イスラーム・フェミニズム

Islamic feminism

☆ イスラーム・フェミニズムは、イスラームにおける女性の役割に関わるフェミニズムの一形態である。性別に関係なく、すべてのムスリムが公私において完全に 平等であることを目指している。イスラム・フェミニストは、イスラムの枠組みに基づいた女性の権利、男女平等、社会正義を提唱している。イスラムに根ざし ているとはいえ、この運動の先駆者たちは世俗的、西洋的、あるいは非イスラム的なフェミニズムの言説も利用しており、統合されたグローバルなフェミニズム 運動の一部としてのイスラム・フェミニズムの役割を認識している。

| Islamic feminism

is a form of feminism concerned with the role of women in Islam. It

aims for the full equality of all Muslims, regardless of gender, in

public and private life. Islamic feminists advocate for women's rights,

gender equality, and social justice grounded in an Islamic framework.

Although rooted in Islam, the movement's pioneers have also utilized

secular, Western, or otherwise non-Muslim feminist discourses, and have

recognized the role of Islamic feminism as part of an integrated global

feminist movement. Advocates of the movement seek to highlight the teachings of equality in the religion, and encourage a questioning of patriarchal interpretations of Islam by reinterpreting the Quran and Hadith. Prominent thinkers include Amina Wadud, Leila Ahmed, Fatema Mernissi, Azizah al-Hibri, Riffat Hassan, Asma Lamrabet, and Asma Barlas. |

イ

スラーム・フェミニズムは、イスラームにおける女性の役割に関わるフェミニズムの一形態である。性別に関係なく、すべてのムスリムが公私において完全に平

等であることを目指している。イスラム・フェミニストは、イスラムの枠組みに基づいた女性の権利、男女平等、社会正義を提唱している。イスラムに根ざして

いるとはいえ、この運動の先駆者たちは世俗的、西洋的、あるいは非イスラム的なフェミニズムの言説も利用しており、統合されたグローバルなフェミニズム運

動の一部としてのイスラム・フェミニズムの役割を認識している。 この運動の提唱者たちは、宗教における平等の教えを強調し、コーランやハディースを再解釈することで、家父長制的なイスラム解釈に疑問を投げかけることを奨励している。 著名な思想家には、アミーナ・ワドゥード、レイラ・アーメド、ファテマ・メルニッシ、アジザ・アル・ヒブリ、リファト・ハッサン、アスマ・ラムラベット、アスマ・バルラスなどがいる。 |

| Definition and background Islamic feminists Main article: Hermeneutics of feminism in Islam Since the mid-nineteenth century, Muslim women and men have been critical of restrictions placed on women regarding education, seclusion, veiling, polygyny, slavery, and concubinage. Modern Muslims have questioned these practices and advocated for reform.[1] There is an ongoing debate about the status of women in Islam. Conservative Islamic feminists use the Quran, the Hadith, and prominent women in Muslim history as evidence for the discussion on women's rights. Feminists argue that early Islam represented more egalitarian ideals, while conservatives argue that gender asymmetries are "divinely ordained".[2] Islamic feminists are Muslims who interpret the Quran and Hadith in an egalitarian manner and advocate for women's rights and equality in the public and personal sphere. Islamic feminists critique patriarchal, sexist, and misogynistic understandings of Islam.[3] Islamic feminists understand the Qur'an as advocating gender equality.[4] Islamic feminism is anchored within the discourse of Islam with the Quran as its central text.[5] The historian Margot Badran states that Islamic feminism "derives its understanding and mandate from the Qur’an, seeks rights and justice for women, and for men, in the totality of their existence."[6][4] Islamists are advocates of political Islam, the notion that the Quran and hadith mandate an Islamic government. Some Islamists advocate women's rights in the public sphere but do not challenge gender inequality in the personal, private sphere.[7] Su'ad al-Fatih al-Badawi, a Sudanese academic and Islamist politician, has argued that feminism is incompatible with taqwa (the Islamic conception of piety), and thus Islam and feminism are mutually exclusive.[8] Badran argues that Islam and feminism are not mutually exclusive.[9] Islamic feminists have differed in their understandings and definitions of Islamic feminism. Islamic scholar Asma Barlas shares Badran's views, discussing the difference between secular feminists and Islamic feminism and in countries where Muslims make up 98% of the population, it is not possible to avoid engaging “its basic beliefs.”[10] Elizabeth Segran states that just talking about human rights mentioned in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) does not create immediate resonance with ordinary Muslim women; since Islam is the source of their values, integrating human rights frameworks with Islam makes sense.[11] South African Muslim scholar Fatima Seedat agrees with both Barlas and Badran about the importance of feminism in the Islamic world. However, she debates the term “Islamic Feminism” is unnecessary since feminism is a “social practice, not merely of personal identity.”[12] Seedat believes the convergence of both Islamic and feminism creates more conflict and opens more doors for “Islamists” to interpret or misinterpret the Qur'an to suit their political needs. She believes it is important to speak about and illustrate how feminism has existed in the lines of the Qur'an. By separating the two and giving their own space, it will be more inclusive to everyone (men, women, Muslims and non-Muslims). In the same article, “Feminism, and Islamic Feminism: Between Inadequacy and Inevitability,” Seedat explains that the existence of such a term separates Muslims and isolates them from the rest of the world and the universal feminist movement. She states in her essay the importance of sharing with the rest of the world what Islam has to offer feminism, and to show the true image of Islam by not referring to themselves as Islamic feminists. Some Muslim women writers and activists have eschewed identifying themselves as Islamic feminists out of a belief Western feminism is exclusionary to Muslim women and women of color more generally.[13] Azizah al-Hibri, a Lebanese-American Muslim scholar, has identified herself as a "womanist".[14] Context in the Quran Islamic feminists understand the Quran as advocating gender equality.[4] In the view of feminist legal scholar Azizah al-Hibri, the Quran teaches all human beings are creations of God from one soul, who were divided into nations and tribes to know each other, and the most honored individuals are those who are the most pious. Therefore, al-Hibri writes that the Quran recognizes differences between human beings while asserting their natural equality and no man is recognized as superior by their gender alone.[15] Early Muslims and modern Islamic Feminists Modern Muslim feminists and progressive Muslims have taken early figures in Islamic history as role models including Khadijah,[16] Aisha, Hafsa, Umm Salama, Fatima, and Zaynab bint Ali. Zainab Alwani cites Aisha as an empowered and intelligent woman who repeatedly confronted the misogyny of other sahaba.[17] Moroccan feminist Asma Lamrabet has also argued Aisha was an empowered female intellectual against what Lamrabet sees as a misogynistic intellectual history.[18] Lamrabet has also praised Umm Salama as a feminist figure.[19] Iranian revolutionary thinker Ali Shariati wrote Fatemeh is Fatemeh, a biography of Muhammad's daughter Fatima, that holds her as a role model for women.[20] Ednan Aslan suggests Fatima is an example of female empowerment in early Islam, as she was not afraid to oppose Abu Bakr and demand her inheritance.[21] Some Muslim feminists have asserted Muhammad himself was a feminist.[22] |

定義と背景 イスラム・フェミニスト 主な記事 イスラームにおけるフェミニズムの解釈学 19世紀半ば以来、ムスリムの女性や男性は、教育、隠遁、ベール、多妻、奴隷、妾などに関して女性に課せられた制限に批判的であった。現代のムスリムはこ れらの慣習に疑問を呈し、改革を提唱している[1]。イスラムにおける女性の地位については現在も議論が続いている。保守的なイスラムのフェミニストたち は、女性の権利に関する議論の証拠としてコーランやハディース、イスラムの歴史における著名な女性たちを用いている。フェミニストたちは、初期のイスラム 教はより平等主義的な理想を表していたと主張し、保守派はジェンダーの非対称性は「神の定め」であると主張している[2]。 イスラム・フェミニストとは、コーランとハディースを平等主義的に解釈し、公的・個人的領域における女性の権利と平等を主張するイスラム教徒のことであ る。イスラム・フェミニストは家父長制的、性差別的、女性差別的なイスラム理解を批判する[3]。イスラム・フェミニストはコーランを男女平等を提唱する ものとして理解している[4]。 歴史家のマーゴット・バドランは、イスラム・フェミニズムは「コーランからその理解と使命を得ており、女性の権利と正義を追求し、男性に対しても、その存 在の全体において」[6][4]と述べている。 イスラム主義者は政治的イスラムを提唱しており、コーランとハディースがイスラム政府を義務付けているという考え方を提唱している。スーダンの学者であり イスラム主義政治家であるスアド・アル=ファティ・アル=バダウィは、フェミニズムはタクワ(イスラムの信心深さの概念)と相容れないものであり、した がってイスラムとフェミニズムは相互に排他的であると主張している[8]。 イスラームのフェミニストたちは、イスラームのフェミニズムに対する理解や定義が異なっている。イスラム学者のアスマ・バーラスはバドランの見解を共有 し、世俗的なフェミニストとイスラム的なフェミニズムの違いについて論じており、イスラム教徒が人口の98%を占める国々では「その基本的な信条」との関 わりを避けることはできない[10]。 エリザベス・セグランは、女性差別撤廃条約(CEDAW)で言及されている人権について話すだけでは、一般のムスリム女性たちの心にすぐに響くことはない と述べている。イスラームは彼女たちの価値観の源であるため、人権の枠組みをイスラームと統合することは理にかなっている[11]。 南アフリカのムスリム学者であるFatima Seedatは、イスラム世界におけるフェミニズムの重要性についてBarlasとBadranの両者に同意している。しかし彼女は、フェミニズムは「単 なる個人的アイデンティティではなく、社会的実践」であるため、「イスラム・フェミニズム」という用語は不要であると論じている[12]。シーダットは、 イスラムとフェミニズムの融合はより多くの対立を生み、「イスラム主義者」が自分たちの政治的ニーズに合わせてコーランを解釈したり、誤訳したりする門戸 を開くことになると考えている。彼女は、フェミニズムがコーランの中でどのように存在してきたかを語り、説明することが重要だと考えている。この2つを分 離し、それぞれのスペースを与えることで、すべての人(男性、女性、イスラム教徒、非イスラム教徒)をより包括的にすることができる。同じ記事「フェミニ ズム、そしてイスラム・フェミニズム: 不十分さと必然性の狭間で」において、シーダットはこのような用語の存在がムスリムを分離し、世界の他の国々や普遍的なフェミニズム運動から孤立させてい ると説明している。彼女はエッセイの中で、イスラムがフェミニズムに提供できるものを世界の人々と共有し、自分たちをイスラム・フェミニストと呼ばないこ とで、イスラムの真の姿を示すことの重要性を述べている。 イスラム教徒の女性作家や活動家の中には、西洋のフェミニズムはイスラム教徒の女性や有色人種の女性を排斥するものであるという考えから、イスラムのフェ ミニストと名乗ることを避けている者もいる[13]。レバノン系アメリカ人のイスラム学者であるアジザ・アル・ヒブリは、自らを「女性論者」と名乗ってい る[14]。 クルアーンにおける文脈 フェミニストの法学者であるアジザ・アル=ヒブリの見解では、コーランは全ての人間は一つの魂から生まれた神の創造物であり、お互いを知るために国や部族 に分けられ、最も敬われるのは最も敬虔な個人であると説いている[4]。それゆえアル=ヒブリは、コーランは人間の自然な平等性を主張しながらも、人間同 士の違いを認めており、いかなる人間も性別だけによって優れていると認められることはないと書いている[15]。 初期のムスリムと現代のイスラム・フェミニスト 現代のムスリムフェミニストや進歩的ムスリムは、ハディージャ、[16]アイシャ、ハフサ、ウンム・サラマー、ファティマ、ザイナブ・ビント・アリーな ど、イスラーム史における初期の人物をロールモデルとしている。ザイナブ・アルワニはアイシャを、他のサハバの女性差別に繰り返し立ち向かった、力を与え られた聡明な女性として挙げている[17]。モロッコのフェミニストであるアスマ・ラムラベトもまた、ラムラベトが女性差別的な知識人の歴史と見ているも のに対して、アイシャは力を与えられた女性知識人であったと主張している[18]。 ラムラベトはまた、ウンム・サラマをフェミニストの人物として賞賛している[19]。 イランの革命思想家であるアリ・シャリアーティは、ムハンマドの娘ファティマの伝記である『ファテメはファテメである』を著し、彼女を女性のロールモデル としている[20]。 エドナン・アスランは、ファティマはアブ・バクルに反対し、遺産相続を要求することを恐れなかったことから、初期イスラームにおける女性のエンパワーメン トの例であると示唆している[21]。 ムハンマド自身がフェミニストであったと主張するムスリムフェミニストもいる[22]。 |

| History In the past 150 years or so, many scholarly interpretations have developed from within the Islamic tradition itself that seek to redress social wrongs perpetrated against Muslim women.[23] For example, new Islamic jurisprudence is emerging that seeks to forbid practices like female genital mutilation, equalize family law, support women as clergy and in administrative positions in mosques, and supports equal opportunities for Muslim women to become judges in civil as well as religious institutions.[23] Modern feminist Islamic scholars perceive their work as restoration of rights provided by God and the Prophet but denied by society.[23] Nineteenth century The modern movement of Islamic feminism began in the nineteenth century. Aisha Taymur (1840 - 1902) was a prominent writer and early activist for women's rights in Egypt. Taymur's writings criticized male domination over women and celebrated women's intellect and courage.[24] Another early Muslim feminist activist and writer was Zaynab Fawwaz (1860 - 1914). Fawwaz argued for women's social and intellectual quality with men and wrote a book of biographies of famous women.[25] An early feminist activist in the Bengal region was Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, known as Begum Rokeya (1880 - 1932). Hossain was an activist for women's education and writer. She criticized patriarchy in South Asian societies and the practice of purdah, the veiling and segregation of women.[26] Egyptian jurist Qasim Amin, the author of the 1899 pioneering book Women's Liberation (Tahrir al-Mar'a), is often described as the father of the Egyptian feminist movement. In his work, Amin criticized some of the practices prevalent in his society at the time, such as polygyny, the veil, and purdah, i.e. sex segregation in Islam. He condemned them as un-Islamic and contradictory to the true spirit of Islam. His work had an enormous influence on women's political movements throughout the Islamic and Arab world, and is read and cited today.[citation needed] Despite Qasim Amin's effects on modern-day Islamic feminist movements, present-day scholar Leila Ahmed considers his works both androcentric and colonialist.[27] Muhammad 'Abdu, an Egyptian nationalist[28] and proponent of Islamic modernism, could easily have written the chapters of his work that show honest considerations of the negative effects of the veil on women.[29] Amin even posed many male-centered misconceptions about women, such as their inability to experience love, that women needlessly talk about their husbands outside their presence, and that Muslim marriage is based on ignorance and sensuality, of which women were the chief source.[30] Lesser known, however, are the women who preceded Amin in their feminist critique of their societies. The women's press in Egypt started voicing such concerns since its very first issues in 1892. Egyptian, Turkish, Iranian, Syrian and Lebanese women and men had been reading European feminist magazines even a decade earlier, and discussed their relevance to the Middle East in the general press.[31] Twentieth century Aisha Abd al-Rahman, writing under her pen name Bint al-Shati ("Daughter of the Riverbank"), was one of the first to undertake Quranic exegesis, and though she did not consider herself to be a feminist, her works reflect feminist themes. She began producing her popular books in 1959, the same year that Naguib Mahfouz published his allegorical and feminist version of the life of Muhammad.[32] She wrote biographies of early women in Islam, including the mother, wives and daughters of the Prophet Muhammad, as well as literary criticism.[33] Queen Soraya of Afghanistan headed reform so that women could get an education and the right to vote. The Syrian-born queen of Afghanistan believed that women should be equal to men. A women’s magazine and a women’s organization to protect girls and women from abuse and domestic violence were also founded by Queen Soraya, argued by some to be the Muslim world’s first feminist. She also arranged for young Afghan men and women to take higher education abroad. The liberal reforms were not received kindly by the ultra-conservative Islamists who orchestrated a widespread rebellion in 1928. In order to spare the country and people from the horrors of a long civil war, King Amanullah, and Queen Soraya abdicated and went into exile with their family in 1929 to Rome. Moroccan writer and sociologist, Fatema Mernissi was a prominent Muslim feminist thinker. Her book Beyond the Veil explores the oppression of women in Islamic societies and sexual ideology and gender identity through the perspective of Moroccan society and culture.[34] Mernissi argued in her book The Veil and the Male Elite that the suppression of women's rights in Islamic societies is the result of political motivation and its consequent manipulative interpretation of hadith, which runs counter to the egalitarian Islamic community of men and women envisioned by Muhammad.[35] Mernissi argued that the ideal Muslim woman being "silent and obedient" has nothing to do with the message of Islam. In her view, conservative Muslim men manipulated the Quran to preserve their patriarchal system in order to prevent women from sexual liberation; thus enforcing justification of strict veiling and limiting their rights.[34] A later 20th-century Islamic feminist is Amina Wadud. Wadud was born into an African-American family and converted to Islam. In 1992, wadud published Quran and Woman, a work that critiqued patriarchal interpretations of the Quran.[36] Some strains of modern Islamic feminism have opted to expunge hadith from their ideology altogether in favor of a movement focusing only on Qur'anic principles. Riffat Hassan has advocated one such movement, articulating a theology wherein what are deemed to be universal rights for humanity outlined in the Qur'an are prioritized over contextual laws and regulations.[37] She has additionally claimed that the Qur'an, taken alone as scripture, does not present females either as a creation preceded by the male or as the instigator of the "Fall of Man".[38] This theological movement has been met with criticism from other Muslim feminists such as Kecia Ali, who has criticized its selective nature for ignoring elements within the Muslim tradition that could prove helpful in establishing more egalitarian norms in Islamic society.[39] Twenty-first century Islamic feminist scholarship and activism has continued into the 21st century. In 2015, a group of Muslim activists, politicians, and writers issued a Declaration of Reform which, among other things, supports women's rights and states in part, "We support equal rights for women, including equal rights to inheritance, witness, work, mobility, personal law, education, and employment. Men and women have equal rights in mosques, boards, leadership and all spheres of society. We reject sexism and misogyny."[40] The Declaration also announced the founding of the Muslim Reform Movement organization to work against the beliefs of Middle Eastern terror groups.[41] Asra Nomani and others placed the Declaration on the door of the Islamic Center of Washington.[41] Feminism in the Middle East is over a century old, and having been impacted directly by the war on terror in Afghanistan, continues to grow and fight for women's rights and equality in all conversations of power and everyday life.[42] Muslim feminist writers today include Aysha Hidayatollah, Kecia Ali, Asma Lamrabet, Olfa Yousef, and Mohja Kahf. Muslim women in politics Muslim majority countries have produced several female heads of state, prime ministers, and state secretaries such as Lala Shovkat of Azerbaijan, Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan, Mame Madior Boye of Senegal, Tansu Çiller of Turkey, Kaqusha Jashari of Kosovo, and Megawati Sukarnoputri of Indonesia. In Bangladesh, Khaleda Zia was elected the country's first female prime minister in 1991, and served as prime minister until 2009, when she was replaced by Sheikh Hasina, who maintains the prime minister's office at present making Bangladesh the country with the longest continuous female premiership.[43] |

歴史 過去150年ほどの間に、イスラームの伝統の内部から、ムスリム女性に対する社会的過ちを是正しようとする多くの学術的解釈が発展してきた。 [例えば、女性性器切除のような慣習の禁止、家族法の平等化、聖職者としての女性やモスクの管理職としての女性の支援、宗教機関だけでなく民事機関におい てもムスリム女性が裁判官になる機会の平等化を支援しようとする新しいイスラーム法学が出現している[23]。現代のフェミニストのイスラーム学者は、自 分たちの仕事を神と預言者によって与えられたが社会によって否定された権利の回復であると認識している[23]。 19世紀 イスラム・フェミニズムの近代的な動きは19世紀に始まった。 アイシャ・テイムール(1840年~1902年)は著名な作家であり、エジプトにおける女性の権利のための初期の活動家であった。テイミュールの著作は女性に対する男性の支配を批判し、女性の知性と勇気を称えた[24]。 もう一人の初期のムスリムフェミニスト活動家であり作家であったのは、ザイナブ・ファウワズ(Zaynab Fawwaz 1860 - 1914)であった。ファウワズは女性の男性に対する社会的・知的な資質を主張し、有名な女性の伝記本を書いた[25]。 ベンガル地方の初期のフェミニスト活動家は、ベガム・ロケヤとして知られるロケヤ・サカワット・ホサイン(Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain、1880年 - 1932年)であった。ホセインは女性教育の活動家であり、作家でもあった。彼女は南アジア社会における家父長制と、女性のベール着用と隔離であるプル ダーの慣習を批判した[26]。 エジプトの法学者カシム・アミンは、1899年の先駆的な著書『女性の解放』(Tahrir al-Mar'a)の著者であり、しばしばエジプトのフェミニズム運動の父と称される。その著作の中でアミンは、一夫多妻制、ヴェール、プルダ(イスラム 教における男女隔離)など、当時の社会で広まっていた慣習のいくつかを批判した。彼はそれらを非イスラム的であり、イスラムの真の精神に反するものとして 非難した。彼の著作はイスラム世界とアラブ世界の女性の政治運動に多大な影響を与え、今日でも読まれ、引用されている[要出典]。 カシーム・アミンは現代のイスラム・フェミニスト運動に影響を与えたにもかかわらず、現在の学者レイラ・アフメッドは彼の著作をアンドロセントリックで植 民地主義的であるとみなしている[27]。エジプトのナショナリストであり[28]、イスラム・モダニズムの提唱者であるムハンマド・アブドゥは、ベール が女性に与える悪影響についての率直な考察を示す著作の章を容易に書くことができたであろう。 [29]アミンは、女性は愛を経験することができない、女性は夫の前で夫のことを不必要に話す、イスラム教徒の結婚は無知と官能に基づいており、その主な 原因は女性である、といった男性中心の女性に対する多くの誤解さえも提起した[30]。 しかし、あまり知られていないのは、アミンに先駆けてフェミニズムによる社会批判を行った女性たちである。エジプトの女性報道機関は、1892年の創刊号 からそのような懸念を表明し始めた。エジプト、トルコ、イラン、シリア、レバノンの女性や男性は、その10年も前からヨーロッパのフェミニズム雑誌を読ん でおり、一般紙で中東との関連性を論じていた[31]。 20世紀 アイシャ・アブド・アル=ラーマンは、ビント・アル=シャティ(「川岸の娘」)というペンネームで執筆し、コーランの釈義を最初に手がけた一人であった。 彼女は、ナギブ・マフフーズがムハンマドの生涯の寓話的でフェミニズム的な版を出版したのと同じ年である1959年に、人気のある本の制作を開始した [32]。彼女は、預言者ムハンマドの母、妻、娘など、イスラム教における初期の女性の伝記や、文学評論を執筆した[33]。 アフガニスタンのソラヤ王妃は、女性が教育と選挙権を得られるように改革を指揮した。シリア出身のアフガニスタン女王は、女性は男性と平等であるべきだと 考えていた。女性誌や、虐待や家庭内暴力から少女や女性を守るための女性団体もソラヤ王妃によって設立され、イスラム世界初のフェミニストと主張する人も いる。彼女はまた、アフガニスタンの若い男女が海外で高等教育を受けられるよう手配した。自由主義的な改革は、1928年に広範な反乱を組織した超保守的 なイスラム主義者には好意的に受け止められなかった。国と国民を長い内戦の恐怖から救うため、アマヌッラー国王とソラヤ王妃は退位し、1929年に家族と ともにローマに亡命した。 モロッコの作家で社会学者のファテマ・メルニッシは、著名なムスリムフェミニスト思想家である。彼女の著書『Beyond the Veil』は、イスラム社会における女性の抑圧と、モロッコの社会と文化の視点から見た性的イデオロギーとジェンダー・アイデンティティを探求している。 [34]メルニシは著書『ベールと男性エリート』の中で、イスラム社会における女性の権利の抑圧は、政治的動機とその結果としてのハディースの操作的解釈 の結果であり、ムハンマドによって構想された男女平等主義のイスラム共同体とは逆行するものであると主張した[35]。メルニシは、「沈黙し従順である」 という理想的なムスリム女性はイスラムのメッセージとは無関係であると主張した。彼女の見解では、保守的なムスリム男性は、女性の性的解放を妨げるために 家父長制を維持するためにコーランを操作し、その結果、厳格なベールの正当性を強制し、女性の権利を制限した[34]。 20世紀後半のイスラム・フェミニストはアミーナ・ワドゥッドである。ワドゥドはアフリカ系アメリカ人の家庭に生まれ、イスラム教に改宗した。1992年、ワドゥドはコーランの家父長制的解釈を批判した著作『コーランと女性』を出版した[36]。 現代のイスラム・フェミニズムの中には、コーランの原則のみに焦点を当てた運動を支持するために、ハディースをイデオロギーから完全に排除することを選択 した系統もある。リファット・ハッサンはそのような運動の一つを提唱しており、クルアーンに概説されている人類の普遍的権利と見なされるものを、文脈上の 法律や規則よりも優先させるという神学を明確にしている[37]。さらに彼女は、クルアーンを単独で聖典として捉えた場合、女性を男性に先行する被造物と しても、「人間の堕落」の扇動者としても提示していないと主張している。 [38]この神学的な動きは、ケシア・アリのような他のムスリムフェミニストからの批判にさらされており、ケシアはその選択的な性格が、イスラム社会にお いてより平等主義的な規範を確立する上で役に立つと証明できるイスラム教の伝統内の要素を無視していると批判している[39]。 21世紀 イスラム・フェミニストの研究と活動は21世紀に入っても続いている。 2015年、ムスリムの活動家、政治家、作家のグループが改革宣言を発表し、その中で特に女性の権利を支持し、その一部を次のように述べている。モスク、 役員会、指導者、社会のあらゆる領域において、男女は同等の権利を有する。私たちは性差別と女性差別を拒否します」[40] 宣言はまた、中東のテロ集団の信条に反対するために活動するムスリム改革運動組織の設立を発表した[41]。 アスラ・ノマニらはワシントンのイスラム・センターのドアに宣言を貼った[41]。 中東のフェミニズムは100年以上の歴史があり、アフガニスタンでの対テロ戦争から直接影響を受け、権力と日常生活のあらゆる会話において女性の権利と平等のために成長し、戦い続けている[42]。 今日のムスリムフェミニスト作家には、アイシャ・ヒダヤトラ、ケシア・アリ、アスマ・ラムラベット、オルファ・ユセフ、モハヤ・カーフなどがいる。 政治におけるムスリム女性 アゼルバイジャンのララ・ショフカト、パキスタンのベナジル・ブット、セネガルのマメ・マディオール・ボワイエ、トルコのタンス・チラー、コソボのカク シャ・ジャシャリ、インドネシアのメガワティ・スカルノプトリなど、イスラム教徒が多数を占める国々は、何人もの女性国家元首、首相、国務長官を輩出して いる。バングラデシュでは、カレダ・ジアが1991年に同国初の女性首相に選出され、2009年まで首相を務めたが、シェイク・ハシナに交代し、現在も首 相の座を維持している。 |

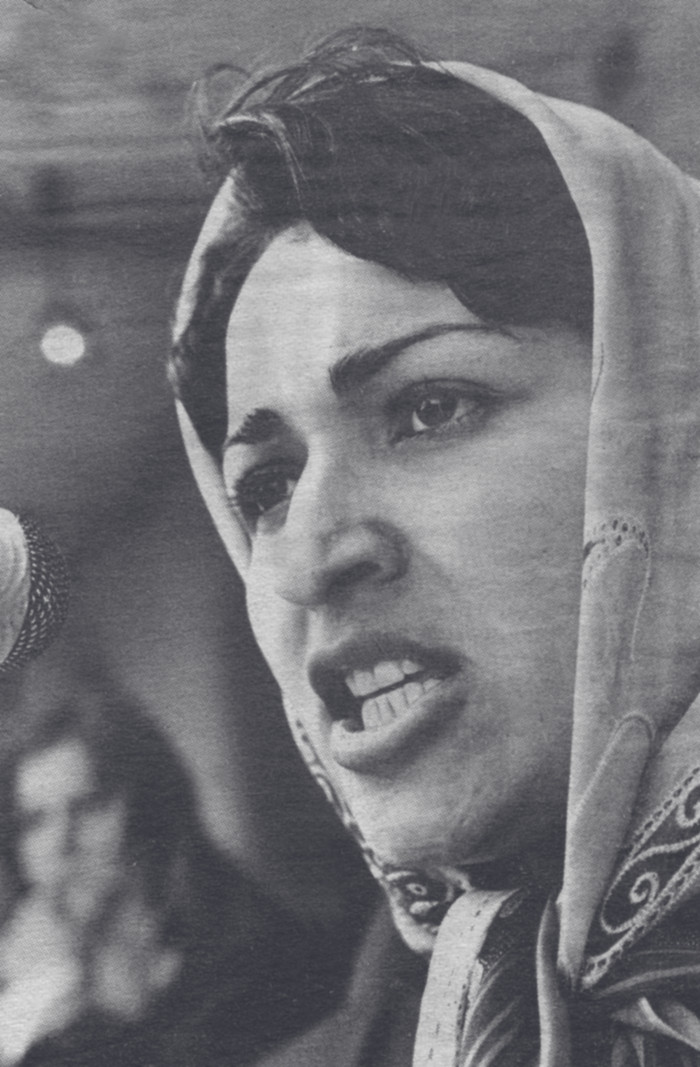

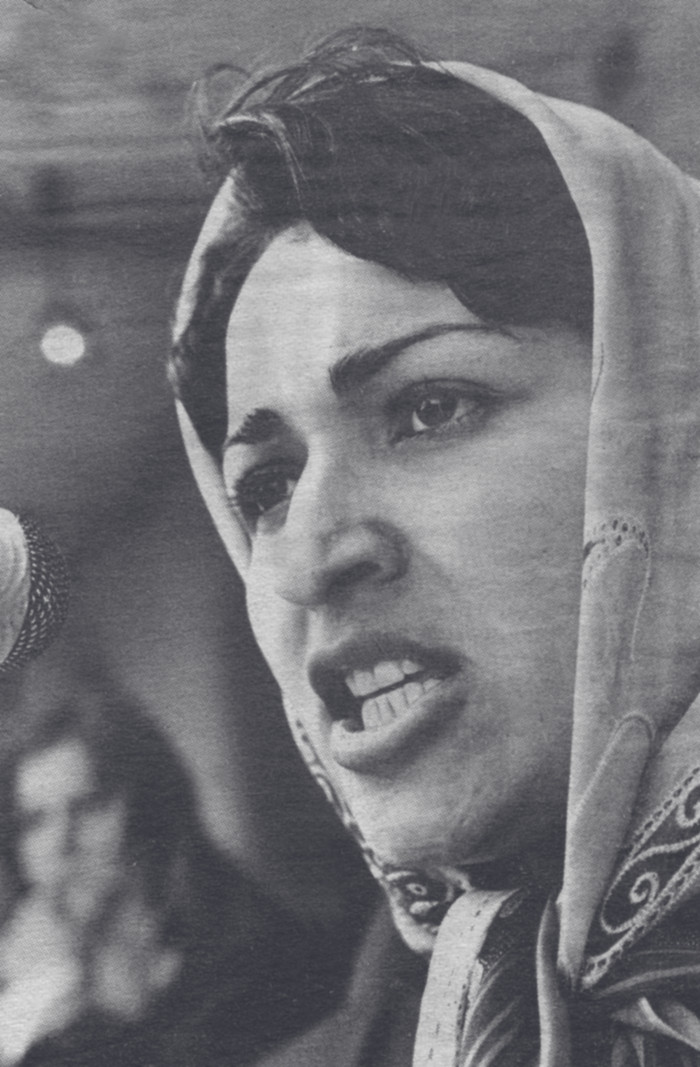

| Muslim feminist groups and initiatives Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan Main articles: Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan and Meena Keshwar Kamal  Meena Keshwar Kamal (1956 - 1987), founder of RAWA The Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) is a women's organization based in Quetta, Pakistan, that promotes women's rights and secular democracy. The organization aims to involve women of Afghanistan in both political and social activities aimed at acquiring their human rights and continuing the struggle against the government of Afghanistan based on democratic and secular - not fundamentalist - principles, in which women can participate fully.[44] The organization was founded in 1977 by a group of intellectuals led by Meena (she did not use a last name). They founded the organization to promote equality and education for women; it continues to "give voice to the deprived and silenced women of Afghanistan". Before 1978, RAWA focused mainly on women's rights and democracy, but after the coup of 1978, directed by Moscow, and the 1979 Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan, "Rawa became directly involved in the war of resistance, advocating democracy and secularism from the outset".[45] In 1979 RAWA campaigned against the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, and organized meetings in schools to mobilize support against it, and in 1981, launched a bilingual feminist magazine, Payam-e-Zan (Women's Message).[45][46][47] RAWA also founded Watan Schools to aid refugee children and their mothers, offering both hospitalization and the teaching of practical skills.[47][48] Sisters in Islam  Zainah Anwar Sisters in Islam (SIS) is a Malaysian civil society organization committed to promoting the rights of women within the frameworks of Islam and universal human rights. SIS work focuses on challenging laws and policies made in the name of Islam that discriminate against women. As such it tackles issues covered under Malaysia's Islamic family and syariah laws, such as polygamy,[49] child marriage,[50] moral policing,[51] Islamic legal theory and jurisprudence, the hijab and modesty,[52] violence against women and hudud.[53] Their mission is to promote the principles of gender equality, justice, freedom, and dignity of Islam and empower women to be advocates for change.[54] They seek to promote a framework of women's rights in Islam which take into consideration women's experiences and realities; they want to eliminate the injustice and discrimination that women may face by changing mindsets that may hold women to be inferior to men; and they want to increase the public knowledge and reform laws and policies within the framework of justice and equality in Islam.[54] Prominent members are Zainah Anwar[55] and co-founder amina wadud.[56] Musawah In 2009, twelve women from the Arab world formed the global movement Musawah, whose name means "equality" in Arabic. Musawah advocates for feminist interpretations of Islamic texts and calls on nations to abide by international human rights standards such as those promulgated in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Musawah's approach is modeled after that of Sisters in Islam. Secular feminists have criticized Musawah, arguing that Islam is shaky ground on which to build a feminist movement, given that interpretation of Islamic sources is subjective.[11] Sister-hood Sister-hood is an international platform for the voices of women of Muslim heritage founded in 2007 by Norwegian film-maker and human rights activist Deeyah Khan through her media and arts production company Fuuse.[57] Sister-hood was relaunched in 2016 as a global online magazine and live events platform promoting the voices of women of Muslim heritage. Sister-hood magazine ambassadors include Farida Shaheed from Pakistan, Egyptian Mona Eltahawy, Palestinian Rula Jebreal, Leyla Hussein of Somali heritage and Algerian Marieme Helie Lucas. Women Living Under Muslim Laws (WLUML) Women Living Under Muslim Laws is an international solidarity network established in 1984 that advocates for both Muslim and non-Muslim women who live in states governed by Islamic law. The group does research on Islamic law and women and advocacy work.[58] Muslim Women's Quest for Equality Muslim Women's Quest for Equality is an Indian activist group that petitioned the Supreme Court of India against the practices of talaq-e-bidat (triple talaq), nikah halala and polygyny under the Muslim personal laws as being illegal and unconstitutional[59][60] in September 2016. Ni Putes Ni Soumises Ni Putes Ni Soumises, whose name translates to Neither Whores nor Submissives, is a French feminist organization founded by Samira Bellil and other young women of African backgrounds, to address the sexual and physical violence that women in Muslim majority neighborhoods in France faced.[61] International conferences on Islamic feminism Few international conferences on Islamic feminism have taken place. One international congress on Islamic feminism was held in Barcelona, Spain in 2008.[62] Musawah ('equality'; in Arabic: مساواة) is a global movement for equality and justice in the Muslim family, led by feminists since 2009, "seeking to reclaim Islam and the Koran for themselves".[63] Musawah movement operates on the principle that patriarchy within Muslim countries is a result of the way male interpreters have read Islamic texts,[63] and that feminists can progressively interpret the Quran to achieve the goal of international human rights standards.[63] The first female Muslim 'ulema congress was held in Indonesia in 2017.[64] The women ulema congress issued a fatwa to lift the minimum age for girls to marry to 18.[64] Malaysian feminist Zainah Anwar informed the congress that women have an equal right to define Islam and that women need to fight against male domination in Quranic interpretations.[64] During the congress, Nur Rofiah, a professor in Quranic studies, stated that, Islam asks every human being to elevate the status of humankind, and polygamy does not, and that polygamy is not the teaching of Islam[64] |

ムスリムフェミニストのグループとイニシアティブ アフガニスタン女性革命協会 主な記事 アフガニスタン女性革命協会、ミーナ・ケシュワル・カマル  ミーナ・ケシュワル・カマル(1956年~1987年)RAWA創設者 アフガニスタン女性革命協会(RAWA)はパキスタンのクエッタを拠点とする女性団体で、女性の権利と世俗民主主義を推進している。この組織は、アフガニ スタンの女性を政治的・社会的活動に参加させ、人権を獲得し、女性が全面的に参加できる民主主義的・世俗的(原理主義的ではない)原則に基づくアフガニス タン政府との闘いを継続することを目的としている[44]。 この組織は、ミーナ(彼女は姓を使わなかった)を中心とする知識人グループによって1977年に設立された。彼らは女性の平等と教育を促進するために組織 を設立し、「アフガニスタンの奪われ、沈黙している女性たちに声を与える」活動を続けている。1978年以前、RAWAは主に女性の権利と民主主義に焦点 をあてていたが、モスクワの指示による1978年のクーデターと1979年のソ連によるアフガニスタン占領後、「ラワは当初から民主主義と世俗主義を提唱 し、抵抗戦争に直接関与するようになった」[45]。 [1979年、ラワはアフガニスタン民主共和国に反対するキャンペーンを展開し、学校での反対集会を組織して支持を動員し、1981年にはバイリンガルの フェミニスト雑誌『パヤム=エ=ザーン(女性のメッセージ)』を創刊した[45][46][47]。ラワはまた、難民の子どもたちとその母親を支援するた めにワタン・スクールを設立し、入院治療と実践的な技術の指導の両方を提供した[47][48]。 イスラムの姉妹たち  ザイナ・アンワル シスターズ・イン・イスラム(SIS)はマレーシアの市民団体で、イスラム教と普遍的人権の枠組みの中で女性の権利の促進に取り組んでいる。SISの活動 は、イスラムの名の下に作られた女性を差別する法律や政策に異議を唱えることに重点を置いている。一夫多妻制、[49]児童婚、[50]道徳的取り締ま り、[51]イスラム法理論と法学、ヒジャーブと慎み深さ、[52]女性に対する暴力とフッド[53]など、マレーシアのイスラム家族法とシリヤ法の下で 扱われている問題に取り組んでいる。 [54]女性の経験と現実を考慮したイスラームにおける女性の権利の枠組みを推進し、女性が男性より劣っているとする考え方を変えることで、女性が直面し うる不公正と差別をなくし、イスラームにおける正義と平等の枠組みの中で、一般の知識を増やし、法律と政策を改革することを目指している[54]。 ムサワ 2009年、アラブ世界の12人の女性が、アラビア語で「平等」を意味する世界的な運動ムサワを結成した。ムサワはイスラーム教典のフェミニズム的解釈を 提唱し、女性差別撤廃条約で公布されたような国際人権基準を遵守するよう各国に呼びかけている。ムサワのアプローチは、シスターズ・イン・イスラムをモデ ルとしている。世俗的なフェミニストたちはムサワを批判しており、イスラム教の典拠の解釈が主観的であることを考えると、イスラム教はフェミニスト運動を 構築するための不安定な基盤であると主張している[11]。 シスターフード Sister-hoodは、2007年にノルウェーの映画製作者であり人権活動家であるディーヤ・カーンによって、彼女のメディア・芸術制作会社であるFuuseを通して設立された、イスラム教の血を引く女性の声を伝える国際的なプラットフォームである[57]。 Sister-hoodは2016年に、イスラム教の血を引く女性の声を促進する世界的なオンライン・マガジンおよびライブ・イベント・プラットフォーム としてリニューアルされた。Sister-hood誌のアンバサダーには、パキスタンのファリダ・シャヒード、エジプトのモナ・エルタハウィ、パレスチナ のルラ・ジェブリアル、ソマリアの血を引くレイラ・フセイン、アルジェリアのマリエム・ヘリー・ルーカスがいる。 イスラム法の下で生きる女性たち(WLUML) Women Living Under Muslim Lawsは1984年に設立された国際連帯ネットワークで、イスラム法に支配された国家に住むイスラム教徒と非イスラム教徒の女性のために活動している。 イスラム法と女性に関する研究やアドボカシー活動を行っている[58]。 平等のためのムスリム女性の探求 Muslim Women's Quest for Equality(平等のためのムスリム女性の探求)はインドの活動家グループで、2016年9月にインドの最高裁判所に対し、イスラム個人法の下でのタ ラーク・エ・ビダート(トリプル・タラーク)、ニカー・ハラーラ、多夫多妻制の慣行は違法であり違憲であるとして請願した[59][60]。 ニ・プテス・ニ・スミーズ Ni Putes Ni Soumisesは「娼婦でも服従者でもない」と訳され、サミラ・ベリルやアフリカ系の若い女性たちによって設立されたフランスのフェミニスト組織であ り、フランスのイスラム教徒が多数を占める地域の女性たちが直面する性的・身体的暴力に対処するために設立された[61]。 イスラム・フェミニズムに関する国際会議 イスラム・フェミニズムに関する国際会議はほとんど開かれていない。2008年にスペインのバルセロナでイスラム・フェミニズムに関する国際会議が1つ開 催された[62]。 ムサワ(「平等」、アラビア語ではمساواة)は、2009年以来フェミニストたちによって率いられ、「イスラム教とコーランを自分たちのために取り戻 そうとしている」ムスリム家庭の平等と正義を求める世界的な運動である[63]。 ムサワ運動は、イスラム諸国内の家父長制は男性解釈者がイスラム教のテキストを読んできた結果であり[63]、フェミニストは国際人権基準の目標を達成す るためにコーランを漸進的に解釈することができるという原則に基づいて活動している[63]。 2017年にインドネシアで初の女性ムスリム「ウレマ」会議が開催された[64]。女性ウレマ会議は、女子の結婚最低年齢を18歳に引き上げるファトワを 発表した。 [64]マレーシアのフェミニストであるザイナ・アンワルは、女性にはイスラム教を定義する平等な権利があり、女性はコーラン解釈における男性支配と戦う 必要があると大会に伝えた[64]。大会の中で、コーラン研究の教授であるヌール・ロフィアは、イスラム教はすべての人間に人類の地位を高めるよう求めて おり、一夫多妻制はそうではない、一夫多妻制はイスラム教の教えではない、と述べた[64]。 |

| Areas of campaign Personal law See also: Islamic marital jurisprudence  Manal al-Sharif speaking at the Oslo Freedom Forum in 2012 about the #Women2Drive campaign she co-founded. One of such controversial interpretations involve passages in the Quran that discuss the idea of a man's religious obligation to support women.[65] Some scholars, such as anthropologist Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban in her work on Arab-Muslim women activists' engagement in secular religious movements, argue that this assertion of a religious obligation "has traditionally been used as a rationale for the social practice of male authority."[65] In some countries the legislative and administrative application of male authority is used to justify denying women access to the public sphere through the "denial of permission to travel or work outside the home, or even drive a car."[65] On Sept. 26, 2017 Saudi Arabia announced it would end its longstanding policy banning women from driving in June 2018.[66] Various female activists had protested the ban, among them Saudi women's rights activists Manal al-Sharif,[67] by posting videos of them driving on social media platforms. One of the women's rights activists from Saudi Arabia, Loujain al-Hathloul had been imprisoned for more than 3 years and was sentenced on 28 December 2020 to a total of 5 years and 8 months in prison for allegedly conspiring against the kingdom in alignment with foreign nations following her protest against the ban on driving for women in Saudi. Two years and ten months of her prison sentence was reduced leaving only 3 months of time left to serve. However, the charges against her were false and the authorities denied arresting her for protesting against driving ban on women in Saudi Arabia. The prosecutors who were charged with torturing her during detention; sexually and otherwise, were cleared of charges by the government stating lack of evidence.[68] Islamic feminists have objected to the MPL legislation in many of these countries, arguing that these pieces of legislation discriminate against women. Some Islamic feminists have taken the attitude that a reformed MPL which is based on the Quran and sunnah, which includes substantial input from Muslim women, and which does not discriminate against women is possible.[69] Such Islamic feminists have been working on developing women-friendly forms of MPL. (See, for example, the Canadian Council of Muslim Women for argument based on the Qur'an and not on what they call medieval male consensus.) Other Islamic feminists, particularly some in Muslim minority contexts which are democratic states, argue that MPL should not be reformed but should be rejected and that Muslim women should seek redress, instead, from the civil laws of those states. Islamic feminists have been active in advocating for women's rights in the Islamic world. In 2012, Jordanian women protested against laws that allowed the dropping of charges if a rapist marries his victim, Tunisian women marched for equality for women in a new constitution, Saudi women protested against the ban against car driving, and Sudanese women created a silent wall of protest demanding freedom for arrested women.[11] Equality in the mosque See also: Islamic Bill of Rights for Women in the Mosque  Woman sitting at the threshold of the main building of Hazratbal shrine in Srinagar as the sign on the gate reads "Ladies Are Not Allowed" A survey by the Council on American Islamic Relations showed that two out of three mosques in 2000 required women to pray in a separate area, up from one out of two in 1994.[70] Islamic feminists have begun to protest this, advocating for women to be allowed to pray beside men without a partition, as they do in Mecca.[71][72] In 2003, Asra Nomani challenged the rules at her mosque in Morgantown, West Virginia, that required women to enter through a back door and pray in a secluded balcony.[70] She argued that Muhammad didn't put women behind partitions, and that barriers preventing women from praying equally with men are just sexist man-made rules.[70] The men at her mosque put her on trial to be banished.[70] In 2004, some American mosques had constitutions prohibiting women from voting in board elections.[73] In 2005, following public agitation on the issue, Muslim organizations that included the CAIR and the Islamic Society of North America issued a report on making mosques "women-friendly", to assert women's rights in mosques, and to include women's right to pray in the main hall without a partition.[70] In 2010, American Muslim Fatima Thompson and a few others organized and participated in a "pray-in" at the Islamic Center of Washington in D.C.[70] Police were summoned and threatened to arrest the women when they refused to leave the main prayer hall. The women continued their protest against being corralled in what they referred to as the "penalty box" (a prayer space reserved for only women). Thompson called the penalty box "an overheated, dark back room."[70] A second protest also staged by the same group on the eve of International Women's Day in 2010 resulted in calls to the police and threats of arrest again.[70] However, the women were not arrested on either occasion.[70] In May 2010, five women prayed with men at the Dar al-Hijrah mosque, one of the Washington region's largest Islamic centers.[71] After the prayers, a member of the mosque called Fairfax police who asked the women to leave.[71] However, later in 2010, it was decided that D.C. police would no longer intervene in such protests.[74] In 2015 a group of Muslim activists, politicians, and writers issued a Declaration of Reform which states in part, "Men and women have equal rights in mosques, boards, leadership and all spheres of society. We reject sexism and misogyny."[40] That same year Asra Nomani and others placed the Declaration on the door of the Islamic Center of Washington.[41] Equality in leading prayer Main article: Women as imams In 'A Survey and Analysis of Legal Arguments on Woman-Led Prayer in Islam named "I am one of the People"' Ahmed Elewa states that not because of external expectation but in due course with enlightened awareness Muslim communities should adopt women lead mixed gender prayers. In the same research paper Silvers emphasizes on example of Umm Salama who insisted that women are 'one of the people' and suggests women to assert their inclusion with equal rights. Elewa and Silvers research calls contemporary prohibitions of women lead prayer frustrating.[23] According to currently existing traditional schools of Islam, a woman cannot lead a mixed gender congregation in salat (prayer). Traditionalists like Muzammil Siddiqi states that women are not supposed to lead prayer because "It is not permissible to introduce any new style or liturgy in Salat." In other words, there must be no deviation from the tradition of men teaching.[75] Some schools make exceptions for Tarawih (optional Ramadan prayers) or for a congregation consisting only of close relatives. Certain medieval scholars—including Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (838–923), Abu Thawr (764–854), Isma'il Ibn Yahya al-Muzani (791–878), and Ibn Arabi (1165–1240) considered the practice permissible at least for optional (nafl) prayers; however, their views are not accepted by any major surviving group. Islamic feminists have begun to protest this. On March 18, 2005, Amina Wadud led a mixed-gender congregational Friday prayer in New York City. It sparked a controversy within the Muslim community because the imam was a woman, Wadud, who also delivered the khutbah.[76] Moreover, the congregation she addressed was not separated by gender. This event that departed from the established ritual practice became an embodied performance of gender justice in the eyes of its organizers and participants. The event was widely publicized in the global media and caused an equally global debate among Muslims.[76] However, many Muslims, including women, remain in disagreement with the idea of a woman as imam. Muzammil Siddiqi, chairman of the Fiqh Council of North America, argued that prayer leadership should remain restricted to men.[76] He based his argument on the longstanding practice and thus community consensus and emphasized the danger of women distracting men during prayers. The events that occurred in regards to equality in the mosque and women leading prayers, show the enmity Muslim feminists may receive when voicing opposition toward sexism and establishing efforts to combat it. Those who criticize Muslim feminists state that those who question the faith's views on gender segregation, or who attempt to make changes, are overstepping their boundaries and are acting offensively. On the other hand, people have stated that Islam does not advocate gender segregation. Britain's influential Sunni imam, Ahtsham Ali, has stated, "gender segregation has no basis in Islamic law" nor is it justified in the Quran.[77] Elewa and Silvers deduce that with lack of any explicit evidence to contrary one ought to assume, women lead prayer adds nothing new to God established worship but just a default state of command expects men and women both to lead the prayer.[23] Internet & social media impact Internet & social media debates opened up easy access to religious texts for Muslim women which helps them understand scriptural backing for the gender equality rights they which they fight for.[78] Dress code Main article: Islamic feminist views on dress codes See also: Haya (Islam), Islam and clothing, Awrah, Purdah, and Hijab by country Another issue that concerns Muslim women is dress code. Islam requires both men and women to dress modestly, but there is a difference in opinion about what type of dress is required. according to Leila Ahmed, during the prophet Muhammed's lifetime, the veil was observed only by his wives; its spread to the wider Muslim community was a later development.[79] Islamic feminist Asma Barlas says that the Quran only requires women to dress modestly, but it doesn't require them to veil.[80] Despite the controversy over hijab in sections of Western society, the veil is not controversial in mainstream Islamic feminist discourse, except in those situations where it is the result of social pressure or coercion. There is in fact strong support from many Muslim feminists in favor of the veil, though they generally believe that it should be voluntarily chosen. Many Muslim men and women now view the veil as a symbol of Islamic freedom.[81] While there are some Islamic scholars who interpret Islamic scripture as not mandating hijab,[82] many Islamic feminists still observe hijab as an act of religious piety or sometimes as a way of symbolically rejecting Western culture by making a display of their Muslim identity. Such sentiment was expressed, among others, by Muslim U.S. Congresswoman Ilhan Omar who stated in an interview with Vogue, “To me, the hijab means power, liberation, beauty, and resistance."[83] The annual event World Hijab Day, observed on February 1 (the anniversary of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's return from exile to Iran), is also celebrated by many Islamic feminists. Meanwhile, publicist Nadiya Takolia stated that she had actually adopted hijab after becoming a feminist, saying the hijab "is not about protection from men's lusts," but about "telling the world that my femininity is not available for public consumption...and I don't want to be part of a system that reduces and demeans women."[84] On the other side, there are some Islamic feminists, such as Fadela Amara and Hedi Mhenni, who do oppose hijab and even support legal bans on the garment for various reasons. Amara explained her support for France's ban of the garment in public buildings: "The veil is the visible symbol of the subjugation of women, and therefore has no place in the mixed, secular spaces of France's public school system."[85] When some feminists began defending the headscarf on the grounds of "tradition", Amara said: "It's not tradition, it's archaic! French feminists are totally contradictory. When Algerian women fought against wearing the headscarf in Algeria, French feminists supported them. But when it's some young girl in a French suburb school, they don't. They define liberty and equality according to what colour your skin is. It's nothing more than neocolonialism."[85] Mhenni also expressed support for Tunisia's ban on the veil: "If today we accept the headscarf, tomorrow we'll accept that women's rights to work and vote and receive an education be banned and they'll be seen as just a tool for reproduction and housework."[86] Sihem Habchi, director of Ni Putes Ni Soumises, expressed support for France's ban on the burqa in public places, stating that the ban was a matter of 'democratic principle' and protecting French women from the 'obscurantist, fascist, right-wing movement' that she claims the burqa represents.[87][88] Masih Alinejad began the movement My Stealthy Freedom in protest of forced hijab policies in Iran. The movement began as a Facebook page where women uploaded pictures of themselves defying Iran's mandatory hijab laws.[89] Mahmoud Arghavan, however, noted that Islamic feminists have criticized My Stealthy Freedom as supporting Islamophobia, though Alinejad has countered this criticism.[90] |

キャンペーン分野 個人法 こちらもご参照ください: イスラム夫婦法  2012年、オスロ・フリーダム・フォーラムで、自身が共同創設した#Women2Driveキャンペーンについて語るマナル・アル・シャリフ。 人類学者のキャロリン・フルーア=ロバンのように、アラブ・イスラムの女性活動家が世俗的な宗教運動に参加することを研究している学者の中には、この宗教 的義務の主張が「伝統的に男性の権威の社会的実践の根拠として用いられてきた」と主張する者もいる[65]。 「いくつかの国では、男性権威の立法的・行政的適用が、「家庭外での旅行や仕事、あるいは車の運転の許可の拒否」を通じて、女性の公共圏へのアクセスを拒 否することを正当化するために用いられている[65]。2017年9月26日、サウジアラビアは、女性の運転を禁止する長年の政策を2018年6月に終了 すると発表した[66]。さまざまな女性活動家が、その中でもサウジアラビアの女性の権利活動家であるマナル・アル・シャリフ[67]が運転している動画 をソーシャルメディアプラットフォームに投稿することで、禁止に抗議していた。サウジアラビアの女性の権利活動家の一人であるルジャイン・アル=ハスルー ルは、3年以上投獄されていたが、サウジでの女性の運転禁止に対する抗議に続き、外国と連携して王国に対して陰謀を企てた疑いで、2020年12月28日 に合計5年8カ月の実刑判決を言い渡された。彼女の実刑判決のうち2年10カ月は減刑され、残された刑期は3カ月のみとなった。しかし、彼女に対する容疑 は虚偽であり、当局はサウジアラビアの女性運転禁止に抗議した彼女を逮捕したことを否定した。勾留中に性的な拷問を加えたとして起訴された検察は、証拠不 十分として政府から嫌疑を晴らされた[68]。 イスラムのフェミニストたちは、これらの国の多くでMPL法制に反対しており、これらの法制は女性を差別していると主張している。一部のイスラム・フェミ ニストは、コーランとスンナに基づき、ムスリム女性からの実質的な意見を取り入れ、女性を差別しない改革されたMPLは可能であるという態度をとっている [69]。(例えば、中世の男性のコンセンサスと呼ばれるものでなく、クルアーンに基づいた議論については、カナダ・ムスリム女性評議会を参照のこと)。 他のイスラーム・フェミニスト、特に民主主義国家であるムスリム少数派の文脈にある一部のイスラーム・フェミニストは、MPLは改革されるべきではなく否 定されるべきであり、ムスリム女性はその代わりにその国家の民法に救済を求めるべきだと主張している。 イスラムのフェミニストたちは、イスラム世界における女性の権利擁護に積極的である。2012年、ヨルダンの女性はレイプ犯が被害者と結婚すれば告訴を取 り下げることができるという法律に抗議し、チュニジアの女性は新憲法における女性の平等を求めてデモ行進し、サウジアラビアの女性は車の運転禁止に抗議 し、スーダンの女性は逮捕された女性の自由を求めて沈黙の壁を作った[11]。 モスクにおける平等 以下も参照: モスクにおける女性のためのイスラム権利章典  スリナガルにあるハズラトバル廟の本殿の敷居に座る女性。門には "Ladies Are Not Allowed "と書かれている。 アメリカ・イスラム関係評議会の調査によると、2000年には3つのモスクのうち2つが女性に別の場所で祈ることを要求しており、1994年の2つに1つ から増加している[70]。イスラムのフェミニストたちはこれに抗議し始め、メッカで行われているように、女性も仕切りなしで男性のそばで祈ることを許可 されるよう提唱している[71][72]。 [71][72]2003年、アスラ・ノマニはウェストバージニア州モーガンタウンにあるモスクで、女性は裏口から入り、奥まったバルコニーで祈らなけれ ばならないという規則に異議を唱えた[70]。 2004年、アメリカのいくつかのモスクでは、女性が役員選挙で投票することを禁止する憲法が制定されていた[73]。2005年、この問題に関する世論 の煽りを受け、CAIRや北米イスラム協会を含むイスラム教団体は、モスクにおける女性の権利を主張し、女性が仕切りのない本堂で祈る権利を含む、「女性 に優しい」モスクの実現に関する報告書を発表した[70]。 2010年、アメリカ人のイスラム教徒であるファティマ・トンプソンと他の数人は、ワシントンのイスラム・センターで「祈り込み」を組織し、参加した [70]。女性たちは、彼女たちが「ペナルティ・ボックス」(女性だけが入れる祈りのスペース)と呼ぶ場所に収容されることへの抗議を続けた。トンプソン はペナルティ・ボックスのことを「過熱した暗い奥の部屋」と呼んだ[70]。2010年の国際女性デーの前夜にも同じグループによって2回目の抗議が行わ れ、警察に通報され、再び逮捕の脅迫があった[70]。 [70] 2010年5月、5人の女性がワシントン地域最大のイスラム教センターのひとつであるダール・アル・ヒジュラ・モスクで男性とともに礼拝を行った [71]。 礼拝後、モスクのメンバーがフェアファックス警察に通報し、フェアファックス警察は女性たちに退去を求めた[71]。 しかし、2010年の後半には、D.C.警察はもはやこのような抗議行動に介入しないことが決定された[74]。 2015年、イスラム教徒の活動家、政治家、作家のグループが改革宣言を発表した。私たちは性差別と女性差別を拒否します」[40]。同年、アスラ・ノマニらはこの宣言をワシントン・イスラミック・センターのドアに掲げた[41]。 祈りの指導における平等 主な記事 導師としての女性 アーメド・エレワは「"I am one of the People "と名付けられたイスラームにおける女性主導の祈りに関する法的議論の調査と分析」の中で、外的な期待からではなく、ムスリム・コミュニティは啓発された 意識の下で、やがて女性が男女混合の祈りを導くことを採用すべきだと述べている。同じ研究論文の中でシルバーズは、女性は「民衆の一人」であると主張した ウンム・サラマの例を強調し、女性が平等な権利を持って自分たちの包容力を主張するよう提案している。ElewaとSilversの研究では、女性が礼拝 をリードすることの現代的な禁止を挫折と呼んでいる[23]。 現在存在するイスラム教の伝統的な流派によれば、女性は男女混合の会衆をサラート(礼拝)で導くことはできない。Muzammil Siddiqiのような伝統主義者は、女性が祈りを導くことは想定されていないと述べている。"サラートに新しいスタイルや典礼を導入することは許されな い "からである。言い換えれば、男性が教えるという伝統から逸脱してはならないということである[75]。タラウィ(任意のラマダン礼拝)や近親者だけで構 成される会衆については例外とする流派もある。ムハンマド・イブン・ジャリール・アル・タバーリー(838-923)、アブ・タウル(764-854)、 イスマイル・イブン・ヤヒヤ・アル・ムザーニー(791-878)、イブン・アラビー(1165-1240)ら中世の学者の中には、少なくとも任意の(ナ フル)礼拝ではこの習慣が許されると考えた者もいるが、彼らの見解は現存する主要なグループには受け入れられていない。イスラムのフェミニストたちはこれ に抗議し始めている。 2005年3月18日、アミーナ・ワドゥドはニューヨークで男女混合の金曜礼拝を行った。イマームが女性であるワドゥドであり、彼女もまたクトゥバを行っ たため、ムスリム・コミュニティ内で論争を巻き起こした[76]。さらに、彼女が演説した会衆は性別で分けられていなかった。既成の儀式慣行から逸脱した このイベントは、その主催者と参加者の目には、ジェンダー正義の具現化されたパフォーマンスと映った。この出来事は世界的なメディアで広く知られ、イスラ ム教徒の間でも同様に世界的な議論を巻き起こした[76]。しかし、女性を含む多くのイスラム教徒は、女性が導師を務めるという考え方に反対したままであ る。北米フィク評議会の議長であるMuzammil Siddiqiは、祈りの指導者は男性に限定されたままであるべきだと主張した[76]。彼は、長年の慣行とそれゆえのコミュニティのコンセンサスに基づ いて議論を展開し、女性が祈りの最中に男性の気を散らす危険性を強調した。 モスクにおける平等と女性が礼拝をリードすることに関して起こった出来事は、性差別に対する反対を表明し、それに対抗する努力を確立する際に、ムスリム フェミニストが受けるかもしれない敵意を示している。ムスリムフェミニストを批判する人々は、男女隔離に関する信仰の見解に疑問を呈する人々や、変化を起 こそうとする人々は、境界を踏み越え、攻撃的な行動をとっていると述べる。その一方で、イスラム教は男女分離を推奨していないと述べる人々もいる。イギリ スの有力なスンニ派のイマームであるアッシャム・アリは、「男女の分離はイスラム法に根拠がない」と述べており、コーランにおいても正当化されていない [77]。エレワとシルバーズは、反対の明確な証拠がない以上、女性が祈りをリードすることは、神が確立した礼拝に何も新しいことを加えるものではなく、 ただ男女両方が祈りをリードすることを期待する命令のデフォルト状態に過ぎないと考えるべきだと推論している[23]。 インターネットとソーシャルメディアの影響 インターネットとソーシャルメディアの議論は、ムスリム女性にとって宗教的なテキストへの容易なアクセスを可能にし、彼女たちが戦う男女平等の権利の聖典的な裏付けを理解するのに役立っている[78]。 ドレスコード 主な記事 ドレスコードに関するイスラム・フェミニストの見解 以下も参照: ハヤ(イスラーム)、イスラームと服装、アワラー、プルダ、国別のヒジャブ ムスリム女性に関するもう一つの問題は、ドレスコードである。レイラ・アーメッドによると、預言者ムハマンドの存命中、ベールは彼の妻たちによってのみ守られていた。 イスラムのフェミニストであるアスマ・バーラスは、コーランは女性に慎み深い服装を要求しているだけで、ベールを被ることは要求していないと言う[80]。 西洋社会の一部ではヒジャーブに関する論争があるにもかかわらず、社会的圧力や強制の結果である場合を除き、主流のイスラム・フェミニストの言説ではベー ルは論争になっていない。実際、多くのムスリムフェミニストからベールを支持する強い支持があるが、彼らは一般的にベールは自発的に選択されるべきである と考えている。 イスラム教の聖典をヒジャーブを義務付けていないと解釈するイスラム学者もいるが[81]、多くのイスラム・フェミニストは、宗教的敬虔さの行為として、 あるいは時にはイスラム教徒であることを誇示することによって西洋文化を拒絶する象徴的な方法としてヒジャーブを守っている。そのような感情は、とりわけ イスラム教徒の米国下院議員イルハン・オマルによって表明され、彼は『ヴォーグ』誌とのインタビューで「私にとって、ヒジャーブは力、解放、美、そして抵 抗を意味する」と述べている[83]。2月1日(ホメイニ師がイランへの亡命から帰還した記念日)に行われる年次行事「世界ヒジャーブ・デー」もまた、多 くのイスラム・フェミニストによって祝われている。一方、パブリシストのナディヤ・タコリアは、フェミニストになってから実際にヒジャーブを取り入れたと 述べ、ヒジャーブは「男性の欲望から身を守るため」ではなく、「私の女性らしさは公の場では利用できないと世界に伝えるため......そして、私は女性 を矮小化し、卑下するシステムの一部になりたくないのです」と語った[84]。 その一方で、ファデラ・アマラやエディ・メンニのように、ヒジャーブに反対し、さまざまな理由からヒジャーブの法的禁止を支持するイスラム・フェミニスト もいる。アマラは、フランスが公共施設でのヒジャーブ禁止を支持する理由をこう説明する: 「ヴェールは、女性の被支配の目に見える象徴であり、したがってフランスの公立学校システムの混在した世俗的な空間にはふさわしくない」[85]。一部の フェミニストが「伝統」を理由にスカーフを擁護し始めたとき、アマラは言った: 「伝統ではなく、古風なものです!フランスのフェミニストたちはまったく矛盾している。アルジェリアの女性たちがアルジェリアでスカーフ着用に反対して 戦ったとき、フランスのフェミニストたちは彼女たちを支持した。しかし、フランス郊外の学校に通う若い女性の場合は、それを支持しない。彼らは肌の色に よって自由と平等を定義する。それは新植民地主義以外の何ものでもない」[85]。また、ムヘンニはチュニジアのベール禁止令への支持も表明している。 「今日、私たちがスカーフを受け入れるなら、明日は、女性が働き、選挙権を持ち、教育を受ける権利が禁止され、生殖と家事のための道具とみなされることを 受け入れるでしょう」[86]。 Ni Putes Ni Soumisesのディレクターであるシヘム・ハブチは、公共の場でのフランスのブルカ禁止への支持を表明し、禁止は「民主主義の原則」の問題であり、ブ ルカが象徴していると彼女が主張する「猥褻主義、ファシスト、右翼運動」からフランスの女性を守ることだと述べた[87][88]。 マシ・アリネジャド(Masih Alinejad)は、イランにおける強制的なヒジャブ政策に抗議するため、「My Stealthy Freedom」という運動を始めた。この運動は、女性たちがイランの強制的なヒジャブ法に反抗する写真をアップロードするフェイスブックのページとして 始まった[89]。しかしマフムード・アルガヴァンは、イスラムのフェミニストたちが「私のステルスな自由」はイスラム恐怖症を支持していると批判してい るが、アリネジャドはこの批判に反論していると指摘している[90]。 |

| Criticism "Islamic feminism" as a concept has been heavily scrutinized and criticized by more secular-minded feminists, including Muslim ones.[91] Iranian feminist Mahnaz Afkhami, for example, stated the following about secular Muslim feminists like herself: "Our difference with Islamic feminists is that we don’t try to fit feminism in the Qur’an. We say that women have certain inalienable rights. The epistemology of Islam is contrary to women’s right…I call myself a Muslim and a feminist. I am not an Islamic feminist – that’s a contradiction in terms.”[92] Hakimeh Entesari, an Iranian academic, also said, "The thoughts and writings of these people [Islamic feminists] suffer from a fundamental problem, and that is the absolute detachment of this movement from the cultural and indigenous realities of Islamic societies and countries..." She also believes that the use of the term "Islamic feminism" is wrong and it should be "Muslim feminists".[93] Maria Massi Dakake, an American Muslim academic, criticized Asma Barlas' assertion the Quran is inherently anti-patriarchal and sought to undo patriarchal social structures. Dakake writes, "She [Asma Barlas] makes a number of important and substantial points about the limitations to traditional "patriarchal" rights of fathers and husbands in the Quran. However, the conclusion that the Qur'an is "anti-patriarchal" as such is hard to reconcile with the Quran's fairly explicit endorsement of male leadership - even if not absolute authority - over the marital unit in 4:34."[94] Ibtissam Bouachrine, a professor at Smith College, has critiqued the writings of Fatema Mernissi. According to Bouachrine, Mernissi, in her book, The Veil and the Male Elite, critiques male interpretations of Quran 33:53, but not of Quran 24:31, "which evokes the veil in the context of the feminine body in public space." She also criticizes how Mernissi focuses on the hadith over the Quran because it is easier to criticize the hadith than the Quran which is seen as the word of God, but the hadith are the words of human beings. Bouachrine also critiques how Mernissi presents Muhammad as a "revolutionary heretic who sides with women against the Arabian male elite and their patriarchal values" but does not critique Muhammad's marriage to nine-year-old Aisha. Bouachrine also states that Mernissi does not mention that Zaynab was the former wife of Muhammad's adopted son.[95] Bouachrine also critiques Amina Wadud’s interpretation of 4:34 in Quran and Woman. According to Bouachrine, although 4:34 seems to call for men to physically discipline their wives, "Wadud argues that the Qur’an would not encourage violence against women and therefore the obedience required of women is to God not to the husband." Wadud also proposes that daraba means to set an example instead of to use physical force. According to Bouachrine, these reinterpretations do not help women in the Muslim world suffering from domestic violence.[95] On a slightly different note, Ahmadian, head of Isfahan Institute of Theology stated: "Some have created a fake title which is called "Islamic Feminism" in order to solve the conflict between Islam and feminism, that is considered to be a paradoxical combination and its principles are not consistent with the principles of Islam religion. Based on Islamic teachings, there are differences between the roles and positions of men/women, and this distinction doesn't lower the dignity of women in any way.[96] While Seyed Hussein Ishaghi, Ph.D. in Islamic Theology, had the following to say: "It is more appropriate to call Islamic feminism a woman-oriented interpretation of Islam religion... A group in the interaction of Islamic and Western culture faced an identity crisis; and on the other hand, in this confrontation, a group with its heart attached to Western culture denied religious teachings. That group promoted materialistic viewpoints by considering the mentioned beliefs as class or superstitious."[97] |

批判 「例えば、イランのフェミニストであるマフナズ・アフカミは、自身のような世俗的なムスリムフェミニストについて次のように述べている[91]: 「私たちとイスラムのフェミニストとの違いは、コーランにフェミニズムを当てはめようとしないことです。私たちは、女性には侵すことのできない権利がある と言います。イスラムの認識論は女性の権利に反している。私は自分のことをムスリムでありフェミニストだと言っていますが、イスラムのフェミニストではあ りません。 イランの学者であるハキメ・エンテサリもまた、「これらの人々(イスラム・フェミニスト)の思想や著作は根本的な問題に苦しんでいる。彼女はまた、「イスラム・フェミニズム」という用語の使用は間違っており、「イスラム・フェミニスト」であるべきだと考えている[93]。 アメリカのムスリム学者であるマリア・マッシ・ダカケは、アスマ・バーラスのコーランは本質的に反父長制的であり、家父長制的な社会構造を元に戻そうとす るものであるという主張を批判している。ダカケは、「彼女(アスマ・バーラス)は、コーランにおける父親と夫の伝統的な "家父長的 "権利の制限について、多くの重要かつ実質的な指摘をしている。しかし、クルアーンが「反父長制的」であるという結論は、クルアーン4章34節において、 夫婦の単位に対する男性のリーダーシップ(絶対的な権威ではないにせよ)をかなり明確に支持していることとの整合性が取りにくい」[94]。 スミス・カレッジの教授であるイブティッサム・ブアクリネは、ファテマ・メルニシの著作を批評している。Bouachrineによると、Mernissi は彼女の著書、The Veil and the Male Eliteの中で、コーラン33:53の男性解釈を批判しているが、コーラン24:31については批判していない。また、メルニシがコーランよりもハ ディースに焦点を当てるのは、神の言葉とされるコーランよりもハディースの方が批判しやすいが、ハディースは人間の言葉だからだと批判している。ブアクリ ネはまた、メルニシがムハンマドを「アラブの男性エリートとその家父長制的価値観に対して女性の味方をする革命的異端者」として紹介しているが、ムハンマ ドが9歳のアイシャと結婚したことについては批判していないと批判する。ブアクリネはまた、メルニシはザイナブがムハンマドの養子の前妻であったことに触 れていないと述べている[95]。 ブアクリネはまた、『コーランと女』の4:34のアミナ・ワドゥドの解釈を批判している。ブアクリネによれば、4章34節は男性が妻を肉体的に躾けるよう 求めているように見えるが、「ワドゥドは、クルアーンは女性に対する暴力を奨励しておらず、従って女性に求められる服従は夫ではなく神に対するものである と主張している」。また、ダラバとは物理的な力を行使するのではなく、手本を示すことを意味するとワドゥドは提唱している。Bouachrineによれ ば、これらの再解釈は家庭内暴力に苦しむイスラム世界の女性たちの助けにはならない[95]。 少し異なる点として、イスファハン神学研究所の責任者であるアフマディアンは次のように述べている: 「イスラムとフェミニズムの間の対立を解決するために、"イスラム・フェミニズム "と呼ばれる偽の称号を作り出した者がいるが、それは逆説的な組み合わせであり、その原理はイスラム教の原理と一致していないと考えられている。イスラム の教えに基づけば、男女の役割や立場には違いがあり、この違いは女性の尊厳を下げるものではない[96]。 イスラム神学の博士であるセイエド・フセイン・イシャギは次のように述べている: 「イスラム・フェミニズムはイスラム教の女性志向の解釈と呼ぶ方が適切である。イスラム文化と西洋文化の相互作用の中で、ある集団はアイデンティティの危 機に直面した。一方、この対立の中で、西洋文化に心を寄せるある集団は宗教の教えを否定した。そのグループは、言及された信仰を階級的あるいは迷信的なも のとみなすことによって、唯物論的な視点を促進した」[97]。 |

| List of Muslim feminists, Wiki |

|

| Feminism in Egypt Feminism in India Gender roles in Afghanistan Golden Needle Sewing School International Conference on Population and Development Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan Women in Lebanon Women's rights in Iran Women's rights in Saudi Arabia Women's rights in Kuwait Women's rights movement in Iran General Hermeneutics of feminism in Islam List of Muslim feminists Abortion and Islam LGBT in Islam Female figures in the Qur'an Feminationalism Gender segregation and Islam History of feminism Postcolonial feminism Purplewashing Rada (fiqh) Rights and obligations of spouses in Islam Role of women in religion Sex segregation in Iran Taliban treatment of women Women in Islam World Hijab Day Glossary of Islam Gender roles in Islam Islamic clothing |

エジプトのフェミニズム インドのフェミニズム アフガニスタンのジェンダー役割 金針裁縫学校 人口と開発に関する国際会議 アフガニスタン女性革命協会 レバノンの女性たち イランの女性の権利 サウジアラビアの女性の権利 クウェートにおける女性の権利 イランの女性の権利運動 一般 イスラームにおけるフェミニズムの解釈学 ムスリムフェミニスト一覧 中絶とイスラーム イスラームにおけるLGBT クルアーンにおける女性像 フェミニズム ジェンダー分離とイスラーム フェミニズムの歴史 ポストコロニアル・フェミニズム パープルウォッシング ラーダ イスラームにおける配偶者の権利と義務 宗教における女性の役割 イランにおける性分離 タリバンによる女性の扱い イスラームにおける女性 世界ヒジャーブ・デー イスラム用語集 イスラームにおける性別役割 イスラムの服装 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_feminism |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆