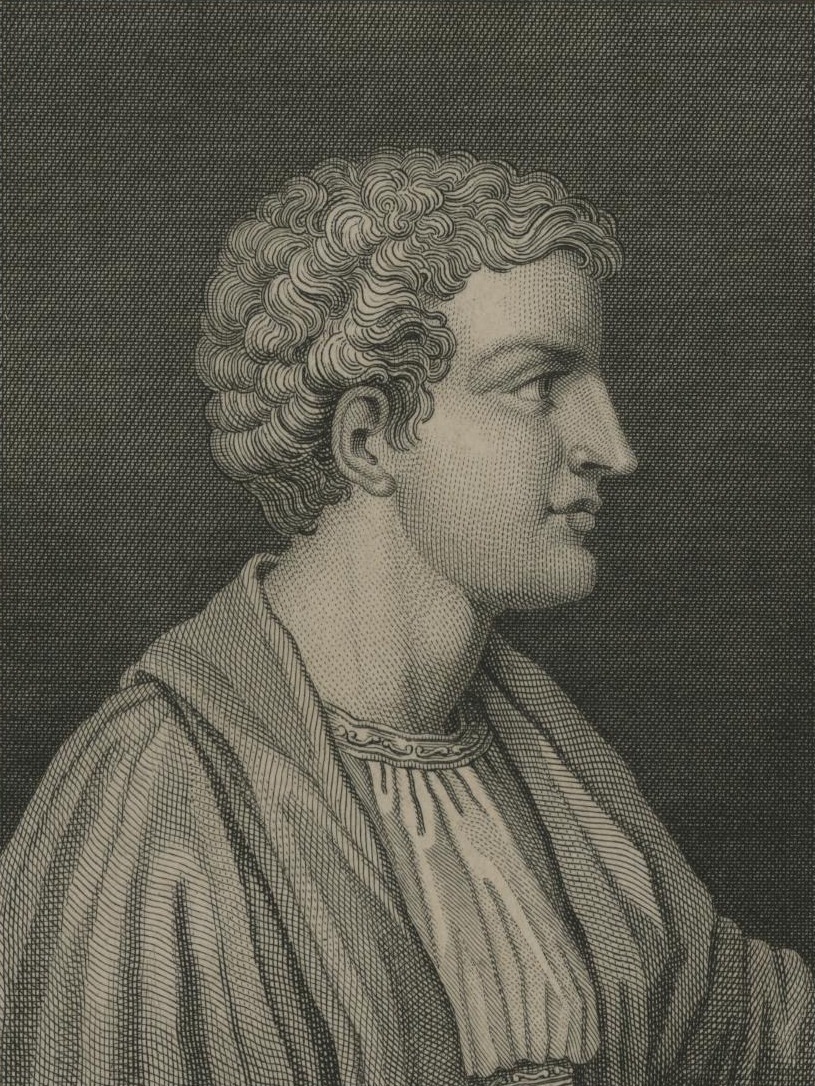

ホラティウス

Quintus Horatius

Flaccus, 65 BC to 8 BC

☆

クィントゥス・ホラティウス・フラッカス(古典ラテン語: [ˈʷiːʊ (h)ɔˈraːˈɫakːʊs]; 紀元前65年12月8日 -

紀元前8年11月27日)[1]、英語圏では一般にホラティウス(/ˈhɒr↪Ll_26As/

)として知られ、アウグストゥス(オクタヴィアヌスとしても知られる)の時代のローマを代表する抒情詩人であった。修辞学者クインティリアヌスは、彼の

Odesを読むに値する唯一のラテン語の抒情詩とみなした:「彼は時に高尚でありながら、魅力と気品にあふれ、多彩な人物像を描き、言葉の選び方には大胆

さを感じさせる」[nb 1]。

ホラティウスはまた、エレガントなヘキサメーター[五歩格?]の詩(諷刺と書簡)や辛辣なイアンビック詩(エポデス)も作った。ヘキサメーテールは愉快で

ありながらまじめで、親しみやすい調子で、古代の風刺詩人ペルシウスにこう言わしめた:「ホラティウスは、友人が笑うと、彼のあらゆる欠点を狡猾に指弾

し、いったんその中に入ると、心の琴線に触れる」[nb 2]と評した。

彼のキャリアは、ローマが共和制から帝国へと大きく変化した時期と重なる。紀元前42年のフィリッピの戦いで敗れた共和国軍の将校であった彼は、オクタ

ヴィアヌスの右腕であったマエケナスと親しくなり、新体制のスポークスマンとなった。ある論者にとっては、政権との関わりは、彼が強い独立性を維持する微

妙なバランスであった(彼は「優雅な横取りの達人」であった)[2]が、他の論者にとっては、ジョン・ドライデンの言葉を借りれば「行儀のよい宮廷奴隷」

であった[3][nb 3]。

| Quintus Horatius

Flaccus (Classical Latin: [ˈkʷiːntʊs (h)ɔˈraːtiʊs ˈfɫakːʊs]; 8 December

65 BC – 27 November 8 BC),[1] commonly known in the English-speaking

world as Horace (/ˈhɒrɪs/), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the

time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian

regarded his Odes as the only Latin lyrics worth reading: "He can be

lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in

his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words."[nb 1] Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Satires and Epistles) and caustic iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are amusing yet serious works, friendly in tone, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: "as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings".[nb 2] His career coincided with Rome's momentous change from a republic to an empire. An officer in the republican army defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian's right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep")[2] but for others he was, in John Dryden's phrase, "a well-mannered court slave".[3][nb 3] |

クィントゥス・ホラティウス・フラッカス(古典ラテン語:

[ˈʷiːʊ (h)ɔˈraːˈɫakːʊs]; 紀元前65年12月8日 -

紀元前8年11月27日)[1]、英語圏では一般にホラティウス(/ˈhɒr↪Ll_26As/

)として知られ、アウグストゥス(オクタヴィアヌスとしても知られる)の時代のローマを代表する抒情詩人であった。修辞学者クインティリアヌスは、彼の

Odesを読むに値する唯一のラテン語の抒情詩とみなした:

「彼は時に高尚でありながら、魅力と気品にあふれ、多彩な人物像を描き、言葉の選び方には大胆さを感じさせる」[nb 1]。 ホラティウスはまた、エレガントなヘキサメーターの詩(諷刺と書簡)や辛辣なイアンビック詩(エポデス)も作った。ヘキサメーテールは愉快でありながらま じめで、親しみやすい調子で、古代の風刺詩人ペルシウスにこう言わしめた: 「ホラティウスは、友人が笑うと、彼のあらゆる欠点を狡猾に指弾し、いったんその中に入ると、心の琴線に触れる」[nb 2]と評した。 彼のキャリアは、ローマが共和制から帝国へと大きく変化した時期と重なる。紀元前42年のフィリッピの戦いで敗れた共和国軍の将校であった彼は、オクタ ヴィアヌスの右腕であったマエケナスと親しくなり、新体制のスポークスマンとなった。ある論者にとっては、政権との関わりは、彼が強い独立性を維持する微 妙なバランスであった(彼は「優雅な横取りの達人」であった)[2]が、他の論者にとっては、ジョン・ドライデンの言葉を借りれば「行儀のよい宮廷奴隷」 であった[3][nb 3]。 |

Life Horatii Flacci Sermonum (1577) Horace can be regarded as the world's first autobiographer.[4] In his writings, he tells far more about himself, his character, his development, and his way of life, than any other great poet of antiquity. Some of the biographical material contained in his work can be supplemented from the short but valuable "Life of Horace" by Suetonius (in his Lives of the Poets).[5] Childhood He was born on 8 December 65 BC[nb 4] in Apulia, in southern Italy.[6] His home town, Venusia, lay on a trade route in the region of Apulia at the border with Lucania (Basilicata). Various Italic dialects were spoken in the area and this perhaps enriched his feeling for language. He could have been familiar with Greek words even as a young boy and later he poked fun at the jargon of mixed Greek and Oscan spoken in neighbouring Canusium.[7] One of the works he probably studied in school was the Odyssia of Livius Andronicus, taught by teachers like the 'Orbilius' mentioned in one of his poems.[8] Army veterans could have been settled there at the expense of local families uprooted by Rome as punishment for their part in the Social War (91–88 BC).[9] Such state-sponsored migration must have added still more linguistic variety to the area. According to a local tradition reported by Horace,[10] a colony of Romans or Latins had been installed in Venusia after the Samnites had been driven out early in the third century. In that case, young Horace could have felt himself to be a Roman[11][12] though there are also indications that he regarded himself as a Samnite or Sabellus by birth.[13][14] Italians in modern and ancient times have always been devoted to their home towns, even after success in the wider world, and Horace was no different. Images of his childhood setting and references to it are found throughout his poems.[15] Horace's father was probably a Venutian taken captive by Romans in the Social War, or possibly he was descended from a Sabine captured in the Samnite Wars. Either way, he was a slave for at least part of his life. He was evidently a man of strong abilities however and managed to gain his freedom and improve his social position. Thus Horace claimed to be the free-born son of a prosperous 'coactor'.[16] The term 'coactor' could denote various roles, such as tax collector, but its use by Horace[17] was explained by scholia as a reference to 'coactor argentarius' i.e. an auctioneer with some of the functions of a banker, paying the seller out of his own funds and later recovering the sum with interest from the buyer.[18] The father spent a small fortune on his son's education, eventually accompanying him to Rome to oversee his schooling and moral development. The poet later paid tribute to him in a poem[19] that one modern scholar considers the best memorial by any son to his father.[nb 5] The poem includes this passage: If my character is flawed by a few minor faults, but is otherwise decent and moral, if you can point out only a few scattered blemishes on an otherwise immaculate surface, if no one can accuse me of greed, or of prurience, or of profligacy, if I live a virtuous life, free of defilement (pardon, for a moment, my self-praise), and if I am to my friends a good friend, my father deserves all the credit... As it is now, he deserves from me unstinting gratitude and praise. I could never be ashamed of such a father, nor do I feel any need, as many people do, to apologize for being a freedman's son. Satires 1.6.65–92 He never mentioned his mother in his verses and he might not have known much about her. Perhaps she also had been a slave.[16] |

人生 ホラティイ・フラッチ説教集(1577年) ホラティウスは世界最初の自伝作家と見なすことができる[4]。 その著作の中で、彼は自分自身について、自分の性格について、自分の成長について、自分の生き方について、古代の他のどの偉大な詩人よりもはるかに多くの ことを語っている。彼の著作に含まれる伝記の一部は、スエトニウス(『詩人列伝』所収)による短いが貴重な『ホラティウスの生涯』から補足することができ る[5]。 幼少期 紀元前65年12月8日[nb 4]、南イタリアのアプーリア州で生まれた[6]。故郷のヴィーナスィアは、ルカニア(バジリカータ)との国境に位置するアプーリア州の交易路上にあっ た。この地域ではさまざまなイタリア方言が話されており、そのことが彼の言語感覚を豊かにしたのだろう。少年時代からギリシア語に親しんでいた可能性もあ り、後に近隣のカヌージウムで話されていたギリシア語とオスカン語の混血の専門用語をからかった[7]。 [8] 社会戦争(紀元前91~88年)に参加した罰としてローマに追放された地元の家族の犠牲の上に、退役軍人がそこに定住した可能性もある[9]。ホラティウ スが伝えた地元の伝承[10]によれば、3世紀初頭にサムニテ人が追い出された後、ヴィーナスティアにはローマ人かラテン人のコロニーが設置された。その 場合、幼いホラティウスは自分自身をローマ人[11][12]だと感じていたかもしれないが、生まれつきのサムニテ人またはサベリウス人だと考えていたこ とを示す記述もある[13][14]。近世も古代も、イタリア人は広い世界で成功を収めた後でも常に故郷に愛着を抱いており、ホラティウスもその例に漏れ なかった。彼の詩のいたるところに、幼少期の舞台のイメージやそこへの言及が見られる[15]。 ホラティウスの父親は、おそらく社会戦争でローマ人に捕らえられたヴェニューティア人か、あるいはサムナイト戦争で捕らえられたサビニ人の子孫であろう。 いずれにせよ、彼は少なくとも生涯の一部は奴隷だった。しかし、彼は有能な人物であったことは明らかで、自由を獲得し、社会的地位を向上させることに成功 した。このようにホラティウスは、裕福な「コアクター」の息子として生まれたと主張している[16]。「コアクター」という用語は、徴税人などさまざまな 役割を示すことができるが、ホラティウス[17]が使用した「コアクター・アルゲンタリウス」は、「コアクター・アルゲンタリウス」、すなわち銀行家のよ うな機能を持つ競売人であり、自分の資金から売り手に支払いを行い、後に買い手から利子をつけてその金額を回収する、という意味であるとスコリアは説明し ている[18]。 父親は息子の教育に小金を費やし、最終的には息子の学校教育と道徳的成長を監督するためにローマに同行した。詩人は後に詩[19]で父に賛辞を送ったが、ある現代の学者は、息子による父への最高の記念碑とみなしている[nb 5] : もし私の性格に小さな欠点がいくつかあっても、それ以外は品行方正で道徳的であり、そうでなければ無垢な表面に散らばったわずかな傷しか指摘できず、誰も 私の貪欲さや奢りや浪費を非難できず、汚れのない高潔な生活を送り(ちょっと自画自賛をお許しください)、友人にとって良き友人であれば、父はすべての称 賛に値する...。そして、もし私が友人たちにとって良き友人であるならば、父はすべての称賛に値するだろう...。そのような父を私は決して恥じること はできないし、多くの人民がそうであるように、自由民の息子であることを謝る必要もない。風刺1.6.65-92 彼は詩の中で母親について一度も触れていないし、母親についてよく知らなかったのかもしれない。おそらく彼女も奴隷だったのだろう[16]。 |

| Adulthood Horace left Rome, possibly after his father's death, and continued his formal education in Athens, a great centre of learning in the ancient world, where he arrived at nineteen years of age, enrolling in The Academy. Founded by Plato, The Academy was now dominated by Epicureans and Stoics, whose theories and practices made a deep impression on the young man from Venusia.[20] Meanwhile, he mixed and lounged about with the elite of Roman youth, such as Marcus, the idle son of Cicero, and the Pompeius to whom he later addressed a poem.[21] It was in Athens too that he probably acquired deep familiarity with the ancient tradition of Greek lyric poetry, at that time largely the preserve of grammarians and academic specialists (access to such material was easier in Athens than in Rome, where the public libraries had yet to be built by Asinius Pollio and Augustus).[22] Rome's troubles following the assassination of Julius Caesar were soon to catch up with him. Marcus Junius Brutus came to Athens seeking support for the republican cause. Brutus was fêted around town in grand receptions and he made a point of attending academic lectures, all the while recruiting supporters among the young men studying there, including Horace.[23] An educated young Roman could begin military service high in the ranks and Horace was made tribunus militum (one of six senior officers of a typical legion), a post usually reserved for men of senatorial or equestrian rank and which seems to have inspired jealousy among his well-born confederates.[24][25] He learned the basics of military life while on the march, particularly in the wilds of northern Greece, whose rugged scenery became a backdrop to some of his later poems.[26] It was there in 42 BC that Octavian (later Augustus) and his associate Mark Antony crushed the republican forces at the Battle of Philippi. Horace later recorded it as a day of embarrassment for himself, when he fled without his shield,[27] but allowance should be made for his self-deprecating humour. Moreover, the incident allowed him to identify himself with some famous poets who had long ago abandoned their shields in battle, notably his heroes Alcaeus and Archilochus. The comparison with the latter poet is uncanny: Archilochus lost his shield in a part of Thrace near Philippi, and he was deeply involved in the Greek colonization of Thasos, where Horace's die-hard comrades finally surrendered.[25] Octavian offered an early amnesty to his opponents and Horace quickly accepted it. On returning to Italy, he was confronted with yet another loss: his father's estate in Venusia was one of many throughout Italy to be confiscated for the settlement of veterans (Virgil lost his estate in the north about the same time). Horace later claimed that he was reduced to poverty and this led him to try his hand at poetry.[28] In reality, there was no money to be had from versifying. At best, it offered future prospects through contacts with other poets and their patrons among the rich.[29] Meanwhile, he obtained the sinecure of scriba quaestorius, a civil service position at the aerarium or Treasury, profitable enough to be purchased even by members of the ordo equester and not very demanding in its work-load, since tasks could be delegated to scribae or permanent clerks.[30] It was about this time that he began writing his Satires and Epodes. He describes[31] in glowing terms the country villa which his patron, Maecenas, had given him in a letter to his friend Quinctius: "It lies on a range of hills, broken by a shady valley which is so placed that the sun when rising strikes the right side, and when descending in his flying chariot, warms the left. You would like the climate; and if you were to see my fruit trees, bearing ruddy cornils and plums, my oaks and ilex supplying food to my herds, and abundant shade to the master, you would say, Tarentum in its beauty has been brought near to Rome! There is a fountain too, large enough to give a name to the river which it feeds; and the Hebrus itself does not flow through Thrace with cooler or purer stream. Its waters also are good for the head and useful for digestion. This sweet, and, if you will believe me, charming retreat keeps me in good health during the autumnal days." The remains of Horace's Villa are situated on a wooded hillside above the river at Licenza, which joins the Aniene as it flows on to Tivoli. |

成人期 ホラティウスは、おそらく父の死後ローマを離れ、古代世界の学問の中心地であったアテネで正規の教育を受け、19歳でアカデミーに入学した。プラトンに よって創設されたアカデミーは、エピクロス派とストア派に支配され、その理論と実践はヴィーナシア出身の青年に深い印象を与えた[20]。一方、彼は、キ ケロの息子で怠け者のマルクスや、後に彼が詩を宛てたポンペイウスなど、ローマの若者のエリートたちに混血し、たむろしていた。 [21]当時は文法学者や学問の専門家のものであったギリシアの抒情詩の伝統に深く親しんだのもアテネであったと思われる(そのような資料へのアクセス は、アシニウス・ポリオやアウグストゥスによって公共図書館がまだ建設されていなかったローマよりもアテネの方が容易であった)[22]。 ユリウス・カエサル暗殺後のローマの問題は、すぐに彼を追いつめることになった。マルクス・ユニウス・ブルートゥスが共和政への支援を求めてアテネを訪れ た。ブルータスは町中で盛大なレセプションを開き、ホラティウスを含むそこで学ぶ若者たちの支持者を募りながら、学術的な講義に出席した[23]。ホラ ティウスは教育を受けた若いローマ人なら高い階級で軍務に就くことができ、トリブヌス・ミリトゥム(典型的な軍団の6人の上級士官の1人)となった。 [24][25]オクタヴィアヌス(後のアウグストゥス)とその仲間であったマルコ・アントニーがフィリッピの戦いで共和国軍を粉砕したのは紀元前42年 のことであった。ホラティウスは後に、盾を持たずに逃走した自分自身にとって恥ずべき日であったと記録しているが[27]、彼の自虐的なユーモアは許容さ れるべきである。さらに、この出来事によって、彼は、戦いで盾を捨てた有名な詩人たち、とりわけ彼の英雄アルカイオスやアルキロクスと自分を同一視するこ とができた。後者の詩人との比較は不気味である: アルキロクスはフィリッピ近郊のトラキアの一部で盾を失い、ホラティウスの死に物狂いの仲間たちが最終的に降伏したタソス島のギリシャ植民地化に深く関 わった[25]。 オクタヴィアヌスは敵対勢力に早期の恩赦を与え、ホラティウスはすぐにそれを受け入れた。ヴィーナシアにあった父の領地は、退役軍人の入植のために没収さ れたイタリア全土の領地のひとつであった(同じ頃、ヴァージルも北部の領地を失った)。ホラティウスは後に、自分が貧困に陥ったことが詩作を始めるきっか けになったと語っている[28]。その一方で、彼はスクリバ・クァエストリウスという官職を得た。これはエアリウムまたは財務省の公務員職で、オルド・エ クエステルのメンバーでも購入できるほど有益な職であり、仕事は書記や常任書記に任せることができたため、仕事量はそれほど多くなかった[30]。 彼は友人クィンティウスに宛てた手紙の中で、パトロンであったマエケナスから贈られた田舎の別荘について熱烈な言葉で描写している[31]: 「丘の連なりの上にあり、木陰の谷によって分断され、太陽が昇るときは右側を、戦車に乗って降りてくるときは左側を暖めるように配置されている。この気候 を気に入るだろう。そして、私の果樹が赤々と実をつけ、トウモロコシやプラムが実り、オークやイレックスが群畜に食料を供給し、主人に豊かな木陰を提供し ているのを見れば、タレンタムはその美しさにおいてローマに近づいたと言うだろう!ヘブルス川はトラキアを流れる川としては、これ以上冷たく清らかな流れ はない。その水は頭にもよく、消化にも役立つ。この甘く、そして私を信じてくれるなら魅力的な隠れ家は、秋の日々を健康に保ってくれる」。 ホラティウスの別荘跡は、リチェンツァの川の上流にある森の丘の中腹にある。 |

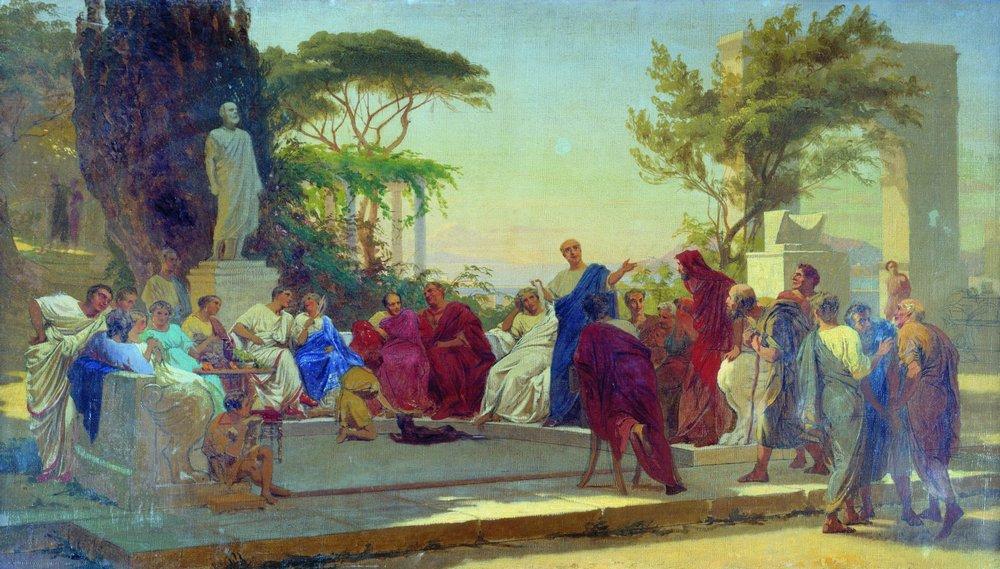

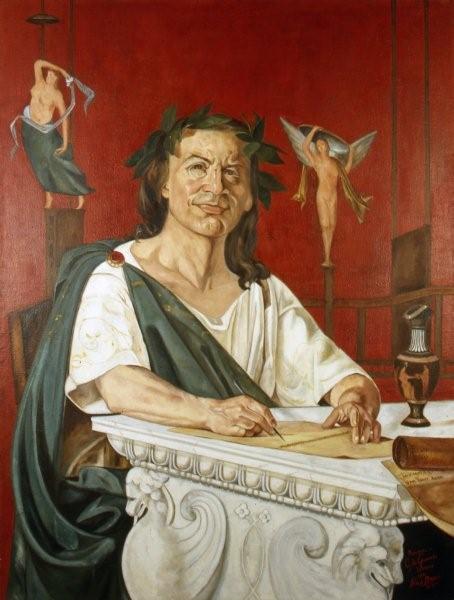

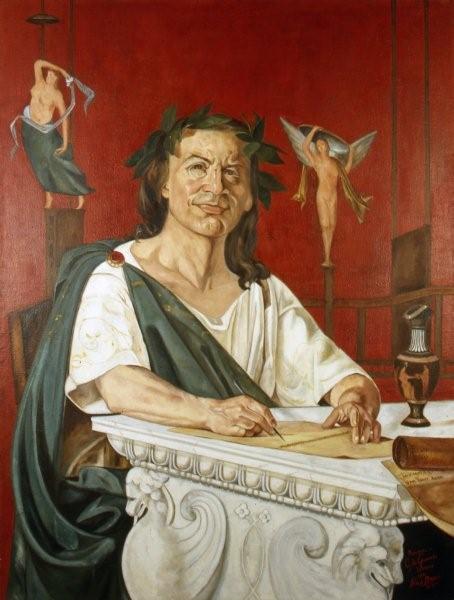

Poet Horace reads his poems in front of Maecenas, by Fyodor Bronnikov  Horace reciting his verses, by Adalbert von Rössler. The Epodes belong to iambic poetry. Iambic poetry features insulting and obscene language;[32][33] sometimes, it is referred to as blame poetry.[34] Blame poetry, or shame poetry, is poetry written to blame and shame fellow citizens into a sense of their social obligations. Each poem normally has a archetype person Horace decides to shame, or teach a lesson to. Horace modelled these poems on the poetry of Archilochus. Social bonds in Rome had been decaying since the destruction of Carthage a little more than a hundred years earlier, due to the vast wealth that could be gained by plunder and corruption.[35] These social ills were magnified by rivalry between Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and confederates like Sextus Pompey, all jockeying for a bigger share of the spoils. One modern scholar has counted a dozen civil wars in the hundred years leading up to 31 BC, including the Third Servile War under Spartacus, eight years before Horace's birth.[36] As the heirs to Hellenistic culture, Horace and his fellow Romans were not well prepared to deal with these problems: At bottom, all the problems that the times were stirring up were of a social nature, which the Hellenistic thinkers were ill qualified to grapple with. Some of them censured oppression of the poor by the rich, but they gave no practical lead, though they may have hoped to see well-meaning rulers doing so. Philosophy was drifting into absorption in self, a quest for private contentedness, to be achieved by self-control and restraint, without much regard for the fate of a disintegrating community. — V. G. Kiernan[37] Horace's Hellenistic background is clear in his Satires, even though the genre was unique to Latin literature. He brought to it a style and outlook suited to the social and ethical issues confronting Rome but he changed its role from public, social engagement to private meditation.[38] Meanwhile, he was beginning to interest Octavian's supporters, a gradual process described by him in one of his satires.[19] The way was opened for him by his friend, the poet Virgil, who had gained admission into the privileged circle around Maecenas, Octavian's lieutenant, following the success of his Eclogues. An introduction soon followed and, after a discreet interval, Horace too was accepted. He depicted the process as an honourable one, based on merit and mutual respect, eventually leading to true friendship, and there is reason to believe that his relationship was genuinely friendly, not just with Maecenas but afterwards with Augustus as well.[39] On the other hand, the poet has been unsympathetically described by one scholar as "a sharp and rising young man, with an eye to the main chance."[40] There were advantages on both sides: Horace gained encouragement and material support, the politicians gained a hold on a potential dissident.[41] His republican sympathies, and his role at Philippi, may have caused him some pangs of remorse over his new status. However, most Romans considered the civil wars to be the result of contentio dignitatis, or rivalry between the foremost families of the city, and he too seems to have accepted the principate as Rome's last hope for much needed peace.[42] In 37 BC, Horace accompanied Maecenas on a journey to Brundisium, described in one of his poems[43] as a series of amusing incidents and charming encounters with other friends along the way, such as Virgil. In fact the journey was political in its motivation, with Maecenas en route to negotiate the Treaty of Tarentum with Antony, a fact Horace artfully keeps from the reader (political issues are largely avoided in the first book of satires).[41] Horace was probably also with Maecenas on one of Octavian's naval expeditions against the piratical Sextus Pompeius, which ended in a disastrous storm off Palinurus in 36 BC, briefly alluded to by Horace in terms of near-drowning.[44][nb 6] There are also some indications in his verses that he was with Maecenas at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, where Octavian defeated his great rival, Antony.[45][nb 7] By then Horace had already received from Maecenas the famous gift of his Sabine farm, probably not long after the publication of the first book of Satires. The gift, which included income from five tenants, may have ended his career at the Treasury, or at least allowed him to give it less time and energy.[46] It signalled his identification with the Octavian regime yet, in the second book of Satires that soon followed, he continued the apolitical stance of the first book. By this time, he had attained the status of eques Romanus (Roman 'cavalryman', 'knight'),[47] perhaps as a result of his work at the Treasury.[48] |

詩人 マエケナスの前で詩を朗読するホラティウス(フョードル・ブロニコフ作)  詩を朗読するホラティウス(Adalbert von Rössler作)。 エポデスはイアンビック詩に属する。イアンビック詩は侮辱的で卑猥な言葉を特徴とし[32][33]、非難詩と呼ばれることもある[34]。非難詩、ある いは恥辱詩とは、同胞を非難し、恥辱を与えて社会的義務を自覚させるために書かれる詩である。各詩には通常、ホラティウスが恥をかかせる、あるいは教訓を 与えようと決めた人格の典型が登場する。ホラティウスはこれらの詩をアルキロクスの詩をモデルにした。略奪と汚職によって得られる莫大な富のために、 100年あまり前にカルタゴが滅亡して以来、ローマの社会的絆は衰退していた[35]。ユリウス・カエサル、マルコ・アントニー、セクストゥス・ポンペイ のような連合軍が、より多くの戦利品の分け前をめぐって対立したことで、こうした社会悪は拡大した。ある現代の学者は、ホラティウスが生まれる8年前のス パルタクスによる第三次隷属戦争を含め、紀元前31年までの100年間に起こった内戦を12件も数えている[36]。ヘレニズム文化の継承者として、ホラ ティウスと彼の仲間であるローマ人は、これらの問題に対処する準備が十分ではなかった: ヘレニズムの思想家たちには、このような問題に取り組む資格がなかったのである。ヘレニズムの思想家たちの中には、富裕層による貧困層の抑圧を非難する者 もいたが、善意ある支配者たちがそうすることを望んでいたかもしれないが、実践的な指針を与えることはなかった。哲学は、崩壊しつつある共同体の運命をあ まり顧みることなく、自制心と自制心によって達成されるべき私的満足の探求、自己への吸収へと流れ込んでいた。 - V.G.キアナン[37]。 ホラティウスがヘレニズム的な背景を持つことは、このジャンルがラテン文学特有のものであったとしても、彼の『風刺』には明らかである。一方、彼はオクタ ヴィアヌスの支持者たちに興味を持たれ始めていたが、それは彼がある諷刺小説の中で述べている段階的な過程であった[19]。ホラティウスもすぐに紹介さ れ、慎重な期間を経て受け入れられた。マエケナスだけでなく、その後アウグストゥスとも純粋に友好的な関係であったと信じるに足る理由がある[39]。一 方、ある学者は、この詩人を「鋭く、上昇志向の強い若者で、チャンスを狙っていた」と非情に評している[40]: ホラティウスは励ましと物質的な支援を得、政治家たちは反体制派の可能性のある人物を押さえることができた[41]。彼の共和主義的なシンパシーとフィリ ピでの役割は、新しい地位に対する自責の念を彼に抱かせたかもしれない。しかし、ほとんどのローマ人は、内戦はcontentio dignitatis、つまり都市の有力者一族間の対立の結果であると考えており、彼もまた、必要とされる平和のためのローマの最後の希望として公爵位を 受け入れたようである[42]。 紀元前37年、ホラティウスはマエケナスのブルンディシウムへの旅に同行し、彼の詩[43]の中で、楽しい事件やヴァージルなど道中の友人たちとの魅力的 な出会いの連続として描かれている。ホラティウスは、おそらくオクタウィアヌスの海賊セクストゥス・ポンペイウスに対する遠征にもマエケナスとともに参加 していたと思われるが、その遠征は紀元前36年にパリヌルス沖で嵐に見舞われ、ホラティウスは溺死寸前であったことを簡単に述べている[41]。 [44][nb 6] また、オクタウィアヌスが大敵アントニウスを破った紀元前31年のアクティウムの戦いに、マエケナスとともにいたことを示唆する詩もある[45][nb 7] その頃ホラティウスはすでにマエケナスから有名なサビネス農園の贈与を受けており、おそらく『サティレス』第1巻の出版から間もなくのことであった。この 贈与には5人の借家人からの収入も含まれており、この贈与が彼の財務省でのキャリアに終止符を打ったか、少なくとも時間と労力を割くことを許したのであろ う[46]。この贈与は彼がオクタヴィアヌス政権と同一視していることを示すものであったが、その直後に出版された『諷刺集』第2巻では、彼は第1巻のよ うな非政治的な立場を続けている。この頃、彼はおそらく財務省での仕事の成果として、エクエス・ロマーヌス(ローマの「騎兵」、「騎士」)の地位を獲得し ていた[47]。 |

| Knight Odes 1–3 were the next focus for his artistic creativity. He adapted their forms and themes from Greek lyric poetry of the seventh and sixth centuries BC. The fragmented nature of the Greek world had enabled his literary heroes to express themselves freely and his semi-retirement from the Treasury in Rome to his own estate in the Sabine hills perhaps empowered him to some extent also[49] yet even when his lyrics touched on public affairs they reinforced the importance of private life.[2] Nevertheless, his work in the period 30–27 BC began to show his closeness to the regime and his sensitivity to its developing ideology. In Odes 1.2, for example, he eulogized Octavian in hyperboles that echo Hellenistic court poetry. The name Augustus, which Octavian assumed in January of 27 BC, is first attested in Odes 3.3 and 3.5. In the period 27–24 BC, political allusions in the Odes concentrated on foreign wars in Britain (1.35), Arabia (1.29) Hispania (3.8) and Parthia (2.2). He greeted Augustus on his return to Rome in 24 BC as a beloved ruler upon whose good health he depended for his own happiness (3.14).[50] The public reception of Odes 1–3 disappointed him, however. He attributed the lack of success to jealousy among imperial courtiers and to his isolation from literary cliques.[51] Perhaps it was disappointment that led him to put aside the genre in favour of verse letters. He addressed his first book of Epistles to a variety of friends and acquaintances in an urbane style reflecting his new social status as a knight. In the opening poem, he professed a deeper interest in moral philosophy than poetry[52] but, though the collection demonstrates a leaning towards stoic theory, it reveals no sustained thinking about ethics.[53] Maecenas was still the dominant confidante but Horace had now begun to assert his own independence, suavely declining constant invitations to attend his patron.[54] In the final poem of the first book of Epistles, he revealed himself to be forty-four years old in the consulship of Lollius and Lepidus i.e. 21 BC, and "of small stature, fond of the sun, prematurely grey, quick-tempered but easily placated".[55][56] According to Suetonius, the second book of Epistles was prompted by Augustus, who desired a verse epistle to be addressed to himself. Augustus was in fact a prolific letter-writer and he once asked Horace to be his personal secretary. Horace refused the secretarial role but complied with the emperor's request for a verse letter.[57] The letter to Augustus may have been slow in coming, being published possibly as late as 11 BC. It celebrated, among other things, the 15 BC military victories of his stepsons, Drusus and Tiberius, yet it and the following letter[58] were largely devoted to literary theory and criticism. The literary theme was explored still further in Ars Poetica, published separately but written in the form of an epistle and sometimes referred to as Epistles 2.3 (possibly the last poem he ever wrote).[59] He was also commissioned to write odes commemorating the victories of Drusus and Tiberius[60] and one to be sung in a temple of Apollo for the Secular Games, a long-abandoned festival that Augustus revived in accordance with his policy of recreating ancient customs (Carmen Saeculare). Suetonius recorded some gossip about Horace's sexual activities late in life, claiming that the walls of his bedchamber were covered with obscene pictures and mirrors, so that he saw erotica wherever he looked.[nb 8] The poet died at 56 years of age, not long after his friend Maecenas, near whose tomb he was laid to rest. Both men bequeathed their property to Augustus, an honour that the emperor expected of his friends.[61] |

騎士 オデ1~3番は、彼の芸術的創造性の次の焦点となった。紀元前7世紀から6世紀にかけてのギリシアの抒情詩の形式とテーマを取り入れた。ギリシア世界の断 片的な性質が、彼の文学的英雄たちが自由に自己表現することを可能にし、ローマの宝物庫からサビネの丘にある自分の領地へと半引退したことも、おそらく彼 にある程度の力を与えたのだろう[49]が、彼の歌詞が公的な問題に触れたときでさえ、私生活の重要性を強調していた[2]。例えば、Odes 1.2では、ヘレニズムの宮廷詩を髣髴とさせる大げさな表現でオクタヴィアヌスを賛美している。オクタヴィアヌスが紀元前27年1月に名乗ったアウグス トゥスという名は、Odes 3.3と3.5で初めて証明されている。紀元前27年から24年にかけて、政治的な言及はブリテン(1.35)、アラビア(1.29)、イスパニア (3.8)、パルティア(2.2)における対外戦争に集中していた。紀元前24年にローマに帰還したアウグストゥスに対しては、自らの幸福をその保健に依 存する最愛の統治者として挨拶している(3.14)[50]。 しかし、『詩編』1~3が世間に受け入れられたことで、アウグストゥスは失望した。彼はこの成功のなさを、帝国の廷臣たちの嫉妬と、文学的徒党から孤立し ていたことが原因だと考えている[51]。彼は最初の書簡集を、騎士としての新しい社会的地位を反映した都会的な文体で、さまざまな友人や知人に宛てた。 冒頭の詩で、彼は詩よりも道徳哲学に深い関心を抱いていることを公言している[52]が、この書簡集ではストイックな理論への傾倒は見られるものの、倫理 についての持続的な考察は見られない[53]。 [54]書簡集第1巻の最後の詩で、彼はロリウスとレピドゥスの領事時代、すなわち紀元前21年には44歳であり、「小柄で、太陽が好きで、早熟な白髪 で、短気だがなだめやすい」人物であったことを明らかにしている[55][56]。 スエトニウスによれば、書簡集第2巻は、アウグストゥスが自分宛の詩的な書簡を望んだことに端を発している。実際、アウグストゥスは多量の手紙を書く人 で、ホラティウスに個人秘書を依頼したこともあった。ホラティウスは秘書の仕事は断ったが、詩の手紙を書きたいという皇帝の要望には応じた[57]。この 書簡は、特に彼の継子であるドルススとティベリウスの紀元前15年の軍事的勝利を称えたものであったが、この書簡とそれに続く書簡[58]の大部分は文学 論と批評に費やされていた。また、ドゥルースとティベリウスの勝利を記念するオデ曲[60]や、アウグストゥスが古代の風習を復興させるという方針に従っ て復活させた世俗競技会(長い間廃れていた祭)のためにアポロ神殿で歌われるオデ曲の執筆も依頼されていた(『カルメン・サエクラーレ』)。 スエトニウスは、晩年のホラティウスの性行為に関する噂話をいくつか記録しており、彼の寝室の壁は猥褻な絵や鏡で覆われており、どこを見てもエロチカなも のが見えたと主張している[nb 8] 詩人は56歳で亡くなったが、友人のマエケナスに遅れることなく、彼の墓の近くに安置された。二人とも財産をアウグストゥスに遺贈したが、これは皇帝が友 人に期待した栄誉であった[61]。 |

| Works The dating of Horace's works isn't known precisely and scholars often debate the exact order in which they were first 'published'. There are persuasive arguments for the following chronology:[62] Satires 1 (c. 35–34 BC)[nb 9] Satires 2 (c. 30 BC) Epodes (30 BC) Odes 1–3 (c. 23 BC)[nb 10] Epistles 1 (c. 21 BC) Carmen Saeculare (17 BC) Epistles 2 (c. 11 BC)[nb 11][nb 12] Odes 4 (c. 11 BC)[nb 13] Ars Poetica (c. 10–8 BC)[nb 14] |

作品 ホラティウスの作品の年代は正確にはわかっておらず、学者たちはしばしば最初に「出版」された正確な順序について議論する。以下の年代については説得力のある議論がある[62]。 風刺1(紀元前35-34年頃)[nb 9] 。 サティレス2(紀元前30年頃) エポデス(紀元前30年) オデス1~3(紀元前23年頃)[nb 10] 書簡1(紀元前21年頃) カルメン・サエクラーレ(紀元前17年) 書簡2(紀元前11年頃)[nb 11][nb 12] 。 オデス4(紀元前11年頃)[nb 13] アルス・ポエティカ(紀元前10~8年頃)[nb 14] |

| Historical context Horace composed in traditional metres borrowed from Archaic Greece, employing hexameters in his Satires and Epistles, and iambs in his Epodes, all of which were relatively easy to adapt into Latin forms. His Odes featured more complex measures, including alcaics and sapphics, which were sometimes a difficult fit for Latin structure and syntax. Despite these traditional metres, he presented himself as a partisan in the development of a new and sophisticated style. He was influenced in particular by Hellenistic aesthetics of brevity, elegance and polish, as modelled in the work of Callimachus.[63] As soon as Horace, stirred by his own genius and encouraged by the example of Virgil, Varius, and perhaps some other poets of the same generation, had determined to make his fame as a poet, being by temperament a fighter, he wanted to fight against all kinds of prejudice, amateurish slovenliness, philistinism, reactionary tendencies, in short to fight for the new and noble type of poetry which he and his friends were endeavouring to bring about. — Eduard Fraenkel[64] In modern literary theory, a distinction is often made between immediate personal experience (Urerlebnis) and experience mediated by cultural vectors such as literature, philosophy and the visual arts (Bildungserlebnis).[65] The distinction has little relevance for Horace[citation needed] however since his personal and literary experiences are implicated in each other. Satires 1.5, for example, recounts in detail a real trip Horace made with Virgil and some of his other literary friends, and which parallels a Satire by Lucilius, his predecessor.[66] Unlike much Hellenistic-inspired literature, however, his poetry was not composed for a small coterie of admirers and fellow poets, nor does it rely on abstruse allusions for many of its effects. Though elitist in its literary standards, it was written for a wide audience, as a public form of art.[67] Ambivalence also characterizes his literary persona, since his presentation of himself as part of a small community of philosophically aware people, seeking true peace of mind while shunning vices like greed, was well adapted to Augustus's plans to reform public morality, corrupted by greed—his personal plea for moderation was part of the emperor's grand message to the nation.[68] Horace generally followed the examples of poets established as classics in different genres, such as Archilochus in the Epodes, Lucilius in the Satires and Alcaeus in the Odes, later broadening his scope for the sake of variation and because his models weren't actually suited to the realities confronting him. Archilochus and Alcaeus were aristocratic Greeks whose poetry had a social and religious function that was immediately intelligible to their audiences but which became a mere artifice or literary motif when transposed to Rome. However, the artifice of the Odes is also integral to their success, since they could now accommodate a wide range of emotional effects, and the blend of Greek and Roman elements adds a sense of detachment and universality.[69] Horace proudly claimed to introduce into Latin the spirit and iambic poetry of Archilochus but (unlike Archilochus) without persecuting anyone (Epistles 1.19.23–25). It was no idle boast. His Epodes were modelled on the verses of the Greek poet, as 'blame poetry', yet he avoided targeting real scapegoats. Whereas Archilochus presented himself as a serious and vigorous opponent of wrong-doers, Horace aimed for comic effects and adopted the persona of a weak and ineffectual critic of his times (as symbolized for example in his surrender to the witch Canidia in the final epode).[70] He also claimed to be the first to introduce into Latin the lyrical methods of Alcaeus (Epistles 1.19.32–33) and he actually was the first Latin poet to make consistent use of Alcaic meters and themes: love, politics and the symposium. He imitated other Greek lyric poets as well, employing a 'motto' technique, beginning each ode with some reference to a Greek original and then diverging from it.[71] The satirical poet Lucilius was a senator's son who could castigate his peers with impunity. Horace was a mere freedman's son who had to tread carefully.[72] Lucilius was a rugged patriot and a significant voice in Roman self-awareness, endearing himself to his countrymen by his blunt frankness and explicit politics. His work expressed genuine freedom or libertas. His style included 'metrical vandalism' and looseness of structure. Horace instead adopted an oblique and ironic style of satire, ridiculing stock characters and anonymous targets. His libertas was the private freedom of a philosophical outlook, not a political or social privilege.[73] His Satires are relatively easy-going in their use of meter (relative to the tight lyric meters of the Odes)[74] but formal and highly controlled relative to the poems of Lucilius, whom Horace mocked for his sloppy standards (Satires 1.10.56–61)[nb 15] The Epistles may be considered among Horace's most innovative works. There was nothing like it in Greek or Roman literature. Occasionally poems had had some resemblance to letters, including an elegiac poem from Solon to Mimnermus and some lyrical poems from Pindar to Hieron of Syracuse. Lucilius had composed a satire in the form of a letter, and some epistolary poems were composed by Catullus and Propertius. But nobody before Horace had ever composed an entire collection of verse letters,[75] let alone letters with a focus on philosophical problems. The sophisticated and flexible style that he had developed in his Satires was adapted to the more serious needs of this new genre.[76] Such refinement of style was not unusual for Horace. His craftsmanship as a wordsmith is apparent even in his earliest attempts at this or that kind of poetry, but his handling of each genre tended to improve over time as he adapted it to his own needs.[72] Thus for example it is generally agreed that his second book of Satires, where human folly is revealed through dialogue between characters, is superior to the first, where he propounds his ethics in monologues. Nevertheless, the first book includes some of his most popular poems.[77] |

歴史的背景 ホラティウスはアルカイック・ギリシャから借用した伝統的な音律で作曲し、風刺や書簡にはヘキサメーターを、エポデスにはイアムーブを用いた。彼のオード は、アルカイックやサフィックスなど、ラテン語の構造や構文に適合しにくい、より複雑な小節を特徴としていた。このような伝統的な様式にもかかわらず、彼 は新しい洗練された様式の開発に尽力した。彼は、カリマコスの作品に見られるような、簡潔、優雅、洗練といったヘレニズムの美学に個別主義的な影響を受け ていた[63]。 ホラティウスは、自らの才能に突き動かされ、ヴァージル、ヴァリウス、そしておそらく同世代の他の詩人たちの模範に励まされ、詩人としての名声を得ようと 決意するやいなや、闘争心の気質であった彼は、あらゆる偏見、アマチュア的な杜撰さ、俗物主義、反動的な傾向と闘い、要するに、彼と彼の友人たちがもたら そうとしていた詩の新しい高貴なタイプのために闘おうとした。 - エドゥアルド・フラエンケル[64]。 現代の文学理論では、個人的な体験(Urerlebnis)と文学、哲学、視覚芸術などの文化的なベクトルによって媒介された体験 (Bildungserlebnis)を区別することが多い[65]。しかし、彼の個人的な体験と文学的な体験は互いに関係しているため、この区別はホラ ティウス[要出典]にはほとんど関係がない。例えば『諷刺』1.5では、ホラティウスがヴァージルや他の文学仲間たちと実際に行った旅行が詳細に語られて おり、これは彼の前任者であるルシリウスの『諷刺』と類似している[66]。しかし、多くのヘレニズムに影響を受けた文学とは異なり、彼の詩は少数の同好 の士や詩人仲間のために書かれたものではなく、またその効果の多くを難解な引用に頼っているわけでもない。アンビヴァレンスもまた彼の文学的人格を特徴づ けている。というのも、貪欲のような悪徳を避けながら真の心の平穏を求める、哲学的に自覚的な人民の小さな共同体の一員であるという彼の表現は、貪欲に堕 落した公衆道徳を改革しようとするアウグストゥスの計画にうまく適合していたからである。 ホラティウスは、『エポデス』のアルキロコス、『風刺』のルキリウス、『オード』のアルカイオスなど、異なるジャンルで古典として確立された詩人たちの例 に倣うことが一般的であったが、後にバリエーションのために、また彼のモデルが実際に直面している現実に適していなかったために、その範囲を広げた。アル キロコスやアルカエウスはギリシア貴族であり、彼らの詩は社会的・宗教的機能を持ち、聴衆にはすぐに理解できるものであったが、ローマに移されると単なる 作為や文学的モチーフになってしまった。ホラティウスは、アルキロクスの精神とイアンビック詩をラテン語に導入したが、(アルキロクスのように)誰も迫害 しなかったと誇らしげに語っている(書簡1.19.23-25)。それは単なる自慢ではなかった。彼のエポデスはギリシアの詩人の詩をモデルにした「非難 詩」であったが、本当のスケープゴートを標的にすることは避けた。ホラティウスが自らをまじめで精力的な悪者への対抗者として見せたのに対して、ホラティ ウスはコミカルな効果を狙い、弱くて無力な時代の批評家というペルソナを採用した(たとえば、最後のエポードにおける呪術師カニディアへの降伏に象徴され ている)。 [70]彼はまた、アルカイオスの叙情的手法をラテン語に初めて導入したと主張し(『書簡』1.19.32-33)、実際にアルカイオスのメートル法と テーマ(愛、政治、シンポジウム)を一貫して用いた最初のラテン語詩人であった。彼は他のギリシアの抒情詩人をも模倣し、それぞれの頌歌をギリシア語の原 典への言及で始め、それから分岐させるという「モットー」技法を用いた[71]。 風刺詩人ルシリウスは元老院議員の息子であり、同輩を平気で非難することができた。ルキリウスは無骨な愛国者であり、その率直さと露骨な政治性によって同 胞に親しまれ、ローマの自己認識の重要な代弁者であった[72]。彼の作品は真の自由、リベルタスを表現していた。彼の作風には「計量的破壊主義」と構造 の緩さがあった。ホラティウスはその代わりに、斜に構えた皮肉な風刺のスタイルを採用し、ありきたりの人物や匿名の対象を嘲笑した。彼のリベルタスは哲学 的な展望の私的な自由であり、政治的・社会的な特権ではなかった[73]。彼の風刺は(オデの緊密な抒情的メートルに対して)比較的緩やかであるが [74]、ホラティウスがその杜撰な基準を嘲笑したルシリウスの詩(風刺1.10.56-61)[nb 15]と比べると、形式的で高度に統制されている。 書簡集はホラティウスの最も革新的な作品のひとつと考えられる。ギリシア・ローマ文学にはこのようなものはなかった。ソロンがミムネルムスに宛てた哀歌 や、ピンダルがシラクサのヒエロンに宛てた抒情詩など、詩が手紙に似ていることはあった。ルキリウスは書簡の形をとった風刺詩を書いたし、カトゥルスやプ ロプロティウスも書簡詩を書いた。しかし、ホラティウス以前には、哲学的な問題に焦点を当てた書簡はおろか、詩による書簡集全体を作曲した者はいなかった [75]。ホラティウスにとって、このような洗練された文体は珍しいものではなかった[76]。例えば、人間の愚かさが登場人物同士の対話を通して明らか にされる『風刺』第2巻は、独白で倫理を説く第1巻よりも優れているというのが一般的な見解である[72]。とはいえ、第一詩集には彼の最も人気のある詩 がいくつか含まれている[77]。 |

| Themes Horace developed a number of inter-related themes throughout his poetic career, including politics, love, philosophy and ethics, his own social role, as well as poetry itself. His Epodes and Satires are forms of 'blame poetry' and both have a natural affinity with the moralising and diatribes of Cynicism. This often takes the form of allusions to the work and philosophy of Bion of Borysthenes[nb 16] but it is as much a literary game as a philosophical alignment. By the time he composed his Epistles, he was a critic of Cynicism along with all impractical and "high-falutin" philosophy in general.[nb 17][78] The Satires also include a strong element of Epicureanism, with frequent allusions to the Epicurean poet Lucretius.[nb 18] So for example the Epicurean sentiment carpe diem is the inspiration behind Horace's repeated punning on his own name (Horatius ~ hora) in Satires 2.6.[79] The Satires also feature some Stoic, Peripatetic and Platonic (Dialogues) elements. In short, the Satires present a medley of philosophical programmes, dished up in no particular order—a style of argument typical of the genre.[80] The Odes display a wide range of topics. Over time, he becomes more confident about his political voice.[81] Although he is often thought of as an overly intellectual lover, he is ingenious in representing passion.[82] The "Odes" weave various philosophical strands together, with allusions and statements of doctrine present in about a third of the Odes Books 1–3, ranging from the flippant (1.22, 3.28) to the solemn (2.10, 3.2, 3.3). Epicureanism is the dominant influence, characterising about twice as many of these odes as Stoicism. A group of odes combines these two influences in tense relationships, such as Odes 1.7, praising Stoic virility and devotion to public duty while also advocating private pleasures among friends. While generally favouring the Epicurean lifestyle, the lyric poet is as eclectic as the satiric poet, and in Odes 2.10 even proposes Aristotle's golden mean as a remedy for Rome's political troubles.[83] Many of Horace's poems also contain much reflection on genre, the lyric tradition, and the function of poetry.[84] Odes 4, thought to be composed at the emperor's request, takes the themes of the first three books of "Odes" to a new level. This book shows greater poetic confidence after the public performance of his "Carmen saeculare" or "Century hymn" at a public festival orchestrated by Augustus. In it, Horace addresses the emperor Augustus directly with more confidence and proclaims his power to grant poetic immortality to those he praises. It is the least philosophical collection of his verses, excepting the twelfth ode, addressed to the dead Virgil as if he were living. In that ode, the epic poet and the lyric poet are aligned with Stoicism and Epicureanism respectively, in a mood of bitter-sweet pathos.[85] The first poem of the Epistles sets the philosophical tone for the rest of the collection: "So now I put aside both verses and all those other games: What is true and what befits is my care, this my question, this my whole concern." His poetic renunciation of poetry in favour of philosophy is intended to be ambiguous. Ambiguity is the hallmark of the Epistles. It is uncertain if those being addressed by the self-mocking poet-philosopher are being honoured or criticised. Though he emerges as an Epicurean, it is on the understanding that philosophical preferences, like political and social choices, are a matter of personal taste. Thus he depicts the ups and downs of the philosophical life more realistically than do most philosophers.[86] |

テーマ ホラティウスはその詩作活動を通して、政治、恋愛、哲学と倫理、彼自身の社会的役割、詩そのものなど、相互に関連したテーマを数多く展開した。彼のエポ ソードと諷刺は「非難詩」の一形態であり、両者ともシニシズムの道徳主義や放言と自然な親和性を持っている。これはしばしばボリステネスのビオンの作品や 哲学[nb 16]への言及という形をとるが、哲学的な整合性と同様に文学的なゲームでもある。 彼が『書簡集』を執筆する頃には、あらゆる非実用的で「高尚な」哲学一般とともにシニシズムを批判していた[nb 17][78]。 例えば、『風刺』2.6でホラティウスが自分の名前(Horatius ~ hora)を繰り返し洒落る背景には、エピクロスの感情であるcarpe diemがある[79]。要するに、『サティレス』には、このジャンルの典型的な議論スタイルである、個別主義的な哲学的プログラムが、順不同に並べられ ているのである[80]。 オデは幅広いテーマを扱っている。彼はしばしば過度に知的な愛好家と考えられているが、情熱を表現することにかけては独創的である[82]。『オデス』に はさまざまな哲学的要素が織り込まれており、『オデス』1~3巻の約3分の1には、軽妙なもの(1.22、3.28)から厳粛なもの(2.10、3.2、 3.3)まで、教義の引用や記述が見られる。エピクロス主義が支配的な影響を及ぼしており、ストイシズムのおよそ2倍の数のオードを特徴づけている。 例えば、Odes 1.7は、ストイックな男らしさと公的義務への献身を称賛する一方で、友人たちとの私的な楽しみも提唱している。一般的にはエピクロス派のライフスタイル を好むが、この抒情詩人は風刺詩人と同様に折衷的であり、『オデス』2.10ではローマの政治的問題の解決策としてアリストテレスの黄金平均を提唱してい る[83]。 ホラティウスの詩の多くには、ジャンル、抒情詩の伝統、詩の機能についての考察も多く含まれている[84]。アウグストゥスによって企画された公的な祝祭 で「世紀讃歌」(Carmen saeculare)が公に演奏された後、この書物では詩的な自信がより高まっている。この中でホラティウスは、より自信をもってアウグストゥス皇帝に直 接語りかけ、彼が賛美する者に詩的不滅を与える力を宣言している。彼の詩集の中では、死んだヴァージルが生きているかのように宛てた第12番の頌詩を除け ば、最も哲学的でない詩集である。その頌歌では、叙事詩の詩人と抒情詩の詩人がそれぞれストア派とエピクロス派に寄り添い、苦く甘いペーソスのムードに包 まれている[85]。 書簡の最初の詩は、この詩集の残りの部分の哲学的な基調をなしている: 「だから今、私は詩も他の遊びもすべて脇に置く: 何が真実で、何がふさわしいか、これが私の関心事であり、これが私の疑問であり、これが私の全心配事である」。哲学のために詩を放棄したのは、曖昧さを意 図している。曖昧さは書簡の特徴である。この自嘲的な詩人哲学者が語りかけている相手が、尊敬されているのか批判されているのかは定かではない。彼はエピ クロス主義者として登場するが、それは政治的・社会的選択と同様、哲学的嗜好も人格の問題であるという理解の上に立っている。そのため、彼は哲学的人生の 浮き沈みを、他の哲学者よりも現実的に描いている[86]。 |

Reception Horace, portrayed by Giacomo Di Chirico The reception of Horace's work has varied from one epoch to another and varied markedly even in his own lifetime. Odes 1–3 were not well received when first 'published' in Rome, yet Augustus later commissioned a ceremonial ode for the Centennial Games in 17 BC and also encouraged the publication of Odes 4, after which Horace's reputation as Rome's premier lyricist was assured. His Odes were to become the best received of all his poems in ancient times, acquiring a classic status that discouraged imitation: no other poet produced a comparable body of lyrics in the four centuries that followed[87] (though that might also be attributed to social causes, particularly the parasitism that Italy was sinking into).[88] In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ode-writing became highly fashionable in England and a large number of aspiring poets imitated Horace both in English and in Latin.[89] In a verse epistle to Augustus (Epistle 2.1), in 12 BC, Horace argued for classic status to be awarded to contemporary poets, including Virgil and apparently himself.[90] In the final poem of his third book of Odes he claimed to have created for himself a monument more durable than bronze ("Exegi monumentum aere perennius", Carmina 3.30.1). For one modern scholar, however, Horace's personal qualities are more notable than the monumental quality of his achievement: ... when we hear his name we don't really think of a monument. We think rather of a voice which varies in tone and resonance but is always recognizable, and which by its unsentimental humanity evokes a very special blend of liking and respect. — Niall Rudd[91] Yet for men like Wilfred Owen, scarred by experiences of World War I, his poetry stood for discredited values: My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The Old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.[nb 19] The same motto, Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, had been adapted to the ethos of martyrdom in the lyrics of early Christian poets like Prudentius.[92] These preliminary comments touch on a small sample of developments in the reception of Horace's work. More developments are covered epoch by epoch in the following sections. |

レセプション ジャコモ・ディ・キリコが描くホラティウス ホラティウスの作品の受容は、時代によってさまざまであり、彼自身の存命中にも顕著な変化があった。しかし、アウグストゥスは後に紀元前17年の百年祭の ための儀式的な頌歌を依頼し、また頌歌4の出版を奨励した。彼の『オデス』は古代における彼の詩の中で最も評判が高く、模倣を思いとどまらせる古典的な地 位を獲得した。その後の4世紀において、これに匹敵するような詩集を生み出した詩人は他にいなかった[87](ただし、これは社会的な原因、特にイタリア が陥っていた寄生主義に起因しているのかもしれない)[88]。 17世紀から18世紀にかけて、イギリスではオデを書くことが非常に流行し、多くの詩人志望者が英語とラテン語の両方でホラティウスを模倣した[89]。 紀元前12年にアウグストゥスに宛てた詩の書簡(Epistle 2.1)の中で、ホラティウスはヴァージルや彼自身を含む同時代の詩人たちに古典の地位を与えるべきだと主張した[90]。 オード集第3巻の最後の詩で、彼は自分自身のために青銅よりも耐久性のある記念碑を作ったと主張した(「Exegi monumentum aere perennius」, Carmina 3.30.1)。しかし、ある現代の学者にとっては、ホラティウスの人格的な資質は、彼の業績の記念碑的な質よりも注目すべきものである: 彼の名前を聞いても、記念碑を思い浮かべることはない。私たちはむしろ、声色や響きはさまざまだが常に聞き分けられる声、そしてその感傷的でない人間性によって、好意と尊敬の非常に特別な融合を呼び起こす声を思い浮かべるのである。 - ニール・ラッド[91] しかし、ウィルフレッド・オーウェンのように、第一次世界大戦の体験によって傷ついた人々にとって、彼の詩は信用されない価値観の代弁者であった: わが友よ、君はこんなにも熱心に語ることはないだろう。 わが友よ、絶望的な栄光のために熱狂する子供たちに、こんなにも高い熱意をもって語ることはないだろう、 古い嘘:Dulce et decorum est プロ・パトリア・モリ[nb 19]。 同じモットー、Dulce et decorum est pro patria moriは、プルデンティウスのような初期のキリスト教詩人の歌詞の中で、殉教のエートスに適応されていた[92]。 これらの予備的なコメントは、ホラティウスの作品の受容における展開のほんの一例に触れたものである。それ以上の展開については、以下のセクションでエポックごとに取り上げている。 |

| Antiquity Horace's influence can be observed in the work of his near contemporaries, Ovid and Propertius. Ovid followed his example in creating a completely natural style of expression in hexameter verse, and Propertius cheekily mimicked him in his third book of elegies.[nb 20] His Epistles provided them both with a model for their own verse letters and it also shaped Ovid's exile poetry.[nb 21] His influence had a perverse aspect. As mentioned before, the brilliance of his Odes may have discouraged imitation. Conversely, they may have created a vogue for the lyrics of the archaic Greek poet Pindar, due to the fact that Horace had neglected that style of lyric (see Influence and Legacy of Pindar).[93] The iambic genre seems almost to have disappeared after publication of Horace's Epodes. Ovid's Ibis was a rare attempt at the form but it was inspired mainly by Callimachus, and there are some iambic elements in Martial but the main influence there was Catullus.[94] A revival of popular interest in the satires of Lucilius may have been inspired by Horace's criticism of his unpolished style. Both Horace and Lucilius were considered good role-models by Persius, who critiqued his own satires as lacking both the acerbity of Lucillius and the gentler touch of Horace.[nb 22] Juvenal's caustic satire was influenced mainly by Lucilius but Horace by then was a school classic and Juvenal could refer to him respectfully and in a round-about way as "the Venusine lamp".[nb 23] Statius paid homage to Horace by composing one poem in Sapphic and one in Alcaic meter (the verse forms most often associated with Odes), which he included in his collection of occasional poems, Silvae. Ancient scholars wrote commentaries on the lyric meters of the Odes, including the scholarly poet Caesius Bassus. By a process called derivatio, he varied established meters through the addition or omission of syllables, a technique borrowed by Seneca the Younger when adapting Horatian meters to the stage.[95] Horace's poems continued to be school texts into late antiquity. Works attributed to Helenius Acro and Pomponius Porphyrio are the remnants of a much larger body of Horatian scholarship. Porphyrio arranged the poems in non-chronological order, beginning with the Odes, because of their general popularity and their appeal to scholars (the Odes were to retain this privileged position in the medieval manuscript tradition and thus in modern editions also). Horace was often evoked by poets of the fourth century, such as Ausonius and Claudian. Prudentius presented himself as a Christian Horace, adapting Horatian meters to his own poetry and giving Horatian motifs a Christian tone.[nb 24] On the other hand, St Jerome, modelled an uncompromising response to the pagan Horace, observing: "What harmony can there be between Christ and the Devil? What has Horace to do with the Psalter?"[nb 25] By the early sixth century, Horace and Prudentius were both part of a classical heritage that was struggling to survive the disorder of the times. Boethius, the last major author of classical Latin literature, could still take inspiration from Horace, sometimes mediated by Senecan tragedy.[96] It can be argued that Horace's influence extended beyond poetry to dignify core themes and values of the early Christian era, such as self-sufficiency, inner contentment and courage.[nb 26] |

古代 ホラティウスの影響は、ほぼ同時代のオウィッドやプロペルティウスの作品にも見られる。オウィッドは彼に倣ってヘクサメートル詩で完全に自然な表現様式を 作り出し、プロプロティウスは第3のエレジー集で生意気にも彼を真似た[nb 20] 彼の書簡集は彼ら自身の詩文のモデルとなり、またオウィッドの亡命詩を形成した[nb 21]。 彼の影響には倒錯的な側面もあった。先に述べたように、彼のオデの輝きは模倣を妨げたかもしれない。逆に、ホラティウスがその抒情詩のスタイルを軽視して いたために、古代のギリシアの詩人ピンダルの抒情詩の流行が生まれたのかもしれない(ピンダルの影響と遺産を参照)[93]。イアンビックというジャンル は、ホラティウスのエポデスが出版された後、ほとんど消滅したように思われる。オヴィッドの『トキ』はこの形式に対する稀な試みであったが、それは主にカ リマコスに触発されたものであり、マルティアルの中にもいくつかのイアンビックな要素があるが、そこでの主な影響はカトゥルスであった[94]。ルシリウ スの風刺に対する大衆の関心の復活は、ホラティウスが彼の洗練されていない文体を批判したことに触発されたのかもしれない。ホラティウスとルキリウスはと もにペルシウスによって良い手本とされていたが、ペルシウスは自身の諷刺をルキリウスの辛辣さとホラティウスの優しさの両方が欠けていると批評していた [nb 22] ユヴェナールの辛辣な諷刺は主にルキリウスの影響を受けていたが、そのころにはホラティウスは学校の古典であり、ユヴェナールはホラティウスを尊敬して 「金星のランプ」と遠回しに呼ぶことができた[nb 23]。 スタティウスはホラティウスに敬意を表し、サッフィック調とアルカイック調の詩を1編ずつ作り、臨時詩集『シルヴァエ』に収録した。古代の学者たちは、学 者詩人カエシウス・バッソスをはじめ、オデの抒情詩のメートルについて解説を書いている。デリヴァティオと呼ばれるプロセスによって、彼は音節の追加や省 略によって確立された音律を変化させたが、これは若かりしセネカがホラティウス派の音律を舞台に適応させる際に借用した技法である[95]。 ホラティウスの詩は古代後期まで学校のテキストとして使われ続けた。ヘレニウス・アクロとポンポニウス・ポルフィリオの作品とされるものは、ホラティウス に関するより大きな学問の名残である。ポルフィリオが詩を非時系列順に並べたのは、その一般的な人気と学者へのアピールのためである。ホラティウスは、ア ウソニウスやクラウディアヌスといった4世紀の詩人たちからしばしば想起された。プルデンティウスはキリスト教ホラティウスとして自らを提示し、ホラティ ウス的な音律を自分の詩に適応させ、ホラティウス的なモチーフにキリスト教的な調子を与えた[nb 24] 一方、聖ジェロームは異教的なホラティウスに対して妥協のない反応を示し、こう述べている: 「キリストと悪魔の間にどんな調和があるというのか。6世紀初頭には、ホラティウスとプルデンティウスはともに、時代の混乱を生き延びようと奮闘していた 古典的遺産の一部となっていた。古典ラテン文学の最後の主要な作家であったボエティウスは、時にはセネカ悲劇を媒介として、ホラティウスからインスピレー ションを得ることができた[96]。ホラティウスの影響は詩の域を超え、自己充足、内的満足、勇気といった初期キリスト教時代の中核的なテーマや価値観を 威厳あるものにしたと主張することができる[nb 26]。 |

Middle Ages and Renaissance Horace in his Studium: German print of the fifteenth century, summarizing the final ode 4.15 (in praise of Augustus). Classical texts almost ceased being copied in the period between the mid sixth century and the Carolingian revival. Horace's work probably survived in just two or three books imported into northern Europe from Italy. These became the ancestors of six extant manuscripts dated to the ninth century. Two of those six manuscripts are French in origin, one was produced in Alsace, and the other three show Irish influence but were probably written in continental monasteries (Lombardy for example).[97] By the last half of the ninth century, it was not uncommon for literate people to have direct experience of Horace's poetry. His influence on the Carolingian Renaissance can be found in the poems of Heiric of Auxerre[nb 27] and in some manuscripts marked with neumes, notations that may have been an aid to the memorization and discussion of his lyric meters. Ode 4.11 is neumed with the melody of a hymn to John the Baptist, Ut queant laxis, composed in Sapphic stanzas. This hymn later became the basis of the solfege system (Do, re, mi...)—an association with western music quite appropriate for a lyric poet like Horace, though the language of the hymn is mainly Prudentian.[98] Lyons[99] argues that the melody in question was linked with Horace's Ode well before Guido d'Arezzo fitted Ut queant laxis to it. Ovid[100] does testify to Horace's use of the lyre while performing his Odes. The German scholar Ludwig Traube once dubbed the tenth and eleventh centuries The age of Horace (aetas Horatiana), and placed it between the aetas Vergiliana of the eighth and ninth centuries, and the aetas Ovidiana of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Horace was a substantial influence in the ninth century as well, and Traube concentrated too much on Horace's Satires.[101] Almost all of Horace's work found favour in the Medieval period, with scholars associating Horace's different genres with the different ages of man. A twelfth-century scholar encapsulated the theory: "...Horace wrote four different kinds of poems on account of the four ages, the Odes for boys, the Ars Poetica for young men, the Satires for mature men, the Epistles for old and complete men."[102] It was then thought that Horace had composed his works in the order in which they had been placed by ancient scholars.[nb 28] This schematism involved an appreciation of Horace's works as a collection, the Ars Poetica, Satires and Epistles appearing to find favour as well as the Odes. The later Middle Ages, however, gave special significance to Satires and Epistles, considered Horace's mature works. Dante referred to Horace as Orazio satiro, and he awarded him a privileged position in the first circle of Hell, with Homer, Ovid and Lucan.[103] Horace's popularity is revealed in the large number of quotes from all his works found in almost every genre of medieval literature, and also in the number of poets imitating him in quantitative Latin meter. The most prolific imitator of his Odes was the Bavarian monk, Metellus of Tegernsee, who dedicated his work to the patron saint of Tegernsee Abbey, St Quirinus, around the year 1170. He imitated all Horace's lyrical meters then followed these up with imitations of other meters used by Prudentius and Boethius, indicating that variety, as first modelled by Horace, was considered a fundamental aspect of the lyric genre. The content of his poems however was restricted to simple piety.[104] Among the most successful imitators of Satires and Epistles was another Germanic author, calling himself Sextus Amarcius, around 1100, who composed four books, the first two exemplifying vices, the second pair mainly virtues.[105] Petrarch is a key figure in the imitation of Horace in accentual meters. His verse letters in Latin were modelled on the Epistles and he wrote a letter to Horace in the form of an ode. However he also borrowed from Horace when composing his Italian sonnets. One modern scholar has speculated that authors who imitated Horace in accentual rhythms (including stressed Latin and vernacular languages) may have considered their work a natural sequel to Horace's metrical variety.[106] In France, Horace and Pindar were the poetic models for a group of vernacular authors called the Pléiade, including for example Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay. Montaigne made constant and inventive use of Horatian quotes.[107] The vernacular languages were dominant in Castilia and Portugal in the sixteenth century, where Horace's influence is notable in the works of such authors as Garcilaso de la Vega, Juan Boscán, Sá de Miranda, Antonio Ferreira and Fray Luis de León, the last writing odes on the Horatian theme beatus ille (happy the man).[108] The sixteenth century in western Europe was also an age of translations (except in Germany, where Horace wasn't translated into the vernacular until well into the seventeenth century). The first English translator was Thomas Drant, who placed translations of Jeremiah and Horace side by side in Medicinable Morall, 1566. That was also the year that the Scot George Buchanan paraphrased the Psalms in a Horatian setting. Ben Jonson put Horace on the stage in 1601 in Poetaster, along with other classical Latin authors, giving them all their own verses to speak in translation. Horace's part evinces the independent spirit, moral earnestness and critical insight that many readers look for in his poems.[109] Age of Enlightenment During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, or the Age of Enlightenment, neoclassical culture was pervasive. English literature in the middle of that period has been dubbed Augustan. It is not always easy to distinguish Horace's influence during those centuries (the mixing of influences is shown for example in one poet's pseudonym, Horace Juvenal).[nb 29] However a measure of his influence can be found in the diversity of the people interested in his works, both among readers and authors.[110] New editions of his works were published almost yearly. There were three new editions in 1612 (two in Leiden, one in Frankfurt) and again in 1699 (Utrecht, Barcelona, Cambridge). Cheap editions were plentiful and fine editions were also produced, including one whose entire text was engraved by John Pine in copperplate. The poet James Thomson owned five editions of Horace's work and the physician James Douglas had five hundred books with Horace-related titles. Horace was often commended in periodicals such as The Spectator, as a hallmark of good judgement, moderation and manliness, a focus for moralising.[nb 30] His verses offered a fund of mottoes, such as simplex munditiis (elegance in simplicity), splendide mendax (nobly untruthful), sapere aude (dare to know), nunc est bibendum (now is the time to drink), carpe diem (seize the day, perhaps the only one still in common use today).[96] These were quoted even in works as prosaic as Edmund Quincy's A treatise of hemp-husbandry (1765). The fictional hero Tom Jones recited his verses with feeling.[111] His works were also used to justify commonplace themes, such as patriotic obedience, as in James Parry's English lines from an Oxford University collection in 1736:[112] What friendly Muse will teach my Lays To emulate the Roman fire? Justly to sound a Caesar's praise Demands a bold Horatian lyre. Horatian-style lyrics were increasingly typical of Oxford and Cambridge verse collections for this period, most of them in Latin but some like the previous ode in English. John Milton's Lycidas first appeared in such a collection. It has few Horatian echoes[nb 31] yet Milton's associations with Horace were lifelong. He composed a controversial version of Odes 1.5, and Paradise Lost includes references to Horace's 'Roman' Odes 3.1–6 (Book 7 for example begins with echoes of Odes 3.4).[113] Yet Horace's lyrics could offer inspiration to libertines as well as moralists, and neo-Latin sometimes served as a kind of discrete veil for the risqué. Thus for example Benjamin Loveling authored a catalogue of Drury Lane and Covent Garden prostitutes, in Sapphic stanzas, and an encomium for a dying lady "of salacious memory".[114] Some Latin imitations of Horace were politically subversive, such as a marriage ode by Anthony Alsop that included a rallying cry for the Jacobite cause. On the other hand, Andrew Marvell took inspiration from Horace's Odes 1.37 to compose his English masterpiece Horatian Ode upon Cromwell's Return from Ireland, in which subtly nuanced reflections on the execution of Charles I echo Horace's ambiguous response to the death of Cleopatra (Marvell's ode was suppressed in spite of its subtlety and only began to be widely published in 1776). Samuel Johnson took particular pleasure in reading The Odes.[nb 32] Alexander Pope wrote direct Imitations of Horace (published with the original Latin alongside) and also echoed him in Essays and The Rape of the Lock. He even emerged as "a quite Horatian Homer" in his translation of the Iliad.[115] Horace appealed also to female poets, such as Anna Seward (Original sonnets on various subjects, and odes paraphrased from Horace, 1799) and Elizabeth Tollet, who composed a Latin ode in Sapphic meter to celebrate her brother's return from overseas, with tea and coffee substituted for the wine of Horace's sympotic settings: Quos procax nobis numeros, jocosque Musa dictaret? mihi dum tibique Temperent baccis Arabes, vel herbis Pocula Seres[116] What verses and jokes might the bold Muse dictate? while for you and me Arabs flavour our cups with beans Or Chinese with leaves.[117] |

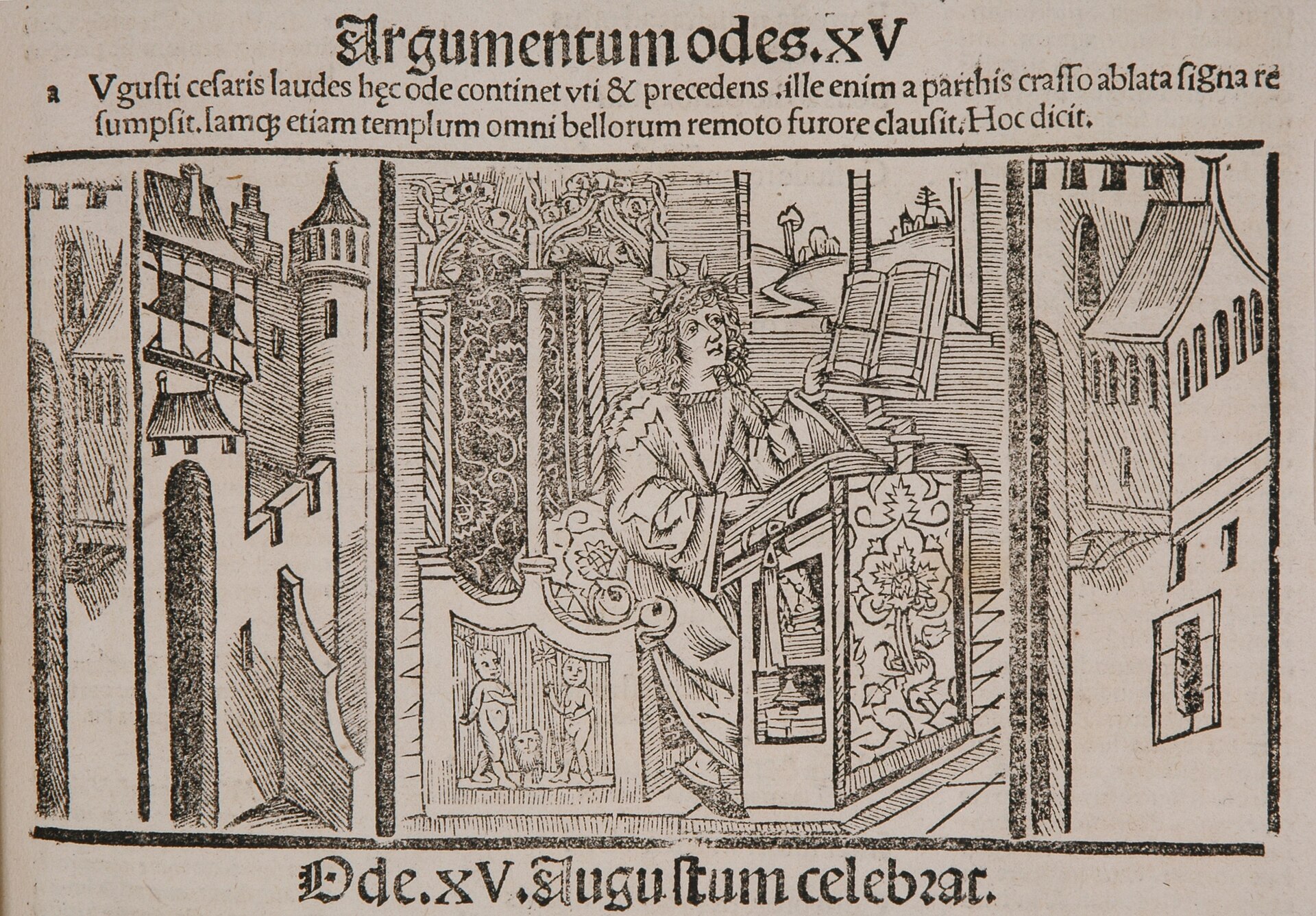

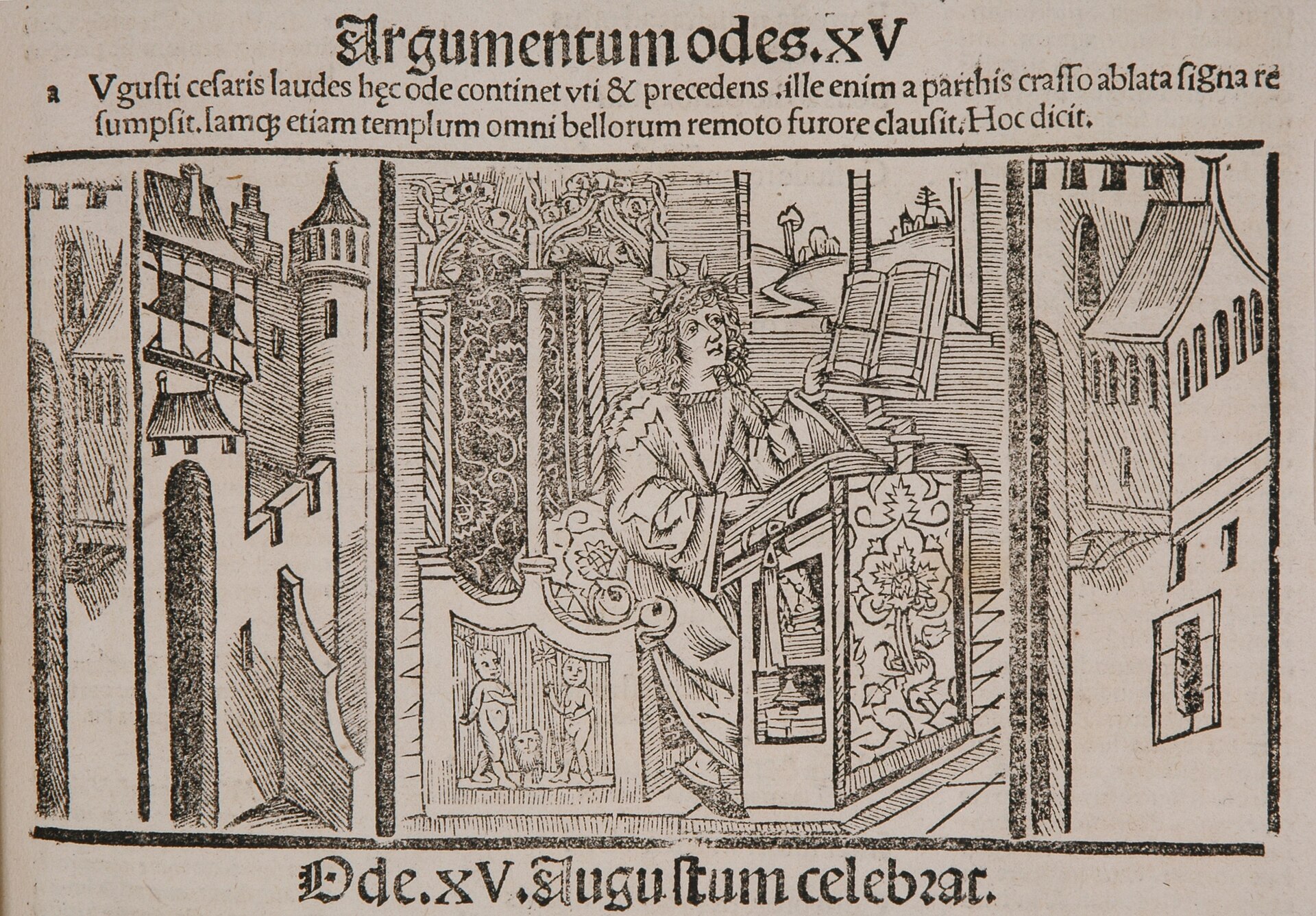

中世とルネサンス ホラティウスの『シュトゥディウム』: 15世紀のドイツの印刷物で、最後のオード4.15(アウグストゥス賛歌)を要約している。 6世紀半ばからカロリング朝の復興期にかけて、古典的なテキストはほとんど書写されなくなった。ホラティウスの作品は、おそらくイタリアから北ヨーロッパ に輸入されたわずか2、3冊の書物の中にしか残っていない。これらは、9世紀に現存する6冊の写本の祖先となった。その6冊の写本のうち2冊はフランス起 源で、1冊はアルザスで制作され、残りの3冊はアイルランドの影響が見られるが、おそらく大陸の修道院(たとえばロンバルディア)で書かれたものである [97]。9世紀後半には、識字能力のある人民がホラティウスの詩に直接触れることは珍しいことではなかった。カロリング朝ルネサンスにおける彼の影響 は、オセールのハイリック[nb 27]の詩や、彼の抒情詩の音律を暗記し、議論するための助けとなったと思われる記譜法であるノームが記されたいくつかの写本に見出すことができる。頌歌 4.11には、洗礼者ヨハネへの賛美歌Ut queant laxisの旋律が記譜されている。この讃美歌は後にソルフェージュ体系(Do, re, mi...)の基礎となったが、讃美歌の言語は主にプルデンティウス語であるにもかかわらず、ホラティウスのような抒情詩人にとっては西洋音楽との結びつ きはきわめて適切である[98]。オヴィッド[100]は、ホラティウスがオードを演奏する際に竪琴を使っていたことを証言している。 ドイツの学者ルートヴィヒ・トラウベは、10世紀と11世紀をホラティウスの時代(aetas Horatiana)と呼び、8世紀と9世紀のヴェルギリアーナの時代と12世紀と13世紀のオヴィディアーナの時代の間に位置づけた。ホラティウスは9 世紀にも大きな影響を与えたが、トラウベはホラティウスの『風刺』に集中しすぎていた[101]。ホラティウスのほとんどすべての作品が中世に支持され、 学者たちはホラティウスの異なるジャンルを人間の異なる時代に関連づけた。12世紀の学者がこの説を要約している: ホラティウスは4つの年齢を考慮して4つの異なる種類の詩を書いた。少年向けの『オデス』、青年向けの『アルス・ポエティカ』、壮年向けの『風刺』、年老いた完全な男性向けの『書簡』である」[102]。 そして、ホラティウスは古代の学者たちによって配置された順序で作品を作曲したと考えられていた[nb 28] この図式主義は、ホラティウスの作品をコレクションとして評価することを含み、詩篇、風刺、書簡はオードと同様に好意を持たれていたようである。しかし中 世後期には、ホラティウスの円熟期の作品とされる『風刺』と『書簡』に特別な意義が与えられた。ダンテはホラティウスをオラツィオ・サティロと呼び、ホメ ロス、オヴィッド、ルカンとともに地獄の第一の輪の中で特権的な地位を与えた[103]。 ホラティウスの人気は、中世文学のほとんどすべてのジャンルで彼の全作品からの引用が数多く見られること、また、ラテン語の量的メートル法で彼を模倣する 詩人の多さからも明らかである。彼の詩を最も多く模倣したのはバイエルンの修道士テーゲルンゼーのメテルスで、彼は1170年頃、テーゲルンゼー修道院の 守護聖人である聖クィリヌスに作品を捧げた。彼はホラティウスの抒情的な音律をすべて模倣し、さらにプルデンティウスやボエティウスが用いた他の音律も模 倣しており、ホラティウスが最初に手本とした多様性が抒情詩というジャンルの基本であると考えられていたことがわかる。しかし、彼の詩の内容は単純な信心 に限定されていた[104]。風刺と書簡の最も成功した模倣者の中には、1100年頃にセクストゥス・アマルシウスと名乗ったゲルマン人作家がおり、彼は 4冊の本を書いた。 ペトラルカはホラティウスを訛音で模倣した重要な人物である。彼のラテン語による詩文は『書簡集』を手本としており、ホラティウスへの手紙を頌歌の形式で 書いている。しかし、彼はイタリア語のソネットを作曲する際にもホラティウスから借用した。ある現代の研究者は、アクセントのあるリズムでホラティウスを 模倣した作家(強調ラテン語や地方語を含む)は、自分たちの作品をホラティウスの多様な拍子の自然な続編と考えていたのではないかと推測している [106]。フランスでは、ホラティウスとピンダールは、例えばピエール・ド・ロンサールやジョアキム・デュ・ベレーを含むプレヤードと呼ばれる地方語の 作家グループの詩的モデルであった。モンテーニュはホラティウスの引用を常に創意工夫を凝らして用いた[107]。16世紀のカスティーリアとポルトガル では地方語が支配的であり、ホラティウスの影響はガルシーラソ・デ・ラ・ベガ、フアン・ボスカン、サ・デ・ミランダ、アントニオ・フェレイラ、フレイ・ル イス・デ・レオンといった作家の作品に顕著であり、最後の作家はホラティウスのテーマbeatus ille(幸福な人)を題材にしたオードを書いている。 [108]西ヨーロッパの16世紀も翻訳の時代であった(ただし、ドイツでは17世紀になるまでホラティウスは翻訳されなかった)。最初のイギリス人翻訳 者はトーマス・ドラントで、1566年の『Medicinable Morall』にエレミヤ書とホラティウスの翻訳を並べた。この年は、スコットランド人のジョージ・ブキャナンが詩篇をホラース風に言い換えた年でもあっ た。ベン・ジョンソンは1601年の『ポエタスター』で、ホラティウスを他の古典的なラテン語の作者たちとともに舞台に立たせ、彼ら全員に自作の詩を与え て翻訳で語らせた。ホラティウスのパートは、多くの読者が彼の詩に求める独立心、道徳的な真摯さ、批判的な洞察力を感じさせる[109]。 啓蒙の時代 17世紀から18世紀にかけての啓蒙時代には、新古典主義文化が浸透していた。この時期のイギリス文学はアウグストゥスと呼ばれている。これらの世紀にお けるホラティウスの影響を区別することは必ずしも容易ではない(混血の影響は、例えばある詩人のペンネームであるホラス・ジュヴェナルに示されている) [nb 29] が、彼の影響力の尺度は、読者と著者の両方において彼の作品に関心を持つ人民の多様性に見出すことができる[110]。 彼の作品の新版はほぼ毎年出版されていた。1612年には3つの新版が出版され(ライデンで2つ、フランクフルトで1つ)、1699年にも出版された(ユ トレヒト、バルセロナ、ケンブリッジ)。廉価版も多く、ジョン・パインが全文を銅版画で彫ったものなど、高級版も作られた。詩人のジェームズ・トムソンは ホラティウスの作品を5冊所有し、医師のジェームズ・ダグラスはホラティウス関連の書物を500冊持っていた。ホラティウスはしばしば『スペクテイター』 誌などの定期刊行物で、善良な判断力、節度、男らしさの象徴として称賛され、モラルの中心的存在となった。 [彼の詩は、simplex munditiis (簡素の中の優雅さ)、splendide mendax (気高く不実)、sapere aude (知る勇気を)、nunc est bibendum (今こそ飲む時)、carpe diem (一日を大切に)などの標語を提供した。) [96] エドマンド・クインシーの『A treatise of hemp-husbandry』(1765年)のような平凡な作品でも、これらは引用された。架空のヒーローであるトム・ジョーンズは彼の詩を感情を込め て朗読していた[111]。彼の作品はまた、1736年にオックスフォード大学が所蔵していたジェームズ・パリーの英語のセリフのように、愛国的な服従と いったありふれたテーマを正当化するためにも使われていた[112]。 どのような友好的なミューズが私の産婦に教えてくれるのだろう ローマの炎を模倣することを シーザーの賛美を響かせるには 大胆なホラティアの竪琴を要求する。 ホラチア風の歌詞は、この時期のオックスフォードやケンブリッジの詩集でますます典型的なものとなり、そのほとんどはラテン語であったが、先の頌歌のよう に英語によるものもあった。ジョン・ミルトンの『リシダス』は、そのような詩集に初めて収録された。この作品にはホラティウス的な響きはほとんどないが [nb 31]、ミルトンとホラティウスとの関係は生涯続くものであった。彼は『オデス』1.5の論争的なヴァージョンを作曲し、『失楽園』にはホラティウスの 「ローマの」オデス3.1-6への言及が含まれている(例えば第7巻は『オデス』3.4のエコーで始まる)[113]。しかしホラティウスの歌詞は道徳主 義者だけでなく自由主義者にもインスピレーションを与えることができ、新ラテン語は時にきわどいもののための一種の目立たないベールとして機能した。例え ば、ベンジャミン・ラヴリングは、サッフィックなスタンザで綴られたドゥルリー・レーンやコヴェント・ガーデンの娼婦たちのカタログや、「淫らな記憶を持 つ」死にゆく女性への賛辞を書いた[114]。アンソニー・アルソップによる結婚の賛歌のように、ホラティウスのラテン語の模倣の中には、ジャコバイトの 大義への叫びを含む政治的に破壊的なものもあった。一方、アンドリュー・マーヴェルは、ホラティウスのオード1.37からインスピレーションを得て、イギ リスの傑作『Horatian Ode upon Cromwell's Return from Ireland』を作曲した。このオードでは、チャールズ1世の処刑に対する微妙なニュアンスの考察が、クレオパトラの死に対するホラティウスの曖昧な反 応と呼応している(マーヴェルのオードは、その微妙さにもかかわらず弾圧され、1776年になってようやく広く出版されるようになった)。サミュエル・ ジョンソンは『オード』を読むのを特に楽しみにしていた[nb 32] アレクサンダー・ポープは『ホラティウスの模倣』(原文のラテン語と一緒に出版された)を直接書き、『エッセイ』や『錠前の破裂』でもホラティウスと呼応 している。ホラティウスはまた、アンナ・スワード(Original sonnets on various subject, and odes paraphrased from Horace, 1799)やエリザベス・トレ(Elizabeth Tollet)のような女性詩人にも魅力的であった。彼は弟の海外からの帰還を祝うために、ホラティウスの同調的な設定のワインの代わりに紅茶とコーヒー を用いたサフィック・メーターのラテン語の頌歌を作曲した: Quos procax nobis numeros, jocosque 私は、私の兄のように アラブのバカンス、あるいはハーブを味わう ポクラ・セレス[116]。 大胆なミューズはどんな詩やジョークを ミューズが命じるだろうか。 アラブ人は豆で杯を飾る あるいは中国の葉で。 |

Horace in an anonymous late 18th to early 19th century engraving Horace's Ars Poetica is second only to Aristotle's Poetics in its influence on literary theory and criticism. Milton recommended both works in his treatise of Education.[118] Horace's Satires and Epistles however also had a huge impact, influencing theorists and critics such as John Dryden.[119] There was considerable debate over the value of different lyrical forms for contemporary poets, as represented on one hand by the kind of four-line stanzas made familiar by Horace's Sapphic and Alcaic Odes and, on the other, the loosely structured Pindarics associated with the odes of Pindar. Translations occasionally involved scholars in the dilemmas of censorship. Thus Christopher Smart entirely omitted Odes 4.10 and re-numbered the remaining odes. He also removed the ending of Odes 4.1. Thomas Creech printed Epodes 8 and 12 in the original Latin but left out their English translations. Philip Francis left out both the English and Latin for those same two epodes, a gap in the numbering the only indication that something was amiss. French editions of Horace were influential in England and these too were regularly bowdlerized. Most European nations had their own 'Horaces': thus for example Friedrich von Hagedorn was called The German Horace and Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski The Polish Horace (the latter was much imitated by English poets such as Henry Vaughan and Abraham Cowley). Pope Urban VIII wrote voluminously in Horatian meters, including an ode on gout.[120] |

18世紀末から19世紀初頭の匿名の版画に描かれたホラティウス ホラティウスの『詩篇』は、アリストテレスの『詩学』に次いで文学理論や批評に影響を与えた。ミルトンは『教育論』の中で両著作を推薦している [118]。ホラティウスの『風刺と書簡』もまた、ジョン・ドライデンのような理論家や批評家に大きな影響を与えた[119]。一方ではホラティウスの 『サッフィック・オード』や『アルカイック・オード』によって親しまれるようになった4行のスタンザのようなもの、他方ではピンダルのオードに関連する緩 やかに構成されたピンダリックに代表されるように、現代の詩人にとって異なる叙情形式の価値をめぐってかなりの議論があった。翻訳が検閲のジレンマに学者 たちを巻き込むこともあった。クリストファー・スマートはオデス4.10を完全に省略し、残りのオデスに番号を振り直した。彼はまた、オデス4.1の末尾 を削除した。トマス・クリーチはEpodes 8と12をオリジナルのラテン語で印刷したが、英語訳は省いた。フィリップ・フランシスは同じ2つのエポードについて英語とラテン語の両方を残した。フラ ンス版のホラティウスはイギリスでも影響力があり、これらも定期的に改竄されていた。 例えば、フリードリッヒ・フォン・ハーゲドホルンは『ドイツのホラーチェ』、マチェイ・カジミエシュ・サルビエフスキは『ポーランドのホラーチェ』と呼ば れた(後者はヘンリー・ヴォーンやエイブラハム・カウリーといったイギリスの詩人たちに模倣された)。ローマ教皇ウルバン8世は痛風に関する頌歌を含め、 ホラティアン・メートルで多くの作品を書いた[120]。 |

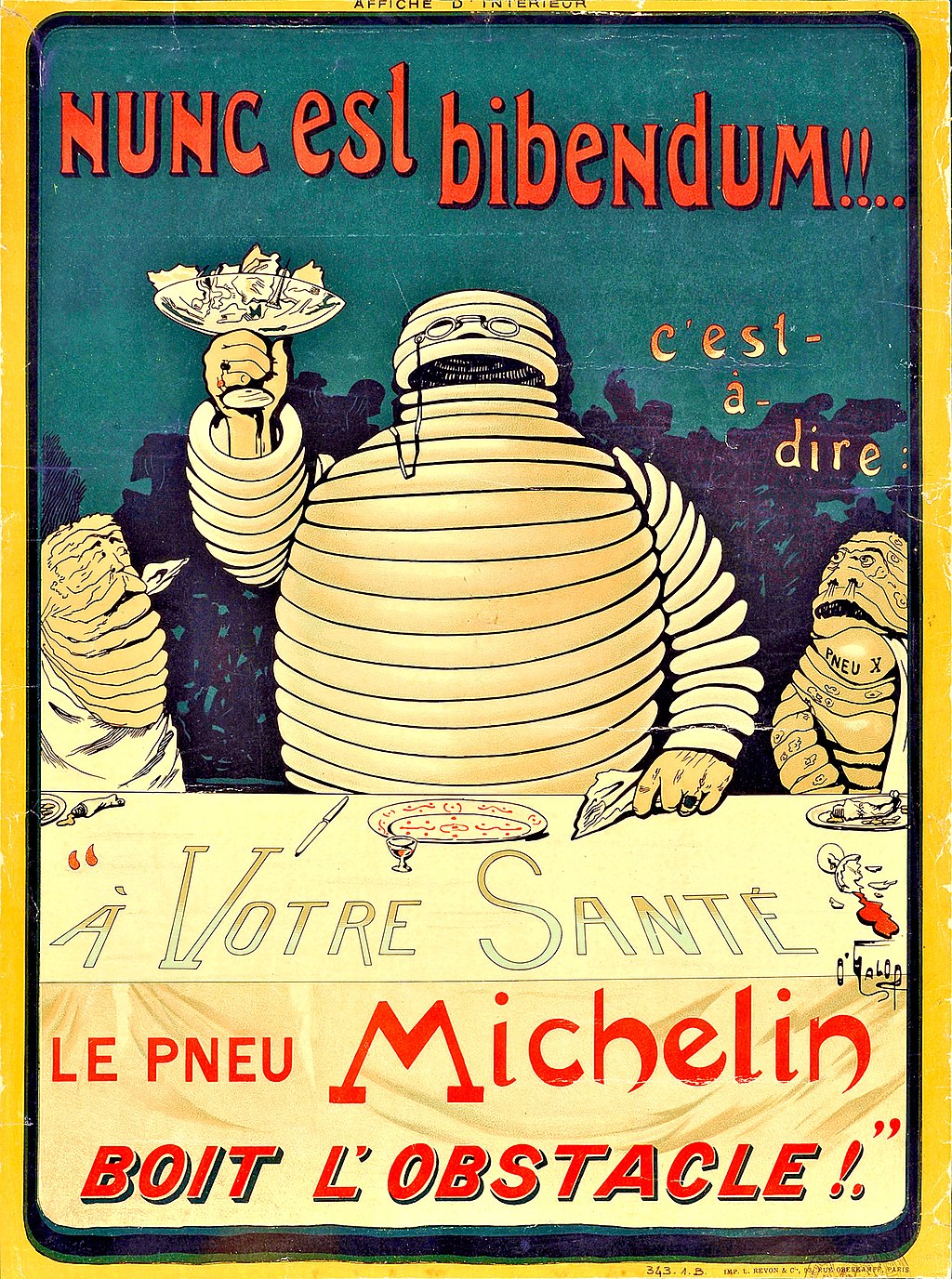

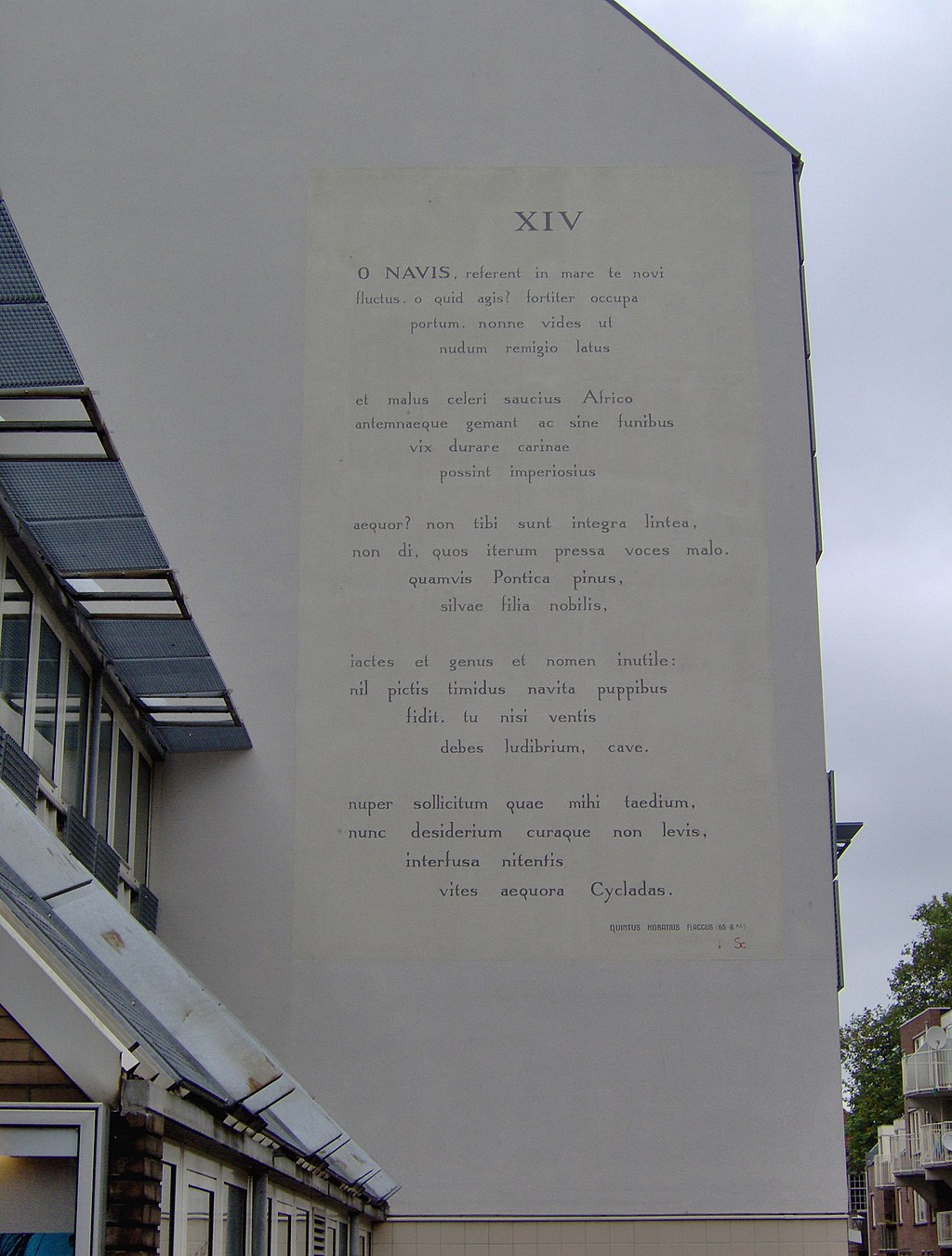

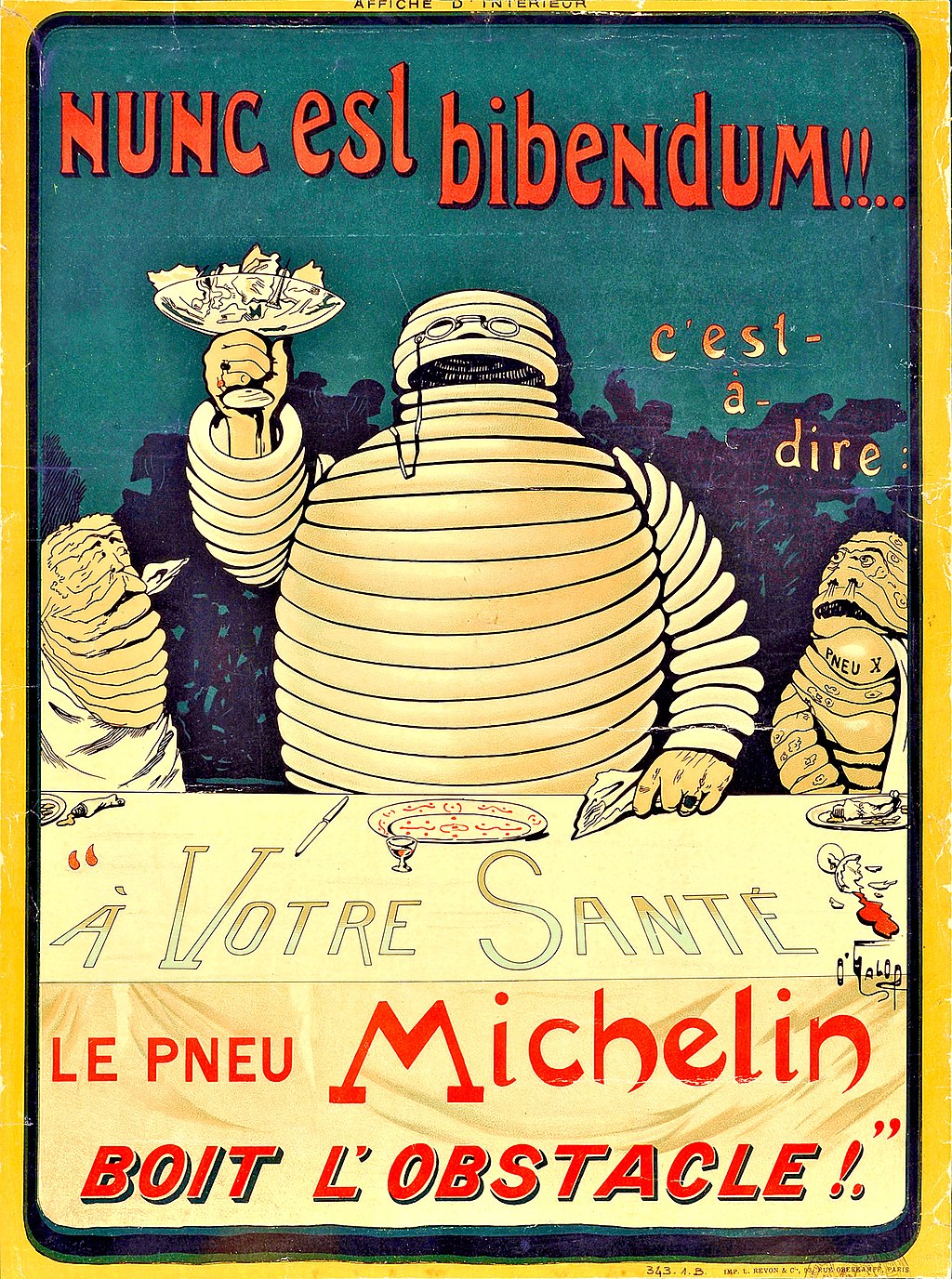

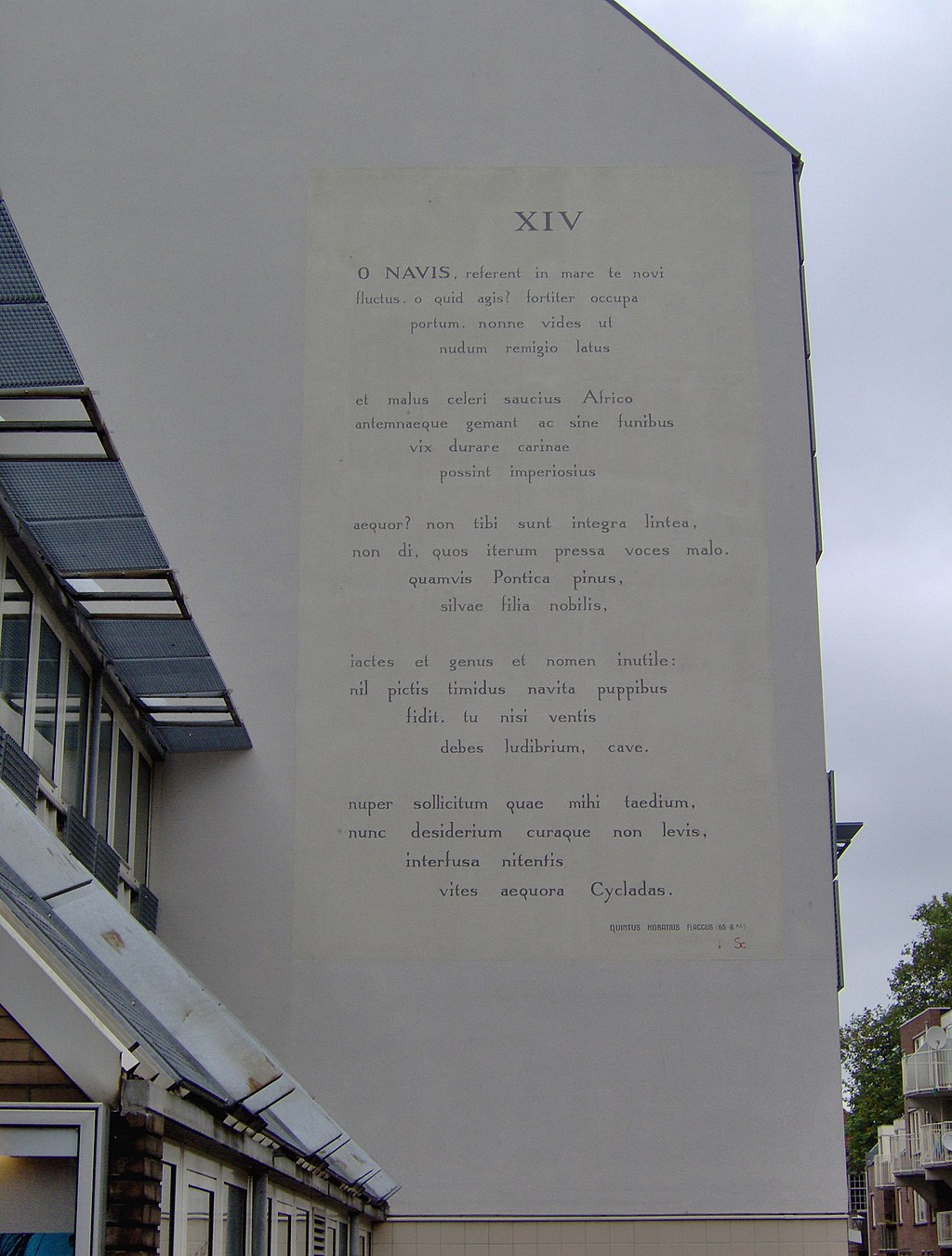

| 19th century on Horace maintained a central role in the education of English-speaking elites right up until the 1960s.[121] A pedantic emphasis on the formal aspects of language-learning at the expense of literary appreciation may have made him unpopular in some quarters[122] yet it also confirmed his influence—a tension in his reception that underlies Byron's famous lines from Childe Harold (Canto iv, 77):[123] Then farewell, Horace, whom I hated so Not for thy faults, but mine; it is a curse To understand, not feel thy lyric flow, To comprehend, but never love thy verse. William Wordsworth's mature poetry, including the preface to Lyrical Ballads, reveals Horace's influence in its rejection of false ornament[124] and he once expressed "a wish / to meet the shade of Horace...".[nb 33] John Keats echoed the opening of Horace's Epodes 14 in the opening lines of Ode to a Nightingale.[nb 34] The Roman poet was presented in the nineteenth century as an honorary English gentleman. William Thackeray produced a version of Odes 1.38 in which Horace's 'boy' became 'Lucy', and Gerard Manley Hopkins translated the boy innocently as 'child'. Horace was translated by Sir Theodore Martin (biographer of Prince Albert) but minus some ungentlemanly verses, such as the erotic Odes 1.25 and Epodes 8 and 12. Edward Bulwer-Lytton produced a popular translation and William Gladstone also wrote translations during his last days as Prime Minister.[125] Edward FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, though formally derived from the Persian ruba'i, nevertheless shows a strong Horatian influence, since, as one modern scholar has observed, "...the quatrains inevitably recall the stanzas of the 'Odes', as does the narrating first person of the world-weary, ageing Epicurean Omar himself, mixing sympotic exhortation and 'carpe diem' with splendid moralising and 'memento mori' nihilism."[nb 35] Matthew Arnold advised a friend in verse not to worry about politics, an echo of Odes 2.11, yet later became a critic of Horace's inadequacies relative to Greek poets, as role models of Victorian virtues, observing: "If human life were complete without faith, without enthusiasm, without energy, Horace...would be the perfect interpreter of human life."[126] Christina Rossetti composed a sonnet depicting a woman willing her own death steadily, drawing on Horace's depiction of 'Glycera' in Odes 1.19.5–6 and Cleopatra in Odes 1.37.[nb 36] A. E. Housman considered Odes 4.7, in Archilochian couplets, the most beautiful poem of antiquity[127] and yet he generally shared Horace's penchant for quatrains, being readily adapted to his own elegiac and melancholy strain.[128] The most famous poem of Ernest Dowson took its title and its heroine's name from a line of Odes 4.1, Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae, as well as its motif of nostalgia for a former flame. Kipling wrote a famous parody of the Odes, satirising their stylistic idiosyncrasies and especially the extraordinary syntax, but he also used Horace's Roman patriotism as a focus for British imperialism, as in the story Regulus in the school collection Stalky & Co., which he based on Odes 3.5.[129] Wilfred Owen's famous poem, quoted above, incorporated Horatian text to question patriotism while ignoring the rules of Latin scansion. However, there were few other echoes of Horace in the war period, possibly because war is not actually a major theme of Horace's work.[130] The Spanish poet Miquel Costa i Llobera published his renowned collection of poems named Horacianes, thus being dedicated to the Latin poet Horace, and employing Sapphics, Alcaics and similar types of stanzas.[131]  Bibendum (the symbol of the Michelin tyre company) takes his name from the opening line of Ode 1.37, Nunc est bibendum. Both W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice began their careers as teachers of classics and both responded as poets to Horace's influence. Auden for example evoked the fragile world of the 1930s in terms echoing Odes 2.11.1–4, where Horace advises a friend not to let worries about frontier wars interfere with current pleasures. And, gentle, do not care to know Where Poland draws her Eastern bow, What violence is done; Nor ask what doubtful act allows Our freedom in this English house, Our picnics in the sun.[nb 37]  Odes 1.14 – Wall poem in Leiden The American poet Robert Frost echoed Horace's Satires in the conversational and sententious idiom of some of his longer poems, such as The Lesson for Today (1941), and also in his gentle advocacy of life on the farm, as in Hyla Brook (1916), evoking Horace's fons Bandusiae in Ode 3.13. Now at the start of the third millennium, poets are still absorbing and re-configuring the Horatian influence, sometimes in translation (such as a 2002 English/American edition of the Odes by thirty-six poets)[nb 38] and sometimes as inspiration for their own work (such as a 2003 collection of odes by a New Zealand poet).[nb 39] Horace's Epodes have largely been ignored in the modern era, excepting those with political associations of historical significance. The obscene qualities of some of the poems have repulsed even scholars[nb 40] yet more recently a better understanding of the nature of Iambic poetry has led to a re-evaluation of the whole collection.[132][133] A re-appraisal of the Epodes also appears in creative adaptations by recent poets (such as a 2004 collection of poems that relocates the ancient context to a 1950s industrial town).[nb 41] |

19世紀 ホラティウスは1960年代まで英語圏のエリートたちの教育において中心的な役割を担っていた[121]。文学的な鑑賞を犠牲にして言語学習の形式的な側 面を衒学的に強調することは、ある方面では不人気であったかもしれないが[122]、彼の影響力を確認することにもなった。 さらば、私があれほど憎んだホラティウスよ。 あなたの欠点ではなく、私の欠点だ。 汝の抒情の流れを理解し、感じないことは呪いである、 あなたの詩を理解することはあっても、愛することはない。 リリカル・バラッズ』の序文を含むウィリアム・ワーズワースの成熟した詩は、偽りの装飾[124]を拒絶している点で、ホラティウスの影響を明らかにして おり、彼はかつて「ホラティウスの陰影に/出会いたい......」[nb 33] ジョン・キーツは『ナイチンゲール頌』の冒頭でホラティウスの『エポデス14章』の冒頭を反響させている[nb 34]。 ローマの詩人は19世紀には名誉英国紳士として紹介された。ウィリアム・サッカレーはホラティウスの'boy'を'Lucy'としたOdes 1.38の版を作り、ジェラード・マンリー・ホプキンスはboyを'child'と無邪気に訳した。ホラティウスはセオドア・マーティン卿(アルバート公 の伝記作者)によって翻訳されたが、エロティックなOdes 1.25やEpodes 8と12など、非紳士的な詩を除いたものだった。エドワード・ブルワー=リットンは大衆向けの翻訳を手がけ、ウィリアム・グラッドストンも首相として晩年 に翻訳を手がけた[125]。 エドワード・フィッツジェラルドの『オマル・ハイヤームのルバイヤート』は、形式的にはペルシア語のルバイヤートに由来しているが、現代のある学者が観察 しているように、それにもかかわらず、ホラチア語の強い影響を示している。 ある現代の学者が観察しているように、」...クオトラインは必然的に「オード」のスタンザを想起させるし、語り手である世に疲れ、老いたエピキュリア ン、オマール自身の一人称も、同情的な激励と「カルペ・ディエム」、そして見事なモラロジーと「メメント・モリ」ニヒリズムを混血させている。 マシュー・アーノルドは友人に政治的な心配をするなと詩で忠告しているが、これは『オデス』2.11の反響である: もし人間の生活が信仰や熱意やエネルギーなしに完結しているとしたら、ホラティウスは......人間の生活の完璧な解釈者であっただろう」[126] クリスティーナ・ロセッティは、ホラティウスが『オデス』1.19.5-6で描いた「グリセラ」や『オデス』1.37のクレオパトラを引きながら、自らの 死を望んでいる女性を着実に描くソネットを作曲した[nb 36] A. E. ハウスマンは『オデス』4. 7はアルキロキア連句で、古代で最も美しい詩とされ[127]、ホラティウスが四連詩を好んだことは一般によく知られているが、ホラティウスは彼自身のエ レジアックかつメランコリックな系統に容易に適合させることができた[128]。アーネスト・ダウソンの最も有名な詩は、そのタイトルとヒロインの名前を 『オデス』4.1の一節「Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae」から取り、かつての炎を懐かしむというモチーフも用いている。キップリングはオデスの有名なパロディを書き、その文体の特異性や特に異常 な構文を風刺したが、オデスの3.5を基にした学校文集『Stalky & Co.』の中の物語『Regulus』のように、ホラティウスのローマ愛国主義をイギリス帝国主義の焦点として用いることもあった[129] 。スペインの詩人ミケル・コスタ・イ・リロベラは、ラテン語の詩人ホラティウスに捧げられ、サフィクス、アルカイックス、そして似たようなタイプのスタン ザを用いた、ホラティウスと名付けられた有名な詩集を出版した[131]。  ビバンダム(ミシュランのタイヤ会社のシンボルマーク)は、頌歌1.37の冒頭の一節、Nunc est bibendumに由来する。 W・H・オーデンとルイス・マクナイスはともに古典の教師としてキャリアをスタートさせ、詩人としてホラティウスの影響を受けた。例えばオーデンは、ホラ ティウスが友人に、開拓戦争への心配が今の楽しみを邪魔しないようにと忠告する『オデス』2.11.1-4と呼応する言葉で、1930年代のもろい世界を 呼び起こした。 そして、穏やかな人よ、知ろうとは思わないでほしい。 ポーランドが東方の弓をどこに引くのか、 どんな暴力が振るわれるのか; どのような疑わしい行為が、この英国の家でのわれわれの自由を許すのか この英国家屋での自由を許してくれる 太陽の下でのピクニックを許しているのは、どんな疑わしい行為なのかを問うこともない[nb 37]。  オデス1.14-ライデンの壁の詩 アメリカの詩人ロバート・フロストは、『The Lesson for Today』(1941年)のようないくつかの長編詩の会話的で感傷的な慣用句において、また『Hyla Brook』(1916年)のような農場での生活を穏やかに擁護することにおいて、ホラティウスの『風刺』を反響させ、頌詩3.13におけるホラティウス のfons Bandusiaeを想起させた。第三千年紀が始まった現在も、詩人たちはホラーチェの影響を吸収し、再構成している。あるときは翻訳として(36人の詩 人による2002年の英米版オード集など)[nb 38]、またあるときは自身の作品へのインスピレーションとして(ニュージーランドの詩人による2003年のオード集など)[nb 39]。 ホラティウスのエポデスは、歴史的に重要な政治的関連性を持つものを除いて、現代ではほとんど無視されている。エポデスの再評価は、近年の詩人たちによる 創造的な翻案(古代の文脈を1950年代の工業都市に置き換えた2004年の詩集など)にも現れている[132][133]。 |

| Translations The Ars Poetica was first translated into English by Thomas Drant in 1556, and later by Ben Jonson and Lord Byron. John Dryden, Sylvæ; or, The second Part of Poetical Miscellanies (London: Jacob Tonson, 1685) with adaptations of three of the Odes, and one Epode. Philip Francis, The Odes, Epodes, and Carmen Seculare of Horace (Dublin, 1742; London, 1743) ——— The Satires, Epistles, and Art of Poetry of Horace (1746) Samuel Johnson favoured these translations. C. S. Calverley, Verses and Translations (1860; rev. 1862) Included versions of ten of the Odes. John Conington, The Odes and Carmen Sæculare of Horace (1863; rev. 1872) ——— The Satires, Epistles and Ars Poëtica of Horace (1869) Theodore Martin, The Odes of Horace, Translated Into English Verse, with a Life and Notes (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1866) Edward Marsh, The Odes of Horace. Translated into English Verse by Edward Marsh (London: Macmillan & Co., 1941). James Michie, The Odes of Horace (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1964) Included a dozen Odes in the original Sapphic and Alcaic metres. More recent verse translations of the Odes include those by David West (free verse), and Colin Sydenham (rhymed). In 1983, Charles E. Passage translated all the works of Horace in the original metres. Horace's Odes and the Mystery of Do-Re-Mi Stuart Lyons (rhymed) Aris & Phillips ISBN 978-0-85668-790-7 |

翻訳 アルス・ポエティカ』は、1556年にトーマス・ドラントによって初めて英訳され、その後ベン・ジョンソンとバイロン卿によって翻訳された。 John Dryden, Sylvæ; or, The second Part of Poetical Miscellanies (London: Jacob Tonson, 1685)には、3つのOdesと1つのEpodeが翻案されている。 Philip Francis, The Odes, Epodes, and Carmen Seculare of Horace (Dublin, 1742; London, 1743). --- サミュエル・ジョンソンはこれらの翻訳を好んだ。 C. C. S. Calverley, Verses and Translations (1860; rev. 1862) オデスのうち10篇を含む。 John Conington, The Odes and Carmen Sæculare of Horace (1863; rev. 1872). --- ホラティウスの風刺、書簡、詩篇 (1869) Theodore Martin, The Odes of Horace, Translated In English Verse, with a Life and Notes (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1866). Edward Marsh, The Odes of Horace. Edward Marsh, The Odes of Horace, Translated into English Verse (London: Macmillan & Co., 1941). James Michie, The Odes of Horace (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1964) オリジナルのSapphic metresとAlcaic metresで12編のOdesが収録されている。 最近の詩によるオデスの翻訳には、デイヴィッド・ウェスト(自由詩)、コリン・シデナム(韻文)などがある。 1983年、チャールズ・E・パサージュがホラティウスの全作品を原文のまま翻訳した。 ホラティウスの詩とドレミの謎 スチュアート・ライオンズ(韻文) アリス・アンド・フィリップス ISBN 978-0-85668-790-7 |

| In literature and the arts The Oxford Latin Course textbooks use the life of Horace to illustrate an average Roman's life in the late Republic to Early Empire.[134] Horace was portrayed by Norman Shelley in the 1976 miniseries I, Claudius. |

文学と芸術 オックスフォードのラテン語教科書では、共和制末期から帝政初期の平均的なローマ人の生活を説明するためにホラティウスの生涯が使われている[134]。1976年のミニシリーズ『I, Claudius』では、ノーマン・シェリーがホラティウスを演じた。 |

| Carpe diem Horatia gens List of ancient Romans Otium Prosody (Latin) Translation Horace's Villa |

カルペ・ディエム ホラティア世代 古代ローマ人のリスト オティウム プロソディ(ラテン語) 翻訳 ホラティウスの別荘 |