遺伝子ドーピング

Gene doping

gene

therapy

☆ 【概要】

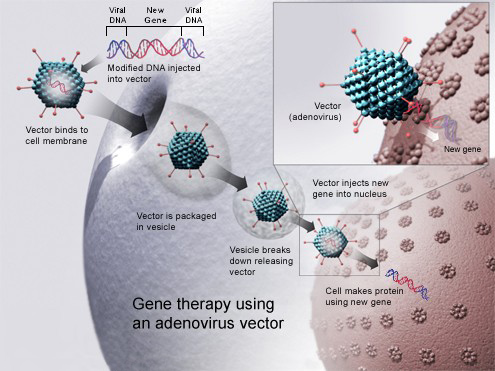

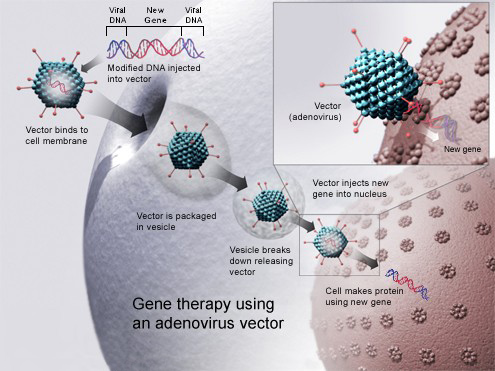

遺伝子ドーピング(Gene doping)とは、遺伝子治療を、その適用が禁止されているスポーツ競技におけるパフォーマンス向上のために、病気の治療以外の目的で、アスリートが 非治療的に利用すること[1][2]。2024年現在、スポーツ競技において、パフォーマンス向上のために遺伝子ドーピングが利用されたという証拠はな い。[3] 遺伝子ドーピングでは、特定のヒトタンパク質の遺伝子発現およびタンパク質生合成を増減するために遺伝子導入を使用します。これは、遺伝子キャリアを直接 その人物に注入するか、その人物から細胞を取り出し、その細胞に遺伝子導入を行い、その細胞をその人物に投与することで実現できる。[1] アスリートによる遺伝子ドーピングへの関心の高まりと、そのリスクや検出方法に関する懸念は、遺伝子治療分野の発展と並行して進展してきました。特に、 1998年にインスリン様成長因子1を過剰発現するトランスジェニックマウスが、高齢でも正常なマウスよりもはるかに強いことが報告され、2002年に遺 伝子治療によりエリスロポエチン(EPO)を遺伝子療法で投与する手法に関する研究が発表され、2004年には、PPARガンマを発現する遺伝子マウスに 投与することで、通常のマウスよりもはるかに高い持久力を持つ「マラソンマウス」が作成されたことが報告された。これらの研究を発表した科学者たちは、す べてアスリートやコーチから技術へのアクセスを求める直接の連絡を受けていた。一般の人がこの活動に気づいたのは、2006年にドイツのコーチの裁判で、 このような努力が証拠として提示された時だった。 研究者自身に加え、世界アンチ・ドーピング機関(WADA)、国際オリンピック委員会、アメリカ科学振興協会などの団体は、2001年に遺伝子ドーピング のリスクについて議論を開始し、2003年にWADAは遺伝子ドーピングを禁止ドーピング行為のリストに追加し、その後間もなく遺伝子ドーピングの検出方 法に関する研究の資金提供を開始した。 遺伝子強化とは、健康なアスリートが、身体能力の向上のために遺伝子操作や遺伝子移入を行うことを指す。遺伝子強化には遺伝子ドーピングも含まれ、アス リートの間で乱用される可能性があり、政治的・倫理的な論争の火種となるおそれがある。[4]

★【遺伝子ドーピングの倫理】

世

界アンチ・ドーピング機関(WADA)は、運動能力の向上のための非治療的な遺伝子操作は、その規範により禁止されていると決定した。当該技術がスポーツ

において禁止されるべきかどうかを判断するためのガイドラインがあり、3つの条件のうち2つを満たす場合、その技術はスポーツにおいて禁止される(健康へ

の害、パフォーマンスの向上、および/または「スポーツの精神」に反する)。[33]

Kayser ら

は、すべての選手が平等にアクセスできる場合、遺伝子ドーピングは競技の公平性を確保すると主張している。一方、批判者は、治療目的以外の目的(能力向

上)のための治療的介入は、医学とスポーツの倫理的基盤を損なうと主張している。[34]

遺伝子治療に伴う高いリスクは、疾患を持つ人々の命を救う可能性によって上回る。重篤な複合免疫不全症の子供たちを対象とした遺伝子治療の臨床試験に携

わったアラン・フィッシャー氏は、「死の危機にある人だけが、遺伝子治療を受ける合理的な理由がある。ドーピングのために遺伝子治療を利用することは、倫

理的に容認できず、科学的にも愚かな行為だ」と述べている[35]。ステロイドのテトラヒドロゲストリノン(THG)などの過去の事例からもわかるよう

に、アスリートは、リスクの高い遺伝子技術をトレーニングプログラムに取り入れることを選択する可能性がある。[4]

主流の見解は、遺伝子ドーピングは、治療目的以外の目的や能力向上目的での治療的介入と同様に危険で非倫理的であり、医学の倫理的基盤とスポーツの精神を

損なうものであるというものである。[5][36][37][8][38]

一方、より広範な理由から人間の能力強化を支持する人々[39]、あるいは「天然」と「人工」の区別は誤った二分法である、あるいは運動能力の向上におけ

る技術の役割を否定する人々は、遺伝子ドーピングに反対も支持もしていない[40]。

| Gene doping is the

hypothetical non-therapeutic use of gene therapy by athletes in order

to improve their performance in those sporting events which prohibit

such applications of genetic modification technology,[1][2] and for

reasons other than the treatment of disease. As of 2024, there is no

evidence that gene doping has been used for athletic

performance-enhancement in any sporting events.[3] Gene doping would

involve the use of gene transfer to increase or decrease gene

expression and protein biosynthesis of a specific human protein; this

could be done by directly injecting the gene carrier into the person,

or by taking cells from the person, transfecting the cells, and

administering the cells back to the person.[1] The historical development of interest in gene doping by athletes and concern about the risks of gene doping and how to detect it moved in parallel with the development of the field of gene therapy, especially with the publication in 1998 of work on a transgenic mouse overexpressing insulin-like growth factor 1 that was much stronger than normal mice, even in old age, preclinical studies published in 2002 of a way to deliver erythropoietin (EPO) via gene therapy, and publication in 2004 of the creation of a "marathon mouse" with much greater endurance than normal mice, created by delivering the gene expressing PPAR gamma to the mice. The scientists generating these publications were all contacted directly by athletes and coaches seeking access to the technology. The public became aware of that activity in 2006 when such efforts were part of the evidence presented in the trial of a German coach. Scientists themselves, as well as bodies including the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), the International Olympic Committee, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, started discussing the risk of gene doping in 2001, and by 2003 WADA had added gene doping to the list of banned doping practices, and shortly thereafter began funding research on methods to detect gene doping. Genetic enhancement includes manipulation of genes or gene transfer by healthy athletes for the purpose of physically improving their performance. Genetic enhancement includes gene doping and has potential for abuse among athletes, all while opening the door to political and ethical controversy.[4] |

遺伝子ドーピング(Gene doping)とは、遺伝子治療を、その適用が禁止されているスポー

ツ競技におけるパフォーマンス向上のために、病気の治療以外の目的で、アスリートが非治療的に利用すること[1][2]。2024年現在、スポーツ競技に

おいて、パフォーマンス向上のために遺伝子ドーピングが利用されたという証拠はない。[3]

遺伝子ドーピングでは、特定のヒトタンパク質の遺伝子発現およびタンパク質生合成を増減するために遺伝子導入を使用します。これは、遺伝子キャリアを直接

その人物に注入するか、その人物から細胞を取り出し、その細胞に遺伝子導入を行い、その細胞をその人物に投与することで実現できる。[1] アスリートによる遺伝子ドーピングへの関心の高まりと、そのリスクや検出方法に関する懸念は、遺伝子治療分野の発展と並行して進展してきました。特に、 1998年にインスリン様成長因子1を過剰発現するトランスジェニックマウスが、高齢でも正常なマウスよりもはるかに強いことが報告され、2002年に遺 伝子治療によりエリスロポエチン (EPO)を遺伝子療法で投与する手法に関する研究が発表され、2004年には、PPARガンマを発現する遺伝子マウスに投与することで、通常のマウスよ りもはるかに高い持久力を持つ「マラソンマウス」が作成されたことが報告された。これらの研究を発表した科学者たちは、すべてアスリートやコーチから技術 へのアクセスを求める直接の連絡を受けていた。一般の人がこの活動に気づいたのは、2006年にドイツのコーチの裁判で、このような努力が証拠として提示 された時だった。 研究者自身に加え、世界アンチ・ドーピング機関(WADA)、国際オリンピック委員会、アメリカ科学振興協会などの団体は、2001年に遺伝子ドーピング のリスクについて議論を開始し、2003年にWADAは遺伝子ドーピングを禁止ドーピング行為のリストに追加し、その後間もなく遺伝子ドーピングの検出方 法に関する研究の資金提供を開始した。 遺伝子強化とは、健康なアスリートが、身体能力の向上のために遺伝子操作や遺伝子移入を行うことを指す。遺伝子強化には遺伝子ドーピングも含まれ、アス リートの間で乱用される可能性があり、政治的・倫理的な論争の火種となるおそれがある。[4] |

| History of gene doping The history of concern about the potential for gene doping follows the history of gene therapy, the medical use of genes to treat diseases, which was first clinically tested in the 1990s.[5] Interest by the athletic community was especially spurred by the creation in a university lab of a "mighty mouse", created by administering a virus carrying the gene expressing insulin-like growth factor 1 to mice; the mice were stronger and remained strong even as they aged, without exercise.[5] The lab had been seeking treatments for muscle wasting diseases, but when their work was made public, the lab was inundated with calls from athletes seeking the treatment, with one coach offering his whole team.[6] The scientist told The New York Times in 2007: "I was quite surprised, I must admit. People would try to entice me, saying things like, 'It'll help advance your research.' Some offered to pay me." He also told the Times that every time similar research is published he gets calls and that he explains that, even should the treatment became ready for use in people, which would take years, there would be serious risks, including death; he also said that even after he explains this, the athletes still want it.[6] In 1999, the field of gene therapy was set back when Jesse Gelsinger died in a gene therapy clinical trial, suffering a massive inflammatory reaction to the drug.[5][7] This led regulatory authorities in the US and Europe to increase safety requirements in clinical trials even beyond the initial restrictions that had been put in place at the beginning of the biotechnology era to deal with the risks of recombinant DNA.[8] In June 2001, Theodore Friedmann, one of the pioneers of gene therapy, and Johann Olav Koss, an Olympic gold medallist in speed skating, published a paper that was the first public warning about gene doping.[8][9] Also in June 2001, a Gene Therapy Working Group, convened by the Medical Commission of the International Olympic Committee noted that "we are aware that there is the potential for abuse of gene therapy medicines and we shall begin to establish procedures and state-of-the-art testing methods for identifying athletes who might misuse such technology".[8] Research was published in 2002 about a preclinical gene therapy called Repoxygen, which delivered the gene encoding erythropoietin (EPO) as a potential treatment for anemia.[5] The scientists from that company also received calls from athletes and coaches.[5] In that same year the World Anti-Doping Agency held its first meeting to discuss the risk of gene doping,[8][10] and the US President's Council on Bioethics discussed gene doping in the context of human enhancement at several sessions.[11][12][13] In 2003, the field of gene therapy took a step forward and a step back; first gene therapy drug was approved, Gendicine, which was approved in China for the treatment of certain cancers,[14] but children in France who had seemingly been effectively treated with gene therapy for severe combined immunodeficiency (non-human) began developing leukemia.[7] In 2003 the BALCO scandal became public, in which chemists, trainers and athletes conspired to evade doping controls with new and undetectable doping substances.[8] In 2003 the World Doping Agency proactively added gene doping to the list of banned doping practices.[5] Also in 2003, a symposium convened by the American Association for the Advancement of Science focused on the issue.[15] Research published in 2004 showed that mice given gene therapy coding for a protein called PPAR gamma had about double the endurance of untreated mice and were dubbed "marathon mice"; those scientists received calls from athletes and coaches.[5] Also in 2004 the World Anti-Doping Agency began to fund research to detect gene doping, and formed a permanent expert panel to advise it on risks and to guide the funding.[5][10] In 2006 interest from athletes in gene doping received widespread media coverage due its mention during the trial of a German coach who was accused and found guilty of giving his athletes performance enhancing drugs without their knowledge; an email in which the coach attempted to obtain Repoxygen was read in open court by a prosecutor.[5][6] This was the first public disclosure that athletes were interested in gene doping.[5] In 2011 the second gene therapy drug was approved; Neovasculgen, which delivers the gene encoding VEGF, was approved in Russia to treat peripheral artery disease.[16][17] In 2012 Glybera, a treatment for a rare inherited disorder, became the first treatment to be approved for clinical use in either Europe or the United States.[18][19] As the field of gene therapy has developed, the risk of gene doping becoming a reality has increased with it.[7] |

遺伝子ドーピングの歴史 遺伝子ドーピングの可能性に対する懸念の歴史は、1990年代に初めて臨床試験が行われた、病気の治療に遺伝子を用いる遺伝子治療の歴史と並行して進んで いる。[5] 特にスポーツ界の関心が高まったのは、大学研究室で「強力なマウス」が作成されたことだった。このマウスは、インスリン様成長因子1(IGF-1)を発現 する遺伝子を含むウイルスをマウスに投与することで作成され、運動をせずに年老いても強靭な体力を維持した。[5] 研究所は筋萎縮性疾患の治療法を探求していたが、研究内容が公表されると、アスリートから治療を希望する電話が殺到し、あるコーチはチーム全員を差し出す と申し出た。[6] 科学者は2007年に『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙に次のように語った:「正直、驚いた。人々は『あなたの研究の進歩に役立つ』などと言って私を誘惑しよ うとした。報酬を支払うという者もいた」と語った。また、同様の研究が発表されるたびに電話がかかってくるが、治療が人間に使用可能になるには何年もかか る上、死を含む深刻なリスクがあることを説明すると、それでもアスリートたちは治療を希望すると言う、と語った。[6] 1999年、ジェシー・ゲルシンガーが遺伝子治療臨床試験で、薬剤による大規模な炎症反応を起こして死亡した事件により、遺伝子治療分野は大きな後退を余 儀なくされた。[5][7] この事件を受けて、米国および欧州の規制当局は、組換えDNAのリスクに対処するためにバイオテクノロジー時代の初期に導入された当初の規制以上に、臨床 試験における安全要件を強化した。[8] 2001年6月、遺伝子治療の先駆者の一人であるセオドア・フリードマンと、スピードスケートのオリンピック金メダリストであるヨハン・オラフ・コスは、 遺伝子ドーピングに関する最初の公的な警告となる論文を発表した。[8][9] 同じ2001年6月、国際オリンピック委員会(IOC)の医療委員会が設置した遺伝子治療作業部会は、「遺伝子治療薬の濫用の可能性を認識しており、この ような技術を濫用する可能性のある選手を特定するための手続きと最先端の検査方法の確立を開始する」と指摘した。[8] 2002年には、貧血の治療薬として、エリスロポエチン(EPO)をコードする遺伝子を投与する前臨床段階の遺伝子治療「レポキシゲン」に関する研究が発 表された。[5] この会社の科学者たちは、選手やコーチたちからも問い合わせを受けた。[5] 同年、世界アンチ・ドーピング機関(WADA)は遺伝子ドーピングのリスクを議論する最初の会議を開催した[8][10]。また、米国大統領のバイオエ シックス諮問委員会は、人間の能力向上という文脈で遺伝子ドーピングを複数のセッションで議論した[11][12]。[13] 2003 年、遺伝子治療分野は前進と後退を同時に経験した。中国で、特定の癌の治療薬として最初の遺伝子治療薬「ジェンディシン」が承認された[14] 一方、重篤な複合免疫不全症(非ヒト)の治療に遺伝子治療で効果が見られたフランスの子供たちに白血病が発症した。[7] 2003年には、化学者、トレーナー、アスリートが新たな検出不能なドーピング物質を使用してドーピング検査を回避する計画を立てた「バルコスキャンダ ル」が公表された。[8] 同年、世界アンチ・ドーピング機関(WADA)は、遺伝子ドーピングを禁止ドーピング行為のリストに積極的に追加した。[5] また2003年、アメリカ科学振興協会(AAAS)が主催したシンポジウムでこの問題が取り上げられた。[15] 2004年に発表された研究では、PPARガンマというタンパク質をコードする遺伝子治療を受けたマウスは、治療を受けていないマウスに比べて約2倍の持 久力があり、「マラソンマウス」と命名された。これらの科学者たちは、選手やコーチたちから問い合わせを受けた。[5] また、2004年には、世界アンチ・ドーピング機関が遺伝子ドーピングの検出に関する研究への資金援助を開始し、そのリスクについて助言し、資金援助の指 針を示す常設の専門家委員会を設立した。[5][10] 2006 年、ドイツ人コーチが、選手たちに無断でパフォーマンス向上薬を投与した容疑で起訴され、有罪判決を受けた裁判で、この問題が取り上げられたことで、遺伝 子ドーピングに対するアスリートの関心がメディアで広く報じられた。この裁判では、コーチがレポキシゲンを入手しようとした E メールが、検察官によって法廷で読み上げられた。[5][6] これは、アスリートが遺伝子ドーピングに関心を持っていることが初めて公になった出来事だった。[5] 2011年に2つ目の遺伝子治療薬が承認された。VEGFをコードする遺伝子を導入する「ネオバスキュルゲン」は、ロシアで末梢動脈疾患の治療薬として承 認された。[16] |

| Agents used in gene doping There are numerous genes of interest as agents for gene doping.[1][20][8] They include erythropoietin, insulin-like growth factor 1, human growth hormone, myostatin, vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, endorphin, enkephalin and alpha-actinin-3.[1][20] The risks of gene doping would be similar to those of gene therapy: immune reaction to the native protein leading to the equivalent of a genetic disease, massive inflammatory response, cancer, and death, and in all cases, these risks would be undertaken for short-term gain as opposed to treating a serious disease.[7][8] Alpha-actinin-3 Alpha-actinin-3 is found only in skeletal muscle in humans, and has been identified in several genetic studies as having a different polymorphism in world-class athletes compared with normal people. One form that causes the gene to make more protein is found in sprinters and is related to increased power; another form that causes the gene to make less protein is found in endurance athletes.[20][21] Gene doping agents could be designed with either polymorphism, or for endurance athletes, some DNA construct that interfered with expression like a small interfering RNA.[20] Myostatin See also: Myostatin-related muscle hypertrophy Myostatin is a protein responsible for inhibiting muscle differentiation and growth. Removing the myostatin gene or otherwise limiting its expression leads to an increase in muscle size and power.[7] This has been demonstrated in knockout mice lacking the gene that were dubbed "Schwarzenegger mice".[22] Humans born with defective genes can also serve as "knockout models"; a German boy with a mutation in both copies of the myostatin gene was born with well-developed muscles.[23] The advanced muscle growth continued after birth, and the boy could lift weights of 3 kg at the age of 4.[7] In work published in 2009, scientists administered follistatin via gene therapy to the quadriceps of non-human primates, resulting in local muscle growth similar to the mice.[7] Erythropoietin (EPO) Erythropoietin is a glycoprotein that acts as a hormone, controlling red blood cell production. Athletes have injected the EPO protein as a performance-enhancing substance for many years (blood doping). When the additional EPO increases the production of red blood cells in circulation, this increases the amount of oxygen available to muscle, enhancing an athlete's endurance.[7][24] Recent studies suggest it may be possible to introduce another EPO gene into an animal in order to increase EPO production endogenously.[23] EPO genes have been successfully inserted into mice and monkeys, and were found to increase hematocrits by as much as 80 percent in those animals.[23] However, the endogenous and transgene derived EPO elicited autoimmune responses in some animals in the form of severe anemia.[23] Insulin-like growth factor 1 Insulin-like growth factor 1 is a protein involved in the mediation of the growth hormone. Administration of IGF-1 to mice has resulted in more muscle growth and quicker muscle and nerve regeneration.[20][7] If athletes were to use this the sustained production of IGF-1 could cause heart disease and cancer.[20] Others Modulating the levels of proteins that affect psychology are also potential goals for gene doping; for example pain perception depends on endorphins and enkephalins, response to stress depends on BDNF, and an increase in synthesis of monamines could improve the mood of athletes.[20] Preproenkephalin has been administered via gene therapy using a replication-deficient herpes simplex virus, which targets nerves, to mice with results good enough to justify a Phase I clinical trial in people with terminal cancer with uncontrolled pain.[7] Adopting that approach for athletes would be problematic since the pain deadening would likely be permanent.[7] VEGF has been tested in clinical trials to increase blood flow and has been considered as a potential gene doping agent; however long term follow up of the clinical trial subjects showed poor results.[7] The same is true of fibroblast growth factor.[7] Glucagon-like peptide-1 increases the amount of glucose in the liver and has been administered via gene therapy to the livers of mouse models of diabetes and was shown to increase gluconeogenesis' for athletes this would make more energy available and reduce the buildup of lactic acid.[7] |

遺伝子ドーピングに使用される薬剤 遺伝子ドーピングの薬剤として注目されている遺伝子は数多くある。[1][20][8] それには、エリスロポエチン、インスリン様成長因子 1、ヒト成長ホルモン、ミオスタチン、血管内皮成長因子、線維芽細胞成長因子、エンドルフィン、エンケファリン、アルファアクチニン-3 などが含まれる。[1][20] 遺伝子ドーピングのリスクは、遺伝子治療の場合と同様であると考えられる。すなわち、天然タンパク質に対する免疫反応により、遺伝性疾患と同等の症状、大 規模な炎症反応、癌、死に至る可能性がある。いずれの場合も、これらのリスクは、重篤な疾患の治療ではなく、短期的な利益のために負うことになる。[7] [8] アルファアクチニン-3 アルファアクチニン-3 は、人間の骨格筋にのみ見られ、いくつかの遺伝子研究で、世界クラスのアスリートでは、一般の人々と異なる多型があることが確認されている。この遺伝子が より多くのタンパク質を産生する形は、短距離選手に見られ、パワーの増加と関連がある。一方、この遺伝子がより少ないタンパク質を産生する形は、持久力ア スリートに見られる。[20][21] 遺伝子ドーピング剤は、いずれの多型も利用して設計することができるほか、持久力アスリートの場合は、小さな干渉 RNA のような発現を妨害する DNA 構造体を設計することも可能だ。[20] ミオスタチン 参照:ミオスタチン関連筋肉肥大 ミオスタチンは、筋肉の分化と成長を阻害するタンパク質だ。ミオスタチン遺伝子を除去したり、その発現を制限したりすると、筋肉のサイズとパワーが増加す る。[7] これは、ミオスタチン遺伝子を欠損した「シュワルツェネッガーマウス」と呼ばれるノックアウトマウスで示されている。[22] 欠損遺伝子を生まれつき持つ人間も「ノックアウトモデル」として利用可能で、ミオスタチン遺伝子の両コピーに突然変異を持つドイツの少年は、発達した筋肉 を持って生まれた。[23] 出生後も筋肉の成長は続き、この少年は 4 歳で 3 kg の重量を持ち上げることができました。[7] 2009 年に発表された研究では、科学者が非ヒト霊長類の大腿四頭筋にフォリスタチンを遺伝子治療で投与したところ、マウスと同様の局所的な筋肉の成長が認められ ました。[7] エリスロポエチン (EPO) エリスロポエチンは、赤血球の産生を制御するホルモンとして機能する糖タンパク質です。アスリートは、パフォーマンス向上物質として EPO タンパク質を長年にわたり注射してきました(血液ドーピング)。追加の EPO によって循環中の赤血球の産生が増加すると、筋肉が利用できる酸素量が増加し、アスリートの持久力が向上します。[7][24] 最近の研究では、動物に別のEPO遺伝子を導入することで、内因性のEPO産生を増加させる可能性が示唆されています。[23] EPO遺伝子はマウスとサルに成功裏に導入され、これらの動物のヘマトクリット値を最大80%増加させることが確認されました。[23] しかし、内因性およびトランスジェニック由来のEPOは、一部の動物で重度の貧血を伴う自己免疫反応を引き起こしました。[23] インスリン様成長因子 1 インスリン様成長因子 1 は、成長ホルモンの媒介に関与するタンパク質です。マウスに IGF-1 を投与すると、筋肉の成長が促進され、筋肉や神経の再生が早まります。[20][7] アスリートがこれを使用すると、IGF-1 の持続的な産生により、心臓病や癌を引き起こす可能性があります。[20] その他 心理に影響を与えるタンパク質のレベルを調節することも、遺伝子ドーピングの潜在的な目標のひとつです。例えば、痛みの知覚はエンドルフィンとエンケファ リンに依存し、ストレスへの反応は BDNF に依存し、モノアミン合成の増加はアスリートの気分を改善する可能性があります。[20] プレプロエンケファリンは、神経を標的とする複製欠損型単純ヘルペスウイルスを用いた遺伝子治療によりマウスに投与され、末期がんで制御不能な痛みのある 人々を対象とした第 I 相臨床試験の実施を正当化するほど十分な結果が得られています。[7] このアプローチをアスリートに採用することは、痛みの麻痺が永続的になる可能性が高いため、問題があります。[7] VEGF は、血流を増加させる目的で臨床試験で試験されており、遺伝子ドーピング剤としての可能性も検討されているが、臨床試験被験者の長期追跡調査では、結果は 不満足だった。[7] 線維芽細胞増殖因子についても同様です。[7] グルカゴン様ペプチド-1は肝臓のグルコース量を増加させ、糖尿病のマウスモデルに遺伝子療法で投与され、グルコース新生を増加させることが示されていま す。アスリートにとって、これはエネルギーの供給を増やし、乳酸の蓄積を減少させる可能性があります。[7] |

| Detection The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) is the main regulatory organization looking into the issue of the detection of gene doping.[10] Both direct and indirect testing methods are being researched by the organization. Directly detecting the use of gene therapy usually requires the discovery of recombinant proteins or gene insertion vectors, while most indirect methods involve examining the athlete in an attempt to detect bodily changes or structural differences between endogenous and recombinant proteins.[7][25][26] Indirect methods are by nature more subjective, as it becomes very difficult to determine which anomalies are proof of gene doping, and which are simply natural, though unusual, biological properties.[7] For example, Eero Mäntyranta, an Olympic cross country skier, had a mutation which made his body produce abnormally high amounts of red blood cells. It would be very difficult to determine whether or not Mäntyranta's red blood cell levels were due to an innate genetic advantage, or an artificial one.[27] First generation of gene doping detecting methods Gene doping detection idea started in 2004 when WADA has put gene doping in the banned list and started investigating a new method that can detect the inserted transgenes. The first generation of gene doping detection techniques used PCR tests that targets the transgenes’ sequences. It can be obtained from a blood sample which will contain endogenous and transgene DNA since a small amount of the transgene will leak into the bloodstream. It can be easily distinguished from endogenous DNA because it lacks introns since the transgene will most likely use cDNA that is obtained by reverse transcriptase from RNA, which has removed its intones though RNA splicing leaving only exon-exon junction that include only the coding sequences and some important sequences like promoters since the viral victors has a limited capacity. Therefore, PCR can target these exon-exon junctions as a unique sequence that is not present in gDNA[28] Real time PCR PCR has many applications in molecular biology field including DNA analysis. The main purpose of PCR is to amplify and double the DNA sequences exponentially. In gene doping detection, If the sequence started to amplify producing an exponential graph, then the test is positive and indicates the presence of the gene in the sample obtained from that person. But if the sequence didn't amplify and a linear graph was produced, then the test is said to be negative and the targeted DNA sequence was not present in that person's sample.[29] Next generation sequencing With the limitation of the first-generation detection methods, it was important to develop a new method that overcomes the previous failures with a high accuracy and can detect the manipulation in DNA sequences that could evade to be detected by PCR methods. The solution was using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) method that can determine the nucleotide orders of the whole genome or targets the exon-exon junctions in transgene and compare it with reference gene sequence. This method is fast accurate and is getting cheaper by the time and has opened a new field in science that wasn't possible before like sequencing the whole genome sequencing.[30] DNA sequencing was established in the 1970s with the two-dimensional chromatography and kept improving until 2001 with the completion of human genome project which costed about three billion dollars and required 15 years to finish sequencing the whole genome. However, with nowadays sequencing technology, whole genome sequencing (WGS) takes only a single day and costs around a thousand dollars. Moreover, a new sequencing technology is under development that will cost only 100 dollars for WGS.[31] There are many NGS techniques that are used in DNA sequencing but the most used method is the one done by illumina[32] |

検出 世界アンチ・ドーピング機関(WADA)は、遺伝子ドーピングの検出に関する問題を検討する主要な規制機関です。[10] 同機関では、直接的な検査方法と間接的な検査方法の両方が研究されています。遺伝子治療の使用を直接検出するには、通常、組換えタンパク質または遺伝子導 入ベクターの発見が必要ですが、間接的な方法では、ほとんどの場合、選手を検査して、体内の変化や、内因性タンパク質と組換えタンパク質の構造上の違いを 検出しようとします。[7][25][26] 間接的な方法は、どの異常が遺伝子ドーピングの証拠であり、どの異常が、珍しいものの、単に自然な生物学的特性であるかを判断することが非常に難しいた め、本質的に主観的になります。[7] 例えば、オリンピックのクロスカントリースキー選手である Eero Mäntyranta は、体内で異常な量の赤血球を生成する突然変異を持っていました。Mäntyrantaの赤血球のレベルが先天的な遺伝的優位性によるものか、人工的なも のか判断するのは非常に困難です。[27] 遺伝子ドーピング検出方法の第一世代 遺伝子ドーピングの検出アイデアは、2004年にWADAが遺伝子ドーピングを禁止リストに追加し、挿入されたトランスジェニックを検出できる新しい方法 の調査を開始したときに始まりました。 第一世代の遺伝子ドーピング検出技術は、転移遺伝子の配列を標的とするPCR検査を使用した。これは血液サンプルから取得でき、血液中に少量の転移遺伝子 が漏れ出すため、内因性DNAと転移遺伝子DNAの両方を含む。内因性DNAと容易に区別できるのは、トランスジェンが逆転写酵素によりRNAから転写さ れたcDNAを使用するため、イントロンが欠如しているからです。RNAスプライシングによりイントロンが除去され、エクソン-エクソン接合部のみが残る ため、コーディング配列とプロモーターなどの重要な配列のみが含まれます。これは、ウイルスベクターの容量が限られているためです。したがって、PCR は、gDNA に存在しない一意の配列として、これらのエクソン-エクソン接合部を標的とすることができる[28] リアルタイム PCR PCR は、DNA 分析を含む分子生物学の分野で多くの応用がある。PCR の主な目的は、DNA 配列を指数関数的に増幅し、倍増することだ。 遺伝子ドーピングの検出では、配列が増幅され、指数関数的なグラフが得られた場合、検査結果は陽性であり、その人物から採取したサンプルにその遺伝子が存 在することを示します。しかし、配列が増幅されず、直線的なグラフが得られた場合、検査結果は陰性であり、その人物のサンプルには対象とする DNA 配列は存在しなかったとみなされます[29]。 次世代シーケンシング 第一世代の検出方法の限界から、以前の失敗を克服し、PCR法で検出を回避できるDNA配列の操作を検出できる高精度な新手法の開発が重要となった。 解決策は、全ゲノムのヌクレオチド順序を決定したり、トランスジェンのエクソン-エクソン接合部を標的とし、参照遺伝子配列と比較できる次世代シーケンス (NGS)手法を採用することだった。この方法は高速で正確であり、時間とともにコストも低下しており、これまで不可能だった全ゲノムシーケンスなど、科 学の新たな分野を開拓しています。[30] DNAシーケンスは、1970年代に2次元クロマトグラフィーによって確立され、2001年にヒトゲノムプロジェクトが完了するまで改良が続けられまし た。このプロジェクトには約30億ドルの費用がかかり、全ゲノムのシーケンス完了までに15年を要しました。 しかし、現在のシーケンス技術では、全ゲノムシーケンス(WGS)は1日で完了し、費用は1,000ドル程度です。さらに、WGSの費用が100ドルに抑 えられる新しいシーケンス技術が開発中です。[31] DNAシーケンスには多くのNGS技術がありますが、最もよく使用されているのはイルミナ社の技術です。[32] |

| Research A 2016 review found that about 120 DNA polymorphisms had been identified in the literature related to some aspect of athletic performance, 77 related to endurance and 43 related to power. 11 had been replicated in three or more studies and six were identified in genome-wide association studies, but 29 had not been replicated in at least one study.[21] The 11 replicated markers were:[21] Endurance ACE Alu I/D (rs4646994) (Called ACE I) ACTN3 577X PPARA rs4253778 G, PPARGC1A Gly482; power/strength markers ACE Alu I/D (rs4646994) (called ACE D) ACTN3 Arg577 AMPD1 Gln12 HIF1A 582Ser MTHFR rs1801131 C NOS3 rs2070744 T PPARG 12Ala The six GWAS markers were:[21] CREM rs1531550 A, DMD rs939787 T GALNT13 rs10196189 G NFIA-AS1 rs1572312 C, RBFOX1 rs7191721 G TSHR rs7144481 C |

研究 2016年のレビューでは、運動能力のいくつかの側面に関連して、約 120 の DNA 多型が文献で確認されており、そのうち 77 は持久力、43 はパワーに関連していることが明らかになりました。11 は 3 件以上の研究で再現され、6 件はゲノムワイド関連研究で確認されましたが、29 は少なくとも 1 件の研究で再現されていませんでした。[21] 再現された11のマーカーは以下の通りです。[21] 持久力 ACE Alu I/D (rs4646994) (ACE Iと呼ばれる) ACTN3 577X PPARA rs4253778 G, PPARGC1A Gly482; パワー/筋力マーカー ACE Alu I/D (rs4646994) (ACE Dと呼ばれている) ACTN3 Arg577 AMPD1 Gln12 HIF1A 582Ser MTHFR rs1801131 C NOS3 rs2070744 T PPARG 12Ala 6つのGWASマーカーは以下の通りです:[21] CREM rs1531550 A, DMD rs939787 T GALNT13 rs10196189 G NFIA-AS1 rs1572312 C, RBFOX1 rs7191721 G TSHR rs7144481 C |

| Ethics of gene doping The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) determined that any non-therapeutic form of genetic manipulation for enhancement of athletic performance is banned under its code. There are guidelines to determine if said technology should be prohibited in sport: if two of the three conditions are met, then the technology is prohibited in sport (harmful to one's health, performance enhancing, and/or against the "spirit of sport").[33] Kayser et al. argue that gene doping could level the playing field if all athletes receive equal access. Critics claim that any therapeutic intervention for non-therapeutic/enhancement purposes compromises the ethical foundations of medicine and sports.[34] The high risks associated with gene therapy can be outweighed by the potential of saving the lives of individuals with diseases: according to Alain Fischer, who was involved in clinical trials of gene therapy in children with severe combined immunodeficiency, "Only people who are dying would have reasonable grounds for using it. Using gene therapy for doping is ethically unacceptable and scientifically stupid."[35] As seen with past cases, including the steroid tetrahydrogestrinone (THG), athletes may choose to incorporate risky genetic technologies into their training regimes.[4] The mainstream perspective is that gene doping is dangerous and unethical, as is any application of a therapeutic intervention for non-therapeutic or enhancing purposes, and that it compromises the ethical foundation of medicine and the spirit of sport.[5][36][37][8][38] Others, who support human enhancement on broader grounds,[39] or who see a false dichotomy between "natural" and "artificial" or a denial of the role of technology in improving athletic performance, do not oppose or support gene doping.[40] |

遺伝子ドーピングの倫理 世界アンチ・ドーピング機関(WADA)は、運動能力の向上のための非治療的な遺伝子操作は、その規範により禁止されていると決定した。当該技術がスポー ツにおいて禁止されるべきかどうかを判断するためのガイドラインがあり、3つの条件のうち2つを満たす場合、その技術はスポーツにおいて禁止される(健康 への害、パフォーマンスの向上、および/または「スポーツの精神」に反する)。[33] Kayser ら は、すべての選手が平等にアクセスできる場合、遺伝子ドーピングは競技の公平性を確保すると主張している。一方、批判者は、治療目的以外の目的(能力向 上)のための治療的介入は、医学とスポーツの倫理的基盤を損なうと主張している。[34] 遺伝子治療に伴う高いリスクは、疾患を持つ人々の命を救う可能性によって上回る。重篤な複合免疫不全症の子供たちを対象とした遺伝子治療の臨床試験に携 わったアラン・フィッシャー氏は、「死の危機にある人だけが、遺伝子治療を受ける合理的な理由がある。ドーピングのために遺伝子治療を利用することは、倫 理的に容認できず、科学的にも愚かな行為だ」と述べている[35]。ステロイドのテトラヒドロゲストリノン(THG)などの過去の事例からもわかるよう に、アスリートは、リスクの高い遺伝子技術をトレーニングプログラムに取り入れることを選択する可能性がある。[4] 主流の見解は、遺伝子ドーピングは、治療目的以外の目的や能力向上目的での治療的介入と同様に危険で非倫理的であり、医学の倫理的基盤とスポーツの精神を 損なうものであるというものである。[5][36][37][8][38] 一方、より広範な理由から人間の能力強化を支持する人々[39]、あるいは「天然」と「人工」の区別は誤った二分法である、あるいは運動能力の向上におけ る技術の役割を否定する人々は、遺伝子ドーピングに反対も支持もしていない[40]。 |

| Doping in sport Human genetic enhancement Stem cell doping |

スポーツにおけるドーピング 人間の遺伝子強化 幹細胞ドーピング |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_doping |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099