日本語

Japanese language

☆

日本語(にほんご、Japanese)

は、日本人が話す日本語族の主要言語である。約1億2,300万人の話者がおり、主に日本で話されている。日本が唯一の国民言語であり、世界中にいる日本

人ディアスポラの中でも話されている。

ジャポニック語族には、琉球語や様々に分類される八丈語も含まれる。ジャポニック語族をアイヌ語族、オーストロネシア語族、朝鮮語族、アルタイ語族など他

の語族とグループ化しようとする試みは何度もあったが、どれも広く受け入れられるには至らなかった。

ジャポニカ語の先史時代や、日本に初めて出現した時期についてはほとんど知られていない。紀元3世紀の中国の文献には、日本語の単語がいくつか記録されて

いるが、実質的な古文書が現れるのは8世紀になってからである。平安時代(794年~1185年)以降、漢語の語彙が大量に流入し、初期中日本語の音韻に

影響を与えた。中世後期(1185-1600)には、文法が大きく変化し、ヨーロッパからの借用語が初めて登場した。近世日本語(17世紀初頭~19世紀

半ば)には、標準語の基礎が関西から江戸に移った。1853年に鎖国が解かれた後、ヨーロッパ言語からの借用語の流入が著しくなり、英語を語源とする単語

が急増した。

日本語は膠着語であり、比較的単純な音韻論、純粋な母音体系、音韻論的な母音と子音の長さ、語彙的に重要なピッチアクセントを持つモーラタイム言語であ

る。語順は通常、主語-目的語-動詞で、助詞が単語の文法的機能を表し、文構造はトピック-コメントである。文末の助詞は、感情的または強調的なインパク

トを加えたり、疑問文を形成したりするのに使われる。名詞には文法上の数や性別がなく、冠詞もない。動詞は主に時制と声調について活用するが、人称につい

ては活用しない。形容詞も活用する。日本語には複雑な敬語体系があり、話し手、聞き手、言及された人物の相対的な地位を示す動詞の形や語彙がある。

日本語の文字システムは、漢字として知られる漢字と、日本人がより複雑な漢字から派生させた2つの独自の音節文字(またはモーラ文字)を組み合わせてい

る:

ひらがな(平仮名、「簡単な文字」)とカタカナ(片仮名、「部分的な文字」)である。ラテン文字(ローマ字)も、輸入された頭字語など限られた形で使用さ

れている。数字については、主にアラビア数字が使われるが、漢数字も使われる。

| Japanese

(日本語,

Nihongo, [ɲihoŋɡo] ⓘ) is the principal language of the Japonic language

family spoken by the Japanese people. It has around 123 million

speakers, primarily in Japan, the only country where it is the national

language, and within the Japanese diaspora worldwide. The Japonic family also includes the Ryukyuan languages and the variously classified Hachijō language. There have been many attempts to group the Japonic languages with other families such as the Ainu, Austronesian, Koreanic, and the now-discredited Altaic, but none of these proposals have gained any widespread acceptance. Little is known of the language's prehistory, or when it first appeared in Japan. Chinese documents from the 3rd century AD recorded a few Japanese words, but substantial Old Japanese texts did not appear until the 8th century. From the Heian period (794–1185), extensive waves of Sino-Japanese vocabulary entered the language, affecting the phonology of Early Middle Japanese. Late Middle Japanese (1185–1600) saw extensive grammatical changes and the first appearance of European loanwords. The basis of the standard dialect moved from the Kansai region to the Edo region (modern Tokyo) in the Early Modern Japanese period (early 17th century–mid 19th century). Following the end of Japan's self-imposed isolation in 1853, the flow of loanwords from European languages increased significantly, and words from English roots have proliferated. Japanese is an agglutinative, mora-timed language with relatively simple phonotactics, a pure vowel system, phonemic vowel and consonant length, and a lexically significant pitch-accent. Word order is normally subject–object–verb with particles marking the grammatical function of words, and sentence structure is topic–comment. Sentence-final particles are used to add emotional or emphatic impact, or form questions. Nouns have no grammatical number or gender, and there are no articles. Verbs are conjugated, primarily for tense and voice, but not person. Japanese adjectives are also conjugated. Japanese has a complex system of honorifics, with verb forms and vocabulary to indicate the relative status of the speaker, the listener, and persons mentioned. The Japanese writing system combines Chinese characters, known as kanji (漢字, 'Han characters'), with two unique syllabaries (or moraic scripts) derived by the Japanese from the more complex Chinese characters: hiragana (ひらがな or 平仮名, 'simple characters') and katakana (カタカナ or 片仮名, 'partial characters'). Latin script (rōmaji ローマ字) is also used in a limited fashion (such as for imported acronyms) in Japanese writing. The numeral system uses mostly Arabic numerals, but also traditional Chinese numerals. |

日本語(にほんご、[ɲɡo]

ⓘ)は、日本人が話す日本語族の主要言語である。約1億2,300万人の話者がおり、主に日本で話されている。日本が唯一の国民言語であり、世界中にいる

日本人ディアスポラの中でも話されている。 ジャポニック語族には、琉球語や様々に分類される八丈語も含まれる。ジャポニック語族をアイヌ語族、オーストロネシア語族、朝鮮語族、アルタイ語族など他 の語族とグループ化しようとする試みは何度もあったが、どれも広く受け入れられるには至らなかった。 ジャポニカ語の先史時代や、日本に初めて出現した時期についてはほとんど知られていない。紀元3世紀の中国の文献には、日本語の単語がいくつか記録されて いるが、実質的な古文書が現れるのは8世紀になってからである。平安時代(794年~1185年)以降、漢語の語彙が大量に流入し、初期中日本語の音韻に 影響を与えた。中世後期(1185-1600)には、文法が大きく変化し、ヨーロッパからの借用語が初めて登場した。近世日本語(17世紀初頭~19世紀 半ば)には、標準語の基礎が関西から江戸に移った。1853年に鎖国が解かれた後、ヨーロッパ言語からの借用語の流入が著しくなり、英語を語源とする単語 が急増した。 日本語は膠着語であり、比較的単純な音韻論、純粋な母音体系、音韻論的な母音と子音の長さ、語彙的に重要なピッチアクセントを持つモーラタイム言語であ る。語順は通常、主語-目的語-動詞で、助詞が単語の文法的機能を表し、文構造はトピック-コメントである。文末の助詞は、感情的または強調的なインパク トを加えたり、疑問文を形成したりするのに使われる。名詞には文法上の数や性別がなく、冠詞もない。動詞は主に時制と声調について活用するが、人称につい ては活用しない。形容詞も活用する。日本語には複雑な敬語体系があり、話し手、聞き手、言及された人物の相対的な地位を示す動詞の形や語彙がある。 日本語の文字システムは、漢字として知られる漢字と、日本人がより複雑な漢字から派生させた2つの独自の音節文字(またはモーラ文字)を組み合わせてい る: ひらがな(平仮名、「簡単な文字」)とカタカナ(片仮名、「部分的な文字」)である。ラテン文字(ローマ字)も、輸入された頭字語など限られた形で使用さ れている。数字については、主にアラビア数字が使われるが、漢数字も使われる。 |

| History Further information: Japanese writing system § History of the Japanese script Prehistory Proto-Japonic, the common ancestor of the Japanese and Ryukyuan languages, is thought to have been brought to Japan by settlers coming from the Korean peninsula sometime in the early- to mid-4th century BC (the Yayoi period), replacing the languages of the original Jōmon inhabitants,[2] including the ancestor of the modern Ainu language. Because writing had yet to be introduced from China, there is no direct evidence, and anything that can be discerned about this period must be based on internal reconstruction from Old Japanese, or comparison with the Ryukyuan languages and Japanese dialects.[3] Old Japanese Main article: Old Japanese Page from the Man'yōshū A page from the Man'yōshū, the oldest anthology of classical Japanese poetry The Chinese writing system was imported to Japan from Baekje around the start of the fifth century, alongside Buddhism.[4] The earliest texts were written in Classical Chinese, although some of these were likely intended to be read as Japanese using the kanbun method, and show influences of Japanese grammar such as Japanese word order.[5] The earliest text, the Kojiki, dates to the early eighth century, and was written entirely in Chinese characters, which are used to represent, at different times, Chinese, kanbun, and Old Japanese.[6] As in other texts from this period, the Old Japanese sections are written in Man'yōgana, which uses kanji for their phonetic as well as semantic values. Based on the Man'yōgana system, Old Japanese can be reconstructed as having 88 distinct morae. Texts written with Man'yōgana use two different sets of kanji for each of the morae now pronounced き (ki), ひ (hi), み (mi), け (ke), へ (he), め (me), こ (ko), そ (so), と (to), の (no), も (mo), よ (yo) and ろ (ro).[7] (The Kojiki has 88, but all later texts have 87. The distinction between mo1 and mo2 apparently was lost immediately following its composition.) This set of morae shrank to 67 in Early Middle Japanese, though some were added through Chinese influence. Man'yōgana also has a symbol for /je/, which merges with /e/ before the end of the period. Several fossilizations of Old Japanese grammatical elements remain in the modern language – the genitive particle tsu (superseded by modern no) is preserved in words such as matsuge ("eyelash", lit. "hair of the eye"); modern mieru ("to be visible") and kikoeru ("to be audible") retain a mediopassive suffix -yu(ru) (kikoyu → kikoyuru (the attributive form, which slowly replaced the plain form starting in the late Heian period) → kikoeru (all verbs with the shimo-nidan conjugation pattern underwent this same shift in Early Modern Japanese)); and the genitive particle ga remains in intentionally archaic speech. Early Middle Japanese Main article: Early Middle Japanese Genji Monogatari emaki scroll A 12th-century emaki scroll of The Tale of Genji from the 11th century Early Middle Japanese is the Japanese of the Heian period, from 794 to 1185. It formed the basis for the literary standard of Classical Japanese, which remained in common use until the early 20th century. During this time, Japanese underwent numerous phonological developments, in many cases instigated by an influx of Chinese loanwords. These included phonemic length distinction for both consonants and vowels, palatal consonants (e.g. kya) and labial consonant clusters (e.g. kwa), and closed syllables.[8][9] This had the effect of changing Japanese into a mora-timed language.[8] Late Middle Japanese Main article: Late Middle Japanese Late Middle Japanese covers the years from 1185 to 1600, and is normally divided into two sections, roughly equivalent to the Kamakura period and the Muromachi period, respectively. The later forms of Late Middle Japanese are the first to be described by non-native sources, in this case the Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries; and thus there is better documentation of Late Middle Japanese phonology than for previous forms (for instance, the Arte da Lingoa de Iapam). Among other sound changes, the sequence /au/ merges to /ɔː/, in contrast with /oː/; /p/ is reintroduced from Chinese; and /we/ merges with /je/. Some forms rather more familiar to Modern Japanese speakers begin to appear – the continuative ending -te begins to reduce onto the verb (e.g. yonde for earlier yomite), the -k- in the final mora of adjectives drops out (shiroi for earlier shiroki); and some forms exist where modern standard Japanese has retained the earlier form (e.g. hayaku > hayau > hayɔɔ, where modern Japanese just has hayaku, though the alternative form is preserved in the standard greeting o-hayō gozaimasu "good morning"; this ending is also seen in o-medetō "congratulations", from medetaku). Late Middle Japanese has the first loanwords from European languages – now-common words borrowed into Japanese in this period include pan ("bread") and tabako ("tobacco", now "cigarette"), both from Portuguese. Modern Japanese "Standard Japanese" redirects here. For other dialects, see Japanese dialects. Modern Japanese is considered to begin with the Edo period (which spanned from 1603 to 1867). Since Old Japanese, the de facto standard Japanese had been the Kansai dialect, especially that of Kyoto. However, during the Edo period, Edo (now Tokyo) developed into the largest city in Japan, and the Edo-area dialect became standard Japanese. Since the end of Japan's self-imposed isolation in 1853, the flow of loanwords from European languages has increased significantly. The period since 1945 has seen many words borrowed from other languages—such as German, Portuguese and English.[10] Many English loan words especially relate to technology—for example, pasokon (short for "personal computer"), intānetto ("internet"), and kamera ("camera"). Due to the large quantity of English loanwords, modern Japanese has developed a distinction between [tɕi] and [ti], and [dʑi] and [di], with the latter in each pair only found in loanwords.[11] |

沿革 さらに詳しい情報 日本語の文字体系 § 日本語の文字の歴史 先史時代 日本語と琉球語の共通の祖先である原ジャポニック語は、紀元前4世紀初頭から半ばにかけて(弥生時代)、朝鮮半島からの渡来人によって日本にもたらされた と考えられている。中国から文字が伝来していなかったため、直接的な証拠はなく、この時代について判別できることは、古日本語からの内部的な復元や、琉球 語や日本の方言との比較に基づかなければならない[3]。 古い日本語 主な記事 古い日本語 万葉集のページ 日本最古の歌集である『万葉集』の一ページ。 最古の文章は漢文で書かれているが、中には漢文訓読法を用いて日本語として読むことを意図したものもあり、日本語の語順など日本語の文法の影響が見られ る。 [5]最古のテキストである『古事記』は8世紀初頭に書かれたもので、すべて漢字で書かれている。 万葉仮名に基づくと、古文書には88の形態素があると推定される。万葉仮名で書かれた文章では、現在「き」「ひ」と発音される各形態に2つの異なる漢字が 使われている、 み」、「け」、「へ」、「め」、「こ」、「そ」、「と」、「の」、「も」、「よ」、「ろ」である。 [7](古事記では88だが、後のテキストはすべて87である)。も1」と「も2」の区別は、古事記が成立した直後に失われたようである)。古事記』には 88個あるが、後世のテキストはすべて87個である[7]。万葉仮名には/je/の記号もあるが、この記号は時代末期になると/e/に統合される。 主格助詞の「つ」(現代の「の」に取って代わられた)は、「まつげ」のような言葉に残っている。主格助詞の「つ」(現代の「の」に取って代わられた)は、 「まつげ」(現代の「まつげの毛」)、「見える」(現代の「見える」)と「聞こえる」(現代の「聞こえる」)には、平叙接尾辞の「ゆ(る)」が残っている (「きこえる」→「きこえる」(平安時代後期から徐々に平叙形に取って代わられた帰属形)→「きこえる」(近世日本語では、下二段活用の動詞はすべてこの ように変化した))。 初期中日本語 主な記事 初期中期の日本語 源氏物語絵巻 11世紀に描かれた源氏物語絵巻(12世紀 初期中日本語は、794年から1185年までの平安時代の日本語である。古典日本語の基礎となり、20世紀初頭まで一般的に使用された。 この時代、日本語は多くの音韻論的発展を遂げたが、その多くは中国語からの借用語の流入に端を発している。子音と母音の音韻の長さの区別、口蓋子音(例: キャー)と唇子音群(例:クワ)、閉音節などがこれに含まれる[8][9]。これは日本語をモーラ時制の言語に変える効果をもたらした[8]。 中期日本語後期 主な記事 中世後期日本語 中世後期の日本語は1185年から1600年までを指し、通常、鎌倉時代と室町時代に大別される。中世後期の日本語は、イエズス会宣教師やフランシスコ会 宣教師など、外来語によって初めて記述されたものであるため、中世後期の日本語の音韻については、それ以前のもの(例えば、Arte da Lingoa de Iapam)よりも優れた文献が存在する。他の音変化としては、/au/が/ɔ↪Lm_2D0/ に統合され、/o↪Lm_2D0 とは対照的に、/p/ が中国語から再導入され、/we/ が /je/ に統合された。また、現代日本語話者にとってより馴染みのある形も現れ始める。連続詞の語尾 -te が動詞の上に減少し始め(例:以前の yomite は yonde)、形容詞の最終モーラの -k- が脱落する(以前の shiroki は shiroi)。 例えば、hayaku > hayau > hayɔɔ、現代日本語では単にhayakuだが、標準的な挨拶であるo-hayō gozaimasu「おはようございます」には別の形が残されている;この語尾は、medetakuから派生したo-medetō「おめでとう」にも見ら れる)。 中世後期の日本語には、ヨーロッパ言語からの最初の借用語がある。この時期に日本語に借用された現在一般的な単語には、ポルトガル語から借用されたパン (「パン」)やタバコ(「タバコ」、現在の「タバコ」)がある。 現代日本語 「標準語」はここにリダイレクトされる。その他の方言については、日本の方言を参照のこと。 現代日本語は江戸時代(1603年から1867年まで)に始まったと考えられている。古語以来、事実上の標準語は関西弁、特に京都弁であった。しかし、江 戸時代に江戸(現在の東京)が日本最大の都市に発展し、江戸方言が標準語になった。1853年に鎖国が解かれて以来、ヨーロッパ言語からの借用語の流入が 著しくなった。1945年以降、ドイツ語、ポルトガル語、英語など、他の言語から多くの言葉が借用された[10]。英語の借用語の多くは特にテクノロジー に関連しており、例えば、パソコン(「パーソナルコンピューター」の略)、インタネット(「インターネット」)、カメラ(「カメラ」)などがある。英語の 借用語が多いため、現代日本語では[tɕi]と[ti]、[dʑi]と[di]の区別が発達し、後者は借用語にのみ見られるようになった[11]。 |

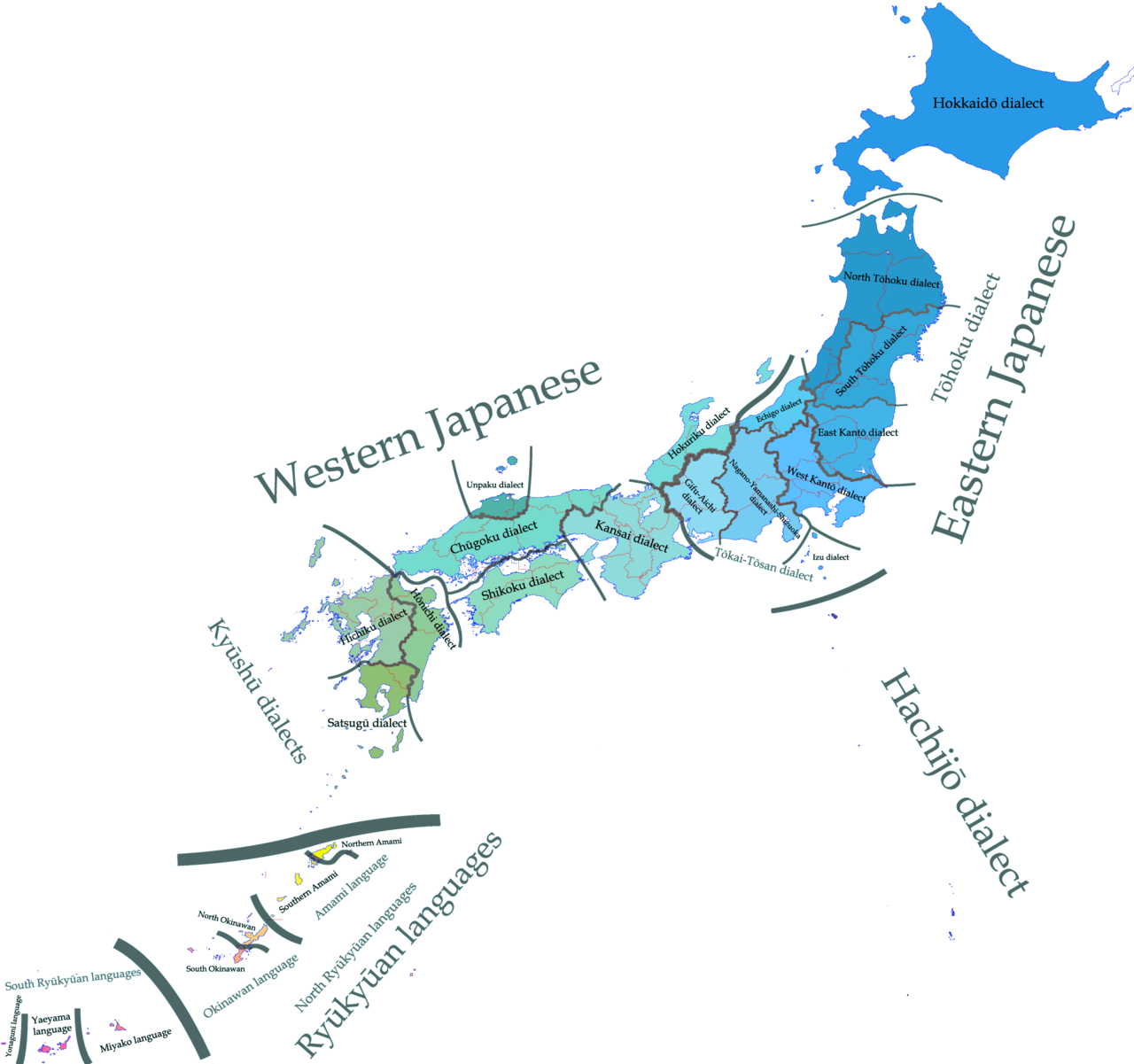

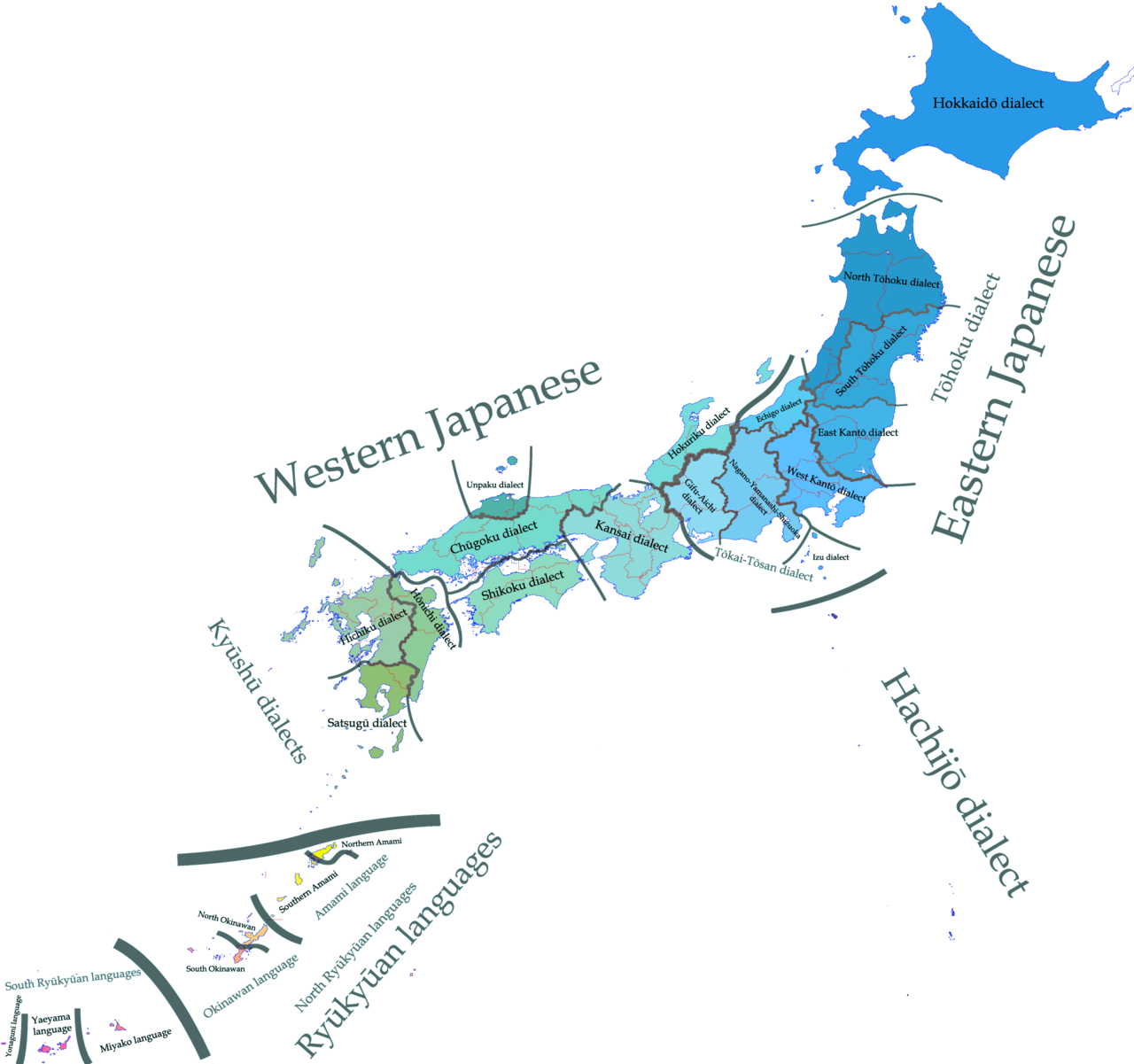

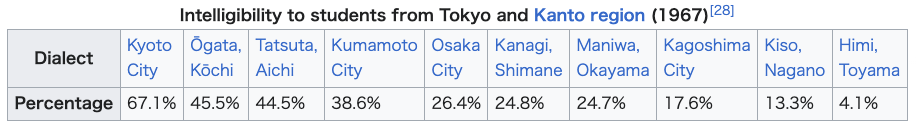

| Geographic distribution Although Japanese is spoken almost exclusively in Japan, it has also been spoken outside of the country. Before and during World War II, through Japanese annexation of Taiwan and Korea, as well as partial occupation of China, the Philippines, and various Pacific islands,[12] locals in those countries learned Japanese as the language of the empire. As a result, many elderly people in these countries can still speak Japanese. Japanese emigrant communities (the largest of which are to be found in Brazil,[13] with 1.4 million to 1.5 million Japanese immigrants and descendants, according to Brazilian IBGE data, more than the 1.2 million of the United States)[14] sometimes employ Japanese as their primary language. Approximately 12% of Hawaii residents speak Japanese,[15] with an estimated 12.6% of the population of Japanese ancestry in 2008. Japanese emigrants can also be found in Peru, Argentina, Australia (especially in the eastern states), Canada (especially in Vancouver, where 1.4% of the population has Japanese ancestry),[16] the United States (notably in Hawaii, where 16.7% of the population has Japanese ancestry,[17][clarification needed] and California), and the Philippines (particularly in Davao Region and the Province of Laguna).[18][19][20] Official status Japanese has no official status in Japan,[21] but is the de facto national language of the country. There is a form of the language considered standard: hyōjungo (標準語), meaning "standard Japanese", or kyōtsūgo (共通語), "common language", or even "Tokyo dialect" at times.[22] The meanings of the two terms (''hyōjungo'' and ''kyōtsūgo'') are almost the same. Hyōjungo or kyōtsūgo is a conception that forms the counterpart of dialect. This normative language was born after the Meiji Restoration (明治維新, meiji ishin, 1868) from the language spoken in the higher-class areas of Tokyo (see Yamanote). Hyōjungo is taught in schools and used on television and in official communications.[23] It is the version of Japanese discussed in this article. Formerly, standard Japanese in writing (文語, bungo, "literary language") was different from colloquial language (口語, kōgo). The two systems have different rules of grammar and some variance in vocabulary. Bungo was the main method of writing Japanese until about 1900; since then kōgo gradually extended its influence and the two methods were both used in writing until the 1940s. Bungo still has some relevance for historians, literary scholars, and lawyers (many Japanese laws that survived World War II are still written in bungo, although there are ongoing efforts to modernize their language). Kōgo is the dominant method of both speaking and writing Japanese today, although bungo grammar and vocabulary are occasionally used in modern Japanese for effect. The 1982 state constitution of Angaur, Palau, names Japanese along with Palauan and English as an official language of the state[24] as at the time the constitution was written, many of the elders participating in the process had been educated in Japanese during the South Seas Mandate over the island[25] shown by the 1958 census of the Trust Territory of the Pacific that found that 89% of Palauans born between 1914 and 1933 could speak and read Japanese,[26] but as of the 2005 Palau census there were no residents of Angaur that spoke Japanese at home.[27] Dialects and mutual intelligibility Main article: Japanese dialects  Map of Japanese dialects and Japonic languages Japanese dialects typically differ in terms of pitch accent, inflectional morphology, vocabulary, and particle usage. Some even differ in vowel and consonant inventories, although this is less common. In terms of mutual intelligibility, a survey in 1967 found that the four most unintelligible dialects (excluding Ryūkyūan languages and Tōhoku dialects) to students from Greater Tokyo were the Kiso dialect (in the deep mountains of Nagano Prefecture), the Himi dialect (in Toyama Prefecture), the Kagoshima dialect and the Maniwa dialect (in Okayama Prefecture).[28] The survey was based on 12- to 20-second-long recordings of 135 to 244 phonemes, which 42 students listened to and translated word-for-word. The listeners were all Keio University students who grew up in the Kanto region.[28] Intelligibility to students from Tokyo and Kanto region (1967)  There are some language islands in mountain villages or isolated islands[clarification needed] such as Hachijō-jima island, whose dialects are descended from Eastern Old Japanese. Dialects of the Kansai region are spoken or known by many Japanese, and Osaka dialect in particular is associated with comedy (see Kansai dialect). Dialects of Tōhoku and North Kantō are associated with typical farmers. The Ryūkyūan languages, spoken in Okinawa and the Amami Islands (administratively part of Kagoshima), are distinct enough to be considered a separate branch of the Japonic family; not only is each language unintelligible to Japanese speakers, but most are unintelligible to those who speak other Ryūkyūan languages. However, in contrast to linguists, many ordinary Japanese people tend to consider the Ryūkyūan languages as dialects of Japanese. The imperial court also seems to have spoken an unusual variant of the Japanese of the time,[29] most likely the spoken form of Classical Japanese, a writing style that was prevalent during the Heian period, but began to decline during the late Meiji period.[30] The Ryūkyūan languages are classified by UNESCO as 'endangered', as young people mostly use Japanese and cannot understand the languages. Okinawan Japanese is a variant of Standard Japanese influenced by the Ryūkyūan languages, and is the primary dialect spoken among young people in the Ryukyu Islands.[31] Modern Japanese has become prevalent nationwide (including the Ryūkyū islands) due to education, mass media, and an increase in mobility within Japan, as well as economic integration. |

地理的分布 日本語はほぼ日本国内だけで話されているが、国外でも話されている。第二次世界大戦前と戦時中、日本は台湾と朝鮮を併合し、中国、フィリピン、太平洋の島 々を部分的に占領した[12]。その結果、これらの国の高齢者の多くは、今でも日本語を話すことができる。 日系移民のコミュニティ(その最大規模はブラジルにあり[13]、ブラジルのIBGEのデータによれば、140万人から150万人の日本人移民とその子孫 がおり、米国の120万人を上回っている)[14]は、日本語を主要言語として使用することがある。ハワイの住民の約12%が日本語を話し[15]、 2008年には人口の12.6%が日本人の血を引いていると推定されている。ペルー、アルゼンチン、オーストラリア(特に東部の州)、カナダ(特にバン クーバーで、人口の1.4%が日本人の祖先を持つ)[16]、アメリカ(特にハワイで、人口の16.7%が日本人の祖先を持つ[17][要出典]、カリ フォルニア州)、フィリピン(特にダバオ地方とラグナ州)にも日本からの移民が見られる[18][19][20]。 公的地位 日本では日本語は公的な地位を持たないが[21]、事実上の国民言語である。標準語とされる言語には、「標準語」を意味する「標準語」と、「共通語」を意 味する「共通語」があり、「東京方言」と呼ばれることもある[22]。方言とは、方言と対をなす概念である。この規範語は、明治維新(1868年、明治維 新)後、東京の上流階級(山の手参照)で話されていた言葉から生まれた。ひょうじゅん語は学校で教えられ、テレビや公式のコミュニケーションで使われてい る[23]。 以前は、標準語(文語、ぶんご、「文語」)は口語(こうご、「口語」)とは異なっていた。文語と口語は文法のルールが異なり、語彙にも多少の違いがある。 文語は1900年頃まで日本語を書く主な方法であったが、その後、口語は徐々にその影響力を拡大し、1940年代まで2つの方法はともに文章を書くのに使 われた。文語は、歴史家、文学者、法律家にとって、今でもある程度の関連性を持っている(第二次世界大戦を生き延びた日本の法律の多くは、現在も文語で書 かれているが、その言語を近代化する努力が続けられている)。現在では、日本語を話すのも書くのも「古語」が主流だが、文法や語彙は現代日本語でも効果的 に使われることがある。 1982年に制定されたパラオのアンガウル州憲法では、州の公用語としてパラオ語、英語とともに日本語が挙げられている[24]。この憲法が制定された当 時、憲法制定に参加した長老の多くが南洋委任統治時代に日本語の教育を受けていた[25]。1958年に行われた太平洋信託統治領の国勢調査では、 1914年から1933年の間に生まれたパラオ人の89%が日本語を話し、読むことができたという結果が出ている[26]が、2005年のパラオ国勢調査 では、アンガウルで家庭で日本語を話す住民はいなかった[27]。 方言と相互理解 主な記事 日本の方言  日本の方言と日本語の地図 日本語の方言は一般的に、音調のアクセント、屈折形態、語彙、助詞の使い方が異なる。また、母音や子音まで異なるものもあるが、これはあまり一般的ではな い。 1967年に行われた調査では、首都圏の学生にとって最も理解できない方言(琉球語と東北方言を除く)は、木曽方言(長野県の山奥)、氷見弁(富山県)、 鹿児島弁、真庭弁(岡山県)の4つであった[28]。 [28] 調査は、135から244の音素を12秒から20秒で録音し、それを42人の学生が聞き、一語一語訳したものである。聞き手はすべて関東地方で育った慶應 義塾大学の学生であった[28]。 東京および 関東圏の学生に対する明瞭さ ( 1967年)  八丈島のような山村や離島[要出典]には、方言が東古文の流れを汲む言語島がある。関西の方言は多くの日本人に話されているか知られており、特に大阪弁はお笑いに関連している(関西弁を参照)。東北地方や北関東地方の方言は、典型的な農民の言葉である。 沖縄県と奄美諸島(行政上は鹿児島県の一部)で話されている琉球語は、日本語族の独立した一派とみなされるほど別個の言語である。それぞれの言語は、日本 語を話す人々には理解できないだけでなく、他の琉球語を話す人々にはほとんどが理解できない。しかし、言語学者とは対照的に、多くの一般日本人は琉球諸語 を日本語の方言とみなす傾向がある。 また、宮廷では当時の日本語の珍しい変種が話されていたようである[29]。おそらく古典日本語の話し言葉であろう。沖縄の日本語は、琉球諸語の影響を受けた標準語の変種であり、琉球諸島の若者の間で話されている主要な方言である[31]。 現代日本語は、教育、マスメディア、日本国内での移動の増加、経済統合により、全国的(琉球諸島を含む)に普及している。 |

| Classification Main article: Classification of the Japonic languages Japanese is a member of the Japonic language family, which also includes the Ryukyuan languages spoken in the Ryukyu Islands. As these closely related languages are commonly treated as dialects of the same language, Japanese is sometimes called a language isolate.[32] According to Martine Irma Robbeets, Japanese has been subject to more attempts to show its relation to other languages than any other language in the world. Since Japanese first gained the consideration of linguists in the late 19th century, attempts have been made to show its genealogical relation to languages or language families such as Ainu, Korean, Chinese, Tibeto-Burman, Uralic, Altaic (or Ural-Altaic), Austroasiatic, Austronesian and Dravidian.[33] At the fringe, some linguists have even suggested a link to Indo-European languages, including Greek, or to Sumerian.[34] Main modern theories try to link Japanese either to northern Asian languages, like Korean or the proposed larger Altaic family, or to various Southeast Asian languages, especially Austronesian. None of these proposals have gained wide acceptance (and the Altaic family itself is now considered controversial).[35][36][37] As it stands, only the link to Ryukyuan has wide support.[38] Other theories view the Japanese language as an early creole language formed through inputs from at least two distinct language groups, or as a distinct language of its own that has absorbed various aspects from neighboring languages.[39][40][41] |

分類 主な記事 日本語の分類 日本語は、琉球列島で話されている琉球語も含むジャポニック語族の一員である。これらの近縁の言語は一般的に同じ言語の方言として扱われるため、日本語は孤立言語と呼ばれることもある[32]。 マルティーヌ・イルマ・ロビーツによれば、日本語は世界のどの言語よりも他の言語との関係を示す試みにさらされてきた。19世紀後半に日本語が言語学者の 関心を集めて以来、アイヌ語、朝鮮語、中国語、チベット・ブルマン語、ウラル語、アルタイ語(またはウラル・アルタイ語)、オーストロネシア語、オースト ロネシア語族、ドラヴィダ語などの言語や語族との系譜的関係を示す試みがなされてきた。 [33]。現代の主な説では、日本語を朝鮮語やアルタイ語族のような北アジアの言語、あるいは東南アジアの諸言語、特にオーストロネシア語族と結び付けよ うとしている。これらの提案はいずれも広く受け入れられてはいない(アルタイ語族自体も現在では議論の余地があると考えられている)[35][36] [37]。 現状では、琉球語との関連だけが広く支持されている[38]。 他の説では、日本語は少なくとも2つの異なる言語グループからの入力によって形成された初期のクレオール言語である、あるいは近隣の言語から様々な側面を吸収した独自の言語であると見なしている[39][40][41]。 |

|

|

| Phonology Japanese phonology Japanese has five vowels, and vowel length is phonemic, with each having both a short and a long version. Elongated vowels are usually denoted with a line over the vowel (a macron) in rōmaji, a repeated vowel character in hiragana, or a chōonpu succeeding the vowel in katakana. /u/ (listenⓘ) is compressed rather than protruded, or simply unrounded. Some Japanese consonants have several allophones, which may give the impression of a larger inventory of sounds. However, some of these allophones have since become phonemic. For example, in the Japanese language up to and including the first half of the 20th century, the phonemic sequence /ti/ was palatalized and realized phonetically as [tɕi], approximately chi (listenⓘ); however, now [ti] and [tɕi] are distinct, as evidenced by words like tī [tiː] "Western-style tea" and chii [tɕii] "social status". The "r" of the Japanese language is of particular interest, ranging between an apical central tap and a lateral approximant. The "g" is also notable; unless it starts a sentence, it may be pronounced [ŋ], in the Kanto prestige dialect and in other eastern dialects. The phonotactics of Japanese are relatively simple. The syllable structure is (C)(G)V(C),[42] that is, a core vowel surrounded by an optional onset consonant, a glide /j/ and either the first part of a geminate consonant (っ/ッ, represented as Q) or a moraic nasal in the coda (ん/ン, represented as N). The nasal is sensitive to its phonetic environment and assimilates to the following phoneme, with pronunciations including [ɴ, m, n, ɲ, ŋ, ɰ̃]. Onset-glide clusters only occur at the start of syllables but clusters across syllables are allowed as long as the two consonants are the moraic nasal followed by a homorganic consonant. Japanese also includes a pitch accent, which is not represented in moraic writing; for example [haꜜ.ɕi] ("chopsticks") and [ha.ɕiꜜ] ("bridge") are both spelled はし (hashi), and are only differentiated by the tone contour.[22] |

音声学 日本語には5つの母音があり、母音の長さには音韻があり、それぞれに短母音と長母音がある。長母音は通常、ローマ字では母音の上に線(マクロン)が引か れ、ひらがなでは母音が繰り返され、カタカナでは母音の後に長音符が付く。また、/u/(リスンⓘ)は突出した形ではなく圧縮された形、または単に丸みの ない形である 日本語の子音には複数の同音異義語を持つものがあるため、音の在庫が多いように感じられるかもしれない。しかし、これらの同音異義語のいくつかは、その 後、音韻化されている。例えば、20世紀前半までの日本語では、音素列/ti/は口蓋化され、音韻的には[tɕi]、およそchi(listenⓘ)とし て実現されていたが、現在では[ti]と[tɕi]は区別され、tī [tiɕ]「洋風茶」やchii [tɕii]「社会的地位」などの言葉に表れている。 日本語の 「r 」は特に興味深いもので、頭頂の中央タップと側方の近似音の間にある。g]も注目すべきもので、文頭でない限り[ŋ]と発音されることがある(関東方言やその他の東部方言)。 日本語の音韻構造は比較的単純である。音節構造は、(C)(G)V(C)[42]、すなわち、中核となる母音を、任意のオンセット子音、グライド/j/、促音子音(っ/ッ、Qとして表される)の最初の部分、またはコーダのモーラ鼻(ん/ン、Nとして表される)が囲む。 鼻音は音韻環境に敏感で、次の音素に同化し、発音には [ɴ, m, n, ɲ, ŋ] が含まれる。オンセット・グライド・クラスターは音節の最初にしか生じないが、2つの子音がモーラ鼻音に続く同音子音である限り、音節をまたいだクラスターは許される。 例えば、[haੱ.ɕi](「箸」)と[ha.ɕi](「橋」)はどちらも「はし」と表記され、音調の輪郭によってのみ区別される[22]。 |

| Grammar Main article: Japanese grammar This section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this section by introducing more precise citations. (November 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Sentence structure Japanese word order is classified as subject–object–verb. Unlike many Indo-European languages, the only strict rule of word order is that the verb must be placed at the end of a sentence (possibly followed by sentence-end particles). This is because Japanese sentence elements are marked with particles that identify their grammatical functions. The basic sentence structure is topic–comment. For example, Kochira wa Tanaka-san desu (こちらは田中さんです). kochira ("this") is the topic of the sentence, indicated by the particle wa. The verb desu is a copula, commonly translated as "to be" or "it is" (though there are other verbs that can be translated as "to be"), though technically it holds no meaning and is used to give a sentence 'politeness'. As a phrase, Tanaka-san desu is the comment. This sentence literally translates to "As for this person, (it) is Mx Tanaka." Thus Japanese, like many other Asian languages, is often called a topic-prominent language, which means it has a strong tendency to indicate the topic separately from the subject, and that the two do not always coincide. The sentence Zō wa hana ga nagai (象は鼻が長い) literally means, "As for elephant(s), (the) nose(s) (is/are) long". The topic is zō "elephant", and the subject is hana "nose". Japanese grammar tends toward brevity; the subject or object of a sentence need not be stated and pronouns may be omitted if they can be inferred from context. In the example above, hana ga nagai would mean "[their] noses are long", while nagai by itself would mean "[they] are long." A single verb can be a complete sentence: Yatta! (やった!) "[I / we / they / etc] did [it]!". In addition, since adjectives can form the predicate in a Japanese sentence (below), a single adjective can be a complete sentence: Urayamashii! (羨ましい!) "[I'm] jealous [about it]!". While the language has some words that are typically translated as pronouns, these are not used as frequently as pronouns in some Indo-European languages, and function differently. In some cases, Japanese relies on special verb forms and auxiliary verbs to indicate the direction of benefit of an action: "down" to indicate the out-group gives a benefit to the in-group, and "up" to indicate the in-group gives a benefit to the out-group. Here, the in-group includes the speaker and the out-group does not, and their boundary depends on context. For example, oshiete moratta (教えてもらった) (literally, "explaining got" with a benefit from the out-group to the in-group) means "[he/she/they] explained [it] to [me/us]". Similarly, oshiete ageta (教えてあげた) (literally, "explaining gave" with a benefit from the in-group to the out-group) means "[I/we] explained [it] to [him/her/them]". Such beneficiary auxiliary verbs thus serve a function comparable to that of pronouns and prepositions in Indo-European languages to indicate the actor and the recipient of an action. Japanese "pronouns" also function differently from most modern Indo-European pronouns (and more like nouns) in that they can take modifiers as any other noun may. For instance, one does not say in English: The amazed he ran down the street. (grammatically incorrect insertion of a pronoun) But one can grammatically say essentially the same thing in Japanese: 驚いた彼は道を走っていった。 Transliteration: Odoroita kare wa michi o hashitte itta. (grammatically correct) This is partly because these words evolved from regular nouns, such as kimi "you" (君 "lord"), anata "you" (あなた "that side, yonder"), and boku "I" (僕 "servant"). This is why some linguists do not classify Japanese "pronouns" as pronouns, but rather as referential nouns, much like Spanish usted (contracted from vuestra merced, "your (majestic plural) grace") or Portuguese você (from vossa mercê). Japanese personal pronouns are generally used only in situations requiring special emphasis as to who is doing what to whom. The choice of words used as pronouns is correlated with the sex of the speaker and the social situation in which they are spoken: men and women alike in a formal situation generally refer to themselves as watashi (私, literally "private") or watakushi (also 私, hyper-polite form), while men in rougher or intimate conversation are much more likely to use the word ore (俺 "oneself", "myself") or boku. Similarly, different words such as anata, kimi, and omae (お前, more formally 御前 "the one before me") may refer to a listener depending on the listener's relative social position and the degree of familiarity between the speaker and the listener. When used in different social relationships, the same word may have positive (intimate or respectful) or negative (distant or disrespectful) connotations. Japanese often use titles of the person referred to where pronouns would be used in English. For example, when speaking to one's teacher, it is appropriate to use sensei (先生, "teacher"), but inappropriate to use anata. This is because anata is used to refer to people of equal or lower status, and one's teacher has higher status. Inflection and conjugation Japanese nouns have no grammatical number, gender or article aspect. The noun hon (本) may refer to a single book or several books; hito (人) can mean "person" or "people", and ki (木) can be "tree" or "trees". Where number is important, it can be indicated by providing a quantity (often with a counter word) or (rarely) by adding a suffix, or sometimes by duplication (e.g. 人人, hitobito, usually written with an iteration mark as 人々). Words for people are usually understood as singular. Thus Tanaka-san usually means Mx Tanaka. Words that refer to people and animals can be made to indicate a group of individuals through the addition of a collective suffix (a noun suffix that indicates a group), such as -tachi, but this is not a true plural: the meaning is closer to the English phrase "and company". A group described as Tanaka-san-tachi may include people not named Tanaka. Some Japanese nouns are effectively plural, such as hitobito "people" and wareware "we/us", while the word tomodachi "friend" is considered singular, although plural in form. Verbs are conjugated to show tenses, of which there are two: past and present (or non-past) which is used for the present and the future. For verbs that represent an ongoing process, the -te iru form indicates a continuous (or progressive) aspect, similar to the suffix ing in English. For others that represent a change of state, the -te iru form indicates a perfect aspect. For example, kite iru means "They have come (and are still here)", but tabete iru means "They are eating". Questions (both with an interrogative pronoun and yes/no questions) have the same structure as affirmative sentences, but with intonation rising at the end. In the formal register, the question particle -ka is added. For example, ii desu (いいです) "It is OK" becomes ii desu-ka (いいですか。) "Is it OK?". In a more informal tone sometimes the particle -no (の) is added instead to show a personal interest of the speaker: Dōshite konai-no? "Why aren't (you) coming?". Some simple queries are formed simply by mentioning the topic with an interrogative intonation to call for the hearer's attention: Kore wa? "(What about) this?"; O-namae wa? (お名前は?) "(What's your) name?". Negatives are formed by inflecting the verb. For example, Pan o taberu (パンを食べる。) "I will eat bread" or "I eat bread" becomes Pan o tabenai (パンを食べない。) "I will not eat bread" or "I do not eat bread". Plain negative forms are i-adjectives (see below) and inflect as such, e.g. Pan o tabenakatta (パンを食べなかった。) "I did not eat bread". The so-called -te verb form is used for a variety of purposes: either progressive or perfect aspect (see above); combining verbs in a temporal sequence (Asagohan o tabete sugu dekakeru "I'll eat breakfast and leave at once"), simple commands, conditional statements and permissions (Dekakete-mo ii? "May I go out?"), etc. The word da (plain), desu (polite) is the copula verb. It corresponds approximately to the English be, but often takes on other roles, including a marker for tense, when the verb is conjugated into its past form datta (plain), deshita (polite). This comes into use because only i-adjectives and verbs can carry tense in Japanese. Two additional common verbs are used to indicate existence ("there is") or, in some contexts, property: aru (negative nai) and iru (negative inai), for inanimate and animate things, respectively. For example, Neko ga iru "There's a cat", Ii kangae-ga nai "[I] haven't got a good idea". The verb "to do" (suru, polite form shimasu) is often used to make verbs from nouns (ryōri suru "to cook", benkyō suru "to study", etc.) and has been productive in creating modern slang words. Japanese also has a huge number of compound verbs to express concepts that are described in English using a verb and an adverbial particle (e.g. tobidasu "to fly out, to flee", from tobu "to fly, to jump" + dasu "to put out, to emit"). There are three types of adjectives (see Japanese adjectives): 形容詞 keiyōshi, or i adjectives, which have a conjugating ending i (い) (such as 暑い atsui "to be hot") which can become past (暑かった atsukatta "it was hot"), or negative (暑くない atsuku nai "it is not hot"). nai is also an i adjective, which can become past (暑くなかった atsuku nakatta "it was not hot"). 暑い日 atsui hi "a hot day". 形容動詞 keiyōdōshi, or na adjectives, which are followed by a form of the copula, usually na. For example, hen (strange) 変な人 hen na hito "a strange person". 連体詞 rentaishi, also called true adjectives, such as ano "that" あの山 ano yama "that mountain". Both keiyōshi and keiyōdōshi may predicate sentences. For example, ご飯が熱い。 Gohan ga atsui. "The rice is hot." 彼は変だ。 Kare wa hen da. "He's strange." Both inflect, though they do not show the full range of conjugation found in true verbs. The rentaishi in Modern Japanese are few in number, and unlike the other words, are limited to directly modifying nouns. They never predicate sentences. Examples include ookina "big", kono "this", iwayuru "so-called" and taishita "amazing". Both keiyōdōshi and keiyōshi form adverbs, by following with ni in the case of keiyōdōshi: 変になる hen ni naru "become strange", and by changing i to ku in the case of keiyōshi: 熱くなる atsuku naru "become hot". The grammatical function of nouns is indicated by postpositions, also called particles. These include for example: が ga for the nominative case. 彼がやった。Kare ga yatta. "He did it." に ni for the dative case. 田中さんにあげて下さい。 Tanaka-san ni agete kudasai "Please give it to Mx Tanaka." It is also used for the lative case, indicating a motion to a location. 日本に行きたい。 Nihon ni ikitai "I want to go to Japan." However, へ e is more commonly used for the lative case. パーティーへ行かないか。 pātī e ikanai ka? "Won't you go to the party?" の no for the genitive case,[43] or nominalizing phrases. 私のカメラ。 watashi no kamera "my camera" スキーに行くのが好きです。 Sukī-ni iku no ga suki desu "(I) like going skiing." を o for the accusative case. 何を食べますか。 Nani o tabemasu ka? "What will (you) eat?" は wa for the topic. It can co-exist with the case markers listed above, and it overrides ga and (in most cases) o. 私は寿司がいいです。 Watashi wa sushi ga ii desu. (literally) "As for me, sushi is good." The nominative marker ga after watashi is hidden under wa. Note: The subtle difference between wa and ga in Japanese cannot be derived from the English language as such, because the distinction between sentence topic and subject is not made there. While wa indicates the topic, which the rest of the sentence describes or acts upon, it carries the implication that the subject indicated by wa is not unique, or may be part of a larger group. Ikeda-san wa yonjū-ni sai da. "As for Mx Ikeda, they are forty-two years old." Others in the group may also be of that age. Absence of wa often means the subject is the focus of the sentence. Ikeda-san ga yonjū-ni sai da. "It is Mx Ikeda who is forty-two years old." This is a reply to an implicit or explicit question, such as "who in this group is forty-two years old?" Politeness Main article: Honorific speech in Japanese Japanese has an extensive grammatical system to express politeness and formality. This reflects the hierarchical nature of Japanese society.[44] The Japanese language can express differing levels of social status. The differences in social position are determined by a variety of factors including job, age, experience, or even psychological state (e.g., a person asking a favour tends to do so politely). The person in the lower position is expected to use a polite form of speech, whereas the other person might use a plainer form. Strangers will also speak to each other politely. Japanese children rarely use polite speech until they are teens, at which point they are expected to begin speaking in a more adult manner. See uchi-soto. Whereas teineigo (丁寧語) (polite language) is commonly an inflectional system, sonkeigo (尊敬語) (respectful language) and kenjōgo (謙譲語) (humble language) often employ many special honorific and humble alternate verbs: iku "go" becomes ikimasu in polite form, but is replaced by irassharu in honorific speech and ukagau or mairu in humble speech. The difference between honorific and humble speech is particularly pronounced in the Japanese language. Humble language is used to talk about oneself or one's own group (company, family) whilst honorific language is mostly used when describing the interlocutor and their group. For example, the -san suffix ("Mr", "Mrs", "Miss", or "Mx") is an example of honorific language. It is not used to talk about oneself or when talking about someone from one's company to an external person, since the company is the speaker's in-group. When speaking directly to one's superior in one's company or when speaking with other employees within one's company about a superior, a Japanese person will use vocabulary and inflections of the honorific register to refer to the in-group superior and their speech and actions. When speaking to a person from another company (i.e., a member of an out-group), however, a Japanese person will use the plain or the humble register to refer to the speech and actions of their in-group superiors. In short, the register used in Japanese to refer to the person, speech, or actions of any particular individual varies depending on the relationship (either in-group or out-group) between the speaker and listener, as well as depending on the relative status of the speaker, listener, and third-person referents. Most nouns in the Japanese language may be made polite by the addition of o- or go- as a prefix. o- is generally used for words of native Japanese origin, whereas go- is affixed to words of Chinese derivation. In some cases, the prefix has become a fixed part of the word, and is included even in regular speech, such as gohan 'cooked rice; meal.' Such a construction often indicates deference to either the item's owner or to the object itself. For example, the word tomodachi 'friend,' would become o-tomodachi when referring to the friend of someone of higher status (though mothers often use this form to refer to their children's friends). On the other hand, a polite speaker may sometimes refer to mizu 'water' as o-mizu to show politeness. |

文法 主な記事 日本語の文法 このセクションは参考文献、関連文献、外部リンクのリストを含むが、インライン引用がないため出典が不明確なままである。より正確な引用を導入すること で、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。(2013年11月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 文の構造 日本語の語順は主語-目的語-動詞に分類される。多くの印欧語と異なり、語順の唯一の厳密な規則は、動詞は文末に置かなければならないということである(文末助詞が続く場合もある)。これは、日本語の文要素には、文法的機能を識別する助詞が付けられているためである。 基本的な文構造はトピック・コメントである。例えば、「こちら田中さんです」(こちらは田中さんです)。「こちら」は助詞「わ」で示される文のトピックで ある。動詞「です」はコピュラであり、一般的には「です」または「ます」と訳される(「です」と訳せる動詞は他にもあるが)。フレーズとしては、「田中さ んです」がコメントである。この文は直訳すると、「この人に関しては、(それは)田中さんです 」となる。このように日本語は、他の多くのアジア言語と同様、しばしば話題優位言語と呼ばれる。これは、話題を主語とは別に示す傾向が強く、両者が必ずし も一致しないことを意味する。象は鼻が長い」は文字通り「象は鼻が長い」という意味である。主語は「象」で、主語は「鼻」である。 日本語の文法は簡潔な傾向があり、文の主語や目的語を述べる必要はなく、文脈から推測できる場合は代名詞を省略することができる。上の例では、「鼻が長 い」は「鼻が長い」という意味になるが、「鼻が長い」は「鼻が長い」という意味になる。一つの動詞が完全な文になることもある: ヤッタ!(やった!) 「[私/私たち/彼ら/その他]は[それ]をした! さらに、形容詞は日本語の文の述語を形成することができるので(下記)、形容詞ひとつで完全な文になる: うらやましい!(うらやましい!)」である。 日本語には一般的に代名詞と訳される単語がいくつかあるが、これらはインド・ヨーロッパ諸語の代名詞ほど頻繁には使われず、機能も異なる。場合によって は、日本語は特別な動詞の形や助動詞に頼って、動作の利益の方向を示す: 「下」は外集団が内集団に利益を与えることを表し、「上」は内集団が外集団に利益を与えることを表す。ここで、内集団には話し手が含まれ、外集団には含ま れないが、その境界は文脈によって異なる。例えば、「おしえてもらっ た」(文字通り、外集団から内集団に利益を与える「説明してもらった」)は、「[彼・それ]が[私・私たち]に[それ]を説明してくれた」を意味する。同 様に、「おしえてあげた」(文字通りには、内集団から外集団への利益を伴う「あげた説明」)は、「[私/私たち]は[彼/彼女たち]に[それ]を説明し た」を意味する。このような受益助動詞は、インド・ヨーロッパ語族における代名詞や前置詞に匹敵する機能を果たし、動作の行為者と受益者を示す。 また、日本語の「代名詞」は、他の名詞と同様に修飾語を取ることができるという点で、現代の印欧語の代名詞(より名詞に近い)とは機能が異なる。例えば、英語ではこうは言わない: とは言わない。(文法的に間違った代名詞の挿入である)。 しかし、日本語では文法的に同じことが言える: 驚いた彼は道を走っていった。 音訳だ: おどろいた彼は道を走っていった。(文法的には正しい) これは、これらの単語が「君」、「あなた」、「僕」などの普通名詞から発展したためでもある。このため、日本語の「代名詞」を代名詞として分類せず、スペ イン語のusted(vuestra mercedの短縮形、「あなたの(威厳のある複数形の)恵み」)やポルトガル語のvocê(vossa mercêの短縮形)のような参照名詞として分類する言語学者もいる。日本語の人称代名詞は一般的に、誰が誰に対して何をしているのか、特別な強調が必要 な場面でのみ使われる。 代名詞として使われる言葉の選択は、話し手の性別と、その言葉が話される社会的状況と相関している。フォーマルな場では男女を問わず、自分のことを「私」 または「私淑」と呼ぶのが一般的だが、ラフな会話や親密な会話では、男性は「俺」または「僕」という言葉を使う傾向が強い。同様に、アナタ、キミ、オマエ (お前、より正式には御前「前の方」)といった異なる言葉は、聞き手の相対的な社会的立場や、話し手と聞き手の間の親しさの度合いに応じて、聞き手を指す ことがある。異なる社会的関係で使われる場合、同じ言葉でも肯定的な意味合い(親密、尊敬)を持つこともあれば、否定的な意味合い(よそよそしい、無礼) を持つこともある。 日本人は、英語では代名詞が使われるような場面で、相手の肩書きを使うことが多い。例えば、恩師に話しかける場合、「先生」を使うのは適切だが、「あな た」を使うのは不適切である。これは、「アナタ」が同等かそれ以下の身分の人を指すときに使われ、「先生」の方が身分が高いからである。 屈折と活用 日本語の名詞には、文法上の数、性別、冠詞のアスペクトがない。名詞の「本」は1冊の本を指すこともあれば、複数の本を指すこともある。「人」は「人」ま たは「人」を意味し、「木」は「木」または「木」を意味する。数が重要な場合は、(多くの場合、対になる単語で)数量を示すか、(まれに)接尾辞をつける か、場合によっては重複(例えば、「人」、「人人」、通常は反復記号で「人人」と書く)で示すことができる。人を表す言葉は通常単数形として理解される。 したがって、田中さんは通常Mx田中を意味する。人や動物を表す言葉は、-tachiのような集合接尾辞(グループを表す名詞接尾辞)をつけることで個人 のグループを表すことができるが、これは真の複数形ではなく、英語の 「and company 」に近い意味になる。田中さんたち」というグループには、田中という名前の人たち以外も含まれる可能性がある。日本語の名詞の中には、「ひとびと」や「わ れわれ」のように実質的に複数形であるものもあるが、「ともだち」は複数形ではあるが単数形とみなされる。 動詞には時制を表す活用があり、過去と現在(または非過去)の2種類がある。現在進行形の動詞の場合、-ている形は、英語の接尾辞ingに似た連続的な (または進行形の)様相を示す。その他、状態の変化を表す動詞では、-ている形は完了形を表す。たとえば、kite iruは「彼らは来た(そしてまだここにいる)」という意味だが、tabete iruは「彼らは食べている」という意味である。 疑問文(疑問代名詞を伴う疑問文と、はい/いいえ疑問文の両方)は肯定文と同じ構造を持つが、語尾でイントネーションが上がる。正式な音域では、疑問助詞 の「か」がつく。例えば、「いいです」は「いいですか」となる。もっとくだけた調子では、話し手の個人的な関心を示すために、助詞の「の」が代わりにつけ られることもある: どうしたの?「どうして来ないのですか?単純な疑問文の中には、聞き手の注意を喚起するために、疑問形のイントネーションでトピックに言及するものもあ る: これは何ですか」、「お名前は何ですか」。 否定語は動詞を屈折させて作る。例えば、パンを食べる(Pan o taberu)は、パンを食べない(Pan o tabenai)になる。パンを食べなかった」は「パンを食べなかった」となる。 いわゆる-te動詞の形は、進行形または完了形のアスペクト(上記参照)、動詞を時間的順序で組み合わせる(「朝ごはんを食べてすぐに出ます」)、単純な命令、条件文、許可(「出かけてもいいですか」)など、さまざまな目的で使われる。 だ」(平易な)、「です」(丁寧な)はコピュラ動詞である。これは英語のbeにほぼ対応するが、動詞が過去形datta(平易な)、deshita(丁寧 な)に活用されるとき、時制を表すマーカーなど他の役割を担うことが多い。日本語で時制を表すことができるのはi形容詞と動詞だけだからである。ある(否 定の「ない」)」と「いる(否定の「ない」)は、それぞれ無生物と生物を表す。例えば、「ねこがいる」、「いい考えがない」などである。 する」という動詞は、名詞から動詞を作るときによく使われる(料理する、勉強する、など)。また日本語には、英語で動詞と副助詞を使って表現される概念を表す複合動詞が非常に多い(例:とびだす「飛び出す、逃げる」、tobu「飛ぶ、跳ぶ」+dasu「出す、発する」)。 形容詞には3つのタイプがある(日本語の形容詞を参照): 形容詞には3つのタイプがある(日本語の形容詞を参照)。i形容詞は、i(い)という活用語尾を持ち(例えば、暑いatsui「暑かった」)、過去になる (暑かったatsukatta「暑かった」)こともあれば、否定になる(暑くないatsuku nai「暑くない」)こともある。naiはi形容詞でもあり、過去になることもある(暑くなかった atsuku nakatta 「it was not hot」)。 暑い日 "atsui hi「暑い日」。 形容動詞keiyōdōshi、またはna形容詞は、コピュラ(通常はna)の形が続く。たとえば 変な人」。 連体詞連体詞は、真の形容詞とも呼ばれる。 あの山は「あの山」である。 形容連体詞も形容動詞も文の述語になることがある。たとえば ご飯が熱い。「ご飯が熱い。 彼は変だ。「彼は変だ。 どちらも屈折するが、真の動詞に見られるような活用の幅はない。現代日本語の連体形は数が少なく、他の単語と違って名詞を直接修飾するものに限られている。文の述語になることはない。例えば、「おおきい」、「この」、「いわれる」、「すごい」などである。 けいようどうし」と「けいようし」は、「けいようどうし」の場合は「に」をつけて副詞を形成する: となる、 また、「keiyōshi 」の場合は 「i 」を 「ku 」に変える: 熱くなる」である。 名詞の文法的機能は、助詞とも呼ばれる後置詞によって示される。例えば、以下のようなものがある: が主格を表す。 彼がやった。「彼がやった。 に」は主格を表す。 田中さんにあげて下さい。「田中さんに渡して下さい」。 田中さんに渡してください。 日本に行きたい、日本に行きたい。 しかし、「へ」の方がより一般的である。 パーティーへ行かないか? は主格[43]や名詞化句に使われる。 私のカメラ "私のカメラ」 スキーに行くのが好きです。 を o で非難格にする。 何を食べますか? は話題を表す。上記の格助詞と共存することができ、「が」や(ほとんどの場合)「お」に優先する。 私は寿司がいいです。(文字どおり)「私としては、寿司はうまいです」。watashiの後の名詞gaはwaの下に隠れる。 注:日本語のwaとgaの微妙な違いは、英語では文のトピックと主語の区別がないため、英語からそのまま導くことはできない。なぜなら、文のトピックと主 語の区別が英語ではなされていないからである。「わ」はトピックを示し、それに基づいて文の残りの部分が説明したり作用したりするが、「わ」によって示さ れる主語は一意的なものではなく、より大きなグループの一部である可能性があるという含意を持つ。 池田さんは四十二歳だ。「Mx池田に関しては、彼らは42歳である。他のグループもその年齢かもしれない。 わ」がないのは、主語が文の中心であることを意味することが多い。 池田さんが四十二歳だ。「池田さんは四十二歳だ"。これは、「このグループの中に42歳の人はいますか?」というような暗黙的または明示的な質問に対する返答である。 ポライトネス 主な記事 日本語の敬語 日本語には、礼儀や形式を表現するための広範な文法体系がある。これは日本社会の階層性を反映している[44]。 日本語は社会的地位の異なるレベルを表現することができる。社会的地位の違いは、仕事、年齢、経験、あるいは心理状態(例えば、頼みごとをする人は丁寧に する傾向がある)など、さまざまな要因によって決まる。立場の低い人は丁寧な話し方をすると思われるが、もう一方の人は平易な話し方をするかもしれない。 見知らぬ人同士でも丁寧に話す。日本の子供は10代になるまで丁寧語を使うことはほとんどなく、10代になると大人びた話し方をするようになる。うち・そ と」を参照のこと。 丁寧語(ていねいご)が一般的な屈折体系であるのに対し、尊敬語(そんけいご)や謙譲語(けんじょうご)は多くの特別な敬語や謙譲語の代用動詞を用いるこ とが多い: いく」は丁寧語では「いきます」になるが、尊敬語では「いらっしゃる」に、謙譲語では「うかがう」「まいる」になる。 敬語と謙譲語の違いは、日本語では特に顕著である。謙譲語は自分や自分のグループ(会社や家族)について話すときに使われるのに対し、尊敬語は相手やその グループについて話すときに使われることが多い。例えば、「さん」(「Mr」、「Mrs」、「Miss」、「Mx」)は敬語の一例である。自分のことを話 すときや、社外の人に自分の会社の人のことを話すときには使わない。社内の上司に直接話すとき、あるいは社内の他の社員と上司について話すとき、日本人は 敬語の語彙と抑揚を使って、グループ内の上司とその言動を指す。一方、他社の人(つまり外集団の人)と話す場合、日本人は平易な、あるいは謙譲語を用い て、内集団の上司の言動を指す。つまり、日本語では、話し手と聞き手の関係(内集団か外集団か)によって、また、話し手、聞き手、三人称の相対的な地位に よって、特定の個人の人、話し方、行動を指すために使われる音域が異なるのである。 日本語のほとんどの名詞は、接頭辞としてo-またはgo-をつけることで丁寧語になる。o-は一般的に日本語由来の言葉に使われ、go-は中国語由来の言 葉につけられる。場合によっては、接頭辞は言葉の固定部分となり、「ごはん」のように通常の会話にも含まれる。このような構文は、その品物の持ち主やその 品物自体への敬意を示すことが多い。たとえば、「ともだち」という言葉は、身分の高い人の友だちを指すときには「おともだち」になる(ただし、母親は子ど もの友だちを指すときにこの形を使うことが多い)。一方、礼儀正しい話し手は、丁寧さを表すために「水」を「お水」と言うことがある。 |

| Vocabulary Main articles: Yamato kotoba, Sino-Japanese vocabulary, and Gairaigo There are three main sources of words in the Japanese language: the yamato kotoba (大和言葉) or wago (和語); kango (漢語); and gairaigo (外来語).[45] The original language of Japan, or at least the original language of a certain population that was ancestral to a significant portion of the historical and present Japanese nation, was the so-called yamato kotoba (大和言葉 or infrequently 大和詞, i.e. "Yamato words"), which in scholarly contexts is sometimes referred to as wago (和語 or rarely 倭語, i.e. the "Wa language"). In addition to words from this original language, present-day Japanese includes a number of words that were either borrowed from Chinese or constructed from Chinese roots following Chinese patterns. These words, known as kango (漢語), entered the language from the 5th century[clarification needed] onwards by contact with Chinese culture. According to the Shinsen Kokugo Jiten (新選国語辞典) Japanese dictionary, kango comprise 49.1% of the total vocabulary, wago make up 33.8%, other foreign words or gairaigo (外来語) account for 8.8%, and the remaining 8.3% constitute hybridized words or konshugo (混種語) that draw elements from more than one language.[46] There are also a great number of words of mimetic origin in Japanese, with Japanese having a rich collection of sound symbolism, both onomatopoeia for physical sounds, and more abstract words. A small number of words have come into Japanese from the Ainu language. Tonakai (reindeer), rakko (sea otter) and shishamo (smelt, a type of fish) are well-known examples of words of Ainu origin. Words of different origins occupy different registers in Japanese. Like Latin-derived words in English, kango words are typically perceived as somewhat formal or academic compared to equivalent Yamato words. Indeed, it is generally fair to say that an English word derived from Latin/French roots typically corresponds to a Sino-Japanese word in Japanese, whereas an Anglo-Saxon word would best be translated by a Yamato equivalent. Incorporating vocabulary from European languages, gairaigo, began with borrowings from Portuguese in the 16th century, followed by words from Dutch during Japan's long isolation of the Edo period. With the Meiji Restoration and the reopening of Japan in the 19th century, words were borrowed from German, French, and English. Today most borrowings are from English. In the Meiji era, the Japanese also coined many neologisms using Chinese roots and morphology to translate European concepts;[citation needed] these are known as wasei kango (Japanese-made Chinese words). Many of these were then imported into Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese via their kanji in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[citation needed] For example, seiji (政治, "politics"), and kagaku (化学, "chemistry") are words derived from Chinese roots that were first created and used by the Japanese, and only later borrowed into Chinese and other East Asian languages. As a result, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese share a large common corpus of vocabulary in the same way many Greek- and Latin-derived words – both inherited or borrowed into European languages, or modern coinages from Greek or Latin roots – are shared among modern European languages – see classical compound.[citation needed] In the past few decades, wasei-eigo ("made-in-Japan English") has become a prominent phenomenon. Words such as wanpatān ワンパターン (< one + pattern, "to be in a rut", "to have a one-track mind") and sukinshippu スキンシップ (< skin + -ship, "physical contact"), although coined by compounding English roots, are nonsensical in most non-Japanese contexts; exceptions exist in nearby languages such as Korean however, which often use words such as skinship and rimokon (remote control) in the same way as in Japanese. The popularity of many Japanese cultural exports has made some native Japanese words familiar in English, including emoji, futon, haiku, judo, kamikaze, karaoke, karate, ninja, origami, rickshaw (from 人力車 jinrikisha), samurai, sayonara, Sudoku, sumo, sushi, tofu, tsunami, tycoon. See list of English words of Japanese origin for more |

語彙 主な記事 大和言葉、漢語、外来語 大和言葉、漢語、外来語である[45]。 日本の原語、あるいは少なくとも歴史上および現在の日本国民のかなりの部分に先祖を持つ特定の集団の原語は、いわゆる大和言葉であった。 学術的な文脈では「和語」と呼ばれることもある。この原語に由来する言葉に加え、現在の日本語には、中国語からの借用語、または中国語の語源から中国語の パターンに従って作られた言葉が数多く含まれている。漢語として知られるこれらの言葉は、5世紀[要出典]以降、中国文化との接触によって日本語に入っ た。新選国語辞典』によると、漢語は語彙全体の49.1%を占め、和語は33.8%である。 8%を占め、その他の外来語は8.8%、残りの8.3%は複数の言語から要素を取り入れた混成語である[46]。 日本語には、物理的な音に対するオノマトペと、より抽象的な言葉の両方の、音の象徴の豊富なコレクションがある。アイヌ語から入ってきた言葉も少なくない。トナカイ」、「ラッコ」、「シシャモ」などはアイヌ語由来の言葉としてよく知られている。 異なる起源の言葉は、日本語では異なる音域を占める。英語におけるラテン語由来の単語のように、漢語は一般的に、同等の大和言葉に比べ、ややフォーマルま たはアカデミックなものとして認識される。実際、ラテン語やフランス語を語源とする英単語は、日本語では一般的に漢語に相当し、アングロサクソン系の単語 は大和言葉に相当する言葉で訳すのが最も適切である。 ヨーロッパの言語から語彙を取り入れる「外来語」は、16世紀のポルトガル語からの借用に始まり、江戸時代の長い鎖国の間にオランダ語からの借用が続い た。19世紀の明治維新と開国とともに、ドイツ語、フランス語、英語から言葉が借用された。現在では英語からの借用がほとんどである。 明治時代、日本人はまた、ヨーロッパの概念を翻訳するために、中国語の語源や形態素を使った新語をたくさん作った。例えば、政治(政治)、化学(化学)な どは中国語の語源に由来する言葉であり、日本人によって最初に作られ使用され、後に中国語や他の東アジアの言語に借用された。その結果、日本語、中国語、 韓国語、ベトナム語は、多くのギリシア語やラテン語由来の単語(ヨーロッパの言語に継承されたものや借用されたもの、あるいはギリシア語やラテン語を語源 とする現代の造語)が現代のヨーロッパの言語間で共有されているのと同じように、語彙の大きな共通コーパスを共有している。 ここ数十年で、和製英語が目立つようになった。wanpatān ワンパターン(<one + pattern、「マンネリ化する」、「一本調子である」)、sukinshippu スキンシップ(<skin + -ship、「身体的接触」)などの単語は、英語の語源を複合した造語ではあるが、日本語以外の文脈ではほとんど意味をなさない; しかし、韓国語のような近隣の言語には例外があり、スキンシップやリモコンといった単語を日本語と同じように使うことがある。 絵文字、布団、俳句、柔道、神風、カラオケ、空手、忍者、折り紙、人力車、サムライ、サヨナラ、数独、相撲、寿司、豆腐、津波、タイクーンなどである。詳しくは日本語由来の英単語リストを参照のこと。 |

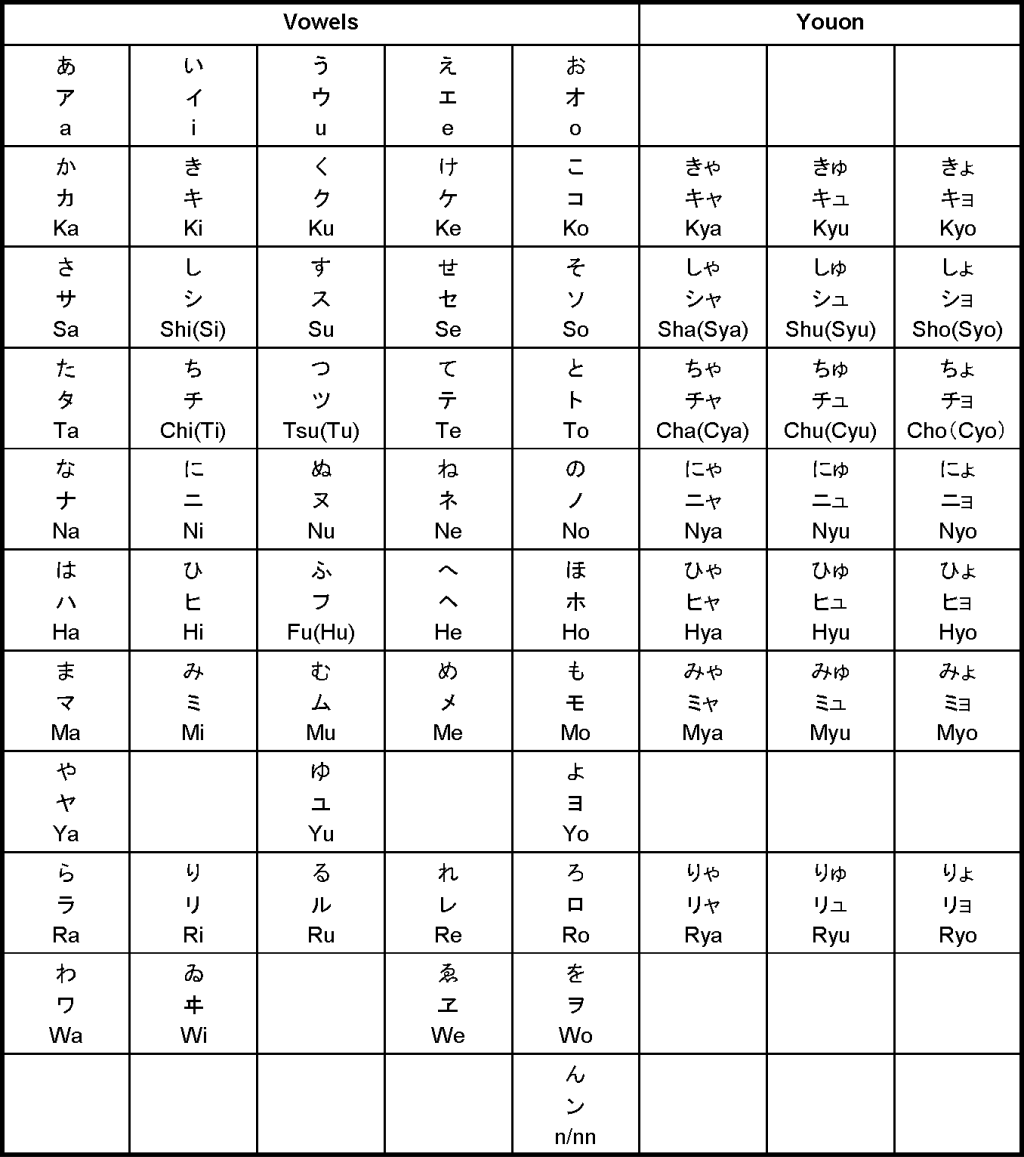

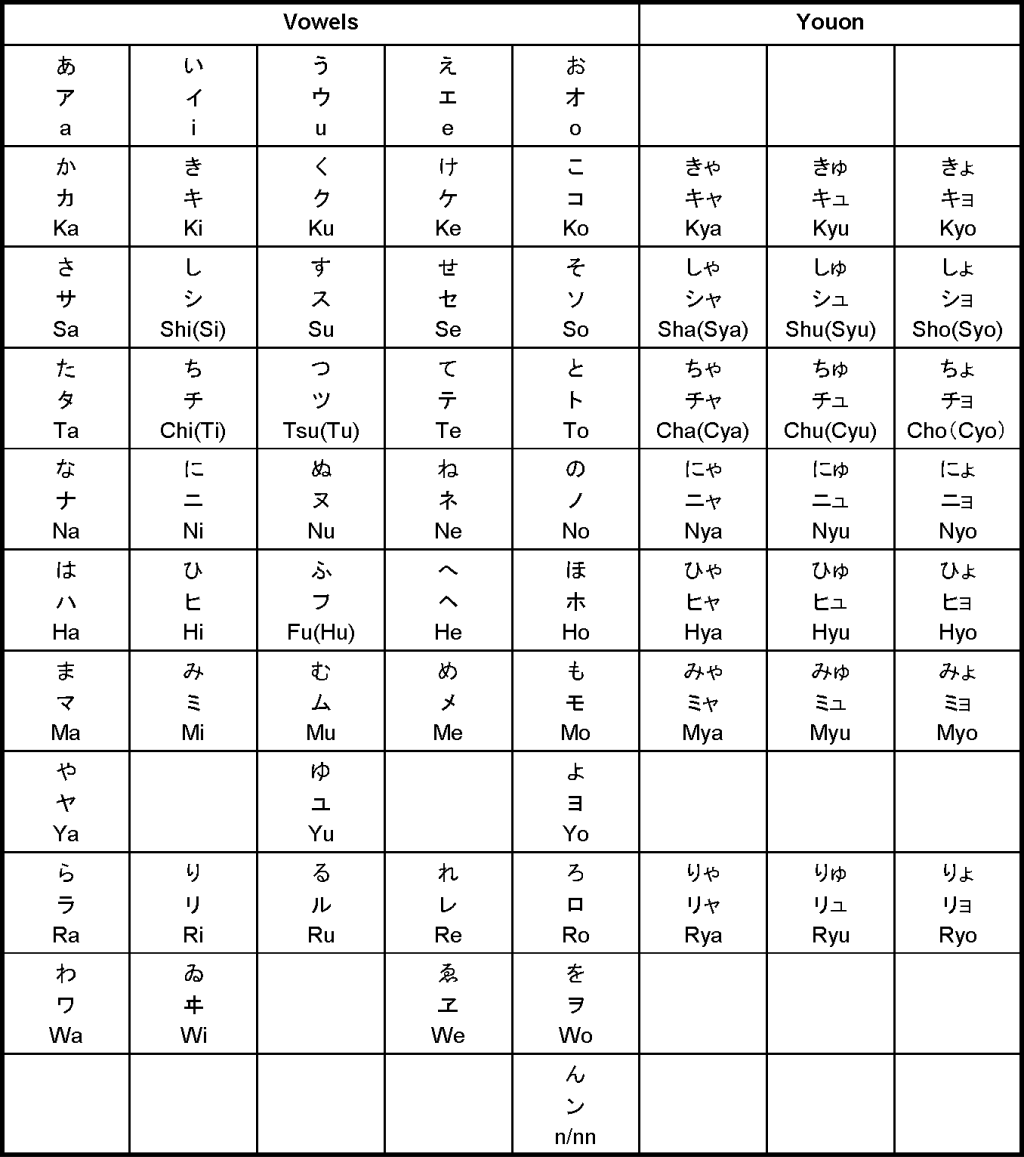

| History Literacy was introduced to Japan in the form of the Chinese writing system, by way of Baekje before the 5th century AD.[47][48][49][50] Using this script, the Japanese king Bu presented a petition to Emperor Shun of Liu Song in AD 478.[a] After the ruin of Baekje, Japan invited scholars from China to learn more of the Chinese writing system. Japanese emperors gave an official rank to Chinese scholars (続守言/薩弘恪/[b][c]袁晋卿[d]) and spread the use of Chinese characters during the 7th and 8th centuries.  Table of Kana (including Youon): Hiragana top, Katakana in the center and Romanized equivalents at the bottom At first, the Japanese wrote in Classical Chinese, with Japanese names represented by characters used for their meanings and not their sounds. Later, during the 7th century AD, the Chinese-sounding phoneme principle was used to write pure Japanese poetry and prose, but some Japanese words were still written with characters for their meaning and not the original Chinese sound. This was the beginning of Japanese as a written language in its own right. By this time, the Japanese language was already very distinct from the Ryukyuan languages.[51] An example of this mixed style is the Kojiki, which was written in AD 712. Japanese writers then started to use Chinese characters to write Japanese in a style known as man'yōgana, a syllabic script which used Chinese characters for their sounds in order to transcribe the words of Japanese speech mora by mora. Over time, a writing system evolved. Chinese characters (kanji) were used to write either words borrowed from Chinese, or Japanese words with the same or similar meanings. Chinese characters were also used to write grammatical elements; these were simplified, and eventually became two moraic scripts: hiragana and katakana which were developed based on Manyogana. Some scholars claim that Manyogana originated from Baekje, but this hypothesis is denied by mainstream Japanese scholars.[52][53] Hiragana and katakana were first simplified from kanji, and hiragana, emerging somewhere around the 9th century,[54] was mainly used by women. Hiragana was seen as an informal language, whereas katakana and kanji were considered more formal and were typically used by men and in official settings. However, because of hiragana's accessibility, more and more people began using it. Eventually, by the 10th century, hiragana was used by everyone.[55] Modern Japanese is written in a mixture of three main systems: kanji, characters of Chinese origin used to represent both Chinese loanwords into Japanese and a number of native Japanese morphemes; and two syllabaries: hiragana and katakana. The Latin script (or rōmaji in Japanese) is used to a certain extent, such as for imported acronyms and to transcribe Japanese names and in other instances where non-Japanese speakers need to know how to pronounce a word (such as "ramen" at a restaurant). Arabic numerals are much more common than the kanji numerals when used in counting, but kanji numerals are still used in compounds, such as 統一 tōitsu ("unification"). Historically, attempts to limit the number of kanji in use commenced in the mid-19th century, but government did not intervene until after Japan's defeat in the Second World War. During the post-war occupation (and influenced by the views of some U.S. officials), various schemes including the complete abolition of kanji and exclusive use of rōmaji were considered. The jōyō kanji ("common use kanji"), originally called tōyō kanji (kanji for general use) scheme arose as a compromise solution. Japanese students begin to learn kanji from their first year at elementary school. A guideline created by the Japanese Ministry of Education, the list of kyōiku kanji ("education kanji", a subset of jōyō kanji), specifies the 1,006 simple characters a child is to learn by the end of sixth grade. Children continue to study another 1,130 characters in junior high school, covering in total 2,136 jōyō kanji. The official list of jōyō kanji has been revised several times, but the total number of officially sanctioned characters has remained largely unchanged. As for kanji for personal names, the circumstances are somewhat complicated. Jōyō kanji and jinmeiyō kanji (an appendix of additional characters for names) are approved for registering personal names. Names containing unapproved characters are denied registration. However, as with the list of jōyō kanji, criteria for inclusion were often arbitrary and led to many common and popular characters being disapproved for use. Under popular pressure and following a court decision holding the exclusion of common characters unlawful, the list of jinmeiyō kanji was substantially extended from 92 in 1951 (the year it was first decreed) to 983 in 2004. Furthermore, families whose names are not on these lists were permitted to continue using the older forms. Hiragana Hiragana are used for words without kanji representation, for words no longer written in kanji, for replacement of rare kanji that may be unfamiliar to intended readers, and also following kanji to show conjugational endings. Because of the way verbs (and adjectives) in Japanese are conjugated, kanji alone cannot fully convey Japanese tense and mood, as kanji cannot be subject to variation when written without losing their meaning. For this reason, hiragana are appended to kanji to show verb and adjective conjugations. Hiragana used in this way are called okurigana. Hiragana can also be written in a superscript called furigana above or beside a kanji to show the proper reading. This is done to facilitate learning, as well as to clarify particularly old or obscure (or sometimes invented) readings. Katakana Katakana, like hiragana, constitute a syllabary; katakana are primarily used to write foreign words, plant and animal names, and for emphasis. For example, "Australia" has been adapted as Ōsutoraria (オーストラリア), and "supermarket" has been adapted and shortened into sūpā (スーパー). |

歴史 識字は、紀元5世紀以前に百済を経由して漢文の形で日本に伝わった[47][48][49][50]。この文字を使って、日本の武王は紀元478年に劉宋 の順帝に請願書を提出した[a]。日本の天皇は7世紀から8世紀にかけて、中国の学者に官位を与え(続守言/薩弘恪/[b][c]袁晋卿[d])、漢字の 使用を広めた。  カナ表(ユンも含む): 上がひらがな、中央がカタカナ、下がローマ字表記である。 当初、日本人は古典中国語で表記し、日本人の名前は音ではなく意味を表す文字で表していた。その後、西暦7世紀には、純粋な日本語の詩や散文を書くために 中国語の音素主義が使われるようになったが、一部の日本語の単語は、元の中国語の音ではなく、意味を表す文字で書かれたままだった。これが、文字言語とし ての日本語の始まりである。この頃には、日本語はすでに琉球の言語とは非常に区別されていた[51]。 この混合様式の例は、AD 712年に書かれた『古事記』である。万葉仮名は、日本語の話し言葉をモーラごとに書き写すために、音に漢字を使った音節文字である。 やがて、文字体系が進化した。漢字は、中国語から借用した言葉や、同じ意味や似た意味を持つ日本語を書くのに使われた。漢字はまた、文法要素を書くのにも 使われた。これらは簡略化され、やがて2つのモーラ文字、ひらがなとカタカナになり、万葉仮名に基づいて発展した。万葉仮名は百済に由来すると主張する学 者もいるが、この仮説は日本の主流の学者によって否定されている[52][53]。 ひらがなとカタカナは漢字から簡略化されたものであり、9世紀ごろに生まれたひらがなは主に女性によって使われていた[54]。ひらがなはインフォーマル な言語とみなされ、カタカナや漢字はよりフォーマルな言語とみなされ、一般的に男性や公式の場で使用された。しかし、ひらがなの使いやすさから、より多く の人々がひらがなを使うようになった。やがて10世紀には、ひらがなはすべての人に使われるようになった[55]。 現代日本語は主に3つの文字が混在している。漢字は中国語由来の文字であり、中国語から日本語への借用語と日本語固有の形態素の両方を表すのに使われる。 ラテン文字(日本語ではローマ字)は、輸入された略語や日本人の名前を書き写す場合など、日本語を母語としない人が単語の発音を知る必要がある場合にある 程度使用される(レストランで「ラーメン」と言う場合など)。アラビア数字は、数を数えるときには漢数字よりもはるかに一般的であるが、統一のような複合 語ではまだ漢数字が使われている。 歴史的には、漢字の使用数を制限する試みは19世紀半ばに始まったが、政府が介入したのは第二次世界大戦の敗戦後である。戦後の占領下で(そして一部のア メリカ政府高官の意見に影響されて)、漢字の全廃やローマ字の独占を含む様々な計画が検討された。その妥協案として生まれたのが常用漢字であり、もともと は常用漢字と呼ばれていた。 日本では小学校1年生から漢字の学習が始まる。文部省が作成した「教育漢字」(常用漢字のサブセット)は、小学校6年生までに学ぶべき簡単な漢字 1,006字を定めている。中学校ではさらに1,130字を学習し、合計2,136字の常用漢字を学習する。常用漢字表は何度か改訂されているが、公認漢 字の総数はほとんど変わっていない。 人名用漢字については、やや複雑な事情がある。人名用漢字は、常用漢字と人名用付加漢字が認められている。未承認文字を含む名前は登録されない。しかし、 常用漢字リストと同様、その基準はしばしば恣意的であり、多くの一般的で人気のある文字が不許可となった。1951年に92字であった常用漢字は、民衆の 圧力と、常用漢字の除外を違法とする判決を受けて、2004年には983字まで大幅に拡大された。さらに、これらのリストに名前が載っていない家族は、旧 字体を使い続けることが許された。 ひらがな ひらがなは、漢字表記のない言葉、漢字表記のなくなった言葉、読者になじみのない珍しい漢字の置き換えに使われる。日本語の動詞(および形容詞)は活用す るため、漢字だけでは日本語の時制や気分を十分に伝えることができない。そのため、動詞や形容詞の活用を表すために、漢字にひらがなを付加する。このよう に使われるひらがなを「送り仮名」と呼ぶ。また、ひらがなを漢字の上や横にふりがなと呼ばれる上付き文字で書いて、正しい読み方を示すこともある。これは 学習を容易にするためであり、また、特に古い読み方や不明瞭な読み方(場合によっては創作された読み方)を明確にするためでもある。 カタカナ カタカナは、平仮名と同様に五十音を構成している。カタカナは主に外来語、動植物の名前、強調のために使われる。例えば、「オーストラリア」は「Ōsutoraria(オーストラリア)」、「スーパーマーケット」は「sūpā(スーパー)」と表記される。 |

| Gender in the Japanese language Main article: Gender differences in Japanese Depending on the speakers’ gender, different linguistic features might be used.[56] The typical lect used by females is called joseigo (女性語) and the one used by males is called danseigo (男性語).[57] Joseigo and danseigo are different in various ways, including first-person pronouns (such as watashi or atashi 私 for women and boku (僕) for men) and sentence-final particles (such as wa (わ), na no (なの), or kashira (かしら) for joseigo, or zo (ぞ), da (だ), or yo (よ) for danseigo).[56] In addition to these specific differences, expressions and pitch can also be different.[56] For example, joseigo is more gentle, polite, refined, indirect, modest, and exclamatory, and often accompanied by raised pitch.[56] Kogal slang In the 1990s, the traditional feminine speech patterns and stereotyped behaviors were challenged, and a popular culture of “naughty” teenage girls emerged, called kogyaru (コギャル), sometimes referenced in English-language materials as “kogal”.[58] Their rebellious behaviors, deviant language usage, the particular make-up called ganguro (ガングロ), and the fashion became objects of focus in the mainstream media.[58] Although kogal slang was not appreciated by older generations, the kogyaru continued to create terms and expressions.[58] Kogal culture also changed Japanese norms of gender and the Japanese language.[58] Non-native study Main article: Japanese language education Many major universities throughout the world provide Japanese language courses, and a number of secondary and even primary schools worldwide offer courses in the language. This is a significant increase from before World War II; in 1940, only 65 Americans not of Japanese descent were able to read, write and understand the language.[59] International interest in the Japanese language dates from the 19th century but has become more prevalent following Japan's economic bubble of the 1980s and the global popularity of Japanese popular culture (such as anime and video games) since the 1990s. As of 2015, more than 3.6 million people studied the language worldwide, primarily in East and Southeast Asia.[60] Nearly one million Chinese, 745,000 Indonesians, 556,000 South Koreans and 357,000 Australians studied Japanese in lower and higher educational institutions.[60] Between 2012 and 2015, considerable growth of learners originated in Australia (20.5%), Thailand (34.1%), Vietnam (38.7%) and the Philippines (54.4%).[60] The Japanese government provides standardized tests to measure spoken and written comprehension of Japanese for second language learners; the most prominent is the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT), which features five levels of exams. The JLPT is offered twice a year. |

日本語におけるジェンダー 主な記事 日本語における性差 女性の代表的な話し言葉は「女性語」、男性の代表的な話し言葉は「男性語」である[57]。 なの」、「かしら」、「ぞう」、「だ」、「よ」など)である。 [例えば、上西語はより穏やかで、丁寧で、上品で、間接的で、控えめで、感嘆詞的であり、しばしば高めの音程を伴う[56]。 コギャル・スラング 1990年代には、伝統的な女性的な話し方や固定観念的な振る舞いが否定され、「コギャル」と呼ばれる10代の「やんちゃ」な少女たちの大衆文化が出現し た。 [彼女たちの反抗的な行動、逸脱した言葉遣い、ガングロと呼ばれる特殊な化粧、ファッションは主流メディアで注目される対象となった[58]。コギャルの スラングは年配の世代には理解されなかったが、コギャルたちは用語や表現を生み出し続けた[58]。 非ネイティブの学習 主な記事 日本語教育 世界中の多くの主要大学が日本語コースを提供しており、世界中の多くの中等学校、さらには初等学校が日本語のコースを提供している。これは第二次世界大戦 前に比べて大幅に増加している。1940年には、日本語の読み書きができ、理解できる日系人以外のアメリカ人はわずか65人しかいなかった[59]。 日本語に対する国際的な関心は19世紀からあったが、1980年代の日本のバブル経済や、1990年代以降の日本の大衆文化(アニメやビデオゲームなど) の世界的な人気を受けて、より広まった。2015年現在、世界で360万人以上が日本語を学んでおり、主に東アジアと東南アジアで学んでいる[60]。 100万人近くの中国人、745,000人のインドネシア人、556,000人の韓国人、357,000人のオーストラリア人が、低・高等教育機関で日本 語を学んでいる[60]。 2012年から2015年の間に、オーストラリア(20.5%)、タイ(34.1%)、ベトナム(38.7%)、フィリピン(54.4%)を起源とする学 習者が大幅に増加した[60]。 日本政府は第二言語学習者のために日本語の会話と筆記の理解度を測る標準試験を提供している。日本語能力試験は年2回実施されている。 |

| Example text | |

| Aizuchi Culture of Japan Japanese dictionaries Japanese exonyms Japanese language and computers Japanese literature Japanese name Japanese punctuation Japanese profanity Japanese Sign Language family Japanesepod101.com[63] Japanese words and words derived from Japanese in other languages at Wiktionary, Wikipedia's sibling project Classical Japanese language Romanization of Japanese Hepburn romanization Rendaku Yojijukugo Other: History of writing in Vietnam |

相槌 日本の文化 日本の辞書 日本語の外来語 日本語とコンピュータ 日本文学 日本名 日本語の句読点 日本語の冒涜 日本手話ファミリー Japanesepod101.com[63] ウィクショナリー(ウィキペディアの兄弟プロジェクト)における日本語の単語と日本語から派生した他の言語の単語 古典日本語 日本語のローマ字表記 ヘボン式ローマ字 連語 謡曲 その他 ベトナムの文字の歴史 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_language |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099