ジュリアン・バンダ『知識人の裏切り』入門

Benda, Julien, 1867-1956, La trahison des clercs

ジュリアン・バンダ『知識人の裏切り』入門

Benda, Julien, 1867-1956, La trahison des clercs

さ まざまな修辞とその時代の挿話が交錯しているバンダのこのポレミックなメッセージは、極度に単純化すると《知識人は本来は真理に携わる者なのに(最近は) 政治的情熱に駆られている》という現状認識とそれに対する苛立ちのように思える。これは、日本におけるその情熱すら失いひたすら政府に媚びへつらう「御用 学者」に対して、いわゆるリベラルな日本の知識人に通底する(全体主義に抗するリベラルな)政治的情熱だと解釈すれば、保守的な「真理フェチ」あるいは夕 方に飛び立つミネルヴァの梟(ふくろう)とも言える哲人の不満(ルサンチマン)や皮肉にも聞こえてしまう。

さて、バンダの本当のところはどうなのか?彼の知識人論はじっくりと読んでみるしかない。

章立て

1.政治的情熱の現代的発展、政治の時代

2.この運動の意味、政治的情熱の性質

3.知識人、知識人の裏切り

4.総括的展望、予測

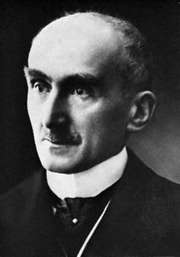

★ジュリアン・バンダ

| Julien Benda

(French: [ʒyljɛ̃ bɛ̃da]; 26 December 1867 – 7 June 1956) was a French

philosopher and novelist, known as an essayist and cultural critic. He

is best known for his short book, La Trahison des Clercs from 1927 (The

Treason of the Intellectuals or The Betrayal by the Intellectuals).[1] |

ジュリアン・バンダ(フランス語: [ʒyljɛ̃

bɛ̃da]、1867年12月26日 -

1956年6月7日)は、フランスの哲学者、小説家であり、エッセイスト、文化批評家としても知られている。1927年に出版された著書『知識人の裏切

り』(原題:La Trahison des Clercs)で最もよく知られている。 |

| Life Born into a Jewish family in Paris, Benda had a secular upbringing.[2] He was educated at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand. After a period at the École Centrale Paris, he turned to history, and graduated at the Sorbonne in 1894.[3] His father's death in 1889 left Benda independently wealthy.[2] He wrote for La Revue Blanche from 1891 to 1903. His articles on the Dreyfus affair were collected and published as Dialogues.[3] He disagreed strongly with Henri Bergson, the leading light of French philosophy of his day, and launched an attack on him in 1911, when Bergson's reputation was at its height.[4] In July 1937 he attended the Second International Writers' Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals to the war in Spain, held in Valencia, Barcelona and Madrid and attended by many writers including André Malraux, Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Spender and Pablo Neruda.[5] Benda survived the German occupation of France and the Vichy regime 1940–1944, in Carcassonne. The journal of Jean Guéhenno described his life there, and his character: "Unbearable, yet likeable."[6] He died in Fontenay-aux-Roses, on 7 June 1956.[3] |

人生 パリでユダヤ人家庭に生まれたバンダは、世俗的な環境で育った。[2] ルイ・ル・グラン高校で教育を受け、パリ中央工科学校に在籍した後、歴史学に転向し、1894年にソルボンヌ大学を卒業した。[3] 1889年に父親が死去したことで、ベナは独立して裕福になった。[2] 1891年から1903年まで『ラ・ルヴュ・ブランシュ』に寄稿した。 ドレフュス事件に関する彼の記事は『対話』としてまとめられ、出版された。[3] 彼は当時のフランス哲学の第一人者であったアンリ・ベルクソンと強く対立し、ベルクソンの名声が絶頂にあった1911年に彼を攻撃した。[4] 1937年7月、スペイン戦争に対する知識人の態度について議論することを目的とした第2回国際作家会議に出席した。この会議はバレンシア、バルセロナ、 マドリードで開催され、アンドレ・マルロー、アーネスト・ヘミングウェイ、スティーヴン・スペンダー、パブロ・ネルーダなど多くの作家が出席した。 バンダは、1940年から1944年にかけてのドイツによるフランス占領とヴィシー政権下において、カルカッソンヌで生き延びた。ジャン・ゲエノの日記に は、彼のその時期の生活と人柄について「耐え難いほどだが、好感の持てる人物」と記されている。[6] 彼は1956年6月7日にフォンテーヌブロー=オー=ローズで死去した。[3] |

| Works Benda is considered to be primarily an essayist.[7] He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times.[8] His single nomination for the Goncourt Prize was in 1912 for L'Ordination. He lost out to André Savignon's novel Les filles de la pluie. Voting was tied, and the casting vote went to Léon Hennique, in a notorious election that caused Hennique to give up the presidency of the Académie Goncourt.[9] La Trahison des Clercs See also: Managerial state Benda is now best remembered for his short 1927 book La Trahison des Clercs, a work of considerable influence. It was translated into English in 1928 by Richard Aldington; the U.S. edition was titled The Treason of the Intellectuals, while the British edition was titled The Great Betrayal. Aldington's translation was republished in 2006 as The Treason of the Intellectuals, with a new introduction by Roger Kimball. This polemical essay argued that European intellectuals in the 19th and 20th centuries had often lost the ability to reason dispassionately about political and military matters, instead becoming apologists for crass nationalism, warmongering, and racism. Benda reserved his harshest criticisms for his fellow Frenchmen Charles Maurras and Maurice Barrès. Benda defended the measured and dispassionate outlook of classical civilization and the internationalism of traditional Christianity. Closing this work, Benda darkly predicts that the augmentation of the "realistic" impulse to domination of the material world, justified by intellectuals into an "integral realism," risked producing an all-encompassing species-wide civilization that would completely cease "to situate the good outside the real world." Human aspirations, specifically after power, would become the sole end of society. In closing, he concludes bitterly, "And History will smile to think that this is the species for which Socrates and Jesus Christ died."[10] Benda's word "clercs" was borrowed by Anne Appelbaum in her 2020 book Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism.[11] Other works Other works by Benda include Belphégor (1918), Uriel's Report (1926), and Exercises of a Man Buried Alive (1947), an attack on the contemporary French celebrities of his time. Most of the titles in the bibliography below were published during the last three decades of Benda's long life; he is emphatically a 20th-century author. In his 1933 publication Discours à la nation européenne, Benda responded to Johann Gottlieb Fichte's Addresses to the German Nation.[12] |

作品 バンダは主にエッセイストとして知られている。[7] 彼はノーベル文学賞に4度ノミネートされた。[8] ゴンクール賞にノミネートされたのは1912年の『叙階』が唯一である。アンドレ・サヴィニョンの小説『雨の娘たち』に敗れた。票は同数となり、決定票は レオン・エニケに渡った。この悪名高い選挙により、エニケはゴンクールアカデミーの会長職を辞任した。 『知識人の裏切り 関連項目:管理国家 バンダは、1927年に出版された短編『知識人の裏切り』で最もよく知られている。この作品は大きな影響を与えた。1928年にリチャード・アルディント ンによって英語に翻訳され、米国版のタイトルは『知識人の反逆』、英国版のタイトルは『大いなる裏切り』であった。アルディントンの翻訳は2006年に 『知識人の反逆』として再版され、ロジャー・キンボールによる新たな序文が付け加えられた。この論争的な論文は、19世紀から20世紀にかけてのヨーロッ パの知識人たちは、政治や軍事問題について冷静に判断する能力を失い、粗野なナショナリズム、好戦主義、人種主義の擁護者になってしまったと論じている。 バンダは、同胞であるフランス人のシャルル・モーラスとモーリス・バレスに対して最も厳しい批判を向けた。バンダは、古典文明の冷静で客観的な見通しと、 伝統的キリスト教の国際主義を擁護した。 この著作の締めくくりとして、バンダは、物質的世界の支配に対する「現実的」衝動の増大を、知識人が「全体的現実主義」として正当化することは、包括的な 種全体の文明を生み出す危険性があり、それは「現実世界の外に善を見出す」ことを完全にやめてしまうだろうと暗に予測している。人間の願望、特に権力への 願望が、社会の唯一の目的となるだろう。最後に、彼は苦々しくこう結んでいる。「そして、ソクラテスとイエス・キリストが死んだのは、この種族のためだっ たのかと、歴史は微笑むだろう」[10] バンダの「clercs」という言葉は、アン・アッペルバウムが2020年に出版した著書『民主主義の黄昏:権威主義の魅惑的な誘惑』で借用している。[11] その他の作品 バンダのその他の作品には、『ベルフェゴール』(1918年)、『ウリエルの報告書』(1926年)、『生き埋めにされた男の演習』(1947年)などが あり、これは同時代のフランスの著名人に対する攻撃である。以下の書誌に挙げたタイトルのほとんどは、バンダの長寿の最後の30年間に出版されたものであ り、彼は断固として20世紀の作家である。 1933年に出版された著書『ヨーロッパ国民への演説』の中で、バンダはヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテの『ドイツ国民への演説』に反応を示している。[12] |

| Bibliography L'ordination – 1911 English translation, The yoke of pity, by Gilbert Cannan – 1913 Les sentiments de Critias – 1917 Belphégor : essai sur l'esthétique de la présente société française – 1919 Les amorandes – 1922 La croix de roses ; précédé d'un dialogue d'Eleuthère avec l'auteur – 1923 Lettres à Mélisande – 1926 La trahison des clercs – 1927 English translation,The Betrayal of the Intellectuals, by Richard Aldington: 1955 (1928). Beacon Press. Introduction by Herbert Read. The Treason of the Intellectuals 2006. Transaction Publishers. Introduction by Roger Kimball. Cléanthis ou du Beau et de l'actuel – 1928 Properce, ou, Les amants de Tibur – 1928 La Fin de l’Éternel – 1929[12] Appositions – 1930 Esquisse d'une histoire des Français dans leur volonté d'être une nation – 1932 Discours à la nation européenne – 1933[12] La jeunesse d'un clerc – 1936 Précision (1930–1937) – 1937 Un régulier dans le siècle – 1937 Un Régulier dans le siècle (Paris, Gallimard) 1938 La grande épreuve des démocraties : essai sur les principes démocratiques : leur nature, leur histoire, leur valeur philosophique. – 1942 Exercice d'un enterré vif, juin 1940-août 1944 – 1945 La France Byzantine, ou, Le triomphe de la littérature pure : Mallarmé, Gide, Proust, Valéry, Alain Giraudoux, Suarès, les Surréalistes : essai d'une psychologie originelle du littérateur – 1945 Du poétique. Selon l'humanité, non-selon les poètes – 1946 Non possumus. À propos d'une certaine poésie moderne – 1946 Le rapport d'Uriel – 1946 Tradition de l'existentialisme, ou, Les philosophies de la vie – 1947 Du style d'idées : réflexions sur la pensée, sa nature, ses réalisations, sa valeur morale – 1948 Trois idoles romantiques : le dynamisme, l'existentialisme, la dialectique matérialiste – 1948 Les cahiers d'un clerc, 1936–1949 – 1949 La crise du rationalisme – 1949 |

書誌 叙階 - 1911年 ギルバート・カナン著『憐れみのくびき』英訳 - 1913年 クリティアスの感情 - 1917年 ベルフェゴール:現在のフランス社会の倫理に関するエッセイ - 1919年 憐れみ - 1922年 薔薇の花飾り:エリュテールと作者の対話に先立つ - 1923年 メリザンドへの手紙 - 1926年 聖職者の裏切り - 1927年 英語訳『知識人の裏切り』リチャード・オルディントン著: 1955 (1928). ビーコン出版。ハーバート・リードによる序。 知識人の反逆 2006. トランザクション・パブリッシャーズ。ロジャー・キンボールによる序。 クレアンティス、あるいは美と現実の世界-1928年 プロプロティウス、あるいはティブールの恋人たち - 1928年 永遠の終わり - 1929[12]. アポジションズ - 1930年 国家であろうとするフランス人の歴史概説 - 1932年 ヨーロッパ国民への演説 - 1933年[12] 聖職者の青春 - 1936年 プレシジョン(1930-1937)-1937年 世紀の常連 - 1937年 1938年『世紀のレギュリエ』(パリ、ガリマール社 民主主義の大いなる冒険:民主主義の原理についてのエッセイ:その性質、歴史、哲学的価値。- 1942 1940年6月-1944年8月、1945年 フランス・ビザンチン、あるいは純粋文学の凱旋:マラルメ、ギド、プルースト、ヴァレリー、アラン・ジロドゥ、スアレス、シュルレアリスム:作家の起源的心理学的エッセイ - 1945年 詩学。詩人ではなく、人類による。 詩を持たない。ある現代詩について - 1946 ウリエルの報告 - 1946年 実存主義の伝統、あるいは人生の哲学 - 1947年 思想の様式について:思想、その性質、業績、道徳的価値についての考察 - 1948年 3つのロマンチックな偶像:ダイナミズム、実存主義、唯物弁証法 - 1948年 ある事務員のノート(1936-1949年) - 1949年 合理主義の危機 - 1949年 |

| Alain Finkielkraut Notes on Nationalism, a 1945 essay by George Orwell dealing with similar themes as Benda's Trahison des Clercs. |

アラン・フィンケルクロート 『国民性についてのノート』は、バンダの『知識人の裏切り』と同様のテーマを扱ったジョージ・オーウェルの1945年のエッセイである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julien_Benda |

リ ンク

文 献

そ

の他の情報

(c) Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j. Copyright 2018