ヤコブ・ベーメ

Jakob Böhme, 1575-1624

☆ ヤコブ・ベーメ(Jakob Böhme、/ˈbeɪmə, ˈboʊ-/;[2] ドイツ語: [ˈbøːmə]; 1575年4月24日 – 1624年11月17日)は、ドイツの哲学者、キリスト教神秘主義者、ルター派のプロテスタント神学者だった。彼はルター派の伝統の中で、多くの同時代人 から独創的な思想家と見なされ、彼の最初の著作『アウロラ』は大きなスキャンダルを引き起こした。現代英語では、彼の名前はヤコブ・ベーメ(古いドイツ語 の綴りを維持)と表記されることがある。17世紀のイギリスでは、ドイツ語の「ベーメ」の現代英語の発音に近づけるため、ベーメンと表記されることもあっ た。 ベーメは、ドイツ観念論やドイツロマン主義などの後の哲学運動に深い影響を与えた。[3] ヘーゲルはベーメを「最初のドイツ人哲学者」と評した。[3]

| Jakob Böhme

(/ˈbeɪmə, ˈboʊ-/;[2] German: [ˈbøːmə]; 24 April 1575 – 17 November

1624) was a German philosopher, Christian mystic, and Lutheran

Protestant theologian. He was considered an original thinker by many of

his contemporaries within the Lutheran tradition, and his first book,

commonly known as Aurora, caused a great scandal. In contemporary

English, his name may be spelled Jacob Boehme (retaining the older

German spelling); in seventeenth-century England it was also spelled

Behmen, approximating the contemporary English pronunciation of the

German Böhme. Böhme had a profound influence on later philosophical movements such as German idealism and German Romanticism.[3] Hegel described Böhme as "the first German philosopher". |

ヤコブ・ベーメ(Jakob Böhme、/ˈbeɪmə,

ˈboʊ-/;[2] ドイツ語: [ˈbøːmə]; 1575年4月24日 –

1624年11月17日)は、ドイツの哲学者、キリスト教神秘主義者、ルター派のプロテスタント神学者だった。彼はルター派の伝統の中で、多くの同時代人

から独創的な思想家と見なされ、彼の最初の著作『アウロラ』は大きなスキャンダルを引き起こした。現代英語では、彼の名前はヤコブ・ベーメ(古いドイツ語

の綴りを維持)と表記されることがある。17世紀のイギリスでは、ドイツ語の「ベーメ」の現代英語の発音に近づけるため、ベーメンと表記されることもあっ

た。 ベーメは、ドイツ観念論やドイツロマン主義などの後の哲学運動に深い影響を与えた。[3] ヘーゲルはベーメを「最初のドイツ人哲学者」と評した。[3] |

| Biography Böhme was born on 24 April 1575[4][5] at Alt Seidenberg (now Stary Zawidów, Poland), a village near Görlitz in Upper Lusatia, a territory of the Kingdom of Bohemia. His father, George Wissen, was Lutheran, reasonably wealthy, but a peasant nonetheless. Böhme was the fourth of five children. Böhme's first job was that of a herd boy. He was deemed to be not strong enough for husbandry. When he was 14 years old, he was sent to Seidenberg, as an apprentice to become a shoemaker.[6] His apprenticeship for shoemaking was hard; he lived with a family who were not Christians, which exposed him to the controversies of the time. He regularly prayed and read the Bible as well as works by visionaries such as Paracelsus, Weigel and Schwenckfeld, although he received no formal education.[7] After three years as an apprentice, Böhme left to travel. Although it is unknown just how far he went, he went at least as far as Görlitz.[6] In 1592 Böhme returned from his journeyman years. By 1599, Böhme was master of his craft with his own premises in Görlitz. That same year he married Katharina, daughter of Hans Kuntzschmann, a butcher in Görlitz, and together he and Katharina had four sons and two daughters.[7][8] Böhme's mentor was Abraham Behem who corresponded with Valentin Weigel. Böhme joined the "Conventicle of God's Real Servants" - a parochial study group organized by Martin Moller. Böhme had a number of mystical experiences throughout his youth, culminating in a vision in 1600 as one day he focused his attention onto the exquisite beauty of a beam of sunlight reflected in a pewter dish. He believed this vision revealed to him the spiritual structure of the world, as well as the relationship between God and man, and good and evil. At the time he chose not to speak of this experience openly, preferring instead to continue his work and raise a family.[citation needed] In 1610 Böhme experienced another inner vision in which he further understood the unity of the cosmos and that he had received a special vocation from God.[citation needed] The shop in Görlitz, which was sold in 1613, had allowed Böhme to buy a house in 1610 and to finish paying for it in 1618. Having given up shoemaking in 1613, Böhme sold woollen gloves for a while, which caused him to regularly visit Prague to sell his wares.[6] |

略歴 ベーメは1575年4月24日[4][5]、ボヘミア王国領の上ルサティア地方、ゲルリッツ近郊のアルト・ツァイデンベルク(現在のポーランド、スタ リー・ザヴィドフ)で生まれた。父親のゲオルク・ヴィッセンはルター派の信者であり、比較的裕福だったが、それでも農民だった。ベーメは5人兄弟の4番目 だった。ベーメの最初の仕事は群畜の少年だった。彼は畜産には力がないと考えられていた。14歳のとき、靴職人見習いとしてザイデンベルクに送られた [6]。靴職人の見習いは厳しく、彼はキリスト教徒ではない家庭で暮らし、当時の論争にさらされた。彼は定期的に祈り、聖書やパラケルスス、ヴァイゲル、 シュヴェンクフェルトなどの幻視家の著作を読んだが、正式な教育は受けていない。[7] 3年間の徒弟時代を終えた後、ボーメは旅に出た。彼がどこまで行ったかは不明だが、少なくともゲルリッツまでは行った。[6] 1592年、ボーメは旅人時代を終えて帰還した。1599年までに、ベーメはゲルリッツに自分の工房を持ち、その道の達人となった。同年、彼はゲルリッツ の肉屋、ハンス・クンツシュマンの娘カタリーナと結婚し、4人の息子と2人の娘に恵まれた。 ベーメの師は、ヴァレンティン・ヴァイゲルと文通していたアブラハム・ベヘムだった。ベーメは、マーティン・モーラーが組織した教区研究グループ「神の真 の僕たちの集会」に参加した。ベーメは、青年期を通じて数々の神秘体験をし、1600 年のある日、ピューター製の皿に反射する太陽の光の美しさに目を奪われたことをきっかけに、その体験の頂点に達した。彼は、この幻視によって、世界の霊的 な構造、そして神と人間、善と悪の関係が明らかになったと信じました。当時、彼はこの体験について公に話すことを避け、その代わりに仕事を続け、家族を養 うことを選んだのです。 1610年、ベーメは別の内なる幻視を経験し、宇宙の統一性をさらに理解するとともに、神から特別な使命を受けたことを悟りました。[要出典] 1613年に売却されたゲルリッツの店は、ベーメが1610年に家を購入し、1618年にその支払いを完了することを可能にした。1613年に靴職人を辞めたベーメは、しばらくの間、羊毛の手袋を販売し、その販売のためにプラハを定期的に訪れていた。[6] |

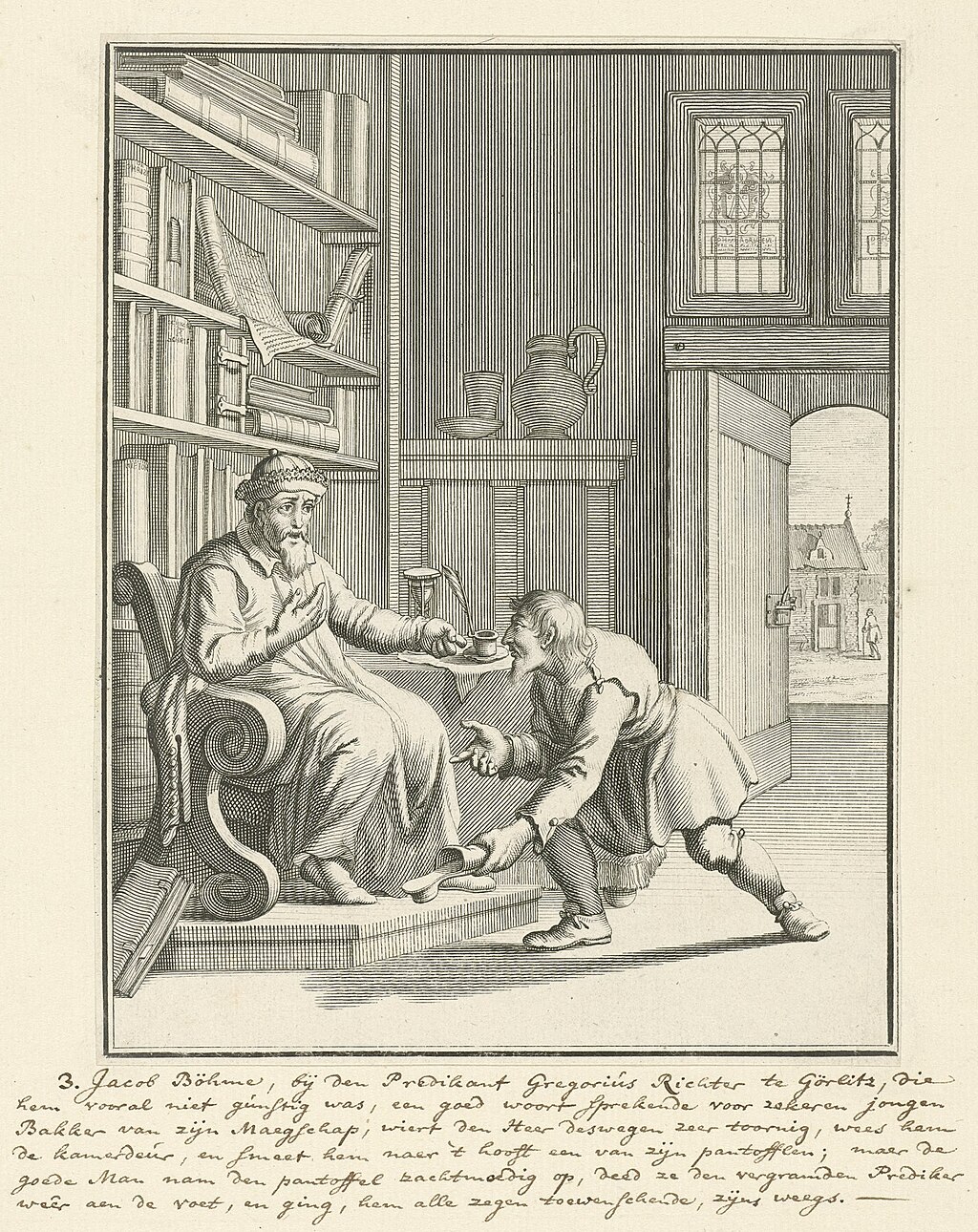

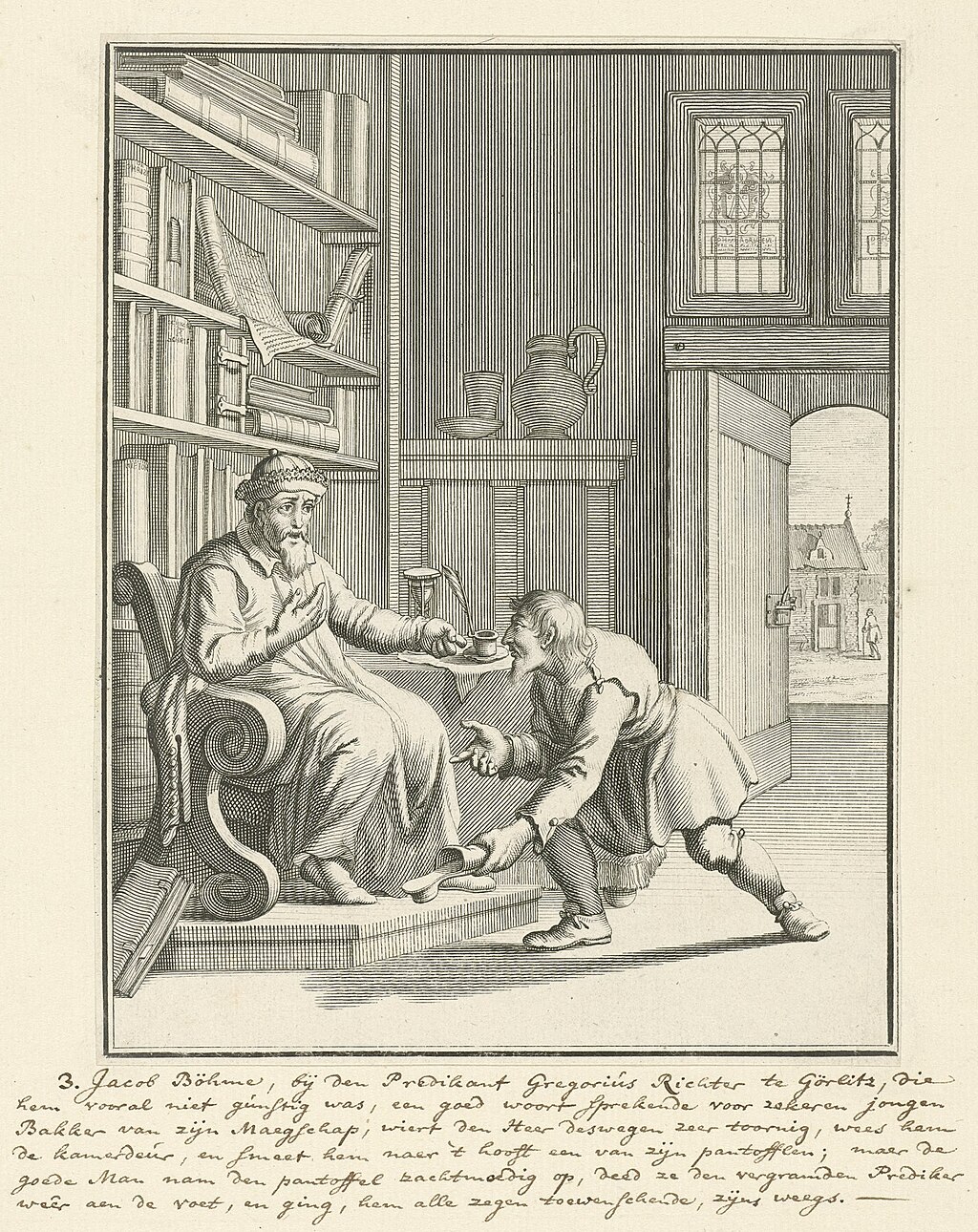

| Aurora and writings There are as many blasphemies in this shoemaker's book as there are lines; it smells of shoemaker's pitch and filthy blacking. May this insufferable stench be far from us. The Arian poison was not so deadly as this shoemaker's poison. — Gregorius Richter following the publication of Aurora.[9]  Joseph Mulder (Amsterdam 1686): Depiction of a possibly legendary episode in the life of Jakob Böhme. The Dutch caption reads: "Jakob Böhme with the preacher Gregor Richter in Görlitz, who was hostile to him in front of everyone, putting in a good word for a certain young baker from his followers. The gentleman became very angry about this, showed him the chamber door and threw one of his slippers at his head. But the good man meekly picked up the slipper, put it back on the foot of the angry preacher, and went on his way, wishing him every blessing." Twelve years after the vision in 1600, Böhme began to write his first book, Morgenröte im Aufgang ("Dawn of the Day in the East"). The book was given the name Aurora (sometimes translated into English as "The Day-spring") by a friend. Böhme originally wrote the book for himself and it was never completed.[10] A manuscript copy of the unfinished work was lent to Karl von Ender, a nobleman, who had copies made and began to circulate them. A copy fell into the hands of Gregorius Richter [de], the chief pastor of Görlitz, who attacked it as being heretical,[why?] speaking against it from the pulpit, and threatened Böhme with exile if he continued working on it. Richter also wrote a pamphlet denouncing Böhme and his work.[11] As a result, Böhme did not write anything for several years; however, at the insistence of friends who had read Aurora, he started writing again in 1618. In 1619 Böhme wrote De Tribus Principiis or The Three Principles of the Divine Essence. It took him two years to finish his second book, which was followed by many other treatises, all of which were copied by hand and circulated only among friends.[12] In 1620 Böhme wrote The Threefold Life of Man, Answers to Forty Questions on the Soul, The Incarnation of Jesus Christ, The Six Theosophical Points, The Six Mystical Points, the Mysterium Pansophicum and Informatorium novissimorum (Of the Last Times). In 1621 Böhme wrote De Signatura Rerum (relying in part on the doctrine of signatures). In 1623 Böhme wrote On Election to Grace, On Christ's Testaments, Mysterium Magnum, Clavis ("Key"). The year 1622 saw Böhme write some short works all of which were subsequently included in his first published book on New Year's Day 1624, under the title Weg zu Christo (The Way to Christ).[8] The publication caused another scandal and following complaints by the clergy, Böhme was summoned to the Town Council on 26 March 1624. The report of the meeting was that: Jacob Boehme, the shoemaker and rabid enthusiast, declares that he has written his book To Eternal Life, but did not cause the same to be printed. A nobleman, Sigismund von Schweinitz, did that. The Council gave him warning to leave the town; otherwise the Prince Elector would be apprised of the facts. He thereupon promised that he would shortly take himself off.[13] I must tell you, sir, that yesterday the pharisaical devil was let loose, cursed me and my little book, and condemned the book to the fire. He charged me with shocking vices; with being a scorner of both Church and Sacraments, and with getting drunk daily on brandy, wine, and beer; all of which is untrue; while he himself is a drunken man." — Jacob Böhme writing about Gregorius Richter on 2 April 1624.[14] Böhme left for Dresden on 8 or 9 May 1624, where he stayed with the court physician for two months. In Dresden he was accepted by the nobility and high clergy. His intellect was also recognized by the professors of Dresden, who in a hearing in May 1624, encouraged Böhme to go home to his family in Görlitz.[7] During Böhme's absence his family had suffered due to the Thirty Years' War.[7] Once home, Böhme accepted an invitation to stay with Herr von Schweinitz, who had a country-seat. While there Böhme began to write his last book, the 177 Theosophic Questions. Böhme fell terminally ill with a bowel complaint forcing him to travel home on 7 November. Gregorius Richter, Böhme's adversary from Görlitz, had died in August 1624, while Böhme was away. The new clergy, still wary of Böhme, forced him to answer a long list of questions when he wanted to receive the sacrament. He died on 17 November 1624.[15] In this short period, Böhme produced an enormous amount of writing, including his major works De Signatura Rerum (The Signature of All Things) and Mysterium Magnum. He also developed a following throughout Europe, where his followers were known as Behmenists. The son of Böhme's chief antagonist, the pastor primarius of Görlitz Gregorius Richter, edited a collection of extracts from his writings, which were afterwards published complete at Amsterdam with the help of Coenraad van Beuningen in the year 1682. Böhme's full works were first printed in 1730. |

オーロラと著作 この靴職人の本には、行数と同じくらい多くの冒涜がある。靴職人のピッチと汚れた黒塗りの臭いがする。この耐え難い悪臭が私たちから遠く離れますように。アリウス派の毒は、この靴職人の毒ほど致命的ではなかった。 — グレゴリウス・リヒター、『オーロラ』出版後に[9]  ジョセフ・ムルダー(アムステルダム、1686年): ヤコブ・ベーメの生涯における伝説的なエピソードの描写。オランダ語のキャプションには次のように書かれている:「ヤコブ・ベーメと、彼に敵対していた説 教者グレゴリウス・リヒターがゲルリッツで出会った。ベーメは、自分の信者であるある若い靴職人のために良い言葉をかけようとした。その紳士はこれに非常 に怒り、彼に部屋のドアを示し、自分のスリッパの一つを彼の頭に投げつけた。しかし、その善良な男は謙虚にスリッパを拾い上げ、怒った説教者の足元に履か せ、彼に祝福を祈りながら去っていった。」 1600年の幻視から12年後、ベーメは最初の著作『Morgenröte im Aufgang』(「東の日の夜明け」)の執筆を開始した。この本は、友人の提案で『アウロラ』(英語では「デイ・スプリング」と訳されることもある)と 名付けられた。ボーメは当初、この本を自分自身のために書いたもので、完成することはなかった。[10] 未完成の原稿の写しは、貴族のカール・フォン・エンダーに貸与され、彼は写しを作成し、流通させ始めた。その写しがゲルリッツの首席牧師グレゴリウス・リ ヒター[de]の手に渡り、彼はこれを異端と非難し[なぜ?]、説教壇から批判し、ボーメが執筆を続けるなら追放すると脅した。リヒターはまた、ボーメと その著作を非難する小冊子を執筆した。[11] その結果、ボーメは数年間何も書かなかったが、アウロラを読んだ友人たちの勧めで、1618年に再び執筆を開始した。1619年、ボーメは『デ・トリブ ス・プリンシピス』または『神のエッセンスの三つの原理』を執筆した。第二の著作を完成させるのに2年を要し、その後多くの論説が執筆されたが、いずれも 手書きで複製され、友人たちの間でしか流通しなかった。[12] 1620年、ボーメは『人間の三つの生命』『魂に関する40の質問への回答』『イエス・キリストの受肉』『六つの神学的な点』『六つの神秘的な点』『パン ソフィカムの神秘』『インフォルミアトリウム・ノヴィッシモルム(最後の時代について)』を執筆した。1621年、ボーメは『物の署名について』(一部は 署名説に依拠している)を執筆した。1623年、ボーメは『恵みへの選択について』『キリストの遺言について』『大神秘』『鍵』を執筆した。1622年、 ベーメはいくつかの短編作品を執筆し、そのすべては1624年の元旦に『キリストへの道』というタイトルで彼の最初の出版物に収録された。[8] この出版は新たなスキャンダルを引き起こし、聖職者たちの苦情を受けて、ベーメは1624年3月26日に市議会に召喚された。会議の報告書には次のように記載されている: 靴職人であり熱狂的な信者であるヤコブ・ベーメは、自身が『永遠の生命へ』という本を執筆したが、印刷は行っていないと主張している。印刷は貴族のジギス ムント・フォン・シュヴァインイツが行った。市議会は彼に町を去るよう警告し、従わない場合は選帝侯に事実を報告すると述べた。彼はその後、間もなく町を 去ると約束した。[13] 昨日、パリサイ人の悪魔が解き放たれ、私と私の小さな本を呪い、その本を火に投じるよう命じたことをお伝えしなければなりません。彼は、私に衝撃的な悪徳 がある、教会と聖餐を軽蔑している、毎日ブランデー、ワイン、ビールで酔っ払っている、と非難しましたが、それはすべて虚偽です。彼自身が酔っ払いなので す。 — ヤコブ・ベーメがグレゴリウス・リヒターについて1624年4月2日に書いたもの。[14] ベーメは1624年5月8日または9日にドレスデンへ出発し、そこで宮廷医の元に2ヶ月間滞在した。ドレスデンでは、貴族や高位の聖職者たちから受け入れ られた。彼の知性はドレスデンの教授たちにも認められ、1624年5月の公聴会で、ベームはゲルリッツの家族のもとへ帰るように勧められた。[7] ベームの不在の間、彼の家族は30年戦争で苦悩していた。[7] 故郷に戻ったベームは、別荘を持つシュヴァインイツ氏からの招待を受け入れた。そこでベーメは最後の著作『177の神学的問題』の執筆を開始した。ベーメ は腸の病気で末期状態となり、11月7日に故郷に戻ることを余儀なくされた。ベーメのゴリッツ時代の敵対者グレゴリウス・リヒターは、ベーメが不在中の 1624年8月に死去していた。新しい聖職者たちは、依然としてベーメを警戒し、彼が聖餐式を受けたいと希望した際、長い質問リストに答えるよう強制し た。彼は1624年11月17日に死去した。[15] この短い期間に、ベーメは『万物の署名』や『大いなる神秘』などの主要作品を含む膨大な著作を残した。また、ヨーロッパ全土に信奉者たち(ベームニスト)を擁するようになった。 ベーメの主な敵対者であったゲルリッツの牧師、グレゴリウス・リヒター(Gregorius Richter)の息子が、ベーメの著作の抜粋を編集し、1682年にコエンラード・ファン・ビューニンゲン(Coenraad van Beuningen)の協力により、アムステルダムで全巻が刊行された。ベーメの著作全巻は、1730年に初めて印刷された。 |

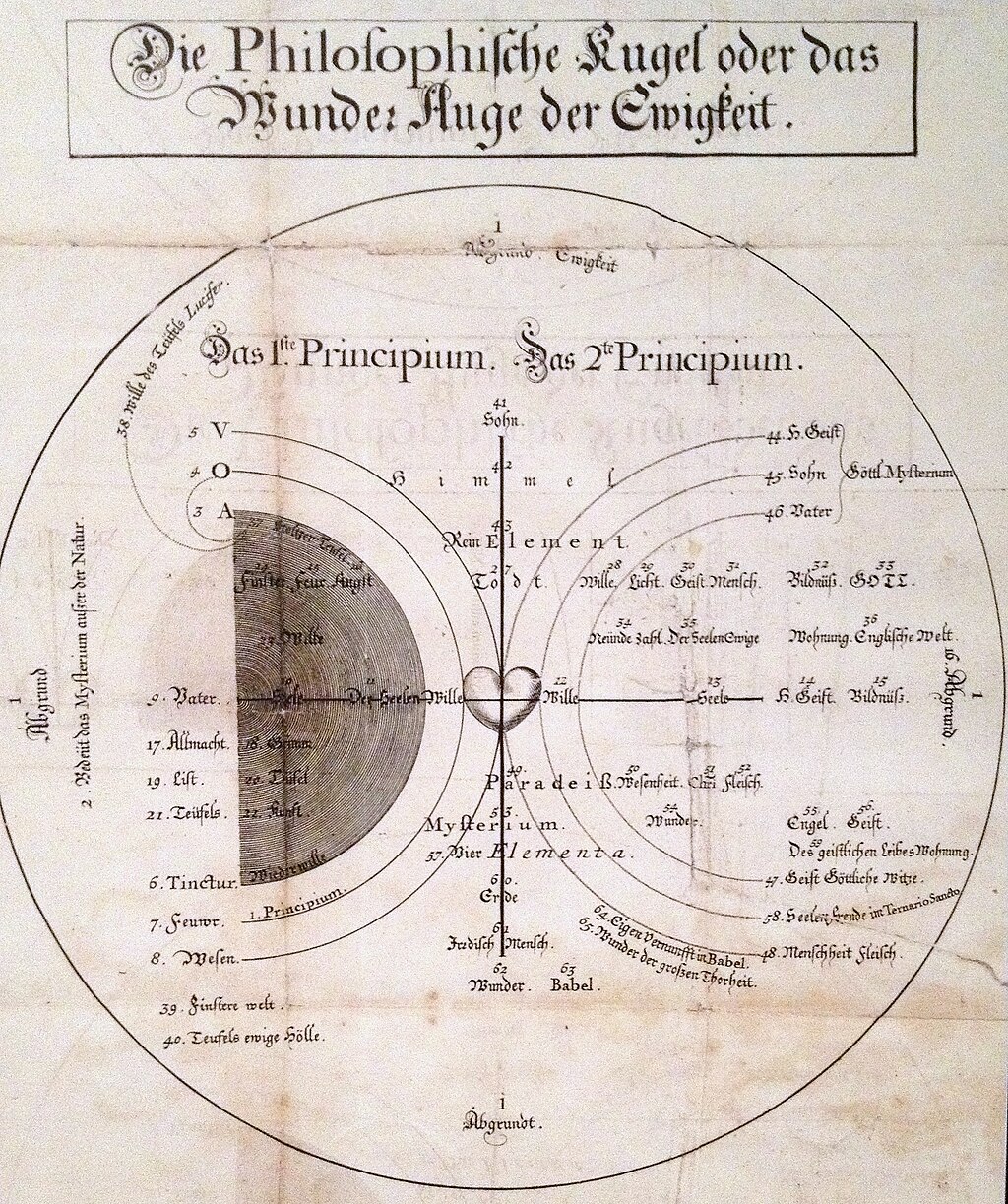

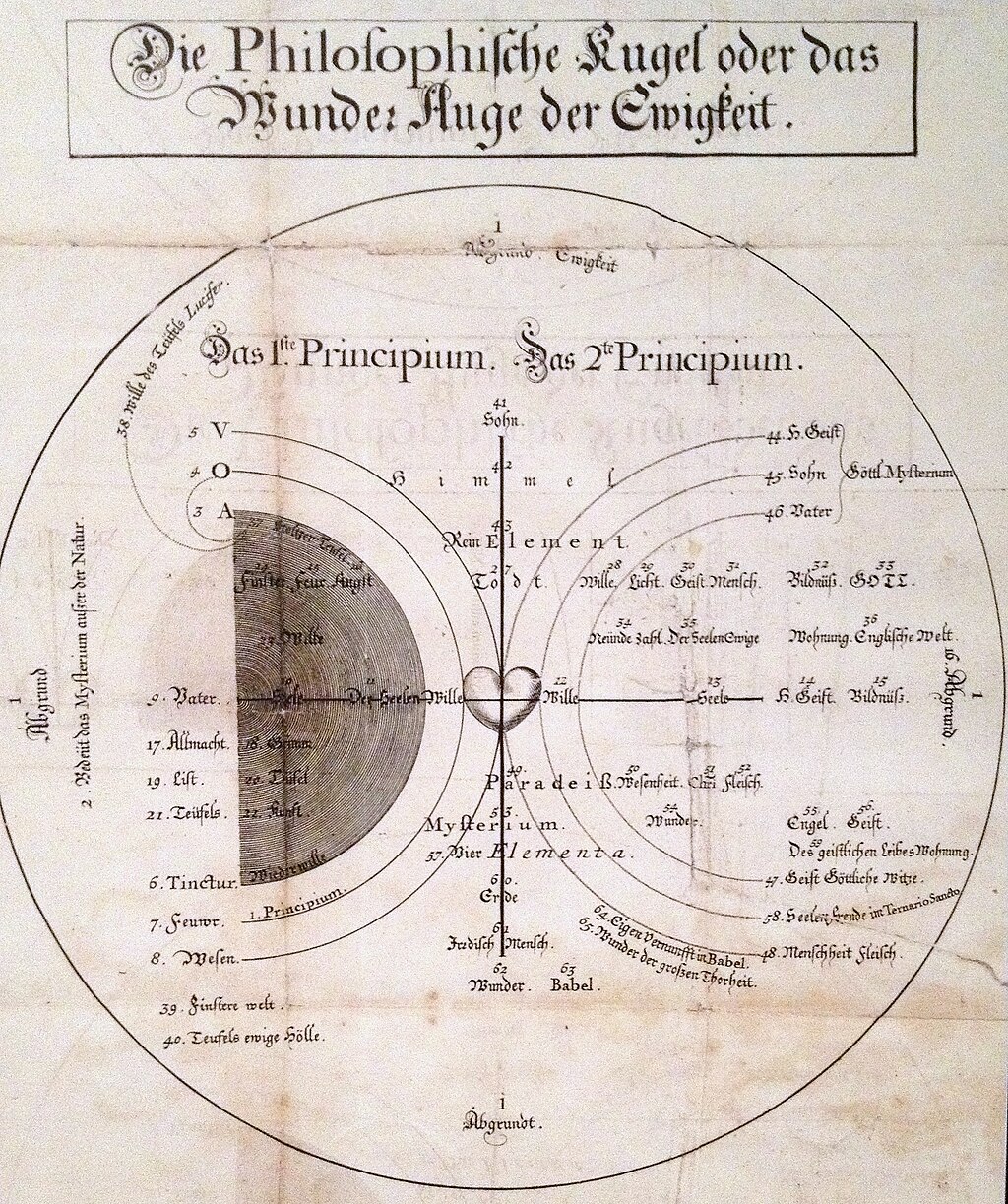

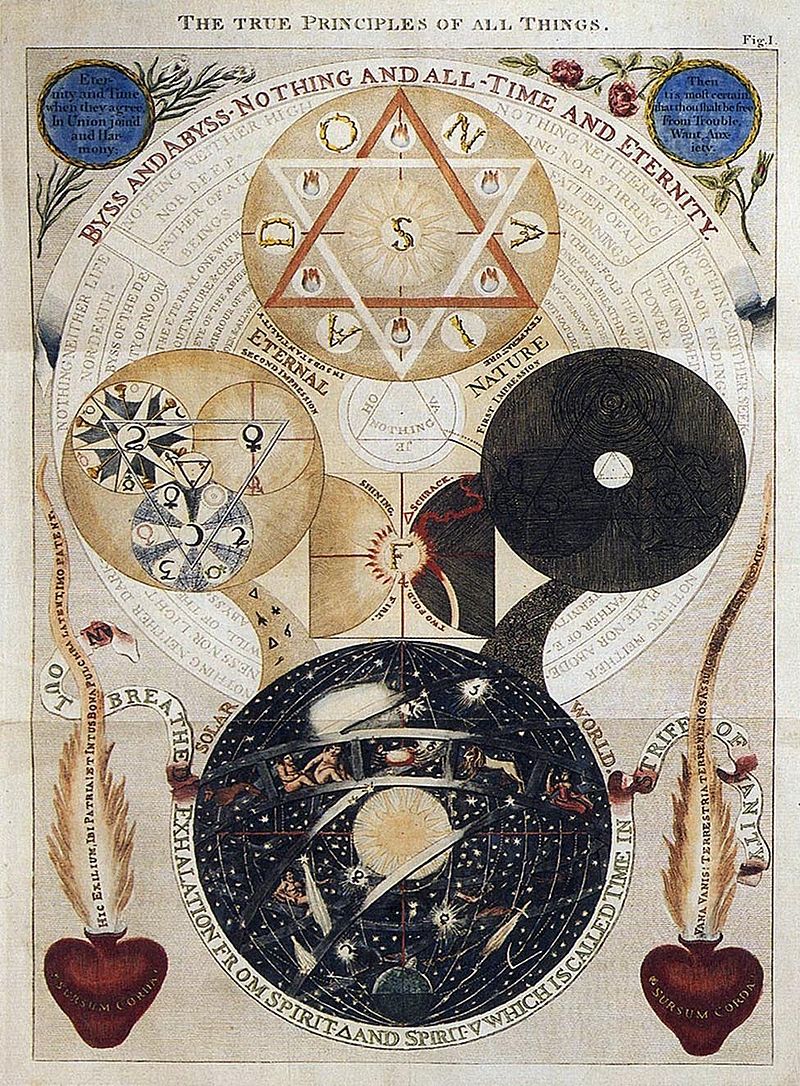

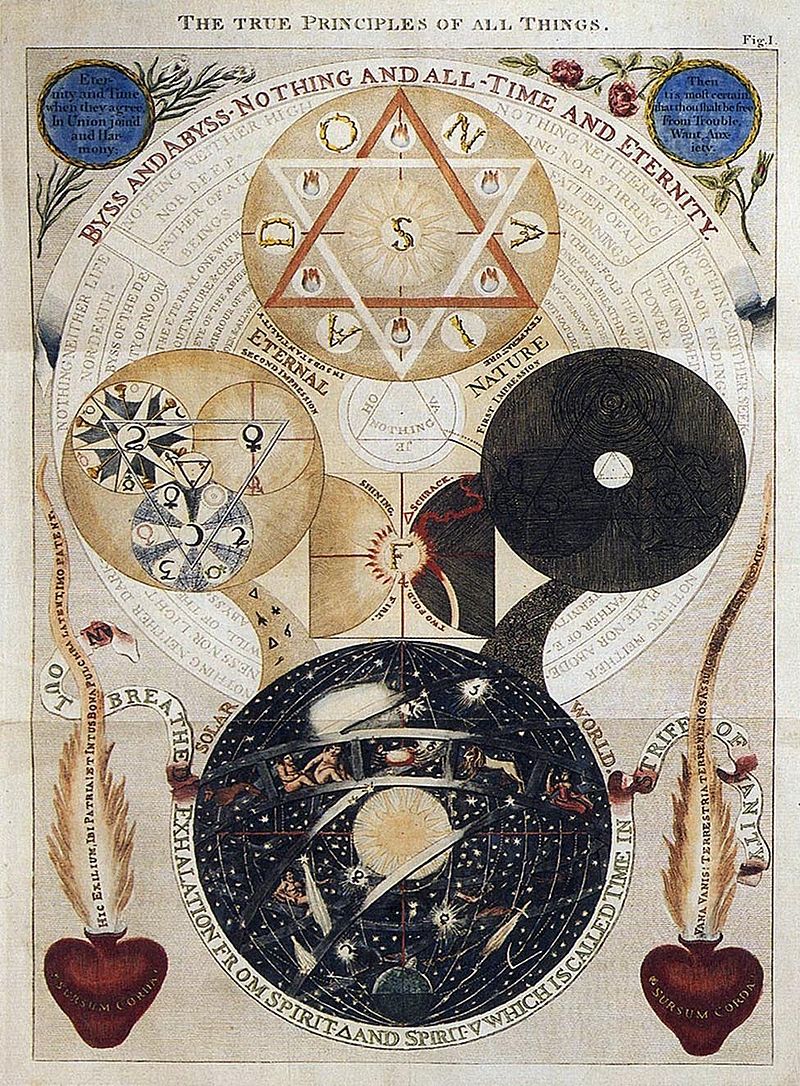

Theology Böhme's cosmogony: The Philosophical Sphere or the Wonder Eye of Eternity (1620). The chief concern of Böhme's writing was the nature of sin, evil and redemption. Consistent with Lutheran theology, Böhme preached that humanity had fallen from a state of divine grace to a state of sin and suffering, that the forces of evil included fallen angels who had rebelled against God, and that God's goal was to restore the world to a state of grace.[citation needed] There are some serious departures from accepted Lutheran theology, such as his rejection of justification by faith alone, as in this passage from The Way to Christ: For he that will say, I have a Will, and would willingly do Good, but the earthly Flesh which I carry about me, keepeth me back, so that I cannot; yet I shall be saved by Grace, for the Merits of Christ. I comfort myself with his Merit and Sufferings; who will receive me of mere Grace, without any Merits of my own, and forgive me my Sins. Such a one, I say, is like a Man that knoweth what Food is good for his Health, yet will not eat of it, but eateth Poison instead thereof, from whence Sickness and Death, will certainly follow.[16] Another place where Böhme may depart from accepted theology (though this was open to question due to his somewhat obscure, oracular style) was in his description of the Fall as a necessary stage in the evolution of the Universe.[17] A difficulty with his theology is the fact that he had a mystical vision, which he reinterpreted and reformulated.[17] According to F. von Ingen, to Böhme, in order to reach God, man has to go through hell first. God exists without time or space, he regenerates himself through eternity. Böhme restates the trinity as truly existing but with a novel interpretation. God, the Father is fire, who gives birth to his son, whom Böhme calls light. The Holy Spirit is the living principle, or the divine life.[18] It is clear that Böhme never claimed that God sees evil as desirable, necessary or as part of divine will to bring forth good. In his Threefold Life, Böhme states: "[I]n the order of nature, an evil thing cannot produce a good thing out of itself, but one evil thing generates another." Böhme did not believe that there is any "divine mandate or metaphysically inherent necessity for evil and its effects in the scheme of things."[19] Dr. John Pordage, a commentator on Böhme, wrote that Böhme "whensoever he attributes evil to eternal nature considers it in its fallen state, as it became infected by the fall of Lucifer... ."[19] Evil is seen as "the disorder, rebellion, perversion of making spirit nature's servant",[20] which is to say a perversion of initial Divine order. |

神学 ボーメの宇宙生成論:『哲学的球体、あるいは永遠の驚異の眼』(1620年)。 ベーメの著作の主な関心事は、罪、悪、そして贖いの本質でした。ルター派の神学と一致して、ベーメは、人類は神の恵みの状態から罪と苦悩の状態に陥った、悪の勢力には神に反抗した堕天使たちが含まれている、そして神の目標は世界を恵みの状態に戻すことであると説きました。 ルター派の神学から大きく逸脱した部分もいくつかあります。例えば、『キリストへの道』の以下の文章では、信仰のみによる義認を否定しています。 なぜなら、「私は意志があり、喜んで善を行いたいが、私の中に宿る肉体がそれを妨げ、実行できない」と言う者は、キリストの功績によって恵みによって救わ れるからだ。私は、彼の功績と苦悩によって自分自身を慰める。彼は、私自身の功績はまったくなく、ただ恵みによってのみ私を受け入れ、私の罪を赦してくれ るからだ。そのような者は、自分の健康に良い食べ物が何であるかを知っているにもかかわらず、それを食べず、その代わりに毒を食べ、その結果、必ず病気や 死に至るような者だ。[16] ボーメが、一般に受け入れられている神学から逸脱しているもう一つの点(ただし、彼のやや曖昧で予言的な表現のため、これは疑問の余地がある)は、宇宙の 進化において堕落は必要な段階であると述べた点である。[17] 彼の神学の問題点は、彼が神秘的な幻視を経験し、それを再解釈して再構成した点にある。[17] F. フォン・インゲンによると、ボーメにとって、神に到達するためには、人間はまず地獄を通過しなければならない。神は時間や空間を超越して存在し、永遠に自 己再生する。ボーメは三位一体を真に存在するものとして再定義するが、新たな解釈を加えている。神、父は火であり、その息子を産む。ボーメは息子を光と呼 ぶ。聖霊は生命の原理、または神聖な生命である。[18] ベーメが、神は悪を望ましい、必要な、あるいは善をもたらすための神の意志の一部であると主張したことは決してなかったことは明らかだ。『三つの生命』で ボーメは次のように述べている:「自然の秩序において、悪は自らから善を生むことはできない。一つの悪は別の悪を生む。」ボーメは、「万物の秩序におい て、悪とその効果に神聖な命令や形而上学的に内在する必然性がある」とは信じていなかった。[19] ベーメの解説者であるジョン・ポルデージ博士は、ベーメは「悪を永遠の性質に帰するときは、それがルシファーの堕落によって感染した、堕落した状態として 捉えている」と書いている[19]。悪は「精神を自然の僕にするという混乱、反逆、倒錯」[20]、つまり、最初の神の秩序の倒錯とみなされている。 |

| Böhme's correspondences in Aurora of the seven qualities, planets and humoral-elemental associations: Dry - Saturn - melancholy, power of death; Sweet - Jupiter - sanguine, gentle source of life; Bitter - Mars - choleric, destructive source of life; Fire - Sun/Moon - night/day; evil/good; sin/virtue; Moon, later = phlegmatic, watery; Love - Venus - love of life, spiritual rebirth; Sound - Mercury - keen spirit, illumination, expression; Corpus - Earth - totality of forces awaiting rebirth. In "De Tribus Principiis" or "On the Three Principles of Divine Being" Böhme subsumed the seven principles into the Trinity: The "dark world" of the Father (Qualities 1-2-3); The "light world" of the Holy Spirit (Qualities 5-6-7); "This world" of Satan and Christ (Quality 4). |

ボーメの『七つの性質の夜明け』における対応関係、惑星と体液・元素の関連性: 乾燥 - 土星 - 憂鬱、死の力; 甘美 - 木星 - 血気、優しい生命の源; 苦い - 火星 - 胆汁質、破壊的な生命の源; 火 - 太陽/月 - 夜/昼;悪/善;罪/徳;月、後には粘液質、水っぽい; 愛 - 金星 - 生命への愛、霊的な再生; 音 - 水星 - 鋭い精神、照明、表現; 肉体 - 地球 - 再生を待つ力の総体。 『三つの原理について』または『神の存在の三つの原理について』において、ベーメは七つの原理を三位一体に統合した: 父の「暗黒の世界」(属性1-2-3); 聖霊の「光の世界」(属性5-6-7); サタンとキリストの「この世界」(属性4)。 |

Jakob Böhme's House in what was Görlitz but is now in a Polish town of Zgorzelec, where he lived from 1590 to 1610 |

ヤコブ・ベーメの故居。かつてはゲルリッツにあったが、現在はポーランドの町ズゴジェレツにあり、1590年から1610年まで彼が住んでいた。 |

| Cosmology In one interpretation of Böhme's cosmology, it was necessary for humanity to return to God, and for all original unities to undergo differentiation, desire and conflict—as in the rebellion of Satan, the separation of Eve from Adam and their acquisition of the knowledge of good and evil—in order for creation to evolve to a new state of redeemed harmony that would be more perfect than the original state of innocence, allowing God to achieve a new self-awareness by interacting with a creation that was both part of, and distinct from, Himself. Free will becomes the most important gift God gives to humanity, allowing us to seek divine grace as a deliberate choice while still allowing us to remain individuals.[citation needed] |

宇宙論 ボーメの宇宙論の一つの解釈では、人類が神に戻り、すべての元の統一性が分化、欲望、衝突を経る必要があった——サタンの反乱のように、 エバがアダムから分離し、善悪の知識を獲得したように——創造が、元の無垢の状態よりも完璧な、贖われた調和の状態へと進化するため、神が、自身の一部で ありながら、自身とは異なる創造物と相互作用することで、新たな自己認識を達成できるようにするためだ。自由意志は、神が人類に与える最も重要な贈り物と なり、私たちは神聖な恵みを意図的な選択として求める一方で、個々人として存在し続けることを可能にする。[出典が必要] |

| Marian views Böhme believed that the Son of God became human through the Virgin Mary. Before the birth of Christ, God recognized himself as a virgin. This virgin is therefore a mirror of God's wisdom and knowledge.[18] Böhme follows Luther in that he views Mary within the context of Christ. Unlike Luther, he does not address himself to dogmatic issues very much, but to the human side of Mary. Like all other women, she was human and therefore subject to sin. Only after God elected her with his grace to become the mother of his son, did she inherit the status of sinlessness.[18] Mary did not move the Word, the Word moved Mary, so Böhme, explaining that all her grace came from Christ. Mary is "blessed among women" but not because of her qualifications, but because of her humility. Mary is an instrument of God; an example of what God can do: It shall not be forgotten in all eternity, that God became human in her.[21] Böhme, unlike Luther, did not believe that Mary was the Ever Virgin. Her virginity after the birth of Jesus is unrealistic to Böhme. The true salvation is Christ, not Mary. The importance of Mary, a human like every one of us, is that she gave birth to Jesus Christ as a human being. If Mary had not been human, according to Böhme, Christ would be a stranger and not our brother. Christ must grow in us as he did in Mary. She became blessed by accepting Christ. In a reborn Christian, as in Mary, all that is temporal disappears and only the heavenly part remains for all eternity. Böhme's peculiar theological language, involving fire, light and spirit, which permeates his theology and Marian views, does not distract much from the fact that his basic positions are Lutheran.[21] |

マリア観 ベーメは、神の御子が聖母マリアによって人間となったと信じていた。キリストの誕生以前、神は自らを処女であると認識していた。したがって、この処女は神 の知恵と知識の鏡である。[18] ベーメは、マリアをキリストの文脈の中で捉えるという点で、ルターに従っている。ルターとは異なり、彼は教義上の問題にはあまり触れておらず、マリアの人 間的な側面を強調している。他の女性たちと同様、マリアも人間であり、したがって罪を犯す存在だった。神が、その恵みによって彼女を御子の母として選んだ 後、初めて彼女は罪のない存在となったのだ[18]。マリアは御言葉を変えたのではなく、御言葉がマリアを変えた、とベーメは説明し、マリアの恵みはすべ てキリストから与えられたものだと述べている。マリアは「女性の中で祝福された者」だが、それは彼女の資格によるものではなく、彼女の謙虚さによるもの だ。マリアは神の道具であり、神が何を成し得るかの例だ:神が彼女において人間となったことは、永遠に忘れられてはならない。[21] ベーメは、ルターとは異なり、マリアが永遠の処女であるとは信じていなかった。イエス誕生後のマリアの処女性は、ベーメにとっては非現実的である。真の救 いはキリストであり、マリアではない。私たちと同じ人間であるマリアの重要性は、彼女が人間としてイエス・キリストを産んだことにある。ベーメによれば、 マリアが人間でなかったならば、キリストは私たちにとって見知らぬ人であり、兄弟ではなかっただろう。キリストは、マリアの中で成長したように、私たちの 中で成長しなければならない。彼女はキリストを受け入れることで祝福された。再生したキリスト教徒において、マリアのように、一時的なものはすべて消え去 り、天的な部分だけが永遠に残る。ボーメの神学とマリア観を貫く、火、光、霊といった独特の神学用語は、彼の基本的な立場がルター派であるという事実か ら、それほど注意をそらすものではない。[21] |

Influences Idealized portrait of Böhme from Theosophia Revelata (1730) Böhme's writing shows the influence of Neoplatonist and alchemical[a] writers such as Paracelsus, while remaining firmly within a Christian tradition. He has in turn greatly influenced many anti-authoritarian and mystical movements, such as Radical Pietism[22][23][24][25][26][27] (including the Ephrata Cloister[28] and Society of the Woman in the Wilderness), the Religious Society of Friends, the Philadelphians, the Gichtelians, the Harmony Society, the Zoarite Separatists, Rosicrucianism, Martinism and Christian theosophy. Böhme's disciple and mentor, the Liegnitz physician Balthasar Walther, who had travelled to the Holy Land in search of magical, kabbalistic and alchemical wisdom, also introduced kabbalistic ideas into Böhme's thought.[29] Böhme was also an important source of German Romantic philosophy, influencing Schelling in particular.[30] In Richard Bucke's 1901 treatise Cosmic Consciousness, special attention was given to the profundity of Böhme's spiritual enlightenment, which seemed to reveal to Böhme an ultimate nondifference, or nonduality, between human beings and God. Jakob Böhme's writings also had some influence on the modern theosophical movement of the Theosophical Society. Blavatsky and W.Q. Judge wrote about Jakob Böhme's philosophy.[31][32] Böhme was also an important influence on the ideas of Franz Hartmann, the founder in 1886 of the German branch of the Theosophical Society. Hartmann described the writings of Böhme as “the most valuable and useful treasure in spiritual literature.”[33] |

影響 『Theosophia Revelata』(1730年)に掲載されたベーメの理想像 ベーメの著作は、パラケルススなどの新プラトン主義者や錬金術師[a] の影響を受けているが、キリスト教の伝統を堅持している。彼は、急進的敬虔主義[22][23][24][25][26][27](エフラタ修道院 [28] や荒野の女たちの会など)、宗教的友愛会、フィラデルフィア人、ギクテリアン、ハーモニー協会、ゾアライト分離派、薔薇十字団、マーティニズム、キリスト 教神智学など。ベーメの弟子であり師である、呪術的、カバラ的、錬金術的な知恵を求めて聖地を訪れたリーグニッツの医師、バルタザール・ヴァルターも、 ベーメの思想にカバラの考えを取り入れた[29]。ベーメは、ドイツのロマン主義哲学の重要な源流でもあり、特にシェリングに影響を与えた。[30] リチャード・バックの 1901 年の論文「宇宙意識」では、ベーメの霊的悟りの深さに特別な注目が払われ、それは、人間と神との究極の非差異、あるいは非二元性をベーメに明らかにしたよ うだった。ヤコブ・ベーメの著作は、神智学協会による現代の神智学運動にも一定の影響を与えた。ブラヴァツキーとW.Q. ジャッジは、ヤコブ・ベーメの哲学について書いている。[31][32] ベーメは、1886年に神智学協会のドイツ支部を設立したフランツ・ハルトマンの思想にも重要な影響を与えた。ハルトマンは、ベーメの著作を「霊的文学に おける最も価値ある有用な宝物」と表現している。[33] |

| Behmenism See also: Boehmian theosophy I do not write in the pagan manner, but in the theosophical. — Jacob Boehme[34]  18th-century illustration by Dionysius Andreas Freher for the book The Works of Jacob Behmen Behmenism, also Behemenism or Boehmenism, is the English-language designation for a 17th-century European Christian movement based on the teachings of German mystic and theosopher Jakob Böhme (1575-1624). The term was not usually applied by followers of Böhme's theosophy to themselves, but rather was used by some opponents of Böhme's thought as a polemical term. The origins of the term date back to the German literature of the 1620s, when opponents of Böhme's thought, such as the Thuringian antinomian Esajas Stiefel, the Lutheran theologian Peter Widmann and others denounced the writings of Böhme and the Böhmisten. When his writings began to appear in England in the 1640s, Böhme's surname was irretrievably corrupted to the form "Behmen" or "Behemen", whence the term "Behmenism" developed.[b] A follower of Böhme's theosophy is a "Behmenist". Behmenism does not describe the beliefs of any single formal religious sect, but instead designates a more general description of Böhme's interpretation of Christianity, when used as a source of devotional inspiration by a variety of groups. Böhme's views greatly influenced many anti-authoritarian and Christian mystical movements, such as the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), the Philadelphians,[35] the Gichtelians, the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness (led by Johannes Kelpius), the Ephrata Cloister, the Harmony Society, Martinism, and Christian theosophy. Böhme was also an important source of German Romantic philosophy, influencing Schelling and Franz von Baader in particular.[30] In Richard Bucke's 1901 treatise Cosmic Consciousness, special attention was given to the profundity of Böhme's spiritual enlightenment, which seemed to reveal to Böhme an ultimate nondifference, or nonduality, between human beings and God. Böhme is also an important influence on the ideas of the English Romantic poet, artist and mystic William Blake. After having seen the William Law edition of the works of Jakob Böhme, published between 1764 and 1781, in which some illustrations had been included by the German early Böhme exegetist Dionysius Andreas Freher (1649–1728), William Blake said during a dinner party in 1825 "Michel Angelo could not have surpassed them".[36] Despite being based on a corrupted form of Böhme's surname, the term Behmenism has retained a certain utility in modern English-language historiography, where it is still occasionally employed, although often to designate specifically English followers of Böhme's theosophy.[c] Given the transnational nature of Böhme's influence, the term at least implies manifold international connections between Behmenists.[37] In any case, the term is preferred to clumsier variants such as "Böhmeianism" or "Böhmism", although these may also be encountered. |

ベーメン主義 参照:ベーメン神学 私は異教徒のやり方で書いているのではなく、神学的なやり方で書いている。 — ヤコブ・ベーメ[34]  18世紀のディオニュシウス・アンドレアス・フレーハーによる『ヤコブ・ベーメンの著作』の挿絵 ベームニズム(Behmenism)は、ドイツの神秘主義者で神智学者であるヤコブ・ベーメ(1575-1624)の教えに基づく17世紀のヨーロッパの キリスト教運動の英語での呼称だ。この用語は、ベーメの神智学の信奉者たち自身によって通常使用されるものではなく、むしろベーメの思想の反対者たちに よって論争的な用語として用いられた。この用語の起源は、1620年代のドイツ文学に遡る。当時、テューリンゲンの反律法主義者エサヤス・シュティフェル やルター派の神学者ペーター・ヴィッドマンなど、ボーメの思想に反対する人々が、ボーメの著作とボーメ派を非難した。1640年代に彼の著作がイギリスで 出版され始めた際、ボーメの姓は「Behmen」または「Behemen」という形に不可逆的に変形され、そこから「Behmenism」という用語が派 生した。[b] ボーメの神学の信奉者は「Behmenist」と呼ばれる。 ベヒメン主義は、特定の正式な宗教派閥の信仰を説明するものではなく、むしろ、多様なグループが敬虔な霊感の源として用いる際に、ボーメのキリスト教解釈 のより一般的な特徴を指定する用語だ。ベーメの見解は、宗教的友愛会(クエーカー教徒)、フィラデルフィア人[35]、ギクテリアン、荒野の女たち協会 (ヨハネス・ケルピウスが指導)、エフラタ修道院、ハーモニー協会、マーティニズム、キリスト教神智学など、多くの反権威主義的、キリスト教神秘主義運動 に大きな影響を与えた。ベーメは、ドイツのロマン主義哲学の重要な源流でもあり、特にシェリングやフランツ・フォン・バーダーに影響を与えた[30]。リ チャード・バックの 1901 年の論文「宇宙意識」では、ベーメの霊的悟りの深さに特別な注目が払われ、それは、人間と神との究極の非差異、あるいは非二元性をベーメに明らかにしたよ うだった。ベーメは、イギリスのロマン主義の詩人、芸術家、神秘主義者ウィリアム・ブレイクにも大きな影響を与えている。1764年から1781年に刊行 されたヤコブ・ベーメの著作のウィリアム・ロウ版(ドイツの初期ベーメ解釈者ディオニシウス・アンドレアス・フレール(1649–1728)がいくつかの 挿絵を収録)を見た後、ウィリアム・ブレイクは1825年の夕食会で「ミケランジェロもこれを超えることはできなかっただろう」と述べた。[36] ベーメの姓の誤った形に基づいているにもかかわらず、ベームニズムという用語は、現代英語の歴史学において、特定のベーメの神学を信奉する英国人を指す場 合によく使用され、依然として一定の有用性を保っている。[c] ベーメの影響は国境を越えたものであるため、この用語は、少なくともベームニスト間の多様な国際的つながりを暗示している。[37] いずれにせよ、この用語は「Böhmeianism」や「Böhmism」のような不格好な変種よりも好まれているが、これらも時々見られる。 |

| Reaction In addition to the scientific revolution, the 17th century was a time of mystical revolution in Catholicism, Protestantism and Judaism. The Protestant revolution developed from Böhme and some medieval mystics. Böhme became important in intellectual circles in Protestant Europe, following from the publication of his books in England, Holland and Germany in the 1640s and 1650s.[38] Böhme was especially important for the Millenarians and was taken seriously by the Cambridge Platonists and Dutch Collegiants. Henry More was critical of Böhme and claimed he was not a real prophet, and had no exceptional insight into metaphysical questions. Overall, although his writings did not influence political or religious debates in England, his influence can be seen in more esoteric forms such as on alchemical experimentation, metaphysical speculation and spiritual contemplation, as well as utopian literature and the development of neologisms.[d] More, for example, dismissed Opera Posthuma by Spinoza as a return to Behmenism.[40] While Böhme was famous across Western Europe and North America during the 17th century, he became less influential during the 18th century. A revival occurred late in that century with interest from German Romantics, who considered Böhme a forerunner to the movement. Poets such as John Milton, Ludwig Tieck, Novalis, William Blake[41] and W. B. Yeats[42] found inspiration in Böhme's writings. Coleridge, in his Biographia Literaria, speaks of Böhme with admiration. Böhme was highly thought of by the German philosophers Baader, Schelling and Schopenhauer. Hegel went as far as to say that Böhme was "the first German philosopher".[43] Danish Bishop Hans Lassen Martensen published a book about Böhme.[44] Several authors have found Boehme's description of the three original Principles and the seven Spirits to be similar to the Law of Three and the Law of Seven described in the works of Boris Mouravieff and George Gurdjieff.[45][46] |

反応 科学革命に加え、17 世紀はカトリック、プロテスタント、ユダヤ教において神秘主義の革命が起こった時代でした。プロテスタントの革命は、ベーメや中世の神秘主義者たちから発 展しました。ボーメは、1640年代から1650年代にかけてイギリス、オランダ、ドイツで彼の著作が刊行された後、プロテスタントヨーロッパの知的サー クルで重要な存在となった。[38] ボーメは特にミレニアル派にとって重要であり、ケンブリッジ・プラトニストやオランダのコレギアンツから真剣に受け止められた。ヘンリー・モアはボーメを 批判し、彼は真の預言者ではなく、形而上学的問題に対する特別な洞察を持っていないと主張した。全体として、彼の著作はイングランドの政治的・宗教的議論 に影響を与えなかったが、錬金術の実験、形而上学的な思索、霊的瞑想、ユートピア文学、新語の発展など、より神秘的な形態においてその影響が見られる。 [d] 例えばモアは、スピノザの『Opera Posthuma』をベームニズムへの回帰と批判した。[40] 17 世紀、ベーメは西ヨーロッパと北米で有名だったが、18 世紀にはその影響力は低下した。18世紀後半、ドイツのロマン派がボーメを運動の先駆者と見なし、再評価の波が起きた。ジョン・ミルトン、ルートヴィヒ・ ティーク、ノヴァリス、ウィリアム・ブレイク[41]、W・B・イェイツ[42]などの詩人は、ボーメの著作からインスピレーションを得た。コリアーは 『文学伝記』でボーメを称賛している。ベーメは、ドイツの哲学者バダー、シェリング、ショーペンハウアーから高く評価された。ヘーゲルは、ベーメを「最初 のドイツの哲学者」とまで述べた[43]。デンマークの司教ハンス・ラッセン・マルテンセンは、ベーメに関する本を出版した。[44] いくつかの著者は、ベーメの 3 つの原初原理と 7 つの霊に関する記述が、ボリス・ムラヴィエフとジョージ・グルジェフの著作で述べられている 3 の法則と 7 の法則と類似しているとの見解を示している。[45][46] |

| Works Aurora: Die Morgenröte im Aufgang (unfinished) (1612) De Tribus Principiis (The Three Principles of the Divine Essence, 1618–1619) The Threefold Life of Man (1620) Answers to Forty Questions Concerning the Soul (1620) The Treatise of the Incarnations: (1620) I. Of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ II. Of the Suffering, Dying, Death and Resurrection of Christ III. Of the Tree of Faith The Great Six Points (1620) Of the Earthly and of the Heavenly Mystery (1620) Of the Last Times (1620) De Signatura Rerum (The Signature of All Things, 1621) The Four Complexions (1621) Of True Repentance (1622) Of True Resignation (1622) Of Regeneration (1622) Of Predestination (1623) A Short Compendium of Repentance (1623) The Mysterium Magnum (1623) A Table of the Divine Manifestation, or an Exposition of the Threefold World (1623) The Suprasensual Life (1624) Of Divine Contemplation or Vision (unfinished) (1624) Of Christ's Testaments (1624) I. Baptism II. The Supper Of Illumination (1624) 177 Theosophic Questions, with Answers to Thirteen of Them (unfinished) (1624) An Epitome of the Mysterium Magnum (1624) The Holy Week or a Prayer Book (unfinished) (1624) A Table of the Three Principles (1624) Of the Last Judgement (lost) (1624) The Clavis (1624) Sixty-two Theosophic Epistles (1618–1624) Books in print The Way to Christ (inc. True Repentance, True Resignation, Regeneration or the New Birth, The Supersensual Life, Of Heaven & Hell, The Way from Darkness to True Illumination) edited by William Law, Diggory Press ISBN 978-1-84685-791-1 Of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ, translated from the German by John Rolleston Earle, London, Constable and Company LTD, 1934. |

作品 オーロラ:夜明けの曙光(未完)(1612年 三つの原理(神の本質に関する三つの原理、1618年~1619年 人間の三つの人生(1620年 魂に関する40の質問への回答 (1620) 化身に関する論文: (1620) I. イエス・キリストの化身について II. キリストの苦悩、死、そして復活について III. 信仰の樹について 六つの大要 (1620) 地上の謎と天の謎について (1620) 最後の時代について (1620) デ・シグニトゥラ・レルム(万物の署名、1621) 四つの気質 (1621) 真の悔悛について (1622) 真の放棄について (1622) 再生について (1622) 予定説について (1623) 悔悛の簡明要約(1623) 大いなる神秘(1623) 神の顕現の表、または三つの世界の解説(1623) 超感覚的な生命(1624) 神の観想または幻視について(未完)(1624) キリストの遺言 (1624) I. 洗礼 II. 晩餐 照明について (1624) 177の神智学上の質問と、そのうちの13に対する回答(未完) (1624) 神秘の偉大さの要約 (1624) 聖週間または祈祷書(未完)(1624年) 三つの原理の表(1624年) 最後の審判について(失われた)(1624年) クラヴィス(1624年) 62の神智学書簡(1618年~1624年) 出版されている書籍 『キリストへの道』(真の悔い改め、真の放棄、再生または新生、超感覚的な生活、天国と地獄、暗闇から真の啓示への道を含む)ウィリアム・ロー編、ディゴリー・プレス ISBN 978-1-84685-791-1 『イエス・キリストの受肉』、ジョン・ロールストン・アール訳、ロンドン、コンスタブル・アンド・カンパニー・リミテッド、1934年。 |

| Veneration In 2022, Jacob Boehme was officially added to the Episcopal Church liturgical calendar along with Johann Arndt with a feast day on 11 May.[47] In popular culture Literature Cormac McCarthy's 1985 novel Blood Meridian includes three epigraphs, the second of which comes from Jacob Boehme: "It is not to be thought that the life of darkness is sunk in misery and lost as if in sorrowing. There is no sorrowing. For sorrow is a thing that is swallowed up in death, and death and dying are the very life of the darkness."[48] Film The Life and Legacy of Jacob Boehme. A documentary directed by Łukasz Chwałko. Premiered: June 2016, Zgorzelec (Poland).[49] |

崇拝 2022年、ヤコブ・ベーメはヨハン・アルントとともに、5月11日を祝日にして、米国聖公会の典礼暦に正式に追加された[47]。 大衆文化 文学 コルマック・マッカーシーの1985年の小説『血のメリディアン』には3つのエピグラフがあり、その2つ目はヤコブ・ベーメの言葉だ:「暗闇の生活は、悲 しみに沈み、失われたものだと考えるべきではない。悲しみはない。なぜなら、悲しみは死に飲み込まれるものであり、死と死は暗闇そのものの生命だから だ。」[48] 映画 『ヤコブ・ベーメの生涯と遺産』。ルカシュ・フワルコ監督によるドキュメンタリー映画。2016年6月、ズゴジェレツ(ポーランド)で初公開。[49] |

| Augoeides – Hermetic starfire body Christian mysticism – Christian mystical practices Friends of God – Medieval mystical group Jane Lead – English dissenter (1624–1704) Sophia – Personification of wisdom in philosophy and religion |

アウゴイデス – ヘルメティック・スターファイア・ボディ キリスト教神秘主義 – キリスト教の神秘主義的実践 神の友 – 中世の神秘主義者集団 ジェーン・リード – イギリスの異端者(1624年–1704年) ソフィア – 哲学および宗教における知恵の擬人化 |

| Aubrey, Bryan (1981). The

influence of Jacob Boehme on the work of William Blake. Durham theses

(Thesis). Durham University. Retrieved 13 December 2022. Bourgeault, Cynthia (2013). The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three: Discovering the Radical Truth at the Heart of Christianity. Shambhala. ISBN 978-0-8348-2894-0. Brown, Dale W. (1996). Understanding Pietism. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 978-0916035648. Brumbaugh, Martin Grove (1899). A History of the German Baptist Brethren in Europe and America. Brethren publishing house. ISBN 9780404084257. Calian, George-Florin (2010). Alkimia Operativa and Alkimia Speculativa: Some Modern Controversies on the Historiography of Alchemy. Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Boehme, Jakob" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 114. Public Domain Debelius, F. W. (1908). "Boehme, Jakob". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. 2 (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 209–211. Deussen, Paul (1910). "Introduction". In Boehme, Jacob (ed.). Concerning the three principles of the divine essence. London: John M. Watkins. Durnbaugh, Donald F. (2001). "Pennsylvania's Crazy Quilt of German Religious Groups". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 68 (1): 8–30. Edwards, Timothy (5 April 2004). Jacob Böhme: The Teutonic Philosopher. 24th Convocation of Ontario College. Ensign, Chauncey David (1955). Radical German Pietism (c. 1675-c. 1760) (Thesis). Boston University. hdl:2144/8771. Episcopal Church (2022). "General Convention Virtual Binder: Resolution A007: Authorize Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2022". www.vbinder.net. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022. Faivre, Antoine (2000). Theosophy, Imagination, Tradition: Studies in Western Esotericism. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4435-X. OCLC 41944660. Gibbons, B. J. (1996). Gender in Mystical and Occult Thought: Behmenism and its Development in England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hessayon, Ariel (2013). "Jacob Boehme's writings during the English Revolution and afterwards: their publication, dissemination and influence". In Hessayon, Ariel; Apetrei, Sarah (eds.). An Introduction to Jacob Boehme: Four Centuries of Thought and Reception. Routledge. pp. 77–97. Hirsch, Emanuel (1951). Geschichte der Neueren Evangelischen Theologie in Zusammenhang mit den allgemeinen Bewegungen des europaischen Denkens (in German). Vol. II. Gutersloh: c. Bertelsmann Verlag. pp. 209, 255, 256. Hutin, Serge (Autumn 1953). "The Behmenists and the Philadelphian Society". The Jacob Boehme Society Quarterly. 1 (5): 5–11. Jaqua, Mark (1984). "The Illumination of Jacob Boehme" (PDF). TAT Journal. 13. TAT Foundation. Retrieved 13 December 2022. Joling-van der Sar, Gerda J. (2003). The Spiritual Side of Samuel Richardson: Mysticism, Behmenism and Millenarianism in an Eighteenth-Century English Novelist – via home.hccnet.nl. Judge, William Q. (1985). "Jacob Boehme and the Secret Doctrine". Theosophical Articles and Notes. Vol. 1. Los Angeles: Theosophy Company. p. 271ff. ISBN 978-0938998297. Kneavel, Ann Callanan (1978). Affinities between William Butler Yeats and Jacob Boehme (PDF) (PhD dissertation). Ottawa, Canada: University of Ottawa. Retrieved 13 December 2022. Magill, Frank N., ed. (2013). The 17th and 18th Centuries: Dictionary of World Biography. Vol. 4. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1135924140. Mills, Jon (2002). The Unconscious Abyss: Hegel's Anticipation of Psychoanalysis. Albany: State University of New York Press. Martensen, Hans Lassen (1885). Jacob Boehme: His Life and Teaching, or Studies in Theosophy. Translated by T. Rhys Evans. London: Hodder and Stoughton. Martin, Michael (24 June 2020). "The Life and Legacy of Jacob Boehme: Review". The Center for Sophiological Studies. Retrieved 21 September 2021. Mundik, Petra (2016). A Bloody and Barbarous God: The Metaphysics of Cormac McCarthy. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826356710. Musès, Charles A. (1951). Illumination on Jakob Böhme. New York: King's Crown Press. Nicolescu, Basarab (1998). "Gurdjieff's philosophy of nature". In Needleman, J.; Baker, G. (eds.). Gurdjieff: Essays and Reflections on the Man and His Teachings. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 37–69. ISBN 978-1-4411-1084-8. A revised version is available: "Gurdjieff's philosophy of nature" (PDF). 2003. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2017. Penman, Leigh T. I. (2008). "A Second Christian Rosenkreuz? Jakob Boehme's Disciple Balthasar Walther (1558–c.1630) and the Kabbalah: With a Bibliography of Walther's Printed Works". In Ahlbäck, T. (ed.). Scripta institute donneriani Aboensis. Vol. XX. Åbo, Finland: Donner Institute. pp. 154–172. Popkin, Richard (1998). "The religious background of seventeenth-century philosophy". In Garber, Daniel; Ayers, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Philosophy. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53720-9. Schopenhauer, Arthur (1903). On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason. Translated by Mme. Karl Hillebrand. London: George Bell and Sons. Stoeffler, F. Ernest (1965). The Rise of Evangelical Pietism. Leiden: E. J. Brill. Stoeffler, F. Ernest (1973). German Pietism During the Eighteenth Century. Leiden: E. J. Brill. Stoudt, John Joseph (1968). Jakob Böhme: His Life and Thought. New York: The Seabury Press. Stoudt, John J. (17 November 2022). "Jakob Böhme: German mystic". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 December 2022. Thune, Nils (1948). The Behemenists and the Philadelphians: A contribution to the study of English mysticism in the 17th and 18th centuries. Uppsala: Almquist and Wiksells. Versluis, Arthur (2007). Magic and Mysticism: An Introduction to Western Esotericism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742558366. von Ingen, F. (1988). Jacob Böhme in Marienlexikon. Eos: St. Ottilien. Weeks, Andrew (1991). Boehme: An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher and Mystic. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0596-3. |

オーブリー、ブライアン (1981). ヤコブ・ベーメがウィリアム・ブレイクの作品に与えた影響。ダーラム論文 (論文). ダーラム大学。2022年12月13日取得。 Bourgeault, Cynthia (2013). The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three: Discovering the Radical Truth at the Heart of Christianity. Shambhala. ISBN 978-0-8348-2894-0. Brown, Dale W. (1996). Understanding Pietism. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 978-0916035648. ブランボー、マーティン・グローブ(1899)。ヨーロッパとアメリカにおけるドイツ・バプテスト兄弟団の歴史。ブレザレン出版社。ISBN 9780404084257。 カリアン、ジョージ・フロラン(2010)。Alkimia Operativa and Alkimia Speculativa: Some Modern Controversies on the Historiography of Alchemy. Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). 「Boehme, Jakob」 . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 114. パブリックドメイン デベリウス, F. W. (1908). 「ボーメ, ヤコブ」. ジャクソン, サミュエル・マカウリー (編). 新シャフ・ヘルツォーク宗教知識事典. 第2巻 (第3版). ロンドンおよびニューヨーク: ファンク・アンド・ワグナーズ. pp. 209–211. デウセン, ポール (1910). 「序文」. ボーメ, ヤコブ (編). 神の本質の三原則について. ロンドン: ジョン・M・ワトキンス. ダーンボー, ドナルド・F. (2001). 「ペンシルベニアのドイツ系宗教団体の雑多な集合体」. Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 68 (1): 8–30. エドワーズ, ティモシー (2004年4月5日). ヤコブ・ベーメ: テュートン哲学者の生涯. オンタリオ大学第24回卒業式. エンサイン, チャンスィー・デイヴィッド (1955). ドイツの急進的ピエティズム (約1675年–約1760年) (学位論文). ボストン大学. hdl:2144/8771. 米国聖公会 (2022). 「総会議事録バーチャルバインダー: 決議 A007: 2022 年の小祭と断食を承認する」. www.vbinder.net. 2022年9月13日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年7月22日に取得。 Faivre, Antoine (2000). 神智学、想像力、伝統:西洋の秘教の研究。ニューヨーク州アルバニー:ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。ISBN 0-7914-4435-X。OCLC 41944660。 ギボンズ、B. J. (1996)。神秘主義とオカルト思想におけるジェンダー:ベームニズムとそのイギリスにおける発展。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ヘッセヨン、アリエル (2013). 「イングランド革命期およびその後のヤコブ・ベーメの著作:その出版、普及、影響」. ヘッセヨン、アリエル; アペトレイ、サラ (編). ヤコブ・ベーメ入門:4世紀にわたる思想と受容. ルートレッジ. pp. 77–97. ヒルシュ、エマニュエル(1951)。『ヨーロッパの思想の一般的な動向と関連した近代福音神学の歴史』(ドイツ語)。第 II 巻。Gutersloh:c. Bertelsmann Verlag。209、255、256 ページ。 ユタン、セルジュ(1953年秋)。「ベーメン派とフィラデルフィア協会」. The Jacob Boehme Society Quarterly. 1 (5): 5–11. ジャクア、マーク (1984). 「ヤコブ・ベーメの啓示」 (PDF). TAT Journal. 13. TAT Foundation. 2022年12月13日取得。 ヨリング=ファン・デル・サール、ゲルダ・J.(2003)。『サミュエル・リチャードソンの精神的な側面:18世紀のイギリス小説家における神秘主義、ベーメン主義、ミレニアリズム』 – home.hccnet.nl 経由。 ジャッジ、ウィリアム・Q.(1985)。「ヤコブ・ベーメと秘密の教義」。『神智学記事と注釈』。第1巻。ロサンゼルス:Theosophy Company。271ページ以降。ISBN 978-0938998297。 Kneavel, Ann Callanan (1978). Affinities between William Butler Yeats and Jacob Boehme (PDF) (PhD dissertation). オタワ、カナダ:オタワ大学。2022年12月13日取得。 Magill, Frank N., 編 (2013). 17 世紀と 18 世紀:世界人物事典。第 4 巻。テイラー&フランシス。ISBN 978-1135924140。 ミルズ、ジョン (2002). 無意識の深淵:ヘーゲルの精神分析の予見。アルバニー:ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。 マーティンセン、ハンス・ラッセン (1885)。ヤコブ・ベーメ:その生涯と教え、あるいは神智学の研究。T. リス・エヴァンス訳。ロンドン:ホッダー・アンド・ストウトン。 マーティン、マイケル (2020年6月24日)。「ヤコブ・ベーメの生涯と遺産:レビュー」。ソフィオロジー研究センター。2021年9月21日取得。 ムンディク、ペトラ(2016)。血まみれで野蛮な神:コーマック・マッカーシーの形而上学。ニューメキシコ大学出版。ISBN 978-0826356710。 ムゼ、チャールズ A.(1951)。ヤコブ・ベーメに関する考察。ニューヨーク:キングス・クラウン・プレス。 ニコレスク、バサラブ(1998)。「グルジェフの自然哲学」。ニードルマン、J.、ベイカー、G.(編)。『グルジェフ:人物と教えに関するエッセイと 考察』。ブルームズベリー出版。37-69頁。ISBN 978-1-4411-1084-8。改訂版が利用可能: 「グルジェフの自然哲学」 (PDF). 2003. p. 12. 2019年11月26日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2017年7月23日に取得。 ペンマン, リー・T・I. (2008). 「第二のキリスト教のローゼンクロイツ? ヤコブ・ベーメの弟子バルタザール・ヴァルター(1558–c.1630)とカバラ:ヴァルターの印刷著作の書誌目録」. In Ahlbäck, T. (ed.). Scripta institute donneriani Aboensis. Vol. XX. Åbo, Finland: Donner Institute. pp. 154–172. ポプキン、リチャード(1998)。「17世紀哲学の宗教的背景」。ガーバー、ダニエル、エアーズ、マイケル(編)。『17世紀哲学のケンブリッジ史』。第1巻。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-53720-9。 ショーペンハウアー、アルトゥール(1903)。『四つの根源の原理について』Mme. Karl Hillebrand 訳。ロンドン:George Bell and Sons。 ストフラー、F. アーネスト (1965)。『福音主義の敬虔主義の台頭』。ライデン:E. J. Brill。 ストフラー、F. アーネスト (1973)。『18 世紀のドイツの敬虔主義』。ライデン:E. J. Brill。 ストゥート、ジョン・ジョセフ(1968)。ヤコブ・ベーメ:その生涯と思想。ニューヨーク:シーベリー・プレス。 ストゥート、ジョン・J.(2022年11月17日)。「ヤコブ・ベーメ:ドイツの神秘主義者」。ブリタニカ国際大百科事典。2022年12月13日取得。 トゥーン、ニルス(1948)。ベヘメニストとフィラデルフィア人:17 世紀および 18 世紀の英国の神秘主義の研究への貢献。ウプサラ:アルムクイストとウィクスセルズ。 Versluis, Arthur (2007). 呪術と神秘主義:西洋の秘教入門。Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742558366. フォン・インゲン、F. (1988)。『マリエンレキシコン』のヤコブ・ベーメ。Eos:聖オティリーエン。 ウィークス、アンドルー (1991)。『ベーメ:17 世紀の哲学者および神秘主義者の知的な伝記』。ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-7914-0596-3。 |

| Bailey, Margaret Lewis (1914).

Milton and Jakob Boehme; a study of German mysticism in

seventeenth-century England. New York: Oxford University Press. Berdyaev, Nikolai (February 1930). "Studies Concerning Jacob Boehme: Etude I. The Teaching about the Ungrund and Freedom". Journal Put' (20): 47–79. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2008. Berdyaev, Nikolai (April 1930). "Studies Concerning Jacob Boehme: Etude II. The Teaching about Sophia and the Androgyne. J. Boehme and the Russian Sophiological Current". Journal Put' (21): 34–62. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2008. Carus, Paul (1900). "A Modern Gnostic". History of the Devil. pp. 151ff. Hartmann, Franz (1891). The Life and the Doctrines of Jacob Boehme, the God-Taught Philosopher: An Introduction to the Study of His Works – via UniversalTheosophy.com. Swainson, William Perkes (1921). Jacob Boehme; the Teutonic philosopher. London: William Rider & Son, Ltd. |

ベイリー、マーガレット・ルイス(1914)。ミルトンとヤコブ・ベーメ:17 世紀のイギリスにおけるドイツ神秘主義の研究。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。 ベルディアエフ、ニコライ(1930 年 2 月)。「ヤコブ・ベーメに関する研究:エチュード I. Ungrund と自由に関する教え」。ジャーナル・プット (20): 47–79。2013年7月25日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2008年5月21日に取得。 ベルジャエフ、ニコライ (1930年4月)。「ヤコブ・ベーメに関する研究:エチュード II. ソフィアと両性具有に関する教え。J. ベーメとロシアのソフィオロジーの流れ」。ジャーナル・プト (21): 34–62。2014年2月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2008年5月21日に取得。 カラス、ポール (1900)。「現代のグノーシス主義者」。悪魔の歴史。151ページ以降。 Hartmann, Franz (1891). 『ヤコブ・ベーメ、神に教えられた哲学者:その生涯と教義』 – UniversalTheosophy.com 経由。 Swainson, William Perkes (1921). 『ヤコブ・ベーメ:ドイツの哲学者』。ロンドン:William Rider & Son, Ltd. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jakob_B%C3%B6hme |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆