英雄崇拝論

Great man theory

偉人論=英雄崇拝論とは、19世紀の歴史学において、歴史は偉人(ヒーロー)の影響によって

大きく説明できるという考え方だ。偉人とは、優れた知性、英雄的勇気、並外れた指導力、神の霊感などの生まれ持った特性によって、歴史に決定的な影響を与

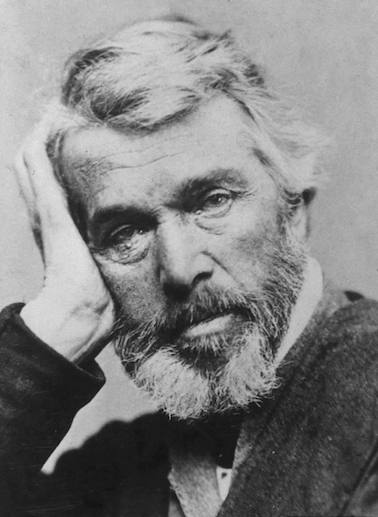

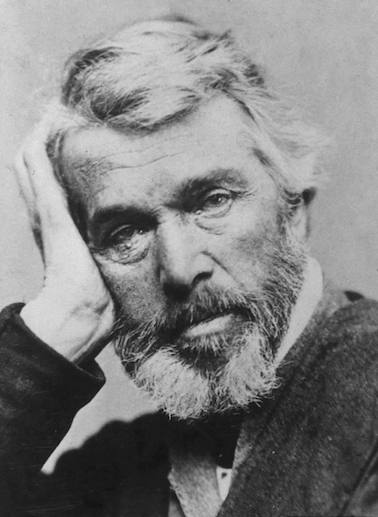

えた、非常に影響力のあるユニークな個人を指す。この説は、スコットランドのエッセイスト、歴史家、哲学者であるトーマス・カーライル(Thomas Carlyle,

1795-1881)が、1840年に

行った英雄主義に関する一連の講義(『歴史における英雄、英雄崇拝、英雄的存在について(邦訳:英雄崇拝論)』として出版)の中で述べたことがその起源と

なっている。

| The

great man theory is a 19th-century approach to the study of history

according to which history can be largely explained by the impact of

great men, or heroes: highly influential and unique individuals who,

due to their natural attributes, such as superior intellect, heroic

courage, extraordinary leadership abilities or divine inspiration, have

a decisive historical effect. The theory is primarily attributed to the

Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle who gave a

series of lectures on heroism in 1840, later published as On Heroes,

Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, in which he states: Universal History, the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here. They were the leaders of men, these great ones; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain; all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realisation and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world: the soul of the whole world's history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these.[1] This theory is usually contrasted with "history from below", which emphasizes the life of the masses creating overwhelming waves of smaller events which carry leaders along with them. Another contrasting school is historical materialism.  Napoleon, a typical great man, said to have created the "Napoleonic" era through his military and political genius. |

偉

人論=英雄崇拝論とは、19世紀の歴史学において、歴史は偉人(ヒーロー)の影響によって大きく説明できるという考え方だ。偉人とは、優れた知性、英雄的

勇気、並外れた指導力、神の霊感などの生まれ持った特性によって、歴史に決定的な影響を与えた、非常に影響力のあるユニークな個人を指す。この説は、ス

コットランドのエッセイスト、歴史家、哲学者であるトーマス・カーライルが、1840年に行った英雄主義に関する一連の講義(『歴史における英雄、英雄崇

拝、英雄的存在について(邦訳:英雄崇拝論)』として出版)の中で述べたことがその起源となっている。 普遍的な歴史、すなわち人間がこの世界で成し遂げたことの歴史は、つまるところ、ここで働いた偉大な人々の歴史である。彼らは人間の指導者であり、これら の偉大な者たちは、一般的な人間の集団が行おうとしたり達成しようとしたりするもののモデルであり、パターンであり、広い意味での創造者である。我々が世 界で達成されているすべてのものは、世界に送られた偉大な人々の中に宿った思考の、外側の物質的結果、現実的実現と具現である。 この理論は通常、「下からの歴史」と対比され、大衆の生活が小さな出来事の圧倒的な波を作り出し、それが指導者を連れて行くことを強調するものである。も う一つの対照的な学派は史的唯物論である。  ナポレオンは、その天才的な軍事力と政治力によって「ナポレオン時代」を築いたと言われる、典型的な偉人である。 |

| Overview Carlyle stated that "The History of the world is but the Biography of great men", reflecting his belief that heroes shape history through both their personal attributes and divine inspiration.[2][3] In his book Heroes and Hero-Worship, Carlyle saw history as having turned on the decisions, works, ideas, and characters of "heroes", giving detailed analysis of six types: The hero as divinity (such as Odin), prophet (such as Mohamet), poet (such as Shakespeare), priest (such as Martin Luther), man of letters (such as Rousseau), and king (such as Napoleon). Carlyle also argued that the study of great men was "profitable" to one's own heroic side; that by examining the lives led by such heroes, one could not help but uncover something about one's own true nature.[4] As Sidney Hook notes, a common misinterpretation of the theory is that "all factors in history, save great men, were inconsequential",[5] whereas Carlyle is instead claiming that great men are the decisive factor, owing to their unique genius. Hook then goes on to emphasize this uniqueness to illustrate the point: "Genius is not the result of compounding talent. How many battalions are the equivalent of a Napoleon? How many minor poets will give us a Shakespeare? How many run of the mine scientists will do the work of an Einstein?"[6] American scholar Frederick Adams Woods supported the great man theory in his work The Influence of Monarchs: Steps in a New Science of History.[7] Woods investigated 386 rulers in Western Europe from the 12th century until the French revolution in the late 18th century and their influence on the course of historical events. The Great Man approach to history was most fashionable with professional historians in the 19th century; a popular work of this school is the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911) which contains lengthy and detailed biographies about the great men of history, but very few general or social histories. For example, all information on the post-Roman "Migrations Period" of European History is compiled under the biography of Attila the Hun. This heroic view of history was also strongly endorsed by some philosophers, such as Léon Bloy, Kierkegaard, Oswald Spengler and Max Weber.[8][9][10] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, proceeding from providentialist theory, argued that "what is real is reasonable" and World-Historical individuals are World-Spirit's agents. Hegel wrote: "Such are great historical men—whose own particular aims involve those large issues which are the will of the World-Spirit."[11] Thus, according to Hegel, a great man does not create historical reality himself but only uncovers the inevitable future. In Untimely Meditations, Friedrich Nietzsche writes that "the goal of humanity lies in its highest specimens".[12] Although Nietzsche's body of work shows some overlap with Carlyle's line of thought Nietzsche expressly rejected Carlyle's hero cult in Ecce Homo.[13][page needed] |

概要 カーライルは「世界の歴史は偉大な人物の伝記に過ぎない」と述べ、英雄が個人の属性と神の霊感の両方を通じて歴史を形成するという信念を反映している [2][3]。 カーライルは著書『英雄と英雄崇拝』において、歴史は「英雄」の決断、作品、思想、人物に左右されていると捉え、6つのタイプの詳細な分析を与えている。 神としての英雄(オーディンなど)、預言者(モハメットなど)、詩人(シェークスピアなど)、司祭(マルティン・ルターなど)、文人(ルソーなど)、王 (ナポレオンなど)である。またカーライルは、偉人の研究は自分の英雄的側面にとって「有益」であり、そのような英雄の歩んだ人生を調べることによって、 自分の本性について何かを発見せずにはいられないと主張した[4]。 シドニー・フックが指摘するように、この理論のよくある誤解は、「歴史におけるすべての要因は、偉大な人物を除けば、取るに足らないものである」[5]、 それに対してカーライルは、代わりに、偉大な人物こそが、そのユニークな才能によって、決定的な要因であることを主張しているのである。そしてフックはこ の独自性を強調して、「天才は才能の複合の結果ではない。ナポレオンに相当する大隊が何人いるだろうか。ナポレオンに相当する大隊は何人いるだろうか、 シェークスピアを生み出す小詩人は何人いるだろうか。アインシュタインに匹敵する仕事をする地雷を踏んだ科学者が何人いるだろうか」[6]。 ウッズは12世紀から18世紀末のフランス革命までの西ヨーロッパの386人の支配者とその歴史的出来事への影響力を調査した[7]。 歴史に対する偉人論は19世紀にプロの歴史家の間で最も流行した。この流派の代表的な著作はEncyclopædia Britannica 11th Edition (1911) で、歴史上の偉人に関する長くて詳しい伝記が載っているが、通史や社会史はほとんどない。例えば、ヨーロッパ史のローマ時代以降の「移民時代」に関する情 報は、すべてフン族のアッティラの伝記の下にまとめられている。この英雄的歴史観は、レオン・ブロイ、キルケゴール、オズワルド・シュペングラー、マック ス・ヴェーバーといった一部の哲学者にも強く支持された[8][9][10]。 ゲ オルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルは摂理論から進んで、「実在するものは合理的である」、「世界史的な個人は世界精神の代理人である」と主張 した[10]。ヘーゲルは「そのような歴史的偉人は、自らの特定の目的が世界精神の意志である大きな問題を含んでいる」と書いている[11]。したがっ て、ヘーゲルによれば、偉人は歴史的現実を自ら作り出すのではなく、不可避の未来を明らかにするのみである。 ニーチェは『非時代的瞑想録』の中で「人類の目標はその最高の標本にある」と書いている[12]。ニーチェの作品群はカーライルの思想路線と重なる部分が あるが、ニーチェは『エッチェ・ホモ』でカーライルの英雄崇拝を明確に否定した[13][要ページ]。 |

| Assumptions This theory rests on two main assumptions, as pointed out by Villanova University:[14] 1. Every great leader is born already possessing certain traits that will enable them to rise and lead on instinct. 2. The need for them has to be great for these traits to then arise, allowing them to lead. This theory, and history, claims these great leaders as heroes that were able to rise against the odds to defeat rivals while inspiring followers along the way. Theorists say that these leaders were then born with a specific set of traits and attributes that make them ideal candidates for leadership and roles of authority and power. This theory relies then heavily on born rather than made, nature rather than nurture and cultivates the idea that those in power deserve to lead and shouldn't be questioned because they have the unique traits that make them suited for the position.[14] |

前提条件 この理論は、ヴィラノヴァ大学が指摘するように、次の2つの主要な前提条件に基づいている[14]。 1. 1.すべての偉大なリーダーは、生まれながらにして、本能的に上昇し導くことができる特定の特性を持っている。 2. 2.これらの特性が生まれ、彼らを導くことを可能にするためには、彼らに対する必要性が大きくなければならない。 この理論と歴史は、これらの偉大なリーダーを、ライバルに打ち勝つために困難に立ち向かい、その過程で信奉者を鼓舞することができた英雄として主張してい る。このようなリーダーたちは、生まれながらにして、権威と権力を持つリーダーとして理想的な特性や属性を持っていたとする説である。この理論は、作られ たというよりも生まれつき、育つというよりも自然に大きく依存し、権力者はその地位に適したユニークな特性を持っているので、導くのが当然であり、疑問を 持たれるべきではないという考えを育んでいる[14]。 |

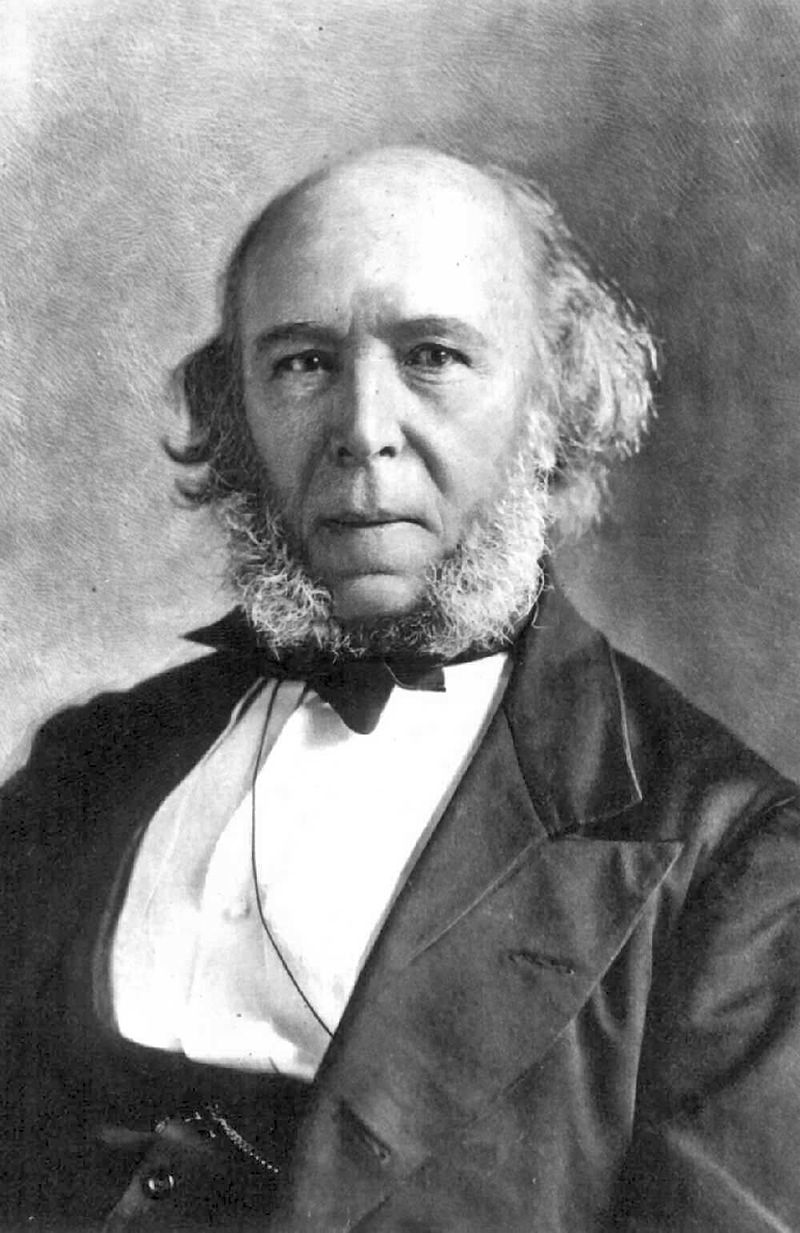

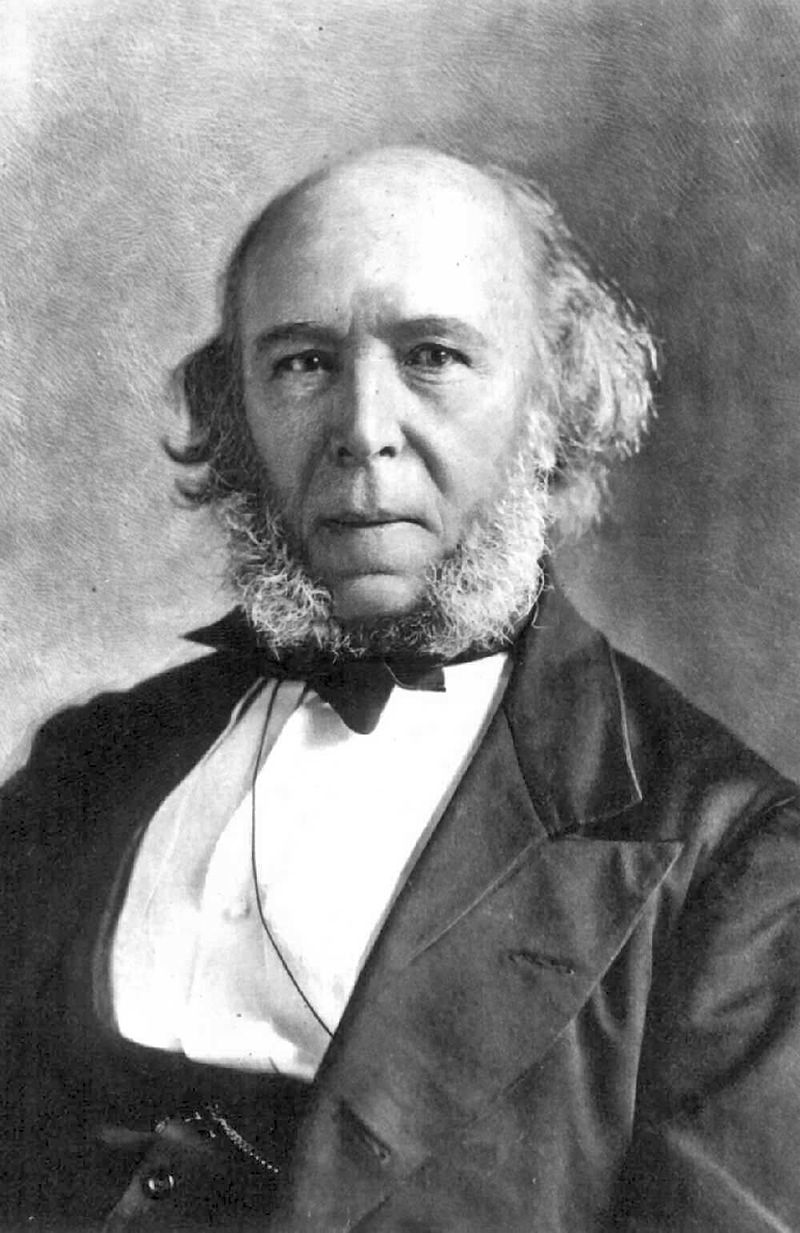

Herbert Spencer's critique One of the most forceful critics of Carlyle's formulation of the great man theory was Herbert Spencer, who believed that attributing historical events to the decisions of individuals was an unscientific position.[15] He believed that the men Carlyle called "great men" were merely products of their social environment: You must admit that the genesis of a great man depends on the long series of complex influences which has produced the race in which he appears, and the social state into which that race has slowly grown. ... Before he can remake his society, his society must make him. — Herbert Spencer, The Study of Sociology[16] |

ハーバート・スペンサーの批判 カーライルによる偉人論の定式化に対する最も強力な批判者の一人がハーバート・スペンサーであり、彼は歴史的出来事を個人の決定に帰することは非科学的な 立場であると考えた[15]。 彼はカーライルが「偉人」と呼ぶ人々は、単に社会環境の産物に過ぎないと考えたのである。 あなたは、偉人の発生が、彼が登場する人種と、その人種がゆっくりと成長してきた社会状態を生み出した、長い一連の複雑な影響に依存することを認めなけれ ばならない。彼が社会を作り直すことができる前に、社会が彼を作らなければならない。 - ハーバート・スペンサー『社会学の研究』[16]。 |

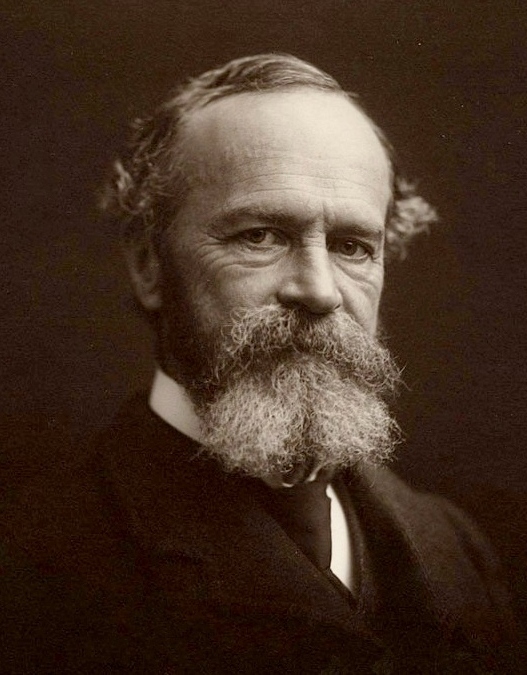

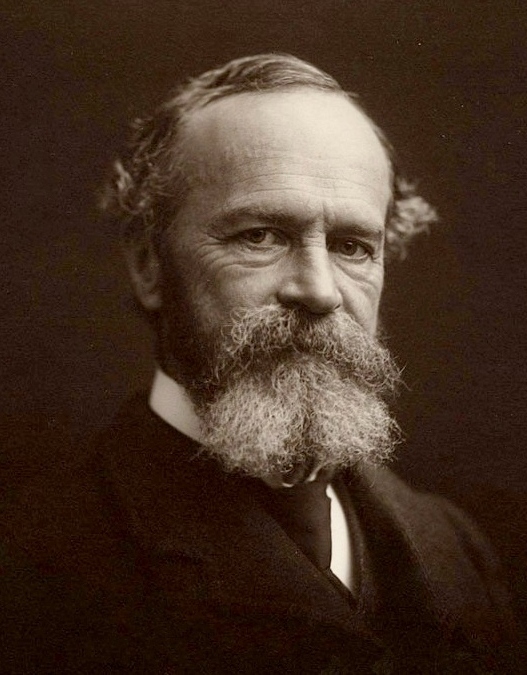

William James' defence William James, in his 1880 lecture "Great Men, Great Thoughts, and the Environment",[17] published in the Atlantic Monthly, forcefully defended Carlyle and refuted Spencer, condemning what James viewed as an "impudent", "vague", and "dogmatic" argument. If anything is humanly certain it is that the great man's society, properly so called, does not make him before he can remake it ... The mutations of societies, then, from generation to generation, are in the main due directly or indirectly to the acts or the examples of individuals whose genius was so adapted to the receptivities of the moment, or whose accidental position of authority was so critical that they became ferments, initiators of movements, setters of precedent or fashion, centers of corruption, or destroyers of other persons, whose gifts, had they had free play, would have led society in another direction. James' defence of the great man theory can be summarized as follows: The unique physiological nature of the individual is the deciding factor in making the great man, who, in turn, is the deciding factor in changing his environment in a unique way, without which the new environment would not have come to be, wherein the extent and nature of this change is also dependent on the reception of the environment to this new stimulus. To begin his argument, he first sardonically claims that these inherent physiological qualities have as much to do with "social, political, geographical [and] anthropological conditions" as the "conditions of the crater of Vesuvius has to do with the flickering of this gas by which I write". He then illustrates his argument by considering the myriad genetic variations that can occur in the earliest stages of sexual reproduction: Now, when the result is the tendency of an ovum, itself invisible to the naked eye, to tip towards this direction or that in its further evolution, - to bring forth a genius or a dunce, even as the rain-drop passes east or west of the pebble, - is it not obvious that the deflecting cause must lie in a region so recondite and minute, must be such a ferment of a ferment, an infinitesimal of so high an order, that surmise itself may never succeed even in attempting to frame an image of it? James argues that genetic anomalies in the brains of these great men are the decisive factor by introducing an original influence into their environment. They might therefore offer original ideas, discoveries, inventions and perspectives which "would not, in the mind of another individual, have engendered just that conclusion ... It flashes out of one brain, and no other, because the instability of that brain is such as to tip and upset itself in just that particular direction." James describes the manifestations of these unique physiological qualities as follows: [T]he spontaneous upsettings of brains this way and that at particular moments into particular ideas and combinations are matched by their equally spontaneous permanent tiltings or saggings towards determinate directions. The humorous bent is quite characteristic; the sentimental one equally so. And the personal tone of each mind, which makes it more alive to certain impressions, more open to certain reasons, is equally the result of that invisible and imaginable play of the forces of growth within the nervous system which, [irresponsive] to the environment, makes the brain peculiarly apt to function in a certain way. James then argues that these spontaneous variations of genius, i.e. the great men, which are causally independent of their social environment, subsequently influence that environment which in turn will either preserve or destroy the newly encountered variations in a form of evolutionary selection. If the great man is preserved then the environment is changed by his influence in "an entirely original and peculiar way. He acts as a ferment, and changes its constitution, just as the advent of a new zoological species changes the faunal and floral equilibrium of the region in which it appears." Each ferment, each great man, exerts a new influence on their environment which is either embraced or rejected and if embraced will in turn shape the crucible for the selection process of future geniuses. The products of the mind with the determined æsthetic bent please or displease the community. We adopt Wordsworth, and grow unsentimental and serene. We are fascinated by Schopenhauer, and learn from him the true luxury of woe. The adopted bent becomes a ferment in the community, and alters its tone. The alteration may be a benefit or a misfortune, for it is (pace Mr. Allen) a differentiation from within, which has to run the gauntlet of the larger environment's selective power. If you remove these geniuses "or alter their idiosyncrasies", then what "increasing uniformities will the environment show? We defy Mr. Spencer or any one else to reply." For James (Barney), then, there are two distinct factors that cause social evolution: 1. The individual, who is unique in his "physiological and infra-social forces, but bearing all the power of initiative and origination in his hands" and 2. The social environment of the individual, "with its power of adopting or rejecting both him and his gifts". He thus concludes: "Both factors are essential to change. The community stagnates without the impulse of the individual. The impulse dies away without the sympathy of the community." James asserts that Spencer's view, conversely, ignores the influence of that impulse and denies the vital importance of individual initiative, is, then, an utterly vague and unscientific conception, a lapse from modern scientific determinism into the most ancient oriental fatalism. The lesson of the analysis that we have made (even on the completely deterministic hypothesis with which we started) forms an appeal of the most stimulating sort to the energy of the individual ... It is folly, then, to speak of the "laws of history" as of something inevitable, which science has only to discover, and whose consequences any one can then foretell but do nothing to alter or avert. Why, the very laws of physics are conditional, and deal with ifs. The physicist does not say, "The water will boil anyhow"; he only says it will boil if a fire is kindled beneath it. And so the utmost the student of sociology can ever predict is that if a genius of a certain sort show the way, society will be sure to follow. It might long ago have been predicted with great confidence that both Italy and Germany would reach a stable unity if some one could but succeed in starting the process. It could not have been predicted, however, that the modus operandi in each case would be subordination to a paramount state rather than federation, because no historian could have calculated the freaks of birth and fortune which gave at the same moment such positions of authority to three such peculiar individuals as Napoleon III, Bismarck, and Cavour. |

ウィリアム・ジェームズの擁護 ウィリアム・ジェームズは1880年に『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌に発表した講演「偉人、偉大な思想、そして環境」[17]において、カーライル を強力に擁護しスペンサーに反論し、ジェームズが「不謹慎」で「曖昧」かつ「独断的」な議論とみなしたことを非難している。 もし人間的に確かなことがあるとすれば、それは、偉大な人間の社会は、正しくそう呼ばれるように、彼がそれを作り変えることができる前に、彼を作ることは ないということだ......」。つまり、社会が世代から世代へと変化していくのは、主として、直接的または間接的に、その天才がその時々の感受性に適合 し、あるいは偶然の権威の地位が決定的で、その才能が自由に発揮されていれば、社会を別の方向に導いたであろう、発酵者、運動の創始者、前例や流行の仕掛 け人、腐敗の中心、あるいは他の人物を破壊する者になった個人の行為や事例によるのである」。 ジェームズの偉人論に対する弁明は、次のようにまとめることができる。個人のユニークな生理的性質が、偉人を作る決定的な要因であり、その人が、環境をユ ニークな方法で変える決定的な要因であり、それなしには、新しい環境は生まれなかったであろう、この変化の程度と性質は、この新しい刺激に対する環境の受 容にも依存する。このような生理的な性質は、「ヴェスヴィオ火山の噴火口と、私が書いているこのガスの明滅との関係」と同じように、「社会的、政治的、地 理的、人類学的条件」に関係していると、彼はまず無邪気に主張する。そして、有性生殖の初期段階で起こりうる無数の遺伝的変異を考えて、自分の主張を説明 する。 さて、その結果、肉眼では見えない卵子が、さらなる進化において、この方向、あるいはこの方向に傾く傾向があるとき、つまり、雨粒が小石の東や西を通るよ うに、天才や間抜けを生み出すとき、その偏向の原因は、非常に深遠で微細な領域にあるはずで、推測自体がそのイメージを描こうと試みることさえ決して成功 しないほどの、高次の無限小であり発酵中の発酵でなければならないことは明白ではないか。 ジェームズは、このような偉人たちの脳の遺伝的異常が、彼らの環境に独自の影響を与えることによって、決定的な要因になると主張している。そのため、彼ら は、「他の人の頭では、そのような結論にならなかったであろう」独自のアイデア、発見、発明、展望を提供するかもしれない......。なぜなら、その脳 の不安定さは、まさにその特定の方向に自らを傾け、動揺させるようなものだからだ"。ジェームズは、こうした独特の生理的性質の現れについて、次のように 説明している。 [特定のアイデアや組み合わせのために、特定の瞬間に脳があちこちと自然に動揺するのだが、それと同じくらい自然に、決まった方向へ永久に傾いたり下がっ たりするのだ。ユーモラスな傾向は極めて特徴的であり、センチメンタルな傾向も同様に特徴的である。そして、ある印象に対してより生き生きとし、ある理由 に対してより開放的になるような、それぞれの心の個人的な調子も、同様に、神経系内の成長の力が、環境に[無反応]に、脳をある方法で特別に機能させやす くする、目に見えない、想像しうる遊びの結果なのである。 そして、ジェームズは、このような天才の自然発生的な変異、すなわち偉人は、社会環境とは因果的に無関係であり、その後、社会環境に影響を及ぼし、その結 果、新たに遭遇した変異を保存するか破壊するか、一種の進化的淘汰が起こると論じている。もし偉大な人物が保存されるなら、環境は彼の影響によって「まっ たく独創的で独特な方法」で変化する。ちょうど新しい動物種の出現が、それが出現した地域の動物相と植物相の均衡を変えるように、彼は発酵物として作用 し、その構造を変えるのだ」。それぞれの発酵物、それぞれの偉人は、環境に新しい影響を及ぼし、それを受け入れるか拒否するか、受け入れられた場合は、未 来の天才を選択するための坩堝を形成することになる。 そして、もしそれが受け入れられれば、将来の天才を選抜するための坩堝を形成することになるのだ。決定的な美的傾向を持つ心の産物は、コミュニティを喜ば せ、あるいは不愉快にする。私たちはワーズワースを採用し、感傷的でない穏やかな心を育てます。ショーペンハウアーに魅了され、彼から苦悩の真の贅沢を学 ぶ。採用された傾向は共同体の中で発酵し、その調子を変える。この変化は、アレン氏の言うように、内部からの差別化であり、より大きな環境の選択的な力の 試練を受けなければならないからである。 もし、このような天才たちを「排除」したり、「特異性を変化」させたりしたら、どんな「増加する均一性を示す環境」になるのだろうか?スペンサー氏、ある いは他の誰一人として、その答えを求めない。ジェームズ(バーニー)にとって、では、社会進化を引き起こす要因は二つに分かれる。 1. 1.個人は、その「生理的および社会的内的な力においてユニークであるが、その手にすべての主導権と発案権を握っている」、2. 2. 2.個人を取り巻く社会的環境、「個人とその才能の両方を採用したり拒絶したりする力を持つ」。 彼はこう結論付けている。「この二つの要素は、変化するために不可欠である。個人の衝動がなければ、共同体は停滞する。個人の衝動は、共同体の共感なしに は消え去る。 ジェームズは、スペンサーの考え方は、逆にその衝動の影響を無視し、個人の自発性の重要性を否定していると主張する。 個人のイニシアチブの重要性を否定するものであり、全く曖昧で非科学的な概念であり、現代の科学的決定論から最も古代の東洋的運命論への転落である。我々 が行った分析の教訓は、(我々が最初に行った完全に決定論的な仮説でさえ)個人のエネルギーに対して最も刺激的な種類の訴えを形成している......。 科学が発見しなければならない必然的なものとして「歴史の法則」を語るのは愚かなことであり、その結果を予言することはできても、変更したり回避したりす ることはできないのです。なぜかというと、物理学の法則はまさに条件付きであり、もしもを扱うものだからです。物理学者は「水はとにかく沸騰する」とは言 いません。その下で火をつければ沸騰すると言うだけです。そして、社会学を学ぶ者が予測できるのは、ある種の天才が道を示せば、社会は必ずそれに従うとい うことだけである。もし誰かがそのプロセスを始めることに成功すれば、イタリアもドイツも安定した統一に達するだろうと、ずいぶん前に確信を持って予測で きたかもしれない。しかし、いずれの場合も、その手口が連邦制ではなく、最高位の国家への従属制になるとは予測できなかった。なぜなら、ナポレオン3世、 ビスマルク、カヴールのような特異な3人に同時に権威ある地位を与えた生まれと運の不運を計算できた歴史家はいなかったからだ。 |

| Other responses Before the 19th century, Blaise Pascal begins his Three Discourses on the Condition of the Great (written it seems for a young duke) by telling the story of a castaway on an island whose inhabitants take him for their missing king. He defends in his parable of the shipwrecked king, that the legitimacy of the greatness of great men is fundamentally custom and chance. A coincidence that gives birth to him in the right place with noble parents and arbitrary custom deciding, for example, on an unequal distribution of wealth in favor of the nobles.[18] Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace features criticism of great-man theories as a recurring theme in the philosophical digressions. According to Tolstoy, the significance of great individuals is imaginary; as a matter of fact they are only "history's slaves," realizing the decree of Providence.[19] In 1926, William Fielding Ogburn noted that Great Men history was being challenged by newer interpretations that focused on wider social forces. While not seeking to deny that individuals could have a role or show exceptional qualities, he saw Great Men as inevitable products of productive cultures. He noted for example that if Isaac Newton had not lived, calculus would have still been discovered by Gottfried Leibniz, and suspected that if neither man had lived, it would have been discovered by someone else.[20] Among modern critics of the theory, Sidney Hook is supportive of the idea; he gives credit to those who shape events through their actions, and his book The Hero in History is devoted to the role of the hero and in history and influence of the outstanding persons.[21] In the introduction to a new edition of Heroes and Hero-Worship, David R. Sorensen notes the modern decline in support for Carlyle's theory in particular but also for "heroic distinction" in general.[22] He cites Robert K. Faulkner as an exception, a proponent of Aristotelian magnanimity who in his book The Case for Greatness: Honorable Ambition and Its Critics, criticizes the political bias in discussions on greatness and heroism, stating: "the new liberalism’s antipathy to superior statesmen and to human excellence is peculiarly zealous, parochial, and antiphilosophic."[23] Ian Kershaw wrote in 1998 that "The figure of Hitler, whose personal attributes – distinguished from his political aura and impact – were scarcely noble, elevating or enriching, posed self-evident problems for such a tradition." Some historians like Joachim Fest responded by arguing that Hitler had a "negative greatness". By contrast, Kershaw rejects the Great Men theory and argues that it is more important to study wider political and social factors to explain the history of Nazi Germany. Kershaw argues that Hitler was an unremarkable person, but his importance came from how people viewed him, an example of Max Weber's concept of charismatic leadership.[24] Charismatic authority Cult of personality Elite theory Folk hero Greatness Heroic theory of invention and scientific development Knight of faith Nouvelle histoire Paradigm shift People's history Philosophy of history Polymath Prosopography Protagonist Revolutionary Structure and agency Timeline of scientific discoveries Übermensch Whig history |

その他の反応 19世紀以前、パスカルは『偉大なるものの条件に関する三つの論考』(若い公爵のために書かれたようだ)の冒頭で、ある島の漂流者の物語を語り、その島の 住民は彼を行方不明の王とみなしている、と述べた。彼は、難破した王のたとえ話で、偉大な人物の正当性は、基本的に習慣と偶然であると弁明する。高貴な両 親のもとで適切な場所に彼を誕生させる偶然と、例えば貴族に有利な富の不平等な分配を決定する恣意的な慣習である[18]。 レオ・トルストイの『戦争と平和』では、哲学的な余談の中で繰り返しテーマとして偉人論への批判が登場する。トルストイによれば、偉大な個人の意義は想像 上のものであり、実のところ彼らは「歴史の奴隷」に過ぎず、摂理の命令を実現するものである[19]。 1926年、ウィリアム・フィールディング・オグバーンは、偉人史がより広い社会的勢力に焦点を当てた新しい解釈によって挑戦されていることを指摘した。 個人が役割を持ち、例外的な資質を示すことを否定しようとはしないが、彼は偉人を生産的な文化の必然的な産物として見ていた。彼は例えばアイザック・ ニュートンが生きていなければ、微積分はやはりゴットフリート・ライプニッツによって発見されていただろうと指摘し、どちらの人物も生きていなければ、他 の誰かによって発見されていただろうと疑っていた[20]。 この理論に対する現代の批判者の中でシドニー・フックはその考えを支持している;彼は彼らの行動を通して出来事を形作る人々を賞賛し、彼の著書『歴史にお けるヒーロー』はヒーローの役割と歴史における、優れた人物の影響に捧げられている[21]。 英雄と英雄崇拝』の新版の序文において、デヴィッド・R・ソレンセンは特にカーライルの理論に対する支持だけでなく、一般的に「英雄的区別」に対する支持 も現代では減少していると指摘している[22]。 彼は例外として、アリストテレスの大義の支持者で、彼の著書The Case for GreatnessにおいてRobert K. Faulknerを引用している。彼はアリストテレス的な大らかさの支持者として、著書The Case for Greatness: Honorable Ambition and Its Criticsにおいて、偉大さとヒロイズムに関する議論における政治的偏向を批判し、次のように述べている[22]。「新しいリベラリズムの優れた政治 家や人間の卓越性に対する反感は特有の熱狂的、偏狭的、反哲学的なものである」[23]と述べている。 イアン・カーショウは1998年に「ヒトラーという人物は、その政治的オーラやインパクトとは区別された個人的属性が、ほとんど高貴でもなく、高揚もせ ず、豊かでもなく、そのような伝統に自明の問題を突きつけていた」と書いている[23]。ヨアヒム・フェストのような一部の歴史家は、ヒトラーには「負の 偉大さ」があったと主張し、これに反論している。これに対し、カーショウは偉人論を否定し、ナチス・ドイツの歴史を説明するためには、より広い政治的・社 会的要因を研究することがより重要であると主張している。カーショウは、ヒトラーは目立たない人物であったが、彼の重要性は人々が彼をどのように見ていた かに由来すると主張しており、マックス・ウェーバーのカリスマ的リーダーシップの概念の一例であると述べている[24]。 カリスマ的権威 カルト・オブ・パーソナリティ エリート理論 フォークヒーロー 偉大さ 発明と科学発展の英雄論 信仰の騎士 ヌーヴェル・ヒストワール パラダイムシフト 人民の歴史 歴史哲学 ポリマス プロソポグラフィー 主人公 革命家 構造と主体性 科学的発見の年表 ユーベルメンシュ ホイッグの歴史 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_man_theory |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Thomas

Carlyle

(4 December 1795 – 5 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian,

and philosopher from the Scottish Lowlands. A leading writer of the

Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art,

literature, and philosophy. Thomas

Carlyle

(4 December 1795 – 5 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian,

and philosopher from the Scottish Lowlands. A leading writer of the

Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art,

literature, and philosophy.Born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Scotland, Carlyle attended the University of Edinburgh where he excelled in mathematics, inventing the Carlyle circle. After finishing the arts course, he prepared to become a minister in the Burgher Church while working as a schoolmaster. He quit these and several other endeavours before settling on literature, writing for the Edinburgh Encyclopædia and working as a translator. He found initial success as a disseminator of German literature, then little-known to English readers, through his translations, his Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825), and his review essays for various journals. His first major work was a novel entitled Sartor Resartus (1833–34). After relocating to London, he became famous with his French Revolution (1837), which prompted the collection and reissue of his essays as Miscellanies. Each of his subsequent works, including On Heroes (1841), Past and Present (1843), Cromwell's Letters (1845), Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850), and History of Frederick the Great (1858–65), were highly regarded throughout Europe and North America. He founded the London Library, contributed significantly to the creation of the National Portrait Galleries in London and Scotland,[1] was elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University in 1865, and received the Pour le Mérite in 1874, among other honours. Carlyle occupied a central position in Victorian culture, being considered not only, in the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the "undoubted head of English letters",[2][3] but a "secular prophet". Posthumously, his reputation suffered as publications by his friend and disciple James Anthony Froude provoked controversy about Carlyle's personal life, particularly his marriage to Jane Welsh Carlyle. His reputation further declined in the 20th century, as the onsets of World War I and World War II brought forth accusations that he was a progenitor of both Prussianism and fascism. Since the 1950s, extensive scholarship in the field of Carlyle Studies has improved his standing, and he is now recognised as "one of the enduring monuments of our literature who, quite simply, cannot be spared."[4] |

トーマス・カーライル(Thomas Carlyle, 1795年12月4日 -

1881年2月5日)は、スコットランド低地出身のエッセイスト、歴史家、哲学者。ヴィクトリア朝時代を代表する作家で、19世紀の芸術、文学、哲学に多

大な影響を与えた。 トーマス・カーライル(Thomas Carlyle, 1795年12月4日 -

1881年2月5日)は、スコットランド低地出身のエッセイスト、歴史家、哲学者。ヴィクトリア朝時代を代表する作家で、19世紀の芸術、文学、哲学に多

大な影響を与えた。スコットランド、ダンフリースシャーのエクルフェチャンに生まれたカーライルは、エディンバラ大学で数学を専攻し、カーライル・サークルを創始した。芸術 課程を卒業後、校長として働きながらブルガー教会の牧師になる準備をした。その後、エジンバラ百科事典に寄稿したり、翻訳家として働いたりしながら、文学 の道に進む。翻訳、『フリードリヒ・シラーの生涯』(1825年)、さまざまな雑誌への評論エッセイなどを通じて、当時イギリスの読者にはほとんど知られ ていなかったドイツ文学の普及者として最初の成功を収めた。最初の大作は『サルトル・レザルトゥス』(1833-34)と題された小説である。ロンドンに 移ってからは、『フランス革命』(1837年)で一躍有名になり、これをきっかけにエッセイ集『雑文集』(Miscellanies)が出版された。英雄 について』(1841年)、『過去と現在』(1843年)、『クロムウェルの手紙』(1845年)、『末日パンフレット』(1850年)、『フリードリヒ 大王の歴史』(1858-65年)など、その後の著作はいずれも欧米で高く評価された。ロンドン図書館を創設し、ロンドンとスコットランドの国立肖像画美 術館の創設に大きく貢献し[1]、1865年にはエディンバラ大学の学長卿に選出され、1874年にはPour le Mérite賞を受賞した。 カーライルはヴィクトリア朝文化の中心的な位置を占め、ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソンの言葉を借りれば「間違いなくイギリス文学の長」[2][3]であ るだけでなく、「世俗の預言者」とみなされた。死後、彼の友人であり弟子でもあったジェイムズ・アンソニー・フロードによる出版物が、カーライルの私生 活、特にジェーン・ウェルシュ・カーライルとの結婚について論争を引き起こしたため、彼の評判は低下した。20世紀に入ると、第一次世界大戦と第二次世界 大戦が勃発し、カーライルがプロイセン主義とファシズムの始祖であるという非難が巻き起こり、カーライルの評判はさらに低下した。1950年代以降、カー ライル研究の分野における広範な研究により、彼の地位は向上し、現在では「われわれの文学の不朽のモニュメントの一人であり、極めて単純に、惜しむことの できない人物」として認識されている[4]。 |

| Biography Early life Thomas Carlyle's Birthplace Silhouettes of Carlyle's father and mother with captions in Carlyle's hand Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James and Margaret Aitken Carlyle in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland. His parents were members of the Burgher secession Presbyterian church.[5] James Carlyle was a stonemason, later a farmer, who built the Arched House wherein his son was born. His maxim was that "man was created to work, not to speculate, or feel, or dream."[6] Nicholas Carlisle, an English antiquary, traced his ancestry back to Margaret Bruce, sister of Robert the Bruce.[7] As a result of his disordered upbringing, James Carlyle became deeply religious in his youth, reading many books of sermons and doctrinal arguments throughout his life. He married his first wife in 1791, distant cousin Janet, who gave birth to John Carlyle and then died. He married Margaret Aitken in 1795, a poor farmer's daughter then working as a servant. They had nine children, of whom Thomas was the eldest. Margaret was pious and devout and hoped that Thomas would become a minister. She was close to her eldest son, being a "smoking companion, counsellor and confidante" in Carlyle's early days. She suffered a manic episode when Carlyle was a teenager, in which she became "elated, disinhibited, over-talkative and violent."[8] She suffered another breakdown in 1817, which required her to be removed from her home and restrained.[9] Carlyle always spoke highly of his parents, and his character was deeply influenced by both of them.[10] Carlyle's early education came from his mother, who taught him reading (despite being barely literate), and his father, who taught him arithmetic.[11] He first attended "Tom Donaldson's School" in Ecclefechan followed by Hoddam School (c. 1802–1806), which "then stood at the Kirk", located at the "Cross-roads" midway between Ecclefechan and Hoddam Castle.[12] By age 7, Carlyle showed enough proficiency in English that he was advised to "go into Latin", which he did with enthusiasm; however, the schoolmaster at Hoddam did not know Latin, so he was handed over to a minister that did, with whom he made a "rapid & sure way".[13] He then went to Annan Academy (c. 1806–1809), where he studied rudimentary Greek, read Latin and French fluently, and learned arithmetic "thoroughly well".[14] Carlyle was severely bullied by his fellow students at Annan, until he "revolted against them, and gave stroke for stroke"; he remembered the first two years there as among the most miserable of his life.[15] Edinburgh, the ministry and teaching (1809–1818) Plaque at 22A Buccleuch Place, Edinburgh[16] In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend the University of Edinburgh (c. 1809–1814), where he studied mathematics with John Leslie, science with John Playfair and moral philosophy with Thomas Brown.[17] He gravitated to mathematics and geometry and displayed great talent in those subjects, being credited with the invention of the Carlyle circle. In the University library, he read many important works of eighteenth-century and contemporary history, philosophy, and belles-lettres.[18] He began expressing religious scepticism around this time, asking his mother to her horror, "Did God Almighty come down and make wheelbarrows in a shop?"[19] In 1813 he completed his arts curriculum and enrolled in a theology course at Divinity Hall the following academic year. This was to be the preliminary of a ministerial career.[20] Carlyle began teaching at Annan Academy in June 1814.[21] He gave his first trial sermons in December 1814 and December 1815, both of which are lost.[22] By the summer of 1815 he had taken an interest in astronomy[23] and would study the astronomical theories of Pierre-Simon Laplace for several years.[24] In November 1816, he began teaching at Kirkcaldy, having left Annan. There, he made friends with Edward Irving, whose ex-pupil Margaret Gordon became Carlyle's "first love". In May 1817,[25] Carlyle abstained from enrolment in the theology course, news which his parents received with "magnanimity".[26] In the autumn of that year, he read De l'Allemagne (1813) by Germaine de Staël, which prompted him to seek a German teacher, with whom he learned the pronunciation.[27] In Irving's library, he read the works of David Hume and Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1789); he would later recall that I read Gibbon, and then first clearly saw that Christianity was not true. Then came the most trying time of my life. I should either have gone mad or made an end of myself had I not fallen in with some very superior minds.[28] Mineralogy, law and first publications (1818–1821) Jane Baillie Welsh by Kenneth Macleay, 1826, shortly before marriage In the summer of 1818, following an expedition with Irving through the moors of Peebles and Moffat, Carlyle made his first attempt at publishing, forwarding an article describing what he saw to the editor of an Edinburgh magazine, which was not published and is now lost.[29] In October, Carlyle resigned from his position at Kirkcaldy, and left for Edinburgh in November.[30] Shortly before his departure, he began to suffer from dyspepsia, which remained with him throughout his life.[31] He enrolled in a mineralogy class from November 1818 to April 1819, attending lectures by Robert Jameson,[32] and in January 1819 began to study German, desiring to read the mineralogical works of Abraham Gottlob Werner.[33] In February and March, he translated a piece by Jöns Jacob Berzelius,[34] and by September he was "reading Goethe".[35] In November he enrolled in "the class of Scots law", studying under David Hume (the advocate).[36] In December 1819 and January 1820, Carlyle made his second attempt at publishing, writing a review-article on Marc-Auguste Pictet's review of Jean-Alfred Gautier's Essai historique sur le problème des trois corps (1817) which went unpublished and is lost.[37] The law classes ended in March 1820 and he did not pursue the subject any further.[38] In the same month, he wrote several articles for David Brewster's Edinburgh Encyclopædia (1808–1830), which appeared in October. These were his first published writings.[39] In May and June, Carlyle wrote a review-article on the work of Christopher Hansteen, translated a book by Friedrich Mohs, and read Goethe's Faust.[40] By the autumn, Carlyle had also learned Italian and was reading Vittorio Alfieri, Dante Alighieri and Sismondi,[41] though German literature was still his foremost interest, having "revealed" to him a "new Heaven and new Earth".[42] In March 1821, he finished two more articles for Brewster's encyclopedia, and in April he completed a review of Joanna Baillie's Metrical Legends (1821).[43] In May, Carlyle was introduced to Jane Baillie Welsh by Irving in Haddington.[44] The two began a correspondence, and Carlyle sent books to her, encouraging her intellectual pursuits; she called him "my German Master".[45] "Conversion": Leith Walk and Hoddam Hill (1821–1826) During this time, Carlyle struggled with what he described as "the dismallest Lernean Hydra of problems, spiritual, temporal, eternal".[46] Spiritual doubt, lack of success in his endeavours, and dyspepsia were all damaging his physical and mental health, for which he found relief only in "sea-bathing". In early July 1821,[47] "during those 3 weeks of total sleeplessness, in which almost" his "one solace was that of a daily bathe on the sands between [Leith] and Portobello", an "incident" occurred in Leith Walk as he "went down" into the water.[48] This was the beginning of Carlyle's "Conversion", the process by which he "authentically took the Devil by the nose"[49] and flung "him behind me".[50] It gave him courage in his battle against the "Hydra"; to his brother John, he wrote, "What is there to fear, indeed?"[51] Repentance Tower near the farm in Hoddam Hill, which Carlyle called "a fit memorial for reflecting sinners."[52] Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien Marie Legendre's Elements of Geometry. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the New Edinburgh Review, and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On Proportion", which Augustus De Morgan later called "as good a substitute for the fifth Book of Euclid as could have been given in that space".[53] Carlyle's translation of Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship (1824) and Travels (1825) and his biography of Schiller (1825) brought him a decent income, which had before then eluded him, and he garnered a modest reputation. He began corresponding with Goethe and made his first trip to London in 1824, meeting with prominent writers such as Thomas Campbell, Charles Lamb, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and gaining friendships with Anna Montagu, Bryan Waller Proctor, and Henry Crabb Robinson. He also travelled to Paris in October–November with Edward Strachey and Kitty Kirkpatrick, where he attended Georges Cuvier's introductory lecture on comparative anatomy, gathered information on the study of medicine, introduced himself to Legendre, was introduced by Legendre to Charles Dupin, observed Laplace and several other notables while declining offers of introduction by Dupin, and heard François Magendie read a paper on the "fifth pair of nerves".[54] In May 1825, Carlyle moved into a cottage farmhouse in Hoddam Hill near Ecclefechan, which his father had leased for him. Carlyle lived with his brother Alexander, who, "with a cheap little man-servant", worked on the farm, his mother with her one maid-servant, and his two youngest sisters, Jean and Jenny.[55] He had constant contact with the rest of his family, most of whom lived close by at Mainhill, a farm owned by his father.[56] Jane made a successful visit in September 1825. Whilst there, Carlyle wrote German Romance (1827), a collection of previously untranslated German novellas by Johann Karl August Musäus, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Ludwig Tieck, E. T. A. Hoffmann, and Jean Paul. In Hoddam Hill, Carlyle found respite from the "intolerable fret, noise and confusion" that he had experienced in Edinburgh, and observed what he described as "the finest and vastest prospect all round it I ever saw from any house", with "all Cumberland as in amphitheatre unmatchable".[55] Here, he completed his "Conversion" which began with the Leith Walk incident. He achieved "a grand and ever-joyful victory", in the "final chaining down, and trampling home, 'for good,' home into their caves forever, of all" his "Spiritual Dragons".[57] By May 1826, problems with the landlord and the agreement forced the family's relocation to Scotsbrig, a farm near Ecclefechan. Later in life, he remembered the year at Hoddam Hill as "perhaps the most triumphantly important of my life."[58] Marriage, Comely Bank and Craigenputtock (1826–1834) 21 Comely Bank In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Welsh were married at the Welsh family farm in Templand. Shortly after their marriage, the Carlyles moved into a modest home on Comely Bank in Edinburgh, that had been leased for them by Jane's mother. They lived there from October 1826 to May 1828. In that time, Carlyle published German Romance, began Wotton Reinfred, an autobiographical novel which he left unfinished, and published his first article for the Edinburgh Review, "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter" (1827). "Richter" was the first of many essays extolling the virtues of German authors, who were then little-known to English readers; "State of German Literature" was published in October.[59] In Edinburgh, Carlyle made contact with several distinguished literary figures, including Edinburgh Review editor Francis Jeffrey, John Wilson of Blackwood's Magazine, essayist Thomas De Quincey, and philosopher William Hamilton.[44] In 1827 Carlyle attempted to land the Chair of Moral Philosophy at St. Andrews without success, despite support from an array of prominent intellectuals, including Goethe.[60] He also made an unsuccessful attempt for a professorship at the University of London.[44] Craigenputtock In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834.[61] He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of Werner", "Goethe's Helena", "Goethe", "Burns", "The Life of Heyne" (each 1828), "German Playwrights", "Voltaire", "Novalis" (each 1829), "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter Again" (1830), "Cruthers and Jonson; or The Outskirts of Life: A True Story", "Luther's Psalm", and "Schiller" (each 1831). He began but did not complete a history of German literature, from which he drew material for essays "The Nibelungen Lied", "Early German Literature" and parts of "Historic Survey of German Poetry" (each 1831). He published early thoughts on the philosophy of history in "Thoughts on History" (1830) and wrote his first pieces of social criticism, "Signs of the Times" (1829) and "Characteristics" (1831).[62] "Signs" garnered the interest of Gustave d'Eichthal, a member of the Saint-Simonians, who sent Carlyle Saint-Simonian literature, including Henri de Saint-Simon's Nouveau Christianisme (1825), which Carlyle translated and wrote an introduction for.[63] Portrait of Carlyle by Daniel Maclise for the Fraser's "Gallery of Literary Characters", June 1833 Most notably, he wrote Sartor Resartus. Finishing the manuscript in late July 1831, Carlyle began his search for a publisher, leaving for London in early August.[64] He and his wife lived there for the winter at 4 (now 33) Ampton Street, Kings Cross, in a house built by Thomas Cubitt.[65][66][67] The death of Carlyle's father in January 1832 and his inability to attend the funeral moved him to write the first of what would become the Reminiscences, published posthumously in 1881.[68] Carlyle had not found a publisher by the time he returned to Craigenputtock in March but he had initiated important friendships with Leigh Hunt and John Stuart Mill. That year, Carlyle wrote the essays "Goethe's Portrait", "Death of Goethe", "Goethe's Works", "Biography", "Boswell's Life of Johnson", and "Corn-Law Rhymes". Three months after their return from a January to May 1833 stay in Edinburgh, the Carlyles were visited at Craigenputtock by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson (and other like-minded Americans) had been deeply affected by Carlyle's essays and determined to meet him during the northern terminus of a literary pilgrimage; it was to be the start of a lifelong friendship and a famous correspondence. 1833 saw the publication of the essays "Diderot" and "Count Cagliostro"; in the latter, Carlyle introduced the idea of "Captains of Industry".[69] Chelsea (1834–1845) In June 1834, the Carlyles moved into 5 Cheyne Row, Chelsea, which became their home for the remainder of their respective lives. Residence in London wrought a large expansion of Carlyle's social circle. He became acquainted with scores of leading writers, novelists, artists, radicals, men of science, Church of England clergymen, and political figures. Two of his most important friendships were with Lord and Lady Ashburton; though Carlyle's warm affection for the latter would eventually strain his marriage, the Ashburtons helped to broaden his social horizons, giving him access to circles of intelligence, political influence, and power.[70] Carlyle's House Carlyle eventually decided to publish Sartor serially in Fraser's Magazine, with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory.[71] That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the French Revolution and set about researching and writing it shortly thereafter. Having completed the first volume after five months of writing, he lent the manuscript to Mill, who had been supplying him with materials for his research. One evening in March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's door appearing "unresponsive, pale, the very picture of despair". He had come to tell Carlyle that the manuscript was destroyed. It had been "left out", and Mill's housemaid took it for wastepaper, leaving only "some four tattered leaves". Carlyle was sympathetic: "I can be angry with no one; for they that were concerned in it have a far deeper sorrow than mine: it is purely the hand of Providence". The next day, Mill offered Carlyle £200 (equivalent to £21,000 in 2019),[72] of which he would only accept £100. He began the volume anew shortly afterwards. Despite an initial struggle, he was not deterred, feeling like "a runner that tho' tripped down, will not lie there, but rise and run again."[73][74] By September, the volume was rewritten. That year, he wrote a eulogy for his friend, "Death of Edward Irving".[75] In April 1836, with the intercession of Emerson, Sartor Resartus was first published in book form in Boston, soon selling out its initial run of five hundred copies.[76][77] Carlyle's three-volume history of the French Revolution was completed in January 1837 and sent to the press.[78] Contemporaneously, the essay "Memoirs of Mirabeau" was published,[79] as was "The Diamond Necklace" in January and February,[80] and "Parliamentary History of the French Revolution" in April.[81] In need of further financial security, Carlyle began a series of lectures on German literature in May, delivered extemporaneously in Willis' Rooms. The Spectator reported that the first lecture was given "to a very crowded and yet a select audience of both sexes." Carlyle recalled being "wasted and fretted to a thread, my tongue ... dry as charcoal: the people were there, I was obliged to stumble in, and start. Ach Gott!"[82] Despite his inexperience as a lecturer and deficiency "in the mere mechanism of oratory," reviews were positive and the series proved profitable for him.[83] Crayon portrait of Thomas Carlyle by Samuel Laurence, 1838 During Carlyle's lecture series, The French Revolution: A History was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to Karl August Varnhagen von Ense that his earlier efforts to popularise German literature were beginning to produce results, and expressed his satisfaction: "Deutschland will reclaim her great Colony; we shall become more Deutsch, that is to say more English, at same time."[84] The French Revolution fostered the republication of Sartor Resartus in London in 1838 as well as a collection of his earlier writings in the form of the Critical and Miscellaneous Essays, facilitated in Boston with the aid of Emerson. Carlyle presented his second lecture series in April and June 1838 on the history of literature at the Marylebone Institution in Portman Square. The Examiner reported that at the end of the second lecture, "Mr. Carlyle was heartily greeted with applause."[85] Carlyle felt that they "went on better and better, and grew at last, or threatened to grow, quite a flaming affair."[86] He published two essays in 1838, "Sir Walter Scott", being a review of John Gibson Lockhart's biography, and "Varnhagen von Ense's Memoirs". In April 1839, Carlyle published "Petition on the Copyright Bill".[87] A third series of lectures was given in May on the revolutions of modern Europe, which the Examiner reviewed positively, noting after the third lecture that "Mr. Carlyle's audiences appear to increase in number every time."[88] Carlyle wrote to his mother that the lectures were met "with very kind acceptance from people more distinguished than ever; yet still with a feeling that I was far from the right lecturing point yet."[89] In July, he published "On the Sinking of the Vengeur"[90] and in December he published Chartism, a pamphlet in which he addressed the movement of the same name and raised the Condition-of-England question.[91] Report in The Examiner of "the speech that gave birth to The London Library",[92] given by Thomas Carlyle 24 June 1840 In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History. Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of [sic] with sufficient éclat; the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad best I have yet given."[93] In the 1840 edition of the Essays, Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833.[94] Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh.[95] Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841.[96] He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books, Anthony Panizzi (despite the fact that Panizzi had allowed him many privileges not granted to other readers), and criticised him in a footnote to an article published in the Westminster Review as the "respectable Sub-Librarian".[97] Carlyle's eventual solution, with the support of a number of influential friends, was to call for the establishment of a private subscription library from which books could be borrowed.[98] Carlyle had chosen Oliver Cromwell as the subject for a book in 1840 and struggled to find what form it would take. In the interim, he wrote Past and Present (1843) and the articles "Baillie the Covenanter" (1841), "Dr. Francia" (1843), and "An Election to the Long Parliament" (1844). Carlyle declined an offer for professorship from St. Andrews in 1844. The first edition of Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: with Elucidations was published in 1845; it was a popular success and did much to revise Cromwell's standing in Britain.[70] Journeys to Ireland and Germany (1846–1865) Thomas Carlyle by Robert Scott Tait, 25 May 1855 Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy as a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland.[99] Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in The Spectator in response to two speeches given by Peel wherein he made many of the same proposals which Carlyle had earlier suggested; he called the speeches "like a prophecy of better things, inexpressibly cheering."[100] In May, he published "Indian Meal", in which he advanced maize as a remedy to the Great Famine as well as the worries of "disconsolate Malthusians".[101] He visited Ireland again with Duffy later that year while recording his impressions in his letters and a series of memoranda, published as Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849 after his death; Duffy would publish his own memoir of their travels, Conversations with Carlyle.[102] Carlyle's travels in Ireland deeply affected his views on society, as did the Revolutions of 1848. While embracing the latter as necessary in order to cleanse society of various forms of anarchy and misgovernment, he denounced their democratic undercurrent and insisted on the need for authoritarian leaders. These events inspired his next two works, "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849), in which he coined the term "Dismal Science" to describe political economy, and Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850). The illiberal content of these works sullied Carlyle's reputation for some progressives, while endearing him to those that shared his views. In 1851, Carlyle wrote The Life of John Sterling as a corrective to Julius Hare's unsatisfactory 1848 biography. In late September and early October, he made his second trip to Paris, where he met Adolphe Thiers and Prosper Mérimée; his account, "Excursion (Futile Enough) to Paris; Autumn 1851", was published posthumously.[103] In 1852, Carlyle began research on Frederick the Great, whom he had expressed interest in writing a biography of as early as 1830.[104] He travelled to Germany that year, examining source documents and prior histories. Carlyle struggled through research and writing, telling von Ense it was "the poorest, most troublesome and arduous piece of work he has ever undertaken".[105] In 1856, the first two volumes of History of Friedrich II. of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great were sent to the press and published in 1858. During this time, he wrote "The Opera" (1852), "Project of a National Exhibition of Scottish Portraits" (1854) at the request of David Laing, and "The Prinzenraub" (1855). In October 1855, he finished The Guises, a history of the House of Guise and its relation to Scottish history, which was first published in 1981.[106] Carlyle made a second expedition to Germany in 1858 to survey the topography of battlefields, which he documented in Journey to Germany, Autumn 1858, published posthumously. In May 1863, Carlyle wrote the short dialogue "Ilias (Americana) in Nuce" (American Iliad in a Nutshell) on the topic of the American Civil War. Upon publication in August, the "Ilias" drew scornful letters from David Atwood Wasson and Horace Howard Furness.[107] In the summer of 1864, Carlyle lived at 117 Marina (built by James Burton)[108] in St Leonards-on-Sea, in order to be nearer to his ailing wife who was in possession of caretakers there.[109] Carlyle planned to write four volumes but had written six by the time Frederick was finished in 1865. Before its end, Carlyle had developed a tremor in his writing hand.[110] Upon its completion, it was received as a masterpiece. He earned a sobriquet, the "Sage of Chelsea",[111] and in the eyes of those that had rebuked his politics, it restored Carlyle to his position as a great man of letters.[112] Carlyle was elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University in November 1865, succeeding William Ewart Gladstone and defeating Benjamin Disraeli by a vote of 657 to 310.[113] Final years (1866–1881) Carlyle and his niece Mary Aitken, 1874 Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall, Thomas Henry Huxley, and Thomas Erskine. One of those that welcomed Carlyle on his arrival was Sir David Brewster, president of the university and the commissioner of Carlyle's first professional writings for the Edinburgh Encyclopædia. Carlyle was joined onstage by his fellow travellers, Brewster, Moncure D. Conway, George Harvey, Lord Neaves, and others. Carlyle spoke extemporaneously on several subjects, concluding his address with a quote from Goethe: "Work, and despair not: Wir heissen euch hoffen, 'We bid you be of hope!'" Tyndall reported to Jane in a three-word telegram that it was "A perfect triumph."[114] The warm reception he received in his homeland of Scotland marked the climax of Carlyle's life as a writer. While still in Scotland, Carlyle received abrupt news of Jane's sudden death in London. Upon her death, Carlyle began to edit his wife's letters and write reminiscences of her. He experienced feelings of guilt as he read her complaints about her illnesses, his friendship with Lady Harriet Ashburton, and his devotion to his labour, particularly on Frederick the Great. Although deep in grief, Carlyle remained active in public life.[115] Engraving depicting the Inaugural Address Amidst controversy over governor John Eyre's violent repression of the Morant Bay rebellion, Carlyle assumed leadership of the Eyre Defence and Aid Fund in 1865 and 1866. The Defence had convened in response to the anti-Eyre Jamaica Committee, led by Mill and backed by Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer, and others. Carlyle and the Defence were supported by John Ruskin, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Charles Dickens, and Charles Kingsley.[116][117] From December 1866 to March 1867,[118] Carlyle resided at the home of Louisa Baring, Lady Ashburton in Menton, where he wrote reminiscences of Irving, Jeffrey, Robert Southey, and William Wordsworth. In August, he published "Shooting Niagara: And After?", an essay in response and opposition to the Second Reform Bill.[119] In 1868, he wrote reminiscences of John Wilson and William Hamilton, and his niece Mary Aitken Carlyle moved into 5 Cheyne Row, becoming his caretaker and assisting in the editing of Jane's letters. In March 1869, he met with Queen Victoria, who wrote in her journal of "Mr. Carlyle, the historian, a strange-looking eccentric old Scotchman, who holds forth, in a drawling melancholy voice, with a broad Scotch accent, upon Scotland and upon the utter degeneration of everything."[120] In 1870, he was elected president of the London Library, and in November he wrote a letter to The Times in support of Germany in the Franco-Prussian War. His conversation was recorded by a number of friends and visitors in later years, most notably William Allingham, who became known as Carlyle's Boswell.[121] Commemoration Medal for Thomas Carlyle, front In the spring of 1874, Carlyle accepted the Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste from Otto von Bismarck and declined Disraeli's offers of a state pension and the Knight Grand Cross in the Order of the Bath in the autumn. On the occasion of his eightieth birthday in 1875, he was presented with a commemorative medal crafted by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm and an address of admiration signed by 119 of the leading writers, scientists, and public figures of the day.[a] "Early Kings of Norway", a recounting of historical material from the Icelandic sagas transcribed by Mary acting as his amanuensis,[122] and an essay on "The Portraits of John Knox" (both 1875) were his last major writings to be published in his lifetime. In November 1876, he wrote a letter in the Times "On the Eastern Question", entreating England not to enter the Russo-Turkish War on the side of the Turks. Another letter to the Times in May 1877 "On the Crisis", urging against the rumoured wish of Disraeli's to send a fleet to the Baltic Sea and warning not to provoke Russia and Europe at large into a war against England, marked his last public utterance.[123] The American Academy of Arts and Sciences elected him a Foreign Honorary Member in 1878.[124] On 2 February 1881, Carlyle fell into a coma. For a moment he awakened, and Mary heard him speak his final words: "So this is Death—well ..."[125] He thereafter lost his speech and died on the morning of 5 February.[126] An offer of interment at Westminster Abbey, which he had anticipated, was declined by his executors in accordance with his will.[127] He was laid to rest with his mother and father in Hoddam Kirkyard in Ecclefechan, according to old Scottish custom.[128] His private funeral, held on 10 February, was attended by family and a few friends, including Froude, Conway, Tyndall, and William Lecky, as local residents looked on.[115] |

略歴 生い立ち トーマス・カーライルの生家 カーライルの父と母のシルエットとカーライル直筆のキャプション トーマス・カーライルは1795年12月4日、スコットランド南西部ダンフリースシャーのエクルフェシャン村で、ジェームズとマーガレット・エイトケン・ カーライルの間に生まれた。両親はブルガー分離派の長老教会の信者であった[5]。ジェームス・カーライルは石工で、後に農夫となり、息子が生まれたアー チ型の家を建てた。彼の信条は「人間は働くために造られたのであって、思索したり、感じたり、夢見たりするために造られたのではない」というものであった [6]。イギリスの古文書学者ニコラス・カーライルは、彼の先祖をロバート・ザ・ブルースの妹であるマーガレット・ブルースにまで遡らせた[7]。乱れた 生い立ちの結果、ジェームズ・カーライルは若い頃から深く信仰するようになり、生涯を通じて多くの説教集や教義論争を読んだ。1791年に最初の妻となる 遠縁の従姉妹ジャネットと結婚。ジャネットはジョン・カーライルを出産し、その後死去した。1795年にマーガレット・エイトケンと結婚。当時は貧しい農 家の娘で、使用人として働いていた。二人の間には9人の子供がいたが、トーマスはそのうちの長男であった。マーガレットは敬虔で信心深く、トーマスが牧師 になることを願っていた。彼女は長男と親しく、カーライルの初期には「喫煙仲間であり、助言者であり、親友」であった。カーライルが10代の頃に躁病を患 い、「高揚し、抑制が利かず、饒舌で暴力的になった」[8]。1817年にも躁病を患い、家から追い出され、拘束されることになった[9]。 カーライルの幼少期の教育は、(ほとんど読み書きができなかったにもかかわらず)読書を教えた母親と、算術を教えた父親から受けた[11]。カーライルは まずエクルフェチャンの「トム・ドナルドソンズ・スクール」に通い、その後、エクルフェチャンとホッダム城の中間に位置する「十字路」にあった「当時カー クにあった」ホッダム・スクール(1802年頃-1806年)に通った。 [しかし、ホッダム城の校長はラテン語を知らなかったため、彼はラテン語を教える牧師に引き渡され、その牧師と「迅速かつ確実な道」を歩むことになる。 [13]その後、アナン・アカデミー(1806-1809年頃)に進学し、初歩的なギリシャ語を学び、ラテン語とフランス語を流暢に読み、算数を「徹底的 によく」学んだ[14]。カーライルはアナンでの仲間たちからひどいいじめを受け、「彼らに反旗を翻し、一撃に一撃を与える」までになった。 エディンバラ、聖職と教育(1809-1818年) エディンバラ、バクルック・プレイス22Aのプレート[16]。 1809年11月、14歳近くになったカーライルは、自宅から100マイルを歩いてエディンバラ大学(1809-1814年頃)に入学し、ジョン・レズ リーに数学を、ジョン・プレイフェアに科学を、トーマス・ブラウンに道徳哲学を学んだ[17]。この頃から宗教に懐疑的な態度を示すようになり、母親に 「全知全能の神が降りてきて、店で手押し車を作ったのだろうか」と聞いて怯えるほどであった[19]。これが牧師としてのキャリアの前段階となった [20]。 1814年6月、カーライルはアナン・アカデミーで教え始め[21]、1814年12月と1815年12月に最初の説教を行ったが、いずれも失われている [22]。1815年の夏までには天文学に興味を持ち[23]、ピエール=シモン・ラプラスの天文学理論を数年間研究することになる[24]。そこでエド ワード・アーヴィングと親しくなり、彼の元教え子のマーガレット・ゴードンはカーライルの「初恋の人」となった。1817年5月、カーライルは神学部への 入学を断念し[25]、両親はその知らせを「寛大」に受け止めた[26]。その年の秋、彼はジェルメーヌ・ド・スタエルの『De l'Allemagne』(1813年)を読み、それをきっかけにドイツ語の教師を探し、発音を学んだ[27]。 ギボンを読んで、キリスト教が真実でないことがはっきりわかりました。その後、私の人生で最も困難な時期がやってきた。非常に優れた知性に出会っていなけ れば、私は発狂していたか、自滅していただろう[28]。 鉱物学、法律、最初の出版物(1818-1821年) ジェーン・ベイリー=ウェルシュ、ケネス・マクレイ著、1826年、結婚直前 10月、カーライルはカークカルディの職を辞し、11月にエディンバラへ向かった。 [1818年11月から1819年4月まで鉱物学のクラスに在籍し、ロバート・ジェイムソンの講義を受け[32]、1819年1月にはアブラハム・ゴット ローブ・ヴェルナーの鉱物学の著作を読みたいとドイツ語の勉強を始めた[33]。 [33]2月と3月にはイェンス・ヤコブ・ベルツェリウスの作品を翻訳し[34]、9月には「ゲーテを読んでいた」[35]。11月には「スコットランド 法のクラス」に入学し、デイヴィッド・ヒューム(弁護人)に師事した。 [1819年12月と1820年1月、カーライルは2度目の出版に挑戦し、マルク=オーギュスト・ピクテによるジャン=アルフレッド・ゴーティエの 『Essai historique sur le problème des trois corps』(1817年)の批評記事を書いたが、これは未発表のまま行方不明になっている[37]。 同月、10月に出版されたデイヴィッド・ブリュースターの『エジンバラ百科事典』(1808-1830)にいくつかの記事を寄稿。5月から6月にかけて、 カーライルはクリストファー・ハンステインの仕事についての評論記事を書き、フリードリヒ・モースの本を翻訳し、ゲーテの『ファウスト』を読んだ [40]。 [40]秋までに、カーライルはイタリア語も学び、ヴィットリオ・アルフィエーリ、ダンテ・アリギエーリ、シスモンディを読んでいたが[41]、ドイツ文 学は依然として彼の最大の関心事であり、彼にとって「新しい天と新しい地」を「啓示」していた[42]。 5月、カーライルはハディントンでアーヴィングからジェーン・バイリー・ウェルシュを紹介される[44]。二人は文通を始め、カーライルは彼女に本を送 り、彼女の知的探求を励ました。彼女は彼を「私のドイツの師匠」と呼んだ[45]。 「改心」: リース・ウォークとホッダム・ヒル(1821-1826年) この時期、カーライルは「精神的、時間的、永遠的な、最も惨めなレルネのヒドラのような問題」[46]と苦闘していた。精神的な疑念、努力の成功の欠如、 消化不良はすべて彼の心身の健康を損ない、彼は「海水浴」によってのみ救いを見出していた。1821年7月上旬[47]、「ほとんど」彼の「唯一の慰めが [リース]とポートベロの間の砂浜で毎日水浴びをすることであった」不眠の3週間の間に、リース・ウォークで彼が水の中に「降りて」いく「事件」が起こっ た。 [48]これはカーライルの「改心」の始まりであり、彼が「正真正銘、悪魔を鼻であしらい」[49]、「悪魔を私の後ろに」投げ捨てたプロセスであった [50]。 ホッダム・ヒルの農場の近くにある悔悟の塔をカーライルは「罪人を反省するのに適した記念碑」と呼んだ[52]。 カーライルは7月、8月、9月にいくつかの記事を書き、11月にはアドリアン・マリー・ルジャンドルの『幾何学の要素』の翻訳を始めた。1822年1月、 カーライルは『ニュー・エジンバラ・レヴュー』誌に「ゲーテの『ファウスト』」を寄稿し、その直後から著名なブラー家の家庭教師を始め、7月までチャール ズ・ブラーとその弟アーサー・ウィリアム・ブラーの家庭教師を務めた。カーライルは、1822年7月にルジャンドルの翻訳を完成させ、自身のエッセイ "On Proportion(比例について)"を前書きした。ゲーテと文通を始め、1824年には初めてロンドンを訪れ、トーマス・キャンベル、チャールズ・ラ ム、サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジら著名な作家と会い、アンナ・モンタグ、ブライアン・ウォーラー・プロクター、ヘンリー・クラッブ・ロビンソンら と親交を深めた。また、10月から11月にかけてエドワード・ストレイチー、キティ・カークパトリックとともにパリを訪れ、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエの比較 解剖学の入門講義に出席し、医学の研究についての情報を収集し、ルジャンドルに自己紹介し、ルジャンドルからシャルル・デュパンを紹介され、デュパンから の紹介の申し出を断りながらラプラスや他の著名人を観察し、フランソワ・マジェンディが「第五対の神経」に関する論文を読むのを聞いた[54]。 1825年5月、カーライルは父親が借りていたエクルフェシャン近郊のホッダム・ヒルのコテージ農家に移り住む。カーライルは、「安い小男の召使いを連れ て」農作業をする弟のアレクサンダー、召使いを一人連れた母親、二人の末の妹のジーンとジェニーと一緒に暮らした[55]。1825年9月、ジェーンはエ クルフェシャン近郊のホッダム・ヒルの農家を訪れ、成功を収めた。その間にカーライルは、ヨハン・カール・アウグスト・ムーセウス、フリードリヒ・ド・ ラ・モット・フーケ、ルートヴィヒ・ティエック、E・T・A・ホフマン、ジャン・ポールらの未訳のドイツ小説を集めた『ジャーマン・ロマンス』(1827 年)を執筆。カーライルはホッダム・ヒルで、エディンバラで経験した「耐え難い喧騒と混乱」から解放され、「どの家からも見たことのない、最も素晴らしく 広大な見晴らし」、「カンバーランド全土が比類なき円形劇場のようである」と彼が評したものを観察した[55]。 彼はここで、リース・ウォーク事件から始まった「改心」を完成させた。1826年5月までに、家主との契約上の問題から、一家はエクルフェチャンの近くの 農場スコッツブリグに引っ越すことを余儀なくされた[57]。後年、彼はホッダム・ヒルでの1年を「おそらく私の人生で最も勝利的に重要な年だった」と回 想している[58]。 結婚、カムリーバンクとクレイゲンパトック(1826年-1834年) 21 コメリー・バンク 1826年10月、トーマス・ウェルシュとジェーン・ウェルシュはテンプランドのウェルシュ家の農場で結婚した。結婚後まもなく、カーライル夫妻は、 ジェーンの母親が借りていたエジンバラのカムリーバンクの質素な家に引っ越した。二人は1826年10月から1828年5月までそこに住んだ。その間に、 カーライルは『ジャーマン・ロマンス』を出版し、未完のまま放置していた自伝的小説『ウォットン・ラインフレッド』を書き始め、『エジンバラ・レヴュー』 誌に最初の論文「ジャン・ポール・フリードリヒ・リヒター」(1827年)を発表した。「カーライルはエジンバラで、エジンバラ・レヴューの編集者フラン シス・ジェフリー、ブラックウッド誌のジョン・ウィルソン、エッセイストのトマス・デ・クインシー、哲学者のウィリアム・ハミルトンなど、著名な文学者た ちと交流した[59]。 [1827年、カーライルはゲーテを含む著名な知識人たちからの支援にもかかわらず、セント・アンドリュース大学の道徳哲学講座の獲得を試みるが成功しな かった[60]。 クライゲンプトック 1828年5月、カーライル夫妻はダンフリースシャーにあるジェーンの質素な農地の母屋クレイゲンパトックに移り住み、1834年5月まで過ごした。 [ヴェルナーの生涯と著作"、"ゲーテのヘレナ"、"ゲーテ"、"バーンズ"、"ハイネの生涯"(それぞれ1828年)、"ドイツの劇作家"、"ヴォル テール"、"ノヴァーリス"(それぞれ1829年)、"ジャン・パウル・フリードリヒ・リヒター再び"(1830年)、"クラザーズとジョンソン、あるい は人生のはずれ: A True Story"、"Luther's Psalm"、"Schiller"(それぞれ1831年)。ドイツ文学史に着手したが完成には至らず、そこからエッセイ『ニーベルンゲン歌曲』、『初期 ドイツ文学』、『ドイツ詩の歴史的調査』(それぞれ1831年)の一部を執筆した。彼は『歴史についての考察』(1830年)で歴史哲学に関する初期の考 えを発表し、『時代の兆し』(1829年)と『特徴』(1831年)という最初の社会批評を書いた[62]。『兆し』はサン=シモン派のメンバーであった ギュスターヴ・デヒタールの興味を引き、彼はカーライルにアンリ・ド・サン=シモンの『新キリスト教主義』(1825年)を含むサン=シモン派の文献を送 り、カーライルはそれを翻訳して序文を書いた[63]。 ダニエル・マクライズによるカーライルの肖像画(1833年6月、フレイザーの『文学人物画廊』のため 最も注目すべきは、『サルトル・レザルトゥス』の執筆である。1831年7月下旬に原稿を書き上げたカーライルは、出版社探しを始め、8月初旬にロンドン に向かった[64]。冬の間、妻とともにキングス・クロスのアンプトン・ストリート4番地(現33番地)にトーマス・キュービットが建てた家で暮らした。 [65][66][67]1832年1月にカーライルの父が亡くなり、葬儀に参列できなかったカーライルは、1881年に死後出版された『回想録』の最初 の作品を書くことになる。この年、カーライルは「ゲーテの肖像」、「ゲーテの死」、「ゲーテの作品」、「伝記」、「ジョンソンのボズウェルの生涯」、 「コーンローの韻文」というエッセイを書いた。1833年1月から5月までのエジンバラ滞在から帰国した3ヵ月後、カーライル夫妻はラルフ・ウォルドー・ エマーソンのクレイゲンパトックへの訪問を受けた。カーライルのエッセイに深い感銘を受けたエマソン(および同じ志を持つ他のアメリカ人)は、文学巡礼の 北の終着駅でカーライルに会うことを決意した。1833年にはエッセイ『ディドロ』と『カリオストロ伯爵』が出版され、後者でカーライルは「産業界の船 長」という考えを紹介した[69]。 チェルシー(1834年-1845年) 1834年6月、カーライル夫妻はチェルシーのシャイン・ロウ5番地に移り住み、その後の生涯を過ごすことになる。ロンドンでの生活は、カーライルの社交 界に大きな広がりをもたらした。彼は多くの一流作家、小説家、芸術家、急進派、科学者、英国国教会の聖職者、政治家たちと知り合うようになった。カーライ ルのアシュバートン卿夫妻との交友は最も重要なものであった。アシュバートン卿夫妻へのカーライルの温かい愛情は、やがてカーライルの結婚生活をぎくしゃ くさせることになったが、アシュバートン夫妻はカーライルの社会的視野を広げるのに役立ち、知性、政治的影響力、権力を持つ人々と接触する機会を彼に与え た[70]。 カーライルの家 カーライルは最終的に『サルトル』をフレイザーズ・マガジンに連載することを決め、1833年11月から1834年8月にかけて連載した。エマソンやミル などが早くから『サルトル』を評価していたにもかかわらず、『サルトル』の評判は芳しくなかった。1834年、カーライルはエジンバラ天文台の天文学教授 職に応募したが落選した[71]。その秋、彼はフランス革命史の出版を手配し、その後すぐに調査と執筆に取り掛かった。5ヶ月の執筆期間を経て第1巻を完 成させた彼は、研究のための資料を提供してくれていたミルに原稿を貸した。1835年3月のある晩、ミルはカーライルの家の前に現れた。彼はカーライルに 原稿が破棄されたことを伝えに来たのだ。ミルの家政婦が原稿を古紙として持ち去り、「ぼろぼろの葉が4枚」残っただけだった。カーライルは同情した。「私 は誰も怒ることはできない。それに関わった人々は、私よりもはるかに深い悲しみを抱えている。翌日、ミルはカーライルに200ポンド(2019年の 21,000ポンドに相当)を提示したが[72]、彼は100ポンドしか受け取らなかった。彼はその直後、新たに一巻を書き始めた。最初の苦闘にもかかわ らず、彼は「つまづいても、そこに横たわることなく、立ち上がって再び走るランナー」のように感じ、躊躇しなかった[73][74]。その年、彼は友人へ の弔辞「エドワード・アーヴィングの死」を書いた[75]。 1836年4月、エマーソンの仲介で『サルトル・レザルトゥス』はボストンで初めて単行本として出版され、すぐに500部の初版が完売した[76] [77]。 カーライルの3巻からなるフランス革命史は1837年1月に完成し、出版社に送られた[78]。 [同時期に、エッセイ『ミラボーの思い出』が出版され[79]、1月と2月には『ダイヤモンドの首飾り』が、4月には『フランス革命の議会史』が出版され た[80]。さらなる経済的安定を必要としていたカーライルは、5月にウィリスの部屋で即興的に行われたドイツ文学の講義シリーズを開始した。スペクテイ ター』紙によると、最初の講義は「非常に混雑した、しかし男女ともに選ばれた聴衆の前で」行われた。カーライルは「一糸まとわぬ姿になり、舌 は......炭のように乾いていた。人々はそこにいて、私はつまずき、始めざるを得なかった。アッ、ゴット!」[82]。講演者としての経験が浅く、 「単なる演説のメカニズムに」欠けていたにもかかわらず、批評は好意的で、このシリーズは彼にとって有益であることが証明された[83]。 サミュエル・ローレンスによるトーマス・カーライルのクレヨン画、1838年 カーライルの講義シリーズ中に『フランス革命史』が正式に出版された: A History』が正式に出版された。カーライルの出世作となった。この年の暮れ、カーライルはカール・アウグスト・ヴァルンハーゲン・フォン・エンセ に、ドイツ文学の普及に以前から取り組んでいた努力が成果を上げ始めていることを報告し、満足感を示した: ドイチュラントが偉大な植民地を取り戻すと同時に、われわれはよりドイチュ的に、つまりよりイギリス的になるであろう」[84] フランス革命は、1838年にロンドンで『サルトル・レザルトゥス』の再刊を促し、ボストンでエマーソンの援助によって『批評と雑文』という形で彼の初期 の著作を集めた。カーライルは1838年4月と6月、ポートマン・スクエアのメリルボーン研究所で文学史に関する2回目の講義を行った。エグザミナー』紙 によると、2回目の講義の終わりに「カーライル氏は心から拍手で迎えられた」[85]。カーライルは、講義が「どんどん良くなり、最後にはかなり燃え上が るような事件に発展した、あるいは発展する恐れがあった」と感じた[86]。1839年4月、カーライルは "Petition on the Copyright Bill "を出版した[87] 5月には近代ヨーロッパの革命に関する第3回講演が行われ、『エグザミナー』誌はこれを肯定的に評価し、第3回講演の後に「カーライル氏の聴衆は毎回増え ているようだ」と記した[88]。 「7月には『ヴェンゲール号の沈没について』[90]を出版し、12月にはチャーティズムという小冊子を出版した。 1840年6月24日、トーマス・カーライルによる「ロンドン図書館を誕生させた演説」[92]を『エグザミナー』誌が報じる。 1840年5月、カーライルは4回目にして最後の講演を行い、それは1841年に『英雄、英雄崇拝、歴史における英雄について』として出版された。この講 義は『歴史における英雄、英雄崇拝、英雄主義について』として1841年に出版された[95]。カーライルは1841年にロンドン図書館の主要な創設者と なった[96]。 [カーライルは大英博物館図書館の設備に不満を抱いていた。大英博物館図書館ではしばしば席を確保することができず(梯子に腰掛けることを余儀なくされ た)、読書仲間との密室状態が強制されて「博物館頭痛」を引き起こし、図書の貸し出しが受けられず、フランス革命やイングランド内戦に関するパンフレット やその他の資料の蔵書目録が不十分であることに不満を抱いていた。特に、彼は印刷本の管理人アンソニー・パニッツィに反感を抱き(パニッツィは他の読者に は認められていない多くの特権を彼に認めていたにもかかわらず)、『ウェストミンスター・レビュー』誌に掲載された記事の脚注で、彼を「立派な副図書館 長」と批判した[97]。 カーライルの最終的な解決策は、影響力のある多くの友人たちの支援を得て、本を借りることができる個人購読図書館の設立を呼びかけることであった [98]。 カーライルは1840年にオリヴァー・クロムウェルを本の題材として選び、どのような形にするか苦慮していた。その間に、彼は『過去と現在』(1843 年)、論文「コヴェナンターのベイリー」(1841年)、「フランシア博士」(1843年)、「長い議会の選挙」(1844年)を書いた。カーライルは 1844年、セント・アンドリュースからの教授就任の申し出を断った。1845年にOliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: with Elucidations(オリヴァー・クロムウェルの手紙と演説:解説付き)の初版が出版された。 アイルランドとドイツへの旅(1846年~1865年) ロバート・スコット・テイトによるトーマス・カーライル(1855年5月25日 カーライルは1846年、チャールズ・ギャヴァン・ダフィを案内人としてアイルランドを訪れ、1848年にはアイルランド問題に関する一連の短い記事を書 いた。アイルランドと英国総督」、「(新アイルランドの)アイルランド連隊」、「連邦の廃止」であり、それぞれアイルランドの問題に対する解決策を提示 し、イングランドとアイルランドとのつながりを維持することを主張している[99]。 1849年4月に『スペクテイター』誌に掲載された「アイルランドとロバート・ピール」(「C.」と署名)というタイトルの記事を書いた。 「100]5月には『インディアン・ミール』を出版し、大飢饉の救済策としてトウモロコシを推し進めるとともに、「不機嫌なマルサス人」の心配を解消した [101]。 カーライルのアイルランドでの旅は、1848年の革命と同様に、彼の社会観に深い影響を与えた。カーライルは、様々な形態の無政府状態や失政から社会を浄 化するために必要なこととして後者を受け入れる一方で、その民主主義の底流を非難し、権威主義的指導者の必要性を主張した。これらの出来事が、彼の次の2 つの著作、『黒人問題に関する折々の談話』(1849年)にインスピレーションを与え、この中で彼は、政治経済を表す「ディスマル・サイエンス」という言 葉を作り出した。これらの著作の非自由主義的な内容は、一部の進歩主義者にとってはカーライルの評判を貶めるものであったが、彼の意見を共有する人々に とっては好意的なものであった。1851年、カーライルは『ジョン・スターリングの生涯』を、ジュリアス・ヘアが1848年に出版した満足のいかない伝記 を正すために執筆した。9月下旬から10月上旬にかけて、彼は2度目のパリ旅行をし、アドルフ・ティエールとプロスペル・メリメに会った。彼の記録『パリ への小旅行(1851年秋)』は死後に出版された[103]。 1852年、カーライルは1830年の時点で伝記を書くことに興味を示していたフリードリヒ大王の研究を始める。1856年、『プロイセン王フリードリヒ 2世の歴史』(History of Friedrich II. of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great)の最初の2巻が印刷所に送られ、1858年に出版された。この間、『オペラ』(1852年)、デイヴィッド・ライングの依頼による『スコット ランド肖像画全国展覧会計画』(1854年)、『プリンツェンラウプ』(1855年)を執筆。1855年10月、ギーズ家の歴史とスコットランドの歴史と の関わりを描いた『ギーズ家』を完成させ、1981年に出版された[106]。1863年5月、カーライルはアメリカ南北戦争を題材にした短編対談『イリ アス(アメリカーナ)・イン・ヌース』(アメリカのイリアス)を執筆した。1864年の夏、カーライルはセント・レオナーズ・オン・シーの117マリーナ (ジェームズ・バートンが建てた)[108]に住んでいた。 カーライルは4巻を書く予定だったが、フレデリックが1865年に完成するまでに6巻を書き上げた。完成後、カーライルは傑作として迎えられた。1865 年11月、カーライルはウィリアム・イワート・グラッドストンの後任として、ベンジャミン・ディズレーリを657対310で破り、エディンバラ大学学長に 選出された[113]。 晩年(1866年-1881年) カーライルと姪メアリー・エイトケン、1874年 1866年4月、カーライルは学長就任演説のためスコットランドを訪れた。この旅には、ジョン・ティンダル、トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー、トーマス・ アースキンらが同行した。カーライルの到着を出迎えたのは、大学の学長であり、カーライルの最初の著作をエディンバラ百科事典に寄稿したサー・デイヴィッ ド・ブリュースターであった。カーライルは、ブリュースター、モンキュア・D・コンウェイ、ジョージ・ハーヴェイ、ニーヴス卿らとともに壇上に上がった。 カーライルはいくつかのテーマについて即興で語り、ゲーテの言葉を引用して演説を締めくくった: 「働け、そして絶望するな: Wir heissen euch hoffen、"私たちはあなたがたに希望を持てと言うのだ!"」というゲーテの言葉を引用して演説を締めくくった。ティンダルはジェーンに「完璧な勝利 だった」と3文字の電報で報告した[114]。故郷スコットランドで受けた温かい歓迎は、カーライルの作家としての人生のクライマックスとなった。まだス コットランドにいたカーライルは、ロンドンでジェーンの突然の訃報を受ける。ジェーンの死後、カーライルは妻の手紙を編集し、回想録を書き始めた。妻の病 気についての訴え、ハリエット・アシュバートン夫人との友情、フリードリヒ大王をはじめとする自分の仕事への傾倒などを読み、カーライルは罪悪感にさいな まれた。深い悲しみに暮れながらも、カーライルは公の場で活動を続けた[115]。 就任演説を描いたエングレーヴィング モラント・ベイの反乱に対するジョン・エア知事の暴力的な弾圧が物議を醸すなか、カーライルは1865年と1866年にエア擁護・援助基金の指導者に就任 した。弁護団は、ミルが主導し、チャールズ・ダーウィンやハーバート・スペンサーらが支援した反エイヤー・ジャマイカ委員会に対抗して招集された。 1866年12月から1867年3月まで[118]、カーライルはメントンのアシュバートン夫人ルイーザ・ベーリングの家に滞在し、アーヴィング、ジェフ リー、ロバート・サウシー、ウィリアム・ワーズワースの回想録を執筆した。8月には「ナイアガラを撃つ: 1868年、ジョン・ウィルソンとウィリアム・ハミルトンの回想録を執筆。姪のメアリー・エイトケン・カーライルはシャイン・ロウ5番地に移り住み、 ジェーンの世話人となり、ジェーンの手紙の編集を手伝う。1869年3月、カーライルはヴィクトリア女王と面会し、ヴィクトリア女王は日記に「歴史家の カーライル氏は奇妙な風貌の風変わりな年老いたスコットランド人で、スコットランドとあらゆるものの完全な堕落について、広いスコットランド訛りの引きず るような憂鬱な声で語っている」と記している[120] 1870年、カーライルはロンドン図書館の会長に選出され、11月には普仏戦争におけるドイツを支持する手紙を『タイムズ』紙に寄せた。彼の会話は後年、 多くの友人や訪問者によって記録され、特にウィリアム・アリンガムはカーライルのボスウェルとして知られるようになった[121]。 トーマス・カーライル記念メダル、正面 1874年春、カーライルはオットー・フォン・ビスマルクからPour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künsteを受諾し、秋にはディズレーリからの国家年金とバース騎士大十字勲章の申し出を断った。1875年の80歳の誕生日には、サー・ジョセフ・エ ドガー・ベームが製作した記念メダルと、当時を代表する作家、科学者、公人119人が署名した賞賛の辞が贈られた[a] 。アイスランドのサガから、メアリーが彼の通訳として書き起こした歴史的資料を再録した『ノルウェーの初期の王たち』[122]と、『ジョン・ノックスの 肖像画』に関するエッセイ(いずれも1875年)は、生前出版された最後の主要著作となった。1876年11月、彼は『タイムズ』紙に「東方問題につい て」という手紙を書き、イギリスがトルコ側に立って露土戦争に参戦しないよう懇願した。1877年5月にも『タイムズ』紙に「危機について」という書簡を 寄稿し、ディズレーリがバルト海に艦隊を派遣しようとしていると噂されることに反対し、ロシアとヨーロッパ全体を刺激してイギリスとの戦争に巻き込まない よう警告した。 1878年、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーは彼を外国人名誉会員に選出した[124]。 1881年2月2日、カーライルは昏睡状態に陥った。彼は一瞬目を覚まし、メアリーは彼が最後の言葉を話すのを聞いた: 「彼が予期していたウェストミンスター寺院への埋葬の申し出は、遺言に従って遺言執行者によって断られた[127]。 [2月10日に執り行われた私的な葬儀には、地元住民が見守る中、家族と、フロイド、コンウェイ、ティンダル、ウィリアム・レッキーを含む数人の友人が参 列した[115]。 |

| Works Main articles: Philosophy of Thomas Carlyle and Thomas Carlyle's prose style Carlyle's "Seal," sketched in 1823. Its Latin motto translates: "May I be wasted so that I be of use."[129] Carlyle's corpus spans the genres of "criticism, biography, history, politics, poetry, and religion."[130] His innovative writing style, known as Carlylese, greatly influenced Victorian literature and anticipated techniques of postmodern literature.[131] In Carlylean philosophy, while not adhering to any formal religion, he asserted the importance of belief during an age of increasing doubt. Much of his work is concerned with the modern human spiritual condition; he was the first writer to use the expression "meaning of life".[132] In Sartor Resartus and in his early Miscellanies, he developed his own philosophy of religion based upon what he called "Natural Supernaturalism",[133] the idea that all things are "Clothes" which at once reveal and conceal the divine, that "a mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one",[134] and that duty, work and silence are essential. Carlyle postulated the Great Man theory, a philosophy of history which contends that history is shaped by exceptional individuals. This approach to history was first promulgated in his lectures On Heroes and given specific focus in longer studies like Cromwell and Frederick the Great. He viewed history as a "Prophetic Manuscript" that progresses on a cyclical basis, analogous to the phoenix and the seasons. His historiographical method emphasises the relationship between the event at hand and all those which precede and follow it, which he makes apparent through use of the present (rather than past) tense in his French Revolution and in other histories. Raising the "Condition-of-England Question"[135] to address the impact of the Industrial Revolution, Carlyle's social and political philosophy is characterised by medievalism,[136] advocating a "Chivalry of Labour"[137] led by "Captains of Industry".[138] In works of social criticism such as Past and Present and Latter-Day Pamphlets, he attacked utilitarianism as mere atheism and egoism,[139] criticised the political economy of laissez-faire as the "Dismal Science",[140] and rebuked "big black Democracy",[141] while championing "Heroarchy (Government of Heroes)".[142] |

作品 主な記事 トマス・カーライルの哲学、トマス・カーライルの散文スタイル 1823年にスケッチされたカーライルの「印章」。ラテン語の標語はこう訳されている: 「役に立てるように、私が無駄になるように」[129]。 カーライルの著作は、「批評、伝記、歴史、政治、詩、宗教」[130]のジャンルにまたがっている。 カーリリアン哲学において、彼は正式な宗教に固執しない一方で、疑念が増大する時代における信仰の重要性を主張した。サルトル・レザルトス』や初期の『雑 話集』において、彼は「自然超自然主義」[133]と呼ばれるもの、すなわち万物は神を現すと同時に隠す「衣」であり、「兄弟愛の神秘的な絆がすべての人 間をひとつにする」[134]、義務、労働、沈黙が不可欠であるという考えに基づく独自の宗教哲学を展開した。 カーライルは、歴史は例外的な個人によって形成されるという歴史哲学である偉人論を提唱した。歴史に対するこのアプローチは、彼の講義『英雄について』で 初めて公布され、クロムウェルやフリードリッヒ大王のような長い研究の中で具体的な焦点が当てられた。彼は歴史を、不死鳥や四季になぞらえた、循環的に進 行する「予言の写本」と見なした。彼の歴史学的手法は、目前の出来事とそれに先行・後続するすべての出来事との関係を強調するものであり、フランス革命や その他の歴史において(過去形ではなく)現在形を用いることによって、それを明らかにしている。 産業革命の影響に対処するために「イングランドの状況問題」[135]を提起したカーライルの社会的・政治的哲学は中世主義によって特徴づけられ [136]、「産業の隊長」[137]に率いられた「労働騎士道」[138]を提唱している。 [138]『過去と現在』や『末日のパンフレット』などの社会批評の作品において、彼は功利主義を単なる無神論とエゴイズムとして攻撃し[139]、自由 放任主義の政治経済を「ディスマル・サイエンス」として批判し[140]、「大黒デモクラシー」を非難し[141]、一方で「ヒーロー・アーキィ(英雄の 政府)」を支持した[142]。 |

| Character Medallion of Carlyle by Thomas Woolner, 1851. James Caw said that it recalled Lady Eastlake's description of him: "The head of a thinker, the eye of a lover, and the mouth of a peasant."[143] James Anthony Froude recalled his first impression of Carlyle: He was then fifty-four years old; tall (about five feet eleven), thin, but at that time upright, with no signs of the later stoop. His body was angular, his face beardless, such as it is represented in Woolner's medallion,[b] which is by far the best likeness of him in the days of his strength. His head was extremely long, with the chin thrust forward; his neck was thin; the mouth firmly closed, the under lip slightly projecting; the hair grizzled and thick and bushy. His eyes, which grew lighter with age, were then of a deep violet, with fire burning at the bottom of them, which flashed out at the least excitement. The face was altogether most striking, most impressive in every way.[144] He was often recognised by his wideawake hat.[145] Carlyle was a renowned conversationalist. Ralph Waldo Emerson described him as "an immense talker, as extraordinary in his conversation as in his writing,—I think even more so." Charles Darwin considered him "the most worth listening to, of any man I know."[146] William Lecky noted his "singularly musical voice" which "quite took away anything grotesque in the very strong Scotch accent" and "gave it a softening or charm".[147] Henry Fielding Dickens recollected that he was "gifted with a high sense of humour, and when he laughed he did so heartily, throwing his head back and letting himself go."[148] Thomas Wentworth Higginson remembered his "broad, honest, human laugh," one that "cleared the air like thunder, and left the atmosphere sweet."[149] Lady Eastlake called it "the best laugh I ever heard".[150] Charles Eliot Norton wrote that Carlyle's "essential nature was solitary in its strength, its sincerity, its tenderness, its nobility. He was nearer Dante than any other man."[151] Frederic Harrison similarly observed that "Carlyle walked about London like Dante in the streets of Verona, gnawing his own heart and dreaming dreams of Inferno. To both the passers-by might have said, See! there goes the man who has seen hell".[152] Higginson rather felt that Jean Paul's humorous character Siebenkäs "came nearer to the actual Carlyle than most of the grave portraitures yet executed", for, like Siebenkäs, Carlyle was "a satirical improvisatore".[153] Emerson saw Carlyle as "not mainly a scholar," but "a practical Scotchman, such as you would find in any saddler's or iron-dealer's shop, and then only accidentally and by a surprising addition, the admirable scholar and writer he is."[154] Paul Elmer More found Carlyle "a figure unique, isolated, domineering—after Dr. Johnson the greatest personality in English letters, possibly even more imposing than that acknowledged dictator."[155] |

キャラクター トーマス・ウールナーによるカーライルのメダイ 1851年 ジェームズ・コーは、イーストレイク夫人がカーライルをこう評したことを思い起こさせると述べている: 「思想家の頭、恋人の目、農民の口」[143]。 ジェームズ・アンソニー・フロードは、カーライルの第一印象を回想している: 彼は当時54歳で、背が高く(約5フィート11)、痩せていたが、当時は直立し、後に猫背になる兆候はなかった。体は角ばっていて、顔はウールナーのメダ イヨン[b]に描かれているような髭のないものだった。頭は非常に長く、顎は前に突き出し、首は細く、口は固く閉じ、下唇はわずかに突き出し、髪は白髪混 じりで太くふさふさしていた。歳をとるにつれて薄くなっていく目は、深い紫色で、その底には炎が燃えており、ちょっとした興奮で火を噴いた。その顔立ち は、すべてにおいて最も印象的で、最も印象的であった[144]。 彼はしばしば、そのワイドウェイクの帽子で見分けられた[145]。 カーライルは有名な会話家であった。ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソンは彼を「絶大な話術の持ち主であり、文章と同様に会話においても非凡であった。チャー ルズ・ダーウィンは彼のことを「私が知っている男の中で、最も傾聴に値する男」[146]と評し、ウィリアム・レッキーは「非常に強いスコットランド訛り からグロテスクなものを完全に取り去り」、「柔らかさと魅力を与えた」彼の「特別に音楽的な声」に注目した[147]。 [147]ヘンリー・フィールディング・ディケンズは、彼が「高いユーモアのセンスに恵まれており、笑うときには頭を後ろに投げ出して身を任せて心から 笑った」と回想している[148]。トーマス・ウェントワース・ヒギンソンは、彼の「広く、正直で、人間的な笑い」を覚えており、それは「雷のように空気 を澄ませ、甘い雰囲気を残した」[149]。 チャールズ・エリオット・ノートンは、カーライルの「本質的な性質は、その強さ、誠実さ、優しさ、気高さにおいて孤独であった。彼は誰よりもダンテに近 かった」[151] フレデリック・ハリソンも同様に、「カーライルはヴェローナの街路を歩くダンテのようにロンドンを歩き回り、自分の心をかじり、インフェルノ(地獄篇)の 夢を見た。ヒギンソンはむしろ、ジャン・ポールのユーモラスなキャラクターであるシーベンケスについて、「まだ描かれている重厚な肖像画のほとんどより も、実際のカーライルに近い」と感じていた[152]。 [153]エマーソンはカーライルを「主として学者ではなく」、「どこの馬具商や鉄商の店でも見かけるような実際的なスコットランド人であり、そして偶然 に、驚くべき追加によってのみ、立派な学者であり作家である」[154]と見ていた。 ポール・エルマー・モアはカーライルを「ユニークで、孤高で、威圧的で、ジョンソン博士に次いでイギリス文学界で最も偉大な人格者であり、おそらくはその 独裁者と認められている人物よりも堂々としている」と評した[155]。 |