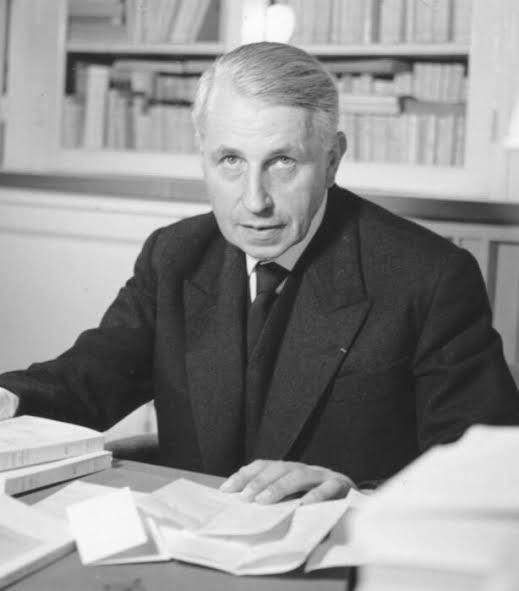

ジョルジュ・バタイユ

Georges Albert Maurice

Victor Bataille, 1897-1962

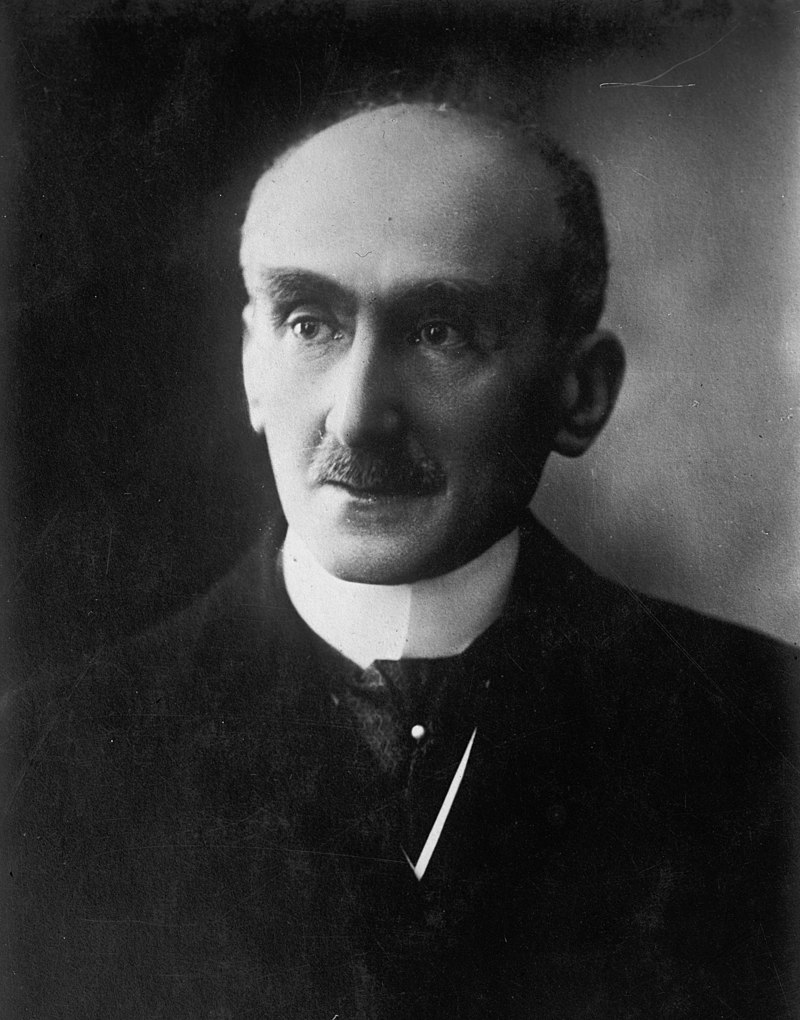

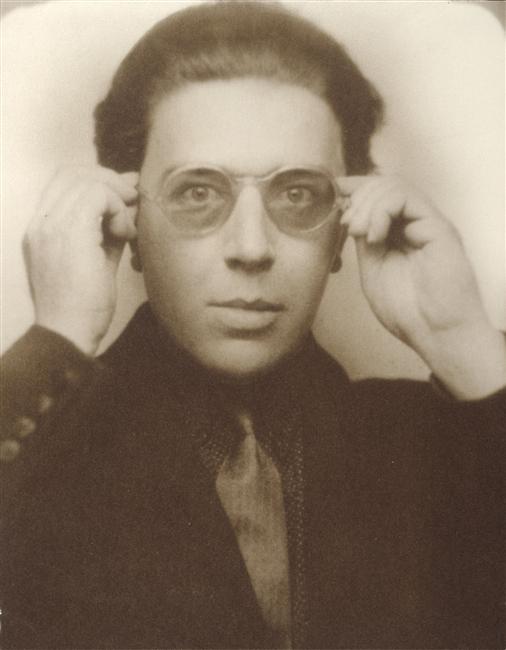

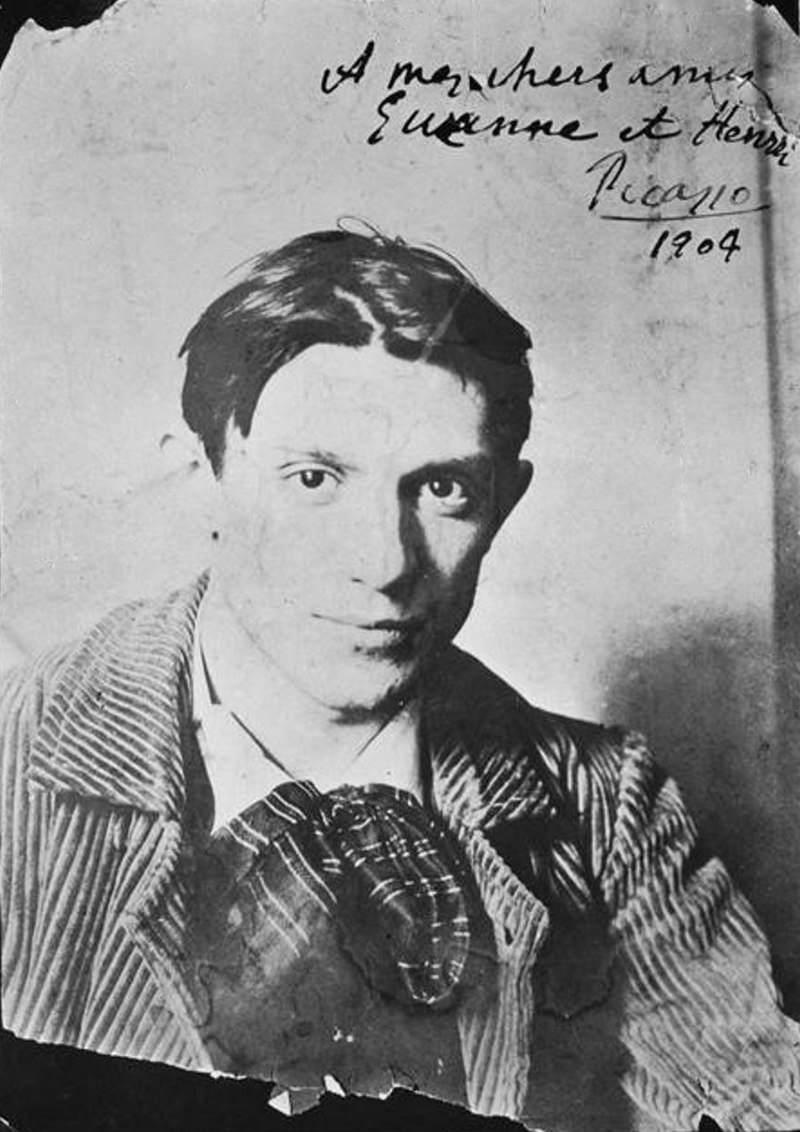

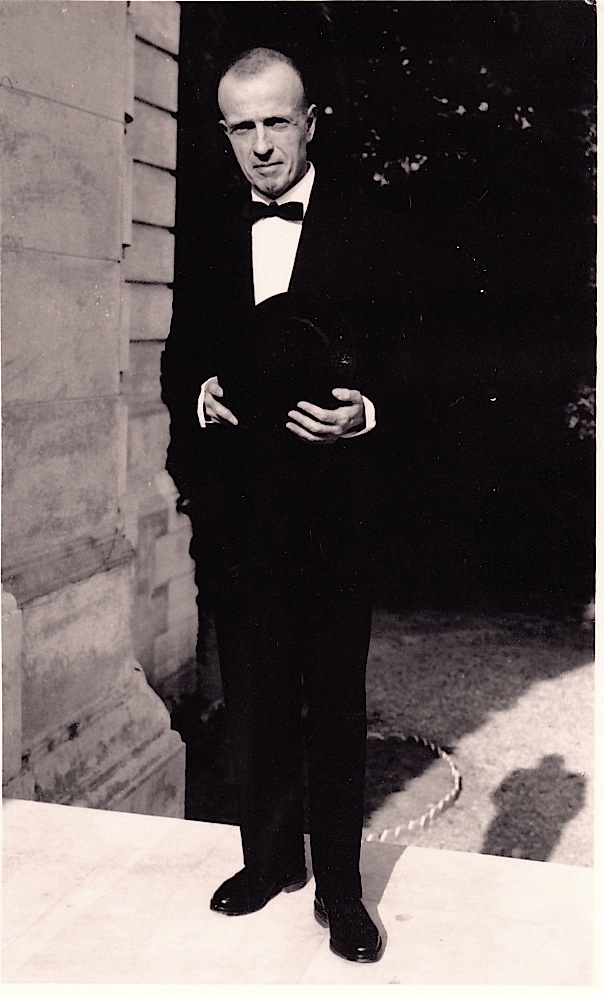

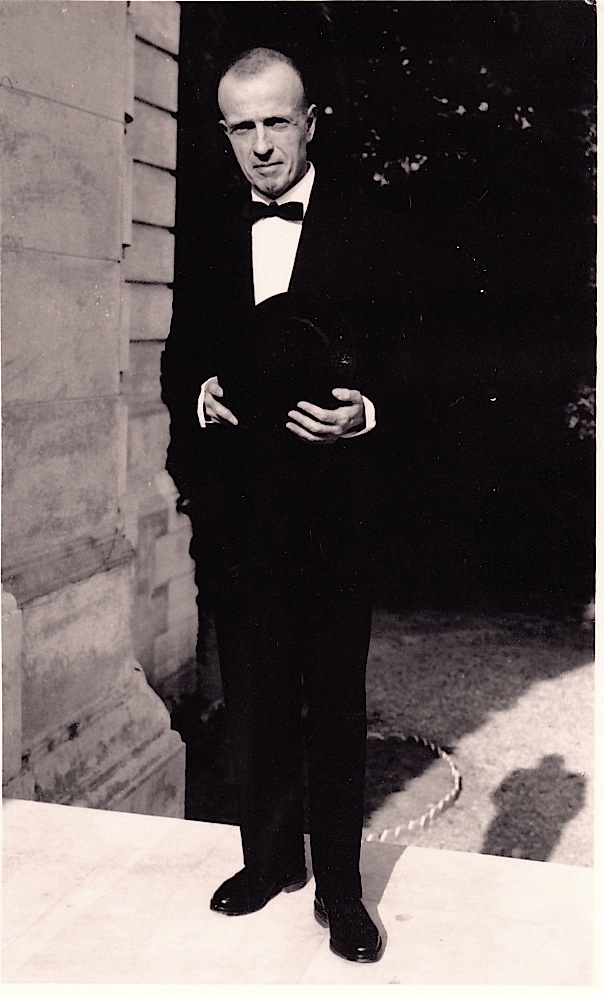

☆ ジョルジュ・アルベール・モーリス・ヴィクトル・バタイユ(Georges Albert Maurice Victor Bataille; 1897年9月10日 - 1962年7月9日)は、哲学、文学、社会学、人類学、芸術史の分野で活躍したフランスの哲学者、知識人。エッセイ、小説、詩などを執筆し、エロティシズ ム、神秘主義、シュルレアリスム、侵犯などのテーマを探求した。彼の作品は、ポスト構造主義を含む、その後の哲学や社会理論の学派に影響を与えることにな る。

| Georges Albert Maurice Victor Bataille

(/bɑːˈtaɪ/; French: [ʒɔʁʒ batɑj]; 10 September 1897 – 9 July 1962) was

a French philosopher and intellectual working in philosophy,

literature, sociology, anthropology, and history of art. His writing,

which included essays, novels, and poetry, explored such subjects as

eroticism, mysticism, surrealism, and transgression. His work would

prove influential on subsequent schools of philosophy and social

theory, including poststructuralism.[2] |

ジョ

ルジュ・アルベール・モーリス・ヴィクトル・バタイユ(/bɑˈˈ Bataille, フランス語: [ʒɔʁʒ batɑj];

1897年9月10日 -

1962年7月9日)は、哲学、文学、社会学、人類学、芸術史の分野で活躍したフランスの哲学者、知識人。エッセイ、小説、詩などを執筆し、エロティシズ

ム、神秘主義、シュルレアリスム、侵犯などのテーマを探求した。彼の作品は、ポスト構造主義を含む、その後の哲学や社会理論の学派に影響を与えることにな

る[2]。 |

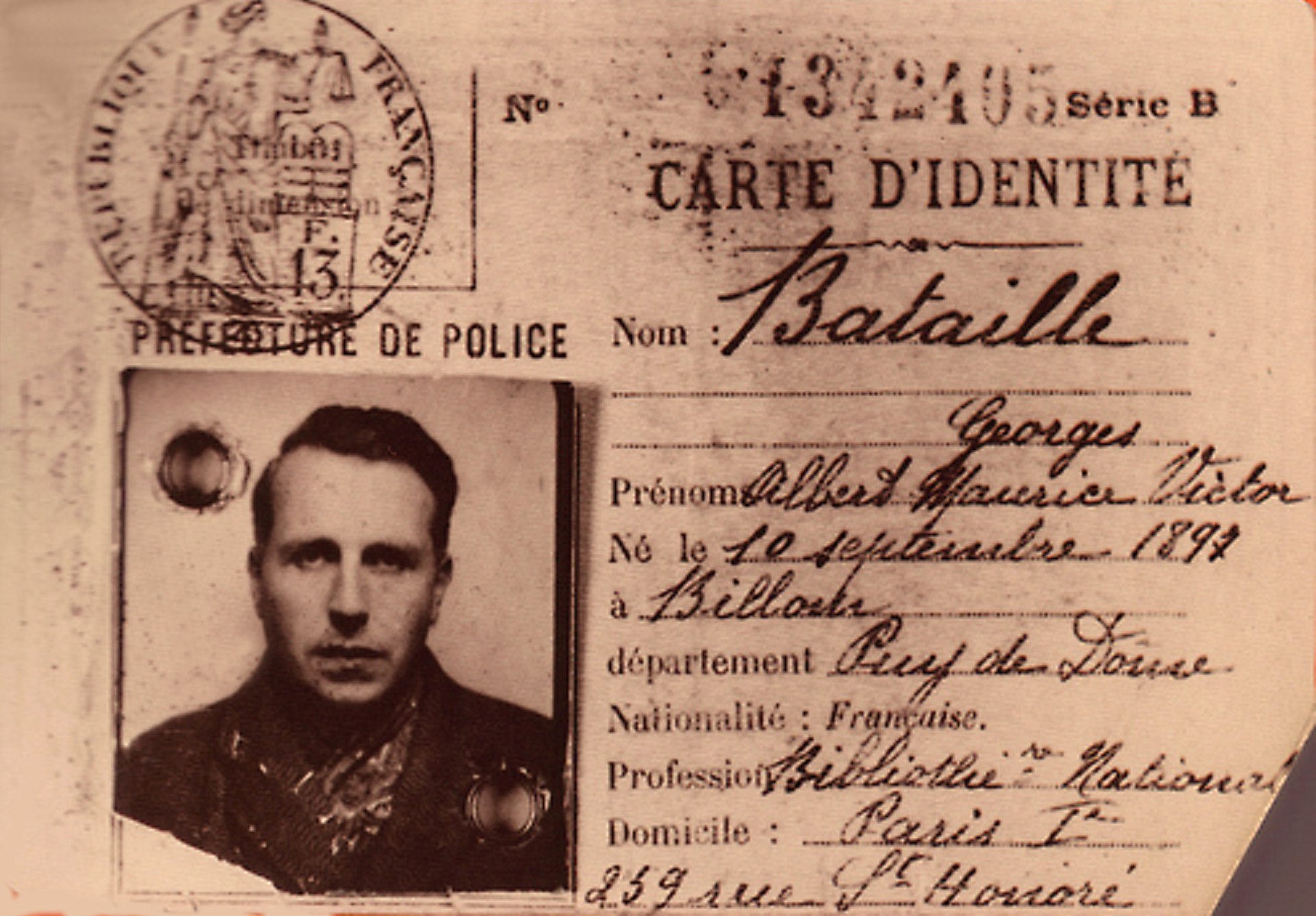

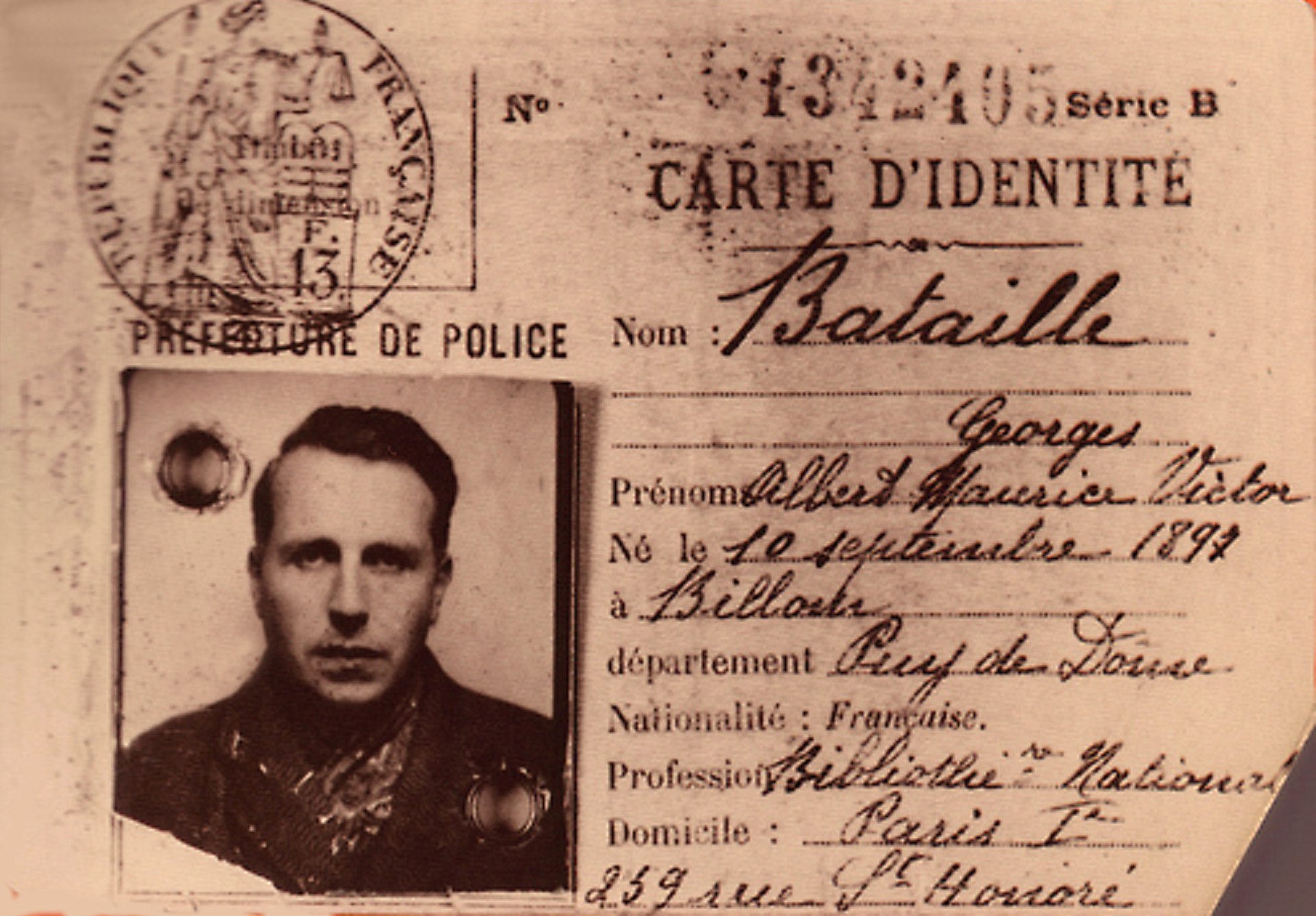

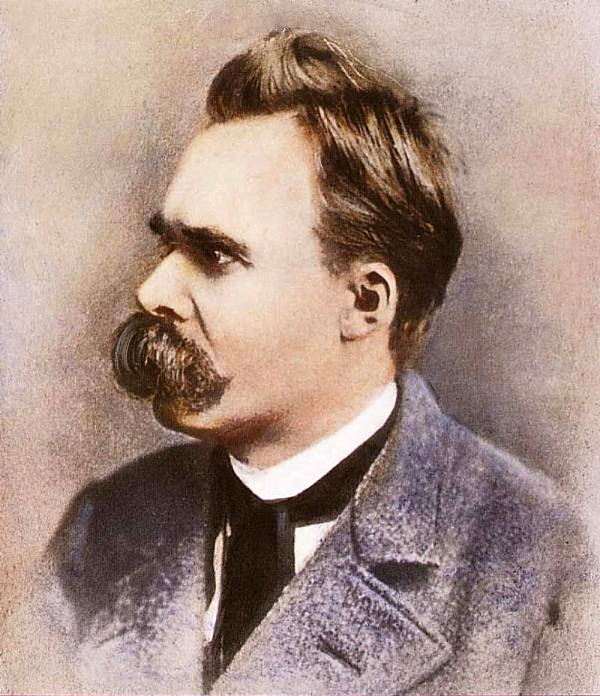

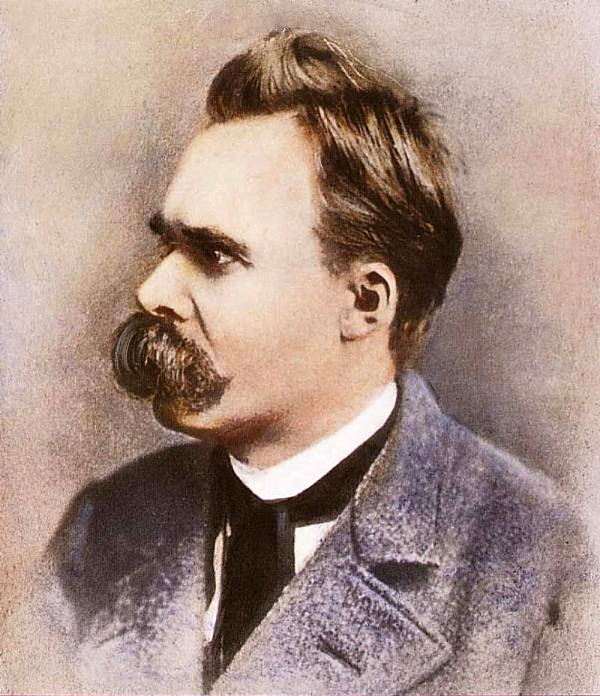

| Early life Georges Bataille was the son of Joseph-Aristide Bataille (b. 1851), a tax collector (later to go blind and be paralysed by neurosyphilis), and Antoinette-Aglaë Tournarde (b. 1865). Born on 10 September 1897 in Billom in the region of Auvergne, his family moved to Reims in 1898, where he was baptized.[3] He went to school in Reims and then Épernay. Although brought up without religious observance, he converted to Catholicism in 1914, and became a devout Catholic for about nine years. He considered entering the priesthood and attended a Catholic seminary briefly. However, he quit, apparently in part in order to pursue an occupation where he could eventually support his mother. He eventually renounced Christianity in the early 1920s.[4] Bataille attended the École Nationale des Chartes in Paris, graduating in February 1922. He graduated with a bachelor's thesis titled L'ordre de la chevalerie, conte en vers du xiiie siècle, avec introduction et notes. Though he is often referred to as an archivist and a librarian because of his employment at the Bibliothèque Nationale, his work there was with the medallion collections (he also published scholarly articles on numismatics). His thesis at the École des Chartes was a critical edition of the medieval poem L'Ordre de chevalerie which he produced directly by classifying the eight manuscripts from which he reconstructed the poem. After graduating he moved to the School of Advanced Spanish Studies in Madrid. As a young man, he befriended, and was much influenced by, the Russian existentialist Lev Shestov, who schooled him in the writing of Nietzsche, Dostoyevsky, and Plato as well as Shestov's own critique of reason and philosophical systematization.[citation needed] |

生い立ち ジョルジュ・バタイユは、徴税人であったジョセフ=アリスティド・バタイユ(1851年生まれ)とアントワネット=アグラエ・トゥルナール(1865年生 まれ)の息子である。1897年9月10日、オーヴェルニュ地方のビロムで生まれ、1898年に一家でランスに移り、そこで洗礼を受ける[3]。無宗教で 育ったが、1914年にカトリックに改宗し、約9年間敬虔なカトリック信者となる。司祭になることを考え、一時カトリックの神学校に通った。しかし、母親 を養えるような職業に就きたいという理由もあったようだ。最終的には1920年代初頭にキリスト教を放棄した[4]。 バタイユはパリの国立シャルト学院に入学し、1922年2月に卒業。学士論文は『L'ordre de la chevalerie, conte en vers du xiiie siècle, avec introduction et notes』(シュヴァレリー騎士団、12世紀の詩による記述、序論と注)。国立図書館に勤務していたため、アーキヴィストや司書と呼ばれることが多い が、彼の仕事はメダイユ・コレクションであった(貨幣学に関する学術論文も発表している)。シャルト大学での卒業論文は、中世の詩L'Ordre de chevalerieの批評版で、詩を再構成した8つの写本を分類して直接作成した。卒業後、マドリードの高等スペイン語学校に移る。若い頃、彼はロシア の実存主義者レフ・シェストフと親しくなり、彼から多くの影響を受けた。彼は、ニーチェ、ドストエフスキー、プラトンの著作や、シェストフ自身の理性批 判、哲学的体系化を学んだ[要出典]。 |

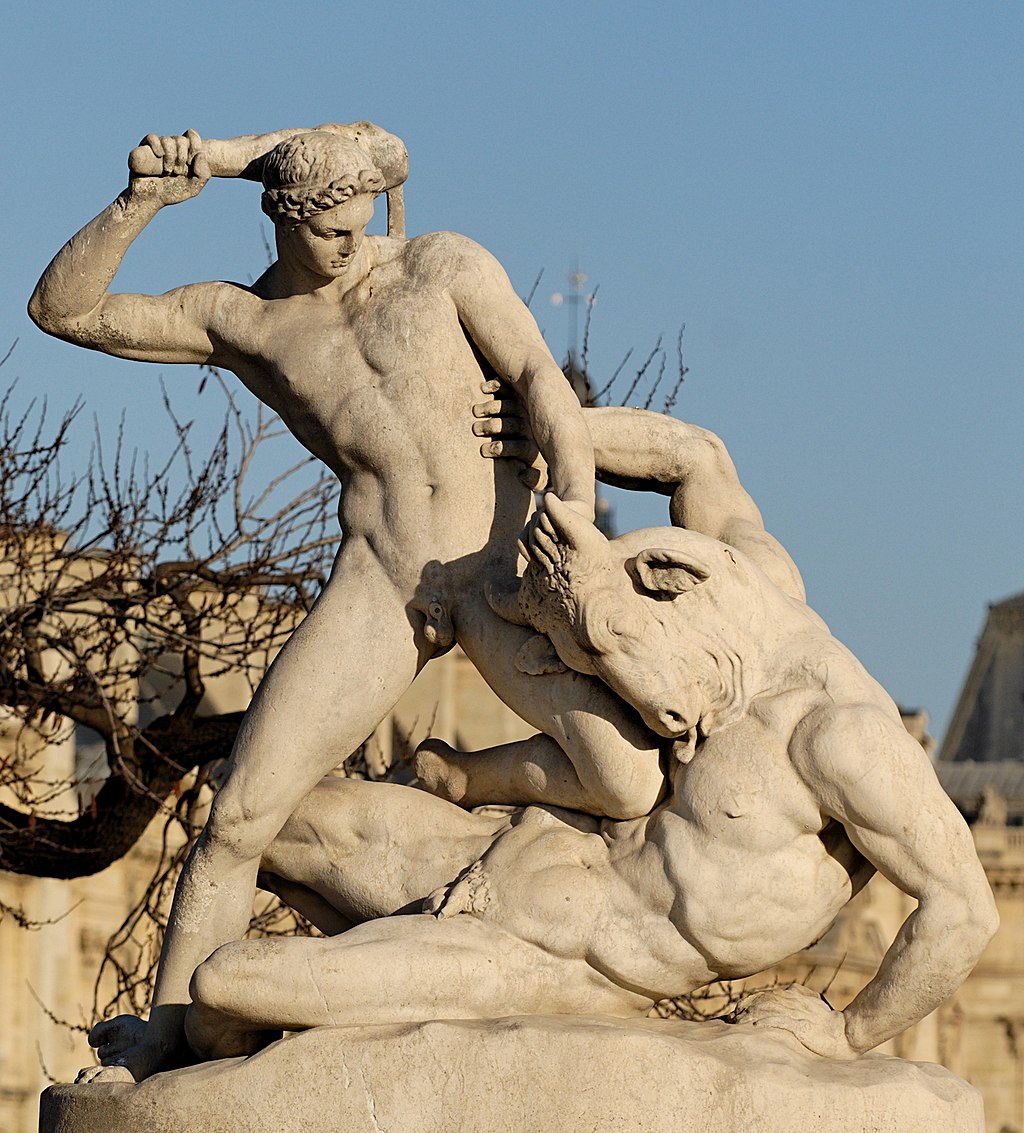

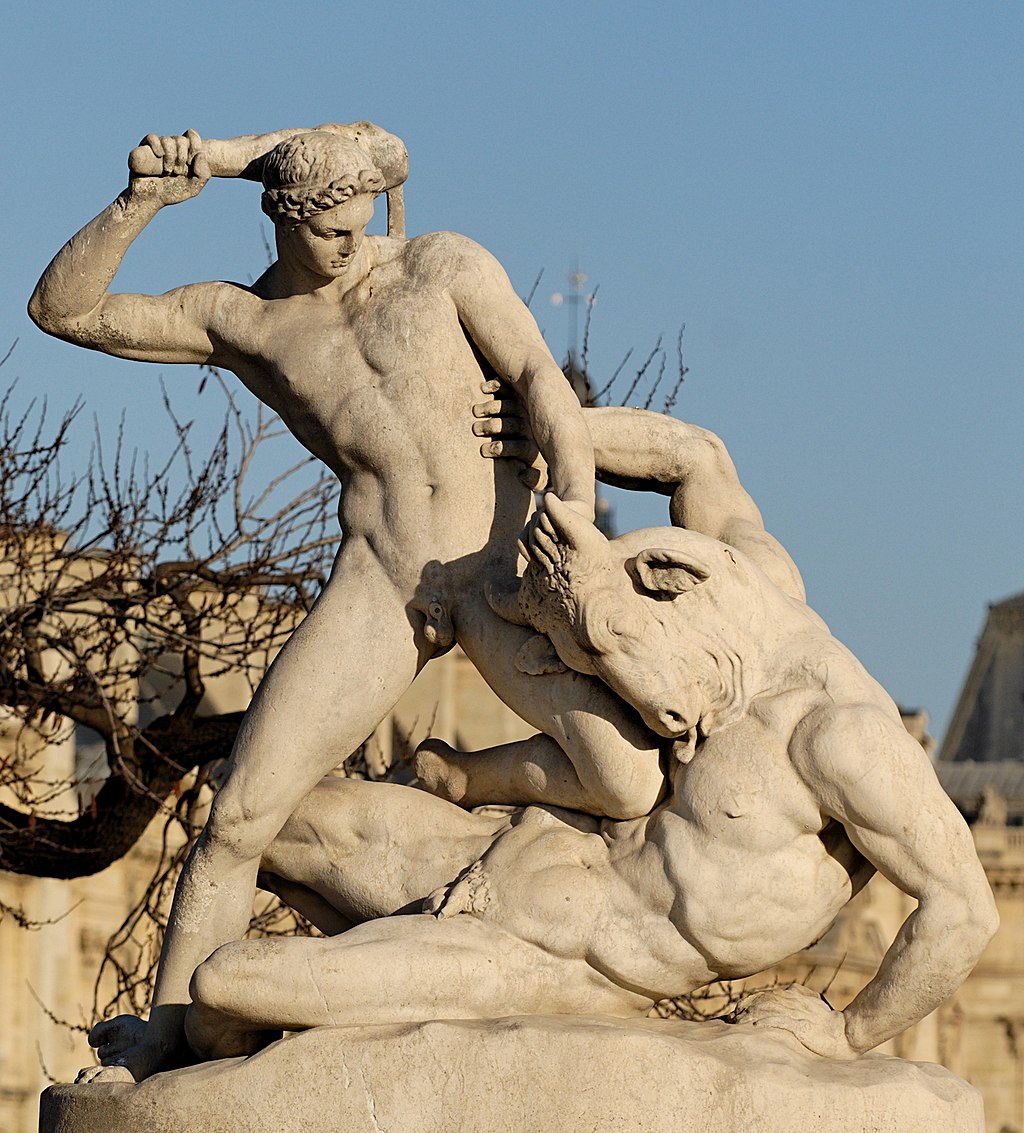

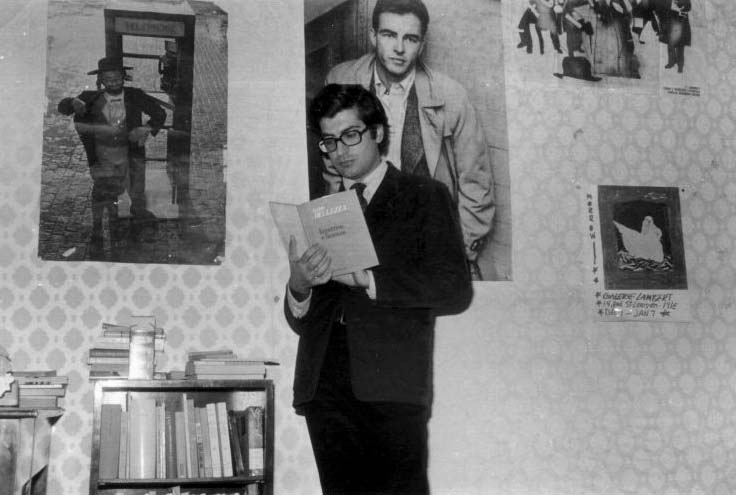

| Career Founder of several journals and literary groups, Bataille is the author of a large and diverse body of work: readings, poems, essays on innumerable subjects (on the mysticism of economy, poetry, philosophy, the arts and eroticism). He sometimes published under pseudonyms, and some of his publications were banned.[citation needed] He was relatively ignored during his lifetime and scorned by contemporaries such as Jean-Paul Sartre as an advocate of mysticism, but after his death had considerable influence on authors such as Michel Foucault, Philippe Sollers, and Jacques Derrida, all of whom were affiliated with the journal Tel Quel. His influence is felt most explicitly in the phenomenological work of Jean-Luc Nancy, but is also significant for the work of Jean Baudrillard, the psychoanalytic theories of Jacques Lacan, Julia Kristeva, and recent anthropological work from the likes of Michael Taussig. Initially attracted to Surrealism, Bataille quickly fell out with its founder André Breton, although Bataille and the Surrealists resumed cautiously cordial relations after World War II. Bataille was a member of the extremely influential College of Sociology which included several other renegade surrealists. He was heavily influenced by Hegel, Freud, Marx, Marcel Mauss, the Marquis de Sade, Alexandre Kojève, and Friedrich Nietzsche,[5] the last of whom he defended in a notable essay against appropriation by the Nazis.[6] Fascinated by human sacrifice, he founded a secret society, Acéphale, the symbol of which was a headless man. According to legend, Bataille and the other members of Acéphale each agreed to be the sacrificial victim as an inauguration; none of them would agree to be the executioner. An indemnity was offered for an executioner, but none was found before the dissolution of Acéphale shortly before the war. The group also published an eponymous review of Nietzsche's philosophy which attempted to postulate what Derrida has called an "anti-sovereignty". Collaborators in these projects included André Masson, Pierre Klossowski, Roger Caillois, Jules Monnerot, Jean Rollin and Jean Wahl. The German philosopher and cultural critic, Walter Benjamin, described Bataille and Acéphale’s fascination with sacrifice as a “pre-fascist aestheticism”.[7] Bataille drew from diverse influences and used various modes of discourse to create his work. His novel Story of the Eye (Histoire de l'oeil), published under the pseudonym Lord Auch (literally, Lord "to the shithouse" — "auch" being short for "aux chiottes," slang for telling somebody off by sending him to the toilet), was initially read as pure pornography, while interpretation of the work has gradually matured to reveal the same considerable philosophical and emotional depth that is characteristic of other writers who have been categorized within "literature of transgression". The imagery of the novel is built upon a series of metaphors which in turn refer to philosophical constructs developed in his work: the eye, the egg, the sun, the earth, the testicle. Other famous novels include the posthumously published My Mother (which would become the basis of Christophe Honoré's film Ma Mère), The Impossible and Blue of Noon, which, with its incest, necrophilia,[8] politics, and autobiographical undertones, is a much darker treatment of contemporary historical reality. During World War II Bataille produced Summa Atheologica (the title parallels Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica) which comprises his works Inner Experience, Guilty, and On Nietzsche. After the war he composed The Accursed Share, which he said represented thirty years' work. The singular conception of "sovereignty" expounded there would become an important topic of discussion for Derrida, Giorgio Agamben, Jean-Luc Nancy and others. Bataille also founded the influential journal Critique. |

経歴 いくつかの雑誌と文学グループの創設者であるバタイユは、読書、詩、無数の主題(経済の神秘主義、詩、哲学、芸術、エロティシズム)に関するエッセイな ど、大規模で多様な著作を残している。生前は比較的無視され、ジャン=ポール・サルトルなど同時代の作家からは神秘主義の擁護者として軽蔑されたが、死後 はミシェル・フーコー、フィリップ・ソレール、ジャック・デリダなど、雑誌『テル・ケル』に所属していた作家に多大な影響を与えた。彼の影響は、ジャン= リュック・ナンシーの現象学的作品に最も顕著に感じられるが、ジャン・ボードリヤールの作品、ジャック・ラカンやジュリア・クリステヴァの精神分析理論、 マイケル・タウシグのような最近の人類学的作品にも多大な影響を及ぼしている。 当初シュルレアリスムに惹かれたバタイユは、すぐに創始者アンドレ・ブルトンと対立したが、第二次世界大戦後、バタイユとシュルレアリストたちは慎重に友 好的な関係を回復した。バタイユは、他のシュルレアリスムの反逆者数名を含む、非常に影響力のある社会学大学のメンバーであった。彼はヘーゲル、フロイ ト、マルクス、マルセル・モース、サド侯爵、アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ、フリードリヒ・ニーチェから多大な影響を受けており[5]、最後のニーチェはナ チスによる流用に対して注目すべきエッセイで擁護している[6]。 人身御供に魅了された彼は、秘密結社アセファールを設立し、そのシンボルは首のない男だった。伝説によると、バタイユとアセファールの他のメンバーは、就 任式として犠牲者になることに同意したが、処刑人になることには同意しなかった。処刑人に対する補償金が提供されたが、戦争直前にアセファールが解散する までに誰も見つからなかった。このグループはまた、デリダが「反主権」と呼ぶものを提起しようとしたニーチェ哲学の同名の評論を出版した。これらのプロ ジェクトの協力者には、アンドレ・マッソン、ピエール・クロソウスキー、ロジェ・カイヨワ、ジュール・モヌロー、ジャン・ロラン、ジャン・ヴァールらがい た。ドイツの哲学者であり文化批評家であるヴァルター・ベンヤミンは、バタイユとアセファールの犠牲への魅力を「ファシズム以前の美学」と評した[7]。 バタイユは様々な影響を受け、様々な言説様式を用いて作品を創作した。彼の小説『眼の物語』(Histoire de l'oeil)は、オーシュ公(Lord Auch)というペンネームで出版され、当初は純粋なポルノグラフィとして読まれていたが、作品の解釈は次第に成熟し、「背理文学」に分類される他の作家 と同じように、哲学的、感情的な深みを見せるようになった。この小説のイメージは、彼の作品の中で展開された哲学的構成要素に言及する一連の比喩の上に構 築されている。 その他の有名な小説には、死後に出版された『私の母』(クリストフ・オノレ監督の映画『Ma Mère』の原作となる)、『不可能』、『真昼の青』などがあり、近親相姦、ネクロフィリア、政治[8]、自伝的な含みを持つこの作品は、現代の歴史的現実をより暗く扱っている。 第二次世界大戦中、バタイユは『Summa Atheologica』(このタイトルはトマス・アクィナスの『Summa Theologica』と類似している)を発表し、『Inner Experience』、『Guilty』、『On Nietzsche』から構成されている。戦後、彼は『呪われた分け前』(The Accursed Share)を書き上げたが、これは30年がかりの仕事であったという。そこで説かれた「主権」という特異な概念は、デリダ、ジョルジョ・アガンベン、 ジャン=リュック・ナンシーらにとって重要な議論のテーマとなった。バタイユはまた、影響力のある雑誌『批評』を創刊した。 |

| Personal life Bataille's first marriage was to actress Silvia Maklès, in 1928; they divorced in 1934, and she later married the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. Bataille also had an affair with Colette Peignot, who died in 1938. In 1946 Bataille married Diane de Beauharnais (author, pseudonym, Selena Warfield),[9] with whom he had a daughter. In 1955 Bataille was diagnosed with cerebral arteriosclerosis, although he was not informed at the time of the terminal nature of his illness.[10] He died seven years later, on 9 July 1962. Bataille was an atheist.[11] Themes At the crossroads of knowledge and the great ideological, philosophical and anthropological debates of his time, his work is both literary and philosophical, multiple, heterogeneous, marginal and escapes labelling: "the traditional categories, the delimitations they establish, prove inappropriate or cumbersome when one wants to account for the whole of his writings". All the more so since he went out of his way to blur the lines, as he himself declared in his last interview with Madeleine Chapsal in March 1961: "I would willingly say that what I am most proud of is having blurred the lines [...], that is to say, having associated the most turbulent and shocking way of laughing, the most scandalous, with the deepest religious spirit". This "scrambling" is all the more evident because of the multiple versions, manuscripts and typescripts of his texts, and also because he often used pseudonyms to sign certain writings (such as erotic stories): Troppmann, Lord Auch, Pierre Angélique, Louis Trente and Dianus. |

私生活 バタイユの最初の結婚は1928年、女優のシルヴィア・マクレズとのもので、1934年に離婚し、後に精神分析家のジャック・ラカンと結婚した。バタイユ はコレット・ペニョとも関係を持ったが、ペニョは1938年に死去。1946年、バタイユはディアーヌ・ド・ボーアルネ(作家、ペンネーム、セレーナ・ ウォーフィールド)と結婚し、娘をもうけた[9]。 1955年、バタイユは脳動脈硬化症と診断されるが、その時点では末期であることは知らされていなかった[10]。7年後の1962年7月9日に死去。 バタイユは無神論者であった[11]。 テーマ バタイユの作品は、文学的であると同時に哲学的であり、多義的であり、異質であり、周縁的であり、レッテル貼りを免れている: 「伝統的なカテゴリーや区切りは、彼の著作全体を説明しようとするとき、不適切であったり、面倒であったりする」。 1961年3月、マドレーヌ・チャプサルとの最後のインタビューで、彼自身が宣言しているように: 「つまり、最も乱暴で衝撃的な笑い方、最もスキャンダラスな笑い方を、最も深い宗教的精神と結びつけたことである」。この "曖昧さ "は、彼のテキストに複数のバージョン、写本、活字があること、また、彼がしばしばペンネームを使って特定の著作(エロティックな物語など)に署名してい たことから、いっそう明白になっている: トロップマン、オーシュ卿、ピエール・アンジェリーク、ルイ・トレンテ、ディアヌスなどである。 |

| Key concepts Base materialism Bataille developed base materialism during the late 1920s and early 1930s as an attempt to break with mainstream materialism, which he viewed as a subtle form of idealism.[12] He argues for the concept of an active base matter that disrupts the opposition of high and low and destabilises all foundations. Inspired by Gnostic ideas, this notion of materialism defies strict definition and rationalisation. Base materialism was a major influence on Derrida's deconstruction, and both thinkers attempt to destabilise philosophical oppositions by means of an unstable "third term." Bataille's notion of materialism may also be seen as anticipating Louis Althusser's conception of aleatory materialism or "materialism of the encounter," which draws on similar atomist metaphors to sketch a world in which causality and actuality are abandoned in favor of limitless possibilities of action. The "accursed share" La Part maudite is a book written by Bataille between 1946 and 1949, when it was published by Les Éditions de Minuit. It was translated into English and published in 1991, with the title The Accursed Share. It presents a new economic theory, which Bataille calls "general economy," as distinct from the "restricted" economic perspective of most economic theory. Thus, in the theoretical introduction, Bataille writes the following: I will simply state, without waiting further, that the extension of economic growth itself requires the overturning of economic principles—the overturning of the ethics that grounds them. Changing from the perspectives of restrictive economy to those of general economy actually accomplishes a Copernican transformation: a reversal of thinking—and of ethics. If a part of wealth (subject to a rough estimate) is doomed to destruction or at least to unproductive use without any possible profit, it is logical, even inescapable, to surrender commodities without return. Henceforth, leaving aside pure and simple dissipation, analogous to the construction of the Pyramids, the possibility of pursuing growth is itself subordinated to giving: The industrial development of the entire world demands of Americans that they lucidly grasp the necessity, for an economy such as theirs, of having a margin of profitless operations. An immense industrial network cannot be managed in the same way that one changes a tire… It expresses a circuit of cosmic energy on which it depends, which it cannot limit, and whose laws it cannot ignore without consequences. Woe to those who, to the very end, insist on regulating the movement that exceeds them with the narrow mind of the mechanic who changes a tire.[13] |

主要概念 基層唯物論 バタイユは1920年代後半から1930年代前半にかけて、観念論の微妙な形態とみなす主流の唯物論と決別する試みとして、基層唯物論を展開した [12]。彼は、高次と低次の対立を破壊し、あらゆる基盤を不安定にする能動的な基層物質の概念を主張する。グノーシス主義の思想に触発されたこの唯物論 の概念は、厳密な定義や合理化を拒むものである。基層的唯物論はデリダの脱構築に大きな影響を与え、両思想家は不安定な "第三項 "によって哲学的対立を不安定にしようと試みている。バタイユの唯物論という概念は、ルイ・アルチュセールの「偶発的唯物論」あるいは「出会いの唯物論」 という概念を先取りしていると見ることもできる。この概念は、同様の原子論的メタファーを用いて、行為の無限の可能性を優先して因果性と実在性が放棄され た世界を描いている。 "呪われた分け前" La Part maudite』はバタイユが1946年から1949年にかけて書いた本で、Les Éditions de Minuitから出版された。1991年に英訳され、『The Accursed Share(呪われた分け前)』というタイトルで出版された。この本は、バタイユが「一般経済」と呼ぶ新しい経済理論を提示したもので、ほとんどの経済理 論が持つ「制限された」経済的視点とは異なるものである。その理論的序論で、バタイユは次のように書いている: 経済成長の拡大には、経済原理の転覆が必要であり、その根拠となる倫理観の転覆が必要である。制限的経済から一般的経済への転換は、実はコペルニクス的転 換を成し遂げる。富の一部(大まかな見積もりは可能)が破壊されるか、少なくとも利益を得ることなく非生産的に使用される運命にあるのであれば、見返りを 求めずに商品を放棄することは論理的であり、避けられないことでさえある。今後、ピラミッド建設に似た純粋で単純な散財はさておき、成長を追求する可能性 自体が贈与に従属することになる: 全世界の産業発展がアメリカ人に要求しているのは、彼らのような経済にとって、利益を生まない余裕を持つことの必要性を明確に把握することである。巨大な 産業ネットワークは、タイヤを交換するのと同じように管理することはできない......それは宇宙エネルギーの回路を表現しており、それに依存し、制限 することはできず、その法則を無視することはできない。最後まで、タイヤを交換する機械工のような狭い心で、自分たちを超える運動を規制しようと主張する 人々には災いがある[13]。 |

| Thus,

according to Bataille's theory of consumption, the accursed share is

that excessive and non-recuperable part of any economy which is

destined to one of two modes of economic and social expenditure. This

must either be spent luxuriously and knowingly without gain in the

arts, in non-procreative sexuality, in spectacles and sumptuous

monuments, or it is obliviously destined to an outrageous and

catastrophic outpouring in war. Though the distinction is less apparent

in Hurley's English translation, Bataille introduces the neologism

"consummation" (akin to a fire's burning) to signal this excess

expenditure as distinct from "consommation" (the non-excess expenditure

more familiarly treated in theories of "restricted" economy). The notion of "excess" energy is central to Bataille's thinking. Bataille's inquiry takes the superabundance of energy, beginning from the infinite outpouring of solar energy or the surpluses produced by life's basic chemical reactions, as the norm for organisms. In other words, an organism in Bataille's general economy, unlike the rational actors of classical economy who are motivated by scarcity, normally has an "excess" of energy available to it. This extra energy can be used productively for the organism's growth or it can be lavishly expended. Bataille insists that an organism's growth or expansion always runs up against limits and becomes impossible. The wasting of this energy is "luxury." The form and role luxury assumes in a society, are characteristic of that society. "The accursed share" refers to this excess, destined for waste. Crucial to the formulation of the theory was Bataille's reflection upon the phenomenon of potlatch. It is influenced by Marcel Mauss's The Gift, as well as by Friedrich Nietzsche's On the Genealogy of Morals. |

こ

のように、バタイユの消費論によれば、呪われた分け前とは、あらゆる経済において、経済的・社会的支出の2つの様式のいずれかに運命づけられた、過剰で回

収不可能な部分のことである。それは、芸術、非生産的な性欲、見世物、豪華な記念碑などに、贅沢を承知で無益に費やされるか、あるいは、戦争という非道で

破滅的な支出に無自覚に運命づけられているかのどちらかである。ハーリーの英訳では、この区別はあまり明確ではないが、バタイユは「消費」(「制限され

た」経済理論でよりよく扱われる非過剰支出)とは異なるこの過剰支出を示すために、「消費」(火の燃焼に似ている)という新語を導入している。 過剰」エネルギーという概念は、バタイユの思考の中心をなすものである。バタイユの探求は、太陽エネルギーの無限の流出や、生命の基本的な化学反応によっ て生み出される余剰に始まる、エネルギーの過剰を生物の規範とする。言い換えれば、バタイユの一般経済における生物は、欠乏に突き動かされる古典派経済の 合理的行為者とは異なり、通常、利用可能なエネルギーの「余剰」を持っている。この余剰エネルギーは、生物の成長のために生産的に使われることもあれば、 浪費されることもある。バタイユは、生物の成長や拡大は常に限界にぶつかり、不可能になると主張する。このエネルギーの浪費が "贅沢 "である。ある社会で贅沢がどのような形をとり、どのような役割を果たすかは、その社会の特徴である。"呪われた分け前 "とは、浪費される運命にある過剰なものを指す。 バタイユは、ポトラッチという現象について考察した。この理論は、マルセル・モースの『贈与』やフリードリヒ・ニーチェの『道徳の系譜』に影響を受けている。 |

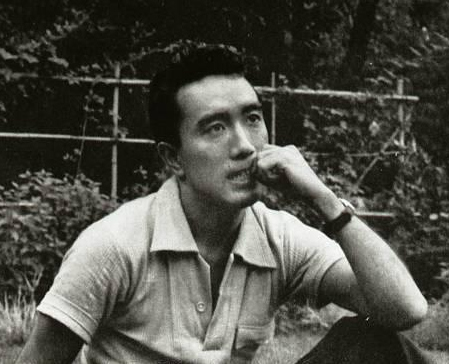

| Bibliography A work-in-progress listing of Bataille's work and English translations can be found at Progressive Geographies. Complete works Georges Bataille, Œuvres complètes (Paris: Gallimard): Volume 1: Premiers écrits, 1922–1940: Histoire de l'œil - L'Anus solaire - Sacrifices - Articles Volume 2: Écrits posthumes, 1922–1940 Volume 3: Œuvres littéraires: Madame Edwarda - Le Petit - L'Archangélique - L'Impossible - La Scissiparité - L'Abbé C. - L'être indifférencié n'est rien - Le Bleu du ciel Volume 4: Œuvres littéraires posthumes: Poèmes - Le Mort - Julie - La Maison brûlée - La Tombe de Louis XXX - Divinus Deus - Ébauches Volume 5: La Somme athéologique I: L'Expérience intérieure - Méthode de méditation - Post-scriptum 1953 - Le Coupable - L'Alleluiah Volume 6: La Somme athéologique II: Sur Nietzsche - Mémorandum - Annexes Volume 7: L'économie à la mesure de l'univers - La Part maudite - La limite de l'utile (Fragments) - Théorie de la Religion - Conférences 1947-1948 - Annexes Volume 8: L'Histoire de l'érotisme - Le surréalisme au jour le jour - Conférences 1951-1953 - La Souveraineté - Annexes Volume 9: Lascaux, ou La naissance de l’art - Manet - La littérature et le mal - Annexes Volume 10: L’érotisme - Le procès de Gilles de Rais - Les larmes d’Eros Volume 11: Articles I, 1944–1949 Volume 12: Articles II, 1950–1961 Georges Bataille: Une liberté souveraine: Textes et entretiens, 2004 (articles, book reviews and interviews not included in Oeuvres Complètes, Michel Surya Ed.) Works published in French Histoire de l'oeil, 1928 (Story of the Eye) (under pseudonym of Lord Auch) L'Anus solaire, 1931 (The Solar Anus) The Notion of Expenditure, 1933 L'Amitié, 1940 (Friendship) (under pseudonym of Dianus; early version of Part One of Le Coupable) Madame Edwarda, 1941 (under pseudonym of Pierre Angélique, fictitiously dated 1937; 2nd Edition: 1945; 3rd Edition: 1956 published with preface in Bataille's name)[14] Le Petit, 1943 (under pseudonym of Louis Trente; fictitious publication date of 1934) L'expérience intérieure, 1943 (Inner Experience) L'Archangélique, 1944 (The Archangelical) Le Coupable, 1944 (Guilty) Sur Nietzsche, 1945 (On Nietzsche) Dirty, 1945 L'Orestie, 1945 (The Oresteia) Histoire de rats, 1947 (A Story of Rats) L'Alleluiah, 1947 (Alleluia: The Catechism of Dianus) Méthode de méditation, 1947 (Method of Meditation) La Haine de la Poésie, 1947 (The Hatred of Poetry; reissued in 1962 as The Impossible) La Scissiparité, 1949 (The Scission) La Part maudite, 1949 (The Accursed Share) L'Abbé C, 1950 L'expérience intérieure, 1954 (second edition of Inner Experience, followed by Method of Meditation and Post-scriptum 1953) L'Être indifférencié n'est rien, 1954 (Undifferentiated Being is Nothing) Lascaux, ou la Naissance de l'Art, 1955 Manet, 1955 Le paradoxe de l'érotisme, Nouvelle Revue Française, n°29, 1er Mai 1955. Le Bleu du ciel, 1957 (written 1935–36) (Blue of Noon) La littérature et le Mal, 1957 (Literature and Evil) L'Erotisme, 1957 (Erotism) Le Coupable, 1961 (Guilty, second, revised edition, followed by Alleluia: The Catechism of Dianus) Les larmes d'Éros, 1961 (The Tears of Eros) L'Impossible : Histoire de rats suivi de Dianus et de L'Orestie, 1962 (The Impossible) Posthumous works Ma Mère, 1966 (My Mother) Le Mort, 1967 (The Dead Man) Théorie de la Religion, 1973 (Theory of Religion) Translated works Lascaux; or, the Birth of Art, the Prehistoric Paintings, Austryn Wainhouse, 1955, Lausanne: Skira. Manet, Austryn Wainhouse and James Emmons, 1955, Editions d'Art Albert Skira. Literature and Evil, Alastair Hamilton, 1973, Calder & Boyars Ltd. Visions of Excess: Selected Writings 1927-1939, Allan Stoekl, Carl R. Lovitt, and Donald M. Leslie, Jr., 1985, University of Minnesota Press. Erotism: Death and Sensuality, Mary Dalwood, 1986, City Lights Books. Story of the Eye, Joachim Neugroschel, 1987, City Lights Books. The Accursed Share: An Essay On General Economy. Volume I: Consumption, Robert Hurley, 1988, Zone Books. The College of Sociology, 1937–39 (Bataille et al), Betsy Wing, 1988, University of Minnesota Press. Guilty, Bruce Boone, 1988, The Lapis Press. Inner Experience, Leslie Anne Boldt, 1988, State University of New York. My Mother, Madame Edwarda, The Dead Man, Austryn Wainhouse, with essays by Yukio Mishima and Ken Hollings, 1989, Marion Boyars Publishers. The Tears of Eros, Peter Connor, 1989, City Lights Books. Theory of Religion, Robert Hurley, 1989, Zone Books. The Accursed Share: Volumes II and III, Robert Hurley, 1991, Zone Books. The Impossible, Robert Hurley, 1991, City Lights Books. The Trial of Gilles de Rais, Richard Robinson, 1991, Amok Press. On Nietzsche, Bruce Boone, 1992, Paragon House. The Absence of Myth: Writings on Surrealism, Michael Richardson, 1994, Verso. Encyclopaedia Acephalica (Bataille et al), Iain White et al., 1995, Atlas Press. L'Abbé C, Philip A Facey, 2001, Marion Boyars Publishers. Blue of Noon, Harry Mathews, 2002, Marion Boyars Publishers. The Unfinished System of Nonknowledge, Stuart Kendall and Michelle Kendall, 2004, University of Minnesota Press. The Cradle of Humanity: Prehistoric Art and Culture, Stuart Kendall, Michelle Kendall, 2009, Zone Books. Divine Filth: Lost Scatology and Erotica, Mark Spitzer, 2009, Solar Books. W.C., (fragmented) novel by Georges Bataille and Antonio Contiero; edited by Transeuropa Edizioni (Massa, 9/2011), ISBN 978-88-7580-150-2; accompanied with music by Alessandra Celletti and Jaan Patterson (Bubutz Records). Collected Poems of Georges Bataille, Mark Spitzer (ed.), 1998, 1999, Dufour Editions. Hardback is titled Collected Poetry of Georges Bataille, 1998. The Sacred Conspiracy: The Internal Papers of the Secret Society of Acéphale and Lectures to the College of Sociology, with additional texts by Roger Caillois, translated by Natasha Lehrer, John Harman and Meyer Barash, Atlas, 2018. |

参考文献 バタイユの作品と英訳の進行中のリストは、Progressive Geographiesに掲載されている。 全集 ジョルジュ・バタイユ、Œuvres complètes(パリ:ガリマール): 第1巻:Premiers écrits、1922年~1940年:Histoire de l'œil - L'Anus solaire - Sacrifices - Articles 第2巻:遺稿、1922年~1940年 第3巻:文学作品:マダム・エドゥアルダ - ル・プティ - ラルカンジェリック - ランポッシブル - ラ・シシパリティ - ラルベー・C - 差異化されない存在は無である - ル・ブルー・デュ・シエル 第4巻:死後の文学作品:詩 - 死者 - ジュリー - 燃える家 - ルイ13世の墓 - 神なる神 - 習作 第5巻:神学大全I:内面的体験 - 瞑想の方法 - 1953年追記 - 罪人 - アレルヤ 第6巻:『神学要論』第2巻:ニーチェについて - 覚書 - 付録 第7巻:宇宙の規模に合わせた経済学 - 呪われた部分 - 有用性の限界(断片) - 宗教論 - 1947年から1948年の講演 - 付録 第8巻:エロティシズムの歴史 - 現実の日々における超現実主義 - 1951年から1953年の講演 - 主権 - 付録 第9巻:ラスコー、あるいは芸術の誕生 - マネ - 文学と悪 - 付録 第10巻:エロティシズム - ギルドレの審判 - エロスの涙 第11巻:論文 I、1944~1949 年 第12巻:論文 II、1950~1961 年 ジョルジュ・バタイユ著『至高の自由:テクストとインタビュー』2004年(論文、書評、インタビューは『全集』には含まれていない。ミシェル・スュルヤ編) フランス語で出版された作品 『Histoire de l'oeil』(『眼の物語』)(オーシュ卿の偽名で)1928年 『L'Anus solaire』(『太陽の肛門』)1931年 『The Notion of Expenditure』(『支出の概念』)1933年 『L'Amitié』(『友情』)(ディアニスの偽名で。『Le Coupable』第1部の初期バージョン)1940年 『マダム・エドゥアルダ』(1941年、ピエール・アンジェリクの偽名で、1937年という架空の出版年。第2版:1945年、第3版:1956年、バタイユの序文付きで出版)[14] 『ル・プティ』(1943年、ルイ・トランテの偽名で、1934年という架空の出版年) L'expérience intérieure, 1943 (Inner Experience) L'Archangélique, 1944 (The Archangelical) Le Coupable, 1944 (Guilty) Sur Nietzsche, 1945 (On Nietzsche) Dirty, 1945 L'Orestie, 1945 (The Oresteia) Histoire de rats, 1947 (A Story of Rats) L'Alleluiah, 1947 (Alleluia: The Catechism of Dianus) Méthode de méditation, 1947 (Method of Meditation) La Haine de la Poésie, 1947 (The Hatred of Poetry; reissued in 1962 as The Impossible) 1949年『分裂』(La Scissiparité) 1949年『呪われた分け前』(La Part maudite) 1950年『C神父』 1954年『内面の体験』(L'expérience intérieure)第2版(『内面の体験』に続き、『瞑想の方法』、『1953年追記』が続く) 区別なき存在は無である、1954年(Undifferentiated Being is Nothing) ラスコー、あるいは芸術の誕生、1955年 マネ、1955年 エロティスムのパラドックス、ヌーヴェル・レヴュー・フランセーズ、第29号、1955年5月1日。 『真昼の青』、1957年(1935年から1936年に執筆) 『文学と悪』、1957年 『エロティシズム』、1957年 『罪人』、1961年(『罪人』第2版、改訂版、それに続く『アレルヤ:ディアニスのカテキズム』 Les larmes d'Éros, 1961 (エロスの涙) L'Impossible : Histoire de rats suivi de Dianus et de L'Orestie, 1962 (不可能) 死後出版された作品 『母』、1966年(『私の母』) 『死者』、1967年(『死せる者』) 『宗教論』、1973年(『宗教論』) 翻訳作品 ラスコー、あるいは芸術の誕生、先史時代の絵画、オースティン・ウェインハウス、1955年、ローザンヌ:Skira。 マネ、オースティン・ウェインハウスとジェームズ・エモンズ、1955年、エディシオン・ダール・アルベール・スキラ。 文学と悪、アラスダー・ハミルトン、1973年、Calder & Boyars Ltd. 過剰のビジョン:1927年から1939年の選ばれた著作、アラン・ストークル、カール・R・ラビット、ドナルド・M・レスリー・ジュニア、1985年、ミネソタ大学出版。 エロティシズム:死と官能性、メアリー・ダルウッド、1986年、シティライツブックス。 視線の物語、ヨアヒム・ノイグロシェル、1987年、シティライツブックス。 呪われた共有:一般経済に関するエッセイ。第1巻:消費、ロバート・ハーレー、1988年、ゾーンブックス。 社会学大学、1937年~39年(バタイユ他)、ベッツィ・ウィング、1988年、ミネソタ大学出版。 有罪、ブルース・ブーン、1988年、ラピス・プレス。 『内なる体験』、レスリー・アン・ボールド、1988年、ニューヨーク州立大学出版。 『わが母、マダム・エドワダ』、『死せる男』、オースティン・ウェインハウス、三島由紀夫とケン・ホリングスのエッセイ付き、1989年、マリオン・ボヤーズ・パブリッシャーズ。 『エロスの涙』、ピーター・コナー、1989年、シティライツ・ブックス。 『宗教の理論』ロバート・ハーレイ著、1989年、ゾーンブックス。 『呪われた分け前:第2巻および第3巻』ロバート・ハーレイ著、1991年、ゾーンブックス。 『不可能』ロバート・ハーレイ著、1991年、シティライツブックス。 『ジル・ド・レイの裁判』リチャード・ロビンソン著、1991年、アモックプレス。 ニーチェについて、ブルース・ブーン、1992年、パラゴン・ハウス。 神話の不在:シュールレアリスムに関する著作、マイケル・リチャードソン、1994年、ヴァーソ。 百科全書アケファリカ(バタイユ他)、イアン・ホワイト他、1995年、アトラス・プレス。 アベ・C、フィリップ・フェイシー、2001年、マリオン・ボヤーズ・パブリッシャーズ。 『真昼の青』ハリー・マシューズ著、2002年、マリオン・ボヤーズ・パブリッシャーズ。 『未完成の無知体系』スチュアート・ケンドール、ミシェル・ケンドール著、2004年、ミネソタ大学出版。 『人類発祥の地:先史時代の芸術と文化』スチュアート・ケンドール、ミシェル・ケンドール著、2009年、ゾーンブックス。 『神聖なる汚物: 失われたスカトロジーとエロティカ、マーク・スピッツァー著、2009年、Solar Books。 W.C.、ジョルジュ・バタイユとアントニオ・コンティエロによる断片的な小説、トランセウロパ・エディツィオーニ(マッサ、2011年9月)編集、 ISBN 978-88-7580-150-2、アレッサンドラ・チェレッティとジャン・パターソンの音楽付き(Bubutz Records)。 ジョルジュ・バタイユ詩集、マーク・スピッツァー編、1998年、1999年、デュフォー出版。ハードカバー版のタイトルは『ジョルジュ・バタイユ詩集』、1998年。 『聖なる陰謀:秘密結社アケファルの内部文書と社会学会での講義』、ロジェ・カイヨワによる追加テキスト、ナターシャ・レフラー、ジョン・ハーマン、メイヤー・バラッシュ訳、アトラス、2018年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Bataille | |

| Georges Albert Maurice Victor Bataille,

né le 10 septembre 1897 à Billom (Puy-de-Dôme) et mort le 9 juillet

1962 à Paris, est un écrivain, philosophe, romancier, poète, essayiste

et bibliothécaire français. Son œuvre se compose d'ouvrages de littérature, mais aussi d'anthropologie, de philosophie, d'économie, de sociologie et d'histoire de l'art. Il ne considère jamais l'écriture comme une fin en soi, mais comme un moyen lui permettant, à travers ses récits, romans, essais philosophiques et revues, de témoigner de ses différentes expériences et fascinations : « Il faut vouloir vivre les grands problèmes, par le corps et par l’esprit1. » Ainsi, sa vie et son œuvre se confondent, mêlant mysticisme et érotisme. À la croisée des savoirs et des grands débats idéologiques, philosophiques et anthropologiques de son temps, son œuvre est à la fois littéraire et philosophique, multiple, hétérogène, marginale et échappe aux étiquetages : « les catégories traditionnelles, les délimitations qu'elles établissent, se révèlent inappropriées ou encombrantes dès lors qu'on veut rendre compte de l'ensemble de ses écrits2 ». D'autant plus qu'il s'est évertué à brouiller les pistes, ainsi qu'il le déclare lui-même dans son dernier entretien, accordé à Madeleine Chapsal en mars 1961 : « Je dirais volontiers que ce dont je suis le plus fier, c'est d'avoir brouillé les cartes […] c'est-à-dire d'avoir associé la façon de rire la plus turbulente et la plus choquante, la plus scandaleuse, avec l'esprit religieux le plus profond3. » Ce « brouillage » est d'autant plus manifeste en raison des multiples versions, manuscrits et dactylogrammes de ses textes, et aussi parce qu'il a souvent usé de pseudonymes pour signer certains écrits (notamment érotiques) : Troppmann, Lord Auch, Pierre Angélique, Louis Trente et Dianus. |

ジョルジュ・アルベール・モーリス・ヴィクトル・バタイユは、1897年9月10日にビヨム(ピュイ・ド・ドーム)で生まれ、1962年7月9日にパリで没したフランスの作家、哲学者、小説家、詩人、エッセイスト、図書館司書である。 文学、人類学、哲学、経済学、社会学、美術史などの分野で活躍した。彼は書くこと自体を目的とはせず、むしろ物語や小説、哲学的エッセイや評論を通して、 自分のさまざまな経験や魅力を表現する手段として捉えていた。「大きな問題を、自分の身体と心で経験したいと思わなければならない」1。このようにして、 彼の人生と作品は融合し、神秘主義とエロティシズムが融合した。 知の交差点にあり、同時代のイデオロギー的、哲学的、人類学的な大論争の交差点にあった彼の作品は、文学的であり哲学的であり、多重的、異質的、周縁的で あり、ラベリングを免れた。1961年3月のマドレーヌ・チャプサルとの最後のインタビューで、彼自身が次のように語っている。「私が最も誇りに思ってい るのは、水を濁したことである(......つまり、最も波乱に満ちた衝撃的な、最もスキャンダラスな笑い方と、最も深遠な宗教的精神とを結びつけたこと である)。この 「混濁 」は、彼のテキストの複数の版、写本、活字のために、また、彼が特定の著作(特にエロチカ)に署名するためにしばしばペンネームを使用したために、より明 白である: トロップマン、オーシュ卿、ピエール・アンジェリーク、ルイ・トレンテ、ディアヌスなどである。 |

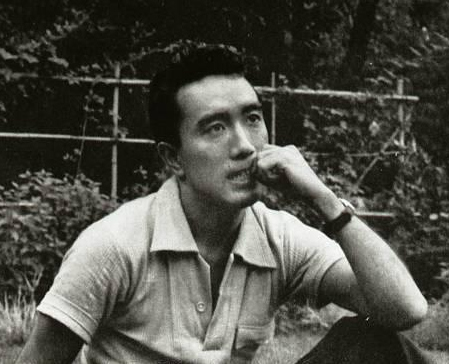

| Biographie Famille et éducation  Georges Bataille, son père et son frère Martial (à droite), vers 1898. Collection Julie Bataille. Le père de Georges, Joseph-Aristide Bataille, a épousé Marie-Antoinette Tournadre alors qu'il avait déjà 35 ans. Successivement économe de collège, employé à la maison centrale de Melun puis receveur buraliste, il a quarante-deux ans à la naissance de son deuxième fils : Georges. L'aîné de Georges, Martial, est celui qui va s'opposer à son frère lorsqu'en 1961 Bataille déclare dans une entrevue avec Madeleine Chapsal que son père était fou4. Joseph-Aristide est atteint de syphilis, maladie qui s'est déclarée entre la naissance de ses deux enfants et qui progresse rapidement. À la naissance de Georges, il est déjà presque aveugle et ses membres sont paralysés, comme Bataille l'évoquera par le biais de la fiction, dans Histoire de l'œil (son premier récit publié, anonymement, en 1928) : « Je suis né d'un père P.G. qui m'a conçu déjà aveugle et qui peu après ma naissance fut cloué dans son fauteuil par sa sinistre maladie »5. Georges n'a que trois ans lorsqu'il est témoin des effets furieux de la maladie de son père : douleurs atroces, troubles des viscères, des sphincters : « il lui arrivait par exemple de conchier ses culottes »6. Georges aime néanmoins ce père qui avait tout d'une « bête ». Il l'aime jusqu'à ce que son amour se transforme en haine quand commencent à se manifester les premiers signes de folie, que Georges constate vers 1911, à l'âge de quatorze ans. Selon lui, l'aveugle criait des insanités à caractère sexuel au médecin venu le soigner, ainsi qu'à sa femme qui perdit la raison pendant un temps7 : « Dis donc, docteur, quand tu auras fini de piner ma femme »8. La famille est alors installée à Reims, sans doute parce que le père y a été muté en 1898. Georges est baptisé à la paroisse Saint-André le 7 août 1898. Toutefois, Marie-Antoinette survit à son époux une quinzaine d'années en compagnie de ses enfants et il n'est plus, ensuite, question de sa folie7. De l'enfance de Georges, on sait peu de choses à l'exception des souvenirs qu'il livre de ses parents. Tous se rapportent d'abord à l'affliction du père. Bataille écrit qu'il s'est adonné au plaisir de l'auto-mutilation avec son porte-plume « pour s'endurcir contre la douleur » dans Le Bleu du ciel, sans qu'il soit possible de distinguer la part autobiographique de ce récit et la part littéraire9. Bataille ne l'a jamais écrit ouvertement, mais il a longtemps été convaincu que son père s'était livré sur lui à des attouchements incestueux, pédérastes, il aurait même parlé de viol10. Un récit inédit, intitulé Le Rêve, décrit ainsi ce père : « Je le vois avec un sourire fielleux et aveugle étendre des mains obscènes sur moi. Ce souvenir me paraît le plus terrible de tous »11. On a fini par convaincre Bataille que ces scènes n'avaient pas pu avoir lieu à la cave comme il le raconte, puisque son père était paralysé, mais il reste sans doute possible que certains gestes du père aient pu paraître obscènes à l'enfant10. C'est cette atmosphère traumatisante que décrit Bernard Noël dans son récit La Maladie de la chairnote 1. Georges étudie au lycée de Reims jusqu'en classe de première, il poursuit ensuite au collège d'Épernay où il est pensionnaire à sa demande, il y obtient son premier baccalauréat en 191412. |

伝記 家族と教育  ジョルジュ・バタイユ、父、弟マルシャル(右)、1898年頃。ジュリー・バタイユ・コレクション。 ジョルジュの父ジョゼフ=アリスティド・バタイユは、35歳の時にマリー=アントワネット・トゥルナドルと結婚した。大学の事務員、ムラン刑務所の職員、 タバコ屋を経て、次男ジョルジュが生まれたのは42歳の時だった。ジョルジュの長男マルシャルは、1961年、バタイユがマドレーヌ・シャプサルのインタ ビューで、父親は精神異常であると断言したとき、兄に立ち向かった人物である4。ジョゼフ=アリスティドは梅毒を患っていた。梅毒は急速に進行する病気 で、二人の子供が生まれる間に発病した。バタイユが『Histoire de l'œil』(1928年に匿名で発表された処女作)の中でフィクションを通して想起させるように、ジョルジュが生まれたとき、彼はすでにほとんど目が見 えず、手足は麻痺していた。「私は、すでに目が見えない私を身ごもり、生まれて間もなく不吉な病気のために肘掛け椅子に閉じこもったP.G.という父親か ら生まれた」5。 耐え難い痛み、内臓や括約筋の障害、「たとえば、ときどきニッカーズの中にウンコを漏らしていた」6。とはいえ、ジョルジュは「動物」としての資質を備え た父を愛していた。しかし、ジョルジュは、「野獣」のような父親を愛していた。1911年、ジョルジュが14歳のとき、狂気の兆候が現れ始め、愛が憎しみ に変わるまで、ジョルジュは父親を愛していた。ジョルジュによると、盲目の男は治療に来た医者や、しばらく正気を失っていた妻に性的な狂気を叫んだ7。 一家はランスに移り住んだ。1898年に父親がランスに赴任したためであろう。ジョルジュは1898年8月7日にサン・アンドレ教区で洗礼を受けた。しか し、マリー=アントワネットは子供たちと一緒にいた夫より15年ほど長生きしており、ジョルジュの狂言7についてはそれ以上触れられていない。ジョルジュ の子供時代については、彼が両親について語った思い出以外、ほとんど知られていない。それらはすべて、まず父親の苦悩に言及している。バタイユは『Le Bleu du ciel』の中で、「痛みから身を守るために」ペン立てで自傷する快楽にふけっていたと書いているが、この記述の自伝的な部分と文学的な部分を区別するこ とはできない9。バタイユはそれについて公には書かなかったが、長い間、父親が近親相姦的、小児性愛的なやり方で自分に触れたと確信しており、レイプにつ いてさえ語っていた10。 Le Rêve(夢)』と題された未発表の記録では、父親について次のように描写している。この記憶は、私にとってあらゆる記憶の中で最も恐ろしいものに思え る」11。バタイユは、父親が半身不随であったため、彼が語るような光景が地下室で繰り広げられたはずはないと最終的に確信したが、それでも、父親の身振 りのいくつかが子供にとって猥褻に映った可能性はある10。ベルナール・ノエルが『La Maladie de la chairnote 1』の中で描いているのは、このトラウマ的な雰囲気である。 ジョルジュはランスのリセで中学1年まで学んだ後、本人の希望でコレージュ・デペルネに進み、1914年に最初のバカロレアを取得した12。 |

| La foi en Dieu, conversion Beaucoup de choses sont difficiles à comprendre, voire inexplicables, dans la démarche de Bataille. Pour quelle raison, affirme-t-il, en 1914, que « son affaire en ce monde était d'écrire, en particulier d'élaborer une philosophie paradoxale »13 ? Il a dix-sept ans à cette date, et rien n'explique pourquoi il découvre Dieu à ce moment-là : son père était irréligieux, sa mère indifférente. Il se convertit en août 1914 à la cathédrale de Reims14 où il assiste aux offices du cardinal Luçon15. Toutefois, il semble qu'il ait reçu le baptême étant enfant16. Dès le mois de septembre de la même année, après la déclaration de guerre par l'Allemagne, Georges est évacué, avec sa mère et son frère, en même temps que les populations réfugiées à Reims depuis le début du mois d'août. Ils s'établissent à Riom-ès-Montagnes dans le Cantal, chez les Tournadre. Le père, incapable de se déplacer, a été laissé sur place, confié aux soins ponctuels d'une femme de ménage17. Georges vit ce départ comme un abandon, il en ressentit une certaine culpabilité, d'autant qu'il ne reverra jamais son père vivant : Joseph-Aristide meurt le 6 novembre 191517. Dans l'esprit de Bataille, la mort du père revient, par un cheminement de pensée complexe, à « la mort d'un dieu ». Sa conversion, passagère, est alors à assimiler à un rapprochement vers un Dieu de consolation. L'influence du christianisme sur sa pensée n'est pas simple à interpréter. Selon Michel Surya, « Georges Bataille ne fut jamais définitivement athée (jamais du moins au sens où l'athéisme ne fut pas pour lui une question), ce n'est pas parce qu'il n'y a pas de Dieu, pas davantage parce que Dieu est mort, mais parce qu'il y a plus fort que Dieu : plus fort parce qu'aveugle (« Dieu dans son infirmité est aveugle quand voir est mon infirmité »), aveugle et fou. Joseph-Aristide Bataille, à sa façon, était la “folie” de Dieu »18. À Riom, Georges mène une vie pieuse dans la maison de ses grands-parents Tournadre. Il passe son temps en promenades et en études, et il prépare son second baccalauréat. Il n'y a que de rares témoignages sur lui à cette époque : il aime chasser, pêcher les truites à mains nues. Entre dix-sept et vingt-trois ans, on le présente plutôt comme un jeune homme modèle, déférent. Le premier texte qu'il écrit en 1918 est un livre pieux, courte plaquette publiée à Saint-Flour : Notre-Dame de Rheims (sic). Il envisage de devenir prêtre, ce dont son oncle Victor le dissuade. Il passe tout de même une année scolaire, d'octobre 1917 à août 1918 au séminaire de Saint-Flour, qu'il quitte à la fin de la guerre pour entrer à Paris à l'École nationale des chartes où il est admis en novembre 1918. Avant d'entrer au séminaire, il est brièvement mobilisé en 1916 et renvoyé en 1917 pour raisons de santé : des problèmes pulmonaires ont été détectés19,note 2. Notre-Dame de Rheims n'est pas à compter dans l'œuvre littéraire de Bataille : anecdotique, autobiographique, il reste seulement un témoignage précis de la jeunesse de l'auteur. L'image des ruines de Notre-Dame de Reims, encore debout, peut être vue comme le symbole de la foi dressée contre l'irréligion, mais inversement, assimilée à l'image de la mère, ses ruines sont aussi le symbole inconscient du doute et de l'abandon : « Elle avait cessé de donner la vie ; elle s'étend comme un cadavre »20. À Paris, il se plonge dans Le Latin mystique de Remy de Gourmont, qui devient son livre de chevet, et Odon de Cluny. Mais, bien que très pieux et très austère, il ne pousse pas aussi loin le déni de la chair que le préconisent Odon de Cluny et Remy de Gourmont21. |

神への信仰、改心 バタイユのアプローチには、理解しがたいもの、不可解なものさえ多い。1914年、なぜ彼は「この世での自分の仕事は書くこと、とりわけ逆説的な哲学を練 り上げることだ」と言ったのだろうか13。父親は無宗教で、母親は無関心だった。1914年8月、ランス大聖堂14で改宗し、ルソン枢機卿の礼拝に出席し た15。しかし、洗礼を受けたのは子供の頃だったようだ16。 同年9月、ドイツの宣戦布告を受け、ジョルジュは母親と弟とともに、8月の初めからランスに避難していた人々とともに避難した。彼らはカンタル地方のリオ ム=エス=モンターニュのトゥルナドレ家に居を構えた。父親は身動きがとれず、掃除婦に預けられた17。ジョルジュはこの旅立ちを育児放棄ととらえ、ある 種の罪悪感を抱いた: ジョゼフ=アリスティドは1915年11月6日に亡くなった17。 バタイユの中では、父の死は「神の死」のようなものだった。彼の改宗は一時的なものであったが、慰めの神との和解に例えられる。キリスト教が彼の思想に与 えた影響を解釈するのは容易ではない。ミシェル・スーリヤによれば、「ジョルジュ・バタイユは決して決定的な無神論者ではなかった(少なくとも彼にとって 無神論が問題ではなかったという意味においては)。ジョゼフ=アリスティド・バタイユは、彼なりのやり方で、神の『狂気』であった」18。 リオムでは、ジョルジュは祖父母のトゥルナドルの家で敬虔な生活を送った。散歩と勉強に明け暮れ、2度目のバカロレアの準備をしていた。狩猟や素手でのマ ス釣りを楽しんでいた。17歳から23歳の間、彼は敬虔で模範的な青年として描かれている。1918年、彼が最初に書いたのは敬虔な書物で、サン・フロー ルで出版された短いパンフレットだった: ノートルダム・ド・ランス』である。司祭になることも考えたが、叔父のヴィクトールが思いとどまらせた。それでも、1917年10月から1918年8月ま での1年間をサン=フルール神学校で過ごし、終戦とともに退学して、1918年11月に入学したパリの国立美術学校に入学した。神学校に入る前、1916 年に短期間動員され、1917年に健康上の理由で除隊した。ランスのノートルダム寺院』は、バタイユの文学作品には数えられない。逸話的、自伝的で、著者 の青年時代の正確な証言でしかない。ランスのノートルダム寺院の廃墟のイメージは、無宗教に対抗する信仰のシンボルとして見ることができるが、逆に、母の イメージと同化して、その廃墟は疑いと放棄の無意識のシンボルでもある:「彼女は命を与えることをやめ、死体のように横たわっていた」20。 パリでは、枕元の本となったレミー・ド・グルモンの『ラテン神秘主義』(Le Latin mystique)と『オドン・ド・クリュニー』(Odon de Cluny)に没頭した。しかし、非常に敬虔で厳格ではあったが、オドン・ド・クリュニーやレミー・ド・グルモンが唱えたような肉体の否定まではしなかっ た21。 |

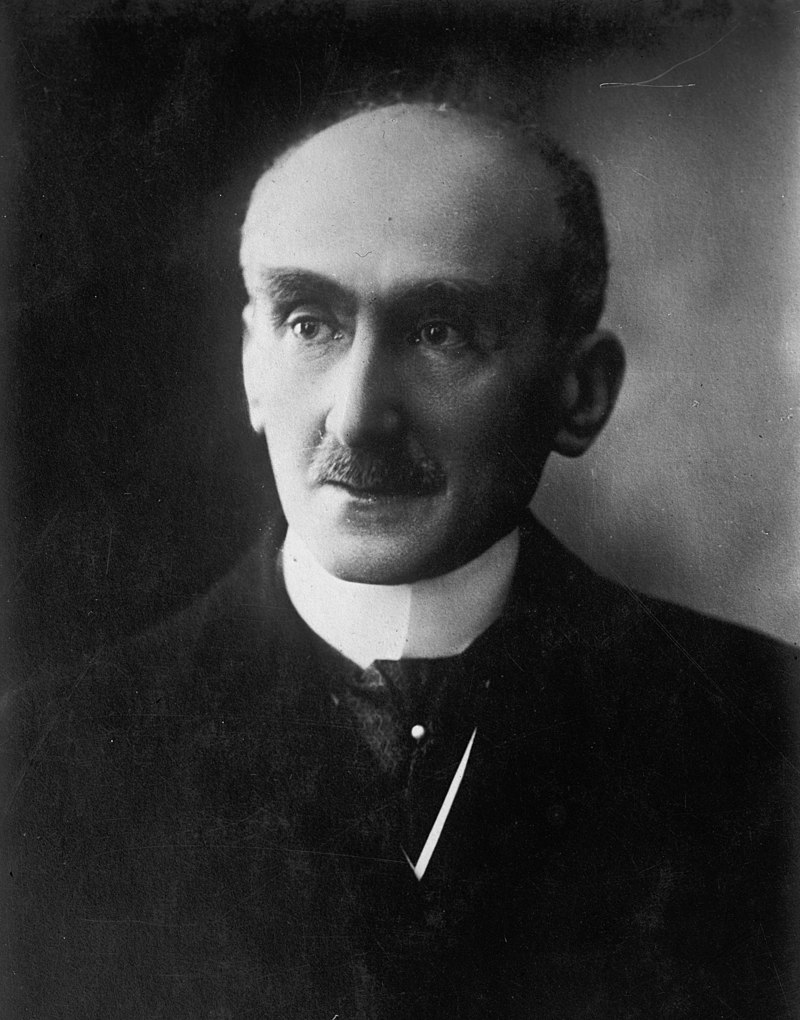

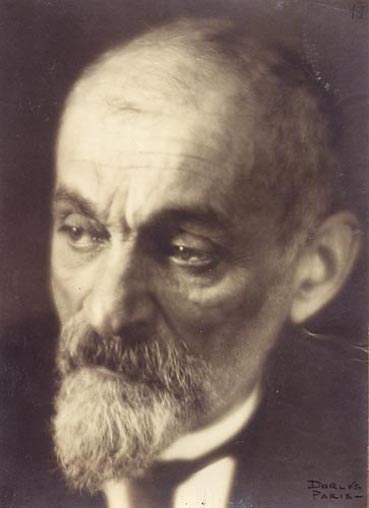

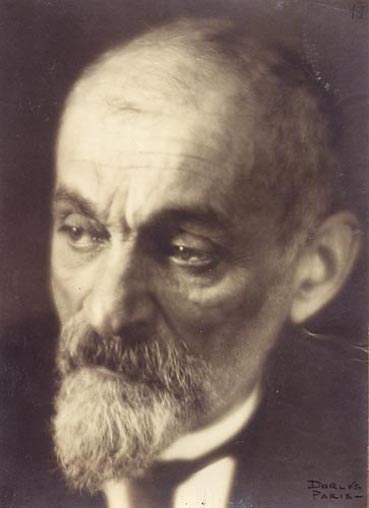

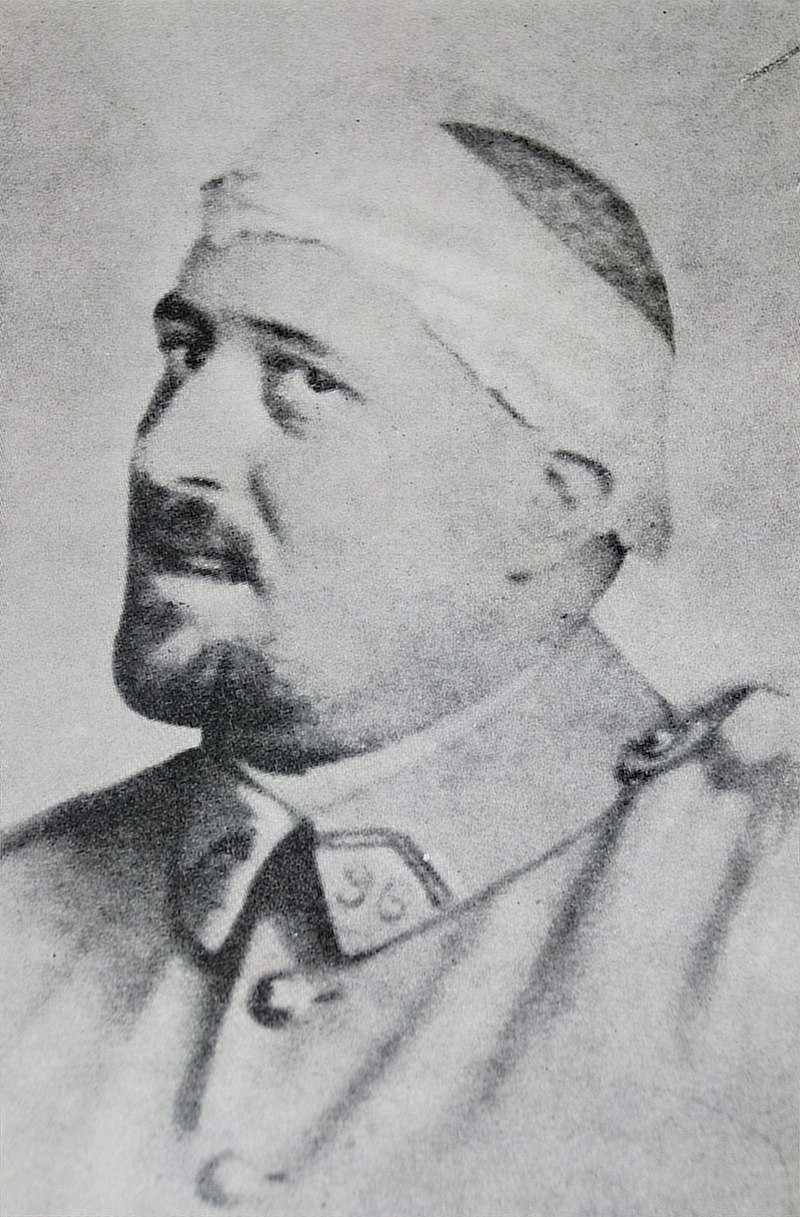

Évolution du jeune homme Casa de Velázquez.  Henri Bergson.  Léon Chestov, 1927.  Las Ventas, arène de Madrid. Bataille a vingt-deux ans lorsqu'il tombe amoureux de Marie Delteil, fille de Jules Delteil, médecin de sa mère, et dont il va demander la main. Expérience douloureuse pour lui comme pour Marie : la demande est refusée en raison des craintes du père sur l'hérédité de Bataille. Déstabilisé, Georges, qui a déjà un penchant pour les femmes22, écrit à sa cousine Marie-Louise Bataille le 9 août 1919 : « Je ne sais plus ce qu'il m'arrivera à travers la tête car il y a déjà longtemps que ma pauvre tête porte je ne sais quoi qui la promet à toutes les aventures »23. En 1920, le jeune homme hésite entre voyager ou vivre en reclus. Il est attiré par l'Orient mais son premier voyage l'emmène en Angleterre pour un séjour d'étude au British Museum de Londres. À cette occasion, il passe trois jours à l'abbaye Notre-Dame de Quarr dans l'île de Wight, séjour fortuit qui n'a aucune influence sur sa décision : entre l'agitation et la contemplation, c'est l'agitation qui l'emporte, semble-t-il24. Lors de son séjour à Londres, il rencontre Henri Bergson, et lit Le Rire qui est une grande déception pour lui. Il revient sur cet événement important à deux reprises, la première fois dans L’Expérience Intérieure : « le rire était révélation, ouvrait le fond des choses. Je dirai l’occasion d’où ce rire est sorti : j’étais à Londres (en 1920) et devais me trouver à table avec Bergson ; je n’avais alors rien lu de lui (ni d’ailleurs, peu s’en faut, d’autres philosophes) ; j’eus cette curiosité, me trouvant au British Museum je demandai le Rire (le plus court de ses livres) ; la lecture m’irrita, la théorie me sembla courte (là-dessus le personnage me déçut : ce petit homme prudent, philosophe !) mais la question, le sens demeuré caché du rire, fut dès lors à mes yeux la question clé (liée au rire heureux, intime, dont je vis sur le coup que j’étais possédé), l’énigme qu’à tout prix je résoudrai (qui, résolue, d’elle-même résoudrait tout)25. » Il y revient plus longuement dans une conférence de 1953 : Non-savoir, rire et larmes : « à Londres, j’ai été reçu dans une maison où l’on recevait également Bergson. [...] j’avais bien lu quelques pages de Bergson, mais j’ai eu la réaction très simple que l’on peut avoir à l’idée que l’on va rencontrer un grand philosophe, on est embarrassé de ne rien connaître, ou presque rien, de sa philosophie. Alors, comme je l’ai d’ailleurs dit dans un de mes livres, mais je voudrais le raconter ici de façon un peu plus précise, je suis allé au British Museum, et j’ai lu Le Rire" de Bergson. Ce n’est pas une lecture qui m’a beaucoup satisfait, mais elle m’a tout de même fortement intéressé. Et je n’ai pas cessé, dans mes diverses considérations sur le rire, de me référer à cette théorie, qui me paraît tout de même l’une des plus profondes que l’on ait développées. J’ai donc lu ce petit livre, qui m’a passionné pour d’autres raisons que le contenu qu’il développait. Ce qui m’a passionné à ce moment-là, c’est la possibilité de réfléchir sur le rire, la possibilité de faire du rire l’objet d’une réflexion. Je voulais de plus en plus approfondir cette réflexion, m’éloigner de ce que j’avais pu retenir du livre de Bergson, mais elle a pris tout d’abord cette tendance, que j’ai cherché à vous représenter, à être en même temps une expérience et une réflexion26. » Après son séjour sur l’île de Wight, il abandonne sa vocation monastique, mais selon Michel Surya, l'abandon de la foi semble plus difficile à dater précisément : « on aurait tort de croire, si vive qu'en ait été la révélation, que le rire remplaça sans délai la révélation qu'il eut en 191427 ». Jean-Jacques Roubine précise que c'est peu à peu qu'il va découvrir « le rire Nietzschéen2 ». Il soutient, en 1922 (30, 31 janvier et 1er février), une thèse sur L'ordre de la chevalerie, conte en vers du xiiie siècle, avec introduction et notes. Reçu deuxième de sa promotion, il est nommé archiviste paléographe, et comme tel, il est envoyé à l'École des hautes études hispaniques de Madrid, actuelle Casa de Velázquez. À Madrid, Bataille, toujours croyant, reste isolé ; il continue de rêver de l'Orient qui reste son seul but. Il décrit son projet dans une lettre à Marie-Louise Bataille : aller au Maroc. Il n'a pas encore découvert l'Espagne qu'il verra plus tard « grave et tragique » et son peuple « angoissé28 ». Enfermé dans sa piété, qu'il efface par la suite en lui superposant l'image d'une danseuse de flamenco, qu'il allait voir chaque soir et dont il dit, en 1946 : « Un petit animal de cette race me semble propre à mettre le feu dans un lit de façon plus ravageante que n'importe quelle créature29. » Bataille s'ennuie. Deux événements le sortent de sa torpeur : la prestation d'un chanteur de flamenco à Grenade, et une corrida du 7 mai 1922 à Madrid où le matador Manuel Granero est mutilé par le taureau qui lui défonce l'œil droit. Le torero meurt, il a à peine vingt ans. Toutefois cette horrible scène ne déclenche pas l'effroi immédiat chez Bataille qui était placé trop loin pour voir. Il va ensuite recréer cet événement en imagination, d'après les récits qu'on lui fait. Plus tard, dans Histoire de l'œil, il consacre un chapitre à cet épisode sanglant intitulé : L'œil de Granero30. À ce moment sans doute, naît en lui ce plaisir mêlé d'angoisse qu'il décrit ainsi : « Jamais, dès lors, je n'allais aux courses de taureaux sans que l'angoisse ne me tendît les nerfs intensément. L'angoisse en aucune mesure n'atténuait le désir d'aller aux arènes. […] Je commençais à comprendre alors que le malaise est souvent le secret des plaisirs les plus grands31. » De retour à Paris, en 1923, Bataille se lie d'amitié avec le vaudois Alfred Métraux auquel il expose une forme de morale cynique (Le Joyeux cynique), acquise par les lectures de Gide, Nietzsche et Dostoïevski. Métraux observe chez son ami une forme de « conversion », un éloignement de toute piété32. État d'esprit qui s'amplifie avec la fréquentation de Léon Chestov qui le guide dans sa lecture de Nietzsche et de Platon : « Léon Chestov philosophait à partir de Dostoïevski et de Nietzsche, ce qui me séduisait. (…). Il se scandalisa de mon aversion outrée pour les études philosophiques et je l'écoutai docilement lorsqu'il me guida avec beaucoup de sens dans la lecture de Platon. C'est à lui que je dois la base de connaissances philosophiques qui, sans avoir le caractère de ce qu'il est commun d'attendre sous ce nom, à la longue n'en sont pas moins devenues réelles. Peu après je devais comme toute ma génération m'incliner vers le marxisme. Chestov était un émigré socialiste et je m'éloignai de lui, mais je lui garde une grande reconnaissance, ce qu'il sut me dire de Platon était ce que j'avais besoin d'entendre33. » Ainsi, l'ancien idéaliste qui envisageait de se faire représentant de Dieu devient bientôt le plus violent de ses apostats. Chestov lui communique sa philosophie de la tragédie. Bataille étudie toute l'œuvre de Chestov, son intention de publier cette étude ne sera jamais menée à bien. En revanche, il cosigne avec Teresa Beresovski-Chestov la traduction d'un livre de Léon Chestov intitulé L'Idée de Bien chez Tolstoï et Nietzsche, philosophie et prédication, qui paraît en 1925 aux Éditions du Siècle. Il est probable que Bataille s'est surtout chargé de la mise en français, sa connaissance du russe étant très rudimentaire34. C'est de cette année que date sa « conversion à rebours », faisant l'expérience que Nietzsche avait faite avant lui : « Les difficultés que rencontra Nietzsche - lâchant Dieu et lâchant le bien, toutefois brûlant de l'ardeur de ceux qui pour le bien ou Dieu se firent tuer - je les rencontrai à mon tour »35. |

若者の進化 カサ・デ・ベラスケス  アンリ・ベルクソン  レオン・チェストフ、1927年  マドリードの闘牛場、ラス・ベンタス。 バタイユは22歳の時、母の主治医であったジュール・デルテイユの娘マリー・デルテイユと恋に落ちる。父親がバタイユの遺伝を心配したため、プロポーズは 断られた。落ち着かないジョルジュは、1919年8月9日、従姉妹のマリー=ルイーズ・バタイユに手紙を書いた。「私の頭はもうどうなってしまうのかわか らない。もう長い間、私のかわいそうな頭は、いろいろな冒険を約束してくれるものをかぶっているから」23。 1920年、青年は旅に出るか世捨て人として生きるか迷った。彼は東洋に魅せられたが、最初の旅はロンドンの大英博物館で学ぶためにイギリスを訪れた。こ の時、彼はワイト島のクアールの聖母マリア修道院で3日間を過ごしたが、これは偶然の訪問であり、彼の決断には何の影響も与えなかった。ロンドン滞在中、 彼はアンリ・ベルクソンに会い、『ル・リール』を読んだ。彼はこの重要な出来事に二度立ち戻る: 「笑いは啓示であり、物事の深淵を開くものだった。この笑いが生まれたきっかけを話そう。私はロンドンにいて(1920年)、ベルクソンと食事をすること になっていた! しかし、その疑問、笑いの隠された意味は、それ以来、私にとって重要な疑問であり(幸福で親密な笑いと結びつき、私はすぐに、自分が笑いに取り憑かれてい ることを知った)、何としてでも解き明かしたい謎であった(解き明かせば、それ自体がすべてを解決することになる)25」。 彼は1953年の『Non-savoir, rire et larmes』と題された講演で、この主題をより長く取り上げている: 「ロンドンで、私はベルクソンももてなされている家に招かれた。[ロンドンでは、ベルクソンももてなされている家に招かれた。ベルクソンについては何ペー ジか読んだことがあったが、偉大な哲学者に会うという考えに対して、私は非常に単純な反応を示した。そこで、著書の中でも述べたが、ここでもう少し詳しく 述べたい。私は大英博物館へ行き、ベルクソンの『Le Rire』を読んだ。あまり満足のいく読み物ではなかったが、とても興味深かった。この理論は、私の笑いに関する様々な考察の中でも、最も深遠なもののひ とつである。だから私はこの小さな本を読み、その内容以外の理由で魅了された。当時の私を魅了したのは、笑いについて考察する可能性、笑いを考察の対象と する可能性だった。私は、ベルクソンの本から得たものから離れるために、この考察にもっともっと深く入り込みたいと思ったが、最初のうちは、私が皆さんに 表現しようとしたような、経験であると同時に考察でもあるという傾向があった26」。 ワイト島に滞在した後、彼は修道士としての召命を放棄したが、ミシェル・スーリヤによれば、信仰の放棄を正確に決めるのは難しいようだ。「いくら鮮明な啓 示があったとしても、笑いが1914年に受けた啓示にすぐに取って代わったと信じるのは間違いだろう27」。ジャン=ジャック・ルビーヌは、彼が次第に 「ニーチェ的な笑い」を発見したと指摘している2 。1922年(1月30日、31日、2月1日)、彼は13世紀に書かれた詩物語『L'ordre de la chevalerie』について、序文と注を添えて論文を提出した。クラスで2位になったバタイユは、古文書学者に任命され、マドリッドのスペイン高等研 究院(現在のベラスケス邸)に派遣された。 マドリードでは、バタイユはまだ信者であったが、孤立したままであった。マリー=ルイーズ・バタイユに宛てた手紙には、モロッコに行くという計画が書かれ ていた。彼はまだスペインを発見していなかった。スペインは後に「重苦しく悲劇的」な国であり、人々は「苦悩していた28 」と語っている。信心深さに囚われ、後にその信心深さをフラメンコ・ダンサーのイメージと重ね合わせることで消し去り、毎晩のようにフラメンコ・ダンサー を見に行き、1946年にはそのダンサーについてこう語っている。「あの種の小さな動物は、どんな生き物よりも破壊的な方法でベッドに火をつけることがで きるように私には思える」29。バタイユは退屈していた。グラナダでのフラメンコ歌手のパフォーマンスと、1922年5月7日にマドリードで行われた闘牛 で、マタドールのマヌエル・グラネロが闘牛に右目を潰されたのだ。この闘牛士はわずか20歳で亡くなった。しかし、この恐ろしい光景を目の当たりにしたバ タイユは、すぐには恐怖を感じなかった。バタイユは聞いた話をもとに、想像の中でこの出来事を再現した。後に、彼は『Histoire de l'œil』の中で、『L'œil de Granero30』と題したこの血なまぐさいエピソードに章を割いている。彼が次のように語る苦悩と快楽が入り混じった体験をしたのは、間違いなくこの 瞬間だった: 「それ以来、闘牛を見に行くときは、神経が極度に緊張した。それ以来、闘牛場へ行くときは、神経が激しく緊張することなしには行けなくなった。[......)私は、不快感がしばしば最大の快楽の秘密であることを理解し始めていた31」。 1923年、パリに戻ったバタイユは、ヴォー州出身のアルフレッド・メトローと親しくなり、ジッド、ニーチェ、ドストエフスキーを読んで身につけたシニカ ルな道徳観(Le Joyeux cynique)を説く。メトローは友人の中に、あらゆる敬虔さから遠ざかる「改心」のようなものを見た32。この心の状態は、ニーチェとプラトンの読書 で彼を導いたレオン・チェストフとの付き合いによって増幅された: 「レオン・チェストフはドストエフスキーとニーチェを基礎に哲学しており、私はそれに惹かれた(...)。彼は、私が哲学の勉強をとんでもなく嫌っている ことにうろたえたが、私は彼がプラトンを感覚的に導いてくれるのを素直に聞いていた。私の哲学的知識の基礎は彼のおかげである。その知識は、一般にその名 のもとに期待されるような性格を持たずとも、長い目で見れば、それに劣らず現実的なものとなった。その直後、私は、私の世代と同じように、マルクス主義に 傾倒した。チェストフは社会主義からの移住者で、私は彼とは距離を置いていたが、彼にはとても感謝している。 こうして、神の代理人になることを目論んでいた元理想家は、やがて最も暴力的な背教者となった。チェストフは彼と悲劇哲学を共有した。バタイユはチェスト フの全著作を研究したが、この研究を出版する意図は実を結ばなかった。しかし、彼はテレサ・ベレゾフスキ=チェストフとの共著で、レオン・チェストフの著 書『トルストイとニーチェのビエンの思想、哲学とプレディシオン』を翻訳し、1925年にエディシオン・デュ・ジエクル社から出版した。バタイユのロシア 語知識はごく初歩的なものであったため、フランス語への翻訳は主にバタイユが担当したと思われる34。ニーチェが遭遇した困難--神を手放し、善を手放 し、しかし善や神のために自らを殺した人々の熱情に燃えていた--に、私は今度は遭遇した」35。 |

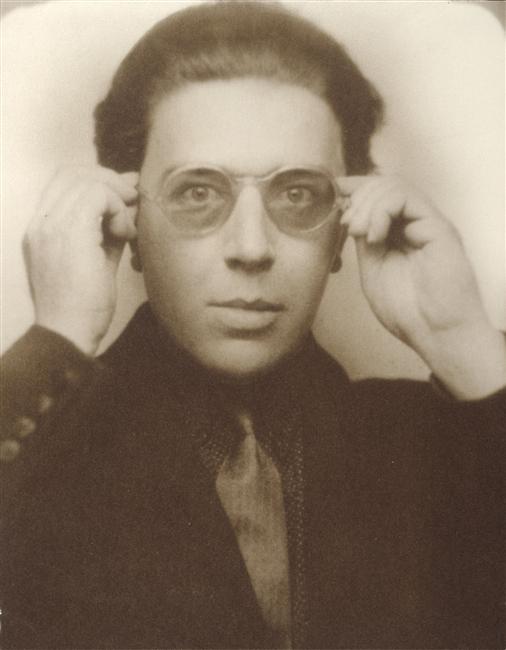

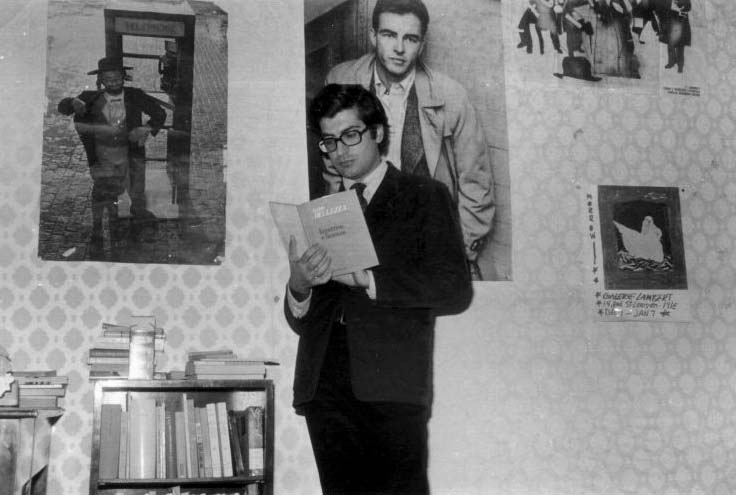

Vers le surréalisme et la débauche André Breton en 1924.  Joan Miró.  Antonin Artaud dans Le juif errant.  Guillaume Apollinaire en 1916.  Lingchi de Fou-Tchou Li, que le Dr Adrien Borel montre à Bataille au cours de sa psychanalyse. 1924 est une année-clé dans la carrière et l'évolution politique de Bataille. « L'année 1924 voit la fondation officielle du groupe surréaliste. On dit souvent d'un mouvement qu'il est « dans l'air », et il est vrai qu'il en est ainsi de celui-ci. Non seulement autour de Breton, mais un peu partout ailleurs, on cherchait à rassembler en vue d'un travail nouveau et efficace. Le mot était, depuis Apollinaire, trouvé. Une revue dirigée par Yvan Goll publie son premier numéro. Elle s'appelle Surréalismenote 3. En fin de compte, le mouvement s'agrège autour de Breton, riche d'une expérience unique et seul capable de lui donner sa charte : le Manifeste du surréalisme. Le groupe a en outre sa permanence au Bureau des recherches surréalistes, 15 rue de Grenelle, et à partir du premier décembre, son organe : La Révolution surréaliste36. » Breton est alors entouré « d'André Masson, et plus tard, de Michel Leiris, Théodore Fraenkel, Georges Limbour, Joseph Delteil, Antonin Artaud, Mathias Lübeck, Jacques-André Boiffard, Jean Carrive, Georges Malkine, Maxime Alexandre, etc. Ils sont presque tous jeunes, certains sont même adolescents37. » Ceux-là participent au Bureau de recherches surréalistes du no 15 rue de Grenelle36. Masson, Leiris, Fraenkel ont une influence considérable sur le futur philosophe, même si Bataille ne se considérait pas comme philosophe et sur sa prise de conscience politique, jusque-là très limitée. « Le surréalisme aussi (on est tenté de dire surtout), était l'enjeu. Celui que, consentant ou non, Bataille allait de près ou de loin partager38. » Mais le Manifeste du surréalisme lui a semblé illisible, l'écriture automatique, ennuyeuse, Breton prétentieux et conventionnel, Aragon décevant39. Nommé bibliothécaire au Département des Médailles de la Bibliothèque nationale cette même année, il rencontre Michel Leiris peu avant son adhésion au surréalisme. Les deux hommes nouent une profonde amitié. Leiris le décrit comme un dandy « très bourgeoisement vêtu », qui « n'avait rien d'un bohème » 40. Leiris a laissé ses impressions sur sa première rencontre avec Bataille en 1924 : « J’admirais non seulement sa culture beaucoup plus étendue et diverse que la mienne, mais son esprit non conformiste marqué par ce qu’on n’était pas encore convenu de nommer l’« humour noir ». J’étais sensible aussi aux dehors mêmes du personnage qui, plutôt maigre et d’allure à la fois dans le siècle et romantique, possédait (en plus juvénile bien sûr et avec une moindre discrétion) l’élégance dont il ne se départirait jamais, lors même que son maintien alourdi lui aurait donné cet air quelque peu paysan que la plupart ont connu, élégance toute en profondeur et qui se manifestait sans aucun vain déploiement de faste vestimentaire. À ses yeux assez rapprochés et enfoncés, riches de tout le bleu du ciel, s’alliait sa curieuse dentition de bête des bois, fréquemment découverte par un rire que (peut-être à tort) je jugeais sarcastique 41. » Bataille est alors, comme il l'écrit plus tard, dans une période « décousue ». Il trouve Dada « pas assez idiot », l'idée d'entrer dans le surréalisme comme on entre en religion lui déplaît déjà. Il aime agiter des idées avec Leiris et Jacques Lavaud, et envisage alors de fonder avec ses compagnons « un mouvement Oui, impliquant un perpétuel acquiescement à toutes choses et qui aurait sur le mouvement Non, qu'avait été Dada la supériorité d'échapper à ce qu'a de puéril une négation systématiquement provocante42. » Déjà « schismatique en puissance43 » comme le qualifie André Masson, Bataille n'a que faire de la moralisation de Breton. Le futur « pape du surréalisme » réunissait rue Fontaine un certain nombre d'amis, tandis que Masson et sa joyeuse bande de la rue Blomet, composée notamment de Joan Miró, Antonin Artaud, Georges Limbour, Leiris, formaient déjà un foyer de dissidence, prônant la liberté sexuelle, contrairement à Breton. Une autre annexe dissidente s'est également formée rue du Château, dans un pavillon remis à neuf grâce à Marcel Duhamel, qui s'y installe en compagnie de Jacques Prévert et Yves Tanguy. Bataille fréquente les deux au moment où paraît la revue Surréalisme, dirigée par Yvan Gollnote 4, à laquelle participent notamment Antonin Artaud, Robert Delaunay, Guillaume Apollinaire (en annexé), Pierre Reverdy, Joseph Delteil. La revue Surréalisme créée par Yvan Goll dans « l'évident dessein de couper l'herbe sous les pieds de Breton 44» s'ouvre à chaque parution avec un Manifeste du surréalisme, dont Maurice Martin du Gard écrit dans Les Nouvelles littéraires du 11 octobre 1924 qu'ils sont moins discutables que celui de Breton, lequel s'est approprié le néologisme surréalisme forgé par Apollinaire en 191744. Le groupe de la rue Blomet se rallie d'abord à celui de la rue du Château, puis au printemps 1924 à la rue Fontaine. Mais les surréalistes comptent alors plusieurs chapelles qui ne trouvent pas toutes à s'exprimer45. Dès 1925, Bataille, qui juge mal Breton tout en l'admirant, est pratiquement le seul à ne pas lui faire allégeance. Sans le savoir, il dispose déjà d'une influence certaine. Il faut tous les efforts de Michel Leiris pour l'amener à collaborer à La Révolution surréaliste à partir d'octobre 1925. Car malgré son admiration pour les surréalistes, Bataille perçoit déjà chez eux un idéalisme ainsi qu'un engourdissement dont il craint qu'il ne le gagne lui-même43. Et à travers l'attitude hautaine d'Aragon à son égard, Bataille perçoit déjà la supercherie du surréalisme. « Notre malheur commun était de vivre dans un monde devenu vide à nos yeux, et d'avoir, à défaut de profondes vertus, la nécessité de nous satisfaire en prenant l'aspect […] de ce que nous n'avions pas le moyen d'être46. » En 1925, Bataille écrit des récits historiques : L'Ordre de la chevalerie, qu'il propose à la Société des anciens textes français qui le refuse, ainsi que Bérinus un récit en prose se déroulant au xive siècle, refusé également par la Société. L'année suivante il commence à donner des articles savants à la revue Aréthuse, en même temps qu'il poursuit son œuvre de fiction avec des textes scandaleux et secrets, dont rien n'est encore publié. Il s'agit notamment d'une nouvelle W.C., texte « violemment opposé à toute dignité »47 dont il prétend avoir brûlé le manuscrit, mais dont Michel Leiris estime qu'il l'a réutilisé sous d'autres formes, dans une des multiples versions du Bleu du ciel48, et qu'il l'a également en partie re-publié en 1945, dans Dirty48. Depuis son arrivée à Paris, Bataille s'est peu à peu lancé dans une débauche qui étonne son ami Leiris. Courant de maison close en maison close, il mène une vie dissolue de débauché et buveur. Michel Surya résume cette période en disant qu'alors, pour Bataille, « le bordel s'est substitué à l'église49 ». Dès 1926, il devient le philosophe débauché qui écrit à la première page de l'Histoire de l'œil : « J'ai été élevé très seul et aussi loin que je me rappelle, j'étais angoissé par tout ce qui est sexuel50 ». À cette époque, Bataille s'adonne aussi à la boisson et au jeu. L'aspect obsessionnel de ses écrits inquiète le docteur Camille Daussenote 5, qui suggère à l'écrivain une psychanalyse auprès du docteur Adrien Borel, psychiatre qui a fondé la Société psychanalytique de Paris et qui reçoit de nombreux artistes parmi lesquels Raymond Queneau, Colette Peignot, Michel Leiris. Cette analyse dure un an, Bataille la déclare peu orthodoxe, mais néanmoins bienfaisante. Le docteur Borel lui montre des photos du supplice de Fou-Tchou Li, découpé vivant. L'image du supplicié rappelle à Bataille le visage torturé de son père, elle jouera un rôle essentiel dans la « méthode de méditation » de l'écrivain. En 1927, il rencontre Sylvia Maklès, juive roumaine née en France, actrice issue de l'académie Charles Dullin, qu'il épouse le 20 mars de l'année suivante. Il continue à fréquenter les boîtes et les bordels « avec sa femme ou sans elle ? De toutes les femmes - ou presque - avec lesquelles il vécut il a fait des complices. Il est douteux que la première qu'on lui connaît ne le fût pas aussi. [...] Non qu'il fût moins amoureux [...] Bataille débauché est aussi sentimental ; qui plus est il ne sera pas le seul que séduira le charme considérable de Sylvia Bataille51 ». Il quitte l'appartement où il vivait avec sa mère et son frère 85 rue de Rennes. Le couple s'installe avenue de Ségur, et par la suite rue Vauvenargues puis à Boulogne-sur-Seine avant de s'établir à Issy-les-Moulineaux. Ils ont une fille prénommée Laurence, née le 10 juin 1930, cinq mois après la mort de sa grand-mère52. On sait peu de choses sur la vie privée des deux époux53, si ce n'est que Georges Bataille n'était pas de nature fidèle54. On sait également qu'il souffrit lorsqu'ils se séparèrent en 1934 et qu'il attendit 1946 pour divorcer : « Le Bleu du ciel témoigne de la crise traversée au moment de la séparation d'avec Sylvia, sans toutefois en être le récit »51. Il a en effet très peu écrit sur son mariage. Selon Laurence Bataille, le personnage d'Édith dans Le Bleu du ciel est sans aucun doute celui de la femme de Bataille55. Michel Surya précise : « La seule évocation littéraire de ce mariage n'est donc pas seulement tardive, elle est aussi, sans recours, négative, portée au pire, comme le furent généralement toutes celles de sa vie privée [...] comme le sera [...] celle de la mort de sa mère, en 1930 »55. Évoquant la mort de sa mère, le 15 janvier 1930, et les scènes du cadavre maternel présentes dans ses textes, Michel Surya interroge : « l'horreur de la mort est réelle, et les pleurs le sont... Mais l'agenouillement, mais les prières, mais la supplication ? »56. Il avait vécu avec elle jusqu'à l'âge de 31 ans. Dans un de ses textes, Bataille fait dire crûment à Louis Trente, auteur pseudonyme du récit intitulé Le Petit : « Je me suis branlé nu, dans la nuit, devant le cadavre de ma mère57 », scène qui réapparaît dans Le Bleu du ciel58. Elle est plus développée encore dans un court texte des Écrits posthumes : « [...] entre l'accouchement qui m'avait donné la vie et la morte pour laquelle j'éprouvais alors un amour désespéré qui s'était exprimé à plusieurs reprises par de terribles sanglots puérils. La volupté extrême de mes souvenirs me poussa à me rendre dans cette chambre orgiaque pour m'y branler amoureusement en regardant le cadavre59 ». De l'avis de Michel Surya, « se branler auprès d'une dépouille aimée » n'en est pas moins « un hommage »56. Dans Ma Mère (inachevé), qui est une sorte de prolongement de Madame Edwarda, le thème de l'érotisme maternel et incestueux est encore évoqué : « Étais-je même amoureux de ma mère ? J'ai adoré ma mère, je ne l'ai pas aimée60 ». Bataille, qui est dès lors obsédé par la mort (« Ma propre mort m'obsède comme une cochonnerie obscène et par conséquent horriblement désirable61 »), s'éloigne un temps de ses plus proches amis. Un épisode de la vie de l'auteur inspire en partie deux récits : Madame Edwarda et surtout Sainte, court récit posthume et inachevé, publié aux Éditions Léo Scheer62. Bataille s'était épris d'une prostituée, Violette, qu'il voulait sortir de sa condition, mais il ne la revit plus après plusieurs visites car elle avait été déplacée. Cet épisode secret a été livré dans un entretien de Michel Surya avec Diane Bataille (née Diane de Beauharnais Kotchoubey) qui précise que Bataille avait dépensé la presque totalité de l'héritage de sa mère pour faire sortir Violette63. |

シュルレアリスムと放蕩へ向けて 1924年のアンドレ・ブルトン  ジョアン・ミロ  『さまよえるユダヤ人』のアントナン・アルトー。  1916年のギヨーム・アポリネール。  バタイユが精神分析中にアドリアン・ボレル博士から見せられた李福寿の『凌遅』。 1924年は、バタイユのキャリアと政治的発展にとって重要な年であった。「1924年、シュルレアリスムは正式に結成された。ある運動について、それは 「宙に浮いている 」とよく言われるが、実際にそうだった。ブルトン周辺だけでなく、あらゆる場所で人々が集まり、新しい効果的な方法で活動しようとしていた。アポリネール 以来、その言葉は見つかっていた。イヴァン・ゴルが監督する雑誌が創刊された。Surréalismenote 3』というタイトルだった。結局、この運動は、ユニークな経験を豊富に持ち、シュルレアリスム宣言という憲章を与えることのできる唯一の人物であったブル トンを中心にまとまった。グループはまた、グルネル通り15番地のシュルレアリスム研究局に常設事務所を構え、12月1日からは独自の機関紙『シュルレア リスム革命』36を創刊した。ブルトンの周囲には、「アンドレ・マッソン、後にミシェル・レイリス、テオドール・フレンケル、ジョルジュ・ランブール、 ジョゼフ・デルテイユ、アントナン・アルトー、マティアス・リューベック、ジャック=アンドレ・ボワファール、ジャン・カリヴ、ジョルジュ・マルキネ、マ キシム・アレクサンドルなどがいた。ほとんど全員が若く、中には10代37歳の若者もいた。彼らは皆、グルネル通り15番地にあったシュールレアリスト研 究局に参加していた36。マッソン、レイリス、フレンケルは、バタイユが自らを哲学者とは考えていなかったにもかかわらず、後に哲学者となる人物や、それ まで非常に限られていた彼の政治意識に多大な影響を与えた。「シュルレアリスムも(何よりもと言いたくなるが)危機に瀕していた。バタイユもまた、(何よ りもそう言いたくなるような)シュルレアリスムが危機に瀕していたのだ38」。しかし彼は、シュルレアリスム宣言は読めず、自動書記は退屈で、ブルトンは 気取り屋で型にはまり、アラゴンは失望していた39。同年、国立図書館のメダル部門の司書に任命された彼は、シュルレアリスムに参加する少し前にミシェ ル・レイリスと知り合った。2人は親しい友人となった。レワは彼を、「ボヘミアン的なところがまったくない」「とてもブルジョワ的な服装の」ダンディだと 評した40。 レイリスは1924年にバタイユと初めて会ったときの印象をこう残している: 私よりはるかに幅広く多様な彼の文化だけでなく、まだ 「ブラック・ユーモア 」として知られていなかった彼の不適合な精神にも敬服した。彼の外見も印象的だった。かなり痩せていて、この時代にふさわしく、かつロマンチックではあっ たが、(もちろん、より若々しく、控えめではあったが)決して遠慮することのないエレガンスを持っていた。彼の目はかなり近く、深く澄んでいて、空の青色 をすべて含んでおり、森の動物のような不思議な歯と組み合わさっていた。 バタイユは、後にこう書いているように、当時は「バラバラ」な時期だった。彼はダダを「馬鹿馬鹿しさが足りない」と感じ、宗教に入るようにシュルレアリス ムに入るという考えをすでに嫌っていた。彼は、レイリスやジャック・ラヴォーとアイデアを出し合うのが好きで、仲間たちとともに「あらゆるものへの永続的 な承諾を意味し、ダダがそうであった『否』運動よりも、体系的に挑発的な否定の幼稚さから逃れるという点で優れているであろう『イエス』運動」の創設を構 想していた42。 アンドレ・マッソンが彼をそう呼んだように、バタイユはすでに「潜在的分裂主義者」43であり、ブルトンの道徳的な主張には何の役にも立たなかった。後に 「シュルレアリスムの教皇」となる彼には、フォンテーヌ通りに多くの友人がいたが、マッソンとブロメ通りにいた愉快な仲間たち(ジョアン・ミロ、アントナ ン・アルトー、ジョルジュ・ランブール、レイリスなど)は、すでにブルトンとは異なり、性的自由を標榜する反体制派の温床を形成していた。また、シャトー 通りには、マルセル・デュアメルが改装したパビリオンに、ジャック・プレヴェールやイヴ・タンギーとともに移った反体制派の別館が形成されていた。バタイ ユは、イヴァン・ゴルノート4が編集した『シュルレアリスム』誌が創刊されると同時に、この2つの雑誌に出入りし、アントナン・アルトー、ロベール・ドロ ネー、ギョーム・アポリネール(補遺)、ピエール・ルヴェルディ、ジョゼフ・デルテイユらが寄稿した。シュルレアリスム』誌はイヴァン・ゴルによって創刊 され、「ブルトンの足元から敷物を引き剥がすという明白な意図」44をもって創刊されたが、毎号シュルレアリスム宣言で幕を開け、モーリス・マルタン・ デュ・ガールは1924年10月11日付の『ヌーヴェル・リテレール』誌に、19174年にアポリネールが造語したシュルレアリスムを流用したブルトンよ りも議論の余地が少ないと書いている。 ブロメ通りのグループは、まずシャトー通りのグループと合流し、1924年春にはフォンテーヌ通りのグループと合流した。しかし、シュルレアリスムにはい くつかの礼拝堂があり、そのすべてが自己表現できるわけではなかった45。1925年の時点で、バタイユは、ブルトンに憧れながらも判断を誤り、事実上、 ただ一人、ブルトンに忠誠を誓わなかった。そうとは知らずに、彼はすでに決定的な影響力を持っていた。1925年10月から『La Révolution surréaliste』に寄稿させるために、ミシェル・レイリスはあらゆる努力を払った。というのも、バタイユはシュルレアリスムへの憧れとは裏腹に、 すでに彼らの中に、彼自身が勝利してしまうことを恐れる理想主義と無感覚さを感じ取っていたからである43。そして、アラゴンの自分に対する高慢な態度を 通して、バタイユはすでにシュルレアリスムの欺瞞を感じ取っていた。われわれの共通の不幸は、われわれの目には空虚となった世界に生きることであり、深遠 な美徳がないために、われわれが存在する手段を持たないものの外見[......]を身にまとうことで自己を満足させなければならないことであった」 46。 1925年、バタイユは歴史物語を書いた。シュヴァレリー騎士団(L'Ordre de la chevalerie)はソシエテ・デ・アンシャン・テキスト・フランセ(Société des anciens textes français)に提案したが却下された。翌年、彼は『Aréthuse』誌に学術論文の執筆を始める一方、スキャンダラスで秘密めいたテクストを使っ たフィクションの執筆を続けたが、いずれもまだ出版されていない。その中には、短編小説『W.C.』も含まれている。この作品は、「あらゆる品位に激しく 反抗する」47もので、バタイユはその原稿を焼却したと主張しているが、ミシェル・レイリス(Michel Leiris)は、彼が別の形で『Bleu du ciel』48の多くのバージョンのひとつに再利用し、1945年には『Dirty』48にも部分的に再出版したと考えている。 パリに到着して以来、バタイユは次第に放蕩の限りを尽くし、友人のレイリスを驚かせた。売春宿を転々とし、放蕩と飲酒の放蕩生活を送っていた。ミシェル・ スーリヤは、バタイユにとって「売春宿が教会に取って代わった」49と、この時期を総括している。1926年まで、彼は『Histoire de l'œil(邦題:歴史)』の最初のページにこう書いた、淫蕩な哲学者になっていた。この時期、バタイユは酒とギャンブルに溺れていた。彼の強迫的な執筆 活動はカミーユ・ドーセン医師註5を悩ませ、パリ精神分析協会を設立し、レイモン・クノー、コレット・ペニョ、ミシェル・レイリスなど多くの芸術家を受け 入れた精神科医アドリアン・ボレル医師の精神分析を受けるよう勧めた。バタイユは、それは正統派ではないが、それにもかかわらず有益であると断言した。ボ レル医師は、生きたまま切り刻まれるフーチュー・リイの写真を見せた。その犠牲者の姿は、バタイユに父親の拷問された顔を思い出させ、作家の「瞑想法」に おいて重要な役割を果たすことになる。 1927年、フランス生まれのルーマニア系ユダヤ人でシャルル・デュラン・アカデミー出身の女優、シルヴィア・マクレスと出会い、翌年3月20日に結婚し た。彼はクラブや売春宿に通い続けた。彼は一緒に暮らしたほとんどすべての女性を共犯者にした。私たちが知っている最初の女性も共犯者でなかったかは疑わ しい。[さらに、シルヴィア・バタイユのかなりの魅力51に誘惑されたのは彼だけではなかった。バタイユは、母と弟と住んでいたレンヌ通り85番地のア パートを出た。夫婦はセギュール通り、ヴォーヴナルグ通り、ブローニュ=シュル=セーヌ通りへと移り住み、イッシー=レ=ムリノーに落ち着いた。祖母の死 から5ヵ月後の1930年6月10日に、ローランスという娘が生まれた52。夫妻の私生活についてはほとんど知られていない53 が、ジョルジュ・バタイユが誠実な人物ではなかったということ以外はわかっている54 。Le Bleu du ciel』は、シルヴィアとの別離時に経験した危機を証言しているが、それについての記述ではない51」。実際、彼は結婚についてほとんど書いていない。 ローレンス・バタイユによれば、『Le Bleu du ciel』のエディットという人物は、間違いなくバタイユの妻である55。ミシェル・スーリヤは、「したがって、この結婚に関する唯一の文学的言及は、遅 れているだけでなく、彼の私生活に関する一般的な言及と同様、否定的であり、最悪の事態に持ち込まれている[......]。ミシェル・スーリヤは、 1930年1月15日の母親の死と、彼のテキストに登場する母親の死体のシーンに言及し、こう問いかける。しかし、ひざまずくこと、祈ること、懇願するこ とはできるだろうか」56。彼は31歳まで彼女と暮らしていた。バタイユは、ある文章の中で、『Le Petit』という物語の作者ルイ・トレンテ(仮名)に、「私は夜、母の死体の前で裸で自慰をした57」と単刀直入に言わせている。それは『Écrits posthumes』の短い文章の中でさらに展開されている。「[...]私に生命を与えてくれた出産と、そのとき私が絶望的な愛を感じた死んだ女性との 間で、ひどい子供のような嗚咽によって何度か表現された。記憶の極度の官能性によって、私はあの淫乱な部屋に行き、死体を見ながら愛情をこめて自慰にふ けった59 」。ミシェル・スーリヤに言わせれば、「愛する死体の横で自慰をする」ことは、「オマージュ」である56。マダム・エドワルダ』の延長線上にある『マ・ メール』(未完)では、母性と近親相姦のエロティシズムというテーマが再び呼び起こされる。私は母を愛していたのだろうか? 死に取り憑かれたバタイユは(「私自身の死は、猥雑で、それゆえに恐ろしく好ましい汚物のように私をとりこにする」61)、一時期、親しい友人たちから距 離を置いた。エドワルダ夫人』と、Éditions Léo Scheerから出版された遺作で未完の短編『サント』である62。バタイユは娼婦のヴィオレットと恋に落ちたが、ヴィオレットは病床にあったため、何度 訪れても二度と会うことはなかった。この秘密のエピソードは、ミシェル・スーリヤによるディアーヌ・バタイユ(旧姓ディアーヌ・ド・ボーハルネ・コチュ ベー)へのインタビューで明らかにされ、バタイユはヴィオレットを連れ出すために母親の遺産をほとんどすべて使い果たしたと述べている63。 |

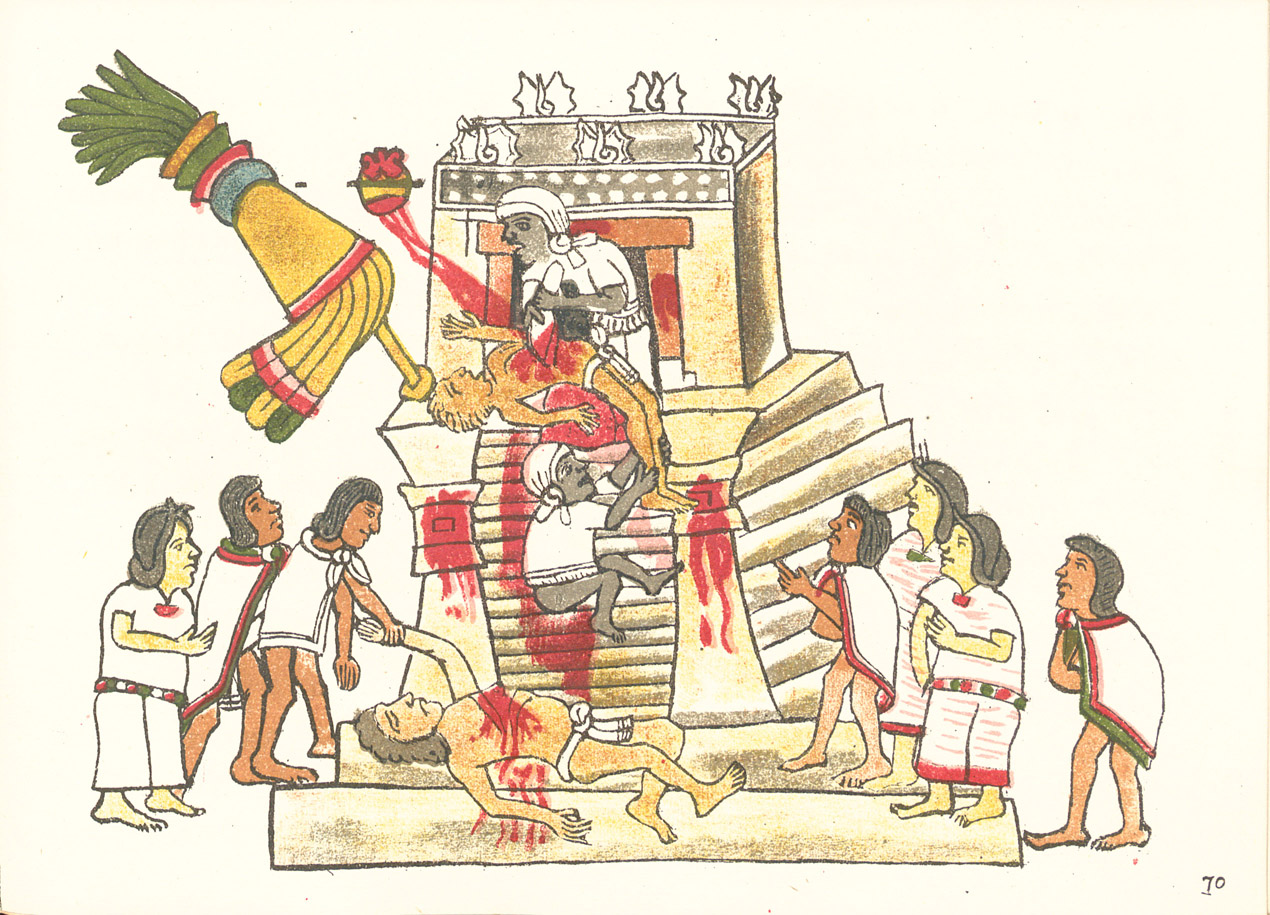

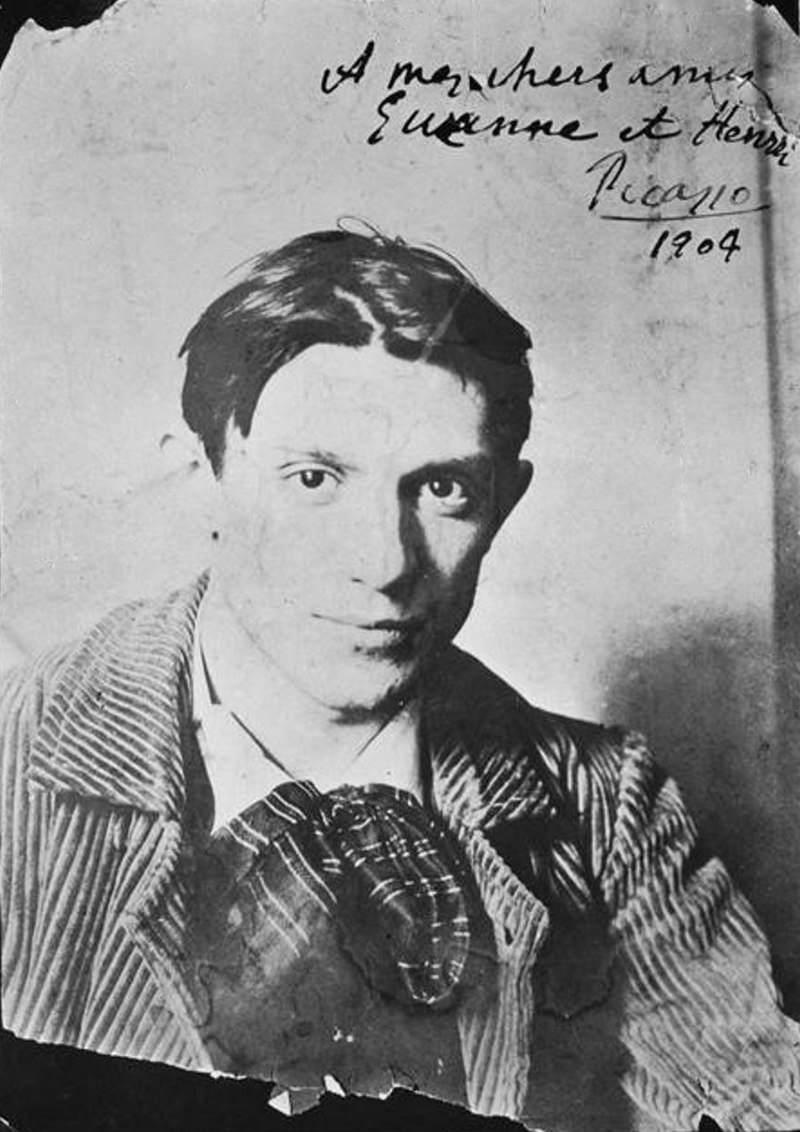

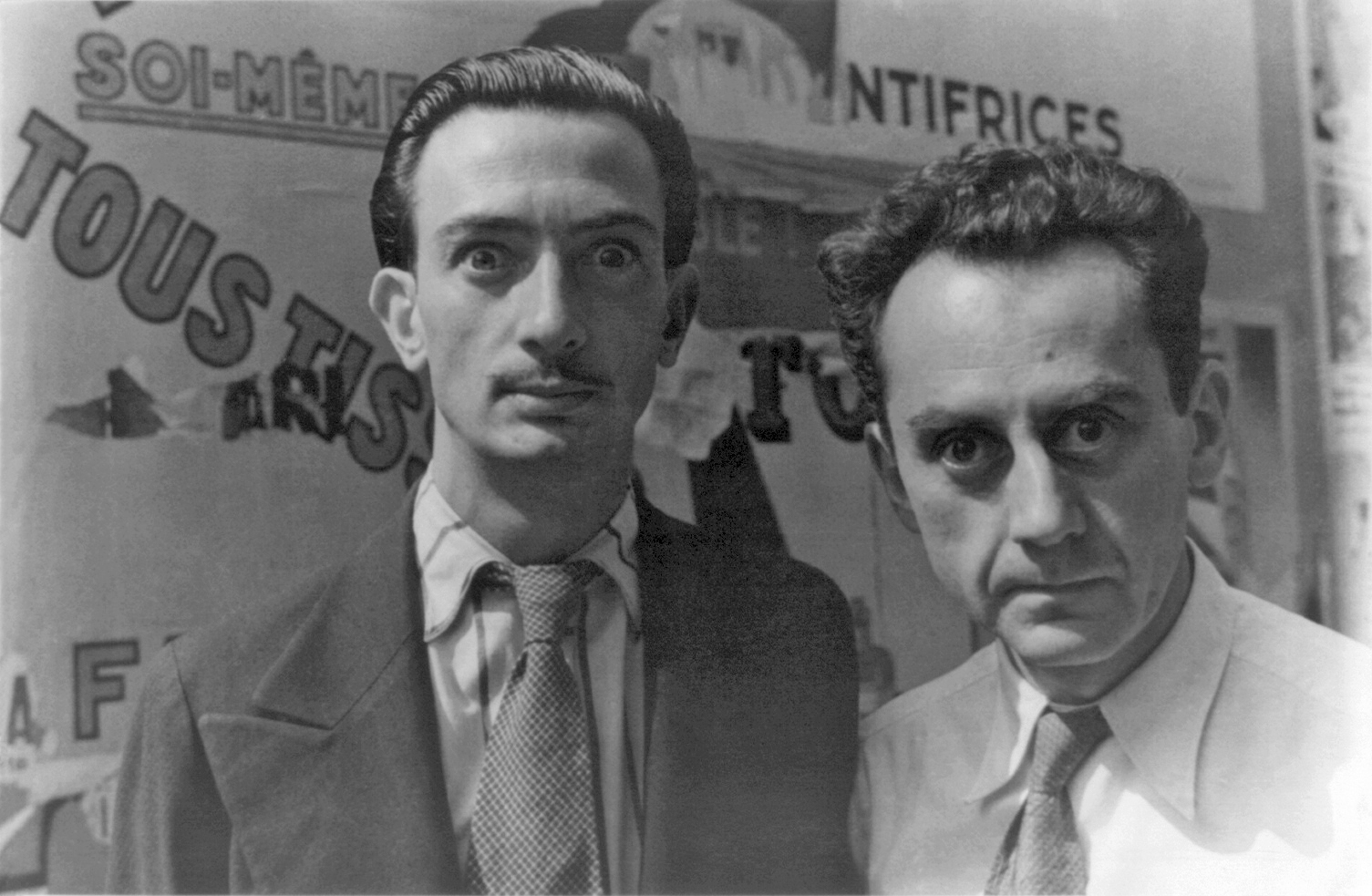

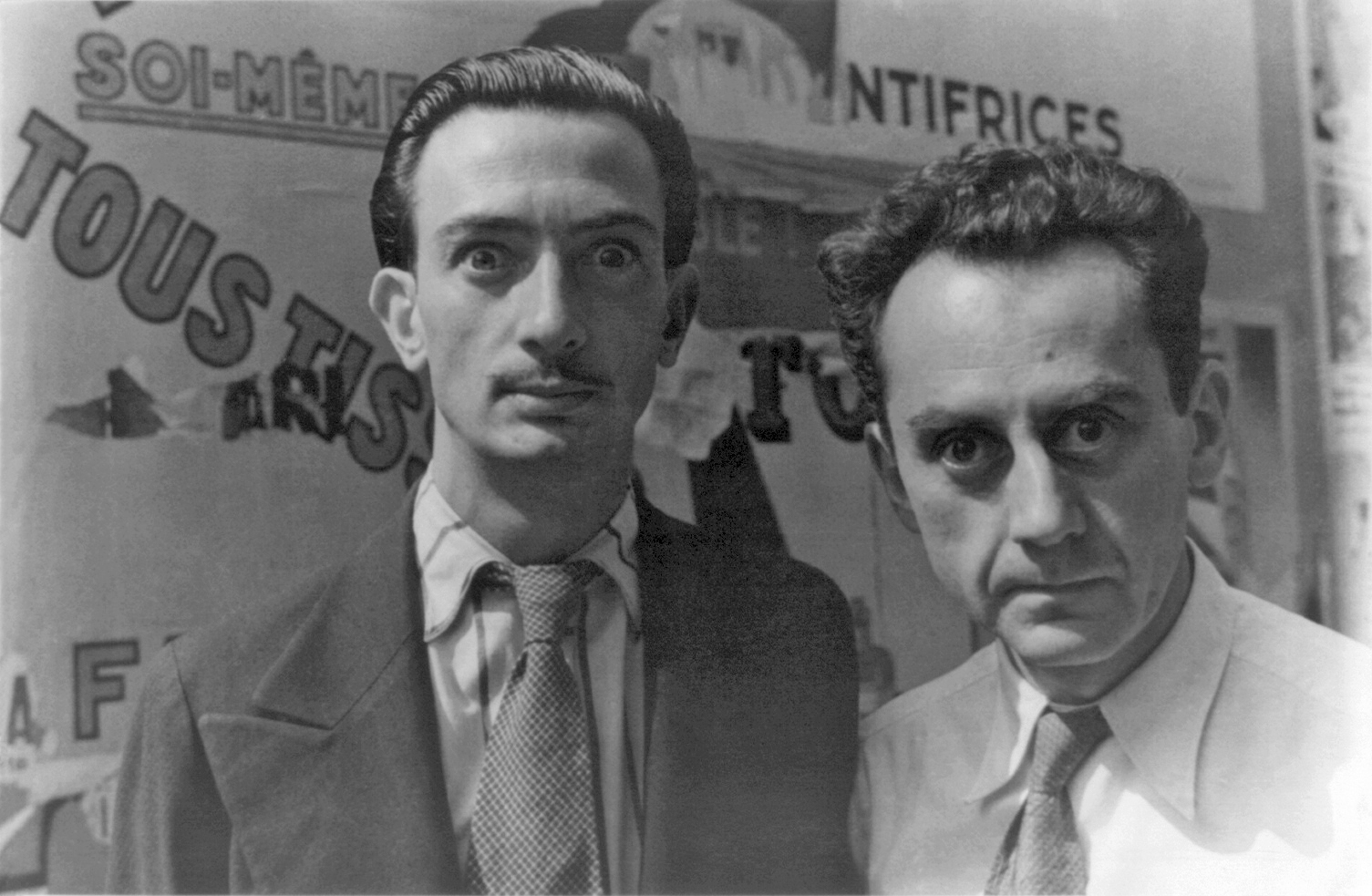

| L'engagement politique, les revues La revue Documents Article détaillé : Documents.  autel de sacrifice humain aztèque, Musée national d'anthropologie de Mexico.  Cérémonie sacrificielle aztèque, Codex Magliabechiano. Dans le but d'élargir le mouvement, accroître ses membres et pallier les exclusions-défectionsnote 6 (Roger Vitrac, Antonin Artaud, Max Ernst, Joan Miró entre autres exclus), Breton convoque un symposium auquel Bataille est invité. Invitation qu'il décline avec cette phrase : « Beaucoup trop d'emmerdeurs idéalistes64. » L'idéalisme est désormais l'ennemi no 1. En 1929, dans le Second manifeste du surréalisme, Bataille est violemment pris à partie par Breton tout comme Vitrac, Masson, Desnos et l’ensemble du « groupe Bataille »65, qui réplique en 1930 par un pamphlet très virulent intitulé Un Cadavre66. La revue Documents va devenir une machine de guerre en réponse aux attaques de Breton. Bataille en est le secrétaire général, Georges Limbour le secrétaire de rédaction, l'équipe est composée de Michel Leiris et d'autres transfuges dont Vitrac, Robert Desnos. Initialement conçue et créée par Georges Wildenstein, fils du marchand d'art Nathan Wildenstein, au début de l'année 1929, pour concurrencer les Cahiers d'art de Christian Zervos, la revue Documents fait appel à Jean Babelon et Pierre d'Espezel, ex-directeurs de la revue Aréthuse à laquelle Bataille a donné des articles sur la numismatique67. Toutefois, ce n’est pas par l’intermédiaire de Babelon et Espezel que Bataille et Leiris sont introduits dans la revue, mais par le muséologue Georges Henri Rivière, qui travaille au Musée d'ethnographie du Trocadéro aux côtés de son directeur Paul Rivet, et les présente à Wildenstein. Leiris et Bataille forment rapidement un groupe composé d’André Schaeffner, Robert Desnos, Jacques Baron, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Roger Vitrac, André Masson, Jacques-André Boiffard, puis plus tard, Jacques Prévert68. Parmi les contributeurs à la revue, se trouve aussi le tout jeune Claude Lévi-Strauss qui n'est pas encore ethnologue et qui signe « Georges Monnet, Député de l'Aisne » (dont il était secrétaire) un article sur Picasso69,70, intitulé « Picasso et le cubisme », étonnamment élogieux pour le peintre, que le jeune critique encense, alors même qu'il déteste le cubisme, et par la suite, Picasso71. La revue est conçue au départ comme une revue scientifique, revue d'art, d'histoire de l'art, et d'ethnographie, dont Carl Einstein est le coordonnateur, donnant à l'ethnographie une place prépondérante qui justifie un des sous-titres de la revue72 : « Doctrine, archéologie, beaux-arts, ethnographie73. » Les trois articles de Bataille dans les premiers numéros sont les plus prudents. Le premier intitulé « Le cheval académique », paru en avril 1929, est une critique de l'esthétique liée aux « platitudes et aux arrogances des idéalistes74 » ; le deuxième, paru dans le numéro 2 de mai 1929, ne fait que remarquer en passant « la valeur bienfaisante des faits sales et sanglants75 ». Le troisième article sur « le langage des fleurs » (numéro 3 de juin 1929) est particulièrement « retors »76. Mais les précautions des trois premiers numéros vont vite laisser la place à des articles beaucoup plus véhéments ; en particulier l'article compte-rendu de la Revue nègre au Moulin-Rouge, intitulé « Black Birds », est l'occasion pour Bataille de ne plus s'en tenir à aucune réserve : « ... nous pourrissions avec neurasthénie sous nos toits, cimetière et fosse commune de tant de pathétiques fatras77. » Un des articles les plus véhéments, intitulé « Figure humaine »78, raille les notions de forme et de ressemblance, qui gouvernent les canons de l'esthétique traditionnelle, établissant une esthétique paradoxale fondée sur ce que Georges Didi-Huberman a nommé « la ressemblance informe » ; « une contre-histoire de l'art » qui, dans « son rapport aux images », « son savoir des images », « son jeu avec les images » met en œuvre une « critique de toute substantialité de l'image »79. Dans « Figure humaine », Bataille soutient qu'il y a des hommes, dans leur diversité et leurs « écarts », mais pas de « nature humaine », décrivant l'espèce humaine comme une « juxtaposition de monstres »80- ce qu'il énoncera plus tard ainsi : « Ma conception est un anthropomorphisme déchiré »81. La révolte commence là. D'autres articles plus violents vont suivre, déplaçant les critères de beauté et de goût vers ceux du désir et de l'intensité, notamment « Le gros orteil », paru dans le numéro 6 de Documents, qui excite « la rage de voir » la vie humaine dans « un mouvement de va-et-vient de l'ordure à l'idéal et de l'idéal à l'ordure » : « Le sens de cet article repose dans une insistance à mettre en cause directement et explicitement ce qui séduit, sans tenir compte de la cuisine poétique, qui n'est en définitive qu'un détournement (la plupart des êtres humains sont naturellement débiles et ne peuvent s'abandonner à leurs instincts que dans la pénombre poétique). Un retour à la réalité n'implique aucune acceptation nouvelle, mais cela veut dire qu'on est séduit bassement, sans transposition, et jusqu'à en crier, en écarquillant les yeux : les écarquillant ainsi devant un gros orteil82. » Documents devient une revue de contre-culture dirigée contre le surréalisme. Tout en utilisant les armes de l’érudition traditionnelle, la revue tend à produire une contre-histoire de l’art65, et se présente comme un véritable défi à la critique d'art traditionnelle et à l'ethnographie, dont elle utilise pourtant les méthodes, avec la collaboration de plusieurs ethnographes et anthropologues. Le contenu de la revue est très diversifié, allant de l'étude des peintures pariétales à la peinture contemporaine et, tout en suivant une « méthodologie de méditation en ethnographie », explore aussi des territoires inattendus tels que le jazz, le music-hall, les instruments de musique, les dessins d'enfants, la bande-dessinée, ou « l'ethnologie de l'art ». Carl Einstein entreprend une « étude ethnographique d'André Masson » qui résume assez bien l'orientation « toutes directions » de la revue qui accueille aussi les peintres Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, Jean Arp, Giorgio De Chirico, Chaim Jacob Lipchitz, Georges Braque. À l'époque où le Musée d'ethnographie du Trocadéronote 7 est dirigé depuis 1927 par Paul Rivet, les ethnologues de la revue réclament une nouvelle conception du musée, fondée sur un retour au concret qui préfigure ce que Claude Lévi-Strauss appellera « le musée d'anthropologie ». Ayant pour ambition d'embrasser la totalité d'une civilisation, selon le principe de « fait social total » introduit par Marcel Mauss, ils critiquent une esthétique qui privilégie la forme aux dépens de l'usage : selon Marcel Griaule, l'ethnographie doit « se méfier du beau, qui est bien souvent une manifestation rare, c'est-à-dire monstrueuse, d'une civilisation »83. Cette nouvelle muséologie consiste à privilégier ce que Bataille appelle « la valeur d'usage », contre « l'art pour l'art » et « la valeur d'échange » ; c'est ainsi qu'il conçoit le musée comme un lieu où l'humanité se déshabille (comme le bordel) : « Un musée est comme le poumon d'une grande ville : la foule afflue chaque dimanche dans le musée comme le sang [...] Le musée est le miroir colossal dans lequel l'homme se contemple enfin sous toutes les faces »84. Documentsnote 8 se situe alors au croisement de trois réseaux : les conservateurs, les ethnologues, et les dissidents surréalistes. Carl Einstein est en particulier très attaché à l’ethnologie et à l’histoire de l’art. Bataille appartient statutairement au groupe des « conservateurs » qui n'était rattaché que de loin au « surréalisme dissident » et n'avait aucun lien avec le groupe des ethnologues72, ce qui explique quelques frictions avec Carl Einstein, ethnologue avant tout. Il est entouré d'une équipe hétéroclite qui comprend des peintres (Alberto Giacometti, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí), des poètes, (Vitrac et Desnos) et des fidèles comme Leiris. Avec eux, la revue Documents se fait le chantre d'une contre-culture, incluant les images et le cinéma, encouragée en cela par les apports de Robert Desnos, mais aussi de Marie Elbé qui ouvre la voie, avec son article sur Gustave Courbet, à ce que le peintre appelait « la réhabilitation du laid » : « Courbet lui-même, socialiste, d'une violence épaisse et joyeuse, se donna comme révolutionnaire et porteur du nouvel évangile de la peinture85. » Bataille retourne les concepts d’érudition et d'esthétique en s’intéressant aussi à la culture de masse : Fantômas et Les Pieds nickelés font partie de sujets traités, interrogeant ainsi la nature de l’érudition. Dès le second numéro, les réticences de Carl Einstein semblent avoir fléchi. Il participe activement à l'élaboration d'un « Dictionnaire critique » qui devient une rubrique régulière nourrie par lui, puis presque exclusivement par Bataille, Leiris, Desnos, Marcel Griaule et Jacques Baron. Les initiateurs en sont Bataille et Leiris86. Dans le numéro 3 de La Révolution surréaliste, en 1925, Leiris avait commencé un glossaire: « Glossaire j'y serre mes gloses »87. Dans le même esprit, il travaille avec Bataille à un dictionnaire de mots « informes » qui se présente comme une enquête ethnographique sur le langage, redéfinissant certaines notions, en les soustrayant aux définitions abstraites, pour les rendre à leurs aspects « concrets ». L'article « Informe » (Documents, no 7, décembre 1929), un des plus courts de la revue, en est la « véritable clé de voûte », car Bataille y « expose de manière presque théorique, mais aussi ludique, le point nodal de la critique des “formes” culturelles de signification, et éclaire de façon générale les enjeux esthétiques »88 de sa pensée : « un dictionnaire, écrit-il, commencerait à partir du moment où il ne donnerait plus le sens mais les besognes des mots. »89. La civilisation aztèque a toujours hanté l'imaginaire de Bataille, qui est aussi fasciné par les sacrifices humains. Le sujet apparaît explicitement dans la revue Documents, dans le numéro 4 de 1930, avec des illustrations de sacrifices aztèques (« Sacrifices humains du Centre-Amérique », article de Roger Hervé), et quelques années plus tard dans La Part maudite (1949). C'est d'ailleurs à partir de son texte « L'Amérique disparue »90, paru en 1928 dans L'Art précolombien. L'Amérique avant Christophe Colomb, et ses articles sur la numismatique parus auparavant dans Aréthuse, que Bataille réussit à convaincre Georges Wildenstein de financer la revue Documents. « Une place privilégiée est faite aux rites sacrificiels dans les pages de Documents. Bataille ne résiste pas à produire une description détaillée des sacrifices hindous sanguinaires91 et se réfère à plusieurs reprises à toutes sortes de mutilations et de décapitations rituelles. Citons les photos d’Éli Lotar prises à La Villette pour l’article « Abattoir »92, les illustrations des sacrifices aztèques, un horrible tableau d'Antoine Caron qui représente, entre autres, un homme fouillant les entrailles de sa victime93. » Dans Documents, le combat contre l'idéalisme et le surréalisme se trouve amplifié. Il s'agit de déconstruire le discours officiel de l'histoire de l'art et d'élaborer une forme de marginalité65. Dans le numéro 4, le sous-titre « Doctrines, archéologie, beaux-arts et ethnographie » fait aussi l'objet de l'ajout « Variétés, Magazine illustré », et Bataille y écrit trois articles dont le ton revient à nier l'existence d'une nature humaine94. Son anti-idéalisme s'y déchaîne : « l'intérêt de la revue de Georges Wildenstein permet de saisir le moment historique où Georges Bataille [...] excède les limites imparties à la revue érudite pour s'attaquer à l'idéalisme funeste95. » Ainsi naît la « machine de guerre contre le surréalisme », selon l'expression de Michel Leiris, qui est surtout une « machine de guerre » contre Breton96. Néanmoins, en quinze numéros, pas une fois le nom de Breton n'est cité97. |