journey to freedom took less than 24 hours.[44] Douglass later wrote of his arrival in New York City: I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the "quick round of blood," I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: "I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions." Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.[45] Once Douglass had arrived, he sent for Murray to follow him north to New York. She brought the basic supplies for them to set up a home. They were married on September 15, 1838, by a black Presbyterian minister, just eleven days after Douglass had reached New York.[44] At first they adopted Johnson as their married name, to divert attention.[37] |

奴隷からの脱出 ダグラスが最初に逃げようとしたのは、彼を奴隷所有者から雇ったフリーランドだったが、失敗に終わった。1837年、ダグラスはボルチモアに住む5歳年上 の自由黒人女性アンナ・マレーと出会い、恋に落ちた。彼女の自由身であることで、ダグラスは自分自身の自由を獲得できる可能性を確信した。マレーは彼を励 まし、援助や金銭面で彼の努力を支えた[37]。  アンナ・マレー・ダグラス、ダグラスの妻として44年間過ごした。肖像画、1860年頃 1838年9月3日、ダグラスはボルチモアでフィラデルフィア・ウィルミントン・ボルチモア鉄道の北行きの列車に乗り込み、脱走に成功した[38]。ボル チモアのフィラデルフィア・ウィルミントン・ボルチモア鉄道の北行きの列車に飛び乗ったのである[38]。彼が乗った場所は、以前は鉄道駅の東側、ハー バー・イーストとリトル・イタリーの近代的な住宅街の間に最近開発された住宅街の一角と考えられていた。この駅は、ボルチモア港の「ザ・ベイスン」の東、 パタプスコ川の北西支流沿いにあるプレジデント・ストリートとフリート・ストリートの交差点に位置していた。しかし、2021年に引用された研究による と、ダグラスが実際に列車に乗ったのは、ボルチモアのカンントン地区にあるボストン通りのフィラデルフィア・ウィルミントン・ボルチモア鉄道のカンントン 駅であったことが示唆されている[39][40][41]。 ダグラスは、チェサピーク湾に注ぐサスケハナ川の南西岸沿い、州北東端のハフォード郡にあるメリーランド州ハーバー・デ・グレイスに到着した。この場所は メリーランド州とペンシルベニア州の州境からわずか32キロほどの距離にあったが、奴隷制を敷くデラウェア州を通る鉄道を利用すれば、そこから先はより簡 単に移動できる。マーレイから支給された水兵の制服に身を包み、マーレイは貯金のうちの一部を旅費として彼に渡した。彼は、自由黒人水兵から入手した身分 証明書と保護証を携行した[37][42][43]。 ダグラス 広大なサスケハナ川を、ハバー・デ・グレースの鉄道蒸気フェリーで対岸のセシル郡ペリービルに渡り、そこから列車で州境を越えてデラウェア湾の入り口にあ る大きな港町ウィルミントン(デラウェア州)に向かった。しかし、鉄道はまだ完成していなかったため、彼は蒸気船でさらに北東のデラウェア川を遡り、奴隷 制度廃止運動の中心地であるペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィアの「クエーカーシティ」に向かった。そして、ニューヨーク市の奴隷廃止論者デイビッド・ラグ ルズの隠れ家へと向かった。自由への旅は、24時間足らずで終わった[44]。ダグラスはその後のニューヨーク到着について、次のように書いている。 自由の地に初めて足を踏み入れたときの気持ちをよく聞かれる。読者もきっと同じ疑問を抱いているだろう。私の経験について、もっと納得のいく答えを出せな いことはほとんどない。新しい世界が私の前に開けたのだ。人生が呼吸や「血液の速い循環」以上のものであるなら、奴隷生活の一年間よりも、一日の方がはる かに充実していた。それは言葉では表現しきれないほど、喜びにあふれた興奮に満ちた時間だった。ニューヨークに到着して間もなく友人に宛てた手紙の中で、 私はこう書いている。「飢えたライオンの巣窟から脱出したときの気分だった」。苦悩や悲しみは、暗闇や雨のように描写できるかもしれない。しかし、喜びや 楽しさは、虹のように、ペンや鉛筆の技量では表現できない[45]。 ダグラスが到着すると、彼はマレーをニューヨークまで北に同行するよう呼び寄せた。彼女は、彼らが家庭を築くために必要な基本的な物資を持ってきた。 1838年9月15日、彼らは黒人長老派の牧師によって結婚した。ダグラスがニューヨークに到着してからわずか11日後のことだった[44]。最初は注目 をそらすために、ジョンソンを夫婦の姓として採用した[37]。 |

| Religious views As a child, Douglass was exposed to a number of religious sermons, and in his youth, he sometimes heard Sophia Auld reading the Bible. In time, he became interested in literacy; he began reading and copying bible verses, and he eventually converted to Christianity.[46][47] He described this approach in his last biography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: I was not more than thirteen years old when, in my loneliness and destitution, I longed for some one to whom I could go, as to a father and protector. The preaching of a white Methodist minister, named Hanson, was the means of causing me to feel that in God I had such a friend. He thought that all men, great and small, bond and free, were sinners in the sight of God: that they were but natural rebels against his government; and that they must repent of their sins, and be reconciled to God through Christ. I cannot say that I had a very distinct notion of what was required of me, but one thing I did know well: I was wretched and had no means of making myself otherwise. I consulted a good coloured man named Charles Lawson, and in tones of holy affection he told me to pray, and to "cast all my care upon God." This I sought to do; and though for weeks I was a poor, broken-hearted mourner, traveling through doubts and fears, I finally found my burden lightened, and my heart relieved. I loved all mankind, slaveholders not excepted, though I abhorred slavery more than ever. I saw the world in a new light, and my great concern was to have everybody converted. My desire to learn increased, and especially did I want a thorough acquaintance with the contents of the Bible.[48][49] Douglass was mentored by Rev. Charles Lawson, and, early in his activism, he often included biblical allusions and religious metaphors in his speeches. Although a believer, he strongly criticized religious hypocrisy[50] and accused slaveholders of "wickedness", lack of morality, and failure to follow the Golden Rule. In this sense, Douglass distinguished between the "Christianity of Christ" and the "Christianity of America" and considered religious slaveholders and clergymen who defended slavery as the most brutal, sinful, and cynical of all who represented "wolves in sheep's clothing".[47][51] In What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?, an oration Douglass gave in the Corinthian Hall of Rochester,[52] he sharply criticized the attitude of religious people who kept silent about slavery, and he charged that ministers committed a "blasphemy" when they taught it as sanctioned by religion. He considered that a law passed to support slavery was "one of the grossest infringements of Christian Liberty" and said that pro-slavery clergymen within the American Church "stripped the love of God of its beauty, and leave the throne of religion a huge, horrible, repulsive form", and "an abomination in the sight of God".[50] Of ministers like John Chase Lord, Leonard Elijah Lathrop, Ichabod Spencer, and Orville Dewey, he said that they taught, against the Scriptures, that "we ought to obey man's law before the law of God". He further asserted, "in speaking of the American church, however, let it be distinctly understood that I mean the great mass of the religious organizations of our land. There are exceptions, and I thank God that there are. Noble men may be found, scattered all over these Northern States ... Henry Ward Beecher of Brooklyn, Samuel J. May of Syracuse, and my esteemed friend [Robert R. Raymonde]".[50] He maintained that "upon these men lies the duty to inspire our ranks with high religious faith and zeal, and to cheer us on in the great mission of the slave's redemption from his chains". In addition, he called religious people to embrace abolitionism, stating, "let the religious press, the pulpit, the Sunday school, the conference meeting, the great ecclesiastical, missionary, Bible and tract associations of the land array their immense powers against slavery and slave-holding; and the whole system of crime and blood would be scattered to the winds."[50] During his visits to the United Kingdom between 1846 and 1848, Douglass asked British Christians never to support American churches that permitted slavery,[53] and he expressed his happiness to know that a group of ministers in Belfast had refused to admit slaveholders as members of the Church. On his return to the United States, Douglass founded the North Star, a weekly publication with the motto "Right is of no sex, Truth is of no color, God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren." In his 1848 "Letter to Thomas Auld", Douglass denounced his former slaveholder for leaving Douglass's family illiterate: Your wickedness and cruelty committed in this respect on your fellow-creatures, are greater than all the stripes you have laid upon my back, or theirs. It is an outrage upon the soul—a war upon the immortal spirit, and one for which you must give account at the bar of our common Father and Creator.[54] Sometimes considered a precursor of a non-denominational liberation theology,[55][56] Douglass was a deeply spiritual man, as his home continues to show. The fireplace mantle features busts of two of his favorite philosophers, David Friedrich Strauss, author of The Life of Jesus, and Ludwig Feuerbach, author of The Essence of Christianity. In addition to several Bibles and books about various religions in the library, images of angels and Jesus are displayed, as well as interior and exterior photographs of Washington's Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church.[57] Throughout his life, Douglass had linked that individual experience with social reform, and, according to John Stauffer, he, like other Christian abolitionists, followed practices such as abstaining from tobacco, alcohol and other substances that he believed corrupted body and soul.[58] Douglass stated himself that he was a teetotaler.[59] According to David W. Blight, however, "Douglass loved cigars" and received them as gifts from Ottilie Assing.[60] Douglass praised the agnostic orator Robert G. Ingersoll, whom Douglass met in Peoria, Illinois, stating, "Genuine goodness is the same, whether found inside or outside the church, and that to be an 'infidel' no more proves a man to be selfish, mean and wicked than to be evangelical proves him to be honest, just and human. Perhaps there were Christian ministers and Christian families in Peoria at that time by whom I might have been received in the same gracious manner ... but in my former visits to this place I had failed to meet them".[61] |

宗教観 ダグラス少年は、幼い頃からさまざまな宗教説教に接し、青年期にはソフィア・オールドが聖書を読むのを耳にすることもあった。やがて彼は識字に興味を持 ち、聖書の詩句を読み、書き写すようになり、ついにはキリスト教に改宗した[46][47]。彼は最後の伝記『フレデリック・ダグラスの生涯と時代』の中 で、この経緯を次のように述べている。 孤独と貧困の中で、父であり守護者であるような存在を求めていた私は、13歳にも満たなかった。ハンソンという名の白人メソジスト派の牧師の説教が、神に そのような友人がいると感じさせるきっかけとなった。彼は、偉大であろうと小さくとも、奴隷であろうと自由人であろうと、人間は皆神の目には罪人であり、 神の統治に対する自然の反抗者であり、罪を悔い改め、キリストを通して神と和解しなければならないと考えていた。私には、自分に何が求められているのかに ついて、非常に明確な考えがあったとは言えないが、一つだけよく分かっていた。私は惨めな人間であり、自分を変える手段を持っていなかったのだ。私は チャールズ・ローソンという名の善良な黒人に相談し、彼は神聖な愛情に満ちた口調で、祈ること、そして「すべての悩みを神に委ねる」よう私に言った。私は そうしようと努めた。数週間、私は悲嘆にくれて落ち込んだまま、疑いと不安を抱えながら過ごしたが、最終的に重荷が軽くなり、心が楽になった。私は奴隷所 有者も含めてすべての人間を愛したが、奴隷制はこれまで以上に嫌悪していた。私は世界を新しい光で見ており、私の最大の関心事は、すべての人を改宗させる ことだった。私の学習意欲は高まり、特に聖書の内容を完全に理解したいと思った。 ダグラス牧師はチャールズ・ローソン牧師に師事し、活動初期には、演説に聖書の引用や宗教的な比喩をしばしば盛り込んだ。彼は信仰心を持っていたが、宗教 的偽善を強く批判し[50]、奴隷所有者を「邪悪」で道徳心にかけ、黄金律に従わないと非難した。この意味で、ダグラスは「キリストのキリスト教」と「ア メリカのキリスト教」を区別し、奴隷制を擁護する宗教家や聖職者を「羊の皮を被ったオオカミ」の代表格として、最も残忍で罪深く、皮肉屋であるとみなした [47][51]。 『奴隷に何を 奴隷に何を? 7月4日は何の日か?』(What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?)と題した演説で、ダグラスがロチェスターのコリンシア・ホールで行った演説[52]では、奴隷制について沈黙を守る宗教者の態度を厳しく批判 し、牧師たちが宗教的に容認されているとして奴隷制を教えるのは「冒涜」であると非難した。奴隷制度を支持する法律は「キリスト教の自由に対する最も重大 な侵害の一つ」であり、アメリカ教会内の奴隷制度支持の聖職者たちは「神の愛の美しさを奪い、宗教の王座を巨大で恐ろしい、嫌悪すべき形にしており」、「 神の御目には忌まわしい存在」[50] である。 ジョン・チェイス・ロード、レナード・イライジャ・ラスロップ、イチャボッド・スペンサー、オービル・デューイといった牧師たちについて、彼は「神の法よ りも人間の法に従うべきだ」と聖書に反して教えていると述べた。さらに彼は、「アメリカの教会について語るが、私が言っているのは、この国の宗教組織の大 部分についてだということははっきり理解してもらいたい。例外もあるが、私は神に感謝している。高潔な人物は、北部の州全体に散らばっているかもしれな い... ブルックリンのヘンリー・ワード・ビーチャー、シラキュースのサミュエル・J・メイ、そして私の尊敬する友人(ロバート・R・レイモンド)である」。 [50] 彼は、「これらの人々に、私たちの仲間たちに高い宗教的信念と熱意を植え付け、奴隷が鎖から解放されるという偉大な使命を後押しする義務がある」と主張し た。さらに彼は、宗教的な人々にも奴隷制度廃止運動に参加するよう呼びかけ、「宗教的な新聞、説教壇、日曜学校、会議、教会、宣教師、聖書、小冊子協会 が、奴隷制度と奴隷所有に対してその莫大な力を結集させれば、犯罪と血のシステム全体が風のように吹き散らされるだろう」と述べた。風の中に散ってしまう だろう」[50]。 1846年から1848年にかけてのイギリス訪問中、ダグラス氏はイギリスのキリスト教徒に対し、奴隷制を容認するアメリカの教会を決して支持しないよう 求めた[53]。また、ベルファストの牧師グループが奴隷所有者を教会の会員として認めないことを知ったことに喜びを表明した。 米国に戻ったダグラスは、週刊誌『ノーススター』を創刊した。この雑誌のモットーは、「正義に性別はなく、真実に色はない。神は私たちの父であり、私たち は皆兄弟である」であった。1848年の「トーマス・オールドへの手紙」で、ダグラスは、自分の家族を非識字にした元奴隷所有者を非難した。 あなたが同胞に対して行った悪意と残酷さは、あなたが私の背中に、あるいは彼らの背中に付けたすべての鞭打ちよりもはるかに大きい。それは魂に対する冒涜 であり、不滅の精神に対する戦争であり、あなたは私たちの共通の父であり創造主である神の法廷で説明責任を果たさなければならない[54]。 無宗派解放神学の先駆者と考えられていることもある[55][56]、ダグラス氏は非常に精神性の高い人物であり、それは彼の家にも表れている。暖炉の飾 り板には、彼の好きな哲学者である『イエスの生涯』の著者、フリードリヒ・シュトラウスと『キリスト教の本質』の著者、ルートヴィヒ・フォーアバッハの胸 像が飾られている。書斎には、いくつかの聖書やさまざまな宗教に関する書籍が置かれているほか、天使やイエスの像、ワシントン・メトロポリタン・アフリカ メソジスト教会(Washington's Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church)の内観・外観の写真も飾られている[57]。生涯を通じて、ダグラスはその個人的な経験を社会改革に結びつけており、ジョン・スタウファー によると、他のキリスト教徒の奴隷廃止論者たちと同様に 、タバコやアルコール、その他、肉体を蝕み魂を汚すようなものを断つといった習慣に従っていた[58]。ダグラス自身は禁酒主義者であると述べていた [59]。しかし、デビッド・W・ブライトによると、「ダグラスは葉巻を愛していた」そうで、オティリー・アッシングから贈られたこともあるという [60]。 ダグラスは、イリノイ州ピオリアで出会った不可知論者の雄弁家ロバート・G・インガソルを賞賛し、「真の善は、教会の中であろうと外であろうと変わらな い。そして、不信心者であることが、人を利己的で卑しく邪悪であると証明するわけではない。福音主義者であることが、人を誠実で公正で人間的であると証明 するわけではない。おそらく、ピオリアには、私が同じように親切に迎え入れてくれたかもしれないキリスト教の牧師やキリスト教の家族もいたのだろうが、私 が以前この地を訪れた際には、彼らに会うことができなかった」[61]。 |

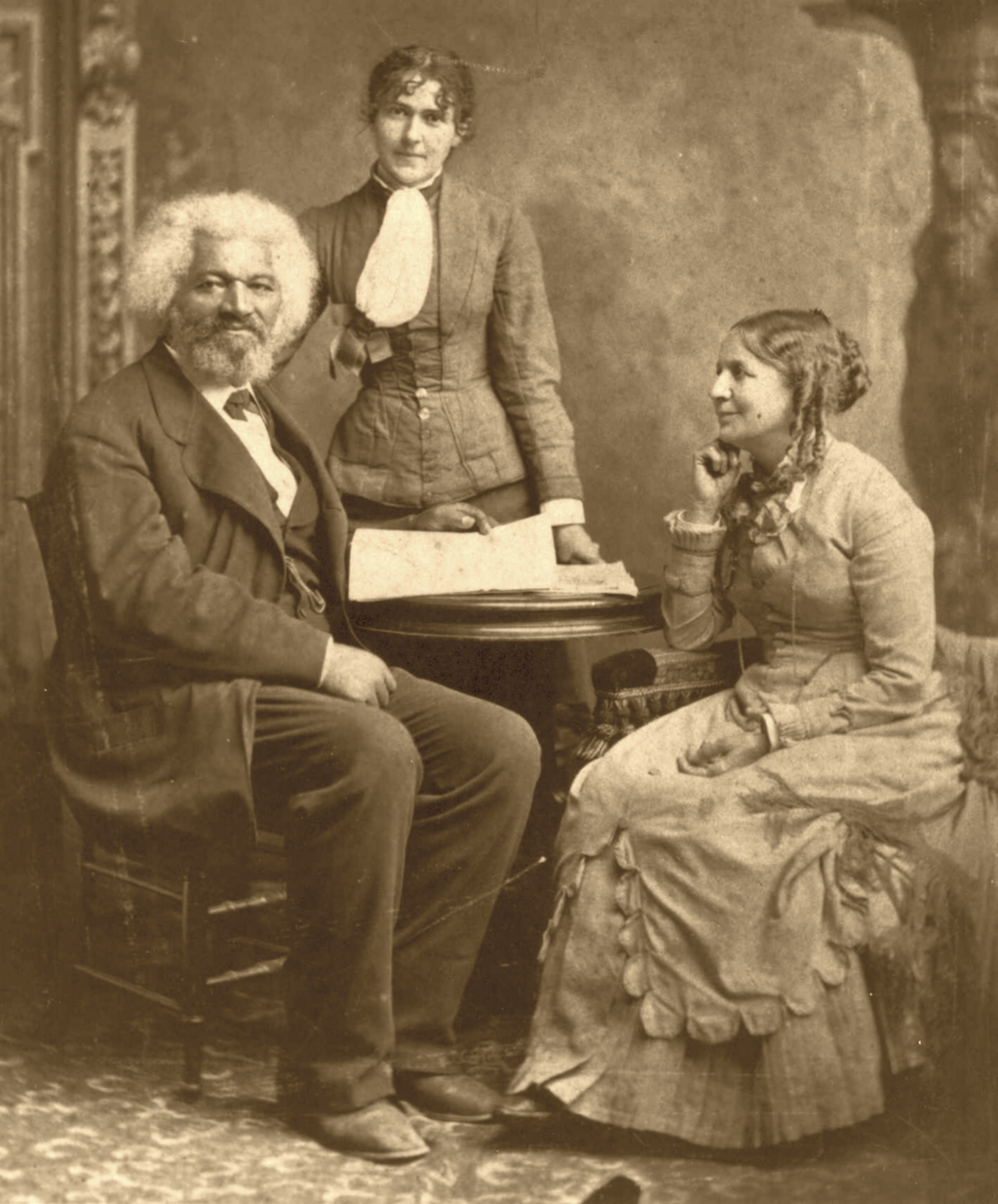

Family life Frederick Douglass after 1884 with his second wife Helen Pitts Douglass (sitting). The woman standing is her sister Eva Pitts. Further information: Douglass family Douglass and Anna Murray had five children: Rosetta Douglass, Lewis Henry Douglass, Frederick Douglass Jr., Charles Remond Douglass, and Annie Douglass (died at the age of ten). Charles and Rosetta helped produce his newspapers. Anna Douglass remained a loyal supporter of her husband's public work. His relationships with Julia Griffiths and Ottilie Assing, two women with whom he was professionally involved, caused recurring speculation and scandals.[62] Assing was a journalist recently immigrated from Germany, who first visited Douglass in 1856 seeking permission to translate My Bondage and My Freedom into German. Until 1872, she often stayed at his house "for several months at a time" as his "intellectual and emotional companion."[63] Assing held Anna Douglass "in utter contempt" and was vainly hoping that Douglass would separate from his wife. Douglass biographer David W. Blight concludes that Assing and Douglass "were probably lovers".[63] Though Douglass and Assing are widely believed to have had an intimate relationship, the surviving correspondence contains no proof of such a relationship.[64] Anna died in 1882. In 1884, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a white suffragist and abolitionist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts Jr., an abolitionist colleague and friend of Douglass's. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College (then called Mount Holyoke Female Seminary), Pitts worked on a radical feminist publication named Alpha while living in Washington, D.C. She later worked as Douglass's secretary.[65] Assing, who had depression and was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer, committed suicide in France in 1884 after hearing of the marriage.[66] Upon her death, Assing bequeathed Douglass a $13,000 trust fund, a "large album", and his choice of books from her library.[67] The marriage of Douglass and Pitts provoked a storm of controversy, since Pitts was both white and nearly 20 years younger. Many in her family stopped speaking to her; his children considered the marriage a repudiation of their mother. But feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton congratulated the couple.[68] Douglass responded to the criticisms by saying that his first marriage had been to someone the color of his mother, and his second to someone the color of his father.[69] |

家族生活 1884年以降のフレデリック・ダグラスと2番目の妻ヘレン・ピッツ・ダグラス(座っている)。立っているのは彼女の妹エヴァ・ピッツ。 詳細情報:ダグラス家 ダグラスとアンナ・マレーには5人の子供たちがいた。ロゼッタ・ダグラス、ルイス・ヘンリー・ダグラス、フレデリック・ダグラス・ジュニア、チャールズ・レモンド・ダグラス、そしてアニー・ダグラス(10歳で死去)。チャールズとロゼッタは、彼の新聞制作を手伝っていた。 アンナ・ダグラス(Anna Douglass)は、夫の公共事業に忠実な支援者であり続けた。 ダグラスと仕事上で関係を持ったジュリア・グリフィス(Julia Griffiths)とオティリー・アッシング(Ottilie Assing)という2人の女性との関係は、度々憶測やスキャンダルを呼んだ[62]。アッシングはドイツから最近移住してきたジャーナリストで、 1856年に『我が絆、我が自由』をドイツ語に翻訳する許可を得るために初めてダグラスを訪ねた。1872年まで、彼女は「知的な伴侶であり、感情的な支 え手」として、しばしば「数か月間」彼の家に滞在していた[63]。 アッシングはアンナ・ダグラスを「完全に軽蔑」しており、ダグラスが妻と別れることを期待していた。ダグラス伝記作家のデビッド・W・ブライトは、アッシ ングとダグラスは「おそらく恋人同士だった」と結論付けている[63]。ダグラスとアッシングは親密な関係にあったと広く信じられているが、現存する書簡 にはそのような関係を示す証拠は含まれていない[64]。 アンナは1882年に死去。1884年、ダグラスはニューヨーク州ホノイヨ出身の白人女性参政権運動家であり奴隷廃止論者でもあったヘレン・ピッツと結婚 した。ピッツは、奴隷制度廃止論者でダグラスと同僚であり友人でもあったギデオン・ピッツ・ジュニアの娘であった。マウント・ホリヨーク大学(当時はマウ ント・ホリヨーク女子神学校と呼ばれていた)を卒業したピッツは、ワシントンD.C.在住中にアルファという急進的なフェミニスト誌で働いていた。その 後、ピッツはダグラスの秘書として働いた[65]。 うつ病を患い、不治の乳がんを宣告されていたアッシングは、結婚の知らせを聞いた後、1884年にフランスで自殺した[66]。結婚の知らせを聞いた後、 アッシングは1884年にフランスで自殺した。彼女の家族は多くが彼女と口をきかなくなった。彼の子供たちは、この結婚を自分たちの母親の否定だと考えて いた。しかし、フェミニストのエリザベス・キャディ・スタントンは、このカップルを祝福した[68]。ダグラスはこの批判に対し、最初の結婚相手は母親と 同じ肌の色の人で、2人目の相手は父親と同じ肌の色の人だったと述べた[69]。 |

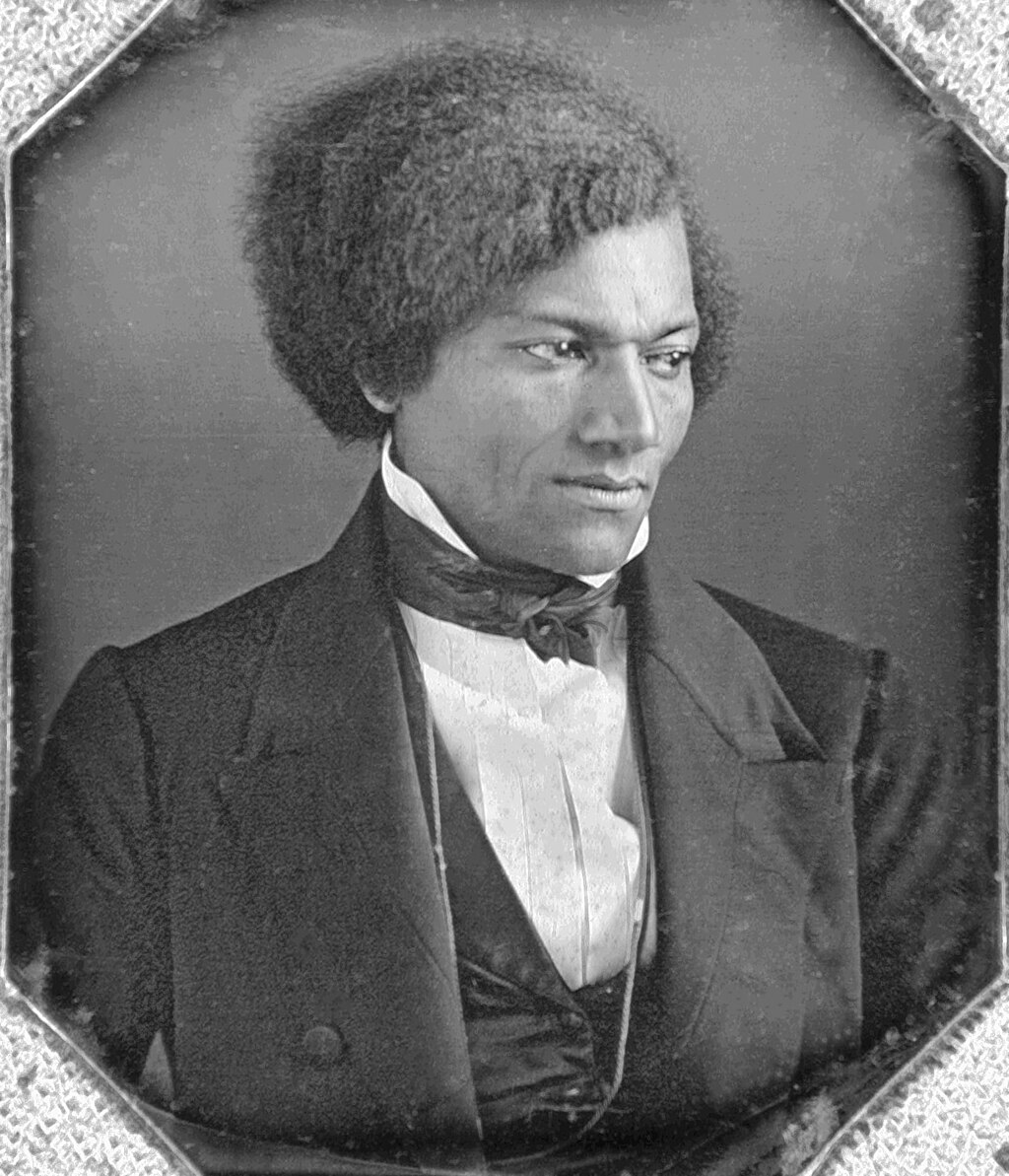

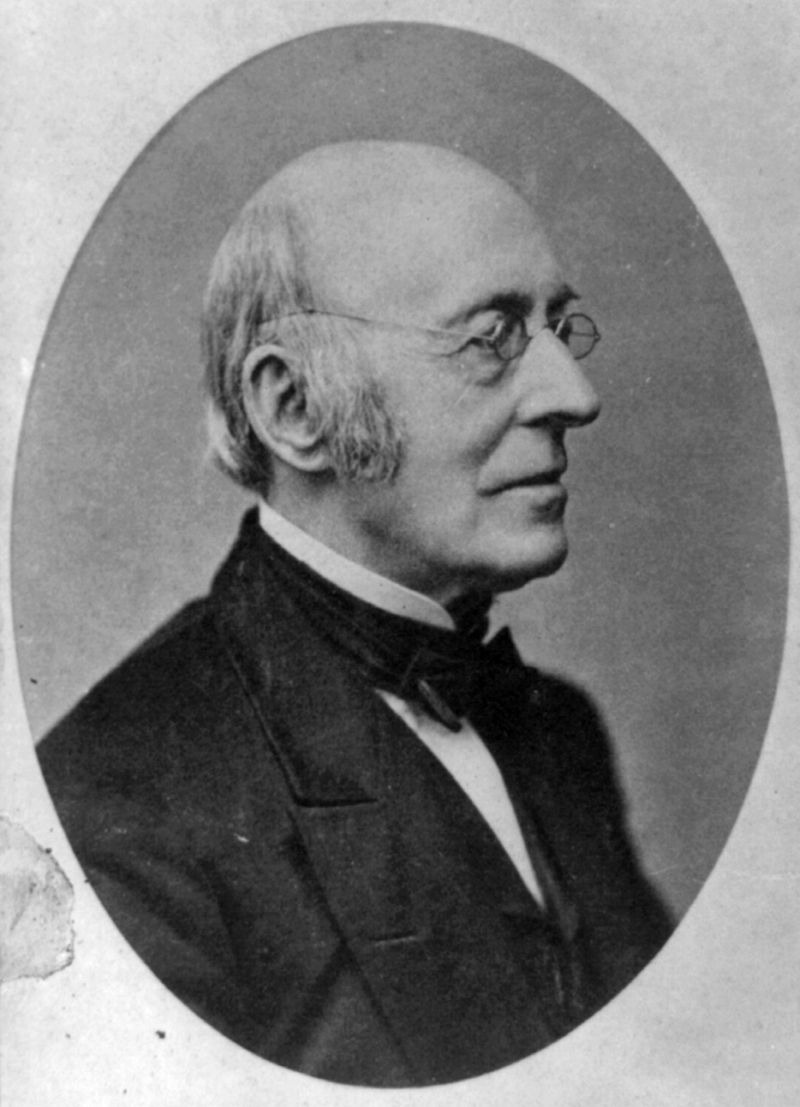

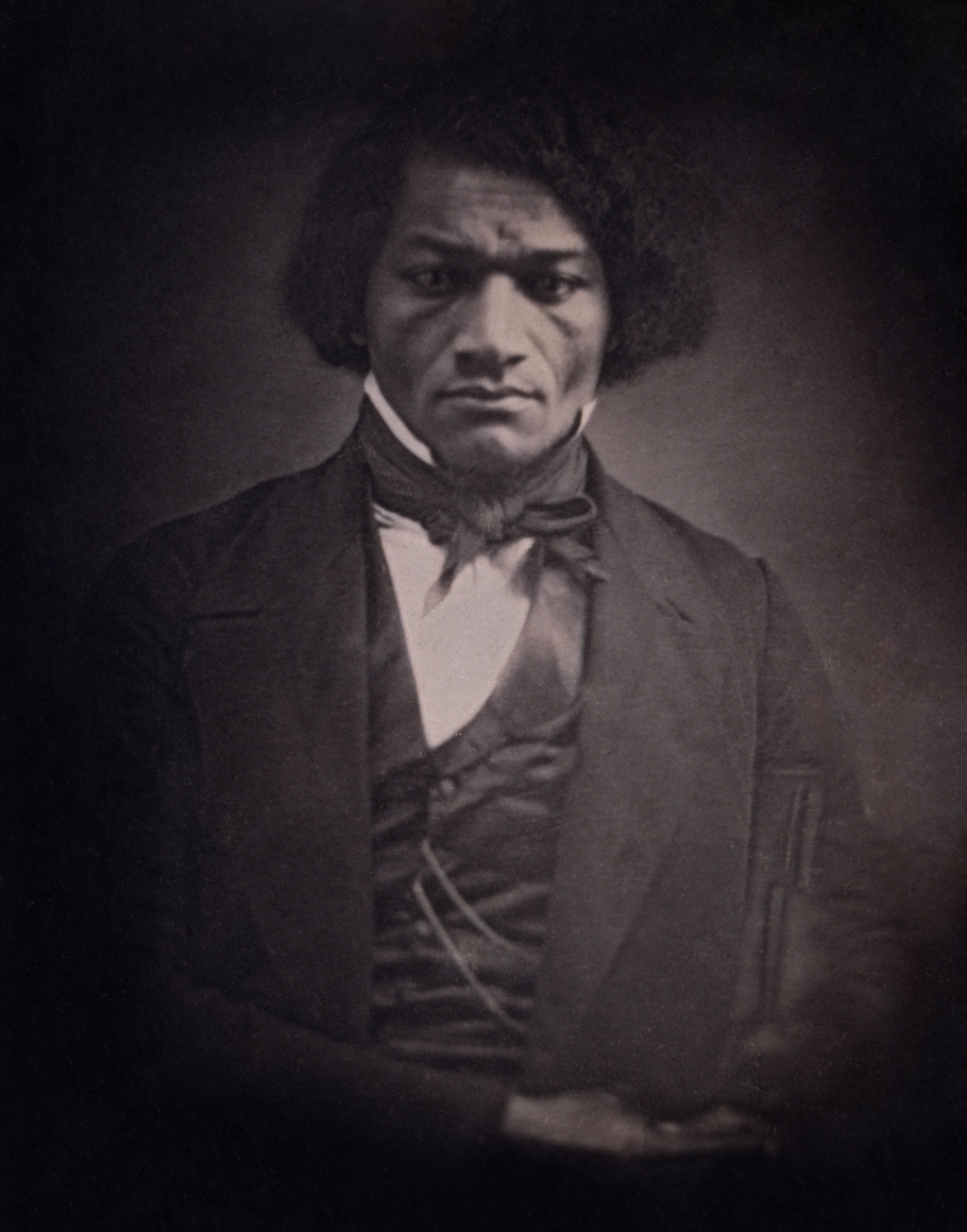

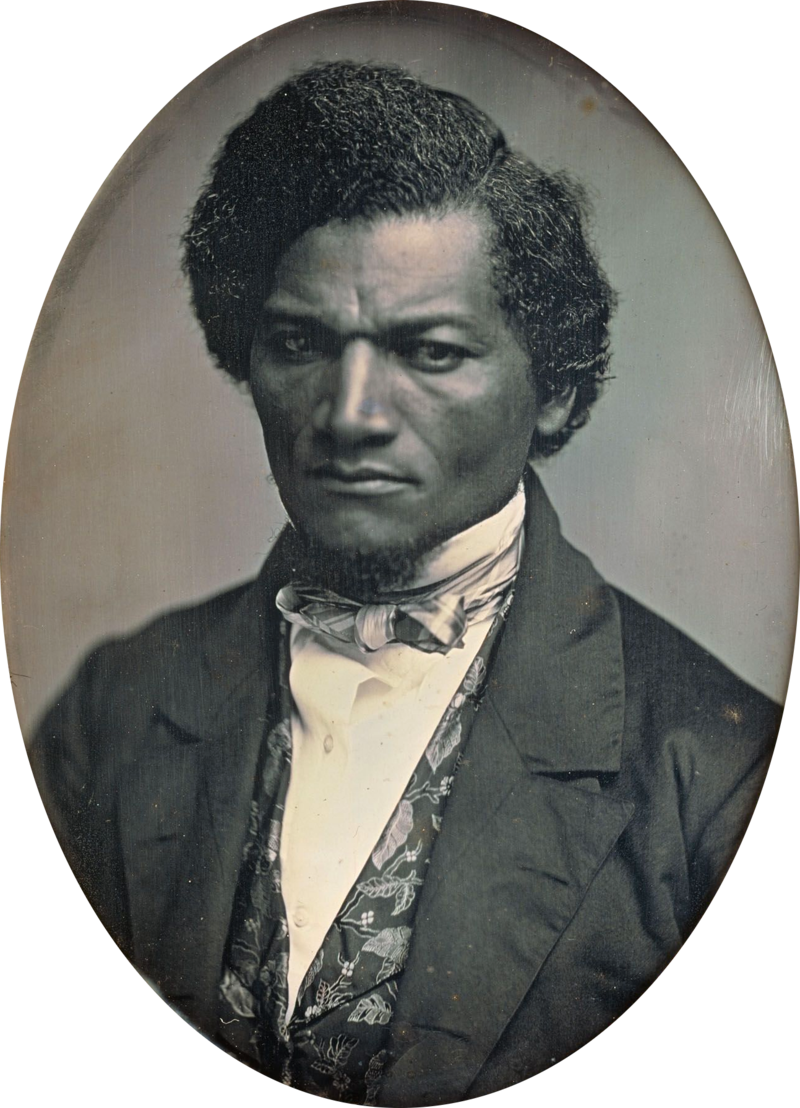

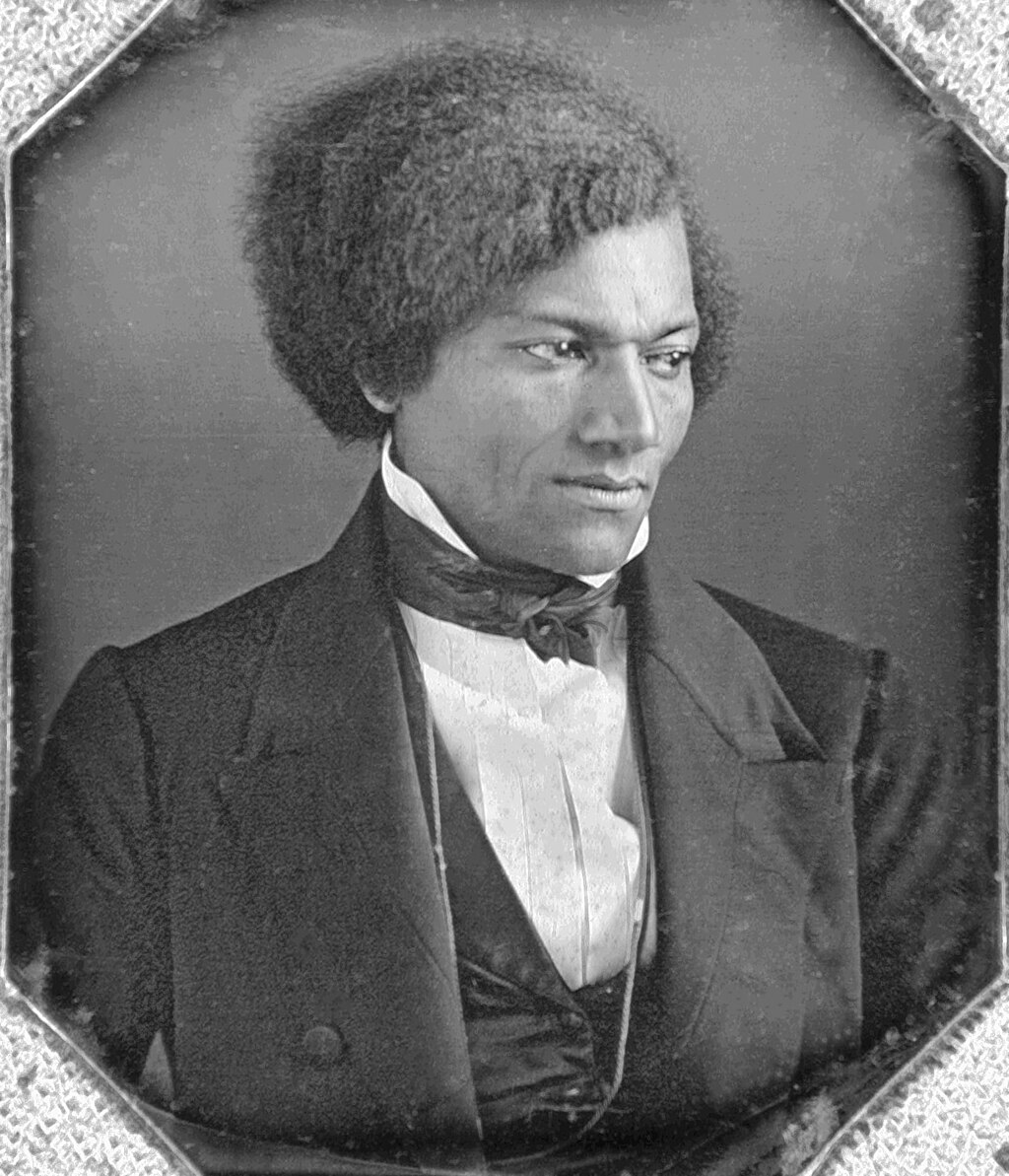

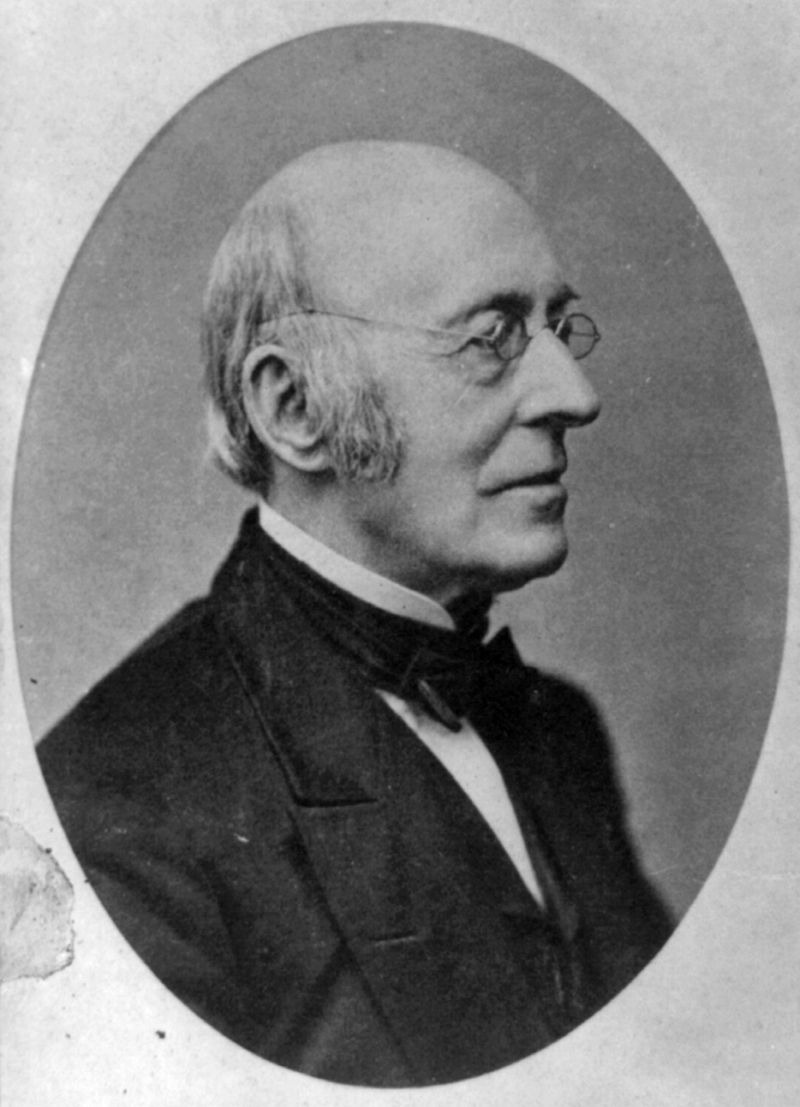

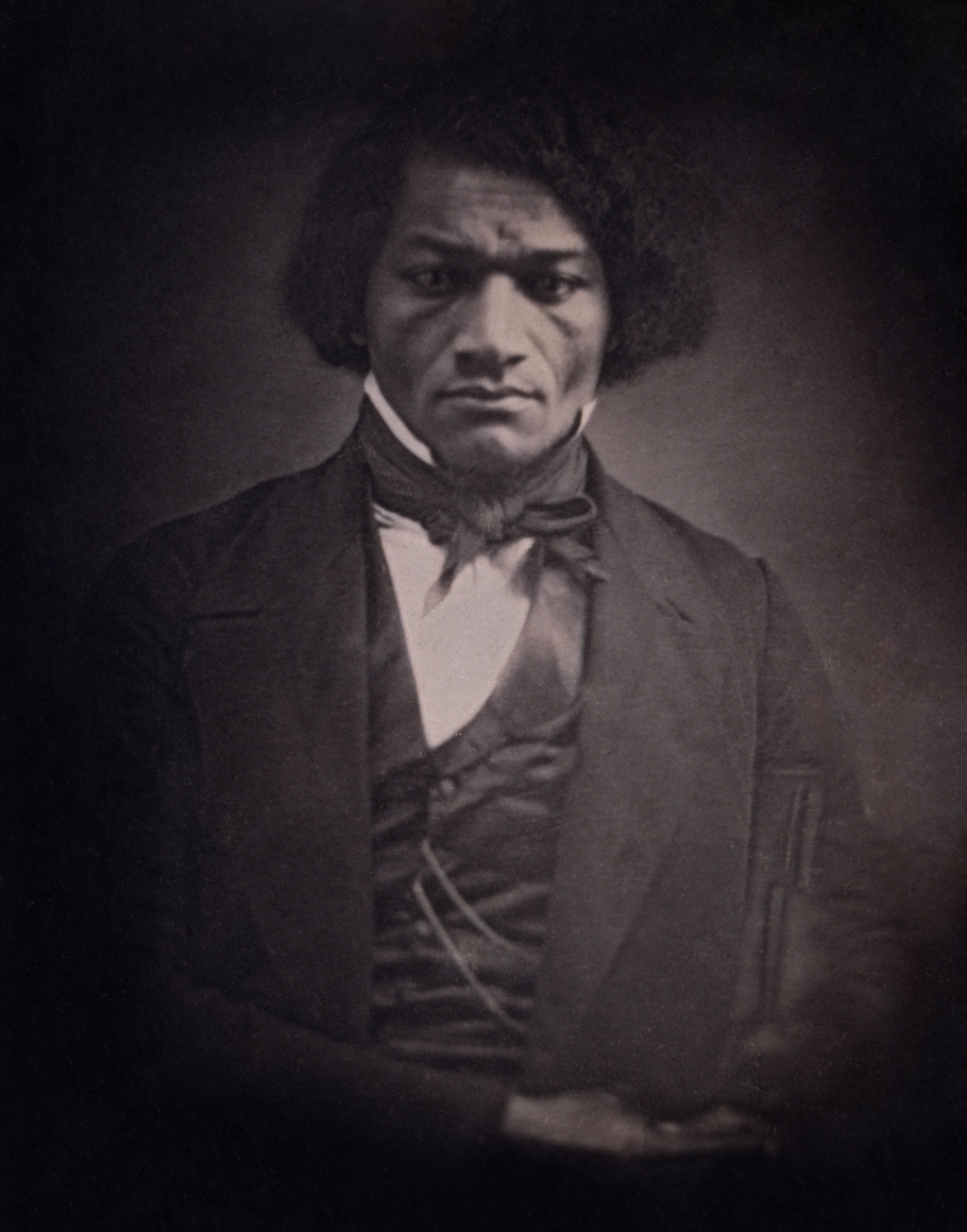

| Career Abolitionist and preacher Further information: Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts  Frederick Douglass, c. 1840s, in his 20s The couple settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts (an abolitionist center, full of former enslaved people), in 1838, moving to Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1841.[70] After meeting and staying with Nathan and Mary Johnson, they adopted Douglass as their married name.[37] Douglass had grown up using his mother's surname of Bailey; after escaping slavery he had changed his surname first to Stanley and then to Johnson. In New Bedford, the latter was such a common name that he wanted one that was more distinctive, and asked Nathan Johnson to choose a suitable surname. Nathan suggested "Douglass", after having read the poem The Lady of the Lake by Walter Scott, in which two of the principal characters have the surname "Douglas".[71][72]  The home and meetinghouse of the Johnsons, where Douglass and his wife lived in New Bedford, Massachusetts Douglass thought of joining a white Methodist Church, but was disappointed, from the beginning, upon finding that it was segregated. Later, he joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, an independent black denomination first established in New York City, which counted among its members Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman.[73] He became a licensed preacher in 1839,[74] which helped him to hone his oratorical skills. He held various positions, including steward, Sunday-school superintendent, and sexton. In 1840, Douglass delivered a speech in Elmira, New York, then a station on the Underground Railroad, in which a black congregation would form years later, becoming the region's largest church by 1940.[57] Douglass also joined several organizations in New Bedford and regularly attended abolitionist meetings. He subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison's weekly newspaper, The Liberator. He later said that "no face and form ever impressed me with such sentiments [of the hatred of slavery] as did those of William Lloyd Garrison." So deep was this influence that in his last autobiography, Douglass said "his paper took a place in my heart second only to The Bible."[75] Garrison was likewise impressed with Douglass and had written about his anti-colonization stance in The Liberator as early as 1839. Douglass first heard Garrison speak in 1841, at a lecture that Garrison gave in Liberty Hall, New Bedford. At another meeting, Douglass was unexpectedly invited to speak. After telling his story, Douglass was encouraged to become an anti-slavery lecturer. A few days later, Douglass spoke at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention, in Nantucket. Then 23 years old, Douglass conquered his nervousness and gave an eloquent speech about his life as a slave.  William Lloyd Garrison, abolitionist and one of Douglass's first friends in the North While living in Lynn, Douglass engaged in an early protest against segregated transportation. In September 1841, at Lynn Central Square station, Douglass and his friend James N. Buffum were thrown off an Eastern Railroad train because Douglass refused to sit in the segregated railroad coach.[70][76][77][78] In 1843, Douglass joined other speakers in the American Anti-Slavery Society's "Hundred Conventions" project, a six-month tour at meeting halls throughout the eastern and midwestern United States. During this tour, slavery supporters frequently accosted Douglass. At a lecture in Pendleton, Indiana, an angry mob chased and beat Douglass before a local Quaker family, the Hardys, rescued him. His hand was broken in the attack; it healed improperly and bothered him for the rest of his life.[79] A stone marker in Falls Park in the Pendleton Historic District commemorates this event. In 1847, Douglass explained to Garrison, "I have no love for America, as such; I have no patriotism. I have no country. What country have I? The Institutions of this Country do not know me—do not recognize me as a man."[80] Autobiography Douglass's best-known work is his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, written during his time in Lynn, Massachusetts[81] and published in 1845. At the time, some skeptics questioned whether a black man could have produced such an eloquent piece of literature. The book received generally positive reviews and became an immediate bestseller. Within three years, it had been reprinted nine times, with 11,000 copies circulating in the United States. It was also translated into French and Dutch and published in Europe. Douglass published three autobiographies during his lifetime (and revised the third of these), each time expanding on the previous one. The 1845 Narrative was his biggest seller and probably allowed him to raise the funds to gain his legal freedom the following year, as discussed below. In 1855, Douglass published My Bondage and My Freedom. In 1881, in his sixties, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892. Travels to Ireland and Great Britain  Plaque to Frederick Douglass, West Bell St., Dundee, Scotland  Douglass in 1847, around 29 years of age Douglass's friends and mentors feared that the publicity would draw the attention of his ex-owner, Hugh Auld, who might try to get his "property" back. They encouraged Douglass to tour Ireland, as many former slaves had done. Douglass set sail on the Cambria for Liverpool, England, on August 16, 1845. He traveled in Ireland as the Great Famine was beginning. The feeling of freedom from American racial discrimination amazed Douglass:[82] Eleven days and a half gone, and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle [Ireland]. I breathe, and lo! the chattel [slave] becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlor—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended.... I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, 'We don't allow niggers in here!' Still, Douglass was astounded by the extreme levels of poverty he encountered in Dublin, much of it reminding him of his experiences in slavery. In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass wrote "I see much here to remind me of my former condition, and I confess I should be ashamed to lift up my voice against American slavery, but that I know the cause of humanity is one the world over. He who really and truly feels for the American slave, cannot steel his heart to the woes of others; and he who thinks himself an abolitionist, yet cannot enter into the wrongs of others, has yet to find a true foundation for his anti-slavery faith."[83] He also met and befriended the Irish nationalist and strident abolitionist Daniel O'Connell,[84][85] who was to be a great inspiration.[86][87] Douglass spent two years in Ireland and Great Britain, lecturing in churches and chapels. His draw was such that some facilities were "crowded to suffocation". One example was his hugely popular London Reception Speech, which Douglass delivered in May 1846 at Alexander Fletcher's Finsbury Chapel. Douglass remarked that in England he was treated not "as a color, but as a man".[88] In 1846, Douglass met with Thomas Clarkson, one of the last living British abolitionists, who had persuaded Parliament to abolish slavery in Great Britain's colonies.[89] During this trip Douglass became legally free, as British supporters led by Anna Richardson and her sister-in-law Ellen of Newcastle upon Tyne raised funds to buy his freedom from his American owner Thomas Auld.[88][90] Many supporters tried to encourage Douglass to remain in England but, with his wife still in Massachusetts and three million of his black brethren in bondage in the United States, he returned to America in the spring of 1847,[88] soon after the death of Daniel O'Connell.[91] In the 21st century, historical plaques were installed on buildings in Cork and Waterford, Ireland, and London to celebrate Douglass's visit: the first is on the Imperial Hotel in Cork and was unveiled on August 31, 2012; the second is on the façade of Waterford City Hall, unveiled on October 7, 2013. It commemorates his speech there on October 9, 1845.[92] The third plaque adorns Nell Gwynn House, South Kensington in London, at the site of an earlier house where Douglass stayed with the British abolitionist George Thompson.[93] On July 31, 2023, the first statue of him in Europe was unveiled in High Street in Belfast.[94] Douglass spent time in Scotland and was appointed "Scotland's Antislavery agent."[95] He made anti-slavery speeches and wrote letters back to the USA. He considered the city of Edinburgh to be elegant, grand and very welcoming. Maps of the places in the city that were important to his stay are held by the National Library of Scotland.[96][97] A plaque and a mural on Gilmore Place in Edinburgh mark his stay there in 1846. "A variety of collaborative projects are currently [in 2021] underway to commemorate Frederick Douglass's journey and visit to Ireland in the 19th century."[98] Return to the United States; the abolitionist movement  Douglass circa 1847–52, around his early 30s After returning to the U.S. in 1847, using £500 (equivalent to $57,716 in 2023) given to him by English supporters,[88] Douglass started publishing his first abolitionist newspaper, the North Star, from the basement of the Memorial AME Zion Church in Rochester, New York.[99] Originally, Pittsburgh journalist Martin Delany was co-editor but Douglass didn't feel he brought in enough subscriptions, and they parted ways.[100][page needed] The North Star's motto was "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren."[101] The AME Church and North Star joined in the freedmen community's vigorous opposition to the mostly white American Colonization Society and its proposal to send free black people to Africa. Douglass also participated in the Underground Railroad. He and his wife provided lodging and resources in their home to more than four hundred fugitive slaves.[101] Douglass also soon split with Garrison, whom he found unwilling to support actions against American slavery.[102] Earlier Douglass had agreed with Garrison's position that the Constitution was pro-slavery, because of the Three-Fifths Clause, the compromise that provided that 60 percent of the number of enslaved people would be added to "the whole Number of free Persons"[103] for the purpose of apportioning congressional seats; and protection of the international slave trade through 1807. Garrison had burned copies of the Constitution to express his opinion. However, Lysander Spooner published The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1846), which examined the United States Constitution as an antislavery document. Douglass's change of opinion about the Constitution and his splitting from Garrison around 1847 became one of the abolitionist movement's most notable divisions. Douglass angered Garrison by saying that the Constitution could and should be used as an instrument in the fight against slavery.[104] On July 24, 1851, "shortly after his announced change of opinion", Douglass delivered a speech titled, "Is the United States Constitution For or Against Slavery".[105] He expressed his changed views again in an 1860 speech in Glasgow, Scotland, titled, "The Constitution of the United States: is it pro-slavery or anti-slavery?". In that speech, he said, "When I escaped from slavery, and was introduced to the Garrisonians, I adopted very many of their opinions.... I was young, had read but little, and naturally took some things on trust. Subsequent reading and experience", however, "brought me to other conclusions". He now believed that "dissolution of the American Union", which Garrison advocated, "would place the slave system more exclusively under the control of the slaveholding States...." In addition, "Mr. Garrison and his friends tell us that while in the Union we are responsible for slavery.... I deny that going out of the Union would free us from that responsibility.... The American people in the Northern States have helped to enslave the black people. Their duty will not be done till they give them back their plundered rights."[106] Letter to his former owner In September 1848, on the tenth anniversary of his escape, Douglass published an open letter addressed to his former master, Thomas Auld, berating him for his conduct, and inquiring after members of his family still held by Auld.[107][108] In the course of the letter, Douglass adeptly transitions from formal and restrained to familiar and then to impassioned. At one point he is the proud parent, describing his improved circumstances and the progress of his own four young children. But then he dramatically shifts tone: Oh! sir, a slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children. It is then that my feelings rise above my control. ... The grim horrors of slavery rise in all their ghastly terror before me, the wails of millions pierce my heart, and chill my blood. I remember the chain, the gag, the bloody whip, the deathlike gloom overshadowing the broken spirit of the fettered bondman, the appalling liability of his being torn away from wife and children, and sold like a beast in the market.[54] In a graphic passage, Douglass asked Auld how he would feel if Douglass had come to take away his daughter Amanda into slavery, treating her the way he and members of his family had been treated by Auld.[107][108] Yet in his conclusion Douglass shows his focus and benevolence, stating that he has "no malice towards him personally," and asserts that, "there is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege, to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other."[54] Women's rights In 1848, Douglass was the only black person to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, in upstate New York.[109][110] Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution asking for women's suffrage.[111] Many of those present opposed the idea, including influential Quakers James and Lucretia Mott.[112] Douglass stood and spoke eloquently in favor of women's suffrage; he said that he could not accept the right to vote as a black man if women could also not claim that right. He suggested that the world would be a better place if women were involved in the political sphere: In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.[112] After Douglass's powerful words, the attendees passed the resolution.[112][113] In the wake of the Seneca Falls Convention, Douglass used an editorial in The North Star to press the case for women's rights. He recalled the "marked ability and dignity" of the proceedings, and briefly conveyed several arguments of the convention and feminist thought at the time. On the first count, Douglass acknowledged the "decorum" of the participants in the face of disagreement. In the remainder, he discussed the primary document that emerged from the conference, a Declaration of Sentiments, and the "infant" feminist cause. He criticized opponents of women's rights: "A discussion of the rights of animals would be regarded with far more complacency by many of what are called the wise and the good of our land, than would be a discussion of the rights of woman."[114] He also noted the link between abolitionism and feminism, the overlap between the communities. His opinion as the editor of a prominent newspaper carried weight, and he stated the position of the North Star explicitly: "We hold woman to be justly entitled to all we claim for man." This letter, written a week after the convention, reaffirmed the first part of the paper's slogan, "right is of no sex."  Memorial Rock at AME Zion, Newburgh, New York After the Civil War, when the 15th Amendment giving black men the right to vote was being debated, Douglass split with the Stanton-led faction of the women's rights movement. Douglass supported the amendment, which would grant suffrage to black men. Stanton opposed the 15th Amendment because it limited the expansion of suffrage to black men; she predicted its passage would delay for decades the cause for women's right to vote. Stanton argued that American women and black men should band together to fight for universal suffrage, and opposed any bill that split the issues.[115] Douglass and Stanton both knew that there was not yet enough male support for women's right to vote, but that an amendment giving black men the vote could pass in the late 1860s. Stanton wanted to attach women's suffrage to that of black men so that her cause would be carried to success.[116] Douglass thought such a strategy was too risky, that there was barely enough support for black men's suffrage. He feared that linking the cause of women's suffrage to that of black men would result in failure for both. Douglass argued that white women, already empowered by their social connections to fathers, husbands, and brothers, at least vicariously had the vote. Black women, he believed, would have the same degree of empowerment as white women once black men had the vote.[116] Douglass assured the American women that at no time had he ever argued against women's right to vote.[117] Ideological refinement  Frederick Douglass in 1856, around 38 years of age In 1850, Douglass was elected the vice president of the American League of Colored Laborers, the first black labor union in the United States, which he had also helped found.[118] Meanwhile, in 1851, he merged the North Star with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper,[119] which was published until 1859.[120] On July 5, 1852, Douglass delivered an address in Corinthian Hall at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. This speech eventually became known as "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?"; one biographer called it "perhaps the greatest antislavery oration ever given."[121] In 1853, he was a prominent attendee of the radical abolitionist National African American Convention in Rochester. Douglass was one of five people whose names were attached to the address of the convention to the people of the United States published under the title, The Claims of Our Common Cause. The other four were Amos Noë Freeman, James Monroe Whitfield, Henry O. Wagoner, and George Boyer Vashon.[122] Like many abolitionists, Douglass believed that education would be crucial for African Americans to improve their lives; he was an early advocate for school desegregation. In the 1850s, Douglass observed that New York's facilities and instruction for African American children were vastly inferior to those for European Americans. Douglass called for court action to open all schools to all children. He said that full inclusion within the educational system was a more pressing need for African Americans than political issues such as suffrage. John Brown  Douglass argued against John Brown's plan to attack the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, painting by Jacob Lawrence See also: Shields Green On March 12, 1859, Douglass met with radical abolitionists John Brown, George DeBaptiste, and others at William Webb's house in Detroit to discuss emancipation.[123] Douglass met Brown again when Brown visited his home two months before leading the raid on Harpers Ferry. Brown penned his Provisional Constitution during his two-week stay with Douglass. Also staying with Douglass for over a year was Shields Green, a fugitive slave whom Douglass was helping, as he often did. Shortly before the raid, Douglass, taking Green with him, travelled from Rochester, via New York City, to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Brown's communications headquarters. He was recognized there by black people, who asked him for a lecture. Douglass agreed, although he said his only topic was slavery. Green joined him on the stage; Brown, incognito, sat in the audience. A white reporter, referring to "Nigger Democracy", called it a "flaming address" by "the notorious Negro Orator".[124] There, in an abandoned stone quarry for secrecy, Douglass and Green met with Brown and John Henri Kagi, to discuss the raid. After discussions lasting, as Douglass put it, "a day and a night", he disappointed Brown by declining to join him, considering the mission suicidal. To Douglass's surprise, Green went with Brown instead of returning to Rochester with Douglass. Anne Brown said that Green told her that Douglass promised to pay him on his return, but David Blight called this "much more ex post facto bitterness than reality".[125] Almost all that is known about this incident comes from Douglass. It is clear that it was of immense importance to him, both as a turning point in his life—not accompanying John Brown—and its importance in his public image. The meeting was not revealed by Douglass for 20 years. He first disclosed it in his speech on John Brown at Storer College in 1881, trying unsuccessfully to raise money to support a John Brown professorship at Storer, to be held by a black man. He again referred to it stunningly in his last Autobiography. After the raid, which took place between October 16 and 18, 1859, Douglass was accused both of supporting Brown and of not supporting him enough.[126] He was nearly arrested on a Virginia warrant,[127][128][129] and fled for a brief time to Canada before proceeding onward to England on a previously planned lecture tour, arriving near the end of November.[130] During his lecture tour of Great Britain, on March 26, 1860, Douglass delivered a speech before the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society in Glasgow, "The Constitution of the United States: is it pro-slavery or anti-slavery?", outlining his views on the American Constitution.[131] That month, on the 13th, Douglass's youngest daughter Annie died in Rochester, New York, just days shy of her 11th birthday. Douglass sailed back from England the following month, traveling through Canada to avoid detection. Years later, in 1881, Douglass shared a stage at Storer College in Harpers Ferry with Andrew Hunter, the prosecutor who secured Brown's conviction and execution. Hunter congratulated Douglass.[132] Photography Douglass considered photography very important in ending slavery and racism, and believed that the camera would not lie, even in the hands of a racist white person, as photographs were an excellent counter to many racist caricatures, particularly in blackface minstrelsy. He was the most photographed American of the 19th century, consciously using photography to advance his political views.[133][134] He never smiled, specifically so as not to play into the racist caricature of a happy enslaved person. He tended to look directly into the camera and confront the viewer with a stern look.[135][136] |

経歴 奴隷廃止論者、説教師 詳細情報: マサチューセッツ州ニューベッドフォードにおける奴隷廃止運動  フレデリック・ダグラス、1840年代頃、20代 夫妻は1838年にマサチューセッツ州ニューベッドフォード(奴隷廃止運動の中心地で、かつて奴隷だった人々が多く住んでいた)に定住し、1841年にマ サチューセッツ州リンに移住した [70] ネイサンとメアリー・ジョンソン夫妻と出会い、しばらく一緒に暮らした後、夫妻はドグラスを自分たちの結婚後の名前にした[37]。ドグラスは母親の旧姓 ベイリーで育ったが、奴隷から逃れた後、まずスタンリー、次にジョンソンと姓を変えていた。ニューベッドフォードでは、ジョンソン姓は一般的であったた め、彼はより特徴的な姓を望み、ネイサン・ジョンソンにふさわしい姓を選ぶよう頼んだ。ネイサンは、ウォルター・スコットの詩『湖上の淑女』を読んだ後、 「ダグラス」を提案した。この詩では、主要な登場人物の2人が「ダグラス」という姓を持っていた。  ジョンソン夫妻がニューベッドフォード(マサチューセッツ州)に住んでいた家兼集会所 ダグラスは白人メソジスト教会に入会しようと思ったが、人種隔離が行われていることを知って、最初からがっかりした。その後、彼はニューヨークで最初に設 立された独立系黒人教派であるアフリカメソジスト監督教会(African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church)に入会した。この教派には、ソジャーナ・トゥルース(Sojourner Truth)やハリエット・タブマン(Harriet Tubman)が所属していた。[73] 1839年に彼は公認の説教師となり、[74] それによって弁論のスキルを磨くことができた。彼は執事、日曜学校監督、聖堂管理人など、さまざまな役職を務めた。1840年、ダグラスがニューヨーク州 エルミラで演説を行った。エルミラは後に「地下鉄道」の駅となり、1940年までにこの地域最大の教会となる黒人教会が設立された。 ダグラスはニューベッドフォードのいくつかの団体にも参加し、定期的に奴隷廃止運動の集会にも出席した。ウィリアム・ロイド・ギャリソンの週刊紙「リベ レーター」を購読していた。彼は後に、「奴隷制への憎しみという感情を私に与えた顔や姿は、ウィリアム・ロイド・ギャリソンほど強い印象を与えたものはな かった」と語った。この影響は深く、ダグラスが最後に出版した自伝の中で、「彼の新聞は聖書に次ぐ私の心の拠り所となった」と語っているほどである [75]。 ギャリソンもまたダグラスに感銘を受け、1839年には早くも『リベレーター』紙で彼の反植民地主義の姿勢について記事を書いていた。ダグラスがギャリソ ンを初めて聞いたのは、1841年、ニューベッドフォードのリバティホールで行われたギャリソンの講演だった。別の会合で、ダグラスは思いがけなく講演を 依頼された。自分の話をした後、ダグラスは奴隷制度廃止運動の講演者になるよう勧められた。数日後、ダグラスはマサチューセッツ奴隷廃止協会の年次総会で 講演した。当時23歳だったダグラスは、緊張を克服し、奴隷としての生活について雄弁に語った。  ウィリアム・ロイド・ギャリソン、奴隷廃止論者であり、ダグラスの北部における最初の友人の一人 リンに住んでいた頃、ダグラスは人種隔離された交通機関に対する初期の抗議活動を行った。1841年9月、リン・セントラル・スクエア駅で、ダグラスと友 人のジェームズ・N・バッファムは、ダグラスが人種隔離車両に座ることを拒否したため、イースタン鉄道の列車から降ろされた[70][76][77 ][78] 1843年、ダグラス氏はアメリカ奴隷廃止協会の「百大会議」プロジェクトに参加し、東部と中西部全域の集会所で6か月間にわたる講演ツアーを行った。こ のツアー中、奴隷制度支持者たちは頻繁にダグラスに詰め寄った。インディアナ州ペンデルトンの講演会で、怒った群衆が地元のクエーカー教徒の家族である ハーディ一家の前でダグラスを追いかけ回して殴りつけ、ハーディ一家がダグラスを救出した。この襲撃でダグラスの手は骨折したが、うまく治らず、彼は生涯 その傷に悩まされることになった[79]。ペンデルトン歴史地区にあるフォールズ公園には、この出来事を記念する石碑がある。 1847年、ダグラスがギャリソンに語った。「私はアメリカを好きではない。愛国心もない。私には祖国がない。いったいどこが祖国なのか?この国の制度は、私を認めていない。私を人間として認めていないのだ。」[80] 自伝 ダグラスの最も有名な作品は、マサチューセッツ州リンに滞在中に執筆された最初の自伝『フレデリック・ダグラスの生涯の物語』(1845年出版)である [81]。当時、黒人がこれほど雄弁な文学作品を書くことができるのか、懐疑的な見方もあった。この本は概ね好評を博し、たちまちベストセラーとなった。 3年以内に9回も重版され、1万1千部がアメリカ国内で流通した。また、フランス語とオランダ語に翻訳され、ヨーロッパでも出版された。 ダグラスはその生涯で3冊の自叙伝を出版し(そのうち3冊目は改訂版)、その都度、前著の内容をさらに充実させていった。1845年の 『Narrative』は彼の最大のベストセラーとなり、おそらく、後述の通り、翌年に法的自由を得るための資金を調達する一助となった。1855年、ダ グラスは『My Bondage and My Freedom』を出版。1881年、60代となったダグラスは『Life and Times of Frederick Douglass』を出版し、1892年に改訂した。 アイルランドとイギリスへの旅  スコットランド、ダンディー、ウェスト・ベル通りにあるフレデリック・ダグラス記念プレート  1847年、29歳頃のダグラス ダグラスの友人や恩師たちは、このことが元所有者ヒュー・オールドの目に留まり、彼が「所有物」を取り戻そうとするのではないかと懸念した。彼らはダグラ スに、かつての奴隷たちがそうしてきたように、アイルランドを旅行するよう勧めた。1845年8月16日、ダグラスはカンブリア号でイギリスのリバプール に向けて出航した。ダグラスはアイルランドを旅行したが、ちょうど大飢饉が始まろうとしていた。 アメリカの人種差別から解放された感覚に、ダグラスは驚かされた。 11日と半日が過ぎ、私は危険な深みを3000マイルも横断した。民主的な政府ではなく、君主制の政府の下にいる。アメリカの青く澄んだ空のかわりに、私 はエメラルドの島(アイルランド)の柔らかな灰色の霧に包まれている。私は呼吸し、奴隷(チャトル)が人間になるのを見る。私は、私の人間としての平等を 疑う者、私を奴隷として主張する者、侮辱を投げかける者を求めて、無駄に周囲を見回す。タクシーを拾い、白人の隣に座り、ホテルに到着し、同じドアから入 り、同じ応接間に案内され、同じテーブルで食事をしたが、誰も不快に思う者はいなかった。私は、あらゆる場面で白人に対する優しさや敬意をもって接されて いることに気づいた。教会に行っても、鼻を上げて軽蔑的な態度で「黒人はここに入れない!」と言われることはない。 それでもダグラスがダブリンで遭遇した極度の貧困には驚かされた。その多くは奴隷時代の経験を思い出させるものだった。ウィリアム・ロイド・ギャリソンへ の手紙の中で、ダグラスは「私はかつての境遇を思い起こさせるものを多く目にする。アメリカ奴隷制に反対の声を上げるのは恥ずかしいと正直に認めるが、人 類の正義は世界共通であることを知っている。アメリカの奴隷を心から思いやる者は、他人の苦難に心を痛めることはできない。また、自分は奴隷廃止論者だと 思っているが、他人の過ちには目を向けられない者は、奴隷廃止の信念の真の基盤を見いだせていないのだ。」[83] また、彼はアイルランド人ナショナリストで、奴隷廃止論者でもあったダニエル・オコンネルと出会い、友人となった。 ダグラスはアイルランドとイギリスで2年間過ごし、教会や礼拝堂で講演を行った。彼の講演は人気を博し、一部の施設は「息苦しくなるほどの人混み」となっ た。その一例が、1846年5月にアレクサンダー・フレッチャーのフィンズベリー・チャペルで行った、大好評を博したロンドンでの歓迎演説である。ダグラ スによれば、イギリスでは「人種としてではなく、一人の人間として」扱われたという。 1846年、ダグラスは、イギリス植民地の奴隷制廃止を議会に働きかけた最後の存命のイギリス人奴隷廃止論者の一人、トーマス・クラークソンと面会した。 この旅行中、ダグラスは法的に自由の身となった。アンナ・リチャードソンと義理の姉エレン・オブ・ニューカッスル・アポン・タインが率いるイギリスの支援 者たちが、彼のアメリカ人所有者トーマス・オールドから自由を買うための資金を調達したのだ。 ニューカッスル・アポン・タインのアンナ・リチャードソンと義理の姉エレンが、彼のアメリカ人所有者トーマス・オールドから自由を買うための資金を調達し たのである[88][90]。多くの支援者がダグラスにイギリスにとどまるよう勧めたが、彼の妻はマサチューセッツに残り、300万人の黒人同胞がアメリ カで奴隷として拘束されていたため、彼は1847年春にアメリカに戻った[88]。 [91]。 21世紀に入り、ダグラスが訪れたことを記念して、アイルランドのコークとウォーターフォード、そしてロンドンの建物に歴史的銘板が設置された。最初の銘 板はコークのインペリアルホテルに設置され、2012年8月31日に除幕された。2つ目の銘板はウォーターフォード市庁舎のファサードに設置され、 2013年10月7日に除幕された。これは、1845年10月9日に彼がそこで演説したことを記念するものである[92]。3つ目のプレートは、ロンドン のサウスケンジントンにあるネル・グウィン・ハウスを飾っている。この場所は、ダグラスがイギリスの奴隷廃止論者ジョージ・トンプソンとともに滞在した家 の跡地である[93]。 2023年7月31日、ヨーロッパで最初の彼の銅像がベルファストのハイストリートで除幕された[94]。 ダグラスはスコットランドで過ごし、「スコットランドの奴隷廃止代理人」に任命された[95]。彼は奴隷廃止の演説を行い、アメリカに手紙を書いた。彼は エジンバラの街を優雅で壮麗、そして非常に歓迎的な場所だと考えていた。彼の滞在中に重要だった市内の場所の地図は、スコットランド国立図書館に保管され ている[96][97]。エジンバラのギルモア・プレイスにあるプレートと壁画は、1846年の彼の滞在を記念している。 「フレデリック・ダグラスの19世紀のアイルランドへの旅と訪問を記念して、現在(2021年)さまざまな共同プロジェクトが進行中である」[98]。 アメリカ合衆国への帰国、奴隷廃止運動  ダグラス、1847年~52年頃、30代前半 1847年にアメリカ合衆国に戻った後、イギリスの支援者から与えられた5ポンド 1847年にアメリカに戻った後、イギリスの支援者から与えられた500ポンド(2023年の価値で57,716ドル相当)を使って、ダグラス氏はニュー ヨーク州ロチェスターのメモリアルAMEジオン教会の地下から、最初の奴隷廃止論者向け新聞「ノーススター」の発行を開始した[99]。当初はピッツバー グのジャーナリスト、マーティン・デラニーが共同編集者を務めていたが、ダグラス氏は購読者を十分に獲得できていないと感じ、 そして彼らは別々の道を歩むことになった[100][ページ番号が必要]。ノーススターのモットーは「正義に性別はない。真実に肌の色はない。神は私たち すべての父であり、私たちは皆兄弟である」[101]であった。AME教会とノーススターは、主に白人で構成されたアメリカ植民地化協会とその提案、すな わち自由の身となった黒人をアフリカに送るという計画に、奴隷解放民のコミュニティが激しく反対する運動に加わった。ダグラスも地下鉄道に参加した。彼と 彼の妻は、400人以上の逃亡奴隷に自宅での宿泊と物資を提供した[101]。 また、ダグラスはやがて、アメリカ奴隷制廃止運動に消極的なガリソンと袂を分かつことになる[102]。それ以前、ダグラスは、奴隷制を容認する憲法であ るとするガリソンの見解に同意していた。その理由は、 奴隷人口の60%を「自由民の総数」に加算するという条項[103]により、議席の配分を行うこと、および1807年までの国際奴隷貿易の保護を目的とし ていた。ギャリソンは、自分の意見を表明するために憲法を焼却した。しかし、ライサンダー・スプナーは『奴隷制の違憲性』(1846年)を出版し、合衆国 憲法を奴隷制廃止の文書として検証した。1847年ごろ、ダグラスが憲法に対する意見を変え、ギャリソンと袂を分けたことは、奴隷廃止運動の最も顕著な分 裂の一つとなった。ダグラスが「憲法は奴隷制と戦うための道具として利用できるし、利用すべきだ」と発言したことで、ギャリソンは激怒した[104]。 1851年7月24日、「意見変更を表明した直後」、ダグラスは「 アメリカ合衆国憲法は奴隷制に賛成か反対か」という題の演説を行った[105]。彼は1860年にスコットランドのグラスゴーで行った演説「アメリカ合衆 国憲法:奴隷制に賛成か反対か」でも、再び自分の考えの変化を表明した。その演説の中で、彼は次のように述べている。「私が奴隷から逃れ、ガリソン派の人 々に紹介されたとき、私は彼らの意見の多くを採用した。私は若く、読んだことも少なかったため、当然のことながら、ある事柄を鵜呑みにしていた。しかし、 その後の読書や経験により、私は別の結論に達した。今では、ガリソンが提唱する『アメリカ連合の解体』は、『奴隷制度を奴隷所有州により排他的に管理下に 置く』ことになる、と信じている。さらに、「ギャリソン氏と彼の友人たちは、合衆国にいる間は奴隷制に責任を負うべきだと言っているが、私は、合衆国から 脱退すればその責任から解放されるわけではないと否定する。北部のアメリカ国民は黒人を奴隷にするのに一役買ってきた。彼らが略奪した権利を黒人たちに返 還するまで、彼らの義務は果たされないだろう。」[106] 以前の主人への手紙 1848年9月、脱走から10周年を迎えたダグラス氏は、以前の主人であるトーマス・オールド氏宛てに公開書簡を発表し、 ールドの振る舞いを非難し、まだールドに拘束されている家族について尋ねた[107][108]。手紙の中で、ダグラスは見事なまでに、形式的で抑制され た表現から親しみのある表現、そして情熱的な表現へと巧みに切り替えている。ある箇所では、彼は誇り高き親として、自身の状況の改善と4人の幼い子供たち の成長について述べている。しかし、彼は劇的に口調を変える。 ああ、奴隷所有者は、私の愛する子供たちについて考え、彼らを見つめる時ほど、完全に地獄の使者であるように私には思えない。その時、私の感情は制御不能 になる。奴隷制の恐ろしい恐怖が、私の前に恐ろしい恐怖とともに立ち現れ、何百万人もの叫び声が私の心を突き刺し、血の気が引く。私は、鎖、猿ぐつわ、血 まみれの鞭、奴隷の打ちひしがれた精神を覆う死のような暗闇、妻や子供たちから引き離され、獣のように市場で売られるという恐ろしい責任を覚えている [54]。 ダグラスが、もし自分がアールドの娘アマンダを奴隷として連れて行ったら、アールドはどのような気持ちになるだろうか、と尋ねた際、ダグラスは、アールド や彼の家族に対して自分や家族がされたような扱いをするだろう、と述べた。彼と彼の家族メンバーがオールドから受けたような扱いをするのだ。[107] [108]しかし、結論でダグラスはその焦点と博愛主義を示し、「彼個人に対して悪意はない」と述べ、「私の家ほど安全な場所はないし、あなたが快適さを 求めるために必要とするものは、私の家には何もないが、私が快く与えないものはない。実際、私は人類が互いにどう接すべきかについて、あなた方に手本を示 すことを光栄に思うべきだ。」[54] 女性の権利 1848年、ダグラスはニューヨーク州北部で開催された初の女性権利会議であるセネカフォールズ会議に、唯一の黒人として出席した[109][110]。 エリザベス・キャディ・スタントンは 集会で女性参政権を求める決議を可決するよう求めた。[111] 出席者の多くは、影響力のあるクエーカー教徒のジェームズ・モットとルクレティア・モットを含め、この考えに反対した。[112] ダグラスが立ち上がり、女性参政権を支持する雄弁な演説を行った。彼は、女性にもその権利が認められないのであれば、黒人として投票権を受け入れることは できないと述べた。彼は、女性が政治の世界に関与すれば、世界はもっと良い場所になるだろうと提案した。 政府に参加する権利を否定することで、女性の地位の低下や大きな不正義の永続化が起こるだけでなく、世界の政府を支える道徳的・知的力の半分が損なわれ、否定されてしまうのだ[1]。 12] ダグラスの力強い言葉の後、出席者は決議を可決した[112][113]。 セネカフォールズ会議の後、ダグラスは『ザ・ノース・スター』紙上で社説を執筆し、女性の権利を主張した。彼は、会議の「際立った能力と尊厳」を思い起こし、会議と当時のフェミニスト思想のいくつかの論点を簡潔に伝えた。 最初の論点として、ダグラス氏は意見の相違に直面した参加者の「礼儀正しさ」を認めた。 残りの部分では、会議で作成された主要文書である「感情の宣言」と「未熟」なフェミニスト運動について論じた。 彼は、女性の人権に反対する人々を批判した。「動物の権利についての議論は、この国の賢者や善良な人と呼ばれる多くの人々から、女性の権利についての議論 よりもはるかに満足のいくものとして受け止められるだろう」[114]。また、奴隷廃止運動とフェミニズムのつながり、両者のコミュニティの重なりについ ても言及している。 著名な新聞の編集者としての彼の意見は大きな影響力を持っており、ノーススターの立場を明確に述べた。「我々は、女性が男性に対して主張する権利をすべて 正当に有すると考える」この手紙は、大会から1週間後に書かれたもので、新聞のスローガン「権利に性別はない」の前半部分を再確認するものだった。  ニューヨーク州ニューバーグのAMEシオンにある記念碑 南北戦争後、黒人男性に投票権を与える第15条修正案が審議されていたとき、ダグラスはスタントン率いる女性権利運動の派閥と袂を分けた。ダグラスはこの 修正案を支持し、黒人男性に参政権を認めることを支持した。スタントンは、黒人男性にのみ参政権を認めるという理由で第15条修正案に反対した。スタント ンは、この修正案が成立すれば、女性の参政権運動が数十年遅れるだろうと予測していた。スタントンは、アメリカ人女性と黒人男性が団結して普通選挙権のた めに戦うべきだと主張し、問題を二分するような法案には反対した[115]。ダグラスとスタントンは、女性の参政権獲得にはまだ十分な男性の支持が得られ ていないが、黒人男性に投票権を与える修正案は1860年代後半に可決される可能性があることを知っていた。スタントンは、女性の参政権を黒人男性の参政 権と結びつけることで、自らの運動を成功に導きたいと考えていた[116]。 ダグラスはそのような戦略はリスクが大きすぎると考えていた。黒人男性の参政権を支持する声は十分ではなかった。女性の参政権運動と黒人男性の参政権運動 を結びつけることは、両者にとって失敗に終わるのではないかと懸念していたのだ。ダグラスによれば、白人女性は、父親、夫、兄弟といった社会的つながりを 介してすでに力を得ており、少なくとも間接的に投票権を持っていた。黒人男性にも選挙権が与えられた暁には、黒人女性も白人女性と同じ程度の権利が与えら れるだろうと彼は信じていた[116]。ダグラス氏は、アメリカ人女性に対して、女性の選挙権に反対したことは一度もないと断言した[117]。 思想の洗練  1856年、38歳前後のフレデリック・ダグラス 38歳 1850年、ダグラスが設立に尽力したアメリカ有色人労働者同盟(全米初の黒人労働組合)の副代表に選出された。 ジェリト・スミスが率いる自由党の新聞と合併し、「フレデリック・ダグラス紙」を創刊した[119]。 1852年7月5日、ダグラスはロチェスター婦人反奴隷制協会の主催する集会で、コリントホールで演説を行った。この演説は後に「奴隷にとって7月4日は 何なのか」として知られるようになり、ある伝記作家は「おそらく史上最高の奴隷廃止演説」と呼んだ[121]。1853年、彼はロチェスターで開催された 急進的な奴隷廃止論者による全米アフリカ系アメリカ人大会の目立った出席者となった。ダグラスはその5人のうちの1人であり、その5人は『The Claims of Our Common Cause(私たちの共通の主張)』というタイトルで出版された、米国国民に向けた大会の演説に名前が記載されていた。他の4人は、エイモス・ノエ・フ リーマン、ジェームズ・モンロー・ウィットフィールド、ヘンリー・O・ワゴナー、ジョージ・ボイヤー・ヴァションであった[122]。 多くの奴隷廃止論者たちと同様、ダグラスはアフリカ系アメリカ人が自分たちの生活を改善するためには教育が不可欠であると考えていた。彼は早期から学校の 分離撤廃を提唱していた。1850年代、ダグラス氏は、ニューヨークのアフリカ系アメリカ人の子供たちに対する施設や教育が、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の子 供たちに対するものよりもはるかに劣っていることに気づいた。ダグラス氏は、すべての学校をすべての子供たちに開放するよう法廷で訴えることを呼びかけ た。彼は、教育システムへの完全な統合は、選挙権のような政治的な問題よりも、アフリカ系アメリカ人にとってより緊急に必要であると述べた。 ジョン・ブラウン  ハーパーズ・フェリーにある兵器庫を攻撃するというジョン・ブラウンの計画に反対するダグラス氏。 参照: シールドス・グリーン 1859年3月12日、ダグラスはデトロイトのウィリアム・ウェブの家で、急進的な奴隷廃止論者ジョン・ブラウン、ジョージ・デバプティストらと会い、奴 隷解放について話し合った[123]。ダグラスは、ブラウンがハーパース・フェリー襲撃を指揮する2か月前に自宅を訪れた際に、ブラウンと再会した。ブラ ウンはダグラスと2週間一緒に過ごした間に暫定憲法草案を執筆した。また、1年以上もダグラスと一緒に過ごしたのは、ダグラスがしばしば支援していた逃亡 奴隷のシールズ・グリーンだった。 襲撃の直前に、ダグラスはグリーンを連れて、ニューヨークを経由してペンシルベニア州チェンバーズバーグにあるブラウンの通信本部へと向かった。そこで黒 人たちに認められ、講演を依頼された。ダグラスは承諾したが、テーマは奴隷制だけだと述べた。グリーンも壇上に上がり、ブラウンは変装して観客席に座って いた。ある白人記者は「ニガー・デモクラシー」について触れ、「悪名高い黒人演説家」による「炎のような演説」と評した[124]。 そこで、秘密を守るために使われなくなった採石場で、ダグラスとグリーンはブラウンとジョン・アンリ・カギと会い、襲撃について話し合った。ダグラスが言 うところの「1日と1夜」にわたる話し合いの後、彼はブラウンを失望させた。ブラウンが自殺行為であると考えたダグラスは、ブラウンに加わることを拒否し たのだ。ダグラスの驚きをよそに、グリーンはダグラスと一緒にロチェスターに戻るのではなく、ブラウンと一緒に行った。アン・ブラウンによると、グリーン はダグラスが戻ってきたら報酬を支払う約束をしたと彼女に話した。しかし、デビッド・ブライトはこれを「現実よりもはるかに事後的な恨み」と呼んだ [125]。 この事件について知られていることはほとんどすべてダグラスから得たものである。ジョン・ブラウンに同行しなかったという人生の転機として、また彼の公的 なイメージにおける重要性として、この事件が彼にとって非常に重要であったことは明らかである。この会合はダグラスによって20年間明かされなかった。彼 は1881年にストーアカレッジで行ったジョン・ブラウンに関する講演で初めてこのことを明かし、ストーアカレッジで黒人教授が担当するジョン・ブラウン 講座の支援金を募ろうとしたが、失敗に終わった。彼は最後の自伝でも、このことを驚くほど鮮やかに言及している。 1859年10月16日から18日にかけて襲撃事件が起こった後、ダグラスにはブラウンを支援しただけでなく、支援が不十分だったという容疑がかけられた [126]。彼はバージニア州の逮捕状により逮捕されそうになり[127][128][129]、予定されていた講演ツアーでイギリスに向かう前に、カナ ダに短期間逃亡した。11月の終わり頃に到着した[130]。1860年3月26日、グラスゴーのスコットランド反奴隷制協会で、ダグラスが「アメリカ合 衆国憲法:奴隷制を支持しているのか、それとも反対しているのか」と題した演説を行い、アメリカ憲法に対する見解を述べた[131]。その月の13日、ダ グラスの末娘アニーがニューヨーク州ロチェスターで亡くなった。翌月、ダグラスはイギリスからカナダを経由して、発覚を避けるために航海で帰国した。 それから数年後の1881年、ダグラスはハーパーズ・フェリーにあるストーラー・カレッジで、ブラウンを有罪判決に導き、死刑執行に踏み切った検事アンドリュー・ハンターと壇上に立った。ハンターはダグラスを祝福した[132]。 写真 ダグラスは、奴隷制と人種差別を終わらせる上で写真が非常に重要だと考えており、たとえ人種差別主義者の白人の手に渡ったとしても、写真は多くの人種差別 的な風刺、特に黒人風ミンストレルショーに対する優れた対抗手段であるため、カメラは嘘をつかないだろうと信じていた。彼は19世紀で最も多く写真を撮ら れたアメリカ人であり、意識的に写真を利用して自らの政治的主張を広めた[133][134]。奴隷として幸せに暮らしている人物の差別的な風刺画に描か れないように、彼は決して笑わなかった。彼はカメラをまっすぐに見つめ、厳しい表情でカメラの前に立つことを好んだ[135][136]。 |

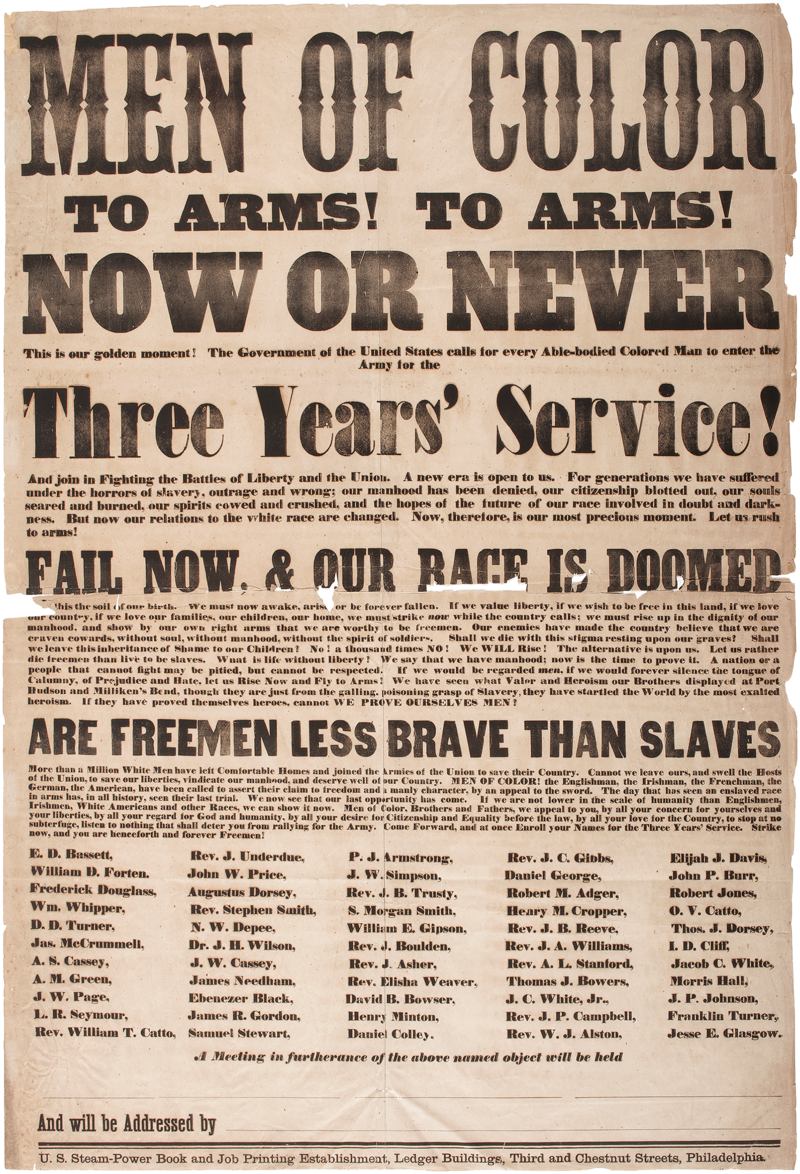

| Civil War years Before the Civil War By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous black men in the country, known for his orations on the condition of the black race and on other issues such as women's rights. His eloquence gathered crowds at every location. His reception by leaders in England and Ireland added to his stature. He had been seriously proposed for the congressional seat of his friend and supporter Gerrit Smith, who declined to run again after his term ended in 1854.[137][138] Smith recommended to him that he not run, because there were "strenuous objections" from members of Congress.[139] The possibility "afflicted some with convulsions, others with panic, more with an astonishing flow of exceedingly select and nervous language", "giving vent to all sorts of linguistic enormities."[140] If the House agreed to seat him, which was unlikely, all the Southern members would walk out, so the country would finally be split.[138][141] No black person would serve in Congress until 1870, just after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. Fight for emancipation and suffrage  1863 broadside Men of Color to Arms!, written by Douglass Douglass and the abolitionists argued that because the aim of the Civil War was to end slavery, African Americans should be allowed to engage in the fight for their freedom. Douglass publicized this view in his newspapers and several speeches. After Lincoln had finally allowed black soldiers to serve in the Union army, Douglass helped the recruitment efforts, publishing his famous broadside Men of Color to Arms! on March 21, 1863.[142] His eldest son, Charles Douglass, joined the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, but was ill for much of his service.[74] Lewis Douglass fought at the Battle of Fort Wagner.[143] Another son, Frederick Douglass Jr., also served as a recruiter. With the North no longer obliged to return slaves to their owners in the South, Douglass fought for equality for his people. Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 on the treatment of black soldiers[144] and on plans to move liberated slaves out of the South. President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of all slaves in Confederate-held territory. (Slaves in Union-held areas were not covered because the proclamation was permissible under the Constitution only as a war measure; they were freed with the adoption of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865.) Douglass described the spirit of those awaiting the proclamation: "We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky ... we were watching ... by the dim light of the stars for the dawn of a new day ... we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries."[145] During the U.S. Presidential Election of 1864, Douglass supported John C. Frémont, who was the candidate of the abolitionist Radical Democracy Party. Douglass was disappointed that President Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for black freedmen. Douglass believed that since African American men were fighting for the Union in the American Civil War, they deserved the right to vote.[146] After Lincoln's death The postwar ratification of the 13th Amendment, on December 6, 1865, outlawed slavery, "except as a punishment for crime." The 14th Amendment provided for birthright citizenship and prohibited the states from abridging the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States or denying any "person" due process of law or equal protection of the laws. The 15th Amendment protected all citizens from being discriminated against in voting because of race.[115] After Lincoln had been assassinated, Douglass conferred with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of black suffrage.[147]  The keynote speaker at the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial, Douglass wrote a critique of the depiction of the black man "still on his knees". On April 14, 1876, Douglass delivered the keynote speech at the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington's Lincoln Park. He spoke frankly about the complex legacy of Lincoln, noting what he perceived as both positive and negative attributes of the late President.[148] Calling Lincoln "the white man's President," Douglass criticized Lincoln's tardiness in joining the cause of emancipation, noting that Lincoln initially opposed the expansion of slavery but did not support its elimination: "He had been ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the humanity of the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people. Lincoln was neither our man or our model".[148] But Douglass also asked, "Can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see if Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word?"[149] He also said: "Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery...." Most famously, he added: "Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined."[148] The crowd, roused by his speech, gave Douglass a standing ovation. Lincoln's widow Mary Lincoln supposedly gave Lincoln's favorite walking-stick to Douglass in appreciation. That walking stick still rests in his final residence, "Cedar Hill" in Washington, D.C., now preserved as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. After delivering the speech, Douglass immediately wrote to the National Republican newspaper in Washington (which published his letter five days later, on April 19), criticizing the statue's design and suggesting the park could be improved by more dignified monuments of free black people. "The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude," Douglass wrote. "What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man."[150] |

南北戦争の時代 南北戦争以前 南北戦争当時、ダグラス氏は黒人種の状態や女性の権利など、さまざまな問題について演説を行うことで知られ、国内で最も有名な黒人男性の一人であった。彼 の雄弁さはあらゆる場所で聴衆を集めた。イギリスやアイルランドの指導者たちから歓迎されたことで、彼の名声はさらに高まった。 彼は友人であり支援者でもあったジェリト・スミスの連邦議会議席を真剣に打診されていたが、スミスは1854年に任期が終了した後、再出馬を辞退した [137][138]。スミスは、連邦議会議員から「激しい反対」があったため、彼に立候補しないよう勧めた[139]。この可能性に「ある者はけいれん を起こし、ある者はパニックに陥り、さらに 驚くほど厳選された神経質な言葉の驚くべき流れ」に悩まされ、「あらゆる種類の言語上の醜態を露呈」していた[140]。下院が彼の議席を認める可能性は 低かったが、もし認めれば南部出身の議員全員が議場を立ち去り、アメリカは最終的に分裂してしまうだろう[138][141]。1870年、第15条修正 案が可決された直後まで、黒人は誰も連邦議会の議員になることはなかった。 奴隷解放と参政権を求めて  1863年、ダグラスが執筆した「有色人種よ、武器を取れ!」というビラ ダグラスと奴隷廃止論者たちは、南北戦争の目的が奴隷制の廃止にある以上、アフリカ系アメリカ人も自由を求めて戦うことを許されるべきだと主張した。ダグ ラスは、この見解を新聞やいくつかの演説で公表した。リンカーンが最終的に黒人兵士を北軍に編入することを許可した後、ダグラスはその募集活動を手助け し、1863年3月21日に有名なビラ「有色人種よ、武器を取れ!」を出版した[142]。彼の長男チャールズ・ダグラス グラスはマサチューセッツ州第54歩兵連隊に入隊したが、兵役期間のほとんどを病気で過ごした[74]。ルイス・ダグラスは第2次シュリバン・ダンカン会 戦(Fort Wagner)で戦った[143]。もう一人の息子フレデリック・ダグラス・ジュニアも募集要員として働いた。 奴隷を南部の所有者に返還する必要がなくなった北部において、ダグラスはその同胞の平等を求めて戦った。ダグラスは1863年に、黒人兵士の待遇[144]と解放奴隷の南部からの移動計画について、エイブラハム・リンカーン大統領と協議した。 リンカーン大統領の奴隷解放宣言は1863年1月1日に発効し、南部連合が支配する地域におけるすべての奴隷の解放を宣言した。(合衆国領内の奴隷は、こ の宣言が戦争対策としてのみ憲法で認められていたため、適用外であった。奴隷解放は、1865年12月6日に第13条修正案が採択されたことで実現し た。)ダグラスはこの宣言を待ち望む人々の心境を次のように表現している。「私たちは、空から降ってくる稲妻を待つように、耳を澄ませて待ってい た。...私たちは、新しい夜明けを、星明かりの中で待っていた。...何世紀にもわたる苦しい祈りの答えを待ち望んでいたのだ。」[145] 1864年のアメリカ大統領選挙では、ダグラスが奴隷廃止を掲げる急進民主党のジョン・C・フレモント候補を支持した。ダグラスが失望したのは、リンカー ン大統領が黒人解放奴隷の選挙権を公に支持しなかったことだった。ダグラスは、南北戦争でアフリカ系アメリカ人男性が北軍のために戦ったのだから、彼らに も選挙権を与えるべきだと信じていた[146]。 リンカーンの死後 南北戦争後の1865年12月6日、第13条修正案が批准され、奴隷制が「犯罪に対する処罰として」を除いて禁止された。第14条は出生による市民権を規 定し、各州が合衆国市民の特権と免除を制限したり、「人」に対して正当な法的手続きや法の平等な保護を否定することを禁じた。第15条は、人種を理由に投 票で差別されることがないよう、すべての市民を保護した[115]。リンカーンが暗殺された後、ダグラスは大統領アンドリュー・ジョンソンと黒人の参政権 について協議した[147]。  奴隷解放記念碑除幕式の基調講演で、ダグラスは「まだひざまずいたまま」の黒人の描写について批判的な文章を書いた。 1876年4月14日、ダグラスはワシントンにあるリンカーン公園の奴隷解放記念碑除幕式で基調講演を行った。彼はリンカーンの複雑な遺産について率直に 語り、故大統領の肯定的および否定的な特徴として彼が感じたことを指摘した[148]。リンカーンを「白人の大統領」と呼び、ダグラス氏はリンカーンが奴 隷解放運動に加わるのが遅かったことを批判し、リンカーンは当初奴隷制の拡大には反対したが、奴隷制の廃止には賛成しなかったと指摘した。「彼は政権の最 初の数年間、いつでも喜んで、有色人種の尊厳を否定し、延期し、犠牲にしてでも白人の福祉を促進する用意があった。リンカーンは我々の仲間でもなければ、 我々の模範でもなかった」[148]。しかし、ダグラスもこう問いかけています。「1863年1月1日、世界がリンカーンが言葉通りの人物であるかどうか を見届けることになったその夜を、有色人種や、万人の自由を願う白人が忘れることができるだろうか?」[149]。また、彼はこうも言っています。「リン カーン氏は、白人の同胞が抱く黒人に対する偏見を共有していたとはいえ、心の底では奴隷制度を嫌悪し憎んでいたことは言うまでもないだろう...」 最も有名なのは、こう付け加えたことだ。「真の奴隷廃止論者の目から見れば、リンカーン氏は遅々として進まず、冷淡で鈍感、無関心に見えた。しかし、政治 家として考慮すべき国民の感情で彼を見れば、彼は迅速で熱心、急進的、そして決断力があった」[148]。 彼の演説に奮起した聴衆は、ダグラスにスタンディングオベーションを送った。リンカーンの未亡人メアリー・リンカーンは、感謝の印としてリンカーンのお気 に入りのステッキをダグラスに与えたと言われている。そのステッキは、ダグラスの最後の住居であるワシントンD.C.の「シーダーヒル」に今も残されてお り、フレデリック・ダグラス国立史跡として保存されている。 演説を終えたダグラス氏は、すぐにワシントンのナショナル・リパブリック紙(4月19日、5日後に彼の手紙を掲載)に手紙を書き、像のデザインを批判し、 公園にはもっと威厳のある黒人奴隷の記念碑を建てるべきだと提案した。 「ここに描かれた黒人は、立ち上がってはいるものの、まだ膝をついて裸のままです」とダグラス氏は書いた。「私が死ぬ前に見たいのは、四つ足の動物のよう に膝をついて横たわるのではなく、人間のように直立した姿で表現された黒人像だ。」[150] |