ハンス・アスペルガー

Hans Asperger, 1906-1980

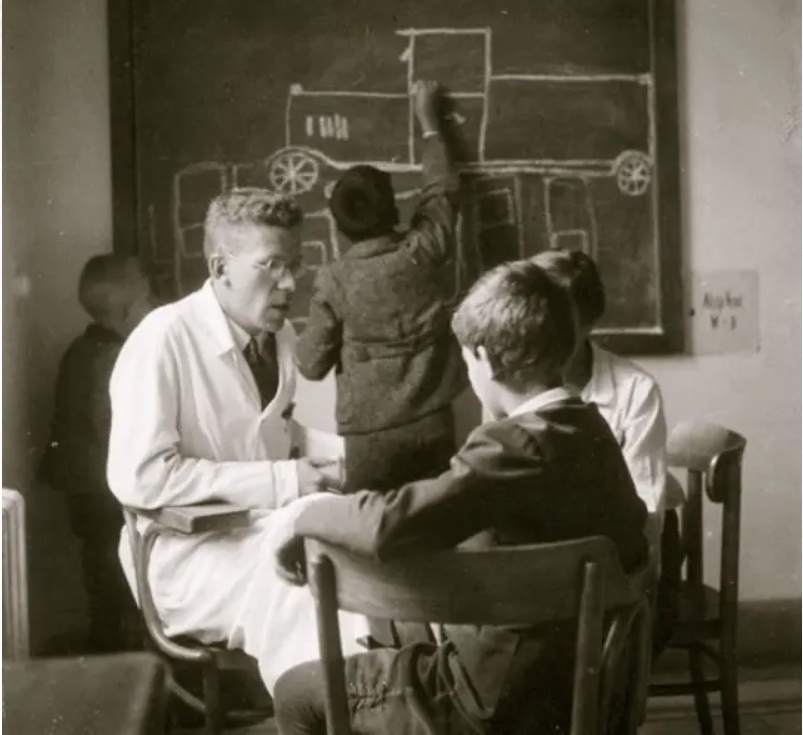

1940

年代のハンス・アスペルガー

| Johann „Hans“

Friedrich Karl Asperger

(* 18. Februar 1906 in Wien; † 21. Oktober 1980 ebenda)[1] war ein

österreichischer Kinderarzt und Heilpädagoge. Er gilt als

Erstbeschreiber des später nach ihm benannten Asperger-Syndroms, einer

Form des Autismus.[2] Seine Rolle während der Zeit des

Nationalsozialismus gilt als umstritten. Da Asperger seine Veröffentlichungen größtenteils in deutscher Sprache verfasste und sie kaum übersetzt wurden, waren seine Arbeiten zunächst international wenig bekannt. Erst in den 1990er Jahren erlangte das Asperger-Syndrom internationale Bekanntheit in Fachkreisen. Die britische Psychologin Lorna Wing führte in den 1980er Jahren die Forschungen Aspergers fort, definierte das Syndrom und benannte es nach seinem Erstbeschreiber.[3] |

ヨハン・ハンス・フリードリッヒ・カール・アスペルガー(Johann

"Hans" Friedrich Karl Asperger, * 1906年2月18日ウィーン生まれ、†

1980年10月21日同上)[1]は、オーストリアの小児科医、養護教諭である。アスペルガー症候群は、後に彼の名を冠した自閉症の一種で、その最初の

記述者と考えられている[2]。 アスペルガーの出版物はほとんどドイツ語で書かれ、ほとんど翻訳されなかったため、当初は国際的にほとんど知られていなかった。アスペルガー症候群が専門 家の間で国際的に認知されるようになったのは、1990年代に入ってからである。1980年代、イギリスの心理学者ローナ・ウィングがアスペルガーの研究 を続け、この症候群を定義し、最初の記述にちなんで命名した[3]。アスペルガー症候群は、心と身体の障害である。 |

| Leben Asperger war der Älteste von drei Brüdern, der Mittlere starb kurz nach der Geburt, der Jüngste fiel 1942 in Russland. Über sein Elternhaus schrieb er: „Wie bin ich erzogen worden? Mit viel Liebe, ja Selbstentäußerung von meiner Mutter, mit großer Strenge von meinem Vater.“[4] Nach dem Besuch eines Humanistischen Gymnasiums absolvierte er an der Universität Wien ein Studium der Medizin. Nach seiner Promotion 1931 arbeitete Asperger als Assistent an der Kinderklinik der Universität Wien, an der er sich 1943 auch habilitierte. Seit 1932 leitete er die heilpädagogische Abteilung der Klinik. Zum Wintersemester 1934 wurde Dr. med. habil. Hans Asperger unter Zuweisung an die medizinische Fakultät der Universität Wien zum Dozenten für das Fach Kinderheilkunde ernannt.[5] Eine seiner kleinen Patientinnen war die spätere Schriftstellerin Elfriede Jelinek, „die sich auf Aspergers Station einer heilpädagogischen Therapie unterziehen [musste]. Asperger war fast immer anwesend und las den Kindern vor.“[6] Asperger war Berater beim Wiener Hauptgesundheitsamt und Gutachter in Sonderschulen sowie bei „schwierigen, nervlich oder psychisch auffälligen Kindern“ in Normalschulen.[7] Von 1957 bis 1962 war Asperger im Vorstand der Innsbrucker Kinderklinik. 1962 wurde er Professor für Pädiatrie und Leiter der Universitäts-Kinderklinik in Wien, was er bis zu seiner Emeritierung im Jahr 1977 blieb. 1967 wurde er zum Mitglied der Gelehrtenakademie Leopoldina gewählt. 1971 erhielt Asperger von der Stadt Wien die Ehrenmedaille der Bundeshauptstadt Wien in Gold. 1972 verlieh ihm die Universität München die Würde eines Doctor medicinae honoris causa. Er wurde am Neustifter Friedhof bestattet.[8] Hans Asperger war seit 1935 mit Hanna Kalmon verheiratet. Das Ehepaar hatte fünf Kinder. Tochter Maria Asperger Felder ist Fachärztin für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, spezialisiert für die Diagnose von Autismus und in Zürich praktizierend.[9] |

生活 アスペルガーは3人兄弟の長男で、真ん中は生まれて間もなく亡くなり、末っ子は1942年にロシアで戦死している。実家について、「私はどのように育てら れたのか」と書いている。母からは愛情たっぷりに、自己表現までしてもらい、父からは厳しくしてもらった」[4] 人文主義の文法学校に通った後、ウィーン大学で医学を学んだ。1931年に博士号を取得した後、アスペルガーはウィーン大学の小児科クリニックで助手とし て働き、1943年には同クリニックでハビリタチオン(大学資格)も取得した。 1932年からは、診療所の療育部長を務めた。1934年の冬学期には、Dr. med. habil. ハンス・アスペルガーは、ウィーン大学医学部の小児科の講師に任命され[5]、彼の患者の一人である後の作家エルフリーデ・イェリネクは「アスペルガーの 病室で治療を受けていた。アスペルガーはほとんど常にその場にいて、子どもたちに本を読んでいた」[6]。アスペルガーはウィーン主要保健局のカウンセ ラーであり、特殊学校だけでなく、普通学校の「困難で神経質、心理的に目立っている子ども」に対する評価者であった[7]。 1957年から1962年まで、アスペルガーはインスブルック小児病院の理事を務めていた。1962年に小児科の教授となり、ウィーン大学付属小児病院の 院長に就任し、1977年に退職するまでその任に就いた。1967年、レオポルディナ学士院会員に選出された。 1971年、アスペルガーはウィーン市から「連邦首都ウィーン栄誉金メダル」を授与された。1972年、ミュンヘン大学から名誉博士号(Doctor medicinae honoris causa)を授与された。ノイシュティフト墓地に埋葬された[8]。 ハンス・アスペルガーは、1935年からハンナ・カルモンと結婚していた。夫妻には5人の子供がいた。娘のマリア・アスペルガー・フェルダーは、児童思春 期精神医学の専門家で、自閉症の診断を専門としており、チューリッヒで開業している[9]。 |

| Arbeiten zu Autismus Am 3. Oktober 1938 hielt er in der Heilpädagogischen Abteilung der Universitätsklinik Wien einen Vortrag, in dem er anhand eines Fallbeispiels die Charakteristika der „autistischen Psychopathen“ darstellte.[10] 1943 reichte Asperger seine Habilitationsschrift ein, eine Beschreibung des später nach ihm benannten Asperger-Syndroms, die 1944 veröffentlicht wurde.[2] Er selbst nannte die Störung „autistische Psychopathie“. Das Wort „autistisch“ entlieh er von Eugen Bleuler, der damit bestimmte Eigenschaften der Schizophrenie beschrieb, um „die Einengung der Person und ihrer Reaktionen auf sich selbst und die damit verbundene Beschränkung der Re-Aktionen auf die Reize der Umwelt“ zu verdeutlichen. Den Begriff „Psychopathie“ würde man heute am ehesten mit „Persönlichkeitsstörung“ übersetzen. Fast gleichzeitig mit Aspergers Publikation erschien Leo Kanners Arbeit zum frühkindlichen Autismus, der große Ähnlichkeiten mit dem „Asperger-Syndrom“ aufwies. Aspergers Veröffentlichung enthielt die Beschreibung von vier Jungen (Fritz, Harro, Ernst und Hellmuth), die er als „autistische Psychopathen“ bezeichnete. Den Genannten war bei durchschnittlicher bis hoher Intelligenz gemeinsam: ein Mangel an Empathie die Unfähigkeit, Freundschaften zu schließen Störungen in Blickkontakt, Gestik, Mimik und Sprachgebrauch intensive Beschäftigung mit einem Interessensgebiet motorische Störungen Sie waren selbstbezogen, konnten sich nicht in andere Menschen versetzen und auf diese eingehen. In ihrem Gefühlsleben wirkten die Jungen disharmonisch, und im oft angstvollen Verhalten fehlte ihnen die affektive Beteiligung.[11] Asperger nannte sie „kleine Professoren“, da sie über das Gebiet ihres Spezialinteresses detailliert sprechen konnten und oft ein erstaunliches Wissen ansammelten. |

自閉症への取り組み 1938年10月3日、ウィーンの大学病院の治療教育学部で講義を行い、事例研究に基づいて「自閉的精神病質者」の特徴を発表した[10]。 1943年、アスペルガーは、後に自身の名を冠したアスペルガー症候群を記述したハビリテーターを提出、1944年に発表した。 彼はその障害を「自閉的精神病質」と名付けた[2]。 彼自身は、この障害を「自閉的精神病質」と呼んでいた。彼は、オイゲン・ブルーレーから「自閉的」という言葉を借りて、精神分裂病のある種の特徴を表現 し、「本人とその反応が自分自身に閉じこもり、その結果、環境の刺激に対する反応が制限される」ことを説明するために使っている。今日、「サイコパス」と いう言葉は、「人格障害」と訳されることがほとんどでしょう。アスペルガーの出版とほぼ同時に、レオ・カナーによる幼児期の自閉症に関する研究が登場し、 「アスペルガー症候群」と大きな共通点を持つようになった。 アスペルガーの出版物には、彼が「自閉的精神病質者」と呼んだ4人の少年(フリッツ、ハロー、エルンスト、ヘルムート)の記述があった。前述した、平均か ら高い知能を持った人たちの共通点。 共感の不足ないしは欠如 友人ができない 視線、ジェスチャー、表情、言語使用における障害 狷介 運動障害 自己中心的で、他人の立場に立って物事を考えることができず、人と関わることができない。アスペルガーは、少年たちを「小さな教授」と呼んだが、それは彼 らが自分の関心のある分野について詳しく話すことができ、しばしば驚くほどの量の知識を蓄積していたからである[11]。 |

| Asperger in der Zeit des

Nationalsozialismus Asperger gehörte einer siebenköpfigen Kommission an, die 200 behinderte Kinder nach ihrer „Bildungsfähigkeit“ kategorisieren sollte, um über ihr Schicksal entscheiden zu können. 35 Kinder wurden als „aussichtslose Fälle“ eingestuft und in der Folge auf den Spiegelgrund überstellt, wo alle starben. Es fehlt die Grundlage, ihn deswegen des Mordes zu bezichtigen, denn bis zur Ermordung dieser Kinder waren noch weitere Schritte nötig, aber er war Teil der Legitimation dieser Morde und trug als Experte die Einteilung in „Brauchbarkeitsstufen“ mit.[12] Während Asperger nach eigenen Aussagen in den Nachkriegsjahren und den Darstellungen seiner Weggefährten Gegner der Nationalsozialisten war, deuten zeitgenössische Dokumente und neue Forschungsergebnisse darauf hin, dass dies keineswegs der Fall war. So heißt es in einer politischen Beurteilung des Personalamts des Reichsgaus Wien vom 1. November 1940 über Asperger: „In Fragen der Rassen- und Sterilisierungsgesetzgebung geht er mit den nat[ional]soz[ialistischen] Ideen konform. In charakterlicher sowie politischer Hinsicht gilt er als einwandfrei.“[13] Zudem wird Aspergers Rolle während der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus in Österreich von Herwig Czech[14] sowie anderen Historikern kritisch bewertet. Czech zufolge[15] gibt es Hinweise dafür, dass Asperger im Rahmen der „Kinder-Euthanasie“ in der Jugendfürsorgeanstalt Am Spiegelgrund auf dem Anstaltsgelände der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Am Steinhof auf der Baumgartner Höhe in Wien (heutige Klinik Penzing) mehrere Kinder an die Anstalt am Spiegelgrund überwiesen habe,[16] in der etwa 800 Kinder ermordet wurden.[17] Nach Einsichtnahme in Aspergers Beschreibungen der Patienten stellte Czech fest, dass diese „härter ausfielen als die des Personals der Anstalt“. Sehr kritisch sieht auch die amerikanische Historikerin Edith Sheffer in ihrem Buch Aspergers Kinder seine Rolle nach 1933. Sie legt dar, dass Asperger mit den führenden Köpfen des Kindereuthanasieprogramms zusammenarbeitete und mindestens 44 junge Patienten in die „Euthanasie“-Anstalt „Am Spiegelgrund“ überwies.[18] Asperger war nicht direkt „Am Spiegelgrund“ tätig; laut den Recherchen von Edith Sheffer verabreichte er selbst keine todbringenden Medikamente. Mit Bezug auf Sheffers Recherchen und ihr Buch Aspergers Kinder – Die Geburt des Autismus im Dritten Reich schrieb Astrid Viciano in der Süddeutschen Zeitung: „Asperger war weder ein überzeugter Gegner noch ein fanatischer Anhänger der Nazis. Er war ein gläubiger Katholik und trat der NSDAP nie bei. Sein Verhalten aber sei exemplarisch für das Abdriften etlicher Menschen in die Mittäterschaft.[19]“ |

国家社会主義時代のアスペルガー アスペルガーは、200人の障害児を「教育能力」に基づいて分類し、その運命を決める7人の委員会のメンバーであった。35人の子供が「絶望的なケース」 に分類され、その後シュピーゲルグランドに移されましたが、そこで全員死亡しました。これらの子供たちが殺害される前にさらなる措置が必要であったため、 このことで彼を殺人で非難する根拠はないが、彼はこれらの殺人の正当化に加担し、専門家として「有用性レベル」に分類するのに役立った[12]。 アスペルガーは、戦後の本人の発言や仲間の証言では、国家社会主義者と対立していたが、現代の資料や新しい研究によって、決してそうではないことがわかっ た。たとえば、1940年11月1日付のウィーン帝国軍人事部によるアスペルガーの政治的評価は、「人種と不妊手術法の問題において、彼は国家社会主義者 の考えに合致している」と述べている。さらに、オーストリアにおける国家社会主義の時代におけるアスペルガーの役割については、ヘルヴィヒ・チェコ [14]や他の歴史家たちによって批判的に評価されている。 チェコによれば[15]、アスペルガーは「子どもの安楽死」の一環として、ウィーンのバウムガルトナー・ヘーエにあった療養所兼老人ホーム、アム・シュタ インホーフ(現在のペンツィング診療所)の敷地内にあった少年福祉施設アム・シュピーゲルグルンドに数人の子どもを紹介し、約800人の子どもが殺された ことが指摘されている[16]。アスペルガーの患者に対する記述を見て、それが「施設の職員よりも過酷な」ものだったことを、チェコは発見している [17]。アメリカの歴史家エディス・シェファーは、著書『アスペルガーの子供たち』の中で、1933年以降の彼の役割についても非常に批判的である。 彼女は、アスペルガーが子供の安楽死計画のリーダーと協力し、少なくとも44人の若い患者を「安楽死」施設「アム・シュピーゲルグルト」に紹介したとして いる。18] アディス・シェファーの研究によれば、アスペルガーは「アム・シュピーゲルグルト」に直接参加していたのではなく、自ら致死の薬を投与してはいないのだ。 シェファーの研究とその著書『アスペルガーの子供たち-第三帝国における自閉症の誕生』について、アストリッド・ヴィチアーノは『Süddeutsche Zeitung』に次のように書いている。 「アスペルガーは、ナチスの確信的な反対者でもなければ、狂信的な支持者でもない。彼は敬虔なカトリック教徒であり、NSDAPには参加しなかった。しか し、彼の行動は、多くの人々が共謀に流されることの模範となっている[19]」。 |

| Werke (Auswahl) Das psychisch abnorme Kind. In: Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. Bd. 51 (1938), H. 49, S. 1314–1317. Die „Autistischen Psychopathen“ im Kindesalter. In: Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten. Bd. 117 (1944), S. 73–136. doi:10.1007/bf01837709. (PDF-Datei). Die medizinischen Grundlagen der Heilpädagogik. In: Monatsschrift für Kinderheilkunde. Band 99, Wien 1950, S. 105–107. Heilpädagogik: Einführung in die Psychopathologie des Kindes für Ärzte, Lehrer, Psychologen und Fürsorgerinnen. Springer, Wien 1952. ISBN 978-3-662-28619-7. (Digitalisat) |

著作(抜粋) 精神異常のある子供。掲載:Wiener klinische Wochenschrift(ウィーン臨床週刊誌)。第 51 巻(1938 年)、第 49 号、1314–1317 ページ。 小児期の「自閉症性精神病質者」。『精神医学および神経疾患アーカイブ』第 117 巻(1944 年)、73-136 ページ。doi:10.1007/bf01837709。(PDF ファイル)。 治療教育学の医学的基礎。月刊小児医学。第 99 巻、ウィーン 1950 年、105-107 ページ。 治療教育学:医師、教師、心理学者、福祉士のための小児精神病理学入門。Springer、ウィーン 1952 年。ISBN 978-3-662-28619-7。(デジタル版) |

| Literatur Maria Asperger-Felder: Zum Sehen geboren, Zum Schauen bestellt... Hans Asperger 1906–1980, Leben und Werk. In: Heilpädagogik. Band 49, Heft 3, 2006, S. 2–11 Arnold Pollak (Hrsg.): Auf den Spuren Hans Aspergers. Fokus Asperger-Syndrom: Gestern, Heute, Morgen. Schattauer, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-7945-3122-6, Manfred Berger: Hans Asperger. Sein Leben und Wirken. In: Heilpädagogik. Heft 4, 2007, S. 29–32. Edith Sheffer: Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna. W.W. Norton & Company, New York 2018, ISBN 978-0-393-60964-6. (deutsche Ausgabe: Aspergers Kinder – Die Geburt des Autismus im „Dritten Reich“. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2018) Uta Frith: Asperger and his syndrome. In: Frith (Hrsg.): Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Cambridge University Press, 1991, online 2009 doi:10.1017/CBO9780511526770.001, S. 1–36. Herwig Czech: Der Kinderarzt und die Nazis. In: Gehirn und Geist Heft 4/2020 und in: Autismus verstehen. Was die Forschung heute weiß (Gehirn und Geist Dossier Heft 1/2021, S. 78–83). online (für Abonnenten) auf Spektrum.de |

参考文献 マリア・アスペルガー・フェルダー:見るために生まれ、見るために生きた…ハンス・アスペルガー 1906–1980、その生涯と業績。Heilpädagogik(治療教育)第 49 巻、第 3 号、2006 年、2–11 ページ アーノルド・ポラック(編):ハンス・アスペルガーの足跡をたどって。アスペルガー症候群に焦点を当てた:昨日、今日、明日。シャッタウアー、シュトゥットガルト 2015 年、ISBN 978-3-7945-3122-6、 マンフレッド・ベルガー:ハンス・アスペルガー。その生涯と業績。掲載:Heilpädagogik(治療教育)。第 4 号、2007 年、29-32 ページ。 エディス・シェファー:『アスペルガーの子供たち:ナチス・ウィーンにおける自閉症の起源』。W.W. Norton & Company、ニューヨーク、2018年、ISBN 978-0-393-60964-6。(ドイツ語版:Aspergers Kinder – Die Geburt des Autismus im „Dritten Reich“。キャンパス、フランクフルト・アム・マイン、2018年) ウタ・フリス:アスペルガーと彼の症候群。Frith (編):自閉症とアスペルガー症候群。ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1991年、オンライン 2009 doi:10.1017/CBO9780511526770.001、1-36 ページ。 ヘルヴィヒ・チェク:『小児科医とナチス』 『Gehirn und Geist』 2020年4月号、および『自閉症を理解する。今日の研究が明らかにしたこと』(『Gehirn und Geist』 2021年1月号、78-83ページ)に掲載。オンライン(購読者限定) Spektru |

| Weblinks Literatur von und über Hans Asperger im Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Internationales Archiv für Heilpädagogik: Hans Asperger (PDF) Annette Baum, Burkhart Brückner: Biographie von Hans Asperger (In: Biographisches Archiv der Psychiatrie (BIAPSY)) On Hans Asperger, the Nazis, and Autism: A Conversation Across Neurologies. Auf: thinkingautismguide.com vom 19. April 2018 WStLA, 1.3.2.209.10, Anmerkung 95: Hinweis auf das Archivgut Nervenklinik für Kinder, Krankengeschichten: verstorbene Mädchen und Knaben 1940–1945, Krankengeschichte Herta Schreiber, Heilpädagogische Abteilung der Universitätskinderklinik Wien, Befund Herta Schreiber, 27 Juni 1941, gez. Dr. Asperger., in: Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv Foto von Asperger im Bildarchiv der ÖNB |

ウェブリンク ドイツ国立図書館のカタログにあるハンス・アスペルガーに関する文献 国際治療教育アーカイブ:ハンス・アスペルガー (PDF) アネット・バウム、ブルクハルト・ブリュックナー:ハンス・アスペルガーの伝記 (『精神医学の伝記アーカイブ (BIAPSY)』所収) ハンス・アスペルガー、ナチス、そして自閉症について:神経学間の対話。thinkingautismguide.com、2018年4月19日 WStLA、1.3.2.209.10、注釈 95:アーカイブ資料「小児神経クリニック、病歴:1940年から1945年に亡くなった少女および少年」への参照 ヘルタ・シュライバー病歴、ウィーン大学小児病院特別教育部門、ヘルタ・シュライバー診断書、1941年6月27日、署名:アスペルガー博士、出典: ウィーン市および州立公文書館 オーストリア国立図書館画像アーカイブ所蔵のアスペルガーの写真 |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Asperger |

| Johann

Friedrich Karl Asperger (/ˈæspɜːrɡər/, German: [hans

ˈʔaspɛɐ̯ɡɐ]; 18

February 1906 – 21 October 1980[1]) was an Austrian physician. Noted

for his early studies on atypical neurology, specifically in children,

he is the namesake of the autism spectrum disorder Asperger syndrome

(AS). He wrote more than 300 publications on psychological disorders

that posthumously acquired international renown in the 1980s. His

diagnosis of autism, which he termed "autistic psychopathy", also

garnered controversy. In the 2010s, further controversy arose over,

Asperger's referral of children to the German Nazi Am Spiegelgrund

clinic responsible for the murder of disabled Patents.[2][3] |

ヨ

ハン・フリードリヒ・カール・アスペルガー(/ˈæsp%ˁər/, German: [hans ˈasp%]; 1906年2月18日 -

1980年10月21日[1])はオーストリアの内科医である。非定型神経学、特に小児に関する初期の研究で知られ、自閉症スペクトラム障害であるアスペ

ルガー症候群(AS)の命名者である。精神疾患について300以上の著作があり、死後、1980年代に国際的に知られるようになった。また、彼の診断した

自閉症は「自閉症的精神病質」と呼ばれ、論争を巻き起こした。2010年代には、アスペルガーがドイツナチスのアム・シュピーゲルグランド診療所に子供を

紹介し、障害者特許の殺害に関与していたことで、さらなる論争が起こった[2][3]。 |

| Hans

Asperger was born in Hausbrunn, Austria, and raised on a farm not far

from the city.[4] The eldest of three sons, he had difficulty finding

friends and was considered a lonely, remote child.[5][6] He was

talented in language; in particular, he was interested in the Austrian

poet Franz Grillparzer, whose poetry he would frequently quote to his

uninterested classmates. He also liked to quote himself and often

referred to himself from a third-person perspective.[5] As a youth, he joined the Wandering Scholars of the Bund Neuland, a conservative Catholic organization within the German Youth Movement. He considered this a formative experience, later stating: "I was molded by the spirit of the German youth movement, which was one of the noblest blossoms of the German spirit."[7] Asperger studied medicine at the University of Vienna under Franz Hamburger[6][8] and practiced at the University Children's Hospital in Vienna. He earned his medical degree in 1931 and became director of the special education section at the university children's clinic in Vienna in 1932.[4] He joined the Austrofascist Fatherland Front on 10 May 1934, nine days after Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss passed a new constitution making himself dictator.[9] Asperger married in 1935 and had five children.[5] |

ハ

ンス・アスペルガーはオーストリアのハウスブランに生まれ、街からほど近い農場で育った[4]。

3人兄弟の長男である彼は、なかなか友達ができず、孤独で辺鄙な子供と思われていた[5][6]。

彼は言語の才能に恵まれ、特にオーストリアの詩人フランツ・グリルパーザーに興味を持っており、彼は興味のないクラスメイトに頻繁に彼の詩を引用したもの

であった。また、自分の言葉を引用するのが好きで、しばしば三人称の視点で自分のことを語っていた[5]。 青年期には、ドイツ青年運動の中の保守的なカトリック組織であるノイラント連邦のワンダーフォーゲル運動に参加した。彼はこれを形成的な体験と考え、後に こう述べている。「私は、ドイツ精神の最も高貴な花の一つであるドイツ青年運動の精神によって形成された」[7]と述べている。 アスペルガーは、ウィーン大学でフランツ・ハンブルガー(下記) [6][8]のもとで医学を学び、ウィーンの大学付属小児病院で診療を行う。1931年に医学の学 位を取得し、1932年にウィーンの大学小児科医院の特殊教育部門の責任者となった[4]。1934年5月10日、エンゲルベルト・ドルフス首相が独裁者 となる新憲法を可決してから9日後にオーストリアファシスト祖国戦線に参加[9]。 1935年に結婚し5人の子供を持った。[5]アスペルガーは1935年に結婚し5人の子供を持った[5]。 |

| During

World War II, he was a medical officer, serving in the Axis occupation

of Yugoslavia; his younger brother died at Stalingrad.[5] Near the end

of the war, Asperger opened a school for children with Sister Viktorine

Zak. The school was bombed and destroyed, Viktorine was killed, and

much of Asperger's early work was lost.[10] Georg Frankl was Asperger's chief diagnostician until he moved from Austria to America and was hired by Leo Kanner in 1937.[11] Asperger published a definition of autistic psychopathy in 1944 that resembled the definition published earlier by a Russian neurologist named Grunya Sukhareva in 1926.[12][13] Asperger identified in four boys a pattern of behavior and abilities that included “a lack of empathy, little ability to form friendships, one-sided conversations, intense absorption in a special interest, and clumsy movements”.[10] Asperger noticed that some of the children he identified as being autistic used their special talents in adulthood and had successful careers. One of them became a professor of astronomy and solved an error in Newton's work he had originally noticed as a student.[14][15]: 89 Another one of Asperger's patients was the Austrian writer and Nobel Prize in Literature laureate, Elfriede Jelinek.[16] In 1944, after the publication of his landmark paper describing autistic symptoms, Hans Asperger found a permanent tenured post at the University of Vienna. Shortly after the war ended, he became director of a children's clinic in the city. It was there that he was appointed chair of pediatrics at the University of Vienna, a post he held for twenty years. He later held a post at Innsbruck. Beginning in 1964, he headed the SOS-Kinderdorf in Hinterbrühl.[4] He became professor emeritus in 1977, and died three years later. AS was named after Hans Asperger and officially recognized in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1994;[17] it was removed from DSM-5 and subsumed into autism spectrum disorder in 2013.[18] |

第

二次世界大戦中は、枢軸国のユーゴスラビア占領に従軍し、弟はスターリングラードで死亡した[5]。戦争末期、アスペルガーはシスター・ヴィクトリーネ・

ザクとともに子供たちのための学校を開いた。学校は爆撃を受け破壊され、ヴィクトリーネは殺され、アスペルガーの初期の作品の多くは失われた[10]。 ゲオルク・フランクルは、オーストリアからアメリカに移り、1937年にレオ・カナーに雇われるまで、アスペルガーの主な診断者であった[11]。 アスペルガーは1944年に自閉症精神病の定義を発表したが、それは1926年にロシアの神経学者であるグルニヤ・スチャレヴァが先に発表した定義に似て いた[12][13]。 アスペルガーは、「共感の欠如、友情を形成する能力の低さ、一方的な会話、特別な興味への激しい吸収、不恰好な動き」といった行動と能力のパターンを4人 の少年で確認した[10] アスペルガーが自閉症として確認した子どもたちの一部が成人期にその特別な才能を使って成功するキャリアを持っていたことに気づいていた。そのうちの1人 は天文学の教授となり、学生時代にもともと気づいていたニュートンの著作の誤りを解決した[14][15]: 89 また、アスペルガーの患者の1人はオーストリアの作家でノーベル文学賞受賞者のエルフリーデ・イェリネクだった[16] 。 1944年、自閉症の症状について述べた画期的な論文を発表した後、ハンス・アスペルガーはウィーン大学で終身雇用のポストを見つけた。終戦後まもなく、 彼はウィーンにある小児科医院の院長となる。そこで、ウィーン大学の小児科の主任教授に任命され、20年間その任に就いた。その後、インスブルックに赴任 した。1964年からはヒンターブリュールのSOSキンダードルフを率いていた[4]。1977年に名誉教授となり、その3年後に死去した。ASはハン ス・アスペルガーにちなんで命名され、1994年に精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル(DSM)の第4版で正式に認められたが[17]、2013年にDSM-5から削除され、自閉症スペクトラム障害に包含された[18]。 |

| Posthumous Asperger syndrome

diagnosis Asperger died before his identification of this pattern of behaviour became widely recognised. This was in part due to his work being exclusively in German and as such it was little-translated; medical academics, then as now, also disregarded Asperger's work based on its merits or lack thereof. English researcher Lorna Wing proposed the condition Asperger's syndrome in a 1981 paper, Asperger's syndrome: a clinical account, that challenged the previously accepted model of autism presented by Leo Kanner in 1943.[19] It was not until 1991 that an authoritative translation of Asperger's work was made by Uta Frith;[20] before this, AS had still been "virtually unknown".[21] Frith said that fundamental questions regarding the diagnosis had not been answered, and the necessary scientific data to address this did not exist.[22] In the early 1990s, Asperger's work gained some notice due to Wing's research on the subject and Frith's recent translation, leading to the inclusion of the eponymous condition in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision (ICD-10) in 1993, and the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th revision (DSM-IV) in 1994, some half a century after Asperger's original research.[citation needed] Despite this brief resurgence of interest in his work in the 1990s, AS remains a controversial and contentious diagnosis due to its unclear relationship to the autism spectrum. In 2010 there was a majority consensus to subsume AS into the diagnosis "Autistic Spectrum Disorder" in the 2013 DSM-5 diagnostic manual.[18] The World Health Organization's ICD-10 Version 2015 describes AS as “a disorder of uncertain nosological validity”.[23] In his 1944 paper, as Uta Frith translated from the German in 1991, Asperger wrote: "We are convinced, then, that autistic people have their place in the organism of the social community. They fulfill their role well, perhaps better than anyone else could, and we are talking of people who as children had the greatest difficulties and caused untold worries to their care-givers."[24] Based on Frith's translation, however, Asperger initially stated: "Unfortunately, in the majority of cases the positive aspects of autism do not outweigh the negative ones."[24] Psychologist Eric Schopler wrote in 1998: Asperger's own publications did not inspire research, replication, or scientific interest prior to 1980. Instead, he laid the fertile groundwork for the diagnostic confusion that has grown since 1980.[25] Since 2009, Asperger's birthday, 18 February, has been declared International Asperger's Day by various governments.[26] |

死後のアスペルガー症候群の診断 アスペルガーは、この行動様式の特定が広く認知される前にこの世を去った。これは、彼の研究がドイツ語のみであったため、ほとんど翻訳されなかったことが 一因である。また、当時も現在も、医学界の学者たちは、アスペルガーの研究の是非を判断して、彼の研究を無視した。イギリスの研究者ローナ・ウィングは 1981年に発表した論文『アスペルガー症候群:臨床的説明』において、それまで受け入れられていたレオ・カナーによる1943年の自閉症モデルに異議を 唱え、アスペルガー症候群という病名を提唱した[19]。 1990年代初頭、アスペルガーの研究はウィングの研究とフリスの最近の翻訳によって注目を集め、1993年には「疾病及び関連保健問題の国際統計分類第 10版(ICD-10)」に、1994年にはアスペルガーの最初の研究から約半世紀後にアメリカ精神医学会の「精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル第4版 (DSM-IV)」にその名が含まれることになった[citation needed][citation]。 1990年代に彼の研究に対する関心が一時的に復活したものの、ASは自閉症スペクトラムとの関係が不明確であるため、依然として論争の的となる診断名で ある。2010年には、2013年のDSM-5診断マニュアルにおいて、ASを「自閉症スペクトラム障害」という診断に収めるという多数決の合意があった [18]。 世界保健機関のICD-10バージョン2015では、ASを「病態学的妥当性が不確かな障害」として記述している[23]。 1991年にウタ・フリスがドイツ語から翻訳した1944年の論文で、アスペルガーは次のように書いている:「我々は、それでは、自閉症の人々は社会共同 体の組織の中で自分の場所を持っていると確信している。彼らはその役割を十分に、おそらく他の誰よりもよく果たしており、私たちが話しているのは、子ども の頃に最大の困難を抱え、養育者に計り知れない心配をかけた人々のことである」[24] しかし、フリスの翻訳に基づき、アスペルガーは当初こう述べていた。"残念ながら、大多数の場合、自閉症のポジティブな側面はネガティブな側面を上回らな い"[24] 心理学者のエリック・ショプラーは1998年にこう書いている。 アスペルガー自身の出版物は、1980年以前は研究、再現、科学的関心を刺激するものではなかった。その代わり、彼は1980年以降に拡大した診断上の混 乱のための肥沃な土台を築いた[25]。 2009年以降、アスペルガーの誕生日である2月18日は、様々な政府によって国際アスペルガー・デーとされている[26]。 |

| Nazi involvement Asperger was a member of a seven-member commission that was to categorize 200 handicapped children according to their "educational ability" in order to decide their fate. 35 children were classified as "hopeless cases" and subsequently transferred to Spiegelgrund, where they all died. There is no basis to accuse him of murder because of this, as further steps were needed before these children were murdered, but he was part of the legitimization of these murders and, as an expert, contributed to the categorization into "usefulness levels." [27] While Asperger, according to his own statements in the postwar years and the accounts of his companions, was an opponent of the National Socialists, contemporary documents and new research indicate that this was by no means the case. For example, a political assessment of Asperger by the personnel office of the Reichsgau Vienna dated November 1, 1940, states: "In questions of racial and sterilization legislation, he conforms to the nat[ional]soc[ialist] ideas. In matters of character as well as politics, he is considered impeccable." Moreover, Asperger's role during the period of National Socialism in Austria is critically evaluated by Herwig Czech as well as other historians. Edith Sheffer, a modern European history scholar, wrote in 2018 that Asperger cooperated with the Nazi regime, including sending children to the Am Spiegelgrund clinic which participated in the euthanasia program.[28] Sheffer wrote a book called Asperger's Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna (2018), further elaborating on her research.[29][30] Another scholar and historian from the Medical University of Vienna, Herwig Czech concluded in a 2017 article in the journal Molecular Autism, which was published in April 2018: Asperger managed to accommodate himself to the Nazi regime and was rewarded for his affirmations of loyalty with career opportunities. He joined several organizations affiliated with the NSDAP (although not the Nazi party itself), publicly legitimized 'race hygiene' policies including forced sterilizations and, on several occasions, actively cooperated with the child ‘euthanasia' program.[2] Dean Falk, American anthropologist from Florida State University, questioned Herwig Czech's and Edith Sheffer's allegations against Hans Asperger in a paper in Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.[3] Czech's reply was published in the same journal.[31] Falk defended her paper against Czech's reply in a second paper.[32] In May 2019, Ketil Slagstad, a Norwegian doctor and historical scholar, added his interpretation of both Sheffer's and Czech's work, in his article "Asperger, the Nazis and the children - the history of the birth of a diagnosis",[33] in which he describes the nuances of the situation. He offers an alternative explanation of Asperger's involvement: citing the challenges of war, a desire to protect his career, and protection of the children for whom he was caring. Slagstad concludes: The story of Hans Asperger, Nazism, murdered children, post-war oblivion, the birth of the diagnosis in the 1980s, the gradual expansion of the diagnostic criteria and the huge recent interest in autism spectrum disorders exemplify the historical and volatile nature of diagnoses: they are historic constructs that reflect the times and societies where they exert their effect. Critically, Slagstad noted: "Historical research has now shown that he [Asperger] was...a well-adapted cog in the machine of a deadly regime. He deliberately referred disabled children to the clinic Am Spiegelgrund, where he knew that they were at risk of being killed. The eponym Asperger’s syndrome ought to be used with awareness of its historical origin."[33] |

ナチスとの関わり アスペルガーは、200人の障害児を「教育能力」に応じて分類し、その運命を決定する7人の委員会のメンバーであった。35人の子供たちは「絶望的なケー ス」に分類され、その後シュピーゲルグランドに移送され、そこで全員死亡した。これらの子供たちが殺害される前にさらなる措置が必要であったので、これに よって彼を殺人で告発する根拠はないが、彼はこれらの殺人の正当化に加担し、専門家として、"有用性レベル "への分類に貢献したのである。[27] 戦後における彼自身の発言や彼の仲間の証言によれば、アスペルガーは国家社会主義者の反対者であったが、現代の資料や新しい研究からは、決してそうではな かったことが示されている。たとえば、1940年11月1日付のウィーン帝国軍人事部によるアスペルガーに対する政治的評価は、次のように記されている。 「人種差別や不妊手術の法律の問題では、彼は国家社会主義者の考えに適合している。政治と同様に人格の問題においても、彼は非の打ちどころがないと考えら れている」。さらに、オーストリアにおける国家社会主義の時代におけるアスペルガーの役割については、ヘルヴィヒ・チェコだけでなく、他の歴史家も批判的 に評価している。 近代ヨーロッパ史の研究者であるエディス・シェファーは2018年に、 アスペルガーは安楽死プログラムに参加したアム・シュピーゲルグルンド診療所に子どもを送るなどナチス政権に協力したと書いている[28]。 シェファーは『アスペルガーの子どもたち』という本を書いている。The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna (2018)という本を書き、彼女の研究をさらに詳しく説明している[29][30]。 ウィーン医科大学の別の学者であり歴史家であるヘルヴィヒ・チェコは、『Molecular Autism』誌の2017年の論文で、2018年4月に出版された論文で結論付けています。 アスペルガーはナチス政権になんとか身を寄せ、その忠誠心の肯定に対して出世の機会で報われた。彼は(ナチス党そのものではないが)NSDAPに所属する いくつかの組織に参加し、強制不妊手術を含む「人種衛生」政策を公に正当化し、何度か、子どもの「安楽死」計画に積極的に協力していた[2]。 フロリダ州立大学のアメリカの人類学者であるディーン・フォークは、『Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders』の論文でハンス・アスペルガーに対するハーウィグ・チェコの主張とエディス・シェファーの主張に疑問を呈した[3] チェコの回答は同誌に掲載されている[31] フォークは2番目の論文でチェコの回答に対して自身の論文を弁護した[32]。 2019年5月、ノルウェーの医師で歴史学者のケティル・スラグスタが、論文「アスペルガーとナチスと子どもたち-ある診断の誕生の歴史」の中で、シェ ファーとチェコの両者の解釈を加え、状況のニュアンスを述べている[33]。彼はア スペルガーの関与について、戦争という困難、自分のキャリアを守りたいという願望、そして世話をしていた子どもたちの保護を挙げて、別の説明をしている。 スラグスタはこう結論づける。 ハンス・アスペルガー、ナチズム、殺された子どもたち、戦後の忘却、 1980年代の診断の誕生、診断基準の漸増、自閉症スペクトラム障害に対する最近の大きな関心といった物語は、診断の歴史的で不安定な性格を例証している。 スラグスタは批判的にこう述べている。「歴史的な研究によって、彼(アスペルガー)は、致命的な体制にうまく適応した歯車であったことが明らかになった。 彼は、障害児が殺される危険があることを知りながら、意図的にアム・シュピーゲルグランドの診療所に障害児を紹介したのである。アスペルガー症候群という 名称は、その歴史的由来を意識して使われるべきものである」[33]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Asperger |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Franz Hamburger

(14 August 1874 in Pitten – 29 August 1954 in

Vöcklabruck) was an Austrian doctor and university lecturer.[1] |

フランツ・ハンブルガー |

| Hamburger

war der Sohn des Papierfabrikanten Wilhelm Hamburger. Er besuchte das

Gymnasium in Wiener Neustadt und legte 1892 die Matura ab. Danach

absolvierte er ein Medizinstudium in Heidelberg, München und Graz. In

Heidelberg wurde er 1892 Mitglied des Corps Rhenania. Er bestand 1898

das medizinische Staatsexamen und wurde im selben Jahr zum Dr. med.

promoviert.[1] Danach war er zeitweilig als Schiffsarzt tätig und

anschließend als Assistenzarzt in Wien und Graz. Seine Fachausbildung

als Kinderarzt absolvierte er ab 1900 bei Theodor Escherich. 1906

habilitierte er sich mit einer Arbeit über arteigenes und artfremdes

Eiweiß und wurde Privatdozent. Ab 1908 war er Vorstand der

Kinderabteilung der Wiener Poliklinik und wurde 1912 zum

außerordentlichen Professor ernannt.[2] Als österreichischer Stabsarzt nahm Hamburger 1914 bis 1917 in Serbien und Italien am Ersten Weltkrieg teil. 1916 wurde er ordentlicher Professor für Kinderheilkunde an der Universität Graz, wo er zudem die Universitätskinderklinik leitete. Nach dem Tod von Clemens von Pirquet erhielt er 1930 einen Ruf an die Universität Wien, wo er zugleich Vorstand der Universitätskinderklinik war.[2] Ab 1931 gehörte er dem Steirischen Heimatschutz an und trat später der NSDAP und dem NS-Ärztebund bei. Nach dem Anschluss Österreichs an das nationalsozialistische Deutsche Reich wurde er Präsident des Wissenschaftlichen Senats der Akademie für ärztliche Fortbildung in Wien. Er gehörte zu den Mitherausgebern der Münchner Medizinische Wochenschrift. Im Sinne der NS-Gesundheitspolitik forderte er die Sterilisierung von „schwachsinnigen“ und diabetischen Kindern. Unter ihm kam es zu einer Zusammenarbeit mit der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt „Am Steinhof“. Durch Adolf Hitler wurde ihm 1944 die Goethe-Medaille für Kunst und Wissenschaft verliehen.[3] 1944 wurde er emeritiert, übernahm aber noch die Leitung der Kinderabteilung im Krankenhaus in Vöcklabruck.[2] Nach dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges wurde er am 2. Juni 1945 von seinen Funktionen entbunden und trat 1947 in den Ruhestand.[1] Hamburger war Autor zahlreicher fachspezifischer Artikel und Bücher. Er forschte zu allen Bereichen der Kinderheilkunde. Herausragend war seine Beteiligung an der Einführung der BCG- und subkutanen Pockenschutzimpfung sowie auf dem Gebiet der Kinder-Tuberkulose und Diphtherie.[1][2] Hamburgers 1951 erschienener Ratgeber „Über den Umgang mit Kindern“ wurde als Beispiel für Befürwortung physischer und psychischer Gewalt in der Kindererziehung nach 1945 angeführt.[4][5] Source: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Hamburger_(Mediziner) |

ハ

ンブルガーは、製紙会社ヴィルヘルム・ハンブルガーの息子である。ウィーン・ノイシュタットの文法学校に通い、1892年にマトゥラーに合格した。その

後、ハイデルベルク、ミュンヘン、グラーツで医学を学んだ。1892年、ハイデルベルクでレナニア部隊の一員となる。1898年に医師国家試験に合格し、

同年博士号を授与された[1]。その後、船医として働き、その後、ウィーンとグラーツで助手を務めた。1900年からテオドール・エシェリヒのもとで小児

科医としての専門教育を受けた。1906年には、種のタンパク質と他の種のタンパク質に関する論文でリハビリテーションを行い、私的な講師となった。

1908年からはウィーン・ポリクリニックの小児科長を務め、1912年には助教授に任命された[2]。 ハンブルガーは、オーストリアの軍医として、1914年から1917年までセルビアとイタリアで第一次世界大戦に参加した。1916年にはグラーツ大学の 小児科の正教授となり、大学の小児科クリニックの責任者も務めた。クレメンス・フォン・ピルケの死後、1930年にウィーン大学に呼ばれ、大学の小児科診 療所の責任者を兼任した[2]。 1931年からシュタイアーマルクに所属し、後にNSDAPとNS医師 会に参加した。オーストリアが国家社会主義ドイツ帝国に併合された後、ウィーンの生涯医学教育アカデミーの科学顧問委員会の会長に就任した。ミュンヘン医 学会誌の共同編集者の一人である。ナチスの健康政策に沿い、「気が弱い」子供や糖尿病の子供を不妊化するよう呼びかけた。彼の下には、療養所兼老人ホーム 「アム・シュタインホフ」との協力関係があった。1944年、アドルフ・ヒトラーから芸術と科学のためのゲーテメダルを授与された[3]。1944年、名 誉教授となったが、引き続きフェックラブラックの病院の小児科の運営を引き受けた[2]。 第二次世界大戦終了後、1945年6月2日にその職を解かれ、1947年に退官した[1]。 ハンブルガーは、数多くの専門的な論文や本を執筆しています。小児科の全領域を研究していた。BCGや天然痘の皮下接種の導入、小児結核やジフテリアの分 野での関わりは卓越していた[1][2]。 ハンブルガーが1951年に出版したガイドブック『子どもとの付き合い方について』は、1945年以降の育児における身体的・心理的暴力を擁護を示す例と して挙げられている[4][5]。 |

History of Asperger syndrome

| Asperger

syndrome (AS) is an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It is a relatively

new diagnosis in the field of autism, but is no longer used and

rejected by many autistic individuals.[1][2] It was named after Hans

Asperger (1906–80), who was an Austrian psychiatrist and pediatrician.

An English psychiatrist, Lorna Wing, popularized the term "Asperger's

syndrome" in a 1981 publication; the first book in English on Asperger

syndrome was written by Uta Frith in 1991 and the condition was

subsequently recognized in formal diagnostic manuals later in the

1990s.[1] Details[3] of Hans Asperger 's actions[4][5] as a

psychiatrist in Nazi era Austria, made public in 2018, incited

reevaluation[6] of the syndrome's name and public lobbying for a

renaming of the syndrome.[7] Under the DSM-5 and ICD-10, patients

formerly diagnosable with Asperger syndrome are diagnosable with Autism

Spectrum Disorder. |

アスペルガー症候群(AS)とは、自閉症スペクトラム障害

(ASD)の一つである。自閉症の分野では比較的新しい診断名であるが、多くの自閉症者によって拒絶され、使われなくなっている[1][2]。イギリスの

精神科医ローナ・ウィングが1981年の出版物で「アスペルガー症候群」という言葉を広めた。1991年にユタ・フリスがアスペルガー症候群に関する最初

の英語本を書き、その後1990年代後半に正式な診断マニュアルでこの症状が認識されるようになった。

[2018年に公開されたナチス時代のオーストリアにおけるハンス・アスペルガーの精神科医としての行動[4][5]の詳細[3]は、本症の名称に対する

再評価[6]と本症の名称変更を求める世論のロビー活動を扇動した。 DSM-5 と ICD-10

では、以前アスペルガー症候群と診断された患者は自閉症スペクトラム障害と診断できる。 |

| Hans Asperger Hans Asperger was director of the University of Vienna Children's Clinic. As a result, he spent most of his professional life in Vienna. Throughout Asperger's career, he was also a pediatrician, medical theorist, and medical professor.[8] His works were published largely in German.[1] He is most well known for his work with mental disorders, especially those in children.[8] As a child, Asperger appeared to have exhibited some features of the very condition named after him, such as social remoteness and talent in language.[9] |

ハンス・アスペルガー ハンス・アスペルガーは、ウィーン大学付属の小児科医院の院長を務めていた。そのため、職業人生のほとんどをウィーンで過ごすことになった。アスペルガー のキャリアを通じて、彼はまた小児科医、医学理論家、医学教授であった[8]。 彼の作品は主にドイツ語で出版された[1]。 彼は精神障害、特に子供の精神障害の研究で最もよく知られている[8]。 子供の頃、アスペルガーは、社会的遠隔性や言語の才能といった、まさに彼の名をとった状態のいくつかの特徴を示していたようであった[9]。 |

| Asperger's research Asperger's 1940 work, Autistic psychopathy in childhood,[10] found that four of the 200 children studied[11] had difficulty with integrating themselves socially. Although their intelligence levels appeared normal, the children lacked nonverbal communication skills, failed to demonstrate empathy with their peers, and were physically clumsy. Their verbal communication was either disjointed or overly formal, and their all-absorbing interest in a single topic dominated their conversations. Asperger named the condition "autistic psychopathy", and described it as primarily marked by social isolation.[12] Asperger described those patients as like "little professors" who talked about their interests at great length,[13] and believed the individuals he described would be capable of exceptional achievement and original thought later in life.[11] Asperger's paper defended the value of high-functioning autistic individuals, writing "We are convinced, then, that autistic people have their place in the organism of the social community. They fulfill their role well, perhaps better than anyone else could, and we are talking of people who as children had the greatest difficulties and caused untold worries to their care-givers." However, he also wrote concerning his other cases, "Unfortunately, in the majority of cases the positive aspects of autism do not outweigh the negative ones."[10] A Soviet child psychiatrist, Grunya Sukhareva, described a similar syndrome that was published in Russian in 1925, and in German in 1926.[14] |

アスペルガーの研究 アスペルガーが1940年に発表した『幼少期の自閉的精神病質』[10]は、研究対象となった200人の子どものうち4人が社会的に統合することが困難で あることを発見した[11]。彼らの知能レベルは正常に見えるが、非言語的なコミュニケーション能力が欠如しており、仲間との共感を示すことができず、身 体的にも不器用であった。言葉によるコミュニケーションはバラバラか、過度に形式的で、一つの話題に没頭することで会話が成立していた。アスペルガーはこ の状態を「自閉症的精神病質」と名付け、主に社会的孤立を特徴とすると述べている[12]。アスペルガーはこれらの患者を自分の興味について非常に長く話 す「小さな教授」のようだと述べ、彼が述べた人々は後年、並外れた業績や独自の考えを持つことができると信じていた[11] 。 アスペルガーの論文は高機能な自閉症者の価値を擁護し、「我々は確信している、自閉症者は社会コミュニティの組織の中でその場所をもっているということ を」書く。彼らはその役割を十分に、おそらく他の誰よりもよく果たしており、私たちが話しているのは、子どもの頃に最も大きな困難を抱え、介護者に計り知 れない心配をかけた人々のことである" と書いている。しかし、彼は他の症例についても、「残念ながら、大多数の症例において、自閉症の肯定的な側面は否定的な側面を上回らない」と書いている [10]。 ソ連の児童精神科医であるグルーニャ・スハレヴァは、同様の症候群を記述し、1925年にロシア語で、1926年にドイツ語で発表している[14]。 |

| Fritz

V. is a pseudonym that Hans Asperger used to refer to his first

patient. This makes him the first person in history to be identified as

having Asperger's Syndrome. Fritz displayed many behavioral problems in

childhood and acted out at school but he had a strong interest in

mathematics and astronomy, particularly the theories of Isaac Newton.

Fritz grew up to become a professor of astronomy and solved an error in

Newton's work he originally noticed as a child. Much of what Asperger

learned about the condition in its early days derives from his meetings

with Fritz, whom he kept track of throughout his life.[10] Fritz V. was born in June 1933 in Austria and was sent to Hans Asperger in autumn of 1939. The school referred him as they considered him "uneducable" by his first day there. He had severe impairment in social integration. Hans Asperger gave a very detailed report of Fritz and his efforts to understand his problems in his case report 'Autistic psychopathy' in childhood.[10] Fritz was a first child of his parents. According to Asperger, his mother was a descendant of "one of the greatest Austrian poets" and she described her family as "in the mad-genius mould." Her family were intellectuals who wrote poetry "quite beautifully." Asperger noticed the genetic component of the syndrome here because Fritz's grandfather and several of his relatives had displayed similar traits and had been expelled from private schools numerous times. His grandfather lived as an eccentric recluse at the time of Asperger's report. He lived alone and was "preoccupied with his own thoughts." Fritz's mother also displayed similar behavior to him. She made poor eye contact, always looked unkempt, dressed rather poorly and walked in a very clunky, military fashion with her arms behind her back. She had problems communicating with her family and when things at home became too stressful she would travel alone to the Alps for weeks at a time and leave the rest of the family to deal with things themselves. Fritz's father was a civil servant and Asperger noted that he was 55 years old at the time of Fritz's birth. Fritz had a normal birth. However, his motor development was delayed and he was very clumsy which worried his parents. He only learned to walk at fourteen months. He also had problems with learning self-help skills such as washing and cleaning. However, he also learnt to talk much earlier at ten months and quickly expressed himself in formal sentence structure "like an adult." Asperger noted that from a young age, Fritz never did what he was told and would often intentionally do the exact opposite. Punishment did not deter him. He was restless and fidgety and had "a destructive urge." Any toys left around him would soon be broken. He did not get along well with other children either. They "wound him up" and he once attacked one with a hammer. He cared little for the danger posed to himself or others. He was kicked out of kindergarten on the first day. He attacked other children, paced about nonchalantly during the lesson and destroyed the coat-rack. Fritz did not care if people were upset with him and seemed to enjoy their angry responses to his disobedience. Despite this, he would also sometimes hug other classmates without provocation. Asperger noted that Fritz was indifferent to the authority of adults and would use abrasive, informal language when speaking to them (he used the informal "du" and never the formal "sie"). He also displayed repetitive movements such as hitting, jumping and echolalia. Fritz had poor eye contact and would never look at people when speaking to them. He also spoke in a dull, monotone voice. He did however, sometimes sing "I don't like to say that" in response to a question or beat rhythms on objects around him. He experienced serious stomach problems from eating non-edible things such as pencils and from licking the tables. He did very poorly in PE because he was very clumsy and never swung in any rhythm. He would frequently run away from class or begin hitting and jumping up and down. When it came to intelligence tests, it was impossible to get a good measure of his intelligence as his responses to test questions varied. Sometimes he would jump up and move around or just answer with nonsense (Asperger implies here it might be deliberate) and other times he might give an answer considerably advanced for his age. Asperger noted that it almost seemed up to chance. To some questions, he would give a very precise answer and to others he would mumble nonsense. Much of what Asperger learned about the syndrome and its effect on health and learning can be seen from his interactions with Fritz. He noted the many behavioral problems that Fritz faced and remarked that these problems he faced from a young age in making relationships with his parents would lead to later problems with his teachers and peers. Children's development relies quite heavily on things such as eye contact and understanding others which Fritz had problems with. Asperger believed Fritz could feel emotions very easily but the problems he had were with displaying them. Many of the traits that have came to be seen as key features of Asperger syndrome can be seen in Asperger's records of Fritz including, difficulty socializing and understanding the thoughts of others, trouble empathizing, special interests, motor problems, sensory issues, avoidance of other classmates and difficulty relating with peers. Asperger recommended to his mother that he would do better with a private tutor than he would in the full classroom but that even still, he would face some difficulties with keeping focus. Much of what Asperger had learned from Fritz has helped with the understanding of Asperger Syndrome today. |

フリッツ・Vは、ハンス・アスペルガーが最初の患者を指す

のに使った仮名である。このことから、彼は歴史上初めてアスペルガー症候群であることが確認された人物となった。フリッツは幼少期に多くの問題行動を起こ

し、学校でも問題行動を起こしたが、数学と天文学、特にアイザック・ニュートンの理論に強い関心を抱いていた。フリッツは成長し、天文学の教授となり、子

供の頃に気づいたニュートンの研究の誤りを解決した。アスペルガーが初期の症状について学んだことの多くは、彼が生涯にわたって記録を取り続けたフリッツ

との出会いに由来している[10]。 フリッツ・Vは1933年6月にオーストリアで生まれ、1939年の秋にハンス・アスペルガーのもとに送られた。学校は、入所初日から彼を「教育不可能」 と見なし、紹介した。彼は、社会的統合に深刻な障害を抱えていたのです。ハンス・アスペルガーは、彼のケースレポート「幼年期の自閉的精神病質」におい て、フリッツと彼の問題を理解するための努力について非常に詳細な報告をしている[10]。アスペルガーによれば、彼の母親は「オーストリアで最も偉大な 詩人の一人」の子孫であり、彼女は自分の家族を "マッド・ジーニアスの型 "と表現している。彼女の一族は、"極めて美しく "詩を書く知識人であった。アスペルガーはここで、フリッツの祖父や親戚の何人かが同様の特徴を示し、私立学校から何度も退学させられていたことから、こ の症候群の遺伝的要素に気づきました。アスペルガーが報告した当時、彼の祖父は風変わりな世捨て人として暮らしていた。彼は一人暮らしで、「自分の考えで 頭がいっぱい」だった。フリッツの母親もまた、彼と似たような行動を見せていた。彼女は視線を合わせるのが苦手で、いつも手入れが行き届いていないように 見え、服装もかなり貧相で、腕を後ろに回して非常に不格好な軍服のような歩き方をしていました。家族とのコミュニケーションもうまくいかず、ストレスがた まると、一人で何週間もアルプスに旅行して、家族のことはそっちのけで、自分たちだけで解決しようとする。フリッツの父親は公務員で、アスペルガーはフ リッツの出生時に55歳であったことを指摘している。 フリッツは普通に生まれた。しかし、運動機能の発達が遅れ、非常に不器用であったため、両親は心配した。歩けるようになったのは14カ月になってから。ま た、洗濯や掃除などの自助努力の習得にも問題があった。しかし、彼は10ヵ月という早い時期に言葉を覚え、「大人のような」正式な文章構成ですぐに自分の 考えを表現するようになった。アスペルガーは、フリッツが幼い頃から言われたことを決してやらず、しばしば意図的に正反対のことをしたと述べている。罰を 受けても、それをやめようとはしなかった。彼は落ち着きがなく、そわそわしていて、「破壊的な衝動」を持っていた。彼の周りに置いてあるおもちゃは、すぐ に壊されてしまう。他の子供たちともうまくいかなかった。ハンマーで殴りかかったこともある。自分も他人も危険な目に遭うのに、ほとんど無頓着だった。幼 稚園は1日目で退園させられた。他の園児を襲い、授業中も平然と歩き回り、コート掛けを壊したのだ。フリッツは、人々が自分に腹を立てても気にせず、自分 の不従順さに人々が怒るのを楽しんでいるように見えた。にもかかわらず、彼は時々、挑発することなく他のクラスメートに抱きつくこともあった。アスペル ガーは、フリッツが大人の権威に無頓着で、大人と話すときには、擦れた非公式の言葉を使うことを指摘した(彼は非公式の「デュ」を使い、正式な「シー」を 使うことはなかった)。また、叩く、跳ぶ、エコーラリアなどの反復的な動作も見られた。フリッツはアイコンタクトが下手で、人と話すときに決して目を合わ せない。また、話し方も鈍く、単調であった。しかし、質問に答えて "I don't like to say that "と歌ったり、周囲の物にリズムを刻んだりすることはあった。鉛筆など食べられないものを食べたり、テーブルをなめたりして、お腹をこわしたこともあっ た。体育の成績は、不器用でリズムをとらないため、非常に悪い。教室から逃げ出したり、殴ったり飛び跳ねたりすることもしょっちゅうだった。知能テストに なると、テストの質問に対する反応がまちまちで、彼の知能を正しく測定することは不可能であった。飛び跳ねて動き回ったり、意味不明なことを答えたりする こともあれば(アスペルガーはここで意図的かもしれないと示唆している)、年齢的にかなり進んだ答えをすることもあった。アスペルガーは、それはほとんど 偶然の産物であると述べている。ある質問には非常に正確な答えを出し、別の質問には無意味なことをつぶやいた。 アスペルガーが症候群とそれが健康や学習に及ぼす影響について学んだことの多くは、フリッツとの交流からうかがい知ることができる。彼は、フリッツが直面 している多くの行動上の問題に注目し、彼が幼い頃から直面している親との関係づくりの問題が、後に教師や仲間との問題につながると指摘した。子どもの発達 は、アイコンタクトや他者理解といったものに大きく依存しており、フリッツはその点で問題を抱えていた。アスペルガーは、フリッツは感情を簡単に感じるこ とができるが、それを表に出すことに問題があると考えた。アスペルガー症候群の主要な特徴として見られるようになった特徴の多くは、フリッツのアスペル ガーの記録に見ることができる。社交性や他者の考えを理解することの難しさ、共感することの問題、特別な興味、運動障害、感覚の問題、他のクラスメートを 避けること、仲間との関係の難しさなどである。アスペルガーは母親に、フリッツは教室で勉強するよりも家庭教師をつけたほうがうまくいくが、それでも集中 力を維持するのが難しいだろうと勧めた。アスペルガーがフリッツから学んだことの多くは、今日のアスペルガー症候群の理解に役立っている。 |

| Relationship to Kanner's work Two subtypes of autism were described between 1943 and 1944 by two Austrian researchers — Austrian-born Asperger and child psychiatrist Leo Kanner (1894–1981).[15] Kanner emigrated to the United States in 1924;[1] he described a similar syndrome in 1943, known as "classic autism" or "Kannerian autism", characterized by significant cognitive and communicative deficiencies, including delayed or absent language development.[16] Kanner's descriptions were influenced by the developmental approach of Arnold Gesell, while Asperger was influenced by accounts of schizophrenia and personality disorders.[17] Asperger's frame of reference was Eugen Bleuler's typology, which Christopher Gillberg has described as "out of keeping with current diagnostic manuals", adding that Asperger's descriptions are "penetrating but not sufficiently systematic".[18] Asperger was unaware of Kanner's description published a year before his;[17] the two researchers were separated by an ocean and a raging war, and Asperger's descriptions were unnoticed in the United States.[11] During his lifetime, Asperger's work, in German, remained largely unknown outside the German-speaking world.[1] The outlook the two had on the causes of Autism and the way it should be reacted to were quite different. Kanner was a bit more censorious of the parents of the autistic children and held their emotional coldness as at least partially responsible (see Refrigerator mother theory) whereas Hans Asperger was more sympathetic to the parents of his patients and even noticed that they had similar symptoms to their kids. Hans Asperger had very high hopes for his patients (his "little professors") and felt that they would benefit most from special tutors who were willing to deal with their many quirks and emotional problems, outside of an academic environment where they would have difficulties interacting with other children, and uncomfortable sensory stimuli and would be likely to disrupt classes. |

カナーの研究との関係 1943年から1944年にかけて、オーストリア出身のアスペルガーと児童精神科医のレオ・カナー(1894-1981)の2人の研究者によって自閉症の 2つの亜型が記述された[15]。カナーは1924年に米国に移住し[1]、1943年に同様の症候群を記述し、「古典的自閉症」または「カナー型自閉 症」として知られ、言語の発達の遅れや欠如など著しい認知およびコミュニケーション上の欠陥により特徴付けられた[16]。 カナーの記述はアーノルド・ゲゼルの発達アプローチに影響を受け、アスペルガーは精神分裂病や人格障害の記述に影響を受けていた[16]。 アスペルガーが参照したのはオイゲン・ブルーラーの類型論であり、クリストファー・ギルバーグはこれを「現在の診断マニュアルにそぐわない」と評し、アス ペルガーの記述は「浸透しているが十分に体系的ではない」と付け加えている[17]。 [アスペルガーはカナーの記述より1年前に発表されたカナーの記述を知らなかった[17]。2人の研究者は海と激しい戦争によって隔てられており、アスペ ルガーの記述はアメリカでは注目されなかった[11]。 アスペルガーの生涯において、ドイツ語による研究はドイツ語圏以外ではほとんど知られていないままだった[1]。 自閉症の原因や対処法について、2人が抱いていた見解は全く異なっていた。カナーは自閉症児の両親を非難し、その感情的な冷たさが少なくとも部分的に原因 であるとした(冷蔵庫の母親説を参照)のに対し、ハンス・アスペルガーは患者の両親に同情的で、彼らが自分の子供と似た症状を持っていることにさえ気づい ていたのである。ハンス・アスペルガーは、自分の患者(「小さな教授」)に対して非常に大きな期待を抱いており、他の子どもたちとの交流が難しく、不快な 感覚刺激を受け、授業を妨害する可能性が高い学業環境の外で、彼らの多くの奇癖や感情問題に喜んで対処してくれる特別な家庭教師から最も恩恵を受けるだろ うと考えていたのである。 |

| Coinage According to Ishikawa and Ichihashi in the Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine, the first author to use the term Asperger's syndrome in the English-language literature was the German physician, Gerhard Bosch.[19] Between 1951 and 1962, Bosch worked as a psychiatrist at Frankfurt University. In 1962, he published a monograph detailing five case histories of individuals with PDD[20] that was translated into English eight years later,[21] becoming one of the first to establish German research on autism, and attracting attention outside the German-speaking world.[22] Lorna Wing coined the term Asperger's syndrome in 1976[23] and is also credited with widely popularizing the term in the English-speaking medical community in her February 1981 publication[24][25][26] of a series of case studies of children showing similar symptoms.[1] Wing also placed AS on the autism spectrum, although Asperger was uncomfortable characterizing his patient on the continuum of autistic spectrum disorders.[11] She chose "Asperger's syndrome" as a neutral term to avoid the misunderstanding equated by the term autistic psychopathy with sociopathic behavior.[27] Wing's publication effectively introduced the diagnostic concept into American psychiatry and renamed the condition as Asperger's;[28] however, her accounts blurred some of the distinctions between Asperger's and Kanner's descriptions because she included some mildly retarded children and some children who presented with language delays early in life.[17] |

造語 日本臨床医学雑誌の石川・市橋によると、英語の文献で初めてアスペルガー症候群という言葉を使ったのはドイツの医師ゲルハルト・ボッシュである[19]。 1951年から1962年までボッシュはフランクフルト大学で精神科医として働いていた。1962年、彼はPDD患者の5つの事例を詳述したモノグラフを 発表し[20]、8年後に英語に翻訳され、ドイツにおける自閉症研究を確立した最初の一人となり、ドイツ語圏外でも注目された[21]。 ローナ・ウィングは1976年にアスペルガー症候群という言葉を作り[23]、1981年2月に同様の症状を示す子どもの一連の事例研究[24][25] [26]を発表し、英語圏の医学界にこの言葉を広く普及したとされる。 アスペルガーは自分の患者が自閉症スペクトラム障害の連続体に特徴づけられることに抵抗があったものの、ウィングはASも自閉症スペクトラムに位置づけて いる[1]。 [11] 彼女は、自閉症的精神病質という用語によって社会病質的行動と同一視される誤解を避けるために、中立的な用語として「アスペルガー症候群」を選んだ [27]。ウィングの出版は、アメリカの精神医学に診断概念を効果的に導入し、この状態をアスペルガーと改名した[28]。しかし彼女の記述は、軽度の遅 滞児や人生の初期に言語の遅れを示した一部の子どもたちも含んでいたために、アスペルガーの記述とカナーの記述との区別の一部をぼかしたものになった [17]。 |

| Early studies The first systematic studies appeared in the late 1980s in publications by Tantam (1988) in the UK, Gillberg and Gilbert in Sweden (1989), and Szatmari, Bartolucci and Bremmer (1989) in North America.[1] The diagnostic criteria for AS were outlined by Gillberg and Gilbert in 1989; Szatmari also proposed criteria in 1989.[27] Asperger's work became more widely available in English when Uta Frith, an early researcher of Kannerian autism, translated his original paper in 1991.[1] AS became a distinct diagnosis in 1992, when it was included in the 10th published edition of the World Health Organization’s diagnostic manual, International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10); in 1994, it was added to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) as Asperger's Disorder.[12] When Hans Asperger observed the autistic like symptoms and behaviors in boys through their social and communication skills, many professionals felt like Asperger's syndrome was just a less severe form of autism. Uta Frith was one of these professionals who had this opinion. She was a professor at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience of University College London, and was also an editor of Autism and Asperger Syndrome. She said that individuals with Asperger's had a "dash of autism". She was one of the first scientists who recognized autism and related disorders as the result of a condition of the brain instead of the outcome of detached parenting. |

初期の研究 最初の体系的な研究は1980年代後半にイギリスのTantam(1988)、スウェーデンのGillbergとGilbert(1989)、北米の Szatmari、BartolucciとBremmer(1989)による出版物で現れた[1] ASの診断基準は1989年にGillbergとGilbertによって概説され、Szatmariも1989年に基準を提案している[27] 初期のカナー式自閉症研究者Uta Frithによって、彼のオリジナルの論文は1991年に訳されて、アスペルガーの仕事は英語でより幅広く利用可能となった. [1] ASは1992年に世界保健機関の診断マニュアルである国際疾病分類(ICD-10)の第10版に含まれ、明確な診断名となり、1994年には精神障害の 診断と統計マニュアル(DSM-IV)の第4版にアスペルガー障害として追加された[12]。ハンス・アスペルガが少年の社会性とコミュニケーション能力 を通じて自閉症に似た症状や行動を観察したとき、多くの専門家はアスペルガー症候群が単に自閉症のそれほど深刻ではない形のように感じるとした。ユタ・フ リスもこのような意見を持った専門家の一人であった。彼女はユニバーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンの認知神経科学研究所の教授で、『Autism and Asperger Syndrome』の編集者でもあった。彼女は、アスペルガー症候群の人は「自閉症のダッシュ」を持っていると言っていました。彼女は、自閉症とその関連 疾患を、放任主義の結果ではなく、脳の状態の結果として認識した最初の科学者の一人であった。 |

| Contemporary Less than two decades after the widespread introduction of AS to English-speaking audiences, there are hundreds of books, articles and websites describing it; prevalence estimates have increased dramatically for ASD, with AS recognized as an important subgroup.[1] However, questions remain concerning many aspects of AS; whether it should be a separate condition from high-functioning autism is a fundamental issue requiring further study.[11] The diagnostic validity of Asperger syndrome is tentative, there is little consensus among clinical researchers about the usage of the term "Asperger's syndrome", and there are questions about the empirical validation of the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria.[17] It is likely that the definition of the condition will change as new studies emerge[17] and it will eventually be understood as a multifactorial heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder involving a catalyst that results in prenatal or perinatal changes in brain structures.[11] There is uncertainty regarding the gender gap between males and females with AS. A person with Asperger's is often remarked as possessing masculine traits like emotional distance from the inability to empathize, and far more boys than girls are diagnosed with Asperger's.[29][unreliable medical source?] Most studies on the syndrome were derived from research on males, neglecting specific attention to females with AS who often go misdiagnosed. For the most part, studies on girls with Asperger's are anecdotal.[29] |

現代 ASが英語圏の人々に広く紹介されてから20年足らずで、ASを説明する書籍や論文、ウェブサイトが何百と存在する。ASDの有病率推定値は劇的に増加 し、ASは重要なサブグループとして認識されている。しかし、ASの多くの側面に関して疑問が残り、高機能自閉症とは別の疾患とするべきかどうかは、さら なる研究を要する根本問題である[1][11]。 [11]アスペルガー症候群の診断的妥当性は暫定的であり、「アスペルガー症候群」という用語の使用について臨床研究者の間でほとんど合意が得られておら ず、DSM-IVやICD-10の基準の経験的妥当性についても疑問がある[17]。新しい研究の出現により状態の定義が変化し、最終的には脳構造の出生 前または周産期の変化をもたらす触媒を含む多因子異質の神経発達障害として理解されると思われる[11]。 ASの男性と女性の間の性差については不明確である。アスペルガー症候群に関する研究の多くは男性を対象としたものであり、誤診されがちな女性のASに対 する特別な配慮はなされていない。ほとんどの場合、アスペルガーの女の子に関する研究は逸話的である[29]。 |

| Changes in DSM-5 In 1994, Asperger's Syndrome was added to the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). The DSM-V made a new, broad diagnosis in 2013 of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This category contains the previous individual diagnoses of Autistic Disorder, Asperger's Syndrome, and other related developmental disorders. ASD is rated on levels of severity on a scale ranging from severe, through moderate, to mild based on clinical presentation.[30] The levels are determined by the amount of support the individual requires. |

DSM-5の変更点 1994年、アメリカ精神医学会の「精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル(DSM-Ⅳ)」にアスペルガー症候群が追加された。DSM-Vでは、2013年に自 閉症スペクトラム障害(ASD)という新たな広義の診断がされた。このカテゴリーには、それまでの個別診断である「自閉性障害」「アスペルガー症候群」、 およびその他の関連する発達障害が含まれる。ASDは、臨床症状に基づいて、重度から中等度、軽度までの尺度で重症度が評価される[30]。 そのレベルは、個人が必要とするサポートの量によって決定される。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Asperger_syndrome |

|

| Am Spiegelgrund clinic Am Spiegelgrund was a children's clinic in Vienna during World War II, where 789 patients were murdered under child euthanasia in Nazi Germany. Between 1940 and 1945, the clinic operated as part of the psychiatric hospital Am Steinhof later known as the Otto Wagner Clinic within the Baumgartner Medical Center located in Penzing, the 14th district of Vienna. Am Spiegelgrund was divided into a reform school and a children's ward, where sick and disabled adolescents were unwitting subjects of medical experiments and victims of nutritional and psychological abuse. Some died by lethal injection and gas poisoning; others by disease, starvation, exposure to the elements, and "accidents" relating to their conditions. The brains of up to 800 victims were preserved in jars and housed in the hospital for decades.[1] The clinic has gained contemporary notoriety, due to publications concerning Hans Asperger and his association with the patient selection process in the Children's Ward.[2][3][4] |

シュピーゲルグルント アム・シュピーゲルグルントは、第二次世界大戦中のウィーンにあった小児科医院で、ナチスドイツの児童安楽死のもと、789名の患者が殺害された。 1940年から1945年にかけて、ウィーン14区のペンツィングにあるバウムガルトナー医療センター内の精神病院アム・シュタインホフ(後にオットー・ ワグナー診療所として知られる)の一部として運営されていた。 アム・シュピーゲルグルントは、少年院と小児病棟に分かれており、病気や障害を持つ青少年が知らず知らずのうちに医学実験の対象となり、栄養的・心理的虐 待の犠牲になっていました。ある者は致死注射(バルビツール)やガス中毒で、またある者は病気、飢餓、風雨にさらされ、その状態に関連した「事故」によっ て死亡した。最大800人の犠牲者の脳は瓶に保存され、何十年も病院に保管された[1]。 ハンス・アスペルガーに関する出版物や、彼が小児病棟の患者選別プロセスに関係していたことから、この診療所は現代でも有名である[2][3][4]。 |

| Beginning in the Spring of 1938,

an extensive network of facilities was established for the

documentation, observation, evaluation and selection of children and

adolescents, whose social behavior, disabilities, and/or parentage did

not comply with the Nazi ideology. The recording of these individuals

often began in infancy. Doctors and midwives across the Reich reported

mental and physical abnormalities in newborns and children to health

authorities. In 1941 in Vienna, seventy-two percent of newborns were

documented within their first year of life by the city's more than 100

maternity clinics. Anyone who came into contact with a health

institution was systematically recorded into a "hereditary database"

which included the patient's genetic information. Over 700,000 Viennese

citizens were entered into this database. Genetic information was

compounded with school assessments and with employer information and

criminal records, when applicable.[5] Many within Vienna's healthcare system adhered to Nazi eugenics, and patients of all ages were funneled into specialized facilities, in which many patients were mistreated and killed.[3] Throughout Germany and Austria, euthanasia centers were established, including Hadamar Euthanasia Centre and Hartheim Euthanasia Centre, for people with mental or physical disabilities. Children were not spared. Many children were "mercifully" sent to children's hospitals, and among the most prominent of these was the Kinderspital (Children's Clinic) Am Spiegelgrund in Vienna. Among the patients were those deemed "Life unworthy of life". As part of the Steinhof psychiatric complex the Spiegelgrund clinic housed state sponsored pediatric euthanasia.[6] Around 789 children died in the Spiegelgrund clinic while the Steinhof complex was responsible for the death of around 7,500 patients by the end of World War II.[7] The clinic operated under the direction of the Fürher's Chancellery and Ministry of the Interior where physicians conducted "all manner" of procedures on the vulnerable and disabled children which were often fatal.[3] The Am Steinhof psychiatric hospital was established in the early 1900s, but from July 1940 to April 1945 it housed the Spiegelgrund Clinic. On 16 March 1945, the Soviet 2nd and Ukrainian 3rd fronts launched the Vienna offensive in an effort to take the city from Nazi forces.[8] After a month of fighting the red army defeated the axis powers and captured Vienna. The liberation of Vienna by soviet forces in the spring of 1945 resulted in the end of the Spiegelgrund clinic.[9] |

1938年の春から、ナチスのイデオロギーに従わない社会的行動、障

害、親を持つ子供や青少年の記録、観察、評価、選別のための大規模な施設網が構築されました。これらの人々の記録は、しばしば幼児期から始まりました。帝

国中の医師と助産師は、新生児と子供の精神的、身体的異常を保健当局に報告した。1941年のウィーンでは、新生児の72%が生後1年以内に、市内に

100以上ある産科診療所によって記録された。医療機関と接触した人は誰でも、患者の遺伝子情報を含む「遺伝データベース」に体系的に記録された。この

データベースには、70万人以上のウィーン市民が登録された。遺伝情報は、学校での評価や、該当する場合は雇用者の情報、犯罪記録と複合された[5]。 ウィーンの医療制度の多くがナチスの優生学に賛同し、あらゆる年齢の患者が専門施設に集められ、そこで多くの患者が虐待され殺された[3]。ドイツとオー ストリア全土で、精神または身体に障害を持つ人々のために、ハダムール安楽死センター、ハルトハイム安楽死センターなどの安楽死施設が設立された。子供た ちもまた、安楽死を免れることはなかった。多くの子供たちが「慈悲深く」子供病院に送られ、中でもウィーンのKinderspital (Children's Clinic) Am Spiegelgrundは有名であった。その中には、「生きるに値しない」と判断された患者も含まれていた。シュタインホーフ精神医学複合施設の一部と して、シュピーゲルグルントの診療所は国家が支援する小児安楽死を収容していました[6]。シュピーゲルグルントの診療所でおよそ789人の子供が死亡 し、シュタインホーフ複合施設は第二次世界大戦の終わりまでにおよそ7500人の患者の死に対して責任がありました[7]。 [シュタインホフ病院は1900年代初頭に設立されたが、1940年7月から1945年4月まではシュピーゲルグルント診療所を収容していた。1945年 3月16日、ソビエト第2戦線とウクライナ第3戦線は、ナチス軍からウィーンを奪うためにウィーン攻勢を開始した[8]。1ヶ月の戦闘の後、赤軍は枢軸国 を破り、ウィーンを占領した。1945年春、ソ連軍によるウィーンの解放により、シュピーゲルグルント診療所は終了した[9]。 |

| Aktion T4 and the children's ward The establishment of a children's ward at the Am Steinhof facility was not possible until the implementation of Aktion T4, a product of the Euthanasia Letter[10] signed by Adolf Hitler. This called for the relocation of approximately 3,200 patients, or about two thirds of the patient population at the time, in July 1940. The order subsequently emptied many of the "pavilions", or buildings, within the grounds. The patients were taken, sometimes after a brief transfer to the institutions of Niedernhart bei Linz or Ybbs an der Donau, to the Hartheim Euthanasia Centre, near Linz. It is likely that Am Steinhof served as a transfer point for patients of other institutions, as well.[11] The gassing of patients at Hartheim began in May 1940; by the end of the summer of 1940, the 3,200 patients from Am Steinhof were systematically brought to the centre.[12] Both the patient selection process and the implementation of the action were carried out by the Commission of Berlin, assembled by Werner Heyde. The institutions themselves were informed only that large-scale transfers were necessary "for the defense of the Reich". On 24 July, just weeks after the transfers began, the children's clinic, Am Spiegelgrund, opened its doors with room for six hundred and forty patients in nine buildings on the grounds.[13] The curative education or special needs department of the Central Children's Home was relocated to Spiegelgrund, along with the department's so-called School Children Observation Centre. This is where children were evaluated to determine their educability. Educability became a part of the patient selection process. Some of the children arrived perfectly healthy, in both mind and body, but were brought to the center due to delinquent behavior, poor upbringing, or unsuitable parentage. They were considered delinquents if they had run away from home or resorted to petty crimes; they were considered inferior if they were born out of wedlock or came from impoverished homes; they were considered "defective" if their parents were alcoholics or criminals.[14] These educable children were not exempt from experimentation and punishment at the hands of their caretakers, since they were often seen as a burden on society. In this way, "the child euthanasia program came to medicalize social belonging, incorporating social concerns as eugenicist criteria."[3] Known officially as the Infant Centre, Building 15 was designated as a Children's Ward, the second of its kind in the Reich after Brandenburg an der Havel. The ward would report any supposed genetic or contagious diseases to the central healthcare office in Vienna, which would determine if "treatment" were necessary.[15] Patient records were evaluated by professionals to determine whether a patient should be euthanized, allowed to live, or observed pending a final decision. One preserved example of the evaluation records belonged to an adult patient, "Klara B.", institutionalized at Steinhof, who was among the 3,200 patients evicted in the summer of 1940. Highlighted in red pen are the terms Jew (German: Jüdin) and her diagnosis of schizophrenia. The red "+"s on the bottom left of her form mark her for euthanasia. She was transferred from the Vienna facility to Hartheim, where she was gassed on 8 August 1940, at the age of 31.[16] She and other institutionalized Jews faced unfavorable odds. Of the approximately 3,200 patients, around 400, or 12.5%, were Jewish, when the Jewish community constituted just 2.8% of Austria's national population in 1933.[17] Those who remained behind or who were later brought to Am Steinhof were in no less danger than those who were removed. The death rates among patients at Am Steinhof increased annually between 1936 and 1945, from 6.54% to 42.76%, respectively. As the death rate climbed, the patient population naturally decreased. In 1936, there were 516 reported deaths; in 1945, there were approximately 2300.[18] Despite the regime's attempts to keep Aktion T4 a secret, the public was in some measure aware of increasing death rates among the institutionalized patients. In July 1940, Anna Wödl, a nurse and the mother of a disabled child, led a protest movement against the evacuation and killing of institutionalized children. Family members and supporters sent many letters to high-ranking officials in Berlin. They also protested outside institutions, but police and the SS soon put an end to the demonstrations.[12] The Austrian Communist Party, the Catholic and Protestant Churches and others formally condemned the killings, and on 24 August 1941, Hitler was pressured to abolish Aktion T4. The abolition, however, did not stop the killings. Other child euthanasia programs, particularly Action 14f13, quickly and quietly took its place. Anna Wödl's protests proved to be in vain; while her son, Alfred Wödl, was spared a transfer to Hartheim, he died of "pneumonia" in the Children's Ward at Am Spiegelgrund on 22 February 1941. His brain was kept for research and housed in the hospital until 2001, when his remains were finally laid to rest.[19] |

アクシオンT4と小児病棟 アム・シュタインホーフの施設に小児病棟を設置することができたのは、アドルフ・ヒトラーが署名した「安楽死の手紙」[10]の成果である「アクシオン T4」が実施されてからのことであった。これは、1940年7月に当時の患者数の約3分の2に当たる約3,200人の患者の移転を求めたものである。この 命令により、敷地内の多くの「パビリオン」(建物)が空にされた。患者は、ニーデルンハート・ベイ・リンツやイブス・アン・デア・ドナウの施設に一時的に 移された後、リンツ近郊のハートハイム安楽死センターへと運ばれた。アム・シュタインホーフは他の施設の患者の移送先としても機能していたと思われる [11]。ハルトハイムでの患者のガス処刑は1940年5月に始まり、1940年の夏の終わりまでにアム・シュタインホーフからの3200人の患者が組織 的にセンターに運び込まれた[12]。 患者の選別過程も行動の実行も、ヴェルナー・ハイデが集めたベルリンの委員会によって行われた。施設自体には、大規模な移送が「帝国の防衛のために」必要 であるとしか知らされていなかった。 移送が始まって数週間後の7月24日、敷地内の9つの建物に640人の患者を収容できる小児科医院アム・シュピーゲルグルントが開院した[13]。 中央児童院の治療教育または特別支援部門は、部門のいわゆる学童観察センターとともにシュピーゲルグルントに移設された。ここでは、子どもたちの教育的可 能性を判断するための評価が行われた。 そして、この教育的配慮が患者選別に反映されるようになった。中には、心身ともに健康でありながら、非行に走ったり、育ちが悪かったり、親に恵まれなかっ たりして、このセンターに運ばれてきた子供たちもいた。家出や軽犯罪を犯した者は非行少年、婚外子や貧困家庭の者は劣等生、両親がアルコール依存症や犯罪 者である者は不良品とみなされた[14]。こうした教育熱心な子供たちは、社会の負担とみなされることが多かったため、世話役の実験や処罰を免れることは なかった。このようにして、「児童安楽死プログラムは社会的帰属を医療化するようになり、社会的関心を優生学的基準として取り込むようになった」[3]。 正式には幼児センターとして知られていた15号館は、ブランデンブルク・アン・デア・ハーフェルに次いで帝国内で2番目の小児病棟として指定された。この 病棟は、遺伝性疾患や伝染性疾患と思われるものをウィーンの中央医療局に報告し、「治療」が必要かどうかを判断するものであった[15]。 患者の記録は、専門家によって評価され、安楽死させるべきか、生かすべきか、最終決定を待つために観察すべきか、判断されました。シュタインホフに収容さ れていた成人患者「クララB」の記録は、1940年夏に退去させられた3,200人の患者のうちの1人である。赤ペンで強調されているのは、ユダヤ人(ド イツ語ではJüdin)という言葉と、彼女の精神分裂病の診断である。用紙の左下にある赤い「+」印は、安楽死対象者であることを示している。彼女は ウィーンの施設からハルトハイムに移送され、1940年8月8日に31歳の若さでガス処刑された[16]。約3,200人の患者のうち、12.5%に当た る約400人がユダヤ人であったが、1933年当時、ユダヤ人社会はオーストリアの全国人口のわずか2.8%を占めていたのである[17]。 アム・シュタインホフに残った者、あるいは後に連れてこられた者も、連れ去られた者に劣らず危険にさらされていた。アム・シュタインホフの患者の死亡率 は、1936年から1945年の間に、それぞれ6.54%から42.76%まで毎年上昇していた。死亡率が上昇するにつれて、患者の数は自然に減少して いった。1936年には516人の死亡が報告されたが、1945年には約2300人であった[18]。 政権がAktion T4を秘密にしようとしていたにもかかわらず、国民は施設に収容された患者の死亡率が増加していることをある程度知っていた。1940年7月、看護師で障 害児の母親でもあったアンナ・ヴェードルは、施設に収容された子供たちの疎開と殺害に反対する抗議運動を率いた。家族や支援者たちは、ベルリンの高官たち に多くの手紙を送った。オーストリア共産党、カトリック教会、プロテスタント教会などが公式に非難し、1941年8月24日、ヒトラーにT4作戦の廃止を 迫った[12]。しかし、この廃止は殺戮を止めることはできなかった。他の児童安楽死プログラム、特に行動14f13がすぐに静かにその座に就いたのであ る。アンナ・ヴェドルの抗議もむなしく、彼女の息子アルフレッド・ヴェドルはハルトハイムへの移送を免れたものの、1941年2月22日にアム・シュピー ゲルグルントの小児病棟で「肺炎」のため死亡してしまったのです。彼の脳は研究のために保管され、2001年まで病院に収容されていたが、彼の遺体はつい に安置されることになった[19]。 |

| Experimentation and child

euthanasia Deputy-führer of the Third Reich, Rudolf Hess, once said that "National Socialism is nothing but applied biology." This idea provides context to Hitler's Darwinian ideas of how to promote the spread of what he believed to be the superior race. Inspired by Darwin's discovery of evolution by natural selection, Nazis coined several terms for those they deemed unfit. For example, the terms Lebensunwertes Leben, which translates to "life unworthy of life"; unnütze Esser, meaning "useless eater"; and Ballastexistenzen, which means "ballast lives", to name a few. To strengthen the Nazi regime and Germany as a whole, utilizing euthanasia to select against individuals who would not produce strong and productive offspring was seen as a merciful gesture.[20] The children who were sent to euthanasia centers such as Am Spiegelgrund were selected on the basis of medical questionnaires. Physicians were bribed to report children with conditions such as intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, any deformities, bed wetting, learning disabilities, along with many other things that would lower their ability to strengthen Hitler's superior race.[21] If a child had any sort of mental or physical condition, their questionnaire would be sent to Hitler's Chancellery, who would recommend "special treatment" despite having never met the children. The victims of Am Spiegelgrund were subjected to torture-like experimental treatments as well as punishments for a variety of offenses. Survivors Johann Gross, Alois Kaufmann, and Friedrich Zawrel described and testified to several of the "treatments", which included electroshock therapy,[22] a so-called "cold water cure" in which Zawrel and Kaufmann recall being repeatedly submerged into freezing bath water until they were blue and barely conscious and had lost control of their bowels;[23][24] a "sulfur cure", which was an injection that caused severe pain in the legs, limiting mobility and ensuring that escape was impossible;[24] spinal injections of apomorphine; injections of phenobarbital; overdoses of sedatives, which would often lead to death when the children were exposed to extreme cold or disease; observed starvation;[25] and efficacy testing of tuberculosis vaccines, for which children were infected with tuberculosis pathogens. Many patients who had been deemed seriously disabled died under mysterious circumstances. Upon inquiry, the hospital staff would blame pneumonia or a fatal muscle conniption caused by the mental state of the patient. In reality, the children were being killed via lethal injection, neglect and disease.[26] Alois Kaufmann, a victim of Am Spiegelgrund, compared the Nazi's approach to child euthanasia to a predator-prey relationship. According to Kaufmann, every two to three weeks, the weakest children would be plucked from the group, never to be seen again. The children that were picked first were "the bedwetters or harelips or slow thinkers".[20] The children who were killed at Am Spiegelgrund often died by overdose of depressants such as morphine, scopolamine, and barbiturates, gassing by carbon monoxide, which was a common Nazi tactic, exposure, and starvation. Once the children died, fake death certificates were fabricated, and the victim's families still had to pay a fee for the special treatment they believed their children were receiving during their time at Am Spiegelgrund.[20] After death, the bodies were subjected to medical experiments. Brains and other body parts were removed, placed in formaldehyde jars or sealed in paraffin wax, to be stored secretly in the basement for "research". In 2002, the last two victims out of the 800 children murdered at the Am Spiegelgrud Clinic were laid to rest. The remains of Anne Marie Tanner, who was four at her time of death, and Gerhard Zehetner, who was 18 months at the time of his death, were buried in the section of the cemetery dedicated to victims of National Socialism.[27] Tanner and Zehtner were murdered as they were seen to be "unfit" by the Nazis. Dr. Heinrich Gross, 19015-2005, was the head of the psychiatric clinic during the war and he was thought to have had a hand in the deaths of Tanner and Zehtner. Allegedly, he injected children with hare lips, stutters, and learning disabilities with drugs that caused lung infections. He then left these "unworthy" children outside to die. Although he admits to knowing about the killings, he denies any personal involvement. It was Dr. Werner Vogt, a physician, that accused Dr. Gross of gross malpractice at the Am Spiegelgrund clinic in 1979.[28] |

実験と子どもの安楽死 第三帝国副総統ルドルフ・ヘスは、かつて「国家社会主義は応用生物学にほかならない」と言ったことがある。この考えは、ヒトラーが優れた人種と信じるもの の普及を促進する方法について、ダーウィン的な考えを持っていたことを背景にしている。ダーウィンの発見した自然淘汰による進化に触発されて、ナチスは自 分たちが不適当と考える人々を表すいくつかの言葉を作り出した。例えば、「生きるに値しない人生」と訳されるLebensunwertes Leben、「役に立たない食べもの」を意味するunnütze Esser、「バラストの命」を意味するBallastexistenzenなどの用語がある。ナチス政権とドイツ全体を強化するために、安楽死を利用し て、強く生産的な子孫を残さない個人を選別することは、慈悲深い行為と見なされていた[20]。 アム・シュピーゲルグルントのような安楽死施設に送られた子どもたちは、医学的な質問票に基づいて選別された。医師は、知的障害、脳性麻痺、ダウン症、奇 形、おねしょ、学習障害など、ヒトラーの優秀な人種を強化する能力を低下させるような症状を持つ子供を報告するよう賄賂を受け取った[21]。子供に何ら かの精神や身体の症状があると、そのアンケートはヒトラー総統府に送られ、ヒトラーは子供に会ったこともないのに「特別扱い」を推奨することになる。ア ム・シュピーゲルグルントの犠牲者は、拷問のような実験的治療と、さまざまな犯罪に対する処罰を受けた。生存者のヨハン・グロス、アロイス・カウフマン、 フリードリヒ・ザウレルは、電気ショック療法[22]、いわゆる「冷水療法」で、ザウレルとカウフマンは、青くなってほとんど意識がなくなり、腸のコント ロールを失うまで繰り返し凍った風呂水に沈められ、そのことを回想して、いくつかの「治療」について説明し証言している[23][24]。 [23][24] 「硫黄治療」と呼ばれる、足に激痛を与え、運動能力を制限し、脱出を不可能にする注射、[24] アポモルフィンの脊髄注射、フェノバルビタールの注射、鎮静剤の過剰投与(極寒や病気にさらされるとしばしば死に至る)、観察飢餓、そして結核ワクチンの 効果テスト(子供たちが結核菌に感染させられる)である。 重度障害者とされた患者の中には、不可解な死を遂げる者も少なくない。病院側は、患者の精神状態が原因で肺炎や筋痙攣を起こしたと説明する。アム・シュ ピーゲルグロントの犠牲者であるアロイス・カウフマンは、ナチスの安楽死への取り組みを捕食者と被食者の関係に例えている[26]。カウフマンによれば、 2週間から3週間ごとに、最も弱い子供たちが集団から引き抜かれ、二度と姿を現すことはなかったという。最初に選ばれた子どもたちは「おねしょをする子、 うさぎ、頭の回転が遅い子」であった[20]。 アム・シュピーゲルグルントで殺された子供たちは、モルヒネ、スコポラミン、バルビツール酸などの鬱剤の過剰摂取、ナチの常套手段である一酸化炭素による ガス処理、被曝、飢餓によって死亡することが多かった。子供たちが死ぬと、偽の死亡証明書が捏造され、犠牲者の家族は、子供たちがアム・シュピーゲルグル ントで過ごしている間、特別な扱いを受けていたと信じて、料金を支払わなければならなかった[20] 死後、遺体は医学実験の対象とされた。脳や体の一部が取り出され、ホルムアルデヒドの瓶に入れられたり、パラフィンワックスに封入され、「研究」のために 地下に密かに保管された。 2002年、アム・シュピーゲルグルント診療所で殺害された800人の子供たちのうち、最後の2人の犠牲者が安らかに眠った。死亡時4歳だったアンネ・マ リー・タナーと死亡時18ヶ月だったゲルハルト・ゼートナーの遺骨は、墓地の国家社会主義の犠牲者に捧げられた区画に埋められた[27]。タナーとゼート ナーはナチスによって「不適格」と見なされ、殺害されたのである。 ハインリッヒ・グロス博士(1915-2005)は、戦時中の精神科診療所の所長であり、タナーとゼートナーの死に関与していたと考えられている。グロス は、兎唇、吃音、学習障害のある子供たちに、肺炎を起こす薬を注射していたと言われている。そして、この「価値のない」子供たちを外に放置して死なせたと いう。彼は、この殺人を知っていたことは認めているが、個人的な関与は否定している。1979年にアム・シュピーゲルグルント診療所での重大な不正行為で グロス博士を告発したのは、医師のヴェルナー・フォクトであった[28]。 |

| Known victims Gehrard Zehetner: A male patient that was admitted to Am Spiegelgrund on 10 October 1942, and subsequently died on 12 December 1943. His brain was found in glass vitrine in the clinic basement; the vitrine was labeled "idiocy".[27] Irma Sperling: A three-year-old female who had learning difficulties and was possibly autistic. She was listed to have a flat head, obvious facial bulges, and a thick jaw. Sperling was declared an idiot by the clinic. Her family received notice of her death in 1945 along with the cost of care receipt.[27] Annemarie Tanner: A female admitted to the clinic in 1943 who was treated by Dr. Gross for rickets. She died 15 months later at the age of four.[27] Said to be poisoned. Dropped off at the Am Spiegelgrund clinic by unwitting parents- unaware they were dropping their daughter off with murderous doctors. Declared a victim of National Socialism.[28] Alois Kauffman: A male survivor of Am Spiegelgrund, currently age 88. He was admitted to Spiegelgrund in 1943 with syphilis, and was treated by Dr. Gross for 22 months.[22] Published a novel titled Hearses- Childhood in Spiegelgrund. Born out of wedlock and given up by his mother at birth. Following the war, Kauffman investigated the crimes committed by the clinic.[29] Rudolf Karger: Admitted to Am Spiegelgrund on 1 September 1941. Survivor. Suffered severe abuse after an escape attempt. Half for several weeks of observation after escape attempt. Remembers that there was not a single day that went by without punishment.[30] Friedrich Zawrel: Sent to Am Spiegelgrund at age 11. Patient of Dr. Gross. Victim of various medical experiments and prolonged solitary confinement. Survivor. Described being tortured and humiliated by Dr. Gross. Received nauseating injections and attempted drownings by orderlies. Explains that he went days without food or water.[31] Labeled a "hereditary defective" on account of alcoholic father.[30] |

既知の犠牲者 ゲアラート・ツェートナー 1942年10月10日にアム・シュピーゲルグルントに入院し、その後1943年12月12日に死亡した男性患者。彼の脳はクリニックの地下のガラス瓶で 発見され、そのガラス瓶は「バカ」とラベル付けされた[27]。 イルマ・スパーリング 3歳の女性で、学習障害があり、自閉症の可能性があった。彼女は平らな頭、明らかな顔の膨らみ、厚い顎を持っていると記載されていた。シュペルリングはク リニックでバカと宣告された。家族は1945年に介護費用領収書とともに彼女の死亡通知を受け取った[27]。 アンネマリー・タナー 1943年に入院した女性で、くる病のためグロス博士の治療を受けた。15ヶ月後、4歳で死亡。無意識のうちに両親によってアム・シュピーゲルグルント診 療所に連れてこられたが、殺人的な医師と娘を引き合わせたとは知らなかった。国家社会主義の犠牲者であると宣言される[28]。 アロイス・カウフマン: アム・シュピーゲルグルントの生存者の男性で、現在88歳。1943年に梅毒でシュピーゲルグルントに収容され、グロス博士のもとで22ヶ月間治療を受け た[22] 「Hearses-Childhood in Spiegelgrund」という小説を出版している。婚外子として生まれ、出生時に母親から見放される。戦後、カウフマンは診療所による犯罪を調査した [29]。 ルドルフ・カーガー 1941年9月1日、アム・シュピーゲルグルントに入所。生存者。脱走未遂の後、ひどい虐待を受けた。脱走未遂の後、数週間の観察のために半身不随にな る。罰を受けない日は一日もなかったと記憶している[30]。 フリードリヒ・ツァウレル 11歳でアム・シュピーゲルグルントに送られる。グロス博士の患者。様々な医学的実験と長期間の独房の犠牲となる。生存者。グロス博士による拷問と屈辱を 受けたと記述。グロス博士による拷問、屈辱、吐き気を催す注射、看護婦による溺死未遂。アルコール依存症の父親を理由に「遺伝的欠陥」のレッテルを貼られ る[30]。 |