Hate crime should be distinguished from hate violence, or hate incidents, which might not necessarily be criminalised[7] Incidents may involve physical assault, homicide, damage to property, bullying, harassment, verbal abuse (which includes slurs) or insults, mate crime, or offensive graffiti or letters (hate mail).[8] Non-criminal actions that are motivated by these reasons are often called "bias incidents".[citation needed]

For example, the criminal law of the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defines a hate crime as a traditional offense like murder, arson, or vandalism with an added element of bias. Hate itself is not a hate crime, but committing a crime motivated by bias against one or more of the social groups listed above, or by bias against their derivatives constitutes a hate crime.[9] A hate crime law is a law intended to deter bias-motivated violence.[10] Hate crime laws are distinct from laws against hate speech: hate crime laws enhance the penalties associated with conduct which is already criminal under other laws, while hate speech laws criminalize a category of speech. Hate speech is a factor for sentencing enhancement in the United States, distinct from laws that criminalize speech.

ヘイトクライムは、必ずしも犯罪化されないヘイト暴力やヘイトインシデントと区別されるべきだ[7]。インシデントには、身体的暴行、殺人、器物損壊、い じめ、嫌がらせ、言葉による虐待(差別的発言を含む)、侮辱、仲間内犯罪、または攻撃的な落書きや手紙(ヘイトメール)が含まれることがある[8]。これ らの動機による非犯罪的行為は、しばしば「バイアスインシデント」と呼ばれる[出典必要]。

例えば、米国の刑法において、連邦捜査局(FBI)はヘイトクライムを、殺人、放火、器物損壊といった伝統的な犯罪に偏見の要素が加わったものと定義して いる。憎悪そのものはヘイトクライムではないが、上記の社会的集団の一つまたは複数に対する偏見、あるいはそれらの派生集団に対する偏見によって動機づけ られた犯罪を犯すことはヘイトクライムを構成する。[9] ヘイトクライム法は、偏見に基づく暴力を抑止することを目的とした法律である。[10] ヘイトクライム法はヘイトスピーチ禁止法とは異なる:ヘイトクライム法は他の法律で既に犯罪とされている行為に対する刑罰を強化する一方、ヘイトスピーチ 法は特定の言説を犯罪化する。米国ではヘイトスピーチは量刑加重の要素であり、言説を犯罪化する法律とは区別される。

The term "hate crime" came into common usage in the United States during the 1980s, but it is often used retrospectively in order to describe events which occurred prior to that era.[11] From the Roman persecution of Christians to the Nazi slaughter of Jews, hate crimes were committed by individuals as well as governments long before the term was commonly used.[6] A major part of defining crimes as hate crimes is determining that they have been committed against members of historically oppressed groups.[12][13]

During the past two centuries, typical examples of hate crimes in the U.S. include the lynching of African Americans, largely in the South, lynchings of Europeans in the East, and lynching of Mexicans and Chinese in the West; cross burnings in order to intimidate black activists or drive black families out of predominantly white neighborhoods both during and after Reconstruction; assaults on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people; the painting of swastikas on Jewish synagogues; and xenophobic responses to a variety of minority ethnic groups.[14]

The verb "to lynch" is attributed to the actions of Charles Lynch, an 18th-century Virginia Quaker. Lynch, other militia officers, and justices of the peace rounded up Tory sympathizers who were given a summary trial at an informal court; sentences which were handed down included whipping, property seizure, coerced pledges of allegiance, and conscription into the military. Originally, the term referred to the extrajudicial organized but unauthorized punishment of criminals. It later evolved to describe executions which were committed outside "ordinary justice". It is highly associated with white suppression of African Americans in the South, and periods of weak or nonexistent police authority, as in certain frontier areas of the Old West.[6]

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the violence against people of Chinese origin significantly increased on the background of accusation of spreading the virus.[15][16][17] In May 2020, the Polish-based "Never Again" Association published its report titled The Virus of Hate: The Brown Book of Epidemic, that documented numerous acts of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as cases of spreading hate speech and conspiracy theories about the epidemic by the Alt-Right.[18] In the U.S., this wave of hate brought back old and harmful stereotypes. The idea of the "Yellow Peril," the belief that Asians are a threat to Western society, reappeared in news stories and social media, reinforcing long-standing fears and suspicions. At the same time, the "Model Minority" myth made it harder for people to see the very real struggles Asian Americans face, painting them as silent and successful, and often excluding them from conversations about racial injustice. As a result, Asian Americans across the country experienced a dramatic rise in hate crimes, from verbal abuse and being spit on to physical attacks in public places. Elderly individuals were especially targeted, with several shocking assaults captured on video. Businesses were vandalized, and many people were harassed simply for wearing a mask or speaking their native language. These were not just random incidents, they were symptoms of deep-rooted racism that was reignited during a time of fear, uncertainty, and misinformation.

「ヘイトクライム」という用語は1980年代にアメリカで一般に広まったが、それ以前の出来事を説明するために遡及的に使われることが多い。[11] ローマによるキリスト教徒迫害からナチスによるユダヤ人虐殺まで、この言葉が一般的になるずっと前から、個人や政府によってヘイトクライムは行われてき た。[6] 犯罪をヘイトクライムと定義する上で重要な要素は、それが歴史的に抑圧されてきた集団の成員に対して行われたものであると認定することだ。[12] [13]

過去2世紀における米国の憎悪犯罪の典型例には、主に南部でのアフリカ系アメリカ人に対するリンチ、東部でのヨーロッパ系住民へのリンチ、西部でのメキシ コ系・中国系住民へのリンチが含まれる。また、再建期前後を通じて、黒人活動家を威嚇したり白人地域から黒人家族を追い出すための十字架焼却、レズビア ン・ゲイ・バイセクシュアル・トランスジェンダーへの暴行、 ユダヤ教のシナゴーグへの卍字の落書き、そして様々な少数民族グループに対する排外的な反応があった。[14]

「リンチする」という動詞は、18世紀のバージニア州クエーカー教徒チャールズ・リンチの行動に由来する。リンチや他の民兵隊幹部、治安判事はトーリー党 支持者を一斉検挙し、非公式の法廷で即決裁判にかけた。言い渡された刑罰には鞭打ち、財産没収、忠誠の誓いの強制、軍隊への徴兵が含まれた。本来この用語 は、司法外で行われる組織的だが非公認の犯罪者処罰を指した。後に「通常の司法」の外で行われる処刑を意味するようになった。この言葉は、南部におけるア フリカ系アメリカ人への白人による抑圧や、旧西部開拓時代の辺境地域など、警察権力が弱いか存在しない時期と強く結びついている。[6]

COVID-19パンデミックにより、ウイルス拡散の非難を背景に、中国系住民に対する暴力事件が著しく増加した。[15][16][17] 2020年5月、ポーランドの「二度と繰り返すな」協会は『憎悪のウイルス:疫病の褐色書』と題する報告書を発表した。これはCOVID-19パンデミッ クを契機に発生した数多くの人種主義、外国人排斥、差別行為、ならびにオルタナ右翼による憎悪表現や疫病に関する陰謀論の拡散事例を記録したものである。 [18] 米国では、この憎悪の波が古く有害な固定観念を蘇らせた。「黄禍論」——アジア人が西洋社会への脅威だという考え——がニュース記事やソーシャルメディア に再登場し、長年根付いた恐怖や疑念を強化した。同時に「模範的少数派」という神話は、アジア系アメリカ人が直面する現実の苦闘を見えにくくした。彼らを 黙って成功する存在として描き、人種的不公正に関する議論から排除しがちだったのだ。結果として全米のアジア系アメリカ人は、公の場での暴言や唾を吐かれ る行為から身体的攻撃に至るまで、ヘイトクライムの急増を経験した。高齢者が特に標的となり、衝撃的な暴行が動画に収められた事例も複数あった。店舗は破 壊され、マスクを着用したり母国語を話したりしただけで嫌がらせを受ける人も多かった。これらは単なる偶発的な事件ではなく、恐怖と不確実性と誤った情報 が蔓延する時期に再燃した、根深い人種主義の症状だった。

Hate crimes can have significant and wide-ranging psychological consequences, not only for their direct victims but for others of the group as well. Moreover, victims of hate crimes often experience a sense of victimization that goes beyond the initial crime, creating a heightened sense of vulnerability towards future victimization.[19] In many ways, hate crime victimization can be a reminder to victims of their marginalized status in society, and for immigrants or refugees, may also serve to make them relive the violence that drove them to seek refuge in another country.[19] A 1999 U.S. study of lesbian and gay victims of violent hate crimes documented that they experienced higher levels of psychological distress, including symptoms of depression and anxiety, than lesbian and gay victims of comparable crimes which were not motivated by antigay bias.[20] A manual issued by the Attorney-General of the province of Ontario in Canada lists the following consequences:[21]

Impact on the individual victim

psychological and affective disturbances; repercussions on the victim's identity and self-esteem; both reinforced by a specific hate crime's degree of violence, which is usually stronger than that of a common crime.

Effect on the targeted group

generalized terror in the group to which the victim belongs, inspiring feelings of vulnerability among its other members, who could be the next hate crime victims.

Effect on other vulnerable groups

ominous effects on minority groups or on groups that identify themselves with the targeted group, especially when the referred hate is based on an ideology or a doctrine that preaches simultaneously against several groups.

Effect on the community as a whole

divisions and factionalism arising in response to hate crimes are particularly damaging to multicultural societies.

Hate crime victims can also develop depression and psychological trauma.[22] They suffer from typical symptoms of trauma: lack of concentration, fear, unintentional rethinking of the incident and feeling vulnerable or unsafe. These symptoms may be severe enough to qualify as PTSD. In the United States, the Supreme Court has accepted the claim that hate crimes cause 'distinct emotional harm' to victims. People who have been victims of hate crimes avoid spaces where they feel unsafe which can make communities less functional when ties with police are strained by persistent group fears and feelings of insecurity.[23] In the United States, hate crime has been shown to reduce educational attainment among affected groups—particularly among black, non-Hispanic victims.[24]

A review of European and American research indicates that terrorist bombings cause Islamophobia and hate crimes to flare up but, in calmer times, they subside again, although to a relatively high level. Terrorists' most persuasive message is that of fear; a primary and strong emotion, fear increases risk estimates and has distortive effects on the perception of ordinary Muslims. Widespread Islamophobic prejudice seems to contribute to anti-Muslim hate crimes, but indirectly; terrorist attacks and intensified Islamophobic prejudice serve as a window of opportunity for extremist groups and networks.[25]

ヘイトクライムは、直接の被害者だけでなく、その集団に属する他の者たちに対しても、重大かつ広範な心理的影響をもたらすことがある。さらに、ヘイトクラ イムの被害者は、最初の犯罪を超えた被害体験をしばしば経験し、将来の被害に対する脆弱性の感覚を強める。[19] 多くの点で、ヘイトクライムの被害体験は、被害者に社会における自らの周縁化された立場を想起させるものであり、移民や難民にとっては、他国に避難を求め た原因となった暴力を再び体験させる役割も果たす可能性がある。[19] 1999年の米国におけるレズビアン・ゲイの暴力的なヘイトクライム被害者を対象とした研究では、反同性愛的偏見を動機としない同種の犯罪の被害者と比 べ、抑うつや不安の症状を含むより高いレベルの心理的苦痛を経験していることが記録されている。[20] カナダ・オンタリオ州司法長官が発行したマニュアルには、以下の影響が列挙されている: [21]

被害者個人への影響

心理的・情緒的障害;被害者のアイデンティティと自尊心への悪影響;これらは通常一般犯罪より激しい憎悪犯罪特有の暴力性によって増幅される。

標的集団への影響

被害者が属する集団全体への恐怖感の拡散。他の構成員に脆弱性を感じさせ、彼らが次の憎悪犯罪の被害者となる可能性を暗示する。

その他の脆弱な集団への影響

特に、複数の集団を同時に敵視するイデオロギーや教義に基づく憎悪が背景にある場合、標的集団と同一視される少数派集団や集団に深刻な影響を及ぼす。

地域社会全体への影響

ヘイトクライムへの反応として生じる分断や派閥争いは、多文化社会において特に有害である。

ヘイトクライムの被害者は、うつ病や心的外傷(PTSD)を発症することもある[22]。彼らはトラウマの典型的な症状に苦悩する:集中力の欠如、恐怖、 事件の意図しない反芻、無防備さや不安感。これらの症状はPTSDと診断されるほど深刻な場合がある。米国最高裁は、ヘイトクライムが被害者に「明確な精 神的損害」をもたらすとの主張を認めている。被害者は安全を感じない場所を避け、持続的な集団的恐怖や不安感によって警察との絆が損なわれると、コミュニ ティの機能低下を招く。[23] 米国では、ヘイトクライムが被害を受けた集団、特に非ヒスパニック系黒人の教育達成度を低下させることが示されている。[24]

欧米の研究をレビューすると、テロ爆弾事件はイスラム恐怖症とヘイトクライムを激化させるが、平穏な時期には再び沈静化する(ただし比較的高い水準で)。 テロリストの最も説得力あるメッセージは恐怖である。根源的で強い感情である恐怖はリスク評価を高め、一般のムスリムに対する認識を歪める。広範なイスラ ム恐怖症的偏見は反ムスリム憎悪犯罪に寄与するようだ。ただし間接的にである。テロ攻撃と強まったイスラム恐怖症的偏見は、過激派グループやネットワーク にとって好機となる窓となるのだ。[25]

Sociologists Jack McDevitt and Jack Levin's 2002 study into the motives for hate crimes found four motives, and reported that "thrill-seeking" accounted for 66 percent of all hate crimes overall in the United States:[26][27]

Thrill-seeking – perpetrators engage in hate crimes for excitement and drama. Often, there is no greater purpose behind the crimes, with victims being vulnerable because they have an ethnic, religious, sexual or gender background that differs from their attackers. While the actual animosity present in such a crime can be quite low, thrill-seeking crimes were determined to often be dangerous, with 70 percent of thrill-seeking hate crimes studied involving physical attacks. Typically, these attacks are perpetrated by groups of young teenagers or adults seeking excitement.[28]

Defensive – perpetrators engage in hate crimes out of a belief they are protecting their communities. Often, these are triggered by a certain background event. Perpetrators believe society supports their actions but is too afraid to act and thus they believe they have communal assent in their actions.

Retaliatory – perpetrators engage in hate crimes out of a desire for revenge. This can be in response to perceived personal slights, other hate crimes or terrorism. The "avengers" target members of a group whom they believe committed the original crime, even if the victims had nothing to do with it. These kinds of hate crimes are a common occurrence after terrorist attacks.

Mission offenders – perpetrators engage in hate crimes out of ideological reasons. They consider themselves to be crusaders, often for a religious or racial cause. They may write complex explanations for their views and target symbolically important sites, trying to maximize damage. They believe that there is no other way to accomplish their goals, which they consider to be justification for excessive violence against innocents. This kind of hate crime often overlaps with terrorism, and is considered by the FBI to be both the rarest and deadliest form of hate crime.

In a later article, Levin and fellow sociologist Ashley Reichelmann found that following the September 11 attacks, thrill motivated hate crimes tended to decrease as the overall rate of violent crime decreased while defensive hate crimes increased substantially. Specifically, they found that 60% of all hate motivated assaults in 2001 were perpetrated against those the offenders perceived to be Middle Eastern and were motivated mainly by a desire for revenge.[29] Levin and McDevitt also argued that while thrill crimes made up the majority of hate crimes in the 1990s, after September 11, 2001, hate crimes in the United States shifted from thrill offenses by young groups to more defensive oriented and more often perpetrated by older individuals respond to a precipitating event.[28]

The motivations of hate-crime offenders are complex. Therefore, there is no one theory that can completely account for hate-motived crimes.[30] However, Mark Austin Walters previously attempted to synthesize three interdisciplinary theories to account for the behavior of hate-crime offenders:

1. Strain Theory: suggests that hate crimes are motivated by perceived economic and material inequality, which results in differential attitudes towards outsiders who may be viewed as "straining" already scarce resources. An example of this can be seen in the discourse surrounding some people's apprehension towards immigrants, who feel as though immigrants and/or refugees receive extra benefits from government and strain social systems.

2. Doing Difference Theory: suggests that some individuals fear groups other than their own and, as a result of this, seek to suppress different cultures.

3. Self-Control Theory: suggests that a person's upbringing determines their tolerance threshold towards others, here individuals with low self-esteem are often impulsive, have poor employment prospects, and have little academic success.

Walters argues that a synthesis of these theories provides a more well-rounded scope of the motivations behind hate crimes, where he explains that social, cultural, and individual factors interact to elicit the violence behavior of individuals with low self-control.[30]

Additionally, psychological perspectives within the realm of behaviorism have also contributed to theoretical explanations for the motivations of hate crimes particularly as it relates to conditioning and social learning. For instance, the seminal work of John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner illustrated that hate, a form of prejudice, was a conditioned emotional response.[31] Later on, the work of Arthur Staats and Carolyn Staats illustrated that both hate and fear were learned behavioral responses.[32] In their experiment, Staats and Staats paired positive and negative works with several different nationalities. The pairing of verbal stimuli was a form of conditioning, and it was found to influence attitude formation and attitude change.

These studies are of interest when considering modern forms of prejudice directed towards ethnic, religious, or racial groups.[32] For instance, there was a significant increase in Islamophobia and hate crimes following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States. Simultaneously, the news media was consistently pairing Islam with terrorism. Thus, the pairing of verbal stimuli in the media contributed to widespread prejudice towards all Arab individuals in a process that is known as semantic generalization, which refers to how a learned behavior can generalize across situations based on meaning or other abstract representations.[33] These occurrences continue today with the social and political discourse that contribute to the context in which people learn, come to form beliefs, and engage in behavioral actions. Although not all individuals with prejudicial attitudes go on to engage in hate-motived crime, it has been suggested that hate-crime offenders come to learn their prejudices through social interaction, consumption of biased news media, political hate speech, and internal misrepresentations of cultures other than their own.[34]

Risk management for hate-crime offenders

Compared to other types of offending, there has been relatively little research directed towards the management of hate-crime offenders.[35] However, risk management for hate-crime offenders is an important consideration for forensic psychology and public safety in order to decrease the potential for future harm. Forensic risk assessments are designed to evaluate the likelihood of re-offending and to aid in risk management strategies. While not specifically designed for hate crime offenders, some of the most common risk assessment tools used to assess risk for hate-crime offenders include the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG;[36]), the Historical Clinical Risk Management 20 (HCR-20;[37]) and the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R;[38]). Research has shown that assessing and addressing risk posed by hate-crime offenders is especially complex, and while existing tools are useful, it is important to incorporate bias-oriented factors (Dunbar et al., 2005). That is, hate-crime offenders do tend to score high risk on tools including both static and dynamic factors, but severity has been found to not be solely related to these factors, illustrating a need to incorporate biases and ideological factors.[39]

社会学者ジャック・マクデヴィットとジャック・レビンによる2002年の憎悪犯罪の動機に関する研究では、四つの動機が確認された。米国全体では憎悪犯罪の66%が「スリル追求」によるものだと報告されている:[26][27]

スリル追求 – 加害者は興奮や劇的な体験を求めて憎悪犯罪に手を染める。多くの場合、犯罪の背後にはより大きな目的はなく、被害者は加害者と異なる民族的・宗教的・性 的・ジェンダー背景を持つため脆弱な立場にある。実際の敵意は極めて低い場合もあるが、スリル追求型犯罪は危険性が高いと判明しており、調査対象の70% が身体的攻撃を伴っていた。典型的には、興奮を求める10代の若者や成人の集団によって実行される。[28]

防衛的 – 加害者は自らのコミュニティを守っているという信念からヘイトクライムに及ぶ。多くの場合、特定の背景となる出来事が引き金となる。加害者は社会が自らの 行動を支持しているものの、行動を起こすには恐れすぎていると信じ、したがって自らの行動には共同体の同意があると考える。

報復的 – 加害者は復讐欲求からヘイトクライムを実行する。これは個人的な侮辱、他のヘイトクライムやテロへの反応として現れる。「復讐者」は、たとえ被害者が無関 係であっても、元々の犯罪を犯したと信じる集団のメンバーを標的にする。この種のヘイトクライムはテロ攻撃後に頻繁に発生する。

使命型加害者 – 加害者はイデオロギー的理由からヘイトクライムを実行する。彼らは自らを宗教的・人種的信条のための十字軍と位置付け、複雑な思想的根拠を主張し、象徴的 に重要な場所を標的として被害を最大化しようとする。無実の人々への過剰な暴力も、自らの目的達成には必要不可欠な手段だと正当化している。この種の憎悪 犯罪はテロリズムと重なり、FBIによって最も稀でありながら最も致死率の高い形態とされている。

レヴィンと社会学者のアシュリー・ライチェルマンは後年の論文で、9.11同時多発テロ後、スリル目的のヘイトクライムは暴力犯罪全体の減少に伴い減少傾 向を示した一方、防衛的ヘイトクライムは大幅に増加したと指摘している。具体的には、2001年のヘイトクライムによる暴行事件の60%が、加害者が中東 系と認識した対象に対して行われ、その動機は主に復讐心によるものだった。[29] レヴィンとマクデヴィットはまた、1990年代にはスリル犯罪がヘイト犯罪の大半を占めていたが、2001年9月11日以降、米国のヘイト犯罪は若年層に よるスリル犯罪から、より防衛的指向で、より頻繁に高齢者が引き金となる事件に対応して犯行に及ぶ形態へ移行したと論じた。[28]

ヘイト犯罪の加害者の動機は複雑だ。したがって、憎悪動機犯罪を完全に説明できる単一の理論は存在しない。[30] しかしマーク・オースティン・ウォルターズは以前、憎悪犯罪者の行動を説明するため、三つの学際的理論を統合しようとした:

1. 緊張理論:憎悪犯罪は、経済的・物質的不平等を認識した結果生じる動機によるものであり、既に乏しい資源を「圧迫」していると見なされる外部者に対する差 別的態度を引き起こすと提唱する。この例は、移民や難民が政府から特別な恩恵を受け、社会システムに負担をかけていると感じる人々の懸念という言説に表れ ている。

2. 差異化理論:一部の個人が自グループ以外の集団を恐れ、その結果として異なる文化を抑制しようとすることを示唆する。

3. 自制理論:人格の育ち方が他者への許容度を決定するとする。ここでは自尊心の低い人格が衝動的で、就職の見通しが悪く、学業的成功も乏しい傾向にある。

ウォルターズは、これらの理論を統合することでヘイトクライムの動機をより包括的に捉えられると主張する。彼は社会的・文化的・個人的要因が相互作用し、自制心の低い個人の暴力行為を引き起こすと説明している。[30]

さらに、行動主義の領域における心理学的視点も、特に条件付けや社会的学習に関連する憎悪犯罪の動機についての理論的説明に貢献している。例えば、ジョ ン・B・ワトソンとロザリー・レイナーの画期的な研究は、偏見の一形態である憎悪が条件付けられた感情的反応であることを示した。[31] その後、アーサー・スタッツとキャロリン・スタッツの研究は、憎悪と恐怖の両方が学習された行動反応であることを示した。[32] 彼らの実験では、スタッツとスタッツは、いくつかの異なる国民について、肯定的な言葉と否定的な言葉を組み合わせた。この言語刺激の組み合わせは条件付け の一形態であり、態度の形成と変化に影響を与えることがわかった。

これらの研究は、民族、宗教、人種グループに対する現代的な偏見を考える上で興味深いものである。[32] 例えば、アメリカへの9.11同時多発テロ事件後、イスラム恐怖症やヘイトクライムが著しく増加した。同時に、ニュースメディアは一貫してイスラム教とテ ロリズムを結びつけて報じた。こうしてメディアにおける言語刺激の結びつけは、意味論的一般化と呼ばれるプロセスを通じて、全てのアラブ人に対する広範な 偏見を助長した。これは、学習された行動が意味や他の抽象的表象に基づいて状況を超えて一般化される過程を指す。[33] このような現象は現在も続いており、人々が学習し、信念を形成し、行動を起こす文脈を形成する社会的・政治的言説に寄与している。偏見を持つ全ての個人が 憎悪動機犯罪に及ぶわけではないが、憎悪犯罪の加害者は社会的相互作用、偏ったニュースメディアの消費、政治的憎悪表現、そして自文化以外の文化に対する 内面的な誤った認識を通じて偏見を学習すると指摘されている。[34]

憎悪犯罪加害者のリスク管理

他の犯罪類型と比較すると、憎悪犯罪加害者の管理に関する研究は比較的少ない。[35] しかし、将来の危害発生の可能性を低減するためには、憎悪犯罪加害者のリスク管理は法心理学と公共安全にとって重要な考慮事項である。法医学的リスク評価 は再犯の可能性を評価し、リスク管理戦略を支援するために設計されている。ヘイトクライム犯罪者向けに特別に設計されたものではないが、ヘイトクライム犯 罪者のリスク評価に用いられる最も一般的なリスク評価ツールには、暴力リスク評価ガイド(VRAG;[36])、ヒストリカル・クリニカル・リスクマネジ メント20(HCR-20;[37])、サイコパシーチェックリスト改訂版(PCL-R;[38])などがある。研究によれば、ヘイトクライム犯罪者がも たらすリスクの評価と対応は特に複雑であり、既存のツールは有用であるものの、偏見指向的要因を取り入れることが重要である(Dunbar et al., 2005)。つまり、ヘイトクライム犯罪者は静的要因と動的要因の両方を含むツールで高リスクを示す傾向があるが、その深刻度はこれらの要因のみに関連し ているわけではないことが判明しており、偏見やイデオロギー的要因を取り入れる必要性を示している。[39]

The Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)[40], the world's largest regional security organisations with 57 members states from Europe, Central Asia and America, passed Ministerial Council Decision No. 9/09 on combating hate crimes[41], to monitor, prevent and control hate crime[42]. As a result, OSCE publishes regular reports capturing the levels of hate crimes recorded and prosecuted in its 57 member states.

Moreover, OSCE's Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) has a mandate to protect victims of hate crime through policy action, advice and support to victim organisations, NGOs and practitioners located in their members[43]. They have produced a series of training programmes, practical guides and policy advice for practitioners supporting hate crime victims both within and outside of the criminal justice system[44]. Recently, OSCE and its ODIHR department acknowledged the complexity that hate crime presents both in relation to its prevention and control, and that hate violence extends beyond what the law understand reaching into the fabric of its members' societies[45]. As a result, they launched a series of victim focused projects, such as EStAR: Enhancing hate crime victim support project, exploring non-punitive approaches to hate violence including community based interventions[46]. In 2025, they took a step further by looking at the potential of restorative justice for preventing and controlling hate violence. ODIHR worked with restorative justice leader, Professor Theo Gavrielides, to publish "Implementing Restorative Justice for Hate Incidents and Hate Crimes - a Practical Guide"[47]. In writing the Guide, Gavrielides carried out fieldwork across the OSCE member states which showed that restorative justice is being used in schools, youth and criminal justice settings across the OSCE member states[48]. However, there is lack of consistency in implementation as well as low awareness among victims and offenders[49]. Gavrielides' OSCE Guide was supported by the Working Group on hate crime victim support, which is part of the European Union High Level Group on combating hate speech and hate crime[50]. The EU High Level Group was set up to support EU Member States to protect and support victims of hate crime through law development and practical support including the better implementation of restorative justice.

欧州安全保障協力機構(OSCE)[40]は、欧州、中央アジア、アメリカから57の加盟国を有する世界最大の地域安全保障機構である。同機構は憎悪犯罪 対策に関する閣僚理事会決定第9/09号[41]を採択し、憎悪犯罪[42]の監視、予防、管理を行っている。その結果、OSCEは57の加盟国で記録さ れ起訴されたヘイトクライムのレベルをまとめた定期報告書を公表している。

さらにOSCEの民主的機関・人権事務所(ODIHR)は、加盟国内の被害者団体・NGO・実務者に対する政策提言・助言・支援を通じ、ヘイト犯罪被害者 を保護する権限を有する[43]。刑事司法制度内外を問わずヘイト犯罪被害者を支援する実務者向けに、一連の研修プログラム・実践ガイド・政策提言を策定 している[44]。近年、OSCE及びそのODIHR部門は、憎悪犯罪の予防と管理における複雑性、並びに憎悪暴力の法的な枠組みを超え加盟国の社会構造 に浸透する性質を認めた。その結果、被害者中心のプロジェクト群を立ち上げた。例えばEStAR(憎悪犯罪被害者支援強化プロジェクト)では、地域社会 ベースの介入を含む、憎悪暴力に対する非懲罰的アプローチを模索している。2025年には、憎悪暴力の予防・管理における修復的司法の可能性を検討する段 階へ進んだ。ODIHRは修復的司法の権威であるテオ・ガブリエリデス教授と協力し、「憎悪事件・憎悪犯罪への修復的司法導入実践ガイド」を出版した [47]。ガイド作成にあたり、ガブリエリデス教授はOSCE加盟国全域で現地調査を実施。その結果、加盟国各国の学校・青少年・刑事司法の現場で修復的 司法が活用されている実態が明らかになった[48]。ただし、実施方法に一貫性が欠けるほか、被害者と加害者の双方における認知度が低い現状も浮き彫りと なった[49]。ガブリエリデスのOSCEガイドは、欧州連合(EU)のヘイトスピーチ及びヘイトクライム対策ハイレベルグループ[50]の一部であるヘ イトクライム被害者支援作業部会の支援を受けた。EUハイレベルグループは、法整備や実践的支援(修復的司法のより良い実施を含む)を通じて、EU加盟国 がヘイトクライムの被害者を保護・支援することを目的として設置された。

Hate crime laws generally fall into one of several categories:

laws defining specific bias-motivated acts as distinct crimes;

criminal penalty-enhancement laws;

laws creating a distinct civil cause of action for hate crimes; and

laws requiring administrative agencies to collect hate crime statistics.[51] Sometimes (as in Bosnia and Herzegovina), the laws focus on war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity with the prohibition against discriminatory action limited to public officials.[citation needed]

Europe and Asia

Council of Europe

Since 2006, with the Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime, most signatories to that Convention – mostly members of the Council of Europe – committed to punish as a crime racist and xenophobic hate speech done through the internet. [52]

Andorra

Discriminatory acts constituting harassment or infringement of a person's dignity on the basis of origin, citizenship, race, religion, or gender (Penal Code Article 313). Courts have cited bias-based motivation in delivering sentences, but there is no explicit penalty enhancement provision in the Criminal Code. The government does not track hate crime statistics, although they are relatively rare.[51]

Armenia

Armenia has a penalty-enhancement statute for crimes with ethnic, racial, or religious motives (Criminal Code Article 63).[51]

Austria

Austria has a penalty-enhancement statute for reasons like repeating a crime, being especially cruel, using others' helpless states, playing a leading role in a crime, or committing a crime with racist, xenophobic or especially reprehensible motivation (Penal Code section 33(5)).[53] Austria is a party to the Convention on Cybercrime, but not the Additional Protocol.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan has a penalty-enhancement statute for crimes motivated by racial, national, or religious hatred (Criminal Code Article 61). Murder and infliction of serious bodily injury motivated by racial, religious, national, or ethnic intolerance are distinct crimes (Article 111).[51] Azerbaijan is a party to the Convention on Cybercrime, but not the Additional Protocol.

Belarus

Belarus has a penalty-enhancement statute for crimes motivated by racial, national, and religious hatred and discord.[51][54]

Belgium

Belgium's Act of 25 February 2003 ("aimed at combating discrimination and modifying the Act of 15 February 1993 which establishes the Centre for Equal Opportunities and the Fight against Racism") establishes a penalty-enhancement for crimes involving discrimination on the basis of gender, supposed race, color, descent, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, civil status, birth, fortune, age, religious or philosophical beliefs, current or future state of health and handicap or physical features. The Act also "provides for a civil remedy to address discrimination."[51] The Act, along with the Act of 20 January 2003 ("on strengthening legislation against racism"), requires the centre to collect and publish statistical data on racism and discriminatory crimes.[51] Belgium is a party to the Convention on Cybercrime, but not the Additional Protocol.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Criminal Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina (enacted 2003) "contains provisions prohibiting discrimination by public officials on grounds, inter alia, of race, skin colour, national or ethnic background, religion and language and prohibiting the restriction by public officials of the language rights of the citizens in their relations with the authorities (Article 145/1 and 145/2)."[55]

Bulgaria

Bulgarian criminal law prohibits certain crimes motivated by racism, xenophobia and sexual orientation (since 2023), but a 1999 report by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance found that it does not appear that those provisions "have ever resulted in convictions before the courts in Bulgaria."[56]

Croatia

The Croatian Penal Code explicitly defines hate crime in article 89 as "any crime committed out of hatred for someone's race, skin color, sex, sexual orientation, language, religion, political or other belief, national or social background, asset, birth, education, social condition, age, health condition or other attribute".[57] On 1 January 2013, a new Penal Code was introduced with the recognition of a hate crime based on "race, skin color, religion, national or ethnic background, sexual orientation or gender identity".[58]

Czech Republic

The Czech legislation finds its constitutional basis in the principles of equality and non-discrimination contained in the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms. From there, we can trace two basic lines of protection against hate-motivated incidents: one passes through criminal law, the other through civil law. The current Czech criminal legislation has implications both for decisions about guilt (affecting the decision whether to find a defendant guilty or not guilty) and decisions concerning sentencing (affecting the extent of the punishment imposed). It has three levels, to wit:

a circumstance determining whether an act is a crime – hate motivation is included in the basic constituent elements. If hate motivation is not proven, a conviction for a hate crime is not possible.

a circumstance determining the imposition of a higher penalty – hate motivation is included in the qualified constituent elements for some types of crimes (murder, bodily harm). If hate motivation is not proven, the penalty is imposed according to the scale specified for the basic constituent elements of the crime.

general aggravating circumstance – the court is obligated to take the hate motivation into account as a general aggravating circumstance and determines the amount of penalty to impose. Nevertheless, it is not possible to add together a general aggravating circumstance and a circumstance determining the imposition of a higher penalty. (see Annex for details)

Current criminal legislation does not provide for special penalties for acts that target another by reason of his sexual orientation, age or health status. Only the constituent elements of the criminal offence of Incitement to hatred towards a group of persons or to the curtailment of their rights and freedoms and general aggravating circumstances include attacking a so-called different group of people. Such a group of people can then, of course, be also defined by sexual orientation, age or health status. A certain disparity has thus been created between, on the one hand, those groups of people who are victimized by reason of their skin color, faith, nationality, ethnicity or political persuasion and enjoy increased protection, and, on the other hand, those groups that are victimized by reason of their sexual orientation, age or health status and are not granted increased protection. This gap in protection against attacks motivated by the victim's sexual orientation, age or health status cannot be successfully bridged by interpretation. Interpretation by analogy is inadmissible in criminal law, sanctionable motivations being exhaustively enumerated.[59]

Denmark

Although Danish law does not include explicit hate crime provisions, "section 80(1) of the Criminal Code instructs courts to take into account the gravity of the offence and the offender's motive when meting out penalty, and therefore to attach importance to the racist motive of crimes in determining sentence."[60] In recent years judges have used this provision to increase sentences on the basis of racist motives.[51][61]

Since 1992, the Danish Civil Security Service (PET) has released statistics on crimes with apparent racist motivation.[51]

Estonia

Under section 151 of the Criminal Code of Estonia of 6 June 2001, which entered into force on 1 September 2002, with amendments and supplements and as amended by the Law of 8 December 2011, "activities which publicly incite to hatred, violence or discrimination on the basis of nationality, race, colour, sex, language, origin, religion, sexual orientation, political opinion, or financial or social status, if this results in danger to the life, health or property of a person, are punishable by a fine of up to 300 fine units or by detention".[62]

Finland

Finnish Criminal Code 515/2003 (enacted 31 January 2003) makes "committing a crime against a person, because of his national, racial, ethnical or equivalent group" an aggravating circumstance in sentencing.[51][63] In addition, ethnic agitation (Finnish: kiihotus kansanryhmää vastaan) is criminalized and carries a fine or a prison sentence of not more than two years. The prosecution need not prove that an actual danger to an ethnic group is caused but only that malicious message is conveyed. A more aggravated hate crime, warmongering (Finnish: sotaan yllyttäminen), carries a prison sentence of one to ten years. However, in case of warmongering, the prosecution must prove an overt act that evidently increases the risk that Finland is involved in a war or becomes a target for a military operation. The act in question may consist of

illegal violence directed against a foreign country or its citizens,

systematic dissemination of false information on Finnish foreign policy or defense

public influence on the public opinion towards a pro-war viewpoint or

public suggestion that a foreign country or Finland should engage in an aggressive act.[64]

France

In 2003, France enacted penalty-enhancement hate crime laws for crimes motivated by bias against the victim's actual or perceived ethnicity, nation, race, religion, or sexual orientation. The penalties for murder were raised from 30 years (for non-hate crimes) to life imprisonment (for hate crimes), and the penalties for violent attacks leading to permanent disability were raised from 10 years (for non-hate crimes) to 15 years (for hate crimes).[51][65]

Georgia

"There is no general provision in Georgian law for racist motivation to be considered an aggravating circumstance in prosecutions of ordinary offenses. Certain crimes involving racist motivation are, however, defined as specific offenses in the Georgian Criminal Code of 1999, including murder motivated by racial, religious, national or ethnic intolerance (article 109); infliction of serious injuries motivated by racial, religious, national or ethnic intolerance (article 117); and torture motivated by racial, religious, national or ethnic intolerance (article 126). ECRI reported no knowledge of cases in which this law has been enforced. There is no systematic monitoring or data collection on discrimination in Georgia."[51]

Germany

The German Criminal Code does not have hate crime legislation, instead, it criminalizes hate speech under a number of different laws, including Volksverhetzung. In the German legal framework motivation is not taken into account while identifying the element of the offence. However, within the sentencing procedure the judge can define certain principles for determining punishment. In section 46 of the German Criminal Code it is stated that "the motives and aims of the perpetrator; the state of mind reflected in the act and the willfulness involved in its commission"[66] can be taken into consideration when determining the punishment; under this statute, hate and bias have been taken into consideration in sentencing in past cases.[67]

Hate crimes are not specifically tracked by German police, but have been studied separately: a recently published EU "Report on Racism" finds that racially motivated attacks are frequent in Germany, identifying 18,142 incidences for 2006, of which 17,597 were motivated by right-wing ideologies, both about a 14% year-by-year increase.[68] Relative to the size of the population, this represents an eightfold higher rate of hate crimes than reported in the US during the same period.[69] Awareness of hate crimes in Germany remains low.[70]

Greece

Article Law 927/1979 "Section 1,1 penalizes incitement to discrimination, hatred or violence towards individuals or groups because of their racial, national or religious origin, through public written or oral expressions; Section 1,2 prohibits the establishment of, and membership in, organizations which organize propaganda and activities aimed at racial discrimination; Section 2 punishes public expression of offensive ideas; Section 3 penalizes the act of refusing, in the exercise of one's occupation, to sell a commodity or to supply a service on racial grounds."[71] Public prosecutors may press charges even if the victim does not file a complaint. However, as of 2003, no convictions had been attained under the law.[72]

Hungary

Violent action, cruelty, and coercion by threat made on the basis of the victim's actual or perceived national, ethnic, religious status or membership in a particular social group are punishable under article 174/B of the Hungarian Criminal Code.[51] This article was added to the Code in 1996.[73] Hungary is a party to the Convention on Cybercrime, but not the Additional Protocol.

Iceland

Section 233a of the Icelandic Penal Code states "Anyone who in a ridiculing, slanderous, insulting, threatening or any other manner publicly abuses a person or a group of people on the basis of their nationality, skin colour, race, religion or sexual orientation, shall be fined or jailed for up to two years."[74] Iceland is a party to the Convention on Cybercrime, but not the Additional Protocol.

India

India does not have any specific laws governing hate crimes in general other than hate speech which is covered under the Indian Penal Code.

Ireland

In legal effect since December 31, 2024 Ireland implemented broad-based comprehensive legislation on hate crimes.[75]

The Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Act 1989 created the offence of inciting hatred against a group of persons on account of their race, colour, nationality, religion, ethnic or national origins, membership of the Traveller community (an indigenous minority group), or sexual orientation.[51][76] Frustration at the low number of prosecutions (18 by 2011) was attributed to a misconception that the law addressed hate crimes more generally as opposed to incitement in particular.[77]

In 2019, a UN rappourteur told Irish representatives at the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, meeting at UN Geneva, to introduce new hate crime legislation to combat the low prosecution rate for offences under the 1989 act – particularly for online hate speech – and lack of training for the Garda Síochána on racially motivated crimes. The rapporteur's points came during a rise in anti-immigrant rhetoric and racist attacks in Ireland and were based on recommendations submitted by the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission and numerous other civil society organisations. Reforms are supported by the Irish Network Against Racism.[78]

The Criminal Justice (Incitement to Violence or Hatred and Hate Offences) Bill known as the "Hate Crime Bill", prohibiting hate speech or incitement to hate crimes based on protected characteristics, is in its Third Stage at the Seanad, Ireland's upper house, as of June 2023 and the Irish Times reports it is likely to become law in late 2023.[79][80] It has drawn concern from the Irish Council for Civil Liberties and from across the political spectrum (specifically from Michael McDowell, Rónán Mullen, and People Before Profit), as well as internationally, from business magnate Elon Musk and political activist Donald Trump Jr.[80] Paul Murphy of People Before Profit said the bill created a "thought crime" by its criminalisation of possessing material prepared for circulation where circulation would incite hatred.[80] Pauline O'Reilly, a Green Party senator said that the existing legislation was "not effective" and outdated, adding that the Gardaí saw a rise of 30% in hate crime in Ireland."[81]

Data published by the Gardaí showed a 29% increase in hate crimes and hate-related incidents from 448 in 2021 to 582 in 2022.[82] The Gardaí recognise that "despite improvements, hate crime and hate related incidents are still under-reported".[83]

Italy

Italian criminal law, at Section 3 of Law No. 205/1993, the so-called Legge Mancino (Mancino law), contains a penalty-enhancement provision for all crimes motivated by racial, ethnic, national, or religious bias.[51] Italy is a party to the Convention on Cybercrime, but not the Additional Protocol.

Kazakhstan

In Kazakhstan, there are constitutional provisions prohibiting propaganda promoting racial or ethnic superiority.[51]

Kyrgyzstan

In Kyrgyzstan, "the Constitution of the State party prohibits any kind of discrimination on grounds of origin, sex, race, nationality, language, faith, political or religious convictions or any other personal or social trait or circumstance, and that the prohibition against racial discrimination is also included in other legislation, such as the Civil, Penal and Labour Codes."[84]

Article 299 of the Criminal Code defines incitement to national, racist, or religious hatred as a specific offense. This article has been used in political trials of suspected members of the banned organization Hizb-ut-Tahrir.[51][85]

Netherlands

In March, 2025, the Dutch Senate voted in favour of a bill by which penalties for crimes with a discriminatory aim can be aggravated by 1/3. Since the Lower Chamber of Parliament already accepted the bill, this legislation will soon become into effect.

Poland

Article 13 of the Constitution of Poland prohibits organizations "whose programmes or activities sanction racial or national hatred".[86]

Russia

Article 29 of Constitution of the Russian Federation bans incitement to riot for the sake of stirring societal, racial, ethnic, and religious hatred as well as the promotion of the superiority of the same. Article 282 of the Criminal code further includes protections against incitement of hatred (including gender) via various means of communication, instilling criminal penalties including fines and imprisonment.[87] Although a former member of the Council of Europe, Russia is not a party to the Convention on Cybercrime.

Slovenia

In 2023, Slovenia introduced a penalty-enhancement provision in its Penal Code. If the victim's national, racial, religious or ethnic origin, sex, colour, descent, property, education, social status, political or other opinion, disability, sexual orientation or any other personal circumstance was a factor contributing to the commission of the criminal offence, it shall be taken into account when determining the penalty.[88]

Spain

Article 22(4) of the Spanish Penal Code includes a penalty-enhancement provision for crimes motivated by bias against the victim's ideology, beliefs, religion, ethnicity, race, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, illness or disability.[51]

On 14 May 2019, the Spanish Attorney General distributed a circular instructing on the interpretation of hate crime law. This new interpretation includes nazis as a collective that can be protected under this law.[89]

Although a member of the Council of Europe, Spain is not a party to the Convention on Cybercrime.

Sweden

Article 29 of the Swedish Penal Code includes a penalty-enhancement provision for crimes motivated by bias against the victim's race, color, nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, or "other similar circumstance" of the victim.[51][90]

Ukraine

The constitution of Ukraine guarantees protection against hate crime:

Article 10: "In Ukraine, free development, use and protection of Russian and other languages of ethnic minorities of Ukraine are guaranteed".

Article 11: "The State shall promote the development of the ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious identity of all indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities of Ukraine".

Article 24: "There can be no privileges or restrictions on the grounds of race, color of the skin, political, religious or other beliefs, sex, ethnic or social origin, property status, place of residence, language or other grounds".[91]

Under the Criminal Codex, crimes committed because of hatred are hate crimes and carry increased punishment in many articles of the criminal law. There are also separate articles on punishment for a hate crime.

Article 161: "Violations of equality of citizens depending on their race, ethnicity, religious beliefs, disability and other grounds: Intentional acts aimed at incitement to ethnic, racial or religious hatred and violence, to demean the ethnic honor and dignity, or to repulse citizens' feelings due to their religious beliefs, as well as direct or indirect restriction of rights or the establishment of direct or indirect privileges of citizens on the grounds of race, color, political, religious or other beliefs, sex, disability, ethnic or social origin, property status, place of residence, language or other grounds" (maximum criminal sentence of up to 8 years in prison).

Article 300: "Importation, manufacture or distribution of literature and other media promoting a cult of violence and cruelty, racial, ethnic or religious intolerance and discrimination" (maximum criminal sentence of up to 5 years in prison).[92]

United Kingdom

For England and Wales, the Sentencing Act 2020 makes racial or religious hostility, or hostility related to disability, sexual orientation, or transgender identity an aggravation in sentencing for crimes in general.[93]

Separately, the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 defines separate offences, with increased sentences, for racially or religiously aggravated assaults, harassment, and a handful of public order offences.

For Northern Ireland, Public Order 1987 (S.I. 1987/463 (N.I. 7)) serves the same purposes.[94] A "racial group" is a group of persons defined by reference to race, colour, nationality (including citizenship) or ethnic or national origins. A "religious group" is a group of persons defined by reference to religious belief or lack of religious belief.

"Hate crime" legislation is distinct from "hate speech" legislation. See Hate speech laws in the United Kingdom.

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) reported in 2013 that there were an average of 278,000 hate crimes a year with 40 percent being reported according to a victims survey; police records only identified around 43,000 hate crimes a year.[95][needs update] It was reported that police recorded a 57-percent increase in hate crime complaints in the four days following the UK's European Union membership referendum; however, a press release from the National Police Chief's Council stated that "this should not be read as a national increase in hate crime of 57 percent".[96][97]

In 2013, Greater Manchester Police began recording attacks on goths, punks and other alternative culture groups as hate crimes.[98]

On 4 December 2013, Essex Police launched the 'Stop the Hate' initiative as part of a concerted effort to find new ways to tackle hate crime in Essex. The launch was marked by a conference in Chelmsford, hosted by Chief Constable Stephen Kavanagh, which brought together 220 delegates from a range of partner organizations involved in the field. The theme of the conference was 'Report it to Sort it' and the emphasis was on encouraging people to tell police if they have been a victim of hate crime, whether it be based on race, religion, sexual orientation, transgender identity or disability.[99]

Crown Prosecution Service guidance issued on 21 August 2017 stated that online hate crimes should be treated as seriously as offences in person.[100]

Perhaps the most high-profile hate crime in modern Britain occurred in Eltham, London, on 24 April 1993, when 18-year-old black student Stephen Lawrence was stabbed to death in an attack by a gang of white youths. Two white teenagers were later charged with the murder, and at least three other suspects were mentioned in the national media, but the charges against them were dropped within three months after the Crown Prosecution Service concluded that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute. However, a change in the law a decade later allowed a suspect to be charged with a crime twice if new evidence emerged after the original charges were dropped or a "not guilty" verdict was delivered in court. Gary Dobson, who had been charged with the murder in the initial 1993 investigation, was found guilty of Stephen Lawrence's murder in January 2012 and sentenced to life imprisonment, as was David Norris, who had not been charged in 1993. A third suspect, Luke Knight, had been charged in 1993 but was not charged when the case came to court nearly 20 years later.[citation needed]

In September 2020, the Law Commission proposed that sex or gender be added to the list of protected characteristics.[101][102]

The United Kingdom is a party to the Convention on Cybercrime, but not the Additional Protocol.

A 2021 investigation by Newsnight and The Law Society Gazette found that alleged hate crimes in which the victim was a police officer were significantly more likely to result in a successful prosecution. The investigation found that in several areas, crimes against police officers and staff constituted up to half of all hate crimes convictions, despite representing a much smaller proportion of reported incidents.[103]

Scotland

Under Scottish Common law the courts can take any aggravating factor into account when sentencing someone found guilty of an offence.[104][105] There is legislation dealing with the offences of incitement of racial hatred, racially aggravated harassment, and prejudice relating to religious beliefs, disability, sexual orientation, and transgender identity.[106] A Scottish Executive working group examined the issue of hate crime and ways of combating crime motivated by social prejudice, reporting in 2004.[107] Its main recommendations were not implemented, but in their manifestos for the 2007 Scottish Parliament election several political parties included commitments to legislate in this area, including the Scottish National Party, which now forms the Scottish Government. The Offences (Aggravation by Prejudice) (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 19 May 2008 by Patrick Harvie MSP,[108] having been prepared with support from the Scottish Government, and was passed unanimously by the parliament on 3 June 2009.[109]

The Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act 2021 comes into force on 1 April 2024.[110] Its introduction was criticised by the Association of Scottish Police Superintendents saying it feared Police Scotland would be deluged by cases, diverting officers from tackling violent offenders and that the Act threatened to fuel claims of "institutional bias" against the force.[111]

Non-crime hate incidents

In March 2024, Scottish Conservatives MSP Murdo Fraser threatened Police Scotland with legal action following his criticism of the Scottish Government's transgender policy was logged as a "hate incident" after being told that his name appears in police records for expressing his view about the policy even though no crime was committed.[112] Fraser had shared a column written by Susan Dalgety for The Scotsman, which claimed the Scottish Government's 'non-binary equality action plan' would lead to children being "damaged by this cult" and commenting "Choosing to identify as 'non-binary' is as valid as choosing to identify as a cat. I'm not sure governments should be spending time on action plans for either."[113]

Eurasian countries with no hate crime laws

The famous fresco Bathing of the Christ, after being vandalized by a Kosovo Albanian mob during the 2004 unrest in Kosovo

Albania, Cyprus, San Marino and Turkey have no hate crime laws.[51] Nonetheless, all of these except Turkey are parties to the Convention on Cybercrime and the Additional Protocol.

North America

Canada

"In Canada the legal definition of a hate crime can be found in sections 318 and 319 of the Criminal Code".[114]

In 1996, the federal government amended a section of the Criminal Code that pertains to sentencing. Specifically, section 718.2. The section states (with regard to the hate crime):

A court that imposes a sentence shall also take into consideration the following principles:

(a) a sentence should be increased or reduced to account for any relevant aggravating or mitigating circumstances relating to the offence or the offender, and, without limiting the generality of the foregoing,

(i) evidence that the offence was motivated by bias, prejudice or hate based on race, national or ethnic origin, language, colour, religion, sex, age, mental or physical disability, sexual orientation, or any other similar factor, ... shall be deemed to be aggravating circumstances.[114]

A vast majority (84 percent) of hate crime perpetrators were "male, with an average age of just under 30. Less than 10 of those accused had criminal records, and less than 5 percent had previous hate crime involvement".[115] "Only 4 percent of hate crimes were linked to an organized or extremist group".[116]

As of 2004, Jewish people were the largest ethnic group targeted by hate crimes, followed by black people, Muslims, South Asians, and homosexuals (Silver et al., 2004).[116] More recently, hate crimes targeting Jews accounted for 67% of all reported hate crimes targeting religions in 2022.[117]

During the Nazi regime in Germany, antisemitism was a cause of hate-related violence in Canada. For example, on 16 August 1933, there was a baseball game in Toronto and one team was made up mostly of Jewish players. At the end of the game, a group of Nazi sympathizers unfolded a Swastika flag and shouted "Heil Hitler." That event erupted into a brawl that pitted Jews and Italians against Anglo Canadians; the brawl went on for hours.[114]

The first time someone was charged for hate speech over the internet occurred on 27 March 1996. "A Winnipeg teenager was arrested by the police for sending an email to a local political activist that contained the message "Death to homosexuals...it's prescribed in the Bible! Better watch out next Gay Pride Week.'"[116]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada saw a sudden rise in hate crimes based on race, religion, and sexual orientation.[118] Statistics Canada reported there was a 72% increase in hate crimes between 2019 and 2021.[119]

Mexico

Alejandro Gertz Manero, Attorney General of Mexico, recommended in August 2020 that all murders involving women be investigated as femicides. An average of 11 women are killed every day.[120]

Murders of LGBTQ individuals are not legally classified as hate crimes in Mexico, although Luis Guzman of the Cohesión de Diversidades para la Sustentabilidad (Codise) notes that there is a lot of homophobia in Mexico, particularly in the states of Veracruz, Chihuahua, and Michoacán. Between 2014 and May 2020, there have been 209 such murders registered.[121]

United States

Main article: Hate crime laws in the United States

Shepard (center), Louvon Harris (left), Betty Bryd Boatner (right) with President Barack Obama in 2009 to promote the Hate Crimes Prevention Act

Hate crime laws have a long history in the United States. The first hate crime[122] laws were passed after the American Civil War, beginning with the Civil Rights Act of 1871, in order to combat the growing number of racially motivated crimes which were being committed by the Reconstruction era—Ku Klux Klan. Following the Reconstruction era, the Jim Crow era emerged. These were laws formed and enforced to segregate and disenfranchise African Americans. These laws were in place to maintain a racial hierarchy by punishing African Americans who resisted or challenged the system. The enforcement of Jim Crow often involved violence and intimidation, including lynchings, bombings, and false arrests. In response, African Americans engaged in various forms of resistance, such as public protests and sit-ins. The modern era of hate-crime legislation began in 1968 with the passage of federal statute, 18 U.S.C.A. § 249, part of the Civil Rights Act which made it illegal to "by force or by threat of force, injure, intimidate, or interfere with anyone who is engaged in six specified protected activities, by reason of their race, color, religion, or national origin."[123] However, "The prosecution of such crimes must be certified by the U.S. attorney general."[124]

The first state hate-crime statute, California's Section 190.2, was passed in 1978 and provided penalty enhancements in cases when murders were motivated by prejudice against four "protected status" categories: race, religion, color, and national origin. Washington included ancestry in a statute which was passed in 1981. Alaska included creed and sex in 1982, and later disability, sexual orientation, and ethnicity. In the 1990s some state laws began to include age, marital status, membership in the armed forces, and membership in civil rights organizations.[125]

Until California state legislation included all crimes as possible hate crimes in 1987, criminal acts which could be considered hate crimes in various states included aggravated assault, assault and battery, vandalism, rape, threats and intimidation, arson, trespassing, stalking, and various "lesser" acts.[126]

Defined in the 1999 National Crime Victim Survey, "A hate crime is a criminal offence. In the United States, federal prosecution is possible for hate crimes committed on the basis of a person's race, religion, or nation origin when engaging in a federally protected activity." In 2009, capping a broad-based public campaign lasting more than a decade, President Barack Obama signed into law the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act. The Act added actual or perceived gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, and disability to the federal definition of a hate crime, and dropped the prerequisite that the victim be engaging in a federally protected activity. Led by Shepard's parents and a coalition of civil rights groups, with ADL (the Anti-Defamation League),[127][128] in a lead role, the campaign to pass the Matthew Shepard Act lasted 13 years, in large part because of opposition to including the term "sexual orientation" as one of the bases for deeming a crime to be a hate crime.[129]

ADL also drafted model hate crimes legislation in the 1980s that serves as the template for the legislation that a majority of states have adopted.[130] As of the fall of 2020, 46 of the 50 states and Washington, D.C. have statutes criminalizing various types of hate crimes.[131] Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia have statutes creating a civil cause of action in addition to the criminal penalty for similar acts. Twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia have statutes requiring the state to collect hate crime statistics.[132] In May 2020, the killing of African-American jogger Ahmaud Arbery reinvigorated efforts to adopt a hate-crimes law in Georgia, which was one of a handful of states without a such legislation. Led in great part by the Hate-Free Georgia Coalition, a group of 35 nonprofit groups organized by the Georgia state ADL,[133] the legislation was adopted in June 2020, after 16 years of debate.[134][135]

According to the FBI Hate Crime Statistics report for 2006, hate crimes increased nearly 8 percent nationwide, with a total of 7,722 incidents and 9,080 offences reported by participating law enforcement agencies. Of the 5,449 crimes against persons, 46 percent were classified as intimidation, and 32 percent as simple assaults. Acts of vandalism or destruction comprised 81 percent of the 3,593 crimes against property.[136]

However, according to the FBI Hate Crime Statistics for 2007, the number of hate crimes decreased to 7,624 incidents reported by participating law enforcement agencies.[137] These incidents included nine murders and two rapes (out of the almost 17,000 murders and 90,000 forcible rapes committed in the U.S. in 2007).[138]

In June 2009, Attorney General Eric Holder said recent killings showed the need for a tougher U.S. hate-crimes law to stop "violence masquerading as political activism."[139]

Leadership Conference on Civil Rights Education Fund published a report in 2009 revealing that 33 percent of hate-crime offenders were under the age of 18, while 29 percent were between the ages of 18 and 24.[140]

The 2011 hate-crime statistics show 46.9 percent were motivated by race, and 20.8 percent by sexual orientation.[141]

In 2015, the Hate Crimes Statistics report identified 5,818 single-bias incidents involving 6,837 offenses, 7,121 victims, and 5,475 known offenders[122]

In 2017, the FBI released new data showing a 17 percent increase in hate crimes between 2016 and 2017.[142]

In 2018, the Hate Crime Statistics report showed 59.5 percent were motivated by race bias and 16.9 percent by sexual orientation.[143]

Prosecutions of hate crimes have been difficult in the United States. Recently, state governments have attempted to re-investigate and re-try past hate crimes. One notable example was Mississippi's decision to retry Byron De La Beckwith in 1990 for the 1963 murder of Medgar Evers, a prominent figure in the NAACP and a leader of the civil rights movement.[144] This was the first time in U.S. history that an unresolved civil rights case was re-opened. De La Beckwith, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, was tried for the murder on two previous occasions, resulting in hung juries. A mixed-race jury found Beckwith guilty of murder, and he was sentenced to life in prison in 1994.[145]

According to a November 2016 report issued by the FBI, hate crimes are on the rise in the United States.[146] The number of hate crimes increased from 5,850 in 2015, to 6,121 hate crime incidents in 2016, an increase of 4.6 percent.[147][148][149]

The Khalid Jabara-Heather Heyer National Opposition to Hate, Assault, and Threats to Equality Act (NO HATE), which was first introduced in 2017, was reintroduced in June 2019 to improve hate crime reporting and expand support for victims as a response to anti-LGBTQ, anti-Muslim and antisemitic attacks. The bill would fund state hate-crime hotlines, and support expansion of reporting and training programs in law enforcement agencies.[150]

According to a 2021 study, in the years between 1992 and 2014, white people were the offenders in 74.5 percent of anti-Asian hate crimes, 99 percent of anti-black hate crimes, and 81.1 percent of anti-Hispanic hate crimes.[151]

Victims in the United States

After a slow decline, the number of hate crimes increased since the mid 2010s.[152]

One of the largest waves of hate crimes in the history of the United States took place during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Violence and threats of violence were common against African Americans, and hundreds of people died due to such acts. Members of this ethnic group faced violence from groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, as well as violence from individuals who were committed to maintaining segregation.[153] At the time, civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and their supporters fought hard for the right of African Americans to vote, as well as for equality in their everyday lives. African Americans have been the target of hate crimes since the Civil War,[154] and the humiliation of this ethnic group was also desired by many anti-black individuals. Other frequently reported bias motivations were bias against a religion, bias against a particular sexual orientation, and bias against a particular ethnicity or national origin.[155] At times, these bias motivations overlapped, because violence can be both anti-gay and anti-black, for example.[156] There are many terms that victims of hate crimes have been subjected to over the years, especially when it comes to minority groups. The African American population is just one of many groups that have been degraded by society. For example, "coon," "sambo," "pickaninny," "jigaboo," "buck," and "mammy" are all slurs and derogatory terms that have been used throughout history against African Americans. These are all examples of ethnophaulisms, which are racial slurs and terms that are used during or motivate hate crimes against African Americans.

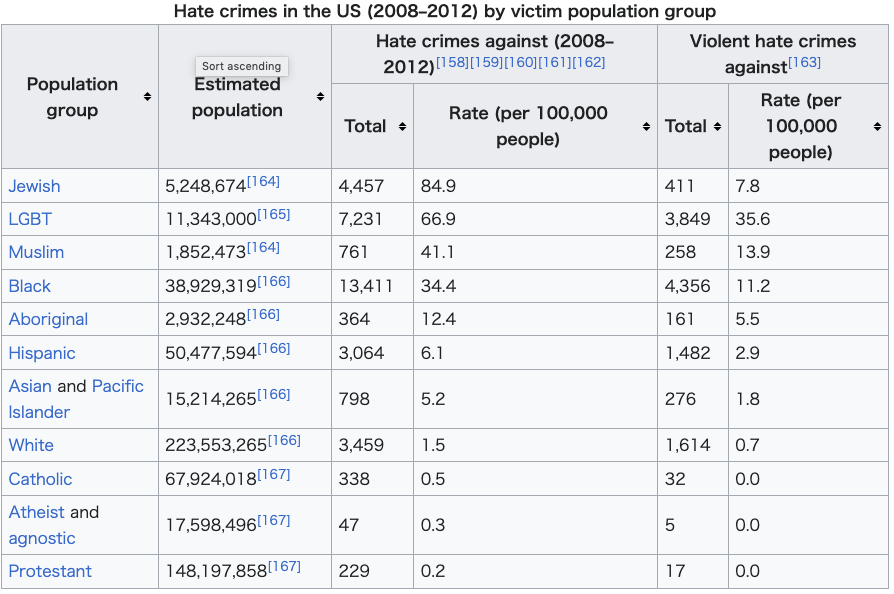

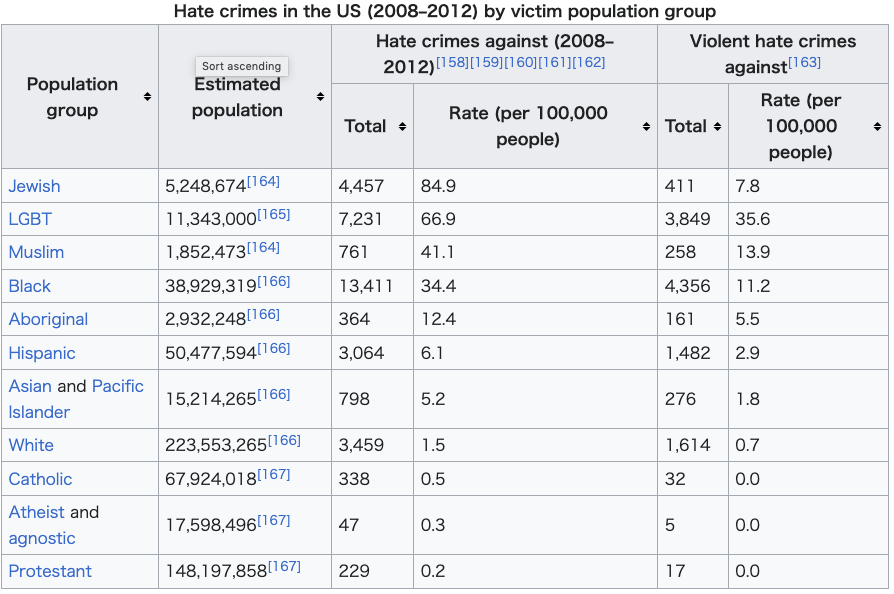

Analysts have compared groups in terms of the per capita rate of hate crimes committed against them to allow for differing populations. Overall, the total number of hate crimes committed since the first hate crime bill was passed in 1997 is 86,582.[157]

Among the groups which are mentioned in the Hate Crimes Statistics Act, the largest number of hate crimes are committed against African Americans.[168] During the Civil Rights Movement, some of the most notorious hate crimes included the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the 1964 murders of Charles Moore and Henry Dee, the 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the 1955 murder of Emmett Till,[154] and the burning of crosses, churches, Jewish synagogues, and other places of worship of minority religions. Such acts began to take place more frequently after the racial integration of many schools and public facilities.[168]

Since then, hate crimes targeting Jews have risen sharply, as in 2023, Antisemitic hate crimes increased by 63% to an all-time high of 1,832 incidents in the United States.[169] Furthermore, Jews comprise roughly 2% of the American population, but represent 68% of all religion-based hate crimes in the country.[170]

High-profile murders targeting victims based on their sexual orientation have prompted the passage of hate crimes legislation, notably the cases of Sean W. Kennedy and Matthew Shepard. Kennedy's murder was mentioned by Senator Gordon Smith in a speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate while he advocated such legislation. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act was signed into law in 2009. It included sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, disably status, and military personnel and their family members.[171][172] This is the first all-inclusive bill ever passed in the United States, taking 45 years to complete.[clarification needed]

Gender-based crimes may also be considered hate crimes. This view would designate rape and domestic violence, as well as non-interpersonal violence against women such as the École Polytechnique massacre in Quebec, as hate crimes.[173][174][175]

Following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the United States experienced a spike in overall hate crimes against Muslim individuals. In the year before, only 28 events had been recorded of hate crimes against Muslims; in 2001, this number jumped to 481. While the number decreased in the following years, the number of Muslim hate crimes remains higher than pre-2001.[176] After the beginning of the Gaza war on October 7, 2023, hate crimes began to increase once again due to the United States allyship with Israel. Palestinian-Americans became a target for hate crimes and were blamed for the conflict leading to violence, including in the case of the Murder of Wadea al-Fayoume, a 6-year-old Palestinian-American boy killed by a white man who was motivated by anti-Muslim extremism.[citation needed]

In May 2018, ProPublica reviewed police reports for 58 cases of purported anti-heterosexual hate crimes. ProPublica found that about half of the cases were anti-LGBT hate crimes that had been miscategorized, and that the rest were motivated by hate towards Jews, blacks or women or that there was no element of a hate crime at all. ProPublica did not find any cases of hate crimes spurred by anti-heterosexual bias.[177]

Anti-trans hate crime

In 2017, shortly after President Donald Trump took office, hate crimes against transgender individuals increased.[178] In June 2020, after the death of several African Americans at the hands of police officers – in particular, George Floyd – triggered protests around the world as part of the Black Lives Matter movement,[179] hate crimes against the black trans community began to increase.[180]

South America

Further information: Social cleansing

Brazil

In Brazil, hate crime laws focus on racism, racial injury, and other special bias-motivated crimes such as, for example, murder by death squads[181] and genocide on the grounds of nationality, ethnicity, race or religion.[182] Murder by death squads and genocide are legally classified as "hideous crimes" (crimes hediondos in Portuguese).[183]

The crimes of racism and racial injury, although similar, are enforced slightly differently.[184] Article 140, 3rd paragraph, of the Penal Code establishes a harsher penalty, from a minimum of one year to a maximum of three years, for injuries motivated by "elements referring to race, color, ethnicity, religion, origin, or the condition of being an aged or disabled person".[185] On the other side, Law 7716/1989 covers "crimes resulting from discrimination or prejudice on the grounds of race, color, ethnicity, religion, or national origin".[186]

In addition, the Brazilian Constitution defines as a "fundamental goal of the Republic" (Article 3rd, clause IV) "to promote the well-being of all, with no prejudice as to origin, race, sex, color, age, and any other forms of discrimination".[187]

Chile

In 2012, the Anti-discrimination law amended the Criminal Code adding a new aggravating circumstance of criminal responsibility, as follows: "Committing or participating in a crime motivated by ideology, political opinion, religion or beliefs of the victim; nation, race, ethnic or social group; sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, affiliation, personal appearance or suffering from illness or disability."[188][189]

Middle East

Israel is the only country in the Middle East that has hate crime laws.[citation needed] Hate crime, as passed by the Israeli Knesset (Parliament), is defined as crime for reason of race, religion, gender and sexual orientation.

Oceania

Australia within February 2025, passed comprehensive and extensive legislation on hate crimes at a federal governmental level.[190]

ヘイトクライム法は一般的に以下のいずれかのカテゴリーに分類される:

特定の偏見に基づく行為を独立した犯罪として定義する法律

刑事罰を加重する法律

ヘイトクライムに対する独立した民事訴訟原因を創設する法律

行政機関にヘイトクライム統計の収集を義務付ける法律[51]時には(ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナのように)、法律は戦争犯罪、ジェノサイド、人道に対する罪に焦点を当て、差別的行為の禁止は公務員に限定される場合がある[出典必要]

ヨーロッパとアジア

欧州評議会

2006年以降、「サイバー犯罪に関する条約の追加議定書」により、同条約の署名国の大半(主に欧州評議会加盟国)は、インターネットを通じた人種差別的・外国人排斥的なヘイトスピーチを犯罪として処罰することを約束した。[52]

アンドラ

出身地、国籍、人種、宗教、ジェンダーに基づく嫌がらせや人格の尊厳侵害を構成する差別的行為 (刑法第313条)。裁判所は量刑において偏見に基づく動機を引用しているが、刑法に明示的な刑罰加重規定は存在しない。政府はヘイトクライムの統計を追 跡していないが、比較的稀である。[51]

アルメニア

アルメニアは、民族的、人種的、宗教的動機に基づく犯罪に対する刑罰加重規定を有する(刑法第63条)。[51]

オーストリア

オーストリアには、犯罪の反復、特に残酷な行為、他人の無力状態の利用、犯罪における主導的役割、人種差別的・外国人嫌悪的または特に非難すべき動機によ る犯罪などの理由による刑罰加重規定がある(刑法第33条(5))。[53] オーストリアはサイバー犯罪条約の締約国であるが、追加議定書には加盟していない。

アゼルバイジャン

アゼルバイジャンは、人種的、民族的、宗教的憎悪に基づく犯罪に対して刑罰加重規定を設けている(刑法第61条)。人種的、宗教的、民族的、あるいは民族 的不寛容に基づく殺人及び重大な身体傷害の加害は、独立した犯罪として規定されている(第111条)。[51] アゼルバイジャンはサイバー犯罪条約の締約国であるが、追加議定書には加盟していない。

ベラルーシ

ベラルーシは人種的、国民的、宗教的憎悪および不和を動機とする犯罪に対する刑罰加重規定を有している。[51][54]

ベルギー

ベルギーの2003年2月25日法(「差別対策及び機会均等・人種主義対策センターの設置を定めた1993年2月15日法の改正を目的とする」)は、ジェ ンダー、推定される人種、肌の色、出自、国民・民族的起源、性的指向、婚姻状況、出生、財産、年齢、 宗教的・哲学的信条、現在または将来の健康、障害または身体的特徴に基づく差別を伴う犯罪に対して刑罰加重を規定している。同法はまた「差別に対処するた めの民事救済を規定している」[51]。同法は、2003年1月20日の法律(「人種主義に対する立法の強化に関する」)とともに、同センターに対し人種 主義および差別的犯罪に関する統計データの収集と公表を義務付けている[51]。ベルギーはサイバー犯罪条約の締約国であるが、追加議定書には署名してい ない。

ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナ

ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナ刑法(2003年制定)は「公職者が人種、肌の色、国民的・民族的背景、宗教、言語などを理由に差別することを禁止する規定を含 み、また公職者が当局との関係において市民の言語権を制限することを禁止している(第145条1項及び2項)」とされている。[55]

ブルガリア

ブルガリア刑法は人種主義、外国人嫌悪、性的指向を動機とする特定の犯罪を禁止している(2023年以降)。しかし欧州人種差別・不寛容対策委員会 (ECRI)の1999年報告書によれば、これらの規定が「ブルガリアの裁判所において有罪判決につながった事例は確認されていない」とされている。 [56]

クロアチア

クロアチア刑法第89条は、ヘイトクライムを「人種、肌の色、性別、性的指向、言語、宗教、政治的その他の信念、国民的・社会的出身、財産、出生、教育、 社会的地位、年齢、健康状態その他の属性に対する憎悪に基づいて行われる犯罪」と明示的に定義している。[57] 2013年1月1日、新たな刑法が施行され、「人種、肌の色、宗教、国民的・民族的背景、性的指向、ジェンダー」に基づくヘイトクライムの認定が追加され た。[58]

チェコ共和国

チェコの法制度は、基本権及び基本的自由に関する憲章に規定された平等及び非差別の原則を憲法上の根拠としている。そこから、憎悪動機による事件に対する 二つの基本的な保護の枠組みが導かれる。一つは刑法を通じ、もう一つは民法を通じる。現行のチェコ刑法は、有罪判決の決定(被告人の有罪・無罪の判断に影 響)と量刑の決定(科される刑罰の程度に影響)の両方に影響を及ぼす。具体的には三つのレベルがある:

犯罪の成立要件を定める要素-憎悪動機は基本構成要素に含まれる。憎悪動機が立証されなければ、憎悪犯罪としての有罪判決は不可能である。

加重刑の適用を定める要素-憎悪動機は特定犯罪(殺人、傷害)の加重構成要件に含まれる。憎悪動機が立証されなければ、基本構成要素に定められた量刑基準に従って刑が科される。

一般的な加重事情として、裁判所は憎悪動機を一般的な加重事情として考慮し、科すべき刑罰の量を決める義務がある。ただし、一般的な加重事情と刑罰加重事情を併合することはできない(詳細は別添参照)。

現行の刑法は、性的指向・年齢・健康状態を理由に他者を標的とする行為に対する特別刑罰を規定していない。集団に対する憎悪の扇動またはその権利・自由の 制限を構成する犯罪要素と一般加重事情のみが、いわゆる「異なる集団」への攻撃を含む。当然ながら、この「集団」は性的指向・年齢・健康状態によっても定 義され得る。したがって、肌の色、信仰、国籍、民族、政治的信条を理由に被害を受け、強化された保護を享受する集団と、 性的指向、年齢、健康を理由に被害を受けながらも強化された保護を認められていない集団との間に、一定の格差が生じている。被害者の性的指向、年齢、健康 を動機とする攻撃に対する保護のこの格差は、解釈によって埋めることはできない。類推解釈は刑法上許容されず、処罰対象となる動機は網羅的に列挙されてい るのである。[59]

デンマーク

デンマーク法には憎悪犯罪に関する明文規定はないが、「刑法第80条第1項は、量刑に際し犯罪の重大性と犯人の動機を考慮するよう裁判所に指示しており、 したがって人種差別的動機を量刑判断において重視するよう求めている」[60]。近年、裁判官はこの規定を根拠に人種差別的動機を理由とした量刑加重を 行っている[51]。[61]

1992年以降、デンマーク治安警察(PET)は明らかな人種差別的動機に基づく犯罪の統計を発表している。[51]

エストニア

2001年6月6日付エストニア刑法第151条(2002年9月1日施行、改正・追加を経て、2011年12月8日法により改正)によれば、「国籍、人 種、肌の色、 性別、言語、出身、宗教、性的指向、政治的意見、あるいは経済的・社会的地位に基づく憎悪、暴力、差別を公然と扇動する行為は、人格の生命、健康、財産に 危険をもたらす場合、300罰金単位以下の罰金または拘禁に処せられる』。[62]

フィンランド

フィンランド刑法515/2003(2003年1月31日制定)は、「その人格の国民、人種、民族的またはこれに相当する集団を理由として犯罪を犯すこ と」を量刑上の加重事情としている。[51][63] さらに、民族扇動 (フィンランド語: kiihotus kansanryhmää vastaan)は犯罪とされ、罰金または2年以下の懲役が科される。検察は民族集団への実際の危険が生じたことを立証する必要はなく、悪意のあるメッ セージが伝達されたことのみを証明すればよい。より悪質な憎悪犯罪である戦争煽動(フィンランド語:sotaan yllyttäminen)は、1年から10年の懲役刑を科す。ただし戦争煽動の場合、検察側はフィンランドが戦争に巻き込まれるリスクや軍事作戦の標的 となる危険性を明らかに高める明白な行為を立証しなければならない。問題となる行為は以下を含む可能性がある:

外国またはその国民に対する違法な暴力行為、

フィンランドの外交政策または防衛に関する虚偽情報の組織的な流布、

世論を戦争支持的な見解へ公然と誘導する行為、または

外国またはフィンランドが攻撃的行為を行うべきだと公然と示唆する行為。[64]

フランス

2003年、 フランスは、被害者の実際のまたは認識された民族、国民、人種、宗教、性的指向に対する偏見を動機とする犯罪に対して、刑罰を加重するヘイトクライム法を 制定した。殺人の刑罰は30年(非ヘイト犯罪)から終身刑(ヘイト犯罪)に引き上げられ、永続的な障害をもたらす暴力攻撃の刑罰は10年(非ヘイト犯罪) から15年(ヘイト犯罪)に引き上げられた。[51][65]

ジョージア

「ジョージア法には、一般犯罪の起訴において人種差別的動機を加重要因とみなす規定は存在しない。ただし、1999年制定のジョージア刑法では、人種差別 的動機を伴う特定の犯罪が特別に定義されている。これには以下が含まれる:人種的、宗教的、国家的、民族的偏見に基づく殺人(第109条)、人種的、宗教 的、国家的、民族的偏見に基づく重傷傷害(第117条)、人種的、宗教的、国家的、民族的偏見に基づく拷問(第126条)。」 (第109条)、人種・宗教・民族的不寛容に基づく重傷傷害(第117条)、人種・宗教・民族的不寛容に基づく拷問(第126条)である。欧州差別撤廃委 員会(ECRI)は、この法律が適用された事例を把握していないと報告している。ジョージアでは差別に関する体系的な監視やデータ収集は行われていな い。」[51]

ドイツ

ドイツ刑法にはヘイトクライムに関する法律は存在しない。代わりに、人民扇動罪(Volksverhetzung)を含む複数の異なる法律の下でヘイトス ピーチを犯罪化している。ドイツの法的枠組みでは、犯罪の構成要件を特定する際に動機は考慮されない。ただし、量刑手続きにおいて、裁判官は刑罰を決定す るための特定の原則を定義することができる。ドイツ刑法第46条では「加害者の動機と目的、行為に反映された精神状態、およびその実行における故意性」 [66]が量刑判断において考慮され得ると規定されている。この条項に基づき、過去の判例では憎悪や偏見が量刑判断に反映されてきた。[67]

ドイツ警察はヘイトクライムを特別に追跡していないが、別途調査は行われている。最近公表されたEU「人種主義に関する報告書」によれば、ドイツでは人種 的動機による攻撃が頻発しており、2006年には18,142件が確認された。このうち17,597件は右翼イデオロギーに動機づけられたもので、いずれ も前年比約14%の増加を示している。[68] 人口規模を考慮すると、これは同時期の米国で報告されたヘイトクライム発生率の8倍に相当する。[69] ドイツにおけるヘイトクライムへの認識は依然として低い。[70]

ギリシャ

法律第927/1979号「第1条第1項は、人種的・民族的・宗教的起源に基づく個人または集団への差別・憎悪・暴力の扇動を、公的な書面または口頭によ る表現を通じて処罰する。第1条第2項は、人種差別を目的とした宣伝活動を行う団体の設立および加入を禁止する。第2条は、公然と攻撃的な思想を表明する 行為を処罰する。第3項は、職業上の行為において人種的理由による商品販売・サービス提供の拒否を処罰する。」[71] 被害者が告訴しなくても検察官は起訴できる。しかし2003年時点で、本法に基づく有罪判決は一度もなかった。[72]

ハンガリー

被害者の実際の、または認識された国民、民族、宗教的地位、あるいは特定の社会的集団への所属を根拠とした暴力行為、残虐行為、脅迫による強制は、ハンガ リー刑法第174条B項により処罰される。[51] この条項は1996年に刑法に追加された。[73] ハンガリーはサイバー犯罪条約の締約国であるが、追加議定書には加盟していない。

アイスランド

アイスランド刑法第233a条は「国民、肌の色、人種、宗教、性的指向を理由に、嘲笑、誹謗、侮辱、脅迫その他の方法で人格または集団を公然と虐待した者 は、罰金または2年以下の懲役に処する」と規定している。[74] アイスランドはサイバー犯罪条約の締約国であるが、追加議定書には加盟していない。

インド

インドには、ヘイトスピーチ(インド刑法で規定)以外のヘイトクライム全般を規制する特定の法律は存在しない。

アイルランド

2024年12月31日より法的効力を有するアイルランドは、ヘイトクライムに関する広範かつ包括的な立法を実施した。[75]

1989年憎悪扇動禁止法は、人種、肌の色、国民、宗教、民族的・国家的起源、トラベラー・コミュニティ(先住少数民族集団)への所属、または性的指向を 理由とした集団に対する憎悪の扇動を犯罪とした。[51][76] 起訴件数の低さ(2011年までに18件)に対する不満は、同法が特定の扇動ではなく憎悪犯罪全般に対処するものだという誤解に起因していた。[77]

2019年、国連ジュネーブで開催された人種差別撤廃委員会において、国連報告者はアイルランド代表に対し、1989年法に基づく犯罪の起訴率が低い状況 に対処するため、新たなヘイトクライム立法を導入するよう求めた。特にオンライン上のヘイトスピーチに対する起訴率の低さと、ガーダ・シオチャーナ(アイ ルランド警察)の人種的動機犯罪に関する訓練不足を指摘した。この勧告は、アイルランド国内で反移民的な言説や人種差別的攻撃が増加する中で出されたもの であり、アイルランド人権平等委員会や多数の市民団体が提出した勧告に基づいている。改革はアイルランド反人種差別ネットワークによって支持されている。 [78]

「ヘイトクライム法案」として知られる刑事司法(暴力や憎悪の煽動、ヘイト犯罪)法案は、保護対象の特徴に基づくヘイトスピーチやヘイト犯罪の煽動を禁止 するものであり、2023年6月現在、アイルランドの上院である上院で第3段階の審議が行われており、アイリッシュ・タイムズ紙は、2023年後半に法制 化される可能性が高いと報じている。[79][80] この法案は、アイルランド市民的自由評議会や、政治のあらゆる分野(特にマイケル・マクダウェル、ロナン・マレン、人民優先党)から、また国際的には、実 業家のイーロン・マスクや政治活動家のドナルド・トランプ・ジュニアからも懸念が寄せられている。[80] 人民優先党のポール・マーフィーは、この法案は、憎悪を煽るような流通を目的とした資料の所持を犯罪化することで、「思想犯罪」を生み出していると述べ た。[80] グリーン党の上院議員であるポーリーン・オライリーは、現行の法律は「効果がない」かつ時代遅れであると述べ、ガーダ(アイルランド警察)がアイルランド におけるヘイトクライムが 30% 増加したと認識していることを付け加えた。[81]

ガーダが公表したデータによると、ヘイトクライムおよびヘイト関連の事件は 2021 年の 448 件から 2022 年には 582 件へと 29% 増加した。[82] ガーダは「改善が見られるものの、憎悪犯罪および憎悪関連事件は依然として過少報告されている」と認識している。[83]

イタリア

イタリア刑法は、1993年法律第205号(通称マンチーノ法)第3条において、人種的、民族的、国民的、または宗教的偏見に基づく動機による全ての犯罪 に対して刑罰加重規定を設けている。[51] イタリアはサイバー犯罪条約の締約国であるが、追加議定書には署名していない。

カザフスタン

カザフスタンでは、人種的・民族的優越性を助長する宣伝を禁止する憲法規定がある。[51]

キルギス

キルギスでは、「国家の憲法は、出身、性別、人種、国民、言語、信仰、政治的または宗教的信念、その他の個人的または社会的特性や状況に基づくあらゆる差別を禁止しており、人種差別禁止は民法、刑法、労働法などの他の法令にも含まれている」[84]。

刑法第299条は、国民・人種的・宗教的憎悪の扇動を特定の犯罪として定義している。この条項は、禁止組織ヒズブ・タハリールの容疑者に対する政治裁判で適用されてきた。[51] [85]

オランダ

2025年3月、オランダ上院は差別的意図を持つ犯罪の刑罰を3分の1加重できる法案を可決した。下院が既に同法案を承認しているため、この法律はまもなく施行される。

ポーランド

ポーランド憲法第13条は、「人種的またはナショナリズム憎悪を容認する綱領または活動を行う組織」を禁止している。[86]

ロシア

ロシア連邦憲法第29条は、社会的・人種的・民族的・宗教的憎悪を煽動する目的での暴動扇動、及びそれらの優越性の主張を禁止している。刑法第282条は さらに、各種通信手段による憎悪(ジェンダーを含む)の扇動に対する保護規定を設け、罰金や禁固刑を含む刑事罰を規定している。[87] ロシアは欧州評議会の元加盟国であるが、サイバー犯罪条約には加盟していない。

スロベニア

2023年、スロベニアは刑法に刑罰加重規定を導入した。被害者の国民、人種、宗教的・民族的出身、性別、肌の色、家系、財産、教育、社会的地位、政治的 その他の意見、障害、性的指向、その他の個人的事情が犯罪の遂行に寄与した要因である場合、刑罰を決定する際にこれを考慮する。[88]

スペイン

スペイン刑法第22条第4項には、被害者のイデオロギー、信条、宗教、民族、人種、国籍、ジェンダー、性的指向、疾病または障害に対する偏見を動機とする犯罪に対する刑罰加重規定が含まれている。[51]

2019年5月14日、スペイン検察総長はヘイトクライム法の解釈に関する通達を配布した。この新たな解釈では、ナチスも同法で保護される集団に含まれる。[89]

スペインは欧州評議会の加盟国であるが、サイバー犯罪条約には加盟していない。

スウェーデン