イブン・ハルドゥーン

Ibn Khaldun, 1332-1406 イスラム暦732–808

AH

Bust

of Ibn Khaldun in the entrance of the Kasbah of Bejaia, Algeria

☆ イブン・ハルドゥーン[Ibn Khaldun] (1332年5月27日 - 1406年3月17日、AH 732年 - 808年)は、アラブのイスラム学者、歴史家、哲学者、社会学者である。 [11][12][13][14] 彼は中世における最も偉大な社会科学者の一人として広く認められており、[15] 多くの学者から歴史学、社会学、経済学、人口学の先駆者であると考えられている。[16][17][18][注2][注3] 彼の最も有名な著書『ムカッディマ』または『プロレゴメナ』(序文)は、彼が自伝で述べているように6ヶ月で書き上げられたものであり[19]、17世紀 および19世紀のオスマン帝国の歴史家であるカティプ・チェレビ、ムスタファ・ナーマ、アフメト・ジェヴデト・パシャらに影響を与えた。彼らはその理論を 用いてオスマン帝国の成長と衰退を分析した。 [20] イブン・ハルドゥーンはティムール朝の創始者ティムールと交流を持った。 彼は最も著名なイスラム教徒およびアラブ人の学者、歴史家の一人であると言われている。[21][22][23] 最近では、イブン・ハルドゥーンの著作は、ニコロ・マキャベリ、ジャンバティスタ・ヴィーコ、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、G.W. ヘーゲル、カール・マルクス、オーギュスト・コント、さらには経済学者のデイヴィッド・リカードやアダム・スミスなどと比較され、彼らの思想はイブン・ハ ルドゥーンに先例(直接的な影響ではない)を見出すことができるという見解が示されている。また、彼は特定の現代イスラム思想家(伝統主義派など)にも影 響を与えている。

| Ibn Khaldun[note 1]

(27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732–808 AH) was an Arab Islamic scholar,

historian, philosopher and sociologist.[11][12][13][14] He is widely

acknowledged to be one of the greatest social scientists of the Middle

Ages,[15] and considered by a number of scholars to be a major

forerunner of historiography, sociology, economics, and demography

studies.[16][17][18][note 2][note 3] His best-known book, the Muqaddimah or Prolegomena ("Introduction"), which he wrote in six months as he states in his autobiography,[19] influenced 17th-century and 19th-century Ottoman historians such as Kâtip Çelebi, Mustafa Naima and Ahmed Cevdet Pasha, who used its theories to analyze the growth and decline of the Ottoman Empire.[20] Ibn Khaldun interacted with Tamerlane, the founder of the Timurid Empire. He has been called one of the most prominent Muslim and Arab scholars and historians.[21][22][23] Recently, Ibn Khaldun's works have been compared with those of influential European philosophers such as Niccolò Machiavelli, Giambattista Vico, David Hume, G. W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, and Auguste Comte as well as the economists David Ricardo and Adam Smith, suggesting that their ideas found precedent (although not direct influence) in his. He has also been influential on certain modern Islamic thinkers (e.g. those of the traditionalist school). |

イブン・ハルドゥーン[注1](1332年5月27日 -

1406年3月17日、AH 732年 - 808年)は、アラブのイスラム学者、歴史家、哲学者、社会学者である。

[11][12][13][14] 彼は中世における最も偉大な社会科学者の一人として広く認められており、[15]

多くの学者から歴史学、社会学、経済学、人口学の先駆者であると考えられている。[16][17][18][注2][注3] 彼の最も有名な著書『ムカッディマ』または『プロレゴメナ』(序文)は、彼が自伝で述べているように6ヶ月で書き上げられたものであり[19]、17世紀 および19世紀のオスマン帝国の歴史家であるカティプ・チェレビ、ムスタファ・ナーマ、アフメト・ジェヴデト・パシャらに影響を与えた。彼らはその理論を 用いてオスマン帝国の成長と衰退を分析した。 [20] イブン・ハルドゥーンはティムール朝の創始者ティムールと交流を持った。 彼は最も著名なイスラム教徒およびアラブ人の学者、歴史家の一人であると言われている。[21][22][23] 最近では、イブン・ハルドゥーンの著作は、ニコロ・マキャベリ、ジャンバティスタ・ヴィーコ、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、G.W. ヘーゲル、カール・マルクス、オーギュスト・コント、さらには経済学者のデイヴィッド・リカードやアダム・スミスなどと比較され、彼らの思想はイブン・ハ ルドゥーンに先例(直接的な影響ではない)を見出すことができるという見解が示されている。また、彼は特定の現代イスラム思想家(伝統主義派など)にも影 響を与えている。 |

Early life and family Ibn Khaldun – Life-size bronze bust sculpture of Ibn Khaldun that is part of the collection at the Arab American National Museum (Catalog Number 2010.02). Commissioned by The Tunisian Community Center and Created by Patrick Morelli of Albany, NY in 2009. It was inspired by the statue of Ibn Khaldun erected at the Avenue Habib Bourguiba in Tunis.[24] Ibn Khaldun's life is relatively well-documented, as he wrote an autobiography (التعريف بابن خلدون ورحلته غربا وشرقا, at-Taʻrīf bi-ibn Khaldūn wa-Riḥlatih Gharban wa-Sharqan;[25] Presenting Ibn Khaldun and his Journey West and East) in which numerous documents regarding his life are quoted word-for-word. Abū Zayd 'Abdu r-Rahman bin Muhammad bin Khaldūn Al-Hadrami, generally known as "Ibn Khaldūn" after a remote ancestor, was born in Tunis in AD 1332 (732 AH) into an upper-class Andalusian family of Arab descent;[11][12] the family's ancestor was a Hadhrami who shared kinship with Wa'il ibn Hujr, a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. His family, which held many high offices in Al-Andalus, had emigrated to Tunisia after the fall of Seville to the Reconquista in AD 1248. Although some of his family members had held political office in the Tunisian Hafsid dynasty, his father and grandfather later withdrew from political life and joined a mystical order. His brother, Yahya Khaldun, was also a historian who wrote a book on the Abdalwadid dynasty and was assassinated by a rival for being the official historiographer of the court.[26] In his autobiography, Khaldun traces his descent back to the time of Muhammad through an Arab tribe from the south of the Arabian Peninsula, specifically the Hadhramaut, which came to the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century, at the beginning of the Islamic conquest: "And our ancestry is from Hadhramaut, from the Arabs of Arabian Peninsula, via Wa'il ibn Hujr also known as Hujr ibn 'Adi, from the best of the Arabs, well-known and respected." (p. 2429, Al-Waraq's edition). Ibn Khaldun's insistence and attachment to his claim of Arab ancestry at a time of Berber dynasties domination is a valid reason to believe his claim of Arab descent.[27][28] |

幼少期と家族 イブン・ハルドゥーン - アラブ系アメリカ国民博物館の所蔵品である等身大のブロンズ胸像(カタログ番号2010.02)。チュニジア人コミュニティセンターの委託により、 2009年にニューヨーク州オルバニーのパトリック・モレリが制作。チュニスのハビブ・ブルギバ大通りに建立されたイブン・ハルドゥーンの像に着想を得て いる。 イブン・ハルドゥンの生涯は比較的よく記録されており、彼が書いた自伝(『イブン・ハルドゥンの定義と西方と東方での旅』)には、彼の生涯に関する多数の 文書が逐語的に引用されている。 [25] 『イブン・ハルドゥーンとその西と東への旅)』では、彼の生涯に関する多数の文書がそのまま引用されている。 アブー・ザイド・アブドゥ・ラフマーン・ビン・ムハンマド・ビン・ハルドゥーン・アル=ハドラマイ(一般的には遠い祖先の名にちなんで「イブン・ハル ドゥーン」として知られる)は、西暦1332年(ヒジュラ暦732年)にチュニスで、アラブ系アンダルシアの上流階級の家庭に生まれた。 イスラム教の預言者ムハンマドの仲間であったワイル・イブン・フジュルの親戚であった。 アル・アンダルスで多くの高位の役職を占めていた彼の家族は、西暦1248年にセビリアがレコンキスタによって陥落した後、チュニジアに移住した。一族の 一部はチュニジアのハフス朝で政治官職に就いていたが、父と祖父は後に政界から身を引き、神秘主義の教団に加わった。彼の兄弟であるヤヒヤ・ハルドゥーン もまた歴史家であり、アブド・ワッディド朝に関する著書を残したが、宮廷の公式歴史家であったためにライバルに暗殺された。 ハルドゥーンは自伝の中で、ムハンマドの時代に遡り、アラビア半島南部のアラブ部族、具体的にはハドラマウト族がイスラム教の征服の始まりである8世紀に イベリア半島にやってきたことを辿っている。「そして、我々の祖先はハドラマウト、アラビア半島のアラブ人、ワイル・イブン・フジュル(別名フジュル・イ ブン・アディ)を経由している。彼はアラブ人の中でも最も優れ、よく知られ、尊敬されていた人物である。」(アル・ワラク版、2429ページ) ベルベル人の王朝が支配していた時代に、イブン・ハルドゥーンがアラブ人の血筋であると主張し、固執したことは、彼がアラブ人であるという主張を信じるに足る理由である。[27][28] |

| Education His family's high rank enabled Ibn Khaldun to study with prominent teachers in Maghreb. He received a classical Islamic education, studying the Quran, which he memorized by heart, Arabic linguistics; the basis for understanding the Qur'an, hadith, sharia (law) and fiqh (jurisprudence). He received certification (ijazah) for all of those subjects.[29] The mathematician and philosopher Al-Abili of Tlemcen introduced him to mathematics, logic and philosophy, and he studied especially the works of Averroes, Avicenna, Razi and Tusi. At the age of 17, Ibn Khaldūn lost both his parents to the Black Death, an intercontinental epidemic of the plague that hit Tunis in 1348–1349.[30] Following family tradition, he strove for a political career. In the face of a tumultuous political situation in North Africa, that required a high degree of skill in developing and dropping alliances prudently to avoid falling with the short-lived regimes of the time.[31] Ibn Khaldūn's autobiography is the story of an adventure, in which he spends time in prison, reaches the highest offices and falls again into exile. |

教育 彼の家族の地位の高さにより、イブン・ハルドゥーンはマグレブの著名な教師たちから学ぶことができた。彼は、コーランを暗記し、コーランを理解するための 基礎であるアラビア語の言語学、ハディース、シャリーア(法律)、フィクフ(法学)を研究し、古典的なイスラム教育を受けた。彼はそれらの科目すべてにつ いて、資格(イジャザ)を取得した。[29] 数学者であり哲学者でもあったトレムセンのアル・アビリは、彼に数学、論理学、哲学を教え、彼は特にアヴェロエス、アヴィセンナ、ラージ、トゥースィーの 著作を学んだ。17歳の時、イブン・ハルドゥーンはペストの大流行により両親を失った。このペストは1348年から1349年にかけてチュニスを襲った大 陸間流行であった。 一族の伝統に従い、彼は政治的なキャリアを目指した。北アフリカの政治情勢が激動する中、当時の短命な政権に巻き込まれないよう、慎重に同盟関係を築き、 またそれを解消する高度な手腕が求められた。[31] イブン・ハルドゥーンの自伝は、彼が刑務所で過ごし、最高官職に就き、再び追放されるという冒険の物語である。 |

| Political career This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Birth home of Ibn Khaldun at Tunis  The mosque in which Ibn Khaldun studied At the age of 20, he began his political career in the chancellery of the Tunisian ruler Ibn Tafrakin with the position of Kātib al-'Alāmah (seal-bearer),[32] which consisted of writing in fine calligraphy the typical introductory notes of official documents. In 1352, Abū Ziad, the sultan of Constantine, marched on Tunis and defeated it. Ibn Khaldūn, in any case unhappy with his respected but politically meaningless position, followed his teacher Abili to Fez. There, the Marinid sultan, Abū Inan Fares I, appointed him as a writer of royal proclamations, but Ibn Khaldūn still schemed against his employer, which, in 1357, got the 25-year-old a 22-month prison sentence. Upon the death of Abū Inan in 1358, Vizier al-Hasān ibn-Umar granted him freedom and reinstated him to his rank and offices. Ibn Khaldūn then schemed against Abū Inan's successor, Abū Salem Ibrahim III, with Abū Salem's exiled uncle, Abū Salem. When Abū Salem came to power, he gave Ibn Khaldūn a ministerial position, the first position to correspond with Ibn Khaldūn's ambitions. The treatment that Ibn Khaldun received after the fall of Abū Salem through Ibn-Amar ʻAbdullah, a friend of Ibn Khaldūn's, was not to his liking, as he received no significant official position. At the same time, Amar successfully prevented Ibn Khaldūn, whose political skills he knew well, from allying with the Abd al-Wadids in Tlemcen. Ibn Khaldūn, therefore, decided to move to Granada. He could be sure of a positive welcome there since at Fez, he had helped the Sultan of Granada, the Nasrid Muhammad V, regain power from his temporary exile. In 1364, Muhammad entrusted him with a diplomatic mission to the king of Castile, Pedro the Cruel, to endorse a peace treaty. Ibn Khaldūn successfully carried out this mission and politely declined Pedro's offer to remain at his court and have his family's Spanish possessions returned to him. In Granada, Ibn Khaldūn quickly came into competition with Muhammad's vizier, Ibn al-Khatib, who viewed the close relationship between Muhammad and Ibn Khaldūn with increasing mistrust. Ibn Khaldūn tried to shape the young Muhammad into his ideal of a wise ruler, an enterprise that Ibn al-Khatib thought foolish and a danger to peace in the country. As a result of al-Khatib's influence, Ibn Khaldūn was eventually sent back to North Africa. Al-Khatib himself was later accused by Muhammad of having unorthodox philosophical views and murdered despite an attempt by Ibn Khaldūn to intercede on behalf of his old rival. In his autobiography, Ibn Khaldūn tells little about his conflict with Ibn al-Khatib and the reasons for his departure. Orientalist Muhsin Mahdi interprets that as showing that Ibn Khaldūn later realised that he had completely misjudged Muhammad V. Back in Ifriqiya, the Hafsid sultan of Béjaïa, Abū ʻAbdallāh, who had been his companion in prison, received him with great enthusiasm and made Ibn Khaldūn his prime minister. Ibn Khaldūn carried out a daring mission to collect taxes among the local Berber tribes. After the death of Abū ʻAbdallāh in 1366, Ibn Khaldūn changed sides once again and allied himself with the Sultan of Tlemcen, Abū l-Abbas. A few years later, he was taken prisoner by Abu Faris Abdul Aziz, who had defeated the sultan of Tlemcen and seized the throne. He then entered a monastic establishment and occupied himself with scholastic duties until 1370. In that year, he was sent for to Tlemcen by the new sultan. After the death of ʻAbdu l-Azīz, he resided at Fez, enjoying the patronage and confidence of the regent. Ibn Khaldūn's political skills and, above all, his good relationship with the wild Berber tribes were in high demand among the North African rulers, but he had begun to tire of politics and constantly switching allegiances. In 1375, he was sent by Abū Hammu, the Abd al-Wadid Sultan of Tlemcen, on a mission to the Dawadida Arabs tribes of Biskra. After his return to the West, Ibn Khaldūn sought refuge with one of the Berber tribes in the west of Algeria, in the town of Qalat Ibn Salama. He lived there for over three years under their protection, taking advantage of his seclusion to write the Muqaddimah "Prolegomena", the introduction to his planned history of the world. In Ibn Salama, however, he lacked the necessary texts to complete the work.[33] Therefore, in 1378, he returned to his native Tunis, which had meanwhile been conquered by Abū l-Abbas, who took Ibn Khaldūn back into his service. There, he devoted himself almost exclusively to his studies and completed his history of the world. His relationship with Abū l-Abbas remained strained, as the latter questioned his loyalty. That was brought into sharp contrast after Ibn Khaldūn presented him with a copy of the completed history that omitted the usual panegyric to the ruler. Under pretence of going on the Hajj to Mecca, something for which a Muslim ruler could not simply refuse permission, Ibn Khaldūn was able to leave Tunis and to sail to Alexandria. |

政治経歴 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は疑問視される可能性があり、削除されることがあります。 (2019年1月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  チュニスのイブン・ハルドゥーン生家  イブン・ハルドゥーンが学んだモスク 20歳のとき、彼はチュニジアの支配者イブン・タフラキンの官房で、カティブ・アル=アラマ(印章係)という役職に就き、政治的なキャリアをスタートさせ た。カティブ・アル=アラマは、公式文書の典型的な序文を美しいカリグラフィーで書くことを職務とする役職であった。1352年、コンスタンチノープルの スルタンであったアブー・ジアドがチュニスに進軍し、これを征服した。尊敬はされていたが政治的には無意味な地位に不満を抱いていたイブン・ハルドゥーン は、師のアビリのあとを追ってフェズへと向かった。そこでマリーン朝のスルタン、アブー・イナン・ファリス1世は彼を勅令の起草者として任命したが、イブ ン・ハルドゥーンはそれでもなお雇用主に対して策謀を巡らせ、1357年には25歳の彼に22か月の実刑判決が下された。1358年にイブン・イナンが死 去すると、宰相アル・ハサン・イブン・ウマルは彼に自由を与え、元の地位と役職に復帰させた。その後、イブン・ハルドゥーンはイブン・イナンの後継者であ るイブン・セーレム・イブラヒム3世に対して策謀を巡らせ、イブン・セーレムの追放された叔父であるイブン・セーレムと共謀した。アブー・サレムが権力を 握ると、イブン・ハルドゥンに大臣の地位を与えた。これは、イブン・ハルドゥンの野望にかなう最初の地位であった。 イブン・ハルドゥンは、アブー・サレムの没落後、イブン・ハルドゥンの友人であるイブン・アマール・アブドゥッラーを通じて受けた待遇を気に入らなかっ た。なぜなら、彼は重要な公職に就くことはなかったからだ。同時に、アマールは、政治的手腕をよく知っていたイブン・ハルドゥーンが、トルセンのワディド 家と同盟を結ぶのをうまく阻止した。そのため、イブン・ハルドゥーンはグラナダへの移住を決意した。フェズでは、グラナダのスルタン、ナスル朝のムハンマ ド5世が一時的な亡命から権力を取り戻すのを助けていたため、グラナダでは歓迎されるだろうと確信していた。1364年、ムハンマドは彼にカスティーリャ 王ペドロ1世(残酷王)との和平条約締結のための外交任務を託した。イブン・ハルドゥーンは見事にこの任務を遂行し、ペドロ王から宮廷に留まり、スペイン の所有地を家族に返還するようという申し出を丁重に断った。 グラナダでは、イブン・ハルドゥーンはムハンマドの宰相イブン・アル・ハティブとすぐに競合する立場となった。イブン・アル・ハティブは、ムハンマドとイ ブン・ハルドゥーンの親密な関係をますます疑いの目で見るようになっていた。イブン・ハルドゥーンは、若きムハンマドを賢明な統治者の理想像に近づけよう としたが、イブン・アル・ハティブはそれを愚かであり、国の平和を脅かすものだと考えた。アル・ハティブの影響により、イブン・ハルドゥーンは最終的に北 アフリカに送還された。アル・ハティブ自身は、後にムハンマドから異端の哲学観を持っていると非難され、殺害された。イブン・ハルドゥーンは昔のライバル の弁護に立ったが、無駄だった。 イブン・ハルドゥーンは自伝の中で、アル・ハティブとの対立や、彼が去った理由についてほとんど語っていない。東洋学者のムフシン・マフディーは、イブン・ハルドゥーンが後にムハンマド5世を完全に誤解していたことに気づいたことを示していると解釈している。 イフリキヤに戻ると、ベジャイアのハフス朝のスルタン、アブー・アブドッラーが、刑務所で同房だった彼を熱烈に歓迎し、イブン・ハルドゥーンを首相に任命 した。イブン・ハルドゥンは、地元ベルベル部族に税金を徴収するという大胆な任務を遂行した。1366年にアブー・イブン・アブドゥラが死去すると、イブ ン・ハルドゥンは再び寝返り、トレムセンのスルタン、アブー・アル・アッバースと同盟を結んだ。数年後、トレムセンのスルタンを破り王座を奪取したア ブー・ファリス・アブドゥル・アジズに捕虜となった。その後、修道院に入り、1370年まで学問的な職務に専念した。その年、彼は新しいスルタンによって トレムセンに呼び戻された。アブドゥ・アッ=ラズィズの死後、彼はフェズに住み、摂政の庇護と信頼を得た。 イブン・ハルドゥーンの政治的手腕、とりわけ、野性的なベルベル部族との良好な関係は、北アフリカの支配者たちから非常に重宝されていたが、彼は政治に疲 れ、常に忠誠を切り替えていた。1375年、彼はトレムセンのアル・ワディド朝のスルタン、アブー・ハムムの命を受け、ビスクラのダワディダ・アラブ部族 への使節団に加わった。西に戻った後、イブン・ハルドゥーンはアルジェリア西部のベルベル人の部族の1つ、カラット・イブン・サラマの町に避難した。彼は そこで3年以上、彼らの保護の下で暮らした。隠遁生活を活かし、世界史の序文となる『ムカッディマ』を執筆した。しかし、イブン・サラマには、その仕事を 完成させるのに必要なテキストが欠けていた。[33] そのため、1378年に彼は生まれ故郷のチュニスに戻った。チュニスはすでにアブー・アル・アッバースに征服されていたが、アブー・アル・アッバースはイ ブン・ハルドゥーンを再び自分の部下として迎え入れた。そこで彼は、ほぼ専ら研究に専念し、世界史を完成させた。アブー・アル・アッバースとの関係は依然 としてぎくしゃくしたままで、後者は彼の忠誠心に疑問を抱いていた。イブン・ハルドゥーンが完成した歴史書の写本をアブー・ル・アッバースに献上した際、 その写本には支配者への賛辞が省かれていたため、両者の関係はさらに悪化した。メッカへの巡礼に行くという口実で、イスラム教の支配者が許可を簡単に拒否 できないことを利用し、イブン・ハルドゥーンはチュニスを離れ、アレキサンドリアへ船で向かうことができた。 |

| Later life This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Ibn Khaldun Statue and Square, Mohandessin, Cairo Ibn Khaldun said of Egypt, "He who has not seen it does not know the power of Islam."[34] While other Islamic regions had to cope with border wars and inner strife, Mamluk Egypt enjoyed prosperity and high culture. In 1384, the Egyptian Sultan, al-Malik udh-Dhahir Barquq, made Khaldun professor of the Qamhiyyah Madrasah and appointed him as the Grand qadi of the Maliki school of fiqh (one of four schools, the Maliki school was widespread primarily in Western Africa). His efforts at reform encountered resistance, however, and within a year, he had to resign his judgeship. Also in 1384, a ship carrying Khaldun's wife and children sank off of Alexandria. After his return from a pilgrimage to Mecca in May 1388, Ibn Khaldūn concentrated on teaching at various Cairo madrasas. At the Mamluk court he fell from favor because during revolts against Barquq, he had, apparently under duress, with other Cairo jurists, issued a fatwa against Barquq. Later relations with Barquq returned to normal, and he was once again named the Maliki qadi. Altogether, he was called six times to that high office, which, for various reasons, he never held long. In 1401, under Barquq's successor, his son Faraj, Ibn Khaldūn took part in a military campaign against the Mongol conqueror, Timur, who besieged Damascus in 1400. Ibn Khaldūn cast doubt upon the viability of the venture and really wanted to stay in Egypt. His doubts were vindicated, as the young and inexperienced Faraj, concerned about a revolt in Egypt, left his army to its own devices in Syria and hurried home. Ibn Khaldūn remained at the besieged city for seven weeks, being lowered over the city wall by ropes to negotiate with Timur, in a historic series of meetings that he reported extensively in his autobiography.[35] Timur questioned him in detail about conditions in the lands of the Maghreb. At his request, Ibn Khaldūn even wrote a long report about it. As he recognized Timur's intentions, he did not hesitate, on his return to Egypt, to compose an equally-extensive report on the history of the Tatars, together with a character study of Timur, sending them to the Merinid rulers in Fez. Ibn Khaldūn spent the next five years in Cairo completing his autobiography and his history of the world and acting as teacher and judge. Meanwhile, he was alleged to have joined an underground party, Rijal Hawa Rijal, whose reform-oriented ideals attracted the attention of local political authorities. The elderly Ibn Khaldun was placed under arrest. He died on 17 March 1406, one month after his sixth selection for the office of the Maliki qadi (Judge). |

晩年 この節では検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は疑問視され、削除される場合があります。 (2019年1月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) イブン・ハルドゥーンの像と広場、モハンディン、カイロ イブン・ハルドゥーンはエジプトについて、「エジプトを見たことのない者はイスラームの力を知らない」と述べている。[34] 他のイスラーム地域が国境紛争や内紛に対処しなければならなかった一方で、マムルーク朝エジプトは繁栄と高度な文化を享受した。1384年、エジプトのス ルタン、アル・マリク・ウッ・ザーヒル・バルクークはハルドゥーンをカーミーヤ神学校の教授に任命し、またマグリブ学派のフィクフ(イスラーム法解釈学) の最高裁判事に任命した(4つの学派のうちの1つであるマグリブ学派は主に西アフリカで広まっていた)。しかし、彼の改革への取り組みは抵抗に遭い、1年 もしないうちに裁判官職を辞さざるを得なくなった。また1384年には、ハルドゥーンの妻子を乗せた船がアレキサンドリア沖で沈没した。 1388年5月にメッカへの巡礼から戻ると、イブン・ハルドゥーンはカイロのさまざまな神学校で教えることに専念した。マムルーク朝の宮廷では、バルクー クに対する反乱のさなか、明らかに強制された状況下で、他のカイロの法学者たちとともにバルクークに対するファトワー(宗教的判決)を出したため、彼は宮 廷での人気を失った。その後、バルクークとの関係は正常に戻り、彼は再びマリキ・カーディーに任命された。 結局、彼は6回もその高位の役職に任命されたが、さまざまな理由により、彼はその地位を長く維持することはなかった。 1401年、バルクの跡を継いだ息子のファラージの治世下、イブン・ハルドゥーンは1400年にダマスカスを包囲したモンゴル人征服者ティムールに対する 軍事作戦に参加した。イブン・ハルドゥーンは、その事業の実現可能性に疑問を抱いており、エジプトに留まりたいと強く願っていた。彼の疑念は正しかった。 若く経験の浅いファラージは、エジプトでの反乱を懸念し、シリアの軍隊を放置して急いで帰国した。イブン・ハルドゥーンは7週間包囲された都市にとどま り、ティムールと交渉するために、ロープで城壁から吊り下げられて降りた。これは歴史的な一連の会合であり、彼は自伝でその詳細を報告している。[35] ティムールはマグレブの土地の状況について詳細に彼に質問した。イブン・ハルドゥーンは、ティムールの要請に応じて、それについての詳細な報告書も作成し た。ティムールの意図を理解したイブン・ハルドゥーンは、エジプトに戻ると、タタール人の歴史について同様に詳細な報告書をまとめ、ティムールについての 人物研究も加えて、フェズのメリニド朝の支配者に送った。 イブン・ハルドゥーンは、その後5年間をカイロで過ごし、自伝と世界史を完成させ、教師や裁判官としても活動した。その間、彼は改革志向の理想が地元の政 治当局の注目を集めた秘密結社「リジャル・ハワ・リジャル」に参加したと非難された。高齢のイブン・ハルドゥーンは逮捕された。彼は1406年3月17 日、マリキ・カーディー(裁判官)に6度目の選出から1か月後に亡くなった。 |

Works Handwriting of Ibn Khaldūn certifying a manuscript copy of al-Muqaddima, MS Atif Efendi [ar] 1936, f. 7a al-Muqaddima and the rest of Kitāb al-ʻIbar Kitāb al-ʻIbar, (full title: Kitāb al-ʻIbar wa-Dīwān al-Mubtadaʼ wa-l-Khabar fī Taʼrīkh al-ʻArab wa-l-Barbar wa-Man ʻĀṣarahum min Dhawī ash-Shaʼn al-Akbār "Book of Lessons, Record of Beginnings and Events in the History of the Arabs and the Berbers and Their Powerful Contemporaries"); begun as a history of the Berbers and expanded to a universal history in seven books.[36][37] Book 1; Al-Muqaddima ('The Introduction'), a socio-economic-geographical universal history of empires, and the best known of his works.[38] Books 2–5; World History up to the author's own time. Books 6–7; Historiography of the Berbers and the Maghreb. Khaldun departs from the classical style of Arab historians[note 4] by synthesising multiple, sometimes contradictory, sources without citations.[39] He reproduces some errors originating probably from his 14th-century Fez source, the work Rawḍ al-Qirṭās by Ibn Abi Zar, yet Al-'Ibar remains an invaluable source of Berber history. Businesses owned by responsible and organized merchants shall eventually surpass those owned by wealthy rulers.[40] Ibn Khaldun on economic growth and the ideals of Platonism Concerning the discipline of sociology, he described the dichotomy of sedentary life versus nomadic life as well as the inevitable loss of power that occurs when warriors conquer a city. According to the Arab scholar Sati' al-Husri, the Muqaddimah may be read as a sociological work. The work is based around Ibn Khaldun's central concept of 'aṣabiyyah, translated as "group cohesiveness" or "solidarity".[41] This social cohesion arises spontaneously in tribes and other small kinship groups; it can be intensified and enlarged by a religious ideology. Ibn Khaldun's analysis looks at how this cohesion carries groups to power but contains within itself the seeds – psychological, sociological, economic, political – of the group's downfall, to be replaced by a new group, dynasty or empire bound by a stronger (or at least younger and more vigorous) cohesion. Some of Ibn Khaldun's views, particularly those concerning the Zanj people of sub-Saharan Africa,[42] have been cited as racist,[43] though they were not uncommon for their time. According to the scholar Abdelmajid Hannoum, Ibn Khaldun's description of the distinctions between Berbers and Arabs were misinterpreted by the translator William McGuckin de Slane, who wrongly inserted a "racial ideology that sets Arabs and Berbers apart and in opposition" into his translation of part of`Ibar translated under the title Histoire des Berbères.[44] Perhaps the most frequently cited observation drawn from Ibn Khaldūn's work is the notion that when a society becomes a great civilization, its high point is followed by a period of decay. This means that the next cohesive group that conquers the diminished civilization is, by comparison, a group of barbarians. Once the barbarians solidify their control over the conquered society, however, they become attracted to its more refined aspects, such as literacy and arts, and either assimilate into or appropriate such cultural practices. Then, eventually, the former barbarians will be conquered by a new set of barbarians, who will repeat the process. Georgetown University Professor Ibrahim Oweiss, an economist and historian, argues that Ibn Khaldun was a major forerunner of modern economists and, in particular, originated the labor theory of value long before better known proponents such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo, although Khaldun did not refer to it as either a labor theory of value or theory.[45] Ibn Khaldun also called for the creation of a science to explain society and went on to outline these ideas in his major work, the Muqaddimah, which states that “Civilization and its well-being, as well as business prosperity, depend on productivity and people’s efforts in all directions in their own interest and profit”.[46] Ibn Khaldun diverged from norms that Muslim historians followed and rejected their focus on the credibility of the transmitter and focused instead on the validity of the stories and encouraged critical thinking.[47] Ibn Khaldun also outlines early theories of division of labor, taxes, scarcity, and economic growth.[48] He argued that poverty was a result of the destruction of morality and human values. He also looked at what factors contribute to wealth, such as consumption, government, and investment. Khaldun also argued that poverty was not necessarily a result of poor financial decision-making but of external consequences and therefore the government should be involved in alleviating poverty. Researchers from Malaysia's Insaniah University College and Indonesia's Tazkia University College of Islamic Economics created a dynamics model based upon Ibn Khaldun's writings to measure poverty in the Muslim nations of South Asia and Southeast Asia.[49] Ibn Khaldun also believed that the currency of an Islamic monetary system should have intrinsic value and therefore be made of gold and silver (such as the dirham). He emphasized that the weight and purity of these coins should be strictly followed: the weight of one dinar should be one mithqal (the weight of 72 grains of barley, roughly 4.25 grams) and the weight of 7 dinar should be equal to weight of 10 dirhams (7/10 of a mithqal or 2.96 grams).[50] Ibn Khaldun's writings regarding the division of labor are often compared to Adam Smith's writings on the topic. The individual being cannot by himself obtain all the necessities of life. All human beings must co-operate to that end in their civilization. But what is obtained by the cooperation of a group of human beings satisfies the need of a number many times greater than themselves. For instance, no one by himself can obtain the share of the wheat he needs for food. But when six or ten persons, including a smith and a carpenter to make the tools, and others who are in charge of the oxen, the ploughing of, the harvesting of the ripe grain, and all other agricultural activities, undertake to obtain their food and work toward that purpose either separately or collectively and thus obtain through their labour a certain amount of food, that amount will be food for a number of people many times their own. The combined labour produces more than the needs and necessities of the workers (Ibn Khaldun 1958, vol. II 271–272)[51] In every other art and manufacture, the effects of the division of labour are similar to what they are in this very trifling one [pin production]; though, in many of them, the labour can either be so much subdivided, nor reduced to so great a simplicity of operation. The division of labour, however, so far as it can be introduced, occasions, in every art, a proportionable increase of the productive powers of labour (Smith 1976a, vol. I, 13–24)[51] Both Ibn Khaldun and Smith shared the idea that the division of labor is fundamental to economic growth, however, the motivations and context for such division differed between them. For Ibn Khaldun, asabiyyah or social solidarity was the underlying motive and context behind the division of labor; for Smith it was self-interest and the market economy.[51] |

作品 イブン・ハルドゥーンの自筆署名入り写本、アル=ムカッディマ、MSアティフ・エフェンディ[ar] 1936年、7a アル=ムカッディマと『キターブ・アル=イバル』の残りの部分 Kitāb al-ʻIbar, (full title: Kitāb al-ʻIbar wa-Dīwān al-Mubtadaʼ wa-l-Khabar fī Taʼrīkh al-ʻArab wa-l-Barbar wa-Man ʻĀṣarahum min Dhawī ash-Shaʼn al-Akbār "Book of Lessons, アラブ人とベルベル人、そして彼らの強力な同時代人たちの歴史における始まりと出来事の記録)として書き始められ、7巻からなる普遍的な歴史に拡大され た。[36][37] 第1巻;アル・ムカッディマ(『序文』)は、帝国の社会経済地理学的普遍史であり、彼の作品の中で最もよく知られている。[38] 第2巻から第5巻;著者の存命中までの世界史。 第6巻から第7巻;ベルベル人とマグレブの歴史。ハルドゥーンは、複数の、時には矛盾する情報源を引用なしで総合することによって、アラブの歴史家の古典 的なスタイルから離れた[注釈4]。彼は、おそらく14世紀のフェズの情報源であるイブン・アビ・ザルの著作『ローダル・キルタス』に由来するいくつかの 誤りを再現しているが、それでも『アル=イバー』はベルベル人の歴史の貴重な情報源であることに変わりはない。 責任感があり、組織化された商人たちが所有する企業は、最終的には富裕な支配者たちが所有する企業を凌駕するだろう。 経済成長とプラトン主義の理想について 社会学の規律に関して、彼は定住生活と遊牧生活の二分法を説明し、戦士たちが都市を征服した際に起こる必然的な権力の喪失についても述べた。アラブの学者 サティ・アル=フスリによると、『ムカッディマ』は社会学的な著作として読むことができる。この著作は、イブン・ハルドゥーンの中心概念である「アサビ ヤ」を基盤としている。「アサビヤ」は「集団凝集性」または「連帯」と訳される。[41] この社会的結束は部族やその他の小規模な親族集団において自然発生的に生じる。それは宗教的イデオロギーによって強化され、拡大される可能性がある。イブ ン・ハルドゥーンの分析は、この結束が集団を権力へと導く一方で、その集団の没落の種子(心理学的、社会学、経済学的、政治学的)を内包しており、より強 固な(あるいは少なくともより若く活力のある)結束によって結びついた新たな集団、王朝、帝国に取って代わられるというものである。イブン・ハルドゥーン の見解の一部、特にサハラ以南のアフリカのザンジ族に関するもの[42]は、人種差別的であると引用されているが[43]、当時としては珍しいものではな かった。学者のアブデルマジド・ハヌムによると、イブン・ハルドゥーンのベルベル人とアラブ人の区別に関する記述は、翻訳者のウィリアム・マクガキン・ ド・スレーンによって誤って解釈され、アラブ人とベルベル人を区別し対立させる「人種的イデオロギー」が、Histoire des Berbères(ベルベル人の歴史)というタイトルで翻訳されたIbarの一部に誤って挿入されたという。 イブン・ハルドゥーンの著作から引用される最も頻繁な指摘は、おそらく、社会が偉大な文明になると、その絶頂期の後に衰退期が訪れるという考え方であろ う。つまり、衰退した文明を征服する次のまとまった集団は、比較すると野蛮人の集団である。しかし、征服した社会に対する支配を固めた後、野蛮人は読み書 きや芸術といった洗練された側面に魅力を感じ、そうした文化的な慣習を吸収したり、あるいはそれを自分たちのものとしてしまう。そして、やがては、かつて の野蛮人が新たな野蛮人たちに征服され、そのプロセスが繰り返されることになる。 ジョージタウン大学の経済学者で歴史学者でもあるイブラヒム・オワイエス教授は、イブン・ハルドゥーンは現代の経済学者の先駆者であり、特に、アダム・ス ミスやデイヴィッド・リカードといった著名な提唱者よりもずっと以前に、労働価値説の起源となったと主張している。ただし、ハルドゥーンは労働価値説や理 論という言葉を使ってはいない。[45] また、イブン・ハルドゥーンは社会を説明する学問の創設を提唱し、その主要な著作『ムカッディマ』でこれらの考えを概説した。同書では、「文明とその繁 栄、そしてビジネスの繁栄は、生産性と人々のあらゆる方向への努力に依存しており、それらはすべて人々の利益と利益追求のためである」と述べている。 イブン・ハルドゥーンは、イスラム教の歴史家たちが従う規範から逸脱し、伝承者の信頼性に重点を置くことを否定し、代わりに物語の妥当性に重点を置き、批判的思考を奨励した。 また、イブン・ハルドゥーンは、初期の分業、課税、希少性、経済成長に関する理論の概要も示している。 彼は、貧困は道徳と人間的価値の崩壊の結果であると論じた。また、消費、政府、投資など、富に貢献する要因についても考察した。ハルドゥーンは、貧困は必 ずしも貧弱な財政的決定の結果ではなく、外的要因の結果であるため、政府は貧困緩和に関与すべきであるとも論じた。マレーシアのインサニア大学カレッジと インドネシアのタズキア大学イスラム経済カレッジの研究者は、南アジアと東南アジアのイスラム教徒の国民の貧困を測定するために、イブン・ハルドゥーンの 著作を基に力学モデルを作成した。 また、イブン・ハルドゥーンは、イスラム金融システムの通貨は本質的価値を持つべきであり、そのため金や銀(ディルハムなど)で造られるべきだと考えてい た。彼は、これらの硬貨の重量と純度を厳格に守るべきであると強調した。1ディナールの重量は1ミスカル(大麦72粒の重量、約4.25グラム)で、7 ディナールの重量は10ディルハム(ミスカルの7分の1、2.96グラム)の重量と同等であるべきであると主張した。[50] イブン・ハルドゥーンの分業に関する著作は、このテーマに関するアダム・スミスの著作と比較されることが多い。 個々の人間は、自分一人では生活に必要なものをすべて手に入れることはできない。文明社会においては、すべての人間が協力しなければならない。しかし、人 間集団が協力して手に入れたものは、自分一人で手に入れられるものよりも何倍もの数の必要を満たす。例えば、食糧として必要な小麦を、自分一人で手に入れ ることはできない。しかし、道具を作る鍛冶屋や大工、そして牛の世話や耕作、収穫、その他農業全般を担当する人々を含め、6人または10人の人格が、食料 と労働力を得るために、個別または集団でその目的のために働き、労働を通じて一定量の食料を得る場合、その量は自分たちの何倍もの人数の食料となる。労働 力を合わせれば、労働者自身の必要量や必需量を上回る生産が可能になる(Ibn Khaldun 1958, vol. II 271–272)[51] 他のあらゆる技術や製造業においても、労働の分業による効果は、このごく些細な作業(ピン製造)におけるものと同様である。しかし、それらの多くでは、労 働はそれほど細分化されることもなく、また、それほど単純な作業に還元されることもない。しかし、労働の分業が導入されうる限り、あらゆる技術において、 労働の生産力は比例的に増加する(スミス 1976a、第1巻、13-24ページ)[51] イブン・ハルドゥーンとスミスは、経済成長には労働の分業が不可欠であるという考えを共有していたが、その動機と背景は両者で異なっていた。イブン・ハル ドゥーンにとって、アサビヤ(asabiyyah)すなわち社会連帯が労働の分業の根底にある動機と背景であった。一方、スミスにとっては、それは利己心 と市場経済であった。[51] |

| Social thought This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Ibn Khaldun's epistemology attempted to reconcile mysticism with theology by dividing science into two different categories, the religious science that regards the sciences of the Qur'an and the non-religious science. He further classified the non-religious sciences into intellectual sciences such as logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, etc. and auxiliary sciences such as language, literature, poetry, etc. He also suggested that possibly more divisions will appear in the future with different societies. He tried to adapt to all possible societies’ cultural behavior and influence in education, economics and politics. Nonetheless, he didn't think that laws were chosen by just one leader or a small group of individual but mostly by the majority of the individuals of a society.[52] To Ibn Khaldun, the state was a necessity of human society to restrain injustice within the society, but the state means is force, thus itself an injustice. All societies must have a state governing them in order to establish a society. He attempted to standardize the history of societies by identifying ubiquitous phenomena present in all societies. To him, civilization was a phenomenon that will be present as long as humans exist. He characterized the fulfillment of basic needs as the beginning of civilization. At the beginning, people will look for different ways of increasing productivity of basic needs and expansion will occur. Later the society starts becoming more sedentary and focuses more on crafting, arts and the more refined characteristics. By the end of a society, it will weaken, allowing another small group of individuals to come into control. The conquering group is described as an unsatisfied group within the society itself or a group of desert bandits that constantly attack other weaker or weakened societies. In the Muqaddimah, his most important work, he discusses an introduction of philosophy to history in a general manner, based on observable patterns within a theoretical framework of known historical events of his time. He described the beginnings, development, cultural trends and the fall of all societies, leading to the rise of a new society which would then follow the same trends in a continuous cycle. Also, he recommended the best political approaches to develop a society according to his knowledge of history. He heavily emphasized that a good society would be one in which a tradition of education is deeply rooted in its culture.[32] Ibn Khaldun (1987) introduced the word asabiya (solidarity, group feeling, or group consciousness), to explain tribalism. The concept of asabiya has been translated as "social cohesion," "group solidarity," or "tribalism." This social cohesion arises spontaneously in tribes and other small kinship groups (Rashed,2017). Ibn Khaldun believed that too much bureaucracy, such as taxes and legislations, would lead to the decline of a society, since it would constrain the development of more specialized labor (increase in scholars and development of different services). He believed that bureaucrats cannot understand the world of commerce and do not possess the same motivation as a businessman.[32] In his work the Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun emphasizes human beings' faculty to think (fikr) as what determines human behavior and ubiquitous patterns. This faculty is also what inspires human beings to form into a social structure to co-operate in division of labor and organization. According to Zaid Ahmand in Epistemology and the Human Dimension in Urban Studies, the fikr faculty is the supporting pillar for all philosophical aspects of Ibn Khaldun's theory related to human beings’ spiritual, intellectual, physical, social and political tendencies. Another important concept he emphasizes in his work is the mastery of crafts, habits and skills. This takes place after a society is established and according to Ibn Khaldun the level of achievement of a society can be determined by just analyzing these three concepts. A society in its earliest stages is nomadic and primarily concerned with survival, while a society at a later stage is sedentary, with greater achievement in crafts. A society with a sedentary culture and stable politics would be expected to have greater achievements in crafts and technology.[32] Ibn Khaldun also emphasized in his epistemology the important aspect that educational tradition plays to ensure the new generations of a civilization continuously improve in the sciences and develop culture. Ibn Khaldun argued that without the strong establishment of an educational tradition, it would be very difficult for the new generations to maintain the achievements of the earlier generations, let alone improve them. Another way to distinguish the achievement of a society would be the language of a society, since for him the most important element of a society would not be land, but the language spoken. He was surprised that many non-Arabs were really successful in the Arabic society, had good jobs and were well received by the community. "These people were non-Arab by descent, but they grew up among the Arabs who possessed the habit of Arabic," Ibn Khaldun once recalled, "[b]ecause of this, they were able to master Arabic so well that they cannot be surpassed."[53] He believed that the reason why non-Arabs were accepted as part of Arab society was due to their mastery of the Arabic language. Advancements in literary works such as poems and prose were another way to distinguish the achievement of a civilization, but Ibn Khaldun believed that whenever the literary facet of a society reaches its highest levels it ceases to indicate societal achievements anymore, but is an embellishment of life. For logical sciences he established knowledge at its highest level as an increase of scholars and the quality of knowledge. For him the highest level of literary productions would be the manifestation of prose, poems and the artistic enrichment of a society.[54] |

社会思想 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。 出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の記載がない項目は、削除される場合があります。 (2024年4月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) イブン・ハルドゥーンの認識論は、科学をクルアーンの科学と非宗教的な科学という2つの異なるカテゴリーに分けることで、神秘主義と神学の調和を図ろうと した。彼はさらに、非宗教的な科学を、論理学、算術、幾何学、天文学などの知的科学と、言語学、文学、詩学などの補助科学に分類した。また、異なる社会で は、将来的にさらに多くの区分が現れる可能性があることも示唆した。彼は、教育、経済、政治の分野において、あらゆる社会の文化的行動や影響に適応しよう とした。しかし、彼は法律は単独の指導者や少数の個人によって選ばれるものではなく、ほとんどの場合、社会の大多数の個人によって選ばれると考えていた。 イブン・ハルドゥーンにとって、国家とは社会内の不正を抑制するための人間社会の必然的なものであったが、国家の手段は力であり、それ自体が不正である。 社会を確立するためには、すべての社会は国家による統治が必要である。彼は、あらゆる社会に存在する普遍的な現象を特定することで、社会の歴史を標準化し ようとした。彼にとって、文明とは人間が存在する限り存在し続ける現象であった。彼は、基本的なニーズが満たされることが文明の始まりであると特徴づけ た。当初、人々は基本的なニーズの生産性を高めるための異なる方法を模索し、拡大が起こる。その後、社会は定住化し、工芸や芸術、より洗練された特性に重 点を置くようになる。社会の終わりには弱体化し、別の小集団が支配権を握るようになる。征服集団は、社会内部の不満を抱えた集団、あるいは常に他の弱体化 した社会を攻撃する砂漠の盗賊集団として描写されている。 彼の最も重要な著作『ムカッディマ』では、同時代の歴史的事象の理論的枠組みの中で観察可能なパターンを基に、歴史への哲学の導入について一般的な方法で 論じている。彼は、あらゆる社会の始まり、発展、文化的な傾向、そして衰退について述べ、それが新たな社会の台頭につながり、その後は同じ傾向が継続的な サイクルで繰り返されると述べている。また、歴史に関する彼の知識に基づいて、社会を発展させるための最善の政治的アプローチを推奨している。彼は、優れ た社会とは、教育の伝統が文化に深く根付いている社会であると強く主張した。[32] イブン・ハルドゥーン(1987年)は、部族主義を説明する際に「アサビヤ(連帯感、集団意識、集団的無意識)」という言葉を導入した。アサビヤの概念 は、「社会的結束」、「集団的連帯」、「部族主義」と訳されている。この社会的結束は、部族やその他の小規模な親族グループにおいて自然発生的に生じる (Rashed,2017)。 イブン・ハルドゥーンは、税金や法律などの官僚主義が過剰になると、より専門化された労働(学者の増加や異なるサービスの開発)の発展が妨げられ、社会の 衰退につながると考えていた。官僚は商業の世界を理解できず、実業家と同じモチベーションを持つことはできないと彼は考えていた。 イブン・ハルドゥーンは著書『ムカッディマ』の中で、人間の行動や普遍的なパターンを決定するものとして、人間の思考能力(フィクル)を強調している。こ の能力はまた、人間が社会構造を形成し、分業や組織化において協力し合うよう促すものでもある。ザイド・アフマド著『都市研究における認識論と人間的側 面』によると、フィクルの能力は、人間の精神、知性、身体、社会、政治的傾向に関連するイブン・ハルドゥーンの理論のすべての哲学的な側面を支える柱であ る。 また、彼の著書で強調されているもう一つの重要な概念は、技術、習慣、スキルの習得である。これは社会が確立された後に起こるものであり、イブン・ハル ドゥーンによれば、社会の達成レベルはこれら3つの概念を分析するだけで決定できる。社会の初期段階では遊牧生活が主であり、生存が主な関心事である。一 方、社会が後期段階に入ると定住生活が主となり、手工業の達成度が向上する。定住文化と安定した政治を持つ社会では、手工業と技術の達成度がより高くなる ことが期待される。 また、イブン・ハルドゥーンは、文明の新しい世代が科学を絶えず向上させ、文化を発展させるために、教育の伝統が果たす重要な側面を、彼の認識論において 強調した。イブン・ハルドゥーンは、教育の伝統がしっかりと確立されていなければ、新しい世代が以前の世代の業績を維持することは非常に困難であり、まし てやそれを向上させることは不可能であると論じた。 また、社会の成果を区別する別の方法として、その社会の言語が挙げられる。彼にとって、社会の最も重要な要素は土地ではなく、話される言語である。彼は、 アラブ人ではない多くの人々がアラブ社会で成功を収め、良い仕事に就き、コミュニティから高く評価されていることに驚いていた。「彼らは血統的には非アラ ブ人だが、アラブ人の間で育ち、アラブ人の習慣を身につけた。」とイブン・ハルドゥーンは回想している。「このため、彼らはアラブ語を極めて習得し、他の 追随を許さないほどだった。」[53] 非アラブ人がアラブ社会の一員として受け入れられたのは、彼らがアラブ語を習得していたからだと彼は考えた。 詩や散文などの文学作品の進歩も、文明の達成を際立たせるもう一つの方法であったが、イブン・ハルドゥーンは、社会の文学的側面が最高レベルに達した時点 で、もはや社会の達成を示すものではなくなり、生活の装飾になると考えていた。論理科学については、学者の増加と知識の質の高まりを知識の最高レベルと位 置づけた。彼にとって、文学的生産物の最高レベルとは、散文、詩、そして社会の芸術的豊かさの顕現である。[54] |

| Religious thought Ibn Khaldun believes that communication between the tangible and intangible world is the basis of every religion, and the credit for its occurrence is the human spirit, as it is the mediator between God and humans. It is immortal by nature and does not perish, and has characteristics that enable it to communicate with God. However, most souls have lost their hidden ability and are connected to the sensory world only. A small number of them still maintain their full ability to communicate with God. These are the ones God chose and they became prophets, so their souls leave the sensory world to receive from God. Their souls abandon the sensory world in order to receive from God what they should convey to humans. Religions arise only from this connection. He believes that religions that rely on institutions of prediction and reconnaissance are false, but they partly contain some truth. A person’s concentration on a specific thing for a long period makes him forget everything and become attached to what he focused on. Only, this focus makes him see the non-sensory world very quickly and in a very imperfect way, and these are pagan religions.[55] Ibn Khaldun agrees with Sufism and believes that if a person maintains his good faith and is stripped of the desire to create a new religion and strives to separate himself from the sensory world, he will be able to approach the divine essence and the ideas of scholars will appear to him clearly. But if he strives in this detachment and mysticism out of a desire to excel over others, he will not communicate with God, but with demons. Also, the human spirit is able to see some things of the future through vision, but on the condition that this spirit be completely upright and very pious and pure, otherwise the vision will come from the devils.[55] |

宗教思想 イブン・ハルドゥーンは、有形世界と無形世界とのコミュニケーションがすべての宗教の基礎であり、その発生の要因は神と人間との仲介者である人間の精神で あると考えている。人間の精神は本質的に不滅であり滅びることがなく、神とコミュニケーションを取る能力を備えている。しかし、ほとんどの魂はその隠され た能力を失っており、感覚世界とのつながりしか持っていない。ごく一部の魂は、神と交信する能力を完全に維持している。神が選んだのはこの魂であり、彼ら は預言者となる。彼らの魂は感覚世界を離れ、神から受け取る。彼らの魂は感覚世界を離れ、人間に伝えるべきことを神から受け取る。宗教は、このつながりか らだけ生じる。彼は、予言や偵察の制度に依存する宗教は偽物であると信じているが、それらにはある程度の真実が含まれている。人格が特定の物事に長期間集 中すると、その人格はすべてを忘れて、集中した物事に執着するようになる。ただ、この集中によって、非感覚的世界を非常に早く、非常に不完全な方法で見る ようになり、これらは異教の宗教である。[55] イブン・ハルドゥーンはスーフィズムに同意し、人格が善い意志を持ち続け、新しい宗教を創始したいという欲望を捨て、感覚世界から離れようと努力すれば、 神の本質に近づくことができ、学者たちの考えがはっきりと見えるようになると信じていた。しかし、もし人格が他人より優位に立つことを望んで、この離脱と 神秘主義に努力を傾けるのであれば、神とではなく悪魔と交信することになるだろう。また、人間の精神はビジョンを通じて未来の一部を見ることができるが、 その精神が完全に正直で、非常に信心深く、純粋であるという条件付きである。そうでなければ、ビジョンは悪魔から来るだろう。[55] |

| Minor works From other sources we know of several other works, primarily composed during the time he spent in North Africa and Al-Andalus. His first book, Lubābu l-Muhassal, a commentary on the Islamic theology of Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, was written at the age of 19 under the supervision of his teacher Al-Abili in Tunis. A work on Sufism, Shifā'u l-Sā'il, was composed around 1373 in Fes, Morocco. Whilst at the court of Muhammed V, Sultan of Granada, Ibn Khaldūn composed a work on logic, ʻallaqa li-s-Sulṭān. |

主作品 他の情報源から、主に北アフリカとアル・アンダルスで過ごした時期に作曲された、いくつかの他の作品が知られている。彼の最初の著書『Lubābu l-Muhassal』は、ファフル・アル・ディーン・アル・ラージーのイスラム神学に関する注釈であり、チュニスの師アル・アビリの監督の下、19歳の 時に書かれた。スーフィズムに関する著作『Shifā'u l-Sā'il』は、1373年頃にモロッコのフェズで執筆された。グラナダのスルタン、ムハンマド5世の宮廷にいた間、イブン・ハルドゥーンは論理学に 関する著作『ʻallaqa li-s-Sulṭān』を執筆した。 |

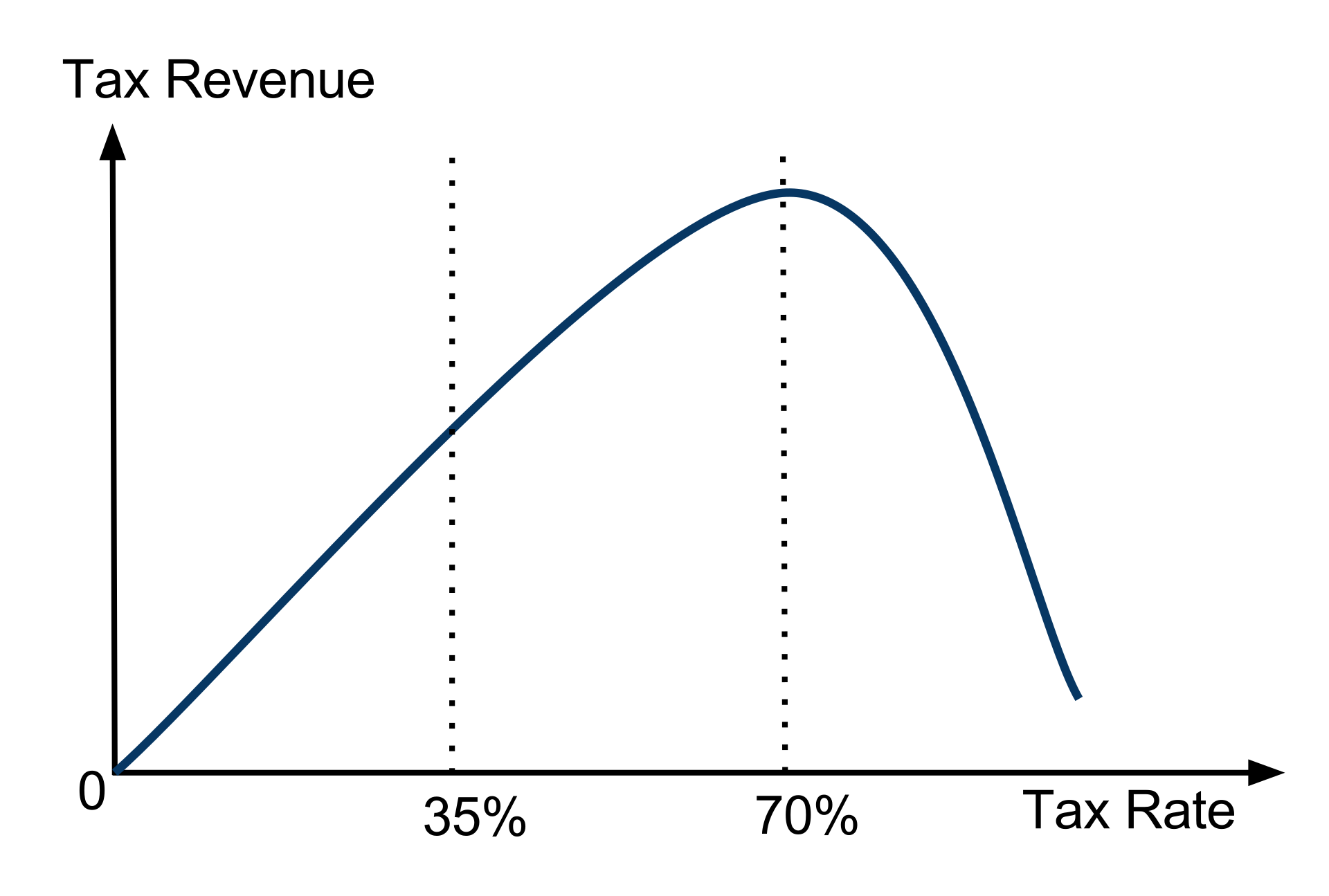

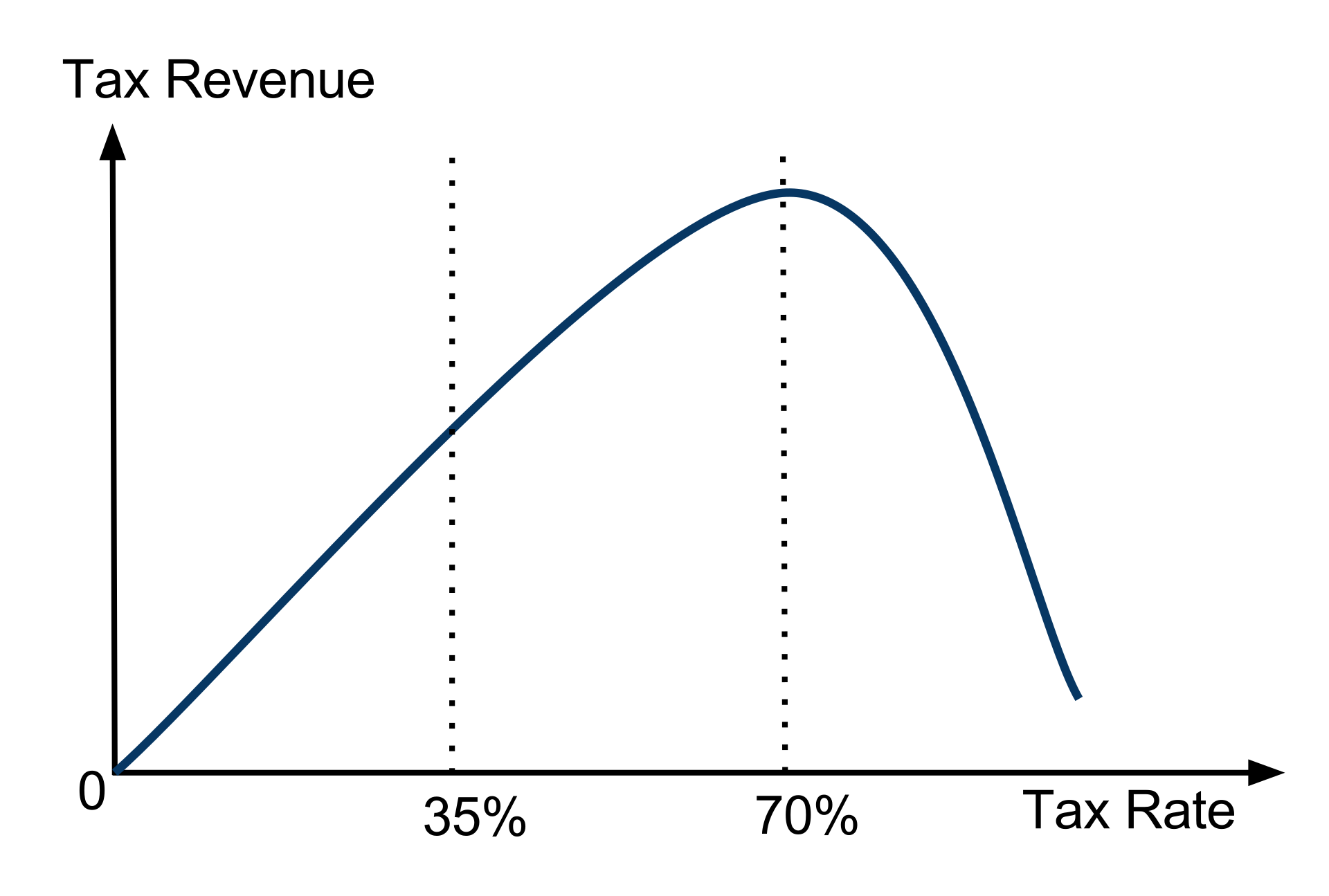

Legacy A Laffer Curve with a maximum revenue point at around a 70%, as estimated by Trabandt and Uhlig (2009).[56] Laffer cites Ibn Khaldun's observation that "at the beginning of the dynasty, taxation yields a large revenue from small assessments. At the end of the dynasty, taxation yields a small revenue from large assessments."[57][58] Egypt Ibn Khaldun's historical method had very few precedents or followers in his time. While Ibn Khaldun is known to have been a successful lecturer on jurisprudence within religious sciences, only very few of his students were aware of, and influenced by, his Muqaddimah.[59] One such student, Al-Maqrizi, praised the Muqaddimah, although some scholars have found his praise, and that of others, to be generally empty and lacking understanding of Ibn Khaldun's methods.[59] Ibn Khaldun also faced primarily criticism from his contemporaries, particularly Ibn Hajar al-`Asqalani. These criticisms included accusations of inadequate historical knowledge, an inaccurate title, disorganization, and a style resembling that of the prolific Arab literature writer, Al-Jahiz. Al-Asqalani also noted that Ibn Khaldun was not well-liked in Egypt because he opposed many respected traditions, including the traditional judicial dress, and suggested that this may have contributed to the reception of Ibn Khaldun's historical works.[59] The notable exception to this consensus was Ibn al-Azraq, a jurist who lived shortly after Ibn Khaldun and quoted heavily from the first and fourth books of the Kitab al-‘Ibar, in developing a work of mirrors for princes.[59] Ottoman Empire Ibn Khaldun's work found some recognition with Ottoman intellectuals in the 17th century. The first references to Ibn Khaldun in Ottoman writings appeared in the middle of the 17th century, with historians such as Kâtip Çelebi naming him as a great influence, while another Turkish Ottoman historian, Mustafa Naima, attempted to use Ibn Khaldun's cyclical theory of the rise and fall of empires to describe the Ottoman Empire.[59] Increasing perceptions of the decline of the Ottoman Empire also caused similar ideas to appear independently of Ibn Khaldun in the 16th century, and may explain some of the influence of his works.[59] Europe In Europe, Ibn Khaldun was first brought to the attention of the Western world in 1697, when a biography of him appeared in Barthélemy d'Herbelot de Molainville's Bibliothèque Orientale. However, some scholars believe that Ibn Khaldun's work may have first been introduced to Europe via Ibn Arabshah's biography of Tamerlane, translated to Latin, which covers a meeting between Ibn Khaldun and Tamerlane.[60] According to Ibn Arabshah, during this meeting, Ibn Khaldun and Tamerlane discussed the Maghrib in depth, as well as Tamerlane's genealogy and place in history.[61] Ibn Khaldun began gaining more attention from 1806, when Silvestre de Sacy's Chrestomathie Arabe included his biography together with a translation of parts of the Muqaddimah as the Prolegomena.[62] In 1816, de Sacy again published a biography with a more detailed description on the Prolegomena.[63] More details on and partial translations of the Prolegomena emerged over the years until the complete Arabic edition was published in 1858. Since then, the work of Ibn Khaldun has been extensively studied in the Western world with special interest.[64] Reynold A. Nicholson praised Ibn Khaldun as a uniquely brilliant Muslim sociologist, but discounted Khaldun's influence.[60] Spanish Philosopher José Ortega y Gasset viewed the conflicts of North Africa as a problem that stemmed from a lack of African thought, and praised Ibn Khaldun for making sense of the conflict by simplifying it to the relationship between the nomadic and sedentary modes of life.[60] |

レガシー トラバンドとウーリッヒ(2009年)の推定によると、最大収益点は約70%となる。[56] ラッファーは、イブン・ハルドゥーンの「王朝の初期においては、課税は少額の評価額から大きな収益を生む。王朝の末期においては、課税は多額の評価額から 小さな収益を生む」という観察を引用している。[57][58] エジプト イブン・ハルドゥーンの歴史的方法は、同時代にはほとんど前例や追随者がいなかった。イブン・ハルドゥーンは宗教学の分野では法学者として成功を収めたこ とで知られているが、彼の『ムカッディマ』を知っていたり、影響を受けていた彼の学生はごくわずかであった。[59] そのような学生の一人であるアル・マクリジーは『ムカッディマ』を賞賛したが、一部の学者は彼の賞賛や他の人々の賞賛は概して中身がなく、イブン・ハル ドゥーンの方法に対する理解に欠けていると指摘している。[59] イブン・ハルドゥーンは同時代人、特にイブン・ハジャル・アル=アスカラーニーから主に批判を受けた。これらの批判には、歴史的知識の不足、不正確な肩書 き、構成の乱れ、多作なアラブ文学作家アル・ジャヒズの文体に似ていることなどに対する非難が含まれていた。アル・アスカラーニーはまた、イブン・ハル ドゥーンが伝統的な法服を含む多くの尊敬される伝統に反対したため、エジプトではあまり好まれていなかったと指摘し、これがイブン・ハルドゥーンの歴史的 著作の受容に貢献した可能性があると示唆した。 [59] このコンセンサスに対する顕著な例外は、イブン・ハルドゥーンのすぐ後に生きた法学者イブン・アル・アズラクで、彼は『君主の鏡』を著すにあたり、『歴史 の根拠』の第1巻と第4巻から多くを引用している。 オスマン帝国 イブン・ハルドゥーンの著作は、17世紀のオスマン帝国の知識人たちにも一定の評価を得た。オスマン帝国の文献にイブン・ハルドゥーンが初めて言及された のは17世紀半ばで、カタプ・チェレビなどの歴史家が彼を大きな影響力を持つ人物として挙げた。一方、トルコ系オスマン帝国の歴史家ムスタファ・ナイマ は、帝国の興亡に関するイブン・ハルドゥーンの循環論を用いてオスマン帝国を説明しようとした。 [59] オスマン帝国の衰退に対する認識が高まるにつれ、16世紀にはイブン・ハルドゥーンとは独立に同様の考えが現れるようになり、彼の著作の影響の一部を説明 できるかもしれない。 ヨーロッパ ヨーロッパでは、イブン・ハルドゥーンの名が西洋世界に知られるようになったのは、1697年にバルテレミー・ダールベロ・ド・モランヴィルの著書『東洋 図書館』に彼の伝記が掲載されてからである。しかし、一部の学者は、イブン・ハルドゥーンの業績は、イブン・アラブシャーが著したティムールラーンの伝記 がラテン語に翻訳され、その中でイブン・ハルドゥーンとティムールラーンの会合について触れられたことにより、初めてヨーロッパに紹介された可能性がある と主張している。[60] イブン・アラブシャーによると、この会合で、イブン・ハルドゥーンとティムールラーンはマグレブについて深く議論し、ティムールラーンの家系や歴史におけ る位置についても話し合った。 [61] イブン・ハルドゥーンは、1806年にシルベストル・ド・サシーの『Chrestomathie Arabe』が彼の伝記と『序説』の一部の翻訳を収録して以来、より注目されるようになった。[62] 1816年には、サシーが再び伝記を『序説』に収録し、より詳細な記述を加えて出版した。 [63] プロレゴメナの詳細と部分的な翻訳は、1858年に完全なアラビア語版が出版されるまで、長年にわたって発表され続けた。それ以来、イブン・ハルドゥーン の研究は西洋世界で広く行われるようになり、特に注目を集めるようになった。[64] レイノルド・A・ニコルソンは イブン・ハルドゥーンを「類まれな才能を持つイスラムの社会学者」と称賛したが、ハルドゥーンの影響力については否定した。[60] スペインの哲学者ホセ・オルテガ・イ・ガセットは、北アフリカの紛争をアフリカの思想の欠如に起因する問題と捉え、それを遊牧生活と定住生活の関係に単純 化することで紛争の意義を明らかにしたイブン・ハルドゥーンを称賛した。[60] |

| Modern historians British historian Arnold J. Toynbee has called Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddimah "the greatest work of its kind."[65] Ernest Gellner, once a professor of philosophy and logic at the London School of Economics, considered Khaldun's definition of government[note 5] the best in the history of political theory.[66] More moderate views on the scope of Ibn Khaldun's contributions have also emerged. Arthur Laffer, for whom the Laffer curve is named, acknowledged that Ibn Khaldun's ideas, as well as others, precede his own work on that curve.[67] Economist Paul Krugman described Ibn Khaldun as "a 14th-century Islamic philosopher who basically invented what we would now call the social sciences".[68] 19th century Scottish theologian and philosopher Robert Flint praised him strongly, "as a theorist of history he had no equal in any age or country until Vico appeared, more than three hundred years later. Plato, Aristotle, and Augustine were not his peers, and all others were unworthy of being even mentioned along with him". Ibn Khaldun's work on evolution of societies also influenced Egon Orowan, who introduced the concept of socionomy.[69] While Ibn Khaldun's record-keeping is usually passed over in favor of recognizing his contributions to the science of history, Abderrahmane Lakhsassi wrote "No historian of the Maghreb since and particularly of the Berbers can do without his historical contribution."[70] Public recognition Public recognition of Ibn Khaldun has increased in recent years. In 2004, the Tunisian Community Center launched the first Ibn Khaldun Award to recognize a Tunisian/American high achiever whose work reflects Ibn Khaldun's ideas of kinship and solidarity. The Award was named after Ibn Khaldun for the convergence of his ideas with the organization's objectives and programs. In 2006, the Atlas Economic Research Foundation launched an annual essay contest[71] for students named in Ibn Khaldun's honor. The theme of the contest is "how individuals, think tanks, universities and entrepreneurs can influence government policies to allow the free market to flourish and improve the lives of its citizens based on Islamic teachings and traditions."[71] In 2006, Spain commemorated the 600th anniversary of the death of Ibn Khaldun by orchestrating an exhibit titled "Encounter of Civilizations: Ibn Khaldun."[72] In 2007, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi has opened in Istanbul, Turkey to commemorate his name. The university promotes a policy of trilingualism. The languages in question are English, Modern Turkish, and Arabic and its emphasis is on teaching social sciences. In 1981 U.S. President Ronald Reagan cited Ibn Khaldun as an influence on his supply-side economic policies, also known as Reaganomics. He paraphrased Ibn Khaldun, who said that "in the beginning of the dynasty, great tax revenues were gained from small assessments," and that "at the end of the dynasty, small tax revenues were gained from large assessments." Reagan said his goal is "trying to get down to the small assessments and the great revenues."[73] The Iraqi Navy named a frigate after Ibn Khaldun. |

近代の歴史家 イギリスの歴史家アーノルド・J・トインビーは、イブン・ハルドゥーンの著書『ムカッディマ』を「その種の著作の中で最も偉大な作品」と呼んだ。[65] かつてロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスの哲学・論理学教授であったエルンスト・ゲルナーは、ハルドゥーンの政治の定義[注釈5]を政治理論史上最 高のものとみなした。[66] イブン・ハルドゥーンの貢献の範囲については、より穏健な見解も出されている。 ラッファー曲線の考案者として知られるアーサー・ラッファーは、イブン・ハルドゥーンの考え方は、ラッファー曲線に関する自身の研究よりも先行していることを認めている。 経済学者のポール・クルーグマンは、イブン・ハルドゥーンを「14世紀のイスラム哲学者であり、今日私たちが社会科学と呼ぶものを基本的に発明した人物」と評している。[68] 19世紀のスコットランドの神学者で哲学者のロバート・フリントは、彼を強く賞賛し、「歴史の理論家として、300年以上後のヴィーコが登場するまで、彼 に匹敵する人物はどの時代にもどの国にも存在しなかった。プラトン、アリストテレス、アウグスティヌスは彼の同時代人ではなく、他のすべての人々は彼と一 緒に語られることさえも不適格であった」と述べた。イブン・ハルドゥーンの社会進化論は、ソシオノミーの概念を導入したエゴン・オローワンにも影響を与え た。[69] イブン・ハルドゥーンの記録管理は、通常、歴史学への貢献を認識するよりも軽視されるが、アブデルラフマーン・ラクサッシは「マグレブの歴史家、特にベル ベル人の歴史家は、彼の歴史的貢献なしには語れない」と述べている。[70] 公的な認知 近年、イブン・ハルドゥーンに対する公の評価は高まっている。2004年には、チュニジア・コミュニティ・センターが、イブン・ハルドゥーンの親族観と連 帯の理念を反映した業績を残したチュニジア系アメリカ人の優秀な人材を表彰する初のイブン・ハルドゥーン賞を創設した。この賞は、イブン・ハルドゥーンの 思想が組織の目的やプログラムと一致していることから、彼の名にちなんで名付けられた。2006年には、アトラス経済研究財団がイブン・ハルドゥーンの名 を冠した学生を対象とした年次論文コンテストを開始した。コンテストのテーマは、「イスラムの教えと伝統に基づき、自由市場を発展させ、市民の生活を向上 させるために、個人、シンクタンク、大学、起業家が政府の政策にどのような影響を与えることができるか」である。[71] 2006年には、スペインが「文明の出会い:イブン・ハルドゥーン」と題した展示会を企画し、イブン・ハルドゥーンの没後600年を記念した。[72] 2007年には、彼の名を記念してトルコのイスタンブールにイブン・ハルドゥン大学が開校した。この大学では3言語政策が推進されている。対象言語は英語、現代トルコ語、アラビア語であり、社会科学の教育に重点が置かれている。 1981年、米国大統領ロナルド・レーガンは、サプライサイド経済政策(レーガノミクス)に影響を与えた人物としてイブン・ハルドゥンを挙げた。彼は、イ ブン・ハルドゥーンの言葉を引用し、「王朝の初期には、少額の課税で大きな税収が得られた」とし、「王朝の末期には、多額の課税で少額の税収が得られた」 と述べた。レーガンは、「少額の課税で大きな税収を得ることを目指している」と述べた。[73] イラク海軍は、イブン・ハルドゥーンにちなんでフリゲート艦にその名を付けた。 |

| Bibliography Kitāb al-ʻIbar wa-Dīwān al-Mubtadaʼ wa-l-Khabar fī Taʼrīkh al-ʻArab wa-l-Barbar wa-Man ʻĀṣarahum min Dhawī ash-Shaʼn al-Akbār Lubābu-l-Muhassal fee Usūlu-d-Dīn Shifā'u-s-Sā'il ʻAl-Laqaw li-s-Sulṭān Ibn Khaldun. 1951 التعريف بإبن خلدون ورحلته غربا وشرقا Al-Taʻrīf bi Ibn-Khaldūn wa Riħlatuhu Għarbān wa Sharqān. Published by Muħammad ibn-Tāwīt at-Tanjī. Cairo (Autobiography in Arabic). Ibn Khaldūn. 1958 The Muqaddimah : An introduction to history. Translated from the Arabic by Franz Rosenthal. 3 vols. New York: Princeton. Ibn Khaldūn. 1967 The Muqaddimah : An introduction to history. Trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N.J. Dawood. (Abridged). Ibn Khaldun, 1332–1406. 1905 'A Selection from the Prolegomena of Ibn Khaldūn'. Trans. Duncan Macdonald |

参考文献 Kitāb al-ʻIbar wa-Dīwān al-Mubtadaʼ wa-l-Khabar fī Taʼrīkh al-ʻArab wa-l-Barbar wa-Man ʻĀṣarahum min Dhawī ash-Shaʼn al-Akbār Lubābu-l-Muhassal fee Usūlu-d-Dīn Shifā'u-s-Sā'il ʻAl-Laqaw li-s-Sulṭān イブン・ハルドゥーン。1951年 イブン・ハルドゥーンの定義と業績:西と東。ムハンマド・イブン・タウィート・アッ=タンジー編。カイロ(アラビア語による自伝)。 イブン・ハルドゥーン。1958年 『ムカッディマ:歴史序説』。アラビア語からフランス・ローゼンタール訳。3巻。ニューヨーク:プリンストン。 イブン・ハルドゥーン。1967年 『ムカッディマ:歴史序説』。フランス・ローゼンタール訳、N.J.ダウード編。(抄訳)。 イブン・ハルドゥーン、1332年~1406年。1905年 『イブン・ハルドゥーンのプロレゴメナからの抜粋』。訳:ダンカン・マクドナルド |

| Al-Zahrawi Chanakya Historic recurrence Historiography of early Islam Ibn Arabi Ibn Tufail List of Muslim historians List of pre-modern Arab scientists and scholars Sayyid Husayn Ahlati Science in medieval Islam Ibn Inabah Ibn Sufi |

アル・ザハラウィー チャナクヤ 歴史の繰り返し 初期イスラームの歴史学 イブン・アラビー イブン・トゥファイル イスラム教史家の一覧 中世以前のアラブの科学者および学者の一覧 サイイド・フセイン・アフラティー 中世イスラームの科学 イブン・イナバ イブン・スーフィー |

| Sources Fuad Baali. 2005 The science of human social organization : Conflicting views on Ibn Khaldun's (1332–1406) Ilm al-umran. Mellen studies in sociology. Lewiston/NY: Edwin Mellen Press. Boulakia, Jean David C. (1971). "Ibn Khaldûn: A Fourteenth-Century Economist". Journal of Political Economy. 79 (5): 1105–1118. doi:10.1086/259818. JSTOR pss/1830276. S2CID 144078253. Walter Fischel. 1967 Ibn Khaldun in Egypt : His public functions and his historical research, 1382–1406; a study in Islamic historiography. Berkeley: University of California Press. Allen Fromherz. 2010 "Ibn Khaldun : Life and Times". Edinburgh University Press, 2010. Ana Maria C. Minecan, 2012 "El vínculo comunitario y el poder en Ibn Jaldún" in José-Miguel Marinas (Ed.), Pensar lo político: Ensayos sobre comunidad y conflicto, Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid, 2012. Mahmoud Rabi'. 1967 The political theory of Ibn Khaldun. Leiden: E.J. Brill. Róbert Simon. 2002 Ibn Khaldūn : History as science and the patrimonial empire. Translated by Klára Pogátsa. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. Original edition, 1999. Weiss, Dieter (1995). "Ibn Khaldun on Economic Transformation". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 27 (1). Cambridge University Press: 29–37. doi:10.1017/S0020743800061560. JSTOR 176185. S2CID 162022220. Further reading Malise Ruthven, "The Otherworldliness of Ibn Khaldun" (review of Robert Irwin, Ibn Khaldun: An Intellectual Biography, Princeton University Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0691174662, 243 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 2 (7 February 2019), pp. 23–24, 26. "More than six centuries after Ibn Khaldun's death the modern world has much to learn from studying him. After the Muqaddima itself, Irwin's intellectual biography... is an excellent place to begin." |

出典 Fuad Baali. 2005 『人間の社会組織の科学:イブン・ハルドゥーン(1332年~1406年)の『群集論』に関する相反する見解』。Mellen studies in sociology. Lewiston/NY: Edwin Mellen Press. Boulakia, Jean David C. (1971). 「Ibn Khaldûn: A Fourteenth-Century Economist」. Journal of Political Economy. 79 (5): 1105–1118. doi:10.1086/259818. JSTOR pss/1830276. S2CID 144078253. ウォルター・フィッシェル著。1967年『エジプトにおけるイブン・ハルドゥーン:彼の公職と歴史研究、1382年~1406年;イスラム史学における研究。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版。 アレン・フロムヘルツ著。2010年「イブン・ハルドゥーン:生涯と時代」。エジンバラ大学出版、2010年。 アナ・マリア・C・ミネカン著、2012年「イブン・ハルドゥーンにおける共同体と権力」ホセ=ミゲル・マリーナス編著『政治を考える:共同体と紛争に関する研究』、マドリード、Biblioteca Nueva、2012年。 マフムード・ラビ著。1967年 イブン・ハルドゥーンの政治理論。ライデン:E.J.ブリル。 ロベルト・サイモン著。2002年 イブン・ハルドゥーン:科学としての歴史と遺産帝国。クララ・ポガツァ訳。ブダペスト:アカデミア・キアド。初版は1999年。 Weiss, Dieter (1995). 「Ibn Khaldun on Economic Transformation」. International Journal of Middle East Studies. 27 (1). Cambridge University Press: 29–37. doi:10.1017/S0020743800061560. JSTOR 176185. S2CID 162022220. 参考文献 マライズ・ルスベン、「イブン・ハルドゥーンの超世俗性」(ロバート・アーウィン著『イブン・ハルドゥーン:知的生活伝』プリンストン大学出版、2018 年、ISBN 978-0691174662、243ページの書評)、『ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』第66巻第2号(2019年2月7日)、23-24、 26ページ。LXVI, no. 2 (7 February 2019), pp. 23–24, 26. 「イブン・ハルドゥーンの死後6世紀以上が経過した現代社会は、彼を研究することから多くを学ぶことができる。『ムカッディマ』自体もそうだが、アーウィ ンの知的伝記は... 始めるのに最適な場所である。」 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_Khaldun |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆