イド・エゴ・スーパーエゴ

Id, ego and superego

☆ Id, ego and superegoは、イド・エゴ・スーパーエゴは、前意識(イド)、自我、超自我とも訳せる。精神分析理論では、イド、エゴ、超自我は、精神分析における 精神構造モデルを定義したジークムント・フロイトの理論に基づき、精神機構における3つの異なる相互作用する要素である。この3つの要素は、フロイトが精 神分析の実践で遭遇した精神生活の基礎構造を説明するのに用いた理論上の概念である。フロイト自身は、ドイツ語で「Das Es(それ)」、「Ich(私)」、「Über-Ich(超自我)」という用語を使用していた。ラテン語の「イド」、「エゴ」、「超自我」という用語は、 彼の翻訳者が選んだもので、現在も使用されている。 精神の自我心理学モデルでは、イドは協調性のない本能的欲望の集合体であり、超自我は批判的かつ道徳的な役割を果たし、自我は本能的欲望の [1] フロイトは自我(イドとの関係において)を馬に乗った人に例えた。騎手は馬に馬具をつけ、馬が持つ優れたエネルギーを制御し、時には衝動を現実的に満足さ せることも必要である。自我はこのように、「あたかもそれが自分自身のものであるかのように、イドの意志を行動に変える習慣」[2] を持っている。 フロイトは、構造化されていない曖昧さや「無意識」という言葉の相反する用法に対応するため、論文『快楽原則の彼方』(1920年)で構造モデル(イド、 自我、超自我)を導入した。彼は、そのモデルを『自我と本能』(1923年)でさらに詳しく説明し、洗練させ、体系化した。

| In psychoanalytic

theory, the

id, ego and superego are three distinct, interacting agents in the

psychic apparatus, defined in Sigmund Freud's structural model of the

psyche. The three agents are theoretical constructs that Freud employed

to describe the basic structure of mental life as it was encountered in

psychoanalytic practice. Freud himself used the German terms das Es,

Ich, and Über-Ich, which literally translate as "the it", "I", and

"over-I". The Latin terms id, ego and superego were chosen by his

original translators and have remained in use. In the ego psychology model of the psyche, the id is the set of uncoordinated instinctual desires; the superego plays the critical and moralizing role; and the ego is the organized, realistic agent that mediates between the instinctual desires of the id and the critical superego;[1] Freud compared the ego (in its relation to the id) to a man on horseback: the rider must harness and direct the superior energy of his mount, and at times allow for a practicable satisfaction of its urges. The ego is thus "in the habit of transforming the id's will into action, as if it were its own."[2] Freud introduced the structural model (id, ego, superego) in the essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) in response to the unstructured ambiguity and conflicting uses of the term "the unconscious mind". He elaborated, refined, and formalized that model in the essay The Ego and the Id (1923).[3] |

精神分析理論では、イド、エゴ、超自我は、精神分析における精神構造モ

デルを定義したジークムント・フロイトの理論に基づき、精神機構における3つの異なる相互作用する要素である。この3つの要素は、フロイトが精神分析の実

践で遭遇した精神生活の基礎構造を説明するのに用いた理論上の概念である。フロイト自身は、ドイツ語で「Das

Es(それ)」、「Ich(私)」、「Über-Ich(超自我)」という用語を使用していた。ラテン語の「イド」、「エゴ」、「超自我」という用語は、

彼の翻訳者が選んだもので、現在も使用されている。 精神の自我心理学モデルでは、イドは協調性のない本能的欲望の集合体であり、超自我は批判的かつ道徳的な役割を果たし、自我は本能的欲望の [1] フロイトは自我(イドとの関係において)を馬に乗った人に例えた。騎手は馬に馬具をつけ、馬が持つ優れたエネルギーを制御し、時には衝動を現実的に満足さ せることも必要である。自我はこのように、「あたかもそれが自分自身のものであるかのように、イドの意志を行動に変える習慣」[2] を持っている。 フロイトは、構造化されていない曖昧さや「無意識」という言葉の相反する用法に対応するため、論文『快楽原則の彼方』(1920年)で構造モデル(イド、 自我、超自我)を導入した。彼は、そのモデルを『自我と本能』(1923年)でさらに詳しく説明し、洗練させ、体系化した[3]。 |

| Translation of the terms The terms "id", "ego", and "superego" are not Freud's own; they are Latinizations by his translator James Strachey. Freud himself wrote of "das Es",[4] "das Ich",[5] and "das Über-Ich"[6]—respectively, "the It", "the I", and "the Over-I". Thus, to the German reader, Freud's original terms are to some degree self-explanatory. The term "das Es" was originally used by Georg Groddeck, a physician whose unconventional ideas were of interest to Freud (Groddeck's translators render the term in English as "the It").[7] The word ego is taken directly from Latin, where it is the nominative of the first person singular personal pronoun and is translated as "I myself" to express emphasis. Figures like Bruno Bettelheim have criticised the way "the English translations impeded students' efforts to gain a true understanding of Freud"[8] by substituting the formalised language of the elaborated code for the quotidian immediacy of Freud's own language. |

語の翻訳 「イド」、「自我」、「超自我」という用語はフロイト自身のものではなく、彼の翻訳者ジェームズ・ストラチーによるラテン語化である。フロイト自身は 「Das Es」(「それ」)、[4]「Das Ich」(「私」)、[5]「Das Über-Ich」(「超自我」)[6]、それぞれ「The It」、「The I」、「The Over-I」と記している。したがって、ドイツ語を母国語とする読者にとっては、フロイトが用いた用語は、ある程度自明である。「das Es」という用語は、当初、フリードの興味を引いた型破りな考えを持つ医師、ゲオルク・グロデックによって使用されていた(グロデックの翻訳者は、この用 語を英語で「the It」と訳している)[7]。ego(自我)という言葉はラテン語から直接借用されたもので、一人称単数人称代名詞の主格であり、「私自身」と訳され、強 調を表す。ブルーノ・ベッテルハイムのような人物は、「英語の翻訳が、精緻に作り上げられたコードの形式化された言語をフロイト自身の日常的な言葉の即時 性に置き換えることによって、学生たちがフロイトの真の意味を理解しようとする努力を妨げている」[8]と批判している。 |

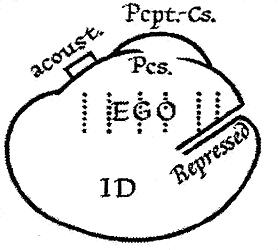

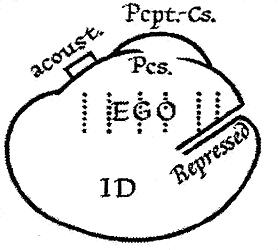

| Psychic apparatus Id Freud conceived the id as the unconscious source of bodily needs and wants, emotional impulses and desires, especially aggression and the sexual drive.[9] The id acts according to the pleasure principle—the psychic force oriented to immediate gratification of impulse and desire.[10] Freud described the id as "the dark, inaccessible part of our personality". Understanding of the id is limited to analysis of dreams and neurotic symptoms, and it can only be described in terms of its contrast with the ego. It has no organisation and no collective will: it is concerned only with satisfaction of drives in accordance with the pleasure principle.[11] It is oblivious to reason and the presumptions of ordinary conscious life: "contrary impulses exist side by side, without cancelling each other. . . There is nothing in the id that could be compared with negation. . . nothing in the id which corresponds to the idea of time."[12] The id "knows no judgements of value: no good and evil, no morality. ...Instinctual cathexes seeking discharge—that, in our view, is all there is in the id."[13] Developmentally, the id precedes the ego. The id consists of the basic instinctual drives that are present at birth, inherent in the somatic organization, and governed only by the pleasure principle.[14][15] The psychic apparatus begins as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured "ego", a concept of self that takes the principle of reality into account. Freud describes the id as "the great reservoir of libido",[16] the energy of desire, usually conceived as sexual in nature, the life instincts that are constantly seeking a renewal of life. He later also postulated a death drive, which seeks "to lead organic life back into the inanimate state."[17] For Freud, "the death instinct would thus seem to express itself—though probably only in part—as an instinct of destruction directed against the external world and other organisms"[18] through aggression. Since the id includes all instinctual impulses, the destructive instinct, as well as eros or the life instincts, is considered to be part of the id.[19] Ego The ego acts according to the reality principle. Since the id's drives are frequently incompatible with social reality, the ego attempts to direct its energy and satisfy its demands in accordance with the imperatives of that reality.[20] According to Freud the ego, in its role as mediator between the id and reality, is often "obliged to cloak the (unconscious) commands of the id with its own preconscious rationalizations, to conceal the id's conflicts with reality, to profess...to be taking notice of reality even when the id has remained rigid and unyielding."[21] Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean the sense of self, but later expanded it to include psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality testing, control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory. The ego is the organizing principle upon which thoughts and interpretations of the world are based.[22] According to Freud, "the ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world. ...The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions... it is like a tug of war... with the difference that in the tug of war the teams fight against one another in equality, while the ego is against the much stronger 'id'."[23] In fact, the ego is required to serve "three severe masters...the external world, the superego and the id."[21] It seeks to find a balance between the primitive drives of the id, the limitations imposed by reality, and the strictures of the superego. It is concerned with self-preservation: it strives to keep the id's desires within limits, adapted to reality and submissive to the superego. Thus "driven by the id, confined by the superego, repulsed by reality" the ego struggles to bring about harmony among the competing forces. Consequently, it can easily be subject to "realistic anxiety regarding the external world, moral anxiety regarding the superego, and neurotic anxiety regarding the strength of the passions in the id."[24] The ego may wish to serve the id, trying to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts, while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the superego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and inferiority. To overcome this the ego employs defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms reduce the tension and anxiety by disguising or transforming the impulses that are perceived as threatening.[25] Denial, displacement, intellectualization, fantasy, compensation, projection, rationalization, reaction formation, regression, repression, and sublimation were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. His daughter Anna Freud identified the concepts of undoing, suppression, dissociation, idealization, identification, introjection, inversion, somatization, splitting, and substitution. "The ego is not sharply separated from the id; its lower portion merges into it.... But the repressed merges into the id as well, and is merely a part of it. The repressed is only cut off sharply from the ego by the resistances of repression; it can communicate with the ego through the id." (Sigmund Freud, 1923)  In a diagram of the Structural and Topographical Models of Mind, the ego is depicted as being half in the conscious, a quarter in the preconscious, and the other quarter in the unconscious. Superego The superego reflects the internalization of cultural rules, mainly as absorbed from parents, but also other authority figures, and the general cultural ethos.[10] Freud developed his concept of the superego from an earlier combination of the ego ideal and the "special psychical agency which performs the task of seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured...what we call our 'conscience'."[26] For him the superego can be described as "a successful instance of identification with the parental agency", and as development proceeds it also absorbs the influence of those who have "stepped into the place of parents — educators, teachers, people chosen as ideal models". Thus a child's super-ego is in fact constructed on the model not of its parents but of its parents' super-ego; the contents which fill it are the same and it becomes the vehicle of tradition and of all the time-resisting judgments of value which have propagated themselves in this manner from generation to generation.[27] The superego aims for perfection.[25] It is the part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual's ego ideals, spiritual goals, and the psychic agency, commonly called "conscience", that criticizes and prohibits the expression of drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions. Thus the superego works in contradiction to the id. It is an internalized mechanism that operates to confine the ego to socially acceptable behaviour, whereas the id merely seeks instant self-gratification.[28] The superego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the Oedipus complex.[29] In the case of the little boy, it forms during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex, through a process of identification with the father figure, following the failure to retain possession of the mother as a love-object out of fear of castration. Freud described the superego and its relationship to the father figure and Oedipus complex thus: The super-ego retains the character of the father, while the more powerful the Oedipus complex was and the more rapidly it succumbed to repression (under the influence of authority, religious teaching, schooling and reading), the stricter will be the domination of the super-ego over the ego later on—in the form of conscience or perhaps of an unconscious sense of guilt.[30] In The Ego and the Id, Freud presents "the general character of harshness and cruelty exhibited by the [ego] ideal — its dictatorial Thou shalt". The earlier in the child's development, the greater the estimate of parental power. . . . nor must it be forgotten that a child has a different estimate of his parents at different periods of his life. At the time at which the Oedipus complex gives place to the super-ego they are something quite magnificent; but later, they lose much of this. Identifications then come about with these later parents as well, and indeed they regularly make important contributions to the formation of character; but in that case they only affect the ego, they no longer influence the super-ego, which has been determined by the earliest parental images. — New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, p. 64. Thus when the child is in rivalry with the parental imago[31] it feels the dictatorial Thou shalt—the manifest power that the imago represents—on four levels: (i) the auto-erotic, (ii) the narcissistic, (iii) the anal, and (iv) the phallic.[32] Those different levels of mental development, and their relations to parental imagos, correspond to specific id forms of aggression and affection.[33] The concept of superego and the Oedipus complex is subject to criticism for its perceived sexism. Women, who are considered to be already castrated, do not identify with the father, and therefore, for Freud, "their super-ego is never so inexorable, so impersonal, so independent of its emotional origins as we require it to be in men...they are often more influenced in their judgements by feelings of affection or hostility."[34] However, Freud went on to modify his position to the effect "that the majority of men are also far behind the masculine ideal and that all human individuals, as a result of their human identity, combine in themselves both masculine and feminine characteristics, otherwise known as human characteristics."[35] |

精神的な装置 イド フロイトは、イドを身体的な欲求や願望、感情的な衝動や欲望、特に攻撃性や性的衝動の無意識的な源として考えました[9]。イドは快楽原則に従って行動し ます。これは、衝動や欲望を即座に満たそうとする心理的な力です[10]。 フロイトはイドを「私たちのパーソナリティの暗く、手の届かない部分」と表現しました。イドの理解は、夢や神経症症状の分析に限られており、自我との対比 という観点でしか説明できない。 組織や集団的意志を持たず、快楽原則に従って衝動の満足のみに関わっている[11]。 理性や通常の意識生活の前提を無視しており、「相反する衝動は互いに打ち消し合うことなく、共存している。イドには否定と対比できるものは何もな い。...イドには時間の概念に相当するものは何もない。」[12] イドには「価値判断がない。善悪も道徳もない。...本能的なカタルシスを求める衝動、それが私たちの考えるイドのすべてである。」[13] 発達段階では、イドは自我に先立つ。イドは、誕生時に備わっている基本的な本能的衝動から成り、肉体的組織に内在し、快楽原則のみによって支配されている [14][15]。精神装置は未分化のイドとして始まり、その一部が構造化された「自我」へと発達し、現実の原則を考慮に入れた自己概念となる。 フロイトはイドを「リビドーの巨大な貯蔵庫」[16]、つまり通常は性的性質を持つ欲望のエネルギー、絶えず生命の再生を求める生命本能と表現している。 彼は後に「有機的生命を無機的な状態に戻す」[17] ことを求める死の衝動も提唱した。フロイトにとって、「死の衝動は、おそらくその一部だけであろうが、外の世界や他の生物に対する破壊本能として、攻撃性 を通して表現されると思われる」[18]。イドには本能的な衝動がすべて含まれているため、破壊的な本能やエロス、生命本能もイドの一部であると考えられ ている[19]。 自我 自我は現実の原則に従って行動する。イドの衝動はしばしば社会的現実と相容れないため、自我はそのエネルギーを現実の要請に従って方向付け、要求を満たそ うとする[20]。フロイトによると、自我はイドと現実の仲介役として、しばしば「イドの(無意識の)命令を、自身の前意識的な合理化で覆い隠し、 イドと現実の葛藤を隠蔽し、イドが頑固で融通の利かないままでも、現実を認識していると主張する」[21]。 もともとフロイトは自我を自己意識という意味で用いていたが、後に判断力、寛容さ、現実の検証、コントロール、計画、防衛、情報の統合、知的能力、記憶と いった精神機能を含む概念へと拡大した。自我は、思考や世界に対する解釈の基盤となる組織化原理である[22]。 フロイトによると、「自我とは、外部の世界からの直接的な影響によって変化したイドの一部である。...自我は、情熱を内包するイドとは対照的に、理性や 常識と呼ばれるものを表す。それは綱引きのようなもので、綱引きでは両チームが対等に戦うのに対し、自我ははるかに強力な「イド」と戦うという違いがあ る。 23] 実際、自我は「3人の厳しい主人...外界、超自我、イド」に仕えることが求められる[21]。自我は、イドの原始的な衝動、現実が課す制限、超自我の制 約のあいだでバランスを見出そうとする。自我は自己保存に関心を向け、イドの欲望を現実に適応し、超自我に従順な範囲内に抑えるよう努める。 このように「イドに駆り立てられ、超自我に束縛され、現実から反発される」自我は、対立する力間の調和をもたらすために奮闘する。その結果、自我は「現実 世界に対する現実的不安、超自我に対する道徳的不安、そしてイドにおける情念の強さに対する神経症的不安」[24]に簡単に陥る可能性がある。自我はイド に奉仕したいと考え、現実を尊重しているふりをしながら、葛藤を最小限に抑えるために現実の細かい部分を無視しようとするかもしれない。しかし、超自我は 常に自我の動きを監視しており、罪悪感や不安、劣等感といった感情で自我を罰する。 これを克服するために、自我は防衛機制を用いる。防衛機制とは、脅威と認識される衝動を偽装したり変換したりすることで、緊張や不安を軽減するものである [25]。フロイトが特定した防衛機制には、否認、転嫁、知性化、空想、補償、投影、合理化、反動形成、退行、抑圧、昇華がある。彼の娘であるアナ・フロ イトは、取り消し、抑圧、解離、理想化、同一化、内面化、逆転、身体化、分裂、代替などの概念を明らかにした。 「自我はイドと明確に分離されているわけではなく、その下層部はイドに融合している。しかし、抑圧されたものもイドに融合しており、その一部でしかない。 抑圧されたものは、抑圧の抵抗によって自我から明確に切り離されているだけであり、イドを通じて自我とコミュニケーションをとることができる。」 (ジークムント・フロイト、1923年  「心の構造と表象モデル」の図では、自我は意識の半分、前意識の4分の1、無意識の4分の1を占めるものと描かれている。 超自我 超自我は、主に親から、またその他の権威者から吸収された文化的ルールの内面化を反映している。[10] フロイトは、自我の理想と「自我の理想からナルシシズム的な満足が得られるように監視する特別な心理的機関」[26] の組み合わせから、超自我の概念を発展させた。自我の理想が確実に満たされるように...私たちが「良心」と呼ぶもの」[26]。彼にとって、超自我は 「親の代理と一体化した成功例」と表現でき、発達が進むにつれ、「親の代わりを務める人々(教育者、教師、理想的な模範として選ばれた人々)」の影響も吸 収する。 したがって、子どもの超自我は、実際には両親ではなく両親の超自我をモデルとして構築される。その内容も同じであり、伝統や世代から世代へと伝播してきた 価値判断のすべてを支えるものとなる[2 7] 超自我は完璧を目指している[25]。それは人格構造の一部であり、主に、しかし完全に無意識というわけではない。個人の自我の理想、精神的な目標、そし て一般的に「良心」と呼ばれる、衝動、空想、感情、行動の表現を批判し禁止する精神的な機関を含む。このように、超自我はイドと相反する働きをする。それ は、自我を社会的に許容される行動に制限するために機能する内面化されたメカニズムである。一方、イドはただ即座の自己満足を求めるだけである[28]。 超自我と自我は、2つの重要な要因の産物である。すなわち、子どもの無力感とエディプスコンプレックスである[29]。 [29] 男の子の場合、去勢への恐怖から母親を愛の的として所有し続けることができず、父への同一化プロセスを経てエディプスコンプレックスが解消される過程で形 成される。フロイトは、超自我と父権的象徴およびエディプス・コンプレックスの関係について、次のように述べている。 超自我は父親の性格を保持しており、エディプスコンプレックスがより強力で、より急速に抑圧(権威、宗教的教え、学校教育、読書の影響による)に屈服する ほど、後に超自我が自我を支配する度合いが厳しくなる。 自我が自我を支配する形、つまり良心の形、あるいは無意識の罪悪感の形として、後々より厳しくなるだろう[30]。 『自我とエス』の中でフロイトは、「(自我の)理想が示す厳格さと残酷さという一般的な特徴、すなわち独裁的な汝は…」について述べている。子どもの発育 の初期段階ほど、親の権力に対する評価が高くなる。 また、子どもの人生におけるさまざまな時期に応じて、親に対する評価が異なることも忘れてはならない。エディプスコンプレックスが超自我に取って代わる時 期には、親は素晴らしい存在である。しかし、その後、子どもは親に対する評価の多くを失う。その後、これらの後期の親に対しても同一視が生じ、実際、人格 形成に重要な影響を及ぼすことはよくある。しかし、この場合、自我にのみ影響を与え、最も初期の親のイメージによって決定された超自我にはもはや影響を与 えない。 —『精神分析入門講義』第64ページ したがって、子どもが親イマゴ[31]と対立しているとき、イマゴが象徴する明白な力である独裁的な「汝、汝の義務」を4つのレベルで感じる。(i) 自己愛、(ii) ナルシシズム、(iii) 肛門愛、(iv) ファリスティック[32]。これらの異なる精神発達レベルと、それらが親イマゴスとの関係は、特定のイドの攻撃性と愛情の形態に対応している[33]。 超自我とエディプスコンプレックスの概念は、その性差別的であると批判されている。去勢済みと見なされる女性は父親と同一化しないため、フロイトにとって 「彼女たちの超自我は、男性に対して我々が要求するほど、決して容赦なく、非人間的でも、感情的な起源から独立しているわけではない...彼女たちは、し ばしば愛情や敵意の感情によって判断が左右されることが多い」[34]。愛情や敵意といった感情によって判断が左右されることが多い」[34]。しかし、 フロイトはその後、自らの見解を修正し、「大多数の男性も、男性的な理想からは程遠い存在であり、人間としてのアイデンティティを持つ人間個人は、人間的 特性として知られる男性的および女性的特性を兼ね備えている」[35]と述べた。 |

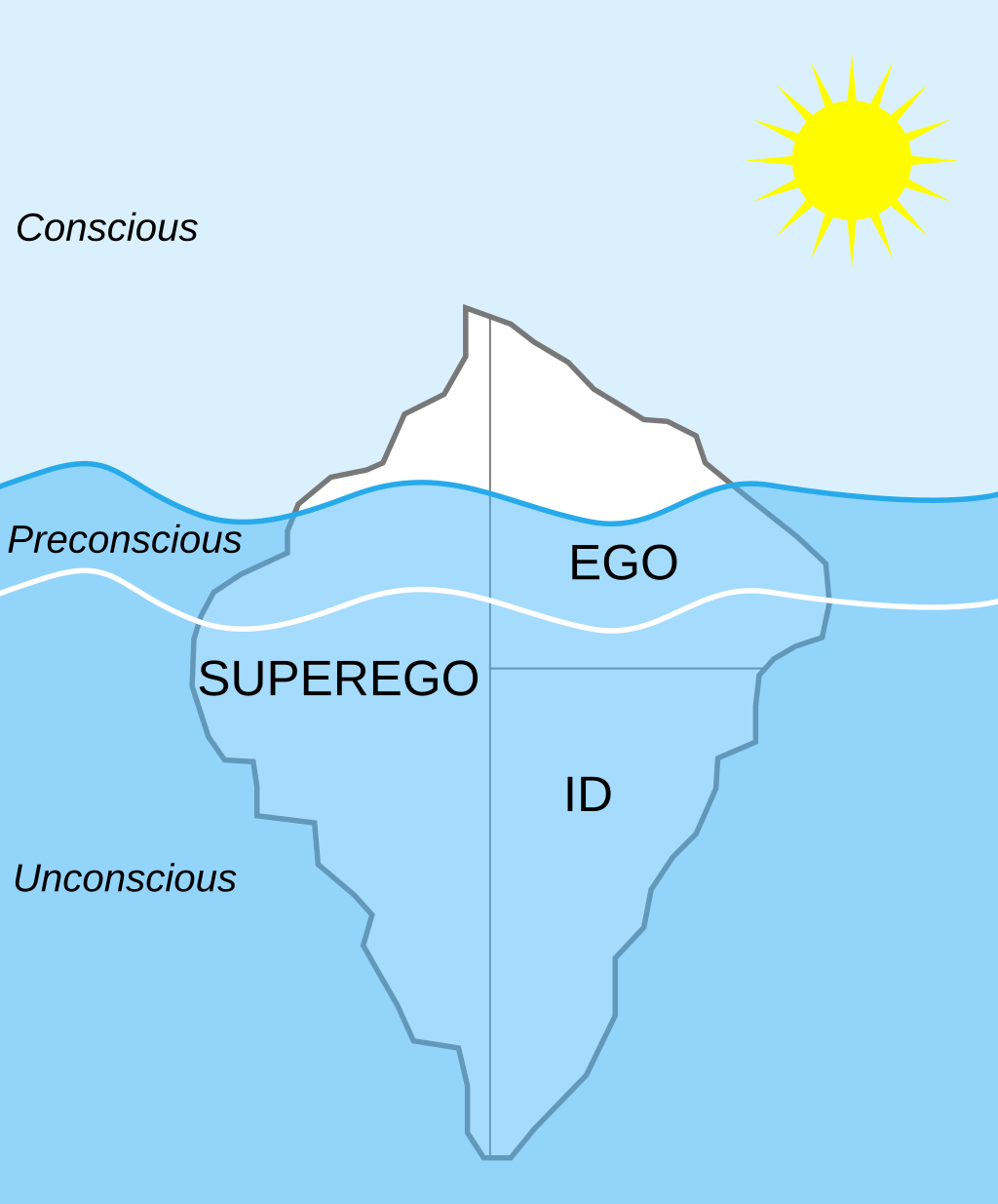

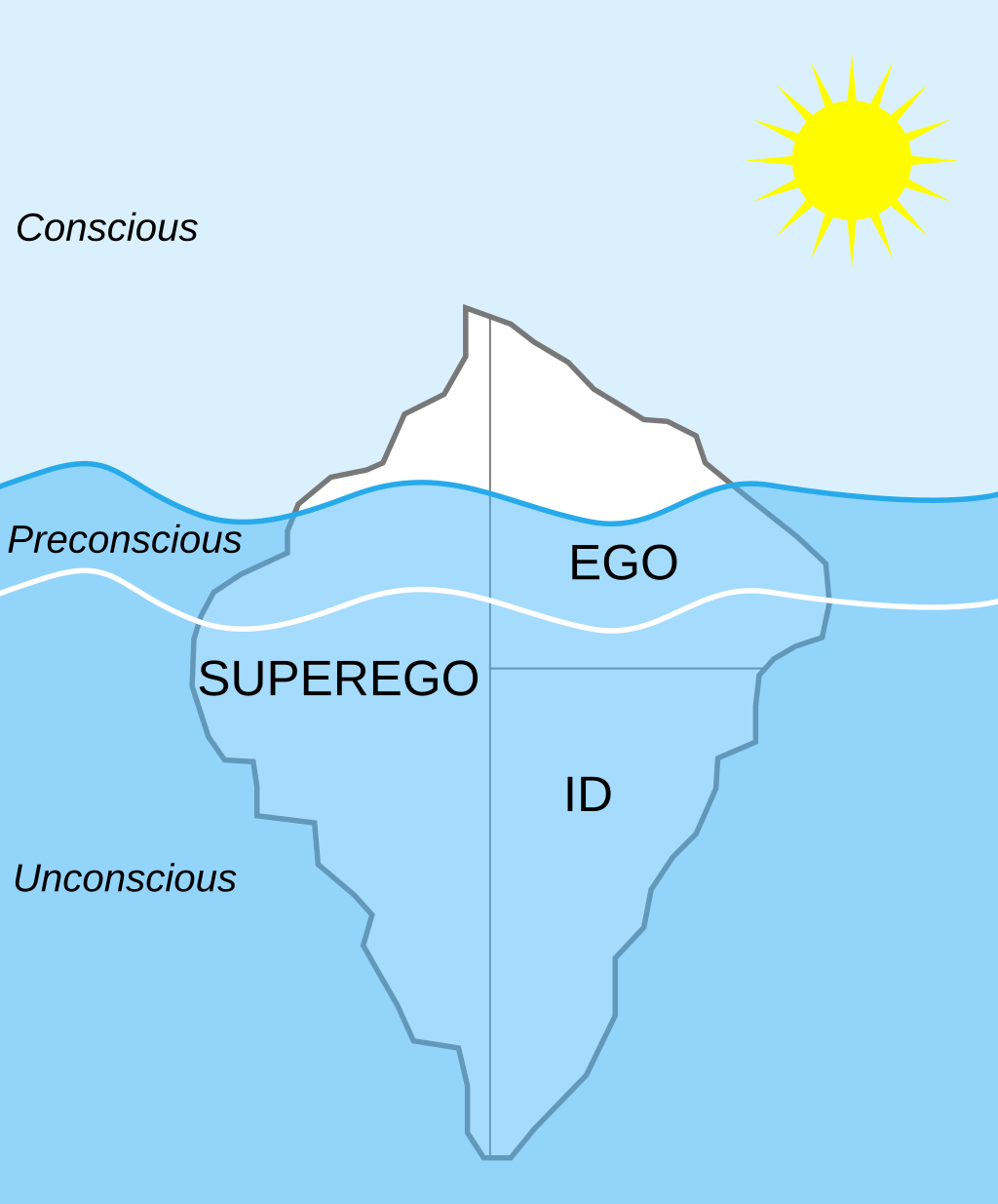

Advantages of the structural

model The iceberg metaphor is often used to explain the psyche's parts in relation to one another. In his earlier "topographic model", Freud divided the psyche into three "regions" or "systems": "the Conscious", that which is present to awareness at the surface level of the psyche in any given moment, including information and stimuli from both internal and external sources; "the Preconscious", consisting of material that is merely latent, not present to consciousness but capable of becoming so; and "the Unconscious", consisting of ideas and impulses that are made completely inaccessible to consciousness by the act of repression. By introducing the structural model, Freud was seeking to reduce his reliance on the term "unconscious" in its systematic and topographic sense—as the mental region that is foreign to the ego—by replacing it with the concept of the 'id'."[36] The partition of the psyche outlined in the structural model is thus one that cuts across the topographical model's partition of "conscious vs. unconscious". Freud favoured the structural model because of the increased degree of precision and diversification that it allowed. Although the id is unconscious by definition, the ego and the superego are both partly conscious and partly unconscious. With the new model, Freud felt he had achieved a more effective classification system for mental disorders than had been available previously: Transference neuroses correspond to a conflict between the ego and the id; narcissistic neuroses, to a conflict between the ego and the superego; and psychoses, to one between the ego and the external world.[37] The three newly presented entities, however, remained closely connected to their previous conceptions, including those that went under different names – the systematic unconscious for the id, and the conscience/ego ideal for the superego.[38] Freud never abandoned the topographical division of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious, though he noted that "the three qualities of consciousness and the three provinces of the mental apparatus do not fall together into three peaceful couples...we had no right to expect any such smooth arrangement."[39] The iceberg metaphor is a commonly used visual metaphor depicting the relationship between the ego, id and superego agencies (structural model) and the conscious and unconscious psychic systems (topographic model). In the iceberg metaphor the entire id and part of both the superego and the ego are submerged in the underwater portion representing the unconscious region of the psyche. The remaining portions of the ego and superego are displayed above water in the conscious region.[9] |

構造モデルの利点 氷山に例えられることの多いフロイトの精神分析学では、精神の各部分を相互に関連づけて説明するのに、しばしばこの比喩が用いられる。 フロイトは、初期の「トポグラフィカル・モデル」において、精神を3つの「領域」または「システム」に分けている。「意識」は、その時点における精神の表 面レベルで認識できるものであり、内部および外部からの情報や刺激を含む。「前意識」は、潜在的に存在しているが、まだ認識されていないが、そうなる可能 性のある要素からなる。「無意識」は、抑圧という行為によって完全に意識から遮断された考えや衝動からなる。フロイトは構造モデルを導入することで、自我 とは無関係な精神領域としての「無意識」という用語への依存度を減らすことを目指していた。無意識を「イド」の概念に置き換えることで、体系的な意味合い と場所的な意味合いの両方において、無意識への依存度を減らすことを目指していたのである。 フロイトが構造モデルを好んだのは、それがより精密で多様性に富んだ分類を可能にするからであった。イドは定義上無意識であるが、自我と超自我はどちらも 部分的に意識的であり、部分的に無意識的でもある。この新しいモデルにより、フロイトはそれまでのものよりも精神障害の分類に効果的な分類体系を確立した と感じていた。 転移神経症は自我とイドの間の葛藤に対応し、自己愛性神経症は自我と超自我の間の葛藤に対応し、精神病は自我と外界の間の葛藤に対応する[37]。 しかし、新たに提示された3つの概念は、イドに対する「系統的無意識」、超自我に対する「良心/自我の理想」など、異なる名称で呼ばれるものも含め、それ までの概念と密接に関連していた[38]。フロイトは決して 意識、前意識、無意識の空間的区分を完全に放棄することはなかったが、彼は「意識の3つの性質と精神装置の3つの領域は、3つの平和なカップルには収まら ない...そのようなスムーズな配置を期待する権利はなかった」[39]と記している。 氷山に例えた比喩は、自我、イド、超自我の機関(構造モデル)と、意識と無意識の精神システム(空間モデル)の関係を表す、よく使われる視覚的比喩であ る。氷山に例えた場合、イドの全体と超自我とエゴの一部が、無意識領域を表す水中に沈んでいる。エゴと超自我の残りの部分は、意識領域である水上に表示さ れている[9]。 |

| Censorship (psychoanalysis) –

Barrier of the conscious and unconscious Ego death – Complete loss of subjective self-identity Plato's theory of soul – Plato's account of the soul as consisting of logical, spirited, and appetitive parts Psychology of self – Study of the representation of one's identity Resistance (psychoanalysis) – Term used in psychoanalysis describing oppositional behaviors |

検閲(精神分析) - 意識と無意識の障壁 エゴの死 - 主観的な自己同一性の完全な喪失 プラトンの魂の理論 - 魂は論理的、精神的な、そして欲望的な部分から構成されているというプラトンの説明 自己の心理学 - 自己同一性の表現の研究 抵抗(精神分析) - 精神分析で使用される用語で、反対の行動を説明する |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Id,_ego_and_superego |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆