進化思想の歴史

History of evolutionary thought

The

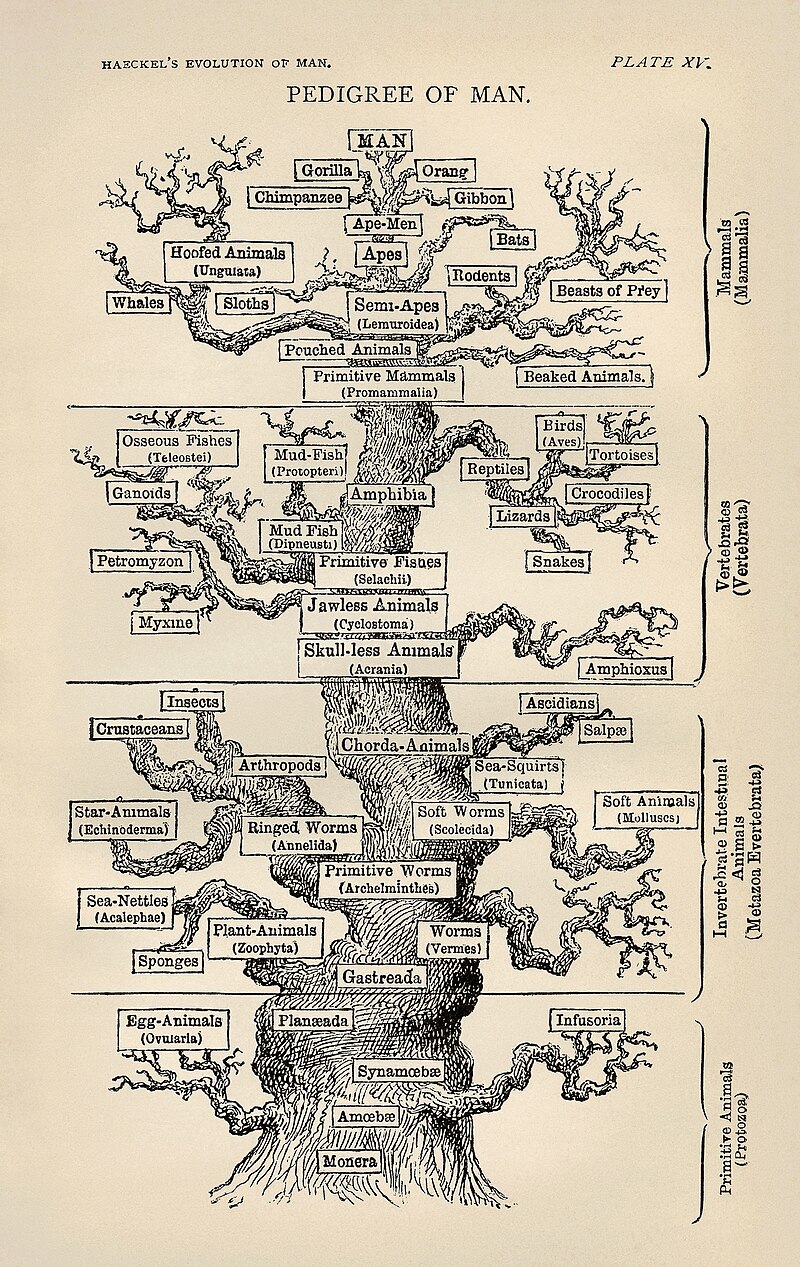

tree of life as depicted by Ernst Haeckel in The Evolution of Man

(1879) illustrates the 19th-century view of evolution as a progressive

process leading towards man.

☆進化思想(Evolutionary thought)とは、種が時間とともに変化することを認識し、そのようなプロセスがどのように作用するかを理解することであり、そのルーツは古代にある。17世 紀後半に近代的な生物分類学が始まると、西洋の生物学的思考に2つの相反する考え方が影響を及ぼした。本質主義、すなわち、すべての種は不変の本質的な特 徴を持っているという信念であり、中世のアリストテレス形而上学から発展した概念であり、自然神学によく適合するものであった。自然学者は種の多様性に注 目し始め、絶滅という概念を持つ古生物学の出現は、自然に対する静的な見方をさらに根底から覆した。ダーウィニズムに先立つ19世紀初頭、ジャン=バティ スト・ラマルクは、進化論として初めて完全な形となる「種の転変」の理論を提唱した。1858年、チャールズ・ダーウィンとアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは新たな進化論を発表し、ダーウィンの『種の起源』(1859年)で詳しく説明した。進化生物学の確立後、自然集団における突然変異や遺伝的多様性の研究が、生物地理学や系統分類学と組み合わされ、進化に関する高度な数学的・因果学的モデ ルが構築された。古生物学と比較解剖学は、生命の進化の歴史をより詳細に再現することを可能にした。1950年代に分子遺伝学が台頭すると、タンパク質配 列と免疫学的検査に基づき、後にRNAとDNAの研究を取り入れた分子進化学が発展した。1960年代には遺伝子を中心とした進化論が台頭し、その後、分 子進化の中立説が登場し、適応論、淘汰の単位、進化の原因としての遺伝的ドリフトと自然淘汰の相対的重要性をめぐる論争が巻き起こった[2]。20世紀後 半には、DNA塩基配列の解読によって分子系統学が発展し、カール・ウーゼによって生命の樹が3ドメイン・システムに再編成された。さらに、新たに認識さ れた共生と遺伝子の水平移動という要因が、進化論にさらなる複雑さをもたらした。進化生物学における発見は、従来の生物学の分野だけでなく、他の学問分野 (例えば、人類学や心理学)や社会全体にも大きな影響を与えた[3]。

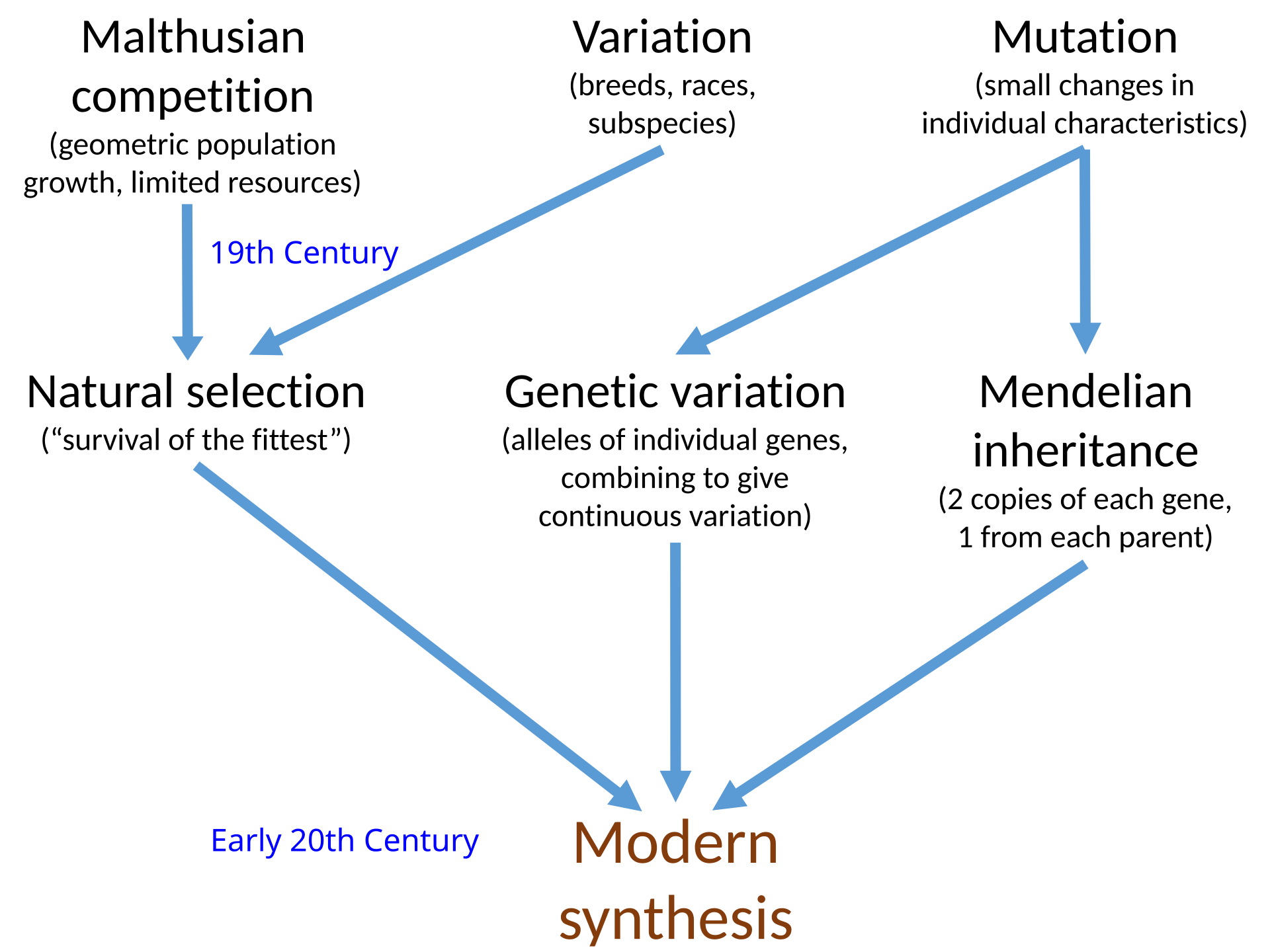

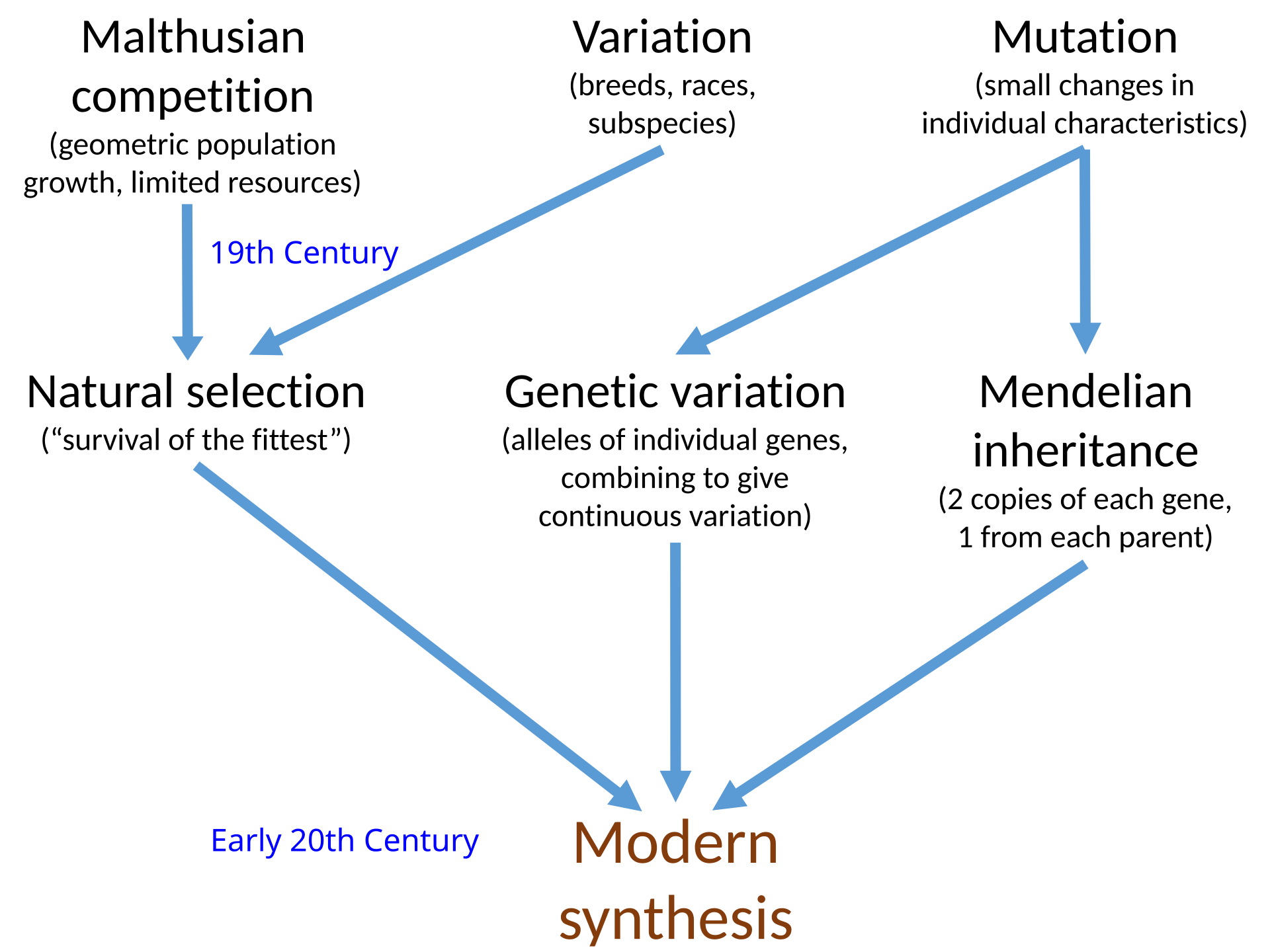

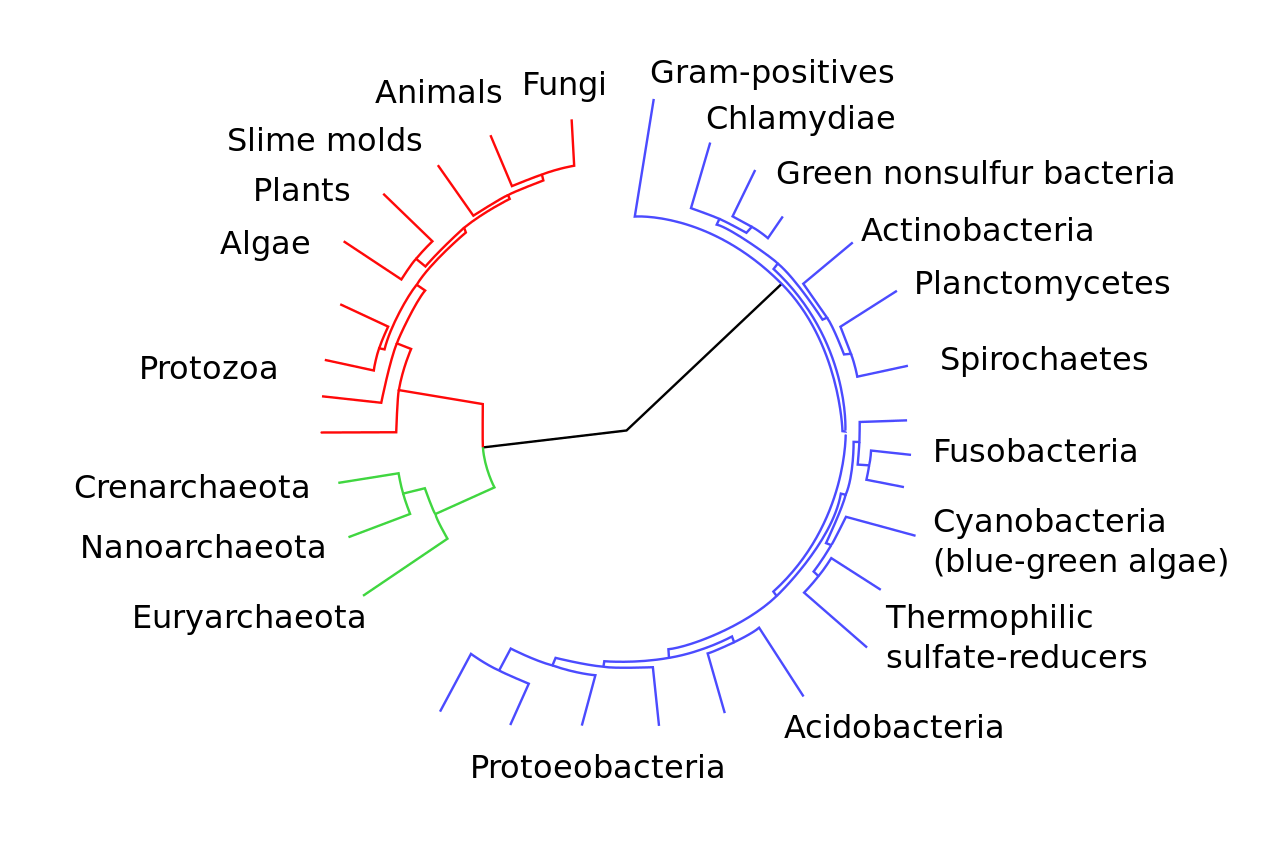

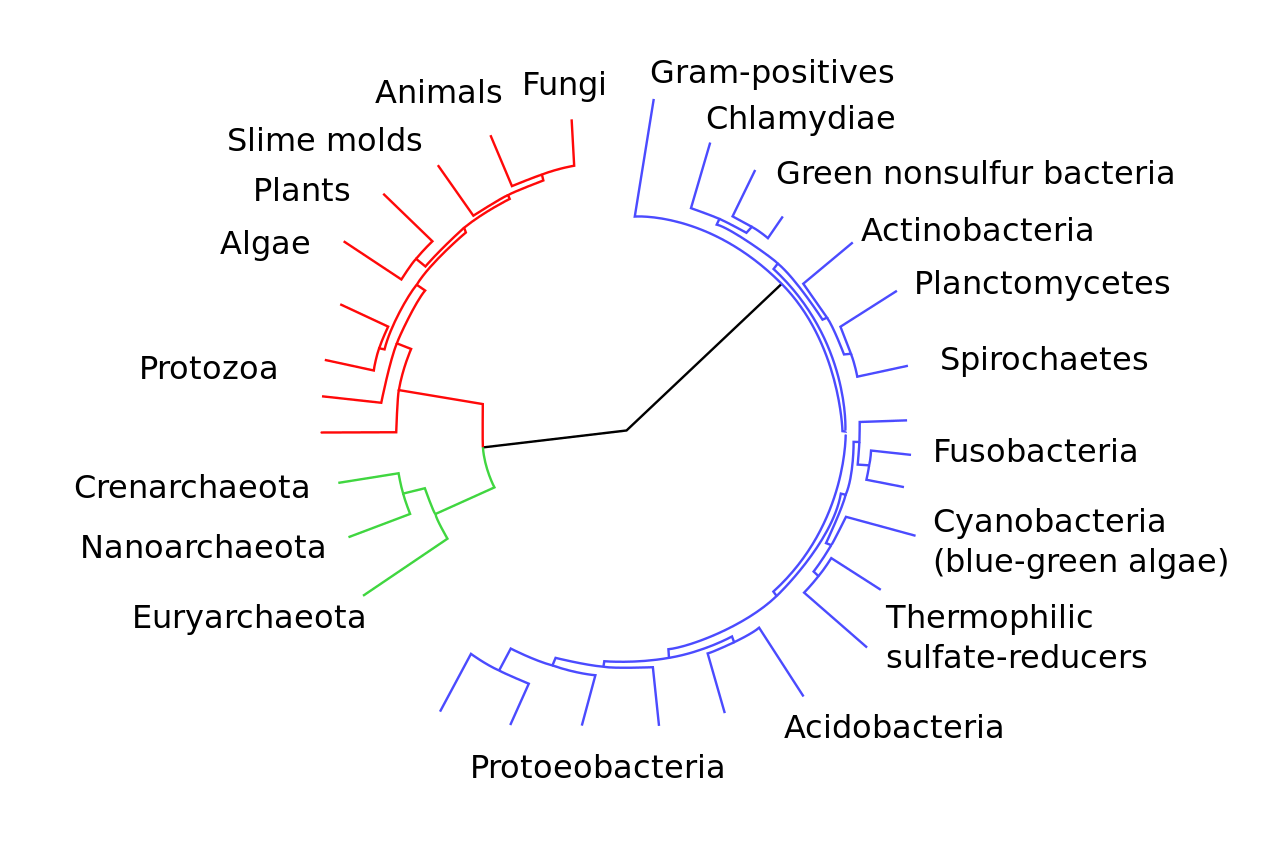

| Evolutionary thought,

the recognition that species change over time and the perceived

understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity. With

the beginnings of modern biological taxonomy in the late 17th century,

two opposed ideas influenced Western biological thinking: essentialism,

the belief that every species has essential characteristics that are

unalterable, a concept which had developed from medieval Aristotelian

metaphysics, and that fit well with natural theology; and the

development of the new anti-Aristotelian approach to science.

Naturalists began to focus on the variability of species; the emergence

of palaeontology with the concept of extinction further undermined

static views of nature. In the early 19th century prior to Darwinism,

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed his theory of the transmutation of

species, the first fully formed theory of evolution. In 1858 Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace published a new evolutionary theory, explained in detail in Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859). Darwin's theory, originally called descent with modification is known contemporarily as Darwinism or Darwinian theory. Unlike Lamarck, Darwin proposed common descent and a branching tree of life, meaning that two very different species could share a common ancestor. Darwin based his theory on the idea of natural selection: it synthesized a broad range of evidence from animal husbandry, biogeography, geology, morphology, and embryology. Debate over Darwin's work led to the rapid acceptance of the general concept of evolution, but the specific mechanism he proposed, natural selection, was not widely accepted until it was revived by developments in biology that occurred during the 1920s through the 1940s. Before that time most biologists regarded other factors as responsible for evolution. Alternatives to natural selection suggested during "the eclipse of Darwinism" (c. 1880 to 1920) included inheritance of acquired characteristics (neo-Lamarckism), an innate drive for change (orthogenesis), and sudden large mutations (saltationism). Mendelian genetics, a series of 19th-century experiments with pea plant variations rediscovered in 1900, was integrated with natural selection by Ronald Fisher, J. B. S. Haldane, and Sewall Wright during the 1910s to 1930s, and resulted in the founding of the new discipline of population genetics. During the 1930s and 1940s population genetics became integrated with other biological fields, resulting in a widely applicable theory of evolution that encompassed much of biology—the modern synthesis. Following the establishment of evolutionary biology, studies of mutation and genetic diversity in natural populations, combined with biogeography and systematics, led to sophisticated mathematical and causal models of evolution. Palaeontology and comparative anatomy allowed more detailed reconstructions of the evolutionary history of life. After the rise of molecular genetics in the 1950s, the field of molecular evolution developed, based on protein sequences and immunological tests, and later incorporating RNA and DNA studies. The gene-centred view of evolution rose to prominence in the 1960s, followed by the neutral theory of molecular evolution, sparking debates over adaptationism, the unit of selection, and the relative importance of genetic drift versus natural selection as causes of evolution.[2] In the late 20th-century, DNA sequencing led to molecular phylogenetics and the reorganization of the tree of life into the three-domain system by Carl Woese. In addition, the newly recognized factors of symbiogenesis and horizontal gene transfer introduced yet more complexity into evolutionary theory. Discoveries in evolutionary biology have made a significant impact not just within the traditional branches of biology, but also in other academic disciplines (for example: anthropology and psychology) and on society at large.[3] |

進

化思想とは、種が時間とともに変化することを認識し、そのようなプロセスがどのように作用するかを理解することであり、そのルーツは古代にある。17世紀

後半に近代的な生物分類学が始まると、西洋の生物学的思考に2つの相反する考え方が影響を及ぼした。本質主義、すなわち、すべての種は不変の本質的な特徴

を持っているという信念であり、中世のアリストテレス形而上学から発展した概念であり、自然神学によく適合するものであった。自然学者は種の多様性に注目

し始め、絶滅という概念を持つ古生物学の出現は、自然に対する静的な見方をさらに根底から覆した。ダーウィニズムに先立つ19世紀初頭、ジャン=バティス

ト・ラマルクは、進化論として初めて完全な形となる「種の転変」の理論を提唱した。 1858年、チャールズ・ダーウィンとアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは新たな進化論を発表し、ダーウィンの『種の起源』(1859年)で詳しく説明し た。ダーウィンの理論は、当初は変化下降説と呼ばれ、同時代にはダーウィニズムまたはダーウィン説として知られていた。ラマルクとは異なり、ダーウィンは 共通の子孫と枝分かれした生命の樹を提唱した。ダーウィンは自然淘汰の考え方に基づき、動物飼育学、生物地理学、地質学、形態学、発生学などの幅広い証拠 を総合して理論を構築した。ダーウィンの研究をめぐる論争によって、進化という一般的概念は急速に受け入れられたが、ダーウィンが提唱した自然淘汰という 具体的なメカニズムは、1920年代から1940年代にかけて起こった生物学の発展によって復活するまで、広く受け入れられることはなかった。それ以前 は、ほとんどの生物学者が進化の原因は他の要因にあると見なしていた。ダーウィニズムの蝕み」(1880年頃~1920年頃)に自然淘汰に代わるものとし て提案されたのは、後天的特徴の遺伝(ネオ・ラマルク主義)、生得的な変化への衝動(正統発生主義)、突然の大きな突然変異(塩基形成主義)などであっ た。メンデル遺伝学は、1900年に再発見されたエンドウ豆の突然変異を用いた19世紀の一連の実験であったが、1910年代から1930年代にかけて、 ロナルド・フィッシャー、J・B・S・ハルデイン、セウォール・ライトによって自然淘汰と統合され、集団遺伝学という新しい学問分野の創設につながった。 1930年代から1940年代にかけて、集団遺伝学は他の生物学分野と統合され、その結果、生物学の大部分を包含する、広く適用可能な進化論が生まれた。 進化生物学の確立後、自然集団における突然変異や遺伝的多様性の研究が、生物地理学や系統分類学と組み合わされ、進化に関する高度な数学的・因果学的モデ ルが構築された。古生物学と比較解剖学は、生命の進化の歴史をより詳細に再現することを可能にした。1950年代に分子遺伝学が台頭すると、タンパク質配 列と免疫学的検査に基づき、後にRNAとDNAの研究を取り入れた分子進化学が発展した。1960年代には遺伝子を中心とした進化論が台頭し、その後、分 子進化の中立説が登場し、適応論、淘汰の単位、進化の原因としての遺伝的ドリフトと自然淘汰の相対的重要性をめぐる論争が巻き起こった[2]。20世紀後 半には、DNA塩基配列の解読によって分子系統学が発展し、カール・ウーゼによって生命の樹が3ドメイン・システムに再編成された。さらに、新たに認識さ れた共生と遺伝子の水平移動という要因が、進化論にさらなる複雑さをもたらした。進化生物学における発見は、従来の生物学の分野だけでなく、他の学問分野 (例えば、人類学や心理学)や社会全体にも大きな影響を与えた[3]。 |

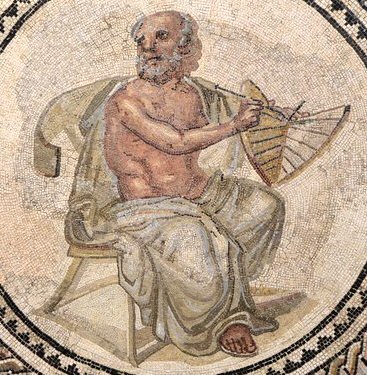

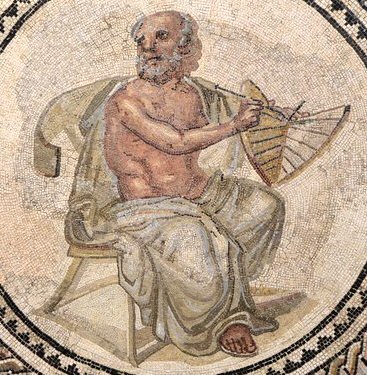

| Antiquity Indigenous cultures Several cultures across the world seem to have a rudimentary understanding of the theory of evolution, seeing humans as descending from certain mammals. These include the Malagasy people, who see humans as descending from indri;[4] the Aboriginal Tasmanians, which see humans as descending from kangaroos;[5] and some Native American cultures, such as the Navajo, whose creation myth details humans changing from animalistic creatures.[6] Greeks  The Greek philosopher Anaximander of Miletus argued that humans originated from fish.[7] See also: Essentialism Proposals that one type of animal, even humans, could descend from other types of animals, are known to go back to the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers. Anaximander of Miletus proposed that the first animals lived in water, during a wet phase of the Earth's past, and that the first land-dwelling ancestors of mankind must have been born in water, and only spent part of their life on land. He also argued that the first human of the form known today must have been the child of a different type of animal (probably a fish), because man needs prolonged nursing to live.[8][9][7] In the late nineteenth century, Anaximander was hailed as the "first Darwinist", but this characterization is no longer commonly agreed.[10] Anaximander's hypothesis could be considered "evolution" in a sense, although not a Darwinian one.[10] Empedocles argued that what we call birth and death in animals are just the mingling and separations of elements which cause the countless "tribes of mortal things".[11] Specifically, the first animals and plants were like disjointed parts of the ones we see today, some of which survived by joining in different combinations, and then intermixing during the development of the embryo,[a] and where "everything turned out as it would have if it were on purpose, there the creatures survived, being accidentally compounded in a suitable way."[12] Other philosophers who became more influential at that time, including Plato, Aristotle, and members of the Stoic school of philosophy, believed that the types of all things, not only living things, were fixed by divine design.[13][14]  Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail from The School of Athens (1509 – 1511) by Raphael Plato was called by biologist Ernst Mayr "the great antihero of evolutionism,"[13] because he promoted belief in essentialism, which is also referred to as the theory of Forms. This theory holds that each natural type of object in the observed world is an imperfect manifestation of the ideal, form or "species" which defines that type. In his Timaeus for example, Plato has a character tell a story that the Demiurge created the cosmos and everything in it because, being good, and hence, "free from jealousy, He desired that all things should be as like Himself as they could be." The creator created all conceivable forms of life, since "without them the universe will be incomplete, for it will not contain every kind of animal which it ought to contain, if it is to be perfect." This "principle of plenitude"—the idea that all potential forms of life are essential to a perfect creation—greatly influenced Christian thought.[14] However, some historians of science have questioned how much influence Plato's essentialism had on natural philosophy by stating that many philosophers after Plato believed that species might be capable of transformation and that the idea that biologic species were fixed and possessed unchangeable essential characteristics did not become important until the beginning of biological taxonomy in the 17th and 18th centuries.[15] Aristotle, the most influential of the Greek philosophers in Europe, was a student of Plato and is also the earliest natural historian whose work has been preserved in any real detail. His writings on biology resulted from his research into natural history on and around the island of Lesbos, and have survived in the form of four books, usually known by their Latin names, De anima (On the Soul), Historia animalium (History of Animals), De generatione animalium (Generation of Animals), and De partibus animalium (On the Parts of Animals). Aristotle's works contain accurate observations, fitted into his own theories of the body's mechanisms.[16] However, for Charles Singer, "Nothing is more remarkable than [Aristotle's] efforts to [exhibit] the relationships of living things as a scala naturae."[16] This scala naturae, described in Historia animalium, classified organisms in relation to a hierarchical but static "Ladder of Life" or "great chain of being," placing them according to their complexity of structure and function, with organisms that showed greater vitality and ability to move described as "higher organisms."[14] Aristotle believed that features of living organisms showed clearly that they had what he called a final cause, that is to say that their form suited their function.[17] He explicitly rejected the view of Empedocles that living creatures might have originated by chance.[18] Other Greek philosophers, such as Zeno of Citiumm the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, agreed with Aristotle and other earlier philosophers that nature showed clear evidence of being designed for a purpose; this view is known as teleology.[19] The Roman Skeptic philosopher Cicero wrote that Zeno was known to have held the view, central to Stoic physics, that nature is primarily "directed and concentrated...to secure for the world...the structure best fitted for survival."[20] Chinese Ancient Chinese thinkers such as Zhuang Zhou (c. 369 – c. 286 BC), a Taoist philosopher, expressed ideas on changing biological species. According to Joseph Needham, Taoism explicitly denies the fixity of biological species and Taoist philosophers speculated that species had developed differing attributes in response to differing environments.[21] Taoism regards humans, nature and the heavens as existing in a state of "constant transformation" known as the Tao, in contrast with the more static view of nature typical of Western thought.[22] Roman Empire Lucretius' poem De rerum natura provides the best surviving explanation of the ideas of the Greek Epicurean philosophers. It describes the development of the cosmos, the Earth, living things, and human society through purely naturalistic mechanisms, without any reference to supernatural involvement. De rerum natura would influence the cosmological and evolutionary speculations of philosophers and scientists during and after the Renaissance.[23][24] This view was in strong contrast with the views of Roman philosophers of the Stoic school such as Seneca the Younger and Pliny the Elder who had a strongly teleological view of the natural world that influenced Christian theology.[19] Cicero reports that the peripatetic and Stoic view of nature as an agency concerned most basically with producing life "best fitted for survival" was taken for granted among the Hellenistic elite.[20] Early Church Fathers Origen of Alexandria In line with earlier Greek thought, the third-century Christian philosopher and Church Father Origen of Alexandria argued that the creation story in the Book of Genesis should be interpreted as an allegory for the falling of human souls away from the glory of the divine, and not as a literal, historical account:[25][26] For who that has understanding will suppose that the first, and second, and third day, and the evening and the morning, existed without a sun, and moon, and stars? And that the first day was, as it were, also without a sky? And who is so foolish as to suppose that God, after the manner of a husbandman, planted a paradise in Eden, towards the east, and placed in it a tree of life, visible and palpable, so that one tasting of the fruit by the bodily teeth obtained life? And again, that one was a partaker of good and evil by masticating what was taken from the tree? And if God is said to walk in the paradise in the evening, and Adam to hide himself under a tree, I do not suppose that anyone doubts that these things figuratively indicate certain mysteries, the history having taken place in appearance, and not literally. — Origen, On the First Principles IV.16 Gregory of Nyssa Gregory of Nyssa wrote: Scripture informs us that the Deity proceeded by a sort of graduated and ordered advance to the creation of man. After the foundations of the universe were laid, as the history records, man did not appear on the earth at once, but the creation of the brutes preceded him, and the plants preceded them. Thereby Scripture shows that the vital forces blended with the world of matter according to a gradation; first it infused itself into insensate nature; and in continuation of this advanced into the sentient world; and then ascended to intelligent and rational beings (emphasis added).[12] Henry Fairfield Osborn wrote in his work on the history of evolutionary thought, From the Greeks to Darwin (1894): Among the Christian Fathers the movement towards a partly naturalistic interpretation of the order of Creation was made by Gregory of Nyssa in the fourth century, and was completed by Augustine in the fourth and fifth centuries. ...[Gregory of Nyssa] taught that Creation was potential. God imparted to matter its fundamental properties and laws. The objects and completed forms of the Universe developed gradually out of chaotic material. [27] |

古代 先住民族の文化 世界各地のいくつかの文化は、進化論の初歩的な理解を持っているようで、人類は特定の哺乳類の子孫であると見ている。これには、人間をインドリの子孫とみ なすマダガスカルの人々[4]、人間をカンガルーの子孫とみなすアボリジニのタスマニア人[5]、創造神話で人間が動物的な生き物から変化したと詳述する ナバホ族などのアメリカ先住民文化が含まれる[6]。 ギリシャ人  ギリシャの哲学者であるミレトスのアナクシマンドロスは、人間は魚から生まれたと主張した[7]。 こちらも参照: 本質主義 ある種の動物(たとえ人間であっても)が他の種類の動物の子孫になる可能性があるという提案は、ソクラテス以前のギリシアの哲学者にまでさかのぼることが 知られている。ミレトスのアナクシマンドは、最初の動物は地球の過去の湿潤期に水中で生活しており、人類の最初の陸上生活者の祖先は水中で生まれ、陸上で 生涯の一部だけを過ごしたに違いないと提唱した。彼はまた、人間が生きるためには長時間の授乳が必要であるため、現在知られている形の最初の人間は異なる 種類の動物(おそらく魚)の子供であったに違いないと主張した[8][9][7]。19世紀後半、アナクシマンドロスは「最初のダーウィン主義者」として 賞賛されたが、この特徴はもはや一般的には同意されていない[10]。アナクシマンドロスの仮説は、ダーウィン的なものではないものの、ある意味で「進 化」とみなすことができる[10]。 エンペドクレスは、我々が動物における誕生と死と呼んでいるものは、無数の「死すべきものの部族」を引き起こす要素の混ざり合いと分離に過ぎないと主張し た[11]。具体的には、最初の動物や植物は今日我々が目にするもののバラバラの部分のようなものであり、その一部は異なる組み合わせで結合することで生 き残り、胚の発達中に混ざり合った。 「プラトン、アリストテレス、ストア派の哲学者など、当時より影響力を持つようになった他の哲学者たちは、生物だけでなく万物の型は神の設計によって固定 されていると信じていた[13][14]。  プラトン(左)とアリストテレス(右)、ラファエロ作『アテネの学派』(1509年 - 1511年)より。 プラトンは生物学者エルンスト・マイヤーから「進化論の偉大なアンチヒーロー」と呼ばれている。この理論は、観察される世界に存在する自然界の物体の種類 はそれぞれ、その種類を定義する理想、形態、または「種」の不完全な現れであるとするものである。例えば、プラトンは『ティマイオス』の中で、登場人物 に、デーミウルゲが宇宙とそこにあるすべてのものを創造したのは、善であり、それゆえ「嫉妬から自由であったので、万物が可能な限り自分自身に似ているこ とを望んだからである」と語らせている。創造主は、考えうるすべての生命体を創造した。「それがなければ、宇宙は不完全なものとなってしまう。」宇宙が完 全なものとなるためには、宇宙が含むべきあらゆる種類の動物を含むことができないからである。この「豊穣の原理」、すなわち生命のすべての潜在的形態が完 全な創造にとって不可欠であるという考え方は、キリスト教思想に大きな影響を与えた[14]。しかし、科学史家の中には、プラトンの本質主義が自然哲学に どれほどの影響を与えたかを疑問視する者もいる。プラトン以降の多くの哲学者は、種は変容する可能性があると信じており、生物学的な種は固定されたもので あり、不変の本質的特徴を有しているという考え方は、17世紀から18世紀にかけて生物分類学が始まるまで重要ではなかったと述べている[15]。 ヨーロッパで最も影響力のあったギリシアの哲学者アリストテレスは、プラトンの弟子であり、その業績が詳細に保存されている最古の自然史家でもある。彼の 生物学に関する著作は、レスボス島とその周辺での博物学研究から生まれたもので、通常はラテン語名で知られる『魂について』(De anima)、『動物の歴史』(Historia animalium)、『動物の生成』(De generatione animalium)、『動物の部位について』(De partibus animalium)の4冊の書物として残されている。アリストテレスの著作には正確な観察が含まれており、身体のメカニズムに関する彼自身の理論に適合 している[16]。しかし、チャールズ・シンガーにとって、「(アリストテレスが)生きとし生けるものの関係をscala naturaeとして(示そうと)努力したことほど驚くべきことはない。 Historia animalium』に記述されたこの自然観は、階層的ではあるが静的な「生命の階梯」あるいは「存在の大いなる連鎖」との関係において生物を分類し、構 造と機能の複雑さに従って生物を配置し、より高い生命力と運動能力を示す生物を「高等生物」と表現した。 「14]アリストテレスは、生物の特徴は、彼が最終原因と呼ぶもの、すなわちその形態がその機能に適していることを明確に示していると考えていた [17]。 この見解は目的論として知られている[19]。ローマの懐疑哲学者キケロは、ゼノンがストア派の物理学の中心的な見解である、自然は主に「生存に最も適し た構造を世界に確保するために...指示され、集中される」という見解を持っていたことが知られていると書いている[20]。 中国 道教の哲学者である荘周(紀元前369年頃~紀元前286年頃)のような古代中国の思想家は、生物種の変化に関する考えを示した。ジョセフ・ニーダムによ れば、道教は生物学的種の固定性を明確に否定しており、道教の哲学者たちは、種は異なる環境に対応して異なる属性を発達させてきたと推測している [21]。道教は人間、自然、天をタオとして知られる「絶え間ない変容」の状態に存在するとみなしており、西洋思想の典型的な、より静的な自然観とは対照 的である[22]。 ローマ帝国 ルクレティウスの詩『De rerum natura』は、ギリシアのエピクロス哲学者たちの思想を最もよく説明している。この詩は、超自然的な関与に言及することなく、純粋に自然主義的なメカ ニズムによる宇宙、地球、生物、人間社会の発展を描写している。De rerum natura』は、ルネサンス期以降の哲学者や科学者の宇宙論的・進化論的思索に影響を与えた[23][24]。この見解は、キリスト教神学に影響を与え た自然界に対する強い目的論的見解を持つ、若きセネカや長老プリニウスのようなストア派のローマ哲学者の見解とは強い対照をなしていた。 [19]キケロは、「生存に最も適した」生命を生み出すことに最も基本的に関わる機関としての自然に対する周縁的でストア的な見方は、ヘレニズムのエリー トたちの間では当然のことであったと報告している[20]。 初期の教父たち アレクサンドリアのオリゲン 3世紀のキリスト教の哲学者であり教父であったアレクサンドリアのオリゲンは、それ以前のギリシア思想に倣い、創世記の天地創造の物語は、人間の魂が神の 栄光から離れていく寓話として解釈されるべきであり、文字通りの歴史的記述として解釈されるべきではないと主張した[25][26]。 理解のある者が、第一の日、第二の日、第三の日、夕べと朝が、太陽や月や星なしに存在したと考えるであろうか。また、第一の日は、いわば空もなかったので あろうか。また、神が夫のように、東のエデンに楽園を植え、そこに目に見え、手に取ることのできる命の木を置き、その実を歯で味わう者が命を得たと考える ほど愚かな者がいるだろうか。また、その木から採ったものを咀嚼することによって、人は善と悪に与る者となったというのか。また、神が夕方に楽園を歩き、 アダムが木の下に身を隠すと言われるなら、これらのことがある種の神秘を比喩的に示しているのであって、歴史は文字通りのものではなく、外見上の出来事で あることを疑う者はいないと思う。 - オリゲン『第一原理について』IV.16 ニッサのグレゴリウス ニッサのグレゴリウスはこう書いている: 聖書は、神性が人間の創造に至るまで、ある種の段階的かつ秩序だった前進を遂げたと告げている。歴史が記録しているように、宇宙の基礎が築かれた後、人間 は一度に地上に現れたのではなく、哺乳類の創造が彼に先行し、植物がそれらに先行したのである。これによって聖典は、生命力が物質の世界とグラデーション に従って融合したことを示している。まず、生命力は無感覚な自然の中に自らを吹き込み、これに続いて感覚のある世界へと進み、そして知的で理性的な存在へ と昇華したのである(強調)[12]。 ヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンは、進化思想史に関する著作『ギリシア人からダーウィンへ』(1894年)の中で次のように述べている: キリスト教教父の間では、天地創造の秩序を部分的に自然主義的に解釈する動きが、4世紀にニッサのグレゴリウスによってなされ、4世紀から5世紀にかけて アウグスティヌスによって完成された。ニッサのグレゴリウスは)天地創造は潜在的なものであると説いた。神は物質にその基本的な性質と法則を与えた。宇宙 の物体と完成された形態は、混沌とした物質から徐々に発展していった。[27] |

Augustine of Hippo Augustine of Hippo, shown in this sixth-century AD Roman fresco, wrote that some creatures may have developed from the "decomposition" of previously existing organisms.[28] In the fourth century AD, the bishop and theologian Augustine of Hippo followed Origen in arguing that Christians should read the Genesis creation story allegorically. In his book De Genesi ad litteram (On the Literal Meaning of Genesis), he prefaces his account with the following: In all sacred books, we should consider the eternal truths that are taught, the facts that are narrated, the future events that are predicted, and the precepts or counsels that are given. In the case of a narrative of events, the question arises whether everything must be taken according to the figurative sense only, or whether it must be expounded and defended also as a faithful record of what happened. No Christian would dare say that the narrative must not be taken in a figurative sense. For St. Paul says: Now all these things that happened to them were symbolic [1 Cor 10:11]. And he explains the statement in Genesis, And they shall be two in one flesh [Eph 5:32], as a great mystery in reference to Christ and to the Church.[29] Later he differentiates between the days of the Genesis 1 creation narrative and 24 hour days that humans experience (arguing that "we know [the days of creation] are different from the ordinary day of which we are familiar")[30] before describing what could be called an early form of theistic evolution:[31][32] The things [God] had potentially created... [came] forth in the course of time on different days according to their different kinds... [and] the rest of the earth [was] filled with its various kinds of creatures, [which] produced their appropriate forms in due time.[33] Augustine deployed the concept of rationes seminales to blend the idea of divine creation with subsequent development.[34] This idea "that forms of life had been transformed 'slowly over time'" prompted Father Giuseppe Tanzella-Nitti, Professor of Theology at the Pontifical Santa Croce University in Rome, to claim that Augustine had suggested a form of evolution.[35][36] Henry Fairfield Osborn wrote in From the Greeks to Darwin (1894): If the orthodoxy of Augustine had remained the teaching of the Church, the final establishment of Evolution would have come far earlier than it did, certainly during the eighteenth instead of the nineteenth century, and the bitter controversy over this truth of Nature would never have arisen. ... Plainly as the direct or instantaneous Creation of animals and plants appeared to be taught in Genesis, Augustine read this in the light of primary causation and the gradual development from the imperfect to the perfect of Aristotle. This most influential teacher thus handed down to his followers opinions which closely conform to the progressive views of those theologians of the present day who have accepted the Evolution theory.[37] In A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896), Andrew Dickson White wrote about Augustine's attempts to preserve the ancient evolutionary approach to the creation as follows: For ages a widely accepted doctrine had been that water, filth, and carrion had received power from the Creator to generate worms, insects, and a multitude of the smaller animals; and this doctrine had been especially welcomed by St. Augustine and many of the fathers, since it relieved the Almighty of making, Adam of naming, and Noah of living in the ark with these innumerable despised species.[38] In Augustine's De Genesi contra Manichæos, on Genesis he says: "To suppose that God formed man from the dust with bodily hands is very childish. ... God neither formed man with bodily hands nor did he breathe upon him with throat and lips." Augustine suggests in other work his theory of the later development of insects out of carrion, and the adoption of the old emanation or evolution theory, showing that "certain very small animals may not have been created on the fifth and sixth days, but may have originated later from putrefying matter." Concerning Augustine's De Trinitate (On the Trinity), White wrote that Augustine "develops at length the view that in the creation of living beings there was something like a growth—that God is the ultimate author, but works through secondary causes; and finally argues that certain substances are endowed by God with the power of producing certain classes of plants and animals."[39] Augustine implies that whatever science shows, the Bible must teach: Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars ... Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking non-sense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. The shame is not so much that an ignorant individual is derided, but that people outside the household of the faith think our sacred writers held such opinions, and, to the great loss of those for whose salvation we toil, the writers of our Scripture are criticized and rejected as unlearned men.[40] |

ヒッポのアウグスティヌス この紀元6世紀のローマのフレスコ画に描かれているヒッポのアウグスティヌスは、いくつかの生物は以前に存在していた生物の「分解」から発展した可能性があると書いている[28]。 紀元4世紀、司教であり神学者であったヒッポのアウグスティヌスは、キリスト教徒は創世記の創造物語を寓意的に読むべきであると主張するオリゲンに従っ た。彼の著書『De Genesi ad litteram(創世記の文字通りの意味について)』の中で、彼はその説明を次のように前置きしている: すべての聖なる書物において、我々は教えられている永遠の真理、叙述されている事実、予言されている未来の出来事、そして与えられている教訓や忠告を考慮 すべきである。出来事の叙述の場合、すべてを比喩的な意味だけでとらえなければならないのか、それとも起こったことの忠実な記録としても説明し、擁護しな ければならないのかという疑問が生じる。この物語を比喩的な意味でとらえてはならない、とあえて言うキリスト教徒はいないだろう。聖パウロは言う: 彼らに起こったこれらのことは、すべて象徴的なことである。そして、創世記にある「二人は一つの肉となる」(エペソ5:32)という記述を、キリストと教 会に関する偉大な神秘として説明している[29]。 その後、彼は創世記1章の天地創造の物語の日々と、人間が経験する24時間の日々とを異なるものとしている(「私たちは(天地創造の日々は)私たちがよく知っている普通の日とは異なることを知っている」と主張している)[30]。 神]が潜在的に創造されたものは...。神]が潜在的に創造したものは... [時の流れの中で]その種類に応じて異なる日に現れた。[そして]大地の残りの部分はさまざまな種類の被造物で満たされ、[被造物は]しかるべき時に適切な形を生み出した[33]。 アウグスティヌスは、神の創造とその後の発展という考えを融合させるためにrationes seminalesという概念を展開した[34]。この「生命の形態が『時間をかけてゆっくりと』変化してきた」という考えによって、ローマの教皇庁立サ ンタ・クローチェ大学の神学教授であるジュゼッペ・タンゼッラ=ニッティ神父は、アウグスティヌスが進化の一形態を示唆したと主張した[35][36]。 ヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンは『ギリシア人からダーウィンへ』(1894年)の中でこう書いている: もしアウグスティヌスの正統性が教会の教えのままであったなら、進化論の最終的な確立はもっと早く、19世紀ではなく18世紀中に確実になされたであろう し、この自然の真理をめぐる激しい論争が起こることもなかったであろう。... アウグスティヌスは、創世記において動物や植物の直接的あるいは瞬間的な創造が説かれているように見えたが、これを第一義的な因果関係とアリストテレスの 不完全なものから完全なものへの段階的な発展という観点から読み解いた。この最も影響力のある教師は、このようにして、進化論を受け入れている現代の神学 者たちの進歩的な見解と密接に一致する意見を信奉者たちに伝えた[37]。 アンドリュー・ディクソン・ホワイトは、『A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom』(1896年)の中で、アウグスティヌスが創造に対する古代の進化論的アプローチを維持しようとしたことについて、次のように書 いている: 昔から広く受け入れられてきた教義は、水、汚物、腐肉が創造主から力を得て、ミミズ、昆虫、そしてマルチチュードの小動物を生み出すというものであった。この教義は、聖アウグスティヌスや多くの教父たちから特に歓迎されていた。 アウグスティヌスは『創世記』(De Genesi contra Manichæos)において次のように述べている。神は人間を肉体的な手で造られたのでも、喉と唇で息を吹きかけられたのでもない。" と述べている。アウグスティヌスは他の著作で、腐肉から昆虫が後に発生したという説や、「ある種の非常に小さな動物は5日目や6日目に創造されたのではな く、腐敗した物質から後に発生したのかもしれない 」という、古い発生説や進化説の採用を示唆している。アウグスティヌスの『三位一体論』(De Trinitate)について、ホワイトは、アウグスティヌスは「生物の創造には成長のようなものがあったという見解を長々と展開し、神は究極的な創造者 であるが、二次的な原因を通して働くという見解を展開し、最後に、ある種の物質には、ある種の植物や動物を生み出す力が神によって与えられていると論じて いる」[39]と書いている。 アウグスティヌスは、科学が示すものが何であれ、聖書が教えなければならないことを暗示している: 普通、キリスト教徒でない者でさえ、地球、天、この世の他の要素、星の運動と軌道について何かを知っている。そして、人民がクリスチャンの膨大な無知を見 せつけ、嘲笑するような、このような恥ずべき事態を防ぐために、あらゆる手段を講じるべきである。恥ずべきことは、無知な個人が嘲笑されることよりも、信 仰の家庭以外の人民が、私たちの聖典の著者がそのような意見を持っていたと考えることであり、私たちがその救いのために労苦している人々の大きな損失とな るように、私たちの聖典の著者が批判され、無学な人間として拒絶されることである[40]。 |

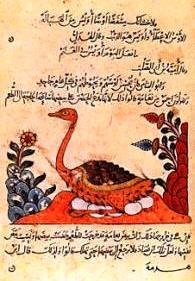

| Middle Ages Islamic philosophy and the struggle for existence See also: Early Islamic philosophy and Science in the medieval Islamic world  A page from the Kitāb al-Hayawān (Book of Animals) by al-Jāḥiẓ Although Greek and Roman evolutionary ideas died out in Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire, they were not lost to Islamic philosophers and scientists (nor to the culturally Greek Byzantine Empire). In the Islamic Golden Age of the 8th to the 13th centuries, philosophers explored ideas about natural history. These ideas included transmutation from non-living to living: "from mineral to plant, from plant to animal, and from animal to man."[41] In the medieval Islamic world, the scholar al-Jāḥiẓ wrote his Book of Animals in the 9th century. Conway Zirkle, writing about the history of natural selection in 1941, said that an excerpt from this work was the only relevant passage he had found from an Arabian scholar. He provided a quotation describing the struggle for existence, citing a Spanish translation of this work: "Every weak animal devours those weaker than itself. Strong animals cannot escape being devoured by other animals stronger than they. And in this respect, men do not differ from animals, some with respect to others, although they do not arrive at the same extremes. In short, God has disposed some human beings as a cause of life for others, and likewise, he has disposed the latter as a cause of the death of the former."[42] Al-Jāḥiẓ also wrote descriptions of food chains.[43] Some of Ibn Khaldūn's thoughts, according to some commentators, anticipate the biological theory of evolution.[44] In 1377, Ibn Khaldūn wrote the Muqaddimah in which he asserted that humans developed from "the world of the monkeys," in a process by which "species become more numerous".[44] In chapter 1 he writes: "This world with all the created things in it has a certain order and solid construction. It shows nexuses between causes and things caused, combinations of some parts of creation with others, and transformations of some existent things into others, in a pattern that is both remarkable and endless."[45] The Muqaddimah also states in chapter 6: We explained there that the whole of existence in (all) its simple and composite worlds is arranged in a natural order of ascent and descent, so that everything constitutes an uninterrupted continuum. The essences at the end of each particular stage of the worlds are by nature prepared to be transformed into the essence adjacent to them, either above or below them. This is the case with the simple material elements; it is the case with palms and vines, (which constitute) the last stage of plants, in their relation to snails and shellfish, (which constitute) the (lowest) stage of animals. It is also the case with monkeys, creatures combining in themselves cleverness and perception, in their relation to man, the being who has the ability to think and to reflect. The preparedness (for transformation) that exists on either side, at each stage of the worlds, is meant when (we speak about) their connection.[46] Christian philosophy Thomas Aquinas on creation and natural processes While most Christian theologians held that the natural world was part of an unchanging designed hierarchy, some theologians speculated that the world might have developed through natural processes. Thomas Aquinas expounded on Augustine of Hippo's early idea of theistic evolution On the day on which God created the heaven and the earth, He created also every plant of the field, not, indeed, actually, but 'before it sprung up in the earth,' that is, potentially... All things were not distinguished and adorned together, not from a want of power on God's part, as requiring time in which to work, but that due order might be observed in the instituting of the world.[41] He saw that the autonomy of nature was a sign of God's goodness, and detected no conflict between a divinely created universe and the idea that the universe had developed over time through natural mechanisms.[47] However, Aquinas disputed the views of those (like the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles) who held that such natural processes showed that the universe could have developed without an underlying purpose. Aquinas rather held that: "Hence, it is clear that nature is nothing but a certain kind of art, i.e., the divine art, impressed upon things, by which these things are moved to a determinate end. It is as if the shipbuilder were able to give to timbers that by which they would move themselves to take the form of a ship."[48] |

中世 イスラーム哲学と生存のための闘争 こちらも参照のこと: 初期イスラーム哲学と中世イスラーム世界の科学  アル=ジャーハイの『動物の書』(Kitāb al-Hayawān)の1ページ。 ローマ帝国の滅亡後、西ヨーロッパではギリシア・ローマ時代の進化論的思想は消滅したが、イスラムの哲学者や科学者にとっては(文化的にギリシア的だった ビザンチン帝国にとっても)失われたわけではなかった。8世紀から13世紀にかけてのイスラム黄金時代、哲学者たちは自然史に関する考えを探求した。その 中には、非生物から生物への変換も含まれていた: 「鉱物から植物へ、植物から動物へ、動物から人間へ」[41]。 中世イスラム世界では、9世紀に学者アル・ジャーハイフが『動物記』を著した。1941年に自然淘汰の歴史について書いたコンウェイ・ジークルは、この著 作からの抜粋が、アラビアの学者から見つけた唯一の関連箇所であると述べている。彼はこの著作のスペイン語訳を引用して、生存のための闘争を描写した引用 文を提供した: 「弱い動物は皆、自分より弱いものをむさぼる。強い動物は、自分より強い動物に食われることを免れない。この点で、人間は動物と異なるところはなく、ある ものは他のものに対して、同じ極端に達することはない。要するに、神はある人間を他の人間の生命の原因として配置し、同様に後者を前者の死の原因として配 置したのである」[42] アル=ジャーハイは食物連鎖に関する記述も書いている[43]。 1377年、イブン・ハルドゥーンは『ムカッディマー』を著し、その中で「種がより多くなる」過程において、人間は「猿の世界」から発展したと主張した [44]。 第1章において彼は次のように書いている:「この世界とその中のすべての創造されたものは、一定の秩序と堅固な構造を持っている。この世界は、原因と原因 となるものとの関連、被造物のある部分と他の部分との結合、存在するあるものの他のものへの変容を、驚くべき、また果てしないパターンで示している」 [45]。 ムカディマは第6章でも述べている: 私たちはそこで、単純な世界と複合的な世界における存在全体が、上昇と下降の自然な順序で配置され、すべてが途切れることのない連続体を構成していること を説明した。各世界の個別主義的な段階の末端にあるエッセンスは、本来、その上か下かのいずれかに隣接するエッセンスに変容するように準備されている。こ れは単純な物質的要素の場合であり、植物の最終段階を構成するヤシやツルの場合であり、動物の(最下)段階を構成するカタツムリや貝の場合である。それは また、賢さと知覚を併せ持つ生き物である猿と、思考し内省する能力を持つ存在である人間との関係においても同様である。それぞれの世界のそれぞれの段階に おいて、どちらの側にも存在する(変容への)備えは、(私たちが)それらのつながりについて語るときに意味される[46]。 キリスト教哲学 創造と自然過程に関するトマス・アクィナス ほとんどのキリスト教神学者は、自然界は不変の設計された階層の一部であるとしたが、一部の神学者は、世界は自然のプロセスを通じて発展したのではないかと推測した。トマス・アクィナスは、ヒッポのアウグスティヌスの神論的進化に関する初期の考えを説明した。 神が天と地を創造されたその日、神は野のあらゆる植物も創造された。万物が区別され、共に飾られなかったのは、神の側に力がなかったからではなく、働くための時間を必要としたからでもなく、世界の制定において正当な秩序が守られるためであった[41]。 自然の自律性は神の善のしるしであり、神が創造した宇宙と、宇宙が自然のメカニズムによって時間をかけて発展してきたという考えとの間に矛盾はないとア クィナスは考えた[47]。しかしアクィナスは、そのような自然のプロセスは、宇宙が根本的な目的なしに発展しえたことを示しているとする人々(古代ギリ シアの哲学者エンペドクレスのような)の見解に異議を唱えた。アクィナスはむしろ次のように主張した: 「それゆえ、自然とはある種の芸術にほかならないことは明らかである。すなわち、神の芸術が事物に印象づけられたものであり、その芸術によって事物は決定 的な目的へと動かされるのである。それはあたかも、船大工が木材に、それによって木材が自らを動かして船の形をとるようなものを与えることができるかのよ うである」[48]。 |

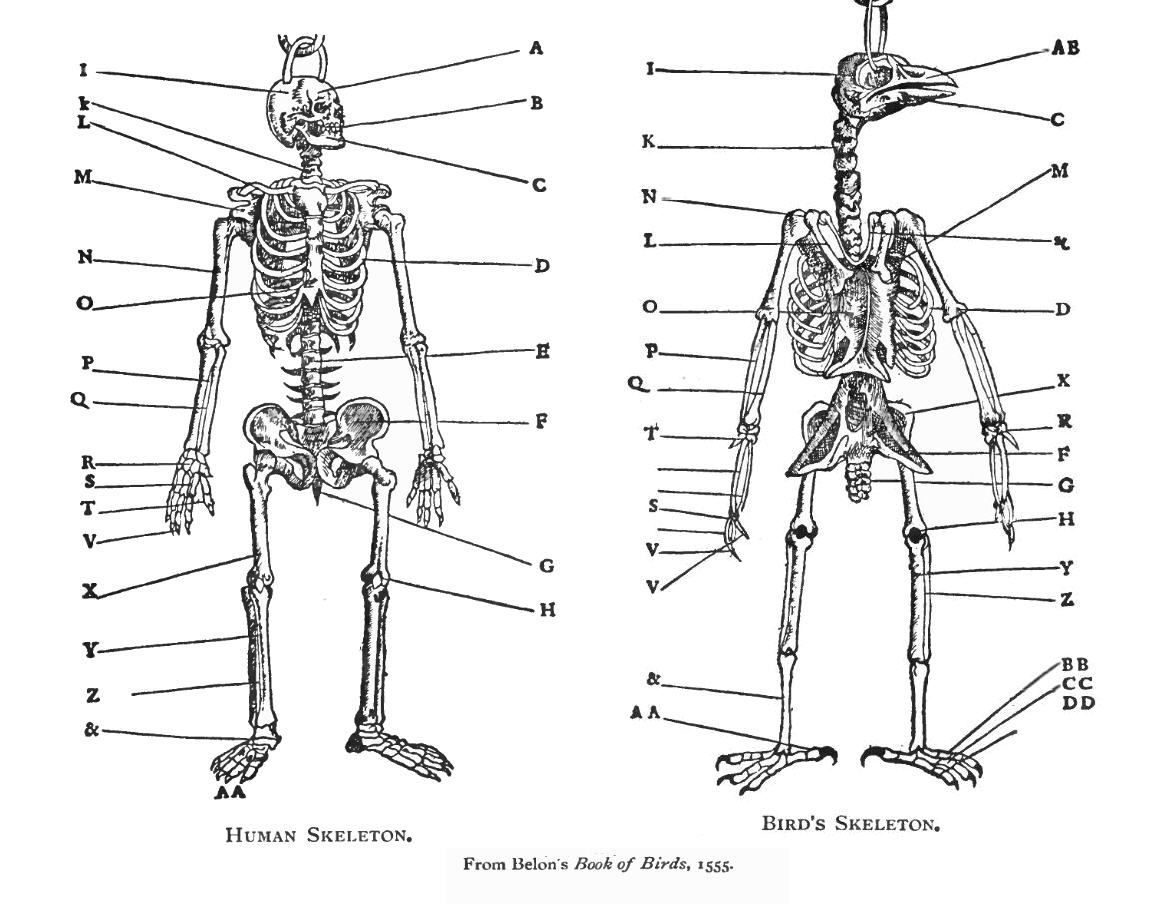

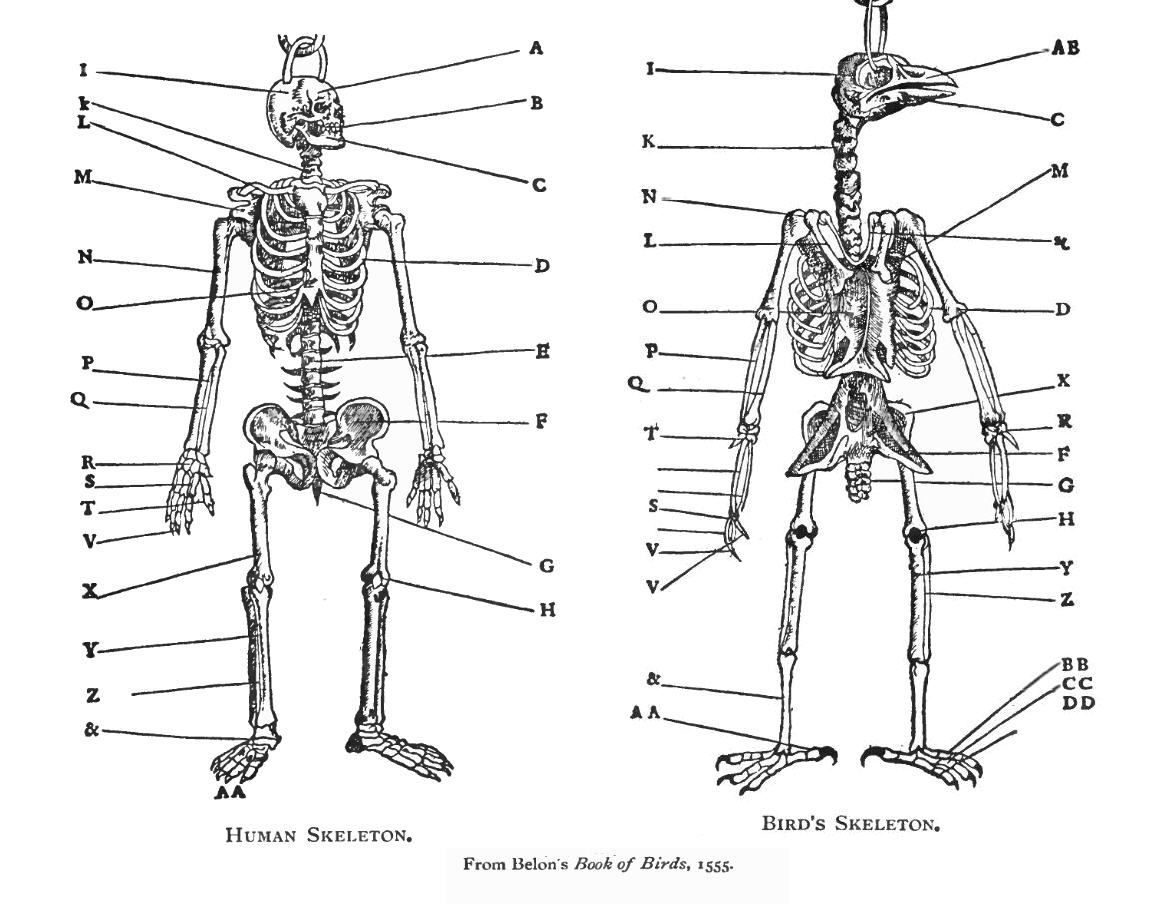

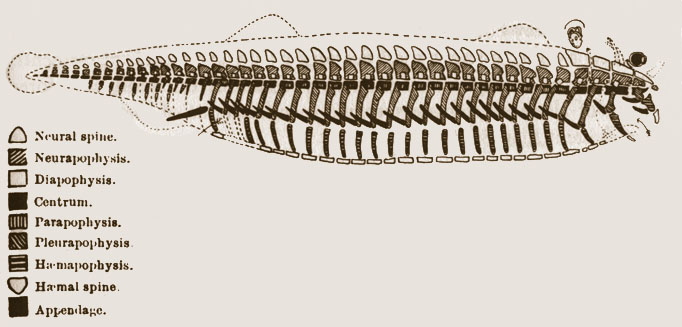

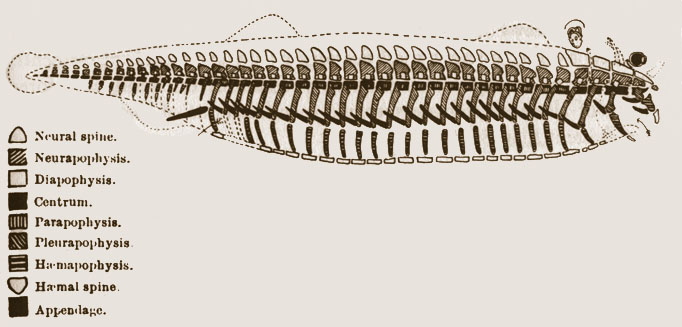

| Renaissance and Enlightenment Main article: Evolutionary ideas of the Renaissance and Enlightenment  Pierre Belon compared the skeletons of humans (left) and birds (right) in his L'Histoire de la nature des oyseaux (The Natural History of Birds) (1555). In the first half of the 17th century, René Descartes' mechanical philosophy encouraged the use of the metaphor of the universe as a machine, a concept that would come to characterise the scientific revolution.[49] Between 1650 and 1800, some naturalists, such as Benoît de Maillet, produced theories that maintained that the universe, the Earth, and life, had developed mechanically, without divine guidance.[50] In contrast, most contemporary theories of evolution, such of those of Gottfried Leibniz and Johann Gottfried Herder, regarded evolution as a fundamentally spiritual process.[51] In 1751, Pierre Louis Maupertuis veered toward more materialist ground. He wrote of natural modifications occurring during reproduction and accumulating over the course of many generations, producing races and even new species, a description that anticipated in general terms the concept of natural selection.[52] Maupertuis' ideas were in opposition to the influence of early taxonomists like John Ray. In the late 17th century, Ray had given the first formal definition of a biological species, which he described as being characterized by essential unchanging features, and stated the seed of one species could never give rise to another.[15] The ideas of Ray and other 17th-century taxonomists were influenced by natural theology and the argument from design.[53] The word evolution (from the Latin evolutio, meaning "to unroll like a scroll") was initially used to refer to embryological development; its first use in relation to development of species came in 1762, when Charles Bonnet used it for his concept of "pre-formation," in which females carried a miniature form of all future generations. The term gradually gained a more general meaning of growth or progressive development.[54] Later in the 18th century, the French philosopher Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, one of the leading naturalists of the time, suggested that what most people referred to as species were really just well-marked varieties, modified from an original form by environmental factors. For example, he believed that lions, tigers, leopards, and house cats might all have a common ancestor. He further speculated that the 200 or so species of mammals then known might have descended from as few as 38 original animal forms. Buffon's evolutionary ideas were limited; he believed each of the original forms had arisen through spontaneous generation and that each was shaped by "internal moulds" that limited the amount of change. Buffon's works, Histoire naturelle (1749–1789) and Époques de la nature (1778), containing well-developed theories about a completely materialistic origin for the Earth and his ideas questioning the fixity of species, were extremely influential.[55][56] Another French philosopher, Denis Diderot, also wrote that living things might have first arisen through spontaneous generation, and that species were always changing through a constant process of experiment where new forms arose and survived or not based on trial and error; an idea that can be considered a partial anticipation of natural selection.[57] Between 1767 and 1792, James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, included in his writings not only the concept that man had descended from primates, but also that, in response to the environment, creatures had found methods of transforming their characteristics over long time intervals.[58] Charles Darwin's grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, published Zoonomia (1794–1796) which suggested that "all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament."[59] In his poem Temple of Nature (1803), he described the rise of life from minute organisms living in mud to all of its modern diversity.[60] |

ルネサンスと啓蒙 主な記事 ルネサンスと啓蒙時代の進化思想  ピエール・ベロンは『鳥類の自然史』(L'Histoire de la nature des oyseaux、1555年)の中で、人間(左)と鳥類(右)の骨格を比較している。 17世紀前半、ルネ・デカルトの機械哲学は、宇宙を機械として隠喩することを奨励し、この概念は後に科学革命を特徴づけることになる[49]。1650年 から1800年にかけて、ブノワ・ド・メイレのような一部の博物学者は、宇宙、地球、そして生命は神の導きなしに機械的に発展してきたと主張する理論を生 み出した。 [50]対照的に、ゴットフリート・ライプニッツやヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダーのような現代の進化論のほとんどは、進化を基本的に精神的な過程とみ なしていた[51]。 1751年、ピエール・ルイ・モーペルテュイは、より唯物論的な方向へと舵を切った。彼は、生殖中に起こる自然な変化が何世代にもわたって蓄積され、人種 や新しい種さえも生み出すと書いており、自然淘汰の概念を一般論として先取りした記述であった[52]。 モーペルテュイの考えは、ジョン・レイのような初期の分類学者の影響と対立するものであった。17世紀後半、レイは生物学的な種の最初の正式な定義を与え ており、それは本質的に不変の特徴によって特徴付けられるとし、ある種の種子が別の種を生み出すことはあり得ないと述べていた[15]。レイや他の17世 紀の分類学者の考えは、自然神学や設計からの議論に影響を受けていた[53]。 進化という言葉(ラテン語のevolutioに由来し、「巻物のように広げる」という意味)は、当初は発生学的な発生を指す言葉として使われていた。種の 発生に関連して初めて使われたのは1762年で、シャルル・ボネが「前形成」という概念にこの言葉を使った時である。この用語は次第に、成長や漸進的な発 展という、より一般的な意味を持つようになった[54]。 18世紀後半、フランスの哲学者ジョルジュ=ルイ・ルクレール(当時の代表的な博物学者の一人、コント・ド・ビュフォン)は、ほとんどの人民が種と呼んで いるものは、実際には、環境要因によって元の形から変化した、よく似た品種に過ぎないと示唆した。例えば、ビュフォンはライオン、トラ、ヒョウ、ヤマネコ はすべて共通の祖先を持っていると考えた。さらに彼は、当時知られていた200種ほどの哺乳類は、38種ほどの動物の原型から派生したのではないかと推測 した。ビュフォンの進化論的発想は限定的で、原型のそれぞれが自然発生によって生じたものであり、変化の量を制限する「内部の型」によって形作られている と考えていた。ビュフォンの著作である『自然史』(Histoire naturelle, 1749-1789)と『自然の彷徨』(Époques de la nature, 1778)には、地球の完全な唯物論的起源に関する理論や、種の固定性を疑問視する彼の考えがよく練られており、非常に大きな影響力を持った。 [もう一人のフランスの哲学者であるドゥニ・ディドロもまた、生物は自然発生によって最初に生じたかもしれず、種は常に、試行錯誤に基づいて新しい形態が 生じ、生き残るか生き残らないかという絶え間ない実験のプロセスを通じて変化していると書いている。 [1767年から1792年にかけて、モンボッド卿ジェームズ・バーネットは、人間が霊長類の子孫であるという概念だけでなく、環境に対応して、生物は長 い時間をかけてその特性を変化させる方法を発見したという概念も著作に含めている。 [チャールズ・ダーウィンの祖父であるエラスマス・ダーウィンは『動物誌』(1794-1796年)を出版し、「すべての温血動物は1本の生きた糸から発 生した」と示唆した。 |

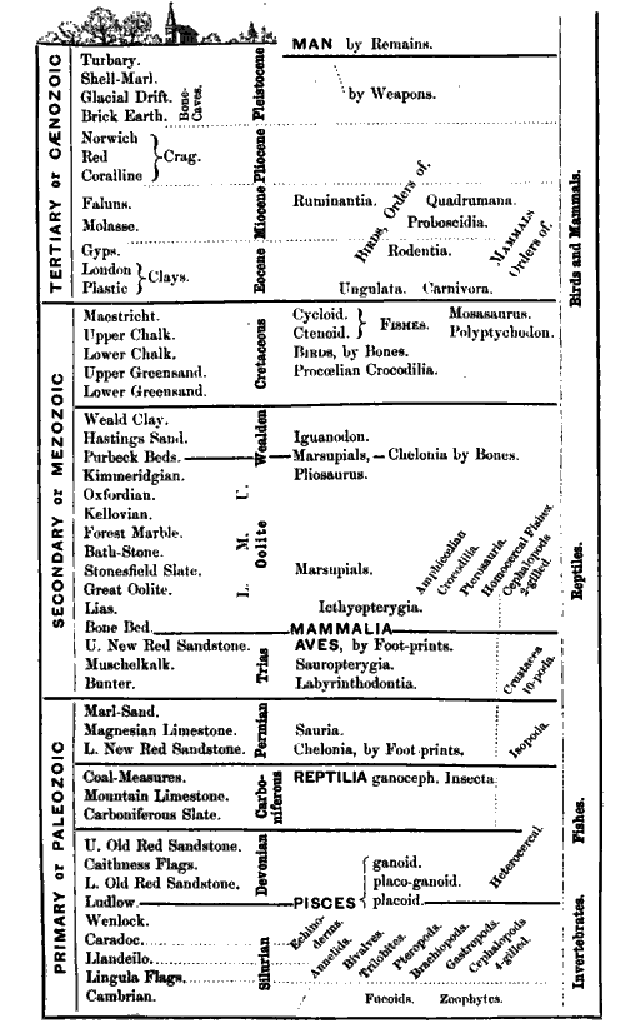

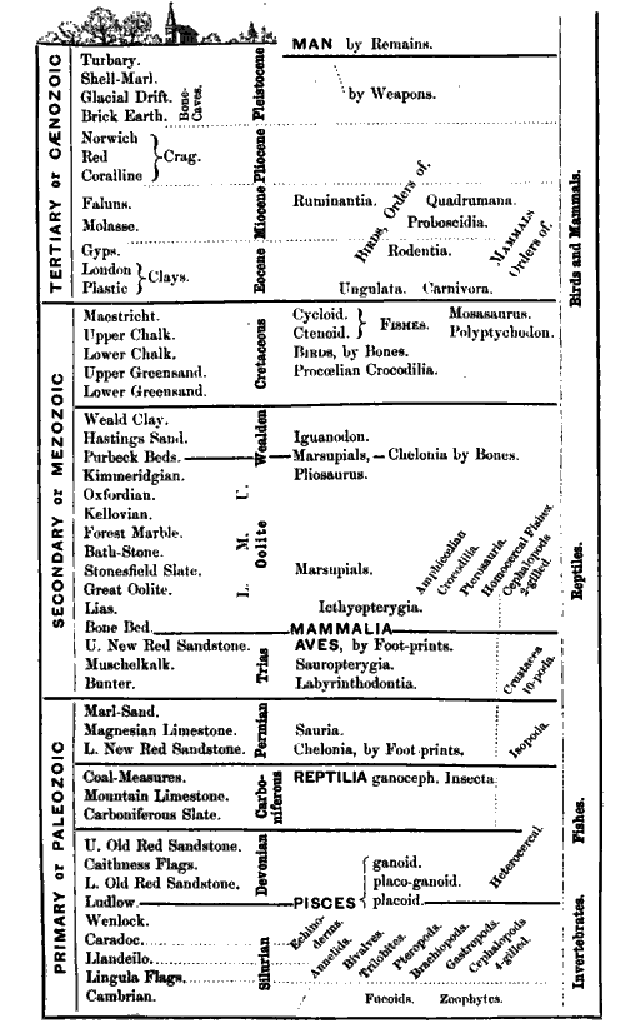

Early 19th century Richard Owen's 1861 geological timescale from Palæontology, showing the appearance of major animal types[61] Paleontology and geology See also: History of paleontology In 1796, Georges Cuvier published his findings on the differences between living elephants and those found in the fossil record. His analysis identified mammoths and mastodons as distinct species, different from any living animal, and effectively ended a long-running debate over whether a species could become extinct.[62] In 1788, James Hutton described gradual geological processes operating continuously over deep time.[63] In the 1790s, William Smith began the process of ordering rock strata by examining fossils in the layers while he worked on his geologic map of England. Independently, in 1811, Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart published an influential study of the geologic history of the region around Paris, based on the stratigraphic succession of rock layers. These works helped establish the antiquity of the Earth.[64] Cuvier advocated catastrophism to explain the patterns of extinction and faunal succession revealed by the fossil record. Knowledge of the fossil record continued to advance rapidly during the first few decades of the 19th century. By the 1840s, the outlines of the geologic timescale were becoming clear, and in 1841 John Phillips named three major eras, based on the predominant fauna of each: the Paleozoic, dominated by marine invertebrates and fish, the Mesozoic, the age of reptiles, and the current Cenozoic age of mammals. This progressive picture of the history of life was accepted even by conservative English geologists like Adam Sedgwick and William Buckland; however, like Cuvier, they attributed the progression to repeated catastrophic episodes of extinction followed by new episodes of creation.[65] Unlike Cuvier, Buckland and some other advocates of natural theology among British geologists made efforts to explicitly link the last catastrophic episode proposed by Cuvier to the biblical flood.[66][67] From 1830 to 1833, geologist Charles Lyell published his multi-volume work Principles of Geology, which, building on Hutton's ideas, advocated a uniformitarian alternative to the catastrophic theory of geology. Lyell claimed that, rather than being the products of cataclysmic (and possibly supernatural) events, the geologic features of the Earth are better explained as the result of the same gradual geologic forces observable in the present day—but acting over immensely long periods of time. Although Lyell opposed evolutionary ideas (even questioning the consensus that the fossil record demonstrates a true progression), his concept that the Earth was shaped by forces working gradually over an extended period, and the immense age of the Earth assumed by his theories, would strongly influence future evolutionary thinkers such as Charles Darwin.[68] |

19世紀初頭 リチャード・オーウェンが1861年に発表した『Palæontology』の地質学的タイムスケール。 古生物学と地質学 こちらも参照のこと: 古生物学の歴史 1796年、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエ(Georges Cuvier)は、生きているゾウと化石に見られるゾウの異なる点について研究結果を発表した。1788年、ジェームズ・ハットンは、深い時間の中で継続 的に作用する漸進的な地質学的プロセスについて記述した[63]。 1790年代、ウィリアム・スミスは、イギリスの地質図を作成する傍ら、地層中の化石を調べることによって、岩層を順序付けるプロセスを開始した。それと は別に、1811年、キュヴィエとアレクサンドル・ブロンニャールは、岩層の層序的連続に基づくパリ周辺の地域の地質学的歴史に関する影響力のある研究を 発表した。キュヴィエは、化石の記録によって明らかになった絶滅のパターンや動物種の遷移を説明するために、破局主義を提唱した[64]。 化石の記録に関する知識は、19世紀の最初の数十年間、急速に進歩し続けた。1840年代には、地質学的なタイムスケールの輪郭が明らかになりつつあり、 1841年にはジョン・フィリップスが、海洋無脊椎動物と魚類が支配的な古生代、爬虫類の時代である中生代、そして現在の哺乳類の時代である新生代という 3つの主要な時代を、それぞれの主要な動物相に基づいて命名した。しかし、キュヴィエと同様に、彼らはその進行を度重なる絶滅の破局的エピソードと、それ に続く新たな創造のエピソードに帰結させた[65]。キュヴィエとは異なり、バックランドやイギリスの地質学者の中の自然神学の提唱者たちは、キュヴィエ が提唱した最後の破局的エピソードを聖書の洪水と明確に結びつける努力をした[66][67]。 1830年から1833年にかけて、地質学者チャールズ・ライエルは、ハットンの考えを基礎として、地質学の破局説に代わる一様主義的な考え方を提唱した 『地質学の原理』を出版した。ライエルは、地球の地質学的特徴は、激変的な(そしておそらくは超自然的な)出来事の産物であるよりも、むしろ、現在観察で きるのと同じ緩やかな地質学的力の結果として説明するのが適切であると主張した。ライエルは進化論的な考え方に反対していたが(化石の記録が真の進歩を示 しているというコンセンサスにさえ疑問を呈していた)、地球が長期間にわたって徐々に働く力によって形作られたという彼の概念と、彼の理論が想定する地球 の膨大な年齢は、チャールズ・ダーウィンなどの将来の進化論的思想家に強い影響を与えることになった[68]。 |

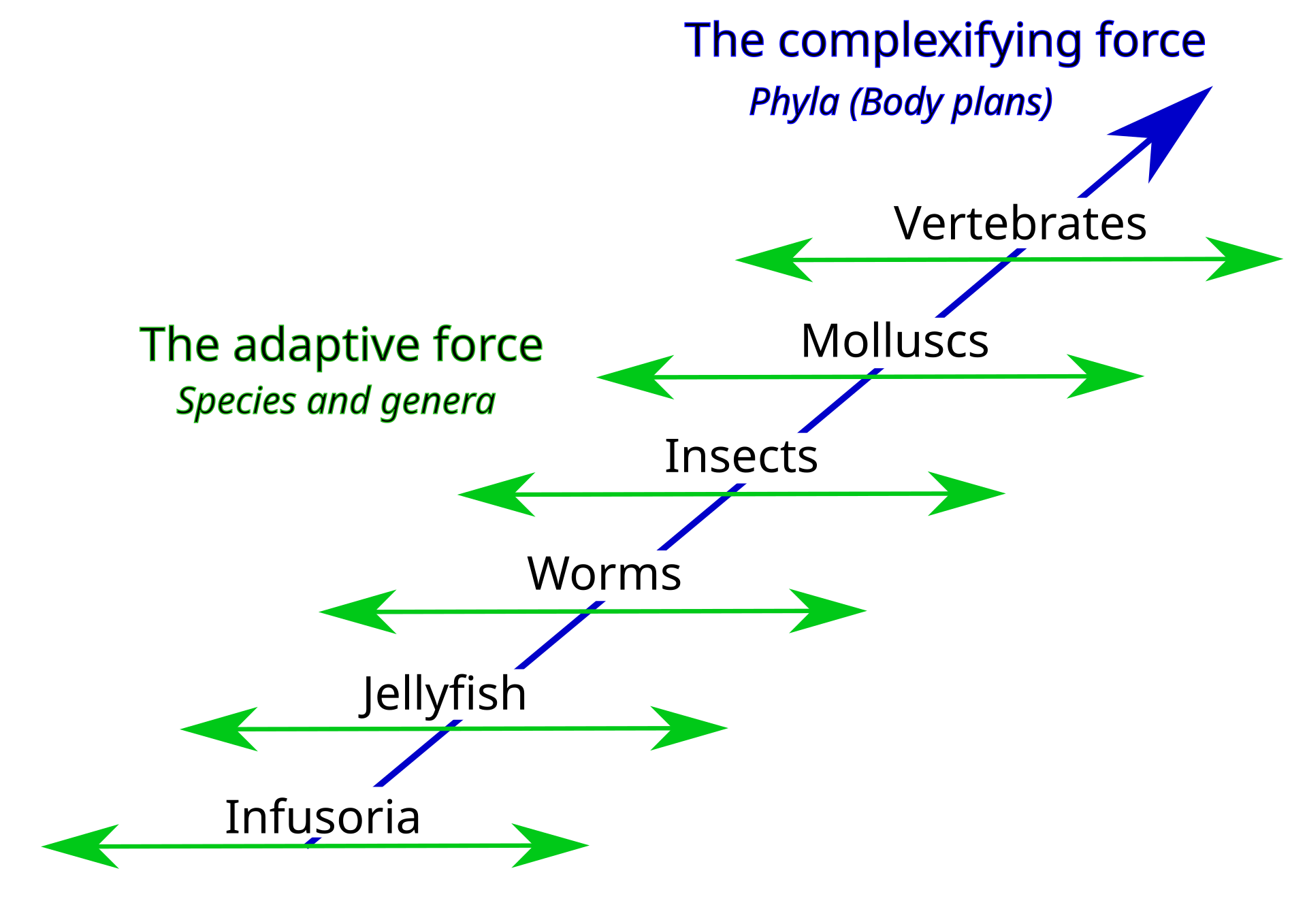

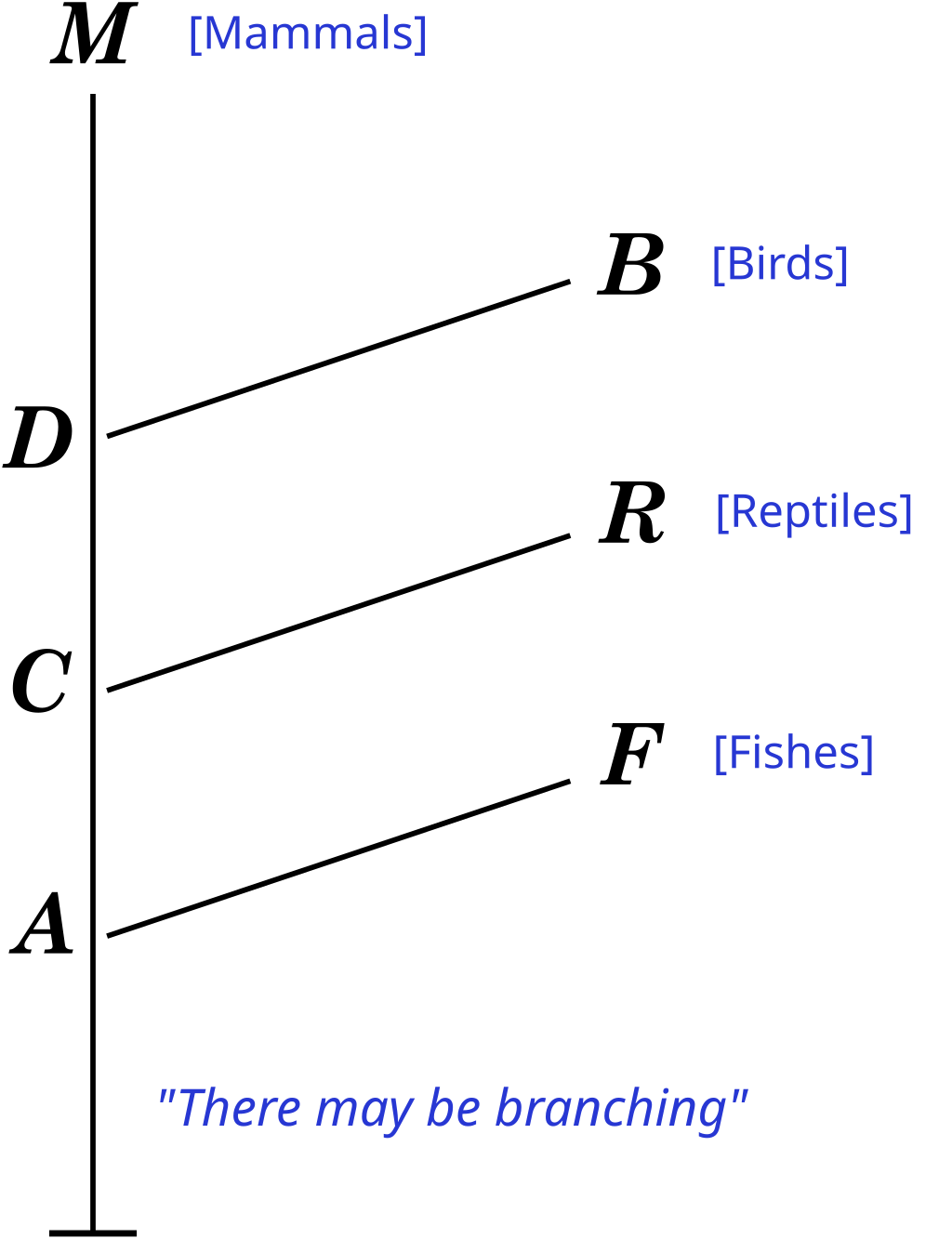

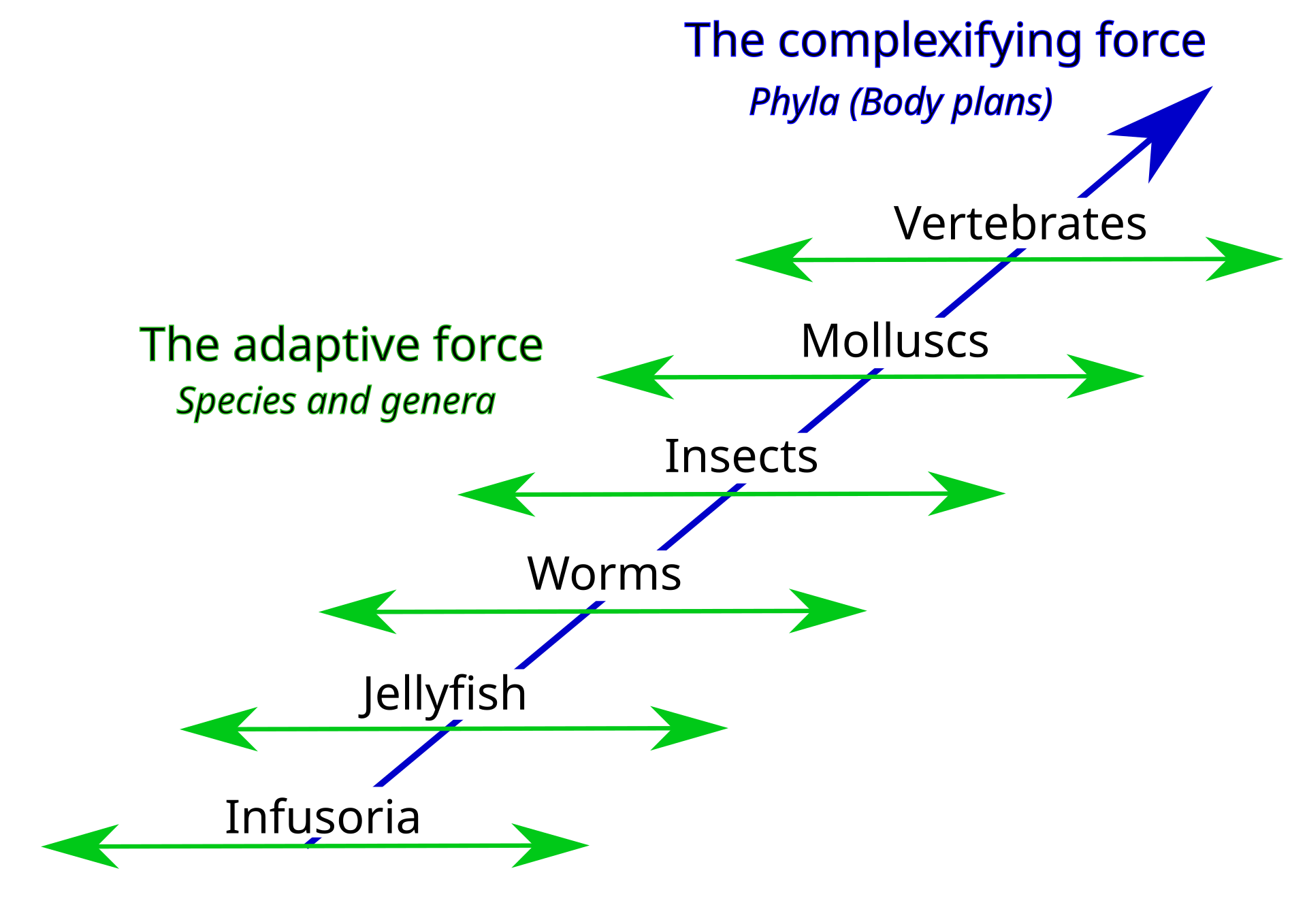

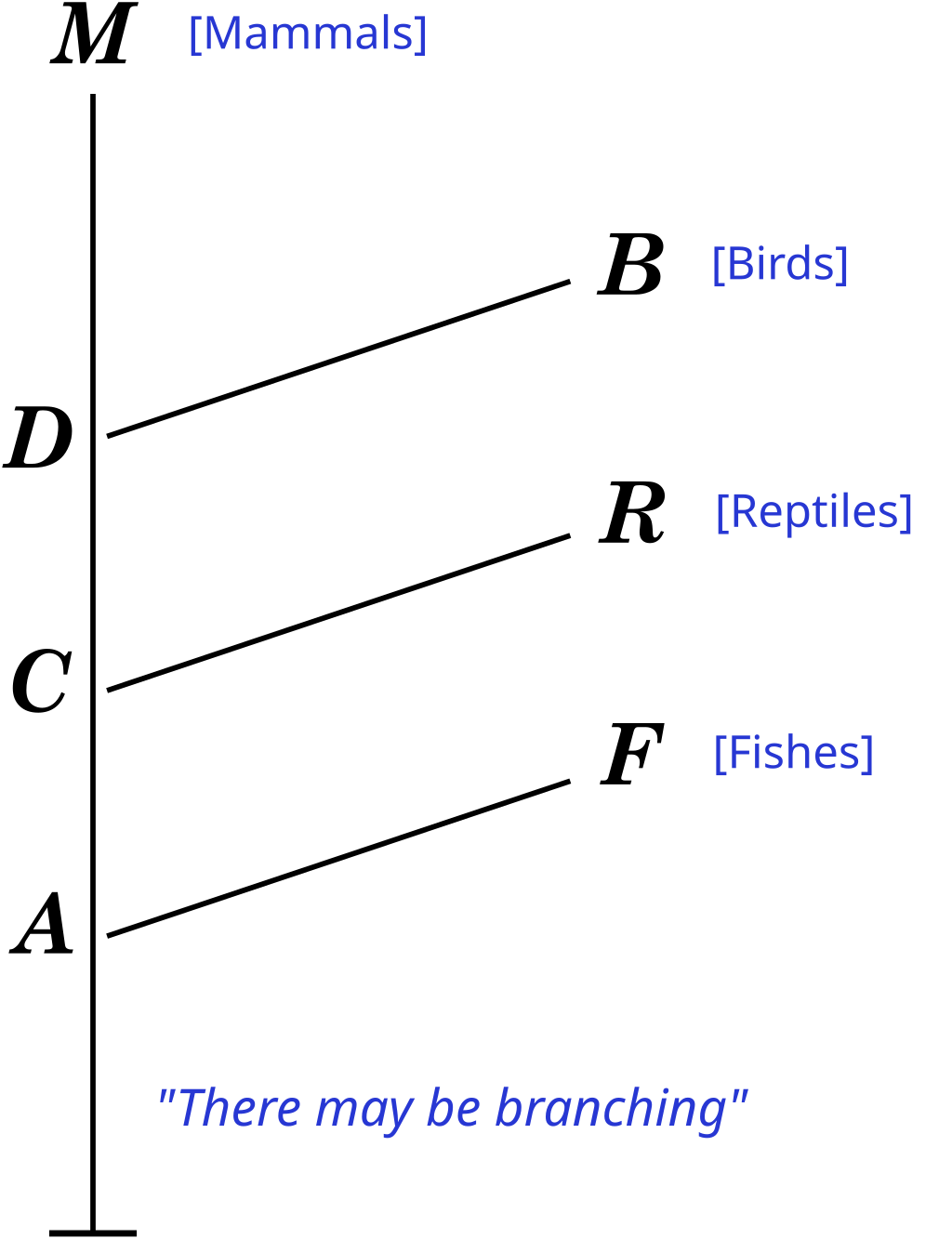

| Transmutation of species Main article: Transmutation of species  Lamarck's two-factor theory involves a complexifying force driving animal body plans towards higher levels (orthogenesis) creating a ladder of phyla, and an adaptive force causing animals with a given body plan to adapt to circumstances (use and disuse, inheritance of acquired characteristics), creating a diversity of species and genera.[69] Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed, in his Philosophie zoologique of 1809, a theory of the transmutation of species (transformisme). Lamarck did not believe that all living things shared a common ancestor but rather that simple forms of life were created continuously by spontaneous generation. He also believed that an innate life force drove species to become more complex over time, advancing up a linear ladder of complexity that was related to the great chain of being. Lamarck recognized that species adapted to their environment. He explained this by saying that the same innate force driving increasing complexity caused the organs of an animal (or a plant) to change based on the use or disuse of those organs, just as exercise affects muscles. He argued that these changes would be inherited by the next generation and produce slow adaptation to the environment. It was this secondary mechanism of adaptation through the inheritance of acquired characteristics that would become known as Lamarckism and would influence discussions of evolution into the 20th century.[70][71] A radical British school of comparative anatomy that included the anatomist Robert Edmond Grant was closely in touch with Lamarck's French school of Transformationism. One of the French scientists who influenced Grant was the anatomist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, whose ideas on the unity of various animal body plans and the homology of certain anatomical structures would be widely influential and lead to intense debate with his colleague Georges Cuvier. Grant became an authority on the anatomy and reproduction of marine invertebrates. He developed Lamarck's and Erasmus Darwin's ideas of transmutation and evolutionism, and investigated homology, even proposing that plants and animals had a common evolutionary starting point. As a young student, Charles Darwin joined Grant in investigations of the life cycle of marine animals. In 1826, an anonymous paper, probably written by Robert Jameson, praised Lamarck for explaining how higher animals had "evolved" from the simplest worms; this was the first use of the word "evolved" in a modern sense.[72][73]  Robert Chambers's Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844) shows fishes (F), reptiles (R), and birds (B) branching from a path leading to mammals (M). |

種の変容 主な記事 種の転換  ラマルクの二要因説には、動物の身体計画をより高いレベルへと駆り立てる複雑化する力(正統発生)と、与えられた身体計画を持つ動物を状況に適応させる適応力(使用と不使用、後天的特徴の継承)が含まれ、種と属の多様性を生み出している[69]。 ジャン=バティスト・ラマルクは1809年の『動物哲学』(Philosophie zoologique)の中で、種の転変(transformisme)の理論を提唱した。ラマルクは、すべての生物が共通の祖先を共有しているとは考え ず、むしろ単純な形態の生命が自然発生によって連続的に生み出されていると考えていた。彼はまた、生得的な生命力が種を時間の経過とともに複雑化させ、存 在の大いなる連鎖に関連する複雑さの直線的な階段を上っていくと考えた。ラマルクは、種が環境に適応することを認識していた。ラマルクは、複雑さを増大さ せる同じ生得的な力が、ちょうど運動が筋肉に影響を与えるように、動物(または植物)の器官を、その器官の使用または不使用に基づいて変化させると述べ て、これを説明した。彼は、このような変化は次の世代に受け継がれ、環境への適応を遅らせることになると主張した。ラマルク主義として知られるようにな り、20世紀まで進化についての議論に影響を与えることになったのは、後天的に獲得された特性の遺伝による適応のこの二次的なメカニズムであった[70] [71]。 解剖学者のロバート・エドモンド・グラントを含む急進的なイギリスの比較解剖学派は、ラマルクのフランスの変容論学派と密接に連絡を取り合っていた。グラ ントに影響を与えたフランス人科学者のひとりが解剖学者エティエンヌ・ジェフロワ・サン・ヒレールで、さまざまな動物の体型の統一性や特定の解剖学的構造 の相同性に関する彼の考えは広く影響を与え、同僚のジョルジュ・キュヴィエとの激しい論争に発展した。グラントは海産無脊椎動物の解剖学と繁殖学の権威と なった。彼はラマルクとエラスムス・ダーウィンの転変と進化論の考えを発展させ、相同性を研究し、植物と動物には共通の進化の出発点があるとさえ提唱し た。若い学生だったチャールズ・ダーウィンは、グラントとともに海産動物の生活環を調査した。1826年、おそらくロバート・ジェイムソンによって書かれ たと思われる匿名の論文は、高等動物が最も単純なミミズからどのように「進化」したかを説明したラマルクを賞賛した。  ロバート・チェンバースの『天地創造の自然史の名残』(1844年)には、哺乳類(M)につながる道から魚類(F)、爬虫類(R)、鳥類(B)が枝分かれしている様子が描かれている。 |

| In

1844, the Scottish publisher Robert Chambers anonymously published an

extremely controversial but widely read book entitled Vestiges of the

Natural History of Creation. This book proposed an evolutionary

scenario for the origins of the Solar System and of life on Earth. It

claimed that the fossil record showed a progressive ascent of animals,

with current animals branching off a main line that leads progressively

to humanity. It implied that the transmutations lead to the unfolding

of a preordained plan that had been woven into the laws that governed

the universe. In this sense it was less completely materialistic than

the ideas of radicals like Grant, but its implication that humans were

only the last step in the ascent of animal life incensed many

conservative thinkers. The high profile of the public debate over

Vestiges, with its depiction of evolution as a progressive process,

would greatly influence the perception of Darwin's theory a decade

later.[74][75] Ideas about the transmutation of species were associated with the radical materialism of the Enlightenment and were attacked by more conservative thinkers. Cuvier attacked the ideas of Lamarck and Geoffroy, agreeing with Aristotle that species were immutable. Cuvier believed that the individual parts of an animal were too closely correlated with one another to allow for one part of the anatomy to change in isolation from the others, and argued that the fossil record showed patterns of catastrophic extinctions followed by repopulation, rather than gradual change over time. He also noted that drawings of animals and animal mummies from Egypt, which were thousands of years old, showed no signs of change when compared with modern animals. The strength of Cuvier's arguments and his scientific reputation helped keep transmutational ideas out of the mainstream for decades.[76]  Richard Owen's 1848 diagram shows his conceptual archetype for all vertebrates.[77] In Great Britain, the philosophy of natural theology remained influential. William Paley's 1802 book Natural Theology with its famous watchmaker analogy had been written at least in part as a response to the transmutational ideas of Erasmus Darwin.[78] Geologists influenced by natural theology, such as Buckland and Sedgwick, made a regular practice of attacking the evolutionary ideas of Lamarck, Grant, and Vestiges.[79][80] Although Charles Lyell opposed scriptural geology, he also believed in the immutability of species, and in his Principles of Geology, he criticized Lamarck's theories of development.[68] Idealists such as Louis Agassiz and Richard Owen believed that each species was fixed and unchangeable because it represented an idea in the mind of the creator. They believed that relationships between species could be discerned from developmental patterns in embryology, as well as in the fossil record, but that these relationships represented an underlying pattern of divine thought, with progressive creation leading to increasing complexity and culminating in humanity. Owen developed the idea of "archetypes" in the Divine mind that would produce a sequence of species related by anatomical homologies, such as vertebrate limbs. Owen led a public campaign that successfully marginalized Grant in the scientific community. Darwin would make good use of the homologies analyzed by Owen in his own theory, but the harsh treatment of Grant, and the controversy surrounding Vestiges, showed him the need to ensure that his own ideas were scientifically sound.[73][81][82] |

1844年、スコットランドの出版

社ロバート・チェンバースは、匿名で『天地創造の自然史』と題する極めて物議を醸す、しかし広く読まれた本を出版した。この本は、太陽系と地球上の生命の

起源について、進化論的なシナリオを提唱した。化石の記録は動物の漸進的な上昇を示し、現在の動物はその本線から枝分かれして人類に至ると主張した。その

転生が、宇宙を支配する法則の中に織り込まれた、あらかじめ定められた計画の展開につながることを暗示していた。この意味では、グラントのような急進主義

者の考えほど完全な唯物論的ではなかったが、人間は動物生命の上昇の最後のステップに過ぎないという暗示は、多くの保守的な思想家を激怒させた。進化を漸

進的な過程として描いた『遺物』をめぐる公開討論の注目度の高さは、10年後のダーウィンの理論に対する認識に大きな影響を与えることになる[74]

[75]。 種の転生に関する考えは啓蒙主義の急進的な唯物論と結びついており、より保守的な思想家たちによって攻撃された。キュヴィエはラマルクとジョフロワの考え を攻撃し、種は不変であるというアリストテレスに同意した。キュヴィエは、動物の各部位は互いに密接に関連しており、解剖学の一部分が他の部分から切り離 されて変化することはあり得ないと考え、化石の記録は、時間の経過とともに徐々に変化するのではなく、破滅的な絶滅の後に再繁殖するというパターンを示し ていると主張した。彼はまた、数千年前のエジプトの動物の絵や動物のミイラが、現代の動物と比較して変化の兆候を示さないことにも言及した。キュヴィエの 主張の強さと彼の科学的名声は、数十年にわたり転生説を主流から遠ざけるのに役立った[76]。  リチャード・オーウェンが1848年に発表した図は、すべての脊椎動物に対する彼の概念的な原型を示している[77]。 イギリスでは、自然神学の哲学が影響力を持ち続けていた。バックランドやセジウィックのような自然神学の影響を受けた地質学者は、ラマルク、グラント、 ヴェスティゲスの進化論を攻撃することを常としていた。 [チャールズ・ライエルは聖典に基づく地質学に反対していたが、種の不変性も信じており、『地質学原理』の中でラマルクの発生理論を批判していた [68]。ルイ・アガシズやリチャード・オーウェンのような理想主義者は、それぞれの種は創造主の心の中にある考えを表しているため、固定され不変である と信じていた。彼らは、種間の関係は発生学や化石の記録における発生パターンから見分けることができると信じていたが、これらの関係は神の思想の根本的な パターンを表しており、漸進的な創造が複雑さを増し、人類に至ると考えていた。オウエンは、脊椎動物の四肢のような解剖学的相同性によって関連する一連の 種を生み出す神の心の「原型」という考えを発展させた。オウエンは公的なキャンペーンを展開し、グラントを科学界から境界づけることに成功した。ダーウィ ンはオウエンが分析した相同性を自身の理論にうまく利用することになるが、グラントへの厳しい仕打ちと『遺物』をめぐる論争によって、自身の考えが科学的 に健全であることを確認する必要性を示した[73][81][82]。 |

| Anticipations of natural selection It is possible to look through the history of biology from the ancient Greeks onwards and discover anticipations of almost all of Charles Darwin's key ideas. As an example, Loren Eiseley has found isolated passages written by Buffon suggesting he was almost ready to piece together a theory of natural selection, but states that such anticipations should not be taken out of the full context of the writings or of cultural values of the time which made Darwinian ideas of evolution unthinkable.[83] When Darwin was developing his theory, he investigated selective breeding and was impressed[84] by John Sebright's observation that "A severe winter, or a scarcity of food, by destroying the weak and the unhealthy, has all the good effects of the most skilful selection" so that "the weak and the unhealthy do not live to propagate their infirmities."[85] Darwin was influenced by Charles Lyell's ideas of environmental change causing ecological shifts, leading to what Augustin de Candolle had called a war between competing plant species, competition well described by the botanist William Herbert. Darwin was struck by Thomas Robert Malthus' phrase "struggle for existence" used of warring human tribes.[86][87] Several writers anticipated evolutionary aspects of Darwin's theory, and in the third edition of On the Origin of Species published in 1861 Darwin named those he knew about in an introductory appendix, An Historical Sketch of the Recent Progress of Opinion on the Origin of Species, which he expanded in later editions.[88] In 1813, William Charles Wells read before the Royal Society essays assuming that there had been evolution of humans, and recognising the principle of natural selection. Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace were unaware of this work when they jointly published the theory in 1858, but Darwin later acknowledged that Wells had recognised the principle before them, writing that the paper "An Account of a White Female, part of whose Skin resembles that of a Negro" was published in 1818, and "he distinctly recognises the principle of natural selection, and this is the first recognition which has been indicated; but he applies it only to the races of man, and to certain characters alone."[89] Patrick Matthew wrote in his book On Naval Timber and Arboriculture (1831) of "continual balancing of life to circumstance. ... [The] progeny of the same parents, under great differences of circumstance, might, in several generations, even become distinct species, incapable of co-reproduction."[90] Darwin implies that he discovered this work after the initial publication of the Origin. In the brief historical sketch that Darwin included in the third edition he says "Unfortunately the view was given by Mr. Matthew very briefly in scattered passages in an Appendix to a work on a different subject ... He clearly saw, however, the full force of the principle of natural selection."[91] However, as historian of science Peter J. Bowler says, "Through a combination of bold theorizing and comprehensive evaluation, Darwin came up with a concept of evolution that was unique for the time." Bowler goes on to say that simple priority alone is not enough to secure a place in the history of science; someone has to develop an idea and convince others of its importance to have a real impact.[92] Thomas Henry Huxley said in his essay on the reception of On the Origin of Species: The suggestion that new species may result from the selective action of external conditions upon the variations from their specific type which individuals present—and which we call "spontaneous," because we are ignorant of their causation—is as wholly unknown to the historian of scientific ideas as it was to biological specialists before 1858. But that suggestion is the central idea of the 'Origin of Species,' and contains the quintessence of Darwinism.[93] |

自然淘汰の先取り 古代ギリシャ以降の生物学の歴史を紐解くと、チャールズ・ダーウィンの重要なアイデアのほとんどすべてを先取りしていることがわかる。その一例として、 ローレン・エイスリーは、ビュフォンが自然淘汰の理論を構築する準備がほぼ整っていたことを示唆する、ビュフォンが書いた孤立した文章を発見したが、その ような先取りは、著作の文脈や、進化に関するダーウィンの考えを考えられなかった当時の文化的価値観から完全に取り外すべきではないと述べている [83]。 ダーウィンが自分の理論を発展させていたとき、彼は選択的繁殖を調査し、ジョン・セブライトの「厳しい冬や食料不足は、弱者や不健康な者を滅ぼすことに よって、最も巧みな淘汰のすべての良い効果をもたらす」という観察に感銘を受けた[84]。 「ダーウィンは、オーギュスタン・ド・カンドルが競争する植物種間の戦争と呼んでいたような、植物学者ウィリアム・ハーバートがよく描写していた競争をも たらす、環境変化が生態系シフトを引き起こすというチャールズ・ライエルの考えに影響を受けた。ダーウィンはトマス・ロバート・マルサスの「生存のための 闘争」という言葉に衝撃を受けた。 1861年に出版された『種の起源』の第3版では、ダーウィンは序章の付録である「種の起源に関する意見の最近の進歩の歴史的概略」の中で、彼が知っているそれらの作家の名前を挙げており、その後の版ではさらにその名前を増やしている[88]。 1813年、ウィリアム・チャールズ・ウェルズは王立協会で、人間の進化があったと仮定し、自然淘汰の原理を認める小論を読んだ。ダーウィンとアルフレッ ド・ラッセル・ウォレスは1858年に共同で理論を発表したとき、この著作を知らなかったが、ダーウィンは後にウェルズが彼らよりも先に原理を認識してい たことを認め、「彼は自然淘汰の原理を明確に認識しており、これは示された最初の認識である。 パトリック・マシューはその著書『海軍の木材と樹木栽培について』(1831年)の中で、「生命は絶えず状況に釣り合っている。... [同じ両親の子孫であっても、環境の大きな相違のもとでは、数世代のうちに、共同繁殖が不可能な別個の種になることさえある」[90]。ダーウィンは第3 版に盛り込まれた簡単な歴史的スケッチの中で、「残念なことに、この見解はマシュー氏によって、別の主題に関する著作の付録の中で、非常に短い文章で散見 されるだけであった......」と述べている。しかし、彼は明らかに自然淘汰の原理を完全に見抜いていた」[91]。 しかし、科学史家のピーター・J・ボウラーが言うように、「大胆な理論化と包括的な評価の組み合わせによって、ダーウィンは当時としてはユニークな進化の 概念を考え出した」。ボウラーはさらに、単純な優先順位だけでは科学史に名を残すには不十分であり、誰かがアイデアを発展させ、その重要性を他の人々に納 得させなければ、本当のインパクトを与えることはできないと述べている[92]。トマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは『種の起源』の受容に関するエッセイの中 で次のように述べている: 新しい種が、個体が持つ特定の型からの変異に外的条件が選択的に作用することによって生じるかもしれないという示唆は、1858年以前の生物学の専門家に とってそうであったように、科学思想史家にとってもまったく未知のものである。しかし、この提案は『種の起源』の中心的な考え方であり、ダーウィニズムの 真髄を含んでいる[93]。 |

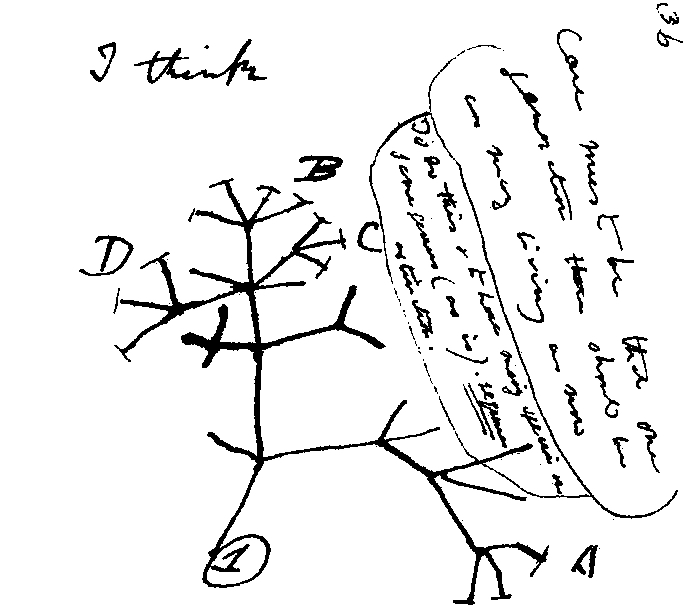

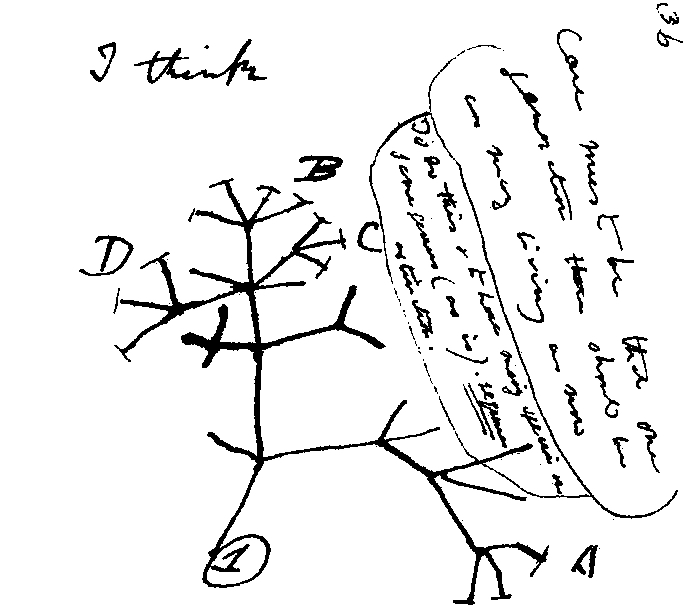

in articles: Inception of Darwin's theory, Development of Darwin's theory, Publication of Darwin's theory, and Natural selection Charles Darwin's first sketch of an evolutionary tree from his "B" notebook on the transmutation of species (1837–1838) The biogeographical patterns Charles Darwin observed in places such as the Galápagos Islands during the second voyage of HMS Beagle caused him to doubt the fixity of species, and in 1837 Darwin started the first of a series of secret notebooks on transmutation. Darwin's observations led him to view transmutation as a process of divergence and branching, rather than the ladder-like progression envisioned by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and others. In 1838 he read the new sixth edition of An Essay on the Principle of Population, written in the late 18th century by Thomas Robert Malthus. Malthus' idea of population growth leading to a struggle for survival combined with Darwin's knowledge on how breeders selected traits, led to the inception of Darwin's theory of natural selection. Darwin did not publish his ideas on evolution for 20 years. However, he did share them with certain other naturalists and friends, starting with Joseph Dalton Hooker, with whom he discussed his unpublished 1844 essay on natural selection. During this period he used the time he could spare from his other scientific work to slowly refine his ideas and, aware of the intense controversy around transmutation, amass evidence to support them. In September 1854 he began full-time work on writing his book on natural selection.[82][94][95] Unlike Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, influenced by the book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, already suspected that transmutation of species occurred when he began his career as a naturalist. By 1855, his biogeographical observations during his field work in South America and the Malay Archipelago made him confident enough in a branching pattern of evolution to publish a paper stating that every species originated in close proximity to an already existing closely allied species. Like Darwin, it was Wallace's consideration of how the ideas of Malthus might apply to animal populations that led him to conclusions very similar to those reached by Darwin about the role of natural selection. In February 1858, Wallace, unaware of Darwin's unpublished ideas, composed his thoughts into an essay and mailed them to Darwin, asking for his opinion. The result was the joint publication in July of an extract from Darwin's 1844 essay along with Wallace's letter. Darwin also began work on a short abstract summarising his theory, which he would publish in 1859 as On the Origin of Species.[96] |

記事の中で ダーウィンの理論の始まり、ダーウィンの理論の発展、ダーウィンの理論の発表、自然淘汰。 チャールズ・ダーウィンが初めて描いた進化系統樹のスケッチ(種の変遷に関するノート「B」、1837-1838年)。 チャールズ・ダーウィンは、HMSビーグル号の第2回航海中にガラパゴス諸島などで観察した生物地理学的パターンから、種の固定性に疑問を抱くようにな り、1837年、ダーウィンは種の転変に関する一連の秘密ノートの最初のものを書き始めた。ダーウィンの観察により、彼は転変を、ジャン=バティスト・ラ マルクや他の人々が思い描いた梯子のような進行ではなく、分岐と分岐のプロセスとして捉えるようになった。1838年、彼はトマス・ロバート・マルサスに よって18世紀後半に書かれた『人口原理に関する試論』の第6版を読んだ。人口の増加が生存競争につながるというマルサスの考えと、育種家がどのように形 質を選択するかというダーウィンの知識が結びつき、ダーウィンの自然選択説が生まれた。ダーウィンは進化に関する自分の考えを20年間発表しなかった。し かし、ジョセフ・ダルトン・フッカー(Joseph Dalton Hooker)を始めとする他の博物学者や友人たちとは、自然淘汰に関する未発表の1844年の小論について語り合った。この間、彼は他の科学的な仕事の 合間を縫って、自分の考えを少しずつ洗練させ、転成をめぐる激しい論争を意識しながら、それを裏付ける証拠を集めていった。1854年9月、彼は自然淘汰 に関する著書の執筆を本格的に開始した[82][94][95]。 ダーウィンとは異なり、アルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは『天地創造の自然史』の影響を受け、博物学者としてのキャリアをスタートさせたとき、すでに種 の転変が起こることを疑っていた。1855年までには、南米とマレー諸島でのフィールドワークでの生物地理学的観察によって、彼は進化の分岐パターンに十 分な確信を持ち、すべての種はすでに存在する近縁種に近接して発生したとする論文を発表した。ダーウィンと同様、ウォレスがマルサスの考えを動物個体群に どのように適用できるかを考えた結果、自然淘汰の役割についてダーウィンが到達した結論と非常に似た結論に達した。1858年2月、ウォレスはダーウィン の未発表の考えを知らず、自分の考えをエッセイにまとめ、ダーウィンに郵送して意見を求めた。その結果、7月にダーウィンの1844年のエッセイからの抜 粋とウォーレスの手紙が共同で出版された。ダーウィンはまた、1859年に『種の起源』として出版することになる、彼の理論を要約した短い抄録の作成に取 り掛かった[96]。 |

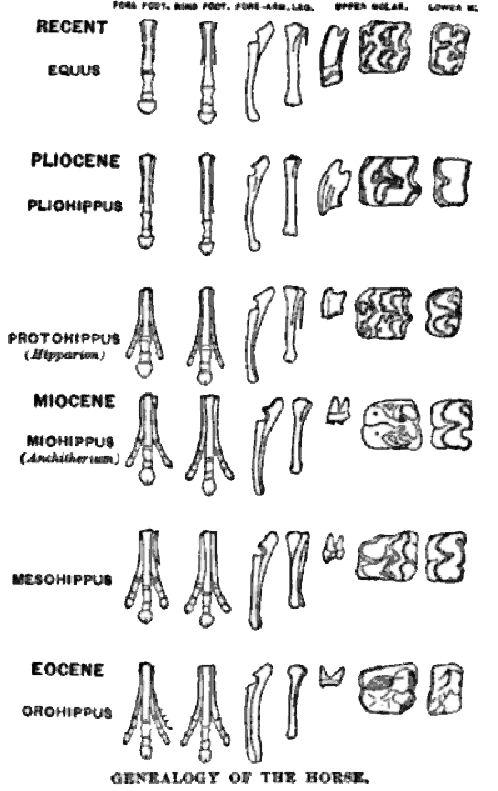

| 1859–1930s: Darwin and his legacy See also: Reactions to On the Origin of Species  Othniel Charles Marsh's diagram of the evolution of horse feet and teeth over time as reproduced in Thomas Henry Huxley's Prof. Huxley in America (1876).[97] By the 1850s, whether or not species evolved was a subject of intense debate, with prominent scientists arguing both sides of the issue.[98] The publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species fundamentally transformed the discussion over biological origins.[99] Darwin argued that his branching version of evolution explained a wealth of facts in biogeography, anatomy, embryology, and other fields of biology. He also provided the first cogent mechanism by which evolutionary change could persist: his theory of natural selection.[100] One of the first and most important naturalists to be convinced by Origin of the reality of evolution was the British anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley. Huxley recognized that unlike the earlier transmutational ideas of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, Darwin's theory provided a mechanism for evolution without supernatural involvement, even if Huxley himself was not completely convinced that natural selection was the key evolutionary mechanism. Huxley would make advocacy of evolution a cornerstone of the program of the X Club to reform and professionalise science by displacing natural theology with naturalism and to end the domination of British natural science by the clergy. By the early 1870s in English-speaking countries, thanks partly to these efforts, evolution had become the mainstream scientific explanation for the origin of species.[100] In his campaign for public and scientific acceptance of Darwin's theory, Huxley made extensive use of new evidence for evolution from paleontology. This included evidence that birds had evolved from reptiles, including the discovery of Archaeopteryx in Europe, and a number of fossils of primitive birds with teeth found in North America. Another important line of evidence was the finding of fossils that helped trace the evolution of the horse from its small five-toed ancestors.[101] However, acceptance of evolution among scientists in non-English speaking nations such as France, and the countries of southern Europe and Latin America was slower. An exception to this was Germany, where both August Weismann and Ernst Haeckel championed this idea: Haeckel used evolution to challenge the established tradition of metaphysical idealism in German biology, much as Huxley used it to challenge natural theology in Britain.[102] Haeckel and other German scientists would take the lead in launching an ambitious programme to reconstruct the evolutionary history of life based on morphology and embryology.[103] Darwin's theory succeeded in profoundly altering scientific opinion regarding the development of life and in producing a small philosophical revolution.[104] However, this theory could not explain several critical components of the evolutionary process. Specifically, Darwin was unable to explain the source of variation in traits within a species, and could not identify a mechanism that could pass traits faithfully from one generation to the next. Darwin's hypothesis of pangenesis, while relying in part on the inheritance of acquired characteristics, proved to be useful for statistical models of evolution that were developed by his cousin Francis Galton and the "biometric" school of evolutionary thought. However, this idea proved to be of little use to other biologists.[105] |

1859-1930s: ダーウィンとその遺産 以下も参照のこと: 種の起源』に対する反応  トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーの『Prof. Huxley in America』(1876年)に掲載された、オトニエル・チャールズ・マーシュによる馬の足と歯の経時的進化の図。 チャールズ・ダーウィンの『種の起源』の出版は、生物学的起源をめぐる議論を根本的に変えた[99]。ダーウィンは、生物地理学、解剖学、発生学、その他 の生物学の分野における豊富な事実を、彼の進化論の枝分かれバージョンで説明できると主張した。彼はまた、進化的変化が持続しうる最初の説得力のあるメカ ニズム、すなわち自然選択説を提供した[100]。 オリジンによって進化の現実性を確信した最初の、そして最も重要な博物学者の一人は、イギリスの解剖学者トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーであった。ハクス リーは、ジャン=バティスト・ラマルクや『天地創造の自然史』(Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation)によるそれ以前の転生的な考えとは異なり、ダーウィンの理論は、自然淘汰が重要な進化のメカニズムであるとハクスリー自身が完全に確信 していなかったとしても、超自然的な関与なしに進化のメカニズムを提供するものであると認識していた。ハクスリーは、自然神学を自然主義に置き換えること によって科学を改革し、専門化し、聖職者によるイギリスの自然科学の支配を終わらせるというXクラブのプログラムの要として、進化論の提唱を行うことにな る。このような努力もあって、英語圏では1870年代初頭までに、進化論は種の起源に関する科学的説明の主流となった[100]。ハクスリーは、ダーウィ ンの理論を一般大衆と科学者に受け入れてもらうためのキャンペーンにおいて、古生物学から得られた進化の新たな証拠を幅広く利用した。その中には、ヨー ロッパで発見された始祖鳥や、北アメリカで発見された歯のある原始的な鳥の化石など、鳥類が爬虫類から進化したという証拠も含まれていた。もうひとつの重 要な証拠は、5本指の小さな祖先から馬が進化したことを示す化石の発見であった[101]。しかし、フランスや南ヨーロッパ、ラテンアメリカの国々など、 英語を話さない国民の科学者の間で進化が受け入れられるのは遅かった。例外はドイツで、アウグスト・ヴァイスマンとエルンスト・ヘッケルの2人がこの考え を支持した。ヘッケルは、ハクスリーがイギリスで自然神学に挑戦するために進化論を用いたように、ドイツの生物学で確立された形而上学的観念論の伝統に挑 戦するために進化論を用いた[102]。 ヘッケルをはじめとするドイツの科学者たちは、形態学と発生学に基づいて生命の進化の歴史を再構築する野心的な計画を率先して開始することになる。 ダーウィンの理論は、生命の発生に関する科学的見解を大きく変えることに成功し、小さな哲学的革命をもたらした[104]。しかしこの理論は、進化の過程 のいくつかの重要な要素を説明することができなかった。具体的には、ダーウィンは種内の形質の変異の原因を説明することができず、形質をある世代から次の 世代へと忠実に受け継がせることができるメカニズムを特定することができなかった。ダーウィンのパンゲネシスの仮説は、部分的には後天的特徴の遺伝に依存 していたが、従兄弟のフランシス・ガルトンと進化思想の「バイオメトリック」学派によって開発された進化の統計モデルには有用であることが判明した。しか し、この考えは他の生物学者にとってはほとんど役に立たないことが判明した[105]。 |

Application to humans This illustration (the root of The March of Progress[106]) was the frontispiece of Thomas Henry Huxley's book Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (1863). Huxley applied Darwin's ideas to humans, using comparative anatomy to show that humans and apes had a common ancestor, which challenged the theologically important idea that humans held a unique place in the universe.[107] Charles Darwin was aware of the severe reaction in some parts of the scientific community against the suggestion made in Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation that humans had arisen from animals by a process of transmutation. Therefore, he almost completely ignored the topic of human evolution in On the Origin of Species. Despite this precaution, the issue featured prominently in the debate that followed the book's publication. For most of the first half of the 19th century, the scientific community believed that, although geology had shown that the Earth and life were very old, human beings had appeared suddenly just a few thousand years before the present. However, a series of archaeological discoveries in the 1840s and 1850s showed stone tools associated with the remains of extinct animals. By the early 1860s, as summarized in Charles Lyell's 1863 book Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, it had become widely accepted that humans had existed during a prehistoric period—which stretched many thousands of years before the start of written history. This view of human history was more compatible with an evolutionary origin for humanity than was the older view. On the other hand, at that time there was no fossil evidence to demonstrate human evolution. The only human fossils found before the discovery of Java Man in the 1890s were either of anatomically modern humans or of Neanderthals that were too close, especially in the critical characteristic of cranial capacity, to modern humans for them to be convincing intermediates between humans and other primates.[108] Therefore, the debate that immediately followed the publication of On the Origin of Species centered on the similarities and differences between humans and modern apes. Carolus Linnaeus had been criticised in the 18th century for grouping humans and apes together as primates in his ground breaking classification system.[109] Richard Owen vigorously defended the classification suggested by Georges Cuvier and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach that placed humans in a separate order from any of the other mammals, which by the early 19th century had become the orthodox view. On the other hand, Thomas Henry Huxley sought to demonstrate a close anatomical relationship between humans and apes. In one famous incident, which became known as the Great Hippocampus Question, Huxley showed that Owen was mistaken in claiming that the brains of gorillas lacked a structure present in human brains. Huxley summarized his argument in his highly influential 1863 book Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature. Another viewpoint was advocated by Lyell and Alfred Russel Wallace. They agreed that humans shared a common ancestor with apes, but questioned whether any purely materialistic mechanism could account for all the differences between humans and apes, especially some aspects of the human mind.[108] In 1871, Darwin published The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, which contained his views on human evolution. Darwin argued that the differences between the human mind and the minds of the higher animals were a matter of degree rather than of kind. For example, he viewed morality as a natural outgrowth of instincts that were beneficial to animals living in social groups. He argued that all the differences between humans and apes were explained by a combination of the selective pressures that came from our ancestors moving from the trees to the plains, and sexual selection. The debate over human origins, and over the degree of human uniqueness continued well into the 20th century.[108] |

人間への適用 このイラスト(『進撃(=進歩前進)の巨人』[106]のルーツ)は、トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーの著書『Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature』(1863年)の扉絵である。ハクスリーはダーウィンの考えを人間に適用し、比較解剖学を使って人間と類人猿が共通の祖先を持っていること を示し、人間が宇宙の中で独自の位置を占めているという神学的に重要な考えに挑戦した[107]。 チャールズ・ダーウィンは、『天地創造の自然史』の中で示唆された、人間が動物から転成の過程によって発生したという考えに対して、科学界の一部で厳しい 反応があることを知っていた。そのため、『種の起源』ではヒトの進化に関する話題をほとんど無視した。このような予防措置にもかかわらず、『種の起源』出 版後の論争では、この問題が大きく取り上げられた。19世紀前半のほとんどの期間、科学界は、地質学的に地球と生命は非常に古いものであることが示されて いたにもかかわらず、人類は現在のほんの数千年前に突然出現したと信じていた。しかし、1840年代から1850年代にかけて考古学的な発見が相次ぎ、絶 滅した動物の遺骸に関連する石器が発見された。1860年代初頭までに、チャールズ・ライエルが1863年に出版した『Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man(人類の古代に関する地質学的証拠)』に要約されているように、人類は文字による歴史が始まる何千年も前の先史時代に存在していたことが広く認めら れるようになった。このような人類の歴史観は、旧来の見解に比べ、人類の進化的起源との整合性が高かった。一方、当時は人類の進化を証明する化石の証拠は なかった。1890年代にジャワ人が発見される以前に発見された唯一の人類の化石は、解剖学的に現生人類か、現生人類に近すぎるネアンデルタール人のもの であり、特に頭蓋の容量という重要な特徴において、人類と他の霊長類との中間種であることを納得させるものではなかった[108]。 それゆえ、『種の起源』の出版直後の論争の中心は、ヒトと現代の類人猿との類似点と相違点にあった。リチャード・オーウェンは、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエと ヨハン・フリードリッヒ・ブルーメンバッハが提案した、ヒトを他の哺乳類とは別の目に分類する分類を強力に擁護し、19世紀初頭にはこれが正統的な見解と なった。一方、トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは、ヒトと類人猿の間に解剖学的に密接な関係があることを証明しようとした。大海馬問題」として知られるよ うになったある有名な事件で、ハクスリーはオーウェンがゴリラの脳にはヒトの脳に存在する構造が欠けていると主張したのは誤りであることを示した。ハクス リーは、1863年に出版した『Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature(自然界における人間の地位に関する証拠)』で、彼の主張をまとめ、大きな影響力を持った。もう一つの視点は、ライエルとアルフレッド・ラッ セル・ウォレスによって提唱された。彼らは、ヒトが類人猿と共通の祖先を共有していることには同意したが、純粋に唯物論的なメカニズムがヒトと類人猿のす べての違い、特にヒトの心のいくつかの側面を説明することができるかどうかには疑問を呈した[108]。 1871年、ダーウィンは『人間の下降』(The Descent of Man)と『性による選択』(Selection in Relation to Sex)を出版した。ダーウィンは、人間の心と高等動物の心の違いは、種類よりもむしろ程度の問題であると主張した。例えば、ダーウィンは道徳を、社会的 集団の中で生きる動物にとって有益な本能から自然に生まれたものだと考えた。彼は、ヒトと類人猿の異なる点はすべて、祖先が樹上から平原に移動したことに よる選択圧と、性淘汰の組み合わせによって説明できると主張した。人間の起源をめぐる議論、そして人間の独自性の程度をめぐる議論は、20世紀まで続いた [108]。 |

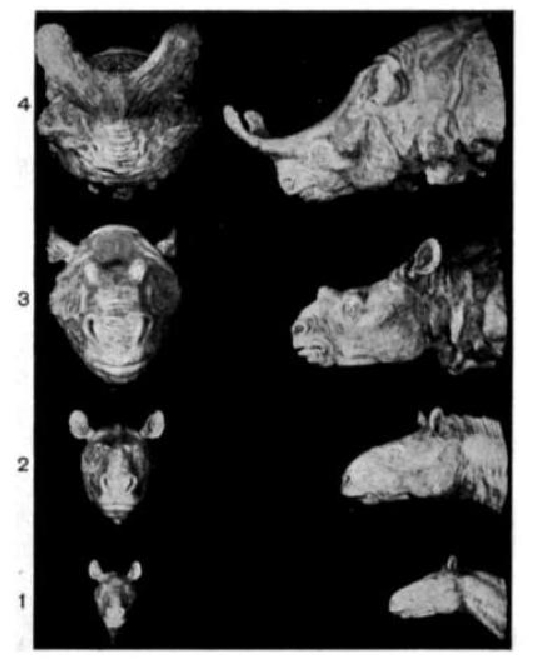

| Alternatives to natural selection Main articles: Alternatives to evolution by natural selection and The eclipse of Darwinism  This photo from Henry Fairfield Osborn's 1917 book Origin and Evolution of Life shows models depicting the evolution of Titanothere horns over time, which Osborn claimed was an example of an orthogenetic trend in evolution.[110] The concept of evolution was widely accepted in scientific circles within a few years of the publication of Origin, but the acceptance of natural selection as its driving mechanism was much less widespread. The four major alternatives to natural selection in the late 19th century were theistic evolution, neo-Lamarckism, orthogenesis, and saltationism. Alternatives supported by biologists at other times included structuralism, Georges Cuvier's teleological but non-evolutionary functionalism, and vitalism. Theistic evolution was the idea that God intervened in the process of evolution, to guide it in such a way that the living world could still be considered to be designed. The term was promoted by Charles Darwin's greatest American advocate Asa Gray. However, this idea gradually fell out of favor among scientists, as they became more and more committed to the idea of methodological naturalism and came to believe that direct appeals to supernatural involvement were scientifically unproductive. By 1900, theistic evolution had largely disappeared from professional scientific discussions, although it retained a strong popular following.[111][112] In the late 19th century, the term neo-Lamarckism came to be associated with the position of naturalists who viewed the inheritance of acquired characteristics as the most important evolutionary mechanism. Advocates of this position included the British writer and Darwin critic Samuel Butler, the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, and the American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope. They considered Lamarckism to be philosophically superior to Darwin's idea of selection acting on random variation. Cope looked for, and thought he found, patterns of linear progression in the fossil record. Inheritance of acquired characteristics was part of Haeckel's recapitulation theory of evolution, which held that the embryological development of an organism repeats its evolutionary history.[111][112] Critics of neo-Lamarckism, such as the German biologist August Weismann and Alfred Russel Wallace, pointed out that no one had ever produced solid evidence for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Despite these criticisms, neo-Lamarckism remained the most popular alternative to natural selection at the end of the 19th century, and would remain the position of some naturalists well into the 20th century.[111][112] Orthogenesis was the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, in a unilinear fashion, towards ever-greater perfection. It had a significant following in the 19th century, and its proponents included the Russian biologist Leo S. Berg and the American paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn. Orthogenesis was popular among some paleontologists, who believed that the fossil record showed a gradual and constant unidirectional change. Saltationism was the idea that new species arise as a result of large mutations. It was seen as a much faster alternative to the Darwinian concept of a gradual process of small random variations being acted on by natural selection, and was popular with early geneticists such as Hugo de Vries, William Bateson, and early in his career, Thomas Hunt Morgan. It became the basis of the mutation theory of evolution.[111][112] |

自然淘汰に代わるもの 主な記事 自然淘汰による進化の代替案とダーウィニズムの蝕み  1917年に出版されたヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンの著書『Origin and Evolution of Life(生命の起源と進化)』に掲載されたこの写真は、タイタンホエールの角の経時的な進化を描いた模型であり、オズボーンは進化の正統的傾向の一例で あると主張している[110]。 進化の概念は、『起源』の出版から数年のうちに科学界に広く受け入れられたが、その原動力としての自然淘汰の受容はそれほど広がらなかった。19世紀後半 における自然淘汰に対する4つの主要な代替案は、有神論的進化論、新ラマルキズム、正統進化論、塩類化論であった。それ以外の時代に生物学者によって支持 されていた選択肢には、構造主義、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエの目的論的だが進化論的ではない機能主義、生命論などがあった。 神論的進化論とは、神が進化の過程に介入し、生物界が設計されたものであると考えられるように進化を導いたという考え方である。この言葉は、チャールズ・ ダーウィンの最大の擁護者であったアメリカのエイサ・グレイによって広められた。しかし、方法論的自然主義の考え方に傾倒し、超自然的な関与を直接訴える ことは科学的に非生産的であると考えるようになったため、この考えは科学者の間で次第に支持されなくなった。1900年までに、有神論的進化論は専門的な 科学的議論からはほとんど姿を消したが、強い大衆的支持を保っていた[111][112]。 19世紀後半には、ネオ・ラマルキズムという用語は、後天的特徴の遺伝を最も重要な進化のメカニズムであるとみなす自然主義者の立場と結び付けられるよう になった。この立場を提唱したのは、イギリスの作家でダーウィン評論家のサミュエル・バトラー、ドイツの生物学者エルンスト・ヘッケル、アメリカの古生物 学者エドワード・ドリンカー・コープなどである。彼らはラマルク主義が、ランダムな変異に淘汰が作用するというダーウィンの考えよりも哲学的に優れている と考えた。コープは、化石の記録から直線的な進化のパターンを探し、それを見つけたと考えた。後天性の特徴の継承は、ヘッケルの進化の再現理論の一部であ り、生物の発生学的な発達は進化の歴史を繰り返すとした[111][112]。ドイツの生物学者アウグスト・ヴァイスマンやアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォ レスなどの新ラマルキズムの批判者は、後天性の特徴の継承について確かな証拠を提示した者はいないと指摘した。このような批判にもかかわらず、ネオ・ラマ ルク主義は19世紀末において自然淘汰に対する最も人気のある代替案であり続け、20世紀に入っても一部の自然主義者の立場であった[111] [112]。 正生論は、生命はより完全なものへと向かって一直線に変化する傾向を生得的に持っているという仮説であった。19世紀にはかなりの支持者がおり、その支持 者にはロシアの生物学者レオ・S・ベルクやアメリカの古生物学者ヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンなどがいた。正統進化論は一部の古生物学者の間で 流行し、彼らは化石の記録は漸進的で一定の一方向的な変化を示していると信じていた。 塩類進化論は、大きな突然変異の結果として新しい種が発生するという考え方である。小さなランダムな変異が自然淘汰によって作用する漸進的なプロセスとい うダーウィンの概念に代わる、より迅速な方法と見なされ、ヒューゴ・デ・フリース、ウィリアム・ベイトソン、そして彼のキャリアの初期にはトーマス・ハン ト・モーガンといった初期の遺伝学者に人気があった。それは進化の突然変異説の基礎となった[111][112]。 |

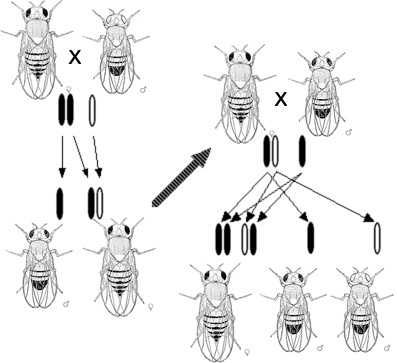

Mendelian genetics, biometrics, and mutation Diagram from Thomas Hunt Morgan's 1919 book The Physical Basis of Heredity, showing the sex-linked inheritance of the white-eyed mutation in Drosophila melanogaster. Main article: Mutationism The rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's laws of inheritance in 1900 ignited a fierce debate between two camps of biologists. In one camp were the Mendelians, who were focused on discrete variations and the laws of inheritance. They were led by William Bateson (who coined the word genetics) and Hugo de Vries (who coined the word mutation). Their opponents were the biometricians, who were interested in the continuous variation of characteristics within populations. Their leaders, Karl Pearson and Walter Frank Raphael Weldon, followed in the tradition of Francis Galton, who had focused on measurement and statistical analysis of variation within a population. The biometricians rejected Mendelian genetics on the basis that discrete units of heredity, such as genes, could not explain the continuous range of variation seen in real populations. Weldon's work with crabs and snails provided evidence that selection pressure from the environment could shift the range of variation in wild populations, but the Mendelians maintained that the variations measured by biometricians were too insignificant to account for the evolution of new species.[113][114] When Thomas Hunt Morgan began experimenting with breeding the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, he was a saltationist who hoped to demonstrate that a new species could be created in the lab by mutation alone. Instead, the work at his lab between 1910 and 1915 reconfirmed Mendelian genetics and provided solid experimental evidence linking it to chromosomal inheritance. His work also demonstrated that most mutations had relatively small effects, such as a change in eye color, and that rather than creating a new species in a single step, mutations served to increase variation within the existing population.[113][114] |