人間行動における模倣

Imitation in Human Behaviour

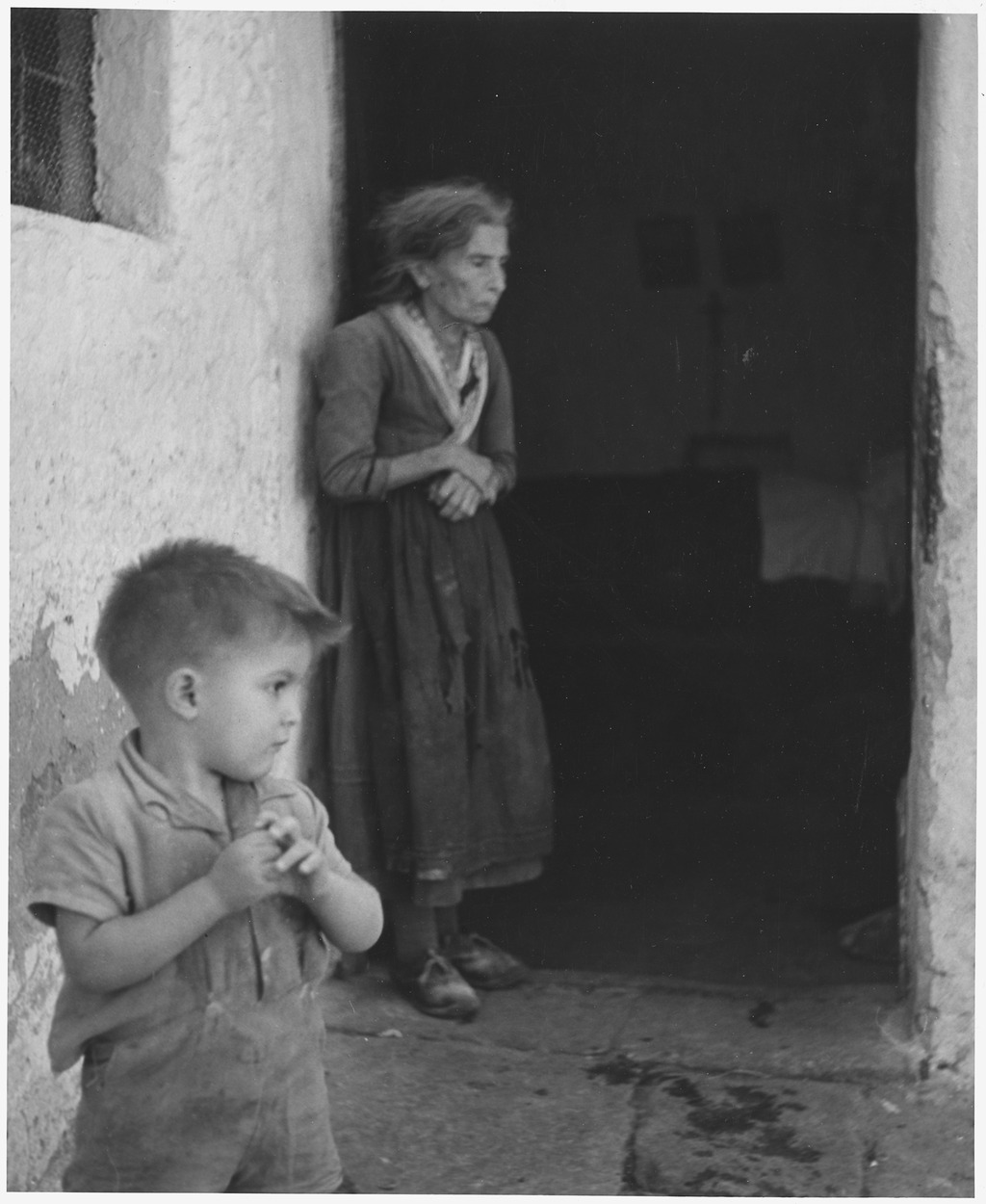

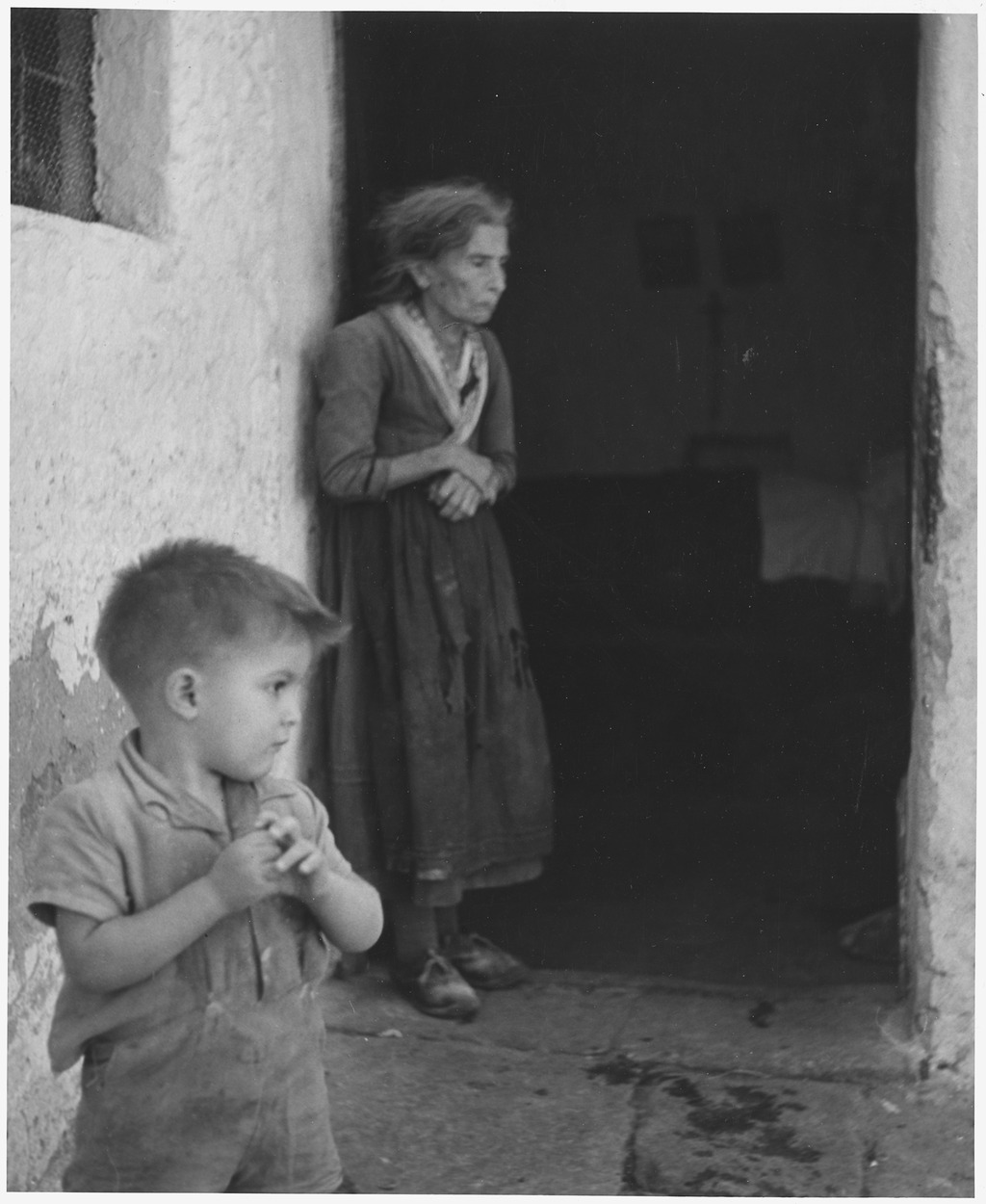

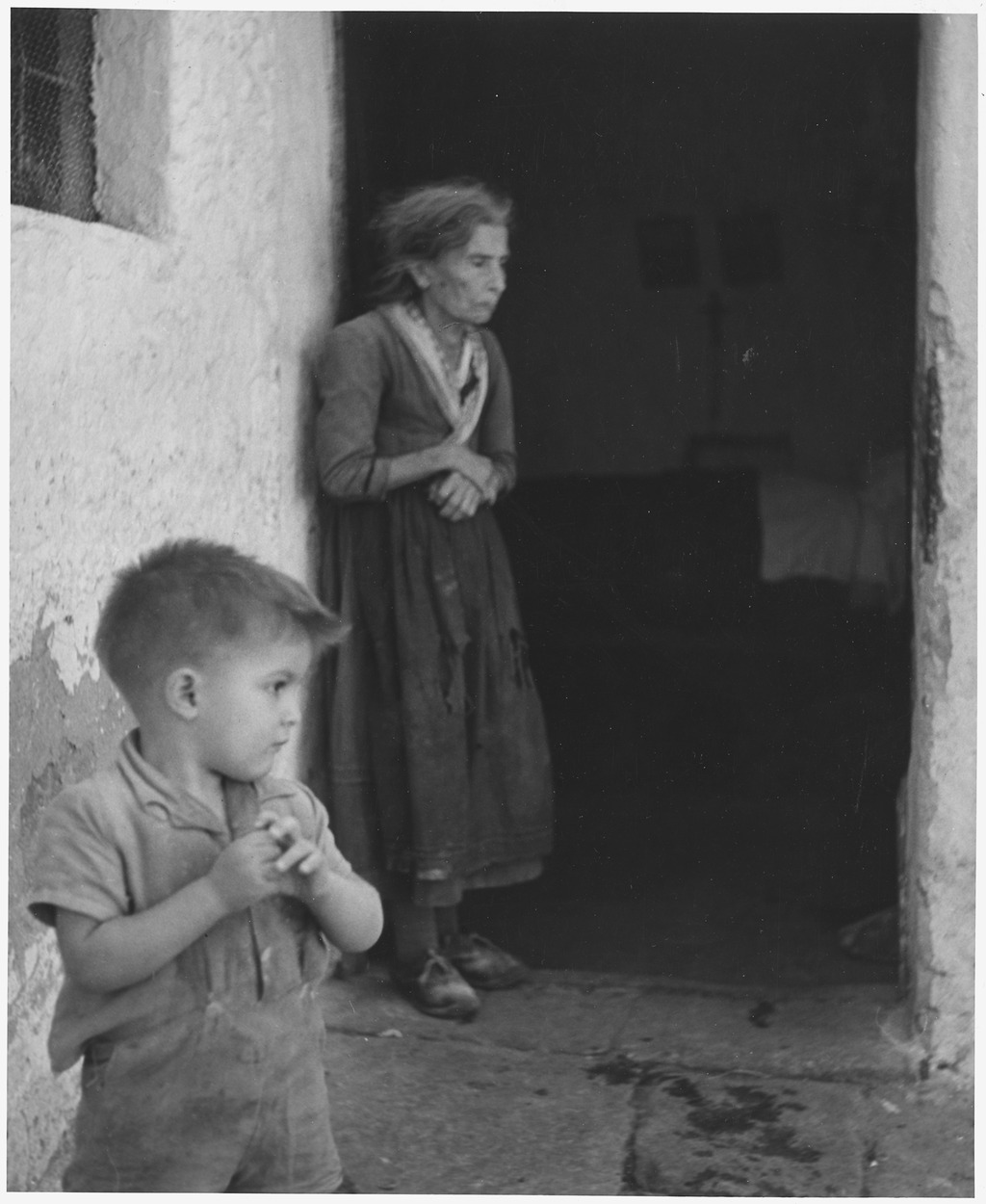

A small boy of Matera, Italy, unconsciously repeats the gesture of his grandmother's hands, ca. 1948 – ca. 1955

☆模 倣(ラテン語 imitatio「模写、模倣」に由来[1])とは、個体が他者の行動を観察し再現する行為である。模倣は学習の一形態でもあり、「伝統の発展、ひいては 我々の文化の形成につながる。遺伝的継承を必要とせず、個体間および世代間で情報(行動、習慣など)を伝達することを可能にする」 [2] 模倣という言葉は、動物の訓練から政治に至るまで、様々な文脈で用いられる。[3] この用語は一般的に意識的な行動を指す。無意識の模倣はミラーリングと呼ばれる。[4]

A toddler imitates his father.(幼児は父親を真似る)

| Imitation

(from Latin imitatio, "a copying, imitation"[1]) is a behavior whereby

an individual observes and replicates another's behavior. Imitation is

also a form of learning that leads to the "development of traditions,

and ultimately our culture. It allows for the transfer of information

(behaviors, customs, etc.) between individuals and down generations

without the need for genetic inheritance."[2] The word imitation can be

applied in many contexts, ranging from animal training to politics.[3]

The term generally refers to conscious behavior; subconscious imitation

is termed mirroring.[4] |

模倣(ラテン語

imitatio「模写、模倣」に由来[1])とは、個体が他者の行動を観察し再現する行為である。模倣は学習の一形態でもあり、「伝統の発展、ひいては

我々の文化の形成につながる。遺伝的継承を必要とせず、個体間および世代間で情報(行動、習慣など)を伝達することを可能にする」 [2]

模倣という言葉は、動物の訓練から政治に至るまで、様々な文脈で用いられる。[3]

この用語は一般的に意識的な行動を指す。無意識の模倣はミラーリングと呼ばれる。[4] |

| Anthropology and social sciences In anthropology, some theories hold that all cultures imitate ideas from one of a few original cultures or several cultures whose influence overlaps geographically. Evolutionary diffusion theory holds that cultures influence one another, but that similar ideas can be developed in isolation. Scholars[5] as well as popular authors[6][7] have argued that the role of imitation in humans is unique among animals. However, this claim has been recently challenged by scientific research which observed social learning and imitative abilities in animals. Psychologist Kenneth Kaye showed[8][9] that the ability of infants to match the sounds or gestures of an adult depends on an interactive process of turn-taking over many successive trials, in which adults' instinctive behavior plays as great a role as that of the infant. These writers assume that evolution would have selected imitative abilities as fit because those who were good at it had a wider arsenal of learned behavior at their disposal, including tool-making and language. However, research also suggests that imitative behaviors and other social learning processes are only selected for when outnumbered or accompanied by asocial learning processes: an over-saturation of imitation and imitating individuals leads humans to collectively copy inefficient strategies and evolutionarily maladaptive behaviors, thereby reducing flexibility to new environmental contexts that require adaptation.[10] Research suggests imitative social learning hinders the acquisition of knowledge in novel environments and in situations where asocial learning is faster and more advantageous.[11][12] In the mid-20th century, social scientists began to study how and why people imitate ideas. Everett Rogers pioneered innovation diffusion studies, identifying factors in adoption and profiles of adopters of ideas.[13] Imitation mechanisms play a central role in both analytical and empirical models of collective human behavior.[14] |

人類学と社会科学 人類学においては、いくつかの理論が存在する。それらは、全ての文化が、ごく少数の原初文化、あるいは地理的に影響が重なる複数の文化のいずれかからアイ デアを模倣していると主張する。進化拡散理論は、文化が互いに影響し合うが、類似したアイデアは孤立した状態で発展し得るとする。 学者[5]や一般向け著述家[6][7]は、模倣が人間において動物の中で唯一無二の役割を果たすと主張してきた。しかしこの主張は、動物における社会的学習と模倣能力を観察した最近の科学的研究によって疑問視されている。 心理学者ケネス・ケイは[8][9]、乳児が成人の音や身振りを模倣する能力は、多くの反復試行における交互のやり取りという相互作用プロセスに依存し、 その中で成人の本能的行動が乳児のそれと同等に重要な役割を果たすことを示した。これらの研究者は、模倣能力に長けた個体が道具製作や言語を含む学習行動 の幅広さを獲得できたため、進化が模倣能力を適応として選択したと仮定している。 しかし研究によれば、模倣行動やその他の社会的学習プロセスは、非社会的学習プロセスに圧倒されたり併存したりする場合にのみ選択される。つまり模倣や模 倣個体が過剰になると、人間は非効率的な戦略や進化的に不適応な行動を集団的に模倣し、適応を必要とする新たな環境状況への柔軟性を低下させるのだ。 [10] 研究によれば、模倣的社会的学習は、新規環境や非社会的学習がより迅速かつ有利な状況において、知識の獲得を妨げる。[11] [12] 20世紀半ば、社会科学者は人々がアイデアを模倣する仕組みと理由の研究を始めた。エヴェレット・ロジャースはイノベーション拡散研究の先駆者となり、ア イデアの採用要因と採用者の特徴を特定した。[13] 模倣メカニズムは、集団的人間行動の分析モデルと実証モデルの両方で中心的な役割を果たす。[14] |

| Neuroscience Humans are capable of imitating movements, actions, skills, behaviors, gestures, pantomimes, mimics, vocalizations, sounds, speech, etc. and that we have particular "imitation systems" in the brain is old neurological knowledge dating back to Hugo Karl Liepmann. Liepmann's model 1908 "Das hierarchische Modell der Handlungsplanung" (the hierarchical model of action planning) is still valid. On studying the cerebral localization of function, Liepmann postulated that planned or commanded actions were prepared in the parietal lobe of the brain's dominant hemisphere, and also frontally. His most important pioneering work is when extensively studying patients with lesions in these brain areas, he discovered that the patients lost (among other things) the ability to imitate. He was the one who coined the term "apraxia" and differentiated between ideational and ideomotor apraxia. It is in this basic and wider frame of classical neurological knowledge that the discovery of the mirror neuron has to be seen. Though mirror neurons were first discovered in macaques, their discovery also relates to humans.[15] Human brain studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) revealed a network of regions in the inferior frontal cortex and inferior parietal cortex which are typically activated during imitation tasks.[16] It has been suggested that these regions contain mirror neurons similar to the mirror neurons recorded in the macaque monkey.[17] However, it is not clear if macaques spontaneously imitate each other in the wild. Neurologist V. S. Ramachandran argues that the evolution of mirror neurons were important in the human acquisition of complex skills such as language and believes the discovery of mirror neurons to be a most important advance in neuroscience.[18] However, little evidence directly supports the theory that mirror neuron activity is involved in cognitive functions such as empathy or learning by imitation.[19] Evidence is accumulating that bottlenose dolphins employ imitation to learn hunting and other skills from other dolphins.[20][21] Japanese monkeys have been seen to spontaneously begin washing potatoes after seeing humans washing them.[22] |

神経科学 人間は動作、行動、技能、行動様式、身振り、パントマイム、模倣、発声、音、言語などを模倣する能力を持つ。脳内に特定の「模倣システム」が存在すること は、ウーゴ・カール・リープマンに遡る古い神経学的知見である。リープマンの1908年のモデル「行動計画の階層的モデル」は今も有効だ。機能の脳内局在 を研究したリープマンは、計画された行動や命令された行動は、脳の優位半球の頭頂葉と前頭葉で準備されると仮定した。彼の最も重要な先駆的業績は、これら の脳領域に損傷を持つ患者を詳細に研究した際、患者が(他の能力と共に)模倣能力を失うことを発見したことだ。彼が「失行症」という用語を提唱し、観念性 失行と観念運動性失行を区別した。ミラーニューロンの発見は、この古典的神経学知識の基本的かつ広範な枠組みの中で捉える必要がある。ミラーニューロンは マカクザルで最初に発見されたが、その発見は人間にも関連している。[15] 機能的磁気共鳴画像法(fMRI)を用いたヒト脳研究により、模倣課題中に典型的に活性化する下前頭皮質と下頭頂皮質の領域ネットワークが明らかになっ た。[16] これらの領域には、マカクザルで記録されたミラーニューロンと同様のミラーニューロンが含まれていると示唆されている[17]。ただし、野生のマカクザル が自発的に互いを模倣するかは明らかではない。 神経学者V.S.ラマチャンドランは、ミラーニューロンの進化が言語などの複雑な技能獲得において重要だったと主張し、ミラーニューロンの発見を神経科学 における最重要の進展と見なしている。[18] しかしながら、ミラーニューロンの活動が共感や模倣学習といった認知機能に関与するという理論を直接裏付ける証拠はほとんど存在しない。[19] バンドウイルカが他のイルカから狩猟技術やその他の技能を模倣によって習得するという証拠が蓄積されつつある。[20][21] ニホンザルは、人間がジャガイモを洗うのを見た後、自発的にジャガイモを洗い始める様子が観察されている。[22] |

| Mirror neuron system Research has been conducted to locate where in the brain specific parts and neurological systems are activated when humans imitate behaviors and actions of others, discovering a mirror neuron system. This neuron system allows a person to observe and then recreate the actions of others. Mirror neurons are premotor and parietal cells in the macaque brain that fire when the animal performs a goal directed action and when it sees others performing the same action."[23] Evidence suggests that the mirror neuron system also allows people to comprehend and understand the intentions and emotions of others.[24] Problems of the mirror neuron system may be correlated with the social inadequacies of autism. There have been many studies done showing that children with autism, compared with typically-developing children, demonstrate reduced activity in the frontal mirror neuron system area when observing or imitating facial emotional expressions. Of course, the higher the severity of the disease, the lower the activity in the mirror neuron system is.[23] |

ミラーニューロンシステム 人間が他者の行動や動作を模倣する際に、脳内のどの部位や神経系が活性化されるかを特定する研究が行われ、ミラーニューロンシステムが発見された。この神 経系により、人格は他者の動作を観察し再現することが可能となる。ミラーニューロンとは、マカクザルの脳内にある前運動野細胞および頭頂葉細胞であり、動 物が目的指向的な行動を行う時、および他者が同じ行動を行うのを見た時に発火する。[23] 証拠によれば、ミラーニューロンシステムは人民の他者の意図や感情を理解する能力も担っている。[24] このシステムの障害は自閉症の社会的適応困難と関連している可能性がある。自閉症児は通常発達児と比べ、顔の感情表現を観察・模倣する際、前頭葉ミラー ニューロン領域の活動が低下することを示す研究が多数存在する。当然ながら、疾患の重症度が高いほど、ミラーニューロンシステムの活動は低下する。 [23] |

| Animal behavior Scientists debate whether animals can consciously imitate the unconscious incitement from sentinel animals, whether imitation is uniquely human, or whether humans do a complex version of what other animals do.[25][26] The current controversy is partly definitional. Thorndike uses "learning to do an act from seeing it done."[27] It has two major shortcomings: first, by using "seeing" it restricts imitation to the visual domain and excludes, e.g., vocal imitation and, second, it would also include mechanisms such as priming, contagious behavior and social facilitation,[28] which most scientist distinguish as separate forms of observational learning. Thorpe suggested defining imitation as "the copying of a novel or otherwise improbable act or utterance, or some act for which there is clearly no instinctive tendency."[29] This definition is favored by many scholars, though questions have been raised how strictly the term "novel" has to be interpreted and how exactly a performed act has to match the demonstration to count as a copy. Hayes and Hayes (1952) used the "do-as-I-do" procedure to demonstrate the imitative abilities of their trained chimpanzee "Viki."[30] Their study was repeatedly criticized for its subjective interpretations of their subjects' responses. Replications of this study[31] found much lower matching degrees between subjects and models. However, imitation research focusing on the copying fidelity got new momentum from a study by Voelkl and Huber.[32] They analyzed the motion trajectories of both model and observer monkeys and found a high matching degree in their movement patterns. Paralleling these studies, comparative psychologists provided tools or apparatuses that could be handled in different ways. Heyes[33][34] and co-workers reported evidence for imitation in rats that pushed a lever in the same direction as their models, though later on they withdrew their claims due to methodological problems in their original setup.[35] By trying to design a testing paradigm that is less arbitrary than pushing a lever to the left or to the right, Custance and co-workers[36] introduced the "artificial fruit" paradigm, where a small object could be opened in different ways to retrieve food placed inside—not unlike a hard-shelled fruit. Using this paradigm, scientists reported evidence for imitation in monkeys[37][38] and apes.[39][40][41] There remains a problem with such tool (or apparatus) use studies: what animals might learn in such studies need not be the actual behavior patterns (i.e., the actions) that were observed. Instead they might learn about some effects in the environment (i.e., how the tool moves, or how the apparatus works).[42] This type of observational learning, which focuses on results, not actions, has been dubbed emulation (see Emulation (observational learning)). In an article written by Carl Zimmer, he looked into a study being done by Derek Lyons, focusing on human evolution, in which he studied a chimpanzee. He first started with showing the chimpanzee how to retrieve food from a box. The chimpanzee soon caught on and did exactly what the scientist just did. They wanted to see if the chimpanzee's brain functioned just like a human brain, so they replicated the experiment using 16 children, following the same procedure; once the children saw how it was done, they followed the same exact steps.[43] |

動物の行動 科学者たちは、動物が無意識の行動を模倣できるかどうか、模倣が人間固有の行為なのか、あるいは人間が他の動物の行為を複雑化した形で行っているのかにつ いて議論している。[25][26] 現在の論争は部分的に定義の問題だ。ソーンダイクは「行動を見ることでその行動を学ぶこと」と定義している。[27] この定義には二つの大きな欠点がある。第一に「見る」という行為に限定するため、音声模倣などを排除してしまう。第二に、プライミングや伝染的行動、社会 的促進といったメカニズムも包含してしまう[28]。これらは多くの科学者が観察学習の別形態として区別している。ソープは模倣を「新規あるいは非日常的 な行為・発話、もしくは明らかに本能的傾向のない行為の複製」と定義することを提案した[29]。この定義は多くの学者に支持されるが、「新規」の厳密な 解釈や、模倣と認められるための行為の一致度合いについては疑問が呈されている。 ヘイズとヘイズ(1952)は訓練したチンパンジー「ヴィキ」の模倣能力を実証するため「真似をしてごらん」手続きを用いた[30]。彼らの研究は被験者 の反応に対する主観的解釈が繰り返し批判された。この研究の再現[31]では、被験者と模範者の一致度が大幅に低いことが判明した。しかし、模倣の忠実度 に焦点を当てた研究は、フォルクルとフーバーの研究[32]によって新たな勢いを得た。彼らは模範者と観察者の両方のサルにおける運動軌跡を分析し、その 動作パターンに高い一致度を見出した。 これらの研究と並行して、比較心理学者は異なる方法で扱える道具や装置を提供した。ヘイズらはラットがモデルと同じ方向にレバーを押す模倣の証拠を報告し たが、後に元の設定における方法論的問題を理由に主張を撤回した。[35] 左か右かレバーを押すという恣意的な操作よりも、より客観的な試験パラダイムを設計しようと試みたカスタンズらは[36]、「人工果実」パラダイムを導入 した。これは小さな物体を異なる方法で開け、内部に置かれた餌を取り出すというもので、硬い殻の果実に似ている。このパラダイムを用いて、科学者らはサル [37][38]や類人猿における模倣の証拠を報告した。[39][40][41] このような道具(または装置)使用研究には問題が残る。動物が学習するのは、観察された実際の行動パターン(すなわち動作)とは限らない。代わりに、環境 における何らかの効果(例えば道具の動き方や装置の作動原理)を学習している可能性がある。[42] この種の観察学習は、行動ではなく結果に焦点を当てるため、エミュレーション(模倣学習)と呼ばれている(エミュレーション(観察学習)参照)。 カール・ジマーの記事では、デレク・ライオンズが人類進化を研究する中で行ったチンパンジー実験を取り上げている。まずチンパンジーに箱から餌を取り出す 方法を示した。チンパンジーはすぐに理解し、科学者が行ったのと同じ行動を正確に再現した。研究者らはチンパンジーの脳が人間の脳と同様に機能するか確認 するため、16人の子供を対象に同じ手順で実験を再現した。子供たちは操作方法を見せられると、全く同じ手順を忠実に再現したのである。[43] |

| mitation in animals Blackbird imitating the vehicle motion alarm. Imitation in animals is a study in the field of social learning where learning behavior is observed in animals specifically how animals learn and adapt through imitation. Ethologists can classify imitation in animals by the learning of certain behaviors from conspecifics.[44] More specifically, these behaviors are usually unique to the species and can be complex in nature and can benefit the individual's survival.[44] Some scientists believe true imitation is only produced by humans, arguing that simple learning though sight is not enough to sustain as a being who can truly imitate.[45] Thorpe defines true imitation as "the copying of a novel or otherwise improbable act or utterance, or some act for which there is clearly no instinctive tendency," which is highly debated for its portrayal of imitation as a mindless repeating act.[45] True imitation is produced when behavioral, visual and vocal imitation is achieved, not just the simple reproduction of exclusive behaviors.[45] Imitation is not a simple reproduction of what one sees; rather it incorporates intention and purpose.[45] Animal imitation can range from survival purpose; imitating as a function of surviving or adapting, to unknown possible curiosity, which vary between different animals and produce different results depending on the measured intelligence of the animal.[45] There is considerable evidence to support true imitation in animals.[46] Experiments performed on apes, birds and more specifically the Japanese quail have provided positive results to imitating behavior, demonstrating imitation of opaque behavior.[46] However the problem that lies is in the discrepancies between what is considered true imitation in behavior.[46] Birds have demonstrated visual imitation, where the animal simply does as it sees.[46] Studies on apes however have proven more advanced results in imitation, being able to remember and learn from what they imitate.[46] Songbirds have specialized brain circuits for song learning and can imitate vocalizations of others. It is well established that birdsong is a type of animal culture transmitted across generations in certain groups. [47] Studies have demonstrated far more positive results with behavioral imitation in primates and birds than any other type of animal.[46] Imitation in non-primate mammals and other animals have been proven difficult to conclude solid positive results for and poses a difficult question to scientists on why that is so.[46] |

動物における模倣 スウェーデンのブラスタッドで、クロウタドリが自動車の警報音を真似ている。 動物における模倣は、社会的学習の分野における研究であり、動物の学習行動、特に模倣を通じて動物がどのように学び適応するかを観察する。動物行動学者 は、同種個体からの特定の行動学習によって動物の模倣を分類できる[44]。より具体的には、これらの行動は通常その種に特有であり、複雑な性質を持ち、 個体の生存に利益をもたらす可能性がある。 [44] 一部の科学者は、真の模倣は人間のみが生み出すと主張し、単なる視覚的学習では真の模倣能力を持つ存在として持続するには不十分だと論じている[45]。 ソープは真の模倣を「新規あるいは非現実的な行動や発声、あるいは明らかに本能的傾向のない行動の模倣」と定義しているが、これは模倣を無意識の反復行為 と捉える点で激しい議論を呼んでいる。[45] 真の模倣は、行動的・視覚的・音声的模倣が達成された時に生じるものであり、単なる排他的行動の再現ではない。[45] 模倣は見たものを単純に再現する行為ではなく、意図と目的を伴うものである。[45] 動物の模倣行動は、生存目的(生存や適応のための機能としての模倣)から未知の可能性としての好奇心まで多岐にわたり、動物種によって異なり、測定された 知能レベルに応じて異なる結果を生む。[45] 動物における真の模倣を支持する証拠は多い。[46]類人猿、鳥類、特にウズラを用いた実験では、不透明な行動の模倣を示す肯定的な結果が得られている。 [46]しかし問題は、行動における真の模倣の定義に相違がある点にある. [46] 鳥類は視覚的模倣を示しており、単に目にした行動を真似るだけだ。[46] 一方、類人猿の研究ではより高度な模倣結果が証明されており、模倣対象を記憶し学習することが可能である。[46] 鳴禽類は鳴き声学習に特化した脳回路を持ち、他者の発声を模倣できる。鳥の鳴き声は特定の集団において世代を超えて伝承される動物文化の一種であることは 確立されている。[47] 霊長類と鳥類における行動模倣の研究は、他のいかなる動物種よりもはるかに良好な結果を示している。[46] 非霊長類哺乳類やその他の動物における模倣行動については、確固たる肯定的結論を導き出すことが困難であり、科学者にとってその理由を解明する難題となっ ている。[46] |

| Theories There are two types of theories of imitation, transformational and associative. Transformational theories suggest that the information that is required to display certain behavior is created internally through cognitive processes and observing these behaviors provides incentive to duplicate them.[48] Meaning we already have the codes to recreate any behavior and observing it results in its replication. Albert Bandura's "social cognitive theory" is one example of a transformational theory.[49] Associative, or sometimes referred to as "contiguity",[50] theories suggest that the information required to display certain behaviors does not come from within ourselves but solely from our surroundings and experiences.[48] These theories have not yet provided testable predictions in the field of social learning in animals and have yet to conclude strong results.[48] New developments There have been three major developments in the field of animal imitation. The first, behavioral ecologists and experimental psychologists found there to be adaptive patterns in behaviors in different vertebrate species in biologically important situations.[51] The second, primatologists and comparative psychologists have found imperative evidence that suggest true learning through imitation in animals.[51] The third, population biologists and behavioral ecologists created experiments that demand animals to depend on social learning in certain manipulated environments.[51] |

理論 模倣に関する理論には、変換理論と連想理論の二種類がある。変換理論は、特定の行動を示すために必要な情報は認知プロセスを通じて内部で生成され、その行 動を観察することで模倣する動機が生まれると主張する[48]。つまり我々はあらゆる行動を再現するコードを既に持ち、それを観察することで模倣が行われ るのだ。アルバート・バンデューラの「社会的認知理論」は変換理論の一例である。 [49] 連想理論(時に「隣接性理論」とも呼ばれる)[50] は、特定の行動を示すために必要な情報は自己内部からではなく、周囲の環境と経験のみから得られると主張する。[48] これらの理論は、動物の社会的学習分野において検証可能な予測をまだ提供しておらず、確固たる結論に至っていない。[48] 新たな進展 動物模倣の分野では三つの主要な進展があった。第一に、行動生態学者と実験心理学者らは、生物学的に重要な状況下において、異なる脊椎動物種に共通する適 応的行動パターンを発見した[51]。第二に、霊長類学者と比較心理学者らは、動物における模倣を通じた真の学習を示唆する決定的な証拠を見出した [51]。第三に、集団生物学者と行動生態学者らは、特定の操作環境下で動物が社会的学習に依存せざるを得ない実験を構築した[51]。 |

| Child development Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget noted that children in a developmental phase he called the sensorimotor stage (a period which lasts up to the first two years of a child) begin to imitate observed actions.[52] This is an important stage in the development of a child because the child is beginning to think symbolically, associating behaviors with actions, thus setting the child up for the development of further symbolic thinking. Imitative learning also plays a crucial role in the development of cognitive and social communication behaviors, such as language, play, and joint attention. Imitation serves as both a learning and a social function because new skills and knowledge are acquired, and communication skills are improved by interacting in social and emotional exchanges. It is shown, however, that "children with autism exhibit significant deficits in imitation that are associated with impairments in other social communication skills."[53] To help children with autism, reciprocal imitation training (RIT) is used. It is a naturalistic imitation intervention that helps teach the social benefits of imitation during play by increasing child responsiveness and by increasing imitative language.[53] Reinforcement learning, both positive and negative, and punishment, are used by people that children imitate to either promote or discontinue behavior. If a child imitates a certain type of behavior or action and the consequences are rewarding, the child is very likely to continue performing the same behavior or action. The behavior "has been reinforced (i.e. strengthened)".[54][self-published source?] However, if the imitation is not accepted and approved by others, then the behavior will be weakened. Naturally, children are surrounded by many different types of people that influence their actions and behaviors, including parents, family members, teachers, peers, and even characters on television programs. These different types of individuals that are observed are called models. According to Saul McLeod, "these models provide examples of masculine and feminine behavior to observe and imitate."[54] Children imitate the behavior they have observed from others, regardless of the gender of the person and whether or not the behavior is gender appropriate. However, it has been proven that children will reproduce the behavior that "its society deems appropriate for its sex."[54] |

子どもの発達 発達心理学者ジャン・ピアジェは、感覚運動期(生後2年までの期間)と呼ばれる発達段階にある子どもが、観察した行動を模倣し始めることに気づいた。 [52] これは子どもの発達において重要な段階である。なぜなら、子どもが象徴的に考え始め、行動と行為を結びつけることで、さらなる象徴的思考の発達への基盤が 築かれるからだ。模倣学習は、言語、遊び、共同注意といった認知的・社会的コミュニケーション行動の発達においても重要な役割を果たす。模倣は学習機能と 社会的機能の両方を担う。新たな技能や知識が獲得されると同時に、社会的・感情的な交流を通じてコミュニケーション能力が向上するからだ。しかし「自閉症 児は模倣能力に著しい欠陥を示し、他の社会的コミュニケーション技能の障害と関連している」ことが示されている。[53] 自閉症児を支援するため、相互模倣訓練(RIT)が用いられる。これは自然主義的模倣介入法であり、子どもの反応性向上と模倣言語の増加を通じて、遊びに おける模倣の社会的利点を教えるのに役立つ。[53] 強化学習(正の強化・負の強化)と罰は、子どもが模倣する人民が行動を促進または中止させるために用いる手段である。子供が特定の行動や動作を模倣し、そ の結果が報酬となる場合、その行動や動作を継続する可能性が非常に高い。この行動は「強化された(すなわち強められた)」と言える。[54][自己出版資 料?] しかし、その模倣が他者から受け入れられ承認されない場合、その行動は弱まる。 当然ながら、子どもは親、家族、教師、仲間、さらにはテレビ番組の登場人物など、行動や振る舞いに影響を与える様々な人民に囲まれている。こうした観察対 象となる異なる個人は「モデル」と呼ばれる。ソール・マクラウドによれば、「これらのモデルは、観察し模倣すべき男性的・女性的行動の例を提供する」 [54]。「子供は、観察した他者の行動を、その人格の性別や行動が性別にふさわしいかどうかに関わらず模倣する。しかし、子供は『その社会がその性別に ふさわしいとみなす行動』を再現することが証明されている[54]。」 |

| Infants Infants have the ability to reveal an understanding of certain outcomes before they occur, therefore in this sense they can somewhat imitate what they have perceived. Andrew N. Meltzoff, ran a series of tasks involving 14-month-old infants to imitate actions they perceived from adults. In this gathering he had concluded that the infants, before trying to reproduce the actions they wish to imitate, somehow revealed an understanding of the intended goal even though they failed to replicate the result wished to be imitated. These task implicated that the infants knew the goal intended.[55] Gergely, Bekkering, and Király (2002) figured that infants not only understand the intended goal but also the intentions of the person they were trying to imitate engaging in "rational imitation", as described by Tomasello, Carpenter and others [55] It has long been claimed that newborn humans imitate bodily gestures and facial expressions as soon as their first few days of life.[56][57] For example, in a study conducted at the Mailman Centre for Child Development at the University of Miami Medical School, 74 newborn babies (with a mean age of 36 hours) were tested to see if they were able to imitate a smile, a frown and a pout, and a wide-open mouth and eyes. An observer stood behind the experimenter (so he/she couldn't see what facial expressions were being made by the experimenter) and watched only the babies' facial expressions, recording their results. Just by looking only at the babies' faces, the observer was more often able to correctly guess what facial expression was being presented to the child by the experimenter.[58] After the results were calculated, "the researchers concluded that...babies have an innate ability to compare an expression they see with their own sense of muscular feedback from making the movements to match that expression."[58] However, the idea that imitation is an inborn ability has been recently challenged. A research group from the University of Queensland in Australia carried out the largest-ever longitudinal study of neonatal imitation in humans. One hundred and nine newborns were shown a variety of gestures including tongue protrusion, mouth opening, happy and sad facial expressions, at four time points between one week and 9 weeks of age. The results failed to reveal compelling evidence that newborns imitate: Infants were just as likely to produce matching and non-matching gestures in response to what they saw.[59] At around eight months, infants will start to copy their child care providers' movements when playing pat-a-cake and peek-a-boo, as well as imitating familiar gestures, such as clapping hands together or patting a doll's back. At around 18 months, infants will then begin to imitate simple actions they observe adults doing, such as taking a toy phone out of a purse and saying "hello", pretending to sweep with a child-sized broom, as well as imitating using a toy hammer.[citation needed] |

乳児 乳児は、特定の結果が発生する前にその理解を示す能力を持っている。したがって、この意味において、乳児は知覚したものをある程度模倣することができる。 アンドルー・N・メルツォフは、14カ月の乳児を対象に、大人から知覚した行動を模倣する一連の課題を行った。この研究で、彼は、乳児は、模倣したい行動 を再現しようとする前に、模倣したい結果を再現できなかったにもかかわらず、何らかの形で意図された目標を理解していることを明らかにしたと結論づけた。 この課題は、乳児が意図された目標を知っていることを示唆している。[55] Gergely、Bekkering、Király (2002) は、乳児は意図された目標だけでなく、Tomasello、Carpenter らが述べた「合理的な模倣」に従事している、彼らが模倣しようとしている人格の意図も理解していると結論づけた[55]。 新生児は、生後数日で身体の動きや表情を模倣すると長い間主張されてきた[56]。[57] 例えば、マイアミ大学医学部メールマン児童発達センターでの研究では、生後平均36時間の乳児74名を対象に、笑顔・しかめっ面・口をとがらせる動作、そ して大きく口と目を開ける動作を模倣できるか検証した。観察者は実験者の背後(実験者がどのような表情を作っているか見えない位置)に立ち、乳児の表情の みを観察して結果を記録した。観察者は、赤ちゃんの顔だけを見て、実験者が提示した表情を正しく推測できる確率がより高かった。[58] 結果を計算した後、「研究者らは結論づけた…赤ちゃんは、見た表情と、その表情を真似るために自分が行う動きからの筋肉のフィードバックを比較する生得的 な能力を持っていると。」[58] しかし、模倣が先天的な能力だという考えは最近疑問視されている。オーストラリアのクイーンズランド大学の研究グループは、ヒトの新生児における模倣行動 に関する史上最大規模の縦断研究を実施した。生後1週間から9週間の間に4回、109人の新生児に舌出し、口を開ける動作、喜びや悲しみの表情など様々な ジェスチャーを見せた。結果は新生児の模倣を裏付ける決定的な証拠を示さなかった。乳児は見たものに対して、一致するジェスチャーと一致しないジェス チャーを同程度の確率で生み出したのである。[59] 生後8ヶ月頃になると、乳児は「パンパン」遊びや「いないいないばあ」で保育者の動きを真似し始める。また手を叩く、人形の背中をポンポン叩くといった慣 れ親しんだジェスチャーも模倣するようになる。18か月頃になると、幼児は大人が行う単純な行動を模倣し始める。例えば、おもちゃの電話をバッグから取り 出して「もしもし」と言う、子供用ほうきで掃くふりをする、おもちゃのハンマーを使う真似をするといった行動である。[出典が必要] |

| Toddlers At around 30–36 months, toddlers will start to imitate their parents by pretending to get ready for work and school and saying the last word(s) of what an adult just said. For example, toddlers may say "bowl" or "a bowl" after they hear someone say, "That's a bowl." They may also imitate the way family members communicate by using the same gestures and words. For example, a toddler will say, "Mommy bye-bye" after the father says, "Mommy went bye-bye."[60] Toddlers love to imitate their parents and help when they can; imitation helps toddlers learn, and through their experiences lasting impressions are made. 12- to 36-month-olds learn by doing, not by watching, and so it is often recommended to be a good role model and caretaker by showing them simple tasks like putting on socks or holding a spoon.[61] Duke developmental psychologist Carol Eckerman did a study on toddlers imitating toddlers and found that at the age of 2 children involve themselves in imitation play to communicate with one another. This can be seen within a culture or across different cultures. 3 common imitative patterns Eckerman found were reciprocal imitation, follow-the-leader, and lead-follow.[62] Kenneth Kaye's "apprenticeship" theory of imitation rejected assumptions that other authors had made about its development. His research showed that there is no one simple imitation skill with its own course of development. What changes is the type of behavior imitated.[63] An important agenda for infancy is the progressive imitation of higher levels of use of signs, until the ultimate achievement of symbols. The principal role played by parents in this process is their provision of salient models within the facilitating frames that channel the infant's attention and organize his imitative efforts. |

幼児 30~36ヶ月頃になると、幼児は親の真似をし始める。仕事や学校の準備をするふりをしたり、大人が言った言葉の最後の一語を真似たりする。例えば、誰か が「あれはボウルだ」と言うと、幼児は「ボウル」や「ボウルだよ」と言うかもしれない。また、家族が使うジェスチャーや言葉を真似て、コミュニケーション の仕方を模倣することもある。例えば、父親が「ママはバイバイに行った」と言うと、幼児は「ママバイバイ」と言うだろう。[60] 幼児は親を真似たり、できる範囲で手伝うのが大好きだ。模倣は幼児の学習を助け、その経験を通じて強い印象が刻まれる。12~36ヶ月の幼児は、見ること でなく行うことで学ぶ。そのため、靴下を履く、スプーンを持つといった簡単な作業を見せることで、良い手本となり世話役となることが推奨されることが多 い。[61] デューク大学の発達心理学者キャロル・エッカーマンは、幼児同士の模倣に関する研究を行い、2歳児が互いにコミュニケーションを取るために模倣遊びに没頭 することを発見した。これは同一文化内でも異なる文化間でも見られる。エッカーマンが発見した3つの一般的な模倣パターンは、相互模倣、リーダー追従、先 導-追従である。[62] ケネス・ケイの「見習い」理論は、他の研究者が模倣の発達について仮定した見解を否定した。彼の研究は、単一の単純な模倣技能とその固有の発達過程は存在しないことを示した。変化するのは模倣される行動の種類である。[63] 乳児期における重要な課題は、象徴の最終達成に至るまで、より高度な記号の使用法を段階的に模倣することである。この過程で親が果たす主たる役割は、乳児の注意を導き、模倣努力を組織化する促進的枠組みの中で、顕著な模範を提供することである。 |

Gender and age differences A small boy of Matera, Italy, unconsciously repeats the gesture of his grandmother's hands, ca. 1948 – ca. 1955 Imitation and imitative behaviors do not manifest ubiquitously and evenly in all human individuals; some individuals rely more on imitated information than others.[64] Although imitation is very useful when it comes to cognitive learning with toddlers, research has shown that there are some gender and age differences when it comes to imitation. Research done to judge imitation in toddlers 2–3 years old shows that when faced with certain conditions "2-year-olds displayed more motor imitation than 3-year-olds, and 3-year-olds displayed more verbal-reality imitation than 2-year-olds. Boys displayed more motor imitation than girls."[65] No other research is more controversial pertaining gender differences in toddler imitation than psychologist, Bandura's, bobo doll experiments.[66] The goal of the experiment was to see what happens to toddlers when exposed to aggressive and non-aggressive adults, would the toddlers imitate the behavior of the adults and if so, which gender is more likely to imitate the aggressive adult. In the beginning of the experiment Bandura had several predictions that actually came true. Children exposed to violent adults will imitate the actions of that adult when the adult is not present, boys who had observed an adult of the opposite sex act aggressively are less likely to act violently than those who witnessed a male adult act violently. In fact "boys who observed an adult male behaving violently were more influenced than those who had observed a female model behavior aggressively". One observation was that while boys are likely to imitate physical acts of violence, girls are likely to imitate verbal acts of violence. |

性別と年齢による差異 イタリア・マテーラの少年が、祖母の手の動きを無意識に真似る様子、1948年頃~1955年頃 模倣と模倣行動は、全ての人間に普遍的かつ均等に現れるわけではない。模倣された情報に依存する度合いは個人によって異なる。[64] 幼児の認知学習において模倣は非常に有用だが、研究によれば模倣には性別と年齢による差異が存在する。2~3歳の幼児の模倣を評価した研究では、特定の条 件下で「2歳児は3歳児より運動模倣が多く、3歳児は2歳児より言語的現実模倣が多かった。また、男の子は女の子よりも運動模倣が多かった。」[65] 幼児の模倣における性差に関して、心理学者バンデューラのボボ人形実験ほど議論を呼んだ研究はない。[66] この実験の目的は、攻撃的な大人と非攻撃的な大人に晒された幼児がどうなるかを観察することだった。幼児は大人たちの行動を模倣するのか、もし模倣するな ら、どちらの性別が攻撃的な大人を模倣する可能性が高いのかを調べるためである。実験開始時、バンデューラはいくつかの予測を立てたが、それらは実際に的 中した。暴力的な大人に晒された子供は、その大人が不在の時でもその行動を模倣する。異性の大人による攻撃的行動を観察した男児は、男性大人による暴力行 動を目撃した男児よりも暴力的に振る舞う可能性が低い。実際「男性大人の暴力行動を観察した男児は、女性のモデルによる攻撃的行動を観察した男児よりも影 響を受けやすかった」。一つの観察結果として、男子は身体的な暴力行為を模倣する傾向がある一方、女子は言葉による暴力行為を模倣する傾向があることが示 された。 |

| Negative imitation Imitation plays a major role on how a toddler interprets the world. Much of a child's understanding is derived from imitation, due to a lack of verbal skill imitation in toddlers for communication.[citation needed] It is what connects them to the communicating world, as they continue to grow they begin to learn more. This may mean that it is crucial for parents to be cautious as to how they act and behave around their toddlers. Imitation is the toddlers way of confirming and dis-conforming socially acceptable actions in society. Actions like washing dishes, cleaning up the house and doing chores are actions you want your toddlers to imitate. Imitating negative things is something that is never beyond young toddlers. If they are exposed to cursing and violence, it is going to be what the child views as the norm of their world, since imitation is the "mental activity that helps to formulate the conceptions of the world for toddlers".[67] So it is important for parents to be careful what they say or do in front of their children.[citation needed] |

否定的な模倣 模倣は幼児が世界を解釈する上で重要な役割を果たす。言葉によるコミュニケーション能力が未発達なため、幼児の理解の多くは模倣から得られる。[出典が必 要] 模倣は彼らをコミュニケーションの世界と結びつける手段であり、成長するにつれてより多くのことを学び始める。これは、親が幼児の前での行動や振る舞いに 注意を払うことが極めて重要であることを意味する。模倣は幼児が社会的に許容される行動を確認し、不適合な行動を認識する手段だ。皿洗いや家の掃除、家事 といった行動は、幼児に模倣してほしい行為である。しかし幼児は、悪いことさえも真似する可能性がある。罵倒や暴力に晒されれば、それが彼らの世界の「普 通」と見なされるだろう。なぜなら模倣とは「幼児が世界観を形成する助けとなる精神活動」だからだ。[67] ゆえに親は、子供の前で発する言葉や行動に細心の注意を払う必要がある。[出典が必要] |

| Autism Children with autism exhibit significant impairment in imitation skills.[53] Imitation deficits have been reported on a variety of tasks including symbolic and non-symbolic body movements, symbolic and functional object use, vocalizations, and facial expressions.[53] In contrast, typically-developing children can copy a broad range of novel (as well as familiar) rules from a very early age.[68] Problems with imitation discriminate children with autism from those with other developmental disorders as early as age 2 and continue into adulthood.[69] Children with autism exhibit significant deficits in imitation that are associated with impairments in other social communication skills. It is unclear whether imitation is mediating these relationships directly, or whether they are due to some other developmental variable that is also reflected in the measurement of imitation skills.[53] On the contrary, research from the early 21st century suggests that people affected with forms of high-functioning autism easily interact with one another by using a more analytically-centered communication approach rather than an imitative cue-based approach,[70] suggesting that reduced imitative capabilities do not affect abilities for expressive social behavior but only the understanding of said social behavior. Social communication is not negatively affected when said communication involves less or no imitation. Children with autism may have significant problems understanding typical social communication not because of inherent social deficits, but because of differences in communication style which affect reciprocal understanding.[71][72] Autistic individuals are also shown to possess increased analytical, cognitive, and visual processing,[73][74][75] suggesting that they have no true impairments in observing the actions of others but may decide not to imitate them because they do not analytically understand them.[76] A 2016 study has shown that involuntary, spontaneous facial mimicry – which supposedly depends on the mirror neuron system – is intact in individuals with autism, contrasting with previous studies and suggesting that the mirror neuron system is not inherently broken in autistic individuals.[77] |

自閉症 自閉症の子供は模倣能力に著しい障害を示す。[53] 模倣の欠如は、象徴的・非象徴的な身体動作、象徴的・機能的な物体の使用、発声、表情など様々な課題で報告されている。[53] 対照的に、通常発達する子供はごく幼い頃から、新規(および既知の)ルールを幅広く模倣できる。[68] 模倣の問題は、2歳という早い時期から自閉症児を他の発達障害児と区別し、成人期まで持続する。[69] 自閉症児は、他の社会的コミュニケーション能力の障害と関連する顕著な模倣障害を示す。模倣がこれらの関係を直接媒介しているのか、あるいは模倣能力の測定にも反映される他の発達変数が原因なのかは不明である。[53] 逆に、21世紀初頭の研究によれば、高機能自閉症の形態を持つ人民は、模倣に基づく手がかり依存型のアプローチではなく、より分析中心のコミュニケーショ ン手法を用いて容易に相互交流できることが示されている[70]。これは、模倣能力の低下が表現的な社会的行動の能力には影響せず、その社会的行動の理解 のみに影響することを示唆している。模倣が少なくても、あるいは全くなくても、社会的コミュニケーションは悪影響を受けない。自閉症児が典型的な社会的コ ミュニケーションを理解するのに重大な問題を抱えるのは、生来の社会的欠陥のためではなく、相互理解に影響するコミュニケーション様式の差異によるもので ある[71][72]。 自閉症者はまた、分析的・認知的・視覚的処理能力が向上していることが示されている[73][74]。[75] これは他者の行動を観察する能力に真の障害はないが、分析的に理解できないため模倣しない選択をしている可能性を示唆している。[76] 2016年の研究では、ミラーニューロン系に依存するとされる不随意の自発的顔面模倣が自閉症者において正常に機能していることが示され、従来の研究結果 と対照的であり、ミラーニューロン系が自閉症者に本質的に欠損しているわけではないことを示唆している。[77] |

| Automatic imitation The automatic imitation comes very fast when a stimulus is given to replicate. The imitation can match the commands with the visual stimulus (compatible) or it cannot match the commands with the visual stimulus (incompatible). For example: 'Simon Says', a game played with children where they are told to follow the commands given by the adult. In this game, the adult gives the commands and shows the actions; the commands given can either match the action to be done or it will not match the action. The children who imitate the adult who has given the command with the correct action will stay in the game. The children who imitate the command with the wrong action will go out of the game, and this is where the child's automatic imitation comes into play. Psychologically, the visual stimulus being looked upon by the child is being imitated faster than the imitation of the command. In addition, the response times were faster in compatible scenarios than in incompatible scenarios.[78] Children are surrounded by many different people, day by day. Their parents make a big impact on them, and usually what the children do is what they have seen their parent do. In this article they found that a child, simply watching its mother sweep the floor, right after soon picks up on it and starts to imitate the mother by sweeping the floor. By the children imitating, they are really teaching themselves how to do things without instruction from the parent or guardian. Toddlers love to play the game of house. They picked up on this game of house by television, school or at home; they play the game how they see it. The kids imitate their parents or anybody in their family. In the article it says it is so easy for them to pick up on the things they see on an everyday basis.[citation needed] |

自動模倣 自動模倣は、模倣すべき刺激が与えられると非常に速く起こる。模倣は、指示と視覚的刺激が一致する場合(適合)と、一致しない場合(不適合)がある。例え ば「サイモン・セイズ」という子供向けゲームでは、大人が与える指示に従うよう求められる。このゲームでは大人が指示を与えつつ動作を示すが、指示内容は 実行すべき動作と一致する場合もあれば、一致しない場合もある。正しい動作で命令を出した大人を真似した子供はゲームに残る。間違った動作で命令を真似し た子供はゲームから脱落する。ここで子供の自動的模倣が作用する。心理的には、子供が視覚的に捉えた刺激は、命令の模倣よりも速く真似される。さらに、対 応する状況では非対応の状況よりも反応時間が速かった。[78] 子供たちは日々、様々な人々に囲まれている。親の影響は大きく、子供たちの行動は親の行動を模倣したものだ。本論文では、母親が床を掃くのを見た直後、子 供がすぐにそれを覚えて母親を真似て床を掃き始めることが確認された。子どもが模倣することで、親や保護者の指示なしに自ら行動を学ぶのだ。幼児はごっこ 遊びを好む。テレビや学校、家庭でごっこ遊びを目撃し、見たままの形で再現する。子どもは親や家族内の誰かを模倣する。日常的に目にする事象を容易に習得 できると記事は述べている。[出典が必要] |

| Over-imitation Over-imitation is "the tendency of young children to copy all of an adult model's actions, even components that are irrelevant for the task at hand."[79] According to this human and cross-cultural phenomenon, a child has a strong tendency to automatically encode the deliberate action of an adult as causally meaningful even when the child observes evidence that proves that its performance is unnecessary. It is suggested that over-imitation "may be critical to the transmission of human culture." Experiments done by Lyons et al. (2007) has shown that when there are obvious pedagogical cues, children tend to imitate step by step, including many unnecessary steps; without pedagogical cues, children will simply skip those useless steps.[80] However, another study suggests that children do not just "blindly follow the crowd" since they can also be just as discriminating as adults in choosing whether an unnecessary action should be copied or not.[81] They may imitate additional but unnecessary steps to a novel process if the adult demonstrations are all the same. However, in cases where one out of four adults showed a better technique, only 40% actually copied the extra step, as described by Evans, Carpenter and others.[82] Children's imitation is selective, also known as "selective imitation". Studies have shown that children tend to imitate older, competitive, and trustworthy individuals.[83] |

過剰模倣 過剰模倣とは「幼児が、目の前の課題とは無関係な要素も含め、大人の模範行動を全て真似する傾向」を指す[79]。この普遍的かつ文化横断的な現象によれ ば、子供は、その行動が不要であることを示す証拠を観察した場合でも、大人の熟議された行動を自動的に因果的に意味のあるものとして認識する強い傾向があ る。過剰模倣は「人間文化の伝達に極めて重要である可能性がある」と示唆されている。Lyonsら(2007)の実験では、明らかな教育的合図がある場 合、子供は多くの不要な手順を含め段階的に模倣する傾向があることが示された。一方、教育的合図がない場合、子供は単にそれらの無駄な手順を省略する。 [80] しかし別の研究によれば、子どもは単に「盲目的に群衆に従う」わけではなく、不要な行動を模倣すべきか否かの選択において大人と同等に判断力を持つことが 示されている。[81] 大人たちの実演がすべて同じであれば、子供たちは、新規のプロセスに対して、追加的だが不必要な手順を模倣するかもしれない。しかし、4人の大人のうち1 人がより優れた技術を示した場合、実際にその余分な手順を模倣したのは40%に過ぎなかったと、エヴァンス、カーペンターらは述べている。[82] 子供たちの模倣は選択的であり、これは「選択的模倣」としても知られている。研究によれば、子供たちは、年長で、競争力があり、信頼できる個人を模倣する 傾向がある。[83] |

| Deferred imitation Piaget coined the term deferred imitation and suggested that it arises out of the child's increasing ability to "form mental representations of behavior performed by others."[52] Deferred imitation is also "the ability to reproduce a previously witnessed action or sequence of actions in the absence of current perceptual support for the action."[2] Instead of copying what is currently occurring, individuals repeat the action or behavior later on. It appears that infants show an improving ability for deferred imitation as they get older, especially by 24 months. By 24 months, infants are able to imitate action sequences after a delay of up to three months, meaning that "they're able to generalize knowledge they have gained from one test environment to another and from one test object to another."[2] A child's deferred imitation ability "to form mental representations of actions occurring in everyday life and their knowledge of communicative gestures" has also been linked to earlier productive language development.[84] Between 9 (preverbal period) and 16 months (verbal period), deferred imitation performance on a standard actions-on-objects task was consistent in one longitudinal study testing participants' ability to complete a target action, with high achievers at 9 months remaining so at 16 months. Gestural development at 9 months was also linked to productive language at 16 months. Researchers now believe that early deferred imitation ability is indicative of early declarative memory, also considered a predictor of productive language development. |

遅延模倣 ピアジェは遅延模倣という用語を提唱し、これは「他者が行った行動の心的表象を形成する」能力の向上から生じるとした[52]。遅延模倣とはまた「行動に 対する現在の知覚的支援がない状態で、以前に目撃した行動または一連の行動を再現する能力」でもある[2]。現在進行中の行動を真似る代わりに、個体は後 になってその行動や振る舞いを繰り返すのだ。乳児は成長に伴い、特に24ヶ月頃までに遅延模倣能力が向上する傾向が見られる。24ヶ月頃には、最大3ヶ月 遅れても行動の連鎖を模倣できるようになる。これは「ある試験環境で得た知識を別の試験環境へ、ある試験対象から別の対象へ一般化できる」ことを意味する [2]。 また、子どもの遅延模倣能力——「日常生活で起こる行動の心的表象を形成する能力」と「コミュニケーションジェスチャーに関する知識」——は、言語能力の 発達早期化とも関連している。[84] 9か月(言語前期)から16か月(言語期)にかけて、対象物に対する標準的な動作課題における遅延模倣の成績は、対象行動を完了する能力を測定した縦断研 究で一貫していた。9か月時点で高成績だった者は16か月後も同様であった。9か月のジェスチャー発達も16か月の生産的言語と関連していた。研究者らは 現在、早期の遅延模倣能力が宣言的記憶の早期発達を示す指標であり、これも生産的言語発達を予測する要素と考えられていると信じている。 |

| Appropriation (sociology) Articulation (sociology) Associative Sequence Learning Cognitive imitation Copycat crime Copycat suicide Identification (psychology) Mimicry Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism |

社会学における流用 社会学における連関 連想的順序学習 認知的模倣 模倣犯罪 模倣自殺 心理学における同一視 擬態 動物磁気に関する王立委員会 |

| Further reading Zentall, Thomas R. (2006). "Imitation: Definitions, evidence, and mechanisms". Animal Cognition. 9 (4): 335–53. doi:10.1007/s10071-006-0039-2. PMID 17024510. S2CID 16183221. Liepmann, H. (1900). Das Krankheitsbild der Apraxie (motorische Asymbolie). Berlin: S. Karger Publ. Liepmann, H. (1905). Über die Störungen des Handelns bei Gehirnkranken. Berlin: S. Karger Verlag. Liepmann, H. (1908). Drei Aufsätze aus dem Apraxiegebiet. Berlin: S. Karger Publ. Liepmann, H. (1920). "Apraxie". Ergebn Ges Med. 1: 516–43. NAID 10008100327. |

さらに読む Zentall, Thomas R. (2006). 「模倣:定義、証拠、およびメカニズム」. Animal Cognition. 9 (4): 335–53. doi:10.1007/s10071-006-0039-2. PMID 17024510。S2CID 16183221。 Liepmann, H. (1900). Das Krankheitsbild der Apraxie (motorische Asymbolie). Berlin: S. Karger Publ. Liepmann, H. (1905). Über die Störungen des Handelns bei Gehirnkranken. ベルリン:S. Karger Verlag。 Liepmann, H. (1908). 失行症に関する 3 つの論文。ベルリン:S. Karger Publ. Liepmann, H. (1920). 「失行症」。Ergebn Ges Med. 1: 516–43. NAID 10008100327。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imitation |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099