日系アメリカ人の強制収容

Internment of Japanese Americans

☆ 第二次世界大戦中、米国は、戦時転住局(WRA)が運営する10の強制収容所に、日系人約12万人を強制的に移住させ収容した。そのほとんどは、米国西部 の内陸部にあった。強制収容された拘留者の約3分の2は米国市民であった。これらの措置は、1941年12月の真珠湾、グアム、フィリピン、ウェーク島に 対する日本帝国の攻撃を受けて、1942年2月19日にフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領が発令した大統領令9066号によって開始された。戦前、ア メリカ本土には約12万7000人の日系アメリカ人が住んでおり、そのうち約11万2000人が西海岸に住んでいた。 そのうち約8万人は二世(アメリカ生まれの日本人で米国籍を持つ)と三世(二世の子供)であった。 残りは日本生まれの一世(米国籍を持たない)移民であった。ハワイ(当時戒厳令下)では、15万人以上の日系アメリカ人が全人口の3分の1以上を占めてい たにもかかわらず、収容されたのは1,200人から1,800人に過ぎなかった。

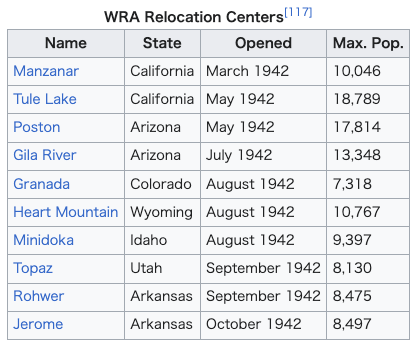

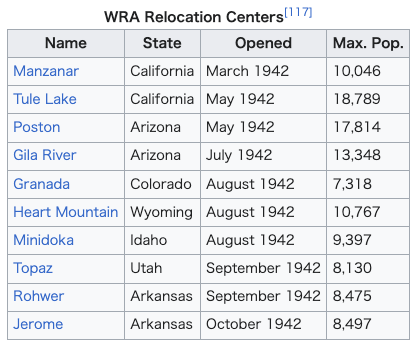

| Internment of Japanese Americans During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and incarcerated about 120,000 people of Japanese descent in ten concentration camps operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), mostly in the western interior of the country. Approximately two-thirds of the detainees were United States citizens. These actions were initiated by Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, following Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, Guam, the Philippines, and Wake Island in December 1941. Before the war, about 127,000 Japanese Americans lived in the continental United States, of which about 112,000 lived on the West Coast. About 80,000 were Nisei ('second generation'; American-born Japanese with U.S. citizenship) and Sansei ('third generation', the children of Nisei). The rest were Issei ('first generation') immigrants born in Japan, who were ineligible for citizenship. In Hawaii (then under martial law), where more than 150,000 Japanese Americans comprised more than one-third of the territory's population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were incarcerated. Internment was intended to mitigate a security risk which Japanese Americans were believed to pose. The scale of the incarceration in proportion to the size of the Japanese American population far surpassed similar measures undertaken against German and Italian Americans who numbered in the millions and of whom some thousands were interned, most of these non-citizens. Following the executive order, the entire West Coast was designated a military exclusion area, and all Japanese Americans living there were taken to assembly centers before being sent to concentration camps in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas. California defined anyone with 1⁄16th or more Japanese lineage as a person who should be incarcerated. A key member of the Western Defense Command, Colonel Karl Bendetsen, went so far as to say “I am determined that if they have "one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp."[6] The United States Census Bureau assisted the incarceration efforts by providing specific individual census data. Internees were prohibited from taking more than they could carry into the camps, and many were forced to sell some or all of their property, including businesses. At the camps, which were surrounded by barbed wire fences patrolled by armed guards, internees lived in often-crowded and sparsely furnished barracks. In its 1944 decision Korematsu v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the removals under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court limited its decision to the validity of the exclusion orders, avoiding the issue of the incarceration of U.S. citizens without due process, but ruled on the same day in Ex parte Endo that a loyal citizen could not be detained, which began their release. On December 17, 1944, the exclusion orders were rescinded, and nine of the ten camps were shut down by the end of 1945. Japanese Americans were initially barred from U.S. military service, but by 1943, they were allowed to join, with 20,000 serving during the war. Over 4,000 students were allowed to leave the camps to attend college. Hospitals in the camps recorded 5,981 births and 1,862 deaths during incarceration. In the 1970s, under mounting pressure from the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) and redress organizations, President Jimmy Carter opened an investigation to determine whether the decision to put Japanese Americans into concentration camps had been justified by the government. He appointed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) to investigate the camps. In 1983, the Commission's report, Personal Justice Denied, found little evidence of Japanese disloyalty at the time and concluded that the incarceration had been the product of racism. It recommended that the government pay reparations to the detainees. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which officially apologized for the incarceration on behalf of the U.S. government and authorized a payment of $20,000 (equivalent to $52,000 in 2023) to each former detainee who was still alive when the act was passed. The legislation admitted that government actions were based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." By 1992, the U.S. government eventually disbursed more than $1.6 billion (equivalent to $4.12 billion in 2023) in reparations to 82,219 Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated. |

日系アメリカ人の強制収容(Internment of Japanese Americans) 第二次世界大戦中、米国は、戦時転住局(WRA)が運営する10の強制 収容所に、日系人約12万人を強制的に移住させ収容した。そのほとんどは、米国西部の内陸部にあった。拘留者の約3分の2は米国市民であった。これらの措 置は、1941年12月の真珠湾、グアム、フィリピン、ウェーク島に対する日本帝国の攻撃を受けて、1942年2月19日にフランクリン・D・ルーズベル ト大統領が発令した大統領令9066号によって開始された。戦前、アメリカ本土には約12万7000人の日系アメリカ人が住んでおり、そのうち約11万 2000人が西海岸に住んでいた。 そのうち約8万人は二世(アメリカ生まれの日本人で米国籍を持つ)と三世(二世の子供)であった。 残りは日本生まれの一世(米国籍を持たない)移民であった。ハワイ(当時戒厳令下)では、15万人以上の日系アメリカ人が全人口の3分の1以上を占めてい たにもかかわらず、収容されたのは1,200人から1,800人に過ぎなかった。 抑留は、日系アメリカ人がもたらすと考えられていた安全保障上のリスクを軽減することを目的としていた。日系アメリカ人の人口規模に比例した抑留の規模 は、数百万人に上り、そのうち数千人が抑留されたドイツ系およびイタリア系アメリカ人に対する同様の措置をはるかに上回っていた。大統領令を受けて、西海 岸全体が軍事排除地域に指定され、そこに住んでいた日系アメリカ人はすべて集合センターに集められた後、カリフォルニア、アリゾナ、ワイオミング、コロラ ド、ユタ、アーカンソーの強制収容所に送られた。カリフォルニア州では、日本人の血統が16分の1以上ある者は収容すべき者と定義された。西部防衛司令部 の主要メンバーであったカール・ベンドセン大佐は、「たとえ彼らに日本人の血が一滴でも流れているなら、収容所に送るべきである」とまで発言した。[6] 米国国勢調査局は、個人の詳細な国勢調査データを提出することで、強制収容を支援した。 収容者は、収容所内に持ち込める以上の量の持ち物を持ち込むことを禁じられ、多くの人々は事業を含む財産の一部またはすべてを売却せざるを得なかった。武 装した警備員が巡回する有刺鉄線で囲まれた収容所では、収容者は、過密で家具もほとんどないバラックで暮らした。 1944年の「コレマツ対合衆国」の判決で、米国最高裁判所は、米国憲法修正第5条の適正手続き条項に基づき、強制退去の合憲性を支持した。裁判所は、そ の決定を排除命令の妥当性のみに限定し、適正手続きを経ずに米国市民を収容することの問題は回避したが、同日、忠誠心のある市民は拘束できないとする判決 を下した。これにより、彼らの釈放が始まった。1944年12月17日、排除命令は撤回され、10か所の収容所のうち9か所は1945年末までに閉鎖され た。当初は米軍への参加が禁止されていた日系アメリカ人であったが、1943年には参加が許可され、2万人が従軍した。 4,000人以上の学生が大学に通うために収容所から外出することが許可された。 収容所の病院では、5,981人の出生と1,862人の死亡が記録された。 1970年代には、日系アメリカ人市民同盟(JACL)や補償団体からの圧力の高まりを受け、ジミー・カーター大統領は、日系アメリカ人の強制収容が政府 によって正当化されたかどうかを判断するための調査を開始した。大統領は、戦時転住及び抑留に関する市民委員会(CWRIC)を任命し、収容所を調査させ た。1983年、委員会の報告書『Personal Justice Denied(邦題:不義への抗い)』は、当時、日系人の不忠誠の証拠はほとんど見当たらず、強制収容は人種差別によるものだったと結論づけた。そして、 政府が被収容者に対して賠償金を支払うことを勧告した。1988年、ロナルド・レーガン大統領は、米国政府を代表して強制収容に対する公式謝罪を行い、同 法成立時に生存していた元収容者一人当たり2万ドル(2023年現在の価値で5万2000ドル相当)の支払いを承認する1988年市民的自由法に署名し た。この法案は、政府の行動が「人種的偏見、戦争ヒステリー、政治的指導力の欠如」に基づいたものだったことを認めた。1992年までに、米国政府は最終 的に、収容されていた82,219人の日系アメリカ人に対して、16億ドル以上(2023年には41億2000万ドル相当)の賠償金を支払った。 |

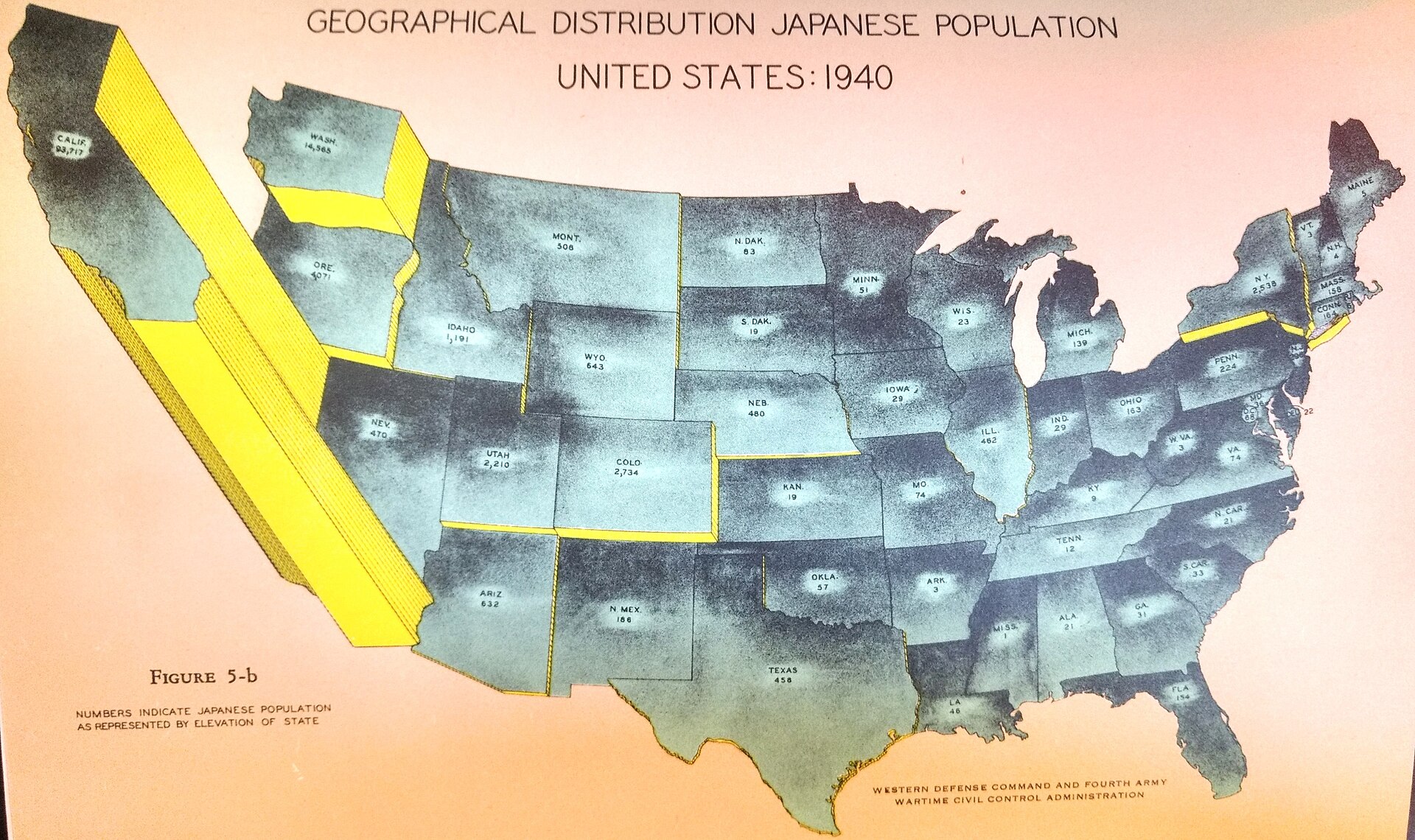

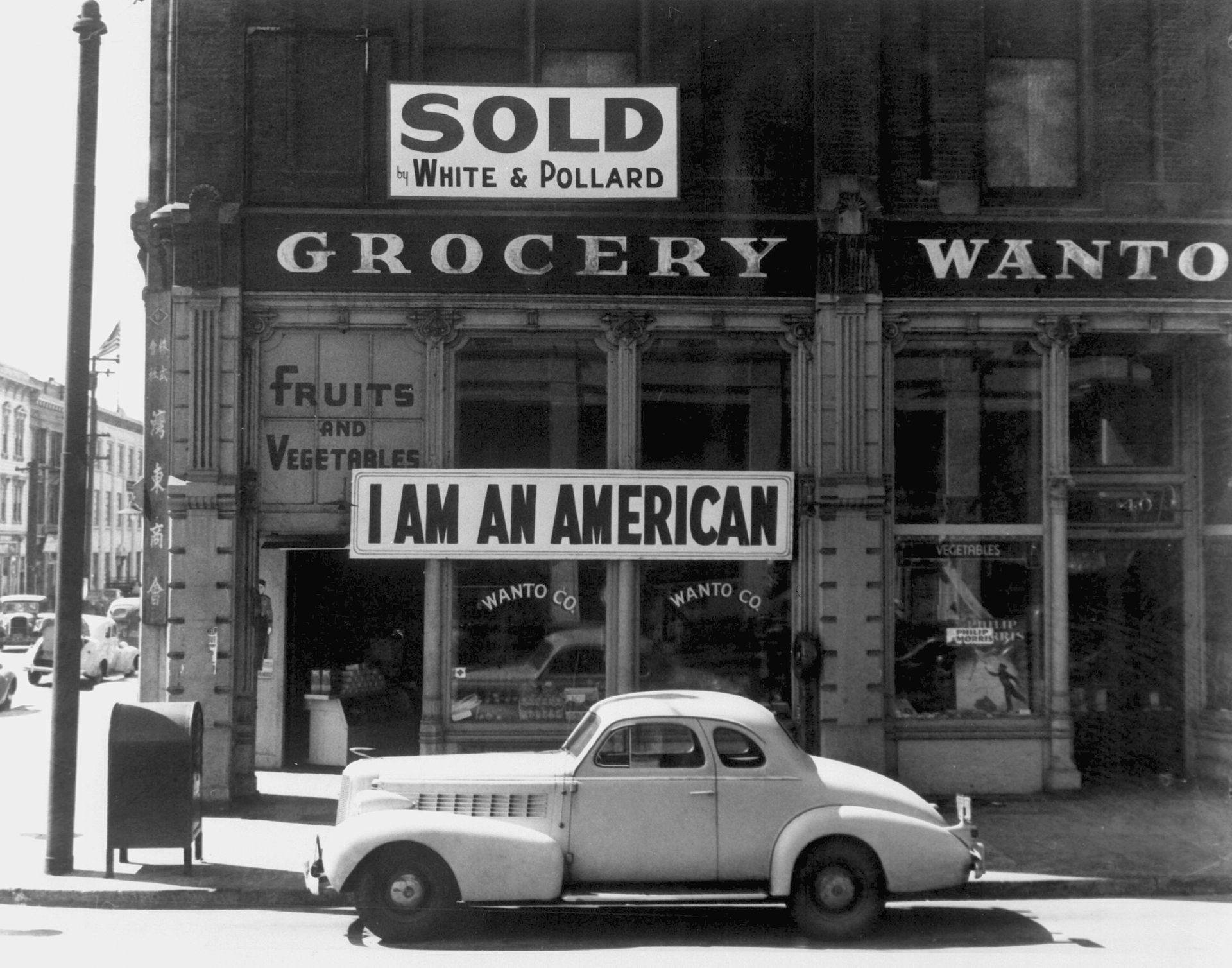

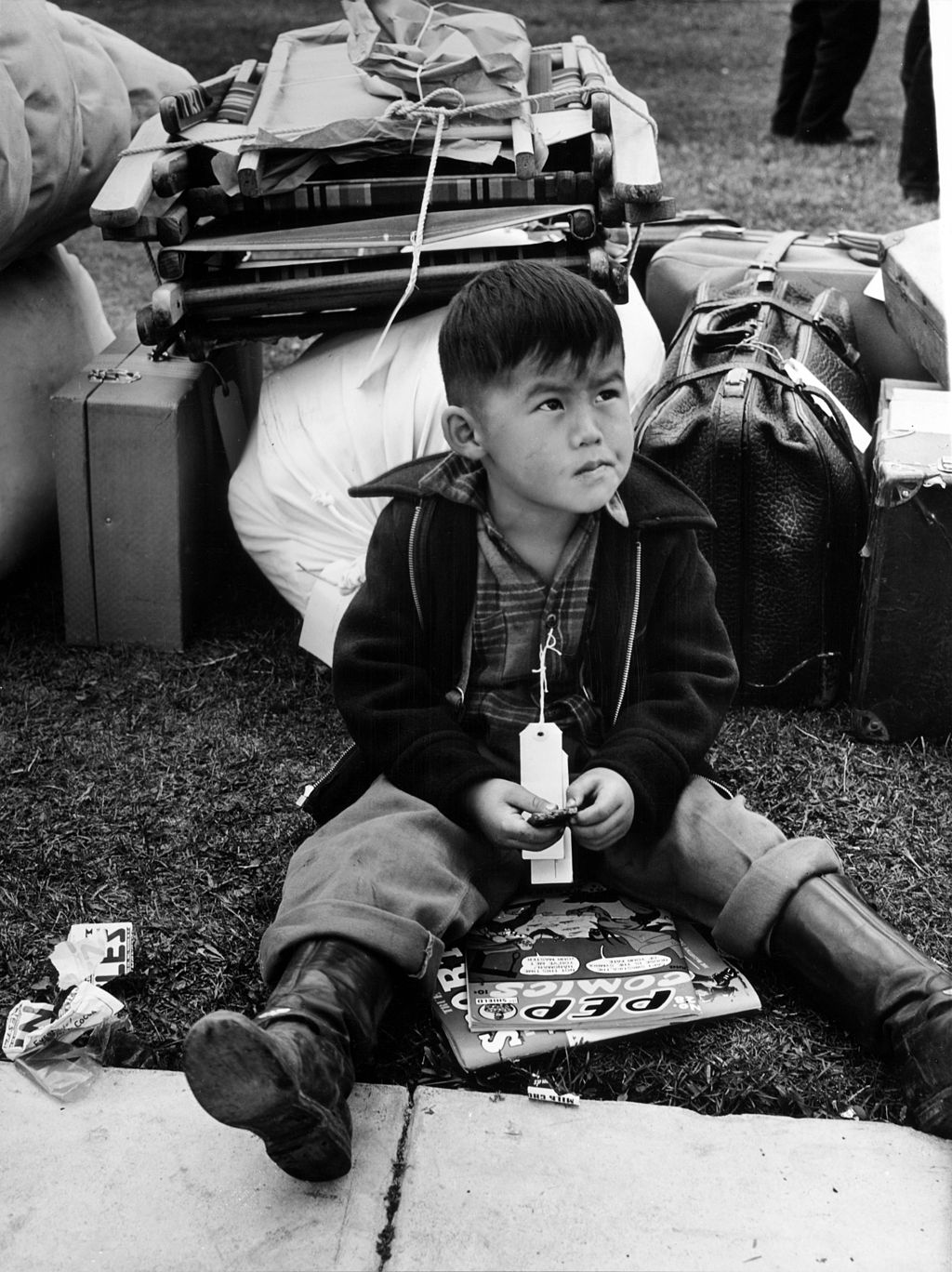

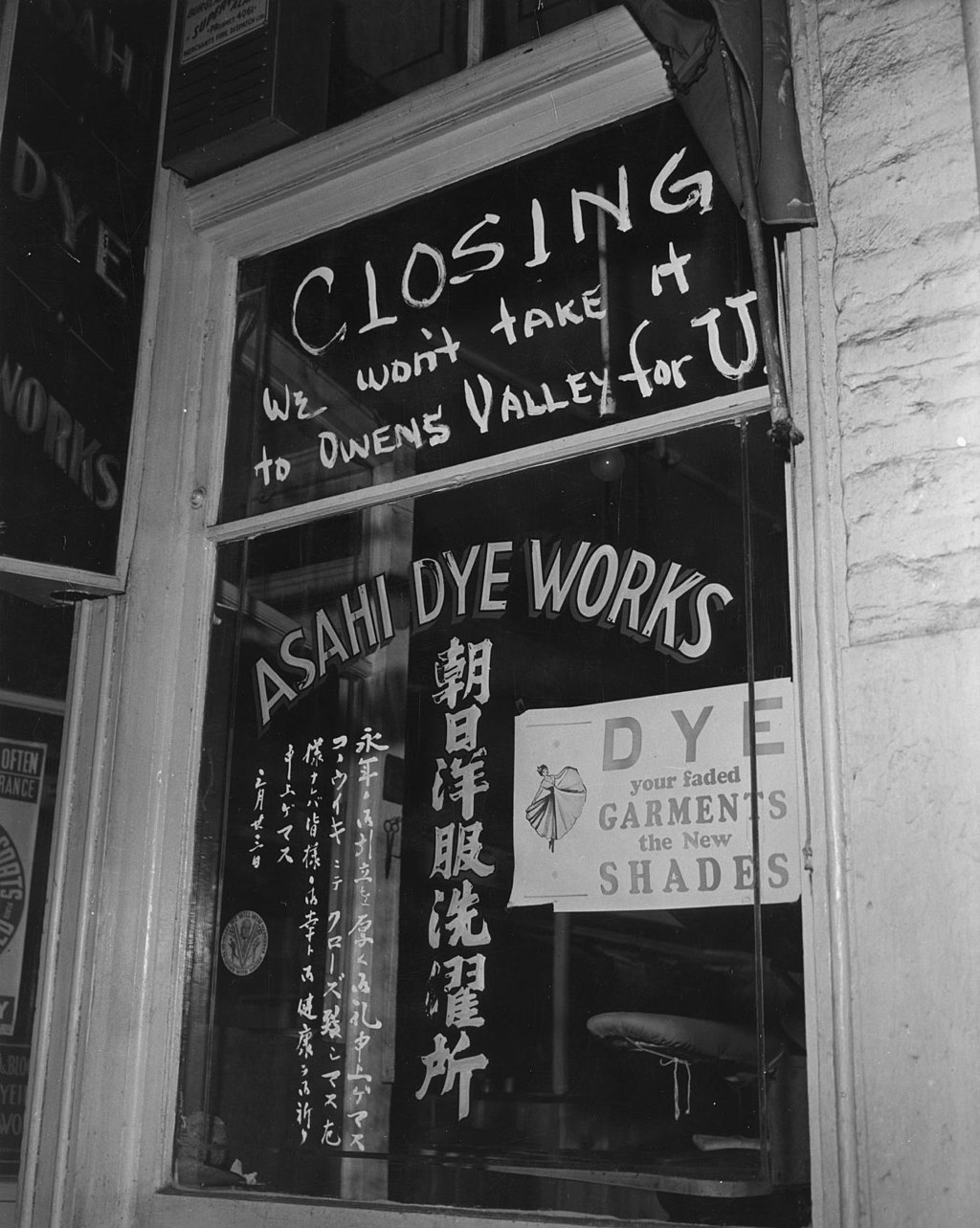

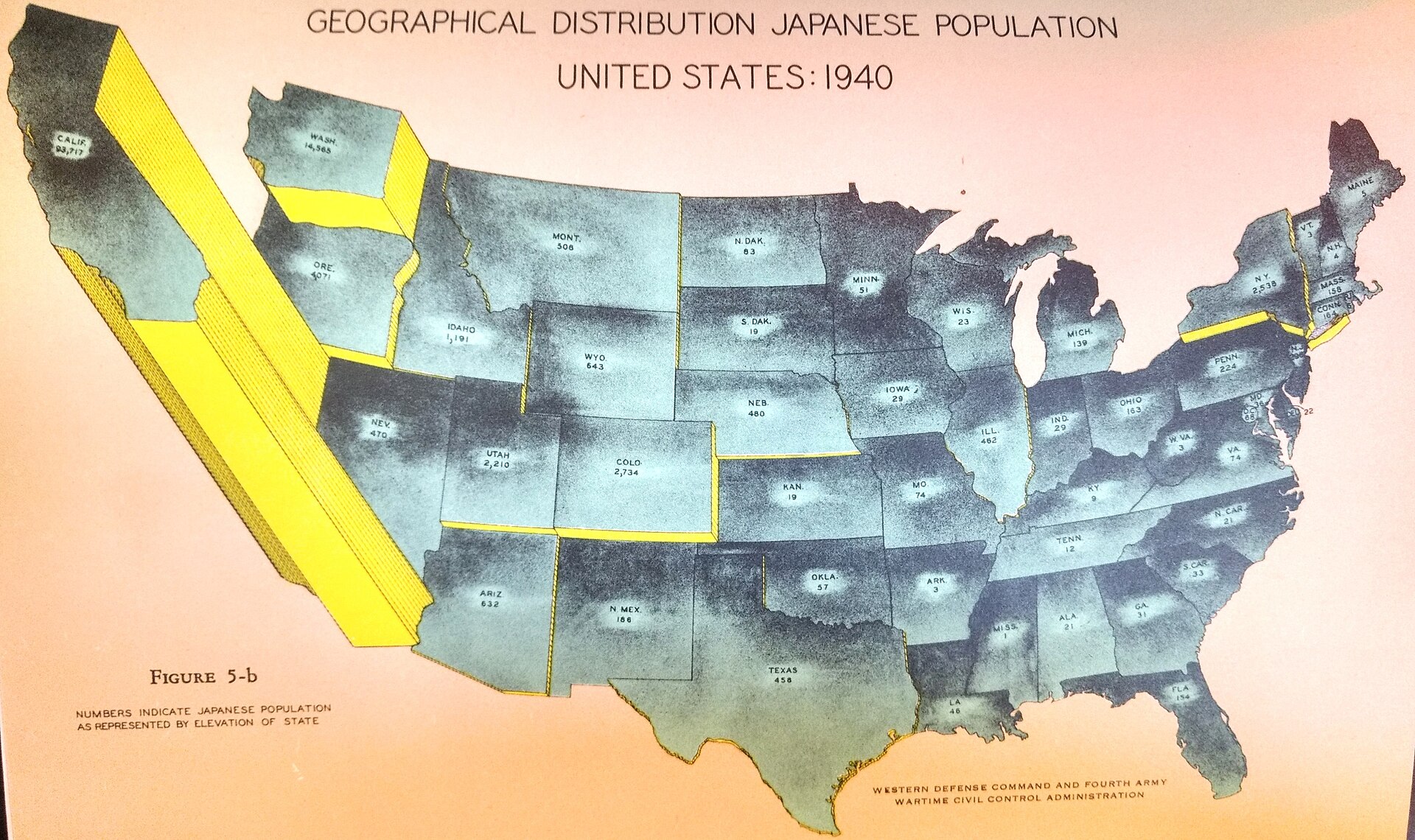

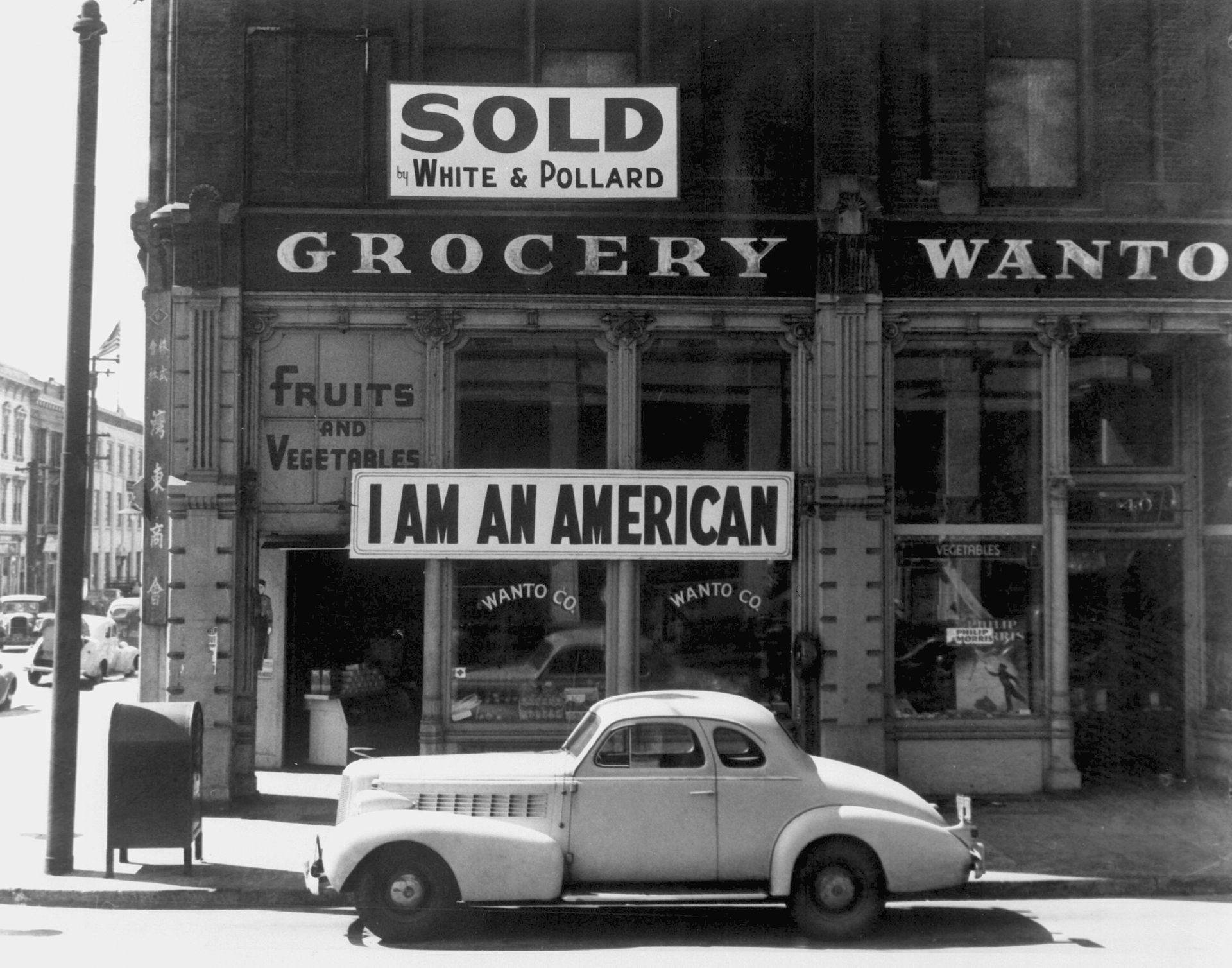

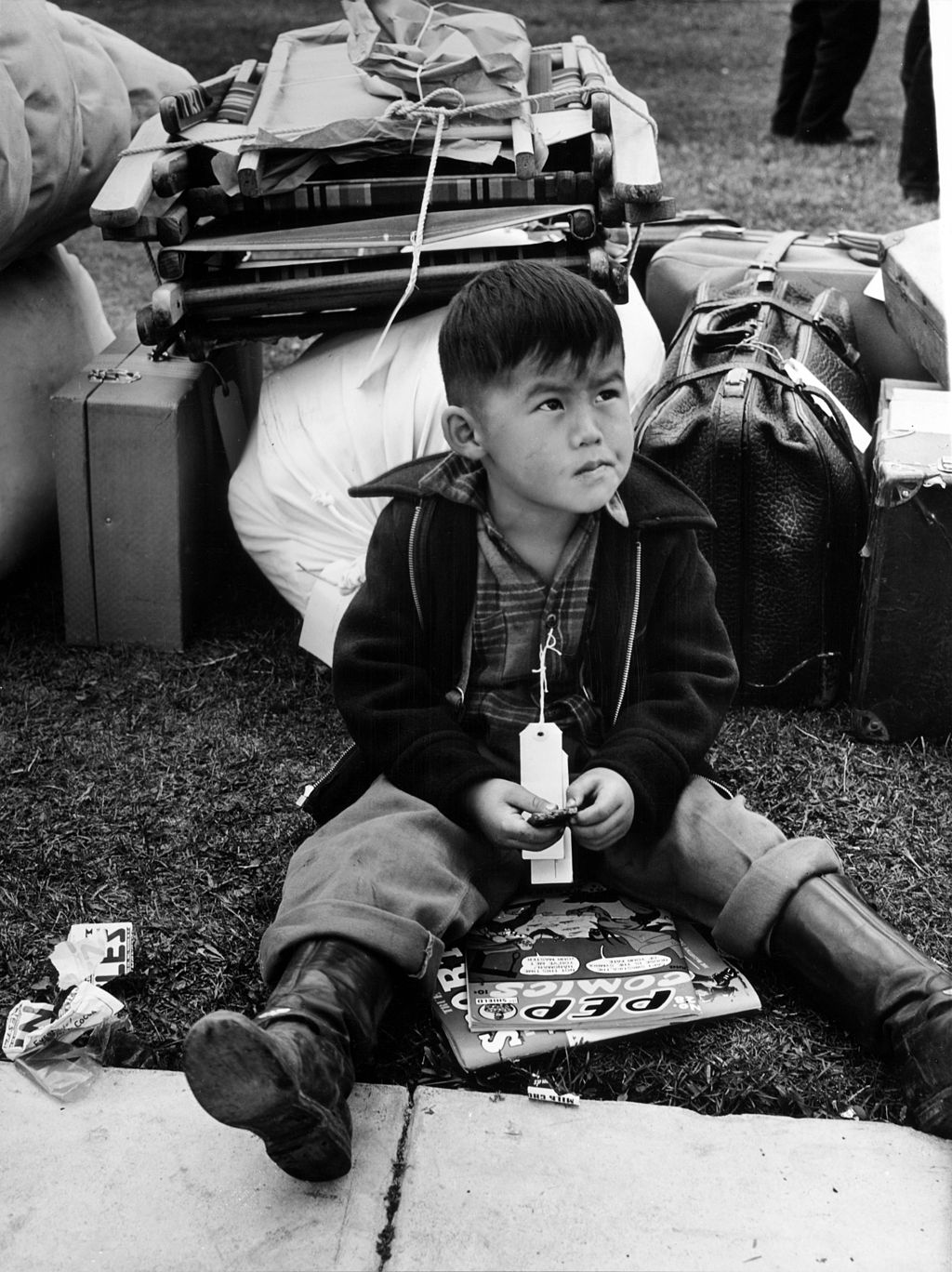

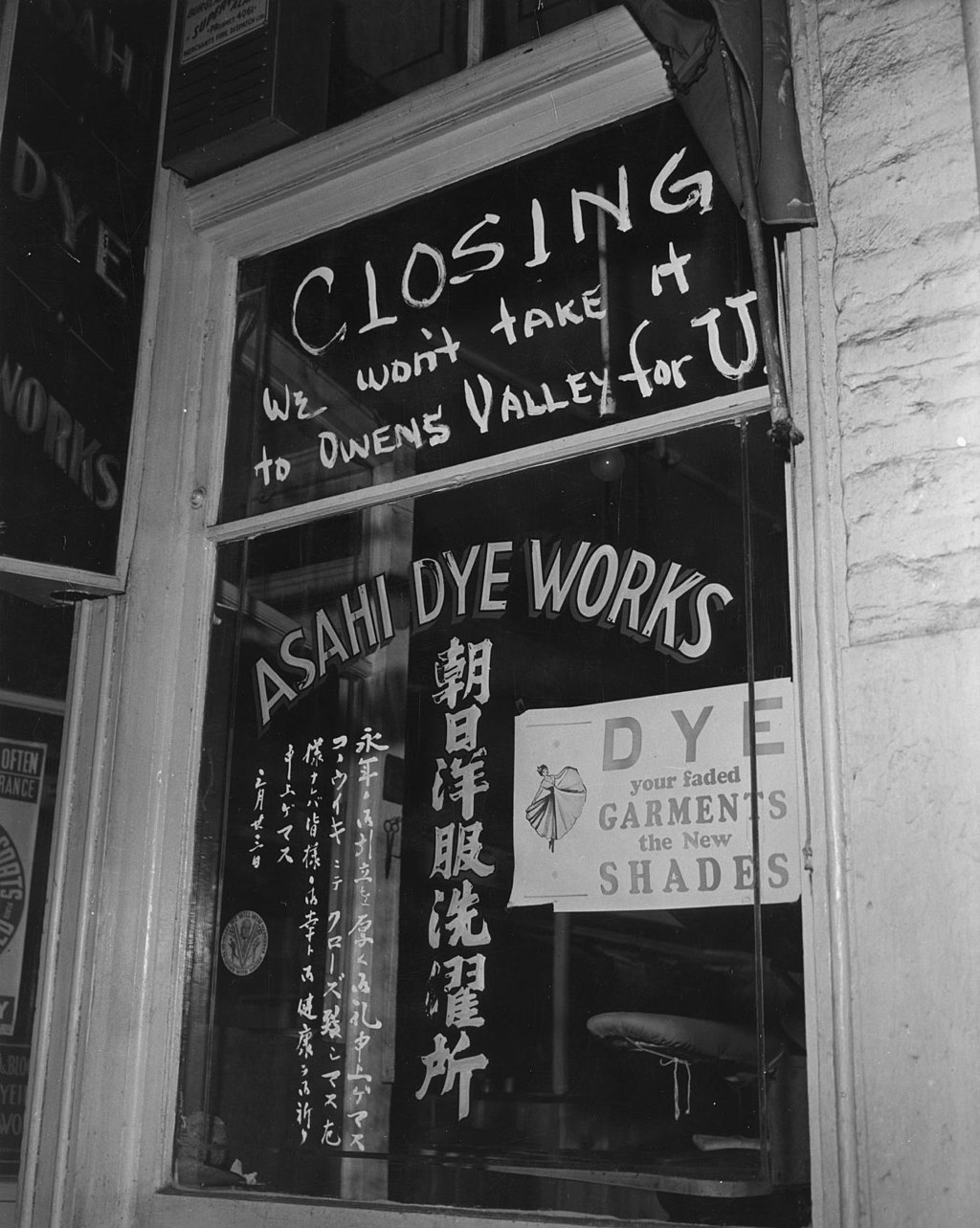

| Background Further information: History of Japanese Americans Japanese Americans before World War II Further information: Japanese American life before World War II Due in large part to socio-political changes which stemmed from the Meiji Restoration—and a recession which was caused by the abrupt opening of Japan's economy to the world economy—people emigrated from the Empire of Japan in 1868 in search of employment.[7] From 1869 to 1924, approximately 200,000 Japanese immigrated to the islands of Hawaii, mostly laborers expecting to work on the islands' sugar plantations. Some 180,000 went to the U.S. mainland, with the majority of them settling on the West Coast and establishing farms or small businesses.[8][9] Most arrived before 1908, when the Gentlemen's Agreement between Japan and the United States banned the immigration of unskilled laborers. A loophole allowed the wives of men who were already living in the US to join their husbands. The practice of women marrying by proxy and immigrating to the U.S. resulted in a large increase in the number of "picture brides."[7][10] As the Japanese American population continued to grow, European Americans who lived on the West Coast resisted the arrival of this ethnic group, fearing competition, and making the exaggerated claim that hordes of Asians would take over white-owned farmland and businesses. Groups such as the Asiatic Exclusion League, the California Joint Immigration Committee, and the Native Sons of the Golden West organized in response to the rise of this "Yellow Peril." They successfully lobbied to restrict the property and citizenship rights of Japanese immigrants, just as similar groups had previously organized against Chinese immigrants.[11] Beginning in the late 19th century, several laws and treaties which attempted to slow immigration from Japan were introduced. The Immigration Act of 1924, which followed the example of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, effectively banned all immigration from Japan and other "undesirable" Asian countries. The 1924 ban on immigration produced unusually well-defined generational groups within the Japanese American community. The Issei were exclusively those Japanese who had immigrated before 1924; some of them desired to return to their homeland.[12] Because no more immigrants were permitted, all Japanese Americans who were born after 1924 were, by definition, born in the U.S. and by law, they were automatically considered U.S. citizens. The members of this Nisei generation constituted a cohort which was distinct from the cohort which their parents belonged to. In addition to the usual generational differences, Issei men were typically ten to fifteen years older than their wives, making them significantly older than the younger children in their often large families.[10] U.S. law prohibited Japanese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens, making them dependent on their children whenever they rented or purchased property. Communication between English-speaking children and parents who mostly or completely spoke in Japanese was often difficult. A significant number of older Nisei, many of whom were born prior to the immigration ban, had married and already started families of their own by the time the US entered World War II.[13] Despite racist legislation which prevented Issei from becoming naturalized citizens (or owning property, voting, or running for political office), these Japanese immigrants established communities in their new hometowns. Japanese Americans contributed to the agriculture of California and other Western states, by introducing irrigation methods which enabled them to cultivate fruits, vegetables, and flowers on previously inhospitable land.[14] In both rural and urban areas, kenjinkai, community groups for immigrants from the same Japanese prefecture, and fujinkai, Buddhist women's associations, organized community events and did charitable work, provided loans and financial assistance and built Japanese language schools for their children. Excluded from setting up shop in white neighborhoods, nikkei-owned small businesses thrived in the Nihonmachi, or Japantowns of urban centers, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle.[15]  A per-state population map of the Japanese American population, with California leading by a far margin with 93,717. A per-state population map of the Japanese American population, with California leading with 93,717, from Final Report, Japanese Evacuation From the West Coast 1942 In the 1930s, the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), concerned as a result of Imperial Japan's rising military power in Asia, began to conduct surveillance in Japanese American communities in Hawaii. Starting in 1936, at the behest of President Roosevelt, the ONI began to compile a "special list of those Japanese Americans who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp in the event of trouble" between Japan and the United States. In 1939, again by order of the President, the ONI, Military Intelligence Division, and FBI began working together to compile a larger Custodial Detention Index.[16] Early in 1941, Roosevelt commissioned Curtis Munson to conduct an investigation on Japanese Americans living on the West Coast and in Hawaii. After working with FBI and ONI officials and interviewing Japanese Americans and those familiar with them, Munson determined that the "Japanese problem" was nonexistent. His final report to the President, submitted November 7, 1941, "certified a remarkable, even extraordinary degree of loyalty among this generally suspect ethnic group."[17] A subsequent report by Kenneth Ringle (ONI), delivered to the President in January 1942, also found little evidence to support claims of Japanese American disloyalty and argued against mass incarceration.[18] Roosevelt's racial attitudes toward Japanese Americans Roosevelt's decision to intern Japanese Americans was consistent with Roosevelt's long-time racial views. During the 1920s, for example, he had written articles in the Macon Telegraph opposing white-Japanese intermarriage for fostering "the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood" and praising California's ban on land ownership by the first-generation Japanese. In 1936, while president, he privately wrote that, regarding contacts between Japanese sailors and the local Japanese American population in the event of war, “every Japanese citizen or non-citizen on the Island of Oahu who meets these Japanese ships or has any connection with their officers or men should be secretly but definitely identified and his or her name placed on a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp." [19] After Pearl Harbor In the weeks immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor the president disregarded the advice of advisors, notably John Franklin Carter, who urged him to speak out in defense of the rights of Japanese Americans.[19]  The San Francisco Examiner, April 1942  Tatsuro Masuda, a Japanese American, unfurled this banner in Oakland, California the day after the Pearl Harbor attack. Dorothea Lange took this photograph in March 1942, just before his internment.  A child is "Tagged for evacuation", Salinas, California, May 1942. Photo by Russell Lee.  A Japanese American shop, Asahi Dye Works, closing. The notice on the front is a reference to Owens Valley being the first and one of the largest Japanese American detention centers. -Tatsuro Masuda, a Japanese American, unfurled this banner in Oakland, California the day after the Pearl Harbor attack. Dorothea Lange took this photograph in March 1942, just before his internment. The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, led military and political leaders to suspect that Imperial Japan was preparing a full-scale invasion of the United States West Coast.[20] Due to Japan's rapid military conquest of a large portion of Asia and the Pacific including a small portion of the U.S. West Coast (i.e., Aleutian Islands Campaign) between 1937 and 1942, some Americans[who?] feared that its military forces were unstoppable. American public opinion initially stood by the large population of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, with the Los Angeles Times characterizing them as "good Americans, born and educated as such." Many Americans believed that their loyalty to the United States was unquestionable.[21] However, six weeks after the attack, public opinion along the Pacific began to turn against Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, as the press and other Americans[citation needed] became nervous about the potential for fifth column activity. Though some in the administration (including Attorney General Francis Biddle and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover) dismissed all rumors of Japanese American espionage on behalf of the Japanese war effort, pressure mounted upon the administration as the tide of public opinion turned against Japanese Americans. A survey of the Office of Facts and Figures on February 4 (two weeks prior to the president's order) reported that a majority of Americans expressed satisfaction with existing governmental controls on Japanese Americans. Moreover, in his autobiography in 1962, Attorney General Francis Biddle, who opposed incarceration, downplayed the influence of public opinion in prompting the president's decision. He even considered it doubtful "whether, political and special group press aside, public opinion even on the West Coast supported evacuation."[22] Support for harsher measures toward Japanese Americans increased over time, however, in part since Roosevelt did little to use his office to calm attitudes. According to a March 1942 poll conducted by the American Institute of Public Opinion, after incarceration was becoming inevitable, 93% of Americans supported the relocation of Japanese non-citizens from the Pacific Coast while only 1% opposed it. According to the same poll, 59% supported the relocation of Japanese people who were born in the country and were United States citizens, while 25% opposed it. The incarceration and imprisonment measures taken against Japanese Americans after the attack falls into a broader trend of anti-Japanese attitudes on the West Coast of the United States.[23] To this end, preparations had already been made in the collection of names of Japanese American individuals and organizations, along with other foreign nationals such as Germans and Italians, that were to be removed from society in the event of a conflict.[24] The December 7th attack on Pearl Harbour, bringing the United States into the Second World War, enabled the implementation of the dedicated government policy of incarceration, with the action and methodology having been extensively prepared before war broke out despite multiple reports that had been consulted by President Roosevelt expressing the notion that Japanese Americans posed little threat.[25] Niihau incident Although the impact on US authorities is controversial, the Niihau incident immediately followed the attack on Pearl Harbor, when Ishimatsu Shintani, an Issei, and Yoshio Harada, a Nisei, and his Issei wife Irene Harada on the island of Ni'ihau violently freed a downed and captured Japanese naval airman, attacking their fellow Ni'ihau islanders in the process.[26] Roberts Commission Several concerns over the loyalty of ethnic Japanese seemed to stem from racial prejudice rather than any evidence of malfeasance. The Roberts Commission report, which investigated the Pearl Harbor attack, was released on January 25 and accused persons of Japanese ancestry of espionage leading up to the attack.[27] Although the report's key finding was that General Walter Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel had been derelict in their duties during the attack on Pearl Harbor, one passage made vague reference to "Japanese consular agents and other... persons having no open relations with the Japanese foreign service" transmitting information to Japan. It was unlikely that these "spies" were Japanese American, as Japanese intelligence agents were distrustful of their American counterparts and preferred to recruit "white persons and Negroes."[28] However, despite the fact that the report made no mention of Americans of Japanese ancestry, national and West Coast media nevertheless used the report to vilify Japanese Americans and inflame public opinion against them.[29] Questioning loyalty Major Karl Bendetsen and Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, questioned Japanese American loyalty. DeWitt said: The fact that nothing has happened so far is more or less . . . ominous, in that I feel that in view of the fact that we have had no sporadic attempts at sabotage that there is a control being exercised and when we have it it will be on a mass basis.[27] He further stated in a conversation with California's governor, Culbert L. Olson: There's a tremendous volume of public opinion now developing against the Japanese of all classes, that is aliens and non-aliens, to get them off the land, and in Southern California around Los Angeles—in that area too—they want and they are bringing pressure on the government to move all the Japanese out. As a matter of fact, it's not being instigated or developed by people who are not thinking but by the best people of California. Since the publication of the Roberts Report they feel that they are living in the midst of a lot of enemies. They don't trust the Japanese, none of them.[27] "A Jap's a Jap" DeWitt, who administered the incarceration program, repeatedly told newspapers that "A Jap's a Jap" and testified to Congress: I don't want any of them [persons of Japanese ancestry] here. They are a dangerous element. There is no way to determine their loyalty... It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen, he is still a Japanese. American citizenship does not necessarily determine loyalty... But we must worry about the Japanese all the time until he is wiped off the map.[30][31] DeWitt also sought approval to conduct search and seizure operations which were aimed at preventing alien Japanese from making radio transmissions to Japanese ships.[32] The Justice Department declined, stating that there was no probable cause to support DeWitt's assertion, as the FBI concluded that there was no security threat.[32] On January 2, the Joint Immigration Committee of the California Legislature sent a manifesto to California newspapers which attacked "the ethnic Japanese," who it alleged were "totally unassimilable."[32] This manifesto further argued that all people of Japanese heritage were loyal subjects of the Emperor of Japan; the manifesto contended that Japanese language schools were bastions of racism which advanced doctrines of Japanese racial superiority.[32] The manifesto was backed by the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West and the California Department of the American Legion, which in January demanded that all Japanese with dual citizenship be placed in concentration camps.[32] By February, Earl Warren, the Attorney General of California (and a future Chief Justice of the United States), had begun his efforts to persuade the federal government to remove all people of Japanese ethnicity from the West Coast.[32] Those who were as little as 1⁄16 Japanese were placed in incarceration camps.[33][34] Bendetsen, promoted to colonel, said in 1942, "I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp."[35] Presidential Proclamations Upon the bombing of Pearl Harbor and pursuant to the Alien Enemies Act, Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526 and 2527 were issued designating Japanese, German and Italian nationals as enemy aliens.[36] Information gathered by US officials over the previous decade was used to locate and incarcerate thousands of Japanese American community leaders in the days immediately following Pearl Harbor (see section elsewhere in this article "Other concentration camps"). In Hawaii, under the auspices of martial law, both "enemy aliens" and citizens of Japanese and "German" descent were arrested and interned (incarcerated if they were a US citizen).[37] Presidential Proclamation 2537 (codified at 7 Fed. Reg. 329) was issued on January 14, 1942, requiring "alien enemies" to obtain a certificate of identification and carry it "at all times".[38] Enemy aliens were not allowed to enter restricted areas.[38] Violators of these regulations were subject to "arrest, detention and incarceration for the duration of the war."[38] On February 13, the Pacific Coast Congressional subcommittee on aliens and sabotage recommended to the President immediate evacuation of "all persons of Japanese lineage and all others, aliens and citizens alike" who were thought to be dangerous from "strategic areas," further specifying that these included the entire "strategic area" of California, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. On February 16 the President tasked Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson with replying. A conference on February 17 of Secretary Stimson with assistant secretary John J. McCloy, Provost Marshal General Allen W. Gullion, Deputy chief of Army Ground Forces Mark W. Clark, and Colonel Bendetsen decided that General DeWitt should be directed to commence evacuations "to the extent he deemed necessary" to protect vital installations.[39] Throughout the war, interned Japanese Americans protested against their treatment and insisted that they be recognized as loyal Americans. Many sought to demonstrate their patriotism by trying to enlist in the armed forces. Although early in the war Japanese Americans were barred from military service, by 1943 the army had begun actively recruiting Nisei to join new all-Japanese American units. |

背景 さらに詳しい情報:日系アメリカ人の歴史 第二次世界大戦前の日系アメリカ人 さらに詳しい情報:第二次世界大戦前の日系アメリカ人の生活 明治維新に端を発する社会政治的変化と、日本経済が世界経済に急激に開放されたことによる不況が主な原因となり、1868年に 職を求めて移住した。[7] 1869年から1924年にかけて、約20万人の日本人がハワイ諸島に移住した。そのほとんどは、同諸島の砂糖プランテーションで働くことを期待した労働 者であった。約18万人がアメリカ本土に移住し、その大半は西海岸に定住して農場や小規模な事業を始めた。[8][9] 1908年までにほとんどが到着したが、この年、日本とアメリカ間の紳士協定によって、熟練労働者以外の移民は禁止された。抜け道として、すでに米国に居 住している男性の妻が夫のもとに合流することが認められた。代理結婚をして米国に移住する女性が増えた結果、「写真花嫁」の数が大幅に増加した。 日系アメリカ人の人口が増加し続ける中、西海岸に住むヨーロッパ系アメリカ人は、競争を恐れてこの民族の流入に抵抗し、アジア人が白人所有の農場や企業を 乗っ取るだろうと誇張した主張をした。 アジア排斥同盟、カリフォルニア合同移民委員会、ゴールデン・ウェストのネイティブ・サンズなどの団体が、この「黄色い脅威」の高まりに対応して結成され た。彼らは、以前に中国人移民に対して同様のグループが組織されたように、日本人移民の財産権と市民権を制限するようロビー活動を行い、成功を収めた。 [11] 19世紀後半から、日本からの移民を抑制しようとするいくつかの法律や条約が導入された。1882年の中国人排斥法にならった1924年の移民法は、日本 やその他の「望ましくない」アジア諸国からの移民を事実上全面的に禁止した。 1924年の移民禁止法により、日系アメリカ人社会にははっきりと世代が区別されるようになった。一世は1924年以前に移住した日本人であり、その中に は日本への帰国を希望する者もいた。[12] それ以降の移民は認められなかったため、1924年以降に生まれた日系アメリカ人は、定義上はすべてアメリカ生まれとなり、法律上は自動的にアメリカ市民 とみなされた。この二世世代は、彼らの両親が属していた世代とは異なる世代を構成していた。世代間の違いに加え、一世の男性は妻よりも10歳から15歳年 上であることが多く、大家族の場合、末っ子とはかなり年齢が離れていた。[10] 米国の法律では、日本からの移民が市民権を取得することは禁じられていたため、彼らが不動産を賃貸または購入する際には、子供たちに頼らざるを得なかっ た。英語を話す子供たちと、ほとんどあるいは完全に日本語で会話する両親とのコミュニケーションは、しばしば困難を伴った。 かなりの数の年長の二世は、その多くが移民禁止令が発令される前に生まれ、米国が第二次世界大戦に参戦するまでに結婚し、すでに自分の家庭を持っていた。 [13] 一世が市民権を取得したり(あるいは財産を所有したり、投票を行ったり、政治的役職に立候補したり)することを妨げる人種差別的な法律があったにもかかわ らず、これらの日本人移民は新しい故郷にコミュニティを築いた。日系アメリカ人は、灌漑技術を導入することで、それまでは不毛の土地であった場所で果物や 野菜、花を栽培することを可能にし、カリフォルニア州やその他の西部諸州の農業に貢献した。 農村部でも都市部でも、同じ日本の都道府県出身者によるコミュニティグループである県人会や、仏教の女性団体である婦人会が、地域イベントを企画したり慈 善活動を行ったり、融資や資金援助を行ったり、子供たちのために日本語学校を設立したりした。白人居住区への出店を禁じられた日系人の小規模企業は、ロサ ンゼルス、サンフランシスコ、シアトルなどの都市中心部の日本町(ジャパタウン)で繁栄した。  州別の日系アメリカ人人口地図。カリフォルニア州が93,717人と、他州を大きく引き離してトップとなっている。 州別の日系アメリカ人人口地図。カリフォルニア州が93,717人と、他州を大きく引き離してトップとなっている。『西海岸からの日系人退去 1942』最終報告書より 1930年代、アジアにおける大日本帝国の軍事力の増強を懸念した米国海軍情報局(ONI)は、ハワイの日系アメリカ人社会に対する監視を開始した。 1936年、ルーズベルト大統領の命により、ONIは「日米間に問題が生じた場合に最初に強制収容所に収容する日系アメリカ人の特別リスト」の作成を開始 した。1939年には、大統領の命令により、ONI、軍事情報部、FBIが共同でより大規模な拘留者インデックスの作成を開始した。[16] 1941年初頭、ルーズベルト大統領はカーティス・マンソンに西海岸とハワイ在住の日系アメリカ人に関する調査を依頼した。FBIおよびONIの職員と協 力し、日系アメリカ人と彼らに詳しい人物への聞き取り調査を行った後、マンソンは「日本人の問題」は存在しないと結論付けた。1941年11月7日に大統 領に提出された彼の最終報告書は、「この一般的に疑わしい民族集団の間には、驚くべき、あるいは並外れた忠誠心が存在することを証明した」[17]。 1942年1月に大統領に提出されたケネス・リングル(ONI)によるその後の報告書でも、日系アメリカ人の不忠誠を裏付ける証拠はほとんど見つからず、 集団収容に反対する意見が述べられた。[18] 日系アメリカ人に対するルーズベルトの差別意識 日系アメリカ人の強制収容を決定したことは、ルーズベルトの長年の人種観と一致していた。例えば、1920年代には、マコン・テレグラフ紙に「アジアの血 がヨーロッパやアメリカの血と混ざり合う」として、白人との結婚に反対する記事を書いており、また、カリフォルニア州が日系一世に土地所有を禁止したこと を賞賛していた。1936年、大統領在任中、彼は個人的に、戦争が勃発した場合の日本人船員と現地の日系アメリカ人住民との接触について、「オアフ島に居 住する全ての日本人市民および非市民で、これらの日本船と接触したり、船員と何らかの関係を持つ者は、秘密裏に、しかし確実に特定され、強制収容所に最初 に収容される者として特別リストに名前が載せられるべきである」と記している。[19] 真珠湾攻撃の後 真珠湾攻撃の直後の数週間、大統領はアドバイザー、特に日系アメリカ人の権利を擁護するよう強く求めたジョン・フランクリン・カーターの助言を無視した。 [19]  1942年4月、サンフランシスコ・エグザミナー紙  真珠湾攻撃の翌日、カリフォルニア州オークランドで、日系アメリカ人のマサダ・タツロウがこの横断幕を広げた。 ドロシア・ラングが、彼の強制収容直前の1942年3月に撮影した写真。  1942年5月、カリフォルニア州サラナスで、「退去」のタグを付けられた子供。 撮影:ラッセル・リー(Russell Lee)。  日系アメリカ人の経営するアサヒ・ダイ・ワークス(Asahi Dye Works)の閉店。 店の前に掲げられた通知は、オーエンズバレーが最初で最大級の日系人強制収容所のひとつであったことを示している。 1941年12月7日の真珠湾攻撃は、軍および政治指導者たちに、日本帝国が米国西海岸への全面侵攻を準備しているのではないかと疑わせた。[20] 日本が1937年から1942年の間に 1937年から1942年にかけて、アジアと太平洋の大部分(米国西海岸の小部分を含む、すなわちアリューシャン列島作戦)を急速に征服したため、一部の アメリカ人[誰?]は、その軍事力は止められないと恐れた。 当初、アメリカ世論は西海岸に多数住む日系アメリカ人に対して好意的な立場を取っていた。ロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙は彼らを「生まれも育ちもアメリカ人で ある善良なアメリカ人」と評した。多くのアメリカ人は彼らのアメリカへの忠誠心は疑う余地がないと考えていた。[21] しかし、真珠湾攻撃から6週間後、西海岸に住む日系アメリカ人に対する世論は変化し始めた。報道機関や他のアメリカ人[要出典]が第五列活動の可能性に神 経質になっていたためである。政府内では、司法長官フランシス・ビドルやFBI長官J・エドガー・フーバーなど、日系アメリカ人が日本の戦争努力のために スパイ活動をしているという噂をすべて否定する者もいたが、世論が日系アメリカ人に敵対する方向に傾くにつれ、政府に対する圧力は高まった。 2月4日(大統領命令の2週間前)の事実と統計局の調査では、大多数のアメリカ人が日系アメリカ人に対する現行の政府管理に満足していると回答した。さら に、強制収容に反対していた司法長官フランシス・ビドルは、1962年の自伝の中で、大統領の決断を促した世論の影響力を過小評価している。彼は、「政治 団体や特殊集団の意見はさておき、西海岸ですら世論が退去命令を支持していたかどうかは疑わしい」とさえ考えている[22]。しかし、日系アメリカ人に対 する厳しい措置への支持は、時が経つにつれて高まっていった。その理由の一つは、ルーズベルト大統領が、世論を沈静化するために自らの権限を行使しようと しなかったことにある。1942年3月にアメリカ世論研究所が実施した世論調査によると、強制収容が不可避となった後、太平洋岸在住の非市民である日本人 を移住させることについては、93%のアメリカ人が賛成し、反対したのはわずか1%だった。同じ世論調査によると、アメリカ生まれでアメリカ国籍を持つ日 本人を移住させることについては、59%が賛成し、反対したのは25%だった。 真珠湾攻撃後に日系アメリカ人に対してとられた収容・投獄措置は、アメリカ西海岸における反日感情の高まりという大きな流れの中に位置づけられる。 [23] その目的のために、日系アメリカ人やドイツ人、イタリア人などの外国人を対象に、紛争時に社会から排除されるべき個人や団体の名簿作成の準備がすでに進め られていた。。12月7日の真珠湾攻撃により、アメリカは第二次世界大戦に参戦し、日系人強制収容という政府の政策が実行に移された。その行動と方法は、 ルーズベルト大統領が検討した複数の報告書が、日系アメリカ人はほとんど脅威ではないという考えを示していたにもかかわらず、戦争が勃発する前に広範囲に わたって準備されていた。 ニイハウ島事件 米国当局への影響については議論の余地があるが、ニイハウ島事件は真珠湾攻撃の直後に起こった。ニイハウ島在住の石松新谷(一世)とヨシオ・ハラダ(二 世)と彼の妻アイリーン・ハラダ(一世)が、不時着して捕虜となった日本海軍の航空兵を暴力的に解放し、その過程でニイハウ島民の仲間を攻撃した事件であ る。 ロバーツ委員会 日系人の忠誠心に対する懸念は、不正行為の証拠というよりも人種的偏見から生じたものと思われた。真珠湾攻撃を調査したロバーツ委員会の報告書が1月25 日に発表され、日系人に対して攻撃に至るまでの間、スパイ行為を行っていたと非難した。[27] 報告書の主な結論は、ウォルター・ショート将軍とハワード・キンメル提督が 真珠湾攻撃時に職務怠慢であったという内容であったが、その報告書には「日本領事館のエージェントや、その他...日本外務省と公の関係を持たない人物」 が日本に情報を流しているという漠然とした記述もあった。これらの「スパイ」が日系人である可能性は低かった。なぜなら、日本の諜報部員はアメリカ人に対 して不信感を抱いており、「白人や黒人」をスパイとして採用することを好んでいたからである。[28] しかし、この報告書には日系アメリカ人のことは一切触れられていなかったにもかかわらず、全米および西海岸のメディアは、この報告書を利用して日系アメリ カ人を中傷し、世論を煽った。[29] 忠誠心を疑う カール・ベンドツェン少佐と西部防衛司令部のジョン・L・デウィット中将は、日系アメリカ人の忠誠心を疑った。デウィットは次のように述べた。 「これまで何も起こらなかったという事実は、ある意味で...不吉である。というのも、散発的な妨害工作が一度もなかったという事実を考慮すると、何らか の統制が取られていると感じられるし、統制が取られているとすれば、それは集団的なものだろうから」[27] さらに、カリフォルニア州知事のカルバート・L・オルソンとの会話の中で、彼は次のように述べた。 今、あらゆる階層の日本人に対して、つまり外国人および非外国人に対して、この国から出て行けという世論が急速に高まっている。南カリフォルニア、特にロ サンゼルス周辺では、日本人を全員立ち退かせようという圧力が政府にかけられている。実際、これは考えなしの人々によって扇動されたものではなく、カリ フォルニア州の良識ある人々によって生み出されたものだ。ロバーツ報告書が発表されて以来、彼らは自分たちが多くの敵に囲まれて生きていると感じている。 彼らは日本人を信用していない。誰も信用していない。[27] 「ジャップはジャップだ」 強制収容プログラムを管理していたデウィットは、繰り返し新聞に「ジャップはジャップだ」と語り、議会で証言した。 私は日系人の誰一人としてここにはいさせたくない。彼らは危険な存在だ。彼らの忠誠心を見極める方法はない... 彼がアメリカ市民であろうとなかろうと、彼が日本人であることに変わりはない。アメリカ市民権は必ずしも忠誠心を決定づけるものではない... しかし、彼が地図から消えるまで、私たちは常に日本人を心配しなければならないのだ。[30][31] また、デウィットは、日本国籍の外国人による日本船への無線送信を阻止することを目的とした捜索・押収作戦の承認を求めたが、司法省はこれを却下した。 FBIが安全保障上の脅威はないと結論づけたように、デウィットの主張を裏付ける可能性のある原因は存在しないと述べたのだ。1月2日、 カリフォルニア州議会合同移民委員会は、カリフォルニアの新聞に「同化できない」と主張する「日系人」を攻撃する声明文を送った。[32] この声明文はさらに、日本人の血を引く人々はすべて日本の天皇の忠実な臣民であると主張し、日本語学校は人種差別の牙城であり、日本人の人種的優越性を唱 える教義を広めていると主張した。[32] この宣言は、ゴールデン・ウェストのネイティブ・サンズ・アンド・ドーターズとカリフォルニア州のアメリカ軍人会によって支持され、1月には、二重国籍を 持つすべての日本人を強制収容所に収容するよう要求した。2月には、カリフォルニア州司法長官(のちに連邦最高裁判所長官)のアール・ウォーレンが、西海 岸から日本人をすべて立ち退かせるよう連邦政府に説得する取り組みを開始した。 日本人の血が16分の1でも流れている者は、強制収容所に収容された。[33][34] ベンデセンは大佐に昇進し、1942年には「日本人の血が一滴でも流れている者は、強制収容所に送らなければならない」と述べた。[35] 大統領布告 真珠湾攻撃を受けて、外国人敵性国民法(Alien Enemies Act)に基づき、大統領布告2525、2526、2527が発令され、日本人、ドイツ人、イタリア人が敵性外国人と指定された。[36] 過去10年間に米政府当局が収集した情報をもとに、真珠湾攻撃直後の数日間で、日系アメリカ人社会の指導者数千人が特定され、収容された(本記事の別のセ クション「その他の強制収容所」を参照)。ハワイでは、戒厳令のもと、「敵性外国人」と日系および「ドイツ系」の市民が逮捕され、収容された(米国市民の 場合は投獄された)。[37] 1942年1月14日には大統領布告第2537号(連邦規則集第7巻第329条に規定)が発令され、「敵性外国人」に対して身分証明書の取得と「常時携 帯」が義務付けられた。[38] 敵性外国人は立ち入り禁止区域への立ち入りを禁じられた。[38] これらの規定に違反した者は「戦争が続く限り、逮捕、拘留、投獄の対象となる」ことになった。[38] 2月13日、太平洋沿岸の外国人およびサボタージュに関する下院小委員会は、大統領に対し、「戦略地域」から危険人物と見なされる「日本人の血筋を持つ者 およびその他の外国人、市民を問わずすべての人々」の即時退去を勧告した。さらに、この勧告には、カリフォルニア、オレゴン、ワシントン、アラスカの「戦 略地域」全体が含まれることが明記された。2月16日、大統領はヘンリー・L・スティムソン陸軍長官に回答を指示した。2月17日、スティムソン長官は ジョン・J・マクロイ次官補、アレン・W・ガリオン陸軍総司令官、マーク・W・クラーク陸軍地上軍副司令官、ベントセン大佐と協議し、デウィット将軍に 「必要と判断される範囲」で重要施設を保護するための避難を開始するよう指示すべきであると決定した。[39] 戦争中、抑留された日系アメリカ人は自分たちの扱いに抗議し、忠誠心のあるアメリカ人として認められるべきだと主張した。多くの人々が、愛国心を示そうと 軍への入隊を試みた。開戦当初は日系アメリカ人の軍務は禁じられていたが、1943年には陸軍が日系アメリカ人だけの部隊に二世を積極的に採用し始めてい た。 |

| Development Executive Order 9066 and related actions Executive Order 9066, signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt[40] on February 19, 1942, authorized military commanders to designate "military areas" at their discretion, "from which any or all persons may be excluded." These "exclusion zones," unlike the "alien enemy" roundups, were applicable to anyone that an authorized military commander might choose, whether citizen or non-citizen. Eventually such zones would include parts of both the East and West Coasts, totaling about 1/3 of the country by area. Unlike the subsequent deportation and incarceration programs that would come to be applied to large numbers of Japanese Americans, detentions and restrictions directly under this Individual Exclusion Program were placed primarily on individuals of German or Italian ancestry, including American citizens.[41] The order allowed regional military commanders to designate "military areas" from which "any or all persons may be excluded."[42] Although the executive order did not mention Japanese Americans, this authority was used to declare that all people of Japanese ancestry were required to leave Alaska[43] and the military exclusion zones from all of California and parts of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona, with the exception of those inmates who were being held in government camps.[44] The detainees were not only people of Japanese ancestry, they also included a relatively small number—though still totaling well over ten thousand—of people of German and Italian ancestry as well as Germans who were expelled from Latin America and deported to the U.S.[45]: 124 [46] Approximately 5,000 Japanese Americans relocated outside the exclusion zone before March 1942,[47] while some 5,500 community leaders had been arrested immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack and thus were already in custody.[8]  The baggage of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, at a makeshift reception center located at a racetrack  Dressed in uniform marking his service in World War I, a U.S. Navy veteran, Hikotaro Yamada, from Torrance enters Santa Anita Assembly Center (April 1942)  Children wave from the window of a special train as it leaves Seattle with Bainbridge Island internees, March 30, 1942 On March 2, 1942, General John DeWitt, commanding general of the Western Defense Command, publicly announced the creation of two military restricted zones.[48] Military Area No. 1 consisted of the southern half of Arizona and the western half of California, Oregon, and Washington, as well as all of California south of Los Angeles. Military Area No. 2 covered the rest of those states. DeWitt's proclamation informed Japanese Americans they would be required to leave Military Area 1, but stated that they could remain in the second restricted zone.[49] Removal from Military Area No. 1 initially occurred through "voluntary evacuation."[47] Japanese Americans were free to go anywhere outside of the exclusion zone or inside Area 2, with arrangements and costs of relocation to be borne by the individuals. The policy was short-lived; DeWitt issued another proclamation on March 27 that prohibited Japanese Americans from leaving Area 1.[48] A night-time curfew, also initiated on March 27, 1942, placed further restrictions on the movements and daily lives of Japanese Americans.[45][page needed] Included in the forced removal was Alaska, which, like Hawaii, was an incorporated U.S. territory located in the northwest extremity of the continental United States. Unlike the contiguous West Coast, Alaska was not subject to any exclusion zones due to its small Japanese population. Nevertheless, the Western Defense Command announced in April 1942 that all Japanese people and Americans of Japanese ancestry were to leave the territory for incarceration camps inland. By the end of the month, over 200 Japanese residents regardless of citizenship were exiled from Alaska, most of them ended up at the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Southern Idaho.[50] Eviction from the West Coast began on March 24, 1942, with Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1, which gave the 227 Japanese American residents of Bainbridge Island, Washington six days to prepare for their "evacuation" directly to Manzanar.[51] Colorado governor Ralph Lawrence Carr was the only elected official to publicly denounce the incarceration of American citizens (an act that cost his reelection, but gained him the gratitude of the Japanese American community, such that a statue of him was erected in the Denver Japantown's Sakura Square).[52] A total of 108 exclusion orders issued by the Western Defense Command over the next five months completed the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast in August 1942.[53] In addition to imprisoning those of Japanese descent in the US, the US also interned people of Japanese (and German and Italian) descent deported from Latin America. Thirteen Latin American countries—Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Peru—cooperated with the US by apprehending, detaining and deporting to the US 2,264 Japanese Latin American citizens and permanent residents of Japanese ancestry.[54][55] |

開発 大統領令9066および関連措置 1942年2月19日にフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領が署名した大統領令9066は、軍司令官が「軍事地域」をその裁量で指定することを認めるも のであり、そこから「あらゆる人々、またはすべての人々を排除することができる」と定めていた。これらの「排除区域」は、「敵国人」の一斉検挙とは異な り、軍司令官が選んだ人物であれば、市民であるか否かに関わらず適用された。最終的に、このような区域は東海岸と西海岸の一部を含み、国土の約3分の1に 及んだ。後に日系アメリカ人の多数に適用されることになる強制退去と収容プログラムとは異なり、この「個人排除プログラム」に基づく直接的な拘束と制限 は、ドイツ系およびイタリア系アメリカ人、そしてアメリカ市民にも適用された。[41] この大統領令により、地域軍司令官は「軍事地域」を指定し、そこから「一部またはすべての人物を排除する」ことが可能となった。[42] 大統領令では日系アメリカ人には言及されていなかったが、この この権限が行使され、日系人全員にアラスカからの退去が命じられ[43]、カリフォルニア州全域とオレゴン州、ワシントン州、アリゾナ州の一部の軍事排除 区域から、政府の収容所に収容されていた被収容者を除いて退去が命じられた。被収容者は日系人だけでなく、ドイツ系やイタリア系の人々も含まれていたが、 その数は比較的少数であった。イタリア系、およびラテンアメリカから追放され米国に送還されたドイツ人も含まれていた。[45]:124[46] 1942年3月までに、約5,000人の日系アメリカ人が立ち入り禁止区域外へ移住した。[47] 一方、真珠湾攻撃直後に約5,500人の地域指導者が逮捕され、すでに拘束されていた。[8]  西海岸の日系人の手荷物は、競馬場に設けられた仮設の受付センターに集められた  第一次世界大戦に従軍したことを示す軍服を身にまとったトーランス出身の米海軍退役軍人、ヒコタロウ・ヤマダが、サンタアニータ集合センターに入場する (1942年4月)  ベインブリッジ島の収容者を乗せた特別列車がシアトルを出発する際、子供たちが窓から手を振る(1942年3月30日) 1942年3月2日、西部防衛司令官ジョン・デウィット将軍は、2つの軍事制限区域の設定を公式に発表した。[48] 軍事地域第1は、アリゾナ州の南半分、およびカリフォルニア州、オレゴン州、ワシントン州の西半分、そしてロサンゼルスより南のカリフォルニア州全域から 構成されていた。軍事地域第2は、それ以外の州をカバーしていた。 デウィットの布告は、日系アメリカ人に対して軍事地域第1からの立ち退きを命じたが、第2の制限区域には留まることができると述べた。[49] 軍事地域第1からの立ち退きは、当初は「自主避難」という形で実施された。[47] 日系アメリカ人は、立ち退き禁止区域外、または第2区域内のどこへでも自由に行くことができたが、移転の手配や費用は各自の負担となった。この政策は短期 間で終わり、デウィットは3月27日に新たな布告を発令し、日系アメリカ人が第1軍管区から立ち退くことを禁止した。[48] 1942年3月27日に始まった夜間外出禁止令により、日系アメリカ人の移動や日常生活はさらに制限された。[45][要出典] 強制退去の対象となった地域には、ハワイと同じくアメリカ合衆国の北西部に位置するアメリカ合衆国の準州であるアラスカも含まれていた。本土の西海岸とは 異なり、アラスカには日本人がほとんどいなかったため、立ち入り禁止区域に指定されることはなかった。しかし、西部防衛司令部は1942年4月、日系アメ リカ人と日本人はすべてアラスカ準州から立ち退き、内陸部の収容所に収容すると発表した。同月末までに、国籍を問わず200人以上の日系住民がアラスカか ら追放され、そのほとんどが南アイダホのミニドカ戦争移住センターに送られた。 1942年3月24日、市民排除命令第1号により、西海岸からの立ち退きが始まり、ワシントン州ベインブリッジ島の227人の日系アメリカ人は、マンザ ナールへの「避難」の準備を6日間で行うよう命じられた。[51] コロラド州知事ラルフ・ローレンス・カーは、アメリカ市民の強制収容を公に非難した唯一の公選の政治家であった( この行為により再選は逃したが、日系アメリカ人社会の感謝の念を得て、デンバーのジャパタウンのサクラスクエアに彼の銅像が建てられた)[52] 西部防衛司令部の発令した108件の排除命令により、1942年8月には西海岸から日系アメリカ人が完全に排除された。 米国在住の日本人系の人々を強制収容したことに加え、米国はラテンアメリカから追放された日本人(およびドイツ人、イタリア人)系の人々も収容した。ボリ ビア、コロンビア、コスタリカ、ドミニカ共和国、エクアドル、エルサルバドル、グアテマラ、ハイチ、ホンジュラス、メキシコ、ニカラグア、パナマ、ペルー の13カ国の中南米諸国は、米国に協力し、2,264人の日系中南米市民および日系永住者を逮捕、拘束し、米国に強制送致した。[54][55] |

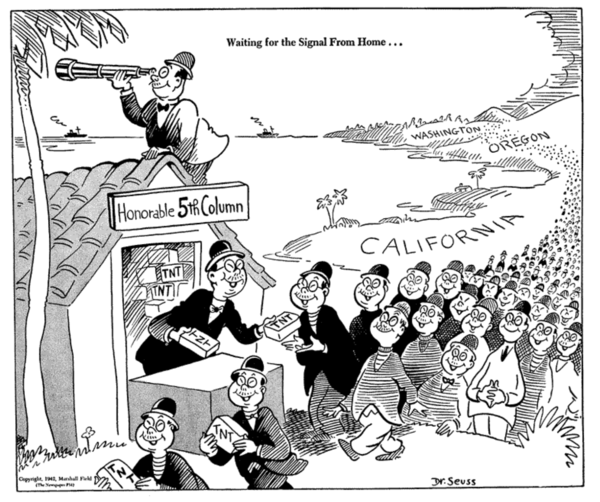

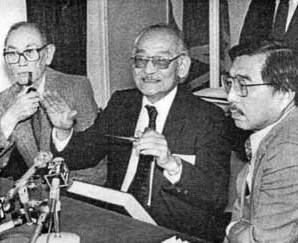

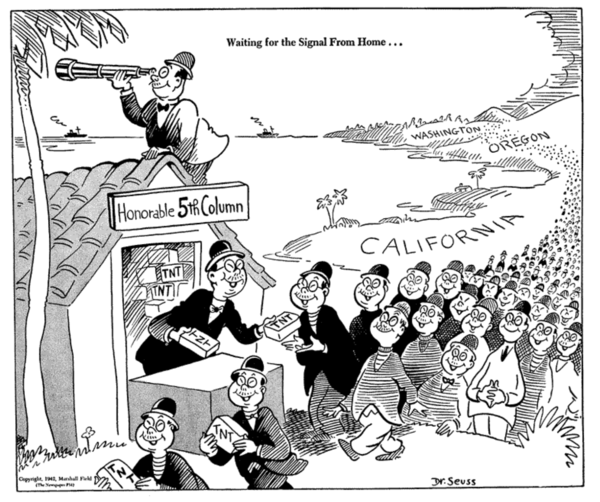

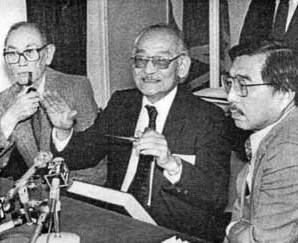

| Support and opposition Non-military advocates of exclusion, removal, and detention  1942 editorial propaganda cartoon in the New York newspaper PM by Dr. Seuss depicting Japanese Americans in California, Oregon, and Washington–states with the largest population of Japanese Americans–as prepared to conduct sabotage against the U.S. The deportation and incarceration of Japanese Americans was popular among many white farmers who resented the Japanese American farmers. "White American farmers admitted that their self-interest required the removal of the Japanese."[32] These individuals saw incarceration as a convenient means of uprooting their Japanese American competitors. Austin E. Anson, managing secretary of the Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association, told The Saturday Evening Post in 1942: We're charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We do. It's a question of whether the White man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. They came into this valley to work, and they stayed to take over... If all the Japs were removed tomorrow, we'd never miss them in two weeks because the White farmers can take over and produce everything the Jap grows. And we do not want them back when the war ends, either.[56] The Leadership of the Japanese American Citizens League did not question the constitutionality of the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Instead, arguing it would better serve the community to follow government orders without protest, the organization advised the approximately 120,000 affected to go peacefully.[57] The Roberts Commission Report, prepared at President Franklin D. Roosevelt's request, has been cited as an example of the fear and prejudice informing the thinking behind the incarceration program.[32] The Report sought to link Japanese Americans with espionage activity, and to associate them with the bombing of Pearl Harbor.[32] Columnist Henry McLemore, who wrote for the Hearst newspapers, reflected the growing public sentiment that was fueled by this report: I am for the immediate removal of every Japanese on the West Coast to a point deep in the interior. I don't mean a nice part of the interior either. Herd 'em up, pack 'em off, and give 'em the inside room in the badlands... Personally, I hate the Japanese. And that goes for all of them.[58] Other California newspapers also embraced this view. According to a Los Angeles Times editorial, A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched... So, a Japanese American born of Japanese parents, nurtured upon Japanese traditions, living in a transplanted Japanese atmosphere...notwithstanding his nominal brand of accidental citizenship almost inevitably and with the rarest exceptions grows up to be a Japanese, and not an American... Thus, while it might cause injustice to a few to treat them all as potential enemies, I cannot escape the conclusion...that such treatment...should be accorded to each and all of them while we are at war with their race.[59] U.S. Representative Leland Ford (R-CA) of Los Angeles joined the bandwagon, who demanded that "all Japanese, whether citizens or not, be placed in [inland] concentration camps."[32] Incarceration of Japanese Americans, who provided critical agricultural labor on the West Coast, created a labor shortage which was exacerbated by the induction of many white American laborers into the Armed Forces. This vacuum precipitated a mass immigration of Mexican workers into the United States to fill these jobs,[60] under the banner of what became known as the Bracero Program. Many Japanese detainees were temporarily released from their camps – for instance, to harvest Western beet crops – to address this wartime labor shortage.[61] Non-military advocates who opposed exclusion, removal, and detention Like many white American farmers, the white businessmen of Hawaii had their own motives for determining how to deal with the Japanese Americans, but they opposed their incarceration. Instead, these individuals gained the passage of legislation which enabled them to retain the freedom of the nearly 150,000 Japanese Americans who would have otherwise been sent to concentration camps which were located in Hawaii.[62] As a result, only 1,200[63] to 1,800 Japanese Americans in Hawaii were incarcerated.[63] The powerful businessmen of Hawaii concluded that the imprisonment of such a large proportion of the islands' population would adversely affect the economic prosperity of the territory.[64] The Japanese represented "over 90 percent of the carpenters, nearly all of the transportation workers, and a significant portion of the agricultural laborers" on the islands.[64] General Delos Carleton Emmons, the military governor of Hawaii, also argued that Japanese labor was "'absolutely essential' for rebuilding the defenses destroyed at Pearl Harbor."[64] Recognizing the Japanese American community's contribution to the affluence of the Hawaiian economy, General Emmons fought against the incarceration of the Japanese Americans and had the support of most of the businessmen of Hawaii.[64] By comparison, Idaho governor Chase A. Clark, in a Lions Club speech on May 22, 1942, said "Japs live like rats, breed like rats and act like rats. We don't want them ... permanently located in our state."[65] Initially, Oregon's governor Charles A. Sprague opposed the incarceration, and as a result, he decided not to enforce it in the state and he also discouraged residents from harassing their fellow citizens, the Nisei. He turned against the Japanese by mid-February 1942, days before the executive order was issued, but he later regretted this decision and he attempted to atone for it for the rest of his life.[66] Even though the incarceration was a generally popular policy in California, it was not universally supported. R.C. Hoiles, publisher of the Orange County Register, argued during the war that the incarceration was unethical and unconstitutional: It would seem that convicting people of disloyalty to our country without having specific evidence against them is too foreign to our way of life and too close akin to the kind of government we are fighting.... We must realize, as Henry Emerson Fosdick so wisely said, 'Liberty is always dangerous, but it is the safest thing we have.'[67] Members of some Christian religious groups (such as Presbyterians), particularly those who had formerly sent missionaries to Japan, were among opponents of the incarceration policy.[68] Some Baptist and Methodist churches, among others, also organized relief efforts to the camps, supplying inmates with supplies and information.[69][70] Statement of military necessity as a justification of incarceration Niihau Incident Main article: Niihau Incident Duration: 18 minutes and 4 seconds.18:04 A Challenge to Democracy (1944), a 20-minute film produced by the War Relocation Authority The Niihau Incident occurred in December 1941, just after the Imperial Japanese Navy's attack on Pearl Harbor. The Imperial Japanese Navy had designated the Hawaiian island of Niihau as an uninhabited island for damaged aircraft to land and await rescue. Three Japanese Americans on Niihau assisted a Japanese pilot, Shigenori Nishikaichi, who crashed there. Despite the incident, the Territorial Governor of Hawaii Joseph Poindexter rejected calls for the mass incarceration of the Japanese Americans living there.[71] Cryptography Main article: Magic (cryptography) In Magic: The Untold Story of U.S. Intelligence and the Evacuation of Japanese Residents From the West Coast During World War II, David Lowman, a former National Security Agency operative, argues that Magic (the code-name for American code-breaking efforts) intercepts posed "frightening specter of massive espionage nets", thus justifying incarceration.[72] Lowman contended that incarceration served to ensure the secrecy of U.S. code-breaking efforts, because effective prosecution of Japanese Americans might necessitate disclosure of secret information. If U.S. code-breaking technology was revealed in the context of trials of individual spies, the Japanese Imperial Navy would change its codes, thus undermining U.S. strategic wartime advantage. Some scholars have criticized or dismissed Lowman's reasoning that "disloyalty" among some individual Japanese Americans could legitimize "incarcerating 120,000 people, including infants, the elderly, and the mentally ill".[73][74][75] Lowman's reading of the contents of the Magic cables has also been challenged, as some scholars contend that the cables demonstrate that Japanese Americans were not heeding the overtures of Imperial Japan to spy against the United States.[76] According to one critic, Lowman's book has long since been "refuted and discredited".[77] The controversial conclusions drawn by Lowman were defended by conservative commentator Michelle Malkin in her book In Defense of Internment: The Case for 'Racial Profiling' in World War II and the War on Terror (2004).[78] Malkin's defense of Japanese incarceration was due in part to reaction to what she describes as the "constant alarmism from Bush-bashers who argue that every counter-terror measure in America is tantamount to the internment".[79] She criticized academia's treatment of the subject, and suggested that academics critical of Japanese incarceration had ulterior motives. Her book was widely criticized, particularly with regard to her reading of the Magic cables.[80][81][82] Daniel Pipes, also drawing on Lowman, has defended Malkin, and said that Japanese American incarceration was "a good idea" which offers "lessons for today".[83] Black and Jewish reactions to the Japanese American incarceration The American public overwhelmingly approved of the Japanese American incarceration measures and as a result, they were seldom opposed, particularly by members of minority groups who felt that they were also being chastised within America. Morton Grodzins writes that "The sentiment against the Japanese was not far removed from (and it was interchangeable with) sentiments against Negroes and Jews."[84] Occasionally, the NAACP and the NCJW spoke out but few were more vocal in opposition to incarceration than George S. Schuyler, an associate editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, perhaps the leading black newspaper in the U.S., who was increasingly critical of the domestic and foreign policy of the Roosevelt administration. He dismissed accusations that Japanese Americans presented any genuine national security threat. Schuyler warned African Americans that “if the Government can do this to American citizens of Japanese ancestry, then it can do this to American citizens of ANY ancestry...Their fight is our fight."[85] The shared experience of racial discrimination has led some modern Japanese American leaders to come out in support of HR 40, a bill which calls for reparations to be paid to African-Americans because they are affected by slavery and subsequent discrimination.[86] Cheryl Greenberg adds "Not all Americans endorsed such racism. Two similarly oppressed groups, African Americans and Jewish Americans, had already organized to fight discrimination and bigotry." However, due to the justification of concentration camps by the US government, "few seemed tactile to endorse the evacuation; most did not even discuss it." Greenberg argues that at the time, the incarceration was not discussed because the government's rhetoric hid the motivations for it behind a guise of military necessity, and a fear of seeming "un-American" led to the silencing of most civil rights groups until years into the policy.[87] United States District Court's opinions  Official notice of exclusion and removal A letter by General DeWitt and Colonel Bendetsen expressing racist bias against Japanese Americans was circulated and then hastily redacted in 1943–1944.[88][89][90] DeWitt's final report stated that, because of their race, it was impossible to determine the loyalty of Japanese Americans, thus necessitating incarceration.[91] The original version was so offensive – even in the atmosphere of the wartime 1940s – that Bendetsen ordered all copies to be destroyed.[92] 91.Lt. Gen. J.L. DeWitt (June 5, 1943). "Final Report; Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast 1942". U.S. Army. Retrieved March 3, 2011. 92. Brian, Niiya (February 1, 2014). Final Report, Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942. Densho Encyclopedia.  Fred Korematsu (left), Minoru Yasui (middle) and Gordon Hirabayashi (right) in 1986 In 1980, a copy of the original Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast – 1942 was found in the National Archives, along with notes which show the numerous differences which exist between the original version and the redacted version.[93] This earlier, racist and inflammatory version, as well as the FBI and Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) reports, led to the coram nobis retrials which overturned the convictions of Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui on all charges related to their refusal to submit to exclusion and incarceration.[94] The courts found that the government had intentionally withheld these reports and other critical evidence, at trials all the way up to the Supreme Court, which proved that there was no military necessity for the exclusion and incarceration of Japanese Americans. In the words of Department of Justice officials writing during the war, the justifications were based on "willful historical inaccuracies and intentional falsehoods". The Ringle Report In May 2011, U.S. Solicitor General Neal Katyal, after a year of investigation, found Charles Fahy had intentionally withheld The Ringle Report drafted by the Office of Naval Intelligence, in order to justify the Roosevelt administration's actions in the cases of Hirabayashi v. United States and Korematsu v. United States. The report would have undermined the administration's position of the military necessity for such action, as it concluded that most Japanese Americans were not a national security threat, and that allegations of communication espionage had been found to be without basis by the FBI and Federal Communications Commission.[95] |

支持と反対 非軍事的な排斥、追放、拘留の支持者  1942年のニューヨークの新聞『PM』に掲載されたドクター・スースによる社説風プロパガンダ漫画。日系アメリカ人が最も多く住んでいたカリフォルニア 州、オレゴン州、ワシントン州の日系アメリカ人が、米国に対する破壊活動を行う準備ができているかのように描かれている。 日系人の国外追放と強制収容は、日系人の農場主を敵視する多くの白人農場主の間で歓迎された。「白人農場主たちは、自分たちの利益のために日系人の排除が 必要だと認めていた」[32]。こうした人々は、日系人の強制収容を、自分たちの競争相手である日系人を根絶する好都合な手段と捉えていた。オースティ ン・E・アンソンは、サラリナス野菜生産出荷業者協会の事務総長であり、1942年に『ザ・サタデー・イブニング・ポスト』誌に次のように語っている。 我々は自分勝手な理由でジャップを追い出したいと思っていると非難されている。我々は追い出したいと思っている。白人が太平洋沿岸に住み続けるのか、それ とも褐色の人種が住み続けるのかという問題だ。彼らはこの谷で働くためにやって来て、居座り続け、土地を乗っ取ろうとしている。もし明日、ジャップが全員 立ち退いたとしても、2週間もすれば彼らがいなくても何とも思わないだろう。なぜなら、白人の農家が彼らの土地をすべて引き継いで耕作できるからだ。そし て、戦争が終わっても彼らを戻すつもりはない。[56] 日系アメリカ人市民同盟の指導部は、西海岸からの日系アメリカ人の排除が合憲であるかどうかを問うことはなかった。むしろ、政府の命令には抗議せずに従う ことがコミュニティにとってより良い結果をもたらすとして、この組織は影響を受けた約12万人に平和的に立ち退くよう勧告した。[57] フランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領の要請により作成された「ロバーツ委員会報告書」は、強制収容政策の背景にあった恐怖と偏見を物語る例として引用さ れている。[32] この報告書は、日系アメリカ人とスパイ活動を結びつけ、真珠湾攻撃と関連付けようとするものであった。[32] ハースト新聞の寄稿者であるコラムニストのヘンリー・マクリーモアは、この報告書によって煽られた世論の高まりを反映して、次のように述べた。 私は西海岸の日本人をすべて内陸の奥深くに即座に追放することに賛成だ。内陸の美しい場所という意味ではない。彼らを追い立て、追い出し、荒れ地に追いや り、彼らに悪い環境を与えよう。個人的には、私は日本人を嫌っている。そしてそれは彼ら全員に当てはまる。[58] 他のカリフォルニアの新聞も、この見解を受け入れた。ロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙の社説によると、 卵が孵化した場所がどこであろうと、毒蛇は毒蛇である。... したがって、日本人の両親から生まれ、日本の伝統の中で育ち、日本的な雰囲気の中で暮らしている日系アメリカ人は、... 名目上は偶然の市民権を得たとしても、ほとんど例外なく、必然的に、そしてごく稀な例外を除いて、アメリカ人ではなく日本人として成長する... したがって、彼ら全員を潜在的な敵として扱うことは一部の人々に対して不公平かもしれないが、私は結論から逃れることができない。彼らの人種と戦争中であ る限り、そのような扱いは彼ら全員に与えられるべきである。 ロサンゼルス選出の連邦下院議員、リーランド・フォード(共和党、カリフォルニア州)もこの流れに加わり、「市民であるか否かに関わらず、すべての日本人 を(内陸部の)強制収容所に収容する」ことを要求した。 西海岸で重要な農業労働力を提供していた日系アメリカ人の収容により、労働力不足が生じ、さらに多数の白人アメリカ人労働者が軍に徴兵されたことで、この 労働力不足は深刻化した。この労働力不足により、ブラセロ・プログラムとして知られるようになった制度の下、これらの職を埋めるためにメキシコ人労働者が 米国に大量に移住することになった。この戦時下の労働力不足に対処するため、多くの日本人抑留者が一時的に収容所から解放され、例えば西洋のビート収穫に 従事した。[61] 排除、強制退去、抑留に反対した非軍事派の支持者 多くの白人アメリカ人農民と同様に、ハワイの白人実業家たちも日系アメリカ人への対応を決定するにあたり、それぞれ独自の動機を持っていたが、彼らは日系 人の抑留に反対した。代わりに、これらの人々は、ハワイにあった強制収容所に送られるはずだった約15万人の日本人アメリカ人の自由を維持することを可能 にする法案の可決に尽力した。[62] その結果、ハワイ在住の日本人アメリカ人のうち、強制収容所に送られたのは1,200人から1,800人であった。[63] ハワイの有力な実業家たちは、同州の人口の多くを占める日系人が収容されることは、同州の経済繁栄に悪影響を及ぼすだろうと結論づけた。[64] 日本人は、ハワイの「大工の90パーセント以上、輸送労働者のほぼ全員、農業労働者のかなりの割合」を占めていた。[64] ハワイの軍政長官であったデロス・カールトン・エモンズ将軍も、真珠湾で破壊された防衛施設の再建には「日本人の労働力が『絶対に不可欠』」であると主張 した。」と主張した。ハワイの経済の繁栄に日系アメリカ人が貢献していることを認識していたエモンズ将軍は、日系アメリカ人の強制収容に反対し、ハワイの ビジネスマンの大半から支持を得ていた。[64] これに対し、アイダホ州知事のチェース・A・クラークは、1942年5月22日、ライオンズクラブでのスピーチで「ジャップはネズミのように暮らし、ネズ ミのように繁殖し、ネズミのように振る舞う。我々は彼らを...この州に永住させたくない」と述べた。[65] 当初、オレゴン州知事チャールズ・A・スプレイグは強制収容に反対し、その結果、州内での強制収容を実施しないことを決定し、また、住民たちに同胞である 二世への嫌がらせをしないよう呼びかけた。彼は1942年2月中旬には日系人に対して敵意を抱くようになり、大統領令が発令される数日前のことだったが、 後にこの決定を後悔し、生涯をかけて償おうとした。 強制収容はカリフォルニア州では概ね支持されていた政策であったとはいえ、全面的に支持されていたわけではなかった。オレンジ郡の新聞「オレンジ郡レジス ター」の発行者R.C.ホイルズは、戦時中、強制収容は非倫理的で違憲であると主張した。 罪を証明する具体的な証拠もないまま、我が国への不忠誠を理由に人々を罪に問うことは、我々の生活様式とはあまりにもかけ離れており、我々が戦っている政 府のやり方にあまりにも似ている。我々は、ヘンリー・エマーソン・フォスディックが賢明にも述べたように、『自由は常に危険であるが、我々が持つ最も安全 なものである』ということを理解しなければならない。 キリスト教のいくつかの宗派(長老派など)の信者たち、特に以前に日本に宣教師を派遣していた人々は、強制収容政策に反対していた。[68] バプテスト派やメソジスト派の教会の中には、収容所への救援活動を行い、収容者に物資や情報を供給したところもあった。[69][70] 抑留の正当化としての軍事的必要性の声明 ニイハウ島事件 詳細は「ニイハウ島事件」を参照 時間:18分4秒 1944年制作の映画『民主主義への挑戦』(20分)は、戦時転住局制作 ニイハウ島事件は、真珠湾攻撃の直後の1941年12月に発生した。日本海軍は、損傷した航空機が着陸して救助を待つための無人島として、ハワイのニイハ ウ島を指定していた。ニイハウ島にいた3人の日系アメリカ人が、不時着した日本軍パイロット、西垣内重則を助けた。この事件にもかかわらず、ハワイ準州知 事ジョセフ・ポインデクスターは、ハワイ在住の日系アメリカ人の強制収容を求める声に反対した。 暗号解読 詳細は「マジック (暗号解読)」を参照 マジック:第二次世界大戦中のアメリカ情報機関と西海岸からの日本人退去の知られざる物語』の中で、元国家安全保障局職員のデビッド・ロウマンは、マジッ ク(アメリカ暗号解読活動のコードネーム)傍受は 「大規模なスパイ網の恐ろしい脅威」をもたらしたと主張し、それゆえに強制収容を正当化した。[72] ローマンは、日系アメリカ人の効果的な起訴には機密情報の開示が必要になる可能性があるため、強制収容は米国の暗号解読努力の機密性を確保するために役立 つと主張した。米国の暗号解読技術が個々のスパイの裁判の過程で明らかになった場合、日本帝国海軍は暗号を変更し、それによって米国の戦時における戦略的 優位性を損なうことになる。 一部の学者は、日系アメリカ人の一部に「不忠誠」な者がいることを理由に「乳幼児、高齢者、精神障害者を含む12万人を収容する」ことが正当化されるとい うローマンの主張を批判または退けている。[73][74][75] ローマンによる マジック・ケーブルの内容に関するローマンの解釈にも異論があり、一部の学者は、このケーブルは、日系アメリカ人がアメリカ合衆国に対するスパイ行為を行 うよう、大日本帝国が打診していたにもかかわらず、日系アメリカ人がそれに応じなかったことを示すものだと主張している。[76] 一人の批評家によると、ローマンの著書は「反論され、信用を失墜して」久しいという。[77] ローマンが導き出した物議を醸す結論は、保守派のコメンテーターであるミシェル・マキンが著書『抑留の弁護:第二次世界大戦と対テロ戦争における「人種プ ロファイリング」の事例』(2004年)で擁護した。[78] マキンが日系人の強制収容を弁護した理由の一つは、彼女が「 アメリカにおけるテロ対策はすべて強制収容に等しいと主張するブッシュ批判者たちによる、絶え間ない誇張報道」に対する反応であった。[79] 彼女は学術界のこの問題への取り組み方を批判し、日系人強制収容に批判的な学者たちには別の意図があることを示唆した。彼女の本は広く批判され、特にマ ジック電報の解釈に関して批判された。[80][81][82] ダニエル・パイスもローマンの意見を引用し、マルキンを擁護し、日系アメリカ人の強制収容は「良い考え」であり、「現代への教訓」を提供していると述べ た。[83] 日系人強制収容に対する黒人とユダヤ人の反応 アメリカ国民は日系人強制収容措置を圧倒的に支持し、その結果、特にアメリカ国内で自分たちも非難されていると感じていたマイノリティグループのメンバー から反対の声はほとんどあがらなかった。モートン・グロジンスは「日本人に対する感情は、黒人やユダヤ人に対する感情と大差なく、また、それらと置き換え られるものであった」と書いている。 NAACPやNCJWも時折は声を上げたが、強制収容に最も強く反対の声を上げたのは、おそらくは全米屈指の有力な黒人向け新聞である『ピッツバーグ・ クーリエ』の編集委員ジョージ・S・スカイラーであった。彼は、日系アメリカ人が国家安全保障上の真の脅威となることはないと主張した。シュカイラーはア フリカ系アメリカ人に対して、「政府が日系アメリカ市民に対してこのようなことをできるのであれば、政府はあらゆる祖先を持つアメリカ市民に対して同じこ とをできるだろう。彼らの戦いは我々の戦いである」と警告した。[85] 人種差別の経験を共有したことで、現代の日系アメリカ人の指導者の中には、奴隷制度とそれに続く差別によって影響を受けたアフリカ系アメリカ人への賠償を 求めるHR 40法案を支持する者も出てきた。[86] シェリル・グリーンバーグは、「すべてのアメリカ人がこのような人種差別を支持していたわけではない。同様に抑圧された2つのグループ、アフリカ系アメリ カ人とユダヤ系アメリカ人は、すでに差別と偏見と戦うために組織化されていた」と付け加えている。しかし、米国政府による強制収容所の正当化により、「避 難を支持する者はほとんどおらず、ほとんどの人はそのことについて議論さえしなかった」とグリーンバーグは主張している。グリーンバーグは、当時、強制収 容が議論されなかったのは、政府のレトリックが軍事上の必要性を装ってその動機を隠していたためであり、「非アメリカ的」と思われることを恐れたことが、 政策が実施されてから何年も経つまで、ほとんどの市民権団体を沈黙させることにつながったと主張している。[87] 米国連邦地方裁判所の意見  公式な排除と立ち退きの通知 日系アメリカ人に対する人種的偏見を表明したデウィット将軍とベンドセン大佐の書簡が回覧され、1943年から1944年にかけて急遽修正された。 [88][89][90] デウィットの最終報告書には、 人種的背景から、日系アメリカ人の忠誠心を見極めることは不可能であり、したがって強制収容が必要であると述べた。[91] 1940年代の戦時下という雰囲気においても、このオリジナル版はあまりにも不快な内容であったため、ベンドセンはすべてのコピーを破棄するよう命じた。 [92]  1986年のフレッド・コレマツ(左)、ミノル・ヤスイ(中央)、ゴードン・ヒラバヤシ(右) 1980年、国立公文書館で「西海岸からの日本人退去:1942年」の最終報告書の原本が発見された。その際、原本と編集版との間に多数の相違点があるこ とを示すメモも発見された。[93] この人種差別的で扇動的な初期の版、およびFBIと海軍情報局(ONI)の報告書は、コラム・ノビス再審理につながり、 フレッド・コレマツ、ゴードン・ヒラバヤシ、ミヌー・ヤスイの3人の有罪判決を、強制退去と収容への不服従に関連するすべての罪状について覆した。 [94] 裁判所は、政府がこれらの報告書やその他の重要な証拠を意図的に隠蔽し、最高裁まで争われた裁判で、日系人の強制退去と収容に軍事的必要性がなかったこと を証明する証拠を隠蔽していたことを認めた。戦時中に司法省の役人が書いた言葉によれば、その正当化は「意図的な歴史の歪曲と意図的な虚偽」に基づいてい る。 リングル報告書 2011年5月、米国政府の訴訟代理人であるニール・カタヤル氏は、1年間の調査の後、チャールズ・ファヒー氏が、平林対米国事件およびコレマツ対米国事 件におけるルーズベルト政権の行動を正当化するために、海軍情報局が作成したリングル報告書を意図的に隠蔽していたことを発見した。この報告書は、ほとん どの日系アメリカ人は国家安全保障上の脅威ではないこと、またFBIと連邦通信委員会によって通信スパイ疑惑は根拠がないことが判明したと結論づけてお り、このような行動の軍事的必要性を主張する政権の立場を弱体化させるものだった。[95] |

| A Challenge to Democracy is a

20-minute short film produced in 1944 by the War Relocation Authority.

The film could be considered a companion piece or sequel to 1942's

Japanese Relocation. This film is more sober in its description. The film makes it clear that the Japanese Americans were forced from their circumstances, and that they were made to live in a rather barren relocation camp, which was surrounded by armed guards. The film states bluntly that the medicine available at the camp was the same as that of everybody else in war time—barely adequate. More positive features of camp life are also shown, whatever their historical accuracy may be: it shows the internees organizing a self-government, schools, and places of worship, as well as contributing to the war effort through industry. It also shows that some families were allowed to leave the camp if they were considered to be loyal enough. |

「民主主義への挑戦」は、1944年に戦時転住局によって制作された

20分の短編映画である。この映画は、1942年の「日系人の転住」の姉妹編または続編と考えることができる。 この映画はより冷静な描写となっている。この映画では、日系アメリカ人が自分たちの環境から強制的に追い出され、武装した警備員に囲まれた殺風景な収容所 での生活を強いられたことが明確に描かれている。この映画では、収容所で入手できる医薬品は戦時中の他の人々と同じもので、ほとんど十分ではなかったこと が率直に述べられている。 歴史的な正確性はともかく、収容所での生活のより前向きな側面も描かれている。収容者たちが自治組織や学校、礼拝所を組織し、また産業活動を通じて戦争へ の貢献を果たしている様子が描かれている。また、忠誠心が十分であるとみなされた一部の家族は収容所から出ることを許されたことも描かれている。 |

| This

is a portion of Lt. Gen. J.L. DeWitt's letter of transmittal to the

Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, June 5, 1943, of his Final Report; Japanese

Evacuation from the West Coast 1942. 1. I transmit herewith my final report on the evacuation of Japanese from the Pacific Coast. 2. The evacuation was impelled by military necessity. The security of the Pacific Coast continues to require the exclusion of Japanese from the area now prohibited to them and will so continue as long as that military necessity exists. The surprise attack at Pearl Harbor by the enemy crippled a major portion of the Pacific Fleet and exposed the West Coast to an attack which could not have been substantially impeded by defensive fleet operations. More than 115,000 persons of Japanese ancestry resided along the coast and were significantly concentrated near many highly sensitive installations essential to the war effort. Intelligence services records reflected the existence of hundreds of Japanese organizations in California, Washington, Oregon and Arizona which, prior to December 7, 1941, were actively engaged in advancing Japanese war aims. These records also disclosed that thousands of American-born Japanese had gone to Japan to receive their education and indoctrination there and had become rabidly pro-Japanese and then had returned to the United States. Emperor-worshipping ceremonies were commonly held and millions of dollars had flowed into the Japanese imperial war chest from the contributions freely made by Japanese here. The continued presence of a large, unassimilated, tightly knit and racial group, bound to an enemy nation by strong ties of race, culture, custom and religion along a frontier vulnerable to attack constituted a menace which had to be dealt with. Their loyalties were unknown and time was of the essence. The evident aspirations of the enemy emboldened by his recent successes made it worse than folly to have left any stone unturned in the building up of our defenses. It is better to have had this protection and not to have needed it than to have needed it an not to have had it – as we have learned to our sorrow. 3. On February 14, 1942, I recommended to the War Department that the military security of the Pacific Coast required the establishment of broad civil control, anti-sabotage and counter-espionage measures, including the evacuation, therefrom of all persons of Japanese ancestry. In recognition of this situation, the President issued Executive Order No. 9066 on February 19, 1942, authorizing the accomplishment of these and any other necessary security measures. By letter dated February 20, 1942, the Secretary of War authorized me to effectuate my recommendations and to exercise all powers which the Executive Order conferred upon him and upon any military commander designated by him. A number of separate and distinct security measures have been instituted under the broad authority thus delegated, and future events may demand the initiation of others. Among the steps taken was the evacuation of Japanese from western Washington and Oregon, California and southern Arizona. Transmitted is the final report of that evacuation ... . 5. There was neither pattern nor precedent for an undertaking of this magnitude and character; and yet over a period of less than ninety operating days, 110,442 persons of Japanese ancestry were evacuated from the West Coast. This compulsory organized mass migration was conducted under complete military supervision. It was effected without major incident in a time of extreme pleasure and severe national stress, consummated at a time when the energies of the military were directed primarily toward the organization and training of an Army of sufficient size and equipment to fight a global war. The task was, nevertheless, completed without any appreciable divergence of military personnel. Comparatively few were used, and there was no interruption in a training program. 6. In the orderly accomplishment of the program, emphasis was placed upon the making of due provision against social and economic dislocation. Agricultural production was not reduced by the evacuation. Over ninety-nine percent of all agricultural acreage in the affected area owned or operated by evacuees was successfully kept in production. Purchasers, lessees, or substitute operators were found who took over the acreage subject to relinquishment. The Los Angeles Herald and Express and the San Diego Union, on February 23, 1943, and the Tacoma News-Tribune, on February 25, 1943, reported increases not only in the value but also in the quantity of farm production in their respective areas. 7. So far as could be foreseen, everything essential was provided to minimize the impact of evacuation upon evacuees, as well as upon economy. Notwithstanding, exclusive of the costs of construction of facilities, the purchase of evacuee motor vehicles, the aggregate of agricultural crop loans made and the purchase of office equipment now in use for other government purposes, the entire cost was $1.46 per evacuee day for the period of evacuation, Assembly Center residence and transfer operations. This cost includes financial assistance to evacuees who voluntarily migrated from the area before the controlled evacuation phase of the program. It also covers registration and processing costs; storage of evacuee property and all other aspects of the evacuee property protection program. It includes hospitalization and medical care of all evacuees from the date of evacuation; transportation of evacuees and their personal effects from their homes to Assembly Centers; complete care in Assembly Centers, including all subsistence, medical care and nominal compensation for work performed. It also reflects the cost of family allowances and clothing as well as transportation and meals during the transfer from Assembly to Relocation Centers... . Continue to Chapter 1 of Lt. Gen. DeWitt's report. Return to the Japanese Internment Page Lt. Gen. J.L. DeWitt to the Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, June 5, 1943, in U.S. Army, Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, Final Report; Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast 1942, Washington D.C.: Govt. Printing Office, 1943, pp. vii-x. Return to top of page http://www.sfmuseum.org/war/dewitt0.html |

これは、J.L.デウィット中将が1943年6月5日に、米陸軍参謀総長に宛てた最終報告書「1942年の西海岸からの日本人の退去」の一部である。 1. 私はここに、太平洋沿岸からの日本人避難に関する最終報告を提出する。 2. 退去は軍事上の必要性から強制された。太平洋沿岸の安全は、現在日本人の立ち入りが禁止されている地域から彼らを排除し続けることを必要としており、軍事 上の必要性が存在する限り、その状態は継続する。真珠湾における敵の奇襲攻撃により、太平洋艦隊の大部分が壊滅的な打撃を受け、西海岸は、艦隊防衛作戦に よって実質的に妨害することができなかった攻撃にさらされることとなった。太平洋岸には11万5千人以上の日系人が居住しており、その多くは戦争遂行に不 可欠な極めて機密性の高い施設に集中していた。 諜報機関の記録によると、1941年12月7日以前にカリフォルニア、ワシントン、オレゴン、アリゾナに存在した数百の日本系組織は、日本の戦争目的を推 進するために積極的に活動していた。これらの記録はまた、何千人ものアメリカ生まれの日本人が教育と洗脳を受けるために日本に行き、熱狂的な親日派となっ てからアメリカに戻ってきたことも明らかにした。天皇崇拝の儀式は一般的に行われ、何百万ドルもの寄付が、当地の日本人から自由意志でなされ、日本の帝国 戦争資金に流れた。敵国と人種、文化、慣習、宗教の面で強いつながりを持つ未同化の緊密な集団が、攻撃を受けやすい国境沿いに存在し続けることは、対処し なければならない脅威であった。彼らの忠誠心は不明であり、時間との戦いでもあった。最近の成功によって大胆になった敵の明白な野望により、防衛体制を万 全に整えることは愚かというより他なかった。この保護策を講じておいて、結局必要がなかった場合の方が、必要だったのに講じていなかった場合よりもましで ある。私たちは、このことを痛いほど学んできた。 3. 1942年2月14日、私は陸軍省に対して、太平洋沿岸地域の軍事的安全保障には、広範囲にわたる民間管理、反妨害破壊活動、および反スパイ活動の策定が 必要であり、それには日系人全員の立ち退きも含まれると勧告した。この状況を認識した大統領は、1942年2月19日、大統領令9066を発令し、これら の措置およびその他の必要な安全保障措置の実施を承認した。1942年2月20日付の手紙で、陸軍長官は私に、私の勧告を実施し、大統領令によって彼およ び彼が指名する軍司令官に与えられたすべての権限を行使することを認めた。このように委任された広範な権限に基づき、いくつかの別個の明確な治安対策が実 施されてきたが、将来、さらなる対策が必要となる可能性もある。 その一環として、ワシントン州西部およびオレゴン州、カリフォルニア州、アリゾナ州南部の日本人を退去させる措置がとられた。 ここに、その退去に関する最終報告を添付する。 5. これほど大規模で性格の異なる事業には、前例もパターンもなかった。しかし、実働90日足らずの間に、西海岸から11万442人の日系人が避難した。この 強制的な組織的大移動は、完全に軍の管理下で行われた。それは、極度の娯楽と深刻な国家的なストレスが重なった時期に、大きな事件もなく実施され、軍のエ ネルギーが主に世界規模の戦争を戦うのに十分な規模と装備の陸軍の編成と訓練に向けられていた時期に完了した。しかし、この任務は、軍の人的資源に目立っ た影響を与えることなく完了した。投入された軍人は比較的少数であり、訓練プログラムに中断はなかった。 6. 計画が秩序正しく達成されたことで、社会および経済の混乱に対する適切な備えが整えられた。 疎開によって農業生産が減少することはなかった。 被災地域の農業用地の99パーセント以上が、疎開者によって所有または運営され、生産が維持された。 放棄された農地を引き継ぐ購入者、賃借者、または代替運営者が見つかった。1943年2月23日付の『ロサンゼルス・ヘラルド・アンド・エクスプレス』紙 と『サンディエゴ・ユニオン』紙、および1943年2月25日付の『タコマ・ニュース・トリビューン』紙は、それぞれの地域における農業生産の価値と量の 増加を報じた。 7. 予測できる限り、避難者および経済への影響を最小限に抑えるために必要なものはすべて提供された。にもかかわらず、避難者の自動車購入費、農業作物ローン 総額、現在他の政府目的で使用されている事務機器の購入費、避難所建設費を除いた費用は、避難、集合センターでの滞在、移動にかかった期間中の避難者1人 1日あたり1.46ドルであった。この費用には、計画の管理避難段階前に自主的にその地域から移住した避難者への財政支援も含まれている。また、登録およ び手続き費用、避難民の所有物の保管、避難民所有物保護プログラムのその他のすべての側面も対象となる。これには、避難の日からすべての避難民の入院およ び医療ケア、避難民および避難民の所有物の自宅から集合センターへの輸送、集合センターでの完全なケア(生活必需品、医療ケア、労働に対するわずかな補償 を含む)が含まれる。また、家族手当や衣類、集合センターから移転センターへの移動中の交通費や食費なども含まれている。 デウィット中将の報告書第1章へ続く。 日系人強制収容のページに戻る J.L.デウィット中将から米陸軍参謀総長宛て、1943年6月5日、米陸軍西部防衛軍および第4軍、最終報告書;1942年の西海岸からの日本人退去、ワシントンD.C.:政府印刷局、1943年、vii-xページ。 ページトップへ戻る |

| Newspaper editorials Editorials from major newspapers at the time were generally supportive of the incarceration of the Japanese by the United States. A Los Angeles Times editorial dated February 19, 1942, stated that: Since Dec. 7 there has existed an obvious menace to the safety of this region in the presence of potential saboteurs and fifth columnists close to oil refineries and storage tanks, airplane factories, Army posts, Navy facilities, ports and communications systems. Under normal sensible procedure not one day would have elapsed after Pearl Harbor before the government had proceeded to round up and send to interior points all Japanese aliens and their immediate descendants for classification and possible incarceration.[96] This dealt with aliens, and the unassimilated. Going even farther, an Atlanta Constitution editorial dated February 20, 1942, stated that: The time to stop taking chances with Japanese aliens and Japanese-Americans has come. . . . While Americans have an inate [sic] distaste for stringent measures, every one must realize this is a total war, that there are no Americans running loose in Japan or Germany or Italy and there is absolutely no sense in this country running even the slightest risk of a major disaster from enemy groups within the nation.[97] A Washington Post editorial dated February 22, 1942, stated that: There is but one way in which to regard the Presidential order empowering the Army to establish "military areas" from which citizens or aliens may be excluded. That is to accept the order as a necessary accompaniment of total defense.[98] A Los Angeles Times editorial dated February 28, 1942, stated that: As to a considerable number of Japanese, no matter where born, there is unfortunately no doubt whatever. They are for Japan; they will aid Japan in every way possible by espionage, sabotage and other activity; and they need to be restrained for the safety of California and the United States. And since there is no sure test for loyalty to the United States, all must be restrained. Those truly loyal will understand and make no objection.[99] A Los Angeles Times editorial dated December 8, 1942, stated that: The Japs in these centers in the United States have been afforded the very best of treatment, together with food and living quarters far better than many of them ever knew before, and a minimum amount of restraint. They have been as well fed as the Army and as well as or better housed. . . . The American people can go without milk and butter, but the Japs will be supplied.[100] A Los Angeles Times editorial dated April 22, 1943, stated that: As a race, the Japanese have made for themselves a record for conscienceless treachery unsurpassed in history. Whatever small theoretical advantages there might be in releasing those under restraint in this country would be enormously outweighed by the risks involved.[101] |

新聞社説 当時、主要な新聞社説は概ね、米国による日本人収容を支持する内容であった。 1942年2月19日付のロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙の社説には、次のように書かれている。 12月7日以来、石油精製所や貯蔵タンク、飛行機工場、陸軍基地、海軍施設、港湾、通信システムなどに近い場所に潜在的な破壊工作員や第五列が存在してい るため、この地域の安全は明白な脅威にさらされている。 常識的な手順に従えば、真珠湾攻撃後、政府は外国人である日本人とその直系子孫を全員拘束し、国内の遠隔地に送って分類し、収容する可能性があったはず だ。 これは外国人と、同化していない人々への対応であった。さらに踏み込んで、1942年2月20日付のアトランタ・コンスティテューション紙の社説は次のように述べている。 日本人外国人および日系アメリカ人に賭けるのはやめるべき時が来た。... アメリカ人は生まれつき(原文のまま)厳しい措置を嫌うが、誰もがこれは総力戦であることを理解すべきである。日本やドイツ、イタリアに野放しになってい るアメリカ人はおらず、国内の敵グループによる大惨事の危険を少しでも冒すことは、この国にとってまったく意味がないことを理解すべきである。[97] 1942年2月22日付のワシントン・ポスト紙の社説は、次のように述べている。 大統領令により陸軍に「軍事地域」を設置し、市民や外国人を排除することを認めるという措置を正当化する唯一の方法は、この措置を総力戦の必要的な付随物として受け入れることである。[98] 1942年2月28日付のロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙の社説は、次のように述べている。 かなりの数の日本人については、どこで生まれていようと、残念ながら疑いの余地はない。彼らは日本のためにあり、スパイ活動や妨害工作、その他の活動に よって可能な限りの支援を行うだろう。そして、カリフォルニア州と米国の安全のためには、彼らを抑制する必要がある。また、米国への忠誠心を確認する確実 なテストはないため、すべての人を抑制する必要がある。真に忠誠心のある人々は理解し、異議を唱えることはないだろう。 1942年12月8日付のロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙の社説には、次のように書かれている。 米国のこれらの地域にいるジャップは、これまでに経験したことのないほど素晴らしい食料や住居とともに、最大限の待遇を受け、最小限の制約しか課されてい ない。彼らは陸軍と同等の食料を与えられ、同等の、あるいはそれ以上の住居を与えられている。...アメリカ国民は牛乳やバターなしでも生きていけるが、 ジャップには供給される。[100] 1943年4月22日付のロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙の社説には、次のように書かれている。 日本人は人種として、良心の呵責を感じない裏切り行為という前代未聞の記録を自ら作り上げてきた。この国で拘束されている人々を解放することに理論上どんなに小さな利点があるとしても、それにかかるリスクの方がはるかに大きいだろう。[101] |