イムレ・ラカトシュ

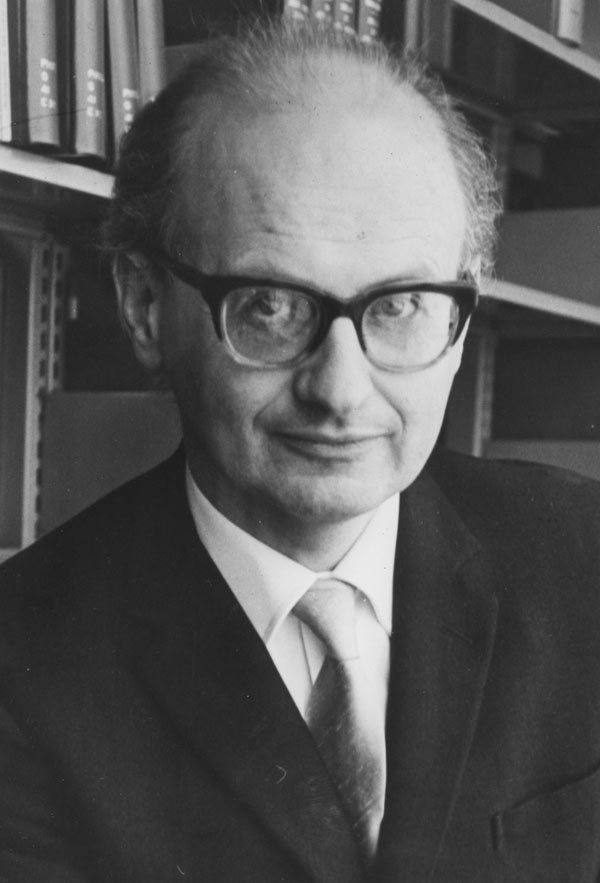

Imre Lakatos, 1922-1974

☆イ ムレ・ラカトシュ(イギリス式発音: /ˈlækətɒs/、[5] アメリカ式発音: /-toʊs/;ハンガリー語: Lakatos Imre [ˈlɒkɒtoʃ ˈimrɛ]; 1922年11月9日 - 1974年2月2日)は、ハンガリーの数学・科学哲学者である。数学の誤謬可能性と、その「証明と反証の方法論」を、公理化以前の発展段階において提唱し たことで知られる。また、科学的研究プログラムの方法論において「研究プログラム」の概念を導入したことでも知られる。

※ イムレ・ラカトシュは、ハンガリー語では姓名の順に発語するのでラカトシュ・イムレと表記するのが正しいが、これまでの慣行にしたがい、イムレ・ラカト シュと表記しています

| Imre Lakatos (UK:

/ˈlækətɒs/,[5] US: /-toʊs/; Hungarian: Lakatos Imre [ˈlɒkɒtoʃ ˈimrɛ]; 9

November 1922 – 2 February 1974) was a Hungarian philosopher of

mathematics and science, known for his thesis of the fallibility of

mathematics and its "methodology of proofs and refutations" in its

pre-axiomatic stages of development, and also for introducing the

concept of the "research programme" in his methodology of scientific

research programmes. |

イムレ・ラカトシュ(イギリス式発音: /ˈlækətɒs/、[5] アメリカ式発音: /-toʊs/;ハンガリー語: Lakatos Imre [ˈlɒkɒtoʃ ˈimrɛ]; 1922年11月9日 - 1974年2月2日)は、ハンガリーの数学・科学哲学者である。数学の誤謬可能性と、その「証明と反証の方法論」を、公理化以前の発展段階において提唱し たことで知られる。また、科学的研究プログラムの方法論において「研究プログラム」の概念を導入したことでも知られる。 |

| Life Lakatos was born Imre (Avrum) Lipsitz to a Jewish family in Debrecen, Hungary, in 1922. He received a degree in mathematics, physics, and philosophy from the University of Debrecen in 1944. In March 1944, the Germans invaded Hungary, and Lakatos, along with Éva Révész, his then-girlfriend and subsequent wife, formed a Marxist resistance group. In May of that year, the group was joined by Éva Izsák, a 19-year-old Jewish antifascist activist. Lakatos, considering that there was a risk that she would be captured and forced to betray them, decided that her duty to the group was to commit suicide. Subsequently, a member of the group took her to Debrecen and gave her cyanide.[6] During the occupation, Lakatos avoided Nazi persecution of Jews by changing his surname to Molnár.[7] His mother and grandmother were murdered in Auschwitz. He changed his surname once again to Lakatos (Locksmith) in honor of Géza Lakatos. After the war, from 1947, he worked as a senior official in the Hungarian Ministry of Education. He also continued his education with a PhD at Debrecen University, awarded in 1948 and also attended György Lukács's weekly Wednesday afternoon private seminars. He also studied at the Moscow State University under the supervision of Sofya Yanovskaya in 1949. When he returned, however, he found himself on the losing side of internal arguments within the Hungarian communist party and was imprisoned on charges of revisionism from 1950 to 1953. More of Lakatos's activities in Hungary after World War II have recently become known. In fact, Lakatos was a hardline Stalinist and, despite his young age, had an important role between 1945 and 1950 (his own arrest and jailing) in building up the Communist rule, especially in cultural life and academia, in Hungary.[8] After his release, Lakatos returned to academic life, doing mathematical research and translating George Pólya's How to Solve It into Hungarian. Still nominally a communist, his political views had shifted markedly, and he was involved with at least one dissident student group in the lead-up to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. After the Soviet Union invaded Hungary in November 1956, Lakatos fled to Vienna and later reached England. He lived there for the rest of his life, however, he never achieved British citizenship.[9] He received a PhD in philosophy in 1961 from the University of Cambridge; his doctoral thesis was entitled Essays in the Logic of Mathematical Discovery, and his doctoral advisor was R. B. Braithwaite. The book Proofs and Refutations: The Logic of Mathematical Discovery, published after his death, is based on this work. In 1960, he was appointed to a position in the London School of Economics (LSE), where he wrote on the philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of science. The LSE philosophy of science department at that time included Karl Popper, Joseph Agassi and J. O. Wisdom.[10] It was Agassi who first introduced Lakatos to Popper under the rubric of his applying a fallibilist methodology of conjectures and refutations to mathematics in his Cambridge PhD thesis. With co-editor Alan Musgrave, he edited the often cited Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, the Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science, London, 1965. Published in 1970, the 1965 Colloquium included well-known speakers delivering papers in response to Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In January 1971, he became editor of the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, which J. O. Wisdom had built up before departing in 1965, and he continued as editor until his death in 1974,[11] after which it was then edited jointly for many years by his LSE colleagues John W. N. Watkins and John Worrall, Lakatos's ex-research assistant. Lakatos and his colleague Spiro Latsis organized an international conference in Greece in 1975, and went ahead despite his death. It was devoted entirely to historical case studies in Lakatos's methodology of research programmes in the physical sciences and economics. These case studies in such as Einstein's relativity programme, Fresnel's wave theory of light and neoclassical economics, were published by Cambridge University Press in two separate volumes in 1976, one devoted to physical sciences and Lakatos's general programme for rewriting the history of science, with a concluding critique by his great friend Paul Feyerabend, and the other devoted to economics.[12] He remained at LSE until his sudden death in 1974 of a heart attack[13] at the age of 51. The Lakatos Award was set up by the school in his memory. His last lectures along with parts of his correspondence with Paul Feyerabend have been published in For and Against Method.[14] |

生涯 ラカトシュは1922年、ハンガリーのデブレツェンでユダヤ人家庭にイムレ(アヴラム)・リプシッツとして生まれた。1944年にデブレツェン大学で数 学、物理学、哲学の学位を取得した。1944年3月、ドイツ軍がハンガリーに侵攻すると、ラカトシュは当時の恋人であり後の妻となるエヴァ・レヴェシュと 共にマルクス主義の抵抗組織を結成した。同年5月には、19歳のユダヤ人反ファシスト活動家エヴァ・イザックが加わった。ラカトシュは、彼女が捕らえられ て抵抗組織を裏切る危険性があると判断し、組織への義務として自殺すべきだと決めた。その後、組織の一員が彼女をデブレツェンに連れて行き、青酸カリを渡 した。[6] 占領期間中、ラカトシュは姓をモルナーに変更することでナチスのユダヤ人迫害を免れた。[7] 彼の母と祖母はアウシュヴィッツで殺害された。ゲザ・ラカトシュに敬意を表し、再び姓をラカトシュ(錠前職人)に変更した。 戦後、1947年からハンガリー教育省の高官として勤務した。同時にデブレツェン大学で博士号を取得(1948年授与)し、ゲオルグ・ルカーチの毎週水曜 午後の非公開セミナーにも参加した。1949 年にはモスクワ国立大学でソフィヤ・ヤノフスカヤの指導のもと学んだ。しかし帰国後、ハンガリー共産党内の論争で敗北した側となり、修正主義の罪で 1950年から1953年まで投獄された. 第二次世界大戦後のハンガリーにおけるラカトシュの活動の詳細が近年明らかになった。実際、ラカトシュは強硬なスターリン主義者であり、若年ながら 1945年から1950年(自身の逮捕・投獄まで)にかけて、ハンガリーにおける共産主義体制の確立、特に文化生活と学界において重要な役割を担ってい た。[8] 釈放後、ラカトシュは学術界に復帰し、数学研究を行うとともにジョージ・ポリアの『問題解決法』をハンガリー語に翻訳した。名目上は共産主義者であった が、その政治的見解は著しく変化しており、1956年のハンガリー革命前夜には少なくとも一つの反体制学生グループに関与していた。 1956年11月にソ連がハンガリーに侵攻すると、ラカトシュはウィーンへ逃亡し、後にイギリスへ渡った。その後生涯をイギリスで過ごしたが、英国国籍は 取得しなかった[9]。1961年にケンブリッジ大学で哲学博士号を取得。博士論文の題名は『数学的発見の論理に関する論考』で、指導教官はR・B・ブレ イスウェイトであった。死後出版された著書『証明と反証:数学的発見の論理』はこの研究に基づいている。 1960年、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス(LSE)の職に任命され、数学哲学と科学哲学に関する著作を執筆した。当時のLSE科学哲学部門に はカール・ポパー、ジョセフ・アガッシ、J・O・ウィズダムが在籍していた[10]。ラカトシュをポパーに紹介したのはアガッシであり、その際、ケンブ リッジでの博士論文で数学に「仮説と反証」という誤謬主義的方法論を適用した点を強調した。 共同編集者のアラン・マスグレイブと共に、彼は1965年にロンドンで開催された国際科学哲学コロキウムの議事録『批判と知識の成長』を編集した。 1970年に出版されたこの1965年のコロキウムには、トーマス・クーンの『科学革命の構造』に対する応答として論文を発表した著名な講演者が含まれて いた。 1971年1月、彼は『英国科学哲学ジャーナル』の編集長に就任した。この雑誌はJ・O・ウィズダムが1965年に退任するまで築き上げたもので、ラカト シュは1974年に死去するまで編集を続けた[11]。その後、長年にわたりロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスの同僚であるジョン・W・N・ワトキ ンスと、ラカトシュの元研究助手だったジョン・ウォラルが共同で編集を担当した。 ラカトシュと同僚スピロ・ラツィスは1975年にギリシャで国際会議を主催したが、ラカトシュの死後も開催を続けた。この会議は物理科学と経済学における 研究プログラムというラカトシュの方法論に基づく歴史的ケーススタディに完全に特化したものだった。アインシュタインの相対性理論プログラム、フレネルの 光波動説、新古典派経済学などの事例研究は、1976年にケンブリッジ大学出版局から2巻に分けて刊行された。1巻は物理科学とラカトシュの科学史再構築 のための一般プログラムに焦点を当て、親友ポール・ファイヤーアバントによる総括的批判を収録。もう1巻は経済学を扱った。[12] 彼は1974年、51歳の若さで心臓発作により急逝するまでロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスに在籍した[13]。同校は彼の追悼としてラカトシュ 賞を設立した。彼の最後の講義とポール・ファイヤーアバントとの書簡の一部は『方法論の賛否』に収録されている[14]。 |

| Philosophical work Philosophy of mathematics Main article: Proofs and Refutations Lakatos's philosophy of mathematics was inspired by both Hegel's and Marx's dialectic, by Karl Popper's theory of knowledge, and by the work of mathematician George Pólya.[15][16] The 1976 book Proofs and Refutations is based on the first three chapters of his 1961 four-chapter doctoral thesis Essays in the Logic of Mathematical Discovery. But its first chapter is Lakatos's own revision of its chapter 1 that was first published as Proofs and Refutations in four parts in 1963–64 in the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. It is largely taken up by a fictional dialogue set in a mathematics class. The students are attempting to prove the formula for the Euler characteristic in algebraic topology, which is a theorem about the properties of polyhedra, namely that for all polyhedra the number of their vertices V minus the number of their edges E plus the number of their faces F is 2 (V − E + F = 2). The dialogue is meant to represent the actual series of attempted proofs that mathematicians historically offered for the conjecture, only to be repeatedly refuted by counterexamples. Often, the students paraphrase famous mathematicians such as Cauchy, as noted in Lakatos's extensive footnotes. Lakatos termed the polyhedral counterexamples to Euler's formula monsters and distinguished three ways of handling these objects: Firstly, monster-barring, by which means the theorem in question could not be applied to such objects. Secondly, monster-adjustment, whereby by making a re-appraisal of the monster it could be made to obey the proposed theorem. Thirdly, exception handling, a further distinct process. These distinct strategies have been taken up in qualitative physics, where the terminology of monsters has been applied to apparent counterexamples, and the techniques of monster-barring and monster-adjustment recognized as approaches to the refinement of the analysis of a physical issue.[17] What Lakatos tried to establish was that no theorem of informal mathematics is final or perfect. This means that we should not think that a theorem is ultimately true, only that no counterexample has yet been found. Once a counterexample is found, we adjust the theorem, possibly extending the domain of its validity. This is a continuous way our knowledge accumulates, through the logic and process of proofs and refutations. (If axioms are given for a branch of mathematics, however, Lakatos claimed that proofs from those axioms were tautological, i.e. logically true.)[18] Lakatos proposed an account of mathematical knowledge based on the idea of heuristics. In Proofs and Refutations the concept of "heuristic" was not well developed, although Lakatos gave several basic rules for finding proofs and counterexamples to conjectures. He thought that mathematical "thought experiments" are a valid way to discover mathematical conjectures and proofs, and sometimes called his philosophy "quasi-empiricism". However, he also conceived of the mathematical community as carrying on a kind of dialectic to decide which mathematical proofs are valid and which are not. Therefore, he fundamentally disagreed with the "formalist" conception of proof that prevailed in Frege's and Russell's logicism, which defines proof simply in terms of formal validity. On its first publication as an article in the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science in 1963–64, Proofs and Refutations became highly influential on new work in the philosophy of mathematics, although few agreed with Lakatos's strong disapproval of formal proof. Before his death, he had been planning to return to the philosophy of mathematics and apply his theory of research programmes to it. Lakatos, Worrall and Zahar use Poincaré (1893)[19] to answer one of the major problems perceived by critics, namely that the pattern of mathematical research depicted in Proofs and Refutations does not faithfully represent most of the actual activity of contemporary mathematicians.[20] |

哲学的著作 数学哲学 主な記事: 証明と反証 ラカトシュの数学哲学は、ヘーゲルとマルクスの弁証法、カール・ポパーの知識論、そして数学者ジョージ・ポリアの著作から影響を受けたものである。 [15][16] 1976年の著書『証明と反証』は、1961年に発表された4章からなる博士論文『数学的発見の論理に関する論考』の最初の3章に基づいている。しかしそ の第1章は、1963年から64年にかけて『英国科学哲学雑誌』に4回に分けて掲載された「証明と反証」の第1章をラカトシュ自身が改訂したものである。 本書の大部分は、数学の授業を舞台にした架空の対話で構成されている。学生たちは代数トポロジーにおけるオイラー特性の定式を証明しようとしている。これ は多面体の性質に関する定理であり、具体的には「あらゆる多面体において、頂点の数Vから辺の数Eを引いた値に面の数Fを加えた値は2である(V − E + F = 2)」というものである。この対話は、数学者が歴史的にこの予想に対して提示した一連の証明の試みを再現したものである。しかしそれらの試みは反例によっ て繰り返し反駁されてきた。学生たちはしばしばコーシーなどの著名な数学者の言葉を引用しており、ラカトシュの膨大な脚注にもその旨が記されている。 ラカトシュはオイラーの定式に対する多面体の反例を「怪物」と呼び、これらに対処する三つの方法を区別した。第一に「怪物排除」であり、これにより当該定 理はそうした対象には適用できない。第二に、怪物の調整。怪物を見直すことで、提案された定理に従わせることができる。第三に、例外処理。これはさらに別 のプロセスである。これらの異なる戦略は質的物理学で取り上げられており、怪物の用語は明らかな反例に適用され、怪物排除と怪物調整の技術は物理的問題の 分析を洗練させるアプローチとして認識されている。[17] ラカトシュが確立しようとしたのは、非形式的数学の定理は最終的でも完全でもないということだ。つまり定理を究極的に真と考えるべきではなく、反例がまだ 発見されていないだけだと考えるべきだという意味である。反例が見つかったら、定理を調整する。その有効性の領域を拡張する可能性もある。これは証明と反 証の論理とプロセスを通じて、我々の知識が継続的に蓄積される方法だ。(ただし、数学の一分野に公理が与えられている場合、ラカトシュはそれらの公理から の証明は同語反復的、すなわち論理的に真であると主張した。)[18] ラカトシュは、発見的手法(ヒューリスティックス)の概念に基づく数学的知識の解釈を提案した。『証明と反証』において「発見的手法」の概念は十分に発展 していなかったが、ラカトシュは予想に対する証明と反例を見つけるためのいくつかの基本規則を示した。彼は数学的「思考実験」が数学的予想と証明を発見す る有効な方法であると考え、時に自身の哲学を「準経験主義」と呼んだ。 しかし彼は同時に、数学コミュニティが「どの証明が有効か否かを決めるための弁証法」を実践しているとも考えた。したがって彼は、証明を形式的妥当性のみ で定義するフレゲやラッセルの論理主義に代表される「形式主義的」証明観とは根本的に対立した。 1963年から64年にかけて『英国科学哲学雑誌』に論文として初掲載された『証明と反証』は、数学哲学の新たな研究に多大な影響を与えた。ただし、形式 的証明に対するラカトシュの強い否定には、賛同する者はほとんどいなかった。死の前、彼は数学哲学に戻り、研究プログラム理論をそこに適用する計画を立て ていた。ラカトシュ、ウォラル、ザハールは、批判者が指摘する主要な問題の一つ、すなわち『証明と反証』に描かれた数学研究のパターンが現代数学者の実際 の活動の大半を忠実に表していないという問題[20]に答えるため、ポアンカレ(1893)[19]を用いている。 |

| Cauchy and uniform convergence In a 1966 text Cauchy and the continuum, Lakatos re-examines the history of the calculus, with special regard to Augustin-Louis Cauchy and the concept of uniform convergence, in the light of non-standard analysis. Lakatos is concerned that historians of mathematics should not judge the evolution of mathematics in terms of currently fashionable theories. As an illustration, he examines Cauchy's proof that the sum of a series of continuous functions is itself continuous. Lakatos is critical of those who would see Cauchy's proof, with its failure to make explicit a suitable convergence hypothesis, merely as an inadequate approach to Weierstrassian analysis. Lakatos sees in such an approach a failure to realize that Cauchy's concept of the continuum differed from currently dominant views. |

コーシーと一様収束 1966年の著作『コーシーと連続体』において、ラカトシュは非標準解析の観点から、特にオーギュスタン=ルイ・コーシーと一様収束の概念に焦点を当て、 微積分の歴史を再検討している。ラカトシュは、数学史家が現在の流行理論に基づいて数学の発展を評価すべきではないと懸念している。例として、彼は連続関 数の級数の和自体が連続であることを示すコーシーの証明を検証する。ラカトシュは、適切な収束仮説を明示的に示していないという理由で、コーシーの証明を 単にワイエルシュトラス的解析への不十分なアプローチと見なす者たちを批判する。ラカトシュは、このような見方において、コーシーの連続体の概念が当時主 流の見解とは異なるという事実を理解できていないと指摘する。 |

| Research programmes Lakatos's second major contribution to the philosophy of science was his model of the "research programme",[21] which he formulated in an attempt to resolve the perceived conflict between Popper's falsificationism and the revolutionary structure of science described by Kuhn. Popper's standard of falsificationism was widely taken to imply that a theory should be abandoned as soon as any evidence appears to challenge it, while Kuhn's descriptions of scientific activity were taken to imply that science is most fruitful during periods in which popular, or "normal", theories are supported despite known anomalies. Lakatos's model of the research programme aims to combine Popper's adherence to empirical validity with Kuhn's appreciation for conventional consistency. A Lakatosian research programme[22] is based on a hard core of theoretical assumptions that cannot be abandoned or altered without abandoning the programme altogether. More modest and specific theories that are formulated in order to explain evidence that threatens the "hard core" are termed auxiliary hypotheses. Auxiliary hypotheses are considered expendable by the adherents of the research programme—they may be altered or abandoned as empirical discoveries require in order to "protect" the "hard core". Whereas Popper was generally read as hostile toward such ad hoc theoretical amendments, Lakatos argued that they can be progressive, i.e. productive, when they enhance the programme's explanatory and/or predictive power, and that they are at least permissible until some better system of theories is devised and the research programme is replaced entirely. The difference between a progressive and a degenerative research programme lies, for Lakatos, in whether the recent changes to its auxiliary hypotheses have achieved this greater explanatory/predictive power or whether they have been made simply out of the necessity of offering some response in the face of new and troublesome evidence. A degenerative research programme indicates that a new and more progressive system of theories should be sought to replace the currently prevailing one, but until such a system of theories can be conceived of and agreed upon, abandonment of the current one would only further weaken our explanatory power and would therefore be unacceptable for Lakatos. Lakatos's primary example of a research programme that had been successful in its time and then progressively replaced is that founded by Isaac Newton, with his three laws of motion forming the "hard core". The Lakatosian research programme deliberately provides a framework within which research can be conducted on the basis of "first principles" (the "hard core"), which are shared by those involved in the research programme and accepted for the purpose of that research without further proof or debate. In this regard, it is similar to Kuhn's notion of a paradigm. Lakatos sought to replace Kuhn's paradigm, guided by an irrational "psychology of discovery", with a research programme no less coherent or consistent, yet guided by Popper's objectively valid logic of discovery. Lakatos was following Pierre Duhem's idea that one can always protect a cherished theory (or part of one) from hostile evidence by redirecting the criticism toward other theories or parts thereof. (See Confirmation holism and Duhem–Quine thesis). This aspect of falsification had been acknowledged by Popper. Popper's theory, falsificationism, proposed that scientists put forward theories and that nature "shouts NO" in the form of an inconsistent observation. According to Popper, it is irrational for scientists to maintain their theories in the face of nature's rejection, as Kuhn had described them doing. For Lakatos, however, "It is not that we propose a theory and Nature may shout NO; rather, we propose a maze of theories, and nature may shout INCONSISTENT".[23] The continued adherence to a programme's "hard core", augmented with adaptable auxiliary hypotheses, reflects Lakatos's less strict standard of falsificationism. Lakatos saw himself as merely extending Popper's ideas, which changed over time and were interpreted by many in conflicting ways. In his 1968 article "Criticism and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes",[24] Lakatos contrasted Popper0, the "naive falsificationist" who demanded unconditional rejection of any theory in the face of any anomaly (an interpretation Lakatos saw as erroneous but that he nevertheless referred to often); Popper1, the more nuanced and conservatively interpreted philosopher; and Popper2, the "sophisticated methodological falsificationist" that Lakatos claims is the logical extension of the correctly interpreted ideas of Popper1 (and who is therefore essentially Lakatos himself). It is, therefore, very difficult to determine which ideas and arguments concerning the research programme should be credited to whom. While Lakatos dubbed his theory "sophisticated methodological falsificationism", it is not "methodological" in the strict sense of asserting universal methodological rules by which all scientific research must abide. Rather, it is methodological only in that theories are only abandoned according to a methodical progression from worse theories to better theories—a stipulation overlooked by what Lakatos terms "dogmatic falsificationism". Methodological assertions in the strict sense, pertaining to which methods are valid and which are invalid, are themselves contained within the research programmes that choose to adhere to them, and should be judged according to whether the research programmes that adhere to them prove progressive or degenerative. Lakatos divided these "methodological rules" within a research programme into its "negative heuristics", i.e., what research methods and approaches to avoid, and its "positive heuristics", i.e., what research methods and approaches to prefer. While the "negative heuristic" protects the hard core, the "positive heuristic" directs the modification of the hard core and auxiliary hypotheses in a general direction.[25] Lakatos claimed that not all changes of the auxiliary hypotheses of a research programme (which he calls "problem shifts") are equally productive or acceptable. He took the view that these "problem shifts" should be evaluated not just by their ability to defend the "hard core" by explaining apparent anomalies, but also by their ability to produce new facts, in the form of predictions or additional explanations.[26] Adjustments that accomplish nothing more than the maintenance of the "hard core" mark the research programme as degenerative. Lakatos's model provides for the possibility of a research programme that is not only continued in the presence of troublesome anomalies but that remains progressive despite them. For Lakatos, it is essentially necessary to continue on with a theory that we basically know cannot be completely true, and it is even possible to make scientific progress in doing so, as long as we remain receptive to a better research programme that may eventually be conceived of. In this sense, it is, for Lakatos, an acknowledged misnomer to refer to "falsification" or "refutation", when it is not the truth or falsity of a theory that is solely determining whether we consider it "falsified" but also the availability of a less false theory. A theory cannot be rightfully "falsified", according to Lakatos, until it is superseded by a better (i.e. more progressive) research programme. This is what he says is happening in the historical periods Kuhn describes as revolutions and what makes them rational as opposed to mere leaps of faith or periods of deranged social psychology, as Kuhn argued. |

研究プログラム ラカトシュが科学哲学に与えた第二の主要な貢献は、「研究プログラム」というモデルである[21]。これはポッパーの反証主義とクーンが記述した科学の革 命的構造との間に見出された矛盾を解決しようとする試みとして提唱された。ポッパーの反証主義の基準は、理論を挑戦する証拠が現れた時点で直ちに放棄すべ きだと広く解釈された。一方クーンの科学的活動に関する記述は、既知の異常現象があるにもかかわらず、一般的な「正常」理論が支持される時期に科学が最も 実り多いと解釈された。ラカトシュの研究プログラムモデルは、ポッパーの経験的妥当性への固執とクーンの慣習的一貫性への評価を統合することを目指してい る。 ラカトシアン研究プログラム[22]は、プログラム全体を放棄しない限り放棄または変更できない理論的前提の「ハードコア」に基づいている。「ハードコ ア」を脅かす証拠を説明するために構築される、より控えめで具体的な理論は補助仮説と呼ばれる。補助仮説は研究プログラムの支持者にとって消耗品と見なさ れる——「ハードコア」を「保護」するために、経験的発見が要求する通りに変更または放棄される可能性がある。ポッパーはこうした場当たり的な理論修正に 敵対的と解釈されることが多いが、ラカトシュは、それらがプログラムの説明力や予測力を高める場合には進歩的、すなわち生産的となり得ると主張した。ま た、より優れた理論体系が考案され研究プログラム全体が置き換えられるまでは、少なくとも許容されるべきだと論じた。ラカトシュにとって、進歩的な研究計 画と退行的な研究計画の異なる点は、補助仮説への最近の変更が、このより大きな説明力/予測力を達成したか、それとも単に新たな厄介な証拠に何らかの対応 を迫られた必要性から行われたかにある。退化的研究プログラムは、現在主流の理論体系に代わる新たな進歩的理論体系を求めるべきことを示唆する。しかし、 そのような理論体系が構想され合意されるまでは、現行の体系を放棄することは説明力をさらに弱めるだけであるため、ラカトシュによれば容認できない。ラカ トシュが、その時代には成功を収めたが次第に置き換えられた研究計画の主要な例として挙げたのは、アイザック・ニュートンが創設したもので、その三つの運 動法則が「ハードコア」を形成している。 ラカトシアン研究計画は意図的に枠組みを提供し、その枠組み内で「第一原理」(「ハードコア」)に基づいて研究が遂行される。この第一原理は研究計画に関 わる者によって共有され、その研究目的のために追加の証明や議論なしに受け入れられる。この点において、クーンのパラダイム概念と類似している。ラカト シュは、非合理的な「発見の心理学」に導かれたクーンのパラダイムを、ポパーの客観的に有効な発見の論理に導かれた、同様に首尾一貫した研究計画で置き換 えようとしたのである。 ラカトシュはピエール・デュエムの考えに従っていた。すなわち、批判を他の理論やその一部に向け直すことで、常に愛着のある理論(またはその一部)を敵対 的な証拠から守ることができるという考え方である。(確認の全体論およびデュエム=クワインの命題を参照)。この反証可能性の側面はポパーも認めていた。 ポパーの理論である反証主義は、科学者が理論を提唱すると、自然が矛盾した観測という形で「ノー」と叫ぶと提案した。ポパーによれば、クーンが描写したよ うに、科学者が自然の拒絶に直面しても理論を維持し続けるのは非合理的である。しかしラカトシュによれば、「我々が理論を提案し、自然が『ノー』と叫ぶ可 能性があるというわけではない。むしろ我々は理論の迷宮を提案し、自然は『矛盾している』と叫ぶ可能性がある」[23]。適応可能な補助仮説で補強された プログラムの「ハードコア」への継続的な固執は、ラカトシュのより緩やかな反証主義基準を反映している。 ラカトシュは、自らの考えを単にポッパーの思想を拡張したものと見なしていた。ポッパーの思想は時代とともに変化し、多くの人々によって相反する形で解釈 されてきたのである。1968年の論文『批判と科学研究プログラムの方法論』[24]において、ラカトシュはポッパー0(いかなる異常現象に対しても理論 の無条件拒否を要求する「素朴な反証主義者」——ラカトシュはこれを誤った解釈と見なしたが、頻繁に言及した)と、 よりニュアンス豊かで保守的に解釈される哲学者としてのポッパー1;そしてポッパー1の正しく解釈された思想の論理的延長であるとラカトシュ が主張する「洗練された方法論的反証主義者」としてのポッパー2(したがって本質的にはラカトシュ自身である)。したがって、研究プログラムに関するどの 思想や議論を誰に帰すべきかを判断するのは非常に困難である。 ラカトシュは自らの理論を「洗練された方法論的反証主義」と呼んだが、これは厳密な意味での「方法論的」——すなわち全ての科学研究が従わねばならない普 遍的方法論的規則を主張する——ものではない。むしろ方法論的と言えるのは、理論が「劣った理論から優れた理論へ」という方法論的進展に従ってのみ放棄さ れるという点においてのみである。この規定は、ラカトシュが「独断的反証主義」と呼ぶ立場によって見落とされている。厳密な意味での方法論的主張、すなわ ちどの方法が有効でどの方法が無効かに関する主張は、それ自体、それらに従うことを選択した研究プログラムの中に含まれており、それらに従う研究プログラ ムが進歩的であるか退行的であるかによって判断されるべきである。ラカトシュは研究プログラム内のこうした「方法論的規則」を、「否定的発見法」(避ける べき研究方法・アプローチ)と「肯定的発見法」(優先すべき研究方法・アプローチ)に分類した。「否定的発見法」が中核を保護する一方、「肯定的発見法」 は中核と補助仮説の修正を一般的な方向へ導く。[25] ラカトシュは、研究プログラムの補助仮説の変更(彼が「問題転換」と呼ぶもの)が全て同等に生産的あるいは許容可能であるわけではないと主張した。彼は、 これらの「問題転換」は、見かけ上の異常を説明することで「ハードコア」を防衛する能力だけでなく、予測や追加の説明という形で新たな事実を生み出す能力 によっても評価されるべきだと考えた。[26] 「ハードコア」の維持しか達成しない調整は、研究プログラムが退化していることを示す。ラカトシュのモデルは、厄介な異常が存在しても継続されるだけでな く、それらにもかかわらず進歩を続ける研究プログラムの可能性を認めている。ラカトシュにとって、基本的に完全には真ではないと分かっている理論を継続す ることは本質的に必要であり、より優れた研究プログラムが最終的に考案される可能性に開かれたままであれば、そうすることで科学的進歩さえも達成し得るの である。この意味で、理論の真偽だけが「反証」や「反駁」の判断基準ではなく、より誤りの少ない理論が存在するかどうかが同時に問われる以上、ラカトシュ にとって「反証」や「反駁」という表現は誤った呼称であると認められている。ラカトシュによれば、理論はより優れた(すなわちより進歩的な)研究計画に よって置き換えられるまでは、正当に「反証」されたとは言えない。これがクーンが革命と呼ぶ歴史的時期に起きていることであり、クーンが主張したように、 単なる信仰の飛躍や狂った社会心理の時期ではなく、それらを合理的なものにしているのだ。 |

| Pseudoscience According to the demarcation criterion of pseudoscience proposed by Lakatos, a theory is pseudoscientific if it fails to make any novel predictions of previously unknown phenomena or its predictions were mostly falsified, in contrast with scientific theories, which predict novel fact(s).[27] Progressive scientific theories are those that have their novel facts confirmed, and degenerate scientific theories, which can degenerate so much that they become pseudo-science, are those whose predictions of novel facts are refuted. As he put it: "A given fact is explained scientifically only if a new fact is predicted with it ... The idea of growth and the concept of empirical character are soldered into one." See pages 34–35 of The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes, 1978. Lakatos's own key examples of pseudoscience were Ptolemaic astronomy, Immanuel Velikovsky's planetary cosmogony, Freudian psychoanalysis, 20th-century Soviet Marxism,[28] Lysenko's biology, Niels Bohr's quantum mechanics post-1924, astrology, psychiatry, and neoclassical economics. |

疑似科学 ラカトシュが提唱した疑似科学の境界基準によれば、理論が未知の現象について新たな予測を全く行わない場合、あるいはその予測の大半が反証された場合、そ の理論は疑似科学的である。これに対し科学的理論は新たな事実を予測する。[27] 進歩的な科学的理論とは、その新たな事実が確認されたものである。一方、退化した科学的理論とは、新たな事実に関する予測が反証されることで、疑似科学へ と退化する可能性があるものである。彼が述べたように: 「ある事実が科学的に説明されるのは、それによって新たな事実が予測される場合のみである…成長の理念と経験的性格の概念は一体となっている」『科学研究 プログラムの方法論』(1978年)34-35頁参照。 ラカトシュ自身が疑似科学の主要な例として挙げたのは、プトレマイオス天文学、イマニュエル・ヴェリコフスキーの惑星起源説、フロイト精神分析学、20世 紀ソビエトマルクス主義[28]、リセンコ生物学、1924年以降のニールス・ボーア量子力学、占星術、精神医学、新古典派経済学である。 |

| Darwin's theory In his 1973 Scientific Method Lecture 1[29] at the London School of Economics, he also claimed that "nobody to date has yet found a demarcation criterion according to which Darwin can be described as scientific". Almost 20 years after Lakatos's 1973 challenge to the scientificity of Darwin, in her 1991 The Ant and the Peacock, LSE lecturer and ex-colleague of Lakatos, Helena Cronin, attempted to establish that Darwinian theory was empirically scientific in respect of at least being supported by evidence of likeness in the diversity of life forms in the world, explained by descent with modification. She wrote that our usual idea of corroboration as requiring the successful prediction of novel facts ... Darwinian theory was not strong on temporally novel predictions. ... however familiar the evidence and whatever role it played in the construction of the theory, it still confirms the theory.[30] |

ダーウィンの理論 1973年にロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで行った科学的方法論講義第1回[29]において、彼はまた「今日に至るまで、ダーウィンを科学的と 評する境界基準を見出した者は誰もいない」と主張した。 ラカトシュがダーウィンの科学的性質に異議を唱えてからほぼ20年後、1991年にLSE講師でラカトシュの元同僚であるヘレナ・クロニンは『蟻と孔雀』 において、ダーウィン理論が少なくとも「変異を伴う祖先からの継承」によって説明される世界の生物多様性における類似性の証拠によって支持されるという点 で、経験的に科学的であることを立証しようとした。彼女はこう記している。 我々が通常考える裏付けとは、新たな事実の予測成功を必要とするものだ…ダーウィン理論は時間的に新たな予測には弱い。…証拠がどれほど馴染み深く、理論 構築でどんな役割を果たそうとも、それは依然として理論を裏付けるのである。[30] |

| Rational reconstructions of the

history of science In his 1970 article "History of Science and Its Rational Reconstructions"[3] Lakatos proposed a dialectical historiographical meta-method for evaluating different theories of scientific method, namely by means of their comparative success in explaining the actual history of science and scientific revolutions on the one hand, whilst on the other providing a historiographical framework for rationally reconstructing the history of science as anything more than merely inconsequential rambling. The article started with his now renowned dictum "Philosophy of science without history of science is empty; history of science without philosophy of science is blind". However, neither Lakatos himself nor his collaborators ever completed the first part of this dictum by showing that in any scientific revolution the great majority of the relevant scientific community converted just when Lakatos's criterion – one programme successfully predicting some novel facts whilst its competitor degenerated – was satisfied. Indeed, for the historical case studies in his 1968 article "Criticism and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes"[24] he had openly admitted as much, commenting: "In this paper it is not my purpose to go on seriously to the second stage of comparing rational reconstructions with actual history for any lack of historicity." |

科学史の合理的な再構築 1970年の論文「科学史とその合理的な再構築」[3]において、ラカトシュは科学的メソッドの異なる諸理論を評価するための弁証法的歴史学メタ手法を提 案した。具体的には、一方では実際の科学史と科学的革命を説明する上で各理論が示す相対的な成功度合いを比較し、他方では科学史を単なる無意味な戯言以上 のものとして合理的に再構築するための歴史学的な枠組みを提供するという方法である。この論文は、今や有名な彼の格言「科学史を伴わない科学哲学は空虚で あり、科学哲学を伴わない科学史は盲目である」で始まっている。 しかし、ラカトシュ自身も協力者たちも、この格言の前半部分を完成させることはなかった。すなわち、いかなる科学的革命においても、関連する科学コミュニ ティの大多数が、ラカトシュの基準(あるプログラムが競合プログラムが衰退する中で新たな事実を成功裏に予測する)が満たされたまさにその瞬間に転換した ことを示すことはなかったのだ。実際、1968年の論文「批判と科学研究プログラムの方法論」[24]における歴史的事例研究について、彼は自らこう認め ている。「本論文では、歴史性の欠如を理由に、合理的な再構築と実際の歴史を比較する第二段階へ真剣に進むことを目的としていない」と。 |

| Criticism Feyerabend Paul Feyerabend argued that Lakatos's methodology was not a methodology at all, but merely "words that sound like the elements of a methodology".[31] He argued that Lakatos's methodology was no different in practice from epistemological anarchism, Feyerabend's own position. He wrote in Science in a Free Society (after Lakatos's death) that: Lakatos realized and admitted that the existing standards of rationality, standards of logic included, were too restrictive and would have hindered science had they been applied with determination. He therefore permitted the scientist to violate them (he admits that science is not "rational" in the sense of these standards). However, he demanded that research programmes show certain features in the long run — they must be progressive... I have argued that this demand no longer restricts scientific practice. Any development agrees with it.[32] Lakatos and Feyerabend planned to produce a joint work in which Lakatos would develop a rationalist description of science, and Feyerabend would attack it. The correspondence between Lakatos and Feyerabend, where the two discussed the project, has since been reproduced, with commentary, by Matteo Motterlini.[33] |

批判 ファイヤーベン ポール・ファイヤーベンは、ラカトシュの方法論は方法論などではなく、単に「方法論の要素のように聞こえる言葉」に過ぎないと主張した[31]。彼は、ラ カトシュの方法論は実践において、ファイヤーベン自身の立場である認識論的無政府主義と何ら異なるなかったと論じた。彼は『自由な社会における科学』(ラ カトシュの死後)の中でこう書いている: ラカトシュは、既存の合理性の基準(論理の基準を含む)が過度に制限的であり、断固として適用されれば科学の発展を阻害したであろうことを認識し認めた。 ゆえに彼は科学者がそれらを破ることを許容した(科学がこれらの基準の意味で「合理的」ではないことを認めている)。しかし彼は、研究プログラムが長期的 には特定の特徴を示すことを要求した——それらは進歩的でなければならない... 私はこの要求がもはや科学的実践を制限しないと論じてきた。いかなる発展もそれに合致するのだ。[32] ラカトシュとファイヤーバントは共同著作を計画していた。ラカトシュが科学の合理主義的記述を展開し、ファイヤーバントがそれを批判するという内容だ。こ の計画について両者が議論した書簡は、後にマッテオ・モッテルリーニによって解説付きで再現されている。[33] |

| Scientific community metaphor,

an approach to programming influenced by Lakatos's work on research

programmes List of Soviet and Eastern Bloc defectors Lakatos Award set up in memory of him Alexander Tarasov-Rodionov, author of "Shokolad" which was formative of Lakatos's early political thinking |

科学コミュニティの隠喩、ラカトシュの研究プログラムに関する研究に影

響を受けたプログラミングへのアプローチ ソ連および東側諸国からの亡命者リスト ラカトシュを記念して設立されたラカトシュ賞 アレクサンダー・タラソフ=ロディオノフ、ラカトシュの初期の政治思想の形成に影響を与えた『ショコラード』の著者 |

| Notes 1. E. Reck (ed.), The Historical Turn in Analytic Philosophy, Springer, 2016: ch. 4.2. 2. Kostas Gavroglu, Yorgos Goudaroulis, P. Nicolacopoulos (eds.), Imre Lakatos and Theories of Scientific Change, Springer, 2012, p. 211. 3. Lakatos, Imre (1970). "History of Science and Its Rational Reconstructions". PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association. 1970: 91–136. doi:10.1086/psaprocbienmeetp.1970.495757. JSTOR 495757. S2CID 145197122. 4. K. Gavroglu, Y. Goudaroulis, P. Nicolacopoulos (eds.), Imre Lakatos and Theories of Scientific Change, Springer, 2012, p. 61. 5. Philosophy of Science: Popper and Lakatos, lecture on the philosophy of science of Karl Popper and Imre Lakatos, delivered to master's students at the University of Sussex in November 2014. 6. "Imre Lakatos". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2021. 7. Brendan Larvor (2013). Lakatos: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 9781134765140. He assumed the name 'Molnár Tibor' during the time in the resistance group 8. Bandy 2010.[page needed] 9. György Kampis, L. Kvasz, Michael Stöltzner (eds.), Appraising Lakatos: Mathematics, Methodology, and the Man, Springer, 2013, p. 296. 10. Scheffler, Israel (2007), Gallery of Scholars: A Philosopher's Recollections, Philosophy and education, vol. 13, Springer, p. 42, ISBN 9781402027109. 11. See Lakatos's 5 Jan 1971 letter to Paul Feyerabend pp. 233–234 in Motterlini's 1999 For and Against Method. 12. These were respectively Method and Appraisal in the Physical Sciences: The Critical Background to Modern Science 1800–1905 by Colin Howson (ed.) and Method and Appraisal in Economics by Spiro J. Latsis (ed.). 13. Donald A. Gillies (September 1996). "Review. Matteo Motterlini (ed). Imre Lakatos. Paul K. Feyerabend. Sull'orlo della scienza: pro e contro il metodo. (On the threshold of Science: for and against method)". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 47 (3). JSTOR 687992. 14. Feyerabend, Paul; Lakatos, Imre (1999). Motterlini, Matteo (ed.). For and Against Method: Including Lakatos's Lectures on Scientific Method and the Lakatos-Feyerabend Correspondence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/9780226467030 (inactive 12 July 2025). ISBN 9780226467030. 15. Larvor, Brendan (1 April 1999). "Lakatos's Mathematical Hegelianism". The Owl of Minerva. 31 (1): 23–44. doi:10.5840/owl199931119. 16. Motterlini, Matteo (2002), Kampis, George; Kvasz, Ladislav; Stöltzner, Michael (eds.), "Professor Lakatos Between the Hegelian Devil and the Popperian Deep Blue Sea", Appraising Lakatos: Mathematics, Methodology, and the Man, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 23–52, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-0769-5_3, ISBN 978-94-017-0769-5, retrieved 29 June 2025 17. "Lakatosian Monsters". Retrieved 18 January 2015. 18. See, for instance, Lakatos's A renaissance of empiricism in the recent philosophy of mathematics, section 2, in which he defines a Euclidean system to be one consisting of all logical deductions from an initial set of axioms and writes that "a Euclidean system may be claimed to be true". 19. Poincaré, H. (1893). "Sur la Généralisation d'un Théorème d'Euler relatif aux Polyèdres", Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences, 117 p. 144, as cited in Lakatos, Worrall and Zahar, p. 162. 20. Lakatos, Worrall and Zahar (1976), Proofs and Refutations ISBN 0-521-21078-X, pp. 106–126, note that Poincaré's formal proof (1899) "Complèment à l'Analysis Situs", Rediconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo, 13, pp. 285–343, rewrites Euler's conjecture into a tautology of vector algebra. 21. Lakatos, Imre. (1970). "Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes". In: Lakatos, Musgrave eds. (1970), pp. 91–195. 22. Bruce J. Caldwell (1991) "The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes: Criticisms and Conjectures" in G. K. Shaw ed. (1991) Economics, Culture, and Education: Essays in Honor of Mark Blaug. Aldershot: Elgar, 1991, pp. 95–107. 23. Lakatos, Musgrave eds. (1970), p. 130. 24. Lakatos, Imre. (1968). "Criticism and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 69(1):149–186 (1968). 25. Great readings in clinical science: essential selections for mental health professionals. Lilienfeld, Scott O., 1960–, O'Donohue, William T. Boston: Pearson. 2012. ISBN 9780205698035. OCLC 720560483. 26. Theoretical progressiveness is if the new theory has more empirical content than the old. Empirical progressiveness is if some of this content is corroborated. (Lakatos ed., 1970, p. 118). 27. See/hear Lakatos's 1973 Open University BBC Radio talk Science and Pseudoscience . 28. Lakatos notably only condemned specifically Soviet Marxism as pseudoscientific, as opposed to Marxism in general. In fact, at the very end of his last LSE lectures on Scientific Method in 1973, he finished by posing the question of whether Trotsky's theoretical development of Marxism was scientific, and commented that "Nobody has ever undertaken a critical history of Marxism with the aid of better methodological and historiographical instruments. Nobody has ever tried to find an answer to questions like: were Trotsky's unorthodox predictions simply patching up a badly degenerating programme, or did they represent a creative development of Marx's programme? To answer similar questions, we would really need a detailed analysis which takes years of work. So I simply do not know the answer, even if I am very interested in it." [Motterlini 1999, p. 109] However, in his 1976 On the Critique of Scientific Reason Feyerabend claimed that Vladimir Lenin's development of Marxism in his auxiliary theory of colonial exploitation had been "Lakatos-scientific" because it was "accompanied by a wealth of novel predictions (the arrival and structure of monopolies being one of them)". And he continued by claiming that both Rosa Luxemburg's and Trotsky's developments of Marxism were close to what Lakatos regarded as scientific: "And whoever has read Rosa Luxemburg's reply to Bernstein's criticism of Marx or Trotsky's account of why the Russian Revolution took place in a backward country (cf. also Lenin [1968], vol. 19, pp. 99ff.) will see that Marxists are pretty close to what Lakatos would like any upstanding rationalist to do ..." [See footnote 9 of p. 315 of Howson (ed.) 1976]. 29. Published in For and Against Method: Imre Lakatos and Paul Feyerabend by Matteo Motterlini (ed.), University of Chicago Press, 1999. 30. Cronin, H., The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today, Cambridge University Press, 1993. pp. 31–32. 31. See Paul Feyerabend. "How to Defend Society Against Science". The Galilean Library. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. 32. Paul Feyerabend (1978). Science in a Free Society. London: NLB. ISBN 0-86091-008-3. 33. Motterlini, M. (1999). For and Against Method. Chicago: UCP. ISBN 9780226467757. |

注 1. E. レック編『分析哲学における歴史的転換』スプリンガー、2016年:第4.2章。 2. コスタス・ガヴログル、ヨルゴス・グダロウリス、P. ニコラコポウロス編『イムレ・ラカトシュと科学的変化の理論』スプリンガー、2012年、211頁。 3. ラカトシュ、イムレ(1970)。「科学史とその合理的な再構築」。PSA:哲学科学協会隔年会議議事録。1970年:91–136頁。doi: 10.1086/psaprocbienmeetp.1970.495757。JSTOR 495757. S2CID 145197122. 4. K. Gavroglu, Y. Goudaroulis, P. Nicolacopoulos (編), Imre Lakatos and Theories of Scientific Change, Springer, 2012, p. 61. 5. 『科学哲学:ポッパーとラカトシュ』——カール・ポッパーとイムレ・ラカトシュの科学哲学に関する講義。2014年11月、サセックス大学の修士課程学生 向けに実施。 6. 「イムレ・ラカトシュ」『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』2021年版。 7. ブレンダン・ラーヴォル(2013)。『ラカトシュ入門』。ラウトレッジ。p. 3。ISBN 9781134765140。彼は抵抗運動グループ在籍中に「モルナー・ティボル」という偽名を使用していた。 8. バンディ 2010。[ページ指定が必要] 9. ジェルジ・カンピス、L. クヴァシュ、マイケル・シュトルツナー(編)『ラカトシュを評価する:数学、方法論、そして人物』スプリンガー、2013年、p. 296。 10. シェフラー、イスラエル(2007年)『学者のギャラリー:哲学者の回想録』哲学と教育、第13巻、シュプリンガー、42頁、ISBN 9781402027109。 11. ラカトシュが1971年1月5日にポール・ファイヤーアバントに送った書簡を参照のこと。モッテルリーニ編『方法論の賛否』(1999年)233-234 頁。 12. これらはそれぞれ、コリン・ハウソン編『物理科学における方法と評価:近代科学の批判的背景 1800–1905』と、スピロ・J・ラッツィス編『経済学における方法と評価』であった。 13. ドナルド・A・ギリーズ(1996年9月)。「書評。マッテオ・モッテルリーニ編。イムレ・ラカトシュ。ポール・K・フェイヤーアバント。『科学の境界 で:方法論の賛否両論』。英国科学哲学ジャーナル。47巻3号。JSTOR 687992。 14. フェイヤーアバント、ポール;ラカトシュ、イムレ(1999年)。モッテルリーニ、マッテオ(編)。『方法の賛否:科学的方法に関するラカトシュの講義と ラカトシュ=フェイヤーアバント書簡集を含む』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。doi:10.7208/9780226467030(2025年7月12日 現在、アクセス不可)。ISBN 9780226467030. 15. ラーヴォル、ブレンダン(1999年4月1日)。「ラカトシュの数学的ヘーゲル主義」。『ミネルヴァの梟』31巻1号:23–44頁。doi: 10.5840/owl199931119。 16. Motterlini, Matteo (2002), Kampis, George; Kvasz, Ladislav; Stöltzner, Michael (eds.), 「ヘーゲルの悪魔とポッパーの深い青の海の間にあるラカトシュ教授」, 『ラカトシュを評価する:数学、方法論、そして人物』, ドルドレヒト: Springer Netherlands, pp. 23–52, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-0769-5_3, ISBN 978-94-017-0769-5, 2025年6月29日閲覧 17. 「ラカトシアン・モンスターズ」. 2015年1月18日閲覧. 18. 例えば、ラカトシュの『近年の数学哲学における経験主義の復興』第2節を参照せよ。同節において彼は、ユークリッド系を初期公理系からの全ての論理的帰結 から成るものと定義し、「ユークリッド系は真であると主張し得る」と記している。 19. ポアンカレ, H. (1893). 「多面体に関するオイラーの定理の一般化について」, Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences, 117 p. 144, ラカトシュ, ウォラル, ザハール, p. 162 に引用. 20. Lakatos, Worrall and Zahar (1976), Proofs and Refutations ISBN 0-521-21078-X, pp. 106–126 は、ポアンカレの形式的証明(1899年)『Complèment à l'Analysis Situs』Rediconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo, 13, pp. 285–343 を、オイラーの予想をベクトル代数の同値命題に書き換えたものであると指摘している。pp. 285–343)は、オイラーの予想をベクトル代数の同値式に書き換えたものであると指摘している。 21. Lakatos, Imre. (1970). 「Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes」. In: Lakatos, Musgrave eds. (1970), pp. 91–195. 22. ブルース・J・コールドウェル(1991)『科学研究プログラムの方法論:批判と推測』G・K・ショー編(1991)『経済学、文化、教育:マーク・ブラ ウグへの献呈論文集』所収。オルダーショット:エルガー、1991年、95–107頁。 23. ラカトシュ、マスグレイヴ編(1970)、p. 130。 24. ラカトシュ、イムレ(1968)。「批判と科学的研究プログラムの方法論」。『アリストテレス学会紀要』69(1):149–186(1968)。 25. 『臨床科学の優れた読本:精神健康専門家のための必須選集』リリエンフェルド、スコット・O.、1960–、オドノヒュー、ウィリアム・T. ボストン:ピアソン。2012年。ISBN 9780205698035。OCLC 720560483。 26. 理論的進歩性とは、新理論が旧理論よりも多くの経験的内容を持つ場合を指す。経験的進歩性とは、この内容の一部が実証された場合を指す。(ラカトシュ編、 1970年、118頁) 27. ラカトシュの1973年BBCラジオ公開講座『科学と疑似科学』を参照せよ。 28. ラカトシュは特にソビエト・マルクス主義を疑似科学的と断罪したが、マルクス主義全般を非難したわけではない。実際、1973年にロンドン・スクール・オ ブ・エコノミクスで行った科学的方法論講義の最終回で、彼はトロツキーによるマルクス主義の理論的発展が科学的であったかという問題を提起し、「より優れ た方法論的・歴史記述的手段を用いてマルクス主義の批判的歴史を構築しようとした者は誰もいない」と述べた。トロツキーの非正統的予測は、単に深刻な退廃 を招いた計画を継ぎはぎしただけなのか、それともマルクスの計画を創造的に発展させたものなのか? こうした疑問に答えるには、何年もかかる詳細な分析が必要だ。だから、たとえ非常に興味があっても、答えはわからない」と述べている。 [Motterlini 1999, p. 109]しかし1976年の『科学的理性の批判について』でファイヤーアバントは、ウラジーミル・レーニンが植民地搾取の補助理論においてマルクス主義を 発展させたことは「ラカトシュ的科学的」であったと主張した。その根拠として「豊富な新規予測(独占の出現と構造はその一つ)を伴っていた」ことを挙げて いる。さらに彼は、ローザ・ルクセンブルクとトロツキーによるマルクス主義の発展も、ラカトシュが科学的と見なすものに近かったと主張した: 「マルクスに対するベルンシュタインの批判へのローザ・ルクセンブルクの反論、あるいはロシア革命が後進国で起きた理由についてのトロツキーの記述(レニ ン[1968]第19巻99頁以降も参照)を読んだ者なら誰でも、マルクス主義者たちがラカトシュが立派な合理主義者に求める行為にかなり近いことを理解 するだろう…」 [ハウソン編(1976)315頁脚注9参照] 29. マッテオ・モッテルリーニ編『方法論をめぐって:イムレ・ラカトシュとポール・ファイヤーアバント』(シカゴ大学出版局、1999年)所収。 30. クロニン, H., 『蟻と孔雀:ダーウィンから現代までの利他主義と性的選択』, ケンブリッジ大学出版局, 1993年. pp. 31–32. 31. ポール・ファイヤーアバント「科学から社会を守る方法」『ガリレイ図書館』参照。2008年4月7日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。 32. ポール・ファイヤーアバント(1978年)。『自由な社会における科学』。ロンドン:NLB。ISBN 0-86091-008-3。 33. モッテリーニ、M.(1999年)。『方法論の賛否』。シカゴ:UCP。ISBN 9780226467757。 |

| References Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Cronin, Helena (1991) The Ant and the Peacock Cambridge University Press Howson, Colin, Ed. Method and Appraisal in the Physical Sciences: The Critical Background to Modern Science 1800–1905 Cambridge University Press 1976 ISBN 0-521-21110-7 Kampis, Kvaz & Stoltzner (eds.) Appraising Lakatos: Mathematics, Methodology and the Man, Vienna Circle Institute Library, Kluwer 2002 ISBN 1-4020-0226-2 Lakatos, Musgrave ed. (1970). Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07826-1 Lakatos (1976). Proofs and Refutations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29038-4 Lakatos (1978). The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes: Philosophical Papers Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Lakatos (1978). Mathematics, Science and Epistemology: Philosophical Papers Volume 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521217695 Lakatos, I.: Cauchy and the continuum: the significance of nonstandard analysis for the history and philosophy of mathematics. Math. Intelligencer 1 (1978), no. 3, 151–161 (paper originally presented in 1966). Lakatos, I., and Feyerabend P., For and against Method: including Lakatos's Lectures on Scientific Method and the Lakatos-Feyerabend Correspondence, ed. by Matteo Motterlini, Chicago University Press, (451 pp), 1999, ISBN 0-226-46774-0 Latsis, Spiro J. Ed. Method and Appraisal in Economics Cambridge University Press 1976 ISBN 0-521-21076-3 Popper, K R, (1972), Objective knowledge: an evolutionary approach, Oxford (Clarendon Press) 1972 (bibliographic summary, no text). Maxwell, Nicholas (2017) Karl Popper, Science and Enlightenment, UCL Press, London. Free online. Zahar, Elie (1973) "Why Einstein's programme superseded Lorentz's", British Journal for the Philosophy of Science Zahar, Elie (1988) Einstein's Revolution: A Study in Heuristic, Open Court 1988 |

参考文献 オックスフォード国家人物事典 クローニン、ヘレナ(1991)『蟻と孔雀』ケンブリッジ大学出版局 ハウソン、コリン編『物理科学における方法と評価:近代科学の批判的背景 1800–1905』ケンブリッジ大学出版局 1976 ISBN 0-521-21110-7 カンピス、クヴァズ、シュトルツナー(編)『ラカトシュを評価する:数学、方法論、そして人物』ウィーン学派研究所図書館、クルワー 2002 ISBN 1-4020-0226-2 ラカトシュ、マスグレイブ編(1970)『批判と知識の成長』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局 ISBN 0-521-07826-1 ラカトシュ(1976)。『証明と反証』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-29038-4 ラカトシュ(1978)。『科学研究プログラムの方法論:哲学論文集 第1巻』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局 ラカトシュ(1978)。数学、科学、認識論:哲学論文集 第2巻。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0521217695 ラカトシュ、I.:コーシーと連続体:非標準解析が数学史と数学哲学に与える意義。Math. Intelligencer 1 (1978), no. 3, 151–161 (本論文は1966年に発表されたものである)。 ラカトシュ, I., フェイエラベンド, P., 『方法論の賛否:ラカトシュの科学方法論講義とラカトシュ=フェイエラベンド書簡集を含む』, マッテオ・モッテルリーニ編, シカゴ大学出版局, (451頁), 1999年, ISBN 0-226-46774-0 ラツィス、スピロ・J編『経済学における方法と評価』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1976年 ISBN 0-521-21076-3 ポッパー、K・R(1972)『客観的知識:進化的アプローチ』オックスフォード(クラレンドン出版)、1972年(書誌概要、本文なし) マクスウェル、ニコラス(2017)『カール・ポッパー、科学と啓蒙』UCLプレス、ロンドン。オンライン無料公開。 ザハール、エリー(1973)「アインシュタインのプログラムがローレンツのプログラムに取って代わった理由」『英国科学哲学ジャーナル』 ザハール、エリー(1988)『アインシュタインの革命:発見的手法の研究』オープンコート、1988年 |

| Further reading Alex Bandy (2010). Chocolate and Chess. Unlocking Lakatos. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-05-8819-5 Cohen, R. S.; Feyerabend, P. K.; Wartofsky, M. W., eds. (1976). Essays in memory of Imre Lakatos. Boston: D. Reidel. ISBN 9789027706546. Reuben Hersh (2006). 18 Unconventional Essays on the Nature of Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-29831-3 Brendan Larvor (1998). Lakatos: An Introduction. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14276-8 Jancis Long (1998). "Lakatos in Hungary", Philosophy of the Social Sciences 28, pp. 244–311. John Kadvany (2001). Imre Lakatos and the Guises of Reason. Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2659-0; author's web site: johnkadvany.com. Teun Koetsier (1991). Lakatos' Philosophy of Mathematics: A Historical Approach. Amsterdam etc.: North Holland. ISBN 0-444-88944-2 Szabó, Árpád The Beginnings of Greek Mathematics (Tr Ungar) Reidel & Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1978 ISBN 963-05-1416-8 |

追加文献(さらに読む) アレックス・バンディ(2010)。『チョコレートとチェス。ラカトシュの解読』。ブダペスト:アカデミアイ・キアドー。ISBN 978-963-05-8819-5 コーエン、R. S.; ファイヤーアバント、P. K.;ワートフスキー、M. W. 編(1976)。『イムレ・ラカトシュ追悼論文集』。ボストン:D. ライデル。ISBN 9789027706546。 ルーベン・ハーシュ(2006)。『数学の本質に関する18の型破りなエッセイ』。シュプリンガー。ISBN 978-0-387-29831-3 ブレンダン・ラーヴォル (1998). 『ラカトシュ入門』. ロンドン: ラウトレッジ. ISBN 0-415-14276-8 ジャンシス・ロング (1998). 「ハンガリーにおけるラカトシュ」, 『社会科学哲学』28号, pp. 244–311. ジョン・カドヴァニー(2001年)。『イムレ・ラカトシュと理性の仮装』。ダーラム・ロンドン:デューク大学出版局。ISBN 0-8223-2659-0;著者ウェブサイト:johnkadvany.com。 テウン・コエツィア (1991). 『ラカトシュの数学哲学:歴史的アプローチ』. アムステルダム他: ノース・ホランド. ISBN 0-444-88944-2 サボー, アルパード 『ギリシャ数学の始まり』(ハンガリー語訳) ライデル & アカデミアイ・キアドー, ブダペスト 1978 ISBN 963-05-1416-8 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imre_Lakatos |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099