家がないとはどういうことか?

What do you think about Homelessness?

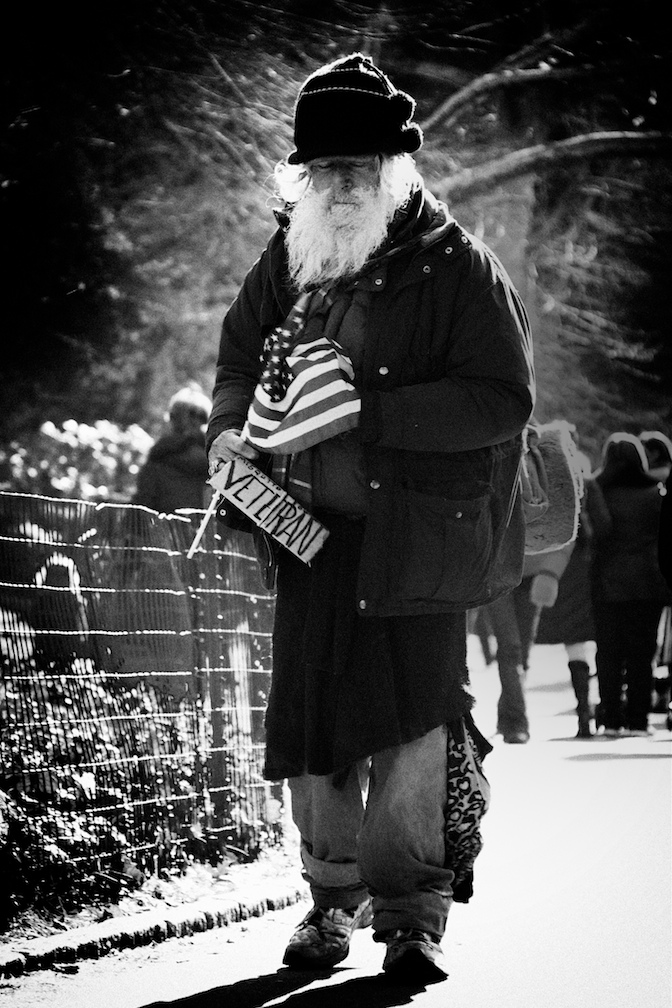

A

homeless man

in Paris

☆ ホームレス(Homelessness or houselessness)とは、安定した安全で機能的な住居を持たない状態のことである。この一般的なカテゴリーには、路上生活 者、家族や友人など一時的な宿泊施設を転々とする者、住居の保証がない寄宿舎に住む者、内紛のために居住地を離れ、国内で難民となった者など、さまざまな 状況が含まれる。 ホームレスの法的地位は地域によって異なる。米国政府のホームレス人口調査では、公共の場所や私的な場所であっても、人間の通常の寝床として設計されてい ない場所で寝泊まりする人々も含まれる。ホームレスと貧困は相互に関連している。ホームレスの数を数え、彼らのニーズを特定する方法論についてはコンセン サスが得られていないため、ほとんどの都市ではホームレスの推定人口しか把握されていない。 2005年には、世界で推定1億人がホームレスとなり、10億人(当時は6.5人に1人)が不法占拠者、難民、または一時的なシェルターで生活している。 旅する無宿者は、過去には浮浪者と呼ばれていた。Bumは、定住するホームレスの一般的な蔑称である。

★bum ; of poor quality or nature, not valid or deserved, not pleasant or enjoyable. - Merriam-Webster.

| Homelessness or

houselessness – also known as a state of being unhoused or

unsheltered

– is the condition of lacking stable, safe, and functional housing. The

general category includes disparate situations, such as living on the

streets, moving between temporary accommodation such as family or

friends, living in boarding houses with no security of tenure,[1] and

people who leave their domiciles because of civil conflict and are

refugees within their country. The legal status of homeless people varies from place to place.[2] United States government homeless enumeration studies[3][4] also include people who sleep in a public or private place, which is not designed for use as a regular sleeping accommodation for human beings.[5][6] Homelessness and poverty are interrelated.[1] There is no methodological consensus on counting homeless people and identifying their needs; therefore, in most cities, only estimated homeless populations are known.[7] In 2005, an estimated 100 million people worldwide were homeless, and as many as one billion people (one in 6.5 at the time) live as squatters, refugees, or in temporary shelters.[8][9][10] Unhoused persons who travel have been termed vagrants in the past; of those, persons looking for work are hobos, whereas those who don't are tramps. Bum is a general term of disparagement for a stationary homeless person. |

ホームレスとは、安定した安全で機能的な住居を持たない状態のことであ

る。この一般的なカテゴリーには、路上生活者、家族や友人など一時的な宿泊施設を転々とする者、住居の保証がない寄宿舎に住む者[1]、内紛のために居住

地を離れ、国内で難民となった者など、さまざまな状況が含まれる。 ホームレスの法的地位は地域によって異なる[2]。米国政府のホームレス人口調査[3][4]では、公共の場所や私的な場所であっても、人間の通常の寝床 として設計されていない場所で寝泊まりする人々も含まれる[5][6]。 ホームレスと貧困は相互に関連している[1]。ホームレスの数を数え、彼らのニーズを特定する方法論についてはコンセンサスが得られていないため、ほとん どの都市ではホームレスの推定人口しか把握されていない[7]。 2005年には、世界で推定1億人がホームレスとなり、10億人(当時は6.5人に1人)が不法占拠者、難民、または一時的なシェルターで生活している [8][9][10]。旅する無宿者は、過去には浮浪者と呼ばれていた。Bumは、定住するホームレスの一般的な蔑称である。 |

| United Nations definition In 2004, the United Nations sector of Economic and Social Affairs defined a homeless household as those households without a shelter that would fall within the scope of living quarters due to a lack of a steady income. The affected people carry their few possessions with them, sleeping in the streets, in doorways or on piers, or in another space, on a more or less random basis.[11] In 2009, at the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Conference of European Statisticians (CES), the Group of Experts on Population and Housing Censuses defined homelessness as: In its Recommendations for the Censuses of Population and Housing, the CES identifies homeless people under two broad groups: Primary homelessness (or rooflessness). This category includes persons living in the streets without a shelter that would fall within the scope of living quarters Secondary homelessness. This category may include persons with no place of usual residence who move frequently between various types of accommodations (including dwellings, shelters, and institutions for the homeless or other living quarters). This category includes persons living in private dwellings but reporting 'no usual address on their census form. The CES acknowledges that the above approach does not provide a full definition of the 'homeless'.[12] Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted 10 December 1948 by the UN General Assembly, contains this text regarding housing and quality of living: Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.[13] The ETHOS Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion was developed as a means of improving the understanding and measurement of homelessness in Europe, and to provide a common "language" for transnational exchanges on homelessness. The ETHOS approach says homelessness is a process (rather than a static phenomenon) that affects many vulnerable households at different points in their lives.[14] The typology was launched in 2005 and is used for different purposes: as a framework for debate,[15] for data collection purposes, policy purposes, monitoring purposes, and in the media. This typology is an open exercise that makes abstraction of existing legal definitions in the EU member states. It exists in 25 language versions, the translations being provided mainly by volunteer translators. Many countries and individuals do not consider housing as a human right. Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter addressed this issue in a 2017 interview, saying, "A lot of people don't look at housing as a human right, but it is." His view contrasts with many Americans who do not believe housing is a basic human right.[16] |

国連の定義 2004年、国連の経済社会問題部門は、ホームレス世帯を、安定した収入がないために、居住区に該当するようなシェルターを持たない世帯と定義した [11]。被災者はわずかな所持品を持ち歩き、多かれ少なかれ不規則に、路上や玄関、橋脚の上、あるいは別の空間で寝泊まりしている[11]。 2009年、国連欧州経済委員会の欧州統計家会議(CES)において、人口・住宅統計に関する専門家グループはホームレスを次のように定義した: 人口・住宅統計に関する勧告の中で、CESはホームレスの人々を2つのグループに分類している: 第一次ホームレス(または屋根なし)。このカテゴリーには、住居に該当するようなシェルターのない路上生活者が含まれる。 二次的ホームレス。このカテゴリーには、さまざまなタイプの宿泊施設(住居、シェルター、ホームレスのための施設、その他の居住施設を含む)を頻繁に行き 来する、通常の居住地を持たない人が含まれる。このカテゴリーには、民間の住居に住んでいるが、国勢調査用紙に「通常の住所がない」と報告した人も含まれ る。 CESは、上記のアプローチが「ホームレス」の完全な定義を提供するものではないことを認めている[12]。 1948年12月10日に国連総会で採択された世界人権宣言の第25条には、住居と生活の質に関して次のような記述がある: すべての人は、食糧、衣服、住居、医療及び必要な社会サービスを含め、自己及び家族の健康及び福祉に十分な生活水準を確保する権利、並びに失業、病気、障 害、寡婦、老齢その他自己の支配の及ばない状況において生計を維持することができない場合の保障を受ける権利を有する」[13]。 ETHOS Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion(ホームレスと住宅排除のETHOS類型論)は、ヨーロッパにおけるホームレスの理解と測定を改善し、ホームレスに関する国境を越えた 交流に共通の「言語」を提供する手段として開発された。ETHOSのアプローチでは、ホームレスとは(静的な現象ではなく)人生のさまざまな局面で多くの 脆弱な世帯に影響を与えるプロセスであるとしている[14]。 この類型論は2005年に発表され、議論の枠組みとして、データ収集目的、政策目的、モニタリング目的、メディア[15]など、さまざまな目的で利用され ている。この類型論は、EU加盟国における既存の法的定義を抽象化した、オープンな演習である。25の言語版があり、翻訳は主にボランティア翻訳者によっ て行われている。 多くの国や個人は、住宅を人権とみなしていない。ジミー・カーター元米大統領は2017年のインタビューでこの問題を取り上げ、「多くの人は住宅を人権と は見ていないが、人権である」と述べた。彼の見解は、住宅が基本的人権であると信じていない多くのアメリカ人とは対照的である[16]。 |

| Other terms Recent[when?] homeless enumeration survey documentation utilizes the term unsheltered homeless. The common colloquial term "street people" does not fully encompass all unsheltered people, in that many such persons do not spend their time in urban street environments. Many shun such locales, because homeless people in urban environments may face the risk of being robbed or assaulted. Some people convert unoccupied or abandoned buildings ("squatting"), or inhabit mountainous areas or, more often, lowland meadows, creek banks, and beaches.[17] Many jurisdictions have developed programs to provide short-term emergency shelter during particularly cold spells, often in churches or other institutional properties. These are referred to as warming centers, and are credited by their advocates as lifesaving.[18] |

その他の用語 最近[いつ?]のホームレス人口調査文書では、unsheltered homelessという用語が使われている。一般的に「路上生活者」と口語で呼ばれるホームレスの多くは、都市部の路上で過ごしているわけではない。都市 環境にいるホームレスの人々は、強盗や暴行に遭う危険性があるため、そのような場所を敬遠する人が多い。無人の建物や放棄された建物を改造したり(「スク ワット」)、山間部や、より頻繁には低地の草原、小川の堤防、海岸に居住する人もいる[17]。 多くの管轄区域では、特に寒い時期に短期間の緊急避難所を提供するプログラムを開発しており、多くの場合、教会やその他の施設の敷地内に設置されている。 これらはウォーミングセンターと呼ばれ、その擁護者たちは人命救助につながると信じている[18]。 |

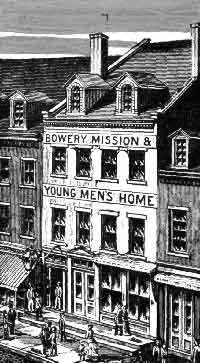

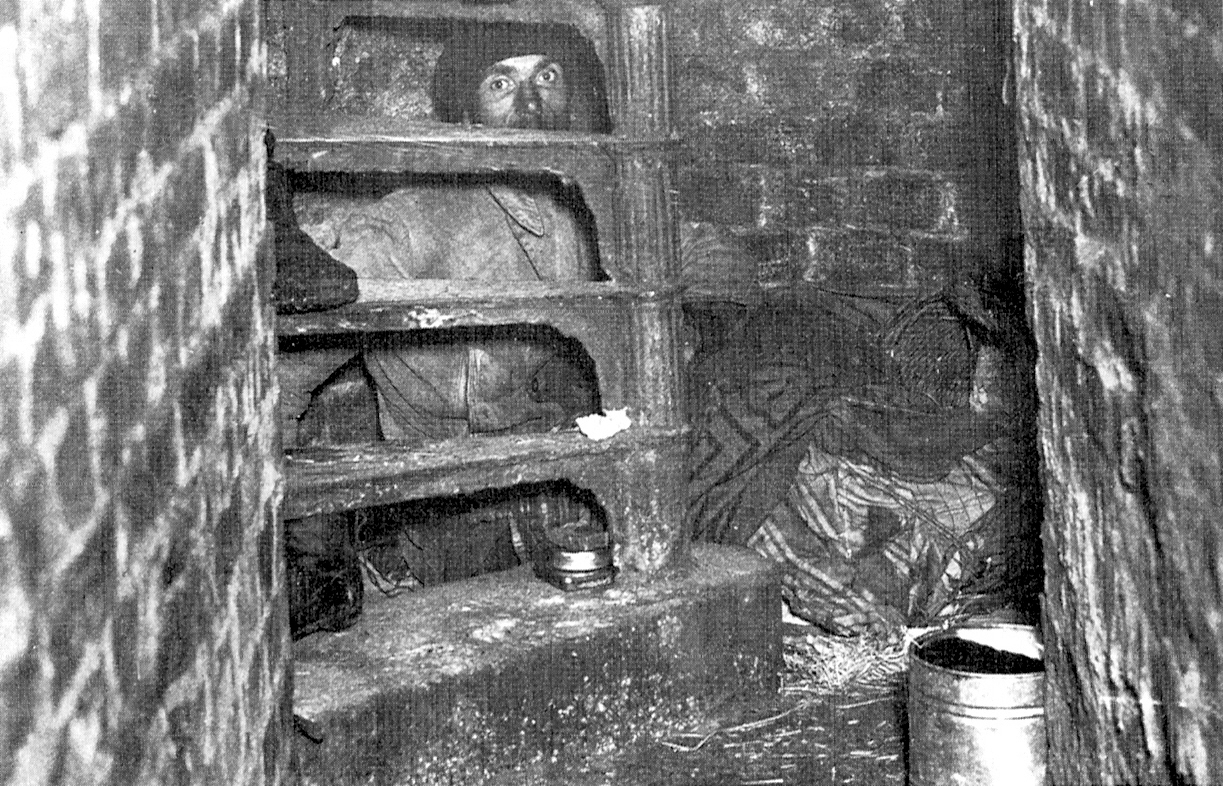

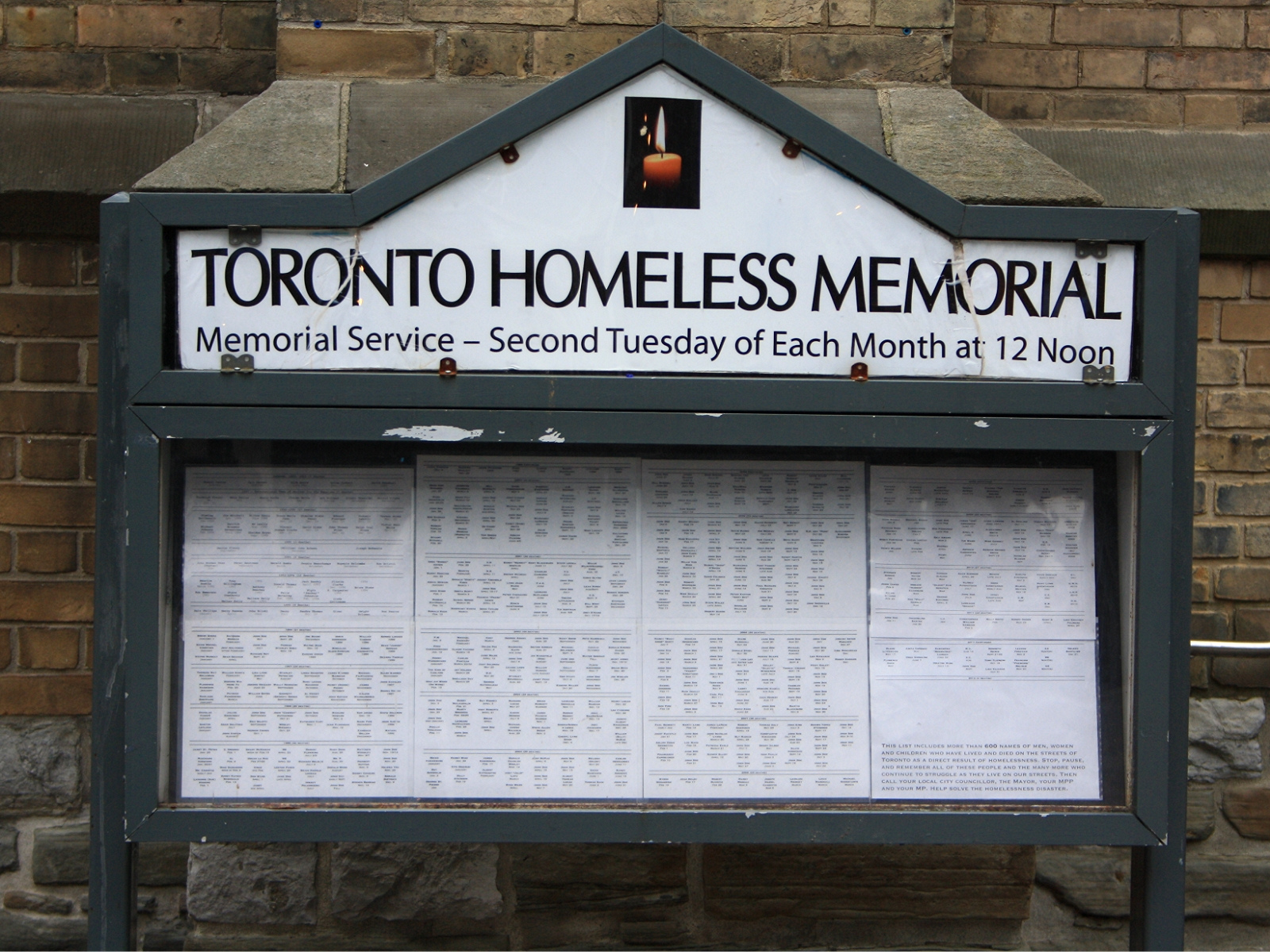

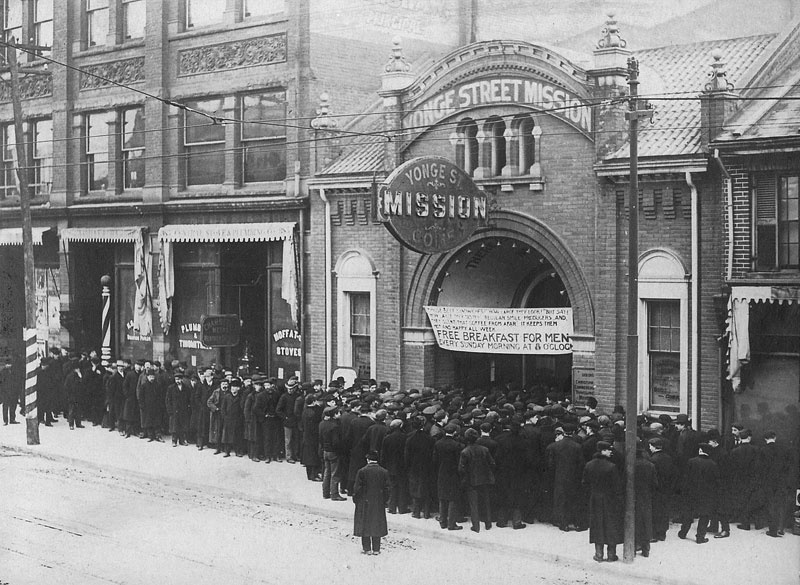

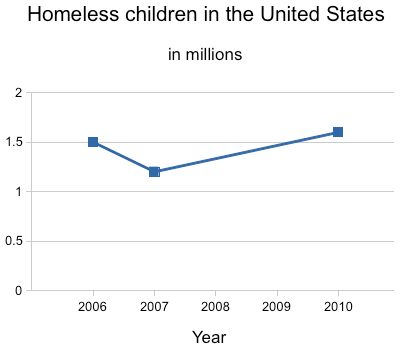

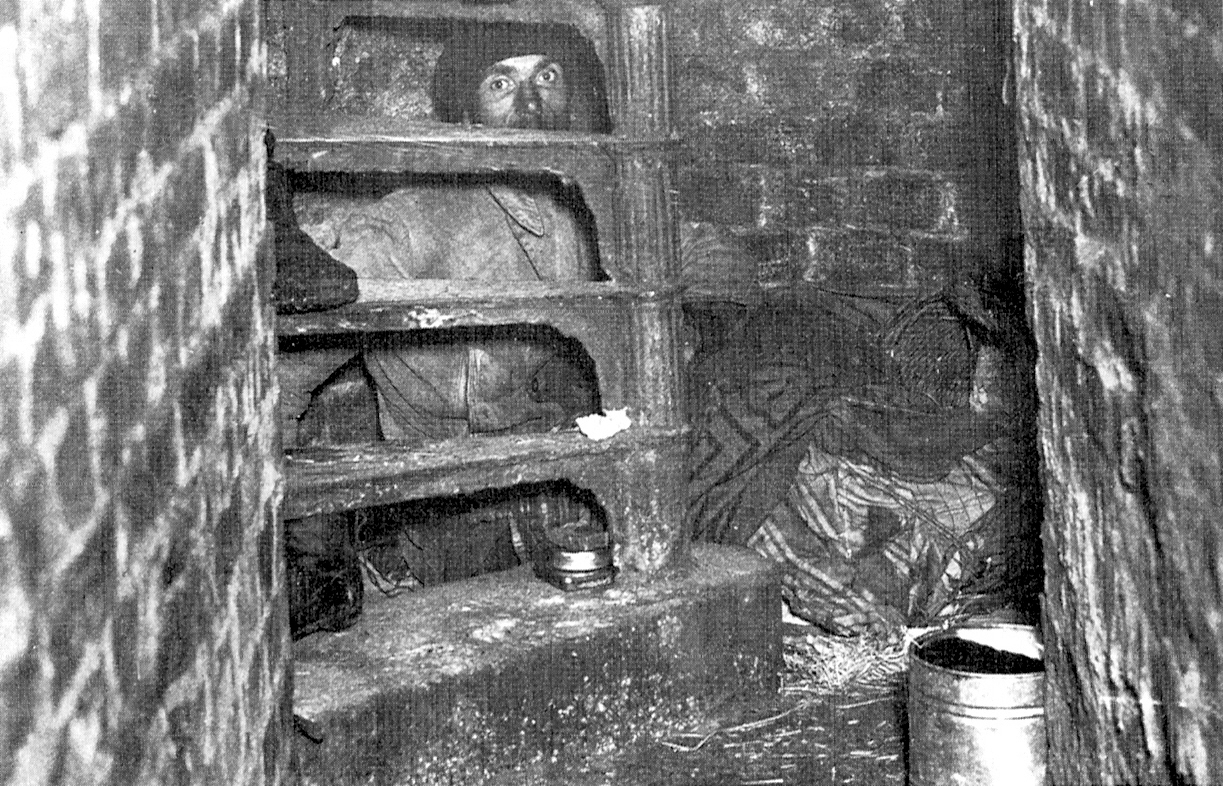

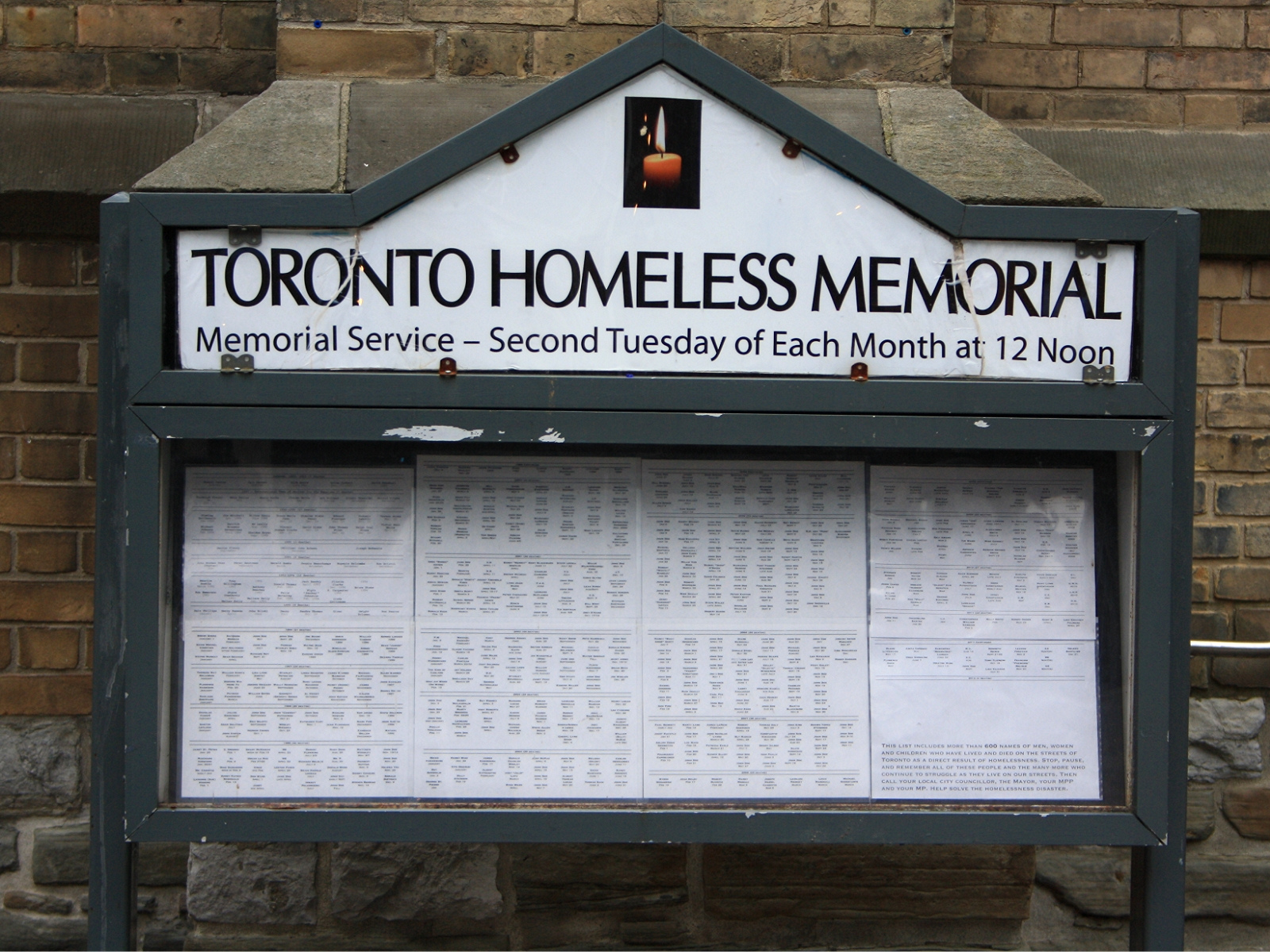

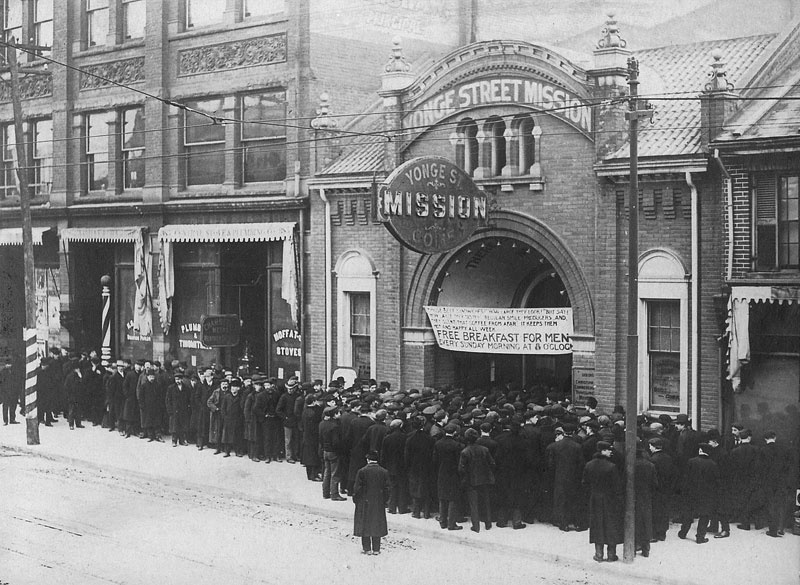

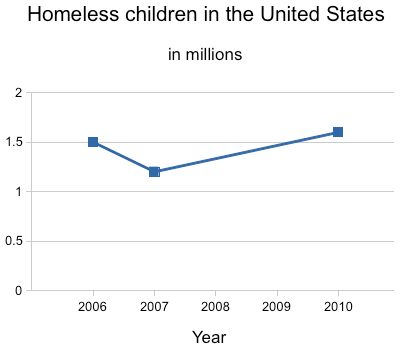

| History This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (February 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Early history through the 19th century Further information: Homelessness in England and Homelessness in the United States  The Bowery Mission in New York City, c. 1800s  German illustration of a homeless mother and her children in the street, before 1883  A homeless man living in a sewer, Vienna, Austria, c. 1900  A memorial to homeless people in Toronto, Canada United Kingdom Following the Peasants' Revolt, English constables were authorized under 1383 English Poor Laws to collar vagabonds and force them to show support; if they could not, the penalty was gaol.[19] Vagabonds could be sentenced to the stocks for three days and nights; in 1530, whipping was added. The presumption was that vagabonds were unlicensed beggars.[19] In 1547, a bill was passed that subjected vagrants to more provisions of the criminal law, namely two years servitude and branding with a "V" as the penalty for the first offense and death for the second. Many vagabonds were among the convicts transported to the American colonies in the 18th century.[20] During the 16th century in England, the state first tried to give housing to vagrants instead of punishing them, by introducing bridewells to take vagrants and train them for a profession. In the 17th and 18th centuries, these were replaced by workhouses but these were intended to discourage too much reliance on state help.[citation needed] United States In the Antebellum South, the availability of enslaved labor made it difficult for poor white people to find work. To prevent them from cooperating with enslaved black people, slaveowners policed poor whites with vagrancy laws.[21] After the American Civil War, a large number (by the hundreds or thousands) of homeless men formed part of a counterculture known as "hobohemia" all over the United States. In smaller towns, hobos temporarily lived near train tracks and hopped onto trains to various destinations.[22][23] The growing movement toward social concern sparked the development of rescue missions, such as the U.S. first rescue mission, the New York City Rescue Mission, founded in 1872 by Jerry and Maria McAuley.[24][25] Modern  Temporary housing for those evicted from their apartments in Sörnäinen, Helsinki, Finland in 1924  Food line at the Yonge Street Mission, Yonge Street, Toronto, Canada, in the 1930s 20th century Further information: Homelessness in the United States § Historical_background The U.S. Great Depression of the 1930s caused an epidemic of poverty, hunger, and homelessness in the United States. When Franklin D. Roosevelt took over the presidency from Herbert Hoover in 1933, he signed the New Deal, which expanded social welfare, including providing funds to build public housing.[26] How the Other Half Lives and Jack London's The People of the Abyss (1903) discussed homelessness and raised public awareness, which caused some changes in building codes and some social conditions. In England, dormitory housing called "spikes" was provided by local boroughs. By the 1930s in England, 30,000 people were living in these facilities. In 1933, George Orwell wrote about poverty in London and Paris, in his book Down and Out in Paris and London. In general, in most countries, many towns and cities had an area that contained the poor, transients, and afflicted, such as a "skid row". In New York City, for example, there was "the Bowery" – traditionally, where people with an alcohol use disorder were to be found sleeping on the streets, bottle in hand. In the 1960s in the U.K., the nature and growing problem of homelessness changed in England as public concern grew. The number of people living "rough" in the streets had increased dramatically. However, beginning with the Conservative administration's Rough Sleeper Initiative,[when?] the number of people sleeping rough in London fell dramatically. This initiative was supported further by the incoming Labour administration from 2009 onwards with the publication of the 'Coming in from the Cold' strategy published by the Rough Sleepers Unit, which proposed and delivered a massive increase in the number of hostel bed spaces in the capital and an increase in funding for street outreach teams, who work with rough sleepers to enable them to access services.[27] Scotland saw a slightly different picture, with the impact of the right to buy ending in a significant drop in available social housing. The 1980s and the 1990s resulted in an ever-increasing picture of people becoming homeless.[citation needed] 2000s In 2001, the Scottish Parliament came into place. It was agreed by all parties that a ten-year plan to eradicate homelessness by the end of 2012 would be implemented. The Minister of Housing[who?] met with the third sector and Local Authorities every six weeks, checking on progress, whilst consultations brought about legislative change, alongside work to prevent homelessness. There was a peak in applications around 2005, but from there onwards figures dropped year on year for the next eight years. However, with a focus on the broader numbers of people experiencing homelessness, many people with higher levels of need got caught in the system. Work from 2017 started to address this, with a framework put in place to work towards a day where everyone in Scotland has a home suitable to meet their needs.[citation needed] In 2002, research showed that children and families were the largest growing segment of the homeless population in the United States,[28][29] and this has presented new challenges to agencies. In the U.S., the government asked many major cities to come up with a ten-year plan to end homelessness.[when?] One of the results of this was a "Housing First" solution. The Housing First program offers homeless people access to housing without having to undergo tests for sobriety and drug usage. The Housing First program seems to benefit homeless people in every aspect except for substance abuse, for which the program offers little accountability.[30] An emerging consensus is that the Housing First program still gives clients a higher chance at retaining their housing once they get it.[31] A few critical voices[who?] argue that it misuses resources and does more harm than good; they suggest that it encourages rent-seeking and that there is not yet enough evidence-based research on the effects of this program on the homeless population.[32] Some formerly homeless people, who were finally able to obtain housing and other assets which helped to return to a normal lifestyle, have donated money and volunteer services to the organizations that provided aid to them during their homelessness.[33] Alternatively, some social service entities that help homeless people now employ formerly homeless individuals to assist in the care process.  Homeless children in the United States.[34] The number of homeless children reached record highs in 2011,[35] 2012,[36] and 2013[37] at about three times their number in 1983.[36] Homelessness has migrated toward rural and suburban areas. The number of homeless people has not changed dramatically but the number of homeless families has increased according to a report by HUD.[38] The United States Congress appropriated $25 million in the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Grants for 2008 to show the effectiveness of Rapid Re-housing programs in reducing family homelessness.[39][40][41] In February 2009, President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, part of which addressed homelessness prevention, allocating $1.5 billion for a Homeless Prevention Fund. The Emergency Shelter Grant (ESG) program's name was changed to Emergency Solution Grant (ESG) program, and funds were reallocated to assist with homeless prevention and rapid re-housing for families and individuals.[42] In January 2024 the United States Supreme Court agreed to make a decision on whether city laws that punish individuals to limit the growth of homeless encampments are in violation of the Constitution's limits for cruel and unusual punishment.[43] |

沿革 このセクションにはオリジナルの研究が含まれている可能性があります。主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで改善してください。独創的な研究のみ からなる記述は削除してください。(2011年2月) (このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 19世紀までの初期の歴史 その他の情報 イギリスのホームレス問題とアメリカのホームレス問題  ニューヨークのバワリー・ミッション(1800年代頃  路上のホームレスの母親と子供たちを描いたドイツのイラスト(1883年以前  下水道で生活するホームレスの男性(1900年頃、オーストリア・ウィーン  カナダ、トロントのホームレス追悼碑 イギリス 農民反乱の後、イギリスの警官は1383年のイギリス貧民法の下で、浮浪者に首輪をつけ、扶養を示すよう強制する権限を与えられた。1547年、浮浪者に さらに刑法の規定を課す法案が可決され、初犯は2年の隷属と「V」の烙印、再犯は死刑とされた[19]。18世紀にアメリカの植民地に移送された囚人の中 には、多くの浮浪者が含まれていた[20]。 16世紀のイギリスでは、国家が浮浪者を処罰する代わりに住居を与えようとしたのが最初で、浮浪者を受け入れて職業訓練を行うブライドウェルを導入した。 17世紀から18世紀にかけて、これらはワークハウスに取って代わられたが、国家の援助に頼りすぎることを抑制することが目的であった[要出典]。 アメリカ合衆国 前世紀南部では、奴隷労働力が利用可能であったため、貧しい白人が仕事を見つけることは困難であった。奴隷化された黒人と協力することを防ぐために、奴隷 所有者は浮浪者法で貧しい白人を取り締まった[21]。 アメリカ南北戦争後、多数の(数百から数千人の)ホームレスの男たちが、アメリカ全土で「ホーボヘミア」として知られるカウンターカルチャーの一部を形成 した。小さな町では、ホーボーは一時的に線路の近くに住み、様々な目的地へ向かう列車に飛び乗った[22][23]。 社会的関心の高まりは、1872年にジェリーとマリア・マコーリーによって設立された米国初のレスキュー・ミッションであるニューヨーク・シティ・レス キュー・ミッションのようなレスキュー・ミッションの発展に火をつけた[24][25]。 近代  1924年、フィンランドのヘルシンキ、ソルナイネンのアパートから追い出された人々のための仮設住宅。  1930年代、カナダ、トロントのヨンジー・ストリートにあるヨンジー・ストリート・ミッションの食料配給ライン 20世紀 さらなる情報 米国のホームレス問題 § 歴史的背景 1930年代の米国大恐慌は、米国に貧困、飢餓、ホームレスの蔓延を引き起こした。1933年にハーバート・フーバーから大統領職を引き継いだフランクリ ン・D・ルーズベルトはニューディールに署名し、公営住宅の建設資金を提供するなど社会福祉を拡大した[26]。 How the Other Half Lives』やジャック・ロンドンの『The People of the Abyss』(1903年)はホームレスについて論じ、人々の意識を高め、建築基準法やいくつかの社会状況に変化をもたらした。イギリスでは、「スパイ ク」と呼ばれる寄宿舎が自治体によって提供された。イギリスでは1930年代までに、3万人がこうした施設に住んでいた。1933年、ジョージ・オーウェ ルは著書『Down and Out in Paris and London』の中で、ロンドンとパリの貧困について書いている。一般的に、ほとんどの国では、多くの町や都市に「スキッドロウ」のような貧困層、過渡的 な生活者、苦悩を抱えた人々を収容する地域があった。たとえばニューヨークには「バワリー」があり、伝統的にアルコール依存症の人々がボトル片手に路上で 寝泊まりしていた。 1960年代のイギリスでは、社会的関心が高まるにつれ、ホームレス問題の性質と深刻さが変化した。路上で "ラフ "に暮らす人々の数が劇的に増加したのだ。しかし、保守党政権のラフ・スリーパー・イニシアチブを皮切りに[いつから?]、ロンドンで寝泊まりする人の数 は劇的に減少した。このイニシアチブは、2009年以降の次期労働党政権によって、ラフ・スリーパー・ユニット(Rough Sleepers Unit)が発表した「寒さの中からやってくる(Coming in from the Cold)」戦略によってさらに支援され、首都におけるホステルのベッド数の大幅な増加と、路上生活者がサービスを利用できるようにするための路上支援 チームへの資金増額が提案され、実現した[27]。 スコットランドでは少し様相が異なり、購入権の影響により、利用可能な社会的住宅が大幅に減少した。1980年代と1990年代は、ホームレスになる人々 が増え続ける結果となった[要出典]。 2000s 2001年、スコットランド議会が発足。2012年末までにホームレスを撲滅するための10年計画を実施することが全政党によって合意された。住宅大臣は 6週間ごとに第三セクターや自治体と面会し、進捗状況を確認する一方、ホームレス対策と並行して法改正のための協議が行われた。申請件数は2005年頃に ピークを迎えたが、その後8年間は年々減少していた。しかし、ホームレス状態にある人々の幅広い数に焦点を当てた結果、より高いレベルのニーズを持つ多く の人々が制度に巻き込まれた。2017年からはこれに対処するための取り組みが開始され、スコットランドに住むすべての人が、それぞれのニーズを満たすに ふさわしい住まいを持つ日を目指して取り組む枠組みが導入された[要出典]。 2002年、米国ではホームレス人口の中で最も増加しているのが子どもと家族であるという調査結果が発表され[28][29]、これは機関にとって新たな 課題となった。 米国では、政府が多くの主要都市に対し、ホームレス状態をなくすための10年計画を策定するよう要請した。ハウジング・ファースト・プログラムは、ホーム レスの人々に、酒気帯び検査や薬物使用検査を受けることなく住居を提供するものである。ハウジング・ファースト・プログラムは、薬物乱用以外のあらゆる面 でホームレスの人々に恩恵をもたらしているようだが、このプログラムではほとんど説明責任を果たしていない[30]。 ハウジング・ファースト・プログラムは、いったん住居を確保すれば、より高い確率でその住居を維持できるというのが、新たなコンセンサスである[31]。 少数の批判的な声[誰?]は、このプログラムは資源を悪用し、利益よりも害をもたらすと主張している。 [32]最終的に住宅やその他の資産を手に入れることができ、普通の生活に戻ることができた元ホームレスの人々の中には、ホームレス時代に援助をしてくれ た団体に寄付をしたり、ボランティアサービスを提供したりする人もいる[33]。  アメリカのホームレスの子どもたち[34]。ホームレスの子どもの数は2011年、[35]2012年、[36]2013年[37]に過去最高を記録し、 1983年の約3倍となった[36]。 ホームレスの数は農村部や郊外へと移動している。HUDの報告書によると、ホームレスの数は劇的に変化していないが、ホームレスの家族の数は増加している [38]。米国議会は、家族ホームレスの減少におけるラピッド・リハウジング・プログラムの効果を示すために、2008年のマッキニー=ヴェントホームレ ス支援補助金に2500万ドルを計上した[39][40][41]。 2009年2月、オバマ大統領は2009年アメリカ復興・再投資法に署名し、その一部としてホームレス予防に取り組み、ホームレス予防基金に15億ドルを 割り当てた。緊急シェルター補助金(ESG)プログラムの名称は、緊急解決補助金(ESG)プログラムに変更され、資金はホームレス予防と家族・個人の迅 速な再入居を支援するために再配分された[42]。 2024年1月、アメリカ合衆国最高裁判所は、ホームレスの野宿者の増加を制限するために個人を罰する市の法律が、残酷で異常な刑罰に対する憲法の制限に 違反しているかどうかについて判断を下すことに合意した[43]。 |

| Causes Major reasons for homelessness include:[44][45][46][47][48] Rent and eviction Gentrification is a process in which a formerly affordable neighborhood becomes popular with wealthier people, raising housing prices and pushing poorer residents out. Gentrification can cause or influence evictions, foreclosures, and rent regulation. Increased wealth disparity and income inequality cause distortions in the housing market that push rent burdens higher, making housing unaffordable.[49][original research?] In many countries, people lose their homes by government orders to make way for newer upscale high-rise buildings, roadways, and other governmental needs.[50] The compensation may be minimal, in which case the former occupants cannot find appropriate new housing and become homeless. Mortgage foreclosures where mortgage holders see the best solution to a loan default is to take and sell the house to pay off the debt can leave people homeless.[51] Foreclosures on landlords often lead to the eviction of their tenants. "The Sarasota, Florida, Herald Tribune noted that, by some estimates, more than 311,000 tenants nationwide have been evicted from homes this year after lenders took over the properties."[44][52] Rent regulation also has a small effect on shelter and street populations.[53] This is largely due to rent control reducing the quality and quantity of housing. For example, a 2019 study found that San Francisco's rent control laws reduced tenant displacement from rent-controlled units in the short-term, but resulted in landlords removing thirty percent of the rent-controlled units from the rental market, (by conversion to condos or TICs) which led to a fifteen percent citywide decrease in total rental units, and a seven percent increase in citywide rents.[54] Economics Lack of jobs that pay living wages, lack of affordable housing, and lack of health and social services can lead to poverty and homelessness.[55] Factors that can lead to economic struggle include neighborhood gentrification (as previously discussed), job loss, debt, loss of money or assets due to divorce, death of breadwinning spouse, being denied jobs due to discrimination, and many others. Moreover, the absence of accessible health and social services further compounds the economic struggle for many. Inadequate healthcare can lead to untreated illnesses, making it difficult for individuals to maintain employment, perpetuating a cycle of poverty. Social services, including mental health support and addiction treatment, are essential for addressing the root causes of economic hardship. However, limited access to these services leaves vulnerable populations without the necessary support systems, hindering their ability to escape poverty.[56] Poverty Poverty is a significant factor in homelessness. Alleviation of poverty, as a result, plays an essential role in eliminating homelessness. Some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have studied 'unconditional cash transfers' (UCTs) to low-income families and individuals to reduce poverty in developing countries. Despite their initial concern about UCT's potentially negative effects on the recipients, the researchers found promising results. The study in Kenya found that assisted households increased their consumption and savings. While the families spent more on their food and food security, they did not incur any expenses on unnecessary goods or services.[57] This study shows that a proper approach to poverty could effectively eliminate this factor as part of a solution to homelessness. Providing access to education and employment to low-income families and individuals must also be considered to combat poverty and prevent homelessness.[58][59] Physical and mental health Homelessness is closely connected to declines in physical and mental health.[60] Most people who use homeless shelters frequently, face multiple disadvantages, such as the increased prevalence of physical and mental health problems, disabilities, addiction, poverty, and discrimination.[61] Studies show that preventive and primary care (which homeless people are not receiving) substantially lower overall healthcare costs.[62] In terms of providing adequate treatment to homeless people for their mental illness, the healthcare system's performance has not been promising, either.[63][64][60] Disabilities, especially where disability services are non-existent, inconvenient, or poorly performing can impact a person's ability to support house payments, mortgages, or rent, especially if they are unable to work.[65] Traumatic brain injury is one main disability that can account for homelessness. According to a Canadian survey,[when?] traumatic brain injury is widespread among homeless people and, for around 70 percent of respondents, can be attributed to a time "before the onset of homelessness"[66] Lack of housing serves as a social determinant of mental health. Being afflicted with a mental disorder, including substance use disorders, where mental health services are unavailable or difficult to access can also drive homelessness for the same reasons as disabilities.[67] A United States federal survey in 2005 indicated that at least one-third of homeless men and women had serious psychiatric disorders or problems. Autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia are the top two common mental disabilities among the U.S. homeless. Personality disorders are also very prevalent, especially Cluster A.[68][69] Discrimination A history of experiencing domestic violence can also attribute to homelessness. Compared to housed women, homeless women were more likely to report childhood histories of abuse, as well as more current physical abuse by male partners.[70] Gender disparities also influence the demographics of homelessness. The experiences of homeless women and women in poverty are often overlooked, however, they experience specific gender-based victimization. As individuals with little to no physical or material capital, homeless women are particularly targeted by male law enforcement, and men living on the street. It has been found that "street-based homelessness dominates mainstream understanding of homelessness and it is indeed an environment in which males have far greater power (O'Grady and Gaietz, 2004)."[71] Women on the street are often motivated to gain capital through affiliation and relationships with men, rather than facing homelessness alone. Within these relationships, women are still likely to be physically and sexually abused.[71] Social exclusion related to sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or sex characteristics can also attribute to homelessness based on discrimination. Relationship breakdown, particularly with young people and their parents, such as disownment due to sexuality or gender identity is one example.[72][73] Human and natural disasters Natural disasters, including but not limited to earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis, tornadoes, and volcanic eruptions can cause homelessness. An example is the 1999 Athens earthquake in Greece, in which many middle class people became homeless, with some of them living in containers, especially in the Nea Ionia earthquake survivors container city provided by the government; in most cases, their only property that survived the quake was their car. Such people are known in Greece as seismopathis, meaning earthquake-struck.[citation needed] War or armed conflict can create refugees fleeing the violence. Whether they be either domestic or foreign to the country, the number of migrants can outstrip the supply of affordable housing, leaving some sections of this population to be homeless. Foster care Transitions from foster care and other public systems can also impact homelessness; specifically, youth who have been involved in, or are a part of the foster care system, are more likely to become homeless. Most leaving the system have no support and no income, making it nearly impossible to break the cycle, and forcing them to live on the streets. There is also a lack of shelter beds for youth; various shelters have stringent admissions policies.[74] Choice Although incredibly uncommon, there do exist some who choose to be homeless as a personal choice.[75] |

原因 ホームレスの主な原因は以下の通り[44][45][46][47][48]。 家賃と立ち退き ジェントリフィケーション(高級化)とは、以前は手頃な価格だった地域が富裕層に人気となり、住宅価格が上昇し、貧しい住民が追い出されるプロセスを指 す。ジェントリフィケーションは、立ち退き、差し押さえ、家賃規制を引き起こしたり、影響を与えたりする。 貧富の格差や所得格差の拡大は、住宅市場の歪みを引き起こし、家賃負担を押し上げ、住宅を手の届かないものにする[49][原文ママ]。 多くの国で、人々は、より新しい高級な高層ビルや道路、その他の政府の必要性を満たすために、政府の命令によって家を失う[50]。 抵当権者が、債務不履行に対する最善の解決策は家を取り上げて売却し、負債を返済することだと考える住宅ローンの差し押さえは、人々をホームレスにする可 能性がある[51]。「フロリダ州サラソタのヘラルド・トリビューン紙は、ある推計によれば、貸主が物件を引き継いだ後、今年全国で31万1,000人以 上の借家人が家から追い出されたと指摘している[44][52]。 家賃規制はシェルターや路上生活者の人口にも少なからず影響を与えている[53]。 これは家賃規制が住宅の質と量を低下させることが主な原因である。例えば、2019年の調査によれば、サンフランシスコの家賃管理法は、短期的には家賃管 理された住戸からの入居者の追い出しを減少させたが、その結果、大家は(コンドミニアムやTICへの転換によって)家賃管理された住戸の30%を賃貸市場 から撤去し、その結果、市全体の総賃貸戸数は15%減少し、市全体の家賃は7%上昇した[54]。 経済 生活賃金を支払う仕事の欠如、手頃な価格の住居の欠如、医療・社会サービスの欠如は、貧困やホームレスにつながる可能性がある[55]。経済的苦境につな がる要因としては、近隣の高級化(前述のとおり)、失業、借金、離婚による金銭や資産の喪失、生計を維持する配偶者の死、差別による仕事の拒否、その他多 数が挙げられる。 さらに、利用しやすい医療サービスや社会サービスがないことが、多くの人々の経済的苦境をさらに悪化させている。不十分な医療は未治療の病気を引き起こ し、個人が雇用を維持することを困難にし、貧困の連鎖を永続させる。メンタルヘルス支援や依存症治療などの社会サービスは、経済的苦難の根本原因に対処す るために不可欠である。しかし、こうしたサービスへのアクセスが制限されているため、社会的弱者は必要な支援システムを持たず、貧困から抜け出す能力を妨 げられている[56]。 貧困 貧困はホームレスの重要な要因である。その結果、貧困の緩和はホームレスの解消に不可欠な役割を果たす。非政府組織(NGO)の中には、開発途上国の貧困 を削減するために、低所得の家庭や個人に対する「無条件現金給付」(UCT)を研究しているところもある。UCTが受給者に悪影響を及ぼすのではないかと いう当初の懸念にもかかわらず、研究者たちは有望な結果を発見した。ケニアでの調査では、支援世帯の消費と貯蓄が増加した。この研究は、貧困に対する適切 なアプローチが、ホームレス問題の解決策の一環として、この要因を効果的に排除できることを示している[57]。貧困と闘い、ホームレス状態を予防するた めには、低所得の家族や個人に教育や雇用へのアクセスを提供することも考慮されなければならない[58][59]。 身体的・精神的健康 ホームレス状態は、身体的・精神的健康の低下と密接な関係がある[60]。ホームレス・シェルターを頻繁に利用する人の多くは、身体的・精神的健康問題の 有病率の増加、障害、依存症、貧困、差別など、複数の不利益に直面している[61]。 ホームレスの人々が受けていない予防医療やプライマリーケアは、医療費全体を大幅に削減するという研究結果もある[62]。 障害、特に障害者サービスが存在しない、不便である、あるいはパフォーマンスが低い場合、特に働くことができない場合、家の支払い、住宅ローン、家賃を支 える人の能力に影響を与える可能性がある[65]。外傷性脳損傷は、ホームレスの原因となりうる主な障害のひとつである。カナダの調査によれば、[い つ?]外傷性脳損傷はホームレスの間に広く見られ、回答者の約70%は「ホームレス状態になる前」の時期に起因している[66]。 住居の欠如は精神衛生の社会的決定要因として機能する。物質使用障害を含む精神障害に罹患しており、メンタルヘルスサービスが利用できない、あるいは利用 が困難であることも、障害と同じ理由でホームレス化を促進する可能性がある[67]。2005年の米国連邦政府の調査では、ホームレスの男女の少なくとも 3分の1が深刻な精神障害や問題を抱えていることが示された。自閉症スペクトラム障害と統合失調症は、米国のホームレスによく見られる精神障害の上位2つ である。人格障害も非常に多く、特にクラスターAが多い[68][69]。 差別 家庭内暴力の経験歴もホームレスの原因となる。収容されている女性と比較して、ホームレスの女性は幼少期の虐待歴を報告する可能性が高く、また男性パート ナーからの身体的虐待を現在受けている可能性も高い[70]。 男女間の格差もホームレスの人口統計に影響を与える。ホームレスの女性や貧困状態にある女性の経験は見過ごされがちであるが、彼女たちはジェンダーに基づ く特有の被害を受けている。物的・物的資本をほとんど持たないホームレスの女性は、特に男性の法執行機関や路上生活者に狙われる。路上でのホームレス生活 は、ホームレス生活の理解の主流を占めており、男性がはるかに大きな力を持っている環境である(O'Grady and Gaietz, 2004)」[71]。路上で生活する女性は、一人でホームレス生活に直面するよりも、男性との関係や所属を通じて資本を得ようとすることが多い。こうし た関係の中で、女性はやはり身体的・性的虐待を受ける可能性が高い[71]。 性的指向、性自認や性表現、性特性に関連する社会的排除も、差別に基づくホームレスの原因となりうる。セクシュアリティや性自認による縁切りなど、特に若 者とその親との関係の断絶はその一例である[72][73]。 人的災害と自然災害 地震、ハリケーン、津波、竜巻、火山噴火などの自然災害はホームレスの原因となる。1999年のギリシャのアテネ地震では、多くの中産階級の人々がホーム レスとなり、特に政府が提供したネア・イオニア地震被災者用コンテナ都市では、コンテナで生活する人々もいた。このような人々は、ギリシャでは地震に襲わ れたという意味のseismopathisとして知られている[要出典]。 戦争や武力紛争は、暴力から逃れる難民を生み出す可能性がある。難民が国内であれ国外であれ、移民の数が手ごろな価格の住宅の供給を上回り、このような人 々の一部がホームレスとなる可能性がある。 児童養護施設 児童養護施設やその他の公的制度からの移行もホームレスに影響を与える可能性がある。具体的には、児童養護施設に入所したことのある、または入所している 若者はホームレスになる可能性が高い。里親制度から脱退する若者のほとんどは、支援も収入もないため、このサイクルを断ち切ることはほぼ不可能であり、路 上生活を余儀なくされる。また、青少年向けのシェルターのベッド数も不足しており、さまざまなシェルターが厳しい入所規定を設けている[74]。 選択 非常に珍しいことではあるが、個人的な選択としてホームレスになることを選ぶ者も存在する[75]。 |

| Challenges Main article: Discrimination against homeless people The basic problem of homelessness is the need for personal shelter, warmth, and safety. Other difficulties include:  Homeless people in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Hygiene and sanitary facilities Hostility from the public and laws against urban vagrancy Cleaning and drying of clothes Obtaining, preparing, and storing food Keeping contact with friends, family, and government service providers without a permanent location or mailing address Medical problems, including issues caused by an individual's homeless state (e.g., hypothermia or frostbite from sleeping outside in cold weather), or issues that are exacerbated by homelessness due to lack of access to treatment (e.g., mental health and the individual not having a place to store prescription drugs) Personal security, quiet, and privacy, especially for sleeping, bathing, and other hygiene activities Safekeeping of bedding, clothing, and possessions, which may have to be carried at all times People experiencing homelessness face many problems beyond the lack of a safe and suitable home. They are often faced with reduced access to private and public services and vital necessities:[76] General rejection or discrimination from other people Increased risk of suffering violence and abuse Limited access to education Loss of usual relationships with the mainstream Not being seen as suitable for employment Reduced access to banking services Reduced access to communications technology Reduced access to healthcare and dental services Targeting by municipalities to exclude from public space[77] Implication of hostile architecture[78] Difficulty forming trust with services, systems, and other people; exacerbating pre-existing difficulty accessing aid and escaping homelessness, particularly present in the chronically homeless.[79] Statistics from the past twenty years, in Scotland, demonstrate that the biggest cause of homelessness is varying forms of relationship breakdown. There is sometimes corruption and theft by the employees of a shelter, as evidenced by a 2011 investigative report by FOX 25 TV in Boston, wherein several Boston public shelter employees were found stealing large amounts of from the shelter's kitchen for their private use and catering over time.[80][81] Homeless people are often obliged to adopt various strategies of self-presentation to maintain a sense of dignity, which constrains their interaction with passers-by, and leads to suspicion and stigmatization by the mainstream public.[82] Homelessness is also a risk factor for depression caused by prejudice. When someone is prejudiced against people who are homeless and then becomes homeless themselves, their anti-homelessness prejudice turns inward, causing depression. "Mental disorders, physical disability, homelessness, and having a sexually transmitted infection are all stigmatized statuses someone can gain despite having negative stereotypes about those groups."[83] Difficulties can compound exponentially. A study found that in the city of Hong Kong over half of the homeless people in the city (56%) had some degree of mental illness. Only 13 percent of the 56 percent were receiving treatment for their condition leaving a huge portion of homeless untreated for their mental illness.[84] The issue of anti-homeless architecture came to light in 2014, after a photo displayed hostile features (spikes on the floor) in London, and took social media by storm. The photo of an anti-homeless structure was a classic example of hostile architecture, in an attempt to discourage people from attempting to access or use public space in irregular ways. However, although this has only recently[when?] came to light, hostile architecture has been around for a long time in many places.[85]: 68 An example of this is a low overpass that was put in place between New York City and Long Island. Robert Moses, an urban planner, designed it this way in an attempt to prevent public buses from being able to pass through it.[86] Healthcare  Student nurse at Jacksonville University School of Nursing takes the blood pressure of a homeless veteran during the annual Stand Down for Homelessness activity in Savannah, Georgia. Health care for homeless people is a major public health challenge. When compared to the general population, people who are homeless experience higher rates of adverse physical and mental health outcomes. Chronic disease severity, respiratory conditions, rates of mental health illnesses, and substance use are all often greater in homeless populations than in the general population.[87][88] Homelessness is also associated with a high risk of suicide attempts.[89][90] Homeless people are more likely to suffer injuries and medical problems from their lifestyle on the street, which includes poor nutrition,[91] exposure to the severe elements of weather, and higher exposure to violence. Yet at the same time, they have reduced access to public medical services or clinics,[92] in part because they often lack identification or registration for public healthcare services. There are significant challenges in treating homeless people who have psychiatric disorders because clinical appointments may not be kept, their continuing whereabouts are unknown, their medicines may not be taken as prescribed, medical and psychiatric histories are not accurate, and other reasons. Because many homeless people have mental illnesses, this has presented a care crisis.[67][93][94] The conditions affecting homeless people are somewhat specialized and have opened a new area of medicine tailored to this population. Skin conditions, including scabies, are common, because homeless people are exposed to extreme cold in the winter, and have little access to bathing facilities. They have problems caring for their feet,[95] and have more severe dental problems than the general population.[96] Diabetes, especially untreated, is widespread in the homeless population.[97] Specialized medical textbooks have been written to address this for providers.[98] Due to the demand for free medical services by homeless people, it might take months to get a minimal dental appointment in a free-care clinic. Communicable diseases are of great concern, especially tuberculosis, which spreads more easily in crowded homeless shelters in high-density urban settings.[99] There has been ongoing concern and studies about the health and wellness of the older homeless population, typically ages 50 to 64 and older, as to whether they are significantly more sickly than their younger counterparts, and if they are under-served.[100][101] A 2011 study led by Dr. Rebecca T. Brown in Boston, conducted by the Institute for Aging Research (an affiliate of Harvard Medical School), Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program found the elderly homeless population had "higher rates of geriatric syndromes, including functional decline, falls, frailty, and depression than seniors in the general population, and that many of these conditions may be easily treated if detected". The report was published in the Journal of Geriatric Internal Medicine.[102] There are government avenues which provide resources for the development of healthcare for homeless people. In the United States, the Bureau of Primary Health Care has a program that provides grants to fund the delivery of healthcare to homeless people.[103] According to 2011 UDS, data community health centers were able to provide service to 1,087,431 homeless individuals.[104] Many nonprofit and religious organizations provide healthcare services to homeless people. These organizations help meet the large need which exists for expanding healthcare for homeless people. There have been significant numbers of unsheltered persons dying of hypothermia, adding impetus to the trend of establishing warming centers, as well as extending enumeration surveys with vulnerability indexes.[105][106] Effect on life expectancy In 1999, Dr. Susan Barrow of the Columbia University Center for Homelessness Prevention Studies reported in a study that the "age-adjusted death rates of homeless men and women were four times those of the general U.S. population and two to three times those of the general population of New York City".[107] A report commissioned by homeless charity Crisis in 2011 found that on average, homeless people in the U.K. have a life expectancy of 47 years, 30 years younger than the rest of the population.[108] Health impacts of extreme weather events See also: Climate change and poverty People experiencing homelessness are at a significantly increased risk of the effects of extreme weather events. Such weather events include extreme heat and cold, floods, storm surges, heavy rain, and droughts. While there are many contributing factors to these events, climate change is driving an increasing frequency and intensity of these events.[109] The homeless population is considerably more vulnerable to these weather events, due to their higher rates of chronic disease, and lower socioeconomic status. Despite having a minimal carbon footprint, homeless people, unfortunately, experience a disproportionate burden of the effects of climate change.[110] Homeless persons have increased vulnerability to extreme weather events for many reasons. They are disadvantaged in most social determinants of health, including lack of housing and access to adequate food and water, reduced access to health care, and difficulty in maintaining health care.[110] They have significantly higher rates of chronic disease including respiratory disease and infections, gastrointestinal disease, musculoskeletal problems, and mental health disease.[111] In fact, self-reported rates of respiratory diseases (including asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema) are double that of the general population.[110] The homeless population often lives in higher-risk urban areas, with increased exposure and little protection from the elements. They also have limited access to clean drinking water and other methods of cooling down.[111] The built environment in urban areas also contributes to the "heat island effect", the phenomenon whereby cities experience higher temperatures due to the predominance of dark, paved surfaces, and lack of vegetation.[112] Homeless populations are often excluded from disaster planning efforts, further increasing their vulnerability when these events occur.[113] Without the means to escape extreme temperatures and seek proper shelter, and cooling or warming resources, homeless people are often left to suffer the brunt of the extreme weather. The health effects that result from extreme weather include exacerbation of chronic diseases and acute illnesses. Pre-existing conditions can be greatly exacerbated by extreme heat and cold, including cardiovascular, respiratory, skin, and renal disease, often resulting in higher morbidity and mortality during extreme weather. Acute conditions such as sunburn, dehydration, heat stroke, and allergic reactions are also common. In addition, a rise in insect bites can lead to vector-borne infections.[111] Mental health conditions can also be impacted by extreme weather events as a result of lack of sleep, increased alcohol consumption, reduced access to resources, and reduced ability to adjust to environmental changes.[111] Pre-existing psychiatric illness has been shown to triple the risk of death from extreme heat.[114] Overall, extreme weather events appear to have a "magnifying effect" in exacerbating the underlying prevalent mental and physical health conditions of homeless populations.[113] Case study: Hurricane Katrina In 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a category-5 hurricane, made landfall in Florida and Louisiana. It particularly affected the city of New Orleans and the surrounding areas. Hurricane Katrina was the deadliest hurricane in the US in seven decades, with more than 1,600 confirmed deaths, and more than 1,000 people missing. The hurricane disproportionately affected marginalized individuals, and individuals with lower socioeconomic status (i.e., 93% of shelter residents were African–American, 32 percent had household incomes below $10,000/year and 54 percent were uninsured).[110] The storm nearly doubled the number of homeless people in New Orleans. While in most cities, homeless people account for one percent of the population, in New Orleans', the homeless account for four percent of the population. In addition to its devastating effects on infrastructure and the economy, the estimated prevalence of mental illness and the incidence of West Nile virus more than doubled after Hurricane Katrina in the hurricane-affected regions.[110] Legal documentation Homeless people may find it difficult to document their date of birth or their address. Because homeless people usually have no place to store possessions, they often lose their belongings, including identification and other documents, or find them destroyed by police or others. Without a photo ID, homeless persons cannot get a job or access many social services, including healthcare. They can be denied access to even the most basic assistance: clothing closets, food pantries, certain public benefits, and in some cases, emergency shelters. Obtaining replacement identification is difficult. Without an address, birth certificates cannot be mailed. Fees may be cost-prohibitive for impoverished persons. And some states will not issue birth certificates unless the person has photo identification, creating a Catch-22.[115] This problem is far less acute in countries that provide free-at-use health care, such as the U.K., where hospitals are open-access day and night and make no charges for treatment. In the U.S., free-care clinics for homeless people and other people do exist in major cities, but often attract more demand than they can meet.[116] Victimization by violent crimes Homeless people are often the victims of violent crime. A 2007 study found that the rate of violent crimes against homeless people in the United States is increasing.[117] A study of women veterans found that homelessness is associated with domestic violence, both directly, as the result of leaving an abusive partner, and indirectly, due to trauma, mental health conditions, and substance abuse.[118] Stigma Conditions such as alcoholism and mental illness are often associated with homelessness.[119] Many people fear homeless people, due to the stigma surrounding the homeless community. Surveys have revealed that before spending time with homeless people, most people fear them, but after spending time with homeless people, that fear is lessened or is no longer there.[120] Another effect of this stigma is isolation.[121] The stigmas of homelessness can thus be divided into three major categories in general: Attributing homelessness to personal incompetency and health conditions (e.g., unemployment, mental health issues, substance abuse, etc.);[122] Seeing homeless people as posing threats to one's safety;[122] De-sanitizing homeless people (i.e., seeing them as pathogens).[123][124] Past research has shown that those types of stigmas are being reinforced through the fact that one is homeless and have a negative impact on effective public policymaking in terms of reducing homelessness.[122][123] When a person lives on a street, many aspects of their personal situations, such as mental health issues and alcoholism, are more likely to be exposed to the public as compared to people who are not homeless and have access to resources that will help improve their personal crises.[122] Such lack of privacy inevitably reinforces stigma by increasing observations of stereotypes for the public. Furthermore, the media often attributes those personal crises to the direct cause of crimes, further leading the public to believe that homeless people are a threat to their safety. Many also believe that contacts with homeless people increase their chance of contracting diseases given that they lack access to stable, sanitary living conditions.[123] Those types of stigmas are intertwined with each other when shaping public opinions on policies related to the homeless population, resulting in many ineffective policies that do not reduce homelessness at all. An example of such ineffective but somewhat popular policies is imposing bans on sleeping on the streets.[123] Relying on the famous contact hypothesis, researchers argue that increasing contact between the homeless population and non-homeless population is likely to change public opinions on this out-group and make the public more well-informed when it comes to policymaking.[125][126] While some believe that the contact hypothesis is only valid on the condition that the context and type of contact are specified, in the case of reducing discrimination against the homelessness population, some survey data indicate that the context (e.g., the proportion of the homeless population in one's city) and type of contact (e.g., TV shows about the homeless population or interpersonal conversations about homelessness) do not produce many variations as they all increase positive attitudes towards homeless people and public policies that aid this group.[122] Given that the restrictions of contexts and types of contact to reduce stigma are minimal, this finding is informative and significant to the government when it comes to making policies to offer institutional support for reducing discrimination in a country and for gauging public opinions on their proposed policies to reduce homelessness.[125][127] |

チャレンジ 主な記事 ホームレス差別 ホームレスの基本的な問題は、個人的なシェルター、暖かさ、安全の必要性である。その他にも以下のような困難がある:  ブラジル、リオデジャネイロのホームレスの人々 衛生設備 一般市民からの敵意と都市部の浮浪を禁止する法律 衣類の洗濯と乾燥 食料の入手、準備、保存 定住地や住所のない友人、家族、行政サービス提供者との連絡の維持 個人のホームレス状態に起因する問題(例:寒い時期に外で寝たことによる低体温症や凍傷)や、治療が受けられないためにホームレス状態によって悪化する問 題(例:精神衛生、処方薬を保管する場所がない)など、医学的問題。 特に睡眠、入浴、その他の衛生活動のための個人的な安全、静けさ、プライバシー 寝具、衣類、所持品の安全な管理(常に携帯しなければならない場合もある ホームレス状態にある人々は、安全で適切な住居がないだけでなく、多くの問題に直面している。彼らはしばしば、民間や公共のサービスや重要な必需品へのア クセスの低下に直面する[76]。 他人からの拒絶や差別 暴力や虐待を受けるリスクの増加 教育へのアクセスが制限される 主流派との通常の関係の喪失 雇用に適していないとみなされる 銀行サービスへのアクセスが制限される 通信技術へのアクセスが減る 医療・歯科サービスへのアクセスの低下 公共空間から排除するための自治体による標的化[77]。 敵対的建築[78]の暗示 サービスやシステム、他の人々との信頼関係の形成が困難で、特に慢性的なホームレスに見られる、援助へのアクセスやホームレス状態からの脱却が以前から困 難であったことを悪化させる[79]。 スコットランドの過去20年間の統計によると、ホームレス状態の最大の原因は、様々な形の人間関係の破綻である。 2011年にボストンのFOX25TVが調査報道した、ボストンの公的シェルターの従業員数名がシェルターの厨房から大量の食料を盗み、長期にわたって私 的利用やケータリングのために使用していたことが発見された事件で証明されているように、シェルターの従業員による汚職や窃盗が行われることもある [80][81]。ホームレスの人々は尊厳の感覚を維持するために様々な自己呈示の戦略を取らざるを得ないことが多く、そのため通行人との交流が制限さ れ、一般の人々から疑惑や汚名を着せられることになる[82]。 ホームレスはまた、偏見によって引き起こされるうつ病の危険因子でもある。ホームレスの人々に対して偏見を持っている人が、自分もホームレスになると、そ の反ホームレス的偏見が内向きになり、うつ病を引き起こす。「精神障害、身体障害、ホームレス、性感染症はすべて、そのようなグループに対する否定的な固 定観念を持っているにもかかわらず、誰かが得ることのできるスティグマ化されたステータスである」[83]。ある調査によると、香港ではホームレスの半数 以上(56%)が何らかの精神疾患を抱えていた。56%のうち治療を受けているのはわずか13%で、ホームレスの大部分は精神疾患の治療を受けていない [84]。 反ホームレス建築の問題は、2014年にロンドンで敵対的な特徴(床にトゲトゲ)が表示された写真をきっかけに明るみになり、ソーシャルメディアを席巻し た。反ホームレス建築の写真は敵対的建築の典型的な例であり、不規則な方法で公共空間にアクセスしたり利用しようとしたりする人々の意欲を削ごうとするも のであった。しかし、このことが明るみに出たのはつい最近だが[85]: 68 敵対的建築物は、ニューヨーク市とロングアイランドの間に設置された低い陸橋がその例である。都市計画家であるロバート・モーゼスは、公共バスが通れない ようにしようと、このように設計した[86]。 ヘルスケア  ジョージア州サバンナで毎年開催される「Stand Down for Homelessness」活動で、ホームレスの退役軍人の血圧を測るジャクソンビル大学看護学部の学生看護師。 ホームレスの人々の健康管理は、公衆衛生上の大きな課題である。一般人口と比較すると、ホームレスの人々は身体的・精神的に不利な結果を経験する割合が高 い。慢性疾患の重症度、呼吸器疾患、精神疾患の罹患率、薬物使用率はすべて、一般集団よりもホームレス集団の方が高いことが多い[87][88]。ホーム レスは自殺未遂のリスクも高い[89][90]。 ホームレスの人々は、栄養状態が悪く[91]、天候の厳しい要素にさらされ、暴力にさらされやすいなど、路上での生活習慣から怪我や医学的問題を抱える可 能性が高い。しかし同時に、公的医療サービスを受けるための身分証明書や登録証がないことが多いこともあり、公的医療サービスや診療所へのアクセスが減少 している[92]。臨床の予約が守られない、居場所がわからない、薬が処方通りに服用されない、病歴や精神科歴が正確でないなどの理由から、精神疾患を抱 えるホームレスの人々の治療には大きな課題がある。多くのホームレスが精神疾患を抱えているため、これはケアの危機を示している[67][93] [94]。 ホームレスの人々が罹患する疾患はやや特殊であり、このような人々に合わせた新たな医療分野が開拓されている。ホームレスの人々は、冬には極寒にさらさ れ、入浴施設をほとんど利用できないため、疥癬を含む皮膚疾患が一般的である。彼らは足のケアに問題があり[95]、一般の人々よりも深刻な歯の問題を抱 えている[96]。糖尿病、特に未治療の糖尿病は、ホームレスの人々に広がっている[97]。医療提供者向けに、これに対処するための専門的な医学教科書 が書かれている[98]。 ホームレスの人々の無料医療サービスに対する需要のため、無料医療クリニックで最低限の歯科診療の予約を取るのに数ヶ月かかることもある。伝染病は大きな 懸念事項であり、特に結核は、高密度の都市環境にある混雑したホームレスシェルターで蔓延しやすい[99]。高齢のホームレス人口(一般的に50歳から 64歳以上)の健康とウェルネスについて、彼らが若年層のホームレス人口よりも著しく病弱であるかどうか、彼らが十分なサービスを受けていないかどうかに ついて、継続的な懸念と研究がなされている[100][101]。 ハーバード大学医学部の関連機関である加齢研究所、ベス・イスラエル・ディーコネス医療センター、ボストン・ヘルスケア・フォー・ザ・ホームレス・プログ ラムが実施した、ボストンのレベッカ・T・ブラウン博士率いる2011年の研究によると、高齢のホームレス集団は、「機能低下、転倒、虚弱、うつ病を含む 老年症候群の割合が一般集団の高齢者よりも高く、これらの症状の多くは、発見されれば容易に治療できる可能性がある」ことがわかった。この報告は Journal of Geriatric Internal Medicine誌に掲載された[102]。 ホームレスのための医療を発展させるための資源を提供する政府の手段もある。2011年のUDSによると、地域保健センターは1,087,431人のホー ムレスの人々にサービスを提供することができた。これらの団体は、ホームレスの人々の医療を拡大するために存在する大きなニーズを満たすのに役立ってい る。 低体温症で死亡するホームレスが相当数いることから、ウォーミングセンターの設置や、脆弱性指標を用いた人口調査の拡大に拍車がかかっている[105] [106]。 平均余命への影響 1999年、コロンビア大学ホームレス予防研究センターのスーザン・バロー博士は、「ホームレスの男女の年齢調整死亡率は、米国の一般人口の4倍、ニュー ヨーク市の一般人口の2~3倍である」という研究報告を行った[107]。2011年にホームレスの慈善団体クライシスが委託した報告書によると、英国の ホームレスの平均寿命は47歳であり、他の人口よりも30歳若い[108]。 異常気象による健康への影響 以下も参照: 気候変動と貧困 ホームレス状態にある人々は、異常気象の影響を受けるリスクが著しく高まる。このような気象現象には、極端な暑さや寒さ、洪水、高潮、豪雨、干ばつなどが ある。これらの現象には多くの要因があるが、気候変動はこれらの現象の頻度と強度を増加させている[109]。ホームレスの人々は慢性疾患の割合が高く、 社会経済的地位が低いため、これらの気象現象に対してかなり脆弱である。二酸化炭素排出量はごくわずかであるにもかかわらず、残念ながらホームレスの人々 は、気候変動の影響による不釣り合いな負担を経験している[110]。 ホームレスの人々は、多くの理由から、異常気象に対する脆弱性を高めている。彼らは、住居の不足、適切な食料と水へのアクセス、医療へのアクセスの低下、 医療維持の困難さなど、健康の社会的決定要因のほとんどにおいて不利な立場に置かれている[110]。呼吸器疾患や感染症、消化器疾患、筋骨格系の問題、 精神疾患を含む慢性疾患の罹患率が著しく高い[111]。実際、自己申告による呼吸器疾患(喘息、慢性気管支炎、肺気腫を含む)の罹患率は、一般人口の2 倍である[110]。 ホームレスの人々は、より危険度の高い都市部に住んでいることが多く、風雨にさらされる機会が多く、風雨から身を守る手段もほとんどない。また、清潔な飲 料水やその他の涼をとる手段へのアクセスも限られている[111]。都市部の建築環境も「ヒートアイランド現象」の一因となっており、暗い舗装された路面 が多く、植生が少ないために都市の気温が高くなる現象である[112]。 ホームレスの人々は、災害計画の取り組みから排除されることが多く、災害発生時の脆弱性をさらに高めている[113]。極端な気温から逃れて適切な避難所 を探したり、冷房や暖房の資源を求めたりする手段を持たないホームレスの人々は、異常気象の矢面に立たされることが多い。 異常気象がもたらす健康への影響には、慢性疾患や急性疾患の悪化がある。心血管疾患、呼吸器疾患、皮膚疾患、腎疾患など、既往症は極端な暑さや寒さによっ て大幅に悪化する可能性があり、異常気象時の罹患率や死亡率が高くなることが多い。日焼け、脱水、熱中症、アレルギー反応などの急性症状もよく見られる。 さらに、虫刺されの増加は、媒介感染症につながる可能性がある[111]。 睡眠不足、アルコール摂取の増加、資源へのアクセスの減少、環境変化への適応能力の低下[111]などの結果、メンタルヘルス状態も異常気象の影響を受け る可能性がある。 既存の精神疾患は、猛暑による死亡リスクを3倍に高めることが示されている[114]。 全体として、異常気象は、ホームレス集団の根底に蔓延している精神的・身体的健康状態を悪化させる「拡大効果」を持つようである[113]。 事例研究 ハリケーン・カトリーナ 2005年、カテゴリー5のハリケーン・カトリーナがフロリダ州とルイジアナ州に上陸した。特にニューオリンズ市とその周辺地域に影響を与えた。ハリケー ン・カトリーナは、米国で過去70年間で最も大きな被害をもたらしたハリケーンであり、死者1,600人以上、行方不明者1,000人以上が確認されてい る。このハリケーンは、社会経済的に疎外された人々や、社会経済的地位の低い人々に不釣り合いな影響を与えた(すなわち、避難所の住民の93%はアフリカ 系アメリカ人であり、32%は世帯収入が年間1万ドル未満であり、54%は無保険であった)[110]。 嵐によって、ニューオーリンズのホームレスの数はほぼ倍増した。ほとんどの都市では、ホームレスは人口の1パーセントを占めるが、ニューオーリンズでは、 ホームレスは人口の4パーセントを占める。インフラと経済への壊滅的な影響に加え、ハリケーン・カトリーナの後、ハリケーン被災地では精神疾患の推定有病 率と西ナイル・ウイルスの発生率が2倍以上になった[110]。 法的文書 ホームレスの人々は、生年月日や住所を記録することが困難な場合がある。ホームレスの人々は通常、所持品を保管する場所がないため、身分証明書やその他の 書類を含む所持品を紛失したり、警察などによって破棄されたりすることが多い。写真付き身分証明書がなければ、ホームレスの人々は仕事に就くことも、医療 を含む多くの社会サービスを利用することもできない。衣料品店、食料配給所、特定の公的給付金、場合によっては緊急シェルターなど、最も基本的な支援への アクセスさえ拒否されることもある。身分証明書の再発行は難しい。住所がないと出生証明書を郵送できない。貧しい人々にとっては、手数料が費用の負担にな ることもある。また、州によっては、写真付きの身分証明書がなければ出生証明書を発行しないところもあり、このようなキャッチ・ツー・カップが生じる [115]。この問題は、昼夜を問わず病院が開放され、治療費が無料である英国のような、自由診療の医療を提供する国でははるかに深刻ではない。アメリカ では、ホームレスやその他の人々のための無料診療所が大都市に存在するが、しばしば対応しきれないほどの需要を集めている[116]。 暴力犯罪による被害 ホームレスの人々はしばしば暴力犯罪の被害者となる。2007年の調査では、アメリカではホームレスに対する暴力犯罪の割合が増加していることがわかった [117]。退役軍人の女性を対象とした調査では、ホームレス状態が、虐待するパートナーとの別れという直接的な理由と、トラウマ、精神状態、薬物乱用に よる間接的な理由の両方において、家庭内暴力と関連していることがわかった[118]。 スティグマ アルコール依存症や精神疾患などの疾患は、しばしばホームレス状態と関連している[119]。ホームレス社会を取り巻くスティグマにより、多くの人々が ホームレスの人々を恐れている。調査によると、ホームレスの人々と過ごす前は、ほとんどの人が彼らを恐れているが、ホームレスの人々と過ごした後は、その 恐怖は軽減されるか、もはや存在しなくなる[120]。このスティグマのもう一つの影響は孤立である[121]。 このようにホームレスのスティグマは、一般的に3つの大きなカテゴリーに分けることができる: ホームレスの原因を個人の無能や健康状態(失業、精神衛生上の問題、薬物乱用など)とすること[122]。 ホームレスの人々を自分の安全を脅かす存在とみなすこと[122]。 ホームレスの人々を除菌すること(すなわち、 過去の研究によって、ホームレスであるという事実を通じて、このようなスティグマが強化され、ホームレスの減少という点で、効果的な公共政策の立案に悪影 響を及ぼすことが示されている[123][124]。 [122][123]路上で生活している場合、精神衛生上の問題やアルコール依存症など、個人的な状況の多くの側面が、ホームレスでなく、個人的な危機を 改善するための資源を利用できる人と比べて、公衆にさらされる可能性が高い[122]。このようなプライバシーの欠如は、公衆に対するステレオタイプの観 察を増加させることによって、スティグマを必然的に強化する。さらに、メディアはしばしばそのような個人的危機を犯罪の直接の原因とし、ホームレスの人々 が自分たちの安全を脅かす存在であると一般大衆をさらに信じ込ませる。また、ホームレスが安定した衛生的な生活環境にアクセスできないことから、ホームレ スと接触することで病気に感染する可能性が高まると考える人も多い[123]。ホームレス人口に関連する政策に対する世論を形成する際、このような種類の スティグマは互いに絡み合い、その結果、ホームレスの数をまったく減らせない、効果のない政策が多く生み出される。そのような効果のない、しかしある程度 人気のある政策の例として、路上での寝泊まりを禁止することが挙げられる[123]。 有名な接触仮説に依拠して、研究者たちは、ホームレス集団と非ホームレス集団との接触を増やすことは、この非集団に対する世論を変化させ、政策立案に関し て世論をよりよく理解させる可能性が高いと主張している[125][126]。接触仮説は、文脈と接触の種類が特定されている場合にのみ有効であるという 考え方もあるが、ホームレス集団に対する差別の削減の場合、いくつかの調査データによれば、文脈(例.ホームレス人口に対する差別を減らす場合、いくつか の調査データによると、文脈(例えば、自分の住む都市におけるホームレス人口の割合)と接触のタイプ(例えば スティグマを減少させるための文脈や接触のタイプの制限が最小限であることを考えると、この発見は、政府にとって、その国における差別を減少させるための 制度的支援を提供するための政策を立てるときや、ホームレス状態を減少させるために提案された政策に対する国民の意見を測定するときに有益であり、重要で ある[125][127]。 |