フードゥー

Hoodoo (spirituality)

☆ フードゥーは、より広い文脈では、精神的な慣習、伝統、信念の集合体として機能する民族宗教であり、南部の米国で奴隷として働かされていたアフリカ系ア メリカ人が、アフリカの伝統的な精神性やアメリカ先住民の植物知識の要素から発展させた、呪術的およびその他の儀式的な慣習を含むものである。フードゥー の実践者は、ルーツワーカー、コンジャー[まじない]・ドクター、コンジャー・マンまたはコンジャー・ウーマン、ルーツ・ドクターと呼ばれる。 フードゥーの地域的な同義語には、ルーツ、ルーツワーク、コンジャーなどがある。自律的な精神体系として、奴隷として連れてこられた西アフリカのイスラ ム教徒が持ち込んだイスラム教やスピリチュアリズムの信仰と融合することが多かった。学者たちはフードゥーを民間信仰と定義している。 フードゥー教を独立した宗教として信仰する者もいれば、アフリカ土着の精神世界とアブラハムの宗教との混成宗教として信仰する者もいる。 多くのフードゥーの伝統は、中央アフリカのバコンゴ族の信仰から影響を受けている。大西洋を横断する奴隷貿易の最初の1世紀の間、アメリカ大陸に運ばれ た奴隷となったアフリカ人の推定52%が、現在のカメルーン、コンゴ、アンゴラ、中央アフリカ共和国、ガボンの国境内に存在した中央アフリカ諸国から来た 人々であった。アフリカ系アメリカ人の大移動に続いて、南部のフードゥーがアメリカ全土に広がったが、フードゥーは黒人が自主的、非自主的に定住した あらゆる場所で実践されていた。

★Not to be confused with Voodoo. For other uses of "Hoodoo", see Hoodoo (disambiguation)./ ヴードゥーとは混同されない。「フードゥー」の他の用法については、フードゥー(曖昧さ回避)を参照のこと。

| Hoodoo

is an

ethnoreligion that, in a broader context, functions as a set of

spiritual observances, traditions, and beliefs—including magical and

other ritual practices—developed by enslaved African Americans in the

Southern United States from various traditional African spiritualities

and elements of indigenous American botanical knowledge.[1][2][3]

Practitioners of Hoodoo are called rootworkers, conjure doctors,

conjure men or conjure women, and root doctors. Regional synonyms for

Hoodoo include roots, rootwork and conjure.[4] As an autonomous

spiritual system it has often been syncretized with beliefs from Islam

brought over by enslaved West African Muslims, and Spiritualism.[5][6]

Scholars define Hoodoo as a folk religion. Some practice Hoodoo as an autonomous religion, some practice as a syncretic religion between two or more cultural religions, in this case being African indigenous spirituality and Abrahamic religion.[7][8] Many Hoodoo traditions draw from the beliefs of the Bakongo people of Central Africa.[9] Over the first century of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, an estimated 52% of all enslaved Africans transported to the Americas came from Central African countries that existed within the boundaries of modern-day Cameroon, the Congo, Angola, Central African Republic, and Gabon.[10] Following the Great Migration of African Americans, southern Hoodoo spread throughout the United States, although Hoodoo was practiced everywhere that Black people settled, voluntarily or involuntarily. |

フードゥーは、より広い文脈では、精神的な慣習、伝統、信念の集合体

として機能する民族宗教であり、南部の米国で奴隷として働かされていたアフリカ系アメリカ人が、アフリカの伝統的な精神性やアメリカ先住民の植物知識の要

素から発展させた、呪術的およびその他の儀式的な慣習を含むものである。[1][2][3]

フードゥーの実践者は、ルーツワーカー、コンジャー・ドクター、コンジャー・マンまたはコンジャー・ウーマン、ルーツ・ドクターと呼ばれる。フードゥーの

地域的な同義語には、ルーツ、ルーツワーク、コンジャーなどがある。[4]

自律的な精神体系として、奴隷として連れてこられた西アフリカのイスラム教徒が持ち込んだイスラム教やスピリチュアリズムの信仰と融合することが多かっ

た。[5][6] 学者たちはフードゥーを民間信仰と定義している。 フードゥー教を独立した宗教として信仰する者もいれば、アフリカ土着の精神世界とアブラハムの宗教との混成宗教として信仰する者もいる。 多くのフードゥーの伝統は、中央アフリカのバコンゴ族の信仰から影響を受けている。[9] 大西洋を横断する奴隷貿易の最初の1世紀の間、アメリカ大陸に運ばれた奴隷となったアフリカ人の推定52%が、現在のカメルーン、コンゴ、アンゴラ、中央 アフリカ共和国、ガボンの国境内に存在した中央アフリカ諸国から来た人々であった。[10] アフリカ系アメリカ人の大移動に続いて、南部のフードゥーがアメリカ全土に広がったが、フードゥーは黒人が自主的、非自主的に定住したあらゆる場所で 実践されていた。 |

| Etymology The first documentation of the word "Hoodoo" in the English language appeared in 1870.[11][12] Its origins are obscure. Still, some linguists believe it originated as an alteration of the word Voodoo – a word that has its origin in the Gbe languages such as the Ewe, Adja, and Fon languages of Ghana, Togo, and Benin – referring to divinity.[13][14] Another possible etymological origin of the word Hoodoo comes from the word Hudu, meaning "spirit work," which comes from the Ewe language spoken in the West African countries of Ghana, Togo, and Benin.[15] Hudu is one of its dialects.[16] According to Paschal Beverly Randolph, the word Hoodoo is from an African dialect.[17] The origin of the word Hoodoo and other words associated with the practice could be traced to the Windward Coast and Senegambia. For example, in West Africa, the word gris-gris (a conjure bag) is a Mande word.[18] The words wanga and mooyo (mojo bag) come from the Kikongo language.[15] Recent scholarly publications spell the word with a capital letter. The word has different meanings depending on how it is spelled. Some authors spell Hoodoo with a capital letter to distinguish it from commercialized hoodoo, which is spelled with a lowercase letter. Other authors have different reasons why they capitalize or lowercase the first letter.[19][20] |

語源 英語における「フードゥー」という語の最初の記録は1870年に登場している。[11][12] その起源は不明である。しかし、一部の言語学者は、ガーナ、トーゴ、ベナンのエウェ語、アジャ語、フォン語などのグベ語派に起源を持つ神を指す「ヴー ドゥー」という語が変化したものであると考えている。[13][14] フードゥーという語のもう一つの語源は、西アフリカのガーナ、トーゴ、ベナンで話されているエウェ語に由来する「霊的な仕事」を意味するHuduという 語である。[15] Huduは方言の一つである。[16] パスカ・ランドルフによると、フードゥーという語はアフリカの方言に由来する。[17] フードゥーという言葉の起源と、この信仰に関連するその他の言葉の起源は、ウィンドワード・コーストとセネガンビアに遡ることができる。例えば、西アフリ カでは、グリグリ(おまじない袋)という言葉はマンデ族の言葉である。 ワングァとムヨ(モジョ・バッグ)という言葉は、キコンゴ語に由来する。 最近の学術出版物では、この単語は大文字で表記されている。この単語は、その表記方法によって異なる意味を持つ。一部の著者は、商業化されたフードゥー (小文字で表記される)と区別するために、フードゥーを大文字で表記している。他の著者は、最初の文字を大文字または小文字にする理由を異にする。 [19][20] |

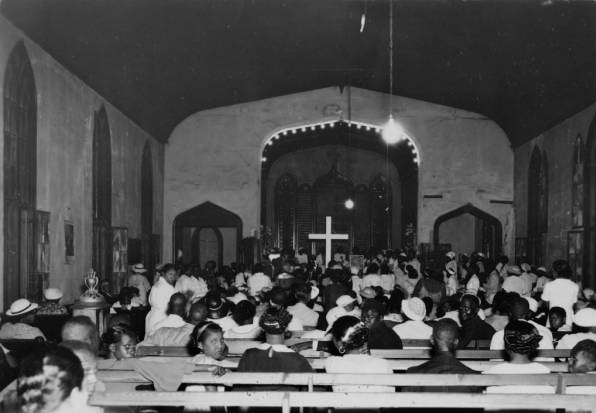

| History Antebellum era See also: Antebellum South  Many Hoodoo practices were hidden in Black churches during and after slavery for African Americans to protect themselves. Scholars call the practice of Hoodoo in Black churches the invisible institution because enslaved Black people concealed their culture and practices from whites within the Christian religion.[21][22] According to Yvonne Chireau, "Hoodoo is an African American-based tradition that makes use of natural and supernatural elements in order to create and effect change in the human experience.."[23] Hoodoo was created by African Americans, who were among over 12 million enslaved Africans from various Central and West African ethnic groups transported to the Americas from the 16th to 19th centuries (1514 to 1867) as part of the transatlantic slave trade.[24] The transatlantic slave trade to the United States occurred between 1619 and 1808, and the illegal slave trade in the United States occurred between 1808 and 1860. Between 1619 and 1860 approximately 500,000 enslaved Africans were transported to the United States.[25] From Central Africa, Hoodoo has Bakongo magical influence from the Bakongo religion[26] incorporating the Kongo cosmogram, Simbi water spirits, and Nkisi and Minkisi practices.[27] The West African influence is Vodun from the Fon and Ewe people in Benin and Togo, following some elements from the Yoruba religion.[28][29] After their contact with European slave traders and missionaries, some Africans converted to Christianity willingly. At the same time, other enslaved Africans were forced to become Christian, which resulted in a syncretization of African spiritual practices and beliefs with the Christian faith.[30] Enslaved and free Africans learned regional indigenous botanical knowledge after they arrived in the United States.[31] The extent to which Hoodoo could be practiced varied by region and the temperament of enslavers. For example, the Gullah people of the coastal Southeast experienced an isolation and relative freedom that allowed the retention of various traditional West African cultural practices. Among the Gullah people and enslaved African Americans in the Mississippi Delta, where the concentration of enslaved people was dense, Hoodoo was practiced under an extensive cover of secrecy.[32][33][34] The reason for secrecy among enslaved and free African Americans was that slave codes prohibited large gatherings of enslaved and free Black people. Enlavers experienced how slave religion ignited slave revolts among enslaved and free Black people, and some leaders of slave insurrections were Black ministers or conjure doctors.[35] |

歴史 南北戦争前 南北戦争前の南部も参照  多くのフードゥー教の慣習は、奴隷制時代および奴隷制廃止後、アフリカ系アメリカ人が自分自身を守るためにブラック教会に隠されていた。学者たちは、ブ ラック教会におけるフードゥー教の慣習を「見えない制度」と呼んでいる。なぜなら、奴隷として黒人たちはキリスト教の宗教の中で、自分たちの文化や慣習 を白人に隠していたからである。[21][22] イボンヌ・チローによれば、「フードゥーは、自然や超自然的な要素を活用して、人間の経験に変化を生み出し、影響を与えるアフリカ系アメリカ人の伝統で ある」[23] フードゥーは、16世紀から19世紀(1514年から1867年)にかけて大西洋奴隷貿易の一環として、中央および西アフリカのさまざまな民族グループ に属する1200万人以上の奴隷としてアメリカ大陸に連れて来られたアフリカ人たちによって生み出された 16世紀から19世紀(1514年から1867年)にかけて、大西洋奴隷貿易の一環として、さまざまな中央および西アフリカの民族グループに属する 1200万人以上の奴隷としてアメリカ大陸に移送された。[24] アメリカ合衆国への大西洋奴隷貿易は1619年から1808年にかけて行われ、アメリカ国内での違法な奴隷貿易は1808年から1860年にかけて行われ た。1619年から1860年の間に、およそ50万人の奴隷としてアフリカ人が米国に連れてこられた。[25] 中央アフリカから、フードゥーはバコンゴの呪術的影響を受けている。バコンゴ宗教は、 宇宙図、Simbiの水の精霊、NkisiとMinkisiの慣習を取り入れている。[27] 西アフリカの影響は、ベナンとトーゴのフォン族とエウェ族のVodunであり、ヨルバ族の宗教からいくつかの要素を受け継いでいる。[28][29] ヨーロッパの奴隷商人や宣教師と接触した後、一部のアフリカ人は自らキリスト教に改宗した。同時に、他の奴隷となったアフリカ人はキリスト教に改宗するこ とを強制され、その結果、アフリカの精神的な慣習や信仰とキリスト教信仰との習合が生じた。[30] 奴隷となったアフリカ人と自由のアフリカ人は、アメリカ合衆国に到着した後、地域の土着の植物に関する知識を学んだ。[31] フードゥーがどの程度実践されたかは、地域や奴隷所有者の気質によって異なっていた。例えば、アメリカ南東部の沿岸地域に住むガラ族の人々は、孤立した 環境で相対的な自由を経験し、さまざまな西アフリカの伝統文化を維持することができた。奴隷の人口が密集していたミシシッピ・デルタのガラ族や奴隷のアフ リカ系アメリカ人の間では、フードゥーは広範囲にわたって秘密裏に行われていた。[32][33][34] 奴隷および自由のアフリカ系アメリカ人の間で秘密裏に行われていた理由は、奴隷法が奴隷および自由の黒人たちの大規模な集会を禁じていたためである。奴隷 制の宗教が奴隷と自由の身となった黒人の間で奴隷反乱に火をつけることを、奴隷制の加害者は経験しており、奴隷反乱の指導者の中には黒人牧師や呪術医もい た。[35] |

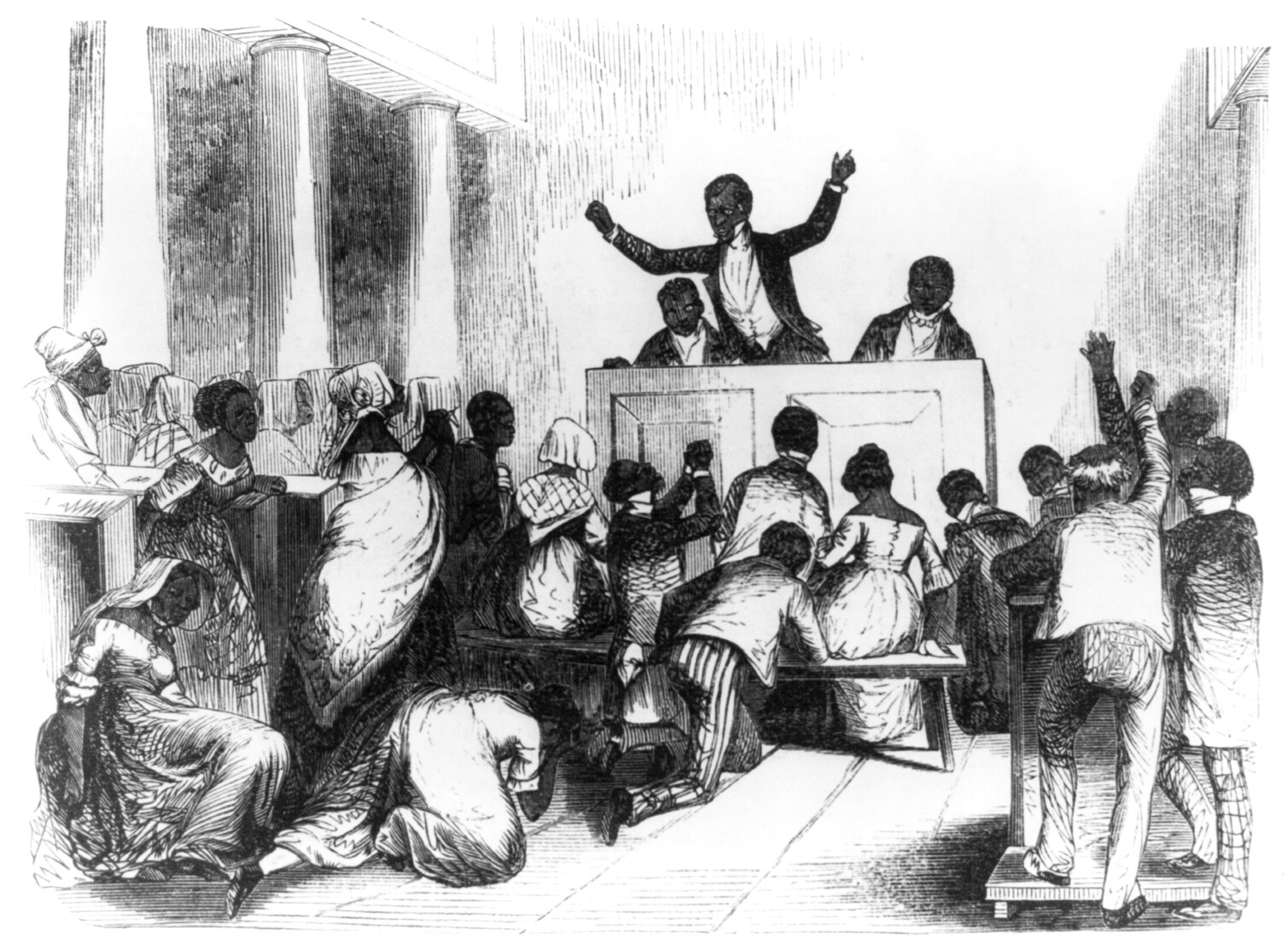

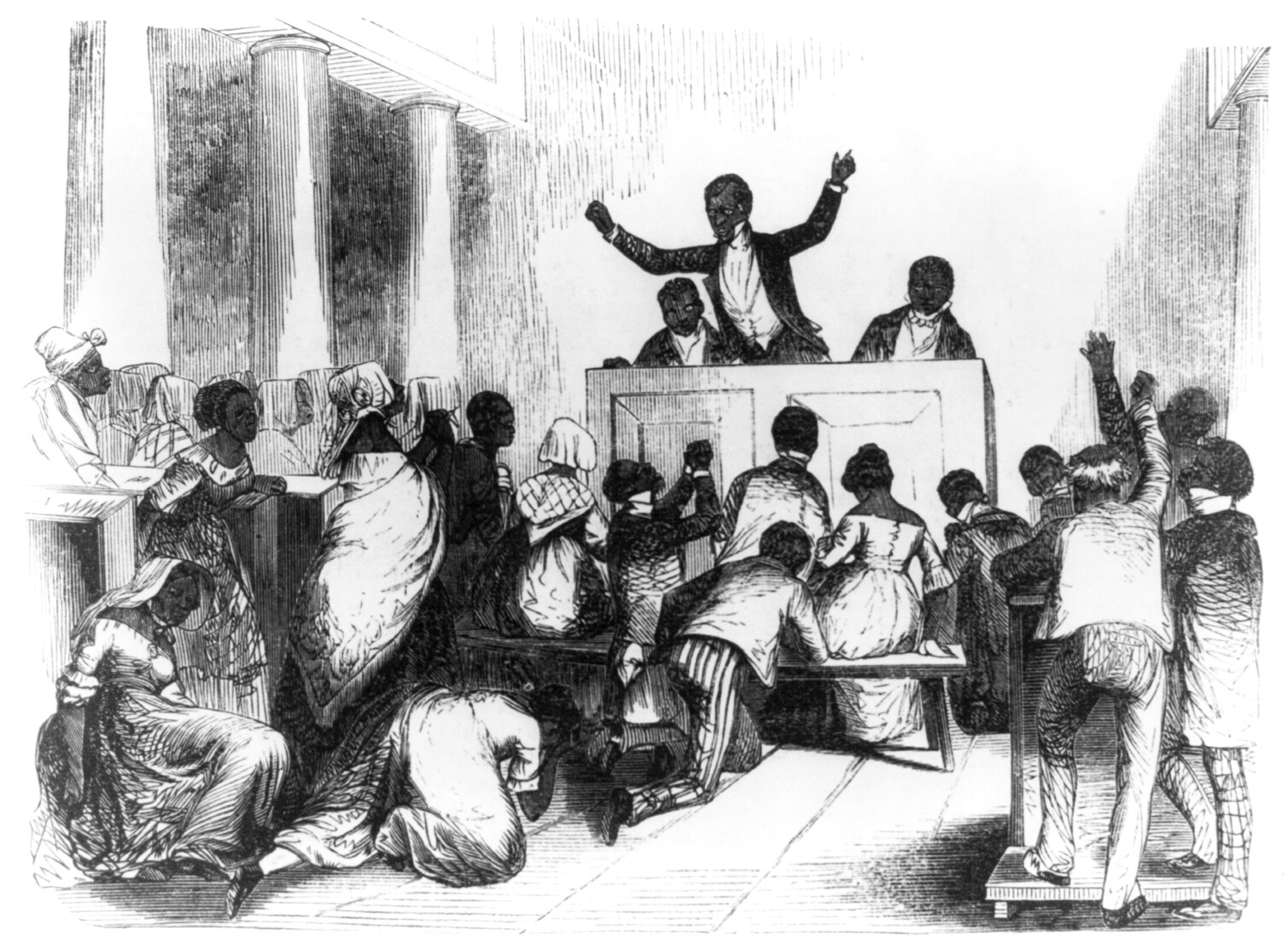

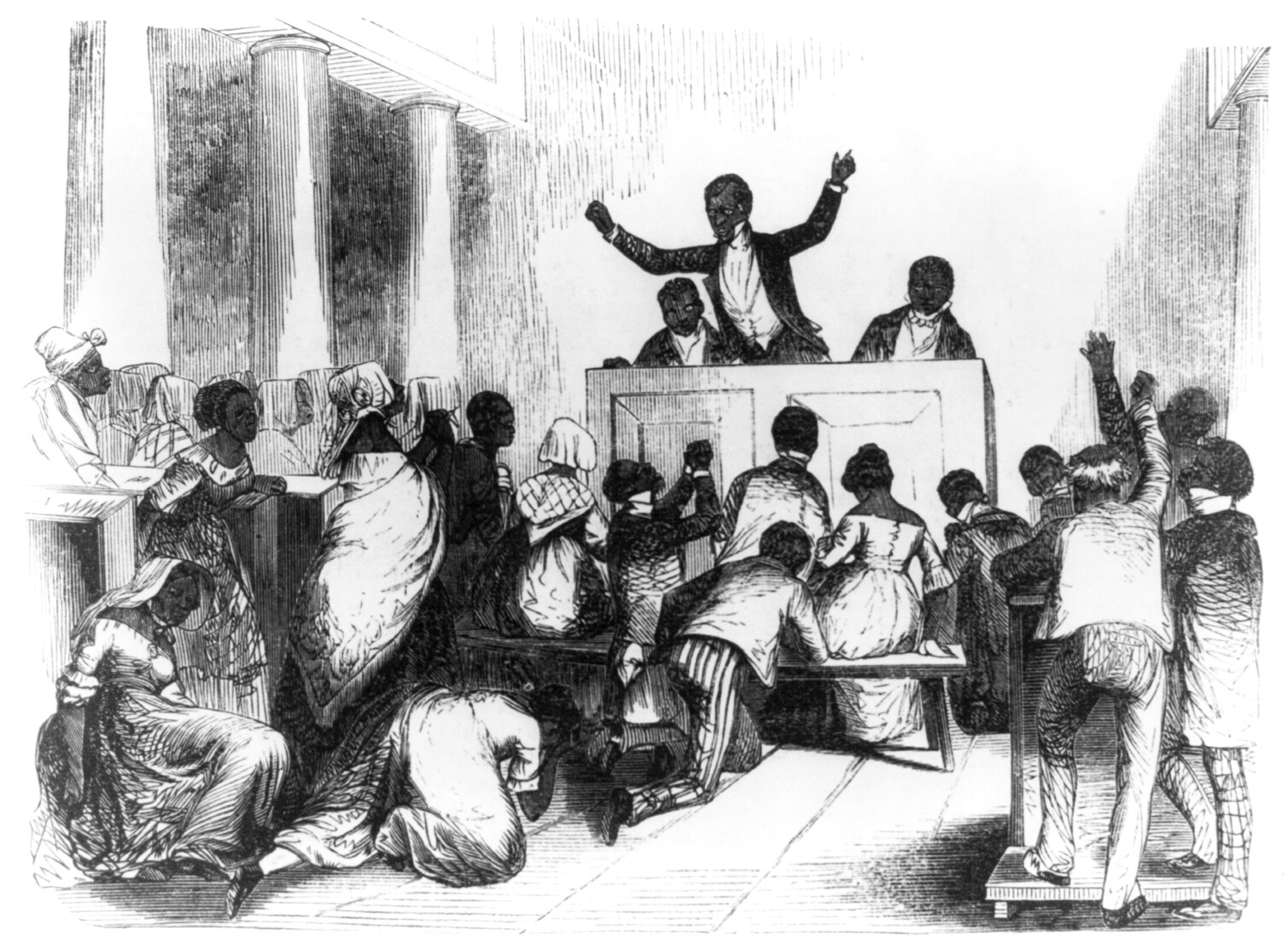

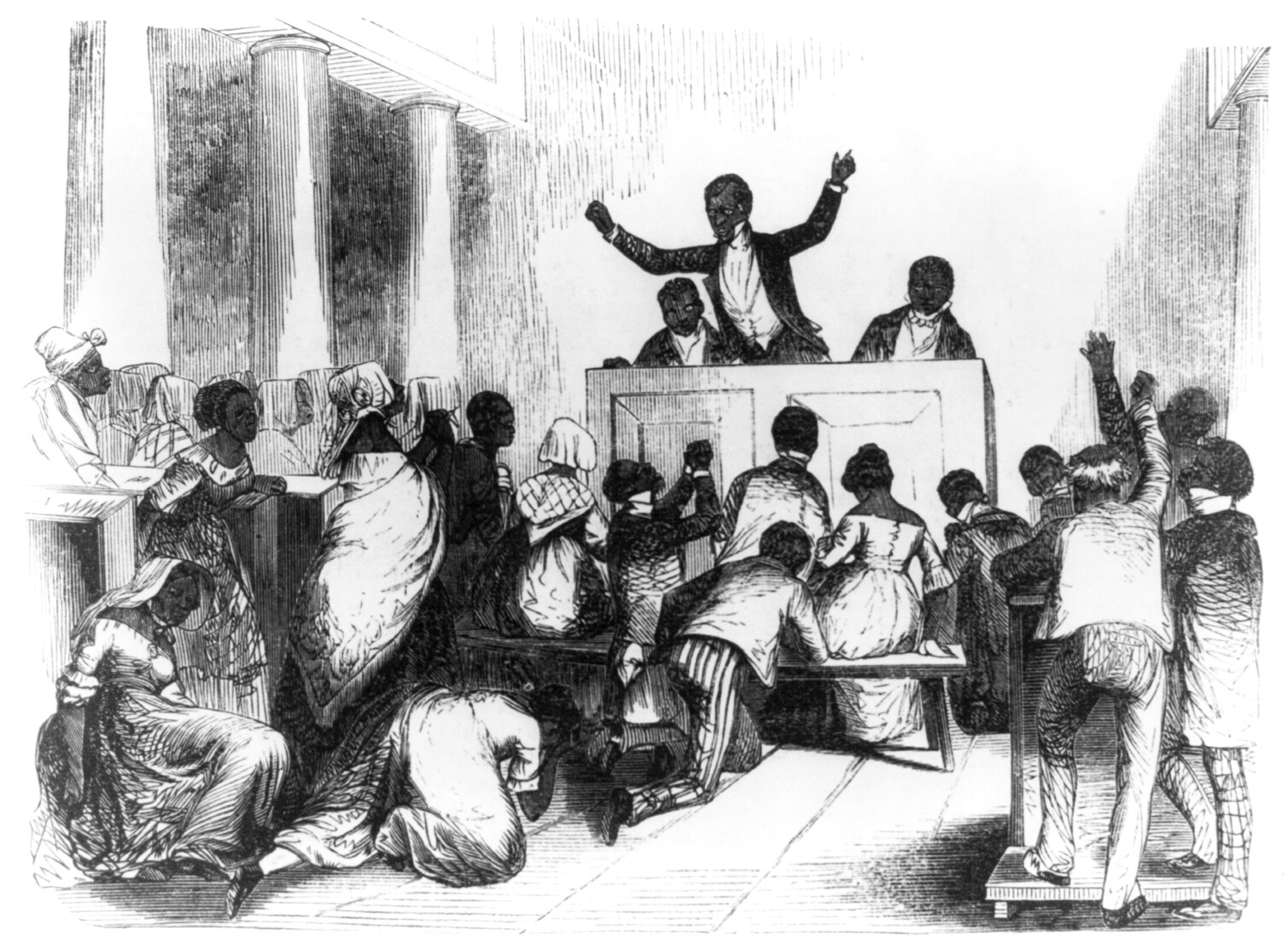

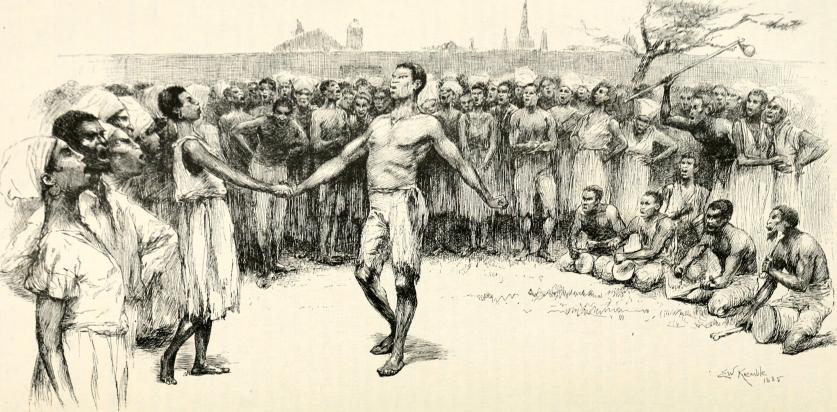

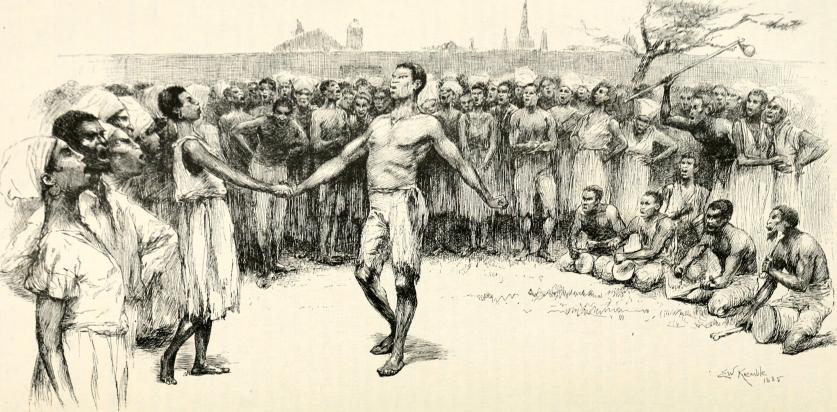

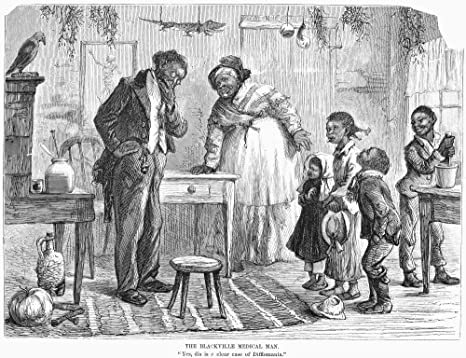

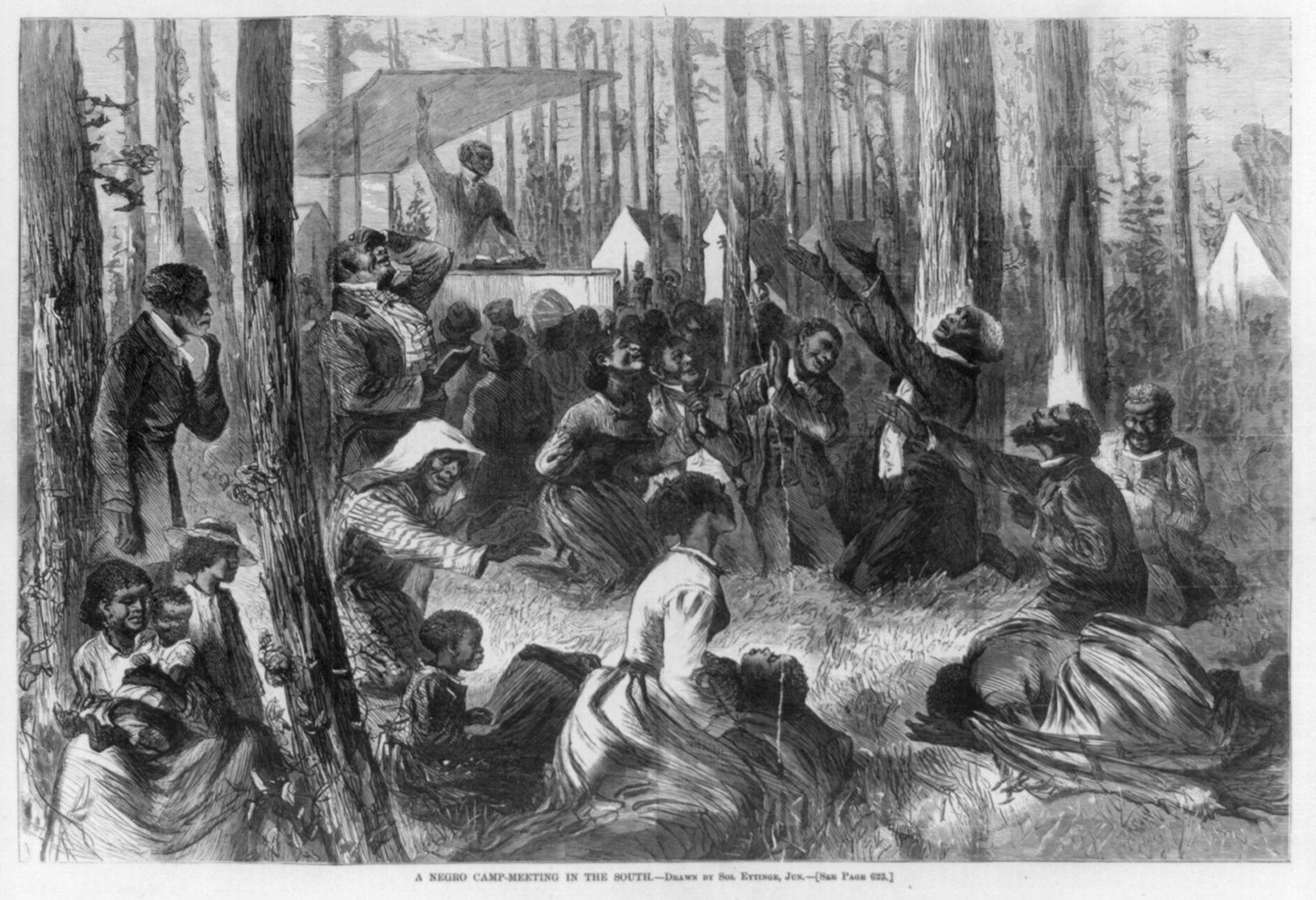

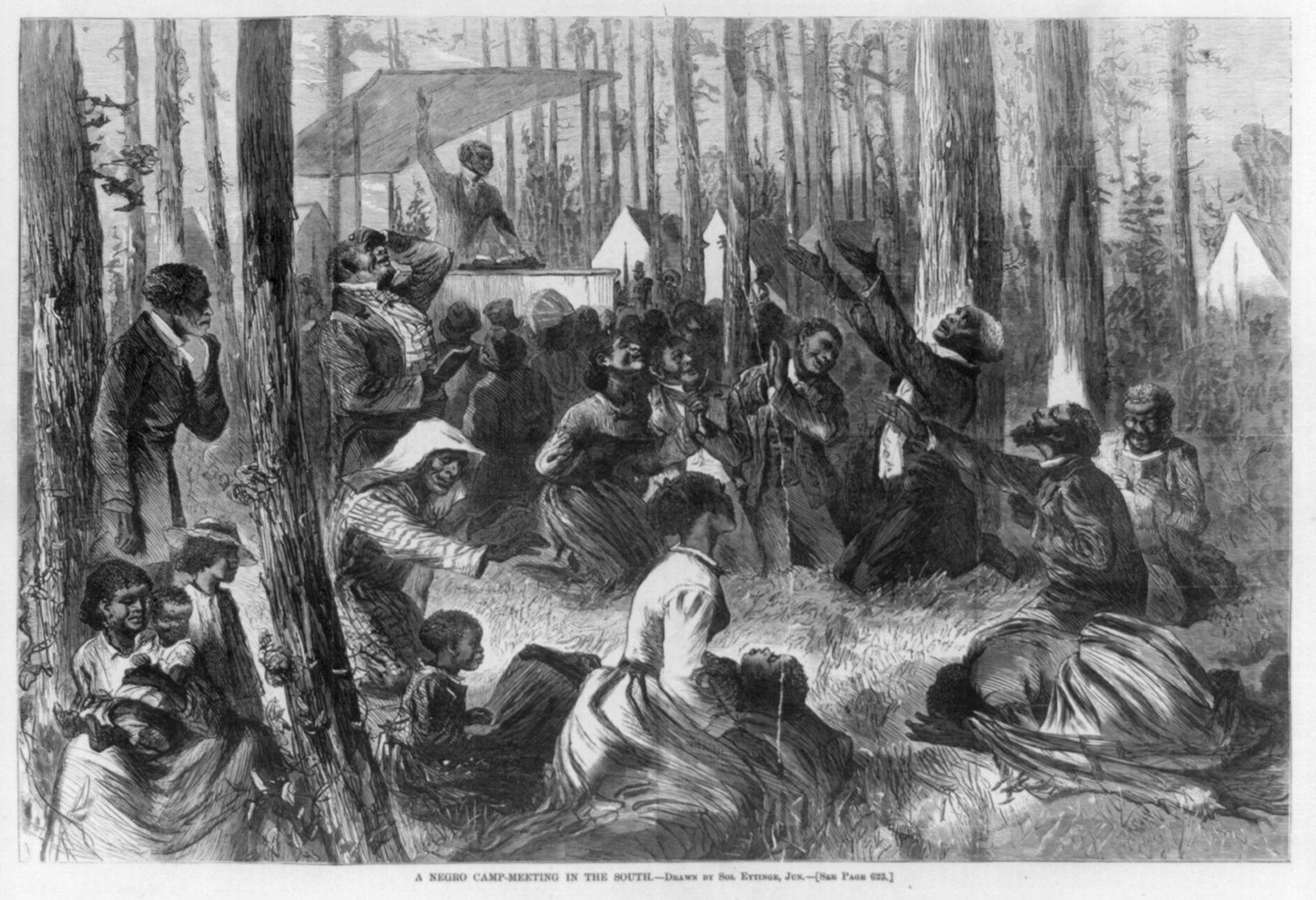

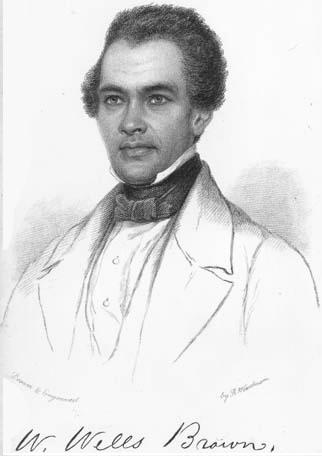

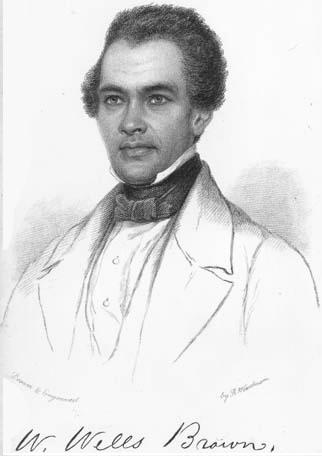

During the slave trade, the majority of Central Africans imported to New Orleans, Louisiana, were Bakongo people. This image was painted in 1886 and shows African Americans in New Orleans performing dances from Africa in Congo Square. Congo Square was where African Americans practiced Voodoo and Hoodoo.[36] The Code Noir was implemented in 1724 in French colonial Louisiana. It regulated the lives of enslaved and free people and prohibited and made it illegal for enslaved Africans to practice their traditional religions. Article III in the Code Noir states: "We forbid any public exercise of any religion other than Catholic."[37] The Code Noir and other slave laws resulted in enslaved and free African Americans conducting their spiritual practices in secluded areas such as woods (hush harbors), churches, and other places.[38] Slaves created methods to decrease their noise when they practiced their spirituality. In a slave narrative from Arkansas, enslaved people prayed under pots to prevent nearby white people from hearing them at such times. A formerly enslaved person in Arkansas named John Hunter said the enslaved people went to a secret house only they knew and turned the iron pots face up so enslavers could not hear them. They would place sticks under wash pots about a foot from the ground because "[I]f they'd put it flat on the ground the ground would carry the sound."[39] Formerly enslaved person and abolitionist William Wells Brown wrote in his book, My Southern Home, or, The South and Its People, published in 1880, about the life of enslaved people in St. Louis, Missouri. Brown recorded a secret Voudoo ceremony at midnight in St. Louis. Enslaved people circled a cauldron, and a Voudoo queen had a magic wand. Snakes, lizards, frogs, and other animal parts were thrown into the cauldron. During the ceremony, spirit possession took place. Brown also recorded other conjure (Hoodoo) practices among the enslaved population.[40] Enslaved Africans in America held on to their African culture. Some scholars assert that Christianity did not have much influence on some of the enslaved Africans as they continued to practice their traditional spiritual practices. Hoodoo was a form of resistance against slavery whereby enslaved Africans hid their traditions using the Christian religion against enslavers.[41][42] This branch of Christianity among the enslaved was concealed from enslavers in "invisible churches." Invisible churches were secret churches where enslaved African Americans combined Hoodoo with Christianity. Enslaved and free Black ministers preached resistance to slavery and the power of God through praise and worship, and Hoodoo rituals would free enslaved people from bondage.[43] William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (W. E. B. Du Bois) studied African American churches in the early twentieth century. Du Bois asserts the early years of the Black church during slavery on plantations were influenced by Voodooism.[44] Black church records from the late nineteenth century into the early twentieth century in the South recorded that some church members practiced conjure and combined Christian and African spiritual concepts to harm or heal members in their community.[45] |

奴隷貿易の時代、ルイジアナ州ニューオーリンズに輸入された中央アフリカ人の大半はバコンゴ人であった。この絵画は1886年に描かれたもので、ニュー オーリンズのアフリカ系アメリカ人がコンゴ広場でアフリカの踊りを披露している様子を描いている。コンゴ広場はアフリカ系アメリカ人がヴードゥー教や フードゥー教を実践する場所であった。 黒人法は1724年にフランス植民地ルイジアナで施行された。これは奴隷と自由民の生活を規制するもので、奴隷のアフリカ人が伝統宗教を信仰することを禁 止し違法とした。黒人法の第3条には次のように記されている。「カトリック以外の宗教の公の実践は一切禁止する」[37] 黒人奴隷法やその他の奴隷法により、奴隷および自由の身となったアフリカ系アメリカ人は、森(口止め情報)や教会、その他の人目につかない場所でスピリ チュアルな実践を行うようになった。[38] 奴隷たちは、スピリチュアリティを実践する際に音を立てない方法を編み出した。アーカンソー州の奴隷による物語では、奴隷たちは、そのような時に近くにい る白人に聞かれないように、鍋の下で祈りを捧げていた。アーカンソー州の元奴隷ジョン・ハンターは、奴隷たちは自分たちだけが知っている秘密の家に行き、 鉄鍋をひっくり返して、奴隷所有者が自分たちの祈りを聞こえないようにしたと語っている。彼らは、洗うための鍋を地面から約30センチの高さの棒の下に置 いた。「もし地面に平らに置いたら、地面が音を伝えてしまうから」だ。 元奴隷であり、奴隷制度廃止論者でもあったウィリアム・ウェルズ・ブラウンは、1880年に出版した著書『My Southern Home, or, The South and Its People』の中で、ミズーリ州セントルイスにおける奴隷の人々の生活について書いている。ブラウンは、セントルイスで真夜中に行われた秘密のブー ドゥー教の儀式を記録している。奴隷の人々は大釜の周りを囲み、ブードゥー教の女王が呪術的な杖を持っていた。蛇、トカゲ、蛙、その他の動物の部位が大釜 に投げ込まれた。儀式の間、憑依現象が起こった。ブラウンは奴隷たちの間で行われていたその他の呪術(フードゥー)の慣習も記録している。[40] アメリカに奴隷として連れて来られたアフリカ人は、自分たちのアフリカ文化を保持し続けた。 一部の学者は、キリスト教は奴隷として連れて来られたアフリカ人の一部にはあまり影響を与えなかったと主張している。なぜなら、彼らは伝統的なスピリチュ アルな慣習を続けていたからだ。フードゥーは、奴隷として連れて来られたアフリカ人がキリスト教を悪用して、奴隷制度に対する抵抗の形として、自分たち の伝統を隠すためのものだった。[41][42] 奴隷として連れて来られた人々の間でのキリスト教の一派は、「見えない教会」で奴隷制度の管理者たちから隠されていた。見えない教会とは、奴隷として連れ て来られたアフリカ系アメリカ人がフードゥーとキリスト教を組み合わせた秘密の教会のことである。奴隷や自由な黒人の牧師たちは、奴隷制度への抵抗と神 の力を賛美と礼拝を通して説き、フードゥー教の儀式によって奴隷を束縛から解放した。[43] ウィリアム・エドワード・バーガート・デュ・ボイス(W. E. B. Du Bois)は、20世紀初頭にアフリカ系アメリカ人の教会について研究した。デュボアは、奴隷制が敷かれていた農園での初期の黒人教会はブードゥー教の影 響を受けていたと主張している。[44] 南部における19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけての黒人教会の記録によると、一部の教会員は魔術を実践し、キリスト教とアフリカの霊的概念を組み合わ せ、地域社会の教会員に害を与えたり、癒やしたりしていたことが記録されている。[45] |

Honey jars or sweetening jars are a tradition in Hoodoo to sweeten a person or a situation in a person's favor. Traditionally, sugar water is used.[46] Known Hoodoo spells date back to the era of slavery in the colonial history of the United States. A slave revolt broke out in 1712 in colonial New York, with enslaved Africans revolting and setting fire to buildings in the downtown area. The leader of the revolt was a free African conjurer named Peter the Doctor, who made a magical powder for the enslaved people to be rubbed on the body and clothes for their protection and empowerment. The Africans who revolted were Akan people from Ghana. Historians suggest the powder made by Peter the Doctor probably included some cemetery dirt to conjure the ancestors to provide spiritual militaristic support from ancestral spirits as help during the slave revolt. The Bakongo people in Central Africa incorporated cemetery dirt into minkisi conjuring bags to activate it with ancestral spirits. During the slave trade, Bakongo people were brought to colonial New York. The New York slave revolt of 1712 and others in the United States showed a blending of West and Central African spiritual practices among enslaved and free Black people.[47][48] Conjure bags, also called mojo bags were used as a resistance against slavery. In the 1830s, Black sailors from the United States utilized conjure for safe sea travel. A Black sailor received a talisman from an Obi (Obeah) woman in Jamaica. This account shows how Black Americans and Jamaicans shared their conjure culture and had similar practices. Free Blacks in northern states had white and Black clients regarding fortune-telling and conjure services.[49] In Alabama slave narratives, it was documented that formerly enslaved people used graveyard dirt to escape from slavery on the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers rubbed graveyard dirt on the bottom of their feet or put graveyard dirt in their tracks to prevent slave catchers' dogs from tracking their scent. Former slave Ruby Pickens Tartt from Alabama told of a man who could fool the dogs, saying he "done lef' dere and had dem dogs treein' a nekked tree. Dey calls hit hoodooin' de dogs". An enslaved conjurer could conjure confusion in the slave catchers' dogs, which prevented whites from catching freedom seekers.[50] In other narratives, enslaved people made a jack ball to know if an enslaved person would be whipped or not. Enslaved people chewed and spat the juices of roots near their enslavers secretly to calm the emotions of enslavers, which prevented whippings. Enslaved people relied on conjurers to prevent whippings and being sold further South.[51] A story from a former slave, Mary Middleton, a Gullah woman from the South Carolina Sea Islands, tells of an incident where an enslaver was physically weakened from conjure. An enslaver beat one of the people he enslaved badly. The enslaved person he beat went to a conjurer, and the conjurer made the enslaver weak by sunset. Middleton said, "As soon as the sun was down, he was down too, he down yet. De witch done dat." Bishop Jamison, born enslaved in Georgia in 1848, wrote an autobiographical account of his life. On a plantation in Georgia, there was an enslaved Hoodoo man named Uncle Charles Hall who prescribed herbs and charms for enslaved people to protect themselves from white people. Hall instructed the enslaved people to anoint roots three times daily and chew and spit roots toward their enslavers for protection.[52] Another slave story talks about an enslaved woman named Old Julie, who was a conjurer known among the enslaved people on the plantation for conjuring death. Old Julie conjured so much death that her enslaver sold her away to stop her from killing people on the plantation with conjure. Her enslaver put her on a steamboat to take her to her new enslaver in the Deep South. According to the stories of freedmen after the Civil War, Old Julie used her conjure powers to turn the steamboat back to where it was docked, forcing her enslaver who tried to sell her to keep her.[53] Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved person, abolitionist, and author wrote in his autobiography that he sought spiritual assistance from an enslaved conjurer named Sandy Jenkins. Sandy told Douglass to follow him into the woods, where they found a root that Sandy told Douglass to carry in his right pocket to prevent any white man from whipping him. Douglass carried the root on his right side as instructed by Sandy and hoped the root would work when he returned to the plantation. The cruel slave-breaker, Mr. Covey, told Douglass to do some work, but as Mr. Covey approached Douglass, Douglass had the strength and courage to resist Mr. Covey and defeated him after they fought. Covey never bothered Douglass again. In his autobiography, Douglass believed the root given to him by Sandy prevented him from being whipped by Mr. Covey.[54] Conjure for African Americans is a form of resistance against white supremacy.[55][56] African American conjurers were seen as a threat by white Americans because slaves went to free and enslaved conjurers to receive charms for protection and revenge against their enslavers.[57] Enslaved Black people used Hoodoo to bring about justice on American plantations by poisoning enslavers and conjuring death onto their oppressors.[58] |

蜂蜜瓶または甘味料瓶は、人格または状況をその人の望むように甘くするためのフードゥー教の伝統である。伝統的には砂糖水が使用される。 [46] 知られているフードゥー教の呪文は、アメリカ合衆国の植民地時代の奴隷制度の時代まで遡る。1712年、植民地時代のニューヨークで奴隷反乱が勃発し、 奴隷となっていたアフリカ人が反乱を起こし、市街地の建物に火を放った。反乱のリーダーはピーター・ザ・ドクターという名の自由なアフリカ人呪術師で、奴 隷たちが身体や衣服に塗って身を守り、力を得るための呪術的な粉末を作っていた。反乱を起こしたアフリカ人はガーナのアカン族であった。歴史家たちは、 ピーター・ザ・ドクターが作った粉末にはおそらく墓地の土が含まれており、奴隷反乱の際には先祖の霊から軍事的・精神的な支援を得るために使われたのでは ないかと推測している。中央アフリカのバコンゴ族は、ミンキシの魔術袋に墓地の土を混ぜ、先祖の霊を呼び起こした。奴隷貿易の時代、バコンゴ族は植民地時 代のニューヨークにも連れてこられた。1712年のニューヨークの奴隷反乱や、アメリカ国内の他の奴隷反乱では、西アフリカと中央アフリカの霊的実践が奴 隷や自由黒人の間で融合していることが示された。1830年代には、米国から来た黒人船員たちが、航海の安全を祈願するためにコンジャーを利用していた。 ジャマイカのオビ(オベア)の女性から護符を受け取った黒人船員もいた。この話は、黒人アメリカ人とジャマイカ人がコンジャー文化を共有し、類似した慣習 を持っていたことを示している。北部の州の自由黒人は、占いやコンジャーのサービスに関して、白人や黒人の顧客を抱えていた。 アラバマ州の奴隷の証言では、かつて奴隷であった人々が地下鉄道で奴隷制度から逃れるために墓地の土を使用していたことが記録されている。自由を求める人 々は、奴隷捕獲人の犬が自分の匂いを追跡できないように、足の裏に墓地の土をこすりつけたり、足跡に土を付けたりした。アラバマ州出身の元奴隷、ルビー・ ピケンズ・タートは、犬を欺くことができた男について、「ここから逃げ出して、犬たちに裸の木に吠えさせてやった。犬たちはそれを魔法だと思った」と語っ た。奴隷の魔術師は、奴隷捕獲者の犬を混乱させ、自由を求める人々を捕まえる白人を妨害することができた。[50] 別の話では、奴隷の人々は、奴隷が鞭打ちされるかどうかを知るためにジャックボールを作った。奴隷の人々は、秘密裏に奴隷所有者の近くにある根の汁を噛ん で吐き出し、奴隷所有者の感情を落ち着かせ、鞭打ちを防いだ。奴隷たちは、鞭打ちや南部へのさらなる売却を防ぐために、呪術師に頼っていた。[51] サウスカロライナ州の海上諸島出身の奴隷、メアリー・ミドルトン(ガラ族の女性)の元奴隷の話によると、呪術によって肉体的弱体化を経験した奴隷所有者が いたという。奴隷所有者が、奴隷として酷く扱っていた人物を殴った。殴られた奴隷は呪術師のもとへ行き、呪術師は日没までに奴隷所有者を弱体化させた。ミ ドルトンは「日が沈むや否や、彼もまた弱った。呪術師の仕業だ」と語った。 1848年にジョージア州で生まれ、奴隷として過ごしたジャミソン司教は、自伝を著している。ジョージア州の農園には、アンクル・チャールズ・ホールとい う名の奴隷のフードゥー教の男がおり、奴隷たちが白人から身を守るための薬草や護符を処方していた。ホールは、奴隷たちに毎日3回根を塗り、護符として それを噛み砕いて奴隷所有者に吐きかけるようにと教えた。 別の奴隷の話では、オールド・ジュリーという名の奴隷の女性が登場する。彼女は、その農園の奴隷たちの間で死を呼び起こす魔術師として知られていた。オー ルド・ジュリーはあまりにも多くの死を呼び起こしたため、彼女の主人は、彼女が魔術を使って農園の人々を殺すのをやめさせるために、彼女を売り飛ばした。 彼女の主人は蒸気船に乗せて、ディープ・サウス(アメリカ南部の奥地)の新しい主人のもとへ連れて行った。南北戦争後の解放奴隷たちの話によると、オール ド・ジュリーは魔術の力で蒸気船を元の停泊地に戻し、自分を売り飛ばそうとした主人に自分を留まらせるよう強制したという。 かつて奴隷であったフレデリック・ダグラスは、奴隷制度廃止論者であり作家でもあったが、自伝の中で、奴隷の魔術師であるサンディ・ジェンキンズに霊的な 助けを求めたと書いている。サンディは、ドウグラスに森の中へついてくるように言った。そこで2人は、サンディがドウグラスに、白人に鞭で打たれないよう にするために右のポケットに入れておくように言った根を見つけた。ドウグラスはサンディの指示通りに根を右側に持ち、農園に戻ったときにその根が効力を発 揮することを願った。残酷な奴隷解放者、コーベイ氏は、ドグラスに仕事を命じたが、コーベイ氏がドグラスに近づくと、ドグラスはコーベイ氏に抵抗する力と 勇気を持っており、戦いの末に彼を打ち負かした。コーベイは二度とドグラスに干渉することはなかった。ドグラスは自伝の中で、サンディから受け取った根が コーベイ氏による鞭打ちを防いだと信じていた。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の魔術は、白人至上主義に対する抵抗の一形態である。[55][56] アフリカ系アメリカ人の魔術師は、奴隷が自由の身となり、奴隷制に反対する魔術や、奴隷制の加害者に対する復讐の魔術を受けるために魔術師のもとへ通うた め、白人アメリカ人にとっては脅威であった。[57] 奴隷として黒人たちは、フードゥーを用いて、奴隷制の加害者を毒殺したり、抑圧者に死をもたらしたりすることで、アメリカの農園で正義をもたらそうとし た。[58] |

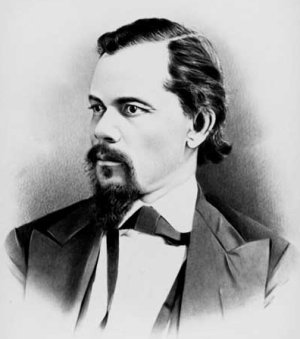

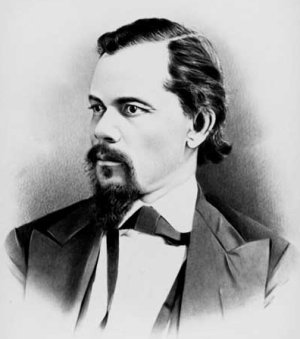

Paschal Beverly Randolph During the era of slavery, occultist Paschal Beverly Randolph began studying the occult and traveled and learned spiritual practices in Africa and Europe. Randolph was a mixed-race free Black man who wrote several books on the occult. In addition, Randolph was an abolitionist who spoke out against slavery in the South. After the American Civil War, Randolph educated freedmen in schools for formerly enslaved people called Freedmen's Bureau Schools in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he studied Louisiana Voodoo and Hoodoo in African American communities, documenting his findings in his book, Seership, The Magnetic Mirror. In 1874, Randolph organized a spiritual organization called Brotherhood of Eulis in Tennessee.[59][60] Through his travels, Randolph documented the continued African traditions in Hoodoo practiced by African Americans in the South. Randolph documented two African American men of Kongo origin who used Kongo conjure practices against each other. The two conjure men came from a slave ship that docked in Mobile Bay in 1860 or 1861.[61][62] |

パスカ・ビバリー・ランドルフ 奴隷制度の時代に、オカルト研究家パスカ・ビバリー・ランドルフはオカルトの研究を始め、アフリカやヨーロッパを旅してスピリチュアルな修行を学んだ。ラ ンドルフは混血の自由黒人男性で、オカルトに関する本を数冊執筆した。さらに、ランドルフは南部の奴隷制度に反対する奴隷制度廃止論者でもあった。南北戦 争後、ランドルフはルイジアナ州ニューオーリンズのフリードメンズ・ビューロー・スクールと呼ばれる元奴隷のための学校で解放奴隷たちに教育を行った。こ こで彼はアフリカ系アメリカ人社会におけるルイジアナ・ヴードゥーとフードゥーを研究し、その成果を著書『Seership, The Magnetic Mirror』にまとめた。1874年、ランドルフはテネシー州で「ブラザーフッド・オブ・エウリス」というスピリチュアルな組織を結成した。[59] [60] ランドルフは、南部の黒人たちが実践するフードゥーにアフリカの伝統が継続していることを、自身の旅を通じて記録した。ランドルフは、コンゴ起源の2人 のアフリカ系アメリカ人が互いにコンゴの魔術を行使していることを記録した。この2人の魔術師は、1860年か1861年にモービル湾に停泊した奴隷船か ら来た。[61][62] |

| Post-emancipation The mobility of Black people from the rural South to more urban areas in the North is characterized by the items used in Hoodoo. White pharmacists opened their shops in African American communities. They began to offer items both asked for by their customers, as well as things they felt would be of use.[63] Examples of the adoption of occultism and mysticism may be seen in the colored wax candles in glass jars that are often labeled for specific purposes such as "Fast Luck" or "Love Drawing." Some African Americans sold hoodoo products in the Black community. An African American woman, Mattie Sampson, was a salesperson in an active mail-order business selling hoodoo products to her neighbors in Georgia.[64] Since the opening of Botanicas, Hoodoo practitioners purchase their spiritual supplies of novena candles, incense, herbs, conjure oils, and other items from spiritual shops that service practitioners of Vodou, Santeria, and other African Traditional Religions.[65]  Black Herman Hoodoo spread throughout the United States as African Americans left the delta during the Great Migration. As African Americans left the South during the Great Migration, they took the practice of Hoodoo to other Black communities in the North. Benjamin Rucker, also known as Black Herman, provided Hoodoo services for African Americans in the North and the South when he traveled as a stage magician. Benjamin Rucker was born in Virginia in 1892. Rucker learned stage magic and conjure from an African American named Prince Herman (Alonzo Moore). After Prince Herman's death, Rucker changed his name to Black Herman in honor of his teacher. Black Herman traveled between the North and South and provided conjure services in Black communities, such as card readings and crafting health tonics. However, Jim Crow laws pushed Black Herman to Harlem, New York's Black community, where he operated his own Hoodoo business and provided rootwork services to his clients.[66] For some African Americans who practiced rootwork, providing conjure services in the Black community for African Americans to obtain love, money, employment, and protection from the police was a way to help Black people during the Jim Crow era in the United States so Black people can gain employment to support their families, and for their protection against the law.[67][68] As Black people traveled to northern areas, Hoodoo rituals were modified because there were not a lot of rural country areas to perform rituals in woods or near rivers. Therefore, African Americans improvised their rituals inside their homes or secluded regions of the city. Herbs and roots needed were not gathered in nature but bought in spiritual shops. These spiritual shops near Black neighborhoods sold botanicals and books used in modern Hoodoo.[69] |

奴隷解放後 南部の農村から北部の都市部へと黒人が移動したことは、フードゥーで使用される品物によって特徴づけられる。白人の薬剤師がアフリカ系アメリカ人のコ ミュニティに薬局を開いた。彼らは顧客が求める品物だけでなく、役に立つと思われる品物も提供し始めた。[63] オカルティズムや神秘主義の採用例としては、ガラス瓶に入った有色の蝋燭に「幸運を呼ぶ」や「愛を引き寄せる」など特定の用途が示されているものがある。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の一部は、ブラックコミュニティでフードゥーの商品を販売していた。アフリカ系アメリカ人の女性、マティ・サンプソンは、ジョージ ア州の近隣住民にフードゥー教の商品を販売する活発な通信販売事業の販売員であった。[64] ボタニカが開店して以来、フードゥー教の実践者は、ヴードゥー教、サンテリア、その他のアフリカ伝統宗教の実践者にサービスを提供するスピリチュアル ショップから、ノヴェナキャンドル、お香、ハーブ、呪術用オイル、その他の物品を購入している。[65]  ブラック・ハーマン・ フードゥーは、アフリカ系アメリカ人が大移動でデルタ地帯を離れるのに伴い、全米に広がった。アフリカ系アメリカ人が大移動で南部を離れるのに伴い、彼 らは北部の他の黒人コミュニティにフードゥーの慣習を持ち込んだ。ブラック・ハーマンとしても知られるベンジャミン・ラッカーは、舞台マジシャンとして 旅をしていた際、北部と南部のアフリカ系アメリカ人にフードゥーのサービスを提供していた。ベンジャミン・ラッカーは1892年にバージニア州で生まれ た。ラッカーは、プリンス・ハーマン(本名アロンゾ・ムーア)という名の黒人から舞台マジックと手品を学んだ。プリンス・ハーマンの死後、ラッカーは師の 名誉を称えてブラック・ハーマンと改名した。ブラック・ハーマンは南北を行き来し、カード占いや保健強壮剤の調合など、黒人コミュニティで手品サービスを 提供していた。しかし、ジム・クロウ法によりブラック・ハーマンはニューヨークの黒人居住区ハーレムへと追いやられ、そこで彼はフードゥー教のビジネス を営み、クライアントにルーツワークのサービスを提供した。 ルーツワークを実践する一部のアフリカ系アメリカ人にとって、黒人コミュニティで魔術サービスを提供することは、アフリカ系アメリカ人が愛や金銭、雇用を 得たり、警察からの保護を受けたりできるように手助けすることであり、それは 家族を養うための雇用を得たり、法による保護を受けたりできるようにするためである。[67][68] 黒人たちが北部地域へと移動するにつれ、森や川の近くで儀式を行う田舎の地域が少なくなったため、フードゥーの儀式も変化していった。そのため、アフリ カ系アメリカ人は、自宅や都市の奥まった場所で儀式を即興で行うようになった。必要なハーブや根は自然界で採取するのではなく、スピリチュアルショップで 購入した。こうしたスピリチュアルショップは黒人居住区の近くにあり、近代フードゥーで使用される植物や書籍を販売していた。[69] |

Protesters with signs in Ferguson After the American Civil War into the present day with the Black Lives Matter movement, Hoodoo practices in the African American community also focus on spiritual protection from police brutality.[70][71] Today, Hoodoo and other African Traditional Religions are present in the Black Lives Matter movement as one of many methods against police brutality and racism in the Black community. Black American keynote speakers who are practitioners of Hoodoo spoke at an event at The Department of Arts and Humanities at California State University about the importance of Hoodoo and other African spiritual traditions practiced in social justice movements to liberate Black people from oppression.[72] African Americans in various African diaspora religions spiritually heal their communities by establishing healing centers that provide emotional and spiritual healing from police brutality. In addition, altars with white candles and offerings are placed in areas where police murdered an African American, and libation ceremonies and other spiritual practices are performed to heal the soul that died from racial violence.[73] African Americans also use Hoodoo to protect their properties from gentrification in their neighborhoods and on sites that are considered sacred to their communities. On Daufuskie Island, South Carolina in the early twentieth century, a Hoodoo practitioner, Buzzard, placed a curse on a developing company that continued to build properties in Gullah cemeteries where Buzzard's ancestors are buried. According to locals, because of the curse, the company and others following have never been able to build properties in the area, and the owner of the company had a heart attack.[74] Locals from Frenier, Louisiana believe the Hurricane of 1915 that wiped out the town was predicted by a Hoodoo lady named Julia Brown who sang a song on her front porch that she would take the town with her when she die because the people in the area mistreated her after she helped them.[75] Black women practitioners of Hoodoo, Lucumi, Palo and other African-derived traditions are opening and owning spiritual stores online and in Black neighborhoods to provide spiritual services to their community and educate African-descended people about Black spirituality and how to heal themselves physically and spiritually.[76] The culture of Hoodoo has inspired the creations of art for some Black artists. In 2017, The Rootworker's Table is an art piece created by artist Renee Stout that showed the culture of Hoodoo portrayed as an altar with a collection of bottled tinctures and a chalkboard with Hoodoo herbal knowledge. The artist grew up in the Hill District of Pittsburgh and saw Hoodoo practitioners who were mainly Black women. Black women played a role in their communities as midwives, healers, and conjure women for their clients.[77] |

ファーガソンでプラカードを掲げる抗議者たち アメリカ南北戦争後から今日まで続くブラック・ライブズ・マター運動に おいて、アフリカ系アメリカ人社会におけるフードゥーの実践は、警察による残虐行為からの霊的な保護にも焦点を当てている。[70][71] 今日、フードゥーやその他のアフリカ伝統宗教は、ブラック・ライブズ・マター運動において、警察による残虐行為やアフリカ系アメリカ人社会における人種 主義に対する多くの方法のひとつとして存在している。フードゥーの実践者である黒人アメリカ人の基調講演者が、カリフォルニア州立大学人文科学部のイベ ントで、抑圧から黒人を開放するための社会正義運動において、フードゥーやその他のアフリカの精神伝統が重要であることを語った。[72] さまざまなアフリカ系ディアスポラ宗教に属するアフリカ系アメリカ人は、警察の暴力から感情的・精神的な癒しを提供するヒーリングセンターを設立すること で、コミュニティを精神的に癒している。さらに、警察官がアフリカ系アメリカ人を殺害した場所には、白いろうそくと供物が置かれた祭壇が置かれ、人種的暴 力によって命を落とした魂を癒やすための供物儀式やその他のスピリチュアルな実践が行われている。20世紀初頭のサウスカロライナ州ドーフィスク島では、 フードゥー教の実践者バザードが、バザードの祖先が埋葬されているガラ族の墓地に不動産開発を続けた開発会社に呪いをかけた。地元住民によると、その呪 いのせいで、その会社およびその系列会社はその後もその地域に物件を建設することができず、その会社のオーナーは心臓発作を起こしたという。[74] ルイジアナ州フレンチーの住民は、1915年のハリケーンで町が全壊したことは 15年に町を壊滅させたハリケーンは、フードゥーの霊媒師ジュリア・ブラウンという女性が、人々を助けた後にその地域の人々に不当に扱われたため、死後 には町を道連れにするという歌を自宅のポーチで歌ったことで予言されたと信じられている。 フードゥー、ルクミ、パロなどアフリカ由来の伝統を実践する黒人女性たちは、オンラインや黒人居住区でスピリチュアルショップを開業し、地域社会にスピ リチュアルサービスを提供したり、アフリカ系の人々に黒人霊性や心身の癒し方を教えたりしている。[76] フードゥーの文化は、一部の黒人アーティストの芸術作品の創作にインスピレーションを与えている。2017年には、アーティストのレネー・スタウトが制 作したアート作品『The Rootworker's Table』では、フードゥーの文化が祭壇として表現され、ビン入りのチンキ剤のコレクションや、フードゥーの薬草知識が書かれた黒板が置かれてい る。アーティストはピッツバーグのヒル地区で育ち、主に黒人女性であるフードゥーの実践者を目にした。黒人女性は、助産師、治療師、顧客のための占い師 として、コミュニティで役割を果たしていた。[77] |

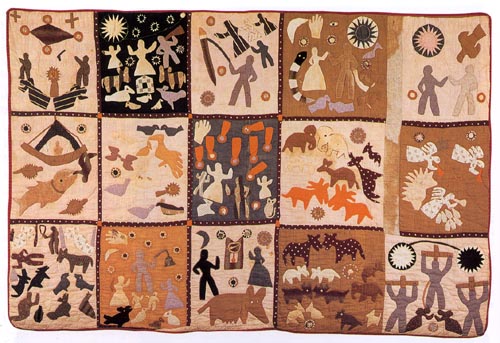

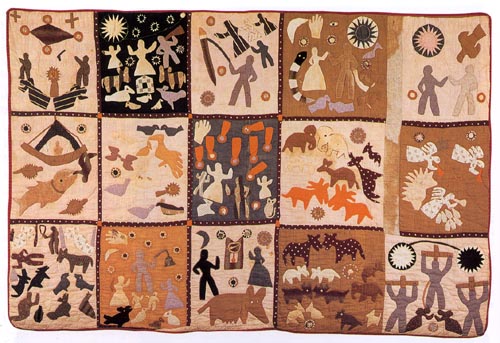

| Central African influence Cultural anthropologist Tony Kail conducted research in African American communities in Memphis, Tennessee, and traced the origins of Hoodoo practices to Central Africa. In Memphis, Kail interviewed Black rootworkers and wrote about African American Hoodoo practices and history in his book "A Secret History of Memphis Hoodoo." For example, Kail recorded at former slave plantations in the American South: "The beliefs and practices of African traditional religions survived the Middle Passage (the Transatlantic slave trade) and were preserved among the many rootworkers and healers throughout the South. Many of them served as healers, counselors, and pharmacists to slaves enduring the hardships of slavery."[78] Sterling Stuckey, a professor of American history who specialized in the study of American slavery and African American slave culture and history in the United States, asserted that African culture in America developed into a uniquely African American spiritual and religious practice that was the foundation for conjure, Black theology, and liberation movements. Stuckey provides examples in the slave narratives, African American quilts, Black churches, and the continued cultural practices of African Americans.[79][80][81] |

中央アフリカからの影響 文化人類学者のトニー・ケイルは、テネシー州メンフィスのアフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティで調査を行い、フードゥー教の起源を中央アフリカにまで遡っ た。メンフィスで、カイルは黒人のルーツワーカーたちにインタビューを行い、著書『メンフィス・フードゥーの秘密の歴史』でアフリカ系アメリカ人の フードゥーの慣習と歴史について書いている。例えば、カイルはアメリカ南部の元奴隷農園で次のように記録している。「アフリカの伝統宗教の信仰と慣習 は、大西洋奴隷貿易(中間航路)を生き延び、南部各地の多くのルーツワーカーやヒーラーたちによって守られてきた。その多くは、奴隷制度の苦難に耐える奴 隷たちの治療師、カウンセラー、薬剤師として働いていた」[78] 米国史の教授であり、米国における奴隷制度とアフリカ系米国人の奴隷文化および歴史の研究を専門とするスターリング・スタッキーは、米国におけるアフリカ 文化は、アフリカ系米国人の独特な精神性と宗教的実践へと発展し、それが呪術、ブラック神学、解放運動の基盤となったと主張している。Stuckeyは、 奴隷の証言、アフリカ系アメリカ人のキルト、黒人教会、そしてアフリカ系アメリカ人の継続的な文化実践を例に挙げている。[79][80][81] |

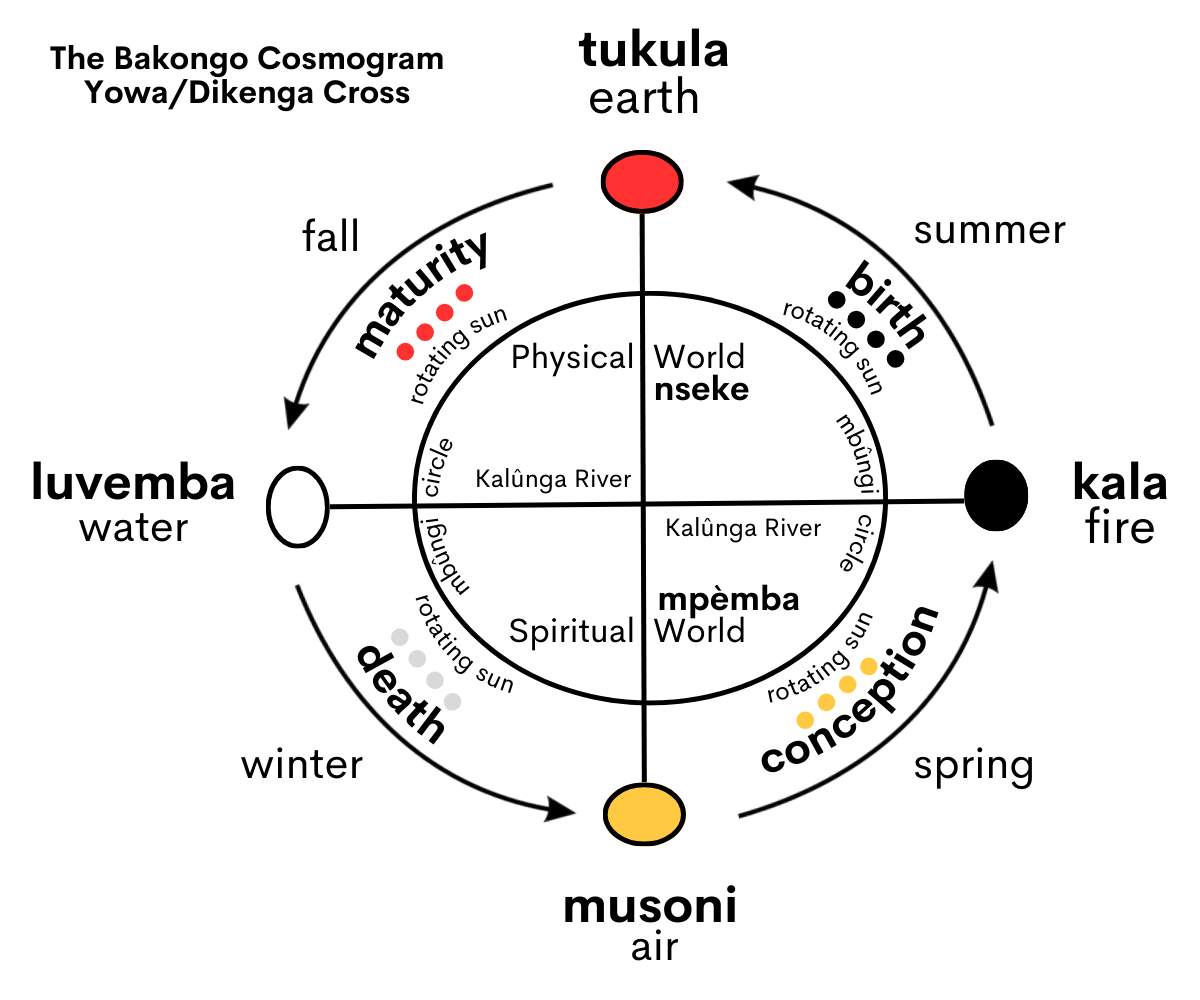

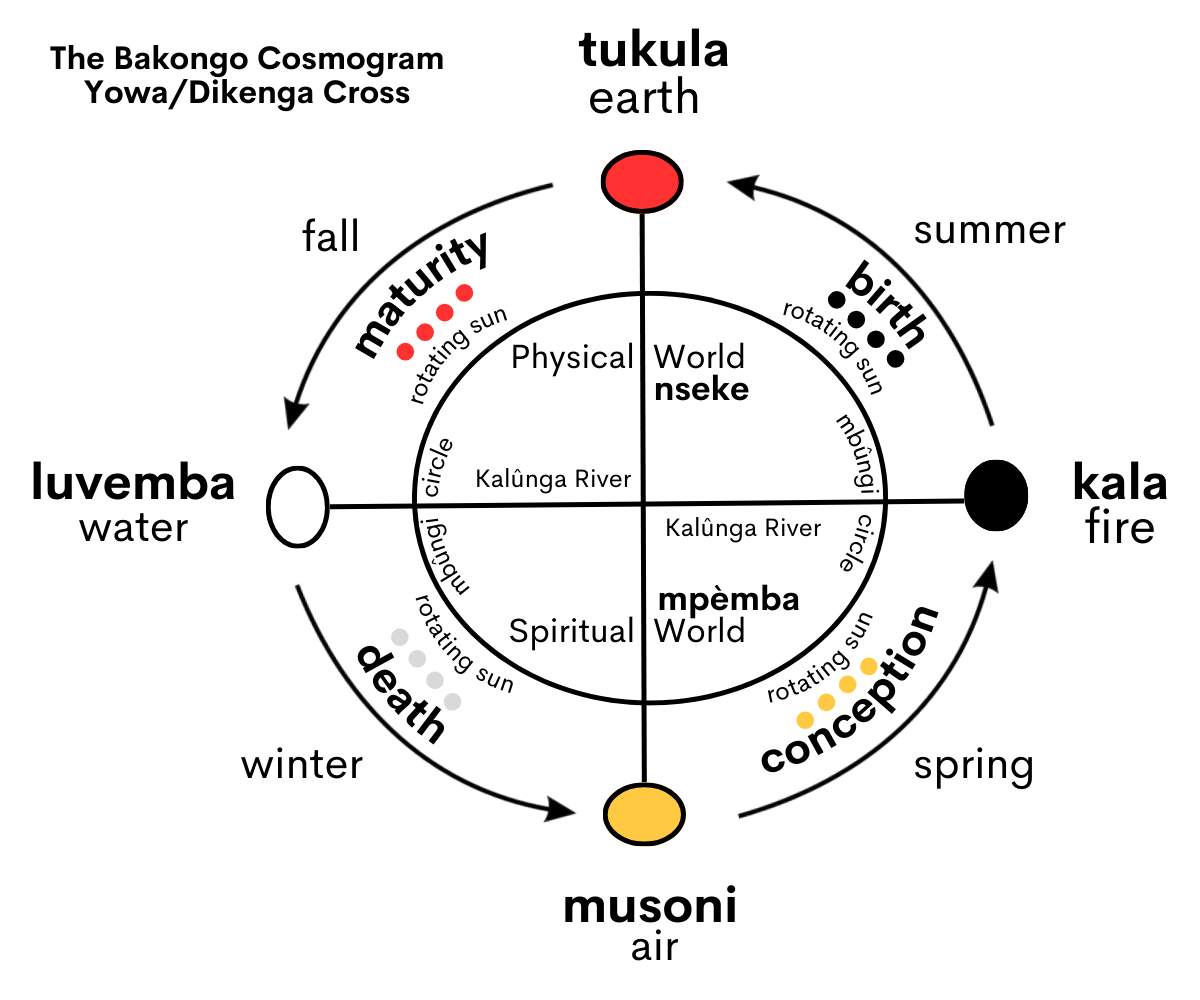

The Kongo cosmogram The Yowa, or Dikenga Cross, is a symbol in Bakongo spirituality that depicts the physical world, the spiritual (ancestral) world, the Kalûnga river (line) that runs between the two worlds, and the four moments of the sun. The Yowa cross is the origin of the crossroads in Hoodoo. The Kongo cosmogram The Bakongo origins in Hoodoo practice are evident. According to academic research, about 40 percent of Africans shipped to the United States during the slave trade came from Central Africa's Kongo region. Emory University created an online database that shows the voyages of the transatlantic slave trade. This database shows many slave ships primarily leaving Central Africa.[82][83] Ancient Kongolese spiritual beliefs and practices are present in Hoodoo, such as the Kongo cosmogram. The basic form of the Kongo cosmogram is a simple cross (+) with one line. The Kongo cosmogram symbolizes the rising of the sun in the east and the sun's setting in the west, representing cosmic energies. The horizontal line in the Kongo cosmogram represents the boundary between the physical world (the realm of the living) and the spiritual world (the realm of the ancestors). The vertical line of the cosmogram is the path of spiritual power from God at the top, traveling to the realm of the dead below, where the ancestors reside.[84][85] The cosmogram, or dikenga, however, is not a unitary symbol like a Christian cross or a national flag.[86] The physical world resides at the top of the cosmogram. The spiritual (ancestral) world resides at the bottom of the cosmogram. At the horizontal line is a watery divide that separates the two worlds from the physical and spiritual, and thus the "element" of water has a role in African American spirituality.[87][88] The Kongo cosmogram cross symbol has a physical form in Hoodoo called the crossroads, where Hoodoo rituals are performed to communicate with spirits and to leave ritual remains to remove a curse.[89] The Kongo cosmogram is also spelled the "Bakongo" cosmogram and the "Yowa" cross.  An example of an African American face jug from the Edgefield District of South Carolina. Historians suggest face jugs may have functioned like an nkisi, a spirit container. Locals call face jugs "voodoo pots" and "ugly jugs." African American face jugs are similar in appearance to face jugs made by Bantu people in the Kongo region.[90][91] The crossroads is a spiritual supernatural crossroads that symbolizes communication between the worlds of the living and the world of the ancestors, divided at the horizontal line. Counterclockwise sacred circle dances in Hoodoo are performed to communicate with ancestral spirits using the sign of the Yowa cross.[92][93] Communication with the ancestors is a traditional practice in Hoodoo that was brought to the United States during the slave trade originating among Bantu-Kongo people.[94][95] In Savannah, Georgia, in a historic African American church called First African Baptist Church, the Kongo cosmogram symbol was found in the basement of the church. African Americans punctured holes in the basement floor of the church to make a diamond-shaped Kongo cosmogram for prayer and meditation. The church was also a stop on the Underground Railroad. The holes in the floor provided breathable air for escaped enslaved people hiding in the basement of the church.[96] The Kongo cosmogram sun cycle also influenced how African Americans in Georgia prayed. It was recorded that some African Americans in Georgia prayed at the rising and setting of the sun.[97] In an African American church on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, Kongo cosmograms were designed into the church's window frames. The church was built facing an axis of an east–west direction so the sun rises directly over the church steeple in the east. The burial grounds of the church also show continued African American burial practices of placing mirror-like objects on top of graves.[98] In Kings County in Brooklyn, New York, at the Lott Farmstead, Kongo-related artifacts were found on the site. The Kongo-related artifacts included a Kongo cosmogram engraved onto ceramics and nkisi bundles that had cemetery dirt and iron nails left by enslaved African Americans. Researchers suggest that iron nails were used to prevent whippings from enslavers. Also, the Kongo cosmogram engravings were used as a crossroads for spiritual rituals by the enslaved African American population in Kings County. Historians suggest Lott Farmstead was a stop on the Underground Railroad for freedom seekers. The Kongo cosmogram artifacts were used as a form of spiritual protection against slavery and for enslaved people's protection during their escape from slavery on the Underground Railroad.[99] Archeologists also found the Kongo cosmogram on several plantations in the American South, including Richmond Hill Plantation in Georgia, Frogmore Plantation in South Carolina, a plantation in Texas, and Magnolia Plantation in Louisiana. Historians call the locations where crossroad symbols were possibly found inside slave cabins and African American living quarters 'Crossroads Deposits.' Crossroads deposits were found underneath floorboards and in the northeast sections of cabins to conjure ancestral spirits for protection. Sacrificed animals and other charms were found where enslaved African Americans drew the crossroads symbols, and four holes were drilled into charms to symbolize the Bakongo cosmogram. Other West-Central African traditions found on plantations by historians include using six-pointed stars as spiritual symbols. A six-pointed star is a symbol in West Africa and in African American spirituality.[100] On another plantation in Maryland, archeologists unearthed artifacts that showed a blend of Central African and Christian spiritual practices among enslaved people. This was Ezekiel's Wheel in the Bible that blended with the Central African Kongo cosmogram. This may explain the connection enslaved Black Americans had with the Christian cross, as it resembled their African symbol. The cosmogram represents the universe and how human souls travel in the spiritual realm after death, entering the ancestral realm and reincarnating back into the family.[101] The artifacts uncovered at the James Brice House included Kongo cosmogram engravings drawn as crossroads (an X) inside the house. This was done to ward a place from a harsh enslaver.[102] Also, the Kongo cosmogram is evident in Hoodoo practice among Black Americans. Archeologists unearthed clay bowls from a former slave plantation in South Carolina made by enslaved Africans, engraving the Kongo cosmogram onto the clay bowls. African Americans used these clay bowls for ritual purposes.[103] |

コンゴ宇宙図 ヨワまたはディケンガ・クロスは、バコンゴ族の精神世界における象徴であり、物理的世界、精神的世界(祖先の世界)、2つの世界の間を流れるカルンガ川 (線)、そして太陽の4つの瞬間を表している。ヨワ・クロスはフードゥーにおける十字路の起源である。 コンゴ宇宙図 フードゥー教のバコンゴの起源は明らかである。学術研究によると、奴隷貿易中に米国に送られたアフリカ人の約40パーセントは、中央アフリカのコンゴ地 域出身であった。エモリー大学は、大西洋横断奴隷貿易の航海を示すオンラインデータベースを作成した。このデータベースは、主に中央アフリカを出発した多 くの奴隷船を示している。[82][83]古代のコンゴ人の精神的な信念と実践は、フードゥー教にも存在しており、例えばコンゴ宇宙図がある。コンゴ宇 宙図の基本的な形は、一本の線を持つシンプルな十字(+)である。コンゴ宇宙図は、東から昇る太陽と西に沈む太陽を象徴し、宇宙のエネルギーを表してい る。コンゴ宇宙図の横線は、物理的世界(生者の領域)と精神的世界(祖先の領域)の境界を表している。この宇宙図の縦の線は、上部の神から祖先が住む下部 の死者の領域へと向かう霊的な力の通り道である。[84][85] しかし、宇宙図(またはディケンガ)は、キリスト教の十字架や国旗のような単一のシンボルではない。宇宙図の上部に物理的世界が存在する。霊的な(祖先 の)世界は、宇宙図の底に存在する。水平線には、物理的および精神的な2つの世界を隔てる水の境界線があり、したがって「水」の要素は、アフリカ系アメリ カ人の精神性において重要な役割を果たしている。[87][88] コンゴ宇宙図の十字のシンボルは、 フードゥー教ではこれを「クロスロード」と呼び、霊との交信や呪いを解くための儀式の残り物を残すために、この場所で儀式を行う。[89] コンゴ族の宇宙図は、「バコンゴ族」の宇宙図や「ヨワ族」の十字架とも呼ばれる。  サウスカロライナ州エッジフィールド地区のブラックアメリカンが用いたフェイスジャグの一例。歴史家は、フェイスジャグはンキシ(nkisi)と呼ばれる 霊の入れ物のような役割を果たしていた可能性があると示唆している。地元民はフェイスジャグを「ヴードゥーポット」や「醜い壺」と呼ぶ。アフリカ系アメリ カ人のフェイスジャグは、コンゴ地方のバンツー族が作ったフェイスジャグと外観が似ている。 交差する道は、生者の世界と祖先の世界のコミュニケーションを象徴する、超自然的でスピリチュアルな交差点である。フードゥーにおける反時計回りの神聖 な円舞は、ヨワ・クロスの印を用いて先祖の霊と交信するために行われる。[92][93] 先祖との交信は、バンツー・コンゴ人の間で始まった奴隷貿易の時代にアメリカ合衆国にもたらされたフードゥーの伝統的な慣習である。[94][95] ジョージア州サバンナにある歴史あるアフリカ系アメリカ人教会、ファースト・アフリカン・バプティスト教会の地下から、コンゴ宇宙図のシンボルが発見され た。アフリカ系アメリカ人は、祈りと瞑想のために、教会の地下室の床に穴を開けてダイヤモンド型のコンゴ宇宙図を作った。この教会は、地下鉄道の停車駅で もあった。床に開けられた穴は、教会の地下室に隠れていた逃亡中の奴隷たちに呼吸できる空気を供給していた。[96] コンゴ宇宙図の太陽のサイクルは、ジョージア州のアフリカ系アメリカ人の祈り方にも影響を与えた。ジョージア州のアフリカ系アメリカ人の中には、太陽が昇 る時と沈む時に祈りを捧げる者もいたことが記録されている。[97] バージニア州イースタンショアのアフリカ系アメリカ人教会では、コンゴの宇宙図が教会の窓枠にデザインされている。この教会は東西方向の軸線に面して建て られており、太陽が東の教会の尖塔の真上に昇るようになっている。この教会の墓地には、墓の上に鏡のようなものを置くというアフリカ系アメリカ人の埋葬の 習慣が今も続いている。 ニューヨーク州ブルックリン区キングス郡のロット農場跡では、コンゴ族に関連する遺物が発見されている。コンゴ族に関連する遺物には、陶器に刻まれたコン ゴ族の宇宙図や、奴隷として強制労働に従事していたアフリカ系アメリカ人によって墓地の土や鉄釘が入れられたンキシの束などがある。研究者たちは、鉄釘は 奴隷制の所有者による鞭打ちを防ぐために使われたのではないかと推測している。また、キングス郡の奴隷であったアフリカ系アメリカ人たちは、コンゴ宇宙図 の刻印を精神的な儀式の交差点として使用していた。歴史家は、ロット農場が自由を求める人々のための地下鉄道の停留所であった可能性を示唆している。コン ゴ宇宙図の遺物は、奴隷制度に対する精神的な保護の形として、また地下鉄道で奴隷制度からの逃亡中の奴隷の保護として使用されていた。 考古学者は、ジョージア州のリッチモンド・ヒル農園、サウスカロライナ州のフロッグモア農園、テキサス州の農園、ルイジアナ州のマグノリア農園など、アメ リカ南部のいくつかの農園でコンゴの宇宙図を発見した。 歴史家は、奴隷小屋やアフリカ系アメリカ人の居住区で発見された可能性のある十字路のシンボルが残る場所を「クロスローズ・デポジット」と呼んでいる。 クロスローズ・デポジットは、先祖の霊を呼び出して守ってもらうために、床板の下や小屋の北東部分に置かれていた。奴隷となったアフリカ系アメリカ人が十 字路のシンボルを描いた場所からは、生け贄の動物やその他の護符が見つかっている。また、護符には4つの穴が空けられており、バコンゴ族の宇宙図を象徴し ている。歴史家がプランテーションで発見した他の西中央アフリカの伝統には、六芒星を精神的なシンボルとして用いるものがある。六芒星は西アフリカとアフ リカ系アメリカ人の精神世界におけるシンボルである。 メリーランド州の別の農園では、考古学者が奴隷たちによる中央アフリカとキリスト教の精神修養の融合を示す遺物を発掘した。これは、聖書に登場するエゼキ エルの車輪と中央アフリカのコンゴの宇宙図が融合したものである。これは、奴隷として扱われた黒人アメリカ人とキリスト教の十字架とのつながりを説明する ものかもしれない。なぜなら、それは彼らのアフリカのシンボルに似ていたからだ。この宇宙図は、宇宙と、死後、人間の魂が霊的な領域を旅し、先祖の領域に 入り、家族に生まれ変わる様子を表している。[101] ジェームズ・ブライス・ハウスで発見された遺物には、家屋内に十字路(X)として描かれたコンゴ宇宙図の彫刻が含まれていた。これは、場所を厳しい奴隷制 から守るために行われた。[102] また、コンゴ宇宙図は、黒人アメリカ人の間で行われるフードゥー教の儀式にも見られる。 サウスカロライナ州の元奴隷農園から、奴隷としてアフリカから連れてこられた人々によって作られた粘土の鉢が発掘された。 粘土の鉢にはコンゴ宇宙図が刻まれていた。 アフリカ系アメリカ人は、これらの粘土の鉢を儀式用に使用していた。[103] |

The 18th-century painting The Old Plantation depicts several examples of Africanisms brought to the Carolinas, including musical instruments, headdresses, dance steps, and spiritual traditions. The Ring shout in Hoodoo has its origins in the Kongo region from the Kongo cosmogram (Yowa Cross). Ring shouters dance in a counterclockwise direction that follows the pattern of the rising of the sun in the east and the setting of the sun in the west. The ring shout follows the cyclical nature of life represented in the Kongo cosmogram of birth, life, death, and rebirth.[104][105][106][107] Through counterclockwise circle dancing, ring shouters build up spiritual energy that results in communication with ancestral spirits and leads to spirit possession by the Holy Spirit or ancestral spirits.[108] Enslaved African Americans performed the counterclockwise circle dance until someone was pulled into the center of the ring by the spiritual vortex at the center. The spiritual vortex at the center of the ring shout was a sacred spiritual realm where the ancestors and the Holy Spirit resided.[109] The ring shout tradition continues in Georgia with the McIntosh County Shouters.[110] At Cathead Creek in Georgia, archeologists found artifacts made by enslaved African Americans that linked to spiritual practices in West-Central Africa. Enslaved African Americans and their descendants, after the emancipation, housed spirits inside reflective materials and used reflective materials to transport the recently deceased to the spiritual realm. Broken glass on tombs reflects the other world. It is believed that reflective materials are portals to the spirit world.[111] |

18世紀の絵画『The Old Plantation』には、楽器、頭飾り、ダンスのステップ、スピリチュアルな伝統など、カロライナに持ち込まれたアフリカ文化のいくつかの例が描かれ ている。 フードゥー教のリング・シャウトは、コンゴの宇宙図(ヨワ・クロス)に起源を持つ。リング・シャウターは、太陽が東から昇り西に沈むパターンに従って、 反時計回りに踊る。輪唱は、金剛界の誕生、生命、死、再生の宇宙図に表現された生命の循環的な性質に従うものである。[104][105][106] [107] 輪唱者は反時計回りの円を描いて踊ることで、 先祖の霊との交信につながり、聖霊または先祖の霊による憑依を引き起こす精神的なエネルギーを蓄える。[108] 奴隷として働かされていたアフリカ系アメリカ人は、反時計回りの輪になって踊り、中央の霊的な渦によって誰かが輪の中心に引き寄せられるまで踊り続けた。 リング・シャウトの中心にある霊的な渦は、祖先と聖霊が宿る神聖な霊的領域であった。[109] リング・シャウトの伝統は、ジョージア州のマッキントッシュ郡で今も続いている。[110] ジョージア州のキャットヘッド・クリークでは、考古学者が西中央アフリカの霊的実践と関連する奴隷として働かされていたアフリカ系アメリカ人が作った工芸 品を発見した。奴隷となっていたアフリカ系アメリカ人とその子孫たちは、解放後、反射材の中に霊を宿らせ、反射材を使って最近亡くなった人を霊的な領域に 運んでいた。墓の割れたガラスはあの世を映し出す。反射材は霊界への入り口であると考えられている。[111] |

Other Kongo influences Archeologists found an intact nkisi nkondi inside a slave cabin in Brazoria, Texas. Simbi water spirits are revered in Hoodoo, originating from Central African spiritual practices. When Africans were enslaved in the United States, they blended African spiritual beliefs with Christian baptismal practices. Enslaved African Americans prayed to Simbi water spirits during their baptismal services.[112][113] In 1998, in a historic house in Annapolis, Maryland called the Brice House, archaeologists unearthed Hoodoo artifacts inside the house that linked to the Kongo people. These artifacts are the continued practice of the Kongo's minkisi and nkisi culture in the United States brought over by enslaved Africans. For example, archeologists found artifacts used by enslaved African Americans to control spirits by housing spirits inside caches or nkisi bundles. These spirits inside objects were placed in secret locations to protect an area or bring harm to enslavers. "In their physical manifestations, minkisi (nkisi) are sacred objects that embody spiritual beings and generally take the form of a container such as a gourd, pot, bag, or snail shell. Medicines that provide the minkisi with power, such as chalk, nuts, plants, soil, stones, and charcoal, are placed in the container."[114][115] Nkisi bundles were found on other plantations in Virginia and Maryland. For example, nkisi bundles were found for healing or misfortune. Archeologists found objects believed by the enslaved African American population in Virginia and Maryland to have spiritual power, such as coins, crystals, roots, fingernail clippings, crab claws, beads, iron, bones, and other items assembled inside a bundle to conjure a specific result for either protection or healing. These items were hidden inside enslaved people's dwellings. These practices were concealed from enslavers.[116] In Darrow, Louisiana, at the Ashland-Belle Helene Plantation, historians and archeologists unearthed Kongo and Central African practices inside slave cabins. Enslaved Africans in Louisiana conjured the spirits of Kongo ancestors and water spirits using seashells. Other charms in several slave cabins included silver coins, beads, polished stones, and bones made into necklaces or carried in pockets for protection. These artifacts provide examples of African rituals at Ashland Plantation. Enlavers tried to stop African practices, but enslaved African Americans disguised their rituals by using American materials, applying African interpretations to them, and hiding the charms in their pockets or making them into necklaces to conceal these practices from their enslavers.[117] In Talbot County, Maryland, at the Wye House plantation, where Frederick Douglass was enslaved in his youth, Kongo-related artifacts were found. Enslaved African Americans created items to ward off evil spirits by creating a Hoodoo bundle near the entrances to chimneys, believed to be where spirits enter. The Hoodoo bundle contained pieces of iron and a horseshoe. Enslaved African Americans put eyelets on shoes and boots to trap spirits. Archaeologists also found small carved wooden faces. The wooden carvings had two faces carved into them on both sides, interpreted to represent an African American conjurer who was a two-headed doctor. In Hoodoo, a two-headed doctor is a conjurer who can see into the future and has knowledge about spirits and things unknown.[118] At the Levi Jordan Plantation in Brazoria, Texas, near the Gulf Coast, researchers suggest that plantation owner Levi Jordan may have transported captive Africans from Cuba back to his plantation in Texas. These captive Africans practiced a Bantu-Kongo religion in Cuba, and researchers excavated Kongo-related artifacts at the site. For example, archeologists found the remains of an nkisi nkondi with iron wedges driven into the figure to activate its spirit in one of the cabins called the "curer's cabin." Researchers also found a Kongo bilongo, which enslaved African Americans created using materials from white porcelain to make a doll figure. In the western section of the cabin, they found iron kettles and iron chain fragments, suggesting that the western section of the cabin was an altar to the Kongo spirit Zarabanda.[119][120][121] |

その他のコンゴの影響 テキサス州ブラゾリアの奴隷小屋で、考古学者が完全な形のンキシー・ンコンディを発見した。 シンビの水の精霊は、中央アフリカの精神修養に由来するフードゥー教で崇拝されている。アフリカ人が米国で奴隷として働かされていた時代、彼らはアフリ カの精神信仰とキリスト教の洗礼の慣習を融合させた。奴隷となったアフリカ系アメリカ人は洗礼式の際にシンビの水の精霊に祈りを捧げた。[112] [113] 1998年、メリーランド州アナポリスのブリス・ハウスと呼ばれる歴史的建造物で、考古学者が家屋からコンゴ族に関連するフードゥー教の遺物を発掘し た。これらの遺物は、奴隷となったアフリカ人が米国に持ち込んだコンゴ族のミンキシーとンキシー文化の継続的な実践である。例えば、考古学者は、奴隷とし て働かされていたアフリカ系アメリカ人が、霊を封じ込めるために使用した品々を発見した。これらの品々には、霊を封じ込めるための隠し場所や、奴隷制の加 害者に害をもたらすためのものが含まれていた。「ミンキシー(ンキシー)は、霊的存在を具現化した神聖なものであり、一般的にひょうたん、壷、袋、巻貝な どの容器の形をしている。ミンキシに力を与える薬、例えばチョーク、木の実、植物、土、石、炭などは、容器の中に入れられる。」[114][115] ンキシの束はバージニア州やメリーランド州の他のプランテーションでも発見されている。例えば、ンキシの束は治療や不幸を祓うために使われた。バージニア 州とメリーランド州の奴隷であったアフリカ系アメリカ人が、霊的な力があると信じていた物、例えばコイン、水晶、根、爪切り、カニの爪、ビーズ、鉄、骨、 その他特定の結果を招来するために束の中に集められた品々が、奴隷居住区の内部に隠されていた。これらの慣習は、奴隷所有者には隠されていた。 ルイジアナ州ダローのアシュランド・ベル・ヘリーン農園では、歴史家や考古学者が奴隷小屋からコンゴや中央アフリカの慣習を発掘した。ルイジアナ州の奴隷 となっていたアフリカ人は、貝殻を使ってコンゴの祖先や水の精霊の霊を呼び起こしていた。他の奴隷小屋では、銀貨、ビーズ、磨かれた石、ネックレスに加工 されたりポケットに入れて持ち歩かれたりして保護の目的で用いられた骨などが、お守りとして用いられていた。これらの遺物は、アシュランド農園におけるア フリカの儀式の例を示している。奴隷所有者たちはアフリカの慣習を止めさせようとしたが、奴隷となっていたアフリカ系アメリカ人は、アメリカの素材を使 い、アフリカの解釈を適用し、護符をポケットに隠したり、ネックレスに加工するなどして、これらの慣習を隠そうとした。 メリーランド州タルボット郡のワイ・ハウス農園では、フレデリック・ダグラスが少年時代に奴隷として働かされていた場所であるが、コンゴ関連の遺物が発見 されている。奴隷となっていたアフリカ系アメリカ人は、悪霊が入り込むと信じられていた煙突の入り口付近にフードゥー・バンドル(魔よけ)を置くこと で、悪霊を追い払うための品々を作っていた。フードゥー・バンドルには鉄片や蹄鉄が含まれていた。奴隷となったアフリカ系アメリカ人は、靴やブーツにア イレットを取り付けて悪霊を閉じ込めた。考古学者は、小さな木彫りの顔も発見した。木彫りには両面に2つの顔が彫られており、2つの頭を持つ医師であるア フリカ系アメリカ人の魔術師を表していると解釈されている。フードゥー教では、2つの頭を持つ医師は未来を見通すことができ、霊や未知の事柄に関する知 識を持つ魔術師である。 テキサス州ガルフコーストに近いブラゾリアのリーバイ・ジョーダン農園では、研究者たちが、農園主のリーバイ・ジョーダンがキューバから捕虜として連れて きたアフリカ人をテキサスの農園に移送した可能性を示唆している。これらの捕虜となったアフリカ人はキューバでバンツー・コンゴ宗教を信仰しており、研究 者はその場所でコンゴ関連の遺物を発掘した。例えば、考古学者は「治療師の小屋」と呼ばれる小屋のひとつで、鉄の楔が打ち込まれてその霊を呼び起こすため のnkisi nkondi(コンゴの神像)の残骸を発見した。また、研究者らは奴隷となったアフリカ系アメリカ人が白磁の素材を使って人形の姿を作り出したコンゴの bilongo(聖像)も発見した。小屋の西部では、鉄瓶と鉄の鎖の破片が発見され、小屋の西部がコンゴのザラバンダの霊を祀る祭壇であったことを示唆し ている。[119][120][121] |

Magical amulets Minkisi (Kongo), World Museum Liverpool - Minkisi cloth bundles were found on slave plantations in the United States in the Deep South.[122] The word goofer in goofer dust has Kongo origins and comes from the Kikongo word Kufwa, which means "to die."[123] The mojo bag in Hoodoo has Bantu-Kongo origins. Mojo bags are also called toby, which is derived from the Kikongo word tobe.[124] The word mojo also originated from the Kikongo word mooyo, which means that natural ingredients have indwelling spirit that can be utilized in mojo bags to bring luck and protection.[125] The mojo bag or conjure bag derived from the Bantu-Kongo minkisi. The nkisi (singular) and minkisi (plural) are objects created by hand and inhabited by a spirit or spirits. These objects can be bags (mojo bags or conjure bags), gourds, shells, or other containers. Various items are placed inside a bag to give it a particular spirit or job to do. Mojo bags and minkisi are filled with graveyard dirt, herbs, roots, and other materials by the Nganga spiritual healer. The spiritual priests in Central Africa became the rootworkers and Hoodoo doctors in African American communities. In the American South, conjure doctors create mojo bags similar to the Ngangas' minkisi bags, as both are fed offerings with whiskey.[126] Another Bantu-Kongo practice in Hoodoo is making a cross mark (Kongo cosmogram) and standing on it to take an oath. This practice is done in Central Africa and the United States in African American communities. When drawn on the ground, the Kongo cosmogram is also used as a powerful protection charm. The solar emblems or circles at the ends and the arrows are not drawn, just the cross marks, which look like an X.[127][94] A man named William Webb helped enslaved people on a plantation in Kentucky resist their oppressors using mojo bags. Webb told the enslaved people to gather some roots and put them in bags, then "march around the cabins several times and point the bags toward the master's house every morning." After following Webb's instructions, according to their beliefs, the enslavers would treat them better.[128] Another enslaved African named Dinkie, known by the enslaved community as Dinkie King of Voudoos and the Goopher King, used goofer dust to resist a cruel overseer on a plantation in St. Louis. Unlike other enslaved people, Dinkie never worked in the same way. He was feared and respected by both Black and white people. Dinkie was known to carry a dried snakeskin, frog, and lizard and sprinkled goofer dust on himself, speaking to the spirit of the snake to wake up its power against the overseer.[129] Henry Clay Bruce, a Black abolitionist and writer, recorded his experience of enslaved people on a plantation in Virginia who hired a conjurer to prevent enslavers from selling them to plantations in the Deep South. Louis Hughes, an enslaved man who lived on plantations in Tennessee and Mississippi, carried a mojo bag to prevent enslavers from whipping him. The mojo bag Hughes carried was called a "voodoo bag" by the enslaved community in the area.[23] Former enslaved person and abolitionist Henry Bibb wrote in his autobiography, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, Written by Himself, that he sought the help of several conjurers during his enslavement. Bibb went to these conjurers (Hoodoo doctors) in hopes that the charms they provided would prevent enslavers from whipping and beating him. The conjurers gave Bibb conjure powders to sprinkle around the bed of the enslaver, put in the enslaver's shoes, and carry a bitter root and other charms for protection.[130] |

呪術的お守り ミンキシ(コンゴ) リバプール世界博物館 - ミンキシの布の束は、アメリカ合衆国南部の奴隷農園で発見された。 [122] 「グーファー・ダスト」の「グーファー」という言葉はコンゴ語に由来し、コンゴ語で「死ぬ」を意味する「クフワ」というキコンゴ語に由来する。[123] フードゥー教の「モジョ・バッグ」はバンツー・コンゴ語に由来する。モジョバッグはトビーとも呼ばれるが、これはキコンゴ語のトベに由来する。 [124] モジョという言葉もまた、キコンゴ語のモヨに由来し、自然界の素材には内在する霊魂が宿っており、モジョバッグに利用することで幸運や保護をもたらすこと ができる、という意味である。[125] モジョバッグまたは呪術バッグは、バンツー・コンゴのミンキシーに由来する。ンキシ(単数形)およびミンキシ(複数形)は、手作業で作成され、霊または複 数の霊が宿る物体である。これらの物体は、袋(モジョ・バッグまたはコンジャー・バッグ)、ひょうたん、貝殻、その他の容器である。特定の霊や役割を与え るために、さまざまな品物が袋の中に入れられる。モジョ・バッグおよびミンキシには、ンガングの霊媒師によって墓地の土、ハーブ、根、その他の材料が詰め られる。中央アフリカの霊能者は、アフリカ系アメリカ人社会でルーツワーカーやフードゥー教の医師となった。アメリカ南部では、呪術医がンガンガのミン キシーバッグに似たモジョバッグを作り、両者ともウイスキーの供物を捧げられる。[126] フードゥーにおけるもう一つのバンツー・コンゴの慣習は、十字架の印(コンゴ・コスモグラム)を作り、その上に立って誓いを立てることである。この慣習 は中央アフリカとアフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティのあるアメリカ合衆国で行われている。地面に描かれる場合、コンゴ・コズモグラムは強力な護符としても 用いられる。太陽の紋章または円の両端と矢印は描かれない。描かれるのは十字架だけである。 ウィリアム・ウェッブという名の男は、ケンタッキー州の農園で奴隷たちがモジョバッグを使って抑圧者に抵抗するのを助けた。ウェッブは奴隷たちに、いくつ かの根を集めて袋に入れ、「毎朝、小屋の周りを数回行進し、袋を主人宅に向ける」ようにと指示した。ウェッブの指示に従った後、彼らの信念によると、奴隷 所有者は彼らをより良く扱うことになった。 ディンキーという名の別の奴隷となったアフリカ人は、奴隷社会ではブードゥー教のディンキー王、あるいはグーファー・キングとして知られていたが、セント ルイスの農園で残酷な監督者に抵抗するためにグーファー・ダストを使用していた。他の奴隷たちとは異なり、ディンキーは決して同じ方法で働かなかった。彼 は黒人からも白人からも恐れられ、尊敬されていた。ディンキーは乾燥させた蛇の皮、カエル、トカゲを持ち歩き、グーファードダストを振りかけ、蛇の霊に語 りかけて、監督者に対する蛇の力を呼び覚ましていたことで知られていた。 黒人奴隷解放論者であり作家でもあったヘンリー・クレイ・ブルースは、バージニア州の農園で奴隷たちが、南部の奥地にある農園に自分たちを売り飛ばさない よう、魔術師を雇ったという経験を記録している。テネシー州とミシシッピ州の農園で奴隷として働いていたルイス・ヒューズは、奴隷所有者が自分を鞭打たな いよう、モジョバッグを所持していた。ヒューズが持っていたモジョバッグは、その地域の奴隷社会では「ヴードゥーバッグ」と呼ばれていた。[23] 元奴隷で奴隷制度廃止論者であったヘンリー・ビブは、自伝『ヘンリー・ビブ、アメリカ人奴隷の生涯と冒険の物語』の中で、奴隷時代に複数の魔術師に助けを 求めたと書いている。ビブは、彼らが提供するお守りが奴隷所有者による鞭打ちや殴打を防ぐことを期待して、これらの呪術師(フードゥー教の医師)のもと を訪れた。呪術師たちは、奴隷所有者のベッドの周りに撒くお守りの粉や、奴隷所有者の靴に入れるもの、苦い根やその他の護符をビブに与えた。[130] |

Brooklyn Museum 22.198 Cane / This cane is from the Arts of Africa collection. Bantu-Kongo people in Central Africa and African Americans in the United States crafted similar canes. Historians noted similar meanings and religious uses of canes between African and African Americans, who carved animals and human figures onto canes to conjure illness. The difference with African American canes is the North American animals and historical events, such as sharecropping and lynchings, carved onto them.[131] Other Bantu-Kongo practices present in Hoodoo include the use of conjure canes. In the United States, these canes are decorated with specific objects to conjure spirits and achieve specific results. This practice was brought to the United States during the transatlantic slave trade from Central Africa. Several African American families still use conjure canes today. In Central Africa, Bantu-Kongo banganga ritual healers use ritual staffs called conjure canes in Hoodoo. These canes conjure spirits and heal people. The banganga healers in Central Africa became the conjure doctors and herbal healers in African American communities in the United States.[132][133] The Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida collaborated with other world museums to compare African American conjure canes with ritual staffs from Central Africa and found similarities between them and other aspects of African American culture that originated from Bantu-Kongo people.[134] Bakongo spiritual protections influenced African American yard decorations. In Central Africa, Bantu-Kongo people decorated their yards and entrances to doorways with baskets and broken shiny items to protect against evil spirits and thieves. This practice is the origin of the bottle tree in Hoodoo. Throughout the American South, in African American neighborhoods, some houses have bottle trees and baskets placed at entrances to doorways for spiritual protection. Additionally, nkisi culture influenced jar container magic. An African American man in North Carolina buried a jar under the steps with water and string for protection. If someone conjured him, the string would turn into a snake. The man interviewed called it inkabera.[135] At Locust Grove plantation in Jefferson County, Kentucky, archeologists and historians found amulets made by enslaved African Americans that had the Kongo cosmogram engraved onto coins and beads. Blue beads were found among the artifacts; in African spirituality, blue beads attract protection to the wearer. In slave cabins in Kentucky and on other plantations in the American South, archeologists found blue beads used by enslaved people for spiritual protection. Enslaved African Americans combined Christian practices with traditional African beliefs.[136][137] Other Kongo influences at Congo Square were documented by folklorist Puckett. African Americans poured libations at the four corners of Congo Square at midnight during a dark moon for a Hoodoo ritual.[138] Historians from Southern Illinois University in the Africana Studies Department documented that about 20 title words from the Kikongo language are in the Gullah language. These title words indicate continued African traditions in Hoodoo and conjure. The title words are spiritual in meaning. In Central Africa, spiritual priests and spiritual healers are called Nganga. In the South Carolina Lowcountry among Gullah people, a male conjurer is called Nganga. Some Kikongo words have an "N" or "M" at the beginning of the word. However, when Bantu-Kongo people were enslaved in South Carolina, the letters N and M were dropped from some title names. For example, in Central Africa, the word for spiritual mothers is Mama Mbondo. In the South Carolina Lowcountry and African American communities, the word for a spiritual mother is Mama Bondo. Additionally, during slavery, it was documented that there was a Kikongo-speaking slave community in Charleston, South Carolina.[139] Robert Farris Thompson was a professor at Yale University who conducted academic research in Africa and the United States and traced Hoodoo's (African American conjure) origins to Central Africa's Bantu-Kongo people in his book Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy. Thompson was an African Art historian who found through his study of African Art the origins of African Americans' spiritual practices in certain regions in Africa.[140] Former academic historian Albert J. Raboteau in his book, Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South, traced the origins of Hoodoo (conjure, rootwork) practices in the United States to West and Central Africa. These origins developed a slave culture in the United States that was social, spiritual, and religious.[141] Professor Eddie Glaude at Princeton University defines Hoodoo as part of African American religious life with practices influenced from Africa that fused with Christianity, creating an African American religious culture for liberation.[142] |

ブルックリン美術館 22.198 杖 / この杖はアフリカ美術コレクションに属する。中央アフリカのバンツー・コンゴ族と米国の黒人アフリカ系アメリカ人は、同様の杖を制作した。歴史家は、杖に 動物の姿や人間の姿を彫り込んで病気を追い払うという、アフリカ人とアフリカ系アメリカ人の杖の持つ意味や宗教的な用途が類似していることを指摘してい る。アフリカ系アメリカ人の杖と異なるのは、北アメリカの動物や歴史的な出来事、例えば小作やリンチなどが彫られている点である。 [131] フードゥーに存在するその他のバンツー・コンゴの慣習には、魔術の杖の使用がある。米国では、特定の目的のために特定の物体で装飾された魔術の杖が、霊 を呼び寄せたり特定の結果を得るために使用される。この慣習は、大西洋奴隷貿易によって中央アフリカからアメリカ合衆国に持ち込まれた。現在でも、アフリ カ系アメリカ人の一部の家庭では、この魔術用の杖が使用されている。中央アフリカでは、バンツー・コンゴ族のバンガンガと呼ばれる呪術師が、フードゥー 教で魔術用の杖と呼ばれる儀式用の杖を使用している。この杖は、霊を呼び寄せたり、人を癒したりする。中央アフリカのバンガンガのヒーラーたちは、米国の アフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティにおける呪術医や薬草療法士となった。[132][133] フロリダ大学のハーン美術館は、他の世界の美術館と協力し、アフリカ系アメリカ人の呪術用の杖と中央アフリカの儀式用の杖を比較し、バンツー・コンゴ族に 起源を持つアフリカ系アメリカ人の文化の他の側面との類似点を見出した。 バコンゴ族の霊的保護は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の庭の装飾に影響を与えた。中央アフリカでは、バントゥー・コンゴ族の人々は、邪悪な霊や盗賊から身を守る ために、バスケットや壊れた光沢のある品々を庭や玄関に飾っていた。この慣習は、フードゥー教のボトルツリーの起源である。アメリカ南部のアフリカ系ア メリカ人の居住区では、霊的保護のためにボトルツリーやバスケットを玄関に置く家もある。さらに、ンキシー文化は壷の呪術にも影響を与えた。ノースカロラ イナ州に住むアフリカ系アメリカ人の男性は、階段の下に水を入れた壷を埋め、糸を結んで魔除けとしていた。誰かが彼に魔法をかけた場合、その糸は蛇に変化 した。この男性はそれをインカンベラと呼んでいた。 ケンタッキー州ジェファーソン郡のローカストグローブ農園では、考古学者と歴史家が、コングの宇宙図が刻まれた硬貨やビーズを身に付けていた奴隷によって 作られたお守りを見つけた。出土品の中には青いビーズもあった。アフリカの霊性において、青いビーズは身に着ける者に保護をもたらす。ケンタッキー州の奴 隷小屋やアメリカ南部の他の農園で、考古学者は奴隷たちが霊的な保護のために使用していた青いビーズを発見した。奴隷となったアフリカ系アメリカ人は、キ リスト教の慣習と伝統的なアフリカの信仰を組み合わせた。 コンゴ広場におけるその他のコンゴの影響は、民俗学者のパケットによって記録されている。アフリカ系アメリカ人は、フードゥー教の儀式のために、暗い月の 夜の真夜中にコンゴ広場の四隅に供物を捧げた。 南イリノイ大学アフリカ研究学科の歴史家たちは、キコンゴ語の約20の敬称語がガラ語に残っていることを記録している。これらの敬称語は、フードゥー教 や呪術におけるアフリカの伝統が継続していることを示している。これらの敬称語は霊的な意味を持つ。中央アフリカでは、霊的な司祭や霊的な治療者はンガン ガと呼ばれる。サウスカロライナ州ローカントリーのガラ族の間では、男性の呪術師はンガンガと呼ばれる。キンコンゴ語のいくつかの単語は、語頭に「N」ま たは「M」が付く。しかし、バンツー・コンゴ人がサウスカロライナで奴隷として扱われていた時代には、いくつかの称号名から「N」と「M」が脱落した。例 えば、中央アフリカでは、霊的な母親を意味する語は「ママ・ムボンダ」である。サウスカロライナのローカントリーやアフリカ系アメリカ人のコミュニティで は、霊的な母親を意味する語は「ママ・ボンダ」である。さらに、奴隷制時代には、サウスカロライナ州チャールストンにキコンゴ語を話す奴隷コミュニティが 存在していたことが記録されている。[139] ロバート・ファリス・トンプソンは、アフリカと米国で学術研究を行い、著書『Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy』でフードゥー教(アフリカ系アメリカ人の呪術)の起源を中央アフリカのバンツー・コンゴ人にまで遡ったイェール大学の教授であ る。トンプソンはアフリカ美術史家であり、アフリカ美術の研究を通じて、アフリカ系アメリカ人の精神的な実践の起源がアフリカの特定の地域にあることを発 見した。[140] 元学術史家のアルバート・J・ラボーテーは著書『奴隷の宗教:南北戦争前の南部における「見えない制度」』で、アメリカにおけるフードゥー(コンジュー ル、ルーツワーク)の起源を西アフリカと中央アフリカにさかのぼっている。これらの起源は、社会的、精神的、宗教的な奴隷文化を米国で発展させた。 [141] プリンストン大学のエディ・グラード教授は、フードゥーをアフリカから影響を受けた慣習がキリスト教と融合した、アフリカ系アメリカ人の宗教生活の一部 であり、解放のためのアフリカ系アメリカ人の宗教文化を生み出したものと定義している。[142] |

West African influence A West African gris-gris bag, the origin of the mojo bag (conjure bag) in Hoodoo[143] Islam A major West African influence in Hoodoo is Islam. As a result of the transatlantic slave trade, some West African Muslims who practiced Islam were enslaved in the United States. Before they arrived in the American South, West African Muslims blended Islamic beliefs with traditional West African spiritual practices. On plantations in the American South, enslaved West African Muslims kept some of their traditional Islamic culture. They practiced Islamic prayers, wore turbans, and the men wore traditional wide-leg pants. Some enslaved West African Muslims practiced Hoodoo. Islamic prayers were used instead of Christian prayers in the creation of charms. Enslaved Black Muslim conjure doctors' Islamic attire was different from that of other slaves, making them easy to identify and ask for conjure services regarding protection from enslavers.[144][145] The Mandingo (Mandinka) were the first Muslim ethnic group imported from Sierra Leone in West Africa to the Americas. Mandingo people were known for their powerful conjure bags called gris-gris (later called mojo bags in the United States). The Bambara people, an ethnic group of the Mandinka people, influenced the making of charm bags and amulets. Words in Hoodoo about charm bags come from the Bambara language. For example, the word zinzin spoken in Louisiana Creole means a power amulet. The Mande word marabout in Louisiana means a spiritual teacher.[146] During the slave trade, some Mandingo people were able to carry their gris-gris bags with them when they boarded slave ships heading to the Americas, bringing the practice to the United States. Enslaved people went to enslaved Black Muslims for conjure services, requesting them to make gris-gris bags (mojo bags) for protection against slavery.[147] |

西アフリカの影響 フードゥー教におけるモジョバッグ(魔術バッグ)の起源である西アフリカのグリグリバッグ[143] イスラム教 フードゥーにおける西アフリカの影響のひとつにイスラム教がある。 大西洋間の奴隷貿易の結果、イスラム教を信仰する西アフリカのイスラム教徒の一部が米国で奴隷となった。 米国南部に到着する前に、西アフリカのイスラム教徒はイスラム教の信仰と伝統的な西アフリカの霊的実践を融合させていた。 米国南部の農園で、奴隷となった西アフリカのイスラム教徒は、イスラム教の伝統文化を一部維持していた。 彼らはイスラム教の祈りを捧げ、ターバンを巻き、男性は伝統的な幅広のズボンを履いていた。西アフリカ系イスラム教徒の奴隷の中には、フードゥー教を信 仰する者もいた。お守りを作る際には、キリスト教の祈りの代わりにイスラム教の祈りが用いられた。奴隷の黒人イスラム教徒の呪術師の服装は、他の奴隷の服 装とは異なり、彼らを識別しやすくし、奴隷制からの保護に関する呪術のサービスを依頼しやすくしていた。[144][145]マンディンゴ(マンディン カ)は、西アフリカのシエラレオネからアメリカ大陸に最初に輸入されたイスラム教徒の民族集団であった。マンディンゴ族は、グリグリ(後にアメリカではモ ジョバッグと呼ばれる)と呼ばれる強力なコンジャーバッグで知られていた。マンディンゴ族の民族集団であるバンバラ族は、お守り袋や魔除けの製造に影響を 与えた。フードゥーにおけるお守り袋に関する用語はバンバラ語に由来する。例えば、ルイジアナ・クレオールで話されるジンジンという言葉は、強力なお守 りを意味する。ルイジアナのマンデ族の言葉maraboutは、霊的な師を意味する。[146] 奴隷貿易の時代、マンディンゴ族の一部は、アメリカ大陸に向かう奴隷船に乗船する際にグリグリ袋を持ち込むことができたため、この習慣はアメリカ合衆国に もたらされた。奴隷となった人々は、魔術のサービスを受けるために奴隷となったブラック・イスラム教徒のもとへ行き、奴隷制度からの保護を目的としたグリ グリ袋(モジョ袋)の作成を依頼した。[147] |

| Vodun Hoodoo also has some Vodun influence. For example, snakeskins are a primary ingredient in goofer dust. Snakes (serpents) are revered in West African spiritual practices because they represent divinity. The West African Vodun water spirit Mami Wata holds a snake in one hand. This reverence for snakes came to the United States during the slave trade, and in Hoodoo, snakeskins are used to prepare conjure powders.[148] Puckett explained that the origin of snake reverence in Hoodoo originates from snake (serpent) honoring in West Africa's Vodun tradition.[149] It was documented by a former slave in Missouri that conjurers took dried snakes and frogs and ground them into powders to "Hoodoo people." A conjurer made a powder from a dried snake and a frog, put it in a jar, and buried it under the steps of the target's house to "Hoodoo the person." When the targeted individual walked over the jar, they had pain in their legs. Snakes in Hoodoo are used for healing, protection, and to curse people.[150][112][113] |

ヴードゥー教 フードゥー教にもヴードゥー教の影響がある。例えば、蛇の皮は魔術の儀式で使用される粉の主要な材料である。蛇(ウミヘビ)は神聖な存在として西アフリ カの精神修行で崇拝されている。西アフリカのヴードゥー教の水の精霊マミ・ワタは片手に蛇を持っている。この蛇に対する崇敬の念は奴隷貿易の時代にアメリ カに伝わり、フードゥー教では蛇の皮が呪術の粉末を調合するために用いられている。[148] パケットは、フードゥー教における蛇崇拝の起源は 西アフリカのヴードゥー教の伝統における蛇(大蛇)崇拝に由来するものである。ミズーリ州の元奴隷が、魔術師が乾燥させた蛇やカエルを粉末にして「フー ドゥーの人々」に与えていたことを記録している。魔術師は乾燥したヘビとカエルの粉末を作り、それを瓶に入れて、標的となる人物の家の階段の下に埋め、 「フードゥーの呪いをかける」のである。標的となった人物が瓶の上を歩くと、足に痛みが生じる。フードゥーにおけるヘビは、治療、保護、呪いのために 用いられる。[150][112][113] |

| Yoruba influences Archaeologists believe there may be Yoruba influences in Hoodoo. The crossroads spirit in Hoodoo, the Man of the Crossroads, may have its origins in the Yoruba people's crossroads spirit, Eshu-Elegba. In West Africa, the Yoruba people leave offerings for Eshu-Elegba at the crossroads.[151] In Hoodoo, the crossroads has spiritual power, and rituals are performed at the crossroads, where there is a spirit that resides to receive offerings. However, the spirit that resides at the crossroads in Hoodoo is not named Eshu-Elegba.[152] Folklorist Newbell Niles Puckett recorded some crossroads rituals in Hoodoo practiced among African Americans in the South and explained their meaning. Puckett wrote, "Possibly this custom of sacrificing at the crossroads is due to the idea that spirits, like men, travel the highways and would be more likely to hit upon the offering at the crossroads than elsewhere."[153] In addition to leaving offerings and performing rituals at the crossroads, sometimes spiritual work or "spells" are left there to remove unwanted energies.[154][155] The belief in an entity that lords over the crossroads is present not only in African Diasporic traditions but also in Indigenous traditions around the world. However, Black Hoodoo practitioners in the Chesapeake region have pushed back on the misinterpretation of that finding, knowing the crossroads artifact to invoke what would later be known as The Man at the Crossroads. As entities shifted, reformed, and were reborn, they married with North American land to emerge as new deities.[citation needed] In Annapolis, Maryland, archaeologists uncovered evidence of West African and Central African practices. A Hoodoo spiritual bundle containing nails, a stone axe, and other items was found embedded four feet below the streets near the capital. The axe inside the Hoodoo bundle showed what archaeologists believe is a cultural link to the Yoruba people's deity Shango. Shango was (and is) a feared Orisha in Yorubaland, associated with lightning and thunder. This fear and respect toward thunder and lightning survived in African American communities. Folklorist Puckett wrote, "and thunder denotes an angry creator." Puckett recorded several beliefs surrounding the fear and respect for thunder and lightning in the African American community. In Hoodoo, objects struck by lightning hold great power. However, Shango and other African deity names were lost during slavery. Therefore, the name Shango does not exist in Hoodoo; it is simply the name "the thunder god." Enslaved and free Black people in New York were known among whites in the area to take an oath to thunder and lightning. During the 1741 slave conspiracy in New York, African American men took an oath to thunder and lightning.[156][157][158] |

ヨルバ族の影響 考古学者は、フードゥーにヨルバ族の影響があるかもしれないと考えている。フードゥーにおける交差路の精神、交差路の男は、ヨルバ族の交差路の精神で あるエシュ・エレグバに起源があるのかもしれない。西アフリカでは、ヨルバ族の人々は岐路にEshu-Elegbaへの供物を残す。[151] フードゥーでは、岐路には霊的な力が宿ると考えられており、供物を受け取る霊が宿る岐路で儀式が行われる。しかし、フードゥーにおける交差点に宿る霊 はエシュ・エレグバとは呼ばれていない。[152] 民俗学者のニューベル・ナイルズ・パケットは、南部のアフリカ系アメリカ人によって行われるフードゥーの交差点の儀式をいくつか記録し、その意味を説明 している。パケットは「おそらく、交差点で生贄を捧げるというこの風習は、霊魂が人間と同じように街道を往来し、他の場所よりも交差点で供物を発見する可 能性が高いという考えによるものだろう」と書いている。[153] 供物を残したり、交差点で儀式を行うことに加えて、 交差点で儀式を行うほか、時には不要なエネルギーを除去するために、霊的な作業や「呪文」がそこに残されることもある。[154][155] 交差点を支配する存在への信仰は、アフリカ系ディアスポラの伝統だけでなく、世界中の土着の伝統にも存在する。しかし、チェサピーク地方のブラック・ フードゥーの実践者たちは、その発見の誤った解釈に異議を唱え、交差道路の遺物が後に「交差道路の男」として知られるようになるものを呼び起こすことを 知っていた。実体が変化し、再形成され、再生するにつれ、それらは北米の大地と結びつき、新たな神として出現した。 メリーランド州アナポリスでは、考古学者が西アフリカと中央アフリカの慣習の証拠を発見した。 釘や石斧、その他の品々を収めたフードゥー教の霊符が、首都近くの道路から4フィート下に埋め込まれた状態で発見された。 フードゥー教の霊符に収められていた斧は、考古学者がヨルバ族の神シャンゴとの文化的つながりであると信じるものを示していた。サンゴは(そして今も) ヨルバランドで畏怖されるオリシャであり、雷や稲妻と関連付けられている。この雷や稲妻に対する畏怖と尊敬の念は、アフリカ系アメリカ人のコミュニティに 生き残っている。民俗学者のパケットは、「そして、雷は怒れる創造主を意味する」と記している。パケットは、アフリカ系アメリカ人のコミュニティにおける 雷や稲妻に対する畏怖と尊敬の念にまつわるいくつかの信念を記録している。フードゥーでは、雷に打たれた物体は大きな力を秘めている。しかし、シャンゴ やその他のアフリカの神の名は奴隷制度の間に失われた。そのため、フードゥー教にはシャンゴという名は存在せず、単に「雷神」と呼ばれる。ニューヨーク の奴隷と自由の身となった黒人たちは、その地域の白人の間で、雷と稲妻に誓いを立てることで知られていた。1741年のニューヨークの奴隷反乱では、アフ リカ系アメリカ人の男性たちが雷と稲妻に誓いを立てた。[156][157][158] |

Blacksmiths are respected in Black communities because of their knowledge of the mysteries of metal and its spiritual properties. Another Yoruba influence in Hoodoo is the use of iron. In West Africa, blacksmiths are respected because they are connected to the spirit of metal (iron). Among the Yoruba, the Orisha spirit Ogun corresponds to iron, and Ogun is called the "god of iron." West African people enslaved in the United States maintained respect for enslaved blacksmiths on the plantation and recognition for iron. Horseshoes, made from metal, are used for protection in Hoodoo. In Maryland, archaeologists unearthed artifacts at the Wye House that linked to the Yoruba people's spiritual belief and practice in the reverence of Ogun. This is why African Americans incorporate horseshoes and metal tools in Hoodoo: because there is a spirit that corresponds to metal that can be invoked for protection from physical and spiritual harm. Yoruba cultural influences survived in Hoodoo, but the names and symbols of Orisha spirits are not present because that information was lost during slavery; therefore, only the natural elements that correspond to each Orisha remain.[159][160] In addition, at the Kingsmill Plantation in Williamsburg, Virginia, enslaved blacksmiths created spoons that historians suggest have West African symbols carved onto them that have a spiritual cosmological meaning. In Alexandria, Virginia, historians found in a slave cabin a wrought-iron figure made by an enslaved blacksmith in the eighteenth century, which looked similar to Ogun statues made by blacksmiths in West Africa by the Edo, Fon, Mande, and Yoruba people. West African blacksmiths enslaved in the United States were highly respected and feared by enslaved Black people because they could forge weapons. Gabriel Prosser was an African American enslaved in Richmond, Virginia, and he was a blacksmith. In 1800, Gabriel Prosser planned a slave revolt in Virginia. Historians assert that Prosser became the leader of the planned rebellion because he was a blacksmith. Slave people respected and feared blacksmiths because of their ability to forge weapons and their connection to the spirit of iron. Prosser and other enslaved blacksmiths made weapons for the rebellion, but the revolt never happened because two enslaved people informed the authorities.[161][162] |

鍛冶屋は、金属の神秘と精神的な性質に関する知識ゆえに、黒人社会で尊敬されている。 フードゥーにおけるもう一つのヨルバ族の影響は、鉄の利用である。西アフリカでは、鍛冶屋は金属(鉄)の精神とつながっているため、尊敬されている。ヨ ルバ族では、オリシャの神オグンが鉄に対応しており、オグンは「鉄の神」と呼ばれている。米国で奴隷として働かされていた西アフリカの人々は、農園で奴隷 として働かされていた鍛冶屋たちを尊敬し、鉄を尊重していた。金属でできた蹄鉄は、フードゥー教の護符として用いられている。メリーランド州では、考古 学者がワイ・ハウスでヨルバ族の精神的な信仰とオグンへの畏敬の念を実践する証拠となる遺物を発掘した。これが、アフリカ系アメリカ人がフードゥーに蹄 鉄や金属製の道具を取り入れる理由である。金属に対応する精霊が存在し、肉体的・精神的な害から身を守るために呼び出すことができるからだ。ヨルバ文化の 影響はフードゥーにも残っているが、奴隷制度の間にその情報が失われたため、オリシャの精霊の名称やシンボルは存在しない。そのため、各オリシャに対応 する自然の要素のみが残っている。 さらに、バージニア州ウィリアムズバーグのキングスミル農園では、奴隷の鍛冶職人たちがスプーンを作っていたが、そのスプーンには西アフリカのシンボルが 刻まれており、精神的な宇宙論的な意味を持っていると歴史家は指摘している。バージニア州アレクサンドリアでは、歴史家が奴隷小屋で18世紀に奴隷の鍛冶 屋が作った錬鉄製の像を発見した。その像は、西アフリカの鍛冶屋が江戸時代、フォン族、マンデ族、ヨルバ族の人々によって作られたオグン像に似ていた。米 国で奴隷として働かされていた西アフリカの鍛冶職人は、武器を鍛造できることから、奴隷として働かされていた黒人たちから尊敬され、恐れられていた。ガブ リエル・プロッサーはバージニア州リッチモンドで奴隷として働かされていたアフリカ系アメリカ人で、鍛冶職人であった。1800年、ガブリエル・プロッ サーはバージニア州で奴隷の反乱を計画した。歴史家たちは、プロッサーが鍛冶職人であったことから、計画された反乱のリーダーとなったと主張している。奴 隷たちは、武器を鍛造する能力と鉄の精霊とのつながりから、鍛冶屋を尊敬し恐れていた。プロッサーと他の奴隷の鍛冶屋たちは反乱のための武器を作ったが、 2人の奴隷が当局に通報したため、反乱は起こらなかった。[161][162] |

Magical amulets A Hoodoo stick was found between the walls of the Bennehan House to curse (hex) the family. At Stagville Plantation in Durham County, North Carolina, archaeologists found artifacts made by enslaved African Americans that linked to spiritual practices found in West Africa. The artifacts included a divining stick, a walking stick, and cowrie shells. The wealthy enslaver Bennehan family owned Stagville Plantation; they enslaved 900 African American people. Stagville was one of many large slave plantations in the American South. Inside the Bennehan house, a walking stick was found between the walls to curse the Bennehan family. An enslaved person secretly placed the walking stick to put evil spirits on their enslavers, cursing the family for enslaving them. The walking stick was carved into an image of a West African snake spirit (deity) called Damballa. In West-Central Africa and African American communities, only initiates trained in the secrets of the serpent and spirits were allowed to have a conjure stick. These sticks conjured illness and healing, and the spirit of a conjure stick can warn the conjurer of impending danger.[163] Cowrie shells were found on the site and were used by enslaved African Americans to connect with the spiritual element of water "to ensure spiritual guidance over bodies of water." In West Africa, cowrie shells were used for money and corresponded to African water spirits.[164] Other African cultural survivals among the Gullah people include giving their children African names. Linguists have noted identical or similar-sounding names in the Gullah Geechee Nation that can be traced to Sierra Leone, a country in West Africa. Some African Americans in South Carolina and Georgia continue to give their children African names for spiritual and cultural reasons. The spiritual sense is for their ancestors to give their children spiritual power and protection. The cultural reason is so their children will know which region in Africa their ancestry is from.[165][166] The practice of carving snakes onto "conjure sticks" to remove curses and evil spirits and bring healing was found in African American communities in the Sea Islands among the Gullah Geechee people. Snake reverence in African American Hoodoo originated from West African societies.[167] Another practice in Hoodoo that has its origins in West Africa is to moisten conjure bags and luck balls with whiskey (rum). It is believed that conjure bags and luck balls have a spirit, and to keep their spirit alive, conjurers feed them whiskey once a week. The practice has its roots in the Guinea Coast of Africa.[168] The practice of foot-track magic in Hoodoo has its origins in the Ghana. A person's foot track is used to send someone away by mixing their foot track with herbs, roots, and insects, specific ingredients used in Hoodoo to send someone away, and grinding into a powder and placing the powder in a container and throwing it into a flowing river that leaves town, and in a few days, the person will leave town.[169][170] Among the Tshi people in Ghana, spirit possession is not limited to people. Still, objects, inanimate and animate, can become possessed by spirits. Folklorist Puckett documented this same belief among Black people in the South.[171] |