サン・ヴィクトルのフーゴー

Hugh of Saint Victor, c.1096-1141

☆ サン・ヴィクトルのフーゴーヒューとも表記)(c. 1096年 - 1141年2月11日)は、ザクセンの正規司祭であり、神秘主義神学の第一人者であり、神秘主義神学の作家であった。

| Hugh

of Saint Victor (c. 1096 – 11 February 1141) was a Saxon canon regular

and a leading theologian and writer on mystical theology. |

サン・ヴィクトルのフーゴー(ヒューとも表記)(c. 1096年 - 1141年2月11日)は、ザクセンの正規司祭であり、神秘主義神学の第一人者であり、神秘主義神学の作家であった。 |

| Life As with many medieval figures, little is known about Hugh's early life. He was probably born in the 1090s. His homeland may have been Lorraine, Ypres in Flanders, or the Duchy of Saxony.[3] Some sources say that his birth occurred in the Harz district, being the eldest son of Baron Conrad of Blankenburg. Over the protests of his family, he entered the Priory of St. Pancras, a community of canons regular, where he had studied, located at Hamerleve or Hamersleben, near Halberstadt.[4] Due to civil unrest shortly after his entry to the priory, Hugh's uncle, Reinhard of Blankenburg, who was the local bishop, advised him to transfer to the Abbey of Saint Victor in Paris, where he himself had studied theology. He accepted his uncle's advice and made the move at a date which is unclear, possibly 1115–18 or around 1120.[5] He spent the rest of his life there, advancing to head the school.[4] |

生涯 中世の多くの人物と同様に、フーゴーの初期の生涯についてはほとんど知られていない。おそらく1090年代に生まれたと思われる。故郷はロレーヌ、フラン ダース地方のイープル、ザクセン公国であった可能性がある。[3] 一部の資料によると、ブランケンブルクのコンラート男爵の長男として、ハルツ地方で生まれたとされている。家族の反対を押し切って、彼はハルバーシュタッ ト近郊のハメルレーベ(またはハマースレーベン)にあった聖パンクラス修道院に入った。 修道院に入って間もなく市民の不安が高まったため、フーゴーの叔父で地元司教のブランケンブルクのラインハルトは、自身が神学を学んだパリのサン・ヴィク トール修道院への転校を勧めた。彼は叔父の助言を受け入れ、時期は不明だが、おそらく1115年から18年、あるいは1120年頃に転校した。[5] 彼は残りの人生をそこで過ごし、学校の責任者に昇進した。[4] |

| Works De claustro anime, 14th-century manuscript. Hereford, Cathedral Library, Manuscript collection, P.5.XII. Hugh wrote many works from the 1120s until his death (Migne, Patrologia Latina contains 46 works by Hugh, and this is not a full collection), including works of theology (both treatises and sententiae), commentaries (mostly on the Bible but also including one of pseudo-Dionysius' Celestial Hierarchies), mysticism, philosophy and the arts, and a number of letters and sermons.[6] Hugh was influenced by many people, but chiefly by Saint Augustine, especially in holding that the arts and philosophy can serve theology. Hugh's most significant works include: De sacramentis christianae fidei (On the Mysteries of the Christian Faith/On the Sacraments of the Christian Faith)[7] It is Hugh's most celebrated masterpiece and presents the bulk of Hugh's thoughts on theological and mystical ideas, ranging from God and angels to natural laws. Didascalicon de studio legendi (Didascalicon, or, On the Study of Reading).[8] The subtitle to the Didascalicon, De Studio Legendi, makes the purpose of Hugh's tract clear. Written for the students at the school of Saint Victor, the work is a preliminary introduction to the theological and exegetical studies taught at the Parisian schools, the most advanced centers of learning in Europe in the 12th century. Citing a wide range classical and medieval sources, and with Augustine as his principal authority, Hugh sets forth a comprehensive synthesis of rhetoric, philosophy, and exegesis, designed to serve as a foundation for advanced theological study. The Didascalicon is primarily pedagogical, and not speculative, in nature. It provides the modern reader with a clear sense of the intellectual equipment expected of, if not always fully possessed by, high medieval theologians. In 1125–30, Hugh wrote three treatises structured around Noah's ark: De arca Noe morali (Noah's Moral Ark/On the Moral Interpretation of the Ark of Noah), De arca Noe mystica (Noah's Mystical Ark/On the Mystic Interpretation of the Ark of Noah), and De vanitate mundi (The World's Vanity).[9] De arca Noe morali and De arca Noe mystica reflect Hugh's fascination with both mysticism and the book of Genesis. In Hierarchiam celestem commentaria (Commentary on the Celestial Hierarchy), a commentary on the work by pseudo-Dionysius, perhaps begun around 1125.[10] After Eriugena's translation of Dionysius in the ninth century, there is almost no interest shown in Dionysius until Hugh's commentary.[11] It is possible that Hugh may have decided to produce the commentary (which perhaps originated in lectures to students) because of the continuing (incorrect) belief that the patron saint of the Abbey of Saint Denis, Saint Denis, was to be identified with pseudo-Dionysius. Dionysian thought did not form an important influence on the rest of Hugh's work. Hugh's commentary, however, became a major part of the twelfth and thirteenth-century surge in interest in Dionysius; his and Eriugena's commentaries were often attached to the Dionysian corpus in manuscripts, such that his thought had great influence on later interpretation of Dionysius by Richard of St Victor, Thomas Gallus, Hugh of Balma, Bonaventure and others.[12] Other works by Hugh of St Victor include: In Salomonis Ecclesiasten (Commentary on Ecclesiastes).[13] De tribus diebus (On the Three Days).[14] De sapientia animae Christi.[15] De unione corporis et spiritus (The Union of the Body and the Spirit).[16] Epitome Dindimi in philosophiam (Epitome of Dindimus on Philosophy).[17] Practica Geometriae (The Practice of Geometry).[17] De Grammatica (On Grammar).[17] Soliloquium de Arrha Animae (The Soliloquy on the Earnest Money of the Soul).[18] De contemplatione et ejus speciebus (On Contemplation and its Forms). This is one of the earliest systematic works devoted to contemplation. It appears not to have been written by Hugh himself, but composed by one of his students, possibly from classnotes from his lectures.[19] On Sacred Scripture and its Authors.[20] Various other treatises exist whose authorship by Hugh is uncertain. Six of these are reprinted, in Latin in Roger Baron, ed, Hugues de Saint-Victor: Six Opuscules Spirituels, Sources chrétiennes 155, (Paris, 1969). They are: De meditatione,[21] De verbo Dei, De substantia dilectionis, Quid vere diligendus est, De quinque septenis ,[22] and De septem donis Spiritus sancti[23] De anima is a treatise of the soul: the text will be found in the edition of Hugh's works in the Patrologia Latina of J. P. Migne. Part of it was paraphrased in the West Mercian dialect of Middle English by the author of the Katherine Group.[24] Various other works were wrongly attributed to Hugh in later thought. One such particularly influential work was the Exposition of the Rule of St Augustine, now accepted to be from the Victorine school but not by Hugh of St Victor.[25] A new edition of Hugh's works has been started. The first publication is: Hugonis de Sancto Victore De sacramentis Christiane fidei, ed. Rainer Berndt, Münster: Aschendorff, 2008. |

作品 14世紀の写本『デ・クラウストロ・アニメ』。 ハーフォード、大聖堂図書館、写本コレクション、P.5.XII. ヒューは1120年代から死ぬまで多くの著作を残した(ミニュス『ラテン教父文書』にはヒューの著作46編が収録されているが、これは完全なコレクション ではない)。その中には神学(論文と格言の両方)、注釈(主に聖書に関するものだが、偽ディオニシウスの『天上の位階』も含まれている)、神秘主義、哲 学、芸術、多数の手紙や説教などがある。 ヒューは多くの人々から影響を受けたが、特に聖アウグスティヌスから影響を受け、芸術と哲学が神学に役立つという考えを強く持っていた。 ヒューの最も重要な著作には以下のようなものがある。 『キリスト教信仰の秘跡について』(De sacramentis christianae fidei)は、ヒューの最も著名な代表作であり、神や天使から自然法則に至るまで、神学と神秘思想に関するヒューの考えの大部分を提示している。 『ディダスカリコン・デ・スタジオ・レゲンディ』(『ディダスカリコン、または、読書について』)[8] 『ディダスカリコン』の副題『デ・スタジオ・レゲンディ』は、ヒューの著作の目的を明確に示している。この著作は、サン・ヴィクトール学派の学生のために 書かれたもので、12世紀のヨーロッパで最も進んだ学問の中心地であったパリの学校で教えられていた神学と解釈学の予備的な入門書である。ヒューは、古典 や中世の幅広い資料を引用し、アウグスティヌスを主な権威として、高度な神学研究の基礎となるよう、修辞学、哲学、解釈学の包括的な統合を提示した。 『ディダスカリコン』は、本質的には教育的なものであり、思索的なものではない。この著作は、中世の神学者たちが期待されていた、あるいは常に完全に所有 していたとは言えない知的装備を、現代の読者に明確に理解させる。 1125年から1130年にかけて、ヒューはノアの方舟をテーマに3つの論文を執筆した。De arca Noe morali(ノアの方舟の道徳的解釈)、De arca Noe mystica(ノアの方舟の神秘主義的解釈 Ark/On the Mystic Interpretation of the Ark of Noah)、『世界の空しさ』(De vanitate mundi)の3つの論文を書いた。[9] 『ノアの箱舟の道徳的解釈』と『ノアの箱舟の神秘解釈』は、ヒューの神秘主義と創世記への関心を反映している。 『Hierarchiam celestem commentaria(天上の階層についての注釈)』は、偽ディオニュシオスによる著作の注釈であり、おそらく1125年頃に着手された。エリウゲナが 9世紀にディオニュシオスを翻訳した後、ディオニュシオスに対する関心はほとんど示されなかったが ヒューの注釈が発表されるまで、ディオニュシオスに対する関心はほとんど示されていなかった。[11] ヒューが注釈を制作することを決めたのは、サン・ドニ修道院の守護聖人であるサン・ドニが偽ディオニュシオスであるという誤った考えが続いていたからかも しれない。ディオニュシオスの思想は、ヒューの他の作品に重要な影響を与えることはなかった。しかし、ヒューの注釈は、12世紀と13世紀におけるディオ ニュシオスへの関心の高まりにおいて主要な部分を占めるようになった。ヒューとエリウゲナの注釈は、ディオニュシオスの著作集の写本にしばしば添えられて おり、その思想は、リチャード・オブ・セント・ヴィクター、トマス・ガルス、ヒュー・オブ・バルマ、ボナヴェントゥラなどによるディオニュシオスの後の解 釈に大きな影響を与えた。 ヒュー・オブ・セント・ヴィクターの他の著作には、以下のものがある。 ソロモンの伝道師(伝道師についての論評)』[13] 3日について』[14] キリストの魂の知恵』[15] 肉体と精神の結合』[16] 哲学についてのディンディムスの要約』[17] Practica Geometriae (幾何学の実践)[17] De Grammatica (文法について)[17] Soliloquium de Arrha Animae (魂の証金についての独白)[18] De contemplatione et ejus speciebus (観想とその形態について) これは、観想に捧げられた最も初期の体系的な作品のひとつである。ヒュー自身が著したものではなく、おそらくは彼の講義のノートから、彼の生徒の一人がま とめたものと思われる。 聖書とその著者たちについて。 ヒューの著作かどうか不明な論文も数多く存在する。そのうちの6編は、Roger Baron編『Hugues de Saint-Victor: Six Opuscules Spirituels, Sources chrétiennes 155』(パリ、1969年)にラテン語で再版されている。それらは次の通りである。『瞑想について』[21]、『神のことばについて』、『愛の本質につ いて』、『真に愛すべきものとは何か』、『五つの七』[22]、『聖霊の七つの賜物』[23] 『魂について』は魂に関する論文である。テキストは、J. P. Migneの『ラテン教父文書』に収録されたヒューの著作版で見ることができる。その一部は、キャサリン・グループの著者によって中世英語のウェスト・マーシア方言に意訳されている。 後世の考えでは、ヒューに誤って帰属された様々な作品が存在する。そのような作品のひとつで特に影響力のあった作品は『アウグスティヌス規則の解説』であ るが、これはビクトリヌス学派の作品であると現在では考えられているが、ヒュー・オブ・セント・ヴィクターの作品ではない。 ヒューの作品の新編が開始された。最初の出版は次の通りである。Hugonis de Sancto Victore De sacramentis Christiane fidei, ed. Rainer Berndt, Münster: Aschendorff, 2008. |

| Philosophy and theology The early Didascalicon was an elementary, encyclopedic approach to God and Christ, in which Hugh avoided controversial subjects and focused on what he took to be commonplaces of Catholic Christianity. In it he outlined three types of philosophy or "science" [scientia] that can help mortals improve themselves and advance toward God: theoretical philosophy (theology, mathematics, physics) provides them with truth, practical philosophy (ethics, economics, politics) aids them in becoming virtuous and prudent, and "mechanical" or "illiberal" philosophy (e.g., carpentry, agriculture, medicine) yields physical benefits. A fourth philosophy, logic, is preparatory to the others and exists to ensure clear and proper conclusions in them. Hugh's deeply mystical bent did not prevent him from seeing philosophy as a useful tool for understanding the divine, or from using it to argue on behalf of faith. Hugh was heavily influenced by Augustine's exegesis of Genesis. Divine Wisdom was the archetypal form of creation. The creation of the world in six days was a mystery for man to contemplate, perhaps even a sacrament. God's forming order from chaos to make the world was a message to humans to rise up from their own chaos of ignorance and become creatures of Wisdom and therefore beauty. This kind of mystical-ethical interpretation was typical for Hugh, who tended to find Genesis interesting for its moral lessons rather than as a literal account of events. Along with Jesus, the sacraments were divine gifts that God gave man to redeem himself, though God could have used other means. Hugh separated everything along the lines of opus creationis and opus restaurationis. Opus Creationis was the works of the creation, referring to God's creative activity, the true good natures of things, and the original state and destiny of humanity. The opus restaurationis was that which dealt with the reasons for God sending Jesus and the consequences of that. Hugh believed that God did not have to send Jesus and that He had other options open to Him. Why he chose to send Jesus is a mystery we are to meditate on and is to be learned through revelation, with the aid of philosophy to facilitate understanding. |

哲学と神学 初期の『ディダスカリコン』は、神とキリストに関する初歩的かつ百科事典的なアプローチであり、ヒューは論争の的となるテーマを避け、カトリックのキリス ト教の常識と考えられるものに焦点を当てた。その中で、彼は、人間が自らを向上させ、神へと近づくのを助ける3つのタイプの哲学または「科学」 [scientia]を概説している。すなわち、理論哲学(神学、数学、物理学)は真理を、実践哲学(倫理学、経済学、政治学)は徳と賢明さを、そして 「機械的」または「非寛容な」哲学(例えば、大工、農業、医学)は肉体的な利益をもたらす。4つ目の哲学である論理学は、他の哲学の準備段階であり、それ らにおいて明確かつ適切な結論を導くために存在する。ヒューの神秘主義的な傾向は、彼が哲学を神を理解するための有用な手段と見なすこと、あるいは信仰を 擁護するために哲学を用いることを妨げることはなかった。 ヒューはアウグスティヌスの『創世記』の釈義から多大な影響を受けていた。神の知恵は創造の原型的な形であった。6日間で世界が創造されたことは、人間が 熟考すべき神秘であり、おそらくは秘跡であった。神が混沌から世界を形作ることは、人間に対して、無知という混沌から立ち上がり、知恵の創造物、すなわち 美の創造物となるべきであるというメッセージであった。このような神秘主義的・倫理的な解釈はヒューに典型的なものであり、彼は創世記を文字通りの出来事 の記録というよりも、道徳的な教訓として興味深いものとして捉える傾向があった。 イエスとともに、秘跡は神が人間に与えた神聖な贈り物であり、人間が自らを贖うためのものだった。ただし、神は他の手段を用いることもできた。ヒューはす べてを「オプス・クリエイティス」と「オプス・ルステリタス」の2つのカテゴリーに分けた。オプス・クリエイティスは創造の業であり、神の創造的活動、物 事の真の善良な性質、そして人間の本源的な状態と運命を指す。opus restorationisは、神がイエスを遣わされた理由と、その帰結を扱うものである。ヒューは、神がイエスを遣わす必要はなく、神には他の選択肢も あったと信じていた。なぜ神がイエスを遣わされたのかは、私たちが熟考すべき謎であり、理解を助ける哲学の助けを借りて、啓示を通じて学ばなければならな い。 |

| Legacy Within the Abbey of St Victor, many scholars who followed him are often known as the 'School of St Victor'. Andrew of St Victor studied under Hugh.[26] Others, who probably entered the community too late to be directly educated by Hugh, include Richard of Saint Victor and Godfrey.[27] One of Hugh's ideals that did not take root in St Victor, however, was his embracing of science and philosophy as tools for approaching God.[citation needed] His works are in hundreds of libraries all across Europe.[citation needed] He is quoted in many other publications after his death,[citation needed] and Bonaventure praises him in De reductione artium ad theologiam. He was also an influence on the critic Erich Auerbach, who cited this passage from Hugh of St Victor in his essay "Philology and World Literature":[28] It is therefore, a source of great virtue for the practiced mind to learn, bit by bit, first to change about in visible and transitory things, so that afterwards it may be able to leave them behind altogether. The person who finds his homeland sweet is a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign place. The tender soul has fixed his love on one spot in the world; the strong person has extended his love to all places; the perfect man has extinguished his. |

遺産 聖ヴィクトル修道院では、彼に従った多くの学者たちが「聖ヴィクトル学派」として知られるようになった。聖ヴィクトルのアンドリューはヒューの弟子であっ た。[26] ヒューから直接教育を受けるには遅れてその共同体に加わったと思われる人物には、聖ヴィクトルのリチャードやゴドフリーなどがいる。[27] しかし、ヒューの理想のひとつで、聖ヴィクトルには根付かなかったものに、神に近づくための手段として科学と哲学を受け入れたことが挙げられる。[要出 典] 彼の著作はヨーロッパ中の数百の図書館に所蔵されている。[要出典] 死後も、彼の著作は多くの出版物で引用されている。[要出典] ボナヴェントゥラは『神学への諸芸術の還元』の中で彼を賞賛している。 また、批評家のエーリヒ・アウエルバッハにも影響を与えた。アウエルバッハは、エッセイ「文献学と世界文学」の中で、聖ヴィクトール・ヒューのこの一節を引用している。 それゆえ、熟練した精神にとって、少しずつ、まず目に見える儚いものについて変化することを学ぶことは、大きな徳の源である。そうすれば、後にそれらを完 全に乗り越えることができるだろう。故郷を愛おしいと感じる者は、まだ初心で、あらゆる土地を故郷のように感じられる者はすでに強い。しかし、全世界を異 郷のように感じられる者が完全である。優しい心を持つ者は、世界の特定の場所に愛を定めている。強い者は、その愛をあらゆる場所に広げている。完全な者 は、その愛を消し去っている。 |

| Works Modern editions Latin text Latin texts of Hugh of St. Victor are available in the Migne edition at Documenta Catholica Omnia, http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/30_10_1096-1141-_Hugo_De_S_Victore.html Henry Buttimer, Hugonis de Sancto Victore. Didascalicon. De Studio Legendi (Washington, DC: Catholic University Press, 1939). Hugh of St Victor, L'oeuvre de Hugues de Saint-Victor. 1. De institutione novitiorum. De virtute orandi. De laude caritatis. De arrha animae, Latin text edited by H.B. Feiss & P. Sicard; French translation by D. Poirel, H. Rochais & P. Sicard. Introduction, notes and appendices by D. Poirel (Turnhout, Brepols, 1997) Hugues de Saint-Victor, L'oeuvre de Hugues de Saint-Victor. 2. Super Canticum Mariae. Pro Assumptione Virginis. De beatae Mariae virginitate. Egredietur virga, Maria porta, edited by B. Jollès (Turnhout: Brepols, 2000) Hugo de Sancto Victore, De archa Noe. Libellus de formatione arche, ed Patricius Sicard, CCCM vol 176, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, I (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001) Hugo de Sancto Victore, De tribus diebus, ed Dominique Poirel, CCCM vol 177, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, II (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002) Hugo de Sancto Victore, De sacramentis Christiane fidei, ed. Rainer Berndt (Münster: Aschendorff, 2008) Hugo de Sancto Victore, Super Ierarchiam Dionysii, CCCM vol 178, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, III (Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming) English translations Hugh of St Victor, Explanation of the Rule of St. Augustine, translated by Aloysius Smith (London, 1911) Hugh of St Victor, The Soul's Betrothal-Gift, translated by FS Taylor (London, 1945) [translation of De Arrha Animae] Hugh of St Victor, On the sacraments of the Christian faith: (De sacramentis), translated by Roy J Deferrari (Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America, 1951) Hugh of Saint-Victor: Selected spiritual writings, translated by a religious of C.S.M.V.; with an introduction by Aelred Squire. (London: Faber, 1962) [reprinted in Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2009] [contains a translation of the first four books of De arca Noe morali and the first two (of four) books of De vanitate mundi]. The Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor, translated by Jerome Taylor (New York and London: Columbia U. P., 1961) [reprinted 1991] [translation of the Didascalicon] Soliloquy on the Earnest Money of the Soul, trans Kevin Herbert (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1984) [translation of Soliloquium de Arrha Animae] Hugh of St Victor, Practica Geometriae, trans. Frederick A Homann (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1991) Hugh of St Victor, extracts from Introductory Notes on the Scriptures and on the Scriptural Writers, trans Denys Turner, in Denys Turner, Eros and Allegory: Medieval Exegesis of the Song of Songs (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1995), 265-274 Hugh of Saint Victor on the Sacraments of the Christian Faith, trans Roy Deferrari (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2007) [translation of De Sacramentis Christianae Fidei] Boyd Taylor Coolman and Dale M Coulter, eds, Trinity and creation: a selection of works of Hugh, Richard and Adam of St Victor (Turnhout: Brepols, 2010) [includes translation of Hugh of St Victor, On the Three Days and Sentences on Divinity] Hugh Feiss, ed, On love: a selection of works of Hugh, Adam, Achard, Richard and Godfrey of St Victor (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011) [includes translations of The Praise of the Bridegroom, On the Substance of Love, On the Praise of Charity, What Truly Should be Loved?, On the Four Degrees of Violent Love, trans. A.B. Kraebel, and Soliloquy on the Betrothal-Gift of the Soul] Franklin T. Harkins and Frans van Liere, eds, Interpretation of scripture: theory. A selection of works of Hugh, Andrew, Richard and Godfrey of St Victor, and of Robert of Melun (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2012) [contains translations of: Didascalion on the study of reading, introduced and translated by Franklin T Harkins; On Sacred Scripture and its authors and The diligent examiner, introduced and translated by Frans van Liere; On the sacraments of the Christian faith, prologues, introduced and translated by Christopher P Evans] The Compendium of Philosophy (Compendium Philosophiae) attributed to Hugh of St Victor in several medieval manuscripts, upon rediscovery and examination in the 20th century, has turned out to have actually been a recension of William of Conches's De Philosophia Mundi.[29][30] |

作品 現代語版 ラテン語テキスト ヒューのラテン語テキストは、ドキュメンタ・カトリカ・オムニアのミーニュ版で閲覧可能。http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/30_10_1096-1141-_Hugo_De_S_Victore.html ヘンリー・バティマー著『ヒュゴニスの『聖ヴィクトール注解』。 ヒュゴ・ド・サン=ヴィクトール著『ヒュゴの作品』。1.『新来者への訓戒』。『祈りの徳』。『慈愛の誉れ』。De arrha animae, Latin text edited by H.B. Feiss & P. Sicard; French translation by D. Poirel, H. Rochais & P. Sicard. Introduction, notes and appendices by D. Poirel (Turnhout, Brepols, 1997) ユグ・ド・サン=ヴィクトール著『ユグ・ド・サン=ヴィクトールの作品』第2巻『マリアの歌』。聖母被昇天の賛美歌。聖母の処女性について。導き出されるのは、マリアの扉、B.ジョレス編(トゥルナウト:ブレポール、2000年) ヒューゴ・デ・サンクトゥス・ヴィクトーレ著『ノアの方舟について』。編者パトリキウス・シカード、ヒューゴ・デ・サンクトゥス・ヴィクトーレ著作集第1巻、第176巻、トゥルナウト:ブレポール社、2001年 ヒューゴ・デ・サンクトゥス・ヴィクトール著『三位一体について』、ドミニク・ポワレル編、CCCM 第177巻、ヒューゴ・デ・サンクトゥス・ヴィクトール著作集第2巻(トゥルナウト:ブレポール、2002年) ヒューゴ・デ・サンクトゥス・ヴィクトール著『キリスト教の秘跡と信仰』、ライナー・ベルント編(ミュンスター:アシェンドルフ、2008年) ヒューゴ・デ・サンクトゥス・ヴィクトル著『ディオニシウスの『教会論』注釈』、ヒューゴ・デ・サンクトゥス・ヴィクトル著作集第3巻、CCCM第178巻(トゥルノー:ブレポール社、近刊) 英訳 ヒュー・オブ・セント・ヴィクター著『聖アウグスティヌスの規則の解説』、アロイシウス・スミス訳(ロンドン、1911年) ヒュー・オブ・セント・ヴィクター著『魂の婚約の贈り物』FSテイラー訳(ロンドン、1945年)[『魂の証拠金』の翻訳 ヒュー・オブ・セント・ヴィクター著『キリスト教信仰の秘跡について』(『秘跡について』)ロイ・J・デフェラーリ訳(ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州:アメリカ中世アカデミー、1951年) 聖ヴィクトール・ヒュー:厳選された霊的著作、C.S.M.V.の修道女による翻訳、アエルレッド・スクワイアによる序文。(ロンドン:フェーバー、 1962年)[ユージン、オレゴン州:Wipf & Stock Publishers、2009年に再版][『ノアの箱舟道徳』の最初の4冊と『世界の空しさ』の最初の2冊(全4冊のうち)の翻訳を含む]。 ヒュー・オブ・セント・ヴィクター著『ディダスカリコン』、ジェローム・テイラー訳(ニューヨークおよびロンドン:コロンビア大学出版局、1961年)[1991年再版][『ディダスカリコン』の翻訳] 『魂の証拠金の独白』、ケビン・ハーバート訳(ウィスコンシン州ミルウォーキー:マーキュリー大学出版局、1984年)[『魂の証拠金の独白』の翻訳] ヒュー・オブ・セント・ビクター著『幾何学の実践』フレデリック・A・ホーマン訳(ミルウォーキー:Marquette University Press、1991年) ヒュー・オブ・セント・ビクター著『聖書と聖書作家に関する入門ノート』抜粋、デニス・ターナー訳、デニス・ターナー著『エロスと寓話: 『雅歌』の中世注解(ミシガン州カラマズー:シトー会出版、1995年)、265-274 『キリスト教信仰の秘跡に関する聖ヒューの著作』、ロイ・デフェラーリ訳(オレゴン州ユージン:Wipf & Stock Publishers、2007年)[『キリスト教信仰の秘跡』の翻訳] ボイド・テイラー・クールマンとデール・M・カルター編、『三位一体と創造:ヒュー、リチャード、聖ヴィクトールのアダムの著作集』(トゥルナウト:ブレポールス、2010年)[ヒュー・オブ・セント・ヴィクター著『神性に関する三日間と文章』の翻訳を含む] ヒュー・ファイス編、『愛について:ヒュー、アダム、アシャール、リチャード、ゴドフリーの作品集』(トゥルナウト:ブレポール社、2011年)[『花婿 の賛美』、『愛の本質について』、『慈愛の賛美について』、『真に愛されるべきものとは?』、『激しい愛の4つの段階』の翻訳を含む。A.B. Kraebel 訳、および『婚約の独白―魂の贈り物』 フランクリン・T・ハーキンズ、フラン・ヴァン・リエール編、『聖書解釈:理論。聖ヴィクターのヒュー、アンドリュー、リチャード、ゴドフリー、およびメ ロンのロバートの作品集』(ベルギー、トゥルナウト:ブレポールス、2012年)[以下を収録: ディダスカリオン著『読解の研究』、フランクリン・T・ハーキンズによる序文および翻訳、聖典とその著者たち、フランシス・ファン・リエールによる序文お よび翻訳、熱心な研究者、クリストファー・P・エヴァンスによる序文および翻訳、 中世の写本でヒュー・オブ・セント・ヴィクターのものとされていた『哲学大全』(Compendium Philosophiae)は、20世紀に再発見され検証された結果、実際にはコンシュのウィリアムの『世界の哲学』の改訂版であることが判明した。[29][30] |

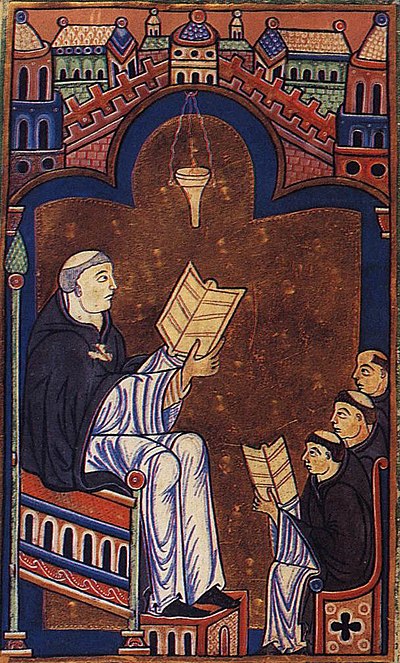

| Art of memory § Principles, where Hugh's Didascalicon and Chronica are referred to. Hendrik Mande The Mystic Ark, painting by Hugh |

記憶術 § 原則、ヒューの『ディダスカリコン』と『クロニカ』が参照されている。 ヘンドリック・マンデ 『神秘の箱舟』、ヒューの絵画 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_of_Saint_Victor |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆