ハーバート・L.A.ハート

H. L. A. Hart, Herbert Lionel Adolphus

Hart, 1907-1992

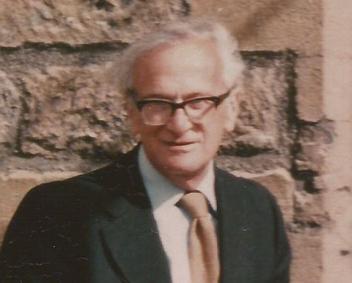

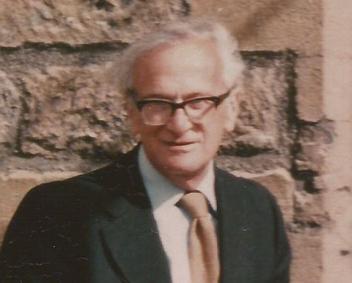

☆ ハーバート・ライオネル・アドルファス・ハート(Herbert Lionel Adolphus Hart FBA, /hɑ-, 1907年7月18日 - 1992年12月19日)はイギリスの法哲学者である。20世紀において最も影響力のある法理論者の一人であり、著書『法の概念』によって普及した法実証 主義の理論の発展に貢献した[2][3]。ハートの貢献は、法の本質、法と道徳の関係、法規則や法制度の分析に重点を置き、「承認規則」のような現代法思 想を形成する概念を導入した。 イギリスのハロゲートで生まれたハートは、オックスフォード大学のニュー・カレッジで古典学の優等学位を取得した後、イギリスの弁護士資格を取得した。第 二次世界大戦中、ハートは英国諜報部に所属し、アラン・チューリングやディック・ホワイトらと仕事をした。戦後、ハートは学界に転身し、1952年にオッ クスフォード大学の法学教授となり、1969年までその職を務めた。 法実証主義に加え、ハートは社会における法の役割について重要な論争を展開した。最も有名なのは、パトリック・デブリン男爵との、法による道徳の強制をめ ぐる論争であり、オックスフォードでの後任者であるロナルド・ドウォーキンとの、法解釈の本質をめぐる論争である。ハートの影響は彼自身の研究だけにとど まらず、ジョセフ・ラズ、ジョン・フィニス、ロナルド・ドウォーキンといった法思想家の指導にも及んだ。

| Herbert Lionel

Adolphus Hart FBA (/hɑːrt/; 18 July 1907 – 19 December 1992) was an

English legal philosopher. One of the most influential legal theorists

of the 20th century, he was instrumental in the development of the

theory of legal positivism, which was popularised by his book, The

Concept of Law.[2][3] Hart's contributions focused on the nature of

law, the relationship between law and morality, and the analysis of

legal rules and systems, introducing concepts such as the "rule of

recognition" that have shaped modern legal thought. Born in Harrogate, England, Hart received a first class honours degree in classical studies from New College, Oxford, before qualifying at the English bar. During World War II, Hart served in British intelligence, working with figures such as Alan Turing and Dick White. Following the war, Hart transitioned to academia, becoming Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Oxford in 1952, a position he held until 1969. In addition to his legal positivism, Hart engaged in important debates on the role of law in society, most famously with Patrick Devlin, Baron Devlin over the enforcement of morality through law, and with his successor at Oxford, Ronald Dworkin, on the nature of legal interpretation. Hart's influence extended beyond his own work, mentoring legal thinkers the likes of Joseph Raz, John Finnis, Ronald Dworkin. |

ハーバート・ライオネル・アドルファス・ハート(Herbert

Lionel Adolphus Hart FBA, /hɑ-, 1907年7月18日 -

1992年12月19日)はイギリスの法哲学者である。20世紀において最も影響力のある法理論者の一人であり、著書『法の概念』によって普及した法実証

主義の理論の発展に貢献した[2][3]。ハートの貢献は、法の本質、法と道徳の関係、法規則や法制度の分析に重点を置き、「承認規則」のような現代法思

想を形成する概念を導入した。 イギリスのハロゲートで生まれたハートは、オックスフォード大学のニュー・カレッジで古典学の優等学位を取得した後、イギリスの弁護士資格を取得した。第 二次世界大戦中、ハートは英国諜報部に所属し、アラン・チューリングやディック・ホワイトらと仕事をした。戦後、ハートは学界に転身し、1952年にオッ クスフォード大学の法学教授となり、1969年までその職を務めた。 法実証主義に加え、ハートは社会における法の役割について重要な論争を展開した。最も有名なのは、パトリック・デブリン男爵との、法による道徳の強制をめ ぐる論争であり、オックスフォードでの後任者であるロナルド・ドウォーキンとの、法解釈の本質をめぐる論争である。ハートの影響は彼自身の研究だけにとど まらず、ジョセフ・ラズ、ジョン・フィニス、ロナルド・ドウォーキンといった法思想家の指導にも及んだ。 |

| Early life and education Herbert Lionel Adolphus Hart was born on 18 July 1907,[4] the son of Rose Samson Hart and Simeon Hart, in Harrogate,[5] to which his parents had moved from the East End of London. His father was a Jewish tailor of German and Polish origin; his mother, of Polish origin, daughter of successful retailers in the clothing trade, handled customer relations and the finances of their firm. Hart had an elder brother, Albert, and a younger sister, Sybil. Hart was educated at Cheltenham College, Bradford Grammar School and at New College, Oxford. He took a first in classical greats in 1929.[6] Hart became a barrister and practised successfully at the Chancery Bar from 1932 to 1940. He was good friends with Richard Wilberforce, Douglas Jay, and Christopher Cox, among others. He received a Harmsworth Scholarship to the Middle Temple and also wrote literary journalism for the periodical John O'London's Weekly.[6] World War II During the Second World War, Hart worked with MI5, a division of British military intelligence concerned with unearthing spies who had penetrated Britain, where he renewed Oxford friendships including working with the philosophers Gilbert Ryle and Stuart Hampshire. He worked closely with Dick White, later head of MI5 and then of MI6. Hart worked at Bletchley Park and was a colleague of the mathematician and codebreaker Alan Turing.[7] Hart's war work took him on occasion to MI5 offices at Blenheim Palace, family home of the Dukes of Marlborough and the place where Winston Churchill had been born.[citation needed] He enjoyed telling the story that there he was able to read the diaries of Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, wife of the founder of the dynasty John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. Hart's wit and humanity are demonstrated by the fact that he particularly enjoyed the passage where Sarah reports that John had been away for a long time, had arrived suddenly, and "enjoyed me straight way in his boots". Another incident at Blenheim that Hart enjoyed recounting was that he shared an office with one of the famous Cambridge spies, Anthony Blunt, a fellow member of MI5. Hart wondered which of the papers on his desk Blunt had managed to read and to pass on to his Soviet controllers. Hart did not return to his legal practice after the war, preferring instead to accept the offer of a teaching fellowship (in philosophy, not law) at New College, Oxford. Hart cites J. L. Austin as particularly influential during this time.[6] The two jointly taught from 1948 a seminar on 'Legal and Moral Responsibility'. Among Hart's publications at this time were the essays 'A Logician's Fairytale', 'Is There Knowledge by Acquaintance?', 'Law and Fact' and 'The Ascription of Responsibility and Rights'. |

生い立ちと教育 ハーバート・ライオネル・アドルファス・ハートは1907年7月18日[4]、ローズ・サムソン・ハートとシメオン・ハートの息子として、両親がロンドン のイーストエンドから移り住んだハロゲートに生まれた[5]。父親はドイツ系とポーランド系のユダヤ人の仕立屋で、母親はポーランド系で、衣料品業界で成 功した小売業者の娘であり、顧客対応と会社の財務を担当していた。ハートには兄のアルバートと妹のシビルがいた。 ハートはチェルトナム・カレッジ、ブラッドフォード・グラマー・スクール、オックスフォードのニュー・カレッジで教育を受けた。1929年に古典の首席を 取った[6]。ハートは法廷弁護士となり、1932年から1940年まで大法院の弁護士として活躍した。リチャード・ウィルバーフォース、ダグラス・ジェ イ、クリストファー・コックスらと親交があった。ハームズワース奨学金を得てミドル・テンプルに入学し、また定期刊行物『John O'London's Weekly』に文芸ジャーナリズムを寄稿した[6]。 第二次世界大戦 第二次世界大戦中、ハートは英国に潜入したスパイの摘発を担当する英国軍情報部のMI5で働き、哲学者のギルバート・ライルやスチュアート・ハンプシャー らと仕事をするなど、オックスフォード大学での友情を新たにした。後にMI5、そしてMI6のトップとなるディック・ホワイトとも親しく仕事をした。ハー トはブレッチリー・パークで働き、数学者であり暗号解読者であったアラン・チューリングの同僚であった[7]。 ハートは戦争中の仕事で、マールボロ公爵家の邸宅であり、ウィンストン・チャーチルが生まれたブレナム宮殿のMI5事務所を訪れることもあった[要出 典]。彼はそこで、王朝の創始者であるジョン・チャーチル第1代マールボロ公爵の妻であるマールボロ公爵夫人サラ・チャーチルの日記を読むことができたと いう話をするのが好きだった。ハートの機知と人間性は、サラが、ジョンが長い間留守にしていて、突然やってきて、「ブーツを履いてまっすぐに私を楽しん だ」と報告している一節を特に楽しんだという事実によって実証されている。ハートがブレナムでの出来事を楽しく語ったもう一つのエピソードは、有名なケン ブリッジ大学のスパイの一人、アンソニー・ブラント(MI5の仲間)とオフィスを共にしたことである。ハートは、ブラントが彼の机の上にあった書類のどれ を読んで、ソ連のスパイに渡したのか不思議に思ったという。 戦後、ハートは弁護士業には戻らず、オックスフォードのニュー・カレッジで(法学ではなく)哲学の教鞭をとることを選んだ。ハートはこの時期に特に影響を 受けた人物としてJ.L.オースティンを挙げている[6]。2人は1948年から「法的責任と道徳的責任」に関するセミナーを共同で教えていた。この時期 にハートが発表した論文には、「論理学者のおとぎ話」、「知己による知識は存在するか」、「法と事実」、「責任と権利の帰属」がある。 |

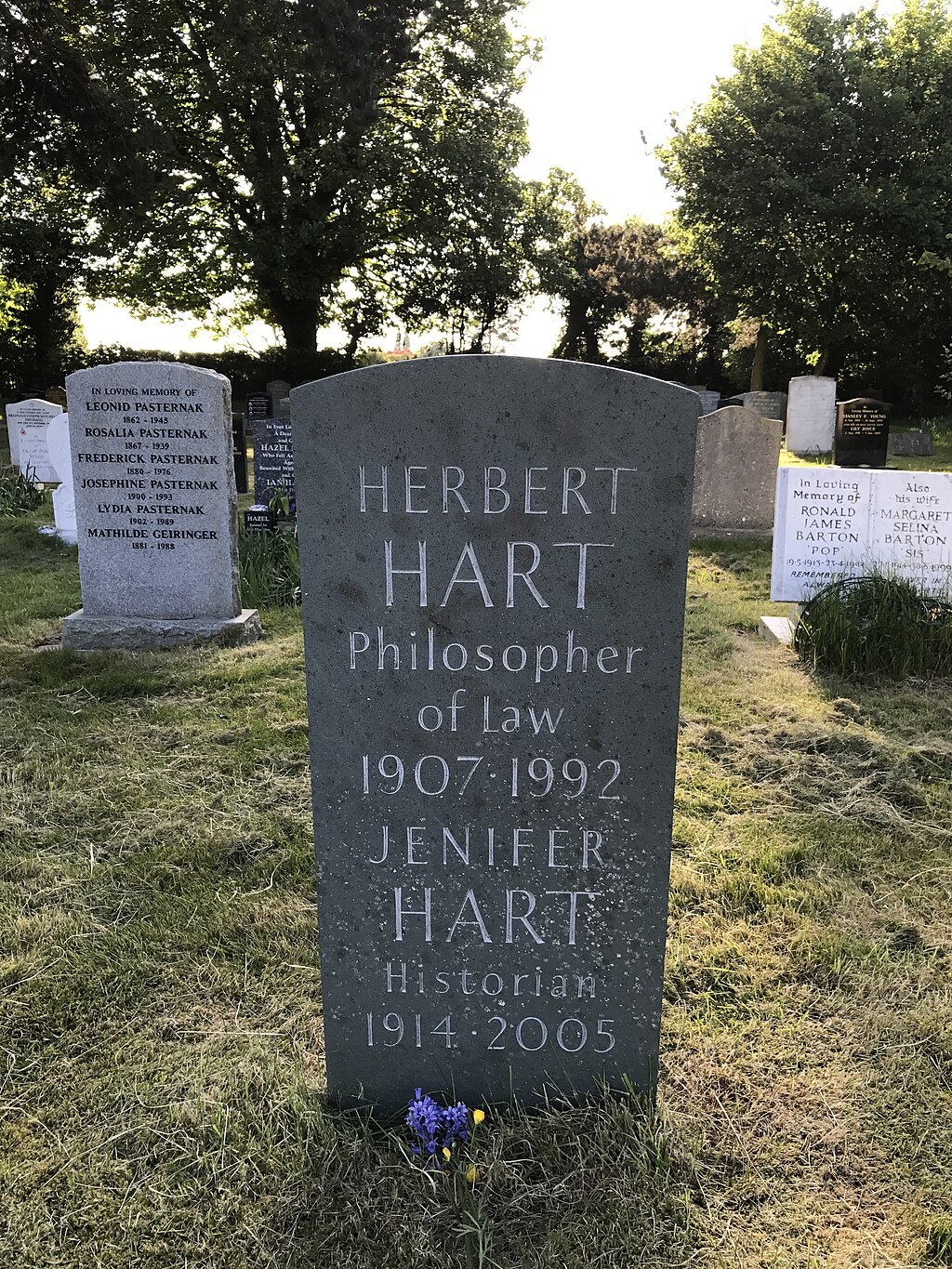

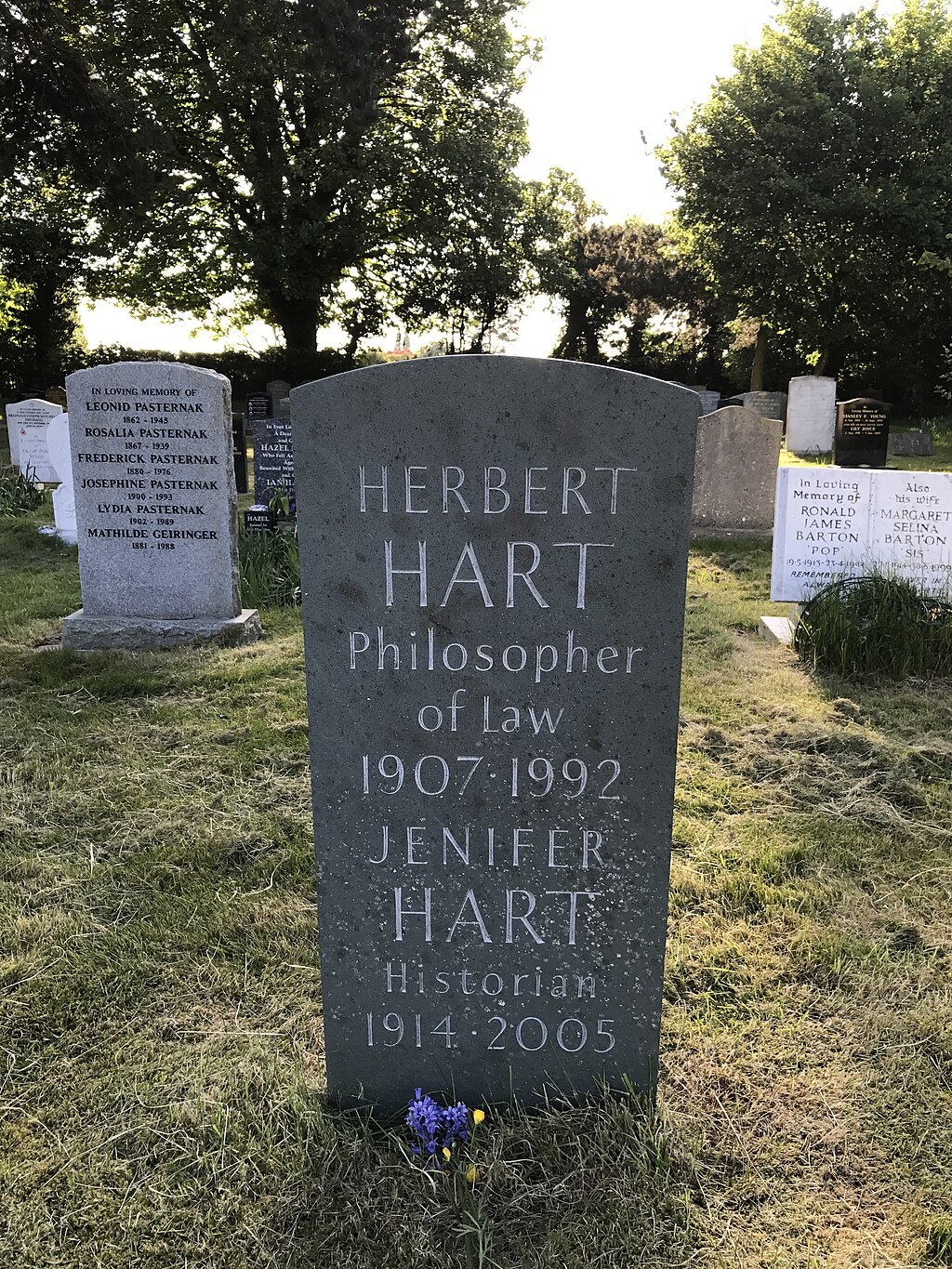

Academic career Hart standing at the entrance to New College, Oxford In 1952, Hart was elected Professor of Jurisprudence at Oxford and was a fellow at University College, Oxford, from 1952 to 1973.[8] It was in the summer of that year that he began writing his most famous book, The Concept of Law, though it was not published until 1961. In the interim, he published another major work, Causation in the Law (with Tony Honoré) (1959). He was president of the Aristotelian Society from 1959 to 1960. He gave the 1962 Master-Mind Lecture.[9] Hart married Jenifer Fischer Williams, a civil servant, later a senior civil servant, in the Home Office and, still later, Oxford historian at St Anne's College (specialising in the history of the police).[10] Jenifer Hart was, for some years in the mid-1930s and fading out totally by decade's end, a 'sleeper' member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Three decades later she was interviewed by Peter Wright as having been in a position to have passed information to the Soviets, and to Wright, MI5's official spy hunter, she explained her situation; Wright took no action. In fact her work as civil servant was in fields such as family policy and so would have been of no interest to the Soviets.[11] The person who recruited her, Bernard Floud, interviewed by Wright shortly after, maintained that he was unable to remember ever having done so. Nor was her husband in a position to convey to her information of use, despite vague newspaper suggestions, given the sharp separation of his work from that of foreign affairs and its focus on German spies and British turncoats rather than on matters related to the Soviet ally. In fact, Hart was anticommunist. The marriage contained "incompatible personalities", though it lasted right to the end of their lives and gave joy to both at times. Hart did joke with his daughter at one point, however, that "[t]he trouble with this marriage is that one of us doesn't like sex and the other doesn't like food",[12] and according to Hart's biographer, LSE law professor Nicola Lacey, Hart was, by his own account, a "suppressed homosexual".[13] Jenifer Hart was believed by her contemporaries to have had an affair of long duration with Isaiah Berlin, a close friend of Hart's. In 1998, Jenifer Hart published Ask Me No More: An Autobiography. The Harts had four children, including, late in life, a son who was disabled, the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck having deprived his brain of oxygen. Hart's granddaughter Mojo Mathers became New Zealand's first deaf Member of Parliament in 2011.[14] There is a description of the Harts' household by the writer on religion Karen Armstrong, who lodged with them for a time to help take care of their disabled son. The description appears in her book The Spiral Staircase.[15] Hart retired from the Chair of Jurisprudence in 1969 and was succeeded by Ronald Dworkin. He subsequently became principal of Brasenose College, Oxford. Hart died in Oxford on 19 December 1992, aged 85.[4] He is buried there in Wolvercote Cemetery, which also contains Isaiah Berlin's grave.  Grave of H. L. A. Hart at the Wolvercote Cemetery in Oxford |

アカデミック・キャリア オックスフォード大学ニュー・カレッジの入り口に立つハート 1952年、ハートはオックスフォード大学の法学教授に選出され、1952年から1973年までオックスフォード大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジのフェロー を務めた[8]。その間に、彼はもう一つの主要な著作である『法における因果関係』(トニー・オノレとの共著)(1959年)を出版した。1959年から 1960年までアリストテレス協会の会長を務めた。1962年にはマスター・マインド・レクチャーを行った[9]。 ハートはジェニファー・フィッシャー・ウィリアムズと結婚し、後に内務省の上級公務員となり、さらに後にオックスフォードのセント・アンズ・カレッジの歴 史家(警察史が専門)となった[10]。ジェニファー・ハートは1930年代半ばの数年間、イギリス共産党の「潜伏」党員であった。30年後、彼女はソビ エトに情報を渡す立場にあったとしてピーター・ライトのインタビューを受け、MI5の公式スパイハンターであるライトに自分の状況を説明した。実際、彼女 の公務員としての仕事は家族政策などの分野であったため、ソビエトにとっては何の興味もないものであった[11]。 彼女をリクルートした人物、バーナード・フラウドは、直後にライトのインタビューを受けたが、そんなことをした覚えはないと言い張った。また、彼女の夫 は、漠然とした新聞の示唆にもかかわらず、外務省の仕事とは峻別され、ソ連の同盟国に関することよりもドイツのスパイやイギリスの裏切り者に焦点を当てて いたため、役に立つ情報を彼女に伝える立場になかった。実際、ハートは反共主義者だった。 結婚生活は「相容れない性格」を含んでいたが、二人は人生の最後まで続き、時に喜びを分かち合った。ハートの伝記作家であるLSE法学教授のニコラ・レイ シーによれば、ハートは彼自身の証言によれば「抑圧された同性愛者」であった[13]。ジェニファー・ハートは、ハートの親友であったアイザイア・バーリ ンと長い間不倫関係にあったと同時代の人々から信じられていた。1998年、ジェニファー・ハートは『Ask Me No More: An Autobiography』を出版した。ハートは4人の子供をもうけたが、そのうちの一人の息子は晩年、首に巻かれたへその緒が脳から酸素を奪い、障害 を負った。 ハートの孫娘モジョ・マザースは、2011年にニュージーランド初の聴覚障害者の国会議員となった[14]。 宗教作家のカレン・アームストロングが、障害のある息子の世話をするために一時期ハートの家に下宿していたことがある。その記述は彼女の著書『らせん階 段』に掲載されている[15]。 ハートは1969年に法学講座を引退し、ロナルド・ドウォーキンが後任となった。その後、オックスフォードのブラセノーズ・カレッジの校長に就任した。 ハートは1992年12月19日にオックスフォードで85歳で死去した[4]。同地のウォルバーコート墓地に埋葬されており、同墓地にはアイザイア・バー リンの墓もある。  オックスフォードのウォルバーコート墓地にあるH.L.A.ハートの墓 |

| Hart's students Many of Hart's former students have become important legal, moral, and political philosophers, including Brian Barry, Ronald Dworkin, John Finnis, John Gardner, Kent Greenawalt, Peter Hacker, David Hodgson, Neil MacCormick, Joseph Raz, Chin Liew Ten and William Twining. Hart also had a strong influence on the young John Rawls in the 1950s, when Rawls was a visiting scholar at Oxford shortly after finishing his PhD. |

ハートの教え子たち ブライアン・バリー、ロナルド・ドウォーキン、ジョン・フィニス、ジョン・ガードナー、ケント・グリナウォルト、ピーター・ハッカー、デイヴィッド・ホジ ソン、ニール・マコーミック、ジョセフ・ラズ、チン・リュー・テン、ウィリアム・トワイニングなど、ハートの教え子の多くは、重要な法哲学者、道徳哲学 者、政治哲学者となっている。ハートはまた、1950年代、ロールズが博士号を取得した直後にオックスフォードの客員研究員として在籍していた頃、若き ジョン・ロールズに強い影響を与えた。 |

| Philosophical method Hart strongly influenced the application of methods in his version of Anglo-American positive law to jurisprudence and the philosophy of law in the English-speaking world. Influenced by John Austin, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Hans Kelsen, Hart brought the tools of analytic, and especially linguistic, philosophy to bear on the central problems of legal theory. Hart's method combined the careful analysis of twentieth-century analytic philosophy with the jurisprudential tradition of Jeremy Bentham, the great English legal, political, and moral philosopher. Hart's conception of law had parallels to the Pure Theory of Law formulated by Austrian legal philosopher Hans Kelsen, though Hart rejected several distinctive features of Kelsen's theory. Significant in the differences between Hart and Kelsen was the emphasis on the British version of positive law theory which Hart was defending as opposed to the Continental version of positive law theory which Kelsen was defending. This was studied in the University of Toronto Law Journal in an article titled "Leaving the Hart-Dworkin Debate" which maintained that Hart insisted in his book The Concept of Law on the expansive reading of positive law theory to include philosophical and sociological domains of assessment rather than the more focused attention of Kelsen who considered Continental positive law theory as more limited to the domain of jurisprudence itself.[16] Hart drew, among others, on Glanville Williams who had demonstrated his legal philosophy in a five-part article, "Language and the Law" and in a paper, "International Law and the Controversy Concerning the Word 'Law'". In the paper on international law, he sharply attacked the many jurists and international lawyers who had debated whether international law was "really" law. They had been wasting everyone's time, for the question was not a factual one, the many differences between municipal and international law being undeniable, but was simply one of conventional verbal usage, about which individual theorists could please themselves, but had no right to dictate to others. This approach was to be refined and developed by Hart in the last chapter of The Concept of Law (1961), which showed how the use in respect of different social phenomena of an abstract word like law reflected the fact that these phenomena each shared, without necessarily all possessing in common, some distinctive features. Glanville had himself said as much when editing a student text on jurisprudence and he had adopted essentially the same approach to "The Definition of Crime".[17] |

哲学的方法 ハートは、英語圏における法学や法哲学への英米正法の適用に強い影響を与えた。ジョン・オースティン、ルートヴィヒ・ヴィトゲンシュタイン、ハンス・ケルゼンの影響を受けたハートは、分析哲学、特に言語哲学の手段を法理論の中心的問題に持ち込んだ。 ハートの手法は、20世紀の分析哲学の入念な分析と、イギリスの偉大な法・政治・道徳哲学者であるジェレミー・ベンサムの法学の伝統を組み合わせたもので あった。ハートの法概念は、オーストリアの法哲学者ハンス・ケルゼンが定式化した純粋法理論と類似していたが、ハートはケルゼンの理論のいくつかの特徴的 な点を否定していた。 ハートとケルゼンの違いで重要なのは、ケルゼンが擁護していた大陸版の正法理論に対して、ハートが擁護していたイギリス版の正法理論に重点を置いていたこ とである。この点についてはトロント大学の『University of Toronto Law Journal』において「Leaving the Hart-Dworkin Debate」と題された論文で研究されており、その中でハートは著書『The Concept of Law』において、大陸的な実定法論を法学そのものの領域に限定して考えていたケルゼンよりも、むしろ哲学的・社会学的な評価領域を含むように実定法論を 拡大解釈することを主張していたと主張していた[16]。 ハートは、とりわけ、5部構成の論文「言語と法」や論文「国際法と『法』という言葉に関する論争」において法哲学を示したグランヴィル・ウィリアムズを参 考にしていた。国際法に関する論文で彼は、国際法が「本当に」法であるかどうかを議論してきた多くの法学者や国際法学者を鋭く攻撃した。というのも、この 問題は、自治体法と国際法の間に多くの違いがあることは否定できないが、事実上の問題ではなく、単に慣習的な言葉の使い方の問題であり、個々の理論家が自 分たちを満足させることはできても、他者に指図する権利はなかったからである。 このアプローチは、『法の概念』(1961年)の最終章でハートによって洗練され、発展させられることになる。この章では、法のような抽象的な言葉がさま ざまな社会現象に関して使用されることが、必ずしもすべてに共通するわけではないが、これらの現象がそれぞれいくつかの特徴的な特徴を共有しているという 事実を反映していることが示された。グランヴィル自身、法学の学生向けテキストを編集する際にそのように語っており、『犯罪の定義』でも基本的に同じアプ ローチを採用していた[17]。 |

| The Concept of Law Main article: The Concept of Law This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Concept of Law" Hart – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Hart's most famous work is The Concept of Law, first published in 1961, and with a second edition (including a new postscript) published posthumously in 1994. The book emerged from a set of lectures that Hart began to deliver in 1952, and it is presaged by his Holmes lecture, Positivism and the Separation of Law and Morals, delivered at Harvard Law School. The Concept of Law developed a sophisticated view of legal positivism. Among the many ideas developed in this book are: A critique of John Austin's theory that law is the command of the sovereign backed by the threat of punishment. A distinction between primary and secondary legal rules, such that a primary rule governs conduct, such as criminal law, and secondary rules govern the procedural methods by which primary rules are enforced, prosecuted and so on. Hart specifically enumerates three secondary rules; they are: The Rule of Recognition, the rule by which any member of society may check to discover what the primary rules of the society are. In a simple society, Hart states, the recognition rule might only be what is written in a sacred book or what is said by a ruler. Hart claimed the concept of rule of recognition as an evolution from Hans Kelsen's 'basic norm' (German: Grundnorm). The Rule of Change, the rule by which existing primary rules might be created, altered or deleted. The Rule of Adjudication, the rule by which the society might determine when a rule has been violated and prescribe a remedy. A distinction between the internal and external points of view of law and rules, close to (and influenced by) Max Weber's distinction between legal and sociological perspectives in description of law. A concept of "open-textured" terms in law, along the lines of Wittgenstein and Waisman, and "defeasible" terms (later famously disavowed): both are ideas popular in Artificial intelligence and law A late reply (published as a postscript to the second edition) to Ronald Dworkin, a rights-oriented legal philosopher (and Hart's successor at Oxford) who criticised Hart's version of legal positivism in Taking Rights Seriously (1977), A Matter of Principle (1985) and Law's Empire (1986). Other work With Tony Honoré, Hart wrote and published Causation in the Law (1959, second edition 1985), which is regarded as one of the important academic discussions of causation in the legal context. The early chapters deal philosophically with the concept of cause and are clearly the work of Hart, while later chapters deal with individual cases in English law and are clearly his co-author's. As a result of his famous debate (Hart–Devlin debate) with Patrick Devlin, Baron Devlin, on the role of the criminal law in enforcing moral norms, Hart wrote Law, Liberty and Morality (1963), which consisted of three lectures he gave at Stanford University. He also wrote The Morality of the Criminal Law (1965). Hart said that he believed Devlin's view of Mill's harm principle as it related to the decriminalisation of homosexuality was "perverse".[18] He later stated that he believed the reforms to the law regarding homosexuality that followed the Wolfenden report "didn't go far enough". Despite this, Hart reported later that he got on well personally with Devlin.[6] Hart gave lectures to the Labour Party on closing tax loopholes which were being used by the "super-rich". Hart considered himself to be "on the Left, the non-communist Left", and expressed animosity towards Margaret Thatcher.[6] |

法の概念 主な記事 法の概念 このセクションでは出典を引用していない。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは、異議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがある。 出典を探す 「法の概念」 Hart - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (November 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) ハートの最も有名な著作は、1961年に初版が出版され、1994年に死後出版された第2版(新しいあとがきを含む)である『法の概念』である。この本 は、ハートが1952年に始めた一連の講義から生まれたもので、ハーバード・ロー・スクールで行われたホームズの講義「実証主義と法と道徳の分離」がその 先駆けとなった。法の概念』では、法実証主義の洗練された見解が展開された。本書で展開された多くのアイデアの中には、以下のようなものがある: 法は刑罰の脅威に裏打ちされた主権者の命令であるというジョン・オースティンの理論に対する批判。 一次的な法的ルールと二次的な法的ルールの区別、例えば、一次的なルールは刑法のような行為を支配し、二次的なルールは一次的なルールが執行され、起訴されるなどの手続き方法を支配する。ハートは具体的に3つの二次的ルールを列挙している: 認識規則とは、社会の成員であれば誰でも、その社会の第一次規則が何であるかを確認することができる規則である。ハートは、単純な社会では、認識ルールは 神聖な書物に書かれていることや支配者の言葉だけかもしれないと述べている。ハートは、ハンス・ケルゼンの「基本規範」(ドイツ語:Grundnorm) から発展したものとして、承認規則という概念を主張した。 変更の規則」とは、既存の主要な規則が作成、変更、削除される可能性のある規則である。 裁きのルール:あるルールに違反した場合に、社会がそれを判断し、救済策を規定するためのルールである。 マックス・ウェーバーの法の記述における法学的視点と社会学的視点の区別に近い(影響を受けた)、法と規則の内的視点と外的視点の区別。 ウィトゲンシュタインやワイスマンの流れを汲む、法における「オープン・テクスチュア」用語の概念と、(後に否定されたことで有名な)「defeasible」用語の概念:どちらも人工知能や法学でよく使われる考え方である。 権利を真剣に考える』(1977年)、『原則の問題』(1985年)、『法の帝国』(1986年)においてハートの法実証主義を批判した権利志向の法哲学 者ロナルド・ドゥオーキン(オックスフォード大学におけるハートの後継者)に対する後期の回答(第2版のあとがきとして出版)。 その他の著作 ハートはトニー・オノレと共同で『Causation in the Law』(1959年、第2版1985年)を執筆・出版し、法的文脈における因果関係についての重要な学術的議論のひとつとみなされている。初期の章で は、原因の概念について哲学的に論じており、明らかにハートの著作である。 道徳規範の強制における刑法の役割について、パトリック・デブリン男爵との有名な論争(ハート=デブリン論争)の結果、ハートはスタンフォード大学で行っ た3つの講義からなる『法・自由・道徳』(1963年)を著した。また、『刑法の道徳』(1965年)も著した。ハートは、同性愛の非犯罪化に関連するミ ルの害悪原則に対するデヴリンの見解は「倒錯している」と考えていたと述べている[18]。 彼は後に、ウォルフェンデン報告に続く同性愛に関する法改正は「十分に進んでいない」と考えていたと述べている。にもかかわらず、ハートは後にデブリンと 個人的に仲が良かったと報告している[6]。 ハートは労働党で、「超富裕層」に利用されている税の抜け穴をふさぐための講義を行った。ハートは自らを「左派、非共産主義的な左派」と考え、マーガレット・サッチャーに反感を示した[6]。 |

| Writings "The Ascription of Responsibility and Rights", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society (1949) Definition and Theory in Jurisprudence (1953) Causation in the Law (with Tony Honoré) (Clarendon Press, 1959) The Concept of Law (Clarendon Press, 1961; 2nd edn 1994; 3rd edn 2012) Law, Liberty and Morality (Stanford University Press, 1963) The Morality of the Criminal Law (Oxford University Press, 1964) Punishment and Responsibility (Oxford University Press, 1968) Essays on Bentham: Studies in Jurisprudence and Political Theory (Clarendon Press, 1982) Essays in Jurisprudence and Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 1983) Festschrift Law, Morality, and Society: Essays in Honour of H. L. A. Hart, edited by P. M. S. Hacker and Joseph Raz (1977) |

著作 責任と権利の帰属」『アリストテレス学会予稿集』(1949年) 法学における定義と理論」(1953年) 法における因果関係(トニー・オノレと共著)(クラレンドン・プレス、1959年) 法の概念(クラレンドン・プレス、1961年、第2版1994年、第3版2012年) 法、自由、道徳(スタンフォード大学出版局、1963年) 刑法の道徳(オックスフォード大学出版局、1964年) 罰と責任(オックスフォード大学出版局、1968年) ベンサム論 法学と政治理論の研究(クラレンドン・プレス、1982年) 法学と哲学のエッセイ』(オックスフォード大学出版局、1983年) 記念論文集 法・道徳・社会 P・M・S・ハッカー、ジョセフ・ラズ編『H・L・A・ハートを記念するエッセイ』(1977年) |

| Hart–Dworkin debate Hart–Fuller debate Legal interpretivism Natural law Lon Fuller |

ハート-ドワキン論争 ハート-フラー論争 法解釈主義 自然法 ロン・フラー |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._L._A._Hart |

|

| The Hart–Dworkin debate

is a debate in legal philosophy between H. L. A. Hart and Ronald

Dworkin. At the heart of the debate lies a Dworkinian critique of

Hartian legal positivism, specifically, the theory presented in Hart's

book The Concept of Law. While Hart insists that judges are within

bounds to legislate on the basis of rules of law, Dworkin strives to

show that in these cases, judges work from a set of "principles" which

they use to formulate judgments, and that these principles either form

the basis, or can be extrapolated from the present rules. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hart%E2%80%93Dworkin_debate |

ハー

ト=ドウォーキン論争は、法哲学におけるH・L・A・ハートとロナルド・ドウォーキンの論争である。この論争の中心は、ハート派の法実証主義、具体的には

ハートの著書『法の概念』で提示された理論に対するドウォーキン派の批判である。ハートが、裁判官は法の規則に基づいて立法を行うことができると主張する

のに対し、ドウォーキンは、このような場合、裁判官は一連の「原則」に基づいて判断しており、これらの原則は現在の規則を基礎とするか、あるいは現在の規

則から推定することができることを示そうと努めている。 |

| The Hart–Fuller debate

is an exchange between the American law professor Lon L. Fuller and his

English counterpart H. L. A. Hart, published in the Harvard Law Review

in 1958 on morality and law, which demonstrated the divide between the

positivist and natural law philosophy. Hart took the positivist view in

arguing that morality and law were separate. Fuller's reply argued for

morality as the source of law's binding power. Nazi informer case The debate discusses the verdict rendered by a decision of a post-war West German court on the following case: "In 1944, defendant, desiring to get rid of her husband, reported to the authorities derogatory remarks he has made about Hitler while home on leave from the German army. Defendant wife having testified against him, the husband was sentenced to death by a military tribunal apparently pursuant to statutes making it illegal to assert or repeat any statements inimical to the welfare of the Third Reich. . . . However, after serving some time in prison, the husband was sent to the front. Following the defeat of the Nazi regime, the wife, as well as the judge who had sentenced her husband, was indicted under § 289 of the German Criminal Code of 1871, for the unlawful deprivation of another's liberty ('rechtswidrige Freiheitsberaubung'). On appeal to a German Court of last resort in criminal cases, held, that the sentencing judge should be acquitted, but that the wife is guilty since she utilised out of free choice a Nazi 'law' which is contrary 'to the sound conscience and sense of justice of all decent human beings' about the death or imprisonment of her husband. — Harvard Law Review, 1951, pp. 1005–7 Philosophy Context Jurisprudence refers to analysis of the philosophy of law. Within jurisprudence there are multiple schools of thought, but the Hart–Fuller debate concerns just legal positivism and natural-law theory.[1] Legal positivists believe that "so long as [an] unjust law is a valid law, one has a legal obligation to obey it".[2] Positivists disregard the morality of valid laws and treat law as the sole source of authority on what is valid. Natural-law theorists see a direct connection between validity and morality.[3] Arguments  H.L.A. Hart In Hart's initial paper, "Positivism and the Separation of Law and Morals", he establishes that the "Command Theory" perspective of Legal Positivism, which was stated by John Austin and holds that laws are commands to human beings, is inadequate as it does not accurately represent the nature of laws.[4] Hart then defends the problem of "the core and the penumbra", which arises when a law's meaning is up for interpretation. The problem of the penumbra arises when the definition of a word in a law is inadequate in deciding the outcome of a case, leading to human interpretation of the law as the deciding factor. An example is a law that refers to a vehicle, which would clearly mean automobile in a core case, but in the penumbra case, the vehicle in question is an airplane, or motorcycle. Hart suggested that rather than interpreting the law with respect to subjective moral values on the given word, the law should be interpreted with respect to the law's purpose. Finally, Hart approaches the criticism of separation of law and morals in an environment of extreme evil law. He discusses the views of Radbruch and Kelsen on the Nazi regime's extremely corrupt legal system. From this discussion, he moves to analyzing the Nazi informer case. In this analysis, he disagrees with the reasoning for the court's ruling, and presents two alternatives: let the woman go unpunished, which he acknowledges is not morally correct, or punish her, and admit that it would set a dangerous precedent of retrospective law. Hart says that these two choices are both evil, which shows that hiding the morality of law is no solution.[5] In Fuller's response to "Positivism and the Separation of Law and Morals", titled "Positivism and Fidelity to Law: A Reply to Professor Hart", he criticizes Hart's failure to acknowledge the morality involved in the creation of law, and rejects his suggestion to interpret an entire law's objective rather than the individual words' meanings.[6] Fuller says that the type of respect we give to human laws must be different from the respect we give a scientific law. For a law to deserve our respect, it must "represent some general direction human effort that we can understand and describe", and the principle of the law must be unconditionally valid. In the first section, "The Definition of Law", Fuller breaks down the difference of opinion between Austin, Gray, Bentham, and Holmes, all positivists whom Hart defended. Fuller says that the positivist claim that however law is defined, it is different from morals, is useless. He then says that Hart's thesis is incomplete due to the useless idea he referenced, and that for it to be complete, he would have to define law in a way that "will make meaningful the obligation of fidelity to law". In the next section, "The Definition of Morality", Fuller likens those who agree with Hart to people building defense for a village, knowing whom they want to protect, but not whom they are protecting them from. The thing they are trying to protect is the integrity of the concept of law, and their defense is a precise definition of law, but the attackers are what their definitions do not apply to. Fuller interprets Hart's examples of the many degrees of "what ought to be" that are immoral, concluding that Hart is reminding positivists that the program that they adopt may come with undesirable moral consequences. Fuller agrees with this point, and follows up with the following observations and questions: 1. Fuller observes that Hart assumes that evil objectives have the same coherence and logic as good objectives, and he disagrees with this, holding that coherence and goodness have more correlation that coherence and evil. He then states his belief that when someone explains their decisions, the decisions will move toward goodness.[7] Finally, he rejects the idea that a legal system will over time work itself toward goodness case by case, arguing that it will instead entrench itself in unjust behavior. 2. Fuller questions the idea that the decline of the separation between law and morality would allow immoral values to be ingrained in the justice system, asking what the protection against this risk would be. He then says that the answer is not in the works of Austin, Gray, Holmes, and Hart, as they break the problem into a state of simplicity that ignores the true dangers. 3. Fuller hypothesizes a situation in which a judge aims to pursue a goal that most citizens would view as morally wrong, and asks whether the judge would be likely to make their decision based on a higher moral principle or aim to keep the interpretation consistent with existing laws and explain the decision in a way that aligns with the laws. 4. Fuller hypothesizes a situation in which he and Hart are in a country where their beliefs are the minority, and they believe that the majority's beliefs are evil. He says they would worry that laws would be manipulated to operate against their beliefs, but doubts that they would worry that someone would challenge those laws, appealing to the majority evil beliefs. He says that even in the most oppressive institutions there is a reluctance to codify extremely evil laws, and that it is clear that the reluctance stems from a tendency to associate law with easily justifiable morals. 5. Fuller says that in populations where the judicial process functions effectively, it is very unlikely that immoral law will be integrated. He defends this by giving the example of commercial law in Britain adopting a "law-is-law" formalism, going against the work in the field by Lord Mansfield. At this time, this situation grew to be a large problem as many commercial cases were taken to arbitration. Fuller says the reason for this shift toward arbitration is that arbitrators are willing to offer a more flexible process that considers the needs of the situation and industry more. At the end, Fuller says that even though Hart rejects "formalism", he believes that Hart's theory leans in the direction of formalism. 6. Fuller references the Pope's 1949 edict to Roman Catholic jurists not to pass sentences based on laws the church sees as unjust,[8] saying that this is an instance of a bias that often influences how one perceives a subject. He says that this is a conflict between two different kinds of law, and that in such a situation, it is difficult to have a meaningful exchange on the topic, which may affect readers of Hart's essay. In Fuller's third section, "The Moral Foundations of a Legal Order", he begins by agreeing with Hart's analysis of the command theory. He then says he predicted that Hart would acknowledge the role of morals in law-making and critiques Hart for not acknowledging the relationship. This brings him to analyzing Austin's Lectures V and VI on Jurisprudence, bringing up the inconsistencies in Austin's theories that could have easily brought him to abandon his command theory. Fuller then asks how the words "fundamental" and "essential" could be defined given Hart's idea of fundamental rules specifying the essential legislative process. He acknowledges that Kelsen's theory had an answer to this, but it is achieved by simplifying reality so much that it can be absorbed by positivism. Fuller says that written constitutions are vital in legal systems, and should be provisionally accepted as good law. In Fuller's fifth section, "The Problem of Restoring Respect for Law and Justice After the Collapse of a Regime That Respected Neither", he looks at the Nazi informer case. Fuller believed none of the Nazi laws were valid, as the entire regime was evil and the law-making process lacked internal morality.[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hart%E2%80%93Fuller_debate |

ハート・フラー論争とは、1958年にハーバード・ロー・レビュー誌に

掲載された、アメリカの法学教授ロン・L・フラーとイギリスの同教授H・L・A・ハートの道徳と法に関するやりとりのことで、実証主義哲学と自然法哲学の

対立を示すものであった。ハートは実証主義の立場から、道徳と法は別物であると主張した。フラーの反論は、法の拘束力の源泉は道徳にあると主張した。 ナチス情報提供者事件 この討論では、戦後の西ドイツの裁判所が以下の事件で下した判決について論じている: 「1944年、被告は夫を追い出したいと考え、ドイツ軍から休暇で帰宅していた夫がヒトラーについて軽蔑的な発言をしたことを当局に報告した。被告人妻が 夫に不利な証言をしたため、夫は、第三帝国の福祉に不都合な発言を主張したり繰り返したりすることを違法とする法令に従って、軍事法廷によって死刑を宣告 された。. . . しかし、服役後、夫は前線に送られた。ナチス政権の敗北後、妻は、夫に判決を下した裁判官と同様に、1871年のドイツ刑法第289条に基づき、他人の自 由を不法に剥奪した罪で起訴された(「retetswidrige Freiheitsberaubung」)。ドイツの刑事裁判の最終審裁判所への控訴審では、判決裁判官は無罪とされるべきだが、妻は、夫の死や投獄につ いて、「すべての良識ある人間の健全な良心と正義感に反する」ナチスの「法律」を自由な選択で利用したのだから、有罪であるとされた。 - ハーバード・ロー・レビュー、1951年、1005-7頁 哲学 文脈 法律学とは、法の哲学の分析を指す。法律学の中には複数の学派があるが、ハート=フラーの論争は、単に法実証主義と自然法理論に関するものである[1]。 法実証主義者は、「(不当な)法律が有効な法律である限り、人はそれに従う法的義務を負う」と考える[2]。自然法論者は、有効性と道徳性の間に直接的な 関係があると考える[3]。 議論  ハート ハートの最初の論文である「実証主義と法と道徳の分離」において、彼はジョン・オースティンによって述べられた、法は人間に対する命令であるとする法実証 主義の「命令理論」の視点が法の本質を正確に表していないため不十分であることを立証している[4]。次にハートは、法の意味が解釈次第である場合に生じ る「核心と半影」の問題を擁護している。ペナンブラの問題は、法律における言葉の定義が事件の結果を決定するのに不十分であり、決定要因として法律の人間 的解釈を導くときに生じる。例えば、ある法律で「乗り物」と定義されている場合、核心的なケースでは明らかに自動車を意味するが、ペナンブラのケースで は、問題の乗り物は飛行機やオートバイである。ハートは、与えられた言葉に対する主観的な道徳的価値観に基づいて法律を解釈するのではなく、法律の目的に基づいて法律を解釈すべきだと提案し た。最後に、ハートは極端な悪法の環境における法と道徳の分離という批判にアプローチする。彼は、ナチス政権の極度に腐敗した法制度に関するラドブルッフ とケルゼンの見解を論じている。この議論から、ナチスの情報提供者事件の分析に移る。この分析において、彼は裁判所の判決理由には同意せず、2つの選択肢 を提示する。それは、その女性を処罰せずに放置することであるが、これは道徳的に正しくないことを彼は認め、あるいは彼女を処罰し、それが遡及法の危険な 前例を作ることになることを認める。ハートは、この二つの選択肢はどちらも悪であり、法の道徳性を隠しても解決にはならないことを示している[5]。 フラーは「実証主義と法と道徳の分離」に対する反論として、「実証主義と法への忠実性」と題して、次のように述べている: ハート教授への返信」と題された「実証主義と法と道徳の分離」に対するフラーの反論の中で、彼はハートが法の創造に関わる道徳を認めていないことを批判 し、個々の言葉の意味ではなく法全体の目的を解釈するという彼の提案を拒絶している[6]。ある法則が私たちの尊敬に値するためには、それは「私たちが理 解し記述することのできる、人間の努力の一般的な方向性を表す」ものでなければならず、法則の原理は無条件に有効でなければならない。 第1章「法の定義」でフラーは、ハートが擁護した実証主義者であるオースティン、グレイ、ベンサム、ホームズの意見の相違を論破している。フラーは、法が どのように定義されようとも、それは道徳とは異なるという実証主義者の主張は無意味であると言う。そして、ハートのテーゼが不完全であるのは、彼が言及し た無駄な考え方のせいであり、完全なものにするためには、「法への忠実義務を意味あるものにする」ような方法で法を定義しなければならないと言う。 次のセクション「道徳の定義」で、フラーはハートに賛同する人々を、村のために防衛を構築する人々に例えている。彼らが守ろうとしているのは法の概念の完 全性であり、彼らの防衛は法の正確な定義であるが、攻撃者は彼らの定義が適用されないものである。フラーは、ハートが例示した「あるべき姿」の多くの程度 が不道徳であると解釈し、ハートは実証主義者たちに、彼らが採用するプログラムが道徳的に望ましくない結果をもたらす可能性があることを思い起こさせてい るのだと結論付けている。フラーはこの指摘に同意し、次のような指摘と疑問を投げかけている: 1. フラーは、ハートが悪の目的も善の目的と同じ首尾一貫性と論理性を持っていると仮定していることを観察し、これには同意せず、首尾一貫性と善は首尾一貫性 と悪よりも相関性が高いとしている。そして、誰かが自分の決定を説明すれば、その決定は善に向かうという信念を述べている[7]。最後に、彼は、法制度が 時間をかけてケース・バイ・ケースで善に向かうという考えを否定し、かえって不公正な行動を定着させると主張している。 2. フラーは、法と道徳の分離が低下することで、不道徳な価値観が司法制度に定着してしまうという考えに疑問を呈し、このリスクから身を守るにはどうしたらよ いかと問う。そして、オースティン、グレイ、ホームズ、ハートの著作の中には、真の危険性を無視した単純化された状態に問題を陥れているため、その答えは ないと言う。 3. フラーは、ほとんどの市民が道徳的に間違っているとみなすような目標を裁判官が追求しようとする状況を仮定し、裁判官はより高い道徳的原則に基づいて決定 を下す可能性が高いのか、それとも既存の法律と整合的な解釈を維持し、法律に沿った形で決定を説明することを目指すのかを問う。 4. フラーは、自分たちの信念が少数派で、多数派の信念は悪だと信じている国に、彼とハートがいると仮定する。彼は、自分たちの信念に反するように法律が操作 されることを心配するだろうが、多数派の邪悪な信念に訴えて、誰かがその法律に異議を唱えることを心配することはないだろうと言う。最も抑圧的な制度で あっても、極端に邪悪な法律を成文化することには消極的であり、その消極性は法律を正当化しやすい道徳と結びつける傾向から生じていることは明らかだと言 う。 5. フラーは、司法手続きが効果的に機能している集団では、不道徳な法律が統合される可能性は極めて低いと言う。フラーは、イギリスの商法がマンスフィールド 卿の研究に反し、「法とは法である」という形式主義を採用した例を挙げて、このことを擁護している。この時、多くの商事事件が仲裁に持ち込まれたため、こ の状況は大きな問題となった。フラー氏によれば、仲裁へのシフトの理由は、仲裁人が状況や業界のニーズをより考慮した、より柔軟なプロセスを提供すること を望んでいるからだという。最後にフラーは、ハートが「形式主義」を否定しているにもかかわらず、ハートの理論は形式主義の方向に傾いていると考えている という。 6. フラーは、ローマ法王が1949年にローマ・カトリックの法学者に対して、教会が不当とみなす法律に基づいて判決を下してはならないという勅令を出したこ とを引き合いに出し[8]、これはしばしば対象の捉え方に影響を与えるバイアスの一例であると述べている。彼は、これは2つの異なる種類の法律の対立であ り、このような状況では、このテーマについて有意義なやりとりをすることは難しく、ハートのエッセイの読者に影響を与えるかもしれないと述べている。 フラーの第3章「法秩序の道徳的基礎」では、まずハートの命令論分析に同意している。そして、ハートが法制定におけるモラルの役割を認めるだろうと予測 し、その関係を認めなかったハートを批判している。そして、オースティンの『法学講義V』『法学講義VI』を分析し、オースティンの理論の矛盾点を指摘す る。次にフラーは、本質的な立法過程を規定する基本的ルールというハートの考えを踏まえ、「基本的」と「本質的」という言葉をどのように定義できるかを問 う。彼は、ケルゼンの理論がこれに対する答えを持っていたことを認めるが、それは実証主義に吸収されるように現実を単純化することによって達成されたもの である。フラーは、成文憲法は法体系において不可欠であり、暫定的に良法として認められるべきだと言う。 フラーの第5章「法と正義のどちらも尊重しない体制の崩壊後、法と正義の尊重を回復する問題」では、ナチスの情報提供者事件を取り上げている。フラーは、 体制全体が悪であり、法制定過程には内的道徳が欠如していたため、ナチスの法律はどれも有効ではなかったと考えていた[9]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆