ヘルスリテラシー

Health literacy

☆ヘルスリテラシー(Health

literacy)

とは、適切な健康上の意思決定を行い、治療の指示に従うために、保健医療情報を入手し、読み、理解し、利用する能力のことである[1]。ヘルスリテラシー

には複数の定義があるが[2]、その理由の一つは、ヘルスリテラシーには、ヘルスリテラシーの要求がなされる状況(または設定)と、その状況に人民がもた

らすスキルの両方が含まれるからである[3]。

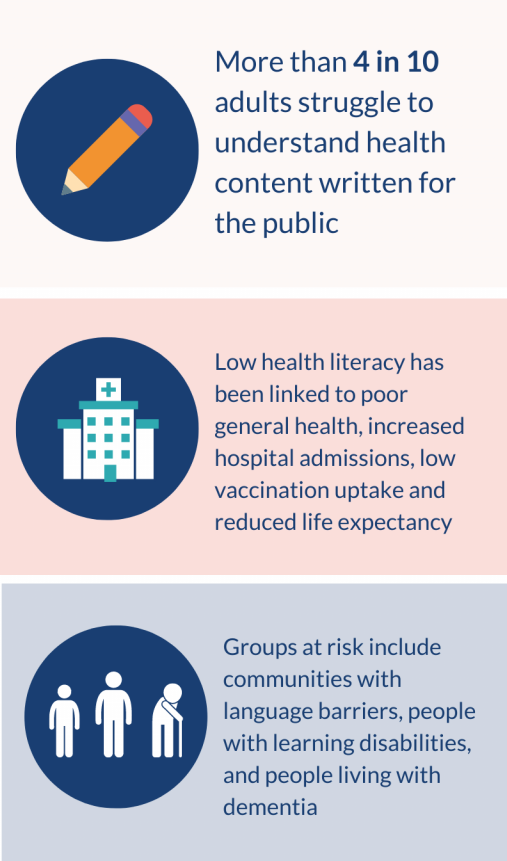

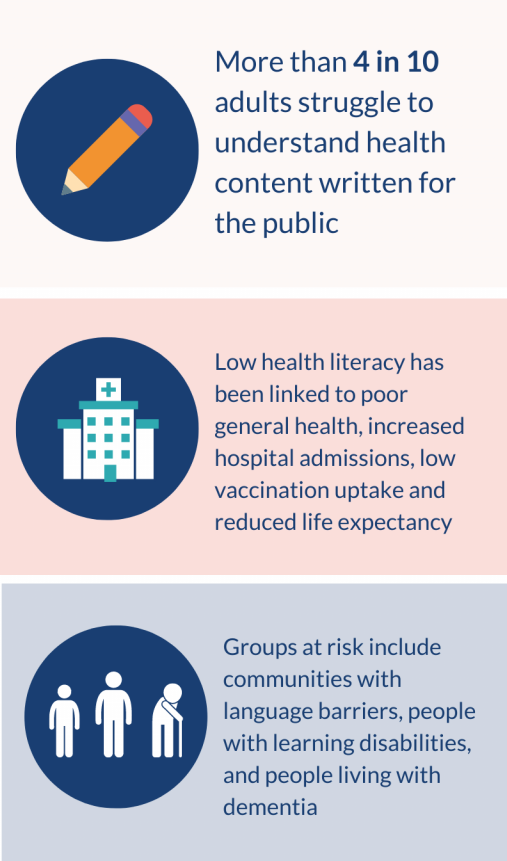

ヘルスリテラシーは健康格差の主な要因であるため、医療専門家にとって継続的かつ増大しつつある関心事である[4]。米国教育省が2003年に実施した成

人識字率国民調査(NAAL)では、参加者の36%がヘルスリテラシーの点で「基礎的」または「基礎以下」のスコアを獲得しており、約8,000万人の米

国人がヘルスリテラシーに限界があると結論づけている[5]。これらの人々は、処方された薬のラベルを読むことを含む一般的な保健業務に困難を抱えている

[6]。しかし、以下の因子がこのリスクを強く高めることが示されている:年齢(特に65歳以上の患者)、限られた英語力または第二言語としての英語、慢

性疾患、教育の少なさ、社会経済的地位の低さ [7] 。 [8]

ヘルスリテラシーの問題に直面する患者は、予防接種や年1回の検診といった重要な医療を見送ることが多く、予約に間に合わなかったり、薬を誤用したり、処

置の準備を誤ったり、さらには早死にしたりする可能性が高い。[9]

情報や図解を簡略化する、専門用語を避ける、「ティーチバック」法を用いる、患者の質問を促すなど、様々な介入により、保健リテラシーの低い人格の保健行

動は改善されている [10] 、 米国保健社会福祉省(HHS)のHealthy People

2020イニシアチブでは、ヘルスリテラシーを差し迫った新たなテーマとして取り上げ、今後10年間で改善することを目標としている[12]。

ヘルシーピープル2030(ヘルシーピープルの第5版)の計画にあたり、HHS[13]は「ヘルシーピープルのためのヘルスリテラシーの定義の更新に関す

る意見募集」を行った。いくつかの提案は、「保健リテラシーは多次元的」であり[14]、ケアや情報を求める個人、医療提供者や介護者、システムの複雑さ

と要求、コミュニケーションのための平易な言語の使用を含む協調的な努力の結果であるという事実を取り上げている。

| Health

literacy is the ability to obtain, read, understand, and use healthcare

information in order to make appropriate health decisions and follow

instructions for treatment.[1] There are multiple definitions of health

literacy,[2] in part because health literacy involves both the context

(or setting) in which health literacy demands are made (e.g., health

care, media, internet or fitness facility) and the skills that people

bring to that situation.[3] Since health literacy is a primary contributing factor to health disparities, it is a continued and increasing concern for health professionals.[4] The 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) conducted by the US Department of Education found that 36% of participants scored as either "basic" or "below basic" in terms of their health literacy and concluded that approximately 80 million Americans have limited health literacy.[5] These individuals have difficulty with common health tasks including reading the label of a prescribed drug.[6] Several factors may influence health literacy. However, the following factors have been shown to strongly increase this risk: age (especially patients 65 years and older), limited English language proficiency or English as a second language, chronic conditions, less education, and lower socioeconomic status.[7] Patients with low health literacy understand less about their medical conditions and treatments and overall report worse health status.[8] Patients who struggle with substantial health literacy challenges often forego important health care such as vaccinations or annual screenings, and are more likely to miss appointments, misuse medication, prepare improperly for procedures, and even die prematurely. [9] Various interventions, such as simplifying information and illustrations, avoiding jargon, using "teach-back" methods, and encouraging patients' questions, have improved health behaviors in persons with low health literacy.[10] The proportion of adults aged 18 and over in the U.S., in the year 2010, who reported that their health care providers always explained things so they could understand them was about 60.6%.[11] This number increased 1% from 2007 to 2010.[11] The Healthy People 2020 initiative of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has included health literacy as a pressing new topic, with objectives for improving it in the decade to come.[12] In planning for Healthy People 2030 (the fifth edition of Healthy People), HHS[13] issued a "Solicitation for Written Comments on an Updated Health Literacy Definition for Healthy People". Several proposals address the fact that "health literacy is multidimensional",[14] being the result of a concerted effort that involves the individual seeking care or information, providers and caregivers, the complexity and demands of the system, and the use of plain language for communication. |

ヘルスリテラシーとは、適切な健康上の意思決定を行い、治療の指示に従

うために、保健医療情報を入手し、読み、理解し、利用する能力のことである[1]。ヘルスリテラシーには複数の定義があるが[2]、その理由の一つは、ヘ

ルスリテラシーには、ヘルスリテラシーの要求がなされる状況(または設定)と、その状況に人民がもたらすスキルの両方が含まれるからである[3]。 ヘルスリテラシーは健康格差の主な要因であるため、医療専門家にとって継続的かつ増大しつつある関心事である[4]。米国教育省が2003年に実施した成 人識字率国民調査(NAAL)では、参加者の36%がヘルスリテラシーの点で「基礎的」または「基礎以下」のスコアを獲得しており、約8,000万人の米 国人がヘルスリテラシーに限界があると結論づけている[5]。これらの人々は、処方された薬のラベルを読むことを含む一般的な保健業務に困難を抱えている [6]。しかし、以下の因子がこのリスクを強く高めることが示されている:年齢(特に65歳以上の患者)、限られた英語力または第二言語としての英語、慢 性疾患、教育の少なさ、社会経済的地位の低さ [7] 。 [8] ヘルスリテラシーの問題に直面する患者は、予防接種や年1回の検診といった重要な医療を見送ることが多く、予約に間に合わなかったり、薬を誤用したり、処 置の準備を誤ったり、さらには早死にしたりする可能性が高い。[9] 情報や図解を簡略化する、専門用語を避ける、「ティーチバック」法を用いる、患者の質問を促すなど、様々な介入により、保健リテラシーの低い人格の保健行 動は改善されている [10] 、 米国保健社会福祉省(HHS)のHealthy People 2020イニシアチブでは、ヘルスリテラシーを差し迫った新たなテーマとして取り上げ、今後10年間で改善することを目標としている[12]。 ヘルシーピープル2030(ヘルシーピープルの第5版)の計画にあたり、HHS[13]は「ヘルシーピープルのためのヘルスリテラシーの定義の更新に関す る意見募集」を行った。いくつかの提案は、「保健リテラシーは多次元的」であり[14]、ケアや情報を求める個人、医療提供者や介護者、システムの複雑さ と要求、コミュニケーションのための平易な言語の使用を含む協調的な努力の結果であるという事実を取り上げている。 |

Definition The ability to read and understand medication instructions is a form of health literacy. The National Library of Medicine defined health literacy as:[15] "The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health literacy information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions." Health literacy encompasses a wide range of skills, and competencies that people develop over their lifetimes to seek out, comprehend, evaluate, and use health information and concepts to make informed choices, reduce health risks, and increase quality of life.[16] Another view of health literacy includes the ability to understand scientific concepts, content, and health research; skills in spoken, written, and online communication; critical interpretation of mass media messages; navigating systems of health care and governance; knowledge and use of community capital and resources; and using cultural and indigenous knowledge in health decision making.[17][18][19] This view sees health literacy as one of the social determinants of health which can reduce inequities in health. |

定義 服薬指導を読んで理解する能力は、保健リテラシーの一形態である。 ナショナリズム(National Library of Medicine)は、保健リテラシーを次のように定義している[15]。 「適切な保健上の意思決定を行うために必要な、基本的な保健リテラシーに関する情報やサービスを入手し、処理し、理解する能力を個人が有している度合い "である。 保健リテラシーには、情報に基づいた選択を行い、健康リスクを低減し、生活の質を高めるために、健康に関する情報や概念を探し出し、理解し、評価し、利用するために、人民が生涯にわたって身につける幅広い技能や能力が含まれる[16]。 ヘルス・リテラシーの別の見方としては、科学的概念、内容、保健研究を理解する能力、話し言葉、書き言葉、オンライン・コミュニケーションの技能、マスメ ディアのメッセージを批判的に解釈する能力、保健医療と統治のシステムを利用する能力、コミュニティ資本と資源の知識と利用、保健の意思決定における文化 的・先住民的知識の利用などがある[17][18][19]。 |

| Impact Health literacy is important in a community because it addresses health inequalities. It is no coincidence that individuals with lower levels of health literacy live, disproportionately, in communities with lower socio-economic standing. A barrier to achieving adequate health literacy for these individuals is a lack of awareness, or understanding of, information and resources relevant to improving their health. This knowledge gap arises from both patients being unable to understand information presented to them and hospitals' inadequate efforts and materials to address these literacy gaps.[20] The levels of health literacy are considered adequate when the population has sufficient knowledge, skills, and confidence to guide their own health, and people are able to stay healthy, recover from illness, and/or live with disability or disease.[20] |

インパクト ヘルスリテラシーが地域社会で重要なのは、それが保健の不平等に対処するためである。保健リテラシーの低い人が、社会経済的地位の低い地域社会に偏って住 んでいるのは偶然ではない。このような人々が十分なヘルスリテラシーを獲得するための障壁は、保健改善に関連する情報や資源に対する認識や理解の欠如であ る。この知識格差は、患者が提示された情報を理解できないことと、病院がこうしたリテラシーの格差に対処するための努力や資料が不十分であることの両方か ら生じる[20]。 保健リテラシーの水準が適切であると考えられるのは、国民が自らの健康を導くのに十分な知識、技能、自信を持ち、人民が健康を維持し、病気から回復し、および/または障害や病気と共存できる場合である[20]。 |

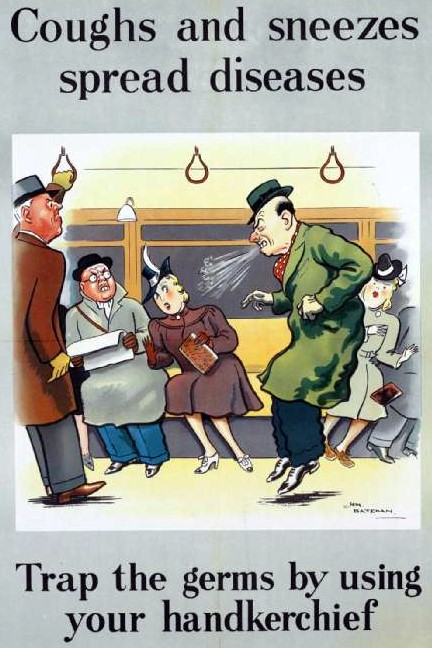

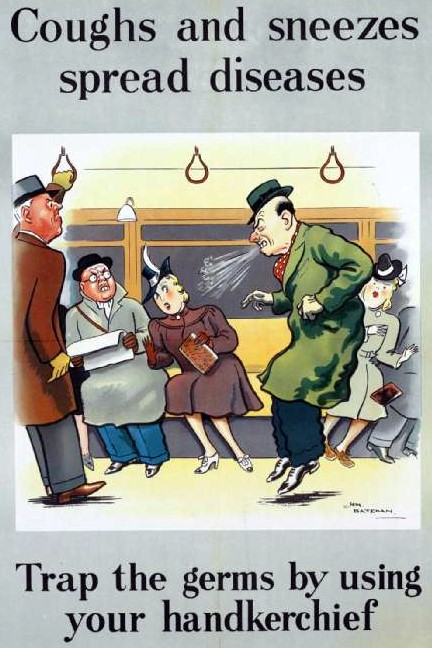

Characteristics A poster about airborne disease transmission encouraging the use of a handkerchief to prevent the spread Factors that contribute to health literacy Many factors determine the health literacy level of health education materials or interventions: readability of the text, the patient's current state of health, language barriers between the clinician and patient, cultural appropriateness of the materials, format and style, sentence structure, use of illustrations, and numerous other factors.[21][22] A study of 69,000 patients conducted in 1995 by two US hospitals found that between 26% and 60% of patients could not understand medication directions, a standard informed consent form, or materials about scheduling an appointment.[23] The 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) conducted by the US Department of Education found that 36% of participants scored as either "basic" or "below basic" in terms of their health literacy and concluded that approximately 80 million Americans have limited health literacy.[5] Results of a systematic review of the literature found that when limited English proficient (LEP) patients receive care from physicians who are fluent in the patients' preferred language, referred to as having language concordance, generally improves outcomes. These outcomes are consistent across patient-reported measures, such as patient satisfaction, and also more such as blood pressure for patients with diabetes.[24] |

特徴 空気感染する病気についてのポスターは、感染拡大を防ぐためにハンカチの使用を奨励している。 保健リテラシーの要因 本文の読みやすさ、患者の現在の健康状態、臨床医と患者の間にある言葉の壁、資料の文化的妥当性、書式と文体、文章構成、イラストの使用、その他多くの要因である。 米国の2つの病院が1995年に実施した69,000人の患者を対象とした調査では、患者の26%から60%が服薬指導、標準的なインフォームド・コンセ ントの書式、予約に関する資料を理解できないことが判明している[23] 。米国教育省が2003年に実施したNAAL(National Assessment of Adult Literacy)では、参加者の36%が保健リテラシーに関して「基礎的」または「基礎以下」のスコアを獲得しており、約8,000万人の米国人が保健 リテラシーに限界があると結論づけている[5]。 文献のシステマティックレビューの結果、英語が不自由な(LEP)患者が、患者が好む言語を流暢に話す医師から治療を受けると、一般的に転帰が改善するこ とがわかった。このような転帰は、患者満足度などの患者報告による指標や、糖尿病患者の血圧などの指標においても一貫している [24] 。 |

| Plain language Plain language refers to the use of writing strategies that help readers find, understand, and apply information to fulfill their needs.[25] It has a vital role to play in improving health literacy. In conjunction with readers education, provider cultural training, and system design, plain language helps people make more informed health choices.[26] Plain language is defined by the International Plain Language Federation as writing whose "wording, structure, and design are so clear that the intended readers can easily find what they need, understand what they find, and use that information."[27] Some key elements of plain language include:[28] Organizing information so most important points come first Breaking complex information into understandable chunks Using simple language or language familiar to the reader Defining technical terms and acronyms Using active voice in subject-verb-object (SVO) sentences when subject/agent/topic coincide Varying sentence length and structure to avoid monotony Using lists and tables to make complex material easier to understand The National Institute of Health (NIH) recommends that patient education materials be written at a 6th–7th grade reading level.[29] The UK's National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) recommends involving patients and non-academic members of the public in writing plain language summaries of research articles.[30][31] |

平易な表現 平易な表現とは、読者が自分のニーズを満たすために情報を見つけ、理解し、活用できるような文章戦略を用いることである[25]。これは保健リテラシーの 向上において重要な役割を担っている。読者教育、医療提供者の文化的訓練、システム設計と連動して、平易な言葉は人民がより多くの情報に基づいた保健の選 択をするのに役立つ[26]。 国際平易語連盟(International Plain Language Federation)により、平易語とは「意図された読者が必要なものを容易に見つけ、見つけたものを理解し、その情報を利用することができるように、 言葉遣い、構造、デザインが明確である」文章と定義されている[27]。 プレーン・ランゲージの重要な要素には以下が含まれる[28]。 最も重要なポイントが最初に来るように情報を整理する 複雑な情報を理解しやすいかたまりにする 簡単な言葉や読者になじみのある言葉を使う 専門用語や略語を定義する 主語・動詞・目的語(SVO)文で、主語・主語・トピックが一致する場合は能動態を使う 単調にならないよう、文の長さや構造を変える。 複雑な内容を理解しやすくするためにリストや表を使用する。 国民保健研究所(NIH)は、患者教育資料は小学校6~7年生レベルの読解力で書くことを推奨している[29]。 英国国立医療研究機構(NIHR)は、研究論文の要約を平易な言葉で書く際に、患者や学術関係者以外の一般市民を参加させることを推奨している[30] [31]。 |

| Assessment There are several tests, which have verified reliability in the academic literature that can be administered in order to test one's health literacy. Some of these tests include the Medical Term Recognition Test (METER), which was developed in the United States (2 minute administration time) for the clinical setting.[32] The METER includes many words from the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) test.[32] The Short Assessment of Health Literacy in Spanish and English populations (SAHL-S&E) uses word recognition and multiple choice questions to test a person's comprehension.[32] The CHC-Test measures Critical Health Competencies and consists of 72 items designed to test a person's understanding of medical concepts, literature searching, basic statistics, and design of experiments and samples.[32] Standardized measures of health literacy are the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), which asks people about a nutrition label,[33] and the Test of Functional Health Literacy (TOFHLA), which asks test-takers to fill in 36 blanks in patient instructions for X-rays and a Medicaid application, from multiple choices, and 4 numbers in medicine dosage forms.[34][35][36] The European Health Literacy Population Survey Following studies in a number of European countries demonstrating that health literacy is limited in a large proportion of the general population, and the publication of WHO’s report Health Literacy: The solid facts (2013),[37] WHO/Europe initiated the Action Network on Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy (M-POHL). 28 European counties are involved in M-POHL and measure health literacy in the population regularly. In the Health Literacy Survey 2019 (HLS19) 17 countries were involved. To measure general health literacy the instrument HLS-EU-Q12 - a short form of the original HLS-EU-Q47 instrument was used in this survey.[38] |

評価 保健リテラシーを検査するために実施できる、学術文献で信頼性が確認されている検査がいくつかある。これらのテストのいくつかには、米国で臨床現場用に開 発された医学用語認識テスト(METER)がある(投与時間2分) [32] 。METERには、Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine(REALM)テストの単語が多く含まれている。 [32] The Short Assessment of Health Literacy in Spanish and English populations(SAHL-S&E)は、単語認識と多肢選択問題を用いて人格の理解度を検査する[32] 。 CHC-TestはCritical Health Competenciesを測定するもので、医学的概念、文献検索、基本統計、実験と標本の設計に関する人格の理解度を検査するように設計された72項目 からなる[32]。 保健リテラシーの標準化された測定法としては、栄養表示について人民を問うNewest Vital Sign(NVS)[33]や、X線検査やメディケイド申請書の患者用説明書の36の空欄を複数の選択肢から埋めることと、薬の剤形の4つの数字を埋める ことを受験者に問うTest of Functional Health Literacy(TOFHLA)がある[34][35][36]。 欧州保健リテラシー人口調査 保健リテラシーが一般人口の大部分において限定的であることを示す多くの欧州諸国における研究、およびWHOの報告書「Health Literacy」(2013年)の発表を受けて、欧州保健リテラシー人口調査が実施された[34][36]: 確かな事実(2013年)[37]を受けて、WHO/欧州は、人口と組織の保健リテラシーの測定に関する行動ネットワーク(M-POHL)を開始した。欧 州28カ国がM-POHLに参加し、定期的に国民の保健リテラシーを測定している。保健リテラシー調査2019(HLS19)には17カ国が参加してい る。この調査では、一般的な保健リテラシーを測定するために、HLS-EU-Q12(オリジナルのHLS-EU-Q47測定器の短縮版)という測定器が使 用された[38]。 |

| Patient safety and outcomes Low health literacy negatively affects the treatment outcome and safety of care delivery.[39] The lack of health literacy affects all segments of the population. However, it is disproportionate in certain demographic groups, such as the elderly, ethnic minorities, recent immigrants,[40] individuals facing homelessness,[41] and persons with low general literacy.[42] These populations have a higher risk of hospitalization, longer hospital stays, are less likely to comply with treatment, are more likely to make errors with medication,[43] and are more ill when they initially seek medical care.[44][45] The mismatch between a clinician's communication of content and a patient's ability to understand that content can lead to medication errors and adverse medical outcomes. Health literacy skills are not only a problem in the general population. Health care professionals (doctors, nurses, public health workers) can also have poor health literacy skills, such as a reduced ability to clearly explain health issues to patients and the public.[46][47] In addition to tailoring the content of what health professionals communicate to their patients, a well arranged layout, pertinent illustrations, and intuitive format of written materials can improve the usability of health care literature. This in turn can help in effective communication between healthcare providers and their patients.[48] Outcomes of low levels of health literacy also include relative expenditures on health services. Because individuals with low health literacy are more likely to have adverse health statuses, their use of health services is also increased.[49] This trend is compounded by other risk factors of low health literacy, including poverty.[50] Homelessness and housing insecurity can hinder good health and recovery in attempts to better health circumstances, causing the exacerbation of poor health conditions.[51] In these cases, a variety of health services may be used repeatedly as health issues are prolonged.[52] Thus overall expenditures on health services is greater among populations with low health literacy and poor health.[53] These costs may be left to individuals and families to pay which may further burden health conditions, or the costs may be left to a variety of institutions which in turn has broader implications for government funding and health care systems. Low levels of health literacy is responsible for 3–5% of healthcare cost—approximately $143 to 7,798 per individual within the healthcare system.[54] |

患者の安全性と転帰 保健リテラシーの低さは、治療結果や医療提供の安全性に悪影響を及ぼす [39] 。しかし、高齢者、少数民族、最近の移民[40]、ホームレス状態に直面している人格[41]、一般的な識字能力が低い人格[42]など、特定の人口集団 では不釣り合いである。これらの集団は、入院リスクが高く、入院期間が長く、治療を遵守しにくく、投薬ミスを起こしやすく[43]、最初に医療を受けたと きの病状が重い[44][45]。 臨床医が伝える内容と、患者がその内容を理解する能力との間にミスマッチがあると、投薬ミスや不利な医療結果につながる。保健リテラシーのスキルは、一般 住民だけの問題ではない。ヘルスケアの専門家(医師、看護師、保健師)も、患者や一般市民に対して健康問題を明確に説明する能力が低いなど、ヘルスリテラ シーのスキルが低い場合がある[46][47]。医療専門家が患者に伝える内容を調整するだけでなく、うまく配置されたレイアウト、適切な図版、直感的な 書式で書かれた資料を作成することで、保健医療文献の使いやすさを向上させることができる。その結果、医療従事者と患者との効果的なコミュニケーションに 役立つことになる。 保健リテラシーの低さの結果には、保健サービスへの相対的な支出も含まれる。ヘルスリテラシーの低い人は健康状態が悪化しやすいため、医療サービスの利用 も増加する。この傾向は、貧困を含むヘルスリテラシーの低さの他の危険因子によってさらに悪化する。 [50] ホームレスや住宅不安は、健康状態の改善や健康状態の回復を妨げ、健康状態の悪化を引き起こす。 [51] このような場合、健康問題が長期化するため、様々な保健サービスが繰り返し利用される可能性がある [52] 。したがって、保健サービスに対する全体的な支出は、ヘルスリテラシーが低く健康状態が悪い集団でより大きくなる [53] 。これらの費用は、個人や家族の負担に任されて健康状態をさらに悪化させるか、あるいは様々な機関に委ねられる可能性があり、ひいては政府の財政や保健医 療制度に広範な影響を及ぼす。 保健リテラシーの低さは、医療費の3~5%、すなわち医療制度における1人当たり約143~7,798ドルの原因となっている[54]。 |

| Risk identification Identifying a patient as having low health literacy is essential for a healthcare professional to conform their health intervention in a way that the patient will understand. When patients with low health literacy receive care that is tailored to their more limited medical knowledge base, results have shown that health behaviors drastically improve. This has been seen with: correct medication use and dosage, utilizing health screenings, as well as increased exercise and smoking cessation. Effective visual aids have shown to help supplement the information communicated by the doctor in the office. In particular, easily readable brochures and videos have shown to be very effective.[55] Healthcare professionals can use many methods to attain patients' health literacy. A multitude of tests used during research studies and three minute assessments commonly used in doctors offices are examples of the variety of tests healthcare professionals can use to better understand their patients' health literacy.[45][56][57] Asking simple single-item questions, such as "How confident are you in filling out medical forms by yourself?", is a very effective and direct way to understand from a patient's point of view how they feel about interacting with their healthcare provider and understanding their health condition.[58] |

リスクの特定 ヘルスリテラシーの低い患者を特定することは、医療従事者が患者が理解できる方法で保健介入を行うために不可欠である。健康リテラシーの低い患者が、その 限られた医学的知識に合わせたケアを受けると、保健行動が劇的に改善することが示されている。これは、正しい薬の使用と服用、保健検診の利用、運動や禁煙 の増加などで見られる。効果的な視覚資料は、診察室で医師が伝える情報を補足するのに役立つことが示されている。特に、読みやすいパンフレットやビデオは 非常に効果的であることが示されている [55] 。調査研究で使用されるマルチチュード検査や、診察室で一般的に使用される3分間評価などは、医療専門家が患者の保健リテラシーをよりよく理解するために 使用できる様々な検査の例である[45][56][57]。 医療書類を自分で記入することにどの程度自信がありますか」というような簡単な単項目の質問をすることは、患者の視点から、医療提供者とのやりとりや自分 の保健状態を理解することについてどのように感じているかを理解するために、非常に効果的で直接的な方法である[58]。 |

| Homelessness Individuals facing homelessness constitute a population that holds intersectional identities, is highly mobile, and is often out of the public eye.[59] Thus the difficulty of conducting research on this group has resulted in little information regarding homelessness as a condition that has increased risk of low health literacy levels among individuals.[51] Nonetheless, studies that do exist indicate that homeless individuals experience increased prevalence of low health literacy and poor health—both physical and mental—due to vulnerabilities brought on by the insecurity of basic needs among homeless individuals.[60][51] The combination of poor health and homelessness has been found to increase the risk for further decline in health status and increased housing insecurity, all of which is highly affected by low levels of health literacy.[52] |

ホームレス ホームレス状態に直面している人々は、交差的なアイデンティティを持ち、移動が多く、人目に触れないことが多い集団である [59] 。そのため、この集団に関する研究を実施することが困難であり、個人の保健リテラシーレベルが低いリスクを高める状態としてのホームレス状態に関する情報 はほとんど得られていない。 51] [51] にもかかわらず、現存する研究は、ホームレス者の基本的ニーズの不安によってもたらされる脆弱性のために、ホームレス者は低いヘルスリテラシーの有病率が 増加し、身体的・精神的両方の健康不良を経験することを示している[60] [51] 。健康不良とホームレス状態の組み合わせは、健康状態のさらなる低下と住居不安の増加のリスクを増加させることがわかっており、これらはすべて低いヘルス リテラシーレベルによって大きな影響を受ける[52]。 |

| Intervention In order to be understood by patients with insufficient health literacy, health professionals must intervene to provide clear and concise information that can be more easily understood. Avoidance of medical jargon, illustrations of important concepts, and confirming information by a "teach back" method have shown to be effective tools to communicating essential health topics with health illiterate patients.[56] A program called "Ask Me 3"[57] is designed to bring public and physician attention to this issue, by letting patients know that they should ask three questions each time they talk to a doctor, nurse, or pharmacist: What is my main problem? What do I need to do? Why is it important for me to do this? There have also been large-scale efforts to improve health literacy. For example, a public information program by the US Department of Health and Human Services encourages patients to improve healthcare quality and avoid errors by asking questions about health conditions and treatment.[58] Additionally, the IROHLA (Intervention Research on Health Literacy of the Ageing population) project, funded by the European Union (EU), seeks to develop evidence-based guidelines for policy and practice to improve health literacy of the ageing population in EU member states.[61] The project has developed a framework and identified and validated interventions which together constitute a comprehensive approach of addressing health literacy needs of the elderly. |

介入 保健リテラシーが不十分な患者に理解してもらうためには、医療専門家が介入して、より理解しやすい明確で簡潔な情報を提供する必要がある。医療専門用語の 回避、重要な概念の図解、「ティーチバック」法による情報の確認は、保健リテラシーの低い患者に必要な保健トピックを伝えるための効果的な手段であること が示されている [56] 。「Ask Me 3」 [57] と呼ばれるプログラムは、患者に医師、看護師、薬剤師と話すたびに3つの質問をするよう知らせることで、この問題に一般の人々や医師の関心を集めることを 目的としている: 私の主な問題は何か? 私の主な問題は何か? なぜそのことが重要なのか? 保健リテラシーを向上させるための大規模な取り組みも行われている。例えば、米国保健福祉省による広報プログラムでは、患者が健康状態や治療について質問 することで、医療の質を向上させ、誤りを回避することを奨励している[58]。さらに、欧州連合(EU)の資金提供を受けたIROHLA (Intervention Research on Health Literacy of the Ageing population)プロジェクトでは、EU加盟国における高齢者の保健リテラシーを向上させるために、政策と実践のためのエビデンスに基づくガイドラ インの策定を目指している[61]。このプロジェクトでは、高齢者の保健リテラシーのニーズに取り組む包括的なアプローチを構成する枠組みを開発し、介入 策を特定・検証している。 |

| Impact on specific conditions Diabetes Low health literacy is associated with poorer knowledge of diabetes and leads to a lower quality self-management of the condition.[62] |

特定の疾患への影響 糖尿病 保健リテラシーの低さは、糖尿病に関する知識の乏しさと関連し、糖尿病の自己管理の質の低下につながる[62]。 |

| eHealth literacy eHealth literacy describes an individual's ability to search for, access, comprehend, and appraise desired health information from electronic sources and to then use such information to attempt to address a particular health problem.[63] It has become an important topic of research due to the increasing use of the internet for health information seeking and health information distribution. Stellefson (2011) states, "8 out of 10 Internet users report that they have at least once looked online for health information, making it the third most popular Web activity next to checking email and using search engines in terms of activities that almost everybody has done."[64] Though in recent years, individuals may have gained access to a multitude of health information via the Internet, access alone does not ensure that proper search skills and techniques are being used to find the most relevant online and electronic resources. As the line between a reputable medical source and an amateur opinion can often be blurred, the ability to differentiate between the two is important.[65] Health literacy requires a combination of several different literacy skills in order to facilitate eHealth promotion and care. Six core skills are delineated by an eHealth literacy model referred to as the Lily model. The Lily model's six literacies are organized into two central types: analytic and context-specific. Analytic type literacies are those skills that can be applied to a broad range of sources, regardless of topic or content (i.e., skills that can also be applied to shopping or researching a term paper in addition to health) whereas context-specific skills are those that are contextualized within a specific problem domain (can solely be applied to health). The six literacies are listed below, the first three of the analytic type and the latter three of the context-specific: Traditional literacy Media literacy Information literacy Computer literacy Scientific literacy Health literacy According to Norman (2006), both analytical and context-specific literacy skills are "required to fully engage with electronic health resources." As the World Wide Web and technological innovations are more and more becoming a part of the healthcare environment, it is important for information technology to be properly utilized to promote health and deliver health care effectively.The utilization of digital health information resources and the integration of digital interactions with healthcare providers offer significant advantages, with the potential to enhance healthcare system efficiency, quality, and accessibility, all while empowering patients.[66] It has also been suggested that the move towards patient-centered care and the greater use of technology for self-care and self-management requires higher health literacy on the part of the patient.[67] This has been noted in several research studies, for example among adolescent patients with obesity.[68] |

eヘルスリテラシー eヘルスリテラシーとは、電子的情報源から希望する保健情報を検索し、アクセスし、理解し、評価し、そのような情報を利用して個別的な健康問題に対処しよ うとする個人の能力のことである。Stellefson(2011)は、「インターネット利用者の10人中8人が、少なくとも一度は健康情報をオンライン で探したことがあると回答しており、ほぼすべての人が行ったことのある活動という点では、電子メールのチェックや検索エンジンの使用に次いで3番目に人気 のあるウェブ活動となっている」と述べている[64]。近年、個人はインターネットを介してマルチチュードの保健情報にアクセスできるようになったかもし れないが、アクセスできるだけでは、最も関連性の高いオンラインおよび電子リソースを見つけるために適切な検索スキルやテクニックが使用されていることを 保証するものではない。信頼できる医学的情報源と素人の意見との境界線が曖昧になることが多いため、両者を区別する能力は重要である[65]。 保健リテラシーは、eヘルス推進とケアを促進するために、いくつかの異なるリテラシー・スキルの組み合わせを必要とする。6つの中核となるスキルは、 Lilyモデルと呼ばれるeヘルスリテラシーモデルによって定義されている。Lilyモデルの6つのリテラシーは、2つの中心的なタイプに整理されてい る。分析型リテラシーとは、トピックや内容に関係なく、幅広い情報源に適用できるスキルである(つまり、保健だけでなく、ショッピングやタームペーパーの リサーチにも適用できるスキル)のに対し、文脈特化型スキルとは、特定の問題領域内で文脈化されたスキルである(保健だけに適用できる)。以下に6つのリ テラシーを挙げるが、最初の3つは分析型、後の3つは文脈特化型である: 伝統的リテラシー メディア・リテラシー 情報リテラシー コンピューター・リテラシー 科学リテラシー 保健リテラシー Norman(2006)によると、分析的リテラシーと文脈特異的リテラシー両方のスキルが、「電子保健資源を十分に活用するために必要である 」という。ワールド・ワイド・ウェブや技術革新が医療環境の一部となりつつある現在、情報技術を適切に活用し、健康を促進し、効果的に医療を提供すること が重要である。デジタル保健情報資源の活用と医療提供者とのデジタルインタラクションの統合は、患者に力を与えながら、医療システムの効率、質、アクセシ ビリティを向上させる可能性があり、大きな利点を提供する[66]。 また、患者中心のケアへの移行や、セルフケアや自己管理のためのテクノロジーの利用拡大には、患者側の保健リテラシーの向上が必要であることが示唆されている[67]。このことは、例えば思春期の肥満患者を対象としたいくつかの調査研究で指摘されている[68]。 |

| Improvement Incorporate information through the university level The United States Department of Health and Human Services created a National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy.[69] One of the goals of the National Action Plan is to incorporate health and science information in childcare and education through the university level. The target is to educate people at an early stage; that way individuals are raised with health literacy and will have a better quality of life. The earlier an individual is exposed to health literacy skills the better for the person and the community.[citation needed] Programs such as Head Start[70] and Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)[71] have impacted society, especially the low-income population. Head Start provides low-income children and their families early childhood education, nutrition, and health screenings. Health literacy is integrated in the program for both children and parents through the education given to the individuals. WIC serves low-income pregnant women and new mothers by supplying them with food, health care referrals, and nutrition education. Programs like these help improve the health literacy of both the parent and the child, creating a more knowledgeable community with health education. Although programs like Head Start and WIC have been working with the health literacy of a specific population, much more can be done with the education of children and young adults. Now, more adolescents are getting involved with their own health care, and education to make informed decisions. Many schools in the United States incorporate a health class in their curriculum. These classes are an opportunity to facilitate and develop health literacy in today's children and adolescents by teaching skills of how to read food labels, the meaning of common medical terms, the structure of the human body, and education on the most prevalent diseases in the United States. |

改善 大学レベルを通じて情報を取り入れる 米国保健社会福祉省は、「ヘルス・リテラシー向上のための国民行動計画」を策定した[69]。この国民行動計画の目標のひとつは、保育や大学レベルまでの 教育に保健や科学の情報を取り入れることである。目標は、早い段階で人民を教育することである。そうすることで、人民は保健リテラシーを身につけて育ち、 より質の高い生活を送ることができるようになる。保健リテラシーのスキルは、人格にとっても地域社会にとっても、早い時期に身につければつけるほどよい [要出典]。 ヘッドスタート[70]や女性・乳幼児・児童(WIC)[71]などのプログラムは、社会、特に低所得者層に影響を与えてきた。ヘッド・スタートは、低所 得層の子どもとその家族に幼児教育、栄養、保健検診を提供する。保健リテラシーは、個人への教育を通じて、子どもと親の双方にプログラムに組み込まれてい る。WICは、低所得の妊婦や新米母親を対象に、食事、保健ケアの紹介、栄養教育などを提供している。このようなプログラムは、親と子の両方の保健リテラ シーを向上させ、保健教育により知識の豊富な地域社会を作るのに役立っている。 ヘッドスタートやWICのようなプログラムは、特定の集団の保健リテラシーに取り組んできたが、子どもや若年成人の教育では、もっと多くのことができる。今、より多くの青少年が自分自身の保健ケアに関与し、情報に基づいた意思決定をするための教育を受けている。 米国の多くの学校では、カリキュラムに保健の授業が組み込まれている。これらの授業は、食品表示の読み方、一般的な医学用語の意味、人体の構造、米国で最 も流行している病気に関する教育などのスキルを教えることで、今日の子供や青少年の保健リテラシーを促進し、発達させる機会となっている。 |

| Framework and potential intervention points Three potential intervention points are culture and society, the health system, and the education system. Health outcomes and costs are the products of the health literacy developed during diversity of exposure to these three potential intervention points. While these potential intervention points include interactions such as those of individuals and the education systems that they are engaged with, their health systems, and societal factors as they relate to health literacy, these points are not components of a causal model. Cultural and societal influences are a significant intervention point for health literacy development, referring to shared ideas, meanings, and values that influence an individual's beliefs and attitudes. As interactions with healthcare systems often first occur at the family level, deeply rooted beliefs and values can shape the experience. Components that reflect the development of health literacy both culturally and societally are native language, socioeconomic status, gender, race, and ethnicity, as well as mass media exposure. The health system is an intervention point in the health literacy framework. For the purposes of this framework, health literacy refers to an individual's interaction with people performing health-related activities in settings such as hospitals, clinics, physician's offices, home health care, public health agencies, and insurers. In the United States, the education system consists of K–12 curricula. In addition to this standard educational setting, adult education programs allow individuals to develop traditional literacy skills founded in comprehension and real-world application of knowledge via reading and writing. Tools for educational development provided by these systems impact an individual's capacity to obtain specific knowledge regarding health. Reflecting components of traditional literacy such as cultural and conceptual knowledge, oral literacy (listening and speaking), print literacy (reading and writing), and numeracy, education systems are also potential intervention points for health literacy development. |

フレームワークと潜在的介入ポイント 3つの潜在的介入ポイントは、文化と社会、保健システム、教育システムである。保健のアウトカムとコストは、これら3つの潜在的介入ポイントに多様にさら される中で培われた保健リテラシーの産物である。これらの潜在的介入点には、ヘルスリテラシーに関連する個人とその教育システム、保健システム、社会的要 因などの相互作用が含まれるが、これらの点は因果関係モデルの構成要素ではない。 文化的・社会的影響は、保健リテラシーの発達にとって重要な介入点であり、個人の信念や態度に影響を与える共有された考え方、意味、価値観を指す。医療制 度との相互作用はしばしば家族レベルで最初に起こるため、深く根ざした信念や価値観が経験を形成する可能性がある。文化的・社会的に保健リテラシーの発達 を反映する要素としては、母国語、社会経済的地位、性別、人種、民族性、マスメディアへの露出などがある。 保健システムは、ヘルスリテラシーの枠組みにおける介入ポイントである。この枠組みでは、ヘルスリテラシーとは、病院、診療所、医院、在宅医療、公衆衛生機関、保険会社など、保健に関連した活動を行う人民と個人の相互作用を指す。 米国では、教育システムは幼稚園から高校までのカリキュラムで構成されている。この標準的な教育環境に加え、成人教育プログラムでは、読み書きを通して、 理解力と知識の実社会での応用に基づいた伝統的な読み書き能力を身につけることができる。このような制度によって提供される教育的発達のためのツールは、 保健に関する特定の知識を得る個人の能力に影響を与える。文化的・概念的知識、オーラルリテラシー(聞くこと・話すこと)、活字リテラシー(読むこと・書 くこと)、数的能力といった伝統的リテラシーの構成要素を反映した教育システムは、保健リテラシー育成のための潜在的介入ポイントでもある。 |

| Development of a health literacy program A successful health literacy program will have many goals that all work together to improve health literacy. Many people assume these goals should communicate health information to the general public; however, in order to be successful, the goals should not only communicate with people but also take into account social and environmental factors that influence lifestyle choices.[72] A good example of this is the movement to end smoking. When a health literacy program is put into place where only the negative side effects of smoking are told to the general public it is doomed to fail. However, when there is a larger program put in – one that includes strategies outlining how to quit smoking, raises tobacco prices, reduces access to tobacco by minors, and reflects the social unacceptability of smoking – it will be much more effective.[72] The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services suggests a National Action Plan to implement a comprehensive Health Literacy Program. They include seven goals:[73] Develop and disseminate health and safety information that is accurate, accessible, and actionable Promote changes in the health care system that improve health information, communication, informed decision making, and access to health services Incorporate accurate, standards-based, and developmentally appropriate health and science information and curricula in child care and education through the university level Support and expand local efforts to provide adult education, English language instruction, and culturally and linguistically appropriate health information services in the community Build partnerships, develop guidance, and change policies Increase basic research and the development, implementation, and evaluation of practices and interventions to improve health literacy Increase the dissemination and use of evidence-based health literacy practices and interventions These goals should be taken into account when implementing a health literacy program. The goals for the outcomes of a Health Literacy Program are:[15] Promoting and protect health and prevent disease Understand, interpret, and analyze health information Apply health information over a variety of life events and situations Navigate the healthcare system Actively participate in encounters with healthcare professionals and workers Understand and give consent Understand and advocate for rights In the creation of a program, it is also important to ensure that all parties involved in health contexts are on the same page. To do this, programs may choose to include the training of case managers, health advocates, and even doctors and nurses.[74][75][76] Due to the common overestimations of health literacy levels of patients, the education of health literacy topics and training in the identification of low health literacy in patients may be able to create significant positive change in the understanding of health messages.[77] The health belief model has been used in the training of health professionals in order to share insight on the knowledge that it has been shown to most likely change health perceptions and behaviors of their patients.[74] The use of the health belief model can provide basis for which patient health literacy may grow. The training of health workers may be seen as a "work around intervention" but is still a viable option and opportunity for mediating the negative outcomes of low health literacy.[75] Effective health literacy programs are created with cultural competency, and individuals working within health institutions can support individuals with low health literacy by being culturally competent themselves.[78] In working to improve the health literacy of individuals, a multitude of approaches may be taken. Systematic reviews of studied interventions reveal that one works to improve health literacy in one patient may not work for another patient.[79] In fact, some interventions were found to worse health literacy in individuals.[79] Nonetheless, studies have illuminated general approaches that help individuals understand health messages. A review of 26 studies concluded that "intensive mixed-strategy interventions focusing on self-management" and "theory basis, pilot testing, emphasis on skill building, and delivery by a health professional" do aid in increasing levels of health literacy among patients.[79] Another study revealed that programs aimed at targeting more than one behavior through increased health literacy are no less successful than programs with a single focus.[80] The importance of dignity and respect is emphasized when creating programs for increasing health literacy of vulnerable individuals.[79] In intervention programs created for homeless individuals in specific, it has been found that "successful intervention programs use aggressive outreach to bring comprehensive social and health services to sites where homeless people congregate and allow clients to set the limits and pace of engagement".[81] A social justice model is recommended for homeless individuals which is based on shared support of the community and their health literacy needs by those who provide services for this underserved group as well as the professionals who create and implement health literacy interventions.[51] |

保健リテラシー・プログラムの開発 成功するヘルスリテラシー・プログラムは、ヘルスリテラシーの向上を目指す多くの目標を持つ。多くの人は、これらの目標は一般の人々に保健情報を伝えるも のだと考えている。しかし、成功させるためには、目標は人民とのコミュニケーションだけでなく、ライフスタイルの選択に影響を与える社会的・環境的要因も 考慮に入れるべきである。一般の人々に喫煙の悪影響だけを伝える保健リテラシー・プログラムを実施した場合、それは失敗する運命にある。しかし、禁煙の方 法を概説する戦略、タバコの値上げ、未成年者のタバコへのアクセスの減少、喫煙の社会的許容性の低さを反映したものなど、より大規模なプログラムが実施さ れれば、それははるかに効果的なものとなる[72]。 米国保健福祉省は、包括的な保健リテラシー・プログラムを実施するための国民行動計画を提案している。それには次の7つの目標が含まれている[73]。 正確で、利用しやすく、実行可能な保健と安全に関する情報を開発し、広める。 保健情報、コミュニケーション、十分な情報に基づいた意思決定、保健サービスへのアクセスを改善するために、保健医療システムの変化を促進する。 大学レベルまでの保育・教育に、正確で、標準に基づいた、発達段階に適した保健と科学に関する情報とカリキュラムを取り入れる。 成人教育、英語教育、文化的・言語的に適切な保健情報サービスを地域で提供する取り組みを支援し、拡大する。 パートナーシップを築き、指導を発展させ、政策を変える。 保健リテラシーを向上させるための基礎研究、実践や介入策の開発、実施、評価を増加させる。 証拠に基づく保健リテラシーの実践と介入策の普及と利用を促進する。 これらの目標は、保健リテラシー・プログラムを実施する際に考慮されるべきである。 保健リテラシー・プログラムの成果に関する目標は以下の通りである [15] 。 保健を促進し、守り、疾病を予防する。 保健情報を理解し、解釈し、分析する。 保健情報をさまざまなライフイベントや状況に適用する。 医療制度を利用する 医療専門家や医療従事者との出会いに積極的に参加する。 同意について理解し、同意する 権利を理解し擁護する プログラムの作成においては、保健に関わるすべての関係者が同じ見解を持つようにすることも重要である。74][75][76]患者の健康リテラシーレベ ルは過大評価されがちであるため、健康リテラシーに関するトピックの教育や、患者の健康リテラシーの低さを識別する訓練を行うことで、保健メッセージの理 解に大きなプラスの変化をもたらすことができる可能性がある。 [77] 健康信念モデルは、患者の健康に対する認識と行動を変える可能性が最も高いことが示されている知識に関する洞察を共有するために、医療従事者の訓練に用い られている [74] 。保健ワーカーの訓練は「回避的介入」とみなされるかもしれないが、低いヘルスリテラシーの否定的な結果を媒介するための実行可能な選択肢であり機会であ る [75] 。 個人の保健リテラシーの向上に取り組む際には、マルチチュードなアプローチがとられうる。研究された介入に関する系統的レビューでは、ある患者のヘルスリ テラシーを向上させるために有効なものが、別の患者には有効でないことが明らかにされている。26の研究のレビューでは、「自己管理に焦点を当てた集中的 な混血の戦略的介入」と「理論的根拠、パイロットテスト、スキル構築の重視、医療専門家による実施」は、患者のヘルスリテラシーのレベルを高めるのに役立 つと結論づけている [79] 。別の研究では、ヘルスリテラシーの向上を通じて複数の行動を標的とすることを目的としたプログラムは、単一の焦点を当てたプログラムよりも成功率が低い わけではないことが明らかにされている [80] 。 [79] 特にホームレスの人々のために作成された介入プログラムでは、「成功する介入プログラムは、ホームレスの人々が集まる場所に包括的な社会的・保健的サービ スをもたらすために積極的なアウトリーチを用い、クライエントが関与の限界とペースを設定できるようにしている」ことが明らかにされている [81] 。ホームレスの人々に対しては、保健リテラシーの介入を作成・実施する専門家だけでなく、この十分なサービスを受けていない集団にサービスを提供する人々 による地域社会と彼らの保健リテラシーのニーズの共有支援に基づく社会正義モデルが推奨されている [51] 。 |

| Role of libraries Through their mission to provide access to knowledge, libraries play an important role in health literacy. Wide and open access to health information is a prerequisite for being able to understand and use that information, and libraries often advocate for and provide access to these resources. Libraries also function as trusted social spaces where people can discuss and inquire about information related to health.[82] By helping people access and understand reliable, high-quality health information, librarians can contribute to improving people's health literacy.[83] Public libraries have increasingly recognized that they can play a role in health literacy. Initiatives by libraries that focused on health literacy have included running educational programs, fostering partnerships with health organizations, computer training for older adults, and using outreach efforts.[83] Library outreach often addresses underrepresented or vulnerable groups who have a higher risk of certain diseases and a lower general level of health literacy. Health literacy efforts for these groups by public libraries include translating health information for and facilitating potentially different cultural attitudes of refugees and immigrant populations, and reaching out to low-income and uninsured people.[83] Medical libraries located in healthcare or higher education settings work with healthcare professionals, medical students, and patients. Health literacy efforts by medical librarians can include raising awareness of the barriers of health literacy faced by patients, and training professionals in communication strategies they might require such as active listening and the use of plain language.[83] Medical librarians can also support medical students and people participating in continuing professional development in tasks that require information literacy skills, such as retrieving biomedical literature and practicing evidence-based medicine.[84][85] Various medical libraries have made an effort to introduce health literacy programs by attempting to define the concept to include the librarian's role as including a set of abilities needed to recognize a health information need, identify likely information sources and use them to retrieve relevant information, and assess the quality of the information and its applicability to a specific health situation.[83] |

図書館の役割 知識へのアクセスを提供するという使命を通して、図書館は保健リテラシーにおいて重要な役割を果たしている。保健情報への広く開かれたアクセスは、その情 報を理解し利用できるようになるための前提条件であり、図書館はしばしばこれらの資源へのアクセスを擁護し提供する。図書館はまた、人々が健康に関連する 情報について議論したり問い合わせたりできる信頼できる社会的空間としても機能している[82]。人々が信頼できる質の高い保健情報にアクセスして理解す るのを助けることによって、図書館員は人々の保健リテラシーの向上に貢献することができる[83]。 公共図書館は、保健リテラシーにおいて役割を果たすことができると認識するようになってきている。保健リテラシーに重点を置いた図書館の取り組みには、教 育プログラムの運営、保健機関とのパートナーシップの育成、高齢者のためのコンピュータ研修、アウトリーチ活動の利用などがある[83]。図書館のアウト リーチ活動は、特定の疾患のリスクが高く、一般的な保健リテラシーのレベルが低い、社会的地位の低いグループや社会的弱者を対象とすることが多い。公共図 書館によるこれらのグループに対する保健リテラシーの取り組みには、難民や移民集団の潜在的に異なる文化的態度のための保健情報の翻訳や促進、低所得者や 無保険者への働きかけなどがある[83]。 ヘルスケアや高等教育の場にある医療図書館は、ヘルスケア専門家、医学生、患者と協力している。医療図書館員による保健リテラシーの取り組みには、患者が 直面する保健リテラシーの障害に対する認識を高めることや、積極的傾聴や平易な言葉の使用など、専門家が必要とするコミュニケーション戦略のトレーニング が含まれる[83]。医療図書館員はまた、生物医学文献の検索やエビデンスに基づく医療の実践など、情報リテラシーのスキルを必要とする作業において、医 学生や継続的専門能力開発に参加している人民を支援することができる[84][85]。 様々な医学図書館が、保健情報の必要性を認識し、情報源となりそうなものを特定し、関連する情報を検索するためにそれらを使用し、情報の質と特定の保健状 況への適用可能性を評価するために必要な一連の能力を含む図書館員の役割を含む概念として定義することを試みることによって、保健リテラシー・プログラム を導入する努力をしている[83]。 |

| Alternative approaches A study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2018 suggested an alternative method of addressing health knowledge deficits due to low health literacy. This alternative method is the use of "culturally-related/accepted" music and singing amongst low-literacy populations. In the example of this study, the music with locally written song lyrics of health messages was shown to increase maternal health knowledge, and more specifically, antenatal care.[86] |

代替アプローチ 2018年にAmerican Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology誌に発表された研究では、ヘルスリテラシーの低さによる保健知識の欠損に対処する代替法が示唆された。この代替方法とは、リテラシー の低い集団の間で「文化的に関連/受容された」音楽や歌を使用することである。この研究の例では、保健メッセージの歌詞が地元で書かれた音楽が、妊産婦の 保健知識、より具体的には妊産婦ケアを高めることが示された[86]。 |

| History The field of health literacy emerged from two groups of experts: physicians, health providers such as nurses[87] and health educators; and Adult Basic Education (ABE) and English as a second language (ESL) practitioners in the field of education. Physicians and nurses are a source of patient comprehension and compliance studies. Adult Basic Education / English for Speakers of Languages Other Than English (ABE/ESOL) specialists study and design interventions to help people develop reading, writing, and conversation skills and increasingly infuse curricula with health information to promote better health literacy. A range of approaches to adult education brings health literacy skills to people in traditional classroom settings, as well as where they work and live.[citation needed] |

歴史 ヘルスリテラシーの分野は、医師、看護師[87]、保健教育者などの保健提供者、そして教育分野の成人基礎教育(ABE)や第二言語としての英語 (ESL)の実践者という2つの専門家グループから生まれた。医師や看護師は、患者の理解度やコンプライアンス研究の情報源である。成人基礎教育/英語以 外の言語を話す人のための英語(ABE/ESOL)の専門家は、人民が読み書きや会話のスキルを身につけるのを助けるための介入策を研究・設計し、より良 い保健リテラシーを促進するために、カリキュラムに保健情報を盛り込むことが増えている。成人教育へのさまざまなアプローチによって、従来の教室での授業 だけでなく、仕事や生活の場でも、人民の保健リテラシー・スキルが身につくようになっている[要出典]。 |

| Biomedical approach The biomedical approach to health literacy that became dominant in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s often depicted individuals as lacking health literacy or "suffering" from low health literacy. This approach assumed that recipients are passive in their possession and reception of health literacy and believed that models of literacy and health literacy are politically neutral and universally applicable. This approach is found lacking when placed in the context of broader ecological, critical, and cultural approaches to health. This approach has produced, and continues to reproduce, numerous correlational studies.[88] |

生物医学的アプローチ 1980年代から1990年代にかけて米国で主流となった保健リテラシーに対する生物医学的アプローチは、しばしば個人を保健リテラシーが欠如している、 あるいは低い保健リテラシーに「苦悩」していると描いた。このアプローチは、受け手が保健リテラシーを持ち、それを受け取ることに受動的であることを前提 としており、リテラシーと保健リテラシーのモデルは政治的に中立で普遍的に適用可能であると信じていた。このアプローチは、保健に対するより広範な生態学 的、批判的、文化的アプローチの文脈に置くと、欠けていることがわかる。このアプローチは、数多くの相関研究を生み出し、現在も再現し続けている [88] 。 |

| Global health Health promotion Mental health literacy mHealth Numeracy § Innumeracy and risk perception in health decision-making (Health numeracy) Nutrition § Nutrition literacy Occupational safety and health literacy Patient safety Universal health care |

グローバル保健 保健 メンタルヘルスリテラシー mヘルス 数的リテラシー § 健康上の意思決定における無数値性とリスク認知 (保健数的リテラシー) 栄養§ 栄養リテラシー 労働安全衛生と保健リテラシー 患者の安全 ユニバーサル・ヘルスケア |

| Nutbeam, D. (2000). "Health

literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health

education and communication strategies into the 21st century". Health

Promotion International. 15 (3): 259–267. doi:10.1093/heapro/15.3.259. Pleasant, A.; Kuruvilla, S. (2008). "A tale of two health literacies? Public health and clinical approaches to health literacy". Health Promot Int. 23 (2). Health Promotion International: 152–9. doi:10.1093/heapro/dan001. PMID 18223203. Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved Feb 28, 2008. Ratzan S. C. (2001). "Health literacy: Communication for the public good". Health Promotion International. 16 (2): 207–214. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.2.207. PMID 11356759. Rootman, I. & Wharf-Higgins, J. (2007), Literacy and Health: Implications for Active Living (PDF), WellSpring, p. 4 "Health Literacy Improvement". health.gov. July 24, 2008. Archived from the original on June 11, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2017. Rudd, R., Moeykens, B. Colton, TC. (1999). Health and literacy: A review of medical and public health literature. In J. Comings, B. Garners, & C. Smith, eds. Annual Review of Adult Learning and Literacy, Volume I. New York, NY: Jossey-Bass. Zarcadoolas C.; Pleasant A.; Greer D. (2005). "Understanding health literacy: An expanded model". Health Promotion International. 20 (2): 195–203. doi:10.1093/heapro/dah609. PMID 15788526. Zarcadoolas, C., Pleasant, A., & Greer, D. (2006). Advancing health literacy: A framework for understanding and action. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA. |

Nutbeam, D. (2000).

「公衆衛生の目標としての保健リテラシー:21世紀に向けた現代の保健教育とコミュニケーション戦略の課題」. Health Promotion

International. 15 (3): 259–267. doi:10.1093/heapro/15.3.259. Pleasant, A.; Kuruvilla, S. (2008). 「二つの保健リテラシーの物語?保健リテラシーに対する公衆衛生と臨床のアプローチ」. Health Promot Int. Health Promot International: 152-9. doi:10.1093/heapro/dan001. PMID 18223203. 2008-10-07にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2008年2月28日取得。 Ratzan S. C. (2001). 「保健リテラシー: 公共の利益のためのコミュニケーション」. Health Promotion International. 16 (2): 207–214. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.2.207. PMID 11356759. Rootman, I. & Wharf-Higgins, J. (2007), Literacy and Health: アクティブな生活への示唆(PDF), WellSpring, p. 4 「Health Literacy Improvement」. health.gov. 2008年7月24日。2018年6月11日に原文からアーカイブされた。2017年3月26日取得。 Rudd, R., Moeykens, B. Colton, TC. (1999). 保健とリテラシー: 医学・公衆衛生文献のレビュー。J. Comings, B. Garners, & C. Smith, eds. Annual Review of Adult Learning and Literacy, Volume I. New York, NY: Jossey-Bass. Zarcadoolas C.; Pleasant A.; Greer D. (2005). 「保健リテラシーを理解する: 拡大モデル」. 保健推進インターナショナル。20 (2): 195–203. doi:10.1093/heapro/dah609. PMID 15788526. Zarcadoolas, C., Pleasant, A., & Greer, D. (2006). 保健リテラシーの向上: A framework for understanding and action. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_literacy |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

cc

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆