エロイーズとピーター・アベラーズ

Héloïse and Peter Abelard

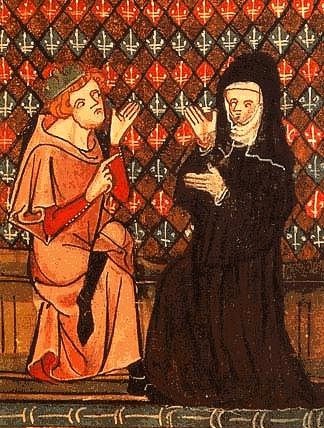

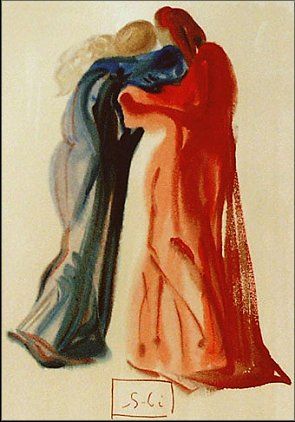

Abelard and Heloise, in a manuscript of the Roman de la Rose (14th century)// Salvador Dalí, Painting of Abelard and Heloise // L'amour de Pierrot- Salvador Dalí, 1920.

☆ エロイーズ(Héloïse) は著名な「文人」であり、愛と友情の哲学者であり、カトリック教会の高位修道院長でもあった。彼女は1147年にヌリウス司教の位を与えられ、司教の地位 と政治的権力を獲得した。中世を代表する論理学者であり神学者であったピーター・アベラールとの恋愛と文通で歴史的にも大衆文化的にも有名であり、アベ ラールは彼女の同僚、協力 者、夫となった。彼女は彼の研究に批判的な知的影響を及ぼし、『ヘロイッサーの問題』(Problemata Heloissae)にあるような多くの挑戦的な問いを彼に投げかけたことで知られている。エロイーズは、学問における女性表象の確立において重要な人物 であり、ジェンダーと結婚に関する論争的な描写で知られ、近代フェミニズムの発展に影響を与えた。

★

ピーター・アベラール(Peter

Abelard)は、中世フランスのスコラ哲学者、代表的な論理学者、神学者、詩人、作曲家、音楽家[4]。

哲学においては、名辞論と概念論による普遍の問題の論理的解決と倫理学における意図の開拓で有名である。しばしば「12世紀のデカルト」と呼ばれ、ル

ソー、カント、スピノザの先駆者と考えられている。

歴史や大衆文化においては、優秀な学生であり、最終的に妻となったエロイーズ・ダルジャントゥイユとの情熱的で悲劇的な恋愛と激しい哲学的交流で最もよく

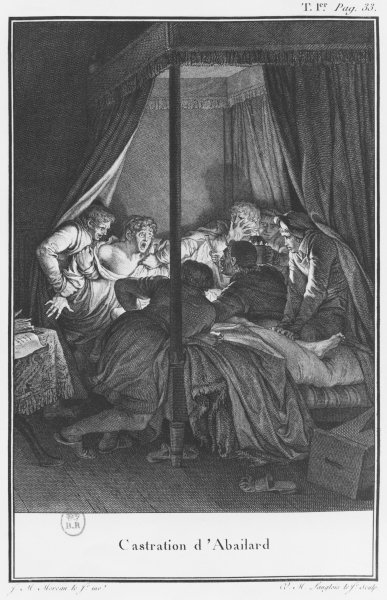

知られている。彼は女性とその教育の擁護者であった。エロイーズをブルターニュの修

道院に送ったのは、彼女に禁断の恋をさせたくない叔父から彼女を守るためだったが、叔父の差し向けた男たちに去勢されてしまう。エロイーズは、アベラール

の教義が教皇イノセント2世によって非難され、アベラールが異端視された際にも、アベラールの配偶者としてアベラールを擁護した。これらの意見の中で、ア

ベラールは愛ゆえに罪を犯した女性の潔白を公言した。

カトリック神学では、虚無の概念を発展させたこと、贖罪の道徳的影響説を導入したことで知られる。彼は(ヒッポのアウグスティヌスと並んで)近代的な自省

的自叙伝作家の最も重要な先駆者であると考えられている。彼は、公に配布された書簡『わが災難の歴史』や公開書簡によって、後の書簡小説や

有名人の告白の道を開き、その基調を作った。

法学においてアベラールは、主観的意図が人間の行為の道徳的価値を決定するため、行

為の法的帰結は単に行為に関係するのではなく、それを犯した人間に関係すると強調した。この教義によって、アベラールは中世に近代法の中心となる個人主体の思想を生み出した。これによ

り、ノートルダム・ド・パリ学校(後のパリ大学)は、法学分野におけるその専門性を認められることになった(後にパリ法学部の創設につながった)。

| Héloïse

(French: [elɔ.iz]; c. 1100–01?[1] – 16 May 1163–64?), variously Héloïse

d'Argenteuil[2] or Héloïse du Paraclet,[2] was a French nun,

philosopher, writer, scholar, and abbess. Héloïse was a renowned "woman of letters" and philosopher of love and friendship, as well as an eventual high-ranking abbess in the Catholic Church. She achieved approximately the level and political power of a bishop in 1147 when she was granted the rank of prelate nullius.[3][4] She is famous in history and popular culture for her love affair and correspondence with the leading medieval logician and theologian Peter Abelard, who became her colleague, collaborator and husband. She is known for exerting critical intellectual influence upon his work and posing many challenging questions to him such as those in the Problemata Heloissae.[5] Her surviving letters are considered a foundation of French and European literature and primary inspiration for the practice of courtly love. Her erudite and sometimes erotically charged correspondence is the Latin basis for the bildungsroman genre and serve alongside Abelard's Historia Calamitatum as a model of the classical epistolary genre. Her influence extends on later writers such as Chrétien de Troyes, Geoffrey Chaucer, Madame de Lafayette, Thomas Aquinas, Choderlos de Laclos, Voltaire, Rousseau, Simone Weil, and Dominique Aury. She is an important figure in the establishment of women's representation in scholarship and is known for her controversial portrayals of gender and marriage which influenced the development of modern feminism. |

エロイーズ(フランス語: [elɔ.iz];

1100-01年頃[1] - 1163-64年5月16日? エロイーズは有名な「文人」であり、愛と友情の哲学者であり、カトリック教会の高位修道院長でもあった。彼女は1147年にヌリウス司教の位を与えられ、 司教の地位と政治的権力を獲得した[3][4]。 中世を代表する論理学者であり神学者であったピーター・アベラールとの恋愛と文通で歴史的にも大衆文化的にも有名であり、アベラールは彼女の同僚、協力 者、夫となった。彼女は彼の研究に批判的な知的影響を及ぼし、『ヘロイッサーの問題』(Problemata Heloissae)にあるような多くの挑戦的な問いを彼に投げかけたことで知られている[5]。 現存する彼女の書簡は、フランスおよびヨーロッパ文学の基礎であり、宮廷恋愛の実践のための主要なインスピレーションであると考えられている。博学で、時 にエロティックな彼女の書簡は、ビルドゥングスロマンというジャンルのラテン語の基礎であり、アベラールの『ヒストリア・カラミタトゥム』と並んで、古典 的な書簡というジャンルのモデルとなっている。彼女の影響は、クレティアン・ド・トロワ、ジェフリー・チョーサー、ラファイエット夫人、トマス・アクィナ ス、ショデルロ・ド・ラクロス、ヴォルテール、ルソー、シモーヌ・ヴァイル、ドミニク・オーリーといった後世の作家にまで及んでいる。 学問における女性表象の確立において重要な人物であり、ジェンダーと結婚に関する論争的な描写で知られ、近代フェミニズムの発展に影響を与えた。 |

| Name Héloïse is variously spelled Heloise, Helöise, Héloyse, Hélose, Heloisa, Helouisa, Eloise, and Aloysia. Her first name is probably a feminization of Eloi, the French form of Saint Eligius, a Frankish goldsmith, bishop, and courtier under Dagobert I much venerated in medieval France. Some scholars alternatively derive it from Proto-Germanic reconstructed as *Hailawidis, from *hailagaz ("holy") or *hailaz ("healthy") and *widuz ("wood, forest"). The details of her family and original surname are unknown. She is sometimes called Heloise of Argenteuil (Héloïse d'Argenteuil) from her childhood convent or Heloise of the Paraclete (Héloïse du Paraclet) from her midlife appointment as abbess of the convent of the Paraclete near Troyes, France. |

名前 Héloïseは、Heloise、Helöise、Héloyse、Hélose、Heloisa、Helouisa、Eloise、Aloysiaな ど様々な綴りがある。彼女のファーストネームは、中世フランスで崇拝されていたダゴベール1世治下のフランク王国の金細工師、司教、廷臣であった聖エリギ ウスのフランス語表記であるエロイの女性化であろう。この語は、*Hailagaz(「聖なる」)または*hailaz(「健康な」)と*widuz (「木、森」)から*Hailawidisとして再構築された原ゲルマン語に由来するという説もある。彼女の家系や元の姓の詳細は不明である。幼少期の修 道院の名前からアルジャントゥイユのヘロワーズ(Héloïse d'Argenteuil)と呼ばれたり、中年期にフランスのトロワ近郊にあるパラクレ修道院の院長に任命されたことからパラクレのヘロワーズ (Héloïse du Paraclet)と呼ばれることもある。 |

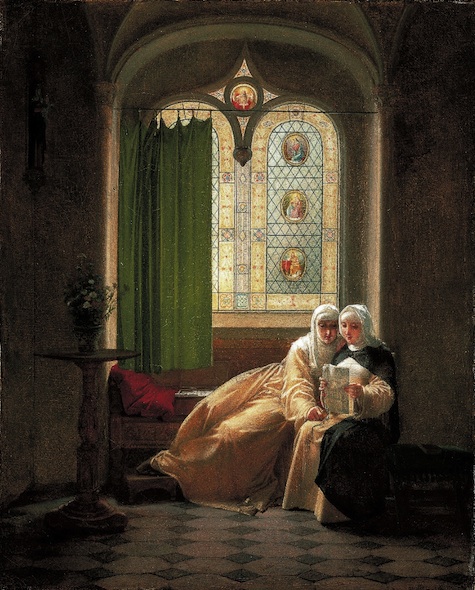

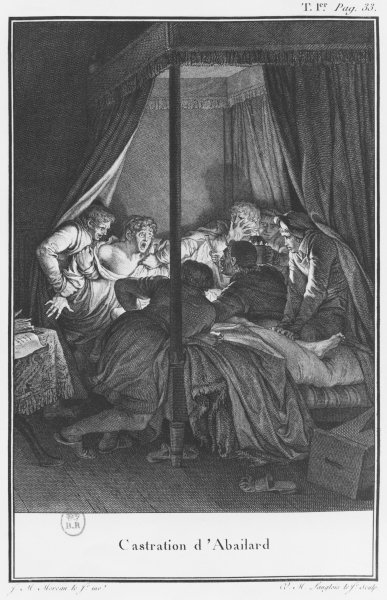

| Life Background and education Early in life, Héloïse was recognized as a leading scholar of Latin, Greek and Hebrew hailing from the convent of Argenteuil just outside Paris, where she was educated by nuns until adolescence. She was already renowned for her knowledge of language and writing when she arrived in Paris as a young woman,[6] and had developed a reputation for intelligence and insight. Abélard writes that she was nominatissima, "most renowned" for her gift in reading and writing. She wrote poems, plays and hymns, some of which have been lost. Her family background is largely unknown. She was the ward of her maternal uncle (avunculus) Canon Fulbert of Notre Dame and the daughter of a woman named Hersinde, who is sometimes speculated to have been Hersint of Champagne (Lady of Montsoreau and founder of the Fontevraud Abbey) or possibly a lesser known nun called Hersinde at the convent of St. Eloi (from which the name "Heloise" would have been taken).[7][8] In her letters she implies she is of a lower social standing than Peter Abélard, who was originally from the lower nobility, though he had rejected knighthood to be a philosopher.[9] Speculation that her mother was Hersinde of Champagne/Fontrevaud and her father Gilbert Garlande contests with Heloise's depiction of herself as lower class than Abelard. Hersinde of Champagne was of lower nobility, and the Garlandes were from a higher social echelon than Abelard and served as his patrons. The Hersinde of Champagne theory is further complicated by the fact that Hersinde of Champagne died in 1114 between the ages of 54 and 80, implying that she would have had to have given birth to Heloise between the ages of 35 and 50. What is known for sure is that her Uncle Fulbert, a canon of Notre Dame collected her to Notre Dame from her childhood home in Argentuil.[10] By her mid teens to early twenties, she was renowned throughout France for her scholarship. While her birth year is disputed, she is traditionally held to be about 15 to 17 when meeting Abelard. By the time she became his student, she was already of high repute herself.[11][12] As a poetic and highly literate prodigy of female sex familiar with multiple languages, she attracted much attention, including the notice of Peter the Venerable of Cluny, who notes that he became aware of her acclaim when he and she were both young. She soon attracted the romantic interest of celebrity scholar Peter Abelard. Heloise is said to have gained knowledge in medicine or folk medicine from either Abelard[13] or his kinswoman Denise and gained reputation as a physician in her role as abbess of Paraclete. Meeting Abelard  Jean-Baptiste Goyet, Héloïse et Abailard, oil on copper, c. 1829. In his autobiographical piece and public letter Historia Calamitatum (c. 1132?), Abélard tells the story of his relationship with Héloïse, whom he met in 1115, when he taught in the Paris schools of Notre Dame. Abelard describes their relationship as beginning with a premeditated seduction, but Heloise contests this perspective adamantly in her replies. (It is sometimes speculated that Abelard may have presented the relationship as fully of his responsibility in order to justify his later punishment and withdrawal to religion and/or in order to spare Heloise's reputation as an abbess and woman of God.)[14] Heloise contrastingly in the early love letters depicts herself as the initiator, having sought Abelard herself among the thousands of men in Notre Dame and chosen him alone as her friend and lover.[15] In his letters, Abelard praises Heloise as extremely intelligent and just passably pretty, drawing attention to her academic status rather than framing her as a sex object: "She is not bad in the face, but her copious writings are second to none."[16] He emphasizes that he sought her out specifically due to her literacy and learning, which was unheard of in most un-cloistered women of his era. It is unclear how old Héloïse was at the time they became acquainted. During the twelfth century in France, the typical age at which a young person would begin attending university was between the ages of 12 and 15.[17] As a young female, Heloise would have been forbidden from fraternizing with the male students or officially attending university at Notre Dame. With university education offered only to males, and convent education at this age reserved only for nuns, this age would have been a natural time for her uncle Fulbert to arrange for special instruction. Heloise is described by Abelard as an adolescentula (young girl). Based on this description, she is typically assumed to be between fifteen and seventeen years old upon meeting him and thus born in 1100–01.[1] There is a tradition that she died at the same age as did Abelard (63) in 1163 or 1164. The term adolescent, however, is vague, and no primary source of her year of birth has been located. Recently, as part of a contemporary investigation into Heloise's identity and prominence, Constant Mews has suggested that she may have been so old as her early twenties (and thus born around 1090) when she met Abelard.[18] The main support for his opinion, however, is a debatable interpretation of a letter of Peter the Venerable (born 1092) in which he writes to Héloïse that he remembers that she was famous when he was still a young man. Constant Mews assumes he must have been talking about an older woman given his respect for her, but this is speculation. It is just as likely that a female adolescent prodigy amongst male university students in Paris could have attracted great renown and (especially retrospective) praise. It is at least clear that she had gained this renown and some level of respect before Abelard came onto the scene. Romantic liaison In lieu of university studies, Canon Fulbert arranged for Heloise's private tutoring with Peter Abelard, who was then a leading philosopher in Western Europe and the most popular secular canon scholar (professor) of Notre Dame. Abelard was coincidentally looking for lodgings at this point. A deal was made—Abelard would teach and discipline Heloise in place of paying rent. Abelard tells of their subsequent illicit relationship, which they continued until Héloïse became pregnant. Abelard moved Héloïse away from Fulbert and sent her to his own sister, Denise,[19] in Brittany, where Héloïse gave birth to a boy, whom she called Astrolabe (which is also the name of a navigational device that is used to determine a position on Earth by charting the position of the stars).[20] Abelard agreed to marry Héloïse to appease Fulbert, although on the condition that the marriage should be kept secret so as not to damage Abélard's career. Heloise insisted on a secret marriage due to her fears of marriage injuring Abelard's career. Likely, Abelard had recently joined Religious Orders (something on which scholarly opinion is divided), and given that the church was beginning to forbid marriage to priests and the higher orders of clergy (to the point of a papal order re-affirming this idea in 1123),[21] public marriage would have been a potential bar to Abelard's advancement in the church. Héloïse was initially reluctant to agree to any marriage, but was eventually persuaded by Abelard.[22] Héloïse returned from Brittany, and the couple was secretly married in Paris. As part of the bargain, she continued to live in her uncle's house. Tragic turn of events  Heloise takes the habit at Argenteuil Fulbert immediately went back on his word and began to spread the news of the marriage. Héloïse attempted to deny this, arousing his wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at Argenteuil, where she had been brought up. Héloïse dressed as a nun and shared the life of the nuns, though she was not veiled. Fulbert, infuriated that Heloise had been taken from his house and possibly believing that Abelard had disposed of her at Argenteuil in order to be rid of her, arranged for a band of men to break into Abelard's room one night and castrate him. In legal retribution for this vigilante attack, members of the band were punished, and Fulbert, scorned by the public, took temporary leave of his canon duties (he does not appear again in the Paris cartularies for several years).[23] After castration,[24] filled with shame at his situation, Abélard became a monk in the Abbey of St Denis in Paris. At the convent in Argenteuil, Héloïse took the veil. She quoted from Cornelia's speech in Lucan's Pharsalia: "Why did I marry you and bring about your fall? Now...see me gladly pay."[25] It is commonly portrayed that Abelard forced Heloise into the convent due to jealousy. Yet, as her husband was entering the monastery, she had few other options at the time,[26] beyond perhaps returning to the care of her betrayer Fulbert, leaving Paris again to stay with Abelard's family in rural Brittany outside Nantes, or divorcing and remarrying (most likely to a non-intellectual, as canon scholars were increasingly expected to be celibate). Entering religious orders was a common career shift or retirement option in twelfth-century France.[27] Her appointment as a nun, then prioress, and then abbess was her only opportunity for an academic career as a woman in twelfth-century France, her only hope to maintain cultural influence, and her only opportunity to stay in touch with or benefit Abelard. Examined in a societal context, her decision to follow Abelard into religion upon his direction, despite an initial lack of vocation, is less shocking. Astrolabe, son of Abelard and Heloise Shortly after the birth of their child, Astrolabe, Heloise and Abelard were both cloistered. Their son was thus brought up by Abelard's sister, Denise, at Abelard's childhood home in Le Pallet. His name derives from the astrolabe, a Persian astronomical instrument said to elegantly model the universe[28] and which was popularized in France by Adelard. He is mentioned in Abelard's poem to his son, the Carmen Astralabium, and by Abelard's protector, Peter the Venerable of Cluny, who wrote to Héloise: "I will gladly do my best to obtain a prebend in one of the great churches for your Astrolabe, who is also ours for your sake". 'Petrus Astralabius' is recorded at the Cathedral of Nantes in 1150, and the same name appears again later at the Cistercian abbey at Hauterive in what is now Switzerland. Given the extreme eccentricity of the name, it is almost certain these references refer to the same person. Astrolabe is recorded as dying in the Paraclete necrology on 29 or 30 October, year unknown, appearing as "Petrus Astralabius magistri nostri Petri filius" (Peter Astrolabe, son of our magister [master] Peter).[29] Later life Heloise rose in the church, first achieving the level of prioress of Argenteuil. At the disbandment of Argenteuil and seizure by the monks of St Denis under Abbot Suger, Heloise was transferred to the Paraclete, where Abelard had stationed himself during a period of hermitage. (He had dedicated his chapel to the Paraclete, the holy spirit, because he "had come there as a fugitive and, in the depths of my despair, was granted some comfort by the grace of God".[30]) They now rededicated it as a convent, and Abelard moved on to St. Gildas in Brittany where he became abbot. Heloise became prioress and then abbess of the Paraclete, finally achieving the level of prelate nullius (roughly equivalent to bishop). Her properties and daughter-houses (including the convents of Sainte-Madeleine-de-Traîne (c. 1142), La Pommeray (c. 1147-51?), Laval (ca. 1153), Noëfort (before 1157), Sainte-Flavit (before 1157), Boran / Sainte-Martin-aux-Nonnettes (by 1163)[31]) extended across France, and she was known as a formidable businesswoman. |

人生 生い立ちと教育 エロイーズは、パリ郊外のアルジャントゥイユ修道院の出身で、思春期まで修道女による教育を受けていた。若い頃にパリに来た時、彼女はすでに言語と文章に 関する知識で名を馳せており[6]、知性と洞察力で評判を高めていた。アベラールは、彼女は読み書きの才能でノミナティッシマ、つまり「最も有名」だった と書いている。彼女は詩、戯曲、賛美歌を書いたが、そのうちのいくつかは失われている。 彼女の家庭環境はほとんど知られていない。母方の叔父(avunculus)であるノートルダムのカノン・フルベールの被後見人であり、エルシンデという 名の女性の娘であった。この女性は、シャンパーニュのエルサン(モンソローの貴婦人でフォンテヴロー修道院の創設者)、あるいはあまり知られていないが、 聖エロイ修道院のエルシンデという修道女(ここから「ヘロワーズ」という名前が取られたのであろう)であったと推測されることもある[7][8]。 彼女の手紙の中では、哲学者になるために騎士の称号を拒否したとはいえ、元々は下級貴族の出身であったピーター・アベラールよりも社会的地位が低いことを 示唆している[9]。シャンパーニュのエルシンデは下級貴族であり、ガルランド家はアベラールよりも社会的地位が高く、彼のパトロンであった。シャンパー ニュのエルシンド説は、シャンパーニュのエルシンドが1114年に54歳から80歳の間で亡くなっているという事実によってさらに複雑になっている。 10代半ばから20代前半にかけて、彼女はその学識でフランス全土に名を馳せていた。彼女の生年には異論があるが、伝統的にはアベラールと出会ったのは 15歳から17歳頃とされている。アベラールの弟子となった頃には、すでに高い評判を得ていた。詩的で多言語に精通した天才的な女性として、クリュニーの ピーター尊者も注目し、彼と彼女が共に若い頃、彼女の評判に気づいたと記している[11][12]。やがて彼女は、著名な学者ピーター・アベラールのロマ ンチックな関心を惹きつけた。 ヘロワーズは、アベラール[13]またはその近親者ドゥニーズから医学または民間療法の知識を得たとされ、パラクレートの修道院長として医師としての名声 を得た。 アベラールとの出会い  ジャン=バティスト・ゴワイエ《エロイーズとアベラール》、銅に油彩、1829年頃。 アベラールは、自伝的作品であり公開書簡でもある『Historia Calamitatum』(1132年頃?)の中で、パリのノートルダム学院で教鞭を執っていた1115年に出会ったエロイーズとの関係を語っている。ア ベラールは、二人の関係は計画的な誘惑から始まったと述べているが、エロイーズは返事の中でこの見方に断固として異議を唱えている。(アベラールは、後に 罰を受け宗教に引きこもることを正当化するため、あるいは修道院長であり神の女であるヘロワーズの名声を保つために、この関係を完全に自分の責任であるか のように見せたのではないかと推測されることもある)[14]。対照的に、ヘロワーズは初期の恋文において、ノートルダム寺院にいる何千人もの男性の中か ら自らアベラールを探し、彼だけを友人として、また恋人として選んだ、自分自身が発端であるかのように描いている[15]。 アベラールは手紙の中で、エロイーズを非常に聡明で、そこそこ可愛いと褒め称え、彼女を性の対象としてではなく、彼女の学問的地位に注目している: 「彼女は顔は悪くないが、その膨大な著作は誰にも引けを取らない」[16]。彼は、特に彼女の識字能力と学識のために彼女を求めたことを強調している。 二人が知り合った当時、エロイーズが何歳であったかは不明である。12世紀のフランスでは、若者が大学に通い始める年齢は12歳から15歳が一般的であっ た[17]。若い女性であったエロイーズは、男子学生と交わることも、ノートルダム寺院の大学に正式に通うことも禁じられていたであろう。大学教育は男性 にのみ提供され、この年齢の修道院教育は修道女にのみ許されていたため、叔父のフルベールが特別な指導を手配するのは自然なことであった。アベラールはヘ ロワーズを思春期の少女と表現している。この記述から、アベラールと出会った時の彼女は一般的に15歳から17歳で、1100年から01年に生まれたと考 えられている[1]。1163年か1164年にアベラール(63歳)と同じ年齢で亡くなったという伝承がある。しかし、思春期という言葉は曖昧であり、彼 女の生年を示す一次資料は見つかっていない。最近、コンスタント・ミューズは、エロイーズがアベラールと出会ったのは、彼女が20代前半の頃(つまり 1090年頃の生まれ)であった可能性を示唆している[18]。しかし、彼の見解の主な根拠は、1092年生まれの尊者ピーターがエロイーズに宛てた手紙 の解釈である。コンスタント・ミューズは、彼がエロイーズを尊敬していることから、年上の女性について語ったに違いないと推測しているが、これは憶測に過 ぎない。パリの男子大学生に混じって思春期の天才少女が大きな名声と(特に回顧的な)賞賛を集めた可能性は高い。少なくとも、アベラールが登場する前に、 彼女がこの名声とある程度の尊敬を集めていたことは明らかである。 恋愛関係 フルベール大僧正は、大学で学ぶ代わりに、当時西ヨーロッパを代表する哲学者であり、ノートルダム寺院で最も人気のある世俗のカノン学者(教授)であった ピーター・アベラールの家庭教師をエロイーズに斡旋した。アベラールは偶然にもこの時、宿を探していた。アベラールは家賃を払う代わりに、エロイーズを教 え、躾けることにした。 アベラールは、その後エロイーズが妊娠するまで続いた二人の不義密通について語る。アベラールはエロイーズをフルベールから引き離し、ブルターニュに住む 実の妹ドゥニーズ[19]のもとに送った。 アベラールはフルベールをなだめるためにエロイーズとの結婚に同意したが、その条件はアベラールのキャリアに傷をつけないように結婚を秘密にすることだっ た。ヘロイーズは、結婚によってアベラールのキャリアが傷つくことを恐れ、極秘結婚にこだわった。おそらく、アベラールは最近修道会に入会したばかりであ り(これについては学者の間でも意見が分かれている)、教会が司祭や高位の聖職者の結婚を禁じ始めていた(1123年にはローマ教皇がこの考えを再確認す る命令を出すほどであった)[21]ことを考えると、公の場での結婚はアベラールの教会での出世の妨げになる可能性があったのであろう。エロイーズは当初 は結婚に同意したがらなかったが、最終的にはアベラールの説得に応じ、ブルターニュから戻ったエロイーズとアベラールはパリで密かに結婚した[22]。契 約の一環として、彼女は叔父の家に住み続けた。 悲劇的な展開  アルジャントゥイユで尼僧服に着替えさせられるエロイーズ フルベールはすぐに約束を反故にし、結婚のニュースを流し始めた。エロイーズはこれを否定しようとし、彼の怒りと罵声を買った。アベラールは、エロイーズ をアルジャントゥイユの修道院に送って救い出した。エロイーズは修道女に扮し、ヴェールは被らなかったが、修道女たちの生活を共にした。フルベールは、エ ロイーズが自分の家から連れ去られたことに激怒し、おそらくアベラールが彼女を追い出すためにアルジャントゥイユで彼女を処分したと考え、ある夜、アベ ラールの部屋に侵入して去勢するよう男たちに手配した。この自警団の襲撃に対する法的報復として、一団のメンバーは処罰され、世間から軽蔑されたフルベー ルは一時的にカノンの職務を離れた(数年間、パリのカルトゥラリーに再び登場することはない)[23]。 去勢後[24]、自分の境遇を恥じて、アベラールはパリのサン・ドニ修道院の修道士となった。アルジャントゥイユの修道院で、エロイーズはヴェールを脱い だ。彼女はルカンの『ファルサリア』に登場するコルネリアの台詞を引用した: 「なぜ私はあなたと結婚し、あなたの堕落を招いたのですか?さあ...私が喜んで償うのを見なさい」[25]。 一般的には、アベラールが嫉妬のためにエロイーズを修道院に押し込めたと描かれている。しかし、夫が修道院に入っていたため、当時、彼女には他の選択肢が ほとんどなかった[26]。おそらく、裏切り者のフルベールのもとに戻るか、パリを再び離れてナント郊外のブルターニュの田舎にいるアベラールの家族のも とに身を寄せるか、離婚して再婚するか(カノン派の学者は独身であることがますます求められていたため、知識人でない男性と再婚する可能性が高い)。修道 会への入信は、12世紀フランスでは一般的なキャリア転換や引退の選択肢であった[27]。修道女、司祭、そして修道院長への任命は、12世紀フランスで 女性として学問的キャリアを積む唯一の機会であり、文化的影響力を維持する唯一の希望であり、アベラールと連絡を取り合い、アベラールに利益をもたらす唯 一の機会であった。社会的な文脈から考察すると、当初は天職に恵まれなかったにもかかわらず、アベラールの指示に従って宗教の道に進むという彼女の決断 は、それほど衝撃的なものではない。 アベラールとエロイーズの息子、アストロラーベ アストロラーベが生まれた直後、エロイーズとアベラールはともに隠修士となった。そのため、息子はアベラールの妹ドゥニーズによって、アベラールが幼少期 に住んでいたル・パレで育てられた。アベラールの名前は、アストロラーベに由来する。アストロラーベは、宇宙を優雅に模型化したといわれるペルシアの天文 器具で[28]、アデラールによってフランスに普及した。アベラールが息子に宛てた詩『カルメン・アストララビウム』にも登場し、アベラールの庇護者で あったクリュニーの尊者ペテロは、エロイーズに宛てて「私は喜んで、あなたのために私たちのものでもあるアストロラーベのために、大教会のひとつに托鉢で きるよう最善を尽くします」と書き送っている。 ペトルス・アストララビウス」は、1150年にナントの大聖堂で記録されており、その後、現在のスイスにあるハウテリーヴのシトー会修道院でも同じ名前が 再び登場する。極端に風変わりな名前であることから、これらの記録が同一人物を指していることはほぼ間違いない。アストロラーベは、年不詳の10月29日 または30日にパラクルテの屍譜に "Petrus Astralabius magistri nostri Petri filius"(ピーター・アストロラーベ、私たちのマジスター(主人)ピーターの息子)として死去したと記録されている[29]。 その後の生涯 エロイーズは教会で出世し、まずアルジャントゥイユの修道院長になった。アルジャントゥイユが解散し、スジェール大修道院長率いるサン・ドニ修道会に接収 されると、エロイーズはアベラールが隠棲していたパラクレテに移された。(彼は「逃亡者としてそこに来て、絶望の淵で、神の恵みによっていくばくかの慰め を与えられた」[30]ため、聖なる霊であるパラクレートに礼拝堂を捧げていた)今、修道院として再献堂され、アベラールはブルターニュの聖ジルダに移 り、そこで修道院長となった。エロイーズはパラクルテの修道院長、修道院長となり、最終的にヌリウス司祭(ほぼ司教に相当)の位を得た。彼女の所有地と娘 の館(サント=マドレーヌ=ド=トレイヌ修道院(1142年頃)、ラ・ポンメレイ修道院(1147-51年頃)、ラヴァル修道院(1153年頃)、ノエ フォール修道院(1157年以前)、サント=フラヴィ修道院(1157年以前)、ボラン修道院/サント=マルタン=オ=ノネット修道院(1163年まで) [31]など)はフランス全土に広がり、彼女は手強いビジネスウーマンとして知られていた。 |

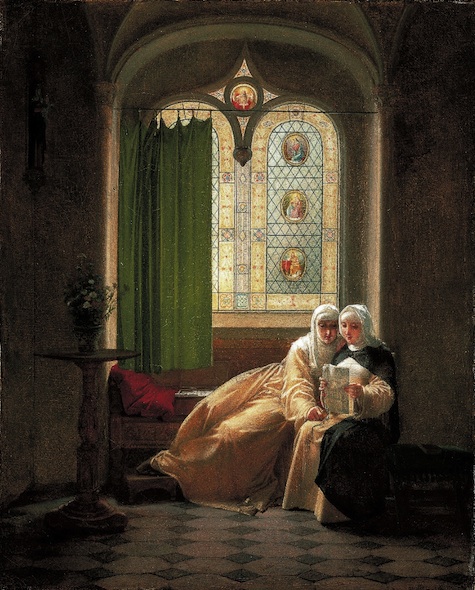

| Correspondence Main article: Letters of Abelard and Heloise  Heloise at the Abbey of the Paraclete by Jean-Baptiste Mallet The primary correspondence existing today consists of seven letters (numbered Epistolae 2–8 in Latin volumes, since the Historia Calamitatum precedes them as Epistola 1). Four of the letters (Epistolae 2–5) are known as the 'Personal Letters', and contain personal correspondence. The remaining three (Epistolae 6–8) are known as the 'Letters of Direction'. An earlier set of 113 letters discovered much more recently (in the early 1970s)[32] is vouched to also belong to Abelard and Heloise by historian and Abelard scholar Constant Mews.[33] Correspondence began between the two former lovers after the events described in the last section. Héloïse responded, both on the behalf of the Paraclete and herself. In letters which followed, Héloïse expressed dismay at problems that Abelard faced, but scolded him for years of silence following the attack, since Abelard was still wed to Héloïse. Thus began a correspondence both passionate and erudite. Héloïse encouraged Abelard in his philosophical work, and he dedicated his profession of faith to her. Abelard insisted that his love for her had consisted of lust, and that their relationship was a sin against God. He then recommended her to turn her attention toward Jesus Christ who is the source of true love, and to consecrate herself fully from then on to her religious vocation. At this point the tenor of the letters changes. In the 'Letters of Direction', Héloïse writes the fifth letter, declaring that she will no longer write of the hurt that Abelard has caused her. The sixth is a long letter by Abelard in response to Héloïse's first question in the fifth letter about the origin of nuns. In the long final, seventh letter, Abelard provides a rule for the nuns at the Oratory of the Paraclete, again as requested by Héloïse at the outset of the fifth letter. The Problemata Heloissae (Héloïse's Problems) is a letter from Héloïse to Abélard containing 42 questions about difficult passages in scripture, interspersed with Abelard's answers to the questions, probably written at the time when she was abbess at the Paraclete. |

対応 主な記事 アベラールとエロイーズの手紙  ジャン=バティスト・マレ作『パラクリート修道院のエロイーズ 現存する主な書簡は、7通の書簡から成る(ラテン語巻ではエピストレ2-8と付されているが、『ヒストリア・カラミタトゥム』ではエピストレ1として付さ れている)。そのうちの4通(エピストレ2-5)は「個人的書簡」として知られ、個人的なやり取りが記されている。残りの3通(Epistolae 6-8)は「指示書」として知られている。もっと最近(1970年代初頭)に発見された113通の書簡[32]は、歴史家でありアベラール研究者であるコ ンスタント・ミューズによって、アベラールとヘロイーズのものであることが証明されている[33]。 前節で述べた出来事の後、二人のかつての恋人たちの間で文通が始まった。エロイーズはパラクルートの代理として、また自分自身の代理として返事をした。続 く手紙の中で、エロイーズはアベラールが直面している問題に落胆を表明したが、アベラールはまだエロイーズと結婚していたため、アベラールが攻撃後何年も 沈黙を守っていたことを叱責した。 こうして、情熱的で博学な文通が始まった。エロイーズはアベラールの哲学的研究を励まし、彼は信仰告白を彼女に捧げた。アベラールは、彼女への愛は欲望か らくるものであり、二人の関係は神に対する罪であると主張した。そして、真の愛の源であるイエス・キリストに目を向け、それからは修道召命に完全に身を捧 げるよう勧めた。 この時点で、書簡の傾向は変わる。エロイーズは「指示の手紙」の第五の手紙で、アベラールが彼女に与えた傷について、もう書かないと宣言する。第6の手紙 は、第5の手紙でエロイーズが最初にした修道女の起源についての質問に対するアベラールの長い手紙である。最後の長い第7の手紙では、アベラールは、第5 の手紙の冒頭でエロイーズが求めた、パラクリート修道院の修道女のための規則を提示している。 Problemata Heloissae (Héloïse's Problems)」は、エロイーズからアベラールへの書簡で、聖典の難解な箇所に関する42の質問と、それに対するアベラールの回答が散りばめられてい る。 |

| Philosophy and legacy Héloïse heavily influenced Abelard's ethics, theology and philosophy of love.[34][35] A scholar of Cicero following in his tradition,[36] Heloise writes of pure friendship and pure unselfish love. Her letters critically develop an ethical philosophy in which intent is centrally placed as critical for determining the moral correctness or "sin" of an action. She claims: "For it is not the deed itself but the intention of the doer that makes the sin. Equity weighs not what is done, but the spirit in which it is done."[37] This perspective influenced Abelard's intention-centered ethics described in his later work Etica (Scito Te Ipsum) (c. 1140), and thus serve as a foundation to the development of the deontological structure of intentionalist ethics in medieval philosophy prior to Aquinas.[38] She describes her love as "innocent" yet paradoxically "guilty" of having caused a punishment (Abelard's castration). She refuses to repent of her so-called sins, insisting that God had punished her only after she was married and had already moved away from so-called "sin". Her writings emphasise intent as the key to identifying whether an action is sinful/wrong, while insisting that she has always had good intent.[39] Héloïse wrote critically of marriage, comparing it to contractual prostitution, and describing it as different from "pure love" and devotional friendship such as that she shared with Peter Abelard.[40] In her first letter, she writes that she "preferred love to wedlock, freedom to a bond."[41] She also states, "Assuredly, whomsoever this concupiscence leads into marriage deserves payment rather than affection; for it is evident that she goes after his wealth and not the man, and is willing to prostitute herself, if she can, to a richer."[41] Peter Abelard himself reproduces her arguments (citing Heloise) in Historia Calamitatum.[40] She also writes critically of childbearing and child care and the near impossibility of coexistent scholarship and parenthood. Heloise apparently preferred what she perceived as the honesty of sex work to what she perceived as the hypocrisy of marriage: "If the name of wife seems holier and more impressive, to my ears the name of mistress always sounded sweeter or, if you are not ashamed of it, the name of concubine or whore...God is my witness, if Augustus, who ruled over the whole earth, should have thought me worthy of the honor of marriage and made me ruler of all the world forever, it would have seemed sweeter and more honorable to me to be called your mistress than his empress."[37] (The Latin word she chose now rendered as "whore", scortum [from "scrotum"], is curiously in medieval usage a term for male prostitute or "rent boy".)[40][42] In her later letters, Heloise develops with her husband Abelard an approach for women's religious management and female scholarship, insisting that a convent for women be run with rules specifically interpreted for women's needs.[43][44] Heloise is a significant forerunner of contemporary feminist scholars as one of the first feminine scholars, and the first medieval female scholar, to discuss marriage, child-bearing, and sex work in a critical way.[45][46] Influence on literature Héloïse is accorded an important place in French literary history and in the development of feminist representation. While few of her letters survive, those that do have been considered a foundational "monument" of French literature from the late thirteenth century onwards. Her correspondence, more erudite than it is erotic, is the Latin basis for the Bildungsroman and a model of the classical epistolary genre, and which influenced writers as diverse as Chretien de Troyes, Madame de Lafayette, Choderlos de Laclos, Rousseau and Dominique Aury. Early development of the legend Jean de Meun, the first translator of Héloïse's work, is also the first person, in around 1290, to quote, in the Roman de la Rose (verses 8729 to 8802), the myth of Héloïse and Abelard, which must have meant that her work was sufficiently popular in order for the readership to understand the allusion. In around 1337, Petrarch acquired a copy of the Correspondence, which already included the Historia Calamitatum (translated by Jean de Meun). Petrarch added many notes to the manuscript before starting to compose in the following year a Chansonnier dedicated to Laure de Sade. The Breton lament song (Gwerz) titled Loiza ac Abalard sings of the ancient druidess picking 'golden grass' with the features of a sorceress-alchemist known as Héloïse. This spread a popular tradition, perhaps originating in Rhuys, Brittany, and going as far as Naples. This text and its later tradition associated magic with rationalism, which remained an important component of Abelardian theology as it was perceived until the twentieth century. In 1583, the Abbey of Paraclet, heavily damaged during the Wars of Religion, was deserted by its monastic residents who disagreed with the Huguenot sympathies of their mother superior. The Abbess Marie de la Rochefoucauld, named by Louis XIII to the position in 1599 in spite of opposition from Pope Clement VIII, set to work on restoring the prestige of the establishment and organised the cult of Héloïse and Abelard. Early modern period Following a first Latin edition, that of Duchesne dated to 1616, the Comte de Bussy Rabutin, as part of his epistolary correspondence with his cousin the marquise de Sévigné, sent her a very partial and unfaithful translation on 12 April 1687, a text which would be included in the posthumous collected works of the writer. Alexander Pope, inspired by the English translation that the poet John Hughes made using the translation by Bussy Rabutin, brought the myth back into fashion when he published in 1717 the famous tragic poem Eloisa to Abelard, which was intended as a pastiche, but does not relate to the authentic letters. The original text was neglected and only the characters and the plot were used. Twenty years later, Pierre-François Godard produced a French verse version of Bussy Rabutin's text. Jean-Jacques Rousseau drew on the reinvented figure in order to write Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse, which his editor published in 1761 under the title Lettres des deux amans. In 1763, Charles-Pierre Colardeau loosely translated the version of the story imagined by Pope, which depicted Héloïse as a recluse writing to Abelard, and spread the sentimental version of the legend over the continent. An edition designed by André-Charles Cailleau and produced by the heiress of André Duchesne further spread amongst reading audiences a collection of these re-imaginings of the figure of Héloïse. Romantic period At the very beginning of the romantic period, in 1807, a neo-Gothic monument was constructed for Héloïse and Abelard and was transferred to the Cimetière de l'Est in Paris in 1817. In 1836, A. Creuzé de Lesser, the former Préfet of Montpellier, provided a translation of 'LI poèmes de la vie et des malheurs d'Eloïse et Aballard' which was published alongside his translation of the 'Romances du Cid' In 1836, the scholar Victor Cousin focused on Héloïse as part of his studies on Abelard. In 1839, François Guizot, the former minister for public education, published the posthumous essay of his first wife, Pauline de Meulan, as a preface to the hugely-popular first edition of the Lettres d'Abailard et d'Héloïse, which were transposed rather than translated into French and in two volumes illustrated by Jean Gigoux. In the same year, the colibri Héloïse (Atthis heloisa) is dedicated to her by the ornithologists René Primevère Lesson and Adolphe Delattre. In 1845, Jean-Pierre Vibert created a species of rose named after Héloïse. Following the romantic tradition, Lamartine published in 1859 a version of Héloïse et Abélard. In 1859, Wilkie Collins published the hugely popular novel The Woman in White, which relies on a similar story involving a male tutor ending up in love with his female pupil, told in an epistolary format. Charles de Rémusat, a biographer of Abelard, wrote in 1877 a play based on the story of the medieval figures. |

哲学と遺産 エロイーズはアベラールの倫理学、神学、愛の哲学に多大な影響を与えた[34][35]。キケロの伝統を受け継ぐキケロの研究者であったエロイーズ [36]は、純粋な友情と純粋な無私の愛について書いている。彼女の手紙は、行為の道徳的な正しさや「罪」を決定するために、意図が中心に置かれる倫理哲 学を批判的に展開している。彼女はこう主張する: 「罪を犯すのは、行為そのものではなく、行為者の意図なのです。衡平は、何がなされたかではなく、それがなされた精神を量るのである」[37]。この視点 は、アベラールの後の著作『エチカ(Scito Te Ipsum)』(1140年頃)に記されている意図中心の倫理学に影響を与え、アクィナス以前の中世哲学における意図主義倫理の脱ontology的構造 の発展の基礎となった。 彼女は自分の愛を「無実」でありながら、逆説的に罰(アベラールの去勢)を引き起こした「有罪」であると述べている。彼女は自分のいわゆる罪を悔い改める ことを拒否し、神が彼女を罰したのは、彼女が結婚し、いわゆる「罪」からすでに離れてからだと主張する。彼女の著作は、ある行為が罪深いか/間違っている かを識別する鍵として意図を強調する一方で、自分には常に善意があったと主張している[39]。 エロイーズは結婚を契約売春と比較し、「純粋な愛」やピーター・アベラールと分かち合ったような献身的な友情とは異なると述べ、結婚を批判的に書いている [40]。 なぜなら、彼女は男ではなく、彼の富を追い求め、できることなら、より裕福な者に身を窶すことを厭わないからである」[41]。ピーター・アベラール自 身、『ヒストリア・カラミタトゥム』において、彼女の主張を(エロイーズを引用して)再現している[40]。彼女はまた、出産と育児、学問と子育ての共存 が不可能に近いことを批判的に書いている。エロイーズは、結婚の偽善性よりも、セックスワークの正直さを好んだようだ: 「妻という名の方が神聖で印象的に思えるなら、私の耳には愛人という名の方がいつも甘美に聞こえる。 神は私の証人です。もし、全地を支配するアウグストゥスが、私を結婚の栄誉に値すると考え、永遠に全世界の支配者としたならば、彼の女帝よりも、あなたの 愛人と呼ばれる方が、私には甘美で名誉なことに思えたでしょう」[37](彼女が現在「娼婦」と表現されているラテン語の単語、スコルトゥム[「陰嚢」か ら]は、不思議なことに、中世の用法では男性娼婦や「レンタルボーイ」を意味する言葉である)[40][42]。 後の書簡の中で、エロイーズは夫のアベラールとともに、女性の宗教的経営と女性の学問のためのアプローチを展開し、女性のための修道院を女性の必要性を特 に解釈した規則で運営することを主張する[43][44]。 エロイーズは、結婚、出産、セックスワークについて批判的に論じた最初の女性学者の一人であり、最初の中世の女性学者として、現代のフェミニスト学者の重 要な先駆者である[45][46]。 文学への影響 エロイーズはフランス文学史やフェミニズム表現の発展において重要な位置を占めている。彼女の書簡はほとんど残っていないが、残っているものは13世紀後 半以降のフランス文学の基礎となる「記念碑」とみなされている。彼女の書簡はエロティックというより博学で、ビルドゥングスロマンのラテン語的基礎であ り、古典的な書簡ジャンルのモデルであり、シュレティアン・ド・トロワ、ラファイエット夫人、ショデルロ・ド・ラクロス、ルソー、ドミニク・オーリーなど 多様な作家に影響を与えた。 伝説の初期の展開 エロイーズの作品の最初の翻訳者であるジャン・ド・ムーンは、1290年頃、『薔薇のロマンス』(8729~8802節)の中で、エロイーズとアベラール の神話を引用した最初の人物でもある。 1337年頃、ペトラルカは、すでに『カラミタトゥム史』(ジャン・ド・ムーン訳)を含む『書簡集』を入手した。翌年、ペトラルカは、ローレ・ド・サドに 捧げるシャンソニエの作曲を始める前に、その写本に多くの注釈を加えた。 Loiza ac Abalardと題されたブルトンの哀歌(Gwerz)は、Héloïseとして知られる魔術師・錬金術師の特徴を持つ「黄金の草」を摘む古代のドルイド レスについて歌っている。この伝承は、おそらくブルターニュのリュイスに端を発し、ナポリにまで広まったと思われる。このテキストとその後の伝統は、魔術 を合理主義と結びつけ、20世紀までアベラール神学の重要な構成要素として認識された。 1583年、宗教戦争で大きな被害を受けたパラクレ修道院は、修道院長のユグノー主義に反対する修道士たちによって見捨てられた。1599年、ローマ教皇 クレメンス8世の反対を押し切ってルイ13世から修道院長に任命されたマリー・ド・ラ・ロシュフコー修道院長は、修道院の威信を回復するために尽力し、エ ロイーズとアベラールの信仰を組織した。 近世 ビュッシー・ラブタン伯爵は、従姉妹のセヴィニエ侯爵夫人との書簡交換の一環として、1687年4月12日に、デュシェスヌによるラテン語の初版に続い て、非常に部分的で不誠実な翻訳を彼女に送った。 アレクサンダー・ポープは、詩人ジョン・ヒューズがビュッシー・ラブタンの翻訳を用いた英訳に触発され、1717年に有名な悲劇詩『アベラールへのエロイ サ』を発表して神話を再び流行させた。原文は無視され、登場人物と筋書きだけが使われた。 その20年後、ピエール=フランソワ・ゴダールが、ビュッシー・ラブタンのテキストをフランス語の詩にしたものを制作した。 ジャン=ジャック・ルソーは、『Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse(ジュリー、あるいは新しいエロイーズ)』を執筆するために、この再創造された人物像を利用した。 1763年、シャルル=ピエール・コラルドーは、ポープが想像したエロイーズをアベラールに手紙を書く世捨て人として描いた物語を緩やかに翻訳し、この感 傷的な伝説を大陸に広めた。 アンドレ・シャルル・カイユローがデザインし、アンドレ・デュシュヌの相続人が制作した版は、エロイーズという人物の再想像を集めたもので、読書家の間に さらに広まった。 ロマン主義時代 ロマン主義時代の初期、1807年にエロイーズとアベラールのためにネオ・ゴシック様式の記念碑が建てられ、1817年にパリのシメティエール・ド・レス トに移された。 1836年、元モンペリエ県知事であったA.クリュゼ・ド・レセールが、「シド歌曲集」の翻訳と並行して「エロイーズとアバラールの人生と苦悩の詩」の翻 訳を出版した。 1836年、学者ヴィクトル・クーザンはアベラール研究の一環として『エロイーズ』を取り上げた。 1839年、元公教育大臣のフランソワ・ギゾーは、彼の最初の妻ポーリーヌ・ド・ムーランの遺稿を、大好評を博した『アベラールとエロイーズの手紙』初版 の序文として出版した。 同年、鳥類学者のルネ・プリムヴェール・レッスンとアドルフ・ドラットルが、コリブリのエロイーズ(Athis heloisa)を彼女に捧げる。 1845年、ジャン=ピエール・ヴィベールはエロイーズにちなんでバラの一種を作り出した。 ロマンチックな伝統に従って、ラマルティーヌは1859年に『エロイーズとアベラール』を出版した。 1859年、ウィルキー・コリンズが『白衣の女』を発表し、大評判となった。この小説は、同じような物語をもとにしたもので、男性の家庭教師が女性の教え 子と恋に落ちるまでを、書簡形式で描いている。 アベラールの伝記作家であるシャルル・ド・レミュザは、1877年に中世の人物の物語をもとにした戯曲を書いた。 |

| Disputed issues Attribution of works The authorship of the writings connected with Héloïse has been a subject of scholarly disagreement for much of their history. The most well-established documents, and correspondingly those whose authenticity has been disputed the longest, are the series of letters that begin with Abelard's Historia Calamitatum (counted as letter 1) and encompass four "personal letters" (numbered 2–5) and "letters of direction" (numbers 6–8) and which include the notable Problemata Heloissae. Most scholars today accept these works as having been written by Héloïse and Abelard themselves. John Benton is the most prominent modern skeptic of these documents. Etienne Gilson, Peter Dronke, and Constant Mews maintain the mainstream view that the letters are genuine, arguing that the skeptical viewpoint is fueled in large part by its advocates' pre-conceived notions.[47] Heloise, Abelard, and sexual consent The great majority of academic scholars and popular writers have interpreted the story of Héloïse's relationship with Abelard as a consensual and tragic romance. However, much controversy has been generated by a quote from Abelard in the fifth letter in which he implies that sexual relations with Heloise were, at least at some points, not consensual. While attempting to dissuade Heloise from her romantic memories and encourage her to fully embrace religion, he writes: "When you objected to [sex] yourself and resisted with all your might, and tried to dissuade me from it, I frequently forced your consent (for after all you were the weaker) by threats and blows."[48] Importantly, this passage runs in stark contrast to Heloise's depiction of their relationship, in which she speaks of "desiring" and "choosing" him, enjoying their sexual encounters, and going so far as to describe herself as having chosen herself to pursue him amongst the "thousands" of men in Notre Dame.[49] Nevertheless, working solely from the sentence in Abelard's fifth letter, Mary Ellen Waithe argued in 1989 that Héloïse was strongly opposed to a sexual relationship,[50] thus presenting her as a victim and depicting an Abelard who sexually harassed, abused, and raped his student. Léon-Marie-Joseph Billardet (1818–1862), Abelard Instructing Heloise. Note Heloise's cowering position in the second panel. Most scholars differ in their interpretation of Abelard's self-depiction. According to William Levitan, fellow of the American academy in Rome, "Readers may be struck by the unattractive figure [the otherwise self praising Abelard] cuts in his own pages....Here the motive [in blaming himself for a cold seduction] is part protective...for Abelard to take all the moral burden on himself and shield, to the extent he can, the now widely respected abbess of the Paraclete—and also in part justificatory—to magnify the crime to the proportions of its punishment."[51] David Wulstan writes, "Much of what Abelard says in the Historia Calamitatum does not ring true: his arrogation of blame for the cold seduction of his pupil is hardly fortified by the letters of Heloise; this and various supposed violations seem contrived to build a farrago of supposed guilt which he must expiate by his retreat into monasticism and by distancing himself from his former lover."[52] Heloise is thus motivated in her responses to Abelard's letters to set the record straight, that if anything she had initiated their relationship. Héloïse's writings express a much more positive attitude toward their past relationship than does Abelard. She does not renounce her encounters as sinful and she does not "accept that [Abelard's] love for her could die, even by the horrible act of...castration."[52] It is important in investigating these allegations of abuse or harassment on Abelard's part to consider the crude sexual ethics of the time (in which a prior relationship was generally taken as establishing consent), Heloise's letters which depict her as complicit if not the initiator of sexual interaction, and Abelard's position as an abbot relative to Heloise, an abbess, towards whom he owed a debt of responsibility and guardianship.[51] By depicting himself—a castrated and now repentant monk—as to blame for their liaison, he denied Heloise her own sexual scandal and maintained the purity of her reputation. An allegation of sexual impropriety on the part of Heloise would furthermore endanger the sanctity of Abelard's property, the Paraclete, which could be claimed by more powerful figures in government or the Catholic Church. Heloise's prior convent at Argenteuil and another convent at St. Eloi had already been shut down by the Catholic hierarchy due to accusations of sexual impropriety by nuns. Monasteries run by male monks were generally in no such danger, so Abelard sealing his reputation as a repentant scoundrel would not harm him. Waithe indicated in a 2009 interview with Karen Warren that she has "softened the position [she] took earlier" in light of Mews' subsequent attribution of the Epistolae Duorum Amantium to Abelard and Héloïse (which Waithe accepts), though she continues to find the passage troubling.[53] Salvador Dalí, Painting of Abelard and Heloise Burial Héloïse's place of burial is uncertain. Abelard's bones were moved to the Oratory of the Paraclete after his death, and after Héloïse's death in 1163/64 her bones were placed alongside his. The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the French Revolution, and now are presumed to lie in the well-known tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery in eastern Paris. The transfer of their remains there in 1817 is considered to have considerably contributed to the popularity of that cemetery, at the time still far outside the built-up area of Paris. By tradition, lovers or lovelorn singles leave letters at the crypt, in tribute to the couple or in hope of finding true love. This remains, however, disputed. The Oratory of the Paraclete claims Abélard and Héloïse are buried there and that what exists in Père Lachaise is merely a monument,[54] or cenotaph. Others believe that while Abelard is buried in the tomb at Père Lachaise, Heloise's remains are elsewhere. Cultural references In literature Jean-Jacques Rousseau's 1761 novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, refers to the history of Héloïse and Abélard. Mark Twain's comedic travelogue The Innocents Abroad (1869) tells a satirical, comedic version of the story of Abélard and Héloïse. Etienne Gilson's 1938 Héloïse et Abélard contains a historical account of their lives. George Moore's 1921 novel, Heloise and Abelard, treats their entire relationship from first meeting through final parting. Charles Williams' 1931 novel The Place of the Lion features a character, Damaris, who focuses her research on Peter Abelard. Helen Waddell's 1933 novel Peter Abelard depicts the romance between the two. Dodie Smith's 1948 novel I Capture the Castle features a dog and a cat named Héloïse and Abélard. Marion Meade's 1976 novel Stealing Heaven depicts the romance and was adapted into a film. Sharan Newman's Catherine LeVendeur series of medieval mysteries feature Héloïse, Abélard, and Astrolabe as occasional characters, mentors and friends of the main character, formerly a novice at the Paraclete. Lauren Groff's 2006 short story "L. DeBard and Aliette" from her collection Delicate Edible Birds recreates the story of Héloïse and Abélard, set in 1918 New York. Wendy Waite's 2008 illustrated rhyming children's story Abelard and Heloise depicts a friendship between two cats named after the medieval lovers. Sherry Jones's 2014 novel, The Sharp Hook of Love, is a fictional account of Abélard and Héloïse. Mandy Hager's 2017 novel, Heloise, tells Heloise's story from childhood to death, with frequent reference to their writings. Rick Riordan's 2017 book, Trials of Apollo: The Dark Prophesy, has a pair of gryphons named Heloise and Abelard. Luise Rinser's 1991 novel Abaelard's Liebe (German) depicts the love story of Héloïse and Abelard from the perspective of their son, Astrolabe. Abelard and Héloïse are referenced throughout Robertson Davies's novel The Rebel Angels. Henry Adams devotes a chapter to Abelard's life in Mont Saint Michel and Chartres James Carroll's 2017 novel The Cloister retells the story of Abelard and Héloïse, interweaving it with the friendship of a Catholic priest and a French Jewish woman in the post-Holocaust twentieth century. Melvyn Bragg's 2019 novel Love Without End intertwines the legendary medieval romance of Héloïse and Abélard with a modern-day historian's struggle to reconcile with his daughter. In art Héloïse et Abeilard, oil on copper, Jean-Baptiste Goyet, 1830. Abaelardus and Heloïse surprised by Master Fulbert, oil, by Romanticist painter Jean Vignaud, 1819 Monument to Abelard and Heloise at Le Pallet by Sylviane and Bilal Hassan-Courgeau Heloise & Abelard, painting by Salvador Dalí Abelard und Heloise, oil on canvas, by Gabriel von Max, circa 1900-15, The Jack Daulton Collection[55] In music Abelard and Heloise is a 1970 soundtrack album by the British Third Ear Band. Mon Abélard, mon Pierre, one track of the quebec singer Claire Pelletier in her album Murmures d'histoire. Pájaros de Portugal, a song of Joaquin Sabina makes reference to their tragedy. In poetry François Villon's "Ballade des Dames du Temps Jadis" ("Ballad of the Ladies of Times Past") mentions Héloïse and Abélard in the second stanza. Their story inspired the poem, "The Convent Threshold", by the Victorian English poet Christina Rossetti. Their story inspired the poem, "Eloisa to Abelard", by the English poet Alexander Pope. In Robert Lowell's poetry collection History (1973), the poem "Eloise and Abelard" portrays the lovers after their separation. Onstage and onscreen Abelard, Heloise and medieval astrolabe portrayed in Michael Shenefelt's stage play, Heloise Ronald Millar's play Abelard & Heloise was a 1971 Broadway production at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre, starring Diana Rigg and Keith Michell, script published by Samuel French, Inc, London, 1970. In the film Being John Malkovich, the character Craig Schwartz (played by John Cusack), a failed puppeteer, stages a sidewalk puppet show depicting correspondence between Héloïse and Abélard. This gets him beaten up by an irate father, due to its sexual suggestiveness. The film, Stealing Heaven (1988), chronicles their story and stars Derek de Lint, Kim Thomson, and Denholm Elliott. The film is based on Marion Meade's 1979 novel of same name. In the 58th episode of The Sopranos (Sentimental Education), Carmela Soprano finds a copy of The Letters of Abelard & Héloïse while using her ex-marital lover Mr. Wegler's bathroom. The book alludes both to the impossibility of Carmela and Mr. Wegler's romantic affair, and arguably, and ironically, to the doomed platonic love between Carmela and her daughter, Meadow: for many years it was a mother-daughter tradition to have tea under the portrait of Eloise at the Plaza Hotel. Anne Carson's 2005 collection Decreation includes a screenplay about Abelard and Héloïse. Henry Miller uses Abelard's "Foreword to Historia Calamitatum" as the motto of Tropic of Capricorn (1938). Howard Brenton's play In Extremis: The Story of Abelard & Heloise was premiered at Shakespeare's Globe in 2006.[56] Michael Shenefelt's stage play, Heloise, 2019 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%C3%A9lo%C3%AFse |

争点 作品の帰属 Héloïseに関連する著作の作者については、その歴史の大半において学問的な見解の相違があった。 アベラールの『ヒストリア・カラミタトゥム』(書簡1)から始まり、4通の「個人的書簡」(書簡2-5)と「指示書」(書簡6-8)を含み、注目すべき 『プロブレマータ・ヘロワッサエ』を含む一連の書簡は、最も確立された文書であり、それに応じてその真偽が最も長く論争されてきたものである。今日、ほと んどの学者が、これらの著作はエロイーズとアベラール自身によって書かれたものであると認めている。ジョン・ベントンは、これらの文書に懐疑的な現代人の 中で最も著名な人物である。エティエンヌ・ギルソン、ピーター・ドロンケ、コンスタント・ミューズは、懐疑的な視点は、その支持者の先入観によって煽られ ている部分が大きいと主張し、これらの書簡が本物であるという主流の見解を維持している[47]。 エロイーズ、アベラール、性的同意 大多数の学者や一般的な作家は、エロイーズとアベラールの関係を、合意の上での悲劇的なロマンスとして解釈してきた。しかし、アベラールが第5の手紙の中 で、エロイーズとの性的関係が、少なくともある時点では同意に基づくものではなかったことを示唆する言葉を引用したことで、多くの論争が巻き起こってい る。アベラールは、エロイーズに恋愛の思い出を思いとどまらせ、宗教を全面的に受け入れるように勧めようとしながら、次のように書いている:"あなた自身 が(セックスに)反対し、全力で抵抗し、私を思いとどまらせようとしたとき、私はしばしば脅しと打撃によって(結局のところ、あなたの方が弱いのだから) あなたの同意を強要した。 「重要なのは、この一節が、エロイーズが二人の関係を描いているのとは対照的であることである。エロイーズは、彼を「望み」「選び」、二人の性的な出会い を楽しみ、ノートルダム寺院にいる「何千人もの」男たちの中から彼を追い求める自分を選んだとまで述べている。 [49]にもかかわらず、メアリー・エレン・ウェイテは1989年、アベラールの5通目の手紙の一文のみから、エロイーズは性的関係に強く反対していたと 主張し[50]、その結果、エロイーズは被害者として描かれ、教え子に性的嫌がらせをし、虐待し、強姦したアベラールが描かれている。 レオ=マリー=ジョゼフ・ビラルデ(1818-1862)『エロイーズを指導するアベラール』。2コマ目のエロイーズがうずくまる姿勢に注目。 アベラールの自虐的な描写についての解釈は、ほとんどの学者で異なっている。ローマにあるアメリカン・アカデミーのフェロー、ウィリアム・レヴィタンによ れば、「読者は、(自画自賛するアベラールが)自分のページで切り取っている魅力のない姿に衝撃を受けるかもしれない......ここで(冷たい誘惑のた めに自分を責める)動機は、アベラールが道徳的な重荷をすべて自分に負わせ、今や広く尊敬されるようになったパラクルートの修道院長をできる範囲で庇護す るためであり、また、罪をその罰の割合にまで拡大する正当化のためでもある。 「弟子の冷たい誘惑に対する彼の傲慢な非難は、エロイーズの手紙によってほとんど補強されていない。この罪と想定される様々な違反は、彼が修道院に引きこ もり、かつての恋人と距離を置くことによって償わなければならない罪の茶番劇を構築するために仕組まれたように見える」[52]。 エロイーズは、アベラールの手紙への返事の中で、二人の関係を始めたのはどちらかといえば自分であることをはっきりさせたいと考えている。エロイーズの文 章は、アベラールよりも二人の過去の関係に対してはるかに肯定的な態度を示している。彼女は自分の出会いを罪深いものとして放棄しておらず、「(アベラー ルの)自分への愛が、たとえ去勢という恐ろしい行為によってでも、死に至る可能性があることを受け入れていない」[52]。 アベラール側の虐待やハラスメントの疑惑を調査する上で重要なのは、当時の粗野な性倫理(事前の関係によって同意が成立すると考えるのが一般的だった)、 性的交流の主導者ではないにせよ加担者として彼女を描いたエロイーズの手紙、そして責任と後見人としての義務を負っていた修道院長エロイーズと相対する修 道院長としてのアベラールの立場を考慮することである。 [51]去勢され、今は悔い改めた修道士であるアベラール自身を、二人の関係を責めるべきものとして描くことで、アベラールはエロイーズ自身の性的スキャ ンダルを否定し、彼女の名声の純粋さを維持した。エロイーズに性的不品行が疑われれば、アベラールの所有物であるパラクルートの神聖さが損なわれ、政府や カトリック教会の権力者がそれを主張する可能性があった。アルジャントゥイユのエロイーズ修道院とサン=エロイの別の修道院は、修道女による性的不品行が 告発されたため、すでにカトリック教会によって閉鎖されていた。男性修道士が運営する修道院は一般的にそのような危険はなかったため、アベラールは懺悔す る悪党という評判を封印していた。 ウェイテは2009年のカレン・ウォーレンとのインタヴューで、ミューズが『Epistolae Duorum Amantium』をアベラールとエロイーズに帰属させた(これはウェイテも認めている)ことを踏まえ、「以前取っていた立場を軟化させた」と述べている が、この一節を問題視し続けている[53]。 サルバドール・ダリ《アベラールとエロイーズの絵 埋葬 エロイーズの埋葬場所は不明。アベラールの遺骨は彼の死後、オラトリオに移され、エロイーズの遺骨は1163/64年に彼の遺骨と一緒に埋葬された。その 後、二人の遺骨は何度も移されたが、フランス革命の波乱の中でも保存され、現在はパリ東部のペール・ラシェーズ墓地にある有名な墓に安置されていると推定 されている。1817年に彼らの遺骨がそこに移されたことは、当時まだパリの市街地から遠く離れていたこの墓地の人気に大いに貢献したと考えられている。 伝統によれば、恋人たちや恋多き独身者たちは、二人への賛辞や真実の愛を求めて、この墓地に手紙を残す。 しかし、これには異論がある。アベラールとエロイーズはそこに埋葬され、ペール・ラシェーズにあるのは単なる記念碑[54]または慰霊碑に過ぎないと主張 するオラトリオ・オブ・ザ・パラクレイト。また、アベラールはペール・ラシェーズにある墓に埋葬されているが、エロイーズの遺骸は別の場所にあるという説 もある。 文化的言及 文学 ジャン=ジャック・ルソーの1761年の小説『ジュリー、あるいは新しいエロイーズ』(Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse)は、エロイーズとアベラールの歴史に言及している。 マーク・トウェインの喜劇的旅行記『The Innocents Abroad』(1869年)は、アベラールとエロイーズの物語を風刺的、喜劇的に描いている。 エティエンヌ・ジルソンの1938年の『Héloïse et Abélard』には、二人の人生の歴史的記述がある。 ジョージ・ムーアの1921年の小説『ヘロイーズとアベラール』は、最初の出会いから最後の別れまで、二人の関係全体を扱っている。 チャールズ・ウィリアムズの1931年の小説『ライオンのいる場所』には、ピーター・アベラールについて研究するダマリスという人物が登場する。 ヘレン・ワッデルの1933年の小説『ピーター・アベラール』は、2人のロマンスを描いている。 ドディ・スミスの1948年の小説『I Capture the Castle』には、エロイーズとアベラールという名の犬と猫が登場する。 マリオン・ミードの1976年の小説『天国を盗め』はこのロマンスを描き、映画化もされた。 シャラン・ニューマンの中世ミステリー『キャサリン・ルヴァンダール』シリーズでは、エロイーズ、アベラール、アストロラーベが時折登場し、元パラクレー トの修練生である主人公の師匠や友人として描かれる。 ローレン・グロフの短編集『Delicate Edible Birds』に収録された2006年の短編「L. DeBard and Aliette」は、1918年のニューヨークを舞台に、エロイーズとアベラールの物語を再現している。 ウェンディ・ウェイトの2008年の挿絵入り韻文童話『アベラールとエロイーズ』は、中世の恋人たちにちなんで名付けられた2匹の猫の友情を描いている。 シェリー・ジョーンズの2014年の小説『The Sharp Hook of Love』は、アベラールとエロイーズの架空の物語である。 マンディ・ヘイガーの2017年の小説『Heloise』は、2人の著作を頻繁に参照しながら、幼少期から死に至るまでのヘロイーズの物語を描いている。 リック・リオーダンの2017年の著書『アポロンの試練』: The Dark Prophesy)には、エロイーズとアベラールという名のグリフォンのペアが登場する。 ルイーズ・リンザーが1991年に発表した小説『Abaelard's Liebe』(ドイツ語)は、エロイーズとアベラールの愛の物語を、彼らの息子アストロラーベの視点から描いている。 アベラールとエロイーズは、ロバートソン・デイヴィスの小説『反逆の天使たち』を通して言及されている。 ヘンリー・アダムスはモンサンミッシェルとシャルトルでのアベラールの生涯に1章を割いている。 ジェームズ・キャロルの2017年の小説『回廊』は、アベラールとエロイーズの物語を、ホロコースト後の20世紀におけるカトリック司祭とフランス系ユダ ヤ人女性の友情と織り交ぜて再話する。 メルヴィン・ブラッグの2019年の小説『終わりなき愛』は、エロイーズとアベラールの伝説的な中世のロマンスを、娘と和解しようとする現代の歴史家の葛 藤と絡めている。 美術 エロイーズとアベイラール、銅に油彩、ジャン=バティスト・ゴワイエ、1830年 フルベール師に驚かされるアベラールとエロイーズ、油彩、ロマン主義の画家ジャン・ヴィニョー作、1819年 シルヴィアーヌとビラル・ハッサン=クルジョーによるル・パレのアベラールとエロイーズの記念碑 エロイーズとアベラール、サルバドール・ダリ作 アベラールとエロイーズ、油彩・カンヴァス、ガブリエル・フォン・マックス作、1900-15年頃、ジャック・ダルトン・コレクション[55]。 音楽 アベラールとエロイーズ』(Abelard and Heloise)は、イギリスのサード・イヤー・バンドによる1970年のサウンドトラック・アルバム。 Mon Abélard, mon Pierreは、ケベック出身の歌手クレール・ペレティエのアルバム『Murmures d'histoire』に収録されている1曲。 Pájaros de Portugal、ホアキン・サビーナの歌は、彼らの悲劇に言及している。 詩では フランソワ・ヴィヨンの "Ballade des Dames du Temps Jadis"(「過ぎ去りし時の貴婦人たちのバラード」)は、第2段でエロイーズとアベラールに言及している。 彼女たちの物語は、ヴィクトリア朝イギリスの詩人クリスティーナ・ロセッティの詩『修道院の閾』にインスピレーションを与えた。 二人の物語は、イギリスの詩人アレクサンダー・ポープの詩「エロイサとアベラール」にインスピレーションを与えた。 ロバート・ローウェルの詩集『History』(1973年)には、「エロイーズとアベラール」という詩があり、別離後の恋人たちの姿が描かれている。 舞台とスクリーン マイケル・シェネフェルトの舞台『Heloise』に描かれたアベラールとエロイーズ、そして中世の天体観測器 ロナルド・ミラーの戯曲『アベラールとエロイーズ』は、ダイアナ・リグとキース・ミッシェル主演で、ブルックス・アトキンソン劇場で1971年にブロード ウェイで上演された。 映画『ビーイング・ジョン・マルコヴィッチ』では、ジョン・キューザック演じるクレイグ・シュワルツが、エロイーズとアベラールの往復書簡を描いた人形劇 を上演する。その性的な暗示のせいで、彼は怒り狂った父親に殴られる。 映画『天国を盗め』(1988年)は彼らの物語を描いたもので、デレク・ド・リント、キム・トムソン、デンホルム・エリオットが出演している。この映画 は、マリオン・ミードの1979年の同名小説に基づいている。 The Sopranos』第58話(Sentimental Education)で、カルメラ・ソプラノは元恋人ウェグラー氏のバスルームで『アベラールとエロイーズの手紙』を見つける。この本は、カルメラとウェ グラー氏のロマンチックな情事の不可能性と、間違いなく、そして皮肉にも、カルメラと彼女の娘メドウの運命的なプラトニック・ラブの両方を暗示している: 何年もの間、プラザホテルのエロイーズの肖像画の下でお茶をするのが母娘の伝統だった。 アン・カーソンの2005年の作品集『Decreation』には、アベラールとエロイーズについての脚本が収められている。 ヘンリー・ミラーは、アベラールの「Historia Calamitatum序文」を『南回帰線』(1938年)のモットーとして使っている。 ハワード・ブレントンの戯曲『In Extremis: The Story of Abelard & Heloise』は2006年にシェイクスピアのグローブ座で初演された[56]。 マイケル・シェネフェルトの舞台劇『エロイーズ』(2019年 |

| Peter Abelard Peter the Venerable Bernard of Clairvaux Astrolabe Stealing Heaven Hildegarde of Bingen Teresa of Avila Sei Shōnagon |

|

| The Letters of Abelard

and Heloise are a series of passionate and intellectual

correspondences written in Latin during the 12th century. The authors,

Peter Abelard, a prominent theologian, and his pupil, Heloise, a gifted

young woman later renowned as an abbess, exchanged these letters

following their ill-fated love affair and subsequent monastic lives. The letters reveal the personal and intellectual relationship between Abelard and Heloise, and provide an intimate glimpse into the societal context of 12th-century Europe. They've played a significant role in the development of Western Epistolary literature, attracting attention from historians, literary scholars, and general readers alike. The Letters of Abelard and Heloise also serve as primary source documents on questions of medieval gender roles, love, and monastic life. |

『アベラールとエロイーズの手紙』は、12世紀にラテン語で書かれた情

熱的で知的な一連の書簡である。著者である著名な神学者ピーター・アベラールとその弟子で、後に修道院長として名を馳せる才能豊かな若い女性エロイーズ

が、不運な恋とその後の修道生活を経て交わした手紙である。 この手紙は、アベラールとエロイーズの個人的かつ知的な関係を明らかにし、12世紀ヨーロッパの社会的背景を親密に垣間見せてくれる。西洋の書簡文学の発 展において重要な役割を果たし、歴史家、文学者、一般読者から注目を集めている。アベラールとエロイーズの手紙』はまた、中世の男女の役割、恋愛、修道院 生活に関する問題についての一次資料としての役割も果たしている。 |

| Publication history Heloise and Abelard, Achille Devaria, 19th c. engraving The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the Historia Calamitatum; secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the Historia Calamitatum in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse).[1] They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work. Early indications It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and Walter Map. While the letters were most likely exchanged by horseman in a public (open letter) fashion readable by others at stops along the way (and thus explaining Heloise's interception of the Historia), it seems unlikely that the letters were widely known outside of their original travel range during the period. Rather, the earliest manuscripts of the letters are dated to the late 13th century. It therefore seems likely that the letters sent between Abelard and Héloïse were kept by Héloïse at the Paraclete along with the 'Letters of Direction', and that more than a century after her death they were brought to Paris and copied.[2] Shortly after the deaths of Abelard and Heloise, Chrétien de Troyes appears influenced by Heloise's letters and Abelard's castration in his depiction of the fisher king in his grail tales.[3] In the fourteenth century, the story of their love affair was summarised by Jean de Meun in the Le Roman de la Rose. Chaucer makes a brief reference in the Wife of Bath's Prologue (lines 677–8) and may base his character of the wife partially on Heloise. Petrarch owned an early 14th-century manuscript of the couple's letters (and wrote detailed approving notes in the margins). First known publications The first Latin publication of the letters was in Paris in 1616, simultaneously in two editions. These editions gave rise to numerous translations of the letters into European languages – and consequent 18th- and 19th-century interest in the story of the medieval lovers.[4] In the 18th century, the couple were revered as tragic lovers, who endured adversity in life but were united in death. With this reputation, they were the only individuals from the pre-Revolutionary period whose remains were given a place of honour at the newly founded cemetery of Père Lachaise in Paris. At this time, they were effectively revered as romantic saints; for some, they were forerunners of modernity, at odds with the ecclesiastical and monastic structures of their day and to be celebrated more for rejecting the traditions of the past than for any particular intellectual achievement.[5] The Historia was first published in 1841 by John Caspar Orelli of Turici. Then, in 1849, Victor Cousin published Petri Abaelardi opera, in part based on the two Paris editions of 1616 but also based on the reading of four manuscripts; this became the standard edition of the letters.[6] Soon after, in 1855, Migne printed an expanded version of the 1616 edition under the title Opera Petri Abaelardi, without the name of Héloïse on the title page. Critical editions and authenticity Critical editions of the Historia Calamitatum and the letters were subsequently published in the 1950s and 1960s. The most well-established documents, and correspondingly those whose authenticity has been disputed the longest, are the series of letters that begin with the Historia Calamitatum (counted as letter 1) and encompass four "personal letters" (numbered 2–5) and "letters of direction" (numbers 6–8). Most scholars today accept these works as having been written by Héloïse and Abelard themselves. John Benton is the most prominent modern skeptic of these documents. Etienne Gilson, Peter Dronke, Constant Mews, and Mary Ellen Waithe maintain the mainstream view that the letters are genuine, arguing that the skeptical viewpoint is fueled in large part by its advocates' pre-conceived notions.[7] Additional love letters More recently, it has been argued that an anonymous series of letters, the Epistolae Duorum Amantium,[8] were in fact written by Héloïse and Abelard during their initial romance (and, thus, before the later and more broadly known series of letters). This argument has been advanced by Constant J. Mews,[9] based on earlier work by Ewad Könsgen.[10] If genuine, these letters represent a significant expansion to the corpus of surviving writing by Héloïse, and thus open several new directions for further scholarship. However, because the second set of letters is anonymous, and attribution "is of necessity based on circumstantial rather than on absolute evidence," their authorship is still a subject of debate and discussion.[11] Recently, Rüdiger Schnell has argued that a close reading reveals the letters as parody, ridiculing their supposed authors by characterizing the male writer as boastful and macho, while simultaneously humiliating himself in pursuit of his correspondent, and the female writer, ostensibly an exemplar of ideal love, as a seeker of sexual pleasure under the cover of religious vocabulary.[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letters_of_Abelard_and_Heloise |

出版の歴史 アベラールとエロイーズの物語は、近代ヨーロッパ文化において絶大な人気を誇っている。第一に、『カラミタトゥム史』、第二に、アベラールとエロイーズの 間に残された7通の書簡(アベラールが3通、エロイーズが4通)であり、写本伝承では常に『カラミタトゥム史』に続いている、第三に、尊者ペテロとエロ イーズの間の4通の書簡(ペテロが3通、エロイーズが1通)である。 [これらの書簡は、現代ではアベラールの著作の中で最もよく知られ、最も広く翻訳されている。 初期の兆候 アベラールとエロイーズの書簡がどのようにして保存されるようになったのかは、よくわかっていない。ウィリアム・ゴーデルやウォルター・マップを含む12 世紀の作家が、二人の関係について簡潔かつ事実関係を記している。この手紙は、途中の停車駅で他の人が読めるように、公開された(オープン・レター)形で 騎手によって交換された可能性が高いが(したがって、ヘロイーズが『ヒストリア』を傍受したことの説明にもなる)、当時、この手紙が本来の旅行範囲外で広 く知られていた可能性は低いと思われる。むしろ、この書簡の最古の写本は13世紀後半のものである。したがって、アベラールとエロイーズの間で交わされた 書簡は、エロイーズが「指図書」とともにパラクレテに保管し、彼女の死後100年以上経ってからパリに持ち込まれ、書写された可能性が高いと思われる [2]。 アベラールとエロイーズの死後まもなく、クレティアン・ド・トロワは、彼の聖杯物語における漁夫の王の描写において、エロイーズの手紙とアベラールの去勢 の影響を受けているようである。チョーサーは『浴場の妻』のプロローグ(677-8行目)で短い言及をしており、妻の性格を部分的にエロイーズに基づいて いると思われる。ペトラルカは14世紀初頭にこの夫婦の手紙の写本を所有していた(そして余白に詳細な承認メモを書いている)。 最初の出版 ラテン語による最初の出版は、1616年にパリで行われた。18世紀、二人は、生前は逆境に耐え、死後は結ばれた悲劇の恋人として崇拝された。この名声に より、二人は革命前の時代から、パリに新しく創設されたペール・ラシェーズ墓地に名誉の場所を与えられた唯一の人物となった。この時代、彼らは事実上、ロ マン主義的な聖人として崇められた。ある人々にとっては、彼らは近代性の先駆者であり、当時の教会や修道院の構造とは対立し、特別な知的業績よりも、過去 の伝統を否定したことで称えられるべき存在であった[5]。 ヒストリア』が最初に出版されたのは、1841年、トゥリチのジョン・カスパー・オレッリによってである。その後、1849年にヴィクトル・クーザンが、 1616年の2つのパリ版に基づきながら、4つの写本の読解にも基づいたオペラ『ペトリ・アベラルディ』を出版した。 批評版と真正性 『Historia Calamitatum』と書簡の批評版は、その後1950年代と1960年代に出版された。最も確立された文書であり、それゆえにその真偽が最も長く論 争されてきたのは、『ヒストリア・カラミタトゥム』(書簡1と数える)から始まり、4通の「個人的書簡」(書簡番号2~5)と「指示書簡」(書簡番号 6~8)を含む一連の書簡である。 今日、ほとんどの学者が、これらの作品はエロイーズとアベラール自身によって書かれたものであると認めている。ジョン・ベントンは、これらの文書に懐疑的 な現代人の中で最も著名な人物である。エティエンヌ・ジルソン、ピーター・ドロンケ、コンスタント・ミューズ、メアリー・エレン・ウェイテは、これらの書 簡が本物であるという主流の見解を維持し、懐疑的な見解は、その擁護者の先入観によって煽られている部分が大きいと主張している[7]。 追加のラブレター 最近になって、エロイーズとアベラールが最初の恋愛中に(したがって、後に広く知られるようになった一連の書簡よりも前に)、匿名の一連の書簡 『Epistolae Duorum Amantium』[8]が実際に書かれたと主張されるようになった。この議論はコンスタント・J・ミューズ[9]がエワド・ケンスゲン[10]の先行研 究をもとに提唱したものである。もし本物であれば、これらの書簡はエロイーズの現存する書簡のコーパスを大幅に拡大するものであり、さらなる研究のために いくつかの新しい方向性を開くものである。 しかし、第二の書簡群は無名であり、その帰属は「絶対的な証拠というよりはむしろ状況証拠に基づくことが必然」であるため、その作者についてはいまだに議 論と考察の対象となっている[11]。 [11] 最近では、リュディガー・シュネル(Rüdiger Schnell)が、精読することによって、この書簡がパロディであることが明らかになり、男性作家は自慢げでマッチョであると同時に、文通相手を追い求 めて自らを辱めるような人物であり、女性作家は、表向きは理想的な愛の模範であるが、宗教的な語彙を隠れ蓑にした性的快楽の探求者であると揶揄している、 と論じている[12]。 |

| Peter Abelard

(/ˈæbəlɑːrd/; French: Pierre Abélard; Latin: Petrus Abaelardus or

Abailardus; c. 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic

philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and

musician.[4] In philosophy, he is celebrated for his logical solution to the problem of universals via nominalism and conceptualism and his pioneering of intent in ethics.[5] Often referred to as the "Descartes of the twelfth century", he is considered a forerunner of Rousseau, Kant, and Spinoza.[6] He is sometimes credited as a chief forerunner of modern empiricism.[7] In history and popular culture, he is best known for his passionate and tragic love affair, and intense philosophical exchange, with his brilliant student and eventual wife, Héloïse d'Argenteuil. He was a defender of women and of their education. After having sent Héloïse to a convent in Brittany to protect her from her abusive uncle who did not want her to pursue this forbidden love, he was castrated by men sent by the uncle. Still considering herself as his spouse even though both retired to monasteries after this event, Héloïse publicly defended him when his doctrine was condemned by Pope Innocent II and Abelard considered a heretic. Among these opinions, Abelard professed the innocence of a woman who commits a sin out of love.[8] In Catholic theology, he is best known for his development of the concept of limbo, and his introduction of the moral influence theory of atonement. He is considered (alongside Augustine of Hippo) to be the most significant forerunner of the modern self-reflective autobiographer. He paved the way and set the tone for later epistolary novels and celebrity tell-alls with his publicly distributed letter, The History of My Calamities, and public correspondence. In law, Abelard stressed that, because the subjective intention determines the moral value of human action, the legal consequence of an action is related to the person who commits it and not merely to the action. With this doctrine, Abelard created in the Middle Ages the idea of the individual subject central to modern law. This eventually gave to School of Notre-Dame de Paris (later the University of Paris) a recognition for its expertise in the area of Law (and later led to the creation of a Faculty of Law of Paris). |

ピーター・アベラール(/ˈæbəl↪Ll_rd/;

French: Pierre Abélard; Latin: Petrus Abaelardus or Abailardus; 1079年頃

- 1142年4月21日)は、中世フランスのスコラ哲学者、代表的な論理学者、神学者、詩人、作曲家、音楽家[4]。 哲学においては、名辞論と概念論による普遍の問題の論理的解決と倫理学における意図の開拓で有名である[5]。しばしば「12世紀のデカルト」と呼ばれ、 ルソー、カント、スピノザの先駆者と考えられている[6]。 歴史や大衆文化においては、優秀な学生であり、最終的に妻となったエロイーズ・ダルジャントゥイユとの情熱的で悲劇的な恋愛と激しい哲学的交流で最もよく 知られている。彼は女性とその教育の擁護者であった。エロイーズをブルターニュの修道院に送ったのは、彼女に禁断の恋をさせたくない叔父から彼女を守るた めだったが、叔父の差し向けた男たちに去勢されてしまう。エロイーズは、アベラールの教義が教皇イノセント2世によって非難され、アベラールが異端視され た際にも、アベラールの配偶者としてアベラールを擁護した。これらの意見の中で、アベラールは愛ゆえに罪を犯した女性の潔白を公言した[8]。 カトリック神学では、虚無の概念を発展させたこと、贖罪の道徳的影響説を導入したことで知られる。彼は(ヒッポのアウグスティヌスと並んで)近代的な自省 的自叙伝作家の最も重要な先駆者であると考えられている。彼は、公に配布された書簡『わが災難の歴史』や公開書簡によって、後の書簡小説や有名人の告白の 道を開き、その基調を作った。 法学においてアベラールは、主観的意図が人間の行為の道徳的価値を決定するため、行為の法的帰結は単に行為に関係するのではなく、それを犯した人間に関係 すると強調した。この教義によって、アベラールは中世に近代法の中心となる個人主体の思想を生み出した。これにより、ノートルダム・ド・パリ学校(後のパ リ大学)は、法学分野におけるその専門性を認められることになった(後にパリ法学部の創設につながった)。 |

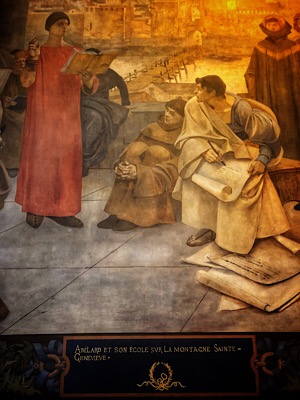

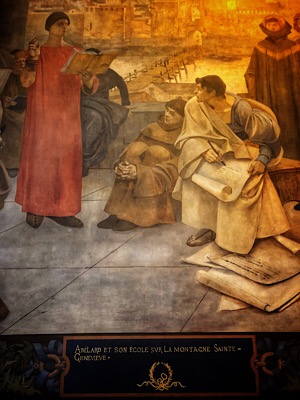

| Early life Page from Apologia contra Bernardum, Abelard's reply to Bernard of Clairvaux Abelard, originally called "Pierre le Pallet", was born c. 1079 in Le Pallet,[9] about 10 miles (16 km) east of Nantes, in the Duchy of Brittany, the eldest son of a minor noble French family. As a boy, he learned quickly. His father, a knight called Berenger, encouraged Abelard to study the liberal arts, wherein he excelled at the art of dialectic (a branch of philosophy). Instead of entering a military career, as his father had done, Abelard became an academic. During his early academic pursuits, Abelard wandered throughout France, debating and learning, so as (in his own words) "he became such a one as the Peripatetics."[10] He first studied in the Loire area, where the nominalist Roscellinus of Compiègne, who had been accused of heresy by Anselm, was his teacher during this period.[11] Career  Abelard Teaching by François Flameng, mural at the Sorbonne Around 1100, Abelard's travels brought him to Paris. Around this time he changed his surname to Abelard, sometimes written Abailard or Abaelardus. The etymological root of Abelard could be the Middle French abilite ('ability'), the Hebrew name Abel/Habal (breath/vanity/figure in Genesis), the English apple or the Latin ballare ('to dance'). The name is jokingly referenced as relating to lard, as in excessive ("fatty") learning, in a secondary anecdote referencing Adelard of Bath and Peter Abelard (and in which they are confused to be one person).[12] In the great cathedral school of Notre-Dame de Paris (before the construction of the current cathedral there), he studied under Paris archdeacon and Notre-Dame master William of Champeaux, later bishop of Chalons, a disciple of Anselm of Laon (not to be confused with Saint Anselm), a leading proponent of philosophical realism.[11] Retrospectively, Abelard portrays William as having turned from approval to hostility when Abelard proved soon able to defeat his master in argument. This resulted in a long duel that eventually ended in the downfall of the theory of realism which was replaced by Abelard's theory of conceptualism / nominalism. While Abelard's thought was closer to William's thought than this account might suggest,[13] William thought Abelard was too arrogant.[14] It was during this time that Abelard would provoke quarrels with both William and Roscellinus.[9] Against opposition from the metropolitan teacher, Abelard set up his own school, first at Melun, a favoured royal residence, then, around 1102–04, for more direct competition, he moved to Corbeil, nearer Paris.[10] His teaching was notably successful, but the stress taxed his constitution, leading to a nervous breakdown and a trip home to Brittany for several years of recovery. On his return, after 1108, he found William lecturing at the hermitage of Saint-Victor, just outside the Île de la Cité, and there they once again became rivals, with Abelard challenging William over his theory of universals. Abelard was once more victorious, and Abelard was almost able to attain the position of master at Notre Dame. For a short time, however, William was able to prevent Abelard from lecturing in Paris. Abelard accordingly was forced to resume his school at Melun, which he was then able to move, from c. 1110–12, to Paris itself, on the heights of Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, overlooking Notre-Dame.[15] From his success in dialectic, he next turned to theology and in 1113 moved to Laon to attend the lectures of Anselm on Biblical exegesis and Christian doctrine.[9] Unimpressed by Anselm's teaching, Abelard began to offer his own lectures on the book of Ezekiel. Anselm forbade him to continue this teaching. Abelard returned to Paris where, in around 1115, he became master of the cathedral school of Notre-Dame and a canon of Sens (the cathedral of the archdiocese to which Paris belonged).[10] |

初期の生活 クレルヴォーのベルナールに対するアベラールの返答『ベルナールに対する弁明』(Apologia contra Bernardum)の1ページ。 アベラールは1079年頃、ブルターニュ公国のナントの東約10マイル(16km)にあるル・パレ[9]で、フランスの小貴族の長男として生まれた。少年 時代、彼はすぐに物事を覚えた。ベレンジェと呼ばれる騎士であった父は、アベラールに教養を学ぶよう勧め、弁証法(哲学の一分野)を得意とした。アベラー ルは、父のように軍人の道に進むのではなく、学者になった。 初期の学問の探求の間、アベラールはフランス全土を放浪し、議論し、学び、(彼自身の言葉を借りれば)「ペリパテティクスのような者になった」[10]。 彼はまずロワール地方で学び、この時期、アンセルムから異端として告発されていたコンピエーニュのノミナリスト、ロスセリヌスが師であった[11]。 経歴  フランソワ・フラマンによるアベラールの教え(ソルボンヌ大学の壁画) 1100年頃、アベラールは旅行でパリにやってきた。この頃、彼は姓をアベラール(Abelard)と改めた。アベラールの語源は、中フランス語の abilite(「能力」)、ヘブライ語のAbel/Habal(創世記に登場する息/尊さ/姿)、英語のapple、またはラテン語のballare (「踊る」)である可能性がある。この名前は、バースのアデラールとピーター・アベラールにまつわる二次的な逸話において、過剰な(「脂肪分の多い」)学 習におけるラードに関連していると冗談めかして言及されている(そして、この二人は同一人物であると混同されている)[12]。 パリのノートルダム大聖堂(現在のノートルダム大聖堂が建設される前)の大教会で、パリの大教会長であり、ノートルダム大聖堂の師であったシャンポーの ウィリアムに師事した。この結果、長い決闘の末、実在論は没落し、アベラールの概念論/名辞論に取って代わられた。アベラールの思想はこの説明から想像さ れるよりもウィリアムの思想に近かったが[13]、ウィリアムはアベラールが傲慢すぎると考えていた[14]。 アベラールは都の教師の反対を押し切り、最初は王室の邸宅であったムランに自分の学校を設立し、1102年から04年にかけて、より直接的に競争するため にパリに近いコルベイユに移った[10]。 帰国後、1108年、シテ島郊外のサン=ヴィクトールの庵で講義をするウィリアムを見つけ、そこでアベラールとウィリアムは再びライバル関係となり、アベ ラールは普遍論をめぐってウィリアムに挑戦した。アベラールは再び勝利を収め、アベラールはノートルダム寺院の修道院長の地位を得ようとした。しかし、し ばらくの間、ウィリアムはアベラールがパリで講義をするのを妨害した。その結果、アベラールはムランでの講義を再開せざるを得なくなり、1110年から 12年にかけて、ノートルダム寺院を見下ろすサント=ジュヌヴィエーヴ山(Montagne Sainte-Geneviève)の高台にあるパリに移転した[15]。 弁証法での成功から、彼は次に神学に目を向け、1113年にラオンに移り、聖書の釈義とキリスト教の教義に関するアンセルムの講義に出席した[9]。アン セルムの教えに感銘を受けなかったアベラールは、エゼキエル書に関する独自の講義を始めた。アンセルムはこの講義を続けることを禁じた。アベラールはパリ に戻り、1115年頃にノートルダム大聖堂学校の校長となり、サンス(パリが属する大司教区の大聖堂)のカノンとなった[10]。 |

| Philosophy Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.[16] Abelard argued for conceptualism in the theory of universals. (A universal is a quality or property which every individual member of a class of things must possess if the same word is to apply to all the things in that class. Blueness, for example, is a universal property possessed by all blue objects.) According to Abelard scholar David Luscombe, "Abelard logically elaborated an independent philosophy of language...[in which] he stressed that language itself is not able to demonstrate the truth of things (res) that lie in the domain of physics."[17] Writing with the influence of his wife Heloise, he stressed that subjective intention determines the moral value of human action. With Heloise, he is the first significant philosopher of the Middle Ages to push for intentionalist ethics. He helped establish the philosophical authority of Aristotle, which became firmly established in the half-century after his death. It was at this time that Aristotle's Organon first became available, and gradually all of Aristotle's other surviving works. Before this, the works of Plato formed the basis of support for philosophical realism. Theology Abelard is considered one of the greatest twelfth-century Catholic philosophers, arguing that God and the universe can and should be known via logic as well as via the emotions. He should not be read as a heretic, as his charges of heresy were dropped and rescinded by the Church after his death, but rather as a cutting-edge philosopher who pushed theology and philosophy to their limits. He is described as "the keenest thinker and boldest theologian of the 12th century"[11] and as the greatest logician of the Middle Ages. "His genius was evident in all he did"; as the first to use 'theology' in its modern sense, he championed "reason in matters of faith", and "seemed larger than life to his contemporaries: his quick wit, sharp tongue, perfect memory, and boundless arrogance made him unbeatable in debate" — "the force of his personality impressed itself vividly on all with whom he came into contact."[18] Regarding the unbaptized who die in infancy, Abelard — in Commentaria in Epistolam Pauli ad Romanos — emphasized the goodness of God and interpreted Augustine's "mildest punishment" as the pain of loss at being denied the beatific vision (carentia visionis Dei), without hope of obtaining it, but with no additional punishments. His thought contributed to the forming of Limbo of Infants theory in the 12th–13th centuries.[19] Psychology Abelard was concerned with the concept of intent and inner life, developing an elementary theory of cognition in his Tractabus De Intellectibus,[20] and later developing the concept that human beings "speak to God with their thoughts".[21] He was one of the developers of the insanity defense, writing in Scito te ipsum, "Of this [sin], small children and of course insane people are untouched...lack[ing] reason....nothing is counted as sin for them".[22] He spearheaded the idea that mental illness was a natural condition and "debunked the idea that the devil caused insanity", a point of view which Thomas F. Graham argues Abelard was unable to separate himself from objectively to argue more subtly "because of his own mental health."[23] Law Abelard stressed that subjective intention determines the moral value of human action and therefore that the legal consequence of an action is related to the person that commits it and not merely to the action. With this doctrine, Abelard created in the Middle Ages the idea of the individual subject central to modern law. This gave to School of Notre-Dame de Paris (later the University of Paris) a recognition for its expertise in the area of Law, even before the faculty of law existed and the school even recognized as an "universitas" and even if Abelard was a logician and a theologian. Poetry and music Abelard was also long known as an important poet and composer. He composed some celebrated love songs for Héloïse that are now lost, and which have not been identified in the anonymous repertoire. (One known romantic poem / possible lyric remains, "Dull is the Star".)[24] Héloïse praised these songs in a letter: "The great charm and sweetness in language and music, and a soft attractiveness of the melody obliged even the unlettered".[25] His education in music was based in his childhood learning of the traditional quadrivium studied at the time by almost all aspiring medieval scholars. Abelard composed a hymnbook for the religious community that Héloïse joined. This hymnbook, written after 1130, differed from contemporary hymnals, such as that of Bernard of Clairvaux, in that Abelard used completely new and homogeneous material. The songs were grouped by metre, which meant that it was possible to use comparatively few melodies. Only one melody from this hymnal survives, O quanta qualia.[25] Abelard also wrote six biblical planctus (laments): Planctus Dinae filiae Iacob; inc.: Abrahae proles Israel nata (Planctus I) Planctus Iacob super filios suos; inc.: Infelices filii, patri nati misero (Planctus II) Planctus virginum Israel super filia Jepte Galadite; inc.: Ad festas choreas celibes (Planctus III) Planctus Israel super Samson; inc.: Abissus vere multa (Planctus IV) Planctus David super Abner, filio Neronis, quem Ioab occidit; inc.: Abner fidelissime (Planctus V) Planctus David super Saul et Jonatha; inc.: Dolorum solatium (Planctus VI). In surviving manuscripts, these pieces have been notated in diastematic neumes which resist reliable transcription. Only Planctus VI was fixed in square notation. Planctus as genre influenced the subsequent development of the lai, a song form that flourished in northern Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries. Melodies that have survived have been praised as "flexible, expressive melodies [that] show an elegance and technical adroitness that are very similar to the qualities that have been long admired in Abelard's poetry."[26] |

哲学 アベラールは世俗的な大学とルネサンス以前の世俗哲学思想の創始者の一人と考えられている[16]。 アベラールは普遍論における概念論を主張した。(普遍とは、同じ言葉がそのクラスのものすべてに適用されるのであれば、物事のクラスの個々の構成員が持た なければならない性質や特性のことである。例えば、青さはすべての青い物体が持つ普遍的な性質である)。アベラールの研究者であるデイヴィッド・ラスコム によれば、「アベラールは論理的に独立した言語哲学を精緻化し......その中で、言語そのものは物理学の領域にある事物(res)の真理を実証するこ とはできないと強調した」[17]。 妻エロイーズの影響を受けて執筆した彼は、主観的意図が人間の行為の道徳的価値を決定することを強調した。エロイーズとともに、彼は意図論的倫理学を推し 進めた中世最初の重要な哲学者である。 彼はアリストテレスの哲学的権威の確立に貢献し、それは彼の死後半世紀で確固たるものとなった。アリストテレスの『オルガノン』が初めて入手できるように なったのはこの時期であり、次第に現存するアリストテレスの他の著作もすべて入手できるようになった。それ以前は、プラトンの著作が哲学的実在論を支持す る基盤となっていた。 神学 アベラールは12世紀最大のカトリック哲学者の一人とされ、神と宇宙は論理によっても感情によっても知ることができ、また知るべきだと主張した。彼の異端 容疑は死後、教会によって取り下げられ、取り消されたため、彼は異端として読まれるべきではなく、むしろ神学と哲学を限界まで押し進めた最先端の哲学者と して読まれるべきである。彼は「12世紀で最も鋭敏な思想家であり、最も大胆な神学者」[11]であり、中世最大の論理学者であると評されている。彼の天 才ぶりは、彼が行ったすべてのことにおいて明らかであった」、「『神学』を現代的な意味で初めて使用した人物として、彼は『信仰問題における理性』を支持 した」、「同時代の人々には、命よりも大きく見えた:彼の素早い機知、鋭い舌鋒、完璧な記憶力、そして限りない傲慢さによって、彼は議論において無敵で あった」、「彼の人格の力は、彼が接触したすべての人々に鮮烈な印象を与えた」[18]。 幼児期に死んだ未受洗者について、アベラールは『パウリ・アド・ロマノスの手紙』の中で、神のいつくしみを強調し、アウグスティヌスの「最も軽い罰」を、 「神の目(carentia visionis dei)を得る望みもなく、しかしそれ以上の罰もなく、神の目(carentia visionis dei)を否定される喪失の苦しみ」と解釈した。彼の思想は、12世紀から13世紀にかけての幼児虚無説の形成に貢献した[19]。 心理学 アベラールは意思と内的生活の概念に関心を持ち、『知性論』(Tractabus De Intellectibus)の中で認知の初歩的な理論を展開し[20]、後に人間は「思考によって神に語りかける」という概念を発展させた[21]。 ......理性を欠いている......彼らには何も罪として数えられない」[22]。彼は精神病が自然な状態であるという考えを先導し、「悪魔が精神 病を引き起こしたという考えを否定した」。 法学 アベラールは、主観的な意図が人間の行為の道徳的価値を決定すること、したがって行為の法的帰結は、単に行為に関係するのではなく、それを犯した人間に関 係することを強調した。この教義によって、アベラールは中世に近代法の中心となる個人主体の思想を生み出した。これにより、ノートルダム・ド・パリ学校 (後のパリ大学)は、法学部が存在する以前から、またアベラールが論理学者であり神学者であったとしても、「ユニヴェルシタス」として認識される以前か ら、法学分野におけるその専門性を認められていたのである。 詩と音楽 アベラールはまた、重要な詩人、作曲家としても古くから知られていた。彼はエロイーズのためにいくつかの有名な恋の歌を作曲したが、それらは現在では失わ れており、匿名のレパートリーでは確認されていない。(エロイーズは手紙の中でこれらの歌を賞賛している: 「言語と音楽における大きな魅力と甘美さ、そしてメロディーの柔らかな魅力は、文字を持たない者にさえも強いるものであった」[25]。アベラールの音楽 教育は、中世の学者志望者のほとんどが当時学んでいた伝統的な四科目の幼少期の学習に基づくものであった。 アベラールは、エロイーズが入会した宗教団体のために賛美歌集を作曲した。1130年以降に書かれたこの讃美歌集は、クレルヴォーのベルナールのような同 時代の讃美歌集とは異なり、アベラールはまったく新しい均質な素材を用いている。歌は拍子ごとにまとめられており、比較的少ない旋律しか使うことができな かった。この讃美歌の旋律は、O quanta qualiaの1曲しか残っていない[25]。 アベラールはまた、6つの聖書のプランクトゥス(嘆きの聖歌)も書いている: Planctus Dinae filiae Iacob; inc: アブラハエ・プロレス・イスラエル・ナタ(Planctus I) イアコブの親孝行(Planctus I); inc: 嬰児の子、父なる誤算 (Planctus II) 処女イスラエルをエプテ・ガラダイトの子の上に立てる(Planctus virginum Israel super filia Jepte Galadite; inc: 独身者たちの祝祭 (Planctus III) プランクトゥス・イスラエル・スーパー・サムソン(プランクトゥスIII アビッサス・ヴェレ・マルタ (Planctus IV) プランクトゥス ダビデがネロニケの子アブネルを継ぐ;inc: 忠実なアブネル (Planctus V) ダビデはサウルとヨナタの上にいる(Planctus David super Saul et Jonatha; inc: Dolorum solatium (Planctus VI). 現存する写本では、これらの曲はディアステマティック・ヌームで記譜されており、信頼性の高い転写は困難である。プランクトゥスVIだけが正方形で記譜さ れている。ジャンルとしてのプランクトゥスは、13世紀から14世紀にかけて北ヨーロッパで繁栄した歌曲形式、ライのその後の発展に影響を与えた。 現存する旋律は、「柔軟で表現力豊かな旋律であり、アベラールの詩において長い間賞賛されてきた特質に非常によく似た優雅さと技術的な巧みさを示してい る」と賞賛されている[26]。 |