感染

Infection

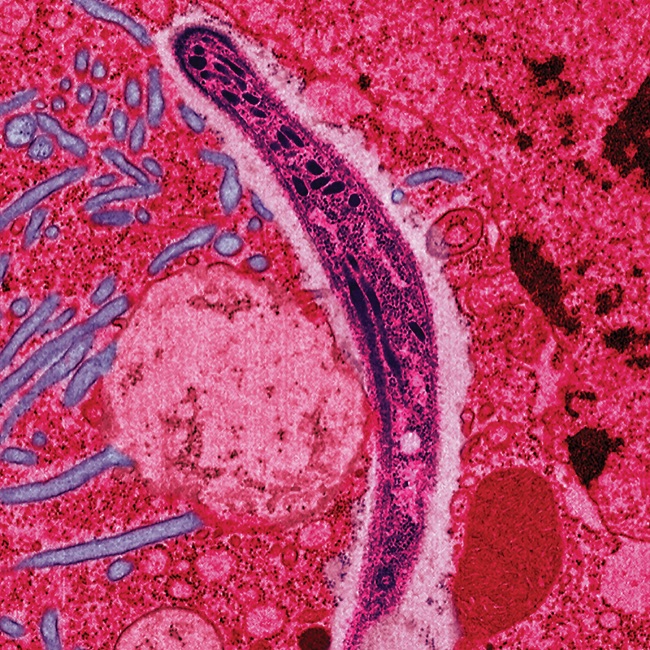

False-colored

electron micrograph showing a malaria sporozoite migrating through the

mosquito midgut epithelial cell

☆感染(infection)とは、病原体による組織への侵入、その増殖、および感染因子とそれらが産生する毒素に対する宿主組織の反応である。 感染症は様々な病原体、特に細菌やウイルスによって引き起こされる。哺乳類の宿主は、多くの場合、炎症を伴う自然反応とそれに続く適応反応で感染に反応する。 感染症は依然として世界的に重大な保健上の問題であり、2013年には約920万人の死亡(全死亡の17%)を引き起こしている[3]。 感染に焦点を当てた医学分野は感染症と呼ばれる[4]。

| An infection is the

invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the

reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they

produce.[1] An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible

disease or communicable disease, is an illness resulting from an

infection. Infections can be caused by a wide range of pathogens, most prominently bacteria and viruses.[2] Hosts can fight infections using their immune systems. Mammalian hosts react to infections with an innate response, often involving inflammation, followed by an adaptive response. Treatment for infections depends on the type of pathogen involved. Common medications include: Antibiotics for bacterial infections. Antivirals for viral infections. Antifungals for fungal infections. Antiprotozoals for protozoan infections. Antihelminthics for infections caused by parasitic worms. Infectious diseases remain a significant global health concern, causing approximately 9.2 million deaths in 2013 (17% of all deaths).[3] The branch of medicine that focuses on infections is referred to as infectious diseases.[4] |

感染とは、病原体による組織への侵入、その増殖、および感染因子とそれ

らが産生する毒素に対する宿主組織の反応である。 感染症は様々な病原体、特に細菌やウイルスによって引き起こされる。哺乳類の宿主は、多くの場合、炎症を伴う自然反応とそれに続く適応反応で感染に反応す る。 感染に対する治療は、感染した病原体の種類によって異なる。一般的な治療薬は以下の通りである: 細菌感染には抗生物質。 ウイルス感染に対する抗ウイルス薬。 真菌感染に対する抗真菌薬。 原虫感染には抗原虫薬。 寄生虫による感染に対する駆虫薬。 感染症は依然として世界的に重大な保健上の問題であり、2013年には約920万人の死亡(全死亡の17%)を引き起こしている[3]。 感染に焦点を当てた医学分野は感染症と呼ばれる[4]。 |

| Types Infections are caused by infectious agents (pathogens) including: Bacteria (e.g. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Clostridium botulinum, and Salmonella spp.) Viruses and subviral agents such as viroids and prions. (E.g. HIV, Rhinovirus, Lyssaviruses such as Rabies virus, Ebolavirus and Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) Fungi, further subclassified into: Ascomycota, including yeasts such as Candida (the most common fungal infection); filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus; Pneumocystis species; and dermatophytes, a group of organisms causing infection of skin and other superficial structures in humans.[5] Basidiomycota, including the human-pathogenic genus Cryptococcus.[6] Parasites, which are usually divided into:[7] Unicellular organisms (e.g. malaria, Toxoplasma, Babesia) Macroparasites[8] (worms or helminths) including nematodes such as parasitic roundworms and pinworms, tapeworms (cestodes), and flukes (trematodes, such as schistosomes). Diseases caused by helminths are sometimes termed infestations, but are sometimes called infections. Arthropods such as ticks, mites, fleas, and lice, can also cause human disease, which conceptually are similar to infections, but invasion of a human or animal body by these macroparasites is usually termed infestation. |

種類 感染症は以下のような感染因子(病原体)によって引き起こされる: 細菌(結核菌、黄色ブドウ球菌、大腸菌、ボツリヌス菌、サルモネラ菌など)。 ウイルスおよびウイロイドやプリオンなどのサブウイルス。(例:HIV、ライノウイルス、狂犬病ウイルスなどのライサウイルス、エボラウイルス、重症急性呼吸器症候群コロナウイルス2) 真菌類はさらに以下のように分類される: カンジダ(最も一般的な真菌感染症)などの酵母を含む子嚢菌門;アスペルギルスなどの糸状菌;ニューモシスチス種;および皮膚糸状菌(ヒトの皮膚やその他の表在性構造物の感染を引き起こす生物群)[5]。 ヒト病原性クリプトコッカス属を含む担子菌類[6]。 寄生虫は通常以下のように分類される。 単細胞生物(マラリア、トキソプラズマ、バベシアなど) 寄生性回虫や蟯虫などの線虫類、条虫類(絛虫類)、フラムシ類(住血吸虫類などの振虫類)などの大寄生虫[8](ワームまたは蠕虫)。蠕虫によって引き起こされる病気は感染症と呼ばれることもある。 マダニ、ダニ、ノミ、シラミなどの節足動物もヒトの病気を引き起こすことがあり、概念的には感染症と似ているが、これらの大型寄生虫によるヒトや動物の体への侵入は通常、侵入と呼ばれる。 |

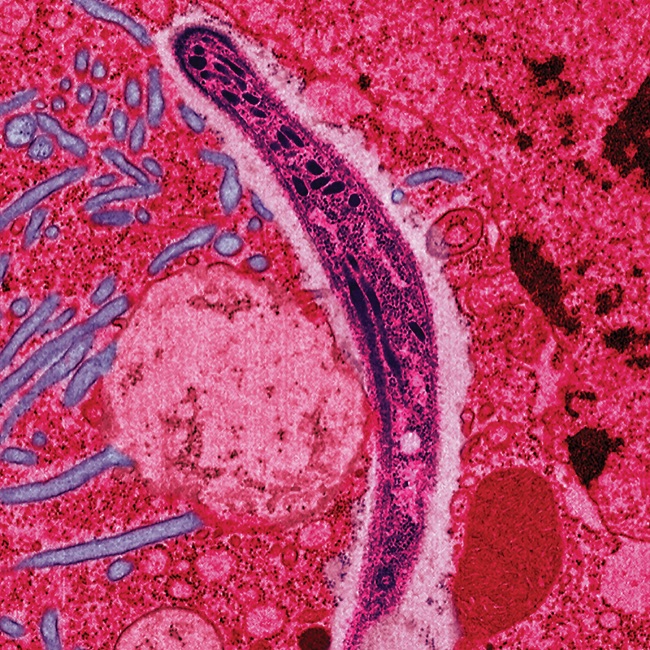

| Signs and symptoms The signs and symptoms of an infection depend on the type of disease. Some signs of infection affect the whole body generally, such as fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss, fevers, night sweats, chills, aches and pains. Others are specific to individual body parts, such as skin rashes, coughing, or a runny nose.[9] In certain cases, infectious diseases may be asymptomatic for much or even all of their course in a given host. In the latter case, the disease may only be defined as a "disease" (which by definition means an illness) in hosts who secondarily become ill after contact with an asymptomatic carrier. An infection is not synonymous with an infectious disease, as some infections do not cause illness in a host.[10] Bacterial or viral As bacterial and viral infections can both cause the same kinds of symptoms, it can be difficult to distinguish which is the cause of a specific infection.[11] Distinguishing the two is important, since viral infections cannot be cured by antibiotics whereas bacterial infections can.[12]  |

徴候と症状 感染の徴候や症状は病気の種類によって異なる。感染の徴候の中には、疲労、食欲不振、体重減少、発熱、寝汗、悪寒、疼痛など、全身に影響を及ぼすものもある。また、皮膚の発疹、咳、鼻水など、個々の身体の部位に特異的なものもある[9]。 場合によっては、感染症は、宿主の経過の大部分、あるいはすべてにおいて無症状であることもある。後者の場合、無症状の保菌者と接触した後に二次的に発病 した宿主においてのみ、その疾病は「疾病」(定義上は疾病を意味する)と定義される。宿主に病気を引き起こさない感染もあるため、感染は感染症と同義では ない。 細菌性またはウイルス性 細菌感染もウイルス感染も同じような症状を引き起こすことがあるため、特定の感染症の原因がどちらであるかを区別することは困難である[11]。ウイルス感染は抗生物質では治癒しないのに対し、細菌感染は治癒するため、両者を区別することは重要である[12]。 |

| Viral infection |

ウィルス感染 |

| In

general, viral infections are systemic. This means they involve many

different parts of the body or more than one body system at the same

time; i.e. a runny nose, sinus congestion, cough, body aches etc. They

can be local at times as in viral conjunctivitis or "pink eye" and

herpes. Only a few viral infections are painful, like herpes. The pain

of viral infections is often described as itchy or burning.[11] |

一

般的に、ウイルス感染は全身性である。すなわち、鼻水、副鼻腔のうっ血、咳、体の痛みなどである。ウイルス性結膜炎や「ピンクアイ」、ヘルペスのように局

所的な場合もある。ヘルペスのように痛みを伴うウイルス感染はごく少数である。ウイルス感染の痛みは、しばしばかゆみや灼熱感と表現される[11]。 |

| Pathogenic viruses |

病原性ウイルス |

| Bacterial infection |

細菌感染 |

| The

classic symptoms of a bacterial infection are localized redness, heat,

swelling and pain. One of the hallmarks of a bacterial infection is

local pain, pain that is in a specific part of the body. For example,

if a cut occurs and is infected with bacteria, pain occurs at the site

of the infection. Bacterial throat pain is often characterized by more

pain on one side of the throat. An ear infection is more likely to be

diagnosed as bacterial if the pain occurs in only one ear.[11] A cut

that produces pus and milky-colored liquid is most likely infected.[13] |

細

菌感染の典型的な症状は、局所の発赤、熱感、腫脹、疼痛である。細菌感染の特徴のひとつは、局所的な痛み、つまり身体の特定の部位に生じる痛みである。例

えば、切り傷が細菌に感染すると、感染部位に痛みが生じる。細菌性の喉の痛みは、多くの場合、喉の片側がより痛むという特徴がある。耳の感染では、片側の

耳だけに痛みが生じる場合、細菌感染と診断される可能性が高い。膿や乳白色の液体が出る切り傷は、感染している可能性が高い[13]。 |

| Pathogenic bacteria |

病原性細菌 |

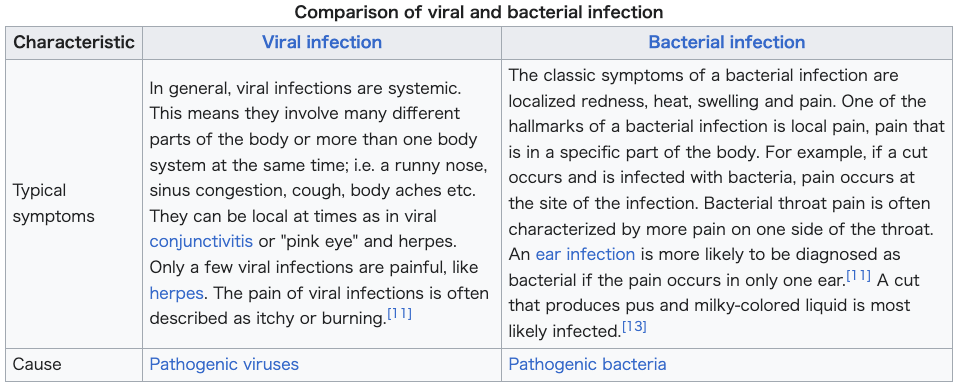

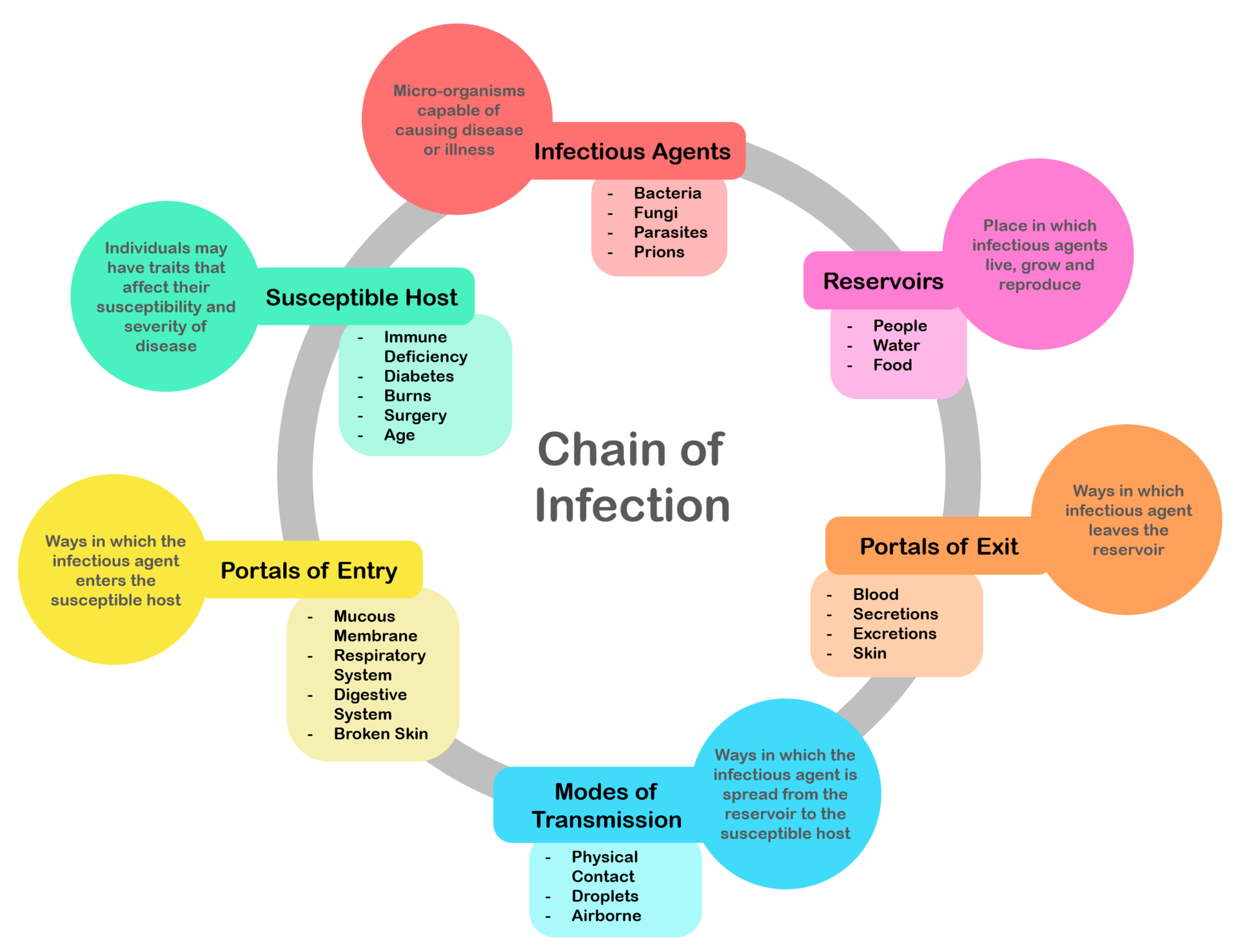

Pathophysiology Chain of infection; the chain of events that lead to infection There is a general chain of events that applies to infections, sometimes called the chain of infection[14] or transmission chain. The chain of events involves several steps – which include the infectious agent, reservoir, entering a susceptible host, exit and transmission to new hosts. Each of the links must be present in a chronological order for an infection to develop. Understanding these steps helps health care workers target the infection and prevent it from occurring in the first place.[15] |

病態生理学 感染の連鎖;感染に至る一連の出来事 感染には一般的な事象の連鎖があり、感染連鎖[14]または伝播連鎖と呼ばれることもある。この連鎖には、感染因子、リザーバー、感受性の高い宿主への侵 入、退出、新たな宿主への感染といったいくつかの段階が含まれる。感染が発生するためには、それぞれのリンクが時系列的な順序で存在しなければならない。 これらのステップを理解することで、保健医療従事者は感染の標的を定め、感染の発生を未然に防ぐことができる[15]。 |

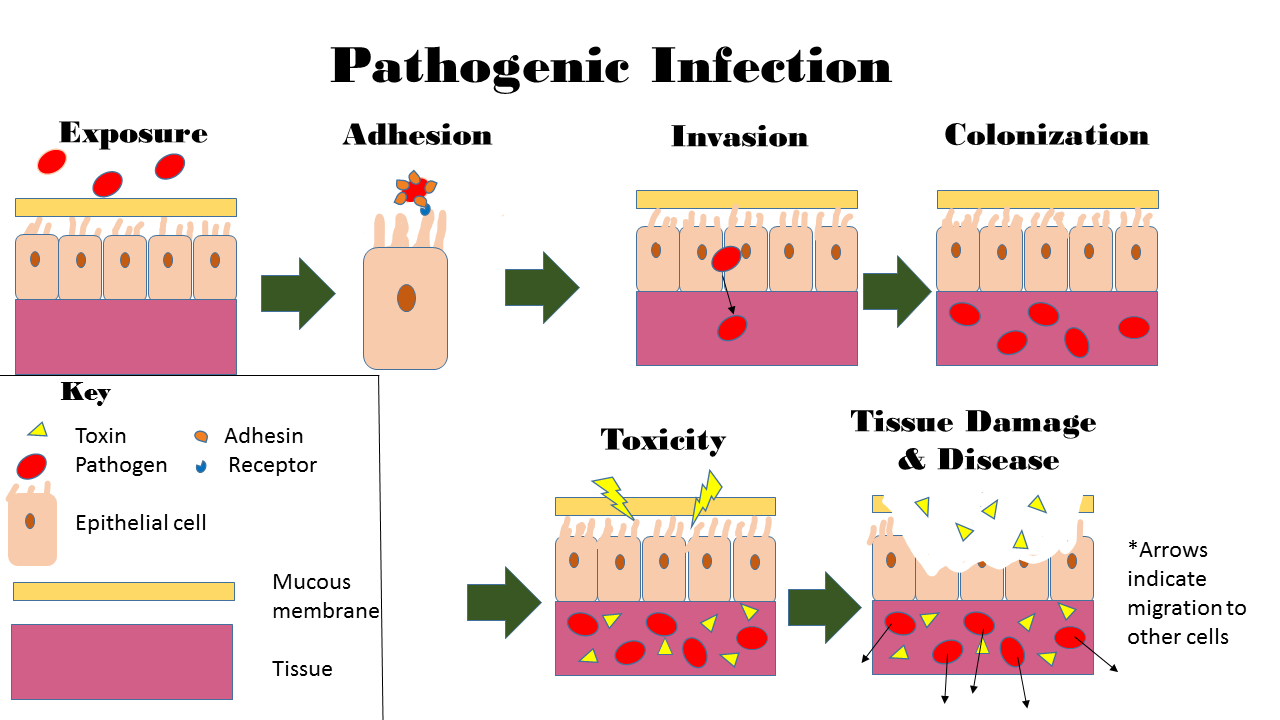

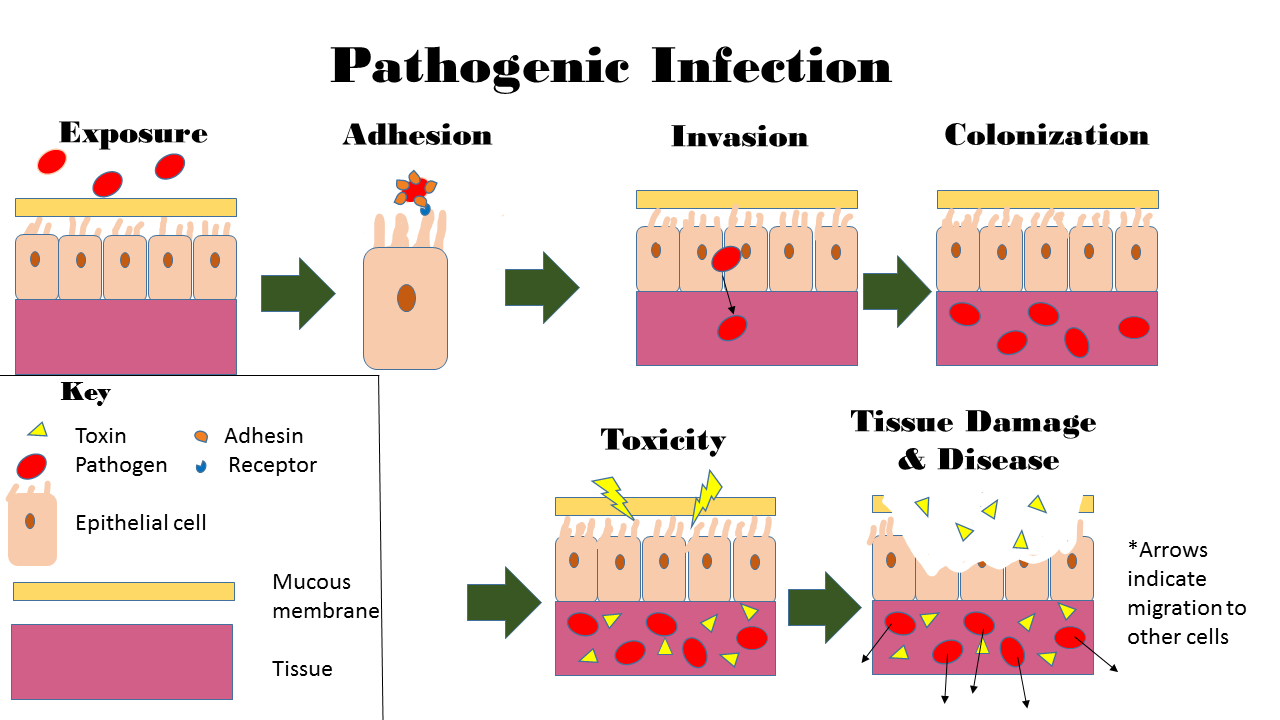

Colonization Infection of an ingrown toenail; there is pus (yellow) and resultant inflammation (redness and swelling around the nail). Infection begins when an organism successfully enters the body, grows and multiplies. This is referred to as colonization. Most humans are not easily infected. Those with compromised or weakened immune systems have an increased susceptibility to chronic or persistent infections. Individuals who have a suppressed immune system are particularly susceptible to opportunistic infections. Entrance to the host at host–pathogen interface, generally occurs through the mucosa in orifices like the oral cavity, nose, eyes, genitalia, anus, or the microbe can enter through open wounds. While a few organisms can grow at the initial site of entry, many migrate and cause systemic infection in different organs. Some pathogens grow within the host cells (intracellular) whereas others grow freely in bodily fluids.[16] Wound colonization refers to non-replicating microorganisms within the wound, while in infected wounds, replicating organisms exist and tissue is injured.[17] All multicellular organisms are colonized to some degree by extrinsic organisms, and the vast majority of these exist in either a mutualistic or commensal relationship with the host. An example of the former is the anaerobic bacteria species, which colonizes the mammalian colon, and an example of the latter are the various species of staphylococcus that exist on human skin. Neither of these colonizations are considered infections. The difference between an infection and a colonization is often only a matter of circumstance. Non-pathogenic organisms can become pathogenic given specific conditions, and even the most virulent organism requires certain circumstances to cause a compromising infection. Some colonizing bacteria, such as Corynebacteria sp. and Viridans streptococci, prevent the adhesion and colonization of pathogenic bacteria and thus have a symbiotic relationship with the host, preventing infection and speeding wound healing.  This image depicts the steps of pathogenic infection.[18][19][20] The variables involved in the outcome of a host becoming inoculated by a pathogen and the ultimate outcome include: the route of entry of the pathogen and the access to host regions that it gains the intrinsic virulence of the particular organism the quantity or load of the initial inoculant the immune status of the host being colonized As an example, several staphylococcal species remain harmless on the skin, but, when present in a normally sterile space, such as in the capsule of a joint or the peritoneum, multiply without resistance and cause harm.[21] An interesting fact that gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, 16S ribosomal RNA analysis, omics, and other advanced technologies have made more apparent to humans in recent decades is that microbial colonization is very common even in environments that humans think of as being nearly sterile. Because it is normal to have bacterial colonization, it is difficult to know which chronic wounds can be classified as infected and how much risk of progression exists. Despite the huge number of wounds seen in clinical practice, there are limited quality data for evaluated symptoms and signs. A review of chronic wounds in the Journal of the American Medical Association's "Rational Clinical Examination Series" quantified the importance of increased pain as an indicator of infection.[22] The review showed that the most useful finding is an increase in the level of pain [likelihood ratio (LR) range, 11–20] makes infection much more likely, but the absence of pain (negative likelihood ratio range, 0.64–0.88) does not rule out infection (summary LR 0.64–0.88). |

コロニー形成 巻き爪の感染。膿(黄色)が出て、その結果炎症(爪の周りが赤く腫れる)が起こる。 感染とは、ある生物が体内に侵入し、増殖することで始まる。これをコロニー形成という。ほとんどのヒトは簡単には感染しない。免疫力が低下している人は、 慢性的あるいは持続的な感染に罹患しやすくなる。免疫系が抑制されている人は、特に日和見感染にかかりやすい。宿主と病原体との境界面では、一般に口腔、 鼻、目、性器、肛門などの開口部の粘膜から侵入するか、開放創から微生物が侵入する。少数の微生物は最初の侵入部位で増殖するが、多くの微生物は移動し、 様々な臓器で全身感染を引き起こす。宿主細胞内(細胞内)で増殖する病原体もあれば、体液中で自由に増殖する病原体もある[16]。 創傷のコロニー形成とは、創傷内で複製を行わない微生物のことであり、感染創では複製を行う微生物が存在し、組織が傷害される。前者の例としては、哺乳類 の結腸にコロニーを形成する嫌気性細菌種が挙げられ、後者の例としては、ヒトの皮膚に存在する様々な種類のブドウ球菌が挙げられる。どちらも感染とはみな されない。感染とコロニー形成の違いは、多くの場合、状況によるものである。非病原性細菌も特定の条件が整えば病原性を持つようになる。コリネバクテリア 属やビリダンス連鎖球菌のような一部のコロニー形成細菌は、病原性細菌の付着やコロニー形成を阻止するため、宿主と共生関係を結び、感染を防ぎ、創傷治癒 を早める。  この図は、病原性感染のステップを表している[18][19][20]。 宿主が病原体に感染し、最終的にどのような結果をもたらすかには、以下のような変数がある: 病原体の侵入経路と、病原体が獲得する宿主領域へのアクセス 個別主義病原体に内在する毒性 最初の接種物の量または負荷 コロニー形成される宿主の免疫状態 一例として、いくつかのブドウ球菌種は、皮膚上では無害であるが、関節包や腹膜などの通常無菌の空間に存在すると、抵抗することなく増殖し、害をもたらす。 ガスクロマトグラフィー質量分析、16SリボソームRNA分析、オミックス、その他の先端技術によって、ここ数十年で人間にとってより明らかになった興味 深い事実は、人間がほぼ無菌であると考えている環境であっても、微生物のコロニー形成は非常に一般的であるということである。細菌が定着していることは普 通であるため、どの慢性創傷が感染と分類され、どの程度進行するリスクがあるのかを知ることは難しい。臨床現場では膨大な数の創傷が見られるにもかかわら ず、評価された症状や徴候に関する質の高いデータは限られている。Journal of the American Medical Associationの 「Rational Clinical Examination Series 」に掲載された慢性創傷のレビューでは、感染の指標としての疼痛増加の重要性が数値化されている。[22] このレビューでは、最も有用な所見として、疼痛レベルの増加[尤度比(LR)の範囲、11~20]は感染の可能性をはるかに高めるが、疼痛がない場合(負 の尤度比の範囲、0.64~0.88)は感染を否定しないことが示されている(要約LR 0.64~0.88)。 |

| Disease Disease can arise if the host's protective immune mechanisms are compromised and the organism inflicts damage on the host. Microorganisms can cause tissue damage by releasing a variety of toxins or destructive enzymes. For example, Clostridium tetani releases a toxin that paralyzes muscles, and staphylococcus releases toxins that produce shock and sepsis. Not all infectious agents cause disease in all hosts. For example, less than 5% of individuals infected with polio develop disease.[23] On the other hand, some infectious agents are highly virulent. The prion causing mad cow disease and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease invariably kills all animals and people that are infected.[24] Persistent infections occur because the body is unable to clear the organism after the initial infection. Persistent infections are characterized by the continual presence of the infectious organism, often as latent infection with occasional recurrent relapses of active infection. There are some viruses that can maintain a persistent infection by infecting different cells of the body. Some viruses once acquired never leave the body. A typical example is the herpes virus, which tends to hide in nerves and become reactivated when specific circumstances arise.[25] Persistent infections cause millions of deaths globally each year.[26] Chronic infections by parasites account for a high morbidity and mortality in many underdeveloped countries.[27][28] |

疾病 宿主の防御免疫機構が損なわれ、微生物が宿主にダメージを与えた場合、疾病が発生する可能性がある。微生物は様々な毒素や破壊的酵素を放出することによ り、組織に損傷を与える。例えば、クロストリジウム・テタニは筋肉を麻痺させる毒素を放出し、ブドウ球菌はショックや敗血症を引き起こす毒素を放出する。 すべての感染因子がすべての宿主に病気を引き起こすわけではない。例えば、ポリオに感染した人のうち、発病するのは5%未満である。狂牛病やクロイツフェ ルト・ヤコブ病の原因となるプリオンは、感染したすべての動物や人民を必ず死に至らしめる。 持続感染は、最初の感染後、身体がその生物を排除できないために起こる。持続感染の特徴は、多くの場合潜伏感染で、活動性感染の再発を繰り返すことであ る。体内の異なる細胞に感染して持続感染を維持するウイルスもある。一度感染すると決して体外に出ないウイルスもある。典型的な例はヘルペスウイルスで、 神経に潜伏する傾向があり、特定の状況が生じると再活性化する[25]。 多くの低開発国では、寄生虫による慢性感染が高い罹患率と死亡率を占めている[27][28]。 |

| Transmission Main article: Transmission (medicine)  A southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus) is a vector that transmits the pathogens that cause West Nile fever and avian malaria among others. For infecting organisms to survive and repeat the infection cycle in other hosts, they (or their progeny) must leave an existing reservoir and cause infection elsewhere. Infection transmission can take place via many potential routes:[29] Droplet contact, also known as the respiratory route, and the resultant infection can be termed airborne disease. If an infected person coughs or sneezes on another person the microorganisms, suspended in warm, moist droplets, may enter the body through the nose, mouth or eye surfaces. Fecal-oral transmission, wherein foodstuffs or water become contaminated (by people not washing their hands before preparing food, or untreated sewage being released into a drinking water supply) and the people who eat and drink them become infected. Common fecal-oral transmitted pathogens include Vibrio cholerae, Giardia species, rotaviruses, Entamoeba histolytica, Escherichia coli, and tape worms.[30] Most of these pathogens cause gastroenteritis. Sexual transmission, with the result being called sexually transmitted infection. Oral transmission, diseases that are transmitted primarily by oral means may be caught through direct oral contact such as kissing, or by indirect contact such as by sharing a drinking glass or a cigarette. Transmission by direct contact, Some diseases that are transmissible by direct contact include athlete's foot, impetigo and warts. Vehicle transmission, transmission by an inanimate reservoir (food, water, soil).[31] Vertical transmission, directly from the mother to an embryo, fetus or baby during pregnancy or childbirth. It can occur as a result of a pre-existing infection or one acquired during pregnancy. Iatrogenic transmission, due to medical procedures such as injection or transplantation of infected material. Vector-borne transmission, transmitted by a vector, which is an organism that does not cause disease itself but that transmits infection by conveying pathogens from one host to another.[32] The relationship between virulence versus transmissibility is complex; with studies have shown that there were no clear relationship between the two.[33][34] There is still a small number of evidence that partially suggests a link between virulence and transmissibility.[35][36][37] |

トランスミッション 主な記事 感染(医学)  ミナミイエカ(Culex quinquefasciatus)は、特に西ナイル熱や鳥マラリアの原因となる病原体を媒介する媒介蚊である。 感染した生物が生き残り、他の宿主で感染サイクルを繰り返すためには、その生物(またはその子孫)が既存のリザーバーを離れ、他の場所で感染を起こさなければならない。感染伝播は以下のような多くの経路で起こりうる。 呼吸器経路としても知られる飛沫接触と、その結果生じる感染は空気感染と呼ばれることがある。感染者が他の人に咳やくしゃみをすると、温かく湿った飛沫に浮遊した微生物が鼻、口、目の表面から体内に侵入する。 糞口感染:食品や水が汚染され(食品を調理する前に手を洗わなかったり、未処理の下水が飲料水源に放出されたりする)、それを食べたり飲んだりした人が感 染する。一般的な糞口感染病原体には、コレラ菌、ジアルジア属、ロタウイルス、腸炎ビブリオ、大腸菌、テープワームなどがある。 性行為感染、その結果を性行為感染と呼ぶ。 経口感染、主に経口手段によって感染する疾患は、キスなどの直接的な経口接触によって感染する場合と、コップやタバコを共有するなどの間接的な接触によって感染する場合がある。 直接接触による感染。直接接触によって感染する病気には、水虫、膿痂疹、いぼなどがある。 車両感染:無生物の貯蔵庫(食物、水、土壌)による感染 [31] 。 垂直感染:妊娠中または出産中に、母親から胚、胎児、または赤ちゃんに直接感染する。既往感染の結果として起こる場合と、妊娠中に後天的に感染する場合がある。 異所性感染:感染物質の注射や移植などの医療行為によって起こる。 媒介感染:媒介生物によって感染する。媒介生物とは、それ自身は病気を引き起こさないが、病原体を宿主から別の宿主に媒介することによって感染を媒介する生物のことである[32]。 病原性と伝播性の関係は複雑であり、両者の間に明確な関係はないという研究結果もある[33][34]。病原性と伝播性の関係を部分的に示唆する証拠はまだ少数である[35][36][37]。 |

| Diagnosis Diagnosis of infectious disease sometimes involves identifying an infectious agent either directly or indirectly.[38] In practice most minor infectious diseases such as warts, cutaneous abscesses, respiratory system infections and diarrheal diseases are diagnosed by their clinical presentation and treated without knowledge of the specific causative agent. Conclusions about the cause of the disease are based upon the likelihood that a patient came in contact with a particular agent, the presence of a microbe in a community, and other epidemiological considerations. Given sufficient effort, all known infectious agents can be specifically identified.[39] Diagnosis of infectious disease is nearly always initiated by medical history and physical examination. More detailed identification techniques involve the culture of infectious agents isolated from a patient. Culture allows identification of infectious organisms by examining their microscopic features, by detecting the presence of substances produced by pathogens, and by directly identifying an organism by its genotype.[39] Many infectious organisms are identified without culture and microscopy. This is especially true for viruses, which cannot grow in culture. For some suspected pathogens, doctors may conduct tests that examine a patient's blood or other body fluids for antigens or antibodies that indicate presence of a specific pathogen that the doctor suspects.[39] Other techniques (such as X-rays, CAT scans, PET scans or NMR) are used to produce images of internal abnormalities resulting from the growth of an infectious agent. The images are useful in detection of, for example, a bone abscess or a spongiform encephalopathy produced by a prion.[40] The benefits of identification, however, are often greatly outweighed by the cost, as often there is no specific treatment, the cause is obvious, or the outcome of an infection is likely to be benign.[41] |

診断 実際のところ、いぼ、皮膚膿瘍、呼吸器系感染症、下痢性疾患などの軽症感染症のほとんどは、臨床症状によって診断され、特定の原因病原体を知らなくても治 療される。病気の原因に関する結論は、患者が個別病原体に接触した可能性、地域社会における微生物の存在、その他の疫学的考察に基づいている。十分な努力 を払えば、既知のすべての感染因子を特異的に同定することができる[39]。 感染症の診断は、ほとんどの場合、病歴聴取と身体診察によって開始される。より詳細な同定技術には、患者から分離された感染因子の培養が含まれる。培養に よって、顕微鏡的特徴の検査、病原体が産生する物質の検出、遺伝子型による直接の同定によって、感染性生物を同定することができる[39]。 多くの感染性生物は、培養や顕微鏡検査なしに同定される。培養では増殖できないウイルスについては特にそうである。病原体の疑いがある場合、医師は患者の血液やその他の体液から、医師が疑っている特定の病原体の存在を示す抗原や抗体を調べる検査を行うことがある[39]。 その他の技術(X線、CATスキャン、PETスキャン、NMRなど)は、感染因子の増殖に起因する内部異常の画像を作成するために使用される。この画像は、例えば骨膿瘍やプリオンによって生じた海綿状脳症の発見に有用である[40]。 しかし、特異的な治療法がなかったり、原因が明らかであったり、感染の結果が良性である可能性が高いことが多いため、同定のメリットはコストに大きく見合うものではないことが多い[41]。 |

| Symptomatic diagnostics The diagnosis is aided by the presenting symptoms in any individual with an infectious disease, yet it usually needs additional diagnostic techniques to confirm the suspicion. Some signs are specifically characteristic and indicative of a disease and are called pathognomonic signs; but these are rare. Not all infections are symptomatic.[42] In children the presence of cyanosis, rapid breathing, poor peripheral perfusion, or a petechial rash increases the risk of a serious infection by greater than 5 fold.[43] Other important indicators include parental concern, clinical instinct, and temperature greater than 40 °C.[43] |

症状診断 診断には、感染症に罹患した際に現れる症状が役立つが、通常、その疑いを確認するためには、さらなる診断技術が必要となる。いくつかの徴候は特に特徴的であり、疾患の徴候であるため、予兆徴候と呼ばれるが、これはまれである。すべての感染に症状がみられるわけではない。 小児では、チアノーゼ、呼吸促迫、末梢灌流不良、点状皮疹があると、重篤な感染症のリスクが5倍以上に高まる[43]。その他の重要な指標としては、親の心配、臨床的直感、40℃を超える体温などがある[43]。 |

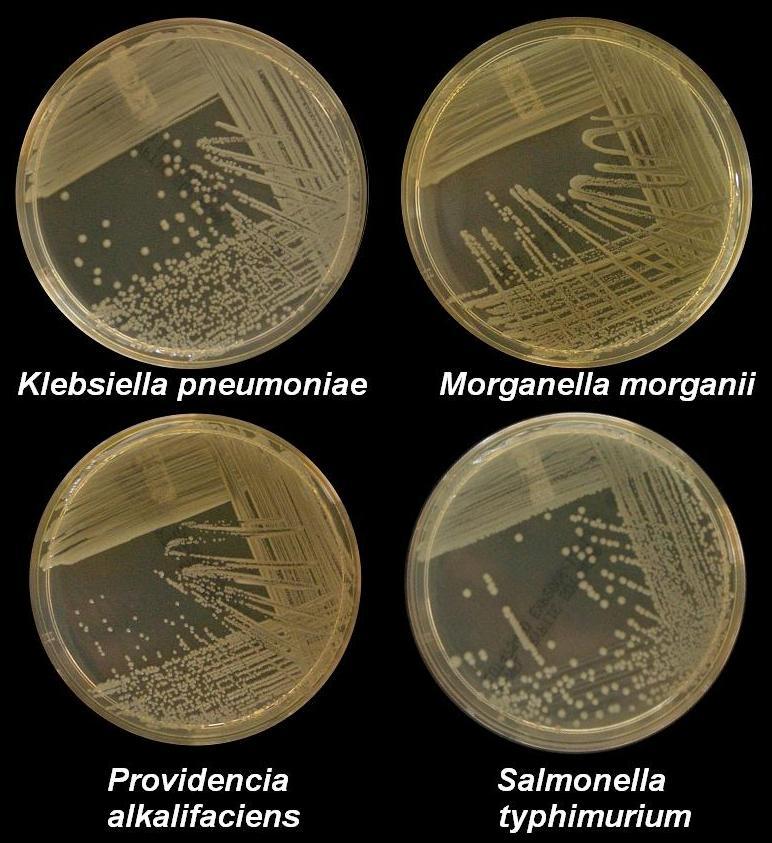

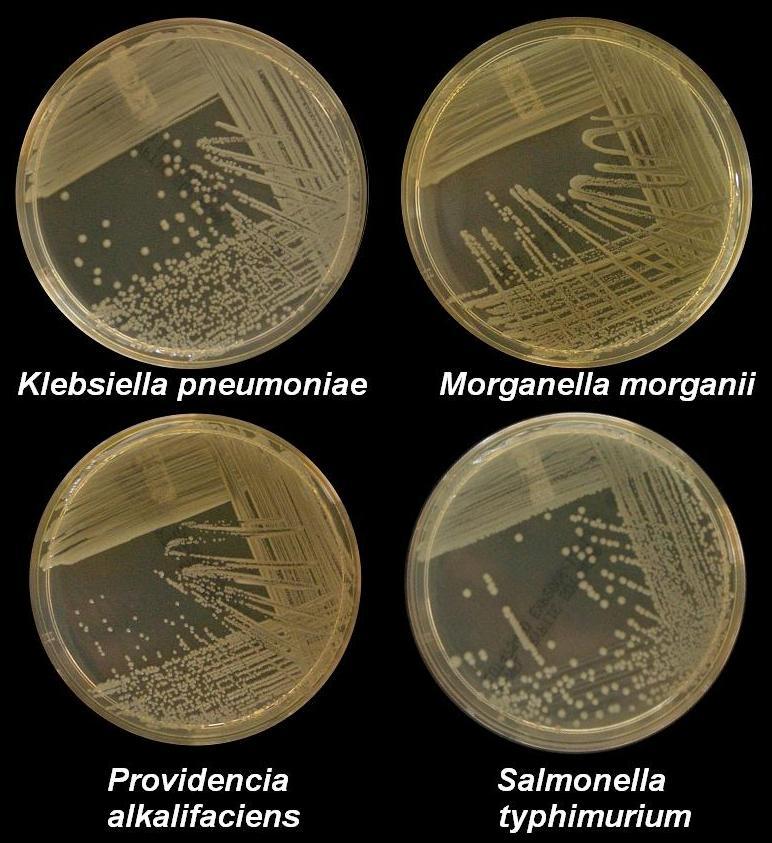

Microbial culture Four nutrient agar plates growing colonies of common Gram negative bacteria Many diagnostic approaches depend on microbiological culture to isolate a pathogen from the appropriate clinical specimen.[44] In a microbial culture, a growth medium is provided for a specific agent. A sample taken from potentially diseased tissue or fluid is then tested for the presence of an infectious agent able to grow within that medium. Many pathogenic bacteria are easily grown on nutrient agar, a form of solid medium that supplies carbohydrates and proteins necessary for growth, along with copious amounts of water. A single bacterium will grow into a visible mound on the surface of the plate called a colony, which may be separated from other colonies or melded together into a "lawn". The size, color, shape and form of a colony is characteristic of the bacterial species, its specific genetic makeup (its strain), and the environment that supports its growth. Other ingredients are often added to the plate to aid in identification. Plates may contain substances that permit the growth of some bacteria and not others, or that change color in response to certain bacteria and not others. Bacteriological plates such as these are commonly used in the clinical identification of infectious bacterium. Microbial culture may also be used in the identification of viruses: the medium, in this case, being cells grown in culture that the virus can infect, and then alter or kill. In the case of viral identification, a region of dead cells results from viral growth, and is called a "plaque". Eukaryotic parasites may also be grown in culture as a means of identifying a particular agent.[45] In the absence of suitable plate culture techniques, some microbes require culture within live animals. Bacteria such as Mycobacterium leprae and Treponema pallidum can be grown in animals, although serological and microscopic techniques make the use of live animals unnecessary. Viruses are also usually identified using alternatives to growth in culture or animals. Some viruses may be grown in embryonated eggs. Another useful identification method is Xenodiagnosis, or the use of a vector to support the growth of an infectious agent. Chagas disease is the most significant example, because it is difficult to directly demonstrate the presence of the causative agent, Trypanosoma cruzi in a patient, which therefore makes it difficult to definitively make a diagnosis. In this case, xenodiagnosis involves the use of the vector of the Chagas agent T. cruzi, an uninfected triatomine bug, which takes a blood meal from a person suspected of having been infected. The bug is later inspected for growth of T. cruzi within its gut.[46] |

微生物培養 一般的なグラム陰性菌のコロニーを生育させている4枚の栄養寒天培地。 多くの診断アプローチは、適切な臨床検体から病原体を分離するための微生物培養に依存している。そして、罹患している可能性のある組織や体液から採取され た検体が、その培地内で増殖できる感染因子の存在について検査される。多くの病原性細菌は、栄養寒天培地(増殖に必要な炭水化物とタンパク質を供給する固 体培地の一種)で、大量の水とともに容易に増殖する。一つの細菌は、コロニーと呼ばれるプレート表面の目に見える盛り上がりに成長し、他のコロニーから分 離している場合もあれば、一緒になって「芝生」のようになっている場合もある。コロニーの大きさ、色、形、形態は、細菌種、その特定の遺伝子構成(菌 株)、およびその増殖を支える環境の特徴である。同定を助けるために、他の成分がプレートに加えられることも多い。プレートには、ある細菌は生育できるが 他の細菌は生育できない物質や、ある細菌には反応して色が変化するが他の細菌には反応しない物質が含まれていることがある。このような細菌学的プレート は、感染性細菌の臨床的同定によく使用される。微生物培養はウイルスの同定にも使用される。この場合の培地とは、ウイルスが感染し、変質または死滅させる ことができる培養細胞である。ウイルス同定の場合、死細胞の領域はウイルス増殖の結果として生じ、「プラーク」と呼ばれる。真核生物の寄生虫もまた、特定 の病原体を同定する手段として培養で増殖させることができる[45]。 適切なプレート培養技術がない場合、生きた動物内での培養を必要とする微生物もいる。マイコバクテリウム・レプラ(Mycobacterium leprae)やトレポネーマ・パリダム(Treponema pallidum)などの細菌は、動物の体内で増殖させることができるが、血清学的および顕微鏡学的手法により、生きた動物を使用する必要はない。ウイル スも通常、培養や動物での増殖に代わる方法で同定される。ウイルスの中には、受精卵で増殖させるものもある。もう一つの有用な同定法は、異種診断、すなわ ち感染因子の増殖を媒介するベクターの使用である。シャーガス病は最も重要な例であり、患者において原因物質であるトリパノソーマ・クルージの存在を直接 証明することは困難であるため、確定診断が困難である。この場合、異所診断では、シャーガス菌であるT. cruziの媒介者である未感染の三葉虫が、感染が疑われる人格から血液を摂取する。この虫はその後、腸内でT. cruziが増殖しているか検査される[46]。 |

| Microscopy Another principal tool in the diagnosis of infectious disease is microscopy.[47] Virtually all of the culture techniques discussed above rely, at some point, on microscopic examination for definitive identification of the infectious agent. Microscopy may be carried out with simple instruments, such as the compound light microscope, or with instruments as complex as an electron microscope. Samples obtained from patients may be viewed directly under the light microscope, and can often rapidly lead to identification. Microscopy is often also used in conjunction with biochemical staining techniques, and can be made exquisitely specific when used in combination with antibody based techniques. For example, the use of antibodies made artificially fluorescent (fluorescently labeled antibodies) can be directed to bind to and identify a specific antigens present on a pathogen. A fluorescence microscope is then used to detect fluorescently labeled antibodies bound to internalized antigens within clinical samples or cultured cells. This technique is especially useful in the diagnosis of viral diseases, where the light microscope is incapable of identifying a virus directly.[48] Other microscopic procedures may also aid in identifying infectious agents. Almost all cells readily stain with a number of basic dyes due to the electrostatic attraction between negatively charged cellular molecules and the positive charge on the dye. A cell is normally transparent under a microscope, and using a stain increases the contrast of a cell with its background. Staining a cell with a dye such as Giemsa stain or crystal violet allows a microscopist to describe its size, shape, internal and external components and its associations with other cells. The response of bacteria to different staining procedures is used in the taxonomic classification of microbes as well. Two methods, the Gram stain and the acid-fast stain, are the standard approaches used to classify bacteria and to diagnosis of disease. The Gram stain identifies the bacterial groups Bacillota and Actinomycetota, both of which contain many significant human pathogens. The acid-fast staining procedure identifies the Actinomycetota genera Mycobacterium and Nocardia.[49] |

顕微鏡検査 感染症の診断におけるもうひとつの主要な手段は顕微鏡検査である。顕微鏡検査は、複合光学顕微鏡のような単純な装置で行うこともあれば、電子顕微鏡のよう な複雑な装置で行うこともある。患者から採取した検体を直接光学顕微鏡で観察することで、多くの場合、迅速に同定することができる。顕微鏡検査は生化学的 染色技術とも併用されることが多く、抗体ベースの技術と併用することで、極めて特異的な検査が可能となる。例えば、人工的に蛍光にした抗体(蛍光標識抗 体)を用いると、病原体上に存在する特定の抗原に結合し、同定することができる。その後、蛍光顕微鏡を用いて、臨床サンプルや培養細胞内で内在化抗原に結 合した蛍光標識抗体を検出する。この技術は、光学顕微鏡ではウイルスを直接同定できないウイルス性疾患の診断に特に有用である[48]。 その他の顕微鏡的手法も、感染因子の同定に役立つことがある。ほとんどの細胞は、マイナスに帯電した細胞分子と色素上のプラス電荷との間の静電引力によ り、多くの塩基性色素で容易に染色される。通常、細胞は顕微鏡下では透明であり、染色剤を使用す ると、背景とのコントラストが増す。ギムザ染色やクリスタルバイオレットのような染料で細胞を染色することで、顕微鏡技師は細胞の大きさ、形、内部および 外部の構成要素、他の細胞との関連を説明することができる。異なる染色法に対する細菌の反応は、微生物の分類学的分類にも用いられる。グラム染色と抗酸菌 染色という2つの方法が、細菌の分類や病気の診断に用いられる標準的な方法である。グラム染色は、多くの重要なヒト病原体を含む細菌群Bacillota とActinomycetotaを同定する。酸破砕染色法では、放線菌属のマイコバクテリウム(Mycobacterium)とノカルジア (Nocardia)を同定する[49]。 |

| Biochemical tests Biochemical tests used in the identification of infectious agents include the detection of metabolic or enzymatic products characteristic of a particular infectious agent. Since bacteria ferment carbohydrates in patterns characteristic of their genus and species, the detection of fermentation products is commonly used in bacterial identification. Acids, alcohols and gases are usually detected in these tests when bacteria are grown in selective liquid or solid media.[50] The isolation of enzymes from infected tissue can also provide the basis of a biochemical diagnosis of an infectious disease. For example, humans can make neither RNA replicases nor reverse transcriptase, and the presence of these enzymes are characteristic., of specific types of viral infections. The ability of the viral protein hemagglutinin to bind red blood cells together into a detectable matrix may also be characterized as a biochemical test for viral infection, although strictly speaking hemagglutinin is not an enzyme and has no metabolic function.[51] Serological methods are highly sensitive, specific and often extremely rapid tests used to identify microorganisms. These tests are based upon the ability of an antibody to bind specifically to an antigen. The antigen, usually a protein or carbohydrate made by an infectious agent, is bound by the antibody. This binding then sets off a chain of events that can be visibly obvious in various ways, dependent upon the test. For example, "Strep throat" is often diagnosed within minutes, and is based on the appearance of antigens made by the causative agent, S. pyogenes, that is retrieved from a patient's throat with a cotton swab. Serological tests, if available, are usually the preferred route of identification, however the tests are costly to develop and the reagents used in the test often require refrigeration. Some serological methods are extremely costly, although when commonly used, such as with the "strep test", they can be inexpensive.[10] Complex serological techniques have been developed into what are known as immunoassays. Immunoassays can use the basic antibody – antigen binding as the basis to produce an electro-magnetic or particle radiation signal, which can be detected by some form of instrumentation. Signal of unknowns can be compared to that of standards allowing quantitation of the target antigen. To aid in the diagnosis of infectious diseases, immunoassays can detect or measure antigens from either infectious agents or proteins generated by an infected organism in response to a foreign agent. For example, immunoassay A may detect the presence of a surface protein from a virus particle. Immunoassay B on the other hand may detect or measure antibodies produced by an organism's immune system that are made to neutralize and allow the destruction of the virus. Instrumentation can be used to read extremely small signals created by secondary reactions linked to the antibody – antigen binding. Instrumentation can control sampling, reagent use, reaction times, signal detection, calculation of results, and data management to yield a cost-effective automated process for diagnosis of infectious disease. |

生化学検査 感染因子の同定に用いられる生化学的検査には、個別感染因子に特徴的な代謝産物や酵素産物の検出が含まれる。細菌はその属や種に特徴的なパターンで炭水化 物を発酵させるので、発酵産物の検出は細菌の同定によく用いられる。これらの検査では通常、細菌を選択的液体培地または固体培地で増殖させた場合に、酸、 アルコール、ガスが検出される[50]。 感染組織からの酵素の単離は、感染症の生化学的診断の基礎を提供することもできる。例えば、ヒトはRNAレプリカーゼも逆転写酵素も作れないが、これらの 酵素の存在は、特定のタイプのウイルス感染に特徴的である。赤血球を結合して検出可能なマトリックスにするウイルスタンパク質ヘマグルチニンの能力も、ウ イルス感染の生化学的検査として特徴づけられるが、厳密に言えばヘマグルチニンは酵素ではなく、代謝機能もない[51]。 血清学的検査法は、微生物の同定に用いられる高感度、特異的、かつしばしば極めて迅速な検査法である。これらの検査は、抗原に特異的に結合する抗体の能力 に基づいている。抗原は通常、感染因子によって作られるタンパク質または糖質であり、抗体と結合する。この結合が一連の現象を引き起こし、検査によって様 々な形で目に見える形で明らかになる。例えば、「連鎖球菌性咽頭炎」はしばしば数分以内に診断され、綿棒を使って患者の咽頭から採取した原因菌である化膿 レンサ球菌が作る抗原の出現に基づいている。血清学的検査が可能であれば、通常、同定には血清学的検査が望ましいが、検査には開発コストがかかり、検査に 使用する試薬には冷蔵保存が必要な場合が多い。血清学的検査法の中には、非常に高価なものもあるが、「溶連菌検査」のように一般的に使用される場合には、 安価になることもある[10]。 複雑な血清学的手法は、イムノアッセイと呼ばれるものに発展してきた。イムノアッセイは、基本的な抗体-抗原結合を基礎として、電磁気的または粒子線的な シグナルを生成し、それを何らかの方法で検出することができる。未知の抗原のシグナルを標準物質のシグナルと比較することで、標的抗原の定量が可能とな る。感染症の診断に役立てるため、イムノアッセイは、感染因子または感染した生物が外来因子に応答して生成するタンパク質のいずれかに由来する抗原を検出 または測定することができる。例えば、イムノアッセイAはウイルス粒子の表面タンパク質の存在を検出することができる。一方、イムノアッセイBは、ウイル スを中和し破壊するために生物の免疫系によって産生される抗体を検出または測定する。 抗体と抗原の結合に関連した二次反応によって生じる極めて小さなシグナルを読み取るために、機器を使用することができる。機器は、サンプリング、試薬の使 用、反応時間、シグナルの検出、結果の計算、データ管理を制御し、感染症診断のための費用効果の高い自動化プロセスをもたらすことができる。 |

PCR-based diagnostics Nucleic acid testing conducted using an Abbott Laboratories ID Now device Technologies based upon the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method will become nearly ubiquitous gold standards of diagnostics of the near future, for several reasons. First, the catalog of infectious agents has grown to the point that virtually all of the significant infectious agents of the human population have been identified. Second, an infectious agent must grow within the human body to cause disease; essentially it must amplify its own nucleic acids to cause a disease. This amplification of nucleic acid in infected tissue offers an opportunity to detect the infectious agent by using PCR. Third, the essential tools for directing PCR, primers, are derived from the genomes of infectious agents, and with time those genomes will be known if they are not already.[52] Thus, the technological ability to detect any infectious agent rapidly and specifically is currently available. The only remaining blockades to the use of PCR as a standard tool of diagnosis are in its cost and application, neither of which is insurmountable. The diagnosis of a few diseases will not benefit from the development of PCR methods, such as some of the clostridial diseases (tetanus and botulism). These diseases are fundamentally biological poisonings by relatively small numbers of infectious bacteria that produce extremely potent neurotoxins. A significant proliferation of the infectious agent does not occur, this limits the ability of PCR to detect the presence of any bacteria.[52] |

PCRベースの診断 Abbott Laboratories ID Now装置を用いて行われた核酸検査 ポリメラーゼ連鎖反応(PCR)法に基づく技術は、いくつかの理由から、近い将来、診断のほぼユビキタスなゴールドスタンダードになるだろう。第一に、感 染因子のカタログは、ヒト集団の重要な感染因子のほぼすべてが同定されるまでになった。第二に、感染因子が病気を引き起こすには、人体内で増殖しなければ ならない。基本的に病気を引き起こすには、感染因子自身の核酸を増幅しなければならない。感染組織におけるこの核酸の増幅は、PCRを用いて感染因子を検 出する機会を提供する。第三に、PCRを指示するために不可欠なツールであるプライマーは、感染因子のゲノムに由来するものであり、それらのゲノムがまだ 知られていないとしても、時間とともに知られるようになるであろう[52]。 このように、あらゆる感染因子を迅速かつ特異的に検出する技術的能力は、現在利用可能である。PCRを標準的な診断手段として使用するために残された唯一 の障害は、そのコストと応用であるが、どちらも克服できるものではない。クロストリジウム感染症(破傷風やボツリヌス症)のように、PCR法の開発から恩 恵を受けられない疾患もある。これらの病気は基本的に、比較的少数の感染性細菌が極めて強力な神経毒を産生する生物学的中毒である。感染菌の著しい増殖は 起こらないため、PCR法による細菌の検出には限界がある[52]。 |

| Metagenomic sequencing This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Infection" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Given the wide range of bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoal, and helminthic pathogens that cause debilitating and life-threatening illnesses, the ability to quickly identify the cause of infection is important yet often challenging. For example, more than half of cases of encephalitis, a severe illness affecting the brain, remain undiagnosed, despite extensive testing using the standard of care (microbiological culture) and state-of-the-art clinical laboratory methods. Metagenomic sequencing-based diagnostic tests are currently being developed for clinical use and show promise as a sensitive, specific, and rapid way to diagnose infection using a single all-encompassing test.[53] This test is similar to current PCR tests; however, an untargeted whole genome amplification is used rather than primers for a specific infectious agent. This amplification step is followed by next-generation sequencing or third-generation sequencing, alignment comparisons, and taxonomic classification using large databases of thousands of pathogen and commensal reference genomes. Simultaneously, antimicrobial resistance genes within pathogen and plasmid genomes are sequenced and aligned to the taxonomically classified pathogen genomes to generate an antimicrobial resistance profile – analogous to antibiotic sensitivity testing – to facilitate antimicrobial stewardship and allow for the optimization of treatment using the most effective drugs for a patient's infection. Metagenomic sequencing could prove especially useful for diagnosis when the patient is immunocompromised. An ever-wider array of infectious agents can cause serious harm to individuals with immunosuppression, so clinical screening must often be broader. Additionally, the expression of symptoms is often atypical, making a clinical diagnosis based on presentation more difficult. Thirdly, diagnostic methods that rely on the detection of antibodies are more likely to fail. A rapid, sensitive, specific, and untargeted test for all known human pathogens that detects the presence of the organism's DNA rather than antibodies is therefore highly desirable. |

メタゲノム配列決定 この記事には検証のための追加引用が必要である。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは削除される可能性がある。 出典を検索する: 「感染" - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (September 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 衰弱させ、生命を脅かす病気を引き起こす細菌、ウイルス、真菌、原虫、蠕虫などの病原体は多岐にわたるため、感染原因を迅速に特定する能力は重要である が、しばしば困難である。例えば、脳に影響を及ぼす重篤な疾患である脳炎の症例の半数以上は、標準治療(微生物学的培養)や最先端の臨床検査法を用いた広 範な検査にもかかわらず、診断されないままである。メタゲノムシークエンシングに基づく診断検査は現在臨床用に開発されており、単一の包括的な検査を用い て感染を診断する高感度、特異的、迅速な方法として有望視されている[53]。この検査は現在のPCR検査と類似しているが、特定の感染因子に対するプラ イマーではなく、非標的の全ゲノム増幅が用いられる。この増幅ステップに続いて、次世代シーケンシングまたは第3世代シーケンシング、アラインメント比 較、数千の病原体と常在菌の参照ゲノムからなる大規模データベースを用いた分類が行われる。同時に、病原体やプラスミドゲノム内の抗菌薬耐性遺伝子の塩基 配列が決定され、分類学的に分類された病原体ゲノムとアライメントされ、抗菌薬耐性プロファイル(抗生物質感受性検査に類似)が作成される。 メタゲノミックシークエンシングは、患者が免疫不全である場合の診断に特に有用である。免疫抑制状態にある患者に深刻な危害を及ぼす可能性のある感染因子 の種類は増え続けているため、臨床スクリーニングはより広範でなければならないことが多い。さらに、症状の発現が非典型的であることが多いため、症状から 臨床診断を行うことは困難である。第三に、抗体の検出に頼る診断法は失敗する可能性が高い。したがって、既知のすべてのヒト病原体に対して、抗体ではなく DNAの存在を検出する、迅速、高感度、特異的、非標的の検査法が強く望まれている。 |

Indication of tests A temporary drive-in testing site for COVID-19 set up with tents in a parking lot There is usually an indication for a specific identification of an infectious agent only when such identification can aid in the treatment or prevention of the disease, or to advance knowledge of the course of an illness prior to the development of effective therapeutic or preventative measures. For example, in the early 1980s, prior to the appearance of AZT for the treatment of AIDS, the course of the disease was closely followed by monitoring the composition of patient blood samples, even though the outcome would not offer the patient any further treatment options. In part, these studies on the appearance of HIV in specific communities permitted the advancement of hypotheses as to the route of transmission of the virus. By understanding how the disease was transmitted, resources could be targeted to the communities at greatest risk in campaigns aimed at reducing the number of new infections. The specific serological diagnostic identification, and later genotypic or molecular identification, of HIV also enabled the development of hypotheses as to the temporal and geographical origins of the virus, as well as a myriad of other hypothesis.[10] The development of molecular diagnostic tools have enabled physicians and researchers to monitor the efficacy of treatment with anti-retroviral drugs. Molecular diagnostics are now commonly used to identify HIV in healthy people long before the onset of illness and have been used to demonstrate the existence of people who are genetically resistant to HIV infection. Thus, while there still is no cure for AIDS, there is great therapeutic and predictive benefit to identifying the virus and monitoring the virus levels within the blood of infected individuals, both for the patient and for the community at large. |

試験の表示 駐車場にテントを張って設置されたCOVID-19の臨時のドライブイン検査会場。 通常、感染症の治療や予防に役立つ場合、あるいは効果的な治療法や予防法を開発する前に病気の経過に関する知識を深めるためにのみ、感染症の病原体を特定 する適応がある。例えば、1980年代初頭、AZTがAIDSの治療薬として登場する以前は、患者の血液サンプルの組成をモニターすることで、たとえその 結果が患者にそれ以上の治療法を提供しないものであったとしても、病気の経過を注意深く追跡していた。このような特定のコミュニティにおけるHIVの出現 に関する研究によって、ウイルスの感染経路に関する仮説が立てられるようになった。病気の感染経路を理解することで、新規感染者数を減らすことを目的とし たキャンペーンにおいて、最もリスクの高いコミュニティに資源を集中させることができた。HIVの特異的な血清学的診断による同定、その後の遺伝子型や分 子レベルでの同定は、ウイルスの時間的・地理的起源に関する仮説の開発を可能にし、その他無数の仮説も可能にした[10]。分子診断ツールの開発により、 医師や研究者は抗レトロウイルス薬による治療の有効性をモニターできるようになった。分子診断法は現在、発病のずっと前に健康な人のHIVを特定するため に一般的に使用されており、HIV感染に対して遺伝的に耐性を持つ人民の存在を証明するために使用されている。このように、AIDSの治療法はまだ存在し ないが、ウイルスを同定し、感染者の血液中のウイルス濃度をモニターすることは、患者にとっても地域社会全体にとっても、治療上および予測上大きなメリッ トがある。 |

| Classification Subclinical versus clinical (latent versus apparent) Symptomatic infections are apparent and clinical, whereas an infection that is active but does not produce noticeable symptoms may be called inapparent, silent, subclinical, or occult. An infection that is inactive or dormant is called a latent infection.[54] An example of a latent bacterial infection is latent tuberculosis. Some viral infections can also be latent, examples of latent viral infections are any of those from the Herpesviridae family.[55] The word infection can denote any presence of a particular pathogen at all (no matter how little) but also is often used in a sense implying a clinically apparent infection (in other words, a case of infectious disease). This fact occasionally creates some ambiguity or prompts some usage discussion; to get around this it is common for health professionals to speak of colonization (rather than infection) when they mean that some of the pathogens are present but that no clinically apparent infection (no disease) is present.[56] Course of infection Different terms are used to describe how and where infections present over time. In an acute infection, symptoms develop rapidly; its course can either be rapid or protracted. In chronic infection, symptoms usually develop gradually over weeks or months and are slow to resolve.[57] In subacute infections, symptoms take longer to develop than in acute infections but arise more quickly than those of chronic infections. A focal infection is an initial site of infection from which organisms travel via the bloodstream to another area of the body.[58] Primary versus opportunistic See also: Coinfection Among the many varieties of microorganisms, relatively few cause disease in otherwise healthy individuals.[59] Infectious disease results from the interplay between those few pathogens and the defenses of the hosts they infect. The appearance and severity of disease resulting from any pathogen depend upon the ability of that pathogen to damage the host as well as the ability of the host to resist the pathogen. However, a host's immune system can also cause damage to the host itself in an attempt to control the infection. Clinicians, therefore, classify infectious microorganisms or microbes according to the status of host defenses – either as primary pathogens or as opportunistic pathogens.[60] Primary pathogens Primary pathogens cause disease as a result of their presence or activity within the normal, healthy host, and their intrinsic virulence (the severity of the disease they cause) is, in part, a necessary consequence of their need to reproduce and spread. Many of the most common primary pathogens of humans only infect humans, however, many serious diseases are caused by organisms acquired from the environment or that infect non-human hosts.[61] Opportunistic pathogens Main article: Opportunistic infection Opportunistic pathogens can cause an infectious disease in a host with depressed resistance (immunodeficiency) or if they have unusual access to the inside of the body (for example, via trauma). Opportunistic infection may be caused by microbes ordinarily in contact with the host, such as pathogenic bacteria or fungi in the gastrointestinal or the upper respiratory tract, and they may also result from (otherwise innocuous) microbes acquired from other hosts (as in Clostridioides difficile colitis) or from the environment as a result of traumatic introduction (as in surgical wound infections or compound fractures). An opportunistic disease requires impairment of host defenses, which may occur as a result of genetic defects (such as chronic granulomatous disease), exposure to antimicrobial drugs or immunosuppressive chemicals (as might occur following poisoning or cancer chemotherapy), exposure to ionizing radiation, or as a result of an infectious disease with immunosuppressive activity (such as with measles, malaria or HIV disease). Primary pathogens may also cause more severe disease in a host with depressed resistance than would normally occur in an immunosufficient host.[10] Secondary infection While a primary infection can practically be viewed as the root cause of an individual's current health problem, a secondary infection is a sequela or complication of that root cause. For example, an infection due to a burn or penetrating trauma (the root cause) is a secondary infection. Primary pathogens often cause primary infection and often cause secondary infection. Usually, opportunistic infections are viewed as secondary infections (because immunodeficiency or injury was the predisposing factor).[60] Other types of infection Other types of infection consist of mixed, iatrogenic, nosocomial, and community-acquired infection. A mixed infection is an infection that is caused by two or more pathogens. An example of this is appendicitis, which is caused by Bacteroides fragilis and Escherichia coli. The second is an iatrogenic infection. This type of infection is one that is transmitted from a health care worker to a patient. A nosocomial infection is also one that occurs in a health care setting. Nosocomial infections are those that are acquired during a hospital stay. Lastly, a community-acquired infection is one in which the infection is acquired from a whole community.[58] Infectious or not One manner of proving that a given disease is infectious, is to satisfy Koch's postulates (first proposed by Robert Koch), which require that first, the infectious agent be identifiable only in patients who have the disease, and not in healthy controls, and second, that patients who contract the infectious agent also develop the disease. These postulates were first used in the discovery that Mycobacteria species cause tuberculosis.[62] However, Koch's postulates cannot usually be tested in modern practice for ethical reasons. Proving them would require experimental infection of a healthy individual with a pathogen produced as a pure culture. Conversely, even clearly infectious diseases do not always meet the infectious criteria; for example, Treponema pallidum, the causative spirochete of syphilis, cannot be cultured in vitro – however the organism can be cultured in rabbit testes. It is less clear that a pure culture comes from an animal source serving as host than it is when derived from microbes derived from plate culture.[63] Epidemiology, or the study and analysis of who, why and where disease occurs, and what determines whether various populations have a disease, is another important tool used to understand infectious disease. Epidemiologists may determine differences among groups within a population, such as whether certain age groups have a greater or lesser rate of infection; whether groups living in different neighborhoods are more likely to be infected; and by other factors, such as gender and race. Researchers also may assess whether a disease outbreak is sporadic, or just an occasional occurrence; endemic, with a steady level of regular cases occurring in a region; epidemic, with a fast arising, and unusually high number of cases in a region; or pandemic, which is a global epidemic. If the cause of the infectious disease is unknown, epidemiology can be used to assist with tracking down the sources of infection.[64] Contagiousness Infectious diseases are sometimes called contagious diseases when they are easily transmitted by contact with an ill person or their secretions (e.g., influenza). Thus, a contagious disease is a subset of infectious disease that is especially infective or easily transmitted. All contagious diseases are infectious, but not vice versa.[65][66] Other types of infectious, transmissible, or communicable diseases with more specialized routes of infection, such as vector transmission or sexual transmission, are usually not regarded as "contagious", and often do not require medical isolation (sometimes loosely called quarantine) of those affected. However, this specialized connotation of the word "contagious" and "contagious disease" (easy transmissibility) is not always respected in popular use. Infectious diseases are commonly transmitted from person to person through direct contact. The types of direct contact are through person to person and droplet spread. Indirect contact such as airborne transmission, contaminated objects, food and drinking water, animal person contact, animal reservoirs, insect bites, and environmental reservoirs are another way infectious diseases are transmitted. The basic reproduction number of an infectious disease measures how easily it spreads through direct or indirect contact.[67][68] By anatomic location Infections can be classified by the anatomic location or organ system infected, including:[69][citation needed] Urinary tract infection Skin infection Respiratory tract infection Odontogenic infection (an infection that originates within a tooth or in the closely surrounding tissues) Vaginal infections Intra-amniotic infection In addition, locations of inflammation where infection is the most common cause include pneumonia, meningitis and salpingitis.[70] |

分類 不顕性感染と臨床感染(潜伏感染と顕性感染) 有症状感染は顕性感染および臨床的感染であるが、活動性はあるが顕著な症状を示さない感染は、不顕性感染、サイレント感染、不顕性感染または潜伏感染と呼 ばれる。不活性または休眠状態の感染を潜伏感染と呼ぶ[54]。潜伏細菌感染の例としては、潜伏結核がある。ウイルス感染にも潜伏性のものがあり、潜伏性 ウイルス感染の例としてはヘルペスウイルス科のものがある[55]。 感染という言葉は、個別病原体の存在を(どんなに少なくても)示すことができるが、臨床的に明らかな感染(言い換えれば、感染症の症例)を意味する意味で 用いられることも多い。この事実は、時として曖昧さを生じさせたり、用法についての議論を促したりする。これを回避するために、保健医療専門家は、病原体 の一部が存在するが、臨床的に明らかな感染(病気ではない)が存在しないことを意味する場合、(感染ではなく)コロニー形成(colonization) と話すのが一般的である[56]。 感染の経過 感染が時間の経過とともにどこでどのように起こるかについては、異なる用語が用いられる。急性感染では、症状は急速に発現し、その経過は急速または長期に わたる。亜急性感染では、急性感染よりも症状の発現に時間がかかるが、慢性感染よりも早く症状が発現する。局所感染とは、最初に感染した部位から菌が血流 を介して体の別の部位に移動することである[58]。 一次感染と日和見感染 日和見感染も参照のこと: 重複感染 多くの種類の微生物が存在するが、健康な人に病気を引き起こすものは比較的少ない。どのような病原体に起因する疾病の出現と重症度は、宿主にダメージを与 える病原体の能力と、病原体に抵抗する宿主の能力によって決まる。しかし、宿主の免疫系は感染を制御しようとして宿主自体にダメージを与えることもある。 したがって臨床医は、感染性微生物または微生物を宿主の防御状態に応じて分類する-一次病原体として、または日和見病原体として分類する-[60]。 一次病原体 一次病原体は、正常で健康な宿主内に存在または活動した結果、疾病を引き起こすものであり、その本質的な病原性(引き起こす疾病の重症度)は、繁殖と拡散 の必要性から生じるものである。ヒトに感染する最も一般的な一次病原体の多くはヒトにのみ感染するが、多くの重篤な疾患は、環境から獲得された、あるいは ヒト以外の宿主に感染する生物によって引き起こされる[61]。 日和見病原体 主な記事 日和見感染 日和見感染病原体は、抵抗力が低下している(免疫不全)宿主や、(例えば外傷によって)体内への異常なアクセスを持つ宿主に感染症を引き起こすことがあ る。日和見感染は、消化管や上気道の病原性細菌や真菌のように、宿主と通常接触している微生物によって引き起こされることもあれば、 (Clostridioides difficile大腸炎のように)他の宿主から獲得した(そうでなければ無害な)微生物や、(外科的創傷感染や複雑骨折のように)外傷の結果として環境 から獲得した微生物によって引き起こされることもある。日和見感染症は、宿主の防御機能の障害を必要とするが、この障害は、遺伝的欠陥(慢性肉芽腫性疾患 など)、抗菌薬や免疫抑制性の化学物質への暴露(中毒やがん化学療法後に起こりうる)、電離放射線への暴露、免疫抑制活性を有する感染症(麻疹、マラリ ア、HIV感染症など)の結果として起こりうる。一次病原体はまた、抵抗力が低下した宿主において、免疫不全の宿主で通常起こるよりも重篤な疾病を引き起 こすこともある[10]。 二次感染 一次感染は事実上、個人の現在の保健上の問題の根本原因とみなすことができるが、二次感染はその根本原因の後遺症または合併症である。例えば、熱傷や貫通 外傷(根本原因)による感染は二次感染である。一次病原体はしばしば一次感染を引き起こし、しばしば二次感染を引き起こす。通常、日和見感染は二次感染と みなされる(免疫不全または外傷が素因であったため)[60]。 その他の感染症 その他の感染には、混血感染、異所性感染、院内感染、市中感染などがある。混血の感染とは、2つ以上の病原体によって引き起こされる感染である。例えば、 虫垂炎はBacteroides fragilisとEscherichia coliによって引き起こされる。2つ目は異所性感染である。このタイプの感染は、保健医療従事者から患者に感染するものである。院内感染もまた、保健医 療の場で起こる感染である。院内感染とは、入院中に発症する感染である。最後に、市中感染とは、地域社会全体から感染するものである[58]。 感染性の有無 ある疾患が感染性であることを証明する1つの方法は、コッホの定説(ロベルト・コッホによって最初に提唱された)を満たすことである。この定説は、第1 に、健康な対照者ではなく、その疾患に罹患した患者においてのみ感染因子が同定可能であること、第2に、感染因子に罹患した患者もその疾患を発症すること を必要とする。これらの定説は、マイコバクテリア(Mycobacteria)種が結核の原因であることを発見する際に初めて用いられた[62]。 しかし、コッホの定説は倫理的な理由から、現代の診療では通常検証することができない。それを証明するには、純粋培養した病原体を健康な個体に実験的に感 染させる必要がある。例えば、梅毒の原因スピロヘータであるトレポネーマ・パリダムは試験管内では培養できないが、ウサギの精巣では培養できる。純粋培養 が宿主となる動物由来であることは、平板培養由来の微生物由来である場合よりも明確ではない。 疫学、すなわち、誰が、なぜ、どこで疾病を発症するのか、そして何が様々な集団が疾病に罹患するかどうかを決定するのかについての研究と分析は、感染症を 理解するために用いられるもう一つの重要な手段である。疫学者は、特定の年齢層の感染率が高いか低いか、異なる地域に住む集団が感染しやすいかどうか、性 別や人種などの他の要因によって、集団内のグループ間の異なる点を明らかにすることができる。研究者はまた、病気の発生が散発的なものなのか、時折発生す るものなのか、風土病なのか、定期的に発生するものなのか、伝染病なのか、パンデミックなのか、世界的に流行するものなのかを評価することもある。感染症 の原因が不明である場合、疫学は感染源の追跡を支援するために用いられることがある[64]。 伝染性 感染症は、病人やその分泌物との接触によって容易に伝播する場合(例えば、インフルエンザ)、伝染病と呼ばれることがある。したがって、伝染性疾患とは、 特に感染力が強い、または感染しやすい感染症のサブセットである。すべての伝染病は感染性であるが、その逆はない。[65][66]媒介感染や性行為感染 など、より特殊な感染経路を持つ他の種類の感染症、伝染性疾患、または伝染性疾患は、通常「伝染性」とはみなされず、しばしば罹患者の医学的隔離(緩やか に隔離と呼ばれることもある)を必要としない。しかし、「伝染性」や「伝染病」という言葉の持つこのような専門的な意味合い(伝染しやすさ)は、一般的な 使用においては必ずしも尊重されていない。 感染症は一般的に、直接接触によって人格から人格へと感染する。直接接触には人格から人格への感染と飛沫感染がある。空気感染、汚染された物体、食物や飲 料水、動物との人格接触、動物の貯蔵庫、虫刺され、環境中の貯蔵庫などの間接的接触も感染症の感染経路である。感染症の基本再生産数は、直接的または間接 的な接触によって感染症がどれだけ容易に広がるかを示す[67][68]。 解剖学的部位による分類 感染症は、感染した解剖学的部位または臓器系によって分類することができ、以下のようなものがある:[69][要出典]。 尿路感染 皮膚感染 呼吸器感染 歯原性感染(歯の内部またはその密接な周辺組織から発生する感染)。 膣感染 羊膜内感染 さらに、感染が最も一般的な原因である炎症部位には、肺炎、髄膜炎、帯状疱疹などがある[70]。 |

| Prevention Main articles: Public health and Infection control  Washing one's hands, a form of hygiene, is an effective way to prevent the spread of infectious disease.[71] Techniques like hand washing, wearing gowns, and wearing face masks can help prevent infections from being passed from one person to another. Aseptic technique was introduced in medicine and surgery in the late 19th century and greatly reduced the incidence of infections caused by surgery. Frequent hand washing remains the most important defense against the spread of unwanted organisms.[72] There are other forms of prevention such as avoiding the use of illicit drugs, using a condom, wearing gloves, and having a healthy lifestyle with a balanced diet and regular exercise. Cooking foods well and avoiding foods that have been left outside for a long time is also important.[citation needed] Antimicrobial substances used to prevent transmission of infections include:[citation needed] antiseptics, which are applied to living tissue/skin disinfectants, which destroy microorganisms found on non-living objects. antibiotics, called prophylactic when given as prevention rather as treatment of infection. However, long term use of antibiotics leads to resistance of bacteria. While humans do not become immune to antibiotics, the bacteria does. Thus, avoiding using antibiotics longer than necessary helps preventing bacteria from forming mutations that aide in antibiotic resistance. One of the ways to prevent or slow down the transmission of infectious diseases is to recognize the different characteristics of various diseases.[73] Some critical disease characteristics that should be evaluated include virulence, distance traveled by those affected, and level of contagiousness. The human strains of Ebola virus, for example, incapacitate those infected extremely quickly and kill them soon after. As a result, those affected by this disease do not have the opportunity to travel very far from the initial infection zone.[74] Also, this virus must spread through skin lesions or permeable membranes such as the eye. Thus, the initial stage of Ebola is not very contagious since its victims experience only internal hemorrhaging. As a result of the above features, the spread of Ebola is very rapid and usually stays within a relatively confined geographical area. In contrast, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) kills its victims very slowly by attacking their immune system.[10] As a result, many of its victims transmit the virus to other individuals before even realizing that they are carrying the disease. Also, the relatively low virulence allows its victims to travel long distances, increasing the likelihood of an epidemic.[citation needed] Another effective way to decrease the transmission rate of infectious diseases is to recognize the effects of small-world networks.[73] In epidemics, there are often extensive interactions within hubs or groups of infected individuals and other interactions within discrete hubs of susceptible individuals. Despite the low interaction between discrete hubs, the disease can jump and spread in a susceptible hub via a single or few interactions with an infected hub. Thus, infection rates in small-world networks can be reduced somewhat if interactions between individuals within infected hubs are eliminated (Figure 1). However, infection rates can be drastically reduced if the main focus is on the prevention of transmission jumps between hubs. The use of needle exchange programs in areas with a high density of drug users with HIV is an example of the successful implementation of this treatment method.[75] Another example is the use of ring culling or vaccination of potentially susceptible livestock in adjacent farms to prevent the spread of the foot-and-mouth virus in 2001.[76] A general method to prevent transmission of vector-borne pathogens is pest control. In cases where infection is merely suspected, individuals may be quarantined until the incubation period has passed and the disease manifests itself or the person remains healthy. Groups may undergo quarantine, or in the case of communities, a cordon sanitaire may be imposed to prevent infection from spreading beyond the community, or in the case of protective sequestration, into a community. Public health authorities may implement other forms of social distancing, such as school closings, lockdowns or temporary restrictions (e.g. circuit breakers)[77] to control an epidemic.  Mary Mallon (a.k.a. Typhoid Mary) was an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever. Over the course of her career as a cook, she infected 53 people, three of whom died. |

予防 主な記事 公衆衛生と感染管理  衛生管理の一つである手洗いは、感染症の蔓延を防ぐ効果的な方法である[71]。 手洗い、ガウンの着用、フェイスマスクの着用などの技術は、人格から人格への感染を防ぐのに役立つ。無菌手技は19世紀後半に医学と外科学に導入され、手 術による感染の発生率を大幅に減少させた。その他にも、違法薬物の使用を避ける、コンドームを使用する、手袋を着用する、バランスのとれた食事と定期的な 運動で健康的なライフスタイルを心がけるなどの予防法がある。食品をよく調理し、長時間屋外に放置された食品を避けることも重要である[要出典]。 感染予防に使用される抗菌物質には、以下のものがある[要出典]。 防腐剤:生体組織や皮膚に塗布する。 消毒薬:非生物に付着した微生物を破壊する。 抗生物質は、感染症の治療ではなく予防として投与される場合、予防薬と呼ばれる。しかし、抗生物質の長期使用は細菌の耐性をもたらす。人間は抗生物質に対 する免疫を持たないが、細菌は免疫を持つ。従って、抗生物質を必要以上に長く使用しないことは、細菌が抗生物質耐性を助長する突然変異を起こすのを防ぐの に役立つ。 感染症の感染を予防したり遅らせたりする方法のひとつは、様々な感染症の異なる特徴を認識することである。評価すべき重要な感染症の特徴には、病原性、感 染者の移動距離、伝染力のレベルなどがある。例えばエボラウイルスのヒト株は、感染者を極めて迅速に無力化し、その後すぐに死に至らしめる。その結果、こ の病気に罹患した者は、最初の感染地域からあまり遠くへ移動する機会がない。したがって、エボラ出血熱の初期段階では、犠牲者は内出血を起こすだけで、感 染力はそれほど強くない。以上のような特徴から、エボラ出血熱の感染拡大は非常に速く、通常は比較的限られた地域内にとどまる。対照的に、ヒト免疫不全ウ イルス(HIV)は、犠牲者の免疫系を攻撃することで、犠牲者を非常にゆっくりと死に至らしめる[10]。その結果、犠牲者の多くは、自分がこの病気にか かっていることに気づく前に、他の人にウイルスを感染させてしまう。また、病原性が比較的低いため、被害者は長距離を移動することができ、流行の可能性が 高まる[要出典]。 感染症の伝播率を低下させるもう一つの効果的な方法は、スモールワールドネットワークの効果を認識することである[73]。伝染病では、感染個体のハブや グループ内での広範な相互作用と、感受性個体の離散的なハブ内での他の相互作用がしばしば見られる。離散的なハブ間の相互作用が少ないにもかかわらず、感 染したハブとの1回または数回の相互作用によって、感染症がジャンプして感受性のハブに広がることがある。したがって、スモールワールド・ネットワークに おける感染率は、感染したハブ内の個体間の相互作用を消去法による場合、いくらか減少させることができる(図1)。しかし、ハブ間の感染ジャンプを防ぐこ とに主眼を置けば、感染率は劇的に低下する。HIVに感染している薬物使用者が密集している地域での注射針交換プログラムの利用は、この治療法の実施に成 功した例である[75]。他の例としては、2001年の口蹄疫ウイルスの蔓延を防ぐために、隣接する農場で感染の可能性のある家畜のリングカリングやワク チン接種を行った例がある[76]。 媒介病原体の感染を防ぐ一般的な方法は、害虫駆除である。 感染が単に疑われる場合、潜伏期間が過ぎ、病気が顕在化するまで、または人格が健康でいられるまで、個人を隔離することができる。集団の場合は検疫が行わ れ、地域社会の場合は、地域社会外への感染拡大を防ぐため、あるいは保護隔離の場合は地域社会内への感染を防ぐため、サニタワール(衛生綱)が敷かれるこ とがある。保健当局は、流行制圧のために、学校閉鎖、戸締まり、一時的な制限(遮断機など)[77]など、その他の社会的距離の取り方を実施することもあ る。  メアリー・マロン(別名チフス・メアリー)は無症状の腸チフス保菌者であった。コックとしてのキャリアを通じて53人に感染し、うち3人が死亡した。 |

| Immunity Infection with most pathogens does not result in death of the host and the offending organism is ultimately cleared after the symptoms of the disease have waned.[59] This process requires immune mechanisms to kill or inactivate the inoculum of the pathogen. Specific acquired immunity against infectious diseases may be mediated by antibodies and/or T lymphocytes. Immunity mediated by these two factors may be manifested by: a direct effect upon a pathogen, such as antibody-initiated complement-dependent bacteriolysis, opsonoization, phagocytosis and killing, as occurs for some bacteria, neutralization of viruses so that these organisms cannot enter cells, or by T lymphocytes, which will kill a cell parasitized by a microorganism. The immune system response to a microorganism often causes symptoms such as a high fever and inflammation, and has the potential to be more devastating than direct damage caused by a microbe.[10] Resistance to infection (immunity) may be acquired following a disease, by asymptomatic carriage of the pathogen, by harboring an organism with a similar structure (crossreacting), or by vaccination. Knowledge of the protective antigens and specific acquired host immune factors is more complete for primary pathogens than for opportunistic pathogens. There is also the phenomenon of herd immunity which offers a measure of protection to those otherwise vulnerable people when a large enough proportion of the population has acquired immunity from certain infections.[78] Immune resistance to an infectious disease requires a critical level of either antigen-specific antibodies and/or T cells when the host encounters the pathogen. Some individuals develop natural serum antibodies to the surface polysaccharides of some agents although they have had little or no contact with the agent, these natural antibodies confer specific protection to adults and are passively transmitted to newborns. |

免疫 ほとんどの病原体への感染は宿主の死亡には至らず、病気の症状が弱まった後、感染した病原体は最終的に排除される。感染症に対する特異的獲得免疫は、抗体および/またはTリンパ球によって媒介される。これら2つの因子によって媒介される免疫には、以下のようなものがある: 病原体に対する直接的な作用。例えば、いくつかの細菌にみられるような、抗体による補体依存性の溶血、オプソノ化、貪食、殺傷などである、 ウイルスが細胞内に侵入できないように中和する、 Tリンパ球は微生物に寄生された細胞を殺す。 微生物に対する免疫系の反応は、しばしば高熱や炎症などの症状を引き起こし、微生物による直接的な被害よりも壊滅的な被害をもたらす可能性がある[10]。 感染に対する抵抗力(免疫)は、疾患の後、病原体の無症候性保菌、類似した構造を持つ生物の保有(交差反応)、またはワクチン接種によって獲得される。防 御抗原と特異的な後天性宿主免疫因子に関する知識は、日和見病原体よりも一次病原体の方がより完全である。群畜免疫という現象もあり、これは集団の十分な 割合が特定の感染から免疫を獲得している場合に、そうでなければ脆弱な人民を保護する手段を提供するものである[78]。 感染症に対する免疫抵抗性は、宿主が病原体に遭遇したときに、抗原特異的抗体および/またはT細胞のいずれかが臨界レベルにあることを必要とする。このような自然抗体は、成人に特異的な防御を与え、新生児に受動的に伝達される。 |

| Host genetic factors The organism that is the target of an infecting action of a specific infectious agent is called the host. The host harbouring an agent that is in a mature or sexually active stage phase is called the definitive host. The intermediate host comes in contact during the larvae stage. A host can be anything living and can attain to asexual and sexual reproduction.[79] The clearance of the pathogens, either treatment-induced or spontaneous, it can be influenced by the genetic variants carried by the individual patients. For instance, for genotype 1 hepatitis C treated with Pegylated interferon-alpha-2a or Pegylated interferon-alpha-2b (brand names Pegasys or PEG-Intron) combined with ribavirin, it has been shown that genetic polymorphisms near the human IL28B gene, encoding interferon lambda 3, are associated with significant differences in the treatment-induced clearance of the virus. This finding, originally reported in Nature,[80] showed that genotype 1 hepatitis C patients carrying certain genetic variant alleles near the IL28B gene are more possibly to achieve sustained virological response after the treatment than others. Later report from Nature[81] demonstrated that the same genetic variants are also associated with the natural clearance of the genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. |

宿主の遺伝的要因 特定の感染因子の感染作用の標的となる生物を宿主と呼ぶ。成熟期または性活動期にある病原体を保有する宿主は、確定宿主と呼ばれる。中間宿主は幼虫期に接 触する。宿主は生きているものであれば何でもよく、無性生殖も有性生殖も可能である[79]。病原体のクリアランスは、治療によって誘発されたものであ れ、自然発生的なものであれ、個々の患者が持つ遺伝子変異に影響されることがある。例えば、ペグインターフェロンα-2aまたはペグインターフェロンα- 2b(商品名ペガシスまたはPEG-イントロン)とリバビリンの併用療法を受けたジェノタイプ1のC型肝炎では、インターフェロンラムダ3をコードするヒ トIL28B遺伝子近傍の遺伝子多型が、治療によるウイルスクリアランスの有意差と関連していることが示されている。この知見は、もともとNature誌 で報告されたものであるが[80]、IL28B遺伝子近傍の特定の遺伝子変異対立遺伝子を持つジェノタイプ1型C型肝炎患者は、治療後に持続的なウイルス 学的反応を達成する可能性が他の患者よりも高いことを示している。後にNature誌[81]は、同じ遺伝子変異がジェノタイプ1型C型肝炎ウイルスのナ チュラルクリアランスにも関連していることを示した。 |

| Treatments When infection attacks the body, anti-infective drugs can suppress the infection. Several broad types of anti-infective drugs exist, depending on the type of organism targeted; they include antibacterial (antibiotic; including antitubercular), antiviral, antifungal and antiparasitic (including antiprotozoal and antihelminthic) agents. Depending on the severity and the type of infection, the antibiotic may be given by mouth or by injection, or may be applied topically. Severe infections of the brain are usually treated with intravenous antibiotics. Sometimes, multiple antibiotics are used in case there is resistance to one antibiotic. Antibiotics only work for bacteria and do not affect viruses. Antibiotics work by slowing down the multiplication of bacteria or killing the bacteria. The most common classes of antibiotics used in medicine include penicillin, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, macrolides, quinolones and tetracyclines.[82][83] Not all infections require treatment, and for many self-limiting infections the treatment may cause more side-effects than benefits. Antimicrobial stewardship is the concept that healthcare providers should treat an infection with an antimicrobial that specifically works well for the target pathogen for the shortest amount of time and to only treat when there is a known or highly suspected pathogen that will respond to the medication.[84] |

治療法 感染症が身体を攻撃する場合、抗感染薬によって感染を抑えることができる。抗感染症薬には、対象となる生物の種類によっていくつかの種類があり、抗菌薬 (抗生物質;抗結核薬を含む)、抗ウイルス薬、抗真菌薬、抗寄生虫薬(抗原虫薬、抗蠕虫薬を含む)などがある。感染症の重症度や種類によって、抗生物質は 経口または注射で投与されることもあれば、局所的に塗布されることもある。脳の重症感染症は通常、抗生物質の静脈内投与で治療する。一つの抗生物質に耐性 がある場合には、複数の抗生物質が使用されることもある。抗生物質は細菌にしか効かず、ウイルスには効かない。抗生物質は細菌の増殖を遅らせたり、細菌を 殺したりすることで効果を発揮する。医療で使用される最も一般的な抗生物質のクラスには、ペニシリン、セファロスポリン、アミノグリコシド、マクロライ ド、キノロン、テトラサイクリンが含まれる[82][83]。 すべての感染症に治療が必要なわけではなく、多くの自己限定性感染症では、治療が有益性よりも副作用を引き起こす可能性がある。抗菌薬スチュワードシップ とは、医療従事者は、対象となる病原体に特異的によく効く抗菌薬で感染を最短時間で治療すべきであり、その薬に反応する病原体が既知であるか強く疑われる 場合にのみ治療すべきであるという概念である[84]。 |

| Susceptibility to infection Pandemics such as COVID-19 show that people dramatically differ in their susceptibility to infection. This may be because of general health, age, or their immune status, e.g. when they have been infected previously. However, it also has become clear that there are genetic factor which determine susceptibility to infection. For instance, up to 40% of SARS-CoV-2 infections may be asymptomatic, suggesting that many people are naturally protected from disease.[85] Large genetic studies have defined risk factors for severe SARS-CoV-2 infections, and genome sequences from 659 patients with severe COVID-19 revealed genetic variants that appear to be associated with life-threatening disease. One gene identified in these studies is type I interferon (IFN). Autoantibodies against type I IFNs were found in up to 13.7% of patients with life-threatening COVID-19, indicating that a complex interaction between genetics and the immune system is important for natural resistance to Covid.[86] Similarly, mutations in the ERAP2 gene, encoding endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 2, seem to increase the susceptibility to the plague, the disease caused by an infection with the bacteria Yersinia pestis. People who inherited two copies of a complete variant of the gene were twice as likely to have survived the plague as those who inherited two copies of a truncated variant.[87] Susceptibility also determined the epidemiology of infection, given that different populations have different genetic and environmental conditions that affect infections. |

感染に対する感受性 COVID-19のようなパンデミックは、人民の感染感受性が劇的に異なることを示している。これは、一般的な保健、年齢、あるいは免疫状態、例えば以前 に感染したことがあるかどうかなどが原因かもしれない。しかし、感染しやすさを決定する遺伝的要因があることも明らかになっている。例えば、SARS- CoV-2感染の40%までは無症状である可能性があり、多くの人民が自然に病気から守られていることを示唆している[85]。大規模な遺伝学的研究によ り、重症SARS-CoV-2感染の危険因子が定義され、重症COVID-19患者659人のゲノム配列から、生命を脅かす病気に関連すると思われる遺伝 子変異が明らかになった。これらの研究で同定された遺伝子の一つがI型インターフェロン(IFN)である。I型IFNに対する自己抗体は、生命を脅かす COVID-19患者の最大13.7%に認められ、遺伝学と免疫系の複雑な相互作用がコビッドに対する自然抵抗性に重要であることを示している[86]。 同様に、小胞体アミノペプチダーゼ2をコードするERAP2遺伝子の変異は、ペスト(Yersinia pestis)菌の感染によって引き起こされるペストに対する感受性を高めるようである。この遺伝子の完全変異型を2コピー受け継いだ人民は、切断型変異 型を2コピー受け継いだ人民よりもペストから生き延びる可能性が2倍高かった[87]。 異なる集団は感染に影響する遺伝的・環境的条件が異なることから、感受性も感染の疫学を決定づけた。 |

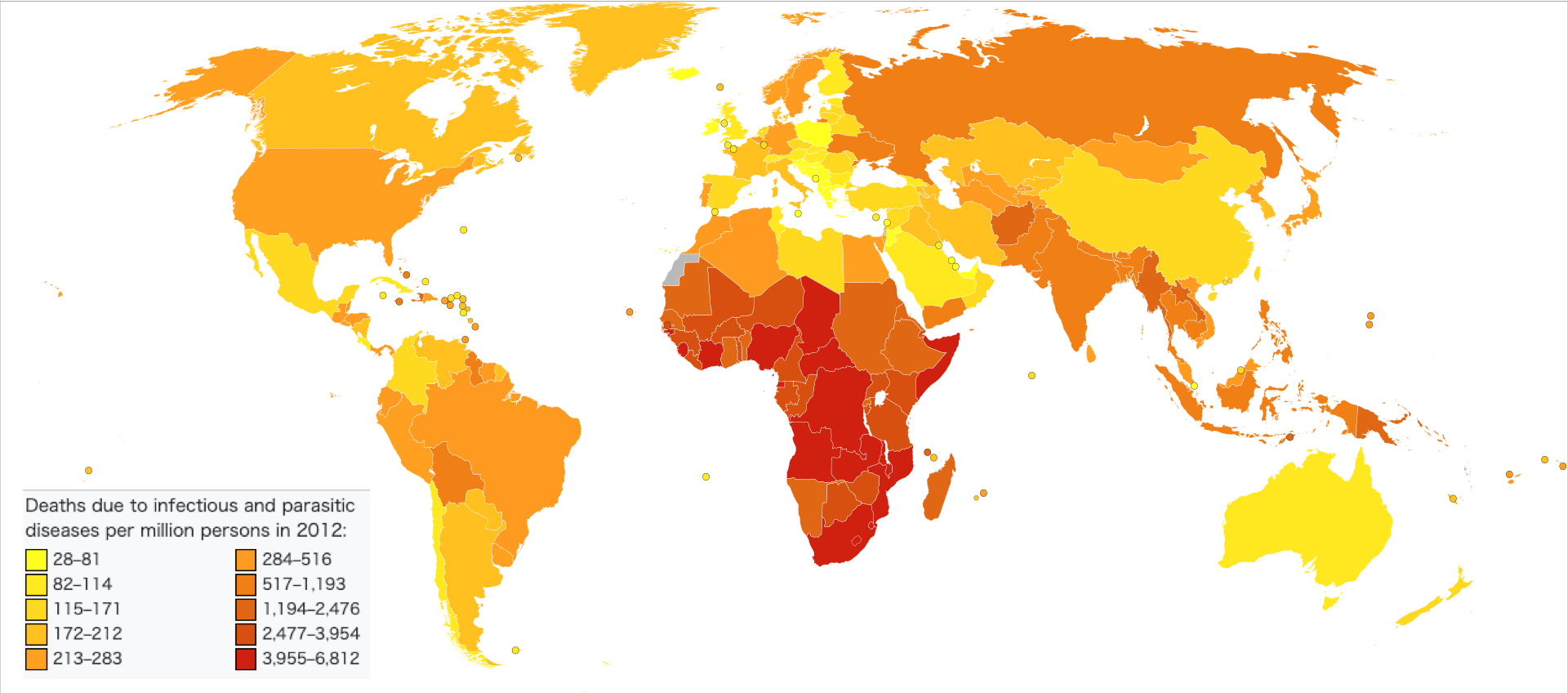

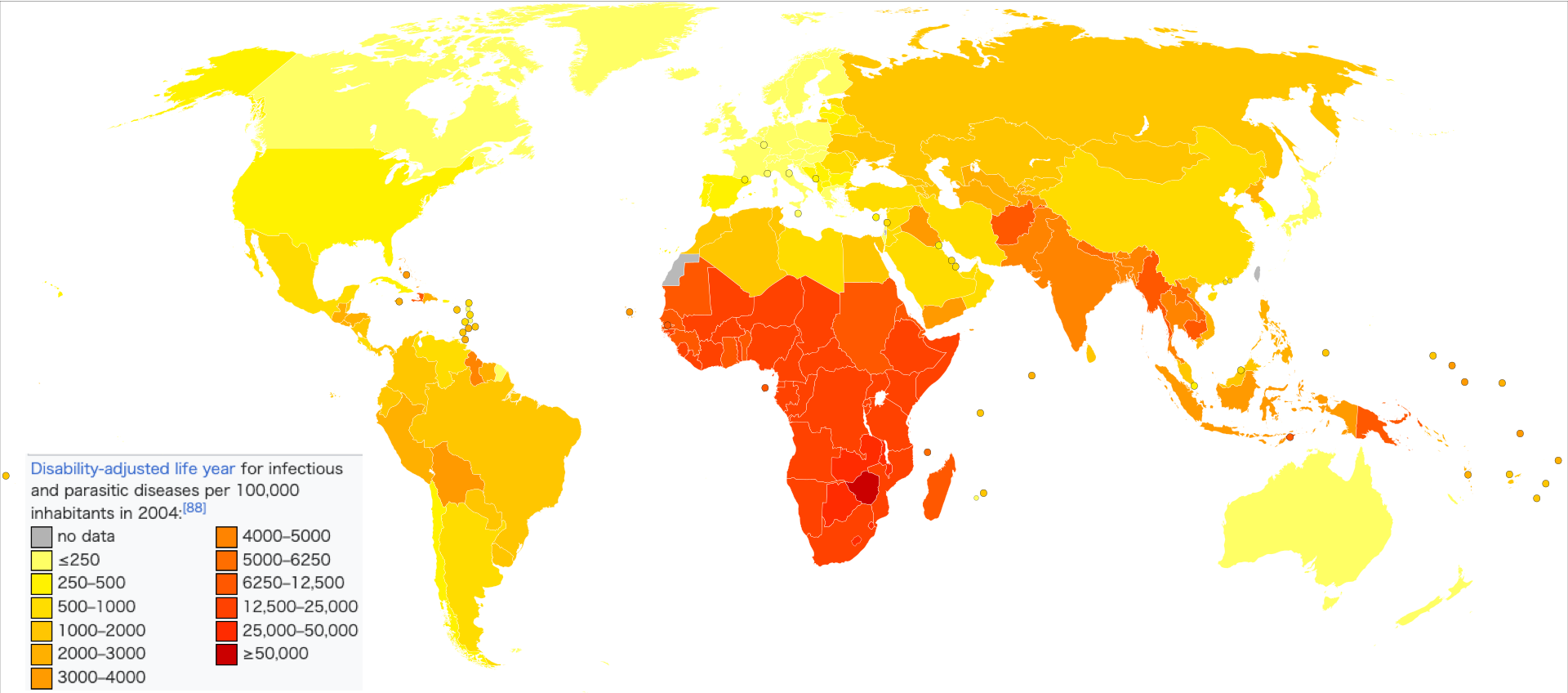

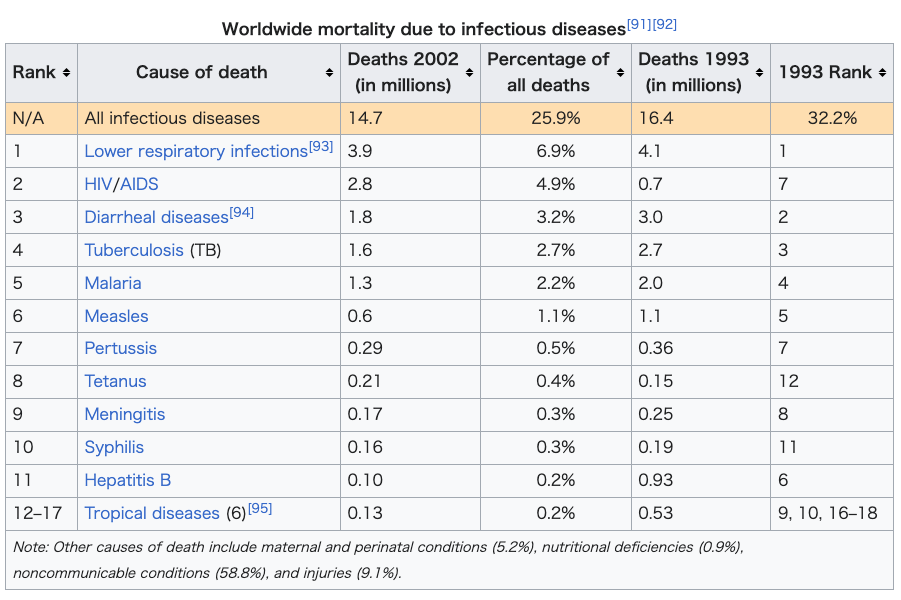

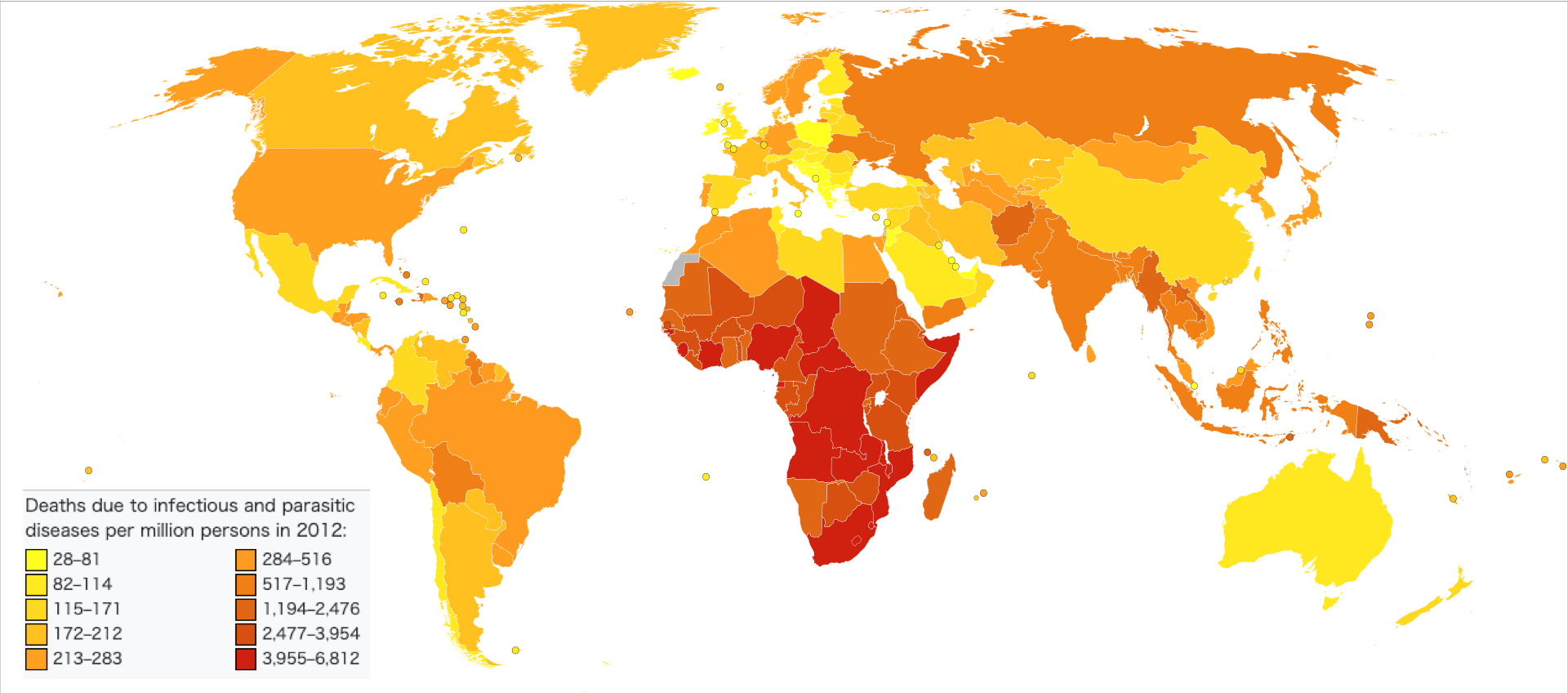

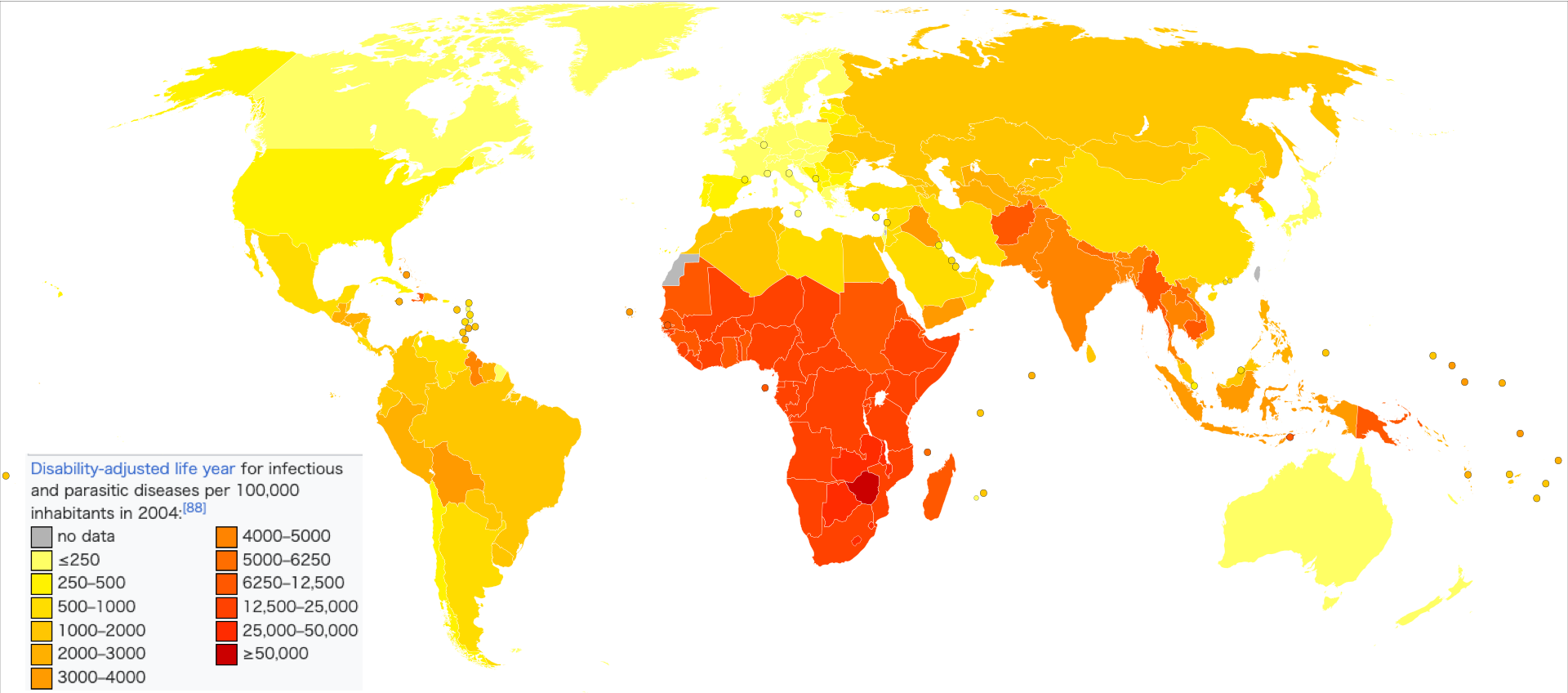

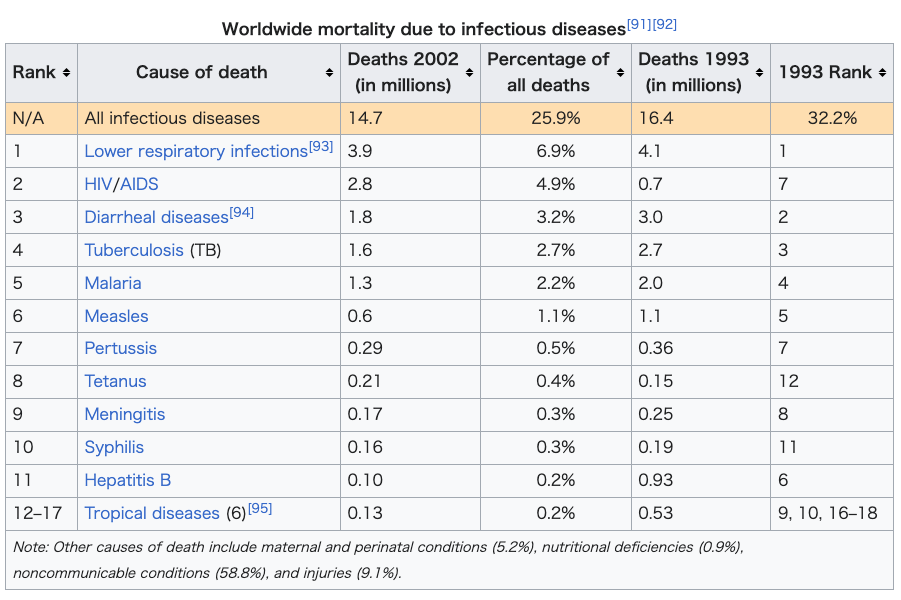

| Epidemiology See also: Epidemic and Pandemic  Deaths due to infectious and parasitic diseases per million persons in 2012: 28–81 82–114 115–171 172–212 213–283 284–516 517–1,193 1,194–2,476 2,477–3,954 3,955–6,812  Disability-adjusted life year for infectious and parasitic diseases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004:[88] no data ≤250 250–500 500–1000 1000–2000 2000–3000 3000–4000 4000–5000 5000–6250 6250–12,500 12,500–25,000 25,000–50,000 ≥50,000 An estimated 1,680 million people died of infectious diseases in the 20th century[89] and about 10 million in 2010.[90] The World Health Organization collects information on global deaths by International Classification of Disease (ICD) code categories. The following table lists the top infectious disease by number of deaths in 2002. 1993 data is included for comparison.  The top three single agent/disease killers are HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. While the number of deaths due to nearly every disease have decreased, deaths due to HIV/AIDS have increased fourfold. Childhood diseases include pertussis, poliomyelitis, diphtheria, measles and tetanus. Children also make up a large percentage of lower respiratory and diarrheal deaths. In 2012, approximately 3.1 million people have died due to lower respiratory infections, making it the number 4 leading cause of death in the world.[96] |

疫学 こちらも参照のこと: 伝染病とパンデミック  2012年、100万人格当たりの感染症および寄生虫症による死亡者数: 28-81 82-114 115-171 172-212 213-283 284-516 517-1,193 1,194-2,476 2,477-3,954 3,955-6,812  2004年の人口10万人当たりの感染症および寄生虫症による障害調整生存年:[88]。 データなし ≤250 250-500 500-1000 1000-2000 2000-3000 3000-4000 4000-5000 5000-6250 6250-12,500 12,500-25,000 25,000-50,000 ≥50,000 20世紀には推定16億8,000万人[89]、2010年には約1,000万人が感染症で死亡している[90]。 世界保健機関(WHO)は、国際疾病分類(ICD)コードのカテゴリー別に世界の死亡者情報を収集している。以下の表は、2002年の死亡者数上位の感染症である。比較のために1993年のデータも含まれている。  HIV/AIDS、結核、マラリアが単剤/疾病による死者のトップ3である。ほぼすべての病気による死亡者数は減少しているが、HIV/AIDSによる死 亡者数は4倍に増加している。小児疾患には百日咳、ポリオ、ジフテリア、麻疹、破傷風などがある。また、下気道疾患や下痢による死亡の大部分も小児が占め ている。2012年には、約310万人が下気道感染症が原因で死亡しており、世界第4位の死因となっている[96]。 |

| 1. Lower respiratory infections |

|

| 2. HIV/AIDS |

|

| 3. Diarrheal diseases |

|

| 4. Tuberculosis (TB) |

|

| 5. Malaria |

|

| 6. Measles |

|

| 7. Pertussis |

7. 百日咳 |

| 8. Tetanus |

|

| 9. Meningitis |

9. 髄膜炎 |

| 10. Syphilis |

|

| 11. Hepatitis B |

|

| 12-17. Tropical diseases |

|

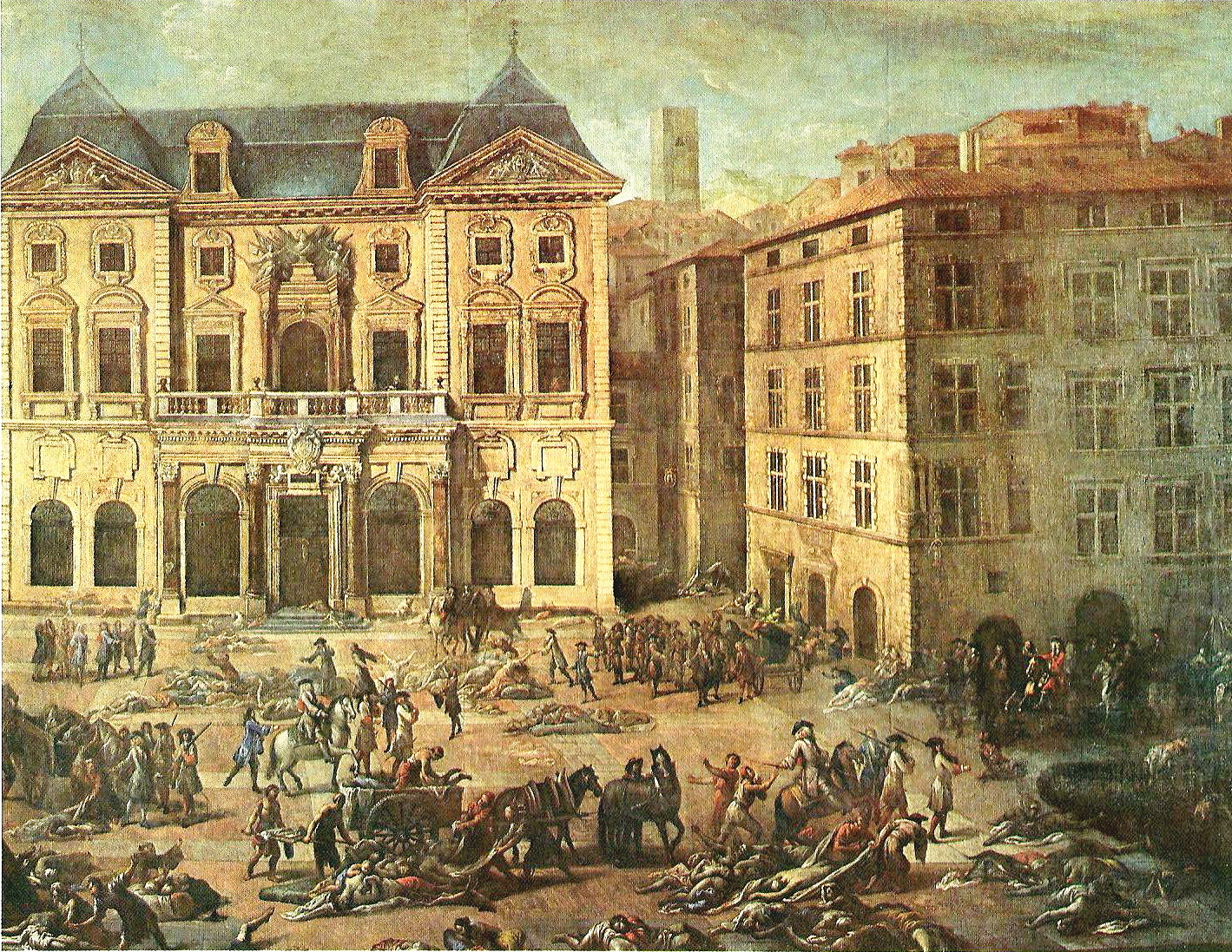

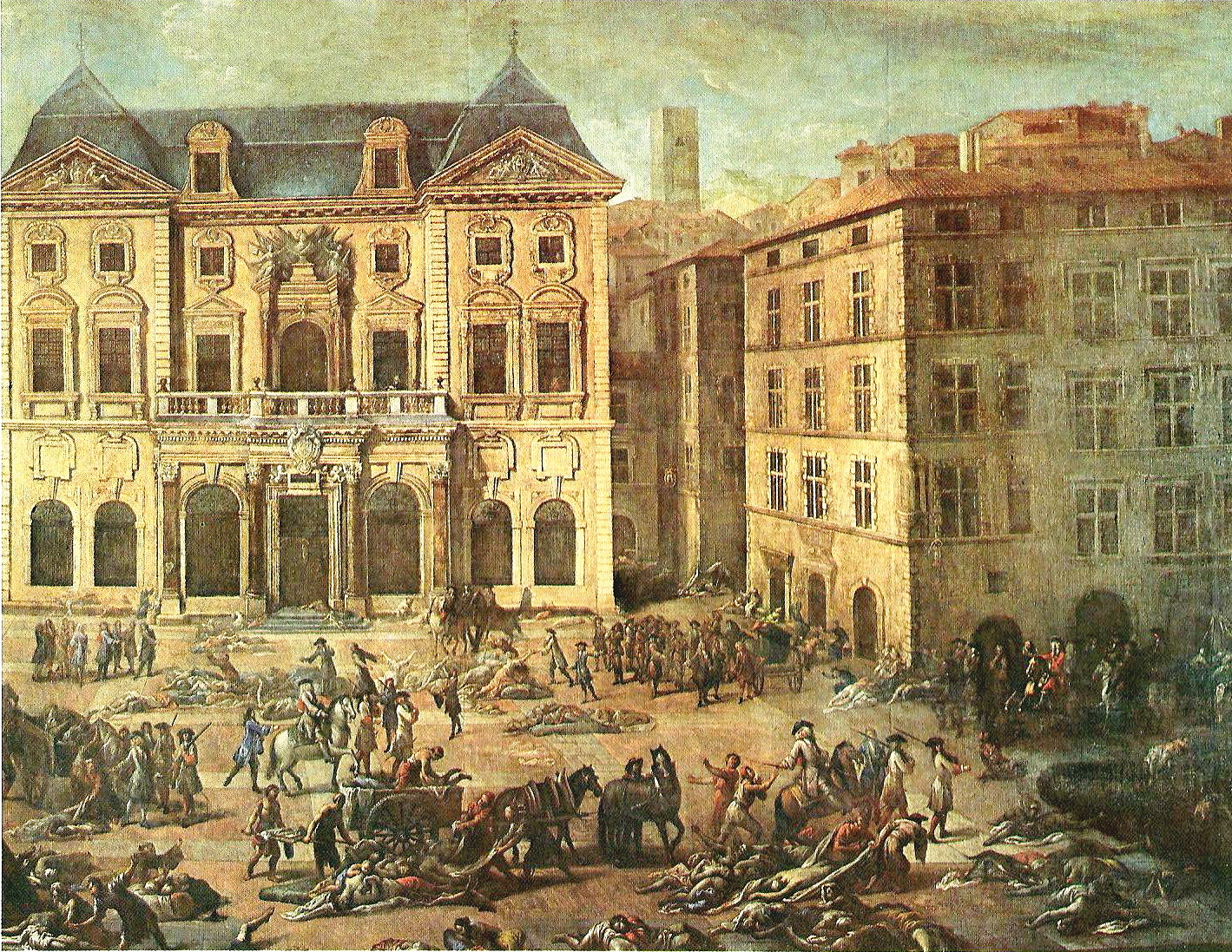

| Historic pandemics See also: List of epidemics  The Great Plague of Marseille in 1720 killed 100,000 people in the city and the surrounding provinces. With their potential for unpredictable and explosive impacts, infectious diseases have been major actors in human history.[97] A pandemic (or global epidemic) is a disease that affects people over an extensive geographical area. For example: Plague of Justinian, from 541 to 542, killed between 50% and 60% of Europe's population.[98] The Black Death of 1347 to 1352 killed 25 million in Europe over five years. The plague reduced the old world population from an estimated 450 million to between 350 and 375 million in the 14th century. The introduction of smallpox, measles, and typhus to the areas of Central and South America by European explorers during the 15th and 16th centuries caused pandemics among the native inhabitants. Between 1518 and 1568 disease pandemics are said to have caused the population of Mexico to fall from 20 million to 3 million.[99] The first European influenza epidemic occurred between 1556 and 1560, with an estimated mortality rate of 20%.[99] Smallpox killed an estimated 60 million Europeans during the 18th century[100] (approximately 400,000 per year).[101] Up to 30% of those infected, including 80% of the children under 5 years of age, died from the disease, and one-third of the survivors went blind.[102] In the 19th century, tuberculosis killed an estimated one-quarter of the adult population of Europe;[103] by 1918 one in six deaths in France were still caused by TB. The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 (or the Spanish flu) killed 25–50 million people (about 2% of world population of 1.7 billion).[104] Today Influenza kills about 250,000 to 500,000 worldwide each year. In 2021, COVID-19 emerged as a major global health crisis, directly causing 8.7 million deaths, making it one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide.[105] |

歴史的パンデミック こちらも参照のこと: 伝染病の一覧  1720年のマルセイユ大疫病では、マルセイユとその周辺の地方で10万人が死亡した。 パンデミック(または世界的流行)とは、広範な地域で人民が罹患する病気のことである。例えば 541年から542年にかけてのユスティニアヌスのペストは、ヨーロッパの人口の50%から60%を死亡させた[98]。 1347年から1352年にかけての黒死病は、5年間でヨーロッパで2,500万人を死亡させた。ペストは、14世紀には旧世界の人口を推定4億5,000万人から3億5,000万人から3億7,500万人まで減少させた。 15世紀から16世紀にかけて、ヨーロッパの探検家たちが天然痘、麻疹、チフスを中南米の地域に持ち込んだことで、原住民の間でパンデミックが発生した。 1518年から1568年にかけての病気の大流行によって、メキシコの人口は2,000万人から300万人にまで減少したと言われている[99]。 ヨーロッパ初のインフルエンザの流行は1556年から1560年にかけて起こり、推定死亡率は20%であった[99]。 天然痘は18世紀に推定6,000万人のヨーロッパ人を死亡させた[100](年間約40万人)[101]。 感染者の最大30%(5歳未満の子どもの80%を含む)がこの病気で死亡し、生存者の3分の1が失明した[102]。 19世紀には、結核はヨーロッパの成人人口の4分の1を死亡させたと推定され[103]、1918年になってもフランスでは6人に1人が結核による死亡であった。 1918年のインフルエンザ・パンデミック(またはスペイン風邪)では、2,500万~5,000万人(世界人口17億人の約2%)が死亡した[104]。今日、インフルエンザは毎年世界中で約25万~50万人を死亡させている。 2021年には、COVID-19が主要な世界的保健危機として浮上し、870万人の死亡を直接引き起こし、世界的な死亡の主要原因のひとつとなった[105]。 |

| Emerging diseases In most cases, microorganisms live in harmony with their hosts via mutual or commensal interactions. Diseases can emerge when existing parasites become pathogenic or when new pathogenic parasites enter a new host. Coevolution between parasite and host can lead to hosts becoming resistant to the parasites or the parasites may evolve greater virulence, leading to immunopathological disease. Human activity is involved with many emerging infectious diseases, such as environmental change enabling a parasite to occupy new niches. When that happens, a pathogen that had been confined to a remote habitat has a wider distribution and possibly a new host organism. Parasites jumping from nonhuman to human hosts are known as zoonoses. Under disease invasion, when a parasite invades a new host species, it may become pathogenic in the new host.[106] Several human activities have led to the emergence of zoonotic human pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and rickettsia,[107] and spread of vector-borne diseases,[106] see also globalization and disease and wildlife disease: Encroachment on wildlife habitats. The construction of new villages and housing developments in rural areas force animals to live in dense populations, creating opportunities for microbes to mutate and emerge.[108] Changes in agriculture. The introduction of new crops attracts new crop pests and the microbes they carry to farming communities, exposing people to unfamiliar diseases. The destruction of rain forests. As countries make use of their rain forests, by building roads through forests and clearing areas for settlement or commercial ventures, people encounter insects and other animals harboring previously unknown microorganisms. Uncontrolled urbanization. The rapid growth of cities in many developing countries tends to concentrate large numbers of people into crowded areas with poor sanitation. These conditions foster transmission of contagious diseases. Modern transport. Ships and other cargo carriers often harbor unintended "passengers", that can spread diseases to faraway destinations. While with international jet-airplane travel, people infected with a disease can carry it to distant lands, or home to their families, before their first symptoms appear. |

新興疾患 ほとんどの場合、微生物は宿主との相互作用や通性相互作用によって共生している。疾病は、既存の寄生虫が病原性を持つようになったり、新たな病原性を持つ寄生虫が新たな宿主に侵入したりすることで出現する。 寄生虫と宿主の共進化により、宿主が寄生虫に対して耐性を持つようになったり、寄生虫がより病原性を進化させ、免疫病理学的疾患を引き起こすこともある。 例えば、環境の変化によって寄生虫が新たなニッチを占めるようになる。例えば、環境の変化によって寄生虫が新たなニッチを占めるようになると、これまで生 息域が限定されていた病原体がより広い範囲に分布するようになり、新たな宿主となる生物も現れる可能性がある。ヒト以外の宿主からヒトに寄生する寄生虫 は、人獣共通感染症(ズーノーシス)として知られている。疾病侵入の下では、寄生虫が新しい宿主種に侵入すると、新しい宿主において病原性を持つようにな る可能性がある。 いくつかの人間活動が、ウイルス、細菌、原虫、リケッチアなどの人獣共通感染症病原体[107]の出現や、媒介感染症の蔓延につながっている: 野生生物の生息地への侵入。農村部における新しい村の建設や住宅開発により、動物は密集した集団生活を余儀なくされ、微生物が突然変異を起こし、出現する機会が生まれる[108]。 農業の変化。新しい作物の導入は、新しい作物害虫とそれらが媒介する微生物を農村に引き寄せ、人民を見慣れない病気にさらす。 熱帯雨林の破壊。森林に道路を建設したり、入植地や商業用地として伐採を行ったりして熱帯雨林を利用するようになると、人民は、それまで知られていなかった微生物を保有する昆虫やその他の動物に遭遇するようになる。 無秩序な都市化。多くの発展途上国で都市が急速に発展しているため、大勢の人民が衛生状態の悪い混雑した地域に集中する傾向がある。こうした状況は伝染病の感染を助長する。 近代的な輸送手段。船舶やその他の貨物運搬船は、しばしば予期せぬ「乗客」を乗せ、遠く離れた目的地まで伝染病を広げる可能性がある。一方、ジェット機や 飛行機による国際的な移動では、感染した人民が最初の症状が出る前に、その病気を遠く離れた土地や家族のもとへ運んでしまう可能性がある。 |