哀悼可能性

Grievability

Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse

☆ 哀悼可能性(Grievability)は、ある(基本的に人の悲しみを誘う)残虐な表象を見せられたときに、それを悲しく思う感情のことをさす。ふつう、(基 本的に人の悲しみを誘う)残虐な表象をみせられると、人間は、1)悲しく思うか——これが哀悼可能性である、2)嫌悪以外の何者ものも感情を覚えないとい う、2つの反応にわかれる。例えば、犬が車にはねられたのか、舌をだして、口から血を少しながしている写真があるとする、それが自分の飼い犬であれば、無 条件に哀悼可能性を覚えるが、見ず知らずの犬、ましては野良犬であった場合は、嫌悪以外の感情を覚えることはない。

★21世紀を生きる我々には、毎日報道やSNSで、そのような残虐な写真(例:泥や埃にまみれた悲しい顔をしたパレスチナの子ども)が溢れている。我々が、それらに哀 悼可能性を覚えてシェアするか、それとも嫌悪感あるいはなんの感情もえずに、やり過ごすのかの違いは、それを見る人たちの、感情や、それを評価する経験、 あるいは、政治や経済についての「背景知識」をベースにしている。また、それらの反応に相反するものがあることも、我々は感じている。さらにそれらを見せ るか/見せないか、あるいは検閲にかけるか/かけずに(消極的/積極的に)推奨するかの判断は、我々自身の社会的判断に基づいている。

| After

the attacks of 9/11, we encountered in the media graphic pictures of

those who died, along with their names, their stories, the reactions of

their families. Public grieving was dedicated to making these images

iconic for the nation, which meant of course that there was

considerably less public grieving for non-US nationals, and none at all

for illegal workers. |

9.11

同時多発テロの後、私たちはメディアで亡くなった人たちの生々しい写真と、その名前、体験談、家族の反応を目にした。国民の悲しみは、これらの画像を国民

にとって象徴的なものにすることに捧げられた。もちろん、米国籍を持たない人々に対する国民の悲しみはかなり少なく、不法就労者についてはまったくなかっ

た。 |

| The

differential distribution of public grieving is a political issue of

enormous significance. It has been since at least the time of Antigone,

when she chose openly to mourn the death of one of her brothers even

though it went against the sovereign law to do so. Why is it that

governments so often seek to regulate and control who will be publicly

grievable and who will not? |

公

的な悲しみの分配の差は、政治的に非常に重要な問題である。少なくともアンティゴーネーの時代からそうであった。彼女は兄弟の一人の死を悼むことを、たと

えそれが主権法に反していたとしても、公然と選んだのである。なぜ政府はしばしば、誰が公に悲嘆に暮れ、誰がそうでないかを規制し、管理しようとするのだ

ろうか? |

| In

the initial years of the AIDS crisis in the US, the public vigils, and

the Names Project broke through the public shame associated with dying

from AIDS, a shame associated sometimes with homosexuality, and

especially anal sex, and sometimes with drugs and promiscuity. It meant

something to state and show the name, to put together some remnants of

a life, to publicly display and avow the loss. What would happen if

those killed in the current wars were to be grieved in just such an

open way? Why is it that we are not given the names of all the war

dead, including those the US has killed, of whom we will never have the

image, the name, the story, never a testimonial shard of their life,

something to see, to touch, to know? Although it is not possible to

singularize every life destroyed in war, there are surely ways to

register the populations injured and destroyed without fully

assimilating to the iconic function of the image. |

ア

メリカにおけるエイズ危機の初期において、市民による追悼集会と「名前プロジェクト」は、エイズで死ぬことにまつわる公的な羞恥心を打ち破った。この羞恥

心は、時には同性愛、特にアナルセックス、時にはドラッグや乱交と結びついていた。名前を公表し、示すこと、人生の名残をまとめること、公に展示し、喪失

を告白することには意味があった。もし現在の戦争で殺された人々が、このようなオープンな方法で悲嘆に暮れるとしたらどうなるだろうか?米国が殺害した戦

没者を含め、すべての戦没者の名前が私たちに知らされないのはなぜだろうか。彼らの姿や名前、物語を知ることはできないし、彼らの人生の証しや、見るべき

もの、触れるべきもの、知るべきものを手にすることもできない。戦争で破壊されたすべての生命を単一化することは不可能だが、イメージの象徴的機能に完全

に同化することなく、傷つき破壊された人々を登録する方法はきっとあるはずだ。 |

| Open

grieving is bound up with outrage, and outrage in the face of injustice

or indeed of unbearable loss has enormous political potential. It is,

after all, one of the reasons Plato wanted to ban the poets from the

Republic. He thought that if the citizens went too often to watch

tragedy, they would weep over the losses they saw, and that such open

and public mourning, in disrupting the order and hierarchy of the soul,

would disrupt the order and hierarchy of political authority as well. |

公

然たる悲嘆は憤怒と結びついており、不公正や耐え難い喪失に直面したときの憤怒は、政治的に大きな可能性を秘めている。プラトンが『共和国』から詩人を追

放しようとした理由のひとつも、結局はそこにある。プラトンは、市民が悲劇を頻繁に見に行けば、その喪失に涙し、そのような公然たる弔いは、魂の秩序と階

層を乱し、政治的権威の秩序と階層をも乱すだろうと考えたのである。 |

| Whether

we are speaking about open grief or outrage, we are talking about

affective responses that are highly regulated by regimes of power and

sometimes subject to explicit censorship. In the contemporary wars in

which the US is directly engaged, those in Iraq and Afghanistan, we can

see how affect is regulated to support both the war effort and, more

specifically, nationalist belonging. When the photos of Abu Ghraib were

first released in the US, conservative television pundits argued that

it would be un- American to show them. |

公

然たる悲嘆であれ憤怒であれ、私たちが語るのは、権力体制によって高度に規制され、時には明確な検閲の対象となる感情反応である。米国が直接関与している

現代の戦争、イラク戦争とアフガニスタン戦争では、戦争努力と、より具体的にはナショナリストの帰属意識を支えるために、情動がどのように規制されている

かを見ることができる。アブグレイブの写真が初めてアメリカで公開されたとき、保守的なテレビ評論家たちは、それを見せるのはアメリカ人らしくないと主張

した。 |

| Judith Butler, Precariousness and Grievability: When is life grievable? https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/blogs/news/2339-judith-butler-precariousness-and-grievability |

|

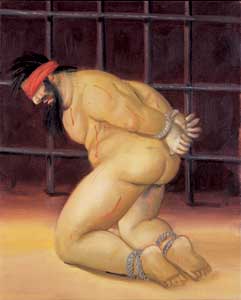

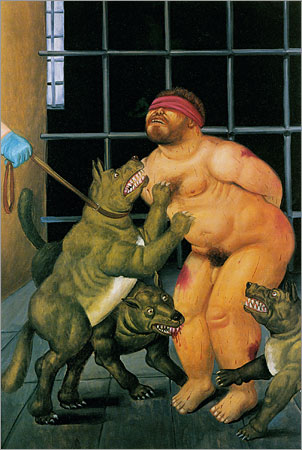

アブ・グレイブ捕虜収容所にて(米兵と被疑者の湾岸戦争捕虜)——フェルナンド・ボテロ作画:CIAはこの戦争を契機に戦争捕虜に国際法で禁止されている拷問を容認した。この「テロとの戦い」における反人道的な尋問手段は現在のアメリカの政治文化そのものである。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆