グアテマラ人への梅毒感染実験

Guatemala syphilis experiments

☆グアテマラ梅毒実験(The Guatemala

syphilis experiments)

は、1946年から1948年にかけてグアテマラで実施された、米国主導の人体実験である。この実験は、タスキギー梅毒実験の末期にも参加した医師ジョ

ン・チャールズ・カトラーが主導した。医師たちは、少なくとも600人の兵士と、さまざまな貧困層(売春婦、孤児、精神病院の入院患者、囚人など)の人々

を含む1,300人に、対象者のインフォームドコンセントなしに梅毒、淋病、陰部皮膚炎を感染させた。治療を受けたのはそのうちの700人だけだった。合

計で5,500人がすべての研究実験に関与し、そのうち83人が1953年末までに死亡したが、これらの死亡がすべて注射によるものかどうかは不明であ

る。

1953年まで、血清学的研究は、国営学校の児童、孤児院、農村部の町民に加え、同じ社会的弱者層を対象に継続された。しかし、患者への意図的な感染は当

初の研究で終了した。

2010年10月1日、米国大統領、国務長官、保健福祉長官は、倫理規定違反についてグアテマラに正式に謝罪した。グアテマラは、この実験を人道に対する

罪として非難した。その後、米国で複数の訴訟が起こされたが、いずれも失敗に終わっている。

ウェルズリー大学のスーザン・モコトフ・レヴァビー教授は、タスキギー梅毒研究の調査を行っていた2005年に、カトラーの保管文書からこれらの実験に関

する情報を発見した。彼女は調査結果を米国政府高官に報告した。

発覚当時NIH所長であったフランシス・コリンズは、この実験を「医学史上の暗黒の1ページ」と呼び、現代の規則ではインフォームドコンセントなしに人体

実験を行うことは禁止されているとコメントした。

| The Guatemala

syphilis experiments were United States-led human experiments conducted

in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948. The experiments were led by physician

John Charles Cutler, who also participated in the late stages of the

Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Doctors infected 1,300 people, including

at least 600 soldiers and people from various impoverished groups

(including, but not limited to, sex workers, orphans, inmates of mental

hospitals, and prisoners) with syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid,

without the informed consent of the subjects. Only 700 of them received

treatment. In total, 5,500 people were involved in all research

experiments, of whom 83 died by the end of 1953, though it is unknown

whether or not the injections were responsible for all these deaths.[1]

Serology studies continued through 1953 involving the same vulnerable

populations in addition to children from state-run schools, an

orphanage, and rural towns. However, the intentional infection of

patients ended with the original study. On October 1, 2010, the U.S. President, Secretary of State, and Secretary of Health and Human Services[2] formally apologized to Guatemala for the ethical violations. Guatemala condemned the experiment as a crime against humanity. Multiple unsuccessful lawsuits have since been filed in the US.[3][4][5] Professor Susan Mokotoff Reverby of Wellesley College uncovered information about these experiments in Cutler's archived papers in 2005 while researching the Tuskegee syphilis study. She shared her findings with United States government officials.[6][7] Francis Collins, the NIH director at the time of the revelations, called the experiments "a dark chapter in history of medicine" and commented that modern rules prohibit conducting human subject research without informed consent.[8] |

グアテマラ梅毒実験は、1946年から1948年にかけてグアテマラで

実施された、米国主導の人体実験である。この実験は、タスキギー梅毒実験の末期にも参加した医師ジョン・チャールズ・カトラーが主導した。医師たちは、少

なくとも600人の兵士と、さまざまな貧困層(売春婦、孤児、精神病院の入院患者、囚人など)の人々を含む1,300人に、対象者のインフォームドコンセ

ントなしに梅毒、淋病、陰部皮膚炎を感染させた。治療を受けたのはそのうちの700人だけだった。合計で5,500人がすべての研究実験に関与し、そのう

ち83人が1953年末までに死亡したが、これらの死亡がすべて注射によるものかどうかは不明である。[1]

1953年まで、血清学的研究は、国営学校の児童、孤児院、農村部の町民に加え、同じ社会的弱者層を対象に継続された。しかし、患者への意図的な感染は当

初の研究で終了した。 2010年10月1日、米国大統領、国務長官、保健福祉長官は[2]、倫理規定違反についてグアテマラに正式に謝罪した。グアテマラは、この実験を人道に 対する罪として非難した。その後、米国で複数の訴訟が起こされたが、いずれも失敗に終わっている。[3][4][5] ウェルズリー大学のスーザン・モコトフ・レヴァビー教授は、タスキギー梅毒研究の調査を行っていた2005年に、カトラーの保管文書からこれらの実験に関 する情報を発見した。彼女は調査結果を米国政府高官に報告した。[6][7] 発覚当時NIH所長であったフランシス・コリンズは、この実験を「医学史上の暗黒の1ページ」と呼び、現代の規則ではインフォームドコンセントなしに人体 実験を行うことは禁止されているとコメントした。[8] |

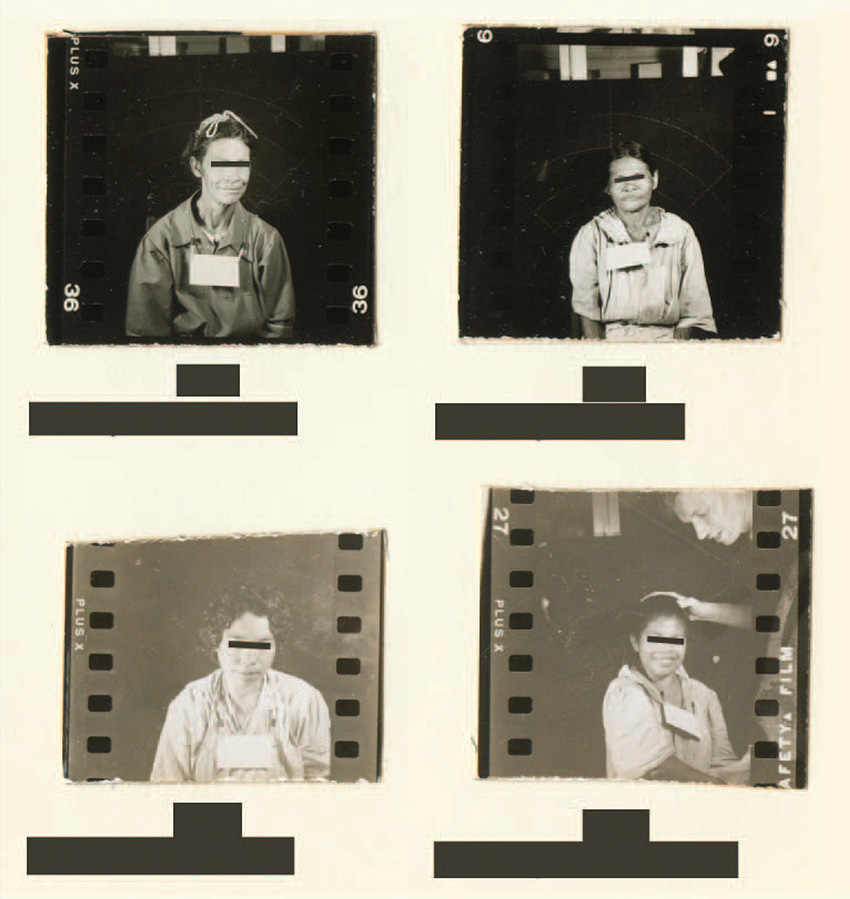

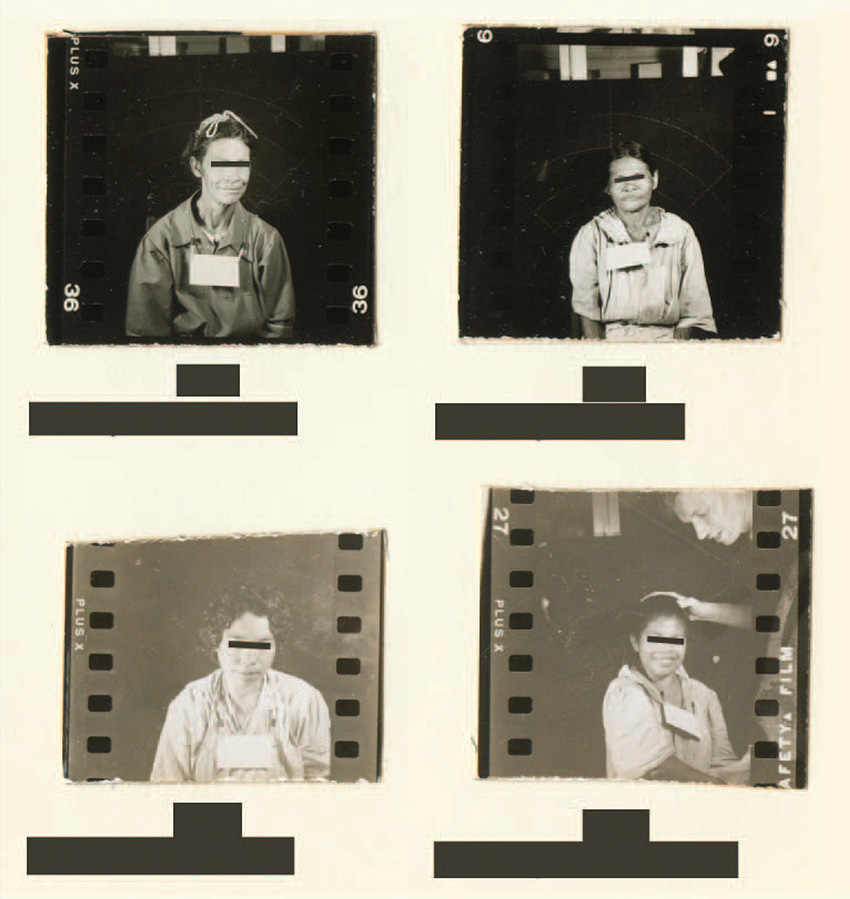

Experiment overview Dr. John Cutler drawing blood from Tuskegee Syphilis study subjects Historical context Rabbits had been used to test treatments for syphilis since the early twentieth century, when Sahachiro Hata injected them with arsphenamine, which became known as "the magic bullet" for treating syphilis. They were later injected in the 1940s with penicillin as part of research into methods for preventing syphilis. Around this same time, there was a push by medical professionals, including the U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Thomas Parran, to further the knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases and discover more viable prophylaxis and treatment options in humans.[citation needed] This search for new methods became stronger and won more supporters with the onset of World War II. This was largely due to an effort to protect the U.S. military forces from widespread infections of STDs such as gonorrhea, as well as the particularly painful regimen of prophylaxis that involved in the injection of a silver proteinate into subjects' penises.[9] At the time, it was estimated that venereal diseases would affect 350,000 soldiers, which would equate to eliminating two armed divisions for an entire year. The cost of these losses, which would amount to about $34 million at the time, made research for STD treatments particularly urgent.[9] The first field trial driven by this push for new developments in STD treatment and preventative measures was the Terre Haute prison experiments from 1943 to 1944, which were conducted and supported by many of the same individuals who would go on to participate in the Guatemalan syphilis experiments only a few years later.[9][10] The goal of this experiment was to find a more suitable STD prophylaxis by infecting human subjects recruited from prison populations with gonorrhea. Though at first the idea of using human subjects was controversial, the support of Dr. Thomas Parran and Colonel John A. Rodgers, Executive Officer of the U.S. Army Medical Corps, enabled Dr. John F. Mahoney and Dr. Cassius J. Van Slyke to begin implementing the experiments. Dr. John Cutler, a young associate of Mahoney, helped conduct the experiments, and went on to lead the Guatemala syphilis experiments.[11] The experiments in Terre Haute were the precursor for the Guatemalan experiments. It was the first to demonstrate how earnestly military leaders pushed for new developments to combat STDs and their willingness to infect human subjects, and also explained why the study clinicians would choose Guatemala: to avoid the ethical constraints related to individual consent, other adverse legal consequences, and bad publicity.[9] Study details The study was led by the U.S. Public Health Service, beginning in 1946, up until 1948.[12] The experiments were initially supposed to be held at a prison in Terre Haute, Indiana, but were moved to Guatemala after researchers had a hard time consistently infecting prisoners with gonorrhea.[13] The move to Guatemala was suggested by Dr. Juan Funes, head of the Guatemalan Venereal Disease Control Department.[14] The experiments were funded by a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the Pan American Sanitary Bureau; multiple Guatemalan government ministries also got involved.[6] A study conducted at the Southern Georgia University argues that the selection of Guatemala as a location to conduct the syphilis experiments was a racially-motivated decision by U.S. authorities, considering that the study featured white physicians and researchers experimenting on subjects deemed by the U.S. as minority groups.[12] Another study argues that the reasoning was due to Guatemalan prisoners' privilege to pay for prostitutes, making it seem that infections were natural due to intercourse with an infected prostitute.[14] The total number of subjects involved in the experiment is unclear. Some sources argue that about 1,500 study subjects were involved, although the findings were never published.[6] Other sources state that over 5,000 individuals participated in the study, including children.[12] The purpose of the study was to observe the efficacy of penicillin in preventing infection of sexually-transmitted diseases after sexual intercourse. As a result, around 696 Guatemalans were intentionally infected with syphilis, gonorrhea and chancroids.[15] The study also aimed to discover medications other than penicillin for various venereal diseases.[12] In archived documents, Dr. Thomas Parran, Jr., the U.S. Surgeon General at the time of the experiments, acknowledged that the Guatemalan work could not be done domestically; in addition details of the program were hidden from Guatemalan officials.[7][16] Furthermore, the participants had not received the opportunity to provide informed consent since the purpose and details of the research were hidden from them as well.[15] Participants were subjected to the syphilis bacteria through permitted visits with infectious female sex workers, paid by funds from the U.S. government.[17] Other attempts at passing the pathogens to participants included pouring the bacteria onto various lightly abraded body parts, such as male subjects' genitalia, forearms and faces. Some subjects were even infected through forced perforation of the spine.[15] Participants who then tested positive for syphilis were treated with penicillin. However, there is no evidence for adequate treatment having been provided to all subjects or whether infected individuals were cured.[15] While the study is known to have officially ended in 1948, doctors continued taking tissue samples and performing autopsies on former participants until 1958.[18] Eighty-three individuals died during the course of the experiment, though it is unclear as to whether or not the inoculations were the source of these deaths.[10] Although the study ran for so long and collected massive amounts of data, the researchers never published anything from the Guatemalan syphilis experiments. The likelihood of researchers attempting to protect themselves by not publishing is low due to their later publishing studies over the Tuskegee syphilis studies. No evidence indicates why the experiments ended or if they were shut down.[19] Study methods The initial attempts to infect subjects of the experiment consisted of workers from the USPHS inoculating prostitutes with germs that had grown in rabbits, and then paying them to have sex with prisoners. Prostitutes in Guatemala were required to be tested twice a week for STD infection at a government clinic. For the purposes of the experiments, infected sex workers were instead sent to Dr. Cutler by the head of the Guatemalan Ministry of Public Health.[20] They operated under an assumption that one prostitute could have sex with up to eight men in 71 minutes, creating a large rate of infection. These attempts failed at producing infections quick enough, due to the prisoners refusing repeated blood drawings.[14] Researchers switched to the direct inoculation of subjects after Cutler accepted an offer from Dr. Carlos Salvado, the director of the Asilo de Alienados, a psychiatric hospital in Guatemala City.[20] This hospital was notably understaffed and lacked rudimentary equipment and medicines. $1500 that was originally intended to go to volunteers at the prison was given to the psychiatric hospital for an antiepileptic drug called Dilantin and other necessary equipment.[14] Doctors would often inject strains of syphilis into patients' spinal fluid or wear away the skin to make infection easier. These strains that they infected patients with were collected from other infected patients or from "street strains", which are not defined.[18] After the patients were exposed to syphilis, only about half of the patients were given treatment for the infection.[20] 83 patients died during the experiments, but the relation between experiment involvement and death was unsubstantiated.[citation needed] In 1947, Cutler began experimenting with gonorrhea on Guatemalan soldiers. About 600 soldiers were infected with the disease after a year and a half. Infected sex workers were used to infect the soldiers, and gonorrheal pus from soldiers' penises were injected into other soldiers.[20] Chancroid experiments were also conducted simultaneously on about 80 soldiers, in which doctors would scratch soldiers' arms and infect the wounds. Consent was given by soldiers' officials or patient doctors, but was not reported to have been given by the subjects themselves.[18]  Patients from the Guatemalan psychiatric hospital who participated as test subjects in the syphilis experiments between 1946 and 1948 A documented subject profile provides a detailed description of what the subjects faced within this experiment:[9] Berta was a female patient in the Psychiatric Hospital... in February 1948, Berta was injected in her left arm with syphilis. A month later, she developed scabies (an itchy skin infection caused by a mite). Several weeks later, Dr. Cutler noted that she also developed red bumps where he had injected her arm, lesions on her arms and legs, and her skin was beginning to waste away from her body. Berta was not treated for syphilis until three months after her injection. Soon after, on August 23, Dr. Cutler wrote that Berta appeared as if she was going to die, but he did not specify why. That same day he put gonorrheal pus from another male subject into both of Berta's eyes, as well as in her urethra and rectum. He also re-infected her with syphilis. Several days later, Berta's eyes were filled with pus from the gonorrhea, and she was bleeding from her urethra. Three days later, on August 27, Berta died.[9][21] Subjects In total, 1,308 people were confirmed to have been a part of this experiment. Of this group, 678 individuals were documented as getting some form of treatment. However, some reports say that up to 5,128 individuals were monitored for symptoms or became a part of the experiment through natural infection.[13] The populations involved consisted of child and adult commercial sex workers, prisoners, soldiers, orphans, leprosy patients, and mental hospital patients.[12][18] Many of these subjects were indigenous Guatemalans and Guatemalans living in poverty.[13] Their ages ranged from 10 to 72, though the average subject was in their 20s. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledges that "the design and conduct of the studies was unethical in many respects, including deliberate exposure of subjects to known serious health threats, lack of knowledge of and consent for experimental procedures by study subjects, and the use of highly vulnerable populations."[22] A total of 83 subjects died, though the exact relationship to the experiment remains undocumented.[9][22] Study clinicians Thomas Parran Thomas Parran was the sixth Surgeon General of the United States, who served from 1936 to 1948. Parran's profound interest in STD research can be seen when he testified before Congress in 1938 for expanded funding for public health prevention efforts and scientific research in the STD field. Prior to his involvement in Guatemala, he oversaw part of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and the Terre Haute prison experiments.[citation needed] Parran described syphilis as being "biologically different" in African Americans and said that African American women "remained infected two and one-half times as long as the white woman." This supposed biological difference in syphilis among races provided justification for the Tuskegee experiments to continue.[9] In Guatemala, he was responsible for granting the final approval for the continuation of the Terre Haute experiments on a new group of patients in Guatemala. He was also aware that intentional and uninformed infection of syphilis was occurring in Guatemala. Parran once said to Dr. Cutler, "You know, we couldn't do such an experiment in this country [United States]", showing he was aware of the ethical issues of what he was doing in Guatemala.[9][23][24] After serving as Surgeon General, Thomas Parran began a career working as the first dean of the new School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh. He retired from his administrative role at the university and became president of the Avalon Foundation, affiliated with the Mellon family, and became active in the A. W Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust. He died in 1968 and the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health named Parran Hall after him in 1969. The building was renamed in 2018 due to his involvement in unethical experimentation.[25] Dr. John F. Mahoney Prior to his involvement in the Guatemalan syphilis experiment, Mahoney graduated from the University of Pittsburgh medical school in 1914. By 1918 he was the Assistant Surgeon at the United States Public Health Service. In 1929, Dr. Mahoney worked as the director of the Venereal Disease Research Lab in Staten Island, where the Terre Haute experiments began in 1943, and where Cutler first assisted him.[citation needed] After stopping the Terre Haute experiments for lack of accurate infection of subjects with gonorrhea, Mahoney moved on to study the effects of penicillin on syphilis. His research found huge success for penicillin treatments and the US army embraced it in STD prescription. Although this seemed promising, Mahoney and his collaborators questioned the long term prospects for eliminating the disease altogether in individuals.[9] Mahoney, Cutler, Parran, and other researchers felt that a smaller, more controlled group of individuals to study would be more helpful in finding this cure. This led to the use of citizens in Guatemala as subjects. Mahoney was a member of the syphilis study section that approved the Guatemala research Grant. During the Guatemala syphilis study, Mahoney was the primary supervisor of the experiments, receiving Cutler's reports on the experiments. In 1946, while the syphilis study was ongoing, John Mahoney was awarded the Lasker award for discovering penicillin as a cure for syphilis.[9] After completion of the Guatemala syphilis study, John F. Mahoney became the chairman of the World Health Organization in 1948. In 1950 he became Commissioner of the New York City Department of Health, where he worked until his death in 1957.[9] Dr. John Charles Cutler The experiments were led by United States Public Health Service Venereal Diseases Research Laboratory physician John Charles Cutler,[26] who had earlier joined the Public Health Service in 1942 and served as a commissioned officer.[27] Cutler participated in the similar Terre Haute prison experiments, in which volunteer prisoners were infected with gonorrhea spanning from 1943 to 1944.[9] Cutler also later took part in the late stages of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, where black Americans were lied to about getting available treatment for syphilis. Over 100 people died due to lack of treatment. In a 1993 documentary about the Tuskegee syphilis study titled "Deadly Deception", Cutler defends his actions saying, "It was important that they were supposedly untreated, and it would be undesirable to go ahead and use large amounts of penicillin to treat the disease, because you'd interfere with the study."[28] While the Tuskegee experiment followed the natural progression of syphilis in those already infected, in Guatemala doctors deliberately infected healthy people with the diseases, some of which can be fatal if untreated. His team created a laboratory in Guatemala supplied by the United States military to discover if there were different transmission rates when the disease was presented to different infectious sites. Cutler created the protocol for infection site research. Cutler and his team discovered that the disease takes 93%-100% if infected through scarification or intracutaneous injection into the foreskin. After the transmission was studied, Cutler focused on the diseases' treatability. People were then recruited and infected and either put into a treatment group or a control group. The treatment group was given orvus-mapharsen or penicillin to see its effects, and the control group was given nothing to stop the disease.[29] The researchers paid prostitutes infected with syphilis to have sex with prisoners, while other subjects were infected by directly inoculating them with the bacterium.[6] Through intentional exposure to gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid, a total of 1,308 people were involved in the experiments. Of that group, with an age range of 10–72, 678 individuals (52%) can be said to have received a form of treatment.[9] However, Cutler claimed all had been treated. Hidden from the public, Cutler used healthy individuals in order to improve what he called "pure science". Dr. Cutler participated in intentional infection experiments in Guatemala until his departure in December 1948.[9] After the Guatemala syphilis study, Cutler was asked by the World Health Organization to head an India-based program for demonstrating venereal disease for Southeast Asia in 1949.[27] John Cutler went on to become Assistant Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service in 1958. In 1967, he would end his tenure when he was appointed professor of International Health at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health. In 1968, he became acting dean of the school and served until 1969. After his death in 2008, his roles in the Tuskegee experiment were publicized and he was stripped of his legacy.[9] Genevieve Stout Genevieve Stout was a bacteriologist for the Pan-American Sanitary Bureau who promoted and established serological research in Guatemalan laboratories. She initiated the VDRL (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory) and Training Center within Central America starting in 1948 and stayed in Guatemala until 1951. Dr. Mahoney appointed her to manage the laboratory in Guatemala after Dr. Cutler left in 1948. Here she conducted several independent serological experiments for STD research with the help of Dr. Funes and Dr. Salvado.[30][9] Dr. Juan Funes and Dr. Carlos Salvado Dr. Funes and Dr. Salvado were also employees of the Pan-American Sanitary Bureau, who remained in Guatemala after their work with Dr. Cutler. Funes was Chief of the Venereal Disease section at the Guatemalan National Department of Health and was responsible for referring sex workers with STDs from the Venereal Disease and Sexual Prophylaxis Hospital (VDSPH) to Cutler. Dr. Carlos Salvado was the director of the Psychiatric Hospital in Guatemala where parts of the syphilis study were conducted. Salvado was an active participant in the intentional exposure experiments.[9] In order to advance in their careers, they opted to stay and continue observations on subjects of the syphilis experiments, including data collection from orphans, inmates, psychiatric patients, and school children. These periodic data collections consisted of blood specimens and lumbar punctures from participants. Data was shipped back to the United States, where many of these blood samples tested positive for syphilis. Funes and Salvado continued collecting samples from participants until 1953.[9] |

実験の概要 タスキギー梅毒研究の被験者から採血するジョン・カトラー博士 歴史的背景 20世紀初頭から、梅毒の治療法をテストするためにウサギが使用されていた。罹患したウサギにヒ素化合物を注射したハタ・サアチロウの研究は、後に「特効 薬」として知られるようになった。その後、1940年代には、梅毒の予防法の研究の一環として、ウサギにペニシリンが注射された。ほぼ同時期に、米国軍医 総監トーマス・パラン博士をはじめとする医療関係者たちは、性感染症に関する知識を深め、より有効な予防法や治療法を人間に対して見つけ出そうと強く働き かけていた。 この新しい方法の模索は、第二次世界大戦の勃発により、より強固なものとなり、より多くの支持者を獲得した。これは、淋病などの性感染症の蔓延から米軍を 守るための取り組みが主な理由であった。また、被験者の陰茎に銀プロテインを注射するという、特に痛みを伴う予防措置もその理由であった。[9] 当時、性病が35万人の兵士に影響を及ぼすことが予測されていた。これは、2つの武装師団を1年間排除することに相当する。この損失額は当時で約3400 万ドルに上り、性病治療の研究が特に急務となった。 この性感染症の治療と予防策における新たな開発の推進力となった最初のフィールド試験は、1943年から1944年にかけて実施されたテラ・ハウト刑務所 での実験であった。この実験は、その数年後にグアテマラでの梅毒実験に参加することになる多くの人物によって実施および支援された。 この実験の目的は、刑務所の受刑者から集めた被験者に淋病を感染させることで、より適切な性病予防法を見つけることだった。当初は被験者として人間を使う という考えに異論もあったが、トーマス・パラン博士とジョン・A・ロジャース大佐(米国陸軍医療部隊の執行官)の支援により、ジョン・F・マホーニー博士 とカッシウス・J・ヴァン・スライク博士は実験を開始することができた。マホニーの若い同僚であったジョン・カトラー博士も実験の実施を手助けし、その 後、グアテマラ梅毒実験を主導した。 テラ・ハウトでの実験は、グアテマラでの実験の先駆けとなった。この実験は、軍の指導者たちがどれほど真剣に性感染症対策の新手法を推進し、被験者に感染 させることに意欲的であったかを初めて明らかにした。また、臨床医がグアテマラを選んだ理由も説明している。それは、個人の同意に関する倫理的な制約、そ の他の不利な法的影響、および悪評を避けるためであった。 研究の詳細 この研究は米国公衆衛生局が主導し、1946年から1948年まで実施された。[12] 当初の実験はインディアナ州テラハ ウトの刑務所で実施される予定であったが、研究者が常に囚人に淋病を感染させるのに苦労したため、グアテマラに場所を移した。[1 3] グアテマラへの移転は、グアテマラ性感染症対策局の局長フアン・フネス博士の提案によるものだった。[14] 実験は米国立衛生研究所(NIH)から米州衛生局への助成金によって資金提供され、複数のグアテマラ政府省庁も関与していた。[6] サザンジョージア大学で行われた研究では、研究対象が米国当局によってマイノリティとみなされた被験者であったことを踏まえ、梅毒実験の実施場所としてグ アテマラが選ばれたのは、米国当局による人種的動機による決定であったと主張している 。別の研究では、その理由は、感染した娼婦との性交渉による感染は当然のことと思わせるために、グアテマラの囚人に娼婦を買う金銭的余裕があったためだと 主張している。 実験の対象となった人数は不明である。一部の情報源によると、約1,500人の被験者が関与したが、その調査結果は公表されていない。[6] 他の情報源によると、5,000人以上の個人が、子供も含めて、この研究に参加したとされている。[12] この研究の目的は、性交渉後の性感染症の感染予防におけるペニシリンの有効性を観察することだった。その結果、グアテマラ人約696人が梅毒、淋病、陰茎 包皮炎に故意に感染させられた。[15] この研究はまた、ペニシリン以外の各種性病治療薬を発見することも目的としていた。[12] 保管されている文書によると、実験当時米国公衆衛生局長官であったトーマス・パラン・ジュニア博士は、グアテマラでの研究は国内では実施できないと認めて おり、さらに、このプログラムの詳細はグアテマラ政府当局者にも隠されていた。[7][16] さらに、研究の目的や詳細が被験者にも隠されていたため、被験者はインフォームドコンセントを得る機会を与えられていなかった。[15] 被験者は、米国政府の資金で雇われた感染した女性性労働者との許可された面会を通じて、梅毒菌に感染させられた。[17] 被験者に病原体を感染させる他の試みには、男性被験者の性器、前腕、顔など、さまざまな軽度に摩耗した身体部位に菌を注ぐことも含まれていた。一部の被験 者は、脊椎を強制的に穿孔することで感染させられた。[15] その後、梅毒の陽性反応を示した被験者はペニシリンで治療された。しかし、すべての被験者に適切な治療が施されたという証拠はなく、感染した個人が治癒し たかどうかについても不明である。[15] この研究は1948年に公式に終了したとされているが、医師たちは1958年まで元被験者の組織サンプル採取と解剖を継続していた。[18] 実験中に83人が死亡しているが 。接種がこれらの死亡の原因であったかどうかは不明である。[10] 研究は長期にわたって実施され、膨大な量のデータが収集されたが、研究者たちはグアテマラ梅毒実験の結果を公表することはなかった。 タスキギー梅毒研究に関する研究結果を後に公表したことから、研究者が公表を避けて自分たちを守ろうとした可能性は低い。 実験が終了した理由や中止されたかどうかを示す証拠はない。[19] 研究方法 実験対象者に感染させる最初の試みは、米国公衆衛生局の職員が娼婦にウサギで培養した細菌を接種し、その後、囚人と性交渉を持つよう彼女らに報酬を支払う というものであった。グアテマラの娼婦たちは、政府の診療所で性感染症の検査を週2回受けることが義務付けられていた。実験の目的のため、感染した性労働 者は、グアテマラ保健省の局長から代わりにカトラー博士のもとに送られた。 彼らは、1人の売春婦が71分間で最大8人の男性と性交渉を持つ可能性があり、それによって感染率が高くなるという仮定のもとで実験を行った。しかし、囚人たちが何度も採血を拒否したため、この試みは感染を迅速に生み出すことに失敗した。 研究者は、グアテマラシティの精神病院「アシーロ・デ・アリーナドス」の院長カルロス・サルバド医師の申し出をカトラーが受け入れた後、被験者への直接接 種に切り替えた。[20] この病院は明らかに人員不足であり、基本的な設備や医薬品も不足していた。刑務所のボランティアに支給される予定だった1500ドルが、抗てんかん薬「ジ ランチン」やその他の必要な設備のために精神病院に支給された。[14] 医師たちは、患者の脊髄液に梅毒の菌株を注入したり、皮膚を削り取って感染を容易にしたりすることもよくあった。患者に感染させたこれらの菌株は、他の感染患者や「通りの菌株」から採取されたもので、定義されていない。 患者が梅毒に感染した後、感染症の治療を受けた患者は全体の約半数にとどまった。[20] 実験中に83人の患者が死亡したが、実験への関与と死亡との因果関係は立証されていない。[要出典] 1947年、カトラーはグアテマラ兵士を対象に淋病の実験を開始した。約600人の兵士が1年半後にこの病気にかかった。感染した娼婦が兵士たちに感染さ せ、兵士たちの陰茎から排出された淋菌膿が他の兵士たちに注射された。[20] 約80人の兵士を対象に、同時期に類丹毒の実験も行われた。この実験では、医師が兵士たちの腕を引っ掻いて傷をつけ、そこから感染させた。同意は兵士の管 理担当者や患者の担当医によって与えられたが、被験者自身によって与えられたという報告はない。[18]  1946年から1948年にかけて梅毒実験の被験者となったグアテマラの精神病院の患者 文書化された被験者プロファイルには、この実験で被験者が直面したことが詳細に記されている。 ベルタは精神病院の女性患者であった。1948年2月、ベルタは左腕に梅毒の注射を打たれた。1か月後、彼女は疥癬(ダニが原因の痒みを伴う皮膚感染症) を発症した。数週間後、カットラー医師は、彼女が腕に注射を打った場所に赤いぶつぶつができ、腕と脚に病変ができ、皮膚が身体から衰え始めていることに気 づいた。ベルタは、注射から3ヶ月経つまで梅毒の治療を受けなかった。 その後まもなく、8月23日、カットラー博士はベルタが死にそうに見えると記したが、その理由は明記していない。 その日、カットラー博士は別の男性被験者の淋菌膿をベルタの両目、尿道、直腸に注入した。また、彼は彼女に梅毒を再感染させた。数日後、ベルタの目には淋 病の膿が充満し、尿道から出血していた。その3日後の8月27日、ベルタは死亡した。[9][21] 被験者 合計で1,308人がこの実験に参加したことが確認されている。このグループのうち、678人が何らかの治療を受けたことが記録されている。しかし、症状 のモニタリング対象となった、あるいは自然感染によって実験に参加した人数は最大で5,128人に上ったという報告もある。[13] 被験者は、児童および成人の商業的性労働者、囚人、兵士、孤児、ハンセン病患者 、精神病院の患者などであった。[12][18] 被験者の多くはグアテマラの先住民や貧困層であった。[13] 被験者の年齢は10歳から72歳であったが、平均年齢は20代であった。 疾病対策センターは、「研究の計画と実施は、多くの点で非倫理的であった。被験者を故意に深刻な健康被害の危険にさらしたこと、被験者が実験手順に関する 知識や同意を得ていなかったこと、非常に影響を受けやすい集団が利用されたことなど」を認めている。[22] 合計83人の被験者が死亡したが、実験との正確な関係は未だ文書化されていない。[9][22] 研究臨床医 トーマス・パラン トーマス・パランは、1936年から1948年まで第6代米国公衆衛生局長官を務めた人物である。パランが性感染症の研究に深い関心を抱いていたことは、 1938年に議会で公衆衛生の予防対策と性感染症分野の科学研究への予算拡大を証言したことからも明らかである。グアテマラでの関与に先立ち、彼はタスキ ギー梅毒実験とテラ・ハウト刑務所実験の一部を監督していた。 Parranは、アフリカ系アメリカ人における梅毒は「生物学的に異なる」と述べ、アフリカ系アメリカ人女性は「白人の女性の2.5倍の期間感染が持続す る」と述べた。この人種間の梅毒における生物学的な違いという想定は、タスキギー実験を継続する正当性を与えるものだった。 グアテマラでは、彼はテラ・ハウト実験を新たな患者グループに対して継続するための最終承認を与える責任を担っていた。また、グアテマラでは意図的に無知 なまま梅毒に感染させることが行われていることも彼は知っていた。かつて、パランはカトラー博士に「この国(米国)ではこのような実験はできないだろう」 と語ったことがあり、グアテマラで行っていたことの倫理的な問題を認識していたことを示している。 軍医総監を務めた後、トーマス・パランはピッツバーグ大学の新設された公衆衛生学部の初代学部長としてキャリアをスタートさせた。彼は大学での管理職を退 き、メロン家が運営するアヴァロン財団の理事長となり、A.W.メロン教育・慈善信託で活躍した。彼は1968年に死去し、ピッツバーグ大学公衆衛生学部 は1969年に彼の名を冠したパーラン・ホールを建設した。この建物は、彼の非倫理的実験への関与を理由に、2018年に改名された。[25] ジョン・F・マホーニー博士 グアテマラ梅毒実験に関わる前、マホーニーは1914年にピッツバーグ大学医学部を卒業した。1918年までに、彼は米国公衆衛生局の外科医補佐となって いた。1929年、マホーニー博士は、1943年にテラハート実験が始まったスタテン島の性病研究所の所長として勤務し、そこでカトラーが初めて彼を補佐 した。 正確な淋病感染対象者の不足によりテラ・ハウトでの実験を中止した後、マホーニーは梅毒に対するペニシリンの効果の研究に移った。彼の研究はペニシリン治 療に大きな成功をもたらし、米国陸軍は性病の処方薬としてペニシリンを採用した。これは有望に見えたが、マホーニーと彼の共同研究者たちは、個人から完全 に病気を根絶するという長期的な見通しに疑問を抱いていた。 マホーニー、カトラー、パラン、およびその他の研究者は、より小規模で管理しやすい対象グループで研究を行った方が、この治療法の発見に役立つと考えた。 これがきっかけとなり、グアテマラの市民を対象に研究が行われることになった。マホーニーは、グアテマラでの研究助成を承認した梅毒研究部門のメンバーで あった。グアテマラでの梅毒研究中、マホーニーは実験の主任監督者となり、カトラーの実験報告を受け取っていた。1946年、梅毒研究が継続中の間、ジョ ン・マホーニーは梅毒の治療薬としてペニシリンを発見したことによりラスカー賞を受賞した。 グアテマラ梅毒研究が完了した後、ジョン・F・マホーニーは1948年に世界保健機関の議長に就任した。1950年にはニューヨーク市保健局の委員となり、1957年に死去するまでその職にあった。 ジョン・チャールズ・カトラー医師 実験は、米国公衆衛生局の性病研究所の医師ジョン・チャールズ・カトラーが主導した。カトラーは1942年に公衆衛生局に入局し、嘱託将校として勤務して いた。カトラーは、 1943年から1944年にかけて、志願した囚人たちに淋病を感染させた。[9] カトラーは、後に、アメリカ黒人に対して梅毒の治療法があることを嘘をついて隠蔽したタスキギー梅毒実験の後半にも参加した。治療を受けられなかったため に100人以上が死亡した。1993年に制作された、タスキギー梅毒研究に関するドキュメンタリー映画『Deadly Deception』の中で、カトラーは自らの行動を擁護し、「彼らが治療を受けられない状態であることが重要だった。そして、研究に支障をきたすため、 ペニシリンを大量に使用して病気を治療することは望ましくない」と述べている[28]。 タスキギー実験では、すでに感染している人々における梅毒の自然経過を追ったが、グアテマラでは医師たちが健康な人々に意図的に感染させた。中には治療し なければ命にかかわる病気もある。彼のチームは、米国軍から提供されたグアテマラの研究所で、病気が異なる感染地域に現れた場合、異なる感染率があるかど うかを調査した。カトラーは感染地域研究のプロトコルを作成した。カトラーと彼のチームは、傷口から感染させるか、包皮に皮下注射をすることで、93%か ら100%の確率で感染することを発見した。感染経路の研究の後、カトラーは病気の治療可能性に焦点を当てた。人々が募集され、感染させられ、治療グルー プまたは対照グループに分けられた。治療グループにはオルバス・マファルセンまたはペニシリンが投与され、その効果を観察した。対照グループには何も投与 せず、病気の進行を止めることはしなかった。[29] 研究者は、梅毒に感染した娼婦に、囚人と性交渉を持つよう報酬を与えた 。一方、他の被験者には細菌を直接接種して感染させた。[6] 淋病、梅毒、陰茎ヘルペスへの意図的な感染により、合計1,308人が実験に参加した。そのグループのうち、年齢が10歳から72歳までの678人 (52%)は、ある種の治療を受けたと言える。[9] しかし、カトラーは全員が治療を受けたとしている。カトラーは一般の人々には知られないように、健康な人々を使って、彼が「純粋な科学」と呼ぶものを改善 しようとした。カトラー博士は、1948年12月にグアテマラを離れるまで、意図的な感染実験に参加していた。[9] グアテマラでの梅毒研究の後、カトラーは1949年に世界保健機関(WHO)からインドを拠点とする東南アジア向け性感染症実証プログラムの責任者に任命された。 ジョン・カトラーは1958年に米国公衆衛生局の外科次官補に就任した。1967年、ピッツバーグ大学大学院公衆衛生学部国際保健学教授に任命され、公職 を退いた。1968年には同大学院の学部長代理となり、1969年までその職にあった。2008年に死去した後、タスキギー実験における彼の役割が公表さ れ、彼の功績は否定された。 ジュヌビエーブ・スタウト ジュヌビエーブ・スタウトは、汎アメリカ衛生局の細菌学者であり、グアテマラの研究所で血清学の研究を推進し、確立した。彼女は1948年に中米で VDRL(性病研究所)とトレーニングセンターを立ち上げ、1951年までグアテマラに滞在した。マホーニー博士は、1948年にカトラー博士が去った 後、グアテマラの研究所の管理を彼女に任せることにした。ここで彼女は、フネス博士とサルバド博士の協力を得て、性感染症の研究のためのいくつかの独自の 血清学実験を行った。[30][9] フネス博士とサルバド博士 フネス博士とサルバド博士もパンアメリカン衛生局の職員であり、カトラー博士との仕事を終えた後もグアテマラに留まった。フネスはグアテマラ国立保健局の 性病課の主任であり、性病および性感染症予防病院(VDSPH)からカトラーのもとへ性病を患う性労働者を紹介する責任者であった。カルロス・サルバド博 士はグアテマラの精神病院の院長であり、梅毒研究の一部がそこで実施された。サルバドは意図的な感染実験に積極的に参加していた。 キャリアアップのために、彼らは滞在を続け、孤児、収監者、精神病患者、児童を対象とした梅毒実験の観察を継続することを選択した。これらの定期的なデー タ収集は、参加者の血液標本と腰椎穿刺から構成されていた。データは米国に送られ、これらの血液サンプルの多くが梅毒陽性と判定された。フネスとサルバド は1953年まで参加者のサンプル収集を続けた。[9] |

| Aftermath Continued Research After the conclusion of the Guatemalan syphilis experiments, many of the samples taken during the experiments were then moved to the United States. Records show that these samples were then given to laboratories across the United States, where they were used for research. Many of the Laboratories using the samples from the Guatemalan syphilis experiments were later given samples from the Tuskegee syphilis experiments. Due to a lack of regulations involving laboratory samples, it is unknown if the samples from the studies are still being used today; however, records show that they were in use by at least 1957.[31] Apology and response In October 2010, the U.S. government formally apologized and announced that the violation of human rights in that medical research was still to be condemned, regardless of how much time had passed.[32][33][34] Following the apology, Barack Obama requested an investigation to be conducted by the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues on November 24, 2010. The Commission concluded nine months later that the experiments "involved gross violations of ethics as judged against both the standards of today and the researchers' own understanding".[9] In a joint statement, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius said: Although these events occurred more than 64 years ago, we are outraged that such reprehensible research could have occurred under the guise of public health. We deeply regret that it happened, and we apologize to all the individuals who were affected by such abhorrent research practices. The conduct exhibited during the study does not represent the values of the US, or our commitment to human dignity and great respect for the people of Guatemala.[32] President Barack Obama apologized to President Álvaro Colom, who had called the experiments "a crime against humanity".[21] It is clear from the language of the report that the U.S. researchers understood the profoundly unethical nature of the study. In fact the Guatemalan syphilis study was being carried out just as the "Doctors' Trial" was unfolding at Nuremberg (December 1946 – August 1947), when 23 German physicians stood trial for participating in Nazi programs to euthanize or medically experiment on concentration camp prisoners."[35] As a response to the dehumanization by human experiment, the Nuremberg Code and Helsinki Code in 1971 were developed to govern ethics in medical research. Research like this deserves the need for informed consent in any type of research in general, and it should prohibit experiments where injury, disability, or death to the participant is reasonably expected. Nevertheless, "science and society should never outweigh the wellbeing of the subject".[36] "The way that this case in Peru was handled though, supports the view that – include monetary redress and criminal investigations – in Guatemala matter. Some would also argue that the Guatemala study constituted torture or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, and the US has an obligation under international law to pursue criminal investigations and provide the victims with adequate financial compensation."[36] The U.S. government asked the Institute of Medicine to conduct a review of these experiments beginning January 2011.[6][9] While the Institute of Medicine conducted their review, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues was asked to convene a panel of international experts to review the current state of medical research on humans around the world and ensure that these sorts of incidents do not occur again.[37] The Commission report, Ethically Impossible: STD Research in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948, published in September 2011, aimed to answer the following four questions: What occurred in Guatemala between 1946 and 1948 involving a series of STD exposure studies funded by the U.S. PHS? To what extent were U.S. government officials and others in the medical research establishment at that time aware of the research protocols and to what extent did they actively facilitate or assist in them? What was the historical context in which these studies were done? How did the studies comport with or diverge from the relevant medical and ethical standards and conventions of the time?[9] The investigation concluded that "the Guatemala experiments involved unconscionable basic violations of ethics, even as judged against the researchers' own recognition of the requirements of the medical ethics of the day."[9][38] Even besides the fact that U.S. never truly apologized for the study, as human rights activists have called for subjects' families to be compensated.[26] As of 2017, the families still have not been compensated even though there have been several lawsuits filed.[39] Lawsuits Manuel Gudiel Garcia v. Kathleen Sebelius Many Guatemalans believed that the U.S. apology was not enough. In March 2011, seven plaintiffs filed a federal class-action lawsuit against the U.S. government claiming damages for the Guatemala experiments. This case argued that the United States was at fault due to not asking for consent. This lawsuit asked for money damages to compensate for medical injuries and loss of livelihood, as most of the families were living in poverty. The suit was dismissed when United States District Judge Reggie Walton determined that the U.S. government has immunity from liability for actions committed outside of the U.S.[40] Estate of Arturo Giron Alvarez v. The Johns Hopkins University In April 2015, 774 plaintiffs launched a lawsuit against Johns Hopkins University, the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the Rockefeller Foundation, seeking $1 billion in damages, seeking to hold the university accountable for the experiment itself because the doctors held important roles on panels that reviewed the federal spending on research for other sexually transmitted diseases. The plaintiffs claimed that Johns Hopkins was actively involved in these experiments, stating "[they] did not limit their involvement to design, planning, funding and authorization of the Experiments; instead, they exercised control over, supervised, supported, encouraged, participated in and directed the course of the Experiments."[41] The hope was that compensation could be attained by targeting private institutions rather than the federal government. In January 2019, U.S. District Judge Theodore Chuang rejected the defendants' argument that a recent Supreme Court decision shielding foreign corporations from lawsuits in U.S. courts over human rights abuses abroad also applied to domestic corporations absent congressional authorization. However, the District Court subsequently ruled in April 2022 in favor of the defendants, holding that Dr. Parran and his colleagues were not acting on behalf of the Rockefeller Foundation and the employees of Johns Hopkins had not aided or abetted any violations of the law committed by Drs. Parran, Mahoney or Cutler.[citation needed] |

その後 継続的な研究 グアテマラでの梅毒実験が終了した後、実験中に採取されたサンプルの多くは米国に移送された。記録によると、これらのサンプルはその後、米国中の研究所に 提供され、研究に使用された。グアテマラでの梅毒実験で採取されたサンプルを使用した研究所の多くは、後にタスキギーでの梅毒実験で採取されたサンプルも 提供された。研究所のサンプルに関する規制が欠如していたため、これらの研究のサンプルが現在も使用されているかどうかは不明であるが、少なくとも 1957年には使用されていたことが記録から明らかになっている。 謝罪と対応 2010年10月、米国政府は正式に謝罪し、その医療研究における人権侵害は、どれほど時間が経過しようとも、依然として非難されるべきであると発表し た。[32][33][34] 謝罪を受けて、バラク・オバマ大統領は2010年11月24日、大統領生命倫理問題調査委員会による調査を要請した。 委員会は9か月後に、実験は「今日の基準と研究者自身の理解の両方から判断して、倫理に著しく反するものだった」と結論付けた。[9] ヒラリー・クリントン国務長官とキャスリーン・セベリウス保健福祉長官は共同声明で次のように述べた。 これらの出来事は64年以上も前のことではあるが、公衆衛生という名目のもとにこのような非難されるべき研究が行われていたことに私たちは憤りを覚える。 このような忌まわしい研究行為によって被害を受けたすべての人々に深くお詫び申し上げる。研究中に示された行為は、米国の価値観、あるいは人間の尊厳に対 する私たちの献身やグアテマラの人々に対する深い敬意を表すものではない。 バラク・オバマ大統領は、この人体実験を「人類に対する犯罪」と非難したアルヴァロ・コロン大統領に謝罪した。[21] 報告書の文言から、米国の研究者がこの研究の非倫理性を深く理解していたことは明らかである。事実、グアテマラの梅毒研究は、ニュルンベルクで「医師裁 判」が展開されていた時期(1946年12月~1947年8月)に行われていた。この裁判では、ナチスが強制収容所の囚人を安楽死させたり医学実験の対象 としたことに関与したとして、23人のドイツ人医師が裁判にかけられた。 人体実験による人間性の否定への対応として、1971年にニュルンベルク綱領とヘルシンキ宣言が策定され、医学研究における倫理規定が定められた。このよ うな研究は、あらゆる種類の研究一般においてインフォームドコンセントが必要であることを示しており、被験者に傷害、障害、死亡が合理的に予想される実験 は禁止されるべきである。しかし、「科学と社会が被験者の幸福を上回ることは決してあってはならない」[36]。「ペルーでのこの事例の処理方法は、グア テマラの問題では金銭的補償と刑事捜査を含めるべきだという見解を裏付けている。また、グアテマラでの研究は拷問または残虐で非人道的な屈辱的な扱いであ り、米国には国際法の下で刑事捜査を追求し、被害者に適切な金銭的補償を行う義務がある」という意見もある[36]。 米国政府は、2011年1月から医学研究所にこれらの実験の再調査を行うよう要請した。[6][9] 医学研究所が再調査を行っている間、生物倫理問題研究のための大統領委員会は、世界中の人体医学研究の現状を再調査し、このような事件が二度と起こらない ようにするため、国際的な専門家のパネルを招集するよう要請された。[37] 委員会の報告書『倫理的に不可能: 1946年から1948年にかけてのグアテマラにおける性病研究』と題された委員会の報告書は、2011年9月に発表され、以下の4つの疑問に答えること を目的としている。 1946年から1948年の間に、米国公衆衛生局(PHS)が資金提供した一連の性病感染研究がグアテマラで実施されたが、その研究とはどのようなものだったのか? 当時の米国政府高官や医療研究機関関係者は、研究計画についてどの程度認識していたのか、また、どの程度積極的に研究を促進または支援していたのか? これらの研究が行われた歴史的背景はどのようなものだったのか? 当時の関連する医学および倫理基準や慣例に照らして、これらの研究はどのように適合し、または逸脱していたのか?[9] 調査は、「グアテマラ実験は、当時の医学倫理の要件に対する研究者の認識に照らして判断しても、非道徳的な基本的な倫理違反を伴っていた」と結論づけた。 [9][38] 米国が 米国が研究について真に謝罪したことは一度もなく、人権活動家は被験者の家族に補償を行うよう求めている。[26] 2017年現在、複数の訴訟が起こされているにもかかわらず、家族への補償はまだ行われていない。[39] 訴訟 マヌエル・グディエル・ガルシア対キャスリーン・セベリウス 多くのグアテマラ人は、米国の謝罪は不十分であると考えていた。2011年3月、7人の原告がグアテマラ実験に対する損害賠償を求めて、米国政府を相手 取って連邦集団訴訟を起こした。この訴訟では、同意を求めなかったことが米国の過失であると主張した。この訴訟では、ほとんどの家族が貧困状態にあるとし て、医療被害と生計手段の損失を補償するための金銭的損害賠償が求められた。 連邦地方裁判所のレジー・ウォルトン判事が、米国政府は米国外で行われた行為については免責されると判断したため、この訴訟は却下された[40]。 アルトゥーロ・ジロン・アルバレス遺産相続人 v. ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学 2015年4月、774人の原告がジョンズ・ホプキンス大学、製薬会社ブリストル・マイヤーズ スクイブ、ロックフェラー財団を相手取り、10億ドルの損害賠償を求める訴訟を起こした。原告は、医師たちが他の性感染症の研究に対する連邦政府の支出を 審査する委員会で重要な役割を担っていたため、大学に実験そのものに対する責任を問うことを求めた。原告はジョンズ・ホプキンス大学がこれらの実験に積極 的に関与していたと主張し、「彼らは実験の設計、計画、資金調達、承認にのみ関与していたわけではなく、実験の管理、監督、支援、奨励、参加、指示を行っ ていた」と述べた。[41] 連邦政府ではなく民間機関を標的にすることで補償が得られることを期待していた。 2019年1月、米国連邦地方裁判所のセオドア・チュアン判事は、海外での人権侵害に関する訴訟について、外国企業を米国内の裁判所での訴訟から保護する 最高裁判所の最近の判決は、議会の承認がない限り、国内企業にも適用されるという被告側の主張を退けた。しかし、連邦地方裁判所はその後、2022年4月 に被告側の主張を認める判決を下し、パラン博士と彼の同僚はロックフェラー財団を代表して行動していたわけではなく、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学の従業員は パラン博士、マホーニー博士、カトラー博士による法律違反を幇助または教唆したわけではないと判断した。[要出典] |

| Human experimentation in the United States Project MKUltra The Plutonium Files Tuskegee syphilis experiment Medical ethics Porton Down Japanese human experimentations Unit 731 Nazi human experimentation Nuremberg Code Guatemala–United States relations |

米国における人体実験 MKウルトラ計画 プルトニウムファイル タスキギー梅毒実験 医療倫理 ポートン・ダウン 日本の人体実験 731部隊 ナチスの人体実験 ニュルンベルク綱領 グアテマラと米国の関係 |

| "Guatemalans

'died' in 1940s US syphilis study". BBC News. 29 August 2011. Archived

from the original on 1 December 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2011. "U.S. apologizes for syphilis experiment in Guatemala". Reuters. 2010-10-01. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2022-08-08. Kakar, Aman (15 March 2011). "Guatemalans file class action suit over US medical experiments". JURIST. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. "Docket for Estate of Arturo Giron Alvarez v. The Johns Hopkins University, 19-1530 - CourtListener.com". CourtListener. Retrieved 2022-03-22. "Garcia v. Sebelius – CourtListener.com". CourtListener. Retrieved 2022-03-22. "Fact Sheet on the 1946-1948 U.S. Public Health Service Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Inoculation Study". United States Department of Health and Human Services. nd. Archived from the original on 2017-12-02. Retrieved 2013-04-15. "Wellesley professor unearths a horror: Syphilis experiments in Guatemala". Boston Globe. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2010. McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (2010-10-01). "U.S. Apologizes for Syphilis Tests in Guatemala". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-10-19. Retrieved 2022-08-08. Ethically Impossible: STD Research in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948 Archived 2016-12-23 at the Wayback Machine, Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, published 2011-09-13, accessed 2015-10-23 Reverby, Susan M. (June 2012). "Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala". Public Health Reviews. 34 (1). doi:10.1007/bf03391665. ISSN 2107-6952. Gurnham, David (June 2013). "Principles, progress and harm in the Guatemala Syphilis Study". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 89 (4): 303. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2013-051113. ISSN 1368-4973. PMID 23687133. S2CID 27950482 – via Academic search Complete. Ford, Julisha (2019-01-01). "Systemic Medical Racism: The Reconstruction of Whiteness Through the Destruction of Black Bodies". Honors College Theses. Rodriguez, Michael A.; García, Robert (December 2013). "First, Do No Harm: The US Sexually Transmitted Disease Experiments in Guatemala". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (12): 2122–2126. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301520. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3828982. PMID 24134370. Löwy, Ilana (February 2013). "The Best Possible Intentions Testing Prophylactic Approaches on Humans in Developing Countries". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (2): 226–237. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300901. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3558769. PMID 23237168. Tanne, Janice Hopkins (2010-10-04). "President Obama apologises to Guatemala over 1940s syphilis study". BMJ. 341: c5494. doi:10.1136/bmj.c5494. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 20921075. S2CID 27929498. "Exposed: US Doctors Secretly Infected Hundreds of Guatemalans with Syphilis in the 1940s". Democracy Now!. 5 October 2010. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2011. Reverby, Susan M. (January 2011). ""Normal Exposure" and Inoculation Syphilis: A PHS "Tuskegee" Doctor in Guatemala, 1946–1948". Journal of Policy History. 23 (1): 6–28. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291. ISSN 0898-0306. S2CID 154326543. Cuerda-Galindo, E.; Sierra-Valenti, X.; González-López, E.; López-Muñoz, F. (2014-11-01). "Syphilis and Human Experimentation From World War II to the Present: A Historical Perspective and Reflections on Ethics". Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (English Edition). 105 (9): 847–853. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2013.08.003. ISSN 1578-2190. Zenilman, Jonathan (April 2013). "The Guatemala Sexually Transmitted Disease Studies: What Happened". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 40 (4): 277–279. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828abc1b. ISSN 0148-5717. PMID 23486488. Spector-Bagdady, Kayte; Lombardo, Paul A. (March 2019). "U.S. Public Health Service STD Experiments in Guatemala (1946-1948) and Their Aftermath". Ethics & Human Research. 41 (2): 29–34. doi:10.1002/eahr.500010. hdl:2027.42/148377. ISSN 2578-2363. PMID 30895754. S2CID 84843464. "US medical tests in Guatemala 'crime against humanity'". BBC News. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2010. "Findings from a CDC Report on the 1946-1948 U.S. Public Health Service Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Inoculation Study" Archived 2010-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 30 September 2010 "He was a champion of public health — but played a role in the horrors of Tuskegee. Should a college expunge his name?". STAT. 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2022-05-03. Spector-Bagdady, Kayte; Lombardo, Paul A. (March 2019). "U.S. Public Health Service STD Experiments in Guatemala (1946–1948) and Their Aftermath". Ethics & Human Research. 41 (2): 29–34. doi:10.1002/eahr.500010. hdl:2027.42/148377. ISSN 2578-2355. PMID 30895754. S2CID 84843464. Staff, Christian Snyder and Janine Faust | The Pitt News (2018-07-11). "Board of Trustees unanimously votes to rename Parran Hall". The Pitt News. Retrieved 2022-05-05. Chris McGreal (1 October 2010). "US says sorry for "outrageous and abhorrent" Guatemalan syphilis tests". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Conducted between 1946 and 1948, the experiments were led by John Cutler, a US health service physician who would later be part of the notorious Tuskegee syphilis study in Alabama in the 1960s. "Obituary: John Charles Cutler / Pioneer in preventing sexual diseases". old.post-gazette.com. Archived from the original on 2022-05-07. Retrieved 2022-05-06. "Nova (Television program). The Deadly Deception | 1 of 1 | 93128dct". University of Georgia Kaltura. Retrieved 2022-05-03. Zenilman, Jonathan (April 2013). "The Guatemala Sexually Transmitted Disease Studies: What Happened". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 40 (4): 277–279. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828abc1b. ISSN 0148-5717. PMID 23486488. Stout, Genevieve W.; Harris, Ad; Wallace, Alwilda L. (June 1957). "Venereal Disease Research Laboratory field consultation services". Public Health Reports. 72 (6): 554–558. doi:10.2307/4589821. ISSN 0094-6214. JSTOR 4589821. PMC 2031296. PMID 13432135. Spector-Bagdady, Kayte; Lombardo, Paul A. (June 2018). "From in vivo to in vitro : How the Guatemala STD Experiments Transformed Bodies Into Biospecimens". The Milbank Quarterly. 96 (2): 244–271. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12318. ISSN 0887-378X. PMC 5987804. PMID 29652094. Hensley, Scott (2010-10-01). "U.S. Apologizes For Syphilis Experiment In Guatemala". NPR. Retrieved 2022-05-05. "U.S. apologizes for newly revealed syphilis experiments done in Guatemala". Washington Post. 2010-10-01. Archived from the original on 2018-12-28. The United States issued an unusual apology Friday to Guatemala for conducting experiments in the 1940s in which doctors infected soldiers, prisoners and mental patients with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Time limitation under the United States Alien Tort Claims Act (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-10 Doyle, Kate (2011-04-25). "Decades Later, NARA Posts Documents on Guatemalan Syphilis Experiments". NSA Archive. Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2022-08-08. "Guatemala syphilis experiments: why the US's apology may not be enough". The Guardian. 2010-10-08. Retrieved 2022-04-28. "U.S. Apologizes for 'Reprehensible' 1940s Syphilis Study in Guatemala". PBS NewsHour. 2010-10-01. Retrieved 2022-05-05. McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (2011-09-14). "Lapses by American Leaders Seen in Syphilis Tests". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2015-09-29. Retrieved 2022-08-08. "In the 1940s, U.S. Researchers Infected Hundreds of Guatemalans With Syphilis. The Victims Are Still Waiting for Treatment". Slate Magazine. 2017-02-26. Archived from the original on 2019-08-21. Retrieved 2022-08-08. "Judge: Lawsuit Over Guatemala Syphilis Experiment to Proceed". VOA. 5 January 2019. Retrieved 2022-05-05. Cook, Michael (2015-04-11). "Victims of Guatemala syphilis experiments to sue Johns Hopkins". BioEdge. Retrieved 2022-04-28. |

「グアテマラ人、1940年代の米国の梅毒研究で「死亡」」BBCニュース。2011年8月29日。オリジナルのアーカイブは2019年12月1日。2011年8月29日取得。 「米国、グアテマラでの梅毒実験について謝罪」ロイター通信。2010年10月1日。オリジナルのアーカイブは2020年11月11日。2022年8月8日取得。 カカー、アマン(2011年3月15日)。「グアテマラ人が米国の医療実験をめぐり集団訴訟を起こす」。JURIST。オリジナルよりアーカイブ。 「Arturo Giron Alvarezの遺産 v. ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学、19-1530 - CourtListener.com」。CourtListener。2022年3月22日取得。 「ガルシア対セベリウス - CourtListener.com」CourtListener.com. 2022年3月22日取得。 「1946年から1948年の米国公衆衛生局による性感染症(STD)予防接種研究に関するファクトシート」米国保健社会福祉省. nd. 2017年12月2日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2013年4月15日閲覧。 「ウェルズリー大学の教授が恐ろしい事実を発見:グアテマラでの梅毒実験」ボストン・グローブ、2010年10月1日。2016年3月3日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年10月2日閲覧。 マクニール、ドナルド・G・ジュニア(2010年10月1日)。「米国、グアテマラでの梅毒検査について謝罪」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。ISSN 0362-4331。オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年10月19日。2022年8月8日取得。 倫理的に不可能:1946年から1948年にかけてのグアテマラにおける性病研究 2016年12月23日アーカイブ分 生物倫理問題研究のための大統領委員会、2011年9月13日発行、2015年10月23日アクセス Reverby, Susan M. (2012年6月). "倫理的な失敗と歴史の教訓:タスキギーとグアテマラにおける米国公衆衛生局の研究調査". Public Health Reviews. 34 (1). doi:10.1007/bf03391665. ISSN 2107-6952. ガーンハム、デイヴィッド(2013年6月)。「グアテマラ梅毒研究における原則、進歩、そして被害」。性感染症。89(4):303。 doi:10.1136/sextrans-2013-051113。ISSN 1368-4973。PMID 23687133。S2CID 27950482 – via Academic search Complete. フォード、ジュリシャ(2019年1月1日)。「Systemic Medical Racism: The Reconstruction of Whiteness Through the Destruction of Black Bodies」(「医療における体系的な人種差別:黒人の身体の破壊による白さの再構築」)。Honors College Theses。 ロドリゲス、マイケル・A.、ガルシア、ロバート(2013年12月)。「First, Do No Harm: The US Sexually Transmitted Disease Experiments in Guatemala」(「まず、害をなすなかれ:グアテマラにおける米国の性感染症実験」)。アメリカ公衆衛生ジャーナル. 103 (12): 2122–2126. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301520. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3828982. PMID 24134370. Löwy, Ilana (2013年2月). "The Best Possible Intentions Testing Prophylactic Approaches on Humans in Developing Countries". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (2): 226–237. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300901. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3558769. PMID 23237168. Tanne, Janice Hopkins (2010-10-04). "President Obama apologises to Guatemala over 1940s syphilis study". BMJ. 341: c5494. doi:10.1136/bmj.c5494. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 20921075. S2CID 27929498. 「暴露:米国の医師が1940年代に数百人のグアテマラ人を梅毒に感染させたことを秘密裏に実施」. デモクラシー・ナウ!。2010年10月5日。オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年12月17日。2011年7月12日取得。 Reverby, Susan M. (2011年1月). ""正常な曝露"と予防接種梅毒:1946年から1948年のグアテマラにおけるPHS「タスキギー」医師". 政策史ジャーナル. 23 (1): 6–28. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291. ISSN 0898-0306. S2CID 154326543. Cuerda-Galindo, E.; Sierra-Valenti, X.; González-López, E.; López-Muñoz, F. (2014-11-01). "Syphilis and Human Experimentation From World War II to the Present: 歴史的観点と倫理に関する考察」。Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas(英語版)。105(9):847-853。doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2013.08.003。ISSN 1578-2190。 ゼニルマン、ジョナサン(2013年4月)。「グアテマラにおける性感染症研究:何が起こったのか」。性感染症。40(4):277- 279。doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828abc1b。ISSN 0148-5717。PMID 23486488。 スペクター=バグダディ、ケイト、ポール・A・ロンバルド(2019年3月)。「グアテマラにおける米国公衆衛生局の性感染症実験(1946 年~1948年)とその余波」。倫理と人間研究。41(2):29-34。doi:10.1002/eahr.500010。hdl: 2027.42/148377。ISSN 2578-2363。PMID 30895754。S2CID 84843464。 「グアテマラにおける米国の医療実験は『人道に対する罪』」BBCニュース。2010年10月1日。オリジナルの2016年1月2日時点でのアーカイブ。2010年10月2日取得。 「1946年から1948年の米国公衆衛生局性感染症(STD)予防接種研究に関するCDC報告書の調査結果」2010年9月30日、米国保健社会福祉省、2010年10月5日アーカイブ、 「彼は公衆衛生のチャンピオンだったが、タスキギーの恐怖の役割を果たした。大学は彼の名前を消すべきか?」STAT. 2018-04-27. 2022-05-03取得。 スペクター=バグダディ、ケイト、ロンバルド、ポール・A. (2019年3月). 「米国公衆衛生局によるグアテマラでの性病実験(1946年~1948年)とその余波」。Ethics & Human Research. 41 (2): 29–34. doi:10.1002/eahr.500010. hdl:2027.42/148377. ISSN 2578-2355. PMID 30895754. S2CID 84843464. スタッフ、クリスチャン・スナイダーとジャニン・ファウスト|ピットニュース(2018年7月11日)。「評議員会は満場一致でパラン・ホールの名称変更を決議した」。ピットニュース。2022年5月5日取得。 クリス・マクグレアル(2010年10月1日)。「米国は「とんでもなく、忌まわしい」グアテマラの梅毒検査について謝罪した」。ガーディアン』。 2010年10月2日閲覧。1946年から1948年にかけて実施されたこの実験は、後に1960年代にアラバマ州で悪名高いタスキギー梅毒研究に参加す ることになる米国衛生局の医師ジョン・カトラーが主導した。 「訃報:ジョン・チャールズ・カトラー/性感染症予防のパイオニア」. old.post-gazette.com. 2022年5月7日アーカイブのオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2022年5月6日閲覧。 「Nova (テレビ番組). The Deadly Deception | 1 of 1 | 93128dct」. ジョージア大学Kaltura. 2022年5月3日閲覧。 ゼニルマン、ジョナサン(2013年4月)。「グアテマラ性感染症研究:何が起こったのか」。性感染症。40(4):277-279。 doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828abc1b。ISSN 0148-5717。PMID 23486488。 Stout, Genevieve W.; Harris, Ad; Wallace, Alwilda L. (June 1957). "Venereal Disease Research Laboratory field consultation services". Public Health Reports. 72 (6): 554–558. doi:10.2307/4589821. ISSN 0094-6214. JSTOR 4589821. PMC 2031296. PMID 13432135. スペクター=バグダディ、ケイト、ポール・A・ロンバルド(2018年6月)。「生体内から生体外へ:グアテマラにおける性感染症実験が人体 を生物試料へと変貌させた経緯」。『ミルバンク・クォータリー』96巻(2号):244-271頁。doi:10.1111/1468- 0009.12318. ISSN 0887-378X. PMC 5987804. PMID 29652094. Hensley, Scott (2010年10月1日). "U.S. Apologizes For Syphilis Experiment In Guatemala". NPR. 2022年5月5日閲覧。 「米国、新たに明らかになったグアテマラでの梅毒実験について謝罪」ワシントン・ポスト。2010年10月1日。オリジナルの2018年12 月28日時点でのアーカイブ。米国は金曜日、医師が兵士、囚人、精神患者に梅毒やその他の性感染症を感染させた1940年代の実験について、グアテマラに 異例の謝罪を行った。 米国外国人不法行為請求権法に基づく時効(PDF)オリジナル(PDF)よりアーカイブ(2016年6月10日) ドイル、ケイト(2011年4月25日)「数十年後、NARAがグアテマラの梅毒実験に関する文書を公開」。NSAアーカイブ。オリジナルよりアーカイブ(2012年4月14日)。2022年8月8日取得。 「グアテマラでの梅毒実験:米国の謝罪は十分ではないかもしれない理由」『ガーディアン』2010年10月8日。2022年4月28日閲覧。 「米国、1940年代のグアテマラでの非難されるべき梅毒研究について謝罪」『PBSニュースアワー』2010年10月1日。2022年5月5日閲覧。 McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (2011年9月14日). "Lapses by American Leaders Seen in Syphilis Tests". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. 2015年9月29日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2022年8月8日閲覧。 「1940年代、米国の研究者が数百人のグアテマラ人を梅毒に感染させた。被害者は今も治療を待っている」『Slate Magazine』2017年2月26日。オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年8月21日。2022年8月8日取得。 「判事:グアテマラ梅毒実験に関する訴訟は進行する」VOA. 2019年1月5日. 2022年5月5日取得。 クック、マイケル(2015年4月11日)。「グアテマラ梅毒実験の被害者、ジョンズ・ホプキンスを提訴へ」BioEdge. 2022年4月28日取得。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guatemala_syphilis_experiments |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099