ジェノサイド・大量虐殺

genocide

Members

of the Sonderkommando burn corpses of Jews in pits at

Auschwitz II-Birkenau, an extermination camp.

★ジェノサイドあるいは大量虐殺(Genocide)とは、ある民族(通常、民 族、国家、人種、宗教的集団と定義される)の全体または一部を意図的に破壊することである。1944年にラファエ ル・レムキンがギリシャ語のγένος(genos、「人種、人々」)とラテン語の接尾辞-caedo(「殺す行為」)を組み合わせて作った言葉である。

☆政治的不安定タスクフォースは、1956年から2016年の間に43件のジェノサイドが発

生し、約5,000万人が死亡したと推定している。国連難民高等弁務官事務所(UNHCR)は、2008年までにさらに5,000万人がこうした暴力によ

り避難を余儀なくされたと推定している。ジェノサイドは 人類の悪の典型であると広く考えられている。[2]

ジェノサイドは「犯罪の中の犯罪」とも呼ばれる。ジェノサイドの扇動は国際法の下で独立した犯罪とみなされており、ジェノサイドが実際に発生していなくて

も起訴可能な未遂犯罪である。

1948年、国連の「ジェノサイド条約」は、ジェノサイドを「国民、種族、人種、宗教的集団の全部または一部を破壊する意図をもって行われる行為」と定義

した。この5つの行為とは、集団の構成員の殺害、深刻な身体的・精神的危害の加害、集団の破壊を目的とした生活条件の強制、出生の防止、集団からの児童の

強制移動である。被害者は、そのグループの実際のメンバーであるか、またはそう見なされたために標的にされるのであって、無作為に選ばれるわけではない。

| Genocide is the

intentional destruction of a people,[a] either in whole or in part. The Political Instability Task Force estimated that 43 genocides occurred between 1956 and 2016, resulting in about 50 million deaths.[1] The UNHCR estimated that a further 50 million had been displaced by such episodes of violence up to 2008.[1] Genocide is widely considered to be the epitome of human evil.[2] Genocide has been referred to as the "crime of crimes".[3][4][5] Incitement to genocide is recognized as a separate crime under international law and an inchoate crime which does not require genocide to have taken place to be prosecutable.[6] In 1948, the United Nations Genocide Convention defined genocide as any of five "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group". These five acts were: killing members of the group, causing them serious bodily or mental harm, imposing living conditions intended to destroy the group, preventing births, and forcibly transferring children out of the group. Victims are targeted because of their real or perceived membership of a group, not randomly.[7][8] |

ジェノサイドとは、民族(人種、政治的、宗教的、種族的集団など)の全

部または一部を意図的に破壊することである。 政治的不安定タスクフォースは、1956年から2016年の間に43件のジェノサイドが発生し、約5,000万人が死亡したと推定している。[1] 国連難民高等弁務官事務所(UNHCR)は、2008年までにさらに5,000万人がこうした暴力により避難を余儀なくされたと推定している。[1] ジェノサイドは 人類の悪の典型であると広く考えられている。[2] ジェノサイドは「犯罪の中の犯罪」とも呼ばれる。[3][4][5] ジェノサイドの扇動は国際法の下で独立した犯罪とみなされており、ジェノサイドが実際に発生していなくても起訴可能な未遂犯罪である。[6] 1948年、国連の「ジェノサイド条約」は、ジェノサイドを「国民、種族、人種、宗教的集団の全部または一部を破壊する意図をもって行われる行為」と定義 した。この5つの行為とは、集団の構成員の殺害、深刻な身体的・精神的危害の加害、集団の破壊を目的とした生活条件の強制、出生の防止、集団からの児童の 強制移動である。被害者は、そのグループの実際のメンバーであるか、またはそう見なされたために標的にされるのであって、無作為に選ばれるわけではない。 [7][8] |

Etymology Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide in 1944. His analysis of Nazi atrocities inflicted on the Poles were adopted by the UN Genocide Convention as its criteria for determining "genocidal intent"  Aftermath of the 1941 Odessa massacre, in which Jewish deportees were killed outside Brizula (now Podilsk) during the Holocaust  Members of the Sonderkommando burn corpses of Jews in pits at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, an extermination camp. Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide in his 1944 book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe,[9][10] combining the Greek word γένος (genos, "race, people") with the Latin suffix -caedo ("act of killing").[11][12] In Axis Rule, Lemkin documents his research of Nazi occupation policies in Europe, and records a case study of the occupation of Poland. Lemkin asserted that Nazi atrocities against Poles consisted of five policies which exposed their "intent to destroy" the Polish nation. These included i) mass-killings of Poles ii) inflicting "serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group" iii) planned deterioration of living conditions "calculated to bring about their destruction" iv) implementation of various "measures intended to prevent births within the group" such as promotion of abortions, burdening pregnant women, etc. v) forced transfer of Polish children to German families. Each of these five markers, according to Lemkin, revealed the Nazi plan to eliminate the Polish identity with certainty. These five criteria were adopted by the 1948 Genocide Convention (CPPCG) as its proof for the concept of genocidal intent.[13] Before the term was coined, there had been various ways of describing such events. Some languages already had words for such killings, including German (Völkermord, lit. 'murder of a people'), Polish (ludobójstwo, lit. 'killing of a people or nation').[14][15][16][17] and Swedish (folkmord, lit. 'murder of a people').[18] After reading about the 1921 assassination of Talat Pasha, the main architect of the Armenian genocide, by Armenian Soghomon Tehlirian, Lemkin asked his professor why there was no law under which Talat could be charged.[9][19][20] He later explained that "as a lawyer, I thought that a crime should not be punished by the victims, but should be punished by a court."[21] In 1941, when describing the "methodical, merciless butchery" of "scores of thousands" of Russians by Nazi troops during the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Winston Churchill spoke of "a crime without a name".[22] Lemkin's Axis Rule in Occupied Europe describes the implementation of Nazi policies in occupied Europe and mentions earlier mass killings.[23] Lemkin defined genocide as follows: "New conceptions require new terms. By "genocide" we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. This new word, coined by the author to denote an old practice in its modern development, is made from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing), thus corresponding in its formation to such words as tyrannicide, homicide, infanticide, etc. Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group."[11] — Raphael Lemkin, "Axis Rule in Occupied Europe", Chapter IX: Genocide, p. 79 The preamble to the 1948 Genocide Convention notes that instances of genocide have taken place throughout history;[24] it was not until Lemkin coined the term and the prosecution of perpetrators of the Holocaust at the Nuremberg Trials that the United Nations defined the crime of genocide under international law in the Genocide Convention.[23] It was several years before the term was widely adopted by the international community. When the Nuremberg trials revealed the inadequacy of phrases like "Germanization", "crimes against humanity" and "mass murder", scholars of international law reached agreement that Lemkin's work provided a conceptual framework for Nazi crimes. A 1946 headline in The New York Times announced that "Genocide Is the New Name for the Crime Fastened on the Nazi Leaders";[25][26] the word was used in indictments at the Nuremberg trials, held from 1945, but solely as a descriptive term, not yet as a formal legal term.[27] The so-called Polish Genocide Trials of Arthur Greiser and Amon Leopold Goth in 1946 were the first trials in which judgments included the term.[28] |

語源 ラファエル・レムキンが「ジェノサイド」という用語を1944年に造語した。 ナチスがポーランド人に対して行った残虐行為に関する彼の分析は、国連のジェノサイド条約で「ジェノサイドの意図」を判断する基準として採用された  1941年のオデッサ大虐殺の余波。ホロコースト中、ユダヤ人の強制収容者がブリズル(現ポディリスク)郊外で殺害された。  特別行動部隊の隊員が、絶滅収容所アウシュビッツ・ビルケナウの穴でユダヤ人の死体を焼却する。 ポーランド人弁護士ラファエル・レムキンは、1944年の著書『占領下ヨーロッパにおける枢軸国の支配』で「ジェノサイド」という用語を造語した。これ は、ギリシャ語の「γένος(ジェノス、人種、民族)」とラテン語の接尾辞「-caedo(殺害行為)」を組み合わせたものである。レムキンは、ナチス によるポーランド人に対する残虐行為は、ポーランド国民を「根絶やしにする」という意図を露わにした5つの政策から構成されていると主張した。これには、 i) ポーランド人に対する大量殺害、ii) 「集団の構成員に深刻な身体的・精神的な危害を加えること」、iii) 「集団の破壊をもたらすことを目的とした生活条件の計画的な悪化」、iv) 中絶の推奨、妊婦への負担など、さまざまな「集団内での出生を防ぐことを目的とした措置」の実施、v) ポーランド人の子供たちをドイツ人の家庭に強制的に移住させること、などが含まれる。レムキンによると、これら5つの特徴はそれぞれ、ナチスがポーランド 人のアイデンティティを確実に消滅させる計画であることを明らかにしている。この5つの基準は、1948年のジェノサイド条約(CPPCG)で、ジェノサ イドの意図の概念を証明するものとして採用された。 この用語が作られる前にも、このような出来事を表現するさまざまな方法があった。ドイツ語(Völkermord、直訳すると「民族の殺害」)、ポーラン ド語(ludobójstwo、直訳すると「民族または国民の殺害」)[14][15][16][17]、スウェーデン語(folkmord、直訳すると 「民族の殺害」)[18]など、このような大量殺害を表す言葉はすでに存在していた。アルメニア人虐殺の主犯であるタラト・パシャが1921年にアルメニ ア人のソグモン・テクリヤンに暗殺された事件について読んだ後、レムキンは教授に、なぜタラトを起訴できる法律がないのか尋ねた。[9][19][20] 教授は後に「弁護士として、犯罪は被害者によって処罰されるべきではなく、法廷によって処罰されるべきだと考えていた」と説明した。 [21] 1941年、ドイツによるソビエト侵攻の際にナチス軍が「何万もの」ロシア人に対して行った「組織的で容赦ない虐殺」について、ウィンストン・チャーチル は「名もなき犯罪」について語った。[22] レムキンの著書『占領下のヨーロッパにおける枢軸国の支配』は、占領下のヨーロッパにおけるナチスの政策の実施について述べ、それ以前の大規模虐殺につい ても言及している。[23] レムキンは、ジェノサイドを次のように定義した。 「新しい概念には新しい用語が必要である。ジェノサイドとは、民族または国家の集団の絶滅を意味する。この新しい言葉は、著者が古い慣行を現代の発展とし て示すために作った造語であり、古代ギリシャ語のgenos(人種、部族)とラテン語のcide(殺害)から作られており、tyrannicide(暴君 殺し)、homicide(殺人)、infanticide(幼児殺し)などの語の形成と一致している。一般的に、ジェノサイドは必ずしも即座に国民を皆 殺しにすることを意味するわけではない。ただし、国民全員を大量殺害する場合は例外である。むしろ、ジェノサイドは、民族集団の生活の基盤を破壊し、その 集団自体を消滅させることを目的とした、さまざまな行動の組織的な計画を意味するものである。このような計画の目的は、政治的・社会的制度、文化、言語、 国民感情、宗教、そして国民集団の経済的存立基盤の崩壊であり、また、そのような集団に属する個人の安全、自由、健康、尊厳、さらには生命の破壊である。 ジェノサイドは、国民集団という存在に対して行われるものであり、関連する行動は、個々人の能力に対してではなく、国民集団のメンバーとして個人に対して 行われるものである。」[11] —ラファエル・レムキン著『占領下ヨーロッパにおける枢軸国の統治』第9章:ジェノサイド、79ページ 1948年の「ジェノサイド条約」の前文では、歴史上、ジェノサイドの事例が繰り返し発生してきたことが指摘されている。[24] レムキンがこの用語を考案し、ニュルンベルク裁判でホロコーストの加害者の起訴が行われるまで、国連は「ジェノサイド条約」で国際法上のジェノサイド犯罪 を定義することはなかった。[23] この用語が国際社会で広く採用されるようになるまでには、さらに数年を要した。ニュルンベルク裁判で「ドイツ化」、「人道に対する罪」、「大量殺人」と いった表現の不適切さが明らかになると、国際法学者たちは、レムキンの研究がナチスの犯罪に対する概念的枠組みを提供しているという点で合意に達した。 1946年のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の見出しには、「ジェノサイドはナチス指導者たちに押し付けられた犯罪の新しい名称である」と発表された。[25] [26] この言葉は、1945年から開催されたニュルンベルク裁判の起訴状にも使用されたが、 が、それはあくまでも説明的な用語としてであり、まだ正式な法律用語としては用いられていなかった。[27] 1946年のアーサー・グライザーとアモン・レオポルド・ゴートのいわゆるポーランド人大量虐殺裁判は、判決にこの用語が盛り込まれた最初の裁判であっ た。[28] |

| Prohibited acts The Genocide Convention establishes five prohibited acts that, when committed with the requisite intent, amount to genocide. Genocide is not just defined as wide scale massacre-style killings that are visible and well-documented. International law recognizes a broad range of forms of violence in which the crime of genocide can be enacted.[29] Killing members of the group Article II(a) While mass killing is not necessary for genocide to have been committed, it has been present in almost all recognized genocides. In certain instances, men and adolescent boys are singled out for murder in the early stages, such as in the genocide of the Yazidis by Daesh,[30] the Ottoman Turks' attack on the Armenians,[31] and the Burmese security forces' attacks on the Rohingya.[32] Men and boys are typically subject to "fast" killings, such as by gunshot.[33] Women and girls are more likely to die slower deaths by slashing, burning, or as a result of sexual violence.[34] The jurisprudence of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), among others, shows that both the initial executions and those that quickly follow other acts of extreme violence, such as rape and torture, are recognized as falling under the first prohibited act.[35] A less settled discussion is whether deaths that are further removed from the initial acts of violence can be addressed under this provision of the Genocide Convention. Legal scholars have posited, for example, that deaths resulting from other genocidal acts including causing serious bodily or mental harm or the successful deliberate infliction of conditions of life calculated to bring about physical destruction should be considered genocidal killings.[29] Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group Article II(b) This second prohibited act can encompass a wide range of non-fatal genocidal acts.[36] The ICTR and International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) have held that rape and sexual violence may constitute the second prohibited act of genocide by causing both physical and mental harm. In its landmark Akayesu decision, the ICTR held that rapes and sexual violence resulted in "physical and psychological destruction".[37] Sexual violence is a hallmark of genocidal violence, with most genocidal campaigns explicitly or implicitly sanctioning it.[29] It is estimated that 250,000 to 500,000 women were raped in the three months of the Rwandan genocide, many of whom were subjected to multiple rapes or gang rape.[38] In Darfur, a systemic campaign of rape and often sexual mutilation was carried out[39] and in Burma public mass rapes and gang rapes were inflicted on the Rohingya by Burmese security forces.[40] Sexual slavery was documented in the Armenian genocide by the Ottoman Turks and Daesh's genocide of the Yazidi.[41] Torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, when committed with the requisite intent, are also genocide by causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group. The ICTY found that both experiencing a failed execution and watching the murder of one's family members may constitute torture.[42] The Syrian Commission of Inquiry (COI) also found that enslavement, removal of one's children into indoctrination or sexual slavery, and acts of physical and sexual violence rise to the level of torture, as well. While it was subject to some debate, the ICTY and, later, the Syrian COI held that under some circumstances deportation and forcible transfer may also cause serious bodily or mental harm.[43] Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction Article II(c)  As part of the Native American genocide, the U.S. federal government promoted bison hunting for various reasons, including as a way of destroying the means of survival of Plains Indians to pressure them to remain on Indian reservations.[44] The third prohibited act is distinguished from the genocidal act of killing because the deaths are not immediate (or may not even come to pass), but rather create circumstances that do not support prolonged life.[12] Due to the longer period of time before the actual destruction would be achieved, the ICTR held that courts must consider the duration of time the conditions are imposed as an element of the act.[45] In the 19th century the United States federal government supported the extermination of bison, which Native Americans in the Great Plains relied on as a source of food. This was done for various reasons, primarily to pressure them onto reservations during times of conflict. Some genocide experts describe this as an example of genocide that involves removing the means of survival.[44] The ICTR provided guidance into what constitutes a violation of the third act. In Akayesu, it identified "subjecting a group of people to a subsistence diet, systematic expulsion from homes and the reduction of essential medical services below minimum requirement"[46] as rising to genocide. In Kayishema and Ruzindana, it extended the list to include: "lack of proper housing, clothing, hygiene and medical care or excessive work or physical exertion" among the conditions.[45] It further noted that, in addition to deprivation of necessary resources, rape could also fit within this prohibited act.[45] In August 2023, founding chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) Luis Moreno Ocampo published a report presenting evidence that Azerbaijan was committing genocide against the ethnic Armenians of Artsakh Nagorno-Karabakh under Article II(c) of the Genocide Convention by placing their historic land under a comprehensive blockade, cutting all access to food, medical supplies, electricity, gas, internet, and stopping all movement of people to and from Armenia.[47] Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group Article II(d) See also: Compulsory sterilization The fourth prohibited act is aimed at preventing the protected group from regenerating through reproduction. It encompasses acts affecting reproduction and intimate relationships, such as involuntary sterilization, forced abortion, the prohibition of marriage, and long-term separation of men and women intended to prevent procreation.[48] Rape has been found to violate the fourth prohibited act on two bases: where the rape was committed with the intent to impregnate a woman and thereby force her to carry a child of another group (in societies where group identity is determined by patrilineal identity) and where the person raped subsequently refuses to procreate as a result of the trauma.[49] Accordingly, it can take into account both physical and mental measures imposed by the perpetrators. Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group Article II(e) See also: Forced assimilation The final prohibited act is the only prohibited act that does not lead to physical or biological destruction, but rather to destruction of the group as a cultural and social unit.[29] It occurs when children of the protected group are transferred to the perpetrator group. Boys are typically taken into the group by changing their names to those common of the perpetrator group, converting their religion, and using them for labor or as soldiers.[50] Girls who are transferred are not generally converted to the perpetrator group, but instead treated as chattel, as played out in both the Yazidi and Armenian genocides.[29] |

禁止行為 ジェノサイド条約では、必要な意図をもって行われた場合にジェノサイドに該当する5つの禁止行為を定めている。ジェノサイドは、目に見える形で、また詳細 に記録された大規模な虐殺と定義されるだけではない。国際法では、ジェノサイドの犯罪が成立しうる暴力の形態を幅広く認めている。 集団の構成員の殺害 第2条(a) 大量殺害はジェノサイドの実行には必ずしも必要ではないが、ほとんどの認定されたジェノサイドでは存在している。特定の事例では、初期段階において、男性 や思春期の少年が殺害の対象として選別されることもある。例えば、ダーイシュによるヤジディ教徒に対するジェノサイド[30]、オスマン帝国トルコ軍によ るアルメニア人に対する攻撃[31]、ミャンマー治安部隊によるロヒンギャ族に対する攻撃[32]などである。男性や少年は、銃撃などによる「迅速な」殺 害の対象となるのが一般的である。 3] 女性や少女は、切りつけられたり、焼かれたり、性的暴力の結果として、よりゆっくりと死ぬ可能性が高い。[34] ルワンダ国際刑事法廷(ICTR)の判例法では、最初の処刑と、レイプや拷問などの他の極端な暴力行為にすぐに続く処刑の両方が、最初の禁止行為に該当す ると認められている。[35] 初期の暴力行為からさらに離れた時点での死が、このジェノサイド条約の規定に該当するかどうかについては、まだ議論が定まっていない。法学者たちは、例え ば、深刻な身体的または精神的な危害を加えること、あるいは、身体的な破壊をもたらすことを目的とした生活条件を故意に与えることなど、その他のジェノサ イド行為に起因する死は、ジェノサイド殺人としてみなされるべきであると主張している。 集団の構成員に深刻な身体的または精神的な危害を加えること 第2条(b) この2つ目の禁止行為には、致死に至らないジェノサイド行為の幅広い範囲が含まれる可能性がある。[36] ICTRおよび旧ユーゴスラビア国際刑事法廷(ICTY)は、レイプや性的暴力は身体的および精神的な危害をもたらすことで、ジェノサイドの2つ目の禁止 行為に該当しうると判断している。ICTRは画期的な判決である「アカイェス判決」において、レイプや性的暴力は「身体的・心理的な破壊」をもたらすもの であると判断した。[37] 性的暴力はジェノサイドの暴力の特徴であり、ほとんどのジェノサイドキャンペーンでは、明示的または暗示的に性的暴力が容認されている。[29] ルワンダ大虐殺の3か月間に25万~50万人の女性がレイプされたと推定されており、 そのうちの多くが複数回または集団レイプの被害に遭ったと推定されている。[38] ダルフールでは、組織的なレイプと性的な損壊が頻繁に行われ[39]、ビルマではビルマ治安部隊がロヒンギャ族に対して集団レイプや集団強姦を行った。 [40] 性的奴隷制は、オスマン・トルコによるアルメニア人虐殺や、ダーイシュによるヤジディ人虐殺で記録されている。[41] 拷問やその他の残虐な、非人道的な、屈辱的な扱いまたは刑罰は、必要な意図をもって行われた場合、集団の構成員に深刻な身体的または精神的な危害をもたら すことで、ジェノサイドにもなる。ICTYは、処刑の失敗を経験することと、家族の殺害を目撃することが、いずれも拷問に該当しうると判断した。[42] シリア調査委員会(COI)も、奴隷化、子どもを教化または性的奴隷として引き離すこと、および身体的・性的暴力行為も拷問に該当すると判断した。議論の 余地はあるものの、ICTYおよびその後任であるシリアCOIは、特定の状況下では、強制退去や強制移住も深刻な身体的または精神的な危害を引き起こす可 能性があると判断した。 集団に対して、その物理的な破壊をもたらすことを目的とした生活条件を故意に与えること 第2条(c)  アメリカ先住民に対するジェノサイドの一環として、米国連邦政府は、平原インディアンの生存手段を破壊し、インディアン居留地にとどまるよう圧力をかける 手段として、さまざまな理由からバイソン狩りを推進した。 3番目の禁止行為は、殺害というジェノサイド行為とは区別される。なぜなら、死は即時的ではなく(あるいは、死が訪れるとも限らない)、むしろ長期間の生 存を支えない状況を作り出すからである。[12] 実際の破壊が達成されるまでに長い期間がかかるため、ICT 法廷は、その状況が課せられる期間を、その行為の要素として考慮しなければならないと裁定した。[45] 19世紀、米国連邦政府は、グレートプレインズのネイティブアメリカンが食料源として頼っていたバイソンの絶滅を支援した。これは、主に紛争時に彼らを保 留地に強制移住させることを目的とした、さまざまな理由によるものであった。ジェノサイドの専門家の中には、これを生存手段の排除を伴うジェノサイドの例 として挙げている者もいる。[44] ICTRは、第三の行為の違反に該当する行為について指針を示した。アカイェスの事件では、「ある集団に最低限の生活を維持するだけの食糧しか与えず、計 画的に家から追い出し、最低限の医療サービスしか提供しない」[46] ことをジェノサイドに該当すると特定した。KayishemaとRuzindanaの事件では、そのリストに「適切な住居、衣類、衛生、医療ケアの欠如、 または過剰な労働や肉体的な負担」という条件が追加された。[45] さらに、必要な資源の剥奪に加えて、レイプもこの禁止された行為に該当しうると指摘した。[45] 2023年8月、国際刑事裁判所(ICC)の初代主任検察官であるルイス・オカンポは、 は、アルツァフ・ナゴルノカラバフのアルメニア人に対して、彼らの歴史的領土を包括的な封鎖下に置き、食糧、医療品、電気、ガス、インターネットへのアク セスをすべて遮断し、アルメニアとの人の往来をすべて停止したことにより、ジェノサイド条約第2条(c)項に基づき、アゼルバイジャンがジェノサイドを 行っているという証拠を提示する報告書を公表した。[47] 集団内での出生を防止することを目的とした措置の強制 第2条(d) 参照:強制不妊手術 第4の禁止行為は、保護された集団が再生産によって再生することを防ぐことを目的としている。これには、不本意な不妊手術、強制中絶、結婚の禁止、生殖を 防ぐことを目的とした男女の長期的な別居など、生殖や親密な関係に影響を与える行為が含まれる。[48] レイプは、次の2つの理由から第4の禁止行為に違反しているとみなされる。レイプが、 女性を妊娠させ、それによって別の集団の子供を身ごもらせることを目的としてレイプが行われた場合(父系制によって集団のアイデンティティが決定される社 会において)、およびレイプされた人がそのトラウマの結果としてその後生殖を拒否した場合である。[49] したがって、加害者によって課された身体的および精神的な措置の両方を考慮に入れることができる。 集団の子どもを別の集団に強制的に移住させる 第2条(e) 参照:強制同化 最後の禁止行為は、身体的な破壊や生物学的破壊には至らず、むしろ文化や社会の単位としての集団の破壊につながる唯一の禁止行為である。[29] 保護された集団の子どもたちが加害者集団に移住させられる場合に発生する。少年は、加害者集団の一般的な名前に改名させられ、宗教を変えさせられ、労働力 や兵士として使役されることで、集団に組み込まれるのが一般的である。[50] 移送された少女は、一般的に加害者集団に改宗させられることはなく、代わりに、ヤズィーディー教徒とアルメニア人の大量虐殺の両方で演じられたように、家 畜のように扱われる。[29] |

| Crime Pre-criminalization view Before genocide was made a crime against national law, it was considered a sovereign right.[51] When Lemkin asked about a way to punish the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide, a law professor told him: "Consider the case of a farmer who owns a flock of chickens. He kills them and this is his business. If you interfere, you are trespassing."[52] As late as 1959, many world leaders still "believed states had a right to commit genocide against people within their borders", according to political scientist Douglas Irvin-Erickson.[51] International law  Human skulls at the Murambi Genocide Memorial Centre in Rwanda  Armenian genocide victims After the Holocaust, which was perpetrated by Nazi Germany during World War II, Lemkin successfully campaigned for the universal acceptance of international laws defining and forbidding genocides. In 1946, the first session of the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution that affirmed genocide was a crime under international law and enumerated examples of such events (but did not provide a full legal definition of the crime). In 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) which defined the crime of genocide for the first time.[53] Genocide is a denial of the right of existence of entire human groups, as homicide is the denial of the right to live of individual human beings; such denial of the right of existence shocks the conscience of mankind, results in great losses to humanity in the form of cultural and other contributions represented by these human groups, and is contrary to moral law and the spirit and aims of the United Nations. Many instances of such crimes of genocide have occurred when racial, religious, political and other groups have been destroyed, entirely or in part. — UN Resolution 96(1), 11 December 1946 The CPPCG was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948[54] and came into effect on 12 January 1951 (Resolution 260 (III)). It contains an internationally recognized definition of genocide which has been incorporated into the national criminal legislation of many countries and was also adopted by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC). Article II of the Convention defines genocide as: ... any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. The first draft of the convention included political killings; these provisions were removed in a political and diplomatic compromise following objections from many diverse countries, and originally promoted by the World Jewish Congress and Raphael Lemkin's conception, with some scholars popularly emphasizing in literature the role of the Soviet Union,[55] a permanent United Nations Security Council member. The Soviets argued that the convention's definition should follow the etymology of the term,[56][57] and Joseph Stalin in particular may have feared greater international scrutiny of the country's political killings, such as the Great Purge.[58] Lemkin, who coined genocide, approached the Soviet delegation as the resolution vote came close to reassure the Soviets that there was no conspiracy against them; none in the Soviet-led bloc opposed the resolution, which passed unanimously in December 1946.[59] Other nations, including the United States,[60] feared that including political groups in the definition would invite international intervention in domestic politics.[57] By 1951, Lemkin was saying that the Soviet Union was the only state that could be indicted for genocide, his concept of genocide, as outlined in Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, covering Stalinist deportations as genocide by default, and differing in many ways from the adopted Genocide Convention. From a 21st-century perspective, it was such a broad coverage that it would include any grossly human rights violation as genocide, and that many events deemed by Lemkin genocidal did not amount to genocide. As the Cold War began, this change was the result of Lemkin's turn to anti-communism in an attempt to convince the United States to ratify the Genocide Convention.[59] Intent Main article: Genocidal intent Genocidal acts like murder, forcible transfer of children and forced sterilization are crimes themselves. What makes those crimes genocide is that they are committed with what has been called the "special intent".[61] The special intent, in the terminology of genocide, is similar to the common law concept of specific intent. Antonio Cassese described it as "an aggravated criminal intent that must exist in addition to the criminal intent accompanying the underlying offense".[62] Article II of the CPPCG defines the purpose of committing the acts: "to destroy in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such". The specific intent is a core factor distinguishing genocide from other international crimes, such as war crimes or crimes against humanity.[63] There is an unresolved "intend debate" over whether specific intent needs to be proven to convict for genocide, or whether a knowledge-based standard should be enough to convict for genocide.[64] Some scholars argue that a knowledge standard would make it easier to obtain convictions. They have argued that intent is too difficult to prove. Those who hold this view believe that causing mass deaths should be enough without any need for a legal requirement to charge a culpable agent for acting with intent.[65] Some of the existing international tribunal cases like Akayesu and Jelisić have rejected the knowledge standard.[66] The acquittal of Jelisić under the more onerous standard was controversial, and one scholar opined that Nazis would have been allowed to go free under the ICTY's ruling.[67] When Radislav Krstić became the first Serb convicted by the ICTY under the purpose standard, the Krstić court explained that its decision did not rule out a knowledge standard under customary international law.[66] "Intent to destroy" In 2007, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) noted in its judgement on Jorgic v. Germany case that, in 1992, the majority of legal scholars took the narrow view that "intent to destroy" in the CPPCG meant the intended physical-biological destruction of the protected group, and that this was still the majority opinion. But the ECHR also noted that a minority took a broader view, and did not consider biological-physical destruction to be necessary, as the intent to destroy a national, racial, religious or ethnic group as a social unit was enough to qualify as genocide.[68] In the same judgement, the ECHR reviewed the judgements of several international and municipal courts. It noted that the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Court of Justice had agreed with the narrow interpretation (that biological-physical destruction was necessary for an act to qualify as genocide). The ECHR also noted that at the time of its judgement, apart from courts in Germany, that there had been few cases of genocide under other Convention states' municipal laws.[69] In the case of "Onesphore Rwabukombe", the German Federal Court of Justice adhered to its previous judgement, and did not follow the narrow interpretation of the ICTY and the ICJ.[70] "In whole or in part" The phrase "in whole or in part" has been subject to much discussion by scholars of international humanitarian law.[71] In the Ruhashyankiko report of the United Nations it was once argued that the killing of only a single individual could be genocide if the intent to destroy the wider group was found in the murder,[72] yet official court rulings have since contradicted this. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia found in Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Trial Chamber I – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2 August 2001)[73] that Genocide had been committed. In Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Appeals Chamber – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2004) ICTY 7 (19 April 2004)[74] paragraphs 8, 9, 10, and 11 addressed the issue of in part and found that "the part must be a substantial part of that group. The aim of the Genocide Convention is to prevent the intentional destruction of entire human groups, and the part targeted must be significant enough to have an impact on the group as a whole." The Appeals Chamber goes into details of other cases and the opinions of respected commentators on the Genocide Convention to explain how they came to this conclusion. The judges continue in paragraph 12, "The determination of when the targeted part is substantial enough to meet this requirement may involve a number of considerations. The numeric size of the targeted part of the group is the necessary and important starting point, though not in all cases the ending point of the inquiry. The number of individuals targeted should be evaluated not only in absolute terms but also in relation to the overall size of the entire group. In addition to the numeric size of the targeted portion, its prominence within the group can be a useful consideration. If a specific part of the group is emblematic of the overall group or is essential to its survival, that may support a finding that the part qualifies as substantial within the meaning of Article 4 [of the Tribunal's Statute]."[75][76] In paragraph 13 the judges raise the issue of the perpetrators' access to the victims: "The historical examples of genocide also suggest that the area of the perpetrators' activity and control, as well as the possible extent of their reach, should be considered. ... The intent to destroy formed by a perpetrator of genocide will always be limited by the opportunity presented to him. While this factor alone will not indicate whether the targeted group is substantial, it can—in combination with other factors—inform the analysis."[74] "A national, ethnic, racial or religious group" The drafters of the CPPCG chose not to include political or social groups among the protected groups. Instead, they opted to focus on "stable" identities, attributes that are historically understood as being born into and unable or unlikely to change over time. This definition conflicts with modern conceptions of race as a social construct rather than innate fact and the practice of changing religion, etc.[77] International criminal courts have typically applied a mix of objective and subjective markers for determining whether or not a targeted population is a distinct group. Differences in language, physical appearance, religion, and cultural practices are objective criteria that may show that the groups are distinct. However, in circumstances such as the Rwandan genocide, Hutus and Tutsis were often physically indistinguishable.[78] In such a situation where a definitive answer based on objective markers is not clear, courts have turned to the subjective standard that "if a victim was perceived by a perpetrator as belonging to a protected group, the victim could be considered by the Chamber as a member of the protected group".[79] Stigmatization of the group by the perpetrators through legal measures, such as withholding citizenship, requiring the group to be identified, or isolating them from the whole could show that the perpetrators viewed the victims as a protected group. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide The convention came into force as international law on 12 January 1951 after the minimum 20 countries became parties. At that time however, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council were parties to the treaty: France and the Republic of China. William Schabas has suggested that a permanent body as recommended by the Whitaker Report to monitor the implementation of the Genocide Convention, and require states to issue reports on their compliance with the convention (such as were incorporated into the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture), would make the convention more effective.[80] UN Security Council Resolution 1674 UN Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 28 April 2006, "reaffirms the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity".[81] The resolution committed the council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.[82] In 2008 the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1820, which noted that "rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute war crimes, crimes against humanity or a constitutive act with respect to genocide".[83] Municipal law Main article: Genocide under municipal laws Since the Convention came into effect in January 1951 about 80 United Nations member states have passed legislation that incorporates the provisions of CPPCG into their municipal law.[84] |

犯罪 犯罪化以前の見解 ジェノサイドが国内法上の犯罪とされる前は、それは主権者の権利であると考えられていた。[51] レムキンがアルメニア人ジェノサイドの加害者を処罰する方法について尋ねたところ、ある法学教授が次のように答えた。「鶏を飼っている農家のケースを考え てみよう。彼は鶏を殺すが、それは彼の仕事である。もしあなたが口出しすれば、それは不法侵入だ」と述べた。[52] 政治学者のダグラス・アーヴィン・エリクソンによると、1959年になっても、多くの世界の指導者たちは「自国の国境内の人々に対して国家がジェノサイド を行う権利がある」と考えていたという。[51] 国際法  ルワンダのムランビ・ジェノサイド記念館に展示されている人間の頭蓋骨  アルメニア人虐殺の犠牲者 第二次世界大戦中にナチス・ドイツによって行われたホロコーストの後、レムキンはジェノサイドを定義し、これを禁じる国際法の普遍的な受け入れを求める運 動を成功させた。1946年、国連総会第1回会期は、ジェノサイドが国際法上の犯罪であることを確認し、その事例を列挙する決議を採択した(ただし、犯罪 の完全な法的定義は提供されなかった)。1948年には、国連総会が「ジェノサイドの防止及び処罰に関する条約(CPPCG)」を採択し、ジェノサイドの 犯罪を初めて定義した。[53] ジェノサイドとは、人類集団全体の存在権を否定することであり、殺人とは個々の人間の生存権を否定することである。このような存在権の否定は人類の良心を 揺るがすものであり、その集団が代表する文化やその他の貢献という形で人類に大きな損失をもたらすものであり、道徳律や国際連合の精神および目的に反する ものである。このようなジェノサイドの犯罪は、人種、宗教、政治などの集団が完全に、あるいは部分的に壊滅させられた際に数多く発生している。 — 1946年12月11日、国連決議96(1) CPPCGは1948年12月9日に国連総会で採択され[54]、1951年1月12日に発効した(決議260(III))。この条約には、ジェノサイド の国際的に認められた定義が含まれており、多くの国の刑法に盛り込まれている。また、国際刑事裁判所(ICC)を設立した国際刑事裁判所規程にも採用され ている。条約の第2条では、ジェノサイドを次のように定義している。 ... 国民、種族的、人種的もしくは宗教的集団を、その全体または一部を破壊する意図をもって、以下の行為のいずれかを行うこと (a) 集団の構成員を殺害すること (b) 集団の構成員に重大な身体的もしくは精神的な危害を加えること (c) 集団の全体または一部の物理的な破壊をもたらすことを目的とした生活条件を、意図的に集団に課すこと (d) 集団内での出生を防止する措置を課すこと、 (e) 集団内の子供たちを別の集団へ強制的に移住させること。 条約の最初の草案には政治的殺人も含まれていたが、多くの多様な国々からの反対意見を受け、政治的・外交的な妥協によりこれらの条項は削除された。この条 約は当初、世界ユダヤ会議とラファエル・レムキンの構想により推進されたもので、一部の学者は文献で常任理事国であるソビエト連邦の役割を強調している [55]。ソ連は、条約の定義は用語の語源に従うべきだと主張し[56][57]、特にヨシフ・スターリンは、大粛清などの自国の政治的殺人に対する国際 的な監視の目を強めることを恐れていた可能性がある[58]。ジェノサイドという用語を考案したレムキンは、決議案の採決が近づくとソ連代表団に近づき、 ソ連に陰謀はないと安心させるために、決議の採決が近づくとソ連代表団に近づいた。ソ連主導のブロックでは決議に反対する国はなく、1946年12月に満 場一致で可決された。[59] その他の国々、アメリカ合衆国を含む[60]は、定義に政治団体を含めることは内政干渉を招くことを恐れた。[57] 1951年までに、レムキンはソビエト連邦だけがジェノサイドで起訴される可能性がある国家であると主張し、著書『占領下のヨーロッパにおける枢軸国の支 配』で概説したジェノサイドの概念では、スターリン主義による強制退去を既定のジェノサイドとして取り上げ、採択されたジェノサイド条約とは多くの点で異 なっていた。21世紀の視点から見ると、それはあまりにも広範な適用範囲であり、人権侵害のほとんどすべてをジェノサイドに含めることになり、レムキンが ジェノサイドとみなした多くの出来事は、ジェノサイドには当たらない。冷戦が始まったとき、この変化は、レムキンが反共主義に転向し、アメリカ合衆国に ジェノサイド条約を批准させる試みを行った結果であった。[59] 意図 詳細は「ジェノサイドの意図」を参照 殺人、児童の強制移送、強制不妊手術などのジェノサイド行為はそれ自体が犯罪である。これらの犯罪がジェノサイドとなるのは、いわゆる「特別の意図」を もって行われるからである。[61] ジェノサイドの用語における「特別の意図」は、英米法の「特定の意図」の概念に類似している。アントニオ・カッセーゼはこれを「基本となる犯罪に伴う犯罪 意思に加えて存在しなければならない、悪質な犯罪意思」と表現している。[62] CPPCGの第2条は、行為の目的を次のように定義している。「国民、民族、人種、宗教的集団を、その全体または一部を破壊する」 特定の意図は、戦争犯罪や人道に対する罪などの他の国際犯罪とジェノサイドを区別する中核的な要因である。[63] ジェノサイドの有罪判決には特定の意図を証明する必要があるのか、あるいは、ジェノサイドの有罪判決には認識に基づく基準で十分であるのかについて、未解 決の「意図の議論」がある。[64] 一部の学者は、認識基準の方が有罪判決を得やすくなると主張している。彼らは、意図を証明するのはあまりにも難しいと主張している。この見解を持つ人々 は、意図を持って行動した責任者を起訴するという法的要件を必要とすることなく、大量殺害を引き起こすだけで十分であると信じている。[65] アカイエスやジェリシッチのような既存の国際法廷の判例のいくつかは、認識基準を否定している。[66] より厳しい基準の下でのジェリシッチの無罪判決は物議を醸し、ある学者は、 。ラディスラフ・クルスティッチが「目的」基準によりICTYで有罪判決を受けた最初のセルビア人となった際、クルスティッチ裁判では、その判決は慣習国 際法における「認識」基準を排除するものではないと説明された。 「破壊する意図」 2007年、欧州人権裁判所(ECHR)は、Jorgic対ドイツの判決において、1992年には大半の法律学者が、保護集団に対する「破壊する意図」と は、物理的・生物学的な意図的な集団絶滅を意味するとの狭義の見解をとっており、現在でもそれが多数意見であると指摘した。しかし、ECHRは少数派がよ り広義の解釈を採り、社会単位としての国民、人種、宗教、民族集団を破壊する意図があれば、生物学的・物理的破壊は必要ないとみなしていることも指摘して いる。 同じ判決において、ECHRはいくつかの国際法廷および国内法廷の判決を再検討した。ECHRは、旧ユーゴスラビア国際刑事法廷および国際司法裁判所が狭 義の解釈(ジェノサイドと見なされる行為には生物学的・物理的破壊が必要であるという解釈)に同意していることを指摘した。ECHRはまた、判決を下した 時点では、ドイツの裁判所を除いて、他の条約加盟国の国内法の下ではジェノサイドの事例はほとんどなかったことも指摘している。[69] 「Onesphore Rwabukombe」事件では、ドイツ連邦裁判所は以前の判決を支持し、ICTYとICJの狭義の解釈に従わなかった。[70] 「全体的または部分的」 「全体的または部分的」という表現は、国際人道法の学者たちによって多くの議論の対象となってきた。[71] かつて国連のルハシャンブキ報告書では、より広範な集団の破壊の意図が殺人行為に見られる場合、たった一人の殺害であってもジェノサイドになり得ると主張 されたことがあったが、[72] それ以降、公式な法廷判決ではこの主張は否定されている。旧ユーゴスラビア国際刑事法廷は、検察官対ラディスラフ・クルスティッチ事件 - 第1審裁判部 - 判決 - IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2001年8月8日)[73]において、ジェノサイドが実行されたと認定した。検察官対ラディスラフ・クルスティッチ事件 - 上訴裁判所 - 判決 - IT-98-33 (2004) ICTY 7 (19 April 2004)[74] の第8、9、10、11項では、この問題の一部を取り上げ、「その部分は、その集団の相当な部分でなければならない。ジェノサイド条約の目的は、人類集団 全体の意図的な破壊を防止することであり、標的とされる部分は、集団全体に影響を及ぼすのに十分な重要性を持っていなければならない。」 上訴裁判所は、他の事例やジェノサイド条約に関する著名な論者の意見を詳細に検討し、この結論に至った理由を説明している。 裁判官は第12項で次のように述べている。「この要件を満たすのに十分な規模の標的集団がいつ決定されるかについては、いくつかの考慮事項が関わってくる 可能性がある。標的集団の規模は、調査の開始点として必要かつ重要な要素であるが、必ずしも調査の終了点であるとは限らない。標的とされた個人の数は、絶 対的な観点だけでなく、集団全体の規模との関連でも評価されるべきである。対象部分の数値上の規模に加え、グループ内でのその突出性も有益な考慮事項とな り得る。グループの特定の部分がグループ全体を象徴するものである場合、またはその存続に不可欠である場合、その部分が条約第4条の「実質的」な要件を満 たすという判断を裏付ける根拠となり得る。」[75][76] 第13項において、裁判官らは加害者による被害者へのアクセスという問題を提起している。「ジェノサイドの歴史上の例は、加害者の活動および支配地域、お よび加害者の到達可能範囲も考慮すべきであることを示唆している。... ジェノサイドの加害者が抱く破壊の意図は、常にその加害者に与えられた機会によって制限される。この要因だけでは対象集団が実質的であるかどうかを示すも のではないが、他の要因と組み合わせることで分析に役立つ可能性がある」[74] 「国民、民族、人種、宗教的集団」 CPPCGの起草者は、保護される集団に政治的または社会的集団を含めることを選択しなかった。その代わり、彼らは「安定した」アイデンティティ、つまり 歴史的に生まれながらのものであり、時間とともに変化することができない、または変化する可能性が低いと理解されている属性に焦点を当てることを選択し た。この定義は、人種が先天的な事実ではなく社会構築物であるという現代的な概念や、宗教を変えることなどと矛盾している。 国際刑事裁判所は、標的とされた集団が明確な集団であるかどうかを判断する際に、客観的および主観的な基準を組み合わせて適用するのが一般的である。言 語、外見、宗教、文化慣習の違いは、集団が明確であることを示す客観的な基準となり得る。しかし、ルワンダ大虐殺のような状況では、フツ族とツチ族は外見 上区別できないことが多かった。 客観的基準に基づく明確な答えが得られないこのような状況では、裁判所は「加害者によって保護されるべき集団に属すると認識された被害者は、法廷によって 保護されるべき集団の構成員とみなされる」という主観的基準に頼るようになった 加害者による法的措置を通じて集団に汚名を着せる行為、例えば、市民権の剥奪、集団の特定の要求、集団の全体からの隔離などは、加害者が被害者を保護され るべき集団と見なしていることを示す可能性がある。 ジェノサイドの防止および処罰に関する条約 この条約は、最低20カ国が締約国となった後、1951年1月12日に国際法として発効した。しかし、この時点では、国連安全保障理事会の常任理事国5カ 国のうち条約締約国となっていたのはフランスと中華民国の2カ国のみであった。ウィリアム・シャバスは、ジェノサイド条約の履行を監視し、条約遵守に関す る報告書の提出を各国に義務付ける常設機関(拷問禁止条約の選択議定書に盛り込まれたような機関)を設置することが、条約の実効性を高めるだろうと提案し ている。[80] 国連安全保障理事会決議1674 2006年4月28日に国連安全保障理事会が採択した国連安全保障理事会決議1674は、「ジェノサイド、戦争犯罪、民族浄化、人道に対する罪から住民を 保護する責任に関する2005年の世界サミット成果文書の第138項および第139項の規定を再確認する」ものである 。[81] この決議は、武力紛争下における民間人の保護を目的とした行動を安全保障理事会に義務づけた。[82] 2008年、国連安全保障理事会は決議1820を採択し、「レイプやその他の形態の性的暴力は、戦争犯罪、人道に対する罪、あるいはジェノサイドの構成要 件となる可能性がある」と指摘した。[83] 地方自治体法 詳細は「地方自治体法におけるジェノサイド」を参照 1951年1月に条約が発効して以来、約80の国連加盟国が、CPPCGの規定を地方自治体法に組み込む法律を制定している。[84] |

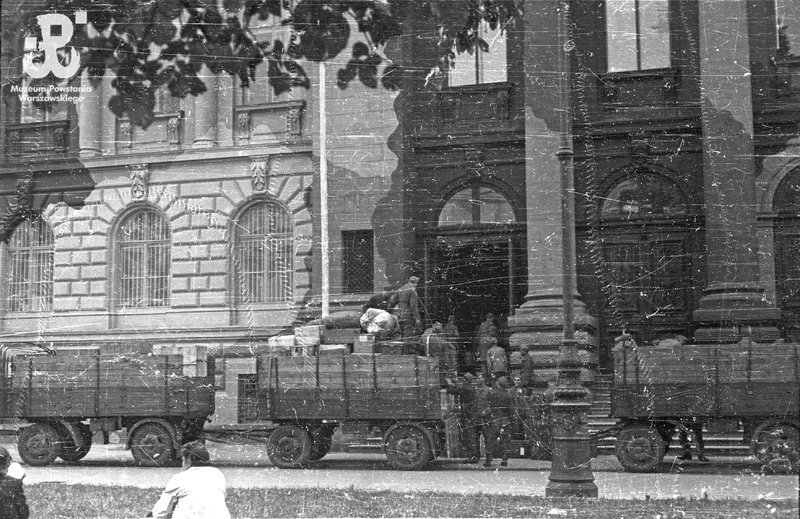

| Other definitions of genocide See also: Genocide definitions Writing in 1998, Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Björnson stated that the CPPCG was a legal instrument resulting from a diplomatic compromise. As such the wording of the treaty is not intended to be a definition suitable as a research tool, and although it is used for this purpose, as it has international legal credibility that others lack, other genocide definitions have also been proposed. They go on to say that none of these alternative definitions have gained widespread support,[85] they postulate that the major reason why no generally accepted genocide definition has emerged is because academics have adjusted their focus to emphasise different periods and have found it expedient to use slightly different definitions. For example, Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn studied all human history, while Leo Kuper and Rudolph Rummel concentrated on the 20th century, and Helen Fein, Barbara Harff, and Ted Gurr looked at post-World War II events.[85] This has been supported by later scholars.[86][87][88] Rouben Paul Adalian writing in 2002 also highlights the difficulty there has been in trying to develop a common definition for genocide among specialists.[89] Yehuda Bauer, has argued that the present definition is problematic, contending that many of what are usually called genocides were not racially motivated. Bauer gave the Rwandan Genocide, where, Bauer argued, both the perpetrators and victims were of the same ethnicity, as an example. He argued that, because of this discrepancy, "clearly, the existing definition of genocide is inadequate and needs to be altered."[90] Cultural genocide and ethnocide This section is an excerpt from Cultural genocide.[edit]  Looting of Polish artwork at the Zachęta building by German forces during the Occupation of Poland, 1944 Cultural genocide or culturicide is a concept described by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944, in the same book that coined the term genocide.[91] The destruction of culture was a central component in Lemkin's formulation of genocide.[91] Though the precise definition of cultural genocide remains contested, the United Nations makes it clear that genocide is "the intent to destroy a national, ethnic, racial or religious group... it does not include political groups or so called 'cultural genocide'" and that "Cultural destruction does not suffice, nor does an intention to simply disperse a group" thus this is what "makes the crime of genocide so unique".[92] While the Armenian Genocide Museum defines culturicide as "acts and measures undertaken to destroy nations' or ethnic groups' culture through spiritual, national, and cultural destruction",[93] which appears to be essentially the same as ethnocide. Some ethnologists, such as Robert Jaulin, use the term ethnocide as a substitute for cultural genocide,[94] although this usage has been criticized as risking the confusion between ethnicity and culture.[95] Cultural genocide and ethnocide have in the past been utilized in distinct contexts.[96] Cultural genocide without ethnocide is concievable when a distinct ethnic identity is kept, but distinct cultural elements are eliminated.[97] Culturicide involves the eradication and destruction of cultural artifacts, such as books, artworks, and structures.[98] The issue is addressed in multiple international treaties, including the Geneva Conventions and the Rome Statute, which define war crimes associated with the destruction of culture. Cultural genocide may also involve forced assimilation, as well as the suppression of a language or cultural activities that do not conform to the destroyer's notion of what is appropriate.[98] Among many other potential reasons, cultural genocide may be committed for religious motives (e.g., iconoclasm which is based on aniconism); as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing in an attempt to remove the evidence of a people from a specific locale or history; as part of an effort to implement a Year Zero, in which the past and its associated culture is deleted and history is "reset". The drafters of the 1948 Genocide Convention initially considered using the term, but later dropped it from inclusion.[99][100][101] The term "cultural genocide" has been considered in various draft United Nations declarations, but it is not used by the UN Genocide Convention.[94] Political and social groups The exclusion of social and political groups as targets of genocide in the CPPCG legal definition has been criticized by some historians and sociologists, for example, M. Hassan Kakar in his book The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982[102] argues that the international definition of genocide is too restricted,[103] and that it should include political groups or any group so defined by the perpetrator and quotes Chalk and Jonassohn: "Genocide is a form of one-sided mass killing in which a state or other authority intends to destroy a group, as that group and membership in it are defined by the perpetrator."[104] In turn some states such as Ethiopia,[105] France,[106] and Spain[107][108] include political groups as legitimate genocide victims in their anti-genocide laws. Some academics such as Norman Naimark and Anton Weiss-Wendt argue that the exclusion of political and social groups in the final 1948 version of the Genocide Convention was a consequence of Soviet lobbying. Though social and political groups were mentioned in initial drafts of the convention, the Soviet Union would not agree to become a signatory, unless they were omitted.[109][110] The United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect states that the definition of genocide reached in the convention was the "result of a negotiating process and reflects the compromise reached among United Nations Member States."[111] Harff and Gurr defined genocide as "the promotion and execution of policies by a state or its agents which result in the deaths of a substantial portion of a group ... [when] the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality".[112] Harff and Gurr also differentiate between genocides and politicides by the characteristics by which members of a group are identified by the state. In genocides, the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality. In politicides the victim groups are defined primarily in terms of their hierarchical position or political opposition to the regime and dominant groups.[113] Daniel D. Polsby and Don B. Kates Jr. state that "we follow Harff's distinction between genocides and 'pogroms', which she describes as 'short-lived outbursts by mobs, which, although often condoned by authorities, rarely persist'. If the violence persists for long enough, however, Harff argues, the distinction between condonation and complicity collapses."[114][115] According to Rudolph Rummel, genocide has three different meanings. The ordinary meaning is murder by the government of people due to their national, ethnic, racial, or religious group membership. The legal meaning of genocide refers to the international treaty, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG). This also includes non-killings that in the end eliminate the group, such as preventing births or forcibly transferring children out of the group to another group. A generalized meaning of genocide is similar to the ordinary meaning but also includes government killings of political opponents or otherwise intentional murder. It is to avoid confusion regarding what meaning is intended that Rummel created the term democide to distinguish from this third meaning.[116] Highlighting the potential for state and non-state actors to commit genocide in the 21st century, for example, in failed states or as non-state actors acquiring weapons of mass destruction, Adrian Gallagher defined genocide as 'When a source of collective power (usually a state) intentionally uses its power base to implement a process of destruction in order to destroy a group (as defined by the perpetrator), in whole or in substantial part, dependent upon relative group size'.[117] The definition upholds the centrality of intent, the multidimensional understanding of destroying, broadens the definition of group identity beyond that of the 1948 definition yet argues that a substantial part of a group has to be destroyed before it can be classified as genocide. Other proposed definitions of genocide include social groups defined by gender, sexual orientation,[118] or gender identity.[119][120] Democide Democide, a term devised by American political scientist Rudolph Rummel, describes "the intentional killing of an unarmed or disarmed person by government agents acting in their authoritative capacity and pursuant to government policy or high command."[121][122][123] This definition covers any murder of any number of persons by any government,[121][122] including government mandated forced labor, concentration camps, extrajudicial summary killings, civil wars, and mass deaths due to government neglect such as government induced famines like Holodomor.[121][122] Rummel estimates that in the 20th century, democide resulted in over 262 million deaths.[124] Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer agreed with Rummel that democide was a more appropriate term in more cases to describe mass atrocities than genocide due to the more inclusive definition of democide versus genocide.[125] Mass Categorical Violence Others argue that the term "genocide" cannot be used for all instances of mass killings, instead being restricted to a select few cases, with the Holocaust being first and foremost.[126] Another proposition is by political scientist Scott Straus, who puts forward "Mass Categorical Violence", or MCV, in which case the term "genocide" would be its extreme subcategory, which would include examples such as the Holodomor, Armenian Genocide, and the Holocaust, with the pinnacle of the genocide subcategory being the "intended total liquidation of a specific population", in which the Holocaust would rank as the "peak of the MCV class and of its genocide subcategory", but at the same time would constitute a category of its own due to its "extraordinary absolute features".[127] Transgender genocide Main article: Transgender genocide In 2013 some international trans activists introduced the term 'transcide' to describe the elevated level of killings of trans people globally. A coalition of NGOs from South America and Europe started the "Stop Trans Genocide" campaign.[128][129] The term "trancide" follows an earlier term, gendercide.[130] Legal scholars have argued that the definition of genocide should be expanded to cover transgender people, because they are victims of institutional discrimination, persecution, and violence.[131][132][133] Brian Kritz argued that existing law should be extended to protect transgender people.[133] Similar arguments have been made regarding extending the legal definition of "crimes against humanity."[134][135] Aside from legal studies, transgender genocide has been examined by scholars of queer studies, hate studies, and other fields.[136] |

ジェノサイドのその他の定義 参照:ジェノサイドの定義 1998年の論文で、クルト・ヨナソンとカリン・ビョルンソンは、CPPCGは外交上の妥協から生まれた法的手段であると述べている。そのため、条約の文 言は研究手段として適切な定義となることを意図したものではなく、この目的で使用されているものの、他の定義にはない国際的な法的信頼性があるため、他の ジェノサイドの定義も提案されている。彼らはさらに、これらの代替的な定義はどれも広く支持を得ていないと述べている。[85] 広く受け入れられるジェノサイドの定義が確立されていない主な理由は、学者たちが研究対象を特定の時代に絞り、若干異なる定義を使用することが得策である と判断しているためであると彼らは推測している。例えば、フランク・チョークとクルト・ヨナソンは全人類の歴史を研究し、レオ・クーパーとルドルフ・ラン メルは20世紀に焦点を絞り、ヘレン・ファイン、バーバラ・ハルフ、テッド・ガールは第二次世界大戦後の出来事を調査した。 85] このことは、後の学者たちによっても支持されている。[86][87][88] 2002年に執筆したルーベン・ポール・アダリアンも、専門家たちがジェノサイドの共通定義を策定しようとしてきたことの難しさを強調している。[89] イェフーダ・バウアーは、現在の定義には問題があると主張し、通常ジェノサイドと呼ばれるものの多くは人種的動機によるものではないと論じている。バウ アーは、加害者と被害者が同じ民族であったルワンダ大虐殺を例として挙げた。彼は、この矛盾があるため、「明らかに、ジェノサイドの現行の定義は不適切で あり、変更する必要がある」と主張した。 文化大虐殺と民族大虐殺 この節は「文化大虐殺」からの抜粋である。  1944年、ポーランド占領中のドイツ軍によるザチェタ美術館のポーランド美術品の略奪 文化大虐殺または文化殺戮は、1944年にポーランド人弁護士ラファエル・レムキンが、同じく「ジェノサイド」という用語を造語した書籍の中で説明した概 念である。[91] レムキンによるジェノサイドの定義では、文化の破壊が中心的な要素であった。[91] 文化大虐殺の正確な定義については議論が続いているが、国連はジェノサイドを「国民、民族、人種、宗教的集団を破壊する意図... 政治集団やいわゆる『文化大虐殺』は含まれない」と明確に定義している。政治集団やいわゆる『文化大虐殺』は含まれない」とし、「文化の破壊だけでは十分 ではなく、単に集団を散り散りにする意図だけでは十分ではない」ため、これが「ジェノサイドという犯罪を非常に独特なものにしている」と述べている。 [92] アルメニア人虐殺博物館は、文化大虐殺を「精神、国民、文化の破壊を通じて、国民や民族集団の文化を破壊する行為や手段」と定義しているが、[93] これは本質的には民族大虐殺と同じであるように見える。ロバート・ジョラン(Robert Jaulin)などの民族学者は、文化大虐殺の代わりに民族大虐殺という用語を使用しているが[94]、この用法は民族と文化の混同を招く恐れがあるとし て批判されている[95]。文化大虐殺と民族大虐殺は、過去には異なる文脈で使用されてきた。[96] 民族大虐殺を伴わない文化大虐殺は、明確な民族アイデンティティが維持されているが、明確な文化要素が排除されている場合に考えられる。[97] 文化抹殺は、書籍、芸術作品、建造物などの文化財の根絶と破壊を伴う。この問題は、文化の破壊に関連する戦争犯罪を定義するジュネーヴ条約やローマ規程を 含む複数の国際条約で取り上げられている。文化大虐殺には、強制同化や、破壊者の考える「ふさわしい」ものではない言語や文化活動の弾圧も含まれる可能性 がある。 無神論に基づく偶像破壊など)や、民族浄化キャンペーンの一環として、特定の地域や歴史から民族の痕跡を消し去るため、あるいはゼロ年計画の一環として、 過去や関連文化を消し去り、歴史を「リセット」するために実行されることもある。1948年のジェノサイド条約の起草者たちは当初、この用語の使用を検討 したが、後に採用を見送った。[99][100][101] 「文化大虐殺」という用語は、国連のさまざまな宣言草案で検討されてきたが、国連のジェノサイド条約では使用されていない。[94] 政治的・社会的グループ CPPCGの法的定義では、ジェノサイドの対象から社会的・政治的グループが除外されていることに対して、一部の歴史家や社会学者から批判が寄せられてい る。例えば、M. ハッサン・カカーは著書『ソ連の侵攻とアフガニスタンの対応、1979年~1982年』で、ジェノサイドの国際的な定義は限定的すぎると主張し [103]、政治グループや加害者によってそう定義されたグループを含めるべきだとし、 「ジェノサイドとは、国家またはその他の当局が、加害者によって定義された集団とその構成員を根絶する意図をもって、一方的に大規模な殺戮を行うことであ る」と述べている。[104] 一方、エチオピア[105]、フランス[106]、スペイン[107][108]などの国々は、反ジェノサイド法において、政治集団をジェノサイドの正当 な被害者として含めている。 ノーマン・ナイマークやアントン・ヴァイスヴェントなどの学者は、1948年のジェノサイド条約最終版で政治・社会集団が除外されたのは、ソビエト連邦の ロビー活動の結果であると主張している。社会集団や政治集団は条約の草案の初期段階では言及されていたが、ソ連はそれらが除外されない限り、署名すること に同意しなかった。[109][110] 国連のジェノサイド防止・保護責任局は、条約で定義されたジェノサイドの定義は「交渉の成果であり、国連加盟国間で合意された妥協案を反映したもの」であ ると述べている。[111] ハルフとガールは、ジェノサイドを「国家またはその代理人による政策の推進と実行により、集団の相当部分の死がもたらされること」と定義している。 [112] ハルフとガールはまた、国家によって集団の構成員が識別される特性によって、ジェノサイドとポリティサイドを区別している。ジェノサイドでは、被害者グ ループは主に共同体の特性、すなわち民族、宗教、国民性によって定義される。政治的虐殺では、犠牲者グループは、主にその階層的位置づけや、体制および支 配的グループに対する政治的反対の観点から定義される。[113] ダニエル・D・ポルスビーとドン・B・ケイツ・ジュニアは、「我々は、ハルフによるジェノサイドと『ポグロム』の区別に従う。彼女はポグロムを『当局に よって黙認されることが多いが、長続きすることはまれな、暴徒による短命な暴動』と説明している。しかし、暴力が長期間にわたって継続する場合には、容認 と加担の区別は崩壊する、とハルフは主張している。」[114][115] ルドルフ・ランメルによると、ジェノサイドには3つの異なる意味がある。一般的な意味は、国民、民族、人種、宗教などの集団に属する人々を政府が殺害する ことである。法的な意味でのジェノサイドは、国際条約である「ジェノサイドの防止及び処罰に関する条約(CPPCG)」を参照する。これには、出生を妨げ たり、集団から別の集団に子供を強制的に移住させたりするなど、最終的に集団を排除する非殺人も含まれる。ジェノサイドの一般的な意味は、通常の意味と類 似しているが、政治的反対派に対する政府による殺害や、その他の意図的な殺人行為も含む。 ルメルは、この3番目の意味を区別するために「デモサイド」という用語を創出した。 21世紀における国家および非国家主体によるジェノサイドの潜在的可能性を強調し、例えば、国家が崩壊した場合や、非国家主体が大量破壊兵器を入手した場 合など、ジェノサイドの定義を「集団的権力(通常は国家)が、集団(加害者によって定義された)を、その集団の規模に依存する全体または大部分を破壊する ために、意図的にその権力を用いて破壊のプロセスを実施すること」と定義したのが、エイドリアン・ギャラガーである。加害者によって定義された)集団の全 体または実質的な部分を、相対的な集団の規模に応じて破壊する』と定義した。[117] この定義は、意図の重要性を維持し、破壊の多面的な理解を提示し、1948年の定義を越えて集団のアイデンティティの定義を拡大している。しかし、集団の 大部分が破壊されて初めてジェノサイドと分類されると主張している。ジェノサイドの他の定義案には、性別、性的指向、[118][119][120] または性自認によって定義される社会集団が含まれる。 デモサイド デモサイド(Democide)とは、アメリカの政治学者ルドルフ・ランメルが考案した用語で、「政府当局者がその権限に基づき、政府の方針や最高司令部 の命令に従って、非武装または武装解除された人物を意図的に殺害すること」を指す。[121][122][123] この定義は、政府による殺人すべてをカバーしており、政府による強制労働、強制収容所、法外な即決処刑、内戦、 ホロドモールのような政府による飢饉など、政府の怠慢による大量死も含まれる。[121][122] ルンメルは、20世紀において、デモサイドが2億6200万人以上の死者を出したと推定している。[124] ホロコーストの歴史家であるイェフーダ・バウアーは、デモサイドの定義がジェノサイドよりも包括的であるため、大量虐殺を説明する場合には、ジェノサイド よりもデモサイドの方がより適切な用語であるというルンメルの意見に同意している。[125] 大量のカテゴリー的暴力 また、大量殺戮のすべての事例に「ジェノサイド」という用語を使用することはできず、その代わりに、ホロコーストを筆頭に、ごく一部の事例に限定されるべ きであるという意見もある。[126] 政治学者スコット・ストラウスは、「大量のカテゴリー的暴力」(Mass Categorical Violence、MCV)という概念を提唱している。この場合、「ジェノサイド」はその極端な下位カテゴリーとなり、 ホロドモール、アルメニア人虐殺、ホロコーストなどが含まれる。ジェノサイドのサブカテゴリーの頂点にあるのは「特定の集団の意図的な完全な消滅」であ り、ホロコーストは「MCVクラスおよびジェノサイドのサブカテゴリーの頂点」に位置づけられるが、同時に「並外れた絶対的な特徴」により独自のカテゴ リーを構成することになる。[127] トランスジェンダー大量虐殺 詳細は「トランスジェンダー大量虐殺」を参照 2013年、一部の国際的なトランスジェンダー活動家が、世界的にトランスジェンダーの人々に対する殺害のレベルが高まっていることを表現するために、 「トランサイド(trancide)」という用語を導入した。南アメリカとヨーロッパのNGO連合は「トランスジェンダー大量虐殺を止めよう」キャンペー ンを開始した。[128][129] 「トランスサイド」という用語は、以前の「ジェンダーサイド」という用語に続くものである。[130] 法学者たちは、トランスジェンダーの人々も制度的な差別、迫害、暴力の被害者であるため、ジェノサイドの定義を拡大してトランスジェンダーの人々も対象と すべきだと主張している。[131][ 132][133] ブライアン・クリッツは、既存の法律を拡大してトランスジェンダーの人々を保護すべきだと主張している。[133] 同様の議論は、「人道に対する罪」の法的定義の拡大についてもなされている。[134][135] 法学研究とは別に、トランスジェンダー大量虐殺は、クィア研究やヘイト研究などの分野の研究者によっても研究されている。[136] |

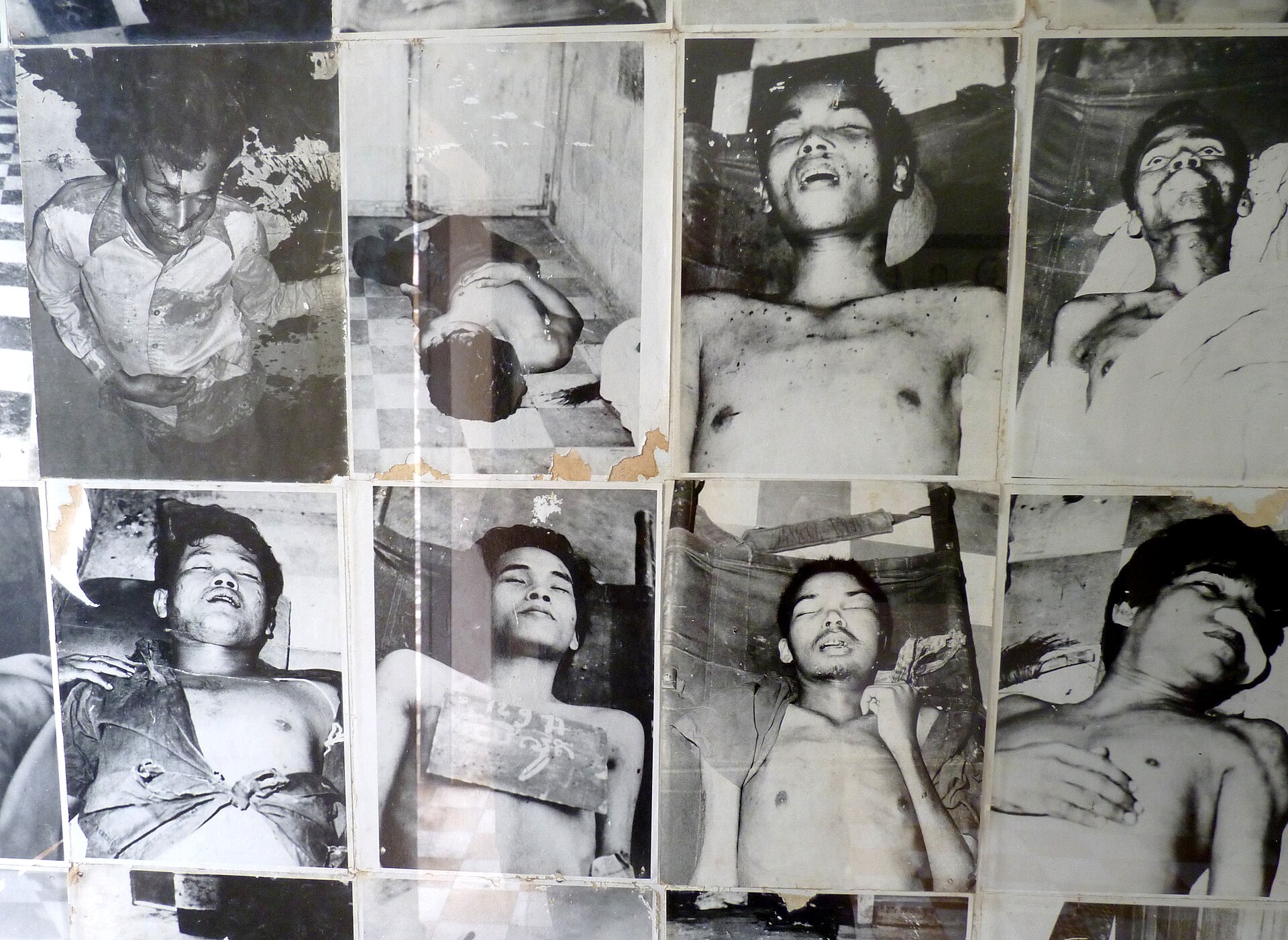

| International prosecution By ad hoc tribunals  Nuon Chea, the Khmer Rouge's chief ideologist, before the Cambodian Genocide Tribunal on 5 December 2011 All signatories to the CPPCG are required to prevent and punish acts of genocide, both in peace and wartime, though some barriers make this enforcement difficult. In particular, some of the signatories—namely, Bahrain, Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, the United States, Vietnam, Yemen, and former Yugoslavia—signed with the proviso that no claim of genocide could be brought against them at the International Court of Justice without their consent.[137] Despite official protests from other signatories (notably Cyprus and Norway) on the ethics and legal standing of these reservations, the immunity from prosecution they grant has been invoked from time to time, as when the United States refused to allow a charge of genocide brought against it by former Yugoslavia following the 1999 Kosovo War.[138] It is commonly accepted that, at least since World War II, genocide has been illegal under customary international law as a peremptory norm, as well as under conventional international law. Acts of genocide are generally difficult to establish for prosecution because a chain of accountability must be established. International criminal courts and tribunals function primarily when the states involved are incapable or unwilling to prosecute crimes of this magnitude themselves.[139] Nuremberg Tribunal (1945–1946) Main article: Nuremberg trials  The Nazi leaders at the Palace of Justice, Nuremberg The Nazi leaders who were prosecuted shortly after World War II for taking part in the Holocaust, and other mass murders, were charged under existing international laws, such as crimes against humanity, as the crime of "genocide' was not formally defined until the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG). Nevertheless, the recently coined term[140] appeared in the indictment of the Nazi leaders, Count 3, which stated that those charged had "conducted deliberate and systematic genocide—namely, the extermination of racial and national groups—against the civilian populations of certain occupied territories in order to destroy particular races and classes of people, and national, racial or religious groups, particularly Jews, Poles, Gypsies and others."[141] International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993–2017) See also: Bosnian genocide and List of Bosnian genocide prosecutions  The cemetery at the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial and Cemetery to Genocide Victims The term Bosnian genocide is used to refer either to the killings committed by Serb forces in Srebrenica in 1995,[142] or to ethnic cleansing that took place elsewhere during the 1992–1995 Bosnian War.[143] In 2001, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) judged that the 1995 Srebrenica massacre was an act of genocide.[144] On 26 February 2007, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in the Bosnian Genocide Case, upheld the ICTY's earlier finding that the massacre in Srebrenica and Zepa constituted genocide, but found that the Serbian government had not participated in a wider genocide on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war, as the Bosnian government had claimed.[145] On 12 July 2007, European Court of Human Rights when dismissing the appeal by Nikola Jorgić against his conviction for genocide by a German court (Jorgic v. Germany) noted that the German courts wider interpretation of genocide has since been rejected by international courts considering similar cases.[146][147][148] The ECHR also noted that in the 21st century "Amongst scholars, the majority have taken the view that ethnic cleansing, in the way in which it was carried out by the Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to expel Muslims and Croats from their homes, did not constitute genocide. However, there are also a considerable number of scholars who have suggested that these acts did amount to genocide, and the ICTY has found in the Momcilo Krajisnik case that the actus reus of genocide was met in Prijedor "With regard to the charge of genocide, the Chamber found that in spite of evidence of acts perpetrated in the municipalities which constituted the actus reus of genocide".[149] About 30 people have been indicted for participating in genocide or complicity in genocide during the early 1990s in Bosnia. To date, after several plea bargains and some convictions that were successfully challenged on appeal two men, Vujadin Popović and Ljubiša Beara, have been found guilty of committing genocide, Zdravko Tolimir has been found guilty of committing genocide and conspiracy to commit genocide, and two others, Radislav Krstić and Drago Nikolić, have been found guilty of aiding and abetting genocide. Three others have been found guilty of participating in genocides in Bosnia by German courts, one of whom Nikola Jorgić lost an appeal against his conviction in the European Court of Human Rights. A further eight men, former members of the Bosnian Serb security forces were found guilty of genocide by the State Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (See List of Bosnian genocide prosecutions). Slobodan Milošević, as the former President of Serbia and of Yugoslavia, was the most senior political figure to stand trial at the ICTY. He died on 11 March 2006 during his trial where he was accused of genocide or complicity in genocide in territories within Bosnia and Herzegovina, so no verdict was returned. In 1995, the ICTY issued a warrant for the arrest of Bosnian Serbs Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić on several charges including genocide. On 21 July 2008, Karadžić was arrested in Belgrade, and later tried in The Hague accused of genocide among other crimes.[150] On 24 March 2016, Karadžić was found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica, war crimes and crimes against humanity, 10 of the 11 charges in total, and sentenced to 40 years' imprisonment.[151][152] Mladić was arrested on 26 May 2011 in Lazarevo, Serbia,[153] and was tried in The Hague. The verdict, delivered on 22 November 2017 found Mladić guilty of 10 of the 11 charges, including genocide and he was sentenced to life imprisonment.[154] International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1994–present) See also: Rwandan genocide  Photographs of Rwandan genocide victims displayed at the Genocide Memorial Center in Kigali The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) is a court under the auspices of the United Nations for the prosecution of offenses committed in Rwanda during the genocide which occurred there during April 1994, commencing on 6 April. The ICTR was created on 8 November 1994 by the Security Council of the United Nations in order to judge those people responsible for the acts of genocide and other serious violations of the international law performed in the territory of Rwanda, or by Rwandan citizens in nearby states, between 1 January and 31 December 1994. So far, the ICTR has finished nineteen trials and convicted twenty-seven accused persons. On 14 December 2009, two more men were accused and convicted for their crimes. Another twenty-five persons are still on trial. Twenty-one are awaiting trial in detention, two more added on 14 December 2009. Ten are still at large.[155] The first trial, of Jean-Paul Akayesu, began in 1997. Akayesu was the first person ever to be convicted of the crime of genocide. In October 1998, Akayesu was sentenced to life imprisonment. Jean Kambanda, interim Prime Minister, pleaded guilty. Trials for deeds committed during the Rwandan genocide have also occurred in national courts, including Désiré Munyaneza, who in 2009 became the first man to be arrested and convicted in Canada on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity,[156] and Yvonne Ntacyobatabara Basebya, who in 2013 became the first Dutch citizen to be convicted for incitement to genocide.[157] Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (from 2003) Main articles: Khmer Rouge Tribunal and Cambodian genocide  Rooms of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum contain thousands of photos taken by the Khmer Rouge of their victims.  Skulls in the Choeung Ek The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, Kang Kek Iew, Ta Mok and other leaders, organized the mass killing of ideologically suspect groups. The total number of victims is estimated at 1.7 million Cambodians between 1975 and 1979, including deaths from slave labour.[158] On 6 June 2003 the Cambodian government and the United Nations reached an agreement to set up the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) which would focus exclusively on crimes committed by the most senior Khmer Rouge officials during the period of Khmer Rouge rule of 1975–1979.[159] The judges were sworn in early July 2006.[160][161][162] The genocide charges related to killings of Cambodia's Vietnamese and Cham minorities, tens of thousands of whom are estimated to have been killed.[163][164] The investigating judges were presented with the names of four suspects charged with genocide on 18 July 2007:[160][165] Nuon Chea, a former prime minister, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity on 15 September 2010. His trial started on 27 June 2011[163][166] and ended on 7 August 2014, with a life sentence imposed for crimes against humanity.[167] Khieu Samphan, a former head of state, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity on 15 September 2010. His trial began on 27 June 2011.[163][166] and also ended on 7 August 2014, with a life sentence imposed for crimes against humanity.[167] Ieng Sary, a former foreign minister, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity on 15 September 2010. His trial started on 27 June 2011, and ended with his death on 14 March 2013. He was never convicted.[163][166] Ieng Thirith, a former minister for social affairs and wife of Ieng Sary, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity on 15 September 2010. Proceedings against her were suspended pending a health evaluation.[166][168] In September 2012, she was released from prison due to advanced Alzheimer's disease; she died on 22 August 2015 at the age of 83 from complications of the disease.[169] By the International Criminal Court Since 2002, the International Criminal Court can exercise its jurisdiction if national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute genocide, thus being a "court of last resort," leaving the primary responsibility to exercise jurisdiction over alleged criminals to individual states. Due to the United States concerns over the ICC, the United States prefers to continue to use specially convened international tribunals for such investigations and potential prosecutions.[170] Darfur, Sudan Main article: War in Darfur  A mother with her sick baby at Abu Shouk IDP camp in North Darfur There has been much debate over categorizing the situation in Darfur as genocide.[171] The ongoing conflict in Darfur, Sudan, which started in 2003, was declared a "genocide" by United States Secretary of State Colin Powell on 9 September 2004 in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[172] Since that time however, no other permanent member of the UN Security Council has done so. In fact, in January 2005, an International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur, authorized by UN Security Council Resolution 1564 of 2004, issued a report to the Secretary-General stating that "the Government of Sudan has not pursued a policy of genocide."[173] Nevertheless, the Commission cautioned that "The conclusion that no genocidal policy has been pursued and implemented in Darfur by the Government authorities, directly or through the militias under their control, should not be taken in any way as detracting from the gravity of the crimes perpetrated in that region. International offences such as the crimes against humanity and war crimes that have been committed in Darfur may be no less serious and heinous than genocide."[173] In March 2005, the Security Council formally referred the situation in Darfur to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, taking into account the Commission report but without mentioning any specific crimes.[174] Two permanent members of the Security Council, the United States and China, abstained from the vote on the referral resolution.[175] As of his fourth report to the Security Council, the Prosecutor has found "reasonable grounds to believe that the individuals identified [in the UN Security Council Resolution 1593] have committed crimes against humanity and war crimes," but did not find sufficient evidence to prosecute for genocide.[176] In April 2007, the Judges of the ICC issued arrest warrants against the former Minister of State for the Interior, Ahmad Harun, and a Militia Janjaweed leader, Ali Kushayb, for crimes against humanity and war crimes.[177] On 14 July 2008, prosecutors at the International Criminal Court (ICC), filed ten charges of war crimes against Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir: three counts of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and two of murder. The ICC's prosecutors claimed that al-Bashir "masterminded and implemented a plan to destroy in substantial part" three tribal groups in Darfur because of their ethnicity. On 4 March 2009, the ICC issued a warrant of arrest for Omar Al Bashir, President of Sudan as the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I concluded that his position as head of state does not grant him immunity against prosecution before the ICC. The warrant was for war crimes and crimes against humanity. It did not include the crime of genocide because the majority of the Chamber did not find that the prosecutors had provided enough evidence to include such a charge.[178] Later the decision was changed by the Appeals Panel and after issuing the second decision, charges against Omar al-Bashir include three counts of genocide.[179] |

国際訴追 臨時法廷による  2011年12月5日、カンボジア・ジェノサイド法廷にて、クメール・ルージュの最高イデオローグ、ヌオン・チェア氏 CPPCGのすべての署名国は、平和時および戦時を問わず、ジェノサイド行為を防止し処罰することが求められているが、いくつかの障壁により、その施行は 困難である。特に、バーレーン、バングラデシュ、インド、マレーシア、フィリピン、シンガポール、米国、ベトナム、イエメン、旧ユーゴスラビアといった一 部の署名国は、自国の同意なしに国際司法裁判所でジェノサイドの訴えを起こされないという条件付きで署名している。[137] これらの留保条項の倫理的および法的立場について、他の署名国(特にキプロスとノルウェー)から抗議があったが、それらの免責条項は、1999年のコソボ 紛争後に旧ユーゴスラビアが米国に対して起こしたジェノサイド容疑の訴追を米国が拒否したときのように、時折発動されてきた。 少なくとも第二次世界大戦以降、慣習国際法における強行規範として、また条約上の国際法においても、ジェノサイドは違法であると一般的に認められている。 ジェノサイドの行為を立証して起訴することは一般的に困難である。なぜなら、一連の責任の所在を明らかにしなければならないからだ。国際刑事裁判所や法廷 は、主に関係国がこのような重大犯罪を自ら起訴できない、あるいは起訴する意思がない場合に機能する。 ニュルンベルク裁判(1945年~1946年) 詳細は「ニュルンベルク裁判」を参照  ニュルンベルク裁判所におけるナチス指導者たち 第二次世界大戦直後にホロコーストやその他の大量虐殺への関与により起訴されたナチス指導者たちは、1948年の「ジェノサイドの防止及び処罰に関する条 約(CPPCG)」が「ジェノサイド」を正式に定義するまで、「ジェノサイド」は「人道に対する罪」などの既存の国際法に則って起訴された。しかし、最近 作られた用語[140]がナチス指導者の起訴状第3項に登場し、起訴された人々は「特定の民族や階級、国民、人種、宗教集団、特にユダヤ人、ポーランド 人、ジプシー、その他を破壊するために、特定の占領地域の民間人に対して、意図的かつ組織的な大量虐殺、すなわち人種的・民族的集団の絶滅を行った」と述 べている[141]。 旧ユーゴスラビア国際戦犯法廷(1993年~2017年) 関連項目:ボスニア・ジェノサイド、ボスニア・ジェノサイド訴追事件一覧  スレブレニツァ・ポトチャリ虐殺犠牲者追悼・墓地の墓地 ボスニア・ジェノサイドという用語は、1995年にスレブレニツァでセルビア軍が犯した殺害行為を指す場合と、1992年から1995年のボスニア紛争中 に他の地域で起こった民族浄化を指す場合がある。2001年、旧ユーゴスラビア国際戦犯法廷(ICTY)は、1995年のスレブレニツァ虐殺を ジェノサイドであると判断した。[144] 2007年2月26日、国際司法裁判所(ICJ)は、ボスニア・ジェノサイド事件において、スレブレニツァとゼパにおける虐殺はジェノサイドであるという ICTYの以前の判断を支持したが、ボスニア政府が主張したように、セルビア政府がボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナ領内で戦争中に広範なジェノサイドに加担した わけではないと判断した。[145] 2007年7月12日、欧州人権裁判所は、ニコラ・ヨルギッチによるドイツの裁判所によるジェノサイド有罪判決に対する上訴を棄却するにあたり、ドイツの 裁判所によるジェノサイドのより広範な解釈は、同様の事例を審理した国際裁判所によって却下されていると指摘した。[146][147][148] ECHRはまた、21世紀において「学者の間では、セルビア軍がボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナでイスラム教徒やクロアチア人を家から追い出すために行った民族 浄化は、ジェノサイドには当たらないという見解が多数を占めている。しかし、これらの行為はジェノサイドに該当するという見解を示す学者も相当数おり、 ICTYはモムチロ・クラジンスキ事件において、プリイェドルではジェノサイドの実行犯が存在したと認定している。「ジェノサイドの罪状に関しては、法廷 は、ジェノサイドの実行犯が存在したという証拠があるにもかかわらず、と認定した。」[149] ボスニアでは、1990年代初頭にジェノサイドに参加した、あるいは加担したとして約30人が起訴された。これまでに、司法取引や一部の有罪判決を経て、 ヴュジャディン・ポポヴィッチとルビシャ・ベイラの2人がジェノサイドの実行犯として有罪判決を受け、ズドラヴコ・トリミルはジェノサイドおよびジェノサ イドの共謀の実行犯として有罪判決を受け、ラディスラフ・クルスティッチとドラゴ・ニコリッチの2人はジェノサイドの幇助の実行犯として有罪判決を受けて いる。さらに3人がドイツの裁判所によりボスニアでのジェノサイドへの関与で有罪判決を受け、うち1人のニコラ・ヨルギッチは欧州人権裁判所で有罪判決に 対する上訴を棄却された。さらに8人の元ボスニア・セルビア治安部隊のメンバーがボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナの国家裁判所によりジェノサイドで有罪判決を受 けた(ボスニア・ジェノサイド訴追リストを参照)。 スロボダン・ミロシェビッチは、セルビアおよびユーゴスラビアの元大統領として、ICTYで裁判にかけられた最も地位の高い政治的人物であった。彼はボス ニア・ヘルツェゴビナ領内でのジェノサイドまたはジェノサイドへの加担の罪で起訴されていた裁判中に2006年3月11日に死亡したため、判決は下されな かった。1995年、ICTYはボスニア・セルビア人のラドヴァン・カラジッチとラトコ・ムラディッチに対して、ジェノサイドを含む複数の容疑で逮捕状を 出した。2008年7月21日、カラジッチはベオグラードで逮捕され、その後ハーグで裁判にかけられ、ジェノサイドを含むその他の罪状で起訴された。 [150] 2016年3月24日、カラジッチはスレブレニツァでのジェノサイド、戦争犯罪、 合計11の罪状のうち10の罪状で有罪とされ、40年の禁固刑を言い渡された。[151][152] ムラディッチは2011年5月26日にセルビアのラザレヴォで逮捕され、[153]ハーグで裁判にかけられた。2017年11月22日に言い渡された判決 では、11の罪状のうち10の罪状について有罪とされ、ジェノサイドを含む罪状について終身刑を言い渡された。 ルワンダ国際刑事裁判所(1994年~現在) 関連項目:ルワンダ大虐殺  キガリのジェノサイド記念センターに展示されているルワンダ大虐殺の犠牲者の写真 ルワンダ国際刑事裁判所(ICTR)は、1994年4月に発生したルワンダにおけるジェノサイドの罪を裁くために設立された国連の管轄下にある裁判所であ る。ICTRは、1994年1月1日から12月31日の間にルワンダ領内で、あるいは近隣諸国のルワンダ国民によって行われたジェノサイドやその他の重大 な国際法違反行為の責任者を裁くために、1994年11月8日に国連安全保障理事会によって設立された。 これまでに、ICTRは19件の裁判を終え、27人の被告に有罪判決を下した。2009年12月14日には、さらに2人の男が罪を認め、有罪判決を受け た。現在も25人が裁判中である。21人は拘禁されたまま裁判を待っており、2009年12月14日にはさらに2人が加わった。10人は依然として逃亡中 である。[155] 最初の裁判は、ジャン=ポール・アカイエスの裁判で、1997年に開始された。アカイエスはジェノサイド罪で有罪判決を受けた最初の人物となった。 1998年10月、アカイエスは終身刑を言い渡された。ジャン・カンバンダ暫定首相は有罪を認めた。 ルワンダ大虐殺中の行為に対する裁判は、国民の法廷でも行われており、2009年には、カナダで戦争犯罪と人道に対する罪で逮捕・有罪判決を受けた初の男 性となったデジレ・ムニャネザ(Désiré Munyaneza)や、2013年には、オランダ国民として初めてジェノサイド扇動罪で有罪判決を受けたイボンヌ・ンタコバラタバラ・バセビヤ (Yvonne Ntacyobatabara Basebya)などがいる。 カンボジア特別法廷(2003年より) 詳細は「クメール・ルージュ法廷」および「カンボジア大量虐殺」を参照  トゥール・スレン虐殺博物館の展示室には、クメール・ルージュが犠牲者を撮影した数千枚の写真が展示されている。  チュンエクの頭蓋骨 ポル・ポト、カン・ケク・イウ、ター・モクなどの指導者たちに率いられたクメール・ルージュは、思想的に疑わしい集団の大量殺害を行った。 1975年から1979年の間に、奴隷労働による死者も含め、170万人のカンボジア人が犠牲になったと推定されている。 2003年6月6日、カンボジア政府と国連は、1975年から1979年のクメール・ルージュ支配下におけるクメール・ルージュの最高幹部による犯罪にの み焦点を当てるカンボジア特別法廷(ECCC)を設置することで合意した。[159] 裁判官は2006年7月初めに宣誓した。[160][161][162] カンボジアのベトナム系住民とチャム族の少数民族に対する大量虐殺容疑に関連して、数万人が殺害されたと推定されている。[163][164] 2007年7月18日、調査官に4人の容疑者の名前が提出された。 元首相のヌオン・チェアは、2010年9月15日にジェノサイド、戦争犯罪、人道に対する罪で起訴された。彼の裁判は2011年6月27日に始まり [163][166]、2014年8月7日に人道に対する罪で終身刑が言い渡されて終了した[167]。 元国家元首のキュー・サムファンは、2010年9月15日に、ジェノサイド、戦争犯罪、人道に対する罪で起訴された。彼の裁判は2011年6月27日に始 まり[163][166]、2014年8月7日に終結し、人道に対する罪で終身刑が言い渡された[167]。 元外相のイエン・サリは、2010年9月15日にジェノサイド、戦争犯罪、人道に対する罪で起訴された。彼の裁判は2011年6月27日に始まり、 2013年3月14日に死去したことで終了した。彼は有罪判決を受けたことはなかった。[163][166] イエン・ティリト(元社会問題担当相でイエン・サリーの妻)は、2010年9月15日に、ジェノサイド、戦争犯罪、人道に対する罪で起訴された。彼女に対 する訴訟手続きは、健康診断の結果が出るまで保留された。[166][168] 2012年9月、彼女はアルツハイマー病の進行により刑務所から釈放された。彼女は2015年8月22日、83歳で死去した。死因は病気の合併症によるも のである。[169] 国際刑事裁判所による 2002年以降、国際刑事裁判所は、国内の裁判所がジェノサイドの調査や起訴を望まない、あるいはできない場合、その管轄権を行使することができる。した がって、容疑者の管轄権を行使する第一義的な責任は個々の国家に委ねられる。米国は国際刑事裁判所(ICC)に懸念を抱いているため、このような調査や起 訴の可能性については、特別に招集された国際法廷を引き続き使用することを望んでいる。 スーダン・ダルフール 詳細は「ダルフール紛争」を参照  北ダルフールのアブ・ショク国内避難民キャンプで病気の赤ん坊を抱く母親 スーダンのダルフールにおける状況をジェノサイドと分類することについては、多くの議論がある。[171] 2003年に始まったスーダンのダルフールにおける紛争は、2004年9月9日にコリン・パウエル米国務長官が上院外交委員会で証言し、「ジェノサイド」 であると宣言した。[172] しかしそれ以来、国連安全保障理事会の他の常任理事国はそうした宣言を行っていない。実際、2005年1月には、2004年の国連安全保障理事会決議第 1564号により承認されたダルフールに関する国際調査委員会が、事務総長宛に「スーダン政府はジェノサイド政策を追求していない」という報告書を提出し ている[1 73] しかし、委員会は「スーダン政府当局が、直接またはその支配下にある民兵組織を通じて、ダルフールでジェノサイド政策を追求し実行したという結論は、その 地域で犯された犯罪の重大性を損なうものと解釈されてはならない。ダルフールで犯された人道に対する罪や戦争犯罪などの国際犯罪は、ジェノサイドに劣らず 深刻で悪質な犯罪である可能性がある」と警告した。[173] 2005年3月、安保理は、委員会の報告を考慮に入れながらも、具体的な犯罪については言及せずに、ダルフール情勢を正式に国際刑事裁判所の検察官に付託 した。[174] 安保理の常任理事国である米国と中国は、付託決議の採決を棄権した。。検察官は、安保理への4回目の報告書提出時点で、「(国連安保理決議1593で特定 された)個人たちが人道に対する罪および戦争犯罪を犯したと信じるに足る相当な理由がある」と結論づけたが、ジェノサイドを立件するに足る証拠は見つけら れなかった。 2007年4月、国際刑事裁判所の判事は、人道に対する罪および戦争犯罪の容疑で、元内務国務大臣のアフマド・ハルーンと民兵ジャンジャウィードのリー ダー、アリ・クシェイブに対して逮捕状を出した。 2008年7月14日、国際刑事裁判所(ICC)の検察官は、スーダンのオマル・アル・バシール大統領に対して、ジェノサイド罪3件、人道に対する罪5 件、殺人罪2件の計10件の戦争犯罪容疑を提出した。ICCの検察官は、バシール大統領が、ダルフール地方の3つの部族集団を、その民族性ゆえに「ほぼ壊 滅させる計画を練り、実行した」と主張した。 2009年3月4日、国際刑事裁判所(ICC)予審裁判所第1部は、オマル・アル=バシール大統領の国家元首としての地位は、ICCによる起訴に対する免 責を付与するものではないとの結論に達し、同大統領に対する逮捕状を発布した。逮捕状は、戦争犯罪と人道に対する罪に対するものであった。ジェノサイド罪 は含まれていなかったが、それは、予審裁判所の大多数が、検察官がこの罪で起訴するのに十分な証拠を提出していないと判断したためである。[178] その後、この決定は控訴裁判所によって変更され、2回目の決定が下された後、オマル・アル=バシールに対する起訴状にはジェノサイド罪の3つの罪状が含ま れている。[179] |

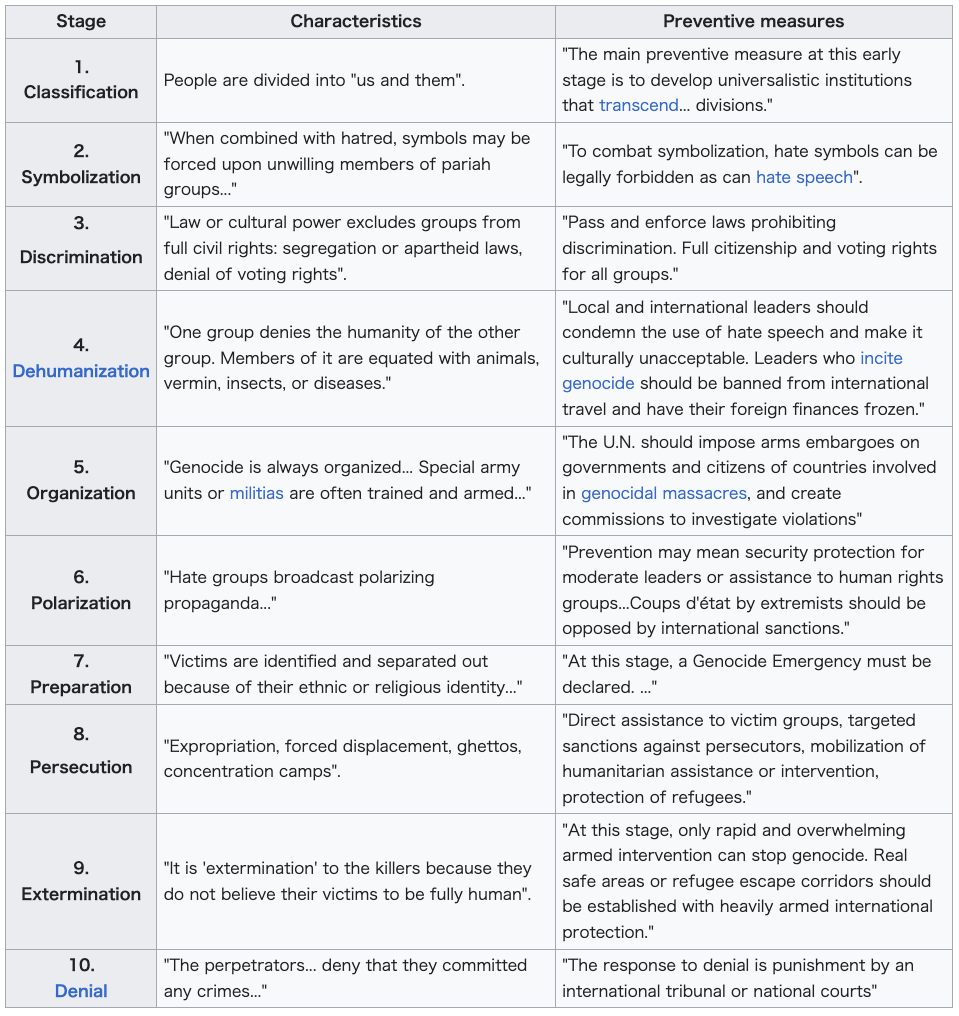

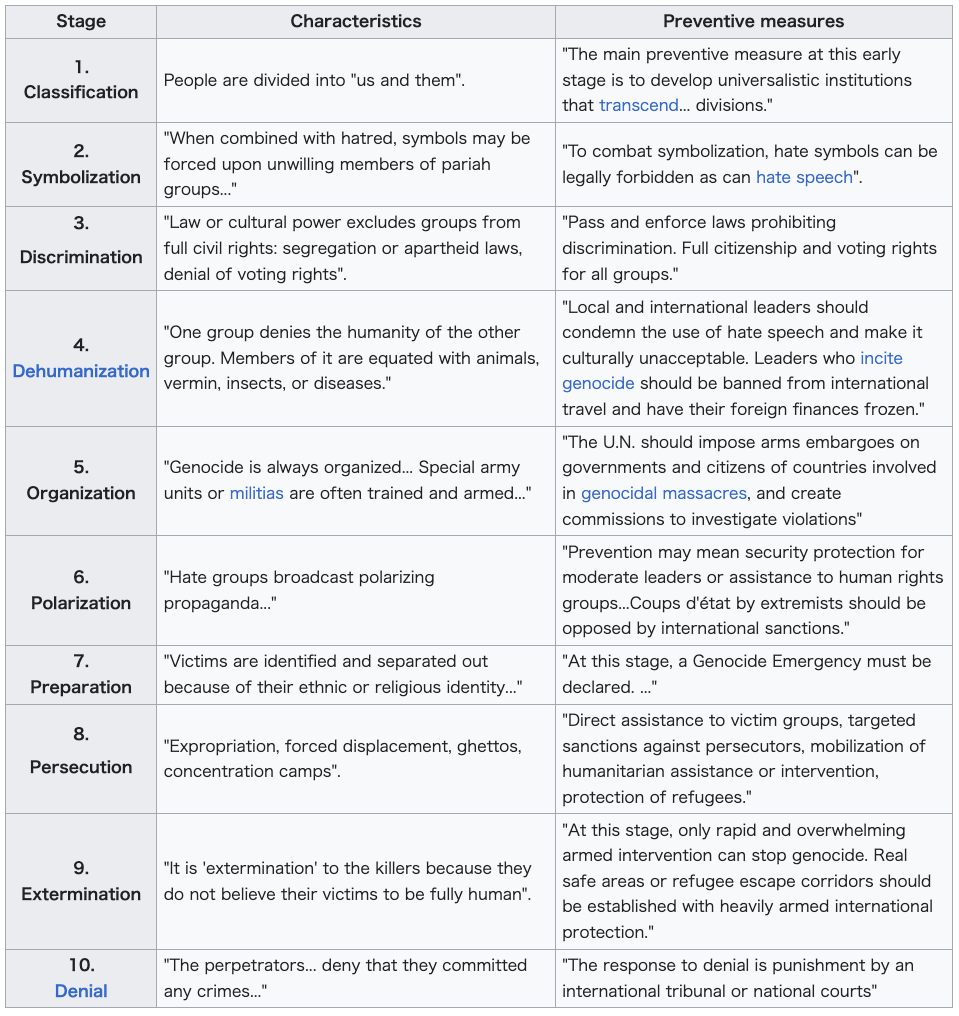

| Examples Main article: Genocides in history For a more comprehensive list, see List of genocides. Naked Soviet POWs held by the Nazis in Mauthausen concentration camp. Political scientist Adam Jones wrote: "[T]he murder of at least 3.3 million Soviet POWs is one of the least-known of modern genocides; there is still no full-length book on the subject in English."[180] The concept of genocide can be applied to historical events. The preamble of the CPPCG states that "at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity." Revisionist attempts to challenge or affirm claims of genocide are illegal in some countries. Several European countries ban the denial of the Holocaust and the denial of the Armenian genocide, while in Turkey referring to the Armenian genocide, Greek genocide, and Sayfo, and to the period of mass starvation during the Great Famine of Mount Lebanon affecting Maronites, as genocides may be prosecuted under Article 301.[181] Historian William Rubinstein argues that the origin of 20th-century genocides can be traced back to the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government in parts of Europe following World War I, commenting: The 'Age of Totalitarianism' included nearly all of the infamous examples of genocide in modern history, headed by the Jewish Holocaust, but also comprising the mass murders and purges of the Communist world, other mass killings carried out by Nazi Germany and its allies, and also the Armenian genocide of 1915. All these slaughters, it is argued here, had a common origin, the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government of much of central, eastern and southern Europe as a result of the First World War, without which surely neither Communism nor Fascism would have existed except in the minds of unknown agitators and crackpots.[182] According to Esther Brito, the way in which states commit genocide has evolved in the 21st century and genocidal campaigns have attempted to circumvent international systems designed to prevent, mitigate, and prosecute genocide by adjusting the duration, intensity, and methodology of the genocide. Brito states that modern genocides often happen on a much longer time scale than traditional ones – taking years or decades – and that instead of traditional methods of beatings and executions less directly fatal tactics are used but with the same effect. Brito described the contemporary plights of the Rohingya and Uyghurs as examples of this newer form of genocide.[183] The abuses against West Papuans in Indonesia have also been described as a slow-motion genocide.[184][185][186][187][188] Stages, risk factors, and prevention Main articles: Ten stages of genocide, Risk factors for genocide, and Genocide prevention Study of the risk factors and prevention of genocide was underway before the 1982 International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide during which multiple papers on the subject were presented.[189] In 1996 Gregory Stanton, the president of Genocide Watch, presented a briefing paper called "The 8 Stages of Genocide" at the United States Department of State.[190] In it he suggested that genocide develops in eight stages that are "predictable but not inexorable".[190][191] The Stanton paper was presented to the State Department, shortly after the Rwandan Genocide and much of its analysis are based on why that genocide occurred. In 2012, he added two additional stages, discrimination and persecution.[192]  |