ポピュリズムの歴史

History of Populism

☆【ポピュリズムとは】ポ ピュリズム(Populism)は、議論の分かれる概念[1][2] で、「一般大衆」の考え方を重視し、多くの場合、この集団をエリートとみなす集団と対立させる、さまざまな政治的立場を指す。多くの場合、反体制や反政治 の感情と関連付けられる。この用語は 19 世紀後半に生まれ、それ以来、さまざまな政治家、政党、運動に、しばしば蔑称的な意味合いで用いられてきた。政治学やその他の社会科学では、ポ ピュリズム についていくつかの異なる定義が用いられており、この用語を完全に排除すべきだと主張する学者もいる。「ポピュリズム」という用語は長い間誤訳の対象とな り、広範でしばしば矛盾した一連の運動や信条を表すのに使われてきた。その使われ方は大陸や文脈にまた がっており、多くの学者が「ポ ピュリズム」は曖昧で拡大解釈されすぎた概念であり、政治的な言説の中で広く用いられているが、その定義は一貫しておらず、 理解も不十分であるとしている[6]。このような背景から、多くの研究がメディア、政治、学術研究においてこの用語の使われ方と拡散を検証しており、これ らの領域間の相互影響に焦点を当て、この概念の進化する意味を形成してきた意味上の変遷をたどっている[7][8]。

★ポ

ピュリズムの言説構造

★【ポピュリズムの歴史】マッドとロヴィラ・カルトヴァッサーは、ポ

ピュリズムは現代的な現象であると主張している。[189]

しかし、古典アテネの民主主義においてポ

ピュリズムの現れを特定しようとする試みも行われてきた。[190]

イートウェルは、実際の「ポピュリズム」という用語は、ローマ共和国で活躍したポピュラーレと並行しているが、これらおよびその他の前近代的な集団は「真

にポピュリスト的なイデオロギーを発展させなかった」と指摘している。[191]

ポピュリズムの起源は、19世紀後半にアメリカ合衆国とロシア帝国で「ポピュリスト」を名乗る運動が台頭した時期に遡ることが多い。[192]ポ

ピュリズムは、民主主義の思想として、また統治の枠組みとして、民主主義の広がりと結びつけられることが多い。[189]

一方、歴史家のバリー・S・ストラウスは、ポ

ピュリズムは古代世界にも見られると主張し、紀元前5世紀のアテネのポピュラーレスを例に挙げた。アテネと、

紀元前2世紀からローマ共和国で活動した政治派閥「ポピュラーレス」を例に挙げています。[193]

歴史家のレイチェル・フォクシーは、17世紀のイングランドの「レベラーズ」も「ポピュリスト」と称することができると主張し、彼らは「平等な自然権が政

治生活を形作るべきだ」と信じていたと指摘しています。[194][clarification needed]

一方、歴史家のピーター・ブリックルは、ポピュリズムをプロテスタント改革と結びつけています。[195][196]

| Although

the term "populist" can be traced back to populares (courting the

people) Senators in Ancient Rome, the first political movements emerged

during the late nineteenth century. However, some of the movements that

have been portrayed as progenitors of modern populism did not develop a

truly populist ideology. It was only with the coming of Boulangism in

France and the American People's Party, which was also known as the

Populist Party, that the foundational forms of populism can fully be

discerned. In particular, it was during this era that terms such as

"people" and "popular sovereignty" became a major part of the

vocabulary of insurgent political movements that courted mass support

among an expanding electorate by claiming that they uniquely embodied

their interests[.] Political historian Roger Eatwell[188] |

「ポピュリスト」という用語は、古代ローマの「ポピュラーレス」(民衆

を支持する)上院議員に遡ることができるが、最初の政治運動は19世紀後半に現れた。しかし、現代のポピュリズムの先駆者と描かれてきた運動の一部は、真

のポピュリスト的イデオロギーを確立しなかった。フランスでのブーランジュ主義の台頭と、アメリカ人民党(ポピュリスト党とも呼ばれる)の出現により、ポ

ピュリズムの基礎的な形態が明確に認識されるようになった。特にこの時代には、「人民」や「人民主権」といった用語が、拡大する有権者層の支持を求め、そ

の利益を唯一代表すると主張する反体制的政治運動の主要な用語として定着した[。] 政治史家ロジャー・イートウェル[188] |

| Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser

argue that populism is a modern phenomenon.[189] However, attempts have

been made to identify manifestations of populism in the democracy of

classical Athens.[190] Eatwell noted that although the actual term

populism parallels that of the Populares who were active in the Roman

Republic, these and other pre-modern groups "did not develop a truly

populist ideology."[191] The origins of populism are often traced to

the late nineteenth century, when movements calling themselves populist

arose in both the United States and the Russian Empire.[192] Populism

has often been linked to the spread of democracy, both as an idea and

as a framework for governance.[189] Conversely, the historian Barry S. Strauss argued that populism could also be seen in the ancient world, citing the examples of the fifth-century B.C. Athens and Populares, a political faction active in the Roman Republic from the second century BCE.[193] The historian Rachel Foxley argued that the Levellers of 17th-century England could also be labelled "populists", meaning that they believed "equal natural rights ... must shape political life"[194][clarification needed] while the historian Peter Blickle linked populism to the Protestant Reformation.[195][196] |

マッドとロヴィラ・カルトヴァッサーは、ポピュリズムは現代的な現象で

あると主張している。[189] しかし、古典アテネの民主主義においてポピュリズムの現れを特定しようとする試みも行われてきた。[190]

イートウェルは、実際の「ポピュリズム」という用語は、ローマ共和国で活躍したポピュラーレと並行しているが、これらおよびその他の前近代的な集団は「真

にポピュリスト的なイデオロギーを発展させなかった」と指摘している。[191]

ポピュリズムの起源は、19世紀後半にアメリカ合衆国とロシア帝国で「ポピュリスト」を名乗る運動が台頭した時期に遡ることが多い。[192]

ポピュリズムは、民主主義の思想として、また統治の枠組みとして、民主主義の広がりと結びつけられることが多い。[189] 一方、歴史家のバリー・S・ストラウスは、ポピュリズムは古代世界にも見られると主張し、紀元前5世紀のアテネのポピュラーレスを例に挙げた。アテネと、 紀元前2世紀からローマ共和国で活動した政治派閥「ポピュラーレス」を例に挙げています。[193] 歴史家のレイチェル・フォクシーは、17世紀のイングランドの「レベラーズ」も「ポピュリスト」と称することができると主張し、彼らは「平等な自然権が政 治生活を形作るべきだ」と信じていたと指摘しています。[194][clarification needed] 一方、歴史家のピーター・ブリックルは、ポピュリズムをプロテスタント改革と結びつけています。[195][196] |

| Europe Main article: Populism in Europe 19th and 20th centuries In the Russian Empire during the late 19th century, the narodnichestvo movement emerged, championing the cause of the empire's peasantry against the governing elites.[197] The movement was unable to secure its objectives; however, it inspired other agrarian movements across eastern Europe in the early 20th century.[198] Although the Russian movement was primarily a movement of the middle class and intellectuals "going to the people", in some respects their agrarian populism was similar to that of the US People's Party, with both presenting small farmers (the peasantry in Europe) as the foundation of society and main source of societal morality.[198] According to Eatwell, the narodniks "are often seen as the first populist movement".[16]  Ilya Repin's painting, Arrest of a Propagandist (1892), which depicts the arrest of a narodnik In German-speaking Europe, the völkisch movement has often been characterised as populist, with its exultation of the German people and its anti-elitist attacks on capitalism and Jews.[16] In France, the Boulangist movement also utilised populist rhetoric and themes.[199] In the early 20th century, adherents of both Marxism and fascism flirted with populism, but both movements remained ultimately elitist, emphasising the idea of a small elite who should guide and govern society.[198] Among Marxists, the emphasis on class struggle and the idea that the working classes are affected by false consciousness are also antithetical to populist ideas.[198] After 1945 populism was largely absent from Europe, in part due to the domination of Marxism–Leninism in Eastern Europe and a desire to emphasise moderation among many West European political parties.[200] However, over the coming decades, a number of right-wing populist parties emerged throughout the continent.[201] These were largely isolated and mostly reflected a conservative agricultural backlash against the centralisation and politicisation of the agricultural sector then occurring.[202] These included Guglielmo Giannini's Common Man's Front in 1940s Italy, Pierre Poujade's Union for the Defense of Tradesmen and Artisans in late 1950s France, Hendrik Koekoek's Farmers' Party of the 1960s Netherlands, and Mogens Glistrup's Progress Party of 1970s Denmark.[201] Between the late 1960s and the early 1980s there also came a concerted populist critique of society from Europe's New Left, including from the new social movements and from the early Green parties.[203] However it was only in the late 1990s, according to Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, that populism became "a relevant political force in Europe", one which could have a significant impact on mainstream politics.[202] Following the fall of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc of the early 1990s, there was a rise in populism across much of Central and Eastern Europe.[204] In the first multiparty elections in many of these countries, various parties portrayed themselves as representatives of "the people" against the "elite", representing the old governing Marxist–Leninist parties.[205] The Czech Civic Forum party for instance campaigned on the slogan "Parties are for party members, Civic Forum is for everybody".[205] Many populists in this region claimed that a "real" revolution had not occurred during the transition from Marxist–Leninist to liberal democratic governance in the early 1990s and that it was they who were campaigning for such a change.[206] The collapse of Marxism–Leninism as a central force in socialist politics also led to a broader growth of left-wing populism across Europe, reflected in groups like the Dutch Socialist Party, Scottish Socialist Party, and German's The Left party.[207] Since the late 1980s, populist experiences emerged in Spain around the figures of José María Ruiz Mateos, Jesús Gil and Mario Conde, businessmen who entered politics chiefly to defend their personal economic interests, but by the turn of the millennium their proposals had proved to meet a limited support at the ballots at the national level.[208] |

ヨーロッパ 主な記事:ヨーロッパのポピュリズム 19世紀および20世紀 19世紀後半のロシア帝国では、支配層に対する帝国の農民の権利を擁護するナロードニチェストヴォ運動が台頭した[197]。この運動は目標を達成するこ とはできなかったが、20世紀初頭、東ヨーロッパ全域で他の農民運動に影響を与えた。[198] ロシアの運動は、主に中産階級や知識層による「人民への回帰」運動だったが、その農業ポピュリズムは、小規模農家(ヨーロッパでは農民)を社会の基盤であ り、社会道徳の主な源泉とするという点で、米国の人民党のポピュリズムと共通していた。[198] イートウェルによると、ナロードニキは「最初のポピュリスト運動」とよく見なされている。[16]  イリヤ・レーピンの絵画「宣伝員の逮捕」(1892年)、ナロードニキの逮捕を描いたもの ドイツ語圏のヨーロッパでは、フォルク運動は、ドイツ人民の称賛と、資本主義やユダヤ人に対する反エリート主義的な攻撃から、しばしばポピュリスト的であ ると特徴づけられてきた[16]。フランスでは、ブールアンジュ運動もポピュリスト的なレトリックやテーマを利用していた。[199] 20世紀初頭、マルクス主義とファシズムの支持者はポピュリズムに傾倒したが、両運動は最終的にエリート主義的であり、社会を導き支配すべき小さなエリー トの存在を強調した。[198] マルクス主義者においては、階級闘争の強調と労働者階級が偽りの意識に支配されているという考えは、ポピュリズムの思想と対立する。[198] 1945年以降、ポピュリズムはヨーロッパからほぼ消え去った。これは、東ヨーロッパでのマルクス・レーニン主義の支配と、西ヨーロッパの多くの政治党派 が穏健さを強調する傾向があったためだ。[200] しかし、その後の数十年で、右派ポピュリズム政党が大陸各地で台頭した。[201] これらの政党は主に孤立しており、当時進行中の農業部門の集中化と政治化に対する保守的な農業反動を反映していた。[202] これには、1940年代イタリアのグイード・ジャンニーニの「一般市民戦線」、1950年代後半フランスのピエール・プワジャの「職人・手工業者防衛連 合」、1960年代オランダのヘンリク・コエコークの「農民党」、1970年代デンマークのモーゲン・グリストルプの「進歩党」などが含まれる。 [201] 1960年代後半から1970年代前半にかけては、 党(1960年代オランダ)、モーゲン・グリストルプの進歩党(1970年代デンマーク)などが含まれる。[201] 1960年代後半から1980年代前半にかけて、ヨーロッパのニュー・レフトから、新たな社会運動や初期の緑の党を含む、社会に対する組織的なポピュリス ト的批判が提起された。[203] しかし、ムッデとロビラ・カルタッサーによると、ポピュリズムが「ヨーロッパで重要な政治勢力」となり、主流政治に重大な影響を与えるようになったのは、 1990年代後半になってからだった。[202] 1990年代初頭のソ連と東欧諸国の崩壊後、中央および東ヨーロッパの多くの国々でポピュリズムが台頭した[204]。これらの国の多くで初めて実施され た複数政党制の選挙では、さまざまな政党が、旧来のマルクス・レーニン主義の与党である「エリート」に対抗する「人民」の代表として自らを位置づけた。 [205] 例えば、チェコの市民フォーラム党は「政党は党員のため、市民フォーラムはすべての人々のため」というスローガンを掲げてキャンペーンを展開した。 [205] この地域の多くのポピュリストは、1990年代初頭のマルクス・レーニン主義から自由民主主義への移行期に「真の革命」は起こらなかったと主張し、そのよ うな変化を推進しているのは自分たちだと主張した。[206] マルクス・レーニン主義が社会主義政治の中心的勢力として崩壊したことは、ヨーロッパ全体で左派ポピュリズムの拡大にもつながり、オランダ社会党、スコッ トランド社会党、ドイツの「左派党」などの団体に反映された。[207] 1980年代後半以降、スペインでは、主に個人的な経済的利益を守るために政界に入った実業家、ホセ・マリア・ルイス・マテオス、ヘスス・ギル、マリオ・ コンデといった人物を中心に、ポピュリスト運動が台頭したが、2000年代に入ると、彼らの提案は全国レベルの投票では限られた支持しか得られなかった。 [208] |

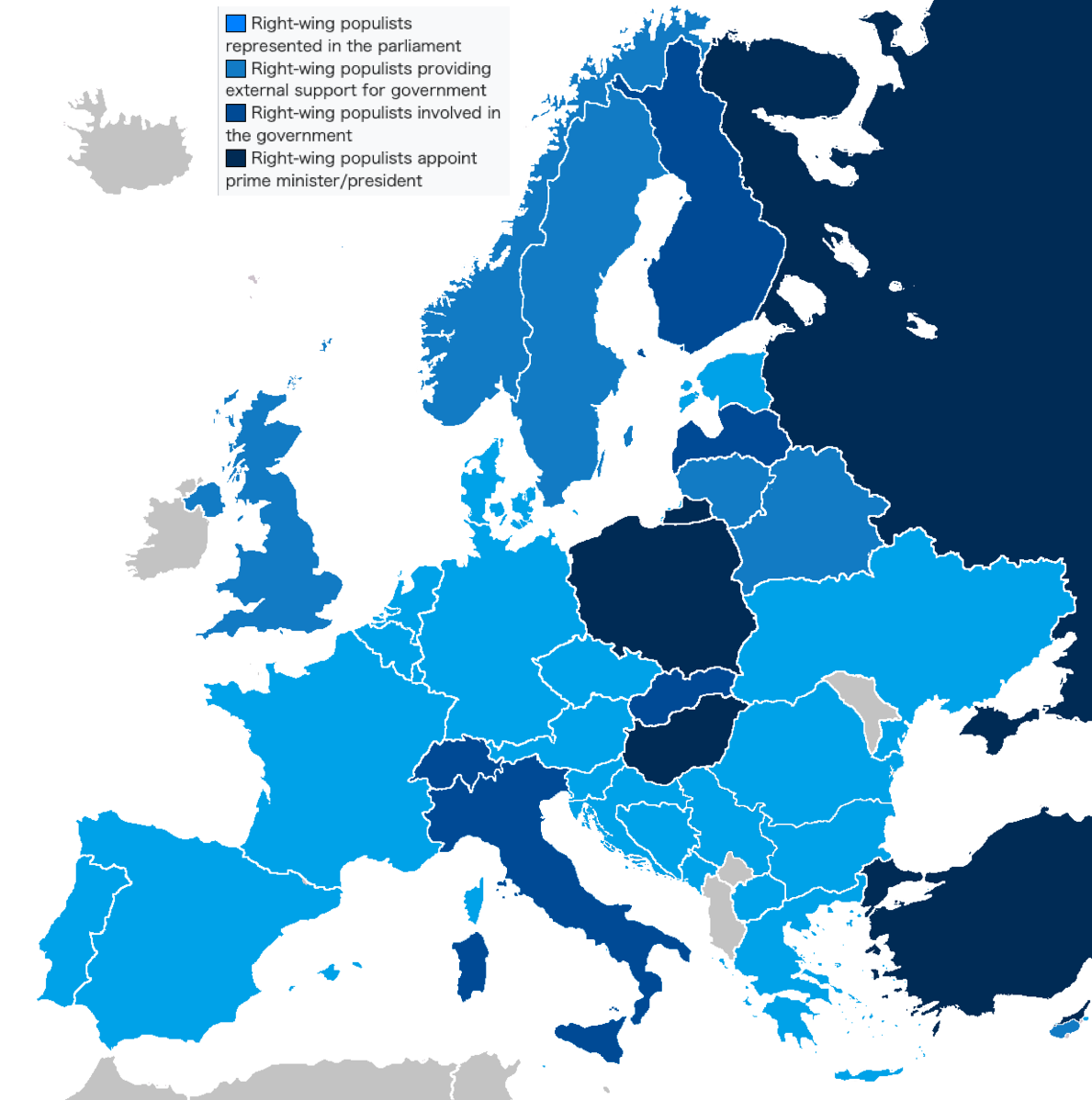

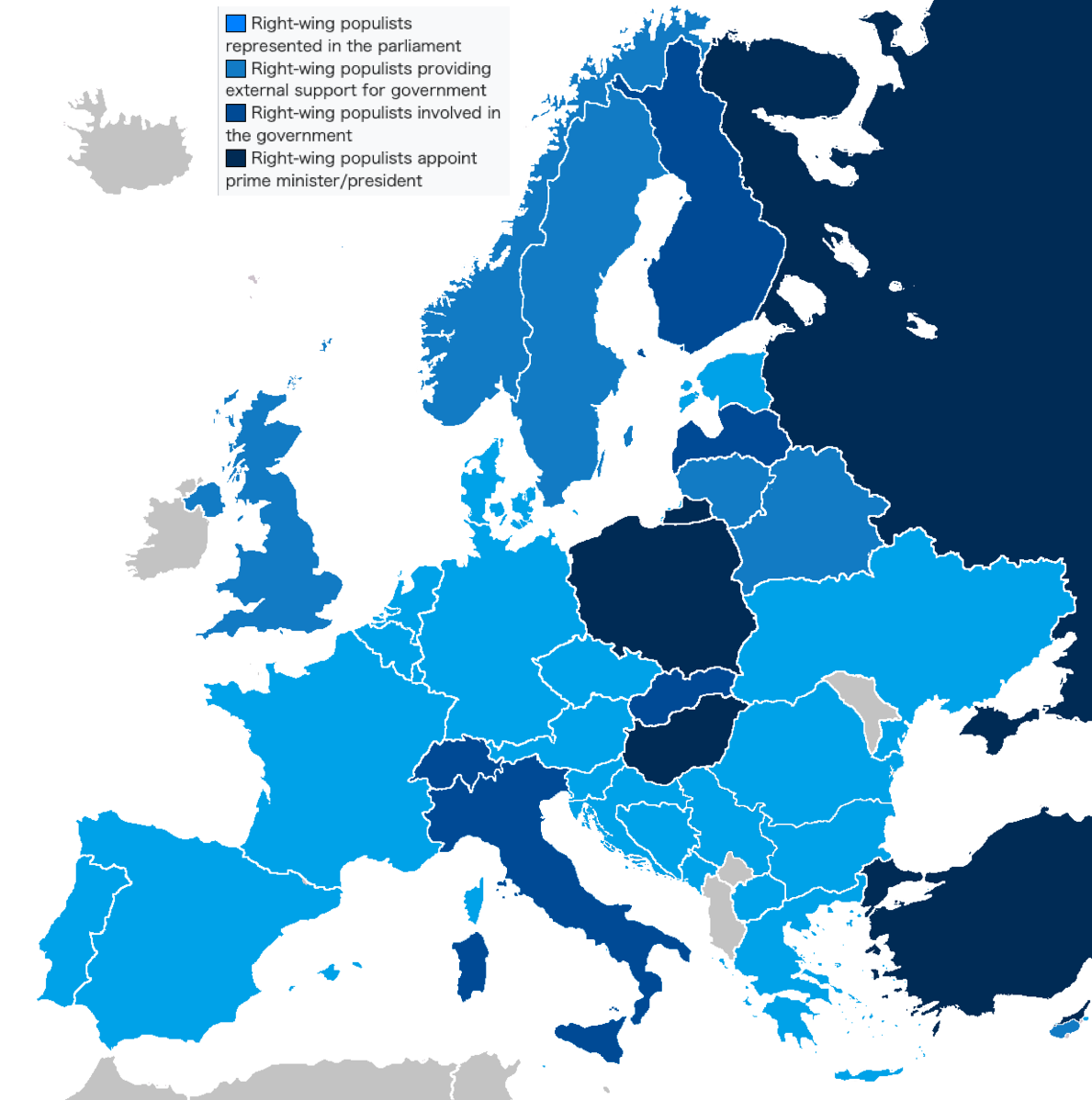

21st century European national parliaments with representatives from right-wing populist parties in July 2023:[citation needed] Right-wing populists represented in the parliament Right-wing populists providing external support for government Right-wing populists involved in the government Right-wing populists appoint prime minister/president  Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder and leader of the French National Front, the "prototypical radical right party" which used populism to advance its cause[209] At the turn of the 21st century, populist rhetoric and movements became increasingly apparent in Western Europe.[210] Populist rhetoric was often used by opposition parties. For example, in the 2001 electoral campaign, the Conservative Party leader William Hague accused Tony Blair's governing Labour Party government of representing "the condescending liberal elite". Hague repeatedly referring to it as "metropolitan", implying that it was out of touch with "the people", who in Conservative discourse are represented by "Middle England".[211] Blair's government also employed populist rhetoric; in outlining legislation to curtail fox hunting on animal welfare grounds, it presented itself as championing the desires of the majority against the upper-classes who engaged in the sport.[34] Blair's rhetoric has been characterised as the adoption of a populist style rather than the expression of an underlying populist ideology.[212] By the 21st century, European populism[213] was again associated largely with the political right.[214] The term came to be used in reference both to radical right groups like Jörg Haider's FPÖ in Austria and Jean-Marie Le Pen's FN in France, as well as to non-radical right-wing groups like Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia or Pim Fortuyn's LPF in the Netherlands.[214] The populist radical right combined populism with authoritarianism and nativism.[202][215] Conversely, the Great Recession also resulted in the emergence of left-wing populist groups in parts of Europe, most notably the Syriza party which gained political office in Greece and the Podemos party in Spain, displaying similarities with the US-based Occupy movement.[206] Like Europe's right-wing populists, these groups also expressed Eurosceptic sentiment towards the European Union, albeit largely from a socialist and anti-austerity perspective rather than the nationalist perspective adopted by their right-wing counterparts.[206] Populists have entered government in many countries across Europe, both in coalitions with other parties as well by themselves, Austria and Poland are examples of these respectively.[216] The UK Labour Party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn has been called populist,[217][218][219] with the slogan "for the many not the few" having been used.[220][221][failed verification][222][failed verification] After the 2016 UK referendum on membership of the European Union, in which British citizens voted to leave, some have claimed the "Brexit" as a victory for populism, encouraging a flurry of calls for referendums among other EU countries by populist political parties.[223] |

21 世紀 2023年7月、右翼ポピュリスト政党の代表者が参加する欧州各国議会:[要出典] 議会に議席を有する右翼ポピュリスト 政府に外部支援を提供する右翼ポピュリスト 政府に関与する右翼ポピュリスト 首相/大統領を任命する右翼ポピュリスト  ジャン=マリー・ルペン、フランス国民戦線の創設者であり指導者、「その目的を推進するためにポピュリズムを利用した典型的な急進右派政党」[209] 21 世紀の変わり目に、西ヨーロッパではポピュリストのレトリックや運動がますます顕著になった[210]。ポピュリストのレトリックは、野党によってよく使 われた。例えば、2001年の選挙キャンペーンでは、保守党党首のウィリアム・ヘイグは、トニー・ブレア率いる与党労働党を「見下すようなリベラルエリー ト」と非難した。ヘイグは、それを「メトロポリタン」と繰り返し表現し、保守派の言説で「ミドル・イングランド」に代表される「人民」との接点が全くない ことをほのめかした。[211] ブレア政権もポピュリスト的な修辞を用い、動物福祉を理由に狐狩りを規制する立法案を提示する際、このスポーツに従事する上流階級に対して、大多数の国民 の願望を代弁する立場を強調した。[34] ブレアの修辞は、潜在的なポピュリスト的イデオロギーの表現ではなく、ポピュリスト的なスタイルの採用と特徴付けられている。[212] 21世紀に入ると、ヨーロッパのポピュリズム[213]は再び主に政治的右派と関連付けられるようになった[214]。この用語は、オーストリアのヨル グ・ハイダー率いるFPÖやフランスのジャン=マリー・ルペン率いるFNのような過激な右派グループだけでなく、シルヴィオ・ベルルスコーニ率いるイタリ アのフォルツァ・イタリアやオランダのピム・フォルトゥイン率いるLPFのような非過激な右派グループにも適用されるようになった。[214] ポピュリストの急進的な右派は、ポピュリズムと権威主義およびナショナリズムを融合させた。[202][215] 一方、大不況は、ヨーロッパの一部で左派ポピュリストのグループ、特にギリシャで政権を獲得したシリアザ党やスペインのポデモス党の出現をもたらし、これ らは米国のオキュパイ運動と類似点を見せた。[206] ヨーロッパの右派ポピュリストと同様、これらの団体も、欧州連合に対してユーロ懐疑的な感情を表明しているが、その見方は、右派が採用しているナショナリ スト的な視点ではなく、主に社会主義的かつ反緊縮財政的な視点によるものである。[206] ポピュリストは、他の政党との連立政権や単独政権として、ヨーロッパの多くの国で政権に参加している。その例としては、それぞれオーストリアとポーランド が挙げられる。[216] ジェレミー・コービンの指導下にある英国労働党は、ポピュリストと呼ばれており[217][218][219]、「少数のためではなく、大多数のために」というスローガンを掲げている[220][221][検証不能][222][検証不能]。 2016年の欧州連合加盟に関する国民投票で英国国民が離脱を投票した後、一部では「ブレグジット」をポピュリズムの勝利と主張し、他の EU 諸国でもポピュリスト政党による国民投票の要求が相次ぎました。[223] |

| North America Main articles: Populism in the United States and Populism in Canada   The 2016 presidential election saw a wave of populist sentiment in the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, with both candidates running on anti-establishment platforms in the Democratic and Republican parties, respectively. In North America, populism has often been characterised by regional mobilisation and loose organisation.[224] During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, populist sentiments became widespread, particularly in the western provinces of Canada, and in the southwest and Great Plains regions of the United States. In this instance, populism was combined with agrarianism and often known as "prairie populism".[225] For these groups, "the people" were yeomen—small, independent farmers—while the "elite" were the bankers and politicians of the northeast.[225] In some cases, populist activists called for alliances with labor (the first national platform of the National People's Party in 1892 calling for protecting the rights of "urban workmen".[226] In the state of Georgia in the early 1890s, Thomas E. Watson led a major effort to unite poor white farmers, and included some African-American farmers.[227][228] The People's Party of the late 19th century United States is considered to be "one of the defining populist movements";[201] its members were often referred to as the Populists at the time.[225] Its radical platform included calling for the nationalisation of railways, the banning of strikebreakers, and the introduction of referendums.[229] The party gained representation in several state legislatures during the 1890s, but was not powerful enough to mount a successful presidential challenge. In the 1896 presidential election, the People's Party supported the Democratic Party candidate William Jennings Bryan; after his defeat, the People's Party's support plunged.[230] Other early populist political parties in the United States included the Greenback Party, the Progressive Party of 1924 led by Robert M. La Follette, Sr., and the Share Our Wealth movement of Huey P. Long in 1933–1935.[231][232] In Canada, populist groups adhering to a social credit ideology had various successes at local and regional elections from the 1930s to the 1960s, although the main Social Credit Party of Canada never became a dominant national force.[233] By the mid-20th century, US populism had moved from a largely progressive to a largely reactionary stance, being closely intertwined with the anti-communist politics of the period.[234] In this period, the historian Richard Hofstadter and sociologist Daniel Bell compared the anti-elitism of the 1890s Populists with that of Joseph McCarthy.[235] Although not all academics accepted the comparison between the left-wing, anti-big business Populists and the right-wing, anti-communist McCarthyites, the term "populist" nonetheless came to be applied to both left-wing and right-wing groups that blamed elites for the problems facing the country.[235] Some mainstream politicians in the Republican Party recognised the utility of such a tactic and adopted it; Republican President Richard Nixon for instance popularised the term "silent majority" when appealing to voters.[234] Right-wing populist rhetoric was also at the base of two of the most successful third-party presidential campaigns in the late 20th century, that of George C. Wallace in 1968 and Ross Perot in 1992.[3] These politicians presented a consistent message that a "liberal elite" was threatening "our way of life" and using the welfare state to placate the poor and thus maintain their own power.[3] Former Oklahoma Senator Fred R. Harris, first elected in 1964, ran unsuccessfully for the US presidency in 1972 and 1976. Harris' New Populism embraced egalitarian themes.[236] In the first decade of the 21st century, two populist movements appeared in the US, both in response to the Great Recession: the Occupy movement and the Tea Party movement.[237] The populist approach of the Occupy movement was broader, with its "people" being what it called "the 99%", while the "elite" it challenged was presented as both the economic and political elites.[238] The Tea Party's populism was Producerism, while "the elite" it presented was more party partisan than that of Occupy, being defined largely—although not exclusively—as the Democratic administration of President Barack Obama.[238] The 2016 presidential election saw a wave of populist sentiment in the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, with both candidates running on anti-establishment platforms in the Democratic and Republican parties, respectively.[239] Both campaigns criticised free trade deals such as the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership but differed significantly on other issues, such as immigration.[240][241][242][243] Other studies have noted an emergence of populist rhetoric and a decline in the value of prior experience in U.S. intra-party contests such as congressional primaries.[244] Nativism and hostility toward immigrants (especially Muslims, Hispanics and Asians) were common features.[245] |

北米 主な記事:アメリカ合衆国のポピュリズム、カナダのポピュリズム   2016年の大統領選挙では、バーニー・サンダースとドナルド・トランプの選挙運動にポピュリズムの波が押し寄せ、両候補は、それぞれ民主党と共和党の反体制プラットフォームを掲げて選挙戦に臨んだ。 北米では、ポピュリズムはしばしば、地域的な動員と緩やかな組織を特徴としている[224]。19 世紀後半から 20 世紀初頭にかけて、ポピュリズムの感情は、特にカナダの西部諸州、およびアメリカ合衆国の南西部とグレートプレーンズ地域で広まった。この場合、ポピュリ ズムは農業主義と結びつき、「大草原のポピュリズム」としてよく知られていた[225]。これらのグループにとって、「人民」とは小規模で独立した農民で ある「ヨーマン」であり、「エリート」とは北東部の銀行家や政治家たちだった。[225] 場合によっては、ポピュリストの活動家たちは労働者との提携を訴えた(1892年の国民人民党の最初の全国綱領では、「都市労働者」の権利の保護を訴え た)。[226] 1890年代初頭のジョージア州では、トーマス・E・ワトソンが貧しい白人農民を団結させる大きな運動を主導し、アフリカ系アメリカ人の農民も参加しまし た。[227][228] 19 世紀後半のアメリカ合衆国における人民党は、「決定的な大衆運動のひとつ」とみなされている[201]。その党員は、当時、しばしば「大衆主義者」と呼ば れていた[225]。その急進的な政策には、鉄道の国有化、スト破りの禁止、国民投票の導入などが含まれていた。[229] この党は 1890 年代にいくつかの州議会で議席を獲得したが、大統領選挙で勝利を収めるほどの力はない。1896 年の大統領選挙では、人民党は民主党の候補者ウィリアム・ジェニングス・ブライアンを支持したが、彼の敗北後、人民党の支持は急落した。[230] 米国におけるその他の初期のポピュリスト政党としては、グリーンバック党、ロバート・M・ラフォレット・シニアが率いた 1924 年の進歩党、1933 年から 1935 年にかけてのヒューイ・P・ロングの「富の分配」運動などが挙げられる。カナダでは、社会信用主義のイデオロギーを掲げるポピュリスト集団が、1930年 代から1960年代にかけて地方選挙や地域選挙でさまざまな成功を収めたが、主要な社会信用党は、全国的な勢力には至らなかった。 20 世紀半ばまでに、米国のポピュリズムは、主に進歩的な立場から、主に反動的な立場へと移行し、当時の反共産主義政治と密接に絡み合うようになった。 [234] この時期、歴史家のリチャード・ホフスタッターと社会学者ダニエル・ベルは、1890 年代のポピュリストの反エリート主義を、ジョセフ・マッカーシーのそれと比較した。[235] すべての学者が、左派の反大企業ポピュリストと右派の反共産主義マッカーシストの比較を認めたわけではなかったが、「ポピュリスト」という用語は、国の問 題の原因をエリートに帰する左派と右派の両グループに適用されるようになった。[235] 共和党の主流派政治家の一部は、このような戦術の有用性を認識し、採用した。例えば、共和党のリチャード・ニクソン大統領は、有権者に訴える際に「沈黙の 多数派」という用語を普及させた。[234] 右派ポピュリストの修辞は、20世紀後半に最も成功した第三党の大統領選挙キャンペーンの2つ、1968年のジョージ・C. ウォレスの1968年とロス・ペローの1992年のキャンペーンの基盤を成した。[3] これらの政治家は、「リベラルなエリート」が「私たちの生活様式」を脅かし、福祉国家を利用して貧しい人々をなだめて自らの権力を維持していると主張する 一貫したメッセージを掲げた。[3] 1964年に初当選した元オクラホマ州上院議員フレッド・R・ハリスは、1972年と1976年に米国大統領選に出馬したが失敗に終わった。ハリスが提唱した「ニュー・ポピュリズム」は、平等主義的なテーマを掲げていた。[236] 21 世紀の最初の 10 年間に、大不況を受けて、2 つのポピュリスト運動が米国で出現した。それは、オキュパイ運動とティーパーティー運動だ。[237] オキュパイ運動のポピュリスト的アプローチはより広範で、その「人民」は「99%」と表現され、その対象とする「エリート」は経済エリートと政治エリート の両方として表現された。[238] ティーパーティーのポピュリズムは生産主義であり、その「エリート」は、オキュパイよりも政党支持者であり、主に(ただし、それだけに限定されない)バラ ク・オバマ大統領の民主党政権と定義されていた。 2016年の大統領選挙では、バーニー・サンダースとドナルド・トランプの選挙運動にポピュリストの感情が波のように押し寄せ、両候補は、それぞれ民主党 と共和党の反体制プラットフォームを掲げて選挙戦に臨んだ。[239] 両陣営は、北米自由貿易協定や環太平洋パートナーシップ協定などの自由貿易協定を批判したが、移民などの他の問題については大きく意見が分かれた。 [240][241][242][243] 他の研究では、米国議会予備選挙などの政党内部での争いにおいて、ポピュリスト的なレトリックの台頭と、これまでの経験の価値の低下が見られたと指摘され ている。[244] ナショナリズムや移民(特にイスラム教徒、ヒスパニック、アジア人)に対する敵意が共通の特徴だった。[245] |

| Latin America Main article: Populism in Latin America  Javier Milei, Argentina President, is a well known libertarian populist.[246] Populism has been dominant in Latin American politics since the 1930s and 1940s,[247] being far more prevalent there than in Europe.[248] Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser noted that the region has the world's "most enduring and prevalent populist tradition".[249] They suggested that this was the case because it was a region with a long tradition of democratic governance and free elections, but with high rates of socio-economic inequality, generating widespread resentments that politicians can articulate through populism.[250] March instead thought that it was the important role of "catch-all parties and prominent personalities" in Latin American politics which had made populism more common.[248] The first wave of Latin American populism began at the start of the Great Depression in 1929 and last until the end of the 1960s.[251] In various countries, politicians took power while emphasising "the people": these included Getúlio Vargas in Brazil, Juan Perón in Argentina, and José María Velasco Ibarra in Ecuador.[252] These relied on the Americanismo ideology, presenting a common identity across Latin America and denouncing any interference from imperialist powers.[253] The second wave took place in the early 1990s;[254] de la Torre called it "neoliberal populism".[154] In the late 1980s, many Latin American states were experiencing economic crisis and several populist figures were elected by blaming the elites for this situation.[253] Examples include Carlos Menem in Argentina, Fernando Collor de Mello in Brazil, and Alberto Fujimori in Peru.[254] Once in power, these individuals pursued neoliberal economic strategies recommended by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[255] Unlike the first wave, the second did not include an emphasis on Americanismo or anti-imperialism.[256] The third wave began in the final years of the 1990s and continued into the 21st century.[256] It overlapped in part with the pink tide of left-wing resurgence in Latin America. Like the first wave, the third made heavy use of Americanismo and anti-imperialism, although this time these themes presented alongside an explicitly socialist programme that opposed the free market.[256] Prominent examples included Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Cristina de Kirchner in Argentina, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua.[257] These socialist populist governments have presented themselves as giving sovereignty "back to the people", in particular through the formation of constituent assemblies that would draw up new constitutions, which could then be ratified via referendums.[258] In this way they claimed to be correcting the problems of social and economic injustice that liberal democracy had failed to deal with, replacing it with superior forms of democracy.[259] |

ラテンアメリカ 主な記事:ラテンアメリカのポピュリズム  アルゼンチンの大統領、ハビエル・ミレイは、よく知られたリバタリアン・ポピュリストだ。[246] ポピュリズムは1930年代から1940年代にかけてラテンアメリカ政治で支配的となり[247]、ヨーロッパよりもはるかに広く普及している [248]。ムッデとロビラ・カルタッサーは、この地域は世界でも「最も持続的で広範なポピュリズムの伝統」を有していると指摘している。[249] 彼らは、この地域は民主的統治と自由選挙の長い伝統がある一方で、社会経済的不平等が深刻であり、政治家がポピュリズムを通じて表現できる広範な不満が生 じていたためだと指摘している。[250] 一方、マーチは、ラテンアメリカの政治において「キャッチオール政党と著名人」が重要な役割を果たしたことが、ポピュリズムの蔓延につながったとの見解を 示している。[248] ラテンアメリカのポピュリズムの最初の波は、1929年の大恐慌の開始とともに始まり、1960年代の終わりまで続いた[251]。さまざまな国で、「人 民」を強調する政治家が権力を握った。その中には、ブラジルのゲトゥリオ・ヴァルガス、アルゼンチンのフアン・ペロン、エクアドルのホセ・マリア・ベラス コ・イバラなどがいた。[252] 彼らはアメリカニズモ思想に依拠し、ラテンアメリカ全体に共通のアイデンティティを提示し、帝国主義諸国の干渉を非難した。[253]第二波は1990年 代初頭に起こり、[254]デ・ラ・トーレはこれを「新自由主義的ポピュリズム」と呼んだ。[154] 1980年代後半、多くのラテンアメリカ諸国は経済危機に直面し、この状況をエリートの責任に転嫁するポピュリスト的な指導者が選出された。[253] 例としては、アルゼンチンのカルロス・メネム、ブラジルのフェルナンド・コルル・デ・メロ、ペルーのアルベルト・フジモリが挙げられる。[254] 権力を掌握した後、これらの指導者は国際通貨基金(IMF)が推奨する新自由主義的な経済政策を推進した。[255] 第1波とは異なり、第2波ではアメリカニズムや反帝国主義は強調されなかった。[256] 第3波は1990年代の終わりに始まり、21世紀まで続いた。[256] これは、ラテンアメリカにおける左翼の復活であるピンクタイドと一部重なっている。第一波と同様、第三波もアメリカニズモと反帝国主義を多用したが、今回 はこれらのテーマが自由市場に反対する明確な社会主義プログラムと共に提示された。[256] 代表的な例には、ベネズエラのウゴ・チャベス、アルゼンチンのクリスティナ・デ・キルチネル、ボリビアのエボ・モラレス、エクアドルのラファエル・コレ ア、ニカラグアのダニエル・オルテガなどが挙げられる。[257] これらの社会主義ポピュリスト政権は、特に、国民投票によって批准される新憲法を起草する憲法制定議会を設立することで、「主権を人民に返還」すると主張 した。[258] このようにして、彼らは、自由民主主義が対処できなかった社会・経済的不公正の問題を是正し、より優れた民主主義形態に置き換えることを主張した。 [259] |

| Oceania During the 1990s, there was a growth in populism in both Australia and New Zealand.[260] In New Zealand, Robert Muldoon, the 31st Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1975 to 1984, had been cited as a populist.[261] Populism has become a pervasive trend in New Zealand politics since the introduction of the mixed-member proportional voting system in 1996.[262][263] The New Zealand Labour Party's populist appeals in its 1999 election campaign and advertising helped to propel the party to victory in that election.[264] New Zealand First has presented a more lasting populist platform; long-time party leader Winston Peters has been characterised by some as a populist who uses anti-establishment rhetoric,[265] though in a uniquely New Zealand style.[266][267] Further information: Populism in New Zealand |

オセアニア 1990年代、オーストラリアとニュージーランドの両方でポピュリズムが台頭した[260]。 ニュージーランドでは、1975年から1984年まで第31代首相を務めたロバート・マルドゥーンがポピュリストとして挙げられていた。[261] 1996年に混血の比例代表制が導入されて以来、ポピュリズムはニュージーランドの政治に広範な傾向となっている。[262][263] 1999年の選挙キャンペーンおよび広告におけるニュージーランド労働党のポピュリスト的なアピールは、同党の選挙での勝利に貢献した。[264] ニュージーランド・ファーストは、より持続的なポピュリストの政策を掲げており、長年の党首であるウィンストン・ピーターズは、反体制的なレトリックを用 いるポピュリストであると一部で特徴づけられているが[265]、そのスタイルはニュージーランド特有のものだ。[266][267] 詳細情報:ニュージーランドのポピュリズム |

| Sub-Saharan Africa In much of Africa, populism has been a rare phenomenon.[268] The political scientist Danielle Resnick argued that populism first became apparent in Africa during the 1980s, when a series of coups brought military leaders to power in various countries.[269] In Ghana, for example, Jerry Rawlings took control, professing that he would involve "the people" in "the decision-making process", something he claimed had previously been denied to them.[269] A similar process took place in neighbouring Burkina Faso under the military leader Thomas Sankara, who professed to "take power out of the hands of our national bourgeoisie and their imperialist allies and put it in the hands of the people".[270] Such military leaders claimed to represent "the voice of the people", utilised an anti-establishment discourse, and established participatory organisations through which to maintain links with the broader population.[271] In the 21st century, with the establishment of multi-party democratic systems in much of Sub-Saharan Africa, new populist politicians have appeared. These have included Kenya's Raila Odinga, Senegal's Abdoulaye Wade, South Africa's Julius Malema, and Zambia's Michael Sata.[272] These populists have arisen in democratic rather than authoritarian states, and have arisen amid dissatisfaction with democratisation, socio-economic grievances, and frustration at the inability of opposition groups to oust incumbent parties.[273] |

サハラ以南のアフリカ アフリカの多くの地域では、ポピュリズムはまれな現象だった[268]。政治学者のダニエル・レスニックは、ポピュリズムがアフリカで初めて顕著になった のは 1980 年代、一連のクーデターによってさまざまな国で軍事指導者が権力を握ったときだと主張している。[269] 例えばガーナでは、ジェリー・ロールズが政権を握り、「意思決定プロセス」に「人民」を参加させることを公約した。これは、これまで人民に否定されてきた ことだと彼は主張した[269]。同様の過程は、隣国のブルキナファソでも、軍事指導者のトーマス・サンカラによって起こった。彼は、「国民的ブルジョア ジーとその帝国主義の同盟者たちの手から権力を奪い、人民の手に委ねる」と公約した。[270] このような軍事指導者は、「人民の声」を代表すると主張し、反体制の言説を利用し、より幅広い国民とのつながりを維持するための参加型組織を設立した [271]。 21 世紀、サハラ以南のアフリカの大部分で多党制民主主義が確立すると、新しいポピュリスト政治家たちが登場した。これには、ケニアのライラ・オディンガ、セ ネガルのアブドゥライ・ワッド、南アフリカのジュリウス・マラマ、ザンビアのマイケル・サタなどが含まれる。[272] これらのポピュリストは、独裁国家ではなく民主主義国家で台頭し、民主化への不満、社会経済的な不満、野党が与党を打倒できないことへの不満の中で現れ た。[273] |

Asia and the Arab world Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines and Narendra Modi of India, 2018. They are both considered populist leaders of the left and right, respectively. In North Africa, populism was associated with the approaches of several political leaders active in the 20th century, most notably Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser and Libya's Muammar Gaddafi.[268] However, populist approaches only became more popular in the Middle East during the early 21st century, by which point it became integral to much of the region's politics.[268] Here, it became an increasingly common element of mainstream politics in established representative democracies, associated with longstanding leaders like Israel's Benjamin Netanyahu.[274] Although the Arab Spring was not a populist movement itself, populist rhetoric was present among protesters.[275] In southeast Asia, populist politicians emerged in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. In the region, various populist governments took power but were removed soon after: these include the administrations of Joseph Estrada in the Philippines, Roh Moo-hyun in South Korea, Chen Shui-bian in Taiwan, and Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand.[276] In India, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which rose to increasing power in the early 21st century adopted a right-wing populist position.[277] Unlike many other successful populist groups, the BJP was not wholly reliant on the personality of its leader, but survived as a powerful electoral vehicle under several leaders.[278] |

アジアとアラブ世界 2018年のフィリピンのロドリゴ・ドゥテルテとインドのナレンドラ・モディ。彼らはそれぞれ、左派と右派のポピュリスト指導者とみなされている。 北アフリカでは、ポピュリズムは20世紀に活躍したいくつかの政治指導者のアプローチと関連付けられていました。特にエジプトのガマル・アブデル・ナセル とリビアのムアンマル・カダフィが代表的です。[268] しかし、ポピュリズム的なアプローチが中東でより広まったのは21世紀初頭で、その頃には地域の政治の重要な要素となりました。[268] ここでは、イスラエルのベンヤミン・ネタニヤフのような長期政権の指導者と結びつき、確立された代表民主制における主流政治の要素としてますます一般的に なった。アラブの春自体はポピュリスト運動ではなかったが、抗議者たちの中にポピュリスト的な言辞が存在した。[275] 東南アジアでは、1997年のアジア金融危機を契機にポピュリスト政治家が台頭した。この地域では、さまざまなポピュリスト政権が権力を掌握したが、すぐ に退陣に追い込まれた。これには、フィリピンのジョセフ・エストラーダ政権、韓国の盧武鉉政権、台湾の陳水扁政権、タイのタクシン・シナワトラ政権が含ま れる。[276] インドでは、21 世紀初頭に勢力を拡大したヒンドゥー教ナショナリストのインド人民党(BJP)が、右派ポピュリストの立場を採用した。[277] 他の多くの成功したポピュリスト集団とは異なり、BJP はその指導者の人格に完全に依存していたわけではなく、複数の指導者のもとで強力な選挙の手段として存続した。[278] |

| Labourism Neopopulism [es] Fiscal populism Argumentum ad populum Black populism Class warfare Communitarianism Demagogue Elite theory Empire of Democracy Extremism Fanaticism Fundamentalism List of populists Iron law of oligarchy Judicial populism Ochlocracy (mob rule) Paternalism Penal populism Politainment Polite populism Political polarization Poporanism Populism in Latin America Post-democracy Radical politics Reactionism Third party (politics) Tyranny of the majority |

労働主義 ネオポピュリズム [es] 財政ポピュリズム 大衆の意見に訴える論法 黒人ポピュリズム 階級闘争 共同体主義 デマゴーグ エリート理論 民主主義の帝国 過激主義 狂信 原理主義 ポピュリストのリスト 寡頭政治の鉄則 司法ポピュリズム オクロクラシー(暴徒政治) 父権主義 刑罰ポピュリズム ポリティメント 礼儀正しいポピュリズム 政治的二極化 ポポラニズム ラテンアメリカにおけるポピュリズム ポスト民主主義 急進的政治 反動主義 第三政党(政治) 多数派の専制 |

| Bibliography Abi-Hassan, Sahar (2017). "Populism and Gender". In Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser; Paul Taggart; Paulina Ochoa Espejo; Pierre Ostiguy (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 426–445. ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0. Adamidis, Vasileios (2021). "Democracy, populism, and the rule of law: A reconsideration of their interconnectedness". Politics. 44 (3): 386–399. doi:10.1177/02633957211041444. S2CID 238649847. Adamidis, Vasileios (2021). "Populism and the Rule of Recognition" (PDF). Populism. 4: 1–24. doi:10.1163/25888072-BJA10016. S2CID 234082341. Adamidis, Vasileios (2019), Manifestations of populism in late 5th century Athens. In: D.A. FRENKEL and N. VARGA, eds., New studies in law and history. Athens: Athens Institute for Education and Research, pp. 11–28. ISBN 978-9605982386 Aiolfi, Théo (2022). "Populism as a Transgressive Style". Global Studies Quarterly. 2 (1). doi:10.1093/isagsq/ksac006. Aiolfi, Théo (2025). The Populist Style: Trump, Le Pen and Performances of the Far Right. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Akkerman, Tjitske (2003). "Populism and Democracy: Challenge or Pathology?". Acta Politica. 38 (2): 147–159. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500021. S2CID 143771470. Akkerman, Tjitske (2011). "Friend or Foe? Right-wing Populism and the Popular Press in Britain and the Netherlands". Journalism. 12 (8): 931–945. doi:10.1177/1464884911415972. S2CID 145697478. Allcock, J. B. (1971). "'Populism': A Brief Biography". Sociology. 5 (3): 371–387. doi:10.1177/003803857100500305. JSTOR 42851097. S2CID 143619229. Albertazzi, Daniele; McDonnell, Duncan (2008). "Introduction: The Sceptre and the Spectre". Twenty-First Century Populism (PDF). Houdmills and New York: Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 1–11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Albertazzi, Daniele; McDonnell, Duncan (2015). Populists in Power. London: Routledge. Anselmi, Manuel (2018). Populism: An Introduction. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-28715-0. Aslanidis, Paris; Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2016). "Dealing with Populists in Government: The SYRIZA-ANEL Coalition in Greece". Democratization. 23 (6): 1077–1091. doi:10.1080/13510347.2016.1154842. S2CID 148014428. Bang, Henrik; Marsh, David (2018). "Populism: A Major Threat to Democracy?". Policy Studies. 39 (3): 352–363. doi:10.1080/01442872.2018.1475640. S2CID 158299409. Berlet, Chip; Lyons, Matthew N. (2000). Right-Wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-57230-568-7. Berman, Sheri (11 May 2021). "The Causes of Populism in the West". Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102503. Boyte, Harry C. (2012). "Introduction: Reclaiming Populism as a Different Kind of Politics". The Good Society. 21 (2): 173–176. doi:10.5325/goodsociety.21.2.0173. JSTOR stable/10.5325/goodsociety.21.2.0173. Brett, William (2013). "What's an Elite to Do? The Threat of Populism from Left, Right and Centre". The Political Quarterly. 84 (3): 410–413. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2013.12030.x. Canovan, Margaret (1981). Populism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovuch. ISBN 978-0-15-173078-0. Canovan, Margaret (1982). "Two Strategies for the Study of Populism". Political Studies. 30 (4): 544–552. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1982.tb00559.x. S2CID 143711735. Canovan, Margaret (2004). "Populism for Political Theorists?". Journal of Political Ideologies. 9 (3): 241–252. doi:10.1080/1356931042000263500. S2CID 144476284. Casullo, María Esperanza (2021). "Populism as Synecdochal Representation: Understanding the Transgressive Bodily Performance of South American Presidents". In Ostiguy, Pierre; Panizza, Francisco; Moffitt, Benjamin (eds.). Populism in Global Perspective: A Performative and Discursive Approach. London: Routledge. pp. 75–94. doi:10.4324/9781003110149-6. ISBN 9781003110149. de la Torre, Carlos (2017). "Populism in Latin America". In Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser; Paul Taggart; Paulina Ochoa Espejo; Pierre Ostiguy (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 195–213. ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0. Dean, Jonathan; Maiguashca, Bice (2020). "Did somebody say populism? Towards a renewal and reorientation of populism studies". Journal of Political Ideologies. 25 (1): 11–27. doi:10.1080/13569317.2020.1699712. hdl:10871/38714. Dobratz, Betty A; Shanks–Meile, Stephanie L. (1988). "The Contemporary Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party: A Comparison to American Populism at the Turn of the Century". Humanity & Society. 12: 20–50. doi:10.1177/016059768801200102. S2CID 148817637. Eatwell, Roger (2017). "Populism and Fascism". In Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser; Paul Taggart; Paulina Ochoa Espejo; Pierre Ostiguy (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 363–383. ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0. Ferkiss, Victor C. (1957). "Populist Influences on American Fascism". Western Political Quarterly. 10 (2): 350–73. doi:10.1177/106591295701000208. S2CID 154969641. Foxley, Rachel (2013). The Levellers: Radical Political Thought in the English Revolution. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8936-7. Fritzsche, Peter (1990). Rehearsals for Fascism: Populism and Political Mobilization in Weimar Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505780-5. Gagnon, Jean-Paul; Beausoleil, Emily; Son, Kyong-Min; Arguelles, Cleve; Chalaye, Pierrick; Johnston, Callum N. (2018). "What is Populism? Who is the Populist?". Democratic Theory. 5 (2): vi–xxvi. doi:10.3167/dt.2018.050201. Hawkins, Kirk A.; Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2019). "Introduction: The Ideational Approach". In Kirk A. Hawkins; Ryan E. Carlin; Levente Littvay; Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.). The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory, and Analysis. Routledge Studies in Extremism and Democracy. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-1-138-71651-3. Inglehart, Ronald; Norris, Pippa (2016). "Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash". SSRN Working Paper Series. Elsevier BV. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2818659. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 85509479. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.1 Laclau, Ernesto (2005). On Populist Reason. London: Verso. March, Luke (2007). "From Vanguard of the Proletariat to Vox Populi: Left-Populism as a 'Shadow' of Contemporary Socialism". SAIS Review of International Affairs. 27 (1): 63–77. doi:10.1353/sais.2007.0013. S2CID 154586793. McDonnell, Duncan; Cabrera, Luis (2019). "The Right-Wing Populism of India's Bharatiya Janata Party (and why comparativists should care)". Democratization. 26 (3): 484–501. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1551885. S2CID 149464986. Mény, Yves; Surel, Yves (2002). "The Constitutive Ambiguity of Populism". In Yves Mény; Yves Surel (eds.). Democracies and the Populist Challenge. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-4039-2007-2. Moffitt, Benjamin (2016). The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. doi:10.11126/stanford/9780804796132.001.0001. ISBN 9781503604216. Mudde, Cas (2004). "The Populist Zeitgeist". Government and Opposition. 39 (4): 541–63. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x. S2CID 67833953. Mudde, Cas; Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2013). "Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America". Government and Opposition. 48 (2): 147–174. doi:10.1017/gov.2012.11. Mudde, Cas; Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-023487-4. Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. "Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda." Comparative political studies 51.13 (2018): 1667–1693. online Ostiguy, Pierre (2009). The High and the Low in Politics: A Two-Dimensional Political Space for Comparative Analysis and Electoral Studies (Report). Working Paper. Kellogg Institute. Ostiguy, Pierre (2017). "Populism: A Socio-Cultural Approach". In Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal; Taggart, Paul; Ochoa Espejo, Paulina; Ostiguy, Pierre (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 73–97. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.3. ISBN 9780198803560. Park, Bill (2018). "Populism and Islamism in Turkey". Turkish Studies. 19 (2): 169–175. doi:10.1080/14683849.2017.1407651. S2CID 149284223. Qadir, Muneeb (2024). A Mad, Mad World: The Global Rise in Rightwing Populism. Daastan. ISBN 978-969-696-962-4. Resnick, Danielle (2017). "Populism in Africa". In Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser; Paul Taggart; Paulina Ochoa Espejo; Pierre Ostiguy (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 101–120. ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0. Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal; Taggart, Paul A.; Ochoa Espejo, Paulina; Ostiguy, Pierre, eds. (2019). The Oxford handbook of populism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-884628-4. OCLC 1141121440. Samoylenko, Dmytro (2024). Populism, Corruption and War: A Close Look at the Era of Volodymyr Zelensky and Ukraine's Politics. Stanley, Ben (2008). "The Thin Ideology of Populism". Journal of Political Ideologies. 13 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1080/13569310701822289. S2CID 144350127. Stier, Sebastian; Posch, Lisa; Bleier, Arnim; Strohmaier, Markus (2017). "When Populists become Popular: Comparing Facebook use by the Right-Wing Movement Pegida and German Political Parties". Information, Communication & Society. 20 (9): 1365–1388. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328519. S2CID 149324437. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2019. Taggart, Paul (2000). Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-20046-7. Taggart, Paul (2002). "Populism and the Pathology of Representative Politics". In Yves Mény; Yves Surel (eds.). Democracies and the Populist Challenge. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 62–80. ISBN 978-1-4039-2007-2. Tindall, George (1966). A Populist Reader. New York: Harper Torchbooks. Tormey, Simon (2018). "Populism: Democracy's Pharmakon?". Policy Studies. 39 (3): 260–273. doi:10.1080/01442872.2018.1475638. S2CID 158416086. Woodward, C. Vann (1938). "Tom Watson and the Negro in Agrarian Politics". The Journal of Southern History. 4 (1): 14–33. doi:10.2307/2191851. JSTOR 2191851. Zaslove, Andrej; Geurkink, Bram; Jacobs, Kristof; Akkerman, Agnes (2021). "Power to the People? Populism, Democracy, and Political Participation: A Citizen's Perspective". West European Politics. 44 (4): 727–751. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1776490. hdl:2066/226276. Further reading General Abromeit, John et al., eds. Transformations of Populism in Europe and the Americas: History and Recent Tendencies (Bloomsbury, 2015). xxxii, 354 pp. Adamidis, Vasileios (2021). "Populism and the Rule of Recognition" (PDF). Populism. 4: 1–24. doi:10.1163/25888072-BJA10016. S2CID 234082341. Adamidis, Vasileios (2021), Populist Rhetorical Strategies in the Courts of classical Athens. Athens Journal of History 7(1): 21–40. Albertazzi, Daniele and Duncan McDonnell. 2008. Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-01349-0 Berlet, Chip. 2005. "When Alienation Turns Right: Populist Conspiracism, the Apocalyptic Style, and Neofascist Movements". In Lauren Langman & Devorah Kalekin Fishman, (eds.), Trauma, Promise, and the Millennium: The Evolution of Alienation. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. Boyte, Harry C. 2004. Everyday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public Life. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Brass, Tom. 2000. Peasants, Populism and Postmodernism: The Return of the Agrarian Myth. London: Frank Cass Publishers. Bevernage, Berber et al., eds. Claiming the People's Past: Populist Politics of History in the Twenty-First Century. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2024. Caiani, Manuela. "Populism/Populist Movements". in The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements (2013). Coles, Rom. 2006. "Of Tensions and Tricksters: Grassroots Democracy Between Theory and Practice", Perspectives on Politics Vol. 4:3 (Fall), pp. 547–61 Denning, Michael. 1997. The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. London: Verso. Emibayer, Mustafa and Ann Mishe. 1998. "What is Agency?", American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 103:4, pp. 962–1023 Foster, John Bellamy. "This Is Not Populism Archived 1 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine" (June 2017), Monthly Review Goodwyn, Lawrence, 1976, Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America. New York: Oxford University Press Götz, Norbert, and Emilia Palonen. 2024. "History: The Moral Economy Perspective", in Research Handbook on Populism, ed. Yannis Stavrakakis and Giorgos Katsambekis (Cheltenham: Elgar), pp. 239–250. Hogg, Michael A., "Radical Change: Uncertainty in the world threatens our sense of self. To cope, people embrace populism", Scientific American, vol. 321, no. 3 (September 2019), pp. 85–87. Kazin, Michael. "Trump and American Populism". Foreign Affairs (Nov/Dec 2016), 95#6 pp. 17–24. Khoros, Vladimir. 1984. Populism: Its Past, Present and Future. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Kling, Joseph M. and Prudence S. Posner. 1990. Dilemmas of Activism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Kuzminski, Adrian. Fixing the System: A History of Populism, Ancient & Modern. New York: Continuum Books, 2008. Laclau, Ernesto. 1977. Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory: Capitalism, Fascism, Populism. London: NLB/Atlantic Highlands Humanities Press. Martelli, Jean-Thomas; Jaffrelot, Christophe (2023). "Do Populist Leaders Mimic the Language of Ordinary Citizens? Evidence from India". Political Psychology. 44 (5): 1141–1160. doi:10.1111/pops.12881. S2CID 256128025. McCoy, Alfred W (2 April 2017). The Bloodstained Rise of Global Populism: A Political Movement’s Violent Pursuit of "Enemies" Archived 2 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, TomDispatch Minkenberg, Michael (2021). "The Radical Right and Anti-Immigrant Politics in Liberal Democracies since World War II: Evolution of a Political and Research Field". Polity. 53 (3): 394–417. doi:10.1086/714167. S2CID 235494475. Morelock, Jeremiah ed. Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism Archived 29 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine. 2018. London: University of Westminster Press. Müller, Jan-Werner. What is Populism? Archived 21 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (August 2016), Univ. of Pennsylvania Press. Also by Müller on populism: Capitalism in One Family Archived 27 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (December 2016), London Review of Books, Vol. 38, No. 23, pp. 10–14 Peters, B. Guy and Jon Pierre. 2020. "A typology of populism: understanding the different forms of populism and their implications." Democratization. Ronderos, Sebastián (March 2021). O'Loughlin, Michael; Voela, Angie (eds.). "Hysteria in the squares: Approaching populism from a perspective of desire". Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society. 26 (1). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan: 46–64. doi:10.1057/s41282-020-00189-y. eISSN 1543-3390. ISSN 1088-0763. S2CID 220306519. Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal, ed. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2019. Rupert, Mark. 1997. "Globalization and the Reconstruction of Common Sense in the US". In Innovation and Transformation in International Studies, S. Gill and J. Mittelman, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Europe Anselmi, Manuel, 2017. Populism. An Introduction, London: Routledge. Betz, Hans-Georg. 1994. Radical Right-wing Populism in Western Europe, New York: St. Martins Press. ISBN 978-0-312-08390-8 Fritzsche, Peter. 1990. Rehearsals for Fascism: Populism and Political Mobilization in Weimar Germany. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505780-5 De Blasio, Emiliana, Hibberd, Matthew and Sorice, Michele. 2011. Popular politics, populism and the leaders. Access without participation? The cases of Italy and UK. Roma: CMCS-LUISS University. ISBN 978-88-6536-021-7 Fritzsche, Peter. 1998. Germans into Nazis. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Hartleb, Florian 2011: After their establishment: Right-wing Populist Parties in Europe, Centre for European Studies/Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Brüssel, (download: [1] Archived 29 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine) Kriesi, H. (2014), The Populist Challenge, West European Politics, vol. 37, n. 2, pp. 361–378. Mudde, Cas. "The populist radical right: A pathological normalcy." West European Politics 33.6 (2010): 1167–1186. online Mudde, Cas (2021). "Populism in Europe: An Illiberal Democratic Response to Undemocratic Liberalism (TheGovernment and Opposition/Leonard Schapiro Lecture 2019)". Government and Opposition. 56 (4): 577–597. doi:10.1017/gov.2021.15. S2CID 236286140. Mudde, C. (2012). The Relationship Between Immigration and Nativism in Europe and North America (PDF). Migration Policy Institute. pp. 14–15. Paterson, Lindsay (2000). "Civil Society: Enlightenment Ideal and Demotic Nationalism". Social Text. 18 (4): 109–116. doi:10.1215/01642472-18-4_65-109. S2CID 143793741. Wodak, Ruth, Majid KhosraviNik, and Brigitte Mral. "Right-wing populism in Europe". Politics and discourse (2013). online Latin America Conniff, Michael L. (2020). "A historiography of populism and neopopulism in Latin America". History Compass. 18 (9). doi:10.1111/hic3.12621. S2CID 225470570. Conniff, Michael L., ed. Populism in Latin America (1999) essays by experts Demmers, Jolle, et al eds. Miraculous Metamorphoses: The Neoliberalization of Latin American Populism (2001) Knight, Alan. "Populism and neo-populism in Latin America, especially Mexico." Journal of Latin American Studies 30.2 (1998): 223–248. Leaman, David (2004). "Changing Faces of Populism in Latin America: Masks, Makeovers, and Enduring Features". Latin American Research Review. 39 (3): 312–326. doi:10.1353/lar.2004.0052. JSTOR 1555484. S2CID 143707412. Stropparo, P. E. (2023). Pueblo desnudo y público movilizado por el poder: Vacancia del Defensor del Pueblo: algunas transformaciones en la democracia y en la opinión pública en Argentina . Revista Mexicana De Opinión Pública, (35). https://doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.24484911e.2023.35.85516 United States Abromeit, John. "Frankfurt School Critical Theory and the Persistence of Authoritarian Populism in the United States" In Morelock, Jeremiah Ed. Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism. 2018. London: University of Westminster Press. Agarwal, Sheetal D., et al. "Grassroots organizing in the digital age: considering values and technology in Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street". Information, Communication & Society (2014) 17#3 pp. 326–41. Evans, Sara M. and Harry C. Boyte. 1986. Free Spaces: The Sources of Democratic Change in America. New York: Harper & Row. Goodwyn, Lawrence. 1976. Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America. New York and London: Oxford University Press.; abridged as The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America. (Oxford University Press, 1978) Hahn, Steven. 1983. Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850–1890. New York and London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-530670-5 Hofstadter, Richard. 1955. The Age of Reform: from Bryan to F.D.R. New York: Knopf. Hofstadter, Richard. 1965. The Paranoid Style in American Politics, and Other Essays. New York: Knopf. Jeffrey, Julie Roy. 1975. "Women in the Southern Farmers Alliance: A Reconsideration of the Role and Status of Women in the Late 19th Century South". Feminist Studies 3. Judis, John B. 2016. The Populist Explosion: How the Great Recession Transformed American and European Politics. New York: Columbia Global Reports. ISBN 978-0-9971264-4-0 Kazin, Michael. 1995. The Populist Persuasion: An American History. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03793-3 Kindell, Alexandra & Demers, Elizabeth S. (2014). Encyclopedia of Populism in America: A Historical Encyclopedia. 2 vol. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-568-6. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.; 200+ articles in 901 pp Lipset, Seymour Martin. "The radical right: A problem for American democracy." British Journal of Sociology 6.2 (1955): 176–209. online Maier, Chris. "The Farmers' Fight for Representation: Third-Party Politics in South Dakota, 1889–1918". Great Plains Quarterly (2014) 34#2 pp. 143–62. Marable, Manning. 1986. "Black History and the Vision of Democracy", in Harry Boyte and Frank Riessman, Eds., The New Populism: The Politics of Empowerment. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Palmer, Bruce. 1980. Man Over Money: The Southern Populist Critique of American Capitalism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Rasmussen, Scott, and Doug Schoen. (2010) Mad as hell: How the Tea Party movement is fundamentally remaking our two-party system (HarperCollins, 2010) Stock, Catherine McNicol. 1996. Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in the American Grain. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3294-1 |

参考文献 Abi-Hassan, Sahar (2017). 「ポピュリズムとジェンダー」 Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser、Paul Taggart、Paulina Ochoa Espejo、Pierre Ostiguy (eds.) 『オックスフォード・ハンドブック ポピュリズム』 オックスフォードおよびニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。426-445 ページ。ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0。 Adamidis, Vasileios (2021). 「民主主義、ポピュリズム、そして法の支配:それらの相互関連性の再考」 Politics. 44 (3): 386–399. doi:10.1177/02633957211041444. S2CID 238649847. アダムディス, ヴァシレイオス (2021). 「ポピュリズムと承認のルール」 (PDF). ポピュリズム. 4: 1–24. doi:10.1163/25888072-BJA10016. S2CID 234082341. アダムディス, ヴァシレイオス (2019), 5世紀後半のアテネにおけるポピュリズムの表れ. D.A. フレンケルとN. ヴァルガ編, 『法と歴史の新研究』. アテネ: アテネ教育研究研究所, pp. 11–28. ISBN 978-9605982386 Aiolfi, Théo (2022). 「越境的なスタイルとしてのポピュリズム」 『グローバル・スタディーズ・クォータリー』 2 (1). doi:10.1093/isagsq/ksac006. Aiolfi, Théo (2025). 『ポピュリストのスタイル:トランプ、ル・ペン、そして極右のパフォーマンス』 エディンバラ:エディンバラ大学出版局。 アッカーマン, ティツケ (2003). 「ポピュリズムと民主主義: 挑戦か病理か?」. アクタ・ポリティカ. 38 (2): 147–159. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500021. S2CID 143771470. アッカーマン, ティツケ (2011). 「友か敵か?イギリスとオランダにおける右派ポピュリズムとマスコミ」. ジャーナリズム. 12 (8): 931–945. doi:10.1177/1464884911415972. S2CID 145697478. Allcock, J. B. (1971). 「『ポピュリズム』:その略伝」 Sociology. 5 (3): 371–387. doi:10.1177/003803857100500305. JSTOR 42851097. S2CID 143619229. アルベルタッツィ、ダニエレ、マクドネル、ダンカン (2008)。「序論:王笏と幽霊」。21 世紀のポピュリズム (PDF)。ホウドミルズおよびニューヨーク:パームグレイブ・マクミラン。1-11 ページ。2015年9月24日にオリジナルからアーカイブ (PDF)。 アルベルタッツィ、ダニエレ、マクドネル、ダンカン (2015)。『権力を持つポピュリストたち』。ロンドン:Routledge。 アンセルミ、マヌエル (2018)。『ポピュリズム:入門』。ロンドン:Routledge。ISBN 978-1-138-28715-0。 アスラニディス、パリ、ロヴィラ・カルトワッサー、クリストバル (2016)。「政府内のポピュリストへの対応:ギリシャの SYRIZA-ANEL 連合」。民主化。23 (6): 1077–1091. doi:10.1080/13510347.2016.1154842. S2CID 148014428. Bang, Henrik; Marsh, David (2018). 「ポピュリズム:民主主義に対する重大な脅威か?」『Policy Studies』39 (3): 352–363. doi:10.1080/01442872.2018.1475640. S2CID 158299409. ベルレット、チップ;ライアンズ、マシュー N. (2000). アメリカにおける右派ポピュリズム:あまりにも近い存在. ニューヨーク:ギルフォード・プレス. ISBN 978-1-57230-568-7. バーマン、シェリー (2021年5月11日). 「西洋におけるポピュリズムの原因」. Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102503. ボイト、ハリー C. (2012)。「序論:異なる政治形態としてのポピュリズムの再評価」。The Good Society. 21 (2): 173–176. doi:10.5325/goodsociety.21.2.0173. JSTOR stable/10.5325/goodsociety.21.2.0173. ブレット、ウィリアム (2013). 「エリートは何をすべきか?左、右、そして中央からのポピュリズムの脅威」. The Political Quarterly. 84 (3): 410–413. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2013.12030.x. キャノヴァン、マーガレット(1981)。『ポピュリズム』。ニューヨーク:Harcourt Brace Jovanovuch。ISBN 978-0-15-173078-0。 キャノヴァン、マーガレット (1982). 「ポピュリズムの研究のための 2 つの戦略」. 政治学研究. 30 (4): 544–552. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1982.tb00559.x. S2CID 143711735. Canovan, Margaret (2004). 「政治理論家にとってのポピュリズム?」 Journal of Political Ideologies. 9 (3): 241–252. doi:10.1080/1356931042000263500. S2CID 144476284. Casullo, María Esperanza (2021). 「換喩的表現としてのポピュリズム:南米大統領の越境的な身体表現を理解する」 Ostiguy, Pierre; Panizza, Francisco; Moffitt, Benjamin (eds.). Populism in Global Perspective: A Performative and Discursive Approach. ロンドン:Routledge. pp. 75–94. doi:10.4324/9781003110149-6. ISBN 9781003110149. デ・ラ・トーレ、カルロス(2017)。「ラテンアメリカのポピュリズム」。クリストバル・ロヴィラ・カルタワサー、ポール・タガート、パウリナ・オチョ ア・エスペホ、ピエール・オスティギー(編)。『オックスフォード・ハンドブック・オブ・ポピュリズム』。オックスフォードおよびニューヨーク:オックス フォード大学出版局。195–213 ページ。ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0。 ディーン, ジョナサン; マイグアシュカ, バイス (2020). 「誰かがポピュリズムと言ったか?ポピュリズム研究の刷新と方向転換に向けて」. 政治イデオロギージャーナル。25 (1): 11–27. doi:10.1080/13569317.2020.1699712. hdl:10871/38714. ドブラッツ、ベティ・A; シャンクス=マイル、ステファニー・L. (1988). 「現代のクー・クラックス・クランとアメリカ・ナチ党:20世紀初頭のアメリカ・ポピュリズムとの比較」。『ヒューマニティ・アンド・ソサエティ』。 12: 20–50。doi:10.1177/016059768801200102。S2CID 148817637。 イートウェル、ロジャー (2017). 「ポピュリズムとファシズム」. クリストバル・ロヴィラ・カルタワサー、ポール・タガート、パウリーナ・オチョア・エスペホ、ピエール・オスティギー (編). 『オックスフォード・ハンドブック・オブ・ポピュリズム』. オックスフォードおよびニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局. pp. 363–383. ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0. Ferkiss, Victor C. (1957). 「アメリカファシズムへのポピュリズムの影響」. Western Political Quarterly. 10 (2): 350–73. doi:10.1177/106591295701000208. S2CID 154969641. Foxley, Rachel (2013). 『レベラーズ:イギリス革命における急進的政治思想』オックスフォードおよびニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-7190-8936-7。 フリッツシェ、ピーター(1990)。『ファシズムのリハーサル:ワイマール・ドイツにおけるポピュリズムと政治動員』オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-505780-5。 ガニョン, ジャン=ポール; ボーソレイユ, エミリー; ソン, キョンミン; アルゲレス, クレヴ; チャレイ, ピエリック; ジョンストン, キャラム・N. (2018). 「ポピュリズムとは何か?ポピュリストとは誰か?」. 民主理論. 5 (2): vi–xxvi. doi:10.3167/dt.2018.050201. Hawkins, Kirk A.; Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2019). 「序論:観念的アプローチ」. Kirk A. Hawkins; Ryan E. Carlin; Levente Littvay; Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.). ポピュリズムの観念的アプローチ:概念、理論、分析. 過激主義と民主主義に関するラウトレッジ研究。ロンドンとニューヨーク:ラウトレッジ。pp. 1–24。ISBN 978-1-138-71651-3。 イングルハート、ロナルド;ノリス、ピッパ(2016)。「トランプ、ブレグジット、そしてポピュリズムの台頭:経済的に恵まれない層と文化的反発」。 SSRN ワーキングペーパーシリーズ。エルゼビア BV。doi:10.2139/ssrn.2818659。ISSN 1556-5068。S2CID 85509479。2019年7月19日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2019年7月15日に取得。1 ラクラウ、エルネスト (2005)。『ポピュリストの理性』。ロンドン:ヴェルソ。 マーチ、ルーク (2007)。「プロレタリアートの先駆者から民衆の声へ:現代社会主義の「影」としての左派ポピュリズム」。SAIS Review of International Affairs. 27 (1): 63–77. doi:10.1353/sais.2007.0013. S2CID 154586793. マクドネル、ダンカン; カブレラ、ルイス (2019). 「インドのインド人民党の右翼ポピュリズム (および比較研究者が注目すべき理由)」。民主化。26 (3): 484–501. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1551885. S2CID 149464986. メニー, イヴ; シュレル, イヴ (2002). 「ポピュリズムの構成的曖昧性」. イヴ・メニー; イヴ・シュレル (編). 『民主主義とポピュリズムの挑戦』. バシングストーク: パルグレイブ・マクミラン. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-4039-2007-2. Moffitt, Benjamin (2016). ポピュリズムのグローバルな台頭:パフォーマンス、政治スタイル、そして代表。パロアルト:スタンフォード大学出版局。doi: 10.11126/stanford/9780804796132.001.0001. ISBN 9781503604216。 ムッデ、カス(2004)。「ポピュリズムの時代精神」。『政府と反対勢力』。39 (4): 541–63。doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x。S2CID 67833953。 Mudde, Cas; Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2013). 「排他的ポピュリズムと包摂的ポピュリズム:現代ヨーロッパとラテンアメリカの比較」. Government and Opposition. 48 (2): 147–174. doi:10.1017/gov.2012.11. Mudde, Cas; Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2017). ポピュリズム:非常に短い入門書。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-023487-4。 ムッデ、カス、クリストバル・ロヴィラ・カルタワッサー。「比較の観点からポピュリズムを研究する:現代および将来の研究課題に関する考察」。比較政治学 51.13 (2018): 1667–1693。オンライン オスティギ、ピエール(2009)。『政治の高次と低次:比較分析と選挙研究のための二次元政治空間』(報告書)。ワーキングペーパー。ケロッグ研究所。 オスティギ、ピエール(2017)。「ポピュリズム:社会文化的アプローチ」。ロヴィラ・カルタワサー、クリストバル、タガート、ポール、オチョア・エス ペホ、パウリーナ、オスティギ、ピエール(編)。『オックスフォード・ハンドブック ポピュリズム』. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. pp. 73–97. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.3. ISBN 9780198803560. パーク、ビル (2018). 「トルコにおけるポピュリズムとイスラム主義」. Turkish Studies. 19 (2): 169–175. doi:10.1080/14683849.2017.1407651. S2CID 149284223. カディール、ムニーブ(2024)。『狂った、狂った世界:世界的な右派ポピュリズムの台頭』。ダースタン。ISBN 978-969-696-962-4。 レスニック、ダニエル(2017)。「アフリカのポピュリズム」。クリストバル・ロヴィラ・カルタワサー、ポール・タガート、パウリナ・オチョア・エスペ ホ、ピエール・オスティギー(編)。『オックスフォード・ハンドブック・オブ・ポピュリズム』。オックスフォードおよびニューヨーク:オックスフォード大 学出版局。101–120 ページ。ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0。 ロヴィラ・カルタワサー、クリストバル;タガート、ポール・A.;オチョア・エスペホ、パウリーナ;オスティギ、ピエール(編) (2019). ポピュリズムのオックスフォード・ハンドブック. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-884628-4. OCLC 1141121440. サモイレンコ、ドミトロ(2024)。『ポピュリズム、腐敗、戦争:ヴォロディミル・ゼレンスキー時代とウクライナの政治を深く考察する』。 スタンリー、ベン(2008)。「ポピュリズムの薄いイデオロギー」。政治イデオロギージャーナル。13 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1080/13569310701822289. S2CID 144350127. スティアー、セバスチャン;ポッシュ、リサ;ブライアー、アルニム;ストロマイヤー、マルクス(2017)。「ポピュリストが人気を博するとき:右派運動 ペギダとドイツの政党によるフェイスブックの利用比較」。情報、コミュニケーション、社会。20 (9): 1365–1388. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328519. S2CID 149324437. 2020年2月22日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2019年12月14日に取得。 タガート、ポール (2000). ポピュリズム. バックingham: オープン大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-335-20046-7. タガート、ポール (2002). 「ポピュリズムと代表政治の病理」. イヴ・メニー、イヴ・シュレル (編). 『民主主義とポピュリズムの挑戦』. ベージングストーク: パルグレイブ・マクミラン. pp. 62–80. ISBN 978-1-4039-2007-2. ティンドール、ジョージ (1966). 『ポピュリスト・リーダー』. ニューヨーク:ハーパー・トーチブックス。 トルミー、サイモン(2018)。「ポピュリズム:民主主義のファルマコン?」。『ポリシー・スタディーズ』。39 (3): 260–273。doi:10.1080/01442872.2018.1475638。S2CID 158416086。 ウッドワード、C. ヴァン (1938)。「トム・ワトソンと農業政治におけるニグロ」 『南部歴史ジャーナル』 4 (1): 14–33. doi:10.2307/2191851. JSTOR 2191851. ザスラブ、アンドレイ; ゲルキンク、ブラム; ジェイコブス、クリストフ; アッカーマン、アグネス (2021)。「人民に権力?ポピュリズム、民主主義、政治参加:市民の視点」。西ヨーロッパの政治。44 (4): 727–751. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1776490. hdl:2066/226276. さらに読む 一般 アブロメイト、ジョンほか編。ヨーロッパとアメリカにおけるポピュリズムの変容:歴史と最近の傾向(ブルームズベリー、2015年)。xxxii、354 ページ。 アダムディス、ヴァシレイオス(2021)。「ポピュリズムと認識のルール」(PDF)。ポピュリズム。4:1–24。doi:10.1163/25888072-BJA10016。S2CID 234082341。 Adamidis, Vasileios (2021), Populist Rhetorical Strategies in the Courts of classical Athens. Athens Journal of History 7(1): 21–40. アルベルタッツィ、ダニエレ、ダンカン・マクドネル。2008 年。21 世紀のポピュリズム:西ヨーロッパの民主主義の幽霊 ベースングストークおよびニューヨーク:パームグレイブ・マクミラン。ISBN 978-0-230-01349-0 Berlet, Chip. 2005. 「疎外が右傾化するとき:ポピュリストの陰謀論、終末論的スタイル、そして新ファシスト運動」 Lauren Langman & Devorah Kalekin Fishman (編)『トラウマ、約束、そしてミレニアム:疎外の進化』 Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ボイト、ハリー・C. 2004. 『日常政治:市民と公共生活の再生』. フィラデルフィア:ペンシルベニア大学出版局. ブラス、トム. 2000. 『農民、ポピュリズム、ポストモダニズム:農業神話の復活』. ロンドン:フランク・キャス出版社. Bevernage, Berber et al., eds. 『人民の過去を主張する:21 世紀のポピュリスト政治史』 英国、ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2024 年。 Caiani, Manuela. 「ポピュリズム/ポピュリスト運動」 『The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements』 (2013) コールズ、ロム. 2006. 「緊張とトリックスター:理論と実践の間の草の根民主主義」, 『政治の展望』第4巻第3号(秋), pp. 547–61 デニング、マイケル. 1997. 『文化戦線:20世紀のアメリカ文化の労働』. ロンドン:ヴェルソ. エミベイヤー、ムスタファとアン・ミシェ。1998. 「エージェンシーとは何か?」、『アメリカ社会学会誌』第103巻第4号、pp. 962–1023 フォスター、ジョン・ベラミー。「これはポピュリズムではない Archived 2017年7月1日 at the Wayback Machine」 (2017年6月)、『マンスリー・レビュー』 グッドウィン, ローレンス. 1976. 『民主主義の約束: アメリカのポピュリスト的瞬間』. ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局 ゴッツ, ノルベルト, エミリア・パロネン. 2024. 「歴史: モラル・エコノミーの視点」, 『ポピュリズム研究ハンドブック』, 編者: ヤニス・スタヴラカキスとゲオルゴス・カツァンベキス (チェルトナム: エルガー), pp. 239–250. ホッグ、マイケル A.、「急進的な変化:世界における不確実性が私たちの自己認識を脅かす。それに対処するため、人民はポピュリズムを受け入れる」、『サイエンティフィック・アメリカン』、第 321 巻、第 3 号(2019 年 9 月)、85-87 ページ。 カジン、マイケル。「トランプとアメリカのポピュリズム」。Foreign Affairs(2016年11月/12月)、95#6 pp. 17–24。 ホロス、ウラジミール。1984年。ポピュリズム:その過去、現在、未来。モスクワ:プログレス出版社。 クリング、ジョセフ・M.、およびプルデンス・S. ポズナー。1990年。活動家のジレンマ。フィラデルフィア:テンプル大学出版。 クズミンスキー、エイドリアン。システムを修復する:古代と現代のポピュリズムの歴史。ニューヨーク:コンティニュアム・ブックス、2008年。 ラクラウ、エルネスト。1977年。マルクス主義理論における政治とイデオロギー:資本主義、ファシズム、ポピュリズム。ロンドン:NLB/アトランティック・ハイランズ・ヒューマニティーズ・プレス。 マルテッリ、ジャン=トマ;ジャフレロット、クリストフ(2023)。「ポピュリスト指導者は一般市民の言語を模倣しているか?インドからの証拠」。『政 治心理学』。44 (5): 1141–1160。doi:10.1111/pops.12881。S2CID 256128025。 マッコイ、アルフレッド・W(2017年4月2日)。『血に染まったグローバル・ポピュリズムの台頭:政治運動の「敵」に対する暴力的な追求』 2017年5月2日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、TomDispatch ミンケンバーグ、マイケル (2021)。「第二次世界大戦以降の自由民主主義における急進的な右派と反移民政治:政治と研究分野の進化」。Polity. 53 (3): 394–417. doi:10.1086/714167. S2CID 235494475. モレロック、ジェレミア編。批判理論と権威主義的ポピュリズム 2020年10月29日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。2018年。ロンドン:ウェストミンスター大学出版局。 ミュラー、ヤン・ヴェルナー。ポピュリズムとは何か?2016年11月21日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ(2016年8月)、ペンシルベニア大学出版 局。ミュラーによるポピュリズムに関するその他の著作:Capitalism in One Family 2016年11月27日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ(2016年12月)、ロンドン・レビュー・オブ・ブックス、第38巻、第23号、10-14ペー ジ Peters, B. Guy and Jon Pierre. 2020. 「ポピュリズムの類型:ポピュリズムの異なる形態とその意味を理解する」 Democratization. ロンデロス、セバスティアン(2021年3月)。オラフリン、マイケル;ヴォエラ、アンジー(編)。「広場でのヒステリー:欲望の観点からポピュリズムに アプローチする」。Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society. 26 (1). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan: 46–64. doi:10.1057/s41282-020-00189-y. eISSN 1543-3390. ISSN 1088-0763. S2CID 220306519. ロヴィラ・カルタワサー、クリストバル編(2017)。『オックスフォード・ハンドブック ポピュリズム』オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-880356-0。2020年10月29日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2019年4月27日に閲覧。 ルパート、マーク。1997年。「グローバル化と米国の常識の再構築」。『国際研究における革新と変革』S. ギル、J. ミテルマン編。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ヨーロッパ アンセルミ、マヌエル、2017年。『ポピュリズム。入門』ロンドン:ラウトレッジ。 ベッツ、ハンス・ゲオルク。1994年。西ヨーロッパの急進的な右翼ポピュリズム、ニューヨーク:セント・マーティンズ・プレス。ISBN 978-0-312-08390-8 フリッツシェ、ピーター。1990年。ファシズムのリハーサル:ワイマール共和国におけるポピュリズムと政治動員。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-505780-5 デ・ブラジオ、エミリアナ、ヒバード、マシュー、ソリス、ミケーレ。2011 年。大衆政治、ポピュリズム、そして指導者たち。参加のないアクセス?イタリアと英国の事例。ローマ:CMCS-LUISS 大学。ISBN 978-88-6536-021-7 フリッツシェ、ピーター。1998 年。ドイツ人をナチスにしたもの。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。 Hartleb, Florian 2011: 設立後:ヨーロッパの右派ポピュリスト政党、欧州研究センター/コンラート・アデナウアー財団、ブリュッセル、(ダウンロード:[1] 2019年5月29日にウェイバックマシンでアーカイブ) クリエシ, H. (2014), ポピュリストの挑戦, 西ヨーロッパ政治, 第37巻, 第2号, pp. 361–378. ムッデ, カス. 「ポピュリスト的極右: 病理的な正常性」. 西ヨーロッパ政治 33.6 (2010): 1167–1186. オンライン ムッデ, カス (2021). 「ヨーロッパのポピュリズム: 民主的でないリベラリズムに対する非リベラルな民主主義的対応 (政府と野党/レナード・シャピロ講演 2019)」. 政府と野党. 56 (4): 577–597. doi:10.1017/gov.2021.15. S2CID 236286140。 Mudde, C. (2012). ヨーロッパと北米における移民とナショナリズムの関係 (PDF). 移民政策研究所。14–15 ページ。 Paterson, Lindsay (2000). 「市民社会:啓蒙の理想と民衆的ナショナリズム」。Social Text. 18 (4): 109–116. doi:10.1215/01642472-18-4_65-109. S2CID 143793741. Wodak, Ruth, Majid KhosraviNik, and Brigitte Mral. 「ヨーロッパの右派ポピュリズム」. Politics and discourse (2013). online ラテンアメリカ Conniff, Michael L. (2020). 「ラテンアメリカにおけるポピュリズムとネオポピュリズムの歴史学」. History Compass. 18 (9). doi:10.1111/hic3.12621. S2CID 225470570. Conniff, Michael L., ed. Populism in Latin America (1999) 専門家によるエッセイ集 デムマーズ, ヨレ, 他編. 『奇跡の変容: ラテンアメリカ・ポピュリズムのネオリベラリズム化』 (2001) ナイト, アラン. 「ラテンアメリカ、特にメキシコにおけるポピュリズムとネオポピュリズム」. Journal of Latin American Studies 30.2 (1998): 223–248. リーマン、デビッド(2004)。「ラテンアメリカにおけるポピュリズムの変貌:仮面、変身、そして不変の特徴」。『ラテンアメリカ研究レビュー』39 (3): 312–326。doi:10.1353/lar.2004.0052。JSTOR 1555484。S2CID 143707412。 ストロパロ、P. E. (2023). 裸の民衆と権力によって動員された公衆:国民擁護官の空席:アルゼンチンの民主主義と世論におけるいくつかの変化. Revista Mexicana De Opinión Pública, (35). https://doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.24484911e.2023.35.85516 アメリカ合衆国 アブロメイト、ジョン。「フランクフルト学派の批判理論とアメリカにおける権威主義的ポピュリズムの持続」モレロック、ジェレマイア編『批判理論と権威主義的ポピュリズム』2018年、ロンドン:ウェストミンスター大学出版局。 Agarwal, Sheetal D. 他「デジタル時代における草の根組織化:ティーパーティーとオキュパイ・ウォールストリートにおける価値観とテクノロジーの考察」『情報、コミュニケーション、社会』 (2014) 17#3 pp. 326–41。 エヴァンス、サラ・M.、ハリー・C・ボイト。1986年。『自由空間:アメリカの民主的変化の源流』。ニューヨーク:ハーパー&ロウ。 グッドウィン、ローレンス。1976 年。民主主義の約束:アメリカのポピュリストの瞬間。ニューヨークおよびロンドン:オックスフォード大学出版局。要約版『The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America』(オックスフォード大学出版局、1978 年) ハーン、スティーブン。1983 年。『南部ポピュリズムの根源:小作農とジョージア州内陸部の変容、1850-1890』. ニューヨークとロンドン:オックスフォード大学出版局, ISBN 978-0-19-530670-5. ホフスタッター, リチャード. 1955. 『改革の時代:ブライアンからF.D.R.まで』. ニューヨーク:ノップフ. ホフスタッター、リチャード。1965年。 『アメリカ政治のパラノイア的スタイル、およびその他のエッセイ』。ニューヨーク:ノフ。 ジェフリー、ジュリー・ロイ。1975年。「南部農民同盟における女性:19世紀後半の南部における女性の役割と地位の再考」。『フェミニスト・スタディーズ』3。 ジュディス、ジョン・B。2016年。『ポピュリストの爆発:大不況がアメリカとヨーロッパの政治を変えた』. ニューヨーク:コロンビア・グローバル・レポート. ISBN 978-0-9971264-4-0 カジン, マイケル. 1995. 『ポピュリストの説得力:アメリカの歴史』. ニューヨーク:ベーシック・ブックス. ISBN 978-0-465-03793-3 キンデル、アレクサンドラ、デマーズ、エリザベス S. (2014)。『アメリカにおけるポピュリズム事典:歴史事典』 2 巻。ABC-CLIO。ISBN 978-1-59884-568-6。2015年10月17日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2015年8月15日取得。901 ページに 200 以上の記事が掲載。 リップセット、シーモア・マーティン。「急進的な右派:アメリカの民主主義にとっての課題」 British Journal of Sociology 6.2 (1955): 176–209. オンライン マイヤー、クリス。「農民の代表権争い:サウスダコタ州における第三政党政治、1889 年~1918 年」 Great Plains Quarterly (2014) 34#2 pp. 143–62. マーブル、マニング。1986 年。「黒人の歴史と民主主義のビジョン」ハリー・ボイト、フランク・リースマン編『新しいポピュリズム:エンパワーメントの政治』フィラデルフィア:テンプル大学出版。 パルマー、ブルース。1980. 『人間対金:アメリカ資本主義に対する南部ポピュリストの批判』。チャペルヒル:ノースカロライナ大学出版局。 ラスムッセン、スコット、およびダグ・シェーン。(2010)『怒りの爆発:ティーパーティー運動が二大政党制を根本から変革する』(ハーパーコリンズ、2010) ストック、キャサリン・マクニコル。1996. 『農村部の急進派:アメリカの穀倉地帯における正義の怒り』。ニューヨーク州イサカ:コーネル大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8014-3294-1 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Populism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

cc

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆