インフォーマル経済

Informal economy

☆

インフォーマル経済[informal economy](非公式部門またはグレー経済)[1][2]とは、いかなる政府による課税や監視も受けていない経済活動の部分を指す[3]。非公式部

門は発展途上国の経済において重要な割合を占めるが、厄介で管理不能なものと見なされることもある。しかしインフォーマル経済は貧困層にとって重要な経済

的機会を提供しており[4][5]、1960年代以降急速に拡大している[6]。インフォーマル経済を公式部門に統合することは重要な政策課題である

[4]。

多くの場合、公式経済とは異なり、インフォーマル経済の活動は国の国民総生産(GNP)や国内総生産(GDP)に含まれない。[4]

ただしイタリアは1987年以降、GDP計算に非公式活動の推計値を含めており、これによりGDPは推定18%増加している[7]。また2014年には、

国際会計基準に沿って売春や麻薬販売を公式GDP統計に含めるよう、複数の欧州諸国がGDP計算方法を正式に変更し、3~7%の増加をもたらした。[8]

非公式部門は労働のグレー市場と表現できる。非公式部門に分類される概念には闇市場(影の経済、地下経済)、アゴリズム、システムDなどがある。関連する

慣用句には「裏金」「帳簿外」「現金仕事」などがある。

| An informal economy

(informal sector or grey economy)[1][2] is the part of any economy that

is neither taxed nor monitored by any form of government.[3] Although

the informal sector makes up a significant portion of the economies in

developing countries, it is sometimes stigmatized as troublesome and

unmanageable. However, the informal sector provides critical economic

opportunities for the poor[4][5] and has been expanding rapidly since

the 1960s.[6] Integrating the informal economy into the formal sector

is an important policy challenge.[4] In many cases, unlike the formal economy, activities of the informal economy are not included in a country's gross national product (GNP) or gross domestic product (GDP).[4] However, Italy has included estimates of informal activity in their GDP calculations since 1987, which swells their GDP by an estimated 18%[7] and in 2014, a number of European countries formally changed their GDP calculations to include prostitution and narcotics sales in their official GDP statistics, in line with international accounting standards, prompting an increase between 3–7%.[8] The informal sector can be described as a grey market in labour. Other concepts that can be characterized as informal sector can include the black market (shadow economy, underground economy), agorism, and System D. Associated idioms include "under the table", "off the books", and "working for cash".  Informal economy: Haircut on a sidewalk in Vietnam. |

インフォーマル経済[informal economy](非公式部門またはグレー経済)[1][2]とは、

いかなる政府による課税や監視も受けていない経済活動の部分を指す[3]。非公式部門は発展途上国の経済において重要な割合を占めるが、厄介で管理不能な

ものと見なされることもある。しかしインフォーマル経済は貧困層にとって重要な経済的機会を提供しており[4][5]、1960年代以降急速に拡大してい

る[6]。インフォーマル経済を公式部門に統合することは重要な政策課題である[4]。 多くの場合、公式経済とは異なり、インフォーマル経済の活動は国の国民総生産(GNP)や国内総生産(GDP)に含まれない。[4] ただしイタリアは1987年以降、GDP計算に非公式活動の推計値を含めており、これによりGDPは推定18%増加している[7]。また2014年には、 国際会計基準に沿って売春や麻薬販売を公式GDP統計に含めるよう、複数の欧州諸国がGDP計算方法を正式に変更し、3~7%の増加をもたらした。[8] 非公式部門は労働のグレー市場と表現できる。非公式部門に分類される概念には闇市場(影の経済、地下経済)、アゴリズム、システムDなどがある。関連する 慣用句には「裏金」「帳簿外」「現金仕事」などがある。  ベトナムの側道での床屋 |

Definition Ice cream street vendor in Mexico The original use of the term 'informal sector' is attributed to the economic development model put forward in 1955 by W. Arthur Lewis, used to describe employment or livelihood generation primarily within the developing world. It was used to describe a type of employment that was viewed as falling outside of the modern industrial sector.[9] An alternative definition from 2007 uses job security as the measure of formality, defining participants in the informal economy as those "who do not have employment security, work security and social security".[10] While both of these definitions imply a lack of choice or agency in involvement with the informal economy, participation may also be driven by a wish to avoid regulation or taxation. This may manifest as unreported employment, hidden from the state for tax, social security or labour law purposes, but legal in all other aspects.[11] In 2016 Edgar L. Feige proposed a taxonomy for describing unobserved economies including the informal economy as being characterized by some form of "non-compliant behavior with an institutional set of rules".[12] He argues that circumvention of labor market regulations specifying minimum wages, working conditions, social security, unemployment and disability benefits gives rise to an informal economy, which deprives some workers of deserved benefits while conveying undeserved benefits to others. The term is also useful in describing and accounting for forms of shelter or living arrangements that are similarly unlawful, unregulated, or not afforded protection of the state. 'Informal economy' is increasingly[when?] replacing 'informal sector' as the preferred descriptor for this activity.[4] Informality, both in housing and livelihood generation has historically been seen as a social ill, and described either in terms of what participant's lack, or wish to avoid. In 2009, the Dutch sociologist Saskia Sassen viewed the new 'informal' sector as the product and driver of advanced capitalism and the site of the most entrepreneurial aspects of the urban economy, led by creative professionals such as artists, architects, designers and software developers.[13] While this manifestation of the informal sector remains largely a feature of developed countries, increasingly systems are emerging to facilitate similarly qualified people in developing countries to participate.[14]  Black market sellers offer watches for sale to US soldiers in Baghdad in 2004. |

定義 メキシコのアイスクリーム販売人 「インフォーマルセクター」という用語の最初の使用は、1955年にW・アーサー・ルイスが提唱した経済発展モデルに由来する。これは主に発展途上国にお ける雇用や生計手段の創出を説明するために用いられた。この用語は、近代的な産業部門の外側にあると見なされた雇用形態を記述するために使われた。[9] 2007年の別の定義では、雇用保障を正式性の尺度とし、インフォーマル経済の参加者を「雇用保障、労働保障、社会保障を持たない者」と定義している。 [10] これらの定義はいずれもインフォーマル経済への関与に選択の余地や主体性の欠如を暗示するが、規制や課税を回避したいという願望が参加の動機となる場合も ある。これは、税務・社会保障・労働法目的で国家から隠蔽される未申告雇用として現れるが、その他の側面では合法である。[11] 2016年、エドガー・L・ファイゲはインフォーマル経済を含む非観察経済を「制度的規則への非順守行動」の一形態として特徴付ける分類法を提案した。 [12] 彼は、最低賃金、労働条件、社会保障、失業・障害給付を規定する労働市場規制の回避がインフォーマル経済を生み出し、一部の労働者から正当な給付を奪いな がら、他の労働者に不当な利益をもたらすと論じている。 この用語は、同様に違法・無規制、あるいは国家の保護を受けられない住居形態や生活様式を説明・分析する際にも有用である。「インフォーマル経済」は、こうした活動を指す表現として「インフォーマルセクター」に取って代わりつつある。 住宅と生計手段の両面におけるインフォーマル性は、歴史的に社会悪と見なされ、参加者が欠くもの、あるいは回避しようとするものとして語られてきた。 2009年、オランダの社会学者サスキア・サッセンは、新たな「インフォーマル」セクターを先進資本主義の産物かつ推進力、そして芸術家・建築家・デザイ ナー・ソフトウェア開発者といった創造的専門職が主導する都市経済の最も起業家精神に富む領域と位置付けた[13]。このインフォーマルセクターの現れは 依然として先進国の特徴であるものの、発展途上国においても同様の資質を持つ人々の参加を促進するシステムが次第に現れつつある[14]。  2004年、バグダッドで闇市場の売り手が米兵に腕時計を売りつける。 |

| History Governments have tried to regulate aspects of their economies for as long as surplus wealth has existed which is at least as early as Sumer. Yet no such regulation has ever been wholly enforceable.[citation needed]  Daily life of the informal economy in the streets of Bolivia Archaeological and anthropological evidence strongly suggests that people of all societies regularly adjust their activity within economic systems in attempt to evade regulations.[citation needed] Therefore, if informal economic activity is that which goes unregulated in an otherwise regulated system then informal economies are as old as their formal counterparts, if not older.[citation needed] The term itself, however, is much more recent.[citation needed] The optimism of the modernization theory school of development had led people in the 1950s and 1960s to believe that traditional forms of work and production would disappear as a result of economic progress in developing countries.[citation needed] As this optimism proved to be unfounded, scholars turned to study more closely what was then called the traditional sector and found that the sector had not only persisted, but in fact expanded to encompass new developments.[citation needed] In accepting that these forms of productions were there to stay, scholars and some international organizations quickly took up the term informal sector (later known as the informal economy or just informality). The term Informal income opportunities is credited to the British anthropologist Keith Hart in a 1971 study on Ghana published in 1973,[15] and was coined by the International Labour Organization in a widely read study on Kenya in 1972.[citation needed] In his 1989 book The Underground Economies: Tax Evasion and Information Distortion, Edgar L. Feige examined the economic implications of a shift of economic activity from the observed to the non-observed sector of the economy. Such a shift not only reduces the government's ability to collect revenues, it can also bias the nation's information systems and therefore lead to misguided policy decisions. The book examines alternative means of estimating the size of various unobserved economies and examines their consequences in both socialist and market oriented economies.[16] Feige goes on to develop a taxonomic framework that clarifies the distinctions between informal, illegal, unreported and unrecorded economies, and identifies their conceptual and empirical linkages and the alternative means of measuring their size and trends.[17] Since then, the informal sector has become an increasingly popular subject of investigation in economics, sociology, anthropology and urban planning. With the turn towards so called post-fordist modes of production in the advanced developing countries, many workers were forced out of their formal sector work and into informal employment. In a 2005 collection of articles, The Informal Economy. Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries, the existence of an informal economy in all countries was demonstrated with case studies ranging from New York City and Madrid to Uruguay and Colombia.[18] |

歴史 政府は、余剰富が存在し始めたシュメール時代以来、経済の諸側面を規制しようとしてきた。しかし、そのような規制が完全に施行されたことは一度もない。[出典が必要]  ボリビアの路上におけるインフォーマル経済の日常 考古学的・人類学的証拠は、あらゆる社会の人々が規制回避のために経済システム内での活動を定期的に調整していることを強く示唆している。[出典が必要] したがって、インフォーマル経済活動とは、規制されたシステムの中で規制を受けない活動であるならば、インフォーマル経済は公式経済と同等か、それ以上に 古い歴史を持つと言える。[出典が必要] ただし、この用語自体ははるかに新しいものである。[出典が必要] 近代化理論派の開発学が抱いた楽観論は、1950年代から1960年代にかけて、発展途上国における経済的進歩の結果として、伝統的な労働形態や生産形態 が消滅すると人々に信じ込ませた。[出典が必要] この楽観論が根拠のないものであることが明らかになると、学者たちは当時「伝統的部門」と呼ばれていたものをより詳細に研究するようになった。その結果、 この部門が存続しているだけでなく、新たな発展を包含する形で拡大していることが判明した。[出典が必要] こうした生産形態が今後も存続することを受け入れる中で、学者や一部の国際機関は「インフォーマル部門」(後にインフォーマル経済または単にインフォーマ リティとして知られる)という用語を迅速に採用した。「インフォーマルな収入機会」という用語は、1973年に出版された1971年のガーナ研究において 英国人類学者キース・ハートが提唱したとされている[15]。また国際労働機関(ILO)が1972年に発表したケニアに関する広く読まれた研究でこの用 語が用いられた[出典必要]。 エドガー・L・ファイゲは1989年の著書『地下経済:脱税と情報歪曲』において、経済活動が観察可能な部門から非観察部門へ移行することの経済的影響を 検証した。このような移行は政府の歳入徴収能力を低下させるだけでなく、国家の情報システムに偏りを生じさせ、誤った政策決定を招く恐れがある。本書は様 々な非観察経済の規模を推定する代替手段を検討し、社会主義経済と市場志向経済の両方におけるその帰結を検証している[16]。ファイゲはさらに、イン フォーマル経済、違法経済、未申告経済、未記録経済の区別を明確化する分類枠組みを構築し、それらの概念的・実証的関連性、および規模と動向を測定する代 替手段を特定している。[17] その後、非公式部門は経済学、社会学、人類学、都市計画においてますます研究対象として注目されるようになった。先進途上国におけるいわゆるポスト・ フォード主義的生産様式への転換に伴い、多くの労働者が公式部門の仕事を失い、非公式雇用に追いやられた。2005年の論文集『先進国と発展途上国におけ るインフォーマル経済』では、ニューヨーク市やマドリードからウルグアイやコロンビアに至る事例研究を通じて、全ての国にインフォーマル経済が存在する事 実が示された。[18] 先進国と発展途上国における研究』では、ニューヨーク市やマドリードからウルグアイやコロンビアに至る事例研究を通じて、全ての国にインフォーマル経済が 存在することが実証された。[18] |

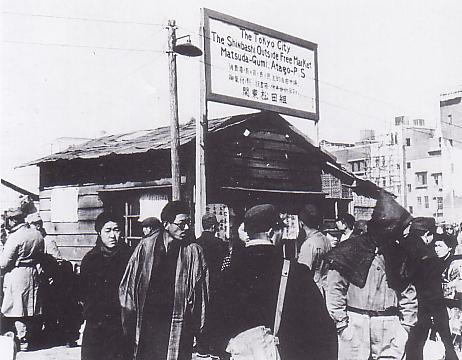

Black market in Shinbashi, Japan, 1946 An influential book on the informal economy is Hernando de Soto's El otro sendero (1986),[19] which was published in English in 1989 as The Other Path with a preface by Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa.[20] De Soto and his team argued that excessive regulation in the Peruvian and other Latin American economies forced a large part of the economy into informality and thus prevented economic development. While accusing the ruling class of 20th century mercantilism, de Soto admired the entrepreneurial spirit of the informal economy. In a widely cited experiment, his team tried to legally register a small garment factory in Lima. This took more than 100 administrative steps and almost a year of full-time work. Feige's review of the Other Path places the work in the context of the informal economy literature.[21] Whereas de Soto's work is popular with policymakers and champions of free market policies like The Economist, some scholars of the informal economy have criticized it both for methodological flaws and normative bias.[22] In the second half of the 1990s many scholars started to consciously use the term "informal economy" instead of "informal sector" to refer to a broader concept which includes enterprises as well as employment in developing, transition, and advanced industrialized economies.[citation needed] Among the surveys about the size and development of the shadow economy (mostly expressed in percent of official GDP) are those by Feige (1989), and Schneider and Enste (2000) with an intensive discussion about the various estimation procedures of the size of the shadow economy as well as a critical evaluation of the size of the shadow economy and the consequences of the shadow economy on the official one.[23][24] Feige's most recent survey paper on the subject from 2016 reviewed the meaning and measurement of unobserved economies and is particularly critical of estimates of the size of the so-called shadow economy which employ Multiple Indicator multiple cause methods, which treat the shadow economy as a latent variable.[25] |

日本・新橋の闇市場、1946年 インフォーマル経済に関する影響力のある書籍として、エルナンド・デ・ソトの『エル・オトロ・センデロ』(1986年)[19]がある。これは1989年 に英語版『ザ・アザー・パス』として出版され、ペルーの作家マリオ・バルガス・リョサによる序文が添えられている。[20] デ・ソトとその研究チームは、ペルーやその他のラテンアメリカ諸国における過剰な規制が経済の大部分をインフォーマル経済へと追いやった結果、経済発展が 阻害されたと主張した。20世紀の支配階級を重商主義と非難しつつも、デ・ソトはインフォーマル経済の起業家精神を称賛した。広く引用される実験では、彼 のチームがリマの小さな縫製工場を合法的に登録しようと試みた。この手続きには100以上の行政上のステップと、ほぼ1年間のフルタイム労働を要した。 フェイジによる『もうひとつの道』の書評は、この研究をインフォーマル経済文献の文脈に位置づけている。[21] デ・ソトの研究は政策立案者や『エコノミスト』誌のような自由市場政策の擁護者に人気がある一方、インフォーマル経済の研究者の中には、方法論的欠陥と規 範的偏向の両方を理由に批判する者もいる。[22] 1990年代後半には、多くの研究者が「インフォーマルセクター」に代わって「インフォーマル経済」という用語を意図的に使用し始めた。これは発展途上国、移行期経済、先進工業国における企業活動と雇用を含むより広範な概念を指すものである。[出典が必要] 影の経済の規模と発展に関する調査(主に公式GDPに対する割合で表現される)としては、ファイゲ(1989年)やシュナイダーとエンステ(2000年) によるものがある。これらは影の経済の規模に関する様々な推定手法について詳細な議論を行い、影の経済の規模と公式経済への影響を批判的に評価している。 [23][24] ファイゲによる2016年の最新調査論文は、観測不能経済の意味と測定法を検証し、特に「影の経済」を潜在変数として扱う多重指標多重原因法を用いた推定 値に対して批判的である。[25] |

Characteristics Waste picker in Indonesia  Street vendor in Colombia  Street vendor in India The informal sector is largely characterized by several qualities: skills gained outside of a formal education, easy entry (meaning anyone who wishes to join the sector can find some sort of work which will result in cash earnings), a lack of stable employer-employee relationships,[26] and a small scale of operations.[4] Workers who participate in the informal economy are typically classified as employed. The type of work that makes up the informal economy is diverse, particularly in terms of capital invested, technology used, and income generated.[4][26] The spectrum ranges from self-employment or unpaid family labor[26] to street vendors, shoe shiners, and junk collectors.[4] On the higher end of the spectrum are upper-tier informal activities such as small-scale service or manufacturing businesses, which have more limited entry.[4][26] The upper-tier informal activities have higher set-up costs, which might include complicated licensing regulations, and irregular hours of operation.[26] However, most workers in the informal sector, even those are self-employed or wage workers, do not have access to secure work, benefits, welfare protection, or representation.[5] These features differ from businesses and employees in the formal sector which have regular hours of operation, a regular location and other structured benefits.[26] According to a 2018 study on informality in Brazil, there are three views to explain the causes of informality. The first view argues that the informal sector is a reservoir of potentially productive entrepreneurs who are kept out of formality by high regulatory costs, most notably entry regulation. The second sees informal forms as "parasitic forms" which are productive enough to survive in the formal sector but choose to remain informal to earn higher profits from the cost advantages of not complying with taxes and regulations. The third argues that informality is a survival strategy for low-skill individuals, who are too unproductive to ever become formal. According to the study the first view corresponds to 9.3 percent of all informal forms, while the second corresponds to 41.9 percent. The remaining forms correspond to low-skill entrepreneurs who are too unproductive to ever become formal. The author suggests that informal forms are to a large extent "parasitic" and therefore eradicating them (e.g., through tighter enforcement) could produce positive effects on the economy. [27] The most prevalent types of work in the informal economy are home-based workers and street vendors. Home-based workers are more numerous while street vendors are more visible. Combined, the two fields make up about 10–15% of the non-agricultural workforce in developing countries and over 5% of the workforce in developed countries.[5] While participation in the informal sector can be stigmatized, many workers engage in informal ventures by choice, for either economic or non-economic reasons. Economic motivations include the ability to evade taxes, the freedom to circumvent regulations and licensing requirements, and the capacity to maintain certain government benefits.[28] A study of informal workers in Costa Rica illustrated other economic reasons for staying in the informal sector, as well as non-economic factors. First, they felt they would earn more money through their informal sector work than at a job in the formal economy. Second, even if workers made less money, working in the informal sector offered them more independence, the chance to select their own hours, the opportunity to work outside and near friends, etc. While jobs in the formal economy might bring more security and regularity, or even pay better, the combination of monetary and psychological rewards from working in the informal sector proves appealing for many workers.[29] The informal sector was historically recognized as an opposition to formal economy, meaning it included all income earning activities beyond legally regulated enterprises. However, this understanding is too inclusive and vague, and certain activities that could be included by that definition are not considered part of the informal economy. As the International Labour Organization defined the informal sector in 2002, the informal sector does not include the criminal economy. While production or employment arrangements in the informal economy may not be strictly legal, the sector produces and distributes legal goods and services. The criminal economy produces illegal goods and services.[5] The informal economy also does not include the reproductive or care economy, which is made up of unpaid domestic work and care activities. The informal economy is part of the market economy, meaning it produces goods and services for sale and profit. Unpaid domestic work and care activities do not contribute to that, and as a result, are not a part of the informal economy.[5] |

特徴 インドネシアの廃品回収業者  コロンビアの路上販売者  インドの路上販売者 非公式部門は主にいくつかの特徴を持つ:正式な教育以外で習得した技能、参入の容易さ(つまりこの部門に加わりたい者は誰でも何らかの仕事を見つけ現金収 入を得られる)、安定した雇用主と従業員の関係の欠如[26]、そして小規模な事業運営である。[4] インフォーマル経済に参加する労働者は通常、雇用者として分類される。インフォーマル経済を構成する仕事の種類は多様であり、特に投資される資本、使用さ れる技術、生み出される収入の面で顕著である。[4][26] その範囲は自営業や無給の家族労働[26]から、路上販売者、靴磨き、廃品回収業者まで及ぶ[4]。上位層には小規模サービス業や製造業など参入障壁の高 い非公式活動が位置する[4][26]。上位層の非公式活動は複雑な免許規制を含む高い設立コストや不規則な営業時間を伴う[26]。しかし、非公式部門 の労働者の大半は、自営業者や賃金労働者であっても、安定した雇用、福利厚生、社会保障、労働組合の保護を受けられない。[5] こうした特徴は、定時営業、固定店舗、その他の制度化された福利厚生を有する公式部門の企業や従業員とは異なる。[26] 2018年のブラジルにおける非公式経済に関する研究によれば、非公式経済の原因を説明する三つの見解がある。第一の見解は、非公式部門は潜在的に生産的 な起業家の貯蔵庫であり、高い規制コスト、特に参入規制によって公式部門から締め出されていると主張する。第二の見解は、非公式形態を「寄生形態」と捉え る。これらは公式部門で生存できるだけの生産性を持つが、税金や規制を遵守しないコスト優位性からより高い利益を得るため、非公式のままでいることを選択 している。第三の見解は、非正規性が低技能者にとっての生存戦略であり、彼らは生産性が低すぎて正規化できないと主張する。本研究によれば、第一の見解に 該当する形態は全非正規形態の9.3%、第二の見解に該当する形態は41.9%を占める。残りの形態は、生産性が低すぎて正規化できない低技能起業家に該 当する。著者は、非公式形態は大部分が「寄生的」であり、したがって(例えば取り締まりの強化を通じて)それらを根絶することは経済にプラスの効果をもた らし得ると示唆している。[27] インフォーマル経済における最も一般的な労働形態は、在宅労働者と路上販売者である。在宅労働者は数が多いが、路上販売者はより目立つ。両者を合わせると、開発途上国では非農業労働力の約10~15%、先進国では労働力の5%以上を占める。[5] 非公式部門への参加は社会的に軽蔑されることもあるが、多くの労働者は経済的または非経済的理由から自発的に非公式事業に従事している。経済的動機には、 税金の回避、規制や免許要件の回避の自由、特定の政府給付を維持する能力などが含まれる。[28] コスタリカの非公式労働者に関する研究では、非公式部門に留まる他の経済的理由と非経済的要因が示された。第一に、非公式部門での仕事の方が公式経済の職 より収入が多いと感じていた。第二に、収入が少なくても非公式部門ではより多くの独立性、自身の労働時間選択の機会、屋外や友人近くで働く機会などが得ら れると認識していた。正規経済の職はより安定性と規則性、あるいはより高い賃金をもたらすかもしれないが、非正規部門で働くことによる金銭的・心理的報酬 の組み合わせは、多くの労働者にとって魅力的であることが証明されている。[29] 非正規部門は歴史的に正規経済に対する対極として認識され、法的に規制された企業以外の全ての所得創出活動を含むとされてきた。しかしこの理解は包括的か つ曖昧であり、その定義に含まれ得る特定の活動がインフォーマル経済の一部と見なされない場合がある。国際労働機関(ILO)が2002年に定義したイン フォーマル経済には、犯罪経済は含まれない。インフォーマル経済における生産や雇用形態は厳密には合法ではないかもしれないが、この部門は合法的な財や サービスを生産・流通させる。犯罪経済は違法な財やサービスを生産する。[5] インフォーマル経済には、無償の家事労働やケア活動で構成される再生産経済・ケア経済も含まれない。インフォーマル経済は市場経済の一部であり、販売と利 益を目的とした財・サービスの生産を行う。無償の家事労働やケア活動はこれに寄与しないため、インフォーマル経済の一部とはみなされない。[5] |

| Statistics See also: List of countries by share of informal employment in total employment See also: List of countries by informal GDP (nominal)  The Narantuul Market in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, colloquially also called Khar Zakh (Black Market) The informal economy under any governing system is diverse and includes small-scaled, occasional members (often street vendors and garbage recyclers) as well as larger, regular enterprises (including transit systems such as that of La Paz, Bolivia). Informal economies include garment workers working from their homes, as well as informally employed personnel of formal enterprises. Employees working in the informal sector can be classified as wage workers, non-wage workers, or a combination of both.[6] Statistics on the informal economy are unreliable by virtue of the subject, yet they can provide a tentative picture of its relevance. For example, informal employment makes up 58.7% of non-agricultural employment in Middle East – North Africa, 64.6% in Latin America, 79.4% in Asia, and 80.4% in sub-Saharan Africa.[30] If agricultural employment is included, the percentages rise, in some countries like India and many sub-Saharan African countries beyond 90%. Estimates for developed countries are around 15%.[5] In recent surveys, the informal economy in many regions has declined over the past 20 years to 2014. In Africa, the share of the informal economy has decreased to an estimate of around 40% of the economy.[31] In developing countries, the largest part of informal work, around 70%, is self-employed. Wage employment predominates. The majority of informal economy workers are women. Policies and developments affecting the informal economy have thus a distinctly gendered effect. |

統計 関連項目: 非正規雇用率別国別一覧 関連項目: 非公式GDP(名目)別国別一覧  モンゴル・ウランバートルのナラントゥール市場。通称「カルザク(闇市場)」とも呼ばれる いかなる統治体制下においても、インフォーマル経済は多様であり、小規模で不定期な参加者(路上販売者や廃品回収業者など)から、より大規模で定期的な事 業体(ボリビアのラパスにおける交通システムを含む)までを含む。インフォーマル経済には、自宅で働く縫製労働者や、公式企業の非公式雇用者も含まれる。 インフォーマル部門で働く従業員は、賃金労働者、非賃金労働者、あるいはその両方の組み合わせとして分類される。[6] インフォーマル経済に関する統計は、その性質上信頼性に欠けるが、その重要性を示す暫定的な見通しを提供し得る。例えば、インフォーマル雇用は中東・北ア フリカ地域では非農業雇用の58.7%、ラテンアメリカでは64.6%、アジアでは79.4%、サハラ以南アフリカでは80.4%を占める。[30] 農業雇用を含めると、インドや多くのサハラ以南アフリカ諸国など一部の国では90%を超える。先進国の推定値は約15%である。[5] 最近の調査では、多くの地域で2014年までの過去20年間にインフォーマル経済は縮小した。アフリカではインフォーマル経済の割合が経済全体の約40% に減少したと推定される。[31] 発展途上国では、非公式労働の大部分(約70%)が自営業である。賃金労働が主流だ。インフォーマル経済労働者の大多数は女性である。したがって、インフォーマル経済に影響を与える政策や動向は、明確なジェンダー効果を持つ。 |

| Estimated size of countries' informal economy To estimate the size and development of any underground or shadow economy is quite a challenging task since participants in such economies attempt to hide their behaviors. One must also be very careful to distinguish whether one is attempting to measure the unreported economy, normally associated with tax evasion,[32] or the unrecorded or non-observed economy,[33] associated with the amount of income that is readily excluded from national income and produce accounts due to the difficulty of measurement. There are numerous estimates of tax noncompliance as measured by tax gaps produced by audit methods or by "top down" methods.[34] Friedrich Schneider and several co-authors[35] claim to have estimated the size and trend of what they call the "shadow economy" worldwide by a currency demand /MIMIC model approach that treats the "shadow economy" as a latent variable. Trevor S. Breusch has critiqued the work and warned the profession that the literature applying this model to the underground economy abounds with alarming Procrustean tendencies. Various kinds of sliding and scaling of the results are carried out in the name of "benchmarking", although these operations are not always clearly documented. The data are typically transformed in ways that are not only undeclared but have the unfortunate effect of making the results of the study sensitive to the units in which the variables are measured. The complexity of the estimation procedure, together with its deficient documentation, leave the reader unaware of how these results have been shorted to fit the bed of prior belief. There are many other results in circulation for various countries, for which the data cannot be identified and which are given no more documentation than "own calculations by the MIMIC method". Readers are advised to adjust their valuation of these estimates accordingly.[36] Edgar L. Feige[37] finds that Schneider's shadow economy "estimates suffer from conceptual flaws, apparent manipulation of results and insufficient documentation for replication, questioning their place in the academic, policy and popular literature". |

各国のインフォーマル経済の推定規模 地下経済や影の経済の規模と発展を推定することは、非常に困難な作業である。なぜなら、こうした経済の参加者は自らの行動を隠そうとするからだ。また、測 定対象が脱税と通常関連付けられる「申告されていない経済」[32]なのか、それとも測定の難しさから国民所得・生産勘定から容易に除外される所得額に関 連する「記録されていない経済」あるいは「観察されていない経済」[33]なのかを区別する際には、細心の注意を払わねばならない。監査手法や「トップダ ウン」手法によって算出される税収ギャップに基づく、税務非遵守の推定値は数多く存在する。[34] フリードリヒ・シュナイダーら複数の共著者は[35]、通貨需要/MIMICモデルアプローチを用いて、いわゆる「シャドー経済」を潜在変数として扱い、 その規模と世界的な傾向を推定したと主張している。トレバー・S・ブルーシュはこの研究を批判し、このモデルを地下経済に適用する文献には、憂慮すべきプ ロクルステスの傾向が蔓延していると専門家に警告している。「ベンチマーキング」の名の下に様々な結果のスライディングやスケーリングが行われるが、これ らの操作は必ずしも明確に文書化されていない。データは通常、宣言されていない方法に変換されるだけでなく、変数の測定単位に研究結果が依存するという不 幸な結果をもたらす。 推定手順の複雑さと不十分な文書化が相まって、読者はこれらの結果が如何に事前信念の枠に収まるよう調整されたかを知らされない。様々な国について流通し ている他の多くの結果も、データが特定できず、「MIMIC法による独自計算」以上の説明が与えられていない。読者はこれらの推定値の評価をそれに応じて 調整すべきである。[36] エドガー・L・ファイゲ[37]は、シュナイダーの影の経済に関する「推定値は概念的な欠陥、結果の明らかな操作、再現のための不十分な文書化に苦悩しており、学術・政策・大衆文献におけるその位置付けを疑問視している」と指摘している。 |

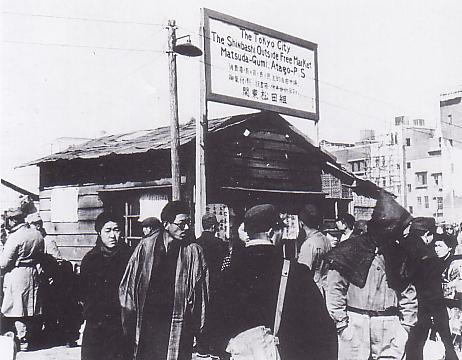

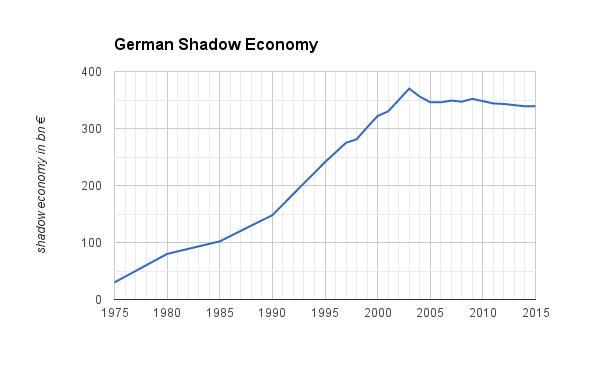

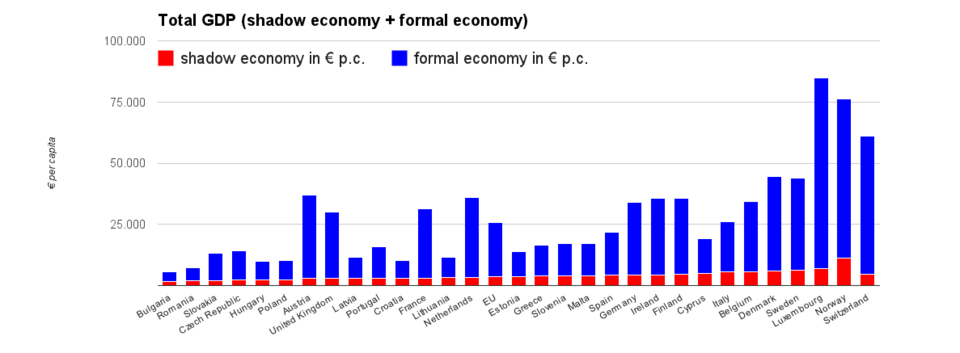

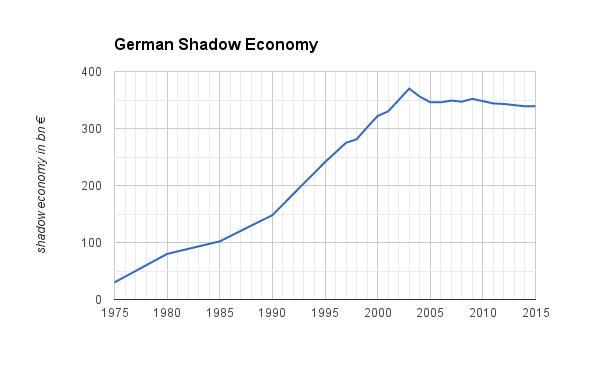

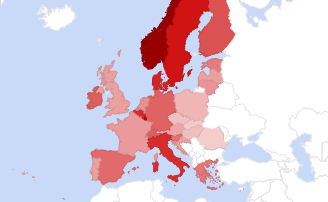

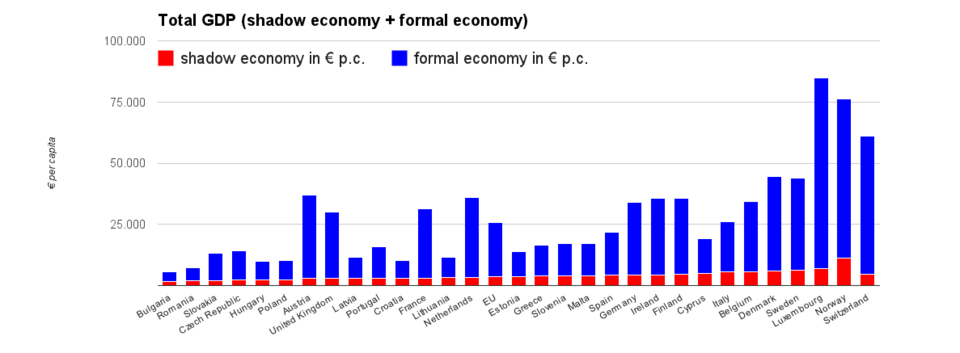

Comparison of shadow economies in EU countries German shadow economy 1975–2015, Friedrich Schneider University Linz[38] As of 2013, the total EU shadow economy had been growing to about 1.9 trillion € in preparation of the EURO[39] driven by the motor of the European shadow economy, Germany, which had been generating approx. 350 bn € per year[38] since the establishment of the Single Market in Maastricht 1993, (see diagram on the right). Hence, the EU financial economy had developed an efficient tax haven bank system to protect and manage its growing shadow economy. As per the Financial Secrecy Index (FSI 2013)[40] Germany and some neighbouring countries, ranked among the world's top tax haven countries. The diagram below shows that national informal economies per capita vary only moderately in most EU countries. This is because market sectors with a high proportion of informal economy (above 45%)[41] like the construction sector or agriculture are rather homogeneously distributed across countries, whereas sectors with a low proportion of informal economy (below 30%)[41] like the finance and business sector (e.g. in Switzerland, Luxembourg), the public service and personal Service Sector (as in Scandinavian countries) as well as the retail industry, wholesale and repair sector are dominant in countries with extremely high GDP per capita i.e. industrially highly developed countries. The diagram also shows that in absolute numbers the shadow economy per capita is related to the wealth of a society (GDP). Generally spoken, the higher the GDP the higher the shadow economy, albeit non-proportional. There is a direct relationship between high self-employment of a country to its above average shadow economy.[42] In highly industrialized countries where shadow economy (per capita) is high and the huge private sector is shared by an extremely small elite of entrepreneurs a considerable part of tax evasion is practised by a much smaller number of (elite) people. As an example German shadow economy in 2013 was €4.400 per capita, which was the 9th highest place in EU, whereas according to OECD only 11.2% of employed people were self-employed (place 18).[43] On the other hand, Greece's shadow economy was only €3.900 p.c (place 13) but self-employment was 36.9% (place 1). An extreme example of shadow economy camouflaged by the financial market is Luxembourg where the relative annual shadow economy is only 8% of the GDP which is the second lowest percentage (2013) of all EU countries whereas its absolute size (€6.800 per capita) is the highest.  Map of the national shadow economies per capita in EU countries. The red scale represents the numbers displayed by the red bars of the diagram on the left.  The total national GDP of EU countries, and its formal and informal (shadow economy) component per capita[39][44] |

EU諸国の影の経済比較 ドイツの影の経済 1975–2015年、フリードリヒ・シュナイダー大学リンツ校[38] 2013年時点で、EU全体の影の経済はユーロ導入に備え約1.9兆ユーロまで拡大していた[39]。その原動力となったのは欧州影の経済の中心であるド イツであり、1993年のマーストリヒト単一市場発足以降、年間約3,500億ユーロを生み出していた[38](右図参照)。したがってEUの金融経済 は、拡大する影の経済を保護・管理するため効率的なタックスヘイブン銀行システムを発展させてきた。金融秘密指数(FSI 2013)[40]によれば、ドイツ及び近隣諸国は世界トップクラスのタックスヘイブン国にランクインしている。 下図が示す通り、EU諸国の国民一人当たりインフォーマル経済規模には大きな差がない。これは建設業や農業などインフォーマル経済比率が高い(45%超) [41]分野が各国で均質に分布する一方、金融・ビジネス分野(例:スイス、ルクセンブルク)、公共サービス・個人サービス分野(例:スカンジナビア諸 国)、小売・卸売・修理業などインフォーマル経済比率が低い(30%未満) [41](例:スイス、ルクセンブルク)や公共サービス・個人的サービス業(例:スカンジナビア諸国)、小売業・卸売業・修理業などのセクターは、極めて 高い一人当たりGDPを有する、すなわち高度に工業化された国々で支配的である。図はまた、絶対値において一人当たり影の経済が社会の富(GDP)と関連 していることも示している。一般的に、GDPが高いほど影の経済も大きくなるが、比例関係にはない。 国の自営業率の高さと、平均を上回る影の経済の規模には直接的な関係がある。[42] 影の経済(一人当たり)が高く、巨大な民間部門がごく少数の起業家エリートによって共有されている高度に工業化された国では、脱税の相当部分がはるかに少 ない(エリート)人々によって行われている。例として、2013年のドイツの闇経済は一人当たり4,400ユーロでEU9位だったが、OECD統計では自 営業者は雇用者のわずか11.2%(18位)だった。[43] 一方、ギリシャの闇経済は1人当たりわずか3,900ユーロ(13位)だったが、自営業者は36.9%(1位)だった。 金融市場によって覆い隠された闇経済の極端な例がルクセンブルクである。同国の相対的な年間闇経済規模はGDPのわずか8%で、EU全加盟国中2番目に低い割合(2013年)である一方、絶対規模(一人当たり6,800ユーロ)は最高である。  EU加盟国の一人当たり闇経済規模マップ。赤色スケールは左図の赤色バーが示す数値を表す。  EU諸国の総国内総生産(GDP)および一人当たり公式・インフォーマル経済(影の経済)構成要素[39][44] |

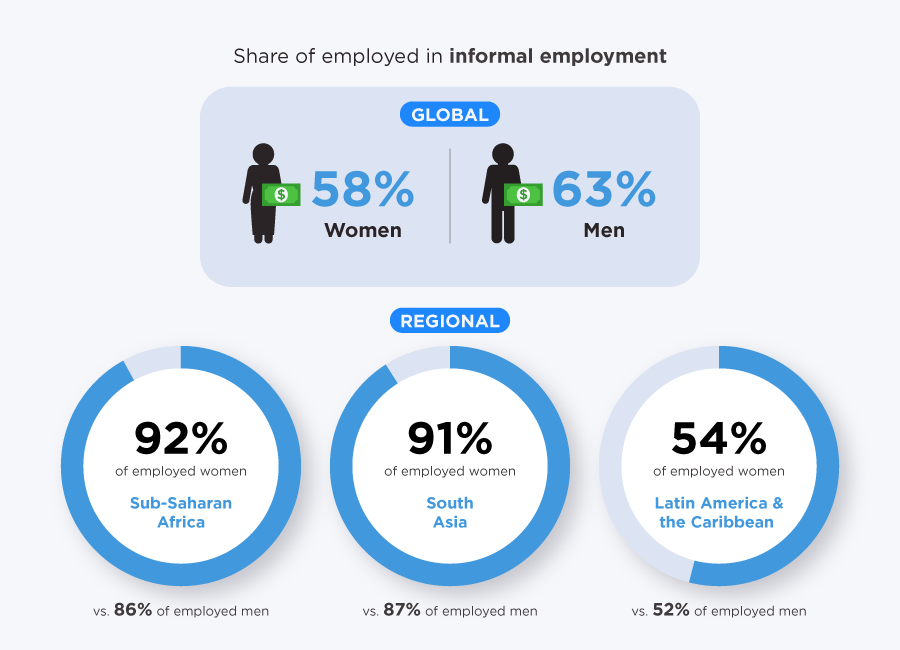

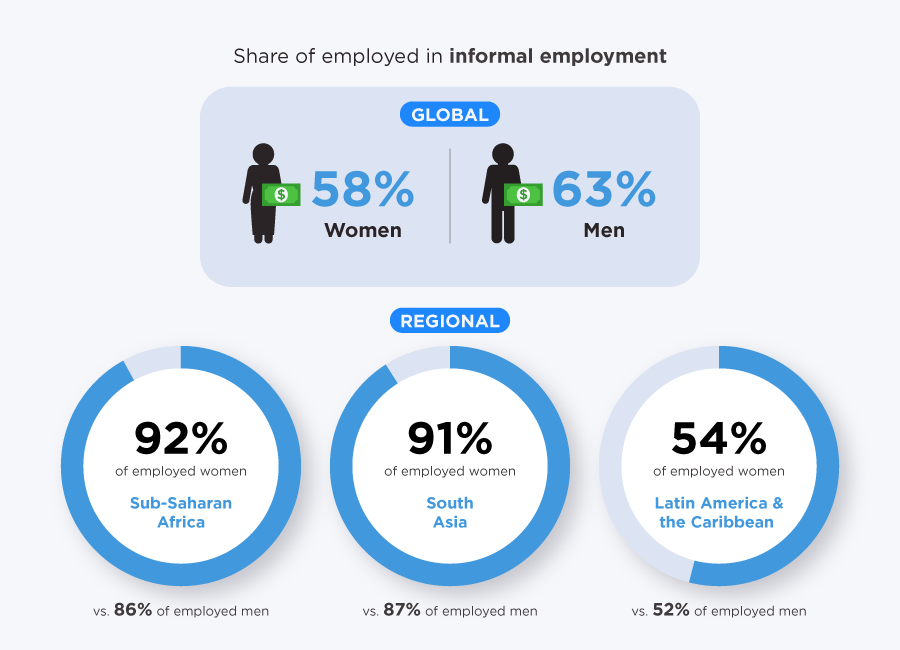

Social and political implications and issues Share of employed in informal employment by gender According to development and transition theories, workers in the informal sector typically earn less income, have unstable income, and do not have access to basic protections and services.[45][46] The informal economy is also much larger than most people realize, with women playing a huge role. The working poor, particularly women, are concentrated in the informal economy, and most low-income households rely on the sector to provide for them.[5] However, informal businesses can also lack the potential for growth, trapping employees in menial jobs indefinitely. On the other hand, the informal sector can allow a large proportion of the population to escape extreme poverty and earn an income that is satisfactory for survival.[47] Also, in developed countries, some people who are formally employed may choose to perform part of their work outside of the formal economy, exactly because it delivers them more advantages. This is called 'moonlighting'. They derive social protection, pension and child benefits and the like, from their formal employment, and at the same time have tax and other advantages from working on the side. From the viewpoint of governments, the informal sector can create a vicious cycle. Being unable to collect taxes from the informal sector, the government may be hindered in financing public services, which in turn makes the sector more attractive. Conversely, some governments view informality as a benefit, enabling excess labor to be absorbed, and mitigating unemployment issues.[47] Recognizing that the informal economy can produce significant goods and services, create necessary jobs, and contribute to imports and exports is critical for governments.[5] As the work in informal sector is not monitored or registered with the state, its workers are not entitled to social security, and they face unique challenges when affiliated in or creating trade unions.[48] Informal economy workers are more likely to work long hours than workers in the formal economy who are protected by employment laws and regulations. A landmark study conducted by the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization found that exposure to long working hours caused an estimated 745,000 fatalities from ischemic heart disease and stroke events in 2016.[49] A systematic review and meta-analysis of health services use and health outcomes among informal economy workers, when compared with formal economy workers, found that these workers are less likely to use health services and more likely to have depression, highlighting their substantial health disadvantage.[50] |

社会的・政治的含意と課題 非正規雇用におけるジェンダー別雇用者比率 発展理論と移行理論によれば、非正規部門の労働者は一般的に収入が低く、収入が不安定であり、基本的な保護やサービスを受けられない。[45][46] インフォーマル経済はまた、多くの人が認識しているよりもはるかに規模が大きく、女性が大きな役割を果たしている。ワーキングプア、特に女性はインフォー マル経済に集中しており、低所得世帯の大半はこのセクターに依存して生計を立てている。[5] しかしインフォーマル事業は成長の可能性に乏しく、従業員を低賃金の仕事に永久に閉じ込めることもある。一方でインフォーマルセクターは、人口の大部分が 極度の貧困から脱却し、生存に十分な収入を得ることを可能にする。[47] また先進国では、正規雇用されている人々が、より多くの利点を得るために、仕事の一部をインフォーマル経済で行うことを選ぶ場合もある。これは「副業」と 呼ばれる。彼らは正規雇用から社会保障、年金、児童手当などを得ると同時に、副業から税金やその他の利点を得ているのだ。 政府の視点から見ると、インフォーマルセクターは悪循環を生み出す可能性がある。非公式部門から税収を得られないため、政府は公共サービスの財源確保に支 障をきたし、それが逆に非公式部門の魅力を高める。逆に、非公式性を余剰労働力の吸収や失業問題緩和の手段と捉え、有益と考える政府もある。[47] インフォーマル経済が重要な財・サービスを生産し、必要な雇用を創出し、輸出入に貢献し得ることを政府が認識することは極めて重要である。[5] 非公式部門での労働は国家による監視や登録の対象外であるため、労働者は社会保障を受ける権利がなく、労働組合への加入や結成においても特有の困難に直面 する。[48] インフォーマル経済の労働者は、雇用法や規制で保護されている公式経済の労働者よりも長時間労働を強いられる傾向が強い。世界保健機関(WHO)と国際労 働機関(ILO)による画期的な研究では、長時間労働への曝露が2016年に虚血性心疾患と脳卒中による死亡を推定74万5000件引き起こしたと報告さ れている。[49] インフォーマル経済労働者と公式経済労働者を比較した医療サービス利用状況と健康結果に関する系統的レビュー及びメタ分析では、インフォーマル経済労働者 は医療サービスを利用する可能性が低く、うつ病を発症する可能性が高いことが判明し、彼らの健康面での著しい不利が浮き彫りとなった。[50] |

Gender A group of Indian women making bamboo products they intend to sell in Dumka, Jharkhand  A girl selling plastic containers for carrying Ganges water, Haridwar, India In developing countries, most of the female non-agricultural labor force is in the informal sector.[51] Female representation in the informal sector is attributed to a variety of factors. One such factor is that employment in the informal sector is the source of employment that is most readily available to women.[52] A 2011 study of poverty in Bangladesh noted that cultural norms, religious seclusion, and illiteracy among women in many developing countries, along with a greater commitment to family responsibilities, prevent women from entering the formal sector.[53] Major occupations in the informal sector include home-based workers (such as dependent subcontract workers, independent own account producers, and unpaid workers in family businesses) and street vendors, which both are classified in the informal sector.[52] Women tend to make up the greatest portion of the informal sector, often ending up in the most erratic and corrupt segments of the sector.[45] In India, women working in the informal sector often work as ragpickers, domestic workers, coolies, vendors, beauticians, construction laborers, and garment workers. According to a 2002 study commissioned by the ILO, the connection between employment in the informal economy and being poor is stronger for women than men.[6] While men tend to be over-represented in the top segment of the informal sector, women overpopulate the bottom segment.[6][45] Men are more likely to have larger-scale operations and deal in non-perishable items while few women are employers who hire others.[6] Instead, women are more likely to be involved in smaller-scale operations and trade food items.[6] Women are under-represented in higher-income employment positions in the informal economy and over-represented in lower-income statuses.[6] As a result, the gender gap in terms of wage is higher in the informal sector than the formal sector.[6] Labor markets, household decisions, and states all propagate this gender inequality.[45] |

ジェンダー ジャールカンド州ダムカで竹製品を作り販売するインド人女性グループ  ガンジス川の水を運ぶプラスチック容器を売る少女、インド・ハリドワール 発展途上国では、非農業部門の女性労働力の大半がインフォーマルセクターに属している[51]。インフォーマルセクターにおける女性の割合が高い背景には 様々な要因がある。その一つは、非公式部門での雇用が女性にとって最も容易に入手可能な雇用源であることだ[52]。2011年のバングラデシュ貧困調査 では、多くの発展途上国における女性の文化的規範、宗教的隔離、非識字率の高さ、そして家族責任への強い関与が、女性の公式部門への参入を妨げていると指 摘されている。[53] 非公式部門の主要な職業には、在宅労働者(従属的な下請け労働者、独立した自営生産者、家族経営事業における無給労働者など)と路上販売業者が含まれ、い ずれも非公式部門に分類される。[52] 女性は非公式部門の最大の割合を占める傾向があり、しばしば同部門で最も不安定で腐敗した分野に追いやられる。[45] インドでは、非公式部門で働く女性は、廃品回収業者、家事労働者、荷役労働者、行商人、美容師、建設労働者、縫製労働者として働くことが多い。 ILOが委託した2002年の研究によれば、インフォーマル経済での雇用と貧困の関連性は、男性よりも女性においてより強い。[6] 男性はインフォーマル部門の上位層に過度に集中する傾向がある一方、女性は最下層に過剰に集中している。[6][45] 男性は大規模な事業運営や非消耗品の取引を行う可能性が高く、他人を雇用する雇用主となる女性はほとんどいない。[6] 代わりに女性は小規模事業や食品取引に関わる傾向が強い。[6] インフォーマル経済において、女性は高収入職に就く割合が低く、低収入層に集中している。[6] その結果、賃金におけるジェンダー格差は公式部門よりインフォーマル経済でより大きい。[6] 労働市場、家計の意思決定、国家体制の全てが、このジェンダー不平等を助長している。[45] |

| Political power of agents Workers in the informal economy lack a significant voice in government policy.[28] Not only is the political power of informal workers limited, but the existence of the informal economy creates challenges for other politically influential actors. For example, the trade unions struggle to organize the informal economy and often formal workers organized in unions have no immediate interest in improving the status of informal workers due to fears of status loss. Yet the informal economy negatively affects membership and investment in the trade unions. Laborers who might be formally employed and join a union for protection may choose to branch out on their own instead. While this hostile attitude is not always the case, the nature of informal employment - low and irregular income that is not enough to pay union dues, fast-changing decentralized work locations and a self-perception of informal workers as self-employed pose barriers to informal economy trade union organizing.[54] As a result, trade unions are inclined to oppose the informal sector, highlighting the costs and disadvantages of the system. Producers in the formal sector can similarly feel threatened by the informal economy. The flexibility of production, low labor and production costs, and bureaucratic freedom of the informal economy can be seen as consequential competition for formal producers, leading them to challenge and object to that sector. Last, the nature of the informal economy is largely anti-regulation and free of standard taxes, which diminishes the material and political power of government agents. Whatever the significance of these concerns are, the informal sector can shift political power and energies.[28] |

インフォーマル経済における労働者の政治的権力 インフォーマル経済の労働者は政府政策において実質的な発言権を持たない。[28] インフォーマル労働者の政治的権力が限定されているだけでなく、インフォーマル経済の存在自体が他の政治的影響力を持つ主体にとって課題を生む。例えば労 働組合はインフォーマル経済の組織化に苦戦し、組合に組織化された公式労働者は地位喪失を恐れてインフォーマル労働者の地位向上に直接的な関心を示さない ことが多い。しかしインフォーマル経済は労働組合の組合員数や投資に悪影響を及ぼす。正規雇用され保護のために組合に加入する可能性のある労働者も、代わ りに独立して事業を展開することを選ぶかもしれない。この敵対的な態度が常に当てはまるわけではないが、インフォーマル雇用の性質―組合費を支払うのに十 分でない低額かつ不規則な収入、急速に変化する分散型の作業場所、そして非公式労働者自身が自営業者であると認識していること―が、インフォーマル経済に おける労働組合の組織化に障壁となっている。[54] その結果、労働組合は非公式部門に反対する傾向があり、そのシステムのコストと欠点を強調する。公式部門の生産者も同様に、インフォーマル経済に脅威を感 じる。インフォーマル経済の生産の柔軟性、低い労働・生産コスト、官僚的制約からの自由は、公式生産者にとって重大な競争要因と見なされ、彼らがこのセク ターに異議を唱える原因となる。最後に、インフォーマル経済の本質は規制に反し標準的な課税を免れるため、政府関係者の物質的・政治的権力を弱体化させ る。こうした懸念の重要性にかかわらず、インフォーマルセクターは政治的権力とエネルギーを転換しうるのである。[28] |

Poverty Informal vendors in Uttar Pradesh The relationship between the informal sectors and poverty certainly is not simple nor does a clear, causal relationship exist. An inverse relationship between an increased informal sector and slower economic growth has been observed though.[45] Average incomes are substantially lower in the informal economy and there is a higher preponderance of impoverished employees working in the informal sector.[55] In addition, workers in the informal economy are less likely to benefit from employment benefits and social protection programs.[5] For instance, a survey in Europe shows that the respondents who have difficulties to pay their household bills have worked informally more often in the past year than those that do not (10% versus 3% of the respondents).[56] |

貧困 ウッタル・プラデーシュ州の非公式販売業者 非公式部門と貧困の関係は決して単純ではなく、明確な因果関係も存在しない。ただし、非公式部門の拡大と経済成長の鈍化には逆相関が認められている。 [45] インフォーマル経済における平均所得は著しく低く、貧困層の労働者が非公式部門で働く割合が高い。[55] さらに、インフォーマル経済の労働者は雇用福利厚生や社会保障制度の恩恵を受けにくい。[5] 例えば欧州の調査では、家計の支払いに困難を抱える回答者は、過去1年間にインフォーマルな仕事に従事した割合が困難のない回答者よりも高かった(回答者 の10%対3%)。[56] |

| Children and child labour This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (April 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  A girl weaving a rug in Egypt Children work in the informal economy in many parts of the world. They often work as scavengers (collecting recyclables from the streets and dump sites), day laborers, cleaners, construction workers, vendors, in seasonal activities, domestic workers, and in small workshops; and often work under hazardous and exploitative conditions. [57][58] It is common for children to work as domestic servants in parts of Latin America and parts of Asia. Such children are very vulnerable to exploitation: often they are not allowed to take breaks or are required to work long hours; many suffer from a lack of access to education, which can contribute to social isolation and a lack of future opportunity. UNICEF considers domestic work to be among the lowest status, and reports that most child domestic workers are live-in workers and are under the round-the-clock control of their employers.[59] Some estimates suggest that among girls, domestic work is the most common form of employment.[60] During times of economic crisis many families experience unemployment and job loss, thus compelling adolescents to supplement their parents’ income by selling goods or services to contribute to the family economy. At the core, youth must compromise their social activities with other youth, and instead prioritize their participation in the informal economy, thus manufacturing a labor class of adolescents who must take on an adult role within the family. Although it revolves around a negative stigma of deviance, for a majority of individuals, mostly people of color, the informal economy is not an ideal choice but a necessity for survival. Participating in the informal economy is becoming normalized due to the lack of resources available in low-income and marginalized communities, and no matter how hard they have to work, will not advance in the economic hierarchy. When a parent is either unemployed or their job is on low demand, they are compelled to find other methods to provide for themselves but most importantly their children. Yet, due to all the limitations and the lack of jobs, children eventually cooperate with their parent/s and also work for their family's economic well-being. By having to assist in providing for the family, children miss out on their childhood because instead of engaging in activities other youth their age participate in, they are obligated to take on an adult role, put the family first and contribute to the family's well-being. The participation of adolescents in the informal economy, is a contentious issue due to the restrictions and laws in place for youth have to work. One of the main dilemmas that arise when children engage in this type of work, is that privileged adults, denounce children participation as forced labor. Due to the participant being young, the adults are viewed as “bad” parents because first they cannot provide for their children, second they are stripping the child from a “normal” childhood, and third, child labor is frowned upon. Furthermore, certain people believe that children should not be working because children do not know the risks and the pressure of working and having so much responsibility, but the reality is that for most families, the children are not being forced to work, rather they choose to help sustain their family's income. The youth become forced by their circumstances, meaning that because of their conditions, they do not have much of a choice. Youth have the capability to acknowledge their family's financial limitations and many feel that it is their moral obligation to contribute to the family income. Thus, they end up working without asking for an allowance or wage, because kids recognize that their parents cannot bring home enough income alone, thus their contribution is necessary and their involvement becomes instrumental for their family's economic survival.[61] Emir Estrada and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo have gone to predominantly Latino communities of Los Angeles, CA. to observe the daily actions of street vendors. They analyze why adults participate in the informal economy. Although it revolves around a negative stigma of deviance, for a majority of individuals, the informal economy is not an ideal choice but an action necessary for survival. While witnessing the constant struggle of Latino individuals to make ends meet and trying to earn money to put food on the table, they witnessed how the participation of children either benefits the family or even hurt it. Through field notes derived from their participation, Estrada states, “children are not the ‘baggage’ that adult immigrants simply bring along. In the case of street vendors, we see that they are also contributors to family processes”.[62] Estrada's findings demonstrate that children are working in order to help contribute to their household income, but most importantly, they play a vital role when it comes to language barriers. The kids are not simply workers, they achieve an understanding of how to manage a business and commerce. |

子どもと児童労働 この節には独自研究が含まれている可能性がある。主張を検証し、出典を明記することで改善してほしい。独自研究のみに基づく記述は削除されるべきだ。(2018年4月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について)  エジプトで絨毯を織る少女 世界中の多くの地域で、子供たちはインフォーマル経済で働いている。彼らはしばしば、ごみ拾い(路上や廃棄物置き場からリサイクル可能な物を集める)、日 雇い労働者、清掃員、建設作業員、行商人、季節労働、家事労働者、小規模工房での労働者として働き、危険で搾取的な環境下で働くことが多い。[57] [58] ラテンアメリカやアジアの一部地域では、子供たちが家事使用人として働くことが一般的である。こうした子供たちは搾取に極めて脆弱である。休憩を取らせて もらえず長時間労働を強いられるケースが多く、教育機会を欠くことで社会的孤立や将来の機会喪失を招く。ユニセフは家事労働を最低の地位に位置づけ、大半 の家事労働児童が住み込みで雇用主の24時間管理下に置かれていると報告している。[59] 一部の推計によれば、少女にとって家事労働は最も一般的な雇用形態であるという。[60] 経済危機時には多くの家庭で失業や職の喪失が発生し、その結果、青少年は家族の生計を支えるため、物品やサービスの販売によって親の収入を補うことを余儀 なくされる。本質的に、青少年は他の若者との社会活動を犠牲にし、代わりにインフォーマル経済への参加を優先せざるを得ず、こうして家族内で大人の役割を 担わねばならない青少年の労働階級が形成されるのである。インフォーマル経済は逸脱行為という否定的な烙印を背負っているが、主に有色人種からなる大多数 の人々にとって、これは理想的な選択ではなく生存の必要性に迫られた手段である。低所得層や周縁化されたコミュニティでは利用可能な資源が不足しているた め、インフォーマル経済への参加は常態化しつつある。そして彼らがどれほど懸命に働こうとも、経済階層において上昇することは叶わない。親が失業中か、あ るいは需要の低い仕事に就いている場合、彼らは自ら、そして何よりも子供たちを支えるための別の手段を模索せざるを得ない。しかし、あらゆる制約と雇用の 不足により、子供たちは最終的に親と協力し、家族の経済的安定のために働くことになる。家族の生計を支えるために、子供たちは幼少期を失う。同年代の他の 子供たちが楽しむ活動に参加する代わりに、大人の役割を担い、家族を最優先し、家族の福祉に貢献することを強いられるのだ。 青少年のインフォーマル経済への参加は、若年労働に関する規制や法律が存在するため、議論の的となる問題である。子どもがこうした労働に従事する際に生じ る主なジレンマの一つは、特権的な大人が子どもの参加を強制労働として非難することだ。参加者が幼いことから、大人は「悪い」親と見なされる。第一に、子 どもを養えないこと、第二に、子どもから「普通の」幼少期を奪っていること、第三に、児童労働は非難されるべき行為だからだ。さらに、子供は労働のリスク やプレッシャー、重い責任を理解できないから働くべきではないと主張する者もいる。しかし現実には、大半の家庭で子供は強制されて働いているわけではな く、自ら進んで家族の収入を支えようとしている。つまり、状況に追い込まれているのだ。つまり、置かれた環境ゆえに選択肢が限られているのである。若者は 家族の経済的限界を認識する能力を持ち、多くの場合、家族の収入に貢献することが道義的義務だと感じている。そのため、彼らは小遣いや賃金を求めずに働く ことになる。子供たちは、親だけでは十分な収入を得られないことを理解しており、自らの貢献が必要不可欠であり、家族の経済的生存に不可欠な役割を果たし ていると認識しているのだ。[61] エミール・エストラーダとピエルレット・オンダニュ=ソテロは、カリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスのラテン系住民が多数を占める地域を訪れ、路上販売業者の日 常行動を観察した。彼らは成人がインフォーマル経済に参加する理由を分析している。インフォーマル経済は逸脱行為という否定的なレッテルを貼られることが 多いが、大多数の人々にとってそれは理想的な選択ではなく、生存のために必要な行動なのである。ラティーノの人々が生活費をやりくりし、食卓に食べ物をも たらすため絶えず奮闘する姿を目の当たりにする中で、彼らは子どもの参加が家族に利益をもたらすか、あるいは逆に害を及ぼすかを観察した。参加型フィール ドノートに基づくエストラダの記述によれば、「子どもは成人移民が単に引き連れる『荷物』ではない。路上販売業者の場合、子供たちも家族のプロセスに貢献 していることがわかる」と述べている[62]。エストラーダの調査結果は、子供たちが家計収入に貢献するために働いていることを示しているが、最も重要な のは、言語の壁に関して子供たちが重要な役割を果たしている点だ。子供たちは単なる労働者ではなく、ビジネスや商取引の管理方法を理解している。 |

| Expansion and growth The division of the economy into formal and informal sectors has a long heritage. Arthur Lewis in his seminal work Economic Development with Unlimited Supply of Labour, published in the 1950s, was the celebrated paradigm of development for the newly independent countries in the 1950s and 1960s. The model assumed that the unorganized sector with the surplus labour will gradually disappear as the surplus labour gets absorbed in the organised sector. The Lewis model is drawn from the experience of capitalist countries in which the share of agriculture and unorganized sector showed a spectacular decline, but it didn't prove to be true in many developing countries, including India. On the other hand, probabilistic migration models developed by Harris and Todaro in the 1970s envisaged the phenomenon of the informal sector as a transitional phase through which migrants move to the urban centers before shifting to formal sector employment. Hence it is not a surprise to see policy invisibility in the informal sector. Curiously, the informal sector does not find a permanent place in the Marxian theory since they anticipate the destruction of the pre-capitalist structure as a result of the aggressive growth of capitalism. To them, in the course of development, 'the small fish is being eaten by the big fish'. Therefore, neither in the Marxian theory nor in the classical economic theory, the unorganized sector holds a permanent place in the economic literature.[63] The informal sector has been expanding as more economies have started to liberalize.[45] This pattern of expansion began in the 1960s when a lot of developing countries didn't create enough formal jobs in their economic development plans, which led to the formation of an informal sector that didn't solely include marginal work and actually contained profitable opportunities.[6] In the 1980s, the sector grew alongside formal industrial sectors. In the 1990s, an increase in global communication and competition led to a restructuring of production and distribution, often relying more heavily on the informal sector.[6] Over the past decade, the informal economy is said to account for more than half of the newly created jobs in Latin America. In Africa it accounts for around eighty percent.[6] Many explanations exist as to why the informal sector has been expanding in the developing world throughout the past few decades. It is possible that the kind of development that has been occurring has failed to support the increased labor force in a formal manner. Expansion can also be explained by the increased subcontracting due to globalization and economic liberalization. Finally, employers could be turning toward the informal sector to lower costs and cope with increased competition. Such extreme competition between industrial countries occurred after the expansion of the EC to markets of the then new member countries Greece, Spain and Portugal, and particularly after the establishment of the Single European Market (1993, Treaty of Maastricht). Mainly for French and German corporations it led to systematic increase of their informal sectors under liberalized tax laws, thus fostering their mutual competitiveness and against small local competitors. The continuous systematic increase of the German informal sector was stopped only after the establishment of the EURO and the execution of the Summer Olympic Games 2004,[38] which has been the first and (up to now) only in the Single Market. Since then the German informal sector stabilized on the achieved 350 bn € level which signifies an extremely high tax evasion for a country with 90% salary-employment. According to the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the key drivers for the growth of the informal economy in the twenty-first century include:[4] limited absorption of labour, particularly in countries with high rates of population or urbanisation excessive cost and regulatory barriers of entry into the formal economy, often motivated by corruption weak institutions, limiting education and training opportunities as well as infrastructure development increasing demand for low-cost goods and services migration motivated by economic hardship and poverty difficulties faced by women in gaining formal employment Historically, development theories have asserted that as economies mature and develop, economic activity will shift from the informal to the formal sphere. In fact, much of the economic development discourse is centered around the notion that formalization indicates how developed a country's economy is; for more on this discussion see the page on fiscal capacity.[64] However, evidence suggests that the progression from informal to formal sectors is not universally applicable. While the characteristics of a formalized economy – full employment and an extensive welfare system – have served as effective methods of organizing work and welfare for some nations, such a structure is not necessarily inevitable or ideal. Indeed, development appears to be heterogeneous in different localities, regions, and nations, as well as the type of work practiced.[4][64] For example, at one end of the spectrum of the type of work practiced in the informal economy are small-scale businesses and manufacturing; on the other "street vendors, shoe shiners, junk collectors and domestic servants."[4] Regardless of how the informal economy develops, its continued growth that it cannot be considered a temporary phenomenon.[4] |

拡大と成長 経済を正規部門とインフォーマル経済に分ける考え方は長い歴史を持つ。アーサー・ルイスが1950年代に発表した画期的な著作『労働力無制限条件下におけ る経済発展』は、1950~60年代に独立した国々にとって著名な発展モデルとなった。このモデルは、余剰労働力が正規部門に吸収されるにつれ、イン フォーマル経済は次第に消滅すると想定していた。ルイスモデルは、農業と非組織部門の割合が劇的に低下した資本主義諸国の経験に基づいているが、インドを 含む多くの発展途上国では実証されなかった。一方、1970年代にハリスとトダロが開発した確率的移動モデルは、非公式部門の現象を、移住者が都市中心部 へ移動し、その後公式部門の雇用へ移行する過渡期として捉えた。したがって、非公式部門における政策の不可視性は驚くべきことではない。興味深いことに、 非公式部門はマルクス主義理論において恒久的な位置を占めない。なぜなら彼らは、資本主義の攻撃的な成長の結果として前資本主義的構造が破壊されると予測 しているからだ。彼らによれば、発展の過程において「小さな魚は大きな魚に食べられていく」のである。したがって、マルクス主義理論においても古典派経済 学においても、非組織的部門は経済文献において恒久的な位置を占めていない。[63] 非公式部門は、より多くの経済が自由化を開始するにつれて拡大してきた。[45] この拡大パターンは1960年代に始まり、多くの発展途上国が経済開発計画において十分な公式雇用を創出しなかったため、非公式部門が形成された。この部 門は単なる周辺的な仕事だけでなく、実際に収益性の高い機会を含んでいた。[6] 1980年代には、このセクターは公式の産業部門と並行して成長した。1990年代には、グローバルな通信と競争の増加が生産と流通の再編をもたらし、し ばしばインフォーマル経済への依存度を高めた。[6] 過去10年間で、ラテンアメリカにおける新規雇用の半数以上がインフォーマル経済によるものとされる。アフリカでは約80%を占める。[6] 過去数十年、発展途上国で非公式部門が拡大した理由については多くの説明がある。発生してきた開発の形態が、増加した労働力を公式な形で支えられなかった 可能性が考えられる。また、グローバル化と経済自由化による下請けの増加も拡大の要因として説明できる。最後に、雇用主がコスト削減と競争激化への対応の ために非公式部門に目を向けている可能性もある。 工業国間のこうした極端な競争は、ECが当時新規加盟国であったギリシャ、スペイン、ポルトガルの市場へ拡大した後、特に単一欧州市場(1993年、マー ストリヒト条約)の確立後に発生した。主にフランスとドイツの企業にとって、これは自由化された税制下での非公式部門の体系的な増加につながり、相互の競 争力を高めると同時に、小規模な地元競合他社に対する優位性を強化した。ドイツの非公式セクターの継続的な体系的な拡大は、ユーロの確立と、単一市場で初 めて(そして現在まで唯一)の2004年夏季オリンピックの開催によってようやく止まった[38]。それ以来、ドイツの非公式セクターは3,500億ユー ロの水準で安定しており、これは給与所得者が90%を占める国としては非常に高い脱税率を意味する。 スウェーデン国際開発協力庁(SIDA)によると、21 世紀におけるインフォーマル経済の成長の主な要因は次のとおりである。[4] 特に人口や都市化の割合が高い国々における、労働力の吸収力の限界 腐敗によって引き起こされることが多い、公式経済への参入における過度なコストや規制上の障壁 教育や訓練の機会、インフラ開発を制限する脆弱な制度 低コストの製品やサービスに対する需要の高まり 経済的困難や貧困によって引き起こされる移住 女性が公式の雇用を得る上で直面する困難 歴史的に、開発理論は、経済が成熟し発展するにつれて、経済活動は非公式の領域から公式の領域へと移行すると主張してきた。実際、経済開発の言説の多く は、公式化が国の経済の発展度合いを示すという概念を中心に展開されている。この言説の詳細については、財政能力のページを参照のこと。[64] しかし、非公式部門から公式部門への移行は、普遍的に適用できるものではないことを示す証拠がある。正規経済の特徴である完全雇用と広範な福祉制度は、一 部の国々において労働と福祉を組織化する効果的な方法として機能してきた。しかし、そのような構造が必然的あるいは理想的であるとは限らない。実際、開発 は地域や国家、そして行われる労働の種類によって異なるように見える。[4][64] 例えば、インフォーマル経済で実践される労働形態のスペクトルの一端には小規模事業や製造業が位置し、他端には「露天商、靴磨き、廃品回収業者、家事使用 人」が存在する。[4] インフォーマル経済がどのように発展しようと、その持続的な成長は一時的な現象とは見なせない。[4] |

Policy suggestions Informal beverage vendor in Guatemala City As it has been historically stigmatized, policy perspectives viewed the informal sector as disruptive to the national economy and a hindrance to development.[65] The justifications for such criticisms include viewing the informal economy as a fraudulent activity that results in a loss of revenue from taxes, weakens unions, creates unfair competition, leads to a loss of regulatory control on the government's part, reduces observance of health and safety standards, and reduces the availability of employment benefits and rights. These characteristics have led to many nations pursuing a policy of deterrence with strict regulation and punitive procedures.[65] In a 2004 report, the Department for Infrastructure and Economic Cooperation under SIDA explained three perspectives on the role of government and policy in relation to the informal economy.[4] Markets function efficiently on their own; government interference would only lead to inefficiency and dysfunction. The informal economy functions outside of government control, largely because those who participate wish to avoid regulation and taxation. The informal economy is enduring; suitable regulation and policies are required. As informal economy has significant job creation and income generation potential, as well as the capacity to meet the needs of poor consumers by providing cheaper and more accessible goods and services, many stakeholders subscribe to the third perspective and support government intervention and accommodation.[4][66] Embedded in the third perspective is the significant expectation that governments will revise policies that have favored the formal sphere at the expense of the informal sector.[4] Theories of how to accommodate the informal economy argue for government policies that, recognizing the value and importance of the informal sector, regulate and restrict when necessary but generally work to improve working conditions and increase efficiency and production.[4] The challenge for policy interventions is that so many different types of informal work exist; a solution would have to provide for a diverse range of circumstances.[45] A possible strategy would be to provide better protections and benefits to informal sector players. However, such programs could lead to a disconnect between the labor market and protections, which would not actually improve informal employment conditions.[45] In a 2014 report monitoring street vending, WIEGO suggested urban planners and local economic development strategists study the carrying capacity of areas regularly used by informal workers and deliver the urban infrastructure necessary to support the informal economy, including running water and toilets, street lights and regular electricity, and adequate shelter and storage facilities.[66] That study also called for basic legal rights and protections for informal workers, such as appropriate licensing and permit practices.[66] An ongoing policy debate considers the value of government tax breaks for household services such as cleaning, babysitting and home maintenance, with an aim to reduce the shadow economy's impact. There are currently systems in place in Sweden[67] and France[68] which offer 50 percent tax breaks for home cleaning services. There has also been debate in the UK about introducing a similar scheme, with potentially large savings for middle-class families and greater incentive for women to return to work after having children.[69] The European Union has used political measures to try to curb the shadow economy. Although no definitive solution has been established, the EU council has led dialogue on a platform that would combat undeclared work.[70] The World Bank's 2019 World Development Report on The Changing Nature of Work[71] discusses the extension of social assistance and insurance schemes to informal workers given that, in 2018, 8 in 10 people in developing countries still receive no social assistance and 6 in 10 work informally. |

政策提言 グアテマラシティの非公式飲料販売業者 歴史的に非難されてきたため、政策の観点では非公式部門は国家経済を混乱させ、発展の妨げと見なされてきた。[65] このような批判の根拠としては、インフォーマル経済は、税収の損失、労働組合の弱体化、不公正な競争の発生、政府による規制管理の喪失、健康および安全基 準の遵守の低下、雇用上の福利厚生や権利の利用可能性の低下をもたらす不正行為であるとの見方がある。こうした特徴から、多くの国々が、厳格な規制と懲罰 的な手続きによる抑止政策を追求している。[65] 2004年の報告書で、SIDA傘下のインフラ・経済協力局は、インフォーマル経済に関する政府と政策の役割について、3つの見解を説明している[4]。 市場はそれ自体で効率的に機能しており、政府の干渉は非効率と機能不全を招くだけである。 インフォーマル経済は、主に規制や課税を避けたいと考える参加者がいるため、政府の統制の外で機能している。 インフォーマル経済は永続的であり、適切な規制と政策が必要である。 インフォーマル経済は、雇用創出と所得創出の潜在力が大きく、また、より安価で入手しやすい商品やサービスを提供することで、貧しい消費者のニーズを満た す能力も備えているため、多くの利害関係者は、この第三の視点に賛同し、政府の介入と対応を支持している。[4][66] この第三の視点には、インフォーマルセクターを犠牲にしてフォーマルな分野を優遇してきた政策を、政府が改めるという大きな期待が込められている。[4] インフォーマル経済への対応理論は、インフォーマル部門の価値と重要性を認識しつつ、必要に応じて規制・制限を行う一方で、概して労働条件の改善、効率性・生産性の向上を図る政府政策を提唱する。[4] 政策介入の課題は、インフォーマル労働の種類が異なる点にある。解決策は多様な状況に対応せねばならない。[45] 可能な戦略として、インフォーマル部門従事者への保護と福利厚生の拡充が挙げられる。しかし、こうしたプログラムは労働市場と保護制度の乖離を招き、実際 には非公式雇用の条件改善につながらない可能性がある。[45] 2014年の路上販売監視報告書でWIEGOは、都市計画者や地域経済開発戦略担当者が非公式労働者が日常的に利用する地域の収容力を調査し、水道・トイ レ、街灯・安定電力供給、適切な避難所・保管施設などインフォーマル経済を支える都市インフラを提供すべきだと提言した。[66] 同報告書はまた、適切な免許・許可制度など、非公式労働者に対する基本的な法的権利と保護を求めている。[66] 現在進行中の政策論議では、影の経済の影響を軽減する目的で、清掃・ベビーシッター・住宅メンテナンスなどの家事サービスに対する政府の税制優遇措置の価 値が検討されている。スウェーデン[67]とフランス[68]では現在、家庭用清掃サービスに対して50%の税制優遇を提供する制度が導入されている。英 国でも同様の制度導入が議論されており、中流家庭の大きな節約効果や、出産後の女性の職場復帰促進が期待されている[69]。欧州連合(EU)は政治的措 置で影の経済抑制を試みている。決定的な解決策は確立されていないが、EU理事会は非申告労働対策プラットフォームに関する対話を主導している[70]。 世界銀行の2019年版『世界開発報告:仕事の本質の変容』[71]では、2018年時点で開発途上国の10人中8人が依然として社会支援を受けておらず、10人中6人が非正規雇用で働いている現状を踏まえ、非正規労働者への社会支援・保険制度の拡充が論じられている。 |

| Asia-Pacific The International Labour Organization mentioned that in most developing nations located in the Asia-Pacific,[72] the informal sector comprises a significant and vital percentage of the labor force. This sector constitutes around 60 percent of the labor force. Informal economy[73] includes economic activities of laborers (legally and in practice) which are not or inadequately covered by official employment contracts or agreements. Informal employment means payment of wagers may not be guaranteed and retrenchment can be implemented without prior notice or compensation from employers. There are generally substandard health and safety conditions as well as nonexistence of social benefits which include sick pay, pension, and health coverage.[74] The informal economy absorbs a larger part of the ever-growing workforce in urban hubs. In 2015, urban populations of Asian countries[75] started to grow while the service sector also continued to increase. These developments contributed to the extensive expansion of urban informal economy in practically all of Asia.[74] In India, the country's informal sector accounted for over 80 percent of the non-agricultural industry during the last 20 years. Inadequate employment denotes the option for majority of India's citizens is to find work in the informal sector which continues to grow because of the contract system and outsourcing of production.[76] An article in First Post (June 2018) said approximately 1.3 billion people or more than 68 percent of employed persons in the Asia-Pacific earn through the informal economy. It is prevalent in the countryside (around 85 percent) and almost 48 percent in urban locations. 2 billion of the global population (61 percent) works in the informal sector.[77] According to an article published in Eco-Business in June 2018, the informal sector has emerged as an essential component of the economic environment of cities in this region. Henceforth, the importance of contribution of informal workers deserves recognition.[78] For a more detailed overview focused on informal employment in South Asian countries, see Informal economy of South Asia. |

アジア太平洋地域 国際労働機関(ILO)によれば、アジア太平洋地域の大半の発展途上国において[72]、非公式部門は労働力の重要な割合を占めている。この部門は労働力 の約60%を構成する。インフォーマル経済[73]とは、労働者の経済活動(法的・実務的に)のうち、公式の雇用契約や協定によってカバーされていない、 あるいは不十分なものを含む。非公式雇用とは、賃金の支払いが保証されない可能性があり、雇用主による事前通知や補償なしに解雇が実施され得ることを意味 する。一般的に、健康と安全の条件は基準以下であり、病気手当、年金、医療保険を含む社会給付は存在しない[74]。インフォーマル経済は、都市部で増え 続ける労働力の大部分を吸収している。2015年、アジア諸国の都市人口[75]は増加し始め、サービス部門も拡大を続けた。これらの動向が、アジアのほ ぼ全域で都市部のインフォーマル経済が大幅に拡大する一因となった。[74] インドでは、過去20年間にわたり非農業部門の80%以上が非公式部門で占められてきた。雇用不足は、契約システムと生産の外部委託によって拡大を続ける 非公式部門で仕事を探すことが、大多数のインド国民にとっての選択肢であることを示している。[76] ファーストポスト誌(2018年6月)の記事によれば、アジア太平洋地域のインフォーマル経済による所得者は約13億人、雇用者の68%以上に上る。これ は農村部(約85%)で顕著であり、都市部でも約48%を占める。世界人口の20億人(61%)がインフォーマル部門で働いている。[77] 2018年6月エコ・ビジネス誌掲載記事によれば、非公式部門は本地域の都市経済環境において不可欠な構成要素として台頭している。したがって非公式労働 者の貢献の重要性は認識されるべきである。[78] 南アジア諸国における非公式雇用に焦点を当てた詳細な概観については、南アジアのインフォーマル経済を参照のこと。 |

| Iconography The triptych La familia informal (The Informal Family, 1992)[79] by painter Herman Braun-Vega, held in the permanent collection of the Ralli Museum in Marbella, explores the theme of the informal economy.[80] Created as part of a series of sixteen paintings on syncretism and mestizaje (racial and cultural mixing) for a retrospective exhibition in Madrid in 1992 during the celebrations of the fifth centenary of the Encounter of Two Worlds, this triptych associates the informal economy in developing countries – defined by the artist as "an economic system linked to survival, autonomous from the State and escaping taxation" – with a reflection on mestizaje and social integration.[81] Drawing inspiration from the architectural structure of Velázquez's Las Meninas, Braun-Vega depicts "popular characters from the informal economy" alongside members of his family and artistic and literary figures, constituting what he calls an "informal family".[81] The work was used in an educational program by the French Ministry of Education, Culture and Francophonie during the 1994-1995 school year, where it was presented in thirteen schools as educational material on subsistence economies and cultural exchange between peoples.[82] |

図像学 画家ヘルマン・ブラウン=ベガによる三連画『ラ・ファミリア・インフォーマル(インフォーマル経済、1992年)』[79]は、マルベージャのラリ美術館 の常設コレクションに所蔵されており、インフォーマル経済というテーマを探求している。[80] この三連画は、1992年にマドリードで開催された回顧展の一環として制作された。同展は「二つの世界の出会い」500周年を記念し、シンクレティズム (融合思想)とメスティサヘ(人種的・文化的混交)をテーマにした16点の連作の一部である。発展途上国におけるインフォーマル経済——作者が「生存に直 結し、国家から自律し、課税を逃れる経済システム」と定義する——を、メスティサヘ文化と社会的統合の考察と結びつけている[81]。ブラウン=ベガはベ ラスケスの『ラス・メニーナス』の構図構造に着想を得て、自身の家族や芸術関係者らと共に「インフォーマル経済の庶民的キャラクター」を描き出している。 ―と、メスティサヘ(混血)と社会統合に関する考察を結びつけている。[81] ベラスケスの『ラス・メニーナス』の構図に着想を得て、ブラウン=ベガは「インフォーマル経済の庶民的キャラクター」を自身の家族や芸術家・文学者らと並 置し、彼が「インフォーマルな家族」と呼ぶ構成を形作っている。[81] この作品は1994-1995年度、フランス教育文化・フランコフォニー省の教育プログラムで使用され、13校で「人々の生計経済と文化交流」に関する教 材として提示された。[82] |

| Agorism Casual employment Counter-economics Doing business as Flea market Gig economy Informal housing Legal personality, a requirement for legitimate businesses Precariat Rotating Savings and Credit Association Substantivism System D Virtual economy |

アゴリズム 非正規雇用 カウンターエコノミクス 個人事業主 フリーマーケット ギグエコノミー 非正規住宅 法人格、合法的な事業に必要な要件 プレカリアート 回転貯蓄信用組合 実体主義 システムD 仮想経済 |

| References |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Informal_economy |

| Further reading World Bank (May 11, 2021). The Long Shadow of Informality: Challenges and Policies. Edited by Franziska Ohnsorge and Shu Yu. Grossman, Shelby. 2021. The Politics of Order in Informal Markets: How the State Shapes Private Governance. Cambridge University Press. Enrique Ghersi (1997). "The Informal Economy in Latin America" (PDF). Cato Journal. 17 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-14. Retrieved 2006-12-18. An article by a collaborator of de Soto. John C. Cross (January 1995). "Formalizing the informal economy: The Case of Street Vendors in Mexico City". Archived from the original on 2006-12-13. Retrieved 2006-12-18. A working paper describing attempts to formalize street vending in Mexico. World Institute for Development Economics Research (September 17–18, 2004). Unlocking Human Potential. United Nations University. Archived from the original on 2006-11-30. Retrieved 2006-12-18. Cervero, Robert (2000). Informal Transport in the Developing World. Nairobi: United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (HABITAT). ISBN 978-9211314533. Douglas Uzzell (November 22, 2004). "A Homegrown Mass Transit System in Lima, Peru: A Case of Generative Planning". City & Society. 1 (1): 6–34. doi:10.1525/city.1987.1.1.6. World Bank policy note on The Informality Trap: Tax Evasion, Finance, and Productivity in Brazil World Bank policy note on Rising Informality – Reversing the Tide Paper estimating the size of the informal economy in 110 developing, transition and developed countries Keith Hart (2000). The Memory Bank. Profile Books. The link is to an online archive of Keith Hart's works. Frey, B.S. (1989). How large (or small) should the underground economy be? In E.L. Feige (Ed.), The underground economy: Tax evasion and information distortion, 111–129. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lipartito, Kenneth; Jaconson, Lisa, eds. (2020). Capitalism's Hidden Worlds. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812251814. Temkin, Benjamin (2009). "Informal Self-Employment in Developing Countries: Entrepreneurship or Survivalist Strategy? Some Implications for Public Policy". Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 9 (1): 135–156. doi:10.1111/j.1530-2415.2009.01174.x. Temkin, Benjamin; Jorge, Veizaga (2010). "The Impact of Economic Globalization on Labor Informality". New Global Studies. 4 (1). doi:10.2202/1940-0004.1083. S2CID 153808289. Temkin Benjamin, The Negative Influence of Labor Informality on Subjective Well-Being, Global Labor Journal, Vol 7, No. 1, (2016) doi:10.15173/glj.v7i1.2545 |

追加文献(さらに読む) 世界銀行(2021年5月11日)。『非公式経済の長い影:課題と政策』。フランツィスカ・オーンゾルゲとシュウ・ユー編。 グロスマン、シェルビー。2021年。『非公式市場における秩序の政治学:国家が私的ガバナンスを形作る方法』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 エンリケ・ゲルシ(1997年)。「ラテンアメリカにおけるインフォーマル経済」(PDF)。『カトー・ジャーナル』17巻1号。2006年12月14日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2006年12月18日に閲覧。デ・ソトの共同研究者による論文。 ジョン・C・クロス(1995年1月)。「インフォーマル経済の公式化:メキシコシティの路上販売業者の事例」. 2006年12月13日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2006年12月18日に取得. メキシコにおける路上販売の公式化を試みた取り組みを記述したワーキングペーパー. 世界開発経済研究所 (2004年9月17日-18日). 人間の可能性を解き放つ. 国連大学. 2006年11月30日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2006年12月18日に取得。 Cervero, Robert (2000). 『発展途上国における非公式交通』. ナイロビ: 国連人間居住センター (HABITAT). ISBN 978-9211314533. ダグラス・ウゼル(2004年11月22日)。「ペルー・リマにおける自生的大衆輸送システム:生成的計画の事例」。『都市と社会』。1巻1号:6–34頁。doi:10.1525/city.1987.1.1.6。 世界銀行政策ノート「非公式経済の罠:ブラジルの脱税、金融、生産性」 世界銀行政策ノート「非公式経済の拡大-流れを逆転させる」 110の開発途上国・移行期国・先進国におけるインフォーマル経済規模の推定論文 キース・ハート(2000年)。『記憶の銀行』。プロファイル・ブックス。リンク先はキース・ハートの著作オンラインアーカイブである。 Frey, B.S. (1989). 地下経済はどれほど大きくなるべきか(あるいは小さくなるべきか)? E.L. Feige (編)『地下経済:脱税と情報歪曲』所収, 111–129. ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局. リパルティート、ケネス;ジャクソン、リサ編(2020)。『資本主義の隠された世界』。ペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィア:ペンシルベニア大学出版局。ISBN 9780812251814。 テムキン、ベンジャミン(2009)。「発展途上国における非公式な自営業:起業家精神か生存戦略か?公共政策への示唆」『社会問題と公共政策の分析』9巻1号:135–156頁。doi:10.1111/j.1530-2415.2009.01174.x。 テムキン、ベンジャミン; ホルヘ、ベイサガ (2010). 「経済的グローバル化が労働の非正規性に与える影響」. 『ニュー・グローバル・スタディーズ』. 4 (1). doi:10.2202/1940-0004.1083. S2CID 153808289. テムキン・ベンジャミン, 「労働の非正規性が主観的幸福度に及ぼす負の影響」, 『グローバル労働ジャーナル』, 第7巻第1号, (2016年) doi:10.15173/glj.v7i1.2545 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Informal_economy |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099