ヒューバート・ドレイファス

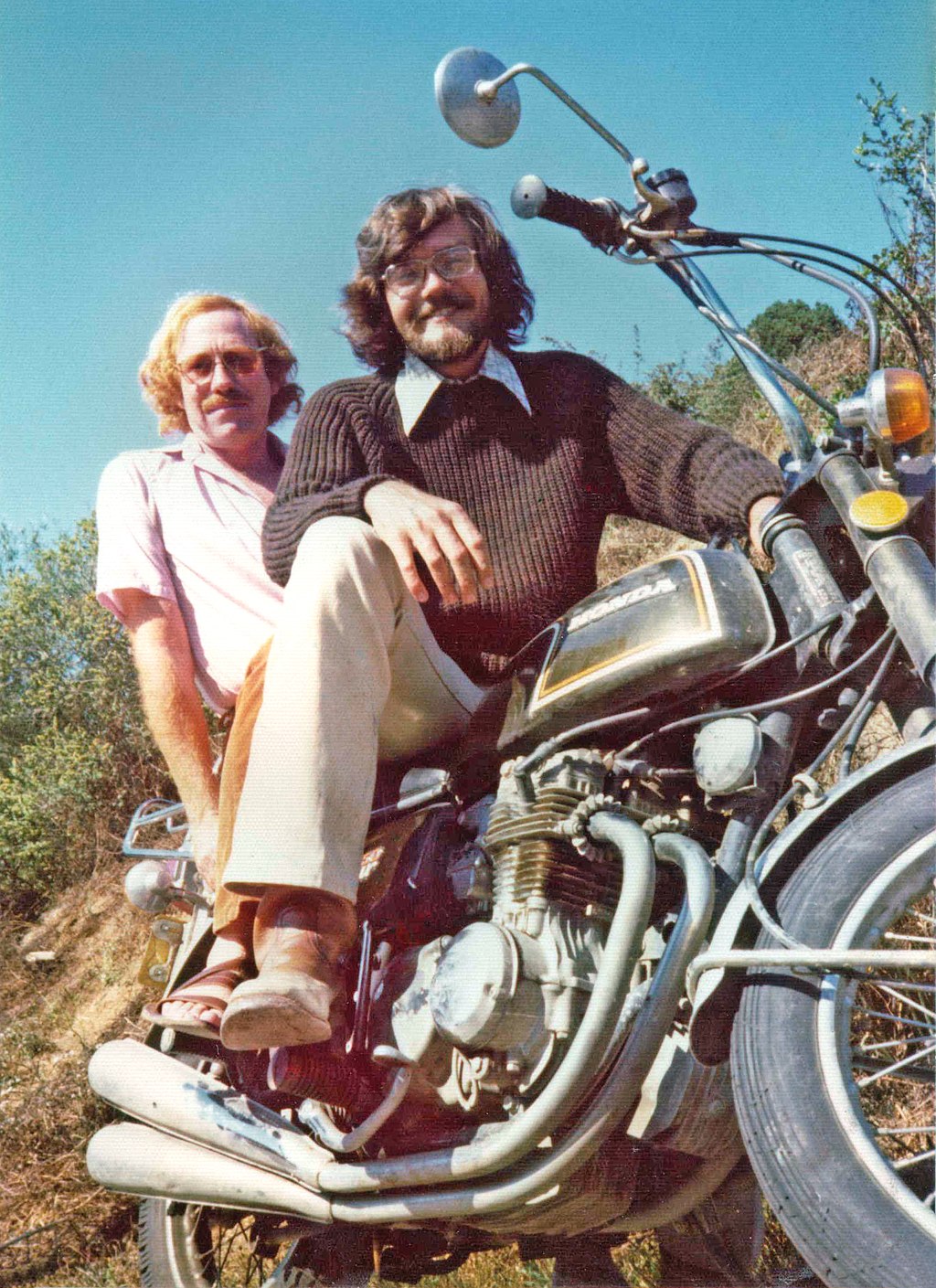

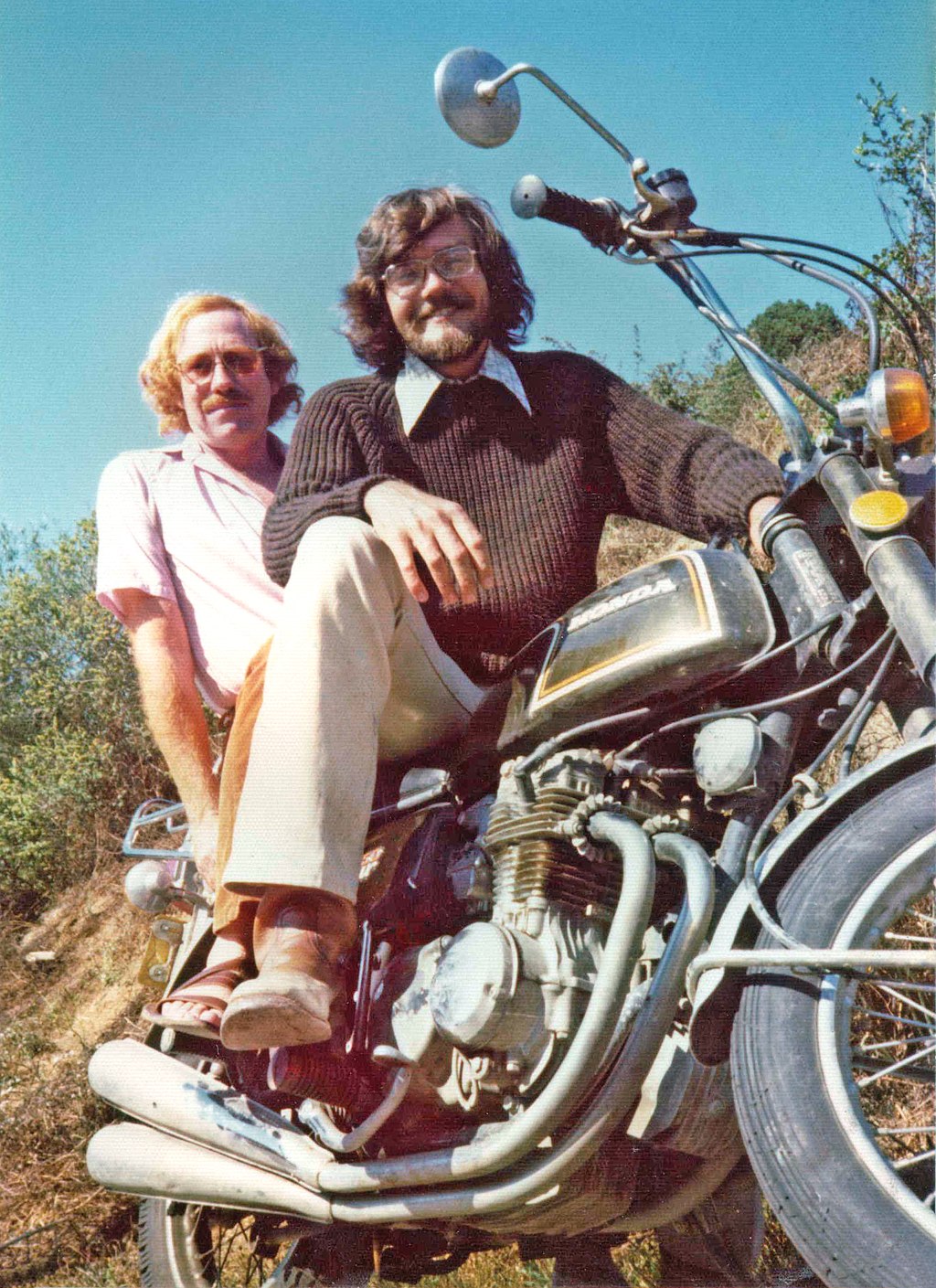

Hubert Dreyfus, 1929-2017

Dreyfus

(left) outside his Berkeley home in 1976

☆ ヒューバート・ドレイファス(/ˈdraɪdraɪs/ DRY-fəs; 1929年10月15日 - 2017年4月22日)はアメリカの哲学者であり、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の哲学教授であった。主な関心は現象学、実存主義、心理学と文学の哲 学、人工知能の哲学的意味合いなどであった。マルティン・ハイデガーの釈義で広く知られ、批評家からは「ドレーデガー」と呼ばれている[4]。 ドレフュスはタオ・ルスポリ監督の映画『Being in the World』(2010年)に登場し[5]、BBCテレビのシリーズ『The Great Philosophers』(1987年)でブライアン・マギーがインタビューした哲学者の一人である[6]。 フューチュラマ』のキャラクターであるヒューバート・ファンズワース教授は、脚本家のエリック・カプランがかつての教え子であったことから、一部彼の名前 がつけられている[3]。

| Hubert Lederer

Dreyfus (/ˈdraɪfəs/ DRY-fəs; October 15, 1929 – April 22, 2017) was an

American philosopher and a professor of philosophy at the University of

California, Berkeley. His main interests included phenomenology,

existentialism and the philosophy of both psychology and literature, as

well as the philosophical implications of artificial intelligence. He

was widely known for his exegesis of Martin Heidegger, which critics

labeled "Dreydegger".[4] Dreyfus was featured in Tao Ruspoli's film Being in the World (2010),[5] and was among the philosophers interviewed by Bryan Magee for the BBC Television series The Great Philosophers (1987).[6] The Futurama character Professor Hubert Farnsworth is partly named after him, writer Eric Kaplan having been a former student.[3] |

ヒューバート・ドレイファス(/ˈdraɪdraɪs/

DRY-fəs; 1929年10月15日 -

2017年4月22日)はアメリカの哲学者であり、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の哲学教授であった。主な関心は現象学、実存主義、心理学と文学の哲

学、人工知能の哲学的意味合いなどであった。マルティン・ハイデガーの釈義で広く知られ、批評家からは「ドレーデガー」と呼ばれている[4]。 ドレフュスはタオ・ルスポリ監督の映画『Being in the World』(2010年)に登場し[5]、BBCテレビのシリーズ『The Great Philosophers』(1987年)でブライアン・マギーがインタビューした哲学者の一人である[6]。 フューチュラマ』のキャラクターであるヒューバート・ファンズワース教授は、脚本家のエリック・カプランがかつての教え子であったことから、一部彼の名前 がつけられている[3]。 |

| Life and career Dreyfus was born on 15 October 1929, in Terre Haute, Indiana, to Stanley S. and Irene (Lederer) Dreyfus.[7][8] He attended Harvard University from 1947.[9] With a senior honors thesis on Causality and Quantum Theory (for which W. V. O. Quine was the main examiner)[9] he was awarded a B.A. summa cum laude in 1951[8] and joined Phi Beta Kappa.[10] He was awarded a M.A. in 1952.[8][10] He was a Teaching Fellow at Harvard in 1952-1953 (as he was again in 1954 and 1956).[11] Then, on a Harvard Sheldon traveling fellowship, Dreyfus studied at the University of Freiburg over 1953–1954.[10] During this time he had an interview with Martin Heidegger.[9] Sean D. Kelly records that Dreyfus found the meeting 'disappointing.'[12] Brief mention of it was made by Dreyfus during his 1987 BBC interview with Bryan Magee in remarks that are revealing of both his and Heidegger's opinion of the work of Jean-Paul Sartre.[13][6] Between 1956 and 1957, Dreyfus undertook research at the Husserl Archives at the University of Louvain on a Fulbright Fellowship.[10] Towards the end of his stay, his first (jointly authored) paper "Curds and Lions in Don Quijote" would appear in print.[12][14] After acting as an instructor in philosophy at Brandeis University (1957–1959),[8][11] he attended the Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, on a French government grant (1959–1960).[10] From 1960, first as an instructor, then as an assistant and then associate professor, Dreyfus taught philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).[8] In 1964, with his dissertation Husserl's Phenomenology of Perception, he obtained his Ph.D. from Harvard.[10][15] (Due to his knowledge of Husserl, Dagfinn Føllesdal sat on the thesis committee but he has asserted that Dreyfus "was not really my student.")[16] That same year, his co-translation (with his first wife) of Sense and Non-Sense by Maurice Merleau-Ponty was published.[7] Also in 1964, and whilst still at MIT, he was employed as a consultant by the RAND Corporation to review the work of Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon in the field of artificial intelligence (AI).[9] This resulted in the publication, in 1965, of the "famously combative" Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence, which proved to be the first of a series of papers and books attacking the AI field's claims and assumptions.[17][18] The first edition of What Computers Can't Do would follow in 1972, and this critique of AI (which has been translated into at least ten languages) would establish Dreyfus's public reputation.[9] However, as the editors of his Festschrift noted: "the study and interpretation of 'continental' philosophers... came first in the order of his philosophical interests and influences."[9] Berkeley In 1968, although he had been granted tenure, Dreyfus left MIT and became an associate professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley,[8][10] (winning, that same year, the Harbison Prize for Outstanding Teaching).[3] In 1972 he was promoted to full professor.[8][10] Though Dreyfus retired from his chair in 1994, he continued as professor of philosophy in the Graduate School (and held, from 1999, a joint appointment in the rhetoric department).[3] He continued to teach philosophy at UC Berkeley until his last class in December 2016.[3] Dreyfus was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2001.[19] He was also awarded an honorary doctorate for "his brilliant and highly influential work in the field of artificial intelligence" and his interpretation of twentieth century continental philosophy by Erasmus University.[3] Dreyfus died on April 22, 2017.[7][12] His younger brother and sometimes collaborator, Stuart Dreyfus, is a professor emeritus of industrial engineering and operations research at the University of California, Berkeley. |

生涯とキャリア ドレファスは1929年10月15日、インディアナ州テレホートでスタンリー・S・ドレファスとアイリーン・ドレファスの間に生まれた[7][8]。 1947年からハーバード大学に通い[9]、W・V・O・クワインが主査を務めた「因果性と量子論」に関する卒業論文で[9]、1951年に学士号を優秀 な成績で授与され[8]、ファイ・ベータ・カッパの会員となった[10]。 [11]その後、ハーバード大学のシェルドン奨学金を得て、1953年から1954年にかけてフライブルク大学に留学した[10] 。 1987年のBBCのブライアン・マギーとのインタビューの中で、ドレフュスはそのことについて簡単に触れているが、それは彼とハイデガーのジャン=ポー ル・サルトルの仕事に対する評価を明らかにするものであった[13][6]。 1956年から1957年にかけて、ドレフュスはフルブライト研究員としてルーヴァン大学のフッサール文書館で研究を行った[10]。 [12][14]ブランダイス大学で哲学の講師を務めた後(1957-1959年)、[8][11]フランス政府の奨学金でパリのエコール・ノルマル・ シュペリウールに通う(1959-1960年)[10]。 1964年、フッサールの『知覚の現象学』という論文でハーバード大学から博士号を取得した。 [同年、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティの『感覚と非感覚』の共訳(最初の妻との共訳)が出版された[7]。 また1964年、まだMITに在籍していた彼は、人工知能(AI)の分野におけるアレン・ニューウェルとハーバート・A・サイモンの仕事を見直すためにラ ンド・コーポレーションにコンサルタントとして雇われた[9]。その結果、1965年に「有名な闘争的な」Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence(錬金術と人工知能)が出版された。 [17][18]『コンピュータにできないこと』の初版は1972年に出版され、このAI批判(少なくとも10ヶ国語に翻訳されている)はドレフュスの社 会的評価を確立することになる: ドレフュスの哲学的関心と影響は、「大陸的 」哲学者の研究と解釈が第一であった」[9]。 バークレー 1968年、終身在職権が与えられていたにもかかわらず、ドレフュスはMITを去り、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の哲学の助教授となった[8] [10](同年、優れた教授に贈られるハービソン賞を受賞)[3]。 1972年、彼は正教授に昇進した[8][10]。 [8][10]ドレフュスは1994年に教授を退いたが、大学院の哲学教授を続けた(1999年からは修辞学部の教授も兼任)[3]。2016年12月の 最後の授業までカリフォルニア大学バークレー校で哲学を教え続けた[3]。 ドレフュスは2001年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[19]。 また、エラスムス大学から「人工知能の分野における彼の輝かしく非常に影響力のある仕事」と「20世紀大陸哲学の解釈」に対して名誉博士号を授与された[3]。 ドレフュスは2017年4月22日に87歳で死去した[7][12]。 彼の弟であり、時には共同研究者でもあったスチュアート・ドレイファスは、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の産業工学とオペレーションズ・リサーチの名誉教授である。 |

| Dreyfus' criticism of AI Main article: Hubert Dreyfus's views on artificial intelligence Dreyfus' critique of artificial intelligence (AI) concerns what he considers to be the four primary assumptions of AI research. The first two assumptions are what he calls the "biological" and "psychological" assumptions. The biological assumption is that the brain is analogous to computer hardware and the mind is analogous to computer software. The psychological assumption is that the mind works by performing discrete computations (in the form of algorithmic rules) on discrete representations or symbols. Dreyfus claims that the plausibility of the psychological assumption rests on two others: the epistemological and ontological assumptions. The epistemological assumption is that all activity (either by animate or inanimate objects) can be formalized (mathematically) in the form of predictive rules or laws. The ontological assumption is that reality consists entirely of a set of mutually independent, atomic (indivisible) facts. It's because of the epistemological assumption that workers in the field argue that intelligence is the same as formal rule-following, and it's because of the ontological one that they argue that human knowledge consists entirely of internal representations of reality. On the basis of these two assumptions, workers in the field claim that cognition is the manipulation of internal symbols by internal rules, and that, therefore, human behaviour is, to a large extent, context free (see contextualism). Therefore, a truly scientific psychology is possible, which will detail the 'internal' rules of the human mind, in the same way the laws of physics detail the 'external' laws of the physical world. However, it is this key assumption that Dreyfus denies. In other words, he argues that we cannot now (and never will be able to) understand our own behavior in the same way as we understand objects in, for example, physics or chemistry: that is, by considering ourselves as things whose behaviour can be predicted via 'objective', context free scientific laws. According to Dreyfus, a context-free psychology is a contradiction in terms. Dreyfus's arguments against this position are taken from the phenomenological and hermeneutical tradition (especially the work of Martin Heidegger). Heidegger argued that, contrary to the cognitivist views (on which AI has been based), our being is in fact highly context-bound, which is why the two context-free assumptions are false. Dreyfus doesn't deny that we can choose to see human (or any) activity as being 'law-governed', in the same way that we can choose to see reality as consisting of indivisible atomic facts... if we wish. But it is a huge leap from that to state that because we want to or can see things in this way that it is therefore an objective fact that they are the case. In fact, Dreyfus argues that they are not (necessarily) the case, and that, therefore, any research program that assumes they are will quickly run into profound theoretical and practical problems. Therefore, the current efforts of workers in the field are doomed to failure. Dreyfus argues that to get a device or devices with human-like intelligence would require them to have a human-like being-in-the-world and to have bodies more or less like ours, and social acculturation (i.e. a society) more or less like ours. (This view is shared by psychologists in the embodied psychology (Lakoff and Johnson 1999) and distributed cognition traditions. His opinions are similar to those of robotics researchers such as Rodney Brooks as well as researchers in the field of artificial life.) Contrary to a popular misconception, Dreyfus never predicted that computers would never beat humans at chess. In Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence, he only reported (correctly) the state of the art of the time: "Still no chess program can play even amateur chess."[18][20][21] Daniel Crevier writes: "time has proven the accuracy and perceptiveness of some of Dreyfus's comments. Had he formulated them less aggressively, constructive actions they suggested might have been taken much earlier."[22] |

ドレフュスのAI批判 主な記事 ユベール・ドレフュスの人工知能に対する見解 ドレフュスの人工知能(AI)批判は、彼が考えるAI研究の4大前提に関わるものである。最初の2つの仮定は、彼が「生物学的仮定」と「心理学的仮定」と 呼ぶものである。生物学的な仮定とは、脳はコンピュータのハードウェアに類似しており、心はコンピュータのソフトウェアに類似しているというものである。 心理学的な仮定とは、心は離散的な表象やシンボルに対して離散的な計算(アルゴリズム・ルールの形で)を実行することで機能するというものである。 ドレフュスは、心理学的仮定の妥当性は、認識論的仮定と存在論的仮定という2つの仮定の上に成り立っていると主張する。認識論的仮定とは、(生物であれ無 生物であれ)すべての活動は、予測規則や法則の形で(数学的に)形式化できるというものである。存在論的前提とは、現実はすべて相互に独立した原子的(不 可分な)事実の集合からなるというものである。この分野の研究者が、知性とは形式的な規則に従うことと同じであると主張するのは認識論的な仮定のためであ り、人間の知識はすべて現実の内部表現から構成されていると主張するのは存在論的な仮定のためである。 この2つの前提に基づき、この分野の研究者たちは、認知とは内部規則による内部記号の操作であり、したがって人間の行動は、かなりの程度、文脈にとらわれ ないと主張する(文脈主義を参照)。したがって、物理法則が物理世界の「外的な」法則を詳述するのと同じように、人間の心の「内的な」法則を詳述する、真 に科学的な心理学が可能なのである。しかし、ドレフュスが否定しているのは、この重要な仮定である。つまり、ドレフュスは、例えば物理学や化学の分野で物 体を理解するのと同じように、自分自身の行動を理解することはできない(今後もできないだろう)と主張する。ドレフュスによれば、文脈のない心理学は矛盾 している。 この立場に対するドレフュスの議論は、現象学と解釈学の伝統(特にマルティン・ハイデガーの仕事)から取られたものである。ハイデガーは、(AIがその基 盤としてきた)認知主義的見解に反して、私たちの存在は実際には高度に文脈に束縛されており、だからこそ2つの文脈自由な仮定は誤りなのだと主張した。ド レイファスは、我々が望むなら、現実を不可分な原子的事実から成るものとして見ることを選択できるのと同じように、人間(あるいはあらゆる)の活動を「法 則に支配されたもの」として見ることを選択できることを否定はしない。しかし、私たちがこのように物事を見たいから、あるいは見ることができるから、それ が客観的な事実であると言うのは飛躍しすぎている。実際、ドレフュスは、それらは(必ずしも)そうではなく、したがって、そうであると仮定する研究プログ ラムは、すぐに理論的にも実際的にも重大な問題に突き当たるだろうと論じている。したがって、この分野の研究者たちの現在の努力は失敗に終わる運命にあ る。 ドレフュスは、人間のような知能を持つ装置やデバイスを手に入れるには、それらが人間のような存在であり、多かれ少なかれ我々のような身体と、多かれ少な かれ我々のような社会的馴化(つまり社会)を持つことが必要だと主張する。(この見解は、身体化心理学(Lakoff and Johnson 1999)や分散認知の伝統に属する心理学者たちに共有されている)。彼の意見は、ロドニー・ブルックスなどのロボット工学研究者や人工生命分野の研究者 の意見と似ている)。 一般的な誤解に反して、ドレフュスはコンピュータがチェスで人間に勝つことはないだろうと予測したことはない。彼は『錬金術と人工知能』の中で、当時の技 術状況を(正しく)報告したに過ぎない: 「いまだにどのチェス・プログラムもアマチュアのチェスにさえ勝てない」[18][20][21]。 ダニエル・クレヴィエは、「ドレフュスのいくつかのコメントの正確さと鋭敏さは、時が証明した。もし彼があまり攻撃的でないコメントをしていたら、彼らが示唆した建設的な行動はもっと早く取られていたかもしれない」[22]。 |

| Webcasting philosophy When UC Berkeley and Apple began making a selected number of lecture classes freely available to the public as podcasts beginning around 2006, a recording of Dreyfus teaching a course called "Man, God, and Society in Western Literature – From Gods to God and Back" rose to the 58th most popular webcast on iTunes.[23] These webcasts have attracted the attention of many, including non-academics, to Dreyfus and his subject area.[24] |

哲学のウェブキャスティング カリフォルニア大学バークレー校とアップル社が2006年ごろから、一部の講義をポッドキャストとして自由に利用できるようにしたところ、ドレフュスが 「西洋文学における人間、神、そして社会-神々から神への往還」という講義を行った際の録音が、iTunesで最も人気のあるウェブキャストの58位にラ ンクインした[23]。こうしたウェブキャストは、ドレフュスとその研究分野に、非学者を含む多くの人々の関心を集めた[24]。 |

| Books 1972. What Computers Can't Do: The Limits of Artificial Intelligence. ISBN 0-06-011082-1 (At Internet Archive) 2nd edition 1979 ISBN 0-06-090613-8, ISBN 0-06-090624-3; 3rd edition 1992 re-titled as What Computers Still Can't Do ISBN 0-262-54067-3 1983. (with Paul Rabinow) Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics. Chicago, Ill: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-16312-3 (At Open Library) 1986 (with Stuart Dreyfus). Mind Over Machine: The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer. New York: Free Press.(At Open Library) 1991. Being-in-the-World: A Commentary on Heidegger's Being and Time, Division I.Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-54056-8, ISBN 978-0-262-54056-8 1992. What Computers Still Can't Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-54067-3 [25] 1997, Disclosing New Worlds: Entrepreneurship, Democratic Action, and the Cultivation of Solidarity (co-author, with Fernando Flores and Charles Spinosa) 2001. On the Internet First Edition. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77516-8; 2nd edition 1979 (At Internet Archive)[26] 2011. (with Sean Dorrance Kelly) All Things Shining: Reading the Western Classics to Find Meaning in a Secular Age. (At Open Library)[27] 2014 Skillful Coping: Essays on the Phenomenology of Everyday Perception and Action, Mark A. Wrathall (ed.), ISBN 9780199654703 [28] 2015 (with Charles Taylor) Retrieving Realism. Harvard University Press, ISBN 9780198796220 [29] 2017 Background Practices: Essays on the Understanding of Being, Mark A. Wrathall (ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198796220 [30] Festschrift 2000. Heidegger, Authenticity, and Modernity: Essays in Honor of Hubert Dreyfus, Volume 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-73127-4.[31] 2000. Heidegger, Coping, and Cognitive Science: Essays in Honor of Hubert L. Dreyfus, Volume 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-73128-2 [31][32] Select articles 1965. Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence. Rand Paper.[18] |

書籍 1972. コンピュータにできないこと: 人工知能の限界. ISBN 0-06-011082-1 (インターネット・アーカイブ) 1979年第2版 ISBN 0-06-090613-8, ISBN 0-06-090624-3; 1992年第3版 改題: What Computers Still Can't Do ISBN 0-262-54067-3 1983. (ポール・ラビノーと共著)ミシェル・フーコー: 構造主義と解釈学を越えて. シカゴ、イリノイ州:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-226-16312-3 (オープンライブラリー) 1986 (スチュアート・ドレイファスと共著). Mind Over Machine: The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer. ニューヨーク: フリー・プレス. 1991. 世界における存在: ハイデガー『存在と時間』第一部の解説: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-54056-8, ISBN 978-0-262-54056-8. 1992. コンピュータにまだできないこと: 人工理性批判. マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-54067-3 [25]. 1997, 『新世界の開示:企業家精神、民主的行動、連帯の育成』(フェルナンド・フローレス、チャールズ・スピノサとの共著) 2001. On the Internet 初版。ロンドン、ニューヨーク: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77516-8; 2nd edition 1979 (At Internet Archive)[26]. 2011. (ショーン・ドランス・ケリーと共著)All Things Shining: (ショーン・ドランス・ケリーと共著) All Things Shining: Reading the Western Classics to Find Meaning in a Secular Age. (オープンライブラリーにて)[27] 2014 スキルフル・コーピング Essays on the Phenomenology of Everyday Perception and Action, Mark A. Wrathall (ed.), ISBN 9780199654703 [28]. 2015 (チャールズ・テイラーと共著) Retrieving Realism. ハーバード大学出版、ISBN 9780198796220 [29]. 2017年 『背景の実践』: マーク・A・ラソール編『存在の理解に関するエッセイ』オックスフォード大学出版局、ISBN 9780198796220 [30]. フェストシュリフト 2000. ハイデガー、真正性、そして現代: ハイデガー、真正性、そして近代:ユベール・ドレフュス記念論集第1巻. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-73127-4.[31]. 2000. ハイデガー、コーピング、認知科学: Hubert L. Dreyfus, Volume 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-73128-2 [31][32]. 論文 1965. 錬金術と人工知能. ランド・ペーパー[18]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubert_Dreyfus |

|

| Hubert Dreyfus's views on artificial intelligence |

|

| Hubert

Dreyfus was a critic of artificial intelligence research. In a series

of papers and books, including Alchemy and AI (1965), What Computers

Can't Do (1972; 1979; 1992) and Mind over Machine (1986), he presented

a pessimistic assessment of AI's progress and a critique of the

philosophical foundations of the field. Dreyfus' objections are

discussed in most introductions to the philosophy of artificial

intelligence, including Russell & Norvig (2021), a standard AI

textbook, and in Fearn (2007), a survey of contemporary philosophy.[1] Dreyfus argued that human intelligence and expertise depend primarily on unconscious processes rather than conscious symbolic manipulation, and that these unconscious skills can never be fully captured in formal rules. His critique was based on the insights of modern continental philosophers such as Merleau-Ponty and Heidegger, and was directed at the first wave of AI research which used high level formal symbols to represent reality and tried to reduce intelligence to symbol manipulation. When Dreyfus' ideas were first introduced in the mid-1960s, they were met with ridicule and outright hostility.[2][3] By the 1980s, however, many of his perspectives were rediscovered by researchers working in robotics and the new field of connectionism—approaches now called "sub-symbolic" because they eschew early AI research's emphasis on high level symbols. In the 21st century, statistics-based approaches to machine learning simulate the way that the brain uses unconscious process to perceive, notice anomalies and make quick judgements. These techniques are highly successful and are currently widely used in both industry and academia. Historian and AI researcher Daniel Crevier writes: "time has proven the accuracy and perceptiveness of some of Dreyfus's comments."[4] Dreyfus said in 2007, "I figure I won and it's over—they've given up."[5] |

ヒュー

バート・ドレフュスは人工知能研究を批判していた。錬金術とAI』(1965年)、『コンピュータにできないこと』(1972年、1979年、1992

年)、『機械より心を』(1986年)などの一連の論文や著書で、彼は人工知能の進歩に対する悲観的な評価と、この分野の哲学的基礎に対する批判を示し

た。ドレフュスの反論は、AIの標準的な教科書であるRussell & Norvig (2021)や、現代哲学のサーベイであるFearn

(2007)など、人工知能哲学の入門書のほとんどで論じられている[1]。 ドレイファスは、人間の知能や専門知識は、意識的な記号操作よりもむしろ主に無意識的なプロセスに依存しており、このような無意識的なスキルは形式的な ルールでは決して完全に捉えることはできないと主張した。彼の批評は、メルロ=ポンティやハイデガーといった近代大陸哲学者の洞察に基づいており、現実を 表現するために高度な形式記号を使用し、知能を記号操作に還元しようとしたAI研究の第一波に向けられたものだった。 ドレフュスの考え方が最初に紹介された1960年代半ばには、嘲笑や敵意にさらされた[2][3]。しかし1980年代までに、彼の視点の多くは、ロボッ ト工学やコネクショニズムという新しい分野に取り組む研究者たちによって再発見された。21世紀には、統計学に基づく機械学習へのアプローチが、脳が無意 識のプロセスを用いて知覚し、異常に気づき、素早い判断を下す方法をシミュレートしている。これらの技術は非常に成功しており、現在、産業界と学界の両方 で広く使われている。歴史家でありAI研究者でもあるダニエル・クレビエは、「ドレフュスのいくつかの発言の正確さと鋭敏さは、時が証明している」と書い ている[4]。ドレフュスは2007年に、「私は勝ったと思っている。 |

| Dreyfus' critique The grandiose promises of artificial intelligence In Alchemy and AI (1965) and What Computers Can't Do (1972), Dreyfus summarized the history of artificial intelligence and ridiculed the unbridled optimism that permeated the field. For example, Herbert A. Simon, following the success of his program General Problem Solver (1957), predicted that by 1967:[6] A computer would be world champion in chess. A computer would discover and prove an important new mathematical theorem. Most theories in psychology will take the form of computer programs. The press reported these predictions in glowing reports of the imminent arrival of machine intelligence. Dreyfus felt that this optimism was unwarranted and based on false assumptions about the nature of human intelligence. Pamela McCorduck explains Dreyfus' position: A great misunderstanding accounts for public confusion about thinking machines, a misunderstanding perpetrated by the unrealistic claims researchers in AI have been making, claims that thinking machines are already here, or at any rate, just around the corner.[7] These predictions were based on the success of an "information processing" model of the mind, articulated by Newell and Simon in their physical symbol systems hypothesis, and later expanded into a philosophical position known as computationalism by philosophers such as Jerry Fodor and Hilary Putnam.[8] Believing that they had successfully simulated the essential process of human thought with simple programs, it seemed a short step to producing fully intelligent machines. However, Dreyfus argued that philosophy, especially 20th-century philosophy, had discovered serious problems with this information processing viewpoint. The mind, according to modern philosophy, is nothing like a digital computer.[7] Dreyfus' four assumptions of artificial intelligence research In Alchemy and AI and What Computers Can't Do, Dreyfus identified four philosophical assumptions that supported the faith of early AI researchers that human intelligence depended on the manipulation of symbols.[9] "In each case," Dreyfus writes, "the assumption is taken by workers in [AI] as an axiom, guaranteeing results, whereas it is, in fact, one hypothesis among others, to be tested by the success of such work."[10] The biological assumption The brain processes information in discrete operations by way of some biological equivalent of on/off switches. In the early days of research into neurology, scientists realized that neurons fire in all-or-nothing pulses. Several researchers, such as Walter Pitts and Warren McCulloch, argued that neurons functioned similar to the way Boolean logic gates operate, and so could be imitated by electronic circuitry at the level of the neuron.[11] When digital computers became widely used in the early 50s, this argument was extended to suggest that the brain was a vast physical symbol system, manipulating the binary symbols of zero and one. Dreyfus was able to refute the biological assumption by citing research in neurology that suggested that the action and timing of neuron firing had analog components.[12] But Daniel Crevier observes that "few still held that belief in the early 1970s, and nobody argued against Dreyfus" about the biological assumption.[13] The psychological assumption The mind can be viewed as a device operating on bits of information according to formal rules. He refuted this assumption by showing that much of what we "know" about the world consists of complex attitudes or tendencies that make us lean towards one interpretation over another. He argued that, even when we use explicit symbols, we are using them against an unconscious background of commonsense knowledge and that without this background our symbols cease to mean anything. This background, in Dreyfus' view, was not implemented in individual brains as explicit individual symbols with explicit individual meanings. The epistemological assumption All knowledge can be formalized. This concerns the philosophical issue of epistemology, or the study of knowledge. Even if we agree that the psychological assumption is false, AI researchers could still argue (as AI founder John McCarthy has) that it is possible for a symbol processing machine to represent all knowledge, regardless of whether human beings represent knowledge the same way. Dreyfus argued that there is no justification for this assumption, since so much of human knowledge is not symbolic. The ontological assumption The world consists of independent facts that can be represented by independent symbols Dreyfus also identified a subtler assumption about the world. AI researchers (and futurists and science fiction writers) often assume that there is no limit to formal, scientific knowledge, because they assume that any phenomenon in the universe can be described by symbols or scientific theories. This assumes that everything that exists can be understood as objects, properties of objects, classes of objects, relations of objects, and so on: precisely those things that can be described by logic, language and mathematics. The study of being or existence is called ontology, and so Dreyfus calls this the ontological assumption. If this is false, then it raises doubts about what we can ultimately know and what intelligent machines will ultimately be able to help us to do. Knowing-how vs. knowing-that: the primacy of intuition In Mind Over Machine (1986), written during the heyday of expert systems, Dreyfus analyzed the difference between human expertise and the programs that claimed to capture it. This expanded on ideas from What Computers Can't Do, where he had made a similar argument criticizing the "cognitive simulation" school of AI research practiced by Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon in the 1960s. Dreyfus argued that human problem solving and expertise depend on our background sense of the context, of what is important and interesting given the situation, rather than on the process of searching through combinations of possibilities to find what we need. Dreyfus would describe it in 1986 as the difference between "knowing-that" and "knowing-how", based on Heidegger's distinction of present-at-hand and ready-to-hand.[14] Knowing-that is our conscious, step-by-step problem solving abilities. We use these skills when we encounter a difficult problem that requires us to stop, step back and search through ideas one at time. At moments like this, the ideas become very precise and simple: they become context free symbols, which we manipulate using logic and language. These are the skills that Newell and Simon had demonstrated with both psychological experiments and computer programs. Dreyfus agreed that their programs adequately imitated the skills he calls "knowing-that." Knowing-how, on the other hand, is the way we deal with things normally. We take actions without using conscious symbolic reasoning at all, as when we recognize a face, drive ourselves to work or find the right thing to say. We seem to simply jump to the appropriate response, without considering any alternatives. This is the essence of expertise, Dreyfus argued: when our intuitions have been trained to the point that we forget the rules and simply "size up the situation" and react. The human sense of the situation, according to Dreyfus, is based on our goals, our bodies and our culture—all of our unconscious intuitions, attitudes and knowledge about the world. This “context” or "background" (related to Heidegger's Dasein) is a form of knowledge that is not stored in our brains symbolically, but intuitively in some way. It affects what we notice and what we don't notice, what we expect and what possibilities we don't consider: we discriminate between what is essential and inessential. The things that are inessential are relegated to our "fringe consciousness" (borrowing a phrase from William James): the millions of things we're aware of, but we're not really thinking about right now. Dreyfus does not believe that AI programs, as they were implemented in the 70s and 80s, could capture this "background" or do the kind of fast problem solving that it allows. He argued that our unconscious knowledge could never be captured symbolically. If AI could not find a way to address these issues, then it was doomed to failure, an exercise in "tree climbing with one's eyes on the moon."[15] |

ドレフュスの批評 人工知能の壮大な約束 ドレフュスは『錬金術とAI』(1965年)と『コンピュータにできないこと』(1972年)の中で、人工知能の歴史を要約し、この分野に浸透している奔 放な楽観主義を嘲笑した。例えば、ハーバート・A・サイモンは、彼のプログラム「General Problem Solver」(1957年)の成功を受けて、1967年までに次のように予測していた[6]。 コンピュータがチェスの世界チャンピオンになる。 コンピュータがチェスの世界チャンピオンになる。コンピュータが新しい数学の重要な定理を発見し、証明する。 心理学のほとんどの理論は、コンピュータ・プログラムの形をとるだろう。 マスコミはこれらの予測を、機械知性の到来が間近に迫っていることを熱狂的に報じた。 ドレフュスは、この楽観論は不当であり、人間の知性の本質に関する誤った仮定に基づいていると感じた。パメラ・マコーダックはドレフュスの立場をこう説明する: それは、AIの研究者たちが行ってきた非現実的な主張、つまり、思考する機械はすでにここにある、あるいはいずれにせよ、すぐそこまで来ているという主張によって引き起こされた誤解である」[7]。 このような予測は、ニューウェルとサイモンが物理的記号システム仮説の中で明確にした、心の「情報処理」モデルの成功に基づいており、後にジェリー・フォ ドーやヒラリー・パットナムといった哲学者たちによって、計算論として知られる哲学的立場へと拡大された[8]。しかしドレファスは、哲学、特に20世紀 の哲学が、この情報処理という視点に重大な問題を発見したと主張した。現代哲学によれば、心はデジタル・コンピュータのようなものではない。 ドレフュスの人工知能研究の4つの前提 ドレフュスは『錬金術とAI』『コンピュータにできないこと』の中で、人間の知性は記号の操作に依存しているという初期のAI研究者の信仰を支えていた4つの哲学的仮定を挙げている。 生物学的仮説 脳は、オン/オフのスイッチに相当する生物学的な方法によって、個別の操作で情報を処理する。 神経学の研究が始まった当初、科学者たちは、ニューロンはオール・オア・ナッシングのパルスで発火することに気づいた。ウォルター・ピッツやウォーレン・ マッカロッホのような何人かの研究者は、ニューロンはブール論理ゲートが動作する方法と同様に機能するため、ニューロンレベルの電子回路で模倣できると主 張した[11]。50年代初頭にデジタル・コンピュータが広く使われるようになると、この議論は拡張され、脳はゼロと1の2進記号を操作する広大な物理的 記号系であることが示唆された。ドレフュスは、ニューロンの発火の動作とタイミングにはアナログ的な要素があることを示唆する神経学の研究を引用すること で、生物学的仮定に反論することができた[12]。しかし、ダニエル・クレヴィエは、「1970年代初頭にはまだそのような信念を持っていた人はほとんど おらず、生物学的仮定についてドレフュスに反論する人はいなかった」と観察している[13]。 心理学的仮定 心は、形式的な規則に従って情報の断片を操作する装置とみなすことができる。 ドレフュスは、私たちが世界について「知っている」ことの多くは、私たちを別の解釈よりもある解釈に向かわせる複雑な態度や傾向から構成されていることを 示すことによって、この仮定に反論した。彼は、私たちが明示的な記号を使うときでさえ、無意識のうちに常識的な知識を背景にしており、この背景がなければ 記号は意味を持たなくなると主張した。ドレフュスの考えでは、このような背景は、明示的な個別の意味を持つ明示的な個別の記号として個々の脳に実装されて いるわけではない。 認識論的前提 すべての知識は形式化できる。 これは認識論、すなわち知識の研究という哲学的な問題に関わる。たとえ心理学的仮定が誤りであることに同意したとしても、AI研究者は(AIの創始者であ るジョン・マッカーシーがそうであったように)、人間が同じように知識を表現するかどうかにかかわらず、記号処理機械がすべての知識を表現することは可能 であると主張することができる。ドレフュスは、人間の知識の多くは記号的ではないから、この仮定には正当性がないと主張した。 存在論的仮定 世界は独立した事実から成り立っており、それは独立した記号によって表現できる ドレフュスはまた、世界に関する微妙な仮定を特定した。AI研究者(そして未来学者やSF作家)はしばしば、形式的で科学的な知識には限界がないと仮定す る。なぜなら彼らは、宇宙のあらゆる現象は記号や科学理論によって記述できると仮定しているからだ。これは、存在するものすべてが、物体、物体の性質、物 体のクラス、物体の関係など、まさに論理、言語、数学によって記述できるものとして理解できると仮定しているのである。存在に関する学問は存在論と呼ば れ、ドレフュスはこれを存在論的仮定と呼んでいる。もしこれが誤りであれば、私たちが最終的に何を知ることができるのか、そして知的機械が最終的に私たち に何をさせることができるのか、疑問が生じることになる。 ノウハウvs.それを知る:直観の優位性 エキスパート・システム全盛期に書かれた『Mind Over Machine』(1986年)の中で、ドレファスは人間の専門知識とそれを捕らえようとするプログラムとの違いを分析した。これは、1960年代にアレ ン・ニューウェルとハーバート・A・サイモンが実践したAI研究の「認知シミュレーション」学派を批判した『コンピュータにできないこと』(What Computers Can't Do)のアイデアを発展させたものである。 ドレフュスは、人間の問題解決や専門知識は、必要なものを見つけるために可能性の組み合わせの中から探し出すプロセスではなく、状況に応じて何が重要で何 が興味深いかという、背景となる文脈の感覚に依存していると主張した。ドレファスは1986年、ハイデガーの「手元にあるもの」と「すぐに使えるもの」の 区別に基づき、これを「知っていること」と「ノウハウ」の違いと表現することになる[14]。 ノウイング・ザットとは、私たちの意識的で段階的な問題解決能力のことである。私たちがこのスキルを使うのは、立ち止まり、一歩下がって、アイデアを一つ ずつ探し出す必要があるような難しい問題に遭遇したときである。このようなとき、アイデアは非常に正確でシンプルなものになる。つまり、文脈にとらわれな い記号となり、論理と言語を使って操作するのである。これらは、ニューウェルとサイモンが心理学的実験とコンピュータープログラムの両方で実証した技術で ある。ドレフュスは、彼らのプログラムが、彼が 「Knowing-That 」と呼ぶスキルを適切に模倣していることに同意した。 一方、「ノウイング・ハウ 」とは、私たちが普通に物事に対処する方法である。私たちは、顔を認識するとき、仕事に向かうとき、正しい言葉を見つけるときなど、意識的な記号的推論を まったく使わずに行動を起こす。他の選択肢を考えることなく、ただ適切な反応に飛びつくのである。ドレフュスは、これこそが専門知識の本質であり、直感が 訓練され、ルールを忘れてただ「状況を把握」し、反応することだと主張した。 ドレフュスによれば、人間の状況判断は、目標、身体、文化、つまり世界に関する無意識の直感、態度、知識のすべてに基づいている。この 「文脈 」や 「背景」(ハイデガーの『Dasein』に関連している)は、私たちの脳に象徴的に記憶されているのではなく、何らかの形で直感的に記憶されている知識の 一形態である。それは私たちが何に気づき、何に気づかないか、何を期待し、どんな可能性を考えないかに影響する。本質的でないものは、(ウィリアム・ ジェームズの言葉を借りて)私たちの 「周辺意識 」に追いやられる。 ドレイファスは、70年代から80年代にかけて実装されたAIプログラムが、この「背景」を捉えたり、AIが可能にするような高速な問題解決を行ったりで きるとは考えていない。彼は、私たちの無意識の知識は決して象徴的に捉えることはできないと主張した。もしAIがこれらの問題に対処する方法を見つけられ ないのであれば、AIは失敗する運命にあり、「月を見ながら木登り」をするようなものだ[15]。 |

| History Dreyfus began to formulate his critique in the early 1960s while he was a professor at MIT, then a hotbed of artificial intelligence research. His first publication on the subject is a half-page objection to a talk given by Herbert A. Simon in the spring of 1961.[16] Dreyfus was especially bothered, as a philosopher, that AI researchers seemed to believe they were on the verge of solving many long standing philosophical problems within a few years, using computers. "Alchemy and AI" In 1965, Dreyfus was hired (with his brother Stuart Dreyfus' help) by Paul Armer to spend the summer at RAND Corporation's Santa Monica facility, where he would write "Alchemy and AI", the first salvo of his attack. Armer had thought he was hiring an impartial critic and was surprised when Dreyfus produced a scathing paper intended to demolish the foundations of the field. (Armer stated he was unaware of Dreyfus' previous publication.) Armer delayed publishing it, but ultimately realized that "just because it came to a conclusion you didn't like was no reason not to publish it."[17] It finally came out as RAND Memo and soon became a best seller.[18] The paper flatly ridiculed AI research, comparing it to alchemy: a misguided attempt to change metals to gold based on a theoretical foundation that was no more than mythology and wishful thinking.[19] It ridiculed the grandiose predictions of leading AI researchers, predicting that there were limits beyond which AI would not progress and intimating that those limits would be reached soon.[20] Reaction The paper "caused an uproar", according to Pamela McCorduck.[21] The AI community's response was derisive and personal. Seymour Papert dismissed one third of the paper as "gossip" and claimed that every quotation was deliberately taken out of context.[22] Herbert A. Simon accused Dreyfus of playing "politics" so that he could attach the prestigious RAND name to his ideas. Simon said, "what I resent about this was the RAND name attached to that garbage".[23] Dreyfus, who taught at MIT, remembers that his colleagues working in AI "dared not be seen having lunch with me."[24] Joseph Weizenbaum, the author of ELIZA, felt his colleagues' treatment of Dreyfus was unprofessional and childish. Although he was an outspoken critic of Dreyfus' positions, he recalls "I became the only member of the AI community to be seen eating lunch with Dreyfus. And I deliberately made it plain that theirs was not the way to treat a human being."[25] The paper was the subject of a short in The New Yorker magazine on June 11, 1966. The piece mentioned Dreyfus' contention that, while computers may be able to play checkers, no computer could yet play a decent game of chess. It reported with wry humor (as Dreyfus had) about the victory of a ten-year-old over the leading chess program, with "even more than its usual smugness."[20] In hope of restoring AI's reputation, Seymour Papert arranged a chess match between Dreyfus and Richard Greenblatt's Mac Hack program. Dreyfus lost, much to Papert's satisfaction.[26] An Association for Computing Machinery bulletin[27] used the headline: "A Ten Year Old Can Beat the Machine— Dreyfus: But the Machine Can Beat Dreyfus"[28] Dreyfus complained in print that he hadn't said a computer will never play chess, to which Herbert A. Simon replied: "You should recognize that some of those who are bitten by your sharp-toothed prose are likely, in their human weakness, to bite back ... may I be so bold as to suggest that you could well begin the cooling---a recovery of your sense of humor being a good first step."[29] Vindicated By the early 1990s several of Dreyfus' radical opinions had become mainstream. Failed predictions. As Dreyfus had foreseen, the grandiose predictions of early AI researchers failed to come true. Fully intelligent machines (now known as "strong AI") did not appear in the mid-1970s as predicted. HAL 9000 (whose capabilities for natural language, perception and problem solving were based on the advice and opinions of Marvin Minsky) did not appear in the year 2001. "AI researchers", writes Nicolas Fearn, "clearly have some explaining to do."[30] Today researchers are far more reluctant to make the kind of predictions that were made in the early days. (Although some futurists, such as Ray Kurzweil, are still given to the same kind of optimism.) The biological assumption, although common in the forties and early fifties, was no longer assumed by most AI researchers by the time Dreyfus published What Computers Can't Do.[13] Although many still argue that it is essential to reverse-engineer the brain by simulating the action of neurons (such as Ray Kurzweil[31] or Jeff Hawkins[32]), they don't assume that neurons are essentially digital, but rather that the action of analog neurons can be simulated by digital machines to a reasonable level of accuracy.[31] (Alan Turing had made this same observation as early as 1950.)[33] The psychological assumption and unconscious skills. Many AI researchers have come to agree that human reasoning does not consist primarily of high-level symbol manipulation. In fact, since Dreyfus first published his critiques in the 60s, AI research in general has moved away from high level symbol manipulation, towards new models that are intended to capture more of our unconscious reasoning. Daniel Crevier writes that by 1993, unlike 1965, AI researchers "no longer made the psychological assumption",[13] and had continued forward without it. In the 1980s, these new "sub-symbolic" approaches included: Computational intelligence paradigms, such as neural nets, evolutionary algorithms and so on are mostly directed at simulated unconscious reasoning. Dreyfus himself agrees that these sub-symbolic methods can capture the kind of "tendencies" and "attitudes" that he considers essential for intelligence and expertise.[34] Research into commonsense knowledge has focused on reproducing the "background" or context of knowledge. Robotics researchers like Hans Moravec and Rodney Brooks were among the first to realize that unconscious skills would prove to be the most difficult to reverse engineer. (See Moravec's paradox.) Brooks would spearhead a movement in the late 80s that took direct aim at the use of high-level symbols, called Nouvelle AI. The situated movement in robotics research attempts to capture our unconscious skills at perception and attention.[35] In the 1990s and the early decades of the 21st century, statistics-based approaches to machine learning used techniques related to economics and statistics to allow machines to "guess" – to make inexact, probabilistic decisions and predictions based on experience and learning. These programs simulate the way our unconscious instincts are able to perceive, notice anomalies and make quick judgements, similar to what Dreyfus called "sizing up the situation and reacting", but here the "situation" consists of vast amounts of numerical data. These techniques are highly successful and are currently widely used in both industry and academia. This research has gone forward without any direct connection to Dreyfus' work.[36] Knowing-how and knowing-that. Research in psychology and economics has been able to show that Dreyfus' (and Heidegger's) speculation about the nature of human problem solving was essentially correct. Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky collected a vast amount of hard evidence that human beings use two very different methods to solve problems, which they named "system 1" and "system 2". System one, also known as the adaptive unconscious, is fast, intuitive and unconscious. System 2 is slow, logical and deliberate. Their research was collected in the book Thinking, Fast and Slow,[37] and inspired Malcolm Gladwell's popular book Blink.[38] As with AI, this research was entirely independent of both Dreyfus and Heidegger.[36] Ignored Although clearly AI research has come to agree with Dreyfus, McCorduck claimed that "my impression is that this progress has taken place piecemeal and in response to tough given problems, and owes nothing to Dreyfus."[36] The AI community, with a few exceptions, chose not to respond to Dreyfus directly. "He's too silly to take seriously" a researcher told Pamela McCorduck.[29] Marvin Minsky said of Dreyfus (and the other critiques coming from philosophy) that "they misunderstand, and should be ignored."[39] When Dreyfus expanded Alchemy and AI to book length and published it as What Computers Can't Do in 1972, no one from the AI community chose to respond (with the exception of a few critical reviews). McCorduck asks "If Dreyfus is so wrong-headed, why haven't the artificial intelligence people made more effort to contradict him?"[29] Part of the problem was the kind of philosophy that Dreyfus used in his critique. Dreyfus was an expert in modern European philosophers (like Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty).[40] AI researchers of the 1960s, by contrast, based their understanding of the human mind on engineering principles and efficient problem solving techniques related to management science. On a fundamental level, they spoke a different language. Edward Feigenbaum complained, "What does he offer us? Phenomenology! That ball of fluff. That cotton candy!"[41] In 1965, there was simply too huge a gap between European philosophy and artificial intelligence, a gap that has since been filled by cognitive science, connectionism and robotics research. It would take many years before artificial intelligence researchers were able to address the issues that were important to continental philosophy, such as situatedness, embodiment, perception and gestalt. Another problem was that he claimed (or seemed to claim) that AI would never be able to capture the human ability to understand context, situation or purpose in the form of rules. But (as Peter Norvig and Stuart Russell would later explain), an argument of this form cannot be won: just because one cannot imagine formal rules that govern human intelligence and expertise, this does not mean that no such rules exist. They quote Alan Turing's answer to all arguments similar to Dreyfus's: "we cannot so easily convince ourselves of the absence of complete laws of behaviour ... The only way we know of for finding such laws is scientific observation, and we certainly know of no circumstances under which we could say, 'We have searched enough. There are no such laws.'"[42] Dreyfus did not anticipate that AI researchers would realize their mistake and begin to work towards new solutions, moving away from the symbolic methods that Dreyfus criticized. In 1965, he did not imagine that such programs would one day be created, so he claimed AI was impossible. In 1965, AI researchers did not imagine that such programs were necessary, so they claimed AI was almost complete. Both were wrong. A more serious issue was the impression that Dreyfus' critique was incorrigibly hostile. McCorduck wrote, "His derisiveness has been so provoking that he has estranged anyone he might have enlightened. And that's a pity."[36] Daniel Crevier stated that "time has proven the accuracy and perceptiveness of some of Dreyfus's comments. Had he formulated them less aggressively, constructive actions they suggested might have been taken much earlier."[4] |

歴史 ドレフュスは、当時人工知能研究の温床であったマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)の教授であった1960年代初頭に、自身の批評を練り始めた。このテー マに関する最初の出版物は、1961年春にハーバート・A・サイモンが行った講演に対する半ページの反論である[16]。ドレフュスは哲学者として、AI の研究者たちが、コンピュータを使えば数年以内に多くの長年の哲学的問題を解決できると信じているように見えたことに特に悩まされていた。 「錬金術とAI」 1965年、ドレファスはポール・アーメルに雇われ(弟のスチュアート・ドレファスの助けもあった)、ランド研究所のサンタモニカ施設で夏を過ごすことに なった。アルマーは公平な批評家を雇ったつもりだったが、ドレフュスがこの分野の土台を崩すことを意図した辛辣な論文を書いたので驚いた。(アルマーはド レフュスが過去に発表した論文について知らなかったと述べている)アルマーはそれを出版するのを遅らせたが、最終的に「自分の気に入らない結論になったか らといって、出版しない理由にはならない」[17]と悟った。 この論文は、AI研究を錬金術になぞらえ、神話と希望的観測に過ぎない理論的基盤に基づいて金属を金に変えようとする見当違いの試みだと、AI研究を平然 と嘲笑した[19]。また、AIが進歩しない限界があると予測し、その限界はすぐに到達するだろうと示唆し、AI研究の第一人者たちの壮大な予測を嘲笑し た[20]。 反響 パメラ・マコーダックによれば、この論文は「騒動を引き起こした」[21]。 AIコミュニティの反応は嘲笑的で個人的なものだった。シーモア・パパートは論文の3分の1を「ゴシップ」として否定し、すべての引用が意図的に文脈から 外されていると主張した[22]。ハーバート・A・サイモンは、ドレフュスが自分のアイデアにランドという権威ある名前を付けるために「政治」を演じてい ると非難した。サイモンは「私が憤慨しているのは、あのゴミにランドという名前がついていることだ」と述べた[23]。 マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で教鞭をとっていたドレフュスは、AIに携わる同僚たちが「私と昼食をとるところを見られるのは憚られた」と回想して いる[24]。ELIZAの著者であるジョセフ・ワイゼンバウムは、同僚たちのドレフュスに対する扱いがプロフェッショナルではなく、幼稚だと感じてい た。彼はドレフュスの立場を率直に批判していたが、「私はAIコミュニティで唯一、ドレフュスと一緒に昼食を食べる姿を目撃された。そして私は、ドレフュ スのやり方は人間を扱うやり方ではないことを、意図的に明らかにした」[25]。 この論文は、1966年6月11日付の『ニューヨーカー』誌に掲載された。その記事は、コンピュータはチェッカーはできるかもしれないが、チェスをまとも にプレイできるコンピュータはまだないというドレフュスの主張について触れている。その記事は、(ドレフュスがそうであったように)軽妙なユーモアを交え て、10歳の子供が一流のチェス・プログラムに勝利したことを、「いつもの自惚れ以上に」報じた[20]。 AIの評判を回復させようと、シーモア・パパートはドレフュスとリチャード・グリーンブラットのMac Hackプログラムとのチェス対戦を企画した。ドレイファスは負け、パパートは満足した[26]。 Association for Computing Machineryの会報[27]は見出しをこうつけた: 「A Ten Year Old Can Beat the Machine- Dreyfus: But the Machine Can Beat Dreyfus」[28]。 ドレファスは印刷物の中で、コンピュータがチェスをすることはないとは言っていないと不満を述べたが、ハーバート・A・サイモンはそれに答えた: 「あなたの歯に衣着せぬ散文に食いついた人の中には、人間的な弱さゆえに噛みつき返そうとする人がいることを認識すべきだ。 正当性が証明される 1990年代初頭までに、ドレフュスの過激な意見のいくつかは主流となった。 予測の失敗 ドレフュスが予見していたように、初期のAI研究者の壮大な予測は実現しなかった。完全に知的な機械(現在では「強力なAI」として知られている)は、 1970年代半ばには予測通りには現れなかった。HAL 9000(その自然言語、知覚、問題解決の能力は、マービン・ミンスキーの助言と意見に基づいていた)は、2001年には現れなかった。「AIの研究者た ち」は、「明らかに説明すべきことがある」[30]とニコラス・フィアンは書いている。(レイ・カーツワイルのような未来学者の中には、いまだに同じよう な楽観論を唱える者もいるが)。 生物学的仮定は、40年代や50年代初頭には一般的であったが、ドレフュスが『コンピュータにできないこと』を出版する頃には、ほとんどのAI研究者がも はや仮定していなかった。 [13] 今でも多くの研究者が、ニューロンの作用をシミュレートすることによって脳をリバースエンジニアリングすることが不可欠であると主張しているが(レイ・ カーツワイル[31]やジェフ・ホーキンス[32]など)、彼らはニューロンが本質的にデジタルであるとは想定しておらず、むしろアナログのニューロンの 作用はデジタル機械によって合理的なレベルの精度でシミュレート可能であると想定している[31](アラン・チューリングは1950年の時点でこれと同じ 見解を示していた)[33]。 心理学的仮定と無意識のスキル 多くのAI研究者は、人間の推論が主に高レベルの記号操作で構成されているわけではないことに同意するようになった。実際、ドレフュスが60年代に初めて 彼の批評を発表して以来、AI研究全般は高レベルの記号操作から離れ、人間の無意識的な推論をより多く捉えることを意図した新しいモデルへと向かってい る。ダニエル・クレヴィエは、1965年とは異なり、1993年までにはAI研究者は「もはや心理学的な仮定はしていない」と書いている[13]。 1980年代には、このような新しい「記号的でない」アプローチには以下のようなものがあった: ニューラルネットや進化的アルゴリズムなどの計算知能のパラダイムは、ほとんどが無意識的な推論のシミュレーションに向けられている。ドレフュス自身は、 これらのサブシンボリックな方法が、彼が知性や専門知識に不可欠であると考える「傾向」や「態度」のようなものを捉えることができることに同意している [34]。 コモンセンス知識に関する研究は、知識の「背景」や文脈を再現することに焦点を当ててきた。 ハンス・モラヴェックやロドニー・ブルックスのようなロボット工学の研究者たちは、無意識のスキルがリバースエンジニアリングするのが最も困難であること にいち早く気づいていた。(モラヴェックのパラドックス参照)ブルックスは、80年代後半にヌーヴェルAIと呼ばれる高レベル記号の使用を直接狙ったムー ブメントの先頭に立つことになる。ロボット研究における位置運動は、知覚と注意におけるわれわれの無意識のスキルを捉えようとするものである[35]。 1990年代から21世紀初頭にかけて、統計学に基づく機械学習へのアプローチは、経済学や統計学に関連する技術を用いて、機械に「推測」、つまり経験や 学習に基づいて不正確で確率的な決定や予測をさせることを可能にした。これらのプログラムは、ドレフュスが「状況を把握し、反応する」と呼んだものに似て いるが、ここでは「状況」は膨大な数値データで構成されている。これらの技術は非常に成功しており、現在、産業界と学界の両方で広く使われている。 この研究はドレフュスの研究とは直接関係なく進んでいる[36]。 ノウハウとノウイング・ザット 心理学と経済学の研究は、人間の問題解決の本質に関するドレフュス(とハイデガー)の推測が本質的に正しかったことを示すことができた。ダニエル・カーネ マンとエイモス・トヴェルスキーは、人間が「システム1」と「システム2」と名付けた2つの異なる方法で問題を解決していることを示す膨大な証拠を集め た。システム1は適応的無意識とも呼ばれ、速く、直感的で、無意識的である。システム2はゆっくりで、論理的で、計画的である。彼らの研究は 『Thinking, Fast and Slow』という本にまとめられ[37]、マルコム・グラッドウェルの人気本『Blink』に影響を与えた[38]。AIと同様、この研究はドレフュスや ハイデガーとはまったく無関係であった[36]。 無視される AI研究は明らかにドレフュスに同意するようになったが、マコーダックは「私の印象では、この進歩は断片的に、そして与えられた厳しい問題に対応して行われたものであり、ドレフュスには何の借りもない」と主張している[36]。 AIコミュニティは、少数の例外を除いて、ドレフュスに直接反応しないことを選んだ。「マービン・ミンスキーはドレフュス(と哲学からの他の批評)に対し て、「彼らは誤解しており、無視されるべきだ」と述べた[39] 。マコーダックは、「ドレフュスがこれほどまでに間違っているのなら、なぜ人工知能の人たちは彼に反論する努力をもっとしなかったのだろうか」と問いかけ ている[29]。 問題の一部は、ドレフュスが批評に用いた哲学の種類にあった。ドレフュスは近代ヨーロッパの哲学者(ハイデガーやメルロ=ポンティなど)の専門家であった [40]。対照的に、1960年代のAI研究者たちは、人間の心についての理解を、経営学に関連する工学原理や効率的な問題解決手法に基づいていた。根本 的なレベルにおいて、彼らは異なる言語を話していた。エドワード・フェイゲンバウムは、「彼は我々に何を提供してくれるのか?現象学だ!あのふわふわした ボールだ。1965年当時、ヨーロッパの哲学と人工知能の間にはあまりにも大きな隔たりがあった。人工知能の研究者が、状況性、身体性、知覚、ゲシュタル トなど、大陸哲学にとって重要な問題に取り組めるようになるまでには、長い年月が必要だった。 もうひとつの問題は、AIは文脈や状況、目的を理解する人間の能力をルールという形で捉えることはできないだろうと主張した(あるいは主張しているように 見えた)ことだ。しかし(後にピーター・ノービグとスチュアート・ラッセルが説明するように)、この形式の議論に勝つことはできない。人間の知性や専門知 識を支配する形式的なルールを想像できないからといって、そのようなルールが存在しないということにはならない。彼らは、ドレフュスと同様の議論に対する アラン・チューリングの答えを引用している: 「行動の完全な法則が存在しないことを、そう簡単に納得することはできない。そのような法則を発見する唯一の方法は科学的観察であり、『もう十分探した。そのような法則は存在しない』」[42]。 ドレフュスは、AIの研究者たちが自分たちの間違いに気づき、ドレフュスが批判した記号的手法から離れ、新たな解決策に向けて取り組み始めることを予期し ていなかった。1965年当時、彼はそのようなプログラムがいつか作られるとは想像していなかったので、AIは不可能だと主張していた。1965年当時、 AI研究者たちはそのようなプログラムが必要だとは想像していなかったので、AIはほぼ完成していると主張していた。どちらも間違っていた。 より深刻な問題は、ドレフュスの批評が非情に敵対的であるという印象である。マコーダックはこう書いている。「彼の軽蔑的な態度は挑発的で、彼が啓蒙した かもしれない人たちとは疎遠になってしまった。そしてそれは残念なことだ」[36] ダニエル・クレヴィエは、「ドレフュスのいくつかのコメントの正確さと鋭敏さは時が証明した。ドレフュスがもっと積極的でなかったなら、彼らが示唆した建 設的な行動はもっと早くから取られていたかもしれない」[4]。 |

| Adaptive unconscious Church–Turing thesis Computer chess Hubert Dreyfus Philosophy of artificial intelligence |

適応的無意識 チャーチ・チューリング論文 コンピュータ・チェス ユベール・ドレフュス 人工知能の哲学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubert_Dreyfus%27s_views_on_artificial_intelligence |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆