フンボルト派の科学

Humboldtian science

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog of Caspar David Friedrich/

German explorer Alexander von Humboldt showed his disgust for slavery and often criticized the colonial policies—he always acted out of a deeply humanistic conviction, borne by the ideas of the Enlightenment.

☆ フンボルト派科学あるいはフンボルト流の科学(Humboldtian science)とは、ドイツの科学者、博物学者、探検家であるアレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトの著作と密接に結びついた 19世紀の科学運動を指す。科学的なフィールドワークとロマン主義時代の感性と美的理想を融合させ、正確さと観察というある種の倫理観を維持していた。こ の言葉は1978年にスーザン・フェイ・キャノンによって作られたものである[2][3]。フンボルトの人生と著作の例によって、彼は博物学で学界の枠を 超え、ポピュラーサイエンスの側面でより多くの人々に働きかけることができた。それは、フランシス・ベーコンという一人の人物にも関係する、より古いベー コン的手法に取って代わった。

| Humboldtian

science refers to a movement in science in the 19th century closely

connected to the work and writings of German scientist, naturalist, and

explorer Alexander von Humboldt. It maintained a certain ethics of

precision and observation, which combined scientific field work with

the sensitivity and aesthetic ideals of the age of Romanticism.[1] Like

Romanticism in science, it was rather popular in the 19th century. The

term was coined by Susan Faye Cannon in 1978.[2][3] The example of

Humboldt's life and his writings allowed him to reach out beyond the

academic community with his natural history and address a wider

audience with popular science aspects. It has supplanted the older

Baconian method, related as well to a single person, Francis Bacon. |

フ

ンボルト派科学あるいはフンボルト流の科学とは、ドイツの科学者、博物学者、探検家であるアレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトの著作と密接に結びついた

19世紀の科学運動を指す。科学的なフィールドワークとロマン主義時代の感性と美的理想を融合させ、正確さと観察というある種の倫理観を維持していた。こ

の言葉は1978年にスーザン・フェイ・キャノンによって作られたものである[2][3]。フンボルトの人生と著作の例によって、彼は博物学で学界の枠を

超え、ポピュラーサイエンスの側面でより多くの人々に働きかけることができた。それは、フランシス・ベーコンという一人の人物にも関係する、より古いベー

コン的手法に取って代わった。 |

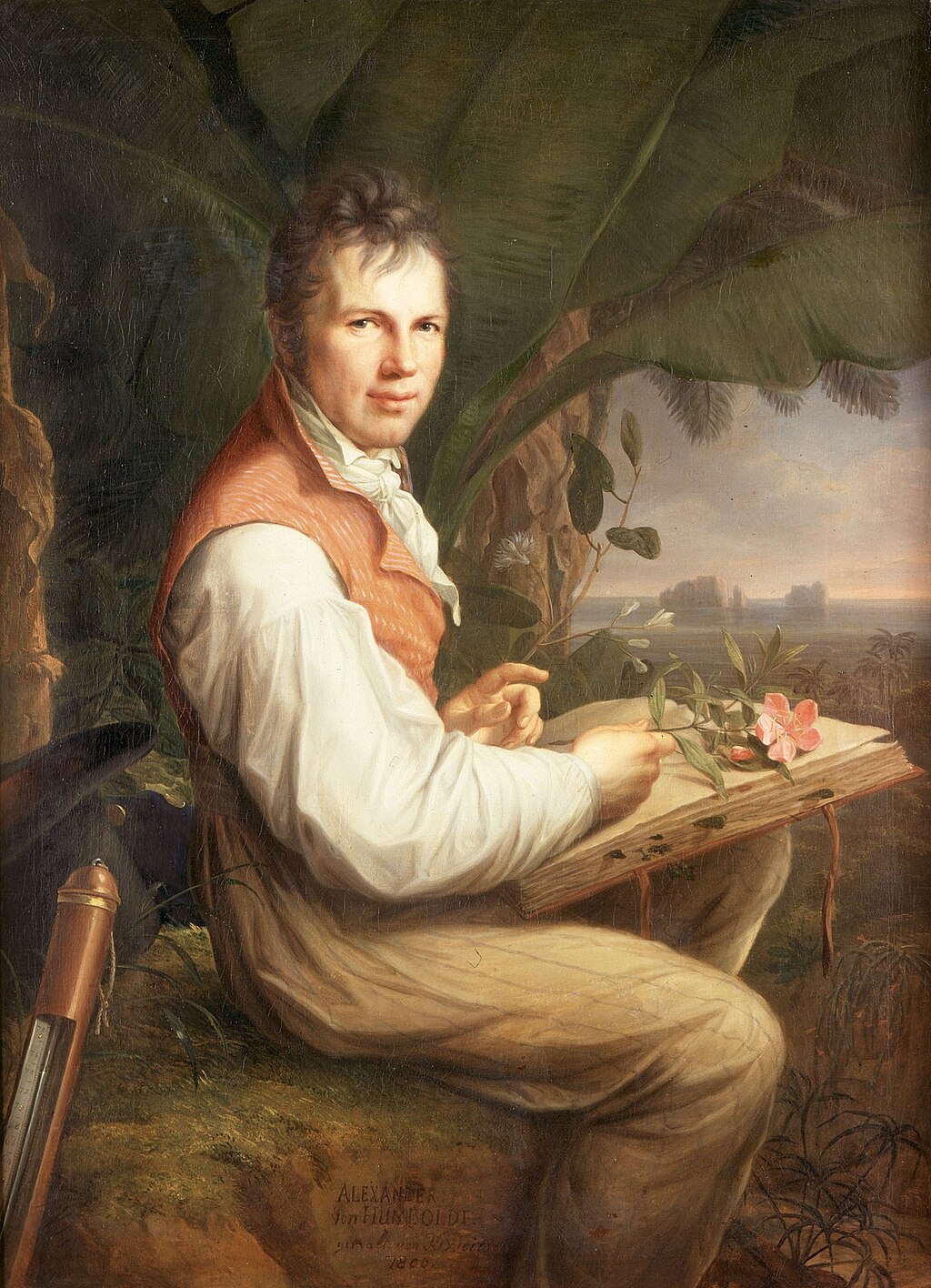

| Brief biography Main article: Alexander von Humboldt  Alexander von Humboldt Humboldt was born in Berlin in 1769 and worked as a Prussian mining official in the 1790s until 1797 when he quit and began collecting scientific knowledge and equipment.[4] His extensive wealth aided his infatuation with the spirit of Romanticism; he amassed an extensive collection of scientific instruments and tools as well as a sizeable library. In 1799 Humboldt, under the protection of King Charles IV of Spain, left for South America and New Spain, toting all of his tools and books.[4] The purpose of the voyage was steeped in Romanticism; Humboldt intended to investigate how the forces of nature interact with one another and find out about the unity of nature. Humboldt returned to Europe in 1804 and was acclaimed as a public hero. The details and findings of Humboldt's journey were published in his Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equatorial Regions of the New Continent (30 volumes). This Personal Narrative was taken by Charles Darwin on his famous voyage on H.M.S Beagle.[5] Humboldt spent the rest of his life mainly in Europe, although he did embark on a short expedition to Siberia and the Russian steppes in 1829. Humboldt's last works were contained in his book, Kosmos: Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung ("Cosmos. Sketch for a Physical Description of the Universe"). The book mainly described the development of a life-force from the cosmos, but also included the formation of stars from nebular clouds as well as the geography of planets. Alexander von Humboldt died in 1859, while working on the fifth volume of Kosmos.[4] Through his travels to South America and his observational records in An Essay on the Geography of Plants as well as Kosmos, an important trend emerged through his techniques of observation, scientific instruments used and unique perspective on nature. Humboldt's novel style has been defined as Humboldtian Science. Humboldt had the ability to combine the study of empirical data with a holistic view of nature and its aesthetically pleasing characteristics, which is now held to be the true definition of the study of vegetation and plant geography.[6] Humboldtian science is one of the first techniques for studying both organic and inorganic branches of science.[7] Examining the interconnectedness of vegetation and its respective environment is one of the new and important aspects of Humboldt's work, an idea labeled as "terrestrial physics," something that scientists who preceded him, such as Linnaeus, failed to do. Humboldtian science is founded on a principle of "general equilibrium of forces." General equilibrium was the idea that there are infinite forces in nature that are in constant conflict, yet all forces balance each other out. Humboldt laid the groundwork for future scientific endeavors by establishing the importance of studying organisms and their environment in conjunction .[8] |

略歴 主な記事 アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト  アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト フンボルトは1769年にベルリンで生まれ、1790年代にプロイセンの鉱業官僚として働いたが、1797年に退職し、科学的な知識や機器の収集を始めた [4]。1799年、フンボルトはスペイン国王シャルル4世の庇護のもと、すべての道具と書物を携えて南米とニュー・スペインへと旅立った。フンボルトは 1804年にヨーロッパに戻り、世間の英雄として賞賛された。フンボルトの旅の詳細と発見は、『新大陸赤道地方旅行記』(全30巻)として出版された。こ の『個人的な物語』は、チャールズ・ダーウィンがH.M.S.ビーグル号で有名な航海をした際に持ち帰ったものである[5]。フンボルトは、1829年に シベリアとロシアの草原への短期探検に出発したものの、その後の生涯を主にヨーロッパで過ごした。フンボルトの最後の著作は『コスモス』である: Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung)』に収められている。この本には、主に宇宙からの生命力の発展が書かれているが、星雲からの星の形成や惑星の地理も含 まれている。アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトは、『コスモス』第5巻の執筆中の1859年に死去した[4]。『コスモス』だけでなく、南米への旅行や 『植物の地理学に関する試論』での観察記録を通じて、彼の観察技術、使用した科学機器、自然に対する独自の視点を通じて、重要な傾向が現れた。フンボルト の斬新なスタイルは、フンボルト的科学と定義されている。フンボルトは経験的なデータの研究と、自然に対する全体的な見方や美的な特徴を組み合わせる能力 を持っており、これは現在では植生学や植物地理学の真の定義であるとされている[6]。 [フンボルトは、植生とその環境との相互関連性を研究することで、リンネのような先達の科学者がなしえなかった「陸上物理学」と呼ばれる新しい重要な側面 に取り組んだ。フンボルトの科学は、「力の一般均衡 」という原則の上に成り立っている。一般均衡とは、自然界には絶え間なく対立する無限の力が存在するが、それでもすべての力は互いに均衡を保っているとい う考え方である。フンボルトは、生物とその環境を結びつけて研究することの重要性を確立し、将来の科学的努力の基礎を築いた。 |

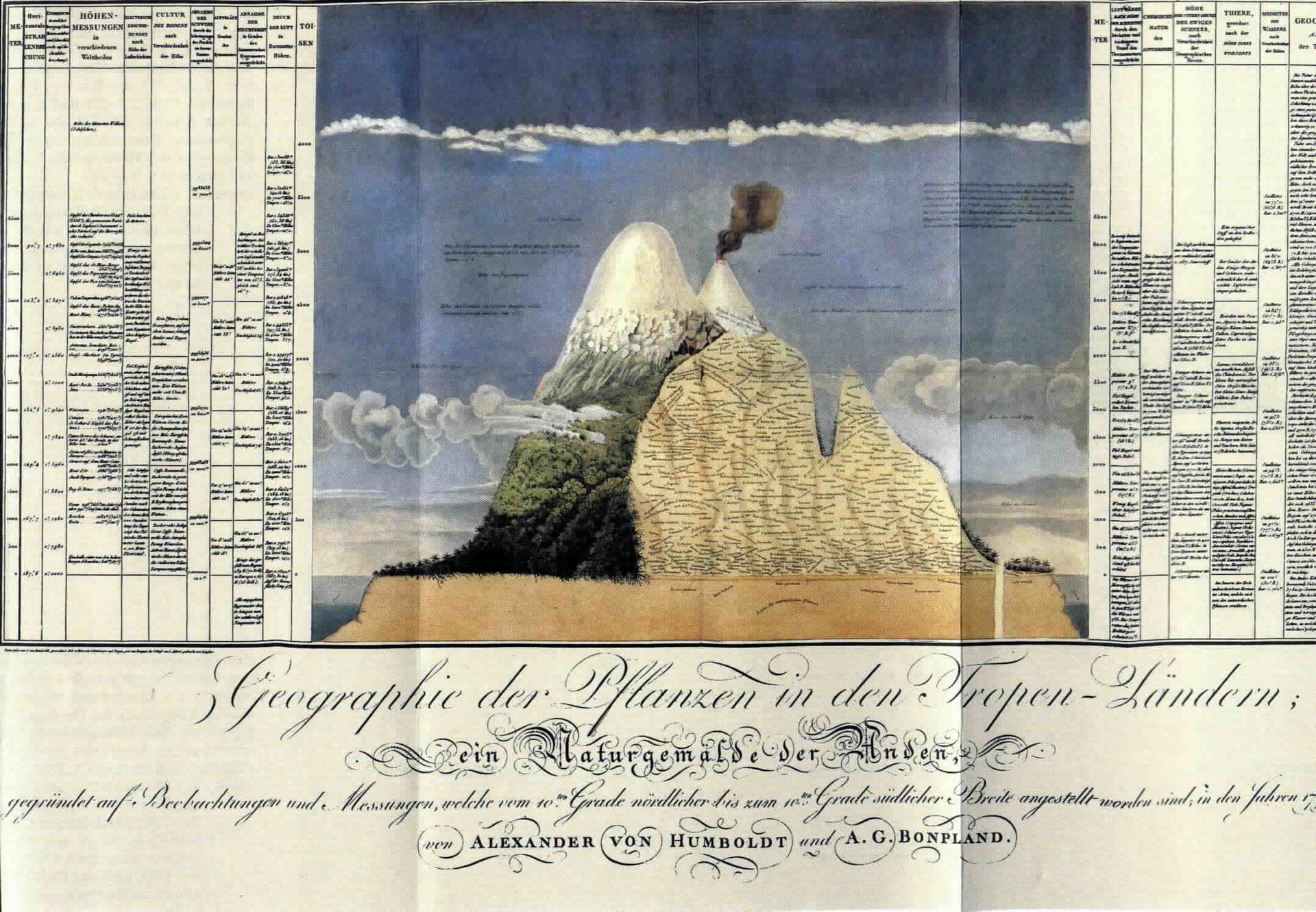

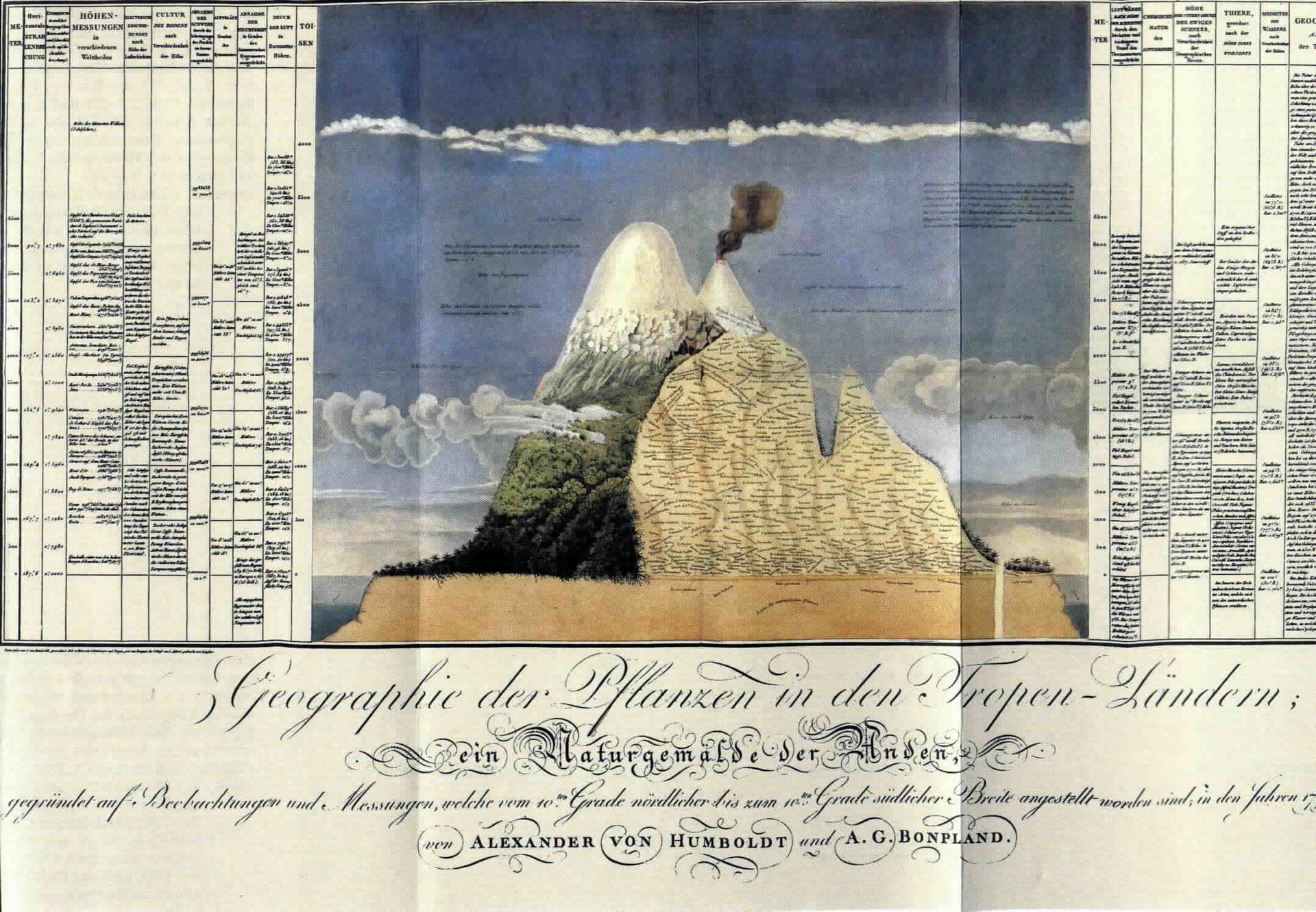

Humboldtian science defined Chimborazo Map, 1807 Humboldtian science includes both the extensive work of Alexander von Humboldt, as well as many of the works of 19th century scientists. Susan Cannon is attributed with coining the term Humboldtian science.[9] According to Cannon, Humboldtian science is, "the accurate, measured study of widespread but interconnected real phenomena in order to find a definite law and a dynamical cause."[10] Humboldtian science is used now in place of the traditional, "Baconianism," as a more appropriate and less vague term for the themes of 19th century science.[11] Natural history in the eighteenth century was the "nomination of the visible".[12] Carl Linnaeus was preoccupied with fitting all nature into taxonomy, fixated on only what was visible. Towards the turn of the eighteenth century, Immanuel Kant became interested in understanding where species derived from, and was less concerned with an organism's physical attributes. Next, Johann Reinhold Forster, one of Humboldt's future partners, became interested in the study of vegetation as an essential way of understanding nature and its relationship with human society. Proceeding Forster, Karl Willdenow examined floristic plant geography, the distribution of plants and regionality as a whole. All of these pieces in the history before Humboldt help to shape what is defined as Humboldtian science. Humboldt took into account both the outward appearance and inward meaning of plant species. His attention to natural aesthetics and empirical data and evidence is what set his scientific work apart from ecologists before him. Nicolson so aptly puts it as: "Humboldt effortlessly combined a commitment to empiricism and the experimental elucidation of the laws of nature with an equally strong commitment to holism and to a view of nature which was intended to be aesthetically and spiritually satisfactory".[13] It was through this holistic approach to science and the study of nature that Humboldt was able to find a web of interconnectedness despite a multitude of extensive differences between different species of organisms.[14] According to Malcolm Nicholson, "Susan Cannon characterized Humboldtian science as synthetic, empirical, quantitative and impossible to fit into any one of our twentieth century disciplinary boundaries."[9] A central element of Humboldtian science was its use of the latest advances in scientific instrumentation to observe and measure physical variables, while attending to all possible sources of error. Humboldtian science revolved around understanding the relationship between accurate measurement, sources of error and mathematical laws.[4] Cannon identifies four distinctive features that marked Humboldtian science out from previous versions of science:[15] insistence on accuracy for all scientific instruments and observations; a mental sophistication in which theoretical mechanisms and entities of past science were taken lightly; a new set of conceptual tools, including isomaps, graphs, and a theory of errors; the application of accuracy, mental sophistication, and tools not to isolated science in laboratories, but to greatly variable real phenomena. |

フンボルト的科学の定義 チンボラソの地図、1807年 フンボルト派の科学には、アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトの広範な研究と、19世紀の科学者の多くの研究が含まれる。スーザン・キャノンは、フンボル ト的科学という言葉を生み出したとされている。キャノンによれば、フンボルト的科学とは、「明確な法則と動的な原因を見出すために、広範囲に広がっている が相互に関連し合っている現実の現象を正確に測定して研究すること」[10]である。フンボルト的科学は、19世紀の科学のテーマを表す、より適切で曖昧 でない言葉として、現在では伝統的な「バコニア主義」の代わりに使われている。 18世紀の博物学は「目に見えるものの命名」であった[12]。カール・リンネはすべての自然を分類学に当てはめることに夢中になり、目に見えるものだけ に執着した。18世紀に入ると、イマヌエル・カントは種がどこから来たのかを理解することに関心を持ち、生物の物理的属性にはあまり関心を示さなくなっ た。次に、後にフンボルトのパートナーとなるヨハン・ラインホルト・フォルスターは、自然や人間社会との関係を理解するための不可欠な方法として、植生の 研究に興味を持つようになった。フォルスターに続いて、カール・ウィルデナウが植物地理学、植物の分布、地域性などを研究した。フンボルト以前の歴史にお けるこれらの断片はすべて、フンボルト的科学と定義されるものの形成に役立っている。フンボルトは植物種の外見と内面の意味の両方を考慮した。自然の美学 と経験的なデータと証拠に注意を払ったことが、彼の科学的な仕事を彼以前の生態学者と一線を画すものにしている。ニコルソンはこう言っている: 「フンボルトは、経験主義や自然の法則の実験的解明へのこだわりと、全体主義や、美学的・精神的に満足できる自然観への同じように強いこだわりを、難なく 結びつけていた」[13]。科学と自然研究に対するこの全体主義的なアプローチによって、フンボルトは、異なる生物種の間には多数の広範な違いがあるにも かかわらず、相互のつながりの網を見出すことができたのである[14]。 マルコム・ニコルソンによれば、「スーザン・キャノンはフンボルトの科学を、総合的で、経験的で、定量的で、20世紀の学問分野の境界のどれにも当てはめ ることが不可能なものとして特徴づけた。フンボルト派の科学は、正確な測定、誤差の原因、数学的法則の関係を理解することを中心に展開されていた[4]。 キャノンは、フンボルト派の科学がそれまでの科学と一線を画す特徴として、以下の4点を挙げている[15]。 すべての科学機器と観測の正確さへのこだわり; 過去の科学の理論的メカニズムや実体を軽んじる精神的洗練; アイソマップ、グラフ、誤差理論などの新しい概念的ツール群; 正確さ、精神的洗練、道具を、実験室での孤立した科学ではなく、大きく変化する現実の現象に適用すること。 |

Humboldt's "terrestrial physicist" Scientific travelers depicted on Humboldt's (and Caspar David Friedrich's) role model Humboldt was committed to what he called 'terrestrial physics.' Essentially Humboldt's new scientific approach required a new type of scientist: Humboldtian science demanded a transition from the naturalist to the physicist. Humboldt described how his idea of terrestrial physics differs from traditional "descriptive" natural history when he stated, "[traveling naturalists] have neglected to track the great and constant laws of nature manifested in the rapid flux of phenomena…and to trace the reciprocal interaction of the divided physical forces."[16] Humboldt did not consider himself an explorer, but rather a scientific traveler, who accurately measured what explorers had reported inaccurately.[17] According to Humboldt, the goal of the terrestrial physicist was to investigate the confluence and interweaving of all physical forces. An incredibly extensive array of precise instrumentation had to be readily available for Humboldt's terrestrial physicist. The expansive amount of scientific resources that characterized the Humboldtian scientist is best described in the book Science in Culture, Thus the complete Humboldtian traveller, in order to make satisfactory observations, should be able to cope with everything from the revolution of the satellites of Jupiter to the carelessness of clumsy donkeys.[18] Just some of such instruments included chronometers, telescopes, sextants, microscopes, magnetic compasses, thermometers, hygrometers, barometers, electrometers, and eudiometers. Furthermore, it was necessary to have multiple makes and models of each specific instrument to compare errors and constancy among each type.[16] |

フンボルトの 「地球物理学者」 フンボルト(とカスパー・ダーヴィト・フリードリヒ)をロールモデルにしたに科学旅行者(エコツーリスト)たち フンボルトは「地球物理学」と呼ばれるものに傾倒していた。本質的にフンボルトの新しい科学的アプローチは、新しいタイプの科学者を必要とした: フンボルトの科学は、自然主義者から物理学者への移行を要求したのである。フンボルトは、彼の考える地球物理学が従来の「記述的」博物学とどのように異な るかを、「(従来の博物学者は)現象の急速な流転に現れている偉大で不変の自然の法則を追跡し......分割された物理的な力の相互作用を追跡すること を怠ってきた。 「フンボルトは自らを探検家ではなく、むしろ探検家たちが不正確に報告したものを正確に測定する科学的な旅行者だと考えていた。フンボルトの地球物理学者 には、信じられないほど広範で精密な計測機器がすぐに利用できなければならなかった。フンボルトの科学者を特徴づける膨大な科学資源は、『文化の中の科 学』に最もよく書かれている、 したがって、フンボルト的な完全な旅行者は、満足のいく観測を行うために、木星の衛星の回転から不器用なロバの不注意まで、あらゆることに対処できなければならない[18]。 クロノメーター、望遠鏡、六分儀、顕微鏡、磁気コンパス、温度計、湿度計、気圧計、電位計、オイディオメーターなどである。さらに、各タイプの誤差や不変性を比較するために、特定の計器ごとに複数のメーカーやモデルを用意する必要があった[16]。 |

| Humboldt's equilibrium One concept that is central to Humboldtian science is that of a general equilibrium of forces. Humboldt explains: "The general equilibrium which reigns amongst disturbances and apparent turmoil, is the result of infinite number of mechanical forces and chemical attractions balancing each other out."[19] Equilibrium is derived from an infinite number of forces acting simultaneously and varying globally. In other words, the lawfulness of nature, according to Humboldt, is a result of infinity and complexity. Humboldtian science promotes the idea that the more forces that are accurately measured over more of the earth's surface results in a greater understanding of the order of nature.[20] The voyage to the Americas produced many discoveries and developments that help to illustrate Humboldt's ideas about this equilibrium of forces. Humboldt produced the Tableau physique des Andes ("Physical Profile of the Andes), which aimed at capturing his voyage to the Americas in a single graphic table. Humboldt meant to capture all of the physical forces, from organisms to electricity, in this single table. Among many other complex empirical recordings of elevation-specific data, the table included a detailed biodistribution.[19] This biodistribution mapped the specific distributions of flora and fauna at every elevation level on the mountain. Humboldt's study of plants provides an example of the movement of Humboldtian science away from traditional science. Humboldt's botany also further illustrates the concept of equilibrium and the Humboldtian ideas of the interrelationship of nature's elements. Although he was concerned with physical features of plants, he was largely focused on the investigation of underlying connections and relations among plant organisms.[21] Humboldt worked for years on developing an understanding of plant distributions and geography. The link between the balancing equilibrium of natural forces and organism distribution is evident when Humboldt states: As in all other phenomena of the physical universe, so in the distribution of organic beings: amidst the apparent disorder which seems to result from the influence of a multitude of local causes, the unchanging law of nature become evident as soon as one surveys an extensive territory, or uses a mass of facts in which the partial disturbances compensate one another.[22] The study of vegetation and plant geography arose out of new concerns that emerged with Humboldtian science. These new areas of concern in science included integrative processes, invisible connections, historical development, and natural wholes.[23] Humboldtian science applied the idea of general equilibrium of forces to the continuities in the history of the generation of the planet. Humboldt saw the history of the earth as a continuous global distribution of such things as heat, vegetation, and rock formations. In order to graphically represent this continuity Humboldt developed isothermal lines.[24] These isothermal lines functioned in the general balancing of forces in that isothermal lines preserved local peculiarities within a general regularity.[24] According to Humboldtian science, nature's order and equilibrium emerged "gradually and progressively from laborious observing, averaging, and mapping over increasingly extended areas."[22] |

フンボルトの均衡 フンボルトの科学の中心的な概念のひとつは、力の一般的な均衡である。フンボルトはこう説明する: 「乱れや見かけの混乱の中に君臨する一般的な均衡は、無限の機械的な力と化学的な吸引力が互いに均衡を保っている結果である。言い換えれば、フンボルトに よれば、自然の法則性は無限性と複雑性の結果である。フンボルトの科学は、より多くの力がより多くの地表で正確に測定されればされるほど、自然の摂理をよ り深く理解することになるという考えを推進している[20]。 アメリカ大陸への航海は、この力の均衡に関するフンボルトの考えを説明するのに役立つ多くの発見と発展をもたらした。フンボルトは、アメリカ大陸への航海 を一枚の図に収めることを目的とした『アンデスの物理的プロフィール』(Tableau physique des Andes)を作成した。フンボルトは、生物から電気に至るまで、あらゆる物理的な力をこの一つの表に収めようとしたのである。標高に特化した多くの複雑 な経験的記録の中で、この表には詳細な生物分布が含まれていた[19]。この生物分布は、山のあらゆる標高レベルにおける動植物の具体的な分布をマッピン グしたものである。 フンボルトの植物研究は、フンボルト的科学が伝統的な科学から離れていった一例を示している。フンボルトの植物学はまた、平衡の概念と、自然の諸要素の相 互関係に関するフンボルトの考え方をさらによく表している。フンボルトは植物の物理的特徴に関心を寄せてはいたが、植物生物間の根底にあるつながりや関係 を調べることに主眼を置いていた。自然の力の均衡と生物の分布との関連は、フンボルトが次のように述べていることからも明らかである: 物理的な宇宙の他のすべての現象と同様に、有機的な生物の分布においても、多数の局所的な原因の影響から生じるように思われる見かけ上の無秩序の中で、広 大な領域を調査したり、部分的な乱れが互いに補い合うような事実の塊を利用したりするとすぐに、自然の不変の法則が明らかになる」[22]。 植生学と植物地理学の研究は、フンボルト派の科学とともに出現した新たな関心事から生まれた。科学におけるこれらの新しい関心領域には、統合的なプロセス、目に見えないつながり、歴史的発展、自然の全体などが含まれていた[23]。 フンボルト派の科学は、力の一般的均衡の考え方を、地球の生成の歴史における連続性に適用した。フンボルトは地球の歴史を、熱、植生、岩層などの連続的な 地球規模の分布としてとらえた。この連続性を図式化するために、フンボルトは等温線を開発した[24]。これらの等温線は、等温線が一般的な規則性の中に 局所的な特殊性を保持するという点で、力の一般的な均衡において機能していた[24]。 フンボルトの科学によれば、自然の秩序と均衡は、「次第に拡大する領域にわたって、手間のかかる観察、平均化、マッピングを行うことによって、徐々に、そ して漸進的に」出現した[22]。 |

| Transformation of Humboldtian science Ralph Waldo Emerson once dubbed Humboldt to be "one of those wonders of the world… who appear from time to time, as if to show us the possibilities of the human mind."[25] When Humboldt first began his studies of organisms and the environment he claimed that he wanted to "reorganize the general connections that link organic beings and to study the great harmonies of Nature".[26] He is often considered one of the world's first genuine ecologists.[26] Humboldt succeeded in developing a comprehensive science that joined the separate branches of natural philosophy under a model of natural order founded on the concept of dynamic equilibrium. Humboldt's work reached far beyond his personal expeditions and discoveries. Figures from all across the globe participated on his work. Some such participants included French naval officers, East India Company physicians, Russian provincial administrators, Spanish military commanders, and German diplomats. As was mentioned previously, Charles Darwin carried a copy of Humboldt's Personal Narrative aboard H.M.S. Beagle.[27] Humboldt's projects, particularly those related to natural philosophy, played a significant role in the influx of European money and travelers to Spanish America in increasing numbers in the early 19th century.[28] Sir Edward Sabine, a British scientist, worked on terrestrial magnetism in a manner that was certainly Humboldtian. Also, British scientist George Gabriel Stokes depended heavily on abstract mathematical measurement to deal with error in a precision instrument, certainly Humboldtian science. Maybe the most prominent figure whose work can be considered representative of Humboldtian science is geologist Charles Lyell. Despite a lack of emphasis on precise measurement in geology at the time, Lyell insisted on precision in a Humboldtian manner.[29] The promotion and development of terrestrial physics under Humboldtian science produced not only useful maps and statistics, but offered both European and Creole societies tools for essentially 're-imaging' America.[30] The lasting impact of Humboldtian science is described in Cultures of Natural History, "Humboldtian science illuminates the reorganization of knowledge and disciplines in the early nineteenth century that defined the emergence of natural history out of natural philosophy."[31] |

フンボルト科学の変貌 ラルフ・ワルド・エマーソンはかつて、フンボルトを「まるで人間の心の可能性を示すかのように、時折現れる...世界の驚異の一人」と呼んだ[25]。 フンボルトが生物と環境の研究を始めた当初、彼は「有機的な存在をつなぐ一般的なつながりを再編成し、自然の偉大な調和を研究したい」と主張していた。 フンボルトはしばしば、世界初の本格的な生態学者の一人と見なされる。フンボルトは、動的平衡の概念に基づく自然秩序のモデルの下に、自然哲学の別々の分 野を統合する包括的な科学を発展させることに成功した。フンボルトの研究は、個人的な探検や発見の域をはるかに超えていた。フンボルトの研究には、世界中 から多くの人々が参加した。フランスの海軍士官、東インド会社の医師、ロシアの地方行政官、スペインの軍司令官、ドイツの外交官などである。前述したよう に、チャールズ・ダーウィンはフンボルトの『個人的な物語』のコピーをH.M.S.ビーグル号に積んでいた[27]。フンボルトのプロジェクト、特に自然 哲学に関連するプロジェクトは、19世紀初頭、スペイン領アメリカへのヨーロッパの資金と旅行者の流入増加に重要な役割を果たした[28]。イギリスの科 学者エドワード・サビーン卿は、確かにフンボルト的な方法で地磁気の研究に取り組んだ。また、イギリスの科学者ジョージ・ガブリエル・ストークスは、精密 機器の誤差に対処するために抽象的な数学的測定に大きく依存していた。フンボルト的科学を代表する最も著名な人物は、地質学者のチャールズ・ライエルであ ろう。当時の地質学では精密な測定が重視されていなかったにもかかわらず、ライエルはフンボルト流の精密さを主張した[29]。 フンボルト的科学の下での地球物理学の推進と発展は、有用な地図や統計を生み出しただけでなく、ヨーロッパ社会とクレオール社会の双方に、本質的にアメリ カを「再イメージ」するためのツールを提供した[30]。 フンボルト的科学の永続的な影響については、『博物学の文化』の中で「フンボルト的科学は、自然哲学から博物学が出現することを規定した、19世紀初頭に おける知識と学問分野の再編成を照らし出している」と述べられている[31]。 |

| Revision of Humboldtian science as a concept In recent years, historian Andreas Daum has explored the history of Humboldtian science as a concept and suggests a fundamental revision.[32] He points out that William Goetzman was the first to establish it. Daum distinguishes between Humboldt's science as an individual form of knowledge production and Humboldtian science as a generalization (and useful ideal type), which later generations coined. Humboldt's science constituted a set of research practices that often defied the ideal of precision and minute comparative data analysis, which Humboldtian science in Cannon's understanding sees as the foundation of large-scale scientific research. Especially in his early years before leaving Europe to the Americas in 1799, Humboldt's research was impromptu, marked by epistemological and personal insecurities, and embedded in his peripatetic way of living. The constant moving around found its expression in an erratic writing style.[33] The revision of Humboldtian Science and a renewed focus on Humboldt’s science undermine the "Humboldt exceptionalism" (Daum)[34] found especially in popular accounts, such as Andrea Wulf's book on the Invention of Nature. This critical approach places Humboldt and his oeuvre firmly in the turbulent epoch he lived in – instead of portraying Humboldt as a man above his time.[35] A review of Humboldtian science encourages historians to study standards of ‘objectivity’ and the belief in instruments yieding precise results as its guarantee. While Humboldt did advocate using widespread comparative measurements and strove to achieve accuracy in his research, his research practices often missed that ideal. |

フンボルト的科学という概念の再考 近年、歴史家アンドレアス・ダウムはフンボルト的科学という概念の歴史を探求し、根本的な再考を提案している[32]。彼はウィリアム・ゲッツマンが最初 にこの概念を確立した人物だと指摘する。ダウムは、知識生産の個別形態としてのフンボルトの科学と、後世の世代が作り出した一般化(そして有用な理想類 型)としてのフンボルト的科学とを区別する。フンボルトの科学は、精密さと詳細な比較データ分析という理想にしばしば背く一連の研究実践を構成していた。 キャノンの理解におけるフンボルト的科学は、大規模な科学研究の基盤をこうした理想に見出している。特に1799年にヨーロッパを離れてアメリカ大陸へ渡 る以前の初期段階において、フンボルトの研究は即興的で、認識論的・個人的な不安定さが特徴であり、彼の放浪的な生活様式に組み込まれていた。絶え間ない 移動は、不安定な執筆スタイルに表れていた。[33] フンボルト科学の再考とフンボルトの科学への新たな焦点化は、特にアンドレア・ウルフの『自然の発明』のような大衆向け著作に見られる「フンボルト例外主 義」(ダウム)[34]を弱体化させる。この批判的アプローチは、フンボルトを時代を超越した人物として描く代わりに、彼とその業績を彼が生き抜いた激動 の時代にしっかりと位置づける。[35] フンボルト科学の再検討は、歴史家たちに「客観性」の基準と、それを保証する精密な結果をもたらすという器具への信頼を研究するよう促す。確かにフンボル トは広範な比較測定の使用を提唱し、研究の正確性を追求したが、その研究実践はしばしばその理想に届かなかった。 |

| History of biology History of ecology History of geography History of geology Romanticism Romanticism in science |

生物学の歴史 生態学の歴史 地理学の歴史 地質学の歴史 ロマン主義 科学におけるロマン主義 |

| 1. Böhme, Hartmut: Ästhetische Wissenschaft, in: Matices, Nr. 23, 1999, S. 37-41 2. Cannon, Susan Faye: Science in Culture: The Early Victorian Period, New York 1978 3. Dettelbach, Michael: "Humboldtian Science", in: Jardine, N./Secord, J./Sparry, E. C.(eds): Cultures of Natural History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1996 4. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 288 5. Cannon, Science in Culture, p. 86 6. Nicolson, Malcolm. 1987. "Alexander von Humboldt, Humboldtian science, and the origins of the study of vegetation." History of Science. 25: 167-194. 7. Home, Roderick Weir. 1995. "Humboldtian Science revisited: an Australian case study." History of Science. 33: 1-22. 8. Cannon, Susan Faye. 1978. Science in culture: the early Victorian period. Kent, Eng:Dawon. 9. Nicolson, "Alexander von Humboldt, Humboldtian science, and the origins of the study of vegetation," p. 167 10. Cannon, Science in Culture, p. 105 11. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 287 12. Nicolson, Malcolm. 1987. "Alexander von Humboldt, Humboldtian science, and the origins of the study of vegetation." History of Science. 25: 169. 13. Nicolson, Malcolm. 1987. "Alexander von Humboldt, Humboldtian science, and the origins of the study of vegetation." History of Science. 25: 180. 14. Home, Roderick Weir. 1995. "Humboldtian Science revisited: an Australian case study." History of Science. 33: 17. 15. Cannon, Science in Culture, p. 104 16. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 289 17. Cannon, Science in Culture, p. 75 18. Cannon, Science in Culture, p. 76 19. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 290 20.Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 291 21. Nicolson, "Alexander von Humboldt, Humboldtian science, and the origins of the study of vegetation," p. 175 22. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 298 23. Nicolson, "Alexander von Humboldt, Humboldtian science, and the origins of the study of vegetation," p. 176 24.Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 295 25. Sachs, Aaron. The Humboldt Current. New York: Viking, 2008, p.4 26. Sachs, Aaron. The Humboldt Current. New York: Viking, 2008, p.2 27. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 300 28. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 301 29. Cannon, Science in Culture, p. 83 30. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 302 31. Jardine et al., Cultures of Natural History, p. 304 32. Daum, Andreas W. (2024). "Humboldtian Science and Humboldt's Science". History of Science. 62. doi:10.1177/00732753241252478. PMID 38770782. 33. Daum, Andreas W. (2019). "Social Relations, Shared Practices, and Emotions: Alexander von Humboldt's Excursion into Literary Classicism and the Challenges to Science around 1800". Journal of Modern History. 91 ((March 2019)): 1–37. doi:10.1086/701757. 34. Daum, Andreas W. Daum (2024). "Humboldtian Science and Humboldt's science". History of Science. 62. doi:10.1177/00732753241252478. 35. Daum, Andreas W. (2024). Alexander von Humboldt: A Concise Biography. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-24736-6. |

1. Böhme, Hartmut: Ästhetische Wissenschaft, in: Matices, Nr. 23, 1999, S. 37-41 2. Cannon, Susan Faye: Science in Culture: The Early Victorian Period, New York 1978 3. Dettelbach, Michael: 「フンボルトの科学」、ジャーディン、N./セコード、J./スパリー、E. C. (編): 『自然史の文化』、ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局 1996 4. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、288 ページ 5. キャノン、『文化における科学』、86 ページ 6. ニコルソン、マルコム。1987年。「アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト、フンボルトの科学、そして植物学の研究の起源」『科学の歴史』25: 167-194。 7. ホーム、ロデリック・ウィアー。1995年。「フンボルトの科学再考:オーストラリアの事例研究」『科学の歴史』33: 1-22。 8. キャノン、スーザン・フェイ。1978年。『文化における科学:ビクトリア朝初期』。英国ケント:ドーワン。 9. ニコルソン、「アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト、フンボルトの科学、および植物学の研究の起源」、167ページ 10. キャノン、『文化における科学』、105ページ 11. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、287 ページ 12. ニコルソン、マルコム。1987 年。「アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト、フンボルトの科学、および植物学の研究の起源」『科学史』25: 169。 13. ニコルソン、マルコム。1987 年。「アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト、フンボルトの科学、そして植物学研究の起源」『科学の歴史』25: 180。 14. ホーム、ロデリック・ウィアー。1995年。「フンボルトの科学を再考する:オーストラリアの事例研究」『科学の歴史』33: 17。 15. キャノン、『文化における科学』、104ページ 16. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、289 ページ 17. キャノン、『文化における科学』、75 ページ 18. キャノン、『文化における科学』、76 ページ 19. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、290 ページ 20. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、291 ページ 21. ニコルソン、「アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト、フンボルトの科学、そして植物学研究の起源」、175 ページ 22. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、298 ページ 23. ニコルソン、「アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト、フンボルトの科学、そして植物学研究の起源」、176 ページ 24. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、295 ページ 25. サックス、アーロン。『フンボルト海流』。ニューヨーク:バイキング、2008 年、4 ページ 26. サックス、アーロン。『フンボルト海流』。ニューヨーク:バイキング、2008 年、2 ページ 27. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、300 ページ 28. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、301 ページ 29. キャノン、『文化における科学』、83 ページ 30. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、302 ページ 31. ジャーディン他、『自然史の文化』、304 ページ 32. Daum, Andreas W. (2024). 「フンボルトの科学とフンボルトの科学」. 科学史. 62. doi:10.1177/00732753241252478. PMID 38770782. 33. Daum, Andreas W. (2019). 「社会的関係、共有された実践、そして感情:アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトの文学的古典主義への遠征と 1800 年前後の科学への挑戦」. 現代史ジャーナル. 91 ((2019年3月)): 1–37. doi:10.1086/701757. 34. Daum, Andreas W. Daum (2024). 「フンボルトの科学とフンボルトの科学」. History of Science. 62. doi:10.1177/00732753241252478. 35. Daum, Andreas W. (2024). 『アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト:簡潔な伝記』. ニュージャージー州プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-691-24736-6. |

| References Cannon, Susan Faye. Science in Culture: The Early Victorian Period. Science History Publications. NY. 1978 Andreas W. Daum, "Humboldtian Science and Humboldt’s Science". History of Science, 62 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/00732753241252478 Andreas W. Daum, “Social Relations, Shared Practices, and Emotions: Alexander von Humboldt’s Excursion into Literary Classicism and the Challenges to Science around 1800”. The Journal of Modern History, 91 (March 2019), 1-37. Andreas W. Daum, Alexander von Humboldt: A Concise Biography. Trans. Robert Savage. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024. Jardine, N; Secord, J.A.; Spary, E.C. Cultures of Natural History. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, NY. 1996 Nicolson, Malcolm. "Alexander von Humboldt, Humboldtian science, and the origins of the study of vegetation." History of Science, 25:2. June 1987 |

参考文献 キャノン、スーザン・フェイ。『文化の中の科学:初期ヴィクトリア朝時代』。サイエンス・ヒストリー・パブリケーションズ。ニューヨーク。1978年 アンドレアス・W・ダウム、「フンボルトの科学とフンボルトの科学」。科学の歴史、62 (2024)、https://doi.org/10.1177/00732753241252478 アンドレアス・W・ダウム、「社会的関係、共有された慣習、そして感情:アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトの文学的古典主義への遠征と 1800 年前後の科学への挑戦」。The Journal of Modern History, 91 (March 2019), 1-37. Andreas W. Daum, Alexander von Humboldt: A Concise Biography. Trans. Robert Savage. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024. ジャーディン、N、セコード、J.A.、スペリー、E.C. 『自然史の文化』 ケンブリッジ大学出版局、ニューヨーク州ケンブリッジ、1996年 ニコルソン、マルコム。「アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト、フンボルトの科学、そして植物学研究の起源」 『科学史』 25:2、1987年6月 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humboldtian_science |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆