知能指数(IQ)

Intelligence quotient, IQ

☆知能指数(IQ)とは、人間の知能を評価するために設計された一連の標 準化されたテストまたは下位テストから得られる合計得点のことである。IQという略語は、心理学者ウィリアム・スターンが1912年の著書で提唱し たブレスラウ大学での知能テストの採点方法を表すドイツ語のIntelligenzquotientという用語から作られたものである。

| An intelligence

quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardised tests

or subtests designed to assess human intelligence.[1] The abbreviation

"IQ" was coined by the psychologist William Stern for the German term

Intelligenzquotient, his term for a scoring method for intelligence

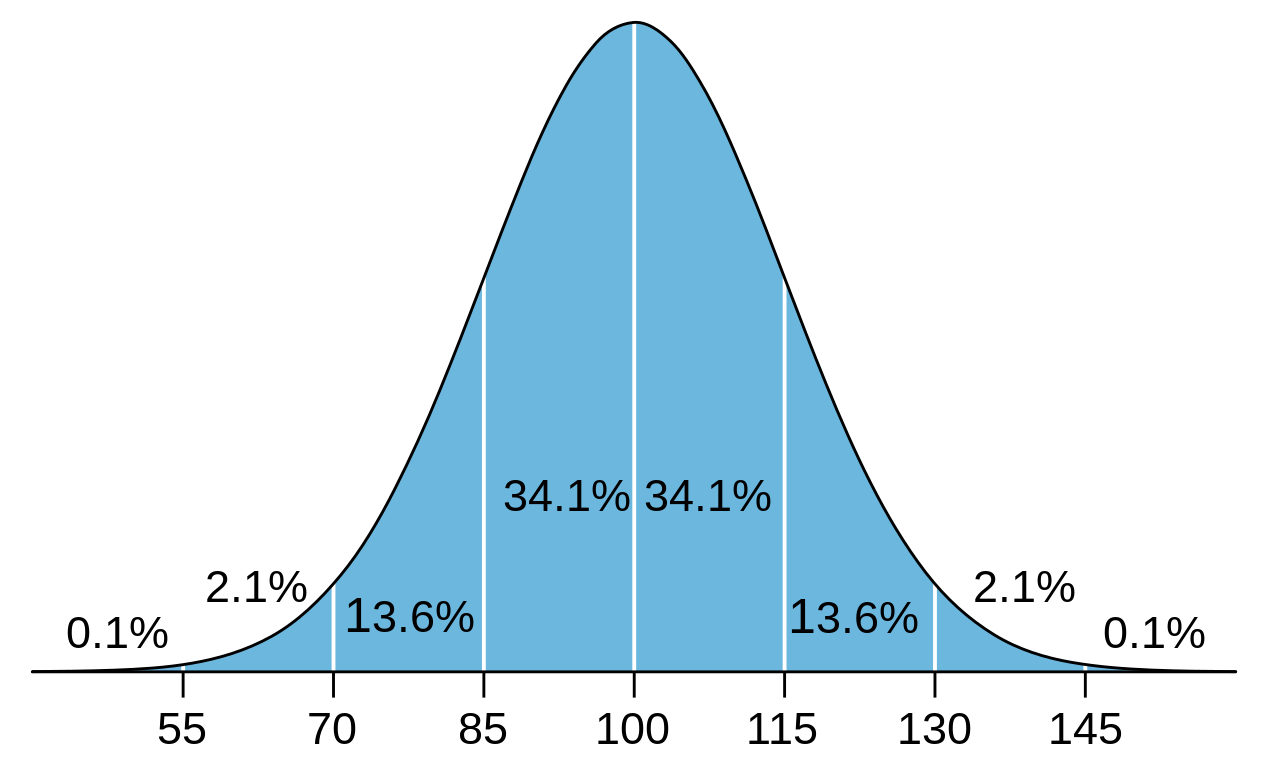

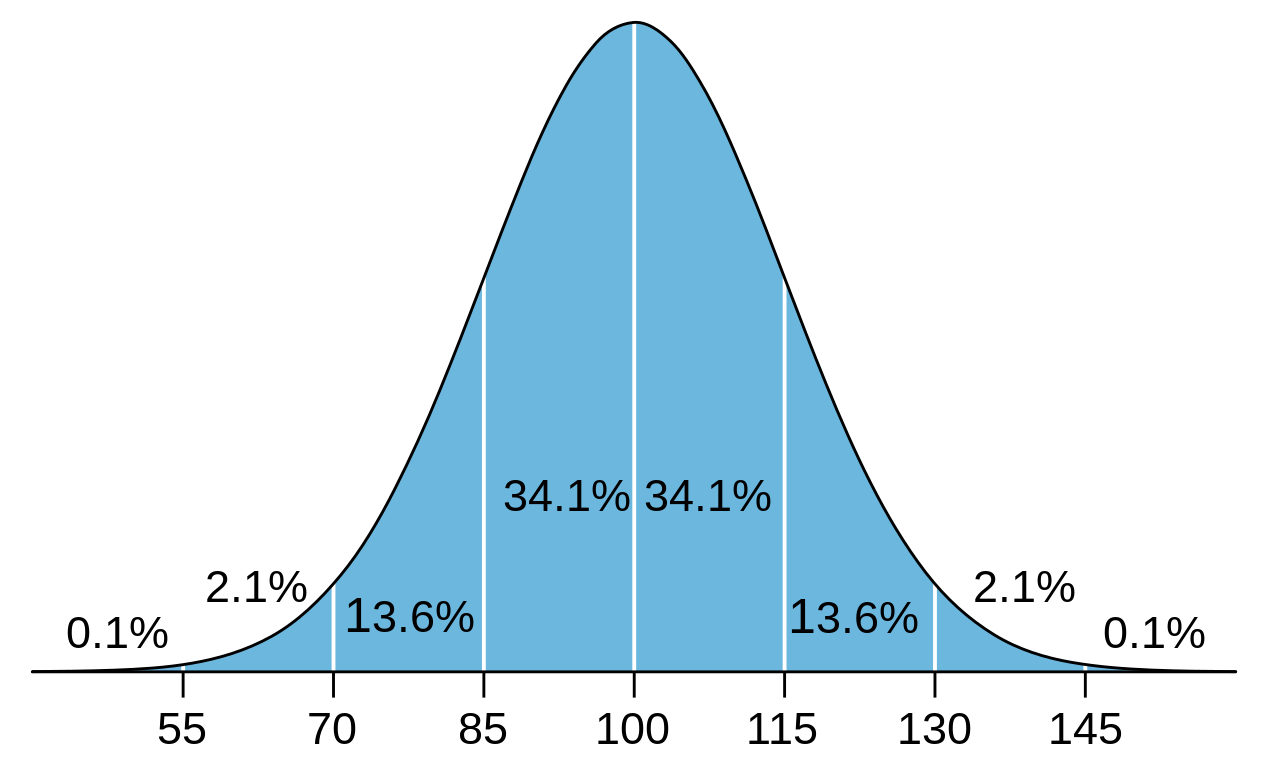

tests at University of Breslau he advocated in a 1912 book.[2] Historically, IQ was a score obtained by dividing a person's mental age score, obtained by administering an intelligence test, by the person's chronological age, both expressed in terms of years and months. The resulting fraction (quotient) was multiplied by 100 to obtain the IQ score.[3] For modern IQ tests, the raw score is transformed to a normal distribution with mean 100 and standard deviation 15.[4] This results in approximately two-thirds of the population scoring between IQ 85 and IQ 115 and about 2 percent each above 130 and below 70.[5][6] Scores from intelligence tests are estimates of intelligence. Unlike, for example, distance and mass, a concrete measure of intelligence cannot be achieved given the abstract nature of the concept of "intelligence".[7] IQ scores have been shown to be associated with such factors as nutrition,[8][9][10] parental socioeconomic status,[11][12] morbidity and mortality,[13][14] parental social status,[15] and perinatal environment.[16] While the heritability of IQ has been investigated for nearly a century, there is still debate about the significance of heritability estimates[17][18] and the mechanisms of inheritance.[19] IQ scores are used for educational placement, assessment of intellectual disability, and evaluating job applicants. In research contexts, they have been studied as predictors of job performance[20] and income.[21] They are also used to study distributions of psychometric intelligence in populations and the correlations between it and other variables. Raw scores on IQ tests for many populations have been rising at an average rate that scales to three IQ points per decade since the early 20th century, a phenomenon called the Flynn effect. Investigation of different patterns of increases in subtest scores can also inform current research on human intelligence. |

知能指数(IQ)とは、人間の知能を評価するために設計された一連の標

準化されたテストまたは下位テストから得られる合計得点のことである[1]。IQという略語は、心理学者ウィリアム・スターンが1912年の著書で提唱し

たブレスラウ大学での知能テストの採点方法を表すドイツ語のIntelligenzquotientという用語から作られたものである[2]。 歴史的には、IQは知能テストを実施することで得られる精神年齢のスコアを、年や月で表されるその人の年代で割ることで得られるスコアであった。現代の IQテストでは、生のスコアは平均100、標準偏差15の正規分布に変換される[4]。この結果、人口の約3分の2がIQ85からIQ115の間でスコア を獲得し、130以上と70以下はそれぞれ約2%となる[5][6]。 知能テストのスコアは知能の推定値である。IQスコアは、栄養状態[8][9][10]、親の社会経済状態[11][12]、罹患率と死亡率[13] [14]、親の社会的地位[15]、周産期環境[16]などの因子と関連していることが示されている。 [16] IQの遺伝率については1世紀近く研究されているが、遺伝率の推定値の重要性[17][18]や遺伝のメカニズムについてはまだ議論がある[19]。 IQスコアは、教育上の位置づけ、知的障害の評価、就職希望者の評価に使用されている。研究面では、職務遂行能力[20]や所得の予測因子として研究され ている[21]。多くの集団のIQテストの生得点は、20世紀初頭以来、10年に3IQポイントずつ平均的に上昇しており、これはフリン効果と呼ばれる現 象である。この現象はフリン効果と呼ばれている。下位検査の得点の上昇のさまざまなパターンを調べることは、人間の知能に関する現在の研究にも役立つ。 ICD-10-PCS Z01.8 ICD-9-CM 94.01 |

| Precursors to IQ testing Historically, even before IQ tests were devised, there were attempts to classify people into intelligence categories by observing their behavior in daily life.[22][23] Those other forms of behavioral observation are still important for validating classifications based primarily on IQ test scores. Both intelligence classification by observation of behavior outside the testing room and classification by IQ testing depend on the definition of "intelligence" used in a particular case and on the reliability and error of estimation in the classification procedure. The English statistician Francis Galton (1822–1911) made the first attempt at creating a standardized test for rating a person's intelligence. A pioneer of psychometrics and the application of statistical methods to the study of human diversity and the study of inheritance of human traits, he believed that intelligence was largely a product of heredity (by which he did not mean genes, although he did develop several pre-Mendelian theories of particulate inheritance).[24][25][26] He hypothesized that there should exist a correlation between intelligence and other observable traits such as reflexes, muscle grip, and head size.[27] He set up the first mental testing center in the world in 1882 and he published "Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development" in 1883, in which he set out his theories. After gathering data on a variety of physical variables, he was unable to show any such correlation, and he eventually abandoned this research.[28][29] Psychologist Alfred Binet, co-developer of the Stanford–Binet test French psychologist Alfred Binet, together with Victor Henri and Théodore Simon, had more success in 1905, when they published the Binet–Simon test, which focused on verbal abilities. It was intended to identify "mental retardation" in school children,[30] but in specific contradistinction to claims made by psychiatrists that these children were "sick" (not "slow") and should therefore be removed from school and cared for in asylums.[31] The score on the Binet–Simon scale would reveal the child's mental age. For example, a six-year-old child who passed all the tasks usually passed by six-year-olds—but nothing beyond—would have a mental age that matched his chronological age, 6.0. (Fancher, 1985). Binet thought that intelligence was multifaceted, but came under the control of practical judgment. In Binet's view, there were limitations with the scale and he stressed what he saw as the remarkable diversity of intelligence and the subsequent need to study it using qualitative, as opposed to quantitative, measures (White, 2000). American psychologist Henry H. Goddard published a translation of it in 1910. American psychologist Lewis Terman at Stanford University revised the Binet–Simon scale, which resulted in the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales (1916). It became the most popular test in the United States for decades.[30][32][33][34] |

IQテストの前身 歴史的には、IQテストが考案される以前から、日常生活での行動を観察することによって人々を知能カテゴリーに分類する試みが行われていた[22] [23]。そうした他の形態の行動観察は、主にIQテストのスコアに基づく分類を検証する上で今でも重要である。検査室の外での行動観察による知能分類 も、IQ検査による分類も、特定のケースで使用される「知能」の定義と、分類手順における推定の信頼性と誤差に左右される。 イギリスの統計学者フランシス・ガルトン(1822-1911)は、人の知能を評価するための標準化されたテストを作成する最初の試みを行った。心理測定 学と人間の多様性の研究と人間の形質の遺伝の研究への統計的手法の応用のパイオニアである彼は、知能は大部分が遺伝の産物であると信じていた(これは遺伝 子を意味しないが、彼は粒子遺伝に関するいくつかのメンデル以前の理論を開発した)。 [24][25][26]彼は、知能と反射神経、筋肉の握力、頭の大きさなど他の観察可能な特徴との間に相関関係が存在するはずだという仮説を立てた。様 々な物理的変数のデータを収集した後、彼はそのような相関関係を示すことができず、最終的にこの研究を放棄した[28][29]。 心理学者アルフレッド・ビネ、スタンフォード・ビネ・テストの共同開発者 フランスの心理学者アルフレッド・ビネは、ヴィクトール・アンリとテオドール・シモンとともに、1905年に言語能力に焦点を当てたビネー・シモンテスト を発表し、さらなる成功を収めた。このテストは、学童の「精神遅滞」を識別することを意図していたが[30]、精神科医による、これらの子どもは「病気」 (「遅滞」ではない)であり、したがって学校から排除され、精神病院でケアされるべきであるという主張とは明確に矛盾していた[31]。ビネー=シモン・ スケールの得点は、子どもの精神年齢を明らかにするものであった。例えば、6歳児が通常通過する課題をすべて通過したが、それ以上の課題は何も通過しな かった6歳児は、精神年齢が彼の年齢である6.0と一致することになる(Fancher, 1985)。(Fancher, 1985)。ビネは、知能は多面的であるが、実践的判断力の支配下にあると考えた。 ビネの見解では、尺度には限界があり、彼は知能の驚くべき多様性と、それに続く、量的尺度とは対照的な質的尺度を用いた研究の必要性を強調した (White, 2000)。アメリカの心理学者ヘンリー・H・ゴダードは、1910年にこの尺度の翻訳を出版した。スタンフォード大学のアメリカ人心理学者ルイス・ター マンは、ビネー=サイモン尺度を改訂し、スタンフォード=ビネー知能尺度(Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales)(1916年)を生み出した。これは数十年にわたり米国で最も人気のあるテストとなった[30][32][33][34]。 |

| General factor (g) Main article: g factor The many different kinds of IQ tests include a wide variety of item content. Some test items are visual, while many are verbal. Test items vary from being based on abstract-reasoning problems to concentrating on arithmetic, vocabulary, or general knowledge. The British psychologist Charles Spearman in 1904 made the first formal factor analysis of correlations between the tests. He observed that children's school grades across seemingly unrelated school subjects were positively correlated, and reasoned that these correlations reflected the influence of an underlying general mental ability that entered into performance on all kinds of mental tests. He suggested that all mental performance could be conceptualized in terms of a single general ability factor and a large number of narrow task-specific ability factors. Spearman named it g for "general factor" and labeled the specific factors or abilities for specific tasks s.[35] In any collection of test items that make up an IQ test, the score that best measures g is the composite score that has the highest correlations with all the item scores. Typically, the "g-loaded" composite score of an IQ test battery appears to involve a common strength in abstract reasoning across the test's item content.[citation needed] |

一般因子(g) 主な記事:g因子 IQテストにはさまざまな種類があり、その項目内容も多種多様である。視覚的なものもあれば、言語的なものもある。テスト項目は、抽象的な推論問題に基づ くものから、算数、語彙、一般知識に集中したものまでさまざまである。 1904年、イギリスの心理学者チャールズ・スピアマンは、テスト間の相関関係を初めて公式に因子分析した。彼は、一見無関係に見える学校の教科の成績が 正の相関関係にあることを観察し、これらの相関関係は、あらゆる種類の精神テストの成績に影響する、根底にある一般的な精神能力の影響を反映していると推 論した。彼は、すべての精神的能力は、単一の一般的能力因子と多数の狭い課題特異的能力因子から概念化できると示唆した。スピアマンはこれを「一般因子」 を意味するgと名付け、特定の課題に対する特定の因子または能力をsと名付けた[35]。IQテストを構成するどのようなテスト項目の集合においても、g を最もよく測定するスコアは、すべての項目スコアとの相関が最も高い複合スコアである。典型的には、IQテストバッテリーの「g負荷」複合スコアは、テス トの項目内容全体にわたって抽象的推論の共通の強さに関与しているようである[要出典]。 |

| United States military selection

in World War I During World War I, the Army needed a way to evaluate and assign recruits to appropriate tasks. This led to the development of several mental tests by Robert Yerkes, who worked with major hereditarians of American psychometrics—including Terman, Goddard—to write the test.[36] The testing generated controversy and much public debate in the United States. Nonverbal or "performance" tests were developed for those who could not speak English or were suspected of malingering.[30] Based on Goddard's translation of the Binet–Simon test, the tests had an impact in screening men for officer training: ...the tests did have a strong impact in some areas, particularly in screening men for officer training. At the start of the war, the army and national guard maintained nine thousand officers. By the end, two hundred thousand officers presided, and two- thirds of them had started their careers in training camps where the tests were applied. In some camps, no man scoring below C could be considered for officer training.[36] In total 1.75 million men were tested, making the results the first mass-produced written tests of intelligence, though considered dubious and non-usable, for reasons including high variability of test implementation throughout different camps and questions testing for familiarity with American culture rather than intelligence.[36] After the war, positive publicity promoted by army psychologists helped to make psychology a respected field.[37] Subsequently, there was an increase in jobs and funding in psychology in the United States.[38] Group intelligence tests were developed and became widely used in schools and industry.[39] The results of these tests, which at the time reaffirmed contemporary racism and nationalism, are considered controversial and dubious, having rested on certain contested assumptions: that intelligence was heritable, innate, and could be relegated to a single number, the tests were enacted systematically, and test questions actually tested for innate intelligence rather than subsuming environmental factors.[36] The tests also allowed for the bolstering of jingoist narratives in the context of increased immigration, which may have influenced the passing of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924.[36] L.L. Thurstone argued for a model of intelligence that included seven unrelated factors (verbal comprehension, word fluency, number facility, spatial visualization, associative memory, perceptual speed, reasoning, and induction). While not widely used, Thurstone's model influenced later theories.[30] David Wechsler produced the first version of his test in 1939. It gradually became more popular and overtook the Stanford–Binet in the 1960s. It has been revised several times, as is common for IQ tests, to incorporate new research. One explanation is that psychologists and educators wanted more information than the single score from the Binet. Wechsler's ten or more subtests provided this. Another is that the Stanford–Binet test reflected mostly verbal abilities, while the Wechsler test also reflected nonverbal abilities. The Stanford–Binet has also been revised several times and is now similar to the Wechsler in several aspects, but the Wechsler continues to be the most popular test in the United States.[30] |

第一次世界大戦におけるアメリカ軍の選抜 第一次世界大戦中、陸軍は新兵を評価し、適切な任務に就かせる方法を必要としていた。このため、ロバート・ヤーキスは、ターマンやゴダードを含むアメリカ の心理測定学の主要な遺伝学者と協力して、いくつかの精神テストを開発した[36]。英語が話せない人や仮病の疑いがある人のために、非言語テストや「パ フォーマンス」テストが開発された[30]。ゴダードによるビネー・サイモンテストの翻訳に基づき、このテストは将校訓練に参加する男性のスクリーニング に影響を与えた: ......テストは、特に将校訓練のための人選において、いくつかの分野で強い影響を与えた。開戦時、陸軍と州兵は9000人の将校を維持していた。戦 争末期には20万人の将校が配属され、その3分の2はテストが適用された訓練キャンプでキャリアをスタートさせた。一部の訓練所では、C点以下の者は将校 訓練に参加することができなかった[36]。 総計175万人の兵士がテストを受け、その結果は初めて大量生産された筆記式の知能テストとなったが、テストの実施に収容所によってばらつきが大きいこと や、知能よりもむしろアメリカ文化への親しみをテストする問題が出題されたことなどから、疑わしいものであり、使いものにならないと考えられていた [36]。 戦後、陸軍心理学者によって推進された積極的な宣伝は、心理学を尊敬される分野にするのに役立った[37]。 当時、現代の人種差別とナショナリズムを再確認するものであったこれらのテストの結果は、論争的で疑わしいものであったと考えられており、それは、知能は 遺伝性であり、生まれつきのものであり、単一の数値に降格させることができること、テストは体系的に実施されること、テスト問題は環境要因を包含するので はなく、生まれつきの知能を実際にテストするものであることなど、ある種の論争的な前提の上に成り立っていた。 [36]またこのテストは、移民の増加という背景のもとでジンゴイスト的な物語を強化することを可能にし、1924年の移民制限法の成立に影響を与えた可 能性がある[36]。 L.L.サーストーンは、7つの関連性のない要素(言語理解、言葉の流暢さ、数の能力、空間的視覚化、連想記憶、知覚速度、推論、帰納)を含む知能のモデ ルを主張した。広く使用されることはなかったが、サース トーンのモデルは後の理論に影響を与えた[30]。 デイヴィッド・ウェクスラーは1939年に彼のテストの最初のバージョンを作成した。このテストは徐々に普及し、1960年代にはスタンフォード・ビーネ を追い越した。IQテストではよくあることだが、新しい研究を取り入れるために何度か改訂されている。その理由のひとつは、心理学者や教育者たちが、ビ ネットの単一スコアよりも多くの情報を求めたからである。ウェクスラーの10以上の下位テストは、これを提供した。もうひとつは、スタンフォード・ビネテ ストは主に言語能力を反映していたのに対し、ウェクスラーテストは非言語能力も反映していたことである。スタンフォード・ビネーテストも何度か改訂され、 現在ではいくつかの点でウェクスラーテストと類似しているが、ウェクスラーテストは米国で最も人気のあるテストであり続けている[30]。 |

| IQ testing and the eugenics

movement in the United States Eugenics, a set of beliefs and practices aimed at improving the genetic quality of the human population by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior and promoting those judged to be superior,[40][41][42] played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States during the Progressive Era, from the late 19th century until US involvement in World War II.[43][44] The American eugenics movement was rooted in the biological determinist ideas of the British Scientist Sir Francis Galton. In 1883, Galton first used the word eugenics to describe the biological improvement of human genes and the concept of being "well-born".[45][46] He believed that differences in a person's ability were acquired primarily through genetics and that eugenics could be implemented through selective breeding in order for the human race to improve in its overall quality, therefore allowing for humans to direct their own evolution.[47] Henry H. Goddard was a eugenicist. In 1908, he published his own version, The Binet and Simon Test of Intellectual Capacity, and cordially promoted the test. He quickly extended the use of the scale to the public schools (1913), to immigration (Ellis Island, 1914) and to a court of law (1914).[48] Unlike Galton, who promoted eugenics through selective breeding for positive traits, Goddard went with the US eugenics movement to eliminate "undesirable" traits.[49] Goddard used the term "feeble-minded" to refer to people who did not perform well on the test. He argued that "feeble-mindedness" was caused by heredity, and thus feeble-minded people should be prevented from giving birth, either by institutional isolation or sterilization surgeries.[48] At first, sterilization targeted the disabled, but was later extended to poor people. Goddard's intelligence test was endorsed by the eugenicists to push for laws for forced sterilization. Different states adopted the sterilization laws at different paces. These laws, whose constitutionality was upheld by the Supreme Court in their 1927 ruling Buck v. Bell, forced over 60,000 people to go through sterilization in the United States.[50] California's sterilization program was so effective that the Nazis turned to the government for advice on how to prevent the birth of the "unfit".[51] While the US eugenics movement lost much of its momentum in the 1940s in view of the horrors of Nazi Germany, advocates of eugenics (including Nazi geneticist Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer) continued to work and promote their ideas in the United States.[51] In later decades, some eugenic principles have made a resurgence as a voluntary means of selective reproduction, with some calling them "new eugenics".[52] As it becomes possible to test for and correlate genes with IQ (and its proxies),[53] ethicists and embryonic genetic testing companies are attempting to understand the ways in which the technology can be ethically deployed.[54] |

アメリカにおけるIQテストと優生学運動 優生学は、劣っていると判断された人々や集団を排除し、優れていると判断された人々を促進することによって、人間の集団の遺伝的な質を向上させることを目 的とした一連の信念と実践であり[40][41][42]、19世紀後半から第二次世界大戦にアメリカが参戦するまでの進歩主義時代のアメリカの歴史と文 化において重要な役割を果たした[43][44]。 アメリカの優生学運動は、イギリスの科学者フランシス・ガルトン卿の生物学的決定論的思想に根ざしていた。1883年、ガルトンは人間の遺伝子の生物学的 な改善と「生まれながらにして」という概念を表現するために初めて優生学という言葉を用いた[45][46]。彼は、人の能力の違いは主に遺伝によって獲 得されるものであり、人類が全体的な質を向上させるために選択的品種改良を通じて優生学を実施することができ、したがって人間が自らの進化を方向付けるこ とができると信じていた[47]。 ヘンリー・H・ゴダードは優生主義者であった。1908年、彼は独自の知的能力テストである『ビネーとシモンの知的能力テスト』を発表し、このテストを心 から奨励した。彼はすぐにこの尺度の使用を公立学校(1913年)、移民(エリス島、1914年)、法廷(1914年)へと広げた[48]。 肯定的な形質の選択的育種によって優生学を推進したガルトンと異なり、ゴダードは「好ましくない」形質を排除するためにアメリカの優生学運動と歩調を合わ せた。当初、不妊手術は身体障害者を対象としていたが、後に貧困層にも拡大された[48]。ゴダードの知能テストは、強制不妊手術のための法律を推進する 優生学者に支持された。州によって不妊手術法の導入のペースは異なっていた。これらの法律は、その合憲性が1927年のバック対ベルの判決で最高裁判所に よって支持され、アメリカでは60,000人以上が不妊手術を受けることを余儀なくされた[50]。 カリフォルニア州の不妊手術プログラムは非常に効果的であったため、ナチスは「不適合者」の出生を防ぐ方法について政府に助言を求めた[51]。ナチス・ ドイツの惨状を考慮して、アメリカの優生学運動は1940年代にその勢いの多くを失ったが、優生学の提唱者(ナチスの遺伝学者オトマール・フライヘル・ フォン・ヴェルシュアーを含む)はアメリカで活動を続け、彼らの考えを促進した。 [その後数十年で、一部の優生学的原理は選択的生殖の自発的な手段として復活し、それを「新しい優生学」と呼ぶ者もいる[52]。遺伝子とIQ(およびそ の代理)を検査し相関させることが可能になるにつれて[53]、倫理学者や胚遺伝子検査企業は、この技術が倫理的に展開されうる方法を理解しようとしてい る[54]。 |

| Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory Psychologist Raymond Cattell defined fluid and crystallized intelligence and authored the Cattell Culture Fair III IQ test. Raymond Cattell (1941) proposed two types of cognitive abilities in a revision of Spearman's concept of general intelligence. Fluid intelligence (Gf) was hypothesized as the ability to solve novel problems by using reasoning, and crystallized intelligence (Gc) was hypothesized as a knowledge-based ability that was very dependent on education and experience. In addition, fluid intelligence was hypothesized to decline with age, while crystallized intelligence was largely resistant to the effects of aging. The theory was almost forgotten, but was revived by his student John L. Horn (1966) who later argued Gf and Gc were only two among several factors, and who eventually identified nine or ten broad abilities. The theory continued to be called Gf-Gc theory.[30] John B. Carroll (1993), after a comprehensive reanalysis of earlier data, proposed the three stratum theory, which is a hierarchical model with three levels. The bottom stratum consists of narrow abilities that are highly specialized (e.g., induction, spelling ability). The second stratum consists of broad abilities. Carroll identified eight second-stratum abilities. Carroll accepted Spearman's concept of general intelligence, for the most part, as a representation of the uppermost, third stratum.[55][56] In 1999, a merging of the Gf-Gc theory of Cattell and Horn with Carroll's Three-Stratum theory has led to the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory (CHC Theory), with g as the top of the hierarchy, ten broad abilities below, and further subdivided into seventy narrow abilities on the third stratum. CHC Theory has greatly influenced many of the current broad IQ tests.[30] Modern tests do not necessarily measure all of these broad abilities. For example, quantitative knowledge and reading & writing ability may be seen as measures of school achievement and not IQ.[30] Decision speed may be difficult to measure without special equipment. g was earlier often subdivided into only Gf and Gc, which were thought to correspond to the nonverbal or performance subtests and verbal subtests in earlier versions of the popular Wechsler IQ test. More recent research has shown the situation to be more complex.[30] Modern comprehensive IQ tests do not stop at reporting a single IQ score. Although they still give an overall score, they now also give scores for many of these more restricted abilities, identifying particular strengths and weaknesses of an individual.[30] |

キャッテル・ホーン・キャロル理論 心理学者レイモンド・キャッテルは流動性知能と結晶化知能を定義し、キャッテル・カルチャー・フェアIIIというIQテストを作成した。 レイモンド・キャッテル(1941)は、スピアマンの一般知能の概念を修正し、2種類の認知能力を提唱した。流動性知能(Gf)は推論を用いて新しい問題 を解決する能力であり、結晶化知能(Gc)は教育と経験に大きく依存する知識ベースの能力であるという仮説が立てられた。また、流動性知能は加齢とともに 低下するが、結晶性知能は加齢の影響をほとんど受けないという仮説が立てられた。この理論はほとんど忘れ去られていたが、後に彼の弟子であるジョン・L・ ホーン(1966)によって復活し、彼はGfとGcはいくつかの要因のうちの2つにすぎないと主張し、最終的には9つか10つの幅広い能力を特定した。こ の理論は引き続きGf-Gc理論と呼ばれている[30]。 ジョン・B・キャロル(1993)は、以前のデータを包括的に再分析した後、3つのレベルを持つ階層的モデルである3層理論を提唱した。最下層は、高度に 専門化された狭い能力(例:帰納法、スペリング能力)で構成される。第二層は幅広い能力からなる。キャロルは8つの第2層の能力を特定した。キャロルはス ピアマンの一般知能の概念を、大部分は一番上の第3層の表現として受け入れた[55][56]。 1999年、キャッテルとホーンのGf-Gc理論とキャロルの3層理論との融合により、キャッテル-ホーン-キャロル理論(CHC理論)が導き出され、g が階層の最上位で、その下に10の広範な能力があり、さらに第3層で70の狭い能力に細分化されている。CHC理論は、現在の広義のIQテストの多くに大 きな影響を与えている[30]。 現代のテストは、必ずしもこれらの広範な能力のすべてを測定しているわけではない。例えば、数量的知識や読み書き能力は、IQではなく学 校での達成度を測定するものとみなされることがある[30]。gは、以前はGfとGcのみに細分化されることが多 く、これらは一般的なウェクスラーIQテストの初期のバ ージョンの非言語的下位テストまたはパフォーマンス下位 テストと言語的下位テストに対応すると考えられていた。最近の研究では、状況はより複雑であることが示されている[30]。総合的なスコアが出ることに変 わりはないが、より限定的な能力の多くについてもスコアが出るようになり、個人の特定の長所と短所が特定されるようになった[30]。 |

| Other theories An alternative to standard IQ tests, meant to test the proximal development of children, originated in the writings of psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) during his last two years of his life.[57][58] According to Vygotsky, the maximum level of complexity and difficulty of problems that a child is capable to solve under some guidance indicates their level of potential development. The difference between this level of potential and the lower level of unassisted performance indicates the child's zone of proximal development.[59] Combination of the two indexes—the level of actual and the zone of the proximal development—according to Vygotsky, provides a significantly more informative indicator of psychological development than the assessment of the level of actual development alone.[60][61] His ideas on the zone of development were later developed in a number of psychological and educational theories and practices, most notably under the banner of dynamic assessment, which seeks to measure developmental potential[62][63][64] (for instance, in the work of Reuven Feuerstein and his associates,[65] who has criticized standard IQ testing for its putative assumption or acceptance of "fixed and immutable" characteristics of intelligence or cognitive functioning). Dynamic assessment has been further elaborated in the work of Ann Brown, and John D. Bransford and in theories of multiple intelligences authored by Howard Gardner and Robert Sternberg.[66][67] J.P. Guilford's Structure of Intellect (1967) model of intelligence used three dimensions, which, when combined, yielded a total of 120 types of intelligence. It was popular in the 1970s and early 1980s, but faded owing to both practical problems and theoretical criticisms.[30] Alexander Luria's earlier work on neuropsychological processes led to the PASS theory (1997). It argued that only looking at one general factor was inadequate for researchers and clinicians who worked with learning disabilities, attention disorders, intellectual disability, and interventions for such disabilities. The PASS model covers four kinds of processes (planning process, attention/arousal process, simultaneous processing, and successive processing). The planning processes involve decision making, problem solving, and performing activities and require goal setting and self-monitoring. The attention/arousal process involves selectively attending to a particular stimulus, ignoring distractions, and maintaining vigilance. Simultaneous processing involves the integration of stimuli into a group and requires the observation of relationships. Successive processing involves the integration of stimuli into serial order. The planning and attention/arousal components comes from structures located in the frontal lobe, and the simultaneous and successive processes come from structures located in the posterior region of the cortex.[68][69][70] It has influenced some recent IQ tests, and been seen as a complement to the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory described above.[30] |

その他の理論 標準的なIQテストに代わるもので、子どもの近位的発達を テストすることを目的としたものは、心理学者レフ・ヴィゴツキー (1896-1934)の晩年の2年間の著作に端を発している。ヴィゴツキーによれば、2つの指標-実際の発達水準と近 接発達領域-を組み合わせることで、実際の発達水準のみを評 価するよりも、心理的発達の著しく有益な指標となる。 [発達のゾーンに関する彼の考え方は、後に多くの心理学的・教育的理論や実践の中で発展し、特に発達の可能性を測定しようとする動的アセスメントの旗印の 下で発展した[62][63][64](例えば、知能や認知機能の「固定された不変の」特性を仮定したり受け入れたりしているとして標準的なIQテストを 批判したルーヴェン・フォイエルシュタインとその仲間たち[65]の研究)。動的評価は、アン・ブラウンやジョン・D・ブランズフォードの研究や、ハワー ド・ガードナーやロバート・スタンバーグが著した多重知能の理論においてさらに精緻化されている[66][67]。 J.P.ギルフォードの「知性の構造」(1967年)モデルは、3つの次元を使用し、それらを組み合わせると、合計120種類の知性が得られるというもの であった。このモデルは1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけて人気を博したが、実用的な問題と理論的な批判の両方によって衰退した[30]。 神経心理学的プロセスに関するアレクサンダー・ルリアの以前の研究は、PASS理論(1997年)につながった。この理論では、学習障害、注意障害、知的 障害、そしてそのような障害への介入に取り組む研究者や臨床家にとって、一般的な1つの要因に注目するだけでは不十分であると主張した。PASSモデル は、4種類のプロセス(計画プロセス、注意・喚起プロセス、同時処理、逐次処理)を対象としている。計画過程には、意思決定、問題解決、活動の実行が含ま れ、目標設定と自己モニタリングが必要である。 注意/覚醒過程では、特定の刺激に選択的に注意を向け、注意散漫を無視し、警戒を維持する。同時処理には、刺激をグループに統合することが含まれ、関係の 観察が必要である。逐次処理には、刺激を直列に統合することが含まれる。計画と注意/覚醒の構成要素は前頭葉に位置する構造から生じ、同時処理と逐次処理 は大脳皮質の後方領域に位置する構造から生じる[68][69][70]。この理論は、最近のIQテストに影響を与え、上述のキャッテル-ホーン-キャロ ル理論を補完するものとみなされている[30]。 |

| Current tests Normalized IQ distribution with mean 100 and standard deviation 15 There are a variety of individually administered IQ tests in use in the English-speaking world.[71][72] The most commonly used individual IQ test series is the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) for adults and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) for school-age test-takers. Other commonly used individual IQ tests (some of which do not label their standard scores as "IQ" scores) include the current versions of the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales, Woodcock–Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities, the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, the Cognitive Assessment System, and the Differential Ability Scales. There are various other IQ tests, including: Raven's Progressive Matrices Cattell Culture Fair III Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scales Thurstone's Primary Mental Abilities[73][74] Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test[75] Multidimensional Aptitude Battery II Das–Naglieri cognitive assessment system Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test Wide Range Intelligence Test AJT Cognitive Test - Indonesia IQ scales are ordinally scaled.[76][77][78][79][80] The raw score of the norming sample is usually (rank order) transformed to a normal distribution with mean 100 and standard deviation 15.[4] While one standard deviation is 15 points, and two SDs are 30 points, and so on, this does not imply that mental ability is linearly related to IQ, such that IQ 50 would mean half the cognitive ability of IQ 100. In particular, IQ points are not percentage points. |

現在のテスト 平均100、標準偏差15の正規化IQ分布 英語圏では、さまざまな個人向けIQテストが使用されている[71][72]。最も一般的に使用されている個人向けIQテストシリーズは、成人向けには Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)、学齢期の受験者向けにはWechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC)である。その他の一般的に使用される個別IQテスト(標準点を「IQ」スコアと表示していないものもある)には、スタンフォード-ビネー知能 尺度、ウッドコック-ジョンソン認知能力テスト、カウフマン子供用評価バッテリー、認知評価システム、および差異能力尺度の現行版がある。 IQテストには他にもさまざまなものがある: レイヴンの累進マトリクス キャッテル・カルチャー・フェアIII レイノルズ知的評価尺度 サーストンの主要精神能力[73][74]。 カウフマン簡易知能検査[75] 多次元適性バッテリーII ダス・ナグリエリ認知評価システム ナグリエリ非言語能力検査 広域知能検査 AJT認知テスト-インドネシア IQ尺度は順序尺度である[76][77][78][79][80]。標準化サンプルの生スコアは通常(順位)、平均100、標準偏差15を持つ正規分布 に変換される[4]。特に、IQポイントはパーセンテージ・ポイントではない。 |

Normalized IQ distribution with mean 100 and standard deviation 15 |

100を平均、15を標準偏差とした時の、知能指数の一般化された分布 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099