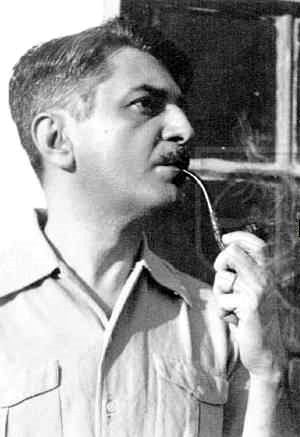

ジルベルト・フレイレ

Gilberto Freyre, 1900-1987

☆ ジルベルト・デ・メロ・フレイレKBE(1900年3月15日-1987年7月18日)は、レシフェ生まれのブラジルの社会学者、人類学者、歴史家、作 家、画家、ジャーナリスト、下院議員。20世紀で最も重要な社会学者の一人とされる彼の最も有名な著作は、Casa-Grande & Senzala(文字通り「母屋と奴隷宿舎」、通常英語ではThe Masters and the Slavesと訳される)という社会学理論である。

| Gilberto de Mello Freyre

KBE (March 15, 1900 – July 18, 1987) was a Brazilian sociologist,

anthropologist, historian, writer, painter, journalist and congressman

born in Recife. Considered one of the most important sociologists of

the 20th century, his best-known work is a sociological treatise named

Casa-Grande & Senzala (literally, "The main house and the slave

quarters", usually translated into English as The Masters and the

Slaves). |

ジルベルト・デ・

メロ・フレイレKBE(1900年3月15日-1987年7月18日)は、レシフェ生まれのブラジルの社会学者、人類学者、歴史家、作家、画家、ジャーナ

リスト、下院議員。20世紀で最も重要な社会学者の一人とされる彼の最も有名な著作は、Casa-Grande &

Senzala(文字通り「母屋と奴隷宿舎」、通常英語ではThe Masters and the Slavesと訳される)という社会学理論である。 |

| Life and work Freyre had an internationalist academic career, having studied at Baylor University, Texas from the age of eighteen and then at Columbia University, where he got his master's degree under the tutelage of William Shepperd.[1] At Columbia, Freyre was a student of the anthropologist Franz Boas.[2] After coming back to Recife in 1923, Freyre spearheaded a handful of writers in a Brazilian regionalist movement. After working extensively as a journalist, he was made head of cabinet of the Governor of the State of Pernambuco, Estácio Coimbra. With the 1930 revolution and the rise of Getúlio Vargas, both Coimbra and Freyre went into exile. Freyre went first to Portugal and then to the US, where he worked as visiting professor at Stanford.[3] By 1932, Freyre had returned to Brazil. In 1933, Freyre's best-known work, The Masters and the Slaves was published and was well received.[citation needed] In 1946, Freyre was elected to the federal Congress.[4] At various times, Freyre also served as director of the newspapers A Província and Diário de Pernambuco.[5] In 1962, Freyre was awarded the Prêmio Machado de Assis by the Brazilian Academy of Letters, one of the most prestigious awards in the field of Brazilian literature.[6] That same year, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[7] Over the course of his long career, Freyre received numerous other awards, honorary degrees, and other honors both in Brazil and internationally. Examples include admission to L'ordre des Arts et Lettres (France), investiture as Grand Officier de La Légion d'Honneur (France), investiture as Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (Great Britain), the Gran-Cruz of the Ordem do Infante Dom Henrique (Portugal), and honorary doctorates at Columbia University and the Sorbonne.[8] Freyre's most widely known work is The Masters and the Slaves (1933). At the time, this was a revolutionary work for the study of races and cultures in Brazil. As Lucia Lippi Oliveira notes, "In the 1930s and 1940s, Freyre was praised as being the creator of a new, positive self-image of Brazil, one that overcame the racism present in authors like Sílvio Romero, Euclides da Cunha, and Oliveira Viana."[9] The book misrepresents slavery in Brazil as a mild form of servitude and has served to consolidate the Brazilian myth of racial democracy. Freyre’s romanticization of racial mixture and disavowal of his society’s racism is comparable to the approach of other Latin American eugenicists, such as Fernando Ortiz in Cuba (Contrapunteo Cubano de Tobacco y Azúcar, 1940), and José Vasconcelos in Mexico (La Raza Cosmica, 1926).[10][11] Since its publication and initial reception, this work has also been criticized for how its "focus on a single identity in modern Brazil resulted not only in factual inaccuracies and distortions of reality but also in a larger societal refusal to acknowledge racism in modern Brazil,"[12] for example. The Masters and the Slaves is the first of a series of three books, which also included The Mansions and the Shanties: The Making of Modern Brazil (1938) and Order and Progress: Brazil from Monarchy to Republic (1957). The trilogy is generally considered a classic of modern cultural anthropology and social history. Other very important contributions of Freyre's were The Northeast (1937) and The English in Brazil (1948). The actions of Freyre as a public intellectual are rather controversial. Labeled as a communist in the 1930s, he later moved to the political Right. He supported Portugal's Salazar government in the 1950s, and after 1964, defended the military dictatorship of Brazil's Humberto Castelo Branco. Freyre is considered to be the "father" of lusotropicalism: the theory whereby miscegenation had been a positive force in Brazil. "Miscegenation" at that time tended to be viewed in a negative way, as in the theories of Eugen Fischer and Charles Davenport.[13] Freyre was acclaimed for his literary style.[citation needed] Of his poem "Bahia of all saints and of almost all sins," Brazilian poet Manuel Bandeira wrote: "Your poem, Gilberto, will be an eternal source of jealousy to me"(cf. Manuel Bandeira, Poesia e Prosa. Rio de Janeiro: Aguilar, 1958, v. II: Prose, p. 1398).[14] Freyre wrote this long poem inspired by his first visit to Salvador.[citation needed] Freyre died on July 18, 1987, in Recife. |

生涯と仕事 18歳からテキサス州のベイラー大学で学び、その後コロンビア大学でウィリアム・シェッパードの指導のもと修士号を取得した。1923年にレシフェに戻っ た後、フレイレはブラジル地域主義運動で一握りの作家の先頭に立った。ジャーナリストとして幅広く活動した後、ペルナンブーコ州知事エスターシオ・コイン ブラの内閣官房長官となる。1930年の革命とゲトゥーリオ・ヴァルガスの台頭により、コインブラとフレイレは亡命。フレイレはまずポルトガルに渡り、そ の後アメリカに渡り、スタンフォード大学の客員教授として働いた[3]。1933年、代表作『The Masters and the Slaves』が出版され、好評を博した[citation needed] 1946年、連邦議会議員に選出される[4] 。 1962年、フレイレはブラジル文学界で最も権威のある賞のひとつであるマチャド・デ・アシス賞をブラジル文学アカデミーから授与された[6]。 同年、アメリカ哲学協会会員に選出された[7]。長いキャリアの中で、フレイレは他にも数多くの賞、名誉学位、その他の栄誉をブラジル国内外から受けた。 例えば、フランス芸術文化勲章(L'ordre des Arts et Lettres)、フランス名誉勲章(Grand Officier de La Légion d'Honneur)、大英帝国騎士団長(Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire)、ポルトガル名誉勲章(Gran-Cruz of the Ordem do Infante Dom Henrique)、コロンビア大学とソルボンヌ大学での名誉博士号などがある[8]。 フレイレの最も広く知られた作品は『主人たちと奴隷たち』(1933年)である。当時、これはブラジルの人種と文化の研究にとって革命的な作品であった。 ルシア・リッピ・オリヴェイラが指摘するように、「1930年代から1940年代にかけて、フレイレは、シルヴィオ・ロメロ、エウクレイデス・ダ・クー ニャ、オリヴェイラ・ヴィアナのような著者に見られる人種主義を克服した、ブラジルに対する新しい肯定的な自己イメージの創造者として称賛された」 [9]。本書は、ブラジルにおける奴隷制を温和な隷属の形態として誤って表現し、ブラジルの人種民主主義神話を強固にする役割を果たした。フレイレの人種 的混血のロマンチック化と彼の社会の人種差別の否認は、キューバのフェルナンド・オルティス(Contrapunteo Cubano de Tobacco y Azúcar, 1940)やメキシコのホセ・ヴァスコンセロス(La Raza Cosmica, 1926)のような他のラテンアメリカの優生主義者のアプローチに匹敵する。 [10][11]その出版と最初の受容以来、この作品はまた、「近代ブラジルにおける単一のアイデンティティに焦点を当てた結果、事実の不正確さや現実の 歪曲を招いただけでなく、近代ブラジルにおける人種差別を認めないより大きな社会をも招いた」[12]などと批判されてきた。 The Masters and the Slaves(主人と奴隷たち)』は、『The Mansions and the Shanties(邸宅と小屋)』を含む3冊からなるシリーズの第1作である: 近代ブラジルの形成』(1938年)、『秩序と進歩』(1953年)がある: ブラジルの君主制から共和制へ』(1957年)である。この3部作は一般に、近代文化人類学と社会史の古典とみなされている。フレイレの他の非常に重要な 貢献は、『北東部』(1937年)と『ブラジルのイギリス人』(1948年)である。 公的知識人としてのフレイレの行動は、かなり物議をかもしている。1930年代に共産主義者のレッテルを貼られた彼は、その後、右派に転じた。1950年 代にはポルトガルのサラザール政権を支持し、1964年以降はブラジルのウンベルト・カステロ・ブランコの軍事独裁政権を擁護した。フレイレはルソトロピ ズムの "生みの親 "とされている。当時の「混血」は、オイゲン・フィッシャーやチャールズ・ダヴェンポートの理論のように否定的に捉えられる傾向にあった[13]。 フレイレはその文体で高く評価された[citation needed]。彼の詩「すべての聖人の、そしてほとんどすべての罪のバイア」について、ブラジルの詩人マヌエル・バンデイラが「あなたの詩、ジルベルト は私にとって永遠の嫉妬の源となるだろう」(cf. Manuel Bandeira, Poesia e Prosa. Rio de Janeiro: フレイレは、サルヴァドールを初めて訪れたときに触発されてこの長編詩を書いた[citation needed]。 1987年7月18日、レシフェで死去。 |

| Selected bibliography The Masters and the Slaves: a study in the development of Brazilian civilization – First published in Portuguese in 1933, under the title "Casa-Grande & Senzala". New World in the Tropics: the culture of modern Brazil The Mansions and the Shanties: the making of modern Brazil – First published in Portuguese in 1936, under the title "Sobrados e Mucambos". The Northeast: Aspects of Sugarcane Influence on Life and Landscape (1937) Sugar (1939) Olinda (1939) A French Engineer in Brazil (1940), second edition published in 1960 Brazilian problems of Anthropology (1943) Continent and Island (1943) Sociology (1945) Brazil: an interpretation The English in Brazil, 1948 Cape Verde Visited by Gilberto Freyre, 1956 Order and Progress: Brazil from monarchy to republic Order and Progress: Brazil from monarchy to republic Recife Yes, Recife No (1960) Poesia Reunida (1980)[15] Men, engineering and social routes (1987) |

|

| Lusotropicalism Mixed Race Day Research Materials: Max Planck Society Archive |

ルソトロピズム 混血の日 研究資料 マックス・プランク協会アーカイブ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilberto_Freyre |

|

| Lusotropicalism

(Portuguese: Lusotropicalismo) is a term and "quasi-theory"[1]

developed by Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre to describe the

distinctive character of Portuguese imperialism overseas, proposing

that the Portuguese were better colonizers than other European

nations.[2][3] Freyre theorized that because of Portugal's warmer climate, and having been inhabited by Celts, Romans, Visigoths, Moors and several other peoples in pre-modern times, the Portuguese were more humane, friendly, and adaptable to other climates and cultures. He saw "Portuguese-based cultures as cultures of ecumenical expansion" and suggested that "Lusotropical culture was a form of resistance against both the 'barbaric' Soviet communist influence, and the also 'barbarian' process of Americanization and capitalist expansion."[3] In addition, by the early 20th century, Portugal was by far the European colonial power with the oldest territorial presence overseas; in some cases its territories had been continuously settled and ruled by the Portuguese for five centuries.[citation needed] Lusotropicalism celebrated both actual and mythological elements of racial democracy and civilizing mission in the Portuguese Empire, encompassing a pro-miscegenation attitude toward the colonies or overseas territories. The ideology is best exemplified in the work of Freyre.[3] |

ルソトロピズム(ポルトガル語: Lusotropicalismo)とは、ブラジルの社会学者ジルベルト・フレイレによって提唱された用語であり「準理論」[1]である。 フレイレは、ポルトガルは温暖な気候であり、前近代にはケルト人、ローマ人、西ゴート人、ムーア人、その他いくつかの民族が居住していたため、ポルトガル 人はより人道的で友好的であり、他の気候や文化に適応することができたと理論化した。彼は「ポルトガルを基盤とする文化は、エキュメニカルな拡張の文化で ある」と考え、「ルソトロピックの文化は、『野蛮な』ソビエト共産主義の影響と、同じく『野蛮な』アメリカ化と資本主義の拡張の両方のプロセスに対する抵 抗の形であった」と示唆した[3]。 さらに、20世紀初頭までに、ポルトガルは海外に最も古い領土を持つヨーロッパの植民地大国であり、場合によっては、その領土は5世紀にわたって継続的に ポルトガル人によって定住し、統治されていた[要出典]。このイデオロギーはフレイレの作品に最もよく例証されている[3]。 |

| Background See also: Historical origins and genetics of the Portuguese people, History of the Portuguese Empire, and Slavery in Portugal  Lisbon in the 1570s had many Black Africans among its population. Some were slaves or slave traders, others were free. There were statues of Black saints in the city churches, European and African dance and fusion cuisine of both Portuguese and African origin.[4] The beginning of the Portuguese Empire is usually traced to the 1415 Conquest of Ceuta in North Africa. In the succeeding decades of the 15th century, Portuguese sailors traveled all over the world: Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488; Vasco da Gama reached India in 1498; and Pedro Álvares Cabral made landfall in Brazil in 1500. At first the Portuguese were interested primarily in lucrative trade opportunities (including the slave trade), and by the end of the 16th century the Portuguese had established trading outposts in Africa, India, Brazil, the Middle East, and South Asia. During this time there was some minimal Portuguese intermarrying with and settlement among African and Asian peoples. It was much more common for the Portuguese to bring Asian and especially African peoples to Europe and Brazil, most often though not always as enslaved people. As early as the 1570s, Lisbon had a sizeable and well-known Black African population of enslaved and free people. During the New Imperialist Scramble for Africa of the 1890s onward, Portugal expanded its coastal African territories in modern Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau inland. Like other European colonial empires, Portugal achieved this expansion primarily through physical and economic violence against native peoples. After the 1910 Portuguese Revolution, and as an official policy of the 1933–1974 Estado Novo dictatorship, Black people in Portuguese Africa were de jure eligible for full Portuguese citizenship and its attendant rights. In practice, Black people hardly ever achieved such status, and during the Estado Novo even white Portuguese born in Africa were denied the same legal rights and protections as whites born in metropolitan Portugal. |

背景 以下も参照のこと: ポルトガル人の歴史的起源と遺伝学、ポルトガル帝国の歴史、ポルトガルの奴隷制度  1570年代のリスボンには、多くのアフリカ系黒人がいた。奴隷や奴隷商人もいれば、自由人もいた。市内の教会には黒人の聖人像があり、ヨーロッパとアフリカのダンスや、ポルトガルとアフリカの両方の起源を持つフュージョン料理があった[4]。 ポルトガル帝国の始まりは、通常、1415年の北アフリカのセウタ征服に遡る。その後15世紀の数十年間、ポルトガルの船乗りたちは世界中を旅した: バルトロメウ・ディアスは1488年に喜望峰を回り、ヴァスコ・ダ・ガマは1498年にインドに到達し、ペドロ・アルヴァレス・カブラルは1500年にブ ラジルに上陸した。当初、ポルトガルは主に有利な貿易機会(奴隷貿易を含む)に関心を持ち、16世紀末にはアフリカ、インド、ブラジル、中東、南アジアに 貿易拠点を築いた。この間、ポルトガルがアフリカやアジアの人々と交配したり、定住したりすることはほとんどなかった。ポルトガルがアジア、特にアフリカ の人々をヨーロッパとブラジルに連れてくることは、常にではなかったが、多くの場合、奴隷として連れてくることの方がはるかに一般的であった。1570年 代にはすでに、リスボンには奴隷として、また自由民として、かなりの数のアフリカ系黒人が住んでいたことはよく知られている。 1890年代以降の新帝国主義によるアフリカ争奪戦の間、ポルトガルはアンゴラ、モザンビーク、ギニアビサウの沿岸アフリカ領土を内陸に拡大した。他の ヨーロッパの植民地帝国と同様、ポルトガルは主に先住民に対する物理的、経済的暴力によってこの拡大を達成した。1910年のポルトガル革命後、1933 年から1974年のエスタード・ノーヴォ独裁政権の公式政策として、ポルトガル領アフリカの黒人は、ポルトガルの完全な市民権とそれに付随する権利を事実 上得ることができた。実際には、黒人がそのような地位を得ることはほとんどなく、エスタード・ノーヴォ時代には、アフリカで生まれたポルトガル系白人でさ え、ポルトガル首都圏で生まれた白人と同じ法的権利や保護を否定されていた。 |

| Application during the Estado Novo See also: Decolonization of the Portuguese Empire Prior to Freyre's publication of Casa-Grande & Senzala, few—if any—Portuguese politicians and colonial administrators conceived of the Portuguese Empire as a multicultural, multiracial, and pluricontinental nation (the idea that Portugal was not a colonial empire but a nation-state spread across continents).[5] They were more likely to think of Portuguese colonialism as a logical historical extension or continuation of the Reconquista.[5] For example, Armindo Monteiro, Portuguese Minister of Colonies between 1931 and 1935, considered himself a "Social Darwinist" and was a proponent of the traditional colonial "civilizing mission" and white saviorism.[5] Monteiro believed Portugal had a "historic obligation" to civilize the "inferior races" who lived in its African and Asian territories by converting them to Christianity and teaching them a work ethic.[5] Portuguese dictator António de Oliveira Salazar strongly resisted Freyre's ideas throughout the 1930s and 1940s, partly because Freyre claimed the Portuguese were more prone to miscegenation than other European nations. He adopted Lusotropicalism only after sponsoring Freyre on a visit to Portugal and some of its overseas territories in 1951 and 1952. Freyre's work Aventura e Rotina (Adventure and Routine) was a result of this trip. Salazar adopted Lusotropicalism by asserting that since Portugal had been a multicultural, multiracial, and pluricontinental nation since the 15th century, losing its overseas territories in Africa and Asia would dismember the country and end Portuguese independence.[3] According to Salazar, in geopolitical terms, losing these territories would decrease the Portuguese state's self-sufficiency. |

エスタード・ノーヴォ時代の適用 こちらもご参照ください: ポルトガル帝国の脱植民地化 フレイレが『カサ=グランデ&センザラ』を出版する以前は、ポルトガルの政治家や植民地行政官で、ポルトガル帝国を多文化・多民族・多大陸国家(ポルトガ ルは植民地帝国ではなく、大陸にまたがる国民国家であるという考え方)として考えていた者はほとんどいなかった[5]。 彼らはむしろ、ポルトガルの植民地主義をレコンキスタの論理的な歴史的延長または継続として考えていた。 [例えば、1931年から1935年にかけてのポルトガルの植民地大臣であったアルミンド・モンテイロは、自らを「社会ダーウィン主義者」であると考え、 伝統的な植民地の「文明化ミッション」と白人の救世主主義の支持者であった[5]。モンテイロは、ポルトガルはアフリカやアジアの領土に住む「劣等民族」 をキリスト教に改宗させ、労働倫理を教えることによって文明化する「歴史的義務」があると信じていた[5]。 ポルトガルの独裁者アントニオ・デ・オリヴェイラ・サラザールは、1930年代から1940年代にかけてフレイレの思想に強く抵抗したが、これはフレイレ がポルトガルは他のヨーロッパ諸国よりも混血しやすいと主張していたためでもあった。彼がルソトロピズムを採用したのは、1951年と1952年にフレイ レを後援してポルトガルとその海外領土を訪問した後のことである。フレイレの作品『Aventura e Rotina(冒険と日常)』は、この旅行の成果である。 サラザールは、ポルトガルは15世紀以来、多文化、多民族、多大陸国家であったため、アフリカとアジアの海外領土を失うことは国を解体し、ポルトガルの独 立を終わらせることになると主張し、ルソトロピズムを採用した[3]。 サラザールによれば、地政学的に、これらの領土を失うことはポルトガル国家の自給率を低下させることになるという。 |

| Critique Freyre's response to criticism The life of Freyre, after he published Casa-Grande & Senzala, became an eternal source of explanation. He repeated several times that he did not create the myth of a racial democracy and that the fact that his books recognized the intense mixing between "races" in Brazil did not mean a lack of prejudice or discrimination. He pointed out that many people have claimed the United States to have been an "exemplary democracy" whereas slavery and racial segregation were present throughout most of US history:[6] "The interpretation of those who want to place me among the sociologists or anthropologists who said prejudice of race among the Portuguese or the Brazilians never existed is extreme. What I have always suggested is that such prejudice is minimal... when compared to that which is still in place elsewhere, where laws still regulate relations between Europeans and other groups". "It is not that racial prejudice or social prejudice related to complexion are absent in Brazil. They exist. But no one here would have thought of "white-only" Churches. No one in Brazil would have thought of laws against interracial marriage ... Fraternal spirit is stronger among Brazilians than racial prejudice, colour, class or religion. It is true that equality has not been reached since the end of slavery.... There was racial prejudice among plantation owners, there was social distance between the masters and the slaves, between whites and blacks.... But few wealthy Brazilians were as concerned with racial purity as the majority were in the Old South".[6] |

批評 批判に対するフレイレの反応 カサ=グランデ&センサラ』を出版した後のフレレの人生は、永遠の釈明の材料となった。彼は何度も、自分は人種民主主義の神話を創作したのではない、自分 の著書がブラジルの「人種」間の激しい混血を認めたからといって、偏見や差別がないわけではない、と繰り返した。彼は、多くの人々がアメリカは「模範的な 民主主義国家」であったと主張している一方で、奴隷制度や人種隔離はアメリカの歴史のほとんどを通じて存在していたと指摘した:[6]。 「ポルトガル人やブラジル人の間に人種的偏見は存在しなかったと言った社会学者や人類学者の中に私を位置づけようとする人々の解釈は極端である。私が常々 申し上げているのは、そのような偏見は、ヨーロッパ人と他のグループとの関係を法律で規制している、他の場所でいまだに行われている偏見と比較すれ ば、......ごくわずかだということです」。 「人種的偏見や顔色に関する社会的偏見がブラジルにないわけではない。存在する。しかし、"白人専用 "の教会など、ここでは誰も考えもしなかっただろう。異人種間の結婚を禁止する法律など、ブラジルでは誰も考えもしなかっただろう......。ブラジル 人の間では、人種的偏見、肌の色、階級、宗教よりも友愛精神が強い。奴隷制度が終わって以来、平等が達成されていないのは事実だが......。農園主の 間には人種的偏見があり、主人と奴隷、白人と黒人の間には社会的距離があった......。しかし、旧南部で大多数が抱いていたような人種の純粋性にこだ わる裕福なブラジル人はほとんどいなかった」[6]。 |

| Eurasianism Lusosphere Overseas province Pluricontinentalism Racial democracy Luso-Africans Assimilados Prazeros Lançados Mestiços Órfãs do Rei Tropicalismo Fifth Empire |

ユーラシア主義 ルソスフィア 海外州 多大陸主義 人種民主主義 ルソ・アフリカ人 同化 喜び 発足 メスチソ 王の遺児 熱帯主義 第五帝国 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lusotropicalism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆