ハンニバル

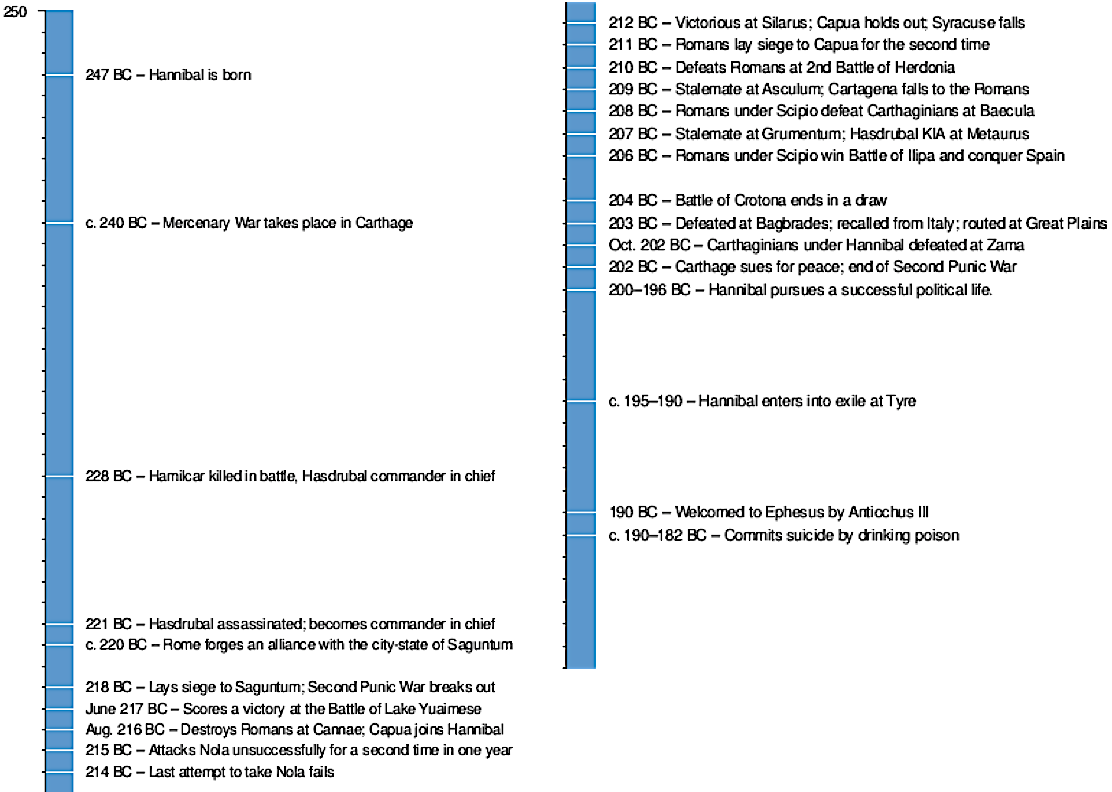

Hannibal, 247 BC - 183/181 BC

☆ ハンニバル(/ˈhænɪbəl/; Punic: ႐𐤍𐤁𐤁, romanized: Ḥannība↪Lm_l; 247年 - 紀元前183年から181年)はカルタゴの将軍、政治家で、第二次ポエニ戦争でローマ共和国との戦いでカルタゴ軍を指揮した。紀元前218年、ハンニバルはローマの同盟国であったイスパニアのサグントゥム(現在のスペイン、サグント)を攻撃し、第二次ポエニ戦争を引き起こした。彼の計画的な戦略によって、それまでローマと同盟関係にあったイタリアのいくつかの都市を征服し、同盟を結ぶことができた。ハンニバルは15年間、南イタ リアの大部分を占領した。ファビウス・マクシムスに率いられたローマ軍は、ハンニバルと直接交戦することを避け、代わりに消耗戦を繰り広げた(ファビアン 戦略)。ヒスパニアでのカルタゴの敗北はハンニバルの増援を妨げ、ハンニバルは決定的な勝利を得ることができなかった。ローマの将軍スキピオ・アフリカヌ ス率いる北アフリカへの反侵攻により、ハンニバルはカルタゴに戻らざるを得なくなった。最終的にハンニバルはザマの戦いで敗れ、ローマ軍の勝利で戦争は終 結した。戦後、ハンニバルはスフェットへの立候補に成功した。彼は、ローマから課せられた戦争賠償金の支払いを可能にするため、政治・財政改革を行った。これらの 改革はカルタゴ貴族やローマの不評を買い、彼は自主的に亡命した。この間、セレウコス朝の宮廷に住み、アンティオコス3世の対ローマ戦争の軍事顧問を務め た。アンティオコスはマグネシアの戦いで敗北し、ローマの条件を受け入れざるを得なくなった。彼の逃亡はビティニア宮廷で終わった。彼はローマ軍に裏切ら れ、服毒自殺した。

| Hannibal

(/ˈhænɪbəl/; Punic: 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, romanized: Ḥannībaʿl; 247 – between 183

and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the

forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during

the Second Punic War. Hannibal's father, Hamilcar Barca, was a leading Carthaginian general during the First Punic War. His younger brothers were Mago and Hasdrubal; his brother-in-law was Hasdrubal the Fair, who commanded other Carthaginian armies. Hannibal lived during a period of great tension in the Mediterranean Basin, triggered by the emergence of the Roman Republic as a great power with its defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War. Revanchism prevailed in Carthage, symbolized by the pledge that Hannibal made to his father to "never be a friend of Rome". In 218 BC, Hannibal attacked Saguntum (modern Sagunto, Spain), an ally of Rome, in Hispania, sparking the Second Punic War. Hannibal invaded Italy by crossing the Alps with North African war elephants. In his first few years in Italy, as the leader of a Carthaginian and partially Celtic army, he won a succession of victories at the Battle of Ticinus, Trebia, Lake Trasimene, and Cannae, inflicting heavy losses on the Romans. Hannibal was distinguished for his ability to determine both his and his opponent's respective strengths and weaknesses, and to plan battles accordingly. His well-planned strategies allowed him to conquer and ally with several Italian cities that were previously allied to Rome. Hannibal occupied most of southern Italy for 15 years. The Romans, led by Fabius Maximus, avoided directly engaging him, instead waging a war of attrition (the Fabian strategy). Carthaginian defeats in Hispania prevented Hannibal from being reinforced, and he was unable to win a decisive victory. A counter-invasion of North Africa, led by the Roman general Scipio Africanus, forced him to return to Carthage. Hannibal was eventually defeated at the Battle of Zama, ending the war in a Roman victory. After the war, Hannibal successfully ran for the office of sufet. He enacted political and financial reforms to enable the payment of the war indemnity imposed by Rome. Those reforms were unpopular with members of the Carthaginian aristocracy and in Rome, and he fled into voluntary exile. During this time, he lived at the Seleucid court, where he acted as military advisor to Antiochus III the Great in his war against Rome. Antiochus met defeat at the Battle of Magnesia and was forced to accept Rome's terms, and Hannibal fled again, making a stop in the Kingdom of Armenia. His flight ended in the court of Bithynia. He was betrayed to the Romans and committed suicide by poisoning himself. Hannibal is considered one of the greatest military tacticians and generals of antiquity, alongside Alexander the Great, Cyrus the Great, Julius Caesar, Scipio Africanus, and Pyrrhus. According to Plutarch, Scipio asked Hannibal "who the greatest general was", to which Hannibal replied "either Alexander or Pyrrhus, then himself".[1] |

ハンニバル(/ˈhænɪbəl/; Punic: ႐𐤍𐤁𐤁, romanized: Ḥannība↪Lm_l; 247年 - 紀元前183年から181年)はカルタゴの将軍、政治家で、第二次ポエニ戦争でローマ共和国との戦いでカルタゴ軍を指揮した。 ハンニバルの父ハミルカル・バルカは、第一次ポエニ戦争におけるカルタゴの指導的将軍であった。彼の弟はマゴとハスドルバルで、義理の弟は他のカルタゴ軍 を指揮した見習いハスドルバルであった。ハンニバルが生きた時代は、第一次ポエニ戦争でカルタゴを破ったローマ共和国が大国として台頭し、地中海沿岸に大 きな緊張が走った時期であった。カルタゴではレバンチズムが蔓延し、ハンニバルが父に誓った「決してローマの友にはならない」という言葉に象徴される。 紀元前218年、ハンニバルはローマの同盟国であったイスパニアのサグントゥム(現在のスペイン、サグント)を攻撃し、第二次ポエニ戦争を引き起こした。 ハンニバルは北アフリカの戦象を駆ってアルプスを越え、イタリアに侵入した。イタリアでの最初の数年間は、カルタゴ軍と一部ケルト軍のリーダーとして、 ティチヌスの戦い、トレビア、トラジメネ湖、カンナエの戦いで次々と勝利を収め、ローマ軍に多大な損害を与えた。ハンニバルは、自分と相手のそれぞれの長 所と短所を見極め、それに従って戦闘を計画する能力に長けていた。彼の計画的な戦略によって、それまでローマと同盟関係にあったイタリアのいくつかの都市 を征服し、同盟を結ぶことができた。ハンニバルは15年間、南イタリアの大部分を占領した。ファビウス・マクシムスに率いられたローマ軍は、ハンニバルと 直接交戦することを避け、代わりに消耗戦を繰り広げた(ファビアン戦略)。ヒスパニアでのカルタゴの敗北はハンニバルの増援を妨げ、ハンニバルは決定的な 勝利を得ることができなかった。ローマの将軍スキピオ・アフリカヌス率いる北アフリカへの反侵攻により、ハンニバルはカルタゴに戻らざるを得なくなった。 最終的にハンニバルはザマの戦いで敗れ、ローマ軍の勝利で戦争は終結した。 戦後、ハンニバルはスフェットへの立候補に成功した。彼は、ローマから課せられた戦争賠償金の支払いを可能にするため、政治・財政改革を行った。これらの 改革はカルタゴ貴族やローマの不評を買い、彼は自主的に亡命した。この間、セレウコス朝の宮廷に住み、アンティオコス3世の対ローマ戦争の軍事顧問を務め た。アンティオコスはマグネシアの戦いで敗北し、ローマの条件を受け入れざるを得なくなった。彼の逃亡はビティニア宮廷で終わった。彼はローマ軍に裏切ら れ、服毒自殺した。 ハンニバルは、アレキサンダー大王、キュロス大王、ユリウス・カエサル、スキピオ・アフリカヌス、ピュロスと並んで、古代における最も偉大な戦術家、将軍 の一人と考えられている。プルタークによると、スキピオはハンニバルに「最も偉大な将軍は誰か」と尋ね、ハンニバルは「アレキサンダーかピュロス、それか ら自分だ」と答えた[1]。 |

Name Circa 1850 engraving of Young Hannibal (left) by Charles Turner Hannibal was a common Semitic Phoenician-Carthaginian personal name. It is recorded in Carthaginian sources as ḥnbʿl[2] (Punic: 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋). It is a combination of the common Phoenician masculine given name Hanno with the Northwest Semitic Canaanite deity Baal (lit, "lord") a major god of the Carthaginians ancestral homeland of Phoenicia in Western Asia. Its precise vocalization remains a matter of debate. Suggested readings include Ḥannobaʿal,[3] Ḥannibaʿl, or Ḥannibaʿal,[4][5] meaning "Baʿal/The lord is gracious", "Baʿal Has Been Gracious",[5][6] or "The Grace of Baʿal".[4] It is equivalent to the fellow Semitic Hebrew name Haniel. Greek historians rendered the name as Anníbas (Ἀννίβας). The Phoenicians and Carthaginians, like many West Asian Semitic peoples, did not use hereditary surnames, but were typically distinguished from others bearing the same name using patronymics or epithets. Although he is by far the most famous Hannibal, when further clarification is necessary he is usually referred to as "Hannibal, son of Hamilcar", or "Hannibal the Barcid", the latter term applying to the family of his father, Hamilcar Barca. Barca (Punic: 𐤁𐤓𐤒, brq) is a Semitic cognomen meaning "lightning" or "thunderbolt",[7] a surname acquired by Hamilcar on account of the swiftness and ferocity of his attacks. Barca is cognate with similar names for lightning found among the Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Arameans, Arabs, Amorites, Moabites, Edomites and other fellow Asiatic Semitic peoples.[8] Although they did not inherit the surname from their father, Hamilcar's progeny are collectively known as the Barcids.[9] Modern historians occasionally refer to Hannibal's brothers as Hasdrubal Barca and Mago Barca to distinguish them from the multitudes of other Carthaginians named Hasdrubal and Mago, but this practice is ahistorical and is rarely applied to Hannibal. |

作品名 1850年頃、チャールズ・ターナーによる若きハンニバル(左)のエングレーヴィング ハンニバルは一般的なセム系フェニキア人とカルタゴ人の名前である。カルタゴの資料にはḥnb/l[2] (Punic: ႐ć𐤍)と記録されている。これは、フェニキア人の男性名ハンノと、カルタゴ人の祖先である西アジアのフェニキアの主要な神である北西セム語系カナン人 の神バアル(Lit, 「主」)の組み合わせである。その正確な発声はまだ議論の余地がある。Ḥannoba/al、[3] Ḥanniba/l、Ḥanniba/al、[4][5]、「バアルの恵み」、「バアルの恵み」、「バアルの恵み」[5][6]などの意味がある。ギリシ アの歴史家はこの名をアンニバス(Ἀννίβας)と表記した。 フェニキア人とカルタゴ人は、多くの西アジア・セム系民族と同様、世襲制の姓を用いなかったが、一般的に、同じ名前を持つ他の人々とは守護霊や蔑称を用い て区別された。ハンニバルは最も有名なハンニバルであるが、さらに明確にする必要がある場合は、通常「ハミルカルの息子ハンニバル」または「バルキドのハ ンニバル」と呼ばれる。バルカ(Punic: 𐤁ဓ, brq)はセム語で「稲妻」または「雷鳴」を意味する[7]。 バルカは、イスラエル人、アッシリア人、バビロニア人、アラメ人、アラブ人、アモリ人、モアブ人、エドム人、その他のアジア・セム系民族の間で見られる雷 を意味する類似の名字と同族である[8]。 [9] 近代史家は時折、ハンニバルの兄弟をハスドルバル・バルカとマゴ・バルカと呼び、ハスドルバルとマゴという他の多数のカルタゴ人と区別しているが、この慣 行は非歴史的であり、ハンニバルに適用されることはほとんどない。 |

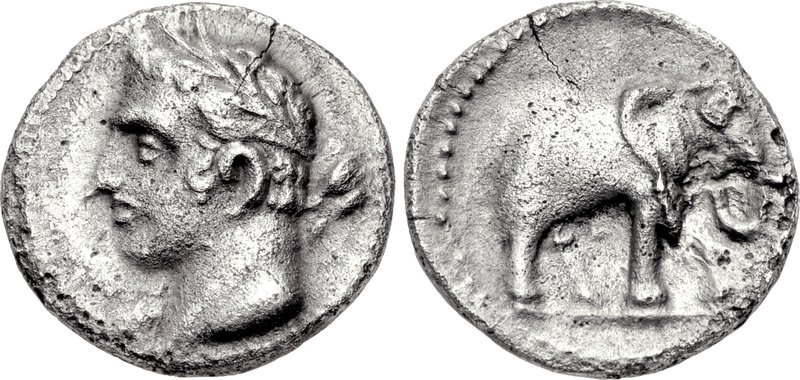

Background and early career A quarter shekel of Carthage, perhaps minted in Spain. The obverse may depict Hannibal with the traits of a young Melqart. The reverse features one of his famous war elephants.[10] Hannibal was one of the sons of Hamilcar Barca, a Carthaginian leader, and an unknown mother. He was born in what is present-day northern Tunisia, one of many Mediterranean regions colonised by the Canaanites from their homelands in Phoenicia, a region corresponding with the Mediterranean coasts of modern Lebanon and Syria. He had several sisters whose names are unknown, and two brothers, Hasdrubal and Mago. His brothers-in-law were Hasdrubal the Fair and the Numidian king Naravas. He was still a child when his sisters married, and his brothers-in-law were close associates during his father's struggles in the Mercenary War and the Punic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.[11] After Carthage's defeat in the First Punic War, Hamilcar set out to improve his family's and Carthage's fortunes. With that in mind and supported by Gades, Hamilcar began the subjugation of the tribes of the Iberian Peninsula (Modern Spain and Portugal). Carthage at the time was in such a poor state that it lacked a navy able to transport his army; instead, Hamilcar had to march his forces across Numidia towards the Pillars of Hercules and then cross the Strait of Gibraltar.[12] According to Polybius, Hannibal much later said that when he came upon his father and begged to go with him, Hamilcar agreed and demanded that he swear that as long as he lived he would never be a friend of Rome. There is even an account of him at a very young age (9 years old) begging his father to take him to an overseas war. In the story, Hannibal's father took him up and brought him to a sacrificial chamber. Hamilcar held Hannibal over the fire roaring in the chamber and made him swear that he would never be a friend of Rome. Other sources report that Hannibal told his father, "I swear so soon as age will permit...I will use fire and steel to arrest the destiny of Rome."[13][14] According to the tradition, Hannibal's oath took place in the town of Peñíscola, today part of the Valencian Community, Spain.[15] Hannibal's father went about the conquest of Hispania. When his father drowned[16] in battle, Hannibal's brother-in-law Hasdrubal the Fair succeeded to his command of the army with Hannibal (then 18 years old) serving as an officer under him. Hasdrubal pursued a policy of consolidation of Carthage's Iberian interests, even signing a treaty with Rome whereby Carthage would not expand north of the Ebro so long as Rome did not expand south of it.[17] Hasdrubal also endeavoured to consolidate Carthaginian power through diplomatic relationships with the native tribes of Iberia and native Berbers of the North African coasts.[18] Upon the assassination of Hasdrubal in 221 BC, Hannibal, now 26 years old, was proclaimed commander-in-chief by the army and confirmed in his appointment by the Carthaginian government. The Roman scholar Livy gives a depiction of the young Carthaginian: "No sooner had he arrived...the old soldiers fancied they saw Hamilcar in his youth given back to them; the same bright look; the same fire in his eye, the same trick of countenance and features. Never was one and the same spirit more skilful to meet opposition, to obey, or to command[.]"[18]  An 1868 illustration of Imilce and her son Haspar Barca by Juan de Dios de la Rada Livy also records that Hannibal married a woman of Castulo, a powerful Spanish city closely allied with Carthage.[18] The Roman epic poet Silius Italicus names her as Imilce.[19] Silius suggests a Greek origin for Imilce, but Gilbert Charles-Picard argued for a Punic heritage based on an etymology from the Semitic root m-l-k ('chief, the 'king').[20] Silius also suggests the existence of a son,[21] who is otherwise not attested by Livy, Polybius, or Appian. The son may have been named Haspar or Aspar,[22] although this is disputed.[23] After he assumed command, Hannibal spent two years consolidating his holdings and completing the conquest of Hispania, south of the Ebro.[24] In his first campaign, Hannibal attacked and stormed the Olcades' strongest centre, Alithia, which promptly led to their surrender, and brought Punic power close to the River Tagus. His following campaign in 220 BC was against the Vaccaei to the west, where he stormed the Vaccaen strongholds of Helmantice and Arbucala. On his return home, laden with many spoils, a coalition of Spanish tribes, led by the Carpetani, attacked, and Hannibal won his first major battlefield success and showed off his tactical skills at the battle of the River Tagus.[25] Rome, fearing the growing strength of Hannibal in Iberia, made an alliance with the city of Saguntum, which lay a considerable distance south of the River Ebro, and claimed the city as its protectorate. Hannibal not only perceived this as a breach of the treaty signed with Hasdrubal, but as he was already planning an attack on Rome, this was his way to start the war. So he laid siege to the city, which fell after eight months.[26] Hannibal sent the booty from Saguntum to Carthage, a shrewd move which gained him much support from the government; Livy records that only Hanno II the Great spoke against him.[18] In Rome, the Senate reacted to this apparent violation of the treaty by dispatching a delegation to Carthage to demand whether Hannibal had destroyed Saguntum in accordance with orders from Carthage. The Carthaginian Senate responded with legal arguments observing the lack of ratification by either government for the treaty alleged to have been violated.[27] The delegation's leader, Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, demanded Carthage choose between war and peace, to which his audience replied that Rome could choose. Fabius chose war.[18] |

背景と初期のキャリア おそらくスペインで鋳造されたカルタゴのクォーター・シケル。裏面には若きメルカルトの特徴を持つハンニバルが描かれている。裏面には彼の有名な戦象が描かれている[10]。 ハンニバルは、カルタゴの指導者ハミルカル・バルカと不詳の母との間に生まれた息子の一人である。彼は現在のチュニジア北部に生まれ、フェニキア(現在の レバノンやシリアの地中海沿岸に相当する地域)の故郷からカナン人によって植民地化された多くの地中海地域のひとつであった。彼には名前不明の姉妹が数人 おり、ハスドルバルとマゴという2人の兄弟がいた。義兄弟には、公正者ハスドルバルとヌミディア王ナラヴァスがいた。姉たちが結婚したとき、彼はまだ子供 であり、義兄弟たちは父の傭兵戦争やプニキア半島征服の際に親しい間柄であった[11]。 第一次ポエニ戦争でカルタゴが敗北した後、ハミルカルは一族とカルタゴの運命を改善しようとした。それを念頭に置き、ガデスの支援を受けたハミルカルは、 イベリア半島(現在のスペインとポルトガル)の諸部族の征服を開始した。当時のカルタゴは、軍隊を輸送できる海軍を持たないほど貧弱な状態であったため、 ハミルカルはヌミディアを横断してヘラクレスの柱に向かい、ジブラルタル海峡を渡って軍隊を進軍させなければならなかった[12]。 ポリュビオスによると、ハンニバルが父と再会し、一緒に行きたいと懇願したところ、ハミルカルは承諾し、生きている限りローマの友になることはないと誓う よう要求したと、ずっと後に語っている。彼が幼い頃(9歳)、父親に海外の戦争に連れて行ってくれるよう懇願したという記述もある。その物語の中で、ハン ニバルの父親は彼を連れて行き、生け贄の間に連れて行った。ハミルカルは部屋の中で燃え盛る火の上にハンニバルを立たせ、ローマの友には決してならないと 誓わせた。他の資料によれば、ハンニバルは父に「私は年齢が許す限りすぐに誓います...私はローマの運命を阻止するために火と鋼鉄を使用します」と言っ たという。 ハンニバルの父はイスパニア征服に赴いた。父が戦いで溺死すると[16]、ハンニバルの義弟ハスドルバルが軍の指揮を引き継ぎ、ハンニバル(当時18歳) は彼の下で将校として仕えた。ハスドルバルはカルタゴのイベリア半島の権益を強化する政策をとり、ローマがエブロ川以南に進出しない限り、カルタゴはエブ ロ川以北に進出しないという条約をローマと締結した[17]。 紀元前221年にハスドルバルが暗殺されると、26歳になったハンニバルは軍によって総司令官に指名され、カルタゴ政府によってその指名が承認された。 ローマの学者リヴィは、若きカルタゴ人をこう描写している: 「彼が到着するやいなや......老兵たちは、若い頃のハミルカルがよみがえったと錯覚した。同じ精神がこれほど巧みに敵に立ち向かい、服従し、命令し たことはなかった」[18]。  1868年、フアン・デ・ディオス・デ・ラ・ラダによるイミルチェとその息子ハスパー・バルカのイラスト リヴィはまた、ハンニバルがカルタゴと密接な関係にあったスペインの有力都市カストゥロの女性と結婚したことを記録している[18]。 [19]シリウスはイミルチェのギリシャ語起源を示唆しているが、ギルバート・シャルル=ピカールはセム語源のm-l-k(「長」、「王」)に由来する語 源に基づき、プニキア人の遺産であると主張した[20]。シリウスは息子の存在も示唆しているが[21]、その息子はリヴィ、ポリュビオス、アッピアヌス には証言されていない。その息子はハスパルまたはアスパーという名前であったかもしれないが[22]、これには異論がある[23]。 指揮官となったハンニバルは、エブロ川以南のイスパニアを征服するために2年を費やした。紀元前220年、ハンニバルは西方のヴァッカイ族と戦い、ヴァッ カイ族の拠点であるヘルマンチツェとアルブカラを襲撃した。多くの戦利品を積んで帰国すると、カルペタニ族に率いられたスペイン諸部族の連合が攻撃してき た。ハンニバルはテージョ川の戦いで初めて戦場で大きな成功を収め、その戦術的手腕を見せつけた[25]。 ローマはイベリア半島におけるハンニバルの強大化を恐れ、エブロ川のかなり南に位置するサグントゥム市と同盟を結び、同市を保護領と主張した。ハンニバル はこれをハスドルバルとの条約違反と受け止めただけでなく、すでにローマへの攻撃を計画していたため、これは戦争を始めるための手段だった。そこで彼はこ の都市を包囲し、8ヵ月後に陥落させた[26]。 ハンニバルはサグントゥムからの戦利品をカルタゴに送ったが、この抜け目のない行動は政府から多くの支持を得た。カルタゴ元老院は、違反したとされる条約 についてどちらの政府も批准していないことを指摘し、法的な反論を行った[27]。代表団のリーダーであるクィントゥス・ファビウス・マクシムス・ヴェル コソスは、カルタゴに戦争と平和のどちらかを選ぶよう要求し、謁見者はローマが選ぶことができると答えた。ファビウスは戦争を選択した[18]。 |

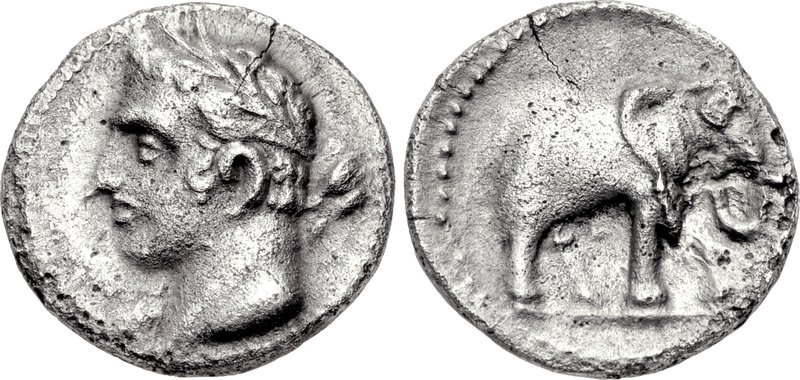

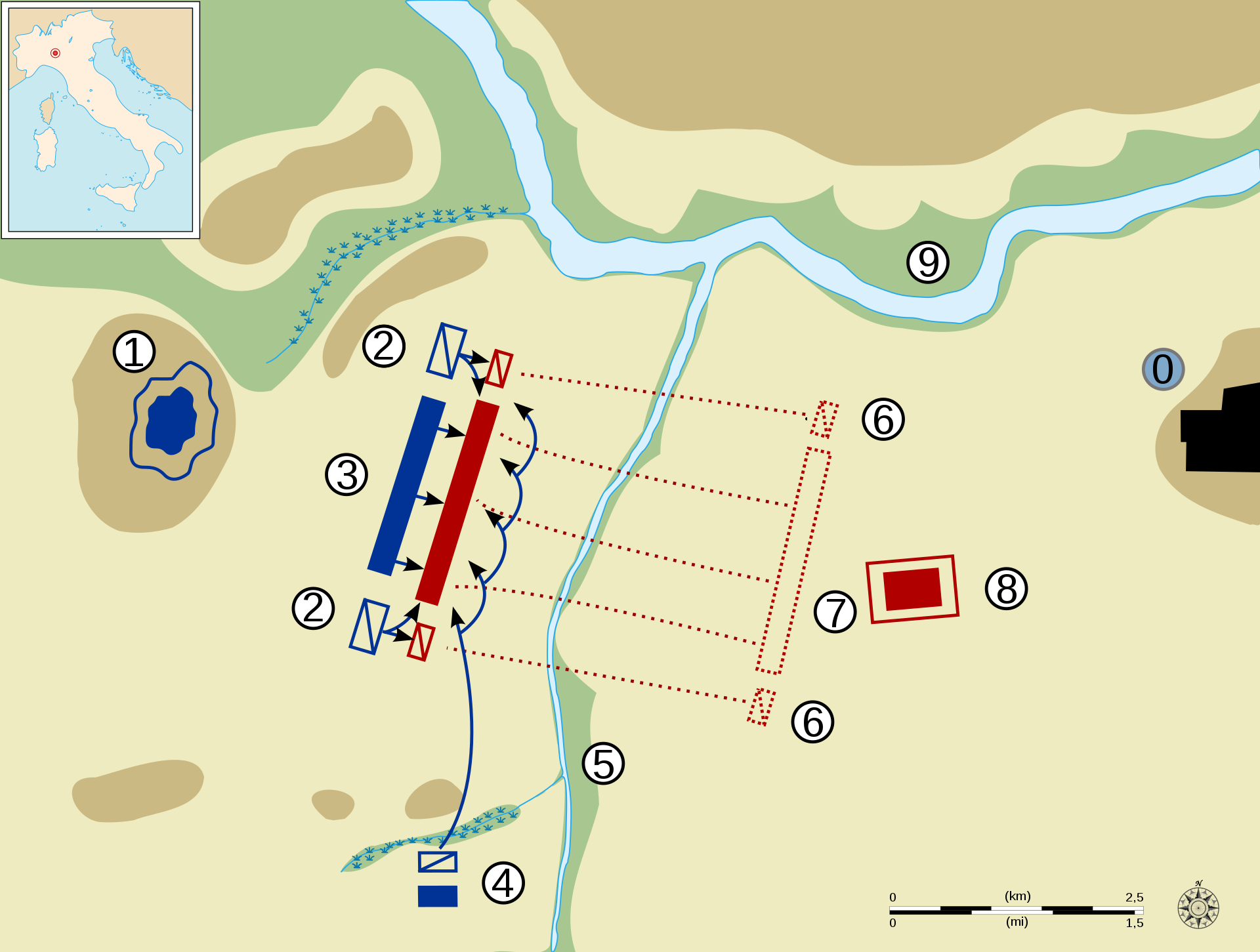

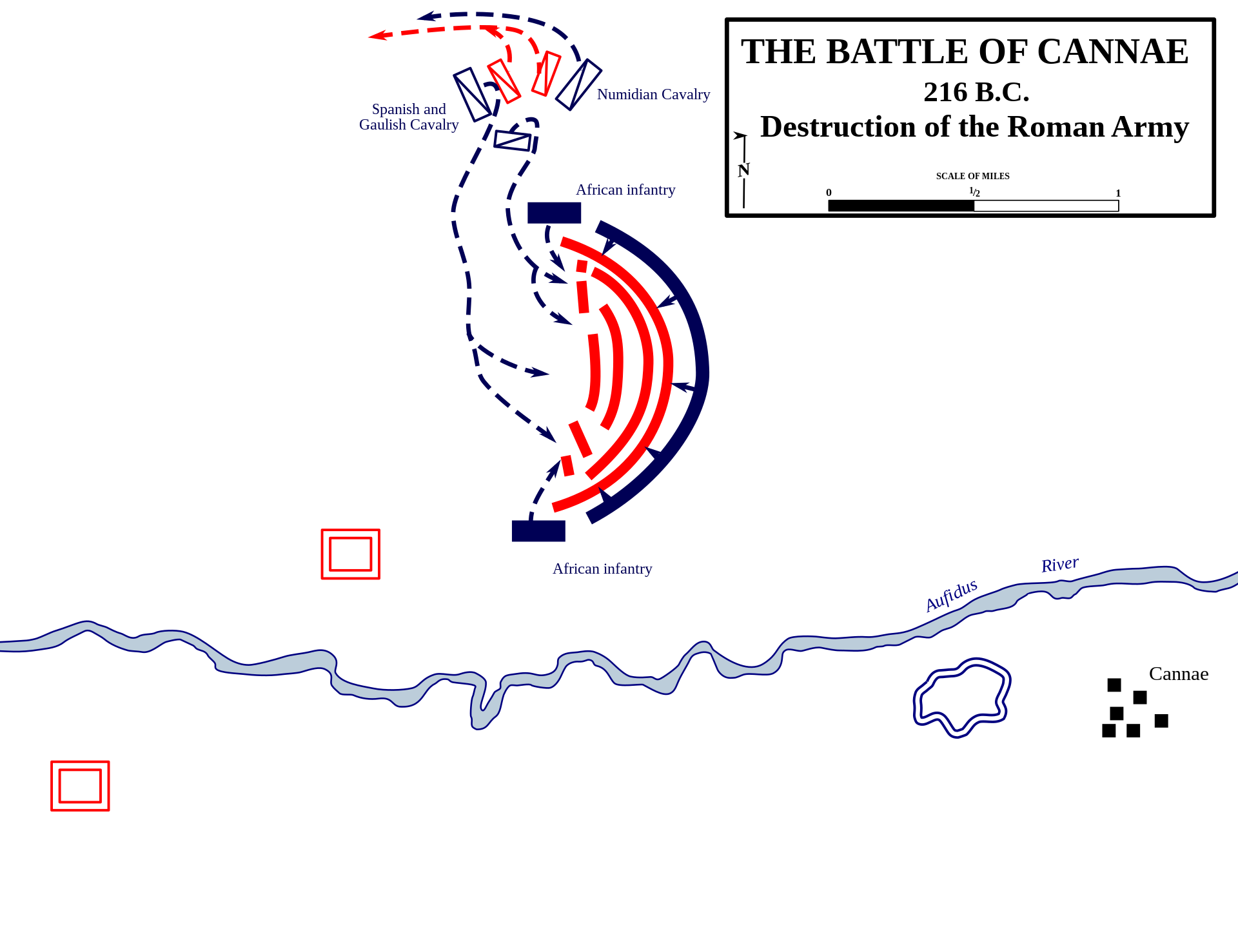

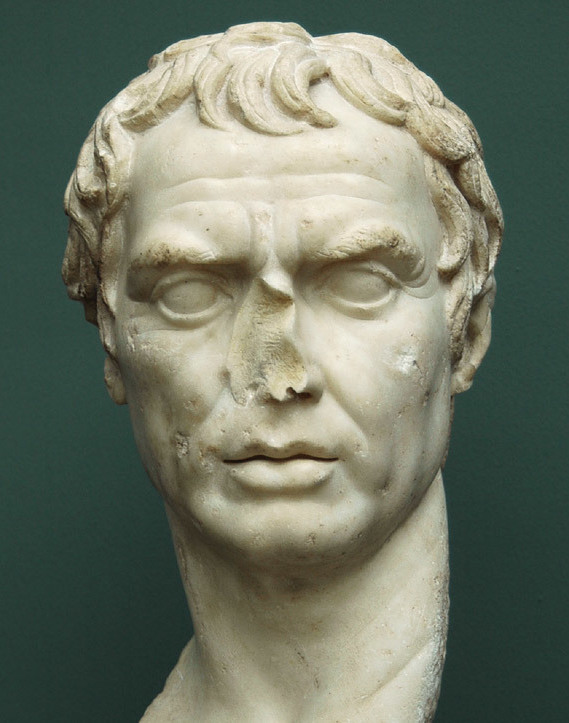

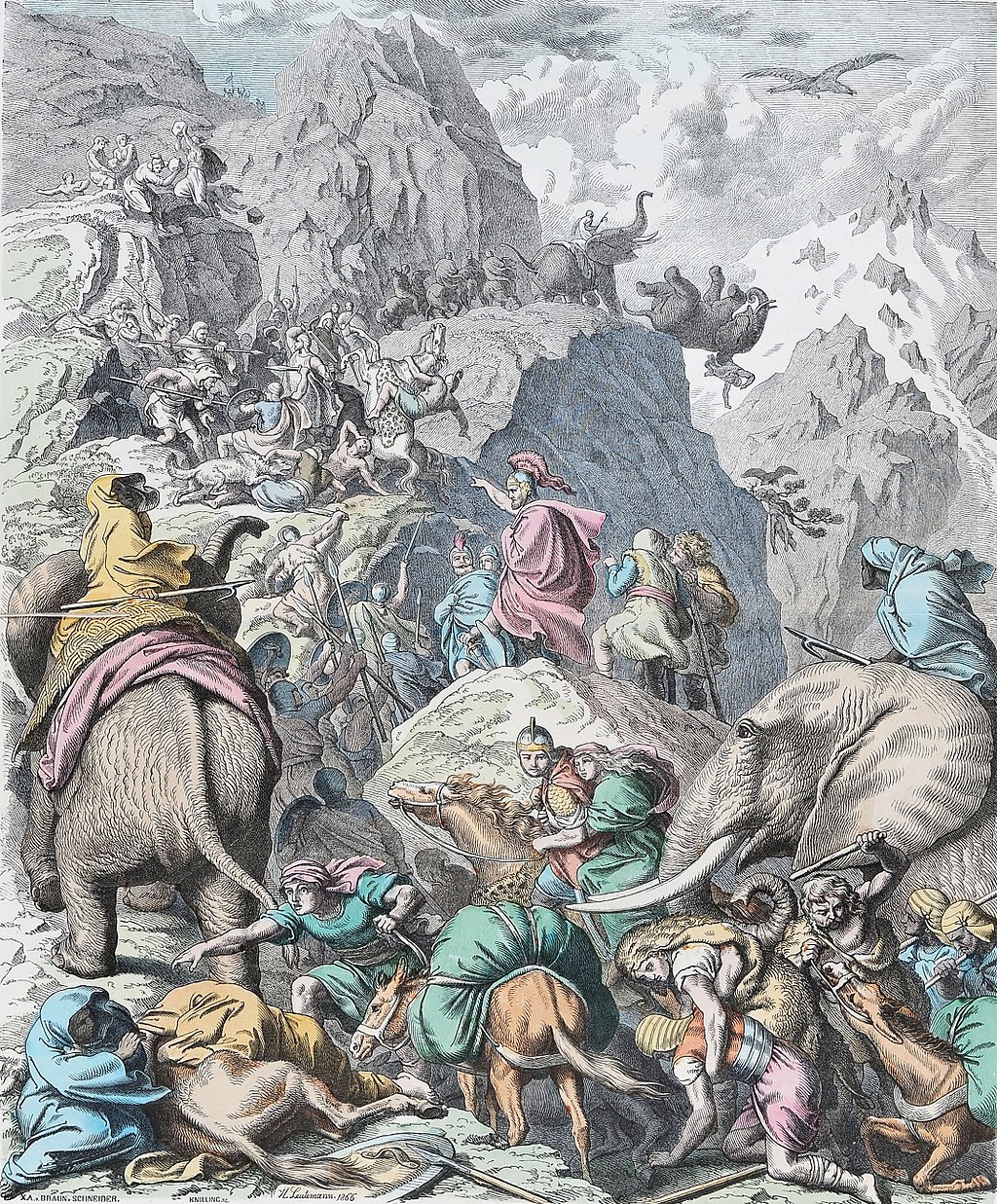

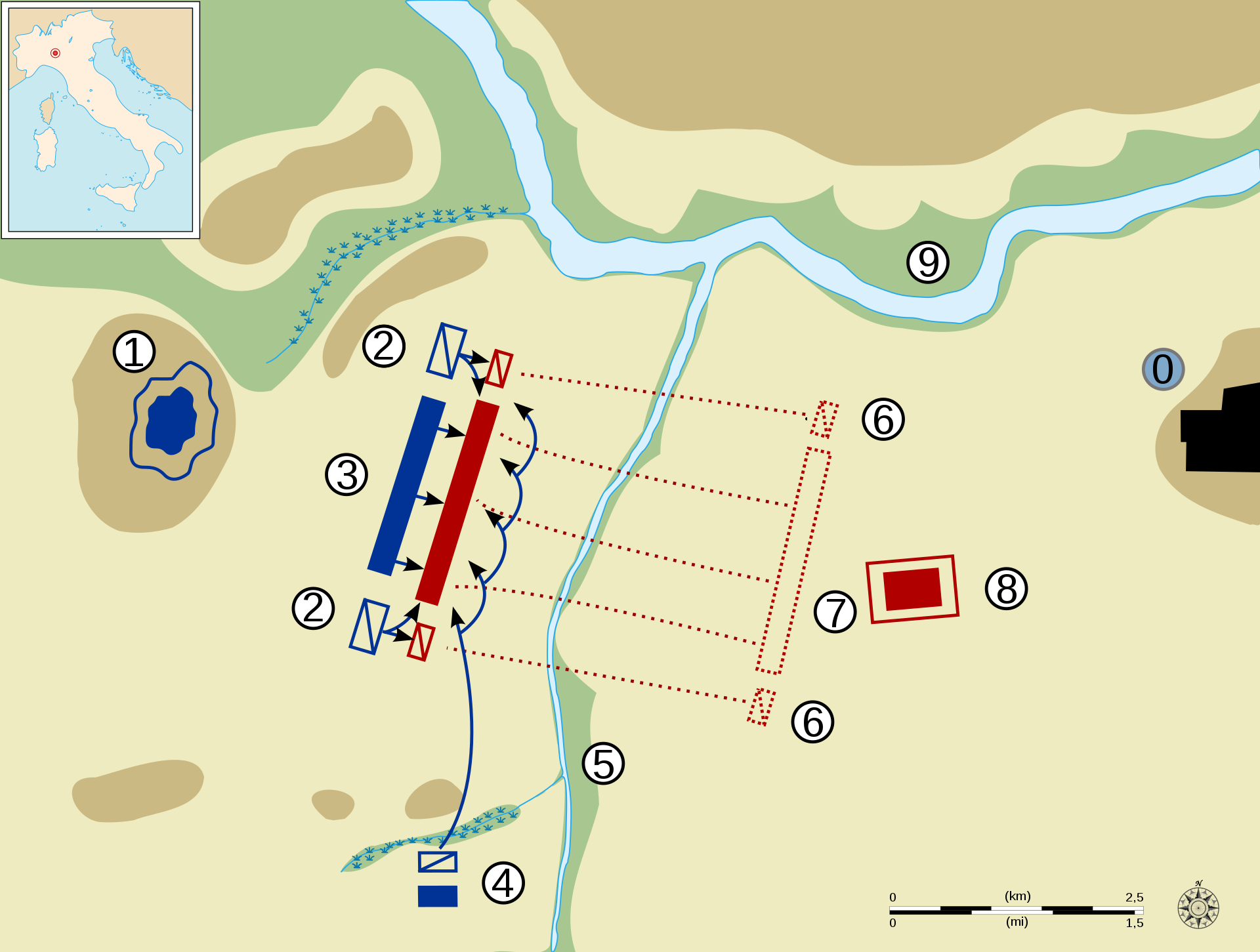

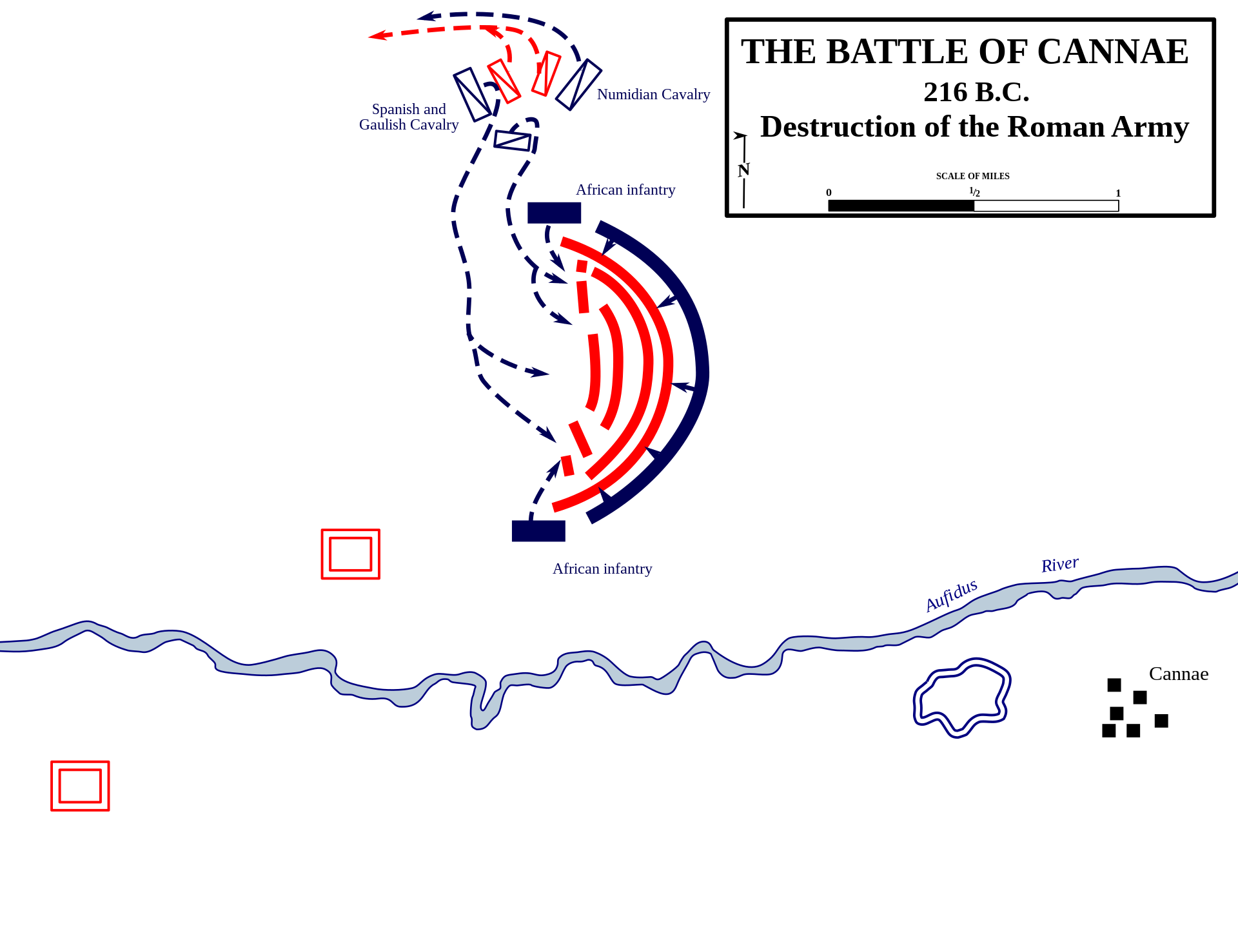

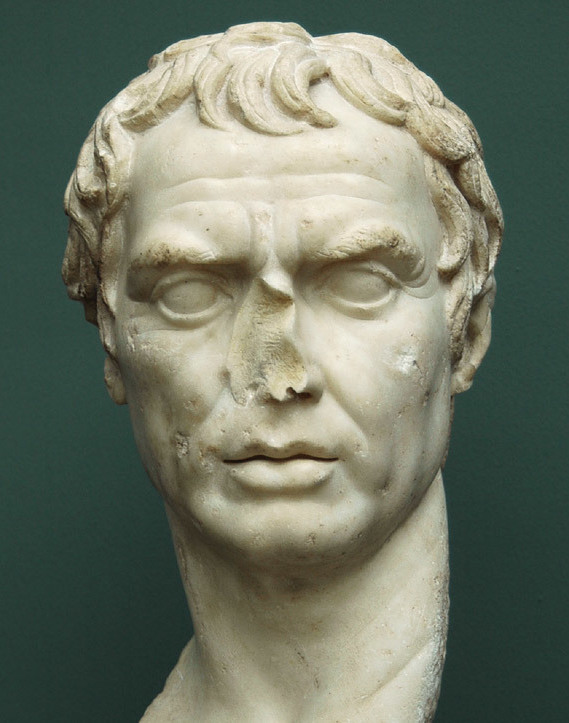

| Second Punic War in Italy (218–204 BC) Main article: Second Punic War Overland journey to Italy Main article: Hannibal's crossing of the Alps  a map of the western Mediterranean showing the route followed by the Carthaginians from Iberia to Italy Hannibal's route from Iberia to Italy This journey was originally planned by Hannibal's brother-in-law Hasdrubal the Fair, who became a Carthaginian general in the Iberian Peninsula in 229 BC. He maintained this post for eight years until 221 BC. Soon the Romans became aware of an alliance between Carthage and the Celts of the Po Valley in Northern Italy. When Hannibal arrived in the Po Valley, roughly 10,000 Celtic tribesmen joined his army.[28] The Celts were amassing forces to invade farther south in Italy, presumably with Carthaginian backing. Therefore, the Romans pre-emptively invaded the Po region in 225 BC. By 220 BC, the Romans had annexed the area as Cisalpine Gaul.[29] Hasdrubal was assassinated around the same time (221 BC), bringing Hannibal to the fore. It seems that the Romans lulled themselves into a false sense of security, having dealt with the threat of a Gallo-Carthaginian invasion, and perhaps knowing that the original Carthaginian commander had been killed. Hannibal departed Cartagena, Spain (New Carthage) in late spring of 218 BC.[30] He fought his way through the northern tribes to the foothills of the Pyrenees, subduing the tribes through clever mountain tactics and stubborn fighting. He left a detachment of 20,000 troops to garrison the newly conquered region. At the Pyrenees, he released 11,000 Iberian troops who showed reluctance to leave their homeland. Hannibal reportedly entered Gaul with 40,000 foot soldiers and 12,000 horsemen.[31] Hannibal recognized that he still needed to cross the Pyrenees, the Alps, and many large rivers.[32] Additionally, he would have to contend with opposition from the Gauls, whose territory he passed through. Starting in the spring of 218 BC, he crossed the Pyrenees and reached the Rhône by conciliating the Gaulish chiefs along his passage before the Romans could take any measures to bar his advance, arriving at the Rhône in September. Hannibal's army numbered 38,000 infantry, 8,000 cavalry, and 38 elephants, almost none of which would survive the harsh conditions of the Alps.[33]  An 1866 illustration of Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps, by Heinrich Leutemann Hannibal outmanoeuvred the natives who had tried to prevent his crossing, then evaded a Roman force marching from the Mediterranean coast by turning inland up the valley of the Rhône. His exact route over the Alps has been the source of scholarly dispute ever since (Polybius, the surviving ancient account closest in time to Hannibal's campaign, reports that the route was already debated). The most influential modern theories favour either a march up the valley of the Drôme and a crossing of the main range to the south of the modern highway over the Col de Montgenèvre or a march farther north up the valleys of the Isère and Arc crossing the main range near the present Col de Mont Cenis or the Little St Bernard Pass.[34] Recent numismatic evidence suggests that Hannibal's army passed within sight of the Matterhorn.[35] Stanford geoarchaeologist Patrick Hunt argues that Hannibal took the Col de Clapier mountain pass, claiming the Clapier most accurately met ancient depictions of the route: wide view of Italy, pockets of year-round snow, and a large campground.[36] Other scholars have doubts, proposing that Hannibal took the easier route across Petit Mount Cenis. Hunt responds to this by proposing that Hannibal's Celtic guides purposefully misguided the Carthaginian general. Most recently, W. C. Mahaney has argued Col de la Traversette closest fits the records of ancient authors.[37] Biostratigraphic archaeological data has reinforced the case for Col de la Traversette; analysis of peat bogs near watercourses on both sides of the pass's summit showed that the ground was heavily disturbed "by thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of animals and humans" and that the soil bore traces of unique levels of Clostridia bacteria associated with the digestive tract of horses and mules.[38] Radiocarbon dating secured dates of 2168 BP or c. 218 BC, the year of Hannibal's march. Mahaney et al. have concluded that this and other evidence strongly supports the Col de la Traversette as being the "Hannibalic Route" as had been argued by Gavin de Beer in 1954. De Beer was one of only three interpreters—the others being John Lazenby and Jakob Seibert—to have visited all the Alpine high passes and presented a view on which was most plausible. Both De Beer and Siebert had selected the Col de la Traversette as the one most closely matching the ancient descriptions.[39] Polybius wrote that Hannibal had crossed the highest of the Alpine passes: Col de la Traversette, between the upper Guil valley and the upper Po river is the highest pass. It is moreover the most southerly, as Varro in his De re rustica relates, agreeing that Hannibal's Pass was the highest in Western Alps and the most southerly. Mahaney et al. argue that factors used by De Beer to support Col de la Traversette including "gauging ancient place names against modern, close scrutiny of times of flood in major rivers and distant viewing of the Po plains" taken together with "massive radiocarbon and microbiological and parasitical evidence" from the alluvial sediments either side of the pass furnish "supporting evidence, proof if you will" that Hannibal's invasion went that way.[40] If Hannibal had ascended the Col de la Traversette, the Po Valley would indeed have been visible from the pass's summit, vindicating Polybius's account.[41][42] By Livy's account, the crossing was accomplished in the face of huge difficulties.[43] These Hannibal surmounted with ingenuity, such as when he used vinegar and fire to break through a rockfall.[44] According to Polybius, he arrived in Italy accompanied by 20,000 foot soldiers, 4,000 horsemen, and only a few elephants. The fired rockfall event is mentioned only by Livy; Polybius is mute on the subject and there is no evidence[45] of carbonized rock at the only two-tier rockfall in the Western Alps, located below the Col de la Traversette (Mahaney, 2008). If Polybius is correct in his figure for the number of troops that he commanded after the crossing of the Rhône, this would suggest that he had lost almost half of his force. Historians such as Serge Lancel have questioned the reliability of the figures for the number of troops that he had when he left Hispania.[46] From the start, he seems to have calculated that he would have to operate without aid from Hispania. Hannibal's vision of military affairs was derived partly from the teaching of his Greek tutors and partly from experience gained alongside his father, and it stretched over most of the Hellenistic World of his time. The breadth of his vision gave rise to his grand strategy of conquering Rome by opening a northern front and subduing allied city-states on the peninsula, rather than by attacking Rome directly. Historical events that led to the defeat of Carthage during the First Punic War when his father commanded the Carthaginian Army also led Hannibal to plan the invasion of Italy by land across the Alps. The task involved the mobilization of between 60,000 and 100,000 troops and the training of a war-elephant corps, all of which had to be provisioned along the way. The alpine invasion of Italy was a military operation that would shake the Mediterranean World of 218 BC with repercussions for more than two decades.[citation needed] Battle of Trebia Main article: Battle of the Trebia  A diagram depicting the tactics used in the Battle of the Trebia Hannibal's perilous march brought him into the Roman territory and frustrated the attempts of the enemy to fight out the main issue on foreign ground. His sudden appearance among the Gauls of the Po Valley, moreover, enabled him to detach those tribes from their new allegiance to the Romans before the Romans could take steps to check the rebellion. Publius Cornelius Scipio was the consul who commanded the Roman force sent to intercept Hannibal. He was also the father of Scipio Africanus.[47] He had not expected Hannibal to make an attempt to cross the Alps, since the Romans were prepared to fight the war in the Iberian Peninsula. With a small detachment still positioned in Gaul, Scipio made an attempt to intercept Hannibal. He succeeded, through prompt decision and speedy movement, in transporting his army to Italy by sea in time to meet Hannibal. Hannibal's forces moved through the Po Valley and were engaged in the Battle of Ticinus. Here, Hannibal forced the Romans to evacuate the plain of Lombardy, by virtue of his superior cavalry.[47] The victory was minor, but it encouraged the Gauls and Ligurians to join the Carthaginian cause. Their troops bolstered his army back to around 40,000 men. Scipio was severely injured, his life only saved by the bravery of his son who rode back onto the field to rescue his fallen father. Scipio retreated across the Trebia to camp at Placentia with his army mostly intact.[47] The other Roman consular army was rushed to the Po Valley. Even before news of the defeat at Ticinus had reached Rome, the Senate had ordered Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus to bring his army back from Sicily to meet Scipio and face Hannibal. Hannibal, by skillful maneuvers, was in position to head him off, for he lay on the direct road between Placentia and Arminum, by which Sempronius would have to march to reinforce Scipio. He then captured Clastidium, from which he drew large amounts of supplies for his men. But this gain was not without loss, as Sempronius avoided Hannibal's watchfulness, slipped around his flank, and joined his colleague in his camp near the Trebia River near Placentia. There Hannibal had an opportunity to show his masterful military skill at the Trebia in December of the same year, after wearing down the superior Roman infantry, when he cut it to pieces with a surprise attack and ambush from the flanks. However, most or all of his war elephants had died of injuries or the cold that winter and none took part in the succeeding battles at Lake Trasimene and/or Cannae.[citation needed] Battle of Lake Trasimene Main article: Battle of Lake Trasimene  The Battle of Lake Trasimene, 217 BC. From the Department of History, United States Military Academy Hannibal quartered his troops for the winter with the Gauls, whose support for him had abated. Fearing the possibility of an assassination attempt by his Gallic allies, Hannibal had a number of wigs made, dyed to suit the appearance of persons differing widely in age, and kept constantly changing them, so that any would-be assassins wouldn't recognize him.[1] In the spring of 217 BC, Hannibal decided to find a more reliable base of operations farther south. Gnaeus Servilius and Gaius Flaminius (the new consuls of Rome) were expecting Hannibal to advance on Rome, and they took their armies to block the eastern and western routes that Hannibal could use.[48] The only alternative route to central Italy lay at the mouth of the Arno. This area was practically one huge marsh, and happened to be overflowing more than usual during this particular season. Hannibal knew that this route was full of difficulties, but it remained the surest and certainly the quickest way to central Italy. Polybius claims that Hannibal's men marched for four days and three nights "through a land that was under water", suffering terribly from fatigue and enforced want of sleep. He crossed without opposition over both the Apennines (during which he lost his right eye[49] because of conjunctivitis) and the seemingly impassable Arno, but he lost a large part of his force in the marshy lowlands of the Arno.[50] He arrived in Etruria in the spring of 217 BC and decided to lure the main Roman army under Flaminius into a pitched battle by devastating the region that Flaminius had been sent to protect. As Polybius recounts, "he [Hannibal] calculated that, if he passed the camp and made a descent into the district beyond, Flaminius (partly for fear of popular reproach and partly of personal irritation) would be unable to endure watching passively the devastation of the country but would spontaneously follow him... and give him opportunities for attack."[51] At the same time, Hannibal tried to break the allegiance of Rome's allies by proving that Flaminius was powerless to protect them. Despite this, Flaminius remained passively encamped at Arretium. Hannibal marched boldly around Flaminius' left flank, unable to draw him into battle by mere devastation, and effectively cut him off from Rome, executing the first recorded turning movement in military history. He then advanced through the uplands of Etruria, provoking Flaminius into a hasty pursuit and catching him in a defile on the shore of Lake Trasimenus. There Hannibal destroyed Flaminius' army in the waters or on the adjoining slopes, killing Flaminius as well (see Battle of Lake Trasimene). This was the most costly ambush that the Romans ever sustained until the Battle of Carrhae against the Parthian Empire. Hannibal had now disposed of the only field force that could check his advance upon Rome. He realized that without siege engines, he could not hope to take the capital. He opted to exploit his victory by entering into central and southern Italy and encouraging a general revolt against the sovereign power.[52] The Romans appointed Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus as their dictator. Departing from Roman military traditions, Fabius adopted the strategy named after him, avoiding open battle while placing several Roman armies in Hannibal's vicinity in order to watch and limit his movements. Hannibal ravaged Apulia but was unable to bring Fabius to battle, so he decided to march through Samnium to Campania, one of the richest and most fertile provinces of Italy, hoping that the devastation would draw Fabius into battle. Fabius closely followed Hannibal's path of destruction, yet still refused to let himself be drawn out of the defensive. This strategy was unpopular with many Romans, who believed that it was a form of cowardice. Hannibal decided that it would be unwise to winter in the already devastated lowlands of Campania, but Fabius had trapped him there by ensuring that all the exit passes were blocked. This situation led to the night Battle of Ager Falernus. Hannibal had his men tie burning torches to the horns of a herd of cattle and drive them up the heights nearby. Some of the Romans, seeing a moving column of lights, were tricked into believing it was the Carthaginian army marching to escape along the heights. As they moved off in pursuit of this decoy, Hannibal managed to move his army in complete silence through the dark lowlands and up to an unguarded pass. Fabius himself was within striking distance but in this case his caution worked against him, as rightly sensing a trick he stayed put. Thus, Hannibal managed to stealthily escape with his entire army intact. What Hannibal achieved in extricating his army was, as Adrian Goldsworthy puts it, "a classic of ancient generalship, finding its way into nearly every historical narrative of the war and being used by later military manuals".[53] This was a severe blow to Fabius' prestige and soon after this his period of dictatorial power ended. For the winter, Hannibal found comfortable quarters in the Apulian plain. Battle of Cannae Main article: Battle of Cannae  The destruction of the Roman army (red) at Cannae, courtesy of the Department of History, United States Military Academy In the spring of 216 BC, Hannibal took the initiative and seized the large supply depot at Cannae in the Apulian plain. By capturing Cannae, Hannibal had placed himself between the Romans and their crucial sources of supply.[54] Once the Roman Senate resumed their consular elections in 216 BC, they appointed Gaius Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemilius Paullus as consuls. In the meantime, the Romans hoped to gain success through sheer strength and weight of numbers, and they raised a new army of unprecedented size, estimated by some to be as large as 100,000 men, but more likely around 50,000–80,000.[55] The Romans and allied legions resolved to confront Hannibal and marched southward to Apulia. They eventually found him on the left bank of the Aufidus River, and encamped 10 km (6 mi) away. On this occasion, the two armies were combined into one, the consuls having to alternate their command on a daily basis. According to Livy, Varro was a man of reckless and hubristic nature and it was his turn to command on the day of battle. This account is possibly biased against Varro as its main source, Polybius, was a client of Paullus's aristocratic family whereas Varro was less distinguished. Some historians have suggested that the sheer size of the army required both generals to command a wing each. This theory is supported by the fact that, after Varro survived the battle he was pardoned by the Senate, which would be peculiar if he were the sole commander at fault.[55] Hannibal capitalized on the eagerness of the Romans and drew them into a trap by using an envelopment tactic. This eliminated the Roman numerical advantage by shrinking the combat area. Hannibal drew up his least reliable infantry in the centre in a semicircle curving towards the Romans. Placing them forward of the wings allowed them room to fall back, luring the Romans after them, while the cavalry on the flanks dealt with their Roman counterparts. Hannibal's wings were composed of the Gallic and Numidian cavalry.[55] The Roman legions forced their way through Hannibal's weak centre, but the Libyan mercenaries on the wings, swung around by the movement, menaced their flanks. The onslaught of Hannibal's cavalry was irresistible. Hannibal's chief cavalry commander, Maharbal, led the mobile Numidian cavalry on the right; they shattered the Roman cavalry opposing them. Hannibal's Iberian and Gallic heavy cavalry on the left, led by Hanno, defeated the Roman heavy cavalry, and then both the Carthaginian heavy cavalry and the Numidians attacked the legions from behind. As a result, the Roman army was hemmed in with no means of escape.  Hannibal counting the rings of the Roman senators killed during the Battle of Cannae, statue by Sébastien Slodtz, 1704, Louvre Due to these brilliant tactics, Hannibal managed to surround and destroy all but a small remnant of his enemy, despite his own inferior numbers. Depending upon the source, it is estimated that 50,000–70,000 Romans were killed or captured.[13] Among the dead were Roman consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus, two consuls for the preceding year, two quaestors, 29 of the 48 military tribunes, and an additional eighty senators. At a time when the Roman Senate was composed of no more than 300 men, this constituted 25–30% of the governing body. This makes the battle one of the most catastrophic defeats in the history of ancient Rome, and one of the bloodiest battles in all of human history, in terms of the number of lives lost in a single day.[55] After Cannae, the Romans were very hesitant to confront Hannibal in pitched battle, preferring instead to weaken him by attrition, relying on their advantages of interior lines, supply, and manpower. As a result, Hannibal fought no more major battles in Italy for the rest of the war. It is believed that his refusal to bring the war to Rome itself was due to a lack of commitment from Carthage of men, money, and material—principally siege equipment. Whatever the reason, the choice prompted Maharbal to say, "Hannibal, you know how to gain a victory, but not how to use one."[56] As a result of this victory, many parts of Italy joined Hannibal's cause.[57] As Polybius notes, "How much more serious was the defeat of Cannae, than those that preceded it can be seen by the behaviour of Rome's allies; before that fateful day, their loyalty remained unshaken, now it began to waver for the simple reason that they despaired of Roman Power."[58] During that same year, the Greek cities in Sicily were induced to revolt against Roman political control, while Macedonian King Philip V pledged his support to Hannibal— initiating the First Macedonian War against Rome.[59] Hannibal also secured an alliance with newly appointed tyrant Hieronymus of Syracuse. It is often argued that, if Hannibal had received proper material reinforcements from Carthage, he might have succeeded with a direct attack upon Rome. Instead, he had to content himself with subduing the fortresses that still held out against him, and the only other notable event of 216 BC was the defection of certain Italian territories, including Capua, the second largest city of Italy, which Hannibal made his new base. However, only a few of the Italian city-states that he had expected to gain as allies defected to him. Stalemate The war in Italy settled into a strategic stalemate. The Romans used the attritional strategy that Fabius had taught them, which, they finally realized, was the only feasible means of defeating Hannibal.[60] Fabius received the name "Cunctator" ("the Delayer") because of his policy of not meeting Hannibal in open battle, but through attrition.[61] The Romans deprived Hannibal of a large-scale battle and instead assaulted his weakening army with multiple smaller armies in an attempt to both weary him and create unrest in his troops.[13] For the next few years, Hannibal was forced to sustain a scorched earth policy and obtain local provisions for protracted and ineffectual operations throughout southern Italy. His immediate objectives were reduced to minor operations centred mainly around the cities of Campania. The forces detached to his lieutenants were generally unable to hold their own, and neither his home government nor his new ally Philip V of Macedon helped to make up his losses. His position in southern Italy, therefore, became increasingly difficult and his chance of ultimately conquering Rome grew ever more remote. Hannibal still won a number of notable victories: completely destroying two Roman armies in 212 BC, and killing two consuls, including the famed Marcus Claudius Marcellus in a battle in 208 BC. However, Hannibal slowly began losing ground—inadequately supported by his Italian allies, abandoned by his government, either because of jealousy or simply because Carthage was overstretched, and unable to match Rome's resources. He was never able to bring about another grand decisive victory that could produce a lasting strategic change. Carthaginian political will was embodied in the ruling oligarchy. There was a Carthaginian Senate, but the real power was with the inner "Council of 30 Nobles" and the board of judges from ruling families known as the "Hundred and Four". These two bodies came from the wealthy, commercial families of Carthage. Two political factions operated in Carthage: the war party, also known as the "Barcids" (Hannibal's family name), and the peace party led by Hanno II the Great. Hanno had been instrumental in denying Hannibal's requested reinforcements following the battle at Cannae. Hannibal started the war without the full backing of Carthaginian oligarchy. His attack of Saguntum had presented the oligarchy with a choice of war with Rome or loss of prestige in Iberia. The oligarchy, not Hannibal, controlled the strategic resources of Carthage. Hannibal constantly sought reinforcements from either Iberia or North Africa. Hannibal's troops who were lost in combat were replaced with less well-trained and motivated mercenaries from Italy or Gaul. The commercial interests of the Carthaginian oligarchy dictated the reinforcement and supply of Iberia rather than Hannibal throughout the campaign. Hannibal's retreat in Italy  A bust of doubtful provenance, possibly of Scipio Africanus, and originally from the Tomb of the Scipios In March 212 BC, Hannibal captured Tarentum in a surprise attack but he failed to obtain control of its harbor. The tide was slowly turning against him, and in favor of Rome. The Roman consuls mounted a siege of Capua in 212 BC. Hannibal attacked them, forcing their withdrawal from Campania. He moved to Lucania and destroyed a 16,000-man Roman army at the Battle of the Silarus, with 15,000 Romans killed. Another opportunity presented itself soon after, a Roman army of 18,000 men being destroyed by Hannibal at the first battle of Herdonia with 16,000 Romans dead, freeing Apulia from the Romans for the year. The Roman consuls mounted another siege of Capua in 211 BC, conquering the city. Hannibal's attempt to lift the siege with an assault on the Roman siege lines failed. He marched on Rome to force the recall of the Roman armies. He drew off 15,000 Roman soldiers, but the siege continued and Capua fell. In 212 BC, Marcellus conquered Syracuse and the Romans destroyed the Carthaginian army in Sicily in 211–210 BC. In 210 BC, the Romans entered into an alliance with the Aetolian League to counter Philip V of Macedon. Philip, who attempted to exploit Rome's preoccupation in Italy to conquer Illyria, now found himself under attack from several sides at once and was quickly subdued by Rome and her Greek allies. In 210 BC, Hannibal again proved his superiority in tactics by inflicting a severe defeat at the Battle of Herdonia (modern Ordona) in Apulia upon a proconsular army and, in 208 BC, destroyed a Roman force engaged in the siege of Locri at the Battle of Petelia. But with the loss of Tarentum in 209 BC and the gradual reconquest by the Romans of Samnium and Lucania, his hold on south Italy was almost lost. In 207 BC, he succeeded in making his way again into Apulia, where he waited to concert measures for a combined march upon Rome with his brother Hasdrubal. On hearing of his brother's defeat and death at the battle of the Metaurus, he retired to Calabria, where he maintained himself for the ensuing years. His brother's head had been cut off, carried across Italy, and tossed over the palisade of Hannibal's camp as a cold message of the iron-clad will of the Roman Republic. The combination of these events marked the end to Hannibal's success in Italy. With the failure of his brother Mago in Liguria (205–203 BC) and of his own negotiations with Phillip V, the last hope of recovering his ascendancy in Italy was lost. In 203 BC, after nearly fifteen years of fighting in Italy and with the military fortunes of Carthage rapidly declining, Hannibal was recalled to Carthage to direct the defense of his native country against a Roman invasion under Scipio Africanus. |

イタリアにおける第二次ポエニ戦争(紀元前218~204年) 主な記事 第二次ポエニ戦争 イタリアへの陸路の旅 主な記事 ハンニバルのアルプス越え  カルタゴ人がイベリアからイタリアまでたどったルートを示す地中海西部の地図 ハンニバルのイベリアからイタリアへのルート この旅は、紀元前229年にイベリア半島でカルタゴの将軍となったハンニバルの義弟ハスドルバルによって計画された。彼は紀元前221年までの8年間、こ のポストを維持した。やがてローマ人は、カルタゴと北イタリアのポー渓谷のケルト人との間に同盟関係があることを知った。ハンニバルがポー渓谷に到着する と、およそ10,000人のケルト人が彼の軍に加わった[28]。 ケルト人は、おそらくカルタゴの後ろ盾を得て、さらに南のイタリアに侵攻するために軍を集結させていた。そのため、ローマ帝国は紀元前225年にポー地方 に先制侵攻した。紀元前220年には、ローマ帝国はこの地域をキサルピナ・ガウルとして併合した[29]。ローマ軍はガロ=カルタゴ侵攻の脅威に対処し、 おそらく本来のカルタゴ人指揮官が殺されたことを知っていたため、誤った安心感を抱いていたようである。 ハンニバルは紀元前218年の晩春、スペインのカルタヘナ(新カルタゴ)を出発した[30]。北方諸部族をかき分けてピレネー山脈のふもとまで行き、巧み な山岳戦術と頑強な戦いによって諸部族を制圧した。彼は新たに征服した地域の守備のために2万の部隊を残した。ピレネー山脈では、故郷を離れたがらない 11,000人のイベリア人部隊を解放した。ハンニバルは40,000人の歩兵と12,000人の騎兵を率いてガリアに入ったと伝えられている[31]。 ハンニバルは、ピレネー山脈、アルプス山脈、多くの大河を越える必要があることを認識していた[32]。紀元前218年の春からピレネー山脈を越え、ロー マ軍が彼の進軍を阻む策を講じる前に、ガリア人の首長たちを融和させながらローヌに到達し、9月にローヌに到着した。ハンニバルの軍勢は歩兵38,000 人、騎兵8,000人、象38頭であったが、アルプスの過酷な環境を生き抜くものはほとんどいなかった[33]。  1866年、ハインリヒ・ロイテマンが描いたアルプス越えをするハンニバルとその軍隊のイラスト。 ハンニバルは、彼の横断を阻止しようとした原住民を出し抜き、地中海沿岸から進軍してきたローマ軍をローヌの谷を内陸に進路を変えてかわした。ハンニバル のアルプス越えの正確なルートは、それ以来、学者たちの論争の的となっている(ハンニバルの遠征に最も近い時代に書かれた古代の記録であるポリビオスは、 そのルートについてすでに議論されていたと報告している)。現代の最も有力な説は、ドロームの谷を行軍し、モンジュネーヴル峠を越える現代の高速道路の南 側で主脈を越えるか、イゼール峠とアルク峠の谷をさらに北上し、現在のモン・セニス峠または小サン・ベルナール峠付近で主脈を越えるかのどちらかを支持し ている[34]。 スタンフォード大学の地質考古学者であるパトリック・ハントは、ハンニバルがクラピエ峠を越えたと主張し、クラピエ峠はイタリアを広く見渡せ、一年中雪が 積もり、大規模なキャンプ場があったという古代のルート描写に最も合致していると主張している。ハントはこれに対し、ハンニバルのケルト人ガイドが意図的 にカルタゴの将軍を誤った方向に導いたと提案している。 最近では、W.C.マハニーがコル・ド・ラ・トラヴェルセットが古代の著者の記録に最も合致すると主張している[37]。生物層序学的考古学的データは、 コル・ド・ラ・トラヴェルセットの事例を補強している。峠の山頂の両側の水路に近い泥炭地を分析した結果、「何千、おそらく何万もの動物や人間によって」 地面は激しく撹乱され、土壌には馬やラバの消化管に関連するユニークなレベルのクロストリジウム菌の痕跡があることが判明した[38]。 放射性炭素年代測定によって、紀元前2168年、もしくはハンニバルが進軍した紀元前218年頃の年代が確認された。Mahaneyらは、1954年に Gavin de Beerによって主張されたように、トラヴェルセットのコルが「ハンニバル・ルート」であったことをこの証拠と他の証拠が強く支持していると結論づけた。 デビアは、アルプスのすべての峠を訪れ、どれが最も妥当であるかという見解を示した、3人しかいない解釈者の一人であった。デ・ビールとシーベルトはとも に、古代の記述に最も近いものとしてコル・ド・ラ・トラヴェルセットを選んでいた[39]。 ポリビウスは、ハンニバルがアルプスの峠のうち最も高い峠を越えたと記している: ギル渓谷上流とポー川上流の間にあるトラヴェルセッテ峠は、最も高い峠である。さらに、ヴァロが『De re rustica』の中で、ハンニバルの峠が西アルプスで最も高く、最も南に位置する峠であることに同意している。マハニーらは、デ・ベールがトラヴェル セット峠を支持した要因として、「古代の地名と現代の地名との比較、主要河川の氾濫時期の綿密な調査、ポー平野の遠望」を挙げ、峠の両側の沖積堆積物から 得られた「大量の放射性炭素、微生物学的、寄生虫学的証拠」と合わせて、ハンニバルの侵攻がこの道を通ったという「裏付けとなる証拠、言うなれば証拠」を 提出したと論じている[40]。 [40] もしハンニバルがコル・ド・ラ・トラヴェルセットに登ったのであれば、ポー渓谷は確かに峠の頂上から見えたはずであり、ポリュビオスの記述を正当化するこ とになる[41][42]。 リヴィウスの記述によれば、横断は大きな困難に直面して達成された[43]が、ハンニバルは酢と火を使って落石を突破するなど、創意工夫によって乗り越え た[44]。 ポリュビオスによれば、彼は2万の歩兵と4,000の騎兵、そしてわずか数頭の象を従えてイタリアに到着した。ポリュビオスはこの件に関して無言であり、 トラヴェルセットのコルの下にある西アルプスで唯一の2段の滝に炭化した岩があったという証拠[45]もない(Mahaney, 2008)。もしポリュビオスがローヌ河横断後に指揮した兵力数の数字が正しければ、彼は兵力のほぼ半分を失ったことになる。セルジュ・ランセルのような 歴史家は、彼がイスパニアを出発したときの兵力数の数字の信頼性に疑問を呈している[46]。彼は当初から、イスパニアからの援助なしに行動しなければな らないことを計算していたようである。 ハンニバルの軍事に関するビジョンは、ギリシア人家庭教師の教えと、父とともに得た経験から導き出されたものであり、当時のヘレニズム世界のほとんどに及 んでいた。その視野の広さが、ローマを直接攻撃するのではなく、北方戦線を展開し、半島の同盟都市国家を制圧することでローマを征服するという彼の壮大な 戦略を生み出した。彼の父がカルタゴ軍を指揮していた第一次ポエニ戦争でカルタゴを敗北させた歴史的な出来事も、ハンニバルにアルプス越えの陸路によるイ タリア侵攻を計画させた。この作戦には、6万から10万の兵士を動員し、戦象軍団を訓練する必要があった。アルプスによるイタリア侵攻は、紀元前218年 の地中海世界を揺るがす軍事作戦であり、その影響は20年以上にも及んだ[要出典]。 トレビアの戦い 主な記事 トレビアの戦い  トレビアの戦いで使用された戦術を描いた図 ハンニバルの危険な行軍はローマ帝国領土に彼を引き入れ、敵が異国の地で主要な問題を解決しようとする試みを挫いた。さらに、ポー渓谷のガリア人の間に突 然現れた彼は、ローマ人が反乱を阻止する手段を講じる前に、それらの部族をローマ人への新しい忠誠から切り離すことを可能にした。プブリウス・コルネリウ ス・スキピオは、ハンニバルを迎え撃つために派遣されたローマ軍を指揮したコンスルである。彼はスキピオ・アフリカヌスの父親でもあった[47]。 ローマ軍はイベリア半島で戦争を戦う準備をしていたため、ハンニバルがアルプス越えを試みるとは予想していなかった。小部隊をガリアに配置したまま、スキ ピオはハンニバルの迎撃を試みた。彼は、迅速な決断と迅速な行動によって、ハンニバルに間に合うように軍隊を海路でイタリアに運ぶことに成功した。ハンニ バル軍はポー渓谷を移動し、ティキヌスの戦いで交戦した。この戦いでハンニバルは、その優れた騎兵によってローマ軍をロンバルディア平原から撤退させた。 彼らの兵力により、スキピオの軍勢は40,000人ほどに増強された。スキピオは重傷を負ったが、倒れた父を救うために戦場に戻った息子の勇敢さによって 命拾いした。スキピオはほとんど無傷のまま、トレビア川を越えてプラセンティアに撤退した[47]。 もう一方のローマ領事軍はポー渓谷に急行した。ティキヌスでの敗北の知らせがローマに届く前から、元老院は領事ティベリウス・センプローニウス・ロンガス に、シチリアから軍を戻し、スキピオを迎え撃ち、ハンニバルに立ち向かうよう命じていた。ハンニバルは巧みな作戦によって、スキピオを援軍するためにセン プロニウスが進軍しなければならないプラセンティアとアルミヌムを結ぶ直通路に位置していたため、彼を阻止することができた。その後、クラスティディウム を占領し、そこから大量の兵糧を引き出した。しかし、センプロニウスはハンニバルの警戒をかいくぐり、ハンニバルの脇をすり抜け、プラセンティアに近いト レビア川近くのキャンプで同僚と合流した。そこでハンニバルは、同年12月のトレビア川で、優勢なローマ軍の歩兵を消耗させた後、側面からの奇襲と待ち伏 せで切り裂き、その卓越した軍事的手腕を発揮する機会を得た。しかし、その冬、彼の軍用象のほとんど、あるいはすべてが負傷や寒さで死んでしまい、その後 のトラジメネ湖やカンナエの戦いには一頭も参加しなかった[要出典]。 トラジメネ湖の戦い 主な記事 トラジメネ湖の戦い  紀元前217年、トラジメネ湖の戦い。 アメリカ陸軍士官学校歴史学科より ハンニバルは冬の間、ガリア人とともに軍を宿営させたが、ガリア人のハンニバルに対する支持は弱まっていた。ガリア同盟軍による暗殺の可能性を恐れたハン ニバルは、年齢が大きく異なる人物の外見に合うように染めたかつらを何本も作らせ、暗殺者となる者が彼を認識できないように常に変え続けた[1]。紀元前 217年の春、ハンニバルはより南方に信頼できる拠点を見つけることにした。グナエウス・セルヴィリウスとガイウス・フラミニウス(ローマの新執政官)は ハンニバルがローマに進攻することを予期しており、彼らは軍隊を率いてハンニバルが利用できる東と西のルートを封鎖した[48]。 中央イタリアへの唯一の代替ルートはアルノ河口にあった。この地域は事実上巨大な湿地帯であり、この特別な季節にはいつも以上に水があふれていた。ハンニ バルは、このルートが困難だらけであることを知っていたが、中央イタリアへの最も確実で確実な早道であることに変わりはなかった。ポリュビオスによれば、 ハンニバルの兵士たちは、疲労と睡眠不足に苦しみながら、3泊4日の行軍を行ったという。紀元前217年の春にエトルリアに到着したハンニバルは、フラミ ニウスが保護するために派遣された地域を荒廃させることで、フラミニウス率いるローマ本軍を戦闘に誘い込むことにした。ポリビウスが回想しているように、 「彼(ハンニバル)は、もし自分が野営地を通過し、その先の地区へと下降すれば、フラミニウスは(一部は民衆の非難を恐れ、一部は個人的な苛立ちから)国 の荒廃を受動的に見ていることに耐えられず、自発的に彼についてきて......攻撃の機会を与えるだろうと計算した」[51]。 同時にハンニバルは、フラミニウスが同盟国を守る力がないことを証明することで、ローマの同盟国の忠誠心を打ち砕こうとした。にもかかわらず、フラミニウ スは受動的にアレーティウムに陣取った。ハンニバルはフラミニウスの左翼を大胆に回り込み、単なる破壊ではフラミニウスを戦闘に引き込むことができず、 ローマから効果的に切り離し、軍事史上初めて記録された旋回運動を実行した。その後、彼はエトルリアの高地を進み、フラミニウスを挑発して急いで追跡さ せ、トラジメヌス湖畔の隘路で彼を捕らえた。そこでハンニバルはフラミニウスの軍勢を水中や隣接する斜面で壊滅させ、フラミニウスも殺害した(トラジメヌ 湖の戦い参照)。これはパルティア帝国とのカルハエの戦いまで、ローマ軍が最も犠牲を払った奇襲であった。ハンニバルは、ローマへの進撃を阻止できる唯一 の野戦部隊を処分した。ハンニバルは、包囲砲がなければ首都を占領することはできないと悟った。ハンニバルは、イタリア中部と南部に進入し、宗主国に対す る一般的な反乱を奨励することで、勝利を利用することを選んだ[52]。 ローマ軍はクィントゥス・ファビウス・マクシムス・ヴェルコソスを独裁者に任命した。ローマの軍事的伝統から離れ、ファビウスはハンニバルの動きを監視し 制限するために、いくつかのローマ軍をハンニバルの周辺に配置しながら、開戦を避けるという、彼の名にちなんだ戦略を採用した。ハンニバルはアプーリアを 荒廃させたが、ファビウスを戦闘に引き込むことはできなかった。そこで彼は、荒廃がファビウスを戦闘に引き込むことを期待し、サムニウムを通ってイタリア で最も豊かで肥沃な州の一つであるカンパニアに進軍することにした。ファビウスはハンニバルの破壊の道を忠実に辿ったが、それでも守勢に回ることを拒ん だ。この戦略は多くのローマ人に不評で、臆病の一種だと考えられていた。 ハンニバルは、すでに荒廃していたカンパニアの低地で冬を越すのは得策ではないと判断したが、ファビウスは出口の峠をすべて封鎖して彼をそこに閉じ込め た。この状況がアガー・ファレルヌスの夜の戦いにつながった。ハンニバルは家畜の群れの角に松明をくくりつけ、近くの高台に追い立てた。ローマ軍の一部 は、動く光の列を見て、カルタゴ軍が高台に沿って逃げるために行進しているのだと騙された。彼らがこの囮を追って出発すると、ハンニバルは完全な沈黙のう ちに、暗い低地を通り抜け、無警戒の峠まで軍隊を移動させることに成功した。ファビウス自身は射程圏内にいたが、この場合は警戒心が仇となり、策略を察知 してじっとしていた。こうしてハンニバルは、全軍を無傷のままこっそりと脱出することに成功した。エイドリアン・ゴールズワーシーが言うように、ハンニバ ルが軍隊を脱出させたことは、「古代のジェネラルシップの古典であり、この戦争に関するほとんどすべての歴史的な物語に登場し、後の軍事マニュアルにも使 用された」[53]。これはファビウスの威信に大きな打撃を与え、この後すぐに彼の独裁的な権力の期間は終わった。冬の間、ハンニバルはアプリア平野に快 適な宿舎を見つけた。 カンネの戦い 主な記事 カンネの戦い  カンナエでのローマ軍の破壊(赤)(提供:アメリカ陸軍士官学校歴史学科 紀元前216年春、ハンニバルは先手を打ち、アプリア平原のカンネにある大規模な補給基地を占領した。紀元前216年、ローマ元老院は領事選挙を再開する と、ガイウス・テレンティウス・ヴァッロとルキウス・アエミリウス・パウルスを領事に任命した。その間、ローマ軍は数の力と重さによって成功を得ようと考 え、前例のない規模の軍隊を新たに編成した。その規模は10万人とも言われているが、5万~8万人程度であった可能性が高い[55]。 ローマ軍と同盟軍団はハンニバルとの対決を決意し、アプリアまで南下した。彼らは最終的にアウフィドゥス川左岸でハンニバルを発見し、10km離れた場所 に野営した。この時、両軍は1つに統合され、領事たちは日替わりで指揮を執ることになった。リヴィによれば、ヴァッロは無謀で思い上がった性格の人物で、 戦いの日は彼が指揮を執った。この記述の主な出典者であるポリュビウスはパウルスの貴族一族の顧客であったのに対し、ヴァロはそれほど著名ではなかったた め、この記述はヴァロに偏っている可能性がある。一部の歴史家は、軍の規模が大きかったため、両将がそれぞれ1つの翼を指揮する必要があったと指摘してい る。この説は、ヴァッロが戦闘を生き延びた後、元老院から赦免されたという事実によって裏付けられている。 ハンニバルはローマ軍の熱心さを利用し、包囲戦術を用いることで罠に引き込んだ。これにより、戦闘区域を狭めることでローマ軍の数的優位をなくした。ハン ニバルは、最も信頼できない歩兵をローマ軍に向かって半円を描くように中央に配置した。彼らを翼の前方に配置することで、後退する余地を与え、ローマ軍を おびき寄せ、その間に側面の騎兵隊がローマ軍に対処した。ハンニバルの翼はガリア騎兵とヌミディア騎兵で構成されていた[55]。ローマ軍団はハンニバル の弱体な中央部を強引に突破したが、翼のリビア傭兵はその動きに振り回され、側面を脅かした。 ハンニバルの騎兵隊の猛攻は抗しがたいものだった。ハンニバルの騎兵総指揮官マハルバルは、右翼の機動力のあるヌミディア騎兵を率い、対抗するローマ騎兵 を粉砕した。ハンノ率いる左翼のイベリア騎兵隊とガリア騎兵隊はローマ重騎兵隊を破り、さらにカルタゴ重騎兵隊とヌミディア騎兵隊が背後から軍団を攻撃し た。その結果、ローマ軍は逃げ場を失い、身動きが取れなくなった。  カンナエの戦いで戦死したローマ元老院議員の指輪を数えるハンニバル像(セバスチャン・スロッズ作、1704年、ルーヴル美術館蔵 こうした見事な戦術により、ハンニバルは劣勢に立たされながらも、少数の残党を除いて敵を包囲し、壊滅させることに成功した。情報源にもよるが、 50,000~70,000人のローマ人が死亡または捕虜になったと推定されている[13]。死者の中には、ローマのルキウス・アエミリウス・パウルス執 政官、前年の執政官2人、準執政官2人、48人の軍事廷僚のうち29人、さらに80人の元老院議員が含まれていた。ローマ元老院が300人以下で構成され ていた当時、これは統治機関の25〜30%を占めていた。このため、この戦いは古代ローマ史上最も破滅的な敗北のひとつであり、1日に失われた人命の数と いう点では、人類史上最も血なまぐさい戦いのひとつとなった[55]。 カンナエの後、ローマ軍はハンニバルと戦闘を行うことを非常にためらい、その代わりに、内線、補給、兵力などの優位性を頼りに、消耗戦によってハンニバル を弱体化させることを好んだ。その結果、ハンニバルは戦争の残りの期間、イタリアで大きな戦いをすることはなくなった。ハンニバルがローマへの侵攻を拒否 したのは、カルタゴが人員、資金、物資(主に包囲戦装備)を提供しなかったからだと考えられている。理由はどうであれ、この選択はマハルバルに「ハンニバ ル、お前は勝利を得る方法は知っているが、勝利を使う方法は知らない」と言わしめた[56]。 この勝利の結果、イタリアの多くの地域がハンニバルの大義名分に加わった[57]。ポリュビオスが「カンナエの敗北が、それ以前の敗北よりもどれほど深刻 であったかは、ローマの同盟国の行動によって知ることができる。 「58]同年、シチリアのギリシア諸都市はローマの政治支配に反旗を翻すよう誘導され、マケドニア王フィリップ5世はハンニバルへの支持を表明し、ローマ に対する第一次マケドニア戦争を開始した[59]。 ハンニバルはまた、新たにシラクサの暴君ヒエロニムスと同盟を結んだ。もしハンニバルがカルタゴから適切な物的援軍を受けていれば、ローマへの直接攻撃で 成功したかもしれないとしばしば論じられる。紀元前216年、ハンニバルが新たな拠点としたイタリア第二の都市カプアを含むイタリア領土の離反が唯一の注 目すべき出来事であった。しかし、ハンニバルが同盟国として獲得すると期待していたイタリアの都市国家のうち、彼に離反したのはわずかなものであった。 膠着状態 イタリアでの戦争は戦略的に膠着状態に陥った。ローマ軍はファビウスから教わった消耗戦法を用いたが、それがハンニバルを破る唯一の有効な手段であること にようやく気づいた[60]。 [ローマ軍はハンニバルから大規模な戦闘を奪い、その代わりに弱体化したハンニバルの軍隊を複数の小規模な軍隊で襲撃し、ハンニバルを疲弊させ、彼の軍隊 に動揺を生じさせようとした。その後数年間、ハンニバルは焦土化政策を維持し、南イタリア全域で長引き、効果のない作戦のために現地で糧食を調達すること を余儀なくされた。彼の当面の目標は、主にカンパニアの都市を中心とした小規模な作戦に絞られた。 彼の麾下に配属された部隊は、概して自力で持ちこたえることができず、彼の本国政府も新しい同盟国であるマケドンのフィリップ5世も、彼の損失を補うのに 役立たなかった。そのため、南イタリアにおけるハンニバルの立場はますます苦しくなり、最終的にローマを征服するチャンスはますます遠のいていった。紀元 前212年にはローマの2つの軍を完全に壊滅させ、紀元前208年には有名なマルクス・クラウディウス・マルセルスを含む2人の執政官を戦死させるなど、 ハンニバルはそれでも多くの特筆すべき勝利を収めた。しかし、ハンニバルはイタリアの同盟国から十分な支援を受けられず、政府からも見捨てられ、嫉妬のた めか、単にカルタゴが手薄になったためか、ローマの資源に太刀打ちできなくなり、徐々に劣勢に立たされるようになった。彼は、永続的な戦略的変化をもたら すような大決戦的勝利を再びもたらすことはできなかった。 カルタゴの政治的意思は、支配者の寡頭政治に具現化されていた。カルタゴには元老院があったが、実権を握っていたのは内部の「三十人貴族評議会」と「百四 人貴族」と呼ばれる支配者一族の裁判官会であった。この2つの機関は、カルタゴの裕福な商業家出身者であった。カルタゴでは、ハンニバルの姓である「バル チッド」とも呼ばれる戦争派と、ハンノ2世が率いる和平派の2つの政治派閥が活動していた。ハンノはカンナエの戦いの後、ハンニバルが要請した援軍を拒否 することに尽力した。 ハンニバルはカルタゴ寡頭政治の全面的な後ろ盾なしに戦争を開始した。彼のサグントゥム攻撃は、ローマとの戦争かイベリアでの威信の失墜かの選択を寡頭政 治に突きつけた。カルタゴの戦略的資源を支配していたのは、ハンニバルではなく寡頭政治であった。ハンニバルは常にイベリアか北アフリカからの援軍を求め ていた。戦闘で失われたハンニバルの軍隊は、イタリアやガリアから来た、あまり訓練されておらず、やる気のない傭兵に取って代わられた。カルタゴの寡頭政 治の商業的利益は、作戦中、ハンニバルよりもむしろイベリアからの援軍と補給を指示した。 イタリアにおけるハンニバルの撤退  スキピオ・アフリカヌスの胸像と思われる。 紀元前212年3月、ハンニバルは奇襲攻撃でタレントゥムを占領したが、港の制圧には失敗した。流れは徐々にハンニバルに逆らい、ローマに傾いていった。 紀元前212年、ローマの執政官たちはカプアを包囲した。ハンニバルは彼らを攻撃し、カンパニアからの撤退を余儀なくさせた。ルカニアに移動したハンニバ ルは、シラルスの戦いで16,000人のローマ軍を壊滅させ、15,000人のローマ人が戦死した。その直後、18,000人のローマ軍がヘルドニアの最 初の戦いでハンニバルに撃破され、16,000人のローマ人が戦死した。紀元前211年、ローマの執政官は再びカプアを包囲し、カプアを征服した。 ハンニバルはローマの包囲線を攻撃して包囲を解こうとしたが失敗した。ハンニバルはローマ軍を撤退させるためにローマに進軍した。彼は15,000人の ローマ兵を引き離したが、包囲は続き、カプアは陥落した。紀元前212年、マルケルスはシラクサを征服し、紀元前211〜210年、ローマ軍はシチリアで カルタゴ軍を壊滅させた。紀元前210年、ローマ帝国はマケドンのフィリップ5世に対抗するため、エートリア同盟と同盟を結んだ。ローマがイタリアに夢中 になっている隙を突いてイリリアを征服しようとしたフィリップは、今度は一度に複数の方面から攻撃を受けることになり、ローマとギリシャの同盟国によって すぐに制圧された。 紀元前210年、ハンニバルはアプーリアのヘルドニア(現在のオルドナ)の戦いでプロコンスラ軍に大敗を喫し、紀元前208年にはペテリアの戦いでロクリ 包囲に従事していたローマ軍を壊滅させ、戦術の優位性を再び証明した。しかし、紀元前209年にタレントゥムを失い、サムニウムとルカニアがローマ軍に よって徐々に再征服されたことで、南イタリアの支配力はほぼ失われた。 紀元前207年、彼は再びアプリアへの進軍に成功し、そこで兄ハスドルバルとローマへの連合進軍のための作戦を練った。メタウルスの戦いで兄が敗北し戦死 したと聞くと、彼はカラブリアに引きこもり、以後数年間、そこで生活を維持した。弟の首は切り落とされ、イタリア全土に運ばれ、ハンニバルの陣営の柵の上 に投げ落とされた。 これらの出来事が重なり、ハンニバルのイタリアでの成功は終わりを告げた。リグーリアにおける兄マゴの失敗(前205-前203年)とフィリップ5世との 交渉の失敗によって、イタリアにおけるハンニバルの地位を回復する最後の希望は失われた。紀元前203年、イタリアでの15年近い戦いの後、カルタゴの軍 事力が急速に低下する中、ハンニバルはスキピオ・アフリカヌス率いるローマの侵攻から祖国を守るため、カルタゴに呼び戻された。 |

| Conclusion of the Second Punic War (203–201 BC) Return to Carthage  The final act of the Second Punic War, the battle of Zama (202 BC) In 203 BC, Hannibal was recalled from Italy by the war party in Carthage. After leaving a record of his expedition engraved in Punic and Greek upon bronze tablets in the Temple of Juno Lacinia at Crotona, he sailed back to Africa.[62] His arrival immediately restored the predominance of the war party, which placed him in command of a combined force of African levies and his mercenaries from Italy. In 202 BC, Hannibal met Scipio in a fruitless peace conference. Despite mutual admiration, negotiations floundered due to Roman allegations of "Punic Faith," referring to the breach of protocols that ended the First Punic War by the Carthaginian attack on Saguntum, and a Carthaginian attack on a stranded Roman fleet. Scipio and Carthage had worked out a peace plan, which was approved by Rome. The terms of the treaty were quite modest, but the war had been long for the Romans. Carthage could keep its African territory but would lose its overseas empire. Masinissa (Numidia) was to be independent. Also, Carthage was to reduce its fleet and pay a war indemnity. Carthage then made a terrible blunder. Its long-suffering citizens had captured a stranded Roman fleet in the Gulf of Tunis and stripped it of supplies, an action that aggravated the faltering negotiations. Fortified by both Hannibal and the supplies, the Carthaginians rebuffed the treaty and Roman protests. The decisive battle of Zama soon followed. The defeat removed Hannibal's aura of invincibility. Battle of Zama (202 BC) Main article: Battle of Zama Unlike most battles of the Second Punic War, at Zama the Romans were superior in cavalry and the Carthaginians had the edge in infantry. This Roman cavalry superiority was due to the betrayal of Masinissa, who had earlier assisted Carthage in Iberia but changed sides in 206 BC with the promise of land, and due to his personal conflicts with Syphax, a Carthaginian ally. Although the ageing Hannibal was suffering from mental exhaustion and deteriorating health after years of campaigning in Italy, the Carthaginians still had the advantage in numbers and were boosted by the presence of 80 war elephants.  Engraving of the Battle of Zama by Cornelis Cort, 1567. Note that Asian elephants are illustrated rather than the very small North African elephants used by Carthage. The Roman cavalry won an early victory by swiftly routing the Carthaginian cavalry. The Romans were also successful in limiting the effectiveness of the Carthaginian war elephants, with tactics such as playing trumpets to frighten the elephants and cause them to run into the Carthaginian lines. Some historians say that the elephants routed the Carthaginian cavalry and not the Romans, whilst others suggest that it was actually a tactical retreat planned by Hannibal.[63] Whatever the truth, the battle remained closely fought. At one point, it seemed that Hannibal was on the verge of victory, but Scipio was able to rally his men. Scipio's cavalry, having routed the Carthaginian cavalry, attacked Hannibal's rear. This two-pronged attack caused the Carthaginian formation to collapse. With their foremost general defeated, the Carthaginians had no choice but to surrender. Carthage lost approximately 20,000 troops with an additional 15,000 wounded. In contrast, the Romans suffered only 2,500 casualties. The last major battle of the Second Punic War resulted in a loss of respect for Hannibal by his fellow Carthaginians. The conditions of defeat were such that Carthage could no longer battle for Mediterranean supremacy. |

第二次ポエニ戦争終結(紀元前203-201年) カルタゴへの帰還  第二次ポエニ戦争の最終幕、ザマの戦い(紀元前202年) 紀元前203年、ハンニバルはカルタゴの軍団によってイタリアから呼び戻された。クロトナのユノ・ラシニア神殿に青銅の石版にポエニ語とギリシア語で刻まれた遠征の記録を残すと、再びアフリカに向かった。紀元前202年、ハンニバルはスキピオと和平交渉に臨んだ。 互いを賞賛していたにもかかわらず、カルタゴのサグントゥム攻撃によって第一次ポエニ戦争が終結した際の規約違反や、立ち往生したローマ艦隊に対するカル タゴの攻撃を指す「ポエニ信仰」に対するローマ側の申し立てにより、交渉は難航した。スキピオとカルタゴは和平協定を結び、ローマはこれを承認した。条約 の条件は極めて控えめなものだったが、ローマ軍にとってこの戦争は長かった。カルタゴはアフリカの領土を維持できるが、海外帝国を失うことになる。マシ ニッサ(ヌミディア)は独立することになった。また、カルタゴは艦隊を縮小し、戦争賠償金を支払うことになった。 その後、カルタゴはとんでもない失態を犯した。カルタゴは、チュニス湾で立ち往生していたローマ艦隊を拿捕し、物資を奪ってしまったのだ。ハンニバルと物 資の両方によって要塞化されたカルタゴ人は、条約とローマの抗議をはねつけた。ザマの決戦はその直後に起こった。この敗北により、ハンニバルは無敵のオー ラを失った。 ザマの戦い(紀元前202年) 主な記事 ザマの戦い 第二次ポエニ戦争のほとんどの戦いとは異なり、ザマではローマ軍が騎兵で優勢であり、カルタゴ軍は歩兵で優勢であった。このローマ軍の騎兵優勢は、イベリ ア半島でカルタゴを支援していたマシニッサが、紀元前206年に土地の約束でカルタゴ側に寝返ったことと、カルタゴの盟友シファクスとの個人的な対立によ るものであった。老齢のハンニバルは、イタリアでの長年の遠征で精神的疲労と健康状態の悪化に苦しんでいたが、カルタゴ軍は依然として数で優位に立ち、 80頭の戦象の存在も追い風となった。  1567年、コルネリス・コルトによるザマの戦いのエングレーヴィング。カルタゴが使用した非常に小さな北アフリカ象ではなく、アジア象が描かれていることに注意。 ローマ騎兵隊はカルタゴ騎兵隊を迅速に撃退し、早い段階で勝利を収めた。ローマ軍はまた、トランペットを鳴らして象を怯えさせ、カルタゴの戦列に突っ込ま せるなどの戦術で、カルタゴの戦象の有効性を制限することにも成功した。ある歴史家は、象がローマ軍ではなくカルタゴ軍の騎兵隊を撃退したと言い、また別 の歴史家は、実際にはハンニバルが計画した戦術的撤退であったと指摘する[63]。一時はハンニバルが勝利するかと思われたが、スキピオが兵を結集させ た。スキピオの騎兵隊はカルタゴ騎兵隊を撃退し、ハンニバルの背後を攻撃した。この二方面からの攻撃により、カルタゴの陣形は崩壊した。 最前線の将軍が敗れ、カルタゴ軍は降伏するしかなかった。カルタゴは約20,000の兵を失い、さらに15,000の負傷者を出した。一方、ローマ軍は 2,500人の死傷者にとどまった。第二次ポエニ戦争最後の大きな戦いは、仲間のカルタゴ人からハンニバルに対する尊敬の念を失わせる結果となった。敗北 の条件は、カルタゴがもはや地中海の覇権を争うことができないことであった。 |

| Later career Peacetime Carthage (200–196 BC)  A bust of Hannibal, Bardo National Museum, Tunisia Hannibal was still only 46 at the conclusion of the Second Punic War in 201 BC and soon showed that he could be a statesman as well as a soldier. Following the conclusion of a peace that left Carthage saddled with an indemnity of ten thousand talents, he was elected suffete (chief magistrate) of the Carthaginian state.[64] After an audit confirmed Carthage had the resources to pay the indemnity without increasing taxation, Hannibal initiated a reorganization of state finances aimed at eliminating corruption and recovering embezzled funds.[65] The principal beneficiaries of these financial peculations had been the oligarchs of the Hundred and Four.[65] In order to reduce the power of the oligarchs, Hannibal passed a law stipulating the Hundred and Four be chosen by direct election rather than co-option. He also used citizen support to change the term of office in the Hundred and Four from life to a year, with none permitted to "hold office for two consecutive years."[65][64] Exile (after 195 BC) Seven years after the victory of Zama, the Romans, alarmed by Carthage's renewed prosperity and suspicious that Hannibal had been in contact with Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire, sent a delegation to Carthage alleging that Hannibal was helping an enemy of Rome.[66] Aware that he had many enemies, not the least of which were due to his financial reforms eliminating corruption, Hannibal fled into voluntary exile before the Romans could demand that Carthage surrender him into their custody.[66] He journeyed first to Tyre, the mother city of Carthage, and then to Antioch, before he finally reached Ephesus, where he was honourably received by Antiochus. Livy states that the Seleucid king consulted Hannibal on the strategic concerns of making war on Rome.[65] According to Cicero, while at the court of Antiochus, Hannibal attended a lecture by Phormio, a philosopher, that ranged through many topics. When Phormio finished a discourse on the duties of a general, Hannibal was asked his opinion. He replied, "I have seen during my life many old fools; but this one beats them all." Another story, according to Aulus Gellius, is that after Antiochus III showed Hannibal the gigantic and elaborately equipped army he had created to invade Greece, he asked him if they would be enough for the Roman Republic, to which Hannibal replied, "I think all this will be enough, yes, quite enough, for the Romans, even though they are most avaricious."[67] In the summer of 193 BC, tensions flared up between the Seleucids and Rome. Antiochus gave tacit support to Hannibal's plans of launching an anti-Roman coup d'état in Carthage, yet it was not carried out.[68] The Carthaginian general also advised equipping a fleet and landing a body of troops in the south of Italy, offering to take command himself.[65] In 190 BC, after having suffered a series of defeats in the Roman–Seleucid War,[69] Antiochus gave Hannibal his first significant military command after spending five years in the Seleucid court.[70] Hannibal was tasked with building a fleet in Cilicia from scratch. Although Phoenician territories like Tyre and Sidon possessed the necessary combination of raw materials, technical expertise, and experienced personnel, it took much longer than expected for it to be completed, most likely due to wartime shortages.[71]  Hannibal with Artaxias I of Greater Armenia in Ayrarat. In July 190 BC, Hannibal ordered his fleet to set sail from Seleucia Pieria along the southern Asia Minor coast in order to reinforce the rest of the Seleucid navy at Ephesus.[72] The following month Hannibal's fleet clashed with the Rhodian navy in the Battle of Side. The faster Rhodian ships managed to heavily damage half of Hannibal's warships through the diekplous manoeuvre, forcing him to retreat.[73] Hannibal had preserved most of his fleet; however, he was in no position to unite with Polyxenidas' fleet at Ephesus since his ships required lengthy repairs.[74] The ensuing Battle of Myonessus resulted in a Roman-Rhodian victory, which cemented Roman control over the Aegean Sea, enabling them to launch an invasion of Seleucid Asia Minor. The two armies faced off in the Battle of Magnesia, north-east of Magnesia ad Sipylum. The battle resulted in a decisive Roman-Pergamene victory.[75] The truce was signed at Sardes in January 189 BC, whereupon Antiochus agreed to abandon his claims on all lands west of the Taurus Mountains, paid a heavy war indemnity and promised to hand over Hannibal and other notable enemies of Rome from among his allies.[76] According to Strabo and Plutarch, Hannibal also received hospitality at the Armenian royal court of Artaxias I. The authors add an apocryphal story of how Hannibal planned and supervised the building of the new royal capital Artaxata.[77] Suspicious that Antiochus was prepared to surrender him to the Romans, Hannibal fled to Crete, but he soon went back to Anatolia and sought refuge with Prusias I of Bithynia, who was engaged in warfare with Rome's ally, King Eumenes II of Pergamon.[78] Hannibal went on to serve Prusias in this war. During one of the naval victories he gained over Eumenes, Hannibal had large pots filled with venomous snakes thrown onto Eumenes' ships.[79] Hannibal also went on to defeat Eumenes in two other battles on land.[80] Death (183–181 BC) At this stage, the Romans intervened and threatened Bithynia into giving up Hannibal.[80] Prusias agreed, but the general was determined not to fall into his enemy's hands. The precise year and cause of Hannibal's death are unknown. Pausanias wrote that Hannibal's death occurred after his finger was wounded by his drawn sword while mounting his horse, resulting in a fever and then his death three days later.[81] Cornelius Nepos[82] and Livy,[83] tell a different story, namely that the ex-consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus, on discovering that Hannibal was in Bithynia, went there in an embassy to demand his surrender from King Prusias. Hannibal, discovering that the castle where he was living was surrounded by Roman soldiers and he could not escape, took poison. Appian writes that it was Prusias who poisoned Hannibal.[84] Pliny the Elder[85] and Plutarch, in his life of Flamininus,[86] record that Hannibal's tomb was at Libyssa on the coast of the Sea of Marmara. According to some, Libyssa was sited at Gebze, between Bursa and Üskudar. W. M. Leake,[87] identifying Gebze with ancient Dakibyza, placed it further west. Before dying, Hannibal is said to have left behind a letter declaring, "Let us relieve the Romans from the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man's death".[88] Appian wrote of a prophecy about Hannibal's death, which stated that "Libyssan earth shall cover Hannibal's remains." This, he wrote, made Hannibal believe that he would die in Libya, but instead, it was at the Bithynian Libyssa that he would die.[84] In his Annales, Titus Pomponius Atticus reports that Hannibal's death occurred in 183 BC,[89] and Livy implies the same. Polybius, who wrote nearest the event, gives 182 BC. Sulpicius Blitho[90] records the death under 181 BC.[89] |

その後の経歴 平時のカルタゴ(紀元前200~196年)  ハンニバルの胸像(チュニジア、バルド国立博物館蔵 紀元前201年の第二次ポエニ戦争終結時、ハンニバルはまだ46歳だったが、すぐに軍人としてだけでなく政治家としても活躍できることを示した。カルタゴ が1万タラントの賠償金を背負うことになった講和の締結後、彼はカルタゴ国家のスフェーテ(最高行政官)に選出された[64]。監査によって、カルタゴが 増税せずに賠償金を支払うだけの財源を有していることが確認されると、ハンニバルは汚職の排除と横領資金の回収を目的とした国家財政の再編成に着手した [65]。 このような財政不正の主な受益者は、百姓のオリガルヒであった[65]。オリガルヒの権力を弱めるために、ハンニバルは百姓を共同選挙ではなく直接選挙で 選ぶことを規定する法律を通過させた。また、市民の支持を利用して百人一首の任期を終身から1年に変更し、「2年連続の在任」は許されなかった[65] [64]。 亡命(紀元前195年以降) ザマでの勝利から7年後、カルタゴが再び繁栄を取り戻したことに危機感を抱いたローマ帝国は、ハンニバルがセレウコス帝国のアンティオコス3世と接触して いることを疑い、ハンニバルがローマの敵に手を貸していると主張する使節団をカルタゴに送った[66]。 ハンニバルには多くの敵がいたが、それは彼の財政改革が腐敗をなくしたことによるものであることを認識していたハンニバルは、ローマ帝国がカルタゴに身柄 の引き渡しを要求する前に、自発的に亡命した[66]。 ハンニバルはまずカルタゴの母都市であるタイレに向かい、次にアンティオキアに向かったが、最終的にエフェソスに到着し、そこでアンティオコスに丁重に迎 えられた。リヴィによれば、セレウコス王はハンニバルにローマとの戦争の戦略的懸念について相談したという。 キケロによれば、アンティオコスの宮廷にいたとき、ハンニバルは哲学者フォルミオの講義に出席した。フォルミオが将軍の任務についての講義を終えたとき、 ハンニバルは意見を求められた。彼はこう答えた。「私はこれまでの人生で多くの年老いた愚か者を見てきたが、この愚か者はそのすべてに勝っている」。ま た、アウルス・ゲリウスによれば、アンティオコス3世がギリシア侵攻のために作った巨大で精巧な装備の軍隊をハンニバルに見せた後、ローマ共和国にはこれ で足りるかと尋ねたところ、ハンニバルは「ローマ人は最も貪欲だが、これだけで十分だろう、そう、まったく十分だ」と答えたという[67]。 紀元前193年夏、セレウコス朝とローマの間に緊張が走った。アンティオコスは、カルタゴで反ローマ・クーデターを起こすというハンニバルの計画を黙認し たが、実行はされなかった[68]。 [65] 紀元前190年、ローマ=セレウコス戦争で連敗を喫したアンティオコスは、セレウコス朝宮廷で5年を過ごした後、ハンニバルに初の重要な軍事指揮権を与え た[69]。ティレやシドンのようなフェニキア領には必要な原材料、技術的専門知識、経験豊富な人材の組み合わせがあったが、戦時中の物資不足のためか、 完成までには予想以上に時間がかかった[71]。  ハンニバルと大アルメニアのアルタクシアス1世(アイララットにて)。 紀元前190年7月、ハンニバルはエフェソスにいるセレウコス朝海軍の残党を増援するため、小アジア沿岸のセレウコス朝ピエリアから出航するよう艦隊に命 じた[72]。ハンニバルは艦隊の大部分を温存していたが、ポリクセニダスの艦隊とエフェソスで合流することはできず、ポリクセニダスの艦隊は長期の修理 を必要としていた[74]。 続くミオネソスの海戦はローマ・ローディアンの勝利となり、ローマはエーゲ海の制海権を固め、セレウコス朝の小アジアへの侵攻を可能にした。両軍は、マグ ネシア・アド・シピルムの北東に位置するマグネシアの戦いで対決した。停戦は紀元前189年1月にサルデスで調印され、アンティオコスはタウルス山脈以西 の領有権を放棄し、多額の賠償金を支払い、ハンニバルをはじめとするローマの著名な敵を同盟国から引き渡すことを約束した[76]。 ストラボとプルタークによれば、ハンニバルはアルタクシアス1世のアルメニア王宮でももてなしを受けた。著者たちは、ハンニバルが新しい王都アルタクシア タの建設を計画し、監督したというアポクリファルな話を付け加えている。 [77]アンティオコスが自分をローマに降伏させる用意があるのではないかと疑ったハンニバルは、クレタ島に逃れたが、すぐにアナトリアに戻り、ローマの 同盟国ペルガモンのエウメネス2世と交戦していたビティニアのプルシアス1世のもとに身を寄せた[78]。エウメネスに勝利した海戦の1つで、ハンニバル は毒蛇の入った大きな壺をエウメネスの船に投げ込ませた[79]。ハンニバルは他にも2度の陸戦でエウメネスを破った[80]。 死(紀元前183年-181年) この段階でローマ軍が介入し、ビティニアにハンニバルを引き渡すよう脅した[80] 。ハンニバルが死んだ正確な年と原因は不明である。パウサニアスは、ハンニバルの死は馬に乗る際に抜き身の剣で指を負傷し、その結果発熱し、3日後に死亡 したと記している[81] 。コルネリウス・ネポス[82]とリヴィ[83]は別の話を伝えている。すなわち、ハンニバルがビティニアにいることを知った元執政官ティトゥス・クイン ティウス・フラミニヌスは、プルシアス王に降伏を要求するために使節団を率いてビティニアに赴いた。ハンニバルは、自分が住んでいた城がローマ兵に囲まれ ていて逃げられないことを知り、毒を飲んだ。アッピアヌスは、ハンニバルを毒殺したのはプルシアスであったと記している[84]。 長老プリニウス[85]とプルタークは『フラミニヌスの生涯』の中で、ハンニバルの墓はマルマラ海沿岸のリビッサにあったと記している[86]。リビッサ はブルサとウスクダルの間のゲブゼにあったとする説もある。W.M.リーク[87]は、ゲブゼを古代のダキビザと同定し、さらに西に位置づけた。ハンニバ ルは死ぬ前に、「ローマ人が老人の死を待つのは忍耐が試され過ぎると考えているので、彼らが長い間経験してきた不安から解放してあげよう」と宣言する書簡 を残したと言われている[88]。 アッピアヌスはハンニバルの死に関する予言について書いている。「リビスの大地がハンニバルの亡骸を覆うだろう 」という予言であった。これはハンニバルにリビアで死ぬと信じ込ませたが、その代わりにビティニア・リビッサで死ぬことになったと書いている[84]。 ティトゥス・ポンポニウス・アッティクスは『Annales』の中で、ハンニバルの死は紀元前183年に起こったと報告しており[89]、リヴィーも同じ ことを示唆している。また『リヴィー』も同じことを示唆している[89]。スルピキウス・ブリトー[90]は紀元前181年に死亡したと記録している [89]。 |