メソアメリカ文化におけるジャガー

Jaguars in Mesoamerican cultures

☆ メソアメリカ文化におけるジャガーの表現には長い歴史があり、図像学的な例は少なくともメソアメリカ年代学の中期形成期まで遡る。 ジャガー(Panthera onca)は、新世界におけるコロンブス到来以前の中米社会の文化や信仰体系において、ライオン(Panthera leo)やトラ(Panthera tigris)と同様に、顕著な関連性と外観を持つ動物である。素早く俊敏で、ジャングル最大の獲物を仕留めるほどの力を持つジャガーは、中南米最大のネ コ科動物であり、最も効率的で攻撃的な捕食動物のひとつである。斑点のある毛皮を持ち、ジャングルに適応したジャガーは、樹上でも水中でも狩りを行い、水 に耐性のある数少ないネコ科動物のひとつである。ジャガーは、その生息地に住むアメリカ先住民の間で、昔も今も崇められている。 メソアメリカ文明の主要な文明では、いずれもジャガーの神が重要な役割を果たしており、オルメカ族など多くの民族にとって、ジャガーは宗教的実践の重要な 一部であった。[4] 熱帯のジャングルやその周辺に暮らす人々にとって、ジャガーはよく知られた存在であり、生活の一部となっていた。ジャガーの巨大な体格、捕食者としての評 判、ジャングルで生き延びるために進化した能力は、ジャガーを畏敬の対象とした。オルメカ族やマヤ族は、この動物の習性を目の当たりにし、ジャガーを威厳 と武勇の象徴として受け入れ、神話に取り入れた。ジャガーは今日も、過去と同様に、このネコ科の動物と共存する人々の生活において重要なシンボルとなって いる。

| The representation

of jaguars in Mesoamerican cultures has a long history, with

iconographic examples dating back to at least the mid-Formative period

of Mesoamerican chronology.[1] The jaguar (Panthera onca) is an animal with a prominent association and appearance in the cultures and belief systems of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican societies in the New World, similar to the lion (Panthera leo) and tiger (Panthera tigris) in the Old World.[2] Quick, agile, and powerful enough to take down the largest prey in the jungle, the jaguar is the biggest felid in Central or South America,[3] and one of the most efficient and aggressive predators. Endowed with a spotted coat and well-adapted for the jungle, hunting either in the trees or water, making it one of the few felines tolerant of water, the jaguar was, and remains, revered among the Indigenous Americans who live in its range. All major Mesoamerican civilizations prominently featured a jaguar god, and for many, such as the Olmec, the jaguar was an important part of religious practice.[4] For those who resided in or near the tropical jungle, the jaguar was well known and became incorporated into the lives of the inhabitants. The jaguar's formidable size, reputation as a predator, and its evolved capacities to survive in the jungle made it an animal to be revered. The Olmec and the Maya witnessed this animal's habits, adopting the jaguar as an authoritative and martial symbol, and incorporated the animal into their mythology. The jaguar stands today, as it did in the past, as an important symbol in the lives of those who coexist with this felid. |

メソアメリカ文化におけるジャガーの表現には長い歴史があり、図像学的

な例は少なくともメソアメリカ年代学の中期形成期まで遡る。 ジャ ガー(Panthera onca)は、新世界におけるコロンブス到来以前の中米社会の文化や信仰体系において、ライオン(Panthera leo)やトラ(Panthera tigris)と同様に、顕著な関連性と外観を持つ動物である。素早く俊敏で、ジャングル最大の獲物を仕留めるほどの力を持つジャガーは、中南米最大のネ コ科動物であり、最も効率的で攻撃的な捕食動物のひとつである。斑点のある毛皮を持ち、ジャングルに適応したジャガーは、樹上でも水中でも狩りを行い、水 に耐性のある数少ないネコ科動物のひとつである。ジャガーは、その生息地に住むアメリカ先住民の間で、昔も今も崇められている。 メソアメリカ文明の主要な文明では、いずれもジャガーの神が重要な役割を果たしており、オルメカ族など多くの民族にとって、ジャガーは宗教的実践の重要な 一部であった。[4] 熱帯のジャングルやその周辺に暮らす人々にとって、ジャガーはよく知られた存在であり、生活の一部となっていた。ジャガーの巨大な体格、捕食者としての評 判、ジャングルで生き延びるために進化した能力は、ジャガーを畏敬の対象とした。オルメカ族やマヤ族は、この動物の習性を目の当たりにし、ジャガーを威厳 と武勇の象徴として受け入れ、神話に取り入れた。ジャガーは今日も、過去と同様に、このネコ科の動物と共存する人々の生活において重要なシンボルとなって いる。 |

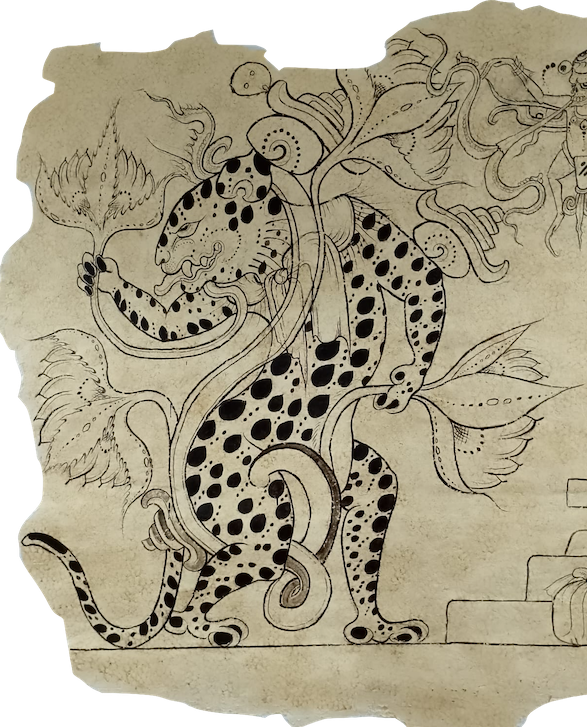

The day sign "Jaguar" from the Codex Laud |

『コデックス・ラウド』の日にちのサイン「ジャガー」 |

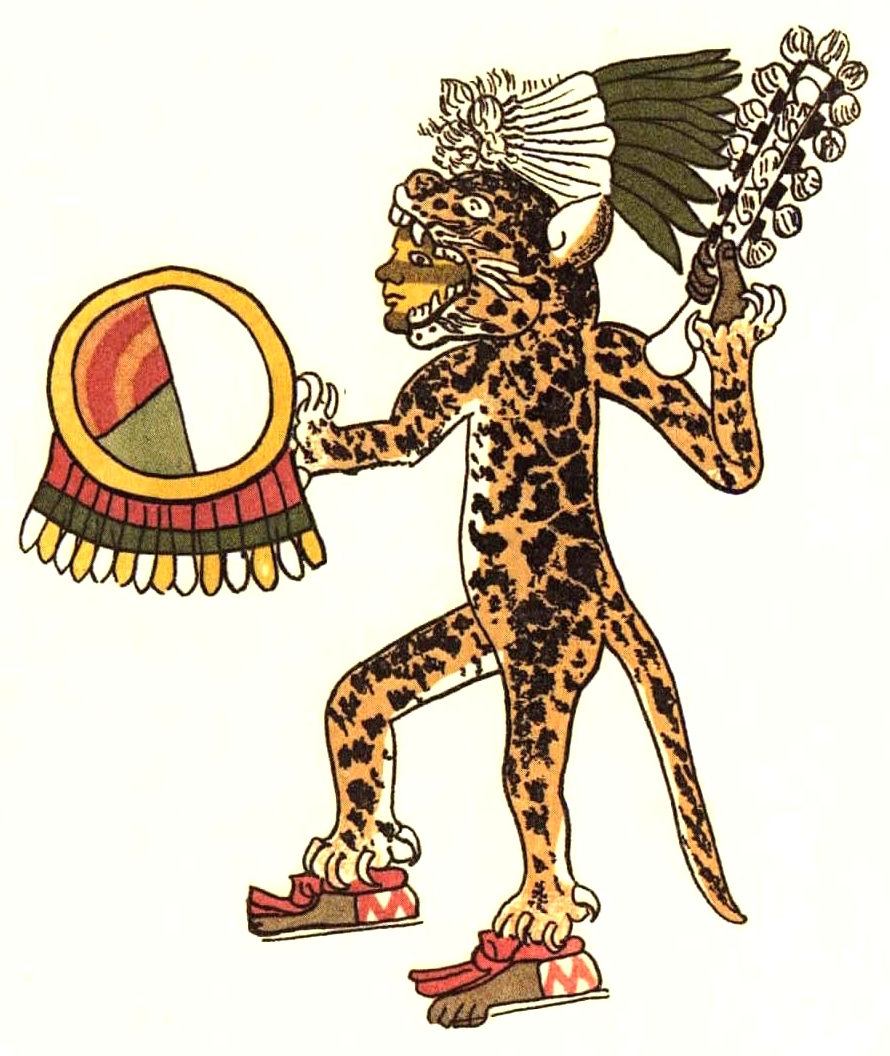

| Jaguars and the Maya See also: Maya jaguar gods  Kukulcan's Jaguar Throne, from the Maya site of Chichen Itza Integration of the jaguar into the sacred and secular realms of the Maya peoples is proven in the archaeological record. The Maya, whose territory spanned the Yucatán Peninsula all the way to the Pacific coast of Guatemala, was a literate society who left documentation of their lives (mostly the lives of the aristocracy) and belief system in the form of books and bas-relief sculpture on temples, stelae, and pottery. Often depicted on these artifacts are the gods the Maya revered and it is no coincidence that these gods often have jaguar attributes. As stated earlier, the jaguar is said to have the ability to cross between worlds, and for the Maya daytime and nighttime represented two different worlds. The living and the earth are associated with the day, and the spirit world and the ancestors are associated with the night. As the jaguar is quite at home in the nighttime, the jaguar is believed to be part of the underworld; thus, "Maya gods with jaguar attributes or garments are underworld gods" (Benson 1998:64). One such god is Xbalanque, one of the Maya Hero Twins who descended to the underworld, and whose entire body is covered with patches of jaguar skin. Another is God L, who is "the primary lord of the underworld" and often is shown with a jaguar ear or jaguar attire, and atop a jaguar throne (Benson 1998: 64-65). Not only is the underworld associated with the ancestors, but it also is understood as, where plants originate. In addition, the Maya's source of fresh water comes from underground pools in the porous limestone that makes up the Yucatán, called cenotes. These associations with water and plants further reinforce the notion of the jaguar as a god of fertility. The jaguar is further associated with vegetation and fertility by the Maya with what is known as the Waterlily jaguar, which is depicted as having water lilies sprouting from its head (Benson 1998:64-67).  Aztec jaguar warrior, from the Codex Magliabechiano No doubt, the jaguar's brilliant coat made it quite desirable, however, not all were allowed to don the jaguar pelt as it became the identification of the ruling class for the Maya. Not only did Maya kings wear jaguar pelts, but they also adopted the jaguar as part of their ruling name, as a symbol of their might and authority. One such ruling family to incorporate the jaguar into their name is known as, Jaguar Paw, who ruled the Maya city of Tikal in the fourth century. Jaguar Paw I was ousted by central Mexicans from Teotihuacán, and it was not until late in the fifth century that the Jaguar Paw family returned to power (Coe 1999: 90). Other Maya rulers to incorporate the jaguar name include, Scroll Jaguar, Bird Jaguar, and Moon Jaguar, just to name a few (Coe 1999: 247-48). In addition to the ruling class, the jaguar also was associated with warriors and hunters. Those who excelled in hunting and warfare often adorned themselves with jaguar pelts, teeth, or claws and were "regarded as possessing feline souls" (Saunders 1998: 26). Archeologists have found a jar in Guatemala, attributed to the Maya of the Late Classic Era (600-900 AD), which depicts a musical instrument that has been reproduced and played. This instrument is astonishing in at least two respects. First, it is the only stringed instrument known in the Americas prior to the introduction of European musical instruments. Second, when played, it produces a sound virtually identical to a jaguar's growl. A sample of this sound is available at the Princeton Art Museum website. |

ジャガーとマヤ 関連情報:マヤのジャガーの神々  チチェン・イッツァのマヤ遺跡にあるククルカンのジャガーの玉座 マヤの人々の神聖な領域と世俗的な領域にジャガーが組み込まれていたことは、考古学的記録によって証明されている。マヤはユカタン半島からグアテマラの太 平洋岸まで広大な領土を支配していたが、文字を読み書きできる社会であり、自分たちの生活(主に貴族階級の生活)や信仰体系を書籍や神殿、石碑、陶器に浮 き彫りにしたレリーフの形で記録に残していた。これらの遺物には、マヤ人が崇拝していた神々がしばしば描かれているが、これらの神々がしばしば豹の属性を 持っているのは偶然ではない。前述の通り、豹には世界を渡る能力があると言われており、マヤ人にとって昼と夜はそれぞれ異なる世界を象徴していた。昼は生 者と大地、夜は霊界と祖先を象徴している。ジャガーは夜に非常に馴染みがあるため、ジャガーは冥界の一部であると考えられている。そのため、「ジャガーの 属性や衣服を持つマヤの神々は冥界の神々である」(Benson 1998:64)。そのような神の1人が、冥界に降り立ったマヤの英雄双子の1人であるXbalanqueであり、その全身はジャガーの皮膚のパッチで覆 われている。もう一人は「冥界の主神」である神Lで、しばしばジャガーの耳やジャガーの装飾品を身につけ、ジャガーの玉座に座っている姿で描かれている (Benson 1998: 64-65)。 冥界は先祖と関連しているだけでなく、植物の起源の地でもあると考えられていた。さらに、マヤ族の水源は、ユカタン半島を構成する多孔質の石灰岩の地下 プールから湧き出る水であり、セノーテと呼ばれている。こうした水や植物との関連性は、ジャガーが豊穣の神であるという考えをさらに強固なものとしてい る。 マヤ族の間では、頭部から睡蓮が生えている姿で描かれる「睡蓮のジャガー」として知られるジャガーが、さらに植物と豊穣の象徴とされている(Benson 1998:64-67)。  アステカのジャガー戦士、マグリアベキアーノ写本より 確かに、ジャガーの鮮やかな毛皮は非常に魅力的であったが、ジャガーの毛皮を身にまとうことが許されたのは一部の人々だけであり、それはマヤ族の支配階級 の象徴でもあった。マヤ王はジャガーの毛皮を身にまとっていただけでなく、権力と権威の象徴として、ジャガーを支配者の名前の一部にも取り入れていた。そ のようにして、ジャガーを名前の一部に取り入れた支配者一族の1つが、4世紀にマヤの都市ティカルを支配したジャガー・ポー(Jaguar Paw)である。ジャガー・ポー1世はテオティワカン(Teotihuacán)の中央メキシコ人によって追放され、ジャガー・ポー一族が再び権力を握っ たのは5世紀後半になってからであった(Coe 1999: 90)。ジャガーの名前を名乗った他のマヤの支配者には、スクロール・ジャガー、バード・ジャガー、ムーン・ジャガーなどがいる(Coe 1999: 247-48)。支配階級に加えて、ジャガーは戦士や狩人とも関連付けられていた。狩猟や戦いに秀でた人々は、しばしばジャガーの毛皮や歯、爪を身にまと い、「猫科の魂を持つ者」とみなされていた(Saunders 1998: 26)。 考古学者は、グアテマラで後期古典期(西暦600年から900年)のマヤ文明に由来すると考えられる壷を発見した。その壷には、再現され演奏された楽器が 描かれている。この楽器には少なくとも2つの驚くべき点がある。まず、ヨーロッパの楽器が持ち込まれる以前のアメリカ大陸で知られていた唯一の弦楽器であ ること。そして、演奏すると、ジャガーの唸り声とほとんど同じ音が出るということだ。この音のサンプルはプリンストン美術館のウェブサイトで聞くことがで きる。 |

| Jaguars and Teotihuacan In the city-state of Teotihuacan jaguar bones have been found in caches of precious or significant objects, including obsidian and greenstone, in both the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon. These caches were placed in the pyramids as they were being built, likely as part of a ceremony to dedicate the pyramids. Analysis of the animal bones has shown that while some of the jaguars had been wild shortly before burial, many had lived in captivity for a long time prior to being placed in the dedicatory cache.[5] |

ジャガーとテオティワカン 都市国家テオティワカンでは、太陽のピラミッドと月のピラミッドの両方で、黒曜石や緑色岩などの貴重な物品や重要な物品の貯蔵品の中からジャガーの骨が発 見されている。これらの貯蔵品はピラミッドが建設されている間にピラミッド内に置かれたもので、おそらくはピラミッドの奉献式の一部として置かれたものと 考えられている。動物の骨の分析により、埋葬される直前に野生であったジャガーもいたが、奉納用貯蔵品に置かれる前に長い間飼育されていたジャガーも多 かったことが明らかになっている。[5] |

| Jaguars and the Olmecs See also: Olmec were-jaguar  Clay jaguar from Monte Albán, provisionally dated from 200 BC to AD 600. Height: 56 cm (22 inches) The Olmec civilization was first defined as a distinctive art style at the turn of the nineteenth century. The various sculpture, figurines, and celts from what now is recognized as the Olmec heartland on the southern Gulf Coast, reveal that these people knew their jungle companions well and incorporated them into their mythology. In the surviving Olmec archaeological record, jaguars are rarely portrayed naturalistically, but rather with a combination of feline and human characteristics. These feline anthropomorphic figures may range from a human figure with slight jaguar characteristics to depictions of figures in the so-called transformative pose, kneeling with hands on knees, to figures that are nearly completely feline. One of the most prominent, distinctive, and enigmatic Olmec designs to appear in the archaeological record has been the "were-jaguar". Seen not only in figurines, the motif also may be found carved into jade "votive axes" and celts, engraved onto various portable figurines of jade, and depicted on several "altars", such as those at La Venta. Were-jaguar babies are often held by a stoic, seated adult male. The were-jaguar figure is characterized by a distinctive down-turned mouth with fleshy lips, almond-shaped eyes, and a cleft head similar – it is said – to that of the male jaguar which has a cleft running vertically the length of its head. It is not known what the were-jaguar represented to the Olmec, and it may well have represented different things at different times. |

ジャガーとオルメカ文明 参照:オルメカのジャガーの像  モンテ・アルバン出土の粘土製のジャガーの像。紀元前200年から西暦600年の間に作られたと推定される。高さ:56cm(22インチ) オルメカ文明は、19世紀の変わり目に、独特な芸術様式として初めて定義された。現在ではオルメカ文明の中心地と認識されているメキシコ湾岸南部から出土 したさまざまな彫刻、フィギュリン、鋤形石から、この人々がジャングルの動物をよく知っており、それらを彼らの神話に取り入れていたことがわかる。 現存するオルメカの考古学的記録では、ジャガーは自然主義的に描かれることはほとんどなく、ネコ科の動物と人間の特性を組み合わせた姿で表現されている。 これらのネコ科の擬人像は、ジャガーの特性をわずかに備えた人間像から、いわゆる変身ポーズをとる人物の描写、ひざまずいてひざに手を置く姿、ほぼ完全に ネコ科の動物になっている姿まで、さまざまなものがある。 考古学的な記録に登場するオルメカ文明のデザインの中でも、最も際立った独特な謎めいたデザインのひとつが「変身したジャガー」である。このモチーフは、 彫像だけでなく、ヒスイの「奉納斧」や「楔石」に刻まれたり、ヒスイのさまざまな携帯用彫像に刻まれたり、ラ・ベンタ遺跡などのいくつかの「祭壇」に描か れたりしている。人面豹の赤ん坊は、しばしば座った無表情な大人の男性に抱かれている。 人面豹の像は、肉厚の唇を持つ下向きの口、アーモンド形の目、そして、頭頂部に縦に割れ目がある雄のジャガーの頭部に似た割れ目があるのが特徴である。 オルメカ族にとって人食いジャガーが何を象徴していたのかは不明であり、時代によって異なる意味を持っていた可能性もある。 |

| Other instances of the jaguar in Mesoamerican cultures Tecuanes dances in present-day Mexico  Tecuanes alpuyeca Tēcuani (and its variants tekuani, tekuane, tecuane) means "jaguar" in Nahuatl. In the south-center of Mexico the "danza de los tecuanes" is performed in at least 96 communities. In this region jaguar dances are very popular. There are many variants of jaguar dances. Some of the most popular are the "tecuanes dances", "tlacololeros dances" and "tlaminques dances" [6]  An Olmec transformation figure, thought to show the transformation of a religious authority into a jaguar. Jaguars and naguals The jaguar is important for certain religious authorities in many Mesoamerican cultures, who often associate the jaguar as a spirit companion or nagual, which will protect the religious figures from evil spirits and while they move between the earth and the spirit realm. In order for the religious authorities to combat whatever evil forces may be threatening, or for those who rely on the religious authorities for protection, it is necessary for some religious authorities to transform and cross over to the spirit realm. The jaguar is often a nagual because of its strength, for it is necessary that the religious authorities "dominate the spirits, in the same way as a predator dominates its prey" (Saunders 1998:30). The jaguar is said to possess the transient ability of moving between worlds because of its comfort both in the trees and the water, the ability to hunt as well in the nighttime as in the daytime, and the habit of sleeping in caves, places often associated with the deceased ancestors. The concept of the transformation of a religious authority is well-documented in Mesoamerica and South America and is in particular demonstrated in the various Olmec jaguar transformation figures (Diehl, p. 106). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jaguars_in_Mesoamerican_cultures |

メソアメリカ文化におけるジャガーの他の例 現在のメキシコにおけるテクアネスダンス  テクアネス・アルプイエカ Tēcuani(およびそのバリエーションであるtekuani、tekuane、tecuane)は、ナワトル語で「ジャガー」を意味する。メキシコの 南中央部では、少なくとも96のコミュニティで「ダンサ・デ・ロス・テクアネス」が披露されている。この地域では、ジャガーのダンスが非常に人気がある。 ジャガーのダンスには多くのバリエーションがある。最も人気のあるものには、「テクアネス・ダンス」、「トラコロレロ・ダンス」、そして「トラミンケス・ ダンス」がある。  オルメカ族の変身の像。宗教的権威がジャガーに変身する様子を表していると考えられている。 ジャガーとナワル ジャガーは、多くのメソアメリカ文化における特定の宗教的権威にとって重要な存在であり、彼らはジャガーを霊的な仲間やナワルとして関連付けることが多 い。ナワルは、宗教的権威を悪霊から守り、彼らが地上と霊界の間を移動する間、彼らを保護する存在である。宗教的権威者が脅威となるあらゆる悪の勢力と戦 うため、あるいは宗教的権威者に保護を求める人々を守るためには、一部の宗教的権威者が変身し、霊界を越えていく必要がある。 宗教的権威者が「捕食者が獲物を支配するように、霊を支配する」ことが必要であるため、その強さから、ジャガーはしばしばナグアルとなる (Saunders 1998:30)。ジャガーは、樹上でも水中でも快適に過ごせること、昼でも夜でも狩りができること、そして死者の祖先と関連付けられることが多い洞窟で 眠る習性があることから、世界を行き来する一過性の能力を持っていると言われている。宗教的権威の変身という概念は、メソアメリカと南アメリカで詳細に記 録されており、特にオルメカのさまざまなジャガー変身像に示されている(Diehl、p. 106)。 |

| Ocelot Underwater panther Wayob |

オセロット 水中の豹 ワヨブ |

| Wayob

is the plural form of way (or uay), a Maya word with a basic meaning of

'sleep(ing)', but which in Yucatec Maya is a term specifically denoting

the Mesoamerican nagual, that is, a person who can transform into an

animal while asleep in order to do harm, or else the resulting animal

transformation itself.[1] Already in Classic Maya belief, way animals,

identifiable by a special hieroglyph, had an important role to play. In Maya ethnography In Yucatec ethnography, the animal transformation involved is usually a common domestic or domesticated animal, but may also be a ghost or apparition, for example 'a creature with wings of straw mats'.[2] Moreover, in the 16th century, wild animals such as jaguar and grey fox are mentioned as animal shapes of the sorcerer, together with the ah uaay xibalba or 'underworld transformer'.[3] Some sort of 'devil's pact' seems to be implied. The Yucatec way has its counterparts among other Maya groups. In Tzotzil ethnography, the way (here called wayihel or chanul[4][5]) is more often an animal companion and refers not only to domestic animals, but also to igneous powers such as meteor and lightning. In Tzeltal Cancuc, the nagual animal companion is considered a 'caster of disease'.[6] Other names found are: lab, labil, wayixelal or vayijelal, way and wayxel or wayjel.[7] In the Classic Period  Jaguar way with scarf A Classic Maya hieroglyph is read as way (wa-ya) by Houston and Stuart. These authors assert that a glyph representing a stylised, frontal 'Ahau' (Ajaw) face half covered by a jaguar-pelt represents the way, with syllabic wa and ya elements attached to the main sign clarifying its meaning.[8] Many way animals are distinguished by (i) a shoulder cape or scarf tied in front; (ii) a splashing of jaguar spots or other jaguar characteristics; (iii) the attribute of an upturned 'jar of darkness'; and (iv) fire elements.[9] The Classic wayob include a far wider array of shapes than the 20th-century ones from Yucatán (insofar as the latter have been reported), with specific names assigned to each of them. They include not only many mammals (especially jaguars) and birds, but also apparitions and spooks: hybrids of deer and spider monkey, walking skeletons, a self-decapitating man, a young man within a fire, etc.[10] The animal wayob are likely to be transformative shapes of human beings, the walking skeletons (Maya Death Gods) more particularly of the ah uaay xibalba transformers. At times, the name of the way is followed by an 'emblem glyph' giving the name of a specific Maya kingdom (or perhaps its ruling family).[11] The skeletal way prominent on a Tonina stucco wall carries the severed head of a defeated opponent.[12] |

Wayob

はway(またはuay)の複数形であり、マヤ語の基本的な意味は「眠る」であるが、ユカテク・マヤでは特にメソアメリカのnagual、つまり、害を与

えるために眠っている間に動物に変身することができる人間、またはその結果として生じる動物の変身そのものを示す言葉である[1]。古典マヤの信仰ではす

でに、特別な象形文字によって識別可能なway動物は重要な役割を担っていた。 マヤの民族誌 さらに16世紀には、ジャガーやハイイロギツネのような野生動物が、ア・ウァイ・キシバルバや「冥界の変身者」とともに、魔術師の姿をした動物として言及 されている。ユカテクのやり方は、他のマヤの集団の間でも対応するものがある。ツォツィル族の民族誌では、道(ここではウェイヘルまたはチャヌルと呼ばれ る[4][5])は動物の仲間であることが多く、家畜だけでなく、流星や稲妻のような火成岩の力も指す。ツェルタル・カンクックでは、動物の仲間であるナ グアルは「病を運ぶ者」と考えられている[6]。他の呼び名としては、ラボ、ラビル、ウェイキセラルまたはヴァイジェラル、ウェイ、ウェイキセルまたは ウェイジェルがある[7]。 古典期  スカーフを巻いたジャガー・ウェイ 古典期マヤのヒエログリフは、HoustonとStuartによってウェイ(wa-ya)と読まれている。これらの著者は、ジャガーの毛皮で半分覆われた 様式化された正面向きの「アハウ」(Ajaw)の顔を表すグリフがウェイを表し、主符号に付けられた音節のワとヤの要素がその意味を明確にしていると主張 している[8]。多くのウェイ動物は、(i)前に結ばれた肩のマントまたはスカーフ、(ii)ジャガーの斑点またはその他のジャガーの特徴の散布、 (iii)ひっくり返された「闇の壺」の属性、(iv)火の要素[9]によって区別される。 古典的なワヨブには、(後者が報告されている限りにおいて)ユカタンから出土した20世紀のものよりもはるかに幅広い形状のものが含まれており、それぞれ に特定の名前が割り当てられている。その中には、多くの哺乳類(特にジャガー)や鳥類だけでなく、鹿とクモザルのハイブリッド、歩く骸骨、自ら首を切る 男、火の中にいる若者など、幻影や不気味なものも含まれている[10]。動物のワヨブは人間の変身した姿であると考えられ、歩く骸骨(マヤの死神)は、特 にア・ウアイ・キシバルバの変身者であると考えられる。 時には、ウェイオブの名前の後に、特定のマヤ王国(あるいはその支配者一族)の名前を示す「エンブレム・グリフ」が続くこともある[11]。トニナの漆喰壁に顕著な骸骨のウェイオブは、敗れた相手の切断された頭部を持っている[12]。 |

| Familiar spirit Huay Chivo Power animal Tonal (mythology) Tutelary spirit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wayob |

使い魔 ワイ・チボ パワーアニマル トーナル(神話) 守護霊 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jaguars_in_Mesoamerican_cultures |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆