ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ

Gottfried Wilhelm

Leibniz, 1646-1716

☆

ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ(1646年7月1日[旧暦6月21日] -

1716年11月14日)は、数学者、哲学者、科学者、外交官として活躍したドイツの博識家であり、二進法算術や統計学など、数学の多くの分野に加え、微

積分学を発明した。ライプニッツは、さまざまな分野における知識と能力から「最後の万能の天才」と呼ばれている。産業革命の到来と専門労働の普及により、

彼の存命中にはそのような人物はほとんど見られなくなったからである。[15]

彼は哲学史と数学史の両方において著名な人物である。彼は哲学、神学、倫理学、政治学、法学、歴史学、文献学、ゲーム、音楽、その他の学問に関する著作を

残している。ライプニッツは物理学や技術にも大きな貢献を果たし、確率論、生物学、医学、地質学、心理学、言語学、コンピュータサイエンスの分野におい

て、はるかに後の時代に現れることになる概念を予見していた。さらに、ライプニッツはドイツのヴォルフェンビュッテルにあるヘルツォーク・アウグスト図書

館で勤務中に目録作成システムを考案し、図書館学の分野にも貢献した。このシステムは、ヨーロッパの多くの大規模な図書館のガイドとして役立つものだっ

た。ライプニッツの幅広い分野にわたる貢献は、さまざまな学術誌や数万通の手紙、未発表の原稿に散見される。彼は複数の言語で執筆したが、主にラテン語、

フラ

ンス語、ドイツ語を使用していた。哲学者として、彼は17世紀の合理主義と観念論の代表的人物であった。数学者としての彼の主な功績は、アイザック・

ニュートンと同時代の展開とは独立し

て、微分積分学の主要なアイデアを発展させたことである。数学者たちは一貫して、微積分の慣用的な表現としてライプニッツの表記法をより正確な表現として

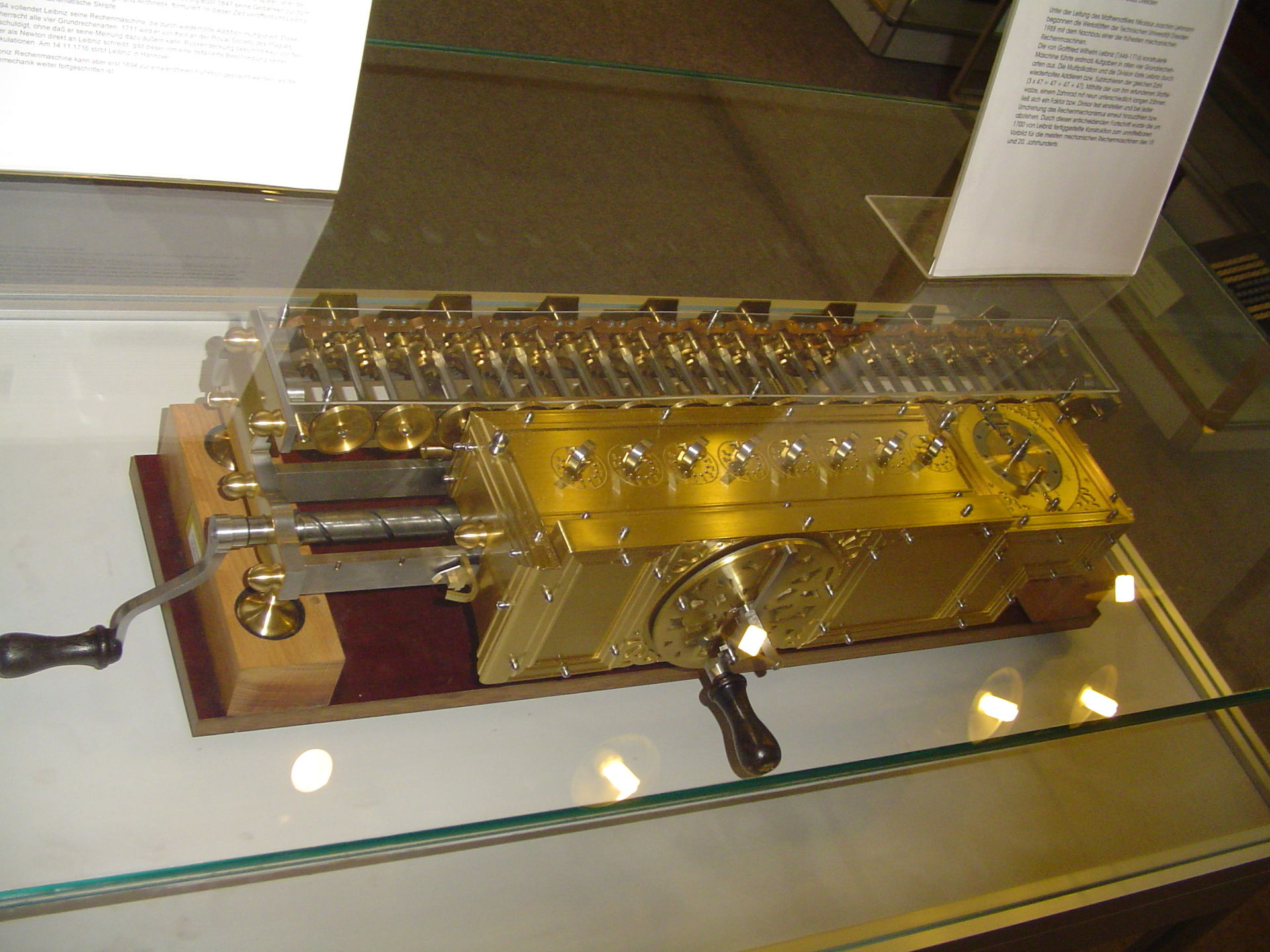

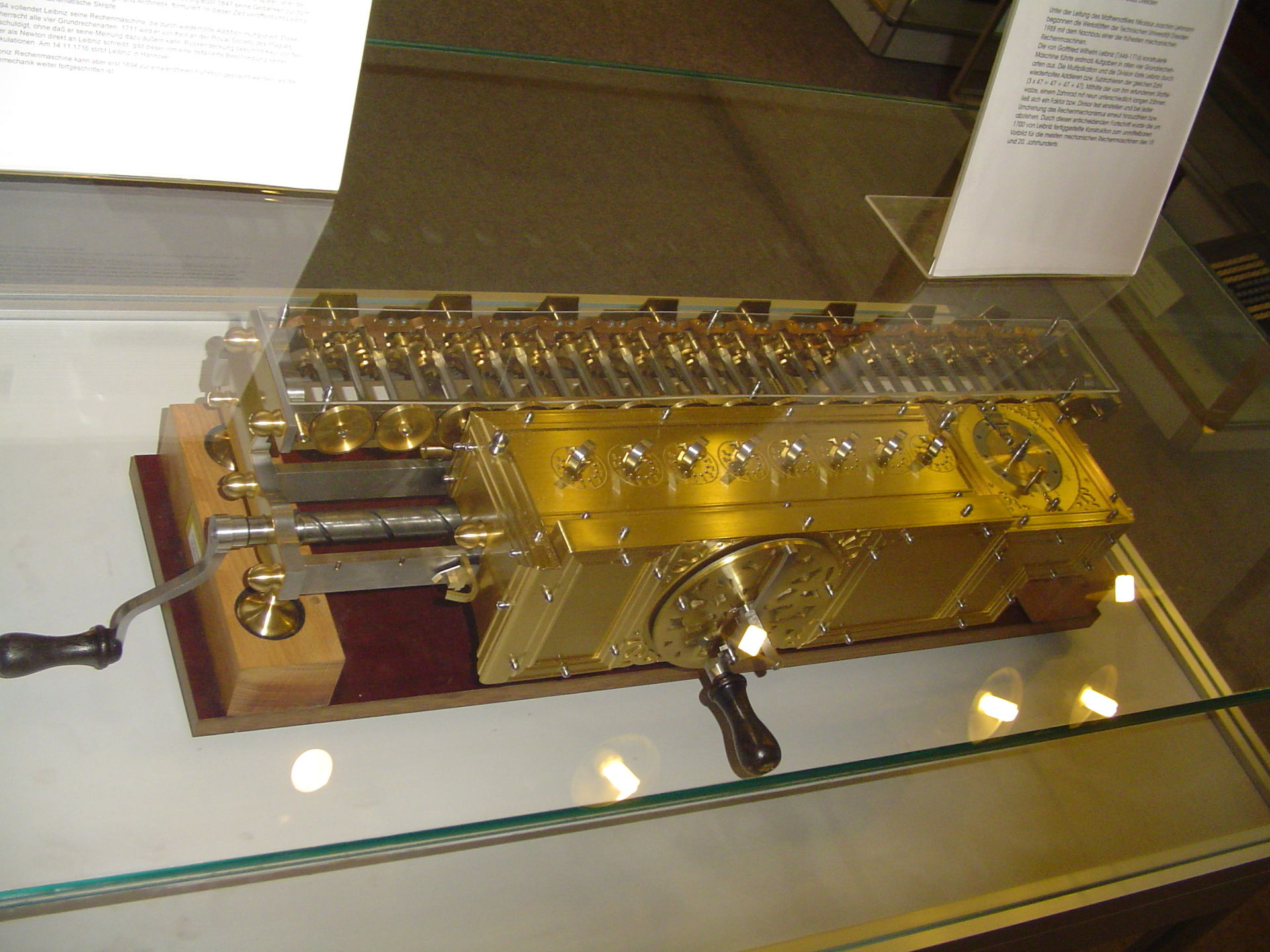

好んできた。20世紀には、ライプニッツの連続の法則と超越論的同質性の法則の概念は、非標準解析によって一貫した数学的定式化がなされた。また、機械式

計算機の分野

における先駆者でもあった。パスカルの計算機に自動乗除算機能を追加する作業を行っている間、彼は1685年に初めてピンホイール式計算機について記述

し、ライプニッツ・ホイールを発明した。このホイールは後に算術計(arithmometer)に用いられ、初の大量生産された機械式計算機となっ

た。

哲学と神学において、ライプニッツは楽観主義者として最もよく知られている。すなわち、彼の結論は、我々の世界はある意味で、神が創造しうる世界の中で最

も良い世界であるというもので、この見解は、例えばヴォルテールの風刺的小説『カンディード』など、他の思想家たちによって揶揄されることもあった。ライ

プニッツは、ルネ・デカルトやバルーフ・スピノザとともに、近世における3人の影響力のある合理主義者のうちの1人であった。彼の哲学は、特に、現実に関

する実質的な知識は、第一原理や先行定義からの推論によって達成できるという前提など、スコラ学の伝統の要素を取り入れている。ライプニッツの業績は、近

代論理学の先駆けであり、様相概念を定義する際に「可能世界」という用語を採用するなど、現代の分析哲学にも影響を与えている。

| Gottfried Wilhelm

Leibniz[a] (1 July 1646 [O.S. 21 June] – 14 November 1716) was a German

polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat

who invented calculus in addition to many other branches of

mathematics, such as binary arithmetic, and statistics. Leibniz has

been called the "last universal genius" due to his knowledge and skills

in different fields and because such people became much less common

after his lifetime with the coming of the Industrial Revolution and the

spread of specialized labor.[15] He is a prominent figure in both the

history of philosophy and the history of mathematics. He wrote works on

philosophy, theology, ethics, politics, law, history, philology, games,

music, and other studies. Leibniz also made major contributions to

physics and technology, and anticipated notions that surfaced much

later in probability theory, biology, medicine, geology, psychology,

linguistics and computer science. In addition, he contributed to the

field of library science by devising a cataloguing system whilst

working at the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, Germany, that

would have served as a guide for many of Europe's largest

libraries.[16] Leibniz's contributions to a wide range of subjects were

scattered in various learned journals, in tens of thousands of letters

and in unpublished manuscripts. He wrote in several languages,

primarily in Latin, French and German.[17][b] As a philosopher, he was a leading representative of 17th-century rationalism and idealism. As a mathematician, his major achievement was the development of the main ideas of differential and integral calculus, independently of Isaac Newton's contemporaneous developments.[19] Mathematicians have consistently favored Leibniz's notation as the conventional and more exact expression of calculus.[20][21][22] In the 20th century, Leibniz's notions of the law of continuity and transcendental law of homogeneity found a consistent mathematical formulation by means of non-standard analysis. He was also a pioneer in the field of mechanical calculators. While working on adding automatic multiplication and division to Pascal's calculator, he was the first to describe a pinwheel calculator in 1685[23] and invented the Leibniz wheel, later used in the arithmometer, the first mass-produced mechanical calculator. In philosophy and theology, Leibniz is most noted for his optimism, i.e. his conclusion that our world is, in a qualified sense, the best possible world that God could have created, a view sometimes lampooned by other thinkers, such as Voltaire in his satirical novella Candide. Leibniz, along with René Descartes and Baruch Spinoza, was one of the three influential early modern rationalists. His philosophy also assimilates elements of the scholastic tradition, notably the assumption that some substantive knowledge of reality can be achieved by reasoning from first principles or prior definitions. The work of Leibniz anticipated modern logic and still influences contemporary analytic philosophy, such as its adopted use of the term "possible world" to define modal notions. |

ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ[a](1646年7月1

日[旧暦6月21日] -

1716年11月14日)は、数学者、哲学者、科学者、外交官として活躍したドイツの博識家であり、二進法算術や統計学など、数学の多くの分野に加え、微

積分学を発明した。ライプニッツは、さまざまな分野における知識と能力から「最後の万能の天才」と呼ばれている。産業革命の到来と専門労働の普及により、

彼の存命中にはそのような人物はほとんど見られなくなったからである。[15]

彼は哲学史と数学史の両方において著名な人物である。彼は哲学、神学、倫理学、政治学、法学、歴史学、文献学、ゲーム、音楽、その他の学問に関する著作を

残している。ライプニッツは物理学や技術にも大きな貢献を果たし、確率論、生物学、医学、地質学、心理学、言語学、コンピュータサイエンスの分野におい

て、はるかに後の時代に現れることになる概念を予見していた。さらに、ライプニッツはドイツのヴォルフェンビュッテルにあるヘルツォーク・アウグスト図書

館で勤務中に目録作成システムを考案し、図書館学の分野にも貢献した。このシステムは、ヨーロッパの多くの大規模な図書館のガイドとして役立つものだっ

た。[16]

ライプニッツの幅広い分野にわたる貢献は、さまざまな学術誌や数万通の手紙、未発表の原稿に散見される。彼は複数の言語で執筆したが、主にラテン語、フラ

ンス語、ドイツ語を使用していた。[17][b] 哲学者として、彼は17世紀の合理主義と観念論の代表的人物であった。数学者としての彼の主な功績は、アイザック・ニュートンと同時代の展開とは独立し て、微分積分学の主要なアイデアを発展させたことである。[19] 数学者たちは一貫して、微積分の慣用的な表現としてライプニッツの表記法をより正確な表現として好んできた。[20][21][22] 20世紀には、ライプニッツの連続の法則と超越論的同質性の法則の概念は、非標準解析によって一貫した数学的定式化がなされた。また、機械式計算機の分野 における先駆者でもあった。パスカルの計算機に自動乗除算機能を追加する作業を行っている間、彼は1685年に初めてピンホイール式計算機について記述し [23]、ライプニッツ・ホイールを発明した。このホイールは後に算術計(arithmometer)に用いられ、初の大量生産された機械式計算機となっ た。 哲学と神学において、ライプニッツは楽観主義者として最もよく知られている。すなわち、彼の結論は、我々の世界はある意味で、神が創造しうる世界の中で最 も良い世界であるというもので、この見解は、例えばヴォルテールの風刺的小説『カンディード』など、他の思想家たちによって揶揄されることもあった。ライ プニッツは、ルネ・デカルトやバルーフ・スピノザとともに、近世における3人の影響力のある合理主義者のうちの1人であった。彼の哲学は、特に、現実に関 する実質的な知識は、第一原理や先行定義からの推論によって達成できるという前提など、スコラ学の伝統の要素を取り入れている。ライプニッツの業績は、近 代論理学の先駆けであり、様相概念を定義する際に「可能世界」という用語を採用するなど、現代の分析哲学にも影響を与えている。 |

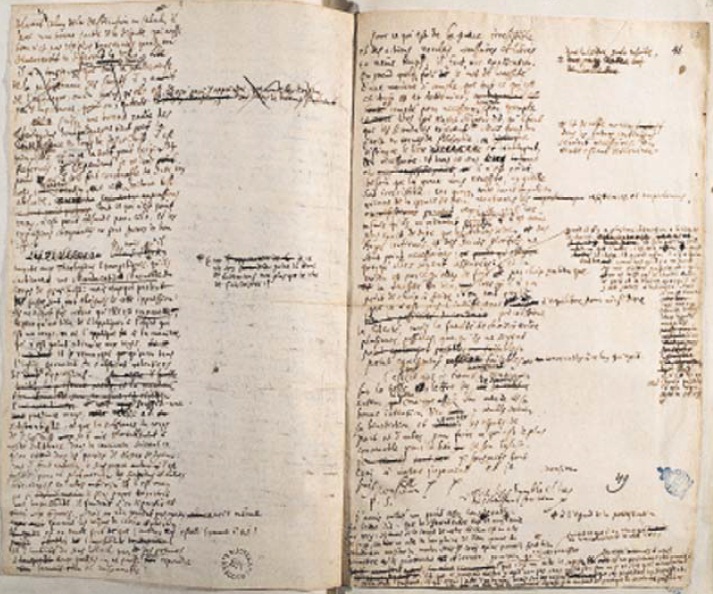

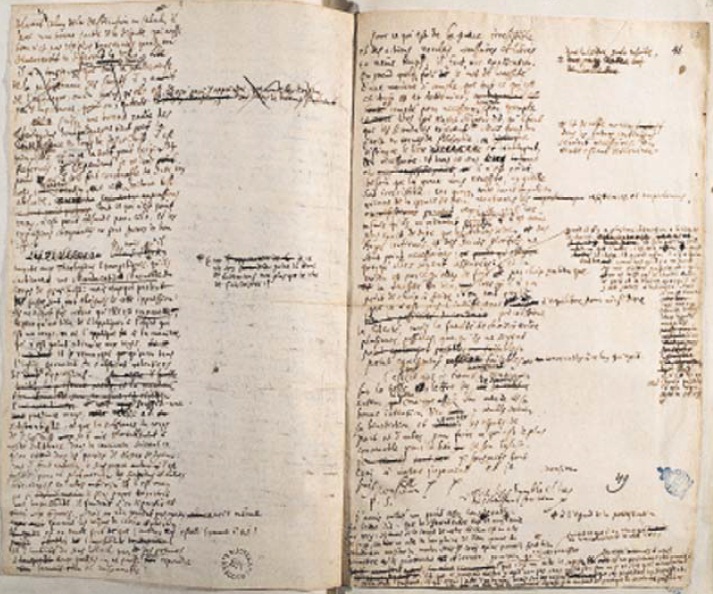

| Biography Early life Gottfried Leibniz was born on July 1 [OS: June 21], 1646, in Leipzig, Saxony, to Friedrich Leibniz and Catharina Schmuck.[24] He was baptized two days later at St. Nicholas Church, Leipzig; his godfather was the Lutheran theologian Martin Geier [de].[25] His father died when he was six years old, and Leibniz was raised by his mother.[26] Leibniz's father had been a Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Leipzig, where he also served as dean of philosophy. The boy inherited his father's personal library. He was given free access to it from the age of seven, shortly after his father's death. While Leibniz's schoolwork was largely confined to the study of a small canon of authorities, his father's library enabled him to study a wide variety of advanced philosophical and theological works—ones that he would not have otherwise been able to read until his college years.[27] Access to his father's library, largely written in Latin, also led to his proficiency in the Latin language, which he achieved by the age of 12. At the age of 13 he composed 300 hexameters of Latin verse in a single morning for a special event at school.[28] In April 1661 he enrolled in his father's former university at age 14.[29][8][30] There he was guided, among others, by Jakob Thomasius, previously a student of Friedrich. Leibniz completed his bachelor's degree in Philosophy in December 1662. He defended his Disputatio Metaphysica de Principio Individui (Metaphysical Disputation on the Principle of Individuation),[31] which addressed the principle of individuation, on 9 June 1663 [O.S. 30 May], presenting an early version of monadic substance theory. Leibniz earned his master's degree in Philosophy on 7 February 1664. In December 1664 he published and defended a dissertation Specimen Quaestionum Philosophicarum ex Jure collectarum (An Essay of Collected Philosophical Problems of Right),[31] arguing for both a theoretical and a pedagogical relationship between philosophy and law. After one year of legal studies, he was awarded his bachelor's degree in Law on 28 September 1665.[32] His dissertation was titled De conditionibus (On Conditions).[31] In early 1666, at age 19, Leibniz wrote his first book, De Arte Combinatoria (On the Combinatorial Art), the first part of which was also his habilitation thesis in Philosophy, which he defended in March 1666.[31][33] De Arte Combinatoria was inspired by Ramon Llull's Ars Magna and contained a proof of the existence of God, cast in geometrical form, and based on the argument from motion. His next goal was to earn his license and Doctorate in Law, which normally required three years of study. In 1666, the University of Leipzig turned down Leibniz's doctoral application and refused to grant him a Doctorate in Law, most likely due to his relative youth.[34][35] Leibniz subsequently left Leipzig.[36] Leibniz then enrolled in the University of Altdorf and quickly submitted a thesis, which he had probably been working on earlier in Leipzig.[37] The title of his thesis was Disputatio Inauguralis de Casibus Perplexis in Jure (Inaugural Disputation on Ambiguous Legal Cases).[31] Leibniz earned his license to practice law and his Doctorate in Law in November 1666. He next declined the offer of an academic appointment at Altdorf, saying that "my thoughts were turned in an entirely different direction".[38] As an adult, Leibniz often introduced himself as "Gottfried von Leibniz". Many posthumously published editions of his writings presented his name on the title page as "Freiherr G. W. von Leibniz." However, no document has ever been found from any contemporary government that stated his appointment to any form of nobility.[39] 1666–1676  Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Leibniz's first position was as a salaried secretary to an alchemical society in Nuremberg.[40] He knew fairly little about the subject at that time but presented himself as deeply learned. He soon met Johann Christian von Boyneburg (1622–1672), the dismissed chief minister of the Elector of Mainz, Johann Philipp von Schönborn.[41] Von Boyneburg hired Leibniz as an assistant, and shortly thereafter reconciled with the Elector and introduced Leibniz to him. Leibniz then dedicated an essay on law to the Elector in the hope of obtaining employment. The stratagem worked; the Elector asked Leibniz to assist with the redrafting of the legal code for the Electorate.[42] In 1669, Leibniz was appointed assessor in the Court of Appeal. Although von Boyneburg died late in 1672, Leibniz remained under the employment of his widow until she dismissed him in 1674.[43] Von Boyneburg did much to promote Leibniz's reputation, and the latter's memoranda and letters began to attract favorable notice. After Leibniz's service to the Elector there soon followed a diplomatic role. He published an essay, under the pseudonym of a fictitious Polish nobleman, arguing (unsuccessfully) for the German candidate for the Polish crown. The main force in European geopolitics during Leibniz's adult life was the ambition of Louis XIV of France, backed by French military and economic might. Meanwhile, the Thirty Years' War had left German-speaking Europe exhausted, fragmented, and economically backward. Leibniz proposed to protect German-speaking Europe by distracting Louis as follows: France would be invited to take Egypt as a stepping stone towards an eventual conquest of the Dutch East Indies. In return, France would agree to leave Germany and the Netherlands undisturbed. This plan obtained the Elector's cautious support. In 1672, the French government invited Leibniz to Paris for discussion,[44] but the plan was soon overtaken by the outbreak of the Franco-Dutch War and became irrelevant. Napoleon's failed invasion of Egypt in 1798 can be seen as an unwitting, late implementation of Leibniz's plan, after the Eastern hemisphere colonial supremacy in Europe had already passed from the Dutch to the British. Thus Leibniz went to Paris in 1672. Soon after arriving, he met Dutch physicist and mathematician Christiaan Huygens and realised that his own knowledge of mathematics and physics was patchy. With Huygens as his mentor, he began a program of self-study that soon pushed him to making major contributions to both subjects, including discovering his version of the differential and integral calculus. He met Nicolas Malebranche and Antoine Arnauld, the leading French philosophers of the day, and studied the writings of Descartes and Pascal, unpublished as well as published.[45] He befriended a German mathematician, Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus; they corresponded for the rest of their lives.  Stepped reckoner When it became clear that France would not implement its part of Leibniz's Egyptian plan, the Elector sent his nephew, escorted by Leibniz, on a related mission to the English government in London, early in 1673.[46] There Leibniz came into acquaintance of Henry Oldenburg and John Collins. He met with the Royal Society where he demonstrated a calculating machine that he had designed and had been building since 1670. The machine was able to execute all four basic operations (adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing), and the society quickly made him an external member. The mission ended abruptly when news of the Elector's death (12 February 1673) reached them. Leibniz promptly returned to Paris and not, as had been planned, to Mainz.[47] The sudden deaths of his two patrons in the same winter meant that Leibniz had to find a new basis for his career. In this regard, a 1669 invitation from Duke John Frederick of Brunswick to visit Hanover proved to have been fateful. Leibniz had declined the invitation, but had begun corresponding with the duke in 1671. In 1673, the duke offered Leibniz the post of counsellor. Leibniz very reluctantly accepted the position two years later, only after it became clear that no employment was forthcoming in Paris, whose intellectual stimulation he relished, or with the Habsburg imperial court.[48] In 1675 he tried to get admitted to the French Academy of Sciences as a foreign honorary member, but it was considered that there were already enough foreigners there and so no invitation came. He left Paris in October 1676. House of Hanover, 1676–1716  Portrait of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Public Library of Hanover, 1703 Leibniz managed to delay his arrival in Hanover until the end of 1676 after making one more short journey to London, where Newton accused him of having seen his unpublished work on calculus in advance.[49] This was alleged to be evidence supporting the accusation, made decades later, that he had stolen calculus from Newton. On the journey from London to Hanover, Leibniz stopped in The Hague where he met van Leeuwenhoek, the discoverer of microorganisms. He also spent several days in intense discussion with Spinoza, who had just completed, but had not published, his masterwork, the Ethics.[50] Spinoza died very shortly after Leibniz's visit. In 1677, he was promoted, at his request, to Privy Counselor of Justice, a post he held for the rest of his life. Leibniz served three consecutive rulers of the House of Brunswick as historian, political adviser, and most consequentially, as librarian of the ducal library. He thenceforth employed his pen on all the various political, historical, and theological matters involving the House of Brunswick; the resulting documents form a valuable part of the historical record for the period. Leibniz began promoting a project to use windmills to improve the mining operations in the Harz Mountains. This project did little to improve mining operations and was shut down by Duke Ernst August in 1685.[48] Among the few people in north Germany to accept Leibniz were the Electress Sophia of Hanover (1630–1714), her daughter Sophia Charlotte of Hanover (1668–1705), the Queen of Prussia and his avowed disciple, and Caroline of Ansbach, the consort of her grandson, the future George II. To each of these women he was correspondent, adviser, and friend. In turn, they all approved of Leibniz more than did their spouses and the future king George I of Great Britain.[51] The population of Hanover was only about 10,000, and its provinciality eventually grated on Leibniz. Nevertheless, to be a major courtier to the House of Brunswick was quite an honor, especially in light of the meteoric rise in the prestige of that House during Leibniz's association with it. In 1692, the Duke of Brunswick became a hereditary Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. The British Act of Settlement 1701 designated the Electress Sophia and her descent as the royal family of England, once both King William III and his sister-in-law and successor, Queen Anne, were dead. Leibniz played a role in the initiatives and negotiations leading up to that Act, but not always an effective one. For example, something he published anonymously in England, thinking to promote the Brunswick cause, was formally censured by the British Parliament. The Brunswicks tolerated the enormous effort Leibniz devoted to intellectual pursuits unrelated to his duties as a courtier, pursuits such as perfecting calculus, writing about other mathematics, logic, physics, and philosophy, and keeping up a vast correspondence. He began working on calculus in 1674; the earliest evidence of its use in his surviving notebooks is 1675. By 1677 he had a coherent system in hand, but did not publish it until 1684. Leibniz's most important mathematical papers were published between 1682 and 1692, usually in a journal which he and Otto Mencke founded in 1682, the Acta Eruditorum. That journal played a key role in advancing his mathematical and scientific reputation, which in turn enhanced his eminence in diplomacy, history, theology, and philosophy.  Pages from Leibniz's papers in the National Library of Poland The Elector Ernest Augustus commissioned Leibniz to write a history of the House of Brunswick, going back to the time of Charlemagne or earlier, hoping that the resulting book would advance his dynastic ambitions. From 1687 to 1690, Leibniz traveled extensively in Germany, Austria, and Italy, seeking and finding archival materials bearing on this project. Decades went by but no history appeared; the next Elector became quite annoyed at Leibniz's apparent dilatoriness. Leibniz never finished the project, in part because of his huge output on many other fronts, but also because he insisted on writing a meticulously researched and erudite book based on archival sources, when his patrons would have been quite happy with a short popular book, one perhaps little more than a genealogy with commentary, to be completed in three years or less. They never knew that he had in fact carried out a fair part of his assigned task: when the material Leibniz had written and collected for his history of the House of Brunswick was finally published in the 19th century, it filled three volumes. Leibniz was appointed Librarian of the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, Lower Saxony, in 1691. In 1708, John Keill, writing in the journal of the Royal Society and with Newton's presumed blessing, accused Leibniz of having plagiarised Newton's calculus.[52] Thus began the calculus priority dispute which darkened the remainder of Leibniz's life. A formal investigation by the Royal Society (in which Newton was an unacknowledged participant), undertaken in response to Leibniz's demand for a retraction, upheld Keill's charge. Historians of mathematics writing since 1900 or so have tended to acquit Leibniz, pointing to important differences between Leibniz's and Newton's versions of calculus. In 1712, Leibniz began a two-year residence in Vienna, where he was appointed Imperial Court Councillor to the Habsburgs. On the death of Queen Anne in 1714, Elector George Louis became King George I of Great Britain, under the terms of the 1701 Act of Settlement. Even though Leibniz had done much to bring about this happy event, it was not to be his hour of glory. Despite the intercession of the Princess of Wales, Caroline of Ansbach, George I forbade Leibniz to join him in London until he completed at least one volume of the history of the Brunswick family his father had commissioned nearly 30 years earlier. Moreover, for George I to include Leibniz in his London court would have been deemed insulting to Newton, who was seen as having won the calculus priority dispute and whose standing in British official circles could not have been higher. Finally, his dear friend and defender, the Dowager Electress Sophia, died in 1714. In 1716, while traveling in northern Europe, the Russian Tsar Peter the Great stopped in Bad Pyrmont and met Leibniz, who took interest in Russian matters since 1708 and was appointed advisor in 1711.[53] Death Leibniz died in Hanover in 1716. At the time, he was so out of favor that neither George I (who happened to be near Hanover at that time) nor any fellow courtier other than his personal secretary attended the funeral. Even though Leibniz was a life member of the Royal Society and the Berlin Academy of Sciences, neither organization saw fit to honor his death. His grave went unmarked for more than 50 years. He was, however, eulogized by Fontenelle, before the French Academy of Sciences in Paris, which had admitted him as a foreign member in 1700. The eulogy was composed at the behest of the Duchess of Orleans, a niece of the Electress Sophia. Personal life Leibniz never married. He proposed to an unknown woman at age 50, but changed his mind when she took too long to decide.[54] He complained on occasion about money, but the fair sum he left to his sole heir, his sister's stepson, proved that the Brunswicks had paid him fairly well. In his diplomatic endeavors, he at times verged on the unscrupulous, as was often the case with professional diplomats of his day. On several occasions, Leibniz backdated and altered personal manuscripts, actions which put him in a bad light during the calculus controversy.[55] He was charming, well-mannered, and not without humor and imagination.[56] He had many friends and admirers all over Europe. He was identified as a Protestant and a philosophical theist.[57][58][59][60] Leibniz remained committed to Trinitarian Christianity throughout his life.[61] |

経歴 幼少期 ゴットフリート・ライプニッツは1646年7月1日(OS: 6月21日)、ザクセン州ライプツィヒでフリードリヒ・ライプニッツとカタリーナ・シュムックの間に生まれた。[24] 2日後、ライプツィヒの聖ニコラス教会で洗礼を受け、 ルター派神学者のマルティン・ガイアー(Martin Geier)[de]であった。[25] ライプニッツが6歳の時に父が死去し、ライプニッツは母の手で育てられた。 ライプニッツの父はライプツィヒ大学の道徳哲学の教授であり、哲学部の学部長も務めていた。少年は父の個人蔵書を受け継いだ。父の死後まもなく、7歳から 蔵書に自由にアクセスできるようになった。ライプニッツの学業は、限られた権威者の研究にほぼ限定されていたが、父親の蔵書のおかげで、大学時代まで読め なかったであろう、多種多様な高度な哲学や神学の著作を学ぶことができた。[27] 父親の蔵書は主にラテン語で書かれており、ライプニッツはラテン語に堪能となり、12歳までにそのレベルに達した。13歳のとき、学校の特別なイベントの ために、彼は300のヘクサメーターのラテン語の詩を1朝で書き上げた。[28] 1661年4月、14歳で父親がかつて学んだ大学に入学した。[29][8][30] そこで彼は、フリードリヒの以前の学生であったヤコブ・トマシウスの指導を受けた。ライプニッツは1662年12月に哲学の学士号を取得した。1663年 6月9日(ユリウス暦5月30日)には、個別化の原理を扱った『形而上学論争論』(Disputatio Metaphysica de Principio Individui)を擁護し、単子論的実体理論の初期のバージョンを提示した。ライプニッツは1664年2月7日に哲学の修士号を取得した。1664年 12月には論文『Specimen Quaestionum Philosophicarum ex Jure collectarum(法哲学の問題集)』を出版し、その論文で哲学と法の理論的・教育的な関係について論じた。1年間の法律研究の後、1665年9月 28日に法学士の学位を取得した。[32] 彼の論文のタイトルは『De conditionibus(条件について)』であった。[31] 1666年初頭、19歳だったライプニッツは最初の著書『De Arte Combinatoria(組み合わせ術について)』を執筆した。 その最初の部分は、1666年3月に彼が擁護した哲学のハビリテーション論文でもあった。[31][33] 『De Arte Combinatoria』はラモン・リュイの『アルス・マグナ』に触発されたもので、幾何学的な形で表現された神の存在証明と運動に関する議論が含まれ ていた。 ライプニッツの次の目標は、通常3年間の研究が必要とされる法学の学位と博士号を取得することであった。1666年、ライプニッツの博士号申請をライプ ツィヒ大学が却下し、法学博士号を授与することを拒否した。その理由は、おそらくライプニッツが相対的に若すぎたためである。[34][35] ライプニッツはその後ライプツィヒを去った。[36] ライプニッツはその後アルトドルフ大学に入学し、すぐに論文を提出した。おそらく おそらくライプツィヒで以前から取り組んでいたものと思われる。[37] 論文のタイトルは『Disputatio Inauguralis de Casibus Perplexis in Jure(曖昧な法的案件に関する就任論争)』であった。[31] ライプニッツは1666年11月に弁護士資格と法学博士号を取得した。その後、アルトドルフでの教職のオファーを断り、「私の考えはまったく別の方向に向 いている」と述べた。[38] 成人してからは、ライプニッツはしばしば「ゴットフリート・フォン・ライプニッツ」と名乗っていた。彼の死後に出版された著作の多くでは、タイトルページ に「フライヘア・G.W.・フォン・ライプニッツ」と表記されている。しかし、同時代の政府による文書で、彼が貴族の地位に任命されたことを示すものは発 見されていない。[39] 1666年-1676年  ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ ライプニッツの最初の職務は、ニュルンベルクの錬金術協会の給料をもらう秘書であった。[40] その時点では、その主題についてほとんど知らなかったが、深い学識があるように装った。ほどなくして、彼はヨハン・クリスティアン・フォン・ボイネブルク (1622年 - 1672年)と出会った。ボイネブルクは、マインツ選帝侯ヨハン・フィリップ・フォン・シェーンボルン(Johann Philipp von Schönborn)の解任された首席大臣であった。ボイネブルクはライプニッツを助手として雇い入れ、その後まもなく選帝侯と和解し、ライプニッツを彼 に紹介した。その後、ライプニッツは選帝侯に法律に関する論文を献上し、職を得ようとした。この策略は功を奏し、選帝侯はライプニッツに選帝侯領の法規の 再起草を手伝うよう依頼した。[42] 1669年、ライプニッツは控訴院の評議員に任命された。フォン・ボイネブルクは1672年に死去したが、ライプニッツは未亡人のもとで働き続け、 1674年に解雇されるまでその地位にあった。[43] フォン・ボイネブルクはライプニッツの評判を高めるために尽力し、ライプニッツの覚書や手紙は好意的に受け止められるようになった。選帝侯への仕えの後 に、ライプニッツは外交的な役割を担うようになった。彼は架空のポーランド貴族のペンネームで、ポーランド王位継承権をドイツ人に与えるよう(成功はしな かったが)主張する論文を発表した。ライプニッツの成人期におけるヨーロッパの地政学上の主な力は、フランス軍と経済力を背景にしたフランスのルイ14世 の野望であった。一方、30年戦争はドイツ語圏のヨーロッパを疲弊させ、分裂させ、経済的に後退させていた。ライプニッツは、次のようにしてルイの気をそ らすことで、ドイツ語圏のヨーロッパを守ろうと提案した。フランスにエジプトを占領させ、その足掛かりとしてオランダ領東インドを最終的に征服させる。そ の見返りとして、フランスはドイツとオランダを放っておくことに同意する。この計画は選帝侯の慎重な支持を得た。1672年、フランス政府はライプニッツ をパリに招いて協議を行ったが[44]、その計画はまもなくフランドル戦争の勃発によって頓挫し、無意味なものとなった。1798年のナポレオンのエジプ ト侵攻の失敗は、ヨーロッパにおける東半球の植民地支配がすでにオランダからイギリスへと移行した後であったため、ライプニッツの計画の知らず知らずのう ちに遅れて実施されたものと見ることができる。 こうしてライプニッツは1672年にパリへと向かった。到着後まもなく、彼はオランダの物理学者であり数学者であったクリスティアーン・ホイヘンスと出会 い、自身の数学と物理学の知識が断片的なものであることに気づいた。ホイヘンスを師として、ライプニッツは独学のプログラムを開始し、すぐに微分積分学の 彼なりの解釈の発見を含む、両分野への大きな貢献を果たすに至った。彼は、当時のフランスを代表する哲学者であるニコラ・マレブランシュとアントワーヌ・ アルノーと出会い、デカルトとパスカルの著作を、出版されたものだけでなく未発表のものも含めて研究した。[45] また、ドイツの数学者エーレンフリート・ヴァルター・フォン・チルンハウスの友人となり、その後生涯にわたって文通を続けた。  ステップ式計算器 フランスがライプニッツのエジプト計画の実施をしないことが明らかになると、選帝侯は甥をライプニッツの護衛としてロンドンのイギリス政府に派遣した。 1673年初頭のことである。[46] そこでライプニッツはヘンリー・オルデンブルクとジョン・コリンズと知り合った。王立協会で、1670年から設計・製作していた計算機のデモンストレー ションを行った。この機械は四則演算(加算、減算、乗算、除算)をすべて実行することができ、協会はすぐに彼を外部会員に迎え入れた。 しかし、選帝侯の死(1673年2月12日)の知らせが届いたため、このミッションは突然終了した。ライプニッツはすぐにパリに戻ったが、当初の予定通り マインツには戻らなかった。[47] 同じ冬に2人のパトロンが急死したことで、ライプニッツは自分のキャリアの新たな基盤を見つけなければならなくなった。 この点において、1669年にブラウンシュヴァイクのヨハン・フリードリヒ公からハノーヴァーを訪問するよう招待されたことは、運命的なものとなった。ラ イプニッツは招待を断ったが、1671年には公爵と文通を始めた。1673年、ブラウンシュヴァイク公はライプニッツに参事官職をオファーした。ライプ ニッツは非常に不本意ながら、2年後にその地位を引き受けたが、それは、彼が好んでいた知的刺激が得られるパリでの就職や、ハプスブルク家の宮廷での就職 の可能性がなくなったことが明らかになってからのことだった。[48] 1675年、ライプニッツはフランス科学アカデミーに外国人名誉会員として入会しようとしたが、すでに十分な数の外国人が在籍していると考えられ、招待は受けられなかった。彼は1676年10月にパリを去った。 ハノーヴァー家、1676年~1716年  ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツの肖像、ハノーヴァー公共図書館、1703年 ライプニッツはロンドンに立ち寄り、ニュートンから、彼の未発表の微積分学の論文を事前に見ていたと非難された後、ハノーヴァーへの到着を1676年の終 わりまで遅らせることができた。[49] これが、数十年後に彼がニュートンから微積分学を盗んだという非難を裏付ける証拠であると主張された。ロンドンからハノーヴァーへの旅の途中、ライプニッ ツはハーグに立ち寄り、そこで微生物を発見したレーウェンフックと出会った。また、傑作『エチカ』を完成させたばかりだったが、まだ出版はしていなかった スピノザと数日間、熱心な議論を交わした。[50] スピノザはライプニッツの訪問から間もなくして亡くなった。 1677年、ライプニッツは自身の希望により、終生その地位に留まることになる枢密顧問官に昇進した。ライプニッツは、ブラウンシュヴァイク家の歴代君主 3人の歴史家、政治顧問、そして最も重要な公爵家の図書館司書として仕えた。それ以来、ブラウンシュヴァイク家に関わる政治、歴史、神学のさまざまな問題 について、ライプニッツはペンを執った。その結果生み出された文書は、その時代の歴史記録として貴重な一部となっている。 ライプニッツは、ハルツ山地の採掘作業を改善するために風車を利用するプロジェクトを推進し始めた。このプロジェクトは採掘作業の改善にはほとんど効果をもたらさず、1685年にエルンスト・アウグスト公によって中止された。[48] 北ドイツでライプニッツを受け入れた数少ない人物の一人に、ハノーファー選帝侯夫人ゾフィー(1630年-1714年)と、その娘でプロイセン王妃のゾ フィー・シャルロッテ(1668年-1705年)がおり、ライプニッツの熱心な弟子であった。また、孫の配偶者で、のちのジョージ2世の妻であるアンバッ ハのカロリーネもいた。彼はこれらの女性たちそれぞれに、文通相手、助言者、友人として接した。そして、彼女たちは皆、ライプニッツを配偶者や後のイギリ ス王ジョージ1世よりも高く評価していた。[51] ハノーファーの人口はわずか1万人ほどであり、その田舎っぽさがやがてライプニッツには煩わしく感じられるようになった。とはいえ、ブラウンシュヴァイク 家の一員として宮廷生活を送ることは、特にライプニッツがブラウンシュヴァイク家と関わりを持つ中で同家の威信が急速に高まっていたことを考えると、非常 に名誉なことだった。1692年にはブラウンシュヴァイク公が神聖ローマ帝国の選帝侯の地位を世襲した。1701年の英国王位継承法により、ウィリアム3 世と義理の姉で後継者のアン女王が亡くなった後、選帝侯夫人ゾフィアとその子孫が英国王家の血筋と定められた。ライプニッツは、この王位継承法に至るまで の取り組みや交渉において一定の役割を果たしたが、常に効果的であったわけではない。例えば、ブランズウィック家の支援を目的として匿名で英国で発表した 論文は、英国議会から正式に非難された。 ブランズウィック家の人々は、ライプニッツが宮廷付きの役人としての職務とは関係のない知的探求に多大な労力を費やしたことを容認していた。例えば、微積 分の完成、数学、論理学、物理学、哲学に関する著作、膨大な書簡のやりとりなどである。彼は1674年に微積分学の研究を開始し、現存するノートにその使 用の最も早い証拠が残っているのは1675年である。1677年には一貫した体系を構築していたが、1684年まで公表することはなかった。ライプニッツ の最も重要な数学論文は、1682年から1692年の間に発表された。通常は、1682年に彼とオットー・メンケが創刊した学術誌『アクタ・エリュディ トーラム』に掲載された。この学術誌は、彼の数学と科学における名声を高める上で重要な役割を果たし、それが外交、歴史、神学、哲学における彼の名声を高 めることにもつながった。  ポーランド国立図書館所蔵のライプニッツの論文のページ 選帝侯エルンスト・アウグストゥスは、ライプニッツにブランズウィック家の歴史をシャルルマーニュの時代、あるいはそれ以前までさかのぼって執筆するよう 依頼した。その本が自分の家系の野望を前進させることを期待してのことだった。1687年から1690年にかけて、ライプニッツはドイツ、オーストリア、 イタリアを広く旅し、このプロジェクトに関連する資料を探し求め、見つけ出した。何十年もの歳月が過ぎたが、歴史書は出版されなかった。次の選帝侯は、ラ イプニッツの明らかな怠慢ぶりに苛立ちを募らせた。ライプニッツは、他の多くの分野でも膨大な成果を残していたため、このプロジェクトを完成させることは なかったが、それは、後援者たちが、3年以内に完成する、系図に注釈を加えただけの短い大衆向けの本で十分満足していたのに対し、ライプニッツは、綿密な 調査と博識に基づいた書物を執筆することに固執したためでもあった。彼らは、ライプニッツが実際には与えられた任務のかなりの部分を遂行していたことを知 る由もなかった。ライプニッツがブラウンシュヴァイク家の歴史のために書き、収集した資料は、19世紀になってようやく出版されたが、3巻にわたる大著で あった。 ライプニッツは1691年にニーダーザクセン州ヴォルフェンビュッテルのアウグストゥス図書館の司書に任命された。 1708年、ジョン・キールは王立協会の機関誌に、ニュートンの承認を得たと見られる形でライプニッツがニュートンの微積分を盗用したと非難する記事を投 稿した。[52] こうしてライプニッツの残りの人生を暗くする微積分の優先権論争が始まった。ライプニッツが撤回を要求したことに対して、王立協会(ニュートンも知らぬ間 に参加していた)が正式に調査を行い、キールの告発を支持した。1900年頃から数学史を研究する歴史家たちは、ライプニッツを無罪とする傾向にあり、ラ イプニッツとニュートンの微積分学のバージョンに重要な違いがあることを指摘している。 1712年、ライプニッツは2年間のウィーン滞在を開始し、ハプスブルク家の宮廷顧問官に任命された。1714年にアン女王が死去すると、1701年の王 位継承法の規定により、選帝侯ジョージ・ルイがイギリス王ジョージ1世となった。ライプニッツは、この喜ばしい出来事を実現させるために多くのことをした が、栄光を手にするのは彼ではなかった。ウェールズ王女、アンナ・マリー・ド・ブルボン(アンネ・マリー・ド・ブルボン)の取りなしにもかかわらず、 ジョージ1世はライプニッツがロンドンに来ることを禁じ、少なくとも30年近く前に父親から依頼されていたブラウンシュヴァイク家史の1巻を完成させるま で、ロンドンに来ることを禁じた。さらに、ジョージ1世がライプニッツをロンドンの宮廷に迎え入れることは、微積分学の優先権争いで勝利を収めたと見なさ れ、英国の公式な社会での地位がこれ以上ないほど高かったニュートンに対する侮辱とみなされる可能性があった。最後に、彼の親しい友人であり擁護者であっ たソフィア・シャルロッテが1714年に亡くなった。1716年、北ヨーロッパを旅行中のロシア皇帝ピョートル大帝がバート・ピルモントに立ち寄り、 1708年からロシアに関心を抱き、1711年に顧問に任命されたライプニッツと会った。[53] 死 ライプニッツは1716年にハノーファーで死去した。当時、彼は人気がなかったため、ハノーファー近郊にいたゲオルク1世(在位1714年 - 1730年)や、彼の個人的な秘書以外の宮廷関係者は誰も葬儀に参列しなかった。ライプニッツは英国王立協会とベルリン科学アカデミーの終身会員であった にもかかわらず、両団体とも彼の死を悼むことはなかった。彼の墓は50年以上も無縁墓であった。しかし、1700年に外国人会員として受け入れていたパリ にあるフランス科学アカデミーの前で、フォンテネルがライプニッツを称賛した。この賛辞は、選帝侯夫人ゾフィアの姪であるオルレアン公爵夫人の依頼で作成 された。 私生活 ライプニッツは生涯結婚しなかった。50歳になってから見知らぬ女性にプロポーズしたが、彼女が返事を決めるのにあまりにも時間がかかったため、考えを変 えた。[54] 彼は時折、金銭について不満を漏らしたが、唯一の相続人である姉の連れ子にかなりの遺産を残したことは、ブランウィック家が彼に十分な報酬を支払っていた ことを証明している。外交的な取り組みにおいては、当時のプロの外交官にありがちだったように、時に不誠実な行動に出ることもあった。ライプニッツは、い くつかの機会に個人的な原稿の日付をさかのぼって変更した。この行為は、微積分論争の際に彼を悪く見せるものとなった。 彼は魅力的で礼儀正しく、ユーモアと想像力に富んでいた。[56] ヨーロッパ中に多くの友人や崇拝者がいた。彼はプロテスタントで哲学的な神学者であると認識されていた。[57][58][59][60] ライプニッツは生涯を通じて三位一体説を信奉していた。[61] |

| Philosophy Leibniz's philosophical thinking appears fragmented because his philosophical writings consist mainly of a multitude of short pieces: journal articles, manuscripts published long after his death, and letters to correspondents. He wrote two book-length philosophical treatises, of which only the Théodicée of 1710 was published in his lifetime. Leibniz dated his beginning as a philosopher to his Discourse on Metaphysics, which he composed in 1686 as a commentary on a running dispute between Nicolas Malebranche and Antoine Arnauld. This led to an extensive correspondence with Arnauld;[62] it and the Discourse were not published until the 19th century. In 1695, Leibniz made his public entrée into European philosophy with a journal article titled "New System of the Nature and Communication of Substances".[63] Between 1695 and 1705, he composed his New Essays on Human Understanding, a lengthy commentary on John Locke's 1690 An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, but upon learning of Locke's 1704 death, lost the desire to publish it, so that the New Essays were not published until 1765. The Monadologie, composed in 1714 and published posthumously, consists of 90 aphorisms. Leibniz also wrote a short paper, "Primae veritates" ("First Truths"), first published by Louis Couturat in 1903 (pp. 518–523)[64] summarizing his views on metaphysics. The paper is undated; that he wrote it while in Vienna in 1689 was determined only in 1999, when the ongoing critical edition finally published Leibniz's philosophical writings for the period 1677–1690.[65] Couturat's reading of this paper influenced much 20th-century thinking about Leibniz, especially among analytic philosophers. After a meticulous study (informed by the 1999 additions to the critical edition) of all of Leibniz's philosophical writings up to 1688, Mercer (2001) disagreed with Couturat's reading.[clarification needed] Leibniz met Baruch Spinoza in 1676, read some of his unpublished writings, and had since been influenced by some of Spinoza's ideas. While Leibniz befriended him and admired Spinoza's powerful intellect, he was also dismayed by Spinoza's conclusions,[66] especially when these were inconsistent with Christian orthodoxy. Unlike Descartes and Spinoza, Leibniz had a university education in philosophy. He was influenced by his Leipzig professor Jakob Thomasius, who also supervised his BA thesis in philosophy.[9] Leibniz also read Francisco Suárez, a Spanish Jesuit respected even in Lutheran universities. Leibniz was deeply interested in the new methods and conclusions of Descartes, Huygens, Newton, and Boyle, but the established philosophical ideas in which he was educated influenced his view of their work. Principles Leibniz variously invoked one or another of seven fundamental philosophical Principles:[67] Identity/contradiction. If a proposition is true, then its negation is false and vice versa. Identity of indiscernibles. Two distinct things cannot have all their properties in common. If every predicate possessed by x is also possessed by y and vice versa, then entities x and y are identical; to suppose two things indiscernible is to suppose the same thing under two names. Frequently invoked in modern logic and philosophy, the "identity of indiscernibles" is often referred to as Leibniz's Law. It has attracted the most controversy and criticism, especially from corpuscular philosophy and quantum mechanics. Sufficient reason. "There must be a sufficient reason for anything to exist, for any event to occur, for any truth to obtain."[68] Pre-established harmony.[69] "[T]he appropriate nature of each substance brings it about that what happens to one corresponds to what happens to all the others, without, however, their acting upon one another directly." (Discourse on Metaphysics, XIV) A dropped glass shatters because it "knows" it has hit the ground, and not because the impact with the ground "compels" the glass to split. Law of continuity. Natura non facit saltus[70] (literally, "Nature does not make jumps"). Optimism. "God assuredly always chooses the best."[71] Plenitude. Leibniz believed that the best of all possible worlds would actualize every genuine possibility, and argued in Théodicée that this best of all possible worlds will contain all possibilities, with our finite experience of eternity giving no reason to dispute nature's perfection.[72] Leibniz would on occasion give a rational defense of a specific principle, but more often took them for granted.[73] Monads  A page from Leibniz's manuscript of the Monadology Leibniz's best known contribution to metaphysics is his theory of monads, as exposited in Monadologie. He proposes his theory that the universe is made of an infinite number of simple substances known as monads.[74] Monads can also be compared to the corpuscles of the mechanical philosophy of René Descartes and others. These simple substances or monads are the "ultimate units of existence in nature". Monads have no parts but still exist by the qualities that they have. These qualities are continuously changing over time, and each monad is unique. They are also not affected by time and are subject to only creation and annihilation.[75] Monads are centers of force; substance is force, while space, matter, and motion are merely phenomenal. He argued, against Newton, that space, time, and motion are completely relative:[76] "As for my own opinion, I have said more than once, that I hold space to be something merely relative, as time is, that I hold it to be an order of coexistences, as time is an order of successions."[77] Einstein, who called himself a "Leibnizian", wrote in the introduction to Max Jammer's book Concepts of Space that Leibnizianism was superior to Newtonianism, and his ideas would have dominated over Newton's had it not been for the poor technological tools of the time; Joseph Agassi argues that Leibniz paved the way for Einstein's theory of relativity.[78] Leibniz's proof of God can be summarized in the Théodicée.[79] Reason is governed by the principle of contradiction and the principle of sufficient reason. Using the principle of reasoning, Leibniz concluded that the first reason of all things is God.[79] All that we see and experience is subject to change, and the fact that this world is contingent can be explained by the possibility of the world being arranged differently in space and time. The contingent world must have some necessary reason for its existence. Leibniz uses a geometry book as an example to explain his reasoning. If this book was copied from an infinite chain of copies, there must be some reason for the content of the book.[80] Leibniz concluded that there must be the "monas monadum" or God. The ontological essence of a monad is its irreducible simplicity. Unlike atoms, monads possess no material or spatial character. They also differ from atoms by their complete mutual independence, so that interactions among monads are only apparent. Instead, by virtue of the principle of pre-established harmony, each monad follows a pre-programmed set of "instructions" peculiar to itself, so that a monad "knows" what to do at each moment. By virtue of these intrinsic instructions, each monad is like a little mirror of the universe. Monads need not be "small"; e.g., each human being constitutes a monad, in which case free will is problematic. Monads are purported to have gotten rid of the problematic: interaction between mind and matter arising in the system of Descartes; lack of individuation inherent to the system of Spinoza, which represents individual creatures as merely accidental. Theodicy and optimism Further information: Best of all possible worlds and Philosophical optimism The Theodicy[81] tries to justify the apparent imperfections of the world by claiming that it is optimal among all possible worlds. It must be the best possible and most balanced world, because it was created by an all powerful and all knowing God, who would not choose to create an imperfect world if a better world could be known to him or possible to exist. In effect, apparent flaws that can be identified in this world must exist in every possible world, because otherwise God would have chosen to create the world that excluded those flaws.[82] Leibniz asserted that the truths of theology (religion) and philosophy cannot contradict each other, since reason and faith are both "gifts of God" so that their conflict would imply God contending against himself. The Theodicy is Leibniz's attempt to reconcile his personal philosophical system with his interpretation of the tenets of Christianity.[83] This project was motivated in part by Leibniz's belief, shared by many philosophers and theologians during the Enlightenment, in the rational and enlightened nature of the Christian religion. It was also shaped by Leibniz's belief in the perfectibility of human nature (if humanity relied on correct philosophy and religion as a guide), and by his belief that metaphysical necessity must have a rational or logical foundation, even if this metaphysical causality seemed inexplicable in terms of physical necessity (the natural laws identified by science). In the view of Leibniz, because reason and faith must be entirely reconciled, any tenet of faith which could not be defended by reason must be rejected. Leibniz then approached one of the central criticisms of Christian theism:[84] if God is all good, all wise, and all powerful, then how did evil come into the world? The answer (according to Leibniz) is that, while God is indeed unlimited in wisdom and power, his human creations, as creations, are limited both in their wisdom and in their will (power to act). This predisposes humans to false beliefs, wrong decisions, and ineffective actions in the exercise of their free will. God does not arbitrarily inflict pain and suffering on humans; rather he permits both moral evil (sin) and physical evil (pain and suffering) as the necessary consequences of metaphysical evil (imperfection), as a means by which humans can identify and correct their erroneous decisions, and as a contrast to true good.[85] Further, although human actions flow from prior causes that ultimately arise in God and therefore are known to God as metaphysical certainties, an individual's free will is exercised within natural laws, where choices are merely contingently necessary and to be decided in the event by a "wonderful spontaneity" that provides individuals with an escape from rigorous predestination. Discourse on Metaphysics For Leibniz, "God is an absolutely perfect being". He describes this perfection later in section VI as the simplest form of something with the most substantial outcome (VI). Along these lines, he declares that every type of perfection "pertains to him (God) in the highest degree" (I). Even though his types of perfections are not specifically drawn out, Leibniz highlights the one thing that, to him, does certify imperfections and proves that God is perfect: "that one acts imperfectly if he acts with less perfection than he is capable of", and since God is a perfect being, he cannot act imperfectly (III). Because God cannot act imperfectly, the decisions he makes pertaining to the world must be perfect. Leibniz also comforts readers, stating that because he has done everything to the most perfect degree; those who love him cannot be injured. However, to love God is a subject of difficulty as Leibniz believes that we are "not disposed to wish for that which God desires" because we have the ability to alter our disposition (IV). In accordance with this, many act as rebels, but Leibniz says that the only way we can truly love God is by being content "with all that comes to us according to his will" (IV). Because God is "an absolutely perfect being" (I), Leibniz argues that God would be acting imperfectly if he acted with any less perfection than what he is able of (III). His syllogism then ends with the statement that God has made the world perfectly in all ways. This also affects how we should view God and his will. Leibniz states that, in lieu of God's will, we have to understand that God "is the best of all masters" and he will know when his good succeeds, so we, therefore, must act in conformity to his good will—or as much of it as we understand (IV). In our view of God, Leibniz declares that we cannot admire the work solely because of the maker, lest we mar the glory and love God in doing so. Instead, we must admire the maker for the work he has done (II). Effectively, Leibniz states that if we say the earth is good because of the will of God, and not good according to some standards of goodness, then how can we praise God for what he has done if contrary actions are also praiseworthy by this definition (II). Leibniz then asserts that different principles and geometry cannot simply be from the will of God, but must follow from his understanding.[86] Leibniz wrote: "Why is there something rather than nothing? The sufficient reason ... is found in a substance which ... is a necessary being bearing the reason for its existence within itself."[87] Martin Heidegger called this question "the fundamental question of metaphysics".[88][89] Symbolic thought and rational resolution of disputes Leibniz believed that much of human reasoning could be reduced to calculations of a sort, and that such calculations could resolve many differences of opinion: The only way to rectify our reasonings is to make them as tangible as those of the Mathematicians, so that we can find our error at a glance, and when there are disputes among persons, we can simply say: Let us calculate, without further ado, to see who is right.[90][91][92] Leibniz's calculus ratiocinator, which resembles symbolic logic, can be viewed as a way of making such calculations feasible. Leibniz wrote memoranda[93] that can now be read as groping attempts to get symbolic logic—and thus his calculus—off the ground. These writings remained unpublished until the appearance of a selection edited by Carl Immanuel Gerhardt (1859). Louis Couturat published a selection in 1901; by this time the main developments of modern logic had been created by Charles Sanders Peirce and by Gottlob Frege. Leibniz thought symbols were important for human understanding. He attached so much importance to the development of good notations that he attributed all his discoveries in mathematics to this. His notation for calculus is an example of his skill in this regard. Leibniz's passion for symbols and notation, as well as his belief that these are essential to a well-running logic and mathematics, made him a precursor of semiotics.[94] But Leibniz took his speculations much further. Defining a character as any written sign, he then defined a "real" character as one that represents an idea directly and not simply as the word embodying the idea. Some real characters, such as the notation of logic, serve only to facilitate reasoning. Many characters well known in his day, including Egyptian hieroglyphics, Chinese characters, and the symbols of astronomy and chemistry, he deemed not real.[95] Instead, he proposed the creation of a characteristica universalis or "universal characteristic", built on an alphabet of human thought in which each fundamental concept would be represented by a unique "real" character: It is obvious that if we could find characters or signs suited for expressing all our thoughts as clearly and as exactly as arithmetic expresses numbers or geometry expresses lines, we could do in all matters insofar as they are subject to reasoning all that we can do in arithmetic and geometry. For all investigations which depend on reasoning would be carried out by transposing these characters and by a species of calculus.[96] Complex thoughts would be represented by combining characters for simpler thoughts. Leibniz saw that the uniqueness of prime factorization suggests a central role for prime numbers in the universal characteristic, a striking anticipation of Gödel numbering. Granted, there is no intuitive or mnemonic way to number any set of elementary concepts using the prime numbers. Because Leibniz was a mathematical novice when he first wrote about the characteristic, at first he did not conceive it as an algebra but rather as a universal language or script. Only in 1676 did he conceive of a kind of "algebra of thought", modeled on and including conventional algebra and its notation. The resulting characteristic included a logical calculus, some combinatorics, algebra, his analysis situs (geometry of situation), a universal concept language, and more. What Leibniz actually intended by his characteristica universalis and calculus ratiocinator, and the extent to which modern formal logic does justice to calculus, may never be established.[97] Leibniz's idea of reasoning through a universal language of symbols and calculations remarkably foreshadows great 20th-century developments in formal systems, such as Turing completeness, where computation was used to define equivalent universal languages (see Turing degree). Formal logic Main article: Algebraic logic Leibniz has been noted as one of the most important logicians between the times of Aristotle and Gottlob Frege.[98] Leibniz enunciated the principal properties of what we now call conjunction, disjunction, negation, identity, set inclusion, and the empty set. The principles of Leibniz's logic and, arguably, of his whole philosophy, reduce to two: All our ideas are compounded from a very small number of simple ideas, which form the alphabet of human thought. Complex ideas proceed from these simple ideas by a uniform and symmetrical combination, analogous to arithmetical multiplication. The formal logic that emerged early in the 20th century also requires, at minimum, unary negation and quantified variables ranging over some universe of discourse. Leibniz published nothing on formal logic in his lifetime; most of what he wrote on the subject consists of working drafts. In his History of Western Philosophy, Bertrand Russell went so far as to claim that Leibniz had developed logic in his unpublished writings to a level which was reached only 200 years later. Russell's principal work on Leibniz found that many of Leibniz's most startling philosophical ideas and claims (e.g., that each of the fundamental monads mirrors the whole universe) follow logically from Leibniz's conscious choice to reject relations between things as unreal. He regarded such relations as (real) qualities of things (Leibniz admitted unary predicates only): For him, "Mary is the mother of John" describes separate qualities of Mary and of John. This view contrasts with the relational logic of De Morgan, Peirce, Schröder and Russell himself, now standard in predicate logic. Notably, Leibniz also declared space and time to be inherently relational.[99] Leibniz's 1690 discovery of his algebra of concepts[100][101] (deductively equivalent to the Boolean algebra)[102] and the associated metaphysics, are of interest in present-day computational metaphysics.[103] |

哲学 ライプニッツの哲学思想は断片的に見えるが、それは彼の哲学的な著作が主に多数の短い論文、すなわち、雑誌記事、死後かなり経ってから出版された原稿、通 信員への手紙などから構成されているためである。彼は2冊の哲学論文を著したが、そのうち1710年の『神義論』のみが彼の存命中に出版された。 ライプニッツは、哲学者としての出発点を1686年にニコラ・マレブランシュとアントワーヌ・アルノーの間の論争に関する論評として著した『形而上学論 考』としている。これがきっかけとなり、アルノーとの間で広範な書簡のやりとりが行われるようになった。[62] 論文と『形而上学講話』は19世紀まで出版されなかった。1695年、ライプニッツは「物質の本質と伝達に関する新体系」と題した論文で、ヨーロッパ哲学 界に公に登場した。[63] 1695年から1705年の間に、ライプニッツは『人間理解新論』を著した ジョン・ロックの1690年の著書『人間理解に関する試論』に対する長大な注釈である『人間理解に関する新試論』を執筆したが、ロックが1704年に死去 したことを知ると、出版する意欲を失い、結局『新試論』は1765年まで出版されなかった。1714年に執筆され、死後に出版された『モナド論』は、90 の格言から構成されている。 また、ライプニッツは短い論文「Primae veritates」(「第一の真理」)も執筆しており、1903年にルイ・クチュラが初版を出版した(518-523ページ)[64]。この論文は形而 上学に関する彼の見解を要約したものである。この論文には日付が記載されておらず、1689年にウィーンに滞在していたときに執筆されたことは、1999 年にようやく1677年から1690年までのライプニッツの哲学的な著作の批判版が出版されたときに判明した。クチュラのこの論文の解釈は、20世紀のラ イプニッツに関する多くの考え方に影響を与え、特に分析哲学者の間で影響を与えた。1999年の批判版への追加情報をもとに、1688年までのライプニッ ツの哲学著作のすべてを綿密に研究したマーサー(2001年)は、クチュラの解釈に反対した。 ライプニッツは1676年にバルーフ・スピノザと出会い、スピノザの未発表の著作をいくつか読み、それ以来スピノザの思想に影響を受けていた。ライプニッ ツはスピノザと親交を結び、スピノザの強力な知性を賞賛したが、スピノザの結論には落胆もしていた。特に、それらがキリスト教正統派の教義と矛盾する場合 にはそうであった。 デカルトやスピノザとは異なり、ライプニッツは大学で哲学を学んでいた。ライプニッツは、ライプツィヒ大学の教授で、ライプニッツの哲学の学士論文の指導 教員でもあったヤコブ・トマシウスから影響を受けていた。ライプニッツは、ルーテル派の大学でも尊敬されていたスペインのイエズス会士フランシスコ・スア レスの著作も読んでいた。ライプニッツは、デカルト、ホイヘンス、ニュートン、ボイルの新しい方法や結論に深い関心を抱いていたが、彼が教育を受けた際の 確立された哲学思想が、彼らの業績に対する見方に影響を与えた。 原理 ライプニッツは、7つの基本的な哲学原理の1つまたは複数を次のように引用した。[67] 同一性/矛盾。命題が真である場合、その否定は偽であり、その逆も真である。 不可分同異。2つの異なるものは、その性質をすべて共通にすることはできない。xが持つ述語がすべてyも持つ場合、またその逆も成り立つ場合、xとyは同 一である。2つの区別できないものを想定することは、2つの名称で同一のものを想定することである。「区別できないものの同一性」は、近代の論理学や哲学 において頻繁に引用され、しばしば「ライプニッツの法則」とも呼ばれる。これは特に、粒子哲学や量子力学から最も多くの論争や批判を集めている。 十分な理由。「存在するものには存在する十分な理由があり、起こる出来事には起こる十分な理由があり、成り立つ真理には成り立つ十分な理由がある」[68] 前もって定められた調和。「各々の実体の適切な性質により、ある実体に起こることは、他のすべての実体に起こることに一致する。しかし、それらは直接的に 互いに作用することはない」 (『形而上学講義』第14章)落としたグラスが粉々に割れるのは、それが「地面に当たったことを知っている」からであり、地面に当たった衝撃がグラスを割 るように「強制」しているからではない。 連続性の法則。Natura non facit saltus(ラテン語で「自然は飛躍しない」の意)[70]。 楽観主義。「神は常に最善を選ぶ」[71]。 完全性。ライプニッツは、あり得る世界の中で最も優れたものは、あらゆる真の可能性を実現すると信じており、『テオディケー』の中で、このあり得る世界の 中で最も優れたものはあらゆる可能性を含み、我々の有限な永遠の経験は自然の完全性を疑う理由にはならないと論じている。 ライプニッツは、特定の原則について合理的な擁護をすることもあるが、 特定の原理を合理的に擁護することもあったが、より頻繁にはそれらを当然のこととしていた。[73] モナド  モナド論のライプニッツの原稿のページ ライプニッツの形而上学への最も有名な貢献は、モナド論で展開されたモナドの理論である。彼は、宇宙は無限の数のモナドと呼ばれる単純な物質から成り立っ ているという理論を提唱している。[74] モナドは、ルネ・デカルトやその他の機械論哲学の微粒子とも比較することができる。これらの単純な物質またはモナドは、「自然界における究極の存在単位」 である。モナドは部分を持たないが、それ自体が持つ性質によって存在している。これらの性質は時間とともに絶えず変化し、各モナドはそれぞれ独自のもので ある。また、モナドは時間によって影響を受けることはなく、生成と消滅のみに従う。モナドは力の中心であり、物質は力である。空間、物質、運動は単に現象 的なものである。彼はニュートンに対して、空間、時間、運動は完全に相対的なものであると主張した。「私自身の意見としては、私は空間を時間と同じく相対 的なものであると考える。私は空間を共存の秩序であると考える。時間もまた連続の秩序であるように。」[77] アインシュタインは、 自らを「ライプニッツ主義者」と称したアインシュタインは、マックス・ジャマー著『空間の概念』の序文で、ライプニッツ主義はニュートン主義よりも優れて いると述べ、当時の技術的ツールが貧弱でなかったならば、彼の考えはニュートンの考えを凌駕していたであろうと主張している。ジョセフ・アガシは、ライプ ニッツがアインシュタインの相対性理論への道筋を作ったと主張している。 ライプニッツの神の証明は『神義論』にまとめられている。[79] 理性は矛盾律と十分理由律の原則によって支配されている。 推論の原則を用い、ライプニッツは万物の第一の理由は神であると結論づけた。[79] 私たちが目にするもの、経験するものはすべて変化の対象であり、この世界が偶有であるという事実は、世界が空間と時間において異なる方法で配置される可能 性によって説明できる。偶然の世界には、その存在には何らかの必然的な理由があるはずである。ライプニッツは、幾何学の本を例に挙げて、自身の推論を説明 している。この本が無限のコピーの連鎖から複写されたものである場合、その内容には何らかの理由があるはずである。[80] ライプニッツは、「モナス・モナダム」、すなわち神が存在しなければならないと結論付けた。 モナドの本質は、還元不可能な単純性である。原子とは異なり、モナドには物質的または空間的な性質はない。また、モナドは完全に相互に独立しているため、 原子とは異なる。モナド間の相互作用は見かけ上のみである。むしろ、あらかじめ定められた調和の原理により、各モナドはそれぞれ特有のあらかじめプログラ ムされた「指示」に従うため、モナドは「瞬間ごとに何をすべきか」を「知っている」のである。これらの本質的な指示により、各モナドは宇宙の小さな鏡のよ うなものである。モナドは「小さい」必要はない。例えば、人間一人一人がモナドを構成しており、その場合、自由意志は問題となる。 モナドは、デカルトの体系で生じる心と物質の相互作用、 スピノザの体系に内在する個別性の欠如、すなわち個々の生物を単なる偶然として表すという問題を 解消したとされる。 神義論と楽観主義 さらに詳しい情報: 『可能な世界のすべて』と哲学的楽観主義 神義論(神義学)は、この世界に見られる不完全な部分を、それが「可能な世界のすべて」の中で最適であると主張することで正当化しようとする。なぜなら、 全能かつ全知の神によって創造された世界は、より良い世界が神に知られていたり、存在し得るのであれば、不完全な世界を創造することを神が選ぶはずがない からだ。実際、この世界に見られる欠陥は、あり得るすべての世界に存在しなければならない。そうでなければ、神は欠陥のない世界を創造することを選んだこ とになるからだ。[82] ライプニッツは、神学(宗教)と哲学の真理は互いに矛盾することはあり得ないと主張した。理性と信仰はどちらも「神の贈り物」であるため、両者の対立は神 が自らと争っていることを意味するからだ。神義論は、ライプニッツが自身の個人的な哲学体系とキリスト教の教義の解釈を調和させようとした試みである。 [83] このプロジェクトは、啓蒙時代に多くの哲学者や神学者が共有していた、キリスト教の宗教が理性的で啓発的な性質を持つという信念が、ライプニッツにもあっ たことが動機の一つとなっている。また、人間性は正しい哲学や宗教を指針とすれば、完璧なものになり得るというライプニッツの信念、そして、たとえ形而上 学的因果関係が物理的必然性(科学によって特定された自然法則)の観点では説明不可能に見えるとしても、形而上学的必然性には合理的な、あるいは論理的な 基盤がなければならないという彼の信念によっても形作られた。 ライプニッツの見解では、理性と信仰は完全に調和していなければならないため、理性によって擁護できない信仰の教義はすべて拒絶されなければならない。ラ イプニッツは、キリスト教神学の中心的な批判のひとつにアプローチした。[84] 神が善であり、賢明であり、全能であるならば、なぜ悪がこの世に存在するのか? ライプニッツによれば、神の知恵と力は無限であるが、神が創造した人間は、知恵と意志(行動力)の両面で限界がある。このことが、人間が誤った信念や誤っ た決断、自由意志の行使における非効率的な行動をとる傾向を生み出す。神は人間に苦痛や苦悩を恣意的に与えるのではなく、むしろ、人間が誤った決断を認識 し修正するための手段として、また真の善と対比させるために、形而上学的悪(不完全性)の必然的な結果として、道徳的悪(罪)と肉体的悪(苦痛や苦悩)を 許容している。[85] さらに、人間の 人間の行動は究極的には神に由来する先行原因から生じるものであり、したがって形而上学的確実性として神に知られているが、個人の自由意志は自然法則の範 囲内で行使され、選択は単に偶発的に必要とされるものであり、厳格な予定説からの脱却を個人に提供する「素晴らしい自発性」によって決定される。 形而上学講義 ライプニッツにとって、「神は絶対的に完全な存在」である。彼は、この完全性を第6節で最も実質的な結果をもたらす最も単純な形として説明している。この 考えに沿って、彼はあらゆる種類の完全性は「神に最も高い度合いで帰属する」と宣言している(第1節)。ライプニッツの完璧さの定義は特に詳しく述べられ ていないが、彼にとって不完全さを証明し、神が完璧であることを証明する唯一のものは、「人は、自分がなし得るよりも低い完璧さで行動する場合には不完全 に行動する」というものである。神は完璧な存在であるため、不完全に行動することはありえない(III)。神は不完全に行動することができないため、神が 世界に関して下す決定は完璧でなければならない。ライプニッツはまた、神はすべてを最も完全な度合いで行っているため、神を愛する者は傷つくことはない、 と読者を慰めている。しかし、神を愛することは難しい。なぜなら、ライプニッツは、私たちは「神が望むものを望むようにできているわけではない」と考えて いるからだ。なぜなら、私たちは気質を変える能力を持っているからだ(IV)。これに従って、多くの人々は反逆者として行動するが、ライプニッツは、神を 本当に愛する唯一の方法は、「神の意志に従って自分に訪れるものすべて」に満足することであると述べている(IV)。 神は「絶対的に完全な存在」であるため(I)、ライプニッツは、神が神の能力に劣る完全さで行動するならば、それは不完全な行動であると論じている (III)。彼の三段論法は、神が世界をあらゆる面で完璧に創造したという結論で終わる。これは、神と神の意志をどう見るべきかということにも影響する。 ライプニッツは、神の意志に代わるものとして、神は「最高の師」であり、神は自らの善が成功したことを知っていると理解しなければならないと述べている。 したがって、私たちは神の善なる意志に、あるいは理解できる限りそれに従って行動しなければならない(IV)。ライプニッツは、神に対する見方について、 その作品をその作者だけに賞賛することはできないと宣言している。そうすることで、神の栄光と愛を損なうことにならないように。その代わり、その作品をそ の作者に賞賛しなければならない(II)。事実上、ライプニッツは、もし地球が神の意志によって「善」であると言うのであれば、ある種の「善」の基準に 従って「善」ではないというのであれば、この定義に従えば、その反対の行動も賞賛に値するものであるならば、神が成し遂げたことをどうして神を称賛できる のか、と述べている(II)。ライプニッツは、異なる原理や幾何学は、神の意志から単純に生じるものではなく、神の理解に従うものでなければならないと主 張している。[86] ライプニッツは次のように書いている。「なぜ無ではなく、何かがあるのか? 十分な理由は...存在そのものの中に存在理由を内包する必然的存在である実体に見出される」[87]。 マルティン・ハイデッガーは、この問いを「形而上学の根本問題」と呼んだ。[88][89] 象徴的思考と論争の理性的解決 ライプニッツは、人間の推論の多くはある種の計算に還元できると考え、そのような計算によって多くの意見の相違を解決できると考えていた。 我々の推論を修正する唯一の方法は、数学者のそれと同じように、我々の推論をより具体的にすることであり、そうすれば我々の誤りを一目で見つけられる。そして、人々の間で論争がある場合には、単純にこう言える。さっそく計算して、どちらが正しいか見てみよう。 ライプニッツの算術演算機は記号論理学に似ており、このような計算を実行可能にする方法と見なすことができる。ライプニッツはメモを書き残しており [93]、現在では、記号論理学(そして、したがって、ライプニッツの算術)を基礎から理解しようとする試みとして読むことができる。これらの著作は、 カール・イマニュエル・ゲルハルト(Carl Immanuel Gerhardt)が編集した論文集が出版される1859年まで、未発表のままだった。ルイ・クチュラ(Louis Couturat)が論文集を出版したのは1901年のことで、この頃には、チャールズ・サンダース・ピーアス(Charles Sanders Peirce)やゴットロープ・フレーゲ(Gottlob Frege)によって、近代論理学の主要な発展がすでに成されていた。 ライプニッツは、記号が人間の理解にとって重要であると考えていた。彼は、優れた表記法の開発を非常に重視しており、数学における自身のすべての発見を、 この表記法に帰している。彼の微積分学の表記法は、この点における彼の能力を示す一例である。記号や表記法に対するライプニッツの情熱、そして、それらが 論理学や数学の健全な発展に不可欠であるという信念は、彼を記号論の先駆者とした。 しかし、ライプニッツはさらに先を行っていた。文字を「書かれたあらゆる記号」と定義し、さらに「真の」文字を、単にアイデアを体現する言葉としてではな く、アイデアを直接的に表現するものとして定義した。論理学の記号のように、推論を容易にするだけの「実質的な」文字もある。 ライプニッツの時代には、エジプトの象形文字、漢字、天文学や化学の記号など、広く知られた文字も数多くあったが、ライプニッツはそれらを「実質的な」文 字ではないとみなした。[95] その代わりに、彼は「普遍的特性」または「ユニバーサル・キャラクター」の創出を提案した。これは、人間の思考のアルファベットを基盤とし、各基本概念が 独自の「実質的な」文字で表現されるものである。 算術が数、幾何学が線分を表現するように、我々の思考をすべて明確かつ正確に表現できる文字や記号を見つけることができれば、推論の対象となるすべての事 柄において、算術や幾何学でできることすべてを行うことができるのは明らかである。推論に依存するあらゆる研究は、これらの文字を転用し、一種の微積分学 によって遂行されるだろう。 より複雑な思考は、より単純な思考の文字を組み合わせることで表現される。ライプニッツは、素因数分解の唯一性が、普遍的特性における素数の中心的役割を示唆していることに気づいていた。素数を用いて初等概念の集合に番号を付ける直観的または記憶術的な方法はない。 ライプニッツは特性について最初に書いたときには数学の初心者であったため、当初は代数ではなく、普遍的な言語または文字として考えていた。1676年に なってようやく、従来の代数とその表記法をモデルとした「思考の代数」のようなものを考え出した。その結果、特性には論理計算、組み合わせ論、代数、彼の 分析サイトゥス(状況幾何学)、普遍的概念言語などが含まれた。ライプニッツが「普遍算術」と「推論算術」で実際に意図したこと、および現代の形式論理が 「推論算術」にどこまで正当性を持たせているかについては、決して明確にされることはないかもしれない。[97] 記号と計算による普遍言語による推論というライプニッツの考えは、計算を用いて等価な普遍言語を定義するチューリング完全性のような、20世紀における形 式システムにおける大きな発展を驚くほど予見している(チューリング度を参照)。 形式論理学 詳細は「代数論理学」を参照 ライプニッツは、アリストテレスとゴットロープ・フレーゲの間の最も重要な論理学者の一人として知られている。[98] ライプニッツは、現在では論理積、論理和、否定、同一、集合の包含、空集合と呼ばれるものの主な性質を明らかにした。ライプニッツの論理の原則、そして彼 の哲学全体を要約すると、次の2つになる。 我々のすべての観念は、人間の思考のアルファベットを形成する、ごく少数の単純な観念から構成される。 複雑な観念は、算術の掛け算に類似した、均一かつ対称的な組み合わせによって、これらの単純な観念から導かれる。 20世紀初頭に登場した形式論理学も、少なくとも単項否定と、議論の対象となる宇宙全体にわたる量化変数が必要である。 ライプニッツは生前、形式論理に関する著作を一切発表せず、このテーマに関する著作のほとんどは作業草稿であった。バートランド・ラッセルは著書『西洋哲学史』の中で、ライプニッツは未発表の著作の中で論理を200年後に到達するレベルまで発展させていたと主張している。 ラッセルのライプニッツに関する主要な研究では、ライプニッツの最も驚くべき哲学上のアイデアや主張(例えば、基本的なモナドのそれぞれが全宇宙を映し出 すという主張)の多くは、ライプニッツが物事の間の関係を非現実的なものとして拒絶するという意識的な選択から論理的に導かれるものであることが分かっ た。彼は、そのような関係を物事の(現実の)性質であるとみなした(ライプニッツは単項述語のみを認めていた)。彼にとって、「メアリーはジョンの母であ る」という表現は、メアリーとジョンの別々の性質を説明している。この見解は、現在述語論理の標準となっているド・モルガン、ピアス、シュレーダー、そし てラッセル自身の関係論理とは対照的である。特に、ライプニッツもまた、空間と時間は本質的に関係的であると宣言した。[99] ライプニッツが1690年に発見した概念代数学[100][101](ブール代数と演繹的に等価)[102]と関連する形而上学は、現代の計算形而上学において興味深いものである。[103] |

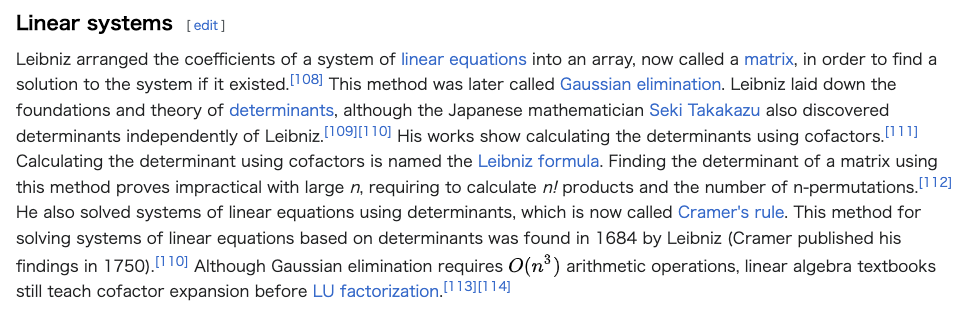

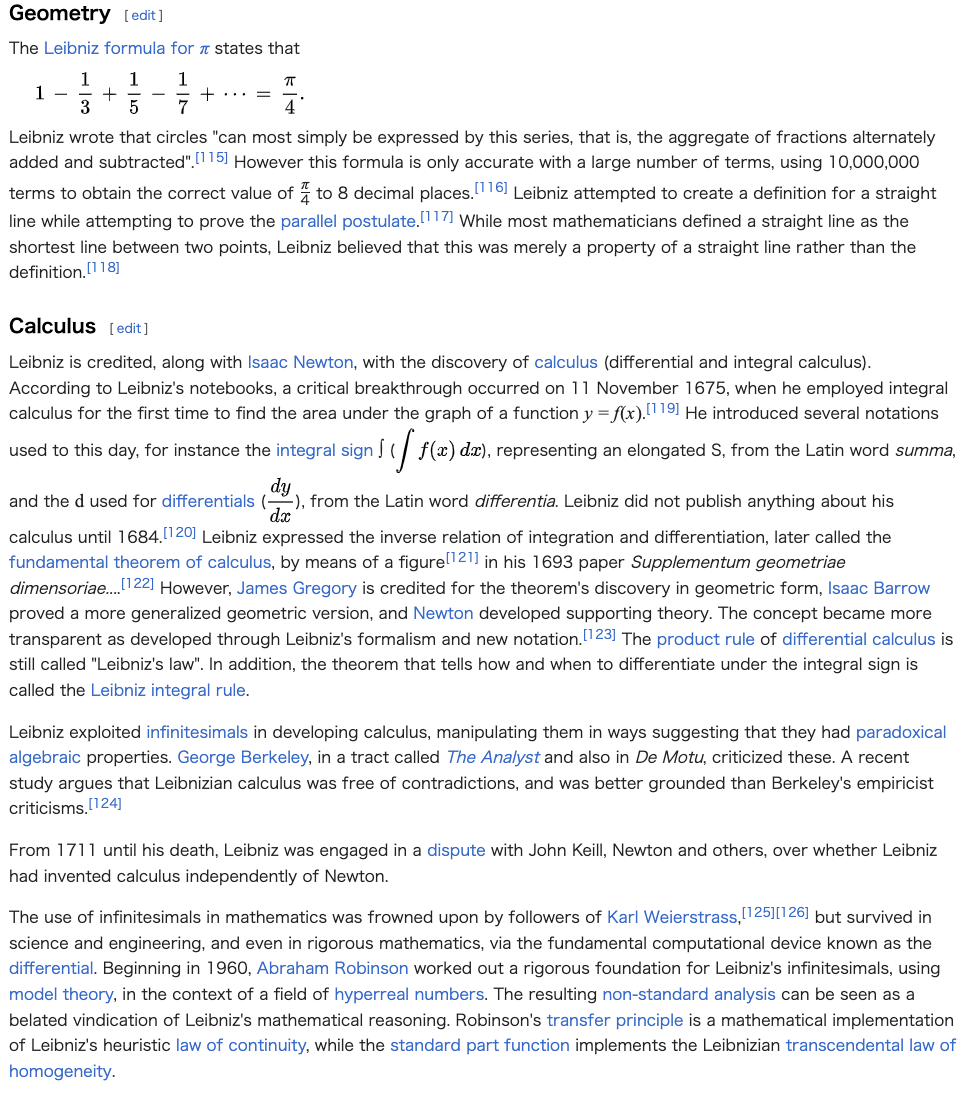

| Mathematics Although the mathematical notion of function was implicit in trigonometric and logarithmic tables, which existed in his day, Leibniz was the first, in 1692 and 1694, to employ it explicitly, to denote any of several geometric concepts derived from a curve, such as abscissa, ordinate, tangent, chord, and the perpendicular (see History of the function concept).[104] In the 18th century, "function" lost these geometrical associations. Leibniz was also one of the pioneers in actuarial science, calculating the purchase price of life annuities and the liquidation of a state's debt.[105] Leibniz's research into formal logic, also relevant to mathematics, is discussed in the preceding section. The best overview of Leibniz's writings on calculus may be found in Bos (1974).[106] Leibniz, who invented one of the earliest mechanical calculators, said of calculation: "For it is unworthy of excellent men to lose hours like slaves in the labor of calculation which could safely be relegated to anyone else if machines were used."[107] |

数学 ライプニッツの時代には三角関数表や対数表に数学的な関数の概念が暗黙のうちに存在していたが、ライプニッツは1692年と1694年に、それを明示的に 使用し、 例えば、横軸、縦軸、接線、弦、垂線など、曲線から派生するいくつかの幾何学概念を表すために、明示的にそれを使用した最初の人物である。(関数概念の歴 史を参照)[104] 18世紀には、「関数」はこれらの幾何学的な関連性を失った。ライプニッツは保険数理科学の先駆者の一人でもあり、終身年金の購入価格や国家債務の清算を 計算していた。[105] 数学とも関連するライプニッツの形式論理学の研究については、前節で述べられている。ライプニッツの微積分に関する著作の最も優れた概説は、Bos (1974) に記載されているかもしれない。[106] 初期の機械式計算機のひとつを発明したライプニッツは、計算について次のように述べている。「機械が使えれば、誰にでも任せられる計算作業に、優れた人間が奴隷のように時間を費やすのはふさわしくない」[107] |

|

|

|

|

| Topology Leibniz was the first to use the term analysis situs,[127] later used in the 19th century to refer to what is now known as topology. There are two takes on this situation. On the one hand, Mates, citing a 1954 paper in German by Jacob Freudenthal, argues: Although for Leibniz the situs of a sequence of points is completely determined by the distance between them and is altered if those distances are altered, his admirer Euler, in the famous 1736 paper solving the Königsberg Bridge Problem and its generalizations, used the term geometria situs in such a sense that the situs remains unchanged under topological deformations. He mistakenly credits Leibniz with originating this concept. ... [It] is sometimes not realized that Leibniz used the term in an entirely different sense and hence can hardly be considered the founder of that part of mathematics.[128] But Hideaki Hirano argues differently, quoting Mandelbrot:[129] To sample Leibniz' scientific works is a sobering experience. Next to calculus, and to other thoughts that have been carried out to completion, the number and variety of premonitory thrusts is overwhelming. We saw examples in "packing", ... My Leibniz mania is further reinforced by finding that for one moment its hero attached importance to geometric scaling. In Euclidis Prota ..., which is an attempt to tighten Euclid's axioms, he states ...: "I have diverse definitions for the straight line. The straight line is a curve, any part of which is similar to the whole, and it alone has this property, not only among curves but among sets." This claim can be proved today.[130] Thus the fractal geometry promoted by Mandelbrot drew on Leibniz's notions of self-similarity and the principle of continuity: Natura non facit saltus.[70] We also see that when Leibniz wrote, in a metaphysical vein, that "the straight line is a curve, any part of which is similar to the whole", he was anticipating topology by more than two centuries. As for "packing", Leibniz told his friend and correspondent Des Bosses to imagine a circle, then to inscribe within it three congruent circles with maximum radius; the latter smaller circles could be filled with three even smaller circles by the same procedure. This process can be continued infinitely, from which arises a good idea of self-similarity. Leibniz's improvement of Euclid's axiom contains the same concept. |

位相 ライプニッツは「解析 situs」という用語を初めて使用した人物であり[127]、この用語は後に19世紀に現在では位相幾何学として知られるものについて使用されるように なった。この状況については2つの見解がある。一方では、Matesは1954年のヤコブ・フレードンタルによるドイツ語論文を引用し、次のように論じて いる。 ライプニッツにとって、点の列のシトゥスはそれらの間の距離によって完全に決定され、その距離が変化すればシトゥスも変化するが、彼の崇拝者であるオイ ラーは、1736年の有名な論文でケーニヒスベルク橋問題とその一般化を解決し、位相幾何学的な変形ではシトゥスは変化しないという意味で 「geometria situs」という用語を使用した。彼は誤って、この概念をライプニッツが最初に提唱したものとしている。... ライプニッツがこの用語をまったく異なる意味で使用していたことは、あまり認識されておらず、したがって、数学の一分野の創始者と見なすことはほとんどで きない。[128] しかし、平野英明はマンデルブロの言葉を引用して、異なる見解を示している。[129] ライプニッツの科学的な業績を少し読むだけでも、衝撃的な体験となる。微積分学や、完成された他の考え方に次いで、予見的な洞察の数と多様性は圧倒的であ る。「パッキング」の例を挙げたが、... 私のライプニッツ・マニアは、そのヒーローが幾何学的なスケーリングを重視していたことを知って、さらに強まった。ユークリッドの公理を厳密化しようとし た『ユークリディスの原論』の中で、彼は次のように述べている。「私は直線に対して多様な定義を持っている。直線は曲線であり、そのどの部分も全体と類似 している。そして、この性質は曲線の間だけでなく、集合の間にも存在する。この主張は今日でも証明できる。[130] マンデルブロが推進したフラクタル幾何学は、ライプニッツの自己相似性と連続性の原理を引用したものだった。「自然は飛躍をしない」[70] ライプニッツが形而上学的な観点から「直線は曲線であり、そのどの部分も全体と類似している」と書いたとき、彼は2世紀以上も先のトポロジーを予見してい たことになる。「パッキング」について、ライプニッツは友人であり、文通相手でもあったデ・ボスに、円を想像し、その中に最大半径で合同な3つの円を内接 させるように指示した。後者の小さな円は、同じ手順でさらに3つの小さな円で埋めることができる。このプロセスは無限に継続することができ、そこから自己 相似性の優れたアイデアが生まれる。ユークリッドの公理に対するライプニッツの改良には、同じ概念が含まれている。 |

| Science and engineering Leibniz's writings are currently discussed, not only for their anticipations and possible discoveries not yet recognized, but as ways of advancing present knowledge. Much of his writing on physics is included in Gerhardt's Mathematical Writings. Physics See also: Dynamism (metaphysics) and Conatus § In Leibniz Leibniz contributed a fair amount to the statics and dynamics emerging around him, often disagreeing with Descartes and Newton. He devised a new theory of motion (dynamics) based on kinetic energy and potential energy, which posited space as relative, whereas Newton was thoroughly convinced that space was absolute. An important example of Leibniz's mature physical thinking is his Specimen Dynamicum of 1695.[131] Until the discovery of subatomic particles and the quantum mechanics governing them, many of Leibniz's speculative ideas about aspects of nature not reducible to statics and dynamics made little sense. For instance, he anticipated Albert Einstein by arguing, against Newton, that space, time and motion are relative, not absolute: "As for my own opinion, I have said more than once, that I hold space to be something merely relative, as time is, that I hold it to be an order of coexistences, as time is an order of successions."[77] Leibniz held a relationist notion of space and time, against Newton's substantivalist views.[132][133][134] According to Newton's substantivalism, space and time are entities in their own right, existing independently of things. Leibniz's relationism, in contrast, describes space and time as systems of relations that exist between objects. The rise of general relativity and subsequent work in the history of physics has put Leibniz's stance in a more favorable light. One of Leibniz's projects was to recast Newton's theory as a vortex theory.[135] However, his project went beyond vortex theory, since at its heart there was an attempt to explain one of the most difficult problems in physics, that of the origin of the cohesion of matter.[135] The principle of sufficient reason has been invoked in recent cosmology, and his identity of indiscernibles in quantum mechanics, a field some even credit him with having anticipated in some sense. In addition to his theories about the nature of reality, Leibniz's contributions to the development of calculus have also had a major impact on physics. The vis viva Leibniz's vis viva (Latin for "living force") is mv2, twice the modern kinetic energy. He realized that the total energy would be conserved in certain mechanical systems, so he considered it an innate motive characteristic of matter.[136] Here too his thinking gave rise to another regrettable nationalistic dispute. His vis viva was seen as rivaling the conservation of momentum championed by Newton in England and by Descartes and Voltaire in France; hence academics in those countries tended to neglect Leibniz's idea. Leibniz knew of the validity of conservation of momentum. In reality, both energy and momentum are conserved (in closed systems), so both approaches are valid. Other natural science By proposing that the earth has a molten core, he anticipated modern geology. In embryology, he was a preformationist, but also proposed that organisms are the outcome of a combination of an infinite number of possible microstructures and of their powers. In the life sciences and paleontology, he revealed an amazing transformist intuition, fueled by his study of comparative anatomy and fossils. One of his principal works on this subject, Protogaea, unpublished in his lifetime, has recently been published in English for the first time. He worked out a primal organismic theory.[137] In medicine, he exhorted the physicians of his time—with some results—to ground their theories in detailed comparative observations and verified experiments, and to distinguish firmly scientific and metaphysical points of view. Psychology Psychology had been a central interest of Leibniz.[138][139] He appears to be an "underappreciated pioneer of psychology"[140] He wrote on topics which are now regarded as fields of psychology: attention and consciousness, memory, learning (association), motivation (the act of "striving"), emergent individuality, the general dynamics of development (evolutionary psychology). His discussions in the New Essays and Monadology often rely on everyday observations such as the behaviour of a dog or the noise of the sea, and he develops intuitive analogies (the synchronous running of clocks or the balance spring of a clock). He also devised postulates and principles that apply to psychology: the continuum of the unnoticed petites perceptions to the distinct, self-aware apperception, and psychophysical parallelism from the point of view of causality and of purpose: "Souls act according to the laws of final causes, through aspirations, ends and means. Bodies act according to the laws of efficient causes, i.e. the laws of motion. And these two realms, that of efficient causes and that of final causes, harmonize with one another."[141] This idea refers to the mind-body problem, stating that the mind and brain do not act upon each other, but act alongside each other separately but in harmony.[142] Leibniz, however, did not use the term psychologia.[143] Leibniz's epistemological position—against John Locke and English empiricism (sensualism)—was made clear: "Nihil est in intellectu quod non fuerit in sensu, nisi intellectu ipse." – "Nothing is in the intellect that was not first in the senses, except the intellect itself."[144] Principles that are not present in sensory impressions can be recognised in human perception and consciousness: logical inferences, categories of thought, the principle of causality and the principle of purpose (teleology). Leibniz found his most important interpreter in Wilhelm Wundt, founder of psychology as a discipline. Wundt used the "… nisi intellectu ipse" quotation 1862 on the title page of his Beiträge zur Theorie der Sinneswahrnehmung (Contributions on the Theory of Sensory Perception) and published a detailed and aspiring monograph on Leibniz.[145] Wundt shaped the term apperception, introduced by Leibniz, into an experimental psychologically based apperception psychology that included neuropsychological modelling – an excellent example of how a concept created by a great philosopher could stimulate a psychological research program. One principle in the thinking of Leibniz played a fundamental role: "the principle of equality of separate but corresponding viewpoints." Wundt characterized this style of thought (perspectivism) in a way that also applied for him—viewpoints that "supplement one another, while also being able to appear as opposites that only resolve themselves when considered more deeply."[146][147] Much of Leibniz's work went on to have a great impact on the field of psychology.[148] Leibniz thought that there are many petites perceptions, or small perceptions of which we perceive but of which we are unaware. He believed that by the principle that phenomena found in nature were continuous by default, it was likely that the transition between conscious and unconscious states had intermediary steps.[149] For this to be true, there must also be a portion of the mind of which we are unaware at any given time. His theory regarding consciousness in relation to the principle of continuity can be seen as an early theory regarding the stages of sleep. In this way, Leibniz's theory of perception can be viewed as one of many theories leading up to the idea of the unconscious. Leibniz was a direct influence on Ernst Platner, who is credited with originally coining the term Unbewußtseyn (unconscious).[150] Additionally, the idea of subliminal stimuli can be traced back to his theory of small perceptions.[151] Leibniz's ideas regarding music and tonal perception went on to influence the laboratory studies of Wilhelm Wundt.[152] |

科学と工学 ライプニッツの著作は現在、その先見性や未だ認識されていない発見の可能性だけでなく、現在の知識をさらに発展させる方法としても議論されている。彼の物理学に関する著作の多くは、ゲルハルトの『数学著作集』に収録されている。 物理学 関連項目: ダイナミズム(形而上学)とコンアトゥス § ライプニッツにおいて ライプニッツは、彼を取り巻く静力学と動力学にかなりの貢献をし、しばしばデカルトやニュートンと意見を異にした。彼は、運動エネルギーと位置エネルギー に基づく運動の新しい理論(力学)を考案し、ニュートンが空間は絶対的であると完全に確信していたのに対し、空間は相対的であると主張した。ライプニッツ の成熟した物理学的思考の重要な例として、1695年の『動学試論』がある。 素粒子とそれを支配する量子力学が発見されるまでは、静力学や動力学では還元できない自然界の側面に関するライプニッツの思索的なアイデアの多くはほとん ど意味をなさなかった。例えば、彼はアルバート・アインシュタインに先駆けて、ニュートンに反対して、空間、時間、運動は絶対的なものではなく相対的なも のであると主張した。「私自身の意見としては、私は空間を時間と同じく相対的なものであると考える。私は空間を共存の秩序であると考える。時間 「[77] ライプニッツは、ニュートンの実体説に反対し、空間と時間に関する関係説の概念を提唱した。[132][133][134] ニュートンの実体説によれば、空間と時間はそれ自体で実体であり、物とは独立して存在する。それに対し、ライプニッツの関係主義は、空間と時間を物体の間 に存在する関係の体系として説明する。一般相対性理論の台頭と、その後の物理学の歴史における研究により、ライプニッツの立場はより好ましいものとして捉 えられるようになった。 ライプニッツのプロジェクトのひとつは、ニュートンの理論を渦巻き理論として再構築することだった。[135] しかし、彼のプロジェクトは渦巻き理論を超えたものだった。なぜなら、その核心には物理学における最も困難な問題のひとつ、 物質の凝集力の起源である。[135] 十分な理由の原理は、最近の宇宙論で提唱されており、量子力学における不可識別子の同一性は、一部ではある意味で彼が予見していたとさえ考えられている分 野である。現実の本質に関する彼の理論に加えて、ライプニッツの微積分学の発展への貢献も物理学に大きな影響を与えている。 ヴィス・ヴィバ ライプニッツのヴィス・ヴィバ(ラテン語で「生きる力」の意)はmv2であり、現代の運動エネルギーの2倍である。彼は、特定の機械システムでは総エネル ギーが保存されることを理解し、それを物質の生得的な動機特性であると考えた。[136] ここでも、彼の考え方は、残念な民族主義的論争を引き起こした。彼の「ヴィス・ヴィバ」は、イギリスではニュートン、フランスではデカルトやヴォルテール が唱えた運動量保存論と対立するものとして見られていた。そのため、これらの国の学者たちはライプニッツの考えを軽視する傾向にあった。ライプニッツは運 動量保存の妥当性を認識していた。実際には、エネルギーも運動量も(閉じた系では)保存されるため、どちらのアプローチも妥当である。 その他の自然科学 地球に溶融核があることを提唱したことで、彼は近代地質学の先駆者となった。発生学においては前形成説を唱えたが、生物は無限の数の可能な微小構造とその 力の組み合わせの結果であるとも提唱した。生命科学と古生物学においては、比較解剖学と化石の研究から得た洞察力により、驚くべき変成論的直観を明らかに した。この主題に関する彼の主要な著作のひとつ『プロトゲエア』は生前には出版されなかったが、最近になって初めて英語で出版された。彼は原始的な有機体 理論を打ち立てた。[137] 医学においては、彼は当時の医師たちに、理論を詳細な比較観察と検証された実験に基づいて構築し、科学的視点と形而上学的視点とをしっかりと区別するよう 促した。 心理学 心理学はライプニッツの中心的な関心事であった。[138][139] 彼は「正当に評価されていない心理学の先駆者」であったようである。[140] 彼は現在では心理学の分野とみなされているトピックについて書いていた。すなわち、注意と意識、記憶、学習(連想)、動機付け(「努力」の行為)、個性の 出現、発達(進化心理学)の一般的な力学などである。『新試論』や『モナドロジー』における彼の議論は、しばしば犬の行動や海の音といった日常的な観察に 依存しており、彼は直感的な類推(時計の同時進行や時計のヒゲゼンマイ)を展開している。また、心理学に適用される公理や原理も考案した。すなわち、気づ かれない小さな知覚から、明確な自己認識の知覚への連続性、因果関係と目的の観点からの心身平行説である。「魂は、願望、目的、手段を通じて、最終的な原 因の法則に従って行動する。肉体は、すなわち運動の法則である、能因の法則に従って作用する。そして、能因と究極原因というこの2つの領域は、互いに調和 する」[141] この考えは心身問題を指しており、心と脳はお互いに作用するのではなく、別々ではあるが調和しながら並行して作用する、と述べている。[142] しかし、ライプニッツは「psychologia」という用語を使用していない。[143] ライプニッツの認識論上の立場は、ジョン・ロックやイギリス経験論(感覚論)に対するものであり、次のように明確に示されている。「Nihil est in intellectu quod non fuerit in sensu, nisi intellectu ipse. 「知性の中に感覚に先立たないものは何もない。ただし、知性そのものは例外である」[144] 感覚的な印象に存在しない原理は、人間の知覚や意識において認識することができる。論理的推論、思考のカテゴリー、因果律、目的論(テレオロジー)などで ある。 ライプニッツは、心理学を学問として確立したヴィルヘルム・ヴントを最も重要な解釈者として見出した。ヴントは、1862年に『感覚知覚の理論に関する寄 稿』のタイトルページに「… nisi intellectu ipse」という引用文を使用し、ライプニッツに関する詳細で意欲的な単行本を出版した 。ヴントは、ライプニッツが提唱した「共観」という用語を、神経心理学的なモデリングを含む実験的な心理学的共観心理学へと発展させた。これは、偉大な哲 学者が創出した概念が心理学的調査プログラムに刺激を与えることができることを示す優れた例である。ライプニッツの思考における一つの原則が重要な役割を 果たした。「別個ではあるが対応する視点の平等性の原則」である。ヴントは、この思考様式(視点主義)を、彼自身にも当てはまるように特徴づけた。「視点 は互いに補い合い、また、より深く考察したときにのみ解決される対立として現れることもある」[146][147] ] ライプニッツの研究の多くは、心理学の分野に多大な影響を与えた。[148] ライプニッツは、私たちが知覚しているにもかかわらず、気づいていない多くの小さな知覚、すなわち「小知覚」があると考えた。彼は、自然界に見られる現象 は既定で連続しているという原則により、意識と無意識の状態の移行には中間段階がある可能性が高いと考えていた。[149] これが真実であるためには、私たちが常に気づいていない心の部分も存在しなければならない。連続性の原理と意識に関する彼の理論は、睡眠の段階に関する初 期の理論と見なすことができる。このように、ライプニッツの知覚理論は、無意識の概念につながる多くの理論のひとつと見なすことができる。ライプニッツは エルンスト・プラトナーに直接的な影響を与え、プラトナーは「無意識」(Unbewußtseyn)という語を最初に作った人物として知られている。 [150] さらに、潜在刺激の概念は、彼の「微少知覚」の理論に遡ることができる。[151] ライプニッツの音楽と音調知覚に関する考え方は、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントの実験室での研究に影響を与えた。[152] |