米国海兵隊占拠時代のハイチ

United States occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934

American

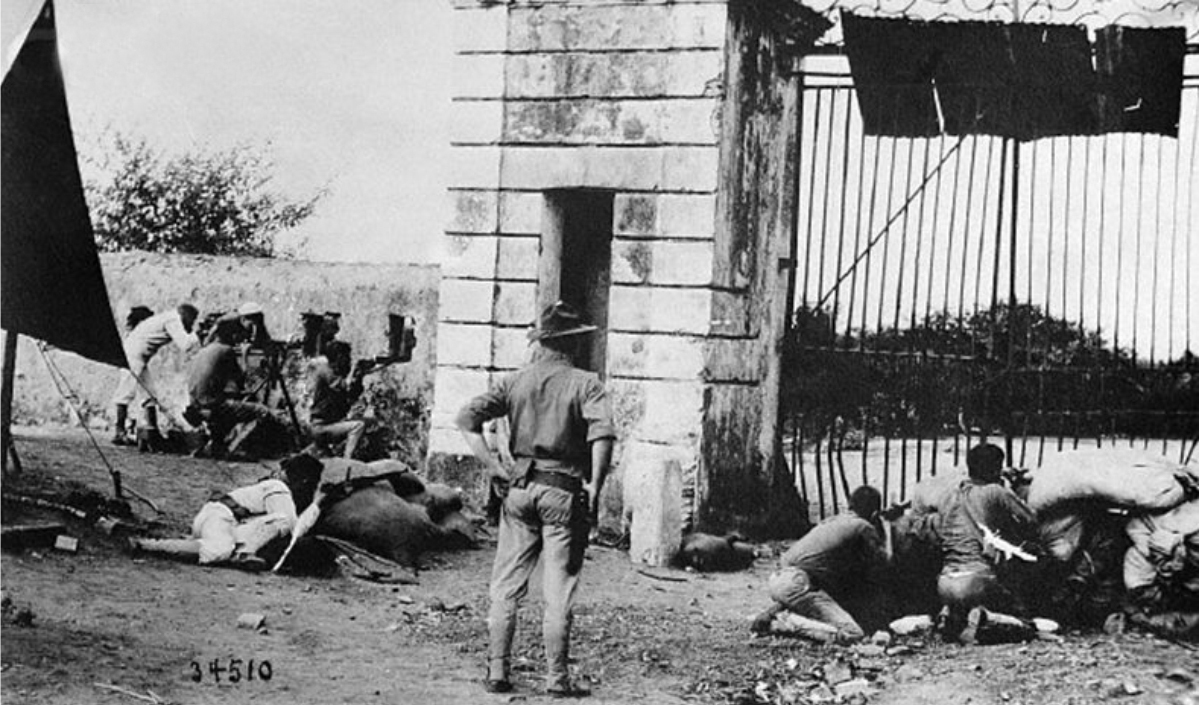

Marines In 1915 defending the entrance gate in Cap-Haitian

☆米国によるハイチ占領は、1915年7月28日に始まった。ニューヨーク国民都市銀行(National City Bank

of New York)

がウッドロウ・ウィルソン米国大統領を説得し、ハイチの政治的・経済的利益を掌握した結果、330人の米海兵隊がハイチのポルトープランスに上陸した。

1915年7月の占領は、政治犯の処刑を命じた大統領ヴィルブルン・ギヨーム・サムに対する暴徒のリンチという事件で頂点に達した、ハイチ国内における長

年の社会経済的不安定の後に実施された。

占領期間中、ハイチでは3人の大統領が誕生したが、米国は海兵隊と憲兵隊による戒厳令のもとで軍事政権として統治した。アメリカはインフラ整備のために強

制労働制度(コルベー制度)を採用したが、これにより数百人から数千人の死者が出た。[6]

占領下では、ほとんどのハイチ人が貧困の中で暮らし続けた一方で、アメリカ人職員は十分な報酬を得ていた。[要出典]

アメリカの占領により、ハイチ建国以来続いていた土地の外国所有を禁じた憲法上の規定は廃止された。

1933年8月の撤退合意をフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領が再確認したことにより、1934年8月1日に占領は終了した。最後の海兵隊部隊は、ア

メリカが創設したハイチ国家憲兵隊への正式な権限移譲の後、1934年8月15日に撤退した。

| The

United States occupation of Haiti began on July 28, 1915, when 330 U.S.

Marines landed at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, after the National City Bank

of New York convinced the President of the United States, Woodrow

Wilson, to take control of Haiti's political and financial interests.

The July 1915 occupation took place following years of socioeconomic

instability within Haiti that culminated with the lynching of President

of Haiti Vilbrun Guillaume Sam by a mob angered by his decision to

order the executions of political prisoners. During the occupation, Haiti had three new presidents while the United States ruled as a military regime through martial law led by Marines and the Gendarmerie. A corvée system of forced labor was used by the United States for infrastructure projects, resulting in hundreds to thousands of deaths.[6] Under the occupation, most Haitians continued to live in poverty, while American personnel were well compensated.[citation needed] The American occupation ended the constitutional ban on foreign ownership of land, which had existed since the foundation of Haiti. The occupation ended on August 1, 1934, after President Franklin D. Roosevelt reaffirmed an August 1933 disengagement agreement. The last contingent of marines departed on August 15, 1934, after a formal transfer of authority to the American-created Gendarmerie of Haiti. |

米国によるハイチ占領は、1915年7月28日に始まった。ニューヨー

ク国民都市銀行がウッドロウ・ウィルソン米国大統領を説得し、ハイチの政治的・経済的利益を掌握した結果、330人の米海兵隊がハイチのポルトープランス

に上陸した。1915年7月の占領は、政治犯の処刑を命じた大統領ヴィルブルン・ギヨーム・サムに対する暴徒のリンチという事件で頂点に達した、ハイチ国

内における長年の社会経済的不安定の後に実施された。 占領期間中、ハイチでは3人の大統領が誕生したが、米国は海兵隊と憲兵隊による戒厳令のもとで軍事政権として統治した。アメリカはインフラ整備のために強 制労働制度(コルベー制度)を採用したが、これにより数百人から数千人の死者が出た。[6] 占領下では、ほとんどのハイチ人が貧困の中で暮らし続けた一方で、アメリカ人職員は十分な報酬を得ていた。[要出典] アメリカの占領により、ハイチ建国以来続いていた土地の外国所有を禁じた憲法上の規定は廃止された。 1933年8月の撤退合意をフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領が再確認したことにより、1934年8月1日に占領は終了した。最後の海兵隊部隊は、ア メリカが創設したハイチ国家憲兵隊への正式な権限移譲の後、1934年8月15日に撤退した。 |

From the Walter V. Brown Collection (COLL/4326), Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections OFFICIAL USMC PHOTOGRAPH |

ウォルター・V・ブラウン・コレクション(COLL/4326)、海兵隊公文書館・特別コレクション所蔵 米国海兵隊公式写真 |

| Background Main article: Haiti–United States relations In the late 1700s, the relationship between Haitians and the United States began when some Haitians fought beside Americans in the American Revolutionary War.[7] Originally the wealthiest region in the Americas when it was the French colony of Saint-Domingue,[8][9] a slave revolt at the colony beginning in 1791 that led to the successful Haitian Revolution in 1804 frightened those living in the Southern United States who supported slavery, raising fears that it would inspire other slaves.[7][10] Such sentiments among wealthy slaveholding Americans strained relations between the United States and Haiti, with the United States initially refusing to recognize Haitian independence while slaveholders advocated for a trade embargo with the newly created Caribbean nation.[10] The Haiti indemnity controversy – which France forced upon Haiti through gunboat diplomacy in 1825 due to France's financial loss following Haiti's independence – resulted with Haiti using much of its revenue to pay debt to foreign nations by the late-1800s.[11]  USS Philadelphia, flagship of the fleet involved in the 1890 Môle Saint-Nicolas affair which saw the United States using gunboat diplomacy in an attempt to obtain Môle-Saint-Nicolas The United States had been interested in controlling Haiti in the decades following its independence from France.[12] As a way "to secure a U.S. defensive and economic stake in the West Indies", according to the United States Department of State, President Andrew Johnson of the United States began the pursuit of annexing Hispaniola, including Haiti, in 1868.[12] In 1890, the Môle Saint-Nicolas affair occurred when President Benjamin Harrison, on the advice of Secretary of State James G. Blaine, ordered Rear-Admiral Bancroft Gherardi to persuade newly assumed President of Haiti Florvil Hyppolite to lease the port to the United States.[13][14] Enforcing gunboat diplomacy upon Haiti, Gherardi aboard USS Philadelphia along with his fleet arrived in the capital city of Port-au-Prince to demand the acquisition of Môle Saint-Nicolas.[14] President Hyppolite refused any agreement as Haitians grew angered by the presence of the fleet, with The New York Times writing that the Haitians' "semi-barbaric minds saw in it a threat of violence".[13][14] Upon returning to the United States in 1891, Gherardi said in an interview with The New York Times that in a short time Haiti would experience further instability, suggesting that future governments in Haiti would abide by the demands of the United States.[13] By the 1890s, Haiti became reliant on importing most of its goods from the United States while it exported the majority of its production to France.[15] The Roosevelt Corollary also affected Haiti's relationship with the United States.[16] By 1910, President William Howard Taft attempted to introduce American businesses to Haiti in order to deter European influence and granted a large loan to Haiti to pay off foreign debts, though this proved to be fruitless due to the size of the debt.[12][17] |

背景 詳細は「ハイチとアメリカ合衆国の関係」を参照 1700年代後半、ハイチ人とアメリカ人の関係は、アメリカ独立戦争で一部のハイチ人がアメリカ人とともに戦ったことから始まった。[7] フランス領サン=ドマング(ハイチ)であった当時はアメリカ大陸で最も裕福な地域であったが、[8][9] 1791年に始まった同植民地での奴隷蜂起は、 1804年のハイチ革命の成功につながったこの事件は、奴隷制を支持していたアメリカ南部の人々を恐怖に陥れ、他の奴隷たちにも影響が及ぶのではないかと いう懸念を生んだ。[7][10] 奴隷制を支持する富裕層アメリカ人のこうした感情は、アメリカとハイチとの関係を緊張させた。アメリカは当初、ハイチの独立を認めようとしなかったが、一 方で奴隷制支持者は 奴隷所有者は、新しく誕生したカリブの国民との貿易禁止を主張した。[10] ハイチ免責論争は、1825年にフランスが砲艦外交によってハイチに強要したもので、これはハイチの独立によるフランスの財政的損失が原因であった。この 論争の結果、ハイチは1800年代後半までに、その収益の多くを外国への債務の支払いに充てるようになった。[11]  USSフィラデルフィアは、1890年のモール・サンニコラ号事件に関与した艦隊の旗艦であり、この事件では、アメリカがモール・サンニコラ号を獲得しようとして砲艦外交を行った 米国は、フランスからの独立後数十年にわたってハイチを支配することに関心を寄せていた。[12] 米国国務省によると、「西インド諸島における米国の防衛および経済的利益を確保する」ため、米国のアンドリュー・ジョンソン大統領は1868年にハイチを 含むイスパニョーラ島の併合を追求し始めた 。1890年、モール・サンニコラス事件が起こった。ベンジャミン・ハリソン大統領が国務長官ジェームズ・G・ブレインの助言を受け、バンクロフト・ゲラ ルディ少将に、就任したばかりのハイチ大統領フロビル・ハイポリットを説得して、米国に港を貸与するよう命じたのだ。ハイチに対して砲艦外交を強行し、ゲ ラルディは艦隊とともにUSSフィラデルフィアに乗艦し、モール・サン・ニコラの獲得を要求するために首都ポルトープランスに到着した。ハイチ人は艦隊の 存在に怒りを募らせ、ヒッポリト大統領はあらゆる合意を拒否した。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、ハイチ人の「 半野蛮な心は、そこに暴力の脅威を見出した」とニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は報じた。[13][14] 1891年にアメリカに帰国したゲラルディは、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙とのインタビューで、ハイチは間もなくさらなる不安定を経験することになるだろう と述べ、ハイチの将来の政府はアメリカの要求に従うことになるだろうと示唆した。 1890年代までに、ハイチは生産物の大半をフランスに輸出する一方で、その大半をアメリカ合衆国からの輸入に頼るようになった。[15] ルーズベルト・コロラリーもまた、ハイチとアメリカ合衆国との関係に影響を与えた。[16] 1910年までに、 1910年、ウィリアム・タフト大統領はヨーロッパの影響力を抑えるために米国企業をハイチに導入しようとし、対外債務を返済するためにハイチに多額の融 資を行ったが、債務の規模が大きかったため、これは実を結ばなかった。[12][17] |

| German presence Main article: Germany–Haiti relations  Personnel from the German Legation and the Hamburg-Amerika Line The United States was not concerned by France's influence, though German influence in Haiti raised concern.[12] Germany had intervened in Haiti, including the Lüders affair in 1897, and had been influencing other Caribbean nations during the previous few decades. Germany had also become increasingly hostile to United States domination of the region under the Monroe Doctrine. The United States' concern over Germany's ambitions was mirrored by apprehension and rivalry between American businessmen and the small German community in Haiti, which, although numbering only about 200 in 1910, wielded a disproportionate amount of economic power.[18] German nationals controlled about eighty percent of the country's international commerce.[citation needed] They owned and operated utilities in Cap-Haïten and Port-au-Prince, including the main wharf and a tramway in the capital, and also had built the railway serving the Plain of the Cul-de-Sac.[19] The German community was more willing to integrate into Haitian society than any other group of Caucasian foreigners, including the more numerous French. Some Germans had married into Haiti's most prominent mixed-race families of African-French descent. This enabled them to bypass the constitutional prohibition against foreigners owning land. The German residents retained strong ties to their homeland and sometimes aided the German military and intelligence networks in Haiti. They also served as the principal financiers of the nation's numerous revolutions, floating loans at high interest rates to the competing political factions.[19] In the lead-up to World War I, the strategic importance of Haiti, along with the German influence there, worried President Wilson, who feared a German presence near the Panama Canal Zone.[10] |

ドイツの存在 詳細は「ドイツとハイチの関係」を参照  ドイツ公使館とハンブルク・アメリカ・ラインの職員 アメリカ合衆国はフランスの影響力には関心を示さなかったが、ハイチにおけるドイツの影響力には懸念を示していた。[12] ドイツは1897年のリュダース事件をはじめとしてハイチに介入しており、その前の数十年間にもカリブ海の他の国々に影響力を及ぼしていた。 また、ドイツはモンロー主義に基づくアメリカ合衆国の地域支配にも敵対心を募らせていた。 ドイツの野望に対する米国の懸念は、1910年にはわずか200人ほどであったものの、不釣り合いなほど大きな経済力を握っていたハイチ在住のドイツ人コ ミュニティに対する米国のビジネスマンたちの不安と対抗心に反映されていた。[18] ドイツ国民は、 同国の国際貿易の約80%をドイツ人が支配していた。[要出典] 彼らは、首都の主要埠頭や路面電車を含む、カパイシャンとポルトープランスにおける公益事業を所有・運営し、また、袋小路平原を走る鉄道も建設していた。 [19] ドイツ人社会は、フランス人を含む他のどの白人外国人グループよりも、ハイチ社会に溶け込もうとする意欲が強かった。 ドイツ人の中には、ハイチで最も著名なアフリカ系フランス人の混血家族と結婚した者もいた。 これにより、彼らは憲法で定められた外国人による土地所有の禁止を回避することができた。ドイツ人居住者は祖国との強い絆を保ち、時にはハイチ国内のドイ ツ軍や諜報網を支援した。また、彼らはハイチの国民が数多く経験した革命の主要な資金提供者でもあり、競合する政治派閥に高金利で融資を行っていた。 第一次世界大戦の直前、ハイチの戦略的重要性とドイツの影響力に懸念を抱いたウィルソン大統領は、パナマ運河地帯付近にドイツが存在することを恐れていた。 |

| Haitian instability In the first decades of the 20th century, Haiti experienced great political instability and was heavily in debt to France, Germany, and the United States.[10][20] The Wilson administration viewed Haiti's instability as a national security threat to the United States.[17] Political tensions were often between two groups; wealthy French-speaking mulatto Haitians who represented the minority of the population and poor Afro-Haitians who spoke Haitian Creole.[21] Various revolutionary armies carried out the coups. Each was formed by cacos, peasant militias from the mountains of the north, who stayed along the porous Dominican border and were often funded by foreign governments to stage revolts.[21] In 1902, a civil war was fought between the government of Pierre Théoma Boisrond-Canal and General Pierre Nord Alexis against rebels of Anténor Firmin,[5] which led to Pierre Nord Alexis becoming president. In 1908, he was forced from power and a series of short lived presidencies came and went:[22][23] his successor François C. Antoine Simon in 1911;[24] President Cincinnatus Leconte (1911–1912) was killed in a (possibly deliberate) explosion at the National Palace;[25] Michel Oreste (1913–1914) was ousted in a coup, as was his successor Oreste Zamor in 1914.[26] Between 1911 and 1915, Haiti had seven presidents because of political assassinations, coups and forced exiles.[12][27] |

ハイチの不安定 20世紀の最初の数十年間、ハイチは深刻な政治的混乱を経験し、フランス、ドイツ、アメリカ合衆国に対して多額の負債を抱えていた。[10][20] ウィルソン政権は、ハイチの不安定をアメリカ合衆国の国家安全保障に対する脅威と捉えていた 。政治的な緊張は、人口の少数派である富裕なフランス語話者の混血ハイチ人と、ハイチ・クレオールを話す貧しいアフリカ系ハイチ人の2つのグループの間で しばしば生じた。 1902年には、ピエール・テオマ・ボワロン=カナル政府とピエール・ノルド・アレクシス将軍が反乱軍のアンテノール・フィルミンと内戦を戦い、ピエー ル・ノルド・アレクシスが大統領に就任した。1908年には、彼は権力の座から追われ、短命な大統領職が次々と誕生した。[22][23] 1911年には、彼の後継者フランソワ・C・アントワーヌ・シモンが就任したが、[24] シントラントス・レコンテ大統領(1911年~1912年)は、国民宮殿での(おそらく意図的な)爆発により死亡した 。[25] ミシェル・オレステ(1913年 - 1914年)はクーデターにより失脚し、後任のオレステ・ザモールも1914年に失脚した。[26] 1911年から1915年の間、ハイチでは政治的な暗殺、クーデター、強制的な亡命が相次ぎ、7人の大統領が誕生した。[12][27] |

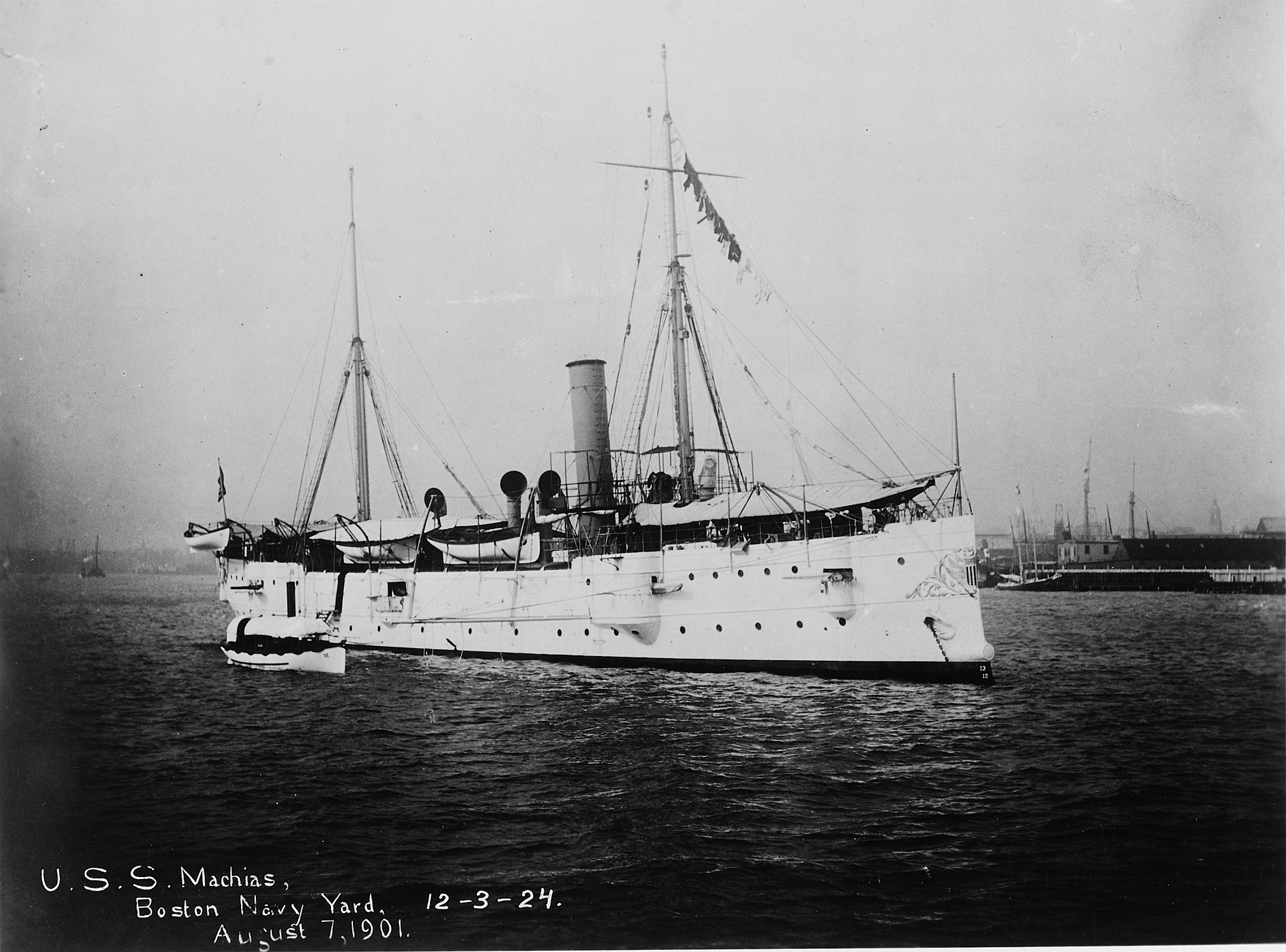

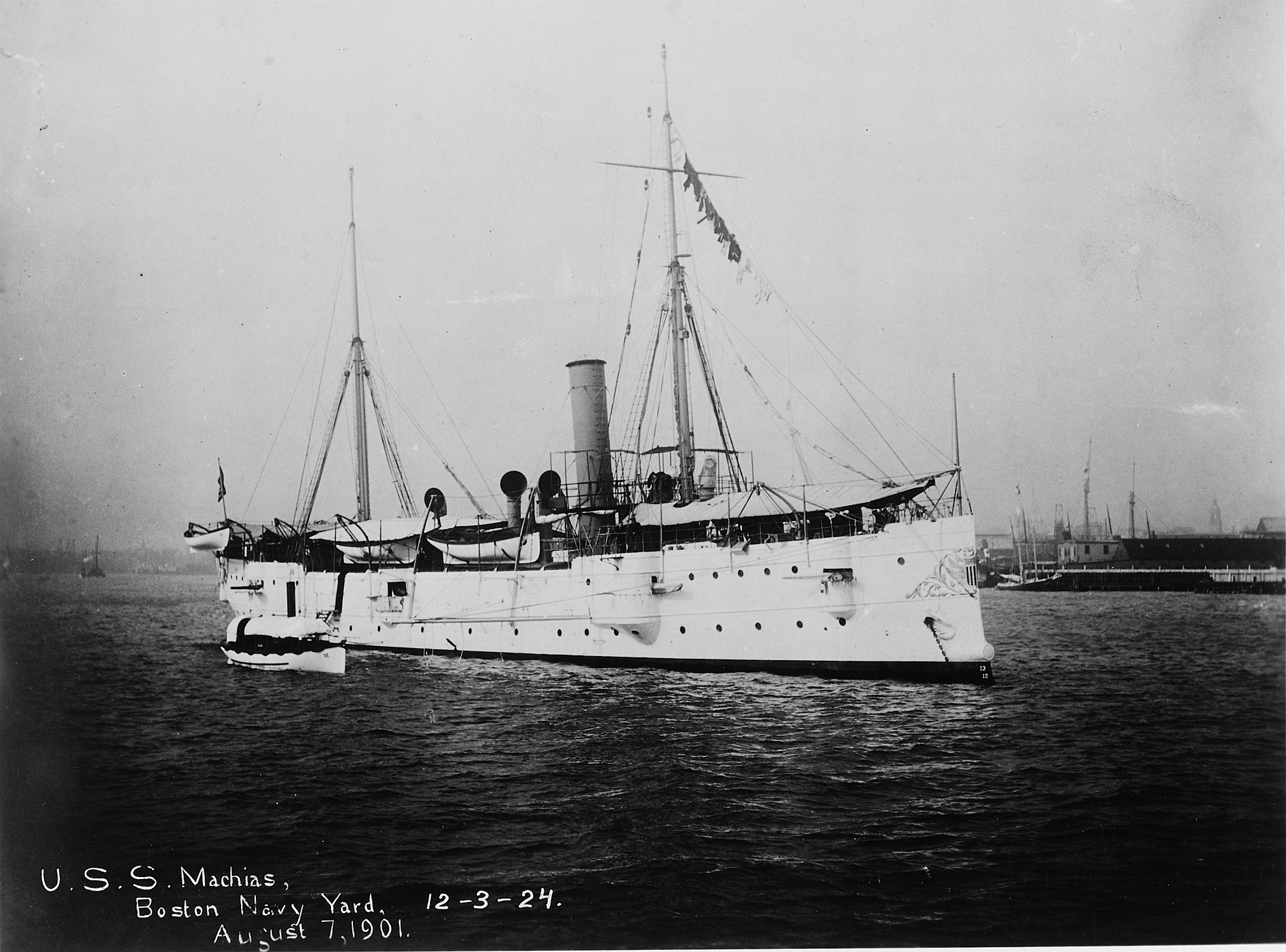

| American financial interests Prior to the intervention of the United States, Haiti's large debt was 80 percent of its annual revenue, though it was able to meet financial obligations, especially when compared to Ecuador, Honduras, and Mexico at that time.[10][17] In the twentieth century, the United States had become Haiti's largest trade partner, replacing France, with American businesses expanding their presence in Haiti.[10] Due to the influence of Germans within Haiti, they were regarded as a threat to American financial interests,[28] with businesses ultimately advocating for policies of invading Haiti.[10] Haitian authorities in 1903 began to accuse the National Bank of Haiti of fraud and by 1908, Haitian Minister of Finance Frédéric Marcelin pushed for the bank to work on the behalf of Haitians, though French officials began to devise plans to reorganize their financial interests.[29] French envoy to Haiti Pierre Carteron wrote following Marcelin's objections that "It is of the highest importance that we study how to set up a new French credit establishment in Port-au-Prince ... Without any close link to the Haitian government."[29] Businesses from the United States had pursued the control of Haiti for years and in 1909, the new president of National City Bank of New York, Frank A. Vanderlip, began to plan the bank's take over of Haiti's finances as part of his larger role of making the bank grow in international markets.[15][30][31] In early 1909, Speyer & Co. promoted a stock to Vanderlip and the bank to invest in the National Railroad of Haiti, which held a monopoly of importing in the Port-au-Prince area.[20] The Haitian government faced conflict with the National City Bank over the railroad regarding payments to creditors, later leading to the bank seeking to control the entirety of Haiti's finances.[15] Vanderlip wrote to Chairman of National City Bank James Stillman in 1910, "In the future, this stock will give us a foothold [in Haiti] and I think we will perhaps later undertake the reorganization of the Government’s currency system, which, I believe, I see my way clear to do with practically no monetary risk".[32] From 1910 to 1911, the United States Department of State backed a consortium of American investors – headed by the National City Bank of New York – to acquire a managing stake of the National Bank of Haiti to create the Bank of the Republic of Haiti (BNRH), with the new bank often holding payments from the Haitian government, leading to unrest.[30][29][28][7] France would also keep a stake in the BNRH.[29] The BNRH was the country's sole commercial bank and served as the Haitian government's treasury.[28] Officials of the Wilson administration were not knowledgeable about Haiti and often relied on information from American businessmen.[21] United States Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan fired established Latin American experts upon his nomination and instead replaced them with political allies.[17] Bryan initially proposed forgiving the debt of Caribbean nations, though President Wilson viewed this as too radical.[17] With his ideas facing rejection, Bryan, who had little information on Haiti, instead relied on the vice president of National City Bank, Roger Leslie Farnham, for information regarding Haiti.[7][10][17][20][21] Farnham had an extensive background working as a financial advisor, lobbyist, journalis, and purchasing agent between the United States and the Caribbean, with American historian Brenda Gayle Plummer writing "Farnham ... is often portrayed by historians as the deus ex machina single-handedly plotting the American intervention of 1915".[20][33] Throughout the 1910s, Farnham demanded successive Haitian governments to grant him control of the nation's customs, the only source of revenue, threatening American intervention when Haiti refused citing national sovereignty.[17] John H. Allen, manager of the BNRH, also met with Bryan for consultation in 1912, with Allen later sharing an account of Bryan being surprised about Haitian culture and stating "Dear me, think of it! Niggers speaking French".[7][17] In 1914, France began to lose its ties to Haiti as it was focusing its efforts on World War I and Farnham suggested to the United States Congress that the BNRH's "active management has been from New York".[7][15] Allen later stated that if the United States permanently occupied Haiti, he supported National City Bank acquiring all shares of BNRH, believing that it would "pay 20% or better".[20] Farnham persuaded Secretary Bryan to have the United States invade Haiti during a telephone call on January 22, 1914.[20] Farnham argued that Haiti was not improving due to continuous internal conflict, that Haitians were not interested in the revolts occurring and that American troops would be welcomed in Haiti.[20] Farnham also exaggerated the role of European influence, even convincing Secretary Bryan that France and Germany – two nations then at war with each other – were plotting in cooperation to obtain the harbor of Môle Saint-Nicholas in northern Haiti.[10][17][21] The businessman concluded that Haiti would not improve "until such time as some stronger outside power steps in".[20] American diplomats would ultimately draft plans to take over Haiti's finances, dubbed the "Farnham Plan".[7] After American officials travelled to Haiti to propose the "Farnham Plan", Haitian legislators denounced their minister of foreign affairs, saying he was "endeavoring to sell the country to the United States" according to a telegram of the US State Department.[7] Due to Haitian opposition to the plan, the BNRH withheld funds from the Haitian government and funded rebels to destabilize the Haitian government in order to justify American intervention, generating 12% gains in interest by holding on to the funds.[7][17] On January 27, 1914, Haitian President Michel Oreste was deposed in a coup. Two generals, Charles and Oreste Zamor, seized control. In response, the USS Montana sent a marine detachment on January 29 into Port-au Prince to protect American interests.[34] On February 5, 1914, military forces from the French cruiser Conde and British HMS Lancaster also landed troops. These units agreed to leave the city and boarded their ships on February 9, 1914.[34] BNRH's Allen telegrammed the State Department on April 8, 1914, requesting that the U.S. Navy sail to Port-au-Prince to deter possible rebellions.[20] In the summer of 1914, the BNRH began to threaten the Haitian government that it would no longer provide payments.[20] Simultaneously, Secretary Bryan telegrammed the United States consul in Cap-Haïtien, writing that the State Department agreed with invading Haiti, telling the consul that the United States "earnestly desires successfully carrying out of Farnham's plan".[20][35]  Gold from Haiti was placed onto the USS Machias by U.S. Marines and transported to 55 Wall Street in 1914 American bankers raised fears that Haiti would default on debt payments despite consistent compliance by Haiti with loan conditions, calling for the seizure of Haiti's national bank.[10] National City Bank officials – acting on behalf of Farnham – demanded the State Department to provide military support to acquire Haiti's national reserves, with the bank arguing that Haiti had become too unstable to safeguard the assets.[7][20] Urged by the National City Bank and the BNRH, with the latter of the two already under direction of American business interests, eight United States marines walked into the national bank and took custody of Haiti's gold reserve of about US$500,000 – about the equivalent to $13,526,578 in 2021 – on December 17, 1914.[7][12][20][36] The Marines packed the gold into wooden boxes, loaded them into a wagon, and transported the gold under the protection of plainclothes clandestine soldiers lining the route to the USS Machias, which transferred its load to the National City Bank's New York City vault on 55 Wall Street.[7][20] The robbery of the gold provided the United States with a large amount of control over the Haitian government, though American businesses demanded further intervention.[10] National City Bank would go on to acquire some of its largest gains in the 1920s due to debt payments from Haiti, according to later filings to the Senate Finance Committee, with debt payments to the bank comprising 25% of Haiti's revenue.[7] |

アメリカの金融的利益 米国の介入以前、ハイチの多額の債務は年間収入の80パーセントに達していたが、特に当時のエクアドル、ホンジュラス、メキシコと比較すると、ハイチは財 政的義務を果たすことができていた。[10][17] 20世紀には、米国はフランスに代わってハイチの最大の貿易相手国となり、米国企業が ハイチにおける存在感を拡大していた。[10] ハイチ国内におけるドイツ人の影響力により、彼らはアメリカの金融的利益に対する脅威とみなされ、最終的に企業はハイチ侵攻政策を支持した。[10] 1903年、ハイチ当局はハイチ国立銀行の不正を告発し始め、1908年には、ハイチの財務大臣フレデリック・マルセランが 財務大臣フレデリック・マルセランは、ハイチ人のために銀行が働くよう強く求めたが、その一方で、フランス政府高官は自国の金融権益を再編する計画を練り 始めていた。[29] ハイチ駐在フランス公使ピエール・カステロンは、マルセランの反対意見を受けて、「我々は、ハイチ政府との密接なつながりを持たずに、ポルトープランスに 新たなフランス信用機関を設立する方法を研究することが最も重要である」と記している。[29] 米国の企業は長年にわたりハイチの支配を追求しており、1909年には、ニューヨーク・ナショナル・シティ銀行の新しい頭取フランク・A・バンダーリップ が、国際市場での銀行の成長という大きな役割の一環として、ハイチの財政を掌握する計画を立て始めた。[15][30][31] 1909年初頭、Speyer & Co.は ヴァンダーリップと銀行に、ポルトープランス地域における輸入の独占権を保有していたハイチ国鉄への投資を促した。[20] ハイチ政府は債権者への支払いに関して、鉄道を巡ってナショナル・シティ・バンクと対立し、後にハイチの財政全体を支配しようとする銀行につながった。 [15] ヴァンダーリップは1910年にナショナル・シティ・バンクのジェームズ・スティルマン会長に宛てて、「 将来、この株式は我々にハイチでの足がかりを与えるだろう。そして、おそらく我々は後に政府の通貨制度の再編に着手することになるだろう。それは、金銭的 なリスクをほとんど伴わずに実行できると確信している」と述べた。[32] 1910年から1911年にかけて、米国国務省は、ニューヨーク・ナショナル・シティ銀行が主導する米国投資家連合を支援し、 ハイチ国民銀行の経営権を取得し、ハイチ共和国銀行(BNRH)を設立した。この新銀行は、しばしばハイチ政府からの支払いを保有し、不安定な状況を引き 起こした。[30][29][28][7] フランスもBNRHの株式を保有していた。[29] BNRHは同国唯一の商業銀行であり、ハイチ政府の財務省としての役割も果たしていた。[28] ウィルソン政権の政府高官はハイチについて詳しくなく、しばしば米国のビジネスマンからの情報に頼っていた。[21] 米国務長官ウィリアム・ジェニングス・ブライアンは、指名された際にラテンアメリカ専門家を解雇し、代わりに政治的同盟者を起用した。[17] ブライアンは当初、カリブ海諸国の債務免除を提案したが、ウィルソン大統領はこれを急進的すぎると考えた。[17] 自身の考えが却下されたため、ハイチについてほとんど情報を持っていなかったブライアンは、代わりにナショナル・シティ・バンクの副頭取 、ロジャー・レスリー・ファーナムにハイチに関する情報を求めた。[7][10][17][20][21] ファーナムは、アメリカとカリブ海諸国間の財務アドバイザー、ロビイスト、ジャーナリスト、購買代理人として幅広い経歴を持ち、アメリカの歴史家ブレン ダ・ゲイル・プラマーは「ファーナムは...しばしば歴史家たちによって、1915年のアメリカの介入を単独で画策したデウス・エクス・マキナとして描か れている」と書いている。[20][ 33] 1910年代を通じて、ファーンハムは歴代ハイチ政府に、唯一の収入源である関税の管理権を要求し、ハイチが拒否するとアメリカによる介入をちらつかせ た。[17] BNRHのマネージャーであるジョン・H・アレンも1912年にブライアンと協議を行った。アレンは後に、ブライアンがハイチ文化に驚き、「なんとまあ、 考えてみろ!ニガーがフランス語を話すなんて」と述べた。[7][17] 1914年、フランスは第一次世界大戦に全力を傾けるためハイチとの関係を失い始め、ファーナムは米国議会にBNRHの「積極的な経営はニューヨークから 行われている」と提案した。[7][15] アレンは後に、米国がハイチを恒久的に占領するならば、BNRHの全株式をナショナル・シティ・バンクが取得することを支持すると述べた。」と述べた。 [20] ファーンハムは1914年1月22日、ブライアン長官に電話で説得し、米国によるハイチ侵攻を実現させた。[20] ファーンハムは、ハイチは内戦が続き改善していないこと、ハイチ人は反乱に興味がないこと、ハイチでは米軍が歓迎されるだろうと主張した。[20] ファーンハムはまた、ヨーロッパの影響力を誇張し、 当時互いに戦争状態にあったフランスとドイツが協力して、ハイチ北部のモール・サンニコラ港を獲得しようと画策していると、ブライアン長官を説得したほど であった。[10][17][21] この実業家は、「より強力な外部勢力が介入するまでは」、ハイチは改善しないだろうと結論づけた。[20] アメリカの外交官たちは最終的に、ハイチの財政を掌握する計画を立案し、「ファーンハム・プラン」と名付けた。[7] 米国政府高官が「ファーンハム・プラン」を提案するためにハイチを訪問した後、米国国務省の電報によると、ハイチの議員たちは外務大臣を非難し、「米国に 国を売り渡そうとしている」と述べた。ハイチがこの計画に反対したため、BNRHは ハイチ政府からの資金を保留し、ハイチ政府を不安定化させるために反乱軍に資金提供を行い、アメリカの介入を正当化しようとした。これにより、資金を保留 することで12%の利得を生み出した。[7][17] 1914年1月27日、ハイチのミシェル・オレステ大統領はクーデターにより失脚した。チャールズ・ザモールとオレステ・ザモールの2人の将軍が権力を掌 握した。これを受けて、アメリカ合衆国の利益を守るため、1月29日にUSSモンタナが海兵隊分遣隊をポルトープランスに派遣した。[34] 1914年2月5日には、フランス巡洋艦コンデとイギリス海軍のHMSランカスターの軍隊も軍隊を上陸させた。これらの部隊は、1914年2月9日に都市 から撤退することに同意し、船に乗り込んだ。[34] 1914年4月8日、BNRHのアレンは国務省に電報を打ち、反乱の可能性を抑止するために米海軍がポルトープランスに向かうよう要請した。[20] 1914年の夏、BNRHはハイチ政府に対して、 支払いを停止すると通告した。[20] 同時に、ブライアン長官はカパイエンに駐在する米国領事に電報を打ち、国務省がハイチ侵攻に同意していることを伝え、米国は「ファーンハムの計画の成功を 切に願っている」と領事に伝えた。[20][35]  ハイチ産の金塊は、アメリカ海兵隊によってUSSマキアス号に積み込まれ、1914年にウォール街55番地に輸送された アメリカの銀行家たちは、ハイチが融資条件を順守しているにもかかわらず、ハイチが債務の支払いを怠るのではないかと懸念を示し、ハイチの国立銀行の差し 押さえを要求した。[10] ナショナル・シティ・バンクの役員たちは、ファーンハムの代理として、ハイチの国家準備金を取得するための軍事支援を国務省に要求した。銀行側は、ハイチ は資産を保護するにはあまりにも不安定な状態になっていると主張した。[7][20] ナショナル・シティ銀行とBNRHの要請により、後者はすでにアメリカの企業利益の指示下にあったが、1914年12月17日、8人のアメリカ海兵隊員が 国民銀行に入り、約50万ドル(2021年現在の価値で約1352万6578ドル)相当のハイチの金準備を保管した 。海兵隊は金を木箱に詰め、馬車に積み込み、道の両側に並んだ私服の秘密部隊の兵士に護衛されて、USSマキアス号に積み込み、同船は金をウォール街55 番地のナショナル・シティ銀行のニューヨーク支店に移送した。金塊強奪により、アメリカはハイチ政府に対して大きな影響力を得たが、アメリカ企業はさらな る介入を要求した。[10] 国民都市銀行は、ハイチからの債務支払により、1920年代に最大の利益を獲得した。これは、後の上院財政委員会への提出書類によると、銀行への債務支払 はハイチの収入の25%を占めていた。[7] |

| American invasion In February 1915, Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, son of a former Haitian president, took power as President of Haiti. The culmination of his repressive measures came on July 27, 1915, when he ordered the execution of 167 political prisoners, including former president Zamor, who was being held in a Port-au-Prince jail. This infuriated the population, which rose up against Sam's government as soon as news of the executions reached them. Sam, who had taken refuge in the French embassy, was lynched by an enraged mob in Port-au-Prince as soon as they learned of the executions.[37] The United States regarded the anti-American revolt against Sam as a threat to American business interests in the country, especially the Haitian American Sugar Company (HASCO). When the caco-supported anti-American Rosalvo Bobo emerged as the next president of Haiti, the United States government decided to act quickly to preserve its economic dominance.[38][verification needed] In April 1915, Secretary Bryan expressed support for invading Haiti to President Wilson, writing "The American interests are willing to remain there, with a view of purchasing a controlling interest and making the bank a branch of the American bank – they are willing to do this provided this government takes the steps necessary to protect them and their idea seems to be that no protection will be sufficient that does not include control of the Customs House."[7][17] On July 28, 1915, United States President Woodrow Wilson ordered 340 United States marines to occupy Port-au-Prince and the invasion took place the same day.[39][40] The Secretary of the Navy instructed the invasion commander, Rear Admiral William Banks Caperton, to "protect American and foreign" interests. Wilson also wanted to rewrite the Haitian constitution, which banned foreign ownership of land, to replace it with one that guaranteed American financial control.[41] To avoid public criticism, Wilson claimed the occupation was a mission to "re-establish peace and order ... [and] has nothing to do with any diplomatic negotiations of the past or the future," as disclosed by Rear Admiral Caperton.[42] Only one Haitian soldier, Pierre Sully, tried to resist the invasion, and he was shot dead by the Marines.[43] |

アメリカの侵略 1915年2月、ヴィルブラン・ギヨーム・サム(Vilbrun Guillaume Sam)が、元ハイチ大統領の息子としてハイチ大統領に就任した。彼の抑圧政策の頂点となったのは、1915年7月27日、サムがポルトープランス刑務所 に収監されていた元大統領ザモール(Zamor)を含む167人の政治犯の処刑を命じたことだった。この処刑のニュースが伝わると、国民は激怒し、サムの 政府に対して蜂起した。フランス大使館に避難していたサムは、処刑のニュースを知るとすぐに、怒りに燃える暴徒によってポルトープランスでリンチされた。 [37] アメリカ合衆国は、サムに対する反米蜂起を、同国におけるアメリカ企業の利益、特にハイチ系アメリカ人砂糖会社(HASCO)に対する脅威とみなした。反 米派のロザルヴォ・ボボがハイチの次期大統領として浮上すると、米国政府は自国の経済的優位性を維持するために迅速に行動することを決定した。[38] [検証必要] 1915年4月、ブライアン長官はウィルソン大統領にハイチ侵攻への支持を表明し、「アメリカ合衆国の利益は、支配権を買い取り、銀行をアメリカ合衆国の 銀行の支店とすることを視野に入れ、そこに留まり続けることを望んでいる。この政府が彼らを守るために必要な措置を講じるのであれば、彼らはこれを望んで いる。そして、彼らの考えでは、税関の管理権を含まない保護は十分ではないということだ」と記した。[7][17] 1915年7月28日、アメリカ大統領ウッドロウ・ウィルソンは340名のアメリカ海兵隊にポルトープランスを占領するよう命令し、同日、侵攻が行われ た。[39][40] 海軍長官は侵攻司令官であるウィリアム・バンクス・ケイパートン少将に「アメリカおよび外国の」利益を保護するよう指示した。また、ウィルソンは、外国人 の土地所有を禁止していたハイチ憲法を改正し、アメリカによる財政支配を保証する憲法に置き換えることを望んでいた。[41] 世論の批判を避けるため、ウィルソンは、この占領は「平和と秩序を再確立する」ための任務であり、 と主張し、キャペルトン少将が明らかにしたように、「過去または未来の外交交渉とは何の関係もない」と主張した。[42] ハイチ軍兵士で抵抗を試みたのはピエール・スリーリただ一人で、彼は海兵隊に射殺された。[43] |

| American occupation Dartiguenave presidency U.S. installs Dartiguenave as president Haitian presidents were not elected by universal suffrage but rather chosen by the Senate. The American occupying authorities therefore looked to find a presidential candidate ready to cooperate with them.[44] Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave, president of the Senate and among the mulatto Haitian elite who supported the United States, agreed to accept the presidency of Haiti in August 1915 after several other candidates had refused. The United States would later go on to install more wealthy mulatto Haitians in positions of power.[45] |

アメリカ軍占領下 ダルティグナヴ大統領 アメリカ軍、ダルティグナヴを大統領に就任させる ハイチの大統領は普通選挙で選ばれるのではなく、元老院によって選出されていた。そのため、アメリカ占領当局は、自分たちに協力する大統領候補を探すこと になった。[44] フィリップ・シュドレー・ダルティグナヴは上院議長であり、アメリカを支持するハイチ混血エリート層の1人であった。彼は、他の候補者が次々と辞退したの ち、1915年8月にハイチ大統領の職を引き受けることに同意した。アメリカはその後、さらに多くの富裕なハイチ混血エリートを権力のある地位に就けた。 [45] |

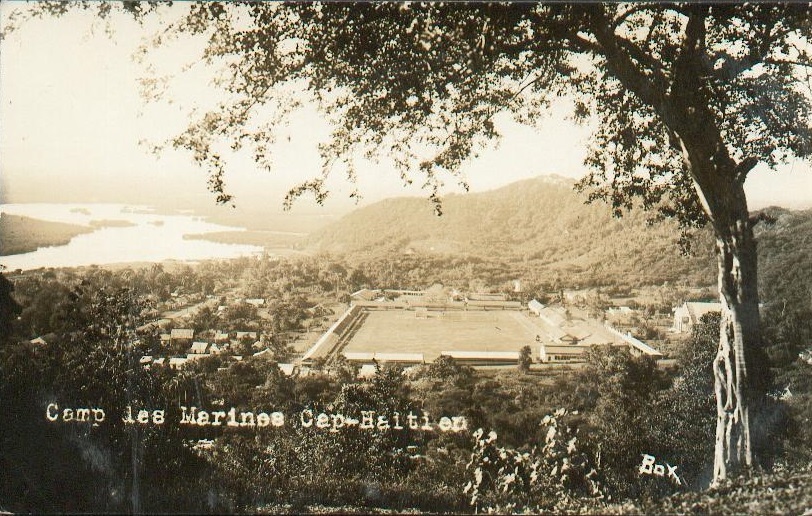

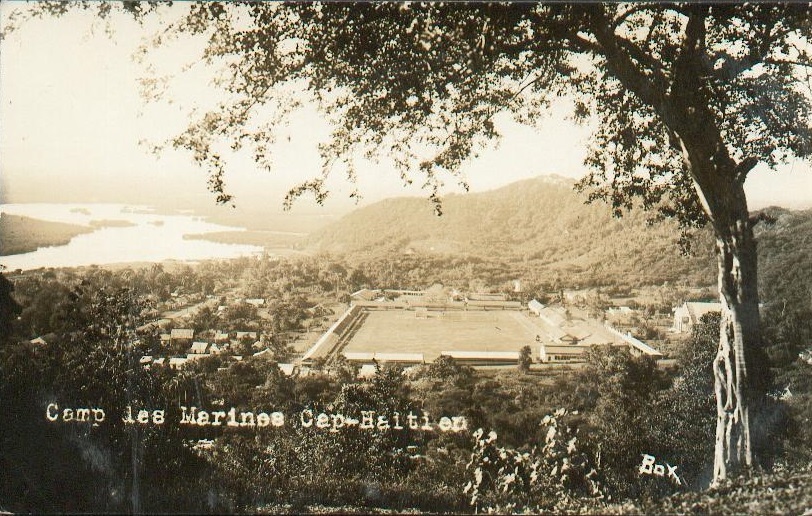

U.S. takeover of Haitian institutions Marine base at Cap-Haïtien For several decades, the Haitian government had been receiving large loans from both American and French banks, and with the political chaos was growing increasingly incapable of repaying their debts. If the anti-American government of Rosalvo Bobo prevailed, there was no guarantee of debt repayment, and American businesses refused to continue investing there. Within six weeks of the occupation, U.S. government representatives seized control of Haiti's customs houses and administrative institutions, including the banks and the national treasury. Under U.S. government control, 40% of Haiti's national income was designated to repay debts to American and French banks.[46] In September 1915, the United States Senate ratified the Haitian-American Convention, a treaty granting the United States security and economic oversight of Haiti for a 10-year period.[47] Haiti's legislature initially refused to ratify the treaty, though Admiral Caperton threatened hold payments from Haiti until the treaty was signed.[48] The treaty gave the President of the United States the power to appoint a customs receiver general, economic advisors, public works engineers; and to assign American military officers to oversee a Haitian gendarmerie.[49] Haiti's economic functions were overseen by the United States Department of State, while the United States Navy was tasked with infrastructure and healthcare works, though the Navy ultimately held more authority.[49] Officials from the United States then wielded veto power over all governmental decisions in Haiti, and Marine Corps commanders served as administrators in the departments.[12] The original treaty was to be in effect for ten years, though an additional agreement in 1917 expanded the United States' power for twenty years.[49] For the next nineteen years, U.S. State Department advisers ruled Haiti, their authority enforced by the United States Marine Corps.[12] The Gendarmerie of Haiti, now known as the Garde d'Haïti, was also created and controlled by U.S. Marines throughout the occupation, initially led by Major Smedley D. Butler.[12][48] Rear Admiral Caperton ordered his 2,500 Marines to occupy all of Haiti's districts, equipping them with airplanes, cars, and trucks.[50] Five airfields were constructed and at least three airplanes were present in Haiti.[5] Marines were tasked with multiple duties for their districts; law enforcement, tax collection, medicine distribution, and overseeing arbitration.[50] Economically and politically, the Haitian government relied on American approval for most projects.[49] The 1915 treaty with the United States proved expensive; the Haitian government had such a limited income that it was difficult to hire public workers and officials.[49] Before utilizing any money, the Haitian government had to obtain approval from an American financial advisor and by 1918, would rely on American officials for approval of any laws due to fears of violating the treaty.[49] |

米国によるハイチ機関の買収 カパイエンにある海軍基地 数十年にわたり、ハイチ政府はアメリカとフランスの銀行から多額の融資を受けていたが、政治的混乱により、その返済能力はますます低下していた。反米的な ロザルヴォ・ボボ政権が勝利した場合、債務返済の保証は全くなく、アメリカの企業はハイチへの投資継続を拒否した。占領から6週間以内に、アメリカ政府の 代表者はハイチの税関や行政機関、銀行や国庫を含む管理権を掌握した。米国政府の管理下において、ハイチの国民所得の40%が米国およびフランスの銀行へ の債務返済に充てられた。[46] 1915年9月、米国上院はハイチ・アメリカ条約を批准した。この条約は、米国に10年間にわたってハイチの安全保障と経済管理を認める内容であった。 [47] ハイチの立法府は当初、条約の批准を拒否したが、ケープルトン提督は条約が締結されるまでハイチからの支払いを保留すると脅迫した。条約が締結されるまで ハイチからの支払いを保留すると脅したが、[48] その条約により、アメリカ合衆国大統領は、税関総監、経済顧問、公共事業技師を任命する権限が与えられ、また、ハイチ国家憲兵を監督するアメリカ軍将校を 任命する権限も与えられた。[49] ハイチの経済機能はアメリカ国務省が監督し、アメリカ海軍はインフラ整備と医療事業を担当したが、最終的には海軍がより大きな権限を有していた。[49] 米国政府高官はハイチにおけるすべての政府決定に対する拒否権を行使し、海兵隊司令官が各省の行政官を務めた。[12] 当初の条約は10年間有効であったが、1917年の追加協定により米国の権限は20年間延長された。[49] その後19年間、米国務省顧問がハイチを統治し、その権限は米国海兵隊によって行使された。[12] ハイチ国家警察(現在のガード・ダティ)も創設され、占領期間を通じてアメリカ海兵隊がこれを統制した。当初はスミッディ・バトラー少佐が指揮を執った。 [12][48] ケイパートン少将は2,500人の海兵隊員にハイチ全土の占領を命じ、 飛行機、自動車、トラックを装備させ、ハイチの全地区を占領するよう命じた。 経済的にも政治的にも、ハイチ政府はほとんどのプロジェクトについてアメリカの承認を必要とした。[49] 1915年のアメリカとの条約は高くついた。ハイチ政府の収入は限られており、公務員や役人を雇用することは困難であった。[49] 資金を活用する前に、ハイチ政府はアメリカの財務顧問の承認を得る必要があり、1918年には条約違反の恐れがあるとして、あらゆる法律の承認をアメリカ の役人に頼るようになっていた。[49] |

| First Caco War The installation of a president without the consent of Haitians and the forced labor of the corvée system enforced upon Haitians by American forces led to opposition of the U.S. occupation began immediately after the marines entered Haiti, creating rebel groups of Haitians who felt they were returning to slavery.[7][12][48] The rebels (called "Cacos", after a local bird sharing their ambush tactics)[51] strongly resisted American control of Haiti. The U.S. and Haitian governments began a vigorous campaign to destroy the rebel armies. Perhaps the best-known account of this skirmishing came from Marine Major Smedley Butler, awarded a Medal of Honor for his exploits. He was appointed to serve as commanding officer of the Haitian gendarmerie. He later expressed his disapproval of the U.S. intervention in his 1935 book War Is a Racket. On November 17, 1915, the Marines captured Fort Rivière, a stronghold of the Caco rebels, which marked the end of the First Caco War.[52]: 201 The United States military issued two Haitian Campaign Medals to U.S. Marine and naval personnel for service in the country during the periods 1915 and 1919–1920. |

第一次カコ戦争 ハイチ人の同意を得ないままの大統領の就任と、アメリカ軍によるハイチ人への強制労働(コルヴェー制度)の強制は、アメリカ占領への反対運動を引き起こ し、海兵隊がハイチに上陸した直後に、奴隷制への回帰と感じたハイチ人の反乱軍が結成された。[7][12][48] 反乱軍(待ち伏せ戦術を共有する地元の鳥にちなんで「カコス」と呼ばれる)は、アメリカによるハイチ支配に強く抵抗した。米国とハイチ政府は、反乱軍の壊 滅を目指して精力的なキャンペーンを開始した。この小競り合いについて最もよく知られているのは、その活躍により名誉勲章を授与された海兵隊少佐スメド リー・バトラーによるものだろう。彼はハイチ憲兵隊の司令官に任命された。その後、彼は1935年の著書『戦争というビジネス』で、米国の介入に反対する 意見を述べた。 1915年11月17日、海兵隊はカコ反乱軍の拠点であったリヴィエール砦を陥落させ、第一次カコ戦争は終結した。[52]:201 米国軍は、1915年から1919年から1920年にかけてのハイチでの任務を称え、海兵隊と海軍の隊員にハイチ従軍章を授与した。 |

| U.S. forces new Haitian constitution Shortly after installing Dartiguenave as president of Haiti, President Wilson pursued the rewriting of the Constitution of Haiti.[12] One of the main concerns for the United States was the ban of foreigners from owning Haitian land.[12] Early leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines had forbidden land ownership by foreigners when Haiti became independent to deter foreign influence, and since 1804, some Haitians had viewed foreign ownership as anathema.[12][53] Fearing impeachment and due to opposition of the legislature, Dartiguenave ordered the dissolution of the senate on April 6, 1916, with Major Butler and Colonel Waller enforcing new legislative elections.[48] Colonel Eli K. Cole would later assume Waller's position as commander of the Marines.[48] The newly elected legislature of Haiti immediately rejected the constitution proposed by the United States.[12] Instead, the legislative body began drafting a new constitution of its own that was in contrast to the interests of the United States.[12][48] Under orders from the United States, President Dartiguenave dissolved the legislature in 1917 after its members refused to approve the proposed constitution, with Major Butler forcing the closing of the senate at gunpoint.[7][12][48] Haiti's new constitution was drafted under the supervision of Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy.[7][54][55] A referendum in Haiti subsequently approved the new constitution in 1918 (by a vote of 98,225 to 768). In Roosevelt's new constitution, Haiti explicitly allowed foreigners to control Haitian land for the first time since Haiti's creation.[15][56] As a result of opposing the United States' effort of rewriting its constitution, Haiti would remain without a legislative branch until 1929.[12] |

米軍、ハイチ新憲法を承認 ウィルソン大統領は、ダルティニャーヴをハイチ大統領に任命した直後に、ハイチ憲法の改正を推進した。[12] 米国の主な関心事のひとつは、外国人のハイチ土地所有の禁止であった。[12] ハイチ独立当初の指導者ジャン=ジャック・デサリンは、外国の影響力を排除するために、外国人の土地所有を禁止していた。1804年以来、一部のハイチ人 は 外国人の土地所有を忌まわしいものと見なすようになった。[12][53]弾劾を恐れ、立法府の反対により、ダルティグナヴは1916年4月6日に元老院 の解散を命じ、バトラー少佐とウォーラー大佐が新たな立法府選挙を実施した。[48] 後にウォーラー大佐の後任として海兵隊司令官に就任したイーライ・コール大佐。[48] 新たに選出されたハイチの立法府は、米国が提案した憲法を即座に拒否した。[12] 代わりに、立法府は米国の利益とは対照的な独自の新しい憲法の起草を開始した。[12][48] 米国の命令により、議員たちが提案された憲法を承認することを拒否したため、1917年にダティグナヴ大統領は議会を解散した。バトラー大佐は銃を突きつ けて上院の閉会を強制した。 ハイチの新しい憲法は、当時海軍次官であったフランクリン・D・ルーズベルトの監督の下で起草された。[7][54][55] その後、1918年にハイチで実施された国民投票で新しい憲法が承認された(98,225対768の票で)。ルーズベルトの新憲法では、ハイチ建国以来初 めて、外国人がハイチの土地を管理することを明確に認めた。[15][56] 米国による憲法改正の試みに反対した結果、ハイチは1929年まで立法機関を持たない状態が続いた。[12] |

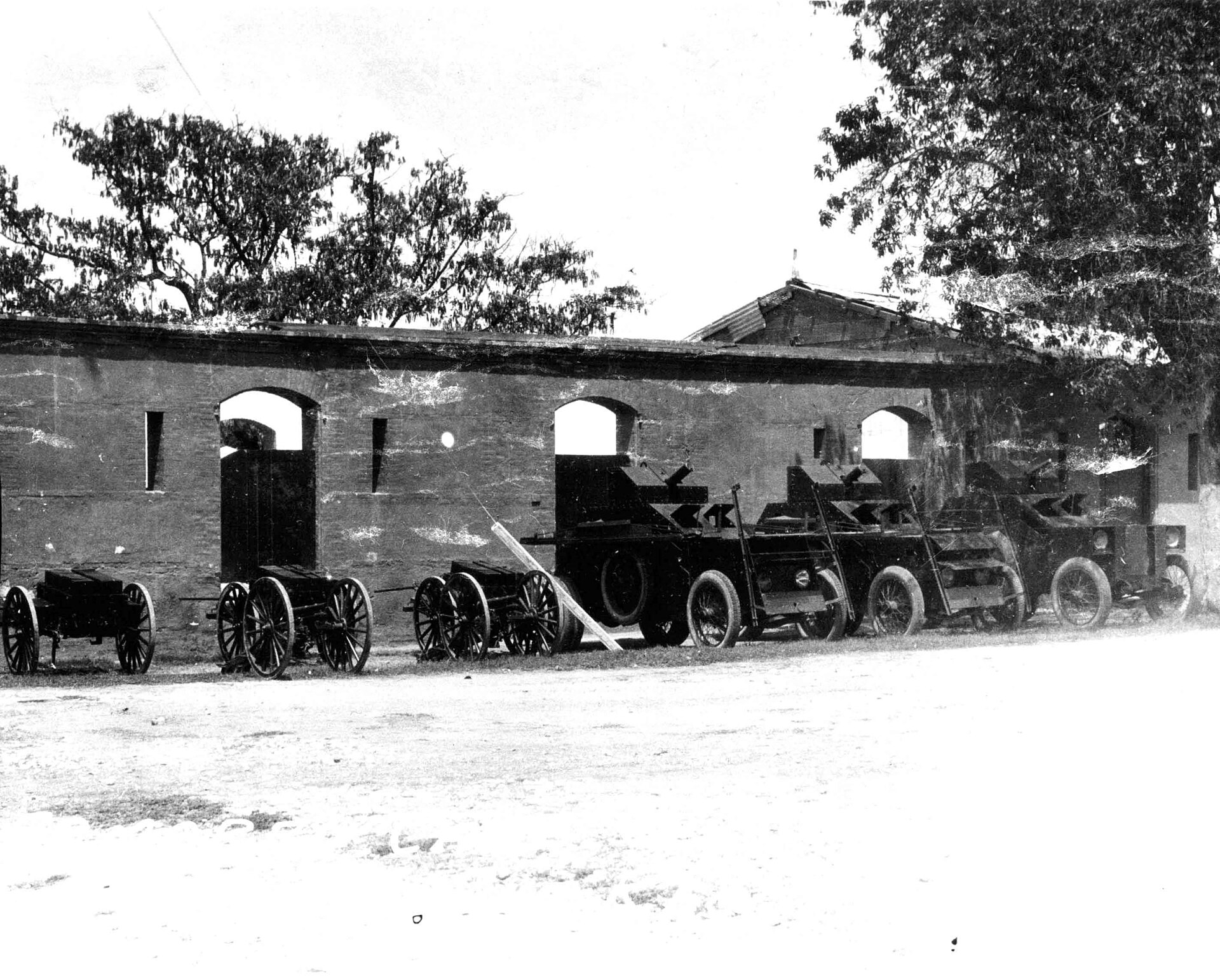

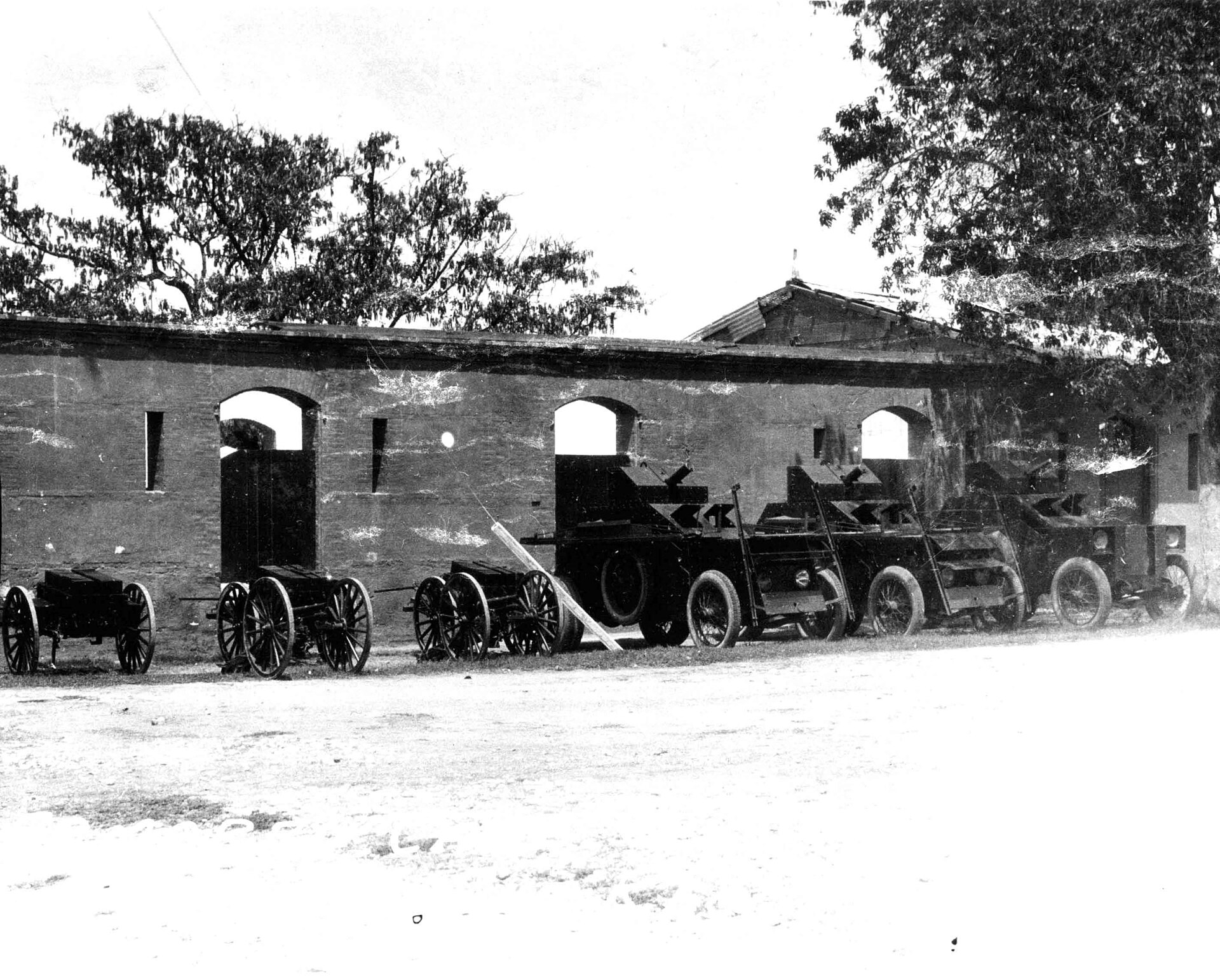

Second Caco War King armored cars of the 1st Armored Car Squadron The end of the First World War in 1918 deprived the Haitians of their main ally in the liberation struggle. Germany's defeat meant its end as a menace to the U.S. in the Caribbean, as it lost control of Tortuga. Nevertheless, the U.S. continued its occupation of Haiti after the war, despite President Woodrow Wilson's claims at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 that he supported self-determination among other peoples.[citation needed] At one time, at least twenty percent of Haitians had been involved in the rebellion against occupation according to Africanologist Patrick Bellegarde-Smith.[11] The strongest period of unrest culminated in a 1918 rebellion by up to 40,000 former cacos and other members of the opposition led by Charlemagne Péralte, a former officer of the dissolved Haitian army.[50][52] The scale of the uprising overwhelmed the Gendarmerie, but U.S. Marine reinforcements helped put down the revolt. For their part, the Haitians resorted to non-conventional tactics, being severely outmatched by their occupiers.[52] Prior to his death, Péralte launched an attack on Port-au-Prince. The assassination of Péralte in 1919 solidified US Marine power over the Cacos.[52]: 211–218 [57][page needed] The Second Caco War ended with the death of Benoît Batraville in 1920,[52]: 223 who had commanded an assault on the Haitian capital that year. An estimated 2,004 Cacos were killed in the fighting, as well as several dozens of US Marines and Haitian gendarmes.[53] |

第二次カコ戦争 第1装甲車中隊のキング装甲車 1918年の第一次世界大戦の終結により、解放闘争におけるハイチ人の主な同盟国は失われた。ドイツの敗北は、トルトゥーガの支配権を失ったことを意味 し、カリブ海における米国への脅威としてのドイツの終焉を意味した。しかし、アメリカは、1919年のパリ講和会議でウッドロウ・ウィルソン大統領が他民 族の自決権を支持すると主張したにもかかわらず、戦後もハイチ占領を継続した。 アフリカ学者のパトリック・ベルグラード=スミスによると、ある時期には、少なくとも20パーセントのハイチ人が占領に対する反乱に関与していたという。 [11] 最も不安定な時期は、1918年の反乱で頂点に達し、最大4万人の元 解散したハイチ軍の元将校シャルルマーニュ・ペラルテが率いる元カコやその他の反対派のメンバーによるものであった。[50][52] この蜂起の規模は国家憲兵団を圧倒したが、アメリカ海兵隊の増援部隊が反乱の鎮圧に貢献した。一方、ハイチ人は非正規の戦術に頼ったが、占領軍に大きく劣 勢であった。[52] ペラルテは死の直前に、ポルトープランスへの攻撃を開始した。1919年のペラルテの暗殺により、米海兵隊のカコスに対する優位は確固たるものとなった。 [52]:211-218[57][要出典] 1920年にベヌワ・バトラヴィルが死亡したことで、第二次カコス戦争は終結した。[52]:223 バトラヴィルは、その年にハイチ首都への攻撃を指揮していた。推定2,004人のカコが戦闘で死亡し、数十人のアメリカ海兵隊員とハイチ人警官も死亡し た。[53] |

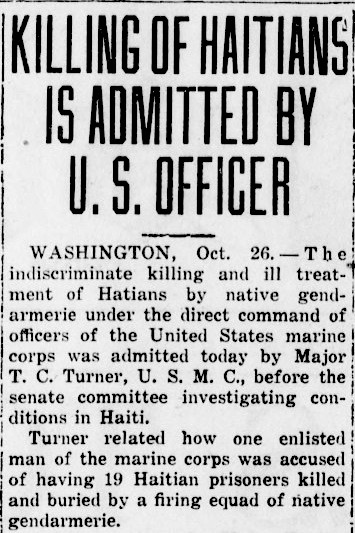

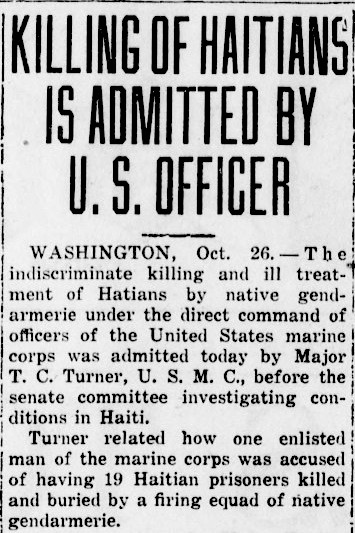

Congressional investigation An October 1921 article from the Merced Sun-Star discussing killings of Haitians by U.S. Marines The educated elite in Haiti was L'Union Patriotique, which established ties with opponents of the occupation in the U.S. They found allies in the NAACP and among both white and African-American leaders.[58] The NAACP sent civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson, its field secretary, to investigate conditions in Haiti. He published his account in 1920, decrying "the economic corruption, forced labor, press censorship, racial segregation, and wanton violence introduced to Haiti by the U.S. occupation encouraged numerous African Americans to flood the State Department and the offices of Republican Party officials with letters" calling for an end to the abuses and to remove troops.[59] Academic W. E. B. Du Bois, who had Haitian ancestry, demanded a response for the Wilson administration's actions and wrote that U.S. troops "have no designs on the political independence of the island and no desire to exploit it ruthlessly for the take of selfish business interests".[11] Based on Johnson's investigation, NAACP executive secretary Herbert J. Seligman wrote in the July 10, 1920, The Nation:[60] "Military camps have been built throughout the island. The property of natives has been taken for military use. Haitians carrying a gun were for a time shot on sight. Machine guns have been turned on crowds of unarmed natives, and United States Marines have, by accounts which several of them gave me in casual conversation, not troubled to investigate how many were killed or wounded." According to Johnson, there was only one reason why the United States occupied Haiti:[20] "[T]o understand why the United States landed and has for five years maintained military forces in that country, why some three thousand Haitian men, women, and children have been shot down by American rifles and machine guns, it is necessary, among other things, to know that the National City Bank of New York is very much interested in Haiti. It is necessary to know that the National City Bank controls the National Bank of Haiti and is the depository for all of the Haitian national funds that are being collected by American officials, and that Mr. R. L. Farnham, vice-president of the National City Bank, is virtually the representative of the State Department in matters relating to the island republic." Two years after Johnson published his findings, a congressional investigation began in the United States in 1922.[20] The report from Congress did not include testimony from Haitians and ignored allegations involving National City Bank of New York and U.S. Marines.[20] Congress concluded the report by defending a continued occupation of Haiti, arguing that "chronic revolution, anarchy, barbarism, and ruin" would befall upon Haiti if the United States withdrew.[20] Johnson described the congressional investigation as "on the whole, a whitewash".[20] |

議会による調査 1921年10月の『マーセッド・サンスター』紙の記事は、米海兵隊によるハイチ人殺害について論じている ハイチの教育を受けたエリート層は、愛国連合であり、米国の占領反対派と関係を築いていた。彼らは、全米有色人地位向上協会(NAACP)や白人およびア フリカ系アメリカ人の指導者たちに味方を見出した。[58] NAACPは、フィールド・セクレタリー(現場書記)であり、公民権運動家でもあるジェームズ・ウェルドン・ジョンソンをハイチの状況調査に派遣した。彼 は1920年に報告書を公表し、「米国による占領によってハイチに持ち込まれた経済腐敗、強制労働、報道検閲、人種隔離、無差別暴力」を非難し、多数のア フリカ系アメリカ人が国務省や共和党役員の事務所に手紙を殺到させ、虐待の停止と軍の撤退を要求した 。 ハイチ系アメリカ人の学者W. E. B. デュボイスは、ウィルソン政権の行動に対する対応を要求し、米軍は「島の政治的独立を企図しておらず、利己的な事業利益のために島を無慈悲に搾取しようと いう願望もない」と書いた。 ジョンソンの調査に基づき、NAACPの事務局長ハーバート・J・セリグマンは1920年7月10日付の『ザ・ナショナル』誌に次のように書いた。 「軍事キャンプが島全体に建設された。先住民の所有地が軍事利用のために接収された。銃を所持していたハイチ人は、一時的に見つけ次第射殺された。武装し ていない先住民の群衆に対して機関銃が向けられ、米国海兵隊は、何人死傷したかを調べることもせず、何人かが私との何気ない会話の中で語ったところによる と、 ジョンソンによると、米国がハイチを占領した理由はただ一つであるという。[20] 「米国がなぜハイチに上陸し、5年間も軍隊を駐留させているのか、また、なぜハイチの男女や子供たち約3,000人が米国のライフルや機関銃で撃ち殺され たのかを理解するには、とりわけ、ニューヨークのナショナル・シティ銀行がハイチに強い関心を抱いていることを知る必要がある。ナショナル・シティ銀行が ハイチ国立銀行を支配し、アメリカ政府関係者によって集められているハイチ国家資金の全額を保管していること、そして、ナショナル・シティ銀行の副頭取で あるR.L.ファーンハム氏が、事実上、島国共和国に関する事項における国務省の代表者であることを知る必要がある。 ジョンソンが調査結果を発表してから2年後、1922年に米国で議会による調査が開始された。[20] 議会の報告書にはハイチ人の証言は含まれておらず、ニューヨーク・ナショナル・シティ銀行と米国海兵隊に関する疑惑は無視された。[20] 議会は 米国が撤退すれば「慢性の革命、無政府状態、野蛮、破滅」がハイチを襲うだろうと主張し、ハイチ占領の継続を擁護して報告を締めくくった。ジョンソンは、 この議会調査を「全体として、隠蔽工作」と評した。 |

Borno presidency President Borno on an official visit to the U.S. in 1926 In 1922, Dartiguenave was replaced by Louis Borno, with the US-appointed General John H. Russell, Jr. serving as High Commissioner. General Russell worked on the behalf of the United States Department of State and was authorized as the representative to carry out treaty works.[49] National City Bank acquires BNRH On August 17, 1922, BNRH was completely acquired by National City Bank, its headquarters was moved to New York City and Haiti's debt to France was moved to be paid to American investors.[15][31][49] Following the acquisition of BNRH, the November 1922 issue of National City Bank's employee journal No. 8 exclaimed "Bank of Haiti is Ours!"[31] According to professor Peter James Hudson, "such control represented the end of independence and, as the BNRH and the republic's gold reserve became mere entries on the ledgers of the City Bank, a sign of a return to colonial servitude".[31] Forced labor The Borno-Russell government oversaw the use of forced labor to expand the economy and to complete infrastructure projects.[11] Sisal was introduced to Haiti as a commodity crop, and sugar and cotton became significant exports.[61] However, efforts to develop commercial agriculture met with limited success, in part because much of Haiti's labor force was employed as seasonal workers in the more-established sugar industries of Cuba and the Dominican Republic. An estimated 30,000–40,000 Haitian laborers, known in Cuba as braceros, went annually to the Oriente Province between 1913 and 1931.[62] The Great Depression disastrously affected the prices of Haiti's exports and destroyed the tenuous gains of the previous decade. Under press laws, Borno frequently imprisoned newspaper press that criticized his government.[49] |

ボルノ大統領 1926年に米国を公式訪問したボルノ大統領 1922年、ダティグナベはルイ・ボルノに交代し、米国が任命したジョン・H・ラッセル・ジュニア将軍が高等弁務官を務めた。ラッセル将軍は米国国務省の代理として働き、条約業務を遂行する代表者として承認された。 ナショナル・シティ・バンクがBNRHを買収 1922年8月17日、BNRHはナショナル・シティ・バンクに完全に買収され、本社はニューヨークに移転し、ハイチがフランスに対して負っていた債務は アメリカ合衆国の投資家への支払いに変更された。[15][31][49] BNRHの買収後、ナショナル・シティ・バンクの の従業員向け機関誌『No. 8』は「ハイチの銀行は我々のものだ!」と叫んだ。[31] ピーター・ジェームズ・ハドソン教授によると、「このような支配は独立の終焉を意味し、BNRHと共和国の金準備がシティバンクの帳簿上の単なる項目と なったことで、植民地時代の隷属への回帰の兆しとなった」[31]。 強制労働 ボルノ=ラッセル政権は、経済の拡大とインフラ整備のために強制労働を監督した。[11] サイザル麻が商品作物としてハイチに導入され、砂糖と綿花が重要な輸出品となった。[61] しかし、商業農業の発展は限定的な成功にとどまった。その理由の一つとして、ハイチの労働力の多くが、より確立されたキューバやドミニカ共和国の砂糖産業 で季節労働者として雇用されていたことが挙げられる。推定30,000人から40,000人のハイチ人労働者が、キューバではブラセロ(bracero) として知られ、1913年から1931年の間、毎年オリエンテ州に渡った。[62] 世界大恐慌はハイチの輸出品の価格に壊滅的な影響を与え、それまでの10年間のわずかな利益を破壊した。報道法の下、ボルノ大統領は政府を批判する新聞社 を頻繁に投獄した。[49] |

| Les Cayes massacre Main article: Les Cayes massacre President Herbert Hoover had become increasingly pressured about the effects of occupying Haiti at the time and began inquiring about a withdrawal strategy.[49] By 1929, Haitians had grown angered with the Borno-Russell government and American occupation, with demands for direct elections increasing.[49] In early December 1929, protests against the American occupation began at the Service Technique de l’Agriculture et de l’Enseignement Professionnel's main school.[49] On December 6, 1929, about 1,500 Haitians peacefully protesting local economic conditions in Les Cayes were fired upon by U.S. Marines, with the massacre resulting in 12 to 22 Haitians dead and 51 injured.[5][49][50][53][63] The massacre resulted in international outrage, with President Hoover calling on Congress to investigate conditions in Haiti the following day.[49][64] Forbes Commission, Borno's resignation President Hoover would later appoint two commissions, including one headed by a former U.S. governor of the Philippines William Cameron Forbes.[52]: 232–233 [5] The commission arrived in Haiti on February 28, 1930, with President Hoover demanding the commission to determine "when and how we are to withdraw from Haiti" and "what we shall do in the meantime".[49] The Forbes Commission praised the material improvements that the U.S. administration had achieved, but it criticized the continued exclusion of Haitian nationals from positions of real authority in the government and the gendarmerie. In more general terms, the commission asserted that "the social forces that created [instability] still remain – poverty, ignorance, and the lack of a tradition or desire for orderly free government."[65][66] The commission concluded that occupation of Haiti was a failure and that the United States did not "understand the social problems of Haiti".[50] With increased calls for direct elections, American officials feared violence if demands were not met.[49] An agreement was made that resulted with President Borno's resignation and the establishment of Haitian banker Louis Eugène Roy as an interim president.[49] In the agreement proposed by the Forbes Commission, Roy would be elected by Congress to serve as president until a direct election for Congress was held, which is when Roy would resign.[49] American officials said that if Congress were to refuse, Roy would be installed as president forcibly.[49] |

レカイ虐殺 詳細は「レカイ虐殺」を参照 ハーバート・フーヴァー大統領は、ハイチ占領の影響について次第に圧力をかけられるようになり、撤退戦略について調査を開始した。[49] 1929年までに、ハイチ人はボーン=ラッセル政権とアメリカの占領に怒りを募らせ、直接選挙を求める声が高まっていた。[49] 1929年12月初旬、 29年12月初旬、アメリカ占領に対する抗議が、農業・職業教育技術サービスの本校で始まった。[49] 1929年12月6日、レカイで地元の経済状況に平和的に抗議していた約1,500人のハイチ人が、 アメリカ海兵隊が発砲し、12人から22人のハイチ人が死亡、51人が負傷する大虐殺となった。[5][49][50][53][63] この虐殺は国際的な非難を招き、フーヴァー大統領は翌日、ハイチの状況を調査するよう議会に要請した。[49][64] フォーブス委員会、ボノの辞任 フーヴァー大統領は後に、フィリピン総督を務めたことのあるウィリアム・キャメロン・フォーブスを委員長とする2つの委員会を任命した。[52]: 232–233[5] 委員会は1930年2月28日にハイチに到着し、フーヴァー大統領は委員会に対して 「いつ、どのようにしてハイチから撤退するか」と「それまでの間、何をすべきか」を決定するよう求めた。[49] フォーブス委員会は、米国政府が達成した物質的な改善を称賛したが、ハイチ国民が政府や憲兵隊の実際の権限のある地位から排除され続けていることを批判し た。より一般的な表現で、委員会は「不安定を生み出した社会的勢力は依然として残っている。すなわち、貧困、無知、そして秩序ある自由な政府を求める伝統 や願望の欠如である」と主張した。[65][66] 委員会は、ハイチ占領は失敗であり、米国は「ハイチの社会的問題を理解していない」と結論付けた。[50] 直接選挙を求める声が高まる中、アメリカ政府高官は要求が満たされない場合の暴力を恐れていた。[49] ボルノ大統領の辞任とハイチ人銀行家ルイ・ユージン・ロイの暫定大統領就任という合意が成立した。[49] フォーブス委員会が提案した合意では、 ロイは議会によって大統領に選出され、議会選挙が実施されるまでその職務を務めることになっていたが、その時点でロイは辞任することになっていた。 [49] アメリカ政府高官は、議会が拒否した場合、ロイは強制的に大統領に就任すると述べた。[49] |

| Vincent presidency Under orders to not interfere with elections, the United States observed elections on October 14, 1930, that resulted with Haitian nationalist candidates being elected.[49] Sténio Vincent was elected President of Haiti by the Congress of Haiti in November 1930.[49] The new nationalist government had a tense relationship with American officials.[49] By the end of 1930, Haitians were being trained by Americans for administration roles of their own nation.[49] When additional American commissions began to arrive in Haiti, popular unrest broke out and President Vincent reached a secret agreement to ease tensions with the United States in exchange to grant more power to American officials to enact their "Haitianization" policies.[49] Franklin D. Roosevelt, who as Assistant Secretary of the Navy said he was responsible for drafting the 1918 constitution,[49] was a proponent of the "Good Neighbor policy" for the US role in the Caribbean and Latin America.[12] The United States and Haiti agreed on August 7, 1933, to end the occupation.[49] On a visit to Cap-Haïtien in July 1934, Roosevelt reaffirmed the August 1933 disengagement agreement. The last contingent of US Marines departed on August 15, 1934, after a formal transfer of authority to the Garde.[67] The U.S. retained influence on Haiti's external finances until 1947, as per the 1919 treaty that required an American financial advisor through the life of Haiti's acquired loan.[49][68] |

ヴィンセント大統領 選挙への介入を禁じられていた米国は、1930年10月14日に行われた選挙を監視し、その結果、ハイチ人ナショナリスト候補が当選した。[49] ステニオ・ヴィンセントは、1930年11月にハイチ議会によってハイチ大統領に選出された。[49] 新しいナショナリスト政府は、米国当局と緊張関係にあった。[49] 1930年末までに、ハイチ人は自国の行政職に就くための訓練をアメリカ人から受けていた。[49] さらに多くのアメリカの委員会がハイチに到着すると、民衆の不安が高まり、ヴィンセント大統領はアメリカ人職員に「ハイチ化」政策を実施する権限を付与す る見返りとして、アメリカとの緊張を緩和する秘密協定を結んだ。[49] 1918年の憲法草案の作成に責任があったと語った海軍次官フランクリン・D・ルーズベルトは、カリブ海および中南米における米国の役割として「善隣外 交」を推進していた。1933年8月7日、米国とハイチは占領の終了に合意した。[49] 1934年7月、カパイシャンを訪問したルーズベルトは、1933年8月の撤退合意を再確認した。1934年8月15日、米海兵隊の最後の部隊が、ガード への正式な権限委譲の後、ハイチを去った。[67] 1919年の条約により、ハイチが獲得した融資の全期間を通じて、アメリカ人財務顧問を置くことが義務付けられていたため、アメリカは1947年までハイ チの対外金融に影響力を維持した。[49][68] |

| Effects Economy The occupation was costly for the Haitian government; American advisors collected about 5% of Haiti's revenue while the 1915 treaty with the United States limited Haiti's income, resulting with fewer jobs for the government to assign.[7][49] Numerous agricultural changes included the introduction of sisal. Sugarcane and cotton became significant exports, boosting prosperity.[69] However, efforts to develop commercial agriculture produced limited results while American agricultural businesses removed the property from thousands of Haitian peasants to produce bananas, sisal and rubber for export, resulting with lower domestic food production.[15][62] Haitian traditionalists, based in rural areas, were highly resistant to U.S.-backed changes, while the urban elites, typically mixed-race, welcomed the growing economy, but wanted more political control.[45][49] Following the end of the occupation in 1934, under the Presidency of Sténio Vincent (1930–1941),[45][70] debts were still outstanding and the U.S. financial advisor-general receiver handled the budget until 1941 when three American and three Haitian directors headed by an American manager assumed the role.[45][49] Haiti's loan debt to the United States was about twenty percent of the nation's annual revenue.[49] Formal American influence on Haiti's economy would conclude in 1947.[68] The United Nations and the United States Department of State would report at the time that Haitian rural peasants, who comprised 90% of the nation's population, lived "close to starvation level".[7][9] |

影響 経済 この職業はハイチ政府にとって負担の大きいものであった。1915年のアメリカとの条約によりハイチの収入は制限され、政府が割り当てる仕事は減少した。 [7][49] 農業では、サイザルの導入など、数多くの変化があった。サトウキビと綿花は重要な輸出品となり、繁栄を後押しした。[69] しかし、商業農業を発展させようとする努力は限定的な成果しか挙げられず、一方でアメリカ合衆国の農業事業者は、輸出用のバナナ、サイザル麻、ゴムを生産 するために、何千ものハイチ人農民から財産を没収し、国内の食糧生産量は減少した。[15][62] 農村部に住むハイチ人の伝統主義者は、米国が支援する変化に強く抵抗したが、都市部のエリート層(多くは混血)は経済成長を歓迎したが、より政治的な統制 を望んでいた。[45][49] 1934年の占領終了後、ステニオ・ヴァンサン大統領(在任1930年~1941年)の下で、 [45][70] 債務は依然として未払いであり、1941年にアメリカ人経営者が率いる3人のアメリカ人と3人のハイチ人の理事がその役割を引き受けるまで、アメリカの財 務顧問兼管財人が予算を管理していた。[45][49] ハイチがアメリカに負っていた貸付金は、国民の年間収入の約20%に相当した。[49] アメリカによるハイチ経済への公式な影響力は1947年に終結した。[68] 国際連合と米国国務省は当時、国民の90%を占めるハイチの農村部の農民たちが「飢餓レベルに近い」生活を送っていると報告した。[7][9] |

| Infrastructure The occupation improved some of Haiti's infrastructure and centralized power in Port-au-Prince, though much of the funds collected by the United States was not used to modernize Haiti.[12][48][45] Corvée forced labor of Haitians, that was enforced by the US-operated gendarmerie, was used for infrastructure projects, particularly for road building. Forced labor would ultimately result in the deaths of hundreds to thousands of Haitians.[5] Infrastructure improvements included 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi) of roads being made usable, 189 bridges built, the rehabilitation of irrigation canals, the construction of hospitals, schools, and public buildings, and drinking water was brought to the main cities. Port-au-Prince became the first Caribbean city to have a phone service with automatic dialing. Agricultural education was organized, with a central school of agriculture and 69 farms in the country.[61][18] The majority of Haitians believed that the public works projects enforced by the US Marines were unsatisfactory.[45] American officers who controlled Haiti at the time spent more on their own salaries than on the public health budget for two million Haitians.[7] A 1949 report by the United States Department of State wrote that irrigation systems that were recently constructed were "not in good condition".[9] Education The United States redesigned the education system. It dismantled the liberal arts education which the Haitians had inherited (and adapted) from the French system.[71] With the Service Technique de l’Agriculture et de l’Enseignement Professionnel, Americans emphasized agricultural and vocational training, similar to its industrial education for minorities and immigrants in the United States.[49][71] Dr. Robert Russa Moton was tasked with assessing the Service Technique, concluding that though the objectives were admirable, performance was not satisfactory and criticized the large amount of funding it received compared to average Haitian public schools, which were in poor condition.[49] Elite Haitians despised the system, believing it was discriminatory against their people.[49][71] The mulatto elite also feared the creation of an educated middle class that would potentially lead to the loss of their influence.[49] |

インフラ この占領によりハイチのインフラの一部は改善され、ポルトープランスに権力が集中したが、アメリカ合衆国が集めた資金の多くはハイチの近代化には使用され なかった。[12][48][45] アメリカ合衆国が運営する憲兵隊によって強制されたハイチ人の強制労働は、インフラプロジェクト、特に道路建設に使用された。強制労働は最終的に何百から 何千ものハイチ人の死につながった。[5] インフラの改善には、1,700キロメートル(1,100マイル)の道路の使用可能化、189の橋の建設、灌漑用水路の修復、病院、学校、公共施設の建 設、主要都市への飲料水の供給などが含まれた。 ポルトープランスは自動ダイヤル式の電話サービスが導入された最初のカリブ海都市となった。農業教育が組織化され、中央農業学校と国内69か所の農場が設 置された。[61][18] 大多数のハイチ人は、アメリカ海兵隊が実施した公共事業プロジェクトは不十分であると考えていた。[45] その当時ハイチを統治していたアメリカ人将校たちは、200万人のハイチ人のための保健予算よりも、自分たちの給料に多くのお金を使っていた。[7] 1949年の米国務省の報告書は、最近建設された灌漑システムは「状態が良くない」と記している。[9] 教育 米国は教育システムを再設計した。 ハイチ人がフランスから受け継ぎ(そして適応した)教養教育を解体したのである。[71] 農業・職業教育サービス(Service Technique de l’Agriculture et de l’Enseignement Professionnel)により、米国は農業および職業訓練を重視し、これは米国における少数民族や移民向けの工業教育に類似していた 。ロバート・ラッサ・モートン博士は、この職業訓練校の評価を任されたが、その目的は立派であるものの、成果は満足のいくものではないと結論づけ、平均的 なハイチ公立学校と比べて多額の資金が投入されていることを批判した。 エリート層は、この制度を自民族に対する差別であると見なし、軽蔑していた。[49][71] 混血エリート層もまた、自分たちの影響力が失われる可能性があるとして、教育を受けた中流階級の誕生を恐れていた。[49] |

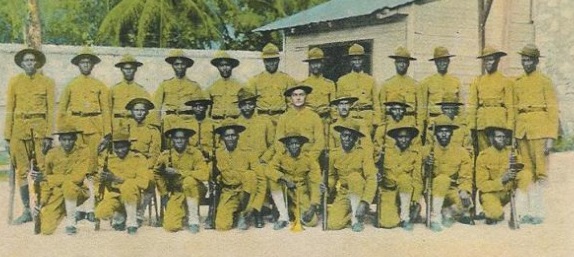

Human rights abuses Gendarmerie of Haiti personnel, who were commanded by United States Marines The United States Marines ruled Haiti as a military regime using a constant state of martial law, operating the newly created Haitian gendarmerie to suppress Haitians who opposed occupation.[11][20] Between 1915 and 1930, Haitians represented only about 35–40% of officers in the gendarmes.[49] During the occupation of Haiti by the United States, human rights abuses were committed against the native Haitian population.[11][12] Such actions involved censorship, concentration camps, forced labor, racial segregation, religious persecution of Haitian Vodou practitioners and torture.[11][12][5] Overall, American troops and the Haitian gendarmerie killed several thousand Haitian civilians during the rebellions between 1915 and 1920, though the exact death toll is unknown.[7][5] During Senate hearings in 1921, the commandant of the Marine Corps reported that, in the 20 months of active unrest, 2,250 Haitian rebels had been killed. However, in a report to the Secretary of the Navy, he reported the death toll as being 3,250.[72] According to Haitian American academic Michel-Rolph Trouillot, about 5,500 Haitians died in labor camps alone.[5] Haitian historian Roger Gaillard, estimated that in total, including rebel combatants and civilians, at least 15,000 Haitians were killed throughout the occupation.[5] According to Paul Farmer, the higher estimates are not supported by most historians outside Haiti.[4] American troops also performed union-busting actions, often for American businesses like the Haitian American Sugar Company, the Haitian American Development Corporation and National City Bank of New York.[11][20] |

人権侵害 ハイチ憲兵隊の隊員は、アメリカ海兵隊の指揮下にあった アメリカ海兵隊は、ハイチを軍事政権として支配し、占領に反対するハイチ人を弾圧するために、新たに創設されたハイチ憲兵隊を運用し、常時戒厳令を敷いて いた[11][20]。1915年から1930年の間、ハイチ人が憲兵隊の将校に占める割合は、わずか35~40%であった 。[49] アメリカによるハイチ占領中、ハイチ先住民に対して人権侵害が行われた。[11][12] 検閲、強制収容所、強制労働、人種隔離、ハイチ人のヴードゥー教信者に対する宗教迫害、拷問などの行為が行われた。[11][12][5] 全体として、アメリカ軍とハイチ国家憲兵隊は、1915年から1920年にかけての反乱の間に、数千人のハイチ民間人を殺害した。正確な死者数は不明であ るが[7][5]。1921年の上院公聴会で、海兵隊司令官は、20か月にわたる暴動で2,250人のハイチ人反乱者が死亡したと報告した。しかし、海軍 長官への報告では、死者は3,250人と報告している。[72] ハイチ系アメリカ人の学者ミシェル=ロルフ・トゥルイヨによると、強制労働収容所だけで約5,500人のハイチ人が死亡した。[5] 。ハイチ人歴史家のロジャー・ガイヤールは、反乱軍の戦闘員と民間人を含め、占領期間中に少なくとも1万5000人のハイチ人が死亡したと推定している。 米軍は、ハイチ系アメリカ人砂糖会社、ハイチ系アメリカ人開発公社、ニューヨーク国民都市銀行などの米国企業のために、労働組合潰しをしばしば行っていた。[11][20] |

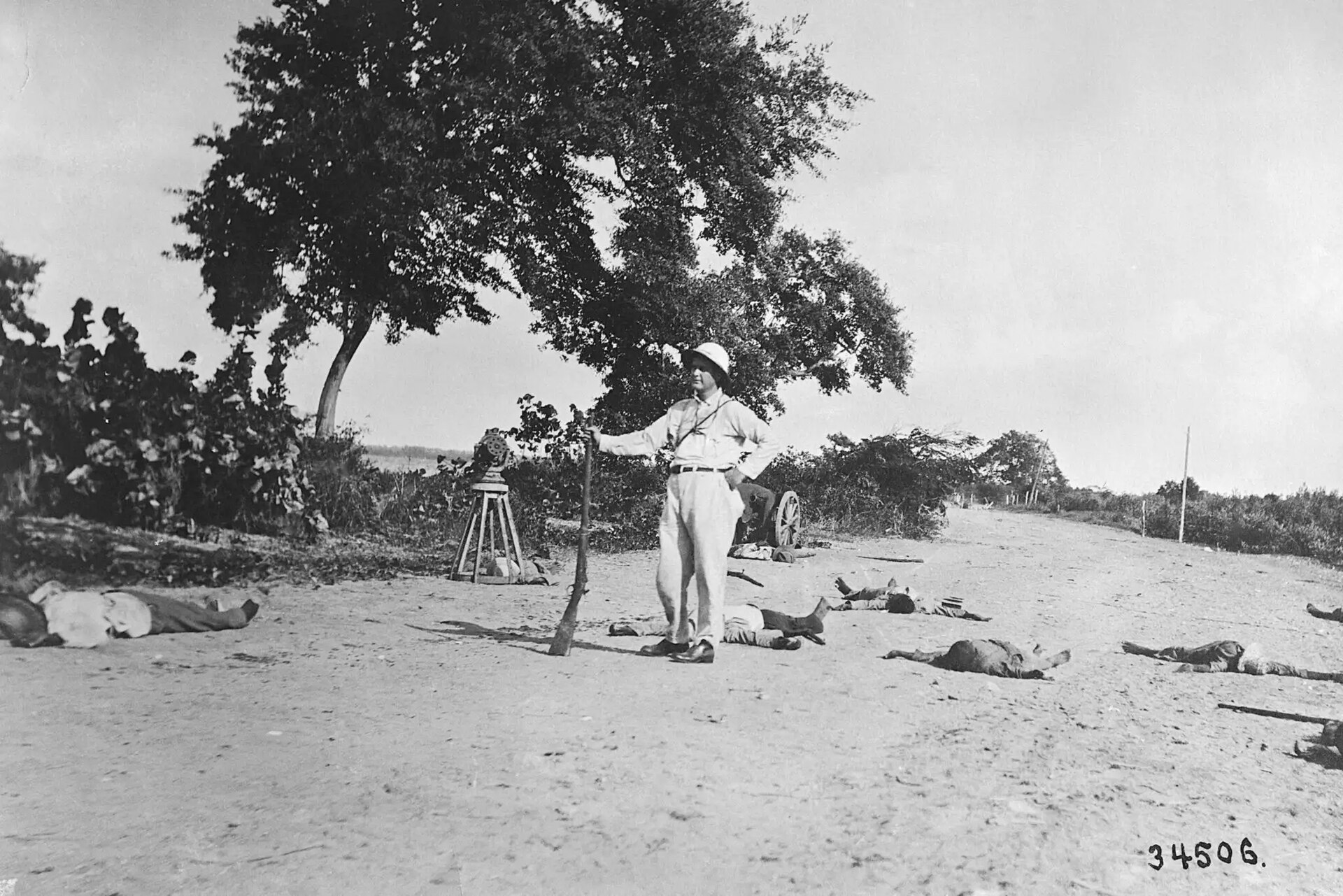

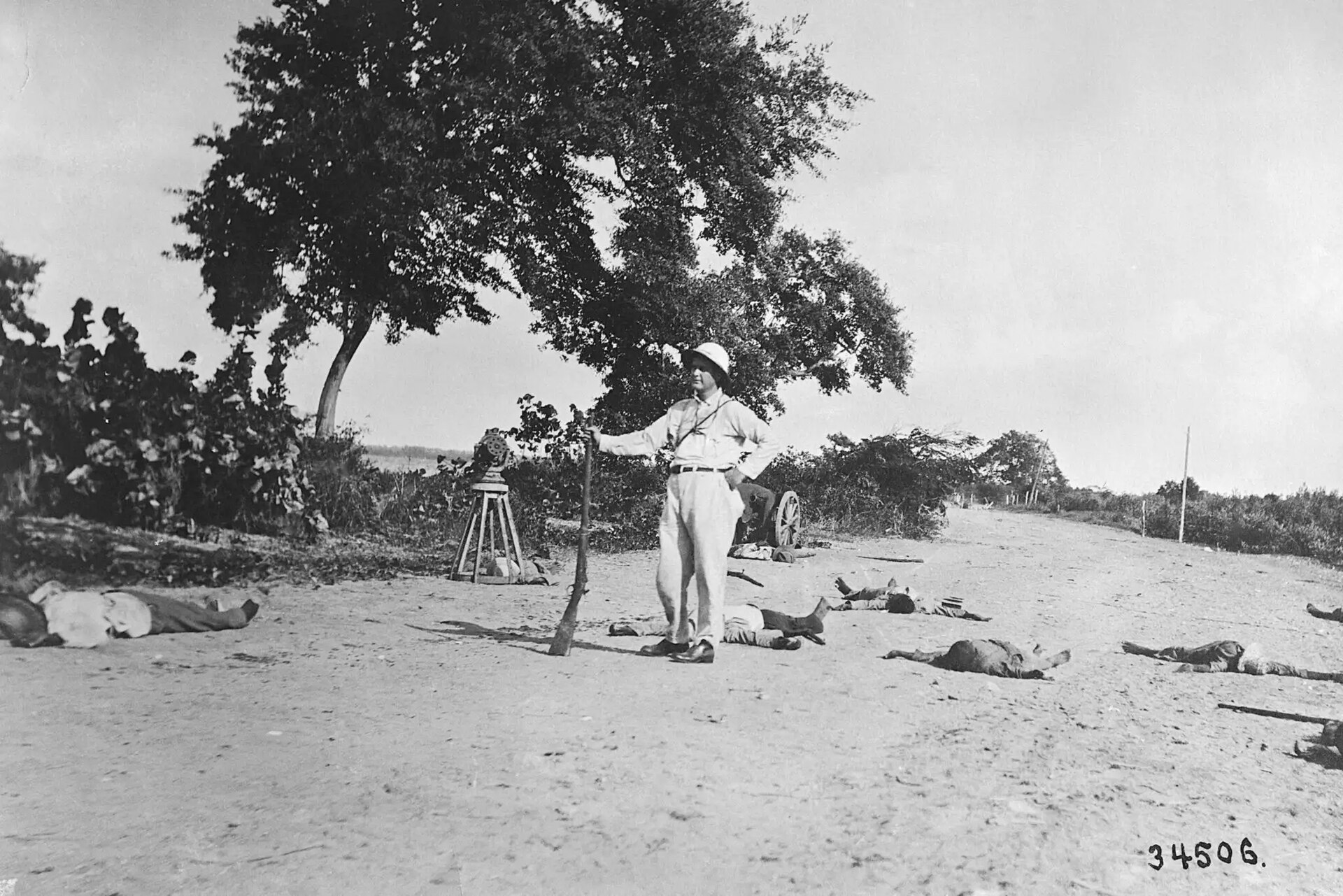

Executions and killings The photograph of Charlemagne Péralte's body distributed by U.S. troops to Haitians Under American occupation, extrajudicial executions were committed against Haitians.[7] During the second Caco war of 1918–1919, many Caco prisoners were summarily executed by Marines and the gendarmerie on orders from their superiors.[5] On June 4, 1916, Marines executed Caco General Mizrael Codio and ten others captured in Fonds-Verrettes.[5] In Hinche in January 1919, Captain Ernest Lavoie of the gendarmerie, a former United States Marine, allegedly ordered the killing of nineteen Caco rebels according to American officers, though no charges were placed due to no physical evidence being presented.[5] During the investigation of two marines accused of illegally executing Haitians, the attorney of the soldiers minimized their actions, saying that such killings were common, prompting larger investigations into the matter.[48] One controversial event occurred when in an attempt to discourage rebel support from the Haitian population, the US troops took a photograph of Charlemagne Péralte's body tied to a door following his assassination in 1919, and distributed it in the country.[11][73]: 218 However, it had the opposite effect, with the image's resemblance to a crucifixion making it an icon of the resistance and establishing Péralte as a martyr.[74]  Black and white photo of a man standing among bodies lying on the ground American poses with dead Haitians killed by U.S. Marine machine gun fire on October 11, 1915 Mass killings of civilians were allegedly committed by United States Marines and their Haitian gendarmerie subordinates.[5] According to Haitian historian Roger Gaillard, such killings involved rape, lynchings, summary executions, burning villages and deaths by burning. Internal documents of the United States Army justified the killing of women and children, describing them as "auxiliaries" of rebels. A private memorandum of the Secretary of the Navy criticized "indiscriminate killings against natives". American officers responsible for acts of violence were given names in Creole such as "Linx" for Commandant Freeman Lang and "Ouiliyanm" for Sergeant Dorcas Lee Williams. According to American journalist H. J. Seligman, Marines would practice "bumping off Gooks", describing the shooting of civilians in a similar manner as killing for sport.[5] Beginning in 1919, American troops began attacking rural villages.[5] In November 1919, villagers in Thomazeau hiding in a nearby forest sent a letter – the only surviving testament of the event – to a French priest asking for protection.[5] In the letter, survivors wrote that at least two American planes bombed and shot at two villages, killing half of the population, including men, women, children and the elderly.[5] On December 5, 1919, American planes bombed Les Cayes in a possible act of intimidation.[5] American pilots were investigated for their actions, though none were condemned.[5] These actions were described by anthropologist Jean-Philippe Belleau as possibly "the first ever carried out by air on civilian populations".[5] |

処刑と殺害 米軍がハイチ人に配布したシャルルマーニュ・ペラルテの遺体の写真 アメリカ占領下では、ハイチ人に対する超法規的処刑が行われた。[7] 1918年から1919年にかけての第二次カコ戦争では、多くのカコの捕虜が上官の命令により海兵隊と憲兵隊によって即決処刑された。[5] 1916年6月4日、海兵隊はフォン・ヴェルテスで捕らえたカコのミズラエル・コディオ将軍と10人を処刑した。[5] 1919年1月、 1919年1月、ヒンチでは、アメリカ海兵隊の退役軍人である憲兵隊のアーネスト・ラヴォワ大尉が、アメリカ人将校によると、19人のカコ反乱軍の殺害を 命じたとされるが、物的証拠が提示されなかったため、告発はされなかった。[5] 2人の海兵隊員がハイチ人を違法に処刑した容疑で調査が行われた際、兵士の弁護士は、そのような殺害は日常茶飯事だったと彼らの行為を軽視し、この件に関 するより大規模な調査を促した。[48] 論争を呼んだ出来事のひとつとして、1919年にシャルルマーニュ・ペラルテが暗殺された後、ハイチ住民の反乱軍への支援を思いとどまらせるために、米軍 がペラルテの死体をドアに縛り付けた状態で撮影し、国内で配布したことが挙げられる 。しかし、その効果は逆で、磔にされた姿に似ていることから、その写真は抵抗運動の象徴となり、ペラルテは殉教者として知られるようになった。  地面に横たわる死体の間から立つ男のモノクロ写真 1915年10月11日、アメリカ海兵隊の機関銃掃射により死亡したハイチ人の死体を掲げるアメリカ人 民間人の大量殺害は、アメリカ海兵隊と彼らのハイチ人憲兵隊の部下によって行われたとされている。[5] ハイチの歴史家ロジャー・ガイヤールによると、このような殺害には強姦、リンチ、即決処刑、村の焼き討ち、焼殺などが含まれていた。 アメリカ陸軍の内部文書では、女性や子供を反乱軍の「協力者」と表現し、彼らの殺害を正当化していた。海軍長官の私的な覚書では、「原住民に対する無差別 殺害」を批判している。暴力行為の責任を負うべきアメリカ人将校たちには、クレオール語で「リンクス」という名前が付けられたフリーマン・ラング司令官 や、「ウィリアムズ」という名前が付けられたドルカス・リー・ウィリアムズ軍曹などがいる。アメリカのジャーナリスト、H. J. セリグマンによると、海兵隊員たちは「グックの始末」を実践し、スポーツとしての殺人と同様に民間人の射殺を行っていたという。 1919年から、アメリカ軍は農村を攻撃し始めた。1919年11月、トマゾーの村人たちは近くの森に身を隠しながら、唯一現存するこの事件の証言となる 手紙をフランス人司祭に送り、保護を求めた。男性、女性、子供、高齢者を含む人口の半分が死亡したと書かれていた。[5] 1919年12月5日、アメリカ軍機がレカイを爆撃し、威嚇行為を行った可能性がある。[5] アメリカ人パイロットたちはその行動について調査されたが、誰も非難されることはなかった。[5] 人類学者のジャン=フィリップ・ベローは、これらの行動を「民間人に対して空から行われた史上初の攻撃」である可能性があると述べた。[5] |

| Forced labor A corvée policy of forced labor was enacted upon Haitians, enforced by the U.S.-operated Haitian gendarmerie in the interest of improving economic conditions to fulfill foreign debts – including payments to the United States – and to improve the nation's infrastructure.[11][12][16] The corvée system was found in Haiti's rural code by Major Smedley D. Butler, who testified that forced labor cut the cost of 1 mile (1.6 km) of road construction from $51,000 per mile to $205 per mile.[48] The corvée resulted in the deaths of hundreds to thousands of Haitians. Haitians were tied together in rope and those fleeing labor projects were often shot.[7] According to Haitian American academic Michel-Rolph Trouillot, about 5,500 Haitians died in labor camps.[5] In addition, Roger Gaillard writes that some Haitians were killed fleeing the camps or if they did not work satisfactorily.[5] Many of the deaths and killings attributed to forced labor occurred during the extensive construction of roads in Haiti.[5] In some instances, Haitians were forced to work on projects without pay and while shackled to chains.[11] The corvée system's treatment of Haitians has been compared to the system of bondage labor enforced upon black Americans during the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War.[11] |

強制労働 強制労働の義務制度がハイチ人に課せられ、米国が関わる対外債務の支払いを含む経済状況の改善と、国民のインフラの改善を目的として、米国が運営するハイ チ憲兵隊によって施行された。[11][12][16] 強制労働制度は、スミデレ・D・バトラー少佐によってハイチの農村法規で発見された。同少佐は、強制労働によって1マイル(1.6km)の道路建設費用が 1マイルあたり5万1000ドルから205ドルに削減されたと証言している。 この強制労働により、何百人から何千人ものハイチ人が命を落とした。ハイチ人は互いにロープで縛られ、労働現場から逃げようとした者は銃撃されることも多 かった。[7] ハイチ系アメリカ人の学者ミシェル=ロルフ・トゥルイヨによると、強制労働収容所で約5,500人のハイチ人が死亡した。[5] また、ロジャー・ガイヤールは、収容所から逃げたり、満足に働かなかったりしたハイチ人が殺害されたと書いている。[5] 強制労働に起因する死や殺人の多くは、 強制労働に起因する死傷者の多くは、ハイチ国内の広範囲にわたる道路建設中に発生した。[5] 場合によっては、ハイチ人は無給で、鎖につながれたままの状態でプロジェクトに従事させられた。[11] 苦役制度によるハイチ人への扱いは、南北戦争後の再建時代に黒人アメリカ人に課せられた奴隷労働制度と比較されている。[11] |

| Racism Many of those tasked with the occupation of Haiti espoused racist beliefs.[7] The first Marine commander ashore assigned was Colonel Littleton Waller, who had a history of racism against mulattos, describing them as "real nigger ... real nigs beneath the surface".[48][75] Wilson's Secretary of State Robert Lansing also held racist beliefs, writing at the time that "the African race are devoid of any capacity for political organization".[7][75] The United States introduced Jim Crow laws to Haiti with racist attitudes towards the Haitian people by the American occupation forces that were blatant and widespread.[7][50][76] Many of the Marines chosen to occupy Haiti were from the Southern United States, specifically Alabama and Louisiana, resulting in increased racial tensions.[5][50] Racism has been recognized as a factor leading to increased violence by American troops against Haitians. One general described Haitians as "niggers who pretend to speak French".[5] Initially, officers and the elites intermingled at social gatherings and clubs. Such gatherings were minimized when families of American forces began arriving.[76] Relations degraded rapidly upon departure of officers for World War I.[76] The Haitian elite found the American junior and non-commissioned officers to be ignorant and uneducated.[76] There were numerous reports of remaining Marines drinking to excess, fighting, and sexually assaulting women.[76] The situation was so bad that Marine general John A. Lejeune, based in Washington, D.C., banned the sale of alcohol to any military personnel.[76] The Americans inhabited neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince in high-quality housing. This neighborhood was called the "millionaires' row".[77] Hans Schmidt recounted a navy officer's opinion on the matter of segregation: "I can't see why they wouldn't have a better time with their crowd, just as I do with mine."[78] American racial intolerance provoked indignation and resentment – and eventually a racial pride that was reflected in the work of a new generation of Haitian historians, ethnologists, writers, artists, and others. Many of these later became active in politics and government. The elite Haitians, mostly mixed-race with higher levels of education and capital, continued to dominate the country's bureaucracy and to strengthen its role in national affairs.[citation needed] Colorism, which had existed since French colonization, had also become prevalent once more under American occupation and racial segregation became common.[11] All three rulers during the occupation came from the country's mixed-race elite.[79] At the same time, many in the growing black professional classes departed from the traditional veneration of Haiti's French cultural heritage and emphasized the nation's African roots.[79] Among these were ethnologist Jean Price-Mars and François Duvalier, editor of the journal Les Griots (the title referred to traditional African oral historians, the storytellers) and future totalitarian president of Haiti. The racism and violence that occurred during the United States occupation of Haiti, inspired black nationalism among Haitians and left a powerful impression on the young Duvalier.[50] |

人種主義 ハイチ占領を任務とする者の多くは人種差別的な信念を信奉していた。[7] 最初に上陸した海兵隊司令官はリトルトン・ウォーラー大佐で、彼は混血の人々に対して人種差別的な歴史を持ち、彼らを「本物のニガー...本物のニガーの 表面下」と表現していた。[48][75] ウィルソンの国務長官ロバート・ランシングも人種差別的な信念を持ち、当時「アフリカ人種は政治的な組織能力を一切持たない」と記している。[7] [75] 」と記している。[7][75] アメリカ合衆国は、ハイチ人に対する人種差別的な態度から、ハイチにジム・クロウ法を導入した。これは、アメリカ占領軍によるあからさまな差別的態度であ り、広く浸透していた。[7][50][76] ハイチ占領に選ばれた海兵隊員の多くはアメリカ南部、特にアラバマ州とルイジアナ州出身であり、人種間の緊張を高める結果となった。[5][50] 人種主義は、アメリカ軍によるハイチ人に対する暴力の増加につながる要因であると認識されている。ある将軍はハイチ人を「フランス語を話すふりをするニ ガー」と表現した。 当初は、士官とエリート層は社交の場やクラブで交流していた。しかし、アメリカ軍の家族が到着し始めると、そのような交流は減少した。[76] 第一次世界大戦への出征により、両者の関係は急速に悪化した。[76] ハイチのエリート層は、アメリカ軍の下士官や准士官が無知で教養がないと感じていた。[76] 残った海兵隊員が過剰に飲酒し、喧嘩をし、女性に性的暴行を加えているという報告が多数寄せられた。[76] 状況は非常に悪かったため、ワシントンD.C.にいた海兵隊司令官ジョン・A・ルジューンは、軍人へのアルコール販売を禁止した。[76] アメリカ軍は、良質な住宅が立ち並ぶポルトープランス近隣に居住していた。この地区は「百万長者の行進」と呼ばれていた。[77]ハンス・シュミットは、 隔離に関する海軍士官の意見を次のように述べている。「なぜ彼らが自分たちだけで楽しい時間を過ごさないのか、私には理解できない。私だって自分の仲間と 楽しい時間を過ごすのに」[78] アメリカ人の人種的不寛容は、憤りと憤慨を呼び起こし、最終的には人種的誇りを生み出した。それは、ハイチの新世代の歴史家、民族学者、作家、芸術家など の作品に反映されている。これらの人々の多くは、後に政治や政府で活躍するようになった。エリート層であるハイチ人の多くは、教育水準が高く、資本家であ る混血の人々であり、国の官僚機構を支配し続け、国民生活における役割を強化した。 フランスによる植民地化以来存在していた人種差別主義も、アメリカの占領下で再び広まり、人種隔離が一般的になった。[11] 占領下における3人の支配者はすべて、混血エリート階級出身であった。[79] 同時に、成長する黒人専門職階級の多くは、 ハイチにおけるフランス文化の伝統的崇拝から離れ、国民のルーツであるアフリカを強調するようになった。[79] その中には、民族学者のジャン・プライス=マルスや、雑誌『グリオ』(タイトルの語源はアフリカの伝統的な口承史家、語り部)の編集者であり、後にハイチ の全体主義大統領となるフランソワ・デュバリエがいた。 アメリカ合衆国によるハイチ占領中に発生した人種主義と暴力は、ハイチ人の間で黒人ナショナリズムを刺激し、若き日のデュバリエに強烈な印象を残した。 [50] |

| Torture The torture of Haitian rebels or those suspected of rebelling against the United States was common among occupying Marines. Some methods of torture included the use of water cure, hanging prisoners by their genitals and ceps, which involved pushing both sides of the tibia with the butts of two guns.[5] |

拷問 ハイチ人反乱軍やアメリカ合衆国に対して反乱を起こした容疑者の拷問は、占領中の海兵隊の間では一般的であった。拷問の方法には、水責め、性器と陰茎を吊り下げる方法(脛骨の両側を2丁の銃の銃床で押す)などがあった。[5] |

| Analysis 20th century Haitian writers and public figures also responded to the occupation. For example, a minister of public education, Dantès Bellegarde raised issues with the events in his book, La Résistance Haïtienne (l'Occupation Américaine d'Haïti). Bellegarde outlines the contradictions of the occupation with the realities. He accused President Wilson of writing the new Haitian Constitution to benefit the Americans, and wrote that Wilson's main purpose was to remove the previous Haitian clause that stated foreigners could not own land in the country. The original clause was designed to protect Haiti's independence from foreign powers.[80] With the clause removed, Americans (including whites and other foreigners) could now own land. Furthermore, Bellegarde discusses the powerlessness of Haitian officials in the eyes of the Occupation because nothing could be done without the consent of the Americans. However, the main issue that Bellegarde articulates is that the Americans tried to change the education system of Haiti from one that was French based to that of the Americans. Even though Bellegarde was resistant he had a plan to build a university in Haiti that was based on the American system. He wanted a university with various schools of science, business, art, medicine, law, agriculture, and languages all connected by a common area and library. However, that dream was never realized because of the new direction the Haitian government was forced to take. Jean Price-Mars[81] associated the reasons behind the occupation to the division between the Haitian elite and the poorer people of the country. He noted that the groups were divided over the practice of Haitian Vodou, with the implication that the elites did not recognize Vodou because they connected it to an evil practice.[82] |

分析 20世紀 のハイチ人作家や著名人も、占領に反応した。例えば、公共教育大臣のダンテス・ベルグラードは、著書『ハイチの抵抗(La Résistance Haïtienne)』(『ハイチ占領(l'Occupation Américaine d'Haïti)』)で、占領下での出来事を問題提起した。ベルグラードは、占領下での現実の矛盾を概説した。彼は、ウィルソン大統領がアメリカ人の利益 のために新しいハイチ憲法を起草したと非難し、ウィルソンの主な目的は、外国人がその国で土地を所有できないと定めた以前のハイチ条項を削除することだっ たと書いた。この条項は、外国勢力からハイチの独立を守るために設けられたものだった。[80] この条項が削除されたことで、アメリカ人(白人やその他の外国人を含む)が土地を所有することが可能になった。さらに、ベルガルドは、アメリカ人の同意な しには何もできないため、占領下にあるハイチ政府高官の無力さを論じている。しかし、ベルガルドが明確に述べている主な問題は、アメリカ人がハイチの教育 システムをフランス式からアメリカ式に変えようとしたことである。ベルガルドは抵抗を示したが、ハイチにアメリカ式の大学を建設する計画を持っていた。科 学、ビジネス、芸術、医学、法律、農業、言語など、さまざまな学部が共通エリアと図書館でつながった大学を彼は望んでいた。しかし、その夢は、ハイチ政府 が新たな方向性を余儀なくされたために、実現されることはなかった。 ジャン・プライス・マース(Jean Price-Mars)[81]は、占領の背景にはハイチの上流階級と貧困層との対立があると指摘した。彼は、両者の対立はハイチ・ヴードゥーの実践をめ ぐるものであり、上流階級がヴードゥーを悪しき慣習と結びつけていたためにヴードゥーを認めようとしなかった、と示唆した[82]。 |

| 21st century Pezullo writes in his 2006 book Plunging Into Haiti: Clinton, Aristide, and the Defeat of Diplomacy that the racism similar to Jim Crow laws in the United States inspired black nationalism within Haiti and ignited future support for Haitian dictator François Duvalier.[50] In a 2013 article by Peter James Hudson published in Radical History Review, Hudson wrote:[20] Ostensibly initiated on humane grounds, the occupation had not fulfilled any of its stated goals of building infrastructure, expanding education, or providing internal or regional stability. Repressive violence emerged as its only purpose and logic. Hudson further stated that the motives of American businessmen to become involved in Haiti were due to racial capitalism motivated by white supremacy.[20] According to a 2020 study which contrasts the American occupations of both Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the United States had a longer and more domineering occupation of Haiti because of perceived racial differences between the two populations. Dominican elites articulated a European–Spanish identity – in contrast to Haitian blackness – which led U.S. policymakers to accept leaving the territory in the population's hands.[83] |

21世紀 ペズロは2006年の著書『Plunging Into Haiti: Clinton, Aristide, and the Defeat of Diplomacy』で、米国のジム・クロウ法に類似した人種主義がハイチ国内で黒人ナショナリズムを刺激し、後にハイチの独裁者フランソワ・デュバリエ への支持に火をつけたと書いている。[50] ピーター・ジェームズ・ハドソンが『Radical History Review』誌に2013年に発表した記事で、ハドソンは次のように書いている。[20] 表向きは人道的な理由から開始された占領は、インフラの整備、教育の拡大、国内や地域的な安定の提供といった、その表明された目標のどれも達成できなかった。抑圧的な暴力が唯一の目的と論理として現れた。 さらにハドソンは、ハイチに関与しようとしたアメリカ人実業家の動機は、白人至上主義に動機づけられた人種資本主義によるものだったと述べている。 2020年の研究によると、アメリカによるハイチとドミニカ共和国の占領を比較したところ、アメリカは両国の人口間に人種的な違いがあると考えたため、ハ イチをより長く、より支配的に占領した。ドミニカ共和国のエリート層は、ハイチの黒人とは対照的に、ヨーロッパ・スペインのアイデンティティを明確にして おり、これがアメリカ政府の政策立案者たちがその領土を人口の手に委ねることを受け入れることにつながった。[83] |

| History of the Dominican Republic History of Haiti Banana Wars Battle of Fort Dipitie Battle of Fort Rivière Dominican Republic–United States relations United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1916–1924) Haiti during World War I Haiti–United States relations Foreign interventions by the United States Foreign policy of the United States Foreign relations of the United States Latin America–United States relations United States involvement in regime change |

ドミニカ共和国の歴史 ハイチの歴史 バナナ戦争 ディピティ砦の戦い リヴィエール砦の戦い ドミニカ共和国とアメリカ合衆国の関係 アメリカ合衆国のドミニカ共和国占領(1916年 - 1924年 第一次世界大戦中のハイチ ハイチとアメリカ合衆国の関係 アメリカ合衆国の外国への介入 アメリカ合衆国の外交政策 アメリカ合衆国の外交関係 ラテンアメリカとアメリカ合衆国の関係 アメリカ合衆国の政権変革への関与 |

| Sources Heinl, Robert (1996). Written in Blood: The History of the Haitian People. Lantham, Md.: University Press of America. Johnson, Wray R. (2019). Biplanes at War: US Marine Corps Aviation in the Small Wars Era, 1915–1934. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813177069. - Total pages: 440 Schmidt, Hans (1995). The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. Weinstein, Brian; Segal, Aaron (1984). Haiti: Political Failures, Cultural Successes (February 15, 1984 ed.). Praeger Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 0-275-91291-4. Weston, Rubin Francis (1972). Racism in U.S. Imperialism: The Influence of Racial Assumptions on American Foreign Policy, 1893–1946. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. |

出典 ハインリ、ロバート(1996年)。Written in Blood: The History of the Haitian People(血で書かれた歴史:ハイチの人々)。メリーランド州ランサム:University Press of America。 ジョンソン、レイ・R. (2019). 『戦時下の複葉機:小規模戦争時代におけるアメリカ海兵隊航空隊、1915年~1934年』ケンタッキー大学出版局。ISBN 9780813177069。 - 全ページ数:440 シュミット、ハンス (1995). 『ハイチ占領期のアメリカ合衆国、1915年~1934年』 ニュージャージー州:ラトガース大学出版。 ワインスタイン、ブライアン、セガル、アーロン(1984年)。ハイチ:政治的失敗、文化的成功(1984年2月15日版)。プラガー出版。175ページ。ISBN 0-275-91291-4。 ウェストン、ルービン・フランシス(1972年)。『米国帝国主義の人種主義:1893年から1946年の米国の外交政策における人種的仮定の影響』。サウスカロライナ州コロンビア:サウスカロライナ大学出版。 |

| Further reading Boot, Max. The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. New York, Basic Books: 2002. ISBN 0-465-00721-X Dalleo, Raphael (2016). American Imperialism's Undead: The Occupation of Haiti and the Rise of Caribbean Anticolonialism. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-3894-3. Gebrekidan, Selam; Apuzzo, Matt; Porter, Catherine; Méheut, Constant (May 20, 2022). "Invade Haiti, Wall Street Urged. The U.S. Obliged". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 23, 2022. Harper's Magazine advertisement: Why Should You Worry About Haiti? by the Haiti-Santo Domingo Independence Society Hudson, Peter (2017). Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-2264-5911-0. Marvin, George (February 1916). "Assassination And Intervention in Haiti: Why The United States Government Landed Marines On The Island And Why It Keeps Them There". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXXI: 404–410. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2009. Renda, Mary A. (2001). Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4938-3. Schmidt, Hans (1995). United States occupation of Haiti (1915-1934). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2203-X. Spector, Robert M. "W. Cameron Forbes in Haiti: Additional Light on the Genesis of the 'Good Neighbor' Policy" Caribbean Studies (1966) 6#2 pp 28–45. Weston, Rubin Francis (1972). Racism in U.S. Imperialism: The Influence of Racial Assumptions on American Foreign Policy, 1893–1946. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-219-2. Primary sources Forbes, William Cameron. Report of the President's Commission for the Study and Review of Conditions in the Republic of Haiti: March 26, 1930 (US Government Printing Office, 1930) online |