八紘一宇

Hakkō ichiu

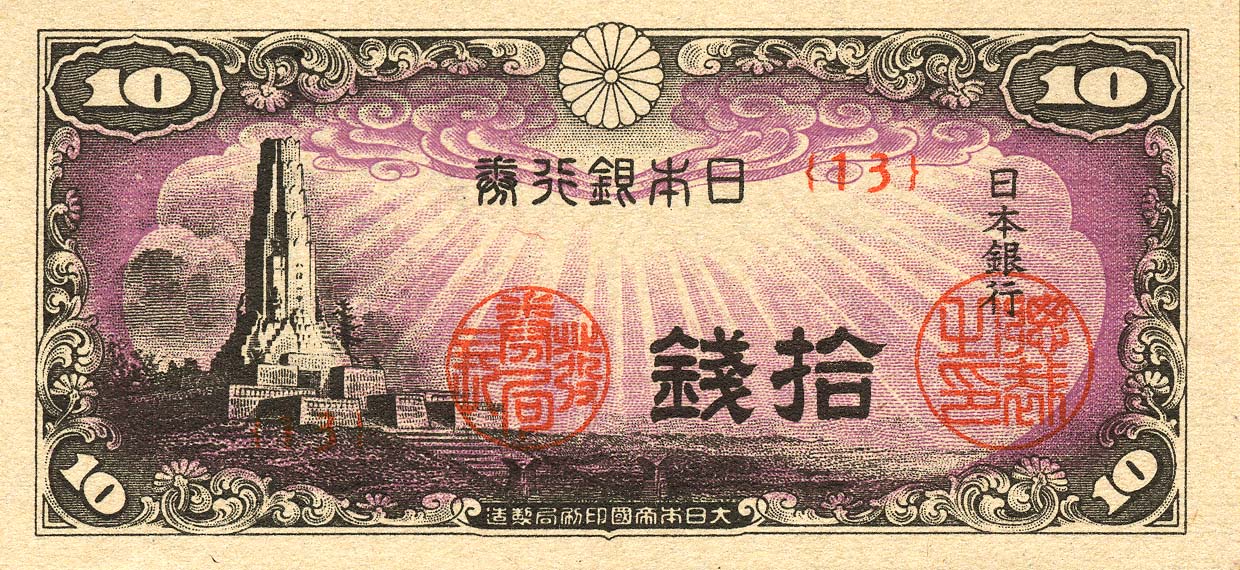

10-sen

Japanese banknote, illustrating the hakkō ichiu monument in Miyazaki,

first issued in 1944

☆ 八紘一宇(はっこういちう、八紘為宇、八紘爲宇)または八紘一宇(はっこういちう、八紘一宇、八紘爲宇)は、大日本帝国が 「世界の八つの隅を統一する 」という神聖な権利を意味する日本の政治スローガンである。このスローガンは大日本帝国のイデオロギーの基礎を形成した。日清戦争から第二次世界大戦にか けて顕著であり、1940年1月8日の近衛文麿首相の演説で広まった[1]。

| Hakkō ichiu (八紘一宇,

"eight crown cords, one roof", i.e. "all the world under one roof") or

hakkō iu (Shinjitai: 八紘為宇, 八紘爲宇) was a Japanese political slogan

meaning the divine right of the Empire of Japan to "unify the eight

corners of the world." The slogan formed the basis of the empire's

ideology. It was prominent from the Second Sino-Japanese War to World

War II and was popularized in a speech by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe

on January 8, 1940.[1] |

八紘一宇(はっこういちう、八紘為宇、八紘爲宇)または八紘一宇(はっ

こういちう、八紘一宇、八紘爲宇)は、大日本帝国が 「世界の八つの隅を統一する

」という神聖な権利を意味する日本の政治スローガンである。このスローガンは大日本帝国のイデオロギーの基礎を形成した。日清戦争から第二次世界大戦にか

けて顕著であり、1940年1月8日の近衛文麿首相の演説で広まった[1]。 |

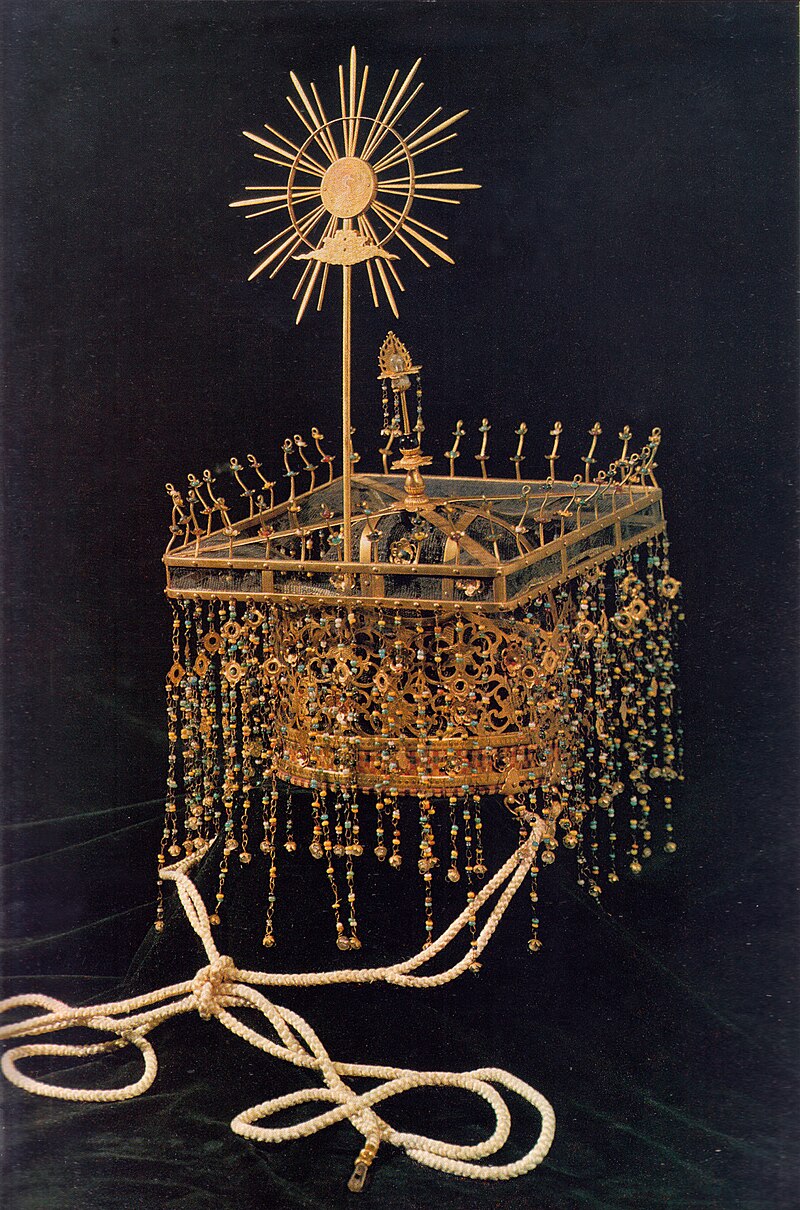

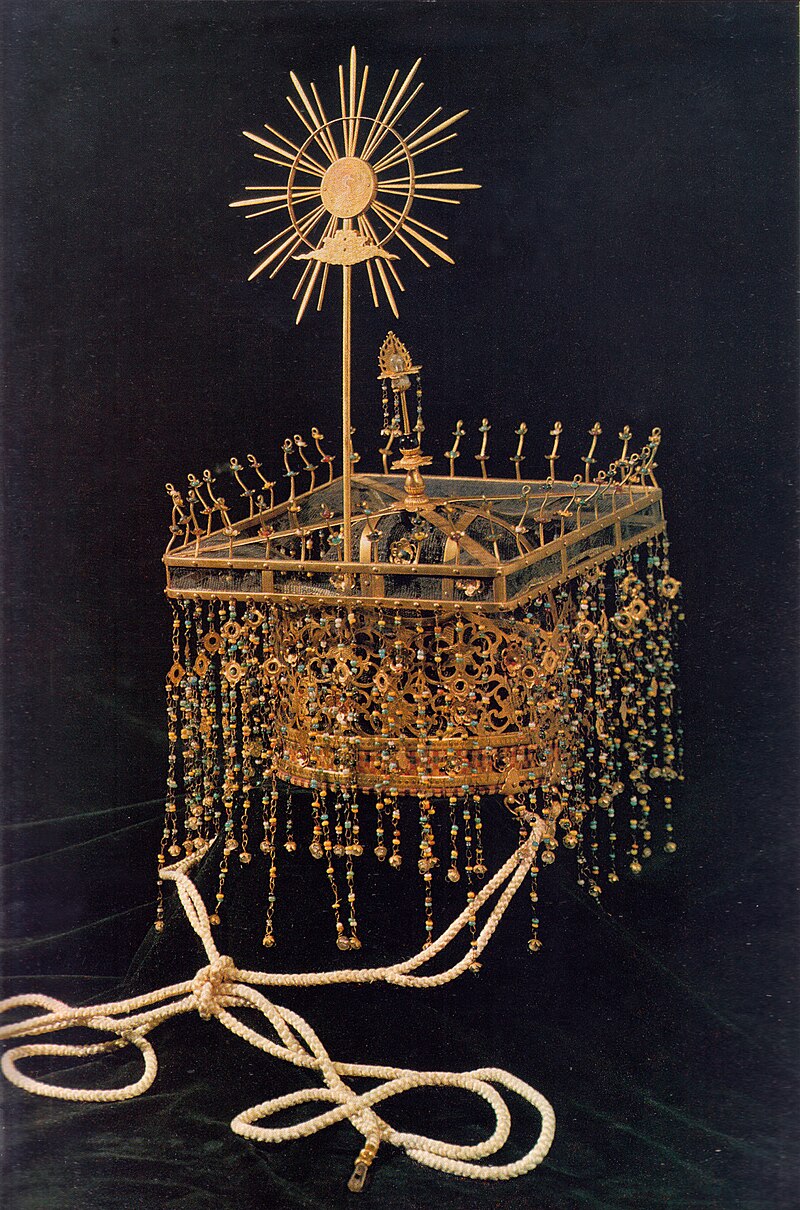

Background The benkan of Emperor Komei The term was coined early in the 20th century by the Nichiren Buddhist activist and nationalist Tanaka Chigaku, who cobbled it from parts of a statement attributed in the chronicle Nihon Shoki to legendary first Emperor Jimmu at the time of his ascension.[a] The emperor's full statement reads: "Hakkō wo ooute ie to nasan" (八紘を掩うて宇と為さん) (in the original kanbun: 掩八紘而爲宇), and means: "I shall cover the eight directions and make them my abode". The term hakkō (八紘), meaning "eight crown cords" ("crown cords" being the hanging decorations of the benkan (冕冠), a traditional Chinese-style crown), was a metaphor for happō (八方), or "eight directions".[3][b] Despite its original universalist meaning, according to the principle of "ichi soku issai, issai soku ichi (one is inseparable from the whole and vice versa)", Tanaka interpreted it as justification for imperialism. To stop this imperialist reinterpretation from spreading, Koyama Iwao (1905–1993), disciple of Nishida, and drawing off the Flower Adornment Sutra, proposed to substitute the words "to be included or to find a place" for the last two characters ("to make them my abode"). That move was rejected by the military circles of the nationalist right.[4][5] |

背景 孝明天皇の弁官 20世紀初頭、日蓮宗の活動家でナショナリストの田中智学が、『日本書紀』に記されている伝説的な初代天皇である神武天皇の即位の際の声明の一部から、こ の言葉を作り出した: 「八紘を掩うて宇と為さん」(原漢文:掩八紘而爲宇)である: 八紘を掩うて宇と為さん」(原文:掩紘八而宇為さん)とは、「八紘を掩うて宇と為さん」を意味する。八紘」とは「八つの冠紐」(「冠紐」とは伝統的な中国 式の冠である弁冠(冕冠)の垂れ飾りのこと)を意味し、「八方」すなわち「八つの方角」の比喩であった[3][b]。 田中は、「一即一切、一即一切」の原則に従って、本来の普遍主義的な意味にもかかわらず、これを帝国主義を正当化するものとして解釈した。この帝国主義的 な再解釈が広まるのを阻止するために、西田の弟子で『花飾経』を引いていた小山巌(1905-1993)は、最後の2文字(「我が住処とする」)を「包摂 する、居場所を見出す」という言葉に置き換えることを提案した。この動きは国粋主義右派の軍部によって拒否された[4][5]。 |

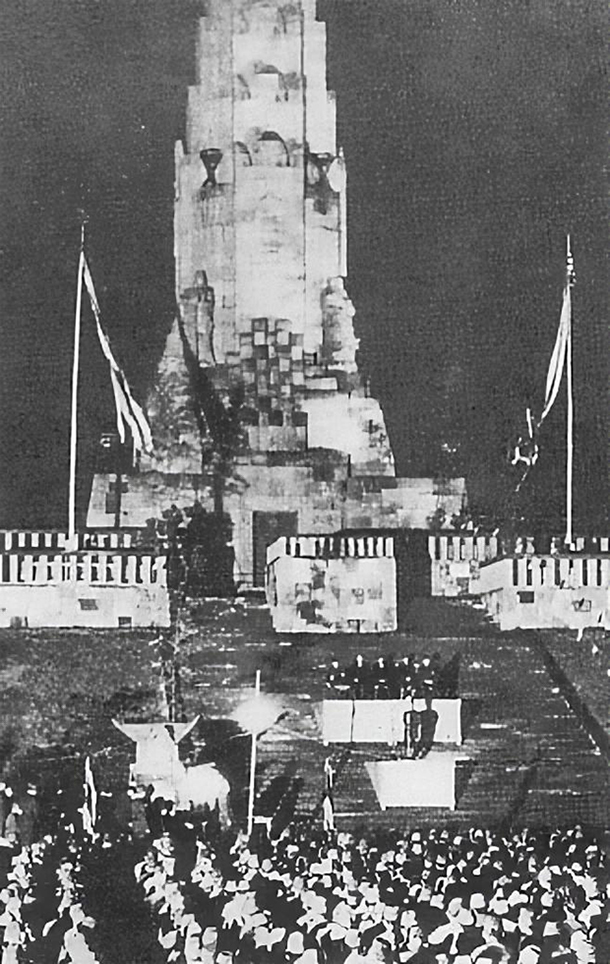

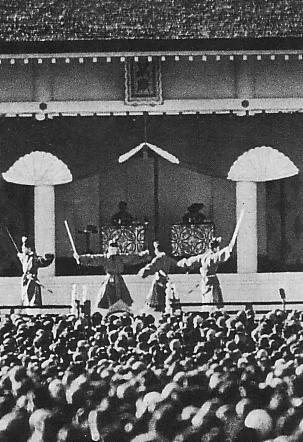

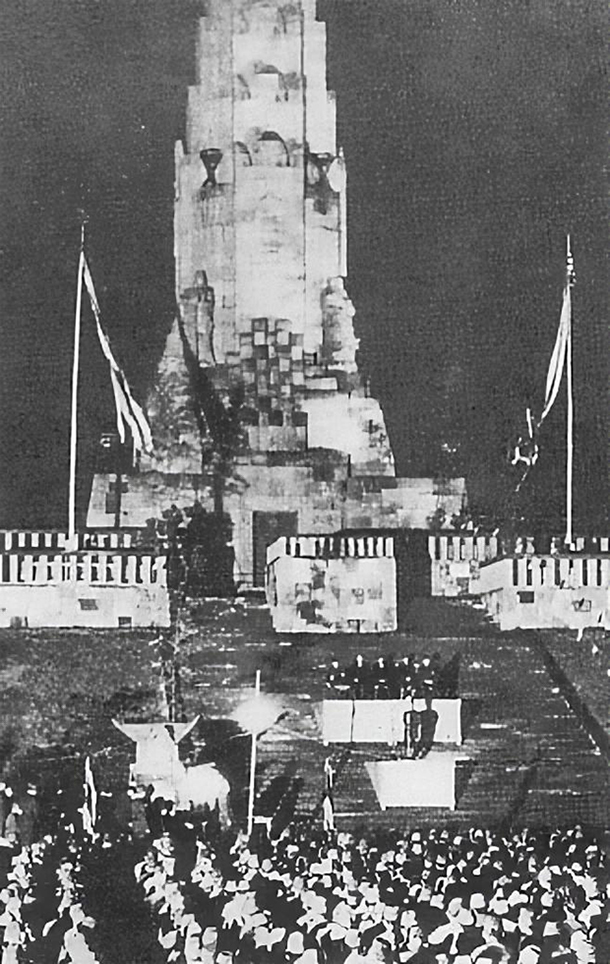

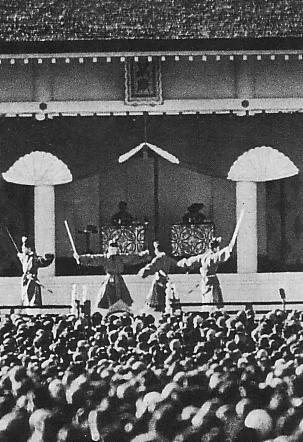

| Origins Further information: Racial Equality Proposal, 1919 and Jewish settlement in Imperial Japan  Founding ceremony of the hakkō ichiu monument on April 3, 1940. It had Prince Chichibu's calligraphy of hakkō ichiu carved on its front side.[6]  Prewar 10-sen Japanese stamp, illustrating the hakkō ichiu and the 2,600th anniversary of the Empire  Emperor Shōwa and Empress Kōjun preside the celebration of the 2,600th anniversary of mythical foundation of the empire in November 1940.  Japanese pilots who gathered under the flag of hakkō ichiu during the Pacific War There were enough Japanese in Western nations that suffered from racial discrimination issues that in 1919, Japan proposed a racial equality clause at the Paris Peace Conference. The proposal, intended to only apply to League of Nations members,[7] received the support of a majority but was vetoed by US President Woodrow Wilson in violation of the rules of the Conference that allowed a majority vote. In 1924, the US Congress enacted the Asian Exclusion Act, outlawing immigration from Asia. Worsened with the economic impact of the Shōwa financial crisis and the Great Depression in the 1930s, which led to a resurgence of nationalist, militarist and expansionist movement, Emperor Shōwa, known more commonly as Hirohito outside Japan, and his reign became associated with the rediscovery of hakkō ichiu as an expansionist element of Japanese nationalistic beliefs.[8] The naval limitations treaties of 1921 and especially 1930 were seen as a mistake[clarification needed] in their unanticipated effect on internal political struggles in Japan, and the treaties provided an external motivating catalyst that provoked reactionary militarist elements to desperate actions, with their presence overtaking civilian and liberal elements in society.[9] The evolution of hakkō ichiu serves as a changing litmus test of those factional relationships during the next decade.[10] The term hakkō ichiu did not enter general circulation until 1940, when the second Konoe administration issued a white paper titled "Fundamental National Policy" (基本国策要綱, Kihon Kokusaku Yōkō), which opened with those words and in which Prime Minister Konoe proclaimed that the basic aim of Japan's national policy was "the establishment of world peace in conformity with the very spirit in which our nation was founded."[11][c] and that the first step was the proclamation of a "new order in East Asia" (東亜新秩序, Tōa Shin Chitsujo), which later took the form of the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere".[12] In the most magnanimous form, the term was used to indicate the making of a universal brotherhood implemented by the uniquely-virtuous Yamato.[13] Because that would bring people under the emperor's fatherly benevolence, force was justified against those who resisted.[14] The Japanese additionally undertook many projects to prove that they supported racial equality. For example, on December 6, 1938, the Five Ministers Council (Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, Army Minister Seishirō Itagaki, Navy Minister Mitsumasa Yonai, Foreign Minister Hachirō Arita and Finance Minister Shigeaki Ikeda), the highest decision-making council at the time,[15][16] took the decision to prohibit the expulsion of the Jews from Japan, Manchuria, and China.[15][16] Thereafter, the Japanese received Jewish refugees despite the opposition of their ally Nazi Germany. 1940 was declared the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of Japan in part to celebrate hakkō ichiu.[17] As part of the celebrations, the government officially opened the hakkō ichiu monument (now Heiwadai Tower) at what is now Miyazaki Peace Park in the city of Miyazaki. |

起源 さらなる情報 1919年の人種平等提案と大日本帝国におけるユダヤ人居留地  1940年4月3日、八紘一宇記念碑の建立式。正面には秩父宮の「八紘一宇」の書が刻まれていた[6]。  戦前の10銭切手(八紘一宇と皇紀2600年を描く  1940年11月、昭和天皇と香淳皇后が皇紀2600年祭を主催した。  太平洋戦争中、白光一宇の旗のもとに集まった日本人パイロットたち 1919年、日本はパリ講和会議に人種平等条項を提案した。国際連盟加盟国のみに適用されることを意図したこの提案は、過半数の支持を得たが[7]、多数 決を認める会議の規則に違反し、ウッドロー・ウィルソン米大統領によって拒否権が発動された。1924年、アメリカ議会はアジア排斥法を制定し、アジアか らの移民を禁止した。 正和金融危機の経済的影響と1930年代の世界恐慌によって悪化し、ナショナリズム、軍国主義、拡張主義運動が復活したため、日本以外ではヒロヒトとして より一般的に知られている昭和天皇とその治世は、日本のナショナリズム信仰の拡張主義的要素としての白光一宇の再発見と結びついた。 [8]。1921年と特に1930年の海軍制限条約は、日本国内の政治闘争に予期せぬ影響を及ぼした点で誤り[要解釈]とみなされ、条約は、反動的な軍国 主義的要素を自暴自棄な行動に駆り立て、その存在が社会における民間人やリベラルな要素を凌駕するような、外的な動機付けとなる触媒を提供した[9]。 白光一宇の進化は、その後の10年間におけるそれらの派閥関係の変化するリトマス試験紙の役割を果たしている[10]。 基本国策要綱」(基本国策要綱、きほんこくさくようこう)と題された白書が発表された1940年まで、「博徒一宇」という言葉は一般に流通することはな かった。 「そしてその第一歩が「東亜新秩序」(東亜新秩序、東亜新秩序)の宣言であり、それは後に「大東亜共栄圏」という形をとることになる。 [12]最も大らかな形では、この用語は、唯一無二の徳のある大和によって実行される普遍的な兄弟愛の実現を示すために使われた[13]。それが人々を天 皇の父としての博愛の下に置くことになるため、抵抗する者に対しては武力が正当化された[14]。 日本人はさらに、人種平等を支持していることを証明するために多くのプロジェクトを行った。例えば、1938年12月6日、当時の最高意思決定機関であっ た五大臣会議(近衛文麿内閣総理大臣、板垣征四郎陸軍大臣、米内光政海軍大臣、有田八郎外務大臣、池田重明蔵相)[15][16]は、日本、満州、中国か らユダヤ人を追放することを禁止する決定を下した。 1940年は、白光一宇を祝う意味もあって、日本建国2600年祭とされた[17]。その祝賀行事の一環として、政府は現在の宮崎市の平和公園に白光一宇記念碑(現在の平和台タワー)を正式にオープンさせた。 |

| World War II As the Second Sino-Japanese War dragged on without conclusion, the Japanese government turned increasingly to the nation's spiritual capital to maintain fighting spirit. Characterization of the fighting as a "holy war" (聖戦, seisen), similarly grounding the current conflict in the nation's sacred beginnings, became increasingly evident in the Japanese press at this time. In 1940, the Imperial Rule Assistance Association was launched to provide political support to Japan's war in China. The general spread of the term hakkō ichiu, neatly encapsulating this view of expansion as mandated in Japan's divine origin, was further propelled by preparations for celebrating the 2,600th anniversary of Jimmu's ascension, which fell in the year 1940 according to the traditional chronology. Stories recounted that Jimmu, finding five races in Japan, had made them all as "brothers of one family".[18] Propaganda purposes After Japan declared war on the Allies in December 1941, Allied governments produced several propaganda films citing the hakkō ichiu as evidence that the Japanese intended to conquer the entire world. To win the support of the conquered, Japanese propaganda included phrases such as "Asia for the Asians!" and emphasized about the perceived need to liberate Asian countries from imperialist powers.[19] Japan's failure to win the war in China was blamed on European nations and the US exploiting their Asian colonies to assist Chinese forces, even though the Chinese received far more assistance from the Soviet Union.[20] In some cases local populations welcomed Japanese troops when they invaded, initially seeing them as preferable to being ruled by Western colonial powers.[19] The Japanese also indoctrinated their soldiers into believing that it was their duty to make Asians "strong again" through force, after being weakened by Western imperialism.[21] The official translation offered by contemporary leaders was "universal brotherhood", but it was widely acknowledged that that expression meant that the Japanese were "equal to the Caucasians but, to the peoples of Asia, we act as their leader".[22] Hence hakkō ichiu could be seen as a euphemism for Japanese supremacy. In fact, the brutality and the racism of the Japanese led the conquered to view the Japanese imperialists as being equal to or sometimes worse than Western imperialists.[19] For example, the economies of most occupied territories were remanaged only to produce raw war materials for Japan.[23] Allied judgment Hakkō ichiu meant the bringing together of the corners of the world under one ruler, or the making of the world's one family.[24] That was the alleged ideal of the foundation of the empire, and, in its traditional context, meant no more than a universal principle of humanity, which was destined ultimately to pervade the whole universe.[24] The way to the realisation of hakkō ichiu was through the benign rule of the Emperor, and therefore the "way of the Emperor," the "Imperial" or the "Kingly way," was a concept of virtue and a maxim of conduct.[24] Hakkō ichiu was the moral goal, and loyalty to the Emperor was the road that led to it.[24] Throughout the years that followed measures of military aggression were advocated in the names of hakkō ichiu, which eventually became symbols for world domination through military force.[24] |

第二次世界大戦 日中戦争が終結することなく長引くにつれ、日本政府は戦意を維持するために国民の精神的資本にますます目を向けるようになった。 戦いを「聖戦」(せいせん)と表現し、同様に現在の紛争を国民の神聖な始まりに基づかせることは、この時期、日本のマスコミでますます顕著になった。1940年、日本の中国での戦争に政治的支援を提供するため、大政翼賛会が発足した。 八紘一宇(はっこういちう)という言葉が一般に広まったのは、神武天皇の即位2600年を祝う準備のためであった。神武は日本に五つの民族を見出し、それらをすべて「一門の兄弟」としたという話が語られていた[18]。 プロパガンダ目的 日本が1941年12月に連合国に宣戦布告した後、連合国政府は、日本が全世界を征服するつもりである証拠として、白光一宇を引用したプロパガンダ映画をいくつか制作した。 被征服者の支持を得るために、日本のプロパガンダには「アジア人のためのアジア!」といったフレーズが含まれ、帝国主義列強からアジア諸国を解放する必要 性が認識されていることが強調された[19]。中国での戦争に勝利できなかった日本の責任は、中国軍がソ連からはるかに多くの援助を受けていたにもかかわ らず、欧州諸国と米国がアジアの植民地を利用して中国軍を援助したことにあった。 [日本軍はまた、西洋帝国主義によって弱体化したアジア人を武力によって「再び強く」することが自分たちの義務であると兵士たちに教え込んだ[21]。 現代の指導者たちによって公式に提示された訳は「普遍的兄弟愛」であったが、その表現は、日本人が「白人とは対等であるが、アジアの人々に対しては、われ われは彼らの指導者として行動する」という意味であることが広く認められていた[22] 。実際、日本人の残忍さと人種主義によって、被征服者は日本帝国主義者を西洋帝国主義者と同等か、時にはそれよりも悪いものとみなすようになった [19]。 例えば、ほとんどの占領地の経済は、日本のために原材料となる戦争資材を生産するためだけに再管理された[23]。 連合国の判断 八紘一宇とは、世界の隅々を一つの支配者のもとにまとめること、あるいは世界の一つの家族をつくることを意味していた[24]。それは帝国の建国の理想と されたものであり、伝統的な文脈においては、最終的に全宇宙に行き渡るように運命づけられた人類の普遍的な原理以上の意味はなかった。 [24]白光一宇の実現への道は天皇の温和な統治にあり、したがって「天皇の道」、「皇道」あるいは「王道」は、徳の概念であり、行動の格言であった。 [24]八紘一宇は道徳的な目標であり、天皇への忠誠はそれに至る道であった[24]。その後の長い年月を通じて、軍事的な侵略の手段が八紘一宇の名の下 に提唱され、それはやがて武力による世界支配の象徴となった[24]。 |

Aftermath Hakkō ichiu monument (renamed Tower of Peace) in 2010 Since the end of the Pacific War, some have highlighted the hakkō ichiu slogan as part of a context of historical revisionism.[25] The hakkō ichiu monument was renamed Heiwa no tou (平和の塔, Tower of Peace) in 1958 and still stands today. The writing "Hakkō ichiu" was removed from it after the Japanese defeat at the insistence of the U.S. military.[26] The tower was the inception point for the torch relay of the 1964 Summer Olympics.[26] After the Olympics, which coincided with worldwide interest in the Japanese Imperial family, the local tourism association successfully petitioned the Miyazaki Prefecture to reinstall the "Hakkō ichiu" characters.[26] |

その後 2010年の八紘一宇記念碑(平和の塔に改称) 太平洋戦争が終結して以来、歴史修正主義の文脈の一部として八紘一宇のスローガンを強調する向きもある[25]。八紘一宇の碑は1958年に平和の塔と改 称され、現在に至っている。1964年夏季オリンピックの聖火リレーの起点となった[26]。 世界的に日本の皇室への関心が高まったオリンピック後、地元の観光協会は宮崎県に「八紘一宇」の文字を再び設置するよう請願し、成功した[26]。 |

| An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus Greater East Asia Conference Hokushin-ron Japanese militarism Japanese nationalism Statism in Shōwa Japan Lebensraum Manifest destiny Moscow, third Rome Nanshin-ron Shinmin no Michi Spazio vitale Tanaka Memorial World domination |

大和民族を核としたグローバル政策の検討 大東亜会議 北辰論 日本軍国主義 日本の国民主義 昭和日本の国家主義 レーベンスラウム マニフェスト・デスティニー モスクワ、第三のローマ 南進論 新民の道 生気のスパツィオ 田中記念 世界制覇 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hakk%C5%8D_ichiu |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆