George Hunt (February 14, 1854 –

1933)

George Hunt (February 14, 1854 –

1933)

以下はウィキペディアGeorge Hunt (February 14, 1854 – 1933) の記述である

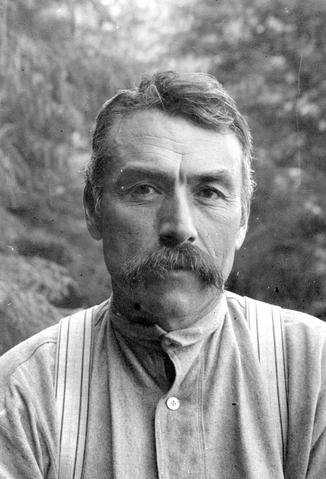

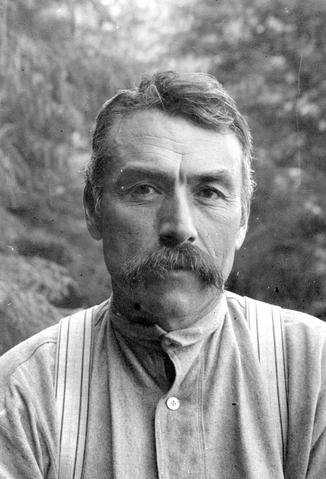

| George Hunt

(February 14, 1854 – 1933) (Tlingit) was a Canadian and a consultant to

the American anthropologist Franz Boas; through his contributions, he

is considered a linguist and ethnologist in his own right. He was

Tlingit-English by birth and learned both those languages. Growing up

with his parents at Fort Rupert, British Columbia in Kwakwaka'wakw

territory, he learned their language and culture as well. Through

marriage and adoption he became an expert on the traditions of the

Kwakwaka'wakw (then known as "Kwakiutl") of coastal British Columbia. |

ジョージ・ハント(1854年2月14日 -

1933年)(トリンギット)はカナダ人で、アメリカの人類学者フランツ・ボースのコンサルタントだった。彼の貢献により、彼自身が言語学者、民族学者と

みなされるようになった。彼はトリンギット人と英語人の間に生まれ、両方の言語を学びました。両親とともにクワクワクワ族の領土であるブリティッシュコロ

ンビア州フォート・ルパートで育ち、彼らの言語と文化も学んだ。結婚や養子縁組を経て、ブリティッシュ・コロンビア州沿岸部のクワクワクワク(当時は「ク

ワキウトル」と呼ばれていた)の伝統の専門家になった。 |

| Working with Boas, Hunt

collected hundreds of items for an exhibit of the Kwakiutl culture for

the World Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, and accompanied 17

people of the tribe there. Boas taught Hunt to write in Kwakiutl, and

the native ethnologist wrote thousands of pages of description of

Kwakiutl culture over the next decades. |

ハントはボアスと協力して、1893年のシカゴ万国博覧会にクワキウト

ル文化を展示するために数百点を収集し、現地で17人の部族民に同伴した。ボアスはハントにクワキウトル語で書くことを教え、この先住民の民族学者はその

後数十年にわたってクワキウトル文化の説明を何千ページにもわたって書き続けた。 |

| George Hunt was born in 1854 at

Fort Rupert, British Columbia (B.C.), the second of eleven children of

Robert Hunt (1828-1893), a Hudson's Bay Company fur trader from Dorset,

England, and Mary Ebbetts (Ansnaq, Anislaga, A'naeesla'ga or Anain)

(1823-1919), a member of the Raven clan of the Taantakwáan (Tongass)

tribe of the Tlingit nation of what is now southeastern Alaska. Mary

was the daughter of Chief Keishíshk' Shakes IV and S’eitlin, a

Deisheetaan (Gaanax.ádi) woman from Aan goon (Angoon). Robert and Mary

were married at the original Fort Simpson, now called Lax-Kw'alaams, on

the Nass River not far from the city of Prince Rupert in northwestern

British Columbia. |

ジョージ・ハントは1854年、ブリティッシュ・コロンビア州(BC

州)のフォート・ルパートで生まれた。 ロバート・ハント(1828-1893)とメアリー・エベッツ(Ansnaq, Anislaga,

A'naeesla'ga or

Anain)(1823-1919)の11人の子供のうちの2番目として、ブリティッシュ・コロンビア州フォート・ルパートで生まれた。メアリーは酋長

Keishíshk' Shakes IVとAan

goon(Angoon)出身のDeisheetaan(Gaanax.ádi)族の女性S'eitlinの娘であった。ロバートとメアリーは、ブリ

ティッシュ・コロンビア州北西部のプリンス・ルパート市からほど近いナス川沿いにある、現在はLax-Kw'alaamsと呼ばれるオリジナルのシンプソ

ン砦で結婚式を挙げた。 |

| Mary Hunt née Ebbetts (Ansnaq,

Anislaga, A'naeesla'ga and Anain), a master Chilkat weaver, was

influential among the Kwakwaka'wakw at Tsaxis, Fort Rupert, and

introduced concepts of Tlingit hereditary privileges and artistic

motifs (reflected on totem poles) into the local society.[citation

needed] Hunt learned his mother's language and culture, as well as

English and elements of his father's culture. Learning the

Kwakwaka'wakw language and the local area from the Kwakwaka'wakw

people, he became an interpreter and guide. |

メアリー・ハント(Mary Hunt née

Ebbetts)(Ansnaq、Anislaga、A'naeesla'ga、Anain)はチルカットの織物の名手で、ルパート要塞のツァクシスのク

ワクワ族の間で影響力を持ち、トリンギットの世襲特権の概念と芸術モチーフ(トーテムポールに反映)を地元社会に導入した。 [引用者]

ハントは母親の言語と文化、英語と父親の文化要素を学んだ。クワクワクワクワの人々からクワクワクワの言語と地元を学び、通訳兼ガイドになった |

| His reputation grew. In the

early 1880s Hunt served as boatman, guide, and interpreter for Bernard

Fillip Jacobsen (brother of Johan Adrian Jacobsen), one of the

explorer/ethnologists of the far-ranging Jesup North Pacific

Expedition.[1] He may have first met Franz Boas, American

anthropologist and organizer of the expedition, at this time as well. |

彼の名声は高まっていった。1880年代初頭、ハントは広範囲に渡るイ

エサップ北太平洋探検隊の探検家・民族学者の一人であるバーナード・フィリップ・ヤコブセン(ヨハン・エイドリアン・ヤコブセンの弟)の船頭、ガイド、通

訳を務めていた。探検隊の主催者であるアメリカの人類学者フランツ・ボースともこのとき初めて会ったのかもしれない |

| Hunt's long collaboration with

Franz Boas, an American anthropologist, began in 1886 when Boas first

visited the Kwakwaka'wakw as part of the Jesup Expedition. Hunt acted

as his interpreter and served to describe and help him understand the

culture and its practices. They continued to work together and later

Boas taught Hunt to write the Kwak'wala language, to record oral

histories and other cultural material. Boas credited Hunt as co-author

in Kwakiutl Texts, second series (1906), one of the numerous volumes

published into the 1930s in relation to the work of the Jesup

expedition.[3] |

ハントとアメリカの人類学者フランツ・ボアスとの長い共同研究は、ボア

スが1886年にイエサップ遠征隊の一員として初めてクワクワクワクを訪れたときに始まった。ハントはボースの通訳として、その文化や習慣を説明し、理解

を助ける役割を果たした。その後、ボアスはハントにクワクワ語の書き方、オーラルヒストリーやその他の文化的資料の記録方法を教え、二人は共同作業を続け

た。ボアスは、ジェサップ探検隊の研究に関連して1930年代に出版された数多くの本のうちの1冊、Kwakiutl Texts, second

series (1906)でハントを共同執筆者として認めている |

| Boas and Hunt worked to organize

and create an exhibit of Kwakiutl and other Native Americans of the

Pacific Northwest at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Hunt collected hundreds of objects for the fair, including a house and

a number of carved poles. He travelled to Chicago in April 1893 with a

group of 17 Kwakiutl Indians from Fort Rupert, British Columbia. They

re-created a village on the fairgrounds, where the Kwakiutl lived

during the period of the fair and "demonstrated their ceremonial

dances, arts and other traditions. For the 'performers' it was an

opportunity to perform songs and dances that had been banned by

Canadian government officials. After the Exposition, most of the

objects from the exhibit were donated to the Field Museum, where many

still can be seen on display today."[4] |

ボアスとハントは、1893年にシカゴで開催された世界コロンビア博覧

会で、クワキウトルをはじめとする太平洋岸北西部のアメリカ先住民の展示を企画・制作するために協力した。ハントはこの博覧会のために、家屋や多くの彫刻

を施した柱など、何百点もの品々を集めた。1893年4月、ブリティッシュコロンビア州のフォート・ルパートから17人のクワキウトル・インディアンのグ

ループとともにシカゴに渡った。彼らは、フェアの開催期間中にクワキウトル族が住んでいた村をフェア会場に再現し、「彼らの儀式用のダンス、芸術、その他

の伝統を実演した」という。パフォーマー」にとっては、カナダ政府当局によって禁止されていた歌や踊りを披露する機会でもあった。博覧会終了後、展示品の

ほとんどはフィールド博物館に寄贈され、現在も多くの展示品を見ることができる」。 |

| Hunt was later instrumental in

the purchase of the Yuquot Whalers' Shrine in 1904, an object that has

since been of some controversy in recent decades. The Yuquot have tried

to reclaim this work. |

ハントはその後、1904年にユコット捕鯨祭礼施設(Yuquot Whalers' Shrine)の購入に尽力したが、この施設はその後、ここ数十年でいくつかの論争を巻き起こしているオブジェクトである。ユコットはこの作品(儀礼的アイテム)の返還を要求している |

| Over the years Hunt wrote as

much as ten thousand pages of ethnological description for Boas.[5]

This work covered every aspect of Kwakwaka'wakw culture, including

potlatch ceremonies in which Hunt participated. When Boas received

texts collected from other speakers, he sent the transcriptions to Hunt

to look over, remarking in a 1931 letter, "In some cases, I can guess

what is wrong but I had rather have you correct it than use my own

uncertain knowledge of Kwakiutl."[6] |

ハントはボアズのために、何年もかけて1万ページにも及ぶ民族誌を書き

上げた。ハントが参加したポトラッチの儀式をはじめ、クワクワクワクワの文化のあらゆる側面を網羅するものであった。ボアスは、他の話者から集めた文章を

受け取った際、その書き起こしをハントに送り、目を通してもらった。1931年の手紙には「場合によっては、何が間違っているか推測できるが、私の不確か

なクワキウトル語の知識を使うよりは、あなたに直してもらった方がましだ」と書かれてある。 |

| In the late 19th and early 20th

century wealthy people began to collect Pacific Northwest Indian art

and totem poles. Chicago businessman James L. Kraft, the founder of

Kraft Inc., donated a Kwakiutl totem pole to the city of Chicago, and

it was installed in a waterfront park in 1929. Forty feet high, it was

carved in traditional fashion from a single cedar pole. After many

decades it was deteriorating. Kraft, Inc. commissioned a replacement

and the original pole was sent to British Columbia for study and

preservation in 1985, as its historical and artistic value was

considerable.[4] |

19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて、富裕層が太平洋岸北西部のイン

ディアンアートやトーテムポールを収集するようになった。クラフト社の創業者であるシカゴの実業家ジェームズ・L・クラフトは、クワキウトルのトーテム

ポールをシカゴ市に寄贈し、1929年、ウォーターフロントの公園に設置された。高さ40フィート、1本の杉の柱から伝統的な方法で彫られたものだ。何十

年も経つと劣化が進んだ。1985年、歴史的・芸術的価値が高いとして、クラフト社が代替品を依頼し、オリジナルのポールは研究と保存のためにブリティッ

シュ・コロンビア州に送られた。 |

| George Hunt's descendant Tony

Hunt, a Kwakwaka'wakw hereditary chief and artist, in 1986 carved a

replacement totem pole, called Kwanusila, replicating the original

design and colors. It was installed at the lakeside park. Hunt's work

is also held by the St. Louis Art Museum, the Fine Arts Museums of San

Francisco and Chicago's Field Museum, in addition to private

collectors.[4] |

ジョージ・ハントの子孫でクワクワクワ族の族長であり芸術家でもあるト

ニー・ハントは、1986年にオリジナルのデザインと色を再現したトーテムポール「Kwanusila」を彫り上げた。このポールは湖畔の公園に設置され

た。ハントの作品は、セントルイス美術館、サンフランシスコ美術館、シカゴのフィールドミュージアムのほか、個人コレクターにも所蔵されている。 |

| George Hunt's descendants also

include Dr. Gloria Cranmer-Webster and the filmmaker Barbara Cranmer.

In addition, the Hunt dynasty of traditional Northwest Coast artists

includes Henry Hunt, his sons Tony, Stanley C. Hunt, and Richard Hunt;

their second cousin, Calvin Hunt; and Corrine Hunt. She designed all of

the gold, silver and bronze medals awarded at the 2010 Vancouver Winter

Olympics and Paralympic games. |

ジョージ・ハントの子孫には、グロリア・クランマー・ウェブスター博士

や映像作家のバーバラ・クランマーもいる。さらに、北西海岸の伝統的な芸術家であるハント一族には、ヘンリー・ハント、その息子トニー、スタンリー・C・

ハント、リチャード・ハント、彼らの2番目のいとこカルヴィン・ハント、そしてコリーヌ・ハントがいる。彼女は、2010年バンクーバー冬季オリンピッ

ク・パラリンピックで授与された金・銀・銅メダルのすべてをデザインした。 |

| In 1986, members of the Boas and

Hunt families held a "reunion" at Tsaxis (Fort Rupert). In 1995, the

Hunt family hosted a potlatch to celebrate the Long House:

Kwakwaka'wakw Big House House of the Chiefs Kanada, Turtle Island. in

Tsaxis, Fort Rupert. Master carver Tony Hunt Sr headed up the Gudzi

Community Big House. The late Henry Hunt Sr shared his skill and

oversaw the carving of the three Sisiutl Heads and Frogs on Tongues.

Tony Hunt Jr, Tommy Hunt Jr., Steven Hunt, George Jr Hunt carved the

Double-Headed Serpent and Frogs on Tongues with Uncle Henry Hunt

Sr.[citation needed] |

1986年、ボアス家とハント家はツァクシ(フォート・ルパート)で

「同窓会」を開催した。1995年、ハント家はロングハウスを祝うためにポトラッチを開催した。Kwakwaka'wakw Big House

House of the Chiefs Kanada, Turtle

Island.を祝うために、フォート・ルパートのTsaxisでポトラッチが開催された。彫刻の名人Tony Hunt Srは、Gudzi

Community Big

Houseを率いていた。故ヘンリー・ハント・シニアは、3つのシシウトルの頭部と舌の上の蛙の彫刻を監督し、その技術を伝えた。トニー・ハント・ジュニ

ア、トミー・ハント・ジュニア、スティーブン・ハント、ジョージ・ジュニア・ハントは、叔父のヘンリー・ハント・シニアと一緒に「両頭の蛇」と「舌上の

蛙」を彫った。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Hunt_(ethnologist) |

●ジェサップ探検隊(Jesup North Pacific Expedition)

The Jesup North Pacific Expedition (1897–1902) was a major anthropological expedition to Siberia, Alaska, and the northwest coast of Canada. The purpose of the expedition was to investigate the relationships among the peoples at each side of the Bering Strait. The multi-year expedition was sponsored by American industrialist-philanthropist Morris Jesup (who was among other things the president of the American Museum of Natural History). It was planned and directed by the American anthropologist Franz Boas. The participants included a number of significant figures in American and Russian anthropology, as well as Bernard Fillip Jacobsen (brother of Johan Adrian Jacobsen), a Norwegian, who settled in the Northwest coast in 1884 where he collected artifacts as well as the stories of the local indigenous people.[1] Local people of the tribes, such as George Hunt (Tlingit), served as interpreters and guides. The expedition resulted in the publication of numerous important ethnographies from 1905 into the 1930s, as well as valuable collections of artifacts and photographs.[2]

「ジェサップ北太平洋探検隊(1897-1902)は、シベリア、アラスカ、カナダ北西部沿岸への大規模な人類学的探検であった。ベーリング海

峡の両岸に住む人々の関係を調査するのが目的であった。この遠征は、アメリカの実業家・慈善家であるモリス・ジェサップ(Morris

Ketchum Jesup,

1830-1908;アメリカ自然史博物館館長など)がスポンサーとなり、数年がかりで行われた。企画・監督は、アメリカの人類学者フランツ・ボアスであ

る。1884年に北西海岸に移住したノルウェー人のバーナード・フィリップ・ヤコブセン(ヨハン・アドリアン・ヤコブセンの弟)は、この地に住む先住民の

話を聞きながら遺物を収集し、アメリカやロシアの人類学の権威者たちが参加した。ジョー

ジ・ハント(トリンギット族)など、現地の部族の人々が通訳やガイドを務めた。この探検により、1905年から1930年代にかけて数多くの重要

な民族誌が出版され、貴重な遺物や写真のコレクションが生まれた」

Russian ethnographer Vladimir Jochelson (1855 - 1937) on a raft in

the Korkodon River during the Jesup North Pacific Expedition.

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099