ドナルド・ダックを読む方法

How to Read Donald Duck

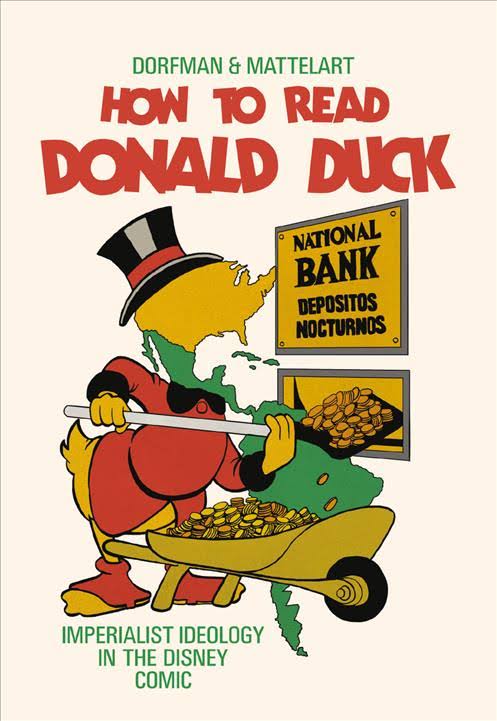

☆ 『ドナルドダックの読み方』(スペイン語:Para leer al Pato Donald)は、アリエル・ドールフマンとアルマンド・マテラートによる1971年の長編エッセイであり、ディズニーの漫画をマルクス主義の観点から、 アメリカ企業の資本主義的プロパガンダであり文化帝国主義であると批判している。1971年にチリで出版され、ラテンアメリカ全域でベストセラーとなっ た。また、文化研究における画期的な作品として今でも評価されている。2018年8月には、ドルフマンによる新たな序文を加えて、米国の一般読者向けに OR Booksから再版された。

| How

to Read Donald Duck (Spanish: Para leer al Pato Donald) is a 1971

book-length essay by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart that critiques

Disney comics from a Marxist point of view as capitalist propaganda for

American corporate and cultural imperialism.[1][2] It was first

published in Chile in 1971, became a bestseller throughout Latin

America[3] and is still considered a seminal work in cultural

studies.[4] It was reissued in August 2018 to a general audience in the

United States, with a new introduction by Dorfman, by OR Books. |

『ド

ナルドダックの読み方』(スペイン語:Para leer al Pato

Donald)は、アリエル・ドールフマンとアルマンド・マテラートによる1971年の長編エッセイであり、ディズニーの漫画をマルクス主義の観点から、

アメリカ企業の資本主義的プロパガンダであり文化帝国主義であると批判している。1971年にチリで出版され、ラテンアメリカ全域でベストセラーとなった

[3]。また、文化研究における画期的な作品として今でも評価されている[4]。2018年8月には、ドルフマンによる新たな序文を加えて、米国の一般読

者向けにOR Booksから再版された。 |

| Summary The book's thesis is that Disney comics are not only a reflection of the prevailing ideology at the time (capitalism), but that they are also aware of this, and are active agents in spreading the ideology. To do so, Disney comics use images of the everyday world: "Here lies Disney's inventive (product of his era), rejecting the crude and explicit scheme of adventure strips, that came up at the same time. The ideological background is without any doubt the same: but Disney, not showing any open repressive force, is much more dangerous. The division between Bruce Wayne and Batman is the projection of fantasy outside the ordinary world to save it. Disney colonizes the everyday world, at hand of ordinary man and his common problems, with the analgesic of a child's imagination". — Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart, How to Read Donald Duck, p. 148 This closeness to everyday life is so only in appearance, because the world shown in the comics, according to the thesis, is based on ideological concepts, resulting in a set of natural rules that lead to the acceptance of particular ideas about capital, the developed countries' relationship with the Third World, gender roles, etc. As an example, the book considers the lack of descendants of the characters.[5] Everybody has an uncle or nephew, everybody is a cousin of someone, but nobody has fathers or sons. This non-parental reality creates horizontal levels in society, where there is no hierarchic order, except the one given by the amount of money and wealth possessed by each, and where there is almost no solidarity among those of the same level, creating a situation where the only thing left is crude competition.[6] Another issue analyzed is the absolute necessity to have a stroke of luck for social mobility (regardless of the effort or intelligence involved),[7] the lack of ability of the native tribes to manage their wealth,[8] and others. |

要約 この本の主張は、ディズニーのコミックは当時の支配的なイデオロギー(資本主義)を反映しているだけでなく、ディズニー自身もそれを認識しており、イデオ ロギーを広める積極的な役割を果たしているということである。ディズニーのコミックは、日常世界のイメージを使用することで、その役割を果たしている。 「ここに横たわるのは、ディズニーの独創的な作品(彼の時代の産物)であり、同じ時期に登場した粗野で露骨な冒険漫画の図式を拒絶している。そのイデオロ ギー的背景は疑いようもなく同じである。しかし、ディズニーは、露骨な抑圧力を示すことなく、はるかに危険である。ブルース・ウェインとバットマンの関係 は、日常世界を救うための空想の投影である。ディズニーは、一般の人々や彼らの共通の問題を扱う日常世界を、子供の想像力という鎮痛剤で植民地化する」。 — アリエル・ドルフマンとアルマンド・マテラート著『ドナルドダックの読み方』148ページ 日常生活との近さは、あくまで表面的なものであり、その理由は、この論文によると、コミックで描かれる世界はイデオロギー的概念に基づいており、資本、先 進国と第三世界の関係、ジェンダーの役割などに関する特定の考えを受け入れることにつながる一連の自然なルールを生み出しているからである。 その一例として、この本ではキャラクターに子孫がいないことを挙げている。[5] 誰もが叔父や甥を持ち、誰もが誰かの従兄弟であるが、父親や息子を持つ人はいない。この親子関係のない現実が、社会に水平的な階層を生み出し、そこでは各 々が所有する金銭や財産の量によって与えられる階層を除いては、ヒエラルキーの秩序は存在せず、同じレベルの人々の間にはほとんど連帯感がなく、残るのは 残るのは粗野な競争だけという状況が生み出される。[6] また、社会的な移動には(努力や知能に関係なく)運が必要不可欠であること、[7] 先住民が富を管理する能力に欠けていること、[8] その他の問題についても分析されている。 |

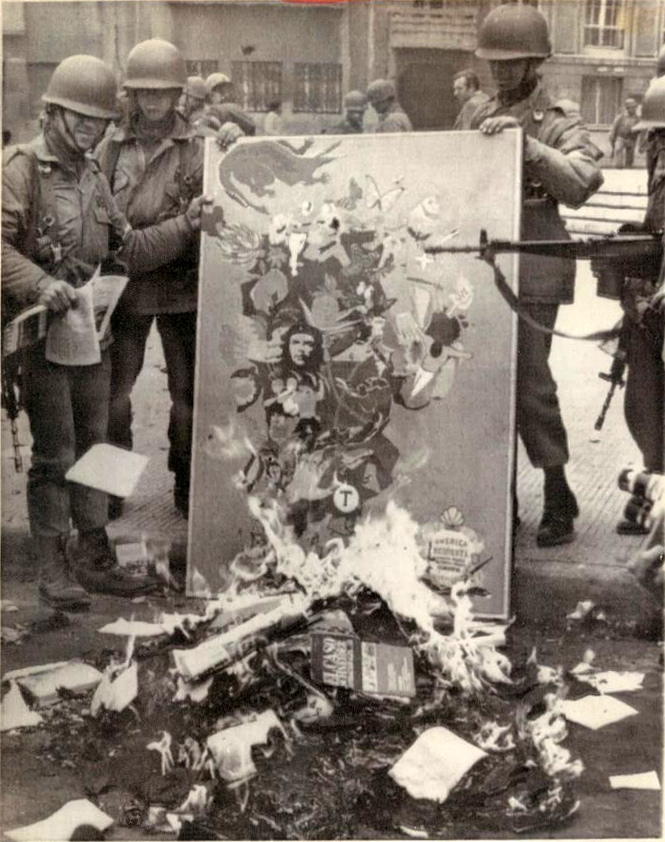

Publication history Soldiers burning books in Chile, 1973 How to Read Donald Duck was written and published by Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, belonging to the Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso, during the brief flowering of democratic socialism under the government of Salvador Allende and his Popular Unity coalition and is closely identified with the revolutionary politics of its era.[9] In 1973, a coup d'état, secretly supported by the United States, brought in power the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. During Pinochet's regime, How to Read Donald Duck was banned and subject to book burning; its authors were forced into exile.[9] Outside Chile, How to Read Donald Duck became the most widely printed political text in Latin America for some time.[3] It was translated into English, French, German, Portuguese, Dutch, Italian, Greek, Turkish, Swedish, Finnish, Danish, Japanese, and Korean[10] and sold some 700.000 copies overall; by 1993, it had been reprinted 32 times by the publisher Siglo Veintiuno Editores.[11] A hardcover edition with a new introduction by Dorfman was published by OR Books in the United States in October 2018.[12] |

出版の歴史 チリで本を燃やす兵士たち、1973年 『ドナルドダックの読み方』は、サルバドール・アジェンデと人民連合の政府による民主的社会主義の短い開花期に、ヴァラパソの教皇庁立カトリック大学に属 するエディシオネス・ウニベルシタリアス・デ・ヴァラパソによって執筆・出版された。この本は、その時代の革命的な政治と密接に関連している。1973 年、アメリカ合衆国の秘密支援を受けたクーデターにより、アウグスト・ピノチェトの軍事独裁政権が誕生した。ピノチェト政権下では『ドナルドダックの読み 方』は発禁となり焚書に処され、著者は国外追放を余儀なくされた。 チリ国外では、『ドナルドダックの読み方』はしばらくの間、ラテンアメリカで最も広く印刷された政治的なテキストとなった。英語、フランス語、ドイツ語、 ポルトガル語、オランダ語、イタリア語、ギリシャ語、トルコ語、スウェーデン語、フィンランド語、デンマーク語、日本語 、韓国語に翻訳され[10]、全体で70万部が販売された。1993年までに、出版社シグロ・ベインティウノ・エディトレスにより32回も再版されている [11]。 ドルフマンによる新たな序文を追加したハードカバー版が、2018年10月に米国のORブックスから出版された[12]。 |

| Reception Thomas Andrae, who has written about Carl Barks, has criticized the thesis of Dorfman and Mattelart. Andrae writes that it is not true that Disney controlled the work of every cartoonist, and that cartoonists had almost completely free hands unlike those who worked in animation. According to Andrae, Carl Barks did not even know that his cartoons were read outside the United States in the 1950s. Lastly, he writes that Barks' cartoons include social criticism and even anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist references.[13] David Kunzle, who translated the book into English, spoke to Carl Barks for his introduction and came to a similar conclusion. He believes Barks projected his own experience as an underpaid cartoonist onto Donald Duck, and views some of his stories as satires "in which the imperialist Duckburgers come off looking as foolish as—and far meaner than—the innocent Third World natives".[14] |

レセプション カール・バルクスについて執筆したトーマス・アンドレは、ドルフマンとマテルアートの論文を批判している。アンドレは、ディズニーがすべての漫画家の作品 を管理していたという主張は正しくなく、アニメーションで働いていた人々とは異なり、漫画家はほぼ完全に自由裁量で仕事をしていたと書いている。アンドレ によると、カール・バルクスは1950年代には、彼の漫画が米国以外でも読まれていることを知らなかったという。最後に、彼は、バークスの漫画には社会批 判や反資本主義、反帝国主義の要素さえ含まれていると書いている。[13] この本を英訳したデイヴィッド・クンツルは、序文を書くためにカール・バルクスにインタビューし、同様の結論に達した。彼は、バルクスが低賃金の漫画家と しての自身の経験をドナルド・ダックに投影したと考え、バルクスの物語のいくつかを「帝国主義的なダックバーガーが、無邪気な第三世界の原住民と同じくら い愚かに、そしてはるかに卑劣に見える」風刺として捉えている。[14] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/How_to_Read_Donald_Duck |

|

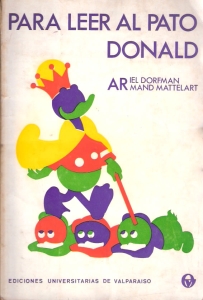

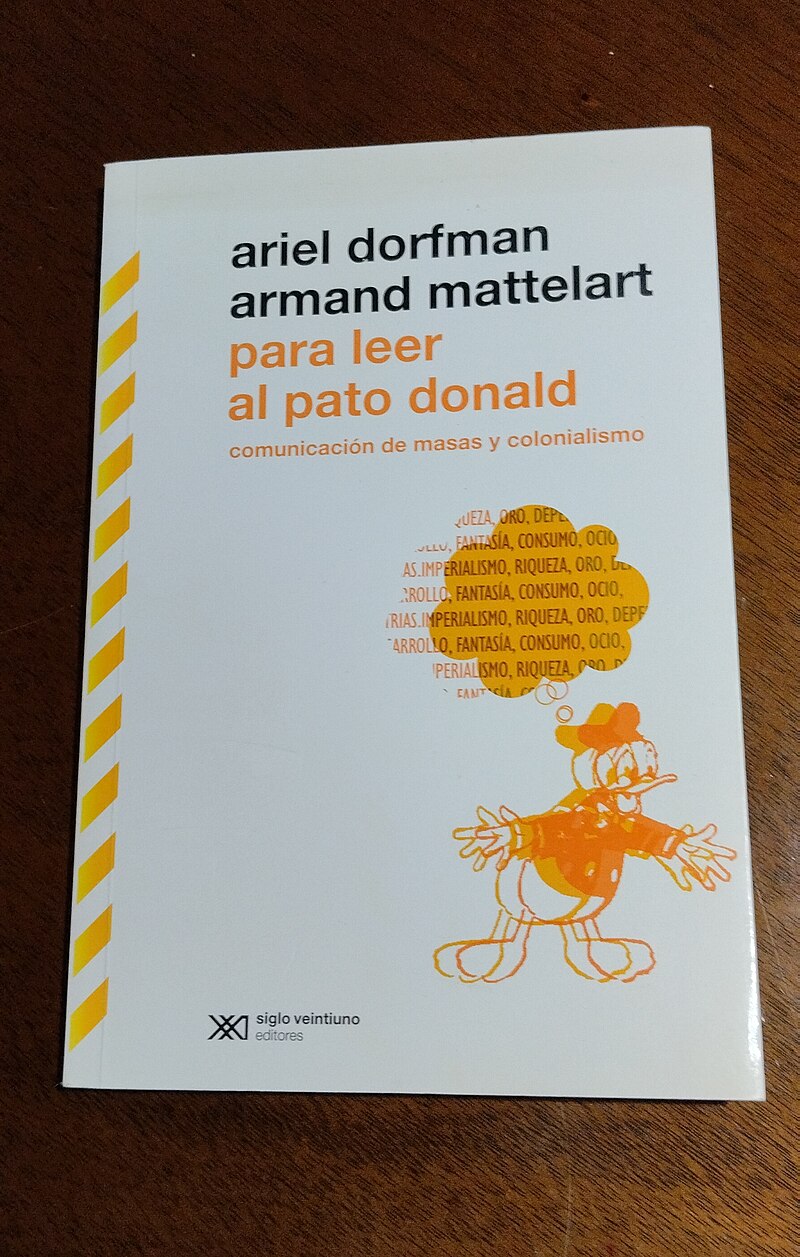

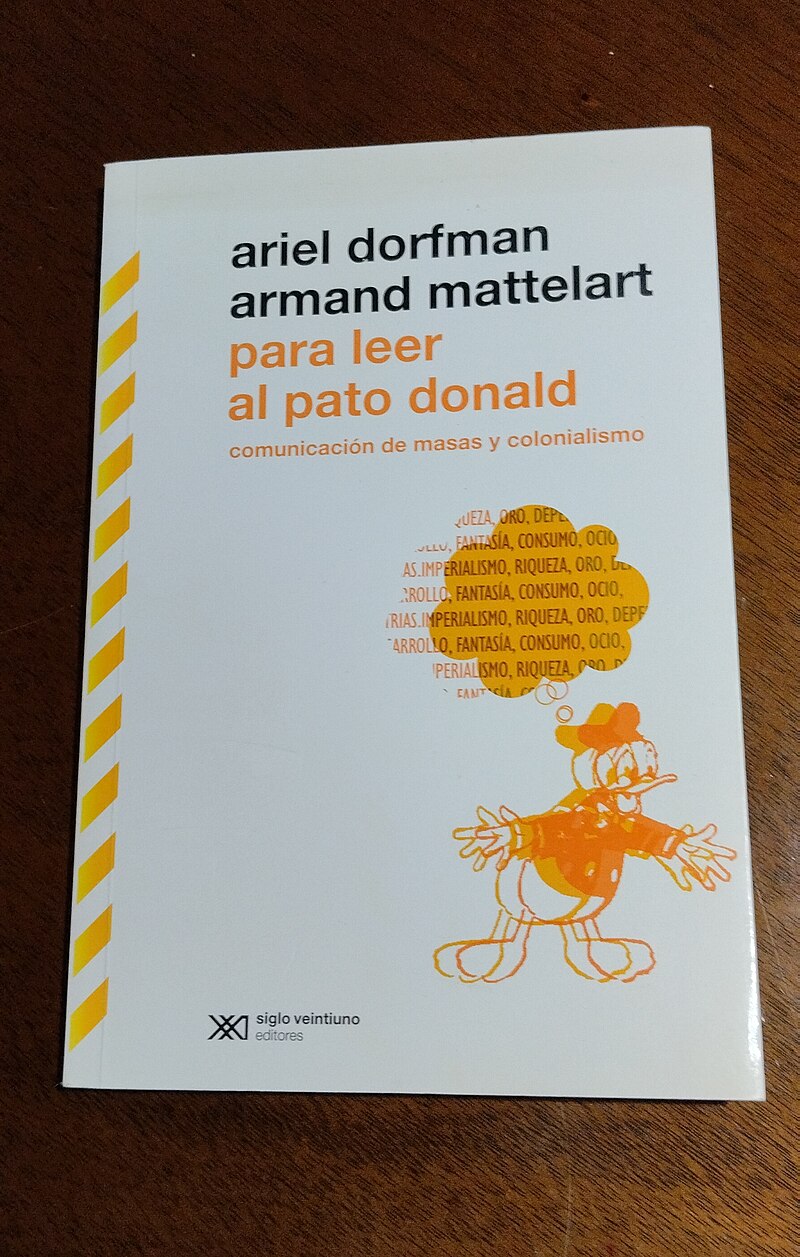

| Para leer al Pato Donald

(1972), de Ariel Dorfman (argentino-chileno) y Armand Mattelart

(belga), es un libro clave de la literatura política de los años

setenta. Es un ensayo —o un «manual de descolonización», tal como lo

describen sus autores— que analiza desde un punto de vista marxista la

literatura de masas, concretamente las historietas cómicas o cómics

publicados por Walt Disney para el mercado latinoamericano. Fue publicado por primera vez en Chile en 1972, se convirtió en un éxito de ventas en toda América Latina y todavía se considera un trabajo fundamental en el campo de los estudios culturales.1 Argumento Su tesis principal es que las historietas de Disney no solo serían un reflejo de la ideología dominante —el de la clase dominante, según los postulados del marxismo—, sino que, además, serían cómplices activos y conscientes de la tarea de mantenimiento y difusión de esa ideología. El mundo que se muestra en los cómics, según la tesis, se basa en conceptos ideológicos, lo que resulta en un conjunto de reglas naturales que conducen a la aceptación de ideas particulares sobre el capital, la relación de los países desarrollados con el Tercer Mundo, roles de género, y otros. Como ejemplo, el libro considera la falta de descendientes de los personajes.2 Todos tienen un tío o un sobrino, todos son primos de alguien, pero nadie tiene padres ni hijos. Esta realidad no parental crea niveles horizontales en la sociedad, donde no hay un orden jerárquico, excepto el dado por la cantidad de dinero y riqueza que posee cada uno, y donde casi no hay solidaridad entre los del mismo nivel, creando una situación donde lo único que queda es la competencia cruda.3 Otro tema analizado es la necesidad absoluta de tener un golpe de suerte para la movilidad social (independientemente del esfuerzo o la inteligencia involucrada),4 la falta de capacidad de las tribus nativas para administrar su riqueza,5 entre otros tópicos.  Para leer al pato Donald. Fotografía de la portada del libro.Siglo XXI Editores. Argentina. Edición del 2002. Historia Para leer al Pato Donald fue escrito y publicado durante el breve florecimiento del socialismo revolucionario bajo el gobierno de Salvador Allende y su coalición de Unidad Popular y está estrechamente identificado con la política revolucionaria de su época.6 En 1973, un golpe de Estado puso en el poder la dictadura militar de Augusto Pinochet. Durante el régimen, el libro fue prohibido y sujeto a la quema de libros. Sus autores fueron forzados al exilio.6 Fuera de Chile, se convirtió en el texto político más impreso en América Latina durante algún tiempo.7 Fue traducido al inglés, francés, alemán, portugués, holandés, italiano, griego, turco, sueco, finlandés, danés, japonés y coreano8 y vendió unas 700.000 copias en total. Ha sido reimpreso 36 veces por el editor Siglo Veintiuno Editores.9 Estructura del libro El libro consta de un prólogo escrito por Héctor Schmucler, e introducción y prólogo de los autores. El análisis de las historietas se desarrolla a lo largo de seis capítulos, a los que siguen uno de conclusiones y un anexo de las publicaciones analizadas. La estructura de la obra es la siguiente: Donald y la política (pról. de Schmucler) Pró-logo para pató-logo (pról. de los autores) Introducción: «Instrucciones para llegar a general del club Disneylandia» Capítulo I: «Tío, cómprame un profiláctico» Capítulo II: «Del niño al buen salvaje» Capítulo III: «Del buen salvaje al subdesarrollado» Capítulo IV: «El gran paracaidista» Capítulo V: «La máquina de las ideas» Capítulo VI: «El tiempo de las estatuas muertas» Conclusión: «¿El Pato Donald al poder?» Anexo: Números de las revistas analizadas |

アリエル・ドーフマン(アルゼンチ

ン・チリ人)とアルマ ンド・マテラート(ベルギー人)による『Para leer al Pato Donald』(1972 年)は、1970

年代の政治文学における重要な本である。この本は、マルクス主義的な視点から大衆文学、とりわけウォルト・ディズニーがラテンアメリカ市場向けに出版した

コミック・ストリップやコミックを分析したエッセイであり、著者が言うところの「脱植民地化マニュアル」である。 1972 年にチリで初めて出版されたこの本は、ラテンアメリカ全土でベストセラーとなり、現在でもカルチュラル・スタディーズの分野における代表的な著作とみなされている1。 論旨 その主なテーゼは、ディズニーのコミックスは支配的なイデオロギー(マルクス主義の 定義によれば支配階級のイデオロギー)の反映であるだけでなく、そのイデオロギーを 維持し広めるという仕事に積極的かつ意識的に加担しているというものである。 この論文によれば、マンガに描かれる世界はイデオロギー的な概念に基づい ており、その結果、資本、先進国と第三世界との関係、ジェンダーの役割など に関する特定の考え方が受け入れられるようになる一連の自然なルールが生み出 されている。 その一例として、本書では登場人物に子孫がいないことを考察している2。誰にでも叔父や甥がおり、誰もが誰かのいとこにあたるが、誰も親や子を持たない。 このような親を持たない現実が、社会に水平的なレベルを生み出し、そこでは、それぞれが所有する金や富の量によって与えられる以外の階層的な秩序は存在せ ず、同じレベルの者同士の連帯はほとんどなく、残されたのは生の競争だけという状況を生み出している3。また、社会的な流動性を高めるためには、(努力や 知性に関係なく)幸運に恵まれることが絶対的に必要であること4、先住民族には富を管理する能力がないこと5などもテーマとして分析されている。  ドナルド・ダックを読む。本の表紙の写真.Siglo XXI Editores. アルゼンチン。2002年版。 歴史 Para leer al Pato Donald』は、サルバドール・アジェンデ政権と彼の人民統一連合が革命的社会主義を短期間開花させた時代に書かれ、出版されたもので、当時の革命政治 と密接に関連している6。1973年、クーデターによりアウグスト・ピノチェトの軍事独裁政権が誕生した。1973年のクーデターにより、アウグスト・ピ ノチェトの軍事独裁政権が誕生した。著者は亡命を余儀なくされた6。 英語、フランス語、ドイツ語、ポルトガル語、オランダ語、イタリア語、ギリシャ語、トルコ語、スウェーデン語、フィンランド語、デンマーク語、日本語、韓 国語に翻訳され8、合計70万部が売れた。出版社Siglo Veintiuno Editoresによって36回再版されている9。 本の構成 本書は、エクトル・シュムクレール(Héctor Schmucler)による序文と、著者らによる序論と序文で構成されている。コミックスの分析は 6 章で展開され、結論の章と分析した出版物の付録が続く。 本書の構成は以下の通りである: ドナルドと政治(シュムクレールによる序文)。 病理ロゴのためのプロローグ(著者らによる序文) 序章:「ディズニーランド・クラブの将軍になるための指南書 第一章:「おじさん、予防薬を買って」。 第二章:「子どもからよい野蛮人へ」。 第三章:「良い野蛮人から未発達の野蛮人へ」。 第四章:「偉大なる落下傘兵」。 第五章:「アイデア・マシン 第六章:「死んだ彫像の時代」。 結論:「ドナルド・ダックが権力を握る? 付録:分析された雑誌の問題 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Para_leer_al_Pato_Donald |

|

| Seduction of the Innocent

is a book by German-born American psychiatrist Fredric Wertham,

published in 1954, that warned that comic books were a negative form of

popular literature and a serious cause of juvenile delinquency. The

book was taken seriously at the time in the United States, and was a

minor bestseller that created alarm in American parents and galvanized

them to campaign for censorship. At the same time, a U.S. Congressional

inquiry was launched into the comic book industry. Subsequent to the

publication of Seduction of the Innocent, the Comics Code Authority was

voluntarily established by publishers to self-censor their titles. In

the decades since the book's publication, Wertham's research has been

disputed by scholars. Overview and arguments Seduction of the Innocent cited overt or covert depictions of violence, sex, drug use, and other adult fare within "crime comics" – a term Wertham used to describe not only the popular gangster/murder-oriented titles of the time, but superhero and horror comics as well. The book asserted that reading this material encouraged similar behavior in children. Comics, especially the crime/horror titles pioneered by EC, were not lacking in gruesome images; Wertham reproduced these extensively, pointing out what he saw as recurring morbid themes such as "injury to the eye".[1] Many of his other conjectures, particularly about hidden sexual themes (e.g. images of female nudity concealed in drawings or Batman and Robin as gay partners), were met with derision within the comics industry. Wertham's claim that Wonder Woman had a bondage subtext was somewhat better documented, as her creator William Moulton Marston had admitted as much;[citation needed] however, Wertham also claimed Wonder Woman's strength and independence made her a lesbian.[2] At this time homosexuality was still viewed as a mental disorder by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Wertham also claimed that Superman was both un-American and fascistic.[3] Wertham critiqued the commercial environment of comic book publishing and retailing, objecting to air rifles and knives advertised alongside violent stories. Wertham sympathized with retailers who did not want to sell horror comics, yet were compelled to by their distributors' table d'hôte product line policies. Seduction of the Innocent was illustrated with comic-book panels offered as evidence, each accompanied by a line of Wertham's commentary. The first printing contained a bibliography listing the comic book publishers cited, but fears of lawsuits compelled the publisher to tear the bibliography page from any copies available, so copies with an intact bibliography are rare. Early complete editions of Seduction of the Innocent are collected avidly by book and comic book collectors. Beginning in 1948, Wertham wrote and spoke widely, arguing about the detrimental effects that comics reading had on young people. Consequently, Seduction of the Innocent serves as a culminating expression of his sentiments about comics and presents augmented examples and arguments, rather than wholly new material.[4] Wertham's concerns were not limited to comics' impact on boys: He also expressed a concern for the effect of impossibly proportioned female characters on girl readers. Writer A. David Lewis claims that Wertham's anxiety over the perceived homosexual subtext of Batman and Robin was aimed at the depiction of family within this context, rather than focused on the moral character of homosexuality itself.[5] Will Brooker also writes in Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon that Wertham's notorious reading of Batman and Robin as a homosexual couple was not of his own invention, but was suggested to him by homosexual males whom he interviewed.[6] Influence This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this section by introducing more precise citations. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Seduction of the Innocent caught the attention of Senator Estes Kefauver. Kefauver had a reputation as a mob hunter, and it was a known fact that the mob had strong connections with the distribution of comics and magazines. He saw Wertham's agenda as a tool he could use against the organized crime within the industry. As a platform from where he could spread his message more efficiently, Wertham appeared before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. In testimony before the committee, he compared the comic book industry to Adolf Hitler.[7] The hearing was broadcast on television, which was quickly becoming a new mass medium, and made other media join in. It made headlines on The New York Times's front page. Even if the government didn't act beyond the hearing, and Kefauver lost interest in comics after he was selected as a presidential candidate, the public damage was already done. The hearing was in April, and the same summer 15 publishers went out of business. At EC Comics, Mad was the only surviving title.[8] The committee's questioning of their next witness, EC publisher William Gaines, focused on violent scenes of the type Wertham had described. At the time, Wertham was also the Court's appointed psychiatric expert during the trial of the Brooklyn Thrill Killers, a gang of youths who had brutalized people and killed two men during the summer of 1954. Wertham asserted that the gang leader's behaviour had been caused by comic books, and most specifically pornographic ones. The case helped fuel the public outrage against comic books. Nights of Horror, an underground fetish series that Wertham had used as evidence during the trial, was banned by the State of New York: the case against that comic eventually went to the Supreme Court, which upheld the ban in 1957.[9] Although the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency's final report did not blame comics for crime, it recommended that the comics industry tone down its content voluntarily. Publishers then developed the self-censorship body the Comics Code Authority. Criticism According to a 2012 study by Carol L. Tilley, Wertham "manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence" in support of the contentions expressed in Seduction of the Innocent.[4] He misprojected both the sample size and substance of his research, making it out to be more objective and less anecdotal than it truly was.[10][failed verification] He generally did not adhere to standards worthy of scientific research, instead using questionable evidence for his argument that comics were a cultural failure.[11] Wertham used New York City adolescents from troubled backgrounds with previous evidence of behavior disorders as his primary sample population. For instance, he used children at the Lafargue Clinic to argue that comics disturbed young people, but according to a staff member's calculation seventy percent of children under the age of sixteen at the clinic had diagnoses of behavior problems.[12] He also used children with more severe psychiatric disorders which required hospitalization at Bellevue Hospital Center, Kings County Hospital Center, or Queens General Hospital.[citation needed] Statements from Wertham's subjects were sometimes altered, combined, or excerpted so as to be misleading. Relevant personal experience was sometimes left unmentioned. For instance, in arguing that the Batman comics condoned homosexuality because of the relationship between Batman and his sidekick Robin, there is evidence Wertham combined two subjects' statements into one, and did not mention the two subjects had been in a homosexual relationship for years prior. He failed to inform readers that a subject had been recently sodomized. Despite subjects specifically noting a preference for or the superior relevance of other comics, he gave greater weight to their reading Batman.[13] Wertham also presented as firsthand stories that he could have only heard through colleagues.[citation needed] His descriptions of comic content were sometimes misleading, either by exaggeration or elision. He mentions a "headless man" in an issue of Captain Marvel while the comic only shows Captain Marvel's face splashed with an invisibility potion,[14] not a decapitated figure. He exaggerated a 13-year-old girl's report of stealing in a comic from "sometimes" to "often".[15] He compared the Blue Beetle to a Kafkaesque nightmare, failing to mention that the Blue Beetle is a man and not an insect.[citation needed] In other countries While it had been the US comic industry itself that imposed self-censorship in the form of the Comics Code Authority, France had already passed the Loi du 16 juillet 1949 sur les publications destinées à la jeunesse (Law of July 16, 1949 on Publications Aimed at Youth) in response to the post-liberation influx of American comics. As late as 1969, the law was invoked to prohibit the comic magazine Fantask —which featured translated versions of Marvel Comics stories — after seven issues. The government agency charged with upholding the law, particularly in the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s, was called the Commission de surveillance et de contrôle des publications destinées à l'enfance et à l'adolescence (Committee in Charge of Surveillance and Control over Publications Aimed at Children and Adolescents). After the May 1968 social upheaval in France, key comics artists, including Jean Giraud, staged a revolt in the editorial offices of the comic magazine Pilote, demanding and ultimately receiving more creative freedom from editor-in-chief René Goscinny.[16] West Germany from 1954 had the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien (Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young Persons), a government agency intended to weed out publications, including comics, considered unhealthy for German youth. This agency came about because of the "Gesetz über die Verbreitung jugendgefährdender Schriften" law passed on June 9, 1953, itself resulting from the "provisions for the protection of young persons" clause in Article 5 of the German constitution, regulating freedom of expression.[17] The German comics industry in 1955 instituted the Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle für Serienbilder (Voluntary Self-Control for Comics).[18] Dutch Minister of Education Theo Rutten of the Catholic People's Party published a letter in the October 25, 1948, issue of the newspaper Het Parool directly addressing educational institutions and local government bodies, advocating the prohibition of comics. He stated, "These booklets, which contain a series of illustrations with accompanying text, are generally sensational in character, without any other value. It is not possible to act against the printers, publishers or distributors of these novels, nor can anything be achieved by not making paper available to them, as the necessary paper is available on the free market".[19] Exceptions were made for a small number of "healthy" comic productions from the Toonder studio, which included the literary comic strip Tom Poes.[20] Legacy Comics publisher Dynamite Entertainment (The Lone Ranger, The Shadow, Conan) would adopt the title for a series of crime comics, beginning in 2015.[21] Max Allan Collins crime novel, Seduction of the Innocent (June 2013), the third book in his Jack & Maggie Starr series, is a murder mystery set around a fictionalized version of Frederic Wertham's crusade against comic books. |

『無邪気な誘惑(無垢と称する者の

誘惑)』(Seduction of the

Innocent)は、ドイツ生まれのアメリカ人精神科医フレデリック・ワーサムが1954年に発表した本で、漫画は大衆文学の負の形であり、少年犯罪の

深刻な原因であると警告した。この本は当時アメリカで真剣に受け止められ、アメリカ人の親たちに不安を抱かせ、検閲を求める運動に駆り立てた。同時に、米

国議会ではコミックブック業界に関する調査が開始された。『無邪気な誘惑』の出版後、コミックコード委員会が自主的に設立され、出版社は自社のタイトルを

自主規制した。この本が出版されてから数十年の間、Werthamの研究は学者たちによって論争の的となってきた。 概要と論争 『無邪気な誘惑』は、暴力、セックス、ドラッグの使用、その他の成人向けの内容をあからさまに、あるいは隠れて描いていると指摘している。この用語は、当 時人気だったギャングや殺人犯を題材にした作品だけでなく、スーパーヒーローやホラーのコミックも指していた。この本は、このような作品を読むと子供たち も同様の行動をとるようになると主張している。 特にEC社が先駆者となった犯罪/ホラー作品には、おぞましいイメージが欠けていたわけではない。 ワートナムはそれらのイメージを広範囲にわたって再現し、「目に障害を与える」といった反復的な病的なテーマを指摘した。[1] 彼の他の推測の多く、特に隠された性的テーマ(例えば、絵の中に隠された女性の裸のイメージや、バットマンとロビンがゲイのパートナーであるというイメー ジ)については、コミック業界内で嘲笑の的となった。ワンダーウーマンの生みの親であるウィリアム・モールトン・マーストンがそのように認めていたため、 ワンダーウーマンには緊縛の暗示があるというワーサムの主張は、いくらか裏付けがあった。しかし、ワーサムはまた、ワンダーウーマンの強さと自立心は彼女 をレズビアンにしているとも主張した。[2] この当時、同性愛は『精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル』によって、まだ精神障害と見なされていた。ワーサムはまた、スーパーマンは非アメリカ的でファシス ト的であるとも主張した。[3] ワーサムは、コミック出版や小売りの商業環境を批判し、暴力的なストーリーと並んで宣伝されている空気銃やナイフに異議を唱えた。ワーサムは、ホラーコミックを販売したくないが、卸売業者のテーブル・ドート製品ライン政策によって販売せざるを得ない小売業者に同情した。 『無邪気な誘惑』は、証拠として提示されたコミックのページとともに、それぞれにワートハムの解説が添えられていた。初版には、引用されたコミック出版社 の一覧が記載されていたが、訴訟を恐れた出版社は、入手可能なすべてのコピーからそのページを破り取ったため、その一覧が残っているものはほとんどない。 初期の完全版『無邪気な誘惑』は、書籍やコミックのコレクターの間で熱心に収集されている。 1948年から、ワーサムは執筆や講演を通じて、若者に対する漫画の悪影響について論じ続けた。その結果、『無邪気な誘惑』は、漫画に対する彼の感情の頂 点を示すものとなり、全く新しい内容というよりも、より多くの例や論拠を示すものとなった。[4] ワーサムの懸念は、漫画が少年たちに与える影響に留まらなかった。彼は、不自然なプロポーションの女性キャラクターが少女読者に与える影響についても懸念 を示した。作家のA・デイヴィッド・ルイスは、バットマンとロビンの同性愛的な背景をワーサムが懸念していたのは、同性愛の道徳的な性格そのものに焦点を 当てたものではなく、この文脈における家族の描写に向けられたものだったと主張している。[5] ウィル・ブルッカーも著書『バットマン・アンマスクド:カルチャー・アイコンの分析』の中で、ワーサムがバットマンとロビンを同性愛カップルとして悪名高 い解釈をしたのは彼自身の考えによるものではなく、彼がインタビューした同性愛者の男性たちから示唆されたものだったと書いている。[6] 影響 この節には一般的な参考文献の一覧が含まれているが、対応するインラインの十分な引用が不足している。より正確な引用を導入することで、この節を改善する のを手伝ってほしい。 (2017年5月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 無邪気な誘惑は、エスティス・ケファウバー上院議員の注意を引いた。ケファウバーはギャング狩りの名手として知られており、ギャングがコミックや雑誌の流 通と強い結びつきがあることは周知の事実であった。彼は、ワーサムの主張を業界内の組織犯罪に対抗する手段として利用できると考えた。ワーサムは、より効 率的にメッセージを広めることができる場として、上院の少年非行小委員会に出席した。委員会での証言で、ワーサムはコミック業界をアドルフ・ヒトラーにな ぞらえた。 この公聴会は、当時急速に新たなマスメディアとして台頭しつつあったテレビで放映され、他のメディアもこれに追随した。このニュースは『ニューヨーク・タ イムズ』紙の一面を飾った。たとえ政府がこの公聴会以上の行動を起こさず、ケファウバーが大統領候補に選出された後にコミックへの関心を失ったとしても、 すでに社会的なダメージは与えられていた。この公聴会は4月に行われたが、その夏には15の出版社が倒産した。ECコミックスでは、『マッド』だけが生き 残ったタイトルだった。[8] 委員会が次の証人であるEC出版社のウィリアム・ゲインズを尋問した際には、ワーサムが説明したような暴力的な場面が焦点となった。 当時、ワーサムはブルックリンのスリラー殺人犯(1954年夏に2人の男性を残忍に殺害した若者グループ)の裁判で、裁判所が任命した精神医学の専門家で もあった。ウェルサムは、ギャングのリーダーの行動はコミックブック、特にポルノコミックによって引き起こされたと主張した。この事件は、コミックに対す る世間の怒りにさらに油を注ぐこととなった。ウェルサムが裁判で証拠として提出したアングラフェチ雑誌『Nights of Horror』は、ニューヨーク州によって発禁処分となった。このコミックに対する訴訟は最終的に最高裁まで持ち込まれ、1957年に発禁処分が支持され た。 上院の少年非行小委員会の最終報告書では、犯罪の原因をコミックに求めることはなかったが、コミック業界が自主的に内容を抑制することを勧告した。その後、出版社は自主検閲団体「コミック・コード・オーソリティ」を設立した。 批判 キャロル・L・ティリーによる2012年の研究によると、ワーサムは『無邪気な誘惑』で主張された内容を裏付けるために「証拠を操作し、誇張し、妥協し、 捏造した」という。[4] 彼はサンプルサイズと 研究のサンプルサイズと内容を誤って提示し、実際よりも客観的で逸話的でないものに見せかけた。[10][検証失敗] 彼は一般的に科学的研究にふさわしい基準を守らず、代わりに、漫画は文化的な失敗であるという主張のために疑わしい証拠を使用した。[11] ワースタムは、問題を抱えた家庭環境で育ち、行動障害の兆候が見られるニューヨーク市の青少年を主なサンプル人口として使用した。例えば、彼はラファー ジュ・クリニックの子供たちを、漫画が若者に悪影響を与えているという主張の根拠として使用したが、同クリニックの16歳未満の子供の70%が、行動上の 問題を抱えていると診断されていたというスタッフの計算結果がある。[12] また、ベルビュー病院センター、キングス・カウンティ病院センター、クイーンズ総合病院への入院が必要な、より重度の精神障害を持つ子供たちも使用した。 [要出典] ウェルサムの取材対象者の証言は、時に改変されたり、組み合わせられたり、抜粋されたりして、誤解を招くような内容となっていた。関連する個人的な経験 は、時に言及されないまま残されることもあった。例えば、バットマンと相棒のロビンの関係を理由に、バットマンのコミックが同性愛を容認していると主張す る際に、ウェルサムが2人の対象者の証言を1つにまとめ、その2人が何年も前から同性愛関係にあったことを言及しなかったという証拠がある。彼は、ある被 験者が最近、肛門性交をされたという事実を読者に知らせなかった。被験者たちが、他のコミックを好むことや、他のコミックの方がより適切であることを明確 に指摘していたにもかかわらず、彼はバットマンを読んでいることの方に重きを置いた。[13] また、ワーサムは、同僚から聞いただけの話を、あたかも自分が直接聞いたかのように紹介した。[要出典] 彼のコミックの内容に関する記述は、誇張や省略により、時に誤解を招くものであった。彼は『キャプテン・マーベル』の号で「首なし男」について言及してい るが、コミックではキャプテン・マーベルの顔に透明人間薬が飛び散っているだけであり、首が切断された姿は描かれていない。彼は、13歳の少女が「時々」 ではなく「よく」窃盗を働いていると誇張して伝えた。[15] 彼はブルー・ビートルをカフカ的な悪夢に例えたが、ブルー・ビートルが昆虫ではなく人間であることを言及しなかった。[要出典] 他国では コミックコード局による自主規制が米国のコミック業界自身によって課されたものである一方で、フランスはすでに、アメリカン・コミックスの流入が解放後に 増加したことに対応して、1949年7月16日法(1949年7月16日、青少年向け出版に関する法律)を可決していた。1969年になってようやく、こ の法律が発動され、マーベル・コミックの翻訳版を掲載していたコミック雑誌『ファンタスク』は7号で廃刊となった。特に1950年代と1960年代前半に は、この法律の施行を担当する政府機関は「児童および青少年向け出版物の監視および管理委員会(Commission de surveillance et de contrôle des publications destinées à l'enfance et à l'adolescence)」と呼ばれていた。1968年5月のフランス社会の激変の後、ジャン・ジローを含む主要な漫画家たちは、漫画雑誌『ピロッ ト』の編集室で編集長レネ・ゴシニーに、より自由な創作を要求し、最終的にそれを勝ち取った。 1954年より西ドイツには、ドイツの若者にとって不健全とみなされた出版物(漫画を含む)を排除することを目的とした政府機関である 「Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien(若者に有害なメディアに関する連邦局)」が存在した。この機関は、1953年6月9日に可決された「青少年に有害な出版物の流通に関する法 律」によって設立された。この法律自体は、表現の自由を規制するドイツ憲法第5条の「青少年保護規定」から派生したものである。[17] 1955年には、ドイツのコミック業界が「コミックの自主規制」を設立した。[18] カトリック人民党のオランダ教育大臣テオ・ルッテンは、1948年10月25日付の新聞『ヘット・パロール』に、教育機関や地方自治体に直接呼びかける内 容の手紙を掲載し、漫画の禁止を提唱した。彼は「挿絵と文章で構成されるこれらの小冊子は、一般的にセンセーショナルな内容であり、それ以上の価値はな い。これらの小説の印刷業者、出版社、販売業者に対して措置を講じることは不可能であり、また、必要な紙は自由市場で入手できるため、紙を供給しないこと で何かを達成することもできない」と述べた。[19] トーンダー・スタジオの少数の「健全な」漫画作品には例外が認められ、その中には文学的な漫画『トム・プース』も含まれていた。[20] レガシー コミックス出版社のダイナマイト・エンターテインメント(『ローン・レンジャー』、『ザ・シャドウ』、『コナン』)は、2015年より犯罪をテーマにしたコミックシリーズのタイトルとして採用している。[21] マックス・アラン・コリンズの犯罪小説『無邪気な誘惑』(2013年6月)は、同氏のジャック&マギー・スター・シリーズの3作目であり、フレデリック・ワーサムによるコミックに対する反対運動を題材にしたフィクションを軸とした殺人ミステリーである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seduction_of_the_Innocent |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

The New Spirit(Donald Duck) by Andy Warhol

☆

☆

☆